By Moyo Lawuyi

A new report released on Nov. 10 by the Ontario Living Wage Network (OLWN) revealed the living wage required to make ends meet in the GTA is $27.20 per hour, raising concerns amongst many student workers at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU).

According to the report, this was a 4.6 per cent increase from last year’s livable wage of $26 with the GTA having the highest living wage rate in the province to date.

A living wage is not the same as the minimum wage, which is set by the provincial government. “The living wage reflects what people need to earn to cover the actual costs of living in their community,” reads the OLWN’s website.

“Despite the annual October 1st increase to the provincial minimum wage to $17.60, there is still no place in Ontario where you could work full-time and cover all your expenses,” the report said.

Zachat Ochalefu, a fourth-year fashion student, works part-time as a stylist at a clothing store. She says that while she works between 15 to 20 hours per week, and earns $17.50 per hour, this is not enough to cover her expenses in Toronto.

She says that if she earned Ontario’s livable wage, she would worry less about getting hours at work, spending money on groceries and paying rent.

“I think [working part-time] has made me more tired,” she said. “Because of the wage that I’m earning, I have to work more hours if I want to have rent but then I don’t have those hours because I have to be at school,” said Ochalefu.

“There is still no place in Ontario where you could work full-time and cover all your expenses”

According to Hub Insights, a publication of the Business Career Hub at TMU, as of Fall 2024, 925 TMU students were employed in Career Boost positions. Career Boost is TMU’s employment program for full-time domestic undergraduate students. In the program, students can only hold one position at a time, work only under a certain number of hours and most positions earn under $20 per hour, which is low compared to Ontario’s livable wage of $27.20 per hour.

TMU does not publish data on the number of students working off campus while

studying; however, Statistics Canada data show that in the 2023-24 year, 35 per cent of university students aged 18 and 52 per cent of university students aged 22 were working.

Sara Chapman, a fourth-year real estate management student, is working as a host at a restaurant downtown. Apart from tips, she earns $17.60 per hour. She says that with this pay, it can sometimes be challenging to make enough in Toronto.

“I think going up to $27 [per hour] would be amazing,” said Chapman. “It would probably help a lot with bills and everything, and if you aren’t working as much hours, you’ll still get a decent amount of money.”

“I have to work more hours if I want to have rent, but then I don’t have those hours because I have to be at school”

Chapman says her work hours at the restaurant are inconsistent. Because of this, she sometimes feels pressured to take on extra hours during busy periods to get more money, despite the potential impact on her academic life.

“If there’s an assignment due one night, I can’t work on it because I’m working, so I’ll have to stay up later to do that,” she said.

Chapman hopes the university can help students struggling financially in the city. She suggested TMU can provide more student discounts and the government can also offer more student grants instead of loans.

“[Students] still have to build up enough money to start paying the student loans back, even a couple months after graduating,” she said.

While the OLWN does not include student-specific expenses, such as tuition, in its calculations for the living wage rates across the province, the calculations consider rental costs in the province.

Craig Pickthorne is the communications coordinator at the OLWN. He says shelter costs like rent, renters’ insurance and utilities account for 40 per cent of the new $27.20 livable wage rate.

In 2025, the City of Toronto’s ‘Average Market Rent’ for a one-bedroom apartment in the city was $1,715. Pickthorne says rent is one sector that the provincial government can focus on to ensure people’s wages align with the $27.20 rate.

“The government can make people’s paychecks go further by bringing in some kind of strengthened rent control,” he said. “That’s an opportunity to help make sure that the living wage rates don’t fly out of control every year.”

By Garrett Raakman

Between Nov. 12 and 14, students at the Lincoln Alexander School of Law at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) voted on a proposed $140 levy to fund the operations of the Lincoln Alexander Law Students Society (LALSS). If implemented, every student at the law school would have an additional $140 fee added to their tuition.

The levy would go towards funding student groups and the law school’s over 30 clubs. The law society previously voted on the levy in 2023 when the majority of eligible students voted “no.”

Kien Azinwi, the head of the “Vote Yes” campaign, a group of students campaigning for the levy, and a fourth-year Juris Doctor candidate, called voting for the levy “a direct investment in the unique, vibrant and diverse community that defines the Lincoln Alexander School of Law.”

She also emphasized that the lack of a levy has hurt the society’s ability to hold more engaging events.

“From our inception, we have been operating on a budget allocated to us by the law school administration,” said Azinwi. “The problem we face today is one of success. Our student community has grown and flourished beyond initial expectations. We now have over 30 vibrant student clubs, each with a unique mission and a desire to serve our incredibly diverse student body.”

The LALSS supports the proposed levy, which was initially brought forward by a group of students, in addition to numerous other clubs like the Lincoln Alexander

Black Law Students Association and the Muslim Law Students Association.

In several posts on the LALSS Instagram page urging law students to vote for the levy, the clubs and LALSS says the levy “is not another university fee. It is a collective investment by students, for students; a commitment to support, engage and build community for our generation and for every generation that follows.”

According to LALSS president Iman Nadeem, the amount that they would be receiving from the students would be

around $63,000. Nadeem said that the levy would help law students with building professional networks.

“It’s really important that law students have access to the tools, especially with the most diverse law school in Canada,” she said.

“A lot of these students are coming from backgrounds where they don’t have access to the network, the tools, just the general knowledge to be able to engage in that space, and putting money towards professional development for these students helps them with that.”

Other law schools in Ontario also charge

student levies. For instance, the Queen’s University School of Law charges a flat $50 per term. The LALSS argues that the proposed levy would help make Lincoln Alexander more competitive compared to other law schools.

When asked what she would say to people on the fence about voting yes, Azinwi emphasized the culture of Lincoln Alexander.

“Think about the club events that have enriched your experience, the networks you’ve started to build, more subsidized services and programming that could be possible and the unique culture that sets us apart,” said Azinwi.

The Eyeopener Masthead

Editor-in-Chief

Negin “According to Who” Khodayari

Special Issue

Managing Editor

Daniel “Left Twix” Opasinis

News Editors

Shumaila “BEST” Mubarak

Vihaan “PAGE” Bhatnagar

Amira “YET” Benjamin

Arts & Culture Editor

Lama “Quote Check” Alshami

Business & Technology Editor

Jerry “Tall Glass of Water” Zhang

Communities Editor

Daniel “Right Twix” Opasinis

Features Editor

Edward “Bunker” Lander

Fun & Satire Editor

Dylan “North Pole” Marks

Sports Editors

Jonathan “Difuser” Reynoso

Victoria “Mos Mos” Cha

Production Editors

Jasmine “What Son” Makar

Sarah “Dr. Hartman” Grishpul

Photo Editors

Ava “Moose” Whelpley

Rachel “Draft Draft Draft” Cheng

Pierre-Philipe “Internet Girl”

Wanya-Tambwe

Media Editors

Divine “Vine” Amayo

Lucas “Intersectional” Bustinski

Digital Producer

Anthony “Muscle Memory” Lippa-Hardy

Circulation Manager

Sherwin “Zzzz” Karimpoor

General Manager

Liane “Governance” McLarty

Design Director

Vanessa “Snow Patrol” Kauk

Contributors

Kaitlin “Clean” Pao

Caitlin “Welcome” Chung

Erika “Professor” Sealey

Avari “Q’s & A’s” Nwaesei

Eliza “Sources” Nwaesei

Jordyn “Call-in” Misura

Ella “Bedtime” Miller

Daniyah “Em-Dash!” Yaqoob

Moyo “Making Cents” Lawuyi

Garrett “Say Yes” Raakman

Omolegho “Office Hunter” Akhibi

Myrtle “2560x1440” Manicad

Eunice “Art Connoisseur” Soriano

Ogimaa “Close and Personal” Kwe

Emma “TEA!” Yerxa

Alacea “Lamp Post Victim” Yerxa

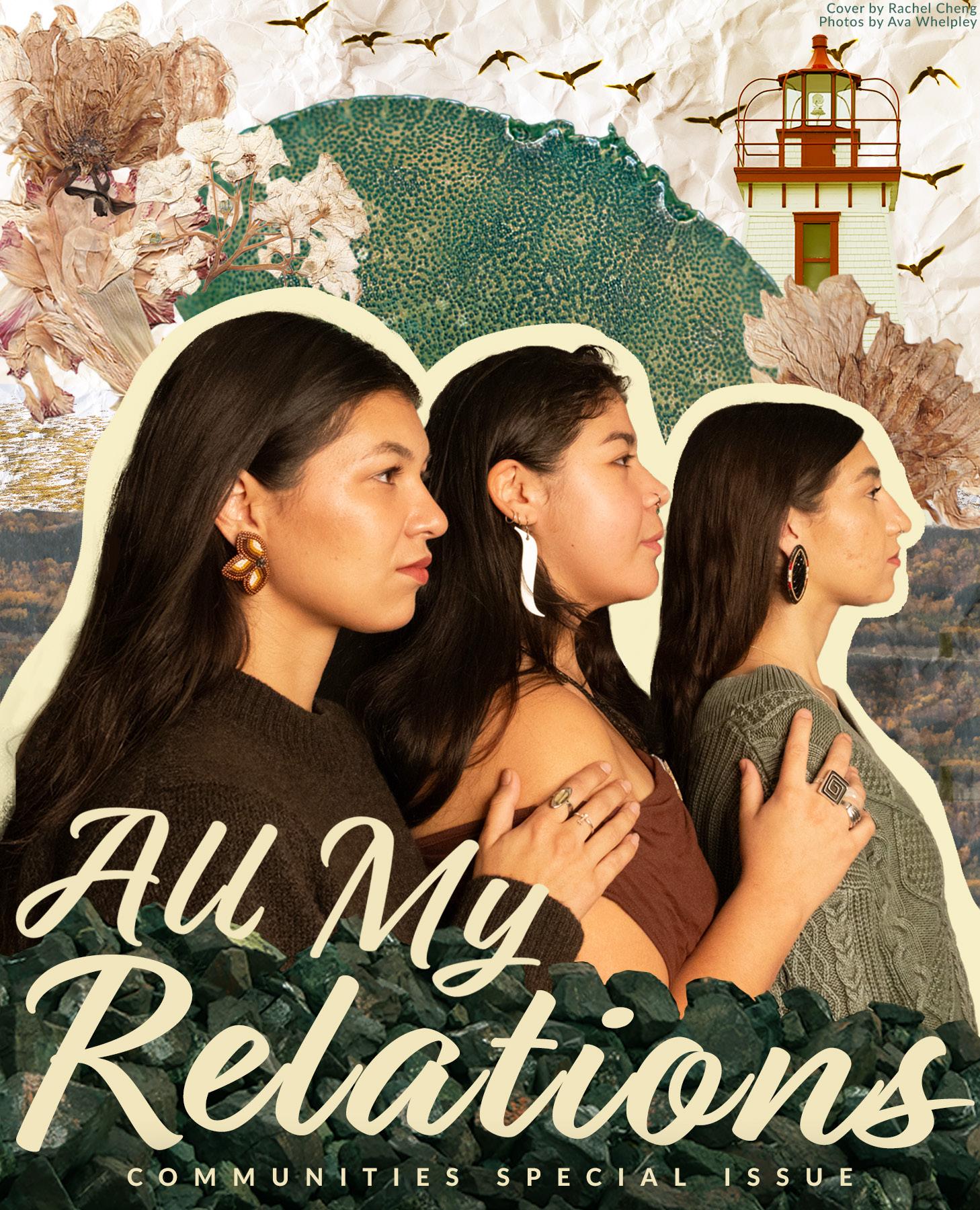

BY DANIEL OPASINIS

Iwant to start by saying, the writers in this issue are at some of the earliest points of their careers in journalism. To take on a project like this— covering sensitive topics about Canada’s Indigenous peoples—is already an impressive accomplishment. I’m so proud of the work that was done by the passionate students in this paper and hope All My Relations sets a good tone for Indigenous reporting on campus.

Indigenous stories need to be told. This was at the core of what made me choose an Indigenous theme for this year’s communities special issue. More so, I believe that the brunt of Indigenous reporting should not be hoisted by Indigenous people alone. All My Relations was made to be an opportunity for Indigenous and non-Indigenous student journalists to gain experience reporting on Indigenous peoples, in a positive way.

My mom was born in Cobourg Ont. after my family moved to this province from Dalhousie, N.B. Our Indigenous ancestry traces back to Eel River Bar First Nation—the neighbouring reserve.

I didn’t grow up with a lot of the culture. Sure, we spoke about being native and every once-in-a-while would hear a story of Eel River Bar from my grandma but a lot of what it means to be an Indigenous person came later in my life.

When I was four years old, my mom had her life taken from her,

becoming one of far too many Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). Her passing was rough on my family and instilled in me a constant reminder of who I am and where I come from. I think she’d be happy to know the role she’s played in my life, even though she was only here for a portion of it.

According to the Canadian government, Indigenous women make up 10 per cent of homicide cases across the country, a gross disproportionate statistic.

In the summer of 2023 my family was invited to Whitefish River First Nation to attend the unveiling of an MMIWG monument. We spent nearly a week with elders in the community, it was the first time I felt like I belonged around other native folk.

I remember feeling like my mom would have loved it. The small town out in the bush, the kindness granted to us by people we had only just met. We sat in a circle outside the lodge one night sharing messages to our loved ones, bawling our eyes out as we kept their stories alive. We passed around a basket of strawberries, a heart medicine. Every seed on the skin of that berry felt special.

Although the teachings, ceremony and customs were not my own, Anishinaabe people set me up with skills that I’ll carry through life, I couldn’t be more grateful for that.

I went on to travel to San Fe-

lipe Chenla, Guatemala, in February 2024. The trip was during my program at Durham College—a knowledge exchange with Mayan youth in a local community. Studying in media, art and design-focused programs, our goal was to teach the kids storytelling skills using the technology available to them. In return, they shared their traditional practice of storytelling—and lots of great food—for us to bring home to the work we do.

I was sitting outside the village’s high school one night, when a Mayan elder visited to share his story of living through a U.S.-sparked civil war that had ravaged rural communities across Guatemala.

I brought with me on the trip sage, sweetgrass and cedar, which I learned are way harder than you think to explain to customs agents. I didn’t know why I packed them, until I met that elder. I ran to my room to grab the medicines and rushed back trying to catch the man before he left for his walk home.

I watched him hold the braid of sweetgrass, grazing his fingers through its tail as he smiled. He said something loosely translated from Quiché—their Indigenous language—to mean ‘I’ve seen this before.’

Throughout the production process of All My Relations, I’ve been reflecting on my own feelings surrounding my Indigeneity. I never want to come off as the authority figure of ‘the Indigenous life’—I grew up in the suburbs after all. This issue has taught me not only how to navigate Indigenous reporting but how to acknowledge my own lack in knowledge and when to look to my community for help.

I hope you find this issue as beautiful as I do.

With love from me and all my relations,

they are at the frontier of this Indigenous renaissance.

At its core, the prophecy of the seven fires is an Annishinaabe teaching that describes different moments throughout Indigenous history since the journey to Turtle Island and the hardships during colonization.

Currently, humanity exists in the seventh fire, which is described as the rebirth or renaissance where all people will turn to Indigenous knowledge keepers in hopes of restoring balance and harmony on earth.

Storytellers at Saagajiwe Indigenous Studios (Saagajiwe) believe

Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU)’s Indigenous hub, Saagajiwe, operates within the Creative School and provides opportunities for students to engage with Indigenous knowledge and research while aiming to create community.

Saagajiwe organizes events for Indigenous and Creative School students at TMU throughout the year that centre around engaging in Indigenous art and knowledge.

Derek Sands, Saagajiwe coordinator, recalled the types of events put on by the hub as largely successful.

“In the past, the Bell Media workshop and the speaker series

was the big one we did [from] 2024 to 2025,” he said.

For the speaker series workshops, Saagajiwe invited Indigenous speakers such as Sarain Fox, Ryan J. Lindsay and Wendell G. Collier to speak about their experience as storytellers in the industry.

This brought in people from the TMU and beyond. They also hosted a graduate workshop which was an opportunity for selected TMU students to connect with industry professionals at Bell Media.

“I think everyone took a lot from it…[it gave] them a really good picture of what the industry is all about,” Sands explained.

Emma Yerxa, fourth-year crimi-

nology student and events and communications ambassador for Saagajiwe explained what events are going on for the 2025-26 year.

“Right now we’re primarily focusing on using Jesse Wente’s expertise…doing movie screenings,” said Yerxa.

Jesse Wente, the Indigenous storyteller in residence at TMU, will be curating the catalog based on his personal DVD collection.

He hopes to inspire students with stories and places that folks may not have been exposed to in the past, such as those from Indigenous filmmakers across the globe.

Read more at theeyeopener.com

BY CAITLIN CHUNG

While it may be difficult to locate Indigenous-owned brick and mortar businesses in the city, these online Indigenous businesses have found different avenues to interact with customers face-to-face.

On downtown campuses like Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), studentrun initiatives like the Mutual Market on Gould Street and the annual Pwaaganigaawin/Pow Wow at Kerr Hall Quad have hosted various Indigenous vendors since the re-opening of in-person events in 2023 after the COVID-19 lockdowns.

From beadwork to designer wear, here are how some Indigenous businesses, both TMU alumni and not, are drawing people together through their culturally-reflective creations.

Zhalii Handmade Creations - Zoe Stefura Zoe Stefura, a graphic designer and TMU creative industries graduate, first launched Zhalii—“pretty” in Michif—Handmade Creations at the height of the pandemic.

After moving to Toronto from Winnipeg, Red River, Treaty 1 Territory, Stefura found solace in learning how to bead with her cousins back at home over Zoom. While she credits the crafting knowledge to her Métis roots, the designer said her Ukrainian background similarly upholds the culture of beadwork.

Nudges of familial encouragement, hours of online tutorials and many book rentals later, Stefura made her instantly-successful business debut on Instagram in 2020.

In an attempt to fill the market gap in “everyday beadwork” and as per her mother’s requests for lighter earware, she began selling flat stitch style earrings. Now, she creates studs, simple dangles and gold threaders alongside a collection of keychains and pop sockets—sourcing all her materials from neighbouring small businesses, as much as possible

coming from Indigenous businesses.

Through beading and vending, Stefura said she was able to strengthen the bonds between her family and the Indigenous community at large.

“It really doesn’t feel like work a lot of the time,” she said. “It’s more like a cultural exchange for me, like a lot of Indigenous people will tell you, beadwork is medicine.”

Her most popular item, turquoise and gold studs on 18 karat gold backings with vegan leather, immediately went out of stock at TMU’s most recent powwow.

Stefura said she hopes to maintain her in-person presence at markets this winter season and continue to connect with customers face-to-face.

Sticks & Bones Studios - Mary Commanda Mary Commanda, of Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nations, founded Sticks & Bones Studios over a decade ago under a simple concept: dreamcatchers adorned with beautiful branches and skull motifs.

Despite spending half her life on the reserve—and the rest just minutes away— Commanda said she had to ask her mother to re-teach her how to weave.

“My vision wasn’t in the weave, necessarily,” said Commanda. “It was in the materials that I use, the asymmetricalness that I bring to the table and kind of getting that out of me onto the dreamcatcher.”

The artist said her drive for a creative outlet intensified while being boxed in the corporate realm for over ten years. Prior to employment, Commanda had originally attended Georgian College for hotel and resort administration and later, TMU for hospitality and tourism management.

Now, the TMU alumna said she uses her business knowledge to sell custom dreamcatchers, leatherwork, artwork, moccasins and bone bead jewelry—all while hosting workshops and facilitating community work.

In Commanda’s sourcing hierarchy, purchas-

ing materials from her own reserve is a priority.

Other Indigenous communities follow closely and local small businesses are often her last resort. Though, for dreamcatchers specifically, the artist frequently picks up “cool-looking” branches on her reserve property or during strolls through urban wooded areas like Rosedale Valley Road.

Apart from connecting with the land, the business owner said she hopes her work will ultimately help Indigenous people initiate their journeys of reconnecting with their communities.

Neechi By Nature - Shane Kejick (Kelsey)

When Shane Kejick, born as Shane Kelsey to Irish origins, first set his mind on setting up Neechi By Nature in 2020, not even those closest to him lent him support in pursuing this endeavour.

He adopted Kejick, the last name of his Anishinaabe Ojibwe great-grandmother from Shoal Lake, as a homage to his Indigenous heritage.

Kejick initially rose to fame as hip hop rap artist Tombz The Nish in Montreal, overcoming barriers upon barriers to successfully launch his Indigenous luxury street wear

brand in 2022. Growing up in poverty, he said his challenging upbringing inevitably taught him how to be resourceful.

When Kejick first launched his line, he began with three items: a button up shirt, a pair of matching shorts and a toque in the middle of summer. He then rapidly expanded to a vast selection of ready to wear runway pieces and custom designs worn by celebrities he admired—like Ashley Callingbull, Miss Universe Canada 2024.

“There were a lot of barriers,” said Kejick. “But being able to sell my stuff, being able to make my art and having space to do that now, I’m very appreciative and happy for that.”

Though the multidisciplinary artist could not attend TMU’s powwow as a third-time vendor this year, his reasons lie in his current commitments to support emerging artists, bridge gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and expand his brand globally.

“Right now, [Indigenous businesses] still feel like a niche and it still feels like I am segregated from the country,” said Kejick. “But to truly uplift us is to have us seen in daily life.”

BY ERIKA SEALEY

Canadian Indigenous history is deep and can often seem complicated. This quiz will test your knowledge and see how much you really know about Canada’s Indigenous past.

1. What was the Sixties Scoop?

a. A practice in the 1960s of removing Indigenous children from their homes and adopting them into non-Indigenous families.

b. A series of reports on the Indigenous community.

c. The period where Indigenous children were taken to residential schools.

d. A series of treaties made between the Indigenous community and the federal government in the 1960s.

2. Inuk civil servant Mary Simon made history in 2021 as the first Indigenous person to hold which office?

a. Leader of the official opposition.

b. Speaker.

c. Governor General.

d. Parliamentary secretary.

3. When were Indigenous peoples first allowed to vote in federal elections without losing their status?

a. 1901.

b. 1920.

c. 1950.

d. 1960.

4. Why is the Royal Proclamation of 1763 significant to Indigenous rights?

a. It granted Indigenous peoples the right to vote.

b. It reserved some land for Indigenous peoples.

c. It recognized Indigenous peoples as an independent nation.

d. It sought to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society.

5. What is the significance of Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut?

a. It is regarded as the last residential school, closing in 1957.

b. It is regarded as the last residential school, closing in 1997.

c. It was the first residential school, opening in 1831.

d. It is the site of about 200 unmarked graves.

6. Before 1985, Indigenous peoples could go through enfranchisement. What does that mean?

a. They could sell their land to the federal government.

b. They could stop paying taxes.

c. They could register to attend Canadian universities.

d. They could give up their formal recognition as Indigenous.

7. What happened in Cypress Hills, Sask., in 1873?

a. The Nakoda nation was robbed by American hunters.

b. Treaty six was signed between the Nakoda nation and the federal government.

c. Many members of the Nakoda nation were killed by American hunters.

d. Saskatchewan’s first residential school was opened.

BY KAITLIN PAO

PHOTOS BY EUNICE SORIANO

Between the rush of lectures, deadlines and commuting, it’s easy to move around Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU)’s campus without noticing our surroundings. If you pause for a moment, hidden in plain sight, Indigenous artworks across campus quietly remind us of the histories, voices and traditions that deserve to be remembered.

SLC “Concrete Indians” photograph installation

Located at the heart of TMU’s campus, this 10 by 15.7 foot grey-scale photograph of Tee Lyn Duke, an Anishinaabekwe dancer, hangs in the Student Learning Centre (SLC) right above the west entrance to the Library.

Done by Anishinaabe photographer Nadya Kwandibens, this photograph is featured in her “Concrete Indians” series, highlighting contemporary Indigenous identity and decolonization.

In this piece, Duke is seen in her regalia, standing in the middle of Spadina Station’s long hallway. The contrast of the cities’ dull and industrial transit systems to Duke’s cultural pieces and unshaken stance is what makes this piece powerful.

She is seen looking directly into the camera, displaying strength. This stylistic choice has been historically used in the art scene to invoke discomfort and convey a message. The morphed faces

of her fellow commuters’ glances do not trouble her. This piece is a beautiful testament to Indigenous pride and the refusal to be erased.

RAC “Everything you think you need to be, you already are” installation

Shining below a skylight at the northern rotunda of TMU’s Recreation and Athletic Centre (RAC), lies Anishinaabe artist Caroline Brown’s inspiring panoramic installation.

The piece features the quote “Everything you think you need to be, you already are” by Joanne Okimawininew Dallaire, Elder and senior advisor of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation at TMU.

With the words weaving throughout the work, flowing through the subject’s hair and translated in Cree, this piece is a reminder of self-acceptance and balance, encouraging students to celebrate who they are.

Through Indigenous cultural symbols like the Wolf Clan Paw Print, natural elements from sunrise to moonrise and bilingual text in Cree and English, the piece connects identity, nature and movement.

Installed in a space of energy and renewal, the work offers an affirmation of belonging and highlights the strength of Indigenous presence on campus.

Gould and Victoria Streets, the “Ring” sculpture

Running from class to class, you are sure to encounter the infamous “Ring” sculpture that lies east of the Gould Street and Nelson Mandela Walk intersection.

This large steel ring was designed by Matthew Hickey and Jacqueline Daniel from Two Row Architect, an Indigenousowned architectural firm, based in the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation.

The sculpture pays homage to the land’s history as part of the Dish With One Spoon Territory. It features imagery representing the seven grandparent teachings—humility, courage, honesty, wisdom, truth, respect and love—along with the lunar moon phases and the constellation Pleiades.

This piece’s presence serves as a reminder of the Indigenous territory on which the university stands, elevating Indigenous presence, and inviting the campus community to engage with Indigenous culture, teachings and relationships to the land.

Kerr Hall Quad Bird of Spring sculpture

Sitting on the west side of TMU’s Kerr Hall Quad is Inuit artist Abraham Etungat’s seven-foot-tall bird sculpture.

This large-scale bronze sculpture was not always this size. “Bird of spring” is one of four copies of a small soapstone carving by Etungat.

Originally, Welcoming the Bird of Spring (1986) was a carving that depicts our familiar bird—however, it is standing beside a human figure.

With both beings being connected through this shared piece of stone, it acts as a representation of the land. The bird and human are represented at the same height, mimicking each other’s form, reaching up-

wards. This concept depicts the relationship between differing forms—human and bird— unified through composition and tradition.

Today, the enlarged Bird of Spring invites those passing through the Quad to take the place of the missing human figure—a reminder that our relationship with the land and all living beings continues. Standing before it, one becomes part of Etungat’s vision: grounded in respect, lifted by connection.

Kerr Hall Paisajes de Nosotros (Landscapes of Us) mural

Lastly, a hard-to-miss piece is the Paisajes de Nosotros (Landscapes of Us) mural on the west-facing wall of Kerr Hall, at Gould Street and Nelson Mandela Walk.

The mural was created by Inuk artist Niap (Nancy Saunders), Peruvian ShipiboKonibo artist Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano and curated by Gerald McMaster.

The large piece blends Arctic and Amazonian cultures through colour, pattern and the use of geometry, capturing cultural ties and the Earth’s elements.

Embodying the ice, northern lights and Inuit cosmologies, the piece acts as a tribute to the North while connecting to the Amazon through notable ancient kené designs that symbolize plant songs of the Shipibo-Konibo peoples.

The work’s message is one of connection, respect and global Indigenous unity, reminding passersbys that all life is interwoven across regions, cultures and the shared land we stand on.

WHEN DANIKA VICKERS opens her laptop every week and clicks the button to join the Zoom meeting, she knows that for the next couple of hours, her entire community will be in her living room. She sees the faces of her aunties, sitting a little too close to the camera, squinting as they ask “is this thing on?” She hears one of her uncles whispering the latest vocab words and practicing his glottalized resonants while thinking he’s on mute. A notification bearing the name of a chief—who moved to Hawai’i—pings in the corner of the screen, alerting Vickers he’s coming to tonight’s meeting.

Vickers is a Haíɫzaqv language warrior and instructor. For the last few years, she has devoted countless hours to teaching her language to other members of her nation. Every week Vickers hosts a free virtual class for anyone who is ready to take on the behemoth task of learning Haíɫzaqvḷa. It’s important to her that her class is virtual since her nation is flung all over the globe.

Much progress has been made in the last decade over endangered Indigenous languages on Turtle Island. According to the Assembly of First Nations, every single one of the Indigenous languages within so-called Canada, save Inuktitut, are on the brink of extinction as first speakers die and the next generation struggles to carry on their ancestral tongues. Vickers’ language, Haíɫzaqvḷa, was recently featured in a documentary by The Guardian which explored the lives of the seven fluent speakers left. Seven people in the entire world.

THE LOSS OF LANGUAGE WAS NEVER an organic phenomenon. According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, it was part of the Canadian government’s cultural genocide against Turtle Island’s Indigenous peoples. Children who were abducted and sent to residential schools for decades were not permitted to speak their languages and ultimately lost them, either due to being made to forget or the trauma associated with the words they were punished for speaking.

In

of her family. “My late Nan and Papa George were residential school survivors. My late Nan was one of our last speakers who could create new words about the modern world around us and our language.”

“They had eight kids. One of them is my ǧáǧṃa, my grandma, and she was a boarding school survivor. She was put into that, which is very similar to residential schools, [but was] more in the community–not any less violent. My mom is a Sixties Scoop survivor and was taken off rez and put into the foster care system,” she said.

It was after another move to Atlanta with her mother and siblings that Vickers had a realization that re-routed her life. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Vickers began listening to the podcasts about Indigenous storytellers such as All My Relations and Two Crees in a Pod. While listening she came across Wôpanâak language revitalizer Jessie Little Doe Baird. On the podcast, Little Doe Baird recounted a dream in which her ancestors spoke to her but she was unable to understand their words.

“That really hit home, because I start to think about all my ancestors who never had to speak English, were never beaten into speaking English and being on the other side and having no one to talk to,” said Vickers.

Inspired by her ancestors, Vickers began learning Haíɫzaqvḷa through Zoom classes. Her work would bring her back to Haíɫzaqv territory in British Columbia where she began a 900-hour language immersion program and became involved in multiple language revitalization projects, including the Endangered Languages Project and the creation of an interactive, online Haíɫzaqvḷa dictionary through FirstVoices—an international organization promoting the revitalization of Indigenous languages. This is Vickers’ way of doing good, a core tenet of the Haíɫzaqv Nation, “Haíɫzaqv” literally meaning “to act and speak in a good way.”

introducing students—especially non-Indigenous students to Kanyen’kéha— Martin is also teaching a different way to look at the world

Language and knowledge keepers though, never stopped fighting to protect what is rightfully theirs. Against the colonizing forces, some Indigenous people did pass on languages to their children—elders, like Marie Wilcox, who spent the final years of her life painstakingly typing every Wukchumni word she could remember into an online dictionary that has since outlived her. In popular culture too, young people are taking up the challenge of re-introducing their languages to the world, as is the case with the Polaris Prize-winning album, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa by Jeremy Dutcher.

At the age of six, Vickers’ mother moved to Québec, where Vickers got her first job as her mom’s translator. Young Vickers quickly picked up on the French spoken around her, which meant she was to accompany her mom as she ran errands deep in francophone territory. This experience would crystallize for Vickers, becoming formative in her belief that language is both nation and connection.

“I am the first out of four generations to not be classified as a survivor,” said Vickers

“We actually have stories from our old people that, when we are not doing things in a good way, when we are not [upholding responsibilities], our people suffer the consequences and we lose people, and people are taken to the spirit world because of it,” says Vickers. “It's really embedded. Like, okay, we should be doing things in a good way, which is really complicated these days because of all the colonial systems.”

The state—which is so often the perpetrator of the colonial violence at the heart of Indigenous language loss—now also bears the responsibility to reconcile their past actions of language suppression and eradication. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission recognized this, requesting the Canadian government enact an Aboriginal Languages Act in its 14th of 94 Calls to Action in 2015.

Similar programs have been implemented in New Zealand/Aotearoa where the state government implemented a program to ensure 20 per cent of the population will speak te reo Māori by 2040. So far, according to their website, the Canadian government has not announced any similarly ambitious legislation.

While the federal government continues to stall on enacting Call to Action 14 as well as Call to Action 10—which asks that Indige-

All but one of Canada’s languages are critically Meet four people committed Haílzaqvla, Dene

BY ELLA

BY RACHEL PHILIPE WANYA-TAMBWE

nous language programs become credit courses—many have taken language re vitalization into their own hands from within colonial institutions.

Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) currently hosts four Indigenous language and culture courses, all focusing on Kanyen’kéha and Haudenosaunee cultures. Each of these courses were developed by Brandon Tehanyatarí:ya’ks Martin who says he has another oral storytellingbased course at TMU in the works.

In introducing students—espe cially non-Indigenous students to Kanyen’kéha—Martin is also teaching a different way to look at the world.

In speaking Kanyen’kéha, individual relationships to people and things are highly considered. The way that verbs are conju gated is entirely dependent on who is talking to whom.

This means that the entire language can slide and shift in 14 different ways that don’t ex ist in English, all depending on the relationship between speak ing parties, Martin explains.

Martin is also able to take ad vantage of the descriptive nature of Kanyen’kéha to teach his stu dents words for modern tech nologies and phenomena that may not have existed when Indigenous languages were most widely used. As Vickers alluded to before, not every language has this capability, which is also part of why it is so important to protect and preserve the work of people who speak Indigenous languages as a first language, also called ‘L1’ speakers, Martin shares.

“The word that we have for television is kaya'tárha. So it's kind of like ‘a picture that is set up.’ Similarly for a computer, we would

Canada’s Indigenous critically endangered. committed to the revitalization of and Kanyen’kéha

RACHEL CHENG, PIERREWANYA-TAMBWE & AVA WHELPLEY

ceremonial pipe carrier. These Unity Riders brought Elliott into the company of other Mohawk nations, including McDonald Herne and her children.

“[McDonald Herne] is a first language speaker and—all her kids—she's raised them as first language speakers,” said Elliott of the Bear Clan Mother. “So they were about my age and I knew them and they were speaking the language together. They knew the songs. But usually when we're at protests [we’re] speaking English. It's hard, really, to find spaces that are just language spaces.”

kindly hawk swoops down and volunteers to take messages across the river to help the animal family stay in touch while the bridge is rebuilt.

"11,000 years of history will not disappear with Janvier"

As she carried her own daughter, Elliott thought back to this feeling in her own childhood, meeting kids like her who spoke Kanyen’kéha. She says she wanted that future for her child but it wasn’t as simple as just putting her daughter in a bilingual school. To cradle her daughter in the Mohawk language, Elliott had to learn it first for herself.

“When I started the [language] program, I was a single mother with a baby,” says Elliott of when she started at Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa, a language school near Brantford, Ont. “I had a nine-month old and I was raising her on my own on welfare, on assisted housing. I dropped out of university for health problems.”

“That's how we teach the numbers—I go through the full creation story with the children and through the telling of the creation story, each of the numbers show up and we explain their origin and where they come from. Like ‘two’ being from the two twins that were born, ‘three’ from the three sisters,” says Elliott on implementing Mohawk epistemology into her teaching.

Still, Elliott sees that far too often the best Kanyen’kéha speakers are forced to leave her community in Six Nations if they want to practice with fluent speakers, or get paid for their thousands of hours of work learning Kanyen’kéha.

—the word that I learned for that would be ‘words set up,’” said Martin.

“The descriptive nature of Kanyen’kéha lends itself well to being able to pro-

Still, access to post-secondary education remains a huge barrier to Indigenous peoples in Canada, with Indigenous enrolment consistently ranking over 20 points behind the general population. The Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario estimates that 22,500 Indigenous students have been prevented from attending postsecondary education due to inadequate government funding. Universities remain integral in manufacturing legitimacy for the study of Indigenous languages but hefty tuition fees may keep Indigenous students out. Not to mention, the development of L1 speakers has to happen long before university.

“Think about what you want your daughter to be like,”

Otsistohkwί:yo Elliott was pregnant with her first child when Bear Clan Mother, Louise McDonald Herne asked this. Elliott was raised by her father, a Mohawk land defender and protester from Six Nations of the Grand River. At the age of 14, Elliott would meet a delegation of the Sioux Unity Riders from North Dakota who were spurred on by a vision from their

Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa was only able to pay participants $300 per week for a program which equated to a full-time job in terms of work according to Elliott. Monday to Friday, for seven hours per day, he clocked in at Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa where she was fully immersed in Kanyen’kéha. In order to attend, Elliott had to put her daughter into a daycare provided by Ontario Works for parents living below the poverty line.

“Being a single mom, I needed people to watch my children,” said Elliott. “I did not have a choice [in] the daycare she went to when she was nine months old. They didn't have any speakers, there was no option for it. There is still no option for immersion childcare. Either you are making no money, and if you have means to not make money and just stay at home and just speak the language, some people do have to do that.”

When Elliott became proficient in Kanyen’kéha she was given the opportunity to become a traditional storyteller at her daughter’s daycare. That job would eventually blossom into a full-time job at Everlasting Tree School—a first-of-its-kind Kanyen’kéha immersion school—as their resident storyteller and, increasingly, drama teacher. Elliott visits every class at the school and shares traditional stories like the origins of the Great Bear and the Big Dipper. Elliott has also written some of the first-ever Mohawk-language children’s plays to be performed at the Everlasting Tree School.

Elliott also points to the advantages of Kanyen’kéha as a language that easily lends itself to painting pictures. In addition to these traditional stories, she writes stories about specific issues in students’ lives: Haudensosaunee territory spans the borders of Canada and the U.S. and during the pandemic one child found himself separated from his father who was stuck on the other side.

Elliott’s story features a young animal who crosses a bridge every day—across a raging river—to visit his father. One day a storm knocks the bridge down and the animal is trapped on the opposite side of the river. A

“Our speakers—if they want to be teachers—not only do they have to learn a language but they have to get their bachelor’s degree,” said Elliott. “These are some of the most expert people out there and they're getting paid pennies on the dollar for what they do. If Canada was really serious about reversing the effects that they did through residential schools by the basic destruction of our languages, they would be supporting the revitalization of it, not just through a grant—a one time grant here and there.”

WILLIS JANVIER UNDERSTANDS THE value of a good teacher. Of all the people spoken to in this article he was the only L1 speaker, having grown up immersed in his language in Clearwater River, Dene Nation near La Loche, Sask.

Janvier would spend his days at school being taught Dene by his grandmother who worked at his elementary school. He spent his nights hanging out in the corner of his dad’s office as he broadcasted hockey games in Dene for Saskatchewan’s Indigenous radio network, MBC.

In spite of this, Janvier’s father didn’t influence his career as a podcaster at Dene Yati Media, a business he created during the pandemic. Janvier says it’s the fear of failure, rather, that pushed him to create his podcast, bolstered by a conversation he had with his sister about taking the leap of faith. He committed to promoting his language full time after overcoming addiction and the relentless slog of a blue-collar job shovelling dirt into holes day after day.

“I was in Fort Saint John in B.C. and on the way there, I was sitting next to an archeologist from the area and I said, ‘what's the oldest thing you found?’” said Janvier of an interaction he had while on tour promoting Dene Yati Media. “[He said] ‘11,000 years ago.’ I said, ‘my language is that old,’ you know. The words that I speak are that old.”

11,000 years of history will not disappear with Janvier, nor will it falter in his daughter who he has spoken to in Dene since birth. Like Elliott, Janvier committed early on to making sure that his daughter understood the legacy that she was a part of. Janvier says his daughter, who is 13 going on 14 (something she won’t let him forget), introduces herself to others as a Dene woman, something her dad is assuredly proud of.

“She always says I love you in Dene,” says Janvier about the next generation speaker he helped raise.

BY JASMINE MAKAR VISUALS BY AVA WHELPLEY AND RACHEL CHENG

It’s the one-year anniversary of Mari Amirbekyan’s grandfather’s passing and her family is having a commemorative dinner in his honour. Sitting around a table back home in Armenia, everyone is sharing memories of him—remembering the hikes he would take, the ice cream he would buy for them and, of course, the father figure he is to so many around him.

The conversations and the shared love in the room fill her with a new sense of connection—one she didn’t know she could tap into—and a new appreciation for her Armenian heritage.

“We were just bonding over what that small [Armenian] community had given each other and I felt very at home there for the first time in a while,” she said. “I hadn’t realized that I could connect with my family in that way…this couldn’t have hap pened anywhere else but right here, on the land that he grew up on and raised us on.”

Amirbekyan was born in Yerevan, Armenia but left when she was just twoyears-old. She’s since lived in many different cities across the U.S. but eventually landed in Toronto and went on to study at the University of Toronto, before moving back south of the border.

cially now that she’s older.

“We went home in May and I visited my family…I think that’s when I felt very connected to my country. I was like, ‘okay, this is where I’m from’,” said Fulinara. “I still consider the Philippines my home, because that’s where my family comes from, that’s my heritage. I feel like a home for me doesn’t have to be a place. It’s always the people, and those are my people.”

Having been brought up in a multicultural area in Toronto, Fulinara emphasized how she never felt particularly isolated from her culture but instead felt like she was encouraged to embrace it—something her parents in particular instilled in her.

Fulinara’s parents wanted her and her sister to feel connected to their roots. “Yes, we’re born in Canada but our whole family is in the Philippines, like you’re Filipino and don’t be ashamed of where you come from,” she said.

With family being such a big part of her upbringing and the values she holds, Fulinara said that too is just part of her culture. “I feel like that’s a lot of what being Filipino is. It’s to be family-oriented, sharing, being hospitable to other peo-

“I need to be vocal about it, and this is who I am and these are my roots”

She’s been travelling back to Armenia for years since she was eight-years-old, de spite leaving her homeland when she was a child. Through these visits, Amirbekyan has grown more connected to her family as well as the land.

“I was always taught to be careful with the land and I was always taught to look at our mountains that we have there [in Armenia], they are very sacred to us…We feel extremely connected to the mountains themselves and we feel like…they’re part of our history,” said Amirbekyan.

She went on to explain how it feels when she visits home—when she’s in the place she belongs—rather than on borrowed land. “Being Indigenous to that area is very special and I like being able to talk about how I feel when I’m back home, versus when I’m on somebody else’s land.”

According to the United Nations, Indigenous peoples “have in common a historical continuity with a given region prior to colonization and a strong link to their lands. They maintain, at least in part, distinct social, economic and political systems. They have distinct languages, cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems. They are determined to maintain and develop their identity and distinct institutions and they form a non-dominant sector of society.”

Lindsay Fulinara feels a deep connection to her heritage when she’s back in her native land, the Philippines. The first-year business management student at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) was born in Toronto but raised by two first-generation Filipino immigrant parents.

Fulinara travelled to the Philippines this past summer break and she explained the deep connection to her heritage, espe -

adds that the Assyrian community continues to experience threats to cultural identity, representation and security.

genocide. Amirbekyan acknowledged the pain that the genocide has caused for her community and how it unites Armenians today.

Siby Diomande, a fourth-year business management student at TMU, shares similar sentiments as Fulinara. He’s also someone who is physically far from their native land but continuously feels a strong connection to their heritage.

Diomande is from Ivory Coast, a country in West Africa with a population of approximately 31 million people, according to the

Diomande, who was brought up in a multitude of countries, was raised by two Ivorian parents and said he’s never felt at home anywhere but the Ivory Coast, despite never living there himself.

“I’ve always gone there, that’s probably the place I’ve travelled to the most. So I don’t really feel disconnected from it,” he said. “Both of my parents are from there, there’s that cultural aspect of it, like they were raised there their entire lives, so they passed that down to me and my siblings.”

While living in seven different countries and now attending school in Toronto, Diomande has often visited family who still live in the Ivory Coast, with his most recent trip back having been in December 2024.

“I would say that’s just the place that means the world to me. So, regardless of the fact that I haven’t lived there, I’m always going to care for it more than any other place on earth,” he said. “I feel like something about being from the Ivory Coast has a lot of pride attached to it.”

The feeling of pride and connection to land is a shared sentiment among native people around the world—people like Sara Glyana, who was born in Iraq to an Assyrian family, sharing the same feelings towards her heritage and homeland.

According to the Underrepresented Nations & Peoples Organization (UNPO), Assyrians are “one of the Middle East’s oldest surviving Indigenous populations. Spread across Iraq, Syria and Turkey.” UNPO also

Glyana, who immigrated to Canada when she was 16, has remained “deeply rooted” within her community and her culture, despite the population being so small. “Assyrians, they obviously were Indigenous to Iraq and some parts of Syria…but over time, we are merely a minority,” she said.

Similar to the sentiments shared by Diomande, Glyana expressed the pride that comes with being Assyrian and wants everyone to see her community’s beauty in it the same way she does.

“I need to defend this, and I need to be vocal about it, and this is who I am and these are my roots…[Since] I moved here, I think I always go the extra mile when I introduce myself, you know, I’m Iraqi, I always claim my nationality. I’m Iraqi but I’m an Assyrian Iraqi,” said Glyana.

With Assyrians being persecuted and “structurally marginalized across the region” according to the UNPO, Glyana said she has had a bittersweet relationship with the land.

“[There’s a] very strange fondness of the land among Middle Easterners in general... because obviously the land carries…our history there and it just still feels like this was the land where your ancestors walked,” said Glyana. “But at the same time, there is a little bit of sadness that’s just buried. I tried to suppress it because of the war and just the persecution… a large amount of our history was destroyed.”

The Armenian genocide was the “extermination of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and the surrounding regions during 19151923,” according to The Armenian Genocide Museum Institute Foundation. The genocide took nearly 1,500,000 Armenian lives, which is estimated to be 65 per cent of the population at the time, as stated by The Genocide Education Project.

“The genocide is a massive part of our identity, and everybody, every single Armenian that exists today is a descendant of somebody who survived or somebody who left,” said Amirbekyan. “So it’s something that despite there being so many different groups of Armenians globally, we can all relate to it.”

Although the genocide has had many effects on the community, Amirbekyan wishes people would see more of the culture and personal identity, beyond it.

“Sometimes I worry that [the genocide] is also a tiring point,” she said. “I kind of wish, not that we didn’t talk about it as much, but that it wasn’t such a prominent definer of our identity, because we have so many other beautiful and positive things that make us Armenian.”

“I’m always going to care for it more than any other place on earth”

In contrast to Glyana’s connection to her land, assistant professor of so cial work at TMU and aca demic coordinator, Indigenous knowledges and experiences certificate for the Chang School of Continuing Education, Shane Young, explained how land relationships are often complicated, especially for those who do not have as much of a connection.

“I think if we’re looking at the Indigenous experience, and maybe some folks who do not have a connection to land but are maybe yearning for…the sense of connection to land, that’s going back to that blood memory, the memory and experience of ancestors, which lives in the fabric of their being,” said Young.

Similar to the persecution Assyrians experience, the Armenian people have also gone through tremendous grief with the Armenian

In his research, Young focused on a multitude of topics, including Indigenous identity. Young explained how Indigenous identity can be disrupted through external forces.

“Just thinking about the many colonial disruptions of the Indigenous identity and experience in this country, and I would even further say globally…those are in our history, but also, how do they tie into current reality? So we could talk about intergenerational trauma,” said Young.

Young further explained that Indigenous recognition can be important for many communities because of what government recognition can provide, stating that “even internationally, I think not having that global recognition at the local level can mean not having access to [supports ext.], but even on the international level, not recognizing is also problematic.”

“You are a reason to live:” A letter to the land, from

BY DANIYAH YAQOOB VISUALS BY RACHEL CHENG

The Mediterranean Sea was quiet, calm and blue-as-ever, as a ship sailed over its surface in late September, this atmosphere was shared with the world through videos across social media.

The Conscience, a large white boat—with its name flanking its side panels in bold letters, was one of dozens part of the Global Sumud Flotilla, a global humanitarian mission whose aim was to break Israel’s illegal siege on Gaza. Nearly 100 health care workers, journalists and activists were on board the Conscience, according to their website.

Among them was Mskwaasin Agnew, a Cree and Dene harm reduction practitioner living in Toronto and a contributor to Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU)’s Yellowhead Institute. In a black t-shirt, a red tatreez bag hanging cross-body and a skirt with ribbons the colour of Palestine’s flag, Agnew began the trip by singing the Bear Song, a prayer meant to be carried from her native land to the lands of Palestine.

The Conscience set sail on Sept. 30—National Truth and Reconciliation Day in “socalled” Canada. On this day, allies wear orange for all the Indigenous families, communities and especially children impacted by residential schools—people who were stripped of their culture and agency. The day is a reminder of the atrocities the Canadian government committed against Indigenous peoples.

It was fitting, then, that when Agnew livestreamed from a point at sea, the sun behind her tinted the sky in an orange hue, the waves of the sea reflecting that same orange. Those on board the ship also wore orange accessories as they sailed toward a land where, now, Palestinian children are losing their youth at the hands of a similar colonial system

“It’s like fate,” Agnew said in a video from aboard the ship, the salty air stirring the strands of her braid, held together by an orange band. “My ancestors survived so I could be here,” she said.

Over the last two years, as Palestinians have faced a genocide in Gaza, many Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island have been vocal and proud in their solidarity. A statement signed by the Assembly of First Nations in December 2023 had called for a ceasefire and the immediate end of the Israeli occupation of Gaza. However, the solidarity between most Indigenous peoples and Palestine goes further back than 2023— many Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island say it’s because the struggle of Palestinians reflects their struggles and their ancestors. Their love for their land is reflected in the Palestinians’ love for theirs.

Israeli settler colonialism, apartheid, and occupation are only possible because of international support.”

Eva Jewell, an associate professor at TMU’s sociology department, was among the signees. At the time, professors around the world, particularly in the U.S., were being fired from their jobs over expressing pro-Palestine sentiments, as reported by The Intercept. But that didn’t worry Jewell, who couldn’t help but feel shock at watching the genocide in Gaza unfold—and the parallels to the suffering of her own people.

“They see themselves through my story and I see them through my story as well”

“Our conversations with Palestinian communities and connections to them actually preceded Oct. 7,” says Jewell. “The politics of who is actually settling on the land aside, we understand what it’s like to have our land stolen from us.”

Jewell is a member of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation and grew up on the reserve—more specifically, on the grounds of Mount Elgin Indian Residential School.

Mount Elgin began operations in 1851, becoming one of Canada’s first residential schools. It was one of many where Indigenous children were forced into farm labour, assimilated with the help of the Methodist church and made to live in abysmal conditions, according to the residential school database The Children Remembered. The school closed in 1946. As of Nov. 18, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation recorded sixteen deaths at Mount Elgin.

Jewell says her grandparents, greatgrandparents and even great-greatgrandparents went to residential schools. The forced assimilation attempted to change their understanding of the land, to see it as a resource, just like the colonizers do, she says.

“We are descendants of the land and it’s our relative,” says Jewell. That connection is what makes settler violence against the land—from Turtle Island to Palestine—all the more “gut-wrenching,” she said.

Israel, in addition to its genocide of the people, is committing what is widely considered an ‘ecocide’ on Palestinian land— that is, the deliberate destruction of the natural environment.

According to the Institute for Middle East Understanding, in 1948, Israel uprooted native Palestinian trees and crops to replace them with four million non-native European species. Now, pine trees grow in parts of Palestine, where they had never grown before. Since 1967, Israel has uprooted more than two million trees in the occupied Palestinian territories. Among them, nearly one million olive trees were also destroyed.

Maher El-Masri, professor at TMU’s Faculty of Community Services, said that in Palestine, the children grew up learning about the sanctity of olive trees.

“We love the look of the olives. We decorate our homes with olive branches. Our soap is made from olive oil,” he said. “It’s like no soap you will ever, ever try.”

El-Masri was born in the Gaza Strip, to a Gazan mother and a father who was forcibly displaced to Gaza during the Nakba of 1948. ElMasri had left Gaza in the 1990s to pursue an academic career abroad. But he says he misses his land with sincerity.

As a child, El-Masri grew up visiting olive groves and sitting amongst citrus trees. He spent hot summer days under the shade of the branches, enjoying a picnic with his family. And then there was the beach, Gaza’s shore. At least once during the summer, every family in Gaza would have an outing and a meal there, he says. With them, they would take special fruits and a special rice. It didn’t matter how poor a family was, El-Masri says—at least once, the parents would take their kids to the beach and bask in Gaza’s sun.

“We have a special connection with the land,” El-Masri said. “And I mean that with every interpretation of the word.”

The people of Gaza used to take leave from their jobs, as doctors and engineers and government employees, to join the olive harvest. El-Masri says nothing compares to the oil that came from it: the look of it, the smell. Now, he says Israeli settlers burn olive trees, uproot them from their native soil or simply cut the branches so that the trees turn into stumps.

Israel has also destroyed more than 100 historical sites in Gaza amidst its indiscriminate bombing campaigns. On Oct. 19, 2023, Israel struck the Church of Saint Porphyrius, claiming many lives. Kitab al-Wilaya shared some of the damage. The structure now looks nothing like the church El-Masri played in.

“I thought about what my ancestors went through and all the ways that they resisted settler colonialism”

On Oct. 26, 2023, weeks into Israel’s relentless bombing of Gaza, Indigenous peoples worldwide signed a letter of solidarity with Palestine. In it, they wrote, “It has been heartbreaking and unsurprising to see the colonial powers in Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe line up behind this genocide.

It wasn’t until her mother’s generation and her own that her family began to reclaim the land as an extension of themselves. Jewell spent long days on the reserve near London, Ont., playing in the front yard of her mother’s house. At school, she was taught “bush skills” from an Ojibwe teacher, like how to walk through a forest without making noise. Despite the best attempts of Canadian colonizers, Indigenous practices lived on.

El-Masri played in the old city of Gaza, near the Kitab al-Wilaya Mosque, which shares a wall with the Church of Saint Porphyrius, considered to be one of the oldest in the world. To him, it was a symbolic depiction of the way Jewish, Christian and Muslim Palestinians lived in harmony. The history the streets of Gaza held were known to him. He played in the shade of the church until the sun set and the dim flicker of the kerosene lamps called him home.

“It makes me so frustrated to see these colonial settlers who have no respect for the land,” he says.

El-Masri lost his older brother during Israel’s genocide in Gaza. He lost his cousins—the family lost their home. Pretty much everything El-Masri had known in Gaza is now bombed. And yet, the Palestinians stay on their land. When one of the ‘ceasefires’ was announced earlier this year, scenes from Gaza showed Palestinians walking back towards the rubble in droves. When journalists asked them where they were going, they proudly said they were going home.

“Home for them is not the walls, it is the land,” says El-Masri. “The connection is something only natives can understand. And that’s why the people of Gaza endured this genocide.”

If they must die, then they will do it on their homeland, he says.

When El-Masri came to North America in the 1990s, he would be asked: Where are you from? And when he responded Palestine, he would often be met with confusion. They would ask: What is that? Or: Do you mean Pakistan?

They all responded that way, except for one group, he said: the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island.

“Every time, not once did I meet an Indigenous person without having an immediate connection with them, without even talking politics,” says El-Masri, holding back tears.

Around 2008, El-Masri was introduced to an Indigenous elder who was very informed on the situation in Palestine. El-Masri saw his grandmother in her. She would see him in a room of 200 people and point to him, pulling him aside to chat at whatever event they attended.

“The thing is, they see themselves through my story and I see them through my story as well,” says El-Masri.

Jewell similarly sees her own people reflected in Palestinians.

Read more at theeyeopener.com

BY JORDYN MISURA

For a long time, I thought reconnecting meant finding an answer. Something that would lead you to a moment when you finally knew who you were, where you came from and where you belonged.

What I’ve learned through the process of writing this story and hearing the stories of others: it isn’t about finding one thing that makes everything fall into place. It’s about experiencing many moments until who you are slowly starts to make sense.

In high school, I remember hearing about residential schools—briefly. It felt like it was always a lesson or a class that my teachers had to get through and didn’t know nearly enough about. They were superficial lessons, stripped of the pain that lived behind the words “residential school” and “colonialism.” When I was in eleventh grade, 21 unmarked graves were found in Kamloops, B.C., a two-hour drive from my hometown of Kelowna.

“My journey reconnecting with my identity isn’t done, I think it’s just starting”

When the news broke, something in me shifted. I never knew something so horrific was so close and in such a familiar place. My family began talking about our own history and stories that had never been shared. I was too young and too immature back then—but as I pursued journalism and learned more about reconciliation, I started to understand that reconnection and recon ciliation begin with listening—to family, to history and to silence.

I’ve learned that reconnecting looks different for everyone. Some people grow up around their cul ture, knowing exactly where they come from, while others spend years trying to trace their lineage, filling in the missing parts of their story. For many, the process is buried under the pure weight of destroyed history. The generations of trauma, silence, disconnection and survival. Barriers are not just personal but systematic, rooted in policies and laws that were implemented to separate Indigenous peoples from their spirituality, culture, land, language and everything that makes them who they are.

her way back to her culture. She told me her journey started even before she realized, in moments of her own curiosity.

“I always wanted to know what being Native meant because I always felt spiritual even as a child. And I didn’t know that part of that spirituality was linked to the spirit of my ancestors, and the spirit of their knowledge that lives on within me. We call it blood memory,” she

McMann’s journey isn’t about a single destination, it’s one of progress.

When she and I spoke, she expressed that there is still a long way to go, wanting to learn more about her ancestors, their journey and contributions—understanding them deeper than just their names.

“I think it’s my job to move forward and try to reclaim these ancestral stories so we can give them to our future generations. That’s a part of what shapes my identity,” she said.

she visited her family’s reserve, Serpent River First Nation, for the first time since she was a baby when she received her Indigenous name from an elder.

“I was meeting family members, my blood, but I felt super disconnected because I was 20 years old and it was my first time meeting them. I felt like I had missed out on a lot of knowledge and family time with them.”

“I think it’s my job to move forward and try to reclaim these ancestral stories”

only left small pieces to put back together.

“One thing I do remember my dad telling me is that he is labeled as adopted on his birth certificate because my grandparents lost their last name when they went to residential schools. He said that when my grandparents went to the residential schools they were asked to say their last name, but the people there didn’t understand them, so they just put their last name down as McCloud. Like ‘oh, here’s your new last name’,”

“I’ve learned that reconnecting looks different for everyone”

When I began working on this story, I wanted to understand exactly what reconnecting really looked like today. What does it mean to reclaim your identity in a world that continues to try and erase it?

That’s when I asked Gabrielle McMann, a mixed Ojibwe Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) graduate from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and an accomplished journalist. She has advocated for Indigenous issues since high school, began to report on her community once she came to TMU, and has spent years finding

Her journey hasn’t been linear—a lot of her family history was lost due to the unfortunate passings of her great grandparents at a very early age, with children too young to understand conversations about the oppression and colonialism that had affected their family. Through her mother, grandmother, Indigenous communities and TMU, McMann started to find her way back to her culture and traditions with their shared stories, knowledge and kindness, welcoming her with open arms.

“I think a lot of people are in the same place,” she said. “We’re not only reconnecting for ourselves, but for the future generations to come.”

McMann’s words remind me that recon nection is about the intention of learning. It’s about showing up to the table wanting to learn and advocate for recognition.

While she sat with her family, looking at old photos of her grandparents and of her father, hearing stories about where he grew up and of his childhood fishing and swimming, and where he used to play, it helped her feel closer to her heritage. That same summer, she attended a powwow and watched her cousins—who had grown up immersed in their tradi tion—dance in ribbon skirts. They shared their knowledge and told her stories while teaching her how to make dreamcatchers and drums.

For Ashley Bartley, who’s also mixed Ojibwe, reconnection started with loss, and began with returning home. At 20,

“My journey reconnecting with my identity isn’t done, I think it’s just starting now which has a bunch of mixed emotions as I still am disconnected, but I definitely feel more connected than what I once was. It’s kind of up and down.”

Bartley’s path also hasn’t been easy. She hadn’t learned that her great aunts, and nookmis , meaning grandmother, had attended residential schools until after her father’s passing when she was 15. It was a history that was never talked about; a family history shaped by intergenerational trauma and colonial policies that

The first church-run residential school opened in 1831, with the last one closing down in 1997. For a period of over 150 years, more than 150,000 children were taken from their families. And for Bartley, the story of her nookmis serves as a reminder of the colonial abuse inflicted to erase Indigenous people’s identity. Residential schools didn’t just steal children away from their families but also wipe away names, language and culture.

Bartley describes her reconnection as an emotional journey, in finding a sense of belonging, reclaiming the stories almost lost and leaning on community.

“Talk to your elders. Surround yourself with your community. Reconnect with your spirit guides—I feel my dad everywhere I go. Take it day by day.”

“I felt like I had missed out on a lot of knowledge and family time”

For both McMann and Bartley, family has been their compass. Taking presence in their communities, listening to stories passed down and having support while navigating a past full of oppression, their stories tell me that it’s not about feeling Indigenous enough but knowing that you always were. I learned that reconnecting is about listening, showing up for others and remembering the generations who came before, while creating a space for the ones who will come after.

As Indigenous fashion claims it’s place on the runway, representation and respect is slowly following

BY AVARI NWAESEI

The Eyeopener sat down with awardwinning Indigenous fashion designer Angela DeMontigny, to talk about the progression and challenges facing Indigenous fashion and artists today.

Q: How would you say your Indigenous background influences your work as a designer?

A: It’s a source of inspiration and a way to talk to people and educate them about our culture, history, legends, cosmology and whatever I feel inspired to create around a specific theme.

Q: How do you incorporate traditional cultural elements into your work?

A: I usually do it as a design element.

Either traditional beadwork, embroidery or a textile print design.

Q: How does Indigenous fashion reframe our understanding of fashion more broadly?

A: I would say that the western fashion industry has been completely influenced by Indigenous fashion. Anything that has fringe on it comes from Indigenous fashion, even though many American designers would probably not acknowledge that.

It’s about the whole process of copying and taking on appropriating cultural elements from a culture that they tried to eradicate. It’s a bizarre thing in a sense, you love our art and our fashion and our culture, but you don’t love us as people.

Now, it’s important for us to take back our cultural identities and use Indig -

BY ELIZA NWAESEI

Alacea Yerxa sits in her lecture waiting for class to begin. As a fifth-year biomedical sciences student at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), she’s ready to dive into the course material for the day. But then, something unexpected happens— a moment so simple and crucial, she almost doesn’t notice it at first. Her professor opens the lecture by highlighting the work of an Indigenous researcher.

It was a small moment but for Yerxa it revealed something she hadn’t realized had been missing. As an Indigenous Sci ence, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) student, courses in her first year and part of her second year had yet to include an Indigenous perspective. There has never been a single refer ence. Yet here, it was quietly wo ven into one of her classes.

“The first time hear ing something Indig enous related within my course, I didn’t actually realize I was missing this aspect of my education,” said Yerxa. “That was just one little step, so small, but was so impactful for me.”

Despite this moment, Yerxa, speaking for herself, does not believe that Indig enous students in STEM feel fully represented and supported at TMU.

“I think there are efforts being made, so I would like to acknowledge that,” said Yerxa. “But it’s also a very low to minimal representation.”

She noted that programs like biomedical sciences and biology are where the most efforts are being made to include Indigenous perspectives, but feels the integration continues to be limited in other STEM fields.

The class explored how western medicine has historically borrowed from Indigenous medicine practice without giving proper recognition. Reflecting on the moment, Auger posed a question, “why was that really the only time I’ve heard about it in my education degree as a science student?”

Recognizing this gap, TMU’s Faculty of Science created the role of advisor to the dean, Indigenous education in 2022. The position focuses on advancing Indigenous perspectives, advising on culturally informed pedagogies and helping increase accessibility to STEM for Indigenous students.

Jordan Auger, another biomedical sciences student, pointed out that she also has not come across many Indigenous perspectives in her courses. Although non-Indigenous herself, Auger recalled that in her four years at TMU, Indigenous perspectives had only come up once in her program during a critical thinking course.

enous fashion as a way to say, ‘this is who we are, we are still here.’ Doing it in our own way as a means of expressing ourselves and our art.

Q: Today, how do you feel about how Indigenous fashion is represented in mainstream media?

A: I think we have come a very long way in the sense that when I first started self-identifying as an Indigenous designer, Indigenous fashion was [relatively] unknown. Nobody knew what it was, what it meant, what it looked like. People had preconceived ideas and it was very difficult to get any traction or respect from the mainstream fashion industry in that regard. Now, because we’ve been doing it for so many decades there’s definitely more media attention around

it and more Indigenous media.

Q: What challenges do you think Indigenous designers face today?

A: Well, the same challenges we’ve always had. Specifically in Canada, it is more about the ability to have a fashion business because of the lack of industry support that there is now, and the ability to scale up your business and have production and those kinds of things. So, I think Indigenous fashion has really moved into the area of art and more oneof-a-kind types of pieces. The designers in the States have more opportunity to have production capacity as far as manufacturing goes and having lines and collections that they can sell to people.

Read more at theeyeopener.com

An Outreach office for the Faculty of Science—SciXchange—launched Stoodis Science which provides Indigenous and non-Indigenous students opportunities to explore the Indigenous ways of knowing and how they relate to Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Math

However the question remains— has this been enough?