The infamous gunpowder plotters of 1605 used invisible ink made from orange juice to send secret messages. Try this experiment to make your own

You will need

A lemon or lime

Paper (thick paper like watercolour paper works best)

A cotton bud or small paintbrush, to write with

A hairdryer or iron

An adult to help!

Cut the lemon or lime into wedges and squeeze the juice into a small bowl or cup.

Dip your cotton bud or paintbrush into the juice and write your message.

Leave your paper to dry (this can take up to 30 minutes). Your message should now be invisible!

To reveal your secret message, carefully use a hairdryer or iron to heat the paper. Ta-da!

Finally, think about your experiment. What is it about lemon or lime juice that makes this work? Why does heat reveal the message? See page 7

Did you know? Letters played an important part in the Gunpowder Plot, but they could easily get into the wrong hands. Invisible ink was one solution – because it stays visible once heated, the plotters could tell if anyone had tried to read their secrets. But it was also a letter that stopped them: a man called Lord Monteagle received a mysterious note warning him to stay away from Parliament on 5 November. He showed it to the king’s men and Guy Fawkes was caught handed!red-

2nd century

What: communal toilets for sitting and chatting while you do your business. The Romans’ version of toilet paper was a sponge on a stick (tersorium). It was for wiping a er they’d used the toilet. Where: Housesteads Roman Fort – Hadrian’s Wall

13th century

Loos have come a long way since the Romans’ sociable seats. Check out these historic inventions and give them your own gross rating!

16th century

What: Chamber pots were portable toilets used mostly at night. The contents were thrown away or the wee used to wash clothes. Henry VIII had a close stool, a chamber pot in a wooden box with a comfy seat. He even had a ‘groom of the stool’ for wiping the royal bottom!

10 /

What: garderobes or long drops, indoor loos with deep cesspits below for the waste to drop into. A ‘gong farmer’ was employed to clear them out. Worst job ever?!

Where: Old Sarum

10 / 10 /

16th-18th

century

What: the rst ushing loo, Ajax, invented by Sir John Harington. He had a meeting at Old Wardour Castle in 1592 to talk about his idea – probably inspired by its stinky long drops! It took another 200 years for his invention to really catch on, with some early examples installed at Audley End House in 1775. These were called ‘water closets’ – which is why you might see the initials ‘WC’ when you’re looking for the loo.

What: thunderboxes, toilets enclosed in wooden boxes with a lid and brass handle for ushing. The name comes from the echoing sound they made when they were used! Where: Brodsworth Hall 10 / 10 /

19th century

MYTH ALERT!

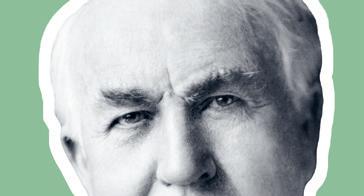

Many people think Thomas Crapper invented the ushing toilet. He didn’t – but he did patent some bits that made them work better.

Toilets have been called some funny things over the years. Heard these ones?

a er our friend Sir John Harington)

Telephone

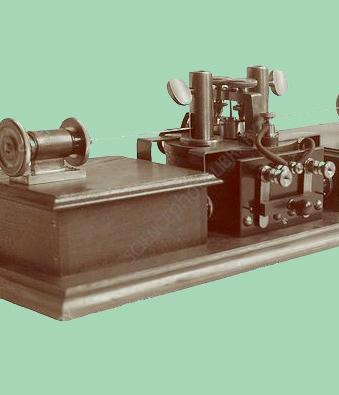

Scottish inventor Alexander Graham Bell was awarded a patent for the world’s rst telephone on 7 March 1876. Italian inventor Antonio Meucci had shown his own device in 1854 and patented it in 1871 – but he couldn’t a ord to renew his patent when it ran out in 1874. In 1878, Queen Victoria invited Bell to Osborne on the Isle of Wight. She described his invention as ‘most extraordinary’.

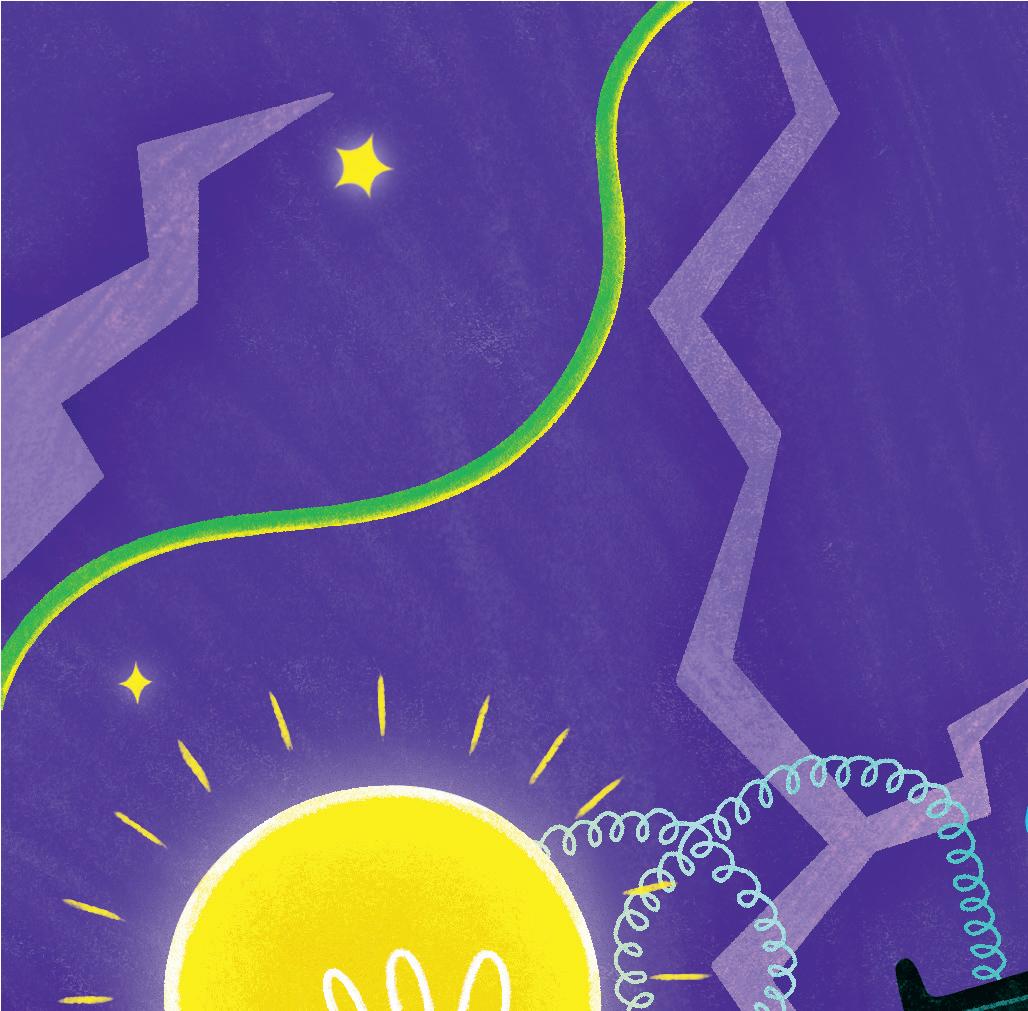

Lightbulb

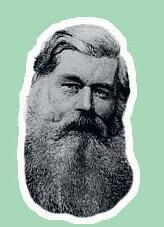

American inventor Thomas Edison had almost 1,000 patents to his name – including one for the incandescent electric lamp, granted on 27 January 1880. One of his biggest competitors was Englishman Joseph Swan, who successfully demonstrated his working bulb in February 1879. Though they were rivals, they formed the Edison & Swan United Electric Light Company together in 1883.

Radio

The race to invent radio was a head-to-head between Italian Guglielmo Marconi and Serbian Nikola Tesla (the car company is named a er him). Tesla invented a key component called the Tesla coil in the 1890s, and was awarded two patents in 1900. Marconi was granted a patent for radio communication in 1897 –even though he drew on the work of earlier inventors, including Tesla!

A patent is the legal right to make and sell an invention. It means others can’t copy your ideas.

Inventors are o en racing to reach the nish line, patent their ideas and get their names in the history books. So who really got there rst?

Which American inventor famously said: ‘Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration’?

a) Thomas Edison

b) Alexander Graham Bell

c) Nikola Tesla

Put these inventions in historical order:

a) Photograph

What did people use to clean their teeth before toothpaste was invented in the 19th century?

b) Electric battery

c) Telephone 4 2

a) Ground bones

a) 1969

When did British scientist Tim Berners-Lee invent the World Wide Web?

b) 1979

c) 1989

b) Sewers

c) The wheel

Which of these did the Romans NOT bring to Britain?

a) Under oor heating

Who invented the rst programmable computer?

a) Charles Babbage b) Bill Gates c) Alan Turing

1 3 5 6 7 ?

Did the Duke of Wellington inspire the development of the Wellington boot?

a) True b) False

See a pair at Walmer Castle. How it works: when you heat lemon juice, it causes a chemical reaction. Carbon reacts with oxygen in the air which makes the juice turn a darker colour. Your message becomes visible.

The castle was one of the greatest medieval inventions – and Dover was one of the best. In the great siege of 1216, Hubert de Burgh’s knights and soldiers defended an attack by Prince Louis of France

Crossbowmen re down at defenders on the battlementsfrom atallsiegetower.

Dover is the rst ‘concentric’ castle in western Europe, with inner and outer rings of walls around the keep.

Catapultscalledmangonelsperriersandareused toatinghugestones thewalls.

Defenders on the walls hide behind ‘merlons’ before popping up to re arrows and throw stones through the ‘crenels’ (gaps).

The walls of the great tower are six metres thick – that’s about four average 11-year-olds lying head to toe!

The barbican is the rst line of defence, a twin-towered gatehouse surrounded by a deep ditch.

Miners,protectedbya woodenhutonwheels, digintotheditchand eventuallybringdown oneofthetowers.

Run a hot bath

Sir John Gri n

Gri n inherited

Audley End House in 1762 and made lots of improvements, such as a service gallery on the second oor. Coal was winched up the outside of the house from ground level and used to heat water for the bedrooms. Better than carrying up buckets when you fancied a bath.

England’s nest country houses were the rst to enjoy inventions we take for granted today

Beat the chill

Most UK homes had no central heating until the 1970s or 80s, relying on coal res or electric heaters

Wrest Park had an early example of a central heating system in the 19th century. Warm air rose from a coal-burning boiler in the basement through decorative brass grilles in the walls of the antelibrary and oor of the staircase hall.

Power up

Osborne was one of the rst country houses in England to have electricity installed, in the late 19th century. The lights in the Durbar Room and the huge drawing room chandeliers were wired in 1893. There are also some original Edison & Swan lightbulbs in the Osborne collection.

Electricity appeared in the late 19th century, but it wasn’t commonplace in UK homes until the 1930s

Take a shower

Clean it up

Eltham Palace was a glamorous party house in the 1930s, complete with all the latest technology. The Courtaulds had an audio system for broadcasting music across the ground oor. And, for cleaning up, there was a centralised vacuum cleaner in the basement, with its pipes built into the walls and hose sockets in each room’s skirting boards.

Prince Albert was a big fan of new technology, and there are lots of examples of 19thcentury innovations at Osborne. His private bathroom had a plumbed-in bath and ushing toilet and Queen Victoria’s even had a shower, which was unusual for the time.

Summon the servants

Audley End House was one of the rst to have a mechanical bell system for calling servants, installed in the 1760s. Each of the main rooms had a lever or pull connected by long wires to a bell in the servants’ quarters.

Hush, little Ada

At the age of 12, Ada designs a ying machine, experimenting with wire, paper, feathers and silk for the wings.

How the daughter of a famous poet became the mother of computer programming

Augusta Ada Byron is born in London on 10 December 1815. Her father is the famous poet Lord Byron. He and her mother, Annabella, separate when she is just a few weeks old.

Excellent, Miss Byron. Your mother will be most pleased

Worried that she might grow up to be a poet like her father, Ada’s mother encourages her interest in maths and science from a young age.

It will be like a horse with a steam engine inside and an immense pair of wings xed on the outside…

In 1833, at the age of 17, Ada meets the mathematician Charles Babbage at a party. It’s the start of a lifelong friendship. Soon a er, he shows her his invention, an early calculating machine called the di erence engine.

Yes, I understand. It’s absolutely fascinating

In 1843, Ada translates a French paper on Babbage’s latest idea, the analytical engine. She adds lots of her own notes explaining how it could work.

I do not believe that my father was (or ever could have been) such a Poet as I shall be an Analyst g Ada Lovelace Day is held on the second Tuesday in October each year to celebrate the achievements of women in STEM

In 1835 Ada moves to number 12 St James’s Square, London, with her husband. You can see a blue plaque to Ada at the house today.

In one of the notes, she describes how the machine could compute a sequence of numbers – and writes the world’s very rst computer algorithm.