Francesco Sismondini

Dear friends,

Let me begin with a simple but vital question:

Did Europe make peace, or did peace make Europe?

Our nations have grown strong through peace, through the faith that dialogue is stronger than weapons, and through the belief that the future belongs to those who build bridges, not walls.

But today we look upon a darkening horizon.

International relations are faltering. The rule of law gives way once again to the rule of power. The logic of domination spreads in politics, in economics, and in culture.

And so we must ask ourselves: what is our duty?

What must the European Democrat Students do in this defining moment?

It is the same question our founding fathers asked in the ashes of war.

Through courage, friendship, and cooperation, not greed or nationalism, they built the foundations of the Europe we live in today: a continent open to knowledge, to solidarity, to hope.

But nothing they built is eternal. Peace, democracy, access to education, they survive only if we choose

them, defend them, and renew them every single day.

Today the European Union is debating its new sevenyear budget.

We cannot stand by while education becomes the first victim of political short-sightedness. We must fight to keep European funds where they belong, in the hands of those who will shape the future, not destroy it.

Education is not expendable. It is not a luxury. It is the foundation of peace.

If someone wants to cut it to finance the culture of war, we refuse. We stand up. We shout it loud: NOT IN OUR NAME!

We, the youth of Europe, will not be silent. We will make ourselves heard in classrooms, in squares, in every forum where the future of our continent is decided.

Because this is not just about budgets. It is about who we are and who we choose to become.

Thank you for reading.

May the voices within Bullseye rise together, drop by drop, to form the tide of a new European Enlightenment.

With warm regards,

Francesco Sismondini

Chairman

Montenegro has emerged as a standout success story on the Western Balkan path toward the European Union, demonstrating that steadfast political orientation, bold reform action, and clear foreign-policy alignment can yield tangible progress. As fellow EU leaders have noted, Montenegro is “on good track” to join the bloc by 2028.

First and foremost, Montenegro has consistently aligned its external policy with the European Union’s standards and the broader trans-Atlantic agenda. Prime Minister Milojko Spajić has publicly affirmed that Montenegro’s strategic direction embraces full EU membership, active participation in NATO, and good-neighbourly relations. In October 2025, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised Montenegro’s progress, noting: “I know you are determined to close all chapters … and to become, as you put it, ‘the 28th by ’28.’” Such alignment distinguishes Montenegro within the region and ensures that its foreign policy is seen as credible, reliable, and stable, key attributes for any future member state.

Secondly, in terms of reforms, Montenegro has made commendable strides. Under PM Spajić’s leadership, the country has intensified efforts toward comprehensive action plans covering public administration reform, digital transformation, transparency, and open data. These efforts contribute directly to fulfilling the accession criteria that the EU requires of aspiring members. Montenegro’s institutions are actively reshaping regulatory frameworks and demonstrating practical commitment to European norms and standards, proof that words have turned into actions.

Thirdly, the country enjoys strong domestic consensus for the European path. Even though no country is free of internal political debates, Montenegro’s tone has

increasingly become one of prioritising EU integration over delay. This consensus helps ensure stability and continuity in reform implementation. Montenegro’s relatively small size and unified objective have rendered its reform agenda more manageable than in many larger or more fragmented states in the Western Balkans.

In championing these advances, Prime Minister Milojko Spajić deserves particular recognition. Under his leadership, Montenegro has set an ambitious timetable of closing all negotiation chapters by the end of 2026 and joining the EU by 2028. His pro-reform government has emphasised transparency, economic modernisation, and deeper integration into European norms. He has repeatedly affirmed that the EU remains Montenegro’s strategic direction and that nothing will divert the country from that path.

From a friendly neighbouring vantage point in Serbia, I am personally delighted to see Montenegro succeed. As someone from Serbia, I feel proud and happy for our neighbours who are advancing so strongly on this European journey.

Finally, the praise coming directly from Europe speaks volumes. During her visit to Podgorica in October 2025, Ursula von der Leyen reaffirmed that “the goal of Montenegro’s accession to the European Union is truly within reach.” Her words underscored both the progress achieved and the need to sustain momentum. As we look ahead, I am truly excited that we will host our EDS Council Meeting in Montenegro at the end of November together with the youth branch of the Europe Now Movement. I am especially grateful to Tamara Crnogorčić, President of Mladi Evrope / The Youth of Europe, and Ivana Vukićević, International Secretary, whose dedication and support have been instrumental in making this event possible.

I am confident it will be a great success bringing together over sixty delegates from more than twenty-five countries to celebrate Montenegro’s European spirit, the commitment of its young generation, and its inspiring journey toward full EU membership.

Vladimir Kljajic

Sofia Kubrakova

August 6th, 2025, Wednesday, 10:00 a.m. This was not an ordinary summer day in Poland. This date will be remembered in history as the day Karol Nawrocki was sworn in as President of the Republic of Poland. The event stirred a wide range of emotions across society and in political circles. Some citizens viewed the day with fear and anxiety about the consequences of his presidency, and even within the ruling camp there was hope until the very end that the swearing-in would not take place. On the other

hand, a large part of society greeted their chosen candidate with great sympathy, proudly watching Karol Nawrocki arrive majestically (as today’s youth would say, “with aura”) in his presidential limousine. Dubbed by right-wing media as the president of all Poles (which in practice is true), he opened a new chapter in Polish politics.

In Gdańsk, the city of the new president, within the Law and Justice party (the largest right-wing party in Poland), rumors had circulated for years about Karol Nawrocki’s potential candidacy for the presidency.

Yet he had never directly dealt with politics. At the University of Gdańsk, he obtained a doctorate in the humanities, and from then on, his official activities were tied to history. Four years later, he became the director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. In 2021, he was appointed President of the Institute of National Remembrance, a state institution dedicated to historical memory.

However, during the presidential campaign, the nation discovered another side of the main figure in this story. If you’ve wondered about the meaning of the title of this article, here is the explanation. Information began circulating about Nawrocki’s past, which quickly became arguments against his competence for the country’s highest office. It turned out that Karol Nawrocki had connections with a gangster from a pimping gang, had been photographed with him, and had spent time in that environment in the past. In his youth, while working at a seaside hotel, he was involved in illegally bringing prostitutes inside. The current president also took part in football hooligan brawls, something he does not hide but rather proudly admits, since boxing is his lifelong passion. In one interview, he said: “I’ve been fighting with my fists my whole life.” He participated in many such fights, though he explains they were “only with those who wanted it, under agreed rules.” This sport clearly became a lasting part of his identity. A historian with a love for the boxing ring is now President of Poland. Nothing captured this better than a photo taken right after he assumed office, showing a famous Polish boxing coach entering the Belweder Palace (the president’s second residence) for a training session with Karol.

You might think these aspects of his past negatively impacted his image as president. But not entirely –in fact, quite the opposite! After careful analysis, it is clear that the controversies did not harm his standing

among most voters. During the campaign, his past became one of the strongest themes used in social media, now one of the most important tools in politics. Funny memes and edits transformed the president’s past into something relatable, building trust through screens. With the algorithm feeding people more and more of such content, it felt as though everyone personally knew “good old Karol” cheering for the same football club as them.

This raises the question: how could a man with no political experience, a suspicious past, no foreign language skills, and a goofy smile gain the trust of 10.6 million citizens? Shouldn’t the highest office in the country require decades of political experience and the highest possible competence? Why did people choose “Karol the Fan” over the mayor of the capital, Rafał Trzaskowski? The clear answer lies in the current state of Polish society. People are primarily concerned with simple, everyday matters – life’s most accessible aspects. Everyone has attended a match of their favourite team, and many enjoy the energy of combat sports. Most people are more focused on everyday life than on pursuits like science, art, or national causes. After conversations with people of all ages and backgrounds, one conclusion emerged: Nawrocki’s image was built to resemble that of an ordinary citizen. This made him blend seamlessly among the people, giving the impression he was “one of them,” which earned massive sympathy from voters. They thought: finally, someone like us – on our level. Even his use of nicotine pouches in public was received warmly, because “who doesn’t like a bit of nicotine?” Whether at a debate or the UN General Assembly, he appeared as a relatable figure.

In a time of crises, conflicts, and wars, people long for simplicity and peace. To them, a president who feels like the funny, easy-going uncle seems the right choice. People don’t vote for competence, they vote for familiarity – for our Karol.

He began his presidency with a honeymoon phase, drawing attention both at home and abroad. Some even dubbed him the new leader of Law and Justice (informally), while others called him a statesman. Indeed, he entered the office with a bang!

Right-wing Nawrocki – even leaning toward far-right positions closer to the Confederation party (far –right Eurosceptic party). But did Jarosław Kaczyński (leader of Law and Justice) lose control of him too quickly? With Nawrocki’s move into the presidential palace, Kaczyński lost full control over him. Although most staffers in the presidential chancellery came from Kaczyński’s circle, Nawrocki began breaking free from their grip. This became evident during his coordination with the government following Russian drone strikes on Poland. Such dynamics between the president and the ruling camp displeased Kaczyński. Another example: a seemingly ordinary photo of Polish politicians at the UN General Assembly showed Nawrocki and the foreign minister smiling warmly at each other. The pressure from Kaczyński was immense, and soon Nawrocki was forced to explain himself. After all, without Law and Justice, he would not have achieved his position.

From the start, it was clear: the President and the Government are fighting in the ring. By late August, he

had vetoed seven bills, blocking necessary measures for the country. He even altered some bills himself before resubmitting them to parliament, wanting the triumph and credit for his own camp. This is what the next five years are likely to look like. Unfortunately, the Polish state suffers from this, leading to decline and division. The president’s populism fuels hatred among the people, and Poland ceases to function under such a radical leader. Continued vetoes will paralyze the country’s development, while the blame will fall on the government, though the president’s decisions are ultimately responsible.

Yet Nawrocki seems to forget what powers he has and doesn’t have. He desires more authority and rights, even though in Poland’s parliamentary system the president’s role is limited. He openly supports shifting Poland to a presidential system, like the United States. His statements often suggest he already feels he has more power than he actually does. Nawrocki has ambitions and possible plans to amend the constitution, chiefly to change the system of government into a presidential one. Such a shift would be disastrous, giving Poland an authoritarian character.

This is an overhand punch for the state. At a time when Europe faces multiple crises and Poland’s large eastern neighbour wages an increasingly aggressive hybrid war against it, the last thing needed is internal escalation.

The new president’s first official foreign visit was to Washington, where in early September he met Donald Trump in the Oval Office – an inspiring moment for

Nawrocki. But it wasn’t their first meeting: thanks to Law and Justice’s contacts in the White House, Nawrocki had already met Trump during his candidacy and even received his endorsement. Besides visits to Finland, Germany, and France, his trip to Italy deserves mention. In Rome, Nawrocki met Giorgia Meloni to discuss, among other topics, the EU’s deal with Mercosur countries. Yet his lack of experience showed: the main goal of convincing the Italian government to oppose the deal failed. Was this due to weak diplomatic skills?

He also took part in the 80th UN General Assembly session, where he delivered a long, decisive, and clear speech. He did not speak in English, but in Polish, highlighting this choice at the start. Even so, the address sounded professional, showing he had been well-prepared, with strong support from his presidential staff. Nawrocki tackled Poland’s key issues in a firm and straightforward manner. However, one theme consistently returned in his international appearances: war reparations from Germany. He raised this again during his September visit to Berlin. As a historian, he treats the matter with particular seriousness, insisting on their payment and presenting his stance in a very traditional way. Yet, after so many years, this rhetoric appears outdated and out of step with modern international politics.

Much has already happened, and certain patterns are clear. But remember: five years still lie ahead. In politics, everything can change overnight. We will be closely watching the actions of our Polish SARMATIAN. He is certainly a unique case in politics. He has already reshaped Polish politics, and there is still much more to come.

Petar Ivic

A Framework Reborn

Launched in 2015, the Three Seas Initiative (3SI) unites 13 EU countries situated between the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas with the goal of closing the historical infrastructure gap between Central/Eastern Europe and the West. It focuses on three critical sectors: energy, transport, and digital infrastructure. While the initiative made early strides, geopolitical turbulence and underfunding have threatened its momentum. Yet, with Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and China's assertive global expansion through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), 3SI's strategic value has surged, making its revival not only timely but essential.

Geopolitical Imperatives: Ukraine and the China Factor

The war in Ukraine exposed Europe's dependence on Russian energy and the vulnerabilities in EastWest dominated infrastructure networks. 3SI, with its North-South axis focus, provides a structural realignment that boosts both civilian and military mobility. Simultaneously, China's increasing investment footprint in ports and digital networks across Central and Southeastern Europe threatens to fragment EU

unity and create potential dependencies. Notably, China’s investment in the Port of Piraeus and the debtladen Montenegro highway project are cautionary tales. 3SI acts as a countermeasure, offering an EUcompliant and Western-backed platform that aligns with democratic norms and avoids the pitfalls of Chinese debt diplomacy.

America's Stake: Energy, Security, and Influence

The United States has consistently supported the Three Seas Initiative, seeing it as a vital tool to promote transatlantic cohesion, energy independence from Russia, and a buffer against Chinese influence. Politically, this support is bipartisan: President Donald Trump’s 2017 appearance in Warsaw emphasized highlevel backing, while House Resolution 672 codified bipartisan support in Congress. Economically, 3SI serves as a vehicle for American LNG exports and infrastructure investments, securing new markets while strengthening allies. The US International Development Finance Corporation’s $300 million pledge to the 3SI Investment Fund, though modest, is a strategic down payment. For this role to grow, financial and institutional engagement must deepen.

For the European Union, a revitalized 3SI offers multiple benefits:

• Energy Diversification: Projects like the Baltic Pipe (operational since November 2022) and the Krk LNG terminal in Croatia have already enhanced regional independence from Russian gas. The Krk terminal alone is expanding its capacity to 6.1 billion cubic meters annually.

• Military Mobility: Corridors such as Via Carpathia and Rail Baltica are crucial for both economic integration and NATO’s logistical readiness. Rail Baltica is expected to be 43% construction-ready by the end of 2025.

• Digital Sovereignty: The proposed 3 Seas Digital Highway and regional cybersecurity cooperation can mitigate risks from Chinese telecom systems and protect cross-border infrastructure. Estonia’s leadership in digital governance is a key asset for regional progress.

Importantly, 3SI complements rather than competes with the EU. Its goals align with REPowerEU, the Digital Single Market strategy, and the Green Deal.

Success Stories and Why More Is Needed

So far, the Three Seas Initiative has produced several notable successes. The 3SI Investment Fund has backed Greenergy Data Centers, now the largest and most secure data center in the Baltic region, strengthening digital resilience across the area. The fund has also supported Enery Development GmbH, a renewable energy platform expanding solar and wind projects across Central Europe. Strategic investments in Port Burgas have enhanced Black Sea trade potential and countered Chinese maritime ambitions in the region.

Despite these wins, the fund has only raised €1.3 billion as of early 2025, far short of the needed €3-5 billion, and significantly below the hundreds of billions required to match the infrastructure scale of China's BRI. The 3SI lacks a permanent institutional structure and remains overly reliant on Poland's political leadership. Private capital mobilization is still limited, and many EU mechanisms are cumbersome or underfunded.

Project Proposals: Pathways Forward

To ensure the 3SI's continued relevance and competitiveness against China's Belt and Road, several actions are essential. The initiative needs institutionalization through a permanent secretariat,

potentially based in Warsaw or Bucharest, to provide year-round operational leadership and continuity.

Broadening the investment base is equally critical, which means attracting private investors by offering blended finance tools and expanding partnerships with Japan, the UK, and Nordic countries. The region also requires cybersecurity coordination through a regional hub that can coordinate threat intelligence and protect critical infrastructure, building on the Atlantic Council's recommendations.

Finally, the 3SI should integrate Ukraine, Serbia, and Moldova by prioritizing transport and energy projects that include these associated states and support postwar reconstruction.

The Three Seas Initiative is no longer a peripheral experiment; it is an indispensable framework for European resilience and Western strategic autonomy. It provides a democratic, rules-based alternative to the BRI, rooted in transatlantic cooperation and regional ownership. But to truly rival China’s influence, it needs scale, speed, and structure.

While the initiative has proven its worth, especially through energy diversification and transport modernization, it remains underleveraged. Its future depends on transforming from a summits-based forum into a fully institutionalized mechanism capable of attracting major capital and implementing region-wide strategic projects. The EU and the U.S. should treat 3SI not as a niche coalition, but as a core pillar of their strategic architecture.

The time for revival is now, or risk ceding the region’s future to more malign actors.

Vladimir Kljajic

Lithium, Cobalt, Rare Earths: The New Strategic Commodities

In the 21st century, critical raw materials from lithium and cobalt to rare earth elements have become the backbone of the green industrial revolution. These resources are no longer mere commodities; they are strategic assets underpinning electric vehicles, grid energy storage, renewable technologies, semiconductors, and advanced defence systems.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global demand for lithium rose by nearly 30 percent in 2024, far exceeding the growth pace of the previous decade. At the same time, supply chains have become increasingly concentrated, particularly in refining and processing, raising major concerns about resilience, security, and dependence.

One of the most pressing challenges is the People’s Republic of China's dominance in the extraction and processing of critical minerals. China currently controls between 60 and 90 percent of global refining capacity for key battery metals and rare earths. Its recent decision to tighten export controls on rareearth magnets and related raw materials has sent shockwaves through global markets.

The message is clear: raw materials are now instruments of geopolitical influence. In response, Western governments are moving beyond traditional market mechanisms and embracing the idea that these materials must be treated as strategic assets, much like energy resources were treated in the 20th century.

Among the new policy instruments gaining traction is the price floor for critical minerals. A price floor establishes a guaranteed minimum price or ensures minimum revenue for producers to encourage investment in non-Chinese extraction and refining capacity.

The U.S. Department of Defense has already applied such mechanisms for rare-earth magnets, while ongoing proposals under the Trump administration’s resource security agenda aim to expand these measures to lithium and cobalt. The rationale is simple: if China can influence global prices through oversupply or export restrictions, the West must stabilize its own markets to protect industrial investment.

“Without predictable prices, there is no predictable supply. A price floor is not protectionism — it’s strategic insurance.”

These mechanisms help de-risk new projects, attract private financing, and counteract price manipulation and dependency. They are now being discussed among G7 economies as part of a broader effort to build resilient and diversified supply chains.

In this global race, nations with resources and strategic geography can gain a decisive advantage, if they act wisely. Serbia is one such country. Sitting atop one of Europe’s most promising lithium deposits, the Project Jadar, Serbia holds the potential to become a key partner in the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials strategy.

By aligning its resource development with EU environmental standards and industrial priorities, Serbia could move beyond raw-material exports and

build domestic value chains: mining, refining, battery production, and recycling. This would not only create jobs and foster technology transfer but also position Serbia as a regional hub for clean technology supply chains.

As the European Commission accelerates its 2026 plan to stockpile strategic minerals and diversify imports, partnerships with countries like Serbia are becoming a crucial part of the European response to Chinese dominance.

Investment in critical raw materials requires long lead times, regulatory clarity, and stable pricing frameworks. Yet, while demand soars, supply-side investment rose by only around 5 percent in 2024, according to the IEA. Without mechanisms like guaranteed minimum pricing or price floors, many new projects may remain unviable amid volatile commodity cycles and geopolitical leverage.

That’s why price-floor mechanisms are emerging as essential policy tools. They provide certainty to investors, shield producers from predatory pricing, and sustain industrial scaling in strategic jurisdictions.

Just as oil defined the geopolitics of the 20th century, critical minerals will define the geopolitics of the 21st century. Nations that convert their geological potential into industrial and technological power will shape the global balance of influence in the decades ahead.

For Serbia with its lithium reserves, proximity to EU markets, and growing industrial capacity, the moment to act is now. By coupling resource wealth with good governance, environmental protection, and industrial strategy, Serbia can secure not only raw materials but also a place at the value-chain table of the green era.

Aleksa Jovanović

Introduction

Donald Trump’s “America First” policy marked a shift in U.S. foreign relations, focusing on national interests, rejecting multilateralism, and reducing international entanglements. This approach raised questions about whether it represented a modern-day version of the Monroe Doctrine, originally articulated by President James Monroe in 1823 to limit European influence in the Americas. This essay examines whether Trump’s “America First” policy is an extension of the Monroe Doctrine in today’s globalized world, exploring historical parallels, differences, and broader implications.

The Monroe Doctrine: Origins of an American Sphere

The Monroe Doctrine initially aimed to prevent European powers from interfering in Latin America, declaring the Western Hemisphere a sphere of influence under U.S. control. Over time, it became more interventionist, with the U.S. justifying military actions in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Panama to protect national interests. The doctrine continued to justify U.S.

interventions during the Cold War, but by the late 20th century, it had become criticized for its imperialistic tendencies. Nevertheless, the core idea that the U.S. had a special role in protecting the hemisphere from outside powers remained entrenched in U.S. foreign policy.

“America First”: The Trump Doctrine in Context

Trump’s “America First” policy marked a sharp departure from multilateralism, focusing on a transactional approach where U.S. interests were prioritized. Trump questioned the value of NATO, withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement and the Iran Nuclear Deal, and argued that international agreements often disadvantaged the U.S. His policy was primarily about defending American economic interests, including through protectionist measures like tariffs on China and Europe. Trump’s foreign policy was an extension of his domestic policy, aimed at maximizing economic advantage and reducing reliance on others.

Trump’s policy echoed the Monroe Doctrine’s nationalist vision, seeking to limit foreign influence in regions the U.S. considered critical. His administration's approach to Latin America, particularly regarding Venezuela, was explicitly tied to the Monroe Doctrine. National Security Advisor John Bolton in 2019 stated that “the Monroe Doctrine is alive and well” under Trump, focusing on limiting Chinese and Russian influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Trump extended the Monroe Doctrine’s logic to the global stage. Just as the Monroe Doctrine justified U.S. interventions in Latin America, Trump applied this logic worldwide, especially in relation to China

and Russia. His emphasis on economic nationalism, military readiness, and reducing international involvement reflected a worldview where the U.S. defends its global position and avoids unnecessary entanglements, similar to the Monroe Doctrine’s desire to avoid involvement in European affairs.

While Trump’s “America First” shares similarities with the Monroe Doctrine, there are key differences. The Monroe Doctrine was a regional policy focused on the Americas, whereas “America First” was a global strategy. Trump’s approach extended to China, Europe, and the Middle East, shifting U.S. foreign policy to view China as a strategic competitor. His treatment of NATO and other alliances departed from the Monroe Doctrine’s focus on regionalism, as Trump expressed skepticism about NATO and sought to renegotiate these relationships.

The ideological component also differed. The Monroe Doctrine framed the U.S. as a defender of democracy and liberty in the Western Hemisphere, while Trump’s “America First” was more pragmatic and transactional, focused on economic and military gains rather than spreading democratic ideals or upholding international norms.

Trump’s foreign policy fragmentation underscored the importance of a united U.S.-EU partnership. The rise of authoritarian regimes like China and Russia in response to U.S. retrenchment necessitates close cooperation between the U.S. and the EU to defend democratic values and maintain global stability. A strong transatlantic alliance will ensure that Western ideals of democracy, security, and economic prosperity are protected in an increasingly multipolar world.

Trump’s “America First” doctrine shared nationalist and interventionist elements with the Monroe Doctrine. Both policies emphasized U.S. primacy and sought to limit foreign influence in regions critical to U.S. interests. However, Trump’s approach was broader and focused more on economic and military readiness rather than ideological pursuits. His policies contributed to a more fragmented world order, with the U.S. retreating from its role as a global leader, potentially leaving a vacuum in the international system.

Ultimately, Trump’s foreign policy reasserted a vision of American exceptionalism rooted in national selfinterest, echoing the Monroe Doctrine’s regionalism but applying it globally. Whether this becomes a lasting framework for U.S. foreign policy or is seen as a temporary deviation from the post-WWII order will depend on future administrations. Regardless, maintaining a united U.S.-EU front in a fragmented world remains crucial to defending democratic principles and ensuring stability in the global landscape.

Celea Tiberiu Edward Gabriel

In today’s polarised Europe, a worrying trend is taking root: the overuse (and misuse) of political labels like “fascist”, “extremist”, or “far-right”. What were once precise academic or legal terms have now become political weapons. And alarmingly, their targets are no longer fringe movements, but mainstream democratic forces, including those rooted in Christian democracy.

This matters deeply for the European Democrat Students, for the European People’s Party, and for every young conservative who still believes that liberty, responsibility, and tradition have a legitimate place in 21stcentury European Politics.

Across the continent, sovereigntist and national-conservative parties have surged in popularity.

Whether it’s Fratelli d’Italia in Italy, Rassemblement National in France, AfD in Germany, Vlaams Belang in Belgium, or AUR in Romania, these parties are now regular participants in electoral life.

And yet, the conversation around them often lacks nuance. Instead of being scrutinized for their platforms, policies, or conduct in parliament, they are hastily branded with the darkest labels in European political memory: fascists. Often, the ones applying those labels are more influenced by Marx or Engels, rather than Dahl or Schuman, but taken all together this results in a rhetorical environment where the line between democratic dissent and authoritarian extremism is deliberately blurred.

This does not just affect the far edges of politics, it’s starting to engulf the democratic center-right as well.

Christian democracy played a foundational role in rebuilding Europe after World War II. Parties like CDU, EPP, and DC in Italy offered a path beyond totalitarianism, one based on the dignity of the person, subsidiarity, and solidarity. Yet today, even these values are under suspicion. When parties express skepticism toward federalism, open-ended migration policies, or progressive cultural agendas, they are often accused of harboring far-right sympathies.

This shift is dangerous. If defenders of the democratic right are grouped with historical fascists or current extremists, we risk eroding the very pluralism European democracy is built.

Political scientists such as Cas

Muddle have long warned against the blurred categorization of “populist radical right” and true authoritarian threats, emphasizing that many of these parties operate within democratic norms, despite their illiberal rhetoric. Others, like Enzo Traverso, note that overusing the term “fascist” to describe all dissenters from liberal orthodoxy ultimately dilutes its historical significance.

Historical memory is a sacred European asset. But when weaponized, it becomes dangerous. Today, media and academic discourse increasingly use “fascism” as a catch-all insult to silence political opponents.

This undermines both democratic dialogue and the unique lessons of history. Roger Griffin, a foremost expert on fascism, defined it as a revolutionary ultranationalism seeking a rebirth through authoritarianism and violence. Most contemporary parties, even when controversial, fall far from this mark.

And yet, narratives persist. A simple comparison: Fratelli d’Italia under Giorgia Meloni is governed by NATO and EU commitments, not fascist manifestos. AUR in Romania participates in free elections, debates EU policies, and supports parliamentary mechanisms. Of course, not excuse their excesses, but they do suggest a democratic, not authoritarian framework.

EDS has always stood for more than partisan loyalty. We stand for democracy. For pluralism. For the right of students across Europe to think freely and defend their values, conservative, liberal, centrist, or otherwise.

If the current wave of political labelling continues unchecked,

young Christian Democrats could find themselves politically homeless. Already we see campus events shut down, like the October 2024 cancellation of a student-organised Suella Braverman talk at Cambridge, over protest fears despite no real security threat and being called „far right”.

EDS should be the place where these voices are heard, not stifled. Where rigorous disagreement replaces cheap slogans. Where history is remembered, but not manipulated.

A Responsible Way Forward

We must defend the right to label dangerous ideologies for what they are. But that also requires the courage to be intellectually honest. There is a world of difference between a party that questions immigration policy and one that glorifies violence. Between a leader who critiques EU bureaucracy and one who seeks to dismantle democracy.

Let’s revive our commitment to precision in political discourse. Let’s call extremists what they are. But let’s also protect the space where democratic conservatism can breathe. Let’s challenge sovereigntists with arguments, not slurs.

Now more than ever, we must be precise, we must be brave, and we must speak up.

Andrea Mghames

On 22nd June 2025, a suicide bomber attacked Mar Elias Church in Damascus during Sunday liturgy, killing 25 Christians and injuring dozens. The response from Europe? Silence. No outrage, no action. If Christian Democracy still stands for moral courage, it must raise its voice, not only for its values but for its people. Headlines fade, our responsibility must not.

Reclaim the Centre-Right

As young Christian Democrats, we must reject both authoritarian nostalgia and progressive intolerance. When the blood of Christians runs in Middle Eastern churches, and the response from European institutions is silence, something has gone deeply wrong. And when, in our own democracies, the parties most rooted in Christian values are hastily labeled “fascists” or “far-right”, that silence becomes complicity.

Let’s not allow our tradition, the tradition of Adenauer, Schuman, and De Gasperi to be erased through guilt by association. Let’s defend what makes Christian democracy worth fighting for: responsibility, human dignity, and the courage to think freely.

Let us not whisper. Let us lead with clarity, courage, and conviction.

Lebanon faces a critical challenge with Hezbollah’s continued armed presence within its borders. The Shiite militant group operates both as a political party and an independent military force, maintaining a vast arsenal of rockets, missiles, and conventional weapons. The question of disarming Hezbollah has dominated Lebanese politics for decades, raising concerns about national sovereignty, regional security, and the potential for renewed conflict with Israel.

Hezbollah’s Military Autonomy

Hezbollah’s military wing is independent of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), with command structures, logistics, and specialized units operating outside state control. Estimates suggest the group possesses tens of thousands of rockets and missiles, including short- and medium-range systems, anti-tank weapons, and drones capable of reconnaissance and attack.

The organization justifies its armed status as essential for defending Lebanon against Israel, citing the 2006 Lebanon War and repeated cross-border

skirmishes. Hezbollah leadership has repeatedly rejected international calls for disarmament, framing such demands as foreign interference that would weaken Lebanon’s defense capabilities. Naim Qassem, Hezbollah’s deputy secretary-general, has consistently argued that disarmament is not negotiable while threats from Israel persist.

The United States and other international actors have emphasized the need for Lebanon to consolidate its monopoly on force. In 2024, the U.S. approved $230 million in support for the LAF and Internal Security Forces (ISF) to strengthen their operational capabilities and enable the Lebanese state to enforce law and security throughout the country (Reuters, 2025).

Israel monitors Hezbollah closely, viewing its arsenal as a direct threat. Israeli strikes in southern Lebanon have targeted weapons depots and command centers, including operations that killed Hassan Nasrallah and other senior commanders. While these strikes disrupt

Hezbollah’s leadership, they do not directly remove the group’s extensive military capabilities.

Efforts to disarm Hezbollah face significant domestic obstacles. Politically, Hezbollah holds substantial parliamentary representation and maintains alliances with other parties, giving it influence over government decisions. Socially, the group provides essential services in Shiite-majority regions, including healthcare, education, and welfare, which reinforce loyalty among local populations.

This dual role as a political actor and provider of social services complicates attempts to enforce disarmament. Any aggressive move to seize weapons could provoke internal conflict, destabilizing an already fragile state and risking violent confrontation between Hezbollah and Lebanese security forces.

The continued presence of Hezbollah’s military wing undermines the Lebanese government’s authority and complicates national security. The group’s control of substantial weapon stockpiles allows it to act independently of state institutions, raising the potential for clashes with Israel and other regional actors.

Recent Israeli operations, which have killed key leaders and targeted weapons facilities, highlight the persistent risk of escalation. Even with high-level strikes, Hezbollah retains enough operational capability to conduct retaliatory attacks, demonstrating that leadership decapitation does not equate to full disarmament.

Disarmament of Hezbollah would require a combination of political negotiation, international support, and domestic consensus. Strengthening the Lebanese Armed Forces to enforce state authority over all armed groups is essential. Concurrently, incentives could be explored for Hezbollah to integrate its fighters into state security institutions while preserving the political role of the organization.

Diplomatic engagement involving regional and international stakeholders is also critical. Pressure from allies, alongside security guarantees and economic support, could create an environment where partial disarmament or integration becomes feasible.

Lebanon remains at a crossroads between maintaining Hezbollah’s armed status and pursuing a path toward disarmament. While the killing of Hassan Nasrallah and other commanders has disrupted the group’s leadership, its operational capabilities remain largely intact. Disarmament is not solely a military challenge; it involves political negotiation, social considerations, and regional diplomacy.

The stakes are high: failure to disarm could perpetuate Lebanon’s vulnerability to external threats and internal instability, while a managed disarmament process could strengthen the state’s authority and reduce the risk of future military conflict with Israel. Achieving this balance will require careful coordination between Lebanese authorities, Hezbollah, and the international community, with a focus on long-term stability and security.

Over the last few years, EU enlargement to the Western Balkans has returned to the heart of Brussels’ political debate. In an era marked by war and energy insecurity, the European project is once again defined by geography and geopolitics. Stability in the Balkans is no longer a matter of aspiration; it is a strategic necessity. Within this context, the Adriatic–Ionian Initiative (AII) stands out as one of Europe’s most pragmatic instruments of regional cooperation. For over two decades, it has transformed dialogue into projects and regional rhetoric into measurable outcomes.

Founded in 2000 in Ancona, the AII brings together eight countries: four EU members (Italy, Greece, Croatia, Slovenia) and four aspirants (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia). Geography is only part of the story: the Initiative converts physical proximity into functional cooperation, linking candidate and member states in a single policy ecosystem.

The Adriatic–Ionian basin has always been a crossroads of trade, culture, and strategic

competition. Today, with overlapping transport and energy corridors, it is crucial for the EU’s connectivity and resilience. Supported by European funding, the AII inspired the EU Strategy for the Adriatic and Ionian Region (EUSAIR) — a framework built on four pillars: Blue Growth, Connecting the Region, Environmental Quality, and Sustainable Tourism. Its ambition is simple yet essential: to align regional development with EU standards while fostering trust among neighbours whose histories are often entangled in rivalry.

Concrete results are visible under the Blue Growth pillar, which aims to harness the potential of Europe’s seas and coasts. The ELEMED project, launched in 2016, examined the technical and financial feasibility of low-carbon shore-side electricity in Eastern Mediterranean ports. In 2018, the first cold-ironing facility in the region was inaugurated at the port of Killini, Greece, allowing ships to connect directly to onshore electric power. The participating ports of Piraeus, Killini, and Koper became testbeds for zero-emission maritime transport.

Another example is BLUEAIR, an Interreg ADRION project with over €2.2 million in funding, linking 31 partners across all eight AII countries. It promotes innovation in aquaculture, maritime technologies, and skills for the blue economy — bridging research and industry throughout the macro-region.

Connecting Infrastructure and Energy Across Borders

Beyond the maritime sphere, the Connecting the Region pillar focuses on infrastructure and energy cooperation. The AII’s annual forums — most recently held in Crete in 2025 — have advanced projects on renewable energy grids and low-emission transport corridors. In parallel, the CYROS project has mapped an Adriatic-Ionian cycling network from Italy to Greece,

promoting sustainable tourism and intermodality. Behind these visible initiatives lies the EUSAIR Facility Point, backed by €11.5 million in EU funds, which has helped harmonise planning and governance across participating states.

Does Regional Cooperation Actually Accelerate Enlargement?

Critics argue that regional initiatives like the AII risk turning into bureaucratic forums with limited impact, duplicating the bilateral accession process managed by the European Commission. Indeed, the Western Balkans’ integration has often stalled despite numerous frameworks. Yet what distinguishes the AII is its applied dimension: it connects political dialogue to investment, infrastructure, and administrative capacity-building. Rather than replacing the accession process, it reinforces it by creating habits of cooperation that treaties alone cannot guarantee.

The Adriatic–Ionian framework has also served as a diplomatic accelerator for EU enlargement. By promoting continuous interaction among member and candidate states, the AII has provided a neutral, policy-driven environment where countries like Montenegro could align with EU standards well before the formal negotiation process. Through EUSAIR’s project coordination and governance benchmarking, Montenegro has demonstrated administrative readiness and cross-border engagement — two benchmarks essential for accession.

Montenegro, which will host the next European Democratic Students (EDS) meeting in Podgorica this November, embodies this process. An EU candidate since 2010, it has advanced further than any other Western Balkan country in the negotiation chapters.

The setting is symbolically fitting: a forum of young Europeans meeting in a city that aspires to join the Union their generation will shape.

The story of Montenegro’s European path is also the story of Italy’s consistent belief in the region’s European destiny. Long before the AII was founded, Italian diplomacy — through figures like Foreign Minister Gianni De Michelis — had promoted stability and dialogue in the Western Balkans, anticipating the cooperative vision that the Initiative would later institutionalise. This early approach laid the groundwork for Italy’s long-term commitment to regional cooperation, which continues to inform its leadership within the AII today.

To invest in the AII is to invest in structured, sustainable enlargement. Neglecting it would leave a vacuum readily filled by others: China, through Belt and Road port investments in Piraeus and Bar; Russia, through energy networks; and Turkey, through cultural and economic outreach. The Adriatic–Ionian Initiative offers a European alternative — anchoring connectivity and infrastructure to transparency, environmental protection, and EU regulatory standards. It demonstrates that Europe can compete not by coercion but by cohesion.

The future of the EU in the Western Balkans depends on credible mechanisms, shared standards, and long-term vision. For young Europeans, engagement must go beyond optimism: it means supporting concrete instruments of cooperation, advocating for sustained EUSAIR funding, and ensuring that enlargement remains a living political priority. The Adriatic–Ionian experience proves that integration is not only a treaty to be signed, but a daily practice of cooperation.

Domagoj Cigić

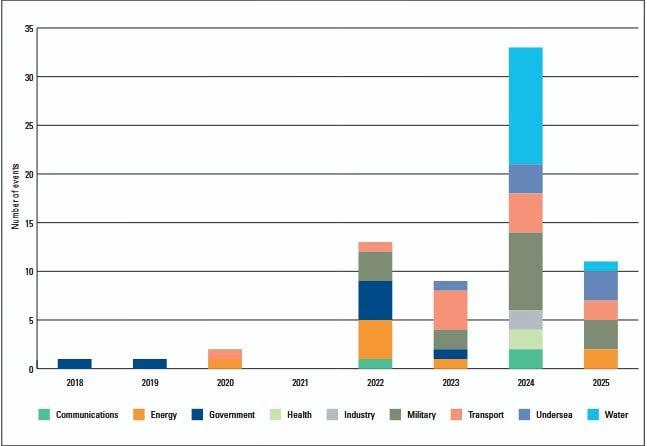

The European Union today faces persistent pressure from Russia through a combination of disinformation, election interference, bribery, energy manipulation, cyberattacks, and military provocations like drone and aircraft incursions. This strategy aims to destabilize the bloc from within, testing both political cohesion and military resolve. The question is whether Brussels has the tools and political will to respond effectively.

In Moldova's 2025 elections, Russian operatives orchestrated a vast vote-buying scheme, funneling cash to voters and local officials to tilt the outcome away from the proEuropean coalition. Despite the operation, Moldova's EUaligned government narrowly held power, but the margin was close enough to reveal just how vulnerable European democracies have become to foreign manipulation.

Election Interference: Moldova and Czech Republic

The 2025 Moldovan parliamentary elections exposed how Russia operates on the ground. Investigations revealed payments linked to Ilan Shor, a convicted businessman with Kremlin ties, who organized a network to buy votes and bribe officials. ProRussian parties simultaneously spread disinformation on social media, falsely portraying

EU integration as a threat to Moldova's sovereignty. The proEuropean coalition survived, but the scale of the interference demonstrated that hybrid tactics can nearly reshape a country's political future.

The 2025 Czech parliamentary elections showed similar patterns inside an EU member state. Networks linked to oligarch Konstantin Malofeev reportedly financed far-right and Eurosceptic parties, while amplifying disinformation campaigns that exploited fears around inflation, migration, and distrust in Brussels. Czech intelligence publicly warned of Russian funding channels targeting politicians and media outlets, further eroding democratic trust.

These operations share a common

structure: financial corruption combined with narrative warfare. Russian operatives don't just spread propaganda; they pay for influence and mobilize networks that appear local but serve Moscow's interests.

Energy as a Weapon

Energy remains one of Russia's most effective leverage points. Hungary's continued deep reliance on Russian gas and nuclear technology, cemented by a 2024 Rosatom deal for new nuclear reactors, grants Moscow outsized influence over Budapest's political decisions. This energy dependence complicates the EU's ability to present a united front on sanctions and energy policy.

Separately, Moscow's disinformation campaigns exploit

Russia's pressure increasingly includes overt military provocations. In 2024 and early 2025, drone incursions and unauthorized aircraft flights were recorded over Baltic and Polish airspace, raising tensions along NATO's eastern flank. NATO has responded by intensifying air patrols and reconnaissance missions to deter further violations and signal alliance readiness. These probing actions blur the lines between political subversion and military threat.

cybersecurity investments. Enhanced cooperation with NATO has improved intelligence sharing and joint military readiness. The Digital Services Act seeks to hold online platforms accountable for harmful content.

economic anxieties related to the EU's green transition. False narratives blame climate policies for inflation and job losses, messages that resonate particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. These campaigns deepen societal divisions and weaken popular support for EU initiatives, even when energy dependence itself is not the direct cause.

Corruption and bribery compound the problem. Moldova's leaked documents expose payments to officials and campaign operatives designed to buy loyalty and block pro-EU reforms. Across Eastern and Central Europe, similar flows of Russian money infiltrate political parties, media outlets, and civil society organizations, undermining democratic institutions and eroding public trust in governance.

Cyberattacks add another layer of complexity. EU cybersecurity agencies reported a surge in phishing and hacking campaigns targeting electoral systems in Lithuania, Poland, and Finland. Meanwhile, disinformation efforts have become more decentralized and harder to detect. Kremlin narratives spread through Telegram channels and fake local news websites posing as independent outlets. Russian troll operations deploy coordinated teams across blogs and forums using sockpuppets, social bots, and large-scale orchestrated campaigns to promote pro-Putin and pro-Russian propaganda.

Slovakia saw a marked increase in pro-Russian media pushing antiEU narratives ahead of elections, shaping public opinion in subtle but effective ways.

The EU has strengthened its defenses through sanctions targeting actors involved in hybrid operations, a coordinated Hybrid Toolbox enabling rapid response, and increased

However, these efforts remain uneven. Some member states lack the political will or resources to counter hybrid threats effectively. Internal EU divisions and differing national interests, particularly around energy ties to Russia, sometimes delay unified action. While Poland and the Baltic states treat hybrid warfare as an existential threat, other member states remain distracted or hesitant.

Europe's strength lies in its ability to adapt quickly, close legal loopholes, and coordinate political, technological, and military responses across the bloc. Russia's pressure is persistent and multifaceted. If the EU cannot build consensus on energy independence and enforcement of digital accountability, Moscow will continue to exploit these vulnerabilities. Europe must move beyond declarations of concern and implement coordinated countermeasures with real consequences for both external actors and member states that undermine collective security.

Alex Zamborský

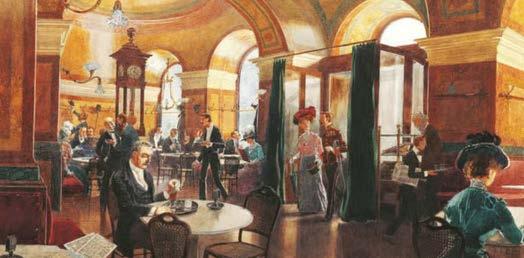

Vienna, the multinational capital city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries an international metropolis and hub for cultural and artistic novelties. Furthermore, the city gave rise to an economic school that revolutionized the way scholars and policymakers think about economics. Four men from Vienna, Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and their followers Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek, left an indelible mark on the world of economics with their rigorous championing of values such as freedom, entrepreneurship, and free markets. Their ideas opposed the omnipotent authority of the state personified in communist ideology. Moreover, all four of them were able to theoretically demonstrate the deficiencies of a centrally planned economy even before it empirically collapsed in communist countries in the late 1980s.

The Austrian School of Economics perceives the individual and their choices as the most important

unit of analysis. The prices of goods and services on the free markets are crucial signals reflecting the preferences of countless individuals participating in the market exchange. Prices as signals provide information to both suppliers and consumers and allow them to increase their utility from transactions. Consequently, the Austrian school perceives private property not only as a right but also as a necessity within a functioning society. It is not a surprise that Hayek, Mises and other representatives of the Austrian School opposed excessive state interventions into economics and rightfully perceived centrally planned economies as flawed ones from their definition. Ludwig von Mises had already, in the year 1920, contradicted the concept of economic calculation advocated by the supporters of socialism. Mises, in his works, theoretically proved that a central planner lacks sufficient information about countless transactions that occur on the market every single day. Thus, central planning omits prices as signals, leads to an inefficient allocation of scarce resources, and results in shortages. On the contrary, free markets allow entrepreneurs to discover opportunities for more efficient allocation of resources, leading to an increased well-being for society as a whole.

The economists from the Austrian School did not just revolve around free markets and the critique of socialism but had a much broader scope of interest.

Their other focus of interest was money, more precisely, how the supply of money influences prices in economics. Hayek famously repeated throughout his career that money is not neutral and that an increase in the money supply leads not only to inflation but also to the distortions of capital structures. Consequently, representatives of the Austrian School agreed that excessive inflation is a negative phenomenon that should be avoided at all costs. The inflation negatively impacts the economic welfare of the citizens and has further negative political and societal consequences, such as political instability. Furthermore, it can lead to the emergence of totalitarianism that Hayek personally witnessed during his lifetime and that forced him to emigrate to the United Kingdom.

The intellectual heritage of Carl Menger that emerged in Vienna in the year 1871 by publishing his pioneering work, Principles of Economics, was crowned more than a century later in Stockholm. The Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded Menger´s intellectual successor, Friedrich von Hayek, with the Nobel Prize in economics for his persistent lifelong work. By this time, the school of thought that emerged in Vienna had left the hermetically sealed doors of lecture rooms and libraries and conquered the world. The values of liberty, economic freedom, entrepreneurship and innovation have found numerous supporters among policymakers, central bankers and intellectuals and are becoming even more relevant in the current world.

Finlay Thacker-McPherson

Europe has become the world’s preeminent regulatory power, shaping global norms across data, privacy, and finance through its vast economic influence and signature regimes like GDPR. With its implementation of the MiCA (Markets in Crypto Assets) framework, the EU faces a critical crossroads: will it double down on bureaucracy, or unleash the kind of bold, principles-driven regulatory approach that built the Single Market? The crypto industry is fast- paced and extremely mobile; only by approaching crypto assets with clear and growthfostering regulatory frameworks can the EU compete with the likes of Dubai, Singapore and the United States to become a true leader and bastion of economic freedom. The choice is not just regulatory; it is existential: Europe must choose between stagnation and future relevance, between cautious conformity and daring optimism. Progress depends on boldness, not more red tape.

from Fintech: When Rules Help Incumbents and Hurt Innovators

With its implementation of MiCA, the EU must be aiming to escape the trap of stagnation and overregulation. Previously, the European Union has approached regulatory frameworks with a ‘heavily regulate first, ask questions later’ approach, which has largely led to stagnation and limited competitiveness on the world stage against powers such as the United States. Europe’s previous experience with fragmented fintech licensing shows how well-intentioned rules can burden smaller innovators while empowering incumbents. MiCA risks repeating this pattern unless it prizes clarity and proportion over complexity. The EU must have a proportionate, crypto-friendly view at the heart of its regulatory framework in order to foster its usage and display to crypto innovators and users that the EU is a viable place in which to invest and hold

assets. The EU, with is access to the Single Market and various strong financial institutions, could be seen as a leader in crypto assets, but only if it chooses to deregulate, promote ‘light- touch’ regulation, foster innovation, and break the previously adhered to cultural and economic choice of stagnation and bureaucratic inertia.

The European Single Market was, after all, built on the idea of contestability and openness, and the EU’s crypto regulations should follow suit. It cannot allow for there to be a process in which national governments decide that they will place additional regulations or requirements on top of

MiCA in order to moat up and ring fence crypto assets in their own nation. If this were to occur, there would be a scenario in which richer nations are able to add national requirements to their cryptocurrency regulations that harm those who are looking to move them across borders, to properly reflect the very foundations of the Single Market, the implementation of MiCA must call for a harmonising and truly borderless approach to crypto. In addition to this, smart regulation protects consumers not by building walls but by creating predictable pathways and ensuring European harmony. As economists Ludwig von Mises posited, ‘Freedom is indivisible. As soon as one starts to restrict it, one enters a decline on which it is difficult to stop’. Europe has so often erred on the side of decline and overregulation; it is imperative that this time is different, and that MiCA represents a shedding of the old bureaucratic EU in favour of a new, open, innovative European Union.

Capital Stays Where It’s Welcomed: Europe’s Competitiveness Gap

Europe is already facing stiff competition to attract crypto innovators and investment from across the world. Dubai’s VARA and Singapore's MAS have built clear, fast, and investor- friendly rules for cryptocurrencies, which have clearly signposted these locations as forward- thinking leaders in the space. According to Mitrade, Dubai, ‘virtual asset transaction volumes across regulated entities under VARA surged to nearly AED 2.5 trillion ($680 billion)’ from the beginning of 2025 to now, with plans to grow Dubai’s virtual assets sector from 0.5% of its economy to 3% in place. Dubai’s emphasis on clear, quick and credible rules has been the hallmark of its approach to crypto. If it is to compete with them, the EU needs to

adopt similarly clear and fast rules that give investors a reason to not only trust Europe but stay there for the long term. At the heart of this effort to compete needs to be a dedication to light-touch regulation, making it easier for investors to know where they stand with the EU rather than strangling potential growth in this sector with complex and hard-to-manoeuvre rules. A pillar of this effort should be the fast-tracking of Crypto-Asset Service Provider (CASP) licenses, which are required for companies wishing to provide a platform on which crypto-assets can be traded,

exchanged or held as assets. Such a move would highlight to companies and investors that the European Union is serious about welcoming the possibilities that come with a wider crypto asset sector that is supported and not regulated into non-existence.

Europe’s future as a digital finance leader depends on rejecting old comfort and daring for new progress: MiCA must become a true passport for innovation, not a bureaucratic moat. Only by embracing boldness, harmonisation, and principled freedom, rather than defaulting to caution and red tape, can the EU seize this moment, ignite growth, and show the world it still knows how to lead.

Sotiris Paphitis

On the morning of 7 January 2015, two men armed with rifles stormed the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine known for its irreverent caricatures. Within minutes, twelve people lay dead: cartoonists, editors, police officers, and staff members. The attack was shocking in its violence, but also in its symbolism. It was not just an assault on individuals, but on satire, on journalism, and on the principle of free expression itself.

The images of that day—the black-clad gunmen fleeing into the streets, the grief of survivors, the global marches under the banner “Je suis Charlie”—became etched in collective memory. Yet ten years later, as we look back, the meaning of the attacks and their aftermath feels less straightforward than it did in the raw days of mourning. If the initial reaction was one of unity, the years that followed revealed the complexity of the lessons to be drawn. What, in truth, did we learn from Charlie Hebdo?

At the heart of the attack was the question of freedom of expression. The killers sought to silence voices they found offensive, to make fear a substitute for argument. The immediate response was defiance: the insistence that satire, however biting, must not be driven underground. In those first days, free expression was celebrated with a fervour rarely seen in liberal democracies. The right to shock, offend, and provoke was reaffirmed as essential to democratic life.

But over time, a more uncomfortable reality surfaced. It became clear that while many defended the principle of free expression, they were less willing to embrace it in practice. Some voices argued that Charlie Hebdo had gone too far, that mocking religion—particularly a religion practiced by marginalized communities in France—was not an act of bravery but of insensitivity. Others pointed out the selective nature of solidarity: millions marched for Charlie Hebdo, yet similar violence in less visible parts of the world rarely drew

such global outrage.

This tension revealed a paradox. Defending free speech is easiest when one agrees with what is being said. It becomes far harder when speech feels abrasive, uncomfortable, or unjust. The lesson of Charlie Hebdo is that free expression must be defended not because we like or endorse its content, but because once violence becomes an acceptable response to words or images, democracy itself is imperilled. At the same time, freedom does not erase responsibility: a society committed to pluralism must hold space for civility even while legally protecting the right to offend.

Closely tied to this is the question of secularism and pluralism. France’s tradition of laïcité—strict separation of religion from the state—formed part of the context for the attacks and their aftermath. To many in France, the caricatures published by Charlie Hebdo were consistent with a secular culture that places no belief beyond satire. Yet for many Muslims, they represented humiliation and exclusion, reinforcing a sense that their faith was treated not with equality, but with disdain.

The attackers themselves were French-born, shaped by both marginalization and radical ideology. Their violence cannot be reduced to social disadvantage, but the alienation felt by many in immigrant communities cannot be ignored either. The past decade has shown that secularism, when rigidly applied, can risk being experienced as hostility toward religion rather than neutrality. The challenge for France, and for Europe more broadly, is how to uphold a secular public sphere while allowing religious identity to be lived with dignity. Here, the lesson is subtle: secularism should not mean the erasure of belief, but its equal treatment within a democratic framework. Integration cannot be built through exclusion.

Another area where lessons have been uneven

concerns counterterrorism. The scale of the Charlie Hebdo attack, followed shortly by the Bataclan massacre and other acts of terror, led to sweeping changes in security law. Surveillance was expanded, emergency powers prolonged, and new offences created to clamp down on expressions of extremism. Some of these measures likely prevented further attacks; others stretched the limits of civil liberty. France’s years-long state of emergency became a warning of how temporary exceptional powers can quietly harden into permanent features of law.

Here too lies an enduring lesson: terrorism tests the resilience of democratic institutions. It tempts societies to abandon liberty in pursuit of safety, to fight violence with disproportionate repression. But to do so risks vindicating the extremist claim that democracy is a façade. Let us also remember Benjamin Franklin’s warning: Any society that would give up a little liberty to gain a little security deserves neither liberty nor security, and will lose both. If the purpose of terrorism is to provoke overreaction, then the strongest answer lies in restraint. A decade on, we are reminded that the rule of law is not a luxury of peace but a necessity in times of crisis.

Even the memory of Charlie Hebdo has become contested. The phrase “Je suis Charlie” captured a moment of global solidarity, but it soon became divisive. Did proclaiming it mean unconditional endorsement of the magazine’s editorial stance, or merely defense of its right to publish? Was solidarity universal, or did it reveal the West’s tendency to prioritize its own tragedies over those elsewhere?

Over time, the unanimity of grief fractured into disagreement. The slogan faded, leaving behind not only a memory of unity but also a warning of how fragile solidarity can be.

And yet, despite the divisions, despite the ambiguities, the decade since the attack leaves one undeniable truth: the values tested that day remain worth defending. Free expression, pluralism, and the rule of law are never secured once and for all; they must be reaffirmed again and again, especially when they are challenged. The danger lies not only in forgetting the victims but in forgetting the questions their deaths forced us to confront.

Ten years on, the world remains unsettled. Debates over freedom of speech, cultural sensitivity, radicalization, and security continue in every democracy. There are no final answers, only ongoing debates. But perhaps that is the clearest lesson of all: democracy does not mean the resolution of conflict, but the willingness to live with it, to manage it without violence, and to defend the principles that allow it to persist.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo was meant to silence. A decade later, we can honour its victims not only by remembering their work but by refusing to abandon the freedoms for which they died. The freedom to speak, to draw, to laugh—even irreverently—remains the heartbeat of democratic life. And it is in keeping that heartbeat alive, despite fear and division, that we prove violence has not won.

Sotiris Paphitis

In recent weeks, the streets of Kathmandu and other Nepali cities have filled with a generation demanding change. The so-called Gen Z protests, triggered by the government’s ban on several social media platforms, have evolved into a broader challenge to corruption, nepotism, and the culture of impunity that many feel has gripped the political class. The demonstrations have not been without tragedy: dozens of young people have been killed in clashes with security forces, hundreds more injured, and the political system itself stands shaken.

Beyond the immediate grievances lies a deeper question. What is missing in Nepal’s public life — and in much of global politics — is humility. The ability of leaders to admit fallibility, to govern with restraint, and to treat power as stewardship rather than entitlement has rarely felt so absent.

Humility in governance does not mean timidity. It means an awareness that authority is granted by citizens and must remain answerable to them. It requires transparency in decision-making, a

willingness to listen to criticism, and the capacity to accept mistakes openly. Humility is a safeguard against hubris: the conceit that office confers superiority rather than responsibility.

When public officials lose this perspective, power becomes detached from service. Nepotism is justified as tradition, corruption dismissed as pragmatism, and dissent regarded as a nuisance rather than a democratic right. Humility, in this sense, is not a private virtue but a civic necessity.

The protests in Nepal expose what happens when humility is absent. The government’s decision to restrict social media was presented as a technical measure but was perceived as an attempt to silence criticism. For a young generation already frustrated by unemployment, inequality, and the visible privilege of political families, the ban became a spark.

Instead of dialogue, the state responded with curfews and force. Security personnel fired on demonstrators; parliament was besieged; public trust collapsed

further. The cycle was familiar: arrogance at the top met by defiance from below, each side escalating, until lives were lost.

The tragedy is that humility could have prevented much of this. A government willing to consult, to explain, to listen, and to adjust might have avoided the impression of censorship. Leaders who admitted mistakes rather than doubling down might have prevented bloodshed.

Humility is more than a moral posture. It has practical value for democratic life:

• It builds trust. Citizens are more willing to comply with law and policy when they believe leaders are open and accountable.

• It improves decision-making. Leaders who seek feedback and accept limits craft policies that are more effective and durable.

• It strengthens resilience. In times of crisis, humility prevents overconfidence and prepares institutions to adapt rather than entrench.

The alternative is what Nepal has witnessed: arrogance breeding resistance, opacity fueling suspicion, and violence eroding legitimacy.

If Nepal’s leaders wish to recover authority, humility must become visible in practice. This could mean independent investigations into abuses during the protests, recognition of victims, and real reforms against nepotism. It could mean engaging with youth not as agitators but as citizens whose concerns about jobs, education, and dignity are legitimate. Above all, it could mean restraining the reflex to silence criticism and instead treating dissent as part of democratic life.

Of course, humility cannot be staged. Empty apologies and cosmetic gestures will only deepen cynicism. True humility may involve loss of face, even loss of office, but it is precisely that willingness to bear risk for the public good that gives politics credibility.

Nepal is not unique. Across democracies, from Europe to Asia to the Americas, politics has grown louder, harsher, and more self-assertive. Leaders

promise strength, not reflection; dominance, not service. Yet history shows that societies endure not because leaders pretend to be infallible, but because institutions are capable of correction. Humility is what allows a system to learn rather than to break.

This is not a new insight. In 2005, shortly before becoming Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel observed in an interview: “We must never forget our responsibilities as politicians to our country and its citizens. We must always remain humble before our people.” At the time, her words may have seemed like a reminder of political decorum. Two decades later, they read as a warning against the arrogance that corrodes trust in government and widens the gap between rulers and the ruled. In an era of rising populism and institutional fragility, Merkel’s call for humility is not merely a personal virtue — it is a condition for democratic survival.

The deaths in Nepal’s streets are a tragedy, but they are also a message. Citizens — especially young citizens — no longer accept politics as entitlement. They demand service, transparency, and respect. What they are calling for, in essence, is humility.

For Nepal and for democracies everywhere, the lesson is the same: power without humility is brittle. It provokes resistance, erodes trust, and ultimately consumes itself. Power tempered by humility, however, can rebuild legitimacy and preserve the fragile but vital promise of democratic life.

Nowadays, Greece, like many other European countries, is confronting a deepening housing challenge. Rising rents, a shortage of affordable units, and limited new construction are placing growing strain on young people, families, and students. In response to this EU-wide phenomenon, the Greek Government has introduced a holistic set of policies aimed at delivering immediate relief while addressing structural weaknesses in the housing market.

Who Benefits from Greece's Housing Programs?

Central to the package is the Housing Benefit Program. It targets low- and middle-income households facing increased living costs. Through direct financial assistance, temporary rent subsidies, and refund arrangements, the program helps households preserve their homes in the face of market price volatility. Beyond providing economic support, these measures contribute to greater stability and dignity for renters across the country.

Assistance for students

Recognizing that students are particularly vulnerable

to rising rents, the “Student Housing Allowance”, introduced in 2023 offers financial support to those studying away from home. Eligibility is determined by income, property ownership, residency status, and academic performance, striking a balance between need and merit. It follows an aggregation pattern, where the higher number of students living together leads to a higher allowance. This allowance is intended to ensure that higher education remains accessible irrespective of students’ financial circumstances and aims to the alignment of student-living culture with the rest of Europe. Finally, it removes the student demand out of the real estate market significantly, leading to lower prices in the long run.

Is Homeownership Still Achievable for Young Greeks?

To broaden access to home ownership, the government has introduced the “Σπίτι Μου” (My Home) program. It provides, low-interest loans to firsttime buyers, with a focus on young couples who lack access to conventional financing. By lowering barriers to ownership, the scheme promotes economic independence and restores the feasibility of buying

a home for a new generation while at the same time contributes to the fight of the demographic problem.

Increasing housing supply

On the supply front of housing, the “Renovate & Rent” initiative refurbishes vacant or underused buildings and converts them into long-term, affordable rental units. This approach revitalizes neglected urban areas while increasing the stock of both rental and sale properties, making better use of existing structures rather than allowing them to remain idle.