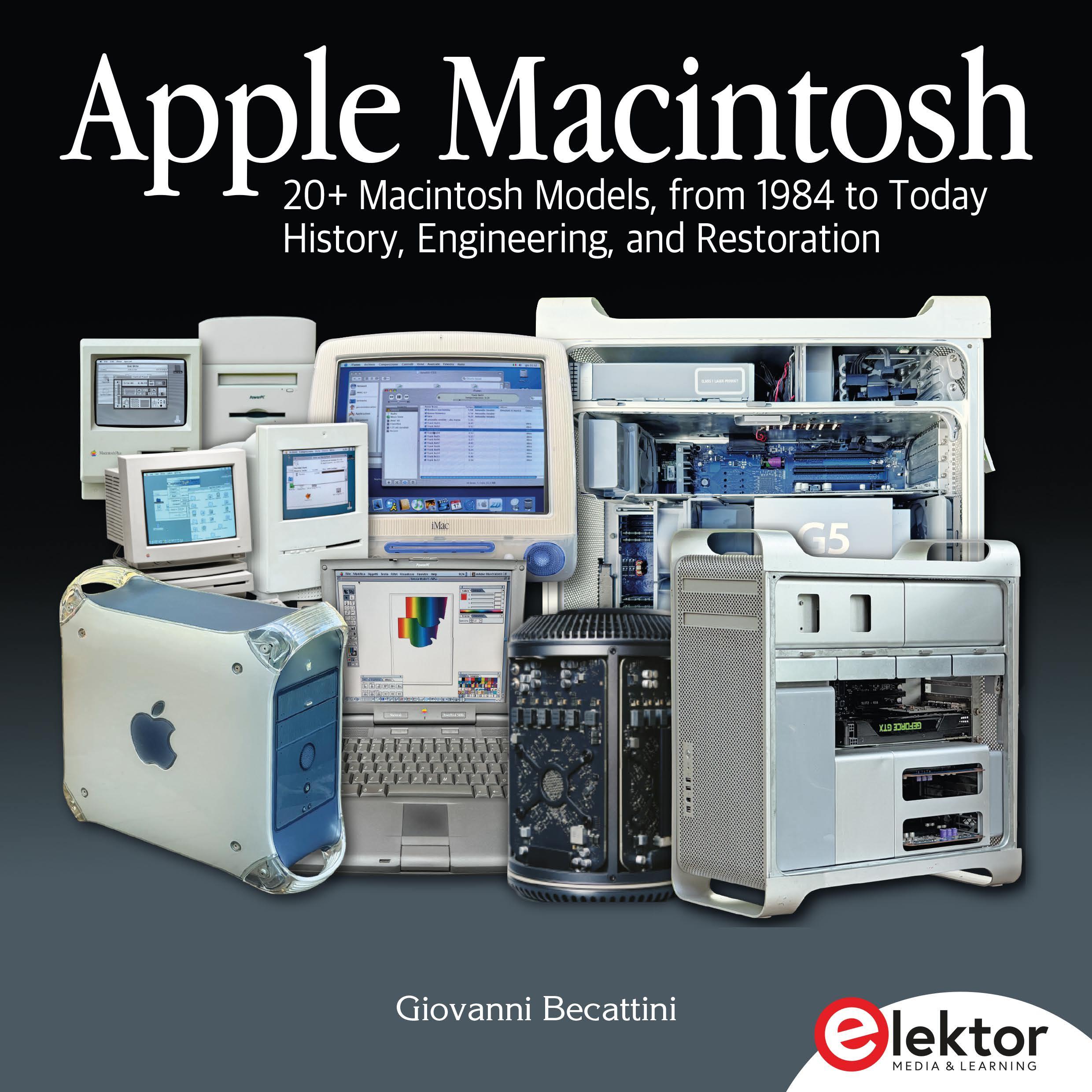

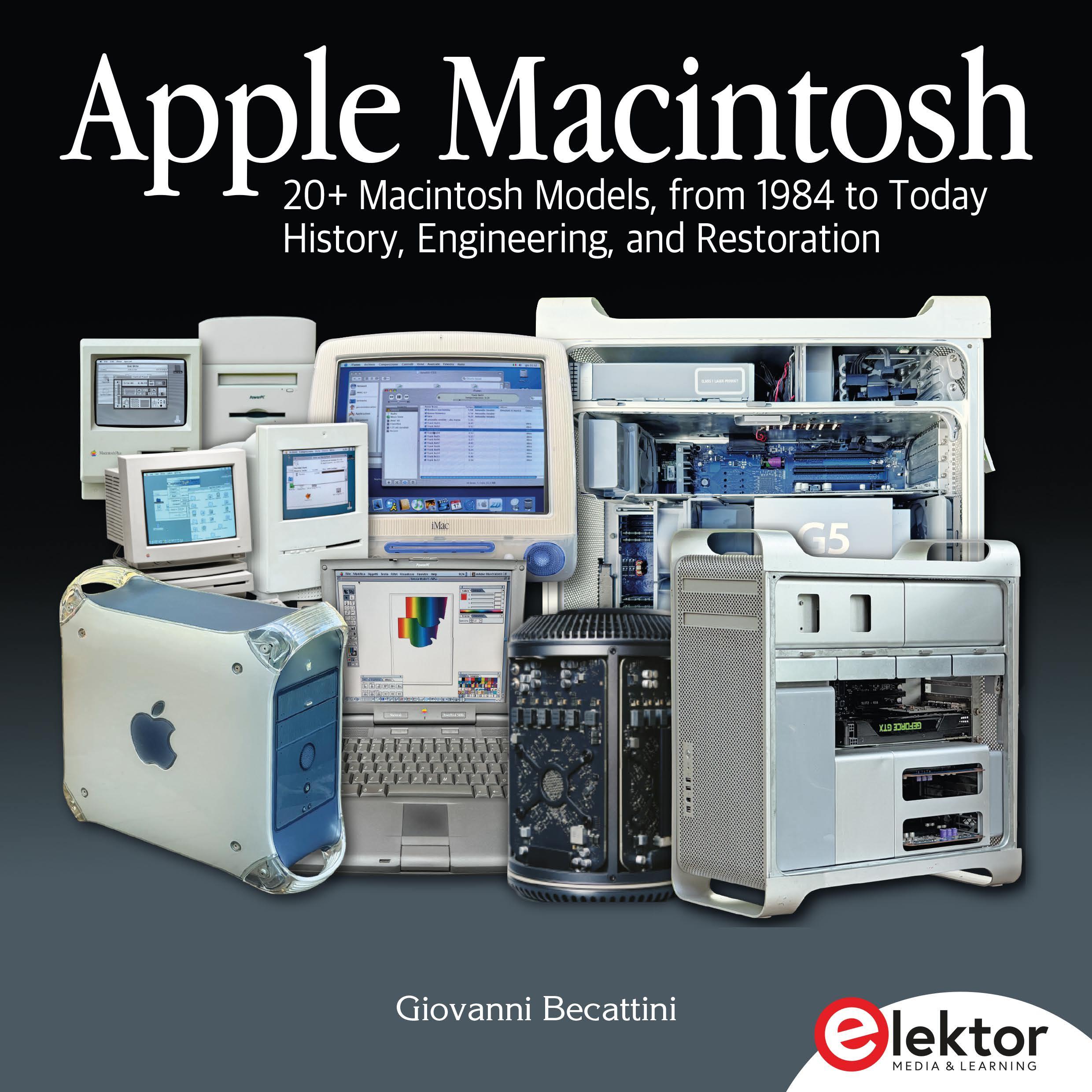

20+ Macintosh Models, from 1984 to Today History, Engineering, and Restoration

Giovanni Becattini

● This is an Elektor Publication. Elektor is the media brand of Elektor International Media B.V.

● All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form, including photocopying, or stored in any medium by electronic means, whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication, without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1P 9HE. Applications for the copyright holder's permission to reproduce any part of the publication should be addressed to the publishers.

● The author, editor, and publisher have used their best efforts in ensuring the correctness of the information contained in this book. They do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability to any party for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in this book, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause.

● Apple and Macintosh trademarks and logos are acknowledged and remain their property.

● ISBN 978-3-89576-704-3, hard cover.

● © Copyright 2025 Elektor International Media B.V.

● Editors: Elektor Team

Thisbookisnotmeanttobehistoryinthestrict sense.Itis,rather,astoryofadmiration—written byanengineerandentrepreneurwhohasspenta lifetimesurroundedbycircuits,screens,andthe quiethumofcomputers.

Iliketothinkofmyselfasanapprenticehistorian, tryingtocapture—inwordsandpictures—the lovestoriesbehindthosecompaniesthatmade scienceandtechnologypartofoureverydaylives, and,attimes,asmallpartofourhearts.

Ihappilyleavethepursuitofprecisionandscholarly rigortothosefarmorequalifiedthanI.Thisaimsto be,simply,theMacintoshbookfortherestofus.

Apple is not just another computer company. More than anyone else, it transformed technology into something people could desire, love, and even identify with—much like a luxury brand. Users were not only buying a tool; they were buying a vision, a way of life. Apple understood this earlier and better than any competitor.

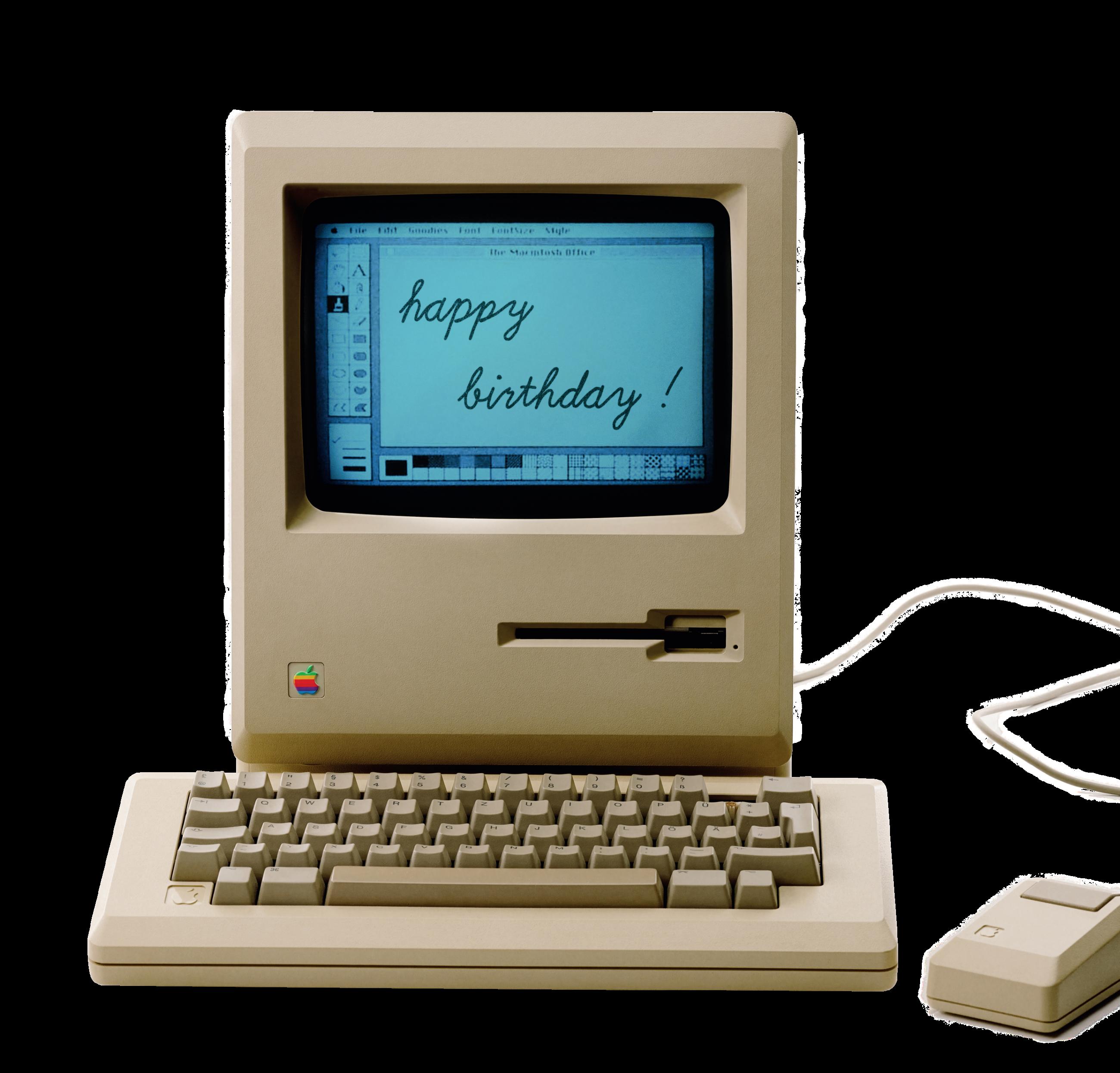

At the heart of this transformation lies the Macintosh. When it was launched in 1984, it was radically different from anything before. With its graphical interface and mouse, it made computing approachable and friendly. What seems obvious today—clicking on icons, dragging files, pointing instead of typing commands—was unheard of back then. The Macintosh not only changed the way people related to technology. The Macintosh forced the entire industry to rethink the way we use computers.

This book tells that story. It follows the Macintosh from its beginnings through some of its most significant models, showing not only their technical role but also their cultural impact. Many of these machines can now be appreciated as pieces of industrial design, even modern art.

A simple description could never be enough. That is why this book combines history and technical detail with carefully prepared photographs, aiming to show each Macintosh as it truly deserves to be seen.

Giovanni "Gianni" Becattini giovanni.becattini.books@gmail

To my wife and my family

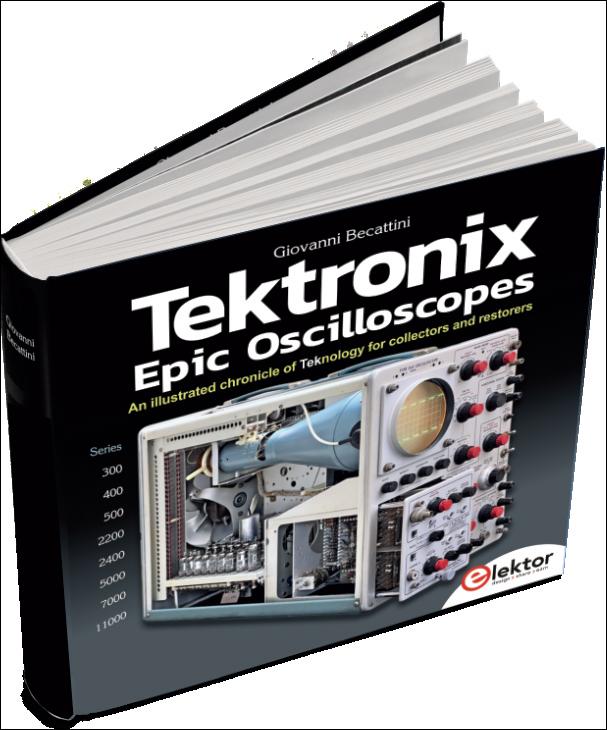

Epic

A 600-page hard cover, real paper book about Tektronix and their most classical oscilloscopes. Available worldwide from Elektor Books

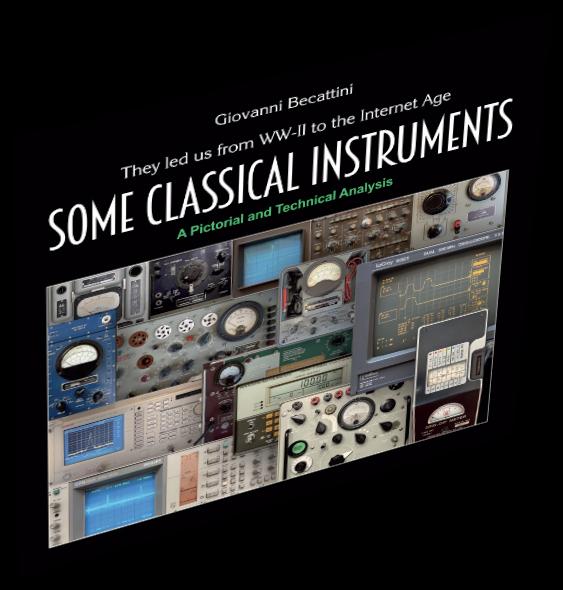

A 380-page hard cover, real paper illustrated handbook dedicated to vintage scopes repair and preservation.

Available worldwide from Elektor Books

A 590-pages rich collection of descriptions, advice, technical notes, photographs, and original schematics about the radio equipment from WW-II to the first ‘70s.

Tektronix

Epic

Oscilloscopes

Volume 2

Many new models reviewed like the 11303, DSA 602A, 324, 564B etc,

(In preparation)

An in-depth look at the most classic Tektronix 7000-Series oscilloscopes: models, technologies and restoration techniques. (In preparation) New

Available worldwide from Elektor Books Real Paper! New!

Vintage Radio Equipment

Volume 2

Many new devices and complement about those of volume 1. Includes the Collins KWM-2 and 30L-1.

(In preparation)

A 1029-page review of many classic instruments from the fifties through the nineties of the great Hewlett-Packard: spectrum analyzers, generators, oscilloscopes, voltmeters, frequency meters, up to handheld calculators and Series-80 computers.

It all began on a long flight from Rome to Fort Worth, Texas. To pass the time, I started editing some photos I had brought with me and sketching the outline of a small booklet I called Surplus Photo Parade. The concept was simple: a publication made mostly of images, with only minimal text. I had often noticed how few good photos of these legendary instruments existed online—most were dim, low-resolution scans from old manuals.

A book dedicated to more than 20 charming instruments that are neither Tektronix nor HewlettPackard, from WW-II to the 90s.

(In preparation)

The story and the restoration of a classical organ based on vacuum tube. A short 70-pages document rich of beautiful photos, technical descriptions and suggestions.

But part of the fascination of vintage electronics lies in their look. Their knobs, dials, meters, and even their typography have a beauty of their own. So I asked myself: why should art books exist only for painting or architecture? Aren’t these instruments also works of art—objects that blend design, craftsmanship, and engineering elegance?

With my joy, Elektor Books International shared this vision. What began as a pastime at 10,000 meters turned into a series of hard cover, beautifully printed books on glossy paper, created with the same care as fine art volumes.

One title after another, the collection has grown into something I never expected: what I like to call the Library of Vintage Electronics.

20+ Macintosh Models, from 1984 to Today History, Engineering, and Restoration

From the dawn of the Mac (1984) to the Macintosh LC (1990)

From the fading of Steve Jobs’ initial momentum (1990) to the end of the “beige” era (1997)

From Steve Jobs’ return (1997) to the close of the PowerPC era (2006)

From the Mac Pro (2006) to the present day Operating Systems, Networking, Software & Utilities

It was the dawn of the Macintosh era, when personal computers were still a novelty for most people and Apple sought to redefine what a computer could be. Driven by bold ideas, youthful ambition, and no small amount of internal drama, these were the formative years that set the stage for everything to come.

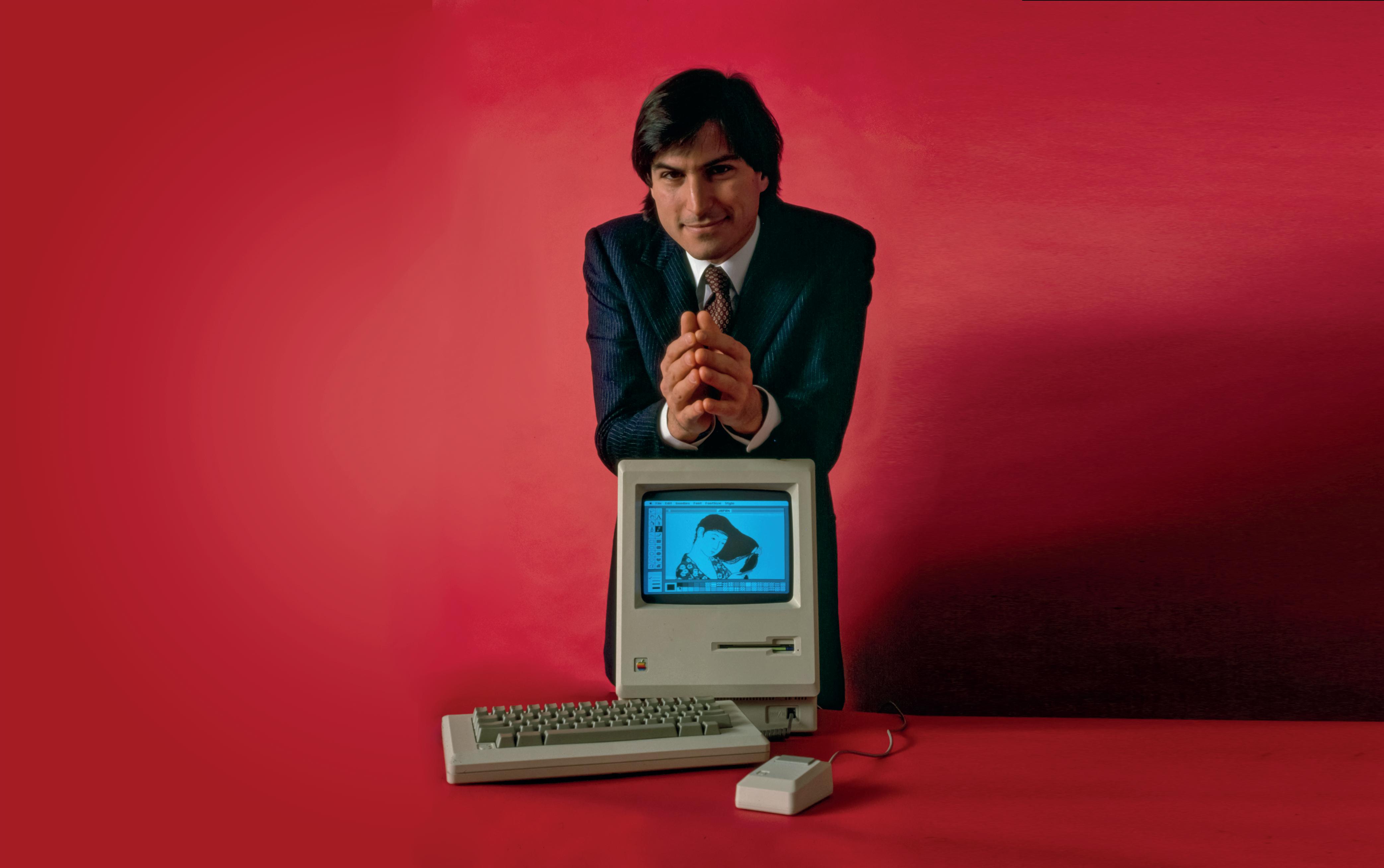

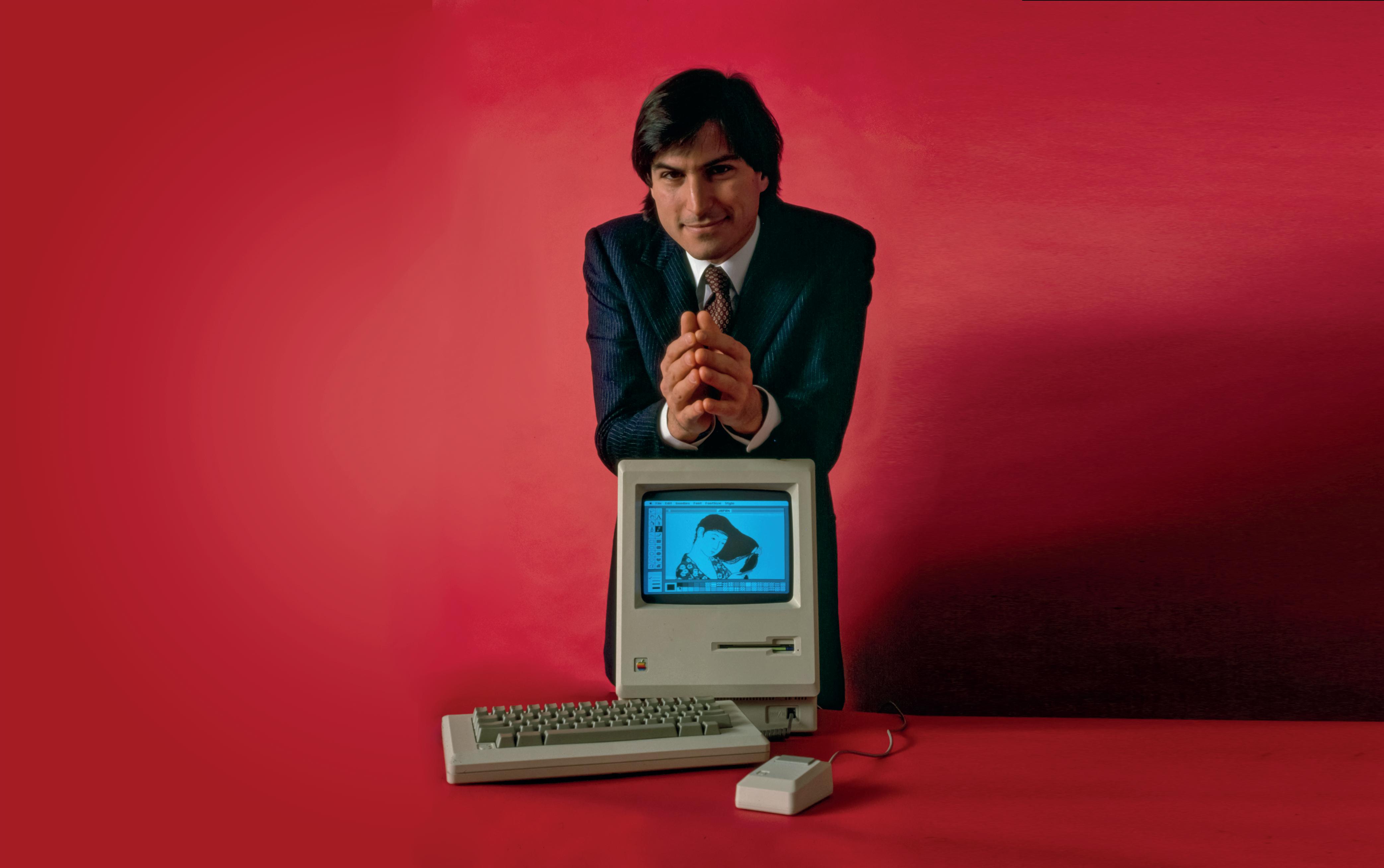

•Just before the introduction of the Macintosh (1984), led by Steve Jobs in his role as Head of Macintosh Development and Chairman, aiming to create “the computer for the masses.”

•The departure of CEO John Sculley (1993).

•Introduction of landmark models: Macintosh 128K, 512K, Plus, SE, Color Classic, Macintosh II, LC, PowerBook, and others

•Company turnover grew from $982 million (1983) to $7.9 billion (1993)

•Steve Jobs ousted from Apple (1985)

•Shift from Motorola 68000 to more advanced 68030/68040 processors (late 1980searly 1990s)

•Launch of the first PowerBook series, starting with the PowerBook 100 (1991), defining Apple’s portable design language for years

•Early development of the PowerPC project through the 1991 AIM Alliance with IBM and Motorola, paving the way for the Macintosh’s next architectural leap

From my point of view, the story we are about to tell truly begins in 1982, when a young engineer opened a small computer shop in Florence, Italy, with a curious palindrome name: SUMUS.

What we had foreseen was finally happening. Back in 1978, we had commissioned an architect to design the enclosure for one of our products and told him that one day computers would be sold in supermarkets. He laughed and said we were totally crazy.

In the early 1980s, those days had arrived—and we found ourselves in the midst of the microcomputer revolution. These were the early, electric days when shop windows glowed with the colored logos of Apple II, Commodore, Sinclair Spectrum, and countless other brands—some destined to greatness, many doomed to vanish within months. The smell of new plastic and freshly printed manuals filled the air, while cardboard boxes piled up faster than we could open them.

The personal computer industry was expanding at an extraordinary pace. Every week brought new machines and new promises, while others disappeared just as quickly. It was a chaotic era, “matta e disperatissima” (“crazy and desperate”), to borrow the words of a great Italian poet—both exhilarating and exhausting.

You have probably guessed by now that the young engineer was me. I had already lived a “previous life” as founder of General Processor, the first Italian personal computer company, in 1975. I sold it in 1981, fearing it could not withstand the overwhelming tide of microcomputers arriving from abroad (and I was right: a few years later the company was forced to close).

Thanks to that background, I had solid technical experience, and SUMUS gave me a privileged vantage point from which to watch the revolution unfold. I witnessed the first timid attempts at graphic interfaces, the fierce wars of incompatible standards, and the emergence of companies that would later dominate the world.

Among all the machines that passed through my hands, one in particular caught my attention—not immediately and not loudly. Its name was Macintosh.

Spectrum: By Bill Bertram - Opera propria, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/ index.php?curid=170050

Vic20: By Evan-Amos - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/ index.php?curid=38582541

C64: Di Bill Bertram - Self-published work by Bill Bertram, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons. wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=180885

In the mid-1970s many eccentric souls around the world began dreaming of building their own computers—often without knowing of each other. I was one of them. I started in 1973 with very little experience, few resources, and enormous passion. My first design used TTL logic and was monstrously complex. Then something sensational happened: the first microprocessors arrived. Thanks to my work at CQ Elettronica Italian magazine, I came into contact with Intel’s Italian importer, who took a liking to me and sent one of the first 8080 samples to reach Italy. It was an extraordinary period: I slept very little and worked obsessively on several projects at once.

In 1975 my first commercial product, the Child 8, based on the Fairchild F8 microprocessor, was ready. Soon after, I found partners and launched what today would be called a startup: General Processor. The company enjoyed a good commercial success, producing Z80-based microcomputers running CP/M—the Child Z, the Model T, and finally the GPS-4, shown in the photo below.

In 1982 I also began importing home computers such as the ZX Spectrum, Commodore VIC-20, C64, and many others. It became clear that the future would be difficult for a small firm like General Processor: a VIC-20 cost less than what we paid for a bare keyboard. I reached an agreement with my partners and focused primarily on the homecomputer business. General Processor held out a few more years but, as I had predicted, was eventually forced to close. Shortly thereafter I left sales as well; electronics was my true path. It was a wise choice that I have never regretted—“Find a job you are passionate about, and you will never work a day in your life.”

Today, General Processor computers are displayed in a few museums and cared for by a small group of passionate restorers.

The computers we sold at the time could be divided into two big categories:

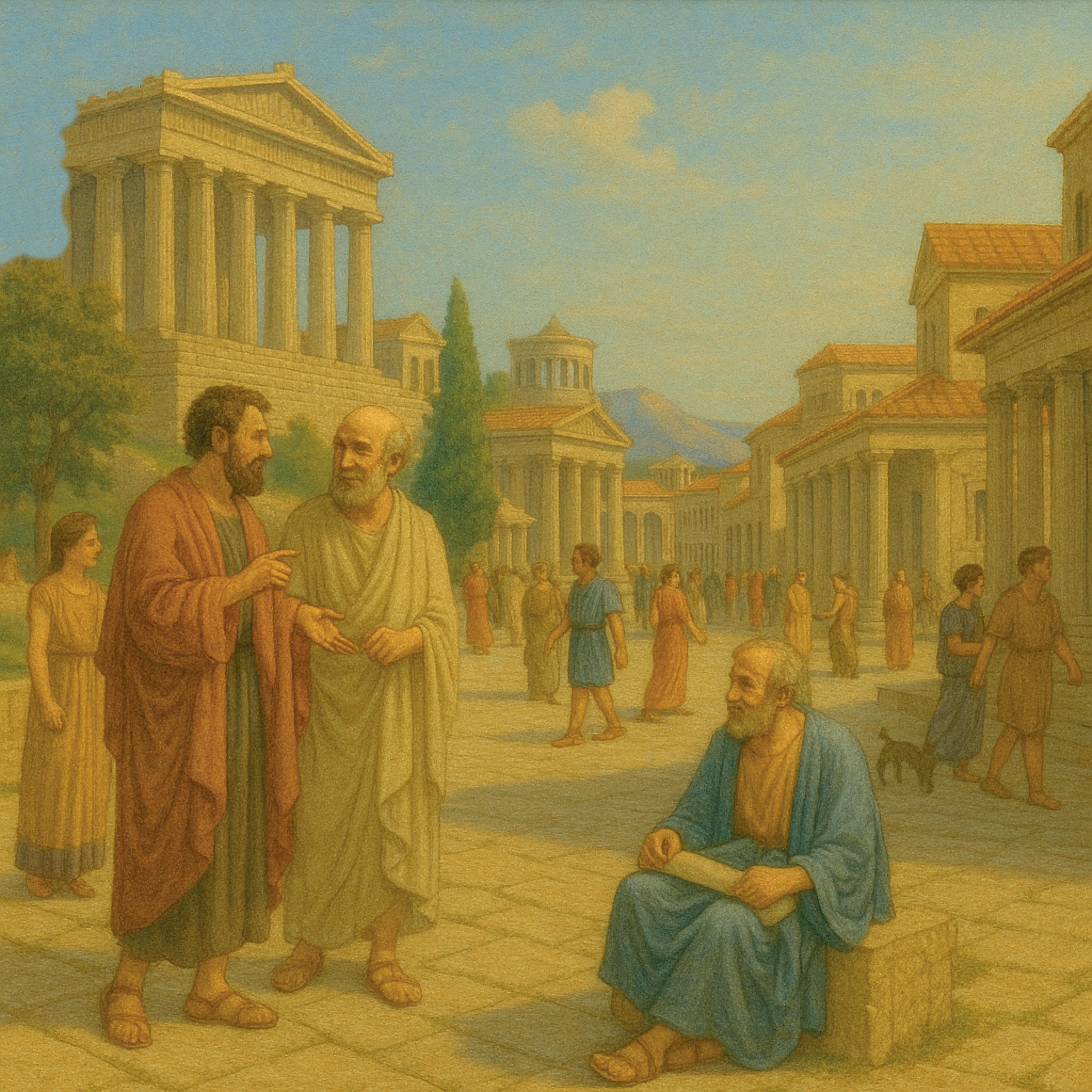

• Microcomputers – These were the children of the revolution that began with the invention of the microprocessor and the Altair computer (it was a stab in the heart when, in 1974, on a flight to London, I saw the Altair advertisement in Popular Electronics: we were no longer the first in that race.) The term “microcomputer” followed from “minicomputer,” the dominant type of system of the 1970s. Microcomputers tried to look like minis, usually with a command-line interface, and were aimed at serious management jobs like accounting, warehouse control, or databases.

• Home computers – Typically represented by the various ZX Spectrum, VIC-20, Commodore 64, and similar machines. These were compact, all-in-one keyboard units, usually connected to a television set, and loading programs from cassette tapes or floppy disks. They were easily programmed in BASIC, but most people used them to play games.

The first category—the microcomputers—found a common operating system: CP/M from Digital Research. We also used it in our computers. Thanks to CP/M, you could turn any Z80- or 8080-based machine into something genuinely useful, with a wide library of available applications. At that time, Digital Research was the leader of the microcomputer software industry.

When IBM decided to enter this new market, they initially intended to use CP/M like everyone else, and went to Digital Research to negotiate. But the story goes that Digital Research treated IBM with condescension, even failing to attend a key meeting. IBM was not a company you could underestimate. Instead, they turned to another supplier and ended up licensing a small operating system from a young man named Bill Gates, whose company Microsoft would become synonymous with personal computing. The rest, as they say, is history.

The IBM PC launched in 1981 and quickly reshaped the industry. By 1983, IBM had sold about 750,000 units, rapidly establishing a business standard based on the Intel 8088 processor and MSDOS. For business users, the PC became the obvious and safe choice.

In the early 1980s, Apple had become a major company thanks to the Apple II, introduced in 1977. That year, dozens of similar microcomputers competed for attention, but the Apple II triumphed—probably less for sheer technical superiority than for Steve Jobs’ marketing genius. Though it appeared years before most of its rivals, it remained competitive for a long time and was much more powerful (and expensive) than later home computers like the Commodore 64 or Sinclair Spectrum. Thanks to its flexibility and expandability, the Apple II became one of the most popular home computers of its era. “I want to put a computer on every desk,” Jobs would say at the time, “and in every home.”

I not only used to sell the Apple II and its clones, but also used one myself. By adding a simple and inexpensive Z-80 expansion card (1980 Microsoft SoftCard or clone), you could run CP/M software on it—a revelation that made the Apple II an incredibly versatile platform. It allowed me to run my first cross-assemblers and even to write my own BASIC interpreter, laying the foundations for my future activities.

But while the Apple II was still selling strongly, the world of personal computers was changing at a frantic pace—and Apple knew that no empire lasts forever.

By the time of the Macintosh launch, Apple was both strong and fragile. Its great success, the Apple II, had already sold 2.1 million units, giving the company a solid financial base and a loyal following in education and small business—though the Apple II line, especially the IIe, was still selling strongly. But it was a design from 1977, increasingly outdated compared to the IBM PC, which was quickly becoming the new industry standard.

Apple urgently needed a successor. The Apple III, introduced in 1980, was supposed to be that successor, but it flopped badly, selling fewer than 100,000 units. Morale inside Apple suffered: for the first time, the company realized that it could stumble—and perhaps fall.

Steve Jobs at Xerox PARC

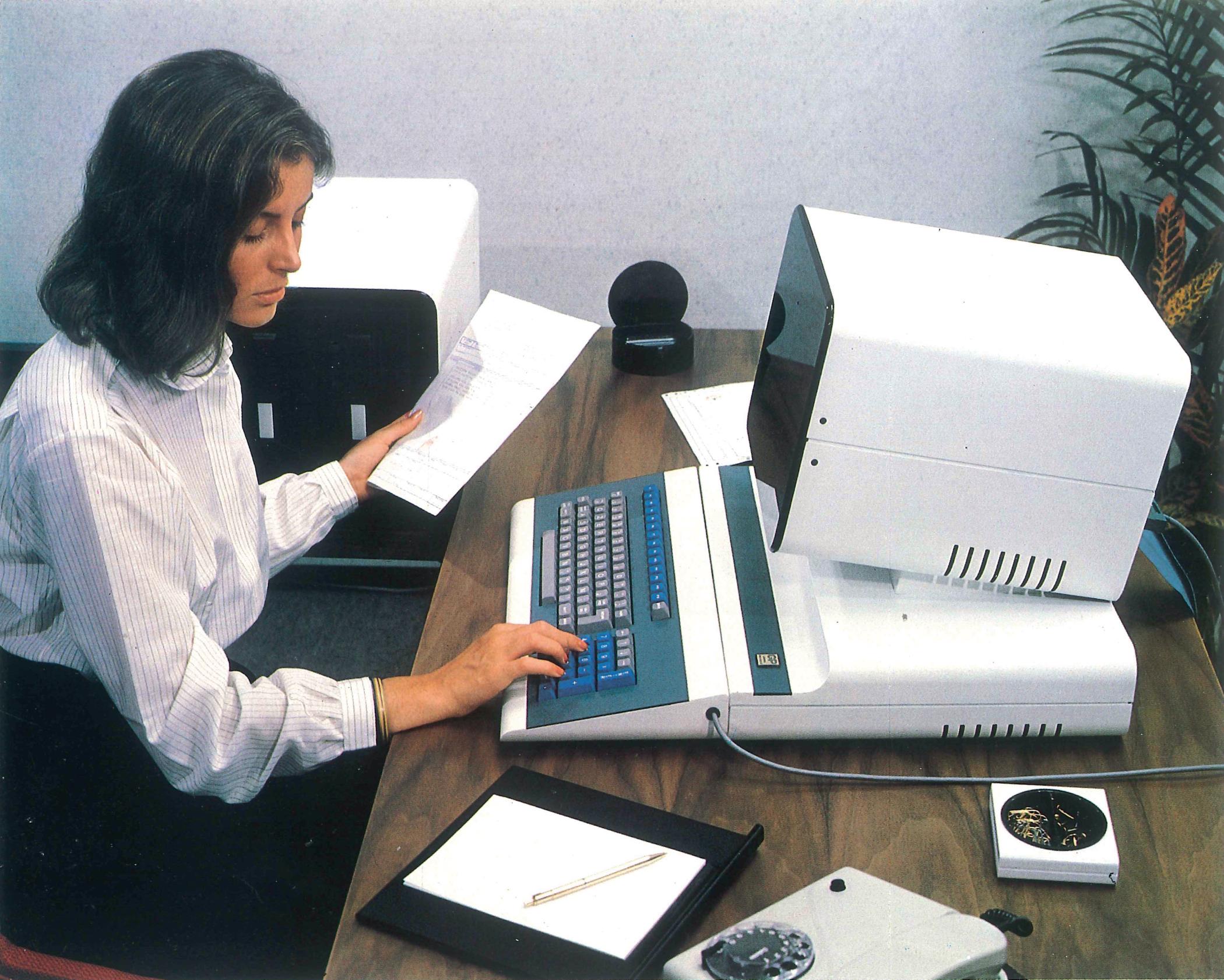

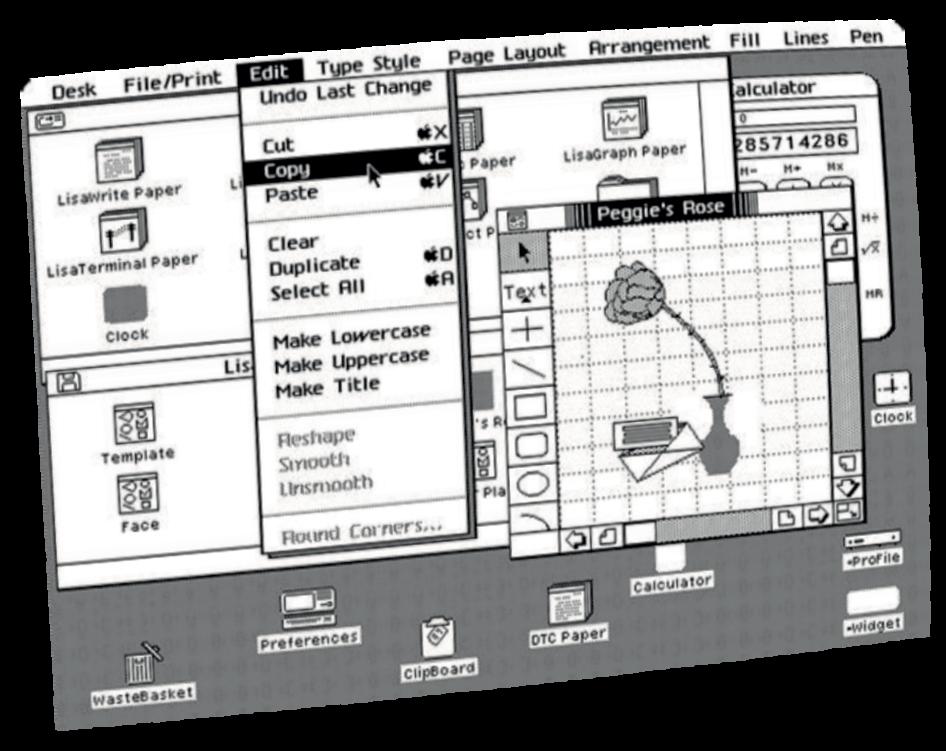

In December 1979, a 24-year-old Steve Jobs visited Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and witnessed something that would change the course of computing history. At PARC, the engineers showed him their experimental computer called Alto, developed back in 1973. It featured technologies revolutionary for the time: a graphical user interface with overlapping windows, the use of a mouse as a pointing device, WYSIWYG text editing, networked computers connected via Ethernet, and high-resolution laser printing.

I first saw the Alto at the Xerox booth during a trade fair in Rome in the first 80s, where my company also had a stand. It was freezing inside because the heating had failed, and the power kept going out. While I was admiring the Alto, another blackout hit, and the Xerox guys told me, “I’m very sorry, you’ll have to come back later — the boot needs about an hour…” (I don’t know if it was true)

Jobs secured the demonstration by allowing Xerox to purchase about $1 million worth of Apple preIPO shares, in exchange for letting a small team from Apple see the research projects at PARC. This arrangement gave Jobs and his engineers access to the future.

What he saw left him thunderstruck. Bill Atkinson, one of the Apple engineers present, later recalled: “Steve was jumping around, practically in orbit. He kept saying, ‘This is it! This is what computers are going to be!’”

At one point Jobs blurted out to the PARC team: “Why aren’t you doing something with this? Don’t you see this is going to change everything?”

The PARC researchers, brilliant but frustrated, knew they were sitting on something extraordinary. Xerox’s management, however, had little interest in commercializing it. Jobs, in contrast, immediately understood its potential. In his words, “Xerox could have owned the entire computer industry, but they just didn’t get it.”

That day, Jobs walked out of the PARC building determined to change Apple forever.

The Xerox Alto computer (courtesy of PARC.)

When you ask who invented something, a safe answer is: the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). According to Wikipedia, PARC has been foundational to numerous revolutionary computer developments — including laser printing, Ethernet, the modern personal computer, the graphical user interface and desktop metaphor, object-oriented programming, ubiquitous computing, electronic paper, amorphous silicon (a-Si) applications, the computer mouse, and very-largescale integration (VLSI) for semiconductors.

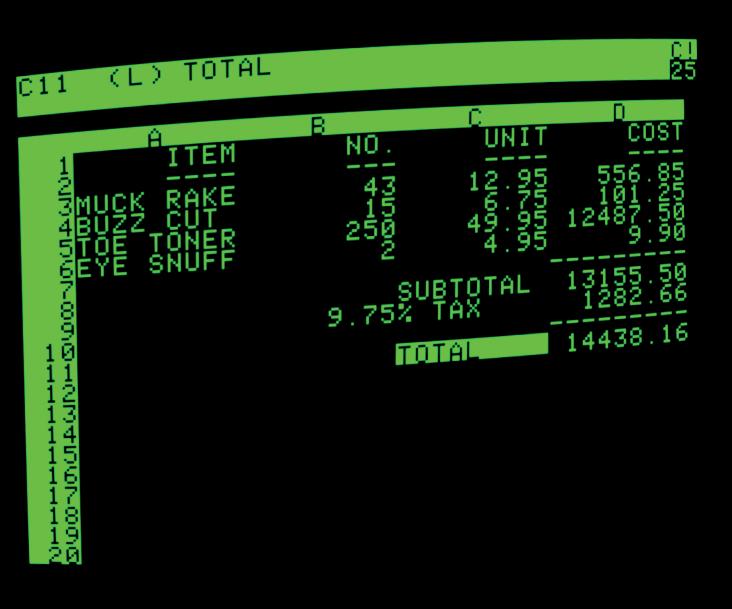

The base photo was licensed from Shutterstock (2548631557), but the screen was originally blank. The screenshot, courtesy of David T. Craig via the Computer History Museum, was adapted to fit the Lisa’s display, adjusted to reflect its slightly curved surface rather than a flat overlay.

After the visit to Xerox, probably in 1980, Apple began designing the Lisa computer with the clear intent of bringing the PARC concepts to the mass market. The project was not simple and took about three years, but in January 1983—one year before the Macintosh—Lisa was announced and became Apple’s first personal computer to adopt a graphical user interface controlled by a mouse.

From a technical perspective, Lisa was advanced but also complicated. It used the Motorola 68000 processor running at 5 MHz, supported 1 MB of RAM expandable to 2 MB, and featured dual 5.25-inch “Twiggy” floppy drives of 871 KB each. The 12-inch black-and-white display offered a resolution of 720 × 364 pixels, much sharper than what IBM PCs could show. Later, the Lisa 2/10 model introduced the “Widget,” a 5 MB internal hard disk.

The Lisa’s operating system, Lisa OS, implemented cooperative multitasking and was bundled with a full suite of office applications—word processor, spreadsheet, project manager—anticipating by decades the concept of integrated productivity software.

Unfortunately, these innovations came at a heavy price. Lisa price was nearly $10,000, placing it far beyond the reach of most customers. Performance was often sluggish, the drives were unreliable, and the software, though visionary, sometimes felt unfinished. The business world, already turning toward the IBM PC standard, was not ready to take the risk. Apple’s first experiment partially failed.

Lisa was a necessary stepping stone. As I have often observed in my career, large innovative projects tend to start overly ambitious and complex. Only through later refinement can the ideal solution emerge.

On the left an image of a Macintosh prototype from 1981 at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. It is accompanied by caption that says:

“Macintosh Prototype System, Apple Computer, ca. 1981 This very early prototype of the Apple Macintosh was hand built by Brian Howard and Dan Kottke. The prototype uses an external Apple II power supply and Apple Disk II floppy drive. It has a single bootstrap EPROM, which loads a 68000 version of the UCSD Pascal Operating System. Apple released the Macintosh computer in 1984, introducing the general public to a userfriendly personal computer. Gift of HS Electronic Supply, X5812.2010”

Photo derived from an original by Victorgrigas - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/w/ index.php?curid=25558522

Time was running out. By late 1983, Apple was under enormous pressure. The Lisa was failing, IBM was ascendant, and investors expected Apple to deliver a credible answer. It was an extremely stressful situation—but Steve Jobs was convinced that this was the right way and had the courage to stay the course in what seemed to be Apple’s boldest gamble.

While Lisa was struggling to win over the business world, another idea was quietly growing inside Apple’s labs. Jef Raskin—a brilliant human–computer interface expert and one of Apple’s first employees—had initiated the Macintosh project in 1979 as a low-cost, user-friendly computer. Raskin often summarized his vision with: “Computers should be like appliances—turn them on and they just work.”

After leaving the Lisa team in 1981, Jobs took over the Macintosh project and radically reshaped it, injecting many of Lisa’s ideas and pushing it to become a powerful yet affordable machine. Within just one year, building on the lessons of Lisa, Apple would unveil the Macintosh: a computer that was powerful, elegant, and—at $2,495—just within the reach of consumers and small businesses.

Looking back, it is easy to forget that Steve Jobs and his team were not prophets with guaranteed success. They were normal peoples with a vision, who could only hope their daring experiment would resonate with real users. Outwardly they projected confidence, but confidence alone does not generate revenue; only adoption could turn their gamble into survival. We must never forget that a single misstep at that fragile stage might well have spelled the end of Apple.

As Jobs himself would later reflect, “Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose.” And yet, they went all in.

The Macintosh debuted on January 24, 1984, at Apple’s annual shareholder meeting in Cupertino. In a theatrical flourish, Steve Jobs pulled the computer from a bag and let it introduce itself with a synthesized voice, declaring: “Never trust a computer you can’t lift.” The demonstration stunned the audience, setting a new standard for product launches.

Marketing played a central role: Apple invested $15 million in advertising, including the now legendary “1984” commercial directed by Ridley Scott, which aired during the Super Bowl and cost almost $1million to produce and broadcast. For a moment, Apple looked unstoppable again.

The Macintosh 128K was a compact all-in-one unit with a 9-inch black-and-white display (512 × 342 pixels), a Motorola 68000 processor at 8 MHz, and 128 KB of RAM. It included two serial ports, a single 3.5-inch floppy drive (400 KB), and no internal hard disk. Despite its limitations, its graphical interface—featuring menus, icons, and a mouse—was a revelation compared to the command-line world of MS-DOS. It looked like the future had finally arrived on the desks of ordinary people.

Steve Jobs introducing the Macintosh in 1984.

Photo derived from an original by Bernard Gotfryd (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Digital ID gtfy.01855, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain). Edited by the author.”

At its launch, the Macintosh made headlines but not profits. Early enthusiasm soon faded as its high price and scarce software limited adoption, forcing Apple to rely once again on the aging Apple II line for revenue. The Macintosh project had drained resources and distracted management, hastening the Apple II’s decline. Yet by 1985–86, improved models like the Macintosh Plus, the LaserWriter printer, and Aldus PageMaker transformed the Mac into the heart of a new phenomenon: desktop publishing. This niche became Apple’s lifeline, giving the Macintosh the credibility it initially lacked. The breakthrough came with the color-capable Macintosh II (1987), which finally brought expansion and performance to match its vision — and secured the platform’s future.

Initial reviews praised the user interface as revolutionary but criticized the machine’s limited memory and lack of expandability. Software was scarce at launch, with only MacPaint and MacWrite available. Developers were hesitant to abandon the vast IBM PC market. In its first year, Apple sold about 250,000 units—a respectable figure, but well below expectations, especially compared to IBM’s sales of over 1.5 million PCs in 1984 alone. The dream had begun, but the climb was steep.

The original Macintosh was not an immediate blockbuster, but its influence was immense. By the end of 1986, Apple had sold about 1 million Macs, securing a loyal user base. Financially, the machine helped stabilize Apple after the failure of the Lisa, though not without internal turmoil. Culturally, it transformed Apple’s image into that of a daring innovator willing to challenge industry giants. Inside the company, it left deep scars—especially the departure of Jobs—but also laid the foundation for a design philosophy centered on user experience, integration, and bold marketing.

Apple had survived its boldest gamble — and, perhaps without realizing it, had just launched the computer that would define its future.

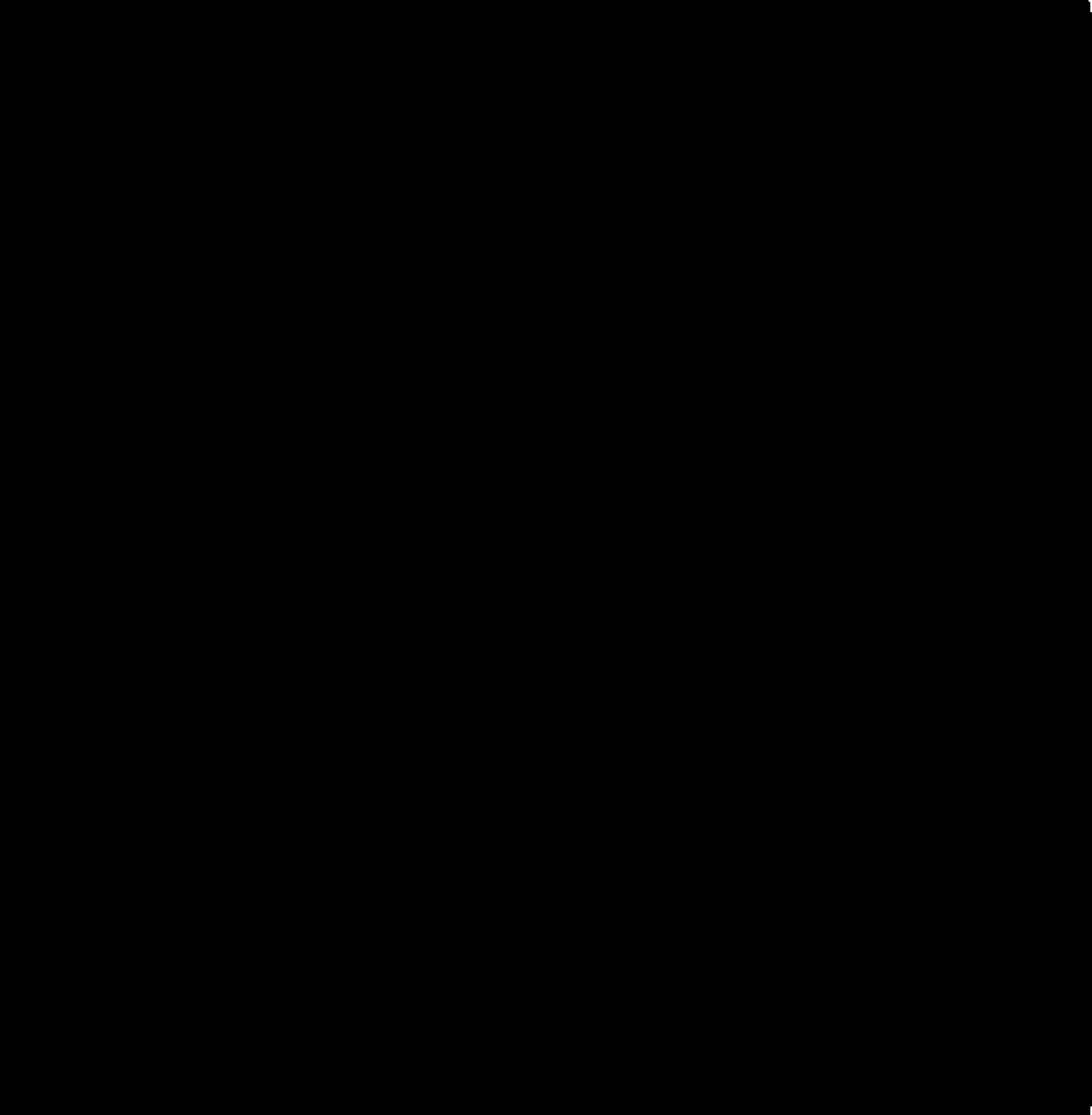

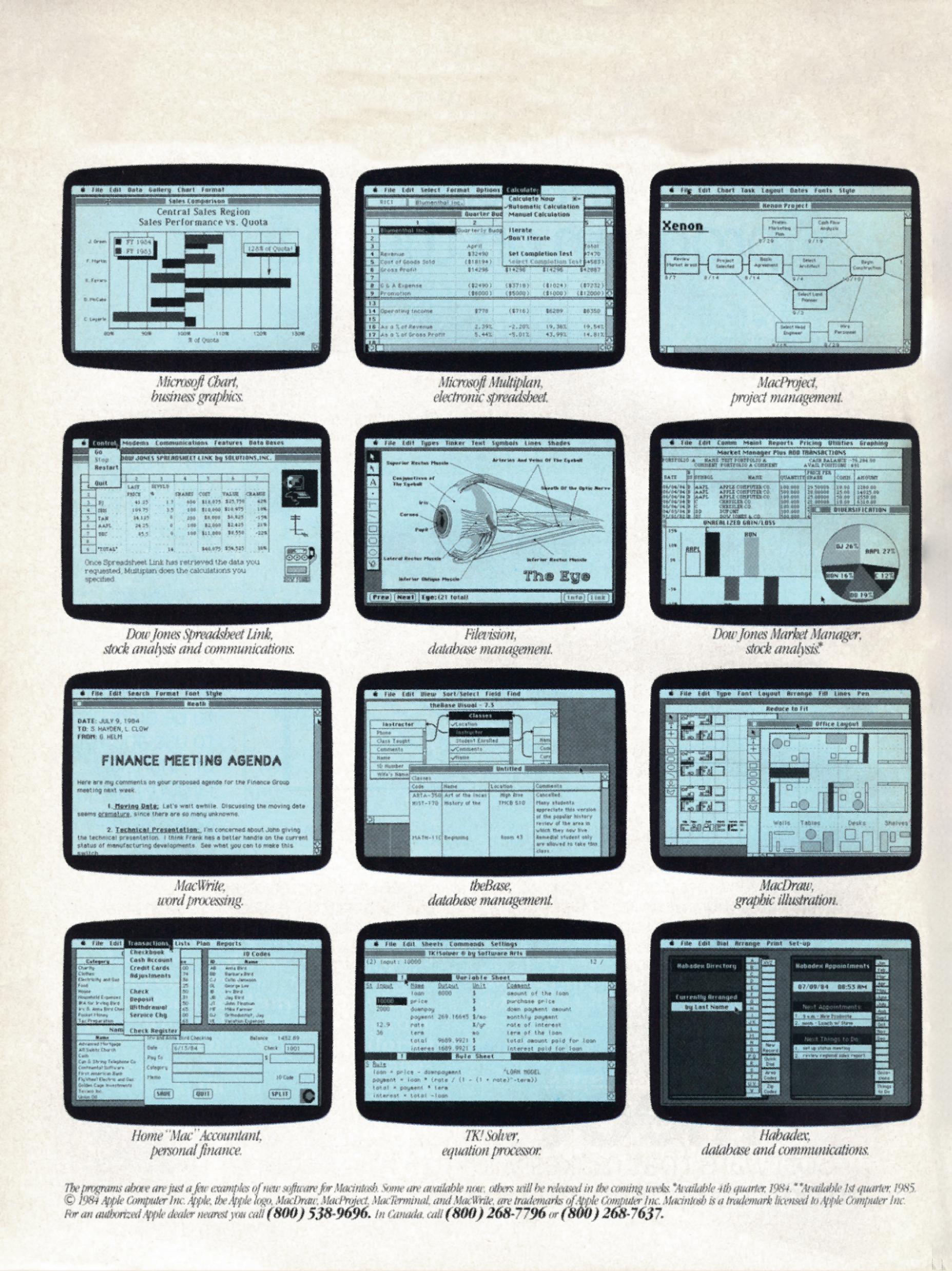

In the 1980s, computer magazines were packed with dense, technical ads — but Apple kept playing a different game, just as they had with the Apple II. Their delightful ads mixed text and graphics, speaking in clear, inviting tones that anyone could understand.

Apple’s pages felt airy, elegant, and striking — more like design spreads than typical advertisements. Take, for example, the launch ad “Introducing Macintosh. What makes it tick. And talk.” or “We interrupt this magazine for some important programs” (on the next page), which showcased a surprisingly rich variety of applications, while quietly easing fears that there might be too few.

Left: the original Macintosh 128K. I normally show only machines I’ve personally handled—tested, serviced, or restored, but here, of course, an exception is necessary, and used a commercial image. As you’ll see in the next chapter, the Macintosh Plus looks almost identical.

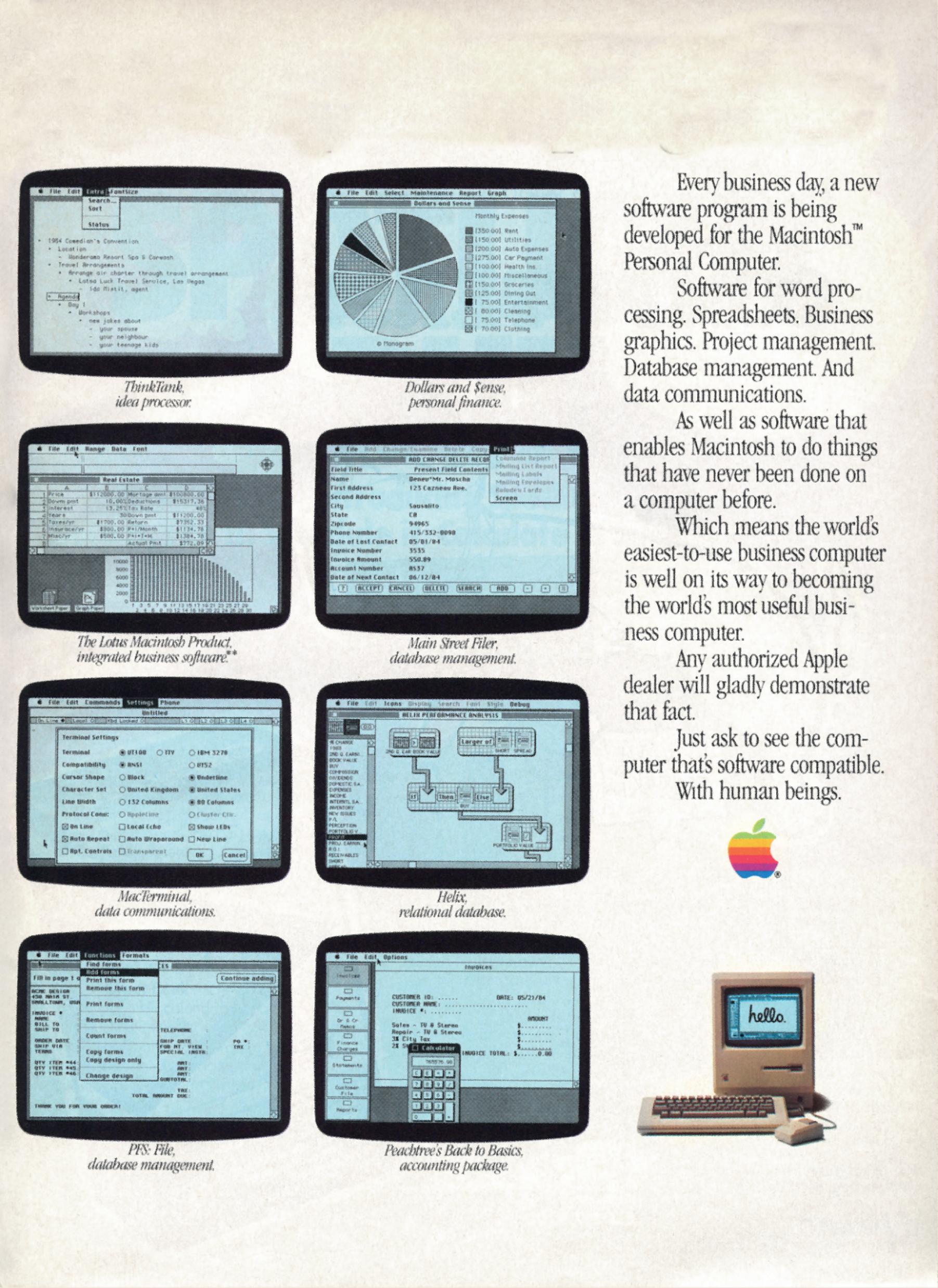

“Introducing Macintosh. And what makes it tick. And talk.” This 1984 Byte magazine ad remains one of Apple’s most memorable. I restored it to its original look, a reminder of the excitement that surrounded the first Macintosh.

Let’s now return to some personal—yet, I hope, interesting—notes. The arrival of our first Macintosh in the computer shop wasn’t exactly shocking. We probably greeted it with curiosity rather than real enthusiasm. I don’t recall its exact price, but it was terribly expensive and not particularly suited to our customer base, who knew us for our aggressively low prices.

Of course, I didn’t miss the chance to play with it. “Nice,” I thought shortsightedly, “but it can’t really compete with the Apple II clones that are so popular.” To me, it felt more like an elegant curiosity than a revolution. I didn’t realize that one small gesture nearby would soon ripple far beyond our shop.