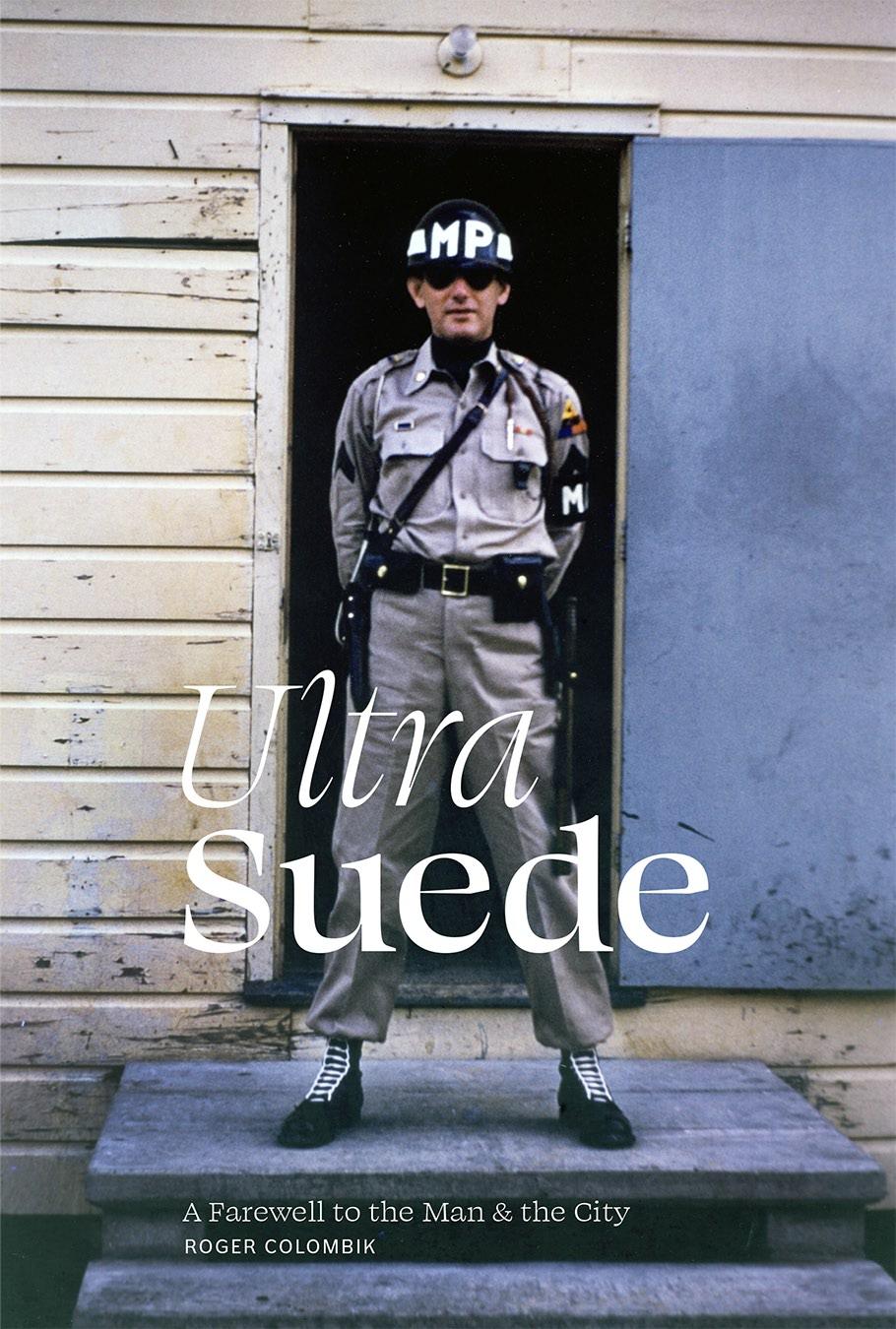

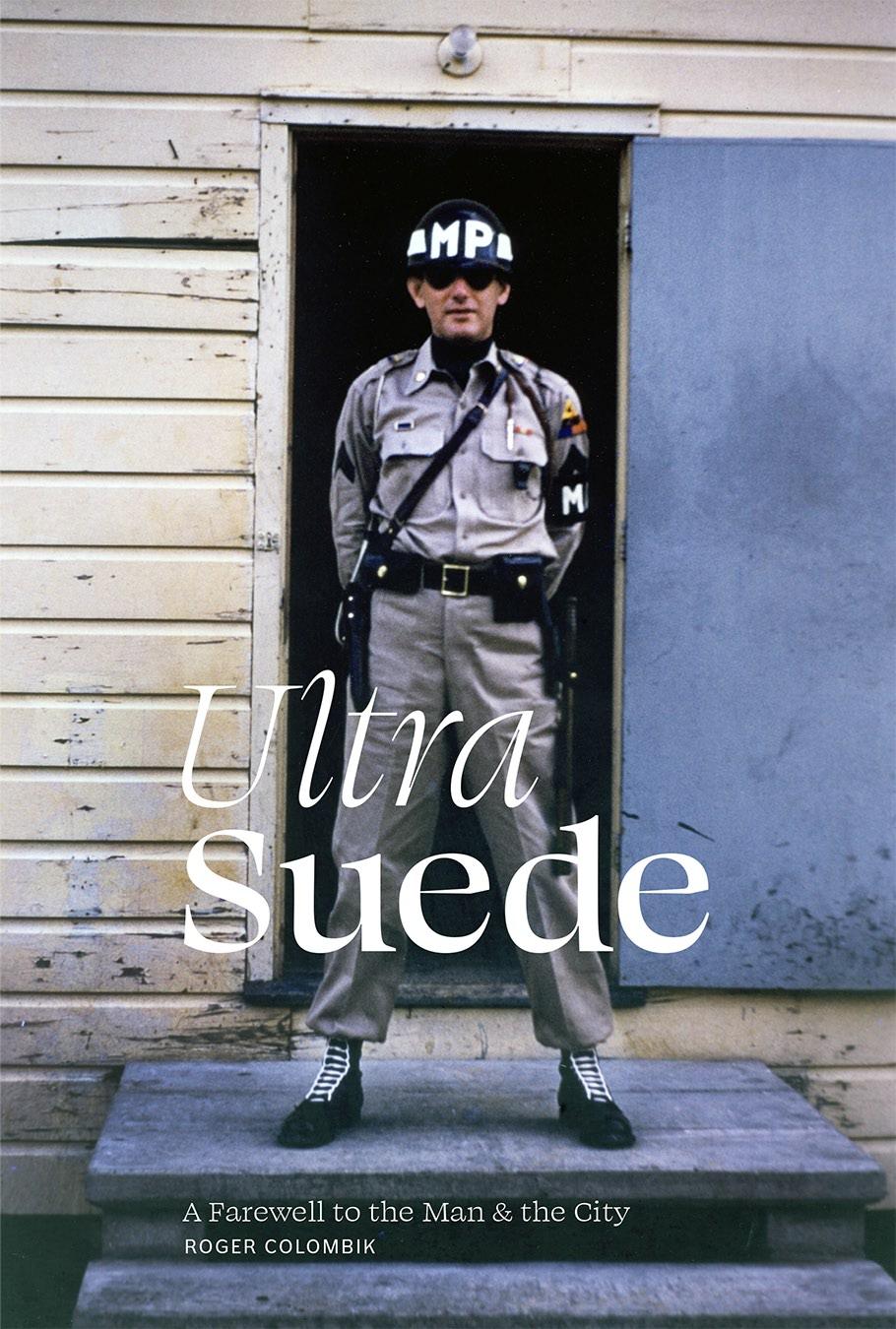

Chicago Born. Chicago Bred. Chicago. All the Way.

44. “. . .I’ll tell ya about it someday.”

The oxygen gauge reads ¾ full, his blood pressure is steady, and the sports section from the Tribune and The Sun Times should keep him occupied. An open can of strawberry BOOST is on the coffee table along with a jar of applesauce if the desire for solid food arises. I try to engage him, asking—

What else? Go. Are you sure? Yes. Go. I’ll be back in an hour. Take two.

You sure. Go. I’ll be fine.

I tape two quarters onto the bike frame for an emergency call and head towards the door. I check his bearing one last time but he’s turned toward the window, already adrift on the waves of his passing life.

Emerging from the darkness of the underpass, the lakefront appears as a mirage, a deep green forever merging with the horizon, a horizon melding into the summer atmosphere of weekend barbeques, soccer games, beachcombers, and the shrieks of children at play in the surf. I instinctively turn north, gliding past park bench conversations and revelries in Polish, Russian, Spanish, and Korean that hover and swirl and tease the imagination. I accelerate along the shoreline, accelerating past all the hospitalizations, prognostications, pills, placebos, and pain. I fly through the old neighborhoods, schoolyards, alleys, and haunts, my past is a film reel spinning faster as legs churn the pedals of the projector that synchronizes every fleeting glimpse with a long-forgotten memory. A little boy and his father kick field goals at Loyola Park, a family—still united—running along the shore at Jarvis St. Beach, the taunting and wiles of boyhood, and hot summer nights with our voices echoing through gangways where the enemy always lies in wait, ready for attack.

I'm laughing, I'm crying, I'm screaming.

Faster now, the years cycling through the evercapricious journey of remembrance in a final goodbye, a grand denouement, a cinematic farewell to the city and the man.

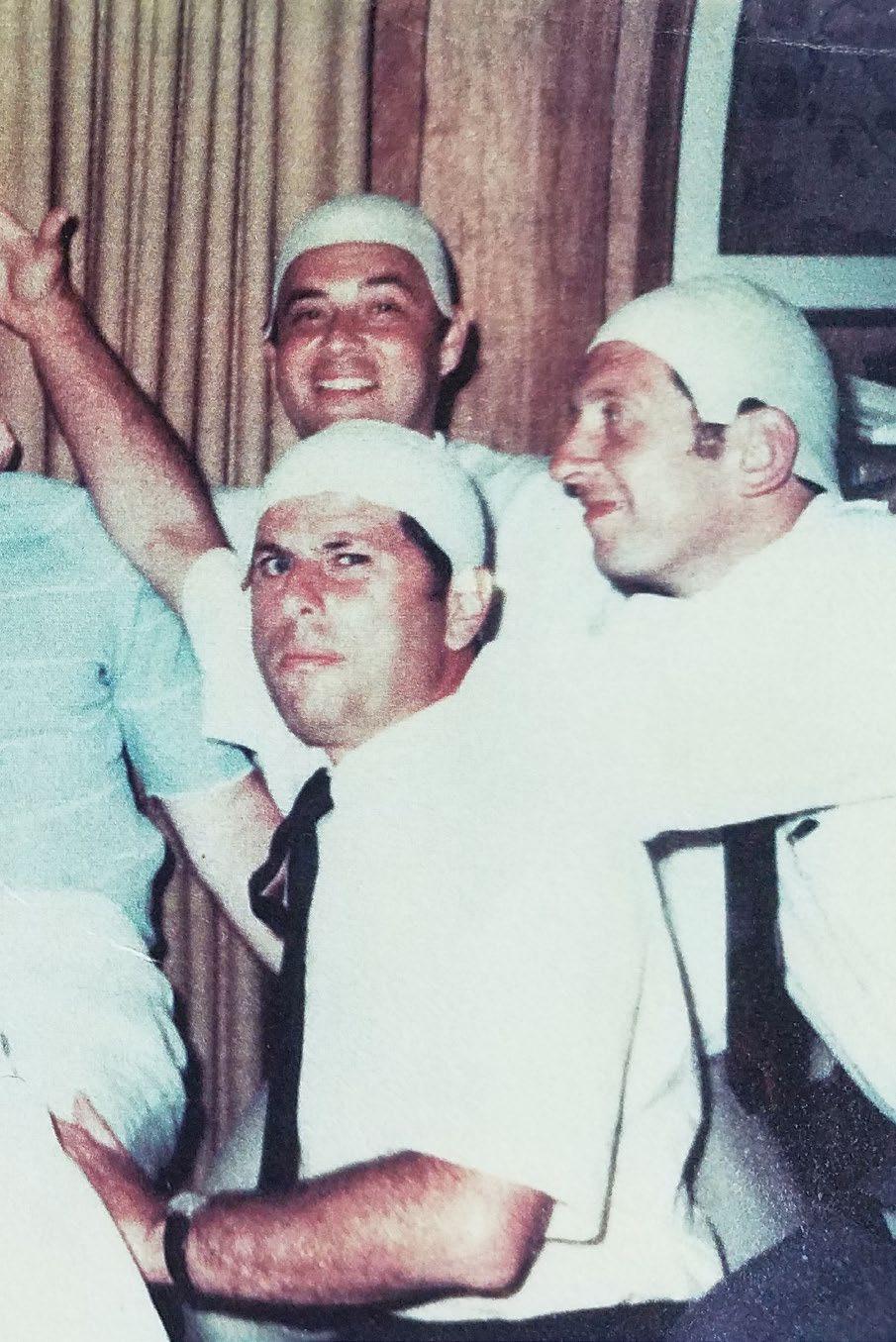

One breath. Then another. A little deeper inhalation follows, building confidence. His mind is on a Fantastic Voyage, trailing a journey of oxygen that is cautiously drawn through the lips, quietly navigates the trachea, and arrives painlessly at its destination—the remaining left lobe. The fear of reprisal, of the spasmodic coughing fits that rupture his universe and rend the air are put to ease, for now, allowing the body to acquiesce into the comforts of family. The dining table is set with fine china, rolled cloth napkins, and genuine silverware as potatoes pirouette in the microwave and steaks sizzle in the broiler. Tonight our father is in a celebratory mood, for real food—enough of that BOOST shit! New resolutions to reclaim the future and defy the odds are espoused with today’s vigor. One More Year!

Possibly. . .a few months. At best, we know that he’ll settle for even one more day to sit at life’s table with children at hand.

Together, we gorge on these moments.

Ran down to the garage to strip the plates off the Lincoln before the repo man arrived. Souvenirs, from a ride through prosperity.

Dad getting on all fours as soon as he arrived home from work so I could run the length of the hallway and crash into him, grasped tight in his arms as he sways me to and fro. • He returns from a run, settles into the armchair as I organize my baseball cards, my face turned away from him as he explains the word divorce. I turn to him long enough to see his sweat coalescing with his tears. • The tears in his eyes as he walks through the woods to greet me in Wisconsin during Parents Weekend at Camp Ojibwa, an overnight camp far away from divorce proceedings and the split. • Kicking field goals together at Loyola Park. • Lacing up the skates at Leone Beach as he stands in the frigid lake front winds to admire my very clumsy, accidental pirouettes on the ice. • Ron Santo hits a foul ball towards the dugout, dad leans over the brick wall to make a catch, the ball smashing out of his grasp. • Craning our necks to gaze at the marvel of Lew Alcindor. • Bobby Hull raises the stick high for his signature slapshot, the puck takes flights, knocks out a fan. • Coming up the stairs after his workout at the Y and he’s juggling a football, tosses it my way, the pigskin covered in signatures of the ’68 Bears. • My deep embarrassment as he stood on the sidelines in his Bermuda shorts, cigar clenched in his teeth and screaming my name all too audibly, much to the amusement of my team. • The night he convinced Bobby Douglass, the Bear’s quarterback to join us for dinner. • Haircuts at the Palmer House, always with Rossi and dad’s evercareful attention to my hair. • The night he returned home from work with his first toupee. • My first grade teacher, Tillie Dahnoff, looks at the roster the first day and asks if I’m Lee Colombik’s son, her student in the 30’s. • Walks along Sheridan Rd. to a corner store for the evening paper and

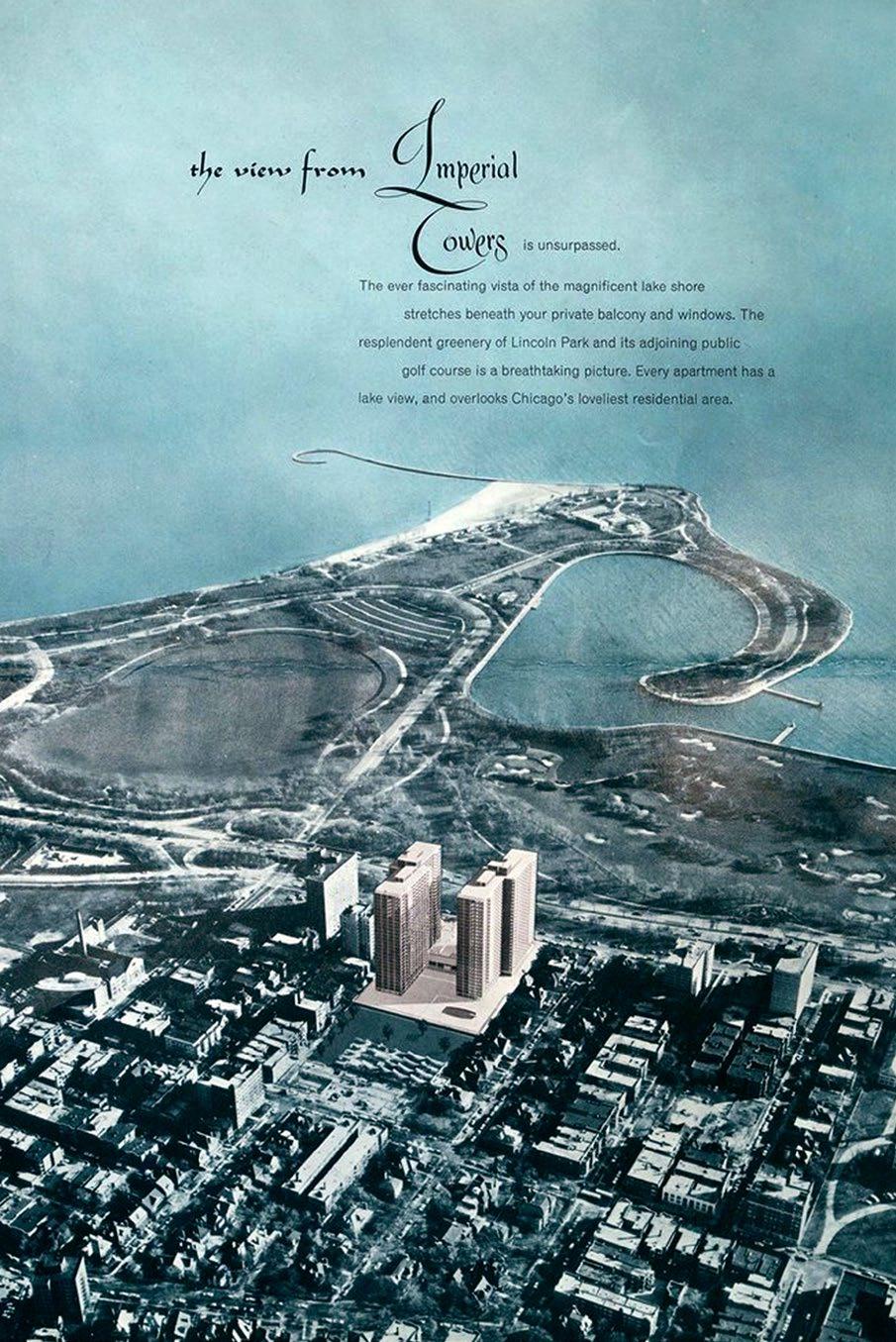

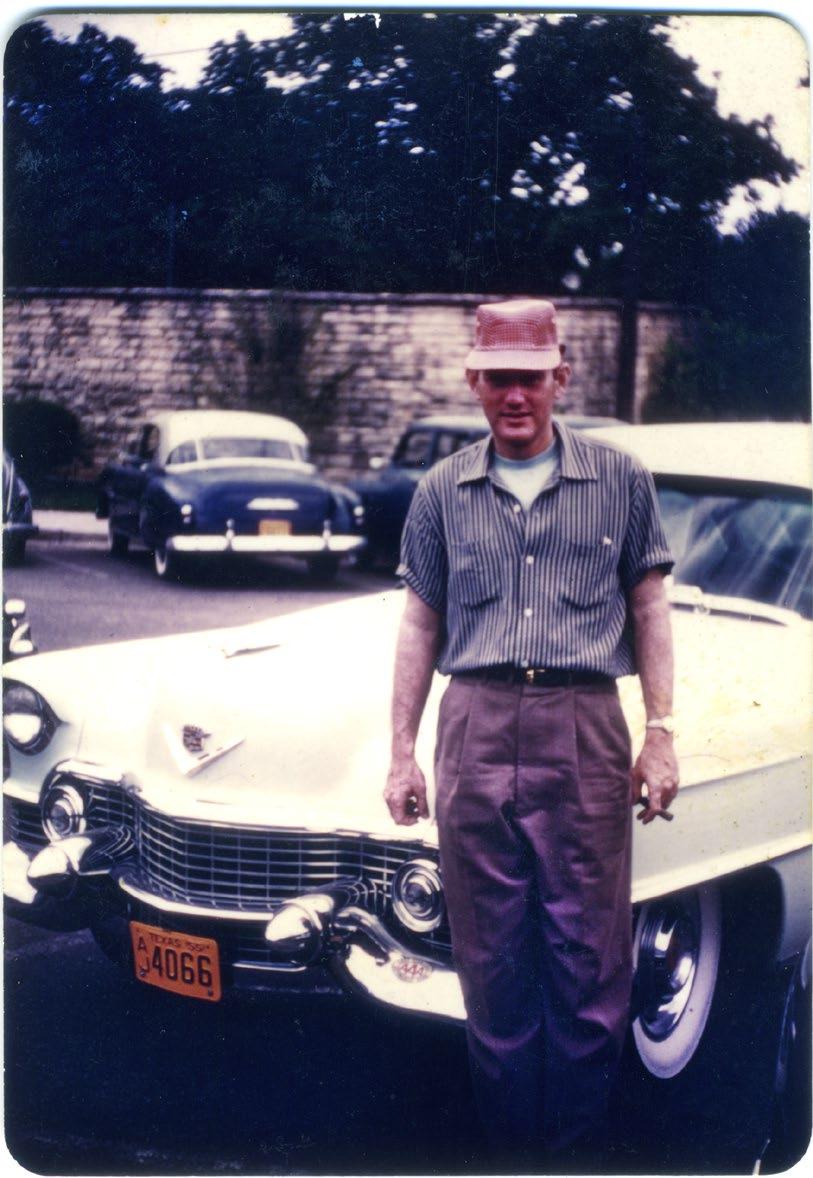

a packet of Hostess cupcakes. • Walks up Jarvis St. to the neighborhood pharmacy for the evening paper and a packet of Hostess cupcakes. • Grilled burgers and Cherry Cokes at the Jarvis St. diner under the “L” tracks. • Post divorce rituals of Wednesday night dinners at Big Boy (double cheeseburger and malt). • Post divorce rituals of every other weekend at his efficiency in Imperial Towers. • And then in the one bedroom condo and lots of trips to the pool. • Plaster hand print at the JCC (still on the shelf). • Dreidels and Chanukah Gelt. • Large, super hard matzo balls in my Passover soup (shouldn’t have said anything). • An old blue Cadillac, big fins. • Opening the passenger door of the caddy while he is driving on the highway and the horror and fear in his expression as he struggles to keep me inside. • He’s smoking a cigar in the caddy and I’m feeling sick in the back seat. Mom yells at him to put it out, hands me a pink pepto pill, quickly vomited all over the back seat at the moment we enter the cemetery for a funeral. Pink on blue. • Driving in the old Buick Electra back and forth, back and forth with the divorce transit. • The trips to Thorndale deli. • The packets of corned beef, the sliced salami, the rye bread, our weekend post-divorce meals. • His rainbow of golf shirts, perfectly folded from the dry cleaner. • His final dry cleaning bills, paid by the family to retrieve the clothes. • His Coppertoned nose at Jarvis beach. • Not a single memory of him swimming in Lake Michigan. • Only his breaststroke in a pool. • Hanging out with “uncle” Frank at the Y, learning how to dry my back with a towel held just so. • Years later, learning that “uncle” Frank was in the Chicago mob. • The sound of the masseuse, the slapping on dad’s back, the smell of the alcohol rubs. • Tennis on clay courts at Northwestern University.

“They found another spot on a piece of film.”

His voice tapers off, settles into a strained, rasping breath that journeys from a Lake Michigan sunrise to a Black Sea coastline. Imagination bears the burden of silence, leans heavily toward the macabre; there will be more invasive surgery, more cutting, more pain, more diminished hopes, more, more, more.

The phone clicks dead and distant.

Another endless stream of numbers from a calling card is pressed in quick succession. A ringtone of emptiness. He disconnected the answering machine. The ringing becomes rhythmic, becomes a chant converging towards prayer until a Bulgarian operator cuts me off, telling me, (I think) to try another day.

The line forms early at the neighborhood shelter, well before preparations for the afternoon meal have begun. The parlance of the barrio echoes through the kitchen as disheveled, corpulent men look on with indifference at the people gathered on the sidewalk. A matriarch from another century, precariously balanced upon swollen ankles takes a seat in the dining hall only to be reprimanded by a worker unloading tomatoes and rancor. She shuffles her tired body back outdoors, where the line of hungry immigrants collapses upon itself into a boisterous horde, as conversations become heated and laughter becomes contagious in a cacophonous melody of Mother Russia. The men huddle together to gesture and taunt, the women remain on the fringe, demurely listening in. A noble mathematician, patiently waiting for a handout corrects me on my verb tenses while a gregarious engineer pleads his case, lamenting “a life as a beggar in these United States”. The elderly, passive to the core, crouch in the shade of an abandoned storefront, in a struggle against gravity’s cruel joke.

It’s a cultural center of sorts, here on this cracked and buckled pavement along Broadway Ave., where the sweet anesthesia of the familiar can find a reprieve from the afflictions of foreignness. These new Chicagoans never mention how difficult life had become before they willingly cast themselves across the sea, into an uncharted realm of possibility.

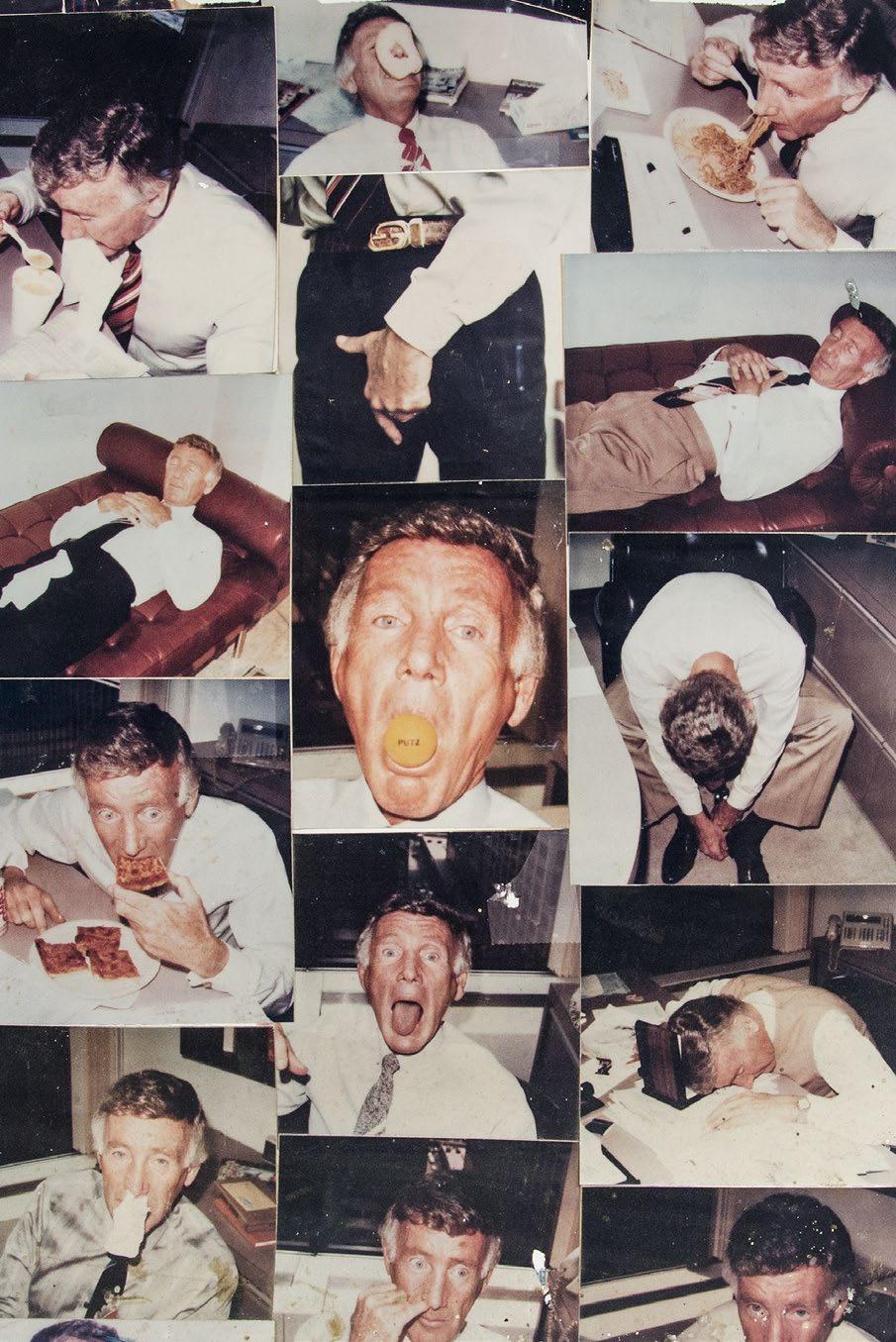

for Harvey L. Warner & Associates

Where the legalese of judicial jurisprudence was permanently adjourned for the profane patois of the street.

In offices high above those precarious Chicago streets, where law books are decoration and doctors with questionable credentials are always on call, Lee Colombik holds court each Friday afternoon with the crew. Blackie, Dom, Searcher, and Harry impatiently watch the ever-teasing taskmaster slowly peel currency straps off stacks of 100s, counting out rewards for the week’s settled cases. They sweep up their earnings and immediately commence a bidding war for new cases on the docket, tossing down bills in a frenzy of salacious commentary and litigious possibilities. Though the mysteries and shenanigans of the whole operation elude me to this day (dad was always reticent on business matters) one thing is clear; my father was adored and trusted for his magnanimity and charm, for his levity and wit. When a new client signed up with the firm, a Polaroid was taken and the portrait stapled to the front cover of the file. The clients, many of whom were suffering genuine injuries often smiled for the photos. My father’s calming presence and jocular manner, directing them to. . .

“Just relax, look right at the camera. Say shit.”

The beginning of the month induces a guarded unease with each trip to the mailroom. Stacks of bills, local circulars, and condo activity schedules are stuffed in the box and left for another day. The check finally arrives on the fifth. He carefully opens and extracts the government-issued benefit, a modest sum that must, somehow, afford him survival through the rest of the long hot summer month.

Settling into the couch, the brown velour cushions swallow up more and more of his frame. He adjusts the valve on the oxygen tank and stares at the check, calculating, balancing, and distributing the accounts in his head. The math doesn't add up. The calls from creditors multiply, bringing new requests each day. He’s always polite on the phone, seemingly at ease in conversation with collection agencies that he knows are feigning a thin veil of civility regarding his condition before they commence a litany of threats.

A few weeks back, snooping children (with the best of intentions to uncover what was really going on) discovered a small scrap of newsprint, clipped from the classifieds. The bold typeface in caps announces

There is a small photograph of a lawyer, a list of abbreviated qualifications, and a phone number. The call is made. A request to discuss his case is denied. Permission can be granted only with the consent of the client. Well, the client is having a bad day. Breathing is difficult, the coughing is painful and the understanding that his children are foraging through his personal matters (while I’m still alive yet!) catalyzes a deepening depression. A very awkward conversation begins. There is no eye contact, just words adrift in the bedroom as siblings try to explain the situation, the desire to help, the unconditional love. . .His silence and obvious embarrassment to discuss his finances slowly

→

eases. He begins to talk, a mea culpa of sorts and as he speaks, a catharsis takes hold, each breath becoming more relaxed, more absolved. He makes the call, grants permission for the family to be informed, hands the phone off, and leaves the room. The conversation with the lawyer is by turns fascinating, horrifying, illuminating, and humorous. She adores our father and admits that she has never handled a case quite like his. The amount of debt is staggering. Almost inconceivable. She explains the third mortgage on the condo and the paper trail of his insolvency. She tries to explain the credit cards and her ongoing bewilderment at the number of years—the two decades that he was able to shuffle accounts and carry on, without consequences.

Q: How did he get away with it for so long?

A: I have no idea.

The credit cards. The cache of plastic stamped with status, declaring Platinum, Gold, and Silver. It makes sense, now. All the subtle clues, as in the imminent arrival of new cards in the mail every few months or his slight hesitation while rifling through the choices in a leather billfold before selecting one to be confidently placed on a restaurant bill. It’s impossible for the family not to feel complicit in the bankruptcy. All the fine meals, the clothes, vacations, health club. . . .Looking back upon the collective era of adolescence and college years it is not difficult to confess to having been spoiled. Rotten. After the conversation with the lawyer, a bit of levity breeches the atmosphere, casting aside his shame and secrecy. A sense of normalcy slips in, just another family gathered around the patriarch, kibitzing, telling jokes.

Hey dad—you know what they say about money and dying, that the last check you write should be for your funeral, and it should bounce!

He begins to laugh. He begins to cough.

The grandfather projects a military presence—officer class, in pressed khakis, long-sleeved buttoned shirt tight at the collar, and polished footwear. He is trim, with short-cropped hair framing a portrait of hardened angular features. Posture is exquisite and with hands clasped behind his back he walks with a marching stride, leading a troop of one on a Sunday afternoon outing in the park.

The child carries a bit too much of the American prosperity around the middle and is struggling to keep up. He is panting, head down, eyes focused upon the next step as he shuffles through the grass. His flip-flops are a definite hindrance. Patches of sweat are spreading across his t-shirt where a mélange of Disney characters parade through their kingdom with exuberance unmatched by the youngster.

Without looking back, the grandfather barks command in Korean. When these orders to pick up the pace are ignored, he switches to English and a more accommodating tone that immediately piques his grandson’s attention. The child begins to accelerate, bearing an expression that wavers between determination and defiance. He’s making quite an effort, arms pumping and knees raised high in an adorable parody of his grandfather’s gestures.

It’s just so damn hard, trying to catch up with

the past.

Tennis with mom and dad at the neighborhood courts. • Family fun on the putting practice greens at the country club. • No more trips to the country club and not understanding why. • His anger and anxiety at my $23 stamp collection bill. • His sports page and a cigar. Always. • Mom was always more help in assembling any toys or models. Always. • Watching him do pushups with the men at the Y, the counting off and the screaming. • Getting together with his buddies as they run sprints and toss the football. • Together at the car shows at McCormick place. • Waiting in line at the car show to shake hands and receive an autograph from Jesse Owens. • Summer days at Rensselaer, the pre-season practice facility for the Bears. • I’m always freezing, nestled beside him in the stands at the Bear games at Wrigley and his frustration at always having to leave in the 3rd quarter because I’m cold. • No matter the brutal temperature, he only wears a driving cap. His ears bright red. • The long walks along the lakefront to attend the games at Soldier Field. • A nose job that he admits nearly killed him. • The heart surgery that nearly killed him. • His panic and pacing in the apartment upon receiving the call that his brother, Bob, just had a heart attack at the Y while playing basketball. • Noticing that dad had a very limited food palette. • He always has a bag of Chips Ahoy! in the fridge. • There’s always candy in the fridge. • Boxes of Fannie May chocolates and Frango Mints, gifts from friends at the office are always in the fridge. • Screaming at the tv when the Jet’s game broadcast is cut off in the final moments so the film Heidi can begin as scheduled at 6pm. • His incessant cursing at the tv while watching football, any team. • His melancholy expression and acquiescence to having to ride the bus to work downtown when he could no longer afford

parking. • Watching him lay out his wardrobe for the workday to come. • Being told by the doorman at Imperial Towers that he’s lookin’ good but he’s forgotten his pants (though he is carrying his briefcase). • Watching him fall off the carpet on the giant slide during our vacation at the Dells. • Watching him crash into a plate glass partition at Uncle Bob’s country club in Florida. • Hearing about his fall over the second floor railing and the crash upon the glass coffee table at the Blink’s home. Amazingly, no serious damage to the body. • His fingers carefully turning the padlock dial in the locker room. • Every meal, eaten slow and patiently, never in a hurry. • One Heineken at the most, enjoyed with a meal. • Dinners in Little Italy, always sitting in the kitchen area, like a family meal. • The table graced with his pals, Fat Harry, Fat Larry and The Whale. • His lottery tickets in the drawers. • Years of checks piled in the closet. • Years of insurance forms and applications—indecipherable—stacked in the closet. • His upbeat public demeanor while having to endure my pitiful play on the field. • Listening to Dixieland records, snapping his fingers. • Picnic at Ravinia while Preservation Hall Jazz Band plays his favorites. • The fragrance of the pool towels • Running through the lobby of Imperial Towers on our way to the pool, the elderly Jews looking aghast at our near naked bodies. • Running sprints at the Loyola University track along the lakefront. • Listening to my mom and dad arguing about money in their bedroom. • The Sherwin Ave. apartment and our millions of moments together. • Parental meetings at Stephen F. Gale Elementary, convened due to my inappropriate behavior (too embarrassing to list). • The intersection at Hollywood and Sheridan, the release onto Lake Shore Drive, the Montrose exit to Imperial Towers.

“Why

do you have to go so far away?”

His candid request interrupts my studies so I push aside the Russian grammar lessons and silently return his gaze

Not quite sure how to explain a life so very different from his.

JULY 7, 2002 *

The threat of a nuclear apocalypse is upon us. Each day is a new adventure for the valiant knights, fearless defenders of the schoolyard in preparation for battle against the sub-human creatures that wander the earth and haunt the cavernous hallways of Stephen F. Gale Public School.

The morning bell provides temporary shelter from the beasts but little in the way of protection from teachers who threaten and scold us with dire consequences of atomic annihilation for failing to suppress our laughter during the air raid drill. The siren drones on and on, careening through the halls where hundreds of children huddle on the floor with backs to the wall, heads tucked in and knees hugged tight to the chest. We perform just as we have been instructed in countless drills that are illustrated in government posters displayed in every classroom.

Those slightly macabre graphic lessons never explained the best part of the emergency—how if we cup our palms to our ears while the siren is broadcast and open and close, and open and close we can create a dissonant harmony of survival in our heads, a bit like a wah-wah peddle for the post-apocalypse generation, playfully keeping the beat while teachers grow impatient and despondent in their failure to guide us to safety and the distant realm of moral values.

We the children are winning the war.

A 12 gauge, double barrel, sawn-off shotgun is discovered under the bed. The stock is well oiled with the patina of time and the serial number is erased. I wrestle with my conscience, trying to formulate a scenario. Such as, how did it arrive, here

A film noir scene comes to mind, scripted from the dog-eared pages of murder that inhabit my father’s treasured library of Capone and Nitti and the O’Banion boys. Fade-in to an ethereal atmosphere in grainy black and white, a cryptic cityscape of gutted buildings and fleeting shadows. It is well past midnight as two men gather under a fire escape in the alley. Fedoras are pulled low concealing the eyes and cigarette smoke is absorbed in the mist of the omnipresent rain. Their overcoats betray the likelihood of a backup. They exchange nods, they exchange cash, but little in the way of conversation. Two sedans continue to idle in the street with extra muscle nestled into the front seats, carefully surveying the transaction.

The movie plays on, transporting me back to the velveteen darkness of the Granada whose stately marquee of theatrical grandeur has long since diminished. Much like my father, whose waning breath barely stirs the air nor rustles the bed, concealing a tale of the weapon below.

→

Finality weighs heavy upon the hearth as the family gathers for a meal. We talk. There is a discussion of his despondency, his rash thinking, the occasional slips of memory. Someone mentions suicide. Suicide? The family psychiatric clinic is called to order. Theories of behavioral patterns, childhood memories, gangster infatuations, and his diminishing options are explicated and diagnosed. We are in accord that all weapons must be confiscated from the scene, that all temptation must be removed.

My brother recalls our father’s last known escapade with a firearm that resulted in a security breach on the upper floors of the condo. Several years ago, a 38 was kept in the nightstand for nocturnal protection. One evening, dressed all the part of a Vegas Wise Guy, he strapped on the holster, turned off the safety, and gave the barrel a few spins. While trying to open the chamber he somehow discharged a missile down into the concrete and metal strata of the 19th floor. After this incident, Douglas convinced him that he was more secure without the bedside heat. The prognostications continue. There was still a shotgun under the bed—an illegal, unlicensed, and unmarked weapon of dubious origins. Everyone agrees that I have to get rid of the gun. I have to get rid of the gun? From the 19th floor of the condo? My covert assignment does not include instructions.

The film reel spins, scanning the celluloid villains of my youth. I search the apartment for clues, methods, accomplices, anything. I need a giant box for delivering flowers—isn’t that how Coppola did it? I picture myself in the elevator, the weapon concealed by a trench coat, my face shadowed by a fedora pulled low. But not low enough to avoid recognition from the horde of Jewish yentas, flooding the compartment with their outrageous hairdos and onerous perfumes, on their way to a poolside summit, where the conversation never veers far from tonight’s broiled chicken and Floridian dreams.

Or, maybe it's just the Polish maids and me, making an inconspicuous exit in the freight elevator, trading quips about the homeland and these strange United States

But reality proves to be much less mysterious and hardly ennobled. While the patriarch is undergoing yet another battery of tests at the hospital, I slip back into the flat and remove the shotgun from under

the bed, gently placing it upon the quilted spread. Its menacing caliber appears temporarily assuaged by the domestic tranquility of paisley pillows. I grab the Travel section of the Sunday Tribune and carefully wrap the weapon in a blanket of promiscuous Caribbean ads.

An escape route is hatched and rehearsed. Unlock the front door. Scan the hallway. Empty, dark, and silent. Perfect. Socks glide silently across the floor. Enter the vestibule, locate the incinerator chute, open the door, and it’s… bombs away. Nineteen floors of metal against metal, stories against storeys in a free-fall of apocryphal tales and absurdist possibilities.

Such as. . .

. . .the urban adventures of an indigent trawler on Monday morning, rummaging through the trash and searching for the discarded jewels of the city. A glint of metal catches his eye. He grabs onto the object, unwrapping the shredded remnants of sun-drenched couples from the barrel. His bewilderment breaks to laughter, recalling a distant childhood of Duesenbergs, speakeasies, and turf wars. Scanning the alley for witnesses, he raises the barrel and strikes a pose of inimical contempt—just like one of the boys, in the city of Capone.

Mission accomplished. The family welcomes my report as a momentary reprieve of comic hilarity from our collective days of sorrow. Douglas inquires if I remembered to check the barrel to make sure the gun wasn’t loaded before I sent it on its precarious journey. I feign an air of conceit and declare, affirmative. I lied.

Breathing heavily he reaches down for one final attempt, embarrassed at the indignity of his repeated failures to complete this most mundane of life’s little chores— tying his shoes.

The laces remain inert as his fingers fumble through finger memory and with tears welling up he shares a rare, unsolicited reflection of fatherly advice—

Don’t piss away your life like I did.

A wounded pigeon, its claws bound in the sinewy detritus of the city is hopping and falling, hopping and falling, as it receives the pitied-eyed but don’t get involved look from the morning commuters with their steaming cups of coffee and daily papers in tow. Inquisitive children stop and point, dragged along by impatient parents with vociferous reprimands of “Don't touch anything!” as the bird continues on its crippled jig of misery.

A drifter in soiled rags, pushing her cart up Chicago Ave. stops before the melee of indifference and picks up the bird in her soiled yet tender hands. Someone in tailored Armani walks by and quips, “she’s got her dinner”, eliciting laughter and derision from the passing assembly. The drifter pays no heed and whispers a matronly song of comfort as she carefully unwinds the suffocating nature of this city, that stifles a longing for flight and willfully binds us to this insensate land.

We roll our father into his new accommodations, a sizable room with the typical accouterments of a care facility. A television hovers above with the muted lunacies of a game show flashing by. An elderly woman sits vigil over her husband’s bedside, raising a hand in a quiet gesture of welcome and understanding. For a man who cherished the camaraderie of his army days, who thrived in the communal and jocular character of YMCA locker rooms, privacy at home was sacrosanct. The reality of a roommate during these final weeks was one more humbling fissure in his venerable armor of solitude. Once again, the family had to deliver the disheartening lecture on finances and why he can’t remain at home.

As he settles into bed, a caregiver approaches with the evening meal. She lifts the stainless cover without much ado, revealing a serving of mini hot dogs and tater tots. The indignity of the platter before him is too much to bear. We try to lighten his mood, reminiscing of the days of yore at Marconi’s in Little Italy, when the fabled characters of Fat Harry, Fat Larry, and the Whale would grace our table, stuffing themselves on rigatoni and quibbling over odds for the evening races at the track. We always dined in the kitchen area where the playful banter of the crew—a rancorous and linguistically creative blend of English and Italian—provided a family atmosphere he treasured. He pushes the tater tots around the plate with his fork before resigning himself to hunger.

Requesting that we open the blinds, the room fills with the hushed luminescence of dusk. A pastoral landscape across the road slowly reveals itself as our eyes adjust to the light. A cemetery comes into view. He closes his eyes and turns away from the window.

The treasured rug that was so carefully coiffed and manicured each Saturday to crown a scalp of immeasurable pride now looked as haggard as the man under its shadow. Slightly askew and hopelessly frayed, it’s become a disintegrating shell awaiting the final act when the performer can tip his hat, so to speak, and bid us adieu in grateful appreciation at the close of the show.

I remember helping my mother with the chores when she spoke of a surprise that evening when dad came home. Surprise. Few other words could ignite the unbridled passions and dogged imagination of childhood. At that age, the concept of hair upon a bald man, a man you have always recognized as bald was beyond novelty. More like fantasy. Or hallucination. And fantastic was the moment when he stood in the foyer waiting for our recognition before he strolled through the hallway like a runway model. Entreaties to touch, to tactilely understand this new substance upon my father’s head elicited shrieks of careful and gentle. He patted my disheveled locks and jokingly mentioned something about youth.

A foam mannequin head was the nighttime repository for his new self-image. Each morning, the tape was carefully applied and the piece tenderly positioned upon his pate with a tug here and swivel there as the comb was delicately swept through the sides to blend the genuine and the artifice.

As the years passed, the toupee adapted to the fashion of the day, as the jet black flattened side-part slowly began to rise, as grey began to encroach the temples, as curls morphed into a full-bodied snow-white pompadour. But the finest of pedigrees and maintenance could not deter the follies of pride, as when a fellow jogger had to tap my father on the shoulder to inform him that his hair was swaying from a low hanging branch some ways back on the trail, or when Roberta, early on in their relationship and anxious to run her fingers through the gorgeous white plumes, slid the piece right off his head.

During the final years, a melancholy, symbiotic relationship developed between my father and his hair, as both entities began to succumb to his worsening financial circumstances and failing health. The hairpiece now seemed to take on the mantle of a security blanket that accompanied him on the humble and disheartening journeys through hospital corridors and the offices of bankruptcy lawyers.

Guiding my father onto the bed, the nurse—ever mindful of appearances and the dignity of age—turns away in laughter and promises not to touch that thing. The piece later disappears along with the man, swept off to the backstage of existence, leaving us to extol the grandeur of the performance.

“.

Final words from the man who never waxed philosophical

Never

quoted Plato nor Proust

Preferring to immerse himself in the back pages of the Trib

Perusing the stats from last night’s big game.

His table conversations never ventured far

Towards personal thoughts or reticent dreams

Preferring to remain entrenched on the surface

As I dove untethered into waters unknown.

Maybe he was saving the best for last

Maybe he had it in him all the time

Absorbing enlightenment vicariously through children

And the Friday night services he sat through undaunted

Silent in prayer with eyes always opened

Where was he drifting during all of those sermons?

The swan song of summer with its many farewells As we journeyed together through each new prognosis Of provident hopes and useless placebos That perjured the body and ravaged the soul.

He eventually traded the doctors for decency Accepting tranquility in morphine’s sweet drip That summoned the courage for a parting farewell In a long-distance call though we’re no longer distant:

“never back down, never be afraid, come back around, I’ll tell ya about it someday”

Can’t recall if I ever heard him recite a prayer in Hebrew. • I do recall him lighting the Yahrzeit candle in honor of his father. • Dad yelling at his father to quit playing with the electric windows while riding in the back seat of the caddy. Grandpa Frank was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. • Dad visiting his father at Grandpa Frank’s apartment. I recall a small room, overstuffed cushions, an old man. • These two recollections are all that exist in memory of my grandfather. • Visiting Uncle Bob and feeling that he was so much more prosperous than dad and lived in a big house with a basement and a pool table. And always a new Cadillac in the garage.

• Our family holiday dinners with Uncle Bob and Aunt Rose, the two brothers seated at opposite ends of the table, always provided the turkey legs. Bob devoured his in minutes, dad carefully nibbled forever. • I just wanted to finish as soon as possible to race downstairs to play pool. • Dad always patting me on the head, observant of how wild my hair was but not saying much. • Watching him carefully remove his hair at the end of the day and carefully place it upon the grey, stuffed mannequin head. • Watching him carefully lay out his clothes for the following day at the office. • Attending the ’76 Olympic Gymnastic trials at Penn State. • Dad pushing the golf cart uphill after the battery died on a course in Pennsylvania. • He absolutely tried to kill the ball with every golf swing or shot with a tennis racket. • Walking to Soldier Field with our salami on rye sandwiches, two each. • Chinese food; he never ventured further than Steak Kow and Egg Foo Young. • Broiled chicken, potatoes and a plate with sliced tomato. • Broiled whitefish, potatoes and a plate with sliced tomato. • I think he would only eat foods that his mother prepared for him.

No stories of adolescent aspirations.

No stories of growing up during the depression.

No stories about Maxwell St. in the 30s & 40s.

No stories about childhood antics in the city.

No stories about his mom and dad.

No stories about army life. No stories at all.

“You really want that ugly fuckin’ thing?”

When I mentioned that I had to have the rose-colored jacket, the ultra suede , featuring lapels from before my time in fashion and matted down a bit in the collar and elbows,

My uncle’s response revealed that he never knew the secret of the inside pocket— the benevolent vault worn close to the heart from which my father withdrew the stashes of cash. Rolls of hundreds in the days of yore as he donned the mantle of the grand provider, lavishing a new prosperity upon his children in a steadfast reminder of his climb to the top.

As when he’d say, “just grab a 100” and our eyes would alight in rapturous greed, shuffling through Franklins for the crisp and the clean that we senselessly tossed at the illicit and frivolous.

Through the passage of years and the reversal of fortunes, the jacket remained in its hallowed shrine, secreted away behind mirrored partitions, delicately draped upon a gold Gucci hanger, a bit out of style and depleted of cash.

In the end, there was just a clean little stash of tens a final 130 , that went towards the body and the ashen remains, cast out in the waves at the Montrose St. harbor.

The summer of 2002 slowly diminishes its power to rattle the ground beneath my feet. There are times when I still feel that I’m balancing on a fault line of memory, a rollicking landscape of aftershocks that unsteadies my ability to decipher between remembrance, invention, apocryphal tales, and what might effectively be called history.

Chicago remains deeply embedded in my identity and imagination. The cultural diversity that defined our classrooms and neighborhoods on the North Side underlined a genuine social integration that is dearly missing or badly fractured in so many communities today. Stephen F. Gale Public School held United Nations festivals with the parents preparing culinary delicacies from Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America for a smorgasbord of taste and friendship. The City of Big Shoulders was an urban carnival of giant sculptures that guided my education and life as an artist. As a tourist, I’m downright giddy about The Bean and everything in Millennium Park.

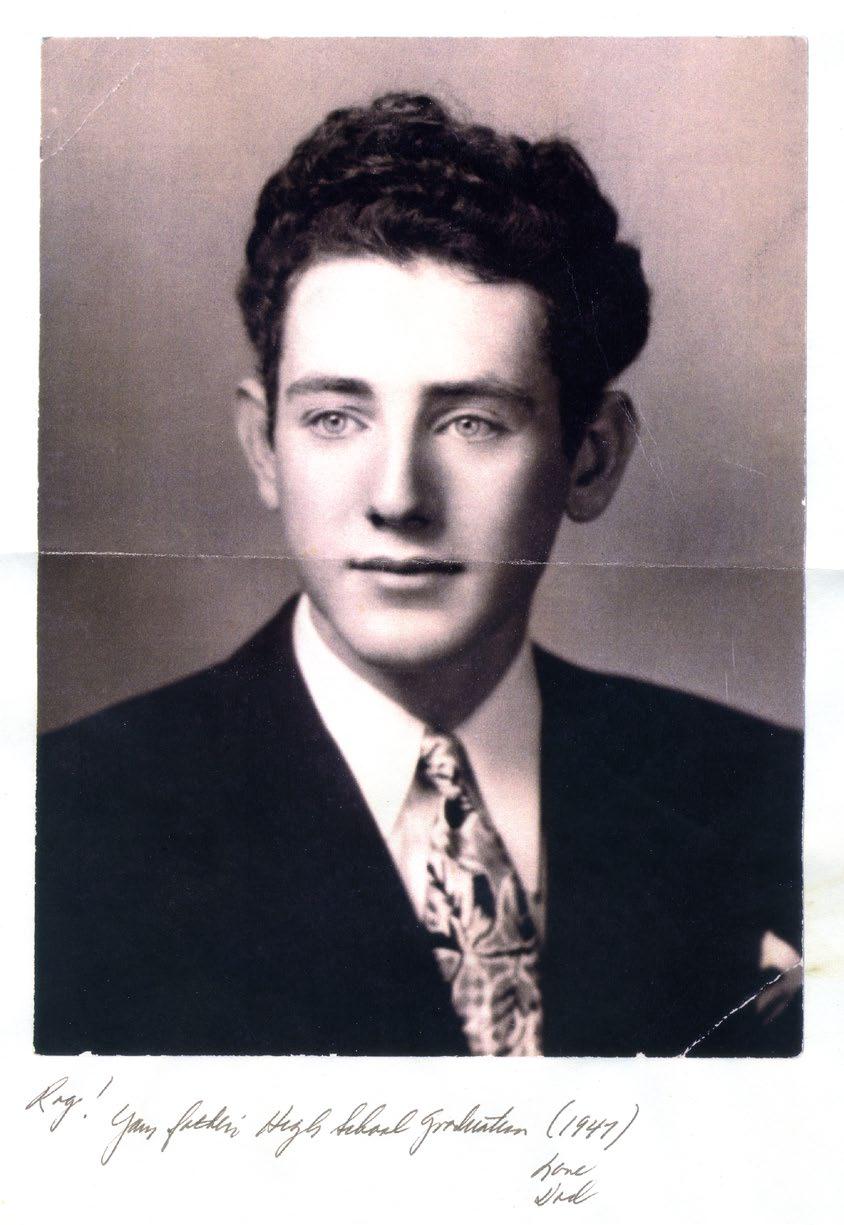

There’s a folder on my desk with newspaper clippings from the summer of 1915. One of the articles has the subheading: Man Finds Young Bride’s Body in Armory After 42-Hour Search. The man was Frank Colombik, my grandfather. The young bride was his wife Celia, one of 844 Chicagoans who perished in the Eastland Ferry disaster on the Chicago River on July 24, 1915.

The direct consequences of this historic tragedy upon my family lay submerged for over a century. My father and my uncle Bob never openly discussed their dad. The grandchildren never received the family lore, never gathered for a fireside chat after holiday feasts to hear of Frank's adventurous migration from Lithuania, his early years in the city, his lifeshattering experience during one the worst maritime disasters in US history… Not a word.

And so here I go accelerating once again into history, mystery, city, and family. A continuous weave into the beautiful unknown.

by Roger Colombik

RC26@txstate.edu • rogercolombik.com • @rogercolombik

All Rights Reserved • Published in 2021 • Design by Katie Gordon Enguri River Press • 1400 Days End Road, Wimberley, Texas, 78676

ISBN:978-0-9899748-4-4