A. Summer 2025

From The Editor

Dr Ed Wilson

Occasionally, in my role as an English teacher, I’m asked by a student to explain the choice of a particular book or poem. The query almost always refers to Shakespeare, and usually revolves around relevance. ‘Wouldn’t it be better to study something that relates to our lives?’

This is a reasonable question. The relevance of a play, or a Renaissance painting, or a seemingly abstract piece of mathematics, isn’t always obvious. Who can blame students for not identifying with Jay Gatsby’s obsession with the past when they believe that their best days lie ahead of them?

The more I am asked this question, the more I find myself thinking that the work may well not be relevant... yet. It can’t always speak to us on our terms. Sometimes, it takes time for our experience to move us closer towards it.

Recently, I went for an early evening run by the sea. In between gasping for breaths, I focused on the light settling on the water. For a moment, I could see exactly what Wordsworth meant when he described the ‘small circles glittering idly’ on Ullswater before melting ‘into ‘one track of sparkling light’. I first read The Prelude a long time ago, but never before had I shared the poet’s view of the world quite so closely.

This was a small experience – a chance alignment of perception with a work of art many years after first encountering it – but it was a special one too. And it had taken a long time to arrive.

Education – particularly the more challenging parts of it – is not just a short-term project. In the day-to-day life of a school, it’s easy to lose sight of this when we’re trying to do everything we can to meet the needs of the immediate moment. But we have to believe that the seeds planted now are valuable, even if they take time to come to fruition.

I hope you enjoy all the wonderful work that has been chosen to appear in this issue, either now or at some point in the future, when you are ready to meet it.

My Favourite Books Jacob N, Year 8

Why did I choose these books?

The Recruit by Robert Muchamore: I chose this because it is the first book of my all-time favourite series. With a gripping plot, diverse but incredible characters, and lots of twists and turns, the series definitely tops my favourite bookshelf.

Robin Hood (Hacking, Heists & Flaming Arrows) by Robert Muchamore: This is one of my recent reads, another series by Robert Muchamore. It follows a boy named Robin, whose dad was framed by corrupt police, and the corrupt town begins to turn against him. This book has gripping plots and incredible cliffhangers, making me go from book to book in only a few days!

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson: This is one of my favourite classics because of the massive build-up to the twist at the end. The mystery is a very clever one, filled with many rabbit holes, and is a complete labyrinth of a mystery. Simply incredible.

Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne: I love this book for its sense of adventure and how it captures the excitement of travel. Phileas Fogg’s journey around the world is full of unexpected twists, clever problem-solving, and thrilling encounters. It’s an absolute classic that keeps you hooked from start to finish.

The Circle by Dave Eggers: This book is a fascinating take on modern technology, privacy and the power of big tech companies. It raises so many interesting questions about surveillance and how much we really control our own online presence. It’s both exciting and slightly unsettling – exactly what I love in a thought-provoking read.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain: I enjoy this book because of the fun and mischievous spirit of Tom Sawyer. His adventures, clever tricks, and the sense of freedom he has make it such a fun and light-hearted read, while still having moments of deeper meaning.

Wildspark by Vashti Hardy: This book is a fascinating mix of adventure and scifi, set in a world where spirits of the dead can be placed into machines. I love the creativity of the story, the strong characters and the emotional depth that makes it so much more than just a fun adventure.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis: This is a true classic with a magical story that has stuck with me since I first read it. The world of Narnia is so well imagined, and the themes of bravery, loyalty and good vs evil make it a book that I always enjoy coming back to.

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame: This is such a beautifully written book, with charming characters and a peaceful, nostalgic feel to it. The friendships between the characters and their adventures along the riverbank make it a comforting and enjoyable read.

The Secret Seven by Enid Blyton: I love mystery stories, and this series is great for that. The Seven always find themselves solving interesting cases, and the way they work together makes their adventures really fun to read. I always dreamt of being in a group of my own! It’s a perfect mix of light-heartedness and excitement.

The Highland Falcon Thief by M.G. Leonard & Sam Sedgman: This book combines two things I love – mysteries and awesome characters. The story is fast-paced and clever, with an exciting mystery to solve while traveling on an incredible train journey. It’s a great modern adventure that keeps you guessing until the end.

What is my all-time favourite book and why?

My all-time favourite book is actually a series – an absolutely incredible one. The CHERUB series by Robert Muchamore, starting with The Recruit, is simply outstanding. It follows James, a boy who endures tough times but perseveres. He is recruited by CHERUB, a secret intelligence agency made up of children, and the series tracks his thrilling missions all the way until he turns eighteen. Packed with twists, gripping adventures, and a cast of diverse, well-developed characters, this series is nothing short of perfect.

What books am I planning to read in the Easter holiday and why?

Robin Hood (Bandits, Dirt Bikes & Trash) by Robert Muchamore: Along with the rest of the Robin Hoods, the previous part of the series is so good! I would like to finish the series!

Robin Hood (Prisons, Parties & Powerboats) by Robert Muchamore: As before.

Robin Hood (Ballots, Blasts & Betrayal) by Robert Muchamore: As before.

Robin Hood (Fury, Fire & Frost) by Robert Muchamore: As before. Technology is Not the Problem by Timandra Harkness: I am really interested in technology, and the effects of technology.

I will probably just find books in general and read them!

William M, Year 7

Life is a weird and wonderful thing. It is mostly a treasured possession. Some love it, some hate it, But where would we be without it?

Life is not endless. At some point, Death will catch up with you. Usually people fear that day, But some look forward to it.

Some people believe that you either go to heaven (or hell). Others say that you live again. Some believe that you could possibly gain enlightenment. Others say that you float around in nothingness.

What people agree on, however, Is that life is too short. Enjoy it whilst you can, And remember, happiness cannot be bought.

The Mystery of the Missing Painting

Zuleikha I-R, Year 9

Florence in the summer of 1503 was a city alive with colour and ambition. The morning light poured over terracotta rooftops, gilding the bustling piazzas and narrow alleys where merchants called out their wares. The air was a heady mix of fresh garlic and sweetly scented flowers. Carts were piled high with wine and overripe fruits that sent the flies crazy. The continuous chatter of artists, scholars and tradesmen was carried in the August breeze along the Arno River. Over all of this loomed the magnificent Santa Maria del Fiore, its morning shadow stretching across the Arno from the Palazzo Vecchio to the Pitti Palace.

The streets buzzed with talk of the art competition between two great masters: Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Both men were eager to win the commission to paint the fresco in the new chapel of the Duomo, and Florence could hardly contain its excitement. Michaelangelo’s bold depiction of Saint Sebastian had already been unveiled to great acclaim and a large crowd had gathered in the Basilica di Santa Croce for the unveiling of Leonardo’s proposal, surely another masterpiece?

Noblemen in rich velvet cloaks, merchants in finely tailored tunics and apprentices clutching their sketchbooks all jostled for a view of the veiled canvas. Young children sat on their parents’ shoulders, giggling and pointing at the sea of people below them. The Mayor of Florence stepped onto the stage grandly and quickly addressed the crowd. His speech came to a close and the audience stood in silent anticipation as he moved forward and, with one swift movement, reached for the veil and swept it aside.

‘What?’ ‘How?’ Whispers swept across the crowd like wildfire and eyes moved in all directions searching for an answer. Michaelangelo laughed, taking the hand of the man next to him who had offered a handshake to celebrate his victory.

The painting was gone, leaving behind only its empty frame. Turning red, Leonardo leapt from his chair. He stared at Michaelangelo accusingly and demanded that the thief be found. The flustered mayor appealed for calm. “Citizens! There must be some simple explanation” the mayor shouted. “The chapel has been under armed guard all night and I inspected the painting myself here last evening. She is rather incredible and she will be found!”

Leonardo approached the mayor furiously. “Your armed guard must be drunk then, or someone who had access to the chapel has taken it,” he said, his eyes fixed on Michaelangelo, who had gone quiet at his observation.

The next day, the mayor summoned the great detective, Signor Vesari. Vesari was a highly respected officer who had solved many complex crimes in the region, including the double murder of the Duke and Duchess of Milan. The following week, in anticipation of his arrival, a large crowd had gathered in the Duomo. Michaelangelo had not shown up. His reputation had suffered greatly following the disappearance of Leonardo’s work. He was aware of the rumours about him and he avoided gatherings for fear of public condemnation.

Vesari entered the great church, accompanied by the mayor, and close behind, his teenage daughter, Claudia. Her expression was one of practised patience. Claudia was a sharp-eyed young woman with a knack for observation, one that her father lacked entirely. Vesari was a rather short and clumsy man with an impressive grey beard which he liked to stroke while he worked. After briefly inspecting the scene of the crime, he turned quite dramatically to address the crowd, clumsily dropping his hat as he did so. Claudia, in a well-rehearsed movement, quickly picked up the hat and placed it under her father’s arm before anyone had noticed.

Leonardo, standing back from the patch of sunlight that fell in the chapel, leaned against a column, his face red, and a close observer might have seen his eyes following the detective as he inspected the empty frame.

“Fear not, citizens of Florence!” bellowed Vesari, turning around, tripping over a paving stone and catching himself with a flourish. “The greatest detective in all of Florence, Signor Vesari, myself, is here to solve this dastardly theft!”

As Vesari began his enquiries by asking irrelevant questions to all present, Claudia slipped out of the church and followed Leonardo back to his workshop to investigate.

In a narrow side street alongside the master’s studio, Claudia stood listening to the chatter of apprentices that came from the high windows on the north wall of his palazzo. A wealthy merchant barged past her and entered the building. Claudia fell in behind him and before the door was closed she was inside the workshop. If anyone had noticed her they would assume she was the man’s servant.

The long room was a mess of sketches, brushes and costumes. Leonardo and the merchant were deep in conversation in two throne-like chairs. Claudia took a broom and, sweeping the floor, she approached the men, being sure not to catch their eyes. “This commission would have settled our debt, Leonardo. You know that the painting was going to be mine,” whispered the merchant. “Perhaps that is why you were finding it so hard to finish it.”

“Well, it seems as though you might have helped yourself already,” Leonardo replied, his angry eyes scanning the room to see if his apprentices were eavesdropping.

Pushing the broom ahead of her, Claudia followed the long table, her quick mind sizing up the various sketches and models amongst the clutter. Many versions of the portrait of an elegant dark-haired lady lay torn and crumpled among them, the work of Leonardo’s team trying to satisfy his perfectionism.

At one end of the studio, Claudia swept the dust behind the model of a mechanical contraption she could not identify. She studied it from the corner of her eye while checking that Leonardo was unaware of her. A flat plate and a wheel that spun it around when a small lever was pushed.

Before she could inspect further, however, her father burst into the room. “I am here to denounce the culprit!” he declared, pointing dramatically at one of Leonardo’s bewildered apprentices. “It’s him! Look at the guilt in his eyes!”

“I don’t think…” Claudia began but Vesari cut her off.

“But of course, I will need evidence before I throw this dirty thief behind bars,” he said turning to glare at the young apprentice before adjusting his hat.

Vesari was so full of his own importance he hadn’t noticed Claudia’s absence at the Duomo, and turning to her now he whispered, “Poor chap, of course it cannot be him. It must be Michaelangelo, who else has anything to gain? If he thinks we have our thief he will relax and give himself away.”

Claudia sighed and threw the young boy an apologetic glance before hurrying after her father. As he strode officiously into the Palazzo Vecchio to meet the mayor, Claudia followed him, alert to the people thronging the lobby of the city hall. On the ornate marble staircase, she saw the merchant who had been in conversation with Leonardo. A boy passed carrying a silver tray of goblets. Claudia stopped him and harshly criticised his badly brushed hair.

“You cannot serve our masters looking like a beast!” she berated him. “Give me the tray and get a haircut at once.” Bewildered, the servant handed over the tray and confidently Claudia swung it up to her shoulder and approached the merchant. He was walking away from the crowd in the lobby and with a man at his side. They pushed open a door secretively, glancing around them as they went in.

“Wine, my lords ?” Claudia enquired, placing her foot in the door before they could close it. The merchant looked at her, confused, as if he recognised her but couldn’t say from where. Taken aback, he let the door fall open and Claudia walked past him, turning to offer a goblet. As she turned, her eyes fell on a large diagram pinned to the wall by the door. Quickly appraising it, she identified the Duomo, and sketches of various saints each placed over a different chapel.

“My friend,” the merchant said to his companion, “You see even this humble maid servant can spot genius when she sees it! This is Michaelangelo’s winning entry for the chapel fresco. The competition is a sham. My gift to the mayor made sure of the result,” he boasted.

Claudia looked as simple as she could, smiling meekly, and left them admiring their cunning. As she walked back to find her father, Claudia considered the case he was investigating. A painting had been stolen from a guarded room, which could only be visited by the two artists and the mayor. Michaelangelo was her father’s suspect, yet the motive was to prevent his rival from winning a competition which the mayor had already decided in his favour. And a wealthy man who had paid for that outcome would claim Leonardo’s painting to settle a debt.

One thing was certain in her mind: her father had no more chance of solving this than painting the cathedral himself!

The following day in the Duomo, a large horde of Florentines had gathered, amongst them Michaelangelo. Word had reached him that Leonardo’s apprentice was the prime suspect and that he had little to fear. The mayor was still trying to get attention for his empty words of reassurance. Michaelangelo was impatiently fiddling with his painting, highlighting details with a fine brush. The sun now fell fully through the cathedral windows on the ornate but quite empty frame of Leonardo’s painting.

Vesari entered confidently and clapped his hands. The cavernous church amplified the sound and stilled the chatter. Both artists had returned to their chairs and the mayor watched the detective, his eyes desperate for a solution.

Claudia followed her father to the front of the audience, and stood beside him, between the two easels. She admired the beauty of Michaelangelo’s saint and considered the stark empty frame of his competitor’s entry.

Vesari cleared his throat. “Between any great rivals, especially when both may be considered a genius, there will be respect but also some hatred,” he began. “A hatred to be beaten, to think that your rival may have surpassed your masterpiece with one of his own. For this reason, I am able to inform the citizens of Florence of the identity of the thief.”

While he spoke, Claudia had edged closer to the empty frame to inspect it. The sunlight had cast a faint shadow of a small lever on its back, where she had expected it to be. She surreptitiously reached over and pushed it gently as her father reached the conclusion of his statement. There was a whirring from the frame and the blank wooden board within it slowly spun around and a mysterious, enigmatic woman’s portrait was revealed.

Vesari was a hasty and clumsy detective, but he was not stupid. As he turned and saw the painting clicking into position and remembered Leonardo’s great skill in engineering as well as art, the solution came to him.

“My fellow citizens, as I was saying, for fear of losing to a rival and the loss of face, the great master Leonardo stole his own painting, which I have now cleverly discovered.”

The Mona Lisa said nothing, but she smirked at the detective, and smiled knowingly at Claudia.

I Must Provide Freddie F, Year 9

A mother of children, who must provide –

But I can’t. I can’t.

They deserve a better life, away from a torn away land like this one, Where happiness isn’t a rarity, and suffering isn’t plentiful. They look up to me – like they should. But who do they see? What do they see?

A flustered soul who cannot meet the needs of their innocent lives, A damaged heart that loves too much to look past this.

Childhood shouldn’t be like this. Motherhood shouldn’t be like this. With no support, with no hope, With no joy. I stand here now,

A failed parent – and with starving children whimpering at me. What should I have done?

Why has no one come to save me?

The world is cruel. Very cruel indeed.

Nathan C, Year 13 (2024)

Philosophy William R, Year 10

You only have power over people, so long as you don’t take everything away from them. When you’ve robbed a man of everything, he’s no longer in your power, he’s free again. How far do you agree?

I fully agree with the statement, as I believe that once you take everything away from somebody, and they have nothing left to lose, they are under no one’s control. I think if a man was stripped of everything he owned and loved, then he would be the most dangerous man, as he would have nothing to live for; his nihilism would give him no purpose other than revenge or destruction.

Firstly, in order to be able to coerce an individual, you need to create a sense of fear, either that of losing something physical such as possessions, or someone close to them, but crucially they still need a tiny piece of hope left so that they’ll continue to be controlled. If this hope is taken away, the individual will see no point in doing the things you force them to, and will either go down fighting in a rebellion, or they’ll choose death over an authoritarian lifestyle. Both are dangerous, as the figure in command loses all control over the individual. A controversial example of this newfound ‘freedom’ caused by an overly oppressive leader is Osama bin Laden, who was stripped of his fortune, his status, exiled from his country, left without a home or neighbourhood, and founded the terrorist group al-Qaeda, whilst commanding deadly attacks that cost many people their lives. This demonstrates how taking everything away from a man who has very strong principles such as faith and ambition can create one of the most infamous and deadly murderers, who operates solely based by their hatred and vengeance. Perhaps the best way to control a man is to work out what he desires and craves the most, and to take everything else except that away, and keep feeding him illusions of his cravings.

Secondly, it is important to note whether the person you want to control fears death or not, as if they don’t, killing them may only make them stronger. Although this sounds clichéd it has been proved time and time again, one notable example being Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, who was stripped of everything including his life, following his denial to stop spreading the word of Christianity, and subsequently flayed and crucified. He became a martyr and grew famous whilst still spreading the word of Christ even after death. He is still

famous to this day and his remarkable death did the very thing it aimed to prevent happening. This proves that taking someone’s life away is not always as final as it seems, and they can still have an impact no matter how much you punish them. Bartholomew did not fear death, perhaps because he knew he would go to a better place, which leads me to my next point that maybe it is harder to control someone who has faith.

I believe that a man who has faith is much harder to control, as he doesn’t value money or possessions, he accepts that he will leave his earthly relationships behind to be with God, and he doesn’t fear death as it only brings him closer to Christ sooner. Therefore he is infinitely harder to have power over, as he is left with nothing to fear, and the easiest things to take away, such as money or loved ones, become an empty threat, and this only builds resentment instead of fear.

Since belief in a god is a spiritual thing and not physical, it is practically impossible to take away, therefore the individual will always have that crucial piece of hope left even after death. Hence Bartholomew the martyr. Therefore, since the thing that matters the most to him would be faith, to take everything else away would be null and void and simply a dangerous, stupid thing to do, only giving him a reason to seek vengeance. An empty man filled with anger and resentment and a belief that an omnipotent, wrathful God is on his side would turn someone not that dangerous into a potential monster.

On the other hand, you could argue that totalitarian governments like that of Joseph Stalin’s or a current situation in North Korea, demonstrate that even when individuals are deprived of wealth, family and common necessities, they can still be controlled through their underlying fear of the government, and through constant surveillance. However, they put up with this in order for survival, and because it’s most likely better than an all-out war. This idea is very similar to that of the Thomas Hobbes and Rousseau argument, where Hobbes would argue that it is better to give up some human rights in order to survive, and Rousseau argues that to give up human rights would be to give up your species’ essence. In today’s world we see Hobbes’ ideas more often as they support the idea of a powerful government and Rousseau would like a world without any type of leviathan. However, there will always be someone at the top of the ladder, and someone on the bottom rung, which is just the natural way of life, but this supports Thomas Hobbes much more than the other.

This means you could argue a totalitarian government will still have control over its people, even if they take everything away from its citizens, simply because the common person knows their situation is better than a chaotic world of turmoil and conflict.

In opposition to this, I believe that the many suppressed people, however much has been taken from them, could rise up and overthrow their leader, purely with the sheer numbers that they possess. To stick with the theme of the Russian Revolution, a brilliant example of this is when two hundred thousand protesters lined the streets in 1905 to demand the Russian monarchy be overthrown. This was evidently successful, and they got what they wished for. Again, this goes to show that even a totalitarian leader cannot have complete power over their people. When everything has been taken from them, they only become angry and it is only a matter of time before they rise up.

Of course, it could be possible to argue that, if only your material possessions are taken away, you may be equally free (without having to lose everything). In today’s world where everything is about what people think of you, and whether you have the latest technology, a very materialistic, double-sided world, to be free of all this baggage and worries could be very peaceful. So much of today’s world is spent worrying about what strangers think of you, that it would be very freeing to be stripped of everything you had. In a strange sense, it would be like starting life again. You would build from the ground up, make new relationships, learn from your past mistakes and have a fresh start. And by not stripping everything from a person, only material wealth, you do not drive them down the path of nihilism and despair, leaving them invested in a fresh start and therefore future hopes, meaning they remain possible to control.

In conclusion, taking absolutely everything from a person only results in one of three things: they rise up against you, they die a martyr and spread the message you tried to contain or they become a powerful enemy. Leaving them with some hope in the future, however, means they could continue to be controlled. This is why I believe that this statement is entirely true and you should only limit what you take from someone so that they still have hope.

Is Nanotech the Future? Amelia

R-B, Year 10

Imagine this. Buildings, roads and bridges that intuitively repair cracks. Technology that can instantly detect and repair diseases and cell damage in your body. The ability to shape existence as we know it in the palm of our hands.

Nanotechnology. A concept so surreal that, for 60.7% of people, it is simply a work of fiction. However, for others it is a reality. Nanotech is paving the way for more advanced and innovative uses of the materials we already have, changing the way we view science as we know it.

But what is nanotechnology? And why is it so groundbreaking?

Well, a nanometre is one-billionth of a metre, smaller than the wavelength of visible light. Think of it like this – if a metre is the earth, a nanometre would be about the size of a marble. When materials are reduced to this size, classic principles of physics no longer fully explain how things work. For example, when the size of a material becomes so small that the movement of electrons becomes restricted, it means that the electrons can only exist as specific energy levels, which can result in the properties of the material changing – it could become magnetic or luminescent.

As well as this, at the nanoscale, a tiny change in size leads to a dramatic change in surface area relative to the volume. This means a much larger proportion of atoms are on the surface. This greatly enhances the material’s properties and leads to significantly faster chemical reactions. Nanotechnology manipulates matter at the atomic and molecular level to create new materials and devices with these unique properties. This could revolutionise consumer products, medicine, environmental issues and electronics.

At Amazon’s Re:Mars conference in 2019, Robert Downey Jr, the founder of the Footprint Coalition and famous face of fictional character ‘Iron Man’ said that “Between robotics and nanotechnology, we could clean up the planet significantly, if not totally, in 10 years.” Let’s take that in for a moment.

Human activities like burning fuel for cooking and heating have contributed to pollution for centuries.The Industrial Revolution significantly accelerated the rate of pollution, with the widespread use of coal-powered factories leading to a dramatic increase in emissions. What Downey Jr is saying is that with nanotechnology, 2400 years of pollution could be reversed – in just 10 years?! How is this possible?

What Downey Jr is referring to here is nanotechnology’s incredible potential in water purification and air pollution control. Nanomaterials can make filters with very small holes that can trap bacteria and viruses, some even acting as catalysts to break down harmful pollutants or kill the germs in water. Nanosensors can even detect miniscule amounts of pollutants in the air, allowing for better monitoring and faster responses to pollution events. This could drastically reduce the impact we have on our planet – possibly reversing the damage we’ve already caused. Isn’t it time we make the right decision to protect our planet?

Nanotechnology is also paving the way in electronics, with quantum computers and flexible, wearable devices becoming “the next big thing” in technology. Nanomaterials are very conductive, which means that computers will have quicker processing speeds and reduced power consumption, so much more efficient tech can be created. The potential to create transistors and other electronic components at the nanoscale will lead to more powerful and energyefficient devices, as more components can be stored in the same chip. Nanocapsules are tiny containers filled with healing agents which rupture upon damage, releasing their contents to repair damage or wear to devices and materials. This has revolutionised manufacturing as we know it, and sparks ideas of even greater uses of nanotechnology.

A whole spectrum of speculation arises when we think about the possibilities nanotechnology opens for engineering and electricity. Certainly, it brings to mind the extreme power and self-healing capabilities of Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, which in Infinity War is revealed to be composed of nanomaterials that repair themselves and have energy sources integrated directly into their structure. While this level of nanotechnology is far beyond our current capabilities, the concepts and basis of his designs can be seen in our lives now. Although we haven’t reached the stage of working with bots at 0.1 to 10 micrometres (which would enable the creation of something this advanced), scientists say that this vision of the future is possibly only mere decades away – considering it was only 30 years ago that smartphones were introduced.

As American philanthropist and businessman Bernard Marcus once said“Nanotechnology in medicine is going to have a major impact on the survival of the human race”. This is becoming increasingly evident as nanotech develops and we begin to see breakthroughs in medicine that are saving countless lives. Targeted drug delivery systems use nanoparticles to improve efficacy and to reduce side effects, and nanosensors are used for early disease detection and personalised medicine. Several diseases have already been detected using nanosensors, such as lung cancer, influenza, and HIV. This radically improves the efficiency of healing patients, as some diseases can be sensed even before symptoms appear. Nanomaterials are also used for cancer therapy, gene therapy, and tissue engineering. They can create scaffolds and promote tissue regeneration which can help with the healing of burns and cuts. Who wouldn’t want to speed up the healing process? These innovative ways in which nanotechnology is being used in healthcare and medicine are drastically improving patients’ outcomes, growing a true sense of hope and opportunity to really make a difference to those in need.

On the other hand, nanotechnology also comes with its own risks. Nanoparticles’ small size allows them to penetrate barriers in the body, bringing toxicity into the bloodstream, potentially causing DNA damage, inflammation and oxidative stress. Therefore, careful handling and regulation are essential to minimise risks associated with their production, use and disposal.

Due to their small size, nanosensors can be embedded in everyday objects, collecting personal data without user knowledge. These can also be susceptible to cyberattacks, which could leak very detailed and personal information to unauthorised users. As nanotechnology is still a novelty, many regulations and security standards are not consistent, creating potential loopholes for misuse.

However, it is clear that the amazing potential to revolutionise medicine, transform materials, and create sustainable energy solutions outweighs the remaining hurdles. Nanotechnology is changing our ideas, developing our society and saving lives. If nanotech is capable of all these incredible, groundbreaking concepts now, what is stopping us from going even bigger –tackling all the major problems we face today? I believe that nanotechnology really can make a difference, improve our livelihoods and revolutionise all aspects of our lives.

So no, nanotechnology is not the future – it’s the present.

Philosophy Alex Y, Year 11

Absolute power refers to a situation where one individual holds complete unrestricted authority inside their institution with the ability to do whatever they please inside their institution without enforceable accountability or the risk of being effectively punished for their wrongdoings. Corruption refers to a situation where one deliberately goes against moral or ethical principles in pursuit of personal gain, often resulting in their moral decay. As Lord Acton famously proposed, ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’, which suggests that moral decay is inevitable once reaching power. However, some argue that, although there have been many examples in history where this has been true, there are also key individuals who have resisted the temptation to be corrupted by their power, suggesting that corruption is not inevitable. In this essay, I will explore examples for both sides presented to us by history. I believe that although the majority of those in power have a degree of corruption, it is also not impossible to resist the temptation.

Throughout history, there have been many instances of corruption from dictators, but today I’m going to focus on Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union from 1924 to 1953. Initially, Stalin was an early communist, joining the Bolshevik party under Lenin and aiming to overthrow the Tsar of Russia and replace the autocracy with a workers’ state. He also advocated for pro-worker policies such as land distribution. However, after Lenin’s death, we see the emergence of a totalitarian state with Stalin at its centre; with it, his focus shifted from the welfare of the people to retaining control. Through the use of the secret police (NKVD) and the Great Purges (1936–1938), Stalin eliminated all perceived threats from his own party, the military and ordinary people, removing any opposition and ensuring no one could challenge or criticize his rule. He did this through show trials, public executions and mass arrests, creating a climate of fear and repression where survival depended on silence.

Another way he removed accountability was through the Gulag system, where dissenters were sent to forced labour camps under harsh conditions, effectively silencing opposition. Additionally, Stalin ensured that he could not be punished through his sole control over the army. Aided by the Purges, he killed many top

military commanders by accusing them of treason; under the 1934 Law on State Crimes, treason was expanded to include any anti-Soviet activities, criticism of Stalin, or alleged conspiracies, allowing for the execution of traitors and their family members as young as 12 years old. By purging competent military leaders, he eliminated the possibility of a Red Army coup. Stalin’s transformation from a revolutionary into a ruthless dictator demonstrates how absolute power enables an environment where corruption is not just likely but inevitable. Without accountability or opposition, Stalin had no restrictions on his actions, allowing his rule to descend into tyranny, repression and brutalitysupporting Acton’s claim that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

However, there are some notable counterexamples, such as José Mujica. Mujica was the president of Uruguay from 2010 to 2015. As president, he had access to the Palacio Legislativo (the presidential palace) and state-funded vehicles, as well as personal luxuries; however, he rejected these and chose to continue living on his farm which he’d bought long before his presidency. This was in line with his belief that political leaders should be of the people, not above them, and should not use their position for personal gain or indulgence. This stands in stark contrast to figures like Saddam Hussein, who used Iraq’s oil wealth to build extravagant palaces, such as Al-Qadisiyyah Palace.

In addition to rejecting unnecessary luxury, Mujica used his power for good. He implemented policies on free education and universal healthcare, which were instrumental in improving the lives and welfare of Uruguay’s population. He recognised that education was key to escaping poverty, achieving social mobility, and boosting the economy. By ensuring education was free, he levelled the playing field for all Uruguayan citizens, including those from lowincome backgrounds. This also helped reduce the influence of drug cartels in the country, as people were more likely to find stable employment and were therefore less likely to turn toward drugs and illegal activities. His universal healthcare policies also demonstrated his commitment to using his power to serve the people. This meant that, regardless of class or income, every citizen had access to free healthcare, reducing the inequality in health outcomes between the rich and the poor. This was especially significant in contrast to countries like the USA, where healthcare is privatised, and the quality of treatment and health outcomes directly depend on one's income.

Finally, in direct contrast to Stalin, whose indifference to his people resulted in millions of deaths such as in the Holodomor famine, Mujica donated 90% of his $12,000 USD per month salary (keeping only $1,200) to social welfare programmes and charities focused on helping the poor and marginalised. Through his selfless actions, it is clear that, although he held the highest office in Uruguay, the power did not compromise his morals. This directly disproves Lord Acton’s statement that power inevitably leads to corruption.

To conclude, while historical examples of dictators like Stalin support Lord Acton’s claim that corruption is an inevitable consequence of power (‘absolute power corrupts absolutely’), the case of José Mujica demonstrates that this is not always the case. I believe that although examples of strong moral integrity resisting the temptation of corruption exist, they are rare. History shows that most leaders, to some extent, succumb to the corrupting influence of power –whether on the extreme level of Stalin’s dictatorship or to a lesser degree. This suggests that while power creates an environment where corruption is likely, moral resistance is not impossible.

Milena D, Year 13 (2024)

How Round Can a Circle Be?

Adam F, Year 13

Introduction

Circles are everywhere, from the face of a clock to the wheel of a car or even a crosssection of the sun but are these objects or any objects really circular? In this essay, by exploring the mathematical topic of perfect circles, I will explain what it means to be round and how this can be quantified, how to define a perfect circle and, if perfect circles don’t exist, does it really matter?

Are Circles Round?

Misconceptions of being round and roundness

The roundness of a shape and whether it is round are two properties which sound synonymous which each other but mathematically this is not the case. Whether an object is round or not round is binary (true or false), whereas an object’s roundness is a measure of its closeness to a perfect circle, that being a circle consisting of an infinite number of points equidistant from a given point.

So, what is roundness?

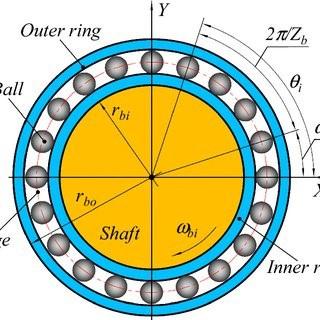

Roundness is commonly measured in engineering to ensure the correct function of parts, which utilise components with circular cross sections. For example, a rotational bearing whose components are not accurately round will be noisy and much more likely to fail prematurely.

The exact definition of roundness, R(X), of a reasonable shape, X, is the ratio of the radius of the inside fitting circle (the largest circle that can fit inside a shape) to the radius of the outside fitting circle (the smallest circle that can fit outside the shape).

R (X) =

Inside fitting circle radius

Outside fitting circle radius

Therefore, using Pythagoras’ theorem, a square of side length 2 would have a roundness of approximately 0.7.

What makes a circle round?

Since primary school, we have been taught that a circle is the only round shape, the only shape with a roundness of 1, and when asked to define what makes it round many may say that it is a shape with a constant width or more simplistically that it is the only shape which can easily roll.

This definition can be further developed into a shape which has a constant width and can freely rotate while maintaining the same maximum displacement from the surface it is rotating on.

However, this definition is not exclusive to circles and there are in fact a whole class of shapes which have these characteristics and therefore could be classified as round.

Reuleux polygons

Reuleaux polygons are curves of constant width made up of an odd number of circular arcs of constant radius. One example of these shapes is the Reuleaux triangle, formed from an equilateral triangle, by drawing circular arcs between each point.

But what differentiates this and other similar shapes from a circle?

Well, in a circle, the distance from the centre to the circumference, the radius, is always constant. Reuleaux polygons may have circular arcs of constant radius but the distance from the centre of the shape to the perimeter does fluctuate. Therefore, for a shape to be round, and subsequently a circle, it must have not just constant width but a constant radius as well.

The Fractal Circle

What is a fractal?

So now it is established that a circle is in fact theoretically round, what do I mean by the question “How round can a circle be?”

This brings us to the topic of fractals.

“A fractal is a curve, surface or higher dimensional geometrical figure which has the property of maintaining its characteristic structure under magnification, with more of the same sort of complexity being revealed.”

In simpler terms a fractal is any shape or structure which consists of similar complexity the closer you look at it.

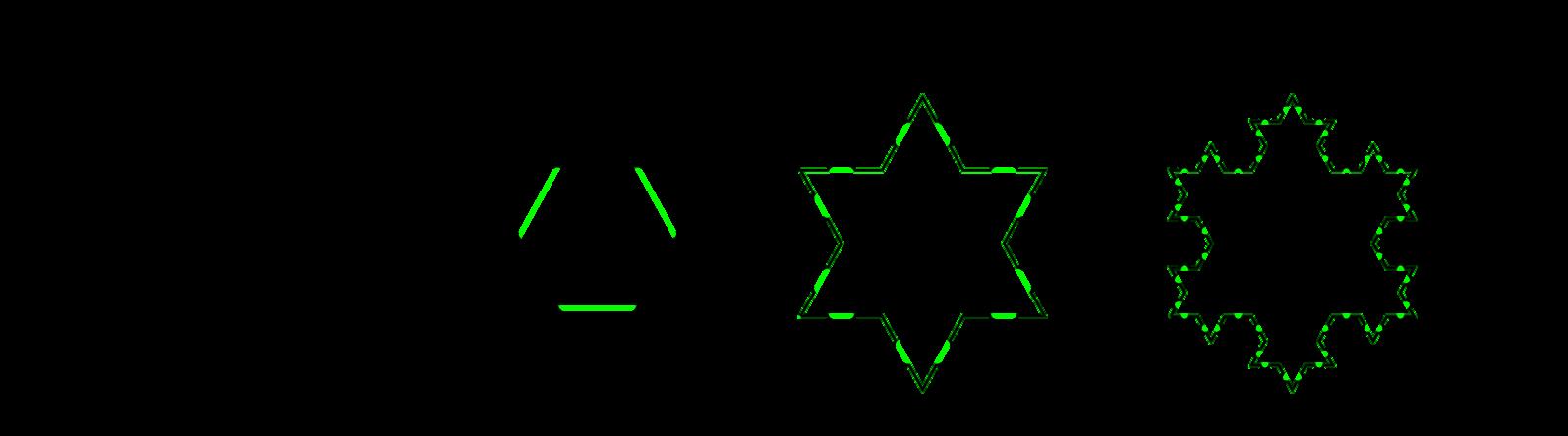

This can be seen through Helge von Koch’s snowflake curve.

Koch started with a single equilateral triangle. He then replaced each line section of the triangle with one with an equilateral triangle shaped bump on its middle third. He then repeated this process again and again, which if the limit was tended to infinity would result in an infinitely detailed snowflake-like curve.

Is a circle a fractal?

It can then be considered if a circle also follows this type of pattern and is in fact a fractal. The definition of a circle states that each point on a circle is the same distance from a given point. Therefore, no matter the minute distance along the circumference, the width of the circle should still remain the same, causing a circle to consist of infinitely small straight lines.

This can be represented by starting with a square, then removing the end thirds of each of the sides and connecting the remaining lines together, forming an octagon with a roundness of 0.92.

This process can then be repeated again, forming a hexadecagon with a roundness of 0.98.

If the limit was tended towards infinity, roundness would tend towards 1, and would eventually result in a polygon consisting of an infinite number of infinitely small sides with an angle of approximately 180 degrees between each side. In other words, a curve with a constant radius or a perfect circle with a roundness of 1.

The Perfect(ish) Circle

Now that it is established that the perfect circle would consist of an infinite number of infinitely small sides with an angle of approximately 180 degrees between them, is there any possibility that such a circle could be created or found?

Well yes and no…

Perfect circles are largely theoretical. No matter how small the individual unit used to form the circle is in real life, whether it’s molecules, atoms, or even quarks, there will still be minuscule discrepancies in the shape’s radius preventing it from being a perfect circle.

Paradoxically, just because we haven’t found a perfect circle, it doesn’t mean that they can’t exist under the right conditions, whether this is extreme pressure or in a vacuum an infinite distance from any matter. This causes a paradox to form, as a perfect circle can only be proved to exist if one is discovered.

"How do you know something in nature is a perfect circle? You might know if you found one, but if you haven't found one, you haven't proved that they don't exist." — David Kinderlehrer.

Perfect(ish) Circles in the universe

Now that it’s been established that perfect circles are largely theoretical, even though their existence cannot be disproved, how circular are the objects that we commonly regard as circles?

One of the most commonly referenced “circular” objects is the sun, but how round actually is its cross section? Gravitational forces pull matter towards the centre of mass, causing most large objects in the universe to appear spherical. However, due to the sun's rotation, it has an equatorial bulge of ten kilometres compared to its polar diameter, which directly impacts the sun’s radius, affecting its roundness.

R (Sun) = 696000 km 696005 km

0.999993... =

But as you can see, although the sun’s not completely round and therefore cannot be called completely circular, it does come pretty close.

Does Roundness Matter?

Despite this seemingly momentous and consequential fact that the existence of the perfect circle is uncertain, the possibly fictional nature of perfect circles doesn’t really matter.

It comes down to the human perception of the world. We simply don’t live life to a high enough resolution to notice these minuscule discrepancies in everyday objects. 1.3 million Earths could fit inside the sun, yet it just takes up a small fraction of the sky, making its minor discrepancies in radius unnoticeable to the human eye. Even on a much smaller scale we can still not detect minor discrepancies in radius. For example, a circle displayed on any tablet or computer is just a combination of lit-up pixels which are small enough to cause a combination of horizontal and vertical lines to appear as a smooth curve.

For this reason, our treatment of everyday circles as perfect circles does not matter. The inconsistencies in radius are so insignificant that they have no perceived effect and sometimes they in fact work in our favour, such as providing greater friction between tyres and the road, helping to prevent cars from slipping and allowing for greater acceleration.

I hope that you have found my essay on one of my favourite mathematical topics, perfect circles, informative and maybe one day they’ll be discovered to be more than just theoretical.

Ava C, Year 13

Forgotten Friday

Olivia C, Year 13

PC RICHARD’S NOTES ON THE CASSIE LOKIN MURDER CASE:

December 20th, 2024: Interrogation between PC Richards and Jack Packham after his multiple murder attempts and murder of Cassie Lokin. Interrogation took place 2 weeks before his conviction and 3 weeks before his relocation to HM Prison Belmarsh.

Interviewee is eager to talk with me, but it seems as though he lacks a sense of gravity. He is distracted; his eyes dart around the room as if he might just find someone there, right behind him.

Q: At any point, did you feel remorse for your actions?

A: Why are these walls so grey? Did you decide that? It’s so dark in here.

Q: Are you able to provide a response to the question?

A: Umm… no, I didn’t feel any.

Q: Hmm, okay, so when did you first start thinking of Cassie again after she left you?

A: … I – I – didn’t stop thinking.

Q: What do you –

A: She wouldn’t leave me alone.

Q: What do you mean by that?

A: You know, she’s always with me… She tells me the right things to do because she always knows what to do and how to execute it. Don’t you have someone like that?

Q: She’s in your head?

A: If that’s what you want to call it, then yeah. But you haven’t experienced it. She’s a part of me.

Q: And is she still a full part of you, now she’s dead?

(Interviewee is suddenly fazed. His dilated pupils finally settle, boring into me, his eyebrows twitch and the room sits in silence.)

He wasn’t stupid, he knew she was dead, when you look at it plainly, but she was definitely still alive for him. Was she a part of him? Yes, he was sure of it, assumed she always was and never doubted that fact. She was painfully beautiful, irritatingly smart and frustratingly perfect in his eyes. His mind searched back to when he first saw her: a warm May evening when she was leaving the old cinema with two of her friends, wearing Levi’s jeans and her hair in a loose French plait. She was an angel, and he – the anti-Christ. His bare feet rooted to the ground when he spotted her, the black concrete beneath him burning the soles of his feet. He saved a mental image of her naive beauty tightly in his mind. She was soon out of sight, round a corner of a contrastingly ugly building, which only made his temporary fixation grow worse. An old Mercedes sounded its horn behind him, and he was forced back into reality, dragging his fixed, dirt-stained, pulsing feet out of the road. Without looking the car’s way once, he held his third finger up, whilst his eyes scrambled back to where he had lost sight of her; he darted to where she was standing, laughing with her friends, just thirty seconds ago. He would miss his appointment with his mother if he pursued this captivation, but he could afford to lose that relationship again if it meant he might have one with Cassie. Cassie Lokin was her full name; she had just graduated from high school that day she walked out of the cinema. He was just about to turn twenty-seven. He was jobless and losing the contract on his flat, but that didn’t faze him now that she was an option.

May 7th, 2024: Call comes in from teenager, Cassie Lokin, of the Islington area, with reports of a “creepy, messy” man who followed her for about half an hour. No action taken unless repetition of the event occurs.

Note: The past 8 years reveal multiple reports that have been recorded relating to a ‘Jack Packham’ from Islington. He has displayed stalking habits and currently holds 3 criminal offences. We believe Packham to be the “creepy” man reported. Islington Police continue to monitor his activity.

HQ: So when did you first speak to her?

A: I suppose it was August? I’d followed her around a while before that and I found her address just a week before. I had a plan for when she would first see me but it didn’t go how I wanted.

Q: Could you go into more detail about this?

A: …Well, when I got there, her father was home. He was meant to be out at the pub that night, but I suppose he was running late that day. I had to wait thirtytwo minutes for him to finally leave. He even saw me sitting in my rusty car down the road but took no notice of me – the ungrateful man. I made sure to wait a few minutes to be certain he was gone before I walked up to his blue, paint-chipped door. I had to prepare what to say, I was so nervous.

Q: Do you get nervous often?

A: Never. She was my first reason to be nervous. Anyway, my plan was all ruined when she opened the door and spoke first. She obviously had no interest in me.

Q: How did that first meeting end?

A: Cassie shut the door and told me to go or she’d call her father.

Q: And you left, like she said?

A: Eventually, yes. I’d do anything she asks me to. ***

August 12th, 2024: Two reports of a homeless man lingering on Primrose Street, including one from Paul Lokin, who has worked closely with the police on previous cases.

August 28th, 2024: Another call comes in from Paul Lokin, concerned about his daughter interacting with “disrespectful” men. ***

Q: So… how did your relationship start?

A: I matched with her online after making an account for her on Facebook. It was a last resort, but I invited her out to that fancy Italian down the road. And she actually came, to my surprise.

Q: She wasn’t surprised to see who you were?

A: Yes, she tried to leave at first, but I convinced her to stay. She didn’t speak much the whole night, and barely touched the meal I had ordered for her. I was furious.

Q: Why?

A: The evening was so messy. It wasn’t what I had planned for us. I had imagined her laughing and making jokes with me and saying that I was more than she had expected. She was pretending to be this innocent angel still, but I just wanted her to open up and tell me the things that no one else knew. ***

December 18th, 2024: Cassie Lokin murdered by Jack Packham within her home on Primrose Street. Packham found intoxicated, just outside the Lokins’ street, breaking down and yelping in pain. No wounds found. Neighbours of the Lokins attended to him before the police arrived. Moments prior to Paul Lokin finding his daughter, Cassie, deceased in their downstairs bathroom, Packham was recognised and the officers on call instantly escorted him away from the scene. ***

Packham couldn’t understand it; Cassie was really gone, but the sounds of her pleas remained to torture him. He had intended to destroy her, to do whatever it took to never see her insufferable face again. The plan was to drive away from the house the moment the action was completed. Yet, he found himself on the floor, mud under his fingernails, grass in his hair, his head lolling over the pavement as cars splashed past him. The screams haunted him; tears rolled from his dark eyes onto the cement of the road underneath him. And just for a moment, an onlooker might have imagined he felt remorse.

“You’re always waiting for that

burst of gunfire”: coping with life after service

Emily C, Year 13

“You are standing in line at Starbucks; the person in front of you is complaining that the barista has got their order wrong. ”This is a latte, not a flat white.” “Why is there no cinnamon powder?” “I asked for this extra hot.” You watch this unfold, detached, disbelieving. A week ago, you were in Afghanistan, trying to keep your platoon alive.

The memories and feelings you experience, says Sergeant George McCafferty (who led the 12 Platoon Delta Company, 5 SCOTS, through two tours in Afghanistan), will never be forgotten: “You come back… it is like nothing [has] happened. Your head is still back in Afghanistan, and when you look around everybody is just getting on with their normal daily life.”

Since the Act of Union in 1707, Britain has fought in over 120 wars, across 170 countries. High levels of British military engagement around the world mean that there are shockingly high numbers of former military personnel returning to civilian life. Since 2000, over 4.3 million personnel in the Armed Forces have fought for the UK. These men and women are now integrated into ‘normal life’, but their lives will never be the same again. They faced conflict that most people will never experience, understand, or see; they went days without sleep to do their duty, risking their lives for their countries. War changes you: “Every time you go out, your senses are heightened, your awareness is heightened, you’re always waiting for that burst of gunfire that’s going to trigger the next thing you are about to do.” We must understand that it is impossible to come back the same person as when you left, especially when the level of communication with those back at home was unstable and unreliable.

McCafferty explained how you are “living on a permanent adrenaline rush”, with the motto “kill or be killed.” They were doing something the majority of us could never comprehend. They made the best of the situation they were in and therefore deserve to feel safe on their return home.

Every year, people across the UK are encouraged to remember the sacrifices of war, but for those who experienced these events, remembering is not the problem –

forgetting is. Individuals’ lives are taken, not only by the conflict, but by the aftermath of these unforgettable experiences. There are struggles we don’t see, everyday things, the things most do without thinking – but to some, these things are daily struggles, new battles to fight.

The disorientating effect of returning to civilian life can place a strain on domestic lives. Of the 130,000 people in the UK who serve in the Army Regular and Reserve, 37.8% are married; 59% of these people experience divorce.* This is in comparison to 42% of marriages that end in divorce in the UK. When the communication is so weak, there is no doubt that relationships will be too. Finding jobs is another story and can be a lot harder depending on what job you do in the military. Many infantry soldiers struggle to find jobs; they join the army at a young age and consequently have limited skills (and in some cases a lack of education) that can be carried forward into the civilian sector. In 2014, over 120,000 veterans were unemployed and were 11% less likely to be in full time employment than the general population.

Support is key for these people in order to be fully functioning in society after combat. It is important that when these men and women come back home, they are supported in the right way. If they are not, the effects can be tragic; over 5000 deaths in 2021 were the result of suicide. 253 of these were veterans (accounting for 5% of all suicides in England and Wales). This is a staggering number that should and can be reduced. Additionally, over 2000 families with someone who served in the Armed Forces were classed as homeless last year, and this is a number rapidly rising year on year. McCafferty says that “if you have a good support network behind you –people who care about you, people who love you – it’s a lot easier to stave off the effects of PTSD.” This suggests that creating connections with those you love is the difference between springing back or sinking when settling back into ‘regular’ life.

In 2023, former Minister of State for Veterans’ Affairs Johnny Mercer said in a speech to the Annual Conference of the Veterans’ Trauma Network that “a large part of this work [that needs to be done] will be increasing awareness” as well as “standardising some of the excellent services they receive right across the country, removing the kind of postcode lottery of opportunities.” It is important that support is easy to access wherever, and whoever, you are; everyone has a role to play in achieving this national ethos and eliminating veteran suffering across the UK.

Even having witnessed death first-hand, ordinary life has to go on. Jobs have to be found. Work has to be done. Relationships have to be re-established and maintained. Coffee has to be bought.

*Statistics taken from Defence news and Gov.uk.

Kitty K, Year 13

Managing Editor: Dr E. Wilson

Editor: Dr J. Hayes

With thanks to: Mrs N. Rayner and Mr I. Rayner

Special thanks to: The Ashford School Marketing Team

A.