Warrior Life

El Camino College Spring/Summer 2023

COMMUNITY ROOTS

A multicultural woman brings communities together via Social Justice Center

A STREAM CRIES FOR HELP

Trapped in a grave of cement, Dominguez Channel struggles to survive

SIMPLY THE BEST Filipino food, matcha, pizza and dog parks

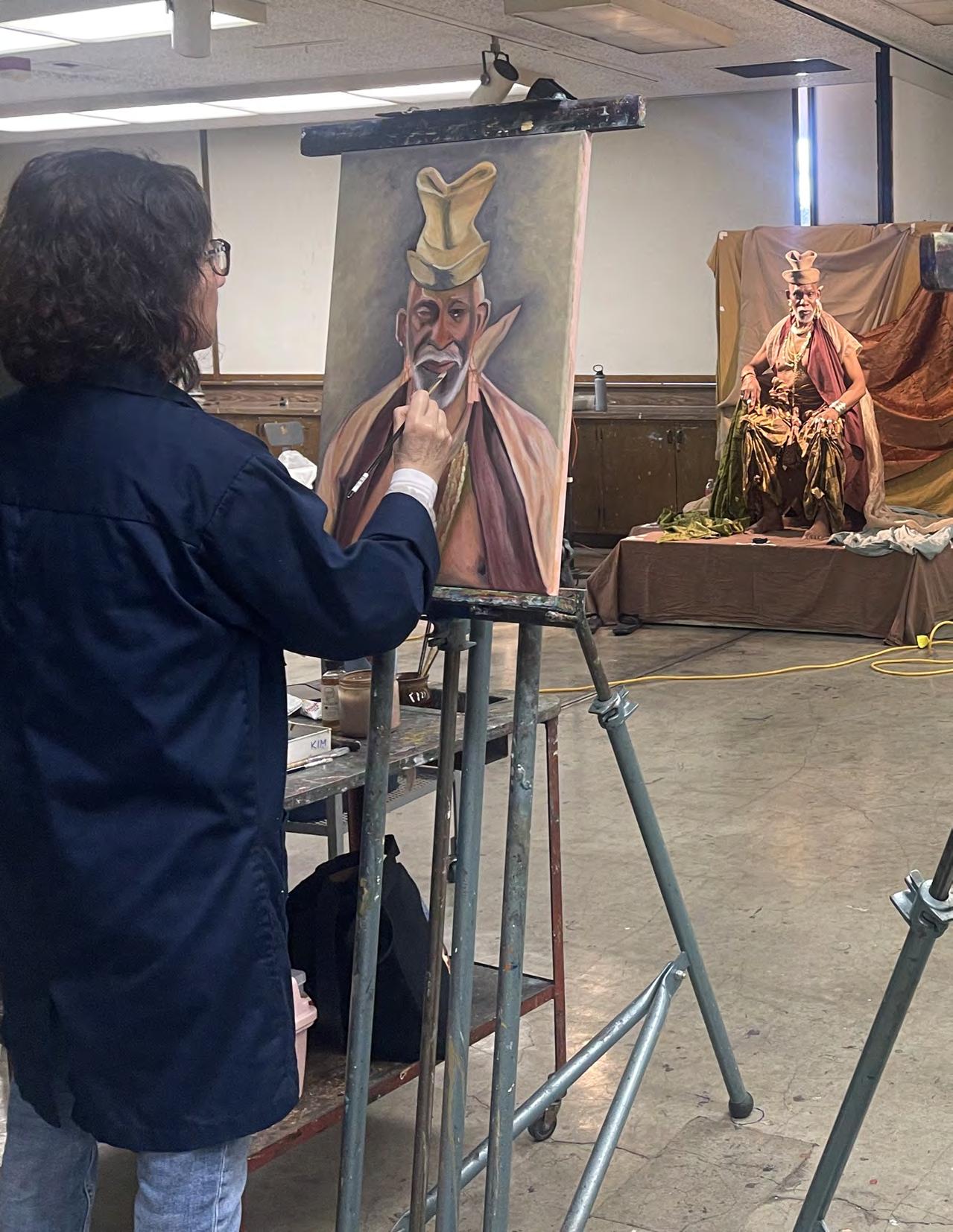

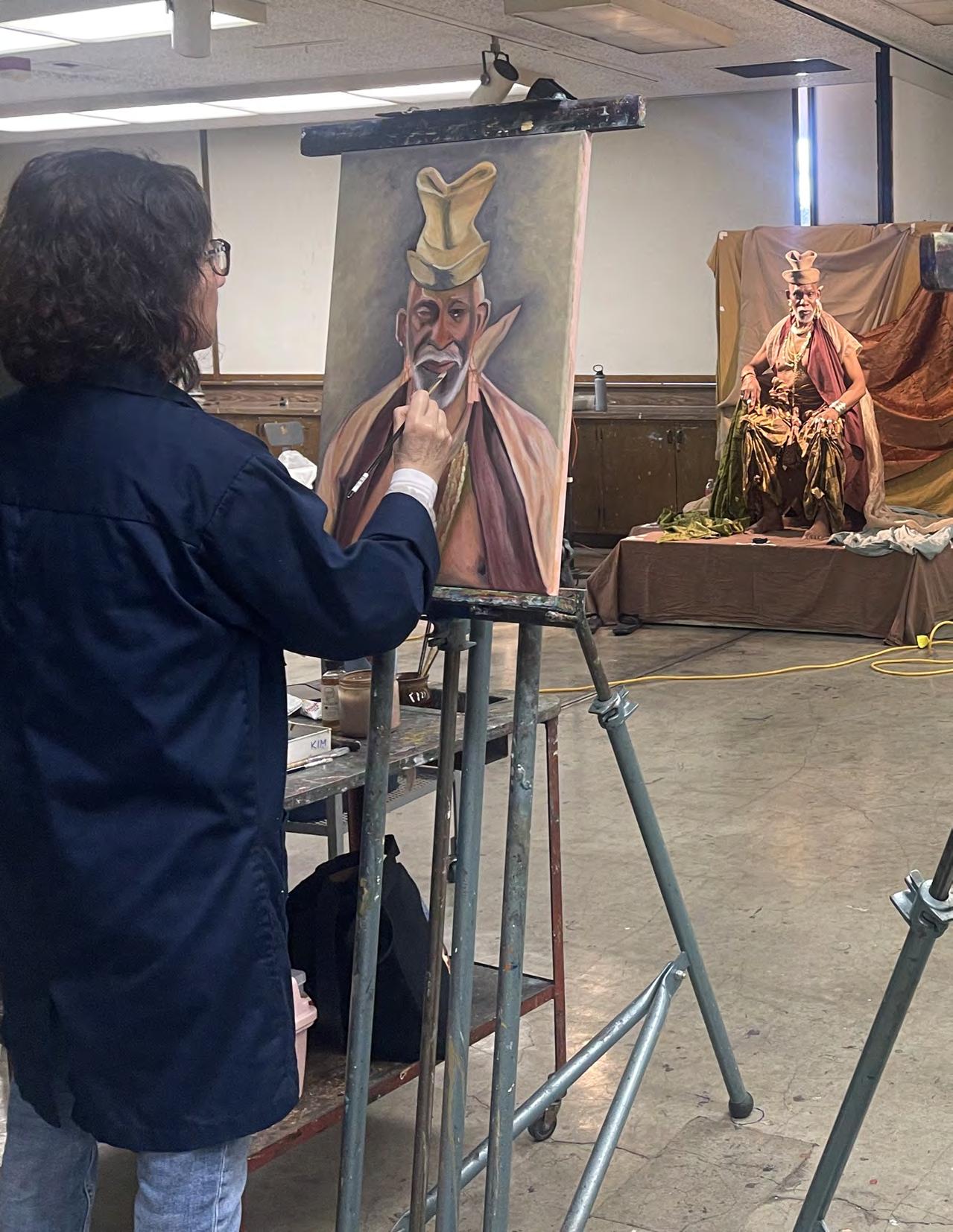

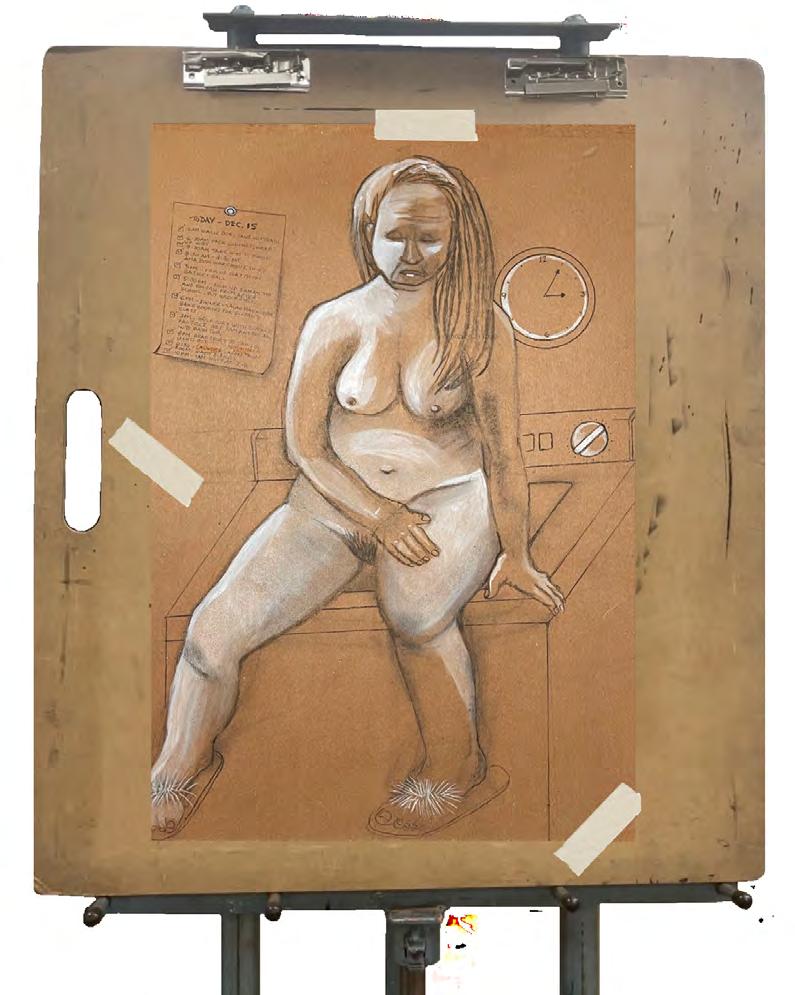

THE NAKED TRUTH

Art models bare all

JORDAN TO THE SOUTH BAY

Student government president advocates for immigrants and refugees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

5-9

BREAKING STANDARDS

Military officer recounts her experiences as a Black female overcoming racial misconceptions and live a life of service

10-11

INTERTWINED BY MIRACLES OF NATURE

Dogs in my life: A second opportunity to do things right

12-21

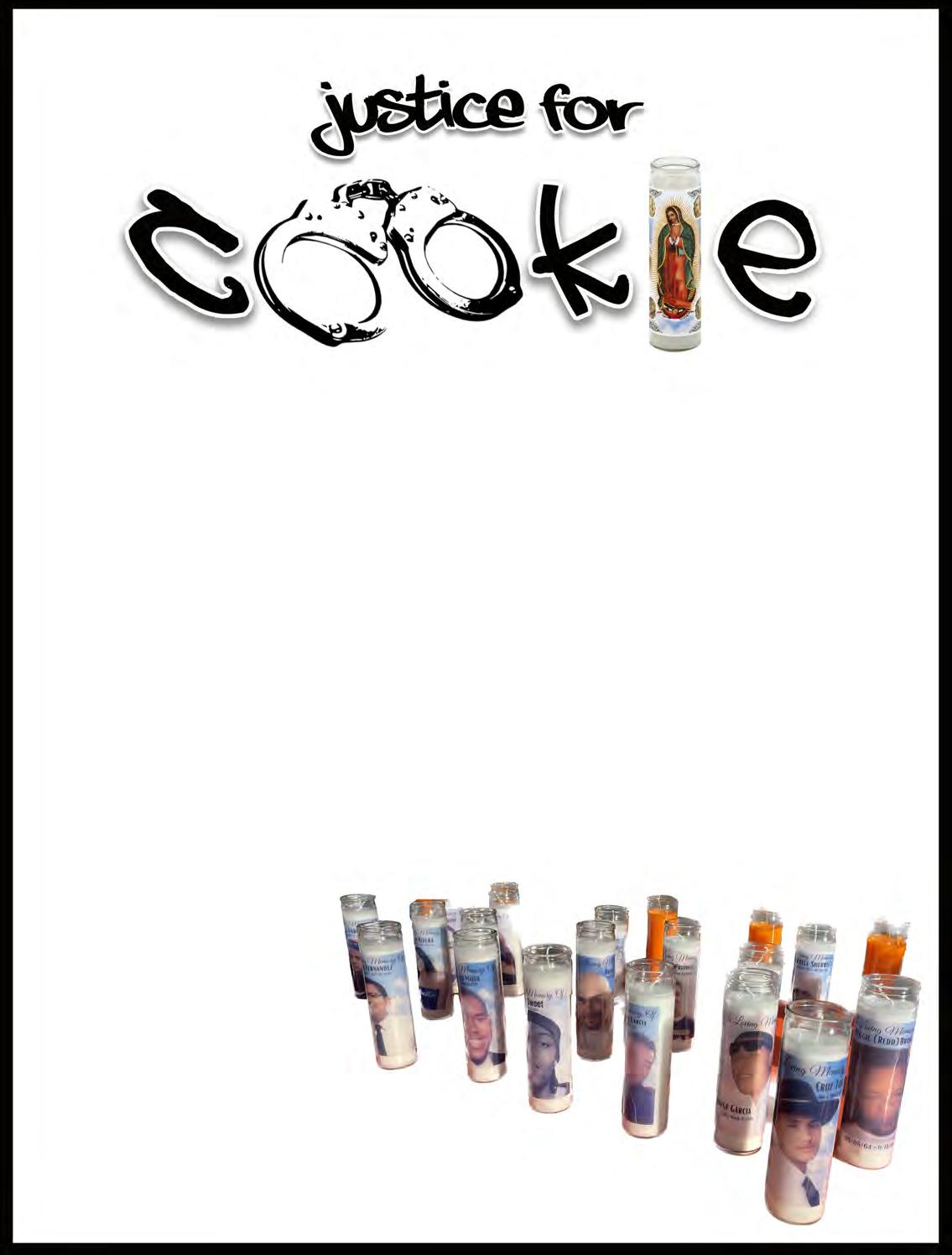

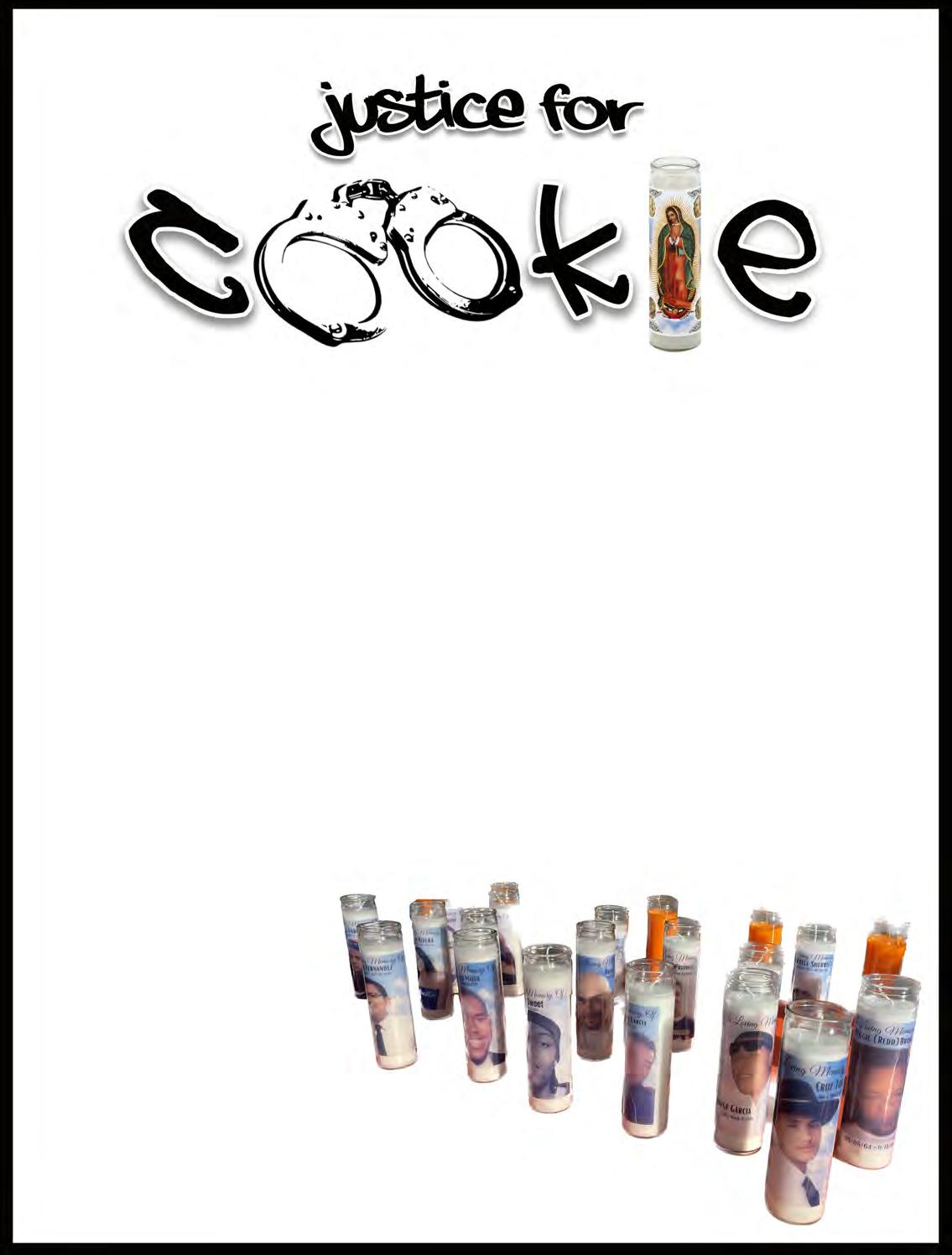

JUSTICE FOR COOKIE

How the murder of Juan Hernandez turned his mom into a powerful leader in the growing movement to heal families and communities

22-25

TAKING THE STAGE

El Camino English Professor converts markers in class to drum sticks for band gigs

26-29

TOP 5 HAUNTED PLACES CLOSE TO ECC

From Downtown L.A. to the South Bay, here’s where you are most likely to encounter a ghost

30-31

LOVE BEYOND BARS

My boyfriend was incarcerated. It felt like I served time too

32-37

FOOD & COMMUNITY CALLING

Chasing after new adventures, a couple stumbles on a place like home

38-39

WHO AM I OUTSIDE OF PLAYING SPORTS?

Switching my dream of professional sports to sports writing

40-41

FILIPINO FOOD GALORE

Here’s some of the best local Filipino restaurants and eateries near El Camino College

42-49

A STREAM CRIES FOR HELP

Trapped in a grave of cement, Dominguez Channel struggles to survive

50-53

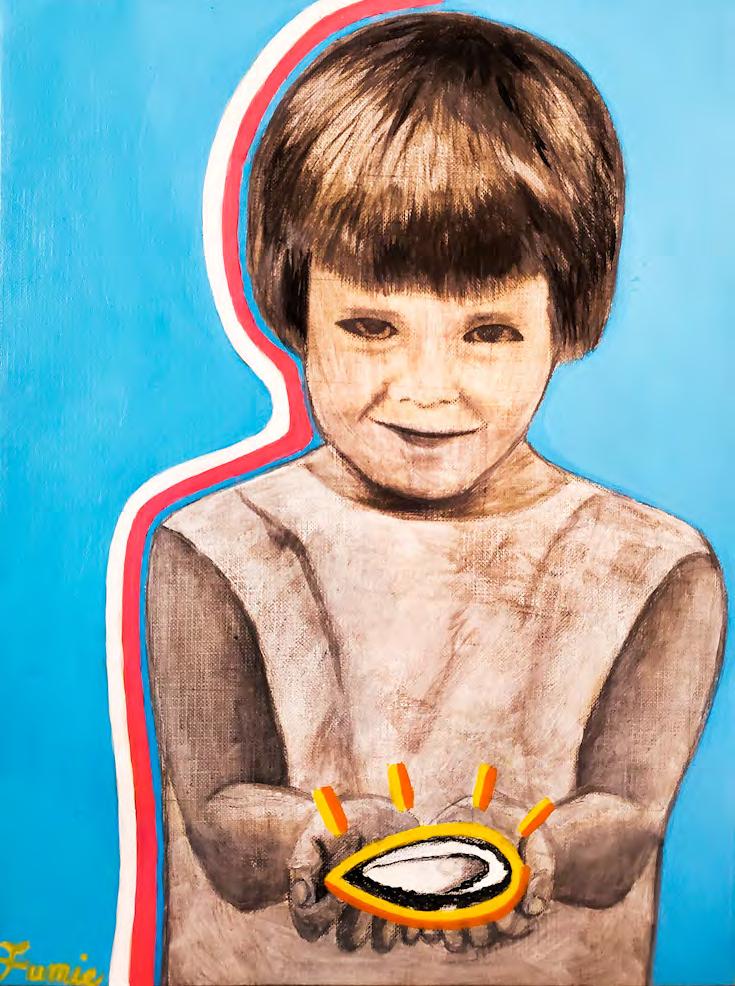

MY LIFE AS AN OYSTER

Searching for gender identity

54

THE NOT-SO-SPICY VACA FAMILY SALSA RECIPE

For those who want to indulge in the taste of a pico de gallo salsa, without the heat, try the Vaca family’s not-so-spicy, not-so-secret recipe

55

MATCHA LOVERS LOCAL GUIDE

From lavender to strawberry, there are delicious ways to drink matcha latte

56-61

COMMUNITY ROOTS

A Bolivian and Puerto Rican woman creates strong roots of community wherever she goes

62-63

IT’S BEEN FIVE YEARS AND I STILL LIKE HIM

Nothing has happened between us, but maybe one day

64-65

A PHOTOGRAPHER’S REFLECTION

My mom’s death was devastating for me as a kid. Now I cover the tragedies of others for the news

66-68

MY GREEN MONSTER OCD

How OCD has affected my everyday life

69

GRAB A SLICE

The Top 5 pizza shops to get a slice near El Camino

70-73

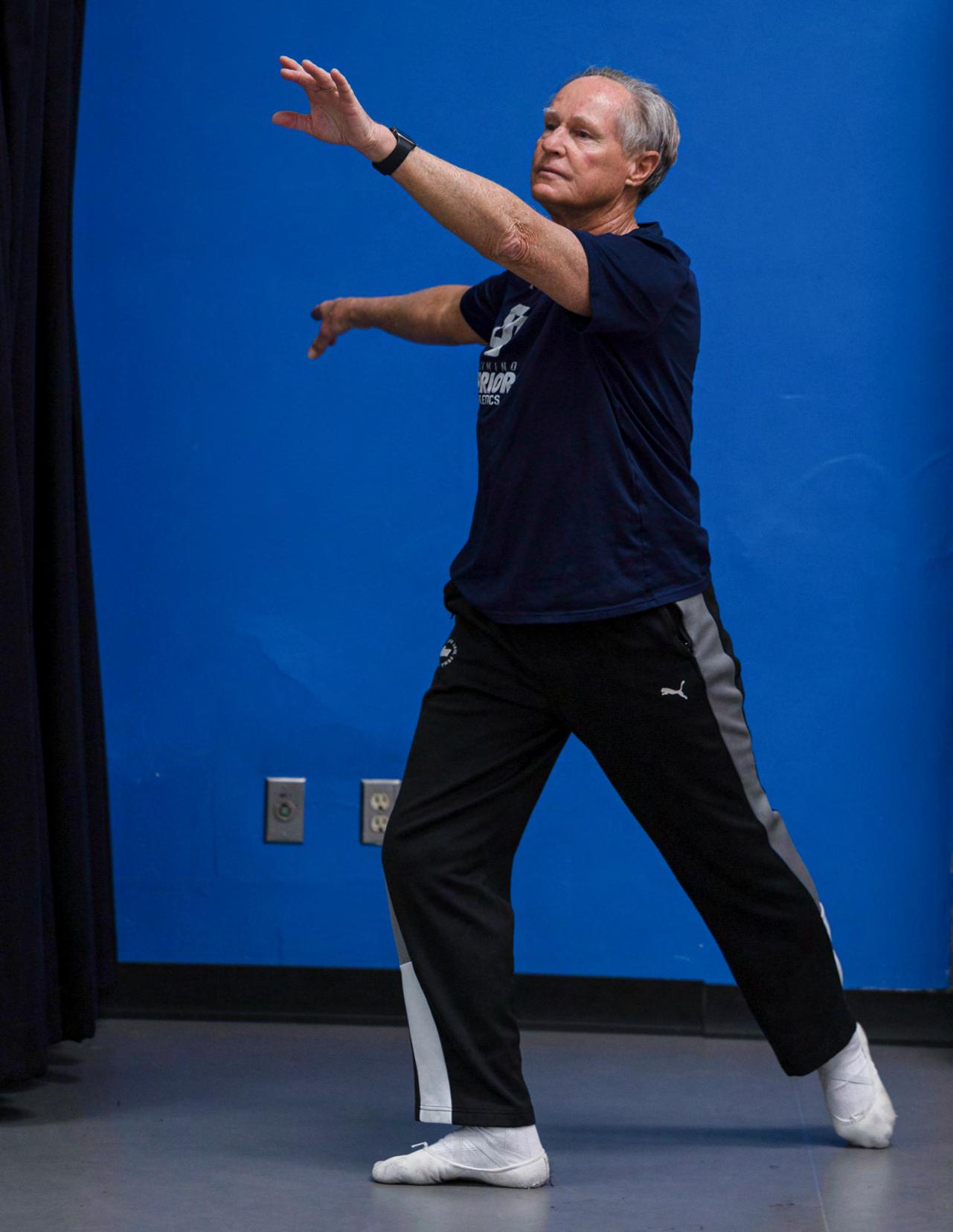

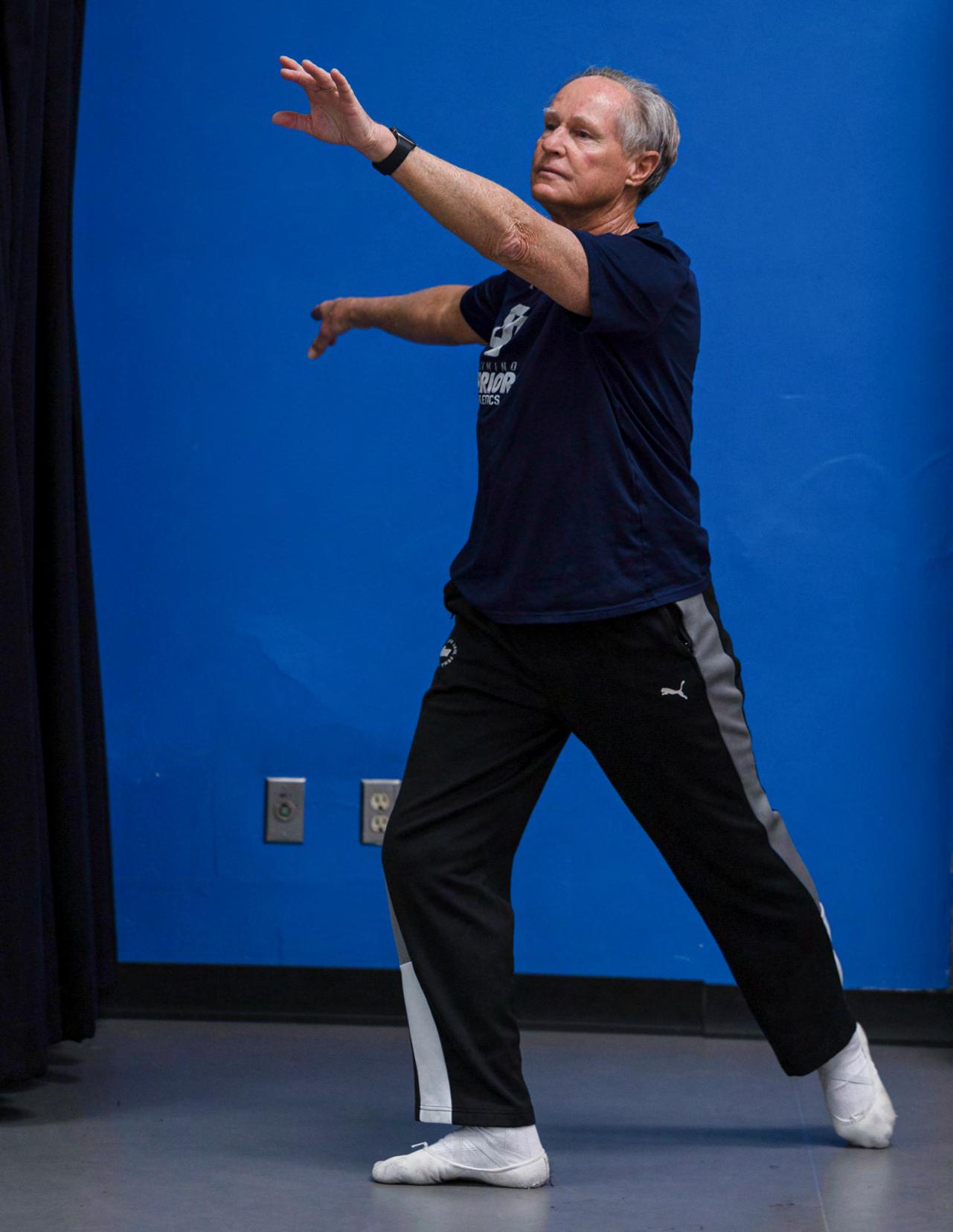

FINDING A CAREER THROUGH DANCE, ONE STEP AT A TIME

For Professor Daniel Berney, dance is more than just movement. It’s his passion.

74-75

BREAKING UP WITH A FRIEND AS AN ADULT

Reflecting on the good and bad of a friendship destroyed by insecurity

76-77

THROUGH FASHION

Unveiling student, faculty and staff expression

78-81

FROM JORDAN TO THE SOUTH BAY

Student government president advocates for immigrant and refugee rights

2 | Warrior Life

82-84

HOW I MESSED UP MY MOM’S MEMORIAL

The conversations, skills and wisdom I miss now that she’s gone

85

TOP 5 PUPUSAS IN THE SOUTH BAY

Need a new Central American food in your diet? Here’s where to try one of “las mejores”

86-90

CLASS DISMISSED

After 30 years in education, Humanities Dean Debra Breckheimer will retire from El Camino

91

BRING THE FLOWER POWER

Just in time for graduation season, here are the Top 5 flower shops within 5 miles of El Camino College

92-93

TEXTING DOES NOT EQUAL LOVE

Life lessons from a victim of a texting relationship

94-103

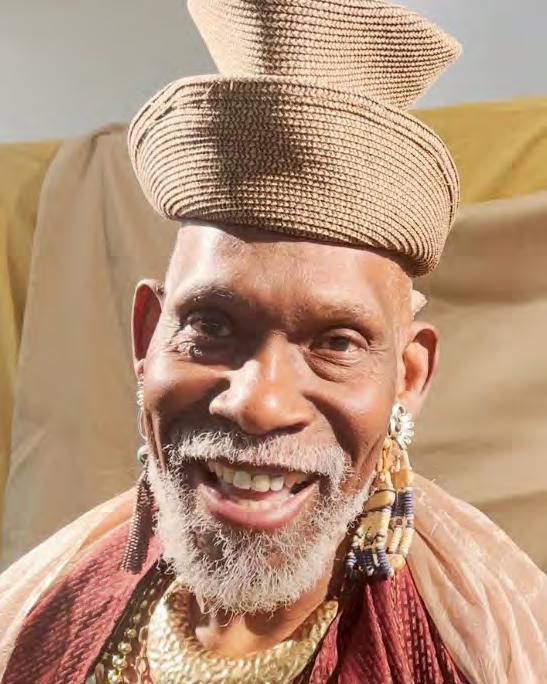

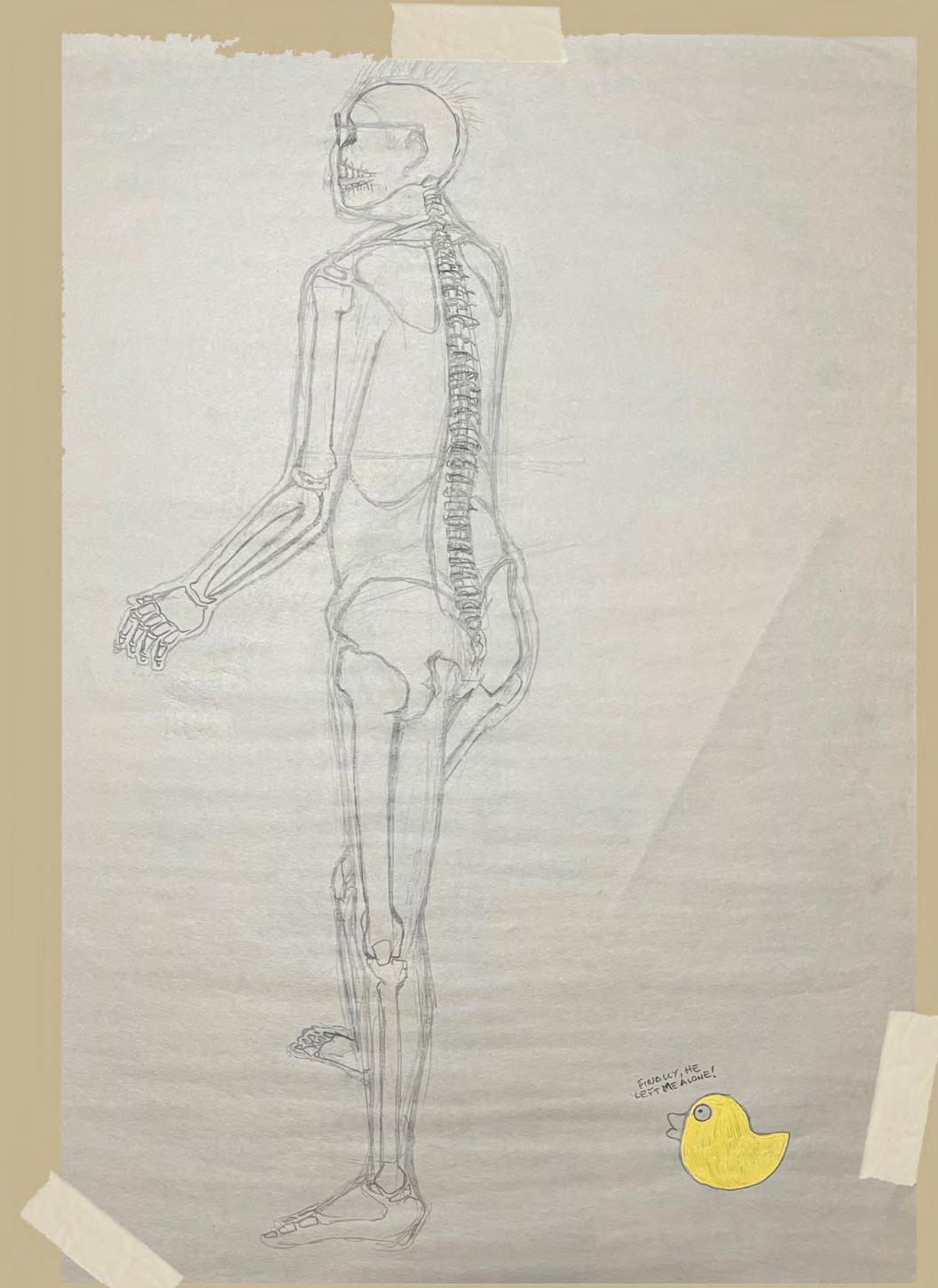

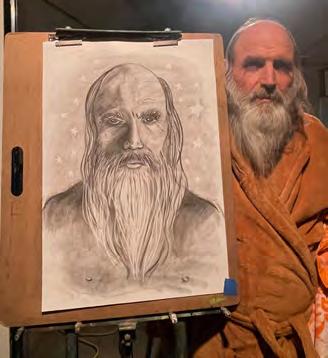

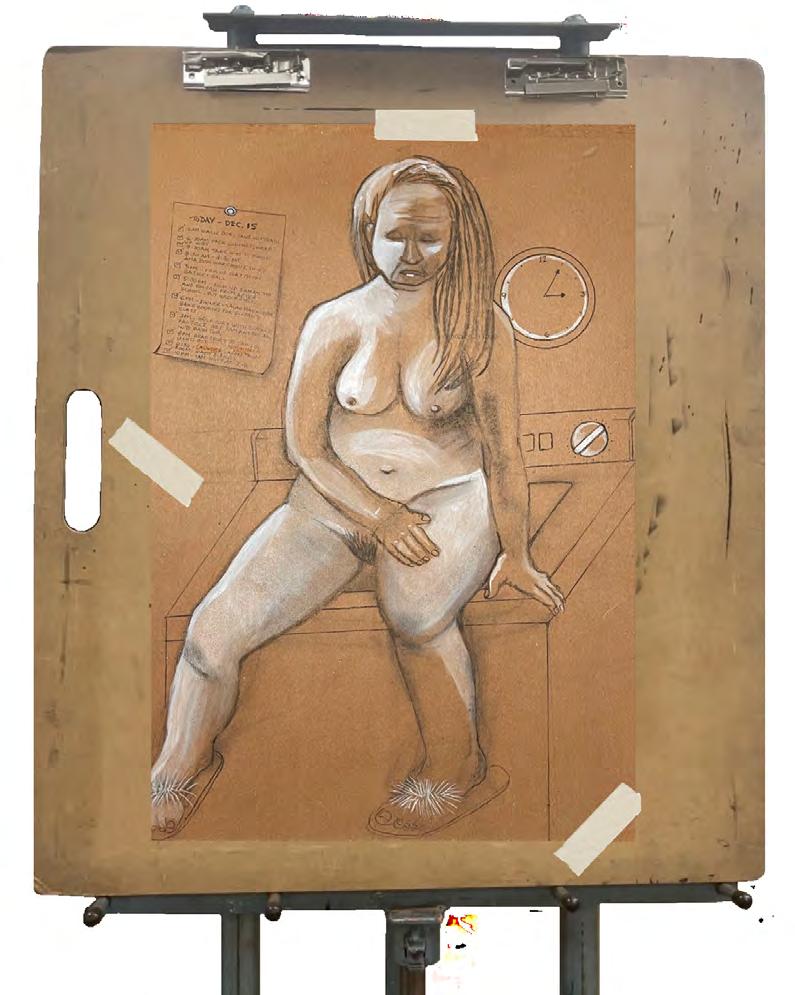

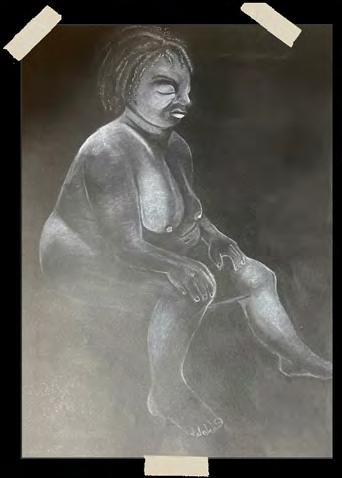

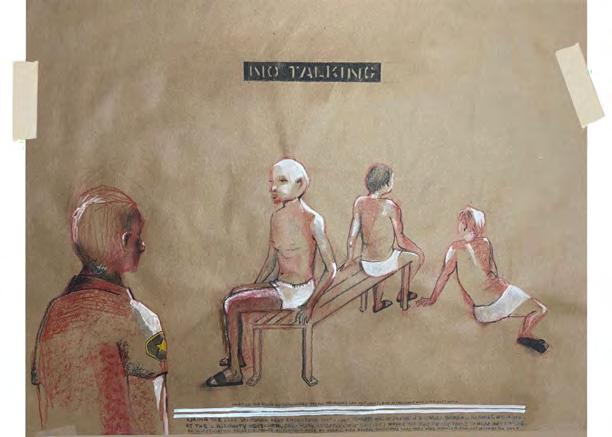

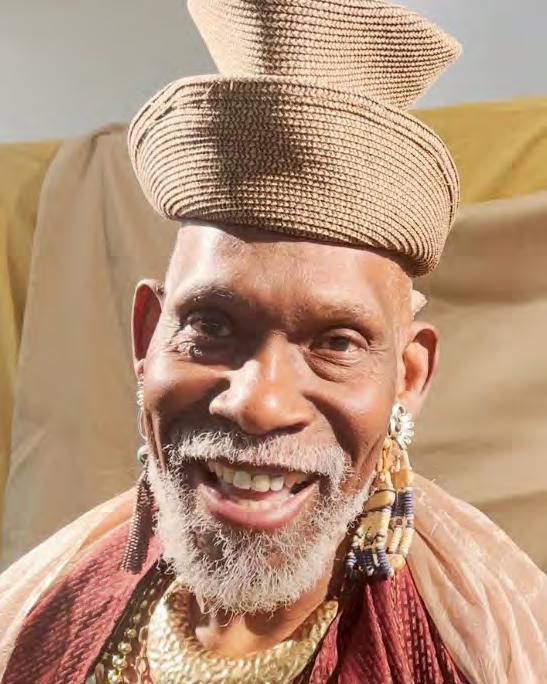

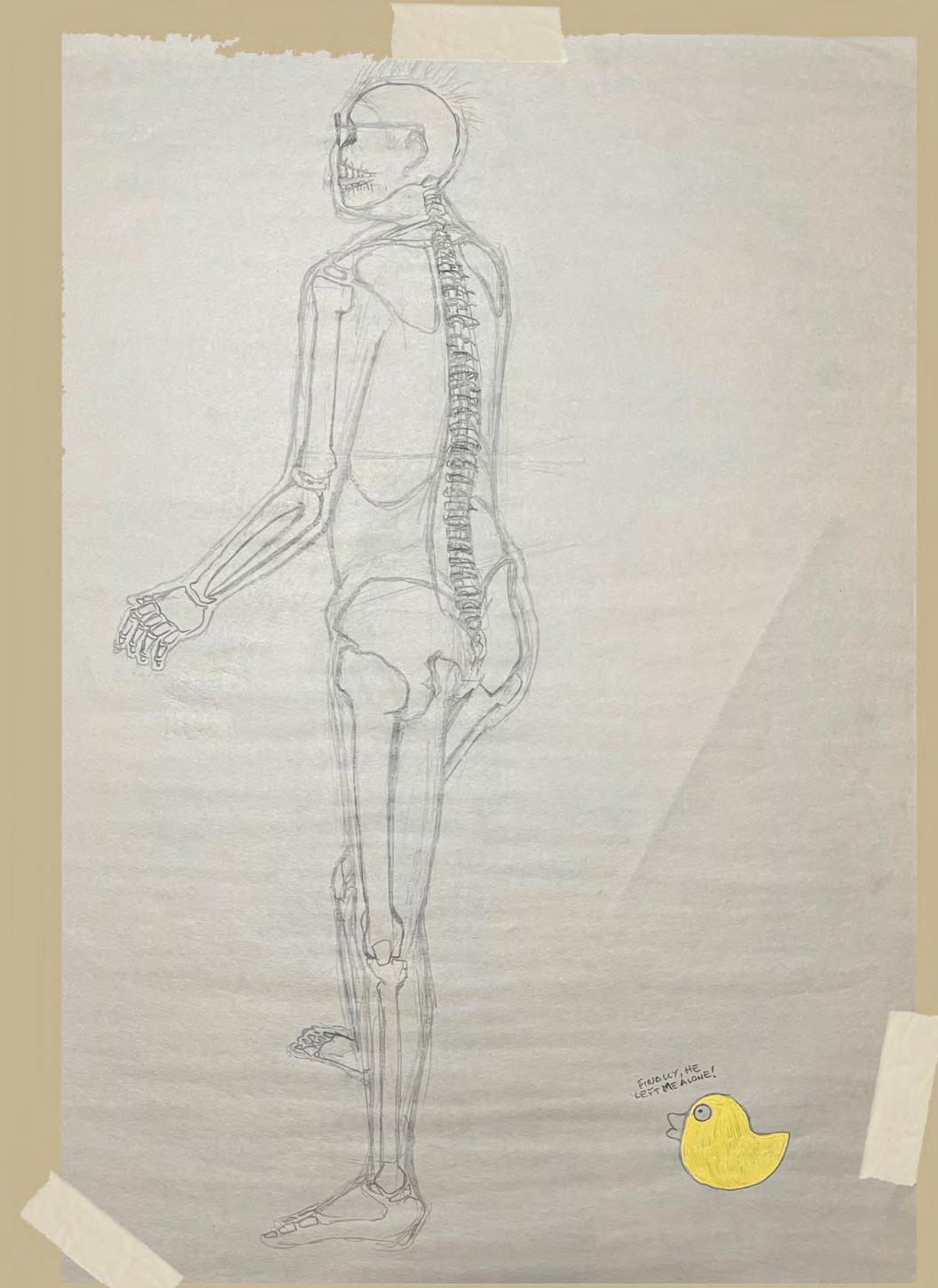

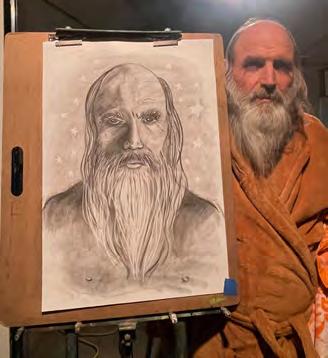

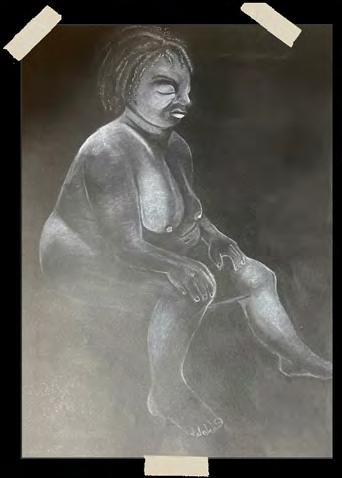

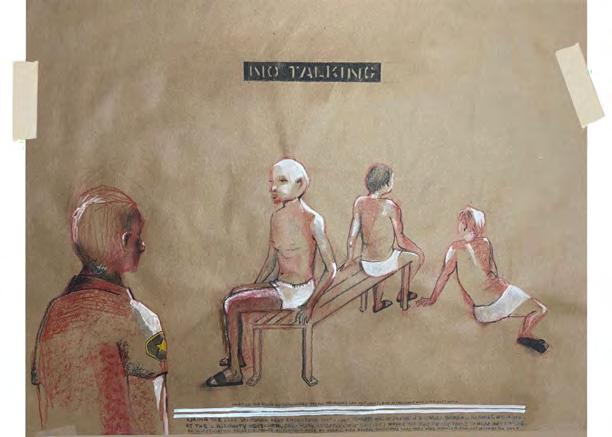

THE NAKED TRUTH

Art models inspire students to portray humanity on all its forms

104-109

A RESTAURANT REBORN

A Japanese restaurant closed down during the pandemic. Now, they’re back with a new Korean take on food

110-113

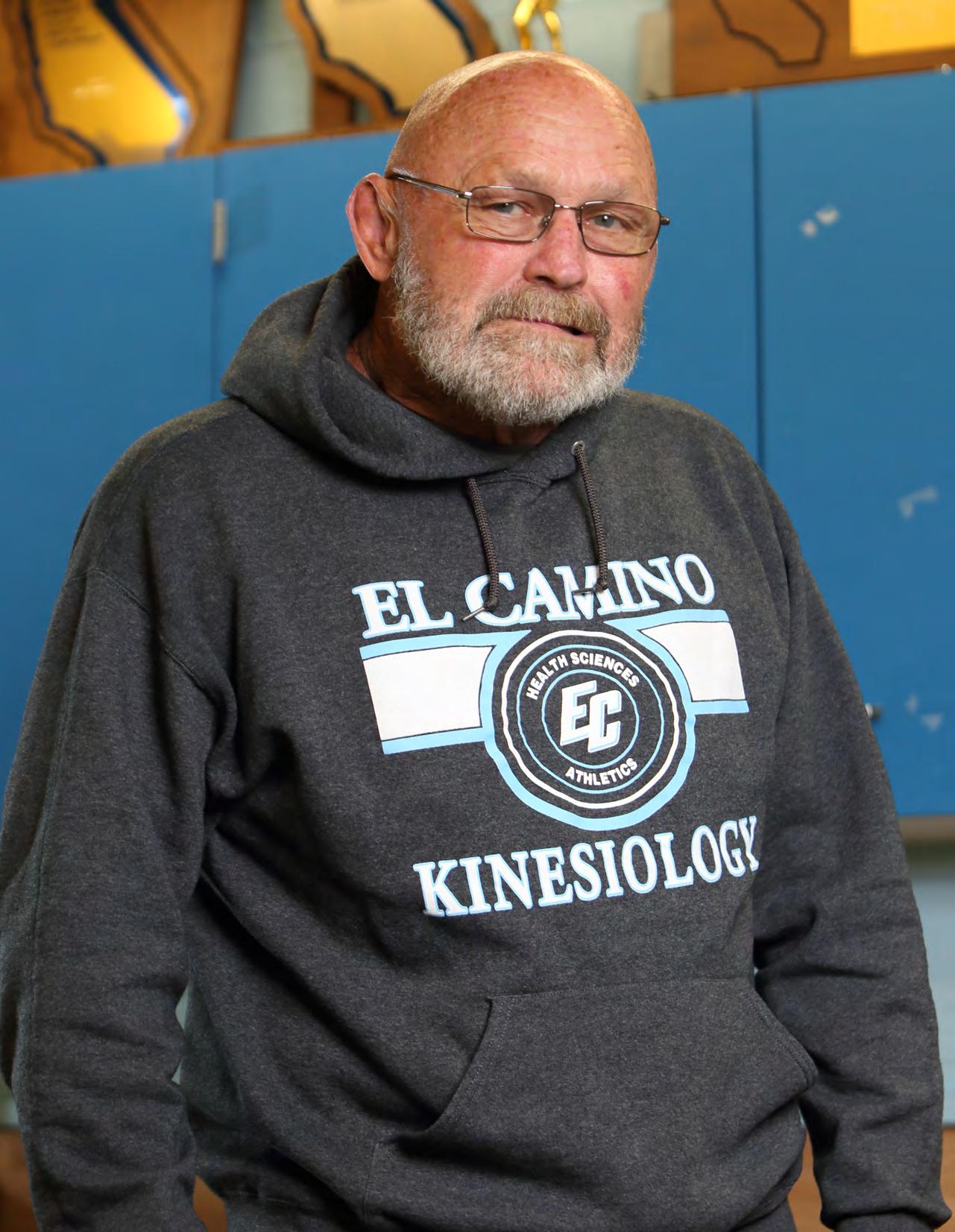

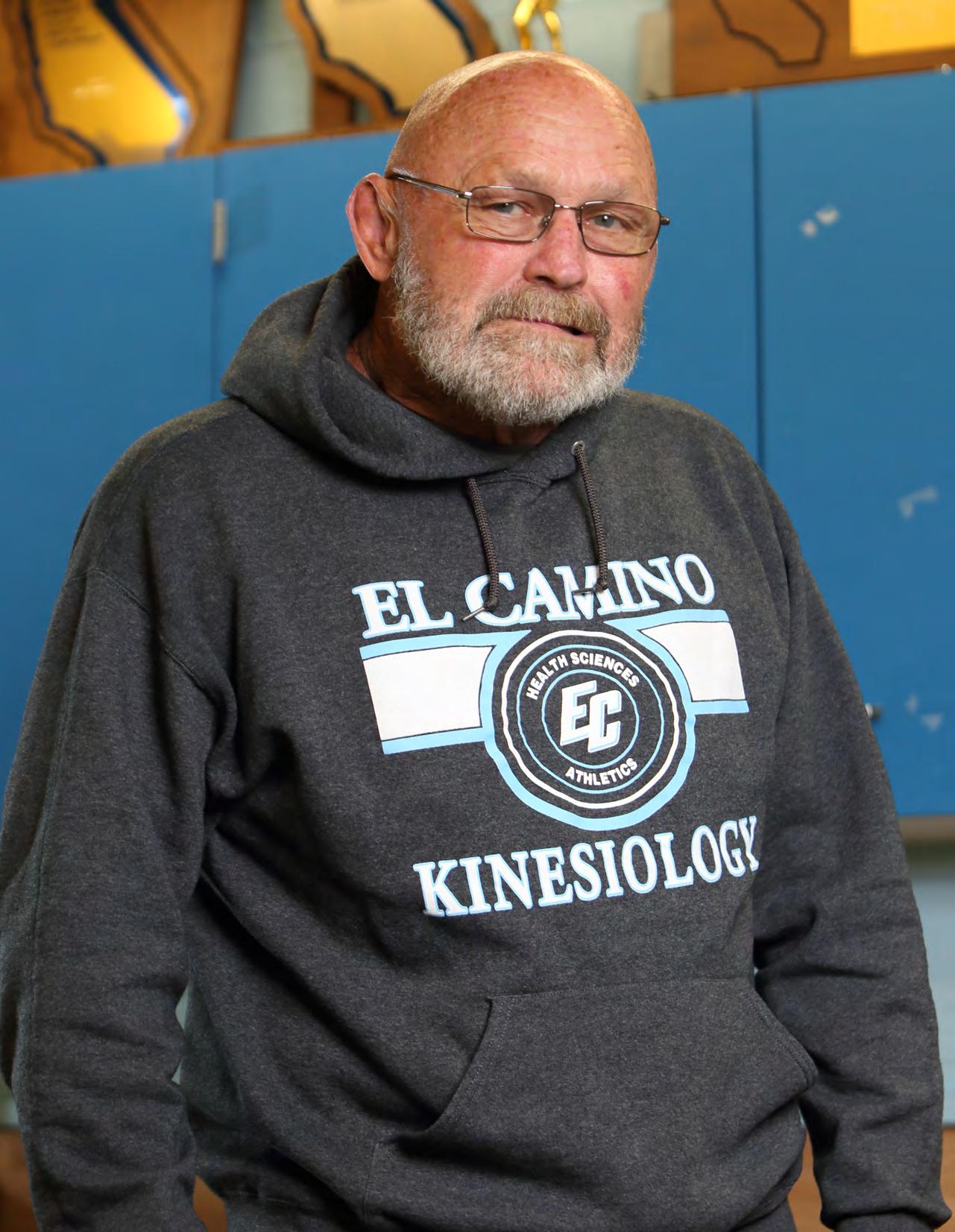

THE JOURNEYMAN

From playing to coaching and representing wrestling, the story of Tom Hazell

114-117

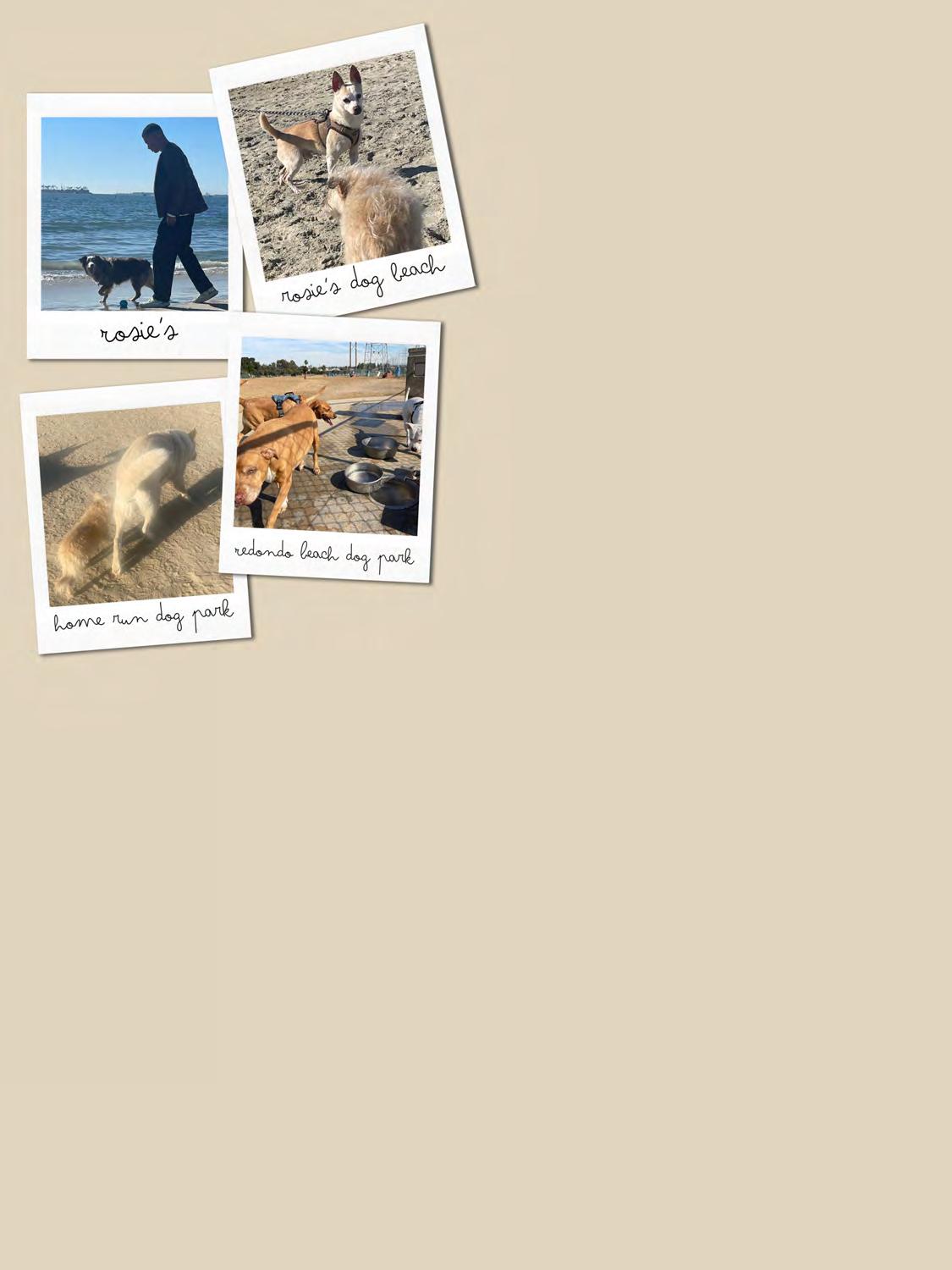

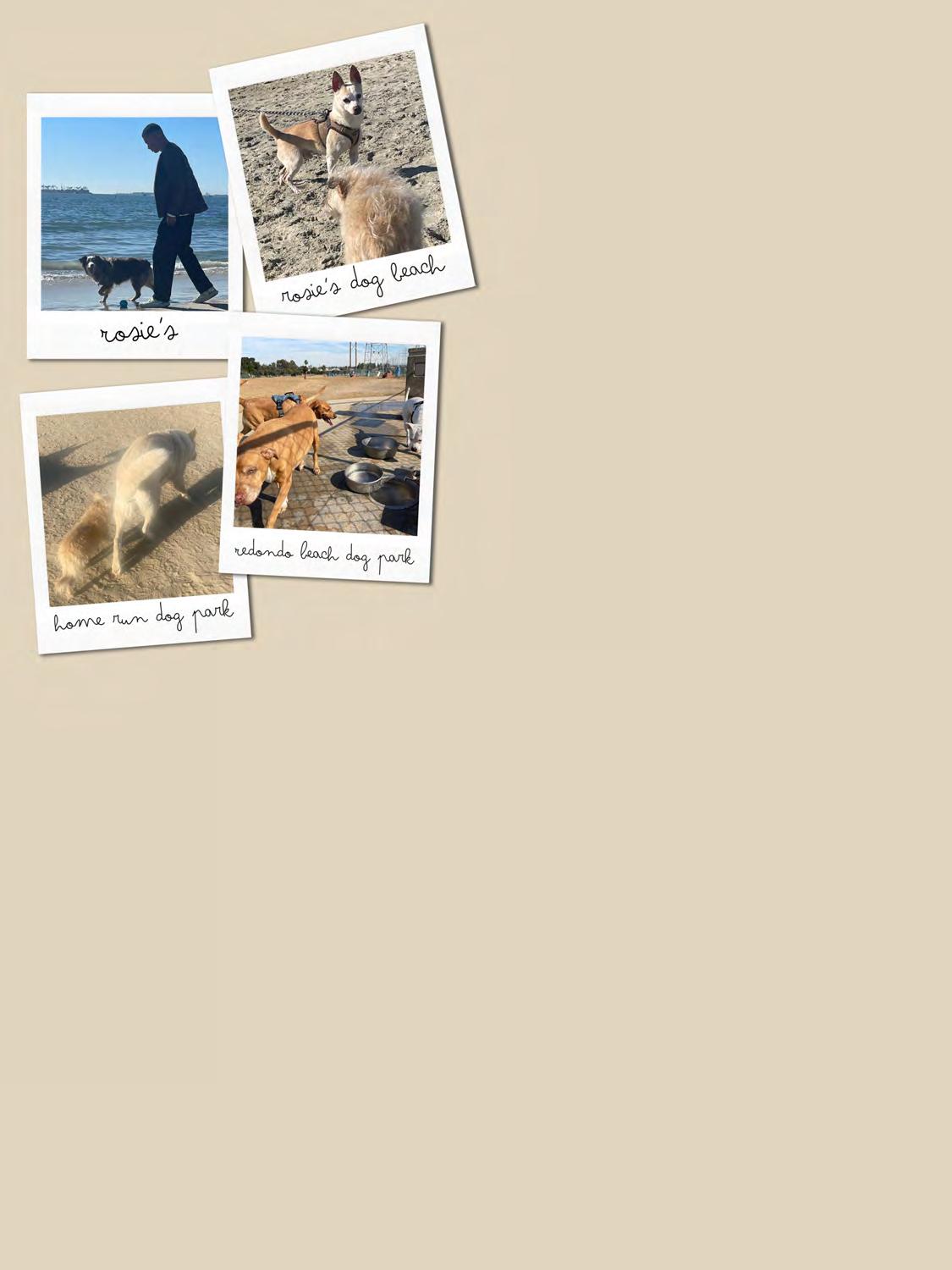

SNIFFING BUTTS HAS NEVER BEEN BETTER

Bob the Dog reports on the best dog parks close to ECC

118

DIFFERENT COUNTRIES, DIFFERENT ME

How moving to another country affected my personality and my social life

Warrior Life | 3

Warrior Life Staff

Writers Illustrators

Alexis Ramon Ponce

Ash Hallas

Brianna Vaca

Delfino Camacho

Hannah Bui

Jesus “Jesse” Chan

Johan Van Wier

Kim McGill

Ma. Gisela Ordenes

Matheus Trefilio

Nindiya Maheswari

Raphael Richardson

Safia Ahmed

Student Media Advisers

Stefanie Frith

Kate McLaughlin

Photographers

Alexis Ramon Ponce

Anthony Lipari

Ash Hallas

Brianna Vaca

Gary Kohatsu

Greg Fontanilla

Hannah Bui

Jesus “Jesse” Chan

Johan Van Wier

Khoury Williams

Kim McGill

Nindiya Maheswari

Raphael Richardson

Safia Ahmed

Photo Advisers

Chuck Bennett

Nguyet Thomas

Letter from the editor

Ash Hallas

Dylan Elliot

Fumie Coello

Ingrid Barrera

Kae Takazawa

Kim McGill

Patrick Morehead

Zamira Recinos

Editor-in-Chief

Elsa Rosales

Support Staff

Jack Mulkey

Jessica Martinez

The journalism program at El Camino College is truly something special. The support from award-winning advisers and support staff, and the collaboration among award-winning writers, photographers and illustrators makes this newsroom one of the best places to earn your certificate or degree. We hope you join us.

We appreciate all faculty, staff and students who were open to working with us to get this issue published and we hope you enjoy the result. These stories and more can also be read at www.eccunion.com.

Thank you,

Elsa Rosales

Warrior Life is a student-run magazine located at El Camino College, 16007 Crenshaw Blvd., Torrance, CA 90506. El Camino College students interested in being a part of the magazine must enroll in Journalism 9 for fall 2023 or contact Stefanie Frith at sfrith@elcamino.edu for more information.

4 | Warrior Life

Warrior Life | 5

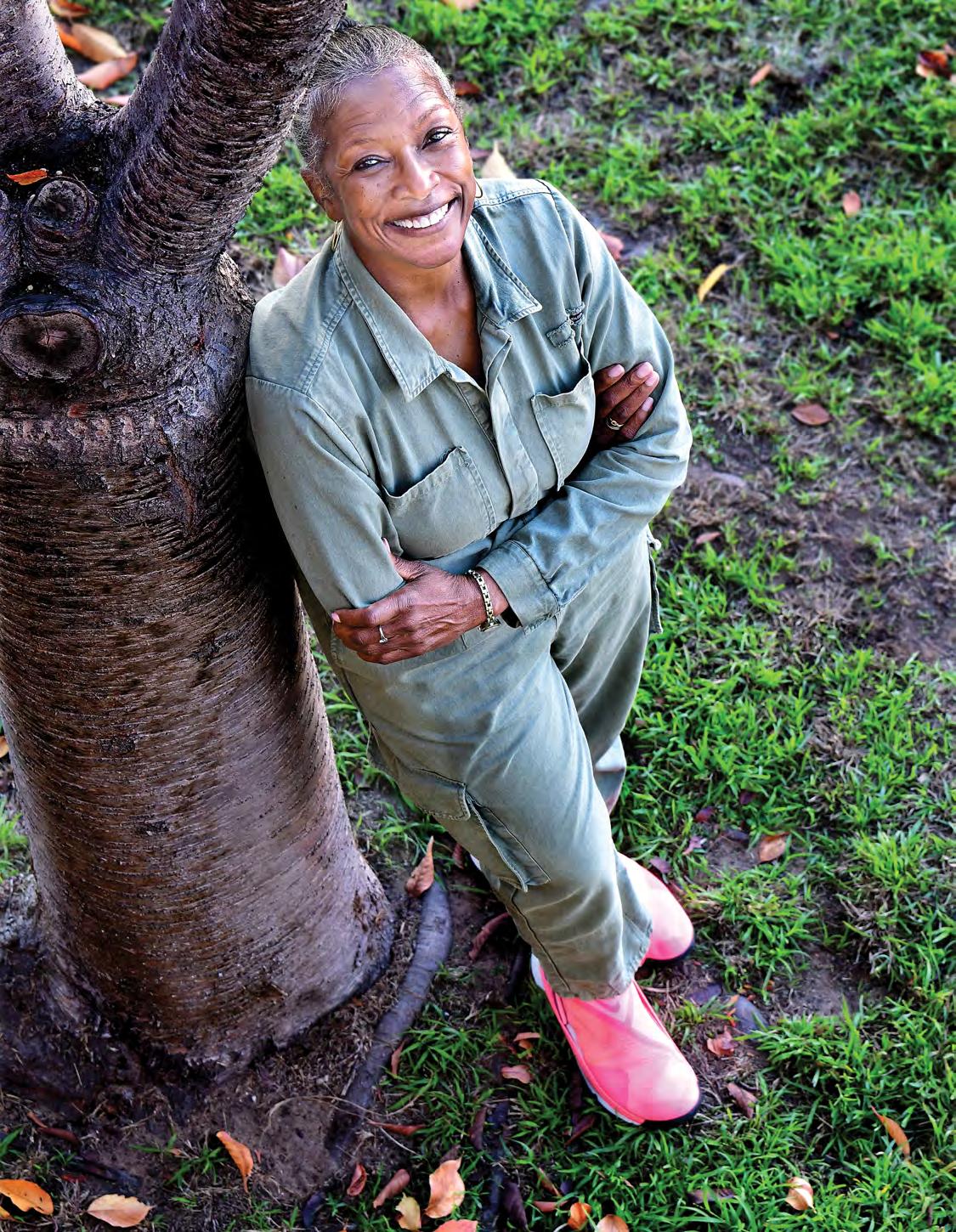

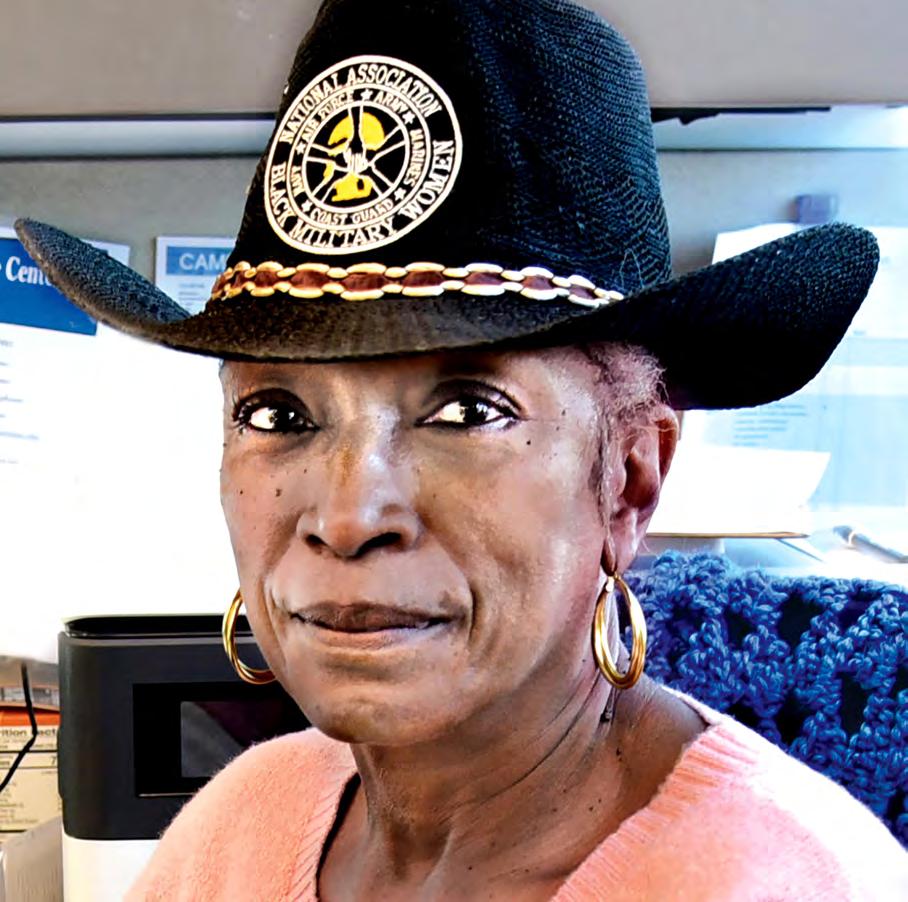

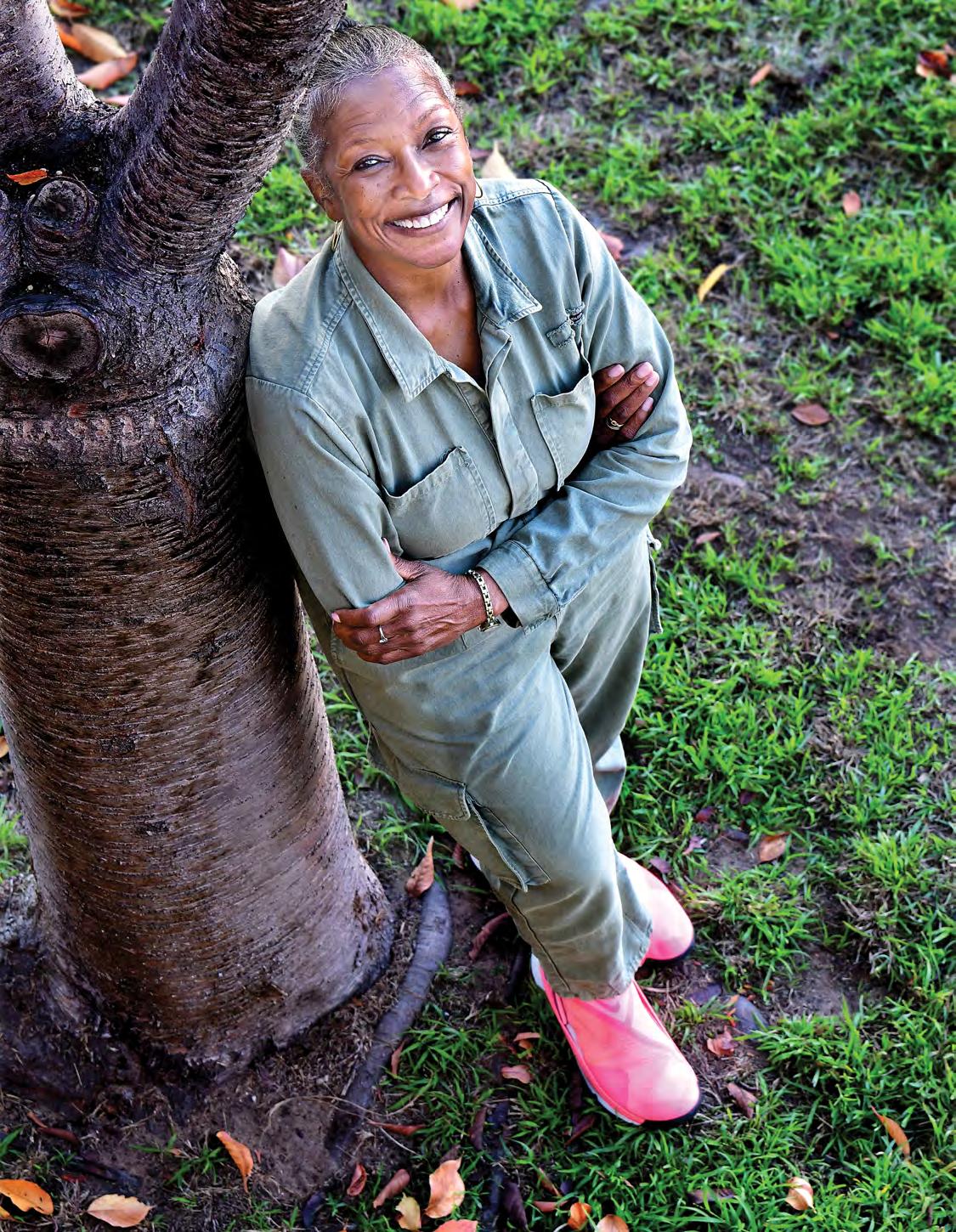

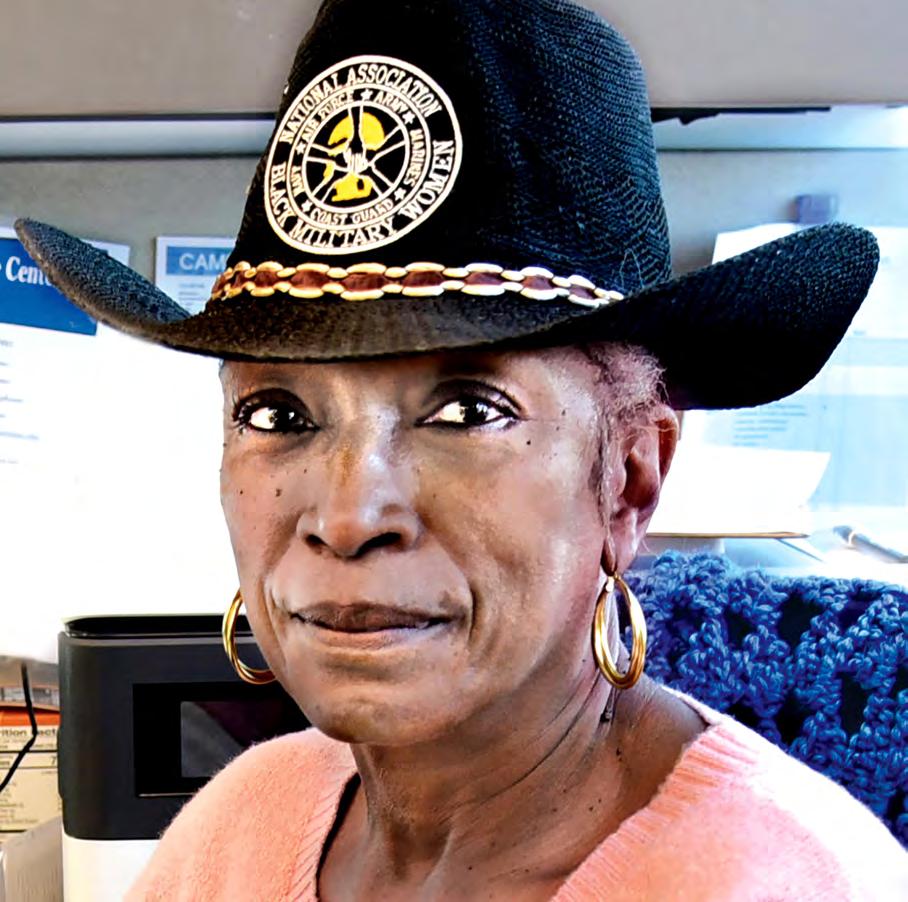

El Camino College Assistant Director of Veterans Services Brenda Threatt relaxes against a cherry blossom tree on the ECC campus in Torrance, Calif. She has been a major in the California State Guard since 2009. (Gary Kohatsu | Warrior Life)

Breaking standards

Story by Safia Ahmed

Photos by Gary Kohatsu, Greg Fontanilla and Safia Ahmed

Entering the military as an older person, she wanted to do something for her country. In 2001, she was given the opportunity to assist the state following the 9/11 terrorist attack. She designed a commemorative license plate in honor of the victims and survivors, which has raised about $15 million in California to support anti-terrorism.

Major Brenda Threatt serves as an assistant director of Veterans Services at El Camino College. She is also a military officer, chaplain and ordained minister at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles. There are very few Black female chaplains, she says.

“It’s easier for people to stereotype than it is to learn about another person and accept them. That’s not just for veterans. It’s how society is with a lot of groups,” Threatt says.

Much of Threatt’s career has been in the veterans’ space. Her role at ECC requires her to manage the center and staff that supports the educational goals of student veterans.

Veterans Services identifies resources that provide veterans with career opportunities, housing and support.

Previously, she worked with homeless veterans in an organization she ran that housed nearly 400 veterans in need of housing.

“The way to prevent homelessness is to give someone the opportunity to have an education and career,” Threatt says. “So in my scheme of working with veterans, this is where you stop veteran homelessness at this stage.”

One of the greatest challenges she has faced at ECC was bridging the gaps between the veterans department and other departments. With Veterans Services, the overall leadership of El Camino has created a space of equity, diversity and inclusion.

“A challenge was helping people to understand and learn who the veteran student is,” Threatt says. “We’re not always going to get it right, but because the leadership is the tuning work, that keeps the

rhythm going.”

Threatt has worked at churches, nonprofit organizations and in city government. She began working as a veteran liaison for then Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa in 2008 and was asked to join the California State Guard as a chaplain.

“I started speaking on the things that civilians and people can do to support their communities,” she says.

One of the primary roles of a chaplain is to provide casualty notifications.

“It’s when a soldier dies and we notify the family it was a casualty,” Threatt says. “When a military person dies, the department of defense has four hours after the confirmation of death to notify their next of kin.”

Another big job Threatt has as a chaplain is suicide prevention.

“I would go to hospitals if there was an attempted suicide, to minister to the victim,” she says. “I still do suicide prevention training. People always look at ministry people differently, especially in the military. Getting soldiers to understand that you can be trusted and that you are not judging them, and I think that’s just with people in general. They think clergy is like we’re flying around pointing fingers.”

Her role in that field requires her to provide

6 | Warrior Life

Military officer recounts her experiences as a Black female overcoming racial misconceptions and lives a life of service

“Every single moment we have to give, we have to be thinking about what we can do this day to have a good day and to help someone else have a good day.”

- Major Brenda Threatt

Soldier Readiness Processing, which prepares and certifies soldiers to go to combat,” Threatt says. “I am one of the persons that will interview them to make sure they are emotionally able to withstand combat. A psychologist will interview them along with a legal team to make sure all their papers are in order.”

Lawrence Moreno, overseer of the Veterans Services office, is a 67-year-old worker who has been involved with ECC for several years in the Student Development Office. He started the discount program at ECC.

“Now it’s called the ASO (Associated Students Organization) discount sticker,” Moreno says. “I started that from scratch because we didn’t have anything like that here.”

He has been assisting with overseeing their student veteran workers and is also in charge of the Veterans Pantry, a subsidiary of the Warrior Pantry. Both pantries provide students with nutritious

food and necessities to help them thrive in class without distractions created by food insecurity.

“I met Brenda originally when I was working at the Student Development Office and I used to also assist with the Warrior Pantry, and Brenda was doing a collaboration with the Warrior Pantry for the veterans and the community,” Moreno says. “She was helping the homeless because Brenda has a really big heart, so she’s always seeing how she can promote relationships with the community and El Camino and the veterans, and that’s where I met her at first and realized she was just a go-getter.”

Threatt has seen students suffering from homelessness and wants to provide help. She wants to find funding, housing resources and partners, and help in providing housing for students that need them.

“I wanted the opportunity to work at the other end of homelessness, which was prevention and education, and I believe that God directs our

Warrior Life | 7

Major Brenda Threatt is the assistant director of Veterans Services at El Camino College. She is also a member of the National Association of Black Military Women. Before landing at ECC in 2019, Threatt served as executive director of the U.S. VETS of Long Beach. (Gary Kohatsu | Warrior Life)

paths,” Threatt says.

Student Services Specialist and School Certifying Official Nina Bailey first met Threatt through the hiring process for the Veterans Center at El Camino College.

“I have been in education for about 30 years and I would rate Brenda, of all my administrators, top five,” Bailey says. “The veterans program at El Camino helps students transition back into a normal environment after serving in the military. Brenda brings resources from off-campus to assist and supplement what the college can’t provide.”

According to Moreno, Threatt is the leader and heart of the office.

“If we lose her it’s like losing the captain of a ship because she’s so great in knowing how to motivate,” Moreno says.

Threatt says the importance of staying involved in these services allows for the world to flourish.

“We are created to take care of one another,” she says. “Communities don’t happen without people, government or business. Nothing happens without people. We have to take care of the well-being of people.”

One of her mottos correlates with a quote from Anne Frank: “How wonderful it is that nobody needs to wait a single moment before starting to

improve the world.”

“Every single moment we have to give, we have to be thinking about what we can do this day to have a good day and to help someone else have a good day,” Threatt says.

In October 2022, Threatt completed her Doctor of Public Administration studies at California Baptist University in Riverside, Calif.

She is a chaplain for the county probation department and volunteers with the Montford Point Marines, a nonprofit veteran organization that honors the first African Americans to serve in the United States Marine Corps.

“My life has been one of service,” Threatt says.

She is the mother of two children, a son and daughter, and has two granddaughters. In her free time, she enjoys sewing and playing with her grandchildren. Threatt also enjoys cooking and is known for her famous fried chicken and likes making intriguing salads.

“People in the military could be a model for civilians,” Threatt says. “When you go into the military, it doesn’t matter what color your skin is. Everybody has that uniform, everybody is an American and everybody takes the same oath, and that oath is to protect and defend the constitution of the United States.”

8 | Warrior Life

Major Brenda Threatt speaks at a Veterans Day event on Thursday, Nov. 10, 2022, at El Camino College’s East Dining Room. Threatt is a chaplain in the California National Guard and the assistant director of Veterans Services at ECC. (Greg Fontanilla | Warrior Life)

(Top) El Camino College Assistant Director of Veterans Services Brenda Threatt acknowleges a fellow worker at ECC on an afternoon in Novemver 2022. She has a special California Department of Motor Vehicles license plate for having created a 9/11 commemorative license plate in 2001, that has generated $15 million in funds for victims and families of terrorist attacks. (Gary Kohatsu | Warrior Life)

(Top) El Camino College Assistant Director of Veterans Services Brenda Threatt acknowleges a fellow worker at ECC on an afternoon in Novemver 2022. She has a special California Department of Motor Vehicles license plate for having created a 9/11 commemorative license plate in 2001, that has generated $15 million in funds for victims and families of terrorist attacks. (Gary Kohatsu | Warrior Life)

Warrior Life | 9

(Bottom) Lawrence Moreno, overseer of the Veterans Services Resource Center, and El Camino College Assistant Director of Veterans Services Brenda Threatt stand with the flags of the United States armed services inside Veterans Services at ECC on Monday, April 11, 2022. (Safia Ahmed | Warrior Life)

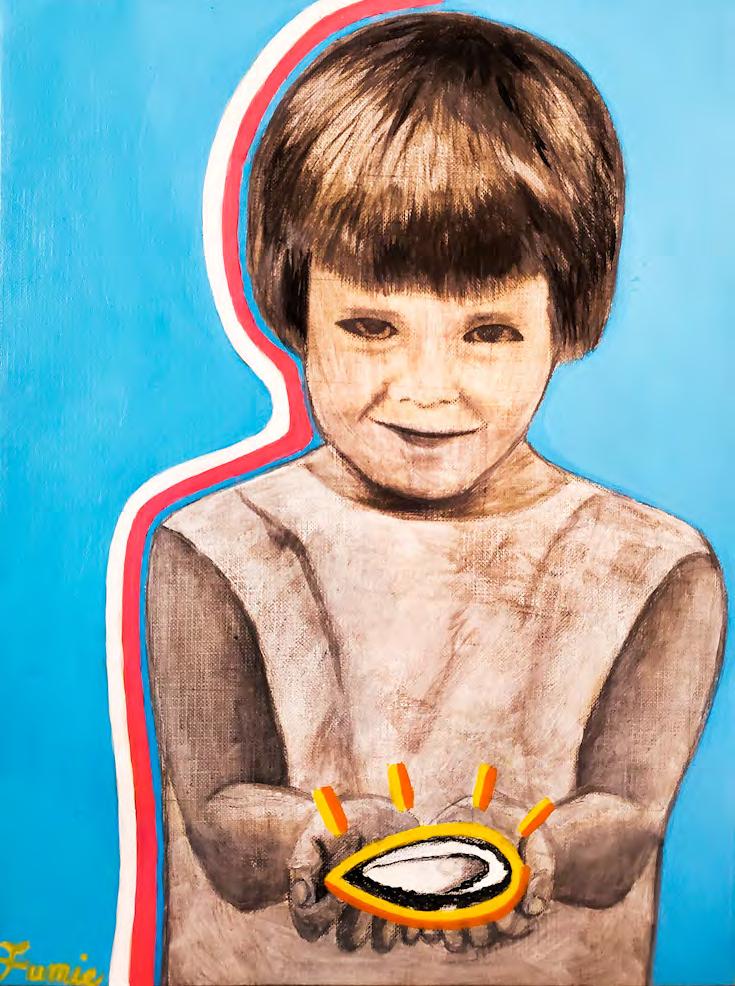

Intertwined by Miracles of nature

Dogs in my life: A second opportunity to do things right

Story and photo by Alexis Ramon Ponce

“Pets belong outside!” she yelled. “They never have to be on our sofa or in bed. Never!”

I had an extremely strict grandma; a great lady, yet strict about animals and their interrelation with humans. The way she taught us to treat animals wasn’t exactly the right way. I discovered that many years later.

Here is where the saying “A dog is man’s best friend” –which has been said many times – makes a presence, but this time for me it has real meaning.

It is especially important to understand that not only dogs, but also any kind of pet might be a great presence in our lives, and they can demonstrate to us in some way the meaning of the words company, support and love.

In 2010, on a sunny day on the island of Oahu in Hawaii, two Chihuahuas came into our lives. My husband and I named them Kiko and Shandy. These hairy twins showed me things in life that I couldn’t learn in school. They came to change our lives forever.

How did they arrive? I’m sure it wasn’t a coincidence. We were going to the movies and on our way, for some reason – maybe destiny – we felt an attraction to go inside a pet store to take a look only.

Immediately, when we were inside that place, we were attracted to a couple of 2-month-old puppies, brother and sister. The connection was immediate. They adopted us at that magical instant and we could not say no.

From that moment on, we started to look for information about the breed, all about Chihuahuas. I

want to start by saying that the correct name of the breed is “Chihuahueño” or Chihuahuan, meaning originally from the state of Chihuahua in Mexico.

According to the American Kennel Club, Chihuahuas are the smallest dog breed in the world. In contrast to their little size is their huge ego, attitude and loud bark.

We found out that Kiko and Shandy’s ancestors are from a breed that was raised for the Mexican royalty in civilizations like the Aztecs and the Toltecs. The ancestor dog was an extinct breed known as the Techichi and it was the alpha; the genesis of the Chihuahua.

Chihuahuas have compact bodies. Nevertheless, they come in different shapes, with weights that range from 2-20 pounds. They have short or long hair. However, they all have something in common. They have big ears, huge, bulging eyes and for sure, a truly short temper.

In the beginning, when I started interacting with my puppies, I used to walk with them in open green areas surrounded by forest.

They are territorial little things and super protective of their pack.

Walking with my lively, full-of-energy pack was a new experience. Every day was a different adventure. Building great memories was the most important thing of all, creating bonds that last forever.

In Hawaii, it is quite common to find hens or roosters and their little ones living free in the wilderness. It was those poultry that immediately caught the attention of

10 | Warrior Life

my Chihuahuas, especially Kiko who, on occasion, ran after them until the chickens went to the top of a tree looking for shelter.

As it was explained in the beginning of this story, as a Latin man, I was raised in a rich, colorful culture that has a special meaning for the word family. Even so, the connection to pets is different to the way people in the United States treat their furry friends.

In my case, I used to see animals as an inferior breed. They always slept outside and never came inside the house. It was unthinkable to see them sleeping on the family couch.

Nonetheless, my little twins changed that vision, my past feelings for pets. I changed from the inside out. In my mind, the words equality, dignity and love started to have great meaning. I never imagined I would not only share a space in our house with them, but share a part of my soul.

Through the years, my husband and I discovered that our very brave, Napoleonic complex-suffering doggies, who acted like lions trapped in tiny bodies, were misunderstood creatures.

As a result of the love they gave us all the time, we filled every space of their lives as well, with love and

compassion. Of course, in the end they gave us more than that.

After 10 years, the moment came to say goodbye. Shandy, along with Kiko, crossed the Rainbow Bridge. Our little Yoda left a year after them, leaving behind a legacy of understanding, respect and love; a great teaching of life that is above all kinds of prejudice.

Now we have a whole new generation of brave Chihuahuas, three to be exact: Camila, Seamus and Tiffany Lulu, every one of them with different personalities – or should I say doggienalities?

Seamus hates baths and getting his nails clipped.

Camila loves eating, but hates other people and all other dogs.

For Tiffany Lulu, our puppy who recently turned a year old, the day is all about playing. She plays with the expensive toys bought in the pet shop, but her favorite toy is a tube sock. She also plays with her favorite living toy, Seamus.

Tiffany Lulu has been known to chew her way through shoes as well. Her youthful vigor has energized her brother and sister, as well as her two dads.

We can’t imagine life before our lives became so intertwined by these miracles of nature.

Warrior Life | 11

Chihuahuas (L-R) Kiko, Yoda and Shandy are memorialized in this painting by Mary Dibble. The Chihuahuas gave unconditional love. They were the light of their owners’ lives and changed their lives forever.

In Culver City, Calif. on Nov. 20, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez and her oldest son, Joseph Hernandez, visit the site where the remains of Juan Hernandez were laid to rest at Holy Cross Cemetery.

Story and photos by Kim McGill

Story and photos by Kim McGill

On Sept. 22, 2020, 21-year-old El Camino College student Juan Hernandez – known to his family and close friends as “Cookie” – left the apartment where he lived nearly his whole life with his parents and brothers on Adams Boulevard in South Central Los Angeles to drive to his job at VIP Collective Marijuana Dispensary at 8113 S. Western Ave.

He never came home.

This is not only a story about a missing young person. It’s also a story about a woman who pushed one of the nation’s largest police departments to find her son, and in the process transformed from a mother to a witness, an investigator, a healer and eventually, a warrior.

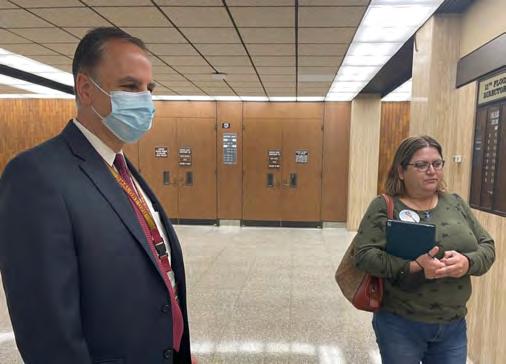

The witness

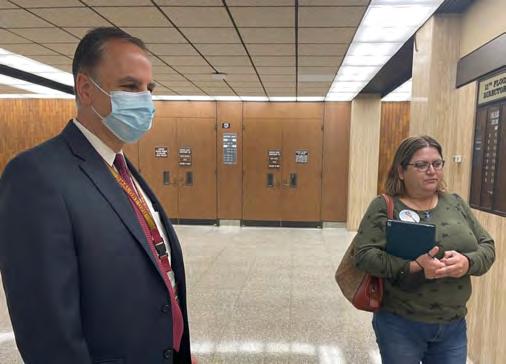

On Feb. 28, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez stood outside Department 41 at Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center in Downtown Los Angeles. Known on the streets and by those who work there as Criminal Court Building or CCB, the massive concrete structure is the largest courthouse in the U.S., with 61 courtrooms and 101 holding cells.

Everyone, no matter how powerful, seems small and insignificant amid the worn marble and tacky wood paneling of its hallways and departments. Thousands of people come and go each day. While things slowed dramatically during COVID lockdowns, Yajaira Hernandez was still among more than two dozen people waiting for their cases to be called.

Her lower face was covered in a black disposable mask – a reality of life under the pandemic – and her brown eyes peered

out from behind black rimmed glasses that perched on top of the mask’s upper edge. Her light brown hair was combed neatly to the side, and blonde highlights brushed against her shoulders. She was dressed in a dark jacket and black and white plaid blouse.

She came to court alone, unlike most of the people leaning on others for support or quietly talking. “I come here so my family doesn’t have to. I want to save them from any more pain,” she says.

Around her neck, she wore a silver chain and heart-shaped charm decorated with a photo of Juan Hernandez, her middle son.

The resemblance between Yajaira Hernandez and her son was uncanny – the same features, same eyes, both wearing glasses – except that in the photo Juan Hernandez was smiling and his mother’s eyes expressed both a fierce determination and a deep sorrow.

Officially, she was in court as a witness for the prosecution in the preliminary

How the murder of Juan Hernandez turned his mom into a powerful leader in the growing movement to heal families and communities

hearing of The People versus Ethan Kedar Astaphan. Astaphan is one of three defendants charged for the killing of Juan Hernandez.

Unofficially, she was there to ensure that the County of Los Angeles would effectively present the evidence she pushed the LAPD to collect.

Juan Hernandez’s murder had happened nearly 18 months earlier, but the LAPD and L.A. County District Attorney’s Office had not communicated much to Yajaira Hernandez about the case.

She was afraid of what she would hear in court, but also anxious to learn about her son’s last hours, including why and how he was killed.

Her disappointment was obvious when she was told to leave the courtroom. With the exception of the law enforcement officers who lead the investigation, all other witnesses are barred from preliminary hearings and trials in order to protect the integrity of their testimony.

It’s only through reporting by the The Union studentproduced newspaper at El Camino College that Yajaira Hernandez learned that her son was allegedly murdered by VIP’s owner – Weijia Peng - and store manager Astaphan, that they dragged Juan Hernandez, possibly unconscious and alive, from the dispensary into the back of an SUV, that while Peng’s girlfriend Sonita Heng drove east to San Bernardino County, Peng and Astaphan injected Juan Hernandez with a lethal dose of ketamine, then dumped his body off a dirt road in a desolate section of the Mojave Desert, that – as daylight broke – they arrived back at the dispensary to remove evidence and clean the location where Juan Hernandez struggled on the floor while being choked, and that later in the day they burned his belongings on an Orange County beach.

The weight of this information caused her shoulders to slump, and her eyes to shift downward, but she did not shed a single tear.

On May 3, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez was back at court. She

was wearing an olive-green sweater with black stars. A large button with Juan Hernandez’s photo was attached just below her left shoulder. She looked tired and her voice was low and somber.

She’s frustrated that the process is so slow.

“People don’t realize that this process is draining. Having to be strong for everyone is exhausting, emotionally and spiritually,” she says. “I wish this system was built differently.”

The prosecutor on the case, Los Angeles County Assistant District Attorney Habib Balian, told her that she doesn’t have to come to every court date. But she feels she needs to be there as much as possible to represent her son.

There are still many months left in the proceedings.

Peng, who was extradited from Turkey where he fled not long after Juan Hernandez’s disappearance, did not appear in court until Nov. 21, 2022 for his arraignment.

Pre-trial hearings were regularly held in December and during the first five months of 2023 to give both Astaphan’s and Peng’s attorneys time to review evidence and prepare a defense. A trial could start in the summer or fall of 2023, but that’s what the D.A.’s office said last spring.

Nothing is certain.

Peng, now 34, remains in custody on $20 million bail and Astaphan, now 29, is detained on $10 million bail. Heng, now 23, is out of custody on a plea agreement that includes her testimony as a state witness against Astaphan and Peng.

Life has moved on for most involved in the case, but not for Yajaira Hernandez, who struggles to heal from the murder of her son.

On Jan. 9, 2023, Astapahan’s defense attorney, L.A. County public defender Larson Hahm, informed the court that Astaphan was married in December, and with permission from the judge, he took a photo of Astaphan in order to process a new I.D.

On April 4, 2023, Balian said that LAPD Detective Daniel Jaramillo – one of two detectives who investigated the case –

Los Angeles County Assistant District Attorney Habib Balian (left) and Yajaira Hernandez wait for the elevator after court on May 3, 2022. Balian told Warrior Life that the persistence of Yajaira Hernandez was the key factor in forcing an

investigation.

Without her pushing the system, Juan Hernandez would still be missing. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

Yajaira Hernandez at Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center in L.A. on May 3, 2022. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

“I’m going to live with this pain forever. We should be able to lay my son to rest, pray for his soul and move on. Instead, we’re praying - and fighting - for justice.”

14 | Warrior Life

- Yajaira Hernandez

was promoted to serve as assistant to LAPD Chief Michael Moore.

Balian also joked about looking forward to his own retirement.

Yajaira Hernandez says that for many family members of people who disappear or are murdered, progress and joy is frozen in time.

“I’m going to live with this pain forever,” she says. “We should be able to lay my son to rest, pray for his soul and move on. Instead, we’re praying - and fighting - for justice.”

The investigator

“I knew immediately that something was wrong,” says Yajaira Hernandez about the morning of Sept. 23, 2020.

She woke up at 5 a.m. She always checked her boys’ rooms first.

Her youngest son, Gabriel Hernandez, was still sleeping. When she looked into Juan Hernandez’s room, his bed was still made, and she says an ominous sensation overtook her.

She rushed outside and found that her car was also missing.

“Juan had never not come home. He never ran away. He was never late without a call or text. And I knew he would never take off with my car,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

He knew how much she depended on her car to get to work.

She checked her phone. She had no missed calls. No texts. Her son didn’t respond to any of her attempts to reach him.

She then called her sister Stephanie Pineda and her boys’ stepfather Mike Burka and asked them to come over.

She called other family members and friends to see if anyone had heard from him. No one had.

His best friend said that they were supposed to meet up, but Juan Hernandez never showed.

Yajaira Hernandez called the dealership where she bought her car and asked them to track it. They said only the police could do that.

She was becoming frantic. She began to

run through possible scenarios. Maybe he’s stranded somewhere without a phone charger. No, he can charge his phone in the car. Maybe he’s been robbed and hurt. Maybe he smoked some weed that was laced with a dangerous substance and he is sick or sleeping it off. Maybe he’s in trouble and afraid to come home.

Yajaira Hernandez made a bargain with her son in her head. “I kept thinking, just come home. No matter what has happened, we can deal with it.”

Pineda and Burka drove to VIP Collective. They spoke with a security guard they described as a tall, slim, Black male.

The Union confirmed through the physical description, court testimony and evidence presented at a later court hearing that the person they spoke to was Jalen Commissiong who another employee, Daniel Romero, referred to as “T.”

According to Daniel, Jalen worked as VIP’s security guard six to seven days a week from 8 a.m. until closing at 10 p.m.

“Juan left yesterday and we haven’t seen him,” Commissiong says to them.

While her family was at VIP, Yajaira Hernandez called the Southwest Division of the LAPD.

They refused to take a missing person report. They told her that her son was an adult and had a right to disappear without checking in with his family. The officers said they had to wait at least 48 hours.

At noon, Yajaira Hernandez, Pineda and Burka drove to the LAPD’s Southwest Division on Martin Luther King Boulevard. Again, they said they wanted to report Juan Hernandez as missing.

The LAPD still refused to investigate it as a missing person case. Young people take off from home without calling their mom all the time, the police said.

Yajaira Hernandez says that the LAPD’s indifference both angered and terrified her. But she was a tough mom who had raised three boys and she was convinced that something horrible had happened to her son.

“Then I want to report my car missing,” she

An altar for Juan Hernandez, built just after his disappearance, remains at the front door of his family’s home in South Central L.A. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

Warrior Life | 15

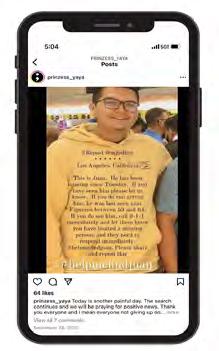

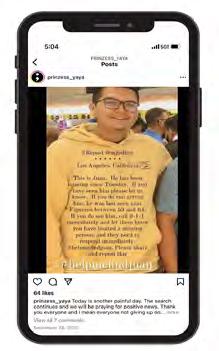

The disappearance and murder of Juan Hernandez and its impact are documented through Instagram posts and a text for ransom. Kim McGill | Warrior LIfe

told the police and she pushed them to take the report. “I wanted LAPD to help me. I wasn’t going to sit there and do nothing.”

At about 3:30 p.m., Yajaira Hernandez, Pineda and Burka went back to the dispensary. All three went inside and spoke to Commissiong. “We closed at 10 and he [Juan Hernandez] left,” Commissiong told them.

Yajaira Hernandez kept questioning him. Commissiong said he couldn’t remember which way Juan Hernandez went, if he was walking or driving, or who else was there when he left.

Yajaira Hernandez then said she needed to speak to E., referring to the store manager Astaphan. “Call him or give me his number.”

According to Yajaira Hernandez, Commissiong told them the store didn’t “want any trouble” or want “anything to do with the police.”

She felt that Commissiong was holding back. She thought he was being evasive, refusing to answer questions and becoming increasingly short and aggressive.

“He was rude. You would have thought they [VIP] would be worried,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

Juan Hernandez never missed work, but no one at the dispensary seemed concerned that he wasn’t there. Astaphan sometimes drove her son home from work, yet he hadn’t called to ask about him.

“I knew something was wrong,” she says. “They were being very sketchy.”

Yajaira Hernandez went to a nearby liquor store with her son’s photo. The staff immediately recognized him and said that he came in every day for snacks. They offered to post a missing person flier once one was created and promised to ask customers if anyone knew anything. She says this is the kind of response she would have expected from VIP unless they were hiding something.

When she returned to the dispensary, Commissiong didn’t want to let her in.

By the time they arrived back home, Yajaira Hernandez was in full detective mode. “I felt I had to do the work that the LAPD was refusing to do,” she says.

Juan Hernandez’s older brother Joseph Hernandez posted a message on Instagram and Facebook. Yajaira Hernandez shared it with all the school and community groups their family was a part of – the PTA, robotics club, a neighborhood academic enrichment program run by USC, and the running groups Juan Hernandez and his mom had been a part

of since he was 14.

“We had a great response from family and friends,” Yajaira Hernandez says. People started to share the post and asked what else they could do to help.

Yajaira Hernandez’s phone number was included on the post and, within 24 hours, she started getting ransom demands.

They terrified her.

One text said they were torturing her son in Tijuana. One person threatened that they had to get the money within 30 minutes or they would cut off a finger. Another gave her 24 hours to pay or they would kill him. She panicked that her son got involved in something dangerous like trafficking for a cartel.

“I begged Juan not to work at the smoke shop because it was unlicensed,” she says.

But he told his mom that he felt responsible for helping with rent and bills. At the start of the pandemic, he was laid off from his job selling timeshares. The nation was shut down and there weren’t many jobs.

Within 48 hours of his disappearance, Yajaira Hernandez had gotten four calls and five texts, all from different people claiming they kidnapped him. They asked for between $5,000 and $10,000.

“We didn’t have the money to pay anyone,” she says. “We live paycheck to paycheck. When I asked people to put Juan on the phone or send me a recording, no one did.”

Yajaira Hernandez says she ended every call and text the same way. “If you do have my son let him know I love him.”

At the same time, dozens of supporters were calling the LAPD to file a missing person report, and the pressure worked. Yajaira Hernandez finally heard from an officer who told her that her son’s disappearance sounded like “foul play.” He promised he would push the missing person unit to investigate.

“That was the first time I felt heard by the LAPD,” she says.

A friend connected Yajaira Hernandez to a retired detective. He told her to tell the LAPD about the ransom demands.

The LAPD immediately said she shouldn’t have posted anything on social media. She shouldn’t have put her number on any flier. “That made me feel like crap,” she says. “Like maybe I put my son in this position.”

But in the end, it was the ransom threats that moved an investigation forward.

In less than 24 hours, LAPD’s Robbery and Homicide Division contacted her. “It was not

16 | Warrior Life

The first post of a cat meme reflects Yajaira Hernandez’s typical lighthearted messages that ended with the killing of her son. Kim McGill | Warrior LIfe

missing persons or homicide that called,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “The LAPD cared more about the extortion for money than Juan’s disappearance.”

Five days after her son’s disappearance, Yajaira Hernandez met with LAPD robbery detectives Jaramillo and Jennifer Hammer. She showed them the ransom threats, but she also shared her suspicions about the dispensary. She didn’t hear back from them until two weeks later. They said they were investigating.

“By then we were doing our own thing,” she says. She and her sons continued to post messages to social media urging people to share any information they had.

Before her son went missing, Yajaira Hernandez posted a few times a month on Instagram – a comical message about falling off the toilet during an earthquake, photos from a birthday dinner with a friend, a onechip challenge and lots of cat memes. She had been on Instagram since 2012 and had a small following of friends and family. Her posts rarely generated more than twenty likes.

After her son’s disappearance, she posted several desperate messages on Instagram and Facebook every day urging people to “#helpmefindJuan.” She started getting thousands of views on videos, and hundreds of likes on regular posts.

“I know I may be overwhelming everyone with my posts,” she wrote on Sept. 25, 2020. “Unfortunately, this is all I can do to spread the word on my baby boy.”

On Sept. 27, 2020, Telemundo broadcast a story about the search as well as a follow-up story covering a vigil the family organized on Sept. 28.

The family also made 10,000 flyers.

From Sept. 23 to Nov. 18, 2020, hundreds of people came out every day to search the streets, parks and tent encampments.

They followed up on every tip from downtown L.A. to San Pedro. They attached flyers to thousands of light poles and talked to everyone they saw. They organized a rally at LAPD headquarters.

“I’m very grateful for the community” Yajaira Hernandez says, and she credits everyone’s actions as “making the difference” in getting the LAPD to investigate. “I wouldn’t have been able to do this alone.”

L.A. City Councilmember Herb Wesson donated an additional 30,000 flyers. Lamar Advertising Company only charged $900 for 13 billboards that were up for six weeks - a fraction of the usual cost. A Go Fund Me

raised thousands of dollars for gas, flyers, shirts and posters.

Nearly two months after Juan Hernandez’s disappearance, Jaramillo met with Hernandez. He told her that the LAPD had worked with the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department to uncover her son’s remains in the desert.

Hammer later testified at Astaphan’s preliminary hearing that the LAPD used cell tower data to track the movement of Astaphan’s and Peng’s phones, eventually leading them to the body.

“Part of me was relieved that Juan was found. But knowing he was dead shattered my world,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

The LAPD told her that they had arrested Astaphan and Heng. They were still looking for Peng.

“I asked if I could see Juan, but they preferred not.” His body was badly decomposed and also impacted by animals scavenging, the LAPD told her. It was another month before his body was released and cremated.

She and her sons chose a spot for his remains in the garden at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City.

Juan Hernandez was one of more than 500,000 people reported missing in the United States in 2020.

According to federal statistics, Los Angeles has the highest number of missing person cases when compared with other U.S. cities. LAPD missing person investigations can be requested and tracked online, although only a fraction of the people reported missing are included.

The California Department of Justice (DOJ) releases annual information on missing persons as reported by law enforcement, and the state’s active missing person cases average about 20,000 on any given day. The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) shares similar data for cases it is investigating across the nation.

This is a fraction of the people who actually disappear that no one notices, or who aren’t reported missing.

California state DOJ policy states that “there is NO waiting period for reporting a person missing. All California police and sheriffs› departments must accept any report, including a report by telephone, of a missing person, including runaways, without delay and will give priority to the handling of the report.”

However, the DOJ only collects data on

Warrior Life | 17

people reported missing by local law enforcement, and while detailed data and resources exist for missing children, the state has little data on people over the age of 18.

Each year, L.A. County buries in a mass grave the cremated remains of over 1,500 people whose identities are either unknown and/or whose bodies are unclaimed by family. The county holds individuals’ remains for three years to allow family members and loved ones a chance to claim them. In December 2022, L.A. buried the remains of 1,624 people who died in 2019.

“The LAPD made me feel like my son was nobody, like he wasn’t valuable enough to look for. This added so much to the pain and anxiety I was going through,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “We do the heavy work and they [police] come and sweep up after us.”

Jaramillo and Balian both told Warrior Life that the persistence of Yajaira Hernandez was the key factor in forcing the start of an investigation and moving it forward. Had she given up hope or been too intimidated to push the system, Juan Hernandez would still be missing.

The healer

As a young mom, Yajaira Hernandez, now 43, married Jose Hernandez, the father of her youngest son, Gabriel Hernandez. He adopted Juan and Joseph and the boys were given the Hernandez name.

Yajaira Hernandez went to school full-time and worked

part-time. She earned an associate’s degree in liberal arts. She started working at the L.A. County Department of Public Social Services (DPSS).

She and her husband separated, but remained good friends.

She was active in her sons’ lives, involving them in sports, science and robotics camps and programs that contributed to their academics.

The Hernandez home just before the end-of-the year holidays in 2022, reflects the love that Yajaira Hernandez has for Tim Burton’s Nightmare Before Christmas, including a tree decorated with ornaments depicting all the characters. Inspirational sayings cover the walls of each room such as “Family, where life begins.”

On her right arm is a tattoo with her three sons. Juan Hernandez has a halo and “Til’ I see you again,” written above his head.

After her son’s murder, Yajaira Hernandez took a leave of absence from work. “I can’t really say my job was supportive, but thankfully, I had a job when I came back,” she says.

On Dec. 21, 2020 the remains of Juan Hernandez were buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City. Yajaira Hernandez was back at work on Jan. 4, 2021.

The mortuary had only two dates available - Dec. 19 which is her mom’s birthday or her own birthday on Dec. 21.

“Life never really stops knocking you down,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

Since her son’s murder, the changes in her life are numerous. “I sleep about two to three hours a night. I’m either overeating or not eating anything,” she says. “I get dressed and go to work to set an example for my sons, but a lot of times I want to quit. I’m constantly praying and watching videos of my son. One moment I’m okay and another I’m breaking down in tears. There’s a piece missing inside me.”

She thinks often of all the moments in her son’s life that she will never experience – his graduation from college, his wedding, the birth of his children.

“Everything we do as a family – every dinner, every conversation, every joke – I think about how much Cookie would have loved it,” she says.

To help herself heal, she began to heal the community.

More than 100 people came out to “Run for Cookie” in Griffith Park on Oct. 16, 2022 to celebrate what would have been Juan Hernandez’s 24th birthday on Oct. 15. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

More than 100 people came out to “Run for Cookie” in Griffith Park on Oct. 16, 2022 to celebrate what would have been Juan Hernandez’s 24th birthday on Oct. 15. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

On April 30, 2022 Yajaira Hernandez joined families impacted by violence at a candlelight vigil in South Central LA.

“I’m here to feel supported and support others,” she says. “Some people are alone, and they turn to alcohol, drugs, the streets to deal with the pain. These are the consequences for the families left behind.”

Speaking to ABC 7 news and Warrior Life at the vigil, Yajaira Hernandez explained that community healing events are essential for her own and others’ healing. “With other survivors, I’m open and honest. I don’t have to hide my pain. I don’t have to hide my emotions. I don’t have to fake a smile for my family or other loved ones. This is for me. This is part of my journey.”

Oya Sherrills works at a healing center for families in Watts. She was at the vigil to honor her brother Terrell Sherrills whose murder remains unsolved. “L.A. needs resources for victims and survivors of crime,” she says. “Families need access to a lot more of the court and police records, as well as opportunities to tell our stories and shift the narrative. We are shut out by law enforcement and the courts.”

Sherrills says family members need healing services but also “healing conditions.”

“It’s really difficult managing grief,” Sherrills says about the struggles surviving family members endure.

“You lose your job, don’t have a place to rest your head, don’t have access to substance abuse treatment and mental health when you self-medicate after tragedy strikes.” she adds.

To celebrate what would have been Juan Hernandez’s 24th birthday, his family worked with Anytime Runners and Rundalay to organize a five-mile “Run for Cookie” in Griffith Park on Oct. 16, 2022. Yajaira Hernandez and her son used to run with the two groups.

“My biggest motivator is supporting my mom,” Joseph Hernandez says. As a toddler, he struggled to pronounce his little brother’s middle nameCarlos. It came out “Cookie,” and the nickname stuck. “Every year, my mom tries to figure out how to cope with Juan’s birthday,” he adds.

“It’s a hard day. This year she thought about having a community event with something that she did with Juan, because their relationship was always through running.”

Rundalay founder Francisco Montes said he saw Juan Hernandez grow up.

“Even at a young age, Juan stepped up when we needed someone to pace a group,” Montes says. “It was amazing to see a 17-year-old lead 30 people without fear. He impacted a lot of people,” he adds, holding back tears.

The run raised more than $1,000 to support families of homicide victims in L.A.

The warrior

Just past sunrise on April 26, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez arrived at Fred Robert Park on Honduras just south of Vernon Avenue on the east side of South Central Los Angeles.

She leaned against a cement table covered in graffiti scratched into the paint.

“We’ve had enough,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “All this hate, all this violence needs to stop. If I can help out one family, then my son didn’t die in vain.”

Slowly other people pulled up – mostly mothers and grandmothers – all there because their family members had been murdered in the streets, violent relationships or by law enforcement. They came to travel to Sacramento for the annual Survivors Speak conference and advocacy day at the California state capitol.

Before boarding the charter bus for the long ride to Sacramento, Yajaira Hernandez spoke to NBC 4 news and Warrior Life.

“Some days are good. Most days are bad,” she says. “When I’m around other victims’ families, I can speak without any regrets, without any shame, without feeling like I’m a burden to them. It’s like a safe space.”

Phillip Lester, who coordinates violence prevention programs for youth in Los Angeles, was also in Sacramento. When he was 14, Lester was shot

Oya Sherrills and her son attended the candlelight vigil on April 30, 2022. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

Yajaira Hernandez (far left) joins families impacted by violence at a candlelight vigil in South Central L.A. on April 30, 2022. “I’m here to feel supported and support others,” she says.

“I fought for Juan when he was alive, and when he was murdered, I did everything possible to find him and bring him home.”

- Yajaira Hernandez

Yajaira Hernandez at the Survivors Speak Conference and Advocacy Day at the State Capitol, Sacramento, Calif., April 24-26, 2022.

20 | Warrior Life

Kim McGill | Warrior Life

twice, and was then shot again at 15.

“I got no services or counseling,” Lester says.

“I was ejected [from the hospital] right back into the streets.”

As he stood on the Capitol steps before entering the building to speak with legislators,

Lester also described how survivors go on living in the same homes and neighborhoods where their loved one was murdered without any access to counseling or peer support, let alone the ability to move.

“People need help after a traumatic situation,” Lester says. “Money must be allocated toward survivors of crime, and to the establishment of Trauma Recovery Centers run by folks like me in the communities where we come from.”

Since Survivors Speaks, Yajaira Hernandez has begun to speak out more often to the media, public officials and to the community about what’s needed to prevent violence and to help survivors seek justice.

Since Survivors Speaks, Yajaira Hernandez has begun to speak out more often to the media, public officials and to the community about what’s needed to prevent violence and to help survivors seek justice.

“Every time I share Juan’s story I’m keeping his memory alive,” she says. “I hope that other families gain some courage, knowledge and resources from our experience.”

On Sept. 23, 2022 she spoke to more than 100 community residents at Los Angeles Trade Tech College about how to push the police to fully investigate a case and report back regularly on the progress.

“I didn’t know anything about LAPD policies,” says Yajaira Hernandez to the audience. She encourages them not to give up no matter how badly they are ignored or dismissed.

“If we don’t fight for our loved ones, no one will. The system won’t do it for us,” she adds.

Reflecting on the past two years, Yajaira Hernandez says she carries a lot of pain, but no regrets. She pauses, bows her head for a moment, takes a deep breath and looks up.

“Like all my kids, I fought for Juan when he was alive,” she says. “And, when he was murdered, I did everything possible to find him and bring him home.”

Yajaira Hernandez (left of podium) and other families fill the steps of the California state capitol at the Survivors Speak Advocacy Day in Sacramento, Calif. on April 26, 2022. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

Warrior Life | 21

Phillip Lester stands on the steps of the California state capitol before going inside to meet with legislators at the Survivors Speak Advocacy Day in Sacramento, Calif. on April 26, 2022. Kim McGill | Warrior Life

22 | Warrior Life

El Camino College English Professor Chris Page relaxes before his punk rock band tudors performs in January 2023 at The Sardine, a bar in San Pedro. This would be tudors first paid gig since the 2020 pandemic lockdowns.

Taking the Stage: Christopher Page

El Camino’s English professor converts markers in class to drum sticks for band gigs

Story by Jesus “Jesse” Chan

Photos by Gary Kohatsu

In a dimly lit room, a drum set lies. As the hush descends, a door opens, and Christopher Page enters, drumsticks in hand. He’s ready. Page spent his childhood in Long Beach reading books, skateboarding in places he wasn’t supposed to, and creating a garage band with his pals. Growing up with an engineer father and an early childhood development mother, Page was often given the freedom to pursue many of his hobbies.

Early on, buckets and pots were used for more than just storage and cooking. Instead, as a youngster sitting in his garage on sweltering summer days, he transformed them into drums. He enjoyed headbanging to Motley Crue, Guns N’ Roses, and Twisted Sister, but his parents were never fans of the music he listened to.The El Camino College English professor and musician, now a drummer for the Los Angeles-based rock band tudors, attributes much of his love of music and writing to his creative youth.

While brushing his slick black hair back, squinting his blue eyes, and crossing his legs. Page recalls certain hobbies that he still pursues and likes that would not have been possible if it had not been for his curiosity as a child Painting, writing, and building were just the beginning of what would become a lifetime of discovery.

Page, on the other hand, jokes that he is not very skilled at such activities.

“My parents were like, ‘Hey, don’t bother me. And do what you want.’ So, you know, that led to me exploring a lot of different things,” Page says. “I found I was interested in a lot of different arts. I’m not good at them, though.”

He chuckles as he reclines on his chair in his ECC office, which is brightly lighted by the wide

window behind his desk. Page is naturally drawn to the arts, which is why other interests have never captured his full attention.

During his childhood, he participated in sports such as soccer, football, hockey, and skating, but only skateboarding piqued his interest. Page tried multiple times to convince his parents to buy him a skateboard, but to no avail. The solution? He built his own.

“I loved [skateboarding] the second I saw it, and for a long time, my parents would not buy me one, so I had to find broken ones, or like I would use rollerblade wheels on my friend’s old deck,” Page says.

Aside from skateboarding, Page’s curiosity wandered so far that books eventually captured his attention. Like his love of music and skateboarding, the inventiveness behind books such as “Lord of the Rings” and “Catch-22,” two of his favorites, only fueled his passion for creative literature.

“‘The Fellowship of the Ring,’ I think I was 11, and I brought that on a family vacation. I read the entire thing in two days,” Page says. “I was so captivated by the world and how it was written. That it was like it could transport you.”

Page enrolled in Cypress College shortly after graduating from Cypress High School. However, like many kids fresh out of high school, he was unclear about what he wanted to do and dropped out. Page worked as a manager at a video store, a clerk at a local library, a furniture mover, and a graphic designer on the side.

But those jobs turned into obligations that frustrated him and prompted him to return to college. A pledge made to himself to better his life and return to education represented an opportunity

Warrior Life | 23

(Above) (L-R) Guitarist Marcus Clayton, drummer Christopher Page and vocalist/bassist David Diaz perform as tudors at The Sardine in San Pedro early in 2023. The performance marked tudors’ first live gig since the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown of businesses.

(Above) (L-R) Guitarist Marcus Clayton, drummer Christopher Page and vocalist/bassist David Diaz perform as tudors at The Sardine in San Pedro early in 2023. The performance marked tudors’ first live gig since the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown of businesses.

24 | Warrior Life

(Left) Drummer Christopher Page had three main passions as a youth: skateboarding, reading and music. He has managed to retain two interests, as a full-time English professor at El Camino College and a part-time musician for tudors, a punk rock band.

to leave professions he did not enjoy behind. As a result, some students may find themselves in one of his English classes at ECC. Page chose El Camino to teach because it reminded him of his days at Cypress College. Page’s desire to attend college was influenced by two factors: student accomplishment at ECC and how far students go to represent their college.

“I love all the things students create here at [El Camino], for example, the newspaper blew me away when I first arrived. The fact that students here in the forensics club did so well on the national stage and students in the general taking center stage when I came for the interview, seeing student work on the wall, really blew me away,” Page says.

After school, however, Page is often introduced onstage with fellow band members, vocalist/ bassist David Diaz and guitarist Marcus Clayton, as tudors. Page enjoys playing music for audiences of 25 or hundreds, even if it means not selling out most venues where he performs.

“I knew the first time I started rehearsing in a garage that I was like, this is what I want to do. This is it,” Page says.

After spending time in bands such as the Mini Golf All-Stars, Confront, Blank Mind, Kryptonite Condoms, and Virginia Wolf. Page formed the band with Diaz and Clayton after bonding over their love of bands like the Descendents.

“I met him at a tutoring center. Chris intimidated me when I first met him because I just thought he was really smart and good at his job,” Diaz says. “I remember wearing a Converge t-shirt, and he was like, ‘You like Converge, too? Cool,’ and I was like, “This dude likes the same music I like. That’s cool.” For Clayton, the band has been an opportunity to be himself and have fun.

“Generally speaking, it’s a nice outlet for all three of us to be loud and ourselves because of work or the stresses of life. We typically can’t play, but it’s always a nice little release,” Clayton says.

Page, Diaz, and Clayton have shared many unforgettable times, but nothing has stopped them from playing together. Diaz recalls one specific memory that makes playing together worthwhile.

“If I remember correctly, Chris forgot the legs to his drum set because he’d always move his drum set from this rehearsal space we were in,” Diaz says. “He had to set his drums up facing the wall, but it was still tight, which is still a super cool memory for us as a band.”

Page is humble, frequently admitting that he does not believe he is a capable drummer. However, his goal is to continue live gigs and, maybe, produce some new albums with his band.

“Honestly, I’m just going to keep going until I can’t anymore. Until my arms fall off,” Page says.

Warrior Life | 25

English Professor Christopher Page is a full-time instructor at El Camino College and in his spare time, a drummer in the punk rock band, Tudors. As a youth, Christopher developed his passion for music, skateboarding and reading novels, including “Lord of the Rings.”

Known originally as the Point Fermin Landslide, Sunken City in San Pedro is all that remains of a neighborhood that slid into the sea over two decades beginning in 1929. The cliffs are treacherous and the ground unstable. Many have tumbled to their deaths.

Kim McGill | Warrior Life

Kim McGill | Warrior Life

26 | Warrior Life

TOP 5 HAUNTED PLACES CLOSE TO ECC

From downtown L.A. to the South Bay, here’s where you are most likely to encounter a ghost

Story, photos and illustrations by

Kim McGill

1 2

The Pico House, location of the 1871 Chinese Massacre, one of the deadliest mass lynchings in U.S. history

The Pico House at 424 N. Main St. in Los Angeles, 90012 is the site where several vicious attacks occurred just outside the hotel’s entrance during the 1871 Chinese Massacre. Guests and staff have reported angry encounters with the ghosts of those who were killed. At the time, Don Pio de Jesus Pico - the last Governor of California under Mexican rule - was a wealthy rancher. The Pico House, built just one year before the massacre, was considered L.A.’s first luxury hotel. But, by his death in 1894, Pico was broke. Historians attribute his downfall to lawsuits, gambling, extravagant spending and womanizing. Could it be that Pico was cursed by the spirits that haunt his hotel?

By 1871, Los Angeles had a thriving Chinese community between Main and Los Angeles Streets along “Calle de Negro” or “N----Alley.” The street got its derogatory name from first Spanish and then American elites who forced Chinese and California’s indigenous Tongva people to live there. When a white saloon owner was accidentally killed in a shootout between rival Huiguan organizations, a mob of 500 white and Mexican men led by law enforcement and elected officials attacked the community, lynched at least 18 Chinese boys and men, and burned Chinatown to the ground. Some attacks occurred just outside the Pico House. Only eight people were convicted and even those convictions were overturned on appeal. Vigilante violence was common in L.A. The region had the highest lynching rate in the U.S. between 1848 and the 1880s. Newspaper editorials regularly claimed that Chinese people were immoral and inferior, and officials pushed the U.S. to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. L.A.’s Chinatown was rebuilt decades later several blocks north by attaching fake “Chinese-themed” movie sets to the buildings. You can still see where set decorations cover the original structures.

Terminal Island where the U.S. destroyed the Japanese American community of Fish Harbor

Terminal Island, centered within the huge ports of L.A. and Long Beach, is reached by driving to the southernmost points of the 110 and 710 Freeways. From 1900 - 1942, at least 3,000 Japanese Americans lived here in the community of Fish Harbor. After the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government forced more than 300,000 Japanese Americans into incarceration camps, confiscating their land and property. Fish Harbor was erased.

to

claim they have seen

A monument – featuring a Torii gate, the traditional entrance

a Japanese Shinto shrine that marks the transition from the everyday world to the sacred – is all that marks the spot. Dock workers

and heard the ghosts of former residents searching the streets for their homes and neighbors.

Warrior Life | 27

The Drum Barracks

The Drum Barracks located at 1052 N. Banning Blvd. in Wilmington, 90744 is Los Angeles County’s only remaining Civil War era military facility. The Union Army fort was in a dangerous location as L.A. County was the only region west of Texas that sided with the Confederacy and was a major supplier of the South’s war campaign. Conditions at the barracks were also harsh given its far isolation from other Union troops and frigid Pacific Ocean winds sweeping across the South Bay. L.A. City Department

of Parks and Recreation operates the site as a museum. Both staff and visitors say they have seen the spirits of Union soldiers roaming the hallways, sitting in chairs or lounging on the front porch. A favorite is Fred who asks if anyone has seen his love, Maria. Reports also include lights turning on and off and the smell of cigar smoke.

Point Vicente Lighthouse 4

On a cliff overlooking the Pacific is the Point Vicente Lighthouse located at 31550 Palos Verdes Dr. W., Rancho Palos Verdes, 90275. Before the lighthouse was built in 1926, a woman was known to walk the cliffs looking for her lover who was lost at sea. Many people claim that she can still be seen at night floating along the lighthouse gallery searching the waves.

3 5

Sunken City

Where San Pedro meets the sea next to Point Fermin Park near Cabrillo Beach you will find the Sunken City. It’s defined by the rubble of a street and concrete foundations from a neighborhood that slowly slid into the ocean over two decades beginning in 1929. Since then, curiosity has drawn thousands here including graffiti writers who see the spot as a street art mecca. But the cliffs are treacherous and the ground unstable. Many have tumbled to their deaths. Others have died by suicide. Some say you can hear their mournful cries warning others to stay away. You also face large fines and arrest if you go beyond the fencing. Some views – and the best way in – are on the far-left corner of Point Fermin Park facing the sea at 807 W. Paseo Del Mar, San Pedro, 90731.

28 | Warrior Life

These ghosts also deserve attention

The Cecil Hotel, 640 S. Main St., Los Angeles, 90014, where a strange glow emanates from the building. Is it the sun or a restless spirit? Redondo Union High School, One Sea Hawk Way, Redondo Beach, 90277 and Zamperini Stadium, 2125 Lincoln Ave., Torrance, 90501 Kim McGill | Warrior Life

The Cecil Hotel would have been in the top five had it not been for the international attention it’s already gotten with the Netflix series on Elisa Lam who mysteriously drowned in the rooftop water tower. The Cecil is arguably the world’s creepiest hotel with numerous murders, suicides and overdoses, two serial killers among its residents, and a wellearned reputation for being haunted. There are also reports that two high schools close to ECC have ghosts. Look for Jake at Redondo High, a student there during World War II. He had a crush on a girl whose jealous boyfriend returned from the war and beat Jake to death. Neighbors say an unknown woman and her two children were murdered after leaving a Torrance High School football game at Zamperini Stadium and that their ghosts are still seen walking home.

Warrior Life | 29

BARS | |

Love Beyond |

My boyfriend was incarcerated. It felt like I served time too.

Story by Nindiya Maheswari Illustration by Ingrid Barrera

Summer 2021. I sat for eight hours on an overnight bus traveling from San Francisco’s Caltrain Station to Union Station in Los Angeles.

I was finally able to visit my boyfriend who was incarcerated at Twin Towers Correctional Facility in Los Angeles. It had been over six months since I last saw him.

It was still dark when I arrived at Union Station at 6 a.m. I walked to Denny’s to get some crispy bacon and eggs.

My visitation was scheduled for 9 a.m. I applied face powder, pink blush and cinnamon colored lipstick at the breakfast table. I wanted to look nice for him.

The weekend is always special because it’s the only time we are allowed to visit incarcerated loved ones. We wake up super early and line up outside the facilities ahead of our visiting time.

According to a 2018 report by FWD.us, 6.5 million adults in the U.S. have an immediate family member currently in jail or prison.

A deputy checked my identification at the security gate and let me in. While in the waiting room, I saw a woman come a minute late to her visit and beg to be let in.

Her bus was late and she traveled 100 miles to see her husband. The deputy had no mercy. He turned her away.

Feeling powerless, I could not say anything or make a scene because there would be repercussions. We could be blacklisted and lose our visitation privileges in the future.

I had to pick my battles. I did not travel for eight hours by bus from San Francisco to L.A. only to be sent home without seeing my boyfriend.

Soon they called my name and I took an elevator to the third floor. As I got out, I saw my boyfriend

sitting behind a glass wall. I ran to him and cried. I saw one of his hands was handcuffed to the booth.

I did not know that we would be separated by the glass wall. I thought I could hold his hands or hug him.

We talked through a phone. He was right in front of me, but his voice sounded so far away.

Laughing together, we put our hands against the glass wall. The visitation was only for 30 minutes.

I did not get to tell all the stuff I’ve been waiting to tell him – how I loved my new job, how I had five boba shops within walking distance from my new apartment.

When visiting time was over, they cut the phone line. The deputy came, handcuffed both of my boyfriend’s hands and took him away.

I got on the elevator with two women I had chatted with in the waiting room. We looked into each other’s eyes and smiled.

We did not say anything but I felt like that was a code. We had to be strong. We would get through this. Together.

I went home to San Francisco the same day. Sixteen hours on a bus for 30 minutes of visitation.

My friends and family figured it was just love. But it’s more than that.

Being there for my boyfriend was my form of resistance to the unjust criminal justice system.

Throughout my visitations, I noticed that the majority of visitors are women. Children and women are heavily impacted by incarceration. It affects family relationships, emotional and economic well-being.

Supporting incarcerated loved ones is not easy nor cheap. Phone calls and commissary in jail and prison are expensive.

I was spending $200 for phone calls per month through a company called Global Telephone Link.

|

30 | Warrior Life

Items sold inside jail and prison are double or triple the regular price.

I spent $100 monthly to buy him 10 cups of Top Ramen, one honey bun, a bag of hot chicharrones and a couple of pouches of tuna.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that made phone calls free in California prisons. That was too late for me. If it was free, I could have talked to him every single day. I would have not felt so lonely. He was my best friend.

I felt like I was being punished too. I couldn’t really talk about it to my friends or family because of the stigma. The isolation became unbearable and took a toll on my mental health. I saw a therapist every week so that I had someone to talk to.

During these tough times, I found healing through making documentaries around the impact of mass incarceration to families. I cried while filming and editing, but felt relief. I released my emotions: anger, sadness, powerlessness, loneliness.

After completing my bachelor’s degree in television production at CSU Northridge, I was hired by a non-profit organization that advocates for communities impacted by incarceration to be their in-house filmmaker.

Not only did I find my dream job but I also found my community and support. I got paid to do things that I love. Things that mattered to me.

My boyfriend eventually came home in December 2021. He was incarcerated for a year as a result of an unhealthy coping method of his

depression and charged with a DUI.

Prior to his incarceration, he suffered from severe depression, anxiety and generational trauma. Jail didn’t make him a better person though. It only added more trauma.

Even after he was released, I felt like I was still being punished. An armed parole officer came to our Torrance apartment once a month and collected his urine for a drug test. He had a key to our front gate so he could knock on our door anytime, unannounced.

The officer had the power to send my boyfriend back to jail for any parole violations. A traffic stop because of a broken tail light could land him back in Twin Towers Correctional Facility.

My heart was beating so fast and I sweated every time I saw a police car while driving with him. I said to myself, “please not today.”.

In December 2022, my boyfriend was released from parole one year early for good behavior. When I heard this news, I felt like a heavy rock was lifted from both of my shoulders. Now I am free, too.

Author’s note: if you or someone you know is impacted by incarceration, contact ECC FIRST (Formerly Incarcerated Reentry Student Thriving) program by email at first@elcamino.edu

Warrior Life | 31

food

& community calling

Chasing after new adventures, a couple stumbles on a place like home

Rickety heavy wheels screeched by on the surgical floor, echoing through the sterile corridors.

With a sense of excitement, she attempts to enlighten her 14-year-old son about her role as an attending physician at the teaching hospital when a patient with exposed stomach organs from a severe accident is rolled in.

“I think I’m gonna pass out,” Julius Obembe stammered, his face turning pale.

And as fast as Obembe’s decision to take on a tour at the hospital where his mother worked, he’s ushered out of the room on a gurney even quicker.

Faced with organs on his first day touring the hospital was enough to bring his parents’ dreams of him becoming a doctor down to earth.

Obembe, having graduated high school at 16 in Lagos, Nigeria, and not planning to go to a university, was sure he’d be pulled into the medical world if he didn’t take matters into his own hands.

He felt a need to expand on his knowledge and experience.

But it was more than just his intense hunger for knowledge that propelled him into the restaurant business and later to owning Torrance’s Sausalido Cafe — it was his rebellious nature, in defiance of his parents’ expectations of a career path.

Now Obembe, 61, and his wife Lucy Liampetchakul, 54, are hard at work running their mom-and-pop restaurant.

Sausalido Cafe is the place to relax and recharge after a difficult day for many El Camino students, employees and the local community. This PanAsian cafe offers an Associated Students Organization (ASO) benefit pass. The cafe is just a couple minutes from El Camino College, at Redondo

Beach Boulevard and Prairie Avenue in Torrance.

Obembe’s way of getting to this point was his determination to gain knowledge and experience, traveling from the bustling city of Lagos, Nigeria, to the serene South Bay at 18. He made the 16-hour journey in hopes of finding his calling.

What awaited him was schooling at California State Dominguez Hills, a path that was made more rewarding by his accomplishments in Nigeria.

He completed the West African Senior School Certificate exam to confirm his graduation from High School at 16. When the results were posted, he, along with some of his classmates did not find their results listed. The delayed results caused him and his 15 classmates to wait anxiously for four long months.

Obembe passed but made up his mind not to continue his education in Nigeria. Instead, he decided to go to a California university. His parents did not warmly receive this decision, as his mother urged him to attend the prestigious 2-year college, Albert Academy, in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where his mother grew up.

“I took the offer to study there with the end outcome being I would be allowed to come to Los Angeles, California,” Obembe says.

While attending the Albert Academy, Obembe applied to several universities including California State Dominguez Hills. At the start of his second year at the college, he received an acceptance letter from California State Dominguez Hills but his parents advised him to complete the school year.

Regardless of his parents’ guidance, he took a break from school. Obembe’s father suggested a job opportunity at a friend’s architectural firm in Lagos, Nigeria. Despite this, Obembe remained

Story by Hannah Bui

Photos by Raphael Richardson

32 | Warrior Life

committed to completing his education in California but that didn’t stop him from working in the meantime.

Starting a new role as a draftsman at his father’s friend’s firm at 17, Obembe found himself in a spacious and lavish office. Drawing plans for houses became his temporary refuge, where Obembe would draft the front view, side view, elevated view, top view, and floor plans and grew to appreciate the position.

Earning a monthly income of $1,500 and an additional $500 bonus for promising designs that encouraged clients to request more work only added to the joys of his job.

“I was like wow. If I saved up my salary, I could buy my own ticket and pay my tuition at Cal State,” he says.

After saving money to do as he planned, the American Embassy sent him a letter to issue his Visa. Days later, his father took him to the travel agency and the American Embassy to get his Visa. That day, his dad told him “you leave tomorrow.”

Obembe was off to California at 18.

That year, he began his academic journey at California State Dominguez Hills, completing his studies at the age of 21.

While Obembe’s education began in an effort to become an English professor, Liampetchakul was occupied with earning a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the same university.

After graduating, Obembe landed a teaching position at a Catholic school, which he held for two years before venturing into the public sector. At the age of 23, he started working for the County of Los Angeles as an Appraiser Assistant, a career which he later left to join the City of Los Angeles as a Tax Collector until age 29.