Magazine of Esperia Study Association for European Languages and Cultures European Minorities Year 10, number 2 March 2023

Colophon: ETCETERA

Magazine of Study Association Esperia

Oude Kijk in 't Jatstraat 26

9712 EK Groningen

editorcie@svesperia.nl

Copyright © 2022 't Hartje

Korreweg 38

9715 AB Groningen

info@thartje.nl

Author

Editorcie 2022-2023

Editors

Ruben Feddes

Tiara Ruidavet

Stijn Bakker

Anne-Roos Peters

Bart Hans

Final Editor

Paula Divić

Ruben Feddes Anne-Roos Peters

Chair Commissioner of Acquisition and Vice-Chair

Tiara Ruidavet Bart Hans

Secretary Commissioner of Promotion

Stijn Bakker Paula Divić

Treasurer Final Editor

No part of this publication may be reproduced and/or published by means of printing, photocopying, audio tape, electronically or in any other way, without written permission from the publisher.

2

3 Index A Word From Your Editorcie 4 A Word From Our Board 5 The Five (+1) Minority Languages of Sweden 6 An Island Divided. 9 Ja Sóc Aquí 12 Welsh: Minority with a Comeback 16 A Minority People as a Justification for Military Action: the Russian Invasions in Ukraine 18 The Language That Went Out With a Bang 20 "Hier maj plat proat'n": Diving Into Low Saxon Dialects 22 Photos 24 A Love Letter to the Moomins (And Anti-Fascism) 26 Why Ethnic Minority Parties Become Successful 29 Interview with the Board of Multi 32 Kosovo, Minorities in Conflict 34 Romani People That Made History 37 Let’s Talk About Frisian 39 Between Two Worlds: Queer Russian Migrants in Berlin 41 Cooking With Koos: M’ semmen 43 Twents Proverbs Quiz 45 Epilogue 46

A Word from Your Editorcie

Dear readers,

I hope we have all restarted our work in this new block, which by the time you read these words will be almost over again. With exams and with the many deadlines coming up, it will be a busy period. We think it’s the perfect opportunity to unwind with your copy of the brand new ETCetera! Last time, we wrote all about our favourite folklore, myths and legends. We have gotten a lot of amazing reactions and feedback from you guys, and for that we are really thankful. This gave us new inspiration and ideas for this edition, and we are proud to present to you our second edition on European Minorities!

In the previous edition, we focused mainly on literature and history. This time we are shifting profiles within our programme to culture and politics. Before you get too worried about all the politics, don’t worry, we will not intimidate you with political theory. We wanted to objectively look at all these groups, languages, and cultures that have a minority place in Europe, and try to shed some light on them and inform you of their situations and struggles.

We have a lot of fun articles in store for you in this edition; we're looking at minority languages such as Welsh, Catalan, Frisian, and Swedish. We’ll also be talking about groups in Russia, Belarus, and Kosovo. We have several interesting interviews with people that know a lot about minorities, or are a minority in their own spaces. We even have a fun quiz about Twents! So sit down (or stand, that’s up to you ;)) and enjoy reading all these pieces we’ve cooked up just for you!

Love, the Editorcie

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this issue are solely those of the interviewees and third parties. They do not necessarily represent or reflect our own personal beliefs as the Editorial Committee or as Study Association Esperia.

4

Word from Our Board

Dear Esperians,

As of writing this introduction, the new year has arrived and winter seems to be ending. Days turn longer with the sun shining evermore brighter, though the temperature could still use a bit of a raise. The second semester is beginning to turn its head, showering us with assignments and deadlines. Third year Esperians, who left during the first semester for a semester abroad, are slowly returning and are being greeted by new faces and old. When reading this edition of ETCetera, I hope you’ll find yourself in a cosy place with a nice cup of coffee or tea and a nice chair to sit in, to read this new issue of the revamped ETCetera.

I was very excited to hear that our wonderful Editorcie had decided to write about European minorities in their next issue. The topic of this edition does strike close to home, specifically Friesland. Esperia organised the Frisian evening on the first of March. This was a collaborative effort together with the Board of study association Multi, of whom you can read more about in an interview in this edition, and student association Bernlef, the Frisian student association in Groningen. The evening was a lot of fun and we delved deeper into the Frisian language and the region in a scientific way!

Since the release of the first ETCetera of this year, the various committees of the association have organised plenty of fun activities. We as the Board are very happy with the amount of lectures being organised and the continued focus on academisation within our association. Of course, this is reflected in the ETCetera, but also on the Travelcie, which this year organised a lecture on the history of Athens for our trip there. We can’t forget though, that our socials were also very fun, as well as our running dinner, which for some people ended up very spicy (sorry for that)! I hope you will enjoy reading this ETCetera, I am certain I will, and that you look forward to the coming events organised by Esperia.

With Love, Sjoerd de Jong

5

The Five (+1!) Minority Languages of Sweden

By Stijn Bakker

When one thinks of language in Sweden, the mind immediately wanders to Swedish, one of the many languages you can study within ELC. However, Swedish only became the official language of the country in 2009 (!!!). Before that, Sweden did not have an official language, although most people spoke Swedish. In this article however, I want to focus on the five languages classified as minority languages in Sweden, and while some seem logical, others might surprise you.

First of all, what does it mean to be an official minority language in Sweden? The five minority languages, as well as Swedish Sign Language, enjoy protections and rights which sets them apart from other languages spoken in Sweden. The minority languages are chosen because they are spoken by certain groups of minorities that are historically connected to Sweden (such as Sweden-Finns and the Sami) or have a history of oppression in Europe and Sweden (such as the Romani people and Jews). The protection of their minority language secures the preservation of their cultural heritage and a safe environment within the country to continue practising their language and traditions. The minority language status ensures the right to schooling in the language and forces governmental institutions to use the language next to Swedish. I will quickly introduce the five languages below. The first three will be languages that are native to Sweden and Scandinavia, the other two came to Sweden mostly through immigration.

Finnish

As you can read in the article about Moomins, Finland has a minority group of Swedish-speakers called the Finland-Swedes. In Sweden, you have the opposite; a small community of Finnish speakers known as the Sweden-Finns. Whereas Finland-Swedes live there due to Finland formerly being part of Sweden, Sweden-Finns mostly came to Sweden via immigration. Finland had for a long time been a lot poorer than Sweden, and throughout the 20th century many Finns moved to Sweden in the hopes of a better future. Nowadays, Finnish people are the biggest

6

minority group in Sweden, and thus their language is in many ways still important in Sweden. In many bigger cities, there are communities of Finns, and there are still Finnish schools throughout the country. The protection of both minorities in both countries is important for, as well as a signifier of, the strong historical and contemporary bond between the two countries.

Meänkieli (or Tornedalen-Finnish) and its varieties

In the north of Sweden next to the Finnish border, there is a region called Tornedalen. In English it is called the Torne Valley, which surrounds the river Torne. In this region, the border has always been blurry, and Finnish settlers, mostly lumberjacks, historically settled in the region. As they were isolated from the rest of the Finnish speaking people, they started to develop a dialect, which now can be seen as its own language called Meänkieli, meaning “our language”. Nowadays, the language is threatened with extinction, as most people in the region deem it more useful to speak either Finnish or Swedish. However, with the protection status it has received from the Swedish government, there is a motion towards saving this endangered language.

Sami languages and their varieties

The Sami are the traditional indigenous population of the northern part of the Scandinavian peninsula. The region they inhabit covers parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Originally, there are thought to have been twelve Sami languages in total, three of which are now extinct, and one has less than ten native speakers left. Of the eight remaining Sami languages, which are all classified as critically endangered, five are spoken in Sweden. These are Southern, Ume, Pite, Lule and Northern Sami. The Sami have for a long time been treated as second-class citizens in Sweden. Until recently in the 20th century, they were not allowed to speak their own language and practise their traditions. Nowadays, there is more awareness and the Sami even have their own governmental body, the Sameting, which decides on matters related to the Sami, such as their language but also reindeer herding, a traditional way of life that many still practise today.

7

Yiddish

There are various Jewish communities all over Europe. Since Sweden was “neutral” during the Second World War, many Jews arrived seeking asylum, making them a significant minority in Sweden. Together with Romani, Yiddish is not a native language of Scandinavia, but it has received minority language status to ensure safety and protection of both groups’ heritage. The Jews have a long history of persecution all over Europe, and with this status they are recognised as an integral part of Swedish society. The law ensures education and freedom of language, which not only feels as a recognition of the past, but also a protection for the future.

Romani and its varieties

Just as with Yiddish, the Romani people have had a history of persecution. Being spread all over Europe, they have always been a minority and have dealt with their own hardships throughout history. In Sweden, the status of Romani people is very much like the Jews, and the recognition of the language as an official minority language can be seen as symbolic more than anything else. Today, between 50,000 and 100,000 people in Sweden identify as Romani, and the language is spoken all over the country.

Swedish Sign Language

Just as most languages, Swedish also has a sign language, which in many ways enjoys the same status as the minority languages. There are about 30,000 signers in Sweden nowadays, and just as with the languages mentioned above, education and government information is all available in sign language because of its status. Swedish Sign Language might have derived from the British one. The Finnish and (strangely enough) Portuguese sign languages evolved from Swedish Sign Language. Danish, while deriving from American Sign Language, is mutually intelligible with Swedish. Finnish, however, is not. The official status of Swedish Sign Language recognises sign language as an important and necessary way of communication. Furthermore, it ensures the inclusion of the deaf community in Swedish society.

8

An Island Divided.

By Tiara Ruidavet & Ruben Feddes

The 20th of July of 1974 saw a seismic shift in life on the small island of Cyprus. With its incredible beaches, dreamy weather and stellar food, it’s easy to see why you’d want to travel there. However, Nicosia is the only city on earth completely divided by territories. Turkey's invasion has now separated the North and South of the country and has led to a lot of tension and division. The north side of the island speaks a different language, uses a different currency and is recognised solely by Turkey as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

Cyprus was once a British colony obtained from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. The majority Greek Cypriots wanted to unify with Greece, but as we know, the British seem to have a habit of throwing the countries they colonise into absolute chaos. Greek Cypriots coexisted peacefully with minority Turkic Cypriots for centuries; they were not divided by ethnicities or religion until colonisation created hostilities. After World War Two, Cyprus once again rallied for independence, the British collaborated with the Turkish to fight back but eventually lost out, leaving Cyprus independent. In the agreement, Cyprus was not allowed to unify with either Greece or Turkey, and the British were able to retain their territories. In 1974, the Turkish government was “concerned” for the well-being of minority Turkish Cypriots due to rising discrimination, and began forcing Greek Cypriots from the North of the island in an abrupt invasion that upended the lives of all civilians.

My friend Aleksandra’s house overlooks the border in Nicosia. She grew up on the south side, witnessing tensions encroaching every part of her life and was eager to share more, showing me pictures of “I don’t forget” stickers plastered around the city.

9

“

Once in a while when you’re just out living your life, you'll catch a glimpse of the gigantic painted flags of Turkey and TRNC on the Kyrenia mountains from the other side. They light up at night, too. It’s like a giant middle finger to the south side. It makes peace talks more difficult in my opinion, because you’re constantly reminded of the conflict. Our side keeps the conflict going as a resistance to this occupation.”

One heartbreaking yet uncommon story concerns Aleksandra’ s grandmother. She lived her entire life in what is now known as northern Nicosia. When the invasion happened, she fled south and left everything behind. After the division, she would go back to the north side to look at her old house from afar.

“

They (the occupiers) forcibly reassigned the homes of Greek Cypriots who lived in the North for generations, everything in there, even down to the furniture. You hear a lot of stories of Turkish Cypriots keeping a room in the house with the original occupant’s belongings, hoping they’ll one day retrieve them, but sometimes border control is difficult and won’t let you bring large items across the border, like a piano. It’ s common to have people from the South asking to recover their belongings or just to look around at the home that was once theirs. Now, my grandma is too old to drive so she hasn’t been able to see her former home in a long time.”

Because of the invasion of 1974, over 50,000 Turkish Cypriots were also displaced from their homes in Southern Cyprus, and are in the same situation as displaced Greek Cypriots who cannot get their belongings back from home.

That doesn’t mean moving around the city or island is necessarily difficult.

“There are three points in Nicosia to cross to the other side. All you need is an ID and you can get through quite easily. There are obviously more checks going by car. Surprisingly, a lot of south-side Cypriots living in Nicosia go to the north side to do their shopping or get their hair or nails done because the currency is weaker than the Euro.

10

Some people see this practice as a betrayal since it’s helping the occupier’s economy and, in a way, acknowledging their existence.”

Aleksandra has never met anyone from the North properly, whether that’s at home or here for her studies. “I went there once in my life, and that was for a friendly basketball game against a northern school’ s team, but it’s not like that ever amounted to anything. The girls from the other team were mean, but I just attributed that to them being from a private school to be honest.”

When it comes to the future, she thinks it’s bleak.

“As time passes, hope for a solution goes with it. The conflict may not be as heavily felt in other cities but people in Nicosia never get to forget, we’re just so desensitised to it. It’s easy to blame the other side, but considering that we used to coexist peacefully, most know that the culprits are the states that used our island as a pawn in their political games. What’s worse is that the moment children attend school, they’re indoctrinated. Hatred is taught and it festers. I don’t see a solution until another war.”

11

Ja Sóc Aquí

By Tiara Ruidavet

Catalonia is an autonomous community with a booming economy, a rich culture, and a difficult past. Franco’s crackdown on Catalan led to various divisive sentiments taking root across different generations. In this article, I felt that it was only right to consult people who know Catalonia best; two friends of mine gave me their perspectives and opinions on a divisive topic in their native region. Here are their thoughts.

1. Tell me more about the area of Catalonia you grew up in.

Irina: Centelles is located in northern rural Catalonia. Catalonia isn’t very big so I’m near the mountains and the coast, which is one of my favourite things about it.

Lu: I'm privileged to say that I was born and raised in the heart of Barcelona. Fun fact: since Barcelona is organised in a grid system, I have no sense of orientation when I’m elsewhere!

2. Did they teach you Catalan at school or did you learn it at home? Where do you speak it most?

Irina: I speak it at home, but also at school. It’s the language used in institutions, except for Spanish and English classes. At university, this depends on your Bachelor and on the number of Catalan speakers. The area I’m from spoke mostly Catalan, so both!

Lu: The law declares that all education is done in Catalan to prevent language extinction. I do believe it's quite controversial since it excludes people, especially internationals or fully Spanish speakers, from learning in our institutions. I learned Catalan from birth simultaneously with Spanish, I studied both in school independently, but all other subjects I took were taught in Catalan. My mother’s family comes from Manresa, so I speak Catalan with her and my dad's family is from Andalucía and I speak Spanish with him. With childhood friends I speak Catalan, but I must say that with friends of the last 5 years, I speak mostly Spanish. Honestly, it depends.

12

3. Which language do you feel more comfortable expressing yourself or communicating in?

Irina: I would say Catalan and English, but I’m also comfortable speaking Spanish.

Lu: It depends on situations and who I’m talking to. Sometimes I cannot find words in Catalan and use Spanish ones, or vice versa. If I’m talking to friends and family, I express my thoughts in Catalan, but if one person doesn’t understand, I switch to Spanish. Personally, I’ve been more comfortable expressing ideas in Spanish lately, but have always guided my train of thought in Catalan. Some words in Catalan are beautifully precise, and others in Spanish have more power to express the weight of an idea. I’m lucky to be trilingual, there’s always a way to find the exact word.

4. In your opinion, how important is language learning in order to teach younger people about their cultures and preserve it? Can you still be Catalan even if you don't necessarily speak it?

Irina: I feel like language is an important part of culture. Idioms carry culture and history. Many Catalan expressions I know refer to rural lifestyles. For example, "escampar la boira'' translates to "scatter the fog", meaning "to leave". These expressions hint at how people lived in the past. However, you can still be Catalan even if you don't speak it. I believe that identity is a feeling, so if someone feels Catalan, then to me they’re Catalan.

Lu: My mum feels very strongly about Catalan, since she was frequently punished for speaking it at school. We’re a cultural minority that unfortunately suffered censorship, repression and violence during the dictatorship.

However, after 2017, when Puigdemont ran a referendum without permission of the Spanish government or the EU, this led to violence in Catalonia. The Spanish government sent military forces to attack citizens attempting to vote. I personally feel like after those events and Puigdemont’s escape, the desire for independence is dying out.

13

Regarding the second question, you can definitely be Catalan without speaking it. Neighbourhoods in Barcelona like La Sagrera are mostly populated by non-Catalan speakers. However, people who feel most Catalan are those who speak it and love the culture.

5. Have you ever felt othered or treated differently in a situation where you spoke Catalan? If so, please elaborate.

Irina: Yes, but I don't feel like elaborating.

Lu: These honestly haven’t affected me profoundly. Once, on holiday in my father's hometown, there was a young boy who ended our friendship after learning I was Catalan. The second time was in Groningen; I was out with other Spanish students and this one guy and I were the only Catalan speakers in the group. The whole night we spoke in Spanish, but there was one moment I asked the Catalan guy something, and when another guy in our group overheard me speaking Catalan, he was surprised and glared at me hatefully. After that, he never spoke to me again.

6. Does this distinction of autonomous communities and regions matter as much outside of Spain or Catalonia?

Irina: It depends on one’s knowledge. I feel like sometimes foreigners are unfamiliar with the different regional cultures and they view Spain stereotypically or as a monolith. For example, many people associate bullfighting with all of Spain, but in reality, there are some regions where bullfighting is illegal.

Lu: The cultural distinction is very important in Spain. This diversity is created by history, colonisation and different monarchies. It also shows political division between different languages spoken in Spain, like Gallego and Vasco. Outside of Spain, it’s quite irrelevant.

7. Would you consider yourself Spanish, or something else? Or perhaps more than one thing?

Irina: Catalan, but when I'm abroad I can identify as Spanish too.

Lu: I consider myself Catalan-Spanish. I previously felt more Catalan than Spanish, probably because I was constantly surrounded by Catalan. As I grew older and developed a love for international environments and

14

languages, I left that bubble and realised that feeling too strongly about a nation and politics is unhealthy.

As a kid, I would attend protests with my mum and wear the independence flag like a superhero. I don't think I would ever do such a thing now. I switched from feeling more Catalan to more Spanish. I do feel both, but I’m sometimes embarrassed for Catalonia when I hear politicians inciting rage. I look at the war in Ukraine and I think this independence debate is pointless. Catalonia and Spain are both amazing and I’m so blessed to have been born in such an incredibly diverse country, so I don’t understand why some hold onto feelings of resentment. This is all my personal opinion after everything I've experienced. Everyone in Spain, especially different generations, will respond differently.

8. What is one thing people should take away from this interview about the identity of Catalan speakers?

Irina: That Catalan is not a dialect of Spanish! Catalan on its own has six dialects.

Lu: I wish people would understand that Catalonia is not a region of hate. Catalan speakers are lucky to know more than one language, and people from all over the world come to experience our beautiful region and culture. We’re very privileged and our conflicting history with politics shouldn’t define us.

It’s difficult to use “ us” when referring to Catalonia because each person has left this political mess differently, but I will say though, our younger generations are choosing to put this aside, because it’s become a serious problem that creates unnecessary division instead of finding real solutions…

We’re citizens of the world, and unfortunately, some people don’t realise we ’re privileged to live in peaceful times. While it’s true that our culture has historically been oppressed for years and a lot of people have unfortunately died defending Catalan culture, this, in my opinion, is no reason to hold grudges.

15

Welsh: Minority with a Comeback

By Ruben Feddes

As we know, there are four different countries within the United Kingdom; the obvious one is England, and Scotland has been in the news a lot regarding independence. Northern Ireland also gets some media attention in regards to Ireland. One country that is often forgotten is Wales. With a little over three million citizens, Wales is the second smallest of the four. They have their own language, Welsh, which sounds a lot like Irish, but is in fact not that similar at all.

Welsh originated somewhere around the 9th century, as a descendent from Brittonic, the language spoken by the inhabitants of the island before Germanic tribes came to England. These people moved to the West of the island, and therefore, there was little influence from these Germanic languages. Over time, the language changed to what was known as Middle-Welsh, this was around the 14th century. During this time, many law manuscripts were written, which are still being used today. In the next 200 years, Welsh got influenced by Middle-English, and went into a decline of speakers because of the introduction of Middle-English.

This changed when in 1588, William Morgan translated the Bible into Modern-Welsh, making Welsh the language that was used in households. Since then, new dialects, grammar and spelling have been introduced, but the language is still very similar to that of the 16th century, and people today can understand the Welsh of that time period.

16

The 'Boston Manuscript', an annotated 14thcentury Welsh

version of the laws

Over time, the number of Welsh speakers has been in decline, being at its lowest in 2001, when only 20% of Welsh people could speak the language. Since then, the government has invested a lot in teaching the language throughout the country. Where in most countries with minority languages this tactic would be futile, Welsh has shown a significant increase.

In a 2022 survey, almost 900,000 people in Wales spoke the language, where half of them claimed they could speak the language fluently, making up almost 30% of its citizens. As of today, Welsh is the only Celtic language that is not considered endangered by UNESCO, showing huge growth.

Surprisingly, there is another part of the world where there is an increase in Welsh speakers; Argentina. The first Welsh people came to Argentina in 1865 as they felt that their culture was in danger in Wales, mainly settling in Patagonia in the South of Argentina. There was little to no contact between Wales and the so-called Chubut Valley, and the number of speakers decreased over the years. This changed in 1965, when more and more Welsh people started to visit the community and stayed there. In around the year 2000, more funding for Welsh teaching was requested and eventually funded by the Welsh government. Currently, there are numerous schools in the Chubut Valley that teach Welsh, both primary and secondary, and the number of speakers is around 5,000 and still growing. There is a clear difference between the dialect spoken there and the language in Wales. Despite being heavily influenced by Spanish, it is still understandable to native Welsh speakers.

Welsh is one of the few minority languages in the world that is growing in numbers of speakers, and the projections for the language are mostly positive, so it won’t be going away anytime soon. Having the highest influence it has seen in years in the country itself, and even spreading to other parts of the world. So maybe we should all learn some Welsh, and in case you ever go and visit the country, pob lwc! (good luck!)

17

A Minority People as a Justification for Military Action: the Russian Invasions in Ukraine

By Bart Hans

When it was decided that the theme of this issue would be minorities, I was pretty excited. Being the politics enthusiast that I am, my mind instantly went to political minorities, not immediately realising the dangerous waters of cancellation I would be navigating. However, I wanted to write something about it, as I feel it is a topic that can be extremely interesting when properly written about. So, I am going to do what I always do, dancing on the line of being cancelled and getting a pass, and talk about Russia, Ukraine, and the Russian minority in the latter country. All of us are familiar with what is happening in Eastern Europe, with the conflict between Russia and Ukraine playing out. This dispute started ever since Crimea’s annexation by Russia in 2014, after the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity. Many ethnic Russians have been living in the Crimea peninsula and the current Donbass region of Ukraine. In fact, ever since the Soviet times, ethnic Russians have spread throughout Eastern Europe. These Russian populations have since lived with the national population of the former Soviet countries. In this piece however, I want to focus on Ukraine, as it is the country I personally have the most experience with.

Now before we touch upon Ukraine, I briefly want to mention the Russian minority that I will be commenting on. Because of the history of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, a large percentage of people living in Eastern Europe are Russian. Some still cling onto this identity, while others have shifted their identity to be geared towards the country they live in. The latter is primarily happening with younger generations, while the older generation still hangs onto their Russian roots. This piece will focus on Russian minorities as the people that cling to their Russian origin, because they are the ones that Russia has interest in.

When Ukraine became an independent country, it was almost a laboratory of some kind to Russia. How far could their influence reach, and what resistance would they meet? Ever since 2014, this resistance would rise as a result of the Revolution of Dignity. I could talk for hours about this subject, but the short version goes like this: former Ukrainian President Yanukovych refused to sign a deal with the European Union for closer connections, opting to seek closer ties with Russia instead.

18

This sparked an outbreak of protests in Ukraine, resulting in Yanukovych fleeing to Russia and the deal with the EU being signed anyway. Russia saw this deal as a threat, as it would expand the EU’s reach closer to its borders, and make Ukraine take a more anti-Russian stance. As a result, Russia claimed the Crimea peninsula, where many ethnic Russians lived, and supported the separatists in the Donbass, who wanted to become independent from Ukraine to seek closer ties with Russia.

When you take a look at where the ethnic Russians all live in Ukraine, it should come as no surprise that these are the areas that are currently fought over. The Donbass region and the Crimea peninsula are the areas where most of the Russian minorities live. In Crimea, the majority of the population there identifies themselves as Russian. Now, one of the reasons that Putin decided to both annex Crimea in 2014 and invade Ukraine in 2022 is to allegedly protect the Russian people in the country. Back in 2014, Putin’s defence for taking the Crimea peninsula went as follows: “We see the rampage of reactionary, nationalist and antisemitic forces in Ukraine, including Kyiv. We understand what worries the [“”] Russian speaking population in the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. Therefore, if we see such uncontrolled crime and hate spreading to the eastern regions of the country, and the people ask us for help, [“”] we retain the right to use all available means to protect those people.” In 2022, Putin would once again highlight antisemitism and protection of the Russian native people as its main goal when it launched its invasion of Ukraine.

This raises the question: Are these Russian minorities truly being used as a justification for Russian invasion? Well, the answer is both yes and no. The majority of the Donbass region and its Russian minorities do in fact want closer ties to Russia. They have been advocating for it ever since 2014 when they declared independence from Ukraine and have asked Russia for support ever since. So, in that sense, no, they are not being used as a tool for invasion, but are rather accepting the request for help. But the answer is also yes, as the Ukrainians themselves did not ask for this, and the Russians in Ukraine are in fact a minority. So, the majority of the Ukrainian population did not want Russian influence in their country, but they still received it. Of course, there are many factors that did cause these events, so this should not be seen as the sole reason for the Russian invasion. But it is an interesting reason nonetheless.

19

The Language That Went Out with a Bang

By Paula Divić

It happened on the 10th of June 1898. Tuone Udaina went for a stroll outside on an unassuming Friday afternoon, probably to soak up the late spring sun while enjoying the lovely sights of Krk, his hometown. The construction on one of the Krk’s roads seemingly caught his attention. As he was walking towards the construction site, Tuone Udaina accidentally stepped on a landmine, which caused him to blow up. By stepping on a landmine, he ended his own life, but more importantly, he made the Dalmatian language go extinct.

The Dalmatian language was one of the many Romance dialects mainly spoken in Dalmatia, a beautiful region on the Croatian seaside to which you should definitely pay a visit (shamelessly promoting my home country). In ancient times, Dalmatia was a Roman province that the Romans named after an Illyrian tribe Dalmatae (Croatian; Delmati) who were at the time inhabiting the Eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. (Italian: lingua dalmatica, dalmatico; Croatian: dalmatski ). The Dalmatian language evolved from Vulgar Latin used by Illyro-Romans and it was the main language throughout the Dalmatian coast, from Fiume (now Rijeka) to Kotor in Montenegro.

Even though almost every town developed its own dialect, two were claimed most important – the Vegliot and the Ragusan dialects. The Vegliot dialect was spoken mainly in the North and its name derives from the Italian name for the island of Krk, Veglia. The Ragusan dialect, which was used in the South, was far more studied and thought of as prestigious. It was the official language of the Republic of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik). The earliest noted mention of the Dalmatian language dates back to the 10th century, and it has been estimated that around 50, 000 people spoke it at the time. The oldest documents written in Dalmatian are in fact the inventories from Ragusa which date back to the 13th century. According

20

to scholars who first became acquainted with it through letters dating from 1325 and 1397, it was a language heavily influenced by Venetian. Up until now, roughly 260 Ragusan words have been identified, some of them being pen “bread”, teta “father”, chesa “house”, and fachir “to do”.

Gradually, because of the growing Venetian influence over the Dalmatian province and the settlement of the Slavic speakers, the Dalmatian language died out. Luckily, by virtue of an Italian scholar Matteo Bartoli and with the help of Tuone Udaina, the Dalmatian language has been analysed and preserved. Namely, Bartoli, himself of Istrian descent, visited Udaina in 1897. You can see how fortunate it all played out since Udaina will have been dead a year later. Nevertheless, Bartoli decided to dig deep into his Dalmatian roots and made the already deaf and toothless 73-year-old Udaina his language informant. On top of that, Dalmatian wasn’t even Udaina’s native language; he had learned it only by listening to his parents’ conversations, who spoke a Vegliot dialect. By the time he acted as an informant, he hadn’t spoken the language for 20 years. Somehow, miraculously, Bartoli managed to write a whole book about the Dalmatian language which reflected on its vocabulary, phonology and grammar. The book was written in Italian and was named Il Dalmatico. It was translated into German and published in 1906. However, the Italian manuscripts were reportedly lost, and so the Italians were in desperate anticipation until 2001 when the book was finally translated back into Italian. All in all, I think we can all agree that it was a good thing Bartoli made it in time before Udaina stepped on a mine.

Further readings:

Il Dalmatico by Matteo Bartoli

The Republic of Ragusa, An Episode of the Turkish Conquest by Luigi Villari

The Great Illyrian Revolt: Rome's Forgotten War in the Balkans by Jason R.

Abdale

21

"Hier maj plat proat'n": Diving Into Low Saxon Dialects

By Anne-Roos Peters

Once you approach the Dutch-German border, you will notice something interesting: the local people around you start to talk differently. It sounds like Dutch, but not quite. It has something German to it and yet feels like something entirely different. Well, my friend, you have entered the territory of Low Saxon dialects. Come along on a journey through the land of kniepertjes, kozak and kapkool.

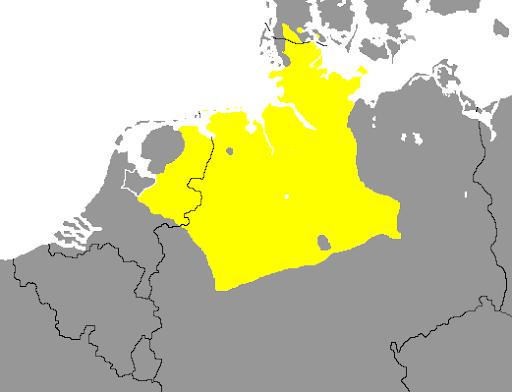

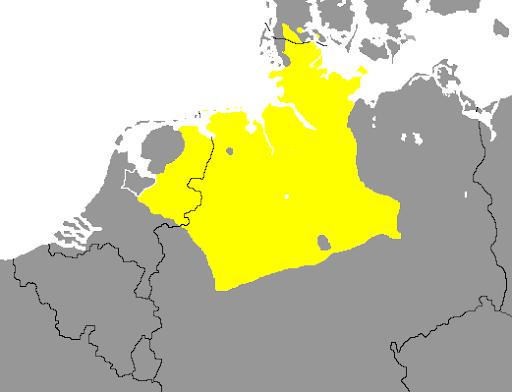

Low Saxon is the umbrella term for a group of West Germanic dialects spoken in the northern parts of Germany and the Netherlands. It comprises Twents, Gronings, Urkers and Hamburgisch, among other dialects. Low Saxon has been recognized as a minority language in both Germany and the Netherlands, but its status varies in different regions. In Germany, Low Saxon is recognized as a regional language in Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg and five other states. In the Netherlands, Low Saxon is recognized as a regional language in the provinces of Groningen, Drenthe, Gelderland, and Overijssel, and it is even taught in some schools. Low Saxon is descended from Old Saxon, a West Germanic language spoken in the early Middle Ages. Old Saxon was the language of the Saxons, a Germanic tribe that inhabited the area around modern-day Lower Saxony in Germany. Over time, Old Saxon evolved into Middle Low German, which was spoken in the Hanseatic League, a mediaeval confederation of merchant guilds that dominated trade in the Baltic Sea and North Sea regions. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Dutch Republic emerged as a major economic and cultural power, and the Dutch language began to spread beyond the borders of the Netherlands and replace Low Saxon as the lingua franca. As a result, the Low Saxon dialects spoken in the northern

22

parts of the Netherlands became heavily influenced by Dutch. In Germany, Low Saxon remained a distinct dialect group, but it also absorbed many loanwords from High German.

To keep it simple, let us take a look at Twents and Gronings. At first sight or well, sound , a dialect such as Twents may just sound like drunken Dutch, but you will start to hear some method to the madness if you take a closer listen. Most of the confusion is usually caused by the passion for contractions that Twents and Gronings have in combination with some vowel shifts and elongated sounds; the verb kiek'n (meaning kijken; to look/watch) is a perfect example of this. Of course, there are words such as onmeunig (ontzettend; incredibly) and mangs (soms; sometimes) that are pretty unique to the Twents dialect and for which you probably need a dictionary. The same goes for Gronings; you can bet it took me five minutes to process their words when someone asked me for a puutje (zakje/tasje; a (plastic) bag). It is also interesting to see the differences among these two dialects: a Groninger would say moak'n (to make) whereas a Tukker would pronounce it as maak'n.

In short, Low Saxon dialects in Germany and the Netherlands have a rich history and unique characteristics that distinguish them from other West Germanic languages. Despite their official recognition as minority languages, Low Saxon dialects face several challenges, including the lack of standardised spelling and grammar and the influence of Standard German and Dutch. Nevertheless, many speakers of Low Saxon are proud of their dialect and are working to preserve and promote it for future generations. Whether you write it as naober or noaber, we are all neighbours on this earth in the end.

23

A Love Letter to the Moomins (and Anti-Fascism)

By Stijn Bakker

For anyone who sits at the Harmony cafeteria on a regular basis, you may have caught a glimpse of me with my coffee mug. Aside from saving me a whopping 15 cents on coffee at the C-Bar and economising on paper cups, another thing that's special about this mug are the two beautiful Moomin illustrations on it. The Moomins are arguably the best children's story characters to have ever been made. Ever since I was a child, I have loved these creatures and the stories that surround them. Later in life, I found out there was so much more to these figures. Throughout my time in university, I have done a book report and written an essay about them, and it was not even in a course for children’s literature. Tove Jansson, the author of these stories and the brain behind the Moomins, combined the fun and lighthearted (though sometimes deeply jarring) stories with meaningful messages and philosophical thoughts. When doing research on this article, which should have just been a light-hearted introduction to the Moomins, I found out a last bit of information about the Moomins that made me love them forever: The Moomins are anti-fascist.

While I understand that this might lead to certain questions, I first want to give a quick rationale and context for this article in a magazine about cultural minorities. While I do not need a lot of reasons to talk about the Moomins, there certainly is one here. In Finland, there is a linguistic minority called the Finland-Swedes (finlandssvenskar in Swedish), a group of people that speak Swedish in a country where most speak Finnish. The reason for this are the close ties between Sweden and Finland that date back centuries. For the longest time, Finland was simply the Eastern part of Sweden and Swedish was the language used by the state. The Swedes were eventually forced out by the Russians and then the Russians left (I am sorry for this oversimplification, but this is an article about the Moomins, not about the interesting yet complicated history of Finland). This left the Finns with their own country, however, some of the Swedish speakers remained. It just so happens to be that Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins, was part of this group of Finland-Swedes. So, while the Moomins are a typical Finnish export product, they were originally written in Swedish, and thus classify as, you guessed it, minority literature.

26

Here’s a short introduction for those unlucky souls that have never heard of the Moomins: the story is about Moomintrolls that live in the harmonious Moominvalley. Even though strange things happen sometimes, the Moomins live a peaceful life with their family and a lot of their friends. The main (although not singular) protagonist, Moomin, still has a lot to learn about the world and looks at it with the childish wonder that we have all had. Through his eyes, and with the primary help of his friend Snufkin, a wise wanderer and einzelgänger, we discover Moominvalley. While this sounds simple, and in many ways it is, we not only learn about the wonderful life of these characters throughout the stories, we also learn about the deeper meaning of life. The importance of identity, why being alone is good sometimes, the need to bond with the people surrounding you, and how music and the arts create the world. These messages, along with many others, are beautifully crafted in engaging stories that want to make you live in Moominvalley yourself, or at least take an extended sabbatical to go there.

While these messages are important for everyone to learn, they are not inherently political. And while Moominvalley does feel like an anarchoCommunist¹ utopia sometimes, politics are not necessarily at the forefront of the stories. Where basic values and wonderings on human life and purpose on Earth are more easily detectable, politics do not seem to interest the Moomins. And why would they? The Moomins live in a fantasy utopia in which nothing is needed and everything is possible.

Yet, there has always been something that attracted me about their way of life: their ideals. This was confirmed when I stumbled upon the picture below. In the picture, we see the Moomin family. Moominpappa is in the front, holding a gun. They have a firm look in their eyes, they are here to protect. Beneath it, we read “Better Run Nazi Scum”. While at first I thought it was a joke - the ever-friendly Moomins taking up guns against the Nazis - I quickly went down a rabbit hole. It turns out that the Moomins have been at the forefront of anti-fascist action for years now.

¹Anarcho-Communism is a society with an absence of a state apparatus (anarchism), combined with communist ideals such as “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs”.

27

While there are numerous reasons for the assumption that the Moomins are anti-fascist, because yes, it is merely an assumption, a few are quite clear.

First of all, Tove Jansson herself was an outspoken anti-Nazist throughout her life, and while she did not include a very clear message in the stories (Moomin never says “I hate Nazis” in any of the stories), the stories do include many narratives of inclusion and acceptance. Jansson herself was queer, and while not accepted in Finland at the time, had relationships with women throughout her life. Characters based on these relationships and on her partners make appearances in her writing. These characters are accepted and included, and can always expect a warm welcome in Moominvalley.

This acceptance, along with the peace-loving nature of the Moomins, makes them the perfect antithesis to fascism. And while this opposition is mostly made up in the mind of the many Moomin fans around the world, this strong and important political stance makes these already delightful creatures even more lovable.

28

Why Ethnic Minority Parties Become Successful, and why this is Important for Eastern European Democracy

By Bart Hans

Democracy is a system where political parties are elected by the people. They all represent specific wishes and cater towards a certain group that they think will vote for them. Because of this, there are parties who paint themselves as ethnic minority parties. To give a quick definition by John Ishiyama and Brandon Stewart, an ethnic minority party represents a group that is a numerical minority in a population. They try to focus on a specific audience rather than trying to widen their appeal in order to win elections. Ethnic minority parties (or EMPs in short) try to mobilise their target audience in order to create a movement within the main political arena, where they feel like they could be drowned out or forgotten about without a specific party. In Europe, there are quite a lot of these parties, examples being the Frisian National Party in the Netherlands, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria in Germany, and the Silesian Regional Party in Poland. All the aforementioned parties are also a part of EU parties, having a say on European levels as well. But what makes some of these parties so successful?

Ishiyama and Stewart list a few potential reasons as to why EMPs could be successful, such as geographical location, the proportionality of an electoral system, and whether a country has regional autonomy or not. Ultimately, it is the parties’ ability to create a substantial following that matters most. They need to have their target audience rally up and vote for them, otherwise they will not have as much of an impact as they would desire. To make things seem more difficult, more competition would also mean less votes. EMPs tend to compete with the radical right parties for the domination of the political space on ethnic minority rights. They

29

both profile themselves as parties that stick up for marginalised groups in society, so it makes sense that they would clash. Yet there is a key difference, as the EMPs battle for more rights, and the radical right have strong opposition to more rights for ethnic minorities. This is shown clearly in Katherine Aha’s research, where she proves that they truly are polar opposites in regard to the issue of minority rights.

Because of this clash, the opportunities for EMPs to become successful are limited, but not impossible. Ishiyama and Stewart showed that an important factor for political success is the organisational capability of the minority parties. This follows back to what was said earlier, that the party needs to be organised enough to amass followers and prevent other parties from taking them away. Dr. Daniel Bochsler also noted that territorial structures of the minorities spread across a country is an important aspect of success. According to him, parties that address territorially concentrated groups of voters have better chances of getting elected to parliament in district-based electoral systems than parties whose voters are spread across the country. This territory theory has proven to be successful in the Netherlands, where the Frisian National Party has amassed 4 out of 43 seats in the Frisian States Provincial, and Groninger Interest has gained 3 out of 43 seats in the Groninger States Provincial. They are also represented by the Independent Senate Group in the Eerste Kamer, giving them a voice in the national level of politics as well.

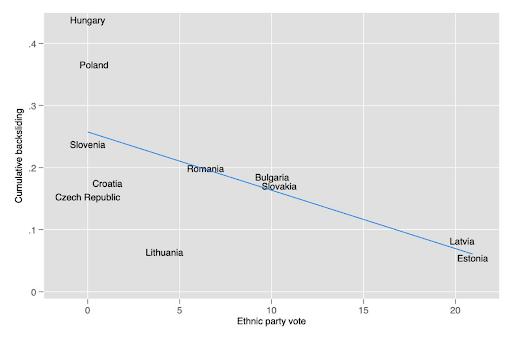

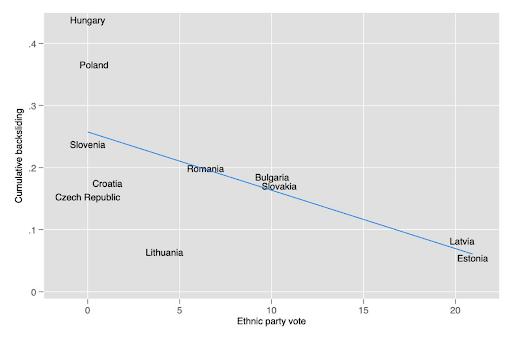

The success of EMPs is not only important for the rights of the minorities, but Professor Jan Rovny from Sciences Po in Paris has also proven that ethnic politics can act as a check on democratic backsliding. He stated that Central and Eastern Europe heavily benefit from ethnic parties to prevent democratic regression. The following graph shows that there is a correlation between democratic backsliding and the ethnic party vote in several Central and Eastern European countries.

30

Figure 1: Cumulative backsliding (total annual democratic regression from 1990-2020) and ethnic party vote share. From:

As is shown here, there is a clear link between the ethnic party vote and the democratic backsliding in post-communist countries. Countries such as Hungary and Poland have slid back more than countries such as Latvia and Estonia ever since democracy was introduced in the 1990s, and the former also has less votes for ethnic

parties, while the latter has significantly more. There are of course outliers such as Lithuania, but the largest number of countries fit well within the median line that Rovny created. This creates an interesting narrative where the influence of EMPs has been beneficial to the general political sphere.

Ethnic minority parties are important parties that come up for the rights of those that do not feel heard. Their success is based on a number of factors such as the political construction, territory, and their organisational capabilities. Furthermore, their success can be a key aspect of keeping democracy in countries, as was shown by Rovny in Eastern Europe. I would suggest the following if you have an interest in this topic:

- Aha, K. (2018). Ethnic heterogeneity and party politics in eastern Europe (thesis). University of North Carolina, North Carolina.

- Bochsler, D. (2011). It is not how many votes you get, but also where you get them. Territorial determinants and institutional hurdles for the success of ethnic minority parties in post-communist countries. Acta Politica

- Ishiyama, J., & Stewart, B. (2021). Organisation and the structure of opportunities: Understanding the success of ethnic parties in postcommunist Europe. Party Politics

31

Rovny, 2023

Interview with the Board of Multi

By Tiara Ruidavet

What initially drew you to studying Minorities and Multilingualism at the RUG?

Fei:.I.was.interested.in

Anthropology and was too late to apply at other universities, so I chose something similar. I didn’t know much about the programme initially but I realised it’s my thing.

Anoek: M&M was my wild card, honestly. After the open day, I was surprised by the lecture one teacher gave. I’ve always been interested in culture and languages so I thought it fit nicely with my interests. Right after that lecture, and right before the deadline, I decided to enrol. It turned out to be the best thing I ever did.

Sam: I really struggled to find a bachelor that I liked; After hours of browsing every single university’s website, I found M&M. It perfectly suited my interests, since I have always been interested in sociology, inequality issues and language. It just seemed like the best choice back then, so I chose it.

How many languages do you all speak?

We all speak Dutch and English! Fei also speaks Mandarin and a bit of German, Anoek knows Drents and Swedish, and finally, Sam speaks Maastrichts and also some German.

What are your plans after M&M? And what are some potential career opportunities for alumni?

Anoek wants to move to Sweden for her Master's degree and to study the Sami people, a minority there.

Fei wants to do a Master’s degree in Leiden on Visual Ethnography so he can create documentaries. He also wants to do a PhD so he can research ethnic minorities in China.

Sam has no idea what he will do yet. There are a lot of options for alumni; you quite literally become a diversity manager, which you can apply on different levels of society. You can research, but you can also do humanitarian work. Besides these specific jobs, you can also professionalise in other things in which you can use your knowledge about minorities, for example, you can become a journalist, reporter or documentary maker. The options are endless.

32

From left to right: Secretary: Sam Kints, Chair: Anoek Withaar, Treasurer: Guo Fei

This issue of the ETCetera is on European minorities, whether they be linguistic, cultural, racial or political. What are some minority groups you can think of living in Groningen and how well do you think they are being accommodated?

There are many different minority groups here as Groningen attracts a lot of international students and teachers. These are all minorities as well as regional minorities, like Frisians or even Groningers. Of course, minorities like the LGBTQ community or people who are neurodivergent are also present. In regards to their accommodation, it’s probably a lot better than in the rest of the Netherlands. One serious problem is the lack of housing for international students. So, while Groningen is definitely putting in effort to accommodate all minorities, there is still room to improve.

I'd like to know more about minority causes you're passionate about that we may not know of.

As a Board, LGBTQ rights are extremely important since all our Board members belong to the community. We also want to promote a safe environment for everyone, including minorities relating to neurodivergence or able-bodiedness. Besides that, we also have some minorities we’ re interested in individually; Anoek is also studying Swedish within ELC so she can combine her knowledge to research the Sami people. There have been efforts to conserve Sami culture with education, but it’s not as effective as people.hoped.

How important is it for you to preserve heritage and tradition while also balancing and ensuring there is sufficient globalisation and integration?

Firstly, we don’t think these things necessarily contradict each other; you can both be a well-globalised citizen while still preserving your heritage and traditions in the way you prefer. People put the notion of globalisation and integration straight across from heritage and tradition so it feels like in order to globalise, you have to abandon your heritage. However, we certainly disagree. Our study is all about embracing diversity and developing your own identity. Having a strong cultural identity doesn’t inherently clash with someone ’s functioning in a country they migrated to for instance. The world is already globalised; we’re already one big social network with the Internet. Just being yourself openly and unapologetically only helps globalisation; it shows the world that there is diversity, which is necessary, since the process of globalisation up until now has been a very White-dominated one. What would you say is the most important thing readers should take away from this interview, be it about Multi or otherwise?

Being a minority is a very fluid concept. Depending on the surrounding society, you can become a minority when it may not have previously been the case. It's also difficult to define what is and isn't a minority, or who is or isn't one. Identity is always changing and so is our society and politics.

33

Kosovo; Minorities in Conflict

By Stijn Bakker

When we, as the Editorcie, decided to write this issue about cultural and linguistic minorities, we also decided to - and now I have to mind my wordsstay out of controversies. Serious topics could of course be covered, but when discussing the serious topic of minorities, we wanted to stay as objective as possible. While the following article will be about one of the most controversial regions in Europe, I will try to give an impartial overview. In this article, I hope to give a general introduction to the situation surrounding Europe’s youngest partially recognised state: Kosovo.

The Balkans have had a turbulent past. Because of centuries of reigns by different empires, most notably the Byzantines, the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire, the people of different cultures and religions have blended and lived together side by side within these territories. In the 19th century, nationalism first began to spread over Europe and different people became more aware of their shared history and culture. This hodgepodge of cultures in the Balkans quickly turned into a powder keg. At the turn of the 20th century, three different wars, collectively known as the Balkan Wars, were fought between the new states that had formed after the demise of the Ottoman Empire. After that, the First World War swept through the region. This Great War shifted the power balance in Europe, and in the Balkans as well.

Yugoslavia was created in an attempt to unite the Southern Slavs and form a state that would be able to defend itself against the surrounding powers. While omitting large swaths of the history, I will make a quick jump to after the Second World War, when Yugoslavia turned into a Socialist state under Josip Broz Tito. Word count and objectivity do not allow me to write much about this part of Yugoslavian history, but I am always willing to talk about this outside of this ETCetera, as everyone knows by now.

34

Anyway, after Tito’s death, things quickly went south and Yugoslavia was dissolved. Ethnic conflicts, wars of independence and insurrection followed, leading to the creation of several new states: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia-Montenegro. The last one parted ways with Serbia in 2006, after which there would be only one more declaration of independence: Kosovo in 2008.

Already in the 1990s, the Kosovo War swept through the region. This conflict was fought between what was still known as Yugoslavia and a rebel army that called itself Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës, or UÇK for short (the “Kosovo Liberation Army”, or “KLA” in English). Only after NATO had intervened by bombing the region to root out Yugoslav forces and force peace, the conflict simmered down. (Note that this is an extreme oversimplification of the events that took place.)

Ever since the Kosovo War, the situation in the region has been tense. The UÇK continued to operate and the Serbo-Montenegran Army was heavily involved in the region. On the 17th of February 2008, the Assembly of Kosovo once again proclaimed independence, after already having done so in 1990, which at the time did not come to fruition. While Serbia tried to fight the case at the International Court of Justice, the Court found that the declaration was not in conflict with any form of international law. Under guidance of the European Union, Serbia and Kosovo have since tried to have a dialogue surrounding Kosovo’s status. While there have been breakthroughs, such as in 2013 when Serbia withdrew all of their official government bodies from the region, most of this period has seen major tensions. Even a few weeks back, tensions once again grew high, as Serbian minorities living in Kosovo demanded more rights, and the Serbian government responded by closing the few border passages between the parties in conflict. With mediation of the European Union, the tension was relieved, and there seems to be a move towards Serbia (partially) recognising Kosovo’s independence, in order for Serbia to be able to become a candidate member of the European Union.

35

While not understating the complicated situation, the basic gist of the Kosovo conflict consists of ethnic division: Albanians are a majority in the region, while being a minority in the whole of Serbia. Therefore, they wanted to be either a part of Albania instead, or be completely independent. A good friend of mine is from Kosovo, and he states that most Kosovans, though certainly not all, actually prefer to be called Albanian, while they are divided on the question of complete independence versus merging with Albania. This example shows that even within Kosovo there exist divisions concerning their identity and independence.

Since Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008, the world has been divided on the legality of this secession. Only 112 of the United Nations’ 193 member states recognise Kosovo as an independent country, and the country did not have any formal relations with the EU for many years, despite being situated in Europe. The recognition of Kosovo somewhat shows an East-West divide, with countries such as the USA and most of Western Europe recognising their independence, whereas Russia, China and most of Eastern Europe see Kosovo as part of Serbia. Furthermore, recognition may also depend on a country’s own struggles with independence movements. Spain, for example, does not recognise Kosovo. This is probably because Spain has its own struggles with Catalonian and Basque independence movements, which would create a national crisis were they to recognise Kosovo’ s autonomy. (If you want to know more about the Catalonian independence movement in Spain, read Tiara’s interview!)

The Kosovan question is an interesting one, as it not only reveals the tensions that are still present in this part of the Balkans, but also translates to international divides. While complicated and controversial, the underlying causes and implications teach us a lot about the past of the region, and the difficult nature of minority problems in certain parts of the world.

36

Romani People That Made History

By Paula Divić

The Romani, also called Roma, are an ethnic group of traditionally nomadic people who originate from Northern India, but are now settled all over the world, mostly Europe. Most Roma are bilingual, speaking Romani, a language closely related to modern Indo-European languages of northern India, and the major language of the country they live in. Large communities of Romani people live in Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina where they face challenges when it comes to integration and are often discriminated against. It is estimated that the Romani world population is approximately two to five million people, a figure which is a consequence of the World War II genocide. The Porajmos, meaning “devouring”, is the name of the genocide of Europe’s Roma and Sinti people by Nazi Germany. It is estimated that between 220,000 to half a million Romani lost their lives during the Porajmos.

Instead of turning this article into a political one, I would like to turn to art and culture, and introduce to you some of the famous faces (which you probably all know) but for some had no idea that they were of Roma descent and also shed light on the more obscure artists with Roma heritage.

Django Reinhardt

As I’m writing this article, the lively and sometimes achingly melancholic tunes of gypsy jazz fill my small room. The man behind the fingertips which caress the guitar strings is one of the greatest names of gypsy jazz Django Reinhardt. Django was born in Liberchie on the 23rd of January 1910 into a Belgian family of Manouche Romani descent. The birth certificate shows that the family named him Jean, so Django then could be just a local version of his name. However, many critics have argued that by calling himself Django, the famous musician actually wanted to show off his

37

heritage. Namely, the word “django” in Romani means “I awake”. Anyhow, Reinhardt spent his early days in Romani encampments, where he got acquainted with many instruments such as the violin, banjo and guitar. He started busking in cafés and soon immersed himself in the industry. Not even a caravan fire in 1928, which severely impeded the use of his two fingers on his left hand, could compromise his remarkable talent for guitar playing. In spite of being told he would never be able to play again, Django taught himself how to play guitar using only three fingers. For most of his career, Reinhardt played a style called swing that reached its peak popularity in the 1930s. In 1946, he even toured the USA with the famous Duke Ellington Orchestra. His most lasting influence on jazz is considered to be the introduction of solos based on melodic improvisation, of which his records are full of. One of my absolute favorite Django tunes is the mist-infused “Manoir des me rêves”, so make sure to give it a listen!

Katarina Taikon-Langhammer

Now this name you might not have heard of before, but Katarina TaikonLanghammer was one of the most influential Swedish Romani activists. Born on the 29th of July 1932, Taikon led a turbulent life as a civil rights leader, a writer and an actress as well. The Swedish activist from the Kalderash caste dedicated her life to improving conditions for Romani people in Sweden and throughout the world. Through debating and writing to Swedish authorities, the Romani were granted the same rights for housing and education as all other Swedes. Her first book, called Zigenereska, describes her own life and childhood, providing an insight into the lives of Swedish Roma and their position in society. Taikon saw that the most important factor when it came to changing the prejudiced mentality of society was to focus on the younger generations and to teach them integrity and acceptance of everyone’ s differences. That is why she started writing children’s books. The most popular book, which also has a TV adaptation, is called Katzitzi, and it is largely based upon Taikon’ s experience of being a Roma child. Because of her tireless and selfless work for the Swedish Romani community, she is often called the Martin Luther King of Sweden. If you want to know more around her, you can read her books, or watch the 2015 documentary about her life!

Finally, here are some famous people that I had no idea were actually of Romani origin: Pablo Picasso, Elvis Presley and Charlie Chaplin!

38

Let’s talk about Frisian

By Ruben Feddes

Frisian: the language that’s the butt of most jokes throughout Groningen and the rest of the country. Why this started is unknown to me, but it is time to look a bit more at this language. That is because Frisian is closest related to probably our favourite language of all: English!

To me that was a surprise, it's so similar that many words are exactly the same. Of course, the spelling might be a bit different at times, but the pronunciation is almost identical.

Here are a few examples; the English word is first, and then the Frisian equivalent:

“Cheese” - tsiis

“Green” - grien

“Day - dei

‘‘Goose’’ - goes

‘‘To feel’’ - fiele

There are many more examples, and we also have some words that are exactly the same such as: “him”, “it” and “ ear”. For the reason of all these similarities, we have to go back in time to the years around 500 and 600 AD. In those years, the Frisians, just like many other Germanic tribes (Angles, Jutes, and Saxons) travelled to England. They stayed there and brought with them their own languages. There the languages of the Frisians and the Angles mixed, and became to what we know today as Old English. This transformation did not just take place over a few decades, but over the course of 200 years, later being influenced by the Vikings and the French. However, it is clear that we still see many similarities between the two languages.

Back to the present day, where since a few years Frisian is an official language in the Netherlands. It is time to look at this language a bit more in detail. To me, every Frisian speaker sounds the same. I asked our lovely Board member Annie to explain Frisian and its dialects a bit more to me:

39

Growing up until she went to school Annie only spoke Frisian with her parents. This is called geef-frysk, which can be compared to Algemeen Nederlands, General American or standard British. Later in school, you learn Dutch as well. In smaller villages, there are many children that do not learn Dutch until the end of primary school since you do not need it. Therefore, for most Frisians, Dutch is a second language to them. Below, you can see a map of the different dialects within the Frisian language, and where to find them.

Now we know that not all Frisian is the same, and that the language is closer to us than you might have thought, it’ s time to practice your Frisian! Annie has generously provided us with some Frisian tongue twisters to get you started! The translation might not be perfect in English, otherwise the meaning would have changed. Good luck!

Bûter, brea en griene tsiis, Wa dat net sizze kin, is gjin oprjochte Fries.

“Butter, bread, and green cheese, who cannot say that, is not a real Frisian.”

Al tsien jier gie Pier ier mei it iepenbier ferfier.

“For ten years Pier always goes with public transport.”

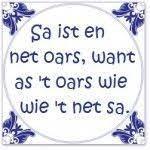

Sa ist en net oars, want as ‘t oars wie wie ‘t net sa.

“So it is and not otherwise, for if it were otherwise, it was not so.”

40

Between Two Worlds: Queer Russian Migrants in Berlin

By Anne-Roos Peters

Migration is a complex and often challenging experience for many individuals, especially for queer Russians who move to Western Europe. With the recent unanimous vote in the Duma to extend the “gay propaganda” law, LGBTQIA+ individuals in Russia face further discrimination and censorship in a country known for its hostile attitude towards queer people. When these queer Russians migrate to Western European countries for more safety, freedom, and equality, they often face new challenges related to their queer identity. This is the story of how queer Russians in Berlin find themselves in between two worlds.

Germany is home to the largest population of Russian speakers outside of the former USSR, with approximately a quarter of a million Russians living in Berlin alone. This vast diaspora should make it easier for queer Russian migrants to settle in their new hometown, but reality tells a different story. The broader Russian community is not always as welcoming towards LGBTQIA+ individuals due to the persistent attempts of the Russian government to construct a strong national identity which heavily ostracises queerness. This exclusion of queerness by the broader Russian community creates a barrier for queer Russians to interact with fellow Russians and feel a sense of belonging based on their shared identity.

Furthermore, the local LGBTQIA+ community may not be accessible due to language barriers and preconceived notions of Russian people. Another factor that could add to the feeling of isolation is the cultural differences between Russians and Germans; it does not help that the latter are often perceived as standoffish. It is evident that sexual identity is not the only identity that is important to LGBTQIA+ migrants: many queer Russian migrants still feel a strong connection with their home country and many of them consider “Russianness” to be a crucial part of their identity. Moreover, Russianness is not understood as an individual feeling that varies from person to person, but rather a shared one based on interaction with others. This makes it even more critical for queer Russian migrants to stay in contact with the local Russian community.

41

Fortunately for the Russian queer community in Berlin, their struggles have not gone unnoticed. In 2011, a group of Russian-speaking queer people noticed the “double discrimination” that queer Russians faced and founded Quarteera, a Russian LGBTQIA+ organisation based in Berlin. Quarteera works towards a more prominent visibility of LGBTQIA+ Russians in Germany and LGBTQIA+ awareness among the Russian-speaking population. Through the events and activities organised by Quarteera, Russian-speaking queer folk can bond over their shared identity and protest against homophobic violence towards Russians whilst showing solidarity with those still living under Russia’s queerphobic regime.

Queer Russian migrants living in Western Europe face some unique challenges based on their multifaceted identities. Whether it is to find love, explore their own identities or feel a sense of belonging in a community filled with like-minded individuals, migrating to Western European countries brings many opportunities for them to escape the homophobic violence in Russia. Moving abroad, however, brings new barriers that make it difficult to smoothly integrate into the local communities; the Russian diaspora in Berlin had brought their traditional, anti-LGBTQIA+ views with them when they moved to their new homes, and the local queer communities are either inaccessible to or unaccepting of queer Russians. This leaves many queer Russian migrants feeling isolated and it negatively impacts their sense of identity. Despite these challenges, there are also inspiring examples of resilience, activism, and community-building among queer Russians. They are often actively engaged in efforts to promote the rights and visibility of their communities, including through advocacy, public education, and direct action, as can be seen with the LGBTQIA+ organisation Quarteera in Berlin. It is a perfect example of what to do when there is no place for you in this world: you make one.

If you found this topic interesting, I highly recommend reading this book: Mole, R. C. M. (ed.) (2021). Queer Migration and Asylum in Europe. London: UCL Press.

42

Cooking with Koos: M’semmen

By Tiara Ruidavet & Koos the Koala

Before delving into this recipe, I will first need to give some context to its non -European origins and how it does in fact tie into the theme of European minorities. The pieds-noirs minorities of North Africa refer to people of French, Spanish and Italian descent who emigrated and grew up in what was formerly French-colonised Algeria, and the French protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia in the 19th and 20th centuries.

My grandparents were born in Morocco to Italian and Spanish immigrant families in the 1930s, growing up in French-speaking Casablanca. After Algerian independence in 1962, many pied-noir families had to leave Algeria and other parts of North Africa to metropolitan France, many had never even been there before. Many pied-noir people described feeling homesick for a place that no longer exists and experienced mistreatment by "native" French upon arriving to mainland France. Famous pied-noirs include Yves Saint Laurent, Marcel Cerdan and Albert Camus.

North African cuisine has always been integral to my family’s reunions (no pied-noir wedding is complete without méchoui d’ agneau or chicken tagine); and my beloved auntie Lydia embraced the amalgamation of all our cultures through the art of cooking. I visited her last summer in Provence and she taught me some recipes from her past life in Casablanca.

M’ semmen (pronounced muh'SEMmin) is a simple cross between a crispy flatbread and soft crêpe eaten at breakfast or tea time in Morocco. Usually served with honey and Moroccan mint tea, my nephews also enjoy it with Nutella.

Ingredients:

600g extra fine semolina (ground durum wheat, griesmeel in Dutch)

300g flour, plus extra for flouring

1 tsp salt

1 tbsp sugar

70g sunflower oil, plus extra to coat dough

70g butter, melted

5g dry instant yeast

450+50ml water (may need more or less depending on flour used, be intuitive)

43

•Bloom yeast in 50ml lukewarm water, mix and set aside for 10 mins.

• In large bowl, combine flour, semolina and sugar. Add salt on one side of bowl before covering with dry mix. Then, make a well in the centre and add yeast solution.

• Add water little by little, mixing well with clean hands as you go before adding more if necessary. More or less than 450ml may be used.

• Knead with hands until a sticky dough is formed. Turn it onto floured surface and knead until smooth for at least 5 mins. (This dough is very stretchy)

• Return dough to bowl and cover, letting rest for 15 mins before transferring to countertop and brushing surface of the dough with oil to prevent sticking.

• Divide into 12 smaller dough balls and cover with cling film to prevent drying out. Let rest for 15 mins.

• Meanwhile, melt butter and combine with sunflower oil.

• Take one small dough ball, covering the rest. Apply butter mixture with fingers to work surface and dough, flattening and spreading out from centre outwards until a large square is formed, careful to not tear the dough. Go back in with butter mix if needed to prevent sticking and tearing.