Children in War a guide to the provision

of services

Second Edition - 2016

Everett Ressler

Anna Belloncle

Lara Horst EPRbook group

Second Edition - 2016

Everett Ressler

Anna Belloncle

Lara Horst EPRbook group

Second Edition - 2016

Everett Ressler

Anna Belloncle Lara Horst

PRbook group

Virginia, USA

First Edition

Copyright © 1993

United Nations Children's Fund Programme Publications 3 UN Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017 USA

Second Edition 2015

Copyright © 2016

EPRbook group Virginia, USA

ISBN: Oh, world be wise The future lies in children’s eyes.

Donna Hoffman

My Children, All Children, Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, 1975.

Photo Credits

Oh, world be wise...

The future lies in children's eyes.

This book is written first and foremost for all the parents and the children who struggle daily to survive in war.

A renewed commitment is needed in 2016 on behalf of children in situations of armed conflict.

[Need an introduction section that introduces the issue and responsive action, setting up the need for this book.

Armed conflict shows humankind at its very worst and its very bestworst when social intercourse is reduced to purposeful attempts to kill, injure, deprive, disrupt and impose upon; best when against all odds people strive to ensure the well-being of those in need. This book attempts to accentuate the positive. The goals are clear - that children in situations of armed conflict do not lose their lives, that they are afforded their rights as human beings and children, that they receive care and basic essentials for development, that their suffering is minimized and that their emergency needs are met. Meeting this challenge requires commitment, effort and determination. To these ends, this book hopes to make the following contributions:

1. To encourage responders to learn from our shared history. This book attempts to provide responders with a historic overview of the ways in which conflict can impact children as well as how people can act to protect and care for children. People have a tendency to think that their situation is unique; sometimes responders (be they parents and community organizations or UN staff) have not had experience in other situations of armed conflicts or in child protection issues when they are required to develop response action. As a result, they feel as though they need to start from scratch in developing response strategies or, on the other extreme, they implement a standard set of program activities, regardless of whether they are best suited for the situation, simply because they are not aware of alternative actions.

Each conflict is like no other, and all others. For centuries humans have done injury to each other, waged war, massacred civilians, forced children to participate in armed conflict, and starved and pillaged villages and cities. At the same time, humans have gone to extraordinary lengths to protect their families and children, to give them the best they can afford; communities and civil society have created systems and programs

to care for the vulnerable children in their midst; civilians have protested egregious violence against children at national and international levels, often at great risk to their own safety. This book is grounded in the belief that though each context has unique elements which need to be carefully considered, human history essentially repeats itself, for the better and for the worse. Understanding our history, allows for rapid and successful response programming.

2. To encourage a holistic view of response programming. The fields of child protection and humanitarian aid have become increasingly specialized in the last 20 years. Isolated programming strategies are often developed for specific sectors, such as education, child protection, health, water and sanitation. This trend has been encouraged by donors who frequently earmark funding by sector (e.g. girls and sexual violence in armed conflict, health in armed conflict, children with disabilities in armed conflict). As a result, field experience suggests that program interventions are sometimes narrowly conceived; for example, education programs may not take into consideration child nutrition issues. This book attempts to provide a holistic framework for assessing and developing response programs. It encourages responders to consider all issues affecting children and to develop response programs based on children’s needs and in coordination with other actors.

3. To provide all responders with a list of programming options. This book is ultimately intended to be a source of ideas. It is hoped that information about programme innovations around the world will stimulate creative programming - new ways to ensure that food reaches the hungry, that basic services are available in the midst of conflict, that children continue to receive essential vaccinations even when routine services are disrupted, that schooling is provided even when schools are closed, that assistance is available to traumatized children even when trained professionals are few and so forth.

Children in War is intended to be a summary. It is short rather than long, generic rather than specific, practical rather than theoretical. Therefore, while

every effort has been made to ensure that authoritative information is included, this book is intentionally a “broad crush stroke” overview.

The book is written for all persons and organizations that act to care for and protect children in situations of armed conflict, referred to as ‘responders’ herein.

In almost all conflict situations adult family members do everything possible to protect and provide for their children; children help each other; community members, committed government personnel and non-governmental organizations (NGO) offer assistance, often a great personal risk. In emergency situations, the primary responders are almost always local professionals (healthcare workers, teachers, etc.), community organizations (churches, mosques, etc.), and a range of non-governmental organizations, both international and national. Even during emergency situations, governments and parents remain the primary duty-bearer for the realization and protection of child rights and, as such, have a unique role to play in response action. At times, local and national systems are not able to provide adequate protection for children. International actors, including NGOs, intergovernmental organizations (such as the United Nations, the European Union) and other governments, often become an important part of protecting children when national actors fail to do so.

Each responder has a unique role to play to the protection and realization of children’s rights in situations of armed conflict. This book is written for all responders, from parents to aid workers to policy makers. Children will only be fully protected if all involved actors work together, building on existing actions and looking for common solutions.

First premise. This book is abashedly positive in its assertion that children’ needs can be met, even in the midst of armed conflict. This assertion is rooted in the fact that the deaths of children in situations of armed conflict are largely preventable, as are other violations of their rights. It is not a foregone conclusion that because there is armed conflict, civilians and children need be the victims of its horrors. Protection or victimization is determined by choices and decisions.

Obviously, it is extremely difficult to ensuring the well-being of children in situations in which armed violence is purposeful. Attempted interventions are often dangerous and obstructed at every turn. Still, review of experience confirms that extraordinary actions can protect and provide for children, even in the most difficult situations.

Second premise. Children are rights-holders. Children have the legal right to care and protection and to develop to their fullest potential. Parents and governments are legally responsible, even during situations of armed conflict, to realize and protect these rights. Child protection is not an act of benevolence but a legal and moral obligation.

Third premise. While this book is specifically addressed to children, it is assumed throughout the children’s needs are best served by helping families provide the necessary care and protection children require. Although not addressed in this book, support is often required to help mothers and fathers meet their own needs as well as the needs of their children.

Fourth premise. The support of all parties must be enlisted to ensure the well-being of children in situations of armed conflict. Families are usually primary care-givers for children. To understand the needs of children in situations of armed conflict, one has to understand the factors that enable or obstruct families’ ability to care for them. Families’ ability to function is shaped

by the social, political, cultural, religious, economic, and legal systems that form the web of life’s interactions; all of which are impacted by armed conflict. Obviously, the behavior of combatants is also of critical importance; all conflicting parties must be encouraged to protect children. Government services have a particularly important role in the welfare of children; during emergency situations their provision of essential goods and services is critical. When families are not able to meet basic needs or protect and provide for their children, the intervention of government and other actors is essential.

Fifth premise. If we want better answers, we must ask better questions. A constant search for better understanding of children’s needs and response action is a fundamental prerequisite to the development and maintenance of effective services for children. This book will be successful if it encourages questioning and continuing re-examinations of whether the needs of children in situations of armed conflict are really being met and, if intervention is required, what strategies prove most effective.

Sixth premise. Local problems are probably best solved by local solutions. Each culture, community, family and conflict situation is unique. Therefore, while the topic of children in situations of armed conflict is discussed in general terms, it is assumed that specific programme strategies must be developed for each situation. No attempt is made to offer prescriptive solutions. Nevertheless, while the ‘lessons learned’ in one situation cannot be rigidly prescribed to another, it would be a misconception to assume that every child, family and conflict situations is so different that lessons learned cannot be shared among experiences and cultures. The needs of each child, family, and culture are both unique and similar to the needs of all other children.

Seventh premise. In emergency programming, adaptation and innovation are necessary if services are to be effective. Health, education, social, legal and many other services exist in every country. It is often assumed that routine arrangements and systems provide sufficient response to meet emergency needs. In many conflict situations, however, deaths and suffering of children are more related to inadequate services and mergence programming than to

direct conflict action (e.g. often more children die from dirty drinking water and the lack of vaccinations that are directly killed during armed violence).

The book begins with an exploration ‘armed conflict’ and ‘children’, attempting to provide functional definitions that help to facilitate response action. The next chapter, entitled “A Basis for Action”, proposes a conceptual framework for response action. It suggests that ….

The second part of the book looks at issues affecting children in armed conflict (e.g., health, education, detention, recruitment by armed groups) and program options. Each chapter provides the reader with a historic review of the issue and trends in response strategies as well as a description of the legal framework around the issue.

It is important to remember that we tend to atomize complexities into discrete problems that are in reality much more organic than reflected. Different types of “needs” and “categorizes of children” (e.g. displaced children, children with disabilities, girls, etc) are discussed throughout the book. It is useful to remember that all issues are related and tell only a fraction of the full story.

At the end of the book, the authors have included an extensive list of reference materials related to the situation of children in armed conflict These resources are divided into three categories: resources for further study, legal instruments and resources, and programming tools.

Theories and assumptions about conflict and childhood drive responsive and protection action for children in situation of armed conflict, though they often go unstated. Throughout history, these theories have changed in reflection of the evolving sociopolitical context in which they were developed. Though it will be impossible to develop a descriptive framework that is able to stand outside of the flow of history, this chapter attempts to propose definitions that will facilitate responsive action. As such, this chapter is addressed to the following questions: What is childhood? What is armed conflict?

Different cultures during different periods of history have had different definitions of childhood. Even today, there numerous debates around the definition of child and childhood. Childhood can be defined chronologically or biologically (by age), psychologically (by emotional changes), functionally (marked by physical or social changes), or culturally (as defined in the societal context).

In the international arena, children are primarily described as persons from 0-18 years of age deserving of protection and care because of their intrinsic vulnerability and evolving capacities; “The [UN Convention on the Rights of the Child] defines a 'child' as a person below the age of 18, unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood younger. The Committee on the Rights of the Child, the monitoring body for the Convention, has encouraged States to review the age of majority if it is set below 18 and to increase the level of protection for all children under 18.”

Some have argued that the definition of ‘child’ in the UN CRC should be dismissed because it is based exclusively on a modern western concept of

childhood (see Boyden, 1992; Freeman, 1983; Macgillivray, 1992; Lewis, 1996) and because it does not pay sufficient attention to the agency of children. Though it may well have its historical roots predominately in western culture, the wide ratification of the UN CRC illustrates a global acceptance of this definition. This definition, specifically in the context of armed conflict, affords children and youth additional protection and, as such, such be jealousy guarded. While upholding to the international definition, to best enable responsive action it is important that the unique characteristics of childhood are acknowledged:

1. Children are not all alike. Each person’s capacities and actions are defined by a host of factors including genetics, personal history, the family situation, the external environment, and access to material and financial resource. Girls and boys, for example, are impacted by and respond to armed conflict differently. As with other groups of people, we should not assume that all children are the same, with the same capacities, responses, and needs. This means that children will respond to conflict differently and may have different needs.

2. Children have evolving capacities. As recognized by the UN CRC, children have evolving capacities, in accordance with their age. This is uncontested; all cultures throughout history have recognized that a three year old does not have the same capacities and needs as a 16 year old. This book assumes that there are at least three age categories of ‘children’, each with unique characteristics: infants and toddlers (0-3), children (3-13), and youth (13-18).

Perhaps the most controversial group of children is that referred to as ‘youth’. The term often refers to young people between the ages of 13 and 25, though definitions vary widely in different cultures and for males and females.

When community and family systems breakdown youth frequently assume adult-like roles, such as caring for younger children, working, and even engaging actively in the armed conflict. Despite increased responsibilities, they frequently do not receive the respect that adults. Youth are often looking for meaning in their lives; “Failure to provide adolescents with a positive and

productive sense of purpose during the upheaval of armed conflict leaves them despairing and vulnerable to those who would seek to manipulate them, pulling them into the conflict and exploiting and harming them in other ways.”

Youth may seem more like adults, than children: in many ways they can care for themselves, they have more ‘adult’ problems and responses, they do not look so innocent, they have opinions and can be demanding. For this and other reasons, youth are often left out of programming, though research shows that they are in desperate need of increased attention. Youth can characterized by a potentially volatile combination of “audacity and insecurity” (7) . Youth may exhibit self-destructive tendencies (ex. antisocial behavior, truancy, sexual promiscuity, substance abuse, etc), particularly after experiencing trauma, that make protective and response programming difficult. This behavior can be in stark contrast to the image of children as “innocent and vulnerable”, victimized by armed conflict.

3. Childhood needs to be understood its social context. In many countries childhood is determined by social rites or status markers rather than age, events that are frequently disrupted during situations of armed conflict. It is important that responders develop programs that are appropriate to local contexts, paying particular attention to local rites of passage for children and youth.

4. Children are active agents in their own lives. Though the rights of children are almost always grossly violated during situations of armed conflict, it is not useful to see children only to passive victims. Children, of all ages, make decisions in accordance with their evolving capacities which affect how the conflict impacts them. Some children chose or are forced to participate in hostilities. Other children work to provide for their families and care for younger children and their elders. In some case, children and youth participate in political activities which drive both conflict and peace building (i.e. Palestinian youth throwing stones at Israel troops, Afghan girl and school, youth involvement in the arab spring, in chile against pinochet, etc).

Children and youth should be “understood and engaged as thoughtful, in-

sightful and active agents who shape their own lives and the communities in which they live and work.” What does this mean in practice? It means that it is not sufficient to talk only to parents, teachers, practitioners, and experts about children’s needs and experiences in situations of armed conflict. Children and youth need to be involved in identifying and responding to issues directly affecting them.

5. Children have rights and responsibilities. The UN CRC confirms that children are rights-holders. As such, governments and parents are legally obligated to protect and fulfill their human rights, even during situations of armed conflict. The fact that children are ‘rights-holders’ often causes concern among adult decision-makers because they fear that this will encourage children to behave selfishly and irresponsibly. As is evident in children’s daily life, however, children’s rights are balance with their responsibility to respect the rights of others.

The prevalence and brutality of armed conflict has gone in cycles throughout history, depending on global politics and economy, population growth and resource scarcity, historic grievances, new technologies, natural resources, ideological shifts, etc. During all armed conflict, children experience egregious acts of violence, abuse and neglect. At the same time, people go to extraordinary lengths to protect and provide for children.

During the last twenty years, academics and practitioners have tended to focus on the ‘exceptionalim’ of the post-Cold War period, arguing that conflicts have become increasingly violent and destructive. They cite the high number of civilian causalities and the significant involvement of children in combat; reportedly, the number of civilian casualties as increased from 5% in World War I to an estimated 90% today. Conflicts in the second half of the 20th century have primarily been intra-state; practitioners and academics argue that the protection of civilians and peace building is particularly difficult in this context.

Chapter 1 - Armed Conflict and Childhood

Though the recent trends in conflict are of deep concern, the ‘exceptionalist’ position may not be the most constructive framework for designing response action. If the fundamental nature of conflict has changed, it is only logical to assume that the response action of the past is no longer useful. This hypothesis is concerning because it encourages responders to disregard the past and constantly reinvent response action, repeating mistakes and waisting times and resources.

There is an anthropological maxim that holds that each situation is like all others, some others, and no others. This to is true of conflict. The responder must strike a delicate balance between learning from the past, recognizing current trends, and acknowledging and adapting to the unique local context of each conflict.

There has always been armed conflict. Combatants have used the killing and injury of civilians to intimidate and injure their opponent throughout history. Genghis Khan, the Mongol leader, is infamous for his massacres of civilians. Acts of brutality are well documented in ancient Assyria, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Asia, Africa and the Americas. Towns and fortresses were looted, burned and destroyed during the wars in the Middle Ages in Europe. During the Thirty Years’ War in western Europe (1618-1648) more civilians were killed than soldiers; “some historians estimated that up to half the population of Germany may have perished during the war.”

The conquering and colonization of the West Indies, Africa, south Asia and the Americas by Europeans resulted in the death of an estimated xxx and the enslavement of xxx inhabitants.

World War I, the Russian Revolution and ethnic cleanings of the Kurds in Turkey in the early 20th century resulted in the death and displacement of tens of

thousands of children. Approximately 50 million people died in WWII, including millions of children; there were roughly 33 million civilians causalities, 11 million people are believed to have been killed in concentration camps, and 20 million people were left homeless. In 1945, the US dropped two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing an estimated 200,000 people.

During the second part of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed in wars in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Wars of liberation in Africa and South Asia, were quickly followed by internal armed conflicts fueled by the Cold War, a fight to control natural resources, and ethnic tensions in young states awash with small arms and light weapons struggling to build weak political and economic systems. Cambodia’s civil war (1975 - 1979) left almost 1/4th of the total population dead. An estimated 100,000 people, including children, were killed directly by the conflict and more than one million died from war-related causes (including terrorism). In the Angolan civil war (between 1980 - 1988), water, food and healthcare supplies were destroyed by both sides of the conflict and an estimated 330,000 children died from war related causes.

Some predicted that the end of the Cold War (1989) would bring global peace because democracy and capitalism would remove the underlaying drivers of conflict. This was not the case. In the 1990s there was a wave of intrastate conflicts characterized by brutal massacres in Yugoslavia, Liberia, Somalia, Sierra Leone, the Central African Republic, the DRC, Rwanda and Uganda, and elsewhere. Because they did not conform to expectations, they were labeled the ‘new wars’. Though these ‘new wars’ are classified as internal conflicts, most of them had an international dimension. States external to the conflict provided financial, military or political assistance to one or more of the combatant groups. Refugees, non-state combatants, weapons and ideologies spilled over into neighboring states, in some cases destabilizing entire regions (e.g. In 1994, refugees from Rwanda fled into DRC, Burundi and Uganda; their presence has contributed to armed conflict for the last 20 years).

Unaccompanied children are a particularly vulnerable group that can be found in every conflict: in the Spanish Civil war it was estimated during 1936 that there were 90,000 unaccompanied children; in 1948 during the Greek civil war, roughly 23,000 children were trafficked out of Greece and some 14,500 unaccompanied children were moved for safety reasons inside Greece; between 1970 and 1984, an estimated 22,000 unaccompanied children left Vietnam.

Children and youth have been involved in arm conflict since ancient times and, simultaneously, society has struggled to put age limits on their engagement. In Sparta, ancient Greece, boys began military training between 7 and 10 but they were not allowed to join the military until 20. In the American civil war, both the Union and the Confederate armies required enlistees to be at least 18. However, recruiters had difficulty confirming the age enlistees. Army statisticians estimate that a total of 250,000 - 420,000 soldiers were under the age of 18 when they enlisted (10-20 percent of all of the soldiers). Young girls often acted as couriers during the Algerian rebellion against the French in the 1950s; “like other rebels and spies who were caught, the girls were tortured until they confessed the whereabouts of their leaders.”

Forced population transfers have also been practiced throughout history, including during the Assyrian Empire, during Roman and Arab invasions, during the Christian reconquest in Spain, in France, England, Hungary, Austria, and Portugal during the middle ages, and during the Napoleonic invasions. The Jews, Roma, Huguenot, Tartars, Native Americans, Jesuits, and many others have been subjected to forceful movement.

In almost all conflicts, violence against women and girls tends to increase. In certain conflicts, sexual violence is used systematically as a weapon of war, ethnic cleansing, or genocide. In almost all cases, women and girls are subjected to increased violence in their homes, communities, and places of displacement. A few of the many examples include the following: An estimat-

American Civil War - 1861–1865

From 1854-1929, 250,000 unaccompnied children placed on ‘orphan trains’ detined for families in the Mid-West…

Mixed results: some successfully integrated, others endured hostile environments (i.e exploitation, abuses…)

Chapter 1 - Armed Conflict and Childhood

ed 200,000 south-east Asian women, primarily Korean, were abducted and force to have sex 20 - 30 times a day for Japanese soldiers during WWII. It is estimated that during a nine-month period after Bangladesh declared their independence from Pakistan and the entry of Pakistani troops in 1971, an estimated 200,000 - 400,000 Bengali women (80% of whom were muslim) were raped by soldiers (Makiya, 1993). It is estimated that between 20,000 and 50,000 women were raped in the early 1990s in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Rape was a systematic weapon of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. It is believed that an estimated that between 250,000 - 500,000 women were raped during the war. In 1998, an survey in Sierra Leone found that 66.7% of respondents had been beaten by an intimate partner. In 2010, it was estimated that 40% of women in Eastern DRC had experienced sexual violence.

Recent Trends in Armed Conflict

Though we do not believe that armed conflict today is of such an egregious and exceptional nature as to constitute a break from human history, we do recognize that many of the conflicts in the last 30 years have had similar characteristics which should be recognized and taken into consideration in the development and implementation of response action:

ICRC recently noted the ‘diversity of situations’ in which armed conflicts in currently being waged, “rang[ing] from contexts where the most advanced technology and weapons systems were deployed in asymmetric confrontations, to conflicts characterized by low technology and a high degree of fragmentation of the armed groups involved.”

Weapons are increasingly automated and long range. Condorcet, an 18th-century French philosopher and mathematician, hailed the military use of gunpowder. He reasoned that enabling combatants to fight at greater distances would reduce the number of causalities. Today, the vast majority of civilian causalities are from small arms and light weapons. New technologies (including drones) are having an ever increased impact around the world, both positive and negative; “This new technology, like certain other advances in

military technology can, on the one hand, help belligerents direct their attacks more precisely against military objectives and thus reduce civilian casualties and damage to civilian objects. It may, on the other hand, also increase the opportunities of attacking an adversary and thus put the civilian population and civilian objects at greater corresponding exposure to incidental harm.”

The global trend towards urbanization and increased population density means that conflicts over the last 150 years have been increasingly fought against an high density, urban backdrop. This is one of the reasons that the gross number of civilians that are impacted and killed in armed conflict has steadily increased.

A number of the current conflicts have been on-going for several decades, including in Afghanistan, Colombia, DRC, Israel and OPT, Somalia, and Sudan. Only a few of the recent conflicts have been definitively resolved through a peace negotiation; notably, several conflicts have re-started despite ceasefires and peace agreements.

In the last 30 years there has been an significant increase in the number of internal conflicts, either between two groups of non-state actors or between a government and a non-state actor. However, almost all of the contemporary conflicts have regional, transnational, multinational or bi-national dynamics. These conflicts tend to have high rates of civilian casualties.

The prevalence and availability of SALW, the multitude of non-state armed groups with informal command structures, the role of resources in conflicts, and confusion between criminal groups and non-state armed groups has blurred the line between combatant and non-combatant.

For the purposes of the humanitarian and the responder, the categorizations of armed conflict are useful in so much as they allow us to better protect and provide for children. To these ends, we will use the definitions of armed con-

flict provided by International Humanitarian Law (IHL). These classifications are important because they determine which legal framework is applicable in a given context. Thus, they will assist responders in identifying appropriate legal remedies and conducting accurate monitoring and advocacy activities. If armed violence does not fall under the classification of an armed conflict, human rights law and national laws still apply.

The term ‘armed conflict’ replaced ‘war’ in the late 20th and early 21st century. This term does not have a standard definition. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) defines it as: “A dispute involving the use of armed force between two or more parties.” IHL distinguishes between International Armed Conflict (IAC) and Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC).

An International Armed Conflict (IAC) occurs when there is a use of armed force between two or more states. An IAC begins at the first use of force. This category of conflict also includes foreign occupation, even when invaders meet no opposition. In the last 50 years, there have only been a few conflicts that fall into this category. Though there is some divergence of opinion, arguably ‘intensity’ and ‘duration’ do not determine that classification of an IAC; this means that the type of violence and how long the violence lasts are not used to determine if two-states are engaged in an IAC.

A Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC) occurs when a state and a nonstate armed group or two (or more) non-state groups are involved in armed hostilities. Two elements are necessary for a conflict to be classified as an NIAC, as per Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions:

1. Involved parties must show a certain degree of internal organization. Jurisprudence suggests that ‘internal organization’ includes “existence of a command structure and disciplinary rules and mechanisms within the armed group, the existence of headquarters, the ability to procure, transport and distribute arms, the group's ability to plan, coordinate and carry out military operations, including troop movements and logistics, its ability

to negotiate and conclude agreements such as cease-fire or peace accords, etc.”

2. The violence must obtain a certain level of intensity. Jurisprudence indicates that the ‘level of intensity’ can be determined by “the number, duration and intensity of individual confrontations, the type of weapons and other military equipment used, the number and calibre of munitions fired, the number of persons and types of forces partaking in the fighting, the number of casualties, the extent of material destruction, and the number of civilians fleeing combat zones.”

NIAC are the most difficult to classify; the lines between criminality and armed conflict are sometimes blurred and states are often hesitant to admit the gravity of internal tensions. Arguably, in recent histories there have been 7 typologies of NIAC:

- Traditional NIACs (as described in Common Article 3) in which governmental armed forces are fighting one or more non-state armed groups in the territory of a specific state;

- An armed conflict in which two or more organized non-state armed groups are engaged in armed hostilities within the boundaries of a single state. This includes ‘failed states’;

- Armed conflicts between a government and one or more organized non-state armed groups that ‘spilled over’ into neighboring countries;

- ‘Multinational NIACs’ have emerged as a recent trend in the last couple of decades. In these conflicts a multinational armed force is fighting with that of a ‘host’ state against one or more non-state armed groups, within its territory;

- Similar to the category described above, in some conflicts UN forces or regional forces (such as the African Union) are sent to support a ‘host’ state against one or more non-state armed groups, within its territory;

- Some argue that there may be a category of ‘cross border’ NIAC in which state forces are engaged in hostilities with a non-state armed group from a neighboring territory that is not controlled or supported by a state (ex. the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah);

- Some argue that a new category of NIAC has emerged in the con-

text of the ‘fight against terrorism’ (i.e. the conflict between Al Qaeda and its ‘affiliates’ and the US across a number of states). However, as of 2011, “ICRC does not share the view that a conflict of global dimensions is or has been taking place. Since the horrific attacks of September 11th 2001 the ICRC has referred to a multifaceted "fight against terrorism". This effort involves a variety of counter-terrorism measures on a spectrum that starts with non-violent responses - such as intelligence gathering, financial sanctions, judicial cooperation and others - and includes the use of force at the other end. As regards the latter, the ICRC has taken a case by case approach to legally analyzing and classifying the various situations of violence that have occurred in the fight against terrorism. Some situations have been classified as an IAC, other contexts have been deemed to be NIACs, while various acts of terrorism taking place in the world have been assessed as being outside any armed conflict. It should be borne in mind that IHL rules governing the use of force and detention for security reasons are less restrictive than the rules applicable outside of armed conflicts governed by other bodies of law.”

Organized crime has resulted in levels of armed violence in some countries that seem comparable to a NIAC. The objective of the armed violence is not a relevant criteria in the classification. As such, each scenario should be examined as per the two criteria described in Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions: organization of the non-state armed group and intensity of the violence. In accordance with this classification, some cases may indeed fall within the categorization of a NIAC.

The classification of armed conflict is often extremely political. For example, over the last 100 years there have been numerous states have refused to classify armed violence as a NIAC, using the term ‘counter-terrorist’ operations instead (i.e. northern Ireland, latin america?, US, etc). This is not a legal classification of armed violence. It would seem that states assume that recognizing the existence of a NIAC will granting a non-state armed group particular legal status or legitimacy and limit the actions that they are able to take during the conflict (i.e. in regard to detention, use of force, etc). Further to this definition, we encourage responders to analyze conflict through

The Russian Revolution- 1917 - 1920

• 5 million homeless children in 1920’s

• 1918: Famine - 4,000+ children taken to Siberian summer camps where food was more plentiful.

• Unaccompanied Polish children in Siberia

Chapter 1 - Armed Conflict and Childhood

the ‘family’s perspective’, categorizing conflict by its impact on families and children, rather than by the actions and intentions of combatants. This will hopefully provide responders with an analysis framework that directly facilitates response action.

Virtually every bookstore contains books about military hardware, battle strategies and war heroes. There are few books, however, that describe the drama and tragedy of how ordinary mothers and fathers under the greatest of difficulties secure food, find protection and provide for their children in the midst of conflict. Life experience in situations of armed conflict can vary wifely:

Some families must survive under heavy shelling and aerial bombardment; people in another community may experience no direct action at all. Families may be forced to cope with disappearance, massacres, torture and repression while families in other places within the same country may continue life routines uninterrupted.

Villages, crops, animals, schools, clinics and infrastructure are purposefully destroyed in some conflicts, while in others the physical damage is light. Sometimes food shortages and the horrors of family are used as weapons, while in other conflicts family food sufficiency is relatively unaffected. Some families experience conflicts as sudden and short interruptions in their lives; others must adapt to a way of life in which armed conflict is at their doorstep for years.

Some families are able to continue life routines in their home village throughout periods of conflict, while other families are forced to abandon home and community. Urban families often have quite different conflict-related experiences than their rural counterparts. Families living in a capital city are often unaware of the full realties of the conflicts occurring far away in rural areas within their own country. Each situation of armed conflict is unique; accordingly, the needs of children

in situations of armed conflict are determined by the peculiar nature of each armed struggle and the cultural, political, social and economic milieux within which it is waged. The nature of conflict is not only nation-specific, but also community-specific.

The following factors might be considered when developing an analysis framework from the Family’s Perspective:

1. Personal characteristics of family and child. The composition and situation of the family are a factors determining the degree and manner in which they family is impacted by armed conflict and their level of resilience. Analysis criteria might include the socioeconomic position, the gender composition, the age of children and parents, the family structure (number of children, wives, etc), the geographic location (urban/rural, displaced, etc), and if any of the family members have a physical or mental disability.

2. Types of violence experienced by the family/child: During a conflict, children and families can subjected to several types of violence (sometimes simultaneously), each with unique implications for response programming: intra-familial violence, violence within the community/between community members, violence acted on the community by an outside actor, two outside actors fighting in the vicinity of the community, violence between armed groups in neighboring communities, acts of terrorism, etc.

3. Type of weaponry used and their impact on the family/child: The type of weapons that are being used in the conflict also impact how the violence is experienced by the family. SALW, land mines, booby traps, cluster munitions, ariel bombing, acts of terrorism (suicide bombings, etc), chemical or biological weapons each have unique risks and impacts for families.

4. Intersection of the identify of the combatants and the identity of the family: The degree to which a conflict disrupts the social and cultural frame-

work by directly impacting the identity of the family. For example, one might ask: Does the conflict have particular gender dynamics which will impact the family? Is the family’s identity directly involved in the conflict, as either victims or combatants? Is the community specifically involved in the conflict? Is the ethnic, religious, political, racial, etc identity of the family a particular part of the conflict?

5. Changing roles in the family: Has the conflict forced a change in gender roles in the family? Are children playing a different role in the family? Are they working? Isolated? Caring for other family members?

6. Role are children and families playing in the conflict: Are children and families actively participating in the conflict? Was their recruitment forced or voluntary? Are they being specifically targeted by the conflict? Are they living in an area in which they have a high risk of being unintentional victims?

7. Resources available to the family before and during the conflict: What resources were available to the family before the conflict? How has their access to shelter, water, food nutrition, clothing, health care, education and money been affected by the conflict? Is this access likely to change in the coming months?

8. Social capital available to the family before and during the conflict: A family’s social capital often determines their ability to access resources, services, and to navigate the conflict dynamics successfully. Analytical questions might include, what social and political connects do families have? What is the level of education and professional expertise in the family? What languages do they speak? Are they literate? What opportunities are open to them and are they able to exploit these opportunities or services?

9. Cohesion of the family and community before and during the conflict: There is significant evidence suggesting that children are substantially less vulnerable physically and psychologically if they remain with their family and community. As such, analysis frameworks should consider if families have been able to remain together? If communities have been able to remain together? To what

More than 140,000 people, over 7,000 of them children, have been killed in Syria’s uprising turned-civil war, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said.

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

degree families and communities were acting as functional units before the conflict? How are they acting during the conflict.

10. Cultural and religious framework in which the family operates: Some cultural and religious frameworks are better able to support families and communities during periods of social upheaval than others. Analysis question might include the ability of the family to make decisions about their well-being, their access to basic rights before and during the conflict, the previous experiences of the family and community, etc. Chapter 2

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that every does”

Margaret Mead

Introduction

The world has made great strides during the last 150 years towards improving measures and actions for child protection. Indeed, child rights have been almost unanimously recognized by states. A remarkable international normative framework has developed to protect and realize child rights during times of peace and conflict. And still, despite global action, children are killed, maimed, persecuted, starved, abused, and exploited during armed conflict. Why? We know from past experience, that the vulnerable always suffer disproportionately because protection systems crumble and social norms become fluid. Belligerents almost always put their cause above the individual wellbeing of civilians; it is in the nature of war. Each time, the situation seems unique, extraordinary in its horrors and sacrifices. Each time, responders search for ways to protect and care for children. In almost all cases, responders have limited time and resources and are working in a high-stakes context. Few have the luxury to take an academic approach to the identification of best practices and the formulation of programming. However, there is much to be learned from the our shared history. This book provides responders with programming options, taken from the last 150 years of our collective history. This chapter specifically describes the historic context in which these programs were developed. It is divided into two sections, the development of the normative framework applicable to children in armed conflict and trends in theory and praxis in humanitarian response for children in armed conflict.

Development of the

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

The principle of humanitarianism is founded on the belief that all human beings are of equal moral worth under natural law. In its early conception, this principle was grounded in the spiritual significance of each individual. Aristotle and the Stoics of early Greece, for example, opposed slavery on this basis. Many humanitarian movements throughout history have had religious ties; they were either considered the work of religious institutions or were required of religious followers. During the Enlightenment period in Europe, humanists reinvent principles of humanitarianism, but grounded it in theories of rationalism as opposed to spiritualism. Humanitarian movements successfully advocated against torture in the 18th century. In the 19th century, they fought against slavery, poor labour conditions, working children, the treatment of persons with mental disabilities, among other things.

In the context of armed conflict, the term ‘humanitarian action’ refers to measures that are focused on alleviating suffering for civilians or persons who are no longer participating in armed hostilities. It is defined by International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and emerged in its modern form with the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Both the ICRC and IHL can be attributed to Henry Dunant, a traveling swiss businessman. In 1859, Dunant witnessed the bloody battle of Lombardy and was horrified by the suffering he saw and the lack of medical assistance provided to the wounded and dying. He wrote a report, entitled ‘A Memory of Solferio’, in which he described the need for a neutral organization focused on providing medical assistance during times of armed conflict, composed of volunteers trained in peacetime. He printed this report and distributed it to the head of every State in Europe. This report ‘stirred the conscience of Europe.’ Dunant established a committee with 4 other swiss citizens which later became the ICRC. It was at the Committee’s bequest that the Swiss government organized an international conference in 1864. The first Geneva Convention was born during this conference; it provided protection for the wounded and sick during armed conflict and established the neutrality of healthcare workers,

‘ orphans, waifs, seperated children.....’

Under the age of 18 not accompanied by a parent or guardian in law or custom.

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

under the emblem of the red cross. The ICRC has remained the guardian of IHL and is mandated to assist victims of international and internal armed conflicts.

The next significant development in the normative framework can be traced to the unique British activist, Eglatyne Jebb. She was charged with ‘aiding the enemy’ by the British government because she organized food shipments for civilians in France, Belgium and Germany during WWI. During her court hearing, she told the judge, “My Lord, I have no enemies below the age of 11”. Jebb was one of the founders of Save the Children. Following WWI, Save the Children UK and Sweden (called Radda Barnen at that time) drafted the first Declaration on the Rights of the Child. This Declaration was adopted by the League of Nations in 1924 and was the first global human rights instrument focused exclusively on children. It stated that children should be given priority in receiving assistance, particularly during emergencies. As Jebb was organizing food shipments, ICRC was becoming increasing vocal in its believe that civilians should be afforded legal protections in times of war. However, The Diplomatic Conference (1929) held at the end of the war focused almost exclusively on prisoners of war because civilian protection was considered too politically sensitive at that time. The conference did, however, recommend that a study be completed in preparation for an international convention for the protection of civilians in armed conflict. ICRC completed the study but could not generate interest; war seemed unlikely in 1934. In 1939 the ICRC and the International Union for Child Welfare prepared the Draft International Convention on the Condition and Protection of Civilians of enemy nationality who are on territory belonging to or occupied by a belligerent. However, they could not continue working on it due to the outbreak of war.

As such, at the outbreak of WWII ICRC did not have a legal instrument to back its negotiations and advocacy regarding civilian protection. Still, they requested repeatedly for the humane treatment of civilians detained by belligerent forces, a requested that was often disregarded. At the end of the war, a

Diplomatic Conference was held (1949), which culminated in the adoption of the four Geneva Conventions. The fourth Convention is addressed specifically to the protection of civilians during interstate armed conflicts and situations of occupation. All four of the conventions have the same Article 3 (called ‘common Article 3’) which extends protection to civilians in intrastate armed conflicts.

As early as 1946, discussions began in the UN on redrafting the Declaration on the Rights of the Child. Initially, the intention was to have the 1924 Declaration reaffirmed by the United Nations, in light of the dissolution of the League of Nations. The process of drafting the new Declaration began in 1948 when the ‘Children’s Charter’ first appeared on the agenda of the UN Social Commission. The Declaration was presented to the UN GA in 1959. This Declaration added to the provisions of the 1924 Declaration in a number of ways, including children’s rights to name and nationality (Principles 3), leisure (Principle 4 and 7) and to have their best interests considered as a priority.

During the 60s, ICRC generated support for two Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions to expand the protections afforded to civilians by the 4th Geneva Convention and Common Article 3. These Protocols were adopted in 1977. Protocol I is addressed to international armed conflict and Protocol II is addressed to non-international armed conflicts.

Public interest in the wellbeing of children during times of armed conflict was heightened by international media coverage in the 60s and 70s. As evidence of the growing concern for children, UNICEF was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1965, in part because of their dedication to aiding children on all sides of conflicts. The UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (art. 23 an 24) and the UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (art. 10) passed by the UN GA in 1966 also recognized that children need specific care and are deserving of additional protection. In 1974, the UN GA adopted a Declaration specifically addressed to the protection of women

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict and children in emergencies and armed conflict . This Declaration “condemns attacks and bombing of civilian populations and prohibits persecution, imprisonment, torture and all forms of degrading violence against women and children.”

The UN International Year of the Child (1979) was a turning point for children internationally; “[it] resulted in increased interest world wide, among aid agencies, welfare and rights practitioners as well as researcher, in learning more about children’s lives and the best ways to working for their welfare.” Increase focused on child rights forced hidden issues into the public eye, issues such as child abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, child prostitution, child pornography, abduction of children, early marriage, and child slavery. Patricia Smkye stated that “the new willingness to face the situation as it is may be one of the biggest achievement of the 1980s.” The combination of public attention and an improved understanding of causes and consequences of rights violations resulted in numerous initiatives that strengthened international and national normative frameworks and laws, programming, and resource allocation. In 1984, ICRC published the first comprehensive analysis of the provisions of IHL that related to the protection of children in situations of armed conflict. In 1986, UNICEF’s Board formally recognized children in situations of armed conflict as particularly vulnerable and in need of extraordinary programming. In 1989, the UN GA adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Notably, 191 countries ratified, acceded to or signed the CRC.

A UN Resolution entitled ‘A World Fit for Children’ (2002) acknowledged that “the 1990s was a decade of great promises and modest achievements for the world’s children.” UNICEF organized the World Summit for Children in 1990. The World Declaration and the Plan of Action adopted during the World Summit for Children was among the most rigorously monitored commitments of the 90s. Simultaneously, Graca Machel’s comprehensive study on the situation of children in armed conflict was completed at the request of the UN Secretary General at the beginning of the 90s. It was the first major

multi-country study which addressed a range of child rights issues (i.e. sexual exploitation, psychosocial needs, violence, injury, etc). This report, presented and accepted by the UN General Assembly in 1996, in many ways set the agenda for the decade which followed.

In 1998, 120 countries adopted the Rome Statute, thereby establishing the International Criminal Court. The ICC is mandated to try perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression. The Rome Statute identified several categories of crimes that are particularly relevant to children, namely genocide through transferring children form one group to another, recruitment of children into armed groups, sexual violence, genocide through preventing births, use of starvation as a weapon of war, attacking schools or hospitals, and attacking humanitarian objects or staff.

The 21st century saw the establishment of extraordinary international mechanisms addressed to children’s welfare in situation of armed conflict. In 2000 the UN General Assembly adopted the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the involvement of children in armed conflict and the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. The normative framework related to children and juvenile justice during times of armed conflict was strengthened by the adoption of the UN Guidelines on Justice in Matters involving Child Victims and Witnesses of Crime (2005). The Paris Principles, adopted two years later, protect children from being prosecuted for war crimes and crimes against humanity and encouraged states to use alternative forms of justice (non-retributive) to hold children accountable for crimes committed during conflict.

The UN Security Council (SC) passed its first resolution (resolution 1261) specifically focused on children and armed conflict in 1999. The Security Council has since passed several resolutions, including: - UN SC resolution 1379 (2003) calls for the ‘naming and shamming’ of parties that recruit and use children in armed conflict; - UN SC resolution 1539 (2004) urges parties engaged in armed con-

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

flict to develop and implement Action Plans to stop the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict. Additionally, it calles on the Secretary General to develop a systematic and comprehensive monitoring and reporting mechanism focused on child rights;

- UN SC Resolution 1612 (2005) calls for the development and implementation of a Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism (MRM) on Children in Armed Conflict, mandated to provide timely and reliable information on six grave child rights violations during situations of armed conflict, namely killing or maiming of children, recruitment or using child soldiers, attacks against schools or hospitals, rape or other grave sexual violence against children, abduction of children, and denial of humanitarian access for children. Resolution 1612, echoing SCR 1539 (2004), calls on belligerent parties to put in place time-bound Action Plans to stop the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict. Finally, this resolution establishes the Security Council Working Group on Children in Armed Conflict (SCWG-CAAC), mandated to review Action Plans and MRM reports. Based on the information it receives, the SCWG-CAAC reports and provides recommendations to the Security Council.

- UN SC resolution 1882 (2009) calls for the ‘naming and shamming’ of parties that commit sexual violence against children and those that kill and maim children with impunity. This resolution also established a link between the UNSCWG-CAAC and the SC’s Sanctions Committees.

The Security Council has recently slowed it’s progress. Notably, Resolution 2068 (2012) was the first SC resolution addressed to children in armed conflict that was not unanimously adopted; Azerbaijan, China, Pakistan and Russia abstained. In July 2013, “the United States refused to hold the annual debate on children and armed conflict during its presidency of the Security Council, reflecting the overall difficulty of negotiating decision on this thematic issue in the current political environment.” A Security Council report released in 2014 argued that “the implementation of the Council’s children and armed conflict agenda, including increased state accountability, is at stake.”

Humanitarian coordination mechanisms were strengthened during the 2000s.

In particular, the UN Cluster approach was adopted in 2005 as part of a larger reform of the UN’s humanitarian response system. The clusters are addressed to food security, health, logistics, nutrition, protection, shelter, water and sanitation and hygiene, camp coordination and camp management, early recovery, education, and emergency telecoms and communication. The cluster systems provides a forum for coordinated action between UN agencies, donors, civil society organization and other stakeholders.

Over the last 25 years there has been a growing awareness that conflict has a unique impact on women and girls, both on an individual and a societal level. In 1985 the UN established the first Working Group focused on refugee women. In 1990, UNHCR adopted the first policy on the protection of refugee women, which became the Guidelines on the Protection of Refugee Women (1991). In the mid-90s UNHCR and other UN agencies began to develop specific guidelines related to reproductive health and protection against Gender Based Violence (GBV) in situations of armed conflict. In 2005, the UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee issued Guidelines for Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings, requiring all humanitarian actors to address GBV regardless of their sector.

In 2000 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1325, the first resolution to link women to the peace and security agenda. This resolution calls for the active participation of women and girls in conflict prevention, conflict resolution, peace building and reconstruction. It acknowledges that women and children are disproportionality affected by armed conflict. These principles have been supported in subsequent resolutions, namely 1820 (2008), 1888 (2009), 1889 (2009), 1960 (2010) and 2106 (2013). One result of this series of resolutions was the appointment of a Special Representative to the Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict.

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

Since the 70s there has been a gradual shift in humanitarian aid, from a ‘fire-fighting’ approach to a ‘development’ approach. In the past, humanitarian aid was primarily focused on the delivery of life-saving services (medical, shelter, food, sanitation and water). Today’s humanitarian programs are more holistic, taking into consideration psychosocial needs, community engagement and empowerment, and the developmental needs of children - including education and play.

Development programs, and subsequently humanitarian aid programs, became increasingly ‘human rights’ focused during the last 40 years. In the 1960s and 70s, development aid was often delivered to young countries just emerging from colonization; it was driven by old alliances, Cold War geopolitics, an attempt to encourage stabilization and prevent conflict, and, perhaps, a touch of guilt. Until the 1970s, development projects aimed to encourage industrialization and economic growth, with little regard for its impact on the human rights of affected populations. The adoption of the UN Declaration on the Right to Development (1986) is evidence of a significant shift in the international discourse, namely the global acknowledgment of the mutual importance of economic development and human rights. It was not until the 90s that development actors began to systematically integrate ‘human rights’ into development and humanitarian aid programs.

By the end of the 90s, the discourse had moved from ‘linking relief and development strategies’ to assuming that relief and development were on a ‘continuum’. The underlying assumption was that development aid could reduce the impact of natural disasters and the likelihood of armed conflict. Additionally, it was understood that if humanitarian relief was correctly delivered it could protect assets and provide a basis for future development. One of the key elements to this approach is the importance of the active participation of the affected population and their ‘ownership’ of programs. The human rights approach to programming became a central part of the relief-development continuum. The human rights approach frames humanitarian aid in terms

MIGRANT CRISIS : THOUSANDS OF UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN ARRIVING IN EUROPE

Salvadorian immigrant Stefany Marjorie, 8, and her sister got stopped by Border Patrol agents this past week in Mission, Texas. GETTY IMAGES

Alone: And worryingly, eight per cent of all children (pictured) - who boarded rickety smugglers boats from war-torn countries like Syria, Libya and Iraq - landed in Italy unaccompanied

Thousands of vulnerable unaccompanied children arriving on Mediterranean rescue boat

Of the tens of thousands of migrants and refugees currently traversing Europe, an estimated 4% to 7% are minors traveling without their parents. (Los Angeles Times, Sept. 15, 2015

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

of respecting rights rather than ‘providing handouts’. As such, life saving aid activities (largely logistic in nature) are now seen as a first brief phase in humanitarian aid, which should be replace with longer-term, more holistic programs.

The humanitarian community went through a period of self-doubt and “a deep sense of moral, political and social crisis” in the 1990s. Public criticism soared as a resulted of negative publicity regarding humanitarian operations in Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (with Rwandese refugees), Northern Iraq (with Kurdish refugees), Bosnia and Kosovo. At the same time there was a rise in isolationist foreign policy. International spending on emergency aid, which had risen sharply throughout the 70s and 80s, declined in the 90s. Some began to argue that humanitarian aid was in fact doing more harm then good. Donor agencies, responding to pressure at home, increased demands for concrete proof of the impact of funded programs.

In this climate, UN agencies struggled to acquire adequate financing; they began to redefine and expand their mandates in search of funding and in response to the move towards ‘holistic’ programming. Against this backdrop, there was an explosion of civil society organizations in the 90s. They played a central role in providing services to civilians affected by armed conflict and have also substantially contributed to the development of the international normative framework, particularly related to child rights.

Arguably, the rapid growth of the civil society sector and the scarcity of financial resources had two results: on the positive side, it forced the humanitarian aid community to professionalize. The 90s saw the birth of many university programs specialized in development, human rights, child rights, and humanitarian aid. NGOs and UN agencies strengthened internal resource management systems, accountability structures, monitoring and evaluation and result-driven programing as a result of competition and donor pressure.

However, it may also have had some negative side effects. Time will tell if the

idealism which characterized the humanitarian field was irrevocably wounded during this process. Ironically, the shift towards holistic programming and the professionalization of the sector increased program overheads (staff salaries, housing, security, office costs, etc) and general costs, which fueled public criticism of the sector. Some humanitarian organizations became ‘donor-driven’ in the scramble for funding. The clarity of their mandate disappeared. Coordination became a critical issue during this period.

In response to the tension described above, the humanitarian community began to look for a new paradigm at the end of the 90s. They reconsidered the old notion that development aid could address the root causes of armed conflict and prevent violence and migration. This argument had been popular in the mid-1940s and briefly in the late 70s and early 80s. It was reopened by the former UN Secretary-General, Boutros-Ghali, in his Agenda for Peace (1992) and the Agenda for Development (1994). Humanitarian and development programs widely adopted a ‘conflict-sensitive’ approach, acknowledging that aid can have a significant impact on conflict dynamics and that all attempts should be made to ensure that programming decreases tension and contributes to peace building.

The focus on peace building and conflict-sensitive programming coincided with concerns about refugee movement. Reeling from the refugees which spread across Europe as a result of the war in the former Yugoslavia and the lasting consequences of other large scale protracted refugee crisis across the world, the international community became explicitly concerned with preventing large scale population movements. The new policy focused on repatriation, provision of safe areas and humanitarian aid.

International humanitarian aid workers have been increasingly targeted by belligerent parties in the last 25 years. Notably, between January 1992 and

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

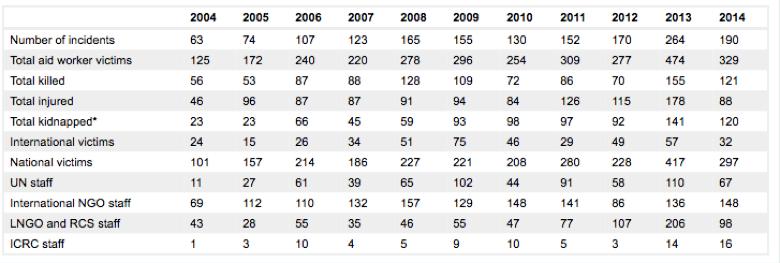

March 2002, 209 UN staff members were killed (111 persons died from gunshot wounds, 52 died as a result of ethnic violence, 28 were killed in airplane accidents, and 16 were killed in bombings or landline explosions), 255 staff members were taken hostage and many others were raped, assaulted or the victim of robbery. In 2003 22 people were killed, including the UN Special Representative in Iraq Sérgio Vieira de Mello, and more than 100 wounded in the bombing of the Canal Hotel in Baghdad. This bombing was specifically targeting the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq, which had been created 5 days previous. Throughout the 2000s, humanitarian aid workers have been systematically targeted. The Aid Worker Security Database recorded the following trends:

There are a number of factors which may have contributed to this trend:

- Since the US invasion of Afghanistan and the beginning of the international ‘war on terror’ in 2001, there have been a number of conflicts in which one of the belligerent parties has engaged in humanitarian activities (i.e. aid distribution, the construction of bridges and schools, etc) as well as armed violence. In those conflicts, it is difficult to distinguish humanitarian aid workers from military actors.

- In certain conflicts, the nationality alone of humanitarian aid workers is sufficient to compromise perceptions of their neutrality (ex. Americans working for INGOs in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, etc).

- The increased presence of for-profit organizations in some conflicts can blur the line between humanitarian and belligerent. For example, in the US-Iraq war there were a host of private actors engaged by the US military,

some directly engaged in hostilities and others engaged in ‘humanitarian’ activities focused on ‘wining the hearts and minds’ of the population.

In December 2001, for the first time the General Assembly passed a resolution appointing a full-time security coordinator and professional security officers at UN HQ in New York. Additionally, “the number of field security officers employed worldwide has almost doubled.” Security procedures, including SOPs and staff training, have been institutionalized across UN agencies and most NGOs. Increased security measures, though necessary to protect humanitarians, may have resulted in an increased distance between UN agencies and INGOs and beneficiaries.

Arguably, the increased focus on children since the 1980s is part of the larger paradigm shifts in the humanitarian community. The 1980s were characterized by a rapid growth of the child rights sector. By the end of the 80s, there was a general global consensus that children have unique needs and are entitled to rights. This not only resulted in the almost global ratification of the UNCRC, it was also evidenced in the vast increase of studies focused on children. Children were recognized during this period as a factor in the development equation, both as beneficiaries and contributors. This shift was accompanied by the growing realization that different categories of people experience conflict and displacement differently. In particular, certain groups were identified as being exceptionally vulnerable and disproportionately suffering the effects of armed conflict. In the mid-1980s, humanitarian programs began to emerge which took into consideration the unique needs and vulnerabilities of women and children, as well as other groups.

The cynical climate of the 90s may have contributed to the rapid growth of the child rights field. Children and child protection became a rallying cry that mobilized common action when many other humanitarian programs were

Chapter 2 - History of Programming for Children in Armed Conflict

under criticism. Humanitarian programs targeting children benefited from the larger shifts in the sector described above, including the human rights approach, ‘holistic’ programs, stronger monitoring and evaluation frameworks, etc.

By the 2000s, the following premises were widely accepted:

- The importance of ‘situation-based analysis’ in program development, ensuring that programs are tailored to the local context and do not cause unintended harm to communities and beneficiaries (called ‘do no harm’ );

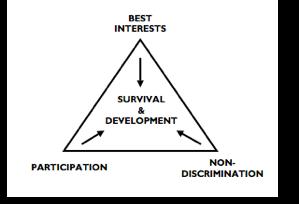

- Rights based programming (with particular attention to the 4 guiding principles of the CRC: best interest, non-discrimination, participation, and survival and development), ensuring that rights are central to the design and implementation of the project;

- Participation of beneficiaries in the design and implementation, with particular attention to building on local traditions and efforts through partnerships. The concept of child participation gained traction during the 1980s and has since become a central pillar in program design;

- Importance of programming across sectors (e.g. linking protection programs to education);

- The importance of rigorous, results-based monitoring and evaluation of programs and a focus on ‘best practices’ in project design.

Though these premises have been widely accepted and have become part of the international programming framework, on the ground they are often used in an ad hoc manner. One of the reasons for this is that each requires substantial time, human resources, and a flexibility in the program cycle that can be difficult in an emergency context and under donor regulations.

Building on these principles and best practice, the next chapter seeks to establish a framework for action based on international law, the notion that children should be considered ‘peace zones’, and an Assessment-Action model. Additionally, Chapter 3 will develop particular guidelines for humanitarian action based on best practice and historic experience. Key reference documents

[this needs to be expanded….]

A plethora of standards and operational guidelines were established in the 90s and 00s, the most notable of which are:

- IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings (MHPSS)

- INEE Good Practice Guidelines

- UNICEF Emergency Field Handbook

- UNICEF Core Commitments for Children in Emergencies

- UNHCR, Guidelines on the Protection of Refugee Women (1991).

- UNHCR Sexual Violence Against Refugees: Guidelines on Protection and Response (1995)

- IAWG, Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations

- UNHCR. “How To Guide: Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations, A Community- Based Response on Sexual Violence Against Women.” Ngara, Tanzania: UNHCR, January 1997.

- UNHCR. “How To Guide: Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations, Building a Team Approach to the Prevention and Response to Sexual Violence, Report of a Technical Mission.” Kigoma, Tanzania: UNHCR, 1998.

- UNHCR. “How To Guide: Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations, From Awareness to Action, Pilot Project To Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation.” Hartisheikh, Ethiopia: UNHCR, December 1997.

- UNHCR. “How To Guide: Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations, Sexual and Gender-based Violence Programme in Guinea.” UNHCR, January 2001.

- UNHCR. “How To Guide: Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations, Sexual and Gender-based Violence Programme in Liberia.” UNHCR, January 2001.

- 2003: UNHCR publishes an update to its 1995 Guidelines, entitled Sexual and Gender-based Violence Against Refugees, Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons: Guidelines for Prevention and Response.

- 2005: Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings are issued in 2005 by a task force of the United Nations Inter-Agency

Standing Committee (IASC).

- GBV AoR (2010) Handbook for Coordinating Gender-based Violence Intervention in Humanitarian Settings

- GBV AoR with UNFPA, a Managing Gender-based Violence Programmes in Emergencies e-learning course and Companion Guide, as well as a Caring for Survivors training manual.

- sphere standards

Même la guerre a des limites (Even war has limites)

ICRC slogan in 1999, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Geneva Conventions

International humanitarian and human rights law serves as a minimum standard, an ethical reference point, a public conscience. The power of international law is not only based on its legal personality. Humanitarian and human rights principles are a moral code, affirmed by generations across the globe. Fundamental to the protection of civilians during times of armed conflict is the recognition that States are obliged by international law to protect and realize the rights of persons within their jurisdiction. All action addressed to children in armed conflict should be rooted in international law as this is both the legal and moral framework of our time.