6 minute read

THE PATH TO HEALING FROM SEXUAL ABUSE

By Mary Knight

I am certain that my memories of childhood sexual abuse are true. I did not remember my abuse until I was thirty-seven years old. Even as a child, I had no conscious memory of the atrocities except while they were occurring.

When discussing recovered memories like mine, the focus tends to be on their credibility. Since I no longer need to spend my time and energy determining the validity of my recollections, my attention has turned to examining the many ways that delayed recall benefited me.

Vacations help us maintain our emotional well-being, especially for those of us with extremely demanding jobs. There is no job as demanding as surviving an abusive childhood. Delayed recall for a child is like taking a vacation from the fear, horror, and shame of the abuse. As a little girl who was molested by both parents, delayed recall gave me a psychological vacation from the abuse.

Delayed recall enabled me to not only do well in school, but also find comfort there. I was always aware that my parents were very critical and that they yelled a lot. In contrast, my teachers were kind and respectful. They complimented me when I worked hard. School was a haven for me, a calm place where things made sense.

My social skills were well-honed in grade school. In school, I associated with high achievers. Many of my long-term friends have graduate degrees.

I had a master’s degree in social work before I recalled my abuse. Two of my articles were published in professional journals. I was appointed by judges to do divorce custody and parenting time evaluations. I testified as a mental health expert on a regular basis.

I now realize that the respect that I received from judges and attorneys was one of the factors that empowered me to trust myself enough to remember what deep down inside I always knew.

I was making strides in becoming self-actualized. I read books on codependency, then took a class about it, and eventually joined a twelve-step group for adult children of alcoholics. (Neither of my parents were alcoholics, but my mother acknowledged alcoholism on the part of her deceased father.) I finally realized that the problems in my first marriage were not all mine, and I insisted on marriage counseling. I began finding ways to have fun, like acting at a community theater. I started dressing in brighter colors, and I quit choosing styles that hid my figure.

During my childhood, forgetting allowed me to develop intellectually and emotionally in tandem with my peers. Remembering what happened to me as a child turned my world upside down. In no way do I want to minimize that fact. Still, I am thankful for my delayed recall.

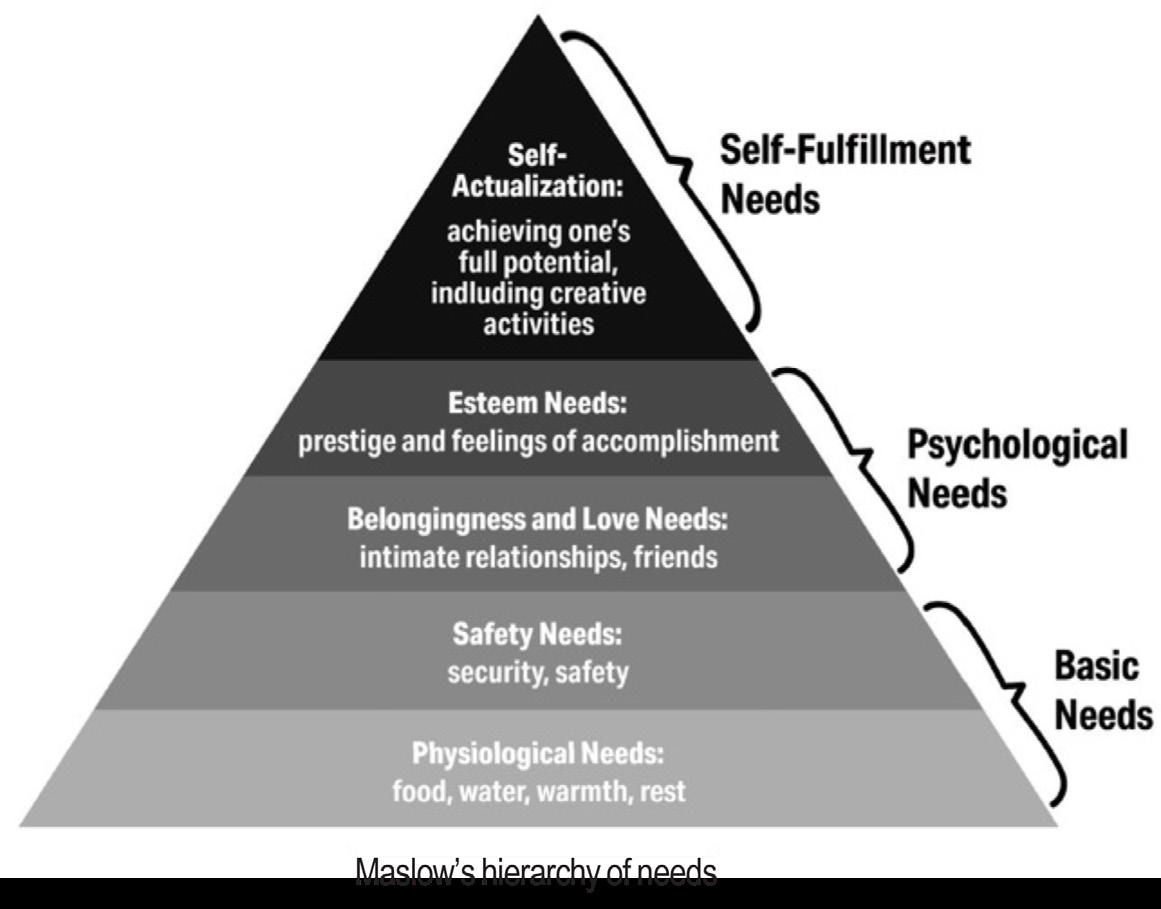

In college, I studied Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In his five-tier model of human needs, Maslow suggests that you must fulfill the lower needs before it is possible to fulfill the higher ones. The lowest needs are physical, such as food, water, and shelter. The next level is safety and security. After that is belongingness and a sense of community. Then come esteem needs, which are associated with accomplishments. Lastly, according to Maslow, is the need to become self-actualized.

When I first learned about Maslow’s hierarchy, it did not make sense to me. I argued with my college professor, insisting that starving people can become self-actualized. I now realize that, on a deeper level, I was speaking for myself. My parents led a double life. In their upper middle-class respectable existence, my physical needs were met. The life that my mind kept hidden from me included food deprivation and torture.

For me, Maslow’s triangle was upside down. I began to meet my higher needs before having the solid foundation that permitted me to process what happened to me as a child. I had the skills and connections by then to enable me to find a sense of community and family that did not include my abusers. My professional accomplishments gave me the confidence to make it on my own.

My safety needs were the last to be satisfied, partly because I had been drawn to men who, like my father, were untrustworthy. I finally feel safe in my own home. Jerry and I married ten years ago. We live in a house we easily can afford. The view from our deck fills me with joy daily. Creative activities, which are a form of self-actualization, absorb a large portion of my time.

Rather than an upside-down or a right-side-up triangle, my process of remembering has consisted of lines that are far from straight. I still have new memories occasionally. Some are brutal, even in the midst of the good life that I now enjoy. To cope, I take good care of myself.

I have a pajama day, indulge in long baths, relax my body with yoga and massage, dance, journal, and hike alone or with my husband. At the same time, I remember myself as the child who did not have these opportunities.

I do not push myself to remember. I am fine with unclear memories. I do not need all the details. The only memories that I need are those that will help me or another person.

While I celebrate everyone’s path to recovery, I am glad mine included delayed recall. I do not know how I would have survived my childhood without it, but it did more than save my life. Delayed recall allowed me to have a life worth living.

About The Author

Mary Knight, MSW, experienced various forms of child sex trafficking, sometimes in her own home. Her parents were her pimps. Knight’s current life is filled with safety, love, joy, and children. Happily married, she is a child advocate, a foster parent, and a grandmother. Knight lives in Bellingham, Washington. She can be contacted by email or through Facebook. Her memoir My Life Now: Essays by a Child Sex Trafficking Survivor is available through Amazon, and can be ordered from any independent book store. Her films are all free on Mary’s YouTube channel.