Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

A report by Will McDonald for Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

September 2025

A report by Will McDonald for Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

September 2025

This report by Will McDonald and commissioned by Esmée Fairbairn Foundation explores private sector action on nature in the UK, and evaluates the current drivers of corporate attention, activity and investment.

In recent years, we have seen a step change in how companies are beginning to understand and measure their impact on biodiversity, which has been driven by investors and consumers, as well as the forthcoming disclosure framework called the Task Force for Nature Based Financial Disclosures, due to be in place at the end of 2025. Esmée commissioned this work to understand the demands and trends in this rapidly developing space As well as informing Esmée’s future work, we hope it will be useful to other organisations and people interested in ensuring a high integrity approach.

A big thank you to the many individuals from all sectors and across the UK who gave their time to be interviewed as part of the project.

The report does not necessarily reflect the views or position of Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, or the people interviewed as part of the research.

Will McDonald

Will McDonald is a sustainability and public policy expert, working across sectors. I specialise in financial services, helping companies, NGOs and policymakers drive better nature and climate outcomes. I spent 10 years at Aviva plc, as Group Director of Sustainability and Public Policy. I led the work (with my jobshare partner) on Aviva’s world leading sustainability strategy. Prior to that I spent a decade in Westminster, including as a Special Adviser in HM Treasury and DWP.

www.willmcdonald.co.uk

Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

Founded in 1961, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation is one of the UK’s largest independent funders. We aim to improve our natural world, secure a fairer future and strengthen the bonds in communities in the UK. We unlock change by contributing everything we can alongside people and organisations with brilliant ideas who share our goals.

www.esmeefairbairn.org.uk

There has been a significant increase in attention on the crisis in nature, the role of the private sector, and the role of nature markets in addressing the crisis in recent years. This research found that, currently, business understands the crisis in nature and understands that business has a role in both the cause and the solution to that crisis. However, business is unsure how to do the right thing, wary of doing the wrong thing, and has many competing pressures.

In different parts of the private sector, and to different degrees, the research found enthusiasm, resignation and overwhelm. The overall picture of current drivers is not a clear one - there are a broad range of sources of business motivation to act, and the relative importance of this mix is changing.

Within this, there is evidence of considerable but piecemeal progress: by sector, firms understand their material issues (some of which are nature-based), and some are moving to act, and there are increasing numbers of examples of the private sector funding nature restoration, nature-based carbon and nature-based solutions.

Two key disconnections emerged from the project:

1. The disconnect between a company or sector, and national and global environmental targets. This is a problem as it means no company can put its finger on what it must do by when, or what its contribution might achieve.

2. The disconnect between the demand side, pushed by TNFD to address material risks within value chains, and the supply side, focused on selling credits. These two sit at either end of the mitigation hierarchy. This has knock-on effects: without demand for credits, investors are unable to see how to secure a financial return on investment.

The research also found considerable confusion on all sides of the market, with terms such as ‘nature investment’ being used to refer to different types of transactions, with different returns. Even use of the term ‘nature’ can be problematic, with interviewees reporting the concept can feel very distant from the business models and priorities of most private sector firms.

The broad scope of this research – all business, all nature - has meant the report is high level. The research was conducted using desk-based research and semi-structured interviews with experts and stakeholders. The report aims to summarise the key findings of that research in a way that is helpful to both demand and supply side, and other key players, notably the UK Government, but also investors and intermediaries.

The findings can inform next steps at a systemic (standards, data, regulation etc) and a practical, project level. During the research it was clear that there have not been many studies on the demand side so far, and deeper understanding (by sector, by size etc) would be valuable for all sides.

This report examines the demand side of business-nature interactions – where and how the private sector is engaging in nature. The supply side in this case are people and organisations such as landowners, land managers, and environmental NGOs, who are looking at how the nature can bring in income from the private sector. There are many forms that this interaction can take.

The research:

• Looked at both financial services and the real economy

• Focused principally on nature in the UK, and less on nature located overseas impacted by UK consumption, or in supply chains.

• Did not cover intermediaries in the market

• Did not cover greenwashing in the depth it merits.

• Did not break down the research into English, Scottish, Welsh or Northern Irish specifics partly because this is (on the whole) more relevant for the supply side.

• Uses the terms ‘nature’ and ‘biodiversity’ interchangeably, although they have different technical meanings.

This research found relatively little existing evidence on nature and UK companies specifically, or SMEs. This research draws on other projects undertaken by the author with UK companies and SMEs to inform the findings.

This report does not include the evidence around the destruction of nature, nor the causes of the damage per se, nor the necessity of its restoration, as these are covered extensively elsewhere (Dasgupta Review, State of Nature Report 2023 etc).

It also does not cover the changing landscape given the Trump Presidency and EU reforms around corporate sustainability, as it was unclear at the time of writing where the policy specifics would settle. It is noted that whilst there is a focus away from all ESG, there remains a strong and growing awareness that companies’ specific impacts and dependencies on specific aspects of nature remain, and so therefore do the risks and opportunities.

It is also worth noting that the research did not look further up the demand chain i.e. at consumption and consumer behaviour. This is an area that would merit further research, given the underlying driver of nature loss, as explored by the Dasgupta Review and the Grantham Institute, among others:

“According to the recent Values Assessment report by the International Panel for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the underlying causes of the biodiversity crisis are strongly linked to a narrow focus on the materialistic values of nature in business and politics. This favours short-term profit and individual material gain over humanity’s other values for nature,

Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

… Currently, biodiversity loss stems mainly from the loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitats. This is principally caused by the increasing encroachment of industrial activities and farming, fuelled by demand from high-consumption lifestyles in wealthy countries.” 1

There is relatively little work going on aimed at consumers to reduce end-consumption.

There has been work on nature in recent years on both the demand and supply sides, but significantly more attention on the latter, and little joining up of the two. Furthermore, work has focused on offset markets, and the supply of projects to those markets, rather than private sector investment or action to reduce harm.

Research around the supply side often contain an assumption that demand will be forthcoming from the private sector, without any analysis of why or how.

For example, the UK Government’s 2023 Nature Markets Framework said “… it is selfevident that the investment and business sectors are already considering their risks, dependencies and impacts on nature and are seeking straightforward financial instruments to support nature recovery. ” 2

A more realistic way to say this would be “a few leading corporates and a minority of investors are looking at the risks, dependencies and impacts on nature, and are slowly getting to grips with direct and financed options to reduce new harm and promote recovery.”

The Aldersgate Group have also highlighted the assumptions latent in current nature discourse: “The Green Finance Strategy assumes that private investment will turn up despite it being hard to see where the Return on Investment will come from for most of the economy.” 3

The private sector is reliant on nature to function – in the narrow sense of GDP (see World Economic Forum analysis) and in the broader sense that business cannot function without clean air and food for example. It is common to see this codified using the language of risks, impacts and materiality.

1 What are the extent and causes of biodiversity loss, December 2022, London School of Economics and Political Science

2 Nature Markets, March 2023, HM Government

3 Strong on Align, more to do on Invest: time for a Transition Plan for Nature, April 2023, Aldersgate Group

For example see World Economic Forum’s description below.

“Nature risks become material for businesses in the following three ways:

1. When businesses depend directly on nature for operations, supply chain performance, real estate asset values, physical security and business continuity

2. When the direct and indirect impacts of business activities on nature loss can trigger negative consequences, such as losing customers or entire markets, legal action and regulatory changes that affect financial performance

3. When nature loss causes disruption to society and the markets within which businesses operate, which can manifest as both physical and market risks.” 4

World Economic Forum

The research found that, currently, businesses know that nature is a problem, but they are unclear what they can or should do about it. This core finding aligns with other recent published and private research:

“Only 14% of businesses said their businesses had no role in supporting nature beyond their legal and regulatory requirements.” 5

CBI research

“The Nature Benchmark results across 2022-2024 show that although some companies are taking significant steps to become more sustainable, the overwhelming majority do not yet really understand how they affect and rely on nature.”

“The … results show that although some companies are taking significant steps to transition to sustainable production, the overwhelming majority do not yet really understand how they affect and rely on nature.

“…only 2% of the biggest 350 [food and agriculture] companies in the world currently disclose their environmental impacts. Furthermore, despite being among the most nature-dependent industries, 0% holistically address their dependencies on nature.”

“only 5% of companies assess their impact, and less than 1% understand dependencies.” 6

4 Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy, World Economic Forum, January 2020

5 Businesses need more guidance to protect and restore nature, survey finds, Edie, December 2022

6 Nature Benchmark 2022-2024, World Benchmarking Alliance

Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

“Recent research shows that although 83% of Fortune Global 500 companies have climate change targets, just 25% have established freshwater consumption targets, with that number dropping to 5% having targets related to biodiversity. Only 5% of companies have assessed their impacts on nature, with less than 1% understanding their dependencies.” 7 8

“The scale of corporate action to protect biodiversity today is limited.” 9

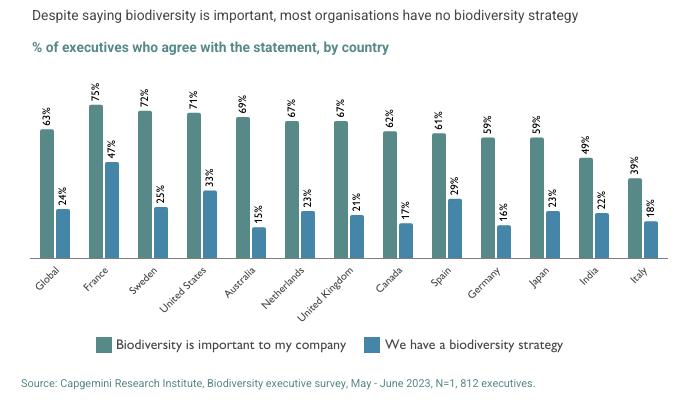

Research by Capgemini reached similar conclusions, labelling this the “say-do” gap 10, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Capgemini research – the “say-do” gap

In summary, awareness of nature is growing, but from a low base, and is focused on larger corporates, and resulting action is lagging further behind still.

7 Leading organizations unveil the actions businesses across 12 sectors should take to contribute towards a nature-positive future, Business for Nature, September 2023

8 Where the world’s largest companies stand on nature, McKinsey Sustainability, September 2023

9 Protecting biodiversity: incentives for corporate action, IMPAX Asset Management, June 2023

10 Preserving the fabric of life, Capgemini, 2023

There are many factors that together have created this dynamic. These are the principal factors that emerged from speaking to those in the private sector in this research:

• Nature is overwhelming as a concept, and is mobile, silent and invisible 11

• Nature doesn’t lend itself to a simplified metrics

• There is no ‘north star’ (such as 1.5 degrees in climate) to rally behind or aim for (although work is underway)

• Top down: it is unclear what UK nature targets mean in practice (i.e. by region, or by industrial sector)

• Bottom up: it is unclear what actions will add up to achieving UK’s nature targets (as is available from the Climate Change Committee on climate, for example)

• Business cannot tackle nature on its own “By definition, global negative externalities require coordinated global action.” 12 ,

• There is a lack of data, both on business activity and on nature

• There is not enough UK Government leadership on business and nature

• And there is little forcing business to engage and act (with some key exceptions 13)

• There is a low level of knowledge about nature within corporates, especially at senior levels 14

• Private sector involvement in nature is not universally accepted

• There are reasons businesses are actively cautious too – cost or greenwashing risk, for example

• What action might look like varies significantly by economic sector, by size and by firm

• Terms like “nature investment” and “nature markets” are used freely but without definition, which is confusing for both demand and supply sides.

In addition, the research found that the private sector:

• Is still very much wrestling with climate disclosure and action, and available resource is focused here

• Instinctively favours local (visible) nature recovery, despite negative impacts on nature often being global / non-local / non-visible

• Does not have access to relevant expertise

• Has a range of competing priorities, such as cost of living, inflation etc.

It is worth underlining what is sometimes implicit in these findings: for a business that operates in an economy where nature is a free resource to be used, there is a strong impetus to keep the status quo. There are no benefits to being a leader in absorbing the costs of externalities.

11 The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, August 2021

12 The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, August 2021

13 E.g. Biodiversity Net Gain

14 “Roel Nozeman, head of biodiversity at ASN Bank and chair of PBAF, said in agreement that research by several accountancy firms led to the same conclusion: knowledge of biodiversity tends to be very low at the board level.” Awareness issues prevent biodiversity investments from taking off, Net Zero Investor, August 2023

“All parties talk about their desire to leave nature in a better state for future generations. But we do not yet have proof or confidence that the supporting policy and action set out so far will deliver them. We have not yet seen a plan from any party that sets out a clear pathway for policy, funding and private sector contributions such as from farming, land use change, biodiversity net gain, local nature recovery strategies to come together and achieve these goals. We simply do not know what difference each of these contributions will make, how they will work together, and whether they will add up to the scale of change needed …” 15

National Trust policy platform 2023

There are some encouraging signs: levels of activity around business and nature have increased at pace in recent months and years. Although this is hard to quantify there are some proxy indicators that came up during the research period:

• The membership of nature business groups, e.g. Finance for Biodiversity Foundation and Business for Nature, continues to grow

• Business-led ‘fringe’ meetings that focus on nature at UK party conferences have increased dramatically

• Most large UK banks and many other corporates now have a ‘Head of Nature’ or equivalent, often appointed in the last 2 years

It is worth emphasising the duality of feedback from business on nature. Nature is at once both understood to be in crisis and business has a role to play here AND nature is not well understood and hard to work with (as outlined above).

The World Economic Forum summed up this twin view. The most cited statistic on nature and business on the one hand: “Our research shows that $44 trillion of economic value generation – more than half of the world’s total GDP – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services and is therefore exposed to nature loss.”, and yet on the other hand: “general confusion persists on what amount of nature loss has occurred, why it relates to human prosperity and how to confront its loss in a practical manner, especially in the business world” 16

15 A path to better things, National Trust, 2023

16 Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy, World Economic Forum, January 2020

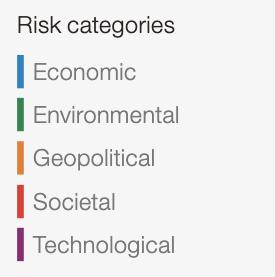

Business also reported mixed messaging about the urgency of action on nature. For example, in the WEF Global Risks Report 2025, nature shows up much more strongly in 10 years than in 2 years’ time. 17 Research participants noted that clear messaging about timelines and expectations was necessary to engage senior managers in private sector firms.

Having looked at where businesses are on nature, we now turn to examine the drivers of action.

3. Current drivers of business attention, activity and investment

The overall picture of current drivers is not a clear one. There are a broad range of sources of business motivation to act, with both the drivers themselves and their relative importance changing over the period in which this research was conducted.

Previous research into this topic has concluded that “organisations taking steps … were doing so for multiple reasons. This included, and were often a combination of, outcome-based investment focussed on ecosystem services, ESG pressure from investors and consumers, increasing offsets

17 The Global Risks Report 2025, World Economic Forum

involving decarbonisation or Biodiversity Net Gain and an element of philanthropic activity.” 18 (note this was in relation to nature-based investment specifically).

Other research (2023) found that “Biodiversity concerns were not the primary drivers for corporate action in the cases that were examined. Aside from where they are required by regulation, actions to protect biodiversity are currently only pursued where they deliver broader corporate objectives. Motivations may be commercial – such as supply chain resilience – or related to other environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives like ensuring a social license to operate.” 19

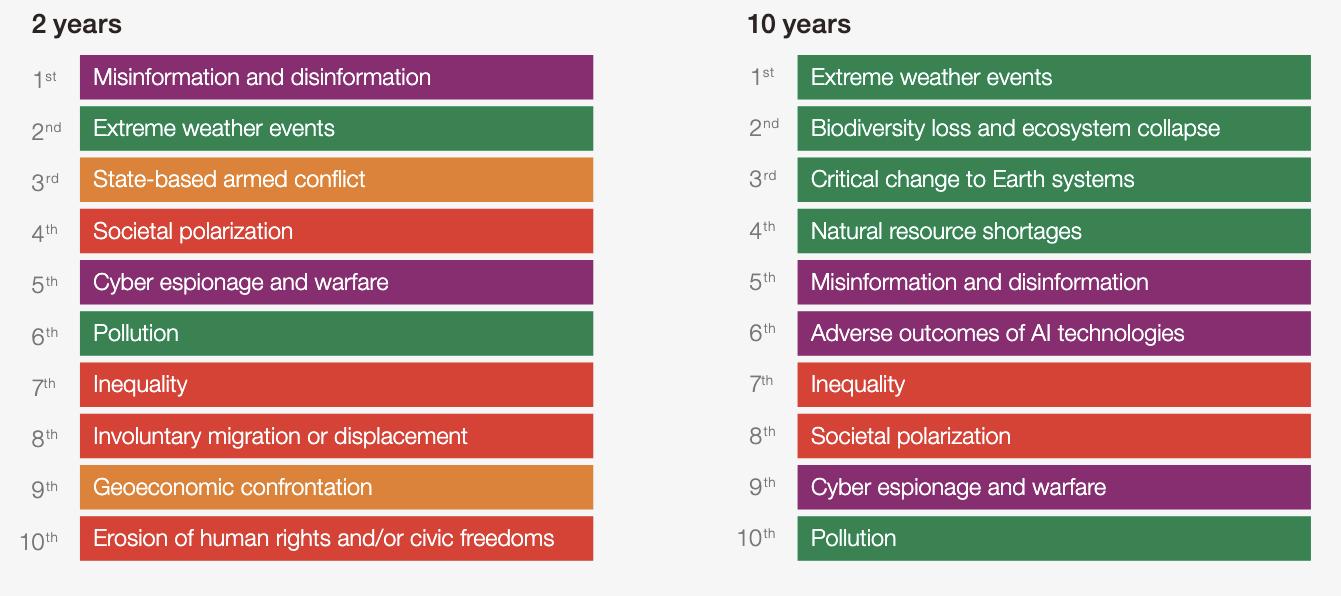

Figure 3 presents the main drivers found in this research, with the circle size representing the relative power of each as a driver of action The ranking of drivers reflects an analytical judgement founded on stakeholder engagement, interviews, research and experience, and is offered as a straw man rather than a definitive, static picture.

Appendix 1 outlines each driver in more detail and gives key examples of relevant activity.

It is a positive that there are so many forces driving companies to consider and act on nature, and it opens up a broad array of actions that could follow to develop these drivers further. It is also true that many, small drivers do not necessarily create a tipping point for companies to embed nature-positive in their supply and value chains.

It is worth noting that not all drivers are as visible as others, which can make evaluation of scale harder. For example, CSR-led activity will often be publicised whereas action to tackle material risks is often commercially confidential and so not public.

This research found that, going forward, many of the drivers are likely to continue to intensify, for example, growing consumer pressure, or climate work taking nature into account.

Other notable developments include the Government’s Call for Evidence on demand drivers 20, further work by the Climate Change Committee on nature, or the inclusion of nature in the Chancellor’s November 2024 letter to the Bank of England.

The research identified three key shifts in particular that are focusing attention in the private sector:

I. An ongoing evolution in standards and frameworks, with an expected increase over time in

a. disclosure

b. mandation, and

c. scrutiny.

TNFD is the most impactful in corporate minds currently, but the cumulative signal from all the work in this space (i.e. SBTN, discussion of nature in Transition Plans) is also focusing minds. The path of TCFD (mandated by the FCA) has set expectations for TNFD. Interviewees also pointed out how much quicker TNFD has been to reach its current status, compared to TCFD, for example levels of company sign up

II. The second shift is a move to be more specific by economic sector. More so than climate, nature is sectorally-specific. There are many examples of sectoral activity currently underway, including:

a. WEF / WBCSD / Business for Nature jointly published sectoral guidance in October 2023 (more below)

b. GRI launching Standards for 40 sectors, including biodiversity, across Oil and Gas (GRI 11), Coal (GRI 12), as well as Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fishing (GRI 13) 21

c. Nature Action 100 maps pathways by sector for companies it engages with 22

20 Question 9 of the Defra Land Use Consultation

d. The Transition Plan Taskforce had both Sector Deep Dives and a Nature Working Group.

e. Joint work with WWF UK and GRI on Nature Positive Pathways 23

These initiatives and others offer (and create expectations around) company activity to address biodiversity concerns in their sectors and companies.

III. An ongoing ramping up of activity by investors, either alone or in alliances, which results in attention on key nature issues in large, listed firms, and onwards into their supply chains. For example, Nature Action 100 (which brings together CERES, IIGCC, and Finance for Biodiversity Foundation) brings together over 190 institutional investors representing $24 trillion in assets. Similarly the Finance for Biodiversity Foundation pledge has been signed by 200 financial institutions. Increasingly, investors are able to build on growing data sets on nature and firms, for example the World Benchmarking Alliance 2023 Nature Benchmark across food and agriculture, paper and forest sectors. The research did not find a diminished focus on nature as a material risk as a result of changing political leadership.

A key conclusion of this research is that activity by sector is more advanced, easier to comprehend and lends itself to increasing action on nature. Interviewees identified strongly with their economic sector when discussing nature, and examples of collaborative action were frequently sectoral.

We have a reasonable understanding of which sectors are the most dependent on, and have the most impact on, nature, and this sectoral understanding is the framework for action by investors in Nature Action 100, for example.

A coordinated project between the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, WEF and Business for Nature developed global pathways 24 to nature positive for 12 global sectors that their analysis led them to prioritise (alphabetical order):

11. Waste management

12. Water utilities and services

The collaboration also concluded that: “Just four global value chains - food, energy, infrastructure, and fashion – drive more than 90% of man-made pressure on biodiversity.” 25

Conversely there are sectors that are less relevant for nature. There is therefore a case for a more explicit focus on certain industries in discussions around nature; businesses in both categories reported wanting more clarity about expectations on them.

The mitigation hierarchy

“As with addressing climate change, … preventing harmful practices is a crucial first step.” 26

The text of the Global Biodiversity Framework at COP15 similarly asks the private sector first to “reduce negative impacts on biodiversity” 27

The research found a current misalignment between the supply and demand sides. On the one hand, the early movers in the private sector have adopted the TNFD approach (essentially looking at material risks, impacts and dependencies in a firm’s value and supply chain). This approach follows the mitigation hierarchy in avoiding and reducing harm first. The supply side however, looking to get private or blended finance into nature restoration projects, is focused on supplying credits (either nature-based carbon or biodiversity).

The regulatory status of the BNG compliance market was needed to make the two sides meet, but other initiatives like BNG will be required if the scale of private finance is to flow into the credits market.

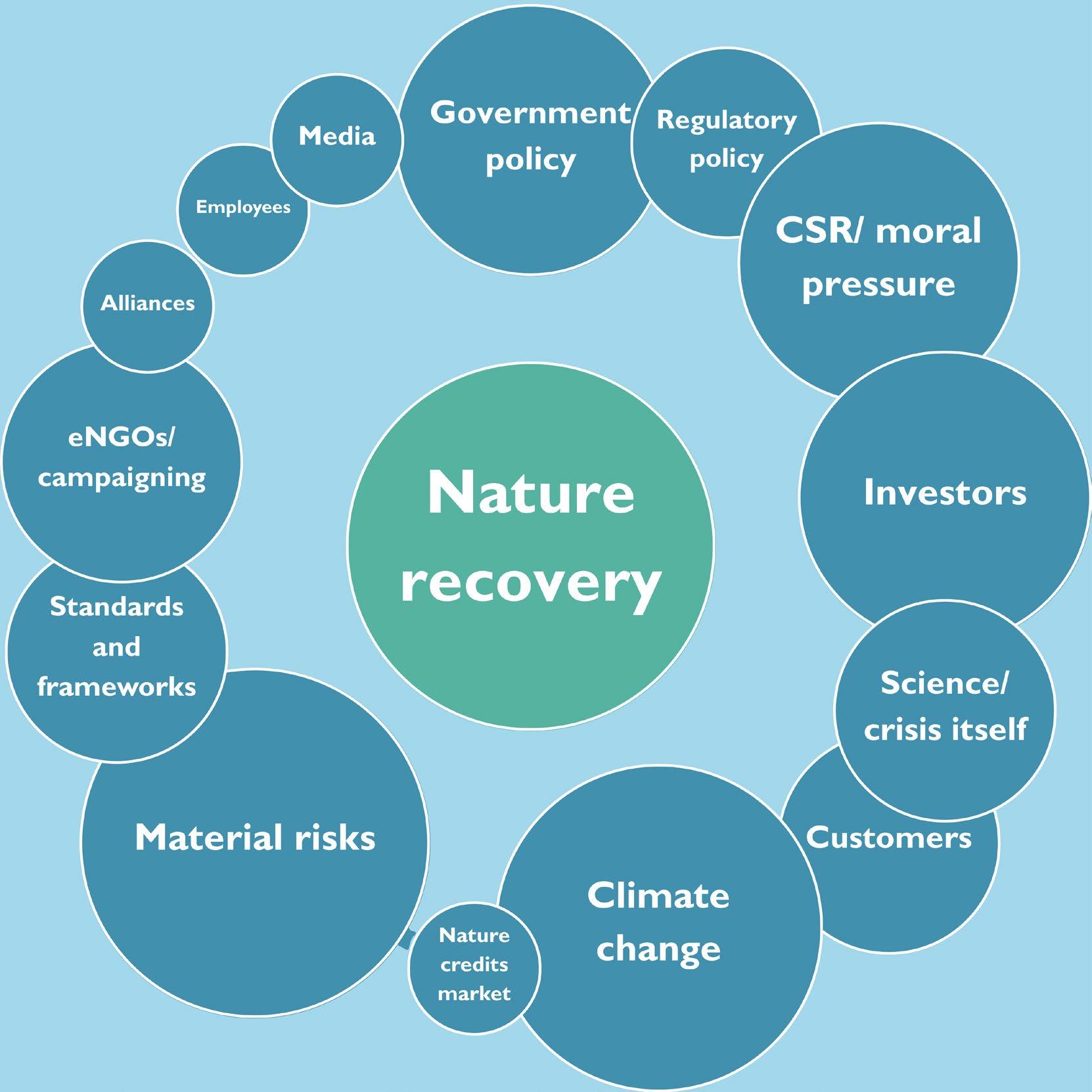

4. Actors: who is active on the demand side?

The research identified a significant number of actors operating to more or less of an extent in the demand side. Many of these have been referenced already in the section above on drivers. This section sets out a high-level map of the categories of key actors (Figure 5).

The principal takeaways from this section of the research is that a) there is no ‘lead’ organization, and b) business would welcome more leadership on nature. While groups such as TNFD have done an impressive job in bringing stakeholders across sectors together to help develop and deliver the framework, they are not and do not want to be a regulatory, delivery or advocacy organisation. A comparison with the climate world shows very much greater Government co-ordination and policy, and a much greater level of supporting / market architecture.

25 Leading organizations unveil the actions businesses across 12 sectors should take to contribute towards a nature-positive future, Business for Nature, September 2023

26 Protecting biodiversity: incentives for corporate action, IMPAX Asset Management, June 2023

27 Convention on Biological Diversity, UN Environment Programme, December 2022

Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

4: Mapping key actors and their interactions

Government policy (global and national)

Regulatory policy

Globally the GBF has had a significant impact on awareness amongst larger companies, partly because of their familiarity with climate COPs and their outcomes. The specificity within GBF is helpful, notably Target 15 on business and finance, and Target 19 on private finance. However GBF feels a long way from any individual company and offers little specific guidance on what to do next.

Whilst the Dasgupta Review and Environment Act have had a similar effect in the UK, it is the specificity of some regulation that focuses minds –CSRD in the EU, or Biodiversity Net Gain and ELMs.

There is no overall ‘voice’ for nature policy in the UK, like the Climate Change Committee on climate or Office for Budget Responsibility on economic / fiscal policy.

Government policy is focused more on the supply side and investment in nature, partly because Defra is the principal actor across Whitehall.

Most proactive businesses would welcome the clarity of proportionate, enabling regulation (i.e. a green taxonomy), and this is a feature of many TCFD / TNFD disclosures. However business expectations of Government leadership are low.

Environmental regulators (EA, NE) are not seen as particularly relevant for business, and furthermore underfunded, untested or focused on the public sector (OEP).

Corporate regulators are either at early stages of work on nature (i.e. Bank of England, Ofwat) or not considering it (other real economy regulators).

Global

• UN SDGs

• Global Biodiversity Framework

• Leaders Pledge for Nature

• EU regulation i.e. CSRD

• Other state action –France Article 29 National

• Dasgupta Review

• Environment Act

• Environmental Improvement Plan

• Biodiversity Net Gain

• Nutrient Neutrality

• ELMs

• Green taxonomy

• Nature investment standards (BSI)

• TNFD

• NGFS work on nature as financial risk

• GFI / UNEP-WCMC work on nature risk to GDP

• Sustainability Disclosure Requirements regime

Corporate Social Responsibility / moral pressure

Investors (including investor alliances)

Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

CSR has been the release valve for the growing pressure to act on nature. CSR can often respond quickly, and bring important benefits in employee and community engagement, however it often drives a local, small-scale, short-term and fragmented approach, that is rarely science-led. It can distract from more substantive action in company operations and supply chains.

A small proportion of investors have for some time recognised the importance of nature and nature loss, and engaged with corporates. Cooperative action (investor alliances) between investors remains a significant driver of corporate action on nature, partly because these alliances are resourced and partly because their actions are not contingent on a policy framework. There are strongly encouraging signs of expansion cf. recent investor activity on deep sea mining, or the further development of NatureAction 100.

• Earthwatch UK Pocket Parks

Corporate alliances

These are voluntary groups of companies, often led by large, big-brand firms. They can focus on an element of nature (i.e. water, timber) or around an economic sector. Whilst hard to generalize, some of these groups are responsible for the most well progressed tangible action-based work, since they are not focused on disclosure but firms’ activities. Due to the firms involved, the ‘nature’ in question is often not in the UK. It is sometimes hard to judge the extent of reach, activity and ambition, either as a proportion of current harm or of the total sector.

There are many – H&M alone has 65+ sustainability memberships and collaborations.

eNGOs / campaigning There has been some highly effective campaigning at Government and the private sector by eNGOs, some of which has also engaged the public. These campaigns have largely contributed to an overall pressure on the private sector, rather than for specific actions, with exceptions such as the water sector.

• Finance for Biodiversity Foundation

• NatureAction 100 (CERES and IIGCC) has 190 institutional investor members

• Natural Capital Investment Alliance (NCIA), part of the Sustainable Markets Initiative.

• UN PRI initiative on forest loss and land degradation

• Business for Nature and Now for Nature campaign (RE/ FS 28)

• ClimateWise (FS)

• Sustainable Markets Initiative (FS)

• WWF Retailers’ Commitment for Nature (RE)

• Responsible Commodities Facility (on soy / deforestation) (RE)

• LEAF Marque (RE)

• Alliance for Water Stewardship (RE/FS)

• Fergal Sharkey

• Chris Packham

• WWF / RSPB / Attenborough

Science / crisis itself

Climate change

While harder to quantify, it is clear that awareness of the crisis itself, and the science and evidence behind it, is a factor in driving private sector attention. There is evidence that the science is helpful internally in firms in making the case for attention on nature, but it is not clear how much this drives action, given the lack of direct link from, say, species loss to a specific business or product.

There is now a strong, pervasive, accepted narrative in climate discussions about the interdependency of climate and nature action. This has become cemented into discourse. This has in turn brought corporate climate resources (FTE, governance, reporting, budgets etc) to bear on nature. This climate ‘muscle’ will prove invaluable in driving progress on nature. This has not yet led to significant tangible action, but there are some low hanging fruit such as nature-based carbon credits, where it is possible to see a pro-nature filter being usefully applied to this existing market.

• IPBES Global Assessment

• JNCC State of Nature report

• Lawton Review

• Dasgupta Review

• ABI Guide to Action on Nature

• Nature-proofing carbon credits

• IIGCC

Standards and Frameworks

Nature markets

Given the climate precedents, standards and frameworks are a powerful driver of corporate attention. They are seen as both helpful in distilling the task, and also a burden.

The rapid progress of TNFD means that it looms large. However, it remains at an early stage, still building towards action at scale.

There is strong awareness of this market and the opportunity for nature recovery; the carbon precedent has helped corporates by increasing familiarity but also made them wary of the complexity and risks. So far very few are engaged in nature markets outside of compliance markets. CSR is therefore the preferred approach (as in, not requiring a financial return nor metrics that directly align with business impacts).

Sustainability linked bonds is one area where market discipline has been brought to bear and there is evidence of a small but steadily growing use of these instruments that are tied to environmental outcomes (in practice these tend not to be nature-based yet though).

Nature markets remain the most talked about

• TNFD

• SBTN

• ISSB

• Transition Plan Taskforce (Working Group on Nature)

• World Benchmarking Alliance

• GRI

• Nature credits / offsets

• Payments for ecosystem services

• Green bonds

• NbS

• LENS

• Environment Bank

Employees

Customers

interaction between corporates and nature, and the focus of much activity.

There is strong evidence that employees (and potential recruits) rate sustainability highly, including nature. There are many examples of employee engagement on nature – volunteering locally, or planting up office sites etc. This is an important driver of corporate attention, especially in a ‘war for talent’ labour market, however it tends to drive smaller scale, hyper localized, CSRtype activity. This activity, e.g. tree planting volunteering or replanting of car park margins, is invaluable in building emotional connection with nature but it does not currently translate into action as a corporate (i.e. on supply chains).

There is evidence of customers being an important driver of tangible action in some sectors (e.g. fashion). However, this is less clear in other, nature-relevant sectors, such as housing. The risk of greenwashing is high here too, as consumertangible aspects are prioritized (labels, marketing) over action on material impacts.

• McKinsey consumer research

Driving

This research was informed by engagement and interviews with a range of stakeholders and resources developed by many organisations in recent years including (alphabetical):

i. Aldersgate Group blog, Time for a Transition Plan for Nature, 2023

ii. BCG, Private Equity Sustainability report, 2023

iii. Business for Nature, Sector actions launch, 2023

iv. Capgemini, Biodiversity report, 2023

v. CISL, Biodiversity loss and land degradation, 2020

vi. CISL, Handbook for Nature-related Financial Risks, 2021

vii. CISL, Integrating Nature: The case for action on nature-related financial risks, 2022

viii. Defra, Nature Markets, 2023

ix. Edie.net Businesses need more guidance to protect and restore nature, 2022

x. Entrade, various

xi. Environmental Finance, Investing in Nature: Private Finance for Nature-based Resilience, 2019

xii. Grantham Institute, What are the extent and causes of biodiversity loss

xiii. Green Finance Institute, various

xiv. Guardian, More than 70% of English water industry under foreign ownership, 2022

xv. HM Treasury, The Dasgupta Review, 2021

xvi. Impax Asset Management, Protecting biodiversity incentives for corporate action

xvii. IUCN, Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions, 2020

xviii. Landscape Enterprise Networks, various

xix. McKinsey, Where the worlds largest companies stand on nature, 2022

xx. National Trust, Policy Platform, 2023

xxi. Nature Action 100, various

xxii. Net Zero Investor, Awareness issues prevent biodiversity investments from taking off, 2023

xxiii. NGFS, Biodiversity and financial stability: building the case for action, 2021

xxiv. PBAF, Paving the way towards a harmonised biodiversity accounting approach for the financial sector, 2020

xxv. Principles for Responsible Banking, Guidance on Biodiversity Target-setting, 2021

xxvi. Responsible Investor, Biodiversity Report, 2023

xxvii. SBTN, Science-Based Targets for Nature: Initial Guidance for Business, 2020

Driving Demand: Business Action on Nature in the UK

xxviii. SIF, SIF Scoping Study: Nature-Related Risks in the Global Insurance Sector, 2021

xxix. Stockholm Resilience Centre. Assessing nature-based solutions for transformative change, 2021

xxx. UN, Summary for Water Conference, 2023

xxxi. UNEP FI, Beyond “Business as Usual”: Biodiversity Targets and Finance, 2020

xxxii. Water UK, Water 2050 A White Paper, 2022

xxxiii. Wessex Water, OBER offers greater green improvements at lower costs

xxxiv. Wessex Water, Outcome based environmental regulation report, 2021

xxxv. World Benchmarking Alliance, Nature Benchmark, 2023

xxxvi. World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report, 2023

xxxvii. World Economic Forum, Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy, 2020

xxxviii. World Economic Forum, New Nature Economy Report, 2020

xxxix. World Economic Forum, Private Equity Investors and Sustainability, 2022

xl. WWF International, Aligning Transition Planning and Nature Related Disclosures, 2023