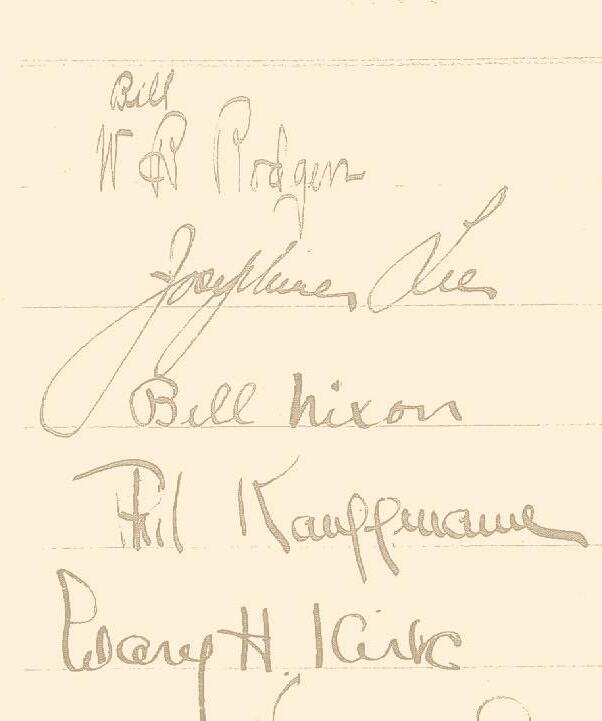

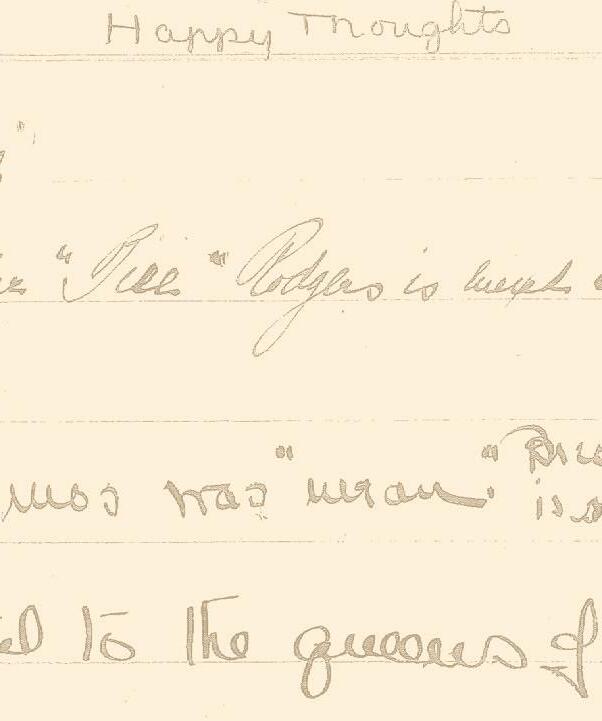

INSCRIPTION FROM WALLIS’ OLDFIELDS YEARBOOK

Dedicated to Win, Allegra, and Wallis

2 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Painting a Family Portrait

2. Meet the Parentals

3. The Startup of Me

4. My Cousin Wallis: the Duchess of Windsor

5. Dead Warfields

6. The Twain Shall Meet

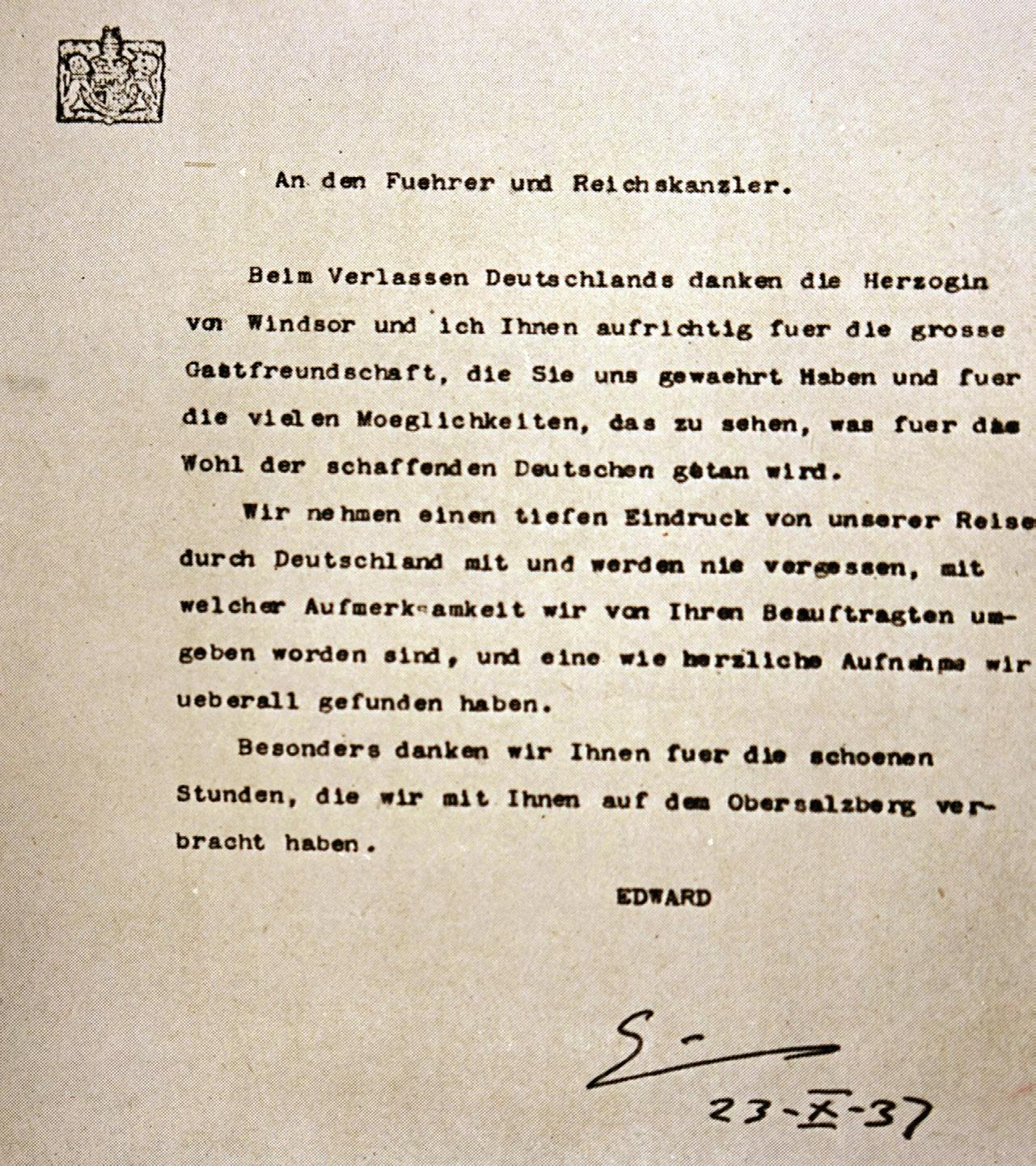

7. The Duchess and Hitler

8. The Duchess and Steamboats

9. Exodus

10. Scionism to Internet Mania

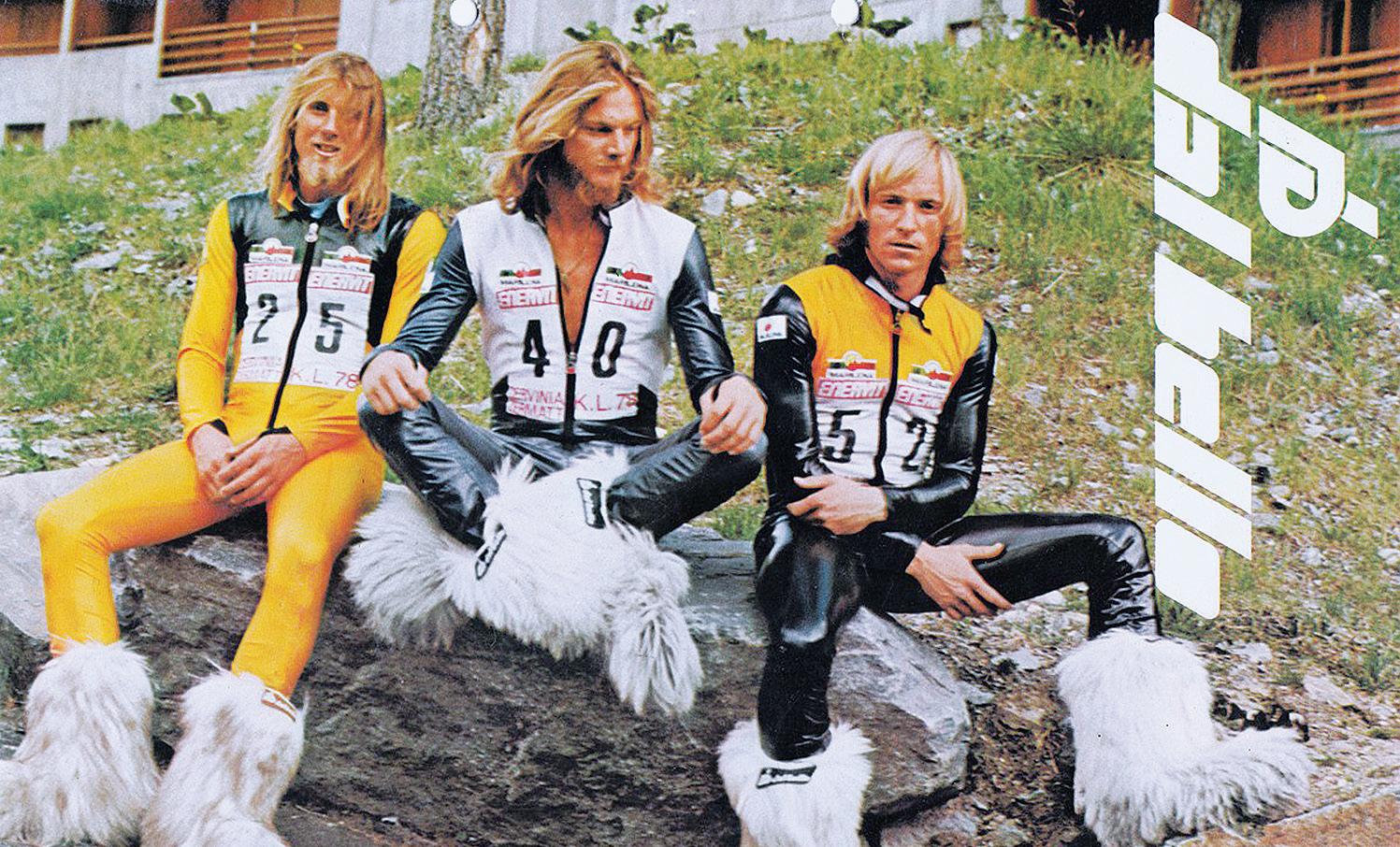

11. Zen and the Art of Speed Skiing

12. The Feminine Mystique: the Duchess and Judy Steir

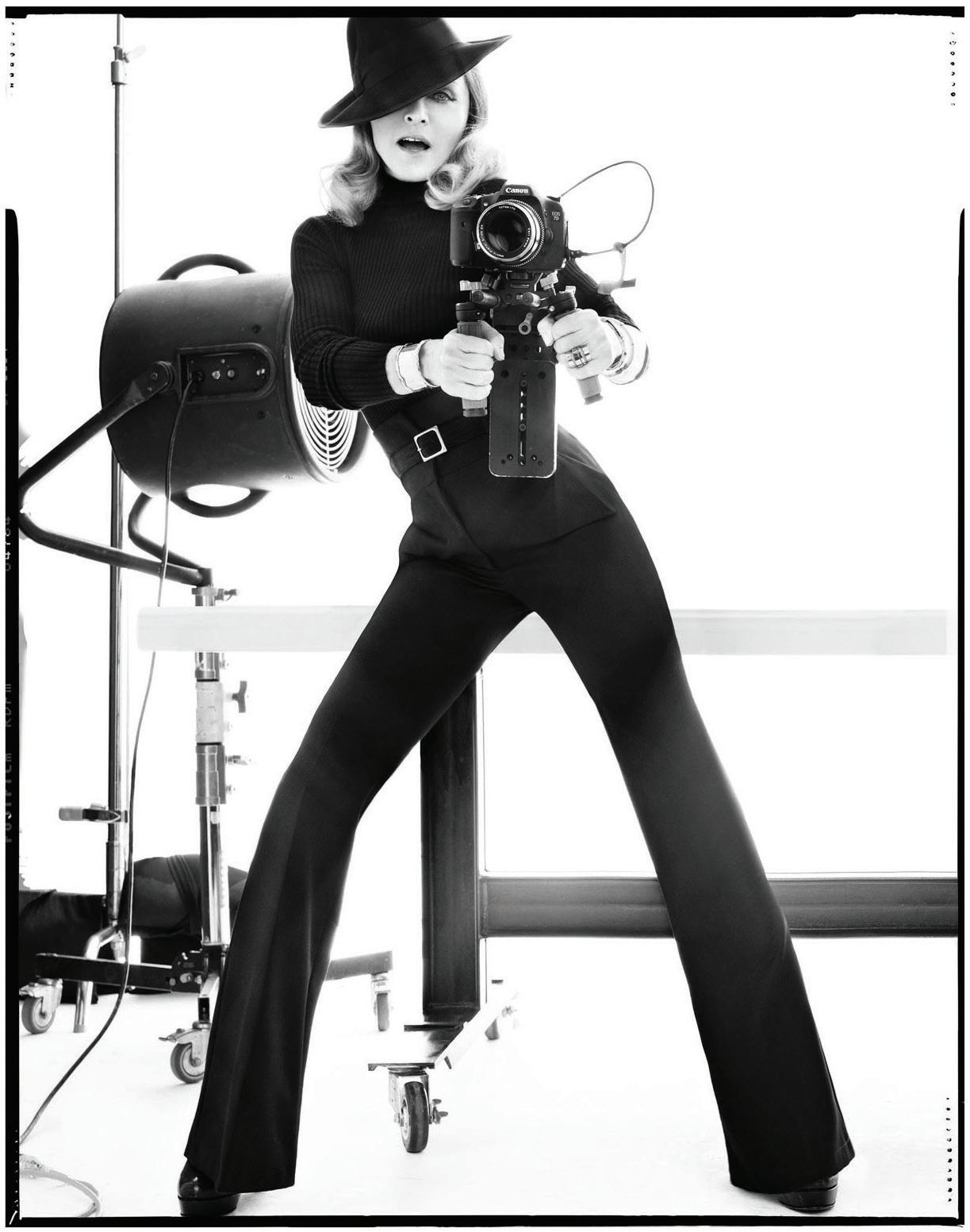

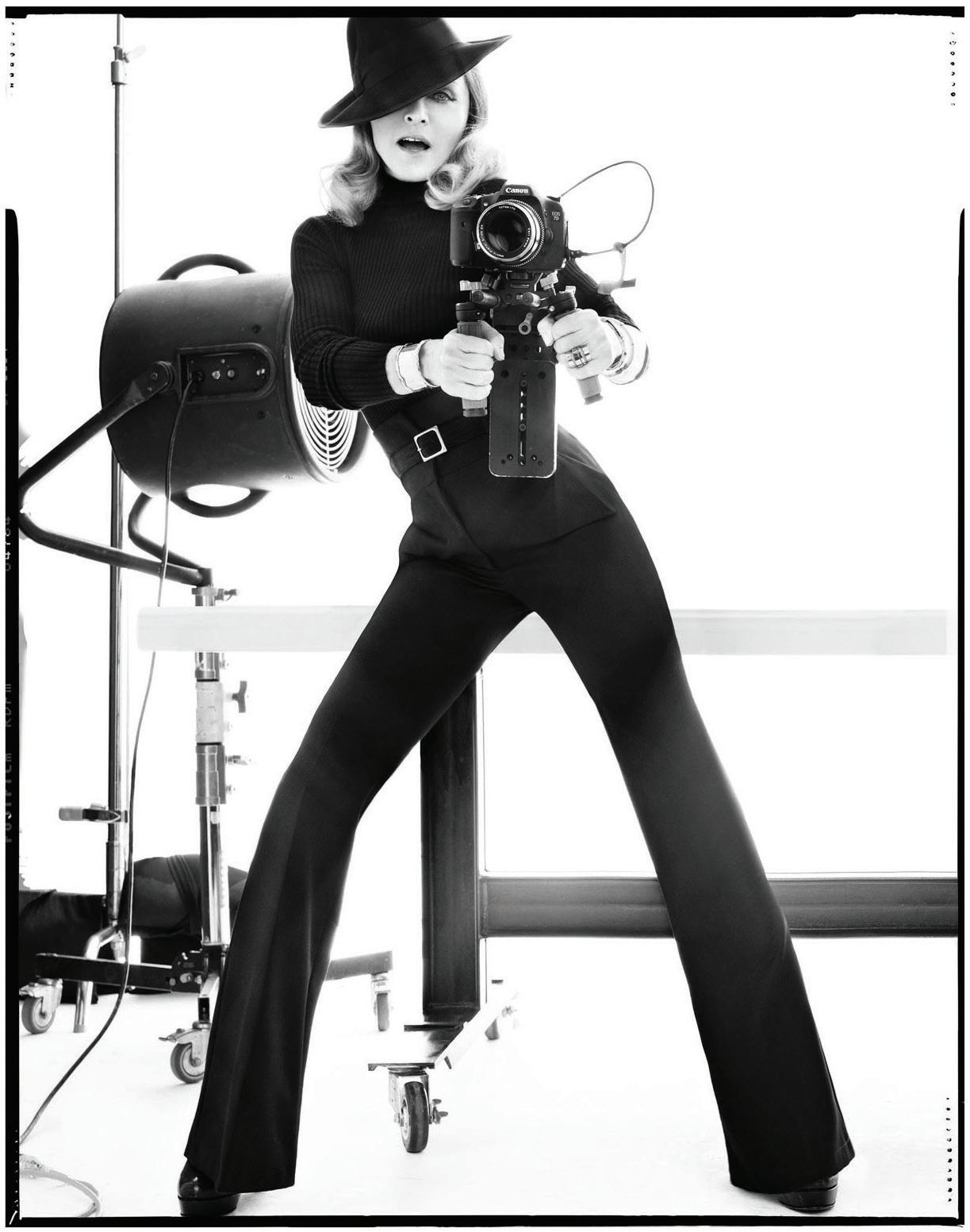

13. W.E.: the Duchess and Madonna

14. The Duchess and Grave Issues

15. Every Chapter Is Extra

The After Book

The Book of Life

Warfield Genealogy

People Index

Select Bibliography

Photo Credits

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 3

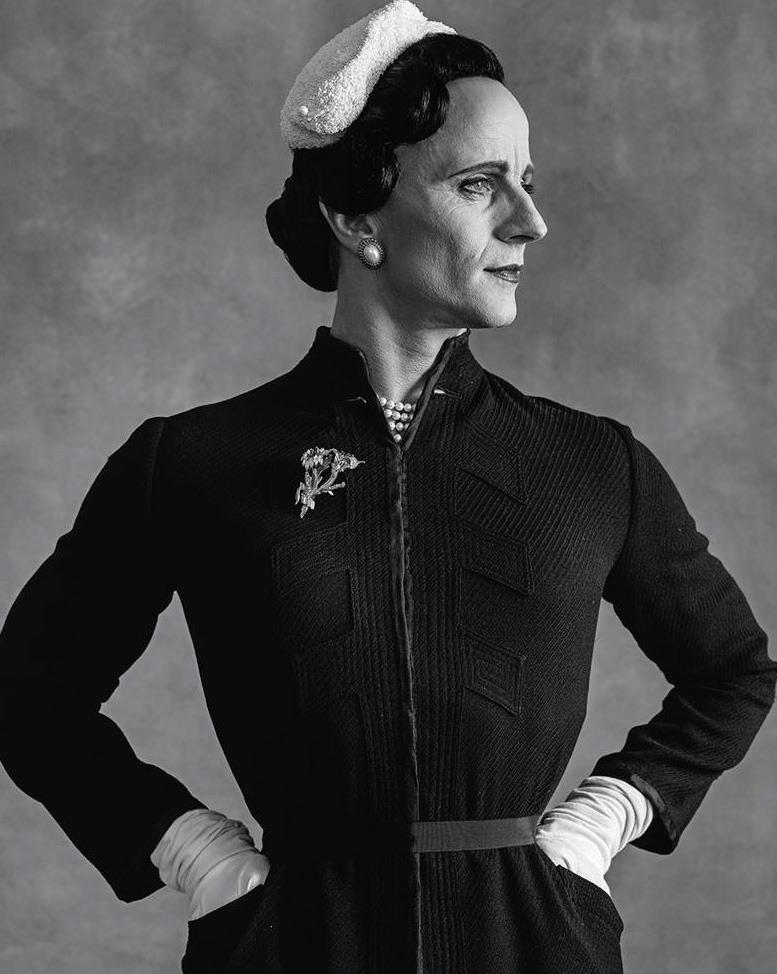

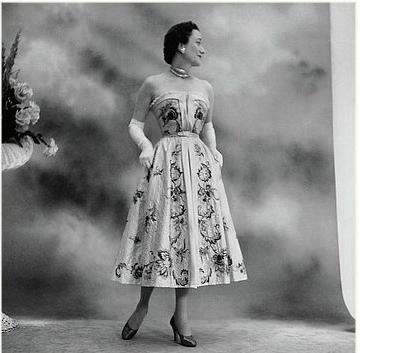

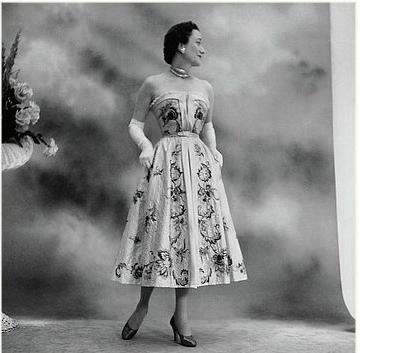

“I am not beautiful, so I have to dress better than everyone else.”

–The Duchess of Windsor

Introduction

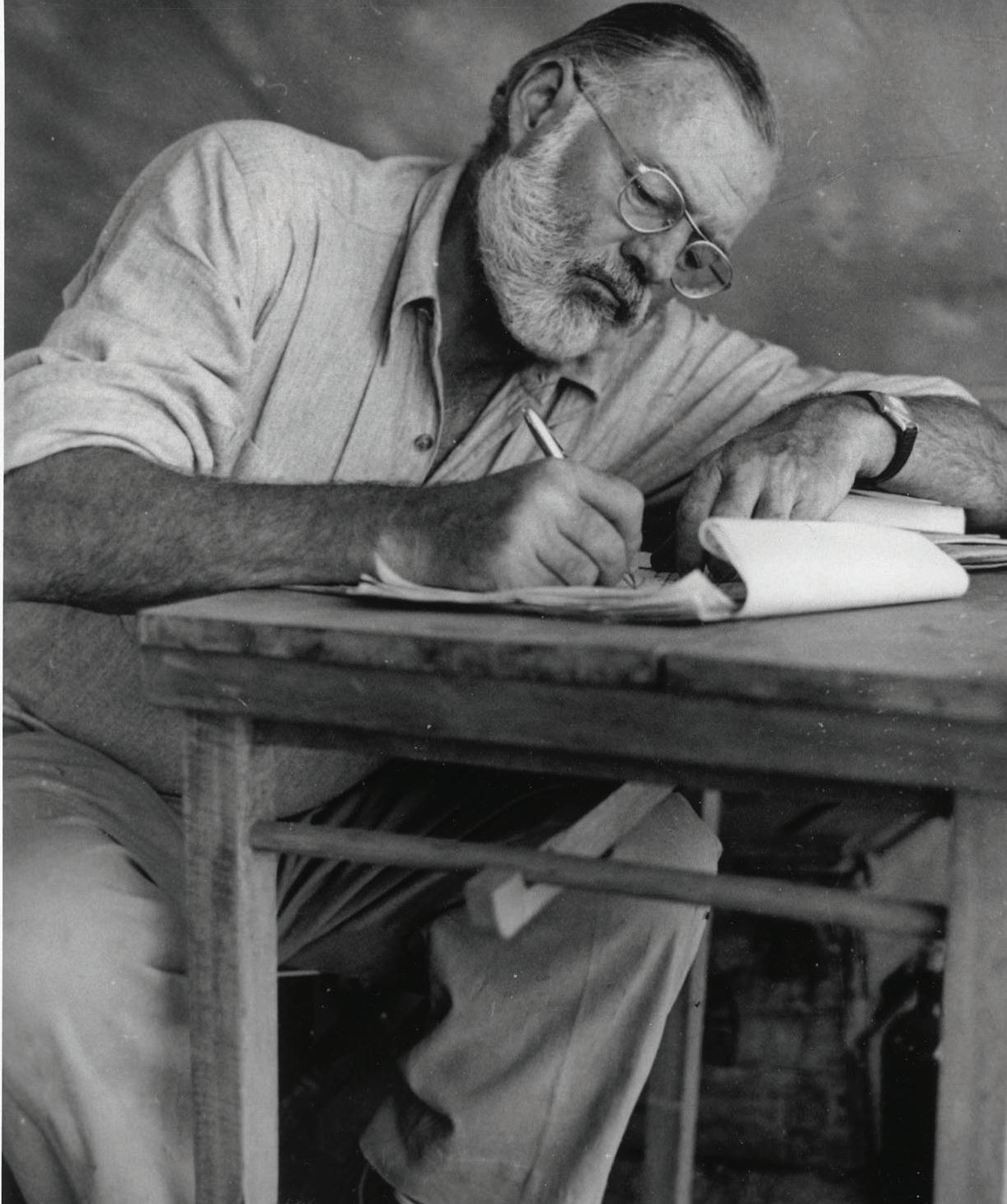

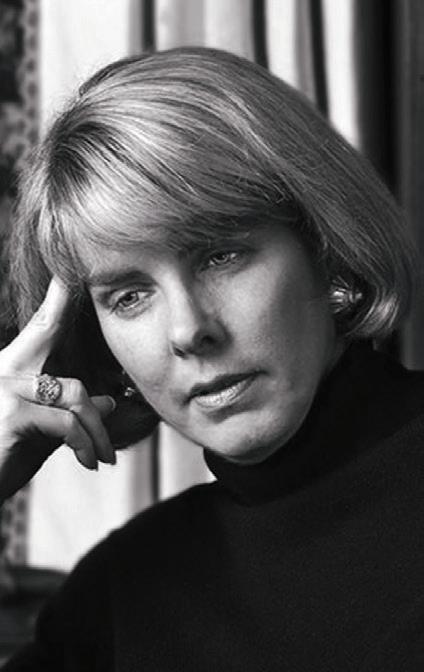

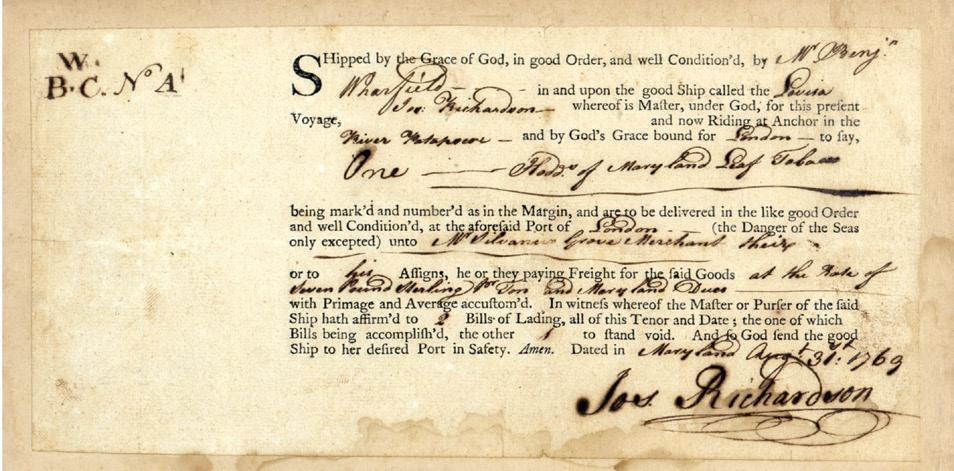

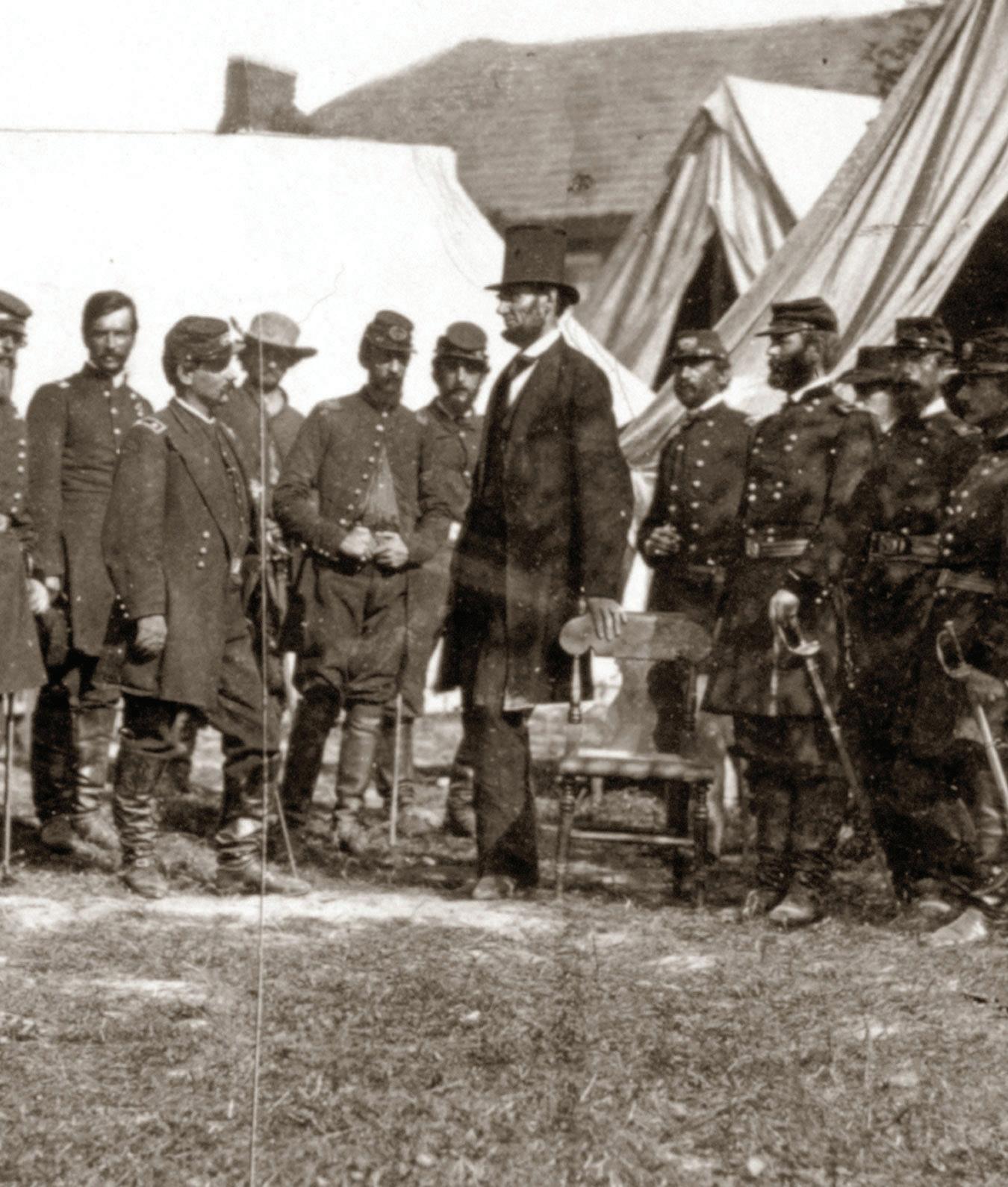

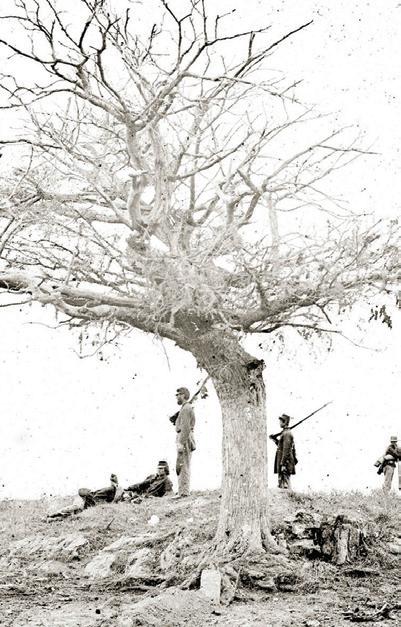

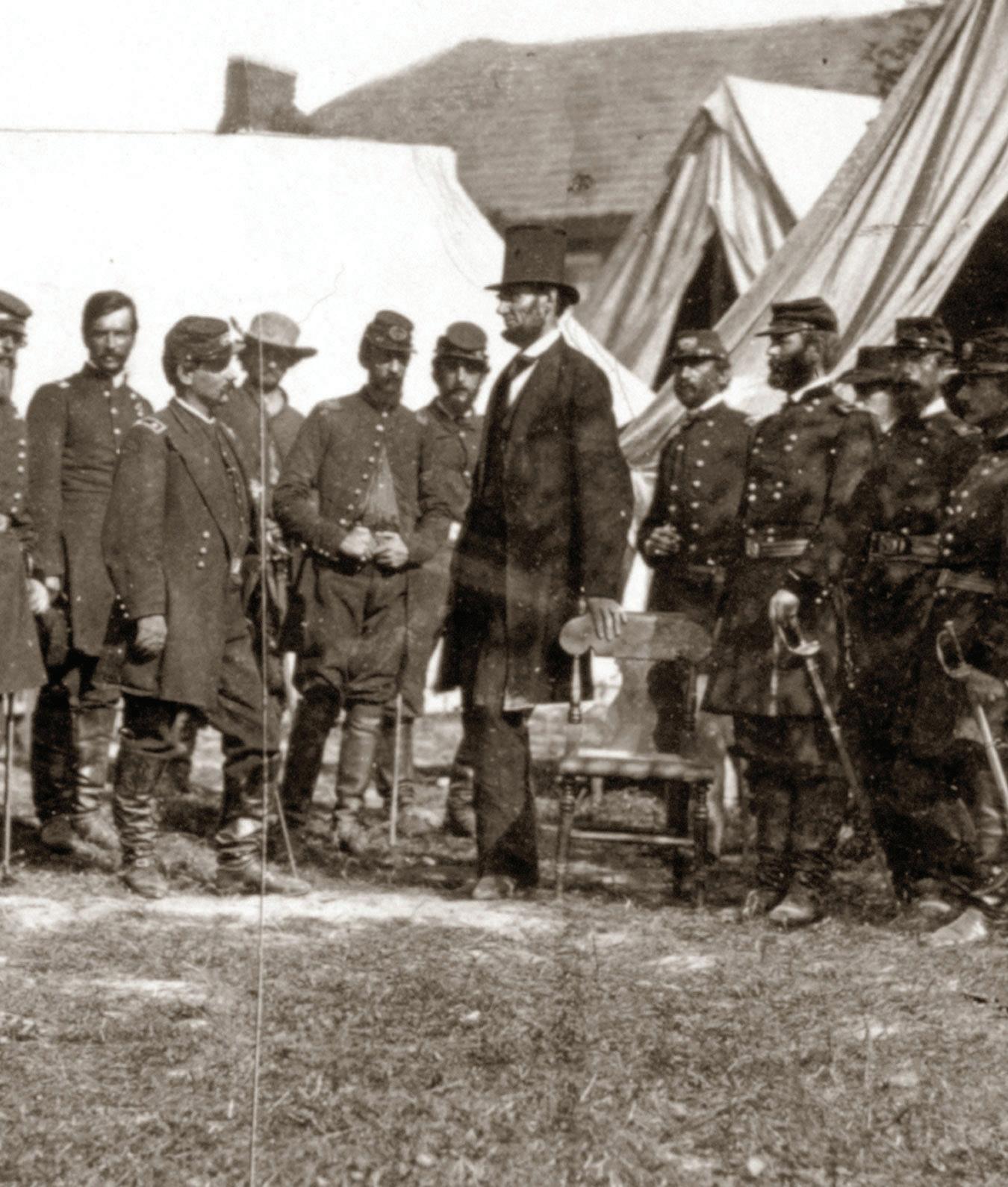

The Duchess and Me began in the spring of 2003 as a non-genuflecting chronicle of various notable members of my family, beginning with Richard Warfield’s departure from London for the New World in 1659, and continuing with Warfields who played significant roles in the Revolutionary War, Civil War, and World War II, and Warfields who thrived as successful businessmen, prominent statesmen, and world-champion athletes. Then I set aside the book, allowing it to simmer, untouched, for 15 years. But the characters involved and their adventures never left me, and in the winter of 2018, with a more seasoned perspective, I felt it was time to finish the project.

As I perused my original manuscript, I realized that my cousin Wallis Warfield Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, whose romance with (and subsequent marriage to) King Edward VIII of England would prompt his abdication in 1936 — sometimes hyperbolically referred to as “the greatest love story of the 20th century” — had been accorded only a cameo. That struck me as skimpy treatment, particularly in light of the fact that, in 2016, two years before I resumed work on the book project, Britain’s Prince Harry had married American actress — and divorcee — Meghan Markle, echoing Wallis and Edward.

It became apparent to me that Wallis’ life — from Baltimore debutante to jet-setting duchess to Parisian dowager — represented an important Warfield adventure, one that cried out for considerably more attention. After all, renowned author, journalist, and wit H. L. Mencken — another Baltimorean — waggishly wrote that the abdication of King Edward VIII to marry Wallis was “the greatest news story since the Resurrection.” And so Warfield family adventures of war and peace morphed into adventures of war and peace

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 5

and love with the addition of previously unexplored aspects of the Duchess of Windsor’s life as seen through a Warfieldian lens.

The Meghan/Harry echo of Wallis and Edward grew even louder in early 2020 when Harry and Meghan surprisingly announced that they would “step back” from their responsibilities as “senior royals,” in effect banishing themselves to independent new lives in the United States, just as Wallis and Edward had lived for decades as exiles, divorced from the monarchy, in France after the abdication. And after Meghan and Harry sat down for a revealing interview with Oprah Winfrey in spring 2021 — openly discussing the antipathy Meghan experienced both within and without the royal family while living in England — the echo was amplified to deafening proportions by a blizzard of print, online, and on-screen stories connecting Meghan and Wallis, who was scorned by the monarchy, the British people, and the press in the wake of Edward’s abdication.

But, in truth, even prior to the Harry/Meghan brouhaha, Wallis existed as something of an evergreen in the public consciousness. In recent years, her saga — and the attendant story of the abdication — has been disinterred, reassessed, poked, prodded, and parsed in at least a dozen books (Wallis in Love, The Real Wallis Simpson, etc.), in film (Madonna’s 2011 feature W.E., 2010’s The King’s Speech), on television (The Crown), and on the stage (Only a Kingdom, written, not incidentally, by the mother of my best friend from high school).

Finally, although I initially planned not to include myself in this book, the more I reflected on my professional career in publishing — and the more I researched my family’s exploits, particularly those of Wallis — the more I realized that my life might also amount to something of a Warfield adventure, one that I hope is worthy of inclusion. Serendipitously, the process of assembling and writing The Duchess of Windsor and Me, as well as going through a series of serious health challenges, has taken me on a journey of self-discovery, while simultaneously connecting me to my heritage.

6 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 7

8 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

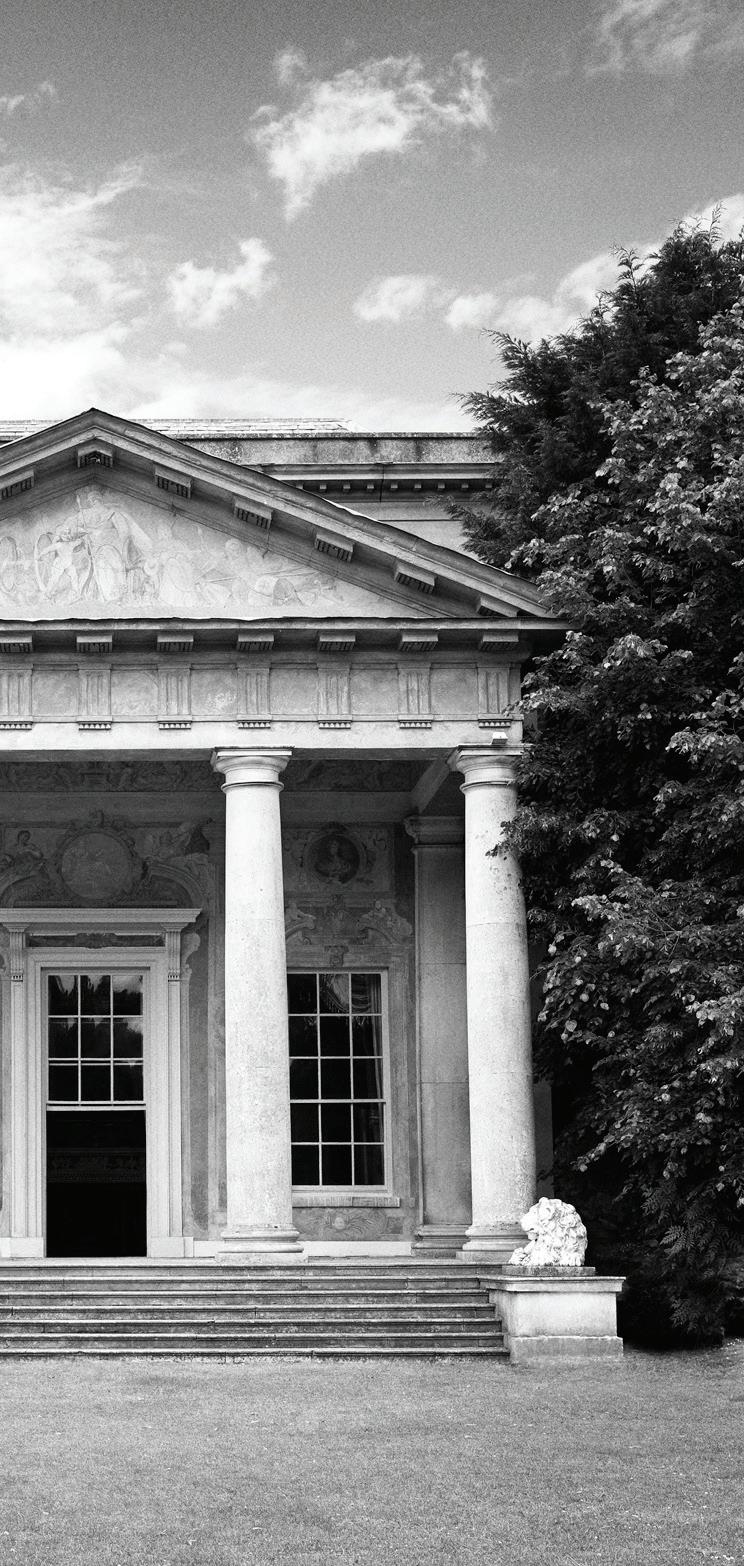

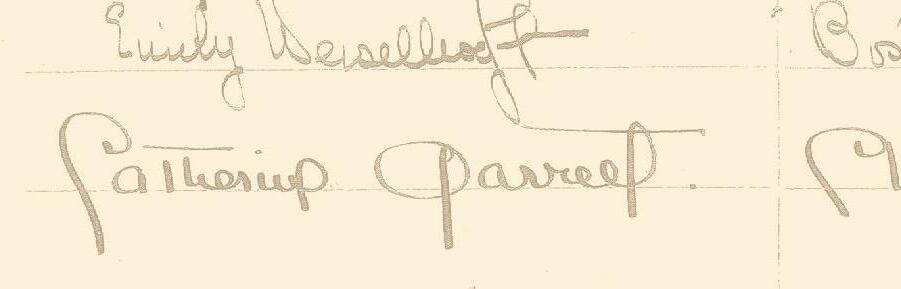

A Warfield family portrait at Oakdale

1Painting a Family Portrait

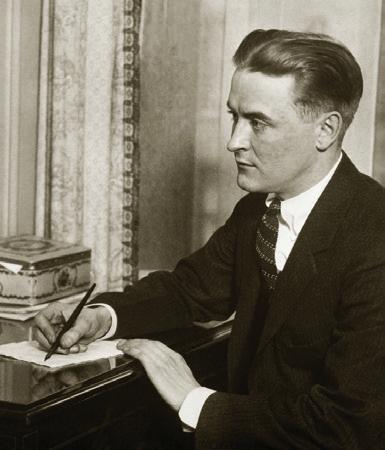

“ Vitality shows not only in the ability to persist, but in the ability to start over.”

–F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

In March of 2003, I was suffering from what appeared to be post-traumatic stress disorder. The digital media company I had created had been restructured with significant losses to me and my investors, while a costly divorce and a scorched-earth family battle only added to my stress.

“Situational depression” my doctor mumbled, raising his eyebrows at my 20-pound weight loss, but not wanting to hear the details of my sleepless nights, which were really sleepless decades. His diagnosis inadequately described my genetic inheritance; it would take 15 years to understand that my insomnia was the result of an “unquiet mind.”

Around that time, I met my second wife, Lynn (now my ex-wife), who described me to her friends as a “train wreck.” I had been hypermanically creating large, messy collages in my apartment; this “art” consisted of images, words, and photographs chosen for their painful significance of loss.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 9

While knowledgeable about fine art, Lynn nonetheless encouraged these crude and amateurish projects because she recognized my need for therapy, having recently gone through her own divorce.

One Sunday morning, as she reclined on her sofa quietly listening to my manic monologues, she said tactfully, “Edwin, perhaps your artistic skills are more verbal than tactile. I think you should write a book.”

“Out of your wreckage…came a book.”

–CAROLYN BLACKWOOD

Poet Robert Lowell’s wife commenting on his 1977 collection, Day by Day

Eventually, I pulled out of my torpor and decided to escape Florida, where I was then living, and return to my hometown, Baltimore. Florida is a favorable onshore tax haven and a suitable AARP rest stop before entering the Pearly Gates; however, it is not an ideal locale for midlife angst, reconciliation of one’s past, or any task requiring cerebral acumen. Soul and history are not in Florida’s DNA, but they are Maryland’s heart.

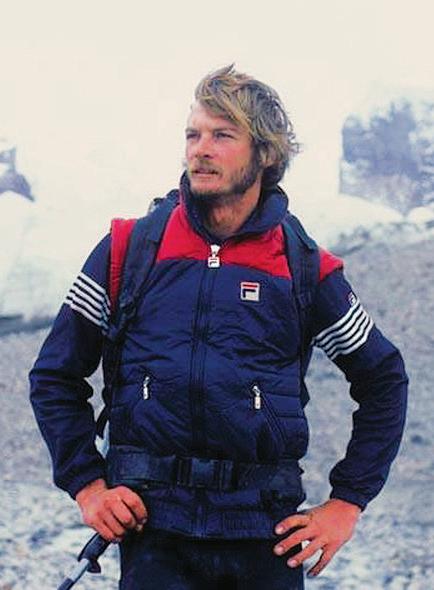

A new start in a familiar place would amount to a personal reclamation project. The Warfield family history heralds a broad swath of politicians, authors, war heroes, governors, one seductress of a king, and a speed skier turned Mt. Everest hang glider. I was eager for rebirth and a Warfield adventure.

10 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

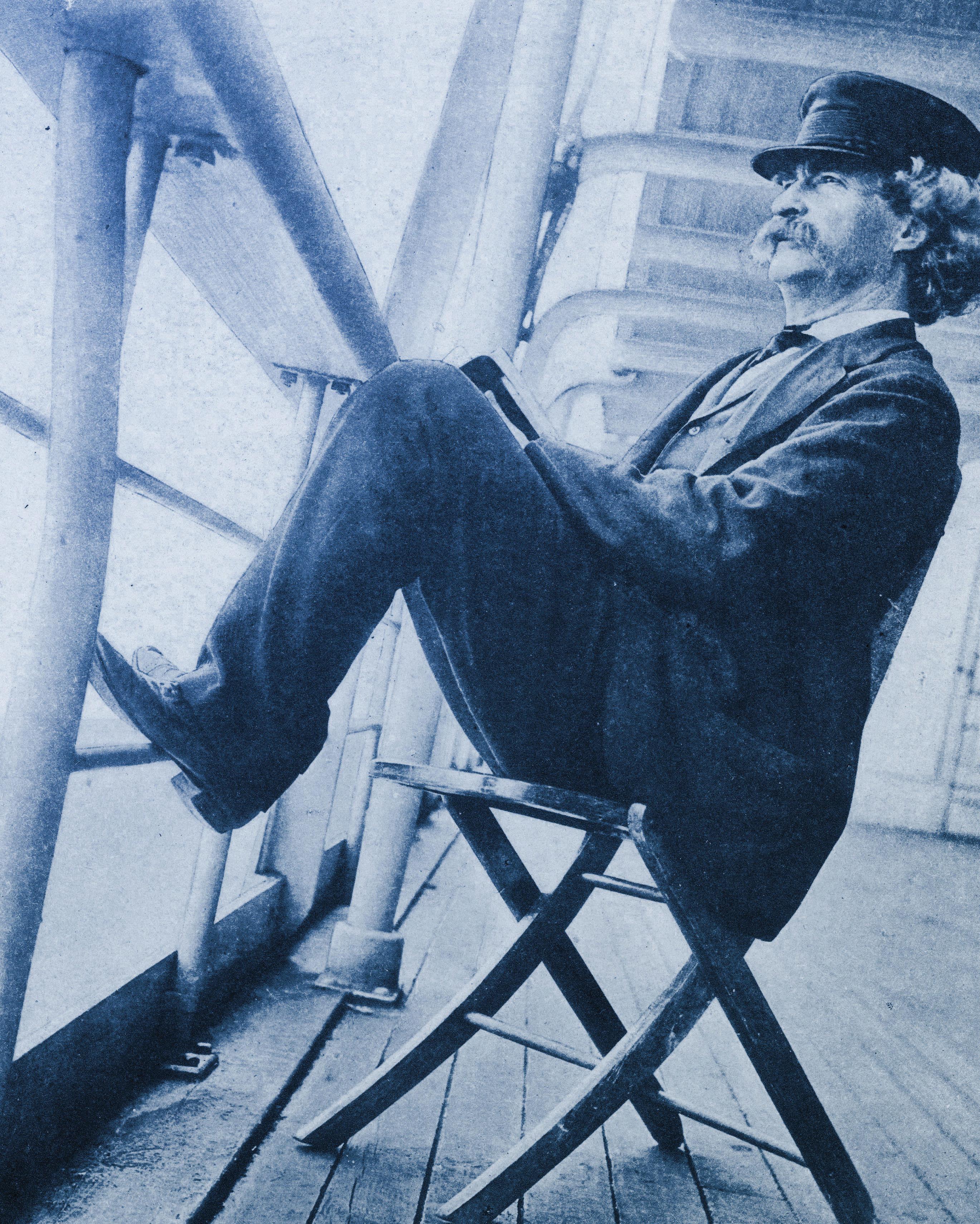

Adventures of Warfield, circa late-19th century

Having reached the half-century mark, I was ready to explore the past — the taxonomy of my heritage. In this exploration, I hoped to absorb from my more illustrious relatives their ability to accept life’s ambiguities and to persevere. I craved what I knew was their preference for adventure over legacy — thus the title of this book.

The [Baltimore] Sun Also Rises

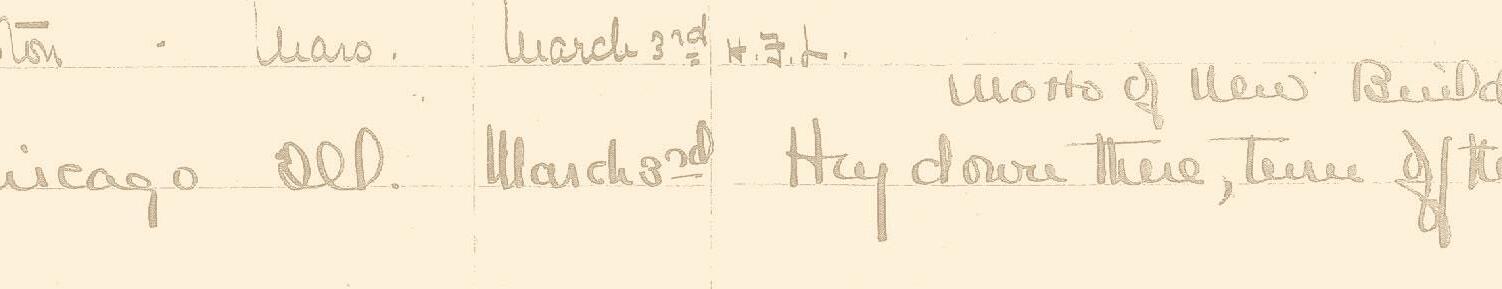

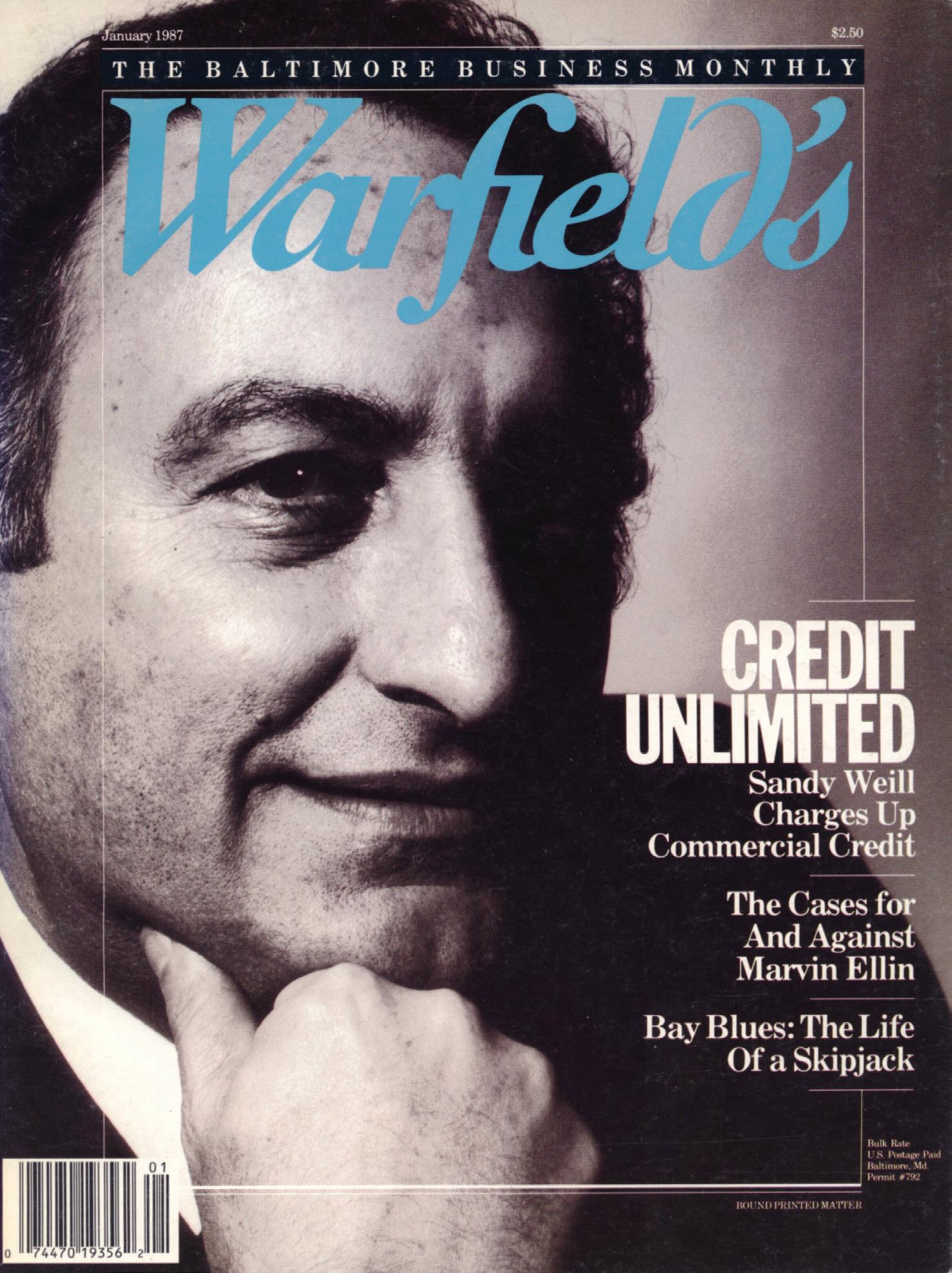

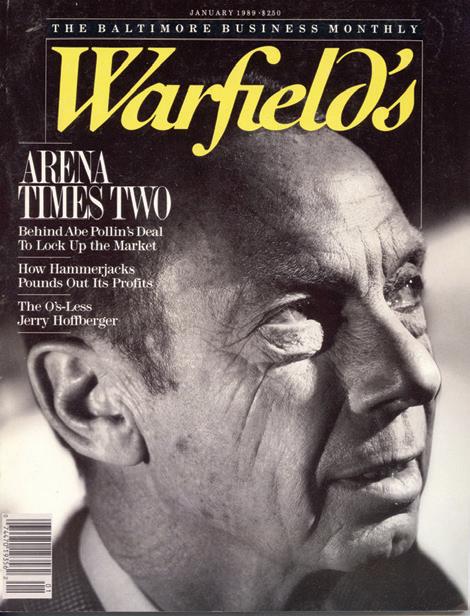

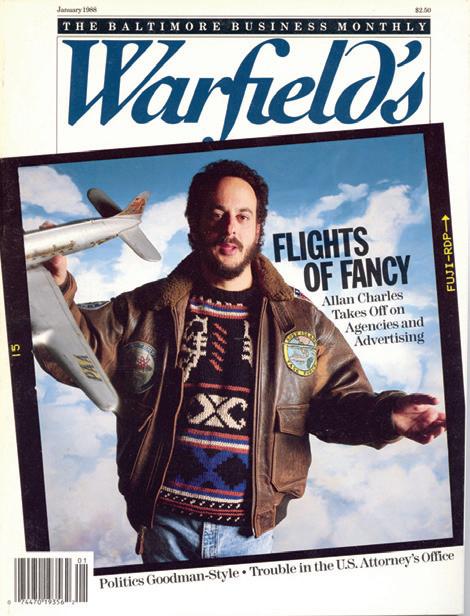

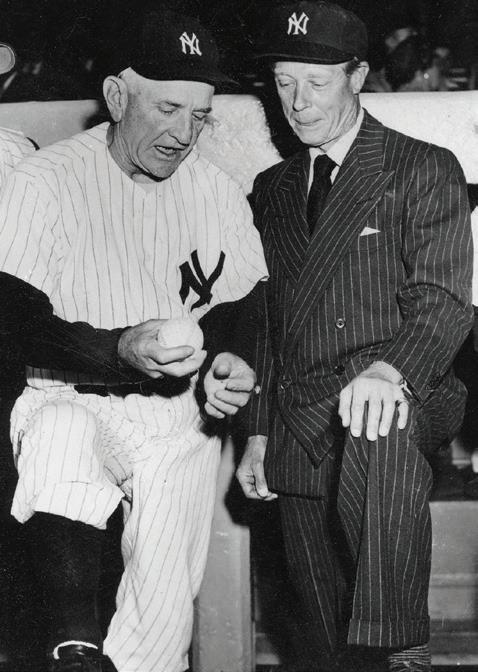

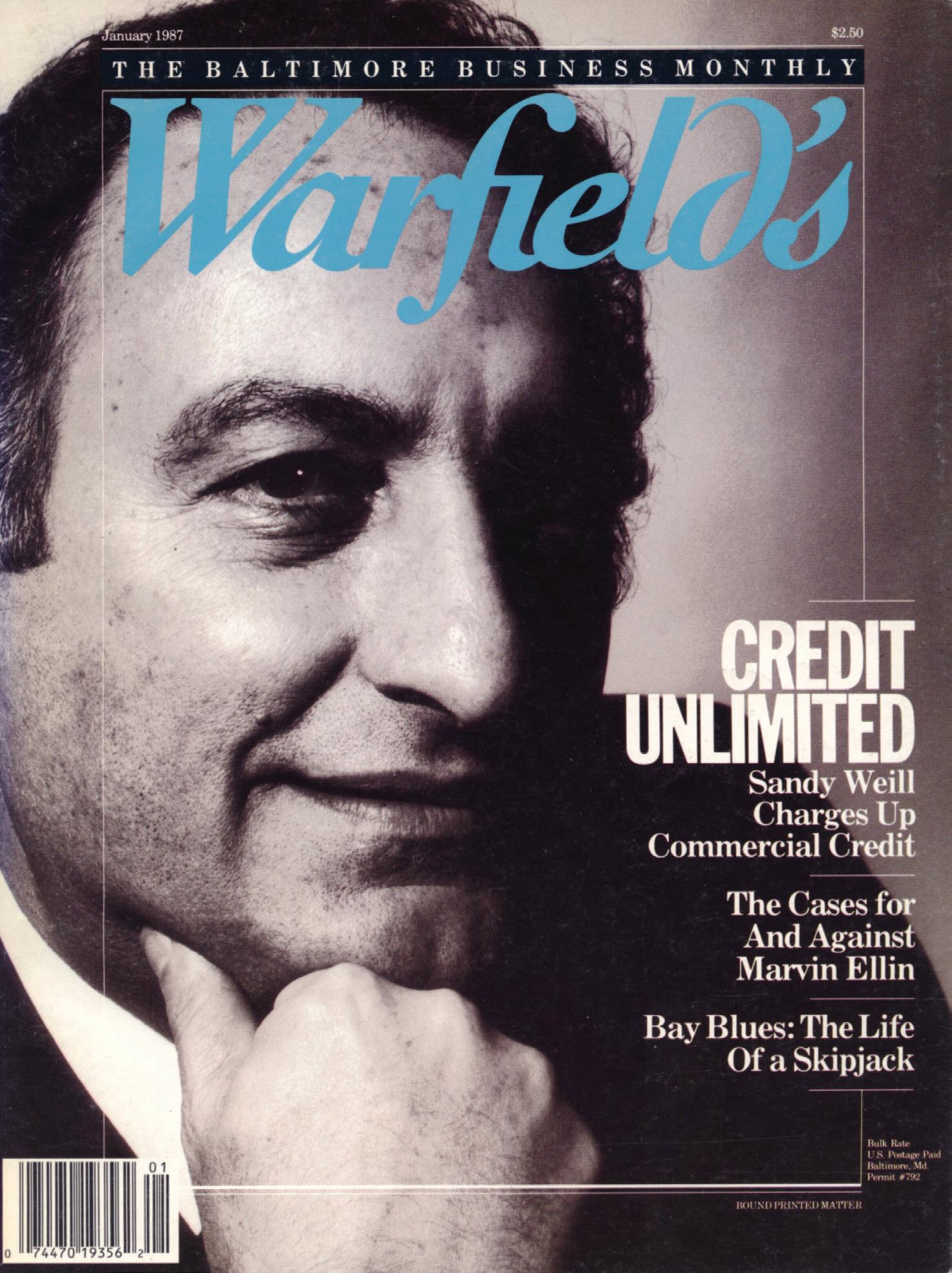

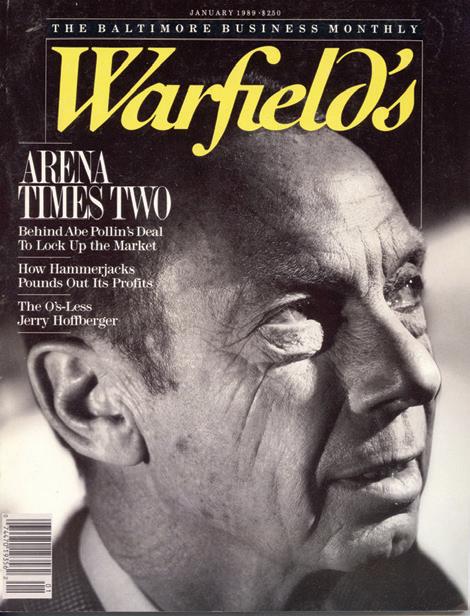

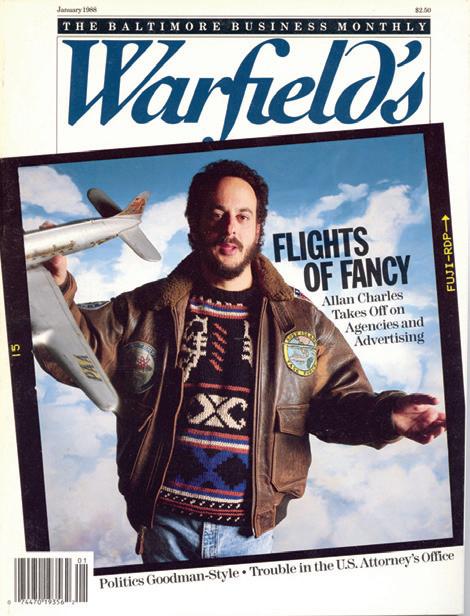

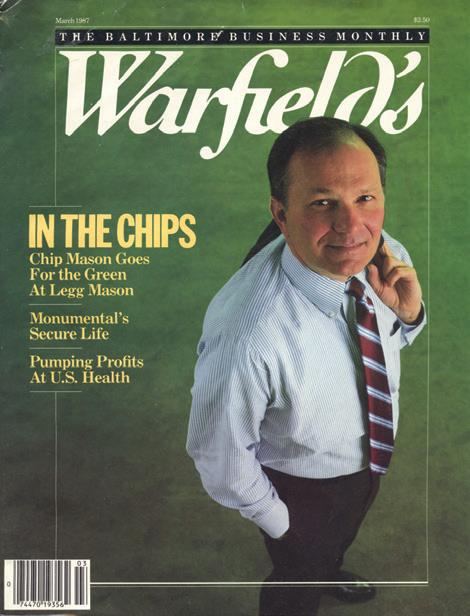

November 20, 2003, was a typically overcast Baltimore day, best captured decades earlier in the smog-induced chiaroscuro photographs of The Baltimore Sun pictorialist A. Aubrey Bodine. I arose with a sense that this might be the start of a new adventure for me — looking for mezzanine funding for the acquisition of a 10-year-old, New York-based financial newsletter.

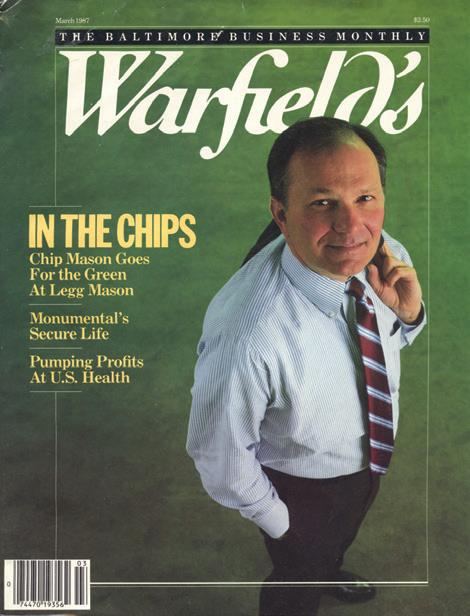

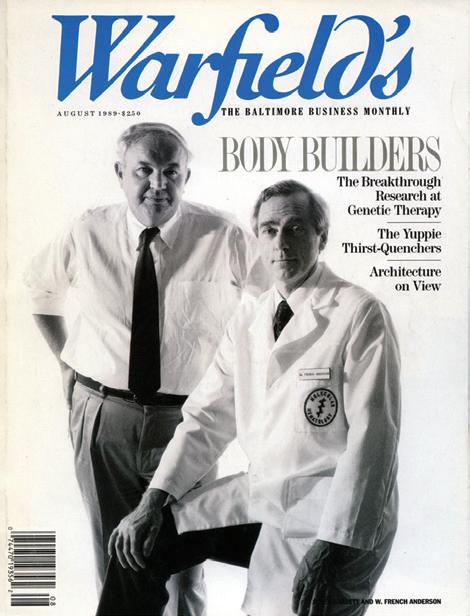

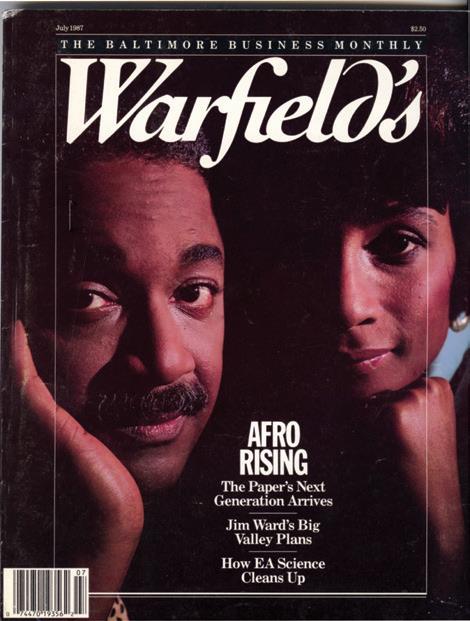

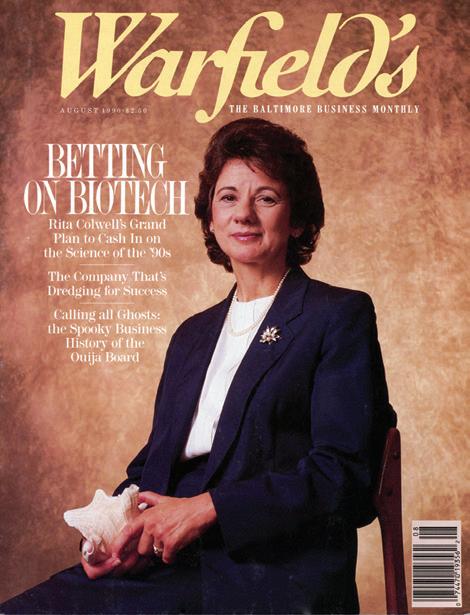

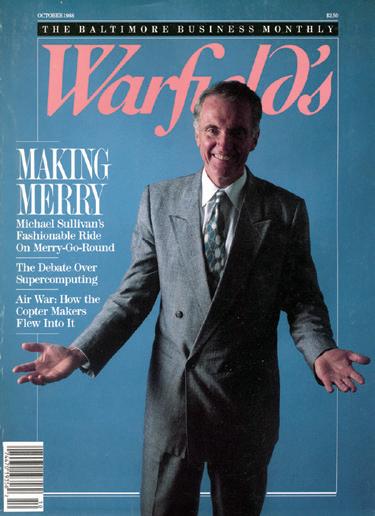

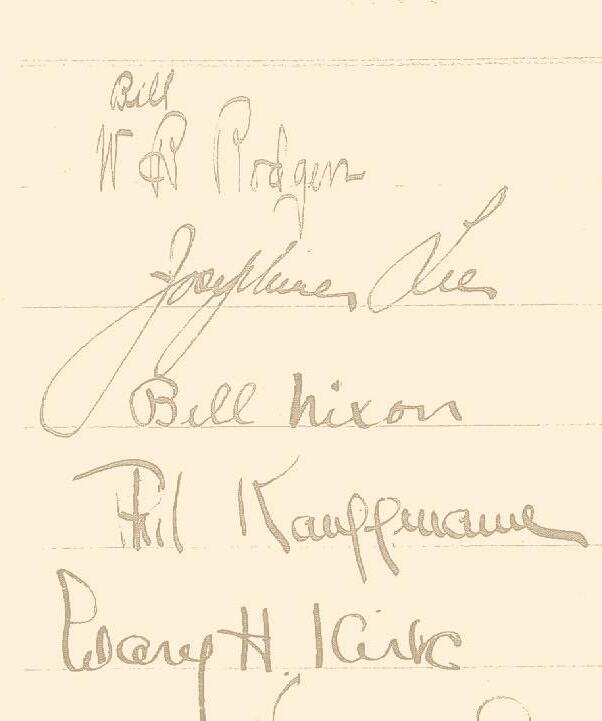

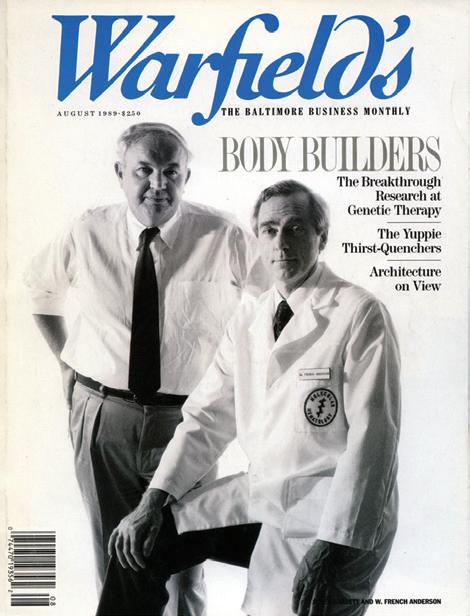

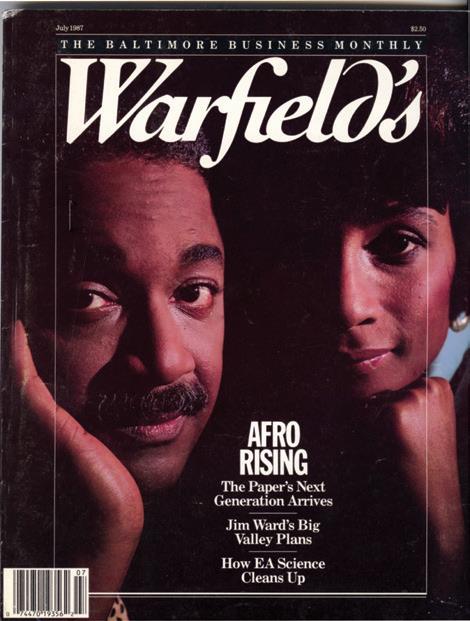

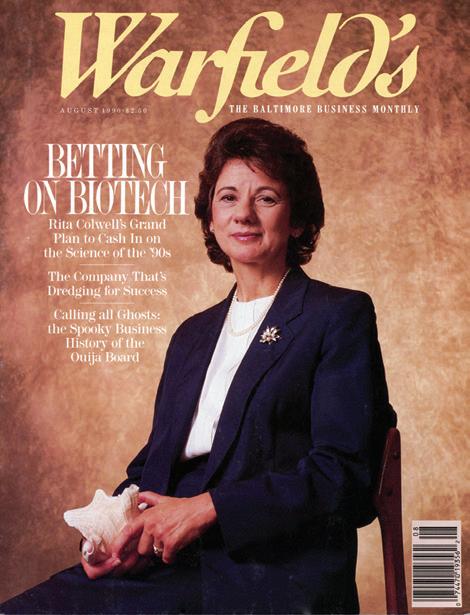

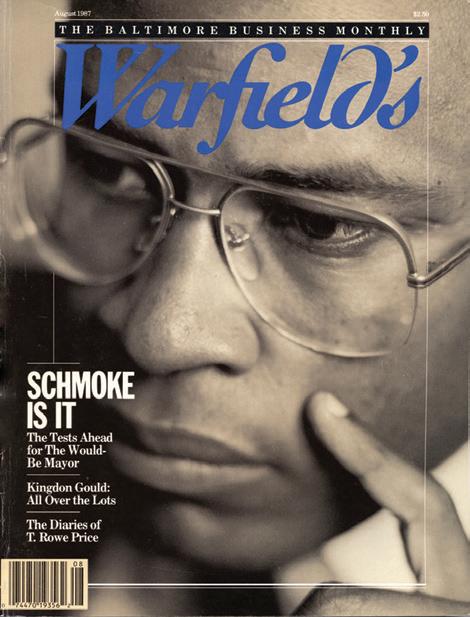

That morning, I was to pick up banker David Lamb, who was flying in from Hartford, Connecticut. Affiliated with Veronis, Suhler & Associates, David had been my investment banker back in 1990 when he assisted me in the buyout of The Daily Record, the legal newspaper that my great-grandfather established in 1888.

One century later, The Daily Record had amassed a hodge-podge of some 80 shareholders: Baltimore Typographical Union members, East Baltimore union pressmen, curmudgeonly lawyers, a law book dealer, a few relatives, my father’s two-percent interest, a Florida legal newspaper publisher, and hard-to-locate trusts and trustees. There were even a few dead shareholders. While I inherited the right to work at the paper, I had to buy out every share.

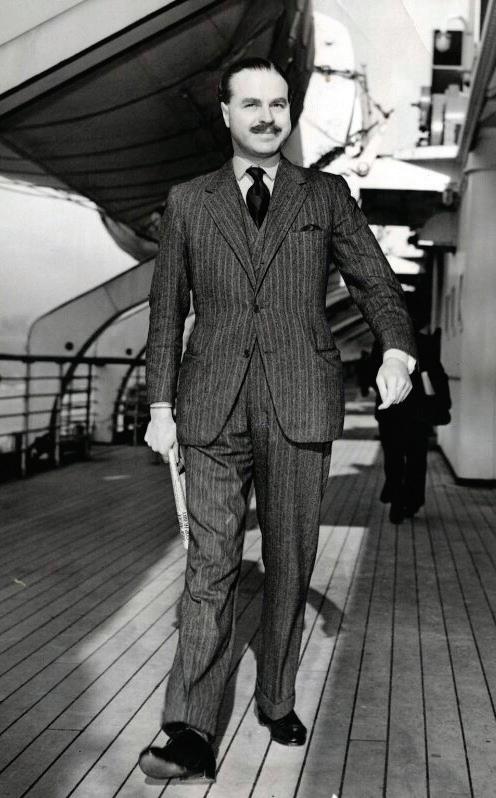

It had been almost 14 years since David and I had worked together. An oldschool gentleman banker despite being only in his early 40s, he was honest, discreet, strategic, and reflective. He arrived in bespoke English shoes and a suitable-for-capital-raising pinstripe suit. As he approached my car, he blurted, “Edwin! Have you seen it?”

“What?”

“The article in The Baltimore Sun.”

“What article?” In my haste to pick up David, I had not read the city’s daily newspaper.

“While I was getting a shoe shine, I read this article in The Baltimore Sun on the Warfields,” David exclaimed.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 11

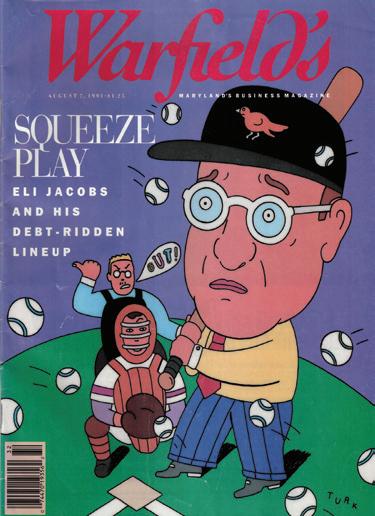

He raced back to the terminal and picked up a copy that included a feature story headlined “Painting a Family Portrait,” which detailed an exhibit that was about to open at the Howard County Historical Society about my family’s rich heritage.

My initial response: What perfect timing! Positive press and a road show in my hometown on the same day. My toned-down second response: the absurdity of it all. Who would really care? Okay, there is the Duchess of Windsor, but most Warfields do not claim her; some even view her as either trailer trash, reprehensible gay icon, or monarchy disrupter.

As I drove, David read aloud: “Richard Warfield was alone when he came to Maryland in the 1600s as an indentured servant, but today his descendants are spread across the state and the world. When Jean Keenan, a Warfield descendant and [Howard County] Historical Society volunteer suggested the display, the society’s executive, Michael Walczak, said he wasn’t sure it would appeal to anyone outside the family.

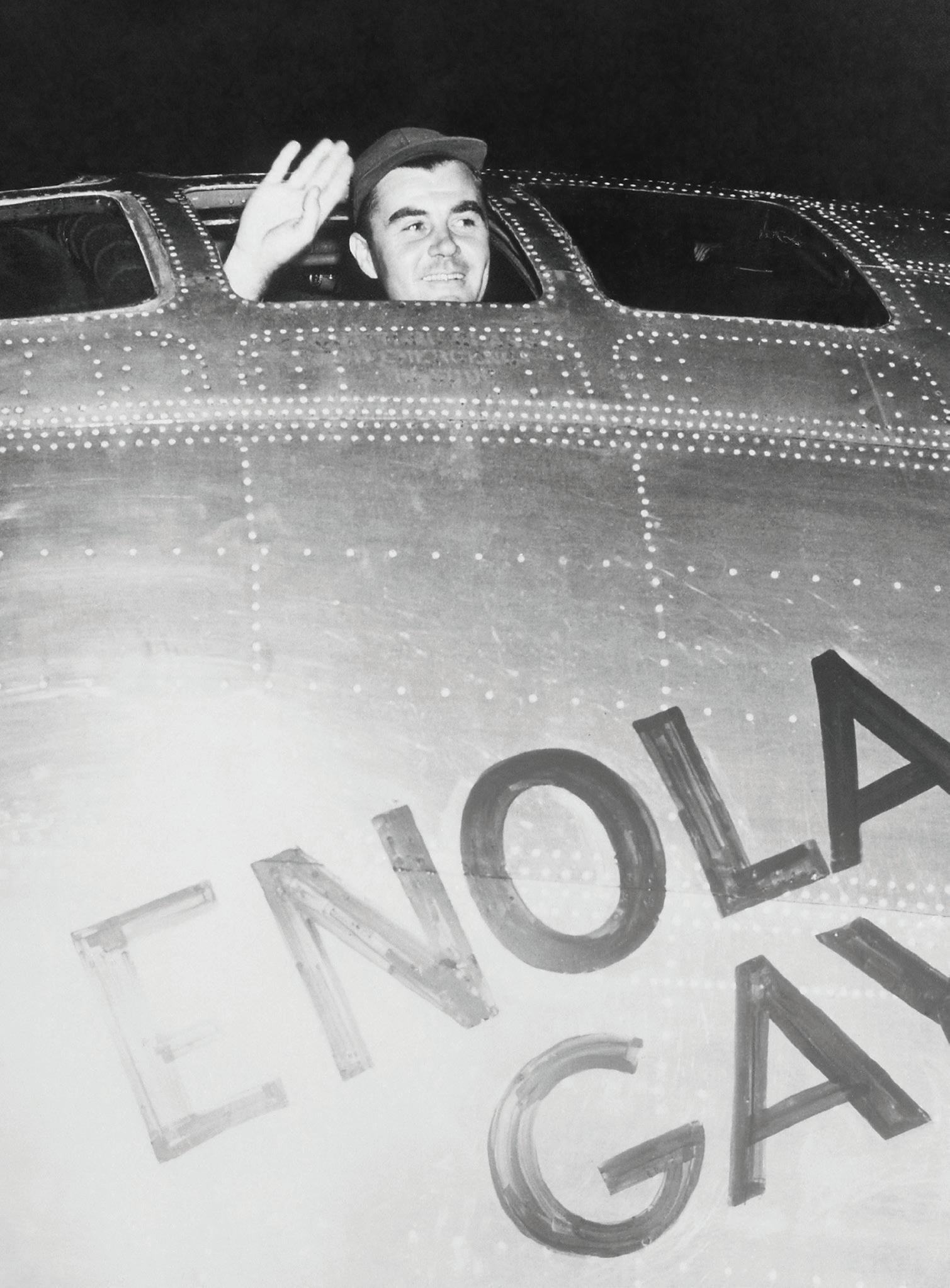

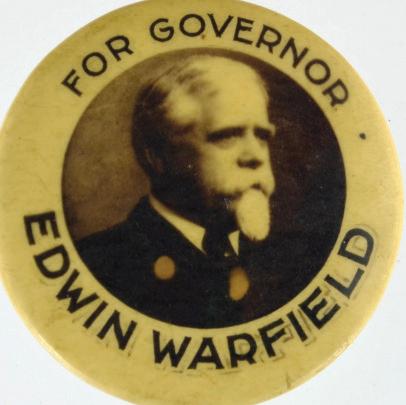

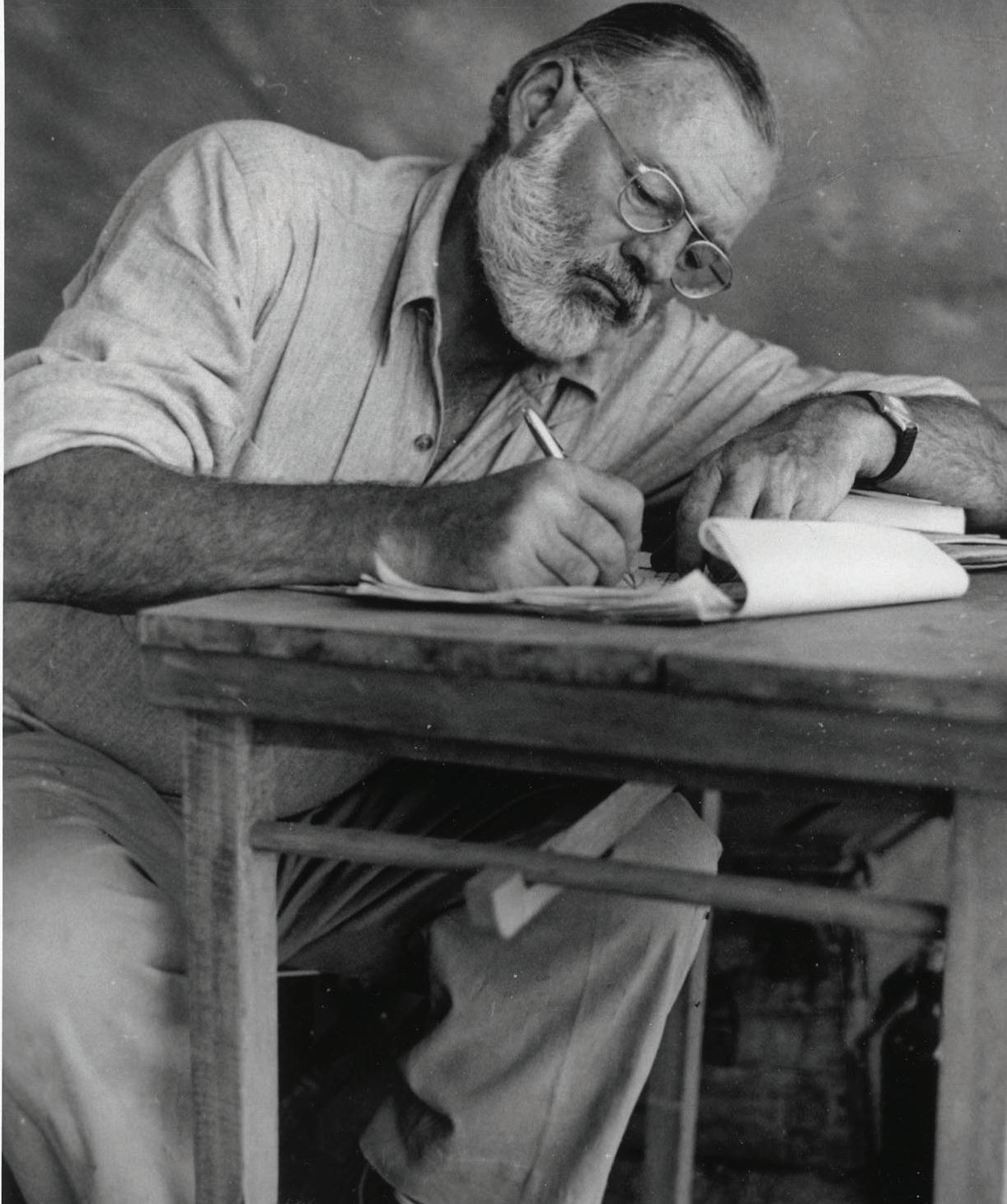

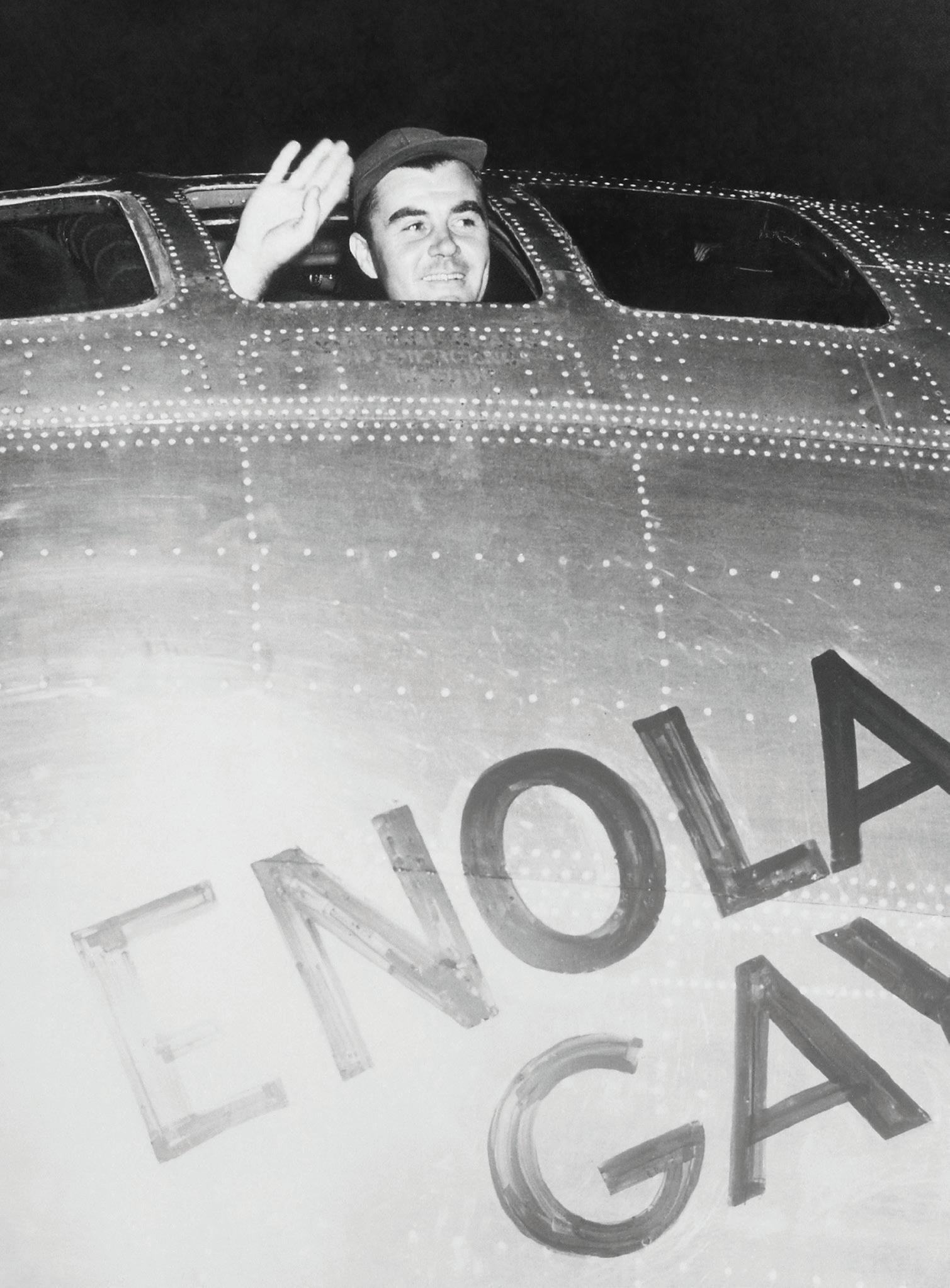

“Its branches include Maryland Governors Charles Carnan Ridgely and Edwin Warfield; The Great Gatsby author F. Scott Fitzgerald; and Paul Warfield Tibbets, who flew the Enola Gay to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Wallis Warfield Simpson, for whom King Edward VIII abdicated the throne of England, is also a relative, among others who were accomplished writers, soldiers, and doctors.”

My brain started to hyperlink…F. Scott Fitzgerald…Hiroshima…mon amour...the Duchess…abdication….

Well, I thought, this is a rather inclusive, if not revisionist, view of the family. I knew the Warfields were virile, but the extent of it was news to me.

David went on: “One of the first Warfields to become well known was Dr. Charles Alexander Warfield, who led a group from what is now Howard County — part of Anne Arundel County at the time — to Annapolis in 1774 to protest the arrival of a ship full of tea. Colonists had put an embargo on tea in protest of British taxes, and angry rebels demanded that the ship’s owner, Anthony Stewart, burn the ship or be hanged. Stewart chose to save his life.”

I was now flashing back to my father and his oft-heard dictum “Lead, follow, or get out of the way.”

12 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

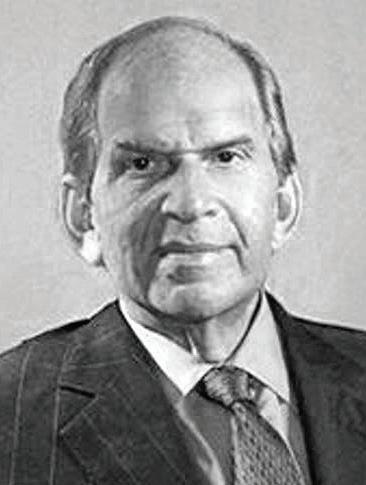

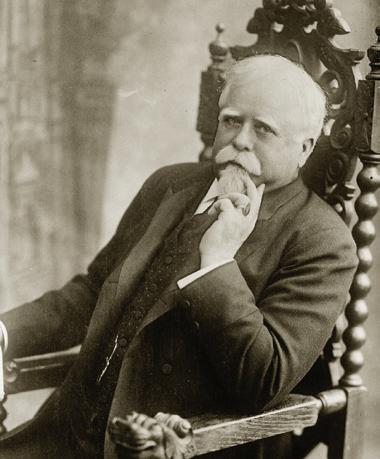

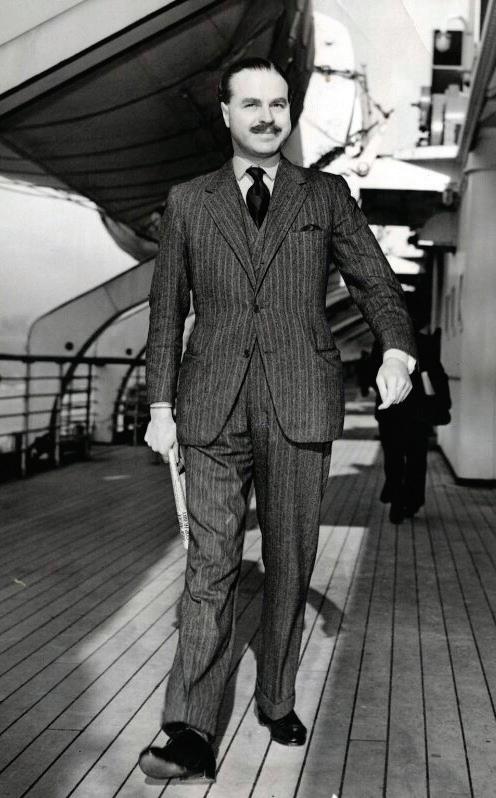

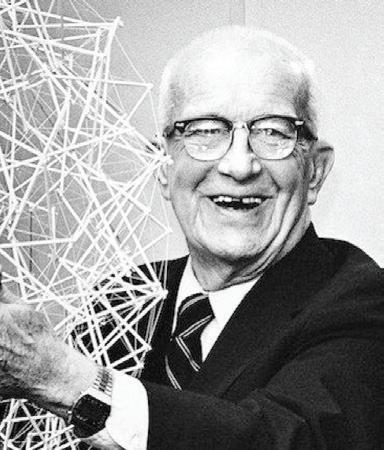

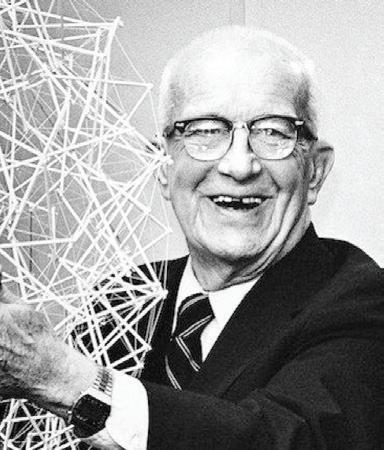

TOP TO BOTTOM:

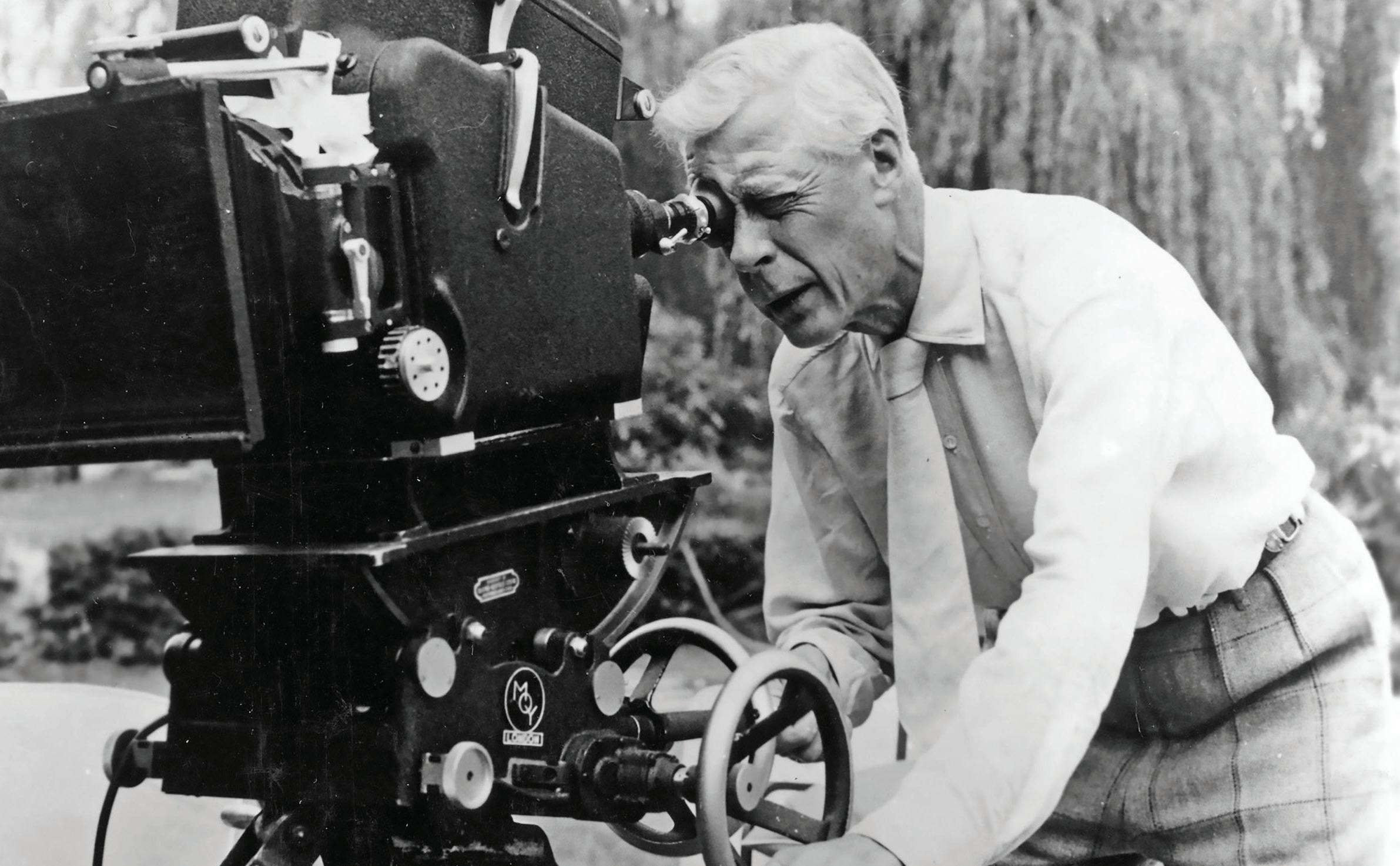

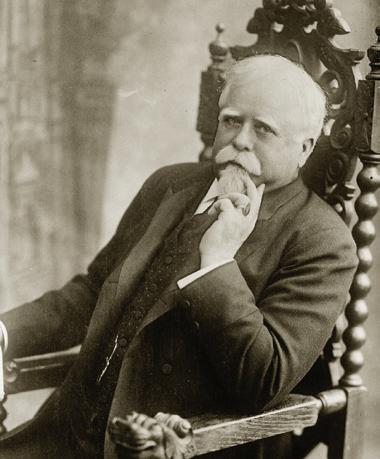

Dr. Charles Alexander Warfield, Governor Edwin Warfield, Paul Warfield Tibbets, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Our meetings with commercial banks and mezzanine capital sources went well that day, but it was hard to focus on fundraising knowing that my relatives were on display. And there was a new one, at least new to me: F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The Warfield/Fitzgerald familial connection traces back to 17th-century Maryland, making F. Scott and the Duchess of Windsor fifth cousins, once removed, as well as seventh cousins. Oh, and something of a non-literal tie exists through Scott’s wife, Zelda. One of the popular alma maters of a handful of Warfields is a place Zelda also frequented: Sheppard Pratt Hospital, described colorlessly on its website as “providers of mental health and addiction services.” (It would take 15 years before I realized I had another important genetic connection to Scott.)

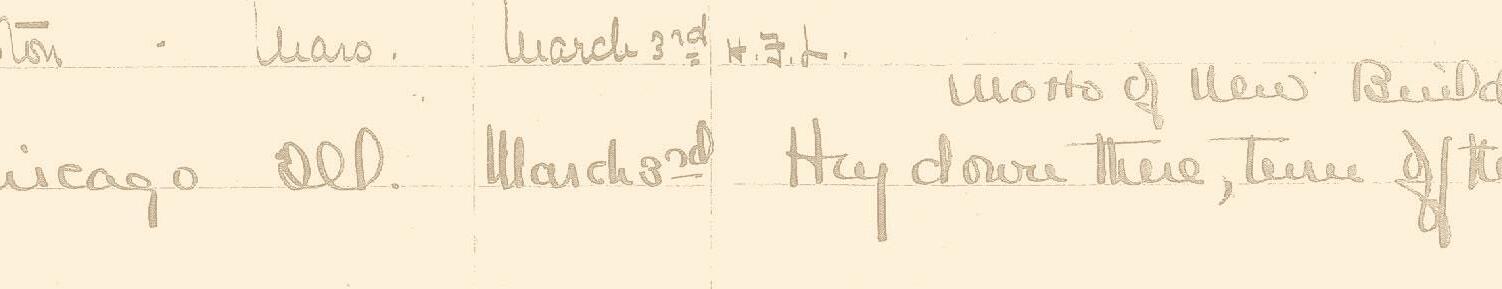

David returned that evening to his home in Massachusetts, and I returned to mine for an evening of online research. Thanks to Google, scripophily.com, ancestry.com, and eBay, I discovered various Warfield relatives. The jigsaw pieces of my family’s history were reassembling into a cascade of revelations and insights.

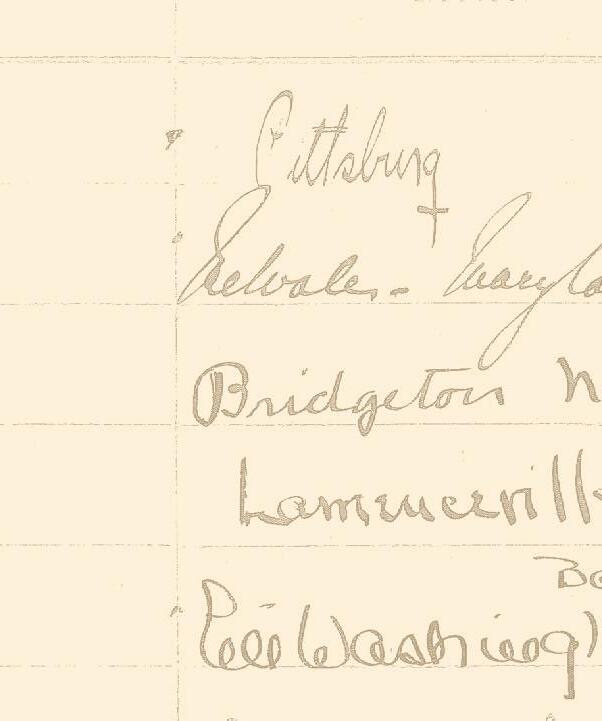

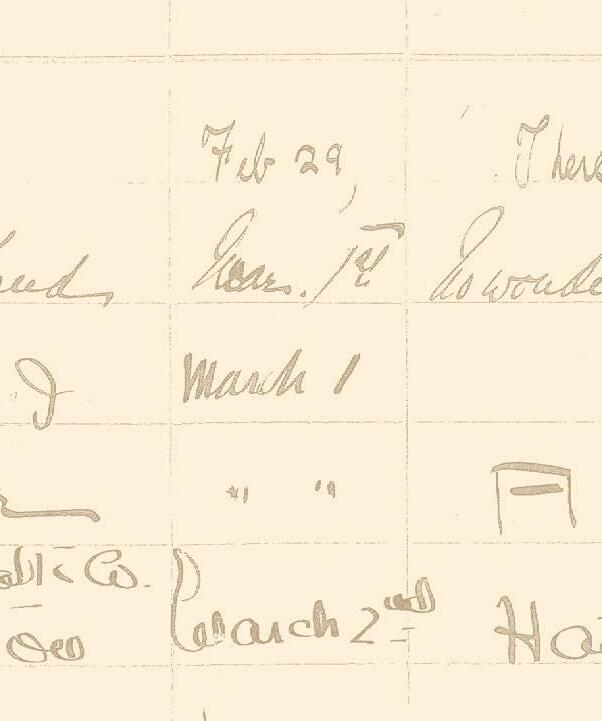

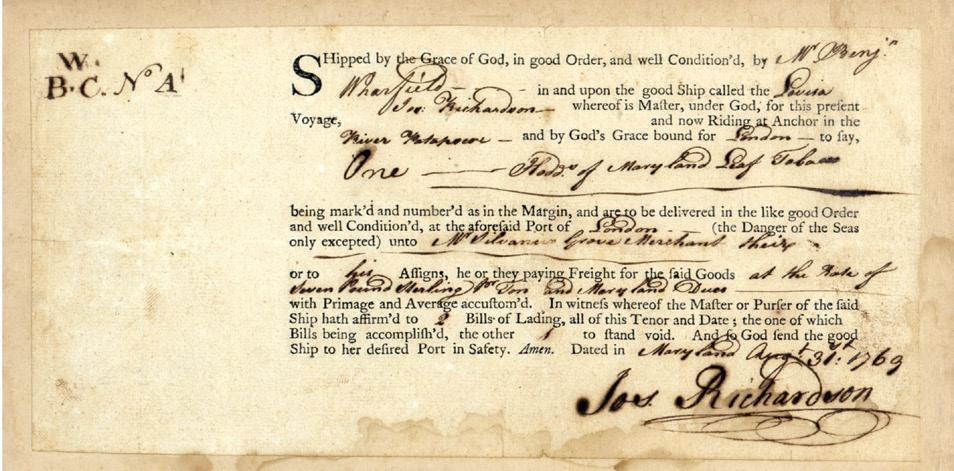

One of my first searches brought up a listing on scripophily.com — a website for historical documents and worthless stock certificates not traded by or on nasdaq, easdaq, LaBranche & Co., nyse, otc, Instinet, the pink sheets, or any other exchanges.

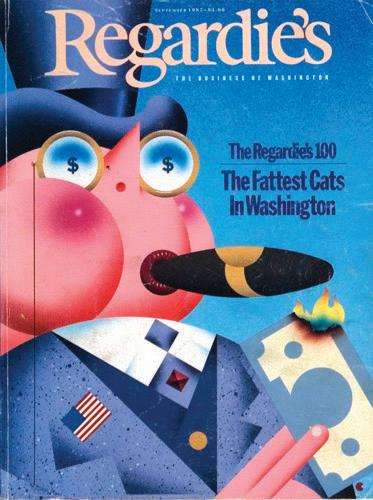

Given that the Warfields are Democrats and middle class — more adventurers than entrepreneurs — my search expectations were modest. Our wealth had peaked before 1860, with a slight uptick in 1889, and then a century of decline.

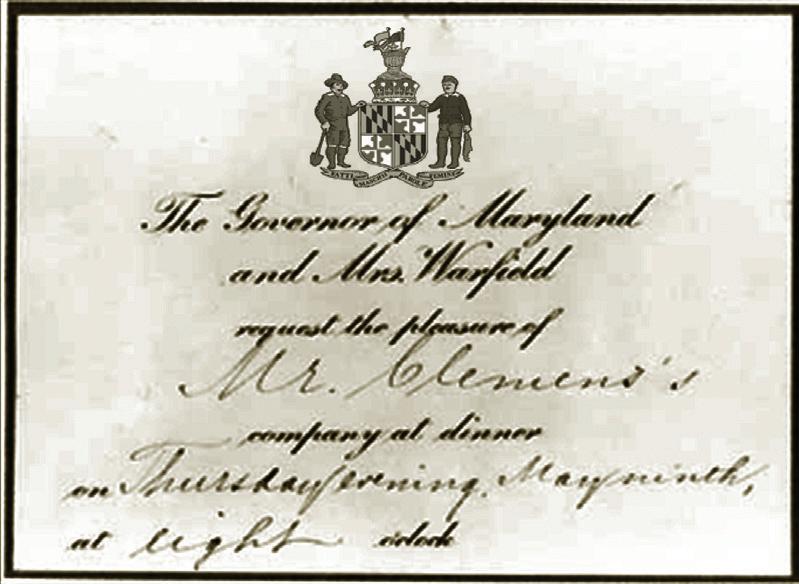

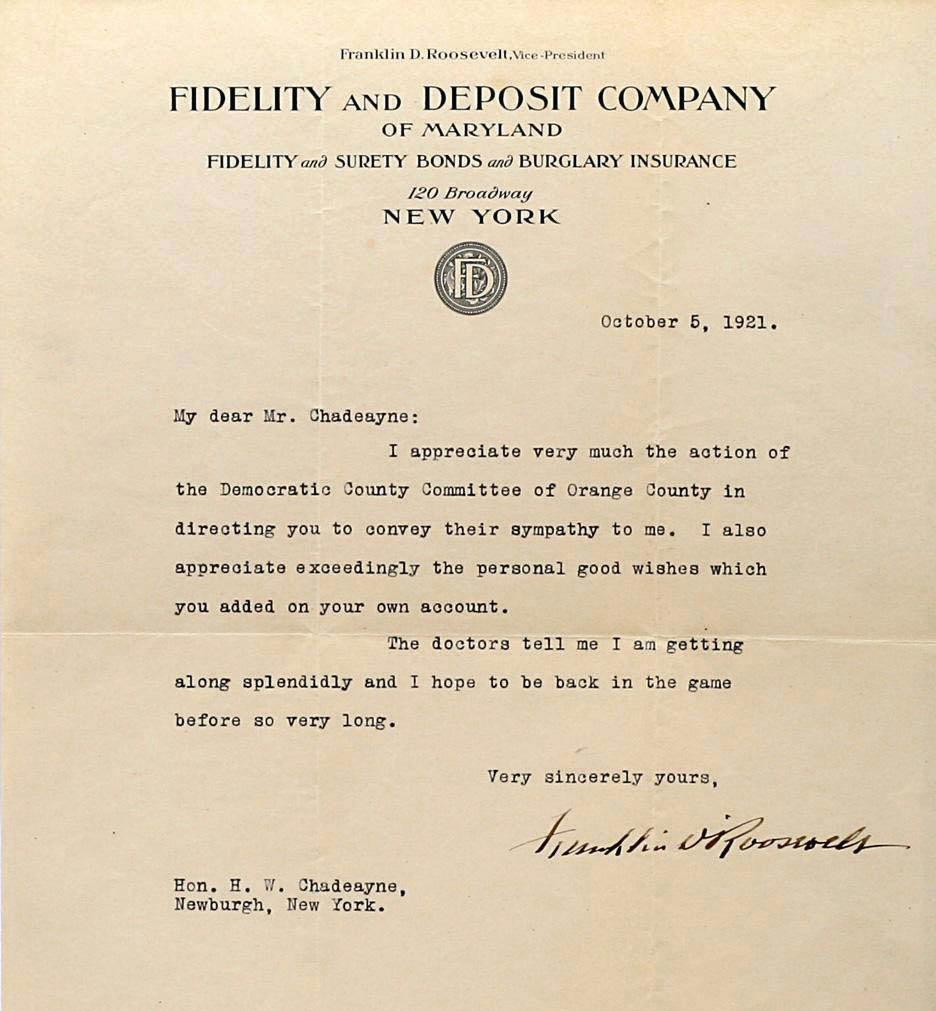

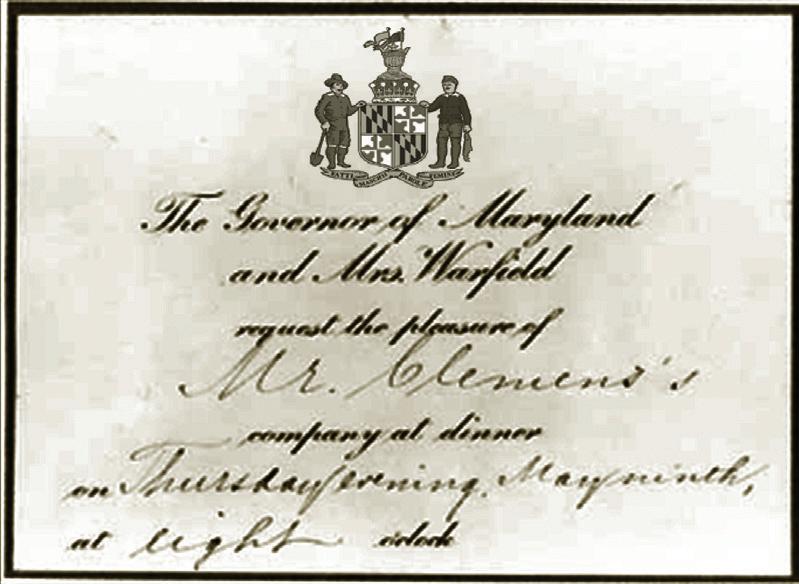

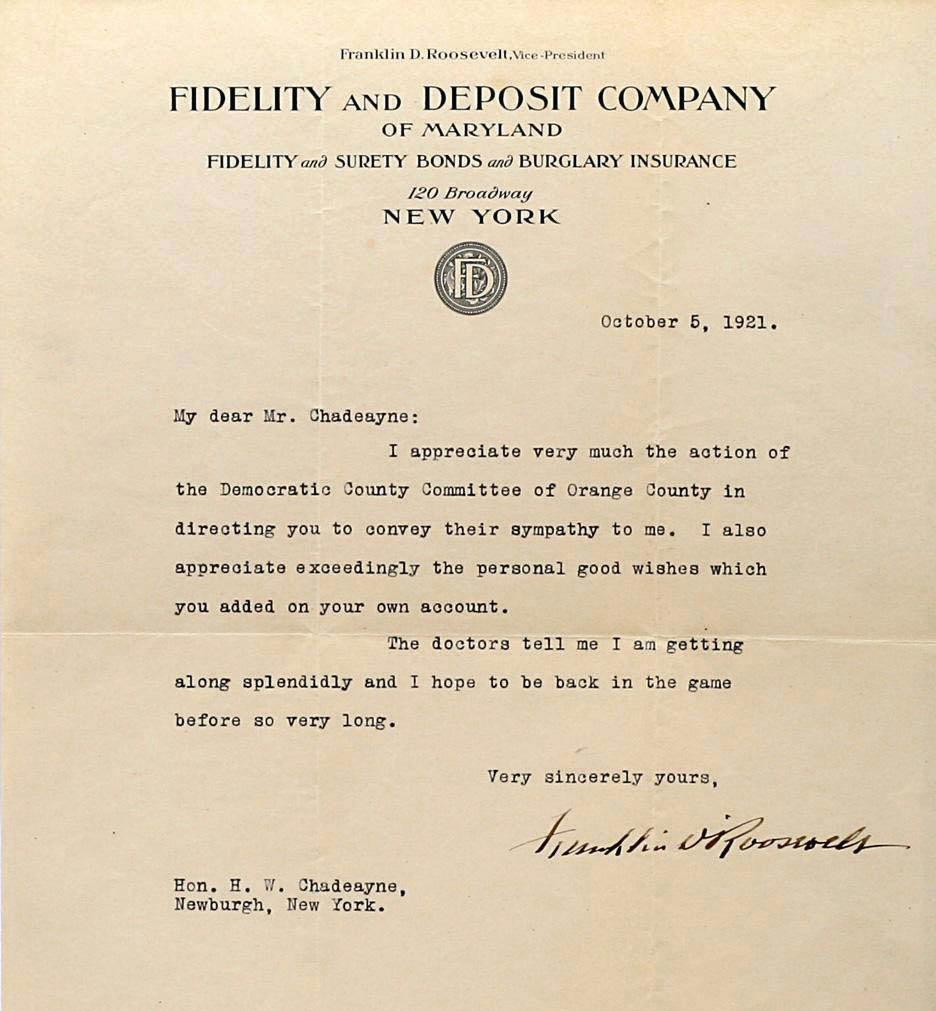

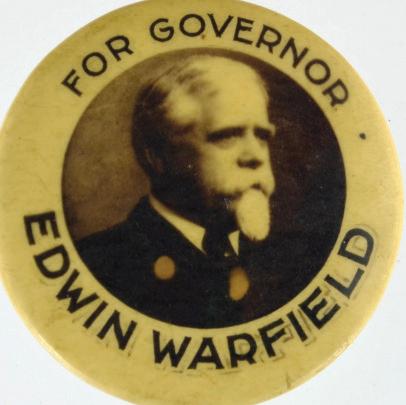

Up for sale on scripophily.com was a dwarf stock certificate from the Slide Mining Company of Ouray, Colorado; it was dated 1893 and signed by Edwin Warfield, president of the Fidelity and Deposit Company. Founded by my great-grandfather Edwin Warfield (later Governor of Maryland, 1904 to 1908), Fidelity and Deposit Company was one of only a handful of companies involved in the bonding business back then.

From the certificate’s inscription: “Ouray was founded in 1876. The first non-Indians in the valley were looking for gold and silver. Ouray is nestled in the San Juan Mountains, the Shining Mountains of the Ute Indians — their sacred hunting grounds.”

The first Edwin Warfield, it seems, had backed gold and silver speculators — derivative adventures in America. Now, I, too, was mining in America, this time for family history.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 13

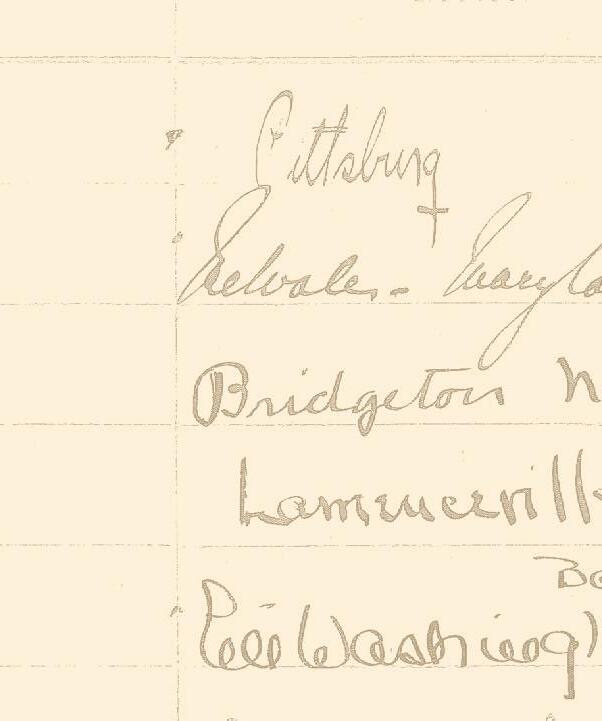

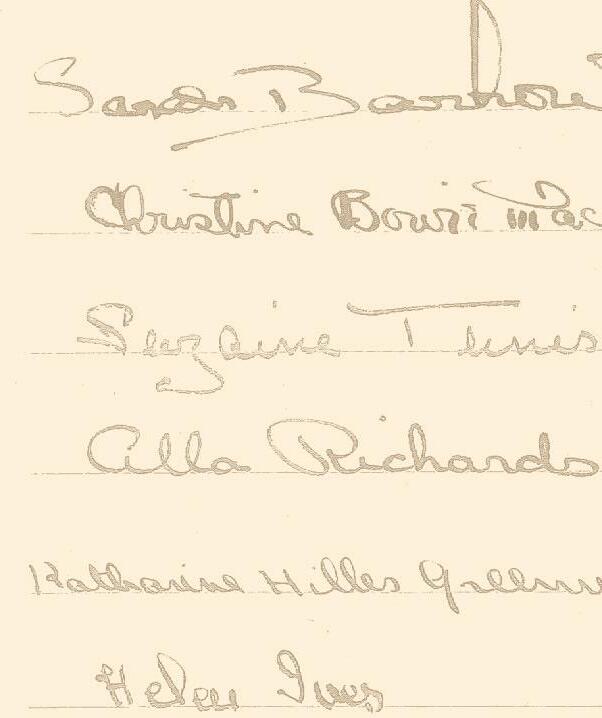

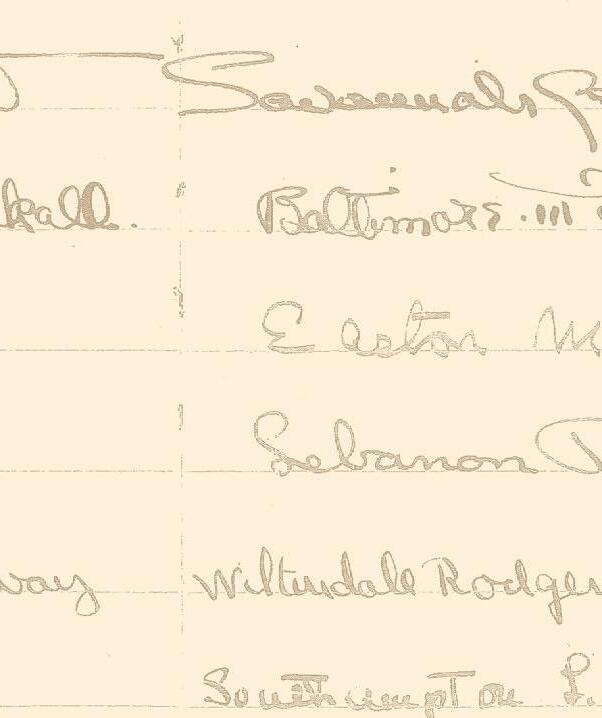

Pictures at an Exhibition

The Warfield exhibit at the Howard County Historical Society opened on November 22. I was expecting a folksy atmosphere, at least from a curatorial perspective, and I was not disappointed. I looked around the room. There were many strains of Warfields, few of whom I knew. The exhibit had brought us all together: teachers, lawyers, farmers, real estate agents, political consultants, a biotech entrepreneur from San Diego, and one Republican Warfield — perhaps the first in 300 years (somebody needed to check his DNA). There definitely was no royalty, just modest, hard-working, made-in-America Warfields.

The day before, I had dropped off a few of my personal heirlooms for the exhibit: a prize cup presented to Governor Edwin Warfield by the City of Baltimore declaring him “the most handsome Governor”; manuscript letters by my grandfather from his trip around the world in 1912-1913; a print of the Governor founding the Fidelity and Deposit Company; and a Gorham silver cup dedicated to the Governor, which I purchased at a local auction. (My father, incidentally, had minimal interest in family artifacts and had sold or given most of them away over the years, a kind of personal purging.)

Before I acquiesced to lending my Warfield items, I negotiated the inclusion of a photograph of my son, Win, resplendent and warrior-like in his high school hockey uniform. I ceremoniously placed it on a table at the end of the exhibit with a small sign that read “Edwin Warfield, West Palm Beach, Florida.”

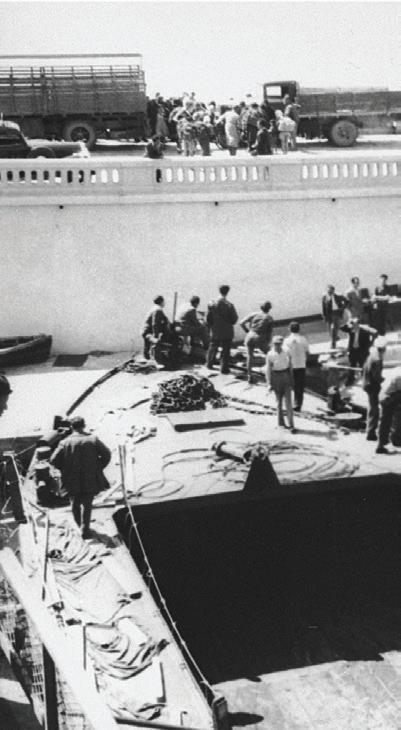

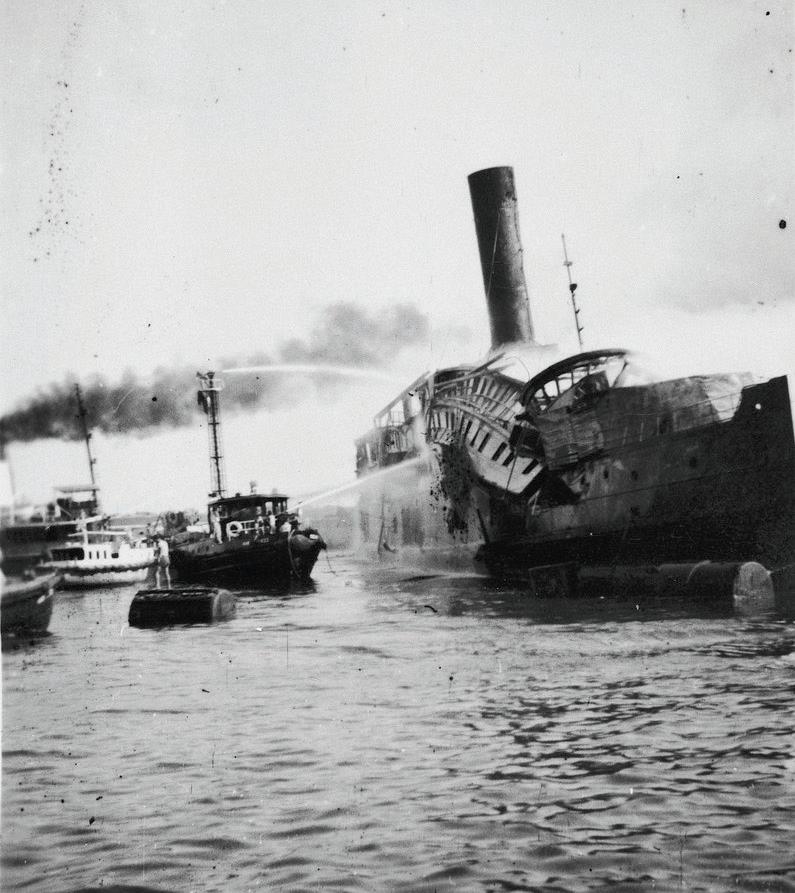

Randomly yet purposefully, I began perusing the exhibit. In the first display case was a piece of charred wood from the Peggy Stewart, the ship that was burned because of its cargo of tea.

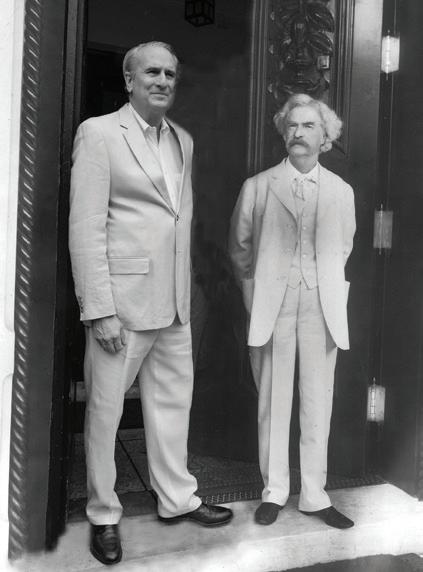

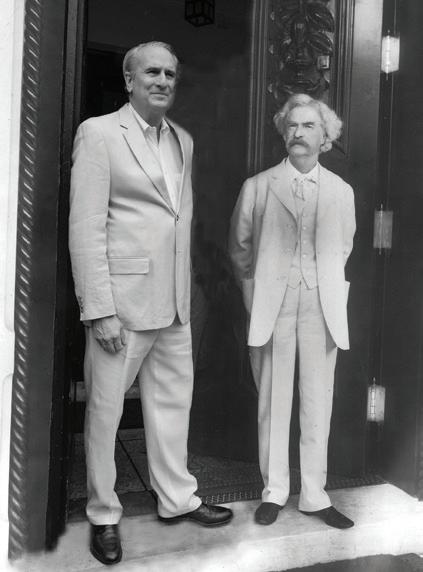

Next, there was a chair believed to have been made by an 18-year-old Edwin Warfield when he worked as a schoolteacher; there was also a photograph of the Governor with prominent late-19th/early-20th century Democratic politician and orator William Jennings Bryan.

I read a framed story about the Governor’s two older brothers, Albert Jr. and Gassaway, both of whom served in the Civil War (the former was imprisoned

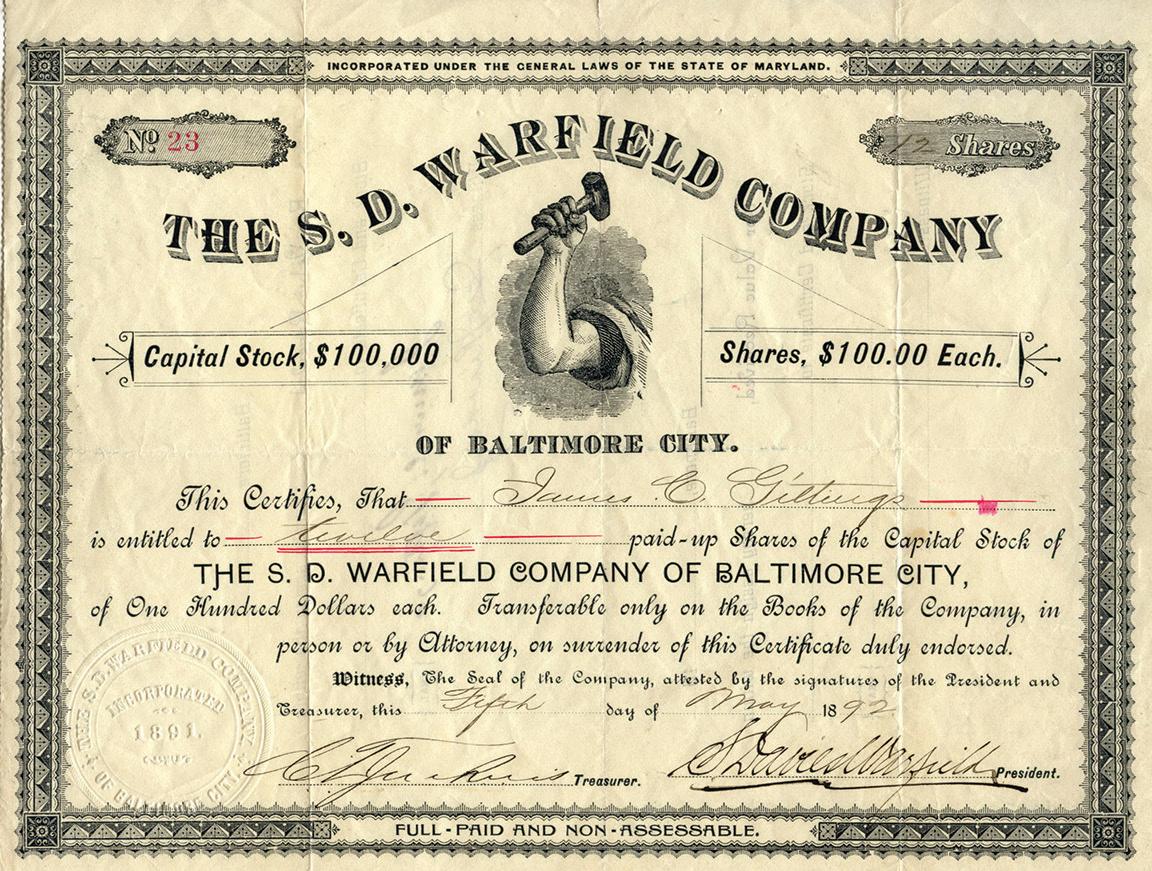

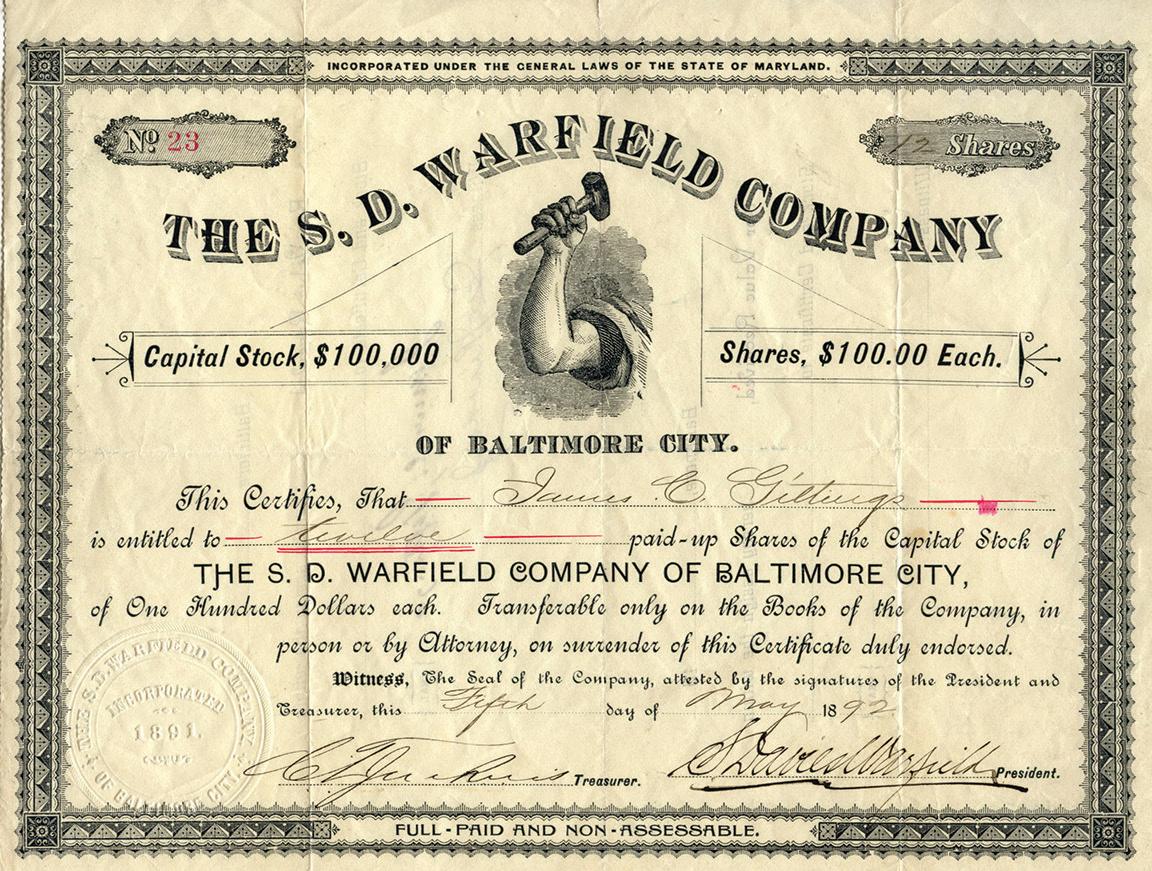

Taking stock: late-19th century certificate from a firm owned by Solomon Davies Warfield, Wallis’ “Uncle Sol”

14 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

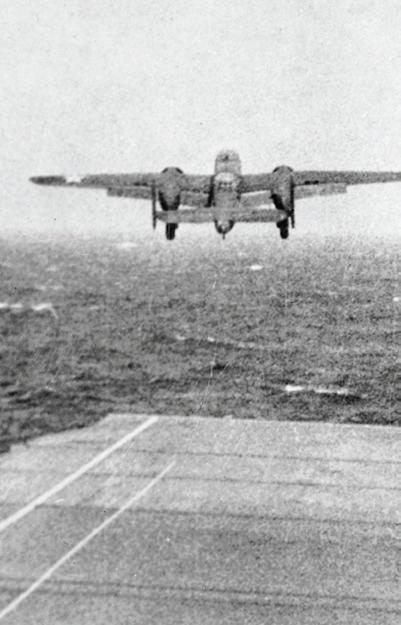

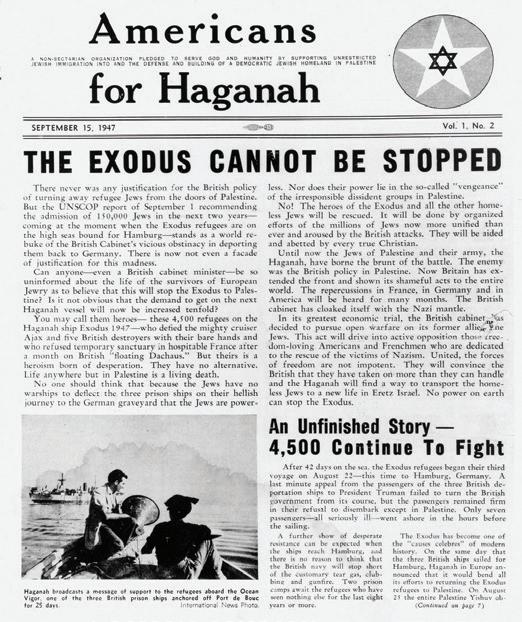

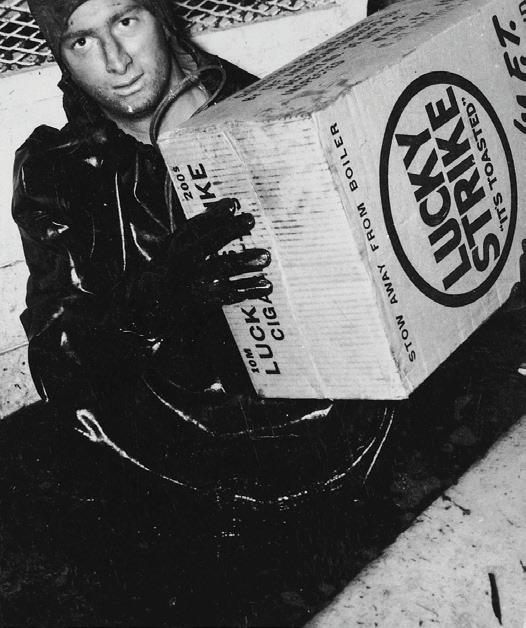

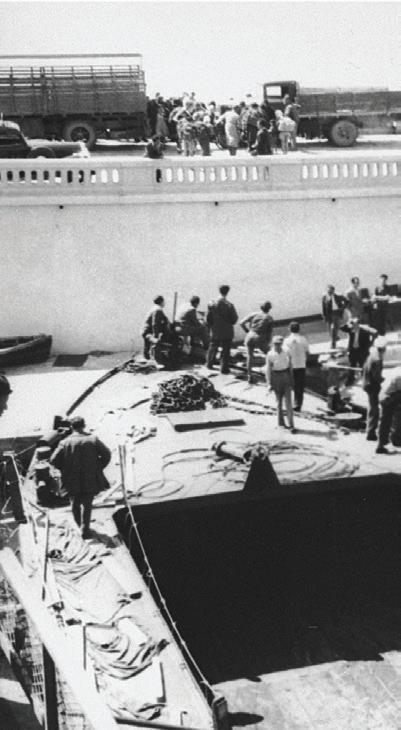

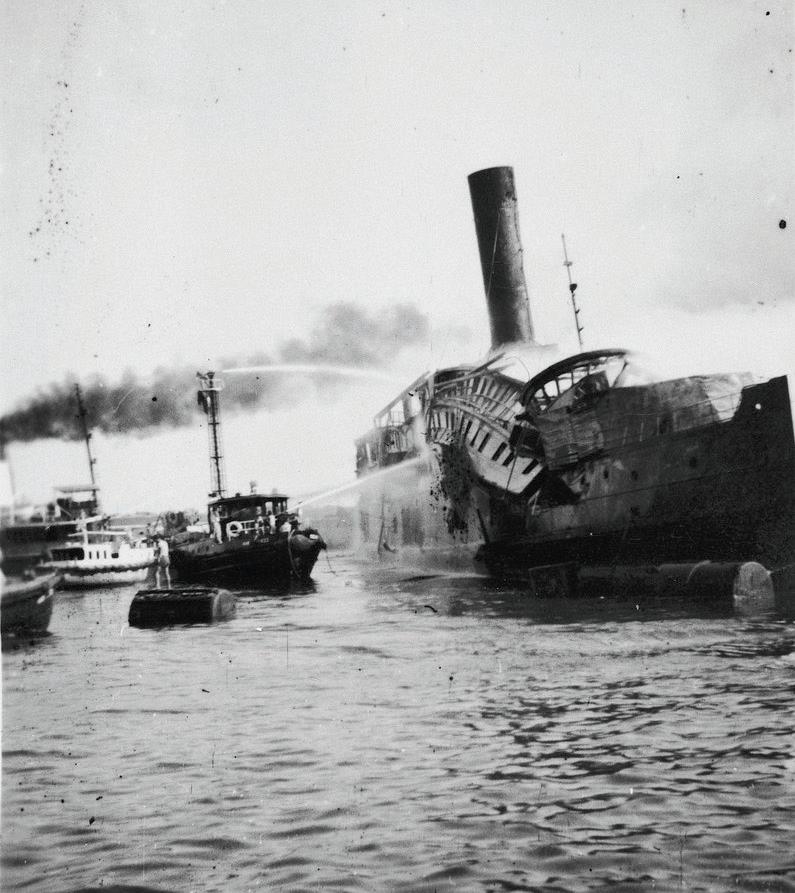

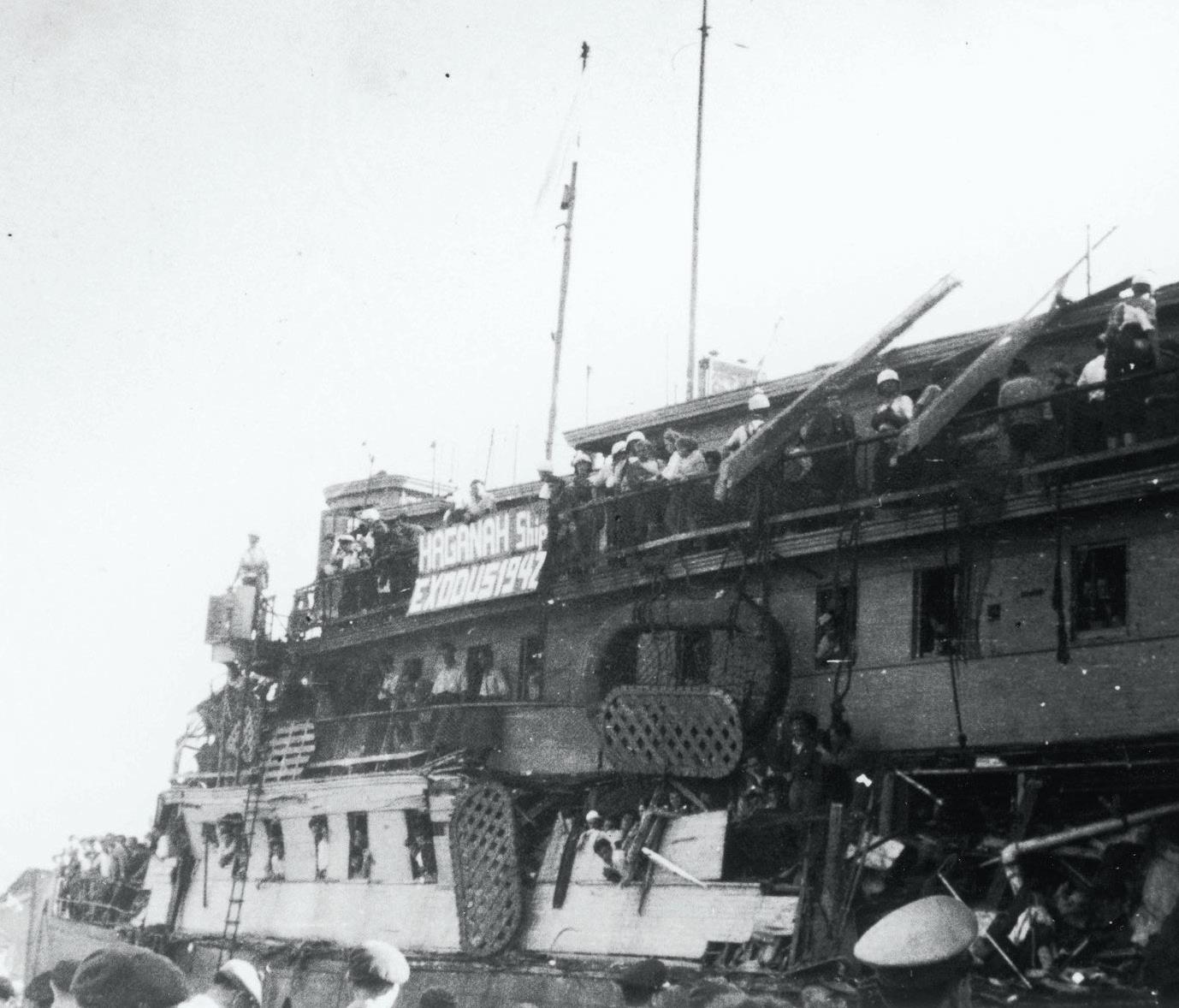

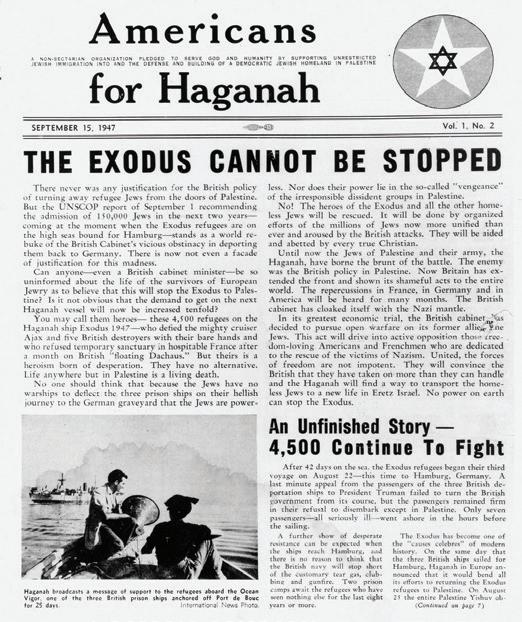

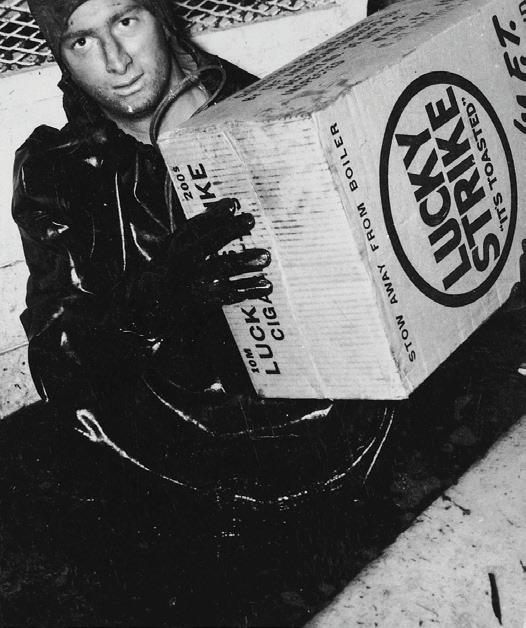

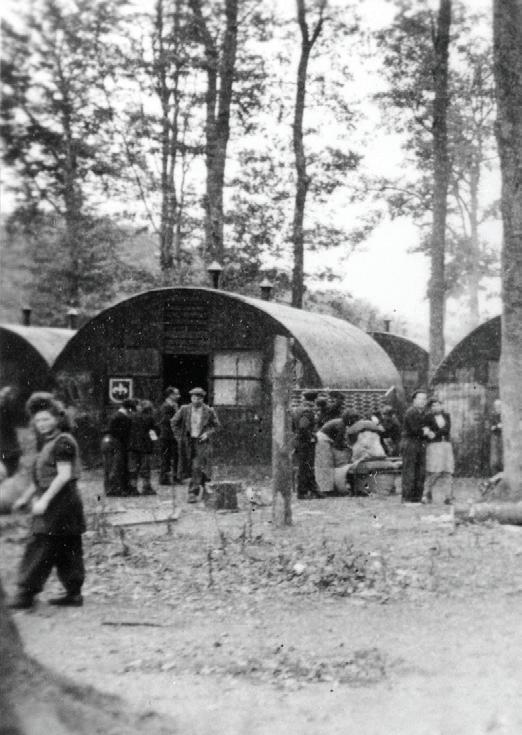

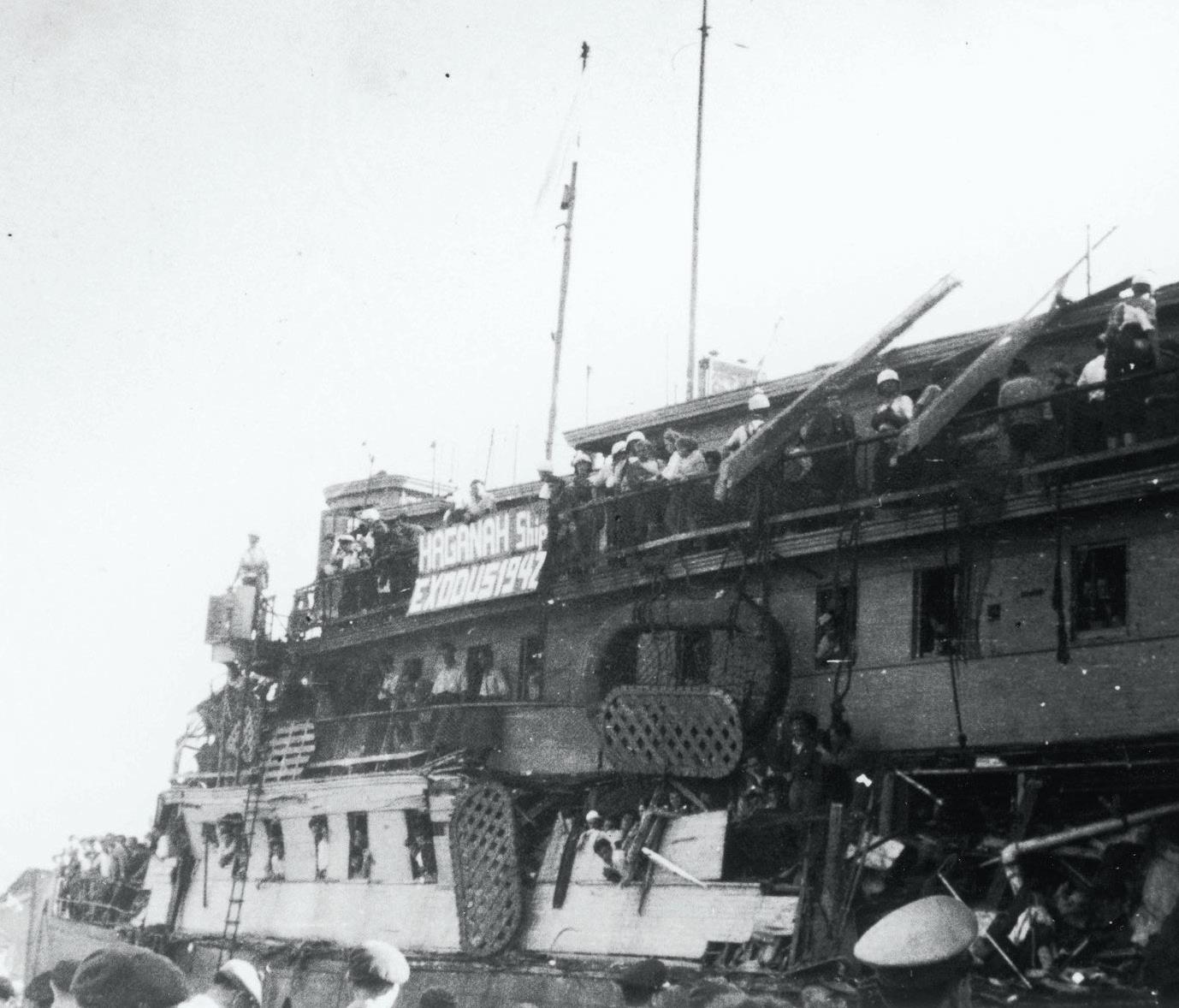

twice, the latter died a prisoner of war). There were pictures of Warfield Church, founded in the town of Warfield, Berkshire, England, and a poster of Paul Warfield Tibbets, and the Enola Gay. I was especially intrigued by the story of the President Warfield, the ship that carried displaced Jews (homeless after WWII) to Israel in 1947.

There were many more photographs, knick-knacks, swords, and uniforms. My curiosity about my past was overwhelming. It was time to drive back to Baltimore. Before leaving, I glimpsed inside a case that included samples of work by various Warfield writers: Professor Joshua Warfield, F. Scott, Warfield Lewis, Clare Hill, and Dr. George Scheele. Warfields as authors. That was news.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 15

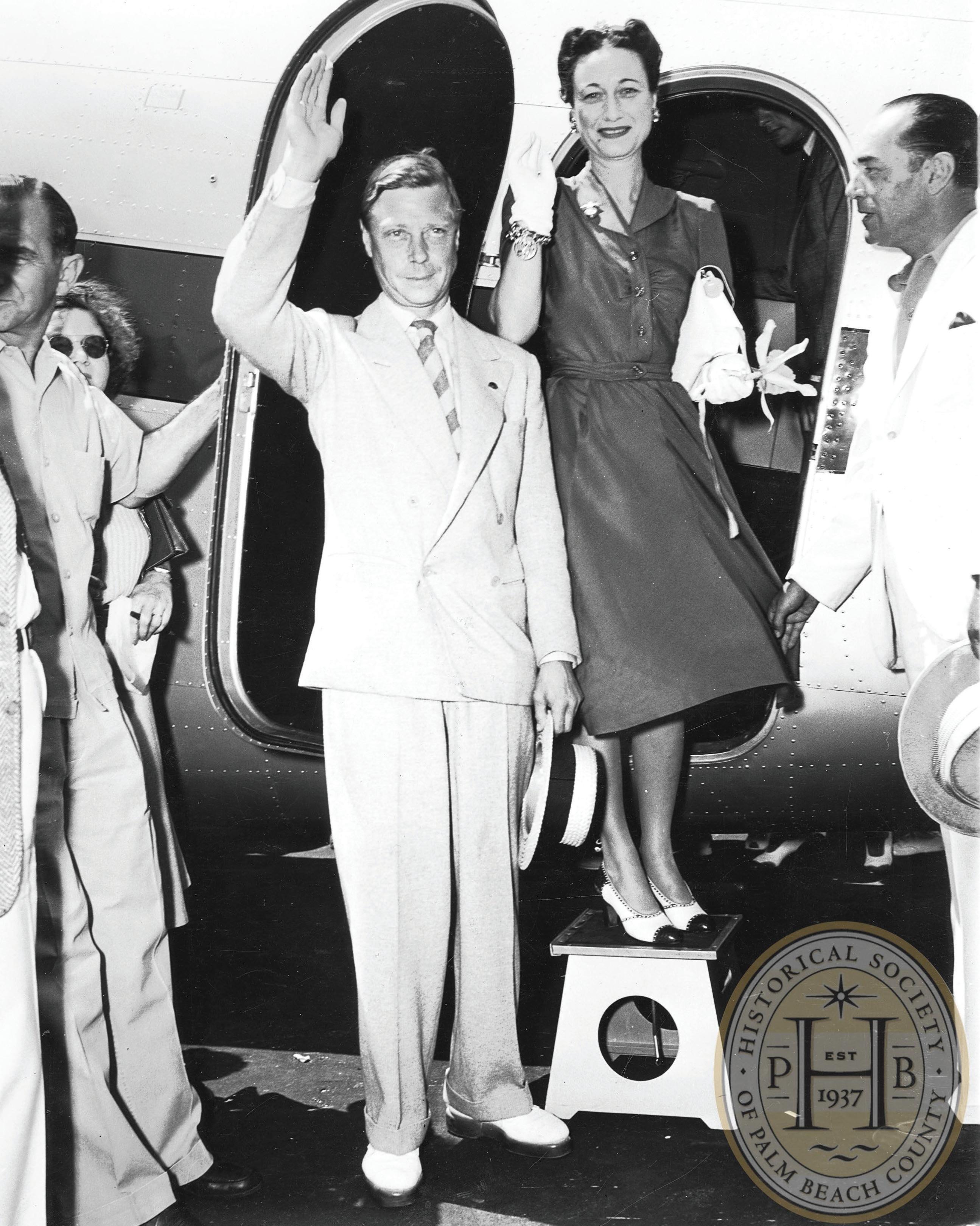

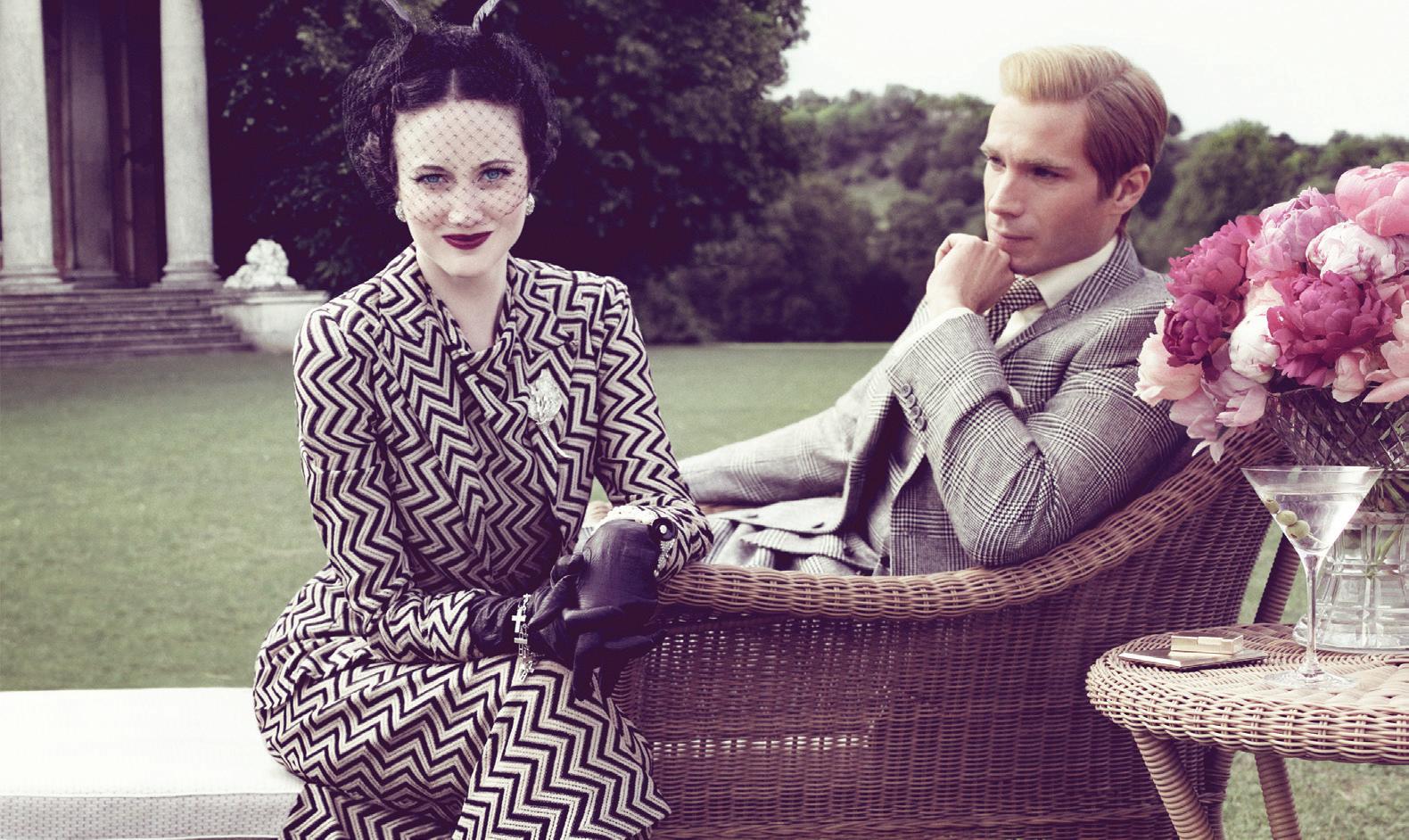

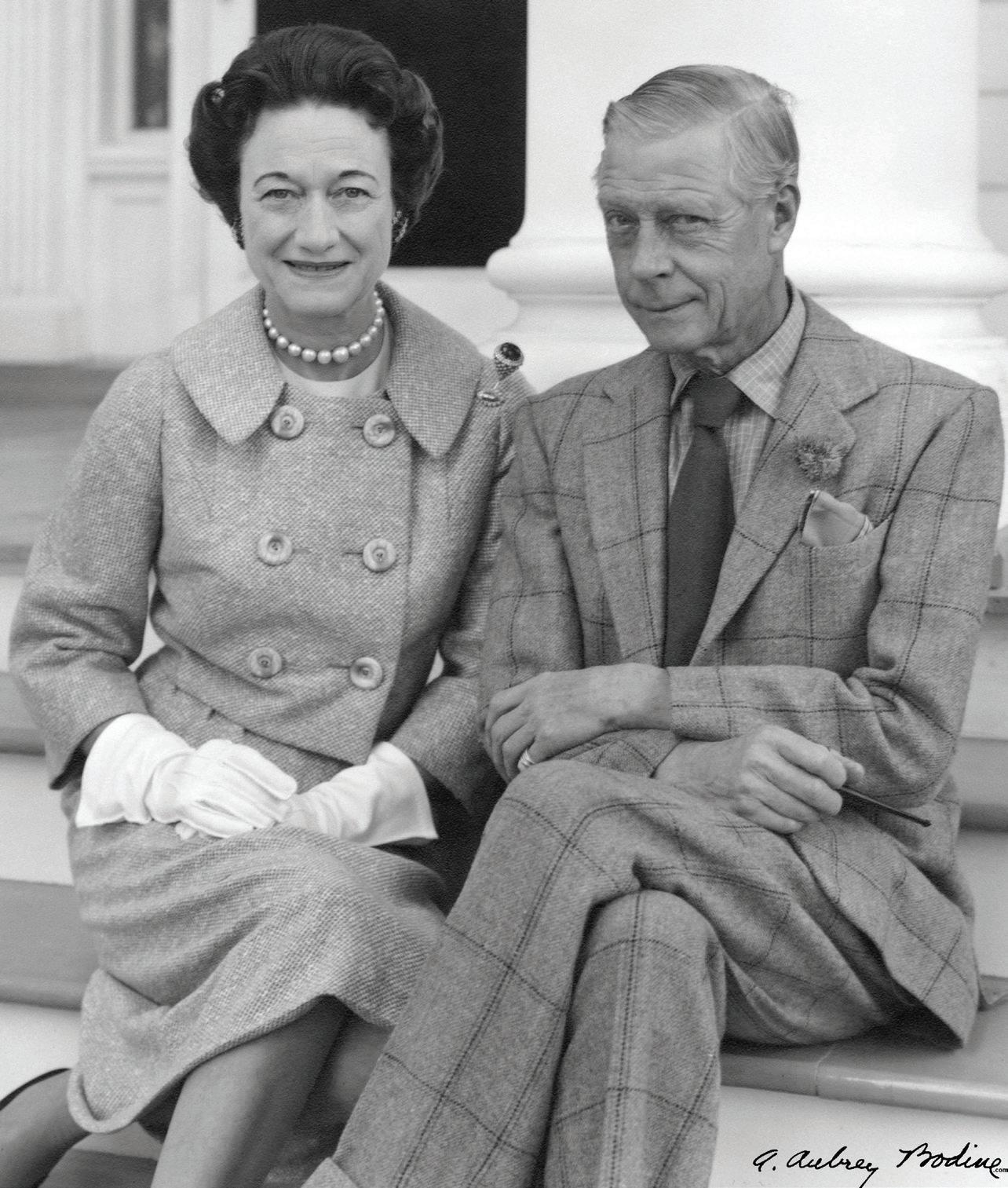

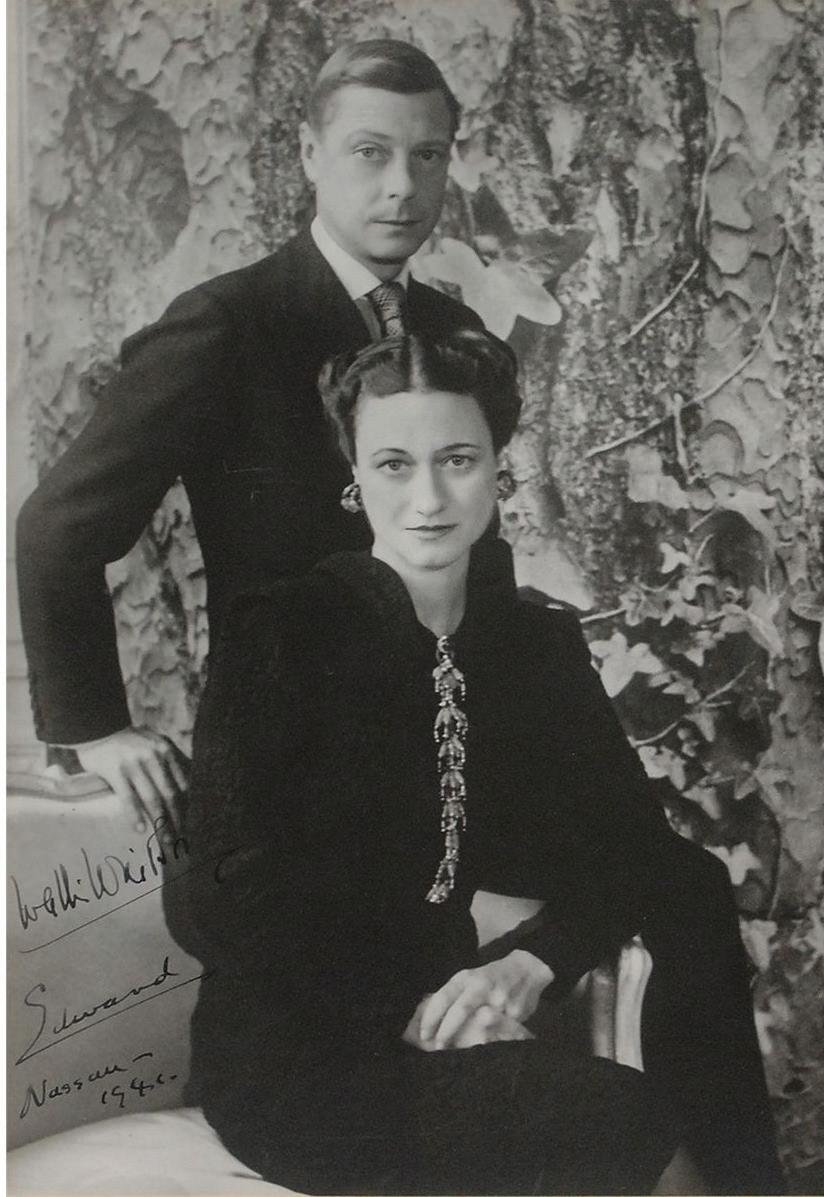

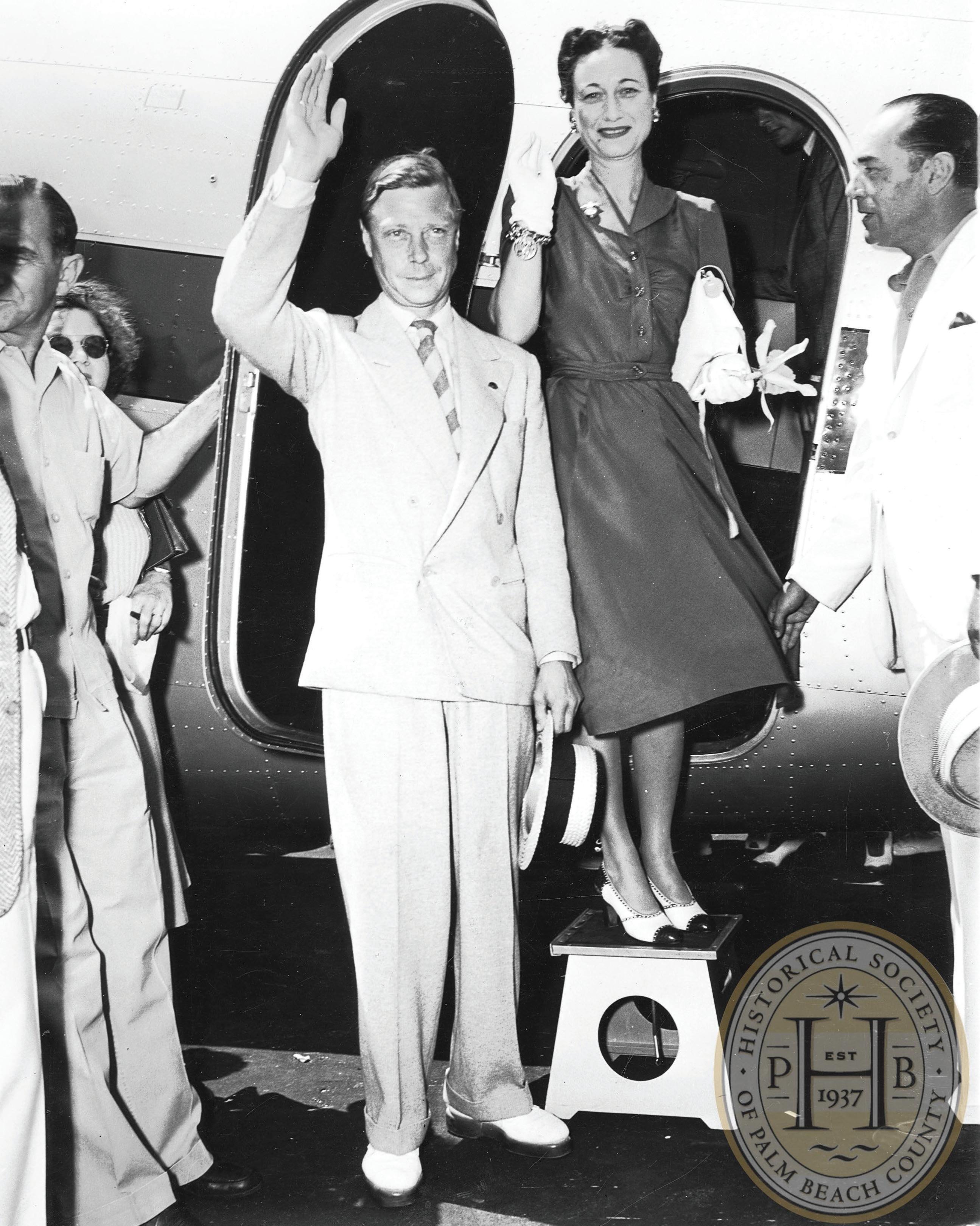

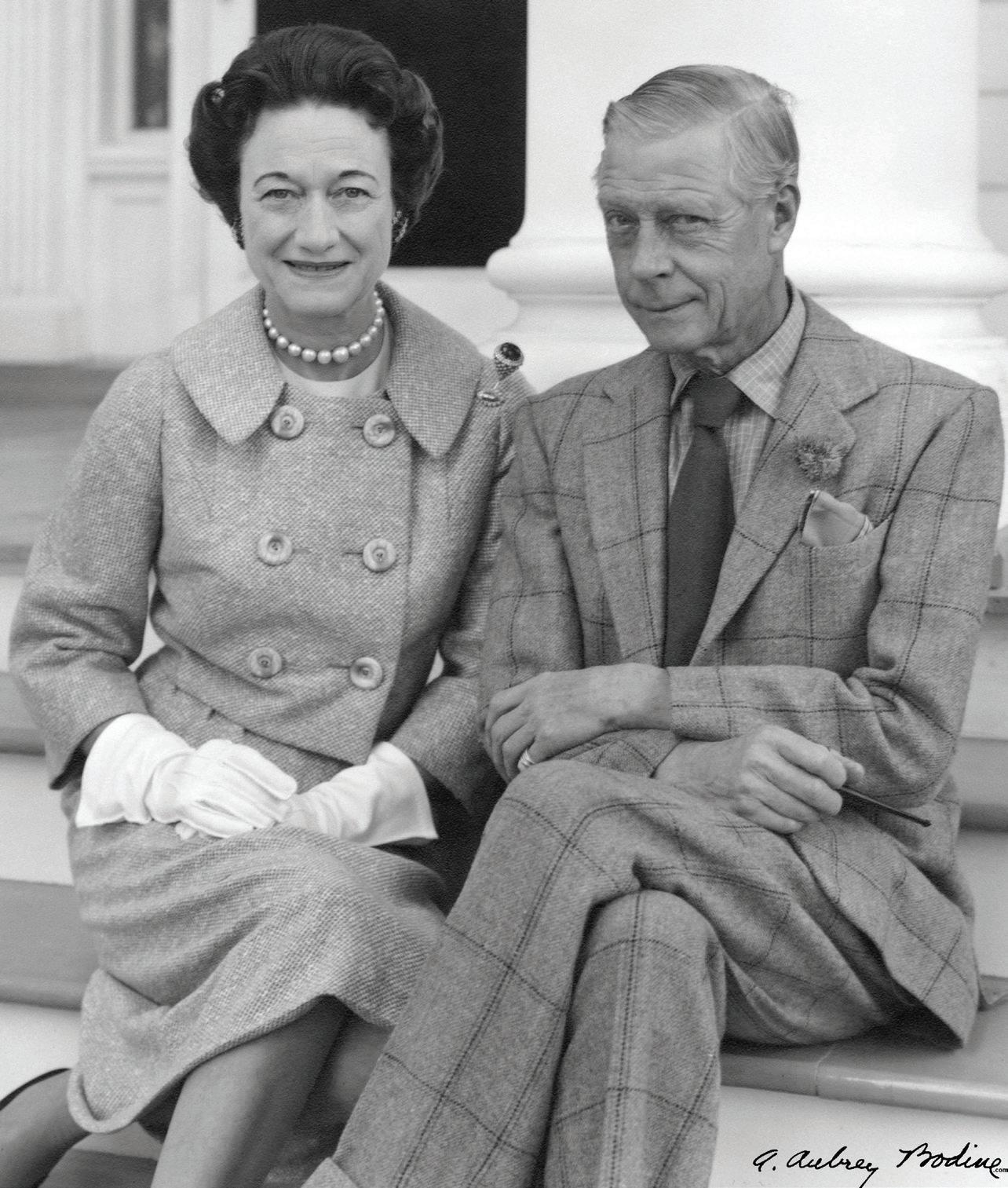

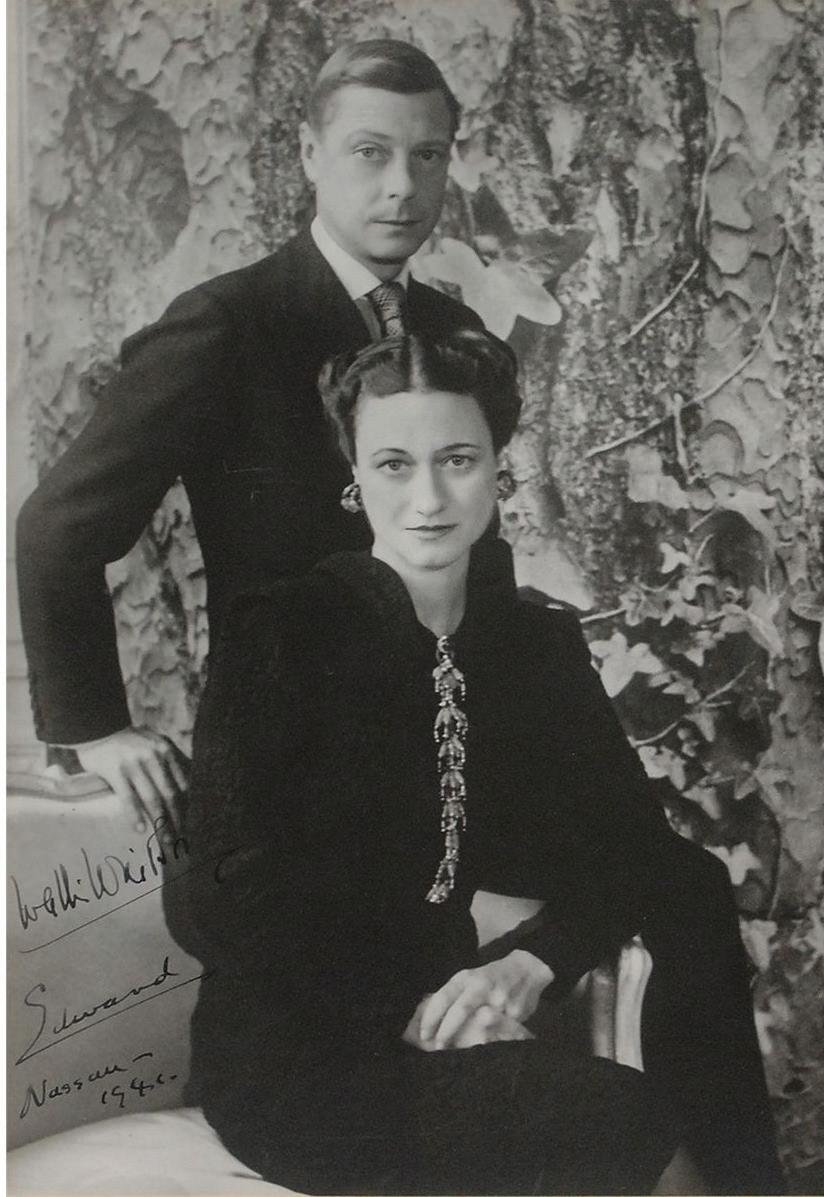

The Duchess and Duke of Windsor in Maryland

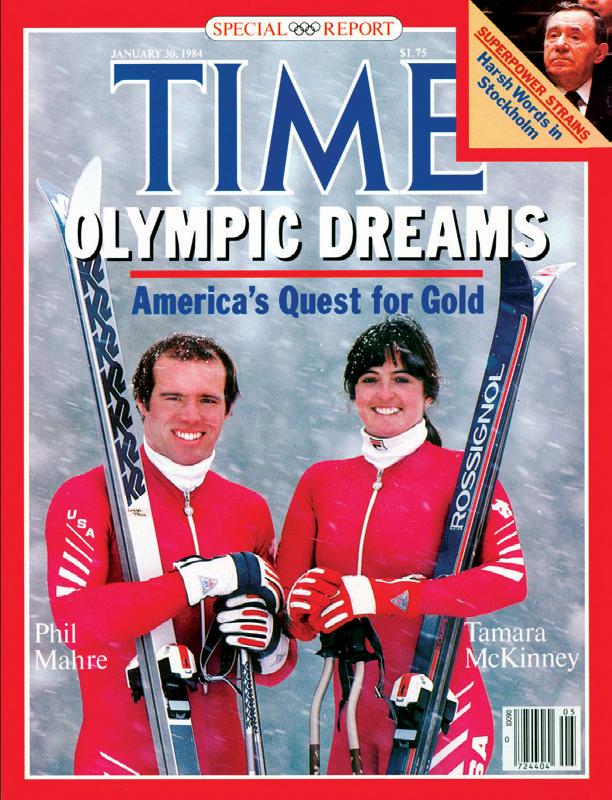

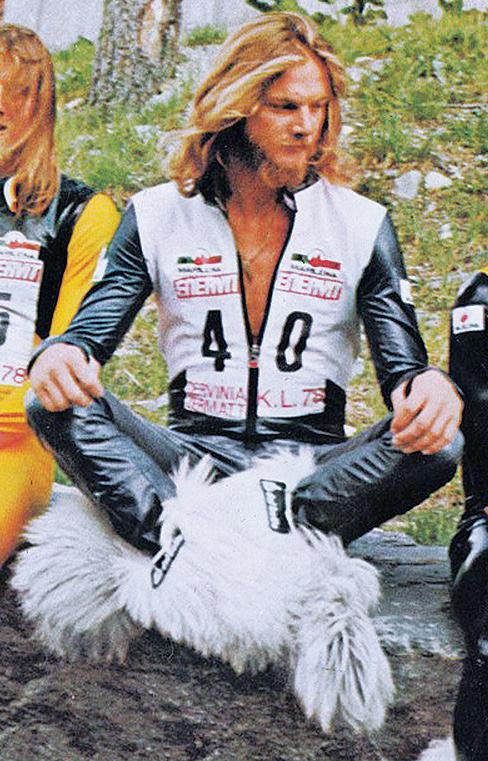

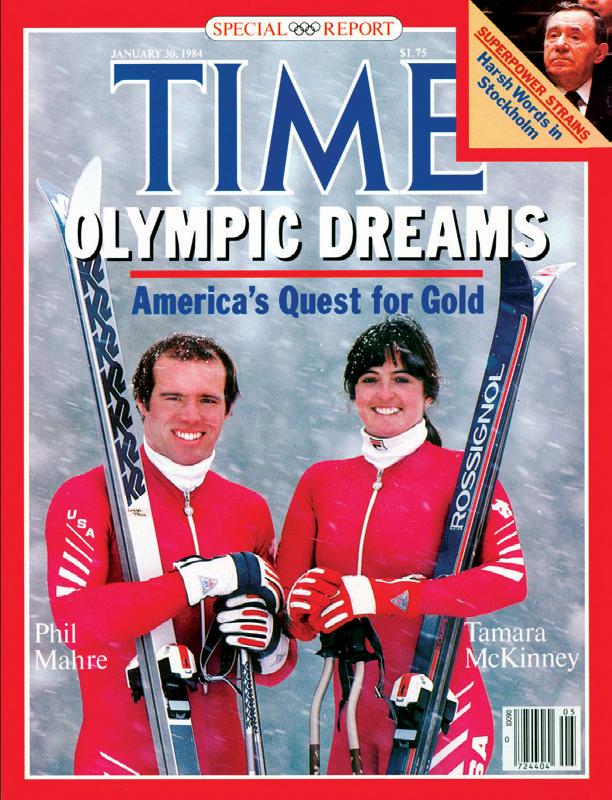

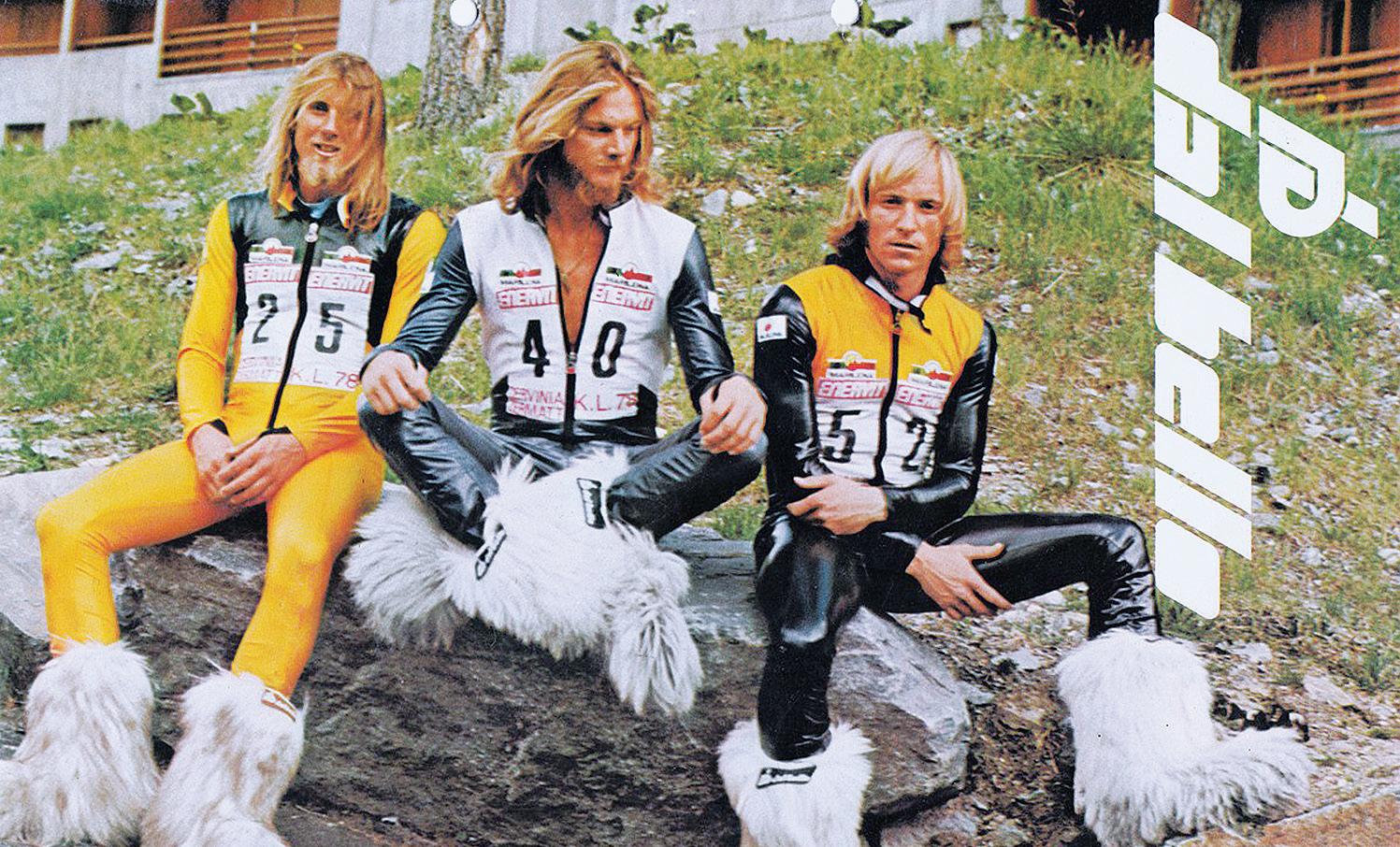

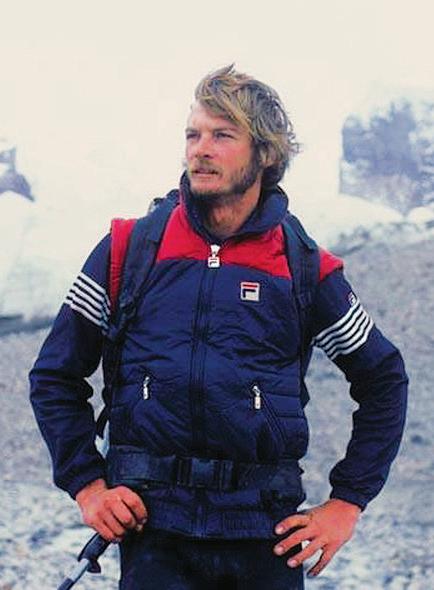

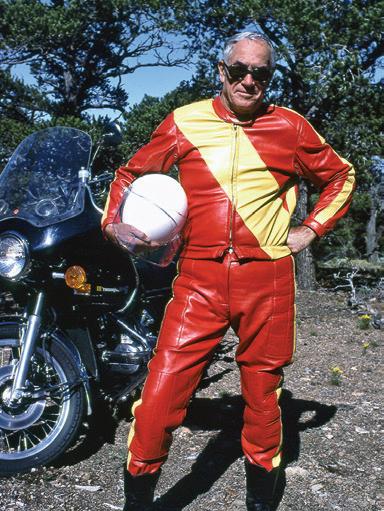

I left knowing that the exhibit had failed to include some important dead Warfields who had inspired me. Where was my cousin Steve McKinney, four-time holder of the World Speed Skiing record? And where was Steve’s sister Tamara, the nine-time U.S. Ski Champion who won four World Cups?

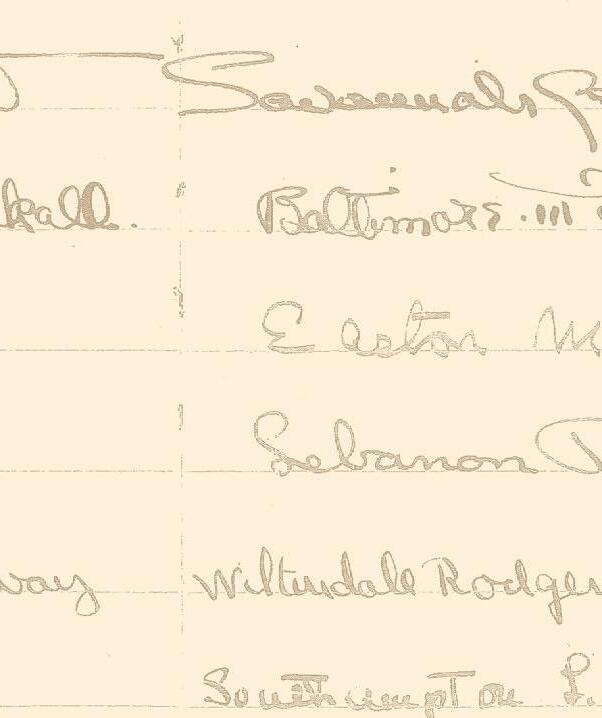

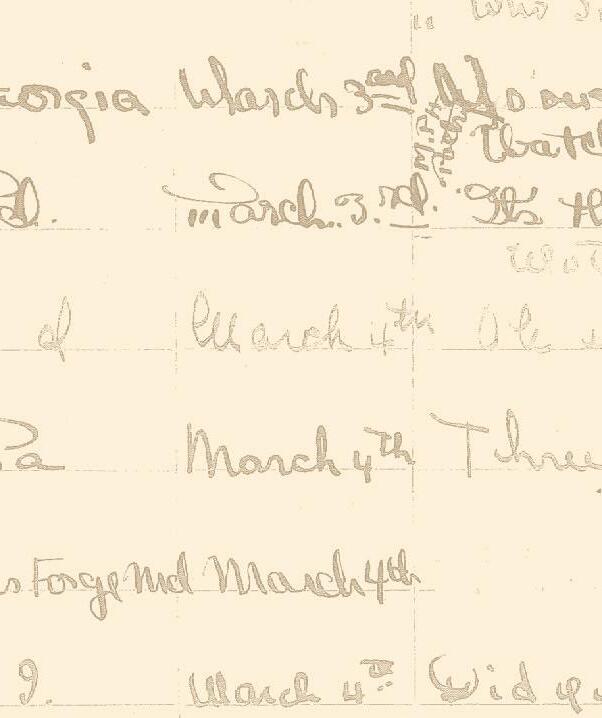

I also came away suspecting that there were many more Warfields waiting to be disinterred and remembered. So I returned to my online search and found one new to me, Solomon Davies Warfield, when I purchased from scripophily.com what the site described as a “beautifully engraved certificate from the S.D. Warfield Company issued in 1892” — a stock certificate, it turns out, for an 1880s “planned community” in Indiantown, Florida. A muscular arm holding a sledgehammer is etched into the certificate’s center.

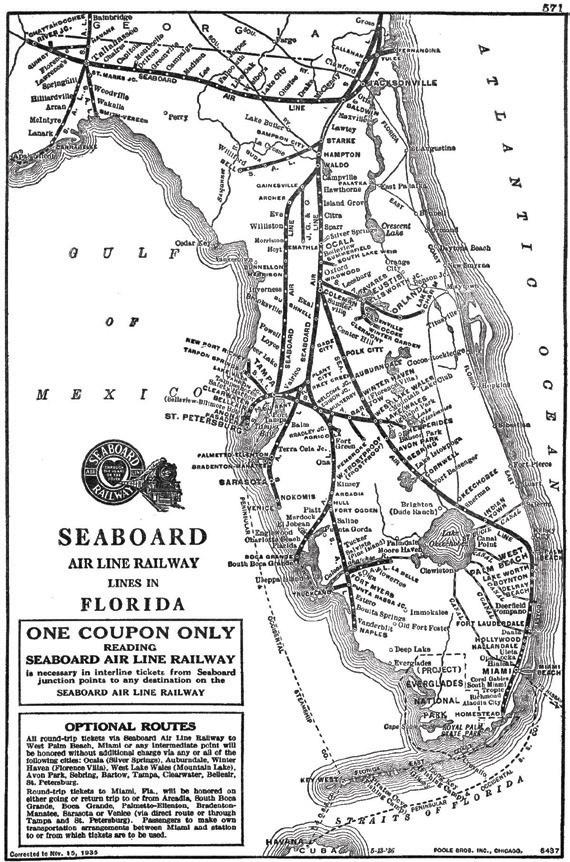

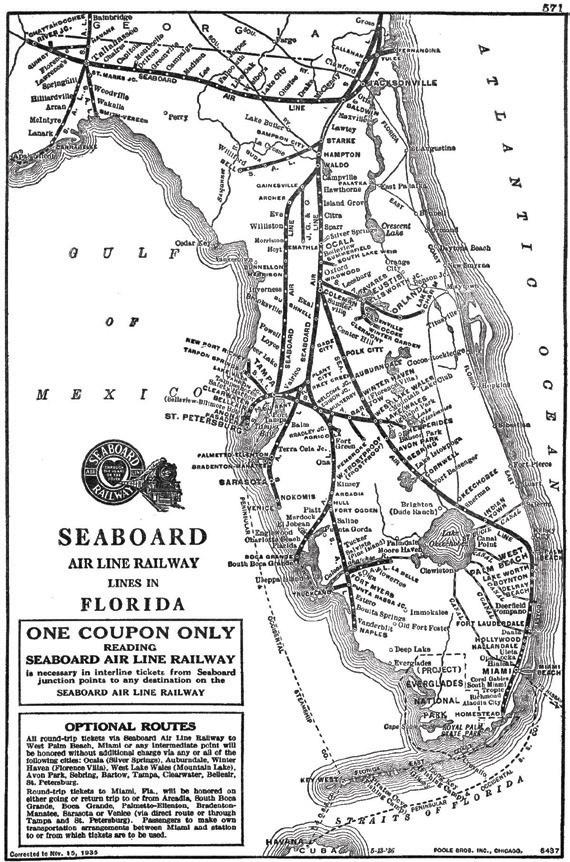

According to the Harvard Business School list of Great American Leaders of the 20th century, Solomon Davies Warfield was a world-class businessman who, as president of Seaboard Air Line Railroad, expanded the route from Virginia and North Carolina south into Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and north into Washington, D.C., and New York. Not insignificantly, he was also the uncle and occasional benefactor of Wallis Warfield before she became the Duchess of Windsor.

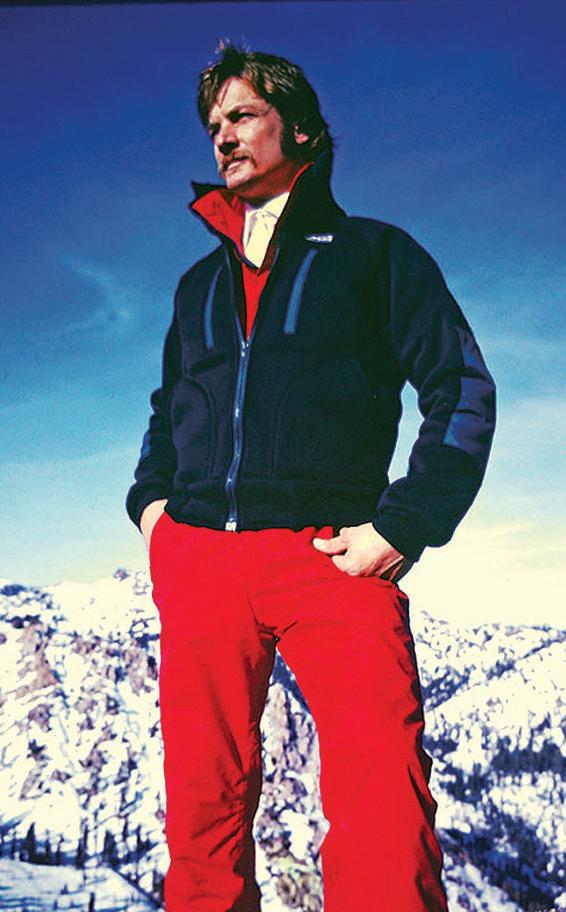

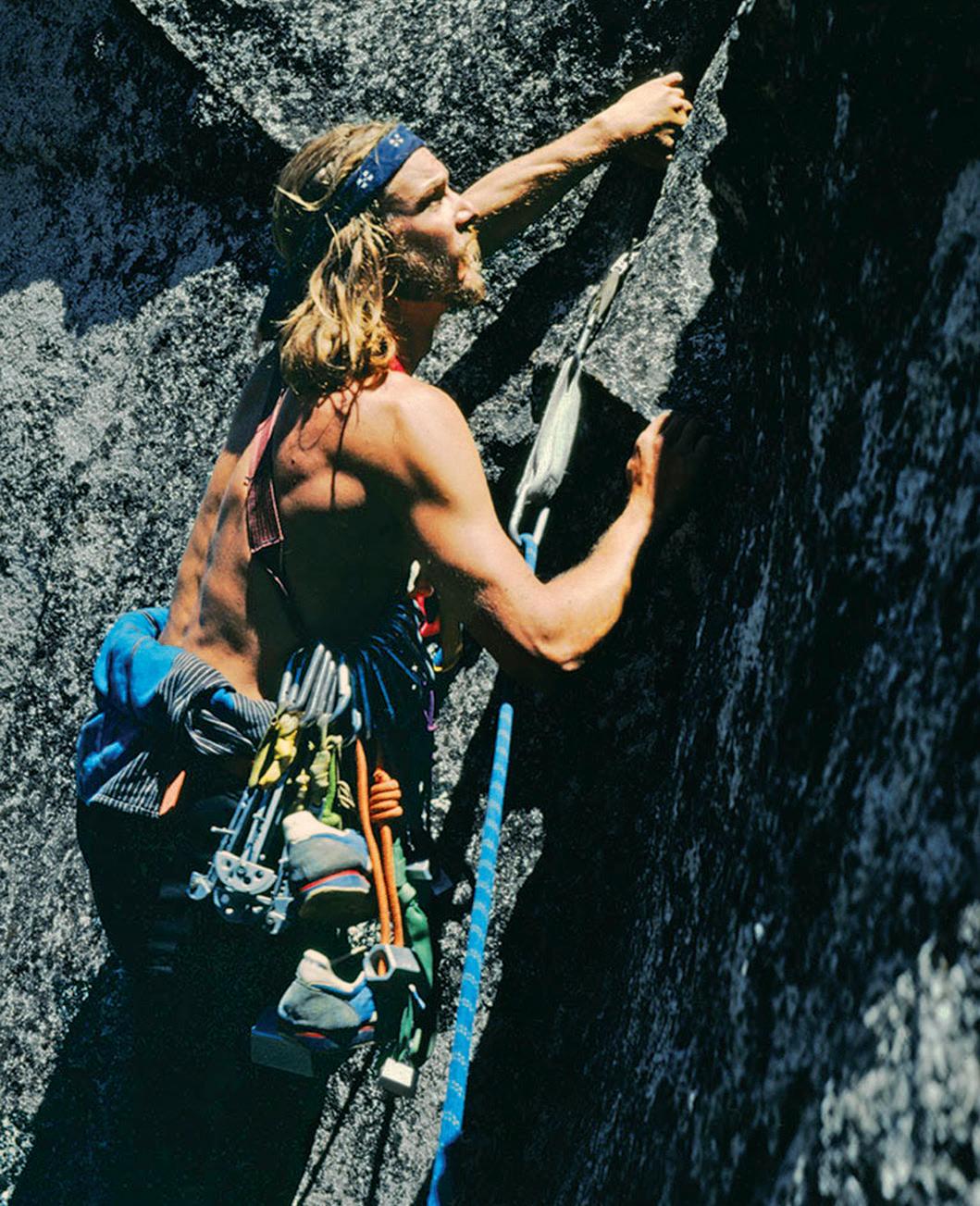

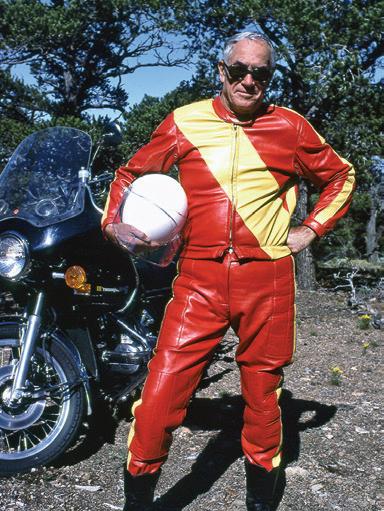

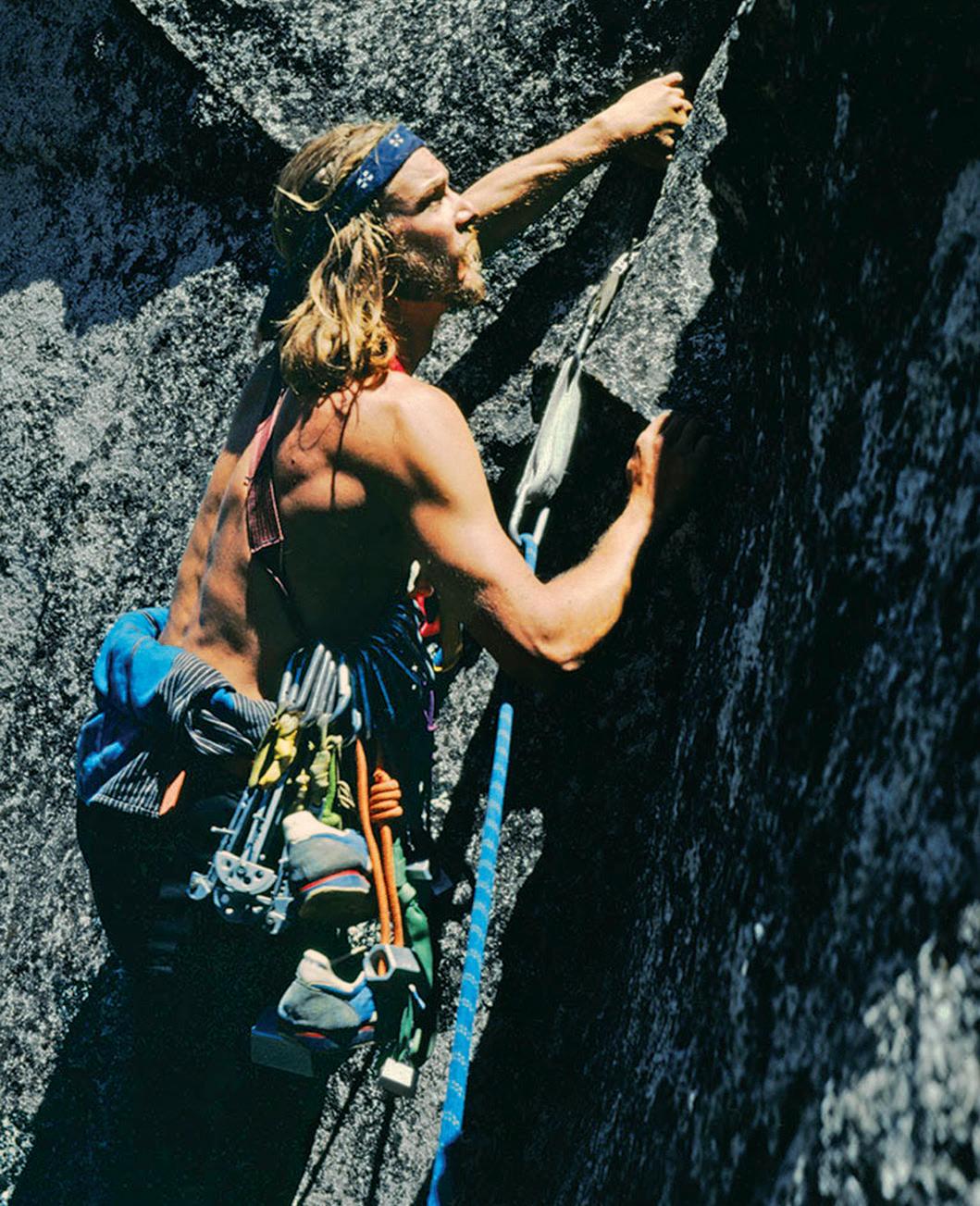

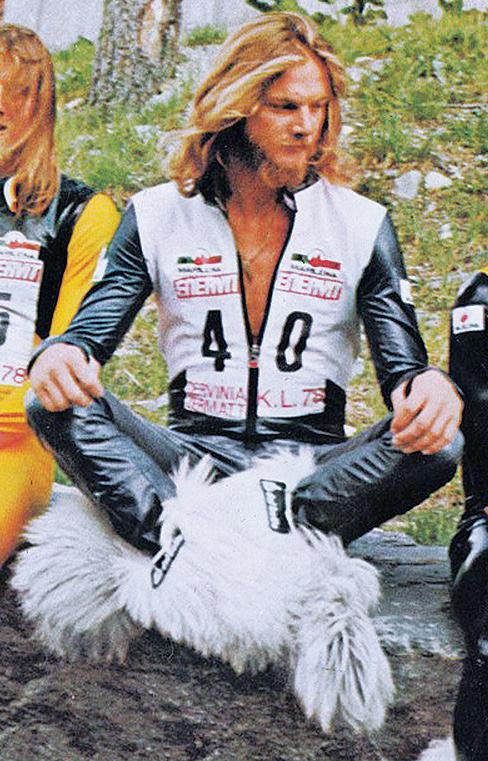

“ You hit that extreme speed and boom! Suddenly, there is no sound, no vision, no vibration. At that crescendo there is no thought at all.”

–STEVE

MCKINNEY, champion speed skier, philosopher, classic Warfield adventurer

It seemed to me that his Warfield Adventure — like Charles Alexander Warfield’s, like Governor Edwin Warfield’s — needed to be told, or retold. At age 50, our ambitions start to collide with our legacies: What of any value will we leave behind? It was becoming increasingly apparent that I was going to write a book. The agony of waking up every morning without my son, who had left for boarding school, triggered an aching longing. And I missed my parents,

16 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

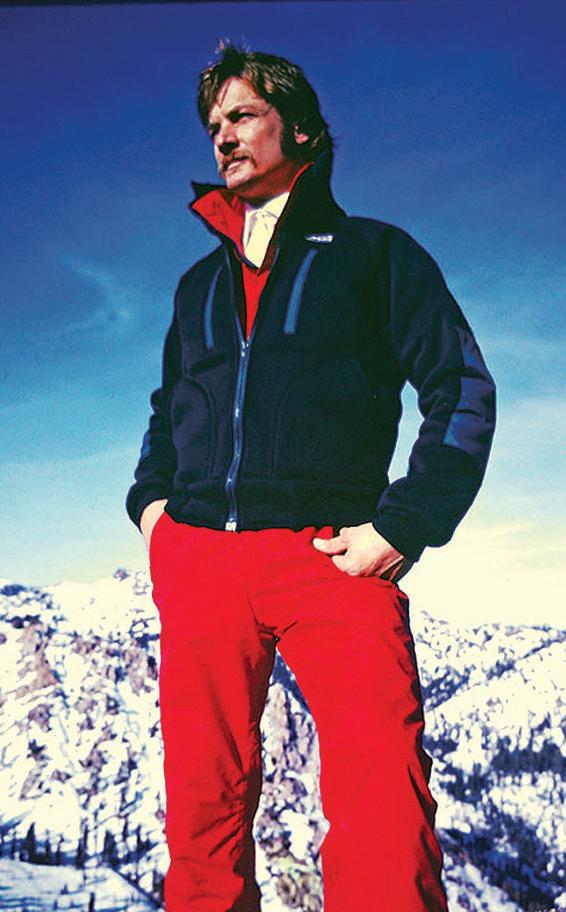

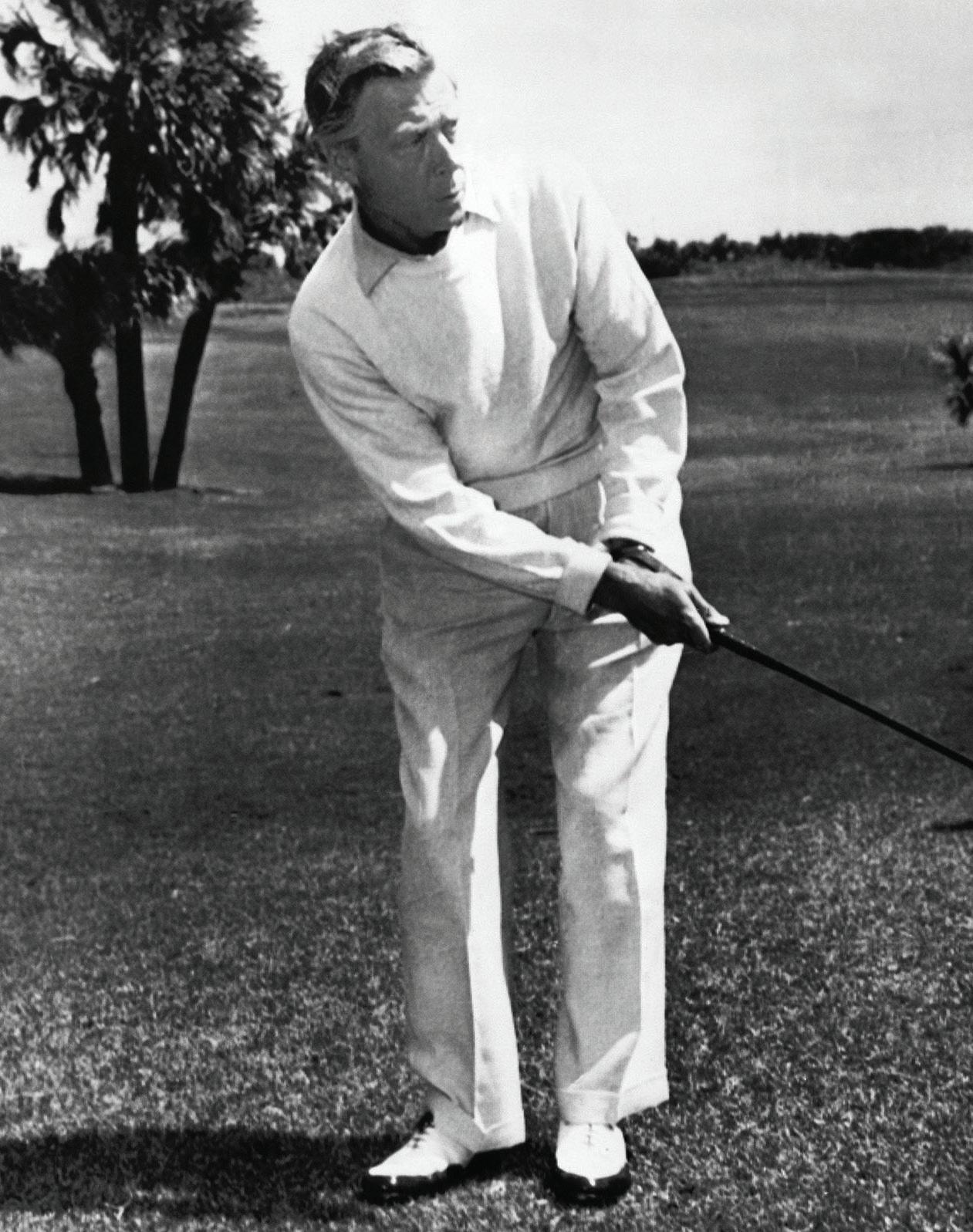

The King of Speed: Steve McKinney

both deceased, wondering for the first time how they might have advised and comforted me. I thought of how my father survived for four days on a tiny life raft in the Pacific after being shot down in his fighter plane during World War II, and yet how his divorce from my mother was even lonelier. And I thought of my first cousin, Steve McKinney, who broke the world speed skiing record in 1974 at 120 mph and then died at age 37 in a car accident.

Emotions were brewing in the lost and found of my brain. Dead Warfields now hung over this barely alive one. My history hit me over the head. In response, I began assembling all of the family photographs I could get my hands on. I rifled through files and called relatives and various newspapers until I had accumulated an impressive collection of Dead Warfield images. Their stories would follow, stories of adventure, war, and love — in effect, my legacies, ones that would form the foundation of a book that also would serve as an adult timeout, a kind of life restructuring, an opportunity to finally connect with my family.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 17

18 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

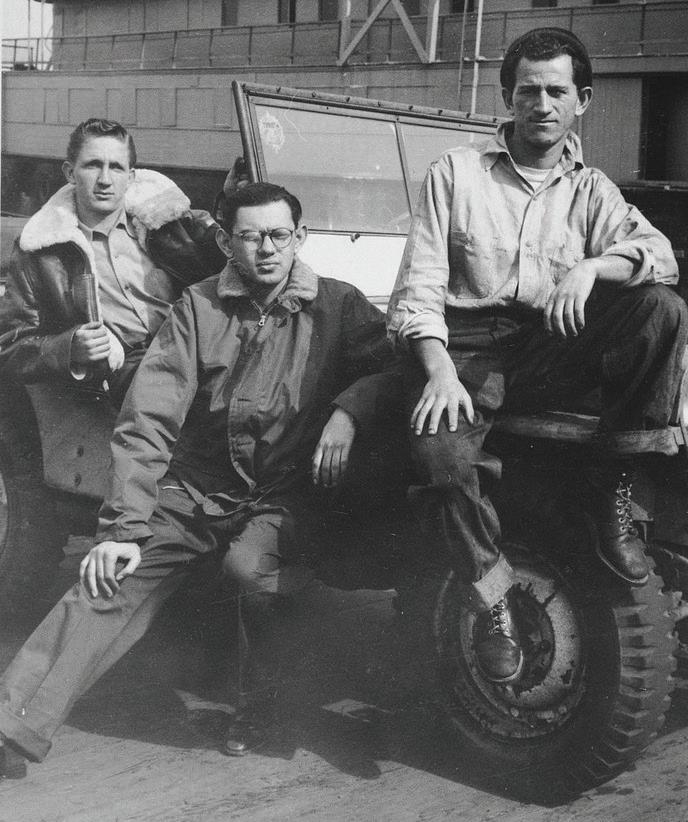

The Right Stuff: Edwin Warfield III with a F-86E Sabre

Meet the Parentals

2

“They called me Wally...which annoyed me mightily.”

–TED WARFIELD

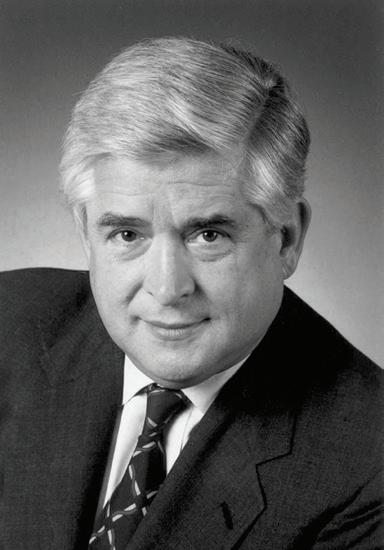

All of my life, people have approached me to share stories of how my father influenced or enriched their lives. I will depend on such history, written and spoken, to tell his story.

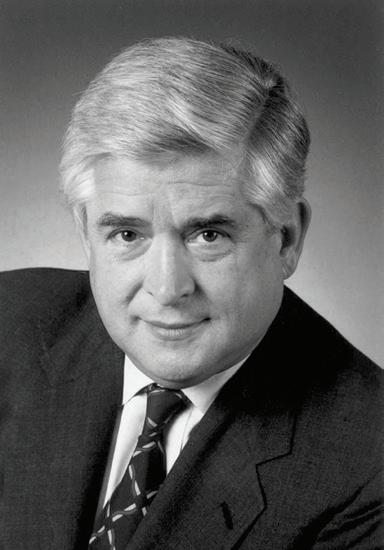

Edwin “Ted” Warfield III was many things to many people: a husband; a father; an award-winning fighter pilot during World War II; a delegate in the Maryland General Assembly, the state’s legislative body; a newspaper publisher; and Adjutant General of the Maryland National Guard. In each of these roles, he left an indelible mark. And, oh, he also was a sixth cousin to Wallis Warfield Simpson, 17 years his senior.

Born on June 3, 1924, Ted grew up on the family’s 265-acre estate known as Oakdale, located 20 miles west of Baltimore in the Central Maryland hamlet of Daisy, Howard County. Oakdale exudes history, lots of history. Based on a land grant issued in 1766, its original house was built two years later by Benjamin Warfield. In 1838, his great-grandson, Albert G. Warfield, constructed a more elaborate manor house on the estate, which he named Oakdale; slave quarters made from logs already existed on the property.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 19

The formidable first Edwin Warfield, a governor of Maryland (1904 to 1908), friend of Mark Twain, and third cousin to the Duchess of Windsor, took up residence at Oakdale in 1891, expanding the manor house to more than 20 rooms. The estate also boasted a tenant house, carriage house, stable, smokehouse, springhouse, gardener’s cottage, wagon shed, and glass octagonshaped greenhouse. His son, Edwin Warfield, Jr., an attorney and newspaper publisher, and Edwin Jr.’s wife, Katharine Lawrence Lee Warfield, moved in upon the death of Edwin Sr. in 1920, and there they raised five children: chronologically, Ted, Frances, Kitty, Louise, and Bobby.

Ted attended the Gilman School (as I would) in Baltimore, and then the Kent School in Connecticut, from which he graduated in 1942, at which point he began studies at Cornell University.

“If civilization is to survive, we must cultivate the science of human relationships — the ability of all peoples, of all kinds, to live together, in the same world at peace.”

–FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

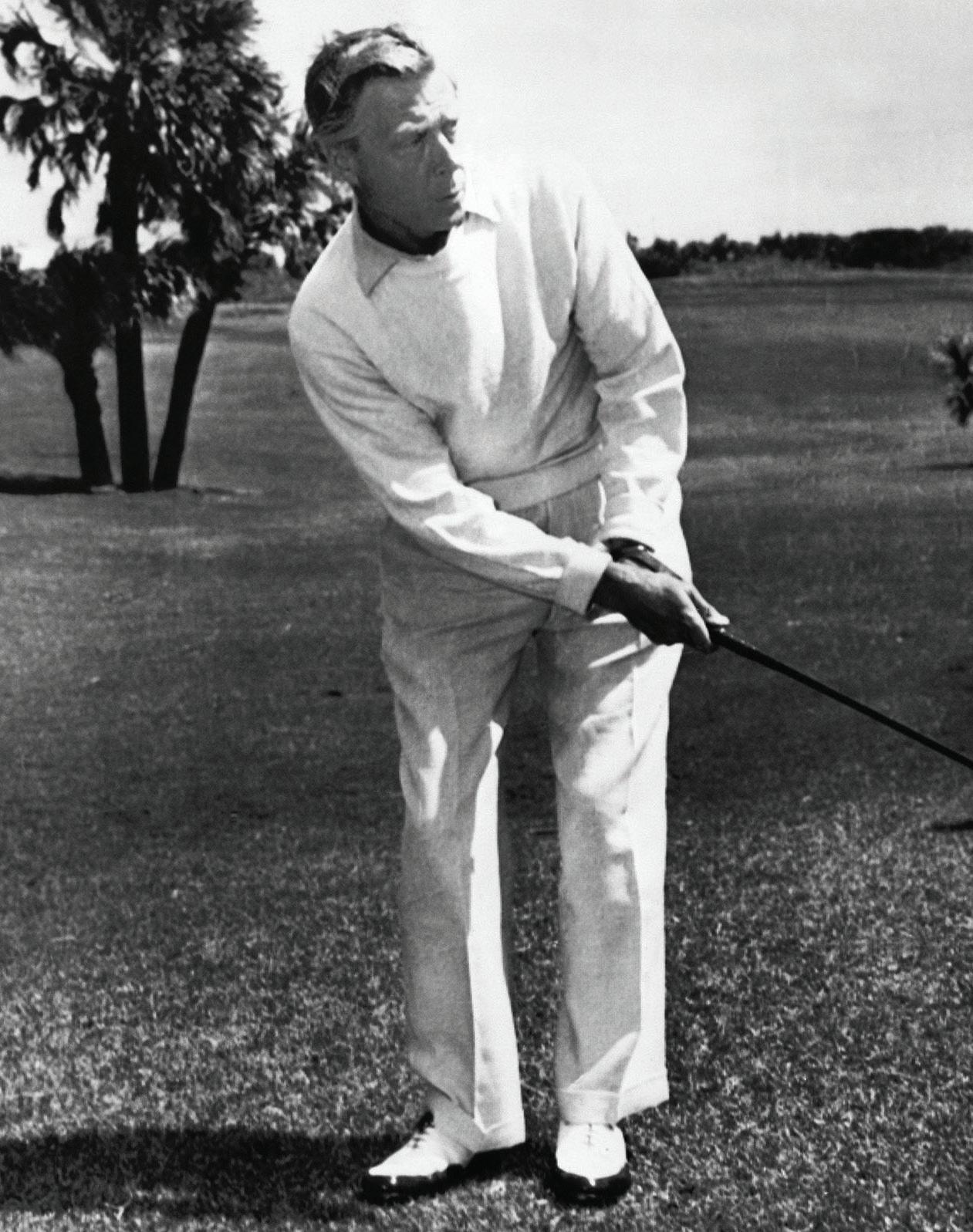

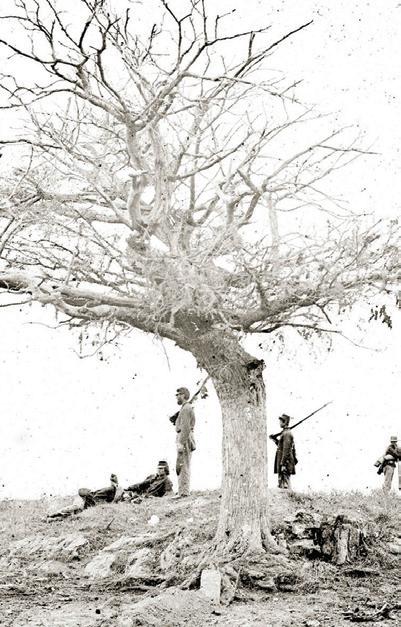

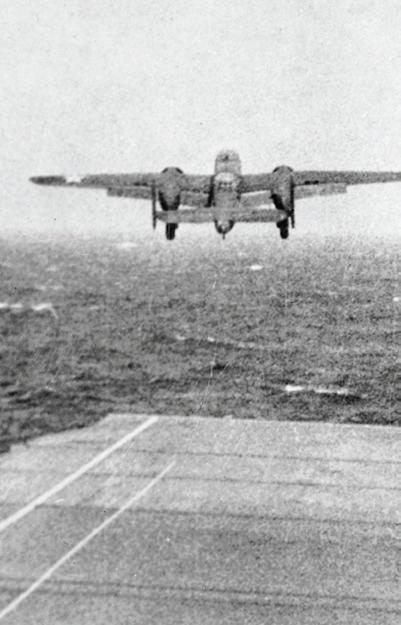

He left Cornell in 1943, in the midst of World War II, to enlist in the Army Air Corps, and trained to fly P-51D Mustangs, the military’s workhorse fighter for much of the war, at Pinellas Field near Tampa. After 125 hours of combat training, he was assigned to the 505 Fighter Group in the Pacific theater, where Mustangs played an important role escorting B-29 bombers in the air war against the Japanese.

Ted was stationed on the island of Iwo Jima in the summer of 1945. The main purpose for securing Iwo Jima was to provide a rescue station for crippled B-29 bombers returning from Japan, as well as to serve as an advance fighter escort base for Mustangs. The invasion of Iwo Jima took place in February 1945, lasted four weeks, and incurred thousands of American casualties.

On July 16, 1945, the atomic bomb was successfully tested in the New Mexico desert. That same month, Ted was flying on a bombing raid over Tokyo when his Mustang was hit by ground fire. His plane leaking gas badly, he knew

20 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Dad — a General in Full.

The U.S. Army Air Forces firebombed Tokyo by night in March 1945. The raids left an estimated 100,000 dead and more than one million homeless.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 21

he would not make it back to base. Miraculously, he was able to stay in the air for another 50 minutes, then parachuted into the Pacific before his Mustang hit the water.

During my lifetime, I must have heard my father tell his adrift-in-the-ocean survival tale what felt like twice a day. Regrettably, it was only during the last four or five recountings that I really listened. Fortunately, he told his story for posterity, including the following account, which appeared in The Baltimore Sun on March 23, 1980. Still, I wish he were still around to tell it to me in person one more time.

The sky was a perfect blue, and the Pacific was as smooth as a millpond. Between daydreams, I reviewed the briefing instructions and tried to keep as comfortable as the little cockpit would let me. The P-51 was a little sweetheart of a plane. It was fast, slim, and trim, but it was designed by an engineer who must have hated pilots my size. Also, the large air scoop to the belly caused the plane to plunge vertically and sink right away if you had to ditch over water.

We were over Japan. From our top cover we watched the Blue and Green [camouflage colors for planes] ruin the day for a lot of Japanese. Over an airfield, I blasted a row of parked planes.

As I pulled up in a tight turn, I heard a loud thump in the nose section. Oil immediately covered the windscreen. I had been hit. About 10 miles from the coast, I remembered the Japanese were not friendly to downed pilots, and you were lucky if you lived to become a POW. I headed for the coast. I planned to bail out near our rescue sub in Tokyo Bay. My radio was out, and hot oil was streaming over my face and goggles.

I sure didn’t want to bail out over Japan, so I headed my limping engine towards Iwo. I was beginning to think I might make it all the way when the engine quit. I bailed, and when the water closed over me, it seemed I would never get back up to the surface with my 160 lbs., G.I. boots, deflated raft, survival vest, and pistol. When I finally surfaced, I inflated the tiny dingy, climbed in, and wretched oil and seawater for an hour.

Day 1 – July 28, 1945

Looking over the meager aspects of my domain, I found a sea anchor, which was a plastic funnel hooked to a cord. A cup to bail with. I tied it to the raft so that I would not lose it. A tiny blacksmith bellows device to keep the raft pumped up. I used it every two hours for the next four days. A book in my survival vest (How to

22 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Live in the Jungle). I threw it overboard. My G.I. boots rubbed the skin of the raft. I threw them overboard. I saved my ‘chute to cover myself with. I found sunburn salve and used it. Four bars of concentrated candy — four tins of water. I resolved to ration myself and decided that I could make it for 10 days with a little fortitude and a lot of luck.

I never lost hope that I would be rescued, even though no one had seen me bail. I lit flares and dyed the water when some B-29s flew over, but on they went.

Day 2 – July 29, 1945

A sunny dawn broke. I bailed. I rested and slept. Some small bits of the candy bar two or three times a day, violent hunger cramps all day. Then my appetite seemed to fade and cause no problem. The raft was tiny, maybe four feet around. The sun was hot, and my face and shins got sunburned. One more night. The sea got rough and choppy. The raft rose and fell like a cork as the Pacific churned into a storm. The sea anchor held the raft true. I heard a plane engine in the distance — the 29th ended.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 23

Four days in the Pacific - July 28 - 31, 1945

Day 3 – July 30, 1945

The third day dawned. The storm abated; the ocean calmed. No sign of rescue. A shark passed the raft, flipped under it sideways, and tapped it with his tail. I was transfixed, did nothing, and he left. An ugly fish with bulging eyes flipped by, and I grabbed it with my bare hands. I looked at it and could not bring myself to eat it. Threw it away. No sign of rescue — no hope of rescue. The third day passed — no aircraft sighted.

Day 4 – July 31, 1945

The fourth day dawned. I was wet, tired, less confident. Toward mid-afternoon, a hum, a buzz, a roar. A Navy B-24 patrol plane approached on the Western horizon. I had no flares remaining, just a small signal mirror. I focused it on the setting sun and pointed it toward the plane. It banked, turned, and flew directly over me. A crewman waved out the back hatch — I cheered, I saluted, I waved. They dropped me an 11-man raft. It seemed as big as a dance floor. I paddled to it, pulled the cord to inflate it and got in it. I knew I was saved. I felt that if I could spend four days in a one-man raft, I could spend 30 days in this larger raft.

I tied my smaller raft alongside in case the bigger one sank. My Navy friends circled for an hour, dropped a Gibson Girl signal radio, a kite to send up the aerial, a kit to turn saltwater into fresh. In the time-honored signal, the Navy pilot rocked his wings and headed south. He had called his patrol mate to circle me while he returned — low on fuel. The second patrol plane arrived on the scene and made lazy circles.

Suddenly, a submarine surfaced beside me. It was the U.S.S. Haddock, and the crew were waving and saluting. They pulled me off the raft. I looked like a Biafran native. They gave me some soup and a Navy uniform. I would’ve preferred some Jack Daniel’s.

I stayed on the Haddock for two weeks. When we arrived in Midway, a message came over the intercom: “We have dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki… the war is over...be careful who you talk to…do not trust anyone.” Soon, a Navy doctor checked me out and said, “You’re back on duty.”

During the war, Ted flew a total of 11 combat missions, putting in dozens of hours that included bomber escort, submarine cover, and strafing targets on land. For his efforts, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, the

24 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 25

Air Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters, the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Unit Citation, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, two Bronze Service Stars, and the Maryland Distinguished Service Cross.

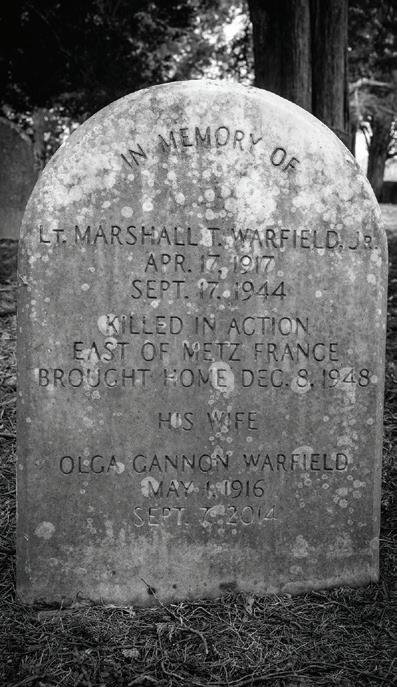

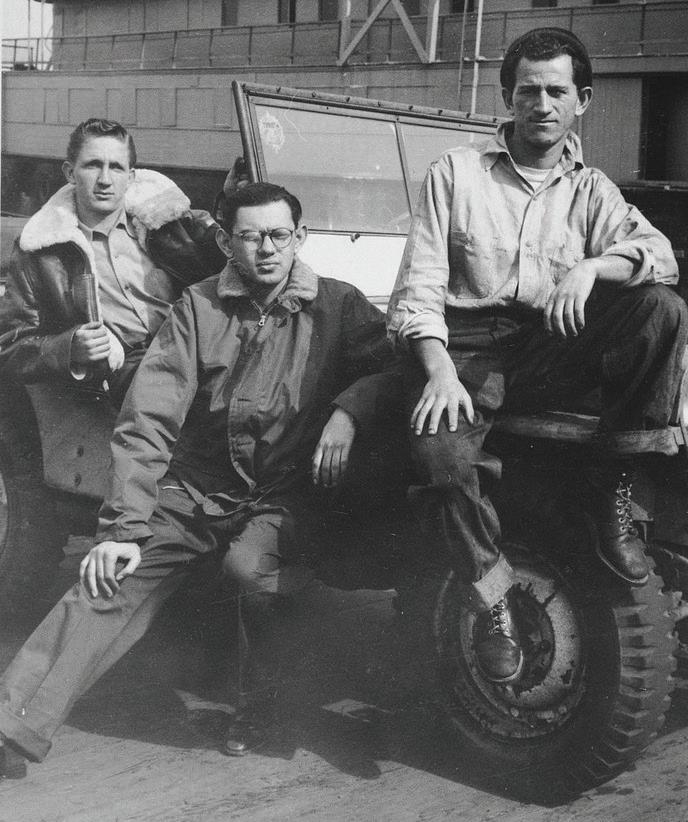

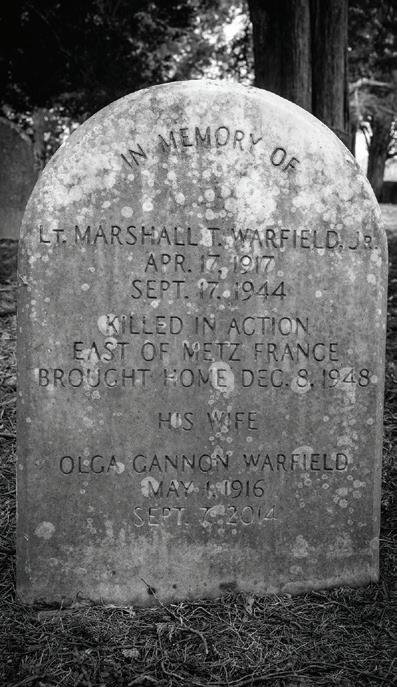

(Ted was not the only member of his family to participate actively in World War II. Two of his first cousins, once removed, brothers Albert G. Warfield and Marshall T. Warfield Jr., served with the U.S. Army in Europe. Albert, a captain in the 29th Division, landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 6, 1944, during the D-Day invasion, and fought with his unit all the way to the Rhine river, ending the war with the rank of major; afterward, he became a member of the Maryland National Guard, ultimately retiring as a lieutenant

26 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

U.S.S. Haddock

On Monday, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m., the Enola Gay, flown by Paul Warfield Tibbets, dropped the nuclear weapon “Little Boy” on Hiroshima. It killed an estimated 70,000 people, including 20,000 Japanese combatants and 2,000 Korean slave laborers.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 27

colonel. Albert went on to a career in investments, rising to become manager of the Baltimore office of Merrill Lynch. He passed away in 1983. Marshall, a first lieutenant in the 712th Tank Battalion, was killed in action east of Metz, in France, in September 1944. Both brothers are buried at Cherry Grove, the Warfield family cemetery, at Oakdale.)

Discharged from the Army in 1946, Ted returned to Baltimore, where, in 1947, he married my mother, Carol Phillips Horton. Ted and Carol divorced in 1964, and, three years later, he married the former Ellen “Niki” Owens. They lived in a new home he had built at Oakdale in 1966. He sold the original manor house, plus 54 acres of the estate, in 1974. Oakdale was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014. (Below, I address my parents’ lives together.)

After studying at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Ted transferred to the University of Maryland, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in agriculture in 1950. That same year, he joined the Maryland Air National Guard unit based at Martin State Airport east of Baltimore; later became the unit’s commander; and, ultimately, was promoted to the rank of brigadier general before rising to commander of the air guard.

In 1952, Ted took over as publisher of The Daily Record, which covered Baltimore’s court and commercial news. The paper began publishing under that name in 1888 under the stewardship of my great-grandfather, the first Edwin Warfield, and later was run by my grandfather, and, eventually, me.

In 1962, running as a Democrat, Ted was successfully elected to the House of Delegates, one-half of the Maryland General Assembly, as a representative from Howard County. He spent eight years in the House, serving as chair of its Agricultural Committee and as a member of the Ways and Means Committee. Unseated in the 1970 election, he segued full time into his role as Adjutant General of the Maryland National Guard, to which he had been appointed earlier that year.

These were turbulent times for the National Guard nationwide, given the growing opposition to the United States’ participation in the Vietnam War. Unrest on American campuses was widespread, and the Guard was frequently called in to quell protests, most famously — and tragically — in 1970 at Kent State University in Ohio, where four students died during a confrontation with soldiers.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 29

Demonstrations also gripped the University of Maryland, located in College Park, just outside Washington, D.C., and for three consecutive springs, 1970 through 1972, my father was ordered to send the Guard there in an effort to maintain peace. He dealt with the potentially explosive situations with what Michael Olesker, a former columnist for The Baltimore Sun, later termed “composure, strength, and heartfelt humanity.”

Ted retired from his Adjutant General post — and the Guard — in 1980. Under his leadership, minority recruitment, a priority for him, increased to 44 percent. To honor his service, the National Guard base at Martin State Airport was named Warfield Air National Guard Base.

During much of this time, my father suffered from alcoholism. Jack Daniel’s began taking over his life in the late 50s, and he remained Jack-impaired until the mid-80s. Around that time, he met a man who changed his life: Father Joseph Martin, a Catholic priest who pioneered the treatment of alcoholism.

In 1983, Father Martin, a recovering alcoholic, co-founded Ashley, a substance-abuse treatment facility located north of Baltimore that takes a compassionate and innovative approach to addiction. It took a couple of visits to Ashley before Father Martin and his staff exorcised Jack Daniel’s from my father’s body. The war within him was over, and every sober day was extra. In my father’s eyes, Father Martin was the equal of Winston Churchill and FDR: They saved the world; Father Martin saved Dad.

Ted’s love of flying, meanwhile, never diminished, and he continued to pilot his own plane, a Cessna 182, until he was 71. He referred to it as “TWA” — Ted Warfield Airlines. In his later years, he bribed doctors in order to pass his physical so that he could continue to fly over the farmland of Howard County; at least, that’s what I’ve heard.

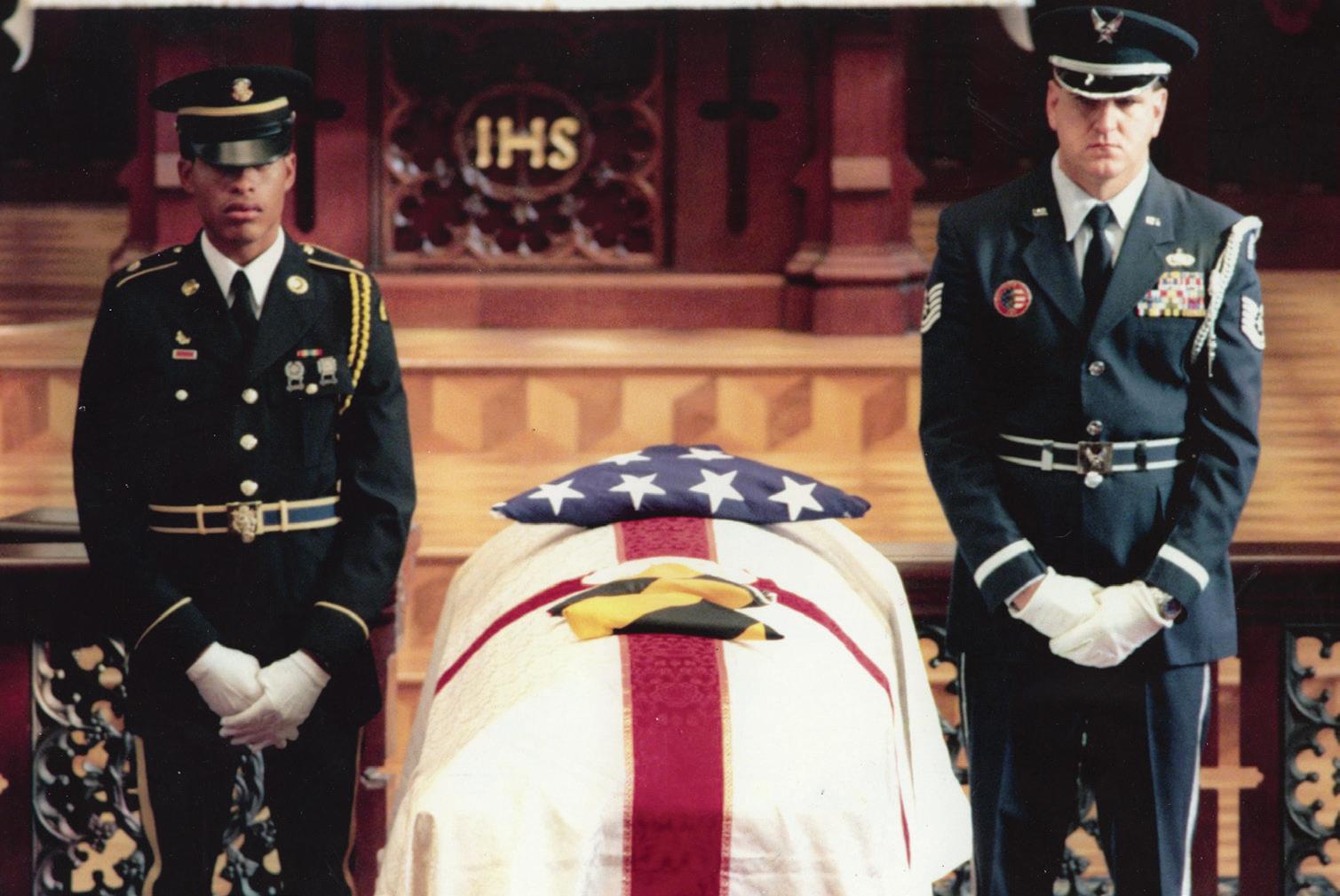

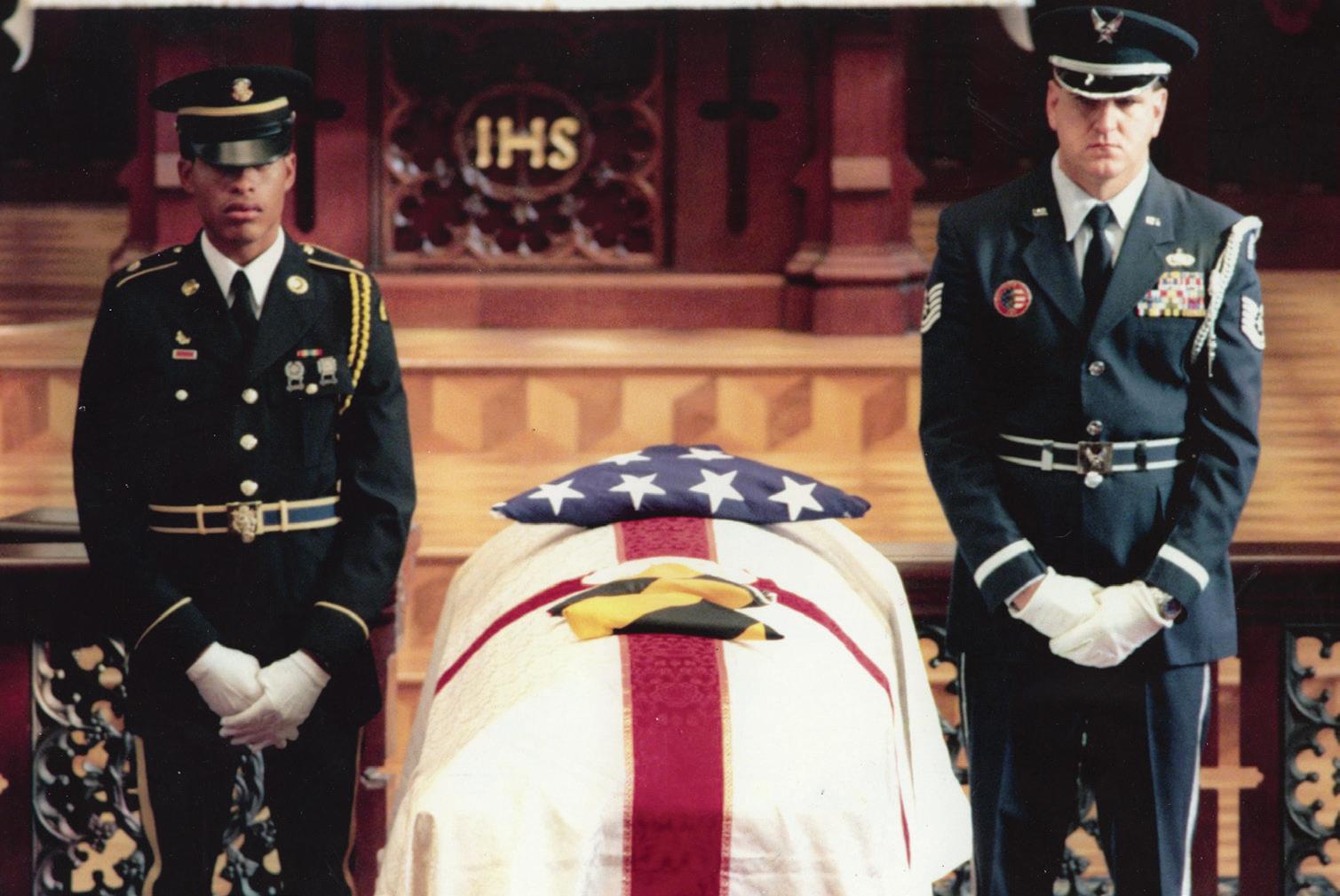

Ted died of congestive heart failure at age 75 on October 4, 1999. His funeral befitted a general from what former NBC anchorman/reporter Tom Brokaw famously called the “Greatest Generation,” also the title of his best-selling 1998 book about Americans who grew up during the Depression and then went on to fight in World War II, as well as serve in support roles on the home front. The pomp and circumstance given my father was very moving, and I will never forget a single detail.

His funeral service was held at St. John Episcopal Church in Ellicott City,

30 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

in Howard County. I delivered the eulogy, highlighting several of his fatherto-son maxims. Regarding loyalty: “A man is lucky if he can count his real friends on one hand.” Leadership: “Lead, follow, or get out of the way.” And the human species: “Be wary of people carrying a Bible in one hand and a dagger in the other.” All of these lessons took me a lifetime to appreciate.

Outside the church, planes from the Maryland Air National Guard swooped down in perfect formation, while Guard members on the ground fired a 21-gun salute. After the ceremony, what appeared to be the entire Maryland State Police force blockaded parts of Route 70 for the funeral motorcade, which made its way from the church to Cherry Grove, located 20 miles west.

Fourteen years later, in 2003, I married for a second time. The ceremony took place in a church near the Fifth Regiment Armory, headquarters of the Maryland National Guard, located in midtown Baltimore. A Methodist minister presided. He asked me, “Are you related to Edwin Warfield — the general of the Maryland National Guard?”

“Yes, he was my father.”

“I was in the National Guard with him,” he continued. “He was a great man.”

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 31

Mother Superior

My mother was born in 1922 in New York City, where, when she was five years old, she and her older brother were put up for adoption. She never knew her birth parents. She and her brother were adopted by a wealthy Park Avenue couple in an attempt, I was told, to salvage their failing marriage. Her adoptive father, William A. Phillips, was a partner at Dillon, Read & Co., an old-line Wall Street investment bank, now Warburg, Dillon, Read. Her mother was Elizabeth B. Phillips. The couple named their new children Carol and John.

That marriage eventually ended in divorce, and Elizabeth married Frank N. Horton. My grandmother and her two children moved to England to live with their new stepfather at his lavish country estate, Idlicote, an Elizabethan manor in the English Cotswolds, and, at age eight, Carol was sent to boarding school.

Later, the couple sold Idlicote and moved to the U.S., maintaining several residences: a suitably grand Park Avenue apartment, a summer home in the mountains of western North Carolina, and a house in Palm Beach. The children attended private boarding schools: John at Choate in Connecticut, Carol at Garrison Forest outside Baltimore.

The Hortons’ Palm Beach house was located within walking distance of the private Bath and Tennis Club (B&T), of which my grandparents were members, and which, in my memory, boasted the most incredible oranges on earth. When we visited, Mother, in an effort to protect us from any potential affluenza infections, booked us into a nondescript motel in Delray, 20 miles south of Palm Beach.

The upside of Carol’s Annie-like adoption was financial security; the downside was the absence of any sense of family or history. As for love, are you serious? The 15th-century maxim “children should be seen and not heard” was extrapolated by my grandmother to include not being seen, too. Given the Hortons’ chilliness, Carol grew up seeking a sense of family elsewhere. (As an adult, she fruitlessly attempted to track down her biological parents, but the adoption agency refused to provide the necessary information.)

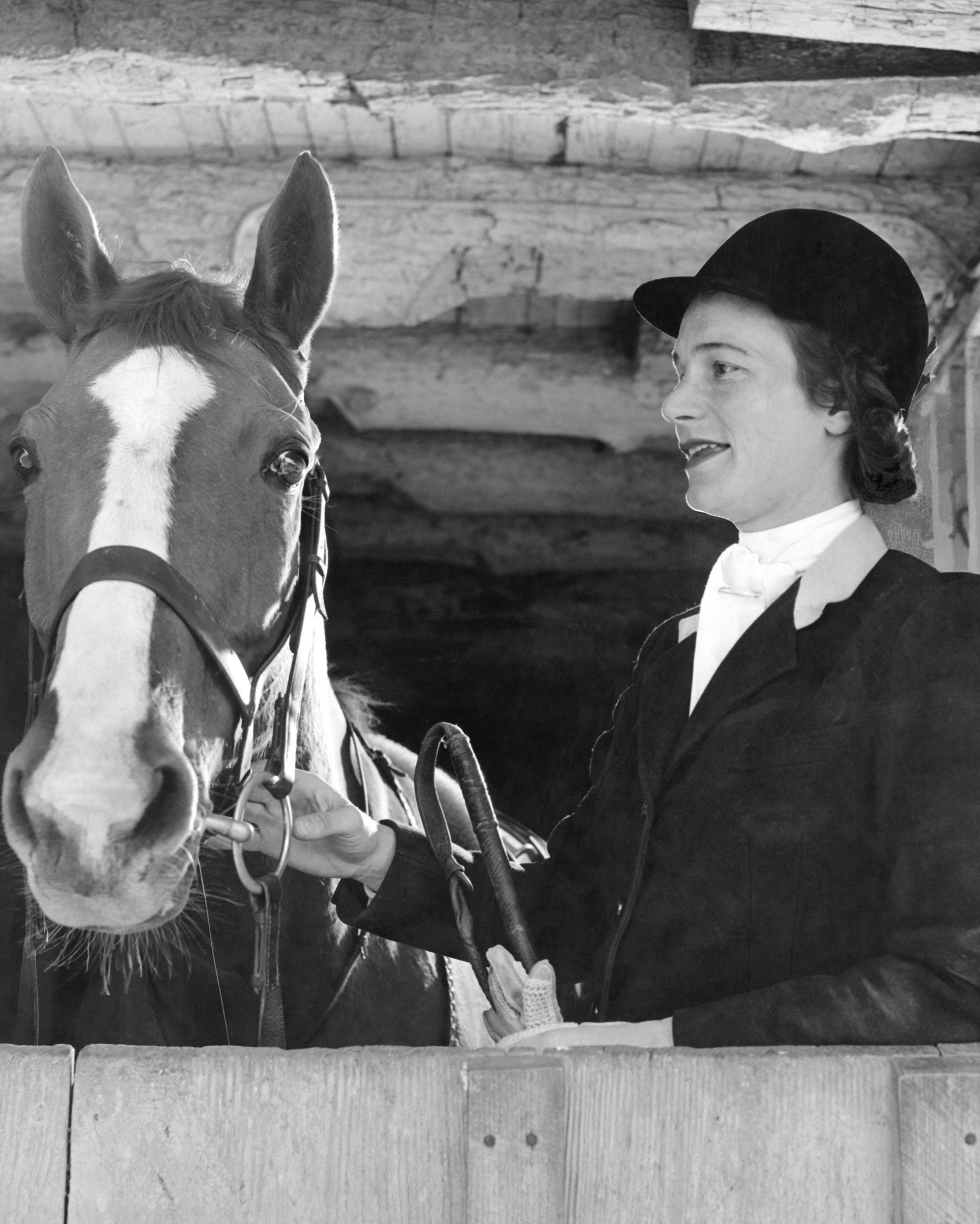

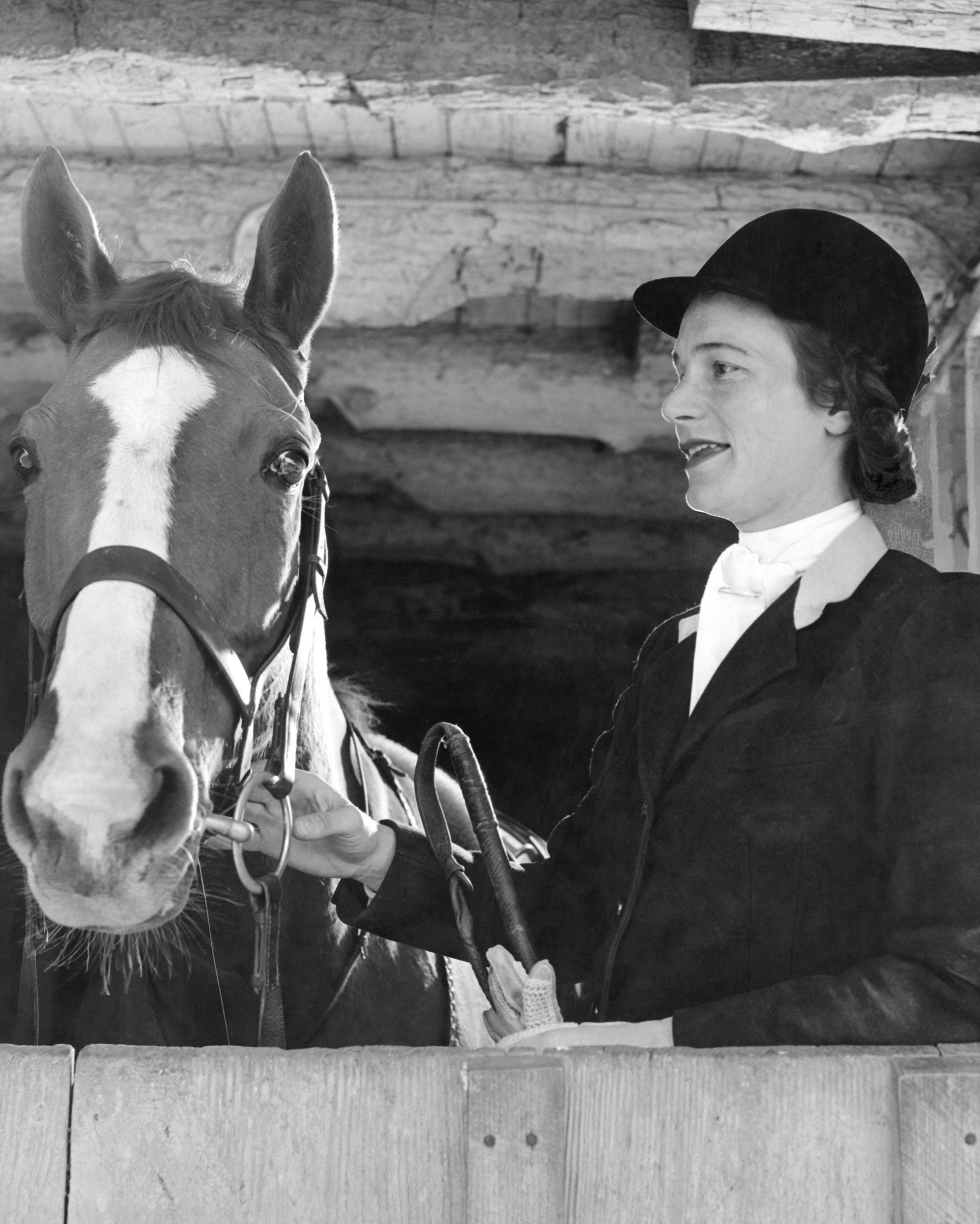

At Garrison Forest in the late 1930s, Carol met — and became friends with — the Warfield sisters, Frances and Kitty. Horsey, feisty, and independent, they exuded an esprit de corps that my mother found irresistible, and they introduced her to their tall, dashing brother, Ted, then 18 and a student at Cornell University, soon to enlist in the Army Air Corps.

32 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Carol was invited by her Warfield girlfriends to share family holidays at Oakdale. Raised in orphanages and boarding schools, she saw in Oakdale and the Warfields the family she desperately craved. Ted and Carol began dating, and she soon dreamed of filling the halls of Oakdale with children and its fields with horses, riding having been one of her childhood passions.

Upon graduating from Garrison Forest, she attended the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women, just north of Philadelphia. And when my father returned from the war, he and Carol resumed their courtship, married in June 1947, and moved into Blenheim, a separate house on the Oakdale property. It was a merger straight out of central casting: money meets history, LLB meets MBA. Eventually, they would have four children: me (the oldest), Beth, Diana, and John.

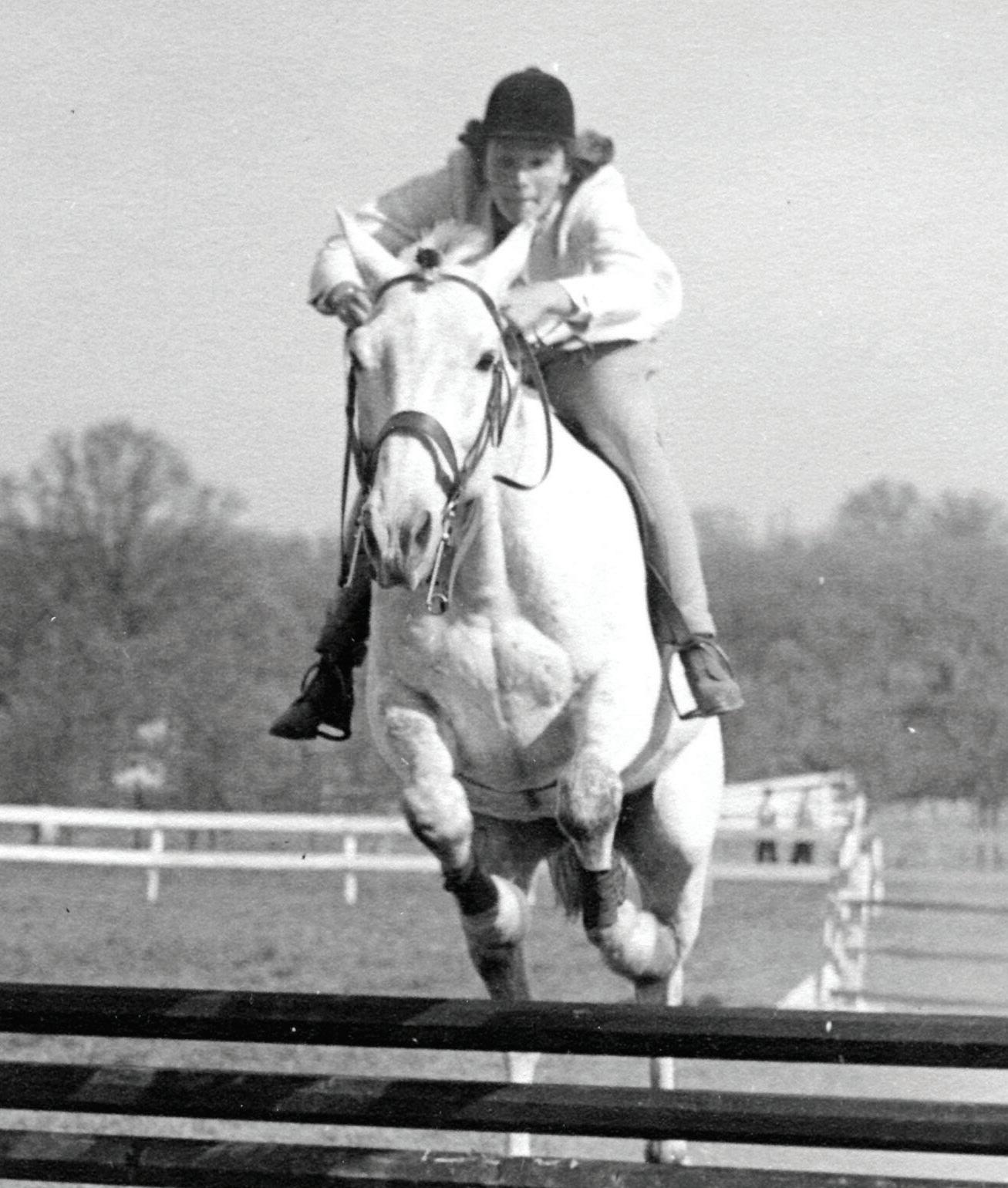

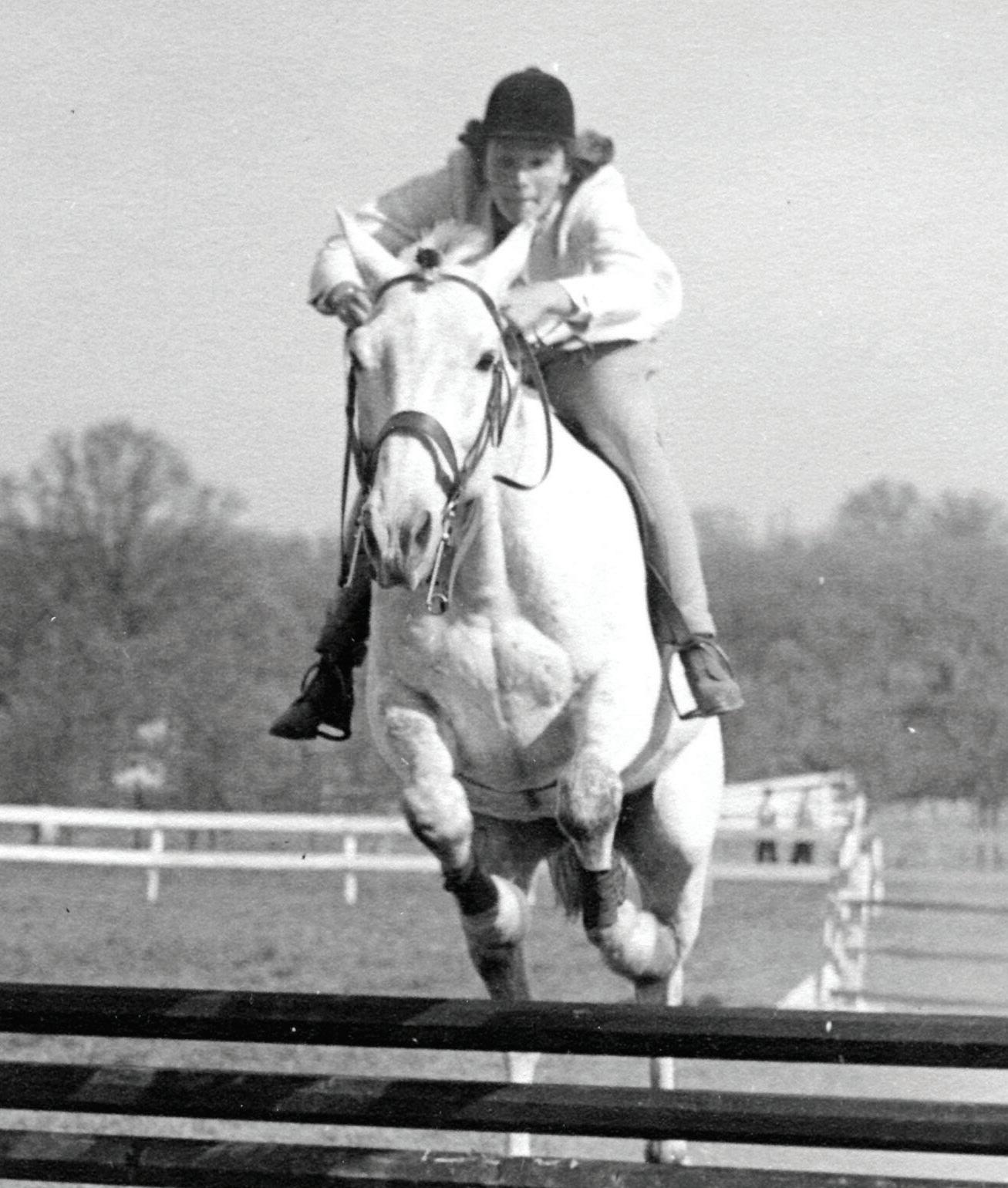

Carol returned to Garrison Forest as a riding instructor, and soon became the Master of Foxhounds of a small hunt in Howard County. Despite her upbringing, she eschewed the accoutrements of the wealthy. Except for good horseflesh, her tastes were simple. Her passions, in order of preference, were horses, children, and men. The horses were fed first. Our evening meals consisted of TV dinners, Hamburger Helper, and Stouffer’s spinach souffle. The only hired help worked in the barn.

34 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Mom — HRH of Hounds

Carol was not well known on the glamorous Madison Square Garden horse show circuit, but, rather, thrived in the world of pony club and girls’ school riding instructors, where she was loved and respected. In a 2001 column in The Chronicle of the Horse magazine, John Strassburger writes, “What we all have in common is a fear of failing. It’s just that for some, it’s a motivation and for others it’s an impediment.

“And that thought reminded me of a Pony Club regional supervisor who was very influential to me and others. Her name was Carol Horton, and she was in charge of our expedition to the 1978 National Rally in Boyce, Virginia. Mrs. Horton was never daunted by any obstacle, nor would she allow us to be. No matter what the problem or concern, her advice was always, ‘Oh, bloody hell, just press on!’”

That attitude — fierce independence and strong will — clashed head on with Ted’s my-way-or-the-highway ethos; ultimately, the highway prevailed in the form of a divorce and a hurtful-to-all-involved custody battle over me, a complicated subject that I address in detail in the next chapter.

Carol had a short-lived second marriage to Phillip Fanning, an ineffectual, fox-hunting gentleman with two middle names and, eventually, three ex-wives, all Masters of Foxhounds. Together, Carol and Phillip had a daughter, also named Carol but known as Mini.

By the 1970s, Carol was divorced for a second time and living with Mini in the Basking Ridge area of New Jersey, where open land for fox hunting was becoming increasingly scarce due to development. Die-hard equestrians had no choice but to relocate, and, in 1979, Carol packed up her belongings and Mini, and moved to the epicenter of Virginia horse country, Middleburg, where she bought a four-acre farm. Appropriate to her priorities, the stable was larger than the house.

Except for a bout with breast cancer that had been in remission, Carol had always been healthy and energetic. To her, Middleburg was heaven on earth, and with her children grown and husbands gone, it was finally time to do what she loved: riding horses each day and fox hunting several times a week.

Back in 1979, I was living in New York and working at Phillips Auctioneers when I visited her for Thanksgiving. As I left after a pleasant stay, we decided that my next visit would be just before the New Year. We talked on the phone

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 35

on Christmas, and she said that she was going fox hunting the next day. Twenty-four hours later, I received a call from my sister Diana in Baltimore: “Mother is in the hospital in Winchester, Virginia,” she told me. “Her horse fell, and she is in a coma.”

I remember being unable to respond. Would she be able to recognize me? Most comas rarely last more than two to four weeks. My mother’s lasted three years. Over time, her condition gradually progressed to what is termed a “vegetative state,” in which the eyes are open and there is some degree of recognition, but no speech. That gave our family hope that further improvement was possible.

36 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

A perfect jump

Carol had led a vigorous and outgoing life. There was never enough daylight for all she wanted to do. I despaired at seeing her in this undignified state, knowing how she would loathe it. Court battles rage over just such medical conundrums: To pull the plug or not. The power to choose life or death for another human being is too great a burden for any mortal. My cousin Steve McKinney, a world-class speed skier and scholar of the Tibetan branch of Buddhism, often quoted from The Tibetan Book of the Dead to explain certain aspects of his philosophy. His approach to life’s journey was similar to my mother’s in grace, passion, and lack of fear.

I bought the book and read about the stages between life and death as both essential and valuable. According to the book, regardless of a lack of measurable brain waves, the mind remains linked to soul and spirit. The physical body loses all importance; gone are lust, aggression, delusion, and pain. These stages provide a gateway to liberation — peaceful and translucent. An excerpt reads:

“Now, when the dream between dawns upon me, I will give up corpse-like sleeping in delusion, And mindfully enter, unwavering, the experience of reality. Conscious of dreaming, I will enjoy the changes as clear light. Not sleeping mindlessly like an animal, I will cherish the practice merging sleep and realization.”

My mother died in Baltimore on October 8, 1982, of pneumonia, age 59, and was laid to rest at Cherry Grove.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 37

Mom and Me: She felt it more important that I ride before I walked.

38 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

The Startup of Me

3

“The secret of getting ahead is getting started.”

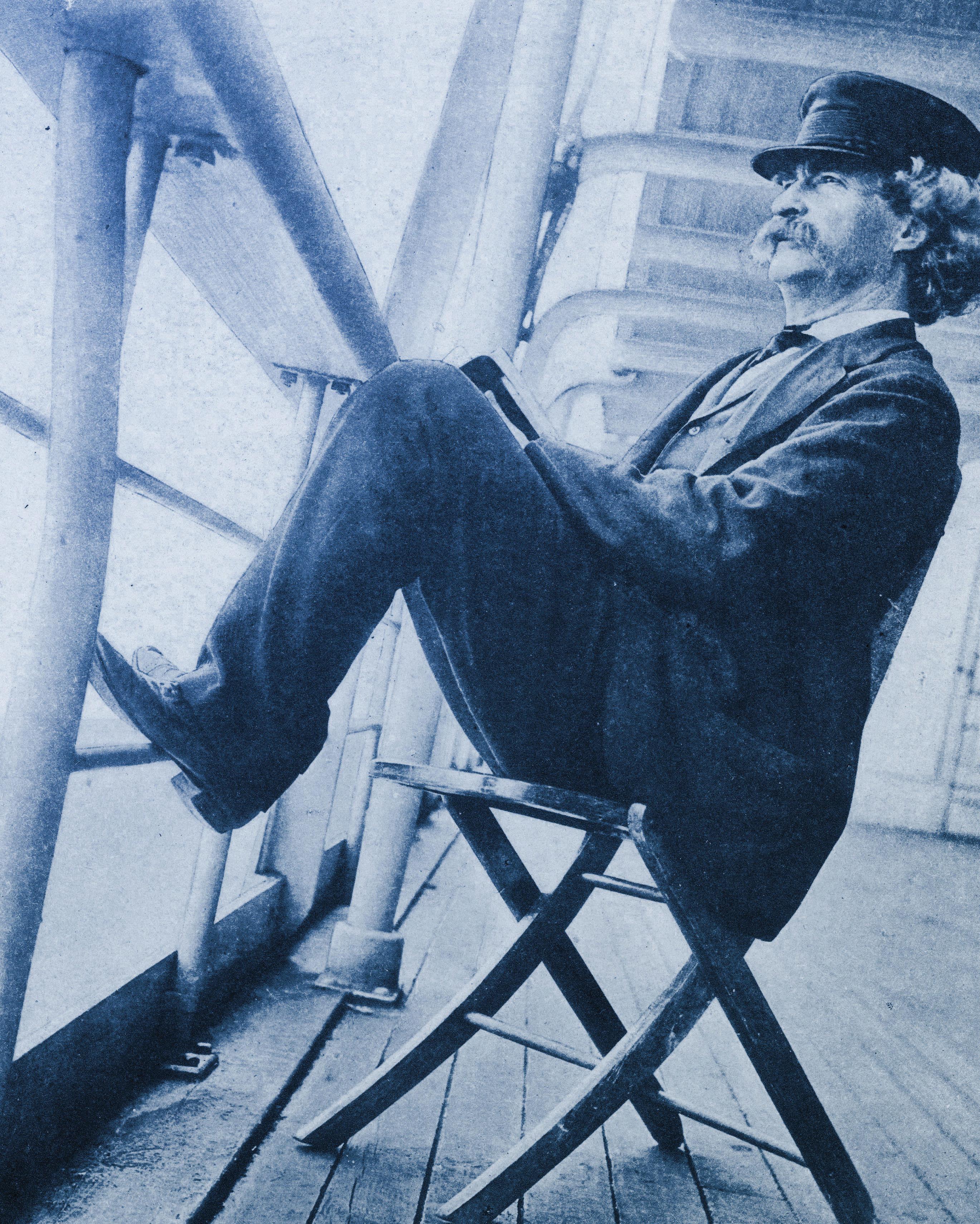

–MARK TWAIN

My birth on April 30, 1954, was poorly timed, at least from my parents’ perspective. The last weekend of April in Maryland marks a WASP celebration more important than Christmas and Thanksgiving combined: the Maryland Hunt Cup — a steeplechase-racing and social-climbing event once chronicled by Charlie Rose on 60 Minutes prior to his ignominious demise. Think of the Hunt Cup as Woodstock with horses, followed in the evening by the more elegant Hunt Ball.

My birth also constituted the long-sought beginning of my mother’s family. Her brother, John, also adopted, would find his family in the gay community of Greenwich Village in the 1950s and 1960s, and later move to New Hope, Pennsylvania, in the 1970s, where he spent his later years with his AfricanAmerican husband.

As for my heritage, it is a curious combination of 50 percent old-line Maryland and 50 percent in need of an ancestry DNA test. My first five years,

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 39

spent at Oakdale, were bucolic, isolated, and relatively uneventful. The estate was — and remains — located in the western Howard County hamlet of Daisy. Back then, Daisy consisted of a mix of farms, the vestiges of racial segregation that included the great-grandchildren of a slave, and Warfields. Literature in our household was limited to the Chronicle of the Horse and Time magazine. It was a lifestyle that could have been portrayed in a Mark Twain novel or a Norman Rockwell painting. In short, Mayberry.

One of my earliest childhood memories is that I could ride a pony before I could walk. The image of my mother teaching me to ride was made by the celebrated Baltimore Sun pictorial photographer A. Aubrey Bodine. For good reasons, my expression of dread implies a premonition that horses symbolized death, as opposed to a highly refined Maryland gentleman’s pursuit.

“I was born modest, but it didn’t last.”

–MARK TWAIN

My cousin Jimmy Stump, a noted steeplechase rider, was killed at age 20 in a race-riding accident. It was morbidly perverse, if not morose, to see his parents, Humpy and Louise, continue to attend steeplechase races afterward. My mother also experienced a serious horse-related accident, falling during a fox hunt. Taken together, these events cemented my aversion to horses, not forgetting my equine-related chores of mucking out stalls, mowing acres upon acres of fields, and creosoting miles of fences during my high school years.

Horses represented death, hard work, and toxic fumes that were probably more harmful than either LSD or Jack Daniel’s. By fifth grade I had announced my retirement from riding and fox hunting, pursuing, instead, the ungentlemanly sport of ice hockey — real boys played ice hockey.

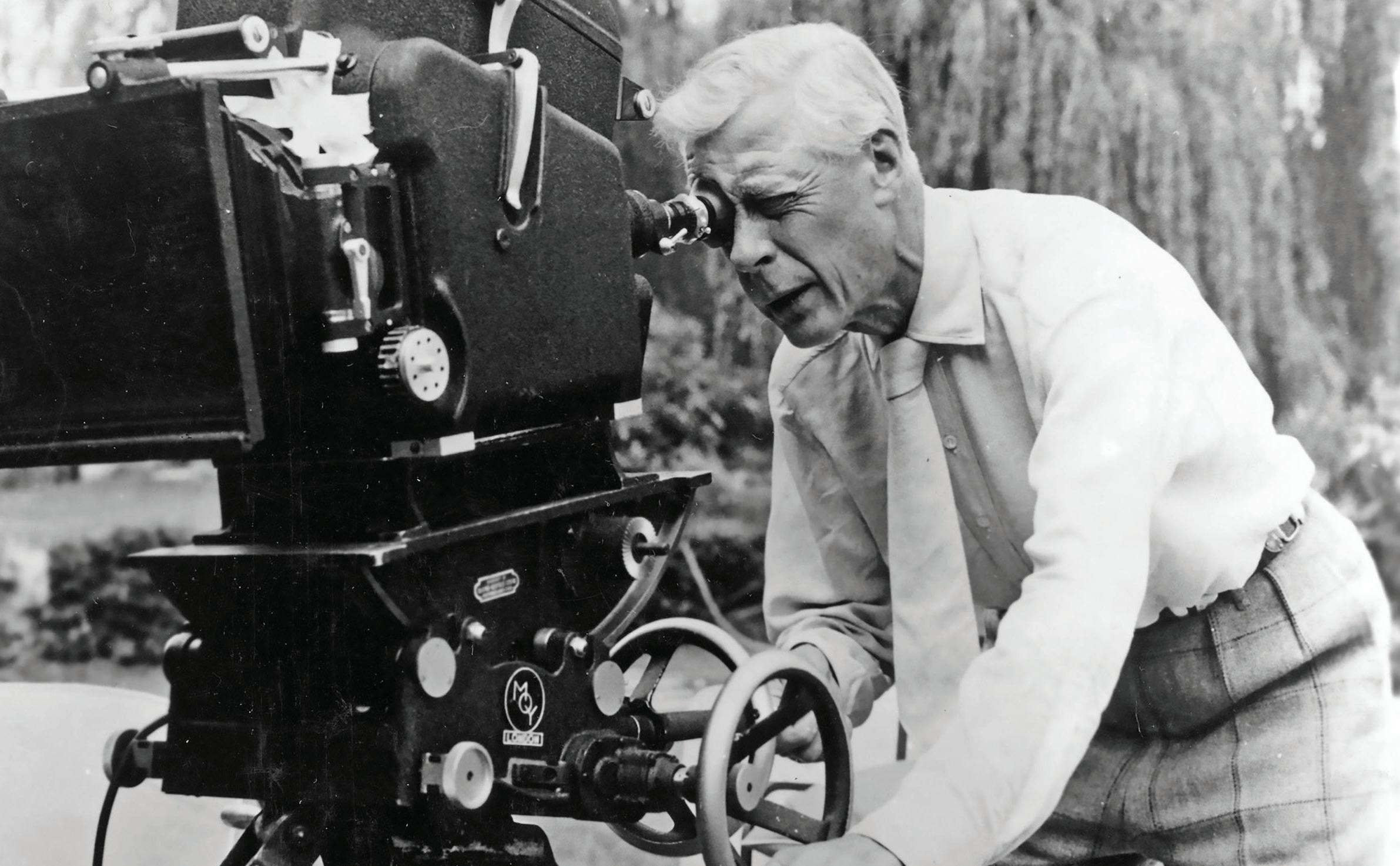

When I started working on this book in 2003, I reached out to Jennifer Bodine, the daughter of A. Aubrey Bodine. My quest was for photos of the President Warfield, a 1920s-built steamship that famously (and infamously) was repurposed in 1947 as the Exodus to ferry 4,500 Jewish immigrants, the majority of them Holocaust survivors, from France to Palestine, at that time under British control.

Mom’s priorities: horses, hounds, children, husbands

40 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

In the process of searching for images of the ship, we stumbled upon an article that appeared in The Baltimore Sun’s Sunday Magazine in the late 1950s that depicted my mother and father, including photos of my mother fox hunting and herding cattle.

The accompanying photos reflect an early childhood safeguarded by matrimonial harmony, a becalmed domesticity, a time of innocence and love — a love that I do not remember. My childhood memories begin, instead, at age six with my parents’ marriage crashing and burning — Jack Daniel’s-spiced arguments, not-so-dangerous liaisons, and the final act, my mother’s exodus from Maryland with her four children in tow.

One particular incident stands out in my mind: an alcohol-infused car accident that chopped a telephone pole in half. My father was driving. Both parents miraculously survived the crash; their marriage did not. Father’s affair with

42 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

TWA: Ted Warfield Airlines — Dad with Mom in the cockpit of his private plane

the bottle deepened; Mother’s affair with a dashing polo player blossomed; their children remained clueless.

Daisy really did resemble Mayberry: The closest restaurant was 15 miles away, while the local general store appeared to be out of the 19th century. Daisy was also an hour’s drive from the Green Spring Valley, where my father’s sisters, fox hunting, and my mother’s aspirational social world existed. Despite her eschewing her Park Avenue/Palm Beach upbringing, she found the Howard County social scene to be nevertheless stultifying, primarily limited to other Warfield spouses.

All this caused Mother’s sense of isolation to worsen. Finally, during the third week of August 1964, she executed the first step in her great escape, loading Beth, Diana, John, and me into the back of our Ford station wagon to visit her bedridden mother in Asheville, North Carolina. Mother was looking for financial support in order to move to what she perceived as the promised land — Far Hills, New Jersey. My grandmother obliged.

Far Hills’ origins date to the mid-1880s, when Evander H. Schley, a land developer and real estate broker from New York, purchased thousands of acres in Bedminster and Bernards townships. In 1887, Schley’s brother, Grant, and Grant’s wife, Elizabeth, arrived by horse-drawn carriage to see Evander’s farms. Elizabeth remarked on the landscape of the “far hills,” thus giving the place its name.

Almost a century later, Far Hills residents included Nicholas Brady, treasury secretary to both Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, as well as chairman of investment bank Dillon, Read & Co.; Malcolm Forbes, publisher of Forbes magazine; and Charles W. Engelhard, Jr., who amassed a fortune in mining and metals.

In addition to this modern-era gentry, Far Hills also featured an equine attraction: fox hunting with the Essex Fox Hounds. Not far away, in the town of Peapack, Jackie Onassis owned a horse farm from the 1970s until her death in 1994. Like my mother, Jackie possessed a passion for fox hunting. Meanwhile, Jackie’s sister, Lee Radziwill, boarded her horses on our farm.

Nicholas Brady’s family — fun-loving, all-American aristocracy — became my Brady Bunch. Their compound included motorbikes, a paddle tennis court, delectable chocolate chip cookies, and a role model marriage: Nick and his wife, Kitty, who had the grace of Grace Kelly, the classic beauty of Brigitte

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 43

44 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 45

Even cowgirls get the blues: Mother herding cattle

Bardot, and the cheerfulness of Florence Henderson. Her french fries were memorable, her hospitality extraordinary.

Their children were similar in age to our family’s: At Far Hills Country Day School, Nick Jr. was in my class; Christopher in my sister Beth’s class; and Anthony in my sister Diana’s. As testosterone-laced teenagers, the Brady boys and I committed various misdemeanors, but Kitty graciously tolerated us, understanding that these were privileged rites of passage.

Kidnapped: Coup d’Edwin

My memories of my father kidnapping me at age 14 remain vague. They have been expunged, deleted. My siblings have only slightly stronger recollections. Not long ago, over dinner, my Middlebury, Vermont-encamped, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy-graduated (at Tufts University), wickedly smart sister Beth mentioned, in passing, the kidnapping. (In the context of sibling rivalry, the fact that I was the only one kidnapped probably would provide fodder for a therapist.)

“We went to a horse event,” she told me. “You stayed home or something to that effect. Dad flew up to pick you up. That is all I recall.”

I’m pretty sure that I have created a psychic firewall related to the incident. The son of a general whose plane was shot down in WWII and a mother who was shipped off to boarding school at age eight definitely has the necessary genetic code to erect firewalls.

“Grin and bear it” or “bloody hell, press on,” my mother often declared.

“Lead, follow, or get out of the way,” my father barked.

Trauma lodges in the deep recesses of our memory. Hit delete. Move on with life. Muck out a stall. Creosote a fence. Grin and bear it. As for bringing in the services of a psychiatrist or therapist, that would not have been on my parents’ radar.

Not surprisingly, a custody battle over me ensued. My memories of this, unlike the kidnapping, are more vivid. There was a courtroom appearance during which the judge took me back to his chambers and asked me which parent I wanted to live with. My 14-year-old response was “both.” Accordingly, the judge awarded joint custody. (Curiously, my brother and sisters never entered the legal picture, with Mother retaining full, uncontested custody of them.)

46 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

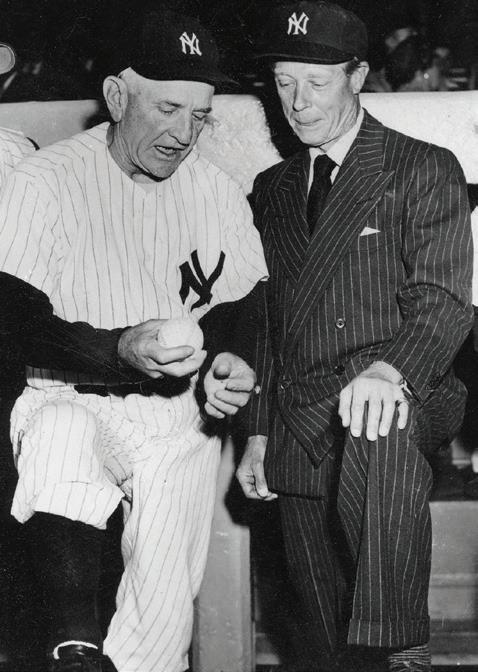

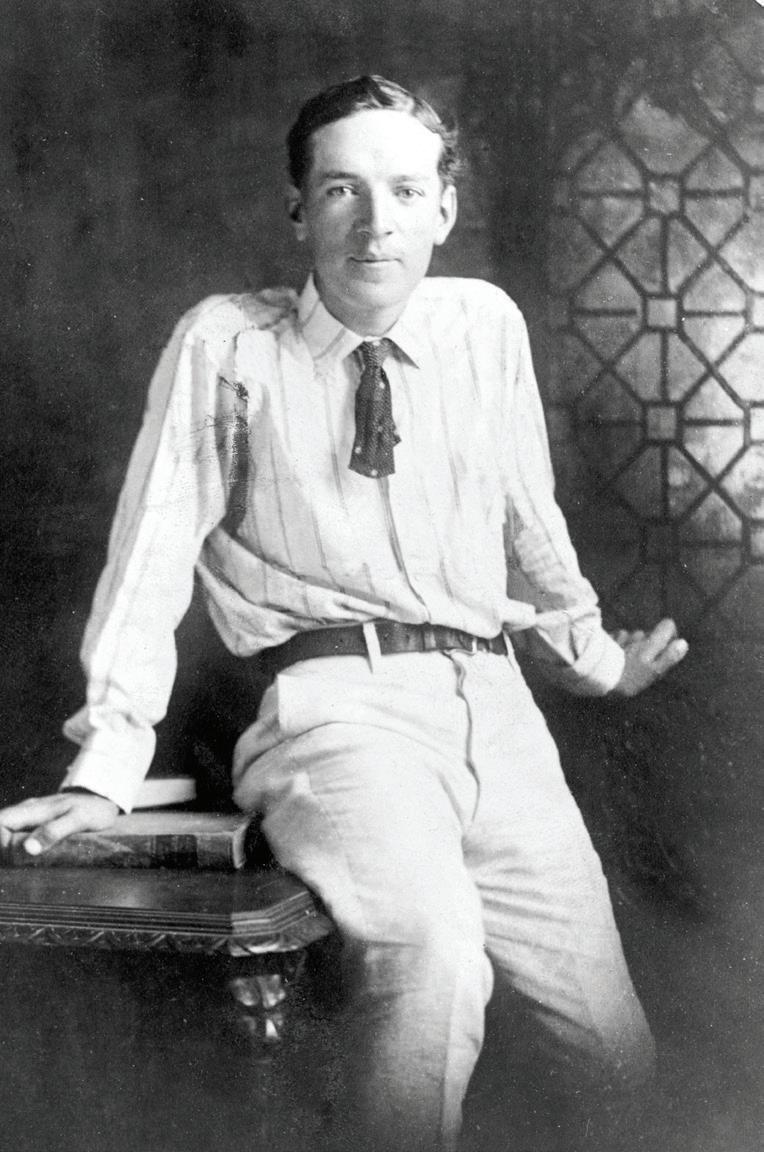

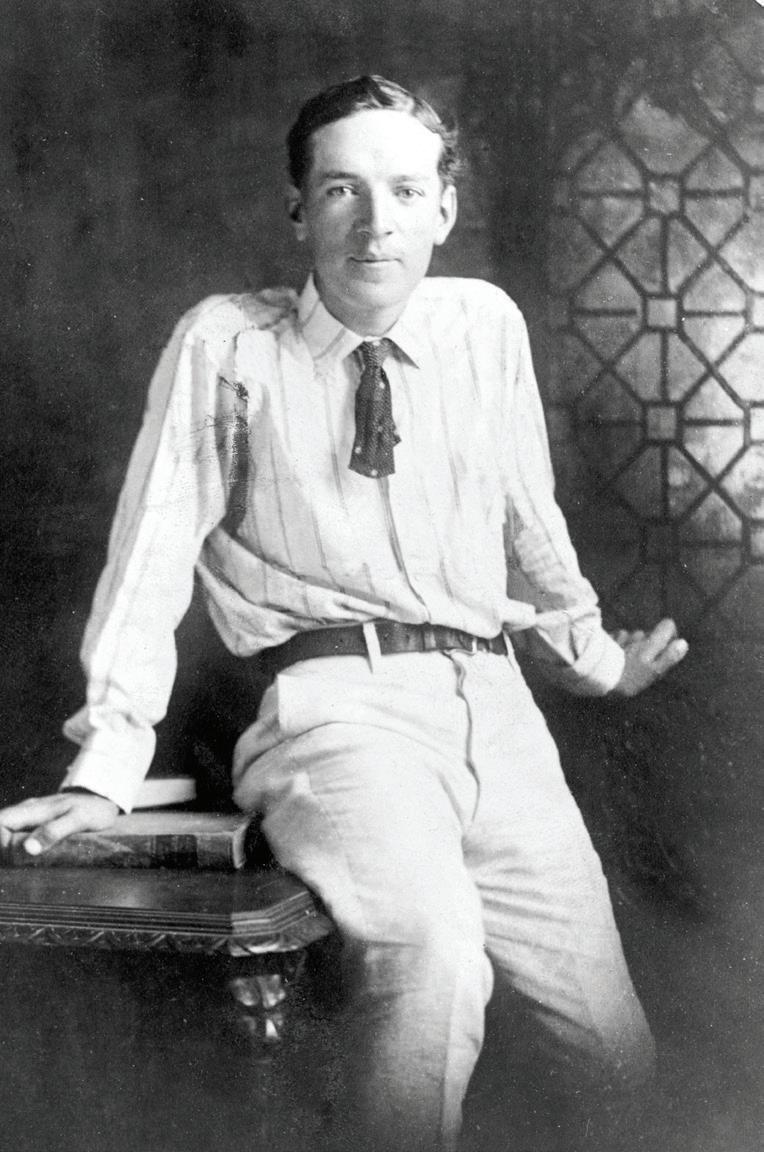

The Importance of Being Ernest: Ernest Simpson, the Hill School graduate and second husband of Wallis Warfield

With the settlement in place, I became a weekday boarder at Gilman School in the fall of 1968. Weekends alternated between Far Hills and Oakdale. Ice hockey, a social life, and the Brady bunch one weekend; skeet shooting, Jack Daniel’s, isolation, Warfields, and more Warfields the next.

Gilman was founded in 1897 as the Country School for Boys. Named after Daniel Coit Gilman, the first president of Johns Hopkins University, it was the first country day school in the U.S.

I was one of approximately a dozen weekday boarding students living unceremoniously in makeshift conditions on the third floor of the school’s main building. Gilman was never meant to be a boarding school. Five-day boarding was a necessary convenience for parents reluctant to send their sons off to a full-time boarding school, as well as for those whose geographical distance from Gilman precluded commuting.

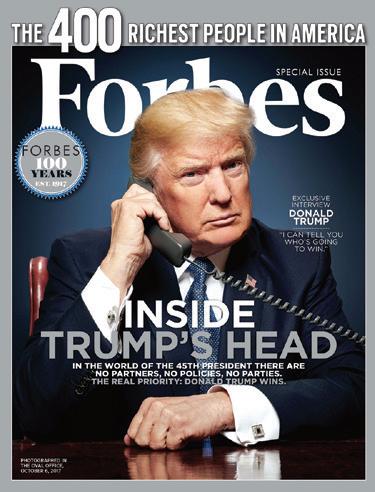

A more convenient solution for the joint-custody arrangement was worked out for the next academic year: I would attend the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, a boarding school equidistant from both parents. At the time, Pottstown was famous for Mrs. Smith’s pies and the iron and steel that were blasted from the town’s furnaces. Among Hill’s more notable alumni are Lamar Hunt, George Patton, Donald Trump Jr., Eric Trump, Oliver Stone, and, significantly, a 1915 grad named Ernest Simpson, who became the second husband of the Duchess of Windsor.

The Hill School was a bleak house, or, in Dickensian terms, Bleak House.

From the rear-view mirror of a 65-year-old, Hill was a depressing place. First and foremost, it was boys-only. Arranged dances with “appropriate” girls’ schools required crossing the state line to Garrison Forest in Maryland or Purnell in New Jersey. The year before my arrival, dozens of students were kicked out of Hill for pharmaceutical dalliances, which, I’m guessing, can be attributed to the school’s dispiriting environment and its lack of female diversions.

At the end of my sophomore year, I changed schools again, rejecting my parents’ and the judge’s judgments. In effect, I gained custody of me, taking control of my own academic decisions by transferring to Milton Academy, fortified by the school’s motto of “Dare to Be True.”

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 47

Milton: Paradise Regained

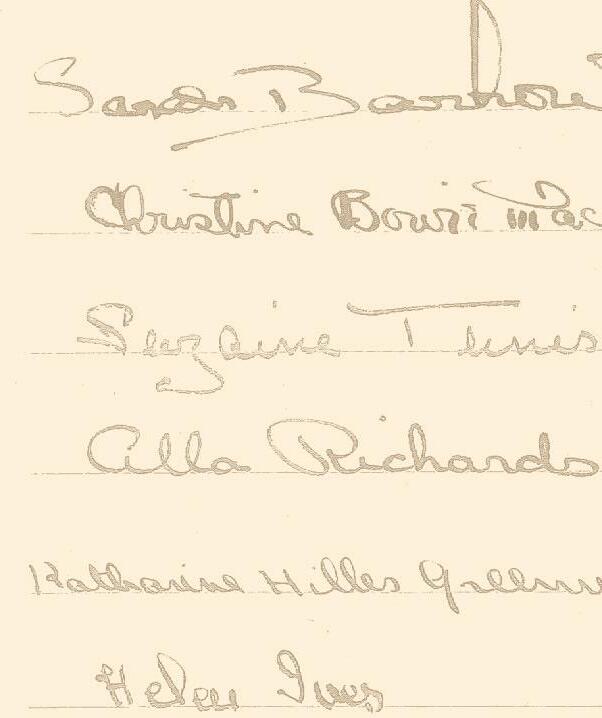

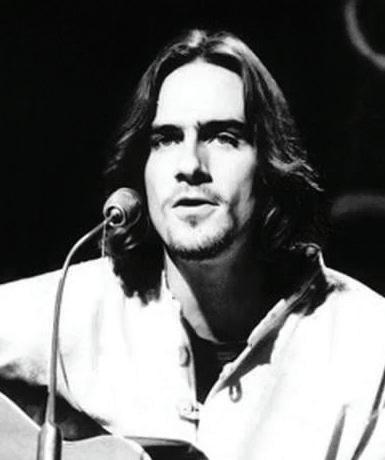

Milton Academy was founded in 1798 via a charter granted by the state of Massachusetts. With the advent of Milton High School, a public institution, in 1866, the academy’s operation ceased, but the school was resurrected 18 years later by John Murray Forbes, a railroad magnate/philanthropist who reestablished it on a new 100-acre site. Illustrious Milton graduates include T.S. Eliot, Buckminster Fuller, and both Ted and Robert Kennedy.

When now asked about my seemingly random choice of schools, I facetiously tell people that my interest was inspired by Milton alum “Sweet Baby” James Taylor, whose music suffused the cultural zeitgeist in 1970. (Later in life, I would learn that I had even more in common with Taylor. While many of his classmates headed to Harvard upon graduation, James headed to McLean Hospital — a psychiatric facility in Belmont, Massachusetts — for eight months. More to come on my psych-ward experience.)

More important, there were girls at Milton, and its proximity to Boston nurtured my burgeoning affection for urban environs — an apparent reaction to a childhood spent in the country. Other criteria for choosing Milton include its curriculum focusing on literature, art, and music, not forgetting its geographical location far removed from both of my parents.

My friends at Milton included other transfer students. Like myself, some were dealing with divorce or, in the case of Marshall Stone, the death of his mother when he was 16. Marshall had been asked to not return to St. Marks, also a Massachusetts prep school, because of his protests against the Vietnam War. Ultimately, he became a pediatric surgeon.

Another friend, Richard Perry, transferred from Deerfield Academy, yet another Massachusetts prep school, where his interest in arbitrage and the inefficiency of markets was kindled. Eventually, he took a post working in the arbitrage department at Goldman Sachs before starting a hedge fund whose assets peaked at $15 billion in 2007.

Then there was Mitch Steir, my senior-year roommate. Mitch was the de facto class ringleader — an amalgam of Ken Kesey, Timothy Leary, and Howard Hughes. We signed non-disclosure agreements at the time, thus our merry prankster activities are not shared herein. Mitch has enjoyed a very successful career in commercial real estate as chairman of Savills Studley. My memories of

48 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

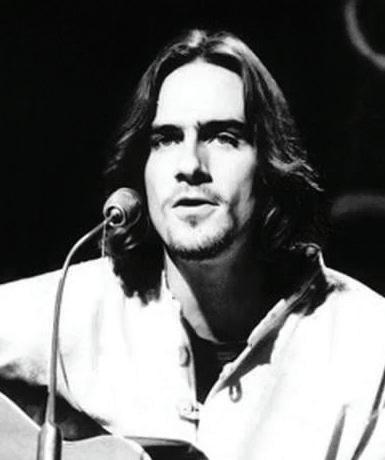

TOP TO BOTTOM: Milton mavericks

T. S. Eliot, Buckminster Fuller, Robert F. Kennedy, James Taylor

Milton remain fond, and some of the friendships I initiated there have continued until today. When you spend 10 months together at a boarding school, the resulting relationships can be almost as important as those with your parents’.

I learned not to drink from finger bowls from my grandmother, leadership and loyalty from my father, and stoicism from both of my parents. However, my intellectual DNA, curiosity, soul, and spirit all came from Milton.

In keeping with the tenor of the times, drugs played a prominent role during my prep school years. At Milton, the nearby graveyard served as our mosh pit, a place where we smoked Nepalese hash. The indulgences at the Hill School consisted of marijuana and, occasionally, LSD. One of my Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds trips got out of control, bringing that particular pharma experiment to an end. By college, my flirtation with drugs had ceased entirely. (At 62, I would be diagnosed with a condition that hinted that these drug forays may have been attributable to self-medication rather than a case of mere youthful exuberance.)

As for alcohol, I was a teetotaler for the first three-and-a-half decades of my life, not a surprising development in lieu of my father’s affair with Jack Daniel’s. In my late 30s, however, I became acquainted with chardonnay, initially drinking on weekends only. Over time, I also developed an interest in malbec, another step in my journey to a wonder drug that would later change my life.

My college years were, like those spent in prep schools, peripatetic; more significantly, they represented an angst-y mashup of the practicality of business and the passion of art. And while my quantitative college scores would have supported a career on Wall Street, my genetic inheritance did not. I was a conflicted, confused boy/man caught between culture and commerce — a prime example of the classic right-brain-versus-left-brain battle. The upshot: I majored in business at McGill University in Montreal, before attending the Sotheby’s Works of Art Course in London.

The year at Sotheby’s was heavenly, with classmates who were similarly passionate about art, a veritable international Noah’s Arc of Eccentrics. Most unforgettable among them: the always-dressed-in-black Ivor Braka, a cross between Frank Zappa and Iggy Pop. Ivor would become a very successful art dealer, specializing in works by Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 49

We made trips to the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Tate, and the Wallace Collection. Such institutions have always been my sanctuary in the city — the perfect antidote for what I call my “unquiet mind.”

I met Amy, my first wife, at the Sotheby’s program. The marriage would last 25 years and produce two beautiful children — Allegra and Win. Amy had been adopted by her stepfather. Like my mother, she would marry into a family with a rich history (emphasis on “history”).

“My mother had a great deal of trouble with me, but I think she enjoyed it.”

–MARK TWAIN

Upon graduation from the program in May 1978, I was offered a job at Sotheby’s Belgravia in London for £5,000 per year (the equivalent of $6,500) to catalogue 19th-century English ceramics. That seemed a too-meager sum to me, so I graciously declined and, instead, returned to New York, where I landed a job at a more acceptable salary in the European painting department of Phillips Auctioneers. Eventually, however, I realized that my passion for art probably would not develop into a sustainable career, so I enrolled at New York University’s Stern School of Business at night, from which I graduated in 1983 with an MBA.

At that point, I needed to make a critical decision: pursue investment banking in New York or return to Baltimore to become the fourth-generation publisher of The Daily Record. My mother, who died the year before, had spent her last three years in a coma, while my father had graduated from an addiction treatment facility, thus ending his affair with Jack Daniel’s.

After a decade-long hiatus, I determined that it was time to reconnect with my Maryland roots, my father, and what amounted to my privileged publishing destiny.

50 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 51

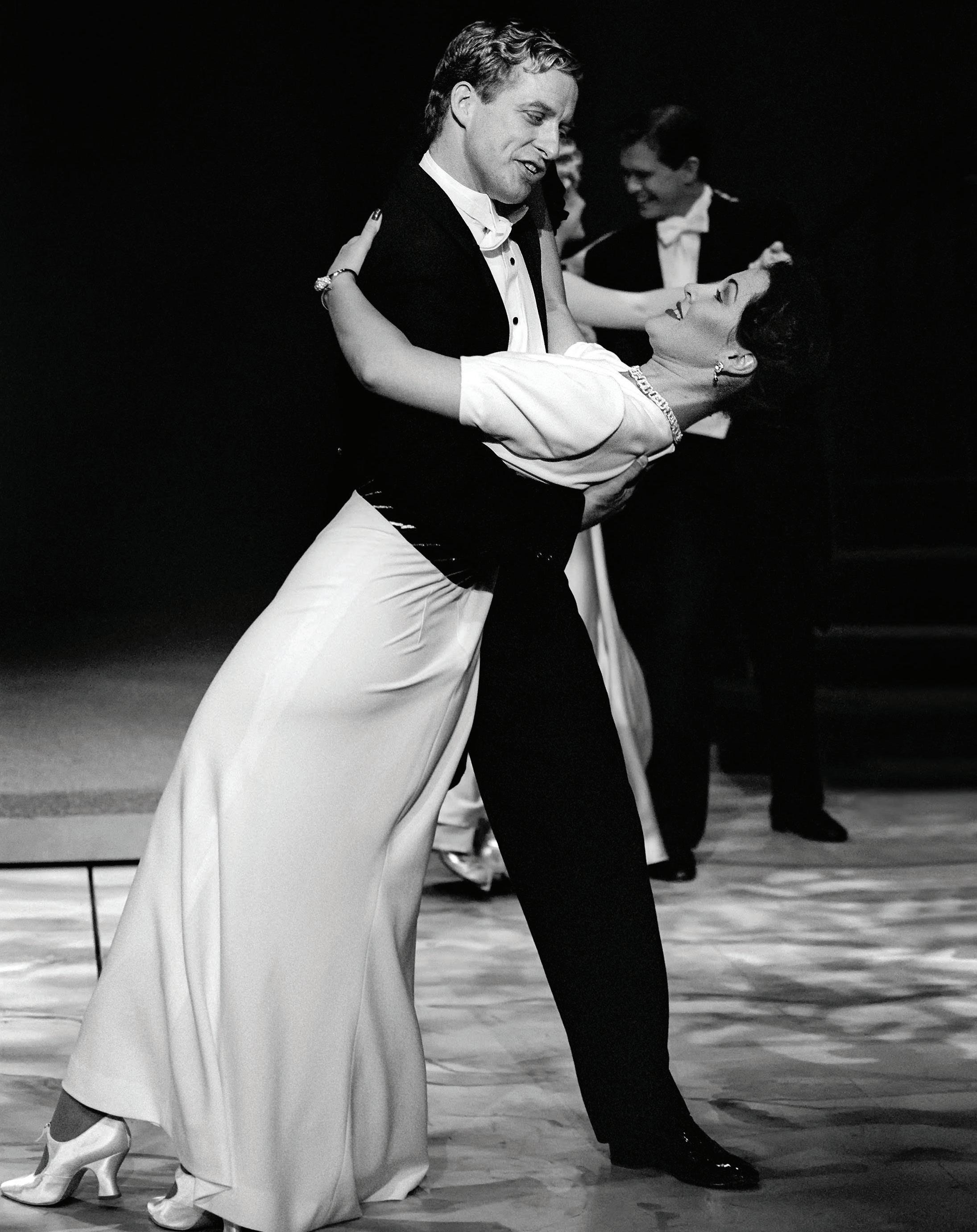

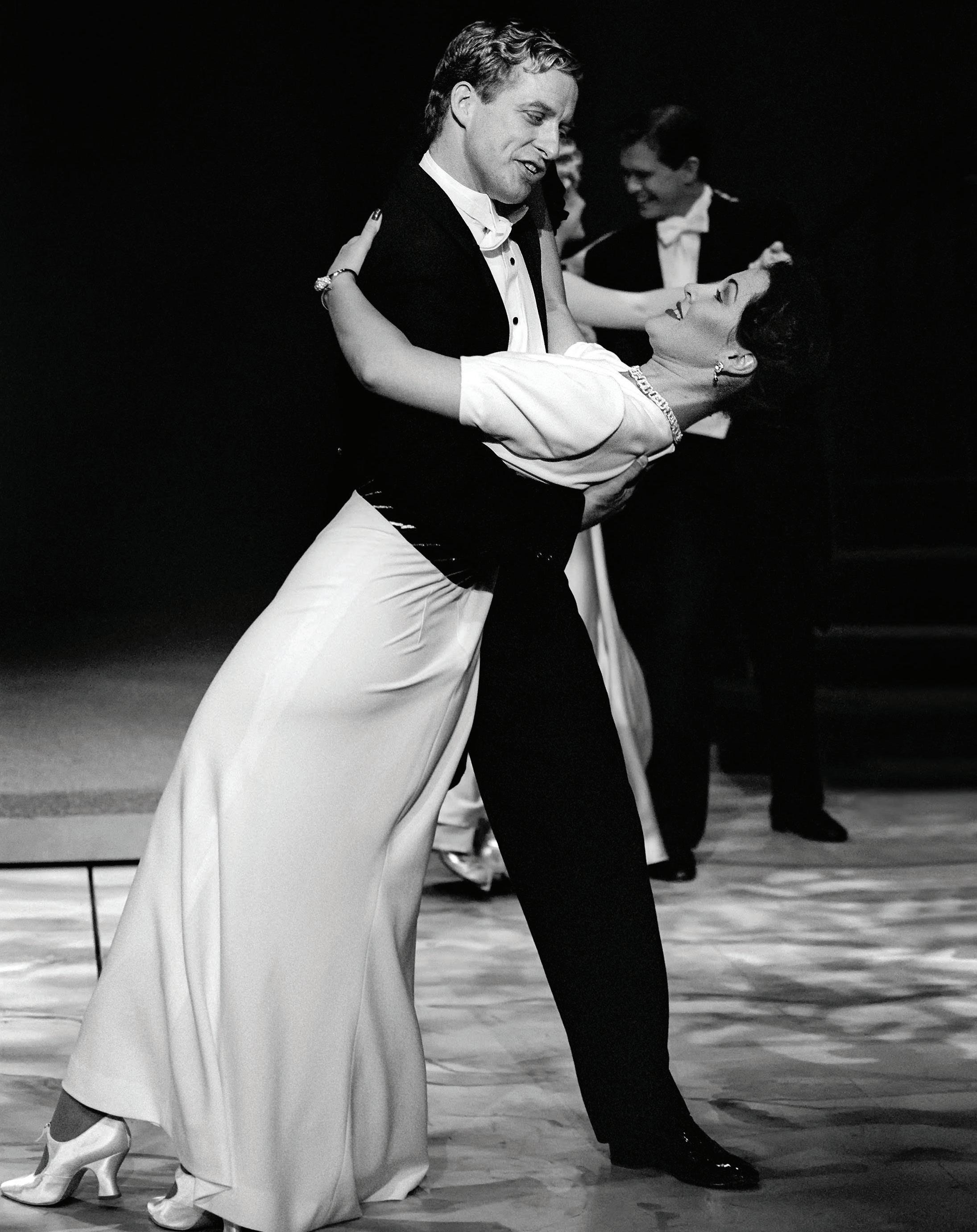

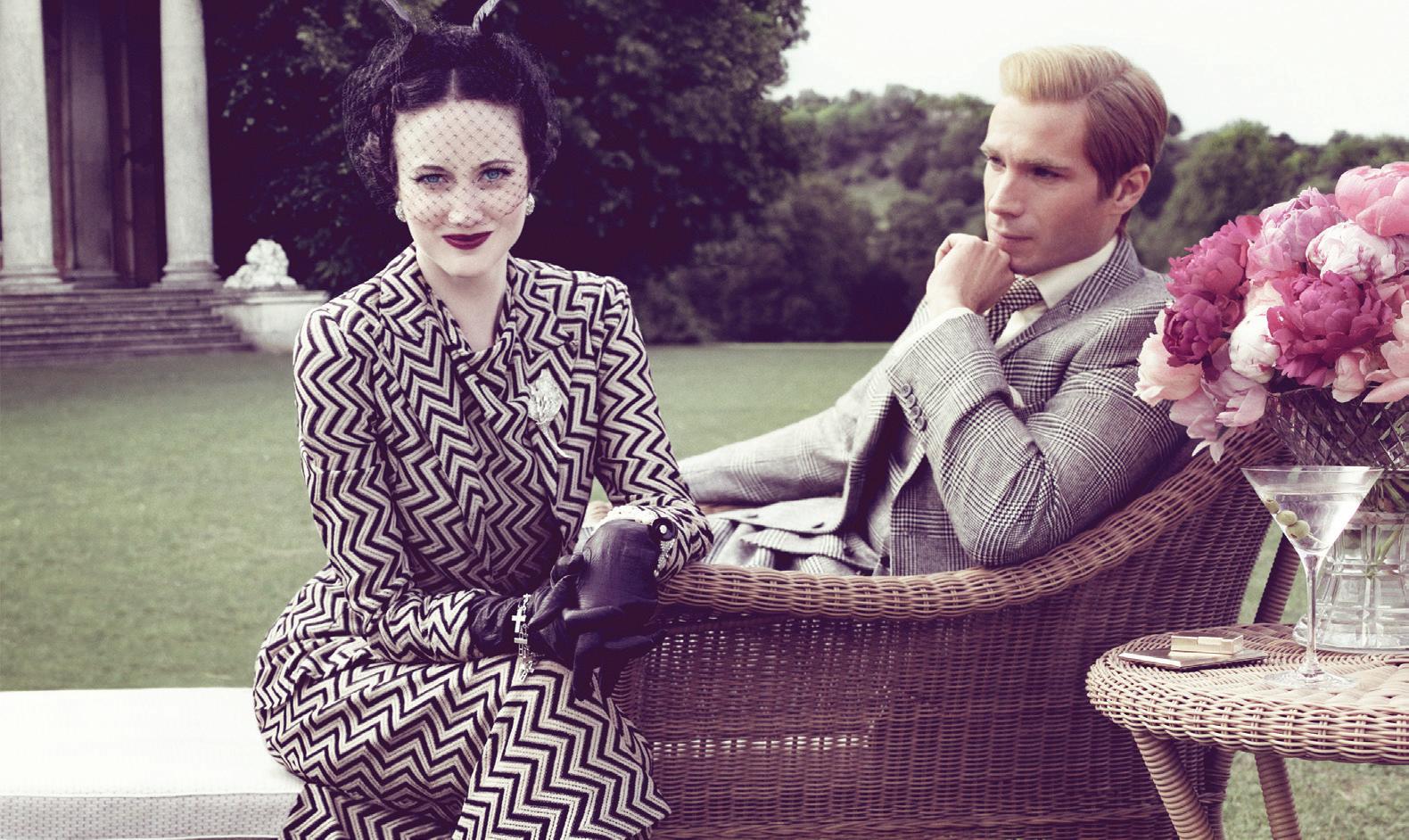

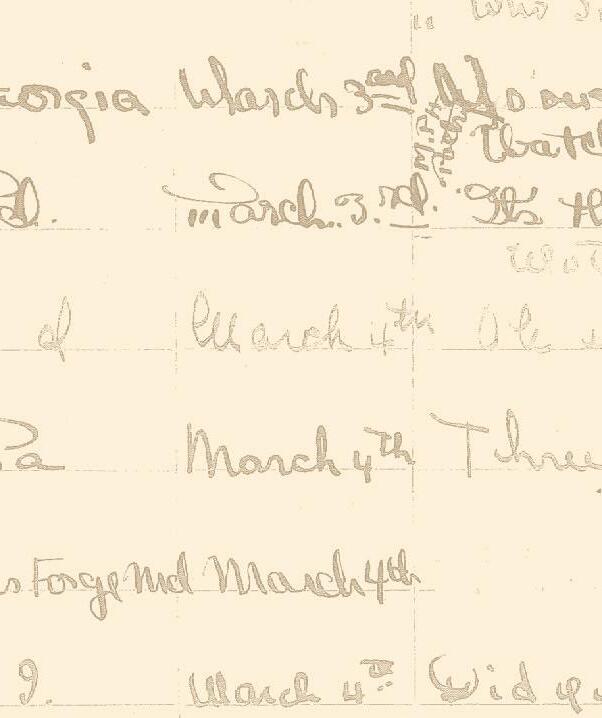

LONG LIVE THE ABDICATION

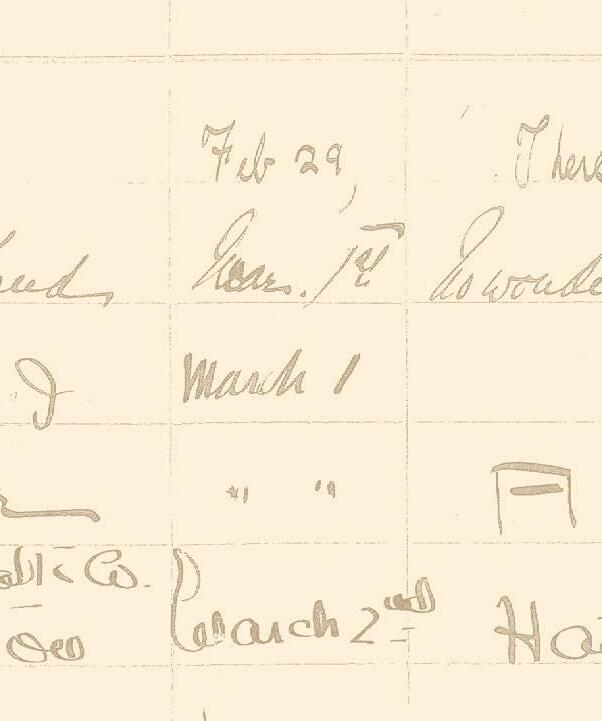

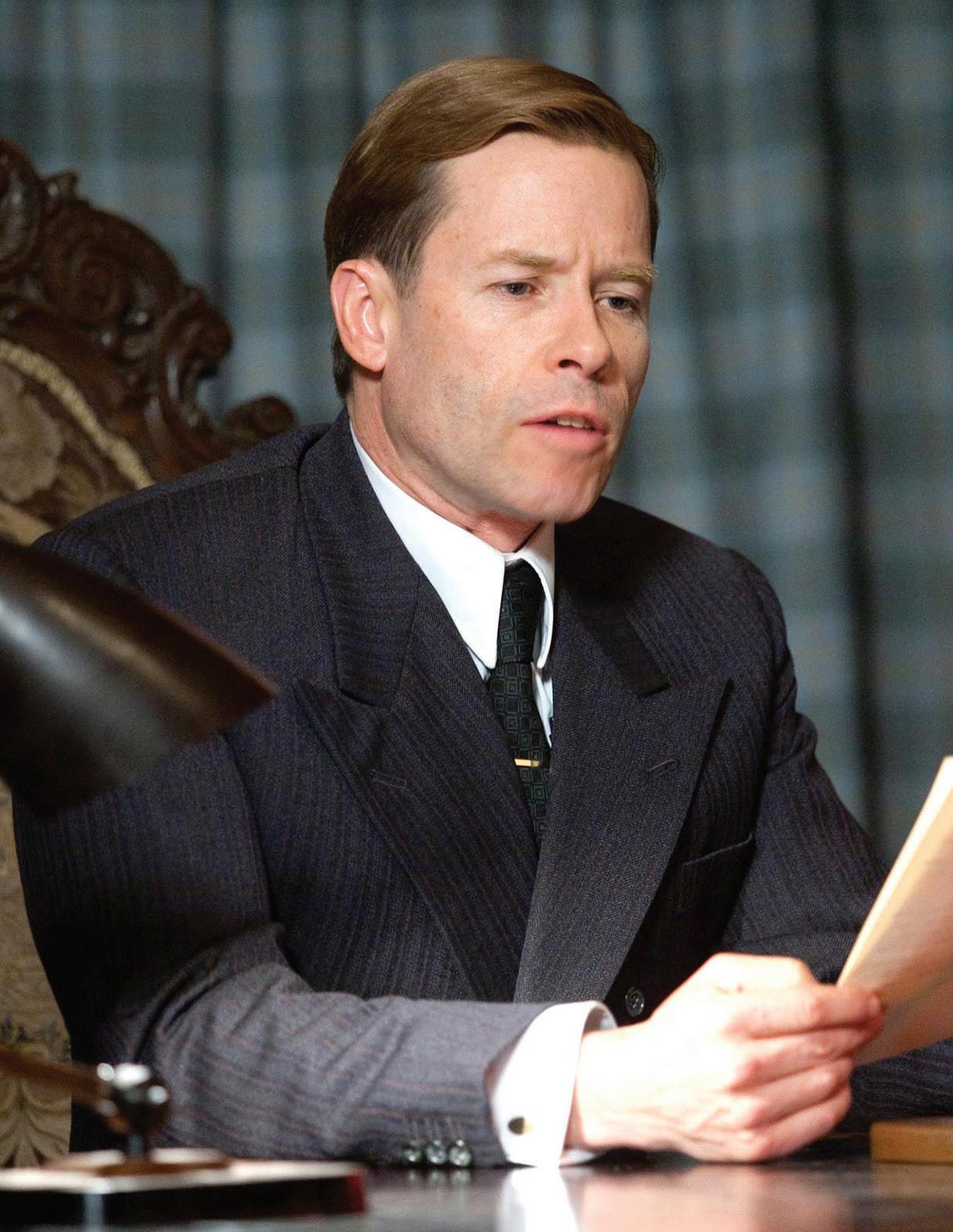

Eward VIII’s abdication of his kingly throne has long fascinated and preoccupied the purveyors of popular culture, who periodically recreate and reimagine the event in books, on the stage, and on both the big and small screens. After all, the guy willingly walked away from perhaps the cushiest gig on earth. He was not beheaded (Louis XVI) or deposed, imprisoned, and shot (Nicholas II) or shamed into resigning (Richard Nixon). Edward just quit. All for the love of a then-still-married commoner. Juicy stuff. Catnip for screenwriters.

Recently, the abdication has experienced a decadelong revival, depicted in Madonna’s 2011 film W.E., in the 2010 movie The King’s Speech (winner of the Oscar for Best Motion Picture), and in the ongoing TV series The Crown (those last two pictured here). Apparently, we can’t get enough of it.

52 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

“The abdication was the greatest news story since the Resurrection.”

– H.L. MENCKEN

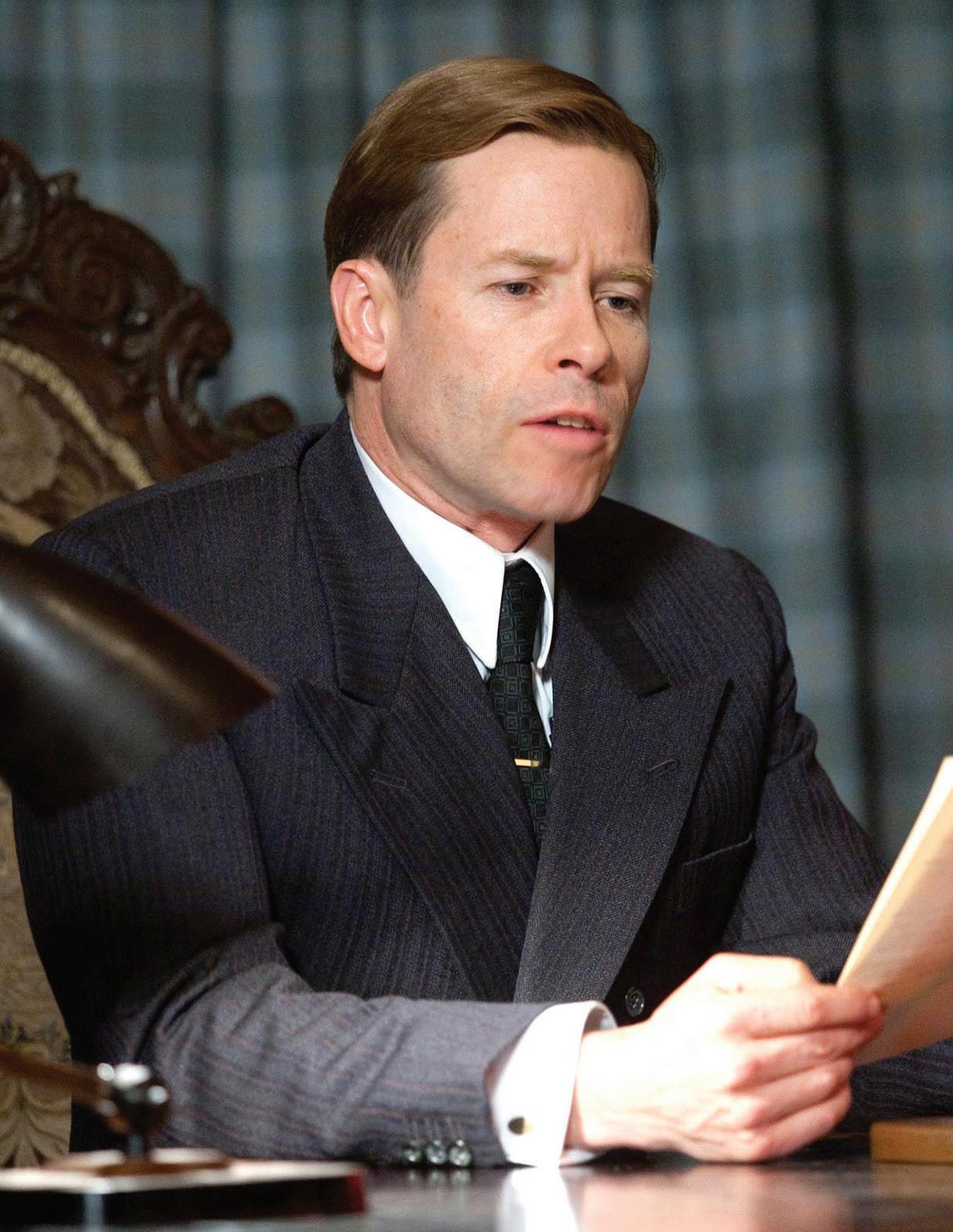

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

King Edward VIII (Guy Pearce) announces his abdication in The King’s Speech; Alex Jennings and Lia Williams portray the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in The Crown; the Duke of Windsor (Alex Jennings) in The Crown; King George VI (Colin Firth, left) receives coaching from Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush) in The King’s Speech; Winston Churchill (John Lithgow, left) confers with King Edward VIII (Alex Jennings) in The Crown; Queen Elizabeth (Claire Foy) tries on new headgear in The Crown.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 53

4 My Cousin Wallis: the Duchess of Windsor

“ You have no idea how hard it is to live out a great romance.”

– WALLIS WARFIELD SIMPSON

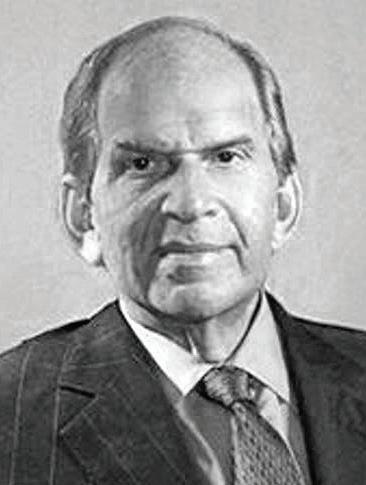

Yes, the Duchess of Windsor was a Warfield, and was, in genealogical terms, my sixth cousin, once removed. In a book that would praise heroes and heroines, the inclusion of the Duchess of Windsor required consideration. The Love Story of the Century, as some have called it, may be merchandisable, but Wallis Warfield Simpson’s character was at the very least controversial.

Gay icon? Oh, yes.

Social butterfly? Indubitably.

Sexual siren? You could make a case.

Nazi sympathizer? The Brits think so.

Hermaphrodite? There’s talk.

Debauchee debutante? Dubious.

The Love Story of the Century has definitely been tarnished, mostly because the Duchess was so much fun to hate. She really never had a chance. It is important to understand that Great Britain probably had never had an heir apparent so adored and so perfectly suited for his future role as king as Edward.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 55

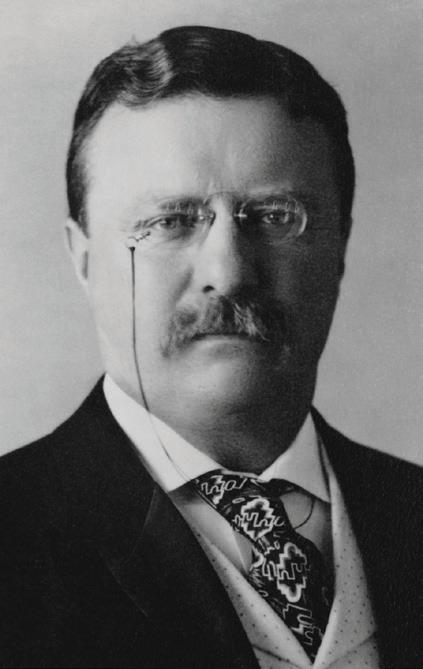

Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David Windsor — the eldest son of King George V and Queen Mary, and, as such, the Prince of Wales — was handsome, articulate, and thoughtful. He had been polished and groomed for the job. As a bonus, he appeared to be especially attuned to the problems of the common man. The monarchy had been feeling insecure for some time about the government deeming it obsolete. If the populace loved Edward, that certainly strengthened its position. Meanwhile, his brother Bertie (Albert), who was next in line to be king, had a speech impediment and lacked Edward’s charisma.

So the public, and even more so the monarchy, simply could not accept his rejection of them when he famously abdicated his throne as King Edward VIII a mere 11 months after ascending to it. And for what? His love for Wallis, a commoner, a divorcee, and an American? This woman had better be damned perfect, or everyone was going to use her as a scapegoat for their rage. Despite the fact that she radiated style, panache, and savoir faire, she still was far from perfect, so that is exactly what happened.

The gossip about the Duchess is fun to read, but, for the most part, impossible to prove. In deference to her admirers, my purpose here is simply to present the aggregated information and, with luck, avoid the burden of personal opinion. The dirt on Wallis continues to titillate long past her death, and the 2018 marriage of American actress Meghan Markle to Prince Harry has served as a catalyst for exhuming her, with myriad headlines screaming variations on the Daily Mail’s “Style snap! Meghan Markle and Wallis Simpson — two glamorous American divorcees who met their smitten princes before they were 34.” The Meghan/Harry union also helped generate a pair of recent Duchessrelated books: Andrew Morton’s Wallis in Love: The Untold Life of the Duchess of Windsor, the Woman Who Changed the Monarchy (2018), and Anna Pasternak’s The Real Wallis Simpson: A New History of the American Divorcee Who Became the Duchess of Windsor (2019).

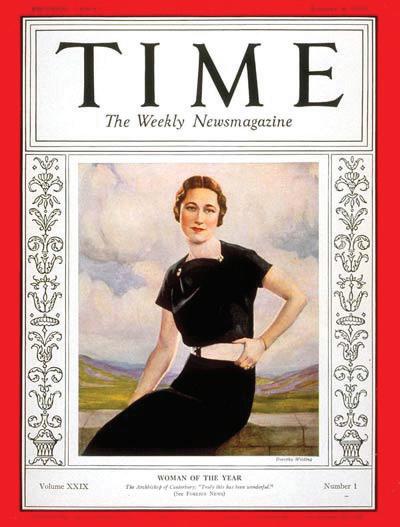

My father used to say that the only thing that terrified him more than being shot down over the Pacific was having to dance with his cousin Wallis. And in a 1996 Baltimore Sun article about a recently released documentary on

56 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

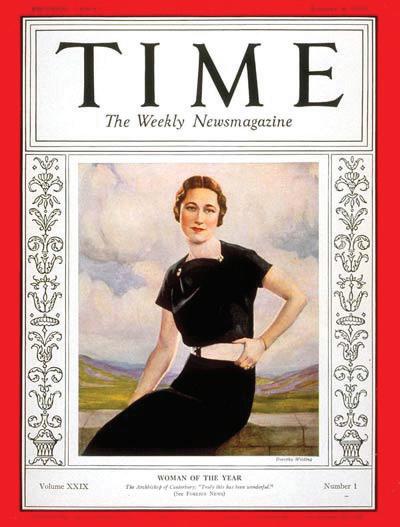

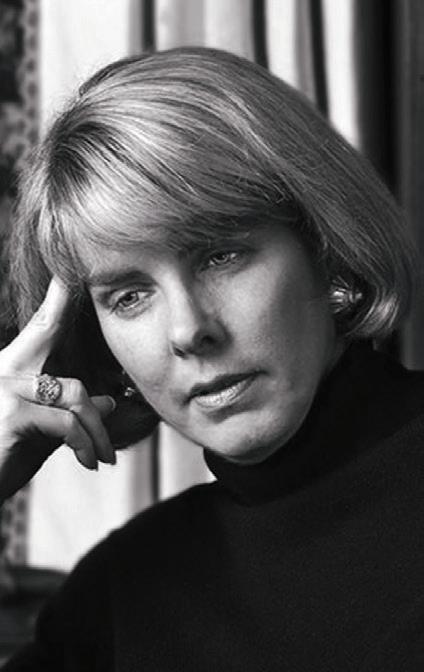

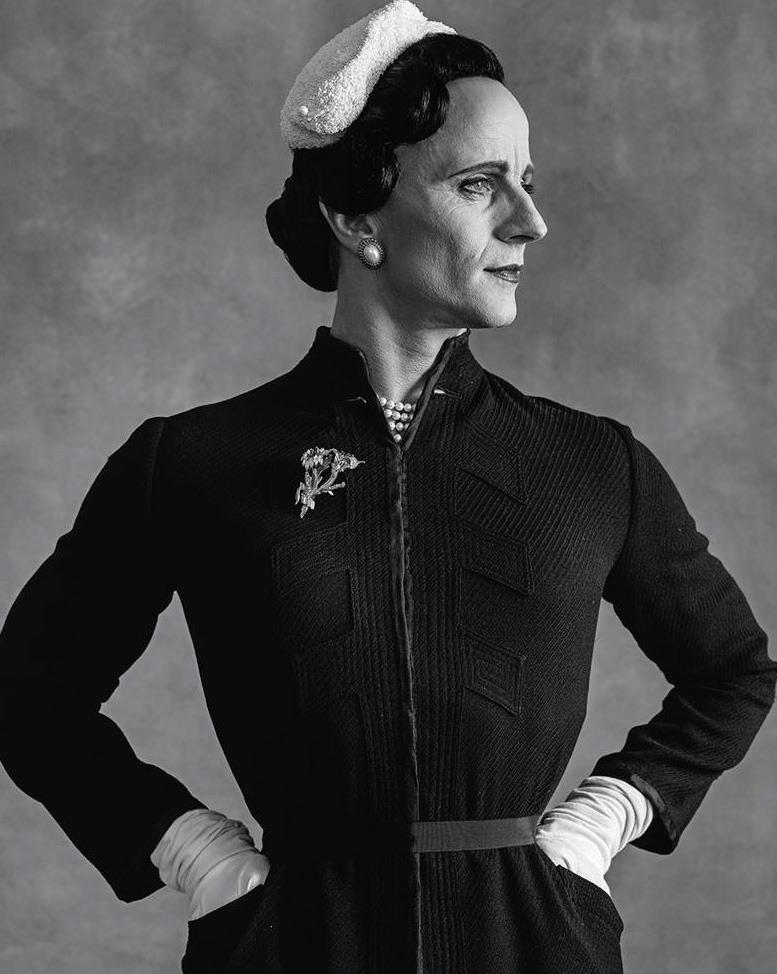

Wallis Warfield Simpson: Time magazine’s 1936 Woman of the Year

Edward VIII, Dad conceded that “she was never so conceited that she forgot her Baltimore roots.”

One could read between the lines that he probably considered her life a bit frivolous — after all, her main skills were decorating and entertaining; she lived extravagantly and self-indulgently — but a good Baltimore boy will always defend a Baltimore girl even if it is with circumlocution.

I’m still not sure if Dad had answers to any of the rumors or myths that have developed over the years about Wallis, but he never engaged in trash talk. Never. One of his favorite quotes was Mark Twain’s “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

“I’ve Danced With a Man, Who’s Danced With a Girl, Who’s Danced With the Prince of Wales.”

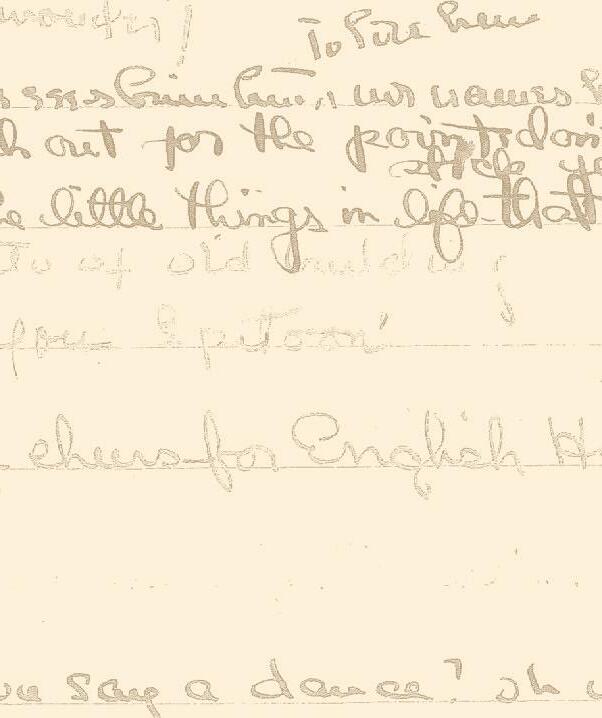

–HERBERT FARJEON, title of his popular 1927 song

Some say the Duchess never loved the Duke (Edward was named Duke of Windsor after his abdication), and that they never had sexual intercourse. Others believe Wallis was devoted to her “David” (Edward’s intimate name), dedicating her life to making him happy: the Love Story of the Century Theory.

Meanwhile, Queen Mary, Edward’s mother, called Wallis “the lowest of the low, a thoroughly immoral woman.” In fact, the Duchess was never allowed anywhere near the royal family after Edward stepped down as king. The title Her Royal Highness should have come automatically with her marriage to the Duke, but Edward’s brother Bertie, who as King George VI took the throne when Edward stepped down, denied it, resulting in a huge insult to Wallis and a lifetime of grievance by the Duke.

Was the Duchess an opportunist or devoted wife? Nazi supporter or allAmerican girl? Most Warfields do not claim her.

However, the Montagues of Virginia do. Her mother was Alice Montague from an old Virginia line. Her father was Teackle Wallis Warfield of the Maryland Warfields. Wallis was their only child. Each family produced a governor of its respective state. The Warfields were a stern, hard-working dynasty; the Montagues were known for their wit and good looks. Wallis did not inherit the latter.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 57

In her 1956 autobiography, The Heart Has Its Reasons: The Memoirs of the Duchess of Windsor (ghosted by Charles Murphy), Wallis writes, “So my legacy was this curious Warfield-Montague admixture, which had the effect of endowing my nature with two alternating sides, one grave, the other gay. If the Montagues were innately French in character and the Warfields British, then I was a new continent for which they contended. All my life, it seems, that battle has raged back and forth within my psyche. Even as a child, when I misbehaved, my mother taught me to believe that it was the Montague deviltry asserting itself; when I was good, she gratefully attributed the improvement to the sober Warfield influence. However, it was my private judgment that when I was being good, I generally had a bad time, and when I was bad, the opposite was true.”

“The fault lay not in my stars but in my genes.”

– EDWARD VIII, the Duke of Windsor

Michael Bloch — assistant to the Duchess of Windsor’s French lawyer, Suzanne Blum — wrote five thoroughly researched books about the Windsors, including his 1996 biography of Wallis, The Duchess of Windsor. In that book, Bloch notes that Wallis’ birth was never registered, and suggests that there was some confusion related to the baby’s gender, which made a name choice for the child difficult.

The questionable nature of the Duchess’ gender is a central theme in Bloch’s Duchess bio. Whether or not it is mere titillation rather than fact seems to be difficult to ascertain for historians, although not for lack of trying. Bloch produces the best available evidence in statements from Dr. John Randell, an expert on gender at London’s Charing Cross Hospital, who gave clinical substantiation that Wallis suffered from androgen insensitivity syndrome, also known as testicular feminization caused by having XY chromosomes. Blum, the attorney to whom the Duchess gave control of her affairs in 1973, claims that the Duchess died a virgin.

58 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon

Wallis’ father died of tuberculosis in 1896 when she was five months old (she was born on June 19 that year), and she and her young mother, Alice, moved into the Baltimore townhouse of Wallis’ paternal grandmother, Anna Warfield. The man of the household was Solomon Davies Warfield, Wallis’s bachelorbusinessman uncle, who became infatuated with Alice. His advances were unrequited and may have precipitated Alice and Wallis’ move to the home of

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 59

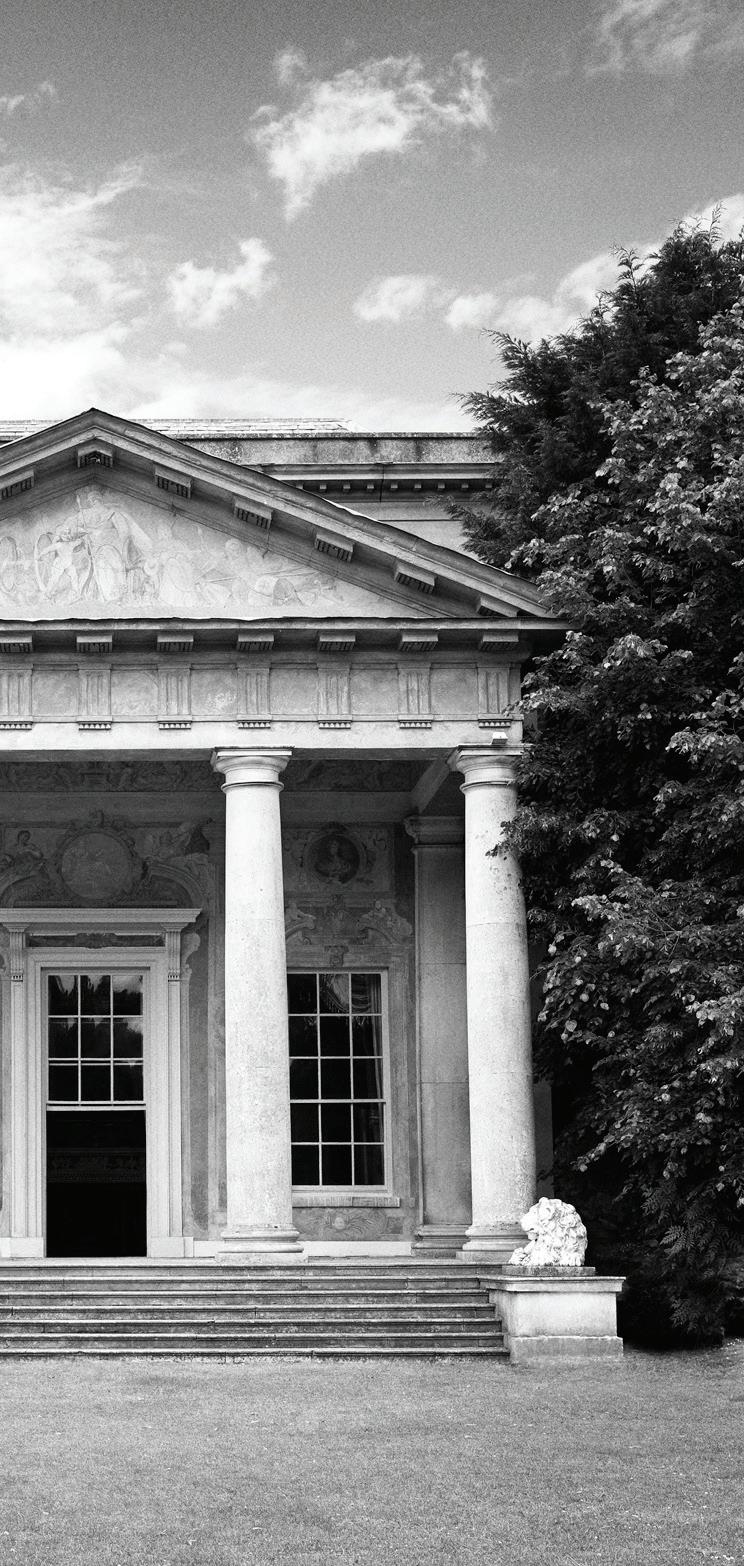

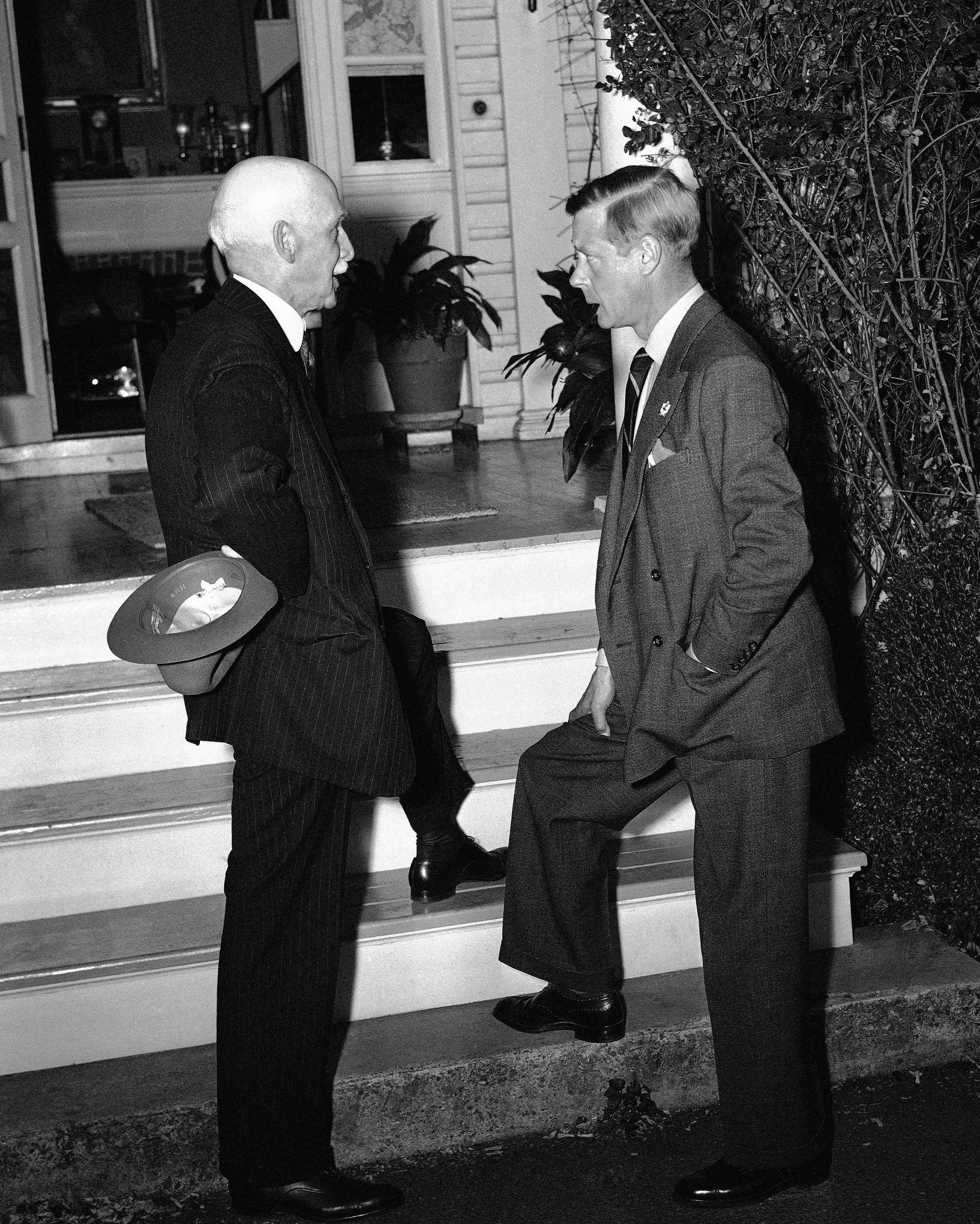

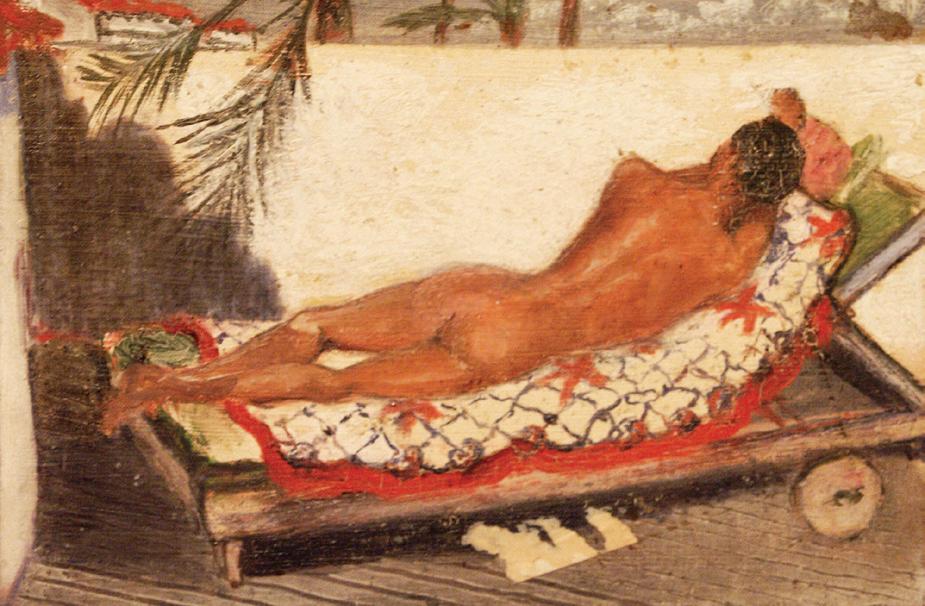

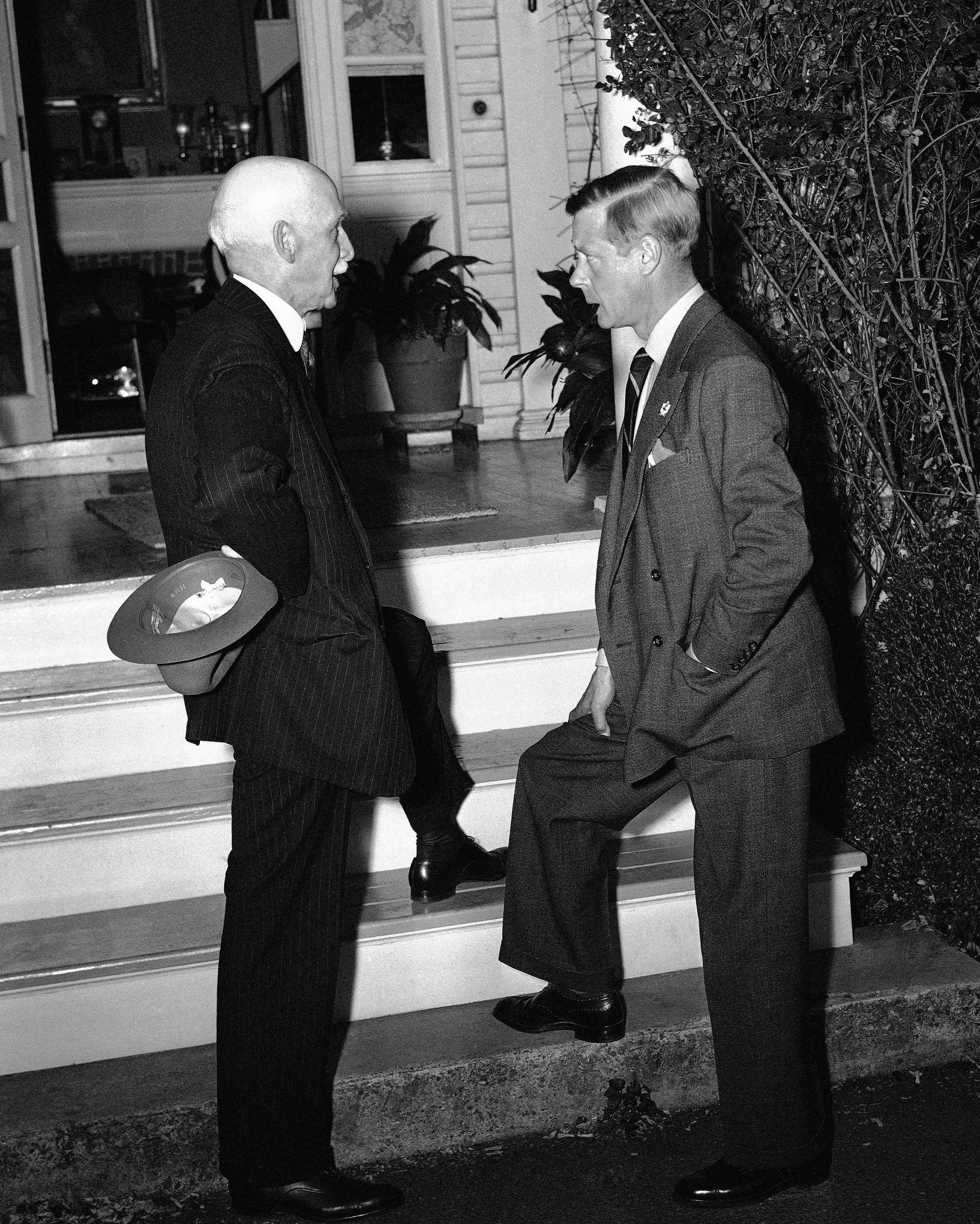

For whom the bell tolls: the Duke at the Maryland estate of Clarence and Eleanor Miles

60 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

Second thoughts on the abdication?

the latter’s Aunt Bessie Merryman until they found a rented apartment of their own. And yet Uncle Sol supported Wallis financially from childhood through young adulthood.

About him, Wallis wrote in her memoir: “Cold of manner, with a distinguished if forbidding countenance, he was already, while still in his thirties, a banker of means and an entrepreneur of daring and imagination in numerous fields, such as transportation, public utilities, and manufacturing.... Of all the Warfield brothers, Uncle Sol was to have the most influence upon me. For a long and impressionable period, he was the nearest thing to a father in my uncertain world, but an odd kind of father — reserved, unbending, silent. Uncle Sol was destined to return again and again to my life — or, more accurately, it was my fate to be obliged to turn again and again to him, usually at some new point of crisis for me and seldom to his liking. I was always a little afraid of Uncle Sol.”

“As the Duchess of Windsor, she created an eternal signature style, which became her personal armor.”

– ANNA PASTERNAK, from The Real Wallis Simpson

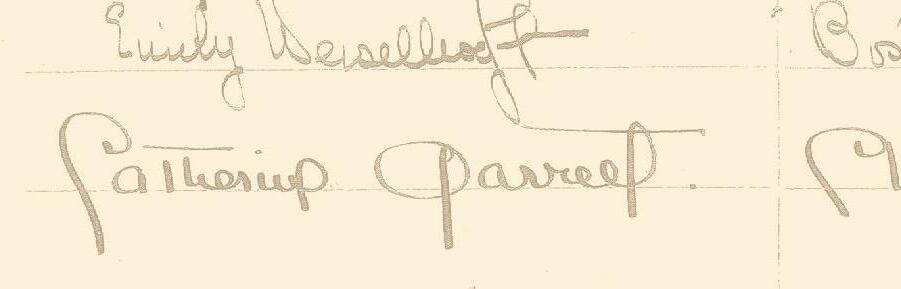

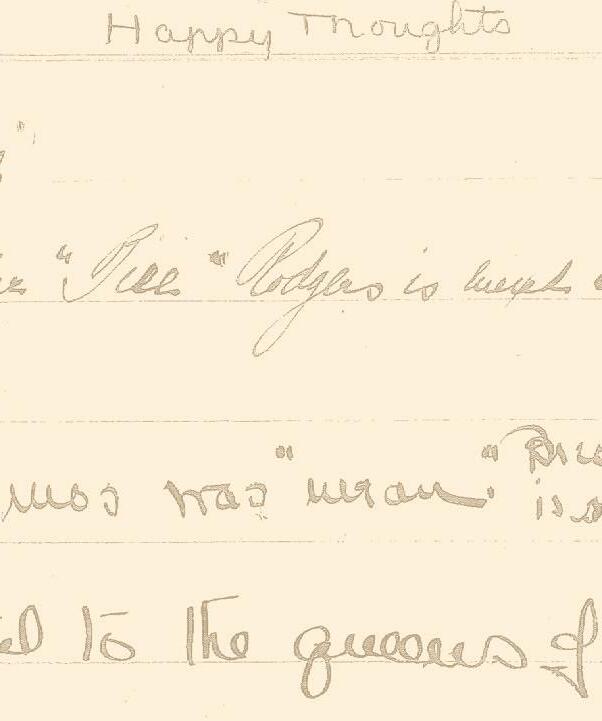

Eventually, Alice remarried; her new husband, John Raisin, was the scion of a wealthy political family, and Wallis was sent to Oldfields, an exclusive girls’ boarding school located outside Baltimore. Alice managed, with help from Uncle Sol, to have Wallis presented in Baltimore society as a debutante at the Bachelors Cotillion.

Wallis was 20 years old when she met Earl Winfield Spencer, Jr., a naval flight officer. They wed several months later, and throughout her unhappy fiveyear marriage she was subjected to his drinking and physical abuse. (Twenty years later, Wallis confided to Herman Rogers, an old friend who gave her in marriage to the Duke of Windsor, that she had never had sexual intercourse with either of her first two husbands — Spencer or Ernest Aldrich Simpson.)

Wallis lived for two years in Warrenton, Virginia, while awaiting her divorce from Spencer, which became official in December 1927. On a trip to New York with Oldfields school chum Mary Rafray, she was introduced to Simpson, the son of a successful English shipping broker.

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME 61

Wallis was 32 when, in July 1928, she and Ernest married and began a comfortable, affluent life in London. Wallis’s mother died a year later, and Wallis sought solace in what would become years of writing letters to her Aunt Bessie, correspondence that chronicle both quotidian and emotional aspects of her life.

Wallis and Ernest’s upper-middle-class life in London was pleasant, albeit lonely for her. His job as a shipping executive provided a considerable income, and Uncle Sol’s will — he died in 1927 — also left a little something for Wallis. The couple moved from a rented townhouse in Marylebone when they bought a flat in fashionable Bryanston Court.

Wallis had a good eye and a knack for entertaining, and soon became known for throwing lively dinner parties. Her cousin Corinne Mustin moved to London with her husband, who worked for the United States Embassy, and soon, Wallis and Ernest were mingling with the American business community in London. One of the embassy wives was Connie Morgan, sister of Thelma, Viscountess Furness, the beautiful socialite and mistress of the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII.

Wallis was presented at court that June, having borrowed formal dresses from Connie and Thelma. This marked her official entry into London society, and soon the Simpsons invited the Prince to dinner at Bryanston Court.

62 THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR AND ME

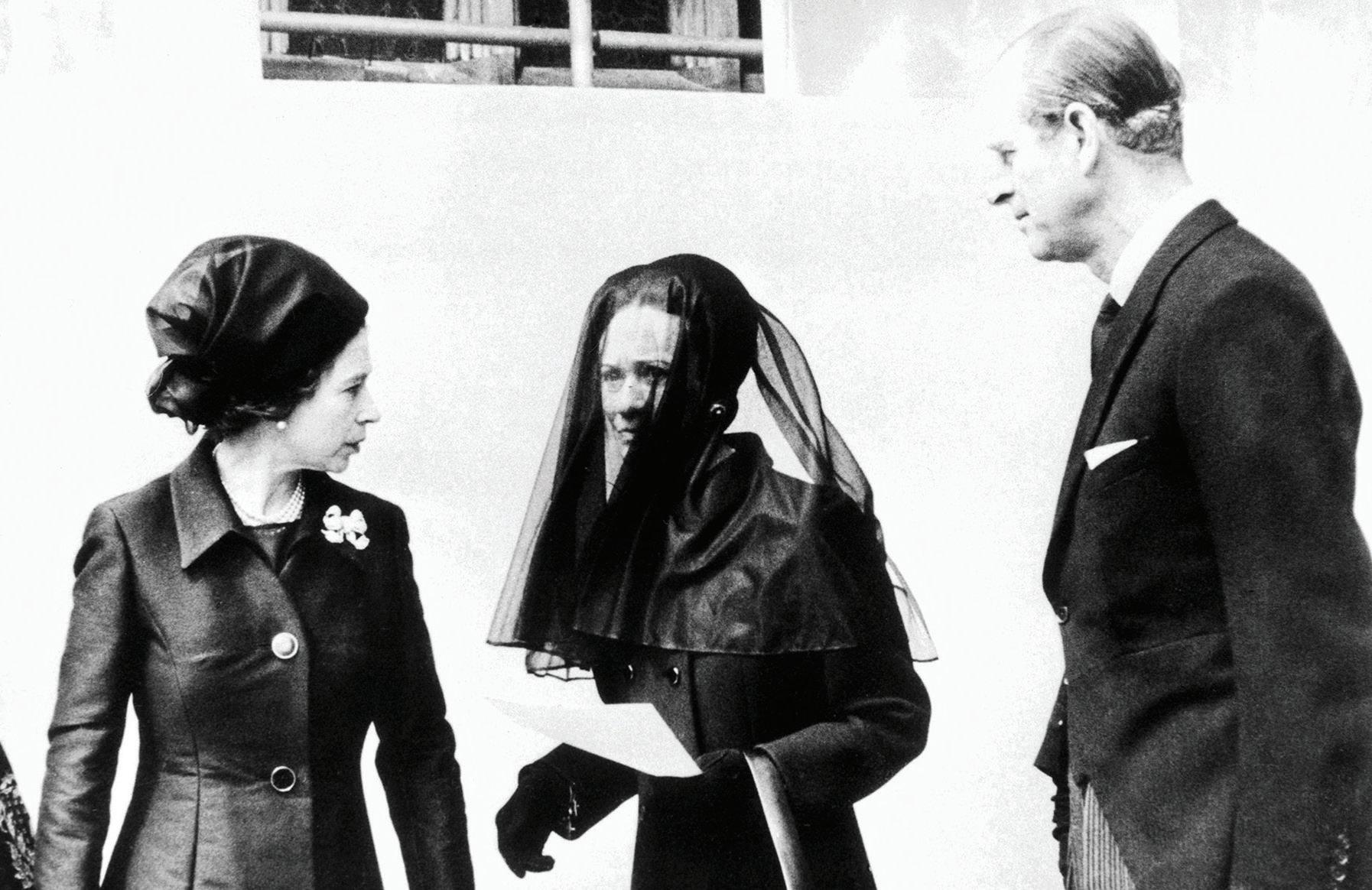

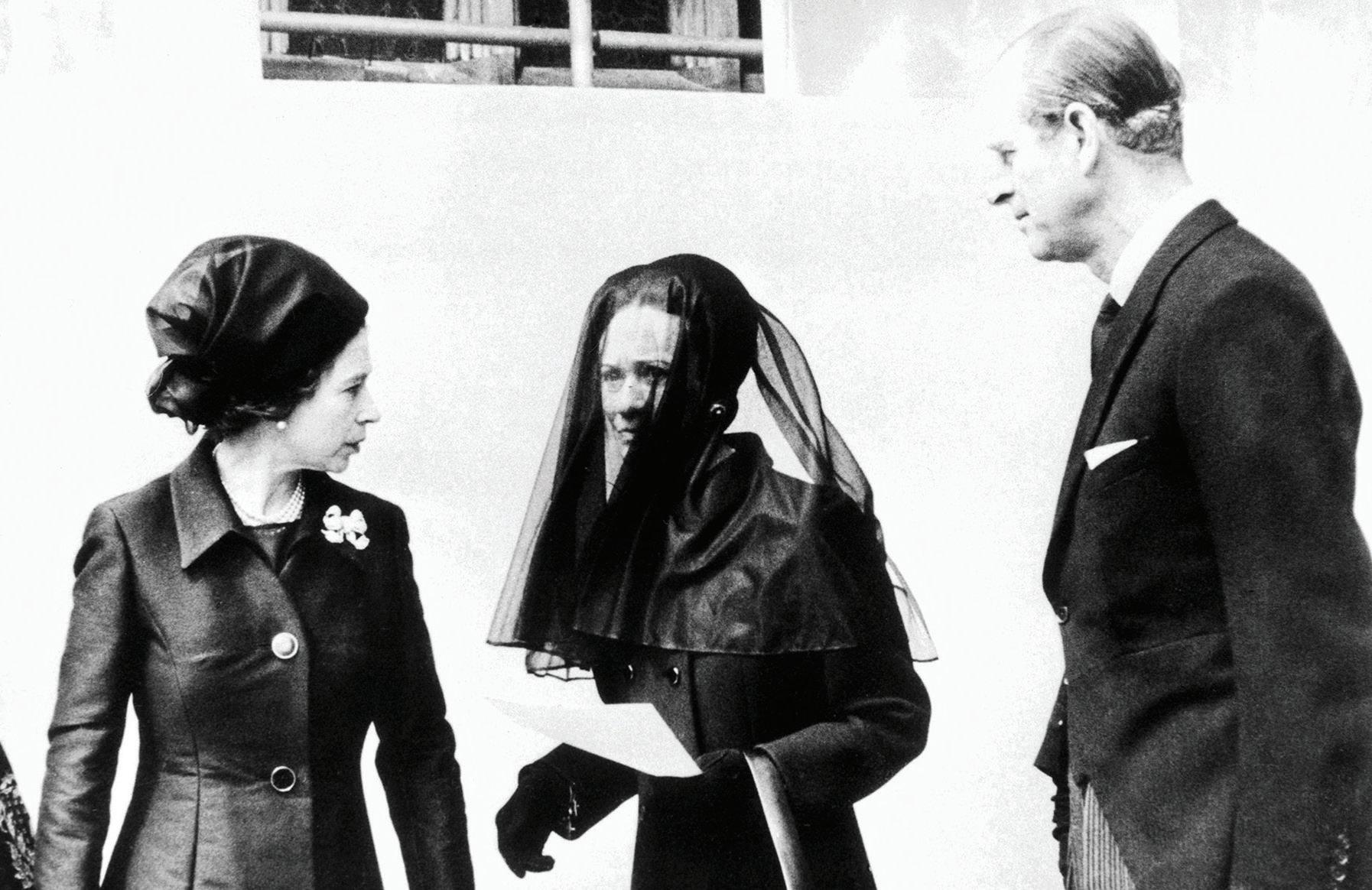

The Duchess of Windsor (second from left) with Prince Philip (left), Queen Elizabeth, and Prince Charles in Paris, May 1972, during the final days of the Duke’s life

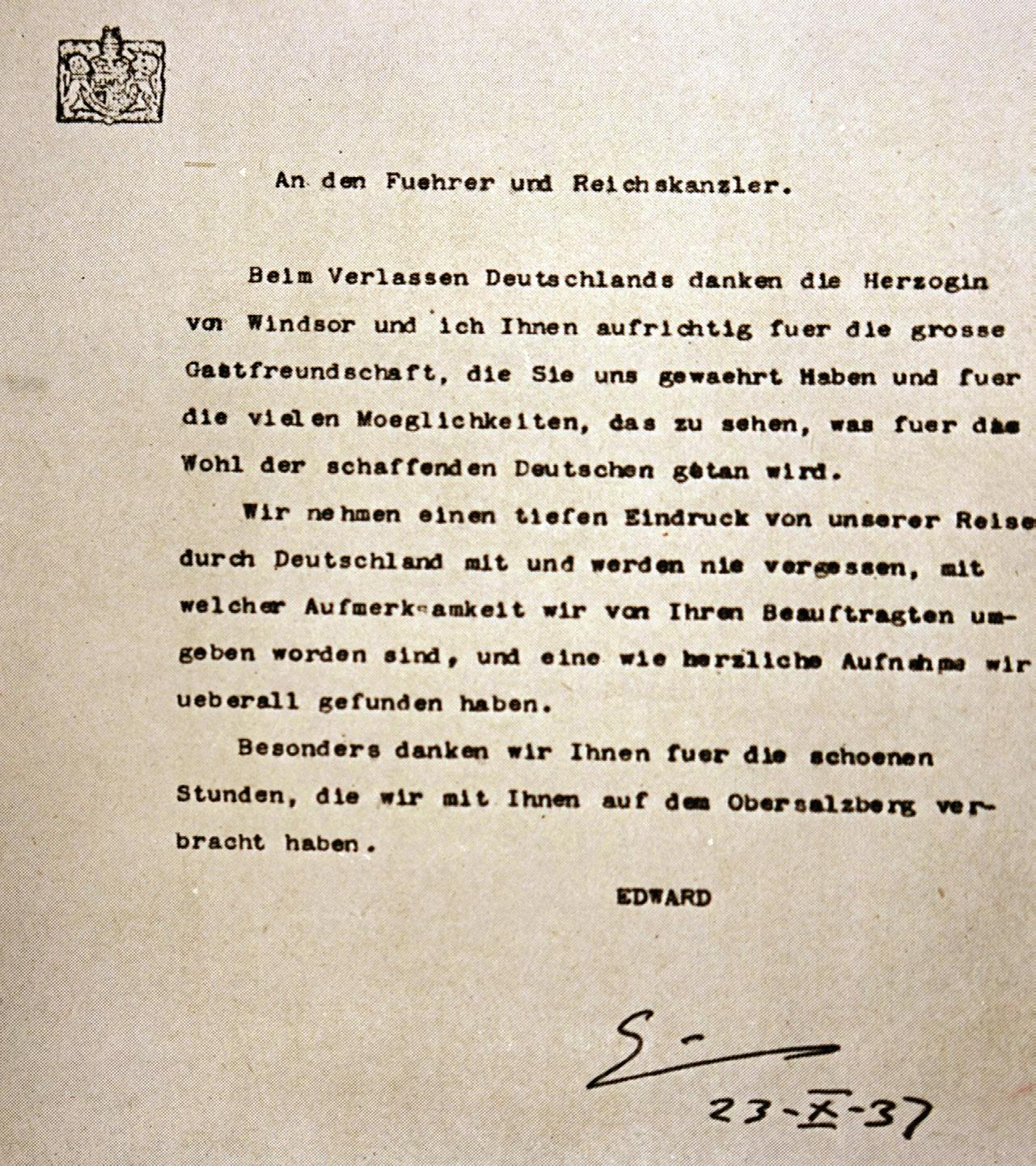

Wallis wrote Bessie that their dinner party carried on until 4 a.m., “so I think the Prince enjoyed himself.” Not long afterward, the Simpsons received the first of what would be many invitations to visit the Prince at his favorite residence, Fort Belvedere, a miniature castle in the countryside near Windsor Castle.