Exit 11

Exit 11

Writing Instructors’

Praise for Exit 11

“What I love about Exit 11 is that anytime I teach a specific writing move to my students, I can readily pull out an essay for demonstration. It is a reflection of the diverse topics taught in our FYWS, different ways a critical argument can be presented and the multiplicity of student voices. Working as a managing editor for more than five years, I greatly appreciate the editorial discussions and how it nurtured me as a teacher and a writer. Exit 11 displays the strong team work of the editors alongside the academic caliber of NYUAD students.”

SWETA KUMARI

“Returning to Exit 11 as a managing editor after three years reminded me why I founded this journal in the first place, to showcase and celebrate the teaching and learning of writing as a mode of expression and knowledge sharing by our Writing Program faculty, instructors and most importantly, the students. The variety of essay topics and writing styles in this double issue exhibit not only the wide range of topics covered in the First Year Writing Seminars each year but also the unique interests and expressions of our students. This publication is a labor of love and dedication of the editorial team to the teaching of writing and celebrating our students’ learning, regardless of the unprecedented challenges we faced in the past two years due to the pandemic and loss of our dear colleague and friend Ken Nielsen. This Issue is a tribute to him for his years of service in shaping the Writing Program where it is today.”

ASMA NOUREEN

“ Exit 11 serves as a testament to the amount of progress students are able to make in their writing within the span of one short semester. If I had to put it down to three words, I would say it is exciting witnessing the range of astute and innovative topics and approaches, inspiring watching the growth students are making, and rewarding to watch their hard work be recognised in the form of published essays.”

AIESHAH ARIF

“One of the qualities of a well written essay is ‘flow’ which aids comprehension even if the reader is only scanning. In technical terms, this means the essay has achieved cohesion which is an elusive quality even for weathered writers. Exit 11 essays portray this cohesion, connectedness of ideas, with great authority. The essays in the anthology are accessible models for teaching analytical frameworks and writing effective introductions. Using student essays as models makes the idea of writing an essay less daunting for a student in First Year Writing Seminars; the idea is: if my peers can achieve this level of excellence, so can I.”

NEELAM HANIF

“The essays within Exit 11 highlight what happens when you consider the audience of your essay to be beyond just your class professor. When we read an essay in this journal that piques our curiosity, we intuit the often difficult to grasp concept of ‘motive’. Simply put, a well motivated essay makes us want to read without explicitly telling us why we should keep reading. Therefore, my favourite essays in the journal are the ones that fluidly integrate motive and make me forget that I’m reading a class paper. Exit 11 also showcases how the different FYWS, regardless of the topic, hold the same core values, yet allow for flexibility in form, style, and approach.”

SAMIA MEZIANE

“As one of the most senior Writing Instructors, I’m proud to have witnessed Exit 11 grow from conception to publication and now into an entire volume of some of the most inspirational and telling writing from students across the disciplines at NYUAD. Many students begin their first year of university under the impression that their voices don’t matter – Exit 11 is proof that this is not true; not only do first-year students perform the same work as seasoned professors through research, but, through the book you hold in your hands, they are able to influence others who are not so far behind in the timeline of their own lives. I continue to be immensely proud of our students at NYUAD and the work they are able to produce through our unique program. I will leave you with a quote from a favorite animated film from my childhood, The Pagemaster: ‘And remember this, when in doubt, look to the books!’”

ZACHARY SHELLENBERGER

“For me, Exit 11 showcases the alchemy of writing, the magic that happens between the blank page and a finished, polished essay. Initial impressions, unformed thoughts and shadows of ideas become sophisticated opinions and revelatory insights that not even the writer knew they were capable of manifesting. Not only does it represent the breathtaking range of material covered across the First Year Writing Seminars, but it’s a fantastic resource for both instructors and students.”

RACHEL WOBUS

“The essays contained within Exit 11 always contain something of the magic that happens inside the classroom–the moments where students bring their whole selves to an assignment. As an instructor, having a resource like this one–where I can show my students exactly what I mean, and how others in their shoes have approached similar questions– is invaluable as we make the leap between knowing and doing the work of writing.”

JAMIE ZIPFEL

“The perspectives and the depth of understanding displayed within the pages of Exit 11 are a testament to the exceptional intellectual curiosity and scholarly rigor fostered within the academic environment of NYUAD. Exit 11 not only serves as a source of inspiration and admiration for fellow students in learning the art of expression but also provides a valuable resource for instructors seeking exemplary work to showcase to future students. As educators, we are constantly in search of outstanding examples of academic writing, and Exit 11 presents an exquisite collection that embodies the ideals of creativity, technical precision, well-researched scholarship, and profound intellectual inquiry that we hope to see more of from the writers of tomorrow.”

AMANDA LEONG

“One of the joys of teaching writing is seeing the techniques that you introduce in the classroom help bring alive a learner’s ideas on the page. It is also in how they develop, adapt or even discard these ideas as they grow as a writer. Exit 11 is a great testimony to the process of writing as embodied in the FYWS.”

DAVID ALLWAY

“Exit 11 showcases the incredible, diverse, and important work students produce in the span of one short semester, and represents in similar ways the value of guidance and support throughout the process, whether in the writing class or for the collection itself. Exit 11 is a testament to the writers whose craft has developed in critical and personal ways and to the FYWS that creates the curated space for this development. There is little that is more fulfilling for a writer than to see their work published, as they are able to put out what they have produced to an audience that may feel more real than the instructor and their peers, and inspire other writers through the creativity and ingenuity of their voices and thoughts.”

MARWA MEHIO

“Readers of Exit 11 will only get to see the final, polished versions of the essays. However, behind each essay there is a tremendous amount of thought and effort that goes into the process of creating it. Each one is a product of time spent reading and engaging with sources, thinking critically about when and how to enter the academic conversation, doing further research as needed to extend the conversation, and weaving these elements together into the draft versions. During the process of finalizing their essays, the authors have received feedback from peers, professors, and the editorial team, and decided how to incorporate that feedback into the final versions that you have before you. Each essay, then, is a testament to the writing process itself—sometimes messy and challenging, but also a powerful means of giving voice to the diverse interests and perspectives of the authors.”

YUSUF SAMARA

Exit 11: A Journal of the First Year Writing Seminars

Issue 07, 2022–2023

Executive Editor Marion Wrenn

Managing Editors Sweta Kumari & Marwa Mehio

Senior Editors

Haewon Yoon / Jamie Zipfel / Yusuf Samara

Associate Editors

David Allway / Hind Saddiki / Idil Barre / Neelam Hanif / Samia Ahmed / Samia Meziane / Zachary Shellenberger

Contributing Editors

Camilla Boisen / Jonathan Sharfman / Lee Gurdial Kaur Singh / Mitchell Atkinson III / Philip Rodenbough / Piia Mustamaki / Sabyn Javeri Jillani / Samuel Mark Anderson / Sohail Karmani / Soha Sarkis / Sun-Hee Bae

Photo Editor Sohail Karmani

Student Assistants Louise Simpson / Grace Shieh

Founding Editor Asma Noureen

Cover Photographer Batool Al Tameemi

Design Consultant Minbar.co

Printer Royal Printing Press LLC

A big thank you to Awam Ampka, Dean of Arts & Humanities, for his enduring support of the Writing Program. We also wish to thank Erich E. Dietrich, Vice Provost of Undergraduate Education, and Lolowa Al Marzooqi, Assistant Vice Provost of Undergraduate Education, for their unparalleled support of The Center for Writing. The digital conversion of Exit 11 was deftly overseen by Cyrus Patell, Global Network Professor of Literature and Professor of English, to whom we send our thanks. Our gratitude also goes to Nisrin Abdulkhadir, Administrative Assistant, who has supported this publication in various ways. And a special thank you to all our readers and writers.

Table of Contents

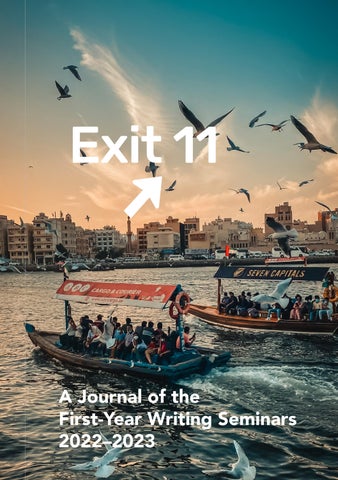

COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Old Dubai

– Batool Al Tameemi

13 Introduction – Marion Wrenn

PHOTOGRAPH: Reflections of Expression

– Abdelrahman Mallasi

Essay 1

20 An Analysis of Wake: Challenging How We Think and Write about History

– Alejandra Pérez Aguilar

26 Outside In - The Intricacy of Creating Dance

– Ruxandra Burian

32 The Subjectivity of Sentiments: A Critical Analysis of Rorty’s Sentimental Education – Udgam Bhattarai

PHOTOGRAPH: Food Distribution in Jangisar

– Sultan Farooq

Essay 2

42 Are We Living through a “Big Data” Scientific Revolution Today? – Aleksandar Boljević

48 The Representation of Female Sexuality in 20th Century Women (2016) Directed by Mike Mills – Anastasiia-Lei Yang

56 A People in Crisis: The Occupation of Three Emirati Islands – Arwa Alabbasi

PHOTOGRAPH: Across the Sands – Muhammed Hazza Amir Ali

64 Clash of Modernity and Non-European Culture: Quest for Chagos Islands’ Return – Danial Zhanbyrshy

71 Racism Beyond Western Discourses: An Analysis of Tunisian President Kais Saied’s Speech – Fatma Ramadhan Alahmadi

80 NATO Bombing of Yugoslavia: The Misleading Focus on the Means of Intervention – Mukhamed Sagyntaiuly

PHOTOGRAPH: Un-gentrified – Miriam Delgado

88 American Dream – Samira Aldybergenova

93 How Many Englishes?: Criteria for Demarking Variances in the English Context – Samuel Legissa

99 The Silencing of Women’s Struggles: A Feminist Analysis of the Movie Everything, Everywhere, All at Once – Tao Ziyue

PHOTOGRAPH: Heritage and Hope – Yana Holovatska

Essay 3

110 The Pressure that Forms the Pearl: Examining the Powerful Narratives in Post-conflict Sri Lanka – Andrew Surendran

120 The Russia-Ukraine War: The Final Death Blow to the Concept of Genocide? – Julia Oleszynska

PHOTOGRAPH: The Young Healer – Mariam Almagboul

134 Pakistan’s Power Dynamics and the Proliferation of Violence: A Case Study of Blasphemy Laws

– Manahil Faisal

144 Change in the Definition of Masculinities in the Korean Pop Industry as Seen Through BTS’s “Boy in Luv (sangnamja)” (2014) and “Black Swan” (2020)

– Suhana Shamshudin Kassam

155 The Moral Proportionality of Jus Post Bellum and How it perpetuates Bystandership – Udgam Bhattarai

PHOTOGRAPH: Stop! A Glimpse of Hamdan Street

– Aryam Alhosani

169 Notable Submissions 2022–2023

Introduction

There is a classic myth in the western tradition that has the G reek goddess Athena springing fully formed from the head of her father, Zeus , king of the gods.

Goddess of wisdom and war, she leaps into the world without the strife of birth, or those messy, awkward teenage years; instead she arrives mighty from the start.

The story of Athena’s birth has always struck me as an apt analogy for the misbelief that some aspiring writers possess: the conviction that polished, perfect prose springs fully formed from the fingertips of “good writers,” as if the first draft is their best draft, all of it effortless. That belief leads some of us to nurture a sense of envy, and also a mighty case of imposter syndrome.

Full confession: I’ve always had a sneaking hunch that everyone else has an easier time at writing than I do, a belief that they possess an ability to produce perfect prose as if it leapt, like the goddess, straight from their fingers onto the page– no muss, no fuss, no false starts, no blank stare at a blank page. Deep down I have a hunch that everyone else has a little bit of Athena in their foreheads, their prose appearing fully formed and figured out the moment they start to write.

On one hand that story some of us tell ourselves is not only exhausting, it’s intensifying as AI and generative predictive technologies become part of our media environment. As the ads for ChatGPT, Gemini, and others promise: writing can be quick and easy and error free. These contemporary promises used to sell the latest technologies tap into a much older set of dispositions about writing. Should it be slow and steady, driven by a will to get the right word in the right order and the rhythm of paragraph right before you let anyone read it? Or should it be fleet and fast and driven by speed? The Italian novelist Italo Calvino confessed to this pickle in his last book: “I am a Saturn who dreams of being a Mercury, and everything I write reflects these two

impulses.” Calvino draws on Greek and Roman mythology to account for how he feels about his writing process: he is a slow worker who dreams of brash speed. That tension is at the heart of writing; and if we trust that writing is a creative act, then we can see that making an argument requires steps and stages, tinkering and trying. Fast or slow, writing is, crucially, a process.

But the myth of Athena’s creation reminds me of the function of all myths: such stories often use the visible to explain the invisible. In other words, I’ve been using the myth of Athena’s birth to name something about the writing process to explain what is largely mysterious and often happens out of sight: all great writing, as many great writers attest, including Anne Lamott in her famous essay “Shitty First Drafts,” comes from trial and error, attempt and failure and feedback, followed by another attempt. The real magic is in the resilience of revision, the space where a writer becomes aware of her instinct, or the sound of her voice as a thinker, and then hones that instinct into her craft.

That sense of self-possession– thinking of ourselves as working writers, as people thinking through the evidence we’ve gathered in order to make sense of what we see or want to say– results in prose that moves a reader to pay attention, to be transported into the urgencies of an essay, and to want to, blue skies, write an essay in response.

The image of Athena leaping from Zeus’ forehead is now more resonant than ever before, and perhaps transcends my own personal conviction that writing is easier for everyone else but yours truly. Generative predictive technology and the artificial intelligence-soaked atmosphere in which we think and write helps burnish the myth that all writing comes easy, or that a machine can read a text sufficiently on our behalf, hiding the mess of a human being engaging with a text, taking notes, annotating the page in order to figure out what another author means to say.

True these tools amplify the seeming speed with which good writing gets crafted. But I’m afraid they also amplify the imposter syndrome that folks feel when they are learning to see writing not only as a means of communication but as a form of organized curiosity or crafted thinking and, crucially, learning to listen to the rhythm of their own minds in the

act of creating an argument or developing an idea. Craft is a tricky word, suggesting the image of the writer as an artist, thoughtful creator, who moves from a hunch about how the right words should flow in the right order to making choices so that a reader can follow the arc of her mind’s work on the page.

Such choices also always belong to a writer making an argument, staging an essay, working across multiple drafts in order to convey ideas to an imagined audience. And all of that work looks like a big squirrely mess until it moves toward a sensible whole aimed at a reader via the writer’s ongoing process.

But all of that mess is basically invisible in this anthology! None of these essays sprang fully formed from the gorgeous minds of their authors. They are instead the result of a process-based pedagogy that led them through a series of low-stakes exercises that helped them figure out their ideas by seeing what they had to say. As you read them, look for the human presence of mind on the page, what Aristotle called ethos, the author’s disposition and decision making that yielded the essay in front of you. Ethos is an ancient concept, and it endures in this era of technological innovation as the ways in which an author establishes trust with the reader, citing sources ethically and well, and using technological resources to amplify their thinking rather than to replace it.

All of that to say that perhaps we do all possess a little bit of the goddess of wisdom in our foreheads ready to spring. But maybe we need to tell the story of her creation a little sideways. Perhaps we can shed light on the way messy essay drafts signal her arrival. Consider that an invitation to read the essays included in this volume for the choices their authors made to craft and convey their ideas. Also consider it an invitation to develop your own story for your writing process. What is the story you tell yourself about “good writing”? Where does it come from? What myths do you hold? How might rethinking the stories you tell yourself about yourself as a thinker and a writer help you imagine your journey as a scholar here at NYUAD, your new intellectual home.

MARION WRENN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF WRITING, ARTS & HUMANITIES, NYUAD

At the BRED Abu Dhabi festival, where culture and creativity converge, a model becomes a canvas against a vibrant backdrop of red, reflecting the festival’s spirit through bold fashion and poised gestures. This photograph, a testament to the power of art as a universal language, captures a moment of silent dialogue between the artist and muse. Through the lens, style transcends mere apparel to express identity and defiance, embodying the festival’s celebration of neo-culture from music to lifestyle. Here, individuality shines within the collective, illustrating how fashion, like art, communicates profound narratives of self-expression and belonging in a world rich with diversity.

“Reflections of Expression” by Abdelrahman Mallasi

Essay 1

An Analysis of Wake: Challenging How We Think and Write about History

ALEJANDRA PÉREZ AGUILAR

In WAKE: The Hidden Stories of Women-Led Slave Revolts, Rebecca Hall argues that the stories of resistance of African and African American slaves have been silenced throughout history, disempowering Black Americans today.1 The graphic novel follows Hall as she uncovers and rewrites the hidden stories of female-led slave revolts in the eighteenth century, to shed light on the history of slave resistance and challenge traditional narratives that downplay women’s role in it. Hall exposes how, living in the wake of slavery, she is haunted by the trauma of the past and the present legacy of slavery as she highlights the need for Black Americans to take pride in the history of resilience of their ancestors to draw on their strength and power to fight for the change they need in the present.2 While Hall challenges the historiography of slavery by confronting white-male centric trends, illustrating the intersection between the political and the personal, and calling out the factual inaccuracy of dominant narratives, she unintentionally reinforces the binary framework trend that perpetuates assumptions related to race and rank.

Putting enslaved women at the center of her narrative of resistance, Hall’s work challenges the white-male centric trend in the historiography of opposition to slavery. Dominant narratives have often focused on the role of the abolitionist movement in ending the institution, and consequently on the role of white abolitionist men that participated in the political movement. Even sources, such as the documentary Racism: A History, 3 that aim to deconstruct and criticize White-centric narratives fail to reverse this

1 Rebecca Hall and Hugo Martínez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2022)

2 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 211

3 Paul Tickell, Racism: A History. (United Kingdom: BBC, 2007)

trend. The documentary does bring light to black political figures of the abolitionist movement, such as Olaudah Equiano,4 who were long neglected by history. Despite this, by continuing to focus on the high-level politics of the abolitionist movement, which were generally inaccessible to black people, particularly women, it ignores the ground-level role of slave revolts in fueling this movement. Indeed, the high monetary cost associated with revolts was a key factor in destabilizing the economy of slavery and bringing about abolition. In light of this, Hall highlights how “this type of resistance was so expensive and time consuming for slavers that [...] it prevented at least a million more people from [...] entering slave trade” and emphasizes the essential role women in these revolts. 5 Here, Hall is also moving away from the restrictive definition of “success” offered by the dominant historiography of slavery that has often describing the Haitian Revolution as history’s only successful slave revolt. 6 She does this by shedding light on the magnitude of the cumulative impact of seemingly unsuccessful and localized revolts in bringing about significant change. Therefore, redirecting the focus of the narrative of opposition to slavery from white abolitionist politics to ground-level slave revolts and recognising the cumulative success of such revolts, Hall reclaims and acknowledges the agency of enslaved people in ending the institution of slavery. This has the potential to evoke the Black American heritage as a source of empowerment to continue to fight for change.

Hall challenges the division between the public and the private spheres imposed in dominant historiography and presents an intersection between the political and the personal. In the introduction to her book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado emphasizes how the division of the private and the public sphere, is arbitrary since they both bleed onto each other.7 The private and public spheres here refer to the separation between what is considered private – the personal and family identities, activities and spaces

4 Tickell. Racism: A History. Episode 1, min. 49

5 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 149

6 Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “Unthinking a Chimera,” in Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2015), 72-83

7 Caroline Criado-Perez, “Introduction: the Default Male,” in Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (New York, New York: Abrams Press, 2021), 18

– and public – broader societal and political realm. This division results in the separation of the political and the personal, which Hall confronts by asserting how, for her, the personal is political. Indeed, she presents her research as one with significant historical and political claims, but also as a deeply personal journey of reconciliation and empowerment with her heritage. Researching the 1712 New York slave revolt, Hall finds judicial records stating that one of the four women involved in the revolt testified but her testimony was not recorded8. In light of this Hall explains how “this is one way in which history erases us”, because “if who we are and what we care about are deemed irrelevant, it won’t be there”.9 Here Hall highlights how the beliefs of a society influence whose voices are deemed valuable and whose are excluded and oppressed, including her voice and that of her ancestors. Thus, reclaiming the voices of the enslaved women and recognizing their power and resistance, Hall also reclaims her voice and her place in the narrative. In other words, rewriting silenced accounts empowers historically silenced groups and encourages them to reclaim their place in the narrative on a political and personal dimension.

One should be cautious however to read Hall’s claims in a simply ideological and political dimension. Instead, going against the dominant trends in the historiography of slavery to amplify alternative narratives, Hall reexamines the biases in knowledge production and offers a more factually accurate narrative. On this topic, Criado argues that the manner in which society produces knowledge is incomplete by “a failure to account for half of humanity” (referring to females).10 She then highlights how the myth of male universality – whereby the reality of (white) males is disguised as universal and objective – affects how knowledge and data is collected, read and interpreted, thus leading to the factual inaccuracy of such knowledge.11 In light of this, Hall explicitly calls out the gender biased historiography of slavery and confronts it by thinking beyond male universality to draw

8 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 33

9 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 33

10 Caroline Criado-Perez, “Introduction: the Default Male,” in Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (New York, New York: Abrams Press, 2021), 18

11 Criado-Perez. Introduction: The Default Male. 20

new historical conclusions. Indeed, Hall reveals how slave revolts were more likely to occur in ships with a larger portion of women onboard, but “historians dismissed this as some kind of statistical fluke”. 12 Then she denounces that “the intuition of historians of slavery was distorted by their beliefs about women”, and “laying aside gendered assumptions” she was able to provide a comprehensive analysis of the reasons behind this data.13

Stressing how gender biases prevent the production of accurate historical knowledge, is essential in recognizing the subjectivity and incompleteness of historical knowledge. Thus, not only does Hall’s narrative challenge the historiography of slavery in its political and ideological dimensions, but also in its methodological failures and factual inaccuracies.

Even so, Rebecca Hall perpetuates assumptions related to race and rank by conforming to the rigid binary framework prevalent in the historiography of slavery that associates white to freedom and black to slavery. In Wake, Rebecca Hall presents black and white people in a sharp dichotomy that equates white to slaver or perpetrator of violence and black with slave or victim of such violence in both the past and present. Indeed, in the illustrations of historical accounts white people appear as commanding officers and slavers, and in the present they continue to be presented as antagonistic characters with a superior rank. An example of the latter are the officers Hall encounters in the Courthouse who prevent her from accessing important historical records.14 While this dichotomy is effective in showcasing the dominant trend in the eighteenth century and how it penetrates today’s society, it oversimplifies the logic behind slavery and rank. More importantly, conforming to this dichotomy Hall fails to challenge the binary framework in the dominant historiography of slavery.

Such a framework preserves the ideas of racial division created in the eighteenth century and perpetuates assumptions related to rank and race. On this topic, Nell Painter argues that while “American tradition equates whiteness with freedom while consigning blackness to slavery”, the reality

12 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 149

13 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 150

14 Hall and Martinez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. 98

and history of slavery is much more complicated.15 Giving an overview of the history of white slavery16 Painter presents race as one among the several justifications for slavery constructed by elites in the course of history, rather than as an intrinsic determinant of the value and status of a person. This is relevant since historiography has disproportionately focused on the racialization of slavery – manifested through the aforementioned binary framework – which sustains ideas of white superiority, including the assumption that freedom lies at the core of whiteness.17 Thus, it is essential to confront this binary historiography to unpack the assumptions that it perpetuates, including that of the white powerful and black powerless logic. This is especially relevant in the context of Wake since one of its central premises highlights how our understanding of the past affects how we think about the present and the future. Thus, adhering to the historiographical racialization of slavery by conforming to its binary logic, Hall perpetuates racial justifications of rank and misses the opportunity to deconstruct the assumptions it underpins.

This essay has shown how, in Wake, Rebecca Hall challenges some of the dominant trends in historiography that have prevented a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of the history of slavery. Particularly, attempting to redefine African American heritage as a source of resilience and empowerment, Hall reveals the key role of slave revolts in eventually bringing an end to slavery, confronts the separation of the personal and the political, and challenges knowledge biases in the historiography of slavery that produce factual inaccuracies. The binary logic she employs between black slave and white slaver leads her to perpetuate assumptions related to race and rank. Even so, Hall’s writing stands out due to her effort to reexamine and rethink the ways in which history is written and its effect on how we think about the present.

15 Nell Irvin Painter, “Introduction.” in The History of White People. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), ix-xii

16 Nell Irvin Painter, “White Slavery.” in The History of White People. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 34–42

17 Painter. White Slavery. 34

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Criado-Perez, Caroline. “Introduction: The Default Male.” In Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, 11–20. New York, New York: Abrams Press, 2021.

Hall, Rebecca, and Martínez Hugo. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2022.

Painter, Nell Irvin. “White Slavery.” In The History of White People, 34–42. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Tickell, Paul. Racism: A History. United Kingdom: BBC, 2007

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. “Unthinking a Chimera.” Essay. In Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, 72–83. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2015.

Outside In - The Intricacy of Creating Dance

RUXANDRA BURIAN

Rolling around in a sea of clouds, Sue Smith creates the illusion of a dream. While she performs soft moves, the blue background provides a calming environment.1 This is one of the many scenes found in the colorful dance film Outside In, with choreography by Victoria Marks. It features dancers from CandoCo Dance Company, an inclusive dance company from the UK. The film features six disabled and non-disabled dancers that come together to create an award winning film about dance, published in 1995 in England. Although Christopher Dunkley states his firm opinion that this film has as its main point the collaboration between disabled and non-disabled dancers,2 I do not share the same opinion. I argue that Outside In pulls back the curtain on the artistic process: inspiration, practice, improvisation, and the performance of a complete and well-practiced show. In contrast with Dunkley’s views, I consider that the dance film shows how disability is not relevant to the creative process, dance being an art form available to all people.

As Ann Cooper Albright states in “Strategic Abilities: Negotiating the Disabled Body in Dance,” disabled people have the capacity to create dance in a unique manner.3 Albright talks about the difficulties non-conventional dancers face, as the world has a very specific image of what a dancer should look like.4 After struggling with disability for a while, Albright realized that she should use her disability to her advantage. Everything different about her makes her special and makes her performances stand out. Therefore, she creates the term

1 Victoria Marks, Outside In, directed by Margaret Williams, London: Arts Council England, 1995. Streaming on Alexander Street Press, 8:39-9:35.

2 Christopher Dunkley, “Arts: Dance with a Difference: Television,” Financial Times, July 29, 1995.

3 Ann Cooper Albright, “Strategic Abilities: Negotiating the Disabled Body in Dance,” in Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, ed. Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ nyulibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1562508, 65.

4 Albright, “Strategic Abilities,” 61.

“strategic abilities” which emphasizes exactly this idea of finding possibilities within disability. It is important for people to not feel restricted by their bodies but rather to find what their limitations can provide. Disabilities should be seen as opportunities rather than confinements and they do not limit dancers’ participation in the creative process. Outside In demonstrates how abled and disabled people come together to create art in the form of dance. Disability does not represent a constraint in this process, but rather an opportunity to create something unique, demonstrating how strategic abilities facilitate a role in the process of creating dance.

The film begins by revealing the first step of the creative process: inspiration, which represents a crucial part in any artistic process, regardless of the disabilities of the artist . The opening scene is particularly suggestive as it introduces the cast and how they connect to create a performance. The scene presents the dancers passing something invisible from one to another. This invisible entity can be perceived as the “inspiration” to create and perform a dance. They are either blowing, inhaling, kissing, or sneezing to transmit it. The movements are not very dynamic, as all the performers are sitting down or lying on each other. However, their faces are highly expressive, and their body language shows their thirst for the “inspiration.” At the very end, Sue Smith blows the “inspiration” for the last time, across the room and the performance begins.5 One thing that does not stand out in this scene is the fact that half of the cast is disabled, proving that anybody can participate in the creative process. Adam Benjamin considers that disability actually encourages the creative process and gives a new meaning to dance. He states that being physically different should not be an impediment when it comes to dancing.6 The scene, although hard to comprehend in the beginning, means to dissipate the preconceptions that exist regarding performers. Anyone can be inspired to create and therefore disability must not be taken into consideration. It is clear to me that this film does not want to have as its main focus the disabled dancers. Therefore, the performers, abled and disabled, come together to find inspiration and pursue the creative process together.

5 Marks, Outside In, 0:35-2:25.

6 Adam Benjamin, “Cabbages and Kings: Disability, Dance and Some Timely Considerations,” in The Routledge Dance Studies Reader, ed. by Alexandra Carter and Janet O’Shea (London: Routledge, 2010), 111.

The following part of the artistic process illustrated in the dance film is the importance of putting time and effort into practicing, a process to which both disabled and abled dancers participate. The scenes that follow the first one show how the dancers begin to train and put together choreographies. The most impactful is the scene where David Toole, a dancer without legs, attempts to learn a dance pattern based on footprints drawn on the floor. The scene, although confusing at first, is intriguing as it feels somewhat contradictory. In the beginning, Toole shows some reluctance as he looks hesitantly at the pattern on the ground. However, he proceeds to place his palms over the prints. Firstly, he takes dainty steps, his rhythm being slow. As he gains confidence, he wipes his palm over his chest and proceeds with the dance. His moves become more energetic, as he starts jumping from one footprint to another and increasing the tempo.7 This scene shows the process that the dancer needs to go through to learn a choreography. It begins with small steps and a lot of practice. Toole’s determination to learn shows results towards the end as he uses his arms to follow the footsteps. This scene displays how outstanding his moves are and how, by having a disability, Toole creates a whole new and unique series of moves. He interprets the footprints in his own way, proving that his strategic abilities help him create something different than what is expected. The whole scene shows how practice is an important part of the final product, as it is the most extensive one.

As the process continues, both abled and disabled dancers must contribute to the creative process with new ideas and moves that can be found through improvisation. In this sense, the performers start what seems an improvised series of moves in order to find the best ones. Representative for this process is the scene where all the dancers come in and out of the stage in dynamic movements and dance two by two at a very fast pace. The scene begins with Toole rolling in with Sue Smith. They perform a series of energetic moves, such as throwing themselves on the ground, jumping and spinning. Then, Smith leaves and Celest Dandeker appears. Every two performers dance together for a few seconds, after which one disappears, and another one comes in. It seems as if there is no fixed choreography because there are not any synchronized moves. They are moving freely and on numerous occasions

7 Marks, Outside In, 3:08-3:49.

seem surprised by the appearance of the next dancer. At one point, Toole comes rolling in his chair and takes Helen Baggett by surprise; she falls onto his chair and he carries her away8. Their movements seem created on the spot as the dancers spin, raise their hands, run, and embrace each other. In this scene, the dancers’ energy can be seen as they proceed to find new ideas to include in their choreography. The whole moment is unique as there is a lot of interaction between the disabled and non-disabled dancers. The performers in wheelchairs are rolling in and out, creating the element of surprise. They are using their smooth moves to help the improvisation, their strategic abilities being an asset to find new innovative dance steps. Improvisation is a big part of the creative process; it challenges the dancers to expand their limits and search further within their abilities.

The process of creation would be incomplete without the final product, a performance where abled and disabled dancers come together to showcase a finalized and well-rehearsed choreography. For that reason, towards the end of the film the dancers show the choreography. The set changes, as the performers are seen through the fog and flashing lights. They are holding rectangular mirrors to create a more impressive show. The dancers present a very organized and synchronized performance.9 Movements repeat from earlier scenes, suggesting that before it was just a rehearsal. One such move is the one in the duet between Toole and Kuldip Singh-Barmi when they both stand on one hand and extend the other one straight up.10 The same move can be seen in the final choreography done by Toole and Baggett.11 Another repeating theme is the kiss that has reoccurred throughout the film from the first scene. The dancers perform unison jumps and head movements12, indicating the effort they put into rehearsing the piece. The scene represents the final step of the creation. Although Dunkley appreciates the artistry of the film, he believes that the piece showcases the relation between disabled

8 Marks, Outside In, 6:35-7:43.

9 Marks, Outside In, 11:17-13:07.

10 Marks, Outside In, 7:50-8:31.

11 Marks, Outside In, 11:49-11:54.

12 Marks, Outside In, 12:13-12:39.

and non-disabled dancers in a humorous manner.13 While the creativity of the film cannot be denied, in this scene the dancers show the passion with which they perform. The most important aspect of including both abled and disabled dancers in this piece is to put together all their skills to create a colorful final product. The performance is customed for these particular dancers, proving that their strategic abilities are irreplaceable. This scene shows through the repeating moves that every step of the creative process is important in order to put together a complete, well-rehearsed show.

Although the final product is usually the only part that the audience sees, Outside In reveals how everything from inspiration to the full performance represents a relevant part in the artistic process. Disabled dancers are included to prove that the creative process has no boundaries and that everybody can be an active participant in it. As Albright states, disability is a trait that can be exploited to create distinctive dance moves.14 Every disabled dancer has strategic abilities that influence the choreography, as the moves created by them and for them cannot be replicated by anyone else. Therefore, every step of the creation is influenced by these dancers, even though, in my opinion, the film does not have as its main focus disability. As I strongly agree with Albright’s visions, I believe that CandoCo is a company that has a further understanding of the distinctive abilities that disabled dancers possess. Outside In is a film that discloses to the audience every part of the intricate process of creating dance, by making use of the uniqueness provided by the disabled dancers.

13 Dunkley, “Arts: Dance with a Difference: Television.”

14 Albright, “Strategic Abilities,” 65.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albright, Ann Cooper. “Strategic Abilities: Negotiating the Disabled Body in Dance.” In Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, edited by Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright, 56–66. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nyulibrary-ebooks/detail. action?docID=1562508

Benjamin, Adam. “Cabbages and Kings: Disability, Dance and Some Timely Considerations.” In The Routledge Dance Studies Reader, edited by Alexandra Carter and Janet O’Shea, 111–21. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2010.

Dunkley, Christopher. “Arts: Dance with a Difference: Television.” Financial Times, July 29, 1995. Factiva.

Marks, Victoria, chor. Outside In, directed by Margaret Williams. London: Arts Council England, 1995. Streaming on Alexander Street Press. 14 minutes.

The Subjectivity of Sentiments: A Critical Analysis of Rorty’s

Sentimental Education

UDGAM BHATTARAI

When Russia first invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the entire international community was shocked and terrified at this act of war. It warranted a very passionate response from people all across the world – within days, people poured onto the streets with slogans into protests, bombarded internet platforms with petitions, and even lobbied with NGOs and INGOs in dealing with the impending humanitarian crisis. People from all across the world, and all different cultures and backgrounds, became united in showing compassion to the horrors of Ukraine, not because of any legal or social obligations, but because they were moved by the love and sympathy they felt. The feelings invoked by the invasion, however, were anything but uniform–the Russians feel very differently about the invasion than the rest of the world, courtesy of the carefully constructed narrative that the government has medicated onto these people over the years.

Such is the power of emotions in driving people towards actions and judgements. In defining the status quo not in terms of rationale but rather the sentimentality that it invokes, emotions help us comprehend and connect with the status quo on a more personal level and act accordingly. In “Human Rights, Rationality and Sentimentality,” Rorty acknowledges this prevalence and significance of sentimentality and identifies the need for a global “Human Rights Culture,” built on the grounds of compassion and empathy (1998: 170). To that end, this idea of “sentimental education” focuses on invoking and accentuating our shared compassion and empathy through sad and sentimental stories so that people can identify as equal stakeholders in the shared moral community (Rorty 1998: 171) and are able to derive their own judgments from feelings of trust and security in the community and act on them (Rorty 1998: 180). But can the people be held accountable for a

differential in their “inherent” feelings? Does this make their emotions and moral judgements any less valid?

In Frames of War, Butler establishes that our understanding of the world is often contingent on the frames in relation to which both we and the world around us exist. She defines framing as the delimitation of context that determines what we can see and what remains concealed (Butler 2009: 8) and framing as a constant process of breaking and reforming said frames to redefine the interpretation according to the premises it lands in (Butler 2009: 10). Thus, by virtue of these definitions, Butler establishes that the constructs that govern our understanding and interpretations of the world around us are inherently very permissible and arbitrary as they change and reform to accommodate the new premises that they land in (2009: 9).

Sentimentality and by relation, sentimentalism and emotions, are largely reliant on said frames for their propagation and interpretation, making them equally as vulnerable to subjectivity as the process itself, such that humans (like the Russians) cannot be held accountable for feeling or acting differently than the rest of the world because it is not their personal prerogative but rather a consequence of the concept of sentiments. By acknowledging this selectivism and dynamism of frames and by relation, emotions and sentiments, this essay establishes that Rorty’s sentimental education is more susceptible to subversion and thematization than it was initially believed to be.

According to Rorty, today’s world is characterized by a glaring inability of people to humanize others outside of their socio-cultural circles. Instead, they resort to normative principles to validate their notions of “supremacy” and “dominance” (1998: 168). He attributes this disparity in human recognition to the foundationalist definition of humans as a direct product of their rationality (Rorty 1998: 171), because “rationality” is governed by distinct socio-cultural norms unique to each community (1998: 170) and the reliance on them only perpetuates said non-uniformity. In response, Rorty establishes that our “ability to feel” makes us human more than our rationality does (1998: 176). To that end, he seeks to provide a common grounding for people to identify with, primarily through sad and sentimental stories such that

people can equate each other not with rationality but with how they feel and the very fact that they can feel at all (Rorty 1998: 176). When people can acknowledge themselves as equal stakeholders in a shared moral community, Rorty believes that they will be driven to act not because it is the rational thing to do but because they reciprocate the feelings of trust and security that the community has nurtured in them (1998: 180).

Butler, on the other hand, attributes this disparity of recognition and relativism to the frames that constrain life and the narratives surrounding it. Butler denotes that the very acknowledgement of a frame is a direct concession of the existence of more factors outside of the frame (2009: 9).

Since frames and narratives are constantly broken down and reformed to reestablish the context, the interpretation also changes and adapts to the premises it lands in (Butler 2009: 10). This leads to a lot of subjectivity and arbitrariness in the narrative because more often than not the frameworks are defined by pre-established socio-cultural notions such that “what is taken for granted in one instant can be thematized critically in other instances” and vice versa (Butler 2009: 10). To that end, Butler also explicates the difficulty in quantifying human life due to the interdependence between the precarity of life and the social frameworks that nurture it (2009: 22).

With these social structures shifting and changing to adapt to the sociopolitical discourse in the world (Butler 2009: 24), the only way to properly define precarity, the inevitable part of human nature derived from the fact that all lives are vulnerable to the possibility of injury and destruction, is to embrace its dynamism (Butler 2009: 22). Hence, these social structures are just as reliant on the precarity of life as it is on them such that the precarity of each life is equally liable in shifting and reconstructing these constructs which directly restructures the precarity of all lives. Thus, through the recognition of this relationship between frames and interpretations, and precarity and social structures, Butler establishes that people can be incited to moral judgements vested not just in the communitarian benefit but also their self-interest (2009: 23).

Rorty and Butler both discuss differential recognition, cultural relativism, and the framing of humanity. But Rorty’s absolutist approach of sentimental

education is at odds with Butler’s critical theory of social ontology because: one, it has an over-reliance on frames and predetermined settings and two, its attempts at defining humanity in finitude is flawed.

Firstly, Rorty’s sentimental education is substantively based on the assumption that sad and sentimental stories are an effective and just means of propagating emotions and feelings across the moral community. These stories, however, inherently require frames to contextualize their material and instantiate it. So, when these stories are reproduced and land in different premises to evoke feelings and sentiments, such frames, by the virtue of their definition, also break and reform to adapt to the circumstances that they land in. They also tend to deviate from their intended context because of their reproducibility, i.e., when reproduced, they diverge from their original purpose and circumstances and warrant appropriate shifts and adjustments. Thus, in progressing sentiments, these stories also further progress the interpretive disparity in the world.

Secondly, the core of Rorty’s proposal that defines people by their ability to feel is flawed. Despite sounding “natural”, intuitive, and persuasive, defining humanity in finitude in any term whatsoever is problematic. But Rorty believes that in grounding “humanity” through feelings so that all people can equally share a moral community, sentimental education can dismantle the normativity of foundationalism, i.e., the grounding of understanding and interpretation in a foundation of pre-established knowledge and information. As an attribute of the precarity of life, sentiments are also largely influenced by socio-cultural structures so even feelings of sympathy and compassion (which Rorty establishes as innate and unwavering) are more often than not governed by what is socially and culturally acceptable as worthy of grief and pity. Rorty’s minimalist “humanity” thus fails to account not only for the fact that the “ability to feel” is subjected to societal frames, but also that socio-political discourse keeps shifting said limitations so “what makes us human” can never be a definite yardstick but a dynamic product of the social constructs that make it livable. It is thus impossible to standardize a global culture for what is essential to human rights globally.

This over-reliance on frames in terms of both propagation of sentiments and

the definition of humanity makes the sentimentality doctrine permissive and vulnerable and opens avenues for condescension and manipulation through the subjugation of its foundations. Thus, the altering and manipulation of the socio-cultural frames that give sentiments shape and meaning could fundamentally alter the type and gravity of sentiments shared by the people and by relation, sentimental education. Likewise, with said frames constantly reforming to accommodate the socio-cultural preconditions of where they land, and the emotions and sentiments they evoke equally susceptible to this subversion, sentimentalism only perpetuates cultural relativism and has barely any net effect on internalized separatism. Hence, sentimentalism, by virtue of its relativity and permissibility, sustains and progresses the very perils of foundationalism that Rorty claims it should have dismantled.

In conclusion, emotions can be a very powerful impetus when it comes to driving people to action such that Rorty’s sentimental education is an admirable mechanism for propagating ideas about the grievability of life and helping people identify their shared precariousness. By attributing the entire basis of moral judgements to sentiments, however, it perpetuates the very relativism and arbitrariness that it was meant to deconstruct. Thus, there arises a need to ground such sentiments with respect to other constructs and frames (if only the Russians could substantiate their feelings and acts with respect to the lives they risked) so that they can change and adapt with the status quo and people can better contextualize their feelings and make apt moral judgements.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Butler, Judith (2009), Frames of War - When is Life Grievable (NY: Verso).

Rorty, Richard (1998), ‘Human Rights, Rationality, and Sentimentality’, in Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers, Vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 167-185.

Jangisar is a village that subsists on agriculture in Thatta, Pakistan. Poverty is prevalent in the Thatta region, and several foundations regularly conduct humanitarian aid initiatives to improve the quality of life in the area. This photograph was taken at a Ramadan food distribution initiative in 2023, where locals gathered to receive aid packages filled with rice, bread, and meats; these packages aimed to feed a household throughout the entire month of Ramadan. The men in the photograph were among the group of individuals who walked from distant villages to receive aid packages.

“Food Distribution in Jangisar” by Sultan

Farooq

Essay 2

Are We Living Through a “Big Data” Scientific Revolution Today?

ALEKSANDAR BOLJEVIĆ

“Science is much more than a body of knowledge,” claimed Carl Sagan, “It is a way of thinking”. This definition is further supported by George Orwell’s claim that science is “a method of thought which obtains verifiable results by reasoning logically from observed fact”. Unfortunately, the general public usually fails to recognize this dimension of science. Instead, it tends to focus on what Orwell referred to as hard sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology. If the definitions proposed by Sagan and Orwell are ignored, science will get reduced to nothing more than data collection. In other words, it will become indistinguishable from big data, a growing field of artificial intelligence that uses advanced statistical methods to thoroughly analyze vast quantities of data. Its end goal is similar to science’s - finding correlations between certain variables to create predictions. It is then natural to wonder whether this will eventually become a new mainstream method of knowledge acquisition, overshadowing the impact that science has had on society until now. However, even if the ever-increasing enthusiasm surrounding big data makes it the driving force of human advancement, big data will never amount to actual science. This conclusion can be derived from a thorough analysis and comparison of the nature of big data and science. Consequently, it suggests that big data’s potential is exaggerated and may end up doing more harm than good to the advancement of human knowledge and understanding.

The accomplishments of big data so far have been astounding and extremely useful in fields ranging from public health to business. Some enthusiasts, like Chris Anderson, go as far as to believe that big data will lead to so-called hypothesis-free science, i.e. science free of mathematical models and equations that have, until now, been the only tools that consistently (yet imperfectly) described the world around us. The reasons for such optimism are rooted in the qualities of big data concerning the three main cornerstones of almost any exploration: time, resources, and accuracy. An early example of big data’s

outstanding performance is tracking the spread of the winter flu virus in the United States (Mayer-Schönberger 2). Whereas it took one to two weeks for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine how the virus spread, Google’s algorithm managed to deliver a more accurate trend in almost real time! Whereas the CDC had to test people for the flu virus, and thus waste both time and medical resources, the algorithm took advantage of the search items that people voluntarily entered in their own time. However, Google did not know why the virus spread that way, just that it did. Quick, modest, and accurate, big data seems like a promising approach to overtaking science.

To understand why this is not the case, a deeper comprehension of the principles underlying big data is necessary. The essential mechanism behind big data is that petabytes ensure that “correlation is enough”, that “numbers speak for themselves”, and that “we can throw the numbers into the biggest computing clusters [...] and let statistical algorithms find patterns where science cannot” (Anderson). The main assumption allowing such statements is that all quantified systems will obey the Gaussian distribution (Succi 2). This ensures that uncertainty will converge to certainty with a sufficient number of measurements (Succi 3). However, this assumption fails when considering complex systems in which events are deeply correlated, unlike the independent events that obey the Gaussian distribution (Succi 2).

Moreover, apart from correlations, big data does not seem to provide anything else, most notably context. It means that big data discoveries can only add to the body of knowledge, but not necessarily the body of understanding. An example of this is J. Craig Venter, who managed to add numerous new species to the catalog of life, yet could not describe most of what he discovered (Anderson).

Another downside of big data is that completely adopting the approach of simple data harvesting and curve-fitting means completely abandoning critical thinking. This attribute is exactly what will eternally distinguish big data from proper science. There is nothing critical in letting a computer determine variables that are correlated, find the correlations, and finally derive predictions. Even more so, this process requires barely any thinking at all, let alone critical. A curve that pleases the data will always exist. As

von Neumann told Fermi: “With four parameters, I can fit an elephant and with five, I can make him wiggle his trunk” (Succi 11). However, there will not always necessarily be an intuitive scientific explanation of the observed phenomena. For example, the derivation of quantum mechanics required, and its development still requires, critical thinking, not (just) big data. This is because big data, on its own, can hardly contribute to hardcore physical sciences that require deep theoretical understanding (Succi 13). While some discoveries are made thanks to big data (such as the Higgs boson), the predictions of the existence of these discoveries always come from theoretical foundations (Mazzocchi 1253).

Another criterion that clearly distinguishes big data from real science is its pure inductive nature. Since “at its core, big data is about predictions”, and these predictions are based solely on previous patterns, big data is, by definition, inductive (Mayer-Schenberger 11). On the other hand, those familiar with the philosophy of science may strongly object to this argument, claiming that even science is, when broken down into its elementary laws, inductive in its nature, just like big data. While there is truth in this proposition, in the sense that these “laws of nature” are not known for certain to be correct, this comparison appears to be deeply unfair. Laws in natural sciences are incredibly interconnected and should just one of them be falsified, multiple areas of science may immediately require thorough revision. For instance, the falsification of the inverse square law of electromagnetism could drastically affect any area that concerns electric current or magnets. Yet, everything seems to work out just fine. Luckily, or unfortunately, this is not the case with big data, where each event is independent and the failure of the algorithm in one case will have little to no effect on other cases. It may not even cause a modification of the algorithm, as outliers are not impossible, just unexpected and improbable, so they could be labeled as nothing more than a deviation (Succi 3).

Furthermore, science is highly unlikely to find false correlations, whereas big data has plenty of them. The reason is that science critically evaluates, while big data does not even consider, if the context makes it sensible for two variables to be correlated. Therefore, while big data suggests that the rate of drowning by falling in a pool appears tightly correlated with Nicolas Cage’s

movies - a deeply interesting fact worth giving a thought - science could never come up with such conclusions as the contexts are completely unrelated (Succi 8). Although this quality perhaps makes big data more fun to work with, true progress in the understanding of the world requires a narrow focus on what genuinely matters in a given scenario.

This leads to another problem with big data: it focuses on what rather than why (Mayer-Schönberger 14). This can also be interpreted as “knowledge rather than understanding” or “correlation rather than causation”. While big data has been immensely useful and powerful in numerous instances, such as tracking the spread of the flu virus or translating between any two languages (Google Translate), what characterizes all of these examples is that “they [researchers] didn’t know, and they designed a system that didn’t care” (Mayer-Schönberger 2). A language-translating algorithm certainly does not understand (and probably does not care about), like Spanish speakers do, what “No hablo ingles” means, yet it will accurately translate it into “I don’t speak English”.

At first, this may seem like an upside of big data. After all, aren’t the researchers supposed to do the thinking and understanding part? Indeed they are. However, it does not seem that many of them are bothered enough to perform these tedious tasks. Their trust is unconditionally given to the algorithms that have no understanding of the context, which may even be impossible for scientists to determine. Just like how Venter was certain that he discovered a new species, yet could say nothing about it. What is hidden behind the “why” is wisdom, i.e. the ability to make the right decisions (Succi 8). Thus, wisdom guides humankind to what to do with the knowledge it has. Knowledge describes how to do something, but it is wisdom that decides if it should be done. If every human had been wise enough, we would have perhaps never come up with things such as atomic bombs, eugenics, or genetic profiling that is being committed against Uyghurs and Turkic minorities in China right now (Munsterhjelm). This is a fundamental problem of big data - it provides too much information, yet too little guidance on how to use it. Without wisdom, humanity is lost both on an individual and global scale, and, as such, it stands as a border between proper science and big data, preventing big data from ever becoming a science.

If big data is not destined to replace the scientific method, then can it at least be considered revolutionary? Although it may seem so, considering the number of new enthusiasts emerging in recent years, such as Anderson and MayerSchönberger, big data, if revolutionary, seems to, ironically, disobey the pattern that has been going on since the creation of information. Every revolutionary change in technology throughout history was preceded by resistance, suspicion, and skepticism of older generations. In his article “Don’t Touch That Dial”, Vaughan Bell gives examples from different centuries of what has been considered “confusing and harmful” at some point in time. Most of those, such as the printing press, radios, and television, had soon been approved, despite initially disturbing those unfamiliar with new technologies (Bell). Still, they were all revolutionary inventions at the time, the carriers of big change.

The suspicion and skepticism of older generations and the later acceptance by younger generations, therefore, seem to be a natural cycle of events, yet it is not present when it comes to big data. Though concerns surrounding data privacy may be interpreted as some sort of resistance, the reality is that most people, including those who are “resisting”, willingly give their personal information to private corporations and joyfully scroll through personalized social media feeds, news, and suggestions (such as which products to buy). The reason for this absence of resistance may be that big data simply is not that revolutionary. In retrospect, inductive reasoning based on a large collection of data has always been present in science. Before modern telescopes and petabyte-storing databases, astronomers were gathering years’ worth of observations of the positions of the stars to arrive at conclusions on how the universe works (such as Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler…). However, at no time in history has humanity been able to store and analyze as much data as it can today. Therefore, big data could be viewed just as a natural by-product of all technological advancements leading up to it rather than a big revolutionary discovery itself.

In conclusion, the evidence is clear - big data stands no chance of ever replacing science. The enthusiastic rumors that foreshadow the end of scientific inquiry should not be considered seriously. Still, their presence is an alert of how easily the essence of science can be misinterpreted and, perhaps even more alarmingly, forgotten. However, this does not mean that big data

should be disregarded in any sense, or that its accomplishments are any less significant. It is still one of humanity’s most powerful tools in its weaponry against ignorance, but those who dare to use it must address its limitations. Big data must be used wisely, and that wisdom can only come from science.

WORKS CITED

Anderson, Chris. “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete.” Wired, 27 June 2008, wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/. Accessed 2022.

Bell, Vaughan. “Don’t Touch That Dial!” Slate, 15 Feb. 2010, https://slate.com/ technology/2010/02/a-history-of-media-technology-scares-from-the-prin ting-press-to-facebook.html. Accessed 2022.

Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor, and Kenneth Cukier. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think. Mariner Books, Boston, Massachusetts, 2014, pp. 1–18.

Mazzocchi, Fulvio. “Could Big Data Be the End of Theory in Science? A Few Remarks on the Epistemology of Data-driven Science.” EMBO Reports, vol. 16, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1250-1255.

Munsterhjelm, Mark. “Scientists Are Aiding Apartheid in China.” Just Security, 18 June 2019, https://www.justsecurity.org/64605/scientists-areaiding-apartheid-in-china/#:~:text=Chin ese%20security%20agency%20 scientists%20have,effectively%20target%20its%20oppre ssive%20measures. Accessed 2022.

Sagan, Carl. “Why We Need to Understand Science.” Skeptical inquirer, vol. 14, no. 3, 1990, pp. 263-269.

Succi, Sauro, and Peter V. Coveney. “Big Data: the End of the Scientific Method?” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol. 377, no. 2142, 18 Feb. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0145

Orwell, George. “What Is Science?” Tribune, 26 Oct. 1945.

ARE WE LIVING THROUGH A “BIG DATA”

The Representation of Female Sexuality in 20th Century Women

ANASTASIIA-LEI YANG

“The power of sexual pleasure and ownership of the sexual self—in all its facets—can free women from what society expects of and accepts from them.” — Jessamy Gleeson

Introduction

In the contemporary, Western world, female sexuality is not a surprising topic for discussion. The borders of feminism have extended from political and intellectual equality to breaking down the ‘biological’ walls between the two sexes. Throughout time, it has been perpetuated that compared to women, ‘biologically’ men are more prone to having increased sexual desire, a need for variety and polyamory, engaging in masturbation, and all other sorts of claims that refer to biological sex differences and evolution as a way to patronize female sexual identity. Not only do most of those claims completely ignore the social gender expectations on sexual behavior, they are, in fact, not true. Studies have found that, aside from the social pressure, women and men have similar levels of sexual desire (Sine). Moreover, one study found that women are sexually aroused (consciously or unconsciously) by all sexual stimuli, whether heterosexual or homosexual, animal or human – compared to men, whose sexual arousal stays within the boundaries of their sexual identity (Rosner). Female sexuality is extremely complex and multifaceted, factoring in individual preferences, motivations, and, most importantly, conflicts between the self and society. Unfortunately, to this day, the media does not represent women in a realistic, fair manner. Even though we are slowly moving away from writing women as love interests—an archetype that presents women solely for the satisfaction and development of the male protagonist—we are still continuously attempting to confine female identity into one-dimensional characters, stripped of the inner conflict, ability to make mistakes, and lustful intentions. Directors such as Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Greta Gerwig (who plays Abbie in 20th Century Women), have repeatedly criticized the ‘good girl’

angel-like representation of women and instead given their characters an opportunity to be human: loving, empathetic, but also angry, emotional, cold, and lustful. For women, sex has always been considered acceptable when intended to create a family. Female sexual desire has been seen as appropriate if directed at a long-term partner to bear children. Male sexual desire, on the other hand, is seen as natural and admissible in any circumstance other than violent (though even that is debatable). While manhood is associated with independence and power, womanhood is equivalent to motherhood and submission. Although hyperbolized, one can assume that to be a woman and to desire means to desire romance, commitment, and motherhood.

One film theory that addresses this issue is counter-cinema theory. As developed by film theorist Laura Mulvey, the theory argues that traditional Hollywood cinema is inherently patriarchal and perpetuates a male gaze that objectifies women. In response to this, Mulvey argues for the creation of a “counter-cinema” that challenges traditional narratives, offers alternative perspectives, and disrupts the male gaze. In terms of female sexual desire, counter-cinema theory aims to offer representations of sexuality that are not filtered through a male perspective. This includes depictions of female desires that are not purely focused on pleasing male partners, as well as allowing female characters to express their sexual intentions and motivations (Mulvey, 40–44). By providing alternative perspectives on sexuality, counter-cinema seeks to challenge the traditional patriarchal structures that have historically defined women’s sexuality as passive and subservient to male desire.

Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex can be seen as a counterpoint to Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze in cinema. It offers a platform for women to share their own perspectives and experiences of sex outside of the narrow confines of mainstream media. By prioritizing the voices and experiences of women, the book challenges traditional power structures and norms surrounding sexuality, and offers a more inclusive understanding of what it means to have a fulfilling sex life (Pickering). Additionally, the book’s emphasis on personal storytelling and subjective experience can be seen as a rejection of the “male gaze” that Mulvey critiques in her theory. Rather than presenting women as passive objects to be looked at and desired, Doing

It foregrounds women’s agency and autonomy in their sexual lives. This emphasis on subjectivity and agency can be seen as a key tenet of countercinema, as it challenges dominant narratives and opens up new possibilities for representation and self-expression.

20th Century Women (2016), directed by Mike Mills, is both an example of the personalization of female sexual experiences advocated by Doing It, as well as a demonstration of Mulvey’s counter-cinema theory, making it a nuanced representation of female sexuality. The film is set in the 1970s and follows the story of Jamie, who is surrounded and influenced by the three significant women in his life. It is an example of a realistic exploration of heterosexual female desire. Each of the three female characters—Julie, Abbie, and Dorothea—tells a different story of sex from the viewpoints of different ages, value systems, and preferences. For the scope of this paper, I will be focusing on Julie and Abbie. I argue that in 20th Century Women, the main female characters, Julie (17 y.o.) and Abbie (24 y.o.) display various attitudes towards romantic relationships, motherhood, and sex, each conveying a complex understanding of female sexuality and subverting societal expectations and gender roles when it comes to sexual behavior. I do want to emphasize that I deliberately focused on the Western heterosexual female identity since other sexualities are outside the scope of this paper, as this film has primarily focused on heterosexuality in its characterization of women.

Julie

Julie’s character represents young women who have no intention of having children but are forced to consider motherhood as a possibility anyway. She engages in frequent one night stands, showing a complete disinterest in motherhood and long-term commitment. The filmmakers communicate this by attributing to Julie sexual promiscuity that is often associated with male behavior, yet contrary to a man, she does not have full control over her reproductive system and choices. In the one sex scene she appears for, she is promised by her sexual partner, Kyle, that he will take responsibility over contraception (in this case, “pulling out”) but he breaks that promise, leaving her with the fear of an unwanted pregnancy. The following day, she takes a two-hour pregnancy test, which highlights how much less reproductive

freedom women had in the 1970s. She is later taken by Abbie to Planned Parenthood, and goes on oral birth control, a choice only women can (or have to) take. Birth control pills have an extensive list of life-threatening side effects that women are told to accept as normal. Interestingly, the trials for invasive male birth control were stopped because “male contraceptives cannot have side effects,” even those that are less severe, revealing the inequality of reproductive health options (Kean). While there is an illusion of sexual equality, since both Julie and Kyle make the same sexual choices, he gets to fulfill his desire without fearing the consequences or feeling a burden of responsibility. For him, each sexual experience is enjoyable and carefree, while for Julie, each encounter is a potentially life-altering event.

Moreover, Julie’s character represents women who do not experience the same physical pleasure as men but derive other forms of pleasure from sex that are not focused on men’s needs. It is well known that only 40% of women orgasm during penetrative sex (McIntosh). When asked what female orgasm feels like, Julie replies: “I don’t have them.” While it is true that one reason for this is that sex is a male-focused pleasure, this does not mean that all women comply with this societal expectation and just “participate” in sex to please their male partners. When Julie is asked why she has sex, she says that she loves how male bodies look, how men sound, and how “desperate” they get, conveying that women are neither “pure” nor passive; they can also objectify bodies, seek dominance, and pursue their own agenda. Contrary to victimizing stories, which often view orgasm as the purpose of sexual pleasure, women do not have sex to satisfy their partners needs, demonstrating that female sexual identity is separate from men’s needs. Through dialogue, Julie speaks for herself, silencing the assumptions that if she does not orgasm, she is not enjoying sex or is doing it for male satisfaction. She, like many other women, has lustful motivations, intentions, and desires independent of the male partners.