Made with Matriarchs:

Crafting Heritage-Oriented Futures with the Karamojong

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at Lawrence Technological University. 2023

Ethan Walker

Thesis Committee:

Scott Shall, Thesis Committee Chair

Edward Orlowski, Committee Member

Dr Joongsub Kim, Committee Member

INSERT BLANK

(18pt space)

Made with Matriarchs: Crafting Heritage-Oriented Futures with the Karamojong (18pt space)

Ethan Walker

Lawrence Technological University, Southfield, Michigan 2023

Ethan Walker

Lawrence Technological University, Southfield, Michigan 2023

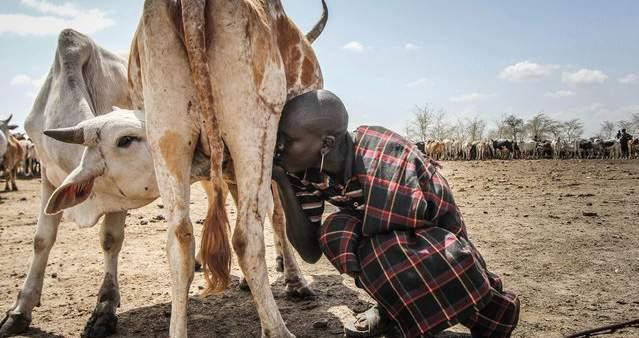

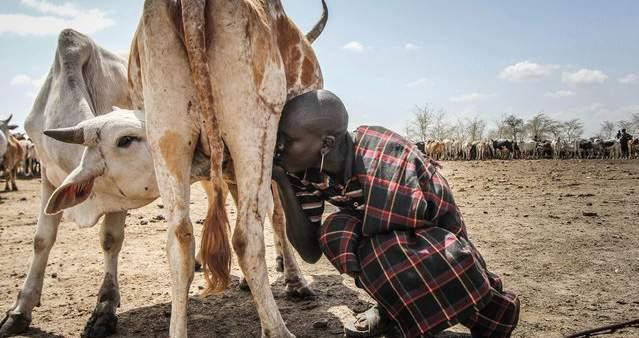

In the rural northeast of Uganda, the ethnic Karamojong are experiencing unprecedented pressures to change their ways of life (Knighton, 2017). As semi-nomadic pastoralists, these peoples are dependent on the health of their herds which is contingent on the health of their ancestral lands. Studies show that land health has deteriorated due to climate change, overgrazing and lack of mobility producing a vulnerability context which has attracted international attention. Interventions by foreign actors and the national government have attempted to improve public health while making recurring calls to transform Karamojong culture away from pastoralism towards sedentism and farming (Dbins, 2013). While appropriate in particular cases, the overwhelming call to cultural transformation undermines pastoral ways of life and could be at odds with the capabilities of the land, potentially undermining the pastoral ways of life. These globalizing influences extend beyond policy-making and have fundamentally altered the process of architectural production and construction in the region.

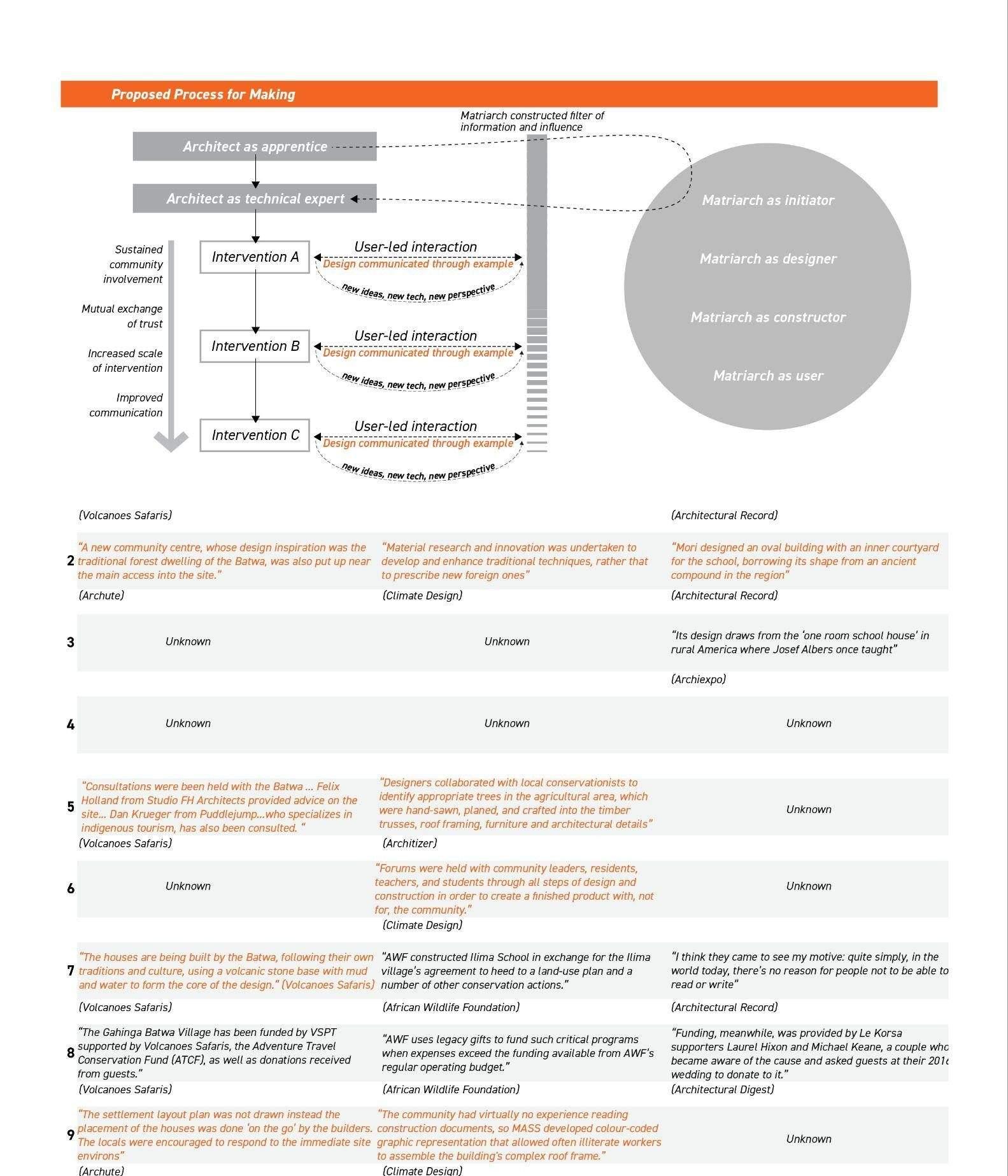

In response, this thesis proposes an iterative, heritage-based approach to design and construction, crafted to mitigate the increasingly harmful effects of globalization upon the traditionally semi-nomadic societies of northern Uganda. In this approach, alternative futures are imagined by reconsidering the role of the architect in relation to the pre-colonial keepers of the built environment; the Matriarchs. When working within this alternative arrangement, architects would work responsively with Matriarchs, lengthening the process of interaction in favor of a responsive design methodology that strengthens the Matriarchs power of architectural self-determination. Strategies to equip pastoralist architecture with greater autonomy are imagined, proposed and filtered through a Matriarch-led process to determine what is appropriated, effective and ultimately in the best interest of their desired way of life.

KEYWORDS: Matriarch; Pastoralism; Globalization; Semi-Nomadic Tribes; Heritage-Based Design

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I am extremely grateful to Scott Shall, Edward Orlowski and Dr Joongsub Kim who were always eager to participate in this geographically distant research. Their well-considered comments perpetually focused the work and for that I am thankful.

)

0.1.TABLE OF CONTENTS

page #3 Part 01: ABSTRACT

page #6 Part 02: ARGUMENT

page #6 2.1. Historical Context

page #7 2.2. Vulnerability and Change

page #8 2.3. An Expanding Legacy of Foreign Interventionism

page #8 2.4. Markers of Impositional Architecture

page #11 2.5. The Relegation of Traditional Building in Karamoja

page #12 Part 03: DESIGN INVESTIGATION

page #11 3.1. Organizational Model of Working

page #12 3.2. Speculative Adaptations to the Built Environment

page #14 3.3. Iterative Acts of Communal Construction

page #19 Part 04: RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

page #19 4.1. Metrics of Success

page #20 4.2. Conclusions

page #21 Appendix A: Literature Review

page #23 Appendix B: Precedent Analysis

page #28 Appendix C: Impositional Framework Analysis

page #29 Appendix D: Photographs of Interventions

page #32 REFERENCES

(18pt space)

0.2.LIST OF FIGURES AND IMAGES

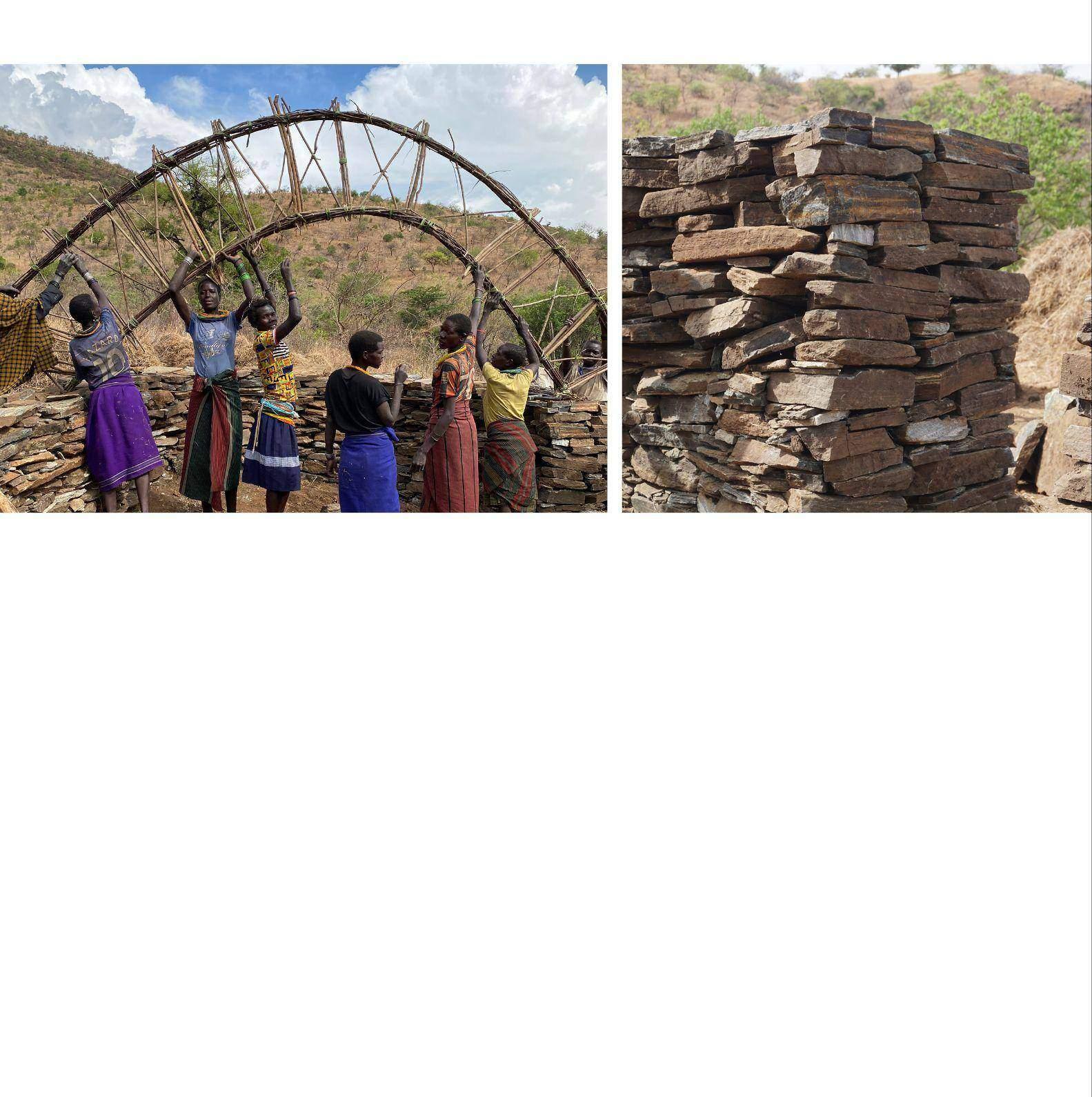

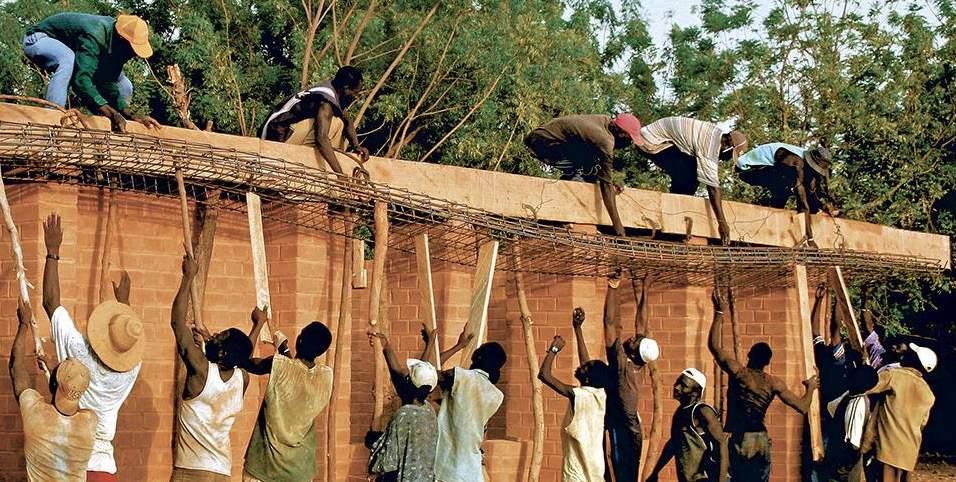

page #3 Figure 1.1: Matriarchs constructing a dwelling near Moroto (Author, 2023)

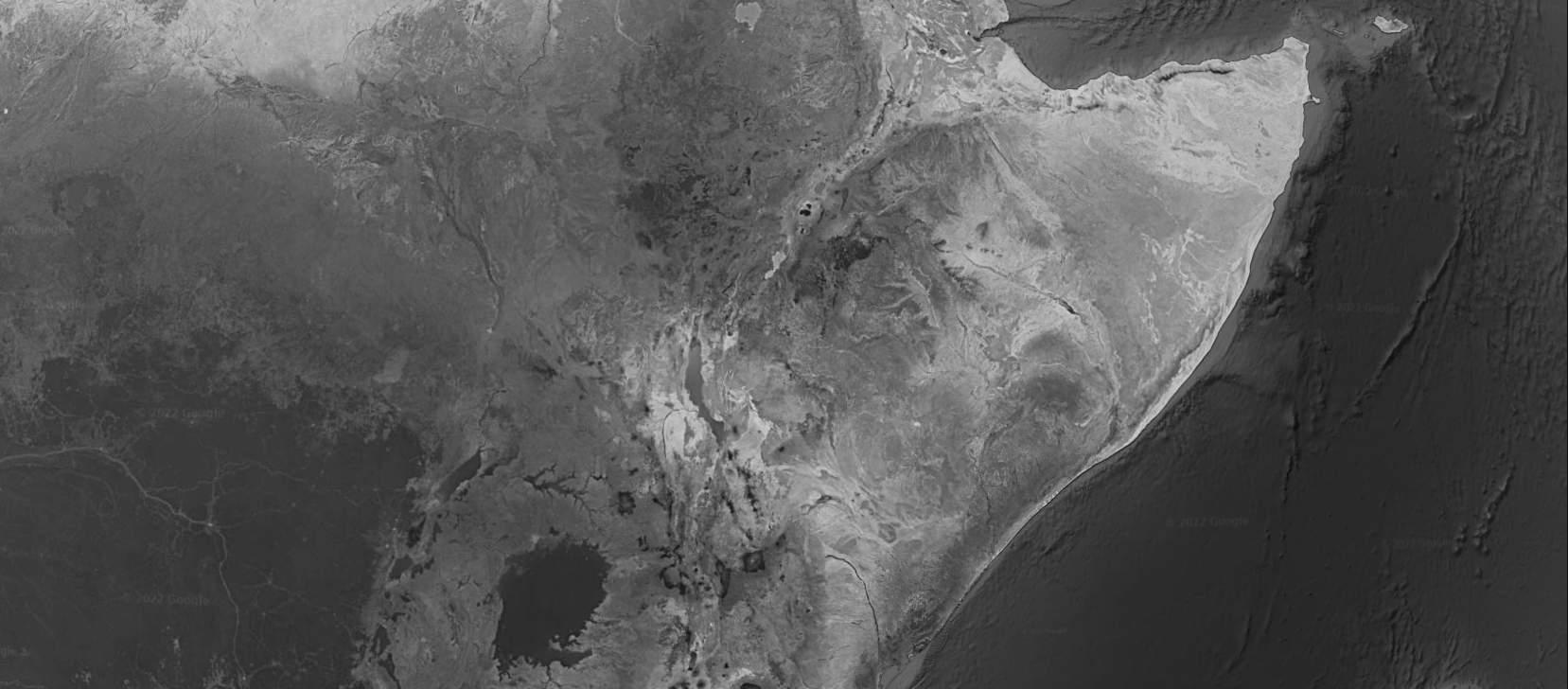

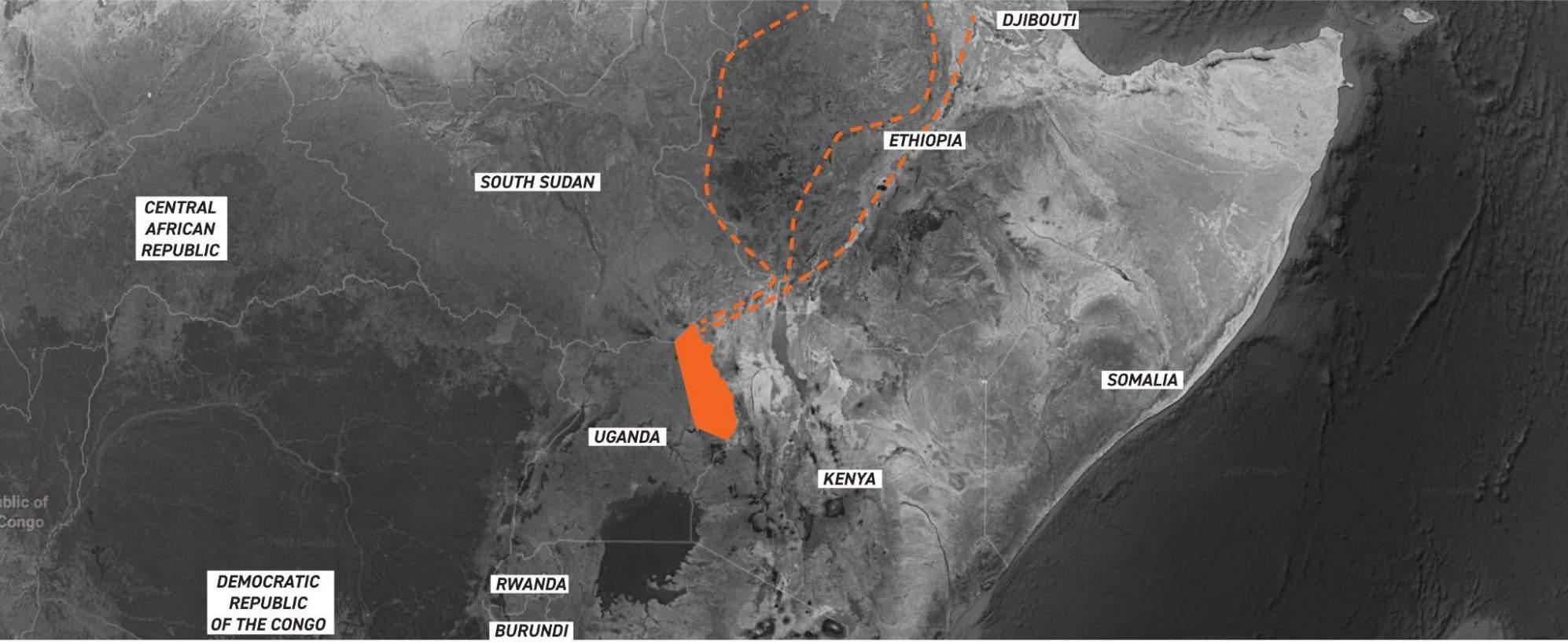

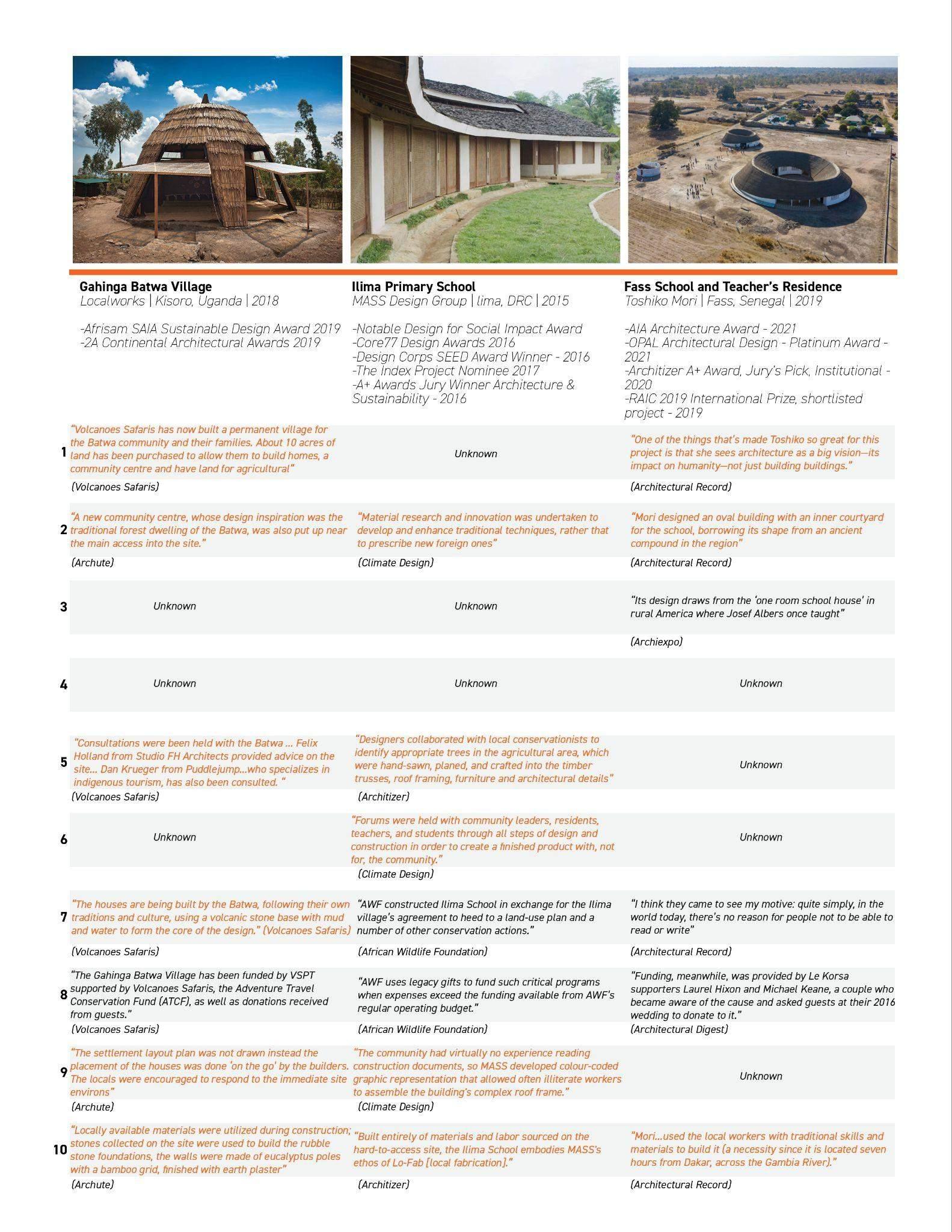

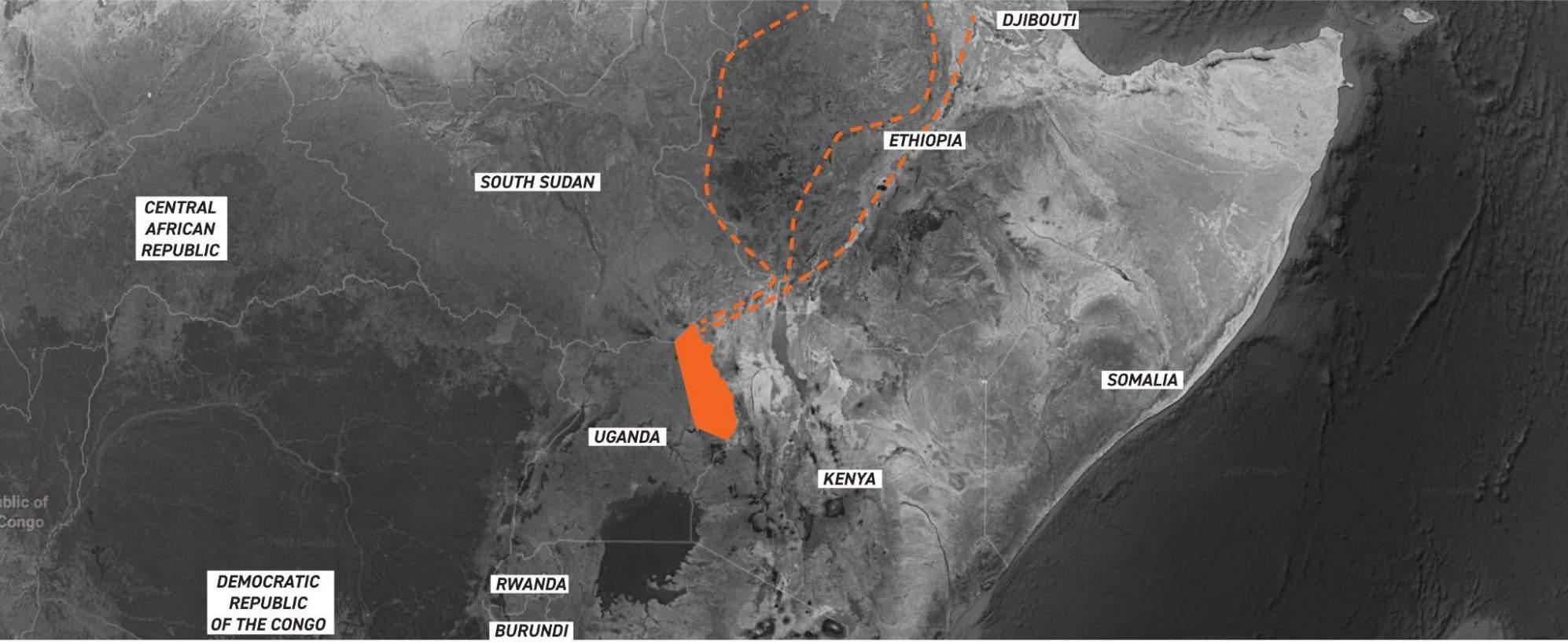

page #6 Figure 2.1: Map of East Africa (Author, 2022)

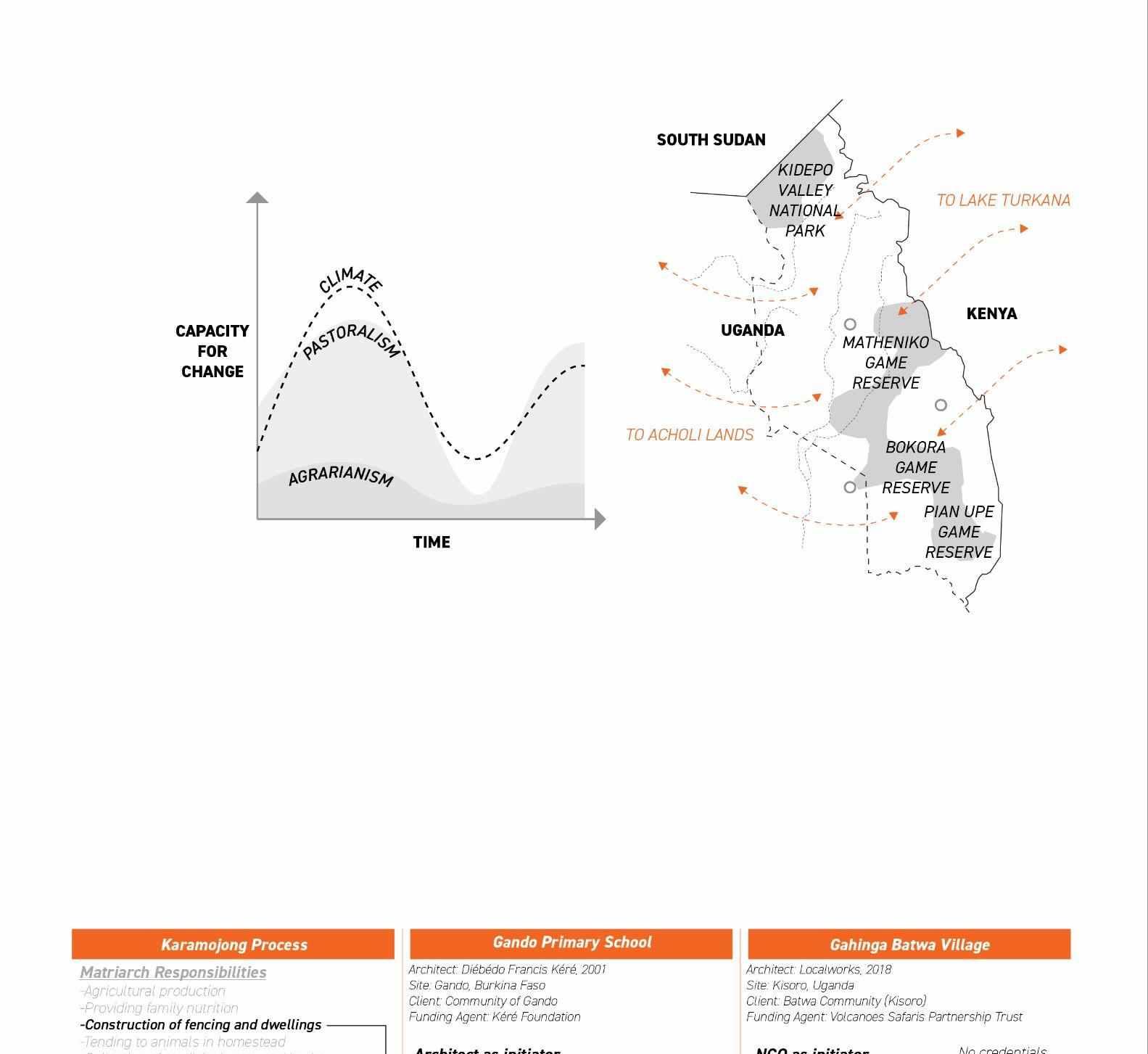

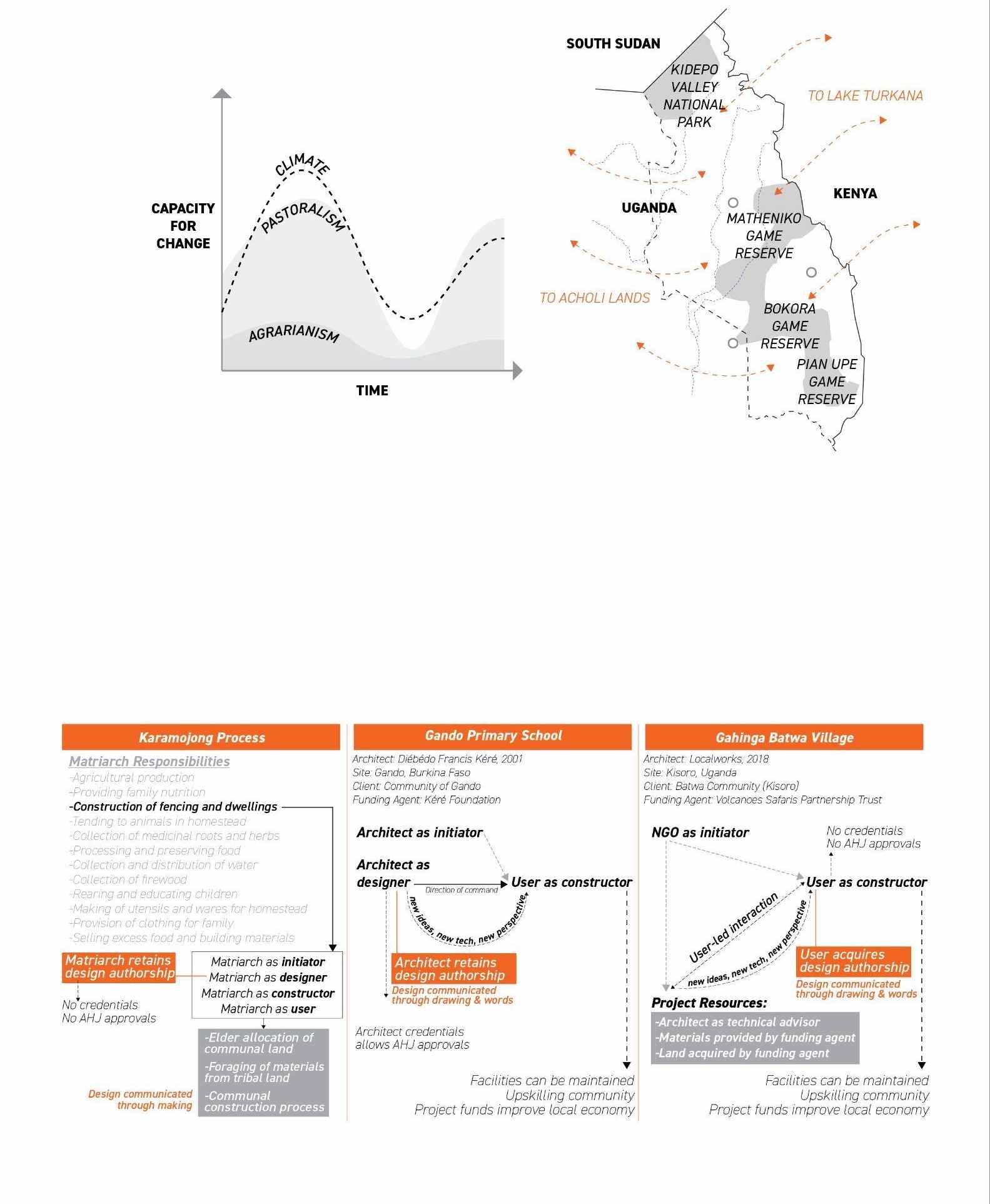

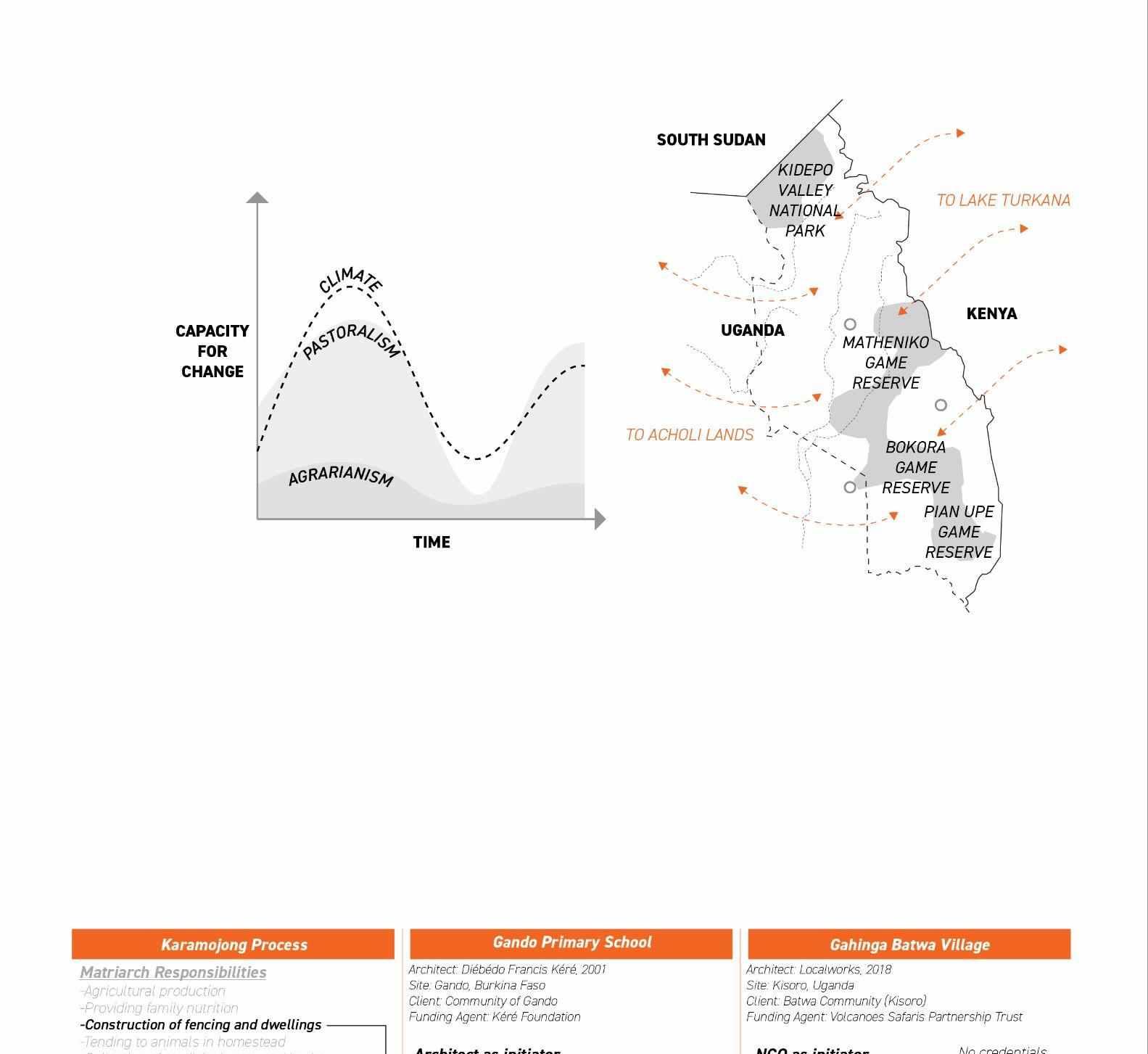

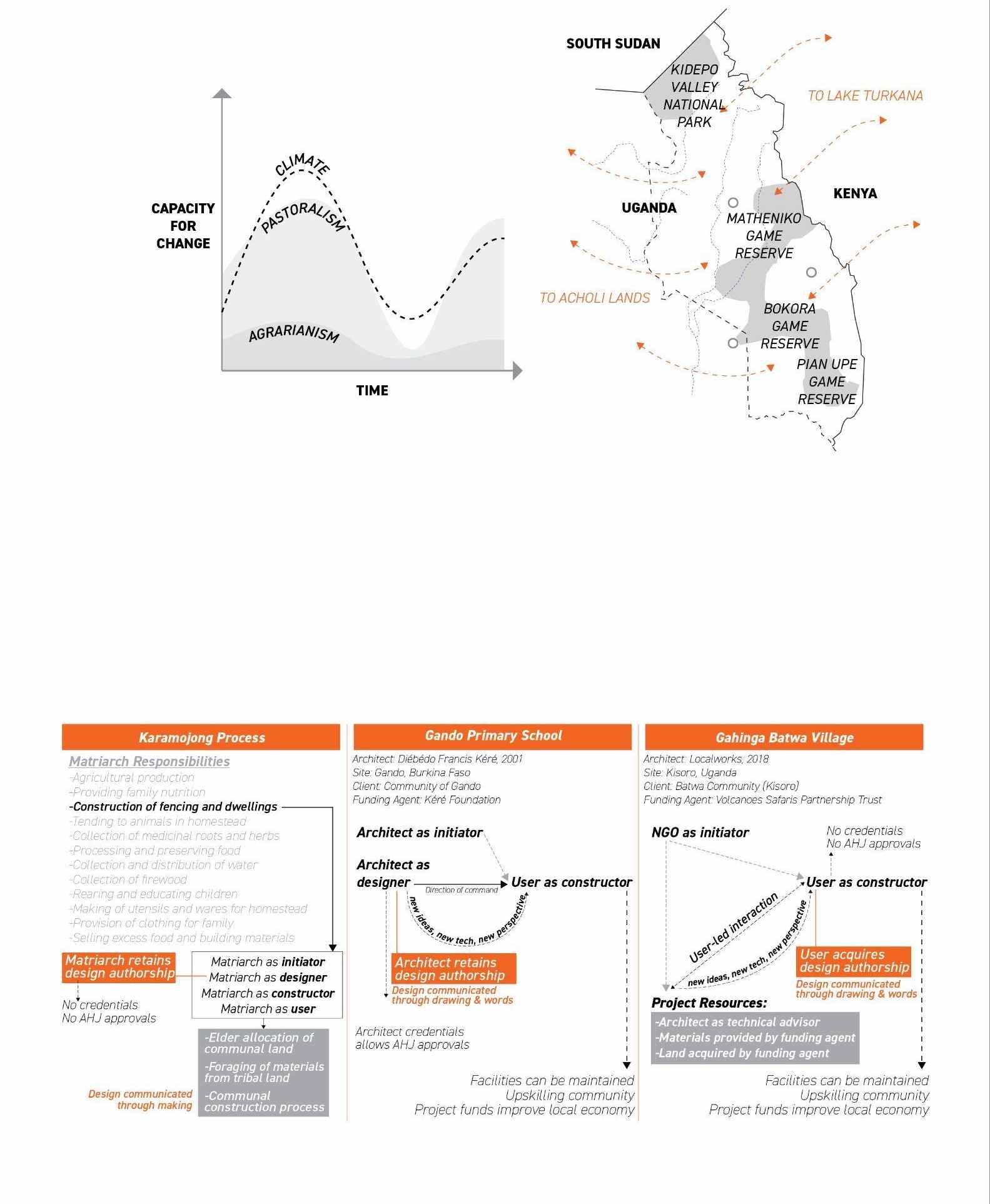

page #7 Figure 2.2: Livelihood Capacity for Change (Author, 2022)

page #7 Figure 2.3: Land Obstruction Map of Karamoja (Author, 2022)

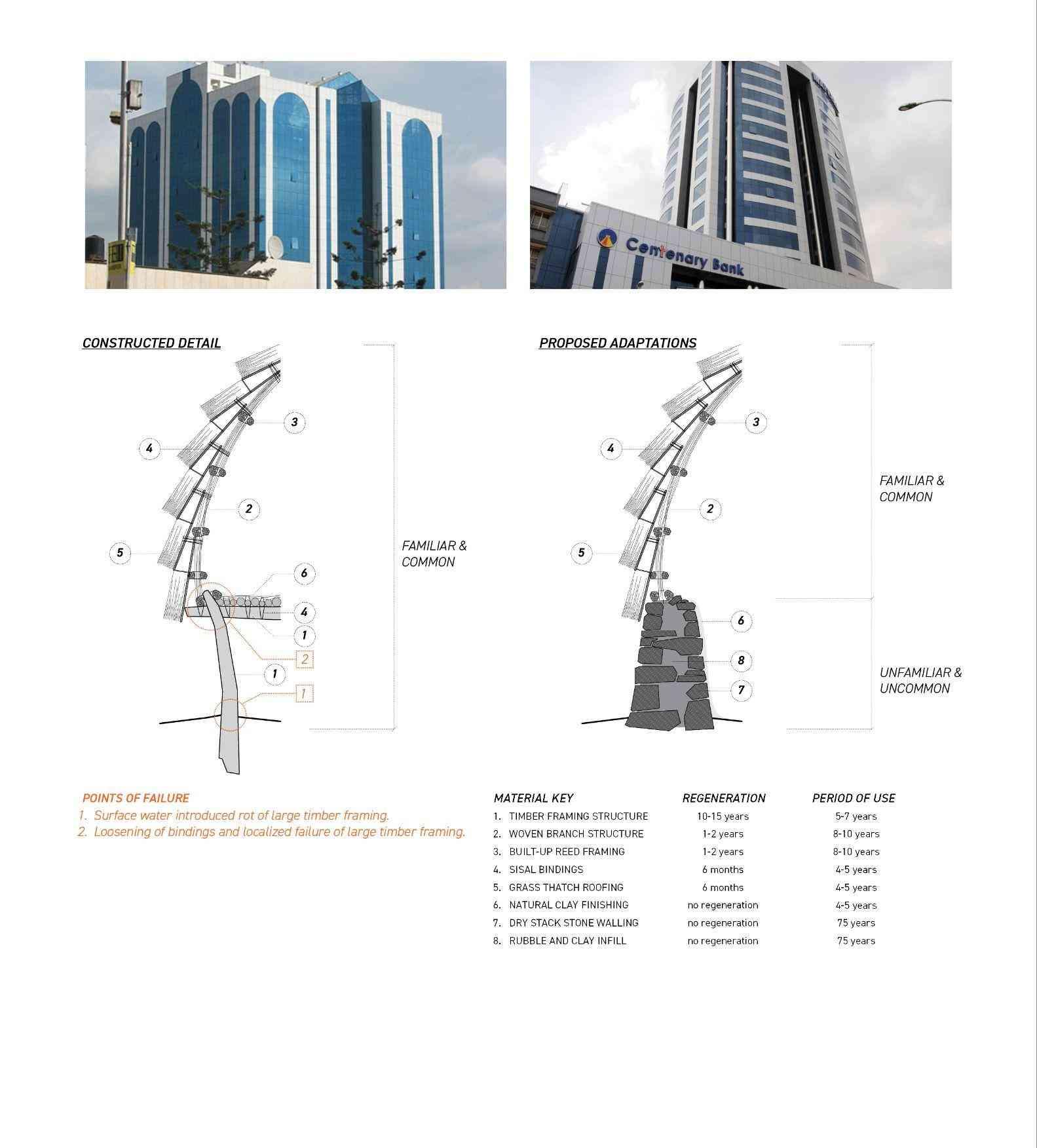

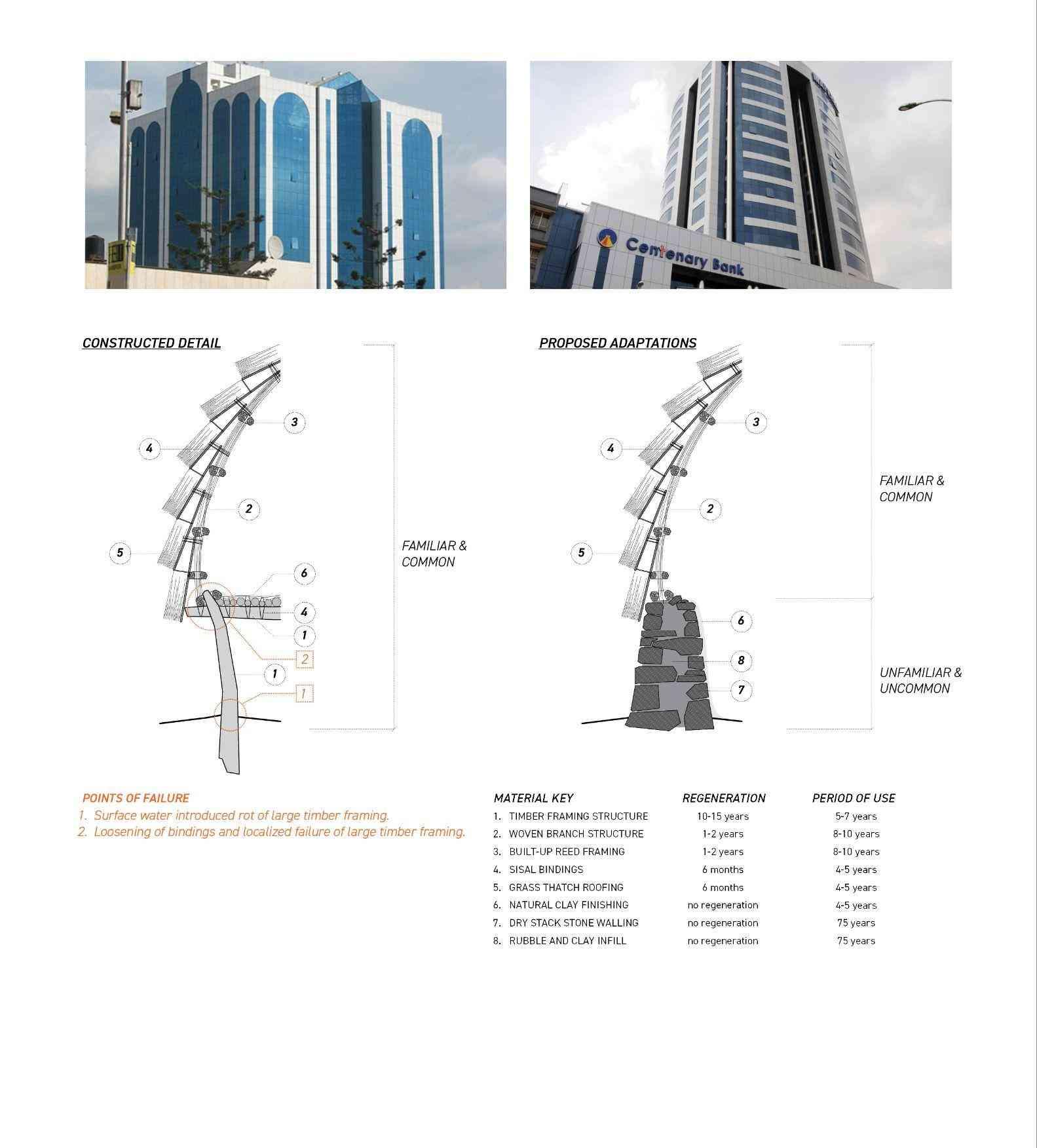

page #9 Figure 2.4: Analysis of Contextual Architecture (Author, 2022)

page #10 Figure 2.5: Models of Intervention (Author, 2022)

page #11 Figure 2.6: Modern Building Designs in Uganda (Ssentoogo & Partners, 2015)

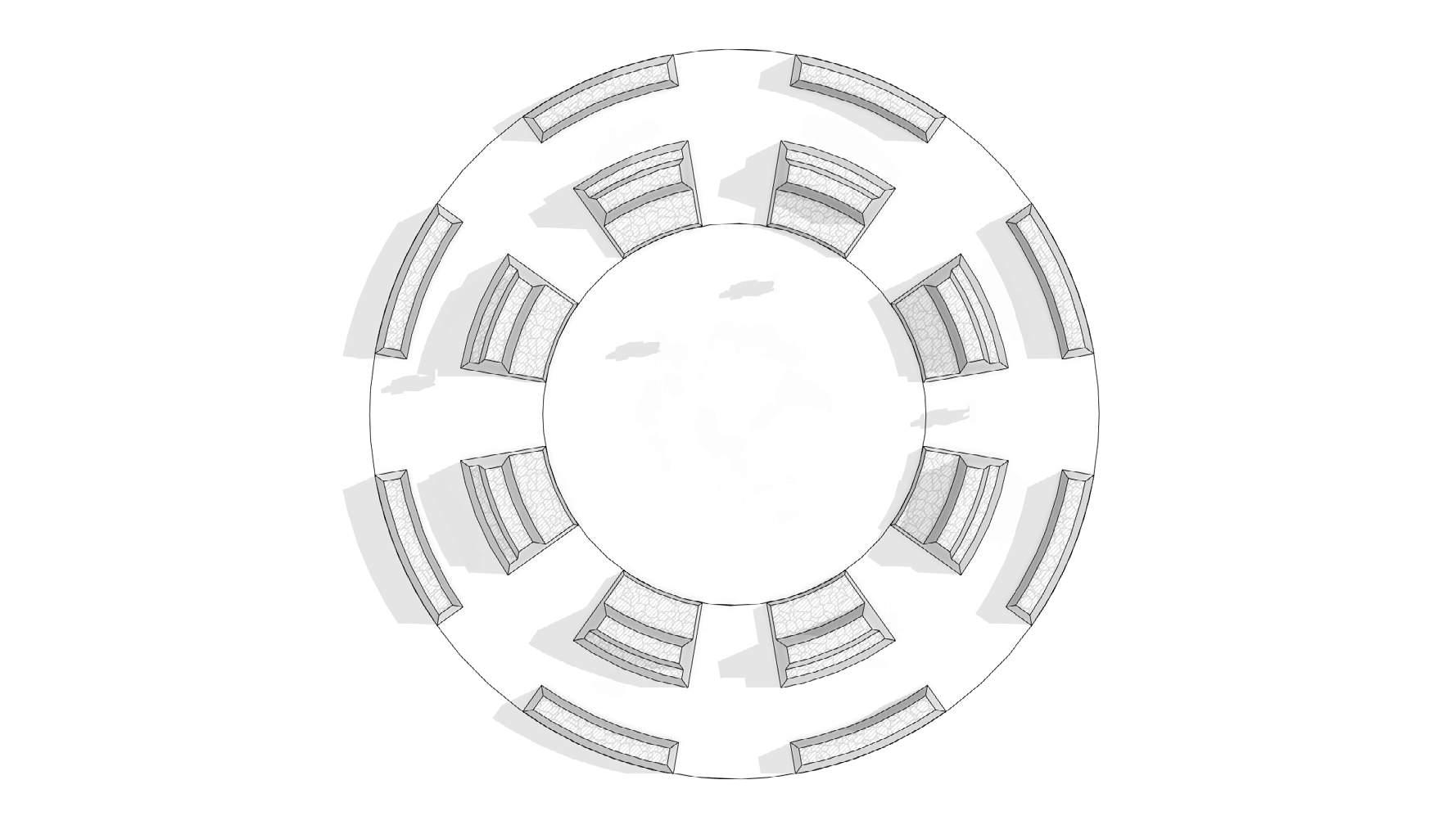

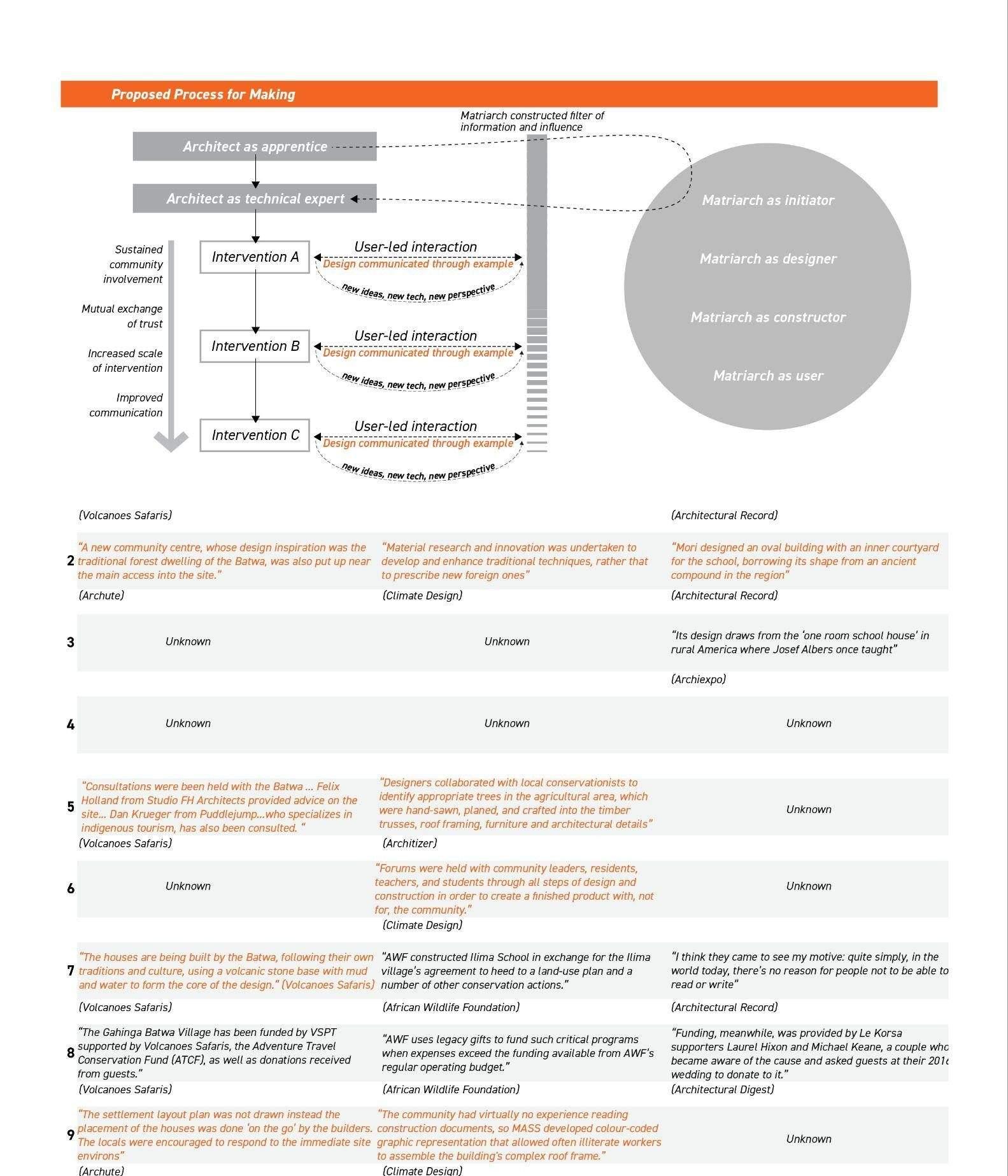

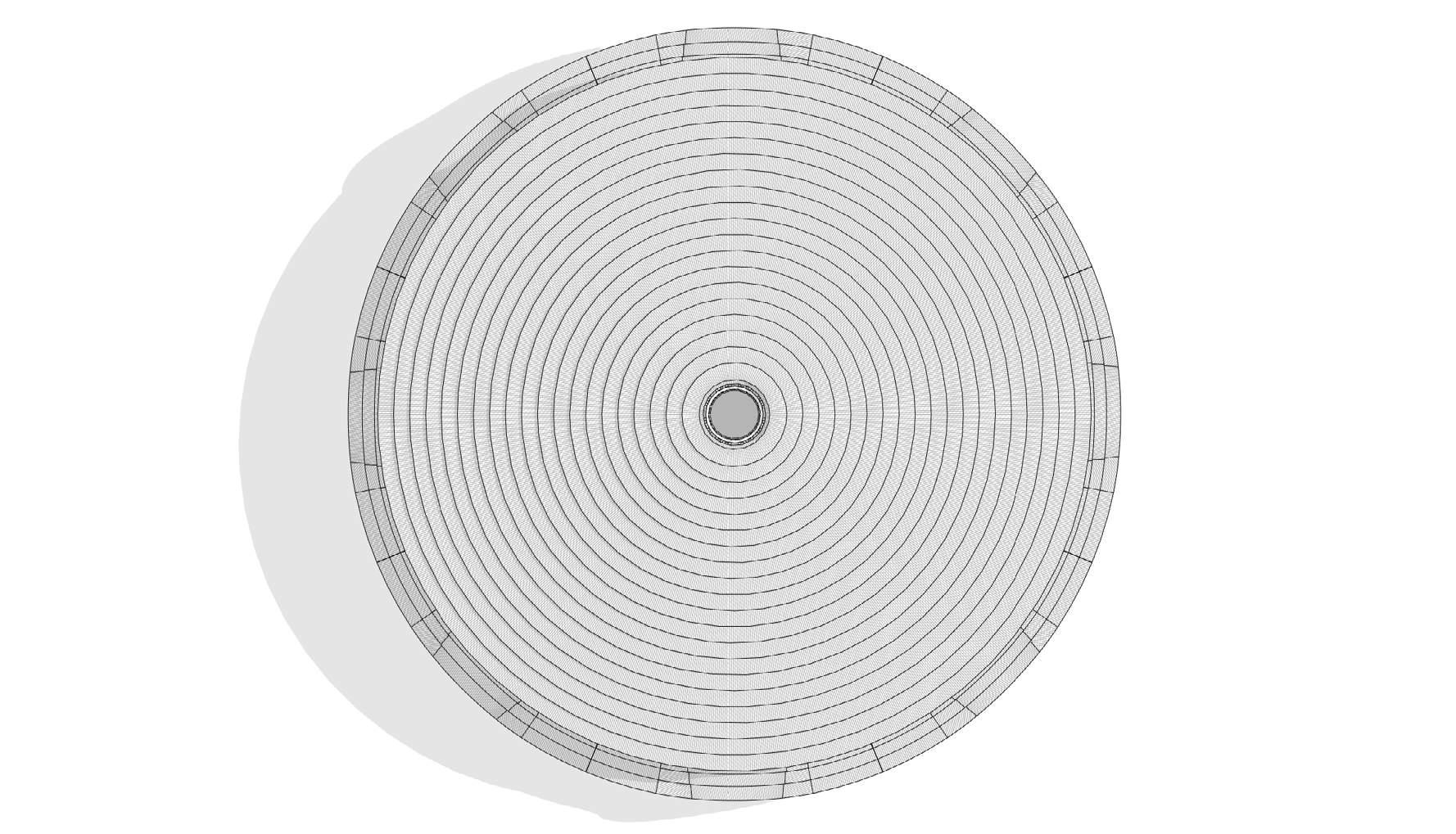

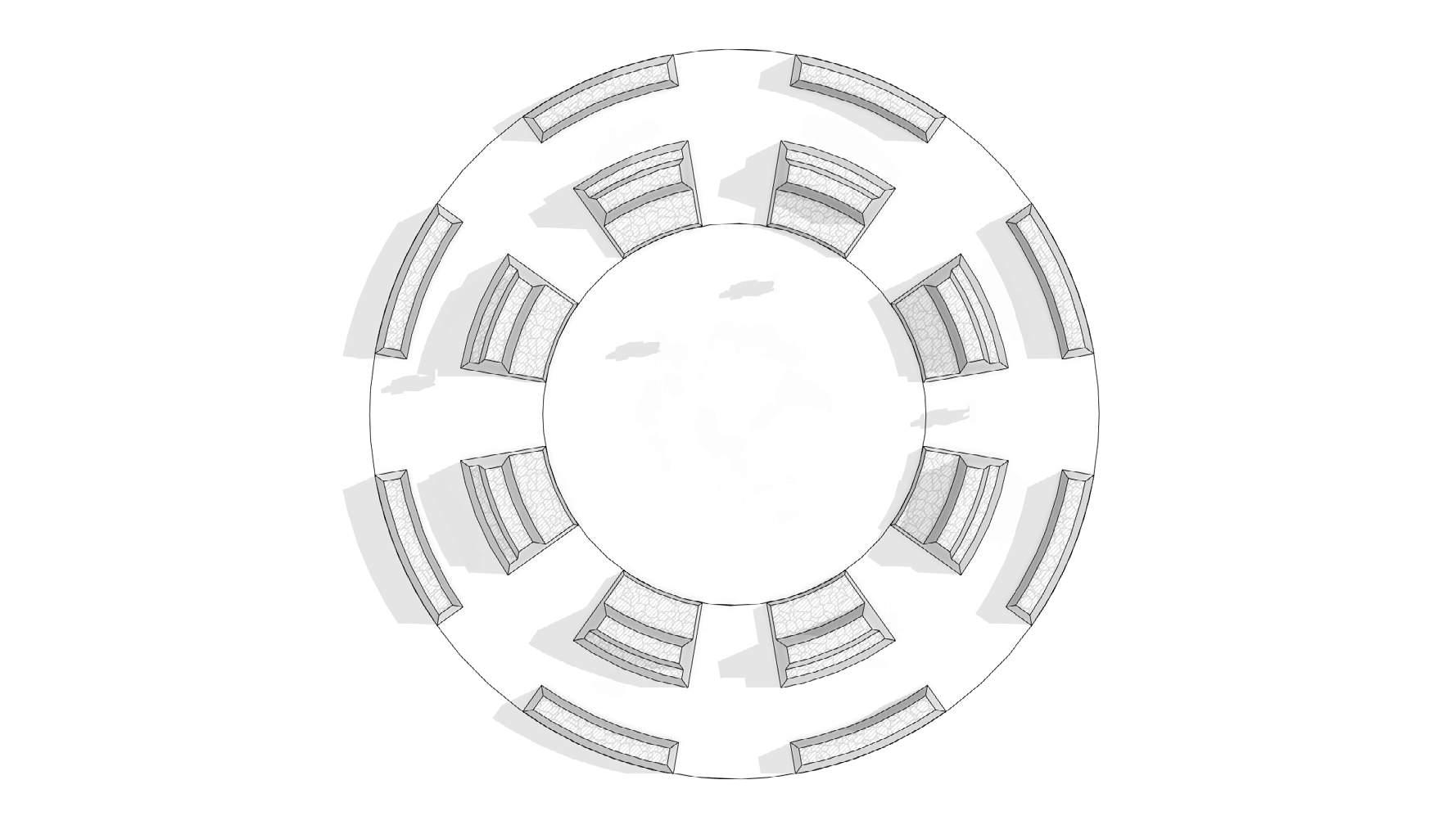

page #12 Figure 3.1: Model of Intervention (Author, 2023)

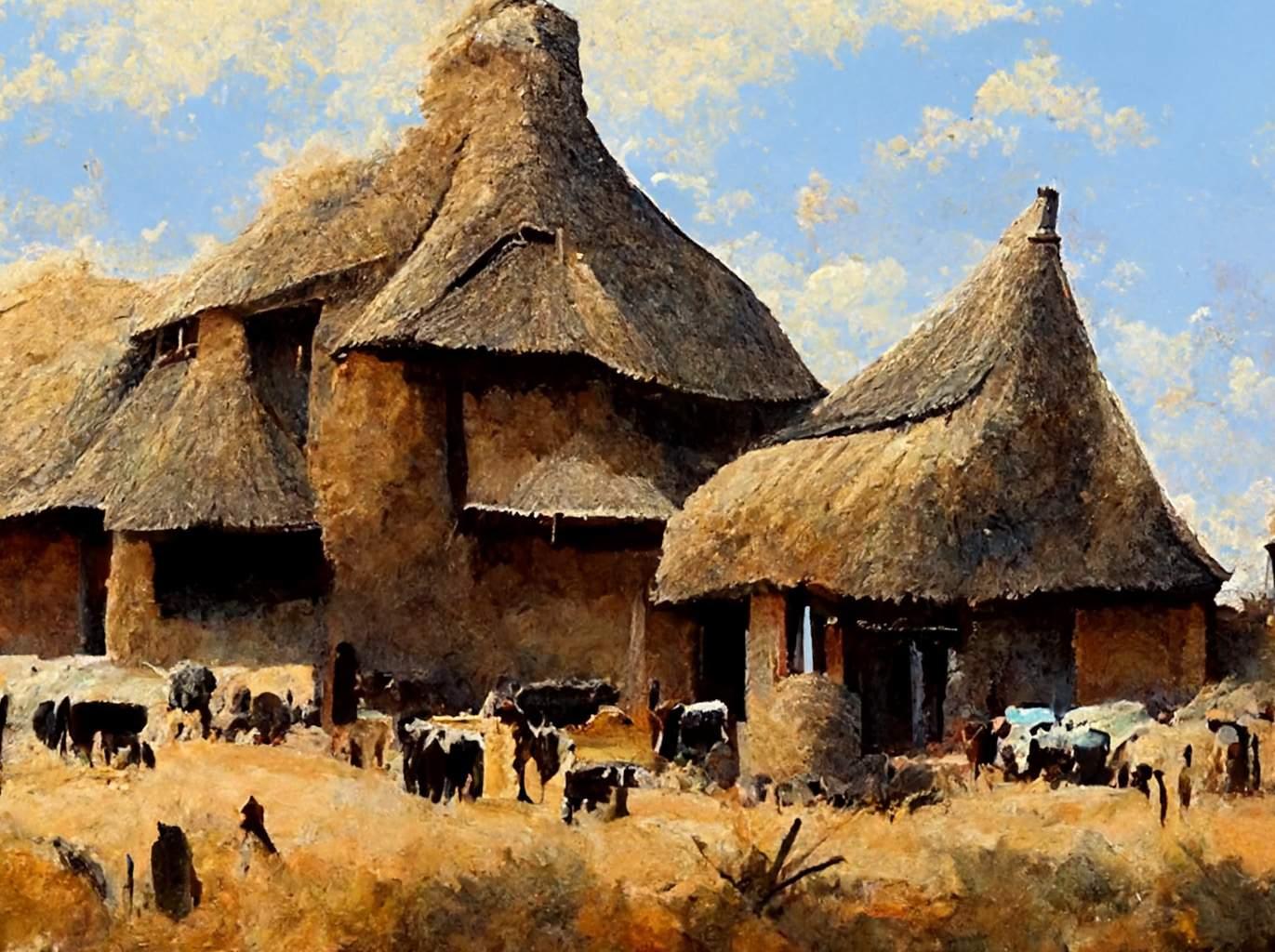

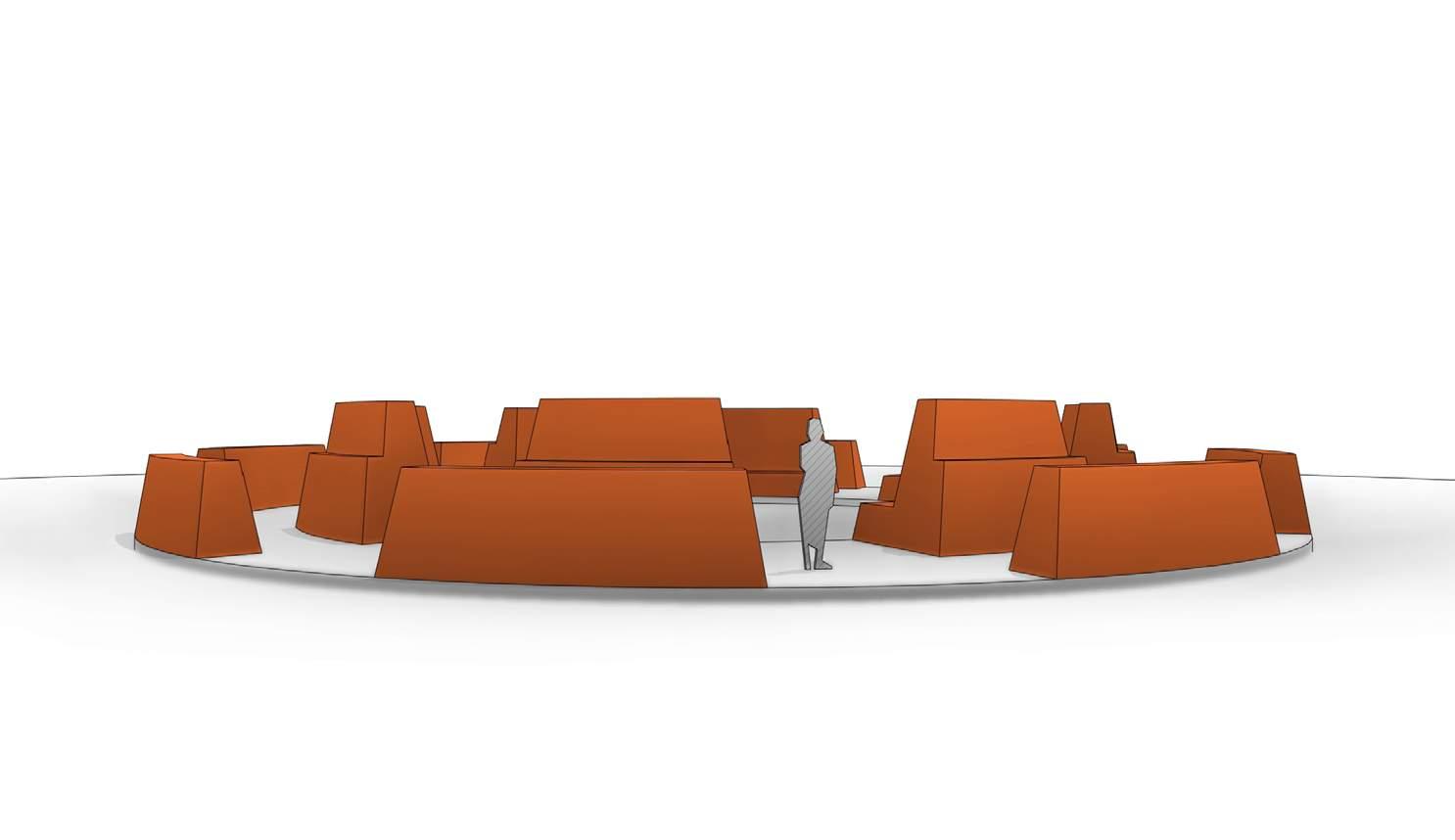

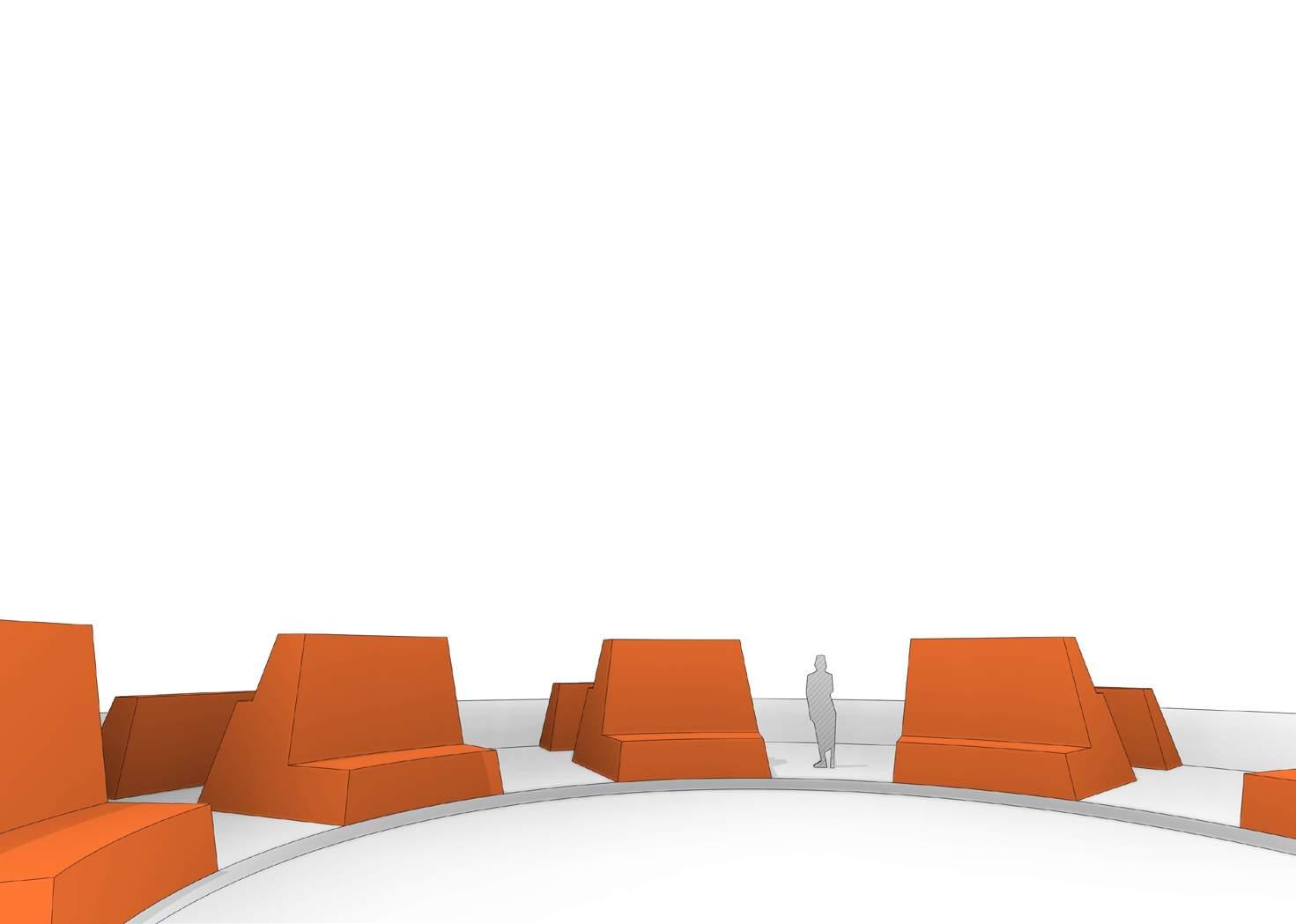

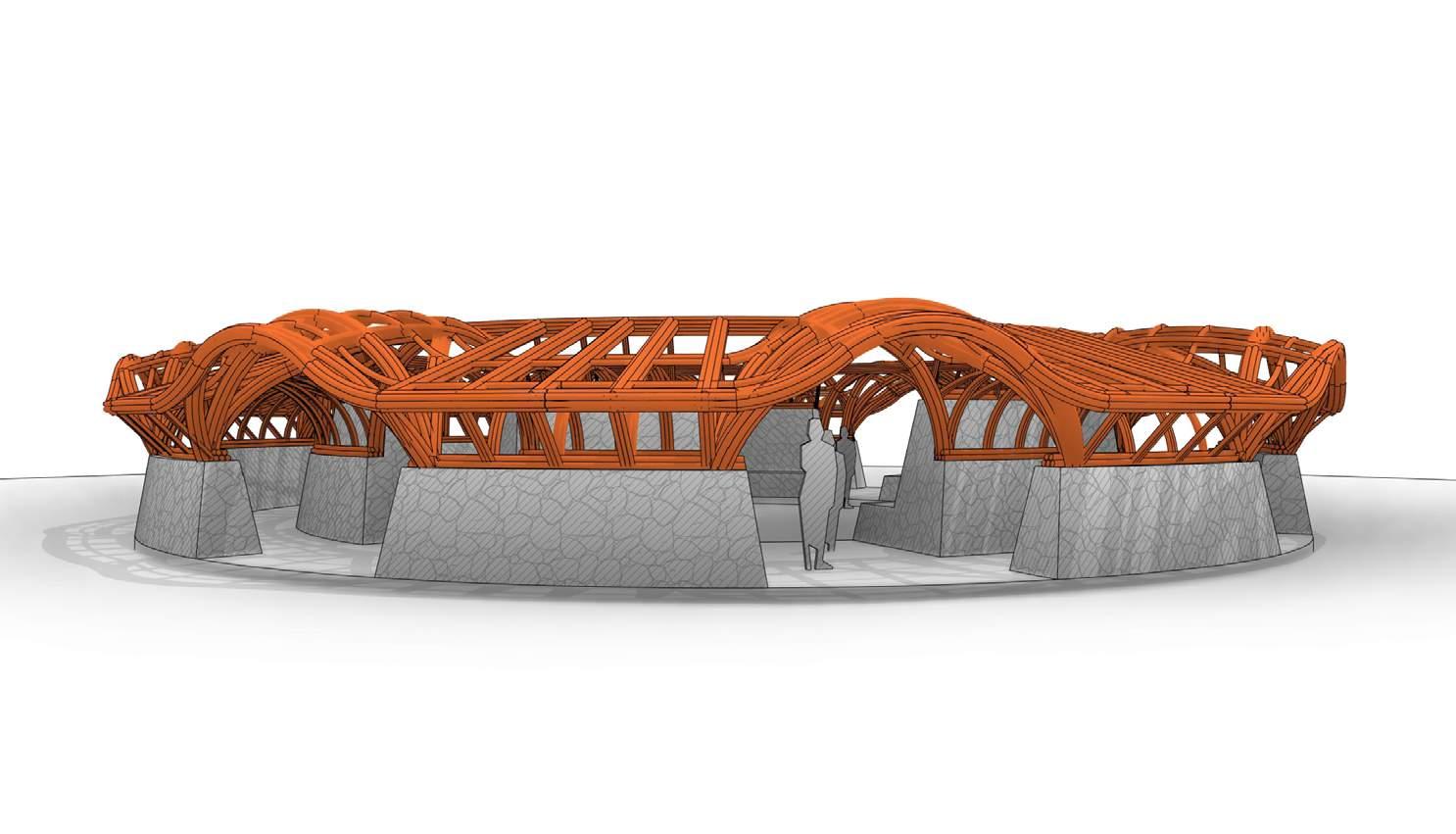

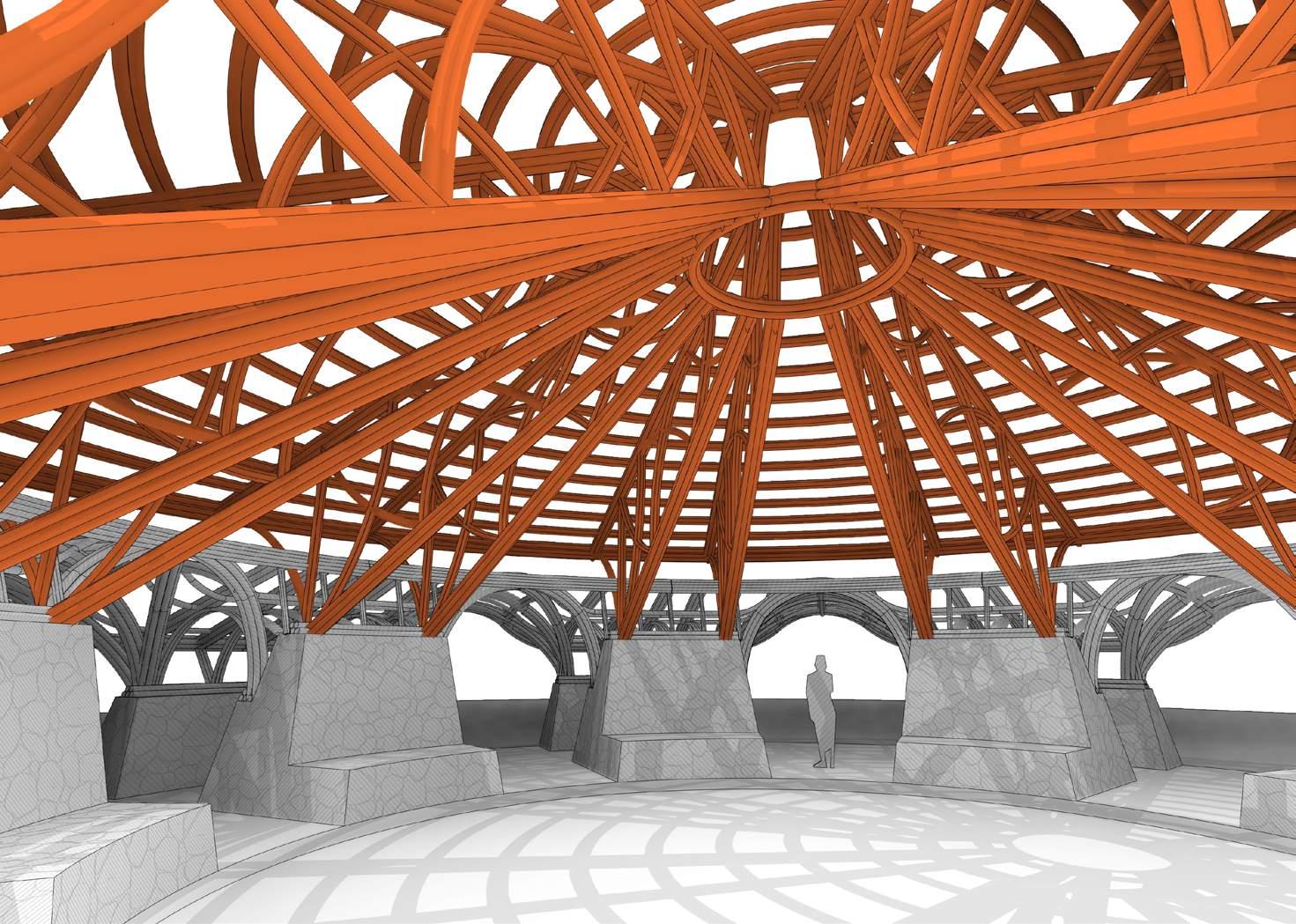

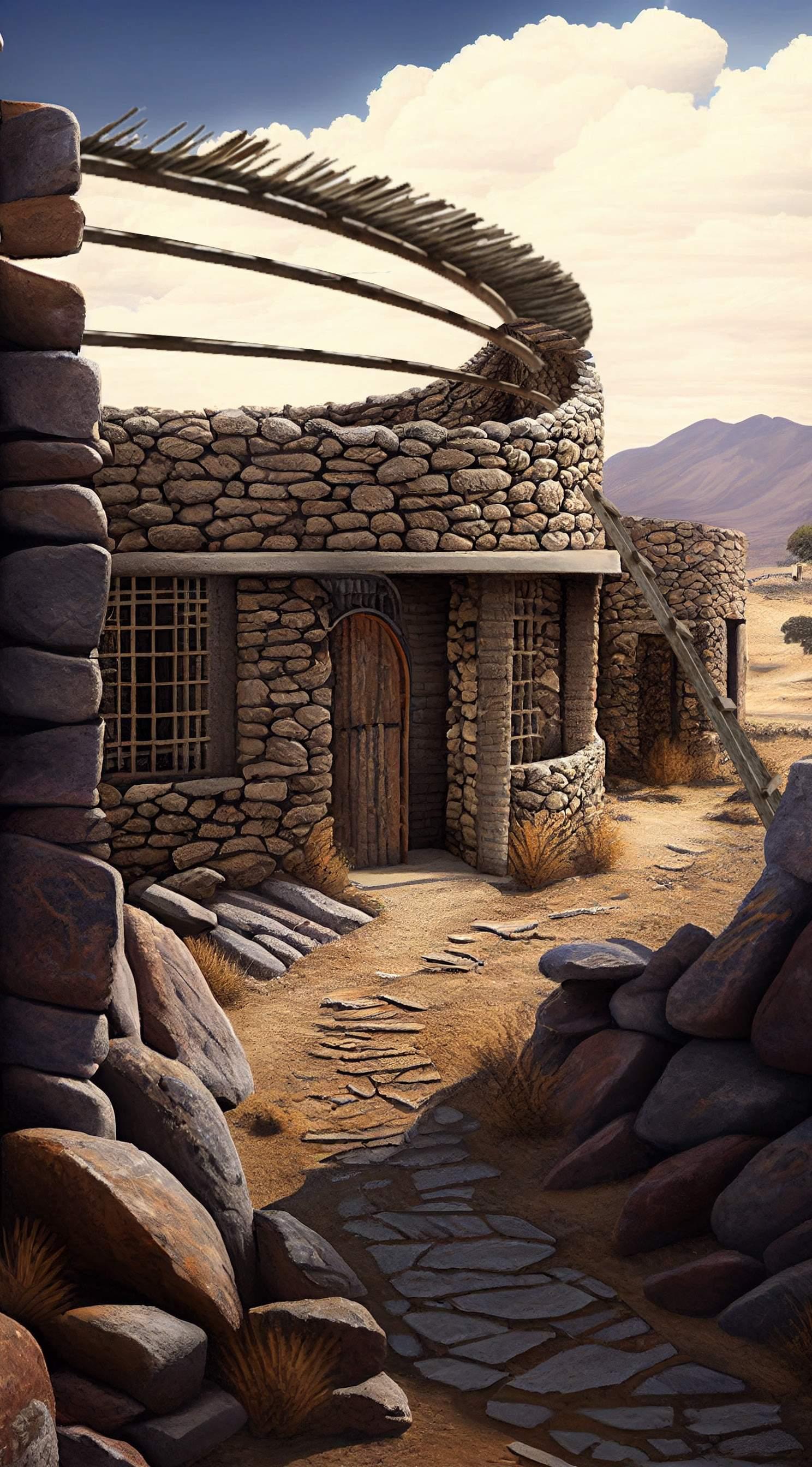

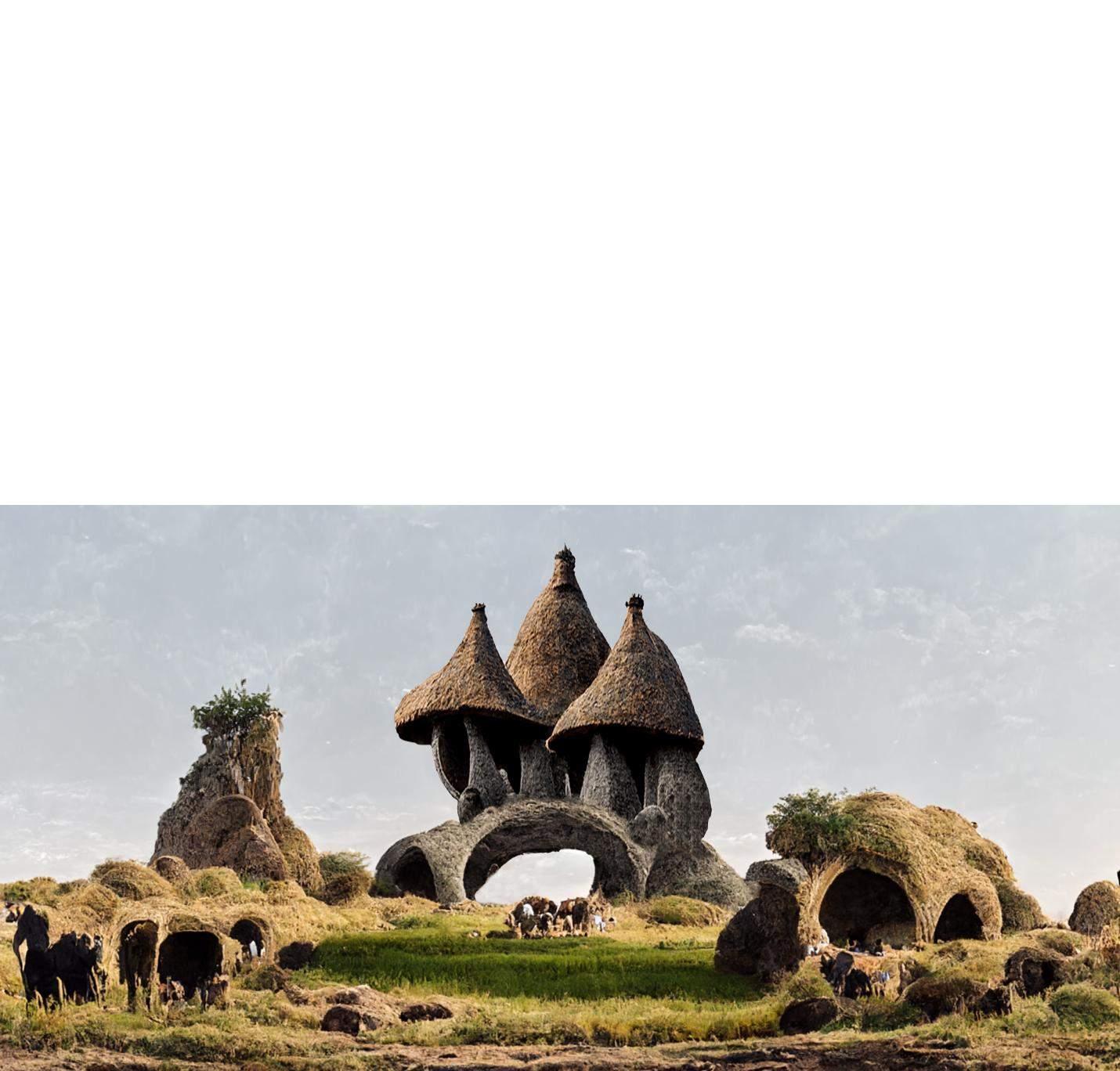

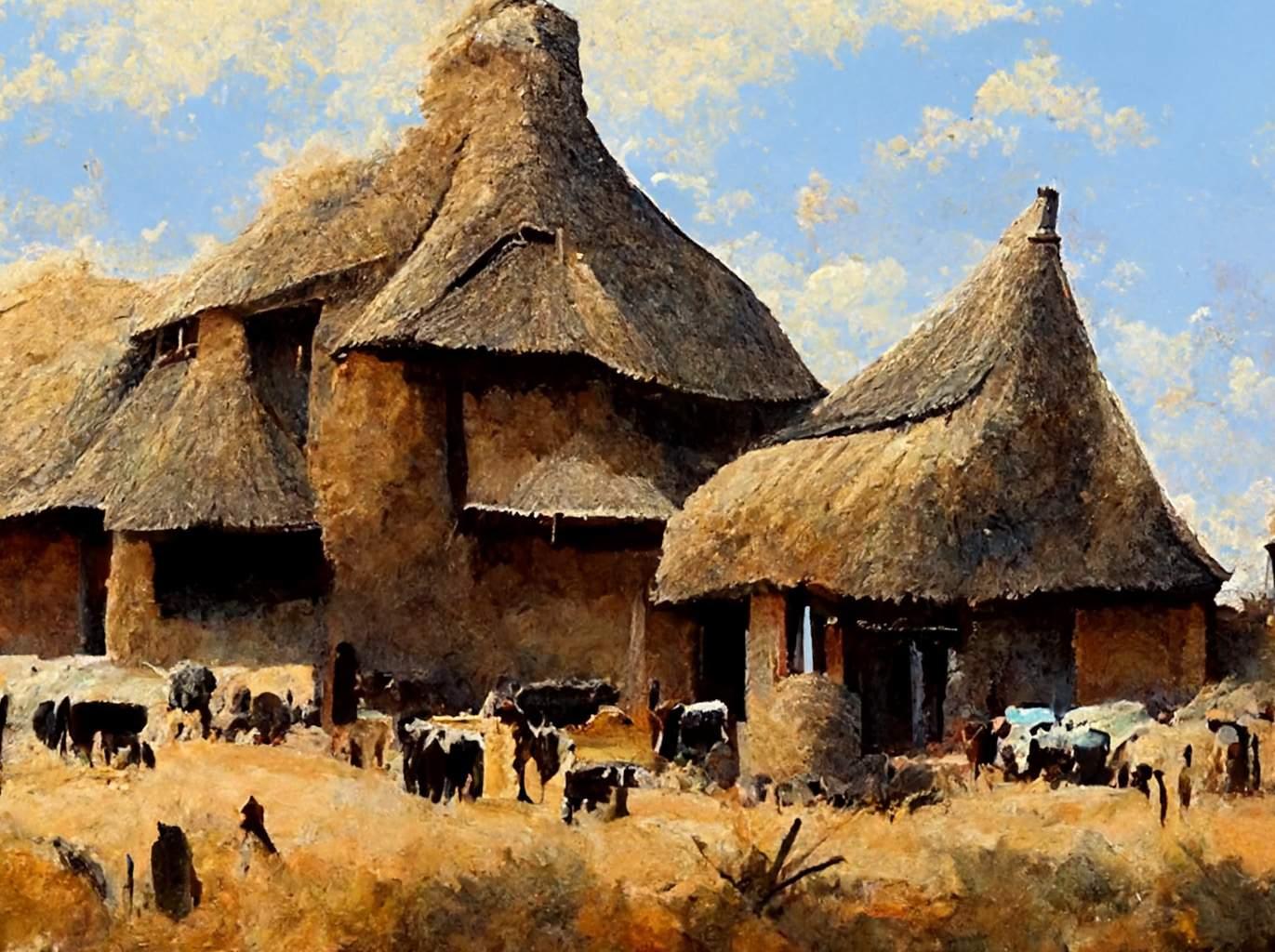

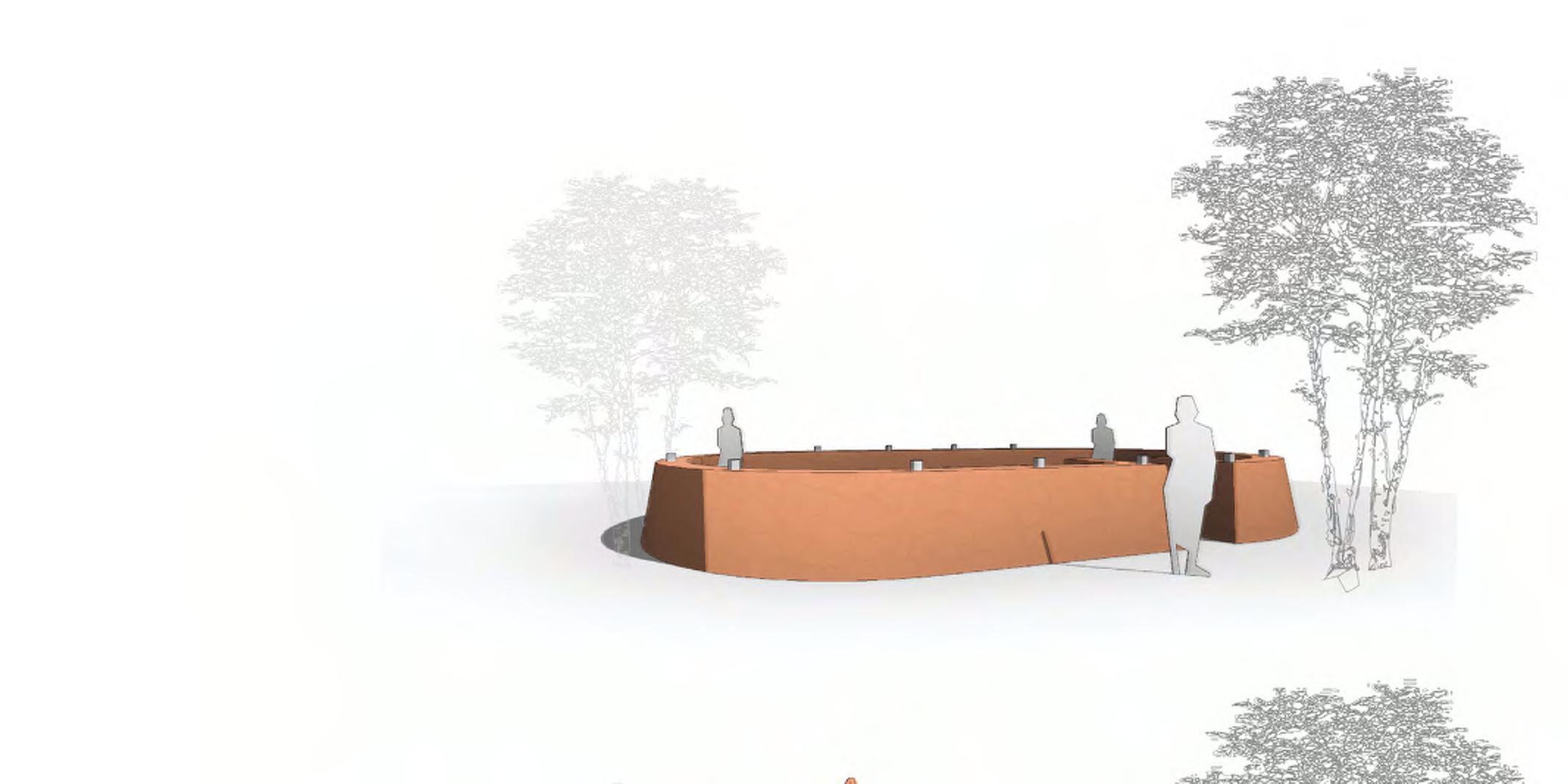

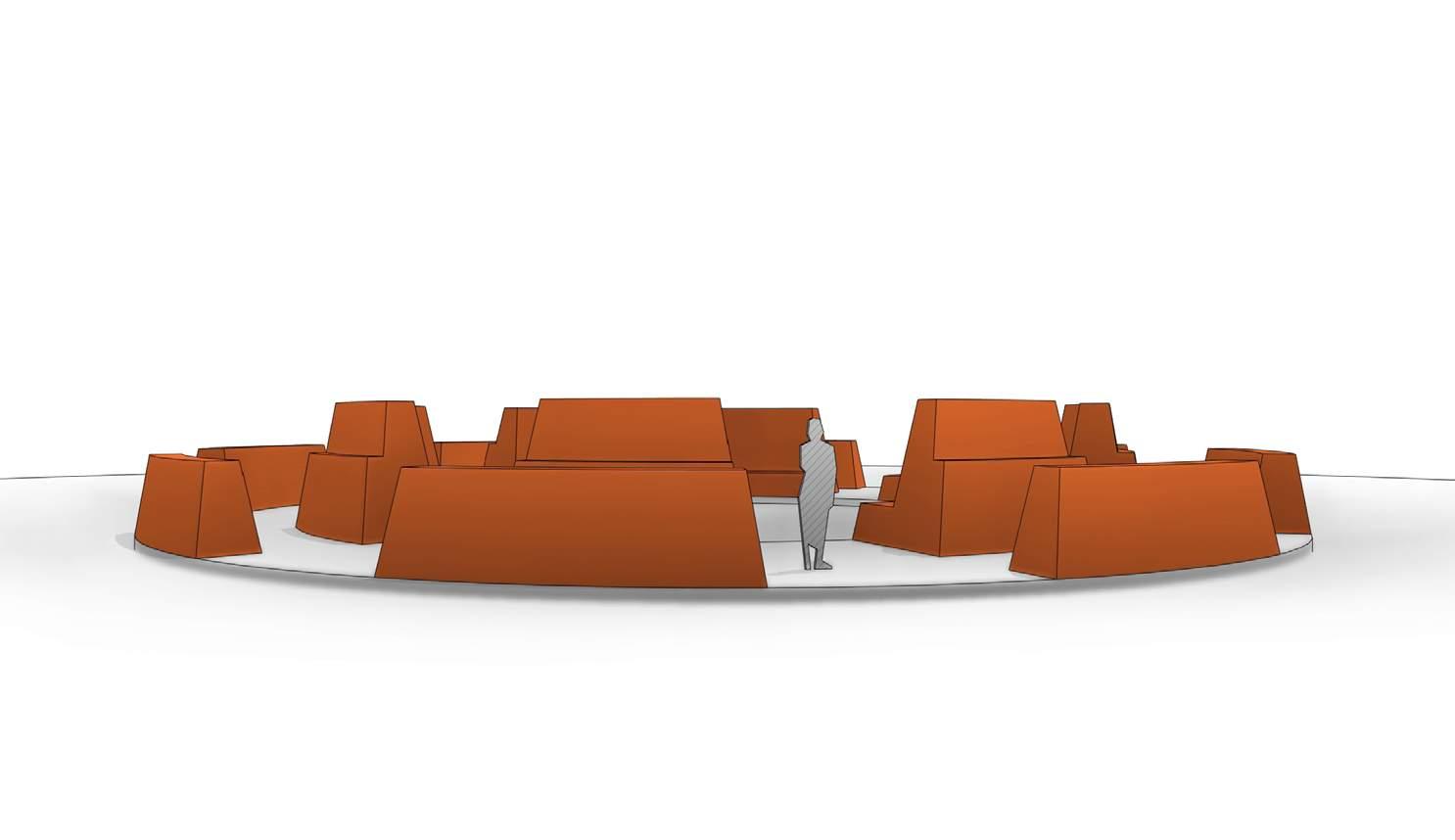

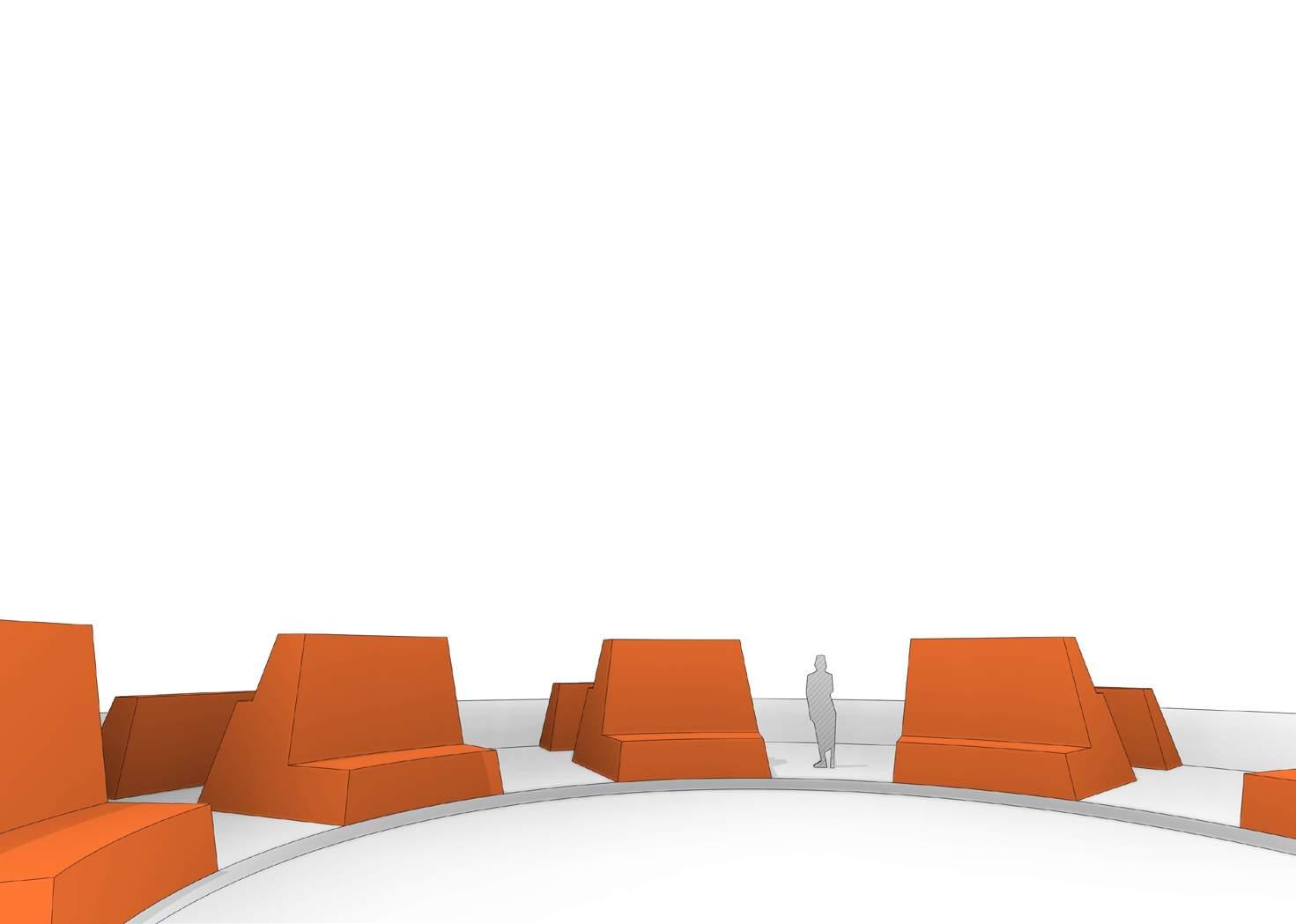

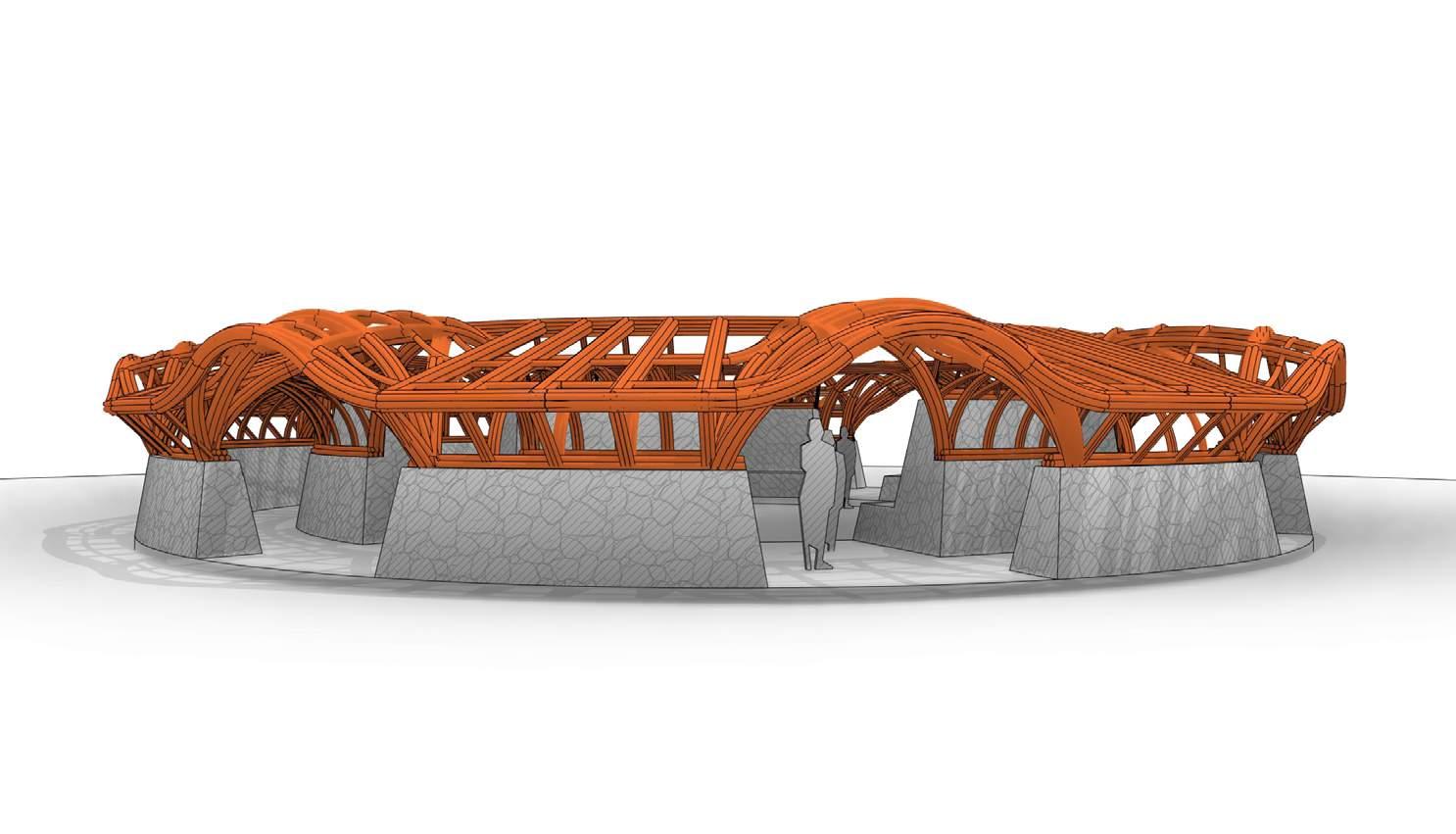

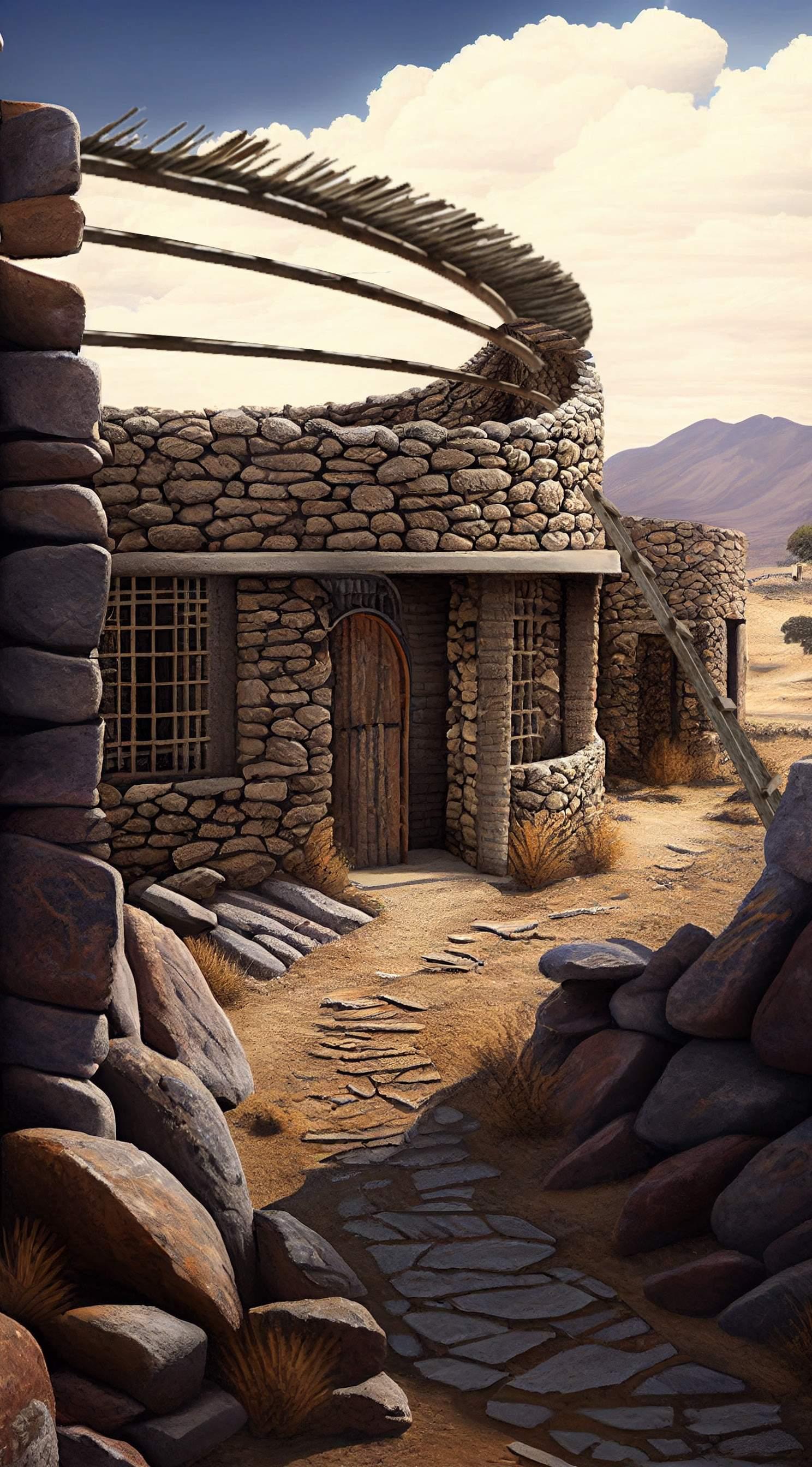

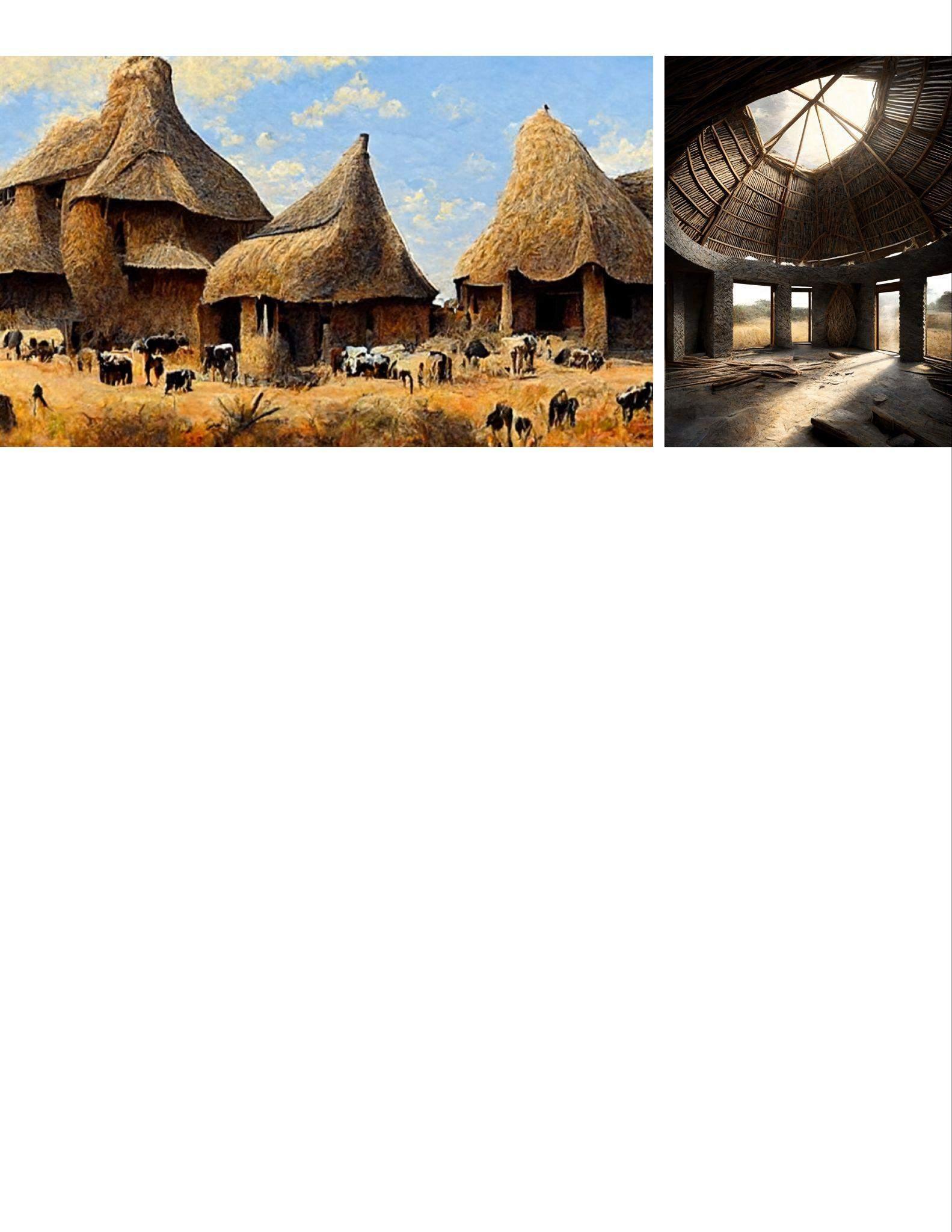

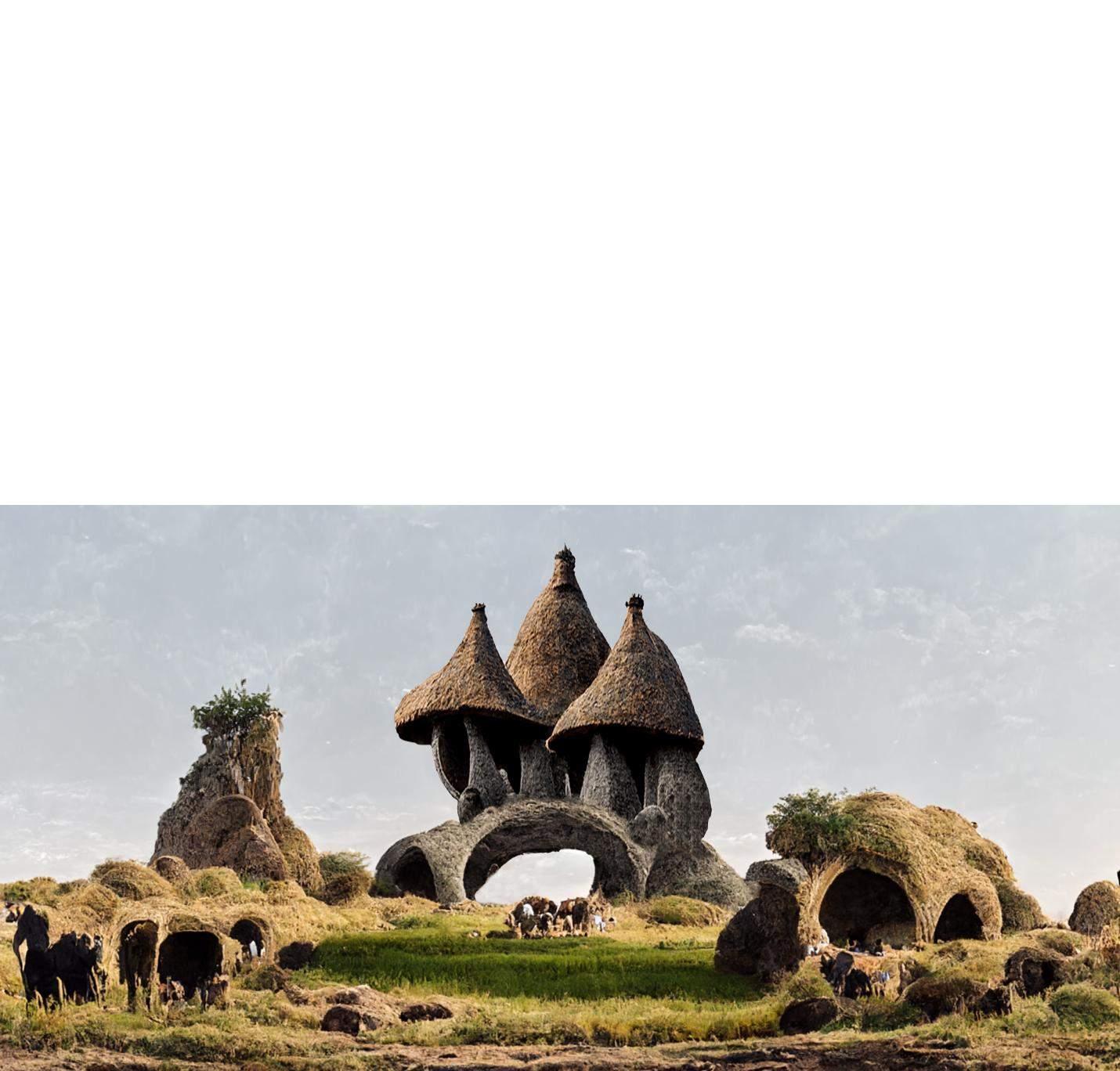

page #13 Figure 3.2: Midjourney image used in conversation with community (Author, 2023)

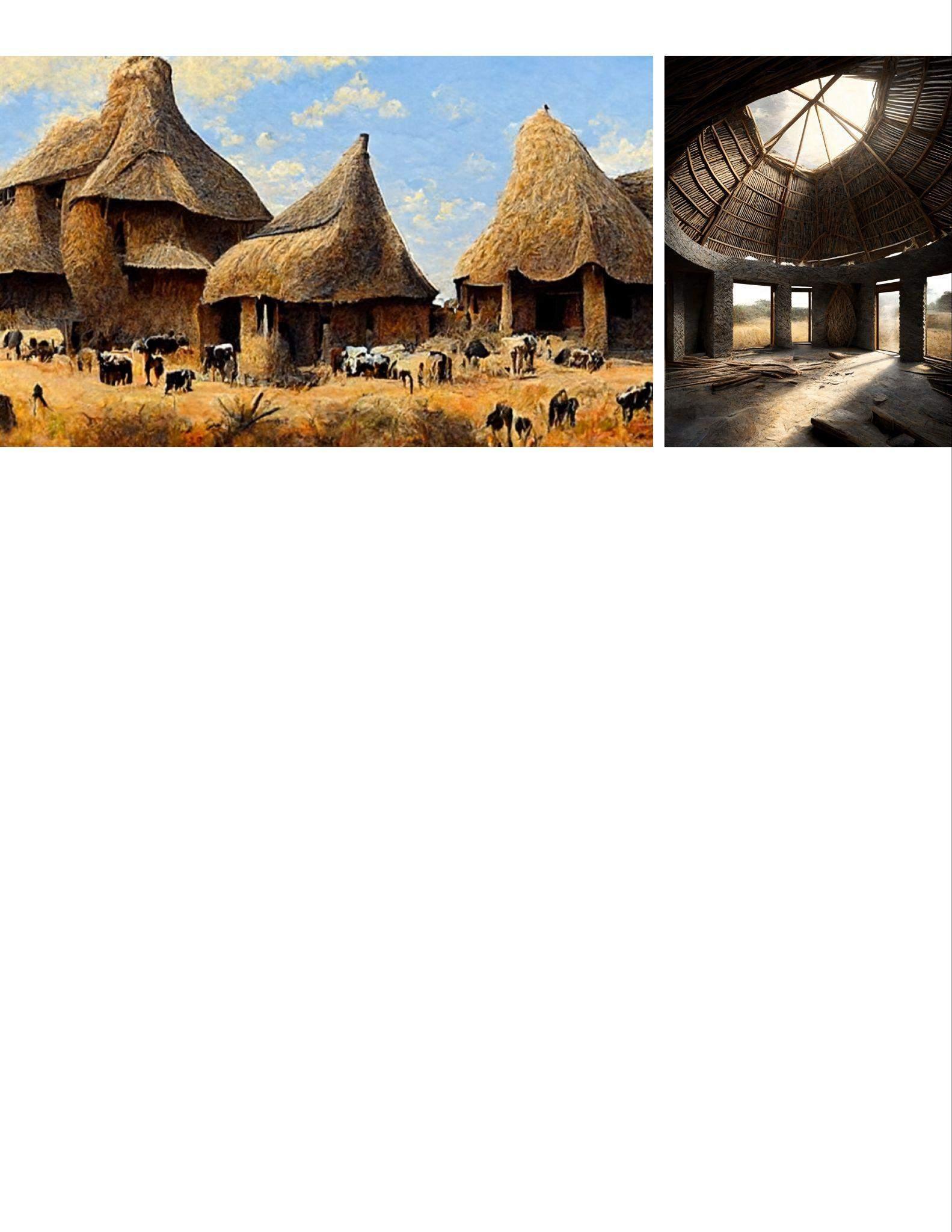

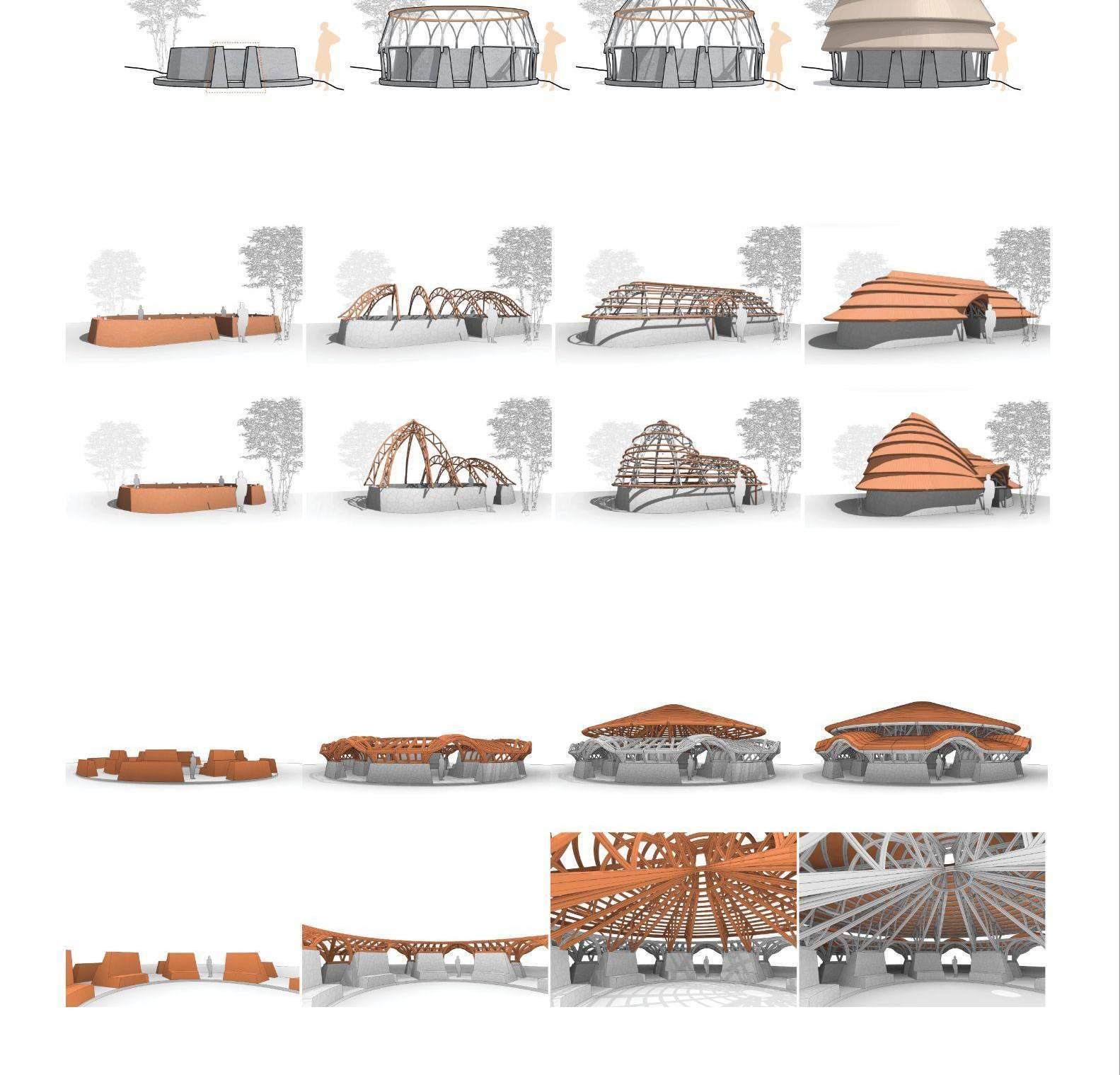

page #14 Figure 3.3: Midjourney images used for speculative adaptations (Author, 2022)

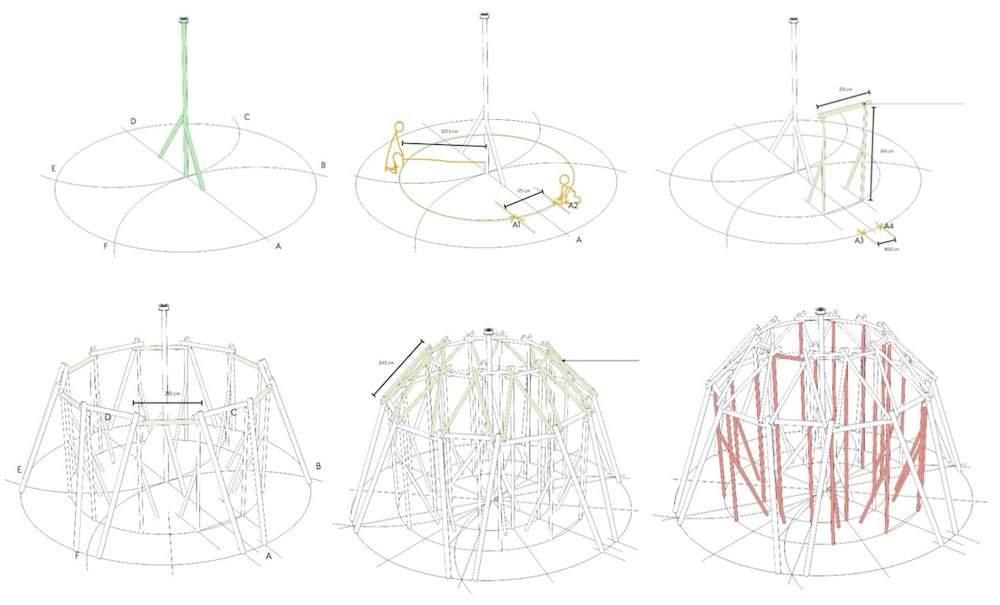

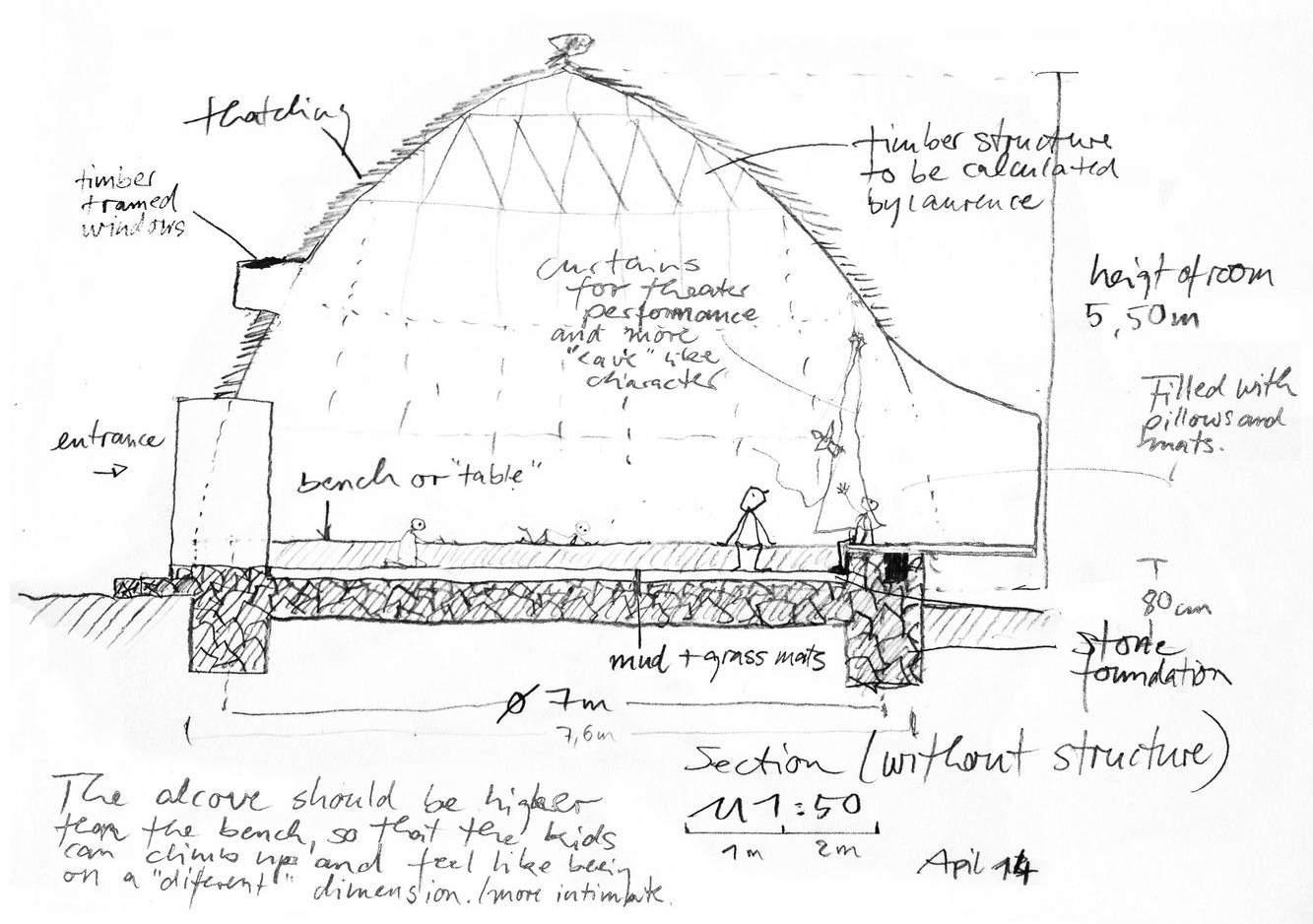

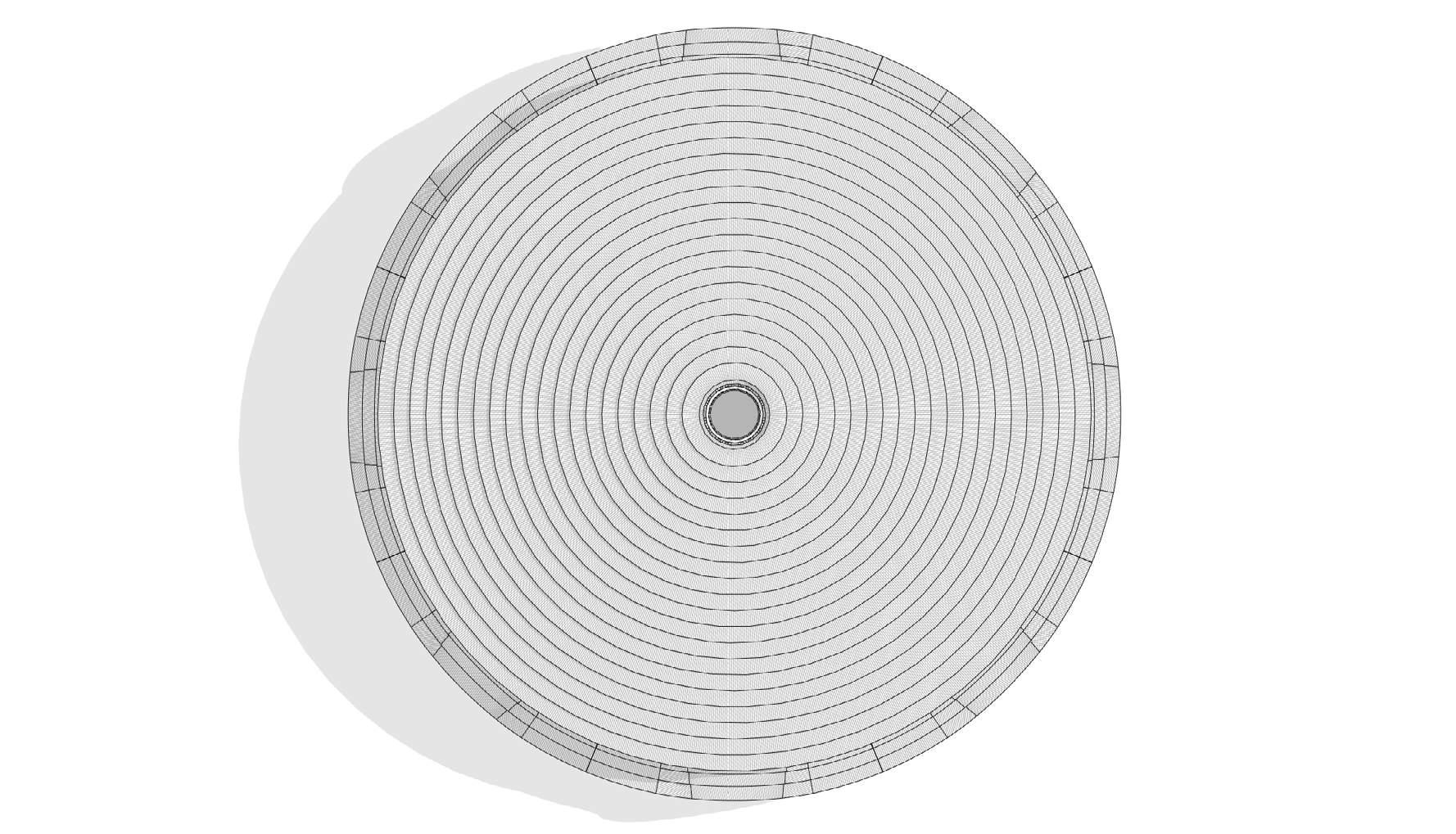

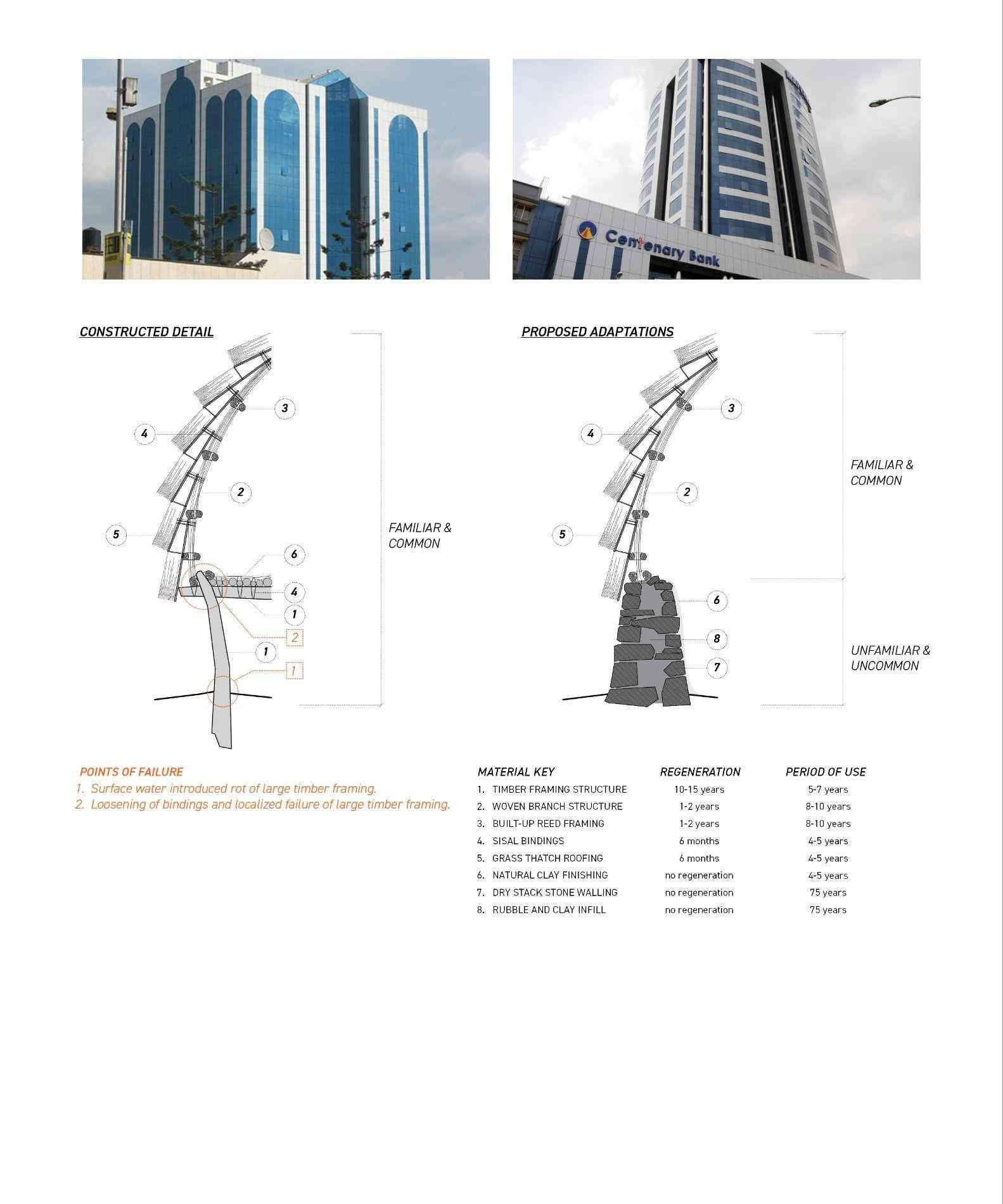

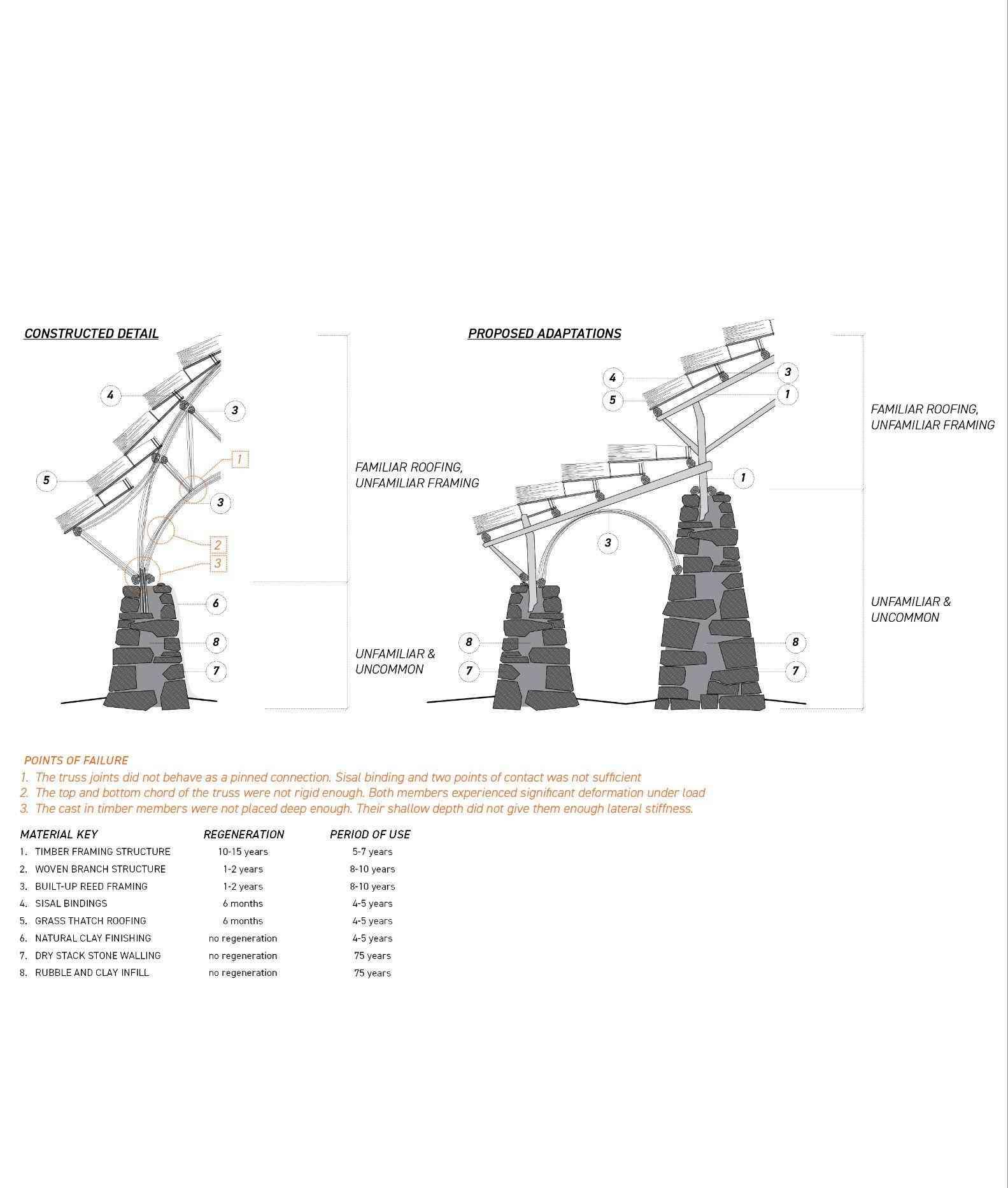

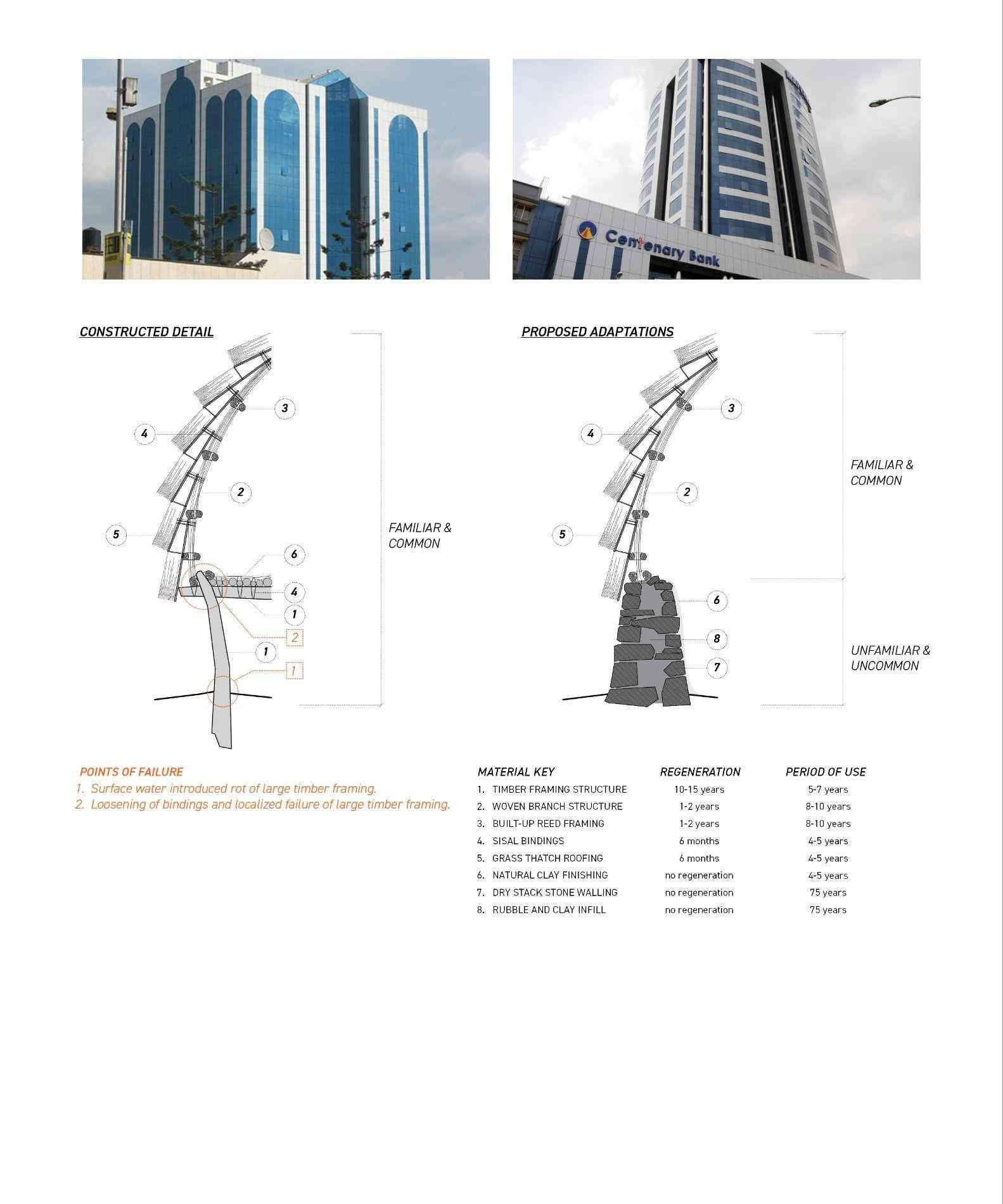

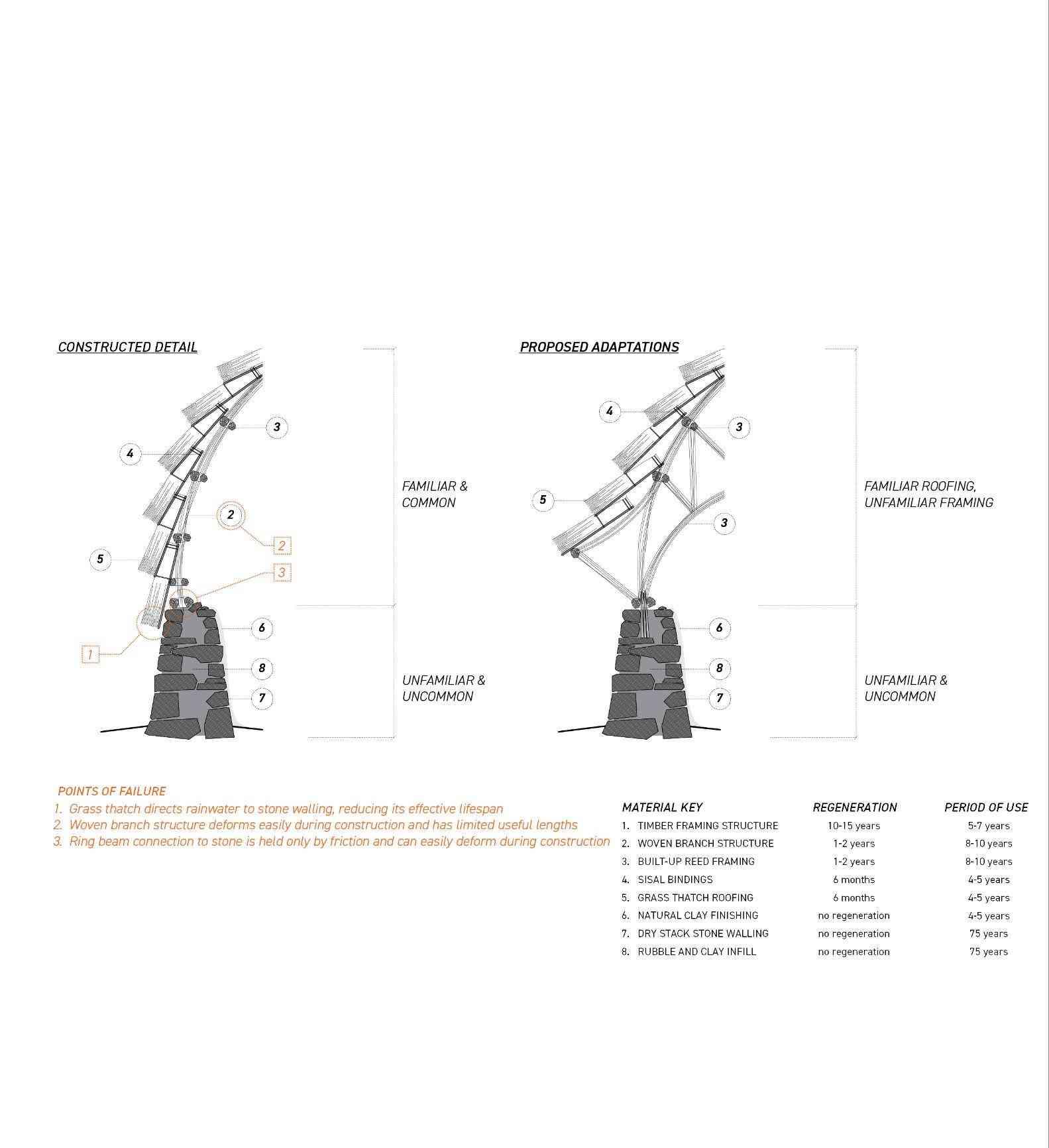

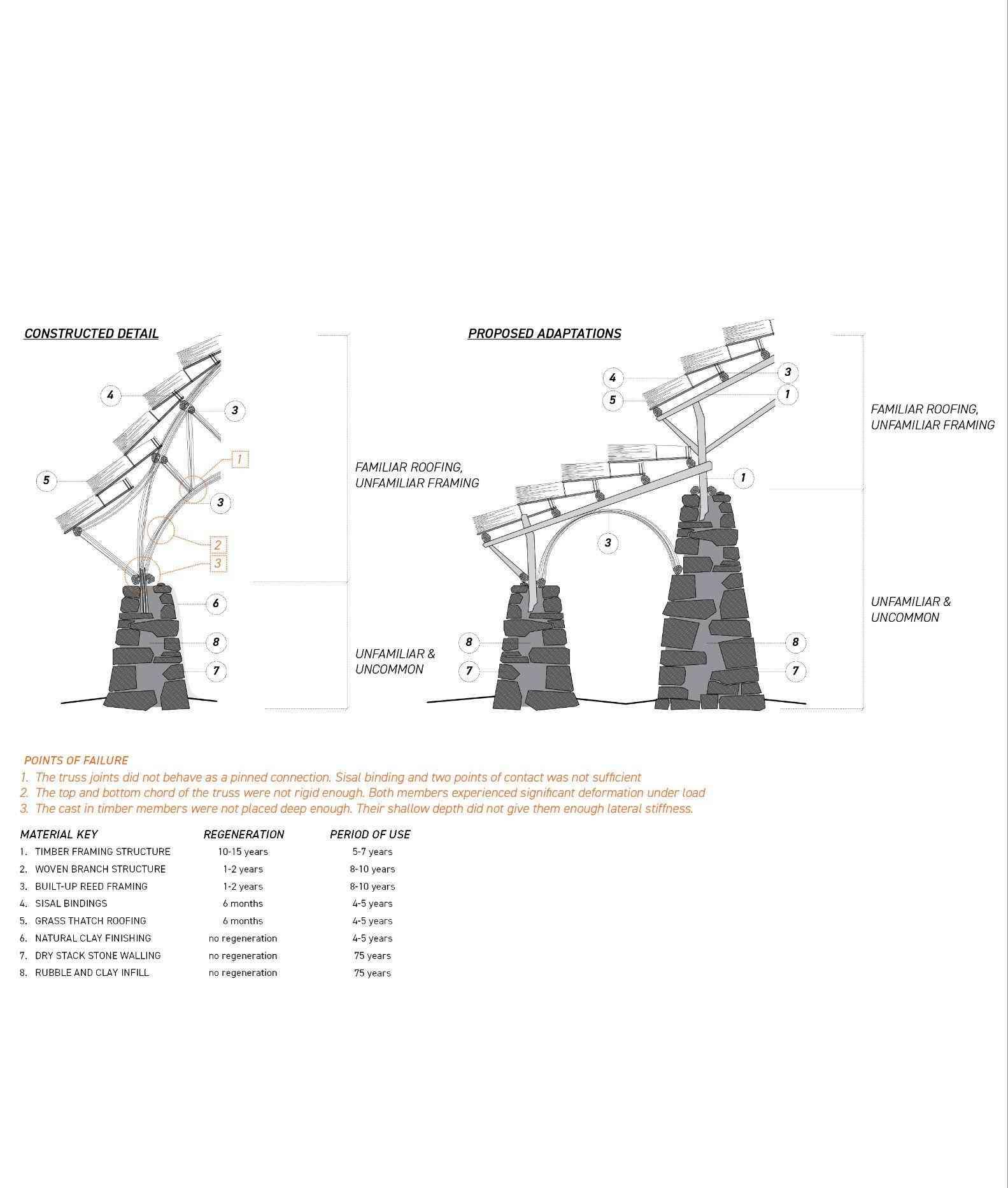

page #15 Figure 3.4: Analytical Section for Intervention #1 (Author, 2023)

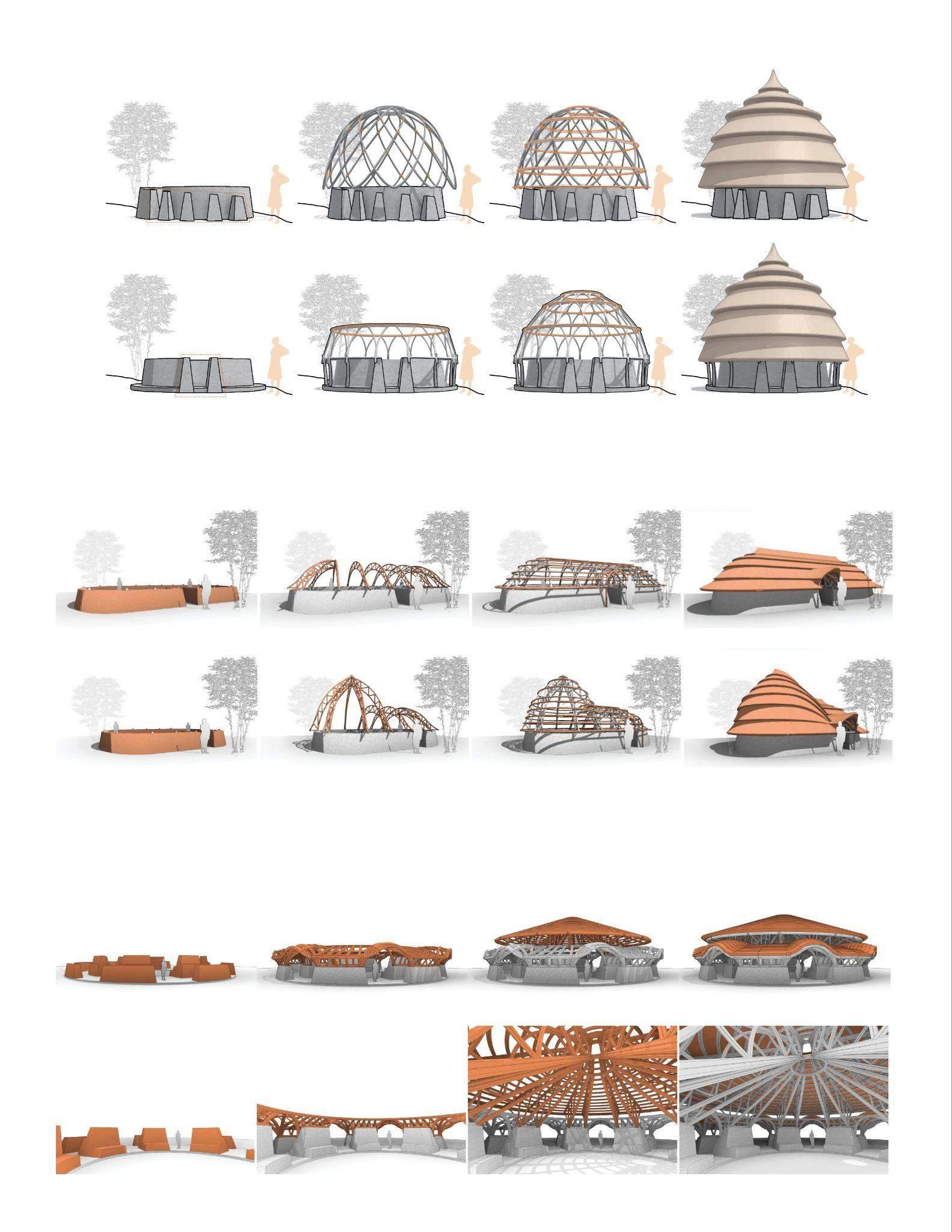

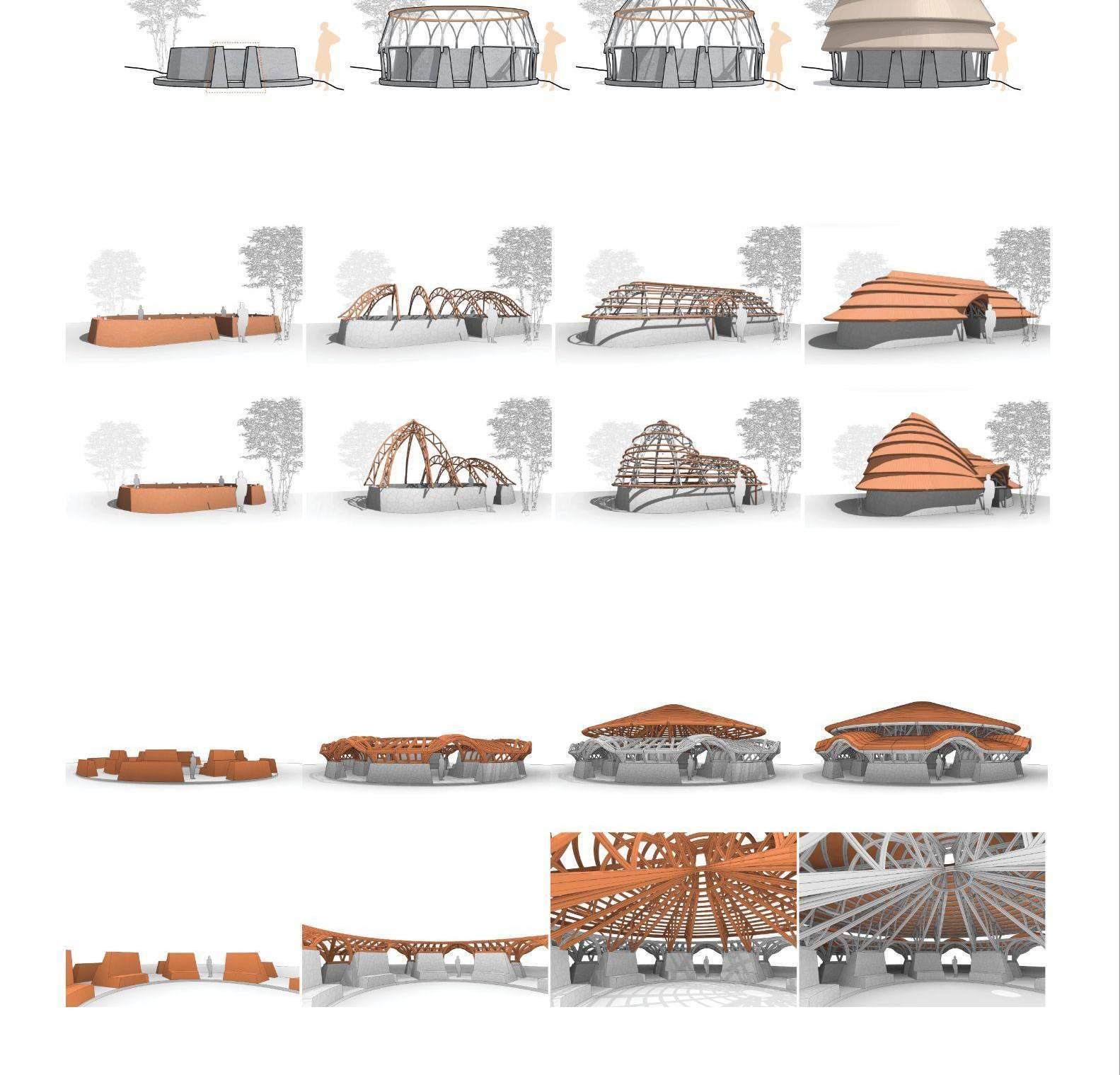

page #16 Figure 3.5: Design Proposals for Intervention #1 (Author, 2023)

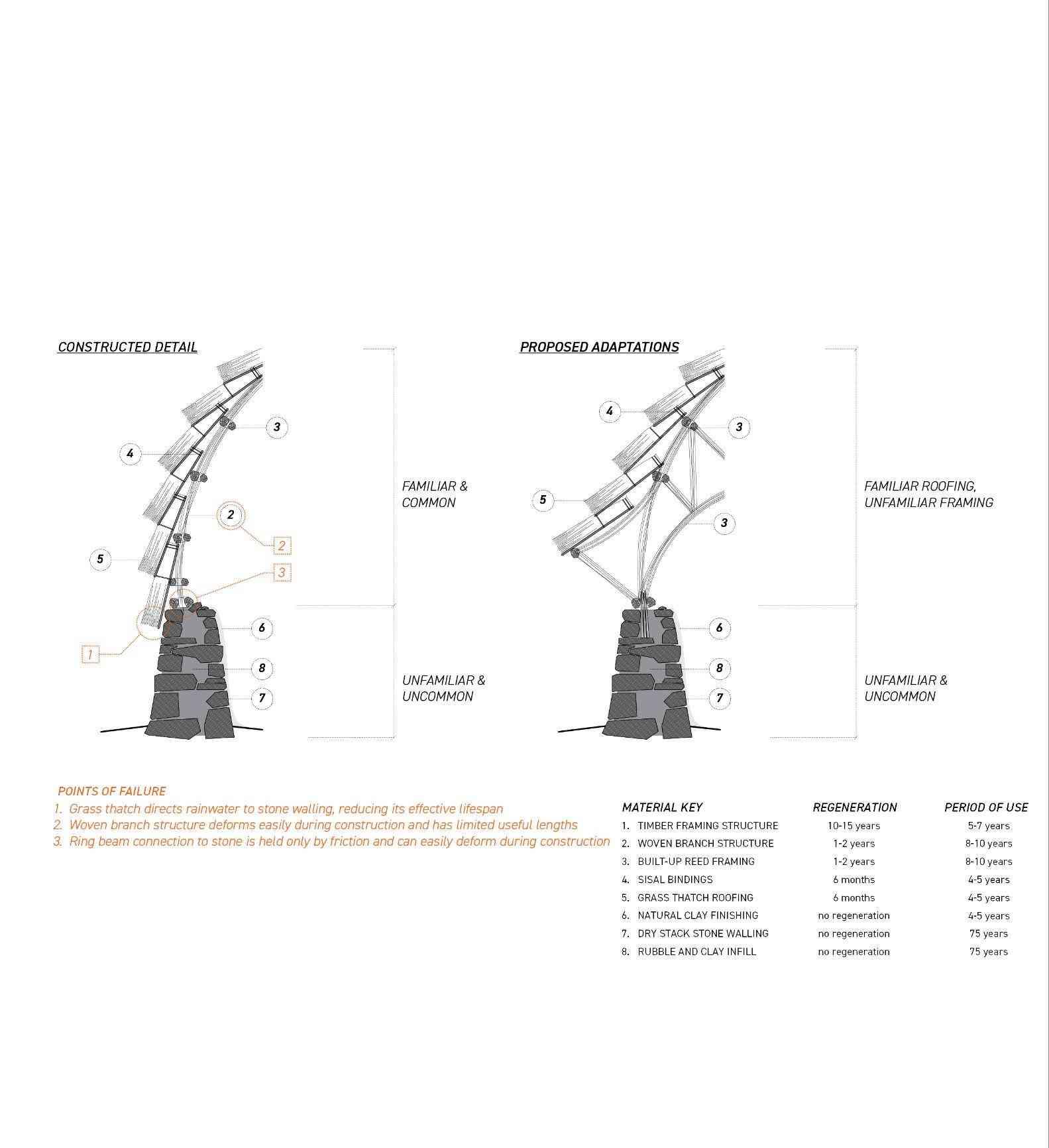

page #16 Figure 3.6: Analytical Section for Intervention #2 (Author, 2023)

page #17 Figure 3.7: Design Proposals for Intervention #2 (Author, 2023)

page #17 Figure 3.8: Analytical Section for the Institute of Animal Science (Author, 2023)

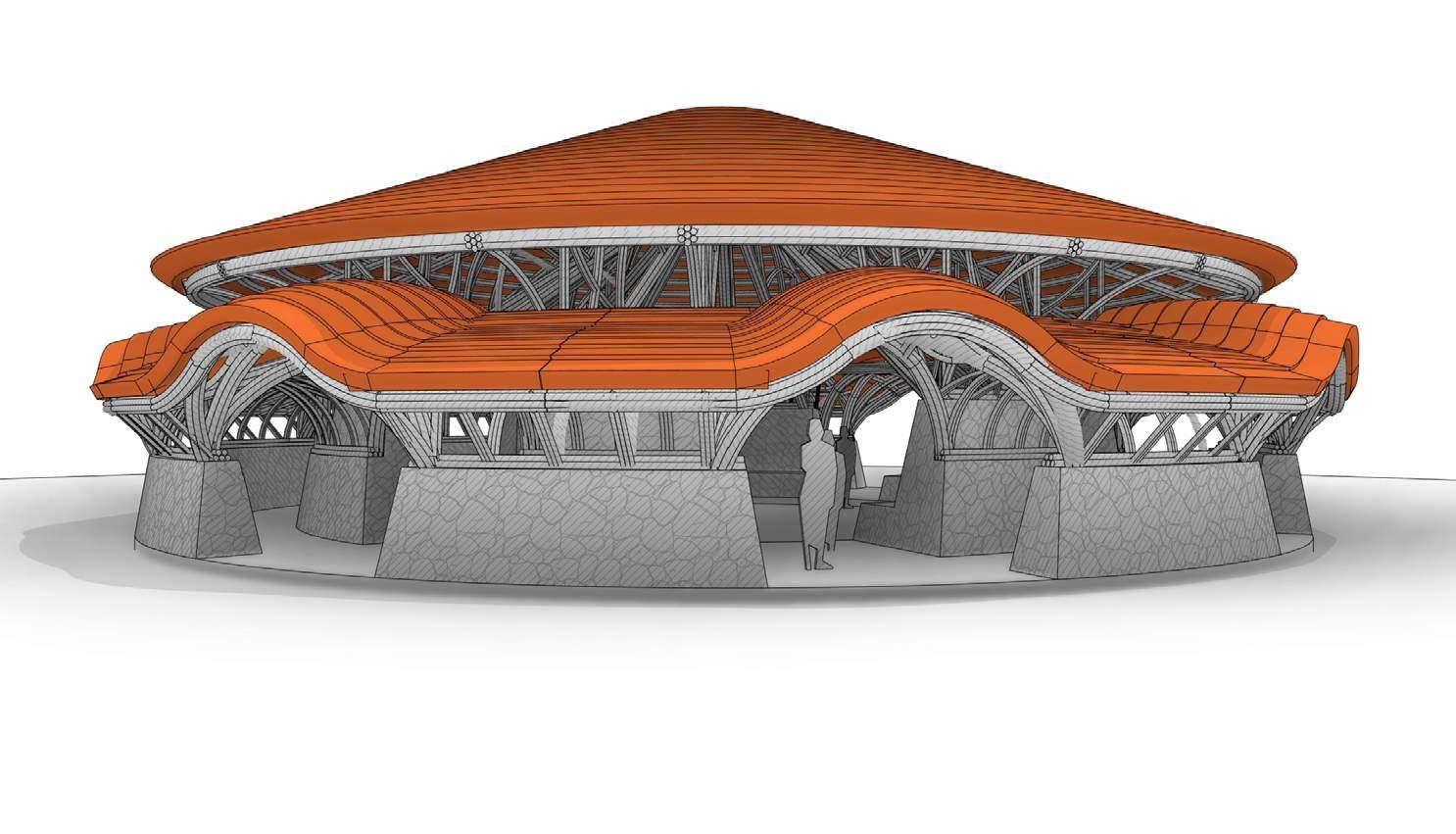

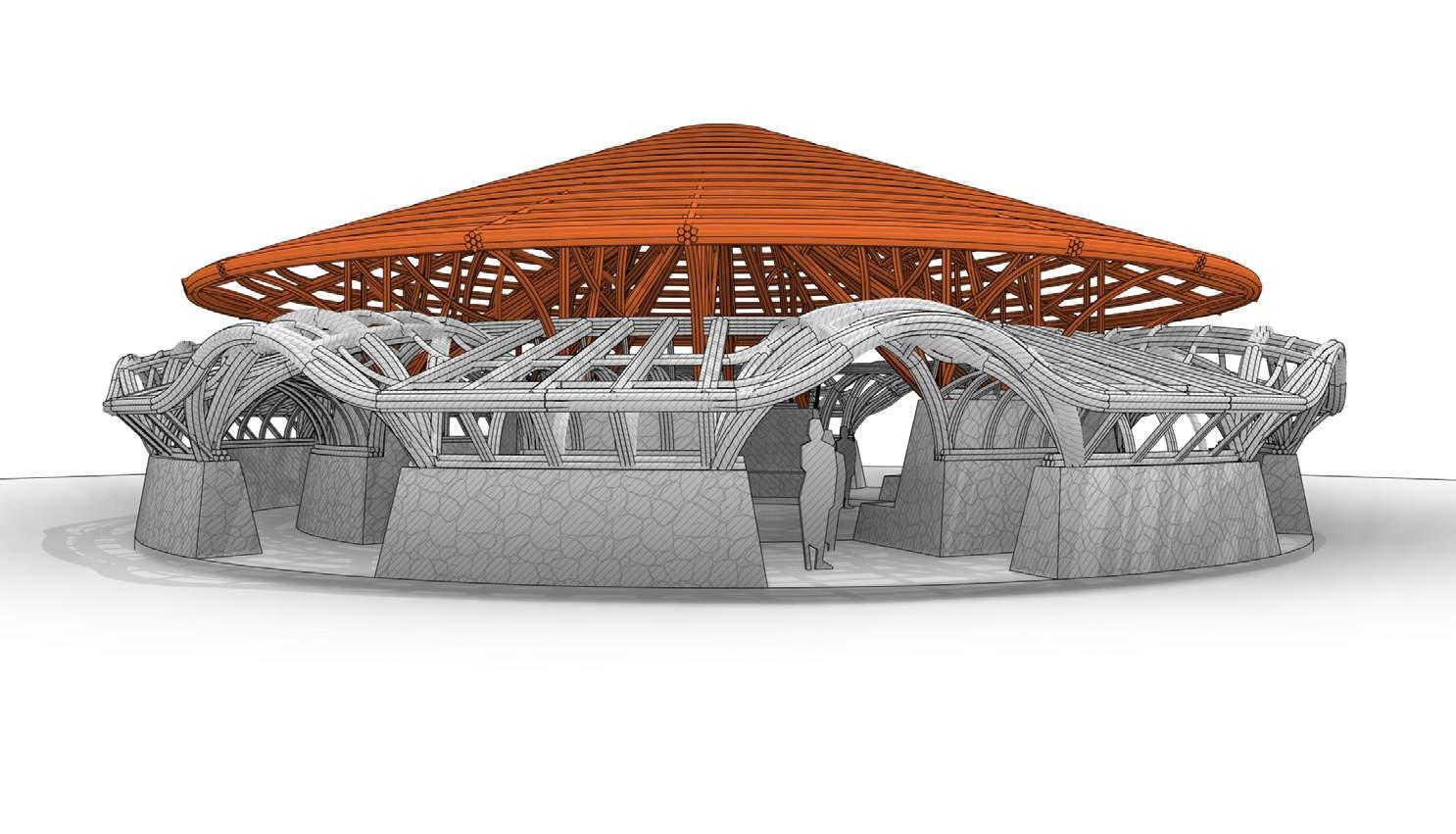

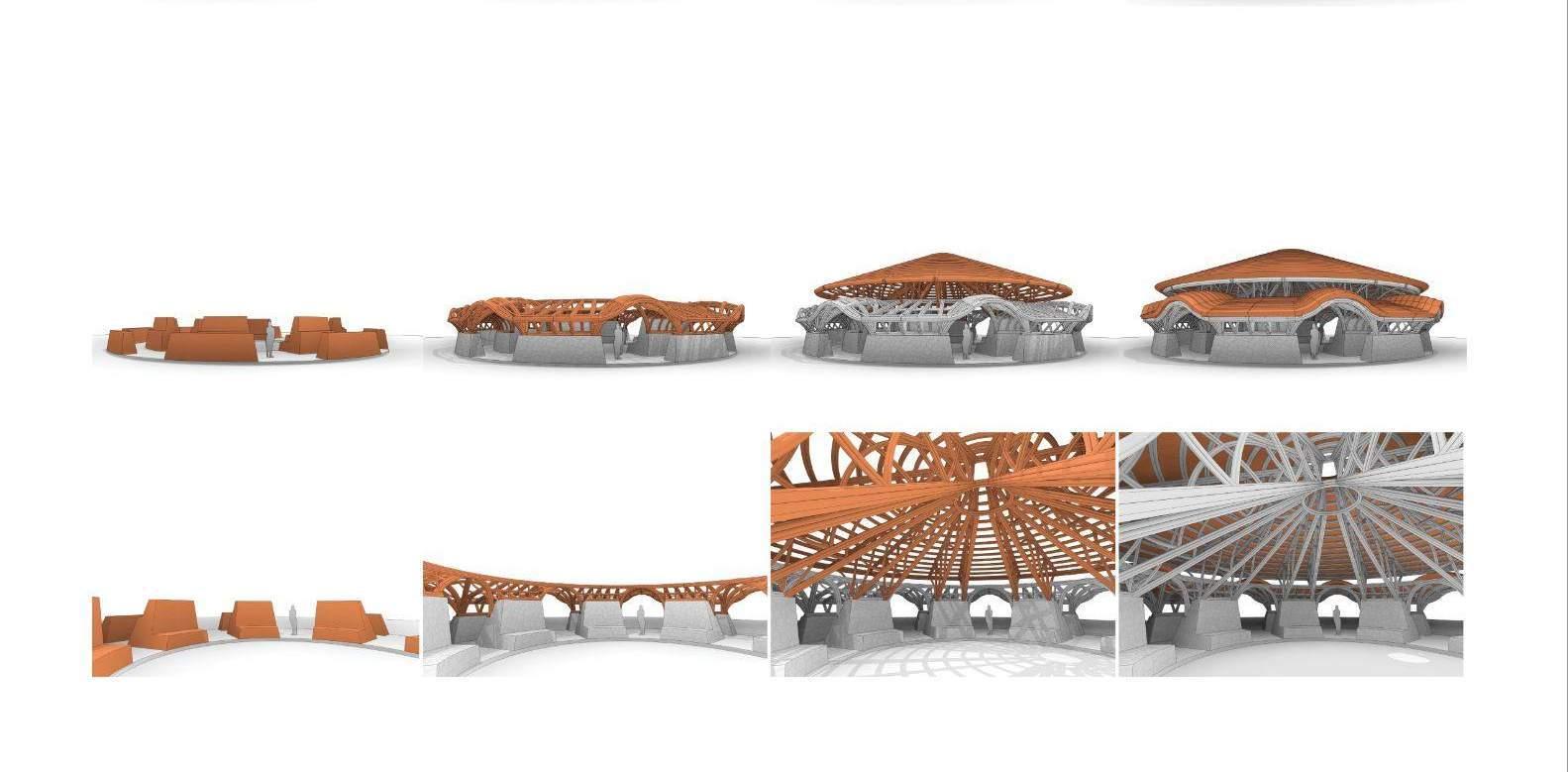

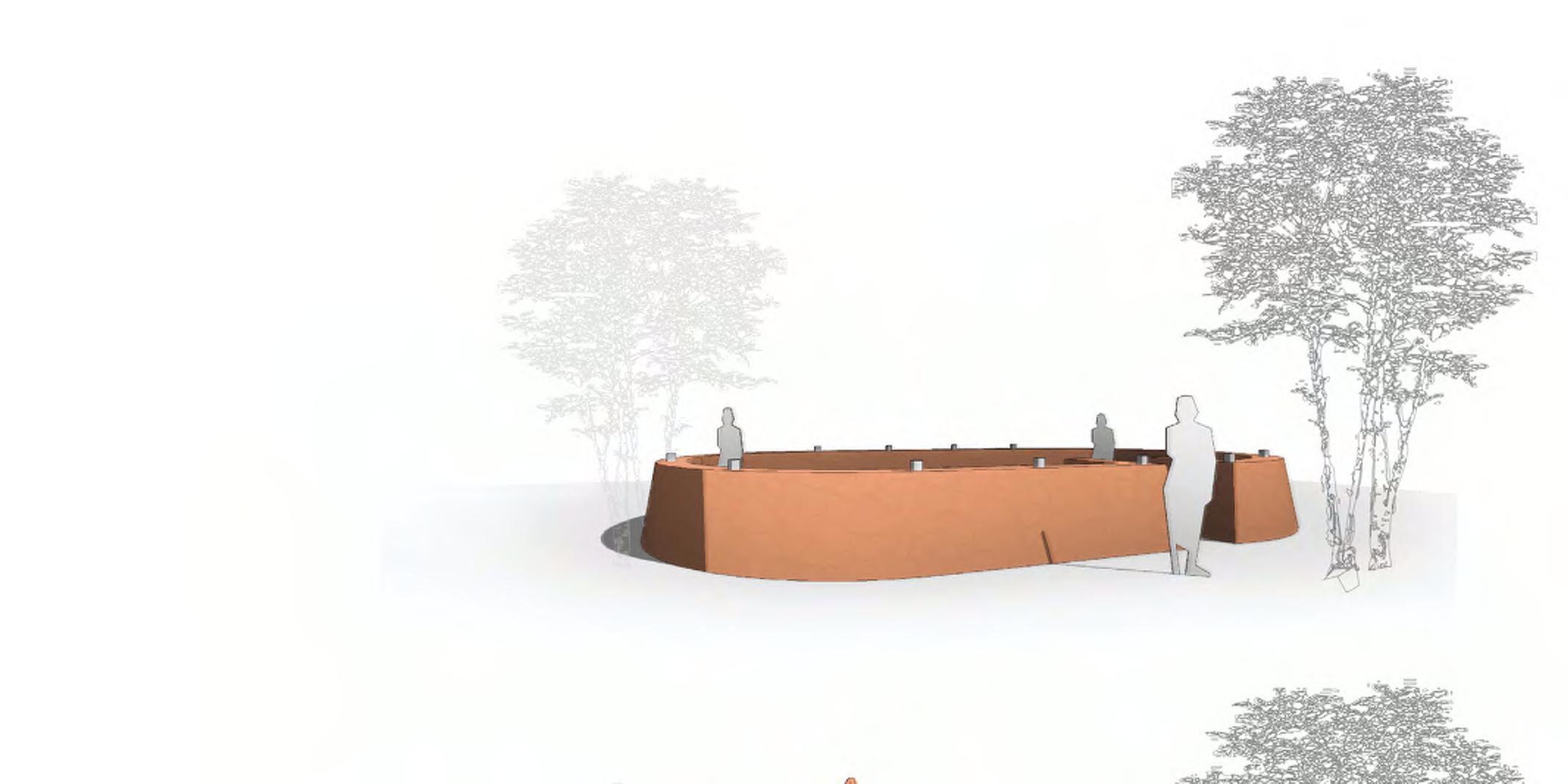

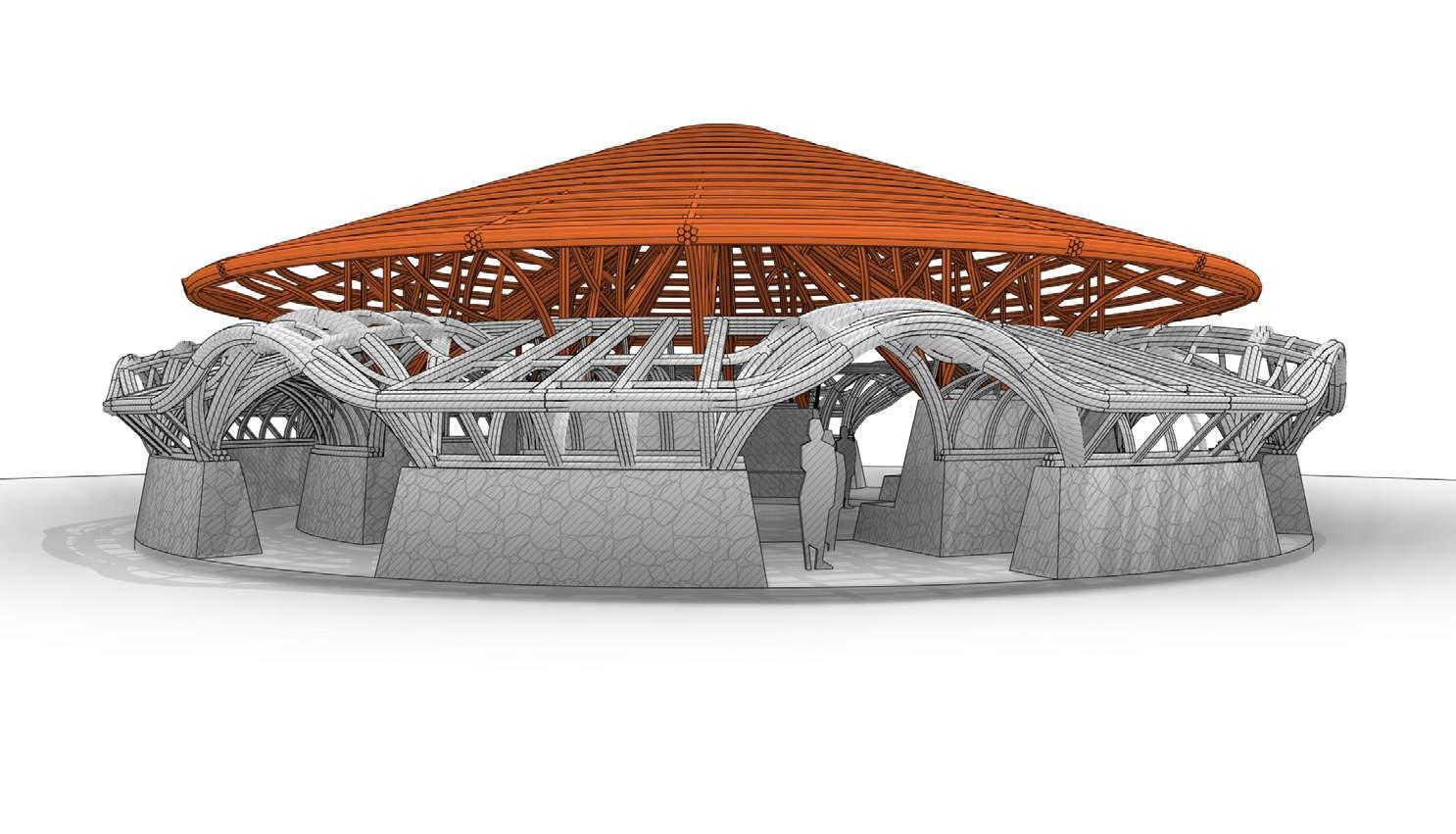

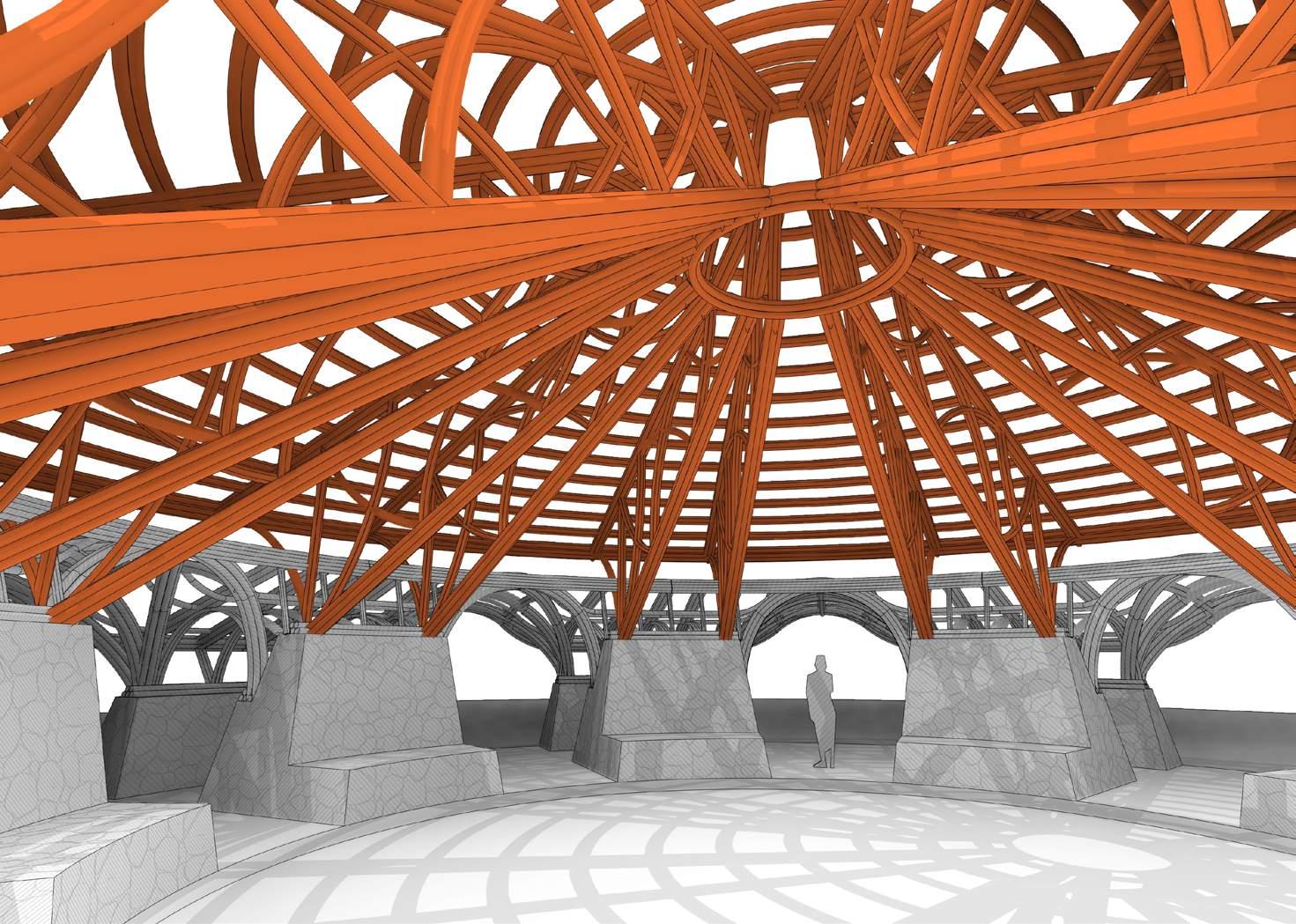

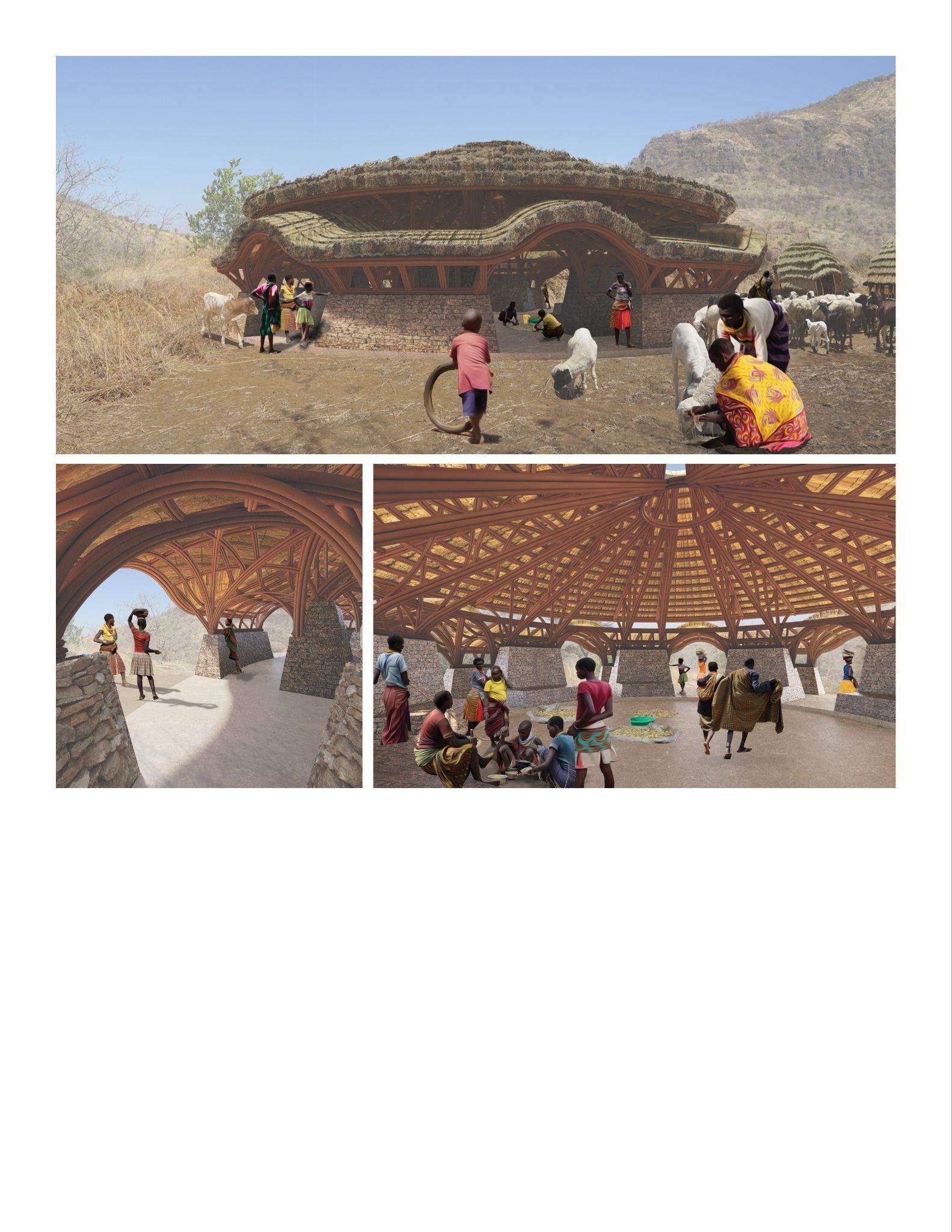

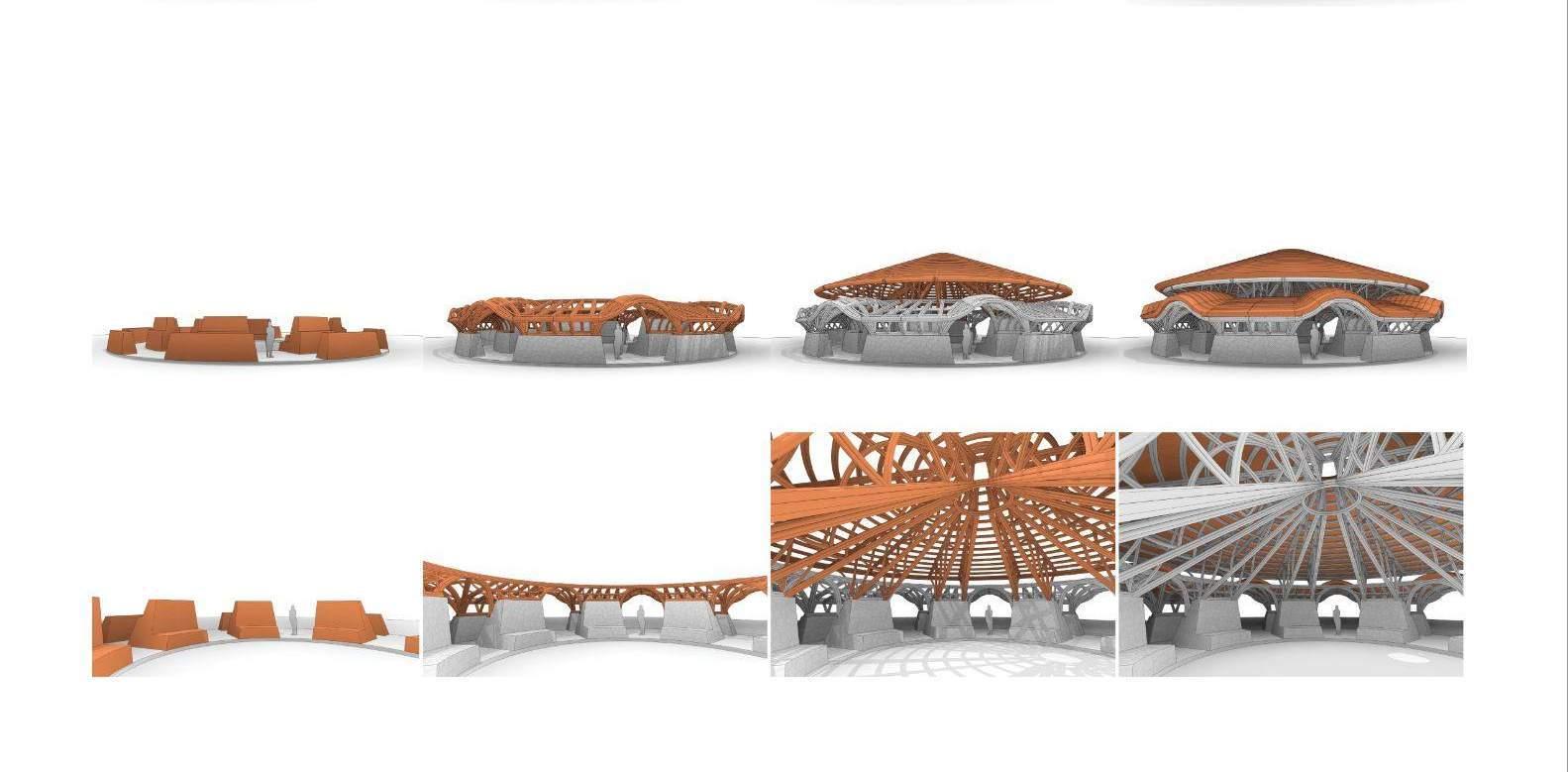

page #18 Figure 3.9: Design Proposal for Institute of Animal Science (Author, 2023)

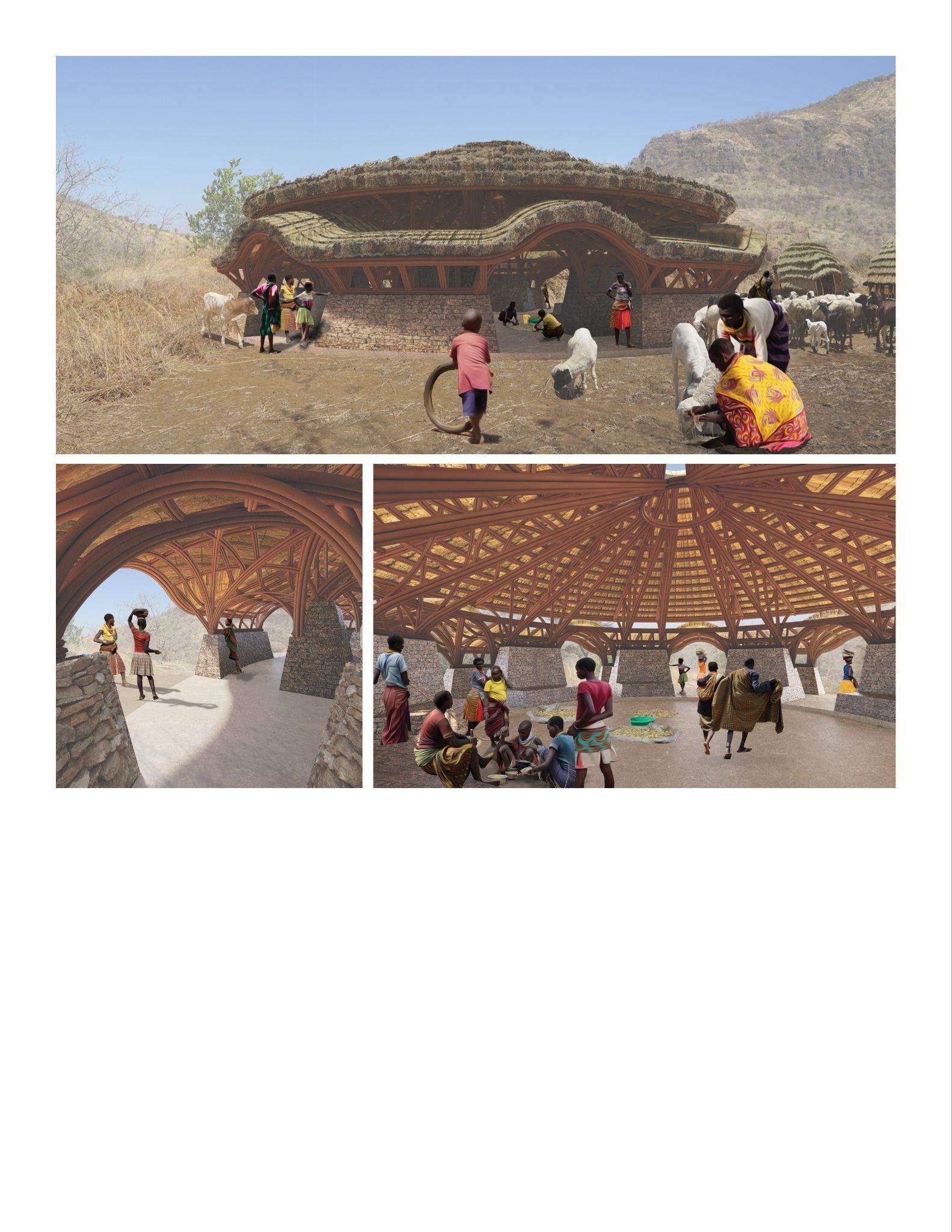

page #18 Figure 3.10: Renderings of the proposed Institute of Animal Science (Author, 2023)

page #19 Figure 4.1: Photographs of successful adaptations (Author, 2023)

page #20 Figure 4.2: Community members reviewing design proposals (Author, 2023) 18pt pace)

0.3.LIST OF TABLES

page #9 Table 2.1: Commonly identified failures in foreign-led interventions (Author, 2023)

(18pt space)

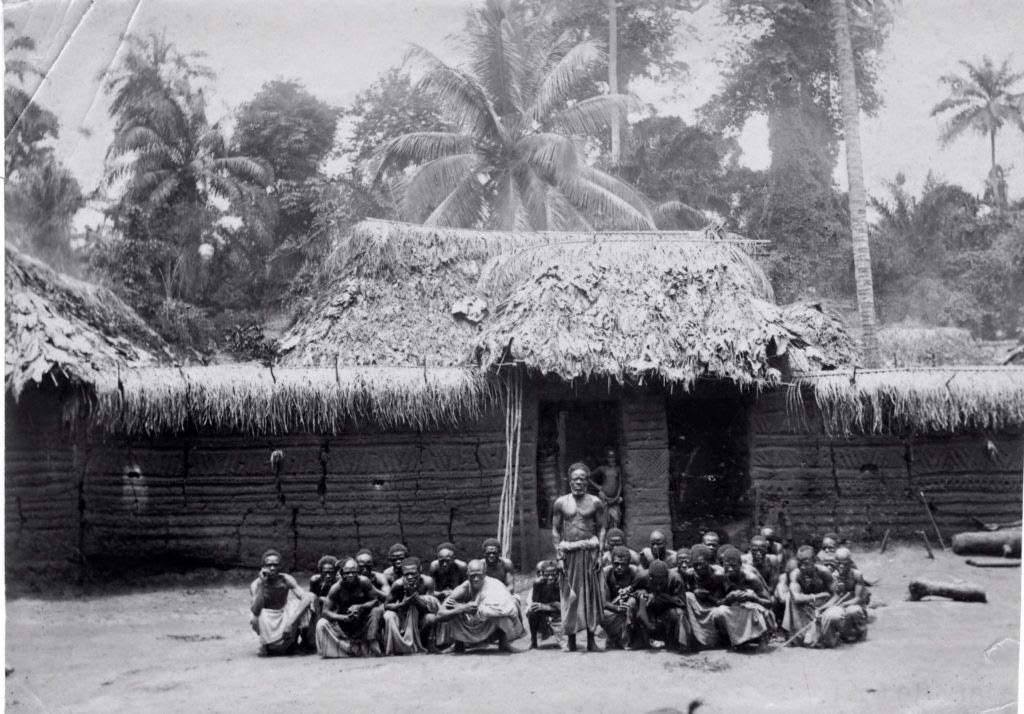

2.1 Historical Context

Northeast Uganda is home to a cluster of semi-nomadic pastoralist tribes known as the Karamojong. Ethnic descendants of Nilotic peoples, these tribes originated in the fertile Nile River valley and migrated south, slowly over time with their cattle in search of good pasture (Waiswa, 2019). For many years, tribal southward migration into Ethiopia and Sudan was inhibited by unpredictable water sources and meager forage for their large herds. Migrating in and out of these lands was only possible in rainy seasons, causing the people to eventually return north to the more dependable waters of the Nile. This obstacle was eventually overcome through the breeding of their cattle with west Asian species which produced the Zebu cattle subspecies, well-adapted to the dry climate and migratory lifestyle of a semi-nomadic people (DAGRIS, 2000). Over time, southward expansion extended along the rift valley into the lowlands around Lake Turkana where water and fertile grazing could be found in all seasons. This valley became home to the nomadic tribes for many years providing safe and productive land which produced significant growth in human and herd populations. From the Turkana Valley, clans split off into distinct groups; some remaining around Lake Turkana, others migrating south to form the Maasai cluster and others migrating westward to the fertile valleys of northeast Uganda. Over time, cultural and linguistic similarities led the tribes in Uganda to establish their collective identity as the Karamojong cluster, composed of approximately fifteen distinct tribal groups.

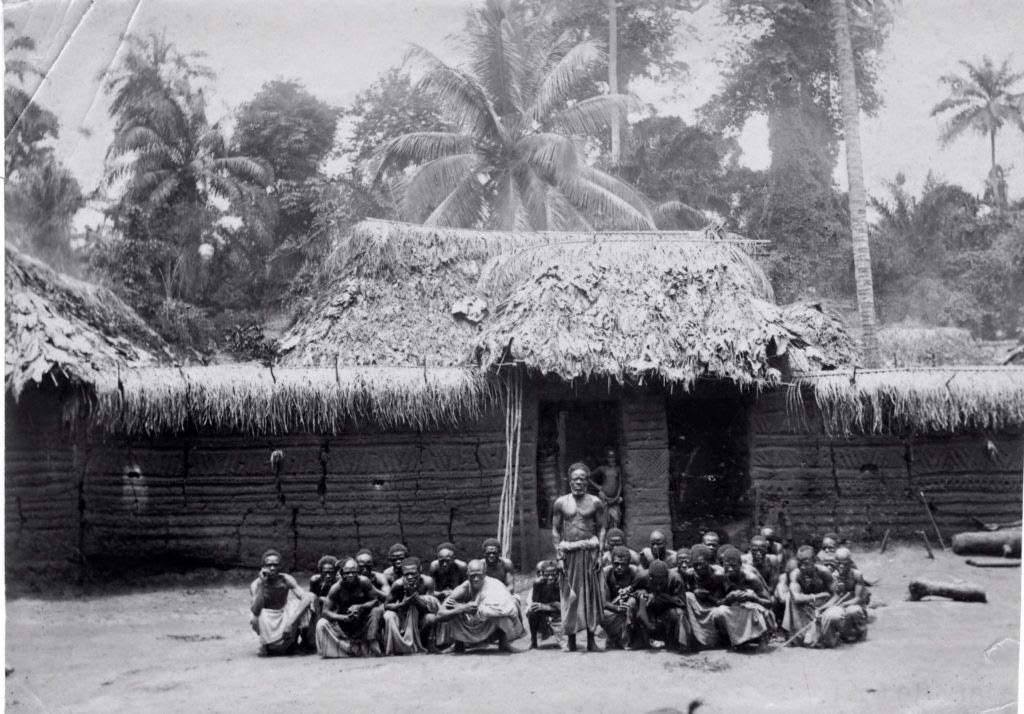

The Karamojong tribes remained insulated for many years, engaging in limited conflict with neighboring tribes. The first notable interaction with foreigners came in the 19th century with the arrival of Arab-led trading caravans. Growing demand for low-cost ivory and labor accelerated expansion beyond the coastal regions, deep into the continental interior where elephants and men could be easily found. Once captured, slaves were marched, often with heavy loads of cargo, to the Swahili coast where they were loaded in ships and transported north to Arabia (Beachey, 1967). While ferocious and often traumatic, the short-term interactions with Swahili traders left little social influence on the Karamojong cultural practices.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Karamojong experienced a new wave of intrusion in the form of British colonization. In 1894, Uganda was established as a protectorate, subjecting all tribes and people to the crown. Contact with the British administration was relatively minimal compared to tribes living in the central region of Uganda. The Karamojong were categorized as a wild tribe and therefore the administrative objective was to avoid conflict (Barber, 1962). However, while direct conflict was limited, colonial rulers introduced a series of legislative changes that restructured traditional institutions to better align with ruling European systems. The first notable act of imposition was the introduction of individual titled land ownership in 1924, organized unequally and in service to the political leaders who were allied with the colonial government (Sabiiti, 2021). The concept of land ownership by an individual was wholly unfamiliar to nomadic communities who operate on a collective model of land use where land is not owned, but a resource to be used in service to their herds. These foreign structures of land ownership that have contributed to a systematic erasure of contiguous tribal lands, often by individuals misrepresenting their legal ownership for financial gain. A second and more impactful act of imposition by British colonial rule came early 1934 with the establishment of the Board of Registration of Architects and Quantity Surveyors. The professionalization of the built environment established foreign procedures for design and construction that displaced traditional building practices and relegated their use to unregulated rural environments. The dissonance in values between the profession and tradition is often manifested through NGO acts of construction. These projects make minimal use of the Matriarch constructors offering menial acts of labor, like crushing stones into gravel by hand, for dismal pay

Part 02: ARGUMENT

Figure 2.1: Map of East Africa (Author, 2022)

By the middle of the 20th century colonial rule was growing increasingly vulnerable and in October of 1962, Uganda gained independence. The following political administrations were marked by intermittent periods of unrest that brought increasing regional instability, particularly in the Idi Amin administration (Kaduuli, 2008). The outgrowth of instability attracted a new scale of foreign intervention, often in support of food supplies or medical assistance. The financial backing and stated altruistic goals of these foreign-run organizations has granted enormous amounts of influence to their operations that remain in effect today. The actions of these organizations are varied and their degree of imposition varies, however the enormous influence they possess in the region has created an alternative nexus of control that has destabilized traditional tribal institutions.

2.2. Vulnerability and Change

Based upon this history, it is clear that Karamoja should be understood as a region facing increasing pressures to change; to move away from the semi-nomadic pastoralist livelihoods that have sustained its people for centuries. Pastoralism often exists in harsh climates surviving on mobility and access to land. As vocational assets are depleted, vulnerability increases, attracting further foreign intervention. Because of this, the elements contributing to vulnerability and change can be expressed in three key relationships: ecological, vocational, social.

Ecological change can be understood through the relationship of pastoralism and climate that are interdependent on each other A pastoralist community relies on herd health which is largely determined by the availability of water, forage, minerals and predictable weather patterns. As forage for grazing lands is depleted, nomadic pastoralist communities vacate that land until it can regenerate. The responsive interval between use and ecological repair produces a mutually beneficial rhythm where pastoralist activities operate sustainably in relatively harsh ecosystems. However, regional climate change has made water sources less predictable and increased the duration of time required for grazing lands to revive which escalates tribal conflict over the scarce resources (Dbins, 2013). Climatological degradation is exacerbated by deforestation of land cover, as a result, the Karamojong often support maladaptations of charcoal production and the expanding footprint of crop lands (Egeru, 2014).

Vocational change can be understood through the pastoralist dependence on mobility and recent pressures towards permanence. Since cattle-based livelihoods rely on temporal conditions such as forage and water, the idea of permanent settlement is unfamiliar to tribes in the Karamoja region. Seasonal migration in search of good pasture between wet and dry seasons has been a normative practice since these tribes lived in the Nile River valley and exists to this day This established cultural practice is facing new pressures never encountered before, largely due to the government requisition of tribal lands for conservation, mineral extraction and farming. The establishment of a national games park has divided tribal lands and made approximately 36% of tribal land unavailable for pastoral activities (Waiswa, 2019). Figure 2.3 below illustrates the extent of land requisition and the navigational barrier it places on nomadic movements. As a result of government actions, the Karamojong are facing the greatest mobility challenges livelihood is at risk owning no livestock

thor, 2022) thor, 2022)

Societal the growing pressures climate change, vocational becoming less influential alternative livelihood (Scoones, 2013). For vocations foreign children and the role educated.

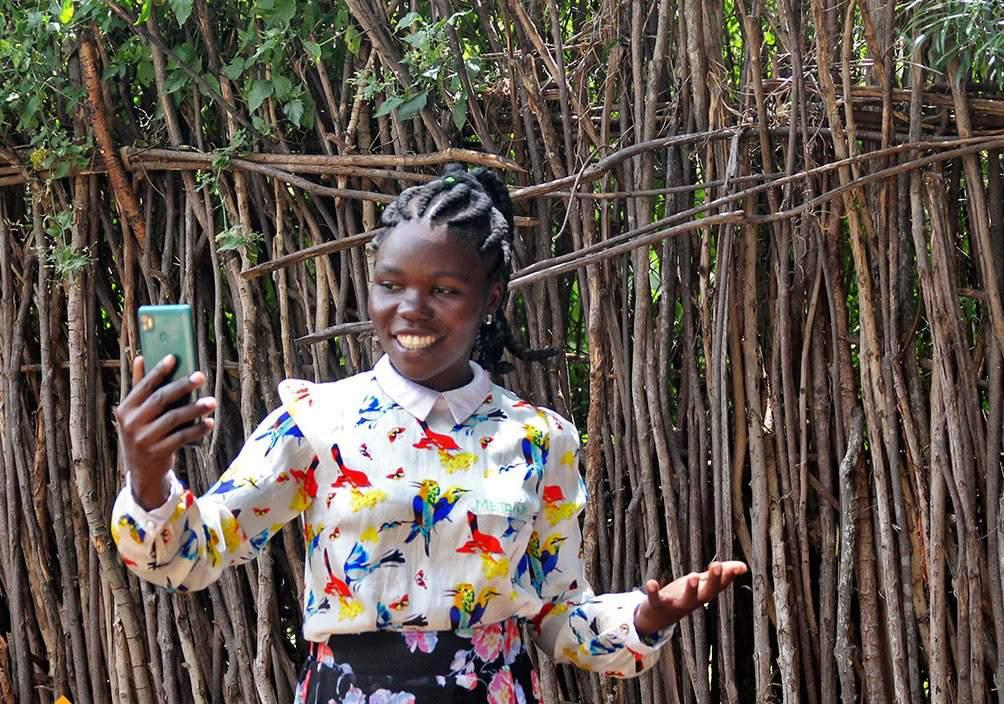

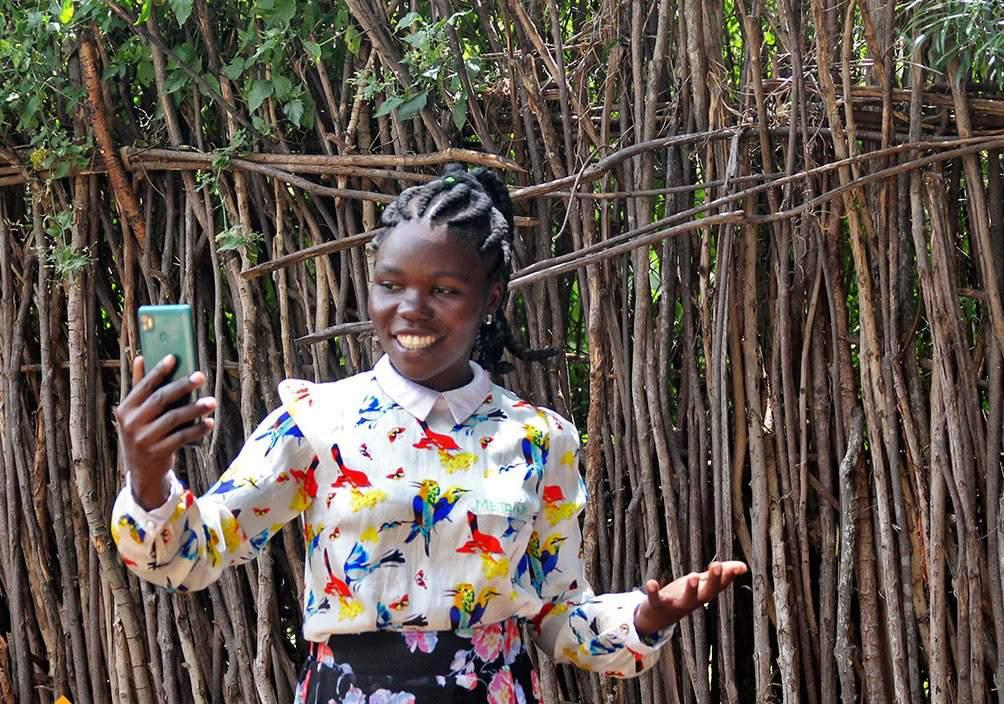

Societal issues are further complicated by the introduction of foreign objects into the region. For example, widespread integration of mobile phone technology has foundationally altered communication channels by giving early adopters access to information and communications that previously did not exist (Butt, 2014). For example, the traditional channels of communication have been altered, allowing powerful outsiders to communicate directly with young men in the communities. In some cases, outsiders have employed young men in profitable cattle raiding expeditions, commercializing activities that have long been curated by elders in the community (Akabwai, 2007).

The introduction of automatic weapons have further destabilized traditional institutions built around warriors and cattle rustling. Since the 1970’s Russian weapons have grown increasingly accessible to the tribes in Karamoja who have historically engaged in frequent, but low mortality cattle raids against neighboring tribes. Cattle raiding is a cultural institution that solidified the promotion of men into warriors and was often undertaken with bows, arrows and spears. However, the proliferation of automatic weapons has dramatically increased the mortality rate of this cultural practice attracting the attention of the national government which has since undergone systematic disarmament campaigns seeking to eradicate this cultural practice.

2 3 An Expanding Legacy of Foreign Interventionism

The historical record displays the resilience of the Karamojong people to cultural change with the majority of their history being defined by self-rule. The arrival of foreigners has introduced a new era of modern history where the Karamojong have been completely subject to foreign rule. British colonial administration was determined by ethnic Europeans based in England. Following Ugandan independence, the region was ruled nationally, however the political boundaries retained the British stake-making process amalgamating 56 tribes with distinct cultural values, histories and perceptions of each other Since its formation as a nation, Uganda has never been ruled by an ethnic Karamojong. As a result, political representation is limited, government funding for services is lacking and contracts for extracting valuable mineral resources are awarded to foreign companies without proportional compensation to host communities.

In addition to political rule, the expanding influence of Non-Governmental Agencies and Religious Organizations has established the normative practice of foreign intervention in Karamoja. Today, over fifty foreign-led organizations operate with projects in conflict mitigation, health, crop production, disaster risk reduction, livelihoods, nutrition, livestock production, conservation, water production, education and child protection. Although benevolent in motivation, the enormous influence of these foreign agents coupled with insufficient accountability has produced a legacy of ill-informed policies that have disadvantaged pastoral methods of livelihood and have been implemented with often paternalistic qualities that undermine their success (ODI, 2018).

In the chorus of messaging into Karamojong communities is a growing call for sedentarization and widespread acceptance of farming as a new full time vocation. Communicated through the lens of improving food security, these calls for cultural change are being championed by a host of NGO’s, by foreign governments, as well as the current Ugandan national government. For example, Ms Flavia Kabahenda Rwabuhoro, Woman MP from Kyegegwa in Western Uganda has leveraged the Karamojong vulnerability to call for government investment in settled agriculture (Monitor, 2022). This sentiment was echoed by the current President Yoweri Museveni who issued statements urging the Karamoja region to intensify their commercial agriculture. Interventions from NGO’s or politicians often operate in support of their own agendas rather than promoting traditional Karamojong institutions and their preferred practices (Pavanello, 2009).

These calls for cultural change demonstrate how vulnerability can be leveraged by outsiders to promote new policy, new livelihoods, and new ways of life. Foreign intervention can be motivated by altruistic intentions, however these policies must contextualize their actions by operating within the values and institutions that define a determined culture.

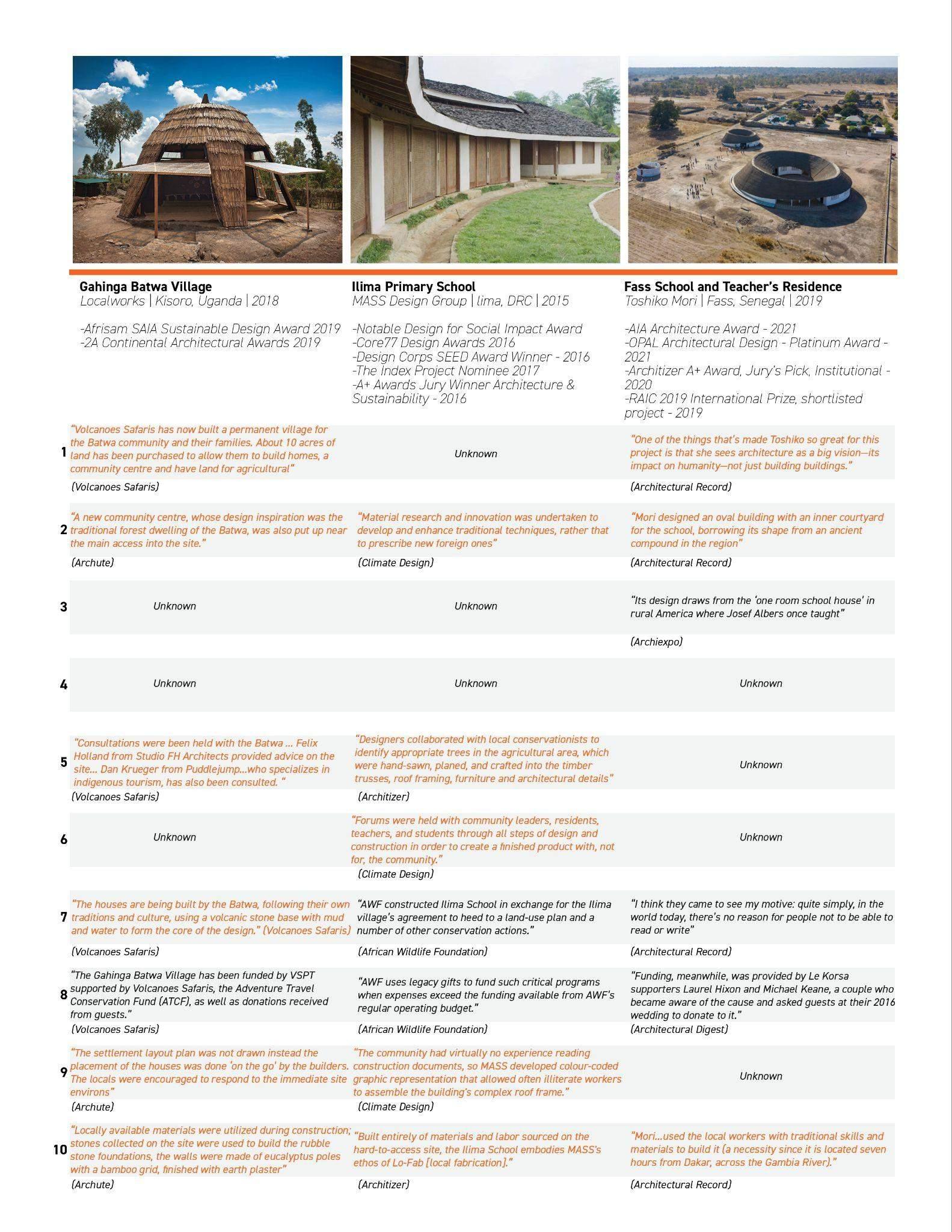

2.4. Markers of Impositional Architecture

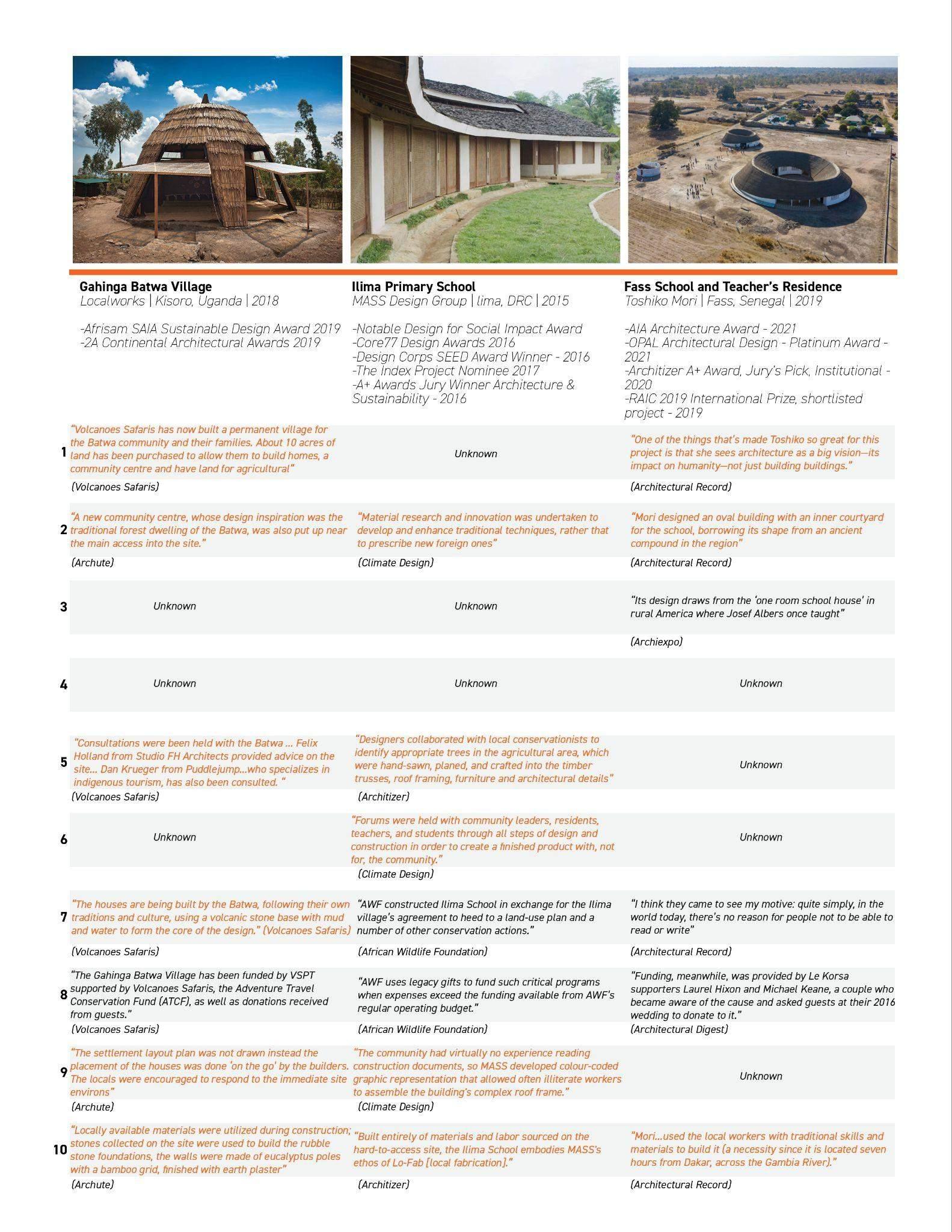

Foreign intervention without contextualization produces imposition. Similarly, works of architecture can be characterized as impositional when they do not alter themselves to accommodate the place in which they are sited. To demonstrate these qualities, an evaluative framework can be used to analyze works of architecture to determine their sensitivity and appropriateness to a particular place.

The basis of the evaluative framework must be well-founded in order to provide useful results. This research made productive use of the growing body of documentation around sociological interventions implemented by NGO’s, government agencies and religious organizations. The most insightful reports describe previous programming and offer sober reflection on the original intent and associated outcome of the work through direct stakeholder feedback. It is in this body of work that a collection of user-defined impositional qualities can be extracted, specifically identifying practices, procedures and situational dynamics that undermined the success of the program. In the table below, recurring markers of imposition have been identified. The identified failures produce a qualitative framework that can be applied to any work of architecture.

A monumental challenge in applying the evaluative framework is the ability to collect complete, accurate information. Architecture firms and funding agents rarely publish information that display their acts of imposition. However, through

careful documentary research and interviews with stakeholders, a more complete understanding of the project's qualities

learned.

Table 2.1: Commonly identified failures in foreign-led interventions

This table above demonstrates the risk of foreign led-interventions, particularly in their ability to understand and respond to needs of user communities. While failure can occur accidentally, it is more common that foreign agents operate knowingly in service to their own priorities and familiar behaviors. Further, the foreign-led attribute of a project suggests a history that predates intervention and a future that follows. Therefore, the duration of an intervention must be carefully considered along with a well-formed exit strategy that operates in the best interest of user communities. Perhaps the most commonly identified failure is the troubling dynamic between the funding agent and user. The injection of funds, programming, and equity produce economic and relational hierarchy that is not easily undone. Interventions based upon economic hierarchy can devalue user communities, framing them as victims in need of repair rather than communities deserving and capable of self-determination. In one report, a Knowledge Generator was quoted saying:

“[Affected people] are deprived of agency and ownership at many levels. They cannot participate in designing the project, in decision-making, their efforts most of the time are ignored… Generally, we see them as victims, helpless, paralysed… we take their agency from them” (ODI, 2018).

To test the usefulness of the evaluative framework the identified markers of imposition were studied in relation to the specific context for each project. The three projects below were selected since they are all recently constructed, internationally awarded, regional projects described being user-focused in online publications. The detailed results

can

be

Commonly Identified Failures Source 01 Design of the building takes priority over strengthening the community. (ODI, 2018) 02 Project fails to consider local customs, traditions and governance. (ODI, 2018) 03 Priorities of the designer are misaligned with long term user needs. (Mercy Corps, 2016) 04 Foreign agents intervene without a well-formed exit strategy (ODI, 2018) 05 The project evolves within a single discipline. (Caffey, 2013) 06 Interventions are made without feedback or accountability (ODI, 2018) 07 Foreign priorities are imposed upon building users. (ODI, 2018) 08 The funding agent is not the end user (ODI, 2018) 09 The project follows a sequence of design unfamiliar to users. (ODI, 2018) 10 Design fails to consider regional materials, climate, and craft. (ODI, 2018)

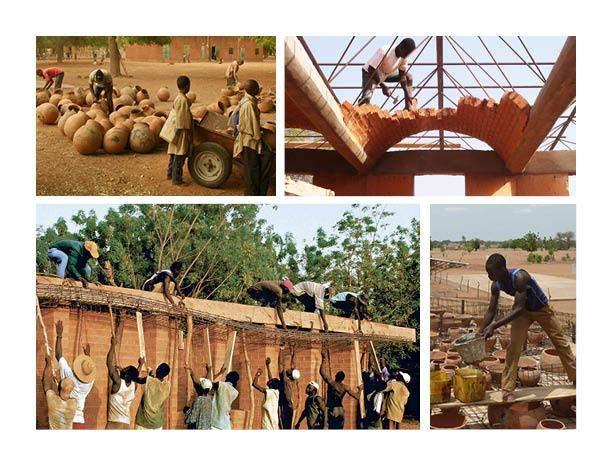

point departure stage projects differentiate themselves by determining that user communities will construct their buildings. When user communities operate as constructor they learn the techniques required to maintain their facilities and benefit from project funds being spent for wages and materials purchased from their communities. Another unique characteristic of these projects is the method in which the design is communicated. Karamojong Matriarch-led construction is often communicated through making while Gando Primary School and Gahinga Batwa Village were documented through a hybrid of drawings and verbal instructions. The success of these projects demonstrates the procedural malleability that exists in architecture. Users can be capable builders. Constructors can acquire design authorship through user led interactions with technical experts. Models of intervention can and should be contextually altered to meet the needs of the users they serve.

2 5 The Relegation of Traditional Building in Karamoja

The architectural profession in Uganda has demonstrated a recurring ambivalence to Karamojong culture, repeatedly failing to contextualize their methods of making. This ambivalence can be understood through the Matriarch, the traditional keeper of the built environment who continues to be excluded from the formalized design and construction industry While this exclusionary act was put forth in the colonial era, the current professional bodies regulating architecture have done little to restore the Matriarchs traditional role. In 2020 the Uganda Architects Registration Board issued its record of all registered and practicing architects. Of the 187 entries, every individual was registered to a company based in the nation's capital, Kampala, approximately 500km from Karamoja (Architects Registration Board, 2020). As a result, any architect working in the Karamoja region should be considered an outsider Perhaps more problematic than numerical representation is the professional trajectory towards “Dubai-Style '' that prefers the importation of foreign design aesthetics instead of a self-confident expression of cultural identity (Stilting, 2019). Designs by Ugandan architects often prefer imported aluminum and glass to appear distinguished and capable of attracting international attention. Figure 2.6 below illustrates the aesthetic qualities of this work in two projects by

Part 03: DESIGN INVESTIGATION

3.1. Organizational Model of Working

This thesis proposes an iterative, heritage-based architectural response to mitigate the increasingly harmful effects of globalization upon the traditionally semi-nomadic societies of northern Uganda. To test the claims of this thesis, an alternative model of engagement has been put forth to recast the role of the architect in support of the Matriarch. In this proposed model of working there are a series of operations that precede the design of a project oriented towards educating the architect and building a productive relationship with the community

pace)

)

For speculations around production of the AI-produced fully illustrated, the scale, of images illustrate designs perspective images

By for making that site an opportunity collecting this testing experimental constructed object provocations also encourages the In o achieve techniques, available The viability wide range 3 The life. This around vulnerability the Matriarch change. From back, mindful as “appropriateness.”

The starting point for my understanding of “appropriate architecture” would be a design posture of “creative observation”; context is everything, and a design needs to be discovered, not invented. The simple question, “what is appropriate?” can be applied to virtually every design decision and has a clarity to it that is often missing from discussions around sustainability (Holland, 2022)

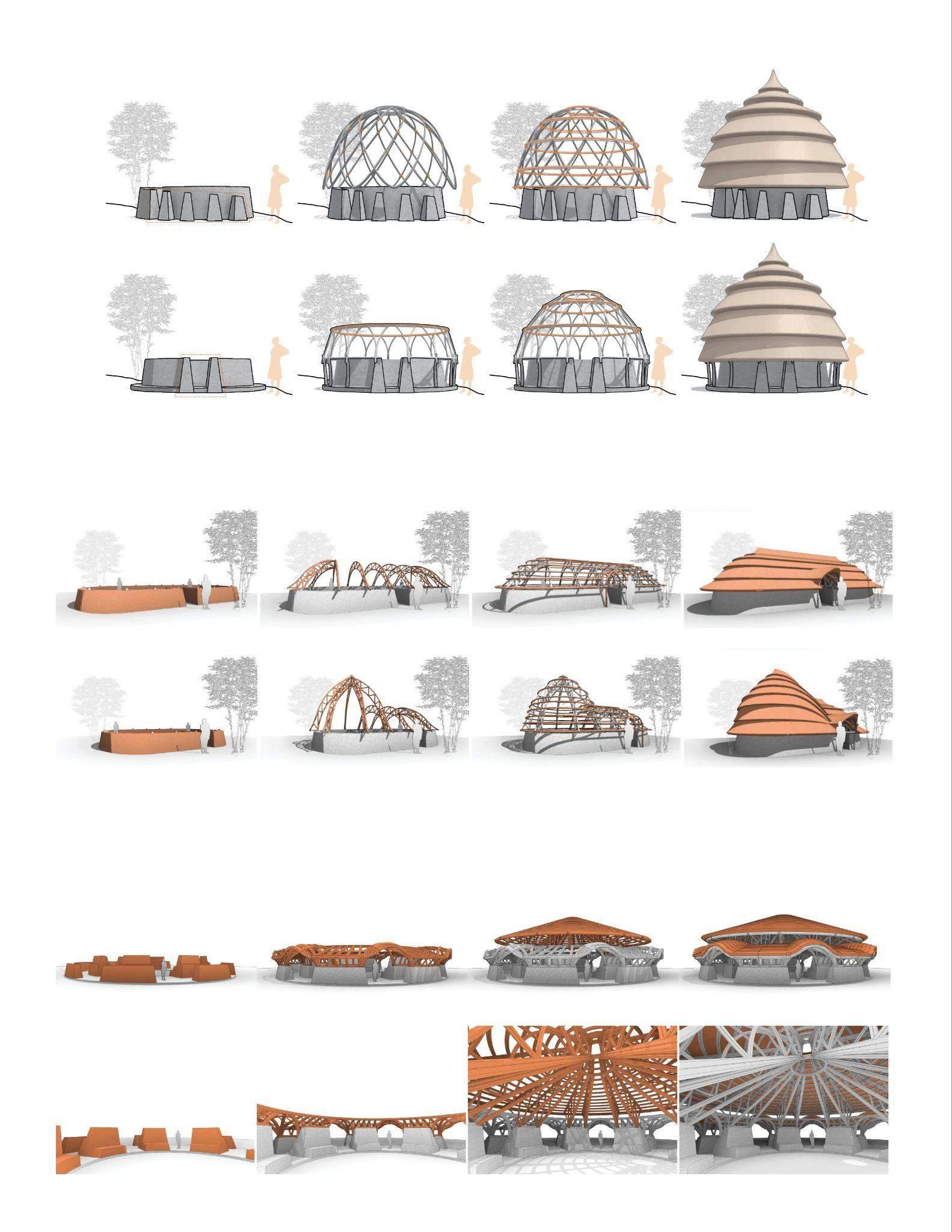

Speculative adaptations should be heavily influenced by the participatory experience of the apprenticeship, however several guiding objectives have been developed to better align current methods of making with a historically-influenced future. First, traditional building practices must evolve to include large structures to accommodate communal gathering, education, and governance. Traditional communities lack large gathering spaces outside the shade of generational trees. As noted in section 2.4 the discrepancy in scale between traditional structures and educational requirements must be explored to provide a contextually oriented future for schools. To prevent impositional methods of construction, communities must develop large structures to accommodate these activities.

Second, natural limestone, infrastructure building

Third, Facilities of outcomes

Fourth, their required. alternative buildings durable legal

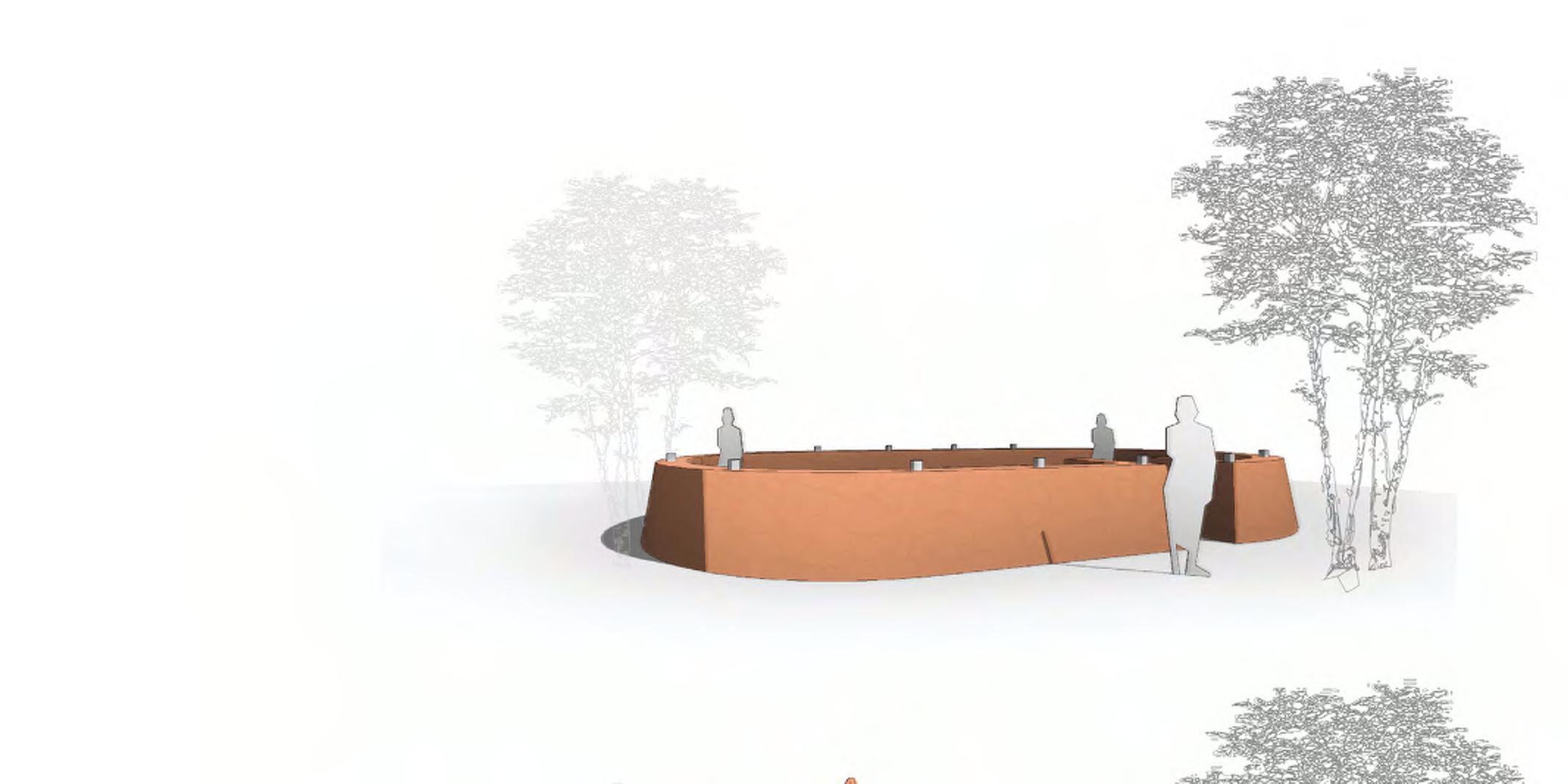

The culmination of the apprenticeship and speculative adaptations to the built environment through serial interventions is the research-based design of an Institute of Animal Science. The Institute of Animal Science is a forward-looking program which institutionalizes traditional knowledge in a way that will promote its usefulness for years to come. The institute will exist with several priorities including the legitimization of current expert cattle-specific practices, the accumulation and associated diffusion of knowledge to outsiders as well as future generations, and the cultural fortification of pastoralism as a legitimate, productive and essential way of life for the Karamojong.

The architectural demands for designing such an institute are complex. First, the typology of an institute is unfamiliar to traditional building and its function use must be integrated contextually Second, the proposed building must resolve the previously described challenges of scale. By committing to a large scale program the building must learn from the speculations and make a well considered proposal for resolving the familiar problem. Third, the necessity to build a large-scale structure will require methods of making that leverage multiple Matriarchs working in teams to accomplish a shared goal. This scale of collaboration is entirely new to the region and this thesis will test its viability by working in different size teams, seeking to better understand the limits of communal construction.

The Institute must also confront the realities of mobility in a semi-nomadic community Since knowledge would need to be collected from each region of Karamoja there are implicit pressures for this institute to account for mobility Architectural strategies for mobility must consider objects that are carried, others that are left, and what is expected to be found. In this capacity the building will reflect the nature of its inhabitants. The living, moving, Matriarch-constructed Institute of Animal Science is not a new invention, but rather the architectural celebration of a culture that already exists.

Figure 3 3: Midjourney images used for speculative adaptations (Author, 2022)

Figure 3 3: Midjourney images used for speculative adaptations (Author, 2022)

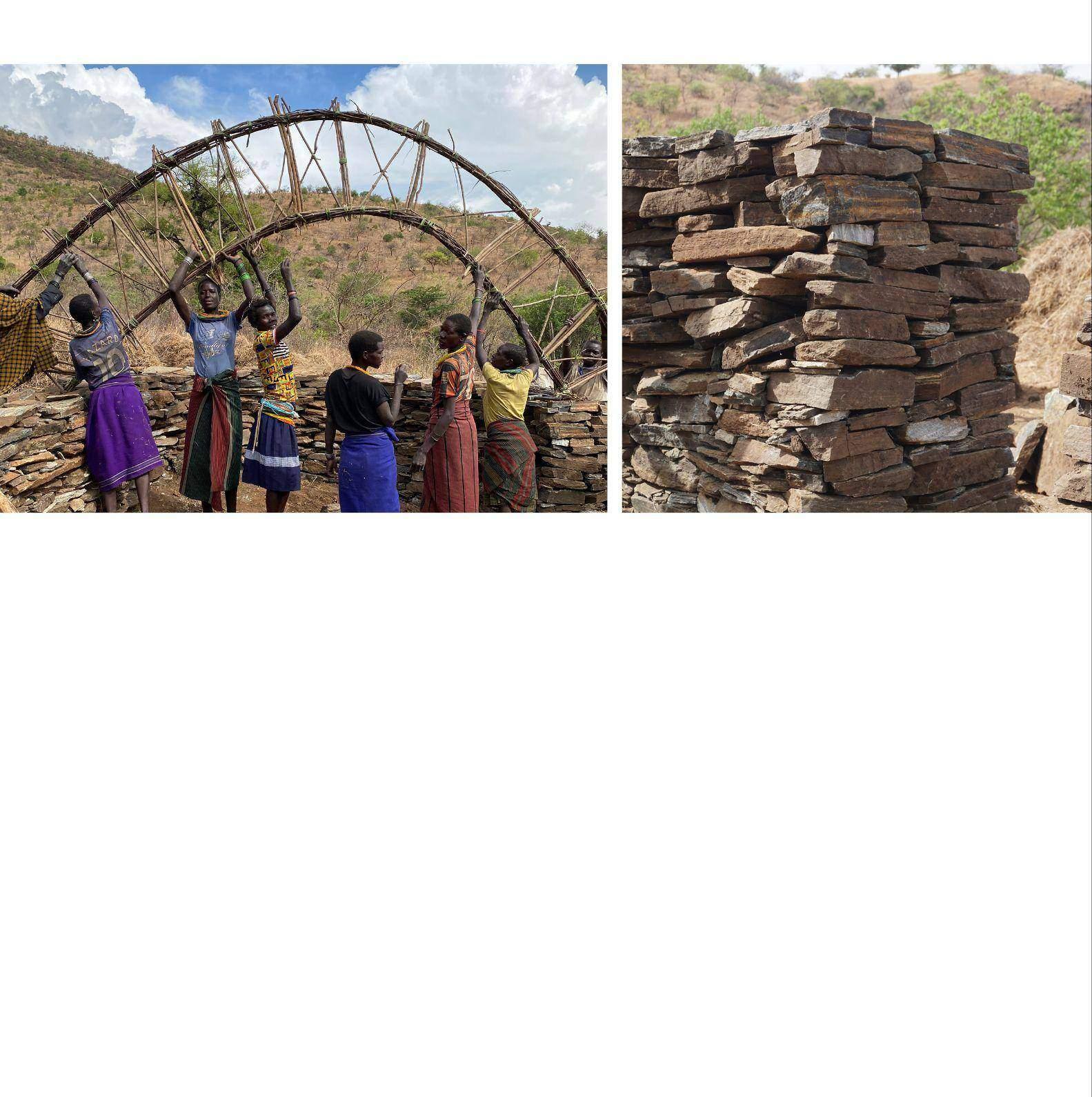

3 3 Iterative Acts of Communal Construction

The previously described Model of Intervention was put into practice in February of 2023. The author traveled to Karamoja, specifically to the Tepeth community living in the foothills of Mount Moroto to participate in the apprenticeship. This community was selected based on their proximity to naturally available building materials as well as their vulnerability context, amplified by recent cattle raiding which has created an immediate need for durable, ecological and forageable structures.

The apprenticeship took place over a duration of four days with a team of seven women working alongside the author Building materials had been previously collected and construction of the granary involved the translation of raw material into a productive form. While the language barrier between instructor and apprentice made verbal

financing If those resources become available in the future, the construction of the institute holds much opportunity in material advancement as well as operating as a valuable community resource A structure of this size would also promote the economic value of the Matriarch as constructor As members of nearby communities see the techniques expressed in these structures there

Part 04: RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

4 1 Metrics of Success

The design investigation has multiple layers of qualitative analysis to understand its success or failure. First, the proposed model of working and specific design for the Institute for Animal Science should be analyzed using the framework of impositional architecture developed earlier in this project. The responsive process of design and construction illustrated in this research scores well in all categories of the framework. One possible exception is item #4 that addresses the exit strategy of a given project. Since the construction of the Institute of Animal Science remains an open possibility in the future, the author has not been able to clearly communicate the future timeline for this intervention. However, in all other categories this project displays a high degree of material, cultural and institutional sensitivity to place.

The second metric for success is in the validation of each stage of the proposed process. The works described previously in section 3.3 describe a successful sequence of operations that display responsive design, user agency and incremental improvements to the built environment. The willingness of the Matriarchs to engage in the speculative adaptations in the work displays their understanding of the increased agency that follows successful interventions. The iterative construction process was also successful in its ability to be constructed in a narrow window of time - five days maximum. By meeting this time constraint, the acts of construction did not require the Matriarchs to forgo other responsibilities in their life. This was particularly important around the final act of construction that was closely aligned with the planting season. Importantly, the series of interventions continue in the community as productive buildings, actively used for their intended purpose.

The third metric for success is in the technical performance of the speculative adaptations. Without doubt, the most impactful success was in the use of dry-stack stone masonry walling that proved to be constructable and capable of carrying necessary roof loads. The needed stone was easily found and community members seemed to welcome the solidity displayed in buildings constructed with this massive material. In speaking with the community, it was clear there high degree of optimism that the plentiful supply of flat stones for construction would lead to future buildings

Lesser making Science. be framing the exists structures, While through subsistence. hiring described This of aligned

4 2 Conclusions

In conclusion, the model of working with Matriarchs put forth in this thesis holds great promise in avoiding acts of imposition common to our profession. Working iteratively, over time, and with humility are qualities that will serve architects well in finding contextual solutions that promote self-determined outcomes for vulnerable communities.

The architecture here emerges from the lessons learned through the iterative design process, capitalizing on the successful adaptations at a scale that matches the capabilities of the builders and the land. Working in this manner, traditional techniques of building can be preserved and find new opportunities of architectural expression. Architects can work creatively in this context, leverage their professional training and experience in support of tradition - and in support of those who build it.

osals (Author, 2023)

osals (Author, 2023)

Appendix A: Literature Review

Scoones, Ian, et al. Pastoralism and Development in Africa Dynamic Change at the Margins Routledge/Earthscan, 2013.

Ian Scoones work, Pastoralism and Development in Africa Dynamic Change at the Margins is being studied to better understand the broader context of issues facing pastoralist communities in East Africa. Karamoja represents a relatively limited area in the cattle belt but exists in a development context familiar to pastoralist communities in eleven countries throughout the Horn of Africa. Scoones work includes relevant issues around pastoral livelihoods, commercialization of economies, access to land, and discussion around alternative livelihoods. Perhaps the most useful aspect is the ongoing support it offers to pastoralist livelihoods as part of a contextually appropriate future. Since the book covers context beyond Karamoja, regionally distinct characteristics of other tribes offer insight into different adaptations of pastoralism. These adaptations exist as case studies, sometimes offering productive solutions and at other times operating as cautionary tales in describing behaviors to avoid.

“African pastoralists are increasingly exposed to globalization and world economic trends. New technologies are becoming available. Rapid urbanization, accompanied by increasing demand from urban populations for milk and meat, is changing the economic geography of the dryland areas.”

“Demand for education among pastoralists, including children actively involved in production, is rapidly increasing. Education is seen by impoverished households as a pathway out of poverty, and by the households actively involved in pastoral production as a way to support their production system in an increasingly globalized world.”

“While the corrupt nature of some land grabbing in pastoral areas of eastern Africa is indicated by its covert and surreptitious nature, some is carried out under the progressivist and triumphal banners of development, national progress, the preservation of natural resources, conservation, regional diversification, anti-traditionalism, and anti-conservatism.”

Caffey, Stephen. “Make/Shift/Shelter: Architecture and the Failure of Global Systems.” Architectural Histories, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, p. 18., https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.av.

Stephen Caffey’s work, Make/Shift/Shelter: Architecture and the Failure of Global Systems is being studied to better understand the capacity of the architectural profession to accommodate the context in which it is operating. In the case of this article, Caffey offers a context of crisis and offers insight into how the profession might better adjust to working in these charged, evolving and often foreign (for the designers) conditions. The centrality of crisis in the writing lends a dystopian quality to the work, however the recalibration of architectural work towards users is helpful. Caffey’s writing attempts to find solutions to capitalistic and globalizing trends which have dominated the design process produced self-sustaining systems that are not easily disrupted. This context, again becomes the motivation to return to the role of user to explore a series of new professional possibilities that engage historical assessment in contemporary practice.

“Over the past forty years a number of individuals and firms have undertaken pro bono, government-funded or NGO-funded initiatives to address the exigencies associated with these forces; a handful of architectural historians have addressed the products of these efforts, but few of the resulting projects have achieved canonical status in architectural history.”

“Once architects and architectural historians begin to transmit and receive knowledge from across disciplinary boundaries, new solutions can begin to emerge.”

“Public interest design need not replace the ithyphallic starchitecture that draws the attention (and the money) of the world’s elites. Rather, by assuming a predominant position in the built environment, design that focuses on those historically excluded from the ben-efitsof good design can complement and perhaps even re-humanize architecture through a series of humanistic reforms and reassertions.”

Dbins, Toolit Ambrose. Climate Change and Pastoralism. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2013.

Ambrose Dbins work, Climate Change and Pastoralism is being studied to better understand the relationship between pastoralist livelihoods and the environments in which they operate. Dbins offers thorough context around pastoralism and subsequently the evolving climatological trends. He goes on to collect large amounts of user feedback in Karamoja on the specific topic of climate change in relation to livelihoods. The insight offered in those interviews is profound, offering multigenerational perspectives that offer the reader tremendous insight into Karamojong communities. While qualitative in nature, Dbins work offers productive framing to better understand productive methodological approaches, limitations of the research and ethical dilemmas in working inside these communities. The work goes on to describe the influence of external agents on pastoralism including the national government and

Part 05:

SUPPORTING MATERIALS

NGO’s. Finally, Dbins offers conclusions, in support of pastoralism, but that require methodological changes to the way communities experience external intervention.

“Pastoralists’ vulnerability has also been heightened by the negative perception of pastoralism as a whole, including policy makers, government and development agencies.”

“A wide range of pastoralists are adapting, although slowly, from pure pastoralism to agro-pastoralism. From the respondents, this shift is attributed to the adverse effects of the recent restricted mobility and external actors’ interventions such as western education and implementing a global view of development and adaptation options across scale.”

[Respondent] “despite the good rains of this year all vegetation nearby has been cleared due to concentration and overgrazing of animals. Mobility has been restricted and we now rotate our animals within the available natural resources which is not good.”

Appendix B: Precedent Analysis

Fass School and Teacher’s Residence

Toshiko Mori

Fass, Senegal

2019

In remote Senegal, the Fass School is the first example of secular education in a region of 110 villages. This example of progressive architecture shows how new ideas can be introduced with sensitivity to tradition through vernacular architecture. The analysis on this project will investigate techniques that pay homage to heritage-based architecture.

Looking closely at the building design, the features of vernacular construction can be described in their materials, climate-oriented design, and highlighting local craft. For example, climate is considered through passive ventilation leveraging breeze block and stack ventilation. Materials such as grass thatch and white, reflective paints create a familiar material palette which make the unique form feel familiar This project uses a steep roof slope to collect precious rainwater and as a result the thatch roof becomes highly visible on both the building interior and exterior –celebrating traditional craft.

● AIA Architecture Award - 2021

● OPAL Architectural Design - Platinum Award - 2021

● Architizer A+ Award, Jury’s Pick, Institutional - 2020

● RAIC 2019 International Prize, shortlisted project - 2019

Photo Credit: Iwan Baan, Sofia Verzbolovskis (Abdel, 2021)

Photo Credit: Iwan Baan, Sofia Verzbolovskis (Abdel, 2021)

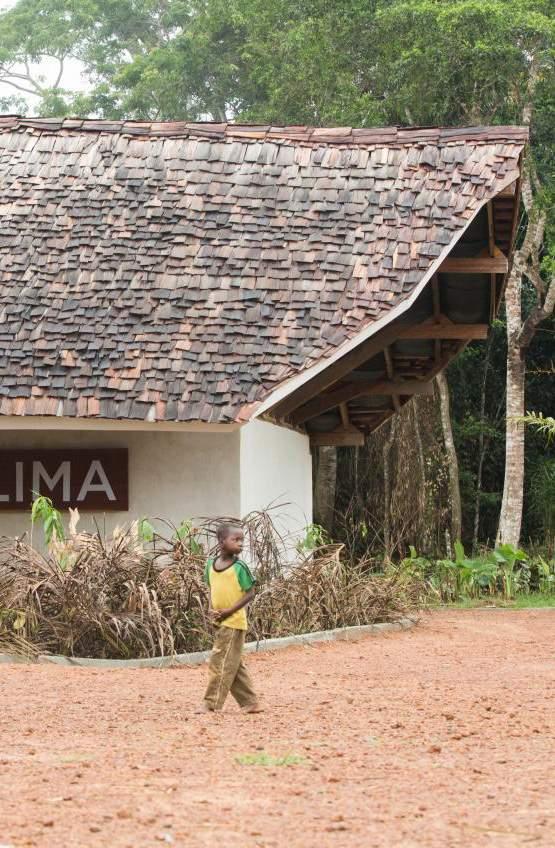

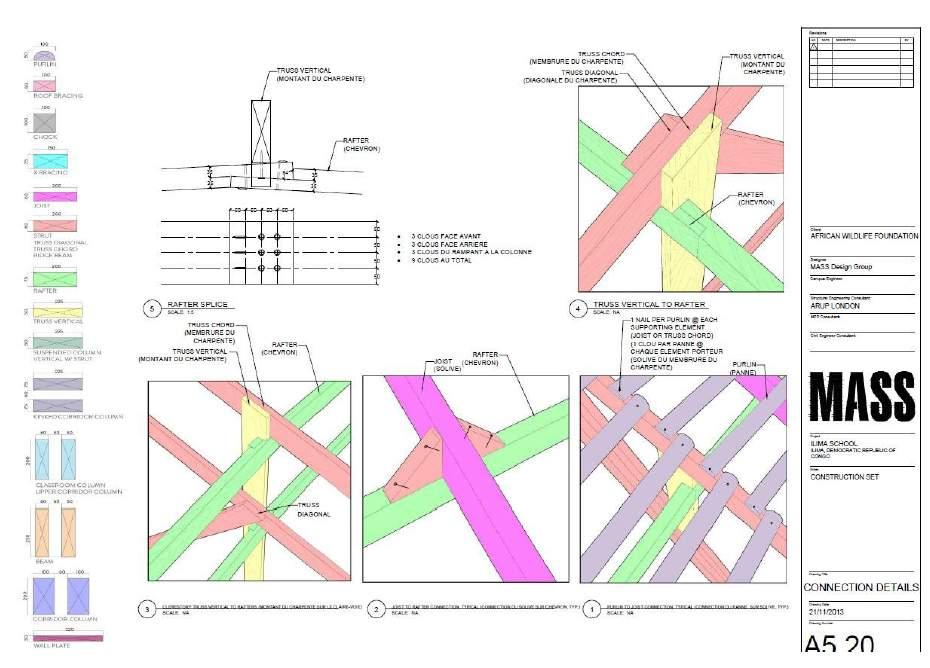

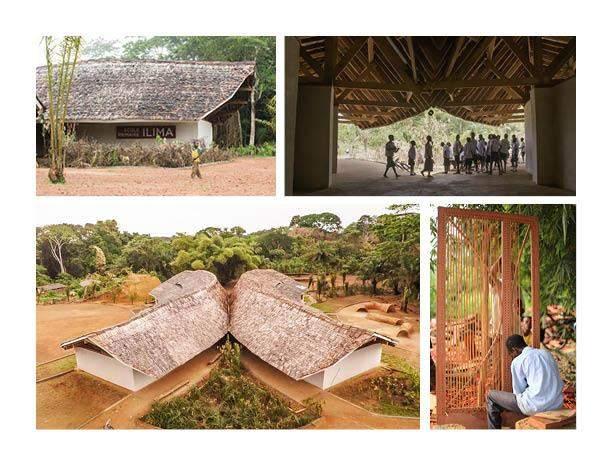

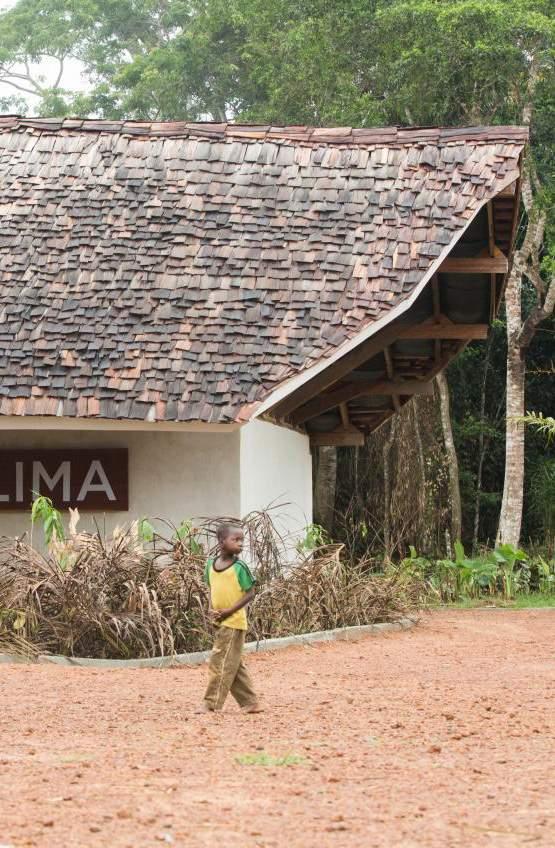

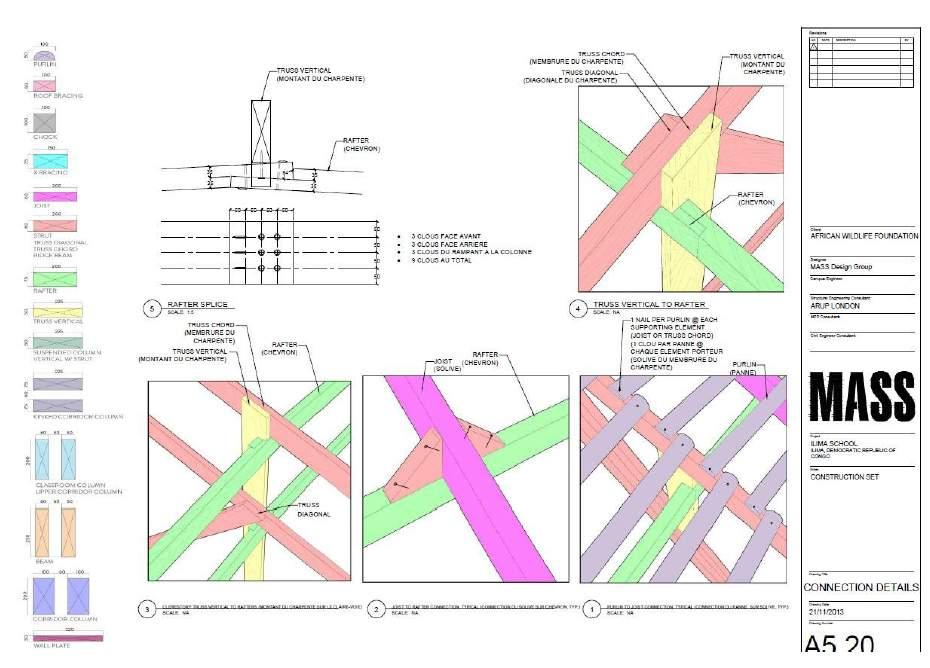

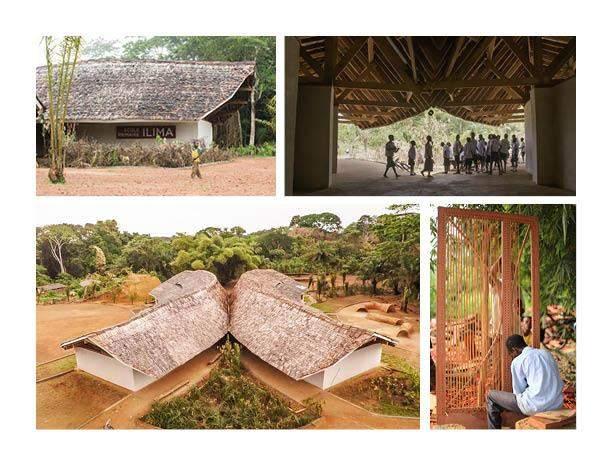

Ilima Primary School

MASS Design Group

lima, Tshuapa Province, DRC 2015

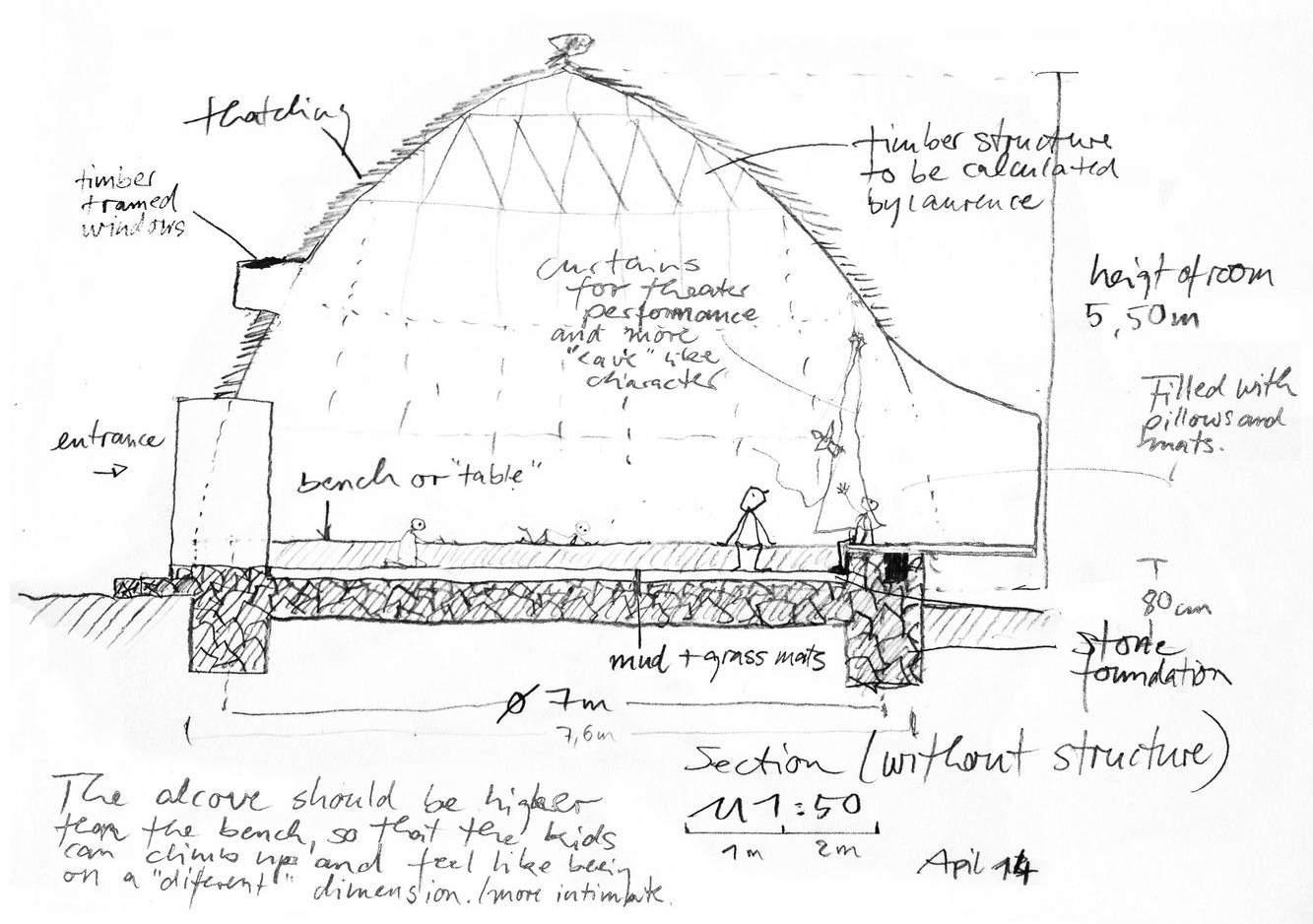

Located in the isolated town of Ilima, MASS Design Group worked closely with the local community to develop a Primary school with a mission much larger than the national curriculum. The school, funded by the African Wildlife Foundation, is intended to raise awareness around issues of wildlife conservation in fragile or transitioning ecosystems. This school will be analyzed for the way it communicates social and ecological concepts through the familiar program of a school.

The design of the school seeks to communicate an ideological framework through the formal configuration of the building. In this case the building is conceived as a bridge between two worlds. The concave classroom blocks face away from each other, illustrating the relationship between humans and wildlife, farmland and natural habitat.

● Notable Design for Social Impact Award Core77 Design Awards 2016

● Design Corps SEED Award Winner - 2016

● The Index Project Nominee 2017

● A+ Awards Jury Winner Architecture and Sustainability - 2016

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the architect (Astbury, 2020)

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the architect (Astbury, 2020)

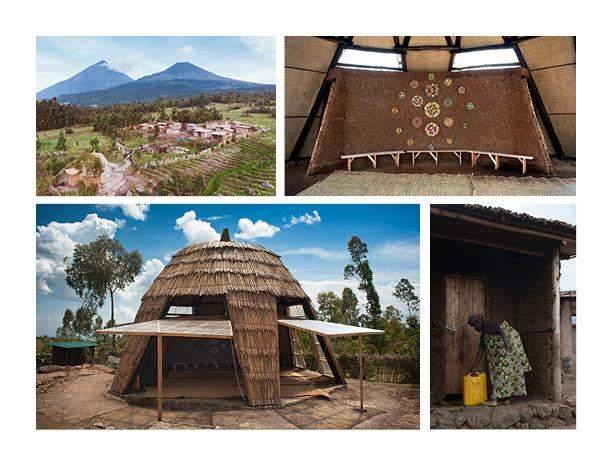

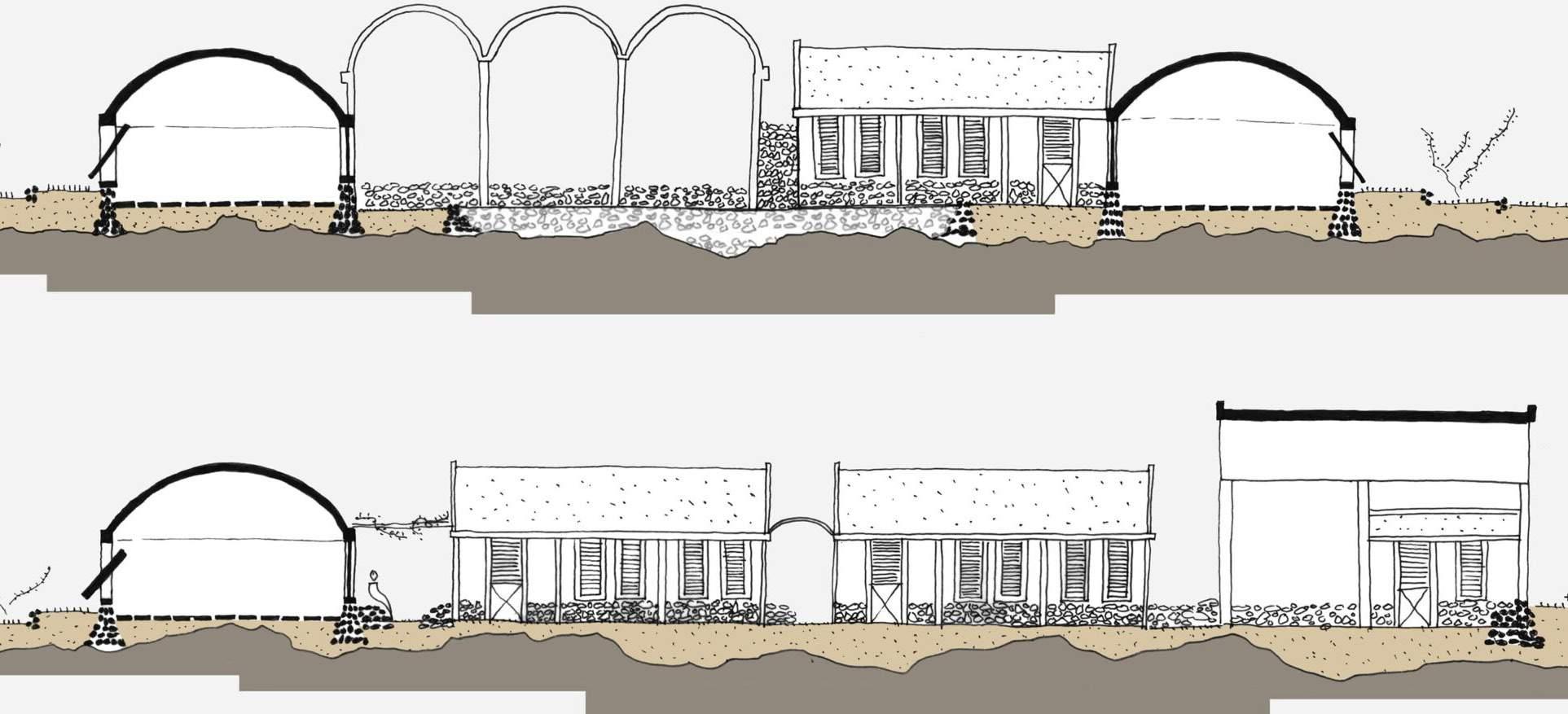

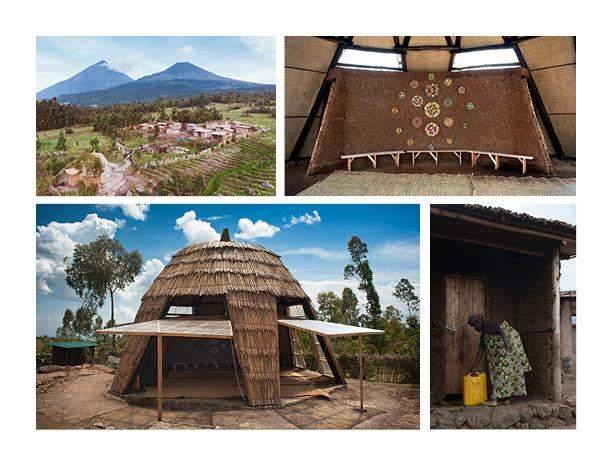

Gahinga Batwa Village Localworks

Kisoro, Uganda 2018

The village constructed by Localworks for the Batwa people living in Kisoro, Uganda is a valuable precedent for the incorporation of contemporary design for indigenous peoples. This project will be analyzed for its integration of heritage-based design features and the extent to which participatory design played a role in the project.

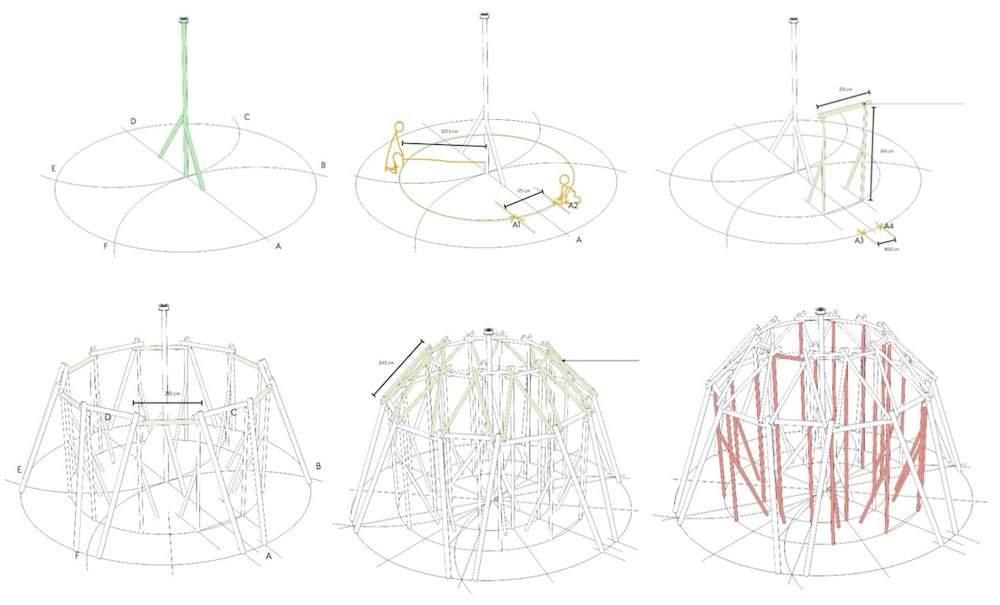

The heritage-based qualities include the use of traditional thatch as a roofing material, the dome-inspired structure which is reminiscent of traditional building forms, and the way openings balance programmatic needs for porosity while retaining a familiar formal expression. The participatory design elements include design workshops and a construction set of drawings that show not a completed form, but a step-by-step illustration for the community to follow in constructing their own space. This inclusive process gave the community valuable skills to maintain their newly constructed buildings.

● Afrisam SAIA Sustainable Design Award 2019/2020

● 2A Continental Architectural Awards 2019

Photo Credit: Will Boase Photography and Craig Howes (Holland, 2020)

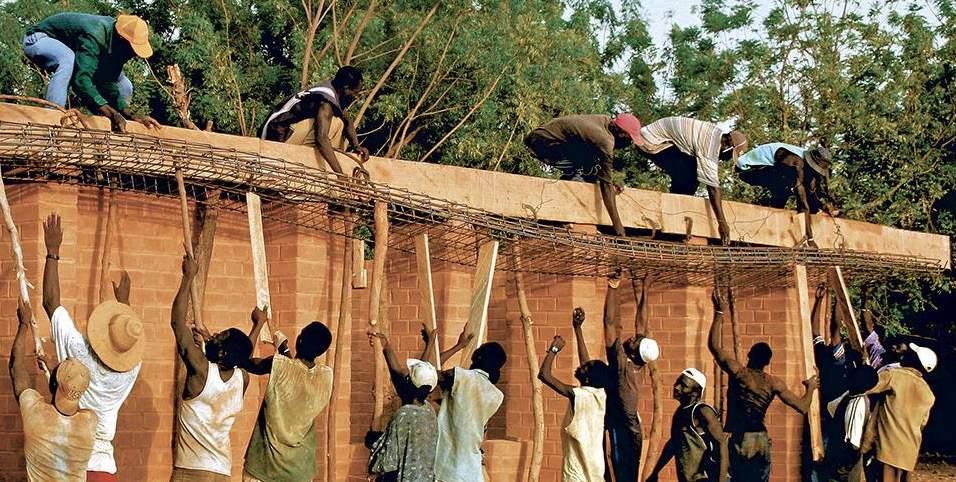

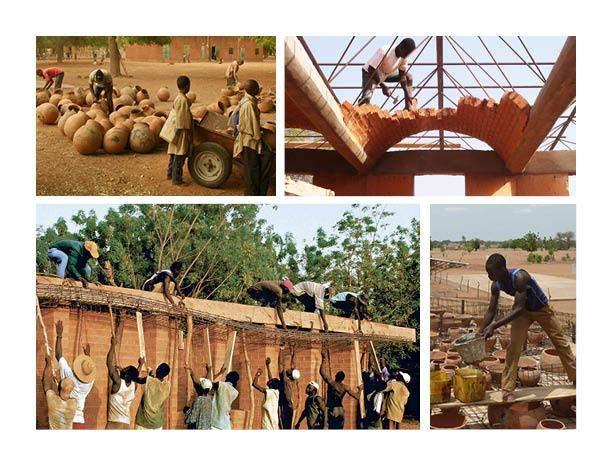

Gando Primary School

Kéré Architecture

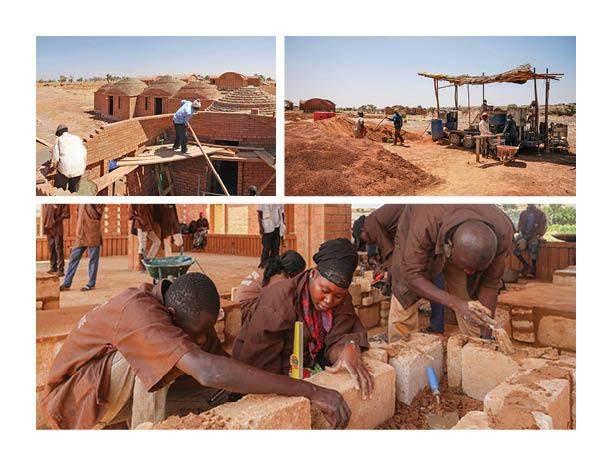

Gando, Burkina Faso 2001

The Gando Primary School is an early precedent for participatory design techniques that were specifically oriented to the user community. In this example, the architect had a thorough understanding of the cultural, social and economic context and oriented the design solutions to capitalize on community assets. Labor and materials were largely purchased from the user community by project funds which not only allowed the community to participate in the act of construction, but also to benefit from the economic stimulus of project funds. The result of this contextually informed design is that users are able to significantly improve their construction skills in a way that allows them to maintain the building over time.

This project is now over twenty years old and continues to offer valuable insight for how industry professionals can work in support of user communities. Francis Kéré subsequently was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2022 demonstrating a growing interest in contextual building practices in the architectural profession.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the architect (Menèdez, 2018)

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the architect (Menèdez, 2018)

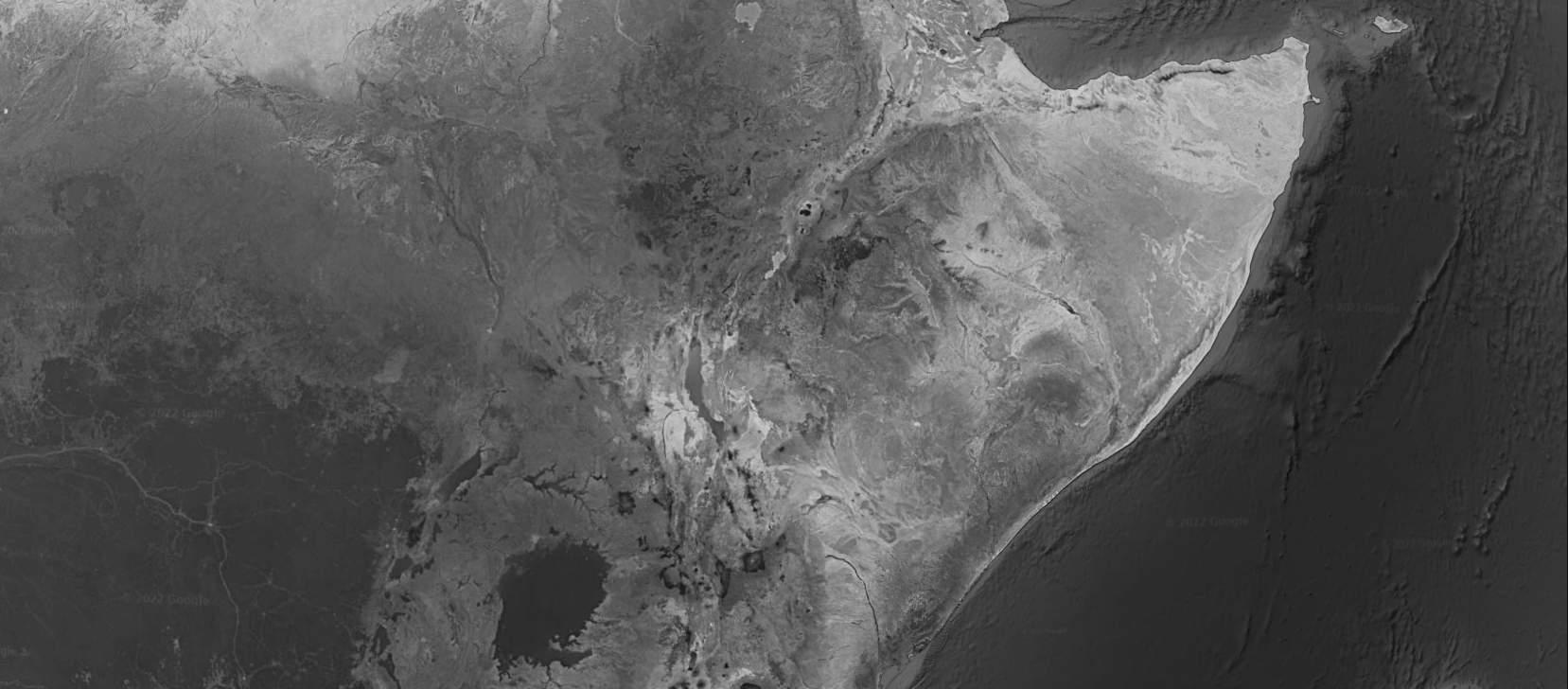

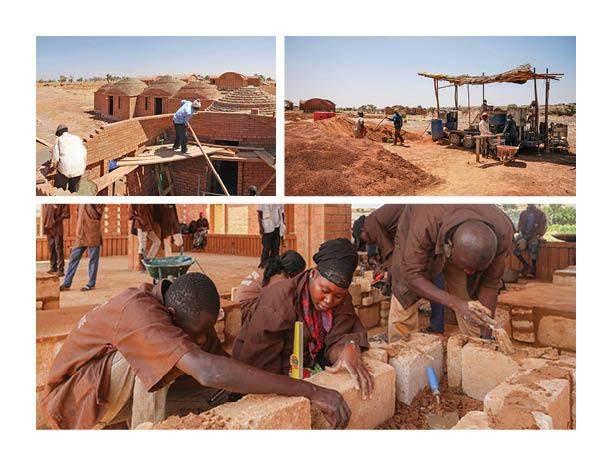

Practical Training College - Sangha LEVS architecten

Sangha, Mali 2013

The practical Training College in Sangha offers a valuable example of participatory design and construction in a way that legitimizes user participation through credentials. This project was developed in conjunction with an educational curriculum that allowed users to construct the building while learning the theoretical and academic principles relevant to their area of study This two-part approach has the productive result of giving members of the community credentials in building construction which allows them to then operate as certified professionals. An added benefit to overlaying the academic and technical training components is the opportunity to experiment with new technologies. In this case, the project experimented with widespread use of hydraulically-compressed earth blocks. The infusion of new technologies balances foreign interventionism with a mindfulness of historic building practices which have leveraged manually compressed earth for centuries.

The project does still rely on the injection of NGO funding and a somewhat top-down foreign influence from Dutch architects, but the outcome for user communities is perhaps the most beneficial compared to other user-constructed projects.

(18pt

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the architect (LEVS)

Appendix D: Photographs of Interventions

Photographs from Apprenticeship

Appendix D: Photographs of Interventions

Photographs from Apprenticeship

Photographs from Intervention #1

Photographs from Intervention #1

Photographs from Intervention #2

Photographs from Intervention #2

REFERENCES

Abdel, Hana. “Fass School and Teachers' Residences / Toshiko Mori Architect.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 30 Oct. 2021, https://www.archdaily.com/949364/fass-school-and-teachers-residences-toshiko-mori-architect.

Akabwai, D. and Atevo, P.E., 2007, The scramble for cattle, power and guns in Karamoja: How can stability be established in the Karamoja region, Uganda?, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University

Almaas, Ingerid Helsing, and Einar Bjarki Malmquist. “Architecture Norway: An Interview with Kenneth Frampton.” Architecture Norway | An Interview with Kenneth Frampton, 10 Aug. 2006, https://architecturenorway.no/stories/people-stories/frampton-06/.

Architects Registration Board - Uganda. Registered and Practicing Architects (2020). https://www.myarb.arbuganda.org/page/practicingArchitects.

Astbury, Jon. “Ilima Primary School in Congo by Mass Design Group.” Architectural Review, 22 July 2020, https://www.architectural-review.com/today/ilima-primary-school-in-congo-by-mass-design-group.

Barber, J. P “The Karamoja District of Uganda: A Pastoral People under Colonial Rule.” The Journal of African History, vol. 3, no. 1, 1962, pp. 111–124., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700002760.

Butt, Bilal. “Herding by Mobile Phone: Technology, Social Networks and the ‘Transformation’ of Pastoral Herding in East Africa.” Human Ecology, vol. 43, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–14., https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-014-9710-4.

Caffey, Stephen. “Make/Shift/Shelter: Architecture and the Failure of Global Systems.” Architectural Histories, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, p. 18., https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.av

Catley, Andy, and Mesfin Ayele. “Applying Livestock Thresholds to Examine Poverty in Karamoja.” Pastoralism, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00181-2.

Dbins, Toolit Ambrose. Climate Change and Pastoralism. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2013.

Dodson, Billy “African Wildlife News: Your Support at Work in Africa's Landscapes.” 2015.

Egeru, Anthony, et al. “Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Forage and Land Cover Changes in Karamoja Sub-Region, Uganda.” Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, p. 6., https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-4-6.

Holland, Felix. “Gahinga Batwa Village.” Localworks, https://localworks.ug/project/gahinga-batwa-village#.

Holland, Felix. “The Joy of Designing and Building Appropriately.” Building Design, 6 July 2022, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/the-joy-of-designing-and-building-appropriately/5117947.article.

Kaduuli, Stephen Charles, 'Forced Migration' in Karamoja Uganda (December 12, 2008). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1315237 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1315237

Knighton, Ben. The Vitality of Karamojong Religion: Dying Tradition or Living Faith? Routledge, 2017.

Menèdez, Ana. “Gando Primary School Library by Kéré Architecture. the Third Piece of the Complex.” Gando Primary School Library by Kéré Architecture. The Third Piece of the Complex | The Strength of Architecture | From 1998, 2018, https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/gando-primary-school-library-kere-architecture-third-piece-complex.

Mukiibi, Peter The Potential of Local Building Materials in the Development of Low Cost Housing in Uganda. 2016, http://www.technoscience.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/2015_9_The-potential-of-local-building-materials.pdf

“NSSF

Workers House.” Ssentoogo & Partners - Architects and Planning Consultants, 2015, http://www.ssentoogoarchitects.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id= 12&Itemid=211.

Overseas Development Institute. A Design Experiment: Imagining Alternative Humanitarian Action Humanitarian Policy Group & ThinkPlace, 18 Jan. 2018, https://odi.org/en/publications/a-design-experiment-imagining-alternative-humanitarian-action/.

–

Pavanello, Sara. “Pastoralists’ Vulnerability in the Horn of Africa - Exploring Political Marginalization, Donors' Policies and Cross-Border Issues.” Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute, London, Nov 2009, https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/5573.pdf.

“Practical Training College.” LEVS Architects, https://www.levs.nl/en/projects/practical-training-college.

Sabiiti, Olive. “The Evolution of Property Rights to Land in Postcolonial Buganda.” The Routledge Handbook of African Law, 2021, pp. 129–150., https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351142366-8.

Schaerer, Philipp. “Built Images: On the Visual Aestheticization of Today's Architecture: Philipp Schaerer.” Transfer Global Architecture Platform, 5 Apr 2017, http://www.transfer-arch.com/built-images/.

Scoones, Ian, et al. Pastoralism and Development in Africa Dynamic Change at the Margins Routledge/Earthscan, 2013.

Stilting , Ronald. “Creating a Truly Contemporary African Hotel.” Corporate Africa News, Nov 2019, https://corporate-africa.com/uganda-an-emerging-oil-and-gas-frontier/.

Waiswa, C.D, et al. Pastoralism In Uganda: Theory, Practice, and Policy 2019.

01 Domestic Organization

Karamojong communities are an evolving network of dwellings, food stores, cattle corrals and communal spaces that produce a complex interconnected neighborhood. Settlements begin with the basic dwelling which belongs to one woman and aggregate into sites which form around central cattle holding spaces. Communities are formed primarily around shared familial connections and generally grow until a population of 1,000 individuals is achieved. A network of fences encircle each dwelling and seamlessly come together to provide protection around other valuable neighborhood assets. Fences are strategically cut back to provide openings between enclosures which require the entrant to bend down passing head first through the opening.

Knighton, Ben. The Vitality of Karamojong Religion: Dying Tradition or Living Faith? Ashgate, 2005.

02 Distinct Value Systems

Pastoralist tribes are distinct with values that often misalign with actors seeking to (perhaps positively) invest or deploy programs inside their communities. Before any interventions are designed there must be a thorough approach to understanding the complex social structures, economies, and values of pastoralist peoples. Issues around collective land ownership, individual net worth, economic production, and environmental stewardship must be investigated from a sympathetic view that seeks to promote existing structures that have proven effective for centuries.

Manzano, P. Pastoralist Ownership of Rural Transformation: The adequate path to change. Development 58, 326–332 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-016-0012-6

03 Pastoralism and Climate

Pastoralism among the Karamojong cannot be understood independent of natural resources, access to land and environmental factors. Policy development around land ownership and access has significantly impacted these tribes. The result of these policies, combined with external factors is a less stable environmental climate that is making pastoralism increasingly difficult.

With less access to historically possessed lands, the remaining grazing lands are overburdened which accelerates the decay of that ecosystem.

Vulnerable livestock produces vulnerable human health and nutrition scenarios, further accelerating intervention from foreign actors.

Ddbins, Toolit Ambrose. Climate Change and Pastoralism. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2013.

04 Integration of Modern Technology

Increased adoption of mobile phone technology among pastoralist tribes in sub-Saharan Africa is changing the landscape of information-sharing. This change is replacing traditional knowledge bases which inform the movements of people and cattle to preferred grazing locations.

Phone based information sharing is responsible for diffusion of knowledge around forage and water resources, predators, park rangers, disease and weather. Beyond the impact of knew knowledge sources, the use of phone communication changes the nature of social power structures of knowledge. Information diffusion is no longer publicly shared or constrained to geographic or tribal regions.

Butt, Bilal. “Herding by Mobile Phone: Technology, Social Networks and the ‘Transformation’ of Pastoral Herding in East Africa.” Human Ecology, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–14. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24762844.

01 Rebirth of Tradition and Craft

African continental education has neglected its own histories in favor of a more Euro-centric curriculum. The impact of this bias is that students are unaware and ill-equipped to propagate traditional skills and knowledge distinct to their region. The impact of this forgotten knowledge is that it will result in the death of the craftsmen, unseen and unsupported through acts of architecture.

Agbo calls for a rebirth of collective knowledge around traditional craft as a way to propagate culture. This rebirth must also include urban and policy changes which recognize the value of indigenous architecture in the urban planning and codification of building codes.

Mathias Agbo, Jr. “Making a Case for the Renaissance of Traditional African Architecture.” Common Edge, https://commonedge.org/making-a-case-for-the-renaissance-of-traditional-african-archite cture/.

02 Ecological Materialism

Finding sustainable design solutions should aspire to achieve a solution that can be described as “appropriate”. This approach relies on an understanding of context, climate, traditional building technology and regional materials. This knowledge is not institutionalized, rather, it must be re-learned with time, budget, and focus in the early project design stages. Seeking appropriateness in design will also include an understanding of how buildings are constructed, local labor skills and common methods of procurement. Thinking holistically will produce more locally meaningful, economically productive works of sustainable architecture.

Holland, Felix. “The Joy of Designing and Building Appropriately.” Building Design, July 2022, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/the-joy-of-designing-and-building-appropriately/5117 947

03 Cultural Anthropology

The nomadic cultures indigenous to Saharan Africa have developed highly ordered societies around the built environment. Space must be constructed quickly, must be lightweight, and must be replaced regularly with forageable materials. These cultures are significantly more transmissive of their values compared to sedentary societies.

The built is owned and maintained by women. As the effects of sedentarization creep in, the woman loses instrumental control over her home. With loss of control, so goes loss of rights.

Prussin, L. (1998). African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place, and Gender. Smithsonian Institution Press.

vs Semi-Nomadic

04 Paternalism

Foreign actors have an established record of working without consideration of the built environment for the end user. The top-down dissemination of rules and aid is formative in the resultant spaces that are produced in refugee camps.

Over time and with decreased funding there is generally a shift to a more hands-off, user-driven approach. While these conditions often produce more context-specific user driven responses, these projects lack resources and developmental significance. Refugee assistance should make a higher priority of participatory design allowing greater agency to refugees in the formation of rules and resources around the spaces they will inhabit. Peirson, Ellen. “Building Refuge: From Emergency Shelter to Home.” Architectural Review, 12 Jan. 2021, https://www.architectural-review.com/building-refuge-from-emergency-shelter-to-home.

First

Heritage-based architecture will mitigate the increasingly harmful effects of globalization upon traditionally nomadic and semi-nomadic societies.

Government & NGO pressures away from pastoralism. “Therefore, we must invest in settled agriculture” Ms Flavia Kabahenda Rwabuhoro, Kyegegwa Woman MP Historical

1894 Legal Frameworks Introduced through Colonization 1924 Introduction of Land Titles and personal land ownership 1960 Arrival of NGO’s and other aid-based foreign actors

weapons

To investigate this claim, this thesis will design an Institute of Animal Science for the semi-nomadic, cattle-based communities in Northern Uganda.

Migration Route of the Karamojong

1979 Introduction of automatic

1923

Christian mission arrives 1600-1700

migration south from Abyssinia 1830’s Formation of tribal identity as Karamojong

established as British Protectorate

Drought-induced

1894-1962 Uganda

2008

Split to form Maasai cluster of tribes

Teso Tobur Matheniko Bokora Pian Dodoth Jie Turkana Suk Tepeth Nyangia Napore Iik Teuso Karamojong Reintegration Housing, Office of the Prime Minister Nakapiripiriti Primary School, Irish Aid Moroto General Referral Hospital, Uganda Ministry of Health AGENTS OF CHANGE NGO’s USAID UNHCR UNHABITAT UNWOMEN UNDP UNFPA International Rescue Committee African Wildlife Foundation Uganda Wildlife Authority Government of Uganda Samaritan’s Purse World Bank National Forestry Authority Catholic Relief Services Mercy Corps Ministry of Health World Vision UNICEF Uganda Peoples Defense Force Church of Uganda World Food Programme Local Government Compassion International Religious Organizations Works of Imposition Government Agencies Sedentarization Rural Expansion Urbanization Overuse of Grazing Land Land Clearing Firewood and Charcoal Loss of cultural identity Accelerated regional climate change Increased number of Farmers Decreased role of Pastoralism “most humanitarian relief workers are unfamiliar with thinking and talking about the built environment” W01_CONTEXT OF THE INVESTIGATION

Widespread access to mobile phone technology

1962 Ugandan Independence

Nomadic

Entire livelihood must be moved by “beast of burden”, often by camel. Extreme imposition of efficiency for all objects to be carried. Formal settlements operate as bases, select persons travel with cattle for long periods of time to find better grazing land. Local Craft Local Materials Local Craft Local Materials Learned Craft Foreign Materials Culturally Harmful Imposition Leading Voices/Practices Diébédo Francis Kéré Anna Herringer ASA Studio MASS Architects Build x Studio Atelier Masōmī Felix Holland TERRAIN architects ETHAN WALKER_THESIS

W02_MARKERS OF IMPOSITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

FAILURES

1 Design of the building takes priority over strengthening community. (Lee, 484)

2 Project fails to consider local customs, traditions and governance. (HPG 2018, 39)

3 Priorities of the designer are misaligned with long term user needs. (Mercy Corps 2016, 23)

4 Foreign agents intervene without a well-formed exit strategy. (HPG 2018, 41)

5 The project evolves within a single discipline. (Caffey, 4)

6 Interventions are made without feedback or accountability. (Sheppard, 158)

7 Foreign priorities are imposed upon building users. (HPG 2018, 27)

8 The funding agent is not the end user. (HPG 2018, 26)

9 The project follows a sequence of design unfamiliar to users. (Sheppard, 152)

10 Design fails to consider regional materials, climate, and craft. (Guarnieri, 25)

RESPONSIVE PRIORITIES

PRIORITIZE COMMUNITY & END USER NEEDS CONTEXTUALIZE DESIGN PROCESS AND RESULTING WORK ADVOCATE FOR STAKEHOLDERS WITHOUT INFLUENCE UTILIZE A WIDE RANGE OF EXPERTISE TO INFORM THE DESIGN

DESIGN WITH STRATEGIES THAT CONSIDER REGIONAL CLIMATE CONSIDER ENERGY SOURCES AND THEIR IMPACTS DESIGN WITH RENEWABLE REGIONALLY-SOURCED MATERIALS IMPROVE BIODIVERSITY AND SUPPORT LOCAL ECOSYSTEMS

SUPPORT LOCAL LABOR AND DEVELOP NEW SKILLS PROMOTE SOLUTIONS THAT RESONATE WITH THE COMMUNITY PROMOTE LOCAL CUSTOMS, TRADITIONS AND GOVERNANCE

IDENTIFY TRADITIONAL SOLUTIONS TO LONG-STANDING ISSUES CONSIDER COMMUNITIES HISTORIES AND SHARED EXPERIENCE

CONSIDER THE PROJECT AFTER CONSTRUCTION. ACCOMMODATE FUTURE CHANGE OF USE DESIGN FOR FUTURE EXPANSION AND REPAIR

Gahinga Batwa Village

Localworks Kisoro, Uganda 2018

The village constructed by Localworks for the Batwa people living in Kisoro, Uganda is valuable precedent for the incorporation of contemporary design for indigenous peoples. This project will be analyzed for its integration of heritage-based design features and the extent to which participatory design played a role in the project.

The heritage-based qualities include the use of traditional thatch as a roofing material, the dome-inspired structure which is reminiscent of traditional building forms, and the way openings balance programmatic needs for porosity while retaining a familiar formal expression. The participatory design elements include design workshops and a construction set of drawings that show not a completed form, but a step-by-step illustration for the community to follow in constructing their own space. This inclusive process gave the community valuable skills to maintain their newly constructed buildings.

1. Afrisam SAIA Sustainable Design Award 2019/2020

2. 2A Continental Architectural Awards 2019

Holland, Felix. “Gahinga Batwa Village.” Localworks, https://localworks.ug/project/gahinga-batwa-village.

“Volcanoes Safaris has now built a permanent village for the Batwa community and their families. About 10 acres of land has been purchased to allow them to build homes, a community centre and have land for agricultural and recreational use.” (Volcanoes Safaris)

“A new community centre, whose design inspiration was the traditional forest dwelling of the Batwa, was also put up near the main access into the site.” (Archute)

Ilima Primary School

MASS Design Group lima, Tshuapa Province, DRC

2015

Located in the isolated town of Ilima, MASS Design Group worked closely with the local community to develop a Primary school with a mission much larger than the national curriculum. The school, funded by the African Wildlife Foundation, is intended raise awareness around issues of wildlife conservation in fragile or transitioning ecosystems. This school will be analyzed for the way it communicates social and ecological concepts through the familiar program of a school.

The design of the school seeks to communicate an ideological frameworks through the formal configuration of the building. In this case the building is conceived as a bridge between two worlds. The concave classroom blocks face away from each other, illustrating the relationship between humans and wildlife, farmland and natural habitat.

1. Notable Design for Social Impact Award Core77 Design Awards 2016

2. Design Corps SEED Award Winner - 2016

3. The Index Project Nominee 2017

4. A+ Awards Jury Winner Architecture and Sustainability - 2016

Clegg, Peter, and Isabel Sandeman. A Manifesto for Climate Responsive Design.

Fass School and Teacher’s Residence

Toshiko Mori Fass, Senegal 2019

In remote Senegal, the Fass School is the first example of secular education in a region of 110 villages. This example of progressive architecture shows how new ideas can be introduced with sensitivity to tradition through vernacular architecture. The analysis on this project will investigate techniques that pay homage to heritage-based architecture. Looking closely at the building design, the features of vernacular construction can be described in their materials, climate-oriented design, and highlighting local craft. For example, climate is considered through passive ventilation leveraging breeze block and stack ventilation. Materials such as grass thatch and white, reflective paints create a familiar material palate which make the unique form feel familiar. This project uses a steep roof slope to collect precious rainwater and as a result the thatch roof becomes highly visible on both the building interior and exterior –celebrating traditional craft.

1. AIA Architecture Award - 2021

2. OPAL Architectural Design - Platinum Award - 2021

3. Architizer A+ Award, Jury’s Pick, Institutional - 2020

4. RAIC 2019 International Prize, shortlisted project 2019 Castro, Fernanda. “New Artist Residency in Senegal / Toshiko Mori.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 31 Jan. 2020, https://www.archdaily.com/608096/new-artist-residency-in-senegal-toshiko-mori.

“One of the things that’s made Toshiko so great for this project is that she sees architecture as a big vision—its impact on humanity—not just building buildings.” (Architectural Record)

POLITICAL BOUNDARIES OF THE DISTRICTS OCCUPIED BY THE KARAMOJONG PEOPLES IN NORTHERN UGANDA. THE MAP BOUNDARIES HAVE NEVER BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE KARAMOJONG TRIBAL LEADERS.

A pastoralist community is dependent on herd health which is directly dependent on land health. As land health is deteriorated, the pastoralist communities vacate that land until it can naturally regenerate. Regional climate change has made water sources less predictable and increased the amount of time for land to naturally regenerate. While many foreign actors suggest agrarianism as a solution to the climate-induced challenges to pastoralism, the ability for these communities to adapt to climate extremes has historically proven successful. The key determinant in success is mobility.

“Pastoralists’ strategies vary from entirely mobile to relatively sedentary lifestyles. Pastoralists also use strategic mobility and selective livestock feeding in order to interface with the instability of their operating conditions with a high degree of diversity within the production system itself, especially in areas where temporal patterns of key resources are predictable.”

Ddbins, Toolit Ambrose. Climate Change and Pastoralism. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2013.

“Consultations were been held with the Batwa ... Felix Holland from Studio FH Architects provided advice on the site... Dan Krueger from Puddlejump...who specializes in indigenous tourism, has also been consulted. Cyprien Serugero, Head of Construction for Volcanoes Safaris oversaw the construction.” (Volcanoes Safaris)

“The houses are being built by the Batwa, following their own traditions and culture, using a volcanic stone base with mud and water to form the core of the design.” (Volcanoes Safaris)

“The Gahinga Batwa Village has been funded by VSPT supported by Volcanoes Safaris, the Adventure Travel Conservation Fund (ATCF), as well as donations received from guests.” (Volcanoes Safaris)

“The settlement layout plan was not drawn instead the placement of the houses was done ‘on the go’ by the builders. The locals were encouraged to respond to the immediate site environs i.e to avoid placing the verandahs on the side facing the strong winds coming from the volcanoes.” (Archute)

“Locally available materials were utilized during construction; stones collected on the site were used to build the rubble stone foundations, the walls were made of eucalyptus poles with a bamboo grid, finished with earth plaster and the roofs are made of metal sheets covered with a papyrus layer above. (Archute)

“Material research and innovation was undertaken to develop and enhance traditional techniques, rather that to prescribe new foreign ones” (Climate Design)

“Mori designed an oval building with an inner courtyard for the school, borrowing its shape from an ancient compound in the region” (Architectural Record)

“Its design draws from the ‘one room school house’ in rural America where Josef Albers once taught” (Archiexpo)

“Designers collaborated with local conservationists to identify appropriate trees in the agricultural area, which were hand-sawn, planed, and crafted into the timber trusses, roof framing, furniture and architectural details of the final facility.” (Architizer)

“Forums were held with community leaders, residents, teachers, and students through all steps of design and construction in order to create a finished product with, not for, the community.” (Climate Design)

“AWF constructed Ilima School in exchange for the Ilima village’s agreement to heed to a land-use plan and a number of other conservation actions.” (African Wildlife Foundation)

“AWF uses legacy gifts to fund such critical programs when expenses exceed the funding available from AWF’s regular operating budget. These gifts provide AWF with the resources and flexibility needed to address the most challenging threats to Africa’s wildlife.” (African Wildlife Foundation)

“The community had virtually no experience reading construction documents, so MASS developed colour-coded graphic representation that allowed often illiterate workers to assemble the building's complex roof frame.” (Climate Design)

“Built entirely of materials and labor sourced on the hard-to-access site, the Ilima School embodies MASS's ethos of Lo-Fab [local

(Architizer)

“I think they came to see my motive: quite simply, in the world today, there’s no reason for people not to be able to read or write” (Architectural Record)

“Funding, meanwhile, was provided by Le Korsa supporters Laurel Hixon and Michael Keane, a couple who became aware of the cause and asked guests at their 2016 wedding to donate to it.” (Architectural Digest)

“Mori...used the local workers with traditional skills and materials to build it (a necessity since it is located

(Architectural

Since the cattle-based livelihood is significantly dependent on temporal conditions such as forage and water, the idea of permanent settlement is relatively unknown to tribes in the Karamojong region. Since these people historically migrated from Abyssinia there have been seasonal (yearly) migrations in addition to 50 or 100 year migrations to and from Lake Turkana or other fertile areas in extreme climate conditions. When the cattle are facing difficulty, the cultural instinct is to relocate to prioritize the health of the livestock. Mobility often initiates violent conflict. Historically, the Karamojong have battled for access to land with Acholi tribes to the east and with the (not so distant) tribal communities in Kenya.

The introduction of national boundaries of South Sudan and Kenya are restricting mobility which has led to increased rates of settlement. While some communities are moving less, their ways of living, building and interacting with the land reflect the mobility to which they are accustomed.

“Herdsmen own no grazing lands, for it is not worthwhile defending plots that they can only use for short periods. Even enemies will not be ejected, if there is surplus grazing or if their ejection would incur too many losses to enforce….There is no defense of territorial boundaries in order to preserve exclusive use of land resources. Karamoja’s borders remain fluid.”

Knighton, Ben. The Vitality of Karamojong Religion: Dying Tradition or Living Faith? Ashgate, 2005.

ACCESS TO LAND NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS MOBILITY

PASTORALISM INDIGENOUS KARAMOJONG

From an anthropological perspective, the ability to comment on indigenous culture and their associated evolutions positive or negative must be mindful of unwanted imposition. In such cases, outside commentary should be made from the position of “Technical Expertise” offered without burden of response.

“Pastoralist systems would rather strive for high added-value products that may involve lower productivity per animal in terms of quantity of product, but higher income for the owner.”

fabrication].”

seven hours from Dakar, across the

River).”

Record)

Gambia

THE TREND IN MARKERS 7 & 8 SHOW A LINK BETWEEN OUTSIDE FUNDING AND AN AGREEMENT THAT MUST BE TAKEN BY THE LOCAL COMMUNITY.

LITTLE IS COMMUNICATED ABOUT EXIT STRATEGY OR DURATION OF MEANINGFUL INVOLVEMENT.

LITTLE IS COMMUNICATED ABOUT EXIT STRATEGY OR DURATION OF MEANINGFUL INVOLVEMENT.

THE TREND IN MARKERS 9 & 10 SHOW ARCHITECTS ARE ABLE TO ADAPT MATERIALS AND THE DESIGN PROCESS TO ACCOMMODATE USER NEEDS.

LITTLE IS COMMUNICATED ABOUT EXIT STRATEGY OR DURATION OF MEANINGFUL INVOLVEMENT.

Manzano, P. Pastoralist Ownership of Rural Transformation: The adequate path to change. Development 58, 326–332 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-016-0012-6 INCREASED SETTLEMENT (AGRICULTURE) COMMUNAL LAND OWNERSHIP & TITLES GOVERNMENT REQUISITION OF LAND GOV-ISSUED MINING CONCESSIONS GOV-ESTABLISHED NATIONAL FORESTS 36% OF ALL LAND IN KARAMOJONG OCCUPIED DISTRICTS SPRINGS / DAMS / WATER WILD PLANTS / FORAGE NATURALLY OCCURRING MINERALS HERD MOBILITY POPULATION MOBILITY INCONSISTENT RAINS/ DROUGHT FLASH FLOODS DEGRADATION OF LAND / EROSION 9 10 4 3 8 6 7 5 1 2 TIME CAPACITY FOR CHANGE AGRARIANISM PASTORALISM CLIMATE SOUTH SUDAN KENYA TO LAKE TURKANA TO ACHOLI LANDS KIDEPO VALLEY NATIONAL PARK MATHENIKO GAME RESERVE BOKORA GAME RESERVE PIAN UPE GAME RESERVE UGANDA PERMANENCE & MOBILITY INDIGENEITY & CULTURAL EVOLUTION

& CLIMATE

PASTORALISM

IDENTIFIED

ETHAN WALKER_THESIS

CONTEXT OF INVESTIGATION SPECULATIVE ADAPTATIONS

MANYATTA ORGANIZATION

The Manyatta is the basic organization for communal Karamojong dwelling. The components for these communities include perimeter fences, domestic dwellings, grain storage, communal areas for gathering and a large cattle corral. Exclusively constructed by women, the Manyatta is an evolving assemblage of materials, family, and cattle living in symbiosis with each other.

The Manyatta organization starts with the smallest unit, the yard (Ekal). This fenced area belongs to one woman and includes a one-roomed hut for sleeping, granaries, and in some cases, a common meeting place. She is solely responsible for the gathering of materials, design, construction and maintenance of all structures in her yard. Yards are arranged to abut each other forming a side (Ewae) with interconnecting low passageways through the fencing.

As sides are formed, additional open spaces will be incorporated for milking the domestic cows and other communal needs. Sides expand over time around one or two large shared cattle corrals that complete the homestead. Members of the homestead are linked through familial ties and as members are married in or die, the homestead will evolve accordingly. The result of this organization is a living, irregularly formed neighborhood of up to 1,000 inhabitants who form a clan. In times of danger, multiple neighborhoods may be constructed adjacent to each other to provide security against attack.

FENCING

Fencing must be considered as a type of landscape walling that provides perimeter security, communal division of space and cattle containment. Sometimes over 3’ thick, fencing around yards and sides are constructed with woven sticks, thorns and branches. Small openings are strategically incorporated in the fences to allow for natural interconnectedness between spaces in the neighborhood. Fencing configurations in a Manyatta represent a constantly evolving building feature. Fences can vary in thickness, curve, and split off to rejoin other fence lines. They represent the most adaptable and living form of construction compared to the dwelling which remains distinct with its own walls, own roof never joining or conjoining other dwellings. The material collected to construct dwellings and fences constitutes the largest construction-based burden on the regional environment.

PREFERRED TREE SPECIES FOR CONSTRUCTION