Gunta Stölzl

Bauhaus Materialty

Bauhaus 1919 to 2023 Raddical innovations in design education

James Volks & Susan Harrison Bauhaus Archive Berlin Museum Of DesignForeword

Upon receiving my assigned topic of ‘Bauhaus Materiality’ , I began delving into the life of one of the figures that played an essential role in the success of Bauhaus’ Materialty sector. I found that Gunta had a very interesting life and encountered many obstacles on her journey, many of which are due to the fact that she is a woman. I found that the more I reserached into Bauhaus and the treatment that woman received, I now have a newfound respect for these woman for tolerating the disrespect. Although accepted into Bauhaus, these women were merely tolerated and I believe this would have made it significantly more difficult to strive forward in such an unwelcoming environment. I thoroughly enjoyed further researching into the personal life of Gunta and following her path through Bauhaus. I found that many of her works are very intriguing when properly looked into and I never would have discovered her if it wasnt for this interesting research topic.

I had the opportunity to read and write about this topic and have come out with a broadened knowledge of Bauhaus’ textile artists and general knowledge about the Bauhaus school. I hope you enjoy the read as much as I enjoyed writing about it.

Production and teaching in the workshops

When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in March/ April 1925, it first had to make do with provisional premises in on old deportment store in the Mauerstrasse. Only a proportion of pupils - albeit many of the most talented - followed the school from its idyllic setting in Weimar to the dirty, industrial city of Dessau. And although Lyonel Feininger, the previous head of the graphic printing workshop, moved to Dessau with the Bauhaus, it was no longer as on active member of the Bauhaus teaching staff. The commercially ineffective workshops of the Weimar Bauhaus were now abandoned (glass, wood, and stone). The graphic printing workshop was also left behind since, although lucrative, it was only capable of reproduction work. In its place a printing workshop was set up in which creative work was also possible.

The woodcarving and stonesculpture workshops were effectively modernized under the single heading of ‘sculpture’ workshop. Both financial and pedagogical arguments were thus respected. The most far-reaching changes were to be felt in two workshops in particular: the printing workshop under Herbert Bayer, with its entirely new orientation, and the weaving workshop. The weaving workshop hod been fully re-equipped from the technical point of view; It also become the earliest workshop to offer a proper training course, designed and implemented by Gunta Stölzl. In both workshops young people were being trained for professions which had effectively never existed before. These Bauhaus years saw not only the production of new industrial designs for furniture, metal, textiles, and modern printed materials but, at the same time, the formulation of new training courses and the preparation of new professions which would operate at the interface of design and technology in the widest possible sense

The textile workshop

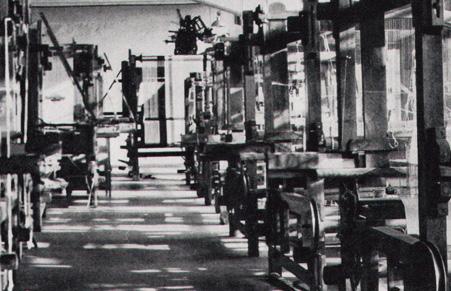

While the printing and advertising workshop hod no registered apprentices, articles of apprenticeship were required in the weaving workshop before students could commence its three-year training course. At the end, students could take their apprentice’s final qualifying examination as well as get a Bauhaus diploma. Although Gunta Stölzl was not mode Young Master of the weaving workshop until 1927, both the organization and content of the weaving course rested in her hands as from 1925. Master weaver Wanke was responsible for technical matters. Gunta Stölzl introduced a very wide range of loom systems suitable for both learning and production purposes, as well as designing the three-year training course. This course was divided into two stages, the first in a teaching workshop and the second in on experimental and model workshop. Gunta Stölzl also taught classes in weave and material theory and – since the Bauhaus had its own dye-worksin dyeing.

With the start of work in Dessau, the weaving workshop moved over to

industrial design. The design process was in part systemized with e.g. one warp worked by a number of students and one material woven in different colours. Woven fabrics were mounted as marketing samples and numbered consecutively together with details of their price and measurements. Students were thus taken through every stage of the production process - from dyeing, through weaving, right up to ordering materials. At the same time, in Klee’s form classes, they learned the rules of patterning and colour design.

A profession was thus created within the textile industry which had rarely been found before - designer. Thanks to their basic training on the hand loom, however, students were equally capable of running small, artistic crafts workshops. Self-employment was at that time on option which many women preferred to a full-time position in trade and industry.

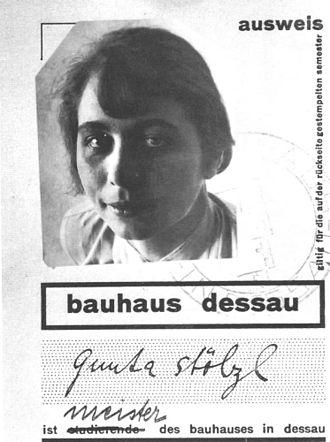

Gunta Stölzl (5 March 1897 – 22 April 1983) was a German textile artist who played a fundamental role in the development of the Bauhaus school’s weaving workshop, where she created enormous change as it transitioned from individual pictorial works to modern industrial designs. She was one of a small number of female teachers on the Bauhaus’ staff and the first to hold the title of “Master”.

Her textile work is thought to typify the distinctive style of Bauhaus textiles. She joined the Bauhaus as a student in 1919, became a junior master in 1927. She was dismissed for political reasons in 1931, two years before the Bauhaus closed under pressure from the Nazis.

The textile department was a neglected part of the Bauhaus when Stölzl began her career, and its active masters were weak on the technical aspects of textile production. She soon became a mentor to other students and reopened the Bauhaus dye studios in 1921. After a brief departure, Stölzl became the school’s weaving director in 1925 when it relocated from Weimar to Dessau and expanded the department to increase its weaving and dyeing facilities. She applied ideas from modern art to weaving, experimented with synthetic materials, and improved the department’s technical instruction to include courses in mathematics. The Bauhaus weaving workshop became one of its most successful facilities under her direction.

Early Life

Stölzl was born in Munich, Bavaria. She attended a high school for the daughters of professionals, graduating in 1913. She began her studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in 1914, where she studied glass painting, decorative arts and ceramics under the well known director Richard Riemerschmid. In 1917 Stölzl’s studies were interrupted by the ongoing war and she volunteered to work as a nurse for the Red Cross, behind the front lines until the end of World War I in 1918. Upon her return home she re-immersed herself in her studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Munich, where she participated in the school’s curriculum reform. It was during this time that Stölzl encountered the Bauhaus manifesto. Having

decided to continue her studies at the newly formed Bauhaus school, Stölzl spent the summer of 1919 in the glass workshop and mural painting classes of the Bauhaus to earn her trial acceptance into Johannes Itten’s preliminary course. By 1920, Stölzl had not only been fully accepted into the Bauhaus school, but had received a scholarship to attend.

Life

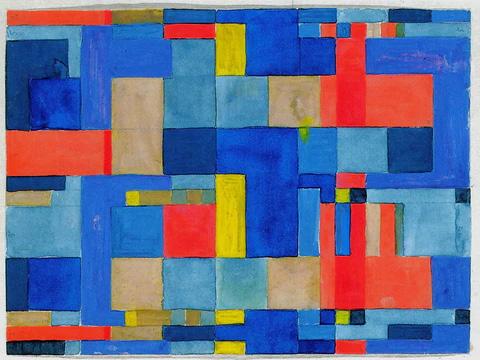

Within Stölzl’s first year at the Bauhaus, she began what she referred to as the “women’s department”, which due to the underlying gender roles within the school, eventually became synonymous with the weaving workshop. Stölzl was very active within the weaving department and was immediately seen as a leader among the pack. At the time, the department was putting emphasis on artistic expression and individual works that reflected the teachings and philosophies of the painters who served as Bauhaus masters.

The Weimar Bauhaus had a very relaxed atmosphere that was almost wholly dependent on the students teaching themselves and one another. Unfortunately, Georg Muche, who was the head of the weaving workshop at the time, had very little interest in the craft itself. He saw weaving and other textile arts as ‘women’s work’ and thus was of very little help with the technical processes involved. This meant the students were left to their own devices to figure out all technical aspects of a craft most had little experience working in. Due to this set-up, it is important to look at the Weimar era works visually as opposed to technically.

In 1921 Stölzl and two of her friends made a trip to Italy to view the art and architecture they had studied for further inspiration. After passing her journeyman’s examination as a weaver and taking courses in textile dyeing at a school in Krefeld, Stölzl was able to reopen the previously abandoned dye studios. It was becoming obvious that she was giving direction to the other students, though unofficially, as neither Muche, the form master nor Helene Börner, the crafts master, could really teach and promote the students in technical aspects. In 1921, Stölzl collaborated with Marcel Breuer on the African

Chair - made of painted wood with a colorful textile weave. The first official Bauhaus exhibition took place in September 1923 in the Haus am Horn building. The building itself, primarily designed by Georg Muche, was a simplistic, highly modern cube structure made largely of steel and concrete. Each room of the house was designed around its specific function and had specially made furniture, hardware etc., which had been produced in the Bauhaus workshops. The weaving workshop participated by creating rugs, wall hangings and other objects for various rooms all of which won favorable reviews.

With this exhibition, Walter Gropius released an essay titled ‘Art and Technology – A New Unity’ which seemed to have a great impact on the women of the weaving workshop. Despite the favorable reviews of their works, the women began to move away from the pictorial imagery and traditional methods they had been working with up to this point and began working abstractly, attempting to make objects more in line with Kandinsky’s teachings of the ‘inner self’

Bauhaus Master

In April 1925, the Weimar Bauhaus closed and reopened in Dessau in 1926. Stölzl, who had previously left the Bauhaus upon graduating to help Itten set up Ontos Weaving Workshops in Herrliberg, near Zurich, Switzerland, returned to become the weaving studio’s technical director, replacing Helene Börner, and work with Georg Muche, who would remain the form master. Although she was not officially made a junior master until 1927, it was clear both the organization and content of the workshop were under her control. It was obvious from the start, the pairing of Muche and Stölzl was not enjoyed by either side, and resulted in Stölzl running the workshop almost single-handedly from 1926 onward.

The new Dessau campus was equipped with a greater variety of looms and much improved dyeing facilities, which allowed Stölzl to create a more structured environment. Georg Muche brought in Jacquard looms to help intensify production. He saw this as especially important now as the workshops were the school’s main source of funding for the new Dessau Bauhaus. The students rejected this and were not happy with the way Muche had used the school’s funds. This, among other smaller events, instigated a student uprising within the weaving department. On March 31, 1927, despite some staff objections, Muche left the Bauhaus. With his departure, Stölzl took over both

as form master and master crafts person of the weaving studio. She was assisted by many other key Bauhaus women, including Anni Albers, Otti Berger and Benita Otte.

Stölzl began trying to move weaving away from its ‘woman’s work’ connotations by applying the vocabulary used in modern art, moving weaving more and more in the direction of industrial design. By 1928, the need for practical materials was highly stressed and experimentation with materials such as cellophane became more prominent.

Stölzl quickly developed a curriculum which emphasized the use of handlooms, training in the mechanics of weaving and dyeing, and taught classes in math and geometry, as well as more technical topics such as weave techniques and workshop instruction. The earlier Bauhaus methods of artistic expression were quickly replaced by a design approach which emphasized simplicity and functionality.

Stölzl considered the workshop a place for experimentation and encouraged improvisation. She and her students, especially Anni Albers, were very interested in the properties of a fabric and in synthetic fibers. They tested materials for qualities such as color, texture, structure, resistance to wear, flexibility, light refraction and sound absorption. Stölzl believed the challenge of weaving was to create an aesthetic that was appropriate to the properties of the material.

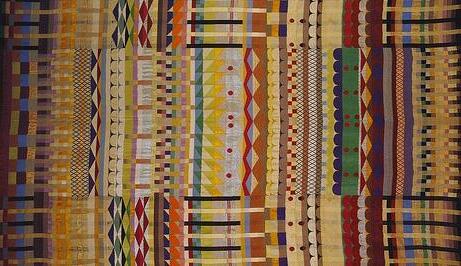

In 1930, Stölzl issued the first ever Bauhaus weaving workshop diplomas and set up the first joint project between the Bauhaus and the Berlin Polytex Textile company which wove and sold Bauhaus designs.

1In 1931 she published an article entitled “The Development of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop”, in the Bauhaus Journal spring issue. Stölzl’s ability to translate complex formal compositions into hand woven pieces combined with her skill of designing for machine production made her by far the best instructor the weaving workshop was to have. Under Stölzl’s direction, the weaving workshop became one of the most successful faculties of the Bauhaus.

1914-1916

Studies glass painting, ceramics and decorative painting at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Munich

1927

Appointed as Jungmeister (Junior Master) for the entire weaving workshop, the Bauhaus’ first and only female master.

‘Development of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop’

1967-69

Dissolves hand weaving business, devotes herself to tapestry and weaving her own designs. the Victoria and Albert Museum acquires designs and fabric samples; major national and international collections.

“Then let us be the decorative ones among the stars of the Bauhaus… weaving is an aesthetic whole with a unity of composition, form, color and substance”

Gunta Stölzl

At the Bauhaus, women were often confronted by a prejudice against weaving which was referred to as ‘purely decorative.’ This quote from Gunta was in response to this.

Important Works

A work from the early years of the Bauhaus, presumed lost for the past 80 years, has been recovered in 2004. Made of painted wood with a colorful textile weave, this chair embodies the spirit of the early Bauhaus like no other object. The seat and back of the chair employ a woven textile.

Gunta Stölzl in a letter to H.M. Wingler, 07.01.1964: "That was the first time we worked together. I produced the fabric. I threaded and tautened the warp directly through the holes in the frame and wove the texture onto the chair itself... the forms were freely invented and without repetitions..."

Excerpt from “Die Entwicklung der Bauhaus Weberei” - The Development of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshoparticle written by Gunta Stölzl in the journal bauhaus, July 1931:

“The transfer to Dessau brought the weaving workshop new and healthier conditions. We were able to acquire the most varied loom systems (shaft machine, Jacquard loom, carpetknotting frame) and in addition, our own dyeing facilities. From now on, there begins a clear and final distinction between two areas of education that initially were fused with each other: The ‘development of functional textiles’ for use in interiors (prototypes for industry) and ‘speculative experimentation’ with materials, form and color in tapestries and carpets.”

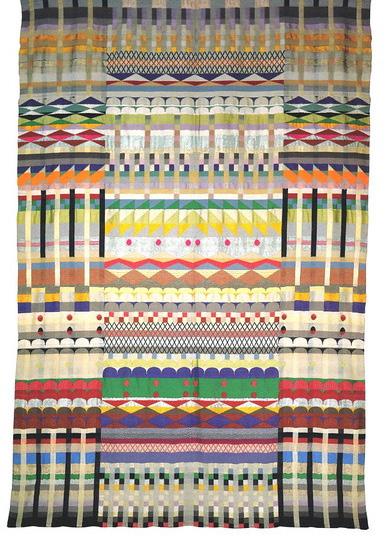

This stunning example of Jacquard weaving was acquired by the Museum in 1929 on the occasion of a Bauhaus exhibition

Endmatter

Websites

GermanyinUSA, A. (2019) Women of the Bauhaus: Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983), @ GermanyinUSA. Available at: https://germanyinusa. com/2019/03/07/womenof-the-bauhaus-guntastolzl-1897-1 (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

Gunta Stölzl (2023) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Gunta_St%C3%B6lzl (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

Works (no date) stolzl. Available at: https://www. guntastolzl.org/Works (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

Images

The African Chair (1921) germanyinusa.com. Available at: https://germanyinusa.com/2019/03/07/ women-of-the-bauhausgunta-stolzl-1897-1983/.

Wall Hanging (no date) Textileartist.org. Available at: https://www.textileartist.org/textile-artist-gunta-stolzl-1897-1983/.

5 Chöre (1928) Guntastolzl. org. Available at: https:// www.guntastolzl.org/ Works.

Published in 2023

Edited by Erika StratilaFor the Bauhaus Archive Berlin Museum of Design for the German Museum of Technology, Trebbiner Str. 9, 10963

Berlin, Germany,

Phone: +49 30 902540

Email: info@ technikmuseum.berlin

Copyright © 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced to be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Text & cover design:

Erika Stratila