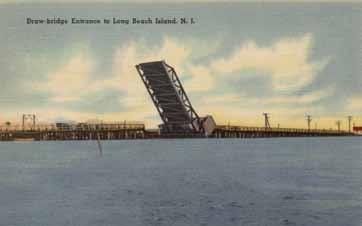

elcome back to Long Beach Island, eighteen miles of special destinations. We have been waiting for you. There is something about this Island that draws people to it and brings them back year after year. In the beginning people swam, floated, and paddled their way across the dangerous waters of Barnegat Bay. Eventually, they built train and car bridges to traverse those waters and even landed small airplanes in sandy fields to reach their special LBI destination. Some people relocated their families, launched new businesses, and made LBI their home. For many, the Island became the special place that drew them back time and again.

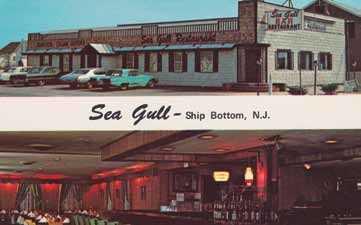

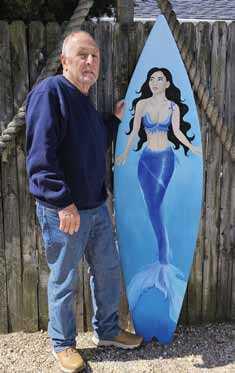

No matter your destination, there is something here that captures the hearts of residents and visitors alike. For some lifetime Islanders, like me, it holds us here and we never leave. I grew up in Harvey Cedars. Ship Bottom has been my home for the past fifty-eight years. It is where my children were raised and where my business has been for the past forty-nine years. It is where I hope to remain forever.

Many visitors to my shop tell me their families have continued to return to LBI for decades. Just as many new visitors say they have found their special place and cannot wait to return. So, I am curious. Is this your first visit to the Island? Has your family vacationed here for generations, or have you returned to make LBI your permanent home? What brought you here and what draws you back? I hope you will stop by and let me know.

Growing up in Harvey Cedars, during the winter we often played games. In addition to Scrabble, which was our mother’s favorite game, we learned to play chess. We also learned to play canasta, and pinochle, with the exception of poker. For me, the most fun was learning palette knife painting with acrylics. Paint brushes for six children were costly, and we hated cleaning them. Wiping a palette knife clean was easy, albeit messy. My sister, Gay, was very talented and helped us. She had taken art lessons from the famous sculptor, Boris Blai. So, she knew what she was doing. I still have one of her paintings that our dad framed. One Christmas as a joke, I offered my son and daughter a piece of my work. Much to my surprise my son hung it in his home, though it may be only during our annual visit.

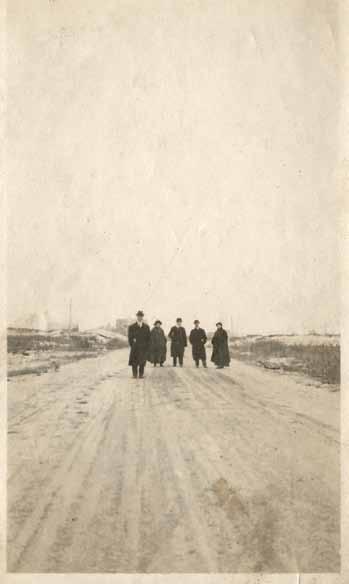

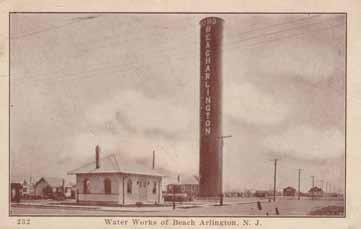

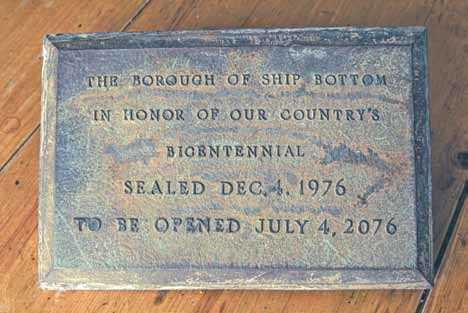

This year as Ship Bottom celebrates its 100th anniversary we are excited to publish in this issue new research about the origins of the borough — brought to light by our historian-editor, Reilly Platten Sharp.

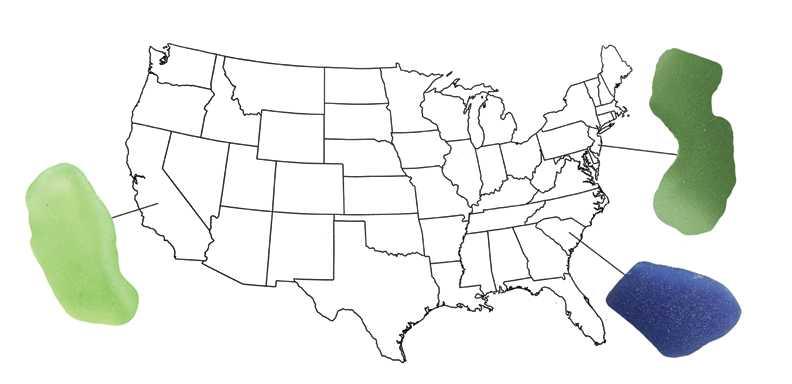

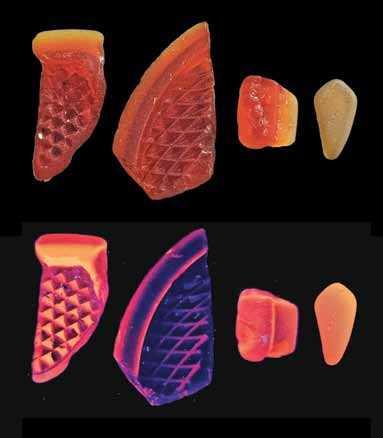

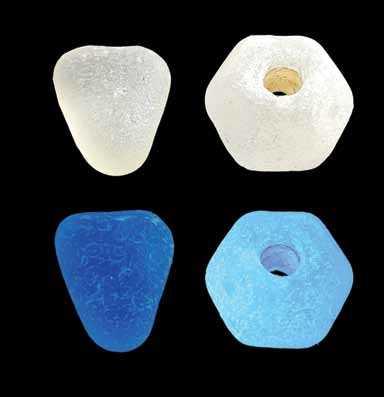

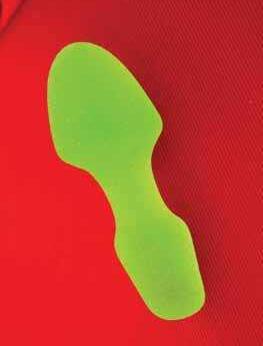

Also in this issue, because of its popularity is an update to “Atomic Sea Glass” by Sara Caruso. In addition to more information, Sara has added great new photographic examples of fluorescent finds under ultraviolet light. During the LBI Sea Glass and Art Festival on October 4 and 5 at Things A Drift in Ship Bottom there will be UV sea glass demonstrations inside the story and outside. For more information see page 102 of this issue.

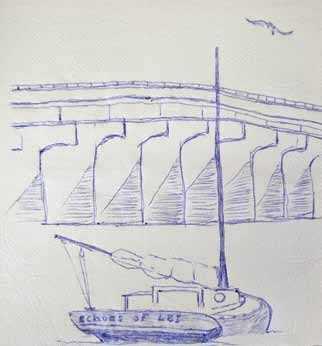

Echoes of LBI has been the original art, history, and lifestyle magazine of Long Beach Island since 2009. As an award-winning collector’s magazine, we have continued to grow, and our circulation of hard copies has expanded. Since the magazine’s inception our writers have conducted hundreds of personal interviews preserving the history of Long Beach Island from those who lived it. In addition to sharing their personal stories, they also share with Echoes never-before-published photographs. These details, many times in conjunction with further research conducted by our writers, historian, and editorial staff, add to the Island’s history that would otherwise be lost. I believe that everyone has a unique story to tell. We would be honored to tell yours within the pages of Echoes. Contact us at echoesoflbi@gmail.com.

Did you know that print is still one of the most trusted forms of communication? There is nothing like the feel of ink on paper. Echoes of LBI Magazine is proud to keep the tradition of quality print alive.

It always takes a village to publish Echoes of LBI. Thank you to all.

Enjoy the sunsets in this issue and the sunsets that take place no matter where you are.

Cheryl Kirby Publisher, Echoes of LBI Magazine

Legendary artist Claude Monet found the flower gardens at Giverny to be his greatest single inspiration for his magnificent paintings.

The same magic was delivered at The Garden Club of LBI’s Outdoor Living Garden Tour and Art Show with twenty-five noted artists from Pine Shores Art Association working plein air. Held on June 24, 2024, the third annual tour opened five private luxurious gardens to visitors.

Located from Barnegat Light to Beach Haven and resplendent in their summer glory, the gardens displayed such features as a sparkling waterfall spilling into a koi pond, a mammoth mimosa loved by hummingbirds, a native garden leading to a freeform pool, relaxing spaces surrounded by cherry laurels and crepe myrtles, and an iron-gated garden almost surrounded by water.

Three charming public gardens maintained by The Garden Club, the Edith Duff Gwinn Garden, and the Pollinator Garden both in Barnegat Light, and the Beach Haven Library Garden were also captured in luminous color by the Pine Shores artists.

Pine Shores Art Association has been engaging artists and art enthusiasts in the community since 1981. They have two studios, in Manahawkin and Tuckerton, where exhibitions, lectures, and classes for adults and children are held.

Besides their on-site work, the award-winning artists generously donated original, framed paintings for an exciting raffle for Garden Tour ticket holders.

This year’s Outdoor Living Garden Tour and Art Show is scheduled for Thursday, June 19, 2025. For ticket information please see thegardencluboflbi.com.

—Gillian Rozicer • Photography by Jeannette Michelson

Oh, arbitrary light!

Oh, night’s magic!

You shoot across the sky like Thors hammer, so quick, so fast, so brief. Silence surrounds me and awe fills the darkness. I stand beneath it all, small and inconsequential.

Oh mighty universe! Oh moment of belief!

Maggie O'Neill

For Jerry Heffner, wildlife photographer and artist, living on Long Beach Island fills him with gratitude and provides a sojourn into the stunning magnificence of living at the shore. “I look around and experience the beauty of nature.”

“We have it all here,” he says. “Whales that breach. Dolphins that play. Beautiful birds like egrets, pelicans, herons, and osprey, who mate, nest and feed their young. All of God’s creation is here all year long.” Although he travels to Europe, there is no need to travel to far-away destinations. Heffner’s artistic repertoire includes work in local parks and beaches in New Jersey that keep his creativity fired up.

Heffner made a quantum leap to art after three decades of work as an engineer working for AT&T and Verizon, managing teams of engineers building the nationwide cellular network. Now retired, he lives year-round on Long Beach Island with his wife Barbara, and Teddy, their beloved yorkie.

His attention to detail as displayed in his work was inspired by his father, a watchmaker. “My father had magic hands, moving into place dozens of miniscule screws and bits into a watch.” Another inspiration for his success comes from a former teacher and former president of Pine Shores Art Association, Tom Rutledge, a gifted artist who “is always willing to share his knowledge, and generous in teaching his techniques. He was always positive in his comments about my work.” Heffner’s work features subjects ranging from photographing sunsets to mating egrets.

In taking photographs of animals in natural settings, Heffner says, “Wildlife photography is an exciting and challenging field that allows a photographer such as myself to capture the beauty of nature and its inhabitant creatures.” According to Heffner, wildlife photography can be an exhilarating and fulfilling experience. Heffner emphasizes and practices ethical wildlife photography:

• Respect animals and their habitats and enable them to thrive in their natural environment.

• Obey interaction rules for both human and animal safety.

• Never do anything to endanger wildlife or their offspring.

• Promote understanding and appreciation for wildlife and the importance of conservation efforts.

• Understand animal behavior and their habits such as feeding patterns, behavior, and activity.

“Be patient and calm,” he says, “Sometimes we need to wait for the spontaneous to happen in nature. Again, I use my zoom lens, but I keep a distance and obey interaction rules for both human and animal safety.”

Embarking on wildlife photography opens new perspectives through a stunning lens of discovery on wildlife. His work has been rewarded with a plethora of awards from Pine Shores Art Association and Judges Choice Awards.

Heffner pours his heart and soul into his work. He says that his aim is to showcase “the Creator’s earth in the most beautiful light.” He does this in landscape and seascape, and in what poet Gerald Manly Hopkins describes as “inscape,” the raw experience of beauty itself. —Fran Pelham • Photography by Jerry Heffner

Bottom

This page, top row, left to right: Kate; Chris; Kara

Bottom row, left to right: Gabrielle and Nicholas; Charles and Ella; Andreas

The breakers fold onto the inlet of Barnegat Bay under the watchful eye of Meade’s Barnegat Light. As the sun climbs, they cast lines along the jetty, navigate the boulders on foot. They are the locals of grizzled mariner faces; who load their catches into buckets, coolers.

A weather-beaten Chris Craft’s small wooden hull moans as waves’ batter sprays, drench the leathery creased face of the small captain, whose steely blue eyes navigate through shoals, swift currents pass the north jetty into the green blue ocean.

Folk’s picnic, climb the light tower. Some furrow in the sand of the small beach, others watch for herons, egrets, pelicans. A series of small boats follow the Chris Craft through the inlet and then the party boats full of mainlanders drinking beer, wine, popping Dramamine, muscle their way through the inlet into the ocean.

As sun drops, the jetty is now empty, beach desolate, light tower closed. The weighted down Chris Craft enters the bay followed by other small craft chugging, churning, cutting through currents, just ahead of the party boats still full of mainlanders.

—G. Emil Reutter

From For Every Season There is Time

"So the seed falls to Earth finds a resting place, waitsto be eaten by birds? choked by thorns? or to fall on rocky ground, where even then, the most tenacious urge will send its root deep, into the very heart of cloven rock In search of water, food, life…"

Timeless moments of peace and wonder repeat in the blue of sky the brown of earth. A whisper of warm wind hiding from the fact of winter from the shrinking light of days waits for nothing but another moment…

A parade of November mallards chat with neighbors in no particular hurry. Led by flamboyant males in iridescent headdress with bright white collars, they waddle pretentiously in single file across the road

In front of impatient drivers who wait nonetheless, watching the procession from pond’s edge to evergreen shelter on the day of the dead…

In the late sky appears a rosy-fingered, fleeting likeness, a reminder of Dawnher promise of rescue

from the loneliness of night yet to come; when there will splash across the canvas of twilit morn colors of a brand new day.

Evening pastel clouds patiently reflect on heaven's brilliance, sail across awareness alongside birds careening wild in the wind as November draws to a cloudy close, with one last moment to rest upon the distant line where Earth becomes air, where embers of daylight glow warmly with tomorrow’s hope fading upward, older, farther away until the mantle of darkness sinks covers all, reveals its emptiness.

—Written and photographed by Joe Guastella

THE PAST ALOOF

Off-season renter at the end of the jetty her easel teetering in puffs of chill breeze chuffing off the prancing inconstant waves she studies she paints her past aloof incongruous she is here she is now.

After a week of days staring at her back the locals

crabbers and fisher folk call her aloof but she’s well past aloof

THINGS ADRIFT

The sea thrusts itself upon the shore Wave after wave, relentless evermore Each tide brings in that which can be swept Onto the beach where it is left

A former shard of glass, now sanded

Smooth and settled where it landed

A mermaid’s purse, a wealth of shells

How many kinds, I cannot tell

The sun will shine upon the beach And drain them of their hues like bleach There, children pick them up by hand With curled up toes beneath the sand

A chunk of wood, gnarled and knotted

Even a shark’s tooth may be spotted I stare at all of Neptune’s gifts And marvel at these things adrift

—Written by Randy

Rush

Photography by Nina Herbst

artist’s eye and brush’s oily tip critically adrift at full sail on the horizon line.

Then it is done and laden with her kit tiptoeing over driftwood and seagrass she crab walks the rocks as the crowd grudgingly parts to let her go past aloof

until they see themselves in full on her canvas bent over bait buckets or casting killies gales of salt mist in their windswept hair.

—Written by John Chmura

Photography by John Keeley

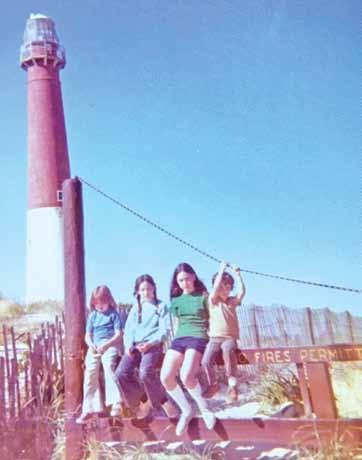

Together most days from sunrise to sunset, Over four years ago since you both first met, Walking is a passion you shared that night, Second date was a walk at Barnegat Light.

Together in nature a week seldom goes by, Sharing outdoor adventures or star filled sky, Walks on a trail, a beach or a mountain hike, Even riding for miles on your electric bike!

Chelsea’s first picture that Mike ever saw, Was her holding a fishing rod, he was in awe, He thought he had gotten his wish “on-line”, For a girl with a fluke was a very good sign!

From camping, to fishing and kayaking too, Always an adventure in whatever you do, So happy for you both and wanted all to know, Today it’s “o-fish-ial,” Chelsea’s a DeMarco!

Love, Mom and Dad

CO NGRATULATIONS

C HELSEA AND M AR K D E M ARCO O CTOBER 19, 2024

—Written by Diane and Vic Stulga Ronnie Mae Photography

Here’s to you master of mysteries, keeper of the tide. Here’s to your vast expanse that dominates our earth, to your undersea mountain ranges, your longitudinal divide that separates old world from new. Discovered Before the Common Era your power is endlessly explored, but never fully understood.

Beautiful, enduring, impregnable, you willingly give up your oil, your minerals, your tidal energy. You release your bounty to feed a world that has not been a good steward, has misused your resources, ignored your science. Now, before all is lost, it is time for people of wisdom to commit to your living ocean, protect your marine life, eliminate costal erosion that shrinks your beaches, prevent plastic pollution that strangles, safeguard your wealth for future generations.

—Nancy Kelly Kunz

You willingly share your waters with adventurous men who sail you, industrious fishermen who troll you, travelers who trust you for tranquil crossings, swimmers who take up your challenge, surfers who ride your foaming white curls, as you crash to shore, deposit shells and beach glass for those who stroll your sands in search of private treasure.

At daybreak, I stand at your tangible edge awed by your majesty, aware of your vastness, grateful for your generosity.

I celebrate you with my morning coffee, as the sun rims your horizon, coaxes my day into existence, and paints the sky one sliver of color at a time. You respond with a kaleidoscope of reflected light.

by Dave Farruggio

Decorating a mantel, living room, poolsode, or patio with gifts from the sea brings serenity to the home

In today’s world, pets of all sorts are viewed as a valued part of the family. The more we know about the creatures we choose to share our homes with, the more we appreciate and respect them. And the more we know, the better we can care for these special members of our family.

Having a hermit crab as a pet is something many children have done, especially if they grew up by or vacationed at the shore. Many of us had plastic tanks, fake mini palm trees, and those toxic brightly painted shells for our hermit friends. As time went on, and more information about hermit crab care came to light, we realized those things were not good for our crustacean comrades. So, we learned how to provide better care for them. Yet, for hermit crabs there still exists the misconception that they are souvenirs, destined to die quickly or to be dumped off at the beach after summer vacation. Over the decades this has led to certain death for countless hermit crabs.

Recently a number of disturbing videos have appeared across social media showing people releasing their hermit crabs at the end of summer. Whether it is for attention or misguided good inten tions, they have sentenced those hermit crabs to death. It is cruel and should never hap pen.

some in painted shells, on local New Jersey beaches. Unlike our native marine hermit crabs that live exclusively in the water, these were found up near the dunes. If you find a Purple Pincher on an LBI beach gently pick it up, place it in an empty insulated lunch bag and bring it to Things A Drift in Ship Bottom, New Jersey. The hermit crabs brought there as rescues are given a full health exam, free of charge, cared for and fostered until a forever home is found. Rescued hermit crabs brought to Things A Drift are never sold, rather they are placed with experienced

The most common species of hermit crabs sold as pets is the Purple Pincher (Coenobita clypeatus) a native species to Haiti. These strictly land hermit crabs do not swim and will drown if placed in the water. They have adapted to tropical temperatures and humidity of that climate and cannot survive northeast coast winters. Even in captivity, hermit crabs need temperatures around 70 to 76 degrees Fahrenheit and 80% humidity to maintain moisture on their gills and molt properly. At the heart of it, abandoning any pet is cruel and unnecessary. There are many who would gladly adopt a hermit crab, so please reach out if necessary. With knowledge, there is no excuse for cruelty.

Last year, there were several posts on New Jersey Facebook groups made by concerned citizens showing Purple Pincher hermit crabs,

Be aware, however, that our beaches are home to two species of indigenous marine hermit crabs, so be careful not to disturb them by mistake. Unlike the colorful Purple Pinchers, New Jersey’s marine hermits, Long-clawed Hermit Crab (Pagurus longicarpus) and the Flat-clawed Hermit Crab (Pagurus pollicaris) are the color of sand and have a flat big claw. Also, their eyes look translucent compared to the solid black eyes of Purple Pinchers. Marine hermits will usually be found in moon snail shells and whelks, but never fancy or painted shells. Plus, they are usually found closer to the water, in tidal pools, or in the surf, while Purple Pinchers are strictly land hermit crabs and cannot survive the ocean. If you find a marine hermit crab, it is best to leave it alone, and if washed ashore, return it to the sea.

With proper care, Purple Pincher hermit crabs can live a long and healthy life. Considering that some have been known to live up to forty years in captivity, they can be a pet that requires commitment well beyond childhood. They are perfect for someone with allergies to pet dander, and they are low maintenance enough that young adults going off to college can safely leave them in their parents’ care.

Hermit crabs are inquisitive and curious, so taking them out daily for enrichment is encouraged. They love exploring dollhouses and LEGO® sets. Setting up an empty kiddie pool or play area for your crabs to enjoy can help keep them busy and provide exercise. Because hermit crabs are nocturnal, this is best done in the

evening. Any time spent outside their regular enclosure should be monitored.

Training you and your child in how to handle hermit crabs can prevent pinches or accidents. It is important to help your crab become accustomed to being handled especially when cleaning their enclosure or checking their health. However, before handling your hermit crab it is super important to wash your hands thoroughly first. Sunscreen, lotion, perfumes, and insect repellent are toxic to hermit crabs. Second, spread your clean hands out as flat as possible, and let your crab walk on them. Be aware, it will tickle. Make sure to do this over a soft area, like a bed or pillow, so if the crab falls it will not get hurt. As everyone’s confi dence grows your hermit crab may climb up your arm. To them, you might as well be a tree. Make sure to never close your hand around the crab or leave skin loose because that's when pinches can happen. Your hermit crab is only trying to hold on for support, not to intentionally harm you. Letting them get used to your touch will help them stay calm during handling.

Hermit crabs are as much of a commitment as any pet. While they do not cuddle like a cat or fetch like fido, they have found a place in many hearts and should be respected. If you are thinking about adopting a hermit crab, as with any pet, it is important to do your research to make sure it is the right fit for you. Echoes of LBI Magazine and Things A Drift have many informative articles and resources to read and download at echoesoflbi.com and thingsadrift.com. —Written and photographed by Sara Caruso

Golden brown sand on edge of the world Ocean bulges, swirls as white caps curling roaring, spraying along beach batters this narrow stretch of protected land resting between bay and sea.

In the distance Atlantic City skyline as Emerald City without the poppy fields. As if we could walk across inlet onto the ocean into the city as sun glint reflects off high risers and water as light up and light down.

Written by G. Emil Reutter

Long Beach Island endured a bitter cold winter this year, with temperatures dropping into single digits on more than a few nights after the holiday season. On several occasions, the beach was blanketed by snow, turning our eighteen miles into a winter wonderland. Many locals found their eyes focused on the night skies as we searched for mystery drones and colorful auroras.

While back on Earth, the Holgate Memory Tree made waves with hundreds of shell memories making the local news and inspiring others to create their own. Hearts were warmed, and fans were fired up, as the Philadelphia Eagles won Super Bowl LIX. Later, the entire Jersey shore would become captivated by the misadventures of one wayward red fox, nicknamed Ziggy, who found herself stranded out on the ice of Barnegat Bay. Happily, rescuers were able to bring her safely ashore, and she is being rehabilitated.

Meanwhile back on LBI the bridge is open. In Ship Bottom, east and west 8th and 9th Street are open and Long Beach Boulevard fully accommodates two-way traffic now that the former Causeway circle has been completely removed. Visitors will find that traffic patterns may continue to change.

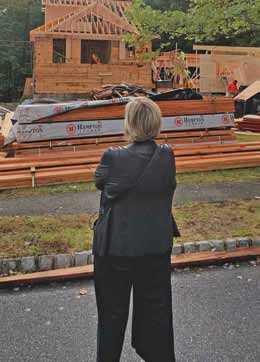

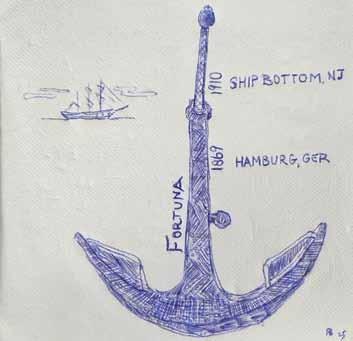

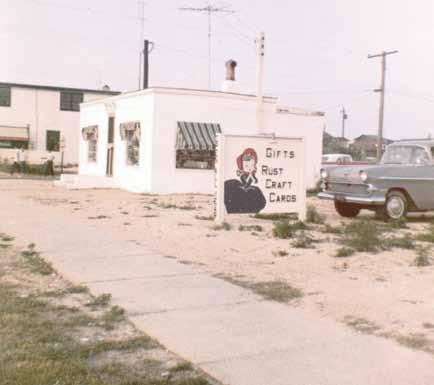

The Southern Ocean Chamber of Commerce moved off Island to a new home at 703 Mill Creek Road, Unit G, in Manahawkin. Atlantic City Electric will use the property to upgrade service to the area. Construction of the new Ship Bottom Borough Hall has been completed with the legendary anchor of the Fortuna restored and returned to its rightful place in front of the building.

LBI welcomes several new businesses with the opening of a bookstore in Surf City, Beach Reads, Surf City Dog House, and Beach Bum Eatery in Beach Haven Terrace. Over the bridge in Manahawkin The Picklr, with its new indoor pickleball courts, opened.

March brought promises of spring with much welcomed showers, warmer breezes, and temperatures that remind us that summer is just around the corner. —Maggie O’Neill

The much-loved annual event, The Garden Club of Long Beach Island’s “Holiday Tour of Homes” saw its fifty-seventh successful undertaking in December. Thanks to the generosity of Islanders who graciously opened their homes to the club’s design teams, the tour encompassed a number of Long Beach Island private homes in a variety of styles that gave attendees a captivating glimpse of the holidays on our barrier island.

Over 1,200 tour attendees traversed Long Beach Island, stopping along the way at five homes magically transformed for the holidays by the immense talents of The Garden Club’s decorators whose breathtaking designs brought the season to life in a style befitting the uniqueness of each venue. In keeping with The Garden Club traditions, fresh cut evergreen trees, greens, flowers, and live plants – together with handmade ornaments and features – were highlights throughout the day and provided holiday décor inspiration.

The Garden Club’s House Tour Luncheon Committee transformed the Brant Beach Yacht Club into a festively decorated, welcoming venue where attendees took time out to relax with a delicious boxed lunch, enjoy tranquil bay views and mingle.

Another highlight of the tour is The Garden Club’s Pop-Up Holiday Boutique which is kindly hosted each year by the Surf City Fire Company. Offerings at the boutique include homemade holiday cookies, lovingly baked and packaged by club members, a variety of beautiful fresh greens, holiday arrangements, and wreaths all handcrafted by The Garden Club’s Greens Committee, along with a wonderful collection of wares and gifts offered by a selection of local shops and artisans.

The Holiday Tour of Homes is one of two annual fundraisers sponsored by The Garden Club of Long Beach Island. Together with the Outdoor Living Tour hosted each year in June, The Garden Club’s raises funds to support local environmental initiatives, including their stewardship of three public gardens on LBI, college scholarships for local teens who pursue environmental studies, and workshops for local youth and seniors to foster a love of gardening and floral design. —Written by Diane Macrides, with Co-chairs Kim Carroll and Paula Brennan • Photography by Don Edwards and Lisa Tyson

I have seen Le Mont-Saint-Michel I gazed upon the Archangel And sat within the Nave Walked along its narrow streets Of stone, so roughly paved

I have seen the Colosseum Wondered through the hypogeum Tried hard to envision The spectacles and cruelties Of the crowds and those imprisoned

I have been to Haleakala Swore that I had stood in Shangri-La Laid eyes upon the silversword And saw Pueo fly

As the clouds became my floor I have been on Mazinaw Lake

Listened to my voice reverberate Fishing from my wooden boat

In the shadow of Bon Echo Rock Etched with words that Whitman wrote

I have walked the streets of Positano In northernmost Salerno On the coastline of Almafi Bejeweled with golden lemons That taste as sweet as they could be

Now here I sit on Manahawkin Bay Not so very far away From my home in southern Jersey

Where the air is gently salted And tempered by the sea

—Written by Randy Rush

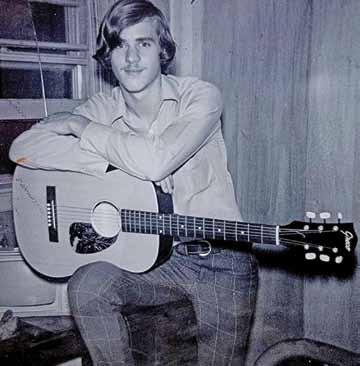

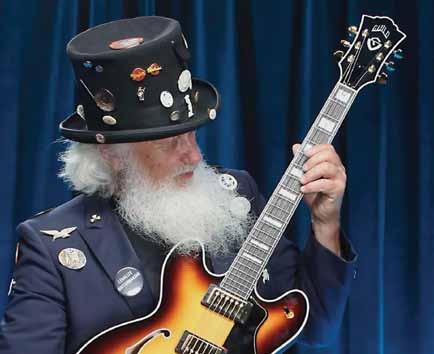

During the summer of 1964, I fell ill to a nasty cold which forced me off the playground and into bed for several days. In an effort to cheer me up, my mother bought me a copy of the Golden Hits of the Four Seasons. It was my first record, which I still own to this day. I played that album repeatedly for weeks. The driving rhythm section, crisp production and multiple part harmonies complimenting Frankie Valli’s vocal range were the perfect musical elements to accompany the lyrics which told the stories of teenage love. For a Jersey boy from Middlesex County, these songs resonated for me as no other had up to that point of my young life.

Later that same year, the world of popular music was turned on its ear with the arrival of The Beatles. When I first heard I Want to Hold Your Hand, I was stunned. I immediately scraped together my earnings from sweeping floors at the local barber shop and ran out to buy my second record — Meet the Beatles.

Though their points of origin were an ocean apart, significant similarities between The Four Seasons and The Beatles existed. Both bands played their own instruments, whether performing live or in the studio. Both groups wrote their own material. Both groups excelled in the use of vocals and harmonies. These elements, which were not the

ate I was about music and agreed to shell out the $20 for a student guitar as long as I promised to take lessons and study hard. So began my lifelong affair with music in general, and the guitar specifically.

norms at the time for most pop groups and singers, really struck a chord with me. Like so many others at the time, I yearned to be a pop star like my heroes. I talked my mom into buying me a guitar. This was no small request. We did not have a lot of money. My dad passed away when I was four years old, leaving my mom to raise two boys on the modest wages of a practical nurse. However, she could see how passion-

Bands and singers started popping up from all over the United States and Great Britain. So too did rock & roll radio stations, as well as record stores. There was a great hunger for pop/rock music, and the industry scrambled to feed that hunger. But underneath that veneer of polished professional acts lay a subculture of local musical talent eagerly trying to show their world that they, too, had something to offer. Inspired and influenced by such regional groups as Danny & the Juniors and the Silhouettes, Dion & the Belmonts, The Tokens, and Little Anthony & the Imperials as well as the Royal Counts, The Sheps, and Johnny Argyle & The Creations, the music scene down the Jersey shore exploded in the early 1960s. Locally, on LBI, The Soundmasters were a popular draw at diners, bars, fraternal halls, churches, libraries, and street corners. Today, the music scene on LBI and the local mainland is vibrant and thriving. Local bars and restaurants provide patrons with entertainment throughout the year — everything from open mic nights and cover bands to karaoke and live music. I have played at open mic nights in several local venues. It was at one of those venues that I first saw

Denise Miller, a local singer, songwriter and guitarist who along with Mary Lutton and Gail Gilrane perform as Ladies Night Out, a country pop trio. Denise also plays and sings with her son, Jon.

The Entertainment Luncheon — South is the brainchild of Johnny Bishop and his wife, Linny. Johnny B, as he is known professionally, grew up on LBI, and is a former member of the acapella group, The Soundmasters. Currently he sings lead vocals with the Joey D & Johnny B Band. A little over two years ago, Johnny and Linny saw a need for a network for local musicians and entertainers to swap ideas and promote local entertainment. Once a month, since March of 2023, they coordinate Entertainment Luncheon — South which has turned out to be a fabulous opportunity for local musicians, mostly oldies and doo-wop artists, but not exclusively. Most of those in attendance are members of the Facebook group Entertainment Luncheon — South and have been specifically invited to attend each event. Amongst the attendees are musicians, singers, promoters, writers, actors, photographers, agents, historians,

journalists, and radio personalities from the New Jersey shore, New York, and Philadelphia. During each three-hour event, people mingle, talk shop, and catch up. Johnny Bishop MC’s each event and keeps things

an important part of the gathering, the entertainment is the highlight of the day. On that afternoon, the Jimmy Givens Quartet was the featured entertainment, with Dorian Parreott on sax, Mark Cohn on keyboard, Jimmy on drums and Altha Morton on vocals.

light. One of the things he has stressed is the brother/sisterhood that exists among all those in attendance. There is no competition among artists here. Johnny’s goal is for everyone to use the opportunity to get exposure amongst industry peers and grow their own brand. You can really feel the love and respect in the room.

Though networking and conversations are

Altha Morton, who fronts the quartet with her soulful voice sang versions of Cabaret, Satin Doll, All of Me, and Georgia, which she absolutely nailed. Dorian Parreott contributed with a masterly rendition of Hello Dolly, sounding remarkably like Satchmo himself.

The show was a fun trip back in time, presenting a chance to reminisce and enjoy the memories that the classic standards evoke. There is a reason they call these songs standards. They are timeless, and that is exactly what this audience is seeking — a journey back to memories that bring smiles to their faces. For at least the three hours we spent together honoring this music and the people that keep it alive, everybody in attendance was able to forget about their daily struggles, remember the good old days, and mingle with those who all had something in common — a

love for the music we grew up on.

Present that afternoon was a friend of mine, Carmen Landolfi, aka Carmonica — a multi-instrumentalist who is known best for his harmonica work with other artists and bands, among them The Pickles. He was gracious enough one time to sit in with me at an open mic night, where he played his harp on a version of Kokomo Arnold’s classic twelve bar blues number called Milk Cow Blues. I figured he could nail that song no matter what key I played it in, because he had a case full of harmonicas, each one tuned to a different key, and because he is very good at playing them.

Sitting with Carmen was Rick Que, who plays bass and guitar for several groups, among them The Broken Bones Band. Rick knows a ton of people in the music business in and around LBI, and he introduced me to Sal LoCicero, front man for the vocal group, Remember When.

Sal LoCicero sang with Johnny Angel & The Creations in the late fifties and early sixties. The band had appeared on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and had recorded several records. An amiable veteran of the entertainment business, Sal shared with me how he first met the other members of Remember When in February of 2024. These guys are true veterans of the doo-wop world; they love playing and singing and giving their

audience a night or afternoon of memories and dancing.

Everyone I talked to at the Entertainment Luncheon — South gathering still performs because they love music, and they get the biggest thrill out of making people smile. It really is that simple. Entertaining the fans and keeping this music alive is what matters.

Oldies and doo-wop shows are performed regularly on LBI and the nearby mainland. Many hotels and restaurants book popular local acts like Chris Fritz, Ty Mares, The Nerds, Shorty Long and the Jersey Horns, and others. Many venues offer evening and sometimes afternoon entertainment from a variety of musical acts featuring classic rock, pop tunes, R&B, soul, folk, and country music and rap. But the oldies and doo-wop crowds can also be found at some of the lesser-known venues in the area such as the Beach Haven Moose Lodge, Manahawkin Elks Lodge, local churches, Ship Bottom

Waterfront Park, Sunset Park in Harvey Cedars, the Municipal Dock in Barnegat, and the Stafford Township Arts Center among others. These shows highlight those groups who keep the oldies alive.

Sal LoCicero shared a video with me of a performance from a prior event. I could sense the enthusiasm and love he and his bandmates have for performing these memorable tunes. In the video I could see how folks who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s got up and took to the dance floor, dancing to the music that tells the stories of their lives. They danced and reminisced, reliving their memories, the joys, and yes, the sorrows that are part of who we are. That is why this music is still so popular. It takes us back to a world we knew and loved. Teen romances, school dances, late nights at the diner, the freedom of youth that we did not really appreciate until we grew up. Oldies shows give us that — a chance to revisit our memories.

So, check out your favorite social media or a local newspaper to find out where some of these groups are playing. You cannot see The Soundmasters perform, but you can catch Remember When, the Joey D & Johnny B Band, Denise Miller, the Jimmy Givens Quartet, or any of the dozens of local performers which are available for our entertainment pleasure down the shore. —Written and photographed by Randy Rush

Long Beach Island’s 18 miles of sun, sand, and surf are enjoyed by countless visitors and locals every year. But for those who are physically or mobility challenged, the joys of the beach can be beyond their reach. Seeing this need, the Borough of Ship Bottom launched a Beach Wheels program in 2002. Since then, the program has been a tremendous success.

Beach Wheels are lightweight wheelchairs constructed from PVC pipes with oversize wheels designed to navigate difficult beach terrain. The Beach Wheels program, which provides the specialized wheelchairs free of charge, operates throughout the year. From June 15th through Labor Day, it is administered by the Ship Bottom Beach Patrol. During the off-season it is operated through the municipal clerk’s office in conjunction with the Ship Bottom code enforcement officer, Matt Bernstein.

“Enjoying the beach is a big part of the human experience,” says Bernstein. “Most people love the feeling of sand on their feet and the wind in their hair.” He sees firsthand the positive impact the program has on physically challenged people of all ages and their loved ones.

According to Bernstein, it takes a team effort to make the Beach Wheels program work. The Ship Bottom office staff, the governing council and the lifeguards are all instrumental in making it a success. Recently, the program and staff received a letter of heartfelt gratitude from Tore Larsen after having utilized the Beach Wheels program for his sister, Molly.

Every other year, the Ship Bottom Borough has the opportunity to apply for a grant that supports handicapped accessibility for its parks and beaches. Last year, the borough secured a Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program to purchase two four-wheel drive

utility terrain vehicles. The service known as the Ship Bottom Beach Taxi provides transportation for physically challenged people who would otherwise struggle to reach the beach. The service is free of charge and runs from Father’s Day weekend to Labor Day.

The Ship Bottom Beach Wheels and Beach Taxi programs put the beach within reach with just a phone call and a reservation.

—Diane Stulga • Photography by Matt Bernstein

For more information about the Beach Wheels and Beach Taxi programs and how to make reservations in your borough contact the following:

• Barnegat Light: (609) 494-9196,

• Harvey Cedars: (609) 494-6905

• Long Beach Township: lbtbp.com/ beachwheels

• Ship Bottom: (609) 494-2171 (summer ext. 145, winter ext. 131)

• Surf City: surfcitynj.org/beaches

• Beach Haven: (609) 494-9481

For as long as I can remember, the statue of King Neptune has stood on the boulevard in Beach Haven Terrace — a sentinel of stone amidst the ebb and flow of tides, watching over the beach, the bay, and all who call Long Beach Island home.

Over the years, my heart grew fond of his presence, as did the hearts of many others in the community. When I heard the news King Neptune was to be sold and moved away, no longer to stand on the boulevard, a fixture in our lives — it felt as though another part of our shared history would be lost. I knew then that I had to do something, for this statue was more than just a piece of art; it was a living memory of our past, a guardian of the present, and a promise to the future.

Perhaps you can sense I am a bit sentimental, especially when it comes to LBI. Our families have gathered on the same street in Beach Haven Park since the 1960s, creating traditions and forming lasting memories too numerous to recount here. For over 20 years, my wife, Cristina, and I have owned our home on the very same street, continuing family traditions and making memories of our own. I knew that if Neptune was to be moved, he must stay close. Then I thought, why not here at our LBI home where he could continue to offer his protection, his strength, his timeless wisdom to us and all that gather here.

With little hesitation, I reached out and a deal was struck.

The statue arrived at our home on a warm afternoon, the sun casting a golden hue over the bay as the delivery truck pulled into our front yard. With careful precision, we placed him on a platform which my brother-in-law and I had built, ensuring he would have a perfect view of the bay. There is deep comfort in knowing King Neptune remains a part of us, his towering form guarding the shores as the sea continues its eternal dance. His presence whispers of resilience — of storms weathered and calm seas ahead. He watches as we go about our lives, a tangible reminder that some things, like the ocean itself, are meant to be constant, ever-present, enduring. My hope, as I stand beside him now, is that King Neptune will never truly leave. That this statue, which has been part of our community for so long, will stay a fixture in the lives of future generations. I hope that, long after I am gone, someone will look upon him with the same reverence, the same affection, and the same sense of belonging that I feel today.

From his new post King Neptune’s trident will still point to the sky, his gaze steadfast upon the bay, a symbol not only of the waters he once ruled but of the strength, unity, and love that binds us together in this place we call home, Long Beach Island. —Dan Marselle

The Garden Club of LBI’s Youth Committee met on January 29 to create flower arrangements for St. Valentine’s Day. Thirteen children in grades three to six gathered with cochairs Ginny Scarlatelli and Jeannette Michelson at the Surf City branch of the Ocean County Library to create Valentine flower arrangements to take home to someone special.

In Victorian times, the colors of flowers were used to convey romantic messages. With that in mind, The Garden Club selected scarlet carnations for love, pink alstroemerias for happiness, and white mini carnations for innocence and purity. Club members, which included Paula Cafone and Pauline Gertzen, also contributed greens from their own gardens.

Working like professional floral designers, mindful of creative elements such as line and balance, the children filled their galvanized, heart-decorated containers with fragrant flowers. To enhance their arrangements, each child also created a cherubic pink cupid. Their beautiful Valentine flowers were soon ready to give away to someone special.

Every year The Garden Club of Long Beach Island sponsors five flower design workshops for children. The program is now in its sixth year. Support for this and all Garden Club community events comes from the Outdoor Living Garden Tour and Art Show, this year on June 19, and the Holiday House Tour, coming on December 10 &11. —Gillian Rozicer • Photography by Jeannette Michelson

At the closing ceremony for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia, Neil Young performed his famous song “Long May You Run”. The Olympic flame was then extinguished. The games were over. Athletes, coaches, families, and spectators all went back to their own lands. Perhaps they brought with them the feeling of community and belonging that is so integral a part of the Olympic experience.

The spirit of the modern Olympic Games has always been embodied and represented by the marathon running race. That race is itself named for The Battle of Marathon (490 BC), at which the greatly outnumbered Athenian army soundly defeated the superior forces of the invading Persian Empire. Pheidippides, who was a courier, a long-distance runner, brought the message of improbable victory and hope back to Athens before collapsing and dying.

It is fitting in a number of ways that Mr. Young chose that particular song. Though it was written about his 1948 Buick Roadmaster hearse. Yes, a hearse. The title “Long May You Run” is a perfect fit as an anthem for the Olympics for every competitor in the games.

Whether female or male, old or young, however able or differently abled they may have been. It was a tribute to the hard work and dedication that those amateur athletes put in to show their mettle or perhaps to discover it. And long may they all run, beyond the end of the games. May they take that spirit home and spread it throughout the world.

And so, it was in that same Olympic spirit that on Sunday, October 13, 2024 The 52nd Annual LBI Run took place. The final, official number of runners who crossed the finish line of the 18-mile course — Holgate to Old Barney — was 628. Every one of those fearless, determined, dedicated folks, ranging in age from 16 to 77, braved unusually warm temperatures and physical exhaustion to complete the Island’s own version of the grueling race that has been memorialized since the time of Ancient Greece.

Compassion Café LBI was represented in the race by Jack Massaro, a veteran customer service staff member at the Café. Jack is a dedicated runner who trains hard year-round. He proudly finished in the top third of all runners, cheered on by a throng of very vocal

Compassion Café staff, parents and volunteers. Jack also had the unwavering support of runners from Achilles International’s NYC chapter, who had been training with him in preparation for the famous New York City Marathon, which followed a few weeks later. A very special shoutout also goes to Jack’s running mate from Achilles, Andrea Quaregna, who was with him every step of the way for the LBI Run. Note: Jack also competed in and finished the London Marathon earlier this spring.

Before the race began, we joined the Compassion Café group stationed at the Beach House Restaurant. There were signs and noisemakers and words of encouragement that went out to all who passed in front of us. Even though we were only at mile number 4 of 18, it probably took close to an hour for the hundreds of runners to pass by in front of us. At first, I believed we were there to cheer on one runner. But that did not turn out to be the case. From our vantage point, it was obvious who the more capable, the more athletic runners were without question. While they certainly raised eyebrows and garnered cheers with their displays of physical prowess, they were NOT the ones who received the loudest cheers, or who moved the crowds of spectators the most. Those who made the greatest impression were those who seemed to be in the most discomfort; those who worked through their physical challenges. There they were, in both body and soul. We witnessed their determination, and we cheered, usually getting a thumbs up in return. We also received something we did not anticipate, something we could keep with us long after we left that day. It was a memory, a picture if you will, of a struggling runner, giving her/his all, one leaden footfall after another, until the race was over and victory obtained. That does not necessarily mean victory on the racecourse, but rather in life itself, for where there is participation there is life. Where there is effort there is life. My favorite hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, once said, “Where there is life there is hope.” That is all we need to remember.

The Sandpaper, Bob Yates, a 77-year-old resident of Beach Haven, continued to run, finally crossing the finish line long after the scorekeepers and organizers went home. He continued to run though the tally was already taken, the crowds had dispersed, and the names were written in the log of history for the race. But for a letter sent by his friend, this man's accomplishment would have been unknown to the world. Of such stuff is the value of friendship realized.

It was truly an inspirational morning, reminiscent of the personal challenges that our own loved ones with special needs face every single day. It reminded me of the quest for recognition, self-respect, accomplishment, and inclusion that is the essence of Compassion Café. It reminded me of the sense of community that can be shared whether participating in a foot race, volunteering at a food bank, gathering supplies for folks in storm-ravaged communities, or being part of a team of emerging customer service representatives, working for their first paycheck.

The value of sports in our lives is that it fosters within us a sense of competition, a sense of camaraderie with teammates, a sense of belonging and participation — even for spectators, even for those on the sidelines. When your favorite team wins, you win along with them. Well, on the day of the LBI Run there was really only one team — with over 1,000 members! The beauty of that day was that it turned out to be for everyone — for those who ran, those who cheered, those who passed out water bottles, those who crossed the finish line, as well as those who did not. So, dear reader, consider joining the winning team and run on down to:

Compassion Café at the Oceanfront Sea Shell Resort 10 S. Atlantic Ave, Beach Haven Tuesday, May 13 through Thursday, September 11, 2025 7 am until 11 am

It was stated that the official number of runners who crossed the finish line was 628. However, this does not include almost 400 runners who were part of the shorter 12K race that finished at The St. Francis RC Center in Long Beach Township. The official results also state that the time for the runner who finished at number 628, Judy Klein, age 65 from Palmyra, New Jersey, was four hours, forty-two minutes, fifty-nine point three six seconds and the eldest runner who finished was Donald Younkin, 76 of Philadelphia. According to a letter to the editor in the October 30th edition of

Compassion Café seeks the integration of teens and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities through paid parttime summer employment in a small coffee shop environment with free hands-on training and ongoing support in an atmosphere of joy, community, love, and unconditional acceptance. By providing meaningful employment our employees gain independence, self-confidence, and work skills for future success. Compassion Café is a 501(c)(3) partnering with local businesses in a true, non-profit model. —Written and photographed by Joe Guastella

It all started in 1957. Though not diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder at the time, as a child I was as A.D.D. as you could get. My kindergarten teacher noticed that during any given lesson, I was more likely to draw anything I could see outside the classroom windows than to follow her instructions. Fortunately, she was ahead of her time and very understanding.

She encouraged me to express myself through my drawings. At the end of the school year, she gave my mother a sheath of drawing paper and advised her to use art to channel my excess mental wanderlust.

During my work career, I traveled up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States, spending a great deal of time in hotels and dining alone in restaurants. Still A.D.D., I could not just sit in a restaurant and stare at the walls. Instead, I took to drawing my fellow diners, the waitstaff or the establishments décor. Most of the time, because I did not carry paper with me, I drew on the restaurant napkins. When I dined at fine restaurants with linen napkins, I always asked the staff for something to draw on, and most of the time they accommodated me.

Over the years, I have enjoyed gifting my artwork to the people I drew. Some liked their caricatures, others critiqued my work and offered suggestions, and others, well, could care less.

I guess it all adds up to channeling my wandering mind and making people happy for a moment. —Artwork and story by Rick Baldt

BRAd ZiFFeR, a native of West Orange, New Jersey, fell in love with LBI as a teenager while summering in Surf City.

Now a successful singer, voice-actor, pianist, and producer, with his own record label, Starlux Records, Brad has his own recording studio where he records voice-overs, and produces, mixes, and masters music for himself and others. His love of oldies and Doo-Wop reaches far and wide. His cover of Bobby Rydell's hit, “Wildwood Days,” is currently available for streaming and digital download.

Brad recently relocated to Manahawkin with hopes of finding the ideal spot for his son to attend school and grow in a family-oriented, healthy environment within close proximity to the beach.

This October, Brad will be performing at the LBI Sea Glass & Art Festival at Things A Drift in Ship Bottom, New Jersey. For information on his upcoming performances, and to hear some of his music, follow him on Facebook, YouTube and Instagram @BradZifferProductions and bradziffer.com.

Brad loves God, the shore, being a dad, and being creative. He now lives where his heart has been calling him all along.

Native New Jersey plants offer numerous incredible benefits, including improved environmental health, reduced maintenance, and support for wildlife. Plants native to Long Beach Island are adapted to local coastal conditions, requiring less water, fertilizer, and pest control. They provide food and shelter for native birds, insects, bees, butterflies, and local wildlife. Many native plants are stunning in their presentation of fragrance and color all year.

On March 27, more than twenty LBI residents launched the first native wildflower garden on the median strip of North Beach. The flowers and grasses will be a highly visible tribute to all the benefits and beauty of native plantings. The intent is to add more gardens in North Beach and to inspire homeowners and other townships to follow.

Long Beach Township Commissioner Al Meehan and Bill Walsh, president of the North Beach Taxpayers Association, the garden’s sponsor, broke ground for the 15 x 30 garden. Gillian Rozicer, vice president of NBTPA created the project and enlisted the help of landscapers Dan Hoch and Jason Austin, and Garden Club member and Master Gardener Debra Cowles.

The native plants in the North Beach Garden were selected to flourish in LBI’s natural coastal barrier island region. Add a few to your own garden and make a difference. —Gillian Rozicer • Photography by Jeannette Michelson

Growing up in New Jersey, my family spent our summers at the Jersey shore. Owning a home on Long Beach Island had long been my dream. In 2020, my family and I made that dream come true when we purchased a house in Beach Haven West. Since then, my family and I have spent our days on the beach soaking up everything LBI has to offer. One of our favorite things to do is to walk the beaches collecting seashells and sea glass. On rainy days and over the winter months we spend time painting the many seashells we find.

In 2024, my boyfriend and I decided to get healthy and quit smoking. To quit smoking, I needed something to fill my free time other than television. Luckily, inspiration came one afternoon when my daughter asked for permission to sell some of our painted LBI seashells at the lemonade stand she had set up with her cousins.

Maybe selling our painted seashells could be a small family business. And just like that, LBI Sea Shells was born.

In the following weeks I set up a website and social media pages for our new business venture. Next, I reached out to Cheryl at Things a Drift in Ship Bottom as an outlet for selling our LBI Sea Shells

It has been a year, and I could never have imagined that starting a business would come out of me quitting smoking. Having a family business has been a great positive life lesson for my children. We hope to eventually turn our family seashell business into an LBI bed and breakfast.

As for me, this experience has affirmed that the most beautiful thing about LBI is not the beaches. It is the people. —Artwork and story by Jennifer Wiecek

For the sixth time in six years the same wild mallard duck has chosen to nest in a planter on our deck. She is a very smart duck because she knows my husband, Vic, feeds her duck food and gives her fresh water every day. After they hatch, her ducklings also enjoy waterfront dining at its finest. When it is time, just as she has done in the past years, momma duck quacks loudly for Vic to come help her bring all of the ducklings down from our deck to the lagoon. Vic carefully gathers each one in his fishing net and gently places them into the water below where she anxiously waits for them. Happily, just as we were dealing with empty nest syndrome, the very next day our beautiful swans arrived with their seven cygnets. We feel blessed to witness these magical moments of motherhood in nature. —Written and photographed by Diane Stulga

Imagine stepping outside your door into a private coastal paradise. Jersey Shore Pavers brings that vision to life. As a premier landscape design and installation company serving the New Jersey shore, they specialize in custom patios, outdoor kitchens, fire pits, and more, turning ordinary yards into luxurious retreats.

Their expert team combines precision craftsmanship with coastal style, creating outdoor spaces perfect for relaxation and entertainment. Carefully chosen native plantings, from salt-tolerant shrubs to pollinator-friendly perennials, enhance the landscape’s beauty and sustainability, thriving naturally in coastal conditions.

To further elevate your property, the team at Jersey Shore Pavers installs elegant, cultured stone features and low-voltage lighting, blending safety with sophistication. Using advanced 3D design technology, they bring your vision to life before construction even begins — ensuring a seamless, personalized experience.

With a deep commitment to quality, sustainability, and customer satisfaction, Jersey Shore Pavers crafts outdoor living spaces that stand the test of time. Let them help you create the coastal escape you've always dreamed of — right in your own backyard.

Laura and Joe Hutchison started Hutchison FIBERGLASS POOLS in 2003. Their son, Joe Jr. would go on to become partner and co-owner in 2017. Through hard work, integrity, and an unparalleled commitment to their customers — Hutchison Fiberglass Pools became and continues to be the premier fiberglass pool company of Ocean County.

Today, more than two decades later, Hutchison Fiberglass Pools is an award-winning family business. These days, Joe Jr. and Laura’s two daughters, Alyssa and Nicole, Laura’s father, Al Vero, and Olivia McKittrick, a close friend who is like a third daughter, are all part of the Hutchison’s in-office team.

From day one, maintaining their commitment to upholding the highest degree of integrity and professionalism has always been and continues to be the Hutchison family’s highest priority. When customers choose Hutchison Fiberglass Pools they become part of the family.

Under the direction of Joe Sr. and Nicole Hutchison the installation department is dedicated to turning the backyard of each customer into a personal oasis. Together with a well-trained crew and a relentless commitment to excellence they successfully make dreams of outdoor living come true.

On the service side of the company, Joe Jr. and Olivia have put together an outstanding service department. With an unsurpassed response time to any issue and an all-inclusive service program — Hutchison’s provides weekly service to more than 350 pools and opens and closes more than 500 pools annually.

The Hutchison family of Hutchison Fiberglass Pools is mindful of giving back to their community in many ways. They believe you can only be as good as the community you are a part of.

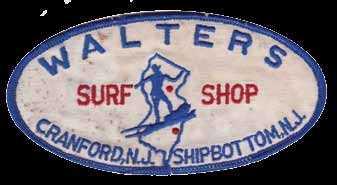

For more than sixty years Walters Bicycles & Pedego LBI in Ship Bottom has been a cornerstone of the business community. In January of 2025, Jason Walters and his wife, Avery, became the third generation to own and manage the family’s legacy business, representing three generations of hard work, quality, and tradition.

“Most of my childhood memories are centered on my dad’s bike shop,” says Jason Walters. “I grew up work ing alongside of my dad. I always knew I would be involved.” Now a Marine Corp veteran, Jason credits his time in the military for changing his outlook on life and for teaching him the value of dedication and service.

Customer service and serving the community have long been a tradition for the Walters family. Walters Bicycles in conjunction with local police departments sponsors the Annual Bike Rodeo held at the Long Beach Island Elementary School on 20th Street in Ship Bottom. Bikes are checked for safety issues and when needed, repairs are made. Participating children receive helmets, horns, and other equipment donated by the Kiwanis Club of Long Beach Island. There is also an obstacle course where the children learn to operate their bikes safely.

the Beach, in 1965 the business was renamed Walters Bicycles when Bob and Margaret became full-time residents of Ship Bottom. Jason’s father, Tom, took over the bike shop in the early 1990s and operated it for more than thirty years before retiring recently. During his tenure it became Walters Bicycles & Pedego LBI

Each generation of Walters has brought something new and exciting to the business. Tom introduced Pedego Electric Bikes. Under Jason and Avery’s ownership, Walters Bicycles continues the tradition of offering innovative and market-changing bikes with the introduction of SE Bikes — a BMX brand with a long history and significant presence in BMX cycling. “It’s an exciting time,” says Jason.

Jason and Avery were married in 2018 at Brant Beach Yacht Club. In a style much befitting a family with a long history of bicycles, the bride and groom rode a bicycle built for two. As an expression of gratitude to their bridesmaids and groomsmen, each member of the wedding party was presented with a bike.

Jason’s grandparents, Bob and Margaret Walters, were originally from Cranford, New Jersey. “My grandfather always wanted to own a bike shop. In 1957, he purchased a garage on Long Beach Boulevard and 5th Street in Ship Bottom and converted it into a retail shop with living quarters upstairs.” Originally named Walters Equipment for

Today, as Jason and Avery raise the fourth generation of Walters they are honored to keep the wheels turning for the next generation.

Walters Bicycles & Pedego LBI is a full-service shop offering maintenance and repairs. The shop carries a wide variety of bikes and cycling gear. —Diane Stulga • Photography courtesy of the Walters family

Our Echoes of LBI family held a mini Chowderfest in 2024. Here are some of our favorite recipes that are sure to be yours too!

iN g R edie NTS:

4 slices thick cut bacon (diced)

1 small chopped onion

3 chopped celery stalks

2 cloves garlic

1/3 cup all-purpose flour

4 cups seafood stock

5 medium chopped red potatoes

1/4 tsp dried thyme

2 bay leaves

d i R e CT i ONS:

4 oz salmon (diced)

4 oz bay scallops

4 oz cod (diced)

4 oz deveined raw shrimp raw

5 oz whole baby clams drained

8 oz heavy cream

1 cup corn

1 cup spinach chopped

2 tbsp well minced parsley

Salt and pepper

In a large stock pot, cook the bacon over medium heat until crispy. Add the celery and onions, cooking until translucent. Add the minced garlic and cook until fragrant, being careful not to burn the garlic. Stir in the flour, coating all, and continue cooking until the flour begins to brown. Very gradually, pour in the seafood stock, about two tablespoons at a time, whisking it into the flour and veggie mixture. There should be no visible liquid between each pour, as it gets absorbed by the roux. Continue until you use all the liquid, pouring more quickly at the end. Add the potatoes, thyme, and bay leaves and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer and continue cooking for fifteen minutes. Add in the cod and salmon, and cook for five minutes. Then add the shrimp and scallops, cook for 3 minutes. Stir in the cream, corn, spinach, and clams, and let those heat through for a minute. Remove from the heat and stir in the fresh parsley. Season with salt and pepper to taste. —From the kitchen of Mary Ann Himmelsbach

iN g R edie NTS:

50 fresh raked clams (soaked, cleaned, and finely chopped)

10 fresh garden tomatoes (diced and remove seeds)

2 ½ cups celery (diced)

2 ½ cups carrots (diced)

1 ½ cups sweet onions (diced)

2 1/2 cups corn

6 bay leaves (remove before serving)

1/4 tsp ground pepper

3 sprigs of fresh thyme (remove before serving)

d i R e CT i ONS:

Gently steam clams until open. Put broth aside. Remove each clam from shell and chop with kitchen shears, rinse, and cook in broth for ten minutes. Combine all ingredients and cook low for forty minutes. Add water if needed, according to amount of broth used. Do not add salt. Serves sixteen. —From the kitchen of Denis Kirby

iNgRedieNTS:

1 lb of large shrimp (peeled & deveined)

1/2 lb scallops

1/2 lb monkfish

1/2 lb fresh lump crabmeat

1/4 lb unsalted butter

4 carrots (diced)

1 onion (diced)

3 stalks of celery (diced)

1 cup small red potatoes (diced)

1/2 cup corn (fresh or frozen)

1/4 cup all-purpose flour

1 1/2 tbsp heavy cream (optional)

2 tbsp minced parsley

Salt and pepper to taste

diReCTiONS:

Se AFOO d S TOC k:

2 tbsp good olive oil

Shells from shrimp

2 yellow onions (chopped)

2 carrots (unpeeled & chopped)

3 stalks celery (chopped)

2 minced garlic cloves

1/2 cup good white wine

1/3 cup tomato paste

1 tbsp kosher salt

1 1/2 tsp black pepper

10 sprigs of thyme with stems

Cut shrimp (saving shells for the stock), scallops, and monkfish into bite-sized pieces. Place them into a bowl with the crabmeat. In a heavybottomed pot, melt the butter; add the carrots, onions, celery, potatoes, and corn – saute over medium-low heat for fifteen minutes, or until the potatoes are barely cooked, stirring occasionally. Add the flour; reduce the heat to low and cook, stirring often, for three minutes. In a separate stockpot, warm oil over medium heat. Add the shrimp shells, onions, carrots, and celery and saute until lightly browned. Add garlic and cook two more minutes. Add 1 1/2 quarts of water, white wine, tomato paste, salt, pepper, and thyme. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for one hour. Strain through a sieve, pressing the solids. You should have approximately one quart of stock. Add the seafood and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer, uncovered, for seven to ten minutes, until the fish is just cooked. Add the heavy cream, if desired, and the parsley. Add salt and pepper to taste, and serve. —From the kitchen of Nancy and Hank Edwards

iN g R edie NTS:

1 1/2 Ibs. medium size fresh shrimp (peeled & deveined)

1 cup shredded Monterey Jack cheese

2 tbsp butter or margarine

1 medium chopped onion

2 (10 3/4 oz.) cans cream of potato soup (undiluted)

3 1/2 cups milk

1/4 tsp ground red pepper or black pepper

d i R e CT i ONS:

Melt butter in a dutch oven over medium heat. Add onions and sautée until tender. Stir in cream of potato soup, milk and pepper, and bring to a boil. Add shrimp; reduce heat and simmer, stirring often until shrimp just turn pink. Stir in cheese until melted. Garnish with fresh parsley if desired. Serve immediately. —From the kitchen of Diane and Rob Roy

It is all about the Brie, try our French double crème Brie.

iN g R edie NTS:

1/2 fresh baguette cut lengthwise 1 wedge of Brie sliced 2 or 3 slices of Italian Prosciutto if desired for additional flavor

diReCTiONS:

Assemble and top with chopped fresh arugula and a generous drizzle of our local honey. For an extra kick try our hot honey.

To elevate this culinary delight, try our hand-wrapped mozzarella.

iN g R edie NTS:

1 focaccia sliced through the middle ½ lb. mozzarella sliced

1 or 2 slices of Italian capocollo for a heartier taste experience Balsamic vinegar or balsamic glaze

Extra virgin olive oil

Roasted red peppers chopped or sliced

Sea salt (optional)

diReCTiONS:

Assemble and top with roasted red peppers, two drizzles of balsamic vinegar or balsamic glaze and a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil. Add a dash of sea salt to taste. Serve with fresh seasonal fruits and your favorite beverage, perhaps a light wine or sparkling water. Most of all enjoy all that life has to offer this summer on LBI.

Humankind has long had a deep fascination with motherof-pearl, its iridescent opal-like surface became a treasure primarily associated with wealth and royalty, such as the ancient civilizations of China, Egypt, India, and Mesopotamia where it was harvested from the depths of the sea floor and used to embellish jewelry, furniture, and architectural structures. Remarkably, its earliest use can be traced back more than 40,000 years to the Bardi Jawi people of indigenous Australia.

Mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre or MOP has a rich history in North American indigenous culture. Nacreous shells were among the things traded between indigenous people for thousands of years where it was used for jewelry, embellishment of clothing and personal adornment. Southwestern tribes such as Navajo and Zuni continue to incorporate mother-of-pearl into their jewelry, fetishes and other art forms.

During the nineteenth century it was widely used to adorn fashionable vanity sets, cigarette cases, snuff boxes, desk sets, highend tableware, and numerous other items in addition to buttons for clothing and jewelry for women and men. Today, mother of pearl is frequently used for inlay on musical instruments, clock and watch dials, luxury cutlery, jewelry, and home decor products.

Over the centuries, the harvesting and processing of nacreous shells — the source of mother-of-pearl — was a large part of the economy for countries with fishing industries, including Japan, the Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, New Zealand, Australia, Korea, and Mexico.

Commercial harvesting of nacreous shells was originally done by individual divers, by freediving sometimes to depths up to sixty feet on a single breath. By the early 1900s, most divers were replaced with trawling vessels. Today, the trade and import of motherof-pearl is highly regulated to protect against overharvesting.

Nacre is the innermost layer of the shell of several species of cephalopods, gastropods, mollusks, including the chambered nautilus, turbans, top shells, abalone, and Pinctada maxima oysters. It is composed of aragonite (calcium carbonate) and conchiolin cemented together by natural biopolymers in a brick-and-mortar structure. These platelets of protein make mother-of-pearl incredibly strong, able to withstand the pressure of the sea. The platelets also interfere constructively with wavelengths of light at different angles, causing their iridescence.

Nacre acts as protection for the mollusk within the shell against irritants, such as parasites. If a parasite enters the shell, the mollusk begins secreting more nacre around the irritant —eventually creating a pearl.

No two layers of nacre are the same even within the same species of shell. Thanks to this uniqueness, its structure, and the hardness of nacre, the stacked layers of mother-of-pearl create an amazing durable display of light and color.

Today, the use of mother-of-pearl continues with two innovative companies located in the same building along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay — Aulson Inlay, LLC and Duke of Pearl, LLC.

The Aulson family history began when Ellen and Doug met in high school in Massachusetts. Ellen went on to become

a teacher of marine and environmental science, and Doug got a degree in industrial engineering. Together with their daughters, Anja, and Jaime, their passion for nature and technology inspired them to start Aulson Inlay, LLC in 2012.

The Duke of Pearl, also known as Chuck Erikson, has a long history with nacreous inlay material dating back to 1963 and 1964 that started with banjo construction and his first attempts at inlay work. Realizing the lack of quality inlay material, the Duke embarked on a journey that included serious experimentation with nacreous materials to create new types of mother-of-pearl laminates. It is a journey that continues to this day with Duke of Pearl, LLC.

Together Duke of Pearl, LLC and Aulson Inlay, LLC create amazing timeless pieces from mother-of-pearl for clients that range from home crafters to large scale manufacturers. Using highly specialized and proprietary processes Duke of Pearl creates strong veneer like sheets from mother-of-pearl.

Aulson Inlay then places the MOP sheets into a computer numerical control machine, a motorized tool that uses a computer program to cut out custom designs for inlay used for everything from musical instruments, jewelry, and fishing lures to surfboards, furniture, backsplashes, and countertops. All the colors in their motherof-pearl products are naturally formed by the mollusk. These natural materials are perfect for home projects due to their lack of chemical dyes and durability.

Aulson Inlay and Duke of Pearl have a wide variety of clientele and projects in their repertoire. For one client in Hawaii, the team designed kitchen cabinet doors. Each piece of veneer was a five by eight-inch sheet that had to be bonded into a big enough piece from which to cut the door. “It was like a huge puzzle,” says Ellen. “The more complicated, the better.”

Nacre is truly the mother of all pearls, and mother-of-pearl seems to have endless possibilities — just ask The Duke. —Written and photographed by Sara Caruso

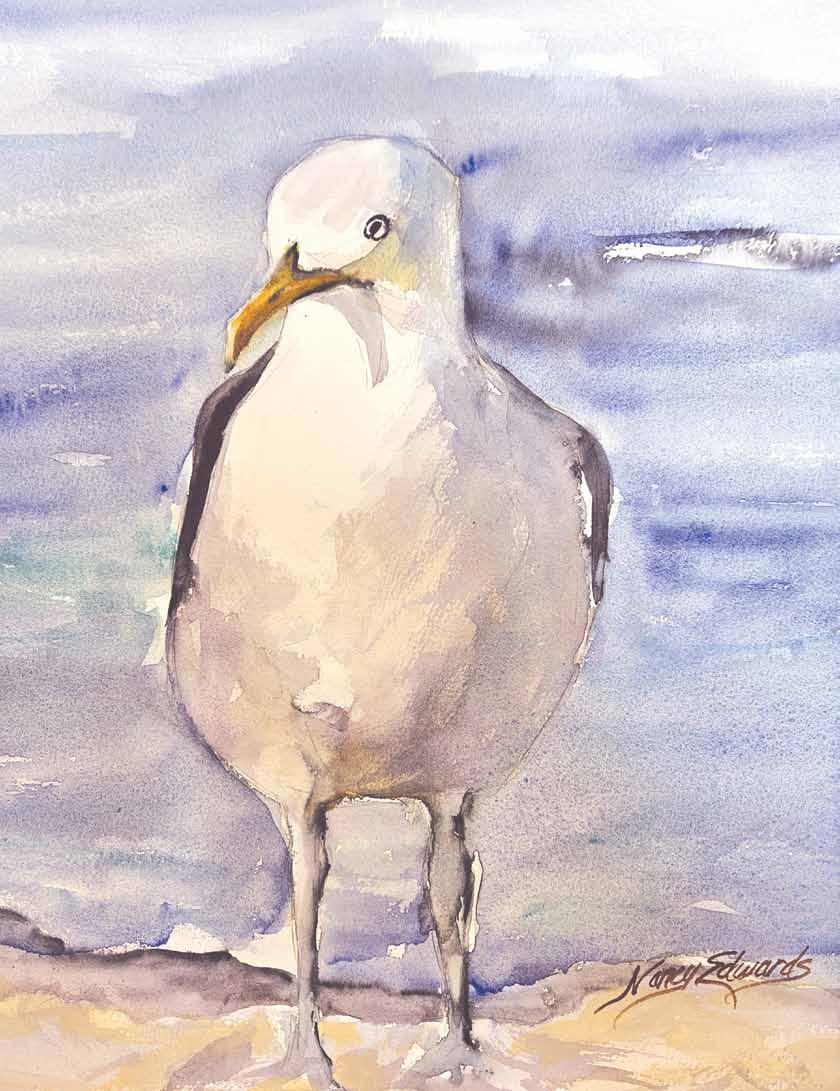

Each Spring, millions of monarch butterflies migrate over 2,500 miles from their winter home in Mexico. Along their journey, they make a stopover in New Jersey, especially around fields of goldenrod like those found at Barnegat Light. Typically, monarchs live only two to six weeks, but the last generation of the year can live up to nine months. If you want to have a truly breathtaking experience, head down to Barnegat Light or the surrounding marshes to see thousands of migrating monarch butterflies. Don't forget your camera! —Artwork and story by Nancy Edwards

Updated from Echoes of LBI – 2018 Spring into Summer Edition

Many of us remember the brightly colored vintage glassware displayed by our grandmothers. With colors of bright lime green, stunning reds and yellows, and electric turquoise, the pieces seemed to glow with a vibrant hue.

Little did we or grandma know that with the help of an ultraviolet or UV flashlight this oddly radiant glassware actually might glow. In fact, several types of UV reactive glass fluoresce under ultraviolet light and can help us peer into the past. To some sea glass collectors, taking a UV flashlight, sometimes called a black-light flashlight to the beach at night may sound strange, but it can be the best way to find some fluorescent sea glass. By understanding some of the history and additives that made these glowing glass jewels, one can better understand these rare treasures.

In 1903, Robert Williams Wood invented Woods Glass, an optical filter made with barium-sodium silicate glass. The purpose of Wood’s glass filter was to block visible light and allow ultraviolet and infrared light to pass through. Though initially used in communications during World War I, Wood’s Glass was used to create ultraviolet or blacklight lightbulbs.

Ultraviolet light is measured in nanometers (nm), which is a unit of length equal to one billionth of a meter used to measure the wavelength of light. Higher nanometers indicate longer wavelengths and lower energy. Shorter wavelengths or lower nm are more energetic. Some materials like manganese are more energetic under a 365nm than a 395nm.

The two most common types of UV flashlights recommended to collectors of glassware are 365nm and 395nm. How intense and what color UV glass fluoresces depends on the type and amount of reactive additive was used when the glass was manufactured. One of the most popular forms of UV reactive glass, uranium glass, was first created in 1880.

Most sea glass collectors have a jar of green sea glass, but some of those pieces might be hiding a secret. Uranium glass, also known as Vaseline glass due to its color resembling petroleum jelly, became popular as decorative Depression glass through the 1930s and early 1940s.

Uranium was used in a wide variety of glass items by the 1930s. It took on the form of kitchenware, utensils, marbles, decorative tile, lamp bases, fish bowls, ashtrays, and even false teeth. When the United States entered WWII, the country's uranium stock was put towards the war effort, but the fad of Depression glass had already begun to wear off. Uranium would not reappear in glass manufacturing until the late 1950s as depleted uranium sources were sold to American glassmakers like Fenton, Mosser, and Degenhart, among others. During manufacturing, uranium oxide, in the form of diuranate, was added to glass for coloration before melting. Antique uranium glass is usually a bright lime green or yellow tint in regular light. Uranium was rarely used in other colors. Even without a UV light, all uranium glass seems to glow a bit on its own. However, it is not the only green fluorescent glass, which has led to confusion.

Lavender sea glass is one of the most popular and sought after colors. In most cases, it starts off as clear and changes to lavender after several years of sunlight exposure. But did you ever wonder why? The sand used in early glassmaking contained a lot of iron impurities which gave the glass hues of green or aqua. In the early days of glassmaking, manganese dioxide, also known as glassmaker’s soap, was added to glass to decolorize the final product. While glass made with manganese was usually clear, it can also be found in some light blue and pink glass.

Though scientists have debated how manganese decolorizes glass,