NAHJ members in U.S. Journalism/ Media Education

PRODUCEDBYZitaArocha

LourdesCuevaChacón

JessicaRetisFedericoSubervi-Vélez

This report was commissioned by the Board of Directors of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ), Washington, DC and prepared by Zita Arocha, El Paso, TX

Lourdes Cueva Chacón, San Diego, CA

Jessica Retis, Tucson, AZ

Federico Subervi-Vélez, Austin, TX

Cover and layout design Elio Leturia

Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0)

©All authors / National Association of Hispanic Journalists 2023

Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this report may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise).

June 2023

1. Executive summary goals

• Assess the demographic and academic working characteristics of NAHJ members who are also educators.

• Offer recommendations that can guide future NAHJ projects that address the educational and professional growth of those academic members.

• Offer a baseline of data that contribute to subsequent studies that delve further into these topics.

Main findings

• A total of 106 (41.2%) of 257 NAHJ academic members responded to the survey.

• Among Latino/Latin American (L/LA) respondents, 54% have non-tenure track jobs as either lecturers, adjuncts or visiting professionals on short-term contracts, with no job security and limited or no benefits.

• 42% of females, compared to 23% percent of males, have non-tenure track jobs.

• 101 work in the U.S.; 41 are concentrated in only two states–California (25) and Texas (16); five work in international settings.

• In California, more than half of the respondents are non-Latinx/Latin American; in Texas the majority are L/LA.

• There are fewer than five NAHJ member respondents in twelve states; there is only one in another 12 states. None of the respondents holds a teaching job in 25 of the nation’s states.

• More than 45% of the respondents are also members and active with AEJMC, which should alert the leadership of both NAHJ and AEJM to avoid overlaps in the dates selected for scheduling their annual conferences.

• Most respondents teach professional skills courses in print or digital journalism, courses that require the most time with students to ensure their development as future news media professionals.

• Most Spanish-language journalism-related courses are skills based and taught by L/LA respondents who are non tenure track.

• Among L/LA respondents, 71% are tasked with teaching professional skills courses in other journalism/media related majors–a percentage that is much lower among White non-Hispanics.

• Respondents indicated the need for more support and guidance for developing educational materials and keeping up with technology, and information about professional and networking opportunities.

2. Introduction/background

This report is based on survey responses from 106 NAHJ members who self-identify as journalism faculty or college teachers of journalism. It is the first in a series of data-based studies of NAHJ members. It was undertaken by the 2020-2022 NAHJ Academic Task Force, as a significant first step in a long-term comprehensive effort to chart the role and underrepresentation of Latino/a/x individuals who teach journalism at colleges and universities throughout the country. Additional information about the work of this Task Force is included in Appendix 1.

The survey participants provided essential data about their ethnic/racial heritage, where and what types of courses they teach, their academic status (i.e., tenured or tenure track, professors of practice, or lecturers, and affiliated faculty), their areas of research expertise, and whether they also teach journalism courses in Spanish. The findings are detailed below.

||| Why chart Latino journalism faculty and why now?

For more than a decade we have suspected, without hard data at hand, that Latino faculty are vastly underrepresented in the nation’s college journalism programs, departments, and schools. This reality underlies the growth of Hispanic student enrollments at state-funded and private institutions of higher learning, including the most prestigious journalism schools in the nation. At the same time, the number of Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs; schools with at least 25% Hispanic enrollment) has grown exponentially over the last few years –– from 229 in 2000 to 559 in 2020-21, according to an Excelencia in Education 2021-22 report. That same report indicates that more than 65% of Hispanic undergraduates attend HSIs. While our study includes respondents from a variety of journalism/communication programs in the U.S., future reports by this academic task force will focus on data from Latinos teaching journalism at HSIs.

The dearth of hard facts about Hispanics who teach journalism at colleges and universities, their role and status, and where and what they teach has shortchanged NAHJ’s ability to support them. NAHJ’s support can be most valuable for Hispanic journalism/media professionals who navigate their way through academic workplaces where their presence can have a profound impact on preparing young Latinos for future careers in news media. This report and future data based studies by the 2020-2022 NAHJ Academic Task Force should contribute to increasing the representation of Latino journalism professors in academia as well as advocate for career trajectories that move them toward tenure and other significant roles in their academic careers.

3. Methodology

The survey was designed by members of the NAHJ Academic Task Force. The questionnaire was distributed using Google Forms and sent via email to all the 257 NAHJ members who were registered as academic members. The NAHJ Headquarters facilitated access to members’ email accounts.

A first email requesting participation in the survey was sent on October 2, 2021 and a second one on October 20, 2021. The survey was further advertised on December 21 in the NAHJEdu private Facebook group and also in three NAHJ Educators newsletters sent on November 30, 2021; February 15, 2022 and March 16, 2022.

In addition to questions about demographics characteristics, including ethnic/racial heritage, the survey asked academic members about their university/college affiliation, their titles and positions, if they had tenure or were on a tenure track, the type of courses they taught (skills and/or theory). Finally, they were asked what NAHJ can do to support their advancement as college professors and instructors.

Of the 257 NAHJ members who were registered as academic members, completed questionnaires were received from 106, which represents a 41.2% response rate.

* For this study, the White non-Hispanic classification includes those who either indicated White, Anglo, or some Anglo-European heritage.

4. Findings & discussion

QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

The first set of data presents the respondents’ basic demographic characteristics, including the self-selected ethnic/racial heritage. (The ethnic/racial categories were based on an open-ended question. Because of the many words, names, labels, and identities indicated by the respondents, these required recoding into more general categories in order to summarize the findings shown below. For a full list of the original words used by the respondents, please contact the authors.)

As observed, of the 106 NAHJ members who responded to this survey, 59 (56%) actually listed a heritage that could be classified as Latinx or Latin American (L/LA). This means that 47 (44%) of NAHJ members who responded to this survey may or may not have a Hispanic heritage; but if so, that was not an identifier they used.

A key finding of this table is that 42% of females, vis-a-vis 23% percent of the males, have non-tenure track jobs. These non-tenure track instructors are either lecturers, adjuncts or visiting professionals on short-term contracts, with no job security and limited or no benefits. However, more than twice as many females than males hold tenured jobs.

A key finding from an analysis of Table 3 is that of the 59 Latinx/LA respondents, 54% have non-tenure track jobs. As stated above, they are lecturers, adjuncts or visiting professionals on limited contracts, with no job security and limited or no benefits. Of this group of Latinx/LA academic members, less than one third (29%) has achieved the job security granted by tenure. Also, in terms of percentages, gender differences by academic status are not notable except that more respondents who indicated Latin American heritage are among the faculty with non-tenure track status.

* Non-Tenure Track; Tenure Track; Tenured; percentages based on N=47.

** One TT respondent indicated non-binary and is thus included among the five TT, but not shown in the table.

Table 4. Non-Latinx and Latin American heritage by gender & academic status*

On the other hand, almost half (49%) of the non-L/LA respondents hold non-tenure track jobs. Also, in contrast, 29% of the White respondents had achieved tenure, which when combined with the others on this table, the percentage increased to 40%. In this analysis, the biggest notable difference is that a vast majority of White and the other tenured non-L/LA faculty are female.

It should also be noted that the number of tenured L/LA respondents is only two less than the Non-Hispanics who are tenured: 17 vis-à-vis 19. However, the percentage of the former is notably lower (29%) vis-à-vis the latter (40%).

The next table shows the states where the respondents worked either in the United States or other international locations.

* Other states with one each: Connecticut, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin.

Of the 106 respondents who are NAHJ members, 101 work in the U.S., five in international settings. However, the U.S. based respondents are heavily concentrated in only two states–California and Texas. It is important to note that in California, which has the largest number of Latinxs in the country, more than half of the 25 NAHJ respondents are non-Latinx/Latin American heritage professors. In Texas, the majority of the respondents are of Latinx/Latin heritage, as is the case in the other three states with more than six respondents, i.e., New York, Florida and Arizona. There are fewer than five NAHJ member respondents in twelve states; there is only one in another 12. At the same time, not a single one of the respondents hold teaching jobs in 25 states of the nation.

Academic and professional organization memberships

Of the 106 survey respondents, many have simultaneous memberships with academic associations such as:

• Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC, n=48)

• Broadcast Education Association (BEA, n=16)

• International Communication Association (ICA, n=12)

• National Communication Association (NCA, n=8)

• International Association for Media Communication Research (IAMCR, n=3)

What these numbers show is that more than 45% of our respondents are also members and active with AEJMC, the largest academic organization that addresses journalism

education. A key point to keep in mind with this finding is that the leadership of both organizations should avoid overlaps in the dates selected for scheduling their annual conferences. Although such will not be the case for the respective conferences in 2023, the overlap in dates has happened numerous times in previous years. This forces NAHJ academic members to choose to attend one or the other when both might be of significant value. There have been no overlaps in the conference dates with the other academic organizations.

With respect to membership in professional journalism organizations, a total of 64 participants indicated they also belong to professional associations such as:

• Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ, n=38)

• National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ, n=9)

• Online News Association (ONA, n=7)

• Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE, n=6)

• Communication Marketing Association (CMA, n=5)

• Native American Journalists Association (NAJA, n=2)

• Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA, n=2)

• Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA, n=2)

These data support the decision to collaborate with SPJ in activities of common interest, including holding joint annual conferences as has been the case in some previous years.

Institutions

Almost all participants responded that their institutions were colleges or universities. The exceptions were three respondents (a Latinx, a white, and another who did not indicate ethnic heritage) who work at K-12 schools, one (Latin American) respondent who works at an academic institution not-affiliated to a university, and another one (Latinx) who works for a non-academic organization.

Most of the survey respondents teach professional skills courses in print or digital journalism. A notable majority of those are L/LA, especially non-tenure track faculty. These are among the courses that require most time with students ensuring their individual development in the respective skills.

* Non-Tenure Track; Tenure Track; Tenured; percentages based on N=89.

The difference between white respondents and L/LA respondents is most striking in this analysis showing that 71% of the latter group is tasked with teaching professional skills courses in other related majors. This pattern cannot be attributed to the respondents’ ethnic/racial heritage. It is the reality of the teaching workload among these particular respondents.

* Advertising, Public Relations, Strategic Communication, Organizational Communication

** Non-Tenure Track; Tenure Track; Tenured; percentages based on N=31.

* Examples of other courses mentioned by a few respondents: Media Management and Entrepreneurship; Social Media; Social Media Analytics; Applied Research Methods; Data journalism and FOIA; Diversity in US Media; Visual Communication; Newspaper Laboratory; Magazine Writing, Web and Social Media; Environmental Journalism; Bilingual Journalism; Covering Latinos/as in the US; Mobile Journalism; Emerging Technology; Business Journalism.

The raw numbers of Table 8 indicate, as would percentages (not shown), the professional journalism courses taught by L/LA NAHJ members, in contrast to the courses taught by White NAHJ members. The data confirm that more L/ LA respondents than White respondents teach primarily skills related courses.

* Theory, research methods, media criticism, media effects, media and culture, media and society

** Non-Tenure Track; Tenure Track; Tenured; percentages based on N=49.

The data from Table 9 confirms in a different way the patterns of the previous tables. Fewer non-tenure track respondents teach non-professional media-related courses than do tenure-track and tenured respondents.

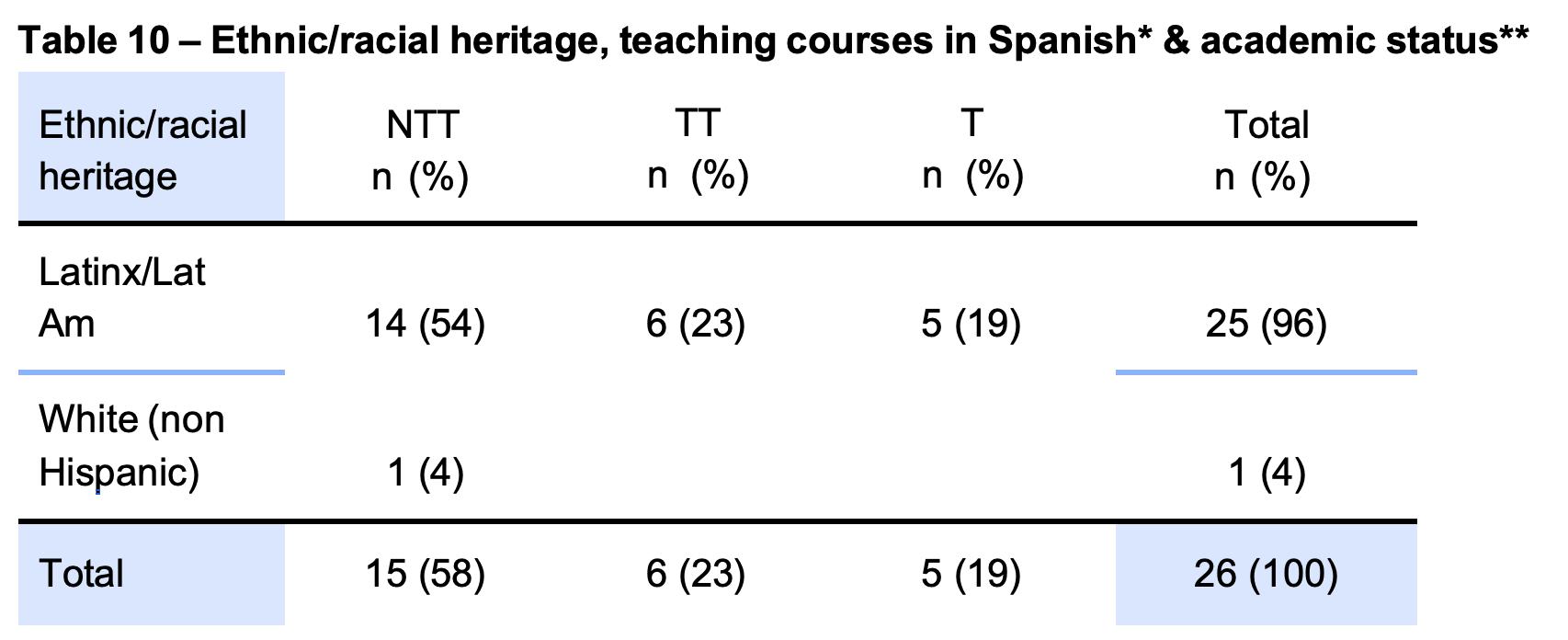

Table 10. Ethnic/racial heritage, teaching courses in Spanish* & academic status**

* Examples of courses mentioned by a few respondents: Reporting for Spanish-language News media; Bilingual Newswriting; Covering Latinx Affairs; Spanish TV News; Border Reporting; Craft of Journalism–Spanish Redacción y Reportaje; Bilingual Magazine Reporting; Diseño Web y Visualización de Datos; Backpack Documentary en Español. This list doesn’t include courses from Puerto Rican universities all of which are taught in Spanish.

As expected, practically all of the courses that are taught in Spanish are taught by L/ LA respondents. Most courses taught in Spanish were related to journalism skills. And again, that teaching responsibility is carried out by the non-tenure track L/LA respondents.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

The survey also sought to understand how NAHJ could support academic members in the same way it supports professional members. To find out, the survey included the following open-ended question:

Please share a few words of what you would like for NAHJ to do to enhance your advancement as a college-instructor. The answer to this question will not be in the directory. It will be used to build an educational action agenda for NAHJ.

Responses were compiled and input into MAXQDA, a data analysis software, where responses were coded using qualitative thematic analysis. This analysis involves multiple iterations of in-depth readings of the responses to interpret common themes or patterns emerging from the answers (Lindlof & Taylor, 2002).

Four themes emerged from the analysis:

A. Educator training and support. Respondents were emphatic about seeking help to develop teaching resources, keeping up with emerging media, as well as developing connections to successful journalists who could interact with their students and serve as role models for them.

For instance, respondents mentioned the need for “help to prepare lessons covering Hispanic trends and issues” or, in general, materials or teaching modules “ready to go for

** Non-Tenure Track; Tenure Track; Tenured; percentages based on N=26.

faculty who would like to incorporate immigration and other beats focused on vulnerable communities. Something that faculty could use to prep story assignments.”

One non-Latino respondent said, “About 65% of my students are Hispanic. I joined NAHJ to learn about opportunities for them to network, and get further training and education.”

Respondents also mentioned the need to keep up with technology, social media practices and other issues that affect journalism. One respondent mentioned: “Technology is changing so rapidly that at times it is difficult to keep up. It would be great to have continuous insights and suggestions from organizations like NAHJ as well as hearing from colleagues on best practices in adapting the latest technology to journalism courses.”

B. Professional opportunities. A second theme that emerged was related to help accessing professional opportunities for instructors as well as for students. Some respondents, as shown in one of the above examples, were looking for opportunities for their NAHJ or Latinx students, but the majority of respondents looked for opportunities to connect with administrators in higher education who would know about teaching opportunities. While this is a task that might fall more squarely on AEJMC, it is possible that senior NAHJ members with such experience can be of assistance for more junior NAHJ members interested in academic job opportunities.

Respondents also mentioned the need for help to transition from practice to teaching. One respondent said, “I would like to get advice on how to break into teaching what I have studied and worked on professionally.”

Finally, some respondents also mentioned the need for “Training on navigating academia.”

C. Support for student chapters. A matter that seemed to worry respondents was how to grow interest and membership of their student chapters. They asked for support and “guidance for maintaining an active student NAHJ chapter” and for ways to connect students with professional opportunities “right now.”

D. Latinx and Spanish-language coverage. The final theme common among participants was a preoccupation related to best practices covering the Latinx communities. Respondents mentioned the constant changes in critical topics related to Latinx communities and the need for tools and strategies to help them incorporate these emerging issues into their teaching strategies. For non-Latino participants, keeping up with best practices was crucial as well as having access to databases “of speakers who can talk about reporting and editing in various media in Spanish.”

5. Conclusions

Although with limitations, this study reveals important issues concerning NAHJ academic members and, most specifically, Latinx/Latin American NAHJ academic members.

The most concerning issue is related to job security. More than half (52%) of all respondents hold a non-tenure track position. That is particularly the case for 56% of the Latinos/Latin Americans and for 44% of those of other ethnic/racial backgrounds. These non-tenure track instructors are either lecturers, adjuncts or visiting professionals on short-term contracts, with no job security and limited or no benefits. A notably larger number of the female respondents are in less secure academic posts.

Looking into tenure-track positions can show the status of the pipeline for increasing Latinx representation among journalism instructors in academia. In this regard, NAHJ academic members show worrisome numbers because, either as a whole (14%) or just among Latinx/LA (17%), instructors in tenure-track positions hold the smallest percentage among all three types of positions.

This study also revealed that U.S.-based respondents are heavily concentrated in only two states–California and Texas. It is important to note that in California, which has the largest number of Latinxs in the country, more than half of respondents are non-Latinx/ Latin American heritage professors. In Texas, the majority of the respondents are of Latinx/Latin heritage, as is the case in the other three states with more than six respondents, i.e., New York, Florida and Arizona. Additionally, there are fewer than five NAHJ member respondents in twelve states and there is only one in another 12. At the same time, not a single one of the respondents hold teaching jobs in 25 states of the nation. Notable absences are Colorado, Utah and Connecticut each of which have a Latinx population of 15% or higher.

Regarding the type of courses that NAHJ instructors teach, although there is an equal percentage of non-tenure versus tenure track instructors who teach skill courses, almost one third (30%) of non-tenure track instructors who teach skill courses are Latinx/LA. Skill courses are among the courses that require most time with students ensuring their individual development in the respective skills. This finding is supported by one of the themes that emerged in the qualitative analysis—educator training and support—where survey respondents requested support for developing teaching materials and modules (for example, to teach immigration reporting) as well as training in emerging technologies impacting journalism.

Another significant finding is that one fourth (24.5%) of the respondents said that they teach journalism courses in Spanish; except for one participant, all of them were Latinx/ LA and more than half do so as non-tenure track instructors.

Finally, responses to the open-ended questions point to NAHJ academic members’ needs for more support and guidance for developing educational materials and keeping up with technology, and information about professional opportunities and networking opportunities.

6. Recommendations

After analyzing the results of this first ever survey of current NAHJ academic members, the authors of this report believe there is a critical need for more detailed and in-depth studies of the state of NAHJ academic members in journalism education at flagship colleges and universities as well as at Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSI).

Future studies should, for example, inquire about years of teaching and/or journalism practice experience and the motivations and expectations for seeking academic jobs. When applicable, questions should be asked about their motivations and goals for moving from the newsroom to the classroom. For those who have taken that path: What have been their major challenges and key lessons learned for success, particularly to overcome roadblocks to academic advancement and job security such as tenure? What lessons could be shared with others aspiring to academic posts?

Armed with this valuable information, NAHJ will be better positioned to grow its academic membership and become an effective advocate for not only increasing the number of Latinx/LA professors in journalism education, but also to enhance their ability to succeed in academia.

With valuable journalism skills, background and understanding of Latino culture, NAHJ’s academic members are uniquely positioned to help educate and prepare the next generation of journalists—be they Latinx or of other racial/ethnic backgrounds—for reporting on the nation’s increasingly diverse communities.

7. Acknowledgements

We wish to express our heartfelt gratitude to each and every respondent. Without their participation this first report on NAHJ academic members would not have been possible. Thank you, muchas gracias.

8. References

GAO (2021). Hispanic underrepresentation in the Media. September 23, 2021. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/blog/hispanic-underrepresentation-media

Lindlof, T. R. & Taylor, B. C. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods. California: Sage.

Researchers

||| Zita Arocha is a writer, journalist and educator. She is a Professor Emerita at the University of Texas El Paso where she taught multimedia journalism for two decades and founded Borderzine, a website for student journalists about border news and culture. A memoir, Guajira, the Cuba Girl, will be published by Inlandia books this fall. She has developed an online course for the Poynter Institute on immigration reporting and storytelling. A former Executive Director of the National Association o Hispanic Journalists, Arocha was inducted to its Hall of Fame in 2016 for her contributions to journalism.

||| Lourdes M. Cueva Chacón, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism & Media Studies at San Diego State University. Cueva Chacón holds a Ph.D. in Journalism (University of Texas at Austin, 2020). She has experience covering the U.S.-Mexico border as well as Latinx communities in the U.S. Her research areas include media sociology, Latinx news media in the U.S., digital-native news media in the Americas, and collaborative journalism in Latin America. Her research has been published in peer-reviewed journals, such as Digital Journalism, Feminist Media Studies, Mass Communication and Society, among others.

||| Jessica Retis, Ph.D., is Professor and Director of the School of Journalism, Director of the Bilingual Journalism M.A., and CUES Distinguished Fellow at the University of Arizona. She holds a Major in Communications (University of Lima), a Master’s in Latin American Studies (National Autonomous University of Mexico) and a Ph.D. in Contemporary Latin America (Complutense University of Madrid). Retis has two decades of journalism experience in Peru, Mexico and Spain and has worked as a college educator for more than three decades in the U.S., Spain and Mexico. She has extensively published research findings in journalism studies, journalism education, bilingual journalism; Latino media in North America, Europe and Asia; Latin American diasporas and the media. Academic Profiles: ORCID | Researchgate | AcademiaEdu | Google Scholar

||| Federico Subervi-Vélez, Ph.D., is Honorary/Fellow of the Latin American, Caribbean and Iberian Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison. He served as professor at four U.S. universities and as a visiting professor at several universities in Latin America and Europe. His most recent co-authored book is Para entender los medios de comunicación de Puerto Rico: Periodismo en entornos coloniales y en tiempos de crisis (Ediciones Filos, 2022). In 2017 the National Association of Hispanic Journalists recognized his teaching, research and community service by inducting him into the organization’s Hall of Fame.

NAHJ members in U.S. Journalism/Media Education

© Zita Arocha | Lourdes Cueva Chacón | Jessica Retis | Federico Subervi-Vélez | National Association of Hispanic Journalists, June 2023