Digital Electronics

The Basics, New Ideas & Applications

Tons

Tons

M.A. Shustov, A.M. Shustov

● This is an Elektor Publication. Elektor is the media brand of Elektor International Media B.V.

PO Box 11, NL-6114-ZG Susteren, The Netherlands

Phone: +31 46 4389444

● All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form, including photocopying, or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication, without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licencing Agency Ltd., 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1P 9HE. Applications for the copyright holder’s permission to reproduce any part of the publication should be addressed to the publishers.

● Declaration

The authors and publisher have used their best efforts in ensuring the correctness of the information contained in this book. They do not assume, or hereby disclaim, any liability to any party for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in this book, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause.

● British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

● ISBN 978-3-89576-712-8 Print

ISBN 978-3-89576-713-5 eBook

● © Copyright 2026 Elektor International Media www.elektor.com

Editor: Clemens Valens

Prepress Production: D-Vision, Julian van den Berg

Printers: Ipskamp, Enschede, The Netherlands

Elektor is the world's leading source of essential technical information and electronics products for pro engineers, electronics designers, and the companies seeking to engage them. Each day, our international team develops and delivers high-quality content - via a variety of media channels (including magazines, video, digital media, and social media) in several languages - relating to electronics design and DIY electronics. www.elektormagazine.com

The reader is presented with a book dedicated to the fundamental principles of digital electronics. A deep study of the presented sections will enable the reader not only to grasp the intricacies of building digital circuits but also to acquire skills in independent design and debugging of electronic constructs of varying complexity.

The structure of the publication includes three main parts:

1. Fundamentals of Digital Electronics: The first part is devoted to outlining the basic principles. Initially, the reader will be introduced to the functioning of key nodes of digital technology through demonstration stands. These stands, easily assembled from available components (LEDs, diodes, resistors, and switches), vividly illustrate the operation of digital elements, allowing for a conceptual understanding of their work. We then proceed to a deeper study of logic elements, tracing their evolution from historical prerequisites to modern implementations based on advanced materials and innovative circuit design solutions. A detailed list of the logic elements discussed is provided in the book’s Table of contents.

2. Innovative Directions in Digital Electronics: The second part of the publication invites the reader to explore new ideas and developments in the field of digital electronics. This section aims to stimulate creative imagination, activate thinking processes, and foster the generation of original projects.

3. Practical Implementation and Application: The concluding third part thoroughly examines the practical use of elements and circuits in digital electronics. An extensive collection of circuits classified by their functional purpose is provided, including electronic switches, pulse generators, pulse-width modulation devices, frequency multipliers and dividers, phase shifters of digital signals, as well as digital frequency filters.

We wish the reader success in mastering the theoretical foundations of digital electronics, applying the acquired knowledge in practice, developing creative potential, and enhancing professional competencies.

Introduction

Logic elements, which form the basis of modern digital technology, are based on the use of Boolean logic. In 1854, English mathematician, philosopher and logician George Boole (1815–1864) in his work "An Investigation of the Laws of Thought: on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities" first proposed to investigate logic statements using mathematical methods. Such logic statements were initially two mutually exclusive concepts, "True" and "False", which were later transformed in mathematical and technical applications into the conditional values 1 or 0 ("log. 1" and "log. 0") [1].

In 1938, American engineer, cryptanalyst and mathematician Claude Elwood Shannon (1916–2001) first applied Boolean logic algebra in practice to describe the operation of relay-contact and electronic-tube circuits in his master’s thesis "A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits" [2].

The first integrated circuits in the world were developed and manufactured in 1959 by Americans Jack St. Clair Kilby (Texas Instruments) and Robert N. Noyce (Fairchild Semiconductor) independently [3].

On 24 July 1958, engineer Jack St. Clair Kilby (1923–2005) proposed fabricating the components of an electrical circuit (resistors, capacitors, and transistors) from a single material and placing them on a common substrate. On 12 September 1958 he created the first analog integrated circuit containing five elements. On 19 September 1958 Jack Kilby demonstrated the first digital integrated circuit by building a two-transistor flip-flop.

In 1959, entrepreneur-scientist Robert Norton Noyce (1927–1990) invented the planar process for manufacturing integrated circuits.

With the introduction of Boolean-logic operations such as "NOT", "AND", "OR", and many others into electronic engineering, logic elements such as NOT, AND, OR, etc., first appeared as vacuum-tube circuits and later as transistor and integrated-circuit implementations [3–6].

Let’s start by defining key terms that will help us better understand how signals and devices work.

• Signal: Think of something that changes over time and carries important information. That is a signal.

• Noise: This is also something that changes over time, but completely randomly and without any useful information. It hinders us from hearing or seeing the useful signal.

• Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): This is simply a comparison of how strong our useful signal is compared to the noise. The higher the SNR, the better.

• Couplings and Interferences: These are unwanted signals or noises that come from external sources (such as from other devices or natural phenomena) and spoil our main signal.

• Electric Signal: This is a signal transmitted using electricity that carries information.

• Analog Signal: Such a signal can smoothly and continuously change its strength (amplitude) and frequency over a very wide range. In nature, almost all signals are analog.

• Digital Signal: Such a signal can only take certain, clearly defined values. Most often there are just two states: "signal present" (logic one, "log. 1") or "no signal" (logic zero, "log. 0"). An analogy would be a switch – on or off.

• Analog devices: Created to work with analog signals that change smoothly over time.

• Digital devices: Designed to work with digital signals consisting of discrete levels (logic ones and zeros).

• Logic Zero: This is a level of electrical signal that digital devices reliably recognize as the absence of a signal or a zero value.

• Logic One: This is a level of electrical signal that digital devices perceive as the presence of a signal or its active value.

Other Important Concepts

• Electric Pulse: A short, sharp spike in voltage or current. Pulses can vary in shape, duration, amplitude, and frequency of occurrence.

• Active Signal Level: The state when the signal is present and performing its function.

• Passive Signal Level: The state when the signal is absent or not performing any function.

• Signal Inversion: A reverse change of the signal. If there was a "zero", it becomes a "one", and vice versa.

• Inverted Output: The output of a device that produces a signal opposite in level to that which is received at the input.

• Direct Output: The output of a device that produces a signal with the same level as that at the input.

• Positive Signal Edge: The moment when the signal transitions from a low level (zero) to a high level (one).

• Negative signal front: The moment when the signal transitions from a high level (one) to a low level (zero).

• Leading signal front: The transition of the signal from the state of "no signal" to "signal present".

• Trailing signal front: The transition of the signal from the state of "signal present" to "no signal".

• Clock signal (strobe): A special signal that acts as "clock" for other devices, indicating exactly when a specific action should be performed.

Mastering the basics of digital technology can be an exciting journey. To make this process as visual and comprehensible as possible, we will examine several special test circuits. These circuits simulate the operation of real logic devices using a minimal set of available components: switches, LEDs, diodes, and resistors.

The circuit for studying the operation of basic logic elements provides a clear illustration of how real logic elements work: Repeater/Inverter, OR/NOR, AND/NAND, Exclusive OR/XOR, and non-classical elements such as Equivalence and Not-Equivalence.

We will familiarize the reader with the definitions of basic logic elements [4–7].

REPEATER – a logic element that has an input and an output and performs the function of repeating a signal. When a control signal X is applied to the input of such an element, the output signal Y will be entirely identical to the input.

NOT – a logic element that has an input and an output, an inverter, performing the function of signal inversion. The output signal Y is "a "mirror" or "inverted" copy of the input: when a logic one is at the input of the element, a logic zero will be at the output, and vice versa.

The logic elements discussed below generally have multiple inputs and one output

OR – a logic element in which the output signal Y takes the value of logic one when at least one of its multiple inputs has a logic one ("log. 1") signal. If all inputs have a logic zero, the output will also be a logic zero ("log. 0").

NOR (NOT-OR) – a logic element that represents a series connection of OR and NOT elements. The output signal Y of the NOR circuit takes the value of logic one when all its inputs are at logic zero. If at least one of the input signals takes the value of logic one, the output signal Y will switch to a logic zero level.

AND – a logic element that performs the function of coincidence. Its equivalent circuit can be represented as two or more (depending on the number of inputs) switches connected in series: the output signal Y will only be logic one if all inputs of this logic element receive a logic one level.

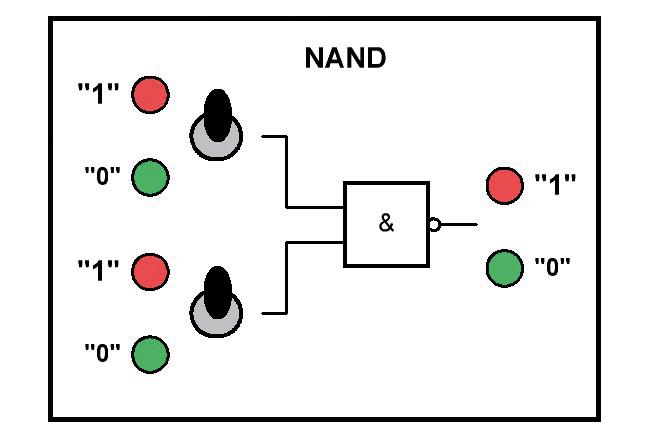

NAND (NOT-AND) – a logic element consisting of series-connected AND elements (or NAND). When logic one levels are simultaneously applied to its inputs, the output Y of the element will be at logic zero. If at least one of the input signals takes the level of logic zero, the signal at the output of the device will immediately switch from "zero" to "one".

XOR (EXCLUSIVE OR) – a logic element whose two-input version produces an output signal Y equal to logic one only when one of its inputs has logic one and the other has logic zero. If this condition is violated, the output signal will take the value of logic zero.

XNOR (EXCLUSIVE NOR) – a logic element whose two-input version produces an output signal Y equal to logic zero only when one of its inputs has logic zero and the other has logic one. If this condition is violated, the output signal will take the value of logic one.

EQUIVALENCE – a more complex logic element that outputs Y as logic one only when all signals at its inputs are identical (equivalent), regardless of whether they are "zero" or "one".

NOT-EQUIVALENCE – a logic element that outputs Y as logic zero only when all signals at its inputs are identical (equivalent), regardless of whether they are "zero" or "one". The "Equivalence" and "Not-Equivalence" devices are not produced industrially.

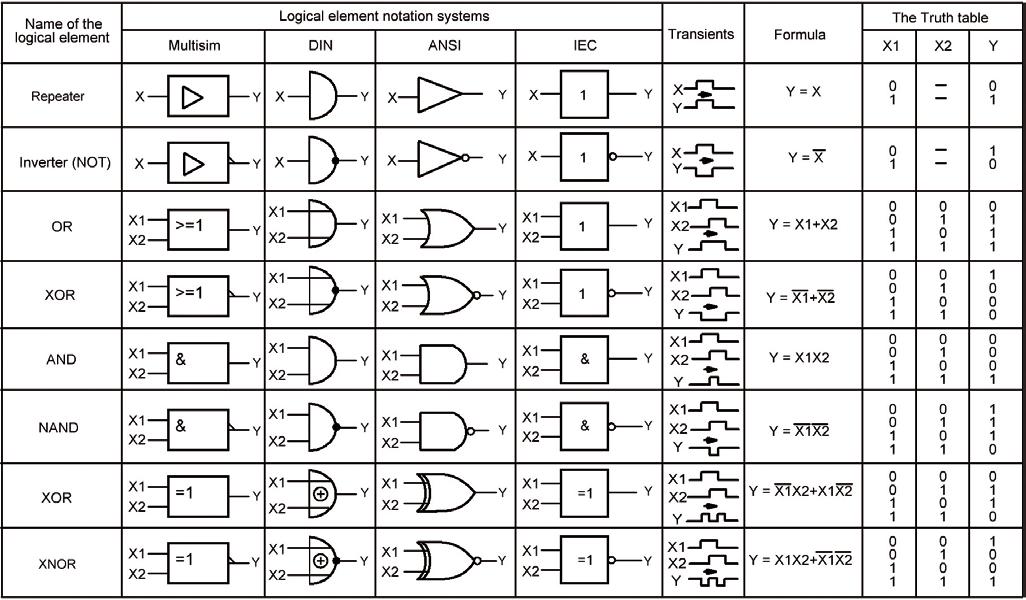

To help the reader easily navigate the designations of logic elements found in technical literature, Table 1.1 presents a summary of symbolic designations adopted in different countries and in schematic modelling programs. The Table also illustrates the relationship of transitional processes at the inputs and outputs of various logic elements, containing formulaic expressions to describe their operation and truth tables.

The truth table vividly displays the response of the output signal Y of the digital IC to all possible combinations of input signals X1, X2 ... Xn.

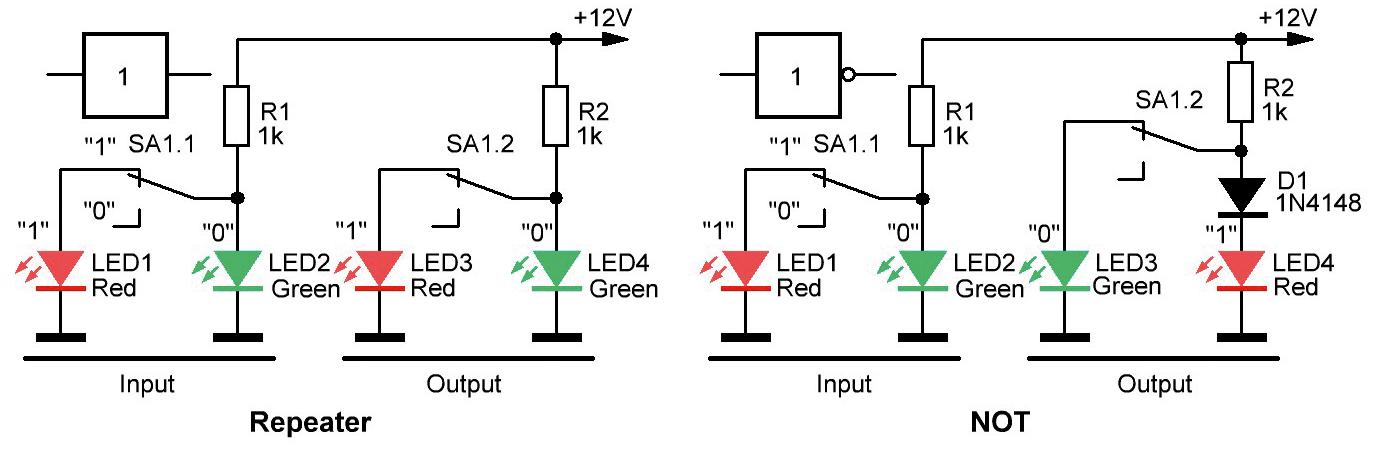

Figure 1.1 presents electrical diagrams that allow for simulating the operation of basic logic elements – Repeater and Inverter (NOT element). For clarity, the green LED will represent "Logic zero" ("log. 0"), and the red LED will represent "Logic one" ("log. 1").

Table 1.1. Logic elements, notation, their functions, truth tables.

The operation of the LED indicators of logic levels is based on the fact that when two different colored LEDs are connected in parallel through a current-limiting resistor to a power supply, all the current will flow through the LED that requires a lower voltage drop sufficient for it to glow brightly [8–10]. For example, a red-emitting LED typically lights up at a voltage drop of 1.7 V … 1.8 V; a green-emitting LED lights up at 1.9 V … 2.0 V.

Therefore, when connecting a red and a green LED in parallel through a current-limiting resistor to a power supply, only the red LED will light up.

To make the green-emitting LED glow while a red-emitting LED is connected in parallel, it is sufficient to artificially shift the voltage range for the red LED’s turn-on by placing a silicon diode in series with it.

A number of modern red and green LEDs have a bright glow with almost the same voltage drop across the LEDs. Therefore, before starting work, it is necessary to check the possibility of extinguishing the green LED when the red LED is connected to it in parallel.

If the green LED remains lit, to ensure precise switching of the LEDs, a diode with a forward voltage drop of 1.0 V–1.5 V should be connected in series with the LED connected directly to the current-limiting resistor, including in place of the 1N4148 diode. You can select such a diode by consulting the reference literature. For comparison, the 1N4148 diode has a forward voltage drop of 0.6 V … 0.7 V.

Using this property of LEDs has allowed for the creation of extremely simple simulators of logic element operations. Thus, in the Voltage Repeater, Figure 1.1, both red-emitting LEDs light up simultaneously at the position of switch SA1, thereby indicating a high-level

voltage (logic one) at both the input and output of the logic element. Switching SA1 will cause the green LEDs to light up, thus characterizing the voltage levels at the input and output of the logic element as "log. 0".

In the Inverter element (NOT gate), Figure 1.1, the output circuit of the simulator is arranged by connecting the red-emitting LED4 in series with the silicon diode D1; in the position shown in the schematic for switch SA1, the input red-emitting LED lights up as "log. 1" and the output green-emitting LED as "log. 0".

Figure 1.1. Simulators of operation of logic elements "Voltage repeater" ("Repeater") and "Inverter" ("NOT").

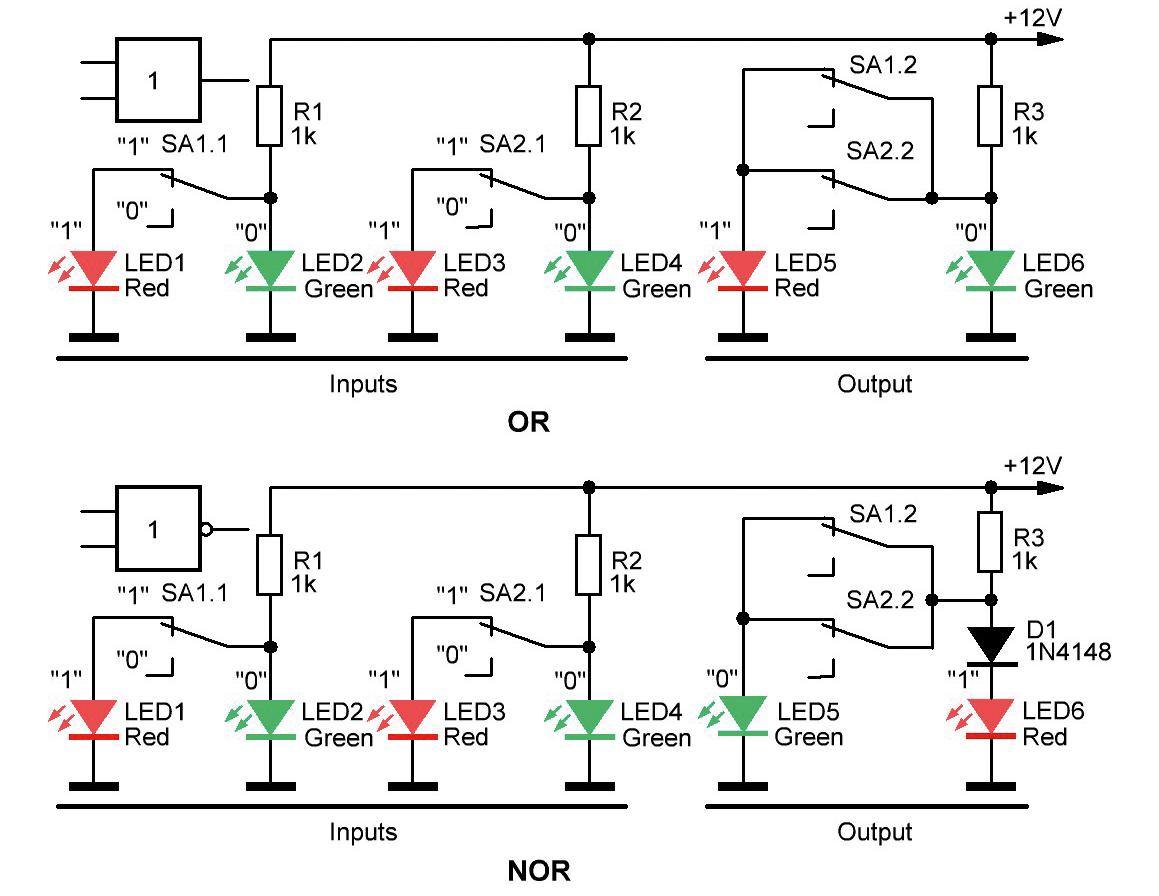

The OR/NOR element simulators, Figure 1.2, contain, unlike the previous ones, two "inputs", to which conditional logic ones and zeros can be fed using switches (toggle switches).

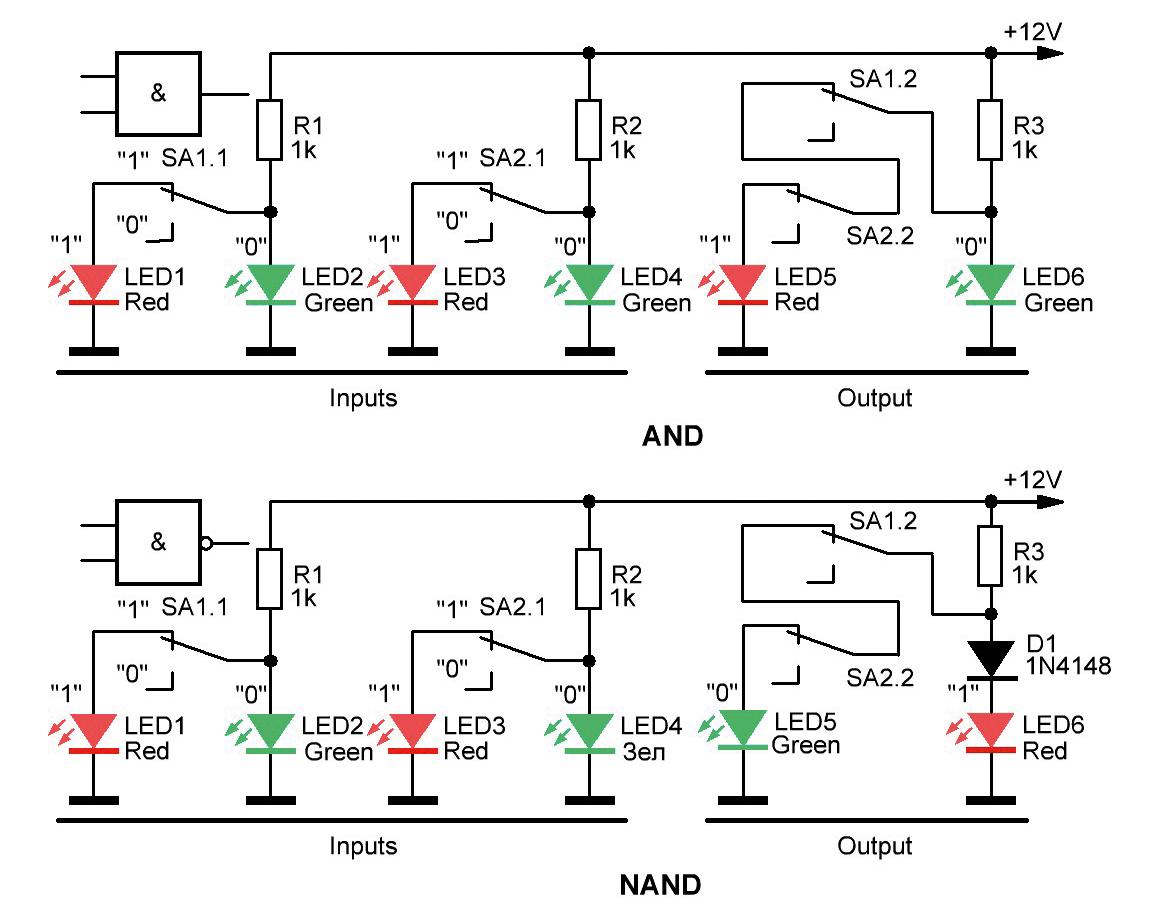

A slight modification in the way the switch keys are connected in the receiving part allows for the creation of AND/NAND element simulators, Figure 1.3. The operation of these elements is clear and requires no additional explanation.

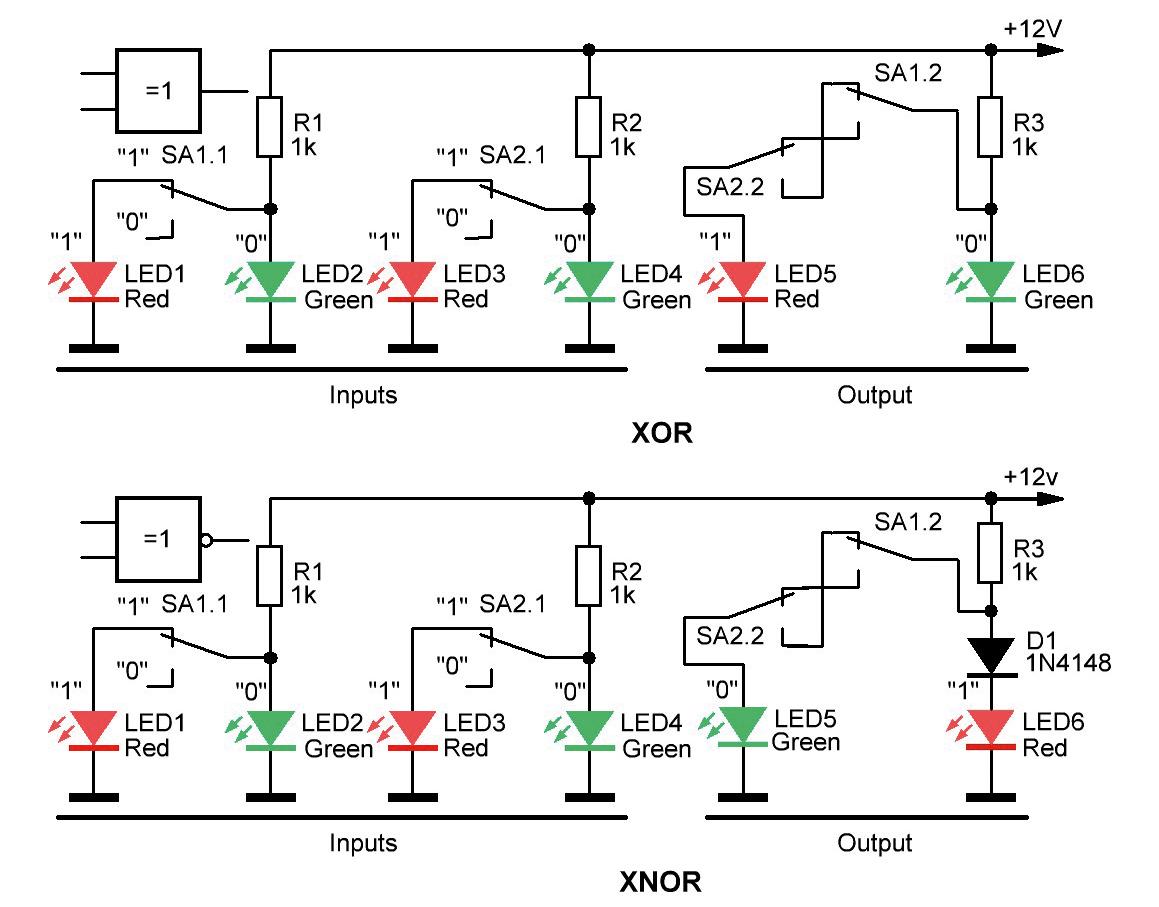

Further straightforward modernization of the switch key connections in the receiving part allows for the creation of two-input XOR/XNOR element simulators, Figure 1.4.

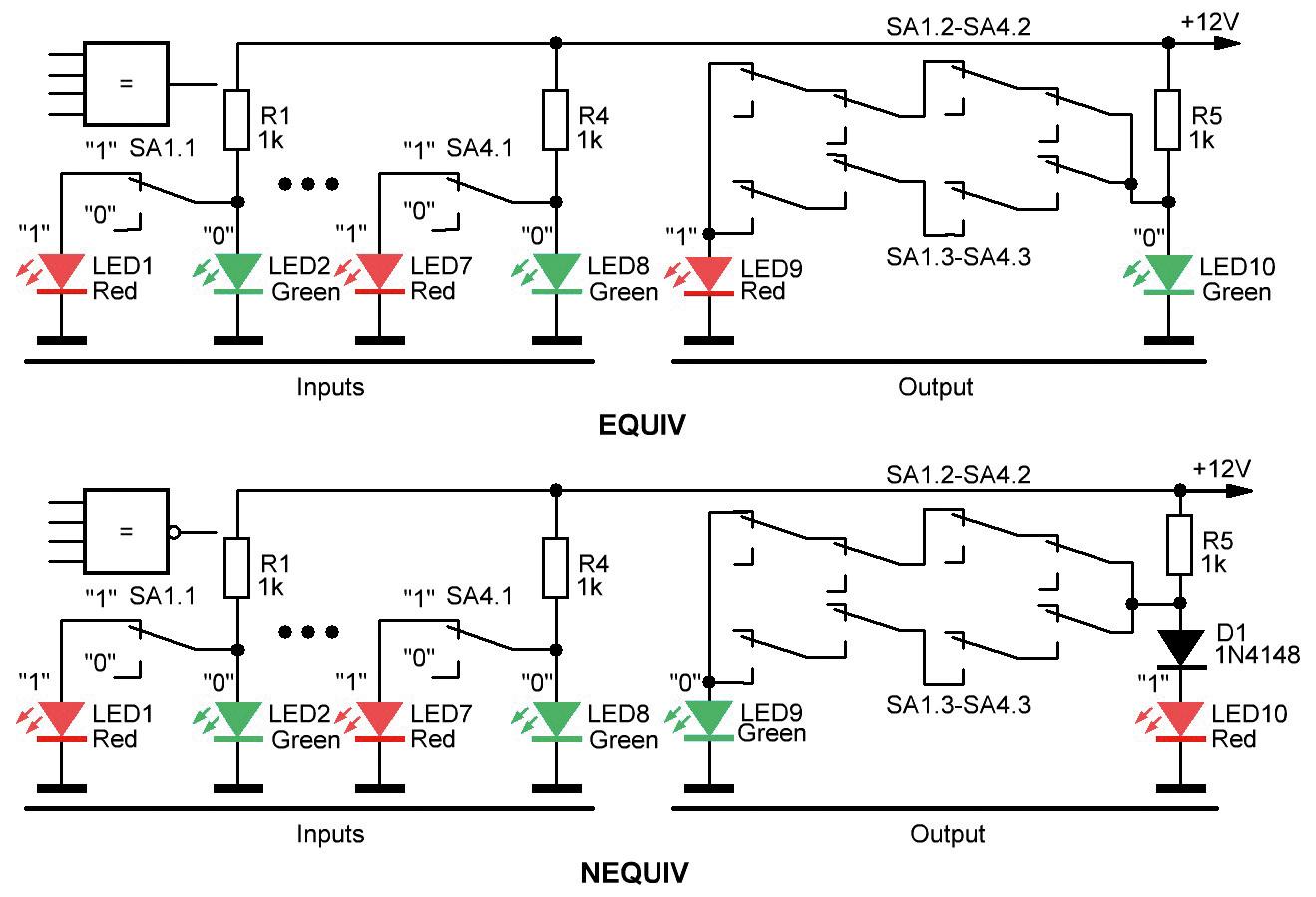

It is important to specifically describe the simulators of the logic elements Equivalence/ XNOR. It should be noted that such elements do not occur in their pure form in nature; no industry in any country produces them, although the usefulness of such elements is selfevident. When necessary, similar logic elements can be created by combining several other logic elements of various purposes.

The simulators of logic elements Equivalence/XNOR shown in Figure 1.5 have been implemented quite simply. It should be noted that imitating the operation of these elements required the use of four inputs, as the two-input version of the Equivalence/XNOR elements turns into the previously described XOR/XNOR elements, Figure 1.4.

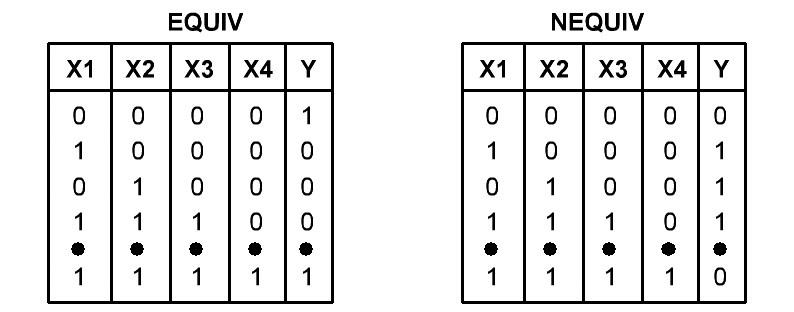

Below, in Figure 1.6, a truth table for the logic elements Equivalence/XNOR is presented.

Figure 1.2. Simulators of operation of logic elements "OR" and "NOR".

Figure 1.3. Simulators of operation of logic elements "AND" and "NAND".

Figure 1.4. Simulators of operation of logic elements "XOR" and "XNOR".

Figure 1.5. Simulators of operation of logic elements "EQUIV" and "NEQUIV".

Figure 1.6. Truth tables for logic elements "EQUIV" and "NEQUIV".

Figure 1.7 shows a fragment of a possible design for the front panel of one of the components of the logic element simulator. For clarity, it is recommended to place an enlarged Table 1.1 on the circuit itself.

Any DC voltage source in the range of 6 V … 15 V can be used to power the test circuit and/or its elements.

It is also important to check if the brightness of the selected LEDs for the test circuit is acceptable: if it seems excessive, one should increase the value of the current-limiting resistors; conversely, if the brightness is low, these values should be decreased. For resistors with a value of 1 kΩ and a supply voltage of 12 V, the current through any of the LEDs is approximately 10 mA.

Commonly available toggle switches can be used as switches for the test circuits, including three-pole switches for the Equivalence/Inverse Equivalence logic element simulator.

Figure 1.7. View of the front panel of one of the elements of the logic element simulator.

Complex Logic Elements

Next, we will consider circuits for visually studying the principles of operation of logic elements with at least three inputs.

The test circuits presented below expands the list of simulators of logic devices and allows for the visual illustration of the operation of more Complex logic elements, such as: Odd parity, Even parity; 3XOR; 3XNOR; =2; ≥2; ≥M, etc.

The principle of operation of the simulators of the logic elements has been described in detail earlier.

The individuality of the properties of the simulated logic elements is determined by the specificity of the connection of the contact groups of the switches responsible for turning the different coloured LEDs on or off.

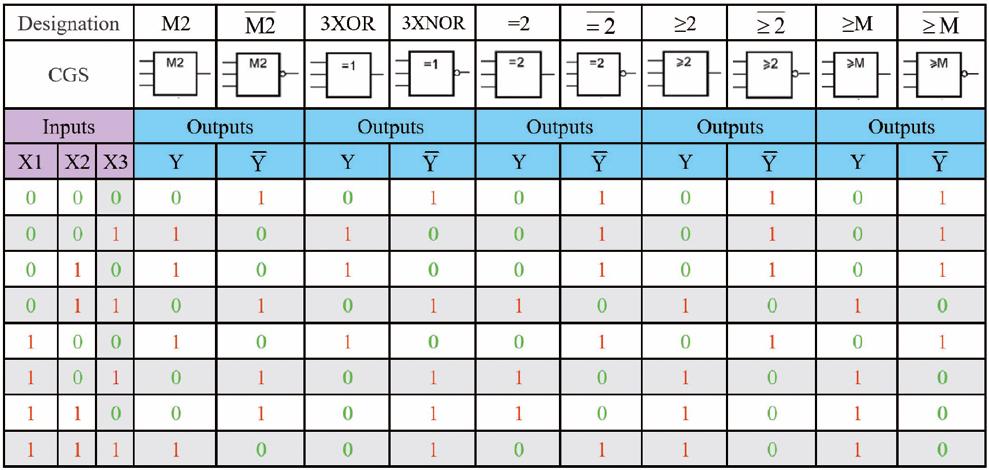

Table 1.2 provides the conditional graphic symbols (CGS) for logic elements and their truth tables, characterizing the response of the logic element when control signals of different levels are applied to its inputs.

Logic elements, when the number of their inputs is reduced, often perform the same functions. Thus, for example, the well-known AND and OR gates, when their inputs are merged, become a single-input element Repeater (Buffer). For more complex-structured logic elements, such metamorphoses can lead to terminologic confusion and the appearance of false synonyms.

It should be noted that the provided truth table is also suitable for describing the operation of logic elements with two inputs. To do this, it is sufficient to remove the column corresponding to input X3 from the table, as well as the rows corresponding to the signal level "log. 1" at this input.

The electrical circuits of the logic element simulators are depicted in Figures 1.8–1.19.

Table 1.2. Truth tables of a series of logic elements.

Designations: M2 – Odd parity; M2 – Even parity; 3XOR – 3XOR; 3XNOR – 3XNOR; =2 – 2 and only 2; 2 = – 2 and only 2-NOT; ≥2 – Logic threshold 2; – Logic threshold 2 - NOT; ≥M – Majority (M≥2); – Majority-NOT (M≥2).

Note: When the rows and column shaded in gray are deleted, the table will correspond to logical elements with two inputs.

Below are definitions of the logic elements to help remember their purpose and principle of operation.

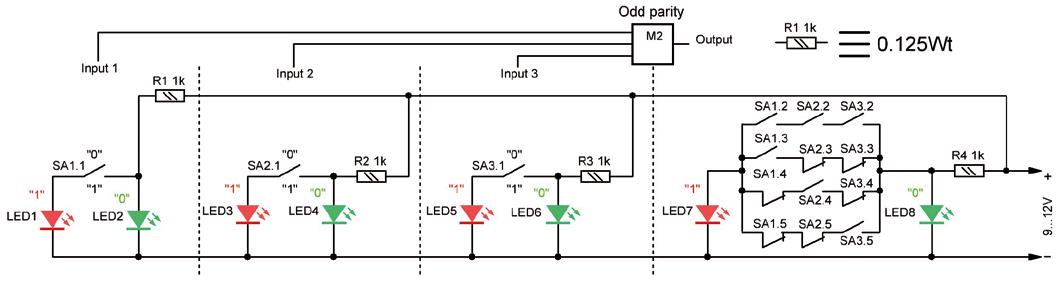

ODD PARITY is a logic element with several inputs and one output, where the level "log. 1" appears only if the level "log. 1" is simultaneously present on an odd number of its inputs (n = 1, 3, 5 …), Figure 1.8.

In the special case where the "Odd parity" logic element has only one input, this element is called a "Repeater", whose output signal repeats the input signal in level. In the case of two inputs, the logic elements "Odd parity" and "XOR" are identical in their functions.

Figure 1.8. Simulator for logic element "Odd parity".

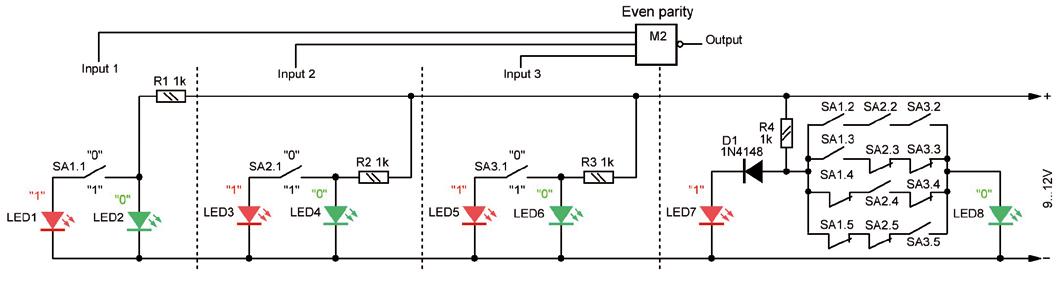

EVEN PARITY is a logic element with several inputs and one output, where the level "log. 1" appears only if the level "log. 1" is simultaneously present on an even number of its inputs (n = 0, 2, 4 …), Figure 1.9.

In the special case where the "Even parity" logic element has only one input, this element is called an "Inverter", whose output signal inverts (flips, changes) the input signal in level. In the case of two inputs, the logic elements "Even parity" and "XNOR" are identical in their functions. The logic element "Even parity" can also be considered as an "Odd parity-NOT" element.

Figure 1.9. Simulator for logic element "Even parity".

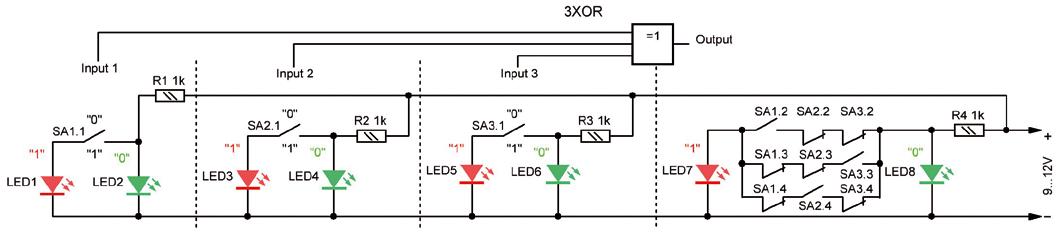

3XOR is a logic element with three inputs and one output, where the level "log. 1" appears under the condition that the level "log. 1" is present only on one of its inputs, Figure 1.10.

The digit before the name of the logic element indicates the number of its inputs. The "3XOR" logic element is a special case of the "nXOR" element, which has n inputs. When n = 1, this logic element becomes a "Repeater".

Figure 1.10. Simulator for logic element "3XOR".

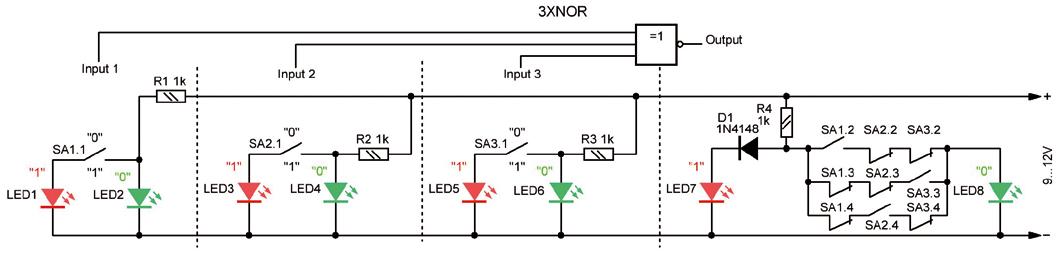

3XNOR is a logic element with three inputs and one output, where the level "log. 0" appears under the condition that the level "log. 1" is present only on one of its inputs, Figure 1.11.

Figure 1.11. Simulator for logic element "3XNOR".

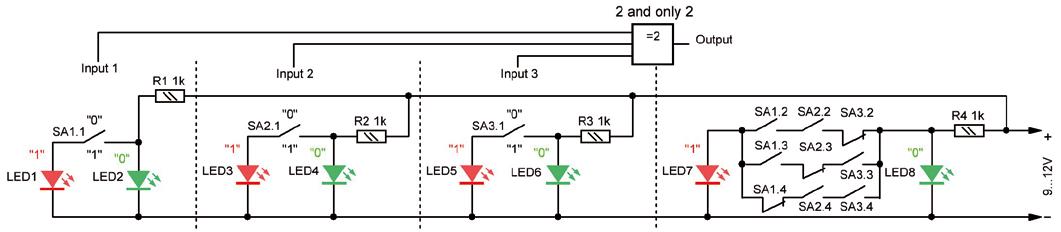

2 AND ONLY 2 is a logic element with several inputs and one output, where the "log. 1" level appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present at two of its inputs, Figure 1.12.

The "2 and only 2" logic element is a special case of the "m and only m" element, where m is less than or equal to the number of inputs n of the logic element. When n = 1, such a logic element is called a "Repeater".

Figure 1.12. Simulator for logic element "2 and only 2".

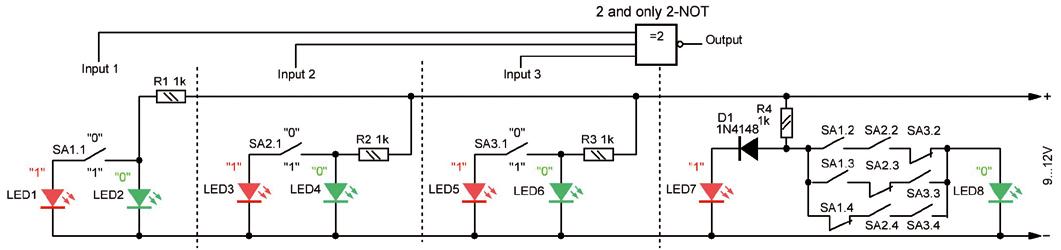

2 AND ONLY 2-NOT is a logic element that has several inputs and one output, on which the "log. 0" level appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present at two of its inputs, Figure 1.13.

Figure 1.13. Simulator for logic element "2 and only 2-NOT".

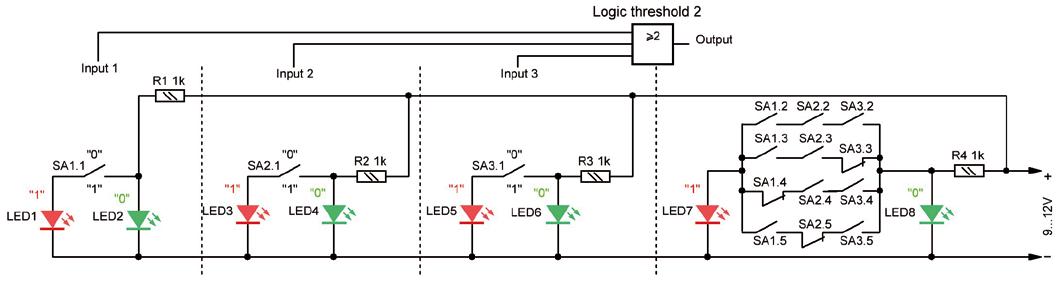

LOGIC THRESHOLD 2 is a logic element that has several inputs and one output, the "log. 1" level on which appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present on at least two of its inputs, Figure 1.14.

The "Logic threshold 2" logic element is a special case of the "Logic threshold n" element.

When n = 1, this logic element is called a "Repeater".

Figure 1.14. Simulator for logic element "Logic threshold 2".

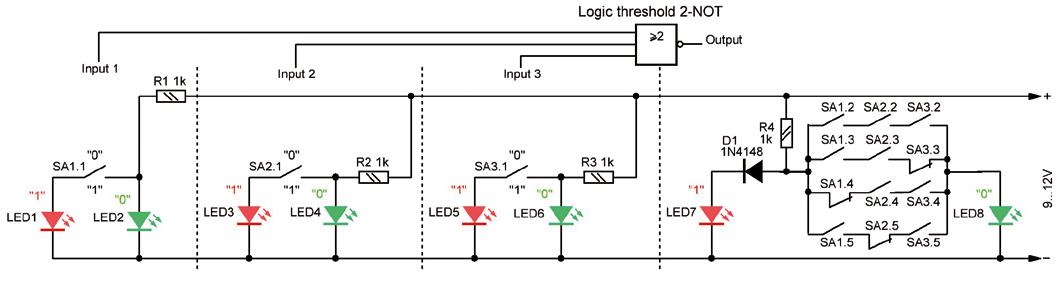

LOGIC THRESHOLD 2-NOT is a logic element with several inputs and one output, the "log. 0" level of which appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present at least at two of its inputs, Figure 1.15.

Figure 1.15. Simulator for logic element "Logic threshold 2-NOT".

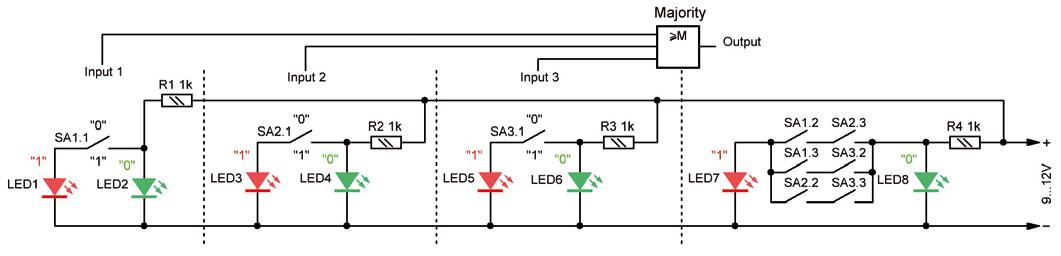

MAJORITY is a logic element that has several inputs and one output, the "log. 1" level on which appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present on most of its inputs, Figure 1.16.

For a three-input "Majority" logic element, the truth table is identical to the truth table for the "Logic threshold 2" logic element, see Table 1.2.

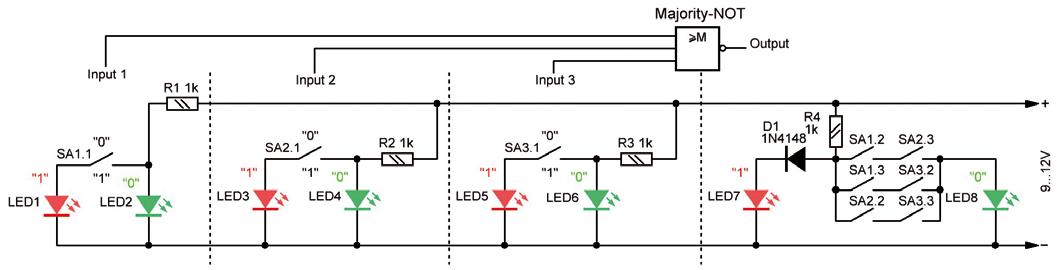

MAJORITY-NOT is a logic element that has several inputs and one output, the "log. 0" level on which appears only if the "log. 1" level is simultaneously present on most of its inputs, Figure 1.17.

A synonym or logic equivalent of the "Majority-NOT" element is the Minority logic element. For a three-input "Majority-NOT" logic element, the truth table is identical to the truth table for the "Logic threshold 2-NOT" logic element, see Table 1.2.

Simulators of logic elements with identical truth tables, for example, Figures 1.14 and 1.16, as well as Figures 1.15 and 1.17, could be implemented using the same circuit, but in order to emphasize the multivariant nature of the solution to the problem, these circuits are deliberately different.

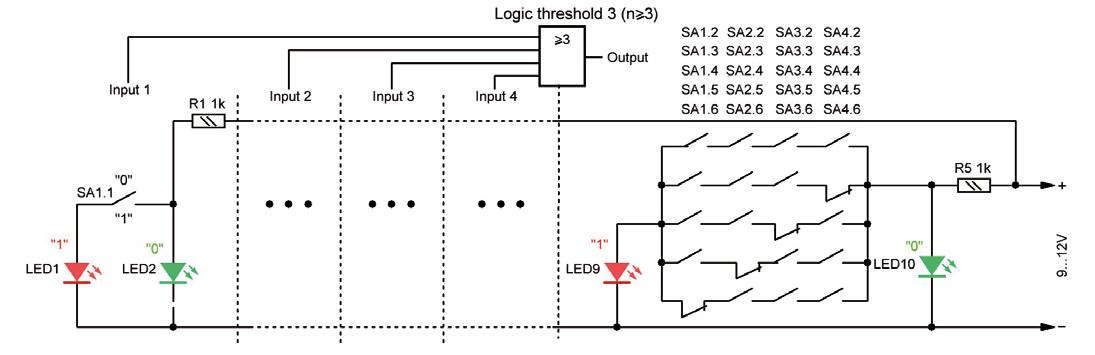

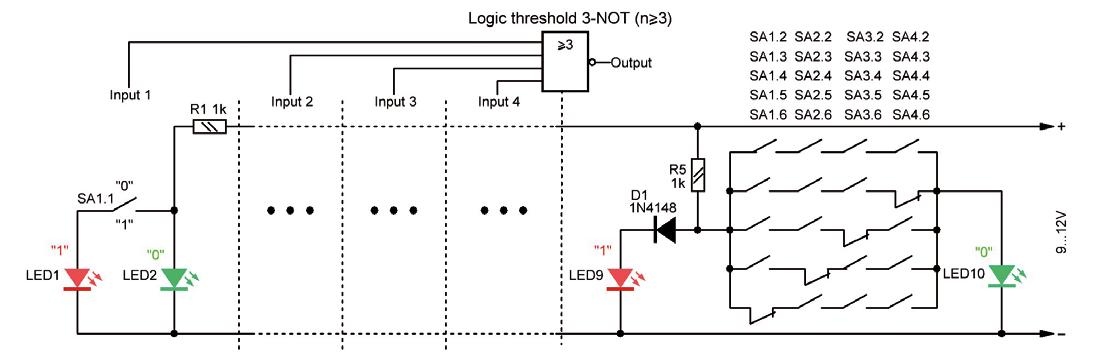

To illustrate that the logic elements "Logic threshold n" and "Logic threshold n-NOT" are functionally significantly different from the logic elements "Majority" and "Majority-NOT," we present below the truth table (Table 3) for the elements "Logic threshold 3" (Y) and "Logic threshold 3-NOT" ( ), as well as the electrical diagrams of the simulators of the logic elements "Logic threshold 3" and "Logic threshold 3-NOT," Figures 1.18 and 1.19.

Table 1.3. Truth tables for logic elements "Logic threshold 3" (Y) and "Logic threshold 3-NOT" ( ).

The analysis of Table 1.3 shows that for the "Logic threshold 3" and "Logic threshold 3-NOT" elements, the level of the output logic signal changes when signals of level "log. 1" are applied to at least three inputs of these logic elements.

Figure 1.20 shows the dynamics of electrical processes at the inputs and outputs of all logic elements mentioned in the article.

Figure 1.18. Simulator for logic element "Logic threshold 3".

Build digital electronics from the ground up—and take it all the way to practical circuits you can use.

This book guides you through the core principles of digital technology with a strongly hands-on approach. You’ll begin with the essentials: signals, devices for working with them, and what “logic 0” and “logic 1” mean in real hardware. Simple demonstration setups made from easy-to-find parts (LEDs, diodes, resistors, switches) help you see how logic behaves, making the theory click before you move on.

From there, you’ll explore a wide range of logic elements and how they’re implemented, including classic logic families such as TTL and CMOS. The fundamentals section covers the building blocks of digital systems: flip-flops, Schmitt triggers, registers, counters and dividers, encoders/ decoders, multiplexers/demultiplexers, plus A/D and D/A conversion and timing circuits.

Next, the book invites you into “new ideas” in digital electronics—universal logic elements, unconventional approaches (including thyristor-based and fractional logic), and creative logic functions that can inspire original designs.

Finally, a large, well-organized collection of application circuits turns knowledge into projects: electronic switches and selectors, pulse generators, PWM regulators, frequency multipliers/dividers, phase shifters, and digital filters.

Study it deeply, and you’ll gain not only understanding—but the ability to design and debug digital circuits independently.

Michael Shustov is a Doctor of Science and has authored 945 publications, including 24 books and 18 inventions.

Andrey Shustov is a Doctor of Electrical Engineering and has authored 44 publications, including 3 books.