Tested by time, John Norris has learned the value of empowering employees.

With

Tested by time, John Norris has learned the value of empowering employees.

Enterprise Minnesota growth consultants Eric Blaha and Ally Johnston explain why the companies that succeed through automation view employee engagement at its core.

2

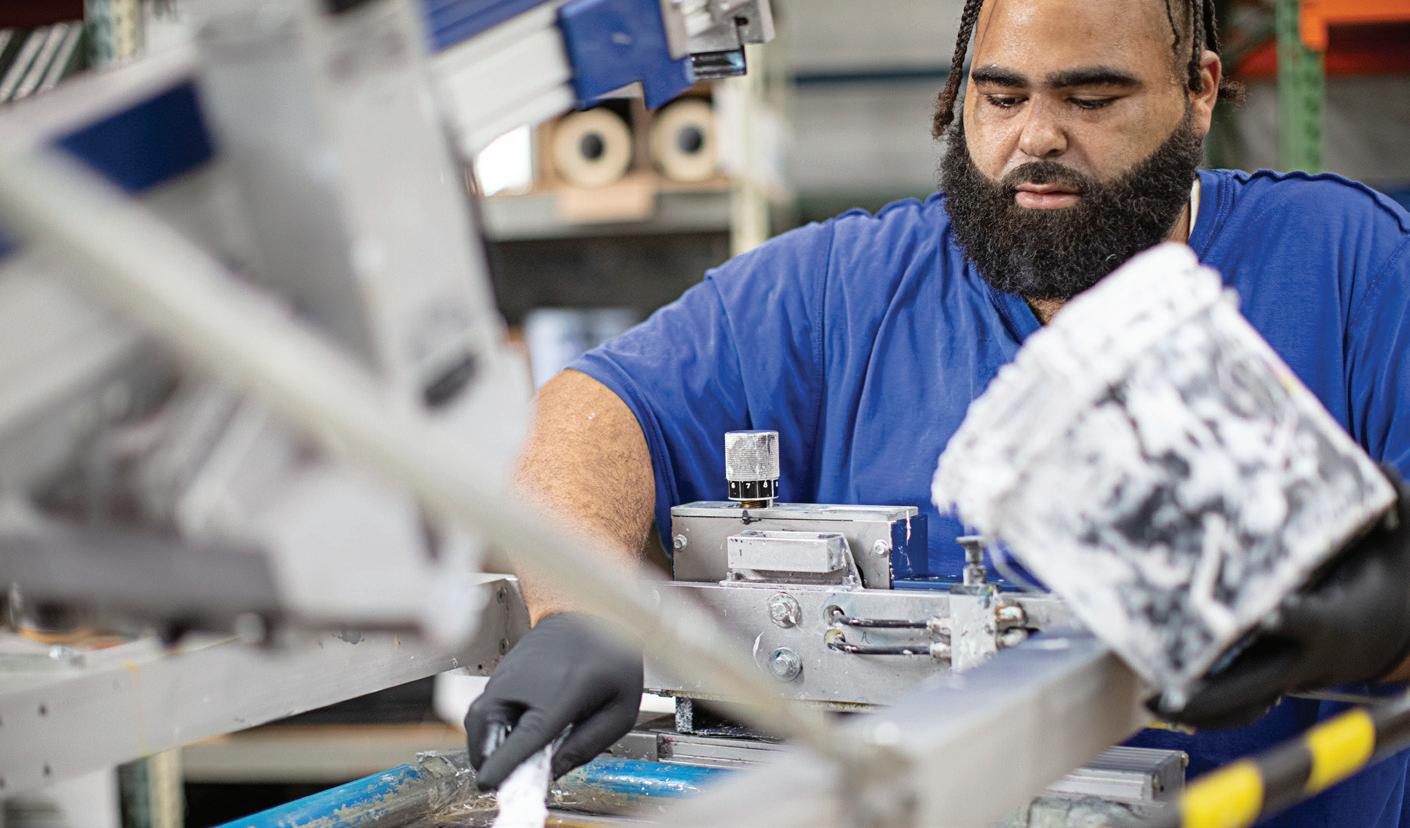

Toppan Merrill invests heavily in technology and talent in Sartell.

Recent data from the National Association of Manufacturers shows how Minnesota’s manufacturers have expanded steeply and steadily in recent years. That growth has generated 300,000 jobs, another 885,000 supporting jobs, $53 billion in output, and an average annual wage of nearly $90,000. Continuing that expansion demands a quality workforce, a persistent challenge for all employers.

That’s why it’s so gratifying to see local technical colleges and nonprofits working closely with manufacturers to help solve our thorny workforce challenges. These allies are on the front lines alongside manufacturers, developing training programs, as well as addressing childcare and housing issues.

begin training future manufacturing employees on those campuses even earlier in their careers.

The state’s Initiative Foundations — born of a grant from 3M’s McKnight Foundation and dedicated to economic growth in six regions across Minnesota — have been long-time partners of Enterprise Minnesota. They support the focus groups and events related to our annual State of Manufacturing® survey, giving them an inside and timely understanding of the challenges facing manufacturers.

Our technical colleges and Minnesota’s Initiative Foundations have developed especially strong bonds with manufacturers in Greater Minnesota.

In recent years, Minnesota’s technical and community colleges have appointed presidents from within. These leaders understand their communities because they live there. They prioritize outreach, and they know the value of local manufacturers.

Fifteen years ago manufacturers often complained about the colleges, and the colleges complained about the manufacturers. Today, they work closely to tackle training and workforce development challenges. The colleges are eager to customize training and implement flexible class schedules that fit the evolving needs of employers and students. In many areas, colleges and manufacturers are working with high schools to identify and

The Initiative Foundations provide grants and business loans and spearhead programs that promote economic growth and stability in the regions they serve. They have taken a lead in addressing the childcare crisis facing Greater Minnesota, knowing quality daycare is a barrier to a stable workforce for manufacturers and other employers. In some areas, the Foundations are also working with local leaders to address housing shortages that also limit workforce growth.

The timing for this valuable cooperation couldn’t be better. Minnesota manufacturing is strong, and global dynamics — starting with COVID and continuing with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and war in the Middle East — are driving many OEMs to seek suppliers closer to home. The state’s manufacturers have already seen increased demand, and we couldn’t be more thankful for the network of allies that will continue to help them take full advantage of these and future opportunities.

Bob Kill is president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota.

Contacts

To subscribe subscribe@enterpriseminnesota.org

To change an address or renew ldapra@enterpriseminnesota.org

For back issues ldapra@enterpriseminnesota.org

For permission to copy lynn.shelton@enterpriseminnesota.org

612-455-4215

To make event reservations events@enterpriseminnesota.org

612-455-4239

For additional magazines and reprints ldapra@enterpriseminnesota.org

612-455-4202

To advertise or sponsor an event chip.tangen@enterpriseminnesota.org

612-455-4225

Enterprise Minnesota, Inc.

2100 Summer St. NE, Suite 150 Minneapolis, MN 55413

612-373-2900

©2024 Enterprise Minnesota ISSN#1060-8281.

All rights reserved. Reproduction encouraged after obtaining permission from Enterprise Minnesota magazine. Enterprise Minnesota magazine is published by

Minnesota

2100 Summer St. NE, Suite 150, Minneapolis, MN 55413

POSTMASTER:

As Bob Kill prepares to close out the last regional rollout of Enterprise Minnesota’s 2023 State of Manufacturing® (SOM) survey data, he reflects that his audiences have evolved from passive listeners to motivated advocates who want to use information to improve their local marketplace.

“That’s what we hoped would happen,” he says.

Kill and his colleagues at Enterprise Minnesota launched the State of Manufacturing in 2009 as an annual survey of small- and medium-sized manufacturers across Minnesota. They hoped to use the SOM’s data to connect Minnesota’s manufacturing advocates to create a coalition that would promote how underappreciated manufacturers provide the job-creating economic engine that sustains their home communities. That

coalition would include the overall business community, companies that provide goods and services to manufacturers, community activists, and educators.

“Manufacturers at the time got zero credit for providing their communities with stable, well-paying jobs, or passing along economic prosperity to their suppliers of goods and services,” Kill recalls. “It’s fair to say that manufacturers were not represented at all.” He says the vision for this first-in-the-nation project required that the SOM survey data would have unassailable credibility. “We knew that if this was going to succeed at all, the numbers had to be meaningful,” he says. Along with Enterprise Minnesota Vice President of Marketing and Organizational Development Lynn Shelton, his team recruited nationally prominent pollster Rob Autry to oversee the collection of data. Autry and his Charleston-based firm, Meeting

The SOM’s success has exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. Autry, recently named America’s top political pollster, has personally overseen each of the 15 surveys. The official public rollout of data has attracted as many as 500 attendees, and regional events can draw over 100 people.

Street Insights, were tasked with conducting a statistically valid sample of 400-plus company executives, complemented by up to 14 regional focus groups. The poll data would provide objective data about the marketplace, Kill says, but the focus groups would give subjective reasons about why manufacturers responded the way they did. The focus groups became popular annual regional events in which manufacturers enjoyed sharing their opinions.

The original plan, Kill says, included releasing the data publicly at a significant Twin Cities-based event, followed by up to a dozen events at regional venues.

The SOM’s success has exceeded even the most optimistic expectations, Kill says. Autry, recently named America’s top political pollster, has personally overseen each of the 15 surveys. The official public rollout of data has attracted as many as 500

“Who would have ever thought that 500 people would show up to hear a pollster describe the results of a poll?”

–Bob Kill, president and CEO, Enterprise Minnesota

attendees, and regional events can draw over 100 people.

“Who would have ever thought that 500 people would show up to hear a pollster describe the results of a poll?” Kill asks, adding that he finds the energy in regional events particularly gratifying.

“People aren’t just passively showing up anymore,” he says. “The poll has brought manufacturers to the party who want to expand the power of public-private connections.”

Legislators, he says, increasingly use the poll data to understand how much manufacturers contribute to their districts, especially when combined with plant tours organized by Enterprise Minnesota. “I’ll always wish we had more legislative involvement, but we help show how some regulations can be much more harmful to small manufacturers than a 4,000-employee company.

“That topic was addressed very openly at every one of this year’s regional meetings,” he says.

While the major Twin Cities rollout

gives the SOM substantial visibility, he says, regional events bring people together to identify and solve problems locally. “There are significant differences between regions in Minnesota,” Kill says.

“There is extreme interest in how we can apply this (SOM) information to make our communities and regions more attractive to maintain and retain and grow our economies.”

This year’s regional rollouts paid particular attention to the ongoing workforce challenges in Greater Minnesota, Kill says, noting that the SOM data was the first place — 10 years ago — to reveal the potential

impact of the impending worker shortage.

“Manufacturers knew what was coming,” Kill says. “And they still do. If you were to listen only to the media, you’d think the workforce issues have gone away,” he adds. “That’s not what we heard in the regional rollouts. People wanted to talk about workable solutions versus just admiring the problem.”

Kill also credits the SOM sponsors, who not only underwrite the considerable costs of the project but also publicize the findings to their own networks. Kill says Enterprise Minnesota carefully crafted industryspecific exclusivity to sponsors so they can

“own” the data to their publics.

“Early on, our Platinum sponsors were more interested in helping get the project off the ground,” Kill says. “Now they see the value on their own terms. Our current roster of sponsors is all interested in manufacturing; they use the poll and our events to connect with small- and medium-size manufacturers. And they also see benefits from working with other sponsors.

“We have some wonderful sponsors,” he says.

Nov. 14, 2023

MinnWest Technology Campus, Willmar

SPONSOR: Southwest Initiative Foundation (SWIF)

Nov. 28, 2023

Alexandria Technical & Community College, Alexandria

SPONSOR: West Central Initiative (WCI)

Dec. 12, 2023

Lakes Region EMS, North Branch

SPONSOR: Initiative Foundation (IF)

Jan. 9, 2024

Owatonna Country Club, Owatonna

SPONSOR: Southern Minnesota Initiative Foundation (SMIF)

Feb. 13, 2024

Minnesota Power, Duluth

SPONSORS: APEX, Entrepreneur Fund, Minnesota Power

March 26, 2024

Roseau Civic Center, Roseau

SPONSOR: Northwest Minnesota Foundation (NWMF)

March 28, 2024

The Forge, Grand Rapids

SPONSOR: Itasca EDC

More

CNC

Despite massive sales,Vistabule’s brass scrapped plans for a new plant and focused on marketing and product development.

There was a time when Vistabule had little need for marketing.

Business was booming for the company that manufactures deluxe teardrop trailers for quick and comfortable jaunts into the wilderness. Customers had to wait up to a year to get a trailer. They’d begun planning a move to a bigger facility, thinking the growth they’d experienced would certainly continue.

Now, they’re glad they didn’t

“We almost pulled the trigger on that,” says company owner Bert Taylor. “A number of things came together to make us think that maybe it wasn’t a good time to do it.”

The most important factor, Taylor says, was the one that matters most: sales.

When COVID sent the world into virtual hibernation, many turned their thoughts to what they could do to safely escape isolation. To folks predisposed to loving the great outdoors, those thoughts turned to internet searches. Some of those searches landed at Vistabule.

“And then,” Taylor says, “we hit kind of a lull. We’d always been able to depend on organic sales.”

Why? Taylor’s theory is that COVID scared people into making big purchases. Many were afraid they’d become one of the millions of people around the globe who died from the deadly virus. When COVID receded, so did their desperate lust for adventure, and then came the lull.

In response, the leadership team at Vistabule got together to address slumping sales. They came up with two answers: a smarter marketing plan, and a new product. One has already paid off, the other they believe will become the key to future growth.

Enterprise Minnesota Business Growth Consultant Amy Hubler crafted a marketing plan for Vistabule built on the company’s strengths, but with an infusion of contemporary messaging. Hubler helped Vistabule with mapping out digital

marketing and organizing the nurturing they do with customers in Vistabule’s Ambassador program (which allows trailer owners to show off their trailer to potential customers). Hubler also helped Vistabule with promotions, getting the company to focus on local RV shows, establishing newsletter and email campaigns, and honing the conversations they have with potential customers at the Vistabule rally.

Hubler’s work was aided by a willing team at Vistabule that was ready to put a plan into action.

“The marketing/customer experience team rallied together to develop a plan with Amy,” says Lily Taylor, Vistabule’s chief administrative officer. “And then we executed the plan fully.”

Vistabule’s website has always displayed gorgeous photos of people in the wild with their teardrop campers — cooking on the built-in stove, gazing at the stars through the Vistabule’s moonroof, campfire and canine companions huddled around.

But what they didn’t have was video. Hubler helped them add customer testimonials to the website, with actual buyers explaining why they chose Vistabule and how their lives have changed because of it.

They also got much more aggressive and strategic with social media. They started posting reel videos to Facebook and TikTok with fun stories from customers such as Ben and Leslie.

“I describe it as a blanket fort, like when

you were a kid. Everything you need is right there,” says Ben as Leslie covers her face and laughs. “Sorry, that’s my description of it and I love it.”

Personal stories like this help potential customers relate to the product, which isn’t a new marketing concept. But to Vistabule, it was a new step in getting their name in front of potential customers.

“We have been humbled in the last year, and it’s something that we saw happen across the entire community of camping or outdoor businesses. We’ve all seen a drop in sales,” Lily Taylor says. The new emphasis on digital marketing and social media, she adds, will enable people to “see more of who we are as a business.”

The other change Vistabule is making is adding a new product. The company was created by Bert Taylor, who honed his vision of the perfect teardrop camper by traveling in one cross country. The model he came up with was a compact camping oasis — small in stature, but big on luxury and amenities. Today the base price for a Vistabule is about $24,000 — a figure that rose substantially, Taylor says, as the

prices of building materials rose. Add in a handful of options, and the price quickly creeps beyond $30,000. Not the most expensive on the market, but certainly on the top shelf.

Yet as he watched sales droop, Taylor decided to offer a more affordable version.

The new emphasis on digital marketing and social media, she adds, will enable people to “see more of who we are as a business.”

So he got to work designing a model that will be debuting soon called the DayTripper.

“We felt the need to embrace a different part of the market. And that led to me designing a smaller trailer,” he says. The new model looks just like a Vistabule, except two feet shorter and without most

of the bells and whistles.

Taylor says he believes the DayTripper has “vast potential.” It’s not for sale yet, but they have several in production and will be hitting the RV show circuit soon with prototypes trying to drum up interest.

“We’re looking forward to developing a marketing program for it. The idea is to get a younger crowd, a more spontaneous crowd, people who may already have a lot of camping equipment and gear but they’re sick of sleeping on the ground. I’m looking forward to taking this trailer on the road and visiting some of these activity groups like, say, Rock Climbers of America, or the beaches of California to see how surfers would use a trailer like this.”

Taylor believes the DayTripper will ultimately be a substantial portion of Vistabule’s sales.

“I don’t see how it would not be. It seems like a no-brainer that if you could get the essence of the Vistabule for half the price, you would. I think it will be a very popular item. We’ll find out.”

—Robb MurraySee what the future of your facility could look like

3D Laser Scanning collects millions of data points— true to scale—showing every surface inside your building: utilities, beams, equipment layout… everything. Whether you need to add, subtract, or reconfigure space, this process provides the data you need and the ability to manipulate it to make informed decisions faster.

Generate Site Models

Jeff Engbrecht, president and founder, Clearwater Composites

Jeff Engbrecht, president and founder, Clearwater Composites

Now in a new facility, Clearwater Composites boosts its bottom line through commonsense improvements.

The suggestion box at Clearwater Composites, a Duluth-based company that manufactures customized carbon fiber components, isn’t a box at all. It’s a “continuous improvement board” on which the company’s not-quite 40 employees can suggest changes to different areas of the business. Anyone can see the suggestions as they walk past the board, and the business’ leaders review those suggestions every other week and implement them as they see fit. Ideas that don’t make the initial cut end up in a figurative “parking lot” on one side of the board for future consideration.

The principle is the same — a lowpressure way to propose improvements — but the implementation is different. Ally Johnston, a business growth consultant at Enterprise Minnesota who’s been working with Clearwater for about six months, says the board is actually the “opposite” of a

suggestion box.

“The suggestion box is a black hole,” Johnston says. “People put things in and they’re locked. We want these to be visual. Anybody can read any idea. It’s meant to be engaging.”

The board is one of several concepts Johnston has pitched to Clearwater as part of a suite of “lean” manufacturing principles to get employees thinking about ways to thwart waste.

“Eliminating waste through people,” she says.

The board is a relatively small change that can nevertheless bring incremental improvements to Clearwater’s bottom line.

Consider the company’s production of carbon fiber pool cues. Staff felt that measuring both the thickness and the weight of each cue after it was molded was redundant. If a given cue’s weight wasn’t correct,

then that meant the thickness wasn’t correct either, and vice versa, explains Jeff Engbrecht, Clearwater’s president and founder.

Staff said the measurements represented wasted data, Engbrecht says. “And they were right, so we stopped doing it. It was a good catch by the team.”

Eliminating the unnecessary measurement saved hours of redundant work over the course of a month.

“That adds up,” Engbrecht says.

“The suggestion box is a black hole. People put things in and they’re locked. We want these to be visual. Anybody can read any idea. It’s meant to be engaging.”

Beyond leaning up its operation, the staff at Clearwater is settling into a new facility in Duluth.

The company produces parts made of carbon fiber and other advanced composites for manufacturers across the United States. Those parts are used in precise measuring equipment, drones, sporting goods, custom bike parts, boats, guns, bows, and more.

Carbon fiber is lightweight but still strong and stiff, Engbrecht explains, and it can replace heavier materials such as steel

or aluminum. It can also be designed to not grow or shrink as it gets hotter or colder, which makes it valuable for precision instruments that need an ultra-stable surface from which to measure.

Clearwater moved to the new facility in early 2022. It boasts about three times more square footage than the previous spot.

“We were space challenged,” Engbrecht says. “We had to make do with what we had.”

The new, larger facility means more storage space for raw materials, which helps insulate the company from supply chain vagaries, plus more space to cut larger batches of carbon fiber, as well as a planned second oven in which to cure finished carbon fiber parts.

tomer’s request.

The company’s revenue has increased by about 50% since the move, Engbrecht says.

Johnston helped the Clearwater staff map out the company’s manufacturing processes and determine where else there might be waste.

The additional space also enables Clearwater employees to make and store new products, such as carbon fiber trusses. They can do more machining inhouse as well, which means the company can produce carbon fiber tubes with slots or holes pre-machined into them at a cus-

They’ve also simplified training materials and work instructions for staff, particularly new hires. Clearwater’s documentation is thorough, of course, but could be overly technical or even overwhelming.

“Sometimes engineers don’t know how to explain things well to other people,” Engbrecht says with a laugh. “It was maybe a little too wordy. You’ve got to keep it simple and keep it in language that people can understand, but you’ve

also got to make sure you hit the details of what’s important.”

The new process breaks down training materials into teachable, bite-sized portions that are easier to digest. That can mean training people better and more quickly. It’s part of the “job instruction” and “job method” principles of lean manufacturing, Johnston says — two more tools in the “house of lean.”

Clearwater and Johnston are currently contemplating a method to conduct “root cause analyses” to solve complex problems at their root, rather than finding Band-Aidstyle workarounds. That can mean repeatedly asking “why?” to work backward, step by step, to determine the point from which a problem cascaded. The fifth “why?” usually reveals the root cause, Johnston says.

“Everyone in manufacturing wants to be a hero, they want to get the product out the door,” Johnston says. “They don’t necessarily fix the machine so it can’t break again, they’ll just put duct tape on it so it’ll still run.”

—Joe Bowen

Instead of providing an overwhelming firehose of detail about how to complete tasks, Nova Flex uses Job Instruction to break down a task into teachable steps.

It was a point of frustration for new hires.

As they started working at Nova Flex, some would get exasperated with the time it took to go from job training to producing the company’s LED lighting. They had to master various soldering skills — often taking two weeks — before they could put their abilities to work.

The St. Cloud company also made training difficult by trying to teach too much information at once. This slowed down the learning process and delayed new employees’ opportunities to hit the ground running. Nova Flex decided that the time was right to improve its onboarding process.

Company leaders turned to Enterprise Minnesota in 2021 to work with Nova Flex on continuous improvement. First up was value stream mapping to remove waste

from its manufacturing operations. Next, they introduced Job Instruction, a Training Within Industry program designed to improve and standardize employee training.

Instead of providing an overwhelming firehose of detail about how to complete a task, Job Instruction teaches trainers to break down a task into understandable steps. These smaller clusters of instruction prevent trainees from getting inundated with information, and it helps them build confidence as they master each step, says Michele Neale, an Enterprise Minnesota business growth consultant who specializes in leadership and talent development. She delivered the Job Instruction program to six Nova Flex employees.

“With Job Instruction, the philosophy is that if the students haven’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught,” says Dawn

Completing value stream mapping at Nova Flex also improved employee engagement and job satisfaction.

“With Job Instruction, the philosophy is that if the students haven’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught.”

–Dawn Loberg, business development consultant, Enterprise Minnesota

Loberg, an Enterprise Minnesota business development consultant. “It’s really about breaking down your processes into actionable items so that the employee can start being productive and adding value and seeing that they are contributing as soon as possible.”

Nova Flex Manufacturing Manager Bob Waline has noticed a major difference since he completed the Job Instruction program with co-workers. First, having the group develop their instructional skills spread training responsibilities among the participants, not just him. It also taught them best practices for effectively teaching employees all the necessary skills. That way, all production staff learn a consistent, unified way to complete tasks no matter who teaches them.

Now, Nova Flex stores each training module in a binder that provides written and visual steps for mastering various skills. The Job Instruction group spent two years creating the training worksheets, meeting weekly to develop and refine the training steps for each task. They started with four or five basic skills and then gradually added training for more intricate work.

The binder includes images, photos, videos, and other material that employees can use to learn new skills or refresh others. Having this resource supports people with different learning styles, Waline says.

Previously, there wasn’t an easy way to adjust training to a visual learner versus someone who learns by reading or doing.

Neale says the cohort that completed Job Instruction transformed the company’s training approach. They incorporated the program’s four-step model to prepare the student, present the operation, try out the performance, and follow up, with the overall objectives to enhance job safety, processes, consistency, and problem solving. “With a little bit of modification in how they train, Nova Flex was able to get that new person adding value in 20 minutes,” she says.

Waline also appreciates that the Job Instruction method holds instructors accountable for the quality and effectiveness of their training. “If they notice a mistake, they stop right there and make sure the training doesn’t continue until the trainee understands what he or she needs to know,” he says. “Before, I think people could give information too quickly and then maybe not notice if the student didn’t have full understanding.”

Now, trainers request feedback, ask clarifying questions of the trainees, or seek a demonstration of the skill to ensure that students understand before going on to the next step, Waline says. Another benefit is that Nova Flex significantly shortened the amount of time it takes to determine whether a new employee is going to be a good fit for a role, says CEO David Kidd.

In addition, trainers benefitted when Nova Flex adopted the Job Instruction approach, too. They gained confidence that they could train others and train them well, where before they generally figured

methods out on their own, Waline says. That sometimes led to inconsistency among how production employees did certain steps depending on who trained them. Now everyone is on the same page.

Nova Flex also deployed Job Instruction to cross-train existing employees. Having employees proficient in at least two skills has helped with engagement and retention because staff can work in a variety of operational areas, such as prep, quality

“With a little bit of modification in how they train, Nova Flex was able to get that new person adding value in 20 minutes.”–Michele Neale, business growth consultant, Enterprise Minnesota

control, or shipping, Waline says.

Kidd observes that the work Nova Flex did with Enterprise Minnesota, including the value stream mapping and Job Instruction initiative, has paid off for the manufacturer. “In order for people to succeed, it’s important for us to give clear direction and training. We find that some of the hardest workers and best performers really appreciate the clarity and direction and the knowledge of how to do their jobs well,” he says.

“We found a number of benefits by doing that — creating engagement and productivity from our current workforce

as well as when we hire new employees,” Kidd adds. “It more quickly onboards them and gives them insights into the whys of the various parts of their jobs.”

Completing value stream mapping at Nova Flex also improved employee engagement and job satisfaction. The work targeted improving production efficiency from customer orders to cash, removing any bottlenecks or overlapping efforts, says Greg Hunsaker, an Enterprise Minnesota business growth consultant. Fine-tuning processes and redesigning the shop layout to improve flow “were a huge hit with Nova Flex,” he says. “They are still using these methods to look at their processes and find waste. And as they keep removing waste, it makes it easier for them to do their jobs and it results in better quality.”

The entire Nova Flex team has taken all of this continuous improvement work to heart. The effect on employee engagement and retention, and the company’s enhanced ability to grow efficiently, were impressive and palpable during Enterprise Minnesota’s three-year follow-up visit, Loberg says.

“What’s so fun is that now you go in there and everyone is happy, everyone is smiling — it’s such a joyful place to work,” Loberg adds. “It was just an absolute delight to see the growth in the people and the streamlined processes. It’s the commitment from their upper management and the investment in their people that helps them all feel like they are adding value to the output and for their clients while helping the company grow.”

Suzy Frisch

Why Van Technologies used a COVID-based lull in business to shore up its already-robust operations.

Folks at Van Technologies Inc., a maker of environmentally friendly coatings, know that earning an ISO certification is not like completing a race. Rather, it’s more like lining up for a marathon.

The Duluth-based company obtained its ISO certification in near-record speed a few years ago, achieving the credential in less than half the eight to 10 months companies typically require, according to Keith Gadacz, a business development consultant for Enterprise Minnesota.

But Larry Van Iseghem — the company’s president, CEO and namesake — says his team continues to build on that platform of accountability, in order to drive performance and maintain ISO

accreditation well into the future.

“I can see a definitive difference pre-ISO 9001 and post-ISO. I believe our operations are more efficient, which makes us much more cost-effective,” he says.

Since 2019, Van Technologies has boosted its output by 34%. And perhaps even more impressive is the fact that it has done so without adding much staff, as its production per labor hour has jumped by more than one-third since the pandemic disruption in 2020.

Gadacz says the strides in productivity are a testament to the work Van Technologies has put into improving its operations.

“I’m impressed that they can deliver the same quality products and more output

with less labor per unit. That’s really what everyone wants to be after,” he says.

Van Iseghem strongly believes the ISO system the company adopted has strengthened an already-robust operation.

“We’ve always maintained a high-quality product, but with the procedural formalities and the adherence to procedures we’ve now adopted, I know, person to person, testing is done much more consistently and accurately,” Van Iseghem says.

Teresa Donahue, the company’s technical manager, agrees. “Having all the documentation and procedures in place has served us well. We did have a good basis prior to getting certified, but everything kind of came together when we developed this quality management system.”

Staff’s confidence in the unwavering quality of Van Technologies’ products, she says, has only grown with additional calibration and verification procedures.

“Having all of our employees engaged in this process and our quality objectives has created more of a team environment,” Donahue says.

Van Iseghem recalls that some clients and employees initially questioned the need for the ISO certification. “They asked: ‘Isn’t this expensive? Isn’t this a waste of time?’”

When COVID forced many people to pause day-to-day activities in 2020, Van Technologies saw its sales slip. Nevertheless, Van Iseghem says the company managed to recover later that year and eke out a small sales increase.

Van Technologies took advantage of the momentary lull to seek ISO certification.

“We were so close to it anyway, why not?” he recalls thinking. “The procedures we instituted in previous years and the attention we paid to detail were very consistent with ISO 9001.”

Van Iseghem launched his coatings company in 1991, shortly after leaving Ikonics, another Duluth-based company, where he had led a successful ISOcertification effort. So, many of the goals of the quality-control program already were ingrained in his thinking about how to run a successful business.

Van Technologies has distinguished itself not only for the quality of its coatings but also for its environmental advantages, with no solvent-based products in its lineup. Rather, the company focuses on specialized water-based coatings and products that can be quickly cured with ultraviolet light.

Van Iseghem says he also recognized the value of the credential.

“It certified to present and future

customers our capabilities, our efficiencies, and our attention to detail,” he says.

“But the benefits I see and that I knew would come are in terms of our operational efficiency gains,” Van Iseghem says. “We’ve saved money by doing this.”

“So, everybody’s on board now. But there were a lot of questions from the onset, even from our vendor relationships. Our vendors view us differently today than they did pre-ISO, because they know that at Van Technologies, we’re going to pay attention to the products we buy from them. And that means they can do a better job,” he says.

An annual audit by an external third party is required to maintain an ISO certification.

“I’m impressed that they can deliver the same quality products and more output with less labor per unit. That’s really what everyone wants to be after, and they’re doing it.”–Keith Gadacz, business development consultant, Enterprise Minnesota

But Van Technologies conducts three additional internal audits each year, and Van Iseghem tapped Gadacz to perform them.

“He’s very thorough and effective, plus he’s a good coach,” Van Iseghem says. “Our people know Keith is going to conduct a thorough audit. So, the attention to doing things correctly according to procedure is heightened. The internal audits are a good reminder and maintenance tool to continue to do things the right way.”

Van Technologies’ continued embrace of scrutiny serves the company well, according to Gadacz.

“They’re probably one of the strongest proponents of using outside eyes to help keep them sharper, stronger and faster,” Gadacz says.

Van Iseghem sings the benefits of continued vigilance.

“You just can’t get certified and leave it. After you get certified, you have to do your audits. I think our internal audits have

been essential to maintain the program. And if you maintain the program, it returns the benefits you seek,” he says.

With the exception of 2020, Van Technologies has consistently grown its sales at a double-digit annual clip, according to Van Iseghem.

Van Technologies does not produce commodity coatings, such as those available at home-improvement stores. Instead, it serves customers with special needs, mostly in the high-end window market. But the company continues to diversify into other areas, including hardwood flooring, retail display fixtures, architectural millwork and doors, kitchen cabinetry, and other wood products.

Its product niche makes the company generally less susceptible to the vagaries of the economy than others in the housing industry.

“When money is tight those that continue to build are the individuals who have the money to do so. And we’re typically involved with the higher end of the market, which tends to be a little more stable than your lower-income housing,” he explains.

Van Technologies continues to seek new opportunities, with an eye toward volume.

Case in point: The company has developed a UV-cured product that is a durable coating for the flooring installed in most semi-trailer trucks.

“When you look at the number of semis on the highway, that’s a very attractive surface area market,” Van Iseghem says.

Van Technologies prides itself on providing coatings specifically tailored to a client’s needs.

“Our business model is: We solve problems. If you’ve got a problem, we’ll help you solve it, if it’s related to the coating industry,” Van Iseghem says.

With that reputation, Van Technologies has not had to be particularly aggressive on the sales and marketing front. Van Iseghem says much of the company’s business comes from referrals.

Increased product demand has Van Technologies shooting to hire an additional chemist and likely needing to physically expand in the near future. At present the company has about 18,100 square feet of production space and 5,200 square feet in another building that houses its offices and lab operations.

Donahue expects to add three or four employees to the 17 already on the company payroll.

Peter Passi

How Sagewood Gear’s small size heightens the need for efficiency.

Brian Gustad, founder of Sagewood

Gear, a Duluth-based maker of knife sheaths and accessories, has been working to apply lean manufacturing principles to his two-person shop for years. But he says, “There’s only so much you can learn from reading books before you need someone to actually come in and show you how you can improve.”

Gesturing toward a bookshelf full of lean manufacturing literature, he says: “There’s a lot of good info, but the problem I had was how do I take enterprise-level manufacturing knowledge and apply it to a micro-manufacturing operation?”

Gustad found help at Duluth’s Entrepreneur Fund, which connected him

with Ally Johnston, a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota.

“What’s cool about Brian is he’s done a lot of lean initiatives on his own,” Johnston says.

Gustad says Johnston initially asked him to do some business analytics and then helped him scrutinize his shop layout.

“Basically, we wanted to completely revamp the entire shop and set it up for better flow — a good layout to optimize some of the equipment he has, including some new CNCs,” Johnston recalls.

The results speak for themselves. Gustad says a movement study showed efficiency improvements for key processes throughout the shop.

Johnston also helped Gustad fine-tune a system he had already adopted to manage inventory. Inspired by Toyota, he uses kanban cards to track the necessary materials and components needed to produce his goods and ensure they always remain in steady supply.

Gustad’s eagerness to try out new ideas has impressed Johnston, who says proposed changes in small settings can often encounter resistance.

“I’ve seen a lot of craft manufacturers who don’t think lean will work for them, because they’re different than other manufacturers — they don’t mass produce at the same level. But that’s not his take. His take is that: ‘I want to figure out how to eliminate as much waste as possible.’” Johnston notes that the small size of the operation only heightens the need for efficiency.

Johnston also credits Gustad for changes he made before her arrival, including what she calls “a strategic pivot.”

At the height of the pandemic, as people spent more time online with stimulus money in their pockets, orders poured into

Sagewood Gear, resulting in a backlog of about 16 weeks for many products.

Gustad struggled to catch up in part because of his diverse product line and the high level of skill required to get orders out the door.

Previously, Sagewood Gear offered three sheath designs for 40 different knife models in three different colors.

Sagewood has since narrowed its sheath selection to one-tenth of that, available in two colors: brown and black.

Gustad also sought to streamline production without sacrificing quality.

With only one part-time employee on the payroll at a time and the prospect of frequent churn, the higher-level leatherwork had typically fallen to Gustad, who realized, “There was no way I could expand, because I was the bottleneck in the whole process.”

Gustad responded both with new designs and with self-built tooling to

“Lean manufacturing is like taking vitamins. You’ve got to stick with it in order to see the benefits.”–Brian Gustad, founder and owner, Sagewood Gear

support new production methods that have cut lead times to no more than four weeks for most products.

“It’s amazing what he can figure out on his own and make work,” Johnston says.

Gustad started leatherworking as a side gig in 2010, while he was still working as an auto mechanic.

Initially, Gustad did a lot of one-off work making unique sheaths for individual knives but says he soon found that was not a very profitable enterprise.

“So, I started moving more into the production-side of things and offering mostly after-market stuff for knives and sheaths,” he says.

Almost all Sagewood Gear’s orders are generated by its online marketing, and it sells products around the globe.

Gustad says Johnston has shaped his approach to business.

“She has taught me how to think when it comes to value streams. For instance, we went through a value stream mapping exercise, and she kind of showed me how

to think about problem solving, without doing it for me,” he says.

This has helped Gustad decide where to focus his efforts.

“I’ve been doing more collaborative work with knife makers. But I’ve also been doing more bolt-on accessories for factory sheaths that people get with their knife. Some of them don’t want to spend 100-some bucks for a custom leather sheath. So, they just stick with the original one. But I offer carry attachments and other accessories, so it can actually be useful, because most factory knife sheaths, or at least the attachments for carrying them on your belt, are kind of garbage,” Gustad says.

Before Enterprise Minnesota entered the picture, Gustad says he felt left to his own devices, adding that he suspects that’s a common feeling for small-scale manufacturers like himself.

“There’s this big gap in knowledge for the small guy on how to become a larger manufacturer,” he says.

The Entrepreneur Fund was able to introduce Enterprise Minnesota to Gustad and fund its early support services. That work has continued with additional assistance from Duluth’s CareerForce Center.

Elena Foshay, Duluth’s director of workforce development, explains CareerForce is able to use a portion of its federal and state dislocated worker funding to support training for existing workers.

“The intention is to help avoid layoffs; it helps a company grow and create more jobs; and maybe it helps individuals earn higher wages,” Foshay says.

She notes that the program can provide up to $10,000 of annual support.

Jim Schottmuller, Enterprise Minnesota’s director of business development, says Sagewood was far enough along in its development that his organization could provide assistance.“It’s tough to suggest process improvements when a company hasn’t developed those processes yet,” Schottmuller says.

Gustad predicts such investments will pay off. “I feel like we need to help smaller businesses like mine, because they start as small fish but can turn into big fish if they just have the appropriate skills and knowledge and help.”

Gustad describes his progress over the past few years as incremental but steady.

“Lean manufacturing is like taking vitamins,” he says. “You’ve got to stick with it in order to see the benefits.”

Peter PassiWe listen to our customers And they have some great things to say

An ongoing series.

Enterprise Minnesota’s Michele Neale has made a career of helping employers improve work cultures.

Business growth consultant Michele Neale distinguishes herself in a crowded field of talented leadership development professionals as one who very noticeably “walks the talk.” Neale is entering her seventh year helping Enterprise Minnesota clients nurture — and retain — their workforce.

While the traditional bottom-line orientation of manufacturing encourages executives to focus on improving processes and productivity, Minnesota’s chronic shortage of workers now motivates them to think seriously about keeping the ones they have. And that’s one reason why Enterprise Minnesota’s Talent and Leadership Development curriculum has become one

of its hottest services.

Industry experts agree that a culture of engaged employees directly impacts a company’s productivity and profitability. Manufacturers that develop a culture of engagement outperform their competitors by 202%, have reduced turnover, and experience fewer safety incidents.

When asked for an elevator-pitch summary description of the work, Neale responds with one word: “self-awareness.”

“Most people never get an opportunity to learn about themselves,” she says. “They don’t stop and think, ‘What am I doing every day to make a difference?’”

“I really want people to become better leaders,” she says, “whether they’re

employees, mid-level leaders, or upperlevel leaders.

Along with colleagues Abbey Hellickson and Nicole Lian, Neale teaches from Enterprise Minnesota’s wide-ranging curriculum on HR and leadership development.

A key component is “Leadership Essentials,” a series about communication skills, versatility, employee engagement, leading change, and accountability. The sessions, she says, emphasize how to better engage employees and transform that engagement into team building. “What can I do to increase retention and encourage employee involvement? How do I lead my team through change, even if I disagree? What accountability do I have to take for myself, and how do I hold others accountable?”

“You could almost pick any company, and those topics would apply, which is why we package it as an essentials series,” she says. “The key is helping leaders make small behavioral changes based on what they learn about themselves and how they lead.”

Helping the sessions succeed, Neale says, is customization. “Connections are important to me. Recognizing individualization of each manufacturer I meet helps me better connect with them and build strong relationships.”

Born outside of New York City, Neale’s family immediately relocated to Pipestone Minnesota, where her father was starting a small manufacturing company.

Her talents in speech competitions at Pipestone High School encouraged an early ambition for corporate law, which evaporated after taking her first political science class at the University of Minnesota, Morris. “I hated it,” she admits today. But she maintained her love of speech, especially rhetoric. “It’s geeky, I know, but I liked learning about Aristotle and Socrates, the concepts of interpersonal relationships, and how people work with one another.” She augmented her studies at the University of Minnesota, Morris by coaching high school speech activities and judging competitions. The speech department added her as a teaching assistant for her junior and senior years.

A key professor admired Neale’s skills in the classroom and encouraged her to apply to grad school. She chose the University of North Dakota, where she could pay tuition by working as a teacher’s assistant, TA-ing for a course in public speaking. (In one memorable class required of members of UND’s heralded

hockey team, three-quarters of her students produced individual “demonstration” speeches on the finer points of taping a hockey stick.) Armed with a master’s degree, she joined the faculty at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, where she spent a year before being wooed away by a more lucrative offer as a fulltime corporate trainer in a telemarketing company. In an intriguing career plot point, Neale discovered that she loved training telemarketers.

She returned to Minnesota after a year, where her position at Fingerhut cemented a career in corporate training.

“I enjoy going after the sales,” she recalls, “just don’t put me out on the line to say, ‘Michele, your income depends on whether or not you get this sale.’ I’m an influencer; if I believe in something, I want to influence you.” The telemarketing gigs gave her a classroom setting where she could teach sales and presentation skills and the value of building relationships.

Neale’s clients and colleagues universally agree that her personality, skillset, and deep experience in human

resources and corporate training have created high demand for her services as a tool to help manufacturers retain employees.

“Michele has an uncanny ability to understand a situation and communicate it to anybody there is, regardless of their title, background, or experience,” says

When asked for an elevator-pitch summary description of the work, Neale responds with one word: “self-awareness.”

Bob Kill, Enterprise Minnesota president and CEO. “She can connect, understand, and communicate with anyone… I mean anyone.”

That strength, he says, grows from respect, her ability to listen, and empathy.

“She cares,” Kill says. “She sees the value of everybody. And that’s why her clients really love her.

“Plus,” he adds, “she’s not afraid to speak her mind, even when situations are uncomfortable, which is also really good.”

He adds that Neale adapts well to diverse clients’ needs, “from sophisticated to the notso-sophisticated. Some are larger companies with a well-defined structure for leadership development at all levels, and others don’t have much structure at all.”

“She is comfortable in her skin,” Kill adds. “Her balance of confidence and competence is perfect. That’s why she can sometimes say things that a client might not want to hear.”

Neale credits her work ethic to her home in Pipestone. “I had an awesome father,” she says, “who I lost too soon to colon cancer.”

“He was a man of connection,” she continues. “When people met him, they remembered him.

“He had a great impact on me in terms of how you treat people and how you work with people and how that relationship is so important,” she says. “When I get up every morning I ask, ‘What difference can I make in the life of somebody I meet today?’”

Tom Mason

Over three years, the Isanti-based business has more than tripled its sales, boosting business by 264% and landing BP on the Inc. 5000 list of America’s fastest-growing private companies.

Blake Pendzimas, founder of BP Metals, sold controlling interest in his company in October, but he’s sticking around to reap the benefits.

John Reinke, managing director of Generation Growth Capital, says his company looked at over a dozen metalworking shops before deciding to make BP Metals one of three Midwest metal manufacturers it purchased in October to assemble a metal manufacturing platform called American Consolidated Metals.

It’s easy to see why BP attracted him.

Over three years, the Isanti-based business has more than tripled its sales, boosting business by 264% and landing BP on the Inc. 5000 list of America’s fastest-growing private companies.

But it didn’t stop there. Reinke and his colleagues were just as impressed by the fact that while running hard, BP also transferred its operations from Blaine to a newly built facility in Isanti and earned its

ISO 9001 certification heading into 2024.

“It showed that the organization was receptive to positive change and operational advancement,” he says. “It certainly signals to us that we’re going to be able to help execute on further growth down the line.

Blake Pendzimas, BP’s founder and owner, realized that maintaining the growth trajectory of his business was going to require adaptations, and improved systems. “(ISO) sets a lot of systems in place, documents things, and really puts a name on every operation we do. That didn’t always happen before,” Pendzimas says.

“I think there’s a lot about owning what you do,” he continues. “I don’t think we had a bad product before, but I think our product will be better going forward.”

Pendzimas had been looking for some outside help when Generation Growth Capital made its offer.

“We have been growing at such a rapid rate over the past few years that it was getting very difficult for me to handle by myself. So, we started looking at what we were worth and what we could do,” he

recalls.

Along with bringing additional capital into the operation, BP’s new venture capital partner brings expertise, new resources, economies of scale, and greater buying power.

What’s more, Generation Growth Capital chose to keep Pendzimas on in a leadership role at BP.

“We’re more about growth than we are about expense reduction or rationalization,” Reinke says. “We tend to be more additive when we come into a company, particularly within the first year. We certainly look to invest in people and add additional people but not necessarily as replacements.”

“So, in Blake’s case, he has a good team. He has a growing business. He’s staying on as an owner and as the president of the company. He’s a young guy with a lot of fire in his belly, and he wants to continue to work and grow the great business he started,” Reinke says.

That growth shows no signs of slowing. BP is currently in the process of doubling the size of its 10,000-squarefoot production plant, with an eye toward

“There’s a lot about owning what you do,” Pendzimas says. “I don’t think we had a bad product before, but I think our product will be better going forward.”

quadrupling its current footprint in the next few years. Reinke says new equipment is on order, too.

At present, BP employs 33 people. Its largest customers are active in the commercial food service, retail fixture, and agricultural equipment markets.

As for what sets BP apart from its competitors, Pendzimas says: “It’s just how well rounded we are with all the things we can accomplish in house.”

Besides talent, he says, “we have some of the biggest, most powerful lasers in the state. We can cut thick metals faster and more economically.”

The company is known for its sheet metal bending, cutting, and welding prowess, says Jim Schottmuller, Enterprise Minnesota’s director of business development.

Keith Gadacz, a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota who has been working with BP since March 2023, says the company began reaping the benefits of the management system it had adopted, even prior to certification.

“That management system has formed

a better structure for their calibration, their equipment maintenance, their scheduling and communication, their open-order capacity, as well as measuring the business to keep track of how it’s going on a scorecard to track their progress,” Gadacz says.

He refers to BP’s progress as “exceptional.”

“They’ve gone up not just one, but two plateaus of improvement. I mean, it really is remarkable where they were when we met to where they are today, and I see them moving up even more in the future,” Gadacz says.

“Keith has been a huge help,” Pendzimas says. “You can run wild without ISO for as long as you can, but eventually you’re going to hit some walls, and there are places you’re going to fail. That’s not to say we’re never going to fail on processes again. But it’s going to help us identify where we went wrong and how to steer the ship straight again,” he says.

Pendzimas says earning ISO certification has long been a personal

goal, now finally realized.

Reinke predicts the credential will increase BP’s opportunities to land work as a tier 1 supplier to OEMs who demand ISO 9001 partners.

“That is definitely a door-opener,” Reinke says.

As for what sets BP apart from its competitors, Pendzimas says: “It’s just how well rounded we are with all the things we can accomplish in house.”

Pendzimas founded BP Metals in Blaine in 2000 but moved the operation to his hometown of Isanti in August 2022, after the community offered to sell him the land he needed to accommodate the current plant and anticipated future

expansions for $1.

Plus, he says, “We really like the work ethic up here in Isanti. I think it’s a different crowd of people than we saw closer to Minneapolis.”

Pendzimas says the most-valued members of his team in Blaine made the move. “Pretty much everybody we wanted to come with us came with us.”

BP also lost a fair number of employees during the move but has had little difficulty finding replacements in Isanti, according to Pendzimas.

“We are aware of a lot of kids coming out of high school who need jobs, and just the connections we have in our community drive a certain level of respect when people walk in the door to apply for a job, because we know their mother or their father or their grandparents,” Pendzimas says.

Pendzimas says new recruits are drawn by the cleanliness of BP’s operations, the opportunities to grow with the business and the culture of the workplace, especially since the relocation to Isanti.

‘All you need to do is pick something and be determined enough to be great at it.’

“Out of high school, I really didn’t have any goals or anything like that,” says Blake Pendzimas. “My dad had a small manufacturing shop. So, I was a self-taught welder at his shop for a number of years before I went out and started BP Metals.”

“I didn’t do any schooling. I am a high-school graduate who decided to jump into an industry and go.” He doesn’t regret his career path.

“A lot of people decide they need to do all these different things to become successful, when really that’s where success comes from.”

Pendzimas contends classroom learning can be overrated, compared with hands-on experience gained through apprenticeships and on-thejob training.

“I see more growth out of people that way than I sometimes do out of schooling. Just going out and doing something, deciding that’s what you’re going to do, sticking with it. Putting in the blood, sweat, and tears, with long days and short nights. Just keep going,” Pendzimas says.

“You’ve got to get up early, stay up late, work hard, and I think you can become good at almost anything.”

He says the town is located in farm country, and its rural nature has been conducive to building a cohesive team.

“On days when it gets hot, sometimes we’ll just close the doors, and we’ll rent 50 tubes, and we’ll go up the street and float the river,” Pendzimas says.

Pendzimas says he thinks the simple act of sharing a meal once a week builds and strengthens the company’s employee culture.

—Peter Passi

You have become a real advocate of observing your local manufacturers first-hand through company tours. Why is that?

I’ve learned of the important role manufacturing has in creating a lot of jobs and its impact on Minnesota’s economy — the importance of manufacturing jobs throughout the state and within local economies is a bit of an under-told story. I hope more legislators take the opportunity to tour different manufacturers in their district, and not just the big ones. It would be great to have stronger recognition that

“You can help stabilize a small community if you help a smaller manufacturer grow from five employees to 15 or 35.”

the smaller manufacturing companies are doing the heavy lifting of creating jobs and keeping our economy moving.

It is exciting to visit businesses you might drive by but not really know what they do, how many people they employ, and how they contribute to our state’s economy. It’s been fabulous to see the range of manufacturers just in my own district. Before being elected to the legislature, I was a member of the Lakeville Chamber of Commerce and the Dakota County Regional Chamber of Commerce. I would attend events, but events are different than touring specific businesses. I have toured the Amazon fulfillment center in my district. It is huge, the size of a couple of football fields. I could see the amazing organization and engineering that goes into a large manufacturing and distribution center like that. But I also toured Hinckley Medical, a great startup by some young guys just out

of college who came up with a new medical gurney device. They’re about to enter a phase where they need to start manufacturing in higher quantities, so they have to decide whether to take that on themselves or find another manufacturer that can make parts for them. As a policymaker, it’s helpful to know what challenges businesses are facing and what is working. Tours help me understand each unique business

and how policy can help and/or hurt a business.

Do you agree that many legislators are surprised to learn how manufacturing is far different than the old stereotypes they might have had about dirty, boring, and repetitive jobs?

One of the first local manufacturers I visited makes small screws for surgeries and things. He had five or six people

making $80,000 or $100,000 a year, and he was looking for more. It’s amazing. You go into this warehouse, and the floors are as clean as a car dealership; the showroom is cleaner than everybody’s garages and probably even their kitchens. There are exciting career opportunities in this industry.

You were the chief advocate in the House for a couple of measures that helped manufacturers directly.

I saw a direct correlation between helping manufacturers — especially small ones — expand and create jobs across the state and strengthening the state economy. These smaller manufacturers can help create the economic backbone of a community. You can help stabilize a small community if you help a smaller manufacturer grow from five employees to 15 or 35. That helps provide a livelihood for 15, 20 families, plus there is the growth-effect value off that. It wasn’t expensive to provide a little incentive to these other manufacturers and business owners to invest in themselves.

I think we could have done more, to be honest. Much of the spending done by the Jobs and Economic Development committees may not have the return that the state should expect, like the small manufacturing grants do. There was more that we could have done with our resources.

What’s behind your reputation as someone who would rather work with people to get things done, outside of mere politics?

That’s what Minnesotans expect. People in my district know that I’m a fiscal conservative, but they also expect us to go to St. Paul and prepare a budget that’s meaningful, not hurtful. I take my job seriously because people send us to St. Paul to build those relationships and figure out areas we can agree on. Supporting manufacturing businesses to expand should be something that both Democrats and Republicans can agree on. I’ll continue to advocate for growth and jobs, as well as fight a lot of the harmful policy that does the opposite.

Speakers/subject-matterexperts focused on collaboration and problem-solving supply chain challenges

Put us to work for you at bremer.com

Tested by time, John Norris has learned the value of empowering employees.

By Mary Lahr SchierPatience, John Norris says, may be his biggest asset as a business owner. And, maybe, his biggest flaw. He tends to let events play out, give employees and partners plenty of leeway and time, and allow products and people more than one chance. Early in his career, that patience coupled with good relationship skills, enabled him to acquire Atscott Manufacturing Inc. in Pine City. In the 2000s, it helped him hang on to Tower Solutions Inc., when he was advised to let it go. And, today, it guides him as he positions his companies for what he sees as opportunity-filled but challenging years ahead and considers what happens after he’s gone.

“Some people may not think patience is a virtue in business, but it has been for me,” Norris says. His holding company, ATS Holdings Inc., owns Atscott, a 60-year-old contract manufacturing company based in a HUBZone; Tower Solutions, which provides quickly assembled towers for government and commercial use; and

For much of his early career, Norris worked like success was only in his hands, but during a retreat one year, he realized that “maybe I should work like everything depends on the people I work with.”

Precision Engineering

Now, a design engineering firm that works with both companies and their clients. Building these businesses has been a slow process, one that’s required complete focus as well as patience.

“There are disconnected owners out there,” says Jim Schottmuller, director of business development at Enterprise Minnesota, “but John’s not one of them. He has a complete understanding of everything that is happening at the company and everything they are doing.”

After flirting with medicine in college, Norris started his career in sales at IBM, a position that built skills in computing, sales, and data analysis he would hone for decades to come. “If you had to pick a company to work for in the ’70s,” Norris says, “it would have been IBM. The training course was phenomenal and opportunities abundant.” After about seven years, he was in the top three percent of salespeople in the company’s division selling computing systems to small firms in the construction and manufacturing businesses. He was “making some pretty good money,” but at the time IBM’s nickname with its employees was “I’ve Been Moved” and a transfer was looming. Norris and his wife, Nancy, did not want

Tower Solutions manufactures portable metal towers that go up quickly, withstand wind and weather, and hold heavy loads. About 90% of current sales are with the government.

to leave Minnesota.

He began circulating his resume, but also talking with his father, Manley. Since 1963, the elder Norris and two others had owned Atscott Manufacturing, which at the time operated out of an old creamery building in Pine City. The firm was born after the closing of Minneapolis-based Scott-Atwater Outdoor Motor Co., where all three had worked. By the late 1970s, Atscott — a name that plays on where the three founders came from — was profitable with two major, blue-chip clients, 3M Co. and Twin Cities computing pioneer Control Data Inc. The company operated entirely manually, however, even using handwritten ledgers for accounting. The move involved a substantial pay cut but “it was obvious the future wouldn’t look too bad if I could keep

the place together,” Norris says. John Norris came on board in 1979, handling sales and helping bring operations up to date.

“I had a background the company needed, and it turned out to be providential,” Norris says. Within two years, Norris’s father developed dementia. By 1984, the younger Norris was running the business. He was 34.

“We had great people,” he recalls. “I didn’t know the basics of machining work, but I managed the business and we were profitable and growing.”

Company ownership was divided, however; a potential problem over time. Norris is one of five siblings and each owned a 10% share in the firm after his father’s death. The remaining shares belonged to one of the other founders and the widow of the third founder. “I was fortunate that my siblings and I were close together, not in age but in camaraderie,” he says. Those relationships allowed him to slowly — and without debt — purchase his siblings’ shares and then those of the other partners. The negotiations took time and patience, but Norris knows how contentious they could have been. “When you’re dealing with family companies it can be problematic for small businesses in a way it wasn’t for us,” he says.

quickly unrolls from its base, which can be mounted on a truck, trailer, or platform. Tower’s owners left the show with hundreds of leads.

“It’s a very unusual product. You look at it and you think, ‘This should be a success,’” says Norris. “It was unique, but it came with new technology and a higher cost that made for a difficult entry into the market.”

Atscott continued to make money in the ’80s and ’90s, even as competition from Japan, then China, grew and as Control Data’s business dissolved. The firm added space and employees and currently has about 70 employees working in 76,000 square feet with annual revenues around $16 million.

While Atscott was a profitable company with a solid client base when Norris started, Tower Solutions was a start-up with a great product in desperate search of the right market. The company’s product — a portable metal tower that could go up quickly, withstand wind and weather, and hold heavy loads — seemed like a natural for commercial uses in communications. But it wasn’t.

Norris remembers a trip to a trade show in Chicago shortly after he became involved with the product in 1999. Attendees were amazed by how quickly and easily the towers could be assembled. Unlike other towers, the Tower system

The owners — at that time Norris was one of three — first concentrated on the commercial market, such as cell towers or mounting lights for nighttime highway construction sites, sporting events, or parking lots. Cell companies vetoed the towers because they weren’t permanent or tall enough for their uses. The price of about $95,000 per tower prohibited some other uses. The company sold a few structures for the 2002 Winter Olympics but finding a reliable, profitable market eluded them. During the Iraq War, the military purchased towers for surveillance and loved them. The towers could go up quickly, even in hostile conditions or bad weather, and cameras, drones and other heavy devices could be mounted on them.

But selling to the government is a slow, laborious process. “You could say the business snow-balled from there,” Norris recalls, “but the snowball rolled very slowly.” The military uses led to other contracts with the Department of Homeland Security, which currently deploys about 100 towers along the northern and southern borders. Tower’s products go up quickly, are rigid, tall, and have the ability to lift loads up to 2,500 pounds or more. They can go up automatically with no human

involvement. “The government needs those characteristics and is willing to pay for it,” Norris says.

The 2000s were a rough period for the young company. The owners did not always agree on direction, and the three owners were the company’s only employees with Atscott manufacturing the towers. Norris believed in the product and also thought it could someday become a cornerstone of Atscott’s business. He took no salary and personally financed all of the company’s debt, including refinancing Atscott to raise funds.

As the years and the losses rolled on, Norris’s advisers urged him to close Tower to preserve Atscott. “I came very close to it,” he says, “but we always had business booked during key moments. There were a lot of humps and bumps. Even at the worst of times, when it looked like we should close it, there was enough on the positive side to keep it going. That’s when patience was helpful.”

By 2010, Norris bought out his fellow owners and brought on engineer and partner Steve Kensinger to run Tower sales and engineering. Kensinger helped broaden the product line, often promising

“I realized that maybe I should trust and depend on the people I work with.”

features that hadn’t been engineered yet. Kensinger’s son, engineer David, is now CEO of the company and did much of the new product engineering. “John never lost focus that there was potential if we could get more products out there and more customers,” David Kensinger says.

Today about 90% of Tower’s business is with the government. Since the product has been around a while, replacement parts made by Atscott are in demand, and the company now refurbishes and rents towers, too. With annual sales of $15 million and seven product lines, Tower accounts for 15 to 35% of Atscott’s annual sales, providing a level of stability against market shifts. While the two companies operate separately, they are now “joined at the hip under ATS Holdings,” Norris says.

It was during the turbulent period in the early 2000s that Norris refined his approach to management. “There’s a saying in Ignatian philosophy, ‘Pray like everything depends on God and work like everything depends on you,’” he says. For much of his early career, that’s what he did — work like success was only in his hands. During a retreat one year, he rethought the expression. “I realized that maybe I should trust and depend on the people I work with,” he recalls.

He shifted his approach from making sure he got everything done to making sure the people around him had the skills, tools, and knowledge they needed to do their jobs and make decisions. It’s led to a focus on employee engagement and skill building. The company frequently uses Pine Technical & Community College for skill development and offers apprenticeships at the company. It’s turned to Enterprise Minnesota for help with plant layout, cybersecurity, leadership skill building and quality, including AS9100 and ISO 9001 certifications.

Ally Johnston, a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota, recently helped Atscott implement “Leading Daily for Results,” a program that provides the tools for teams to measure and communicate priorities. For example, if assembly workers are lacking the parts needed to finish a day’s work, the daily huddle that is part of the program offers a forum to communicate issues more proactively. “They are trying to make each area run like its own business,” she says.

Tower employees recently participated in the Leadership Essentials programs with Michele Neale, a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota. The program helps employees define the leadership skills their company needs and gives them tools to put them into practice. “What I saw at Tower was that every time the employees learned about an action that might work for them, they implemented it,” she says. “It wasn’t ‘oh, that’s a good idea, let’s talk about it.’ They tried it right away.”

Kensinger says Norris has given him a role and trusted his ability to do that role. “He’s very good at analyzing the risks in a situation and being optimistic about it,” he says.

“John is the best owner I have ever

worked with,” says Tim Ellis, a fractional CEO now leading Atscott after 15 years as a consultant and fractional leader at a variety of companies. He admires Norris’s strong appreciation for the value employees bring to the company.

“People in the organization have a huge level of respect for John,” he says. “He knows their names and what they do, their families, and even their medical issues.”

Norris pairs the personal touch with good benefits, annual bonuses, and opportunities for skill building. “When people come here, they tend to stay,” Norris says. The company has many employees with 20, 30 or 40 years of employment. The longest serving employee has been at Atscott 57 years. “I think we are a good employer,” Norris says. “We sure try to be.”

At 74, Norris is looking ahead. He tapped Ellis and Tower CEO David Kensinger to lead each of the two companies, and recently added the word “emeritus” to his title. He’s working with his lawyers and accountants on succession planning to make sure the companies continue in case he’s unable to lead. He still works full-time but in a more supportive role, and “not quite as hard as I used to.”

Norris has seen many ups and downs for manufacturing in the United States over the decades, and he thinks there may be an upswing in the future. Supply chain issues resulting from COVID and conflicts around the world may cause larger firms to rethink how much they manufacture overseas. But the industry also faces

challenges. His top three:

Workforce. Finding people, replacing the institutional knowledge lost when long-time employees retire, and coaching employees to maintain the company’s culture are issues that affect all manufacturers, Norris says. Providing good benefits and ways to engage, train, and reward employees are part of his workforce strategy. Atscott uses contract employment services for some positions and as a recruiting tool, Ellis says. “You get some good workers through the agencies,” he says, “and when we find those, we gobble them up.”

Technology. As companies with government contracts, Tower and Atscott have made big investments in cybersecurity. “If you are doing anything with the government, cybersecurity is a huge concern because it makes moving data around so much more difficult,” Norris says. New manufacturing technologies, such as additive manufacturing and artificial intelligence, may change the industry very quickly. “Metal working has been stable for many, many years with improvements in tooling and sophisticated controls that do more faster and more accurately,” Norris says. “The technology is coming that gives us an opportunity to really change the basics.” As someone who watched Control Data lose its business rapidly 30 years ago, Norris knows how much technology can change an industry. “That was half our business,” he recalls. “It can happen really quickly. You worry about that.”

Inflation and government policy. Inflation from the past three years has been brutal for manufacturers. Changes in state government policy will also affect business going forward. “Let’s just say that some of the new laws in Minnesota are not kind to manufacturing companies,” Norris says, “and it’s a big concern.”