Ethical Dimensions of Architecture: Design Aesthetics

Social Criticism

STUDENT:

DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)

ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828)

ARCH_7042 DESIGNING RESEARCH 2024

PROF. SAMER AKKACH

STUDENT:

DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)

ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828)

ARCH_7042 DESIGNING RESEARCH 2024

PROF. SAMER AKKACH

This essay argues that within the architecture profession is a conflict that exists between ethical and aesthetic design, which reshapes human self-perception and behaviour. This draws similarities to Colomina and Wigley statement that the real ambition of design is to redesign the human. Our argument will discuss the sources below in the literature review, relating to architectural ethics, focussing on ethical design being the medium for preserving traditional culture and expressing human emotion, the ethical tension of balancing the reality of design and the architect’s morality, and finally, social criticism of the ethical implications of architecture’s perception as ‘high art’.

Throughout history design has always presented itself as serving humans; in essence is intrinsically linked with the evolution of human society. According to the book by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, `Are We Humans? Notes on a Archaeology of Design’, the real ambition of design is to redesign the human. The relevance of this statement cannot be underestimated as we live in a time where every minute detail is designed by humans.

In this essay we will explore the multifaceted ethical dimensions of social criticism within architectural design, examining various criticisms of architecture centred around the intersection between aesthetics and ethics. Aiming to clarify the relationship connecting the ethical dimensions of social criticism with the impact of aesthetic design. To do this, we will give a brief review the sources to be used in our discussion.

Alberto Pérez-Gómez’ book, ‘II Philia, Compassion, and the Ethical Dimension of Architecture: Program’, will focus on the topic of ‘Ethical dimensions of Architecture’. His book emphasises architecture’s ethical responsibilities being beyond architectural production, architecture’s role, therefore, is to address fundamental human issues through poetic and critical means.

‘Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas’, edited by Nicholas Ray, provides background to how morality and traditional understandings of ethics in architecture are interpreted in relation to aesthetics and functionality.

‘Out of Site: A Social Criticism on Architecture’ is a collection of essays edited by Diane Ghirardo, examining a diverse range of social criticisms within the architecture profession. Ghirado’s introduction to the book details the implications of professional architects’ self-aggrandising nature. Within this compilation, Margaret Crawford’s essay, ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’, focuses on the architecture profession being at the ‘mercy’ of the power, corporate entities and governments have over society.

‘Ornamentation and Crime’, written by Adolf Loos is a critique on 19th century ethical dilemmas, presenting his belief that European architecture is ‘primitive’ and lacking progress. He suggests that this regression can be solved by minimising ornamentation within architecture.

Janet Stewart’s publication, ‘Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loos’s Cultural Criticism’, examines Adolf Loos’ formation as an architect, interior designer, and artist, that lived through Vienna’s Secession. She offers analysis about Adolf Loos’ architectural ideology and the contradictory nature of his antiquated views.

‘The New Architecture and the Bauhaus’, written by Walter Gropius in 1935, focuses upon his core beliefs of architectural design’s function within society. He attempts to address several ethical dimensions within the architectural profession, many of which are still relevant today. He suggests practical solutions to address the ethical concerns within design and construction.

Architecture’s ethical dimensions have implications for aesthetics, design, and social criticism. It services to individuals and communities while upholding ethical principles, which is a central component of architecture’s context. Architects’ practice and discourse are shaped by their ethical dimensions, which play an extremely important role.

According to Alberto Pérez-Gómez on his book ‘Built up on love’, he proposes that the responsibility of architectural design extends beyond production; it cannot be deregulated through legislation alone. ‘It is like literature and film; architecture finds its ethical praxis in its poetic and critical ability to address the questions that truly matter for our humanity in culturally specific terms.’ Architectural design will ultimately play a crucial role in preserving traditional cultures and valuing those which have been preserved to the best of our ability. As Nicholas Ray discusses in his book, ‘Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas’, there is a philosophical relationship between architecture and the ethical judgement of its position. ‘Architectural value may thus be determined by reference to functionality: if a building is good for people and for their purposes, then it is ‘moral’.’

Nicholas Ray talks about how this kind of modernism does not work at all and that this is a philosophical issue at its core. A common misconception amongst people is that functional, and emotional assessments are secondary in nature, people’s standards for building ethics are based on their desires. A Devon & Van de Poel quote from, ‘Design ethics: The social ethics paradigm,’ says, ‘design is quintessentially an ethical process’ There are various ethical dimensions of architecture that influence how it is practised and how it affects society. In Alberto Pérez-Gómez’s discusses the ethical dimension of architecture, emphasising concepts such as feeling architects and highlights the difficulty of balancing design creativity with social ethical responsibility.

In ‘Are We Human?’, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley state that ‘design discourse acts as if human needs and desires unproblematically organise design’. On this basis, humans design buildings according to their needs and desires without unproblematically organising it, ignoring the deeper architectural ethical issues and social responsibility underlying the design.

Diane Ghirardo critiques the social status that exists in architecture, highlighting the profession’s inseparable connection to art. Classism has been a continual barrier within the profession, highlighting a range of attitudes among architects ranging from elite, to apathetic, to sympathetic. For designers, architecture is more than just a box. ‘Any hack …can build a dumb box…real architecture contains ideas about society and expresses the cosmology of culture.’ This response emphasises the perception of architecture as ‘High Art’. Many architectural professionals present an elite persona, considering themselves the sole discerner of transcendental thought capable of producing design. This produces two issues, firstly, the primary consumers of ‘High Art’ are of high status both socially and culturally. This means designers will opt for wealthy customers over the poorer masses, resulting in the segregation of lower classes. Secondly, professional architects are experts on all matters, able to dictate the customer’s needs, often clients’ needs are unmet due to a lack of consultation. Conversely, architects who engage clients, encounter barriers implementing ethical values within their designs, these obstacles include insufficient funding, disinterest, and political opposition. Unfortunately, architects willing to address ethical issues within design become disenfranchised and apathetic towards social injustice due to these barriers. David Clarke, a professor at Southern Illinois University, opposes the arguments presented in ‘Out of Site’, claiming the discourse is written by latter-day left-wingers. He criticises the writers’ viewpoints on shared housing for promoting socialism, underlining Margaret Crawford’s dislike for the architecture profession’s ‘homes of the homeless’ design, blaming the profession for homelessness. In response, David Clarke emphasises his preference for Democratic Capitalism, advocating for the right to enter freely into contracts for private property.

Social class is another factor that contributes to relationship between design and aesthetics. This is evident at the turn of the nineteenth century, during the shift from classical to modern architecture, where ‘High Art’ is employed in classical architecture. Adolf Loos, a pioneer Modern Architecture lived through the Vienna Secession where his ideologies and design style formed as a reaction to Art Nouveau. His book, ‘Ornament and Crime’, expresses his distaste for decorative facades in Architecture, believing that ornamentation of facade cheapened the natural beauty of the underlying material, the true feature with aesthetic dominance.

Adolf Loos believed society had matured and evolved where Architecture had not, to him, ‘Art Nouveau’ was unevolved and primitive like the artistry of Papuans’ tattoos. Despite his distaste, Adolf Loos appreciated architecture and fine art but as two distinctly separate professions, where the artisans earn are respected and handsomely compensated. Janet Stewart critiques Adolf Loos’ interpretation of social class. Vienna was a city with welldefined social boundaries separating the Bourgeois from ethnic and Industrialist working classes, Aristocrats in the inner city, middle-class around the Ringstrasse, and lower class on the fringe. Adolf Loos disagreed with this, believing social structure should not be based upon Capitalist class structure but ‘evolve’ to a modern structure of stratified estates giving allegiance to royalty. Modernist pioneer, Walter Gropius shared the Adolf Loos’ principles regarding minimalistic facades, free of ornamentation, however he disagreed with the separation of art and architecture. Walter Gropius established the `Bauhaus’ in the Weimar Republic, at the height of Industrialisation, the ‘Bauhaus’ design school was based on a holistic approach to the architecture profession, specialising in art, craft, and technology, he believed that mechanisation was the key to producing inexpensive prefabricated materials for construction. He thought prefabrication was the most cost-effective solution for social housing, unfortunately this was unviable for large scale residential construction. Instead, prefabrication was used predominantly in commercial construction, as corporate businesses were able to absorb the costs of large construction.Regrettably, the minimalist approach to ornamentation did not deter architecture’s reputation as ‘High Art.’ Walter Gropius remarks, ‘Worst of all modern architecture became fashionable in several countries; with the result that formalistic imitation and snobbery distorted the fundamental truth and simplicity on which the renascence was place.’ For Walter Gropius, there were four reasons for curtailing ornamentation: - prominence of structural function; creating economical solutions; and aesthetics that please the human soul.

Walter Gropius’ ideologies echoed Adolf Loos’ arguments about the lack of progress in architecture, stressing the importance of mechanical production taking place. He believed adopting advanced technologies, consisting of synthetic materials - steel, concrete, and glass, would decrease size, weight, and bulk, and increase functional space. This would effectively decrease construction costs. Another cost-effective solution suggested by Walter Gropius was Standardisation. Construction costs could be decreased by minimising production of unnecessary bespoke materials and non-essentials, limiting the need to hire and train trade specialists. Another cost saving strategy was developing generic prefabricated, readily available, simple to use materials.

Adolf Loos and Walter Gropius’s ideation of ethical design are based primarily on a reaction to social class, particularly the elite. Their response to this is clearly laid out in the foundational principles of Modern Architecture, particularly minimalistic and functional design. We argue there is an ethical tension between balancing the reality of design and the architect’s morality. Diane Ghirardo in her social critique, ‘Out of Site’ argues that classism is one of the causes of social inequality within design, stating that architecture is considered a form of ‘High Art’ for the upper class and the belief that only architects are capable of discerning design requirements. Many ethical implications for design arise from this, firstly, it highlights the egotistical nature within the profession, as architects will promote their ‘High Art’ services to those who can afford it. Secondly, as the architect knows best, they often apply what they think is best to designs without consulting the client about their needs.

Adolf Loos is a prime example of what Ghirardo is describing. One of Loos’ infamous criticisms was the crime of ornamentation within architecture, this was his reaction to the Beaux arts that featured heavily in Vienna’s Secession in the 19th Century. He believed that architecture was made beautiful by the nature of the material itself, not ornamentation. Also, Janet Stewart states that Loos disliked the method in which cities were planned around industrial economy causing segregation of class.

Loos point of view has merit, however Stewart argues that Loos preferred cities to be planned like the old estates, where everyone is equal but loyal subjects of a monarch or master. Stewart also highlights Loos thoughts that artisans of fine art should be paid handsomely. While at the same time denouncing Beaux Arts in architecture, calling it too primitive for a progressive society, likening it to Papuans with tattoos and piercings. On one hand Loos is arguing for social equality, while on the other hand, his true colours are shining through. I would argue that Adolf Loos designs ‘High Art’ and his views not only spark social criticism but have ethical implications for social equality in the profession. Having said this, Loos’ views should be taken in the relevance of the era and not by today’s standards. As Loos was a product of the industrial era, his ideations formed through the influence of Colonialism. When viewed in this manner, Loos intention was to remove socio-economic barriers and bring the poorer classes up to a level playing field.

1: Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) , 204-207.

2: Diane Ghirardo, 1991, ‘Can Architects be socially Responsible?’ in Margaret Crawford (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press),

We also argue that the ethical dimension of architecture must be developed and emphasized, and it must bridge the gap between architects and the public. Architecture, as a discipline deeply intertwined with societies, As emphasized by Alberto Pérez-Gómez, the ethical dimension of architecture transcends mere production processes and carries inherent ethical responsibilities that must be foregrounded in practice. (#reference 1). Therefore, ethical architecture design is not just about space and configuration; it also needs to reflect social values and human conditions.

According to Margaret Crawford’s article, ‘Can Architects be socially responsible?’ Architects, as a profession, have steadily moved away from engagement with any social issues, even those that fall within their realm of professional competence. Such as homelessness, the growing crisis in affordable and appropriate housing. (#reference 2) The ethical dimension of architecture is crucial in bridging the gap between architects and societies, it must ensure that the architecture project does not serve economic or aesthetic purposes but needs to address the needs and rights of society. This gap will undermine the societal role of architects and diminish the impact of architecture as a tool to change societies.

The ethical dimension of architecture should be extended beyond the elite circles; it should be included with the wider public. Who are the end users and often the most affected by architectural decisions. The process of architecture needs democratization and the engagement of the public.

With democratisation, that will ensure that the design outcome will reflect and respond to the needs of those most affected by these projects. Ethical architecture, often challenged by the priority of profit over people, should focus on its ability to contribute positively to society and public life, improve living conditions, and protect the environment.

With discussing ethical dimensions in architecture, The Palm islands is a example to of exploring the intersection of design, aesthetics and social criticism. The project was to redevelop the coastline of Dubai and reshape the luxury and modernization of the design. The Palm Island project has been raising crucial issues of conflict between aesthetic and environmental conservation. The project aimed to boost tourism and expand living space, at the same time it also has impact on marine ecosystems, the construction of the process involved large scale of reclamation and disruption of natural coral reefs. The change will have an impact on the ocean’s natural habitat and the sustainability of marine environment. This project illustrates oversight in environmental planning and design development. With allure of economic values and architectural aesthetics and overshadowed the architecture ethical considerations and environmental

Clarke, David.1992. ‘Out of Site and Out of Bounds Review.’ Progressive Architecture, 73(4), 30 April: 131.

Colomina, Beatriz and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design. Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers

Crawford, Margaret. 1991. ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’ In Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (38-39). Seattle: Bay Press.

Devon, Richard and Ibo Van De Poel. 2004. ‘Design ethics: The social ethics paradigm.’ International Journal of Engineering Education 20(3): 461-469.

Ghirardo, Diane. 1991. ‘Introduction.’ In Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture Seattle: Bay Press.

Gropius, Walter. 1965. The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1st ed. 1935. Translated by P. Morton Shand. London: Faber and Faber.

Loos, Adolf. 1908. ‘Ornament and Crime’ in Joseph Masheck (ed.), Ornament and Crime. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. (253-278). London: Penguin.

Pérez-Gómez, Alberto. 2006. ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture.’ In Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (204-207). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT.

Ray, Nicholas. 2005. ‘Ethics and Aesthetics.’ In Nicholas Ray (ed.), Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas (133-134). London: Routledge.

Stewart, Janet. 2000. Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loo’s Cultural Criticism. London: Routledge.

Fig 1. Archimaps, 2019, ‘Villa Muller, Prague’, Tumblr image drawn by David Ebsary, Adelaide, https://archimaps.tumblr.com/post/182230653482/thevilla-scott-turon, accessed 2 April 2024.

Fig 2. Designculture, 2017, ‘Villa Scott, Turin’, image, Drawn by David Ebsary, Adelaide, www.designculture.it/profile/adolf-loos.html, accessed 2 April 2024.

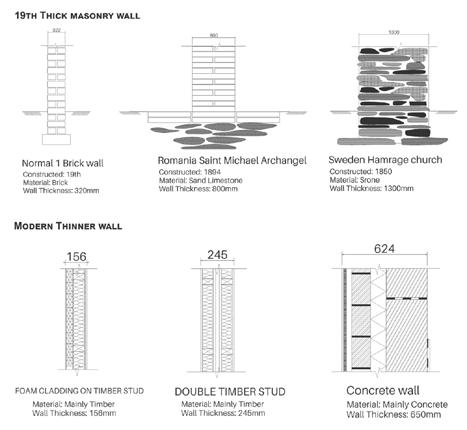

Fig 3. Evolution of Building Elements, n.d., ‘Brick Wall’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://fet.uwe.ac.uk/conweb/house_ages/elements/section2.htm, accessed 5 April 2024. masonry wall and

Research Gate, n.d., ‘Romania Saint Michael’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cross-section-in-theroom-of-the-neo-desert-vernacular-model-house_fig156_247849342

Research Gate, n.d., ‘Sweden Hamrage Church’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://fet.uwe.ac.uk/conweb/house_ages/elements/ section2.htm

Research Gate, n.d., ‘ FOAM CLADDING ON TIMBER STUD’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, http://open-haus.weebly.com/home/the-raincoat

Research Gate, n.d., ‘DOUBLE TIMBER STUD’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://forum.buildhub.org.uk/topic/13558-double-stud-wall-vsicf-party-wall/

Research Gate,n,d ‘Concrete wall’, Image,Dacher,1/2.2021 Detail Roof strcture ‘Feilden Fowles’ ,57