constellations a beginners

guide

pictor

pyxis

centaurus

telescopium

perseus

chamaeleon

scorpius

coma berenices

antlia

cassiopeia

andromeda

cepheus

taurus

horologium

octans

pisces

carina

serpens

canis minor

canes venatici

ursa minor

capricornus

cetus

reticulum sagitta

pheonex

sculptor

delphinus

sagittarius

crux

circinus

sextans

pavo

canis major

corona australis

pegasus

ursa major

corona borealis

scutum

cygnus

piscis austrinus

triangulum

equuleus

corvus crater

volans

triangulum australe

vulpecula

orion

ophiuchus

vela virgo

tuscana

As of right now there are 88 officially recognized constellatons. However, humanity has always been connecting the dots in the sky to form shapes from the stars above. While the names, size and stars that are used in the constellations have changed over time, the ideas and basis of them have been constant. Throughout history humans have naturally formed images in ways that suit what the viewer sees, and thus these formations have reflect the society seeing them.

caelum

camelopardalis

columba

star maps

Star maps depicted stellar locations in the sky according to a coordinate system oriented to either the ecliptic (the Sun’s path in the sky) or the celestial equator (the projection of the Earth’s equator into the heavens). The former system (typically expressed in degrees of celestial latitude and longitude) had astrological significance. The latter system (typically expressed in degrees of decl. and hours of R.A.) was easier to use with the telescope. The stars also were grouped into constellations, whose images were depicted in a geocentric view (as seen from the Earth) or in an external view (as seen from the outside of the celestial sphere, like on the surface of celestial globes.

As far we know, the first people to map the positions of stars were the Chinese astronomers Shi Shen, Gan De and Wu Xian in the third and fourth century BC.

Their work was passed along over the centuries in various media, although inaccurately. The earliest copy we have is a star map from the Tang Dynasty (roughly 9th century AD), discovered in modern times in the ruins of a monastery in the deserts of central Asia.

The early Chinese, Babylonians and Greeks were chiefly interested in how the Sun, Moon and planets moved through the patterns the stars made on the sky. A main aim was astrological predictions. But each culture grouped stars in different “constellations,” and astrologers were never able to agree on a system for prediction. Astrology was a grand first attempt at cosmology—that is, a system for understanding the workings of the universe—however it could never develop into an actual science. For the world is not in fact influenced by

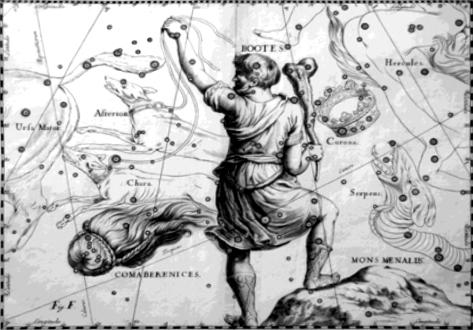

This image depicts the constellation of Boötes, the herdsman. They are true celestial maps in that they have lines of latitude and longitude with degrees marked on the periphery that allow the location of the stars to be plotted. The orientation of both is to the north ecliptic pole. The top map is from Bayer’s Uranometria (1603) and shows a geocentric orientation, where the constellations appear the way we see them from Earth. The figure is drawn from the front, and the curving star pattern of the handle of the Big Dipper asterism is to the upper right.

northern hemisphere southern hemisphere

the positions of stars. After all, the patterns they form would look completely different if they were viewed from some other position in space.

Ancient Greek astronomers such as Hipparchus (ca. 190–120 B.C.) and Ptolemy (ca. 100–178 A.D.) constructed a collection of star catalogs, where naked-eye stars were organized in constellations and listed with their location in celestial latitude and longitude. During the European Middle Ages and early Renaissance, accurate stellar locations became less emphasized, and instead constellation images in manuscripts were less like maps but illustrations of the text. This changed in 1515 A.D., when Albrecht Dürer constructed the first printed European celestial hemispheres, where stars were placed in a radial

grid system oriented to the north and south ecliptic poles. A Golden Age of celestial mapping followed from 1600 to 1800, when Johann Bayer (1572–1625), Johannes Hevelius (1611–1687), John Flamsteed (1646–1719), and Johann Bode (1747–1826) made significant advances in celestial cartography that spawned a number of derivative atlases. Stellar locations were oriented initially to the classical ecliptic coordinate system, then to the equatorial system as the use of the telescope became more common.

The advent of larger telescopes, micrometers, and photographs in the 19th Century created a need to plot ever fainter stars and deep sky objects without the clutter of constellation images, which numbered over 100 as mappers added additional entries to please patrons and fill spaces in

the sky. In 1922, at the IAU 1st General Assembly, 88 constellations were officially approved, and in 1930 Delporte drew adjacent areas in the sky named for constellations but without any images. This tradition continues in today’s telescope-friendly star maps that show unprecedented detail but no constellation figures.

astronomical history

3000 BC: Babylonian astronomical records begin.

140 AC: Ptolemy publishes his star catalogue, listing 48 constellations

1608 AD: Dutch eyeglass maker Hans Lippershey invents the refracting telescope

129 BC: Greek astronomer Hipparchus creates the first star catalogue.

For nearly almost a thousand years, the limitation of lacking technology halted a further understanding of the cosmos. To get more detailed information, humans needed a better eye. When the first telescopes were developed in The Netherlands in the early 1600s, amateurs and experts alike were excited to try them, even though they only had insignificant magnifications of 3X or 4X.

From Galileo’s early models, to Newton’s, to the 1500-foot-long model designed by Johannes Hevelius, astronomers of the 16th and 17th centuries were limited by the quality of the glass needed to make more powerful telescopes. Not that much more could be learned about the stars until such higher magnification capabilities were possible to achieve.

In the late 1770s, German/Czech/Jewish musician William Herschel turned to designing telescopes. After some failures, he developed a powerful enough telescope to make brand-new observations, and immediately began a systematic search and recording of the night sky above Bath, England. In 1781, he was able to discern that Uranus wasn’t another star, but a planet. After putting their observations together, William and Caroline Herschel published “On the Construction of the Heavens” in 1785, which painted a basic picture of The Milky Way.

In the 1800s, humanity’s understanding of the universe exploded thanks to several key advances, which improved star mapping by revealing the distances between and relative movement of stars (not

just their fixed location at a given time of observation). Going from knowing where a star is to knowing how it behaves over time is the cosmological difference between a two-dimensional representation of the Universe and a three-dimensional.

The first advance came in 1838, when the Astronomical Distance Scale was established, using the breakthrough parallax method developed by Friedrich Bessel, this meant that distances between stars and other objects could be measured much more accurately. Then, in the 1850s and 1860s, the development of astronomical spectroscopy (analyzing starlight by wave length) allowed astronomers to access even more information. Called the key to astrophysics due to observers' ability to learn about the spin, magnetic fields, composi-

Lynx is only a faint constellation, with its brightest stars forming a zigzag line. It is usually observed in the Northern Celestial Hemisphere. It was introduced in the late 17th century by the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius.

1784 AD: Charles Messier publishes his catalogue of wstar clusters and nebulas which is still in use today.

1990 AD: The Hubble Space Telescope is launched, producing spectacular images of distant stars, nebulae, and far off galaxies.

tion, and relative motion of stars. Together, the distance scale and spectroscopy gave scientists the ability to make a star map with much greater detail and three-dimensional perspective, no longer confined to plotting two-dimensional positions on the celestial sphere.

In the late 1800s, astrophotography had advanced the field yet again. No longer were humans reliant on what could be observed with the eye and a telescope: astrophotography can reveal nebulae, galaxies, and dimmer stars using a longer exposure time for the film in a camera.

As a result of this direct recordings were now possible, whereas before astronomers had to manually write down the positions of objects and sketch their appearance by hand. In 1923, American Cosmologist

Edwin Hubble calculated the location of the Andromeda galaxy using astrophotography. Hubble could not have discovered the Cepheid variable ‘standard candle’ stars in the Andromeda galaxy if he wasn’t able to photograph it and record the exact position and brightness of the stars at different times. This measurement allowed him to prove that Andromeda was indeed outside our galaxy.

notable constellations

(1) orion

Thanks to his belt, Orion is one of the most noticable constellations to find in the night sky. Look for three bright stars in a line right by each other. Once you locate the belt, you can see his two knees below, upper body, and arms.

(2) ursa major

Ursa Major, also known as the big dipper is a good starting point for locating other constellations. Though it depicts part of a bear it looks like a pot. It’s made of 7 stars, with 3 consisting of the “handle” and the other 4 making up the “pot.”

Merek

Dubhe

Rigel

Mintaka

Alnitak

Alnilam

(2)

(1)

It’s easy to find the little dipper after locating the larger one. Follow the line on the right side of the “pot” from the big dipper, and it will lead you to the north star Polaris, the north star. Polaris is the end of the little dipper’s handle.

(4)

Cassiopeia either looks like a big W or M, depending on where you are. The constellation consists of 5 very bright stars. It’s supposed to resemble the greek mythological princess Cassiopeia, sitting in her chair. The constellation can be seen year round.

Canis Major contains the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, which is the best way to try and find the dog. Start by identifying Orion’s belt and following a line southeast until you get to Sirius, which is the neck of the dog.

cassiopeia (5) canis major

(3) ursa minor

Polaris

Wezen

Sirius

Shedar

(5)

(4)

(3)

stargazing today

For those interested in stargazing, a truly dark sky is breathtaking, but the sad reality is that few of us have easy access to such skies, and astronomers have long been advocating for darker skies and for a reduction in light pollution. When astronomers talk about light pollution, they mean the artificial glow that prevents us from getating a clear view of a starry night sky. However, other voices are concerned about light pollution, with environmentalists, ecologists and healthcare professionals recognising the importance of a natural day–night cycle that includes darkness. Another common casualty of light pollution is the pale band of the Milky Way, the river of stars that stretches high across the autumn skies. Not surprisingly, the worst places for light pollution are major towns

“I have had many letters asking me how to start making a hobby out of astronomy. My answer is always the same. Do some reading, learn the basic facts, and then take out a star map and go outdoors on the first clear night so that you can begin learning the various star and constellation patterns. The cliche that ‘an ounce of practice is worth a ton of theory’ is true in astronomy, as it is in everything else”.

Sir Patrick Moore

and cities. Stargazers who live in more rural locations can be just as bothered by the annoying bright light from a neighbour’s badly adjusted security light. Thankfully, there are a few things you can try to mitigate the unwanted effects of light pollution. For local sources of light pollution, your biggest consideration is where you position your telescope in your garden. You need to find a spot that puts a barrier between yourself and the irksome source of glare. That barrier could be anything–a fence, a tree, the side of a building–so long as it isn’t so big it also masks the part of the sky you want to look at.

Ella Caperton ACCD Type 3

Meryl Pollen Fall 2023

Adobe Caslon