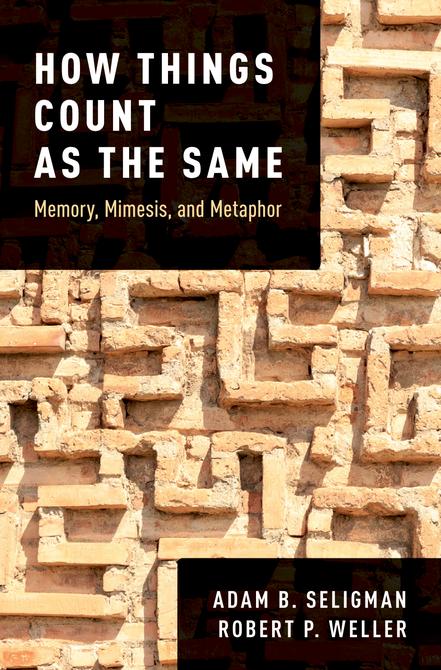

How Things Count as the Same

Memory, Mimesis, and Metaphor z

ADAM B. SELIGMAN AND ROBERT P. WELLER

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–088871–8 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Illustrations

1.1. Yin-yang symbol 12

1.2. Sign, object, interpretant, and ground 16

1.3. Chiang Yee, Lapwings over Merton Field 19

1.4. Gentile Bellini, The Sultan Mehmet II 20

3.1. Japanese turtle and crane 55

3.2. Phylacteries 56

3.3. Garden wall 56

3.4. “Study Lei Feng’s Fine Example; Serve the People Wholeheartedly” 64

3.5. Donated goods 66

3.6. Donated goods 67

3.7. UN refugee camp signage 68

4.1. Oliviero Gatti, from Four Old Testament Scenes after Pordenone (1625) 82

4.2. Rembrandt van Rijn, Abraham’s Sacrifice (1655) 83

4.3. Cups and teapot 87

5.1. Spirit money for sale, Nanjing 2014 116

7.1. Sign, object, interpretant, and ground 136

7.2. Sign for toilets 136

7.3. Squat toilets 137

7.4. Sit-down toilets 137

7.5. Monument against War and Fascism, Vienna 158

7.6. Monument against War and Fascism, Vienna, detail 159

7.7. Jews forced to clean the streets of Vienna, 1938 160

7.8. Holocaust Memorial, Vienna 161

How Things Count as the Same

Introduction

How do human beings craft enduring social groups and long-lasting relationships? Given the myriad differences that divide one individual from another, why do we recognize anyone as somehow sharing a common fate with us? How do we live in harmony with groups that may not share that sense of common fate? Such relationships lie at the heart of the problems of pluralism that increasingly face so many nations today.

This book is an attempt to answer a seemingly simple question: How do we constitute ourselves as groups and as individuals? What counts as the same? Note that “counting as” the same differs from “being” the same. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus was surely right when he pointed out that no one can put her foot in the same river twice.1 Both the river and the foot have changed by the second time. In a sense, she cannot even put her foot into the “same” river once, because feet and rivers change as they interact. Counting as the same is thus not an empirical question about how much or how little one person shares with another or one event shares with a previous event. Heraclitus showed us that nothing is truly the same.

Nevertheless, as humans we construct sameness all the time. In the process, of course, we also construct difference. I am not empirically the same as I was yesterday—things have entered and left my body, I have honed a new skill, my head stopped hurting. From molecules to moods, “I” am not the same. Yet I still consider myself to be the same person and to be different from other people. Feelings of group solidarity are similar. They have to be crafted out of our empirical differences. Thus I may have nothing in common with someone who lives down the street, but when we meet in Paris we will treat each other as the same in some important ways (as Americans, not French citizens, for instance). Ties of citizenship and patriotism, neighborhood, kinship, profession, and all the rest allow us to think of each other as the same in spite of all the real differences that

separate us. In Chinese, many of these ties used to create social alliances refer explicitly to this sameness: “same” surname, “same” school class, “same” place of origin (tong xing, tong xue, tong xiang), and so on. Each of these ties is a social construction, but it can be so powerful that we naturalize it. When we create these unities, of course, we also create differences. The world divides into our people, who share ties with us, and those people, who are not our kin or classmates or fellow patriots; it divides more starkly into the people and the enemies of the people.

The issue of sameness comes up constantly in the study of religion. Rituals must count as the same as previous versions of the ritual in order to succeed. Today’s baptism or funeral is never identical to the one we performed last week, but we still must recognize the two events as alike in some fundamental way. To achieve this, some parts absolutely have to be done properly in order for the ritual to be accepted. In the United States, for instance, the couple must make an avowal of their intention to marry (“I do”); if this does not happen it cannot count as a marriage. Other sorts of variations, however, can be ignored.

Religious denomination is also a matter of counting as the same. When Christians practice pagan rites like placing an evergreen tree in their house near the winter solstice, are they still Christians? For most American Christians the answer is a clear yes; the Christmas tree has become a core part of the ritual itself. For the Puritans who first came from England to Massachusetts, however, the answer was no. Religious splits frequently start from arguments over what counts as the same. In the Russian Orthodox Church, for instance, Patriarch Nikon’s mid-seventeenth-century reform to make Russian and Greek Orthodox ritual practices more “the same” led to a major split from the Old Believers. The most divisive issues included small details of ritual practice like exactly how to hold the fingers while making the sign of the cross or whether processions should move in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. There were major underlying social issues, of course, but the argument centered fully on the construction of sameness and difference through ritual minutiae.2

The idea of syncretism is another important arena for the construction of what counts as the same in religion. A great deal has been written about the concept within religious studies and anthropology.3 In theological circles in particular, syncretism has often historically been viewed as a problem: syncretized religions no longer count as the same. Every globalizing religion has had to deal with the problem that local variations inevitably arise, and they have to decide how much variation is still acceptable (i.e., whether a hybrid practice still counts as “the same” religion) and how much is not.

Plutarch’s essay “On Brotherly Love,” written roughly two thousand years ago, provides what some consider the earliest relevant use of the term “syncretism”:

Then this further matter must be borne in mind and guarded against when differences arise among brothers: we must be careful especially at such times to associate familiarly with our brothers’ friends, but avoid and shun all intimacy with their enemies, imitating in this point, at least, the practice of Cretans, who, though they often quarreled with and warred against each other, made up their differences and united when outside enemies attacked; and this it was which they called “syncretism. . . .” [T]here is a saying that brothers walking together should not let a stone come between them, and some people are troubled if a dog runs between brothers, and are afraid of many such signs, not one of which ever ruptured the concord of brothers; yet they do not perceive what they are doing when they allow snarling and slanderous men to come between them and cause them to stumble.4

Plutarch’s folk etymology—“syn- Crete-ism” meaning an alliance of the Cretans— may have been meant in jest. Nevertheless it captures a fundamental aspect of syncretic pluralism in the way the normally fractious people of Crete recognized their fraternal sameness in the face of an external enemy. The context here is crucial, however. Plutarch is insisting that fraternal loyalty take precedence over other kinds of ties. It is bad enough when we let “snarling and slanderous men” come between us, but he warns us in the same passage not to be “fluid as water” by simply pursuing our own tactical and personal interests no matter where they lead us. Fraternal loyalty here conquers other forms and clearly separates friends from enemies. Plutarch is using the idea of brothers to refer to a kind of inborn sameness, one that all Cretans might share even though they are not literal brothers. As we can see from his description, however, the concept also implies a fundamental difference from all those who are not the same as us, a clear line between friends and enemies, brothers and slanderous strangers. Such a construction of sameness is familiar to all of us, and yet it is not particularly open to genuine pluralism or even to empathy with those who are not the same as us.

The fraternal sameness in Plutarch’s essay never gets to pluralism but stays in the dichotomous group dynamics of us versus them, brothers versus strangers. Real pluralism requires accepting group-level differences. How do we construct sameness and difference in ways that allow us to live with difference instead of seeing it as a threat? In this book, we suggest that there are multiple ways in which we can count things as the same and that each of them fosters different kinds of group dynamics and different sets of benefits and risks for the creation of plural societies. While there might be many ways to understand how people construct sameness, three seem especially important and will form the focus of our analysis. We will call them memory, mimesis, and metaphor.

In brief, “memory” creates sameness through the sharing of narrative forms, prototypically in the stories that materialize shared experiences. This draws the clearest boundary between the group that shares the memory and those outside the group, who do not; it is roughly what Plutarch described. “Mimesis” refers to repeated performances, enactments, and re-creations. We will be primarily concerned with religion, and thus the most relevant focus of mimetic behavior is ritual. Rituals also draw boundaries, but in contrast to memory, they are always capable of being crossed or transcended. Finally, we will use the term “metaphor” loosely, to describe the creation of innovative forms of sameness, drawing new boundaries and suggesting new possibilities. We will be employing these terms in a somewhat creative manner, going beyond existing linguistic, artistic, and philosophical usages. Their importance for our work is to point to particular gestalts (which we shall define in chapter 1 as “schemas” or “grounds”) of understanding what is the same or different.

The book begins by expanding on these themes, exploring the multiple forms and analytic purchases carried by memory, mimesis, and metaphor. Chapter 1 begins by thinking through what it means to count as the same, and the three chapters that follow take up each of the three grounds or schemas in turn. We then explore more empirical applications of our ideas. We begin in chapter 5 with a study of the importance of memory, mimesis, and metaphor to the understanding of the gift. In chapter 6 we analyze the workings of memory and metaphor as Jewish and Christian civilizational tropes. Chapter 7 continues to explore how the three forms of ground interact and transform people’s understandings of themselves in the world, sometimes with enormous consequences.

We argue that as memory, mimesis, and metaphor create different forms of sameness (and so also of difference) they carry with them different possibilities for empathy, for crossing boundaries, and for negotiating the terms of sameness and difference between communities and individuals. Some are more “open” than others, but as the limits of any total transcendence of boundaries are built into our very ways of knowing the world, we can do no better than understand the building blocks of that knowledge.

What Counts as the Same?

Culture and Its Categories

What do we mean when we say that people share a culture? What exactly is shared, and how do we share? These are big questions to which it will not be possible to provide full answers. Indeed, anthropologists have been arguing about this almost since the beginning of the field. Very few anthropologists today accept grand claims of shared cultural themes along the lines of Ruth Benedict’s studies of national character.1 On the other hand, they have also not been quick to accept the idea that individuals alone are what matters. Such theories assume a unified motivation of “rational” choice and the attempt to maximize interests. Part of the problem with both the argument for a national character (which makes culture too muscular) and that for rational choice (which makes culture irrelevant) is that neither extreme has sufficiently questioned how sharing can happen.

Rather than beginning with the assumption of the unity of culture or the priority of the individual decision maker, we will focus on how we come to perceive things as shared. This is just one facet of our basic underlying question: What counts as the same? What lets two people, or two million people, feel that they have the same culture, or for that matter the same class, gender, race, religion, or any other category? This is not a question of how much we actually share but of how and when we come to perceive that we share; not what is the same, but what counts as the same. That is, one of our most fundamental, essential, and foundational acts as humans is the construction of categories of sameness and difference. This book is devoted to a study of this issue.

If we directly experienced the world in its elemental physical nature without the mediation of abstracted categories—as quarks or wave-particles, as an evershifting amalgamation of indeterminacies—there would be no room for social life and no room for humanity as we know it. Shared human life relies on some degree of coherence, however partial and however constructed. To create such

coherence we construct categories, which we understand to be shared, sometimes imperfectly, by others around us.

Charles Renouvier, Emile Durkheim’s teacher, used to say that “the study of categories is everything.”2 It is easy to understand why. What we eat (and, more important, what we do not eat), whom we sleep with and marry (and whom we do not), and how we define and classify natural and social (that is to say, ultimately, moral) phenomena all depend on our cultural categories. Even our understandings of such natural attributes as color, volume, height, and weight are at least in part “culturally” determined and not universally shared. We will not revisit debates about such things as the universality of color terms here.3 We are not trying to argue that culture supersedes biology but simply note that abstraction into categories is a human necessity, whether it stems from our biological makeup or from learning.

The most fundamental categorization that we make is the determination of what counts as the same and what counts as different. Out of the random chaos of existence, where in essence everything is different—even no two snowflakes, we are told, are the same—we determine which differences actually matter. In Gregory Bateson’s terms, we decide which of the infinite possible distinctions “make a difference” and which are peripheral, nugatory, or irrelevant.

Peripheral, nugatory, or irrelevant to what? Peripheral to the classification that we are making at the moment—to our division of phenomena into what is the same and what is different. Determining sameness implies determining difference; one cannot happen without the other. Think, for example, of what it means to share an experience, like going to the beach with friends or on a picnic. There are hundreds, sometimes thousands of other people on the beach, but we do not think of the experience as “shared” with them, only with our friends. We share the experience only with those whom we somehow already counted as “the same”—those we came with, those together with whom we defined an “us” (as opposed to and distinguished from everyone else at the beach). On the picnic too we “shared” our food (even though of course we did not; we each ate separate things), and we count the food as shared with our friends, even though that other couple, sitting under the tree only eight yards away, is also eating tuna fish sandwiches, just like I am. But that doesn’t count as a shared experience; only the sharing with my friends counts, even though my friends are actually eating egg salad. Counting as the same and different is very much part of deciding what is shared and what is not, and that process goes far beyond the physical similarities and differences of tuna salad and egg salad.

As we see from these examples, not all difference matters. That we are eating different food does not mean we are not a “we” (for the purposes of the shared picnic), and that the other folk are eating the “same” food does not mean that

they are “the same” as us. And so, looking at the bookshelves behind one of our computers, there is a book by Merlin Donald titled Origins of the Modern Mind, one by Boman titled Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek, and Homer’s Odyssey. Even though one is very thick and one very thin, two are hardcover and one paperback, one with pictures on the cover and the other two without (not to mention the very different genres and subjects dealt with in the books), we have no difficulty in calling them all books. Cover illustrations, types of binding, height, weight, and all the rest have no relevance to our classification of them all as books. These are differences that do not matter, distinctions that do not make a difference, that do not contain or encode information relevant to classifying something as “a book.” These differences may of course become relevant if I wish to reclassify the books as potential “doorstops” and so may put all the thick books together in a new category as “books good to use as doorstops.”

There are a few points worth teasing out of this example. The first, of the type John Dewey drew our attention to a century ago, is that our categories depend on our practical aims. We define any “thing” for a set of practical aims—for a particular context and not in the abstract. An idea of something, according to Dewey, amalgamates the currently available, physical reality before us together with additional interpretive data that frame this reality in a broader, meaninggiving context, defined by our specific purposes.4 The purpose of books is to read (and cover design is irrelevant, at least for most adults); the purpose of books- as- doorstops is to keep the door open, and so the mass and volume of the book is relevant.

The second point is that the very first definitional move, the primary act of categorization (indeed the very construction of categories, any set of categories) is a determination of sameness. What qualities of a thing make it “the same” as another thing, of the same class or category? This is true, of course, for our classifications of people no less than books or snails. We may, depending on the circumstances (what Dewey would call our specific purposes), base our decisions about sameness on all kinds of different attributes (gender, age, dress, skin color, religion, height, nationality, tribe, ethnicity, etc.).5

All such categorization is a process of abstraction. It abstracts from the infinite concrete characteristics of a thing only that which is relevant for its classification into class x. Thus your being female or 66 years old or Latina will be totally irrelevant for your classification as Jewish, if the relevant context is behavior at a synagogue. Your being Jewish or female will be irrelevant for your membership in the AARP, and so on. We abstract from the multiplicity of differences that characterize all people and all things and decide on one or more relevant attributes (gender, age, whatever) to determine membership in a class of entities sharing the same attributes. Of course this very act itself rests on a further abstraction.

Deciding who is Jewish is no easy task and one continually negotiated. The same is true for all cultural categories.

Third, determining a category of sameness, saying something “is the same as,” determines as well a category of difference: a Jew is not a Christian, a man is not a woman, a Lithuanian is not an American, a black is not a white, and so on (though she may also be 65 years old and Jewish and 5’9” tall). Here of course all manner of complications set in, precisely around the boundaries of those categories. The boundaries of Jewishness or of race or increasingly of sexuality (with, for example, transgendered individuals) are in fact fuzzy and not sheer. And of course some people define themselves as Lithuanian Americans. Thus we cannot ignore the ambiguity that blurs all categories, especially the foundational ones of sameness and difference. Wisely or not, we often struggle against such ambiguity—usually by the definition of ever newer categories. Unfortunately, this solution tends to put off rather than solve the definitional conundrum.6

Such attempts to parse categories ever more closely often lead to social conflict and struggles among the relevant stakeholders. This was the case in 2006 with the Jewish Free School in London, where the school did not accept the conversion of a prospective student’s mother to Judaism (as it was not an Orthodox conversion but performed under the auspices of the Masorati, or Conservative movement in Judaism) and so refused the child entry. This case ultimately reached the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.7 The Court ruled against the school, which was found guilty of racial discrimination under the 1976 Race Relations Act.8 Similar struggles over categories and their social implications are being fought out in various states in the United States over issues of transgender access to bathrooms, with some states defying Obama-era administration guidelines.9 More poignantly, issues of gender definition have arisen in traditional American women’s colleges, such as Smith College, where the ambiguities inherent to a transgendered individual’s self-identification (biological male identifying as female) have complicated college admission policies.10

Such cases highlight that, ambiguity notwithstanding, defining something as the same also defines which categories of difference are relevant to the process of categorization itself. Sameness defines which qualities of a thing are relevant for its entry into whatever category is under consideration (book or doorstop or Jew or woman, as the case may be). At the same time, it tells us about the qualities that deny such entrance (and around which the struggles over “who is a Jew” or a woman are fought). If our category is “tall women,” the race, religion, nationality, and so forth of the particular woman in front of us are irrelevant. Jane is either tall, in which case she is not short, or she is short, in which case she is not tall; all other attributes are irrelevant. They are distinctions that do not make a difference in this case, though they may in other contexts.

Thus, categories create sameness and difference at the same time. They do this by abstracting out from the infinite amount of information that we can theoretically provide about any entity. We treat the abstraction as if it actually were a “thing” because we have defined what it is and what it is not, what about it counts as the same rather than different from other things in the same category. Abstraction, and hence categorization, always involves a loss of information. One implication of this is that the more finely we parse the boundaries between abstracted “things”—the more clearly we delineate the categories by clarifying the line between things and nonthings—the more information we lose. This happens because we can clarify the boundary only by pulling our attention away from the fractal complexities through which concrete entities merge into nonentities. The more of an entity we deem irrelevant for our purposes (whatever these may be; recall Dewey above), the less we know of it.11 This works well enough for Allen keys (hex wrenches), because we need to know only if its dimensions fit the hex bolt we are working on now. It works less well for human relations. Treating human relations as hex bolts (simply because we have, or think we have, the relevant keys) has often led to tragedy.

Note that we have so far been using the word “difference” to indicate two phenomena that might better be separated. That is, bearing in mind all the problems of creating categories that we have just discussed, let us suggest a boundary between two categories of “difference.” The first is the infinite array of difference, uncertainty, and flux that characterizes the physical world—the difference that prevents us from putting our foot into the same river twice. The second are the differences that we humans create at the same time as we create sameness. These are constructed differences, unlike the infinite differences in the physical world. We will term these differences “gaps.”

Gaps are not the naturally adhering differences that are functions of time and space: no two things are in the same space at the same time and so cannot be fundamentally “the same.” They are instead the differences that result from our social process of categorization, from classifying things as the same and different. We create recognizable classes of entities that are socially the same as and socially different from others in the process of organizing the myriad differences of the natural world. Your ears are longer than mine, and hairier, but that is not a distinction that makes a difference; the fact that your skin is black or white, however, may well do so. Recall that blackness and whiteness themselves rely on a constructed gap, and that the categories do not follow directly from the natural differences of skin color (and all else that Americans, for example, pour into the categories of “black” and “white”).

We form social groups out of these categorizations of sameness and difference, establishing and institutionalizing differences between people. Social

life proceeds via boundaries of group membership, participation, and exclusion. We cannot slight this last point about exclusion, no matter how much it may be in disfavor. Just as any classification of sameness implies one of difference, so too does any creation of home, sense of belonging, and shared cultural codes and meanings. The associations we all have with very particular smells, liturgies, foods, and sights— our comfortable, taken- for- granted worlds, whether of our moral codes or our dinner menus— constitute boundaries that both contain us and exclude the other. They define who we are but also who is not one of us.

Sometimes people can cross these boundaries in acts of empathy, and sometimes they cannot. Sometimes empathy fails. Sometimes we manage to cross those borders of sameness to engage with what is different, and sometimes we even manage to redefine those boundaries. Sometimes the redefinition creates a narrower sense of us, and sometimes a broader sense. Sometimes, while we may not manage to cross the boundaries, we can still engage the other across the boundaries—a sort of parallel play, like children in the sandbox. At other times we try to seal ourselves off from the other in an almost hermetically closed fashion (though this usually fails) and turn our back on what is beyond our class of sameness.

There are no general formulae for how these processes occur, but this book does look at some basic mechanisms through which we construct the class of the same, as well as the gaps between similar entities. The relevant entities for us, of course, are social groups—the way they are imagined, constructed, bounded, and defined. We hope to further explore the possibilities for empathy, for movement across the gaps between these groups and the different possibilities and challenges we meet when we “mind the gap” and try to step out of our taken-forgranted worlds.

Minding the Gap

The first challenge of forging an identity—personal, social, or cultural (as we call those largest and vaguest notions of identity)—is the construction of sameness. People must “count” some features as “the same” despite the ineluctable differences that exist in the world. Constructing a category requires us somehow to overcome these differences, whether among snowflakes, books, beliefs, experiences, or peoples. All the differences that make up my personal experience and all those that separate “me” from others must be rendered void or at least unimportant in this process. As nothing really is the same, we need, at all times, to make an interpretive leap of one type or another that allows us to overcome the differences of all natural or material elements (existing in space and time) and

count certain of them as “the same.” This is how we order and so also overcome (at least in part and for a while) the multiplicity of the world.

This is always a social process. Even the construction of individual identity, we would suggest, is at heart a social process. It is not a move of individual mind or nature or of some inherent grid of consciousness, even though each of those things may play its role. It is learned behavior, constantly altered and reproduced through social contact. Just as dogs learn to distinguish their owners from other humans and to differentiate frequent guests to the house from traveling salesmen, so do humans—only our distinctions are more precise, encompass a far wider range of variation, and carry many more implications and consequences than do the dog’s.

Recall that the construction of difference always works at the same time as the construction of sameness. Categories include, but they also always exclude. The gaps that separate categories will themselves differ according to the categories constructed. That is to say, the gaps themselves will reflect the categories of cultural “sameness” and no longer the random, uncategorized differences of nature. When, for example, Jews define “meat” in the laws of kashrut (dietary restrictions), they also define milk (as the kind of food that cannot be eaten together with meat), as well as the category of neither-meat-nor-milk, called “parve” (fruits, vegetables, bread made with oil or margarine rather than butter).12 The definition is not inherent in the materials, and the categories of sameness and difference continue to be negotiated. In antiquity there was, for example, a position articulated by R. Yossi of the Galilee that chicken was not meat and could thus be eaten with milk. Jews from the Arab lands who observe the laws of kashrut do not eat fish with milk. For them, fish counts as meat, but not for the equally observant Jews of Eastern Europe.

In China, too, it is very easy to find elaborate systems of categorization that extend to all aspects of life, certainly also including diet. Often Chinese thinkers embraced both the separateness of categories and the idea that they flow into each other. It is thus easy to find lists of yin and yang contrasts: yin/yang, night/ day, female/male, potential/kinetic energy, tea/wine, eggs/chicken. And it is just as easy to find an insistence that there are no absolute boundaries because yin and yang flow into each other as night flows into day. The yin/yang symbol itself is meant to show both the separateness of the categories (though with a spot of yin in the yang, and of yang in the yin) and their constant change into each other (see figure 1.1).

The same tension between correlative categories and constant change also occurs for all the more elaborate systems developed in China. The Chinese five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) have long lists of categories associated with each (for instance, wood correlates with spring, the liver, a straight punch,

Figure 1.1 Yin-yang symbol.

Source: John Langdon, licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0.

morning, etc.). Yet they also flow into each other in a constant interaction, and the Chinese term might better be translated as “the five movements” rather than the more standard “five elements.” The history of Chinese thought is filled with play with these systems, along with increasingly elaborate ones like the eight trigrams, sixty-four hexagrams, twenty-four celestial asterisms, and so forth. Alongside the love of categories and correlations stood systems of thought that recognized the artificial nature of all such systems, just as we have been arguing here. Laozi thus argues in the Daode Jing:

It is because every one under Heaven recognizes beauty as beauty, that the idea of ugliness exists.

And equally if every one recognized virtue as virtue, this would merely create fresh conceptions of wickedness.

For truly, Being and Not-being grow out of one another; Difficult and easy complete one another.13

That is why, Laozi continues, the sage teaches without using words. The Buddhist tradition has equally embraced complex systems of categories while rejecting the very idea of categories. As the Buddha says in the Diamond Sutra (one of the most influential texts in Chinese Buddhism), describing the bodhisattva, someone who has awakened the faith:

There does not exist in those noble-minded Bodhisattvas the idea of a self, the idea of a being, the idea of a living being, the idea of a person. Nor does there exist . . . the idea of quality (dharma), nor of no-quality. Neither does there exist . . . any idea or no-idea. And why? Because . . . if there existed for these noble-minded bodhisattvas the idea of quality, then they

would believe in a self, they would believe in a being, they would believe in a living being, they would believe in a person. And if there existed for them the idea of no-quality, even then they would believe in a self, they would believe in a being, they would believe in a living being, they would believe in a person.14

All concepts, all categories, all gaps are rejected here. But of course the text can express itself only in concepts and categories and gaps. Like the Daoist text, it recognizes that even sophisticated Buddhist categories like the nonexistence of self and of others exist only by the contrast with ideas of an actual self. No category exists without defining difference.

The nature of the gap thus partakes fully of the nature of the category—not just in Jewish and Chinese thought, but in general. There is no “self” without these gaps, nor is there “culture” or “identity.” We construct individual, group, and cultural differences in the very same move as we construct sameness. Making a category, conceiving of a thing, interweaves saying what it is along with what it is not. This process is inherently social, not some residual category, left over and stitched together from the bits and pieces of a multitude of other beliefs and orientations. As Gregory Bateson explained, making a map (a literal one as well as a more metaphorical “mental map”) is precisely about specifying differences. Like any forms of information, for Bateson, maps show the differences that make a difference.15 Differences make the category and hence the thing-that-is-the-same. Just as a continent only is in its relation to the oceans, and Germany in relation to France, mountains to valleys, meat to milk, and self to nonself, so too one group of people can be “mapped” only vis-à-vis another (Jew to Christian, member of the Middle Kingdom to the rest of the world, Greek to barbarian, etc.).

Lest we be carried away by the impulse to erase these boundaries, to do away with mapping of difference, to make all one, we should take seriously Bateson’s claim that difference is the basis of all information; it is the only way we have of knowing the world and so of living in it. We cannot exist without mapping difference, physical and cognitive, of mountains, seas, or peoples, of ourselves and of our others. Without maps (and so without differences) there is no information, no knowledge, and so no human or social life. The opposite, however, is also the case, as Bateson made clear (based on an earlier remark by Korzybski): “the map is not the territory.”16 It is only the abstracted representation of territory, the way we know territory. Territory (and the world in general) is fractal, ambiguous, ungraspably complex, constantly changing, and slippery of form. Unlike maps that draw boundaries so clearly, territory proper challenges our ideas of boundaries, and—when we look carefully—continually upends our categories of sameness and difference.