AALTO UNIVERSITY MASTER’S THESIS

Author Ella Müller

Title Out of sight, out of mind: Modern architecture and waste

Department Architecture

Major Architecture history and theory

Supervisor Panu Savolainen

Advisor Sanna Lehtinen

Date 08.02.2022

Number of pages 138 Language English

Keywords Architecture theory, modernism, waste, obsolescence, hygiene, dirt, disorder, architecture history

CORRECTED 2ND EDITION 20.10.2022 Slight changes have been made to the layout of the thesis and minor corrections to the text.

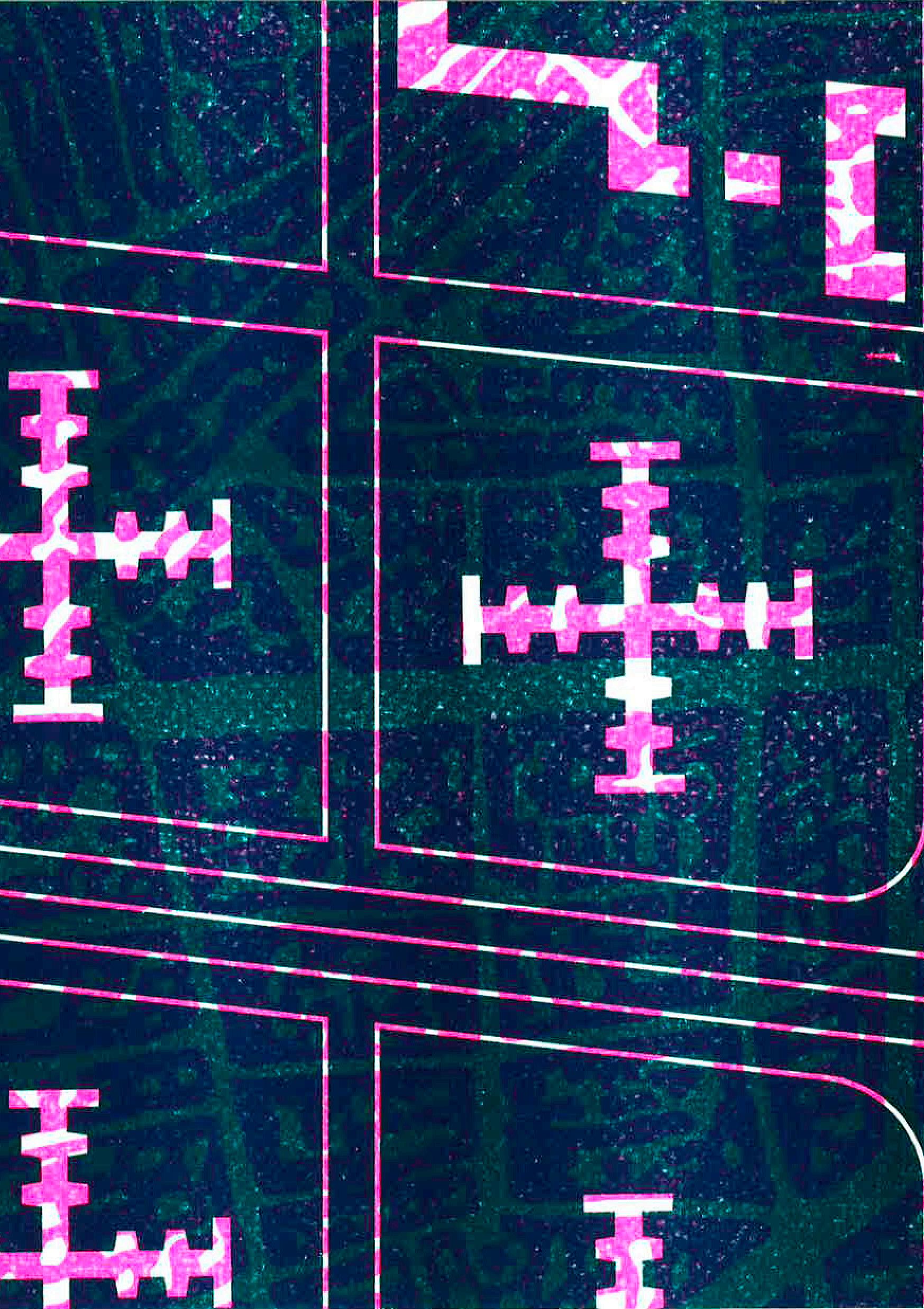

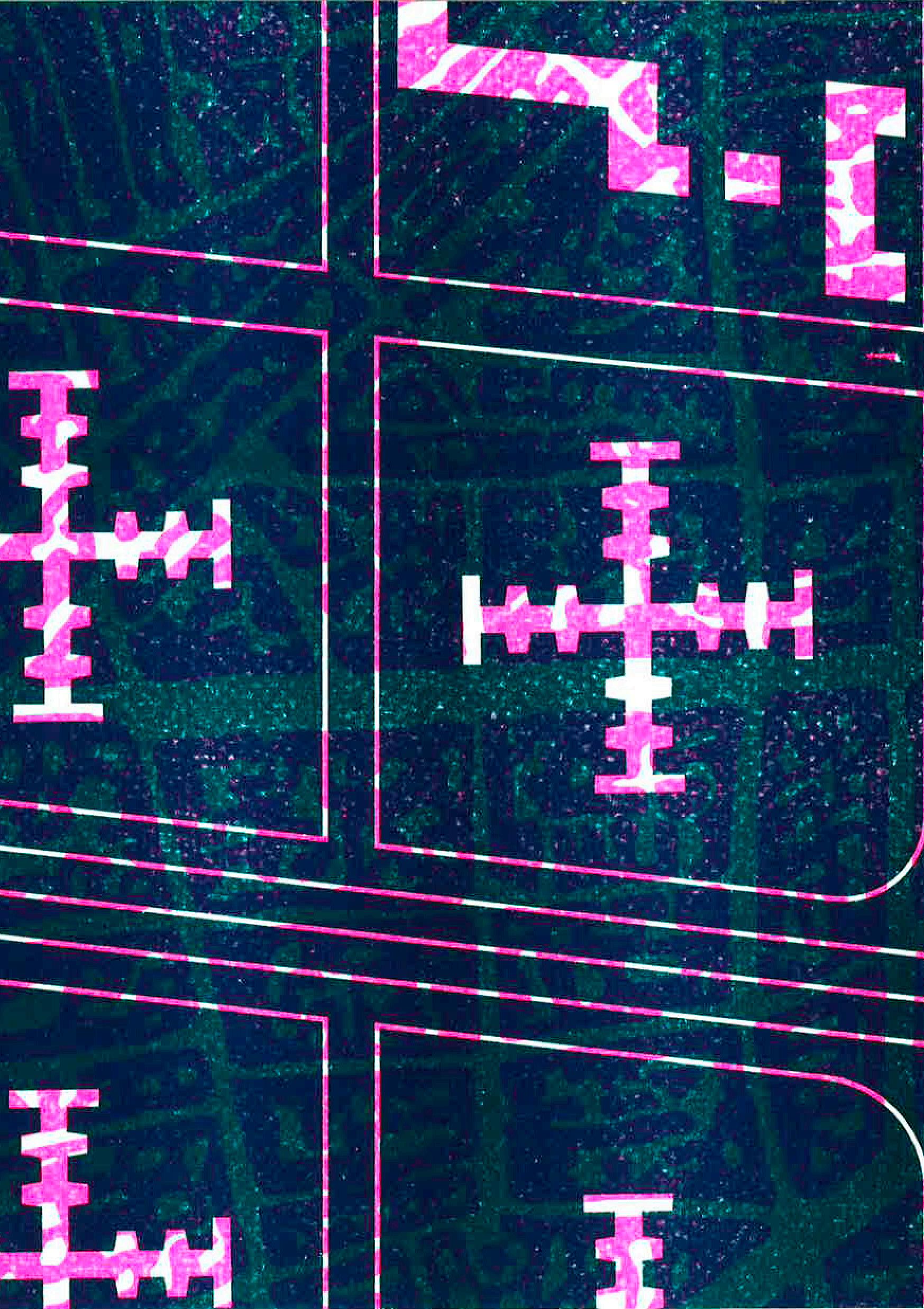

The riso print on the cover portrays

Le Corbusier’s Voisin plan of Paris on top of the old quarters it would have replaced.

ABSTRACT

This master’s thesis examines the ways in which the contemporary building culture produces waste. The environmental crisis and the emerging circular economy have drawn more and more attention to construction waste and its reuse. Instead of adopting the problem-solving approach of waste man agement, this thesis asks how buildings and urban environments come to be defined waste in the first place? The question is explored through the history of modern architecture and construction practice.

This thesis introduces critical discourses on waste in social studies and humanities to architecture theory. In a dive into the history of modern ar chitecture and its founding thought, the canonical narrative of modernism is exposed to multidisciplinary writings about dirt, discard, hygiene, order, and obsolescence. A particular interest is taken on the grounds and reasoning of demolition, which often reveal less about waste itself than its counterpart, the ideal.

A key argument of this thesis is that the modernist ideals of hygiene and order continue to have a waste-producing effect in contemporary built environments. The modern project enforced a strict system of ordering that abjected parts of the existing built heritage as incompatible with new values. The modernist legacy persists in legislation, processes, and cultural understanding of the parties involved in construction and urban development. What we perceive as waste is not merely the material product of a linear eco nomic system but also a cultural discard of the modernist design sensibility. New, more ecological building solutions cannot be considered sustaina ble if the existing is subsequently labelled waste. Circular economy envisions an architecture that utilises the old and existing in innovative ways. However, the promise of sustainability combined with continuous economic growth should not be left unquestioned. This thesis proposes that a multidisciplinary approach is necessary for identifying the roles architecture plays in the environmental crisis and the unequal distribution of its effects.

TIIVISTELMÄ

Tämän diplomityö tarkastelee sitä, miten nykyinen rakentamisen kulttuuri tuottaa jätettä. Ympäristökriisi ja kiertotalous ovat kohdistaneet huomion rakennusjätteeseen ja sen uusiokäyttöön. Sen sijaan, että työ käsittelisi rakennusjätettä jätehallinnan näkökulmasta, se kysyy millä tavoin rakennuksia ja kaupunkiympäristöjä määritetään jätteeksi? Tätä kysymystä lähestytään modernin arkkitehtuurin historian kautta.

Diplomityö esittelee yhteiskuntatiteellisen ja humanistisen jätetutkimuk sen havaintoja arkkitehtuurin teoriaan. Se tarkastelee nykyistä rakennuskulttuuria ja sen ylijäämää sukeltamalla modernismin historiaan ja perustaviin ajatuksiin. Modernismin vakiintunut narratiivi altistetaan monialaisille tek steille, jotka käsittelevät jätettä, likaa, hygieniaa, järjestystä, ja vanhenemista. Työn keskiöön nousevat purkamisen syyt ja sen perusteluun käytetyt argu mentit, jotka usein kertovat vähemmän itse jätteestä kuin sen vastaparista, ideaalista.

Työn keskeinen argumentti on, että modernistiset hygienian ja järjestyk sen ihanteet vaikuttavat edelleen siihen, miten rakennettuja ympäristöjä määritetään jätteeksi. Moderni projekti tavoitteli oli tiukkaa järjestystä, joka sulki ulkopuolelleen osia olemassa olevasta rakennuskannasta uusiin arvoihin sopimattomana. Tämä perinne elää edelleen lainsäädännössä, prosesseissa ja rakentamisen osapuolten kulttuurisessa itseymmärryksessä. Se, minkä määritämme jätteeksi ei ole vain lineaarisen talousjärjestelmän materiaalinen tuote, vaan myös modernistisen suunnitteluajattelun kulttuurinen hylkiö. Uusia, entistä ekologisempia rakentamisen ratkaisuja ei voi pitää kes tävinä, jos vanha samalla leimataan jätteeksi. Kiertotalouden ihanteena on arkkitehtuuri, joka keskittyy uudisrakentamisen sijaan hyödyntämään vanhaa ja olemassa olevaa uusin ja innovatiivisin tavoin. Lupausta kestävy ydestä yhdistettynä jatkuvaan talouskasvuun ei kuitenkaan pidä jättää kyseenalaistamatta. Työn pyrkimyksenä on korostaa monialaisen lähestymistavan tärkeyttä pohdittaessa arkkitehtuurin roolia suhteessa ympäristökriisiin ja sen vaikutusten epätasa-arvoiseen jakautumiseen.

CONTENTS

Abstract 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Critical perspectives on waste 2.1 Dump diving 17 2.2 Rubbish metaphysics 23 2.3 The waste problem 29 2.4 Waste and value 37 3. Sorting architectural discard 3.1 Ornament and grime 49 3.2 Cancer will stifle the city 60 3.3 Convenient homes for standard people 70 3.4 Spaceship earth 78 4. Recycle, reduce, reuse, refuse 4.1 Post mortem 97 4.2 Living in a material world 107 4.3 Architecture of junkspace 115 5. Conclusions 125 6. Bibliography 129

INTRODUCTION

The contemporary architecture discourse is pervaded by notions of the envi ronmental emergency. Numbers are clear: buildings and construction produce almost 40 % of all global CO2 emissions. What more, buildings sprawl over natural environments, destroying ecosystems and wiping out carbon sinks. It is not only the climate change we should be worried about. In 2009 a group of environmental scientists led by Johan Rockström introduced the model of ‘Planetary Boundaries’, illustrating nine processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the earth, and the degree of human impact in each of these processes. Crossing the planetary boundaries signifies entering an area of in creased risk of large scale environmental change and disaster. According to the scientists, the rate of biodiversity loss and the alterations in biochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus have already exceeded the safe zone. In fact, human impact on the planet has grown so significant that some geologists are talking about a whole new geomorphologic era of the Anthropocene.1

There is a widespread understanding that something must be done, but what it is, is not as clear. The position of architecture is essentially instrumental. Historically, buildings have provided shelter, acted as places of worship, and symbols of power. Within the recent centuries, they have acquired a new function as objects of trade in the real estate market. Architects occupy the space between political power and legislation, cultural values and technolog ical and economic realities. Often discussions of the role and responsibility of architects in times of environmental emergency stumble on disciplinary boundaries: It is easier to look outside our field and blame the real-estate

7 1.0

business, construction companies, and politicians for lack of ambition, than to recognize how the planning profession is contributing in environmental destruction.

In this thesis, I will reframe the architect’s role in the environmental crisis by examining the culture of building through the waste it produces. After all, waste is the excess of our lifestyles of abundance, the material product of our disregard for the environment. Waste is the inherent flip side of consump tion, to the extent that it has been proposed that instead of the consumer society, it would be appropriate to speak of a ‘waste society’.2 Yet, waste is elusive and cannot be grasped without a multidisciplinary approach.

Waste is a hybrid concept that occurs somewhere between the ‘cultur al’ and the ‘natural’. Thus, it challenges the ideological divide to human and nature that has influenced Western thinking at least since the Enlightenment, and is still present in disciplinary boundaries today. The human kind has an increased capability to cause harm to the environment, yet, neither natural nor social sciences accept the claim that humans are somehow separate from nature.3 According to sociologist John Urry, the split between the natural and social makes it difficult understand and address the impact of human behav iour in the biosphere.4 The division is particularly evident in the sustainability discourse that positions human society as the contrary force that disturbs the balance of the natural environment. The three aspects of sustainability—en vironment, society, and economy—are often depicted as a non-hierarchical triad, but in practice human society operates within the environment, simultaneously dependent on nature and a part of nature.5

According to ecologist Richard Levins and zoologist Yrjö Haila, “signifi cant changes in the environment are caused by actions practised consistently in vast areas and through long periods of time.”6 Such changes cannot be caused by individuals, but systemic patterns of the specialized society. Thus, change is to be demanded not so much of the individual, but the entire social and organizational system.7 In his book Climate change and the society sociol ogist John Urry emphasizes the importance of understanding how deeply environmental challenges are rooted to societal systems: Systems simultaneously require and give birth to customs. Social life is built on them, and they are not easily changed.8

8

Seemingly insignificant conceptual obscurities can have far reaching consequences. In the article Kestävän kehityksen paradoksit (Paradoxes of sus tainable development) (2007) philosopher Teppo Eskelinen asked how it is possible that ‘sustainable development’ has been understood in a way that the lifestyles of countries and people that consume the most resources are left unquestioned. The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development report Our Common Future (1987) famously defined ‘sus tainable development’ as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” Eskelinen sums up the problematics within the definition in two major con cerns. First, the definition is based on an assumption that future generations share uniform interests, while this is clearly not the case—not even within a single generation. Secondly, the concept of ‘needs’ is ambiguous. Fulfilling biological human needs, such as the need for shelter, has come to depend on complex industrial processes, that in turn require oil, machinery and logistic systems. Since human operations are so comprehensively tied to the eco nomic machinery, specifying what exactly counts as a basic need is no longer straight forward. This leads to a situation where ‘sustainable development’ can be used to justify a contradictory actions.9

Inconsistency is evident in the way we build. Construction industry is thriving, even in European countries, where population growth has stopped and quantitatively speaking there should be no need for more buildings. Old buildings are demolished while still physically sound to make way for new, sustainable ones, despite the fact that even considerable renovations generally result to smaller emissions than renewal.10 Consequently, construction and demolition amount to more than a third of all waste produced in Europe.11 Compared to how much talk there is about municipal waste, the vast amount of construction waste goes virtually unnoticed by the mainstream media. While the public debates on whether or not it is necessary to give out straws in fast food restaurants, physically functioning buildings are smashed into rubble and shipped away by truckloads to make way for new construction. This master’s thesis examines the ways in which the contemporary build ing culture produces waste. The aim is to identify crossings and bridge gaps between architecture and critical discourses on waste in social sciences and

9

humanities. Waste is conventionally understood through the practice of disposal, and lately increasingly recycling. Studies on waste in the field of archi tecture make no exception: Waste is usually discussed in relation to re-use of building parts or building material recycling. Architecture is essentially problem-solving; hence waste is viewed as a problem to be solved. However, humanists and social scientists studying waste are not primarily interested in technical means and measures of managing unwanted material. Following their example, I will look into the culture that produces the waste object in the first place.

Design and building are activities directed at shaping the environment towards some goal or ideal. In forming the urban environment we are si multaneously labelling certain aspects of it dirty and useless. The object of this thesis is to find out what happens before and around demolition deci sions, and how has demolition been promoted by the ideals of architects and urban planners. In his licentiate work about the modernist demolition discourse in Finland, architecture historian Vilhelm Helander distinguished between structures of the organized society—such as legislation, political will, and the economic system—and the ideas and cultural valuations of building practitioners that both contribute to forming the built environ ment. Valuations of architects reflect dominant cultural values but are based on specialized knowledge of the field in which they operate. Founded on history and custom, “valuations change constantly, conforming to practi cal demands, under the pressure of new social and economic factors, and eventually also subject to new ideologies and fashions.”12 Buildings are not to be interpreted solely as the creations of individual artistic minds, but they cannot be reduced as inevitable products of their particular context, either. Planning ideals can, little by little, shape the built environment. This includes aesthetic ideals that “simultaneously express and alter the goals set for the built environment.”13

This thesis approaches the way contemporary architecture produces waste through the architectural history of modernism. The 20th century was a period of profound change in both building and waste production. It was a time of increased quantity and standardized practices. Furthermore, it was a time of intense globalization, of which the story of modernism is a good

10

example. International style replaced the traditional and the local with the global and universal. The progressive modernists who continue to be remem bered by their projects and visions were as much the symptoms as they were the creators of their time.14 In discussing their work, I am not saying that the rest is irrelevant. The texts and projects reviewed in this thesis are both evidence of the past and the present: They tell something of their time, but the fact that they are still remembered is equally revealing of their continued effect in our time.

A significant divide in the texts of early modernists was between local and universal, unique and standard. Modernists saw standardisation as an inevitable course of development, and local traditions often became tram pled under the globalizing strive of modernisation. I have made the conscious decision to repeat, once more, a ‘Western’ and particularly Europe an narrative, often neglecting local nuances and opposing opinions. The importance of the particular, as opposed to the universal, comes up in the texts of waste scholars. Yet, the essential changes in the culture of building that intensified construction waste production in the 20th century were not local but transnational.

This thesis attempts to re-evaluate prevailing design practices by locating architecture within the multidisciplinary framework of critical waste studies. It consists of a qualitative literary review, that juxtaposes discourses on waste with architecture history and theory. The work is an extended piece of archi tecture criticism motivated by environmental justice, through which issues related to architecture and waste are reflected.

Besides introducing a new perspective to architecture theory, approach ing waste from an architectural perspective has the potential to open up the waste discourse to a wider understanding of the way the built environment contributes in waste making. Considering the volume of discard produced in building and demolition, critical analysis on construction waste has been sparse. Scholars of waste and material culture frequently focus on objects close to hand. Buildings have a curious tendency to escape their consideration. Perhaps their scale places buildings within the scope of urban studies, or maybe it is our comprehensive dependency on buildings that makes them difficult to grasp.

11

Diving into unfamiliar situations and problematics is a standard part of an architectural design process. Each new assignment starts with acquiring knowledge. As the process goes on, the designer enters unknown areas that require research. Thus, there is nothing exceptional in adapting an interdisciplinary standpoint. However, the object of this work is not to come up with solutions but rather to reframe the problem of construction waste.

The thesis is built up as a series of essays that range between topics but are simultaneously thoroughly interconnected. Chapter 2. Critical perspectives on waste provides a brief introduction to discourses on waste in social sciences and humanities. The chapter defines ‘waste’ for the purposes of this thesis and constructs the framework through which architecture will be examined. The chapter draws from a selection of literature from various fields such as anthropology, sociology, and philosophy. Recent Finnish publications, such as the introductory book to waste in social sciences Tervetuloa jäteyhteiskuntaan (Welcome to the waste society) by Valkonen & al (2019) and the waste-themed issue of the philosophy magazine Niin & näin (2020), relate my work within the current local discourse. Contemporary writings are combined with international classics, such as anthropologist Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (1966), probably still the most cited work in waste literature. I am using ‘critical waste studies’ as an umbrella term for the research on waste in social studies and humanities. As the chap ter makes apparent, however, there is no unified field of waste studies. The topics raised here provide one lens for a critical re-examination of modern architectural discourse.

Chapter 3. Sorting architectural discard consists of four essays about modern architecture and waste. This chapter depicts the period from the emergence of modern town planning in the 19th century to the environ mental awakening of the 1970s. It is impossible to dig deep into the history and theory of modern architecture within the length of this thesis. This is why I have distilled the historical account into four snapshots that revolve around different scales and design problems and emphasise different aspects put forward in the waste literature. The popular canon of European and North American modernism provides material for examining the ways waste has been defined in relation to architectural ideals. Along the lines of Mary

12

Douglas, “where there is dirt, there is a system.”15 Disorder is the inevitable flipside of order; cleanliness does not exist without dirt. Manifestations, writ ten and built, are thus interpreted as verbalisations and materialisations of a cultural system of ordering. The intention is to examine what kind of order is promoted, what is rejected, and why.

Architecture theory has a vibrant culture of re-theorising history. Rayner Banham started a tradition of critically re-writing the history in his book Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960). In The Origins of Modern Town Planning (1967), Leonardo Benevolo connected the formation of modern town planning practice with societal and political developments of the 19th century and mitigation of epidemics. Mark Wigley and Beatriz Co lomina have analysed modern architecture from the point of view of cleanliness and hygiene in their recent writings. Colomina directly accounts the “intra-canonical” view to Banham in her book X-Ray Architecture (2019), where she explores the relationship between 20th Century architecture and parallel developments in medicine. Wigley’s article Whitewash (2020) revised the history of architecture through concepts of hygiene, particularly the use of the colour white, with reference to recent debates on racial injustice. In the book Obsolescence: An Architectural History (2016), historian Daniel Abram son approaches 20th-century construction culture through the concept of obsolescence. He traces the origins of the use of the term in the American real estate sector and locates it in the modernist architectural discourse. These texts, along with others, have been used as references for this chapter, in terms of both content and form.

Chapter 4. Recycle, reduce, reuse, refuse proceeds to examine our contem porary relationship with the built environment. It focuses on the contemporary phenomena, practices and ideas that contribute to the production of waste today. The chapter consists of three essays exploring three different viewpoints to the contemporary built environment and waste. These could roughly be called the managemental perspective, the philosophical perspec tive and the architecture theory perspective. The chapter begins at a construction waste depot and introduces the practical reality of construction waste management dictated by legislation, technology, and economic considera tions. This is contrasted with a more philosophical outlook on our relation to

13

the spaces we occupy and the objects we use. The chapter ends with a review of two essays in contemporary architecture theory, discussing the architectur al pursuit to order and the sorry results it has produced.

During the process of writing, I was constantly remined by the elusive nature of waste. However hard I tried to focus on the unwanted and discard ed, it kept slipping away and I soon found myself writing about the very opposite of waste, the ideal and aspired for. The very act of writing about waste, focusing one’s attention to its materiality, significance and potential seems to turn it into something else entirely, re-appropriate it as an object of human

interest when by definition it should remain anonymous and unwanted. This difficulty is the very reason why waste should be brought to front.

When discussing something as all-encompassing as waste, it sometimes felt easier to explore the subject trough anecdotes, memories and metaphors rather than sticking to a strict academic form. Last summer, I participated in an architecture workshop in Greenland where our group designed and built a pavilion out of found materials from the local junkyard and on site. This ex perience of rummaging around the dump is described in the second chapter, because the memory of the place became a reference point on which to reflect the texts I read. Using my own voice may give the work a subjective feel, but it would hardly be possible to convey the same message with an appearance of objectivity. After all, the topic of this thesis made me enter strange areas and accept that I can only ever know very little.

14

Urry, 2011, p. 156.

e.g. Valkonen & al, 2019, have named their book Tervetuloa jäteyhteiskuntaan! (Welcome to waste society!)

Haila & Levins, 1992, p. 9; Urry, 2011, p. 8.

Urry, 2011, p. 19.

Economy, on the other hand, is a human concept and as such, it belongs within the sphere of society.

Haila, Levins, 1992, p. 249.

Urry, 2011, p. 156.

Ibid.

Eskelinen, 2007.

Huuhka & al., 2021.

Eurostat, 2021.

Helander, 1972, p. 11.

Ibid., p. 12.

Till, 2007, writes on p. 126 that ”Le Corbusier and the others are not a cause of modernism; they are the symptoms of modernity.”

Douglas, 2002, p. 44.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON WASTE

2.1 Dump diving

This voyage begins in a Greenlandic dump. It is, of course, not the actual starting point of my inquiry into trash, but an editorial move. Writing is about organising thoughts and words, to form a logical story of events that were a complete mess when they actually took place. Much of the sentences and chapters in this thesis were random thoughts, written down one by one, finding their place in the final text through a tedious sorting process. Not everything fits the narrative, and such material is cruelly dropped out.

The junkyard in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, remains unsorted. It is out of sight from the settlement, across the Watson river that springs down masses of meltwater from the inland ice sheet. Kangerlussuaq is located at the head of a 190 km fjord with the same name. The settlement was founded as a US Air Force base during the second world war and is now functioning as the largest international airport in Greenland. With a population of four hundred people, Kangerlussuaq is liveliest around the time big aeroplanes land, or when bad weather delays flights and lengthens layovers. There is a harbour, not actively used, twelve kilometres down the fjord. It can be reached by car but this is about as far as you can drive. Habited areas in Greenland are too distant to be interlinked by a network of roads. Presently under construction, a new 130 km road from Kangerlussuaq to Sisimiut will be the first driveway between settlements.

Due to its remote location, transporting anything to Kangerlussuaq is expensive. Once things are no longer needed, they will not be shipped out.

17 2.0

Instead, they will find a permanent address in the local dump with the rest of Kangerlussuaq’s junk. Past the bridge over Watson River, from the top of the sandy slope, the scrapyard appears in curious contrast to the surrounding scenery. Amidst the ancient landscape of sculptural hills dressed in low shrubbery, sliding into steep gritty banks of the fjord, such a sight of industrial culture has an anomalous presence. Approaching the area, one can start to tell apart items from the patchwork of shapes and colours, glimmering under the shy arctic sun. Not until entering the realm of discarded objects, can one begin to comprehend the vastness of the area.

Most of the contents of the dump are material that cannot be burned: old vehicles, empty oil canisters and fire extinguishers, building parts and domes tic appliances, chiefly out of metal. There is a large stack of old electric poles with wires and beautifully glazed ceramic knobs and an entire staircase with walls and a roof ripped off maybe from the airport, and brought to the dump in one piece. There are old toys from the children’s playground and countless of smaller objects and unidentifiable mechanical parts. Here and there you might find musk ox and reindeer bones, some of them grinded into a heap

18

Approaching Kangerlussuaq junkyard with Kangerlussuaq fjord in the background. Photographed in August, 2021.

Objects in the junkyard: Oil canisters, boxes full of brushes, old vehicles.

of morbid gravel. This is the ending point of the linear economic system, a mirror image of Kangerlussuaq. But like the portrait of Dorian Gray, this image contains a violent presence of history. As lines on a face grow deeper with time, the scrapyard expands.

Much of this stuff has been here for years, even decades. The array of ob jects can be read as an archive of the settlement’s past: Airplane engines, with fans spinning gently in the wind, bright orange industrial washing machines first imported, and finally discarded in large quantities. The American occu pation and aviation history still linger in their leftovers. However, reminders of the past are only partially preserved. In the corner of the dump, right next to the sandy bank sloping steeply into the stream and the fjord, there is an area for burning household waste. During our stay in Kangerlussuaq, it is lit up in open fire every few days, filling the air with a toxic stench.

Amongst the shambles of junk there are pristine leftover materials, some of which are carefully packed as if waiting for future use: steel roofing, timber planks turned silvery grey exposed to weather, unused screws and nails, old shipping boxes filled with thousands of identical cogwheels. By the side of

19

the driveway, there are neatly packed steel elements, that seem rather to be stored than left behind. As locals drive in with their pick up cars, after emp tying the cargo bed of unwanted material, perhaps they fill it up again with useful stuff. A couple of tourists have found the dump and are scavenging for souvenirs. Judging by the tags on oil canisters and cars—saying things like “gangster shit”—the place has been used as a hangout by at least some generation of local youth. But members of the animal kingdom have settled in permanently: a family of arctic foxes is living behind the canisters with the text “explosive” on them, and a flock of ravens is circling around for fresh garbage near the incineration site.

As we get used to rummaging around the dump in search of something useful, we too start to form a relationship with the place. We remember the locations of interesting objects and the easiest routes to them. There is a short age of useable wood material and we have to spend a lot of time scavenging and taking apart palettes, boxes and electricity posts. In this work, we learn to be aware of creosote, asbestos, sharp edges, unstable structures, and flam mable substances. The familiar objects start to lose their magical appeal. They become mere landmarks or obstacles and potential hazards. Tons of worthless stuff you have to pass to find what you are looking for. I remember the words of my colleague who, on the second day of finding inspiration in the dump, burst out: “I find it hard to see anything interesting in trash.”

Surely this is a normal response. After all, waste is by definition some thing that has departed the realm of functioning society as useless and valueless. Even to call an object waste reveals that its initial function and material qualities are less important as defining features than the fact that the object is or should be discarded. And the dump is, by definition, the burial ground of these objects forsaken by human society. The stuff here signifies nothing but a void of meaning and potentiality. Left behind, the turquoise beams, the aluminium sheets, the oil tank, and the Volvo truck are reduced to anonymous heaps of material that occupy space.

Rarely does one come face to face with the extent of human wastefulness as concretely as by paying a visit to a dump. In our everyday lives, throwing things out is so customary that it does not require much thought. Back home, I scrape the burned surface of my toast to the sink and flush it down the

20

drain. I slice pieces of cucumber on top but dump the dried end. Coffee is ready, so I pour it into a cup and toss the used grounds in the compost with the cucumber. I add the rest of the milk and fold the cartoon into a paper bag with other cardboard waste.

We all recognize waste when we see it. But despite being so mundane, waste is difficult to approach—perhaps because so much is done to hide it. Waste travels between enclosed spaces, avoiding attention. Even in clear sight, waste remains elusive. My photos from the Kangerlussuaq dump reveal very little of their subject. The contents of the scrapyard is reduced into a collection of aesthetic objects, their idleness translated into obscure beauty. Where this stuff came from, the picture does not tell. Nor does it tell much about the material qualities of the objects, such as their chemical contents (possible toxicity) or physical structure. The surrounding dump seems to explain all there is to it. Outside its native context, the sight of waste becomes more striking: stranded on the beach, as litter on the streets. Or straying down the sandy bank of Kangerlussuaq fjord, on the way to escape into the ocean.

Waste comes about as a question of logistics and management. Instead of asking “what?” the more proper question considering waste seems to be “where?”. The everyday understanding of waste is so deeply linked with prac tices of disposal, that it seems difficult to conceive waste without relation to removal. But disposal is no simple task. The quantity of waste produced yearly is continuously growing. Simultaneously, the material diversity of dis card has increased. Practices of disposal have become so complex, most of us

21

The gritty banks of Kangerlussuaq fjord in August 2021.

can no longer tell what happens to waste after it leaves the domestic realm. When it is taken out, household waste makes a transition from the private sphere as a public responsibility. In a sense, the bin becomes a gateway between private and public and a means of social control. Rather than a place, the bin can more accurately be understood as a practice.1 It is one small step in the waste management system with immense importance to the functioning of the whole.

Waste is mostly visible to most of us as household waste but in fact, in 2018 only 8,2 % of the waste produced in Europe was discarded by households. The majority of waste is produced in industrial processes and never reaches the average consumer. This is one of the reasons why Max Liboiron, a researcher and founder of the website dischardstudies.com, argues that it is not possible to truly understand waste through everyday experience. In the article Why Discard Studies (2014) Liboiron points out several common misconceptions about waste. For example, it is not the litter from the streets infesting our oceans, but most ocean plastics escape from infrastructure; fac tories, cargo ships, and landfills.

Increased awareness of the human impact on the environment has led to more attention being focused on waste in a variety of fields. Research can be roughly divided into two main streams: waste management and studies of waste in social sciences and humanities. Waste management is essentially problem-solving. It approaches waste in legal terms, as ”any substance or object which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard,” along the lines of the EU Waste Frame Work Directive. Waste management strives towards mitigating the harmful effects of discard by developing more so phisticated ways of dealing with it within the existing societal framework. EU waste policy is founded on a five-step “waste hierarchy” that depicts the preferred order of waste management practices. Disposal into landfills is on the bottom as the last resort, after re-use, recycling and energy recovery are ruled out. The preferred option is to prevent waste from being produced in the first place.2

Despite increased interest in recycling and reuse, most scholarly attention is still directed towards different means and methods of disposal. The least amount of research is done on preventing waste.3 If the culture that produces

22

waste is taken for granted, there is a risk that what is being addressed is the symptom instead of the underlying structures behind it. Approaching waste as mere heaps of physically defined and mathematically quantifiable material can have a neutralizing effect. Social scientists and humanists engaged in the study of discard do not accept waste as a natural category. Instead, it is un derstood as socially constructed and relative. Along with the waste object, researchers are interested in the cultural conceptions and practices where waste is defined. Waste is put into a broader context by examining the “hidden sys tems of infrastructure, economics, and social norms”4 behind the production of waste. Industrialization, capitalism, and global economies become central as the “engines of waste”5.

In this chapter, I will provide an introduction to critical approaches to waste through a reading of seminal works and review of contemporary dis course. I will discuss different ways waste is defined, provide a historical perspective to waste, followed up by contemplation on the social and economic aspects of waste. It is hardly possible to provide a ‘big picture’ of the subject but this chapter introduces some key concepts and ideas put forward in the source literature.

2.2 Rubbish metaphysics

In this thesis, ‘critical waste studies’ is used as an umbrella term for research on waste in social studies and humanities. Sometimes referred to as discard studies or rubbish theory, critical waste studies does not form an organized or consistent field of research. It could be more accurately characterized as a collection of multidisciplinary thought.6 While practices of waste management do not escape the critical outlook, the distinct approaches to waste are not to be understood as contradictory but rather as parallel exercises of prob lem-solving and problem-finding. Where waste management addresses the problematics of waste and disposal based on current political will and tech nical capabilities, critical waste studies has the potential to relate problems to context and make hidden systems apparent.7

To move beyond an everyday conception of waste, it will be helpful to compare the different ways waste has been theorized in critical waste studies.

23

In a review of recent literary contributions, geographer Sarah A. Moore (2012) illustrated the variety of notions of waste in social studies by dividing them into four groups. She conducted the categorization based on two basic questions: “how is waste defined” and “how is waste related to society”. The first question refers to the degree in which a given approach presumes waste to be defined by its own characteristics. On one side, waste constitutes a natural category defined by its own qualities, and on the other side, waste is understood to be relative and defined as an opposition to something else. The second question reveals weather waste is perceived to be a part of society or separate from it. Or, in other words: “Do certain social processes pre-exist objects and subjects or do objects and subjects, together, help to constitute society and space”.8

The traditional perspective to waste is that it is defined by its own characteristics and must be externalized from society not to threaten its functions. This conception aligns with the approach of waste management: the focus is on disposal, not on finding theoretical grounds for avoidance. Taking the hazardous quality of waste as starting point also forms the basis for studies on the uneven geographical and social distribution of environmental and health detriments of waste. Besides negative characteristics, waste can be considered to carry material or economic value, for instance in relation to waste trade. Regardless of what attributes are attached to waste, what these essentialist perspectives have in common is that the nature of waste is not questioned. Instead, attention is placed on practices related to waste. Waste is viewed as a ‘hazard’, ‘commodity’, ‘resource’, ‘object of management’, or ‘archive’.9

An alternative way of understanding waste is as the residual category of cultural categorizations. Like the previous approach, this position situates waste outside the sphere of organized society. But instead of classifying waste based on its intrinsic qualities, waste is defined in opposition to culture. This line of thought was established by anthropologist Mary Douglas in her seminal work Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo that has had a profound influence on the study of waste ever since its publication in 1966. Douglas argued that purity in a spiritual sense cannot be discussed apart from physical cleanliness. Dirt is what falls between cultural categories: What cannot be fitted inside the order of things is understood as disgusting or dan gerous. Maintaining order demands excluding these anomalous elements.10

24

Hazard, resource, commodity, object of management, archive – or matter out of place? Kangerlussuaq, 2021.

The final two groups consist of conceptions that do not posit waste out side the realm of society. Instead, it is understood to contribute in forming society. In the third group Moore identifies definitions of waste as ‘filth’, ‘risk’, or ‘fetish’, characterized by its affective qualities. Here, the power of waste lies in its sensory attributes; Waste becomes active through its profound ability to disgust, forcing people to develop systems for its removal. For instance, human excrement shapes the city by forcing people to build sewage systems to manage it. Thus, refuse does not represent an “outside” but active ly contributes in shaping society. 11

Finally, Moore recognizes approaches where waste is expelled by the socie ty as the “(often) unvalued and indefinable other” in order to enforce individual and societal boundaries. Waste is perceived to have the capacity to transform society but less stress is put on its inert qualities. Instead, waste becomes defined in relation to other things. To this group Moore includes approaches that view waste as a ‘governable object’, ‘actant’, or ‘abject’.12 I will continue to expand on these concepts as they are represented in my source literature.

25

Various theorists have drawn from Foucault’s idea of governmentality in examining how waste is classified as an object of management. Historically, scientific conceptions of disease and contagion have legitimized practices of management and control of certain populations. The transformative power of the discarded object could also be theorized in terms of the ‘actant’. In the work of Bruno Latour and several other writers, some of whom might be categorized as ‘new materialists’, the power to act is not understood to be ex clusive to humans. Instead, humans are links in a network of “actants”, things that act. Together, all objects form a complex non-hierarchical network where each object is connected to other objects. Humans do not act alone: the tools we use, the buildings we live in, as well as the air we breathe are our accom plices. Many writers describe waste as ‘vibrant’ or ‘living’, contradictory to the conventional idea of waste as a passive object of management. Recogniz ing the interconnectedness of all actors on a non-hierarchical plane also leads to questioning the divide between human society and nature.

Julie Kristeva and Georges Bataille are the most notable theorists of “ab jection”. In her book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980) Kristeva gives a psychoanalytical account of the ‘abject’ as something that is simulta neously constitutive of the subject and expelled by the subject. For Kristeva, abjection means exclusion as opposed to identification. The survival of the subject depends on ruling out the abject that “threatens one’s own and clean self.” 13 However, abjection is never complete and the abject remains a con stant threat to the subject. Kristeva follows Bataille in linking the abject to the weakness of the prohibition that is necessary in constituting social order.14

Although the relationship between waste and society is less dualistic, some theories of the last group are akin to Mary Douglas’s work. Her definition of dirt as “matter out of place” is frequently quoted when pondering the metaphysics of waste. The key idea of Douglas’ work was turning her attention from the object to the process that labels it dirty. In doing this, she followed the line of thought initiated by Émile Durkheim’s analysis of the term ‘sacred’. According to Durkheim, sacredness cannot be traced back to any physical features of an object. Instead, it is defined by the act of worship, that entails sustaining the line between sacred and profane.15 Similarly, Doug las theorized dirt as a outcome of the order making practice. Dirt is never

26

“unique” or “isolated” but comes into being in relation to its context: “Dirt is the by-product of a systematic ordering and classification of matter, in so far as ordering involves rejecting inappropriate elements.”16

Some authors have criticized the theoretical contributions that build on Douglas’s thought on their ambiguous use of terminology. Waste and dirt have been used as metaphoric categories under which a wide range of topics are discussed all the way from stains to otherness and gender issues. For in stance, philosopher Olli Lagerpetz states that the level of abstraction is too high and as a result the borders between different forms of abjection become blurred. Dirt is discussed parallel to waste, along with faeces, and even mi nority peoples without distinguishing terms. Instead of precision, questions of cleanliness and dirt become metaphoric. Furthermore, theories tend to overlook the everyday usage of the terms.17

Lagerspetz criticizes current dirt-theory of reductionism. He calls the insistence to find hygienic reasoning behind ruling out certain objects from the cultural sphere ‘hygienic reductionism’, an equivalent of what Mary Douglas calls ‘medical materialism’. According to this line of thought, cultural habits have evolved historically through the avoidance of pathogens. For example dietary restrictions in different cultures are thought to have a rational med ical basis. As opposed to the medical explanation, Douglas reduces dirt to a cultural order making practice. Lagerspetz calls this ‘anthropological reduc tionism’. The focus is shifted from the physical world to the human subject who colours the neutral reality into dirty and clean.18

Contrary to Mary Douglas’ definition, in his book Dirt (2018) Lagers petz views dirt as a very distinctive phenomenon, that cannot be reduced to anything else. ‘Dirt’ is a secondary quality of a ‘dirty’ object, a contaminating additive that only comes to be defined through its contact with the master object.19 The word ‘dirt’ is used to describe a very particular kind of contamination. An object thus soiled, however, does not automatically become waste. Neither does a waste-object necessarily have to be ‘dirty’. Waste and dirt are two different things.

Lagerspetz approaches waste or rubbish as a historical concept related to our contemporary way of life.20 Waste could be described as something that no longer fulfils its given function. It might still be working, but replaced by a

27

more ideal object. Perhaps nothing changed in the object itself, but perceived needs changed rendering the object useless. Many materials and objects are designed to be used and thrown out. For example, chewing gum, tissue, or food packaging are intended to go directly into the bin after use.

In this thesis the term ‘waste’ does not point exclusively to material that has entered or is about to enter the domain of waste management. Outside the legal framework, it is hardly possible to provide an exhaustive defini tion of waste. Ruling something out as waste is a matter of subjective judge ment founded on sociocultural categorization as well as material facts. As the upcoming chapters will reveal, categorization is not a simple or clean cut process. Instead, it is messy, dynamic, and relational. Apart from disposable items and packaging, few things turn into waste overnight. Instead, they wear out and loose value gradually. Furthermore, there are other ways of giving things up besides discarding them. What is no longer ideal to one person might be desirable to another. Calling waste ‘relative’ is an alternative way of saying that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. But simultaneously it is evident that there is a lot of material that no one wants.

Household waste in Kangerlussuaq dump, 2021.

28

2.3 The waste problem

The current ‘waste problem’ in its material and social complexity and geographical magnitude is a relatively new phenomenon. It is epitomized by occurrences such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: a collection of plastic debris, mostly broken down to microparticles, floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It is sometimes said, that only humans produce waste. Schol ars in critical waste studies tend to avoid such claims. It is true, that what we call waste is a human concept, defined by humans for human purposes. However, all processes in nature produce excess material. Within millions of years, other processes have evolved to make use of this excess. Plastics have only been produced since the 1950s and since then, they have accumulated on an unprecedented scale. There is something exceptional in the way the contemporary human population extracts material from nature only to discard it later.

Studies in anthropology show that all societies have practices of organiz ing the environment and ruling out unwanted material. This also applies to historic human populations. However, not all waste survives the test of time.

Nomadic hunter gatherers would frequently abandon their camps in search of better hunting grounds and more fertile lands.21 Yet there is little left of their lifestyle besides tools and arrowheads made out of stone. It is not likely that accumulation of waste would have been an issue for nomadic popula tions since their discard consisted largely of organic materials and was not produced on such a scale for it to pile up. In fact, in Rubbish!: The Archaeology of Garbage Willian L. Rathje and Cullen Murphy write that it was not until the Neolithic Revolution when human beings started forming agricultural settlements that “our species faced its first garbage crisis”.22 According to the authors, of the four basic methods of garbage disposal—dumping, burning, recycling, and source reduction—human beings have always been inclined to dump.23 This only became an issue when the population started growing and forming larger communities.

It is a common misconception to read history as movement towards a higher standard or cleanliness. Throughout history, dense urban settlements have developed waste and sewage management systems. For instance, Rome’s

29

0,0006%

0,0002%

0,0000%

0,0004% 0,0006%

0,0004%

0,0002%

0,0000%

0,0004%

0,0002%

0,0000%

0,0004%

0,0002%

0,0000%

0,0004%

0,0002%

0,0000%

0,0004%

0,0002%

0,0000%

trash garbage rubbish disposable leftover

discard 1800

30

1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020

Right: the entrance of Rome’s sewer, Cloaca maxima in 2022.

Left: Google ngram viewer data of waste terms.

sewer, the Cloaca maxima, was as important for the functioning of the city as its famous aqueducts.24 In Rome, the accumulation of waste is constant ly present. Old buildings have been dumped on the spot and fragmentally reused. The eternal city is literally built on the debris of past epochs.

In the medieval period, lack of waste and sewage infrastructure only became a major problem when agrarian villages grew and densified into urban centres. Lewis Mumford writes about measures that were taken to improve the hygiene of cities in 16th century England. For instance, digging waste underground was prohibited inside the city limits, along with carrying waste during the daytime. Also keeping pigs, that had been maintaining streets clean by consuming garbage, was banned.25

One way of examining changes in waste behaviour is by studying the history of waste-related terms. The English word ‘waste’ and its counterparts in other Germanic languages have original meanings referring to barren or uncultivated land.26 For people dependant on agriculture, areas unsuitable to sustain human habitation must have appeared vast (lat. vastus) and empty.

Enlightenment philosophy theorised a split between the human subject and natural space. Moreover, rational principles strengthened human authority over nature. Around the same time, the term ’waste’ started to gather moral baggage, pointing towards an ideal of proper use that is not attained.27 John Scanlan searches grounds for the altered meaning in the writings of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke. Locke’s work relied on a Calvinist ideal of stewardship of the land that placed humanity as the care keepers of

31

nature appointed by God. In Locke’s interpretation, the idea of stewardship entailed working the land to its full potential. Leaving land to nature was a waste: to fulfil ”God’s will” it must be made efficient through human labour.28

Changes in terminology echo changes in the way of life. Many of the waste-related terms that are now used synonymously originally had more specific meanings indicating the process in which they were produced. For instance the ‘trash’ originally meant branches or twigs and the word ‘rubbish’ is derived from the word ‘rubble’.29 Historian Susan Strasser follows the ex ample of H. De B. Parsons in distinguishing between garbage (food waste) and other kinds of refuse materials since “the offensive odor of decaying meat scraps, fish heads, and banana peels; their commercial value as fertilizer, hog feed, and marketable grease; and the high water content all distinguished them from other kinds of refuse.”30 Along with its affective qualities, garbage was set apart from other kinds of refuse based on how it could be used. A blanket term for refuse material would have been unnecessary, since households did not produce ‘waste’ in general but different materials for secondary use.31

Industrialization altered practices related to waste gradually. In her book Waste and Want (1999), Susan Strasser recounts the changes in waste be haviour of American households from pre-industrial culture to modern consumer society. While early industrial production continued to rely on second ary materials such as rags that were used to make paper and hog fat that was used as raw material for soap, recycling these materials moved out from the household. Initially, the same distributors that delivered goods to consumers took recyclable materials back to factories. But by the end of the 19th cen tury, the two-way trade between producers and consumers was replaced by specialized wholesalers and waste dealers: “a separate, highly organized trade built on a foundation of industrial waste, supplemented by scraps collected from scavenging children and the poorest of the poor.”32 Strasser notes, that this was “the first time in human history, when disposal became separate from production, consumption, and use.”33

This was a significant distinction since production and repair had been integrally connected in the pre-industrial society. Strasser refers to Claude Levi-Strauss’s description of the French bricoleur, “an odd-job man who

32

works with his hands, employing the bricoles, the scraps or odds and ends.” The bricoleur considers every project with respect to what he has on hand, engaging in a “sort of dialogue” between the toolbox and the junk box.34 The separation of disposal and production broke this dialogue. Throwing things out became easier still when cities took responsibility for the collection and disposal of household waste. Municipal waste management was part of the late 19th-century sanitary reform movement, connected to new ideas of hygiene (more in section 3.1). The introduction of municipal waste manage ment had the effect of encouraging disposal, as people got accustomed to the new kind of model of ruling objects out from the domestic sphere. Organized collection and sophisticated equipment promoted the notion of waste as a “technical concern, the province of experts who would take care of whatever problems trash presented.”35 In giving up their discard as a responsibility of the collective waste management, people unwittingly participated in breaking the circulation of material.

The twentieth century saw cities and households transform from relative ly closed circulation to open systems, where the flow of material is one way: materials are extracted from the earth, manufactured into industrial prod ucts, used, and thrown out incapable of returning to ecological cycles.36 New ways of expanding the market of consumer goods became an essential feature of the ‘consumer society’, in which “the growth of markets for new products came to depend in part on the continuous disposal of old things.” According to Strasser, Americans were made to buy more by improved marketing strategies and making changes in products themselves. For instance, introducing fashion to new realms of consumption encouraged consumers to purchase new products before using up the old ones.37 Disposability revolutionized the post-war market. Disposable paper and plastic products promised effortless cleanliness and convenience instead of “the drudgery of old-fashioned life.”38 They increased consumption through design, but also by marketing, which succeeded in infusing disposable products with a promise of a new and im proved way of life.

Several writers have exemplified changes in production and marketing with developments in early 20th-century car production.39 Henry Ford’s in vention of the moving assembly line is often remarked as a necessary con-

33

dition of economic progress and symbol of the mechanization of human work. Ford Model T was the poster child of industrial thinking of its time: “a product that was desirable, affordable, and operable by anyone, just about anywhere; that lasted a certain amount of time (until it was time to buy a new one); and that could be produced cheaply and quickly.”40 Ford offered basic transport in a market that was not yet saturated. Savings in manufacturing costs lowered the cost of the product, making it accessible for a wider group of consumers.41

However, in the 1930s, General Motors overthrew Ford’s market position by taking up annual model changes. The event is a classic example of ‘obsolescence’, the physical equivalent of ‘creative destruction’. Obsoles cence means a product becoming outdated through changes of technology, fashion or lifestyle, even though it is still physically functioning.42 Planned obsolescence refers to a conscious strategy of making the consumer buy the same product over and over again. Nowadays many products are consciously designed not to last physically. Designing with built-in obsolescence forces the consumer to discard the old item and purchase a new one sooner. 43 These strategies make it evident that waste is not only something that follows indus trial production: It exists already in the making of a product.

Besides the quantity of waste, the quality of waste has changed drastically in a short time. This is evident with ocean plastics, and not least with cars. Contemporary products consist of materials that did not show up in the surface of the earth in such large quantities before they were extracted and processed by humans. Their toxicity and the fact that they cannot be returned to ecological cycles has shifted the meaning of ‘waste’ towards something permanent, hazardous, and anthropogenic.

Popular discourse tends to place responsibility of solving the ‘waste prob lem’ in the shoulders of individuals and consumer choice. The general focus on household waste is symptomatic of the individualization of waste production. However, we all act and transact within the limited set of options on market, and our choices are backed by limited knowledge distilled through advertising images. The narrative of the power of the ‘conscious consumer’ is itself a historical creation, that has the effect of shifting focus away from the underlying structures behind the production of waste. Several writers have

34

Abandoned cars in the Kangerlussuaq dump, photographed in August, 2021.

35

A concrete factory in Viikinranta, Helsinki, 2019. Litter in Kyläsaari, Helsinki, 2021.

36

noted, that consumers had to be educated to get accustomed to disposable products and buying new instead of mending.44 Strasser gives accounts of people engaging in downright protest against the new culture of throwaway consumption.45 This leads to questioning whether the greed and indifference that presumably makes people consume and discard unsustainably are, in fact, biological human traits, or culturally transmitted modes of behaviour.46

2.4 Waste and value

Waste is commonly portrayed a something with low or no value or exclud ed from the value system altogether. But this conception of waste is under transition. Contemporary waste management no longer aims at physically eliminating waste (and what use would it be when sheer quantity has made it impossible to hide). Instead, the current strategy is to reappropriate waste. Transition into circular economy has even been regarded to render the whole term ‘waste’ useless.47

Circular economy is described by Ellen Mac Arthur Foundation as a “sys tems solution framework” with the potential to tackle global environmental challenges. It is based on developing more efficient use of material resources by maintaining materials and objects in circulation for as long as possible. In practice, this is done by extending the life cycle of objects by strategies of repair and reuse and recycling materials at their highest value. When prod ucts and materials are kept in circulation, the need for new raw materials will decrease, and ideally, there will be no waste. Circular economy is predicted to provide long-term resilience by combining “business and economic opportu nities” with “environmental and societal benefits”.48

Transition to circular economy requires a comprehensive re-orientation of all actors involved in production and consumption. Consequently, the concept has been picked up in various disciplines as a direction for future development. Perhaps because of its wide use, circular economy has become an ambiguous concept with countless definitions varying particularly on whether the emphasis is on economic growth or environmental factors.49 What definitions do share is a common understanding of the goal of circular econ omy: decoupling the connection between economic growth, use of natural

37

resources and production of waste.50 In a circular future, economic activity will no longer be proportional to the amount of finite resources extracted from the earth’s core.

The circular ideal has already altered practices related to waste. The culture of excluding and hiding unwanted material appears to be coming to an end: “Waste is no longer approached as useless material to get rid of, but nowadays waste is above all material that calls for use and application”, so ciologist Olli Pyyhtinen writes.51 Circular economy renders waste a technical problem and a question of design. To achieve closed material circulation, the entire life cycle of objects has to be taken into account already in the design phase. Materials that evade repurposing signify an error that can be fixed by optimizing processes of production and consumption.52

However, there is still a long way for circular economy to become reality. In 2021, a Finnish broadcasting company news article revealed that only a third of the plastic collected in Finland is successfully recycled into further use. Due to rapid growth, the volume of separately collected plastics exceeds the current recycling capacity. Furthermore, the wide variety of different types of plastics used in production complicates the recycling process. Most of the plastic collected to be recycled end up being burned with energy re covery instead.53 Similar difficulties are apparent in textile recycling. There is a growing market for second-hand clothes but limited options for discarding worn-out items. Several technologies for textile recycling exist, but materi al variety causes difficulties. Most fabrics are blends of different fibres that can only be separated through an energy-intensive chemical process. Textiles made out of a single material can be recycled mechanically, but the quality of the fibres suffers in the process, and a lot of the fabrics recycled are made out of poor quality material in the first place. Dirty or mouldy material could spoil the entire batch of textiles and should thus be disposed of with mixed waste. In practice, this is where most textile waste ends up at present.54

There is hardly anything revolutionary in returning the value to waste from the histrical perspective. According to Strasser, our period of an open-ended economic system appears to be more exceptional.55 Yet, scholars in critical waste studies are sceptical that circular economy will succeed in the total elimination of waste.56 Replacing rubbish bins with recycling facilities

38

does not intervene in the underlying issue of excessive consumption. Recycling may have the effect of making discarding items morally justifiable: “It seems, that the belief in a functioning recycling system acts as absolution for intensifying consumption.”57 While recognizing a need for increased material circulation, Valkonen & al. question the political ideology behind leaving current consumption habits unquestioned: “Looking from the level of a political program it (circular economy) can be seen as an ideological attempt to solve the problems of the consumer society without interfering in consump tion itself.”58 Circular economy does not problematize the “continuous production of new needs and promise of abundance” in the core of the contem porary ‘Western’ way of life.59 On the contrary, moving waste back into the economic realm and redefining it as a raw material justifies its production.

As a resource, waste is subject to the laws of supply and demand and charac terized by scarcity. Hence, the logic of circular economy does not seem to be directed towards the highest goal of the waste hierarchy: preventing waste. 60

Current waste policy both defines and solves the waste problem within the economic framework. But in everyday practice, waste is defined through

39

Sport equipment in the Kangerlussuaq dumpsite, 2021.

several parallel and overlapping classification systems besides economy, such as ideas of health and hygiene, social norms and customs, aesthetic prefer ence, and subjective feeling. The same can be said about other value judgements. Exchange may be a “universal feature of human social life”,61 but not all objects can be characterized as commodities, no more than all value judge ments reduced to economy.

Anthropologist Michael Thompson combined discourses of waste and value in his book Rubbish Theory (1979 / 2017). According to Thompson, rubbish is a category of no value and as such, an essential feature in social practices of classification. He writes that objects are culturally labelled into two distinct categories: transient and durable. “Objects in the transient cat egory decrease in value over time and have finite life-spans. Objects in the durable category increase in value over time and have infinite life-spans.”62 Objects with no value at all form a third category: rubbish. The rubbish state is what follows at the end of the life cycle of transient objects, at the low point of a gradual decrease in value. In Thompson’s theory, an object can move from the transient category through rubbish and eventually be rediscovered as durable. Unlike durable and transient commodities, rubbish is not subject to mechanisms of social control and thus provides a path for this “seemingly impossible” transfer.63

The key insight of Rubbish Theory is recognizing that an item can regain value after being classified as rubbish. Following Mary Douglas, Thompson’s theory is based on the idea that nothing is essentially waste, but rubbish is an effect of sociocultural classifications, that in themselves are dynamic. A shift between different categories of value reflects the status of whoever is in possession of the object: transforming rubbish to durability is a way of producing social distinctions and acquiring cultural, social, and economic capi tal. Thompson’s theory is about social control and the way social hierarchies are built and maintained through commodities. Valkonen & al. note that in the light of the contemporary discourse on waste Rubbish Theory shows several weaknesses. First, seeing rubbish as a state of zero or negative value is misleading since both waste and value are relative. Besides, Thompson’s anthropological reductionist approach completely ignores the materiality of waste in portraying rubbish as passive material on which social classifications

40

are imposed. Furthermore, the life cycles of objects are far more varied and complex than Thompson’s model shows.64

Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff elaborates this point in his article about the social biographies of objects. According to him, the commodity status of an object is not stable or absolute. Shifts and differences reveal “a moral econo my that stands behind the objective economy of visible transactions.”65 Each object is subject to opposite forces of commodification and singularization. While the exchange system strives toward homogenizing value, on the other side items are singularized as unique and thus impossible to transfer. In small scale societies, the classification systems of culture and economy have been in relative harmony, but in complex modern-day societies, they are less con sistent. While sophisticated exchange technology has opened up the world for broad commodification, the homogenizing effect of commodification is contrasted with an increasingly variegated area of private valuation: “The peculiarity of complex societies is that their publicly recognized commoditization operates side by side with innumerable schemes of valuation and sin gularization devised by individuals, social categories, and groups, and these schemes stand in unresolvable conflict with public commoditization as well as with one another.”66 Thus, a social biography of a thing consists not only of visible transactions but various singularizations of it, imposed by individuals and social groups.67

Economic thought pursues a model where everything is reduced to a single unit of value. The more widely the world opens up for commoditization, however, the further the specific individual and sociocultural evalua tions of value depart from the supposedly objective valuation of the market price. Interaction and crossings of the market sphere with sociocultural classifications lead to anomalies and contradictions and “conflicts both in the cognition of individuals and in the interaction of individuals and groups”68 For instance, a favourite item of clothing might be priceless for its owner, even if it is next to rubbish as a commodity. In the same way, differ ent social groups value objects differently. There is a broadly shared cultural understanding of the importance of national landmarks, causing them to be singularized and escape the forces of commodification. But when singu larizing values are held by more restricted groups without the capacity to

41

affect popular opinion, the singularized object may end up being treated as a commodity anyway. Conflicts are apparent in cases of historic pres ervation, when groups with a strong emotional bond to a building (such as residents and locals) or specialized knowledge of its qualities (such as heritage professionals) singularize a historic building, while others evaluate it through its profit-making potential.69

Kopytoff and Thompson make it evident, that it is the valuations of those in power that are realized in visible transactions of commodities. Thus, there is a link between marginalization and the economic value of things. This is evident in processes of segregation and gentrification. Thompson gives an insightful description of the way a “rat-infested slum” of Victorian terraced houses in North-London is transformed into “glorious heritage” once middle-class occupants move into the area formerly housing a working-class and immigrant population.

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has written an entire book about the ways modernity draws lines between us and them, excluding those who do not conform to the dominant ideals. Often enough, dirty work falls in the hands of marginalized people and, on the other hand, dirty work marginalizes people. This applies to lower income groups, as well as gender and ethnic minorities. Furthermore, the ideological paradigm of progress of modernity has a tendency to overlook local and indigenous practices. People who have not internalized the modernist standards of hygiene are easily judged and undermined.

Intercontinental flows of refuse material draw out a global geography of value. For decades, leftovers of the ‘Western’ lifestyle have been shipped to developing countries. Besides discard, second-hand goods leave Europe to lower-income countries. According to an UN report, 1,9 million used cars were exported from the EU in 2018, chiefly to North and West Africa.70 A case study from the Netherlands reveals that the majority of the cars exported to Africa did not have a valid roadworthiness certificate. Regular inspections and strict emission standards are named as reasons for the relatively frequent renewal of the European vehicle stock. Additionally, the disposal of used ve hicles is controlled by environmental protection regulations, making export to lower-income countries a viable option.71

42

Replacing the existing fossil-fuel-powered vehicle stock with electric transit is high on European climate policy. As the proportion of cleaner and more energy-efficient electrical vehicles increases in Europe, a part of the obsolete vehicle stock making way for cleaner transit gets a second life in the streets of the “third world”. In total, the global vehicle fleet is growing, and used vehi cles make up a majority of this growth in developing countries. While used cars may be safer and more energy-efficient than the existing vehicle stock, issues concerning environmental performance and disposal still apply when the vehicles are shipped to Africa. In short, saying that value is relative reveals little of the problematics of global trade of waste and second-hand materials. Like Michael Thompson puts it:

It is clear that one man’s rubbish can be another man’s desirable object; that rubbish, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Yet it would be wrong to explain away this distinction …To say that one man’s meat is another man’s poison is not to explain anything, but simply to pose the next question, which is: what determines which man gets poisoned? 72

43

A Volkswagen Transporter T4 (manufactured between 1990–2003) parked outside a store by the main road in Conakry, the capital of Guinea in West-Africa. Photo taken in December 2019.

Approaching waste through the economic framework without broader cultural and material considerations is not likely to provide technically feasible, let alone environmentally and socially sustainable solutions to the current waste problem. Simultaneously, such an approach evades questions of ethics and social justice.

Like this chapter has revealed, beyond everyday practice, waste anything but easily defined. It is not enough to perceive waste solely through its negative qualities, no more than branding it simply as a resource. As a by-product of order and as such a “necessary condition for society,”73 waste is going nowhere. People will continue to categorize the world based on various overlapping systems of classification and rule out unwanted material. If the waste problem with its environmental and social implications is to be taken seriously, besides technical solutions, critical scrutiny of these systems is re quired. In the following chapter, I will make an attempt to trace the systems of cultural classification that define waste within the architectural discourse of modernism.

44

1

Valkonen & al, 2019, p. 53–79.

2 European Union, 2008.

3 This observation was made by Prof. Iris Borowy, 2020, in Shanghai University & University of Helsinki online workshop The Development of Waste; the Waste of Development.

4 Valkonen & al, 2019, p. 13.

5 Liboiron, Why Discard Studies, 2014.

6 Valkonen & al., 2019, pp. 25–26, who in their own work use the term ‘social scientific waste studies’ to ”describe approaches that are inter ested in waste as a societal and cultural phenomenon.”

7 Liboiron, 2014: “As more attention in popular, policy, activist, engineering and research areas is being focused on waste, it becomes crucial for the humanities and social sciences to contextualize the problems, materialities and systems that are not readily apparent to the invested but casual observer. Our task is to trouble the assumptions, premises and popular mythologies of waste.”

8 Moore, 2012, pp. 781–783; Moore’s classification is also covered by Valkonen & al, 2019, pp. 26–27.

Moore, 2012, pp. 783–787.

Douglas, 2002; Moore, 2012, pp. 787–788.

Moore, 2012, pp. 788–790.

Ibid., pp. 790–792.

Kristeva, 1982, p. 65.

Ibid., p. 64.

Lagerspetz, 2018, p. 83.

Douglas, 2002, p. 44.

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Lagerspetz, 2018.

Ibid., p. 72.

Ibid., p. 48.

Ibid., p. 187.

Rathje & Murphy, 2001, p. 33.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 34

cf. Laporte, 2000, p. 14.

Mumford, 1961, p. 292.

Harris, 1989, as cited in Scanlan, 2005, p. 22.

Scanlan, 2005, pp. 22–24.

Ibid.

Lagerspetz, 2018, 188.

Strasser, 1999, p. 29.

Lagerpetz, 2018, p. 187.

Strasser, 1999, p. 109.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., s. 113.

Ibid., p. 15.

Ibid., p. 188.

Ibid., p. 268.

e.g. Strasser, 1999; Slade, 2006; Braungart & McDonough, 2009.

Braungart & McDonough, 2009, p. 24.

Slade, 2006, p. 31.

Strasser, 1999, writes on p. 192: “Many writers have tried to make a distinction between technological obsolescence and style… In practice, stylistic and technological obsolescence have gone hand in hand throughout the twentieth century… Americans have been tempted to replace many products because new ones worked better and looked more up-to-date.”

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Slade, 2006.

e.g. Strasser, 1999; Liboiron, 2014.

Strasser, 1999, p. 177.

Frugality would most likely be a more beneficiary trait for the survival of a human being in an evolutionary sense.