2

Contents

4 The Invisible Hand, Bradley Ford (story extract)

12. Simon Says, Ellie Jay Bagshawe (poem)

13. Ketchum, Emma Rushfirth, (novel extract)

20. From the Factory Floor, George Bidwell (novel extract)

24. Strawberry Lane, Harry Blackburn (novel extract)

29. Poetry, Iwan Jones

32. Poetry, Jack Lawton

33. 10 Ways I am trying to be a better feminist, Libby Barker (blog)

40. Poetry, Marc Rooney

43. Poetry, Peter Cameron

47. My Ladybird, Ruby Bryant (memoir)

51. Warning, Danger, Alien Spacecraft Approaching! Stacey Beaver (book review)

3

The Invisible Hand

Bradley Ford

4

Grant me, Lord, to know and understand whether a man is first to pray to you for help or to praise you, and whether he must know you before he can call you to his aid. If he does not know you, how can he pray to you? For he may call for some other help, mistaking it for yours.

Saint Augustine, Confessions

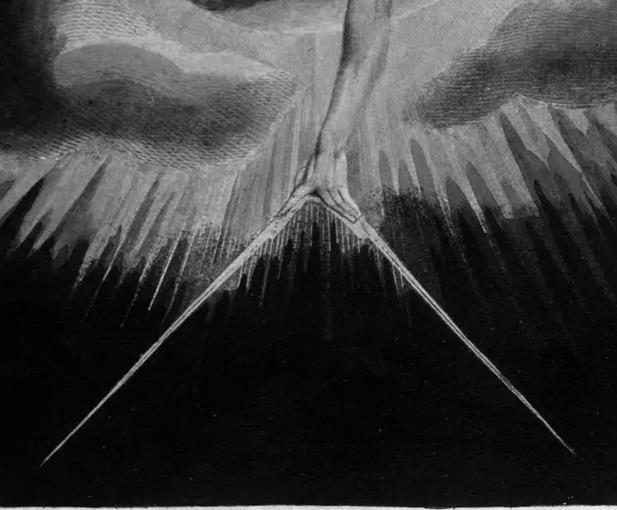

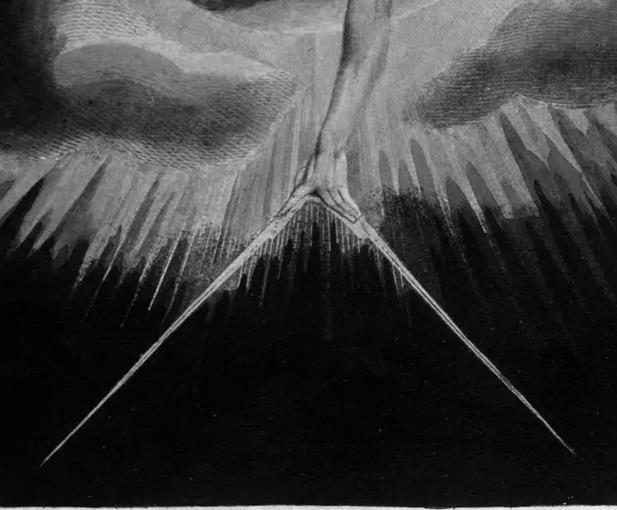

Belief has a strange way of altering gesture. Look at William Blake’s TheAncientofDays, for instance: the holy fingers of a white-haired God, his arm an arcing compass from the clouds guiding our ideas, our decisions, our lives. Look at Michelangelo’s TheCreationofAdam: God creating the first man; their index fingers almost touching, but not quite. Adam is loose, uncertain, perhaps even distracted. God, on the other hand, is rigid in his motives. If we are privy to the gestures of God, do we appropriate his movements and postures? It is curious, the way our bodies behave; how our limbs lift and wobble; how we stretch our arms out in a kind of divine salute to give directions, to provide guidance.

5

When they found me at art galleries, standing in front of these paintings, they took it for an eccentric use of my spare time. I preferred it to their rooms full of smoke and their thick carpets full of ash, their orders for more smoke or sweet tea to relieve dry throats. They would speak about God: how important it was to approach Him to eventually, hopefully, touch His face. Now these men were a distant yet persistent memory, I could regard their exploits with empty lungs and a parched throat. Perhaps they were right. Perhaps they used their spare time more efficiently.

They looked perfectly at home in their long, narrow rooms; but I was always restless. The furniture was burdened by patterned blankets, embroidered shirts, gilded lamps, people. All the refined detritus of a world laid out across an armchair. All of it invisible, obscured by smoke. I had spent long enough in those fog-ceilinged palaces to know that I would prefer to see what is in front of me.

6 •

At the galleries, I would look with my eyes, to begin with. But after a while, I would always have the feeling that I was only accounting for a fifth of what was in front of me. Then

I would look with the rest of my senses, until I began to see. It often took some time, but there would always be at least one painting, one frame, one caption, one overheard phrase, one enthusiast nudging her companion, one tourist gesturing to the vanishing point of a painting that had already vanished.

7

Absence has a strange way of altering belief. He is here, but He is not there. He is invisible, yet He is tangible. On their podiums, one after the other, they would say to us: “Without reliance on God, our job is impossible.” If we voiced any argument, they would clarify: “It can be thought of as the space between two fingers.” Personally, I never questioned it. A man on a podium has a better chance of reaching our minds than a man in the sky. But, it seemed, a man in the sky has a better chance of reaching our hearts than the man who stands on the podium. They are constantly invoking Him, but they never pay their dues: in great halls, in front of greater crowds, they either select a few faces to look at in turn or fix their gaze on the back wall. Have you ever seen even the greatest speaker look up?

•

The jazz singer had her eyes closed, whispering Billie Holiday’s I’llBeSeeingYou to the atrium of a half-empty art gallery. I recognised her from a few of the clubs uptown: Sonata, The Egg. She was known for being overfriendly with her audiences.

Tonight, her face was sharpened with contempt; and without her band, there was silence between her words. Instead of her

8

usual black satin slip, the event organisers had dressed her up in a red-feathered gown that made it difficult to separate her from the exhibits. Either it was of poor quality, or the gown must have been designed to moult over time: red feathers littered the stage.

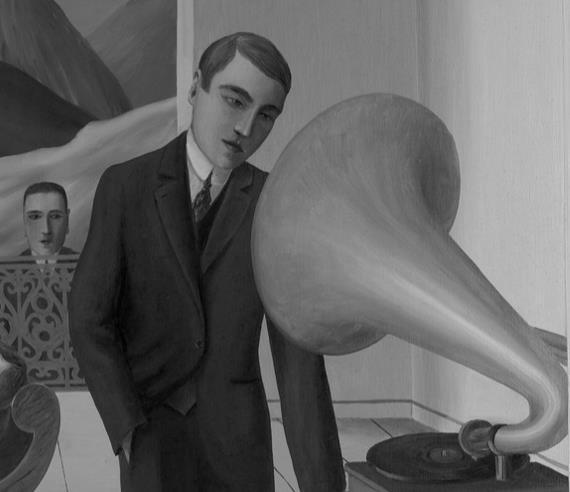

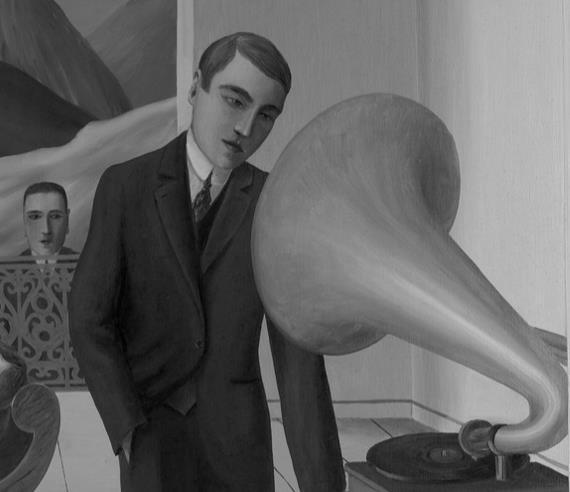

Perfect for a Surrealist exhibition, either way. I turned around to resume my study of René Magritte’s L’Assassinmenacé, a favourite painting of mine, trying not for the first time to figure out whether there is any remorse in the assassin’s eyes. At a glance, they can seem wholly indifferent, although closer scrutiny always reveals a latent melancholy. However far I get, when the rest of the painting is taken into account, his eyes become less interesting. The first thing that strikes me about this man is that he is clearly caught between two states of mind. One: the sudden absence of motive; and, consequentially, two: a new awareness of the presence of music. His gaze is fixed on the horn of a gramophone. Whatever task he has been set, he has wavered from it: his jacket and hat are off, draped over a chair; they have been hastily discarded, his briefcase similarly abandoned beside him. Behind him, on a divan, lies the pale corpse of a naked redhead, a thick dribble of blood leaking from her mouth. A

9

white towel has been draped across her collarbones, covering part of her throat. At first, I think she must have been relaxed when the assassin took her life, reclining on the divan, listening to a record. But when I look closer, the only part of her body that isn’t rigid is below the knee of her left leg. The whole situation begins to look more and more like an arrangement. A setup! Sometimes I feel the need to question this further; but this time, it doesn’t seem important. Hiding behind the partition are two bowler-hatted heavyweights with truncheons and nets. Apathy, underlaid with quiet intent, lines their faces. Three more bowler-hatted heads rise from behind the balcony rail, their arms pinned by their sides. Behind them, mountains. The assassin is surrounded: they are waiting for the right moment to arrest him. By taking his hat off, he has successfully in their eyes renounced himself, removed any affiliation with them, and welcomed their wrath. But they are undecided: he has already been arrested by the music from the gramophone.

“There are seven bowler hats in total.”

A woman. Irish. I did not turn to match the voice with its face.

“Seven? I only count six.”

10

“Give it time.”

A brief silence. Northern Irish.

“You know this painting has been doctored? The original shows three hatlessmen behind the balcony rail. And the main subject’s hat, discarded hastily onto the chair, should be of a markedly different style, not identical to his captors’.”

In contour and intonation, her words were a disquieting reflection of my thoughts.

“It must be hard to sing in a gallery.”

A longer silence. Not from Belfast, then.

“Have you seen the Giacometti sculptures?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Have you really seen them?”

“I didn’t come here to worship.”

The atrium was filling up with visitors; and judging by the shifting contours of the jazz singer’s voice, she had opened her eyes to welcome them:

“I’llbelookingatthemoon,butI’llbeseeingyou…”

The last line of the song was delivered with such intensity that I had to turn and face her. Her efforts were received with silence, despite the full seats facing the makeshift stage. She looked down at her feet, ashamed. I averted my eyes to the ceiling: a new clarity descended. The fluted columns seemed to

11

quiver and vibrate, as if struggling to hide a fraternity of monks wobbling on each other’s shoulders. A fat, waddling figure –– man or woman, I couldn’t say went past the stage and into the sculpture hall, the squeak of its rubber-soled shoes applauding the jazz singer’s performance as she began her next rendition:

“Icoverthewaterfront…”

The sea was grey and apparently boundless. It irritated me. The currents were relentless. Our boat, small and without cover, somehow rocked gently. The petrol engine throbbed and spluttered. The captain, haggard and malnourished, whistled as if the sea and the engine were his bandmates. We were headed for a mass of grey mountains. They didn’t seem to be getting any closer, so I placed my bowler hat over my eyes, inhaled the

12

warm odour of my scalp, and listened to the captain’s lisped whistle until I fell asleep.

I dreamed of a white villa, its plaster cracking. A fat, wet figure apparently female was boarding up its doors and windows. Matted carpets of soaked red feathers littered the footpath, marking where she had been. Only one door remained to be boarded. When she gave up hammering and came out onto the balcony, leaning heavily on the rail, she was quite clearly a man. There was a feeling of expectancy expectancy without apprehension, like a spoiled child opening her fourteenth present.

I forced myself awake. My hat slipped from my face and fell into the water. I immediately focused my attention on the captain to stop myself from dozing off again. He seemed to have whistled himself into existence. If he stopped now, that would be it: the engine would stutter and halt, the sea would give up, and we would both fall gratefully into absence.

The monks welcomed me at the mouth of a cave. They said they were followers of San Giacometti. Confused, I turned to face the shore: the captain was already firing up the petrol

13

•

engine. I watched his back as the boat receded into the sea: he was well fed compared to these narrow monks. One of the monks clasped his hand around my shoulder. His skin was soft and malleable. I had the feeling that if I pressed my thumbs onto his palm, the imprint would ripple and re-arrange its lines as if I had dropped a pebble into a puddle. They led me into the cave. I got the impression they would rather be static, but they were compelled to move by forces beyond themselves. They had the slow, lumbering movements, the soft, crooked necks, the ringed, sallow, cavernous eyes of those whom smoke had not just concealed but consumed. They lifted their arms and beckoned towards proximities beyond my sight, smiling as if they had privileged access to a world beyond this one. I began to regret my departure from their long, narrow rooms. Their smiles were so wide, so self-assured: they did not recognise me.

14

Simon Says

Simon says raise your right hand

Simon says put your right hand down

Simon says raise your left hand

Put your left hand down

Haha! Got you! Simon didn’t say!

Okay let’s try again

Simon says cross your arms

Uncross them

Got you again! Simon didn’t say!

You need to make sure you listen to Simon

Simon is in charge here, not you

Simon says smile, show your teeth, look pretty, show your worth!

Simon says pull that dress down, everyone will think you’re a whore

Simon says wear something sluttier, everyone will think you’re a prude

Simon says come on, loosen up

Simon says show some skin!

Why won’t you listen to Simon?

Simons in charge, not you!

You need to listen more!

Simon says you don’t know how to listen?

Simon says you’re slacking behind everyone else

Simon says you’re worthless

Simon says don’t cry, you’ll ruin your makeup

Simon says you’re only desirable with that pretty little makeup on

Don’t stop now!

Don’t stop!

Why are you stopping!

I said don’t stop!

Did Simon say stop?

No, so keep going!

You’re a pretty little bitch

Simon says you’re a pretty little bitch

Simon says say thank you

Simon says use your manners

You chose to play this game, now you’re complaining?

You’re ruining it for everyone else!

Simon says stop ruining it for everyone else!

Stop ruining it for everyone who’s trying!

You’re not trying!

Try harder!

Do better!

I don’t care if Simon didn’t say, Simon told you to do it so you do it!

Good girl

Simon says you’re a good girl.

Ellie-jaiBagshaw

15

16 Ketchum

Emma Rushfirth

When I dream, I dream of Adrienne. The shape of her face, mainly nice. The way her nose would crook slightly to the right, her plethora of freckles, the exact indents in her cheeks when she would smile. The way she’d rock on her heels when smoking. The heavy Midwestern lilt in her voice, catching on the vowels. The smell of her hair after a day on the slopes. The coldness of her breath. The colour in her cheeks. Her worn overcoat, the marks from her sturdy boots imprinted in the snow.

When I still lived in Ketchum I would dream in pieces: fragmented images of my father that would shock me awake like ice down my back. These dreams began some time before Ketchum and I’ve kept them with me long after. Adrienne used to rock me back to sleep, clammy sweat sticking our bodies together. I never dreamed of her then.

Now, I wake from a dream of her, in the front seat of my Chevy. I feel like I’ve just met God. I feel like I’ve just shook His hand. Pushing open the door, I swing my feet out and crunch my way down the small layby. I light a cigarette.

17 Nell, 2018

Breathe it in, and watch the odd car snake across the desolate Idaho highway.

The wind is biting. I can taste the frost in the air, feel the sting of early morning snow and if I breathe sharply, I can feel the hard peaks in my throat. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen this expansive stretch of white sky. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen Ketchum.

I stub the cigarette out with my heel. There’s a long drive ahead of me. I wipe away the remains of sleep. Tomorrow, it will have been twenty-four years since I last saw Adrienne. I need to be awake.

A cop pulls me over twenty miles away from Ketchum.

I’m surfing through radio static with one hand when I hear the sirens and feel the cool blue light on my face. It takes me a few seconds to realise the sirens are blaring at me, and a few more to manoeuvre the car off the freeway. I shut off the engine, turn around to the backseat, littered with maps, coffee cups, layers of clothes that I’ve shed as the day warmed up. There’s my old afghan on the seat behind me. Small splatters of blood cling to the fabric. I’ve been meaning to get rid of it for years. I can never bring myself to.

He knocks at the window and I roll it down. He’s an older man, in his fifties, with a wiry grey beard and a gut that

18

strains against his uniform. He’s got a pad flipped open in one hand, a pencil in the other.

“You were going pretty fast.”

I smile apologetically and nod. I was cruising at an easy fifty, well below the speed limit, but I know this kind of cop: bored on the stretch of empty road, pulling over any car with a dented bumper or faded plates.

“You in a rush?” He’s looking between me and his pad, face drawn sceptically. I wonder if he recognises me.

I say, “Not particularly,” my voice cracking slightly at the foreignness of speaking. The cop frowns. He looks older with his brow creased and his mouth downturned. Maybe he’s older than I think, sixties not fifties.

He hums thoughtfully at this, peering to look into the backseat. He knocks on the darkened window. “Does this roll down?”

I scramble to oblige, yank the window down. It makes a painful screeching noise which makes both of us wince. “Sorry.”

“This yours?” He points towards the afghan, reaching a hand over to pick at the stained pink material. I swallow. He rubs the material between his fingers thoughtfully. “Could do with a wash.”

19

“She had a nose bleed,” I say. “My daughter. It’s my daughter’s.”

The cop drops the material but doesn’t lean back out the car. He uses the pencil in his hand to poke at the empty coffee cups.

“I’ve just been out to visit her, and her nose just wouldn’t stop bleeding. She’s at college. Started in the fall.” I can feel the cop’s eyes on me, my entire face burning with the heat of the lie. “Out in Boston, of all places, it’s like she doesn’t know there are colleges closer by. It’s like I said to my –”

The words stick in my throat, and I can’t force them out.

“I know how you feel,” the cop says, leaning back out the window. “We were looking around colleges with our youngest the other week. She wants to go to the East Coast. It’s like they can’t wait to get away from here.”

He laughs and I do too. I wind the window up. I’m scared if he looks too hard, he’ll see the cracks in my story, in this mask I’ve grown so used to wearing.

He wants to run my plates. He takes down the numbers in his little notepad, and when he asks for my name, I don’t hesitate to say “Hailey Chiles.” This has been my name for long enough now that it slips out easily. Everything comes up clean. I pretend not to be relieved.

20

There’s an urge, right as he’s leaving, to tell him my real name. To see the way his face would turn, the darkening of his eyes, the flicker of recognition. Would he see the familiarity of my features once he knew who I was? Would he wonder how he didn’t see it straight away?

He stops suddenly a few paces from the car, half turns to face me, and I’m convinced he’s worked it all out. I swallow.

“You think she’ll be okay?” he asks. “My daughter. By herself at college?”

There’s this feeling, in the pit of my stomach, like I’ve missed a step or fallen off the sidewalk. I shrug. I hope it’s reassuring. The cop raises a hand to say goodbye and retreats into his car.

I lean back breathlessly and close my eyes for a second.

When I open my eyes again, the sky has darkened to a deep blue and a thin layer of frost has covered the bonnet of the car.

The motel is just a short drive from where I was parked, 18 miles out of Ketchum, and practically deserted. For a second I think it’s closed, but the dimly lit bulbs flash on the “open” sign and there’s a man in the reception, sucking on the end of a barely lit pipe.

21

-

-

I pay in cash, and the man asks no questions, though does crook an eyebrow when he sees I’m wearing muddy blue trainers instead of snow boots. They’re eight years old, soaked through and peeling apart at the sole.

“No grips on ’em,” the man says. “One patch of black ice and you might take a nasty tumble.” He doesn’t show me to my room – instead, he points to his right. “Three doors down on your left. Don’t leave the shower running all night.”

I want to ask if that’s something guests do often, or if he’s making some clumsy reference to Psycho, but he’s already turned his back on me and is doubled over, trying to relight his pipe.

I follow his instructions – three doors down to my left, the last room in the motel – and push the door open with my shoulder. There’s a particular stench to the room, like something decaying, and a mark on the bedspread the colour of dishwater. I cover my nose with one hand and shut the door with the other, praying that if this man is the descendent of Norman Bates, he’ll at least kill me quickly and with all my clothes on.

Avoiding the bed, I inspect the rest of the room. A beat up desk, a telephone haphazardly stuck to the wall, a lamp

22

with a smashed bulb. The bathroom is a small square with a basin, toilet and shower. I run my fingers over the tiles and count the cracks. Seven, one in the centre of the shower wall the length of my arm. I turn to the mirror. I avoid catching eyes with the woman staring back at me.

I’m tired suddenly. I lay on the stained bedspread. I close my eyes and when I do, I see Adrienne. She is dancing for me, twirling by the fire. There’s a glint in her eyes and a deep feeling in the pit of my stomach that something is going to happen that I can’t stop. I watch her dance, in her ski pants, braids twirling around her head like halos, hoping the act of this is enough to reach back and change her mind, keep her dancing, stop her from leaving me.

I open my eyes and Adrienne is gone.

I am standing smoking in the bristling morning wind when the motel owner appears and asks to bum a cigarette. I pull one out and he holds it for me to light, cupping his hands around the flame to protect it from the breeze.

“I know who you are,” he says, and I feel my breath catch in my throat. I take a drag, hoping the smoke will

23

remind me to breathe. Instead it makes me splutter. I stifle a cough.

I don’t recognise this man, but he could know me. I’m not vain enough to think my face hasn’t been weathered by the years, but there are still certain features that give me away. My height, for one, unusually tall for a woman, and the cluster of moles above my lip.

I drop my cigarette to the floor and crush it slowly under my foot. “Oh yeah?”

“You’re one of those Hemingway fans,” he says. As he exhales, the smoke curls in front of my face. “We get a lot of those lot passing through. Off to visit his grave, I’m guessing.”

I nod, relieved, accepting this disguise he has granted me.

“Are you a fan?”

The man shakes his head, nose scrunching up. “Not for me, darling. I prefer my writers sober and sane.”

I laugh. The man scratches his chin. “I like a good murder, I do. Christie, Capote – though of course, they call that ‘true crime’ nowadays. Do you write?”

“A little,” I shrug. I think about Adrienne. I shake my head no. “Not as much as I used to.”

24

“Well, if you were looking for a story, Ketchum would be the place,” the man says sagely. “Had its very own serial killer, some twenty odd years ago. My Jane was still with us then, God rest her soul. I remember her coming home from work in the evening when that body was found. I bet you heard about it. Gruesome business. Snow was all red from his blood, poor fella.” The man shakes his head sorrowfully.

“I’m not looking for a story,” I say.

“Shame,” the man replies, then drops his cigarette into the melted snow.

(ExtractfromNovel)

25

From the Factory Floor George Bidwell

26

Prologue

There in the fields of East Anglia, standing solitary, is the building. Neat, tidy. A box of industrious walls giving out a hum, a hum so gentle it becomes all sound. It is the cows that groan, and the tractors that plow; it is the rush of unbroken wind. Flatlands surround it without break or challenge.

Inside, everything is processed. The floors reek of ammonia, and the walls appear bleached by the substance. Industrial fans hang heavy from the ceiling and push dust into the air. Glass cabinets line the walls, and contain products produced through the heavyweight doors at the end of the lobby. They feature sugary drinks and condiments made without natural ingredients, they are children’s snacks peppered with e-numbers, they are sachets of porridge in haphazardly constructed cardboard boxes that unpack at the seams and creases. They are products produced elsewhere but packaged in this factory, in the East of England, where a worker could step away from the machines and into unbroken farmland.

Nothing fresh has ever lived in this building and nothing fresh ever will. The vending machines, rusted brown at their

27

joins, display advertisements for the rolling out of double strength squash concentrate. They hold food designed to taste good at the expense of your body. The workers indulge in droves at their moments of rest, paying half of what they would at the supermarket just a kilometer to the west. They stand to eat at lunchtimes, unable by regulation to eat at all within the factory and so are relegated to a cafeteria that sits only half of them. Those that can’t fit eat in cars, or on the damp fields, even in winter. Today the fields are empty, the lobby holds only the receptionist and her jam-jar glasses.

Behind the doors lie the production lines. All twelve of them, separated by aluminum dividers and a walkway through the middle. Each line exactly the same, each line subtly different. The technology does not whizz or whir or rush or roar. The technology trundles. The sound of clanking metal and repetitious buzzes do not fill the air but inhabit it; inhabit it so that it does not register, so that it does not reveal itself but continues regardless. Workers stand in spots marked out for them, they stand by unfinished carboard boxes near the pallets made for packing, by the tail of machines that throw out finished products, by the drill made for pushing on precision placed bottle caps.

28

Behind steel shutters lies the warehouse. It is where forklifts carry pallet to truck and carry boxes from truck to pallet. The rhythm infiltrates even the operators who tap buttons in time, unaware of their function, but following the motions of those who worked here first and taught through demonstration not explanation. The growl of the vehicles hides in the air, drawing no attention to itself and is disturbed only occasionally by thuds and smacks, shatters and wallops.

Except today, the production lines are empty. Today they do not run, and the ring of silence draws attention to the droning soundscape that typically drives production. The walkway is filled. Worker after worker line up, they turn the open space to a navy sea as their uniforms bleed into one. The hairnets only further standardise them. Replacing silence is babble, and natter, and hustle, and whispers, and hushes, and tittering. Laughter that is muted, smiles that are muted, conversations that concern anything but the immediate present. Occasionally, heads turn towards the door, waiting for someone to step into the factory and offer them answers.

A suited man steps to the front of the walkway. He wears no hair net. In a second, every eye in the building is fixed firmly upon his face, bloated and red. The suit is perfect. Professionally tailored. When he speaks, he does so with a

29

Mancunian accent but choppier, as if every word concludes a point. Now, workers’ feet shuffle, their elbows poke and eyebrows raise. He inhales and begins: “After counting the ballot four times,” he turns to the crowd and gently shakes his head, “the union and all of its members have agreed not to proceed with the planned strike action.” He is cut off by the raging crowd and begins to shout over them: “We will not proceed with the planned industrial action on the 5th and 6th of September!”

(ExtractfromNovel)

30

Strawberry Lane

Harry Blackburn

31

In a dream gone by, there is an oak tree. Its leaves are green. Its blood is white.

We are ten years old. I stand on the ground. You stand leagues above me, teetering on an outstretched branch. Reaching. All smiles and brittle bones and raised heels. Reaching, forever. Determined fingers, clawing at the heavens. Dislodging the stars.

In the dream, they fall like summer rain. A cascade of light. They shower you as you perch atop the oak tree. As they reach me, they dissipate, fizzling out in great rockets of spark and flame. You tell me it feels like floating in space. I tell you it feels like going to war. Your hands begin to curl. They begin to wrap. They begin to grasp.

Finally, contact.

Your cries ripple through the endless field. I go to shout, but the sound becomes dry in my mouth. You hoist yourself onto the highest branch, clambering to the zenith. My heartbeat slows. It stops beating altogether.

32

1.

And then, lift. On daring legs, you push yourself to stand. Your hand lifts. Your arms float in mid-air. They soar. And then, you look down at me. And I look up at you. And for just one moment, the oak tree is beneath us. I clap until my skin runs raw. I cheer until my throat catches fire. From here, we can see the whole universe.

You tremble with excitement and your wings begin to burn. The branch beneath you falters. Crack.Crack.Crack.

And I remember your eyes, as wide as fear. A lifetime in a second. The world within an atom. The branch gives way entirely. The earth is ripped from beneath my shoes. Freefall.

And for the first time in my life, I think about death. I hope it feels like a late-night drive. I hope you can see the lights on the motorway. I hope you’re asleep in the backseat. Branch upon branch breaks beneath your body. Falling. Catching. The sound of bark against skin. Wildly flailing limbs. As you near the bottom, you catch on a low-hanging branch, arms outstretched. You grasp at the wood until your fingers are bloodied. You heave yourself up to it, press your

33

body against it. You take a breath. And then, you drop. And you land on your feet. You land in the grass. And you laugh. And you wheeze. And I can’t see you through my tears. And you wrap your arms around me. And you tell me it’s alright.

In the dream, we lay side by side. A breeze rides in from the seafront, rolls over the sheepfold, catches in the canopy. We laugh as spots of warm rain start to fall. We hold out our tongues.

Nothing bad has happened to you.

PartOne Spring

March3rd,2007

You were alive when I first saw the strange blue light. This much I know to be true. The old church bell sounded at midnight and you were still alive.

That was the spring Grandma came to stay and Grandad wasn’t with her. She arrived in mid-March and I was relegated to the bottom of your bunk-bed, and when I complained to Mum all she said was that Grandma would be leaving soon. That she was only here for a few days, love. But days turned to

34

weeks, and weeks turned to months, and by that point

Grandma had bought her own sheets for my bed, and my wardrobe was filled with her clothes, and she spent most of her time holed up in my room.

Despondent. That’s the word we were looking for. The word we couldn’t quite find at the time. I found it recently in a book, and I thought of you. The one set in Japan about the young runaway and the old man who can talk to cats. It means to be sad from a loss of hope.

Each morning we would leave for school and, on the days when Grandma got out of bed, she would sit at the dining room table, jigsaw puzzle sprawled across the oak surface. And when we returned in the afternoon she was still sitting there, and not a single piece would be in place.

Anyway, the evening before the blue light appeared was the same evening we asked why Grandad hadn’t come with her. Some film droned on in the background and you asked if Grandma and Grandad were having a fight and Dad nearly choked on his food. Grandma looked to us, and then to Mum, and then back towards the TV. Mum was silent for a long time. When she finally spoke, all she said was that Grandad wouldn’t be visiting any more. And Mum cried, and so did

35

you and Dad. I was too young then to understand, and it was years before we spoke about it again.

That night, I dreamt of him – of Grandad. He was trapped in a labyrinth. We stood at the entrance, you and I, and shouted for him, but he couldn’t hear us. And he wandered for what felt like an eternity. I woke up crying. The church bell was sounding. Your breath still made the mattress rise and fall above me. And that’s when I saw it.

The strange blue light.

It shone faintly through the curtains, a ghostly, incorporeal ball of fire. Small, at first, but it grew, and grew, and grew, until the whole room was bathed in sapphire. Your room was the ocean, and we were drowning.

At first, I lay there motionless. This was nothing but a stray dream. But no matter how much I willed it to go, the strange blue light was unmoving.

It beckoned to me, whispering in a language I couldn’t decipher, and before I knew it, I was tiptoeing across the bedroom floor, careful not to wake you. I drew back the curtains and opened the window, and the ball of light thanked me. It shrunk to the size of a football and floated through the opening and out the bedroom door.

36

I followed it down the corridor and through the house, and when we reached the living room it stopped. Grandma lay on the sofa, asleep, and the TV stopped its regular thronging and began to spit out static, showing nothing but a grainy storm of black, white and grey. The ball of light hovered above her for a moment, but she didn’t wake. She tossed and turned on the sofa in the throes of a bad dream. And so, the strange blue light moved forward, through the kitchen and out the back door.

It soared across the garden, and I soared across behind it, up to the little path beyond the flower beds. The first breath of summer hung in the air. The strange space between seasons. It lingered there for a moment before starting down the path, beckoning me to follow. But I could no longer hear it, so I stayed where I was. And then, as fast as it had appeared, it vanished. Gone, like the lyrics to a hymn you can’t quite remember. I carried myself back to bed and I fell asleep. I dreamt of the labyrinth.

The next day I told everyone. They nodded, and they smiled, and they laughed.

Yes, love, Mum said, that sounds just wonderful.

37

Of course, they didn’t believe me. And I’ve been meaning to tell you, because I know that you will.

But that was a long time ago now.

Grandma didn’t leave until August that year, and you died a few years later, and I still have that dream about the labyrinth

38

The tide took the same path yesterday. Shrinking the island coastline away. Romantics seek a new spot to play. A signpost moves along with the bay.

An old man's oil has shrunk the same amount. It's a shame the coast is

far away.

IwanJones

39

Thoddaid

Hir a

I feel the call of a glow on a hill or a wildfire ripping through the pristine view from my childhood bedroom window taking with it a native plant species found nowhere else in the UK or a wildfire of spilt blood from pheasants imported from a posh southern estate so posh southern people can come and spill the blood on our land as theirs is too precious to spoil with the stains of innocent deaths our land where you can't plant trees anymore as all the room is taken up by the ghosts of a celtic rainforest that got in the way of human progress march across the global north that got in the way of the lumbering mass growing through the coal lined crevices of a scaled back and crowned itself prince of a wasteland not worthy of a king not worthy of a home where a handkerchief lays in place of what was once a hill that grew to spread the voice of false knowledge that would unite a land under a boot under a boot but at least you're not alone a starving lion cackles through lazily infrastructured broadband which we are told the necessary delayed construction of is part of the reason the wildcats are all gone or maybe they were given suits in a local wool woven style and told to read some Orwell while they grow accustomed to the ways a proper society does things they grow flowers now because veggies have too much nutrition and cost the earth that was salted when the sea was much more unforgiving in its protection of borders not yet drawn out by hand pushingtogether have created the necessary pressure of time to manifest the roofs that shelter a population or four but its scars show on your way to school floods are much worse than when your nain grew up under the roofs that were created through the pressure of time the story

40 Saesneg ar pedwar

doesn't alter much despite the extra nourishment being parceled up and put on dusty uncool shelves that don't cost as much as the chilled version because your light is being parceled up and placed on a shelf too alongside the momentum of lakes sepa rated by a petrified giant eons ago careening to be joined again above iron lifted from the earth and pressed to shape to place back there to take more out it cycles like this until there is no more to take and they resort to pulling out the iron they placed back until the names of the original molecules are left to a book of collected myths.

IwanJones

41

There is a world where in the years to come

I move to new lands unaware of my home

Everyone I kept contact with or kept contact with me Has passed along or chosen to cut ties

I have no money to go home and no body to carry me

At some point in the last few decades I will have heard someone say my name

For the last time it was said properly, inflections, accent and annunciation

People would say my name after

But never with full intent

I will pass forgetting how to say it myself

IwanJones

42 EWAN

iwan ewan ivan uanne euan iwan ij ivan kirk euan iwan ij iwan iwan happy iwan

big town these streets

a thousand footsteps as many eyes all on me or not - maybe? this place that is my home that smells like piss that looks like shit painted gold but is nonetheless home forward going forward too much time spent either side - im early im late. Never on time

where am i? here in that one moment i spend so much time my eyes meet those of a bullish sort of man deep and cruel i think to see his heart would that i was able - he flashes a smile

arriving where i ought to find myself reeling from a day where nothing of consequence has happened

It is 11 am JackLawton

43

44

10 ways I am trying to be a better feminist Libby Barker

A ‘better’ feminist? A lofty goal. One that may even seem impossible to achieve through a simple list of ten things; and yet, what lies ahead is an attempt. Inspired by writers such as Roxanne Gay and Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, I present to you, the ‘better’ feminist manifesto, created in the spirit of trying.

1. Recognising My Privilege

When practicing intersectional feminism, there is a necessity for recognition. As a white woman, I understand I have more privilege than other women. As a woman with a home and food on the table I recognise my privilege. And in recognising this privilege, I understand my voice may be heard more than others, and that I do not get to speak for others or assume the experience of others less privileged than me. It is after recognising the privilege of being white, cis-gendered and able bodied that I hope to create a safe space for those who have less privilege than me.

Having this privilege also means educating myself on my privilege, for example, as a white woman I am less likely to be arrested for the same crime as a person of colour. In fact, according to UK arrest figures in 2021, black people were more than three times as likely to be arrested. Similarly, as a woman who lives in the UK, I have the privilege of driving and choosing my own religion. These things, along with others, are important to recognise because when trying to learn to be a better feminist I must in turn learn what I am

45

fighting for for others, not just for inequalities I personally face.

2. Challenging Others

This one specifically is important to me because in the past I have been someone who would allow those around me to act to act in ways I do not support, and I would give up a piece of myself for their comfort. I believe it is important to call people out and provide them an opportunity for education. For example, when I hear a misogynistic joke from a colleague, I can acknowledge that it would be easier to let it slide, but I know it is the right thing to call them out.

Similarly, I am trying to be better at knowing whento challenge the misogyny of others. In the past I have been rash, turned the conversation argumentative rather than educational, or I have been impatient and called people out in front of others. Something I am trying to practice is patience, wait until it is the right time and when that time comes understand that miseducation is common, and a decent conversation rather than an argument could lead to their respect of feminism rather than further dismissal. This point especially goes for family members, who I feel the most apprehensive about calling out.

Furthermore, as much as I can recognise that everyone has been indoctrinated by society to support misogyny, I must also remember there are only so many times you can use ignorance as an excuse before somebody is outright misogynistic. When

46

that happens, I’m going to be honest with myself and understand that some people do not wish to learn and that you cannot force it upon them. When this happens, and it most likely will, I should reserve my energy but remain stern, clear that I do not agree but I will not continue to argue. There are people out there who are willing to listen and those who are not: I will choose to spend time with those who choose to listen.

I am also pushing myself to challenge the feminism of others, hoping to better it. There are times where, typically men, claim to be feminists despite not actually being interested in full gender equality. I shouldn’t always take someone at their word when they say they are a feminist, a feminist wouldn’t mind being questioned and so I should not feel bad for challenging someone what they say they are a feminist.

This also applies to challenging other feminists when I believe they are wrong or ill-informed, it does not go against feminism to help educate another feminist and I should remember I am helping the cause in the long run, even if I feel uncomfortable doing so.

3. Letting Myself Be Wrong

This is something that comes with learning, and it is learning that not everything I know is correct and not everything I am going to learn will always be correct.

47

There is a certain part of me that hates to be wrong, my pride often gets in the way of my progress and a part of actively trying to be a better feminist is letting go of my pride when being told by somebody else that what I believe I know is incorrect. Similarly, I need to learn how to move on from being wrong and not put myself down for being incorrect; from childhood we are taught things from the patriarchy that we believe to be true, and I shouldn’t hold it against myself that I once believed an incorrect assumption. I should just correct it and move on. How could I possibly educate others and have tough, or uncomfortable, conversations if I cannot let go of being wrong?

4. Loving Myself

Part of being a feminist is loving the things I used to hate about myself: that the misogynistic system ingrained in me to hate. For example, I love the colour pink and my favourite artist is Taylor Swift. I care about how I look, and I love fashion, I don’t like sports, and I love gossiping. Understanding these things about myself, as small and shallow as they seem, is a real battle when considering how long I wished I didn’t like those things because those things did not appeal to men or were “too girly”. From birth women are taught to shape themselves into women men will like, women are shamed for liking things if lots of other women like them, and we are embarrassed about key elements of ourselves such as our bodies. By loving myself, my body, and my interests, I am in a way being a better feminist because I am no longer holding myself to misogynistic standards.

48

5. Questioning What I Know About Gender

Sometimes I feel ridiculous for hating something seemingly so small, such as blue is for boys and pink is for girls, after all how could colours hurt people? However, the world is indoctrinated into a system that works for the patriarchy and part of this system is gender roles. By separating girls and boys into things such as pink and blue and dolls and cars we are immediately creating a separation between men and women which allows the patriarchy to assume one is better than the other. These are trivial examples, but by supporting these assumptions I am in a way supporting the eventual result, which is gender-based violence and the oppression of women.

It is important to challenging these stereotypes in my everyday life, and I do this in the smallest of ways, for example when shopping with my brother I take him round the whole shop, not just the ‘boy’ side.

Similarly, when talking with my nieces and nephews I ask them all the same questions, I don’t just ask my nieces about boys and my nephews about superhero’s. I don’t assume interests based of their gender and I do not belittle an interest solely because it stereotypically “belongs” to one gender.

6. Questioning What I Know About Women

Part of my aim to become a better feminist is trying to destroy the negative and passive stereotypes I hold about women. For example, that women are “bitchy” or “competitive”, I am trying to rid myself of the awful generalisations I had in the past made about women, because by grouping us all together

49

in any way I am ignoring the nuance connected to each person and I am perpetuating the standards set by men. Additionally, by ridding myself of these stereotypes, I am opening myself up to learning more about women, by allowing myself to engage with women without this preestablished “knowledge”: I am making room for more truth. Along with this, I am opening myself up to a larger circle where there are more women and there is more female support. I am no longer going to be held back by assumptions of women’s character and instead be supported by great women. This becomes increasingly important as I am realising the power I hold as one woman trying to do better, because imagine a whole group of both men and women, each motivating one another to do better and be better.

7. Monitoring My Media

This may seem like a smaller issue, but for me it’s important what information I am taking in and what people I may be unknowingly supporting. For example, when finding a new artist I enjoy I should start looking them up, finding out if I truly support them, and if not, I shouldn’t just ignorantly listen to their music because I could in a way be rewarding them for actions I do not support.

Similarly with a movie, regardless of how much I enjoy it, I should think critically about the messages the movie is sending and if I support the humour or the actions of the characters, if the answer is no, then, I shouldn’t watch the movie and I definitely shouldn’t recommend it to others.

50

This also counts for the types of content I’m taking in on social media, it is very easy to cover one side of the story or to make assumptions when on social media, so if I hear a fact or story, I shouldn’t believe or share those things without looking them up first, social media can be false, and I would do good to remember that.

This ties into making sure I’m aware of who I am following and the messages their posts could be sending, if I see something incorrect or hurtful, I should start reporting the post and maybe contacting the person if I know them personally. Likewise, I should be careful of the messages I am sending out on social media, it is very easy to be unaware of those things, and I have began to monitor my own posts more and I try to remember to not be offended if somebody calls me out on something: we all make mistakes and my pride will not get in the way of my growth as a feminist.

8. Being A Feminist For Men Too

As much as there is a privilege to being a man, patriarchy can often hurt them as well as favour them, and there are things I can do to be a better feminist for men. To begin, I shouldn’t just assume other men aren’t feminists. I shouldn’t keep them out of the conversation simply for being a man and I shouldn’t just assume they aren’t open to learning. Moreover, I am trying to educate myself more on the ways patriarchy harms men, for example, the treatment of male mental health and the standard of masculinity men are held to. By supporting men in their issues, I am in turn furthering the feminist movement because as a feminist I believe it is important to acknowledge how patriarchy harms everyone.

51

On top of that, I should let go of my assumptions about men and sexual assault, by letting myself keep hold of these assumptions I am silencing male victims. I need to educate myself on domestic violence, also, something which is mostly talked about in a female victim setting but by learning about this issue and promoting this issue I could help men realise they’re in a situation of domestic abuse or I could help a man feel he has a safe environment within which he can be open about his experiences.

Patriarchy also prevents men from making meaningful relationships with others, by supporting men as well as women and by ridding myself of male stereotypes I am allowing myself to create new relationships with men without the barrier of sexism and harmful assumptions. By having these friendships, I allow myself to be more informed on male issues and hopefully work towards being a better feminist.

9. Helping Women’s Charities

Although this is one that not everyone can do, I recognise that as someone with a job and with a larger income than others I can make donations to charities that need it, and in my efforts to be a better feminist I plan to start donating to women’s charities. These charities can be different every time but, for example, a good place to start could be Well-being of Women, a charity which funds research into improving the health of women, girls and babies in the UK and more.

I also wish to donate more to women in need charities, which is a further step of recognising my privilege, because by doing

52

this I will be a part of the support for women who have less than I do. For example, Women’s Aid.

This also ties into my wish to be more proactive in my feminism, a way to do this is by donating and volunteering. Volunteering is much harder to organise than donating as I would have to find the free time, but by giving free aid to certain female organisations I feel as if I would truly be making a difference.

Another way I wish to help women’s charities is by attending women’s marches when they happen, by attending rallies and marches I am a part of the community who is drawing attention to these issues and these charities.

10. Writing About It

My final step in trying to be a better feminist is writing this list, by doing this I am holding myself accountable, something every feminist should do, because we cannot do better and improve without first setting that goal and then achieving it.

When writing this list, it became apparent to me that being a ‘good’ feminist was not something I could achieve, because it felt quite problematic to assume something so personal could ever have a definite ‘good’. Therefore, I made my aim simply to do better than before and by writing this list and sharing my work, I am in a way already moving myself and others towards the goal of being a better feminist. And what happens, you may think, when I believe I have achieved this goal, well then maybe I will reflect and write a new list.

53

Repetition is hell

Nora was scared of spiders. Nora always had been. It started when she was –very– young. When Nora awoke to find a single spider in her room, it was as though all of the spiders in the world had crawled into her bed. Despite not having much on her-hea–d, every - hair Nora– had on her arm perked up like a stray cat. She was distraught. Of course, we-coul–dn’t–kill–the– spiders either. She no like that. Nora already knew Death. She banged on-the-office–door and we took her into our room. She like. Stopcoddlingher.

Nora was scared of spiders. Even at the zoo the glass cages weren’t enough. We’d hoped that Nora would learn they weren’t that bad. We ended up cleaning her bed sheets for the rest of the week. I read that fear is inherent, butNora was petrified of spiders. I had a fear of clowns as a kid because I thought one lived–in-t–he-f or -est near my house. I used to imagine that he had a little tent that his oversized b–ody and ch ainsaw would emerge from. At leastherfearsarereal.His painted-leather face–an–d-spooky smile made me run home to my mummy. I learned to take the long way–round when–I–was coming home. I’mtakingthetent.

Nora was scared of spiders. Nora had been left alone for the day while I had errands to run. Nora was nervous to be left alone -Nora had never been left alone before. She was watching TV-–and the walls. Alwa–ys–an–e-y-e on the walls. I hadn’t planned to be out for long. Nora knew my office was off lim–its. H ow–-man–ytimesdoesshehavetobetold?When I came home to find her curled up on -my seat, with -snotty tissues and a hurted tummy. It broke my heart. Rulesarerules.I enj oyed her c ompany for the next few months.

Nora was scared of sp iders. When she came back from her weekend visits, I used to make her bedroom up nicely–.W–henever Nora would come home, she would ask me to look for any spiders in her room. Having already looked, I looked again. After a short while of this, Nora began to join in and helped me look for the spiders. Ifeelleftout.She would use her magnifying glass like a tiny detective. She no like lookin under da bed. Dad looks under da bed.

57

-

Nora was scared of spiders. She liked her new room. It was on a high floor, and was incredibly sterile. There were no eight armed bandits to contend with in this room. WellI’mherenow,thathastocountforsomething.

“Why it do the beep dad?” she would ask.

I told her it was because it meant things were okay. She got used to the beep. When I took her home, her room wasn’t made up. We’rebothtired,it’sokay. We had been gone for a long time, but I didn’t think we’d ever have to leave again. I-told her she’d been so strong, and that we had won. This would be her room for as long as she liked. She felt lonely. She found a ball of dust in the corner, which made her cry. She thought it was a spid er nest. I disposed of it, and cleaned her room four times. It didn’t matter. Shedoesn’twa ntto sleepalone.She wanted to stay with the other kids again, and she said she missed da be-epin.

“Daddy can you play the beepin,” she whispered. Of course I obliged.

“I love you daddy. Will mummy ever come home?” she said before falling asleep.

I didn’t sleep for the next month.

Nora was scared of spiders. But she wasn’t scared of dying. She didn’t understand what was happening to her. Whatishappeningtoher?Why?Whyus?I didn’t know why we had to suffer. I couldn’t understand why God had done this to her. In the following weeks someone said to me

“God wanted his angel back.” The only reply we could think of was “Sodowe.”

58

g o o -d n-i g-h t w e l o v e y -o u t o o-

PeterCameron

AHHHHHH MY BRAIN HURTS!

Fauxkis

Fauxkiss

FolkUs

FolkUs

FeauKes

FeauKes

Fohcas

Fohcas

Foucaus

Foucaus

Fuckus

Fuckus

Phockus

Phockus

Hocus

Focus

FwoahKys

Pocus

VoGus

VoGus

VogueKys

VogueKys

FoughCask

FoughCask

Locust

Locust

Repeat that

59

Focus Focus

PeterCameron

My Ladybird

Ruby Bryant

60

There is no real time or place I can prescribe to this memory other than what I have patched together, for this is my first memory. I presume myself to be two or three years old; a tiny toddler with golden ringlets bouncing everywhere and eyes far too big for my face. I am in Wales (my mother tells me) staying in a retreat owned by the Metropolitan Police to support their officers. We were sent here for respite after my Uncle’s cancer diagnosis. I’m here because I’m currently the closest thing my Aunt and Uncle have to a child. My mum, dad, uncle, aunt, and grandparents are with me. My brother may or may not have been there as well, though if he was he was far too young to be anywhere but in someone's arms.

The sun is shining, and a lazy heat has settled for the afternoon. I am playing alone on the grass. It’s tall and wild, littered with dandelion seeds and buttercups. Towering over the garden is a colony of scots pine trees swathed with pearcoloured leaves. It has been so hot that the grass is scorched to sage green and sways stiffly in the fleeting breeze. A dusty gravel path takes me by the wildflower beds filled with purple and yellow blooms. The trail dips up and down along the

61

uneven garden, my small buckled shoes kicking up the dirt behind me. It becomes a game; to allow the momentum of running down into the small dips to get me to the top of the next one.

I am in a white summer dress with scalloped edges and embroidered holes along the hem. I can still remember the texture. Dry, and oddly crinkly, like it had been air-dried. The sun on my shoulders feels like the heat in my consciousness. Even in that moment, I knew that I was doing something important. The sense of duty that came with the outward performance of being the lonesome golden child of the family. Like a role I knew I needed to perform, but I didn’t know for who. This strange, mature knowledge secretly urged me to misbehave. Like a call to do what other kids my age would do. This, obviously, was strange as I wasn’t an outsider to children my age, I just felt like I was missing out on misbehaviour. I keep running up and down the small hills. Up, and down. Up, and down. Up, and on to a straight run. Toddling along, my eyes on my unpracticed feet, I spy a ladybird in my path. She looks giant to me; with her shining eyes and seven black spots on her glossy red back. Completely still and unassuming as I stare down at her. My heart races. It feels like

62

dread and catharsis and all those other words I won’t learn until much later in life. Standonher. Something rotten inside me yearns. I have enough of a grasp of morals to know that killing is wrong, but I still urge myself to do it. It is one of the moments I am most ashamed of, which is probably why it stuck with me. For the longest time, I couldn’t understand why I would do it, other than some profound lack of object permanence. Now, I know it was the start of a lengthy battle with intrusive thoughts, and this was just the first time they won. It would be okay, wouldn’t it, if I had been running and didn’t see her and stepped on her by accident? Itwouldbean accident, I told myself. Theycan’tseeme. Her bright red form stands out starkly from the brightening path in the blinding sun.

I did stand on her. With my right foot. It felt like nothing. To kill her did not feel like anything when I put my foot down. Though I do not think it would have been any better if I could have felt the crunch of her shell.

Stepping back, I peer over the toe of my shoes, heart in my mouth. A tiny orange smear clumps to the dust and dirt. The same orange as a clementine, or a dried peach. All the guilt hits me as I rehearse how it was an accident. I had been

63

running and I didn’t see her. It feels like a swelling in my neck.

Standing straight, with my head held high, I look away and hope for it to disappear. How strange for a thing that felt like nothing to feel like everything. I run off again, back to the adults and away from the regret chasing me. It was an accident. I wasn’t the sort of toddler to be harsh and hurtful and brutish like that.

It still sticks with me; even now I see that ladybird crushed under my foot. It is also strange how that of all things, this is the earliest memory I have. There must be some irony, beyond my grasp, about how taking a life makes me aware of my own. It feels like an irony that I do not have the perspective to see from within myself. This ordeal brought with it that beautifully gut-wrenching twist of my stomach that haunts everything I have done since. Every moment of my childhood that ensured disaster and destruction on my part produced that same sickly feeling that still clings to me now. The

64

(memoir)

feeling is so synonymous with my upbringing that my own mortal dread is nostalgic.

Warning! Danger! Alien spacecraft approaching! Stacey Beaver

65

“Seriously, dude, a chicken truck”. Not exactly W.H. Auden’s FuneralBluesor anything close to an expected eulogy, and yet this is somehow perfect. Ruth Ozeki’s 2022 Women’s Fiction Prize winning novel, The BookofFormandEmptiness,skirts the edges of what is expected in a dazzling display of fourth-wall-breaking, genredefying writing. Ozeki’s novel is unafraid to stare huge issues, and more, in the face. She tackles teenagers coming of age, natural disasters, capitalism and consumerism, and mental health with grief, and manages to do all of this with a level of seriousness and humour that allows the reader to truly understand and connect with the characters.

We are introduced by ‘The Book’ to the fourteen-yearold Benny Oh, who, following the tragic loss of his father, begins to hear the ‘voices’ of everyday objects gathering around him. His mother, Annabelle, suffering her own grief, has found comfort in hoarding, and in a different way the objects she collects also ‘speak’ to her. Facing the challenges of being a newly widowed, single mum, and fighting for her job as a news archivist, Annabelle has allowed their home to become infested by accumulating newspapers, leaving herself

66

and Benny overwhelmed by the barrage of news and debris which builds physical walls between them while they simultaneously struggle with emotional barriers. Through her sometimes very poignant and yet still playful book, Ozeki does occasionally overcomplicate her narrative with Walter Benjamin quotes and ‘The Book’ telling the tale of a multitude of characters and their interactions, often interjected by Benny. It can be difficult to keep up with the story and its action. However, if you are willing to put in the time and concentration, the reward is the enjoyment of a surprisingly beautiful dive into grief and its complexities, with the Chair of the Women’s Prize panel describing it as “a complete joy”. The powerful yet strained relationship between a mother and her son is playfully and unabashedly told here in all its truth with everything expected of a normal day-to-day life of forgetting milk, having an untidy kitchen, and trying to impress a teen who thinks his mum is the most uncool person in the world, despite rocking her beloved sea turtle jumper. This is entwined with the added pressure of the surrounding trauma, which mentally, metaphorically, and literally provides a real sense of the tension felt by the pair and it is beautifully articulated. Through the incapacity of

67

Annabelle and Benny to appreciate each other’s profound loss while battling with their mental health, Ozeki manages to highlight the love and caring intentions of the pair, made clear by the end and the ‘tidy up’ saying: “This is the terminus of your mother’s dreams and all her good intentions, and you are standing on top of it”. The novel is very personal to Ozeki, a practicing Buddhist monk, and was inspired by a Zen parable, and it took eight years to write – with its roots stretching back to the death of her own father in 1998. Following her loss, Ozeki would hear him while doing chores explaining she would be “folding laundry or whatever, and would hear him clear his throat and then he would say my name. I would turn around and there was nobody there.” Following this, on clearing out her parent’s loft, Ozeki found hidden objects, gifts, an empty box labelled “Empty Box”, and polished pebbles from her grandfather’s time in an internment camp in New Mexico. Ozeki discussed the frustration she felt at knowing these objects had stories but “didn’t know what the stories were”, which she found upsetting.

68

Wondering if everything has a story to tell, Ozeki delved into her fourth novel, exploring “voice hearing on a spectrum”. Many people have an internal monologue, some hear it as a voice running through life’s activities in the background and find it useful, while some can find it troublesome with intrusive thoughts and the sarcastic ‘you’re not good enough’ voice we all know and hate, and if lucky learn to love to hate. But what happens when the internal monologue is externalised? Or more disturbingly what happens when the voice leads you to a group of boys who beat you for being different, or to a pair of scissors, which, in this case, tells Benny to stab himself. In this woeful situation, Benny is wrongly diagnosed with a schizoaffective disorder when he is not heard by his psychiatrist. In doing this Ozeki asks “Why is it that some voices are pathologised, some are normal, and some are lionised?”

Equally, I have to ask, why are some ignored? Doesn’t everyone talk or shout at a computer that has stopped working or mutter expletives through our teeth at a pen with no ink while furiously scribbling around a page? Are we not all, therefore, talking to objects in a perfectly acceptable way in everyday life?

69

Through Ozeki’s character construction, we are permitted to explore just this and see how fine the line is between sanity and insanity and all the subtleties in-between. Indeed, grief is a powerful emotion which provokes multiple reactions in people. Ozeki herself turned to Buddhism after losing her parents and realising she was “kind of falling apart” stating “Sickness, old age and death, woke the Buddha up”. Families fight over objects of sentimental significance or even Tupperware. This can be because of the link felt to the person who is gone or wanting part of them around and whether random or not, the feeling of belonging to something larger can offer real comfort in those difficult moments.

Ozeki too suffered from mental health issues in her youth, spending some time in a psychiatric facility. Understanding and portraying that everything is funny and sad, full of love and harm, caring and damaging, and we are all just walking a fine line between our individual normality which this book tells is just fine. So, go. Be your unapologetic self and read, read lots, but start with TheBookofFormandEmptiness!

70

(Bookreview)

Ripe Patrycja Lojas

71

A pool of blood in between my scarred legs. My white satin bed sheets ruined. He will awake soon, disgusted with me. Leaving me like he always does. Before anyone finds him. Relief sweeping over my not-so-holy temple. But today is different. He doesn’t like them grown. At once ripe and impure. It’s why he finds comfort in me. The treasure chest between my legs. Small. Delicate. Not fully grown. I’ve still got a few minutes, five, or maybe more before his gigantic hands ruin me whole. Again. I take this time to remember my surroundings, in detail, a moment I will cherish for life. The sun is only just starting to rise. Pink sunlight is seeping in through the cracks in the blinds. Birds chirping outside of my window. Cars are wheezing past. The almost silent rustling of leaves makes me feel alive. They’re dying, for me, whilst I am being reborn. A whole new me. But for now, I stay still. A statue. Made of rock. Cold as stone. Dark as the night when he started it all.

The world is waking up. Him included. Slowly, he turns to face me. Eyes still closed. Lips slightly parted. Alcohol on his breath. His hand makes its way to my waist, appreciating the familiarity of my protruding hip bone. Drawing circles with his rough hands, taking his time before continuing to explore the

72

region south below my belly button. And then he stops. Eyes spring open. His body tenses. He pushes me away while refusing to meet my gaze and quickly steps out of bed. I stare out of the window at the yellowing leaves rustling in the wind while he puts himself together. I don’t want to face him. Not right now, today, or ever. But I don’t feel shame, disgust, out of control. A wildfire erupts inside of me when he closes the door behind him. Something he never did. I start crying. A smile appears on my sullen face.

Dad, you make me wish I was dead.

73

All rights reserved by the authors. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without prior written permission from the author, with the exception of non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law

UniversityofSalfordEnglishDept2023

74