students

•PAWS-ITIVE IMPACT

•CARING FOR TOMORROW

•UNDER THE MOONLIGHT'S GAZE

•ON THE AIR WITH HENRY HINTON

•CHARTING PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

•ASSIGNMENT IN ADJUSTING

•FIELDING UNCERTAINTY

•PAWS-ITIVE IMPACT

•CARING FOR TOMORROW

•UNDER THE MOONLIGHT'S GAZE

•ON THE AIR WITH HENRY HINTON

•CHARTING PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

•ASSIGNMENT IN ADJUSTING

•FIELDING UNCERTAINTY

Play with dogs every day? Sign me up. That’s what many might say about Mackenzie Johnson’s job at the Humane Society of Eastern North Carolina. Yet, it’s a lot harder than many might think. She and her colleagues must gingerly nurse abused and frightened animals back to health, oversee volunteers, and so much more.

Story by Sean Rocca

Not everyone makes it through medical school, but firstyear student Alissa Meyerhoffer is working hard to make sure she is one of them. Her days start early at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine, and they end late. In between classes like microbiology and anatomy lab, she and her classmates begin studying for a test an entire year away.

Story by Kiarra Crayton

The moon was out and so was Sgt. George Dawkins of ECU Campus Police, on the lookout for suspicious vehicles, fights, threats — you name it — during a long, dark, 12-hour shift. Yet, he realizes that when a call comes in, “It’s more traumatic for them than it is for us.” Dawkins also knows that he has the chance to teach a life lesson when a college student messes up.

Story by Martha Nebab

Starting at 15, when he hung out with a friend during her live radio show, to now, as he contemplates retirement from the broadcasting company he founded in Greenville, Henry Hinton’s voice has permeated the airwaves through eastern North Carolina.

Story by Demetrius Williams

A high poverty rate and other challenges lie outside the doors of SouthWest Edgecombe High School in Pine Tops, North Carolina. Inside, Dr. Lauren Lampron is helping students to envision more. Lampron got to Pine Tops via Teach for America, a nonprofit working to resolve educational inequity in lower income communities.

Story by Jack MeltsnerBetween the pandemic and a chronic teacher shortage, school has not been easy for Elliott Tart and his friends in tiny Roseboro, North Carolina. Teacher turnover in the state began in earnest during the pandemic. The problem of 5,000 teacher vacancies is often more evident in rural schools like Elliott’s than in the state’s urban or suburban areas. Now, Elliott and his peers feel woefully behind.

Story by Anna TartPitt County is growing, and things are changing fast on the picturesque fields of soybeans, cotton, wheat and other crops. Farmers are aging, the price they get for their hard work can slip beyond their control, and often, they don’t know who will do the job when they no longer can. David Davenport and Pattie Mills of the fifth-generation JP Davenport & Sons, Inc. know these changing circumstances all too well.

Story by Alayna BoyerIsabella

Mya

Darian

Savannah

Kaitlyn

Lillian

Susanna

Kasey Lagos

Claire

Aydan

Emma Lyden

Isabella

Katherine

Alyssa

Jacqueline

Countenance (Vol. 8, Issue 1) is a general feature magazine produced by students in the School of Communication at East Carolina University since 2017. The articles were written by students in the Fall 2023 Feature Writing class taught by Cindy Elmore. Countenance was designed by students in Creative Design in Publishing, which was taught by Barbara Bullington in the spring of 2024. Funding for the magazine was provided by the School of Communication.

Questions or feedback can be addressed to Cindy Elmore at elmorec@ecu.edu or 252-328-5306.

by Sean Rocca

by Sean Rocca

Working for the Humane Society can be a demanding job with so many furry faces in need of care. But, in spite of the challenges, there are definite rewards.

When Mackenzie Johnson arrives every morning for work, she is greeted by the barks and whines of the 30 dogs she oversees. As an animal care technician at the Humane Society of Eastern Carolina, she is in charge of making sure the dogs are cared for and happy.

Even for a dog lover, “This is a job that has its

hard moments,” Johnson said. “You have to know why you’re here. Sometimes a six-hour shift can turn into a 13-hour shift, and it really takes a strong mindset. But it is very rewarding. For every claw mark or poop stain on my shirt, I would do it over and over again. I love getting the chance to give the dogs the chance to be a dog.”

Johnson came to the Humane Society from Ohio in 2022. She originally attended Kent State University but felt she needed a change of scenery. So she came to North Carolina knowing she wanted to do something in the animal field.

Johnson said her first interview was with the Humane Society and she fell in love with the organization. She added that being at the Humane Society has given her a sense of purpose: she is not there for the money but instead, to make a difference in the lives of dogs.

The beginning stages are the worst. It’s terrible to see the repercussions of bad owners. These dogs are skinny and scared of humans. It looks like they don’t know how to be a dog and it is hard to see.

In its location on the east side of Greenville, the Humane Society has a small building with some character. Visitors walk up to the front door on large, paw print stepping stones and once inside, see dog posters around the building with sayings such as, “My favorite breed is adopted!” and “Every life isn’t complete without some dog fur.”

In the background, one dog is steadily barking. That dog is Sourdough, who according to Johnson, is very sweet but wants love — all the time.

When Johnson arrives, she unlocks all the kennels for the dogs. She feeds them, gives medication to the ones that need it, cleans their kennels, gives them fresh blankets, and hoses down the kennel. She also has to do what she calls swapping the yards. Each dog gets a minimum of 15 minutes of yard time every morning and afternoon. Swapping the yards is when Johnson brings a different dog from the kennels out to the fields for outdoor time.

The Humane Society has two large fenced-in areas for the dogs to enjoy. Johnson goes to the kennels and takes each dog out one by one for yard time. She first takes out Zane, who is begging to go off the leash while walking to the yard. Sourdough is steadily barking. She puts Zane in the yard and plays

with him for a bit. Tennis balls are scattered all around the yard and Johnson throws some for Zane.

“I don’t have the ball,” Johnson says to Zane, who does not believe that the ball was thrown. Zane then runs with pure joy, his eyes illuminated with the happiness of life. Johnson smiles and laughs while they play, although she has to soon resume her duties. When she leaves, Zane runs to the fence looking crushed because the human left.

Most of the dogs here were surrendered by owners or were pulled from other shelters. Johnson said when she and the other staff members first get the dogs, it is often difficult to see the state they are in.

“The beginning stages are the worst,” Johnson said. “It’s terrible to see the repercussions of bad owners. These dogs are skinny and scared of humans. It looks like they don’t know how to be a dog and it is hard to see.”

One dog, Wafer, came in skinny and terrified of humans. Johnson and the staff had to lay out treats just to get her to come out of her kennel. Wafer would hide in the corner of the kennel and shake out of fear of the caretakers. Wafer’s story is one of many there, Johnson said.

Once, a woman tried to give the Humane Society over 200 cats. The woman had cared for all of them as best she could and knew each one of their names. However, Johnson said the woman could not properly

care for all of them and most looked unhealthy. Johnson said her facility took the kittens but could not make a dent in the full 200.

The animals that come into the Humane Society are an example of a larger issue. According to The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 10 million animals are abused to death in the United States. The Jane Goodall Institute reports that 1 in 3 owners abuse their pets in some way, and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals says that 6.3 million animals enter shelters each year. These shelters do not have enough space to house them all, which then leads to more animals being euthanized.

The Humane Society does not euthanize. Instead, Johnson and the staff are committed to educating people about how to properly care for their pets. They are also trying to give the animals in their care a perfect forever home.

“This is the best part of the job,” said Community Enhancement Coordinator Morgan May. “I love getting updates from owners of our animals, hearing how they are doing and if they were a perfect fit.”

When someone wants to adopt a pet, they fill out an application. The application asks questions about the person's lifestyle, and it goes to Johnson and the other animal care technician, Nila Jayanett. The two then pair up potential owners with the dogs or cats that they feel would best fit the applicant.

Jayanett said she loves this process and any adoption events the organization puts on. She said it is rewarding to see the animals find proper homes.

Director of the Humane Society, Shelby Jolly, also said she enjoys the adoption process. She loves seeing adopters come in and leave with

one of the dogs, knowing it makes a difference in the dogs’ lives.

Besides the staff members, the Humane Society has potential adopters and volunteers in the building almost every day.

Nick Green, a volunteer, said he had fun when he volunteered.

“I got to walk one of the dogs, play with them in the yard, and I got to give them some treats as well. I have always loved dogs, so helping out is both satisfying and really fun for me.”

Johnson and the staff at the Humane Society always welcome volunteers to help play with the animals and give them outside time.

Back in the yard, Zane waits with a ball in his mouth for what seems to him to feel like an eternity in dog time. After a few minutes, Johnson comes back and the glow in Zane’s eyes instantly returns. This time, Johnson has a large toy to sling the tennis ball more easily. Sourdough is still barking on pace.

“Now I can throw it even farther for you,” Johnson said. She and Zane play for a bit longer before the 15 minutes is up and Johnson switches out Zane for another dog. When she goes back to the kennels, an uproar as loud as a rocket ship taking off erupts from the kennels. The dogs all want attention. Johnson sticks her finger in the fence holes and each dog jumps up to give her little kisses. They are hoping for a treat from the 10 boxes of dog biscuits on the counter. Johnson brings Echo to the field next. Echo is deaf but that doesn’t stop Johnson from talking to him anyway.

“You ready for some play time? I’m going to impress you with my throws today,” Johnson says.

After playing with Echo, she walks into Cat Palace, where all the cats are held. She enters to find Jayanett talking about her day with two cats, Hannah and Fleur, in their kennel, and the volunteer playing with a kitten named Horace.

Ashley, a chunky tabby cat, is also in the room in her own kennel. She used to live with other cats but now lives separately because she always ate her roommate's food.

At closing time, Johnson puts all the dogs back into their kennels, makes sure each has fresh water and a blanket before she locks the kennels. Johnson prepares to head home and, as she leaves, she's already excited to be back the next morning.

After walking out of the building, she follows the paw prints back to her car and listens to Sourdough’s bark echo into the night. n

Sean Rocca graduated with his bachelor’s degree in Communication in December, and hopes to work in sports broadcasting.

Her goal is to become a pediatric physician. Reaching that goal means careful time management, studying and not much relaxation. But that doesn't mean she doesn't make time for those around her.

photo by Kiarra Crayton

by Kiarra Crayton

As Alissa Meyerhoffer woke up at 6 a.m. on a November Wednesday morning, she began to prepare for her tiring day as a first-year medical student at East Carolina University.

Alissa watered her plants, sent emails, packed her lunch and got gas on her way to the Brody Medicine building on ECU’s Health Science Campus. She was already more productive than most of the students at the university.

Her early morning start is “a great time to get work done,” Alissa said.

“If you send an email, no one is going to send a reply that early so you can really just knock stuff out without having to worry about ‘Oh someone’s going to reply to me.’ You don't have to see it right then and there.”

As she sat outside on the porch of her apartment, she took in the crisp air, trying to mentally prepare for the day ahead. On this day,

Alissa had biochemistry class, histology and a two-hour anatomy lab, followed by lunch. For the second half of her day, she had the Step 1 prep class and a patient-based learning class.

Her Outlook calendar was filled with varying sizes of blue blocks. She uses the calendar to keep a detailed list of homework assignments, meetings, classes, and what she would like to accomplish for the day.

“I like it when I have a lot to do because that gives me a list of stuff to do, which then allows me to check things off my list,” she said. “I think also whenever I have stuff to do, I feel like there's less time and so I’ll be more likely to do it.”

Even during her undergraduate years at North Carolina State University, Alissa was never stagnant.

Grace Dodge is a three-year friend from N.C. State who first became acquainted with Alissa through a job Alissa had nominated her for. Their friendship grew stronger as they saw each other on a day-to-day basis during Grace’s freshman year and they still keep in contact.

Grace said Alissa always had to juggle things whether it was personal, professional or academic, which Grace thinks helped Alissa to prepare for the pace of medical school. On top of classes, Alissa juggled working in a pharmacy, as a campus tour guide, and by being a “very active mentor” in the Learning and Living Village at N.C. State.

“She’s perfect and she's not one of those people that are so perfect you hate them,” Grace said. “She’s great and you love her for it.”

On this day, Alissa arrived at the Brody building around 7:20 a.m. As she came out from the stairway into the second-floor hallway, Meredith Lamm, another first-year medical student, was standing in the hall, staring intently at the events board that was filled with papers covering all topics from internships and jobs

to research studies students can participate in.

“There was a dental study, and you can't brush your teeth for like three weeks,” Meredith said, only looking up from the board to see who was approaching.

“I can't imagine not brushing my teeth for a day,” Alissa replied.

Meredith wondered aloud if the study paid its participants.

“I don’t know if that would even make me consider it,” Alissa said, laughing.

While completing medical school, students can pursue a variety of specialties and jobs like the ones posted on the events board.

Some might pursue the surgery route, but Alissa wants to become a pediatric physician. After shadowing a heart surgeon last summer, Alissa realized surgery isn’t as glorious as “Grey’s Anatomy” makes it out to be.

For one thing, the operating room “is a really tiny spot. It's really

tedious and it's really important,” Alissa said. “I just don't want to have to go to work every day and say this is life or death for the person. Some people really enjoy that.”

Alissa didn’t have a clear decision on what to do for a career when she entered college. But she knew she wanted to pursue a job in the medical field after she volunteered at WakeMed in the middle of her undergraduate studies at N.C. State. She continued to feel out the medical field and gain experience working with patients, which would later help her when applying for medical school. Through trial and error, she found her desired specialty, pediatric care.

But first, Alissa needed to get through medical school, an ordeal 84% completed in the 2017–2018 class, according to an Association of American Medical Colleges report. However, that isn’t enough to alleviate the physician shortage across the U.S., maybe because the number of applicants in the 20222023 class was down 11.6% from the previous year, according to the

Association of American Medical Colleges website. Physician burnout hasn’t helped the shortage.

However, Alissa is determined to be among the 84% to graduate medical school. On this day, she sat in biochemistry class at 8 a.m., wearing teal scrub pants and a gray shirt, tucked in just enough in the front to see the knot at the top of her pants. Her fiery, gingercolored hair was in a slicked ponytail. She prepared an area where she could write notes on her iPad on the long, curved classroom table where she and several other students sat. Alissa’s black reusable water bottle and cinnamon raisin bagel were on her left. Before the class started, she warned that it was going to be boring.

While waiting for class to start, Alissa greeted each person who entered the room with a wave or “Good morning.” As the first-year class treasurer, she collects the class dues. So when someone came up to her with money, she thanked them, smiling, and added, “I’ll check you off right now.”

The first-year executive board uses the money to organize hot chocolate and cookie days, Valentine’s Day cards and other fun things to “make people feel connected with the rest of the class,” Alissa said.

In between classes Vedika Patel, another first-year medical student, walked over to express her dislike for the newly added Step 1 prep class. Alissa explained their relationship as a product from “trauma-bonding.”

“I would pay any amount of money to not take the Step class,” Vedika said.

“How much though, seriously?” Alissa responded.

“An irresponsible amount,” Vedika replied, laughing nervously.

According to the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination website, the Step 1 exam tests whether a student has learned basic concepts and medical procedures in their first two years of medical school. Those who pass can then move into their second half of medical school when the program includes more hands-on learning.

While Alissa doesn’t want to take the Step class either, “I’ve just made the executive decision to start studying now,” she said, even though the test is more than a year away.

The class was added to the first-year students' schedule because of the overwhelming number of students who were anxious to get ahead and start studying early, said Alyssa Arnold, the senior academic support specialist in the Office of Student Success and Wellness for ECU’s School of Medicine.

To students it seemed as though the 1 p.m. to 1:50 p.m. prep class was added the previous Monday, two days before the students were supposed to attend

the class. However, the calendar for the year, which contains a day-to-day breakdown of classes and their times, was last updated on July 21, 2023. Arnold said the confusion could’ve come from the calendar system not displaying the class until it was closer to the start date.

A student sitting behind Alissa said the class wasn’t about actually studying for the exam, although she still thought it was too early to study. She said the firstyear students were frustrated about the class being displayed so late.

“I just don't think anyone is in the right headspace,” the student added.

The class added to an already tough schedule for the first-year crew, 90 of whom started at Brody in August 2023. The new Wednesday class will help prepare students for an ordeal most people couldn't imagine. The exam is eight hours long, with a 45-minute break and is divided into seven 60-minute blocks. The total exam has 280 questions.

Arnold is a resource to students studying for the Step 1 exam along with other challenges. The Office of Student Success and Wellness offers a wide variety of resources like student success coaches, a basic science liaison, a wellness counselor for mental health and a tutoring program.

Arnold said the main issue for medical students to overcome is the pace and depth of the information presented during classes. Arnold takes her role very seriously as she tries to remind students why they chose medicine and to “help them see the sunshine that's behind the clouds.”

Unlike undergraduates, Arnold said students may have a full 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule based on lecture times.

“Medical students often feel like there's not enough time in the day,” she said, adding that she tries to help students adapt to the pace. “So it's, 'how do we

She’s perfect and she's not one of those people that are so perfect you hate them. She’s great and you love her for it.

manage time to where we can accomplish as much as possible?'”

When students come in to see Arnold, their demeanor depends mostly on how well they are performing academically. When a student is in good academic standing, Arnold said it's easier to bounce back from a bad test or quiz grade. On the flip side, when a student starts to take the slide down the slippery slope of bad grades, a digital notification warning alerts the student of their academic standing in a class. If things don’t improve, Arnold then puts together a plan with the student to try and dig out of the hole.

Arnold said because the medical program is so rigorous, students have the option of taking a leave of absence. This means a student can take a step back from medical school to focus on their personal life and

pick up where they left off a year after taking the leave. For an average student, it might be hard to come back from a bad grade or situation; however, Alissa doesn’t let it get to that point.

According to her friend Grace, “When Alissa is faced with a challenging situation there's almost no need to bounce back. She doesn’t seem to let it get her down in the first place. She’s very much a person who will see something, handle it and keep going. I think she has kind of the perspective of, ‘Alright, here it is, I’m gonna get it done.”’

Following seven hours of classes, Alissa arrived back at her apartment around 8:30 p.m. She settled in, dropping off her book bag and shoes at the door,

putting her lunch bag on the counter and taking a calming shower. She cleaned up around the house and texted her friends to check in on them. She then started to prepare for the next day.

“The overall thing that always comes across to me when Alissa talks about her work and school is how much she cares about what she's doing. And even when it gets really overwhelming between schoolwork…she still always makes time for the people around her,” Grace said.

Through her first semester at medical school, Alissa realized the biggest adjustment was the workload, although she also felt alone at times because she didn’t know anyone at ECU when she arrived. Over the semester she

was able to find her “core group of people.” It helps to have a strong support system when you’re 85 miles away from home.

Alissa hasn't regretted her choice of going to medical school, yet. She said she loves learning the material but sometimes the amount of information is overwhelming. She experienced that feeling in microbiology class during the first week of her second block of classes.

“It’s like, ‘Am I ever going to figure this out?’” Alissa recalled thinking.

So, she sat down with a friend and a second-year mentor to try to reorganize the information in a way that was easier for her to understand. When she does get overwhelmed, she reminds

herself, “Someone knows you can do this.”

With another three years left of medical school, Alissa has faced only a fraction of what’s to come. While she faces the hardships of medical school, she remains undaunted. She thrives in a chaotic environment, so naturally her career choice was the only suitable option. n

Kiarra Crayton is a May 2024 graduate of ECU and was editorin-chief of The East Carolinian. She loved her time at ECU, “and if I could, I would do it all over again!" In my little spare time, I enjoy being outdoors whether it's a short walk or going to an outdoor festival.”

1. Develop and maintain relations

Having people that you can reach out to is imperative. Try to take time out each day to speak to fellow medical students. Seeking advice about any issues you’re currently facing can help create coping strategies.

2. Take a break

When left to fester, feelings of stress, angst and burnout can lead to insomnia, depression and a range of other anxiety-related disorders. Recognise the need to take a step back, breathe and give yourself a break.

3. Exercise regularly

Whether it be a long jog or a 20-minute stroll, exercise has been shown to reduce levels of the body’s stress hormones, while stimulating the production of endorphins.

4. Nail your sleeping pattern

Ensuring you get a good night’s sleep can make a massive difference to your overall level of stress. Losing sleep on a regular basis can lead to increased feelings of stress, anger, sadness and exhaustion. Prioritise getting at least seven hours of sleep per night. Naps of 20 minutes or 90 minutes have been shown to make a big difference to your level of cognition, while also lowering the risk of diabetes, depression and heart disease.

5. Practice mindfulness techniques

Meditating, for example, has been shown in various studies to reduce the reactivity of the amygdala – a region of the brain typically associated with stress. Likewise, breathing exercises have been shown to reduce stress and enhance your mood.

source: International Medical Aid photo: CC0 public domain

What's it like working the graveyard shift as a university police officer? Journalism student Martha Nebab rides along with ECU Police Sgt. George Dawkins to observe a typical evening, and also explores the bigger picture of protecting and serving a university community.

It was 10 p.m. on a quiet November Thursday. A waning gibbous moon hung over Greenville like a half-lidded eye and watched the people below. The air was crisp and getting colder, filled with the rustle of leaves as the cars kicked up a breeze through the streets.

ECU Police Sgt. George Dawkins wasn’t on his way to anywhere in particular. He scanned his surroundings, shifted his eyes across the dash of his car, much like the watchful moon above him. The front windows of Dawkins’s patrol car were cracked open a couple of inches so he could hear what’s outside.

“I usually keep an eye out for anything out of the norm,” he said, “whether that’s people, their actions, or a suspicious vehicle. Any type of disturbance.”

Dawkins said he never followed the same path every night and instead patrolled an area in downtown Greenville and around campus. One hand was on the wheel, the other on the keyboard of a heavy laptop that occupied much of the passenger seat. He typed the license plate numbers of cars he passed.

This was all routine for his first and only shift — the graveyard shift. He clocks out before the moon closes its eye at 6 a.m.

At the intersection of South Elm and East 10th Street, Dawkins typed the plate number of a blue Toyota Camry stopped at the light.

photo by Steve Mantilla, courtesy of ECU News and Communication

by Martha Nebab

by Martha Nebab

Students, most of the time, have a reason to be here. But they’re at a state of life where they’re alone and they experiment with the boundaries they can push. If they push too far, they don’t realize how it’ll affect the rest of their life.

A double take and under his breath, “Registration’s expired.”

He switched on his siren lights without the siren. The traffic light blinked green, but the car jerked to a stop, taillights red. Dawkins unclipped a radio from beside the wheel and spoke over a speaker, “Driver, pull onto Elm.”

Depending on the day of the week, Dawkins said there’s more activity near College Hill related to vehicle issues, pedestrians and traffic. Still, he said, “There’s nothing routine about a traffic stop.”

After the two cars pulled over to the shoulder of South Elm, Dawkins got out and walked to the driver’s side. He pulled a penlight from his vest pocket and scanned the interior as he talked with the driver. After a one-way exchange, Dawkins walked back and plugged the driver’s license into the computer. A few moments later, he said, “The car’s registration is expired, and the car smells like weed.”

Another car parked behind Dawkins, one from Greenville Police. The officer helped Dawkins lead two people out of the car, driver and passenger, and search them. The driver was a black male ECU student wearing a black T-shirt, low-hanging jeans and dreads. The passenger, another black male student, had an

Afro and a light gray sweatshirt. After the search, the two leaned on the hood of Dawkins’s patrol car, arms crossed, stiff, their backs bathed in the light of the two silent siren lights. They watched Dawkins search inside the car for the source of the smell.

The Greenville officer small-talked with the two men to ease tension, their conversations muffled by the passing traffic.

“It’s not a big deal,” the officer shrugged as he reassured the driver, who trembled a little. “You cold, man?” the officer asked with a laugh. “You gotta start walking out the house with a jacket from now on.”

Ten minutes passed as Dawkins searched with bluegloved hands, while the officer and the two students chuckled over the weather and living on campus, their breaths clouded in the cold air.

Dawkins then straightened and walked back to his car. He popped the license out of his laptop and gave it to the driver. Dawkins’s face was stern. He spoke and looked between both men as they shook their heads.

As the men returned to their cars, Dawkins said into the radio on his shoulder, “22, clear me, verbal.”

No weed, he said. “Just a fine powder called ‘kief,’ which is like the dust of the cannabis plant.”

The car belonged to the driver’s girlfriend, so he let them off with a warning. Unless the person has a criminal history, he lets people, especially students, know the dangers of what they’re doing by warning them.

Dawkins understood them. He is a former ECU student, after all. More than a decade ago, he was a fresh-faced business management graduate. Soon after he tossed the cap, Dawkins realized he didn’t want to sit behind a desk. Instead, he went into criminal justice. After a seven-month-long period of law enforcement training, he was hired by ECU Police, where he has remained for the past 13 years.

“When it comes to ECU Police, we kinda have a unique style of policing,” Dawkins said. “Students, most of the time, have a reason to be here. But they’re at a state of life where they’re alone and they experiment with the boundaries they can push. If they push too far, they don’t realize how it’ll affect the rest of their life.”

Around 10:45 p.m., Dawkins patrolled and scanned the mostly empty campus streets.

“Usually, people would be everywhere by now,” he said. “Maybe people are still tired from Halloween weekend.” He chuckled at his joke and smiled a smile rarely seen during his shift.

•The average daily population served is approximately 40,000, including students, faculty, staff and visitors.

•The department's statutory arrest jurisdiction includes all university property as well as streets and sidewalks adjacent to the property.

•The department participates in a mutual aid agreement with other local departments, including the City of Greenville, which gives university officers jurisdiction in much of the city-area surrounding the university.

•The ECU Police Department consists of 55 full-time sworn police officer positions, up to 10 sworn reserve officer positions, and 16 nonsworn departmental personnel.

source: police.ecu.edu

Over the years, Dawkins noticed how ECU’s party atmosphere changed. “A lot of the stuff is the same every year, like larceny, alcohol, drugs. But it’s not as wild as it used to be since COVID, for sure.”

Dawkins remarked it was a slow Thursday. After the traffic stop, there were no reports to respond to, though Dawkins gave warnings to an overcrowded car of football players and an impatient student who rushed a crosswalk.

Lt. Richard Taylor, Dawkins’s superior and a shift manager for ECU Police, worked from 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. that day, with insight into both the day and night shift.

“There’s usually more movement during the day,” Taylor said. “And you have a higher frequency of people around campus. The frequency also increases the opportunity for crime, but not by much.”

By 11 p.m., Dawkins exhausted his on-campus area. He slowed down to enter the off-campus neighborhoods. The windows of the passing houses were dark, barely illuminated by streetlamps, yet he scanned the house fronts with the watchful eye of his headlights. The roads became rougher the further away from campus he drove.

Dawkins said there are two downsides to his job. Since he works every other weekend, over the holidays and during football games, Dawkins almost never has a weekend off. As a result, he spends less time with his family in order to sleep during the day and recharge for the next shift.

Chris Sutton, the field operations captain who’s responsible for the patrol division, said the reality of the job is much grimmer.

“This profession eats into your personal time a lot,” Sutton said. “It’s also a profession where you don’t have as many people going into it as what you have leaving it.”

Sutton has worked for ECU Police for over 23 years. Like him, older officers are slowly working fewer hours or retiring altogether, while the newly hired officers aren’t inclined to work overtime yet, leading some officers to be stretched thin, like Dawkins.

“At some point, we're gonna see a very problematic struggle in this profession,” Sutton said.

Jason Sugg, the newly appointed ECU Police chief, said police departments across the country have seen a general decline in applications since the pandemic three years ago. Fortunately, ECU Police has seen a recent rise in applications, although hiring has been slow. Sugg said a few well-qualified candidates have been given conditional offers to fill the three vacancies, out of 55 positions. Two officers left ECU Police for positions in Raleigh and Charlotte in 2023.

“When the economy is doing well, I’ve seen over time that it isn’t uncommon for people to go into other fields or choose other jobs than being a police officer,” Sugg said. “When you compare police officer salaries to other jobs, like those in tech, a lot of times the police officer salaries are generally lower.”

Across the UNC system, Sugg said universities were experiencing vacancies at varying levels, but felt them more strongly in metropolitan areas such as Raleigh, Greensboro and Charlotte. However, the effects were even felt, and magnified, at smaller universities such as Elizabeth City State, where Sugg served as an interim deputy chief for three months last fall. To combat this, Sugg said the UNC system conducted market studies and used the results to create a new salary structure that increased pay by about 5% for university employees.

“Any time you establish a salary plan that offers more, it’s very helpful for us to recruit and retain people,” he said.

However, the unseen dangers of the job can’t be measured in dollars, such as what Dawkins quietly described as the need to compartmentalize emotions.

“If you allow yourself to feel emotions,” he explained, “it could be dangerous for you or other officers to go down a dark hole.”

Dawkins stopped at an empty street, an emptier look in his eyes. He said the most mentally-taxing reports he’s responded to were those that involved

children, since he’s married with kids. On one report he responded to, a child almost drowned in a pool; another, an accident so terrible he couldn’t describe it; another, a drug search warrant gone awry when a college student shot an ECU police officer.

“Sometimes, you have to realize that the other person on the end of the line needs our help. It’s more traumatic for them than it is for us,” he said. “It’s all something you get used to, when you go through enough of ‘em. You lose emotions.”

Although it’s what an officer is trained to do, Sugg said, this tactic isn’t a healthy habit.

“You have to remember you’re here for a job, so you need to be professional in order to find a positive or reasonable resolution,” he said. “Sometimes, in order to do that, you have to set your own emotions aside.”

To help with this, Sugg said ECU Police does offer confidential mental health services through its employee assistance programs at no cost to the officers. These programs have been in place for longer than 25 years.

“The majority of employees in their career will probably never take advantage of the program, but the fact that they know they are there is one of the best things,” he said.

Sugg also encourages officers to take time off whenever they can.

Officer Anthony Stevenson, who has been with ECU Police for four years, worked for Greenville Police for five years before transferring to ECU. The atmosphere at Greenville Police was very fast-paced, since Stevenson was in a very big department. Although he felt close

to the officers on his shift, “it kind of feels like you’re a number there sometimes.”

While there, Stevenson said the call volume was very high. He could have 18 calls pending as soon as he got to work. Back then, his main focus was to clear each call and move on. Stevenson said he transferred to ECU Police because of its smaller department, where he’s able to develop closer relationships with officers and cultivate connections with people on campus.

“It feels good to have that time to sit there and investigate our own cases and to be able to solve them a lot quicker, because our call volume isn’t as high,” he said.

The ease of getting an education and advancing through ranks at ECU Police also appealed to Stevenson. He said these benefits show he’s able to grow. “It motivates people to put in more work to train and better themselves,

while also rewarding them,” he said. “If there’s no advancement, then people tend to stay the same.”

It was 11:37 p.m. when Dawkins began driving again, making a turn back onto a familiar street that led back to campus. There is a silver lining, he said, a reason he keeps clocking in: “I really enjoy working with the campus community, all the college kids,” he said. “I know it sounds cliché, but it’s true.”

Dawkins said he landed this job right out of college, and it, so far, has checked all his boxes: “You’ll be able to save a life, find a missing juvenile, have the choice to not give a college kid a ticket, but to teach them a life lesson in order to create a better future for them.”

He turned onto Cotanche Street in downtown Greenville. The white streetlamps shone light on his face. A few officers were gathered

around Stilllife, a popular bar where college students let loose and party. Dawkins saluted a Greenville Police officer, who waved back.

Although Dawkins has had days when he didn’t want to get into the patrol car, the atmosphere at ECU helps him turn the key and push through those days.

“I think I have a good job right now. Things could definitely be worse elsewhere.”

The moon that watched Greenville withdrew behind the clouds; its glow grew smaller, kinder. At around 6 a.m., the end of his shift, a car door slammed. The sun woke up just as Dawkins crawled into bed to sleep. n

Martha Nebab is a communication major with a minor in creative writing from Raleigh, North Carolina. After her graduation in December 2024, she hopes to write feature and fiction stories for a magazine or newspaper.

•Always let someone know where you are.

•Familiarize yourself with the locations of the Emergency Blue-Light Phones on campus

•Do not wear headphones while walking or jogging.

•Walk in the center of the sidewalk-away from buildings, doorways, hedges and parked cars.

•Carry a noise-making device (shrill whistles, hand-held alarms).

•Wear shoes and clothes that will allow you to move quickly.

•Enroll in a personal safety course.

For additional safety tips from the East Carolina University Police Department, please visit: police.ecu.edu/safety-tips/

by Demetrius Williams

by Demetrius Williams

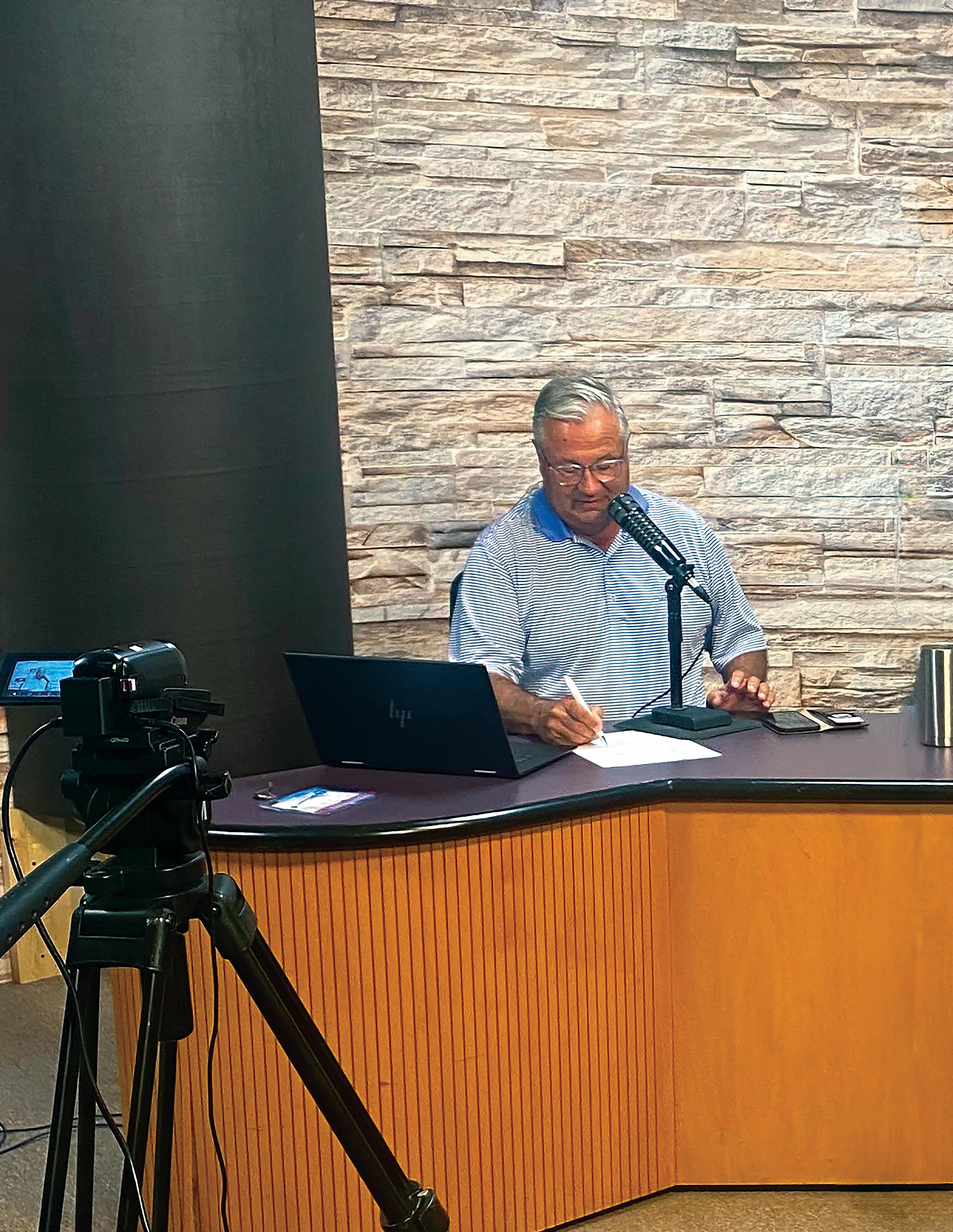

Henry Hinton is recognized by many in Eastern North Carolina thanks to a long-spanning career in broadcasting. Yet, perhaps less well known is the story of how Hinton combined two of his passions — his hometown and radio — into the successful ownership of his own media company.

The year was 1983 and sports radio announcer Henry Hinton had moved from broadcasting East Carolina University football games in Greenville to a similar job in Chapel Hill, where he was the “color” announcer for Carolina football games aired on the Tar Heel Sports Network and WCHL radio. The game was about to start, and Hinton found himself announcing the opening line he had long been calling out at the start of games in Greenville: “Welcome to Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium!” Except, it wasn’t Dowdy-Ficklen. It was UNC’s Kenan Stadium.

Henry Hinton prepares for "Talk of the Town," which is broadcast on two radio stations and also available for viewing on social media and via an app.

by Demetrius Williams“I thought my career was over right there,” Hinton recalled, “but I got to do seven years on the Tar Heel Network. They forgave me. That was a tough one, though. But you make mistakes, and you learn and grow.”

Now 70 Hinton has learned and grown through a long, successful career in radio that has seen him continue to innovate and stay up to date in the digital age. Long before he became president and owner of Inner Banks Media in 2007, radio was a part of Hinton’s life, dating back to high school, when he would hang out with an older friend who had an afternoon show on the air.

“I kind of got bitten by the bug, hanging out with her, pulling her AP wire copy and getting her coffee,” Hinton said. “I was no more than 15 or 16 at the time.”

Hinton's experience in radio started in the 1970s and has developed into a long and multi-faceted career.

Top: Hinton in 1973 on the air at WOOW in downtown Greenville

Bottom: Hinton in studio in 1989 after starting a new company in Greenville An

Hinton’s adventures in radio would take a turn during his sophomore year at ECU. He was on the staff of WECU, the campus station before it became WZMB in 1972. Hinton joined for fun and worked for the campus station for about a year until he was hired by WOOW in 1973.

“It was more a fraternity, a club. Everyone was hanging out, and I had an interest in it. I didn’t think I would ever get serious about it but apparently I was good enough to get hired by the local commercial station, which was [the] only Greenville Top 40 station back in those days,” Hinton explained.

This was an abrupt change in plans for a college student studying to be a teacher and a coach. Hinton said his parents supported his new career.

“They would’ve supported me if I told them I wanted to become a dog catcher; they were just great parents. They liked the fact that I was getting into radio. It was a different time; it was the ‘70s. Getting on to the radio and being on the radio back in those days was a big deal, a lot different than today, to be honest with you,” said Hinton.

Hinton’s radio work in Greenville led to a job offer from WGH radio in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1975, when he was still a senior at ECU. So Hinton would drive to Norfolk on Fridays and work the Saturday and Sunday shifts, then drive back to Greenville on Sunday nights for classes on Monday.

After graduating in 1976, he was hired full time. Hinton said the 50,000-watt WGH AM station was probably the biggest radio property between Atlanta and Washington and one of the top 50 radio stations in the country. His parents were proud to be able to hear him on the air.

Hinton would secure a job at UNC Chapel Hill for the Tar Heel Sports Network and WCHL in 1983. For the next seven years, he worked as general manager for WCHL and as a color announcer on the Tar Heel Sports Network. Hinton broadcast all UNC football and basketball games, home and away. His first year on the network was the legendary Michael Jordan’s last year playing basketball at UNC. Hinton remembers being in the room when Jordan announced he would be playing for the NBA.

Hinton returned to Greenville in 1989, wanting to start his own radio station in a geographic market that was more affordable for a young broadcaster trying to start a company.

He does a great job of inviting people in; people from both sides of the political spectrum like to listen to him. Some probably like what he says, some of them don’t, and others just want to hear what he has to say.

“I turned down several offers to stay with Vilcom and other broadcast companies . . . in the Triangle because I wanted to own my own stations,” Hinton recalled. “I also loved living in Greenville and felt a strong connection to it since I lived here for many years before and attended ECU.”

While Hinton was exploring his options, he met with ECU Athletics Director Dave Hart. Hart told Hinton that ECU would be willing to partner with him to broadcast its games on an FM station. At the time, ECU games were broadcast only on AM radio. Hinton said the offer played a big role in his decision to start his company in Greenville.

Today, according to its website, Inner Banks Media owns and operates six FM radio stations, one low power FM translator and one local cable television

station that covers eastern North Carolina from the Virginia border down to Wilmington, North Carolina. One of its radio stations, WNCT-FM, is a top-3 station in the Greenville-New Bern-Jacksonville metro region.

Inner Banks Media’s talk stations affiliate with national conservative talk radio shows by Sean Hannity, Mark Levin, Glenn Beck, Clay Travis and Buck Sexton. Other stations focus on music or sports, with several sports talk programs produced locally.

In addition to broadcasting ECU games, ECU sports press conferences are also aired live. Financial, health and church programs round out the programming.

Hinton’s own show, “Talk of the Town,” is the most popular show on the station, produced every weekday morning from 7 to 9 a.m. The show publicizes information and events that go on in the Greenville area.

Greenville Mayor P.J. Connelly says Hinton has a presence that evokes attention and helps to spread

the message about things that are happening in the community.

“We’ve seen he has quite the audience that pays attention to his radio show,” Connelly said. “He’s been instrumental in letting people know when issues come up or if we have events that are taking place; he likes to

Whether it be in a car, by the beach or near the pool, listening habits are changing and if you don’t change with it, you’re certainly going to be in trouble...

invite guests on his show to discuss said events. It’s a benefit for our city.”

Connelly says Hinton’s positive personality is one of the many factors that has allowed him to have such a long career in Greenville.

“He does a great job of inviting people in; people from both sides of the political spectrum like to listen to him. Some probably like what he says, some of them don’t, and others just want to hear what he has to say.”

Connelly also mentioned Hinton’s Christmas toy drives in partnership with the Salvation Army and Greenville Fire and Rescue.

“We’re very thankful for what Hinton’s done and what his radio station continues to do,” said Connelly.

Despite his success, Hinton has had to battle the digital age stigma that radio is on the decline. He has continued to innovate his business to combat the notion about radio having no future.

“I don’t think radio is dying; I think radio is changing. I think it’s going to continue to change,” Hinton said.

His company now has its own app for listeners to access broadcasts digitally.

“That would’ve been unheard of five years ago,” said Hinton.

The IBX media app for ECU’s first football game of 2023 generated over 3,000 listeners, not including the thousands listening on radio over the air.

Hinton said his stations’ listenership continues to grow, as do their advertising sales records.

“Whether it be in a car, by the beach or near the pool, listening habits are changing and if you don’t change with it, you’re certainly going to be in trouble in 2023. But radio is not dying. We’ve had a 10-year run of growth year by year that I’m happy with,” Hinton said.

“Anyone that tells me radio is dying, I can refute that.”

Hank Hinton, Henry’s son and co-owner of Inner Banks Media, said his father played a big role in his decision that radio was also the career for him. “I wasn’t sure what I was going to do. I decided I wanted

Henry Hinton Sr. with his son, who is co-owner of Inner Banks Media. photo courtesy of IBX MediaYou got to be focused, you got to be fearless, and you got to have fun.

to work in radio in Raleigh and not work for him at first. It wasn’t until someone left his company and I joined him in 2002,” Hank Hinton recalled. “If it wasn’t for him, I never would’ve thought about going into the radio business, and I’ve been in media sales the last 20 years ever since.”

Hank remembers a lesson from when he first started working in his father’s company and said the message still carries on with him to this day: “The three f’s. You got to be focused, you got to be fearless, and you got to have fun. Focused on the task, fearless in sales; you got to walk into businesses and introduce yourself and you can’t be afraid about it. Nobody wants to buy from somebody who’s nervous about what they are selling.”

And, he added, if you’re not having fun you’re not going to stay in the business. Hank, 45, is proud of his father’s broadcasting career and said he enjoyed listening to him on the air growing up. Yet, unlike his father, Hank has no desire to be on the air, even after his father retires:

“I have tried to stay off the air in our 20-plus years working together. . . I enjoy the media business and would prefer to stay in a management role without being an on-air personality, but I won’t say never.”

Chris Cooke, a former intern at WNCT and now

producer at WITN television, says Hinton played an influential role in his career.

“Being able to mentor under Mr. Hinton was an experience. You really get to see the ins and outs of what goes into producing and broadcasting a daily show. You learn how to manage the soundboard, be an on-site producer and write sports updates,” said Cooke.

Cooke said during his internship he realized how encouraging and influential Hinton is. Cooke said Hinton is a legend in the industry, but that he also takes the time to appreciate and encourage those who show they want to learn radio.

Now 70, Hinton thinks about retirement within the next three to five years, after he fulfills some lingering obligations with Inner Banks Media and pays off some loans. Hinton wants to transition into more of a parttime job, working maybe two to three times a week, with his son taking over the company when he retires.

Even as retirement seems to be knocking at the door, Hinton has marked his name in the history of broadcast radio in the region, from a boy who grew up in Chowan County, to becoming a legend in his own right in radio. n

"The Greatest to Ever Do It!" Demetrius Williams says you’ll see that tagline about him as he makes a name for himself in radio, following his graduation with a degree in Communication in May 2024. “As long I have God, my family and friends by my side, my success has already been guaranteed.”

•An active supporter of higher education, Hinton is a former member of the UNC Board of Governors and chairman of the ECU Foundation Board.

•He was enshrined into the North Carolina Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 2015.

•Hinton and his son, Hank, own Inner Banks Media, which owns and operates six FM radio stations in easter n North Carolina.

•In 2016, Hinton received the Outstanding Alumni Award from his alma mater East Carolina University.

•He is the former chairman of the Greenville-Pitt County Chamber of Commerce and was named Greenville’s Business Leader of the Year in 2002.

source: ncspin.com

Teach For America alumna Lauren Lampron has been the principal at SouthWest Edgecombe High School in Pine Tops, North Carolina, since 2020 and was named the 2021–2022 Edgecombe County Principal of The Year. She's pictured here at a recent Washington County Schools professional development day.

photo by Julie Simpson by Jack Meltsner

by Jack Meltsner

From bringing in specialists who provide career opportunities to introducing a "POWER hour" to help students develop their interests, Dr. Lauren Lampron wants to help students discover the futures education can make possible.

Afive-second beep came over the intercom as 12th grader Jason walked with his elbows tucked in, grabbing onto his backpack through an always open wooden door into Dr. Lauren Lampron’s office. Jason sat down across the principal’s glossy wooden desk anxiously ready for their 9:30 a.m. meeting.

The 5-foot-7, brown-haired woman pulled out a graphic organizer and a dark maroon pen.

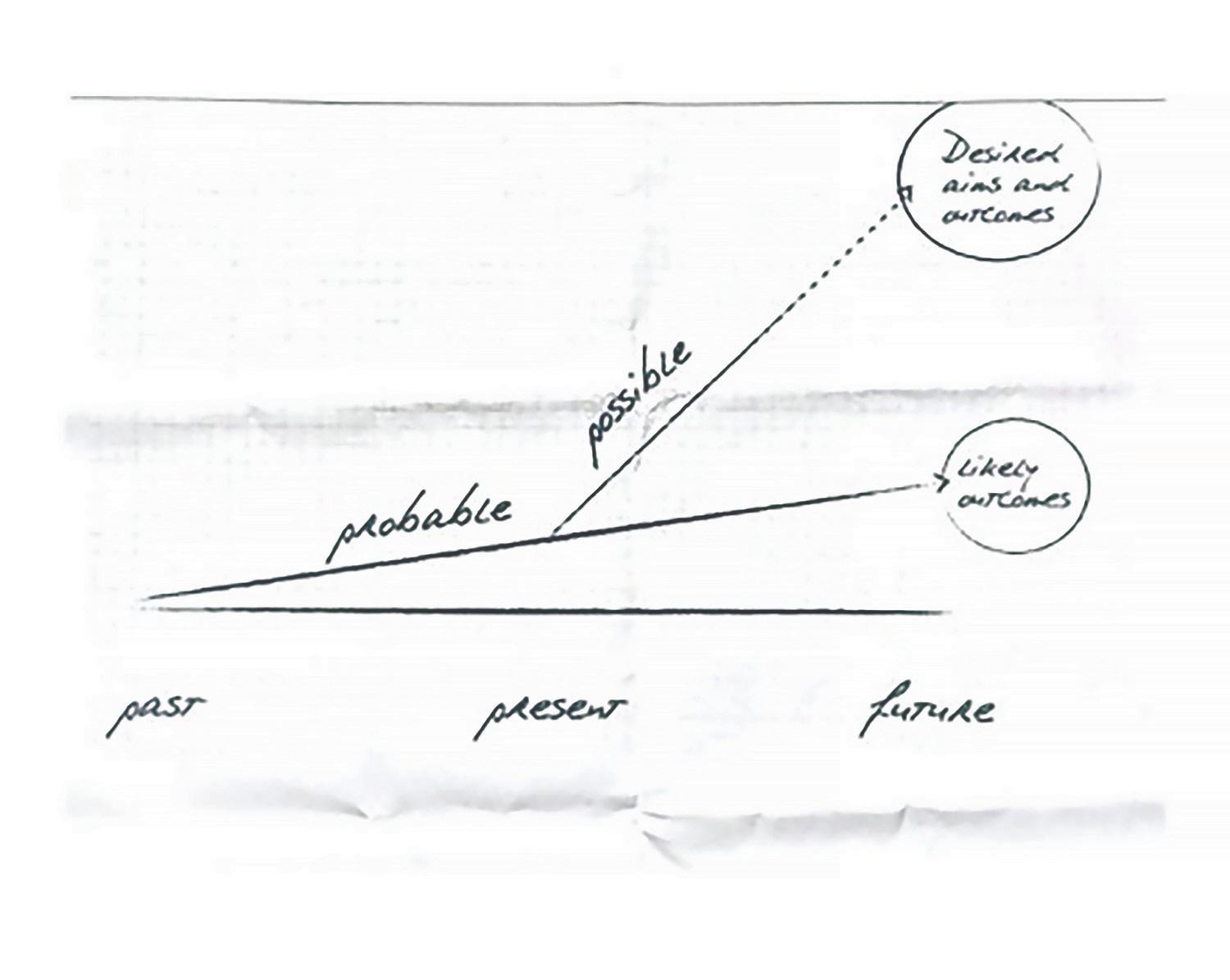

They began one of Lampron’s many exercises designed to help students work through their motivation, desire and interests for life while predicting a possible future beyond high school. The graphic organizer she uses features a graph showing the student’s past, present and future across the x axis.

“We talk about what was your past like, what’s your present, what’s the predictable future and then the probable [future], which is doing a little bit better, and then we want the possible future,” Lampron told Jason. “Basically, what we’re trying to do is fill in all these gaps to change your line from low to high.”

First-generation college student and Teach For America alumna Lauren Lampron has been the principal at SouthWest Edgecombe High School in Pinetops, North Carolina, since 2020 and was named the 2021–2022 Edgecombe County Principal of The Year. The high school serves an area where

We talk about what was your past like, what’s your present, what’s the predictable future and then the probable [future], which is doing a little bit better, and then we want the possible future.

most adults don’t have a higher education and the average income is well below the national average. Lampron works to inspire students who haven’t been exposed to what they can become by getting to know each student on a personal level and providing students with alternative options for college.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 17.4% of Edgecombe County adults older than 25 have at least a bachelor’s degree, far

lower than the national average of 37%. The county’s per capita income in 2022 was $25,813, 31% lower than the $37,641 per capita income in all of North Carolina. Nearly 21% of Edgecombe County residents live in poverty.

Lampron found herself in Edgecombe County through her Teach For America journey. After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in psychology from West Chester University just outside

of Philadelphia, Lampron enrolled in Teach For America, which is a nonprofit organization under the AmeriCorps umbrella that focuses on resolving educational inequity in lower income communities around the country.

Teach For America was created by Princeton University graduate Wendy Kopp in 1989 and recruits recent college graduates and professionals to teach in underserved communities across the country. The program starts with a five-week teaching practicum institute over the summer before a two-year contract at a placement school that’s done simultaneously with graduate school. TFA provides an educational award that can be used to pay for student loans. The program is popular among college graduates with education, psychology and social work degrees who have a passion for impacting others.

Teach For America Kansas City Accelerate Managing Director Johanna Laxton explains that the organization’s mission is to give all students an equal education and facilitate community leadership.

“At its core, Teach For America’s mission is extending educational opportunities and ensuring that every student in the nation has access to an equitable education,” Laxton said. TFA does this by developing and supporting leaders, “whether it be teachers in the classroom currently or past core members who have gone on to do other things, having a really diverse network of equity-oriented leaders working to transform education,” she added.

Lampron followed the mission of Teach For America beginning as a core member teacher while pursuing a master’s degree in school administration before moving into leadership roles where she’s earned awards for her dedication to her students and community.

In October 2023, Lampron was named director of the North Carolina Principal Fellows Program – a state-supported scholarship loan program that prepares future public school leaders.

“I literally think that teaching is the most important profession and so there’s just a lot of pressure to get it right. So, it almost feels like you're a kid yourself,” Lampron said.

Back in 2010, 21-year-old Lampron packed her life into her 2008 Hyundai Tiburon and drove 16 hours to Mississippi for her assigned Teach For America Institute, where she trained during the summer before being placed as a seventh and eighth grade teacher in Edgecombe County. She’s since been the assistant principal and principal at W.A. Pattillo Middle School in Tarboro before joining SouthWest Edgecombe High School, the biggest school in the county, in 2020.

•Teach For America is a leadership development organization and a network of nearly 70,000 leaders who started in the classroom.

•Corps members teach full time for at least two years in schools that are underserved due to systemic racism and/ or poverty.

•Members remain in lifelong pursuit of the opportunity for all children to attain an excellent education.

•At nearly 70,000 strong, ther movement has expanded opportunity for millions of students since 1990.

•4 out of 5 of alumni remain working full-time in education or other careers that impact low-income communities.

source: teachforamerica.org

Lampron makes it a priority to get to know her 757 students and staff on a personal level. She's shown here joining students during their "POWER" hour — an hour each day during which students choose their activities.

Pennsylvania, during her first Thanksgiving break, she was ready to quit. But while she was home, she got a call from a student's parent.

“I went home and there was an incident that happened in our community and a parent called me very early in the morning and I was able to reconnect

I literally think that teaching is the most important profession and so there’s just a lot of pressure to get it right. So, it almost feels like you're a kid yourself.

he and his son,” Lampron said. “I remember really internalizing the fact that the community knows I care about their kids, so it felt like a moral obligation to return.”

Lampron returned to Edgecombe County after the break and found her groove in the classroom. She had gained the respect of her students and was ready to fully commit to helping her students reach their full potential. She used her psychology background to implement what she calls conscious learning for both her staff and students, and started to climb the leadership ladder in the Edgecombe County Public School system.

Along with serving the community they are placed in, Teach For America members often develop a community of young adults who share a passion for helping others. The organization purposely sets up clusters of members at the same schools and districts to help foster a learning and living community that extends beyond the school building. Teach For America members often spend their free time together and become each other’s families away from home, establishing a network of young professionals who share a goal of serving others.

Teach For America Core Members are encouraged to treat their communities like their own, getting to

know the support and lower level staff including janitors, cafeteria workers and bus drivers along with students’ family members and friends who don’t work at the school.

As principal of SouthWest Edgecombe High School, Lampron makes it a priority to get to know her 757 students and staff on a personal level. She’s started programs to help her students grow and find their purpose during and after high school.

Senior Allie Smith notices Lampron’s leadership style. “She’s always so go-gitty, like she’s always gonna be there to talk and listen to my concerns,” she explained.

This year, Lampron introduced an hour-long block called the “POWER” hour, which stands for Plan, Organize, Work, Eat, Relax. It’s an hour each day when students pick what activities they want to do and join several clubs, ranging from anime to fishing.

Lampron explains that this is one way students at SouthWest Edgecombe High are encouraged to discover their passions and become independent young adults who will contribute back to their community. Lampron believes that she is inspiring a new generation in Edgecombe County that will impact the area exponentially.

College advisor Jaleel Gilmore notices Lampron’s mission and sees it play out daily. “She has a really close relationship with all her students. I feel like she makes the students feel like they are a part of a family,” Gilmore said.

Along with college advising, Lampron has brought in specialists who provide students with career and educational opportunities, ranging from the local Fire Academy, Construction Academy, and electrician courses, to prep courses for the SAT and the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery Test.

“We are trying to offer a space where we can tap into all kids and give them a possible future. Our job as teachers is to make sure our kids are safe. Physically, holistically and mentally safe and if we happen to teach them something while they are here that’s great too,” Lampron said. “We’re trying to give kids the opportunity to see themselves as themselves and not what society has told them what they need to be.” n

Jack Meltsner is a senior who will graduate with his degree in communication in December 2024. In his free time, he enjoys watching sports, eating good food and being outside.

•manage budgets

•build community relationships

•help ensure safety

•support teacher development

•promote a positive school climate

•act as lifelong learners who stay up-to-date with evolving educational practices and trends, including engaging in continuous professional development

•foster student success

•deal with disciplinary issues

•inspire and motivate teachers, students and the rest of the school community to achieve academic excellence

•find innovative solutions to improve teaching and learning outcomes

•engage parents in the educational process

•foster open lines of communication to address concerns and keep everyone informed

•analyze data, set goals and work collaboratively with staff to implement strategies that enhance student achievement and school performance

•provide mentoring, coaching and professional development opportunities to ensure that teachers continually enhance their skills and knowledge.

source: facts.net/ "14 Surprising Facts About School Principal"

by Anna Tart

by Anna Tart

For many schools, especially rural ones, fallout from the pandemic is still being felt. Teacher shortages, doubts about ability to catch up and various other challenges are haunting students even though they have long since returned to the classroom setting.

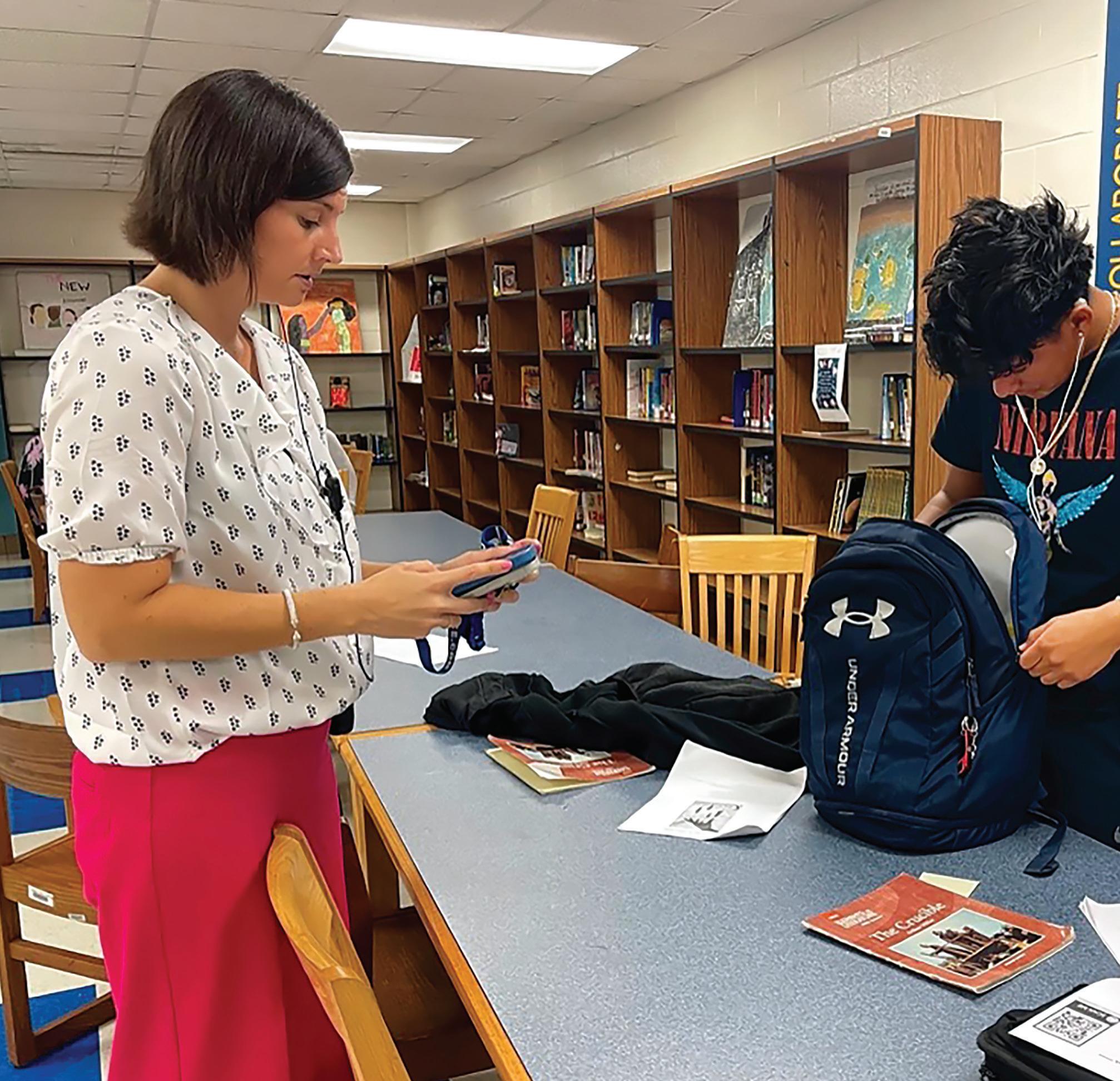

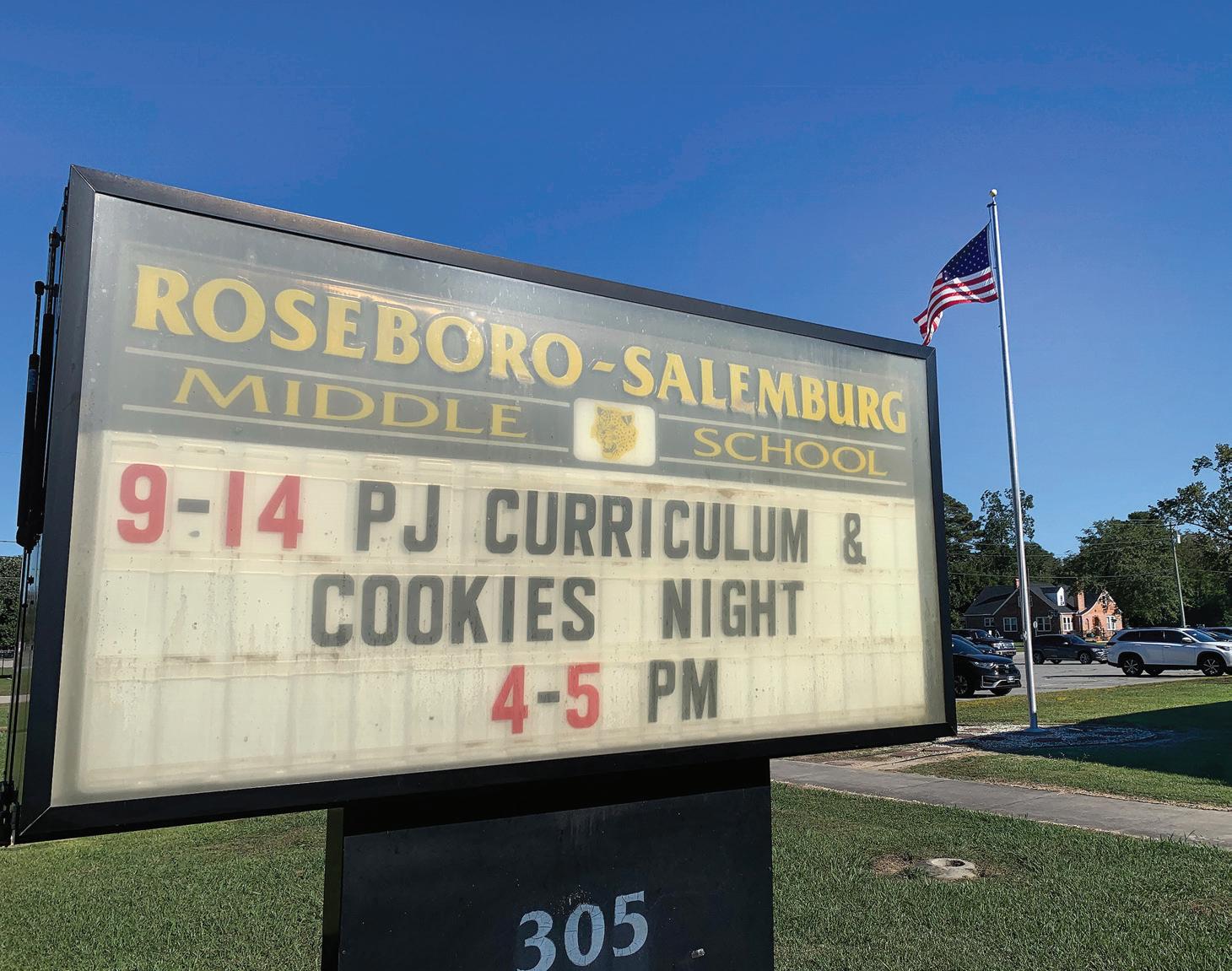

It was 8:05 a.m. as the tardy bell rang through the halls of RoseboroSalemburg Middle School. Instead of sitting in his homeroom class waiting for attendance to be taken, 14-year-old Elliott Tart stared down at the blinding white linoleum tiles of the eighth-grade hallway, surrounded by 113 of his peers. The air around him buzzed with the clatter of students, occasionally pierced by the shouts of teachers, instructing the class to divide into two groups — one for each classroom with a teacher for the day.

It was going to be a difficult morning for the teen as his teachers were forced to cram almost 60 students between the two rooms. Before entering his temporary classroom,

Elliott made sure to snag a spare chair from an empty, neighboring classroom. He knew that despite the uncomfortable stiffness of the red plastic seats, they would soon be in short supply as the classrooms would soon be double their maximum occupancy. It was 2022, and Elliott felt lucky to find a spare chair during the school’s frantic search to fill empty classrooms, let alone have teachers in every class a day or two out of every week that year. This had been a normal occurrence for Elliott since he started middle school in 2020. As in many schools in North Carolina, the persistent lack of teachers in the classroom continues to be a challenge for thousands of students like Elliott.

In 2023, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency for the state’s public education system with more than 5,000 teacher vacancies.

“North Carolina had the nation’s largest increase in teacher turnover rate from 2017 to now, two years after the pandemic,” said Dr. Jerry Johnson, a professor at East Carolina University’s College of Education.

Of these vacancies, schools in rural communities have been hit harder than those in suburban and urban districts. Johnson said that among the state’s five districts with the highest teacher turnover rate, four of the five are in rural areas. This was not surprising “given that North Carolina is getting worse at a faster rate than all other states and we know from a lot of research that it’s more of a challenge for rural areas,” Johnson said.

A report from The Rural School and Community Trust, a non-profit organization working to improve relationships between rural schools and their community, attributes the rural teacher shortage to inadequate funding, lack of amenities, social and geographic isolation, and limited access to professional development opportunities.

Dr. Holly Fales, the assistant dean for undergraduate affairs and educator preparation at ECU’s College of Education, says the geographical location of a school is a key component when considering the rise in teacher vacancies. She said the high rate of attrition in rural areas can be seen among beginning teachers within the first three years of their career.

According to Johnson, teaching in rural areas can be intimidating for beginning teachers as the community often differs significantly from where they completed their teaching program.

“Most rural communities don’t have their own institution for preparing teachers, so that’s a big challenge with recruitment,” he said.

Dr. Shawnda Cherry, the associate director of teacher residency at ECU’s College of Education, adds that teachers in rural districts are often required to take on more responsibilities than those in urban schools. Because staffing ratios are determined by student enrollment, rural schools are allotted fewer teaching positions overall and are faced with having to cover “multiple grade levels or teaching multiple classes within a department.”

Cherry says this can create feelings of professional isolation and inhibit collaboration among colleagues.

Just 25 miles west of Fayetteville, RoseboroSalemburg Middle School is no stranger to the impacts that typically come with being in a small, rural town. According to 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data, just over 1,100 people call the town of Roseboro home. In such a small town, it was not uncommon for Elliott to run into his classmates and teachers outside of school, whether at the park, the library or one of the town’s two strip malls.

The U.S. Census Bureau data also shows a 61% decrease in the percentage of teachers over two years within Roseboro’s working population. In 2019, education instruction was one of Roseboro’s highest

U.S. Census Bureau employment occupation data shows a 61% decline in the percentage of teachers in the town of Roseboro over two years. Roseboro-Salemburg Middle School is one of the schools in this small, rural town attempting to carry on in the midst of the decline.

areas of employment, accounting for almost 15% of the working population, according to Census data. In 2021, however, data shows that those working within educational services dropped to just 5.67% of the total.

Many factors contribute to the growing shortage of teachers in rural public schools; however, this trend exacerbated during the global shutdown brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

On March 16, 2020, North Carolina state officials issued an executive order for schools to close for two weeks amid uncertainty about the impacts of COVID-19. Elliott, who was a fifth grader at the time of the order, was ecstatic to hear the news about this short break from school; however, two weeks soon turned into three weeks, then a month, then for the remainder of the school year. Elliott’s excitement eventually transformed into fear when his academic future collapsed before him. He had hoped that the hiatus from school would be lifted by the time he was promoted from elementary school, but this, too, seemed out of reach.

It felt like I was completely alone during that time. Having to be a student and a teacher at the same time was really hard to manage, so I felt super far behind in school and my grades reflected it.

By the time Elliott was leaving fifth-grade, uncertainty and confusion crashed over him as he walked across the hot pavement of Salemburg Elementary School’s parking lot to receive his certificate of promotion, surrounded by the glare of car windshields and the smell of exhaust fumes instead of the smiling faces of friends and family sitting in the auditorium that would normally house the ceremony.

As Elliott started middle school in August 2020, it proved to be just as rocky as he imagined. He logged on to his computer at 8 a.m. every day only to be met with disarray and confusion. His teachers were not used to the virtual classroom, and many of his peers were not able to properly learn in that setting. This never-ending cycle became the new normal. Elliott’s teachers began to leave their profession, some staying only two weeks into the school year. For the first time in his schooling, Elliott felt inept and powerless, unable to grasp what little material he was given by the few teachers he had.

North Carolina had the nation’s largest increase in teacher turnover rate from 2017 to now, two years after the pandemic.

— Dr. Jerry Johnson, East Carolina University College of Education

Elliott, of course, is just one of many students who struggled academically during the pandemic. In 2020, Allegro West, Elliott’s friend, also started sixth grade at Roseboro-Salemburg Middle School. During the pandemic, she found it difficult to flourish while navigating school in an unstable classroom

The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated an already existing lack of access to the web and computers due to social, economic and educational inequalities across the country. Here are some fast facts about the digital divide:

•Households that are often most affected by this divide include rural households, lowincome households, and Black and Hispanic households.

•24 percent of rural adults say that access to high-speed internet is a “major problem” as opposed to 9 percent of urban adults.

•Over 75,000 students in North Carolina live in rural areas where internet providers have not even installed the lines needed for a highspeed internet connection.

•A 2016 report conducted by Free Press, found that only 54 percent of households with annual income below $20,000 had internet access, as opposed to almost 90 percent of households with income over $100,000.

source: Public Schools First NC

environment as the unprecedented switch to online learning was not something Allegro or her teachers were prepared for. With little communication and instruction from teachers during her sixth-grade year, Allegro spent countless late nights cramming lesson material that she barely understood.

“It felt like I was completely alone during that time,” Allegro said. “Having to be a student and a teacher at the same time was really hard to manage, so I felt super far behind in school and my grades reflected it.”

According to the Congressional Research Service, 83% of teachers said they were struggling to do their job while teaching remotely during the pandemic — and most of these said the district did not prepare them well to do so.

As a result, “the attrition rate was generally flat from 2017 to 2019, but then it spiked during COVID,” Johnson, the ECU professor, said. “It went down a little after the pandemic, but it didn’t come down in North Carolina as it did in other states. In fact, it spiked higher than most other states.”

Of course, with a lack of teachers and access to material during the pandemic, students like Elliott and Allegro are, even today, left struggling academically.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 42% of North Carolina public schools performed below proficient levels in 2022 — up 21% from 2019.

In addition to a lack of teachers during remote learning, the digital divide, or the difference between households with access to the Internet and those without, also challenged rural school districts. According to the Congressional Research Service, 22%

Some points to note about education in a post-pandemic era

•In 2024, on average, teachers made 26.4% less than their similarly educated peers in other professions.

•Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, stress topped the list of reasons teachers quit. Teachers report experiencing stress at about two times the rate of other working adults.

•Among current high school students in the South, just 4% say they would be interested in going into teaching.

source: Southern Regional Education Board

of Americans living in rural areas lack adequate access to the internet, and 20% of youth residing in these areas struggled to complete homework assignments due to poor connections.

Elliott had internet access, yet it was not uncommon for Elliott’s phone to ping frantically throughout his remote school day. He would get a flurry of messages from a friend desperately trying to find a source of connection to submit their homework. Instead of coming over to watch movies as usual, Elliott’s friend Ash would visit multiple times a week just to have access to the internet. He knew it was risky during the pandemic, but Elliott could not imagine the gutwrenching feeling of his friend falling even further behind in their education.

The constant panic that consumed Elliott during his sixth-grade year carried on through his last year in middle school. Despite the return to the classroom, the problems that the pandemic brought remained, including a short supply of teachers. For Elliott, this kept the possibility of adequately learning from his classes out of reach.

Elliott’s final day at Roseboro-Salemburg Middle School last spring was bittersweet. He sat in what used

•84% of parents want to have a personalized pathway plan for their child, outlining classes they could take in K-12 to help them achieve their individual career or college goals.

•The pandemic provided challenges, but also the opportunity to create more flexibility in education. It highlighted the limitations of traditional classroom- based learning. More options for remote learning, hybrid learning models, and other approaches that will accommodate the diverse needs of children and families are in demand.

source:: the74million.org

"With federal pandemic aid for K–12 schools set to expire in the fall of 2024, the most affected districts will likely need extra state and local dollars to continue their recovery efforts, the researchers say, and future life outcomes will be shaped by the extent to which achievement gaps for disadvantaged students, exacerbated by the pandemic, are closed."

source:: gse.harvard.edu

to be his math class awaiting his teachers’ instructions to walk to the gymnasium for their eighth-grade graduation ceremony. As he and his best friends excitedly discussed their summer plans, nervousness about his next step into high school was looming over Elliott like a dark storm cloud. The last three years had thrown several obstacles his way and required a steep learning curve that was almost impossible to manage. Just for the day, however, he decided to push these thoughts aside, instead shifting his focus to celebrating his and his classmates’ journey through the chaos. Despite the uncertain journey ahead of him, Elliott smiled to himself as he sat in the uncomfortable red plastic chair that he managed to snag on the way in for the very last time. n

Anna Tart is a communication major from Fayetteville working toward a master’s degree in communication through the accelerated master's program. When she graduates in 2025, she hopes to pursue a career as either a magazine writer or a television news reporter.

Editor's note:

Elliott Tart is the younger brother of this article's author.

by Alayna Boyer

by Alayna Boyer