8 minute read

Exploring the Zooniverse

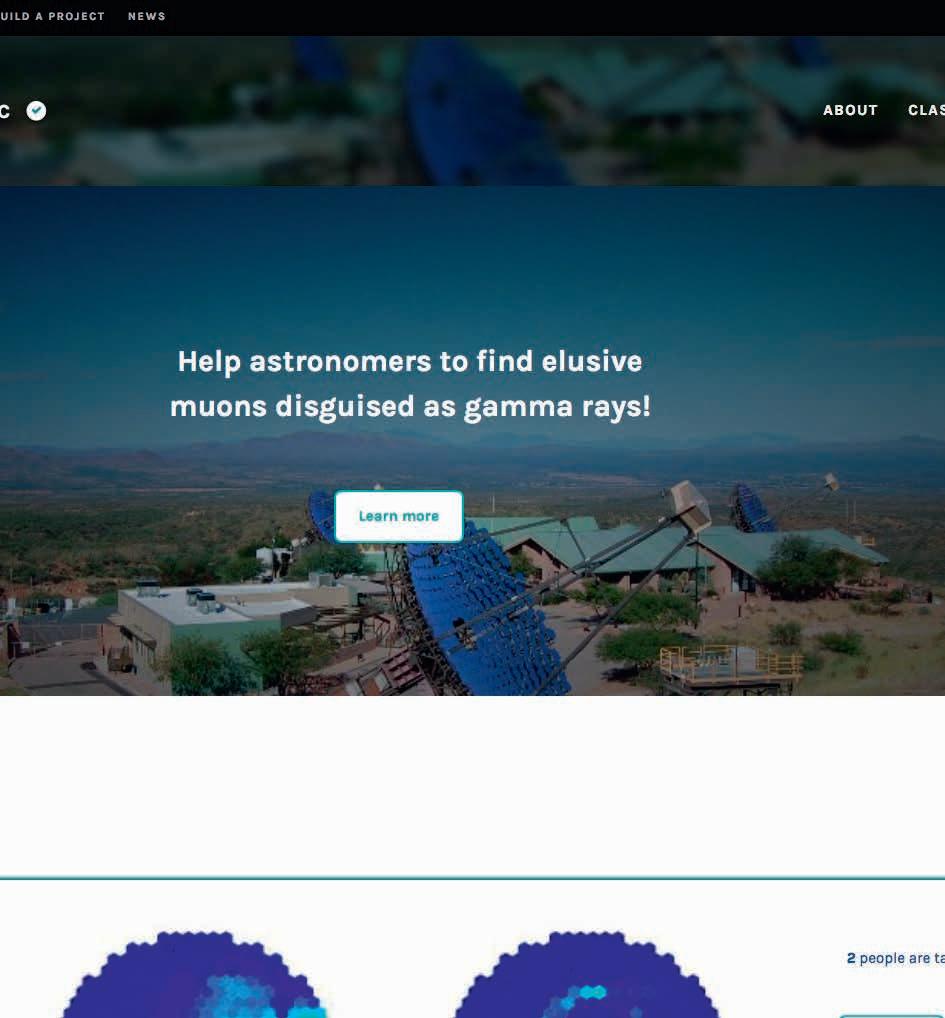

Zooniverse.org is the largest and most popular online citizen science portal where anyone can help with research projects from the comfort of their home. Volunteers simply sign up and look over image or data sets to classify what they see. Those image sets can be anything from new galaxies to penguin populations, taken from devices like telescopes, satellites and camera traps. The images from these projects can be awe inspiring and classification can be addictive, so it is little wonder people are flocking to the site in growing numbers. Zooniverse is making scientific discovery more accessible and more personal for everyone.

Richard Forsyth interviews Chris Lintott, Professor of Astrophysics, University of Oxford and Principal Investigator at Zooniverse.

EU Researcher: Can you explain some of the projects you have live, as there is quite a wide variety in terms of subject matter?

Professor Chris Lintott: What unites the projects on the platform is that, in each case, researchers need help from everyone to sort through their data. That might mean sorting through images of distant galaxies, looking at images of penguins from a camera trap project in Antarctica, or transcribing an old manuscript from a museum archive. In each case, the contributions of thousands or tens of thousands of people add up to something much greater than the sum of its parts, and Zooniverse volunteers have gone on to make remarkable discoveries along the way. Though originally my team and I built the Zooniverse to help with our own research, the variety of the projects goes way beyond that and is astounding.

EUR: Can you take us through a typical process or workflow of a citizen science project?

Prof. CL: Our projects almost all involve pattern recognition, something we have conveniently evolved to be very good at. Volunteers joining a site are presented with an image or video, and complete a series of tasks. We show each image to multiple people, and sometimes to a machine learning algorithm or two too, and combine the results so that we can be confident that they’re accurate (or that we understand the inevitable uncertainty). It sounds simple, but the key is designing the project so the right questions are asked, and that the data the volunteers produce is worth having.

EUR: Well over a million people are involved in your research – from all kinds of backgrounds. The projects have really captured imaginations. What is it about this kind of research that really attracts people to get involved and do they stay loyal as researchers?

Prof. CL: More than two million people registered now, in fact, and you’re right that it’s not just people who are already interested in science. That’s been the most surprising thing, I think – that an enormous range of people, many of whom have never before

considered thinking about, for example, astrophysics, are willing to jump in. The key motivation for most of our volunteers is that they want to help, something that’s meant that we’ve had record levels of contributions during the pandemic, from those who are lucky enough to have spare time. For the researchers, the important thing is to keep their end of the bargain – to be present in the project and to use the contributions of the volunteers to best effect. It can be a virtuous circle in this way – the more a project is able to achieve, the more attractive continued participation is. As for whether people stay loyal, people tend to work hard in a project for a few days, or a few weeks, and then put it down for a while, but they do come back.

EUR: How do you verify your results when so many people are not scientists and may make a lot of mistakes?

Prof. CL: Well, science isn’t all that hard! More seriously, as I said earlier, we have several people look at each image and so mistakes don’t happen. We also often use gold standard data, where we know

what the right answer is, to make sure all is well, and all projects are tested before they end up on the platform.

EUR: Some of your research is incredibly moving. For instance, finding evidence of slavery from space is a powerful project. Studies like this clearly provide a social function, like policing and detective work against injustice, which is different to say studying galaxies. Has citizen science become more than science alone?

Prof. CL: The techniques of citizen science have certainly proved very useful in all sorts of areas. I’m very proud of our Planetary Response Network project, led by Brooke Simmons at Lancaster, which has built projects that have had the crowd assessing the terrible damage from hurricanes in the Caribbean and earthquakes in Nepal, and feeding the results to first responders on the ground. It’s not surprising that people want to help when disaster strikes but what has been interesting is finding that all the work we’ve done for our other scientific projects is of use in these circumstances.

EUR: How much raw data do you think is available these days that has just not been processed? We have so many ways of capturing information – but can a lot of it be in danger of not being processed?

Prof. CL: This is exactly why the form of citizen science that I’m talking about has emerged; you can even say that in some fields, our ability to discover new knowledge is no longer primarily limited by gathering data, but rather by what we choose to do with it. This is especially true if you want to find the interesting and unusual things – the unexpected – that are buried in large datasets. For that, there really is no substitute for a curious crowd of people.

EUR: Are people really the best ‘computers’ of all and if so why?

Prof. CL: We’re very good at particular tasks, and I think the future is in combining our very human abilities to react to the unexpected with machine learning which can do most of the mundane work for us. In work with my own Galaxy Zoo project, we’ve shown how to combine human and machine classifications in a subtle way to provide a result that’s better than either approach alone. In some of the projects – our Gravity Spy project, for example, which we’re expanding thanks to our REINFORCE project, looks at data from Gravitational wave observatories like VIRGO in Italy – it seems surprising that people could help, but the results are really valuable.

EUR: How much time and money does this method save? And would the lofty aims of many of these data or image heavy projects be possible without this kind of crowd science. Saving money must especially appeal to researchers with strict budgets?

Prof. CL: I don’t think saving money is the right way to think about this – in almost all cases, Zooniverse volunteers make possible work you simply couldn’t do any other way. If you want to put a value on it, I think the Zooniverse effort in a typical year is equivalent to a building of 400 people processing data round the clock, but really it’s a completely new way of working.

EUR: Is there something that a project discovered that really ‘wowed’ the Zooniverse team?

Prof. CL: Many things – especially spectacular photos from our ecological camera trap projects which are a favourite of the team. But my favourite discovery is the planet Planet Hunters 1b, the only planet known in a four-star system. I’d love to stand on it (or on a moon – the planet itself is a gas giant) and look up at four suns in the sky.

EUR: I remember classifying galaxies many years ago on Zooniverse, simply to look at what amazing images were out there. I remember thinking, would I be the first pair of eyes on some of those galaxies? Would that be the case? It would be quite a thing to find a new galaxy from your armchair.

Prof. CL: Absolutely. If you time participation in Galaxy Zoo right, you might well be the first person ever to see a galaxy. The telescope, camera and software pipeline are all automatic, so it’s only when it pops up on your screen that humanity encounters it! This is why the projects are so good at identifying the unusual.

EUR: You have a Zooniverse Project Builder on your site. This takes it to yet another level, where even the projects can be built by anyone with the right components. What do you need to build a project? Have you had much uptake?

Prof. CL: Yes, we’ve now run more than two hundred projects, most of them built by researchers using the project builder tool. We got to the point a few years ago where we thought we understood how to design certain types of project, and so could turn that knowledge into the design for a tool. Of course, we still build novel and experimental projects, but most researchers with data and questions to ask can go from logging on to having a project ready for testing in an hour or two.

EUR: Zooniverse seems the most accessible public facing portal for citizen science but do you think with its potential, this could really take off wider as a way for everyone to be involved in valuable scientific research?

Prof. CL: I hope so! We’re growing faster than ever, so I think the future is bright.

www.zooniverse.org

Professor Chris Lintott Principal Investigator and Co-founder of Zooniverse