From soil to sky: curriculum design that grows brighter futures

Dr Rangi Mātāmua on Matariki as a learning journey

Rauwiringa rauropi: Seeing learning as an ecosystem

Maraetai Beach School shines light on littleknown pollution problem

Ni hao, I'm Jing. Lesson 5 is all about being polite and safe when using public transport, showing manaakitanga / respect. Getting around Auckland

How big is your carbon footprint?

Kia ora koutou, I’m Maia and in Lesson 3 we’re going to investigate the personal impact everyone can have on climate change.

What is climate change?

Kia ora! I’m Holly. Great to meet you. I’m here to talk to you about the climate, what it is and why it’s changing.

Hey, Charlie here. This last lesson will help you plan journeys, however you travel.

Safe, active journeys

Namaste, I’m Dev and I’m going to show you some safety rules for pedestrians, cyclists and scooter riders and why they’re so important.

I’m Pene and we’re

BONUS CONTENT

JOIN US ONLINE

Web: gazette.education.govt.nz

Instagram: @edgazettenz

RTLB perspective on supporting refugee and migrant ākonga in central Auckland

Olivia Tinkler, a resource teacher learning & behaviour (RTLB) working across Mount Roskill, Auckland, shares her inquiry into how schools can better support refugeebackground and migrant ākonga – and how building belonging beyond the classroom can strengthen engagement, wellbeing and whānau connection.

‘Tuakana Teina Time’ a living expression of whanaungatanga in Whangārei

At St Francis Xavier Catholic School in Whangārei, a new approach to classroom release time is creating powerful learning connections. ‘Tuakana Teina Time’ (TTT) isn’t just a way to cover CRT – it’s a vibrant, values-based programme that’s enhancing learning, leadership and school culture across all year levels.

Preventing privacy breaches

Privacy Commissioner Michael Webster talks to Education Gazette about the steps schools and kura can take to strengthen their privacy practices.

YouTube: youtube.com/edgazettenewzealand

PUBLISHED BY

Education Gazette is published for the Ministry of Education by NZME. Publishing Ltd. PO Box 200, Wellington. ISSN 2815-8423

All advertising is subject to advertisers agreeing to NZME. Advertising terms and conditions www.nzme.co.nz/media/1522/nzmeadvertising-terms-sept-2020.pdf

KEY CONTACTS

Editorial & feedback gazette@education.govt.nz

Display & paid advertising

Jill Parker 027 212 9277 jill.parker@nzme.co.nz

Vacancies & notices listings Eleni Hilder 04 915 9796 vacancies@edgazette.govt.nz notices@edgazette.govt.nz

STORY IDEAS

We welcome your story ideas. Please email a brief (50-100 words) outline to: gazette@education.govt.nz

DEADLINES

The deadline for display advertising to be in the 21 July 2025 edition of Education Gazette is 4pm on Friday 4 July 2025.

Mānawatia a Matariki

Mānawa maiea te putanga o Matariki. Mānawa maiea te ariki o te rangi. Mānawa maiea te Mātahi o te Tau. Celebrate the rising of Matariki. Celebrate the lord of the skies. Celebrate the new year.

Kia ora koutou, I hope you enjoyed a meaningful long weekend marking Matariki mā Puanga – a time to honour those who have passed, celebrate the present with loved ones, and prepare for the year ahead. As the stars of Matariki rise, they invite us to pause, reflect and reset.

This edition is inspired by those same values. With a special focus on Te Taiao and STEM, we share stories of learners and kaiako imagining and building a better future – for their communities, for the planet and for all living things.

You’ll journey from the subantarctic islands with Moana Lucre-Hedger to student-designed cities full of flying treehouses and insect sanctuaries. You’ll see tamariki using Minecraft to model sustainable farming and meet rangatahi shaping new futures in STEM and Mātauranga Māori. We’re proud to share insights from Dr Rangi Mātāmua – the voice of Matariki in Aotearoa – whose kōrero reminds us that this season is as much about dreaming forward as it is about looking back.

This year’s Matariki theme is inclusion, embracing diversity, and celebrating together, which you will also see reflected here.

Read about the trauma-informed approach of an alternative education provider in Porirua, the collaborative support shown through a He Pikorua journey in Nelson, and a heartwarming carving project at Alexandra Primary that celebrates neurodiversity, identity and belonging.

Wherever you are in your teaching journey, we hope this issue sparks new ideas, strengthens your sense of purpose, and celebrates the role you play in guiding our next generation of kaitiaki.

Noho ora mai rā, nā

Sarah Wilson Ētita | Editor

On the cover Page 8. Ākonga share their love for Te Taiao on the Rātā Track at Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, the largest fenced ecosanctuary in the world. Pukeatua School made termly visits as part of their teaching and learning concept of ‘rauwiringa rauropi’ – a means to increase curiosity about nature and conservation and help ākonga appreciate the uniqueness of their school and their local environment.

Development for Educators

Enhance your skills in understanding and supporting neurodiverse students and those with sensory needs. Our expert-led training provides practical strategies to create inclusive learning environments where every student can thrive.

To see our full range go to: grow.co.nz/upcoming-workshops

Dr Rangi Mātāmua on Matariki as a learning journey

Matariki is more than a public holiday. We spoke with Dr Rangi Mātāmua, leading Māori astronomer and advocate for indigenous science, about how the values of Matariki can shape education and support our next generation of kaitiaki.

Rangiānehu Mātāmua (Tāhoe, Ngāi Tūhoe) is one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s most respected experts in Māori astronomy and Professor of Mātauranga Māori at Massey University. He was named 2023 New Zealander of the Year, is a Fellow of the Royal Society Te Apārangi, and is the Government’s chief advisor on the national Matariki holiday. He is also the author of the award-winning book Matariki: The Star of the Year, and leads the Living by the Stars initiative.

When asked what values within Matariki are especially important for young people, Rangi shared:

“I think the main Matariki principles of honouring the past, celebrating the present, and looking to the future are the most important things. Honouring those that have gone before us and left us a legacy, and the way that we take on that legacy in a modern context – what we do today, celebrating all of the good things, and then thinking about the legacy that we hand on to the next generation.”

He believes schools can meaningfully integrate Matariki beyond a symbolic holiday by drawing on its rich scientific, environmental and cultural significance.

“Matariki is really, really broad in terms of the things that it’s connected to. The different stars are connected to freshwater, saltwater, forests, gardens, rain, weather and coming together as people. There is a lot of science in it, and it’s connected to Māori timekeeping systems and lunar and solar calendar systems.

“It’s understanding the changing positions of the sun, the rising of the stars, the phasing of the moon. It’s not one thing – there are many, many components. Matariki is really a way that connects us to this really broad knowledge system and this knowledge base.”

He sees the environmental rhythms of the season as a particularly valuable learning opportunity.

“Matariki happens at a time when the environment has closed down. From a Māori perspective, when the environment closes and becomes inactive, that’s when people are meant to become inactive. One of the things I know many people talk about is how we have holidays in the time of the year when everything is active, and when everything is cold and ‘inactive’, we’re still active trying to play sports and get out and about, and we get sick. So sometimes, the way we operate is out of step with what happens in an environmental and climate point of view.”

He encourages schools to start with the basics.

“I think the Maramataka would be a really good place to start, but even before that, having an understanding of the changing nature of the sun, the movements of the planets, how to identify stars, the change in the environment. There is a whole environmental and science element to Matariki that I hope becomes the growth point – particularly for education.”

Despite strong community interest, he notes systemic change has been slow.

“I’ve been really trying to work with the Ministry of Education for Matariki to be incorporated more in education without much traction. It could be so big, and it started from a ground-up movement. There is so much potential for it to be utilised much more broadly as an educational tool.”

For teachers who are still on their own learning journey, Rangi offers reassurance.

“I think trying to get as much information as possible and doing their best. There is no Matariki police. There’s a good amount of information that is out there already. We’re all learning. People are learning as they go, and that’s fine.”

“There is no Matariki police. We’re all learning. People are learning as they go, and that’s fine.”

Dr Rangi Mātāmua

Mō Matariki | About Matariki

Matariki marks the Māori new year, or Te Mātahi o te Tau, and begins with the midwinter rising of the Matariki star cluster. Matariki is a time of reflection, celebration and preparation.

The three key principles for Matariki are:

Matariki Hunga Nui | Remembrance Honouring those we have lost since the last rising of Matariki.

Matariki Ahunga Nui | Celebrating the Present Gathering together to give thanks for what we have.

Matariki Manako Nui | Looking to the Future

Looking forward to the promise of a new year.

Each of the nine whetū in the Matariki cluster is associated with aspects of Te Taiao and wellbeing:

» Matariki – wellbeing and health

» Pōhutukawa – remembrance and those who have passed

» Tupuānuku – food from the earth

» Tupuārangi – food from the sky (birds and fruit)

» Waitī – freshwater and its food sources

» Waitā – saltwater and the ocean’s bounty

» Waipuna-ā-rangi – rainfall

» Ururangi – winds and weather

» Hiwa-i-te-rangi – hopes and dreams for the future.

The 2025 theme of Matariki mā Puanga is all about inclusion, embracing diversity and celebrating Matariki together.

Matariki and Puanga are stars that sit in the night sky together to signal the start of the Māori new year for different iwi. Matariki mā Puanga acknowledges and embraces the different traditions, stars and tikanga around celebrating the Māori new year, recognising the regional variations.

We can all connect to the core values of Matariki and Puanga and embrace the diverse ways for marking the new year.

More resources:

» Matariki.com

» Curriculum resources at tki.org.nz

» Kauwhatareo.govt.nz

» Livingbythestars.co.nz

Rauwiringa rauropi: Seeing learning as an ecosystem

At Pukeatua School, the concept of rauwiringa rauropi – an ecosystem of learning –is helping tamariki connect science, culture and local conservation. Through immersive visits to the world’s largest fenced ecosanctuary, ākonga are developing their understanding of biodiversity, Mātauranga Māori and kaitiakitanga.

Pukeatua School is a small country school near Maungatautari mountain, just south of Lake Karāpiro in Waikato.

Last year the school introduced the concept of rauwiringa rauropi (ecosystem) to their teaching and learning – a means to increase curiosity about nature and conservation and help ākonga appreciate the uniqueness of their school and their local environment.

“Rauwiringa rauropi has been a central concept in our teaching,” explains principal Dene Franklin.

“This concept isn’t just about the literal ecosystem in our immediate environment, it’s about the ecosystem of learning

– everything working together, including what we do in the classroom and how we interact in the community.”

As part of their teaching and learning, the school made termly visits to Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, the largest fenced ecosanctuary in the world.

“Through the interactive activities at the sanctuary, ākonga saw how every organism, from the smallest wētā to the tallest rimu, plays a part in maintaining the health of the ngahere,” says Dene.

“Then after each visit, they reflected on their learning through writing, art and science experiments, exploring interdependence in natural systems.

The Manu Korokii Profile Group Education Centre where up to 60 students can be hosted as part of the education programme.

“They also began to identify changes that they could make at home and in the community and developed their ability to spot pests and predators.”

Connecting learning across the curriculum

“One of the focuses of Pukeatua School’s strategic planning has been ensuring tamariki are able to connect their learning across contexts over the year,” says Dene.

Sanctuary Mountain is a great location for crosscurriculum learning, he adds, meeting learning objectives in science, social studies and te ao Māori.

“In science, we’re learning to understand ecosystems, species interactions, and conservation methods. In social studies, we’re exploring the relationship between people and the environment, emphasising community action and responsibility.

“Then in te ao Māori, we’re learning the stories and significance of where we live and the maunga. We’re also learning the traditional uses of flora and fauna. And of course it’s embedding the concept of rauwiringa rauropi, interconnectedness.”

Regular visits to the sanctuary allowed tamariki and kaiako to build their knowledge progressively, he says, and rebuild their relationship after interactions waned during and following the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the first half of the year, students learned about the maunga itself, the ecological roles of different species in the ngahere, the importance of being kaitiakitanga, and native birdlife.

“Ākonga were encouraged to identify and look out for the manu that are represented in our newly developed school values, ‘Pukeatua PRIDE’. PRIDE stands for ‘Practising empathy’, ‘Role-modelling leadership’, ‘showing Integrity’, ‘Demonstrating passion’ and ‘aiming for Excellence’.”

In the second half of the year, students explored ngā rākau (the trees), investigating their role in the ecosystem and their lifecycles, as well as their traditional uses in rongoā (Māori healing system).

“We’ve tied all of this to our kura – our school houses are named after native trees,” adds Dene, highlighting that the final part of his students’ learning was designed to tie everything together.

“Ākonga explored interconnections in the ngahere, observing how birds, insects, trees and water systems interact.

“All of the activities we carried out at Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari were aimed at collecting information, from identifying seedlings, saplings and birds on tally charts to understanding how healthy the ngahere is, what our information tells us, and how this information would be different to somewhere else in the country.”

Pukeatua School students spotting birds during one of their visits to Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari.

Creating tomorrow’s kaitiaki

Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari is the largest fenced ecosanctuary in the world, with 47 kilometres of pest-proof fencing completed in 2006.

Pests within its boundaries were then removed, creating a safe space for “taonga species such as kiwi, takahē, kōkako, hihi, tīeke, kākā, giant wētā and tuatara”, says education programme lead Phil Margetts, one of the small team sharing the mauri and mana of the maunga.

“Our aim is to create tomorrow’s kaitiaki,” he says simply. “It’s our hope that visits to the sanctuary inspire students to take action for nature and pursue their interests in conservation.

“For some students, coming to Sanctuary Mountain is the first time they have been on a bush walk. Just being in the ngahere instils a sense of awe and wonder and provides a new experience for many learners. We hope that this is the spark that ignites a lifelong interest in our native flora and fauna.”

Phil adds that since many ākonga whakapapa to the maunga, visiting with their class is a great way to make connections.

“For all students, the trip is a chance to hear the local stories of the mountain and gain an understanding of its history and importance for mana whenua and the local area.”

He says the sanctuary’s relationship with Pukeatua School is an important one, and his team is thrilled to be part of their ecosystem of learning.

“Rauwiri means ‘to interlace with twigs’ and rauropi is the kupu for ‘organism’,” explains Phil.

“For us, it’s the perfect term to represent the plants,

animals, other organisms, weather and landscapes of an area interacting with each other, but it also perfectly encapsulates all the interconnections Pukeatua ākonga have made this year.

“It brings together all their learning.”

Transformative impact

The school’s relationship with the sanctuary even offered students the experience of a lifetime: a large-scale movement of North Island brown kiwi.

From March 2024, 222 North Island brown kiwi were moved off the mountain to other conservation projects around the North Island.

“From this, we’ve been able to build on our connections with mana whenua and develop a relationship with our local iwi, Ngāti Korokī Kahukura. We plan to further improve our relationship by visiting Pōhara, our local marae.”

“All of this has had a transformative impact on our students,” says Dene, echoing Phil, by pointing out that Sanctuary Mountain was the setting for many students experiencing their first bush walk.

“This inspired awe and built their confidence in outdoor exploration. They’ve also come away with an increased curiosity about nature and conservation, and a heightened sense of kaitiakitanga and pride in their local area.

“It’s been amazing to watch ākonga develop a greater appreciation of the uniqueness of their school and understand how fortunate we are to be able to have such an incredible taonga right on our back doorstep.”

Students enjoying a well earned rest on the Rātā Track.

Students doing some ranger work; identifying the footprints left in tracking tunnels in the sanctuary.

Ngā kōrero a ngā

| What students say

“My favourite thing was going up the tower and seeing all the big trees that looked like broccoli. I also enjoyed counting the steps as we went up. It is pretty special to do what we do at school.” – DJ, Year 8

“I really liked it because the birds were so beautiful. I got to see a saddleback and that was pretty special.” – Blake, Year 2

“What I really enjoyed was making tracking tunnels and seeing the kākā pick all the bark off the trees.” – Aarav, Year 3

“I liked the fact that there were lots of things to do, like challenges and crafts. We got to make traps for the pests, and we got to do challenges like identifying the animals’ footsteps.” – Maia, Year 5

“I liked the trees, the birds and the challenges. My favourite bird was seeing the kiwi.” – Asta, Year 2

“I liked closing my eyes and listening to all of the birds. I could hear tūī, kākā and some pīwakawaka.” – Miafiorella, Year 3

If you’d like to take your class to visit Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, find more information at sanctuarymountain.co.nz/education. They also run virtual sessions for those who are a bit too far away to make the trip.

“Rauwiringa rauropi isn’t just about the literal ecosystem in our immediate environment, it’s about the ecosystem of learning –everything working together.”

Dene Franklin

Teaching electricity?

Teaching electricity?

Easy to follow animated resources about New Zealand’s electricity system available on

CURRICULUM

An anchor to the whenua: Napier Girls’ High grounded in their learning

Perched on Mataruahou, Napier Girls’ High School has embarked on a cross-curricular journey to embed Mātauranga Māori across learning areas. By weaving place-based learning into the refreshed curriculum, kaiako aim to strengthen ākonga identity, environmental awareness and collaboration across subjects.

Year 11 ākonga from Napier Girls’ High School have participated in English and geography excursions this year including visiting places of cultural and historic significance around Ahuriri, Napier.

Napier Girls’ High School | Te Kura Kōhine o Ahuriri, perched proudly on Mataruahou | Bluff Hill in Napier, has been instrumental in shaping the lives of young women since 1884.

At the end of 2024, a small group of teachers at the school began brainstorming ideas around a cross-curricular Mātauranga Māori excursion within their local environment.

Extensive planning went into developing the programme but due to adverse weather conditions, the event had to be postponed.

However, with the programme fully prepared and ready to implement, it’s hoped that it can take place later in 2025 or early in 2026.

Weaving learning across the curriculum

Assistant head of science and head of Year 11 science Vanessa Fraser says the concept of a cross-curricular Mātauranga Māori excursion emerged during a hui with a Ministry of Education subject specialist about the curriculum refresh and the seven key curriculum components.

“As a group, we reflected on how these components could be meaningfully embedded into our existing programmes.

“A key insight came from student feedback, highlighting how important it was for them to feel connected to place

(mātaiahika) as it helped them feel grounded in their learning and valued within the school community,” says Vanessa.

Assistant head of English and specialist classroom teacher Andre Prichard says students also identified a need for mātaiaho (weaving learning across the curriculum), to better understand the links between different subjects and see their learning as interconnected rather than isolated.

“We also noticed that primary schools often have a more integrated approach to the curriculum, while secondary schools tend to work in silos. This prompted us to explore ways of fostering more cross-curricular connections at the secondary level,” says Andre.

Two staff members from the school had been on a haerenga organised by their community of learning and led by an expert on local Māori history and pūrākau, Tipene Cottrell. Tumuaki Dawn Ackroyd had also been on a haerenga led by Tipene and supported this approach.

“As mana whenua, he was especially keen to impress on us the importance of Te Whanganui-a-Orotū to the local hapū of Ahuriri. This made this area a natural focus for the learning we hoped to facilitate.”

This led the group of teachers to design a day where multiple subject areas could draw on the estuary’s history, environment and local partnerships to deepen learning.

“For ākonga, the day provided an opportunity to celebrate te ao Māori and for those from local iwi Ngāti Kahungunu especially, it reinforced the anchor to their whenua.”

Andre Prichard

Kaiako at Napier Girls’ High School were compelled to instill a sense of kaitiakitanga in students for the Ahuriri Estuary by deepening their knowledge and active engagement with the area.

Embedding Mātauranga Māori in learning

The school’s Year 11 rōpū were chosen as the participants in the day because of existing curriculum links, a focus on the place-based curriculum and the opportunities for curriculum redesign afforded by the new Level 1 standards.

Geography already ran an annual field trip and had established links to Mātauranga Māori. English had developed a hīkoi based on an important tipuna, Pania, taking in sites such as Tuhinapo, Karetoki Whare and the reef nearby to Mataruahou | Bluff Hill, where the school sits.

Science and other learning areas were also looking to embed more Mātauranga Māori in their programmes of learning.

Next steps in the planning process meant building on this by involving local community groups.

Ātea A Rangi Educational Trust, which runs the Waka Hourua programme, offered expertise in the historical journey of the Waka Hourua from Hawaiki, while Hawke’s Bay Regional Council helped with water testing of the estuary.

“We were therefore supported by a curriculum developed by local organisations, iwi and mana whenua,” says Vanessa.

In addition, the nearby Waka Ama club generously agreed to host sessions for students, covering the structure and

history of waka in the local area, and culminating in a practical experience paddling the waka ama. Sites like the local Yacht Club also offered to host.

These ready-to-go programmes provided by the school’s community partners greatly reduced the workload for teachers and ensured authentic integration of Mātauranga Māori.

Thinking outside the box

Initially, the planning for the day seemed daunting, says Andre.

“It was a big undertaking, and one quite anathema to high school teachers used to working in silos.”

But when teachers realised the potential of the kaupapa, ideas started to flow.

Science was interested in the physics of the waka, commerce in the activities of mana whenua and the change in economic activity in the estuary over time.

Geography wanted to assess the environmental impacts of industry on the moana, while history hoped to engage tauira in understanding pre-European settlement.

English sought to create a set of tuhituhi (writing) derived from the day, including stories, poems, descriptions, blogs and reflections based on traditional Māori forms such as pūrākau and mōteatea.

Year 11 geography students test the waters at the Tukituki awa, kaitiakitanga in action.

“A key insight came from student feedback … how important it was for them to feel connected to place as it helped them feel grounded in their learning ...”

Vanessa Fraser

Andre says kaiako were supported with some release time from senior management and by the allocation of a budget to cover the day.

“The finer, more precise details were planned and meetings held to get everybody on the same page, whether to learn tikanga for the day or to practise our waiata whakawhetai for our guest speakers, such as Tipene.”

Staff became excited about the opportunities for collaboration, learning outside the classroom and development of Mātauranga in their curriculum areas.

“We all liked having to think outside of the box in terms of the activities we would do, constrained as we were by what was available to us at the estuary,” he says.

Opportunities to learn outside of the classroom, to engage in diverse and different learning experiences (each student participated in at least four rotations), and to work with their friends created a real sense of enthusiasm and excitement among ākonga.

“All students were able to gain a new appreciation of their immediate environment, one that could be shared with friends and whānau, spreading the kaupapa more widely,” explains Andre.

“For ākonga Māori, the day provided an opportunity to celebrate te ao Māori and for those from local iwi Ngāti Kahungunu especially, it reinforced the anchor to their whenua.”

Geography teachers at Napier Girls’ High School already ran an annual field trip and had established links to Mātauranga Māori.

Moana Lucre-Hedger’s transformative haerenga with BLAKE

Curiosity led kaiako Moana Lucre-Hedger on an unforgettable journey through te moana to the remote subantarctic islands of Ihupuku and Maungahuka.

Her experiences with BLAKE Inspire and BLAKE Expeditions have reshaped her teaching, deepened her understanding of Mātauranga Māori and environmental science, and fueled a renewed commitment to nurturing ākonga as future kaitiaki.

Curiosity can lead us down many new paths. For Moana Lucre-Hedger, her curiosity for the environment led to an adventure she would never have expected – a path through the ocean to the wild and isolated subantarctic islands of Ihupuku | Campbell Island and Maungahuka | Auckland Islands on a climate research mission with BLAKE Expeditions.

Moana, a kaiako from Te Kura Kaupapa o Te Raki Paewhenua, says her experience in March this year was unforgettable.

“Voyaging to Ihupuku and Maungahuka has not only fueled my passion for te taiao but it also deepened my understanding of the relationship between environmental science and Mātauranga Māori,” shares Moana. “A question I had pondered just months before the expedition.”

BLAKE Inspire for Teachers

Moana initially signed up for BLAKE Inspire for Teachers, a five-day course fully funded by the Ministry of Education specifically for teachers and one she says “ticked a lot of boxes” for the professional development she was seeking.

Aside from the programme being conveniently aligned with the school holidays and located in Tāmaki Makaurau, Moana says she was initially interested because of the opportunity to spend time with kaiako from across Aotearoa and to learn how other organisations integrate te ao Māori into their research and learning tools.

Application for the 2025 BLAKE Inspire programme is still open with spaces available for term 3 programmes in September/October. For more information visit blakenz.org

“Voyaging to Ihupuku | Campbell Island and Maungahuka | Auckland Islands has not only fueled my passion for te taiao but it also deepened my understanding of the relationship between environmental science and Mātauranga Māori.”

Moana Lucre-Hedger

Moana Lucre-Hedger heading ashore.

“The inspiration I drew from Dr Dan Hikuroa’s workshop, demonstrating how he weaves indigenous knowledge with scientific principles, along with the programme’s thorough integration of kaupapa Māori, affirmed my reasons for attending,” says Moana.

“The outdoor experiences and practical learning activities strengthened my vision for implementing new approaches at my own kura.”

While field trips and class excursions are a great way to get tamariki excited about their natural surroundings, Moana says one of the most profound learnings she took away was how to embrace her own outdoor spaces every day.

“Tamariki love being outside. They learn better, and they understand more,” says Moana. “I learned that you don’t always have to go to another place, you can just step outside, weed the gardens, use the compost bin. Involve the tamariki. The environment is on our back doorstep – we just need to get out there.”

After completing the programme, Moana returned to her kura feeling instantly compelled to share her passion with fellow kaiako and staff members.

Top, bottom and right: Moana thrived being amongst other kaiako, scientists and students in the outdoors.

“I told them to get ready because I want to be the kaiako for environmental studies – that’s what I plan to do in the future!” she says.

From BLAKE Inspire to BLAKE Expeditions

As a participant of BLAKE Inspire, Moana was then selected as part of a 16-strong group of students, teachers and scientists to take part in BLAKE Expeditions – an opportunity Moana says filled her with excitement from the moment she found out.

“I initially thought it might be similar to what our tūpuna would have experienced arriving in Aotearoa; somewhere remote and untouched, where no human impact had been made,” she says.

The vision was a little blurry as she lay aboard HMNZS Canterbury, rolling through big waves on the Royal New Zealand Navy vessel heading south from Bluff – her biggest challenge to overcome being seasickness.

“That and being apart from my husband for almost two weeks were my biggest challenges,” she says.

On arriving at Ihupuku and heading ashore with the scientists and students, Moana realised just how important the area was for scientific research and the depth of knowledge that had been gathered from the area over many years.

“What was amazing to see, was how the students absorbed the knowledge from the scientists. They knew exactly what they were talking about,” she says.

Moana had studied Ihupuku and Maungahuka before leaving home, but said the amount of different flora, fauna and wildlife completely exceeded her expectations.

“It was incredible how different the islands were –one with plenty of plants and animals I had never seen, and the other that looked a lot more familiar.

“Stepping onto Maungahuka, the first noise I heard was bellbirds, then I looked up and saw rata trees, followed by a tui,” she explains.

Bringing knowledge home

Over the last few months, Moana has been working on bringing the knowledge and passion embedded during the trip back to her kura.

“For students that want to go on and study these places there are opportunities for them to be a big part of looking after our planet – it’s really exciting,” she says.

The journey from BLAKE Inspire participant to subantarctic explorer has transformed not only Moana’s teaching approach but also reinforced her commitment to environmental education.

Through her experience, she has shown how fostering curiosity can lead to huge personal and professional growth while also realising opportunities for future environmental leaders within her school community.

A Free Educational Resource for Kiwi Kids

Maraetai Beach School shines light on little-known pollution problem

What type of pollution impacts our health, the environment, wildlife, cultural practices, and even our ability to see the stars? The answer: light pollution – and a group of students from Maraetai Beach School is working to understand and address it.

On the Pōhutukawa Coast, a 45-minute drive east of Tāmaki Makaurau | Auckland, sits coastal town Maraetai. Away from the bright lights of New Zealand’s biggest city, the town offers clear views of the night sky.

As part of a project supported with funding from Curious Minds Participatory Science Platform and facilitated by Te Hononga Akoranga COMET, Maraetai Beach School ākonga

have been exploring their night sky in depth – paying particular attention to light pollution and how levels impact on our environment and health, and on astronomy.

Light pollution, which refers to excess or misdirected artificial light that interferes with natural darkness, has a wide range of impacts. These include disrupting health and sleep, interfering with the ability of wildlife to hunt, navigate and

Students Jake, Harrison, Lucas, Maisy and Arwen with equipment purchased for the project.

reproduce, and obscuring the sky – a barrier for astronomical research and for cultures who use the stars for navigation, storytelling and spiritual practices.

Guided by kaiako Jane Suckling, a group of Year 7 and 8 ākonga embarked on a nine-month project investigating the impact of light pollution on their local environment and learning how to take meaningful action.

Igniting curiosity

The project’s inception came from local scientist and avid stargazer Jordi Blasco, who also founded astrophotography organisation Skylabs. Jordi visited the school, introducing students to the concept of excessive artificial lighting and its potential effects on the night sky.

With the students’ curiosity ignited, Jane says they knew they wanted to collect real data from the Pōhutakawa Coast area and get a better understanding of whether light pollution is an issue locally – not to mention raise awareness about what it is and its effects on both environment and public health.

“One of the first steps in students’ research was a survey,” says Jane. “These were completed by over 170 community members to gauge the level of understanding about light pollution in the area and people’s perception of light pollution impacts.”

“What we really found interesting was the amount of people around the Pōhutukawa Coast who said they were affected by light pollution,” says Year 7 student Lucas. “They knew what it was and thought it was important to reduce it.

“Sixty percent said they were affected by it, and 50 percent thought it was very important to reduce it. Surprisingly, one person thought it wasn’t important at all.”

In addition to the survey, Jordi supported students to host a series of community stargazing events, designed to show the public the beauty of the night sky and the impact of artificial lighting. The events helped connect the community to the issue and sparked conversations about how local lighting choices can minimise light pollution.

Jane says partnering with an external expert such as Jordi has been a gamechanger for the school.

“We were able to access tools and expertise that helped bring the project to life. Jordi worked closely with the students throughout this project, and his support and expertise were invaluable.”

Gathering data

Using a range of research methodologies, ākonga collected a broad suite of information.

“They recorded visual observations of the night sky, documenting environmental conditions and the visibility of common constellations,” explains Jane.

“Students and parents learned to use telescopes and embarked on many stargazing sessions as part of the project. Along the way, they also learned how astronomical observations (and scientific research) can often be hindered by bad weather.”

“[They] have a newfound passion for advocacy and environmental issues. It’s inspiring to see these young minds actively engaging in making a positive impact on their environment!”

Jane Suckling

The final 3D printed version of the sky camera housing.

A prototype of the sky camera housing.

Ākonga also used ‘sky quality metre’ readings to conduct field observations around the coast, measuring the amount of light pollution in various locations – a technology allowing them to gather accurate data on the brightness of the night sky in different areas.

“The sky quality metre scans the sky and tells us how clear the sky is,” says Year 7 ākonga Harrison. “So each night we scanned the sky and put it on a sheet.

“It turns out that the best place for spotting stars was east Maraetai!”

“We also installed All-Sky cameras at various locations,” adds Jane, explaining that All-Sky cameras are devices that take pictures of the entire sky over a period of time to monitor astronomical phenomena including light pollution.

“We used these to record the night sky over a 24-hour period, using time-lapse and long exposure photography.”

“Using the sky cameras, we did a lot of stargazing with Jordi,” adds Harrison. “The first one was installed at the Auckland Botanical Gardens – we looked at Matariki! Then we moved onto more local areas such as the beach.

“Stargazing around the community was really fun. It was so interesting to see the stars, moon and planets up close through our telescope.”

“Analysing how light and darkness changed over time revealed some surprising insights,” says Jane. “For example, students discovered consistently high levels of light pollution in some urban places due to commercial areas and sports fields leaving their lights on all night.”

Putting their research to good use, ākonga then used 3D printers to design and prototype custom enclosures for the AllSky cameras to protect the sensitive camera equipment and ensure their long-term durability in the outdoor environment.

“The process of designing these enclosures was a highlight for students,” says Jane. “They gained experience in design thinking, engineering, technology and materials science.”

Sharing findings

Keen to keep the momentum going, ākonga identified solutions for reducing light pollution to share with their community – and wider.

“They’ve identified small actions that anyone can do at home and are also lobbying commercial landowners to change their lighting systems,” says Jane proudly. “They are so committed to sharing their findings and raising awareness.”

Students’ recommendations include:

» Installing shielded lighting: encourage the use of shielded fixtures that direct light downward, reducing glare and light spill into the sky

» Using motion sensors and timers: implement motion sensors and timers for outdoor lighting to ensure lights are only on when necessary

» Opting for warmer light bulbs: use bulbs with warmer colour temperatures to minimise blue light emissions, which are more disruptive to humans and wildlife

» Promote community awareness: educate community members about the impacts of light pollution and ways to reduce it, and encourage everyone to participate in making changes.

But the learning hasn’t stopped there.

“This is just the beginning,” says Jane, adding that an All-Sky camera and weather station have been installed at the school.

“Our teachers are planning to continue monitoring light pollution in the future and build this into their science programmes.”

The Year 7 and 8 students involved in the project with teacher, Jane Suckling and scientist, Jordi Blasco.

The student research group recently presented their research at Auckland University of Technology’s Curious Minds Conference, alongside other schools.

“Presenting our data and findings at the conference was a very fun experience for everyone,” says Lucas. “We’re all proud of ourselves!”

“What we really found interesting was the amount of people around the Pōhutukawa Coast who said they were affected by light pollution. They knew what it was and thought it was important to reduce it.”

Lucas, Year 7

They have also written a conference paper, ‘Assessing the impact of light pollution on urban environments: A case study in the Pōhutakawa Coast’.

“It really highlights not just their leadership in environmental science but the power of projectbased learning in addressing local issues,” says Jane of the project’s many successes. “It’s a prime example of how young people, when given the tools and support, can lead in environmental research and advocacy.”

She says it’s also been amazing to watch students make connections between light pollution and learning areas outside science, technology and maths, and has noticed “huge personal growth in the students, too”.

“They’ve increased in confidence and resilience and have a newfound passion for advocacy and environmental issues. It’s inspiring to see these young minds actively engaging in making a positive impact on their environment!”

Teach STEM with our easy-to-use resources

• STEM teaching resources including full lesson plans available online.

• Free, teaching PLD on renewable energy with videos hosted by Nanogirl.

• Engaging slide presentations to support learning.

• E-Books available in te reo Māori and English.

Find out more at: schoolgen.co.nz/teachers @schoolgennz or use the QR code

Seini and her dad, Livisi Latailakepa.

PACIFIC LEARNERS

STEM dreams fuelled by Pacific pride

The future of STEM in Aotearoa is being shaped by bright Pacific minds like Seini Latailakepa and Kijiana Tuatoko. Both 2025 Toloa Scholarship recipients, these driven young women balance cultural leadership with academic excellence as they pursue dreams in health science and radiology. Their journeys highlight the strength of identity, resilience and community in breaking stereotypes and redefining success.

In the bustling halls of two Lower Hutt schools, a quiet revolution is underway. Seini and Kijiana, two young Pacific women bound by a shared love for science and a deep connection to their heritage, are quietly rewriting the narrative of who belongs in STEM.

Seini, head girl at St Oran’s College, finds her inspiration close to home. Her father, the school’s Māori and Pacific dean and physics teacher has always led with passion and purpose.

“Seeing Dad teach physics and lead with passion really inspired me,” says Seini. “Some of my siblings also work in science, so it feels natural to follow this path.”

For Kijiana, a Year 12 student at Naenae College, of Samoan and Rotuman descent, the motivation comes from a deep desire to help others.

“I want to study radiology because I want to make a difference in people’s lives,” she says with conviction. In addition to her academic goals, she plays a strong leadership role at school, helping to create an environment where culture and learning thrive together.

Their influence extends well beyond the classroom. Both are preparing to perform at HuttFest, an annual celebration where schools across Lower Hutt showcase their Pasifika heritage through song and dance.

For Seini, who is of Samoan and Tongan descent, this year’s festival holds special meaning. Last year she and her sister led their school’s first-ever Poly group to HuttFest. The performance was such a success that the group has since doubled in size.

“It’s been really good for our girls,” Seini says with a smile. “We’re learning about our culture together, without judgement.”

These two young women aren’t just excelling in STEM, they’re redefining what leadership looks like for Pacific youth.

Facing doubt, leading with strength

Kijiana’s journey is one of grit and determination. She’s candid about the challenges she’s faced.

“I’ve never been the smartest kid in class. People expect me to just settle for achieved, not excellence.”

But rather than internalise those low expectations, she pushed back.

“People will underestimate your skills, but you don’t have to accept that.”

It’s a familiar experience for many Pacific students.

“We get judged and pushed down,” she says. “But confidence in yourself is key. No one should tell you what you can or can’t do.”

Her self-belief is rooted in her Pacific identity and the sense of belonging she found in her community.

“When I’m with other Pacific students, I feel like I can truly be myself. Even if you’re one percent Samoan, you’re still Samoan.”

Preparing for HuttFest adds another layer to her experience. Performing with her peers reminds her that academic ambition and cultural celebration can fuel each other.

Seini has faced her own challenges, particularly adjusting to a new school environment in Lower Hutt after moving from South Auckland.

“At first, I felt I had to act differently to fit in. But I realised being true to myself was what mattered most,” she reflects.

Now, as head girl and daughter of a passionate STEM educator and cultural leader, she leads with authenticity, excelling in chemistry and physics while championing Pacific culture and support networks within her school.

“It’s so important for other Pacific students to see me and feel comfortable taking up space here.”

Seini Latailakepa

The power of identity in STEM

For Seini and Kijiana, cultural identity isn’t separate from their STEM success, it’s the foundation.

“It’s so important for other Pacific students to see me and feel comfortable taking up space here,” says Seini.

By leading her school’s growing Polygroup, she’s created a space where Pacific students can thrive both academically and culturally, whether in the chemistry lab or on the HuttFest stage.

Kijiana agrees. “Celebrating our culture creates a positive space for learning and growth,” she says.

For her, performing in traditional attire at HuttFest is more than just a performance, it’s an act of empowerment.

Together, they are not just participating in STEM, they are leading. They challenge stereotypes, break barriers and show that Pacific students can be innovators, scientists and changemakers.

Inspiring the next generation

Seini and Kijiana’s stories are powerful reminders of what’s possible when education is paired with cultural pride and community support.

Their success is supported by the Ministry for Pacific People’s 2025 Toloa Scholarship, which offers mentorship, resources and encouragement to Pacific students in STEM.

Receiving the scholarship, both say, was a huge confidence boost and strengthened their belief in their dreams. Their advice to others is simple but powerful: “Believe in yourself and just go for it!”

Their achievements stand as proof that Pacific youth can and will excel in STEM, creating a new narrative, one rooted in cultural strength, academic excellence and community leadership.

“We’re here to show that Pacific students belong in STEM and can lead the way,” says Seini.

Kijiana echoes the sentiment. “This is just the beginning, I want to inspire others to dream big and reach their goals.”

Together, they are lighting the path where Pacific voices and talents shape the future of science, technology, engineering and mathematics on stage, in classrooms and beyond.

Dynamic duo! Seini and her dad in the physics lab.

Seini proves that her culture and educational success go hand in hand.

Kijiana is putting her passion for others at the forefront.

TE AO MĀORI

Tipuranga programme enriches community at Waihī Beach School

Since 2023, Waihī Beach School has seen growing enthusiasm for Tipuranga –an optional programme centred on te ao Māori, te reo Māori and Mātauranga Māori. Grounded in hapū collaboration and student choice, the initiative has had a ripple effect across the wider community.

Each Thursday, over half of the children enrolled at Waihī Beach School head out for an optional block of learning called Tipuranga, focused on te ao Māori, te reo Māori and Mātauranga Māori.

Since beginning the programme in 2023, there has been rapid growth and enthusiasm for the offering, which has been carefully designed by local hapū Te Whānau a Tauwhao, kaiako Māori, whānau and ngā tamariki. The positive impact of Tipuranga is felt across all levels of the school community.

Waihī Beach School is proudly a Te Tiriti o Waitangi-led, inclusive and diverse primary school nestled at the northern end of the Western Bay of Plenty.

When tumuaki, Rachael Coll took on the challenge to lead the school six years ago, she brought with her a keen desire to explore what it meant to be Te Tiriti-led within the school community.

“Waihī Beach School was already on a journey with te ao Māori, however I had a feeling that as a community we were ready to go much further,” says Rachael.

Across nearly six years, the community has come together regularly to discuss ways in which Te Tiriti is lived.

There has been intentional transformation in approaches to governance (the constitution has been amended to ensure there is a hapū seat on the Board of Trustees), appointing educators with skills to support understanding, targeted professional learning, connection to wider community organisations who share similar values, and productive relationships have been forged and sustained with the local hapū to chart the direction for the school.

Kaupapa Māori learning

Through consultation processes, whānau expressed a desire

Whetū Watene (Ngāti Kahungunu) Sarah-Kay Coulter (Ngāti Porou) and Kararaina Sydney (Te Whānau a Tauwhao) leading Tipuranga.

for their tamariki to have more exposure to te ao Māori (the Māori world), tikanga Māori (Māori practices) and te reo Māori (the Māori language) each week.

Although the school had been committed to ensuring every tamariki was given a strong foundation in te ao Māori – such as instruction in te reo Māori, waiata, pepeha, pūrākau, kapa haka – in response to the community, this was extended further.

Following a series of board meetings and whānau hui, a pilot was developed and launched in the school in term 3 2023.

Tipuranga, which is loosely translated to mean “a place to grow”, continued in 2024 expanding to a third of the tamariki in the school enrolled. This has increased to over half the school in 2025.

“Tipuranga is in line with our philosophical belief that children and their whānau should have choice and autonomy to control their own learning and we felt this extension programme should be an optional opportunity,” says Rachael.

Tipuranga is inherently strengths-based, which has been diverse and full of rich learning experiences.

These include mahi toi, using locally sourced uku (clay); taonga pūoro (pūrerehua); traditional food and fishing practices; oral literacies (including whakaari) and written texts. Experiential learning has also been embraced by taking children on field trips to deepen connection to waka Mātaatua.

The programme embraced seasonal learning and the curriculum was structured to allow for freedom to explore global, national and local kaupapa.

For example, Taumahekeke o te ao (World Olympic games) became a way in which to explore identity, while responding to questions associated with the national hīkoi and appointment of the Queen in the Kīngitanga movement.

At a local level, the children were exposed to the intersection of STEM and indigenous knowledge systems through outdoor learning in the small native bush grove located on the school grounds.

Empowered educators, inspired learners

Staffing Tipuranga has been key to the success of the programme with Kararaina Sydney (Te Whānau a Tauwhao) guiding the curriculum, supported by experienced educators Sarah-Kay Coulter (Ngāti Porou) and Whetū Watene (Ngāti Kahungunu).

It has been a steep learning curve for all the educators involved as questions were raised about how to plan for learning with the maramataka (Māori lunar calendar) along with the strengths of the children.

Top and bottom: Outdoor learning and music play an important role in Tipuranga.

The team utilised aspects of the Niho Taniwha model as guidance, referred to Te Marautanga o Aotearoa and the strands of the New Zealand Curriculum, considered Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaitia | The Māori Education Strategy, while working collaboratively with the local hapū.

Each week the learning was structured to place emphasis on te taiao (the natural world), with new karakia and waiata composed to support the learning as it progressed.

The educators were all given the opportunity to learn from Harko Brown (an expert in indigenous games), who enriched the programme with a range of physical and cognitive games, ensuring the children could be supported in boisterous and competitive gameplay.

Sarah-Kay says they have seen the ripple effect of Tipuranga in unexpected ways.

Matariki morning at Tipuranga.

“This is from positive whānau dialogue, to extending on concepts associated with environmental learning. As kaiako Māori we have been both awakened and empowered that we can authentically teach our values and it has inspired us to make our teaching resources with the children, all of which are derived from the natural world.”

She adds that there are many rich stories from whānau about the learning in Tipuranga. One family shared that Tipuranga has extended their son’s knowledge and created a foundation where he is curious and eager to ask questions to learn the answers.

“We have noticed his love for sharing all he’s learned in Tipuranga and filtering that knowledge into our home for his younger brother. It has created many conversations about our iwi and whenua. The Māori games were definitely a hit; we’ve had a lot of fun playing them at home too.”

Student feedback highlights the joy and connection felt by tamariki.

“I love Tipuranga because it is so much fun. I get to do lots of creative work and I enjoy learning about our environment and water,” says a Year 6 ākonga.

“We do fun activities, play lots of Māori games, learn about the maramataka and I love learning our special Tipuranga waiata,” says a Year 4 student.

Another Year 6 ākonga shares, “I loved drawing the ngā huruhuru (feathers) of the birds and making puppets to retell the stories.”

Looking ahead

The aspiration for Tipuranga is to continue enhancing the programme for the learners at Waihī Beach School, says Sarah-Kay.

“As the wider teaching team began to see the successes in ākonga engagement and attendance, it was discussed if the programme should be extended to ‘all’ ākonga. However, we feel that this is not the goal, rather whānau and tamariki connect to a learning opportunity they feel aligns with their values.

“We feel passionate that it is time to start sharing and providing the wider education community with rich evidence of our programme and its triumphs as we see there is tremendous opportunity to translate the programme into a broad range of schooling contexts.”

Rachael acknowledges there have been challenges in launching and scaling Tipuranga. A challenge had been making sure there was the physical space to accommodate all the tamariki who wished to join in.

“Originally, we wanted Tipuranga to operate as a mixedage offering – all ākonga together – however due to the size of the group and timetabling, we had to compromise and find solutions to ensure that the programme could fit into wider school life with minimal disruption. This led us to create three smaller groups based on age.

“A further important consideration has been creating a

supportive and collaborative teaching team. Employing more than one teacher into the programme (even when it was just starting out) supported Tipuranga to grow and flourish.”

Inclusive learning

Kararaina says the programme’s impact is clear, and that, “Simply, our tamariki want to come to Tipuranga.”

Staff noticed increased attendance on a Thursday and positive engagement for learning, and Kararaina says there is a genuine excitement to attend on a Thursday, with ākonga saying, “I wish it was Tipuranga every day.’”

Beyond attendance, the programme has fostered strong community ties. They believe Tipuranga breaks down traditional school/home boundaries.

“We have had numerous whānau come into the programme to share their skills with us. One family came in to help us create pūrerehua (Māori musical instruments); while other whānau have come in to share taonga (precious treasures); and wider whānau attending excursions such as walks to learn local stories about our environment.

“With numerous takiwātanga and neurodiverse ākonga with additional learning needs, Tipuranga has created an inclusive learning environment that is geared toward positive associations for schooling and learning.”

Sammy learning how to preserve seasonal produce.

Tamariki learning Waiata composed for Tipuranga.

DESIGN THINKING

Future cities reimagined by young designers in Wellington

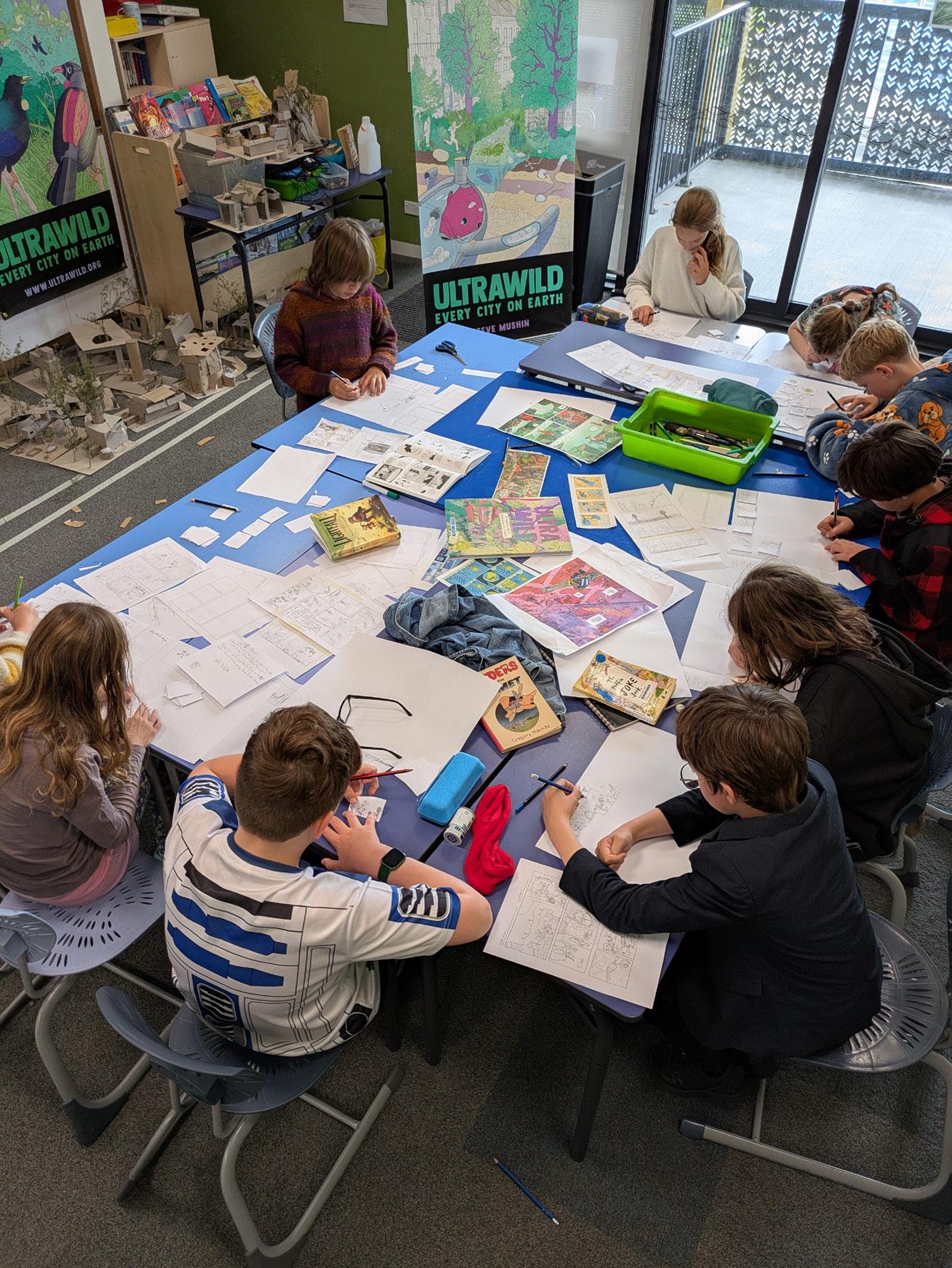

Every class at Te Kura o Tawatawa - Ridgway School took part in a hands-on, imaginative design project led by author and illustrator Steve Mushin. Through drawing, model-making and futuristic thinking, students became ‘ultrawilding’ designers, dreaming up cities built for all species – not just humans.

Deputy principal Nathan Crocker welcomes tamariki, their whānau and Steve to the exhibition.

How can we reimagine cities as thriving habitats for all species, not just people? That was the question posed to tamariki at Te Kura o Tawatawa - Ridgway School, who took part in a 13-day workshop series exploring a new way of designing urban environments.

The workshops, which have made their way across Australia and New Zealand, are led by Wellington-based designer and author Steve Mushin, whose book Ultrawild: An Audacious Plan to Rewild Every City on Earth uses science, engineering, illustration and wildly imaginative ideas to spark thinking and explore the possibilities of high-tech urban rewilding, which he calls ‘ultrawilding’.

Steve invented the term ‘ultrawilding’ to describe using technology to help transform cities into ecosystems that are as ‘wild’ as possible for humans and other species. And he encourages ākonga to have equally wild ideas.

“The goal of my book and workshops is maximum craziness to engage kids with science and engineering ... Research suggests that having crazy ideas, having fun and being playful is an incredibly powerful way to build our creative thinking.”

Steve worked with every class from Years 1–8, bringing the school’s 200 students into a schoolwide inquiry project about how we design the places we live.

Each workshop began with a big question: ‘what species do we design cities for?’

Some students noted they hadn’t thought of humans as a species before, or hadn’t realised how few urban spaces welcome insects, birds, or native flora. Students were challenged to become ultrawilding designers.

Designing for all species

In sessions with Years 1–4, students brainstormed ideas as a group before sketching buildings and inventions of their own.

For Years 5–8, the design process also included building to-scale models using a wide range of materials Steve brought in, including different types of cardboard (such as bendy cardboard), tiny scalemodel humans, and kanuka branches with leaves.

Students could choose the materials they wanted to use based on their ideas, and the hands-on nature of the model-making helped ultrawilding feel more real and achievable.

“A day isn’t long enough to do detailed design work, but it’s enough to start designing an ultrawilded building,” says Steve.

“The simple techniques I taught are essentially how architects start a model. The process of working with your hands, making mistakes, fixing things up, and trying new things is what gives you a really interesting outcome,” he says.

For students who felt less confident in drawing, model-making offered an equally valid and creative way to engage.

Students were encouraged to see mistakes as part of the process and adapt their designs as they worked. Whether it was flying houses, tree-top teleportation pods, or buildings for glow-worms, creativity was celebrated.

STEM, storytelling and sustainability

The project wove together science, maths, engineering, art, literacy and environmental learning. Students wrote stories for their cities, calculated structural needs for futuristic vehicles, and used systems thinking to solve urban design challenges.

Steve Mushin working with ākonga at Te Kura o Tawatawa - Ridgway School.

Futuristic Eco-Friendly For Bird Lovers Tree House.

Students at the illustration extension workshop.

Tea Pot Tree House.

2D treehouses made by Years 1-4 students.

“The kids think about how they could make the future different and better for all,” says Steve. Maths is important. For instance, if you’re getting to school on a flying bike – high above jungles of nīkau, ponga and rimu – you need to work out some details. “A person on a flying bike weighs this much, so how big do the wings have to be?” And creating the story behind the designs is part of literacy learning.

Steve also ran short extension workshops in illustration, storytelling and engineering for interested students.

In engineering, students refined their original designs or created new public buildings. In storytelling, they created comics showing what life could be like in an ultrawilded city, with both human and animal inhabitants.

And in illustration workshops, they drew detailed cityscapes and unique species that might live in their imagined ecosystems.

Each session included kaupapa about designing for all species, rooted in values of kaitiakitanga. Steve talked about the importance of making cities better for every living creature – from huia to insects to humans.

“The design has to be good for all species, and peaceful,” he says. “If a kid really likes machine guns, I might say ‘that’s an amazing-looking gun but could it fire seeds, or launch drones that fly around and look after insects?’”

Culminating in an exhibition

The project culminated in Ultrawilding the Tawatawa/Ridgway: An Exhibition of Future Dreaming, where whānau and community members came to see more than 100 drawings and 100 models on display.

Set to music and ambient forest sounds, the exhibition was a celebration of creativity and future-focused learning.

“It was a joy to witness tamariki completely absorbed in designing, imagining, building, testing, drawing, thinking ahead,” says deputy principal Nathan Crocker.

“You [Steve] created something not just for this moment, but for the future.”

Ngā kōrero a ngā ākonga | What students say

“I used to want to shrink to go into a bird’s nest. My house is a nest in a kauri tree with areas for humans, huia, wētā and insects. There are bird feeders, and animals can climb up a spiral ramp.” – Sabine, Year 7, The Giant Huia Nest

“It floats in the air and can be moved. There are solar panels and pots growing rare trees, a glow-worm farm, and pods that glide you back to the ground.” –Flynn/Aviry, Year 8, The Blimp Treehouse

“I wanted my house to have trees, birds and lizards. Steve helped just enough and talked about Matariki and protecting nature. I didn’t like art before and now I do.” – Spencer, Year 8, Super Slide House

“My treehouse has a teleport station, escalator, nesting room for kea, and a blackout room for kiwi. This project made my imagination bigger.” –Bess, Year 4, Tree House Drawing

A sketch at an illustration extension workshop.

Steve’s book, Ultrawild: An Audacious Plan to Rewild Every City on Earth.

Mātiki Minecraft helps ākonga build future of farming block by block

A 140-year-old South Island farm has been rebuilt block-by-block inside Minecraft to support a new generation of learners. The immersive Mātiki Minecraft resource is teaching ākonga about agriculture, horticulture and sustainability while sparking curiosity, creativity and careers in the primary industries.

In April at the HATA Conference at Mt Hutt College, Methven, Anthony Breeze supported over 50 teachers on how to integrate Mātiki Minecraft into their junior agricultural and horticultural science classes.

ASouth Island farm that played a pivotal role in Aotearoa New Zealand’s farming history has time-travelled into the 21st century, reimagined in Minecraft, the globally popular video game now bringing agricultural science to life for ākonga across the motu.

The resource, Mātiki Minecraft, is a virtual replica of Totara Estate in Oamaru. Lamb from the estate was part of the first shipment of frozen meat ever exported from New Zealand, way back in 1882 – laying the foundations for today’s multibillion-dollar meat industry.

Now built in Minecraft block form, the history is integrated with study units for Years 7 to 10 science and agriculture learning areas. The name ‘Mātiki’ comes from a Māori agricultural tool shaped like a pickaxe, with an adze and chisel edge.

From pasture to pixels

During the game, students tour through acres of virtual farmland, learning about the seven significant primary industries of Aotearoa: beef, sheep and arable farming, kiwifruit and pipfruit production, dairy, and forestry.

“Students learn about early farming practices and can then modernise the online property into a sustainable working farm complete with modern infrastructure, practices and systems,” says Suzy Newman, subject advisor for Sow the Seed.

“Gaming and education can go hand in hand, inspiring students to explore New Zealand’s rich farming history while preparing them for its future.”

Students can visit the historic men’s quarters and cookhouse, wander across paddocks, and meet characters dressed in traditional Kiwiana farming attire – black singlets and stubbies.

Along the way, they learn about tools and technologies used in farming, including artificial insemination, genetics and animal health programmes.

A hands-on learning adventure

Developed by former primary school teacher turned educational technical specialist Anthony Breese of Museograph, Mātiki Minecraft is carefully grounded in realworld geography. Each Minecraft block represents a metre in real life, with topographic data translated into block form using world-building software.

“I personally believe it’s important to understand where we come from, which is why setting the scene at Totara Estate was so great,” says Anthony.

“And also it’s important to provide students with an insight into where our food comes from, which they learn about while innovating during the game too.”

A team of agricultural and horticultural science teachers from Sow the Seed, HATA, and Agribusiness in Schools helped shape the content, ensuring that the Minecraft world offered multi-layered, challenge-based learning aligned with the curriculum.

“It’s STEM played out in a farming environment,” says Suzy.

Mātiki Minecraft teacher workshop

The next online workshop for teachers will be held Tuesday 24 June, 4–5pm. Visit sowtheseed.org.nz

Ākonga from Waerenga O Kuri School using Mātiki Minecraft. Mount Hutt College building an irrigation system.

Top left: Sow the Seed’s agricultural and horticultural science advisor, Suzy Newman.

Top right: Napier Boys’ High School try out Mātiki Minecraft with their teacher Rex Newman, HOD agriculture.

Bottom left: HATA Conference 2025 Teacher training.

Bottom right: The Men’s Quarters and Cook House at Totara Estate, which holds information and activities on dairy farming.

Literacy, numeracy and innovation

Students are encouraged to write stories for their Minecraft characters, fulfilling literacy standards, while numeracy comes into play as they calculate crop loads and farming costs.

There are also scenarios where ākonga experiment and design their own farming solutions.

Fiona Jessep, head of Mount Hutt College’s agriculture department, says, “My husband and I had visited Totara Estate just before I had a go at Mātiki. It was quite surreal walking or flying up the driveway that I had just recently driven up. As a person who has not had much to do with Minecraft, I was blown away by the details that were in the world.”

Fiona’s Year 10 students even built an irrigator to ensure their crops had enough water to grow.

“Students can think about ways we can change things to improve our industries, that suit both the natural environment and our farming and horticultural industries,” says Anthony.

Connecting rural and urban worlds

While some schools may have gardens or access to local farms, Mātiki Minecraft makes this experience possible for urban learners as well.

“Students from non-rural backgrounds get a real-life glimpse into life on the farm,” says Fiona.

One challenge encourages students to build their own farm using information gathered from the Totara Estate Minecraft world and beyond.

Once students have grasped the key industries, they’re encouraged to imagine future-focused solutions like robotic milking systems or rooftop gardens.

“We want students to think about the biodiversity and sustainability of their farms,” says Suzy.

Fiona adds, “I have been teaching Ag/Hort Science for over 25 years, and I am still amazed that people think that it is an easy subject and that our brightest students should not take it.

“The industry is future-focused and therefore needs bright students to come up with the new ideas and methods that will enable New Zealand farmers to navigate challenges such as climate change.”

Support for teachers

Mātiki Minecraft can be used not just in agriculture and horticulture, but also in science and social studies. Teachers don’t need to be Minecraft experts either, as the accompanying website offers cross-curricular unit plans and guidance.

“Teachers can learn as they go to support their class, and maybe they’ll even learn something new from their students,” says Suzy.

“Minecraft is a great game where you can’t just push a button and get an answer from it. And you’re not just creating a poster to present from information you’ve learned in a writing or maths textbook,” says Anthony.

“Instead, students have to work to get their answers through being innovative, using their imaginations.”

Education Gazette first interviewed Governors Bay School | Te Kura o Ōhinetahi in 2021 as their song Fix It Up became a hit across Aotearoa. Read more in Climate change education ignites action at gazette.education.govt.nz.

work

Stencil

on the community pool mural.

Climate education through action: A teacher’s journey in Ōtautahi

This article written by Angie Rayner, a Year 7–8 teacher at Te Kura o Ōhinetahi | Governors Bay School, was first published by the New Zealand Association for Environmental Education (NZAEE) in April 2025. Angie shares her honest reflections, practical insights and inspiring outcomes from teaching the Huringa āhuarangi: Whakareri mai kia haumaru āpōpō I Climate change: Prepare today, live well tomorrow programme.

Iremember being approached by the Christchurch City Council back in 2020, with the hope of a school in the harbour area trialling the climate change learning programme as part of their Coastal Hazards Adaptation Plan engagement. My initial thought was: No way. I had no science background, I wasn’t an environmentalist, and I had no idea where to even start; in fact, I didn’t even own a keep cup.

But I soon realised that I didn’t have to be any of those things. If you are passionate about children’s education, guiding them through an inquiry process, and supporting them to have a voice, then you need to teach this programme.

At the time, our Year 0–8 school situated in the community of Whakaraupō | Lyttelton Harbour was in the process of rewriting our school values. The programme aligned beautifully with what we were encouraging our tamariki to do and to be:

» Ahau – to grow with curiosity and kindness

» Kō Mātou – to connect with others through kotahitanga

» Kō Tātou – to create change in the world as kaitiaki.

The climate change programme promoted these values. Not only has it taken us on a journey of new learning, but we have gone on to share our voice with others in our community, with other schools, with councils, and even across the globe.

Teaching the programme

The programme is very flexible. You can teach it as a standalone unit of work or incorporate it into other areas of learning; follow it activity by activity or adapt the activities to suit you and your class.

It is divided into eight different modules, each building on and complementing the other, with topics such as climate systems, indigenous knowledge, mitigation, adaptation, critical thinking and taking action.

Each module has clearly identified and specific learning

intentions and success criteria. This was helpful for me to understand what key knowledge was needed for the students at each stage. I also found the background reading helpful in giving me a better understanding before teaching it.

Everything is there for you: the visuals, the video links, the lesson sequence and additional resources you can explore for further content.

A component of the programme which I believe is essential to include is the Wellbeing Guide | Te Tai Unuora. Climate change, for some, can be a scary concept. The media does not report it in a positive or hopeful light and a lot of misinformation is out there.

The activities in this guide are woven throughout the teaching modules, helping to alleviate students’ fears by checking in on them, supporting their emotional wellbeing and nurturing hope.

Integrating the programme into our curriculum

The programme aligns easily with an inquiry approach. At the time, we were just delving into renowned educator and author Kath Murdoch’s inquiry cycle. It was clear to see where each of the programme modules sat within this process and how our new school values sat alongside it.

I love that students are encouraged to be critical thinkers and to see other people’s perspectives.

Module Seven, Meaningful Connections: Critical thinking and communication, has a great lesson on understanding our differences and learning about the impact of fake news, with links to both social sciences and health learning areas.

Based on scientific research and explanations, the programme leads beautifully into a science-based inquiry, and there are many other organisations you can tap into to reinforce the learning. House of Science and the Science Learning Hub are both great additions that I have incorporated into the programme.

The programme provides students with opportunities to read, analyse and record data, both secondary and selfcollected, all of which align with the refreshed mathematics and statistics learning areas.

Literacy opportunities within the teaching and learning modules are abundant. School Journal stories can be included in your explicit teaching sessions, with links to specific journals included in the programme. The module activities allow for poetic writing, procedural writing, and the students love the debating lessons.

A particularly successful writing unit I have taught alongside the programme was a spoken word poetry unit. The students loved this style of free speech, and it ended with them entering and placing in the Speaking 4 the Planet competition.

Unexpected outcomes

This is the part of the inquiry that has blown me away the most. I could never have imagined the doors that opened or the opportunities that presented themselves for the students. I think having no expectation of what the outcome is going to be or where each inquiry will lead you, is the best way to approach it.

It was hard at first, trying to help the students understand that ‘taking action’ didn’t mean informing people about climate change by making a poster or slideshow.

I underestimated their creativity and was not prepared for what was about to come.

About halfway through the modules, students begin to feel empowered to make a difference. They realise that even the smallest of steps can create change.

Having learned about ‘Children’s Rights’ and that they can have a voice, this is where, as a teacher, you need to be brave and let what will happen, happen.