JOURNAL OF WRITTEN AND VISUAL ARTS | VOLUME 2/1

Welcome to the East Window Journal of Written and Visual Arts, volume 2/1.

This issue is a space of resistance, an approach toward seeing, loving, grieving, returning.

Across these pages, you’ll encounter works that confront the enduring brutality of Islamophobia, sexual violence, authoritarianism, and the attempted erasure of indigeneity. These pieces do not merely reflect oppression; they intervene in it. They assert that to speak, to make, to remember, and to love in the face of wanton human abrogation is a radical act. From the reclamation of Two-Spirit identities to the insurgent tenderness of queer love and trans activism, the contributions here imagine a world beyond the structures that seek to silence, control, discipline, or vanish our bodies and stories.

There are works that understand erasure as both a threat and a strategy. What does it mean to disappear in defiance? What does it mean to leave traces deliberately, for someone else to find and carry forward? The queer archive is alive in this issue—not simply as a repository of the past, but as a mechanism for historical intervention—a way to remake what has been taken away and imagine what has never yet been.

This is a journal of rupture and repair. It is a place where love is not apolitical but rather a revolutionary form of care. It is a return to truths that were buried, a future spoken into being, and a refusal to forget. We thank the contributors of this issue (selected from an open call for submissions as well as by invitation) for sharing their truths and their stories within our pages.

Welcome. Let this be a home for the work that will not remain silent.

EAST WINDOW EDITORIAL TEAM, 2025

AMITIS MOTEVALLI is an artist born in Iran. She explores the cultural resistance and survival of people living in poverty, conflict, and war. Through many mediums including sculpture, video, performance, and collaborative public art, her work juxtaposes iconography with iconoclasm, asking questions about violence, domination, occupation, and the path to decolonization while invoking the significance of a secular grassroots struggle. She is equally known for her work in educational justice, working with youth and communities to gain equal access to civil rights, privacy, and pedagogy without profiling. Motevalli is invested in research, collaboration, and the potential of art to expand thought. In the fall of 2014, she was the visionary and overseer of the city-wide initiative called LA/Islam Arts Initiative, which brought together multiple institutions with local organizations, artists, curators, and thinkers to question art historical definitions of Islamic art and regions. For her current project, Motevalli is working internationally with a broad spectrum of transnational Muslims in order to research what defines home, life, and labor in the urgency of survival. She is particularly concerned in collaborating with women, girls, and femme and queer Muslims who come from places of political and religious conflict and collaborating on public art projects. She currently lives and works in Los Angeles, exhibiting art internationally as well as organizing to create an active and resistant cultural discourse through information exchange, either in art, pedagogy, or organizing artists and educators.

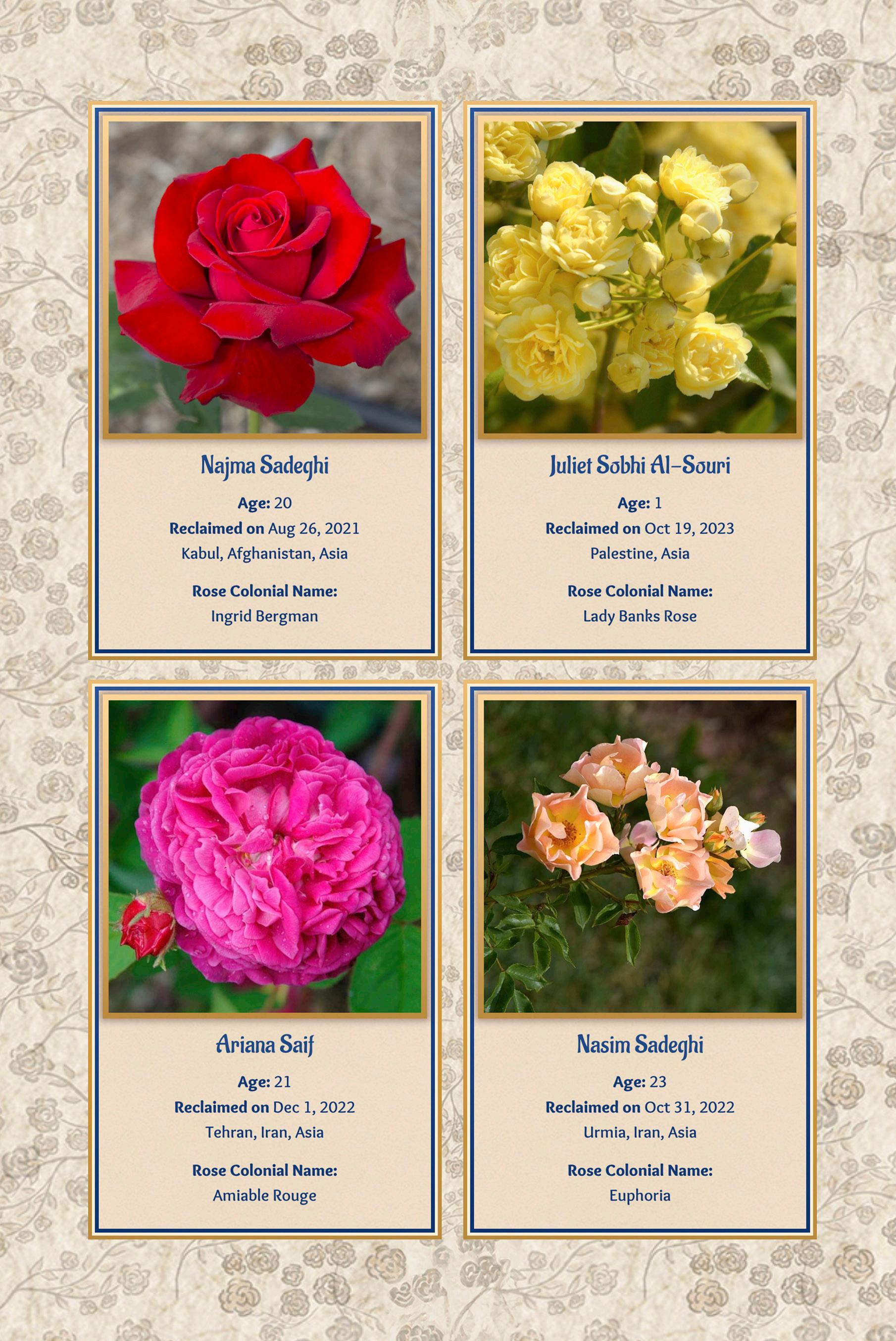

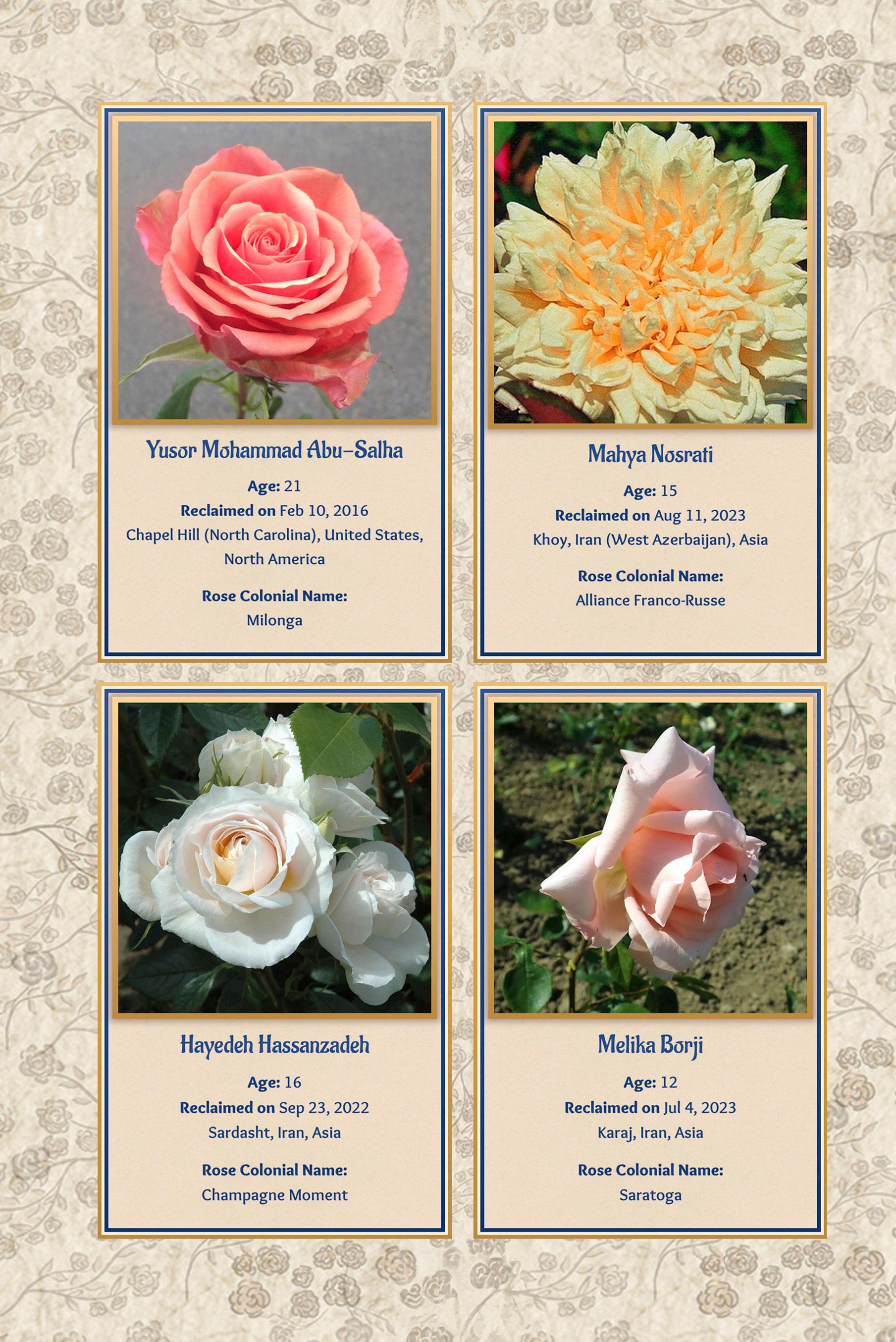

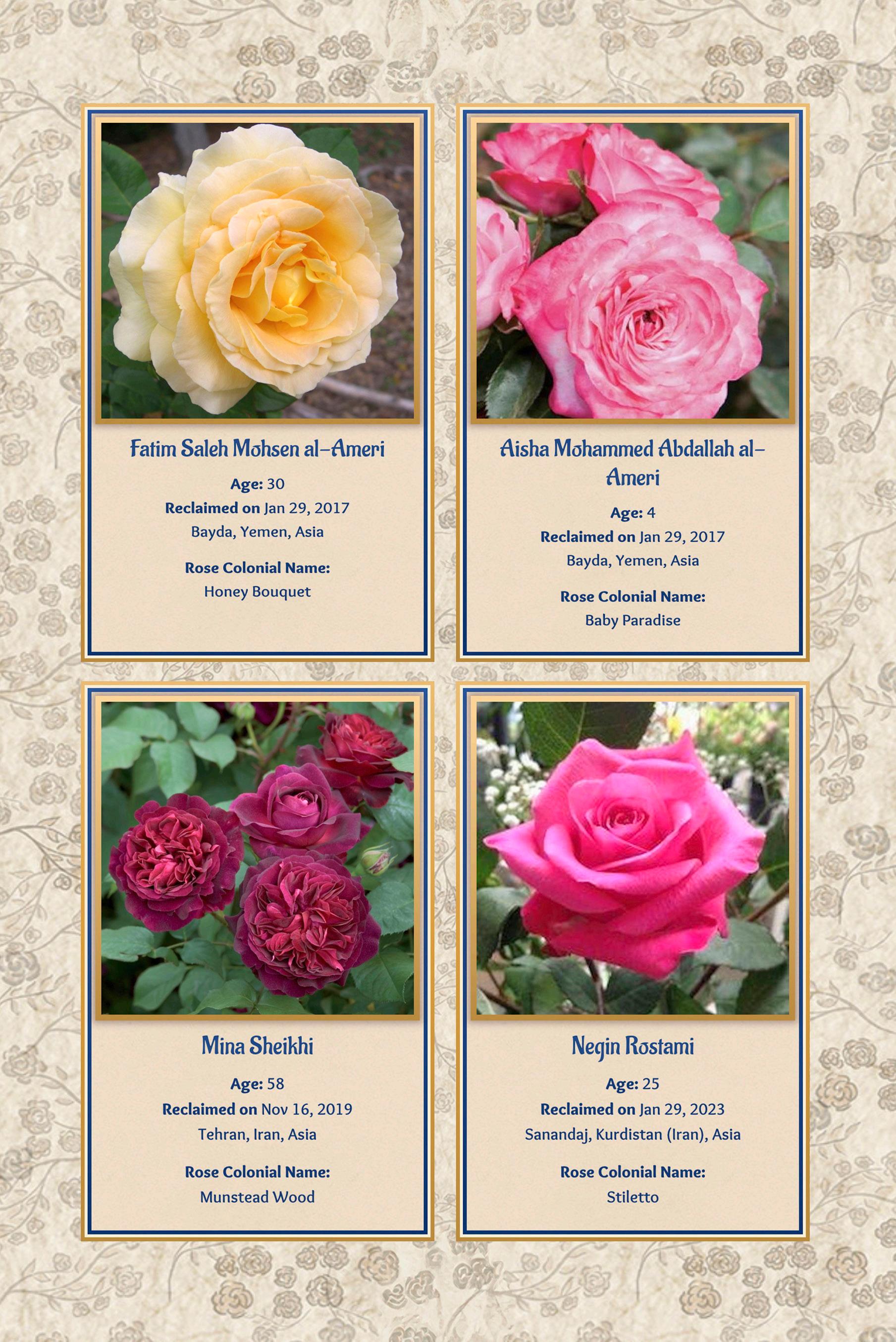

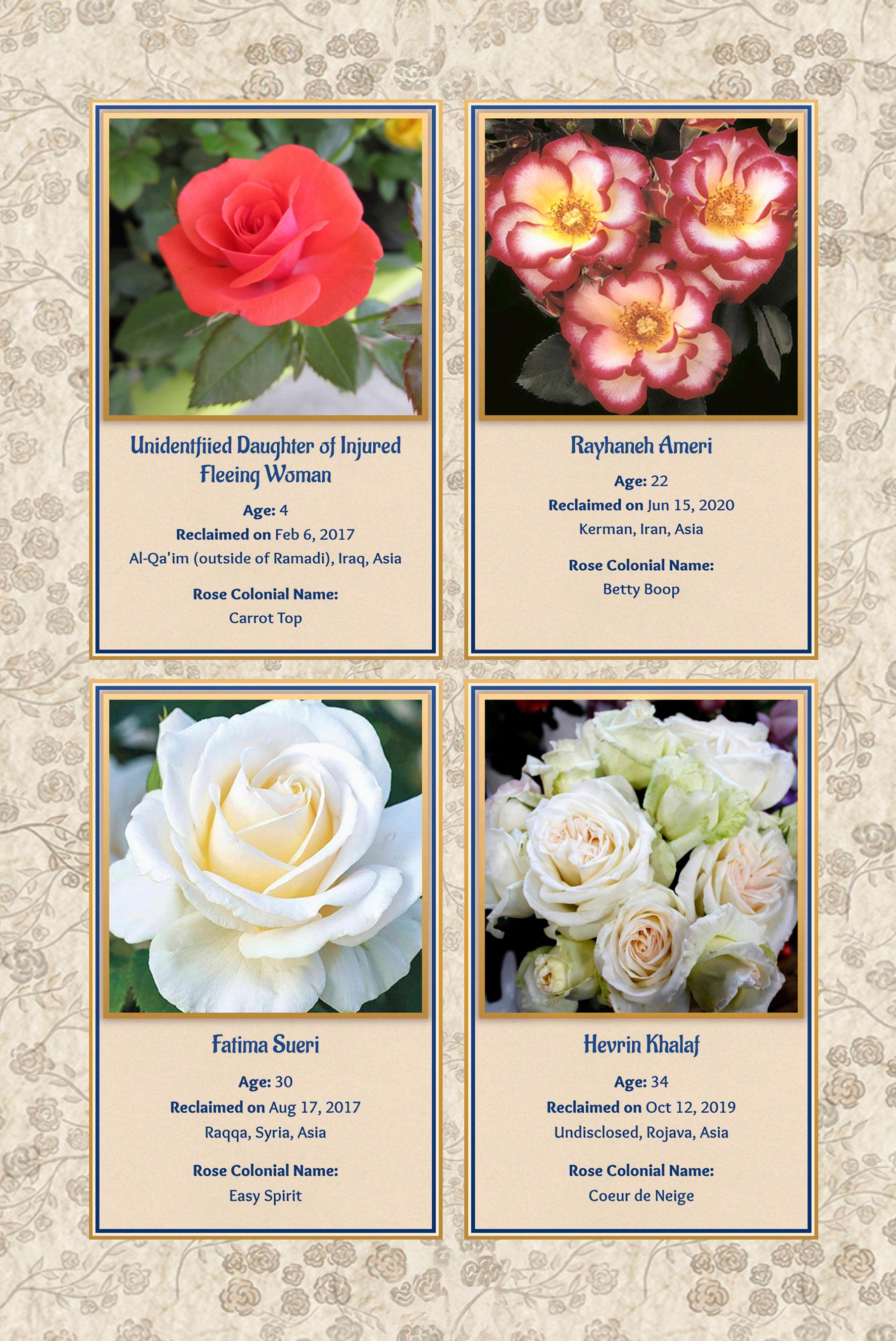

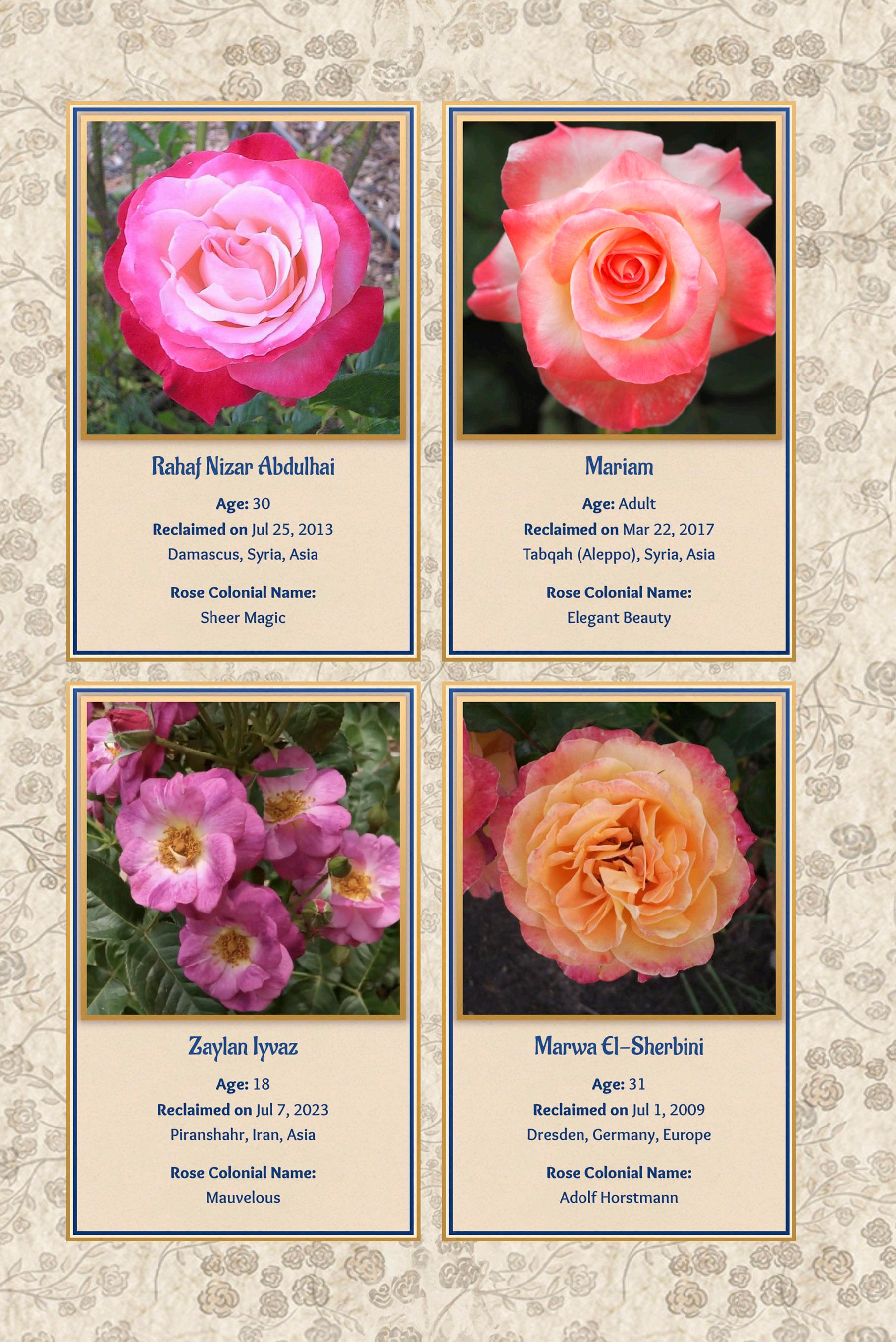

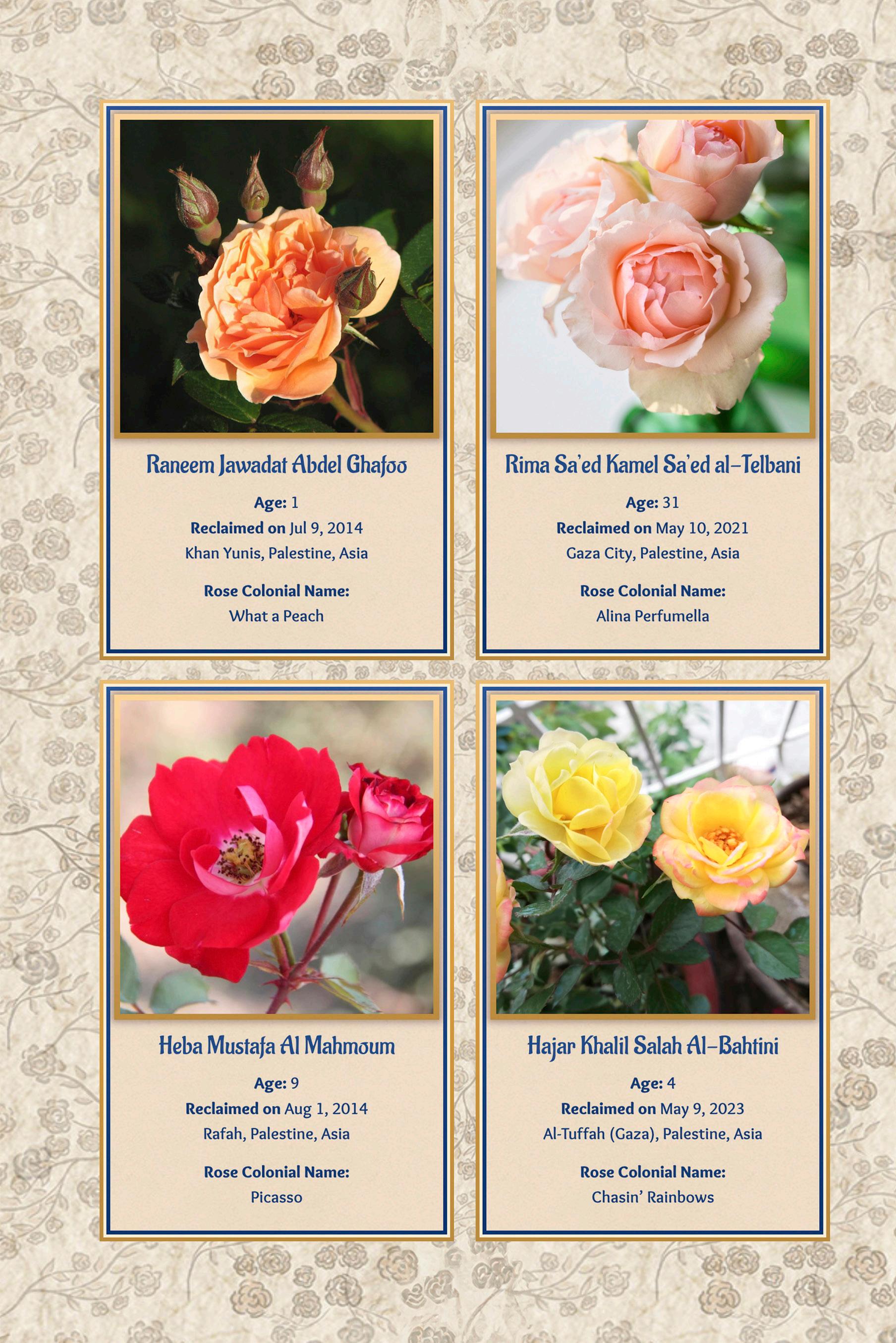

ROSES BY OTHER NAMES

I have long had an interest in the portrayal of individuals originating from South, Central, and West Asia, as well as North and East Africa, particularly within the contexts of the United States and Europe. A significant portion of my early career was dedicated to creating artworks that responded to these external perceptions. However, at a certain juncture, I resolved to produce work that addressed the lived experiences of those individuals whom these perceptions misrepresented.

In 2009, I became acutely aware of the narratives surrounding the events unfolding in Iran. I had the opportunity to travel to Iran to vote and engage in the electoral process, motivated by the hope for substantive change. Following the rigged elections, widespread protests erupted, prompting a government crackdown. The subsequent year, I was invited to hold a solo exhibition commemorating the one-year anniversary of those elections. Drawing upon my extensive experience in organizing and collaborating with revolutionary movements in the United States and my focused research on global revolutionary movements, I established connections with others that had endured similar traumas during electoral processes. I employed a common Iranian aesthetic in my art, taken from Shia street and populist art, to represent the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the Freedom Summer. This culminated in presenting the first-ever Farsi translation of Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech from the 1961 Democratic National Convention on the exhibition’s window. For this piece, viewers outside of the window could watch me write her speech in gold ink, backward so it could be read from the outside.

The following year, I fervently followed various uprisings collectively termed the “Arab Spring.” I closely researched these movements, noting how they were subject to external intervention, co-optation, and ultimately transformed into an automated manifestation of the so-called “War on Terror.” The world collectively watched as well-armed organizations such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS engaged in actions that the US and its allied military forces could not undertake.

In 2012, I was awarded the Danish International Visiting Artist (DIVA) residency to work in an ethnic enclave in Denmark. The neighborhood where I resided, like many others, faced constant aggression from neo-Nazi groups. The residents, who had fled war and poverty, were systematically denied the right to

practice their religion and faced discrimination in educational institutions, often relegated to menial employment. During this time, I observed the direct and opportunistic recruitment efforts by ISIS.

I recruited a Third World feminist perspective to respond to the narratives surrounding the uprisings that were co-opted into automated civil wars. In 2014, I began to follow the case of what was referred to as Europe’s first female suicide bomber, which inspired my Golestān Revisited project, evolving into a comprehensive multimedia endeavor. My focus shifted from responding to engaged occupation and warfare—whether through direct combat, media propaganda, or everyday interactions—to fostering connections within my community and initiating projects centered on reparations.

ABOUT ROSES BY OTHER NAMES

In 2015, I started work on Golestān Revisited, a multi component project cycle which is an act of reparations by renaming roses stolen during the Crusades as a memorial to women, girls, and femmes martyred during the neo-crusades. I use the term martyr here not in a Western context, connoting agency or choice, but in the regional context as victims of war. I was initially sparked by the story of Hasna Aït Boulahcen, who was implicated in the Paris Bataclan nightclub bombing in 2015 and subsequently labeled “Europe’s first female suicide bomber.” I was in the Rose Garden at the Huntington Library when I received an alert suggesting that she may not have been a suicide bomber and might not have been involved in the attacks. The news included an audio recording of Hasna pleading for her life while in an apartment with her cousin and another man who may have been involved in the Bataclan attack. During her interaction with police, gunfire and an explosion were heard. It became evident that neither the men in her home nor the police prioritized her survival. The emotional impact of listening to that recording was profound, encapsulating much of what I had observed over the years of conflict, particularly following the rebellions. As I walked through the gardens, I felt a surge of anger upon reading the names inscribed on the placards beside the roses. This moment spurred deeper reflection; since these hybridized roses bore origins from my homeland and its neighbors, I believed that they should be named in honor of the numerous women who have been killed in the ongoing “War on Terror” and its various manifestations.

THE ESSENCE OF THE ROSE IN THIS PROJECT

Roses are a robust and essential object of imperialism in my framework of decolonization and liberation. My very first bath was in rosewater, and they have always held significant meaning for me, as they are integral to our culinary traditions and medicinal practices. Their association evokes a sense of home and familial connections, reminding me of celebrations, funerals, and other rituals. For millennia, roses have been utilized by family healers and perfumers. They serve multiple purposes: as a cosmetic astringent, a diuretic, and an anti-inflammatory, while also uplifting spirits and alleviating grief, depression, premenstrual syndrome, and menopausal symptoms. The tea derived from both the petals and rose hips has been employed for sore throats and colds, while rose water finds application in various beverages and dishes. The renowned physician, polymath, and scientist Ibn Sina (Avicenna) documented these benefits extensively.

I frequently visited rose gardens, particularly with my mother, and was always curious about the significance of their names. I often pondered why the roses did not possess the same fragrance as those in Iran, as European cultivars could never replicate the aroma.

Much of my aesthetic sensibility has been shaped by Iranian and Islamic art, wherein roses feature prominently across literature and visual arts. Throughout the region—encompassing Iran, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, and beyond—roses serve as potent metaphors.

ROSES IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

My research has revealed that roses were introduced to Europe from Damascus during the Second Crusade. The French endeavored to hybridize these roses to achieve a comparable scent when planted in Europe, yet their attempts were ultimately unsuccessful. Despite this, they continued to hybridize, producing numerous variations and establishing a distinct rose culture. Europeans began to utilize roses for perfumes and medicinal purposes, often crediting themselves as the originators of these resources, which were indigenous to the lands they had invaded and plundered during the Crusades.

The nomenclature surrounding roses was largely established during the Enlightenment period. It was during this time that much of the resources plundered

during the Crusades and Reconquista invasions and occupations were becoming available to more of the aristocracy of Europe. While hybridization predates the Crusades, the full experiment with non-indigenous plants and resource appropriation were not recognized in Europe until the late 17th century.

Initially, hybridizers named roses after themselves or their relatives. Subsequently, commissioned roses began to bear the names of nobility, royalty, and celebrities, with Josephine Bonaparte among the first to commission roses named after herself, her spouse, and members of her court and nobility.

Roses have also adopted symbolic meanings within European and American contexts. The maintenance of colonial legacies is often perpetuated not through overt violence but through collective engagement in celebratory, leisurely, and aesthetically pleasing activities. This engagement fosters a form of neo-colonialism, devoid of explicit malice yet rooted in the idealization of paradisiacal landscapes. Poetry frequently references roses, which have become emblematic of various royal lineages, connoting prestige. In the United States, roses symbolize access to land and leisure, historically enticing European settlers to occupy new territories as part of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. The Rose Parade, in particular, represents a notable commercial initiative aimed at encouraging migration from the Midwest to Southern California, where roses can flourish year-round.

Universally, roses symbolize gestures of love, though their thorns remind us of heartache and struggle.

Currently, the cultivation and commercial production of roses represent a significant industrial enterprise, generating substantial revenue, particularly for those harvested for the floral trade. The market for garden roses also contributes to their status as markers of high society and European cultural identity.

In this project, I have undertaken the renaming of roses as a form of resistance and a small practice of reparations, honoring women, girls, femmes, and non-masculine individuals of diverse ages, religions, and backgrounds who have become martyrs (again, used in the regional context) as a consequence of these neo-crusade conflicts.

ROSES BY OTHER NAMES: THE MARTYRS

These martyrs, most commonly victims without agency, hail from various regions, specifically related to conflicts in South, Central, and West Asia, as well as North and East Africa. Regionally, the term martyr has been used to describe people who have been killed in conflict, whether they chose to engage or not. It is in particular used in reference to religious wars and genocides. Additionally, I document the experiences of martyrs in transit, fleeing conflict due to famine, health crises exacerbated by warfare and sanctions, domestic violence as a byproduct of war, and suicides stemming from these circumstances. I also address war-related deaths within the diaspora, including those resulting from bullying or hate crimes, and acknowledge the fatalities of women not indigenous to these lands yet affected by the ramifications of war. The documentation encompasses deaths at the hands of colonial oppressors and those who vigilantly align with these oppressors, including groups such as Al-Qaeda, ISIS, ISIL, and Al-Shabaab. Some of the roses are named after femmes who are recognizable, like 6-year-old Hind Rajab pleading for her life while Isreali military tanks surrounded her and her sister in Gaza, or 19-year-old LaVena Johnson, a US soldier in Iraq who was raped and mutilated by another soldier while in her bunker, to women who would otherwise never be recognized internationally and sometimes not even locally.

The names of the martyrs are derived from research and translation, with spelling variations often encountered. For women whose names remain unknown due to cultural practices, I designate the rose as Unknown Woman or employ other means of honoring them without contravening the beliefs of their communities. Transgender individuals are referred to by their chosen names, and some women who have adopted stage names are noted in the text but not included in the labeling.

Most narratives surrounding these women are based on the circumstances of their deaths, as this constitutes the primary information available. If additional details regarding their survivors or lives are accessible, I incorporate that information. It is important to note that some martyrs have contested histories and may have been accused of perpetrating violence against others; however, I maintain a presumption of innocence in the absence of conclusive evidence.

A COLLABORATIVE ENDEAVOR

My research encompasses a diverse array of sources, including online databases, news reports, and discussions with journalists, as well as social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. Furthermore, I have engaged directly with kin and survivors, traveling to various countries to observe and converse with individuals directly impacted by the consequences of war and its attendant threats, including sanctions, environmental degradation, famine, and internal strife. Collaboration, rather than the extractive gesture that echoes the stealing of roses from their indigenous regions, is essential to my practice. I have also conducted extensive research on roses in numerous countries, exploring their indigenous origins as well as their colonial cultivators. My project would not have been possible without the assistance of many friends and colleagues, in particular Mahin Emrani, Maryam Hosseinzadeh, Fiona Brown, Parisa Parnian, Nazila Noebashiri, and the design of the database by the serendipitously named Alicia St. Rose.

Roses By Other Names is a project by artist Amitis Motevalli with support from Creative Capital. Rosesbyothernames.org

JONA FINE is a non-binary queer poet, writer, and artist. They have a Masters in Writing and Poetics and recently received their Masters in Social Work. They are obsessed with circles and are currently working on a novel where Open Circle lives in the moment of 11 AM perpetually on repeat. They live with their leopard gecko named Max and a fish tank full of baby shrimp. When they aren’t thinking about mental health, their love language is feeding their friends big bowls of salad and cuddling.

Dear D,

let’s play pretend let’s try this whole thing over again I’ll be your dad and I swear this time to say yes that everything will be just as it seems without the hidden underbelly you come out to me and I say isn’t this the best day of our lives? a sharing of your innermost secret isn’t this the best day of our lives that you don’t even have to have secrets?

let’s pretend that you don’t have to be afraid anymore what would you wear?

Tell me about all the boys whose hands are held gentle in your hands let’s pretend that holding hands is more comfortable for you than being thrown down the school stairs because it is because it should be because we are pretending I’m your dad and you told me and I held you and we cried together I wish I could be honest and tell you I am crying right now I am cradling my computer and crying know that we have never met but I love you

Dear D, I wish we could keep playing pretend to keep you safe to keep you more than just ok to validate your gayness to every blade of grass in every park on every street corner

I wish I could be so sure that when we hang up you are safe I know that we have never met but I love you You can come back on anytime you want 24/7 and it might not be me next time but someone will always be waiting for you on the other end

Dear D, I hope you write back soon

BETH SANDERS I use photography to tell stories that reveal the beauty and depth within us all. Through my lens, I capture moments of love, strength, and vulnerability—fragments of life that remind us how extraordinary we truly are.

With conceptual photography, I go beyond what we see on the surface, creating images that explore emotions, dreams, and the stories we carry inside. Every photograph is a reflection—a way to help you see your own beauty and feel the connection we all share.

My work invites you to step into these visual stories, to feel understood, and to discover the wonder and meaning within your own life. Through photography, I hope to show that we’re all part of something beautiful.

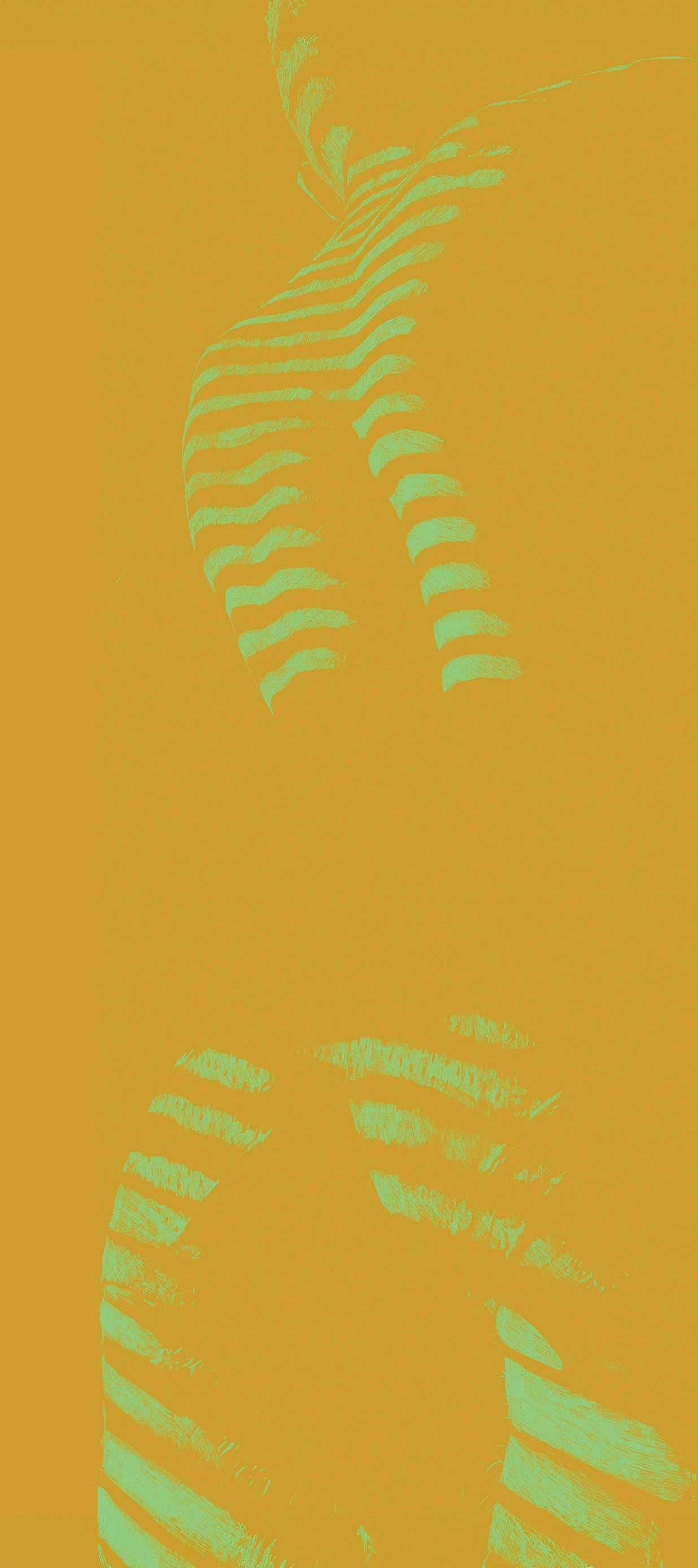

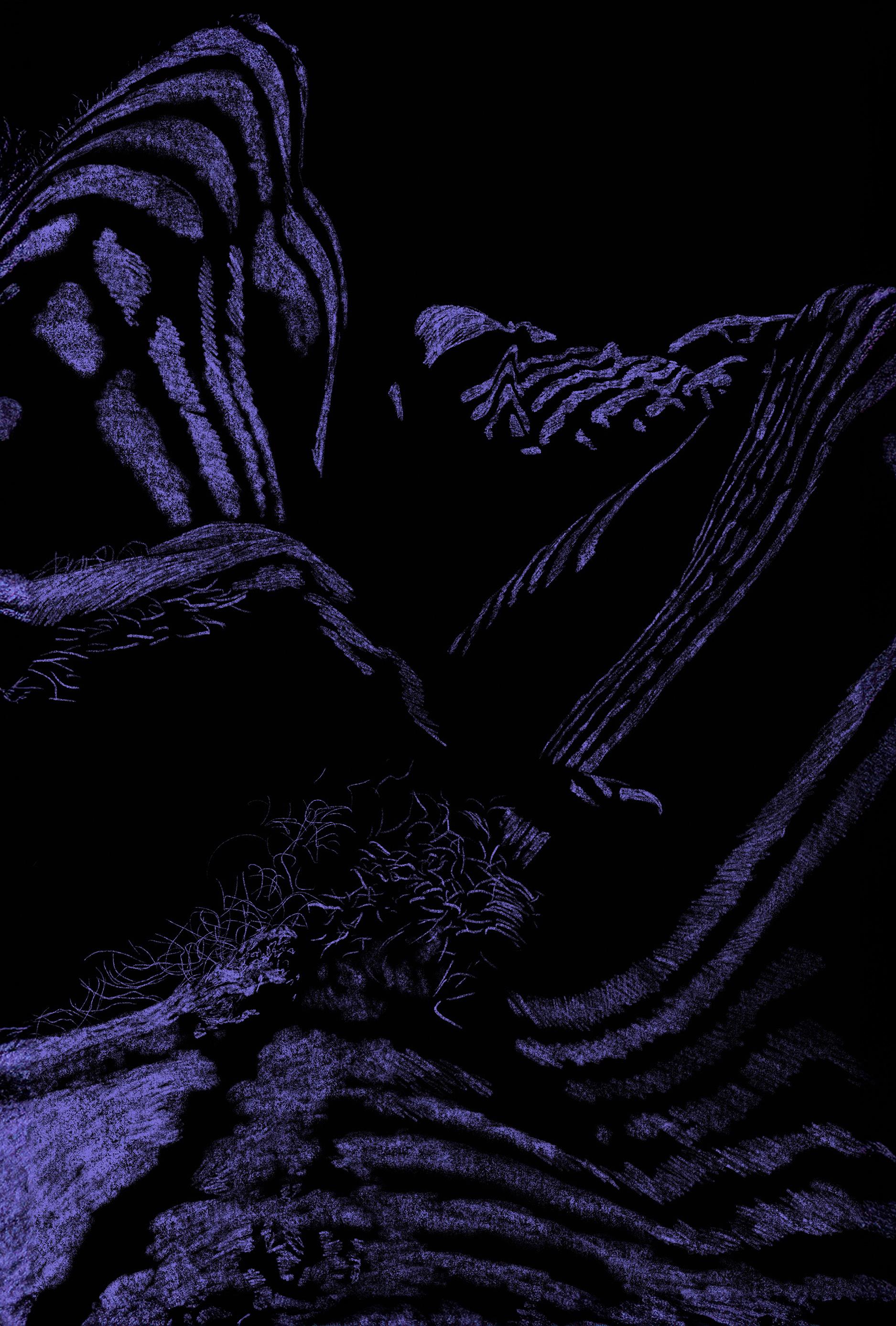

This project is a journey through loss, identity, and redefinition. After the loss of my breasts to cancer, I found myself questioning the meaning of femininity—how it is shaped by society and how it feels when those definitions no longer fit.

Through photography, I explore the beauty that remains and the strength that emerges in its absence. Each image reflects the quiet struggle to rediscover selfworth and the profound resilience found in letting go of what the world deems “essential.”

This work is a tender search for a new ideal—one that honors vulnerability, celebrates survival, and embraces a broader, deeper understanding of what it means to be feminine.

ASHIA AJANI is a sunshower, a glass bead, a carnivorous plant, an overripe nectarine. Hailing from Denver, Colorado—Queen City of the Plains and the unceded territory of the Cheyenne, Ute, and Arapahoe peoples—Ajani’s writing is a kaleidoscope of their work as an eco-griot and abolitionist. They are the author of one collection of poems, Heirloom (Write Bloody Publishing 2023), and a forthcoming work of lyric essays, Tending the Vines (Timber Press, TBA).

A BLACK HAIR STUDY IN COMMENSALISM, I.E. GREASE AND GLORY IN THE MARSHLANDS OF MY SCALP

sit still, knees dig into small shoulders seating me steady as my grandmother’s raisined fingers grease the chitlin circuit of my scalp singing soft bayou hymns: you’re safe here. if i could maroon into the forest of my hair i would: no questions asked no notebooks left behind, unspoiled restore me back better, fill my knocked around head with box braids reminiscent of Mississippi cypress against a swamp of salty skin. this overgrown railroad of twist and coil rejects the dirty promise of industry the dust and rust honeyed into fertilizer where an insurgent bloom can emerge evergreen.

here, there is no clank of metal no concrete coffins covering my most authentic kinkycurl iterations as memory begs my safe return any shoreline edge erosion is my responsibility and mine alone the fuzz of new growth, an epiphytic marvel marking tendrils territory for dispersal & comes with the wind, wind, rush. the naps at my kitchen signal season for an emergent abundance, untamed kanekalon bundles irritate me into length retention— this is the veneration we make to protect our best selves

& let our treetops seduce success under the golden sun.

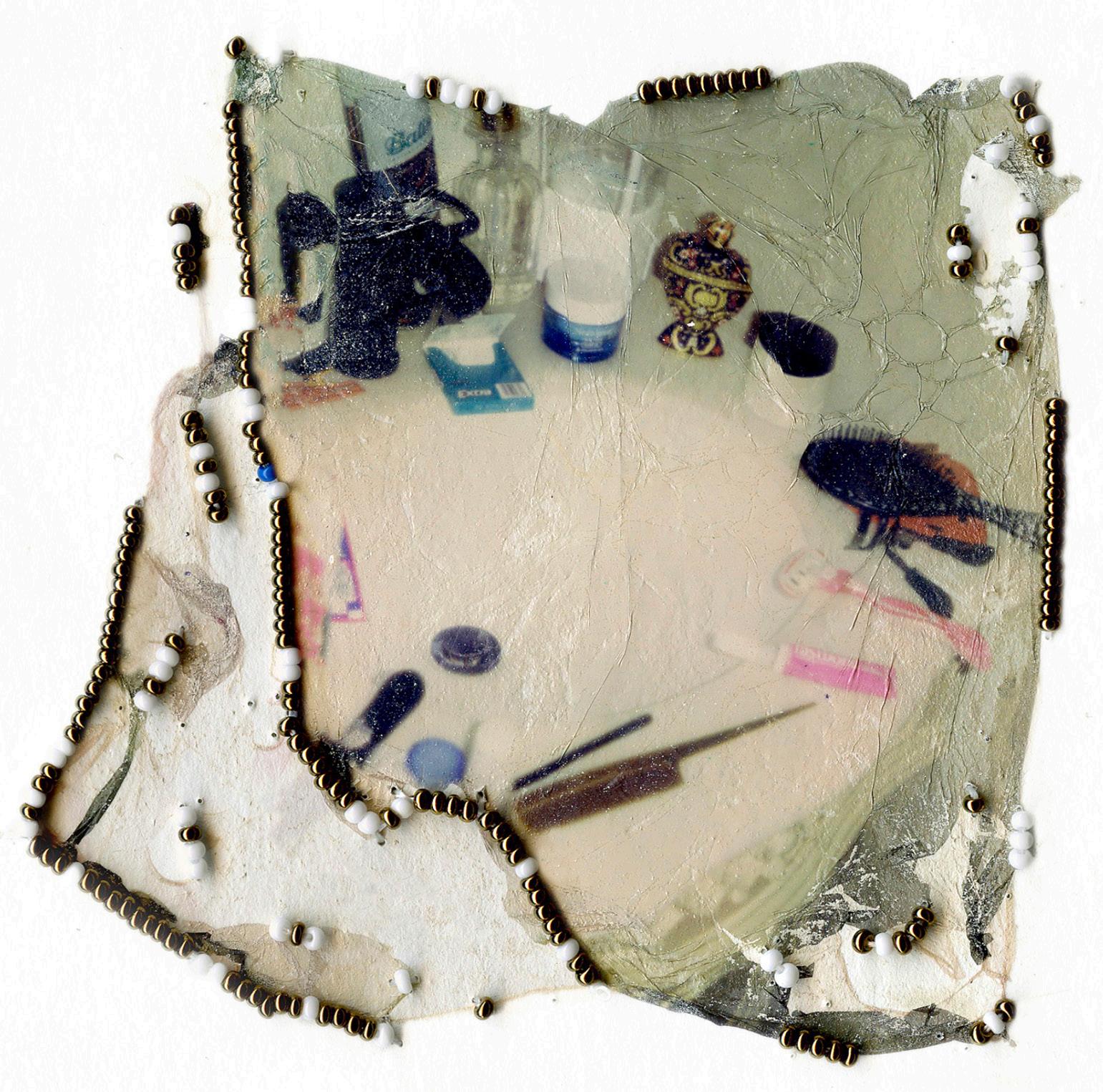

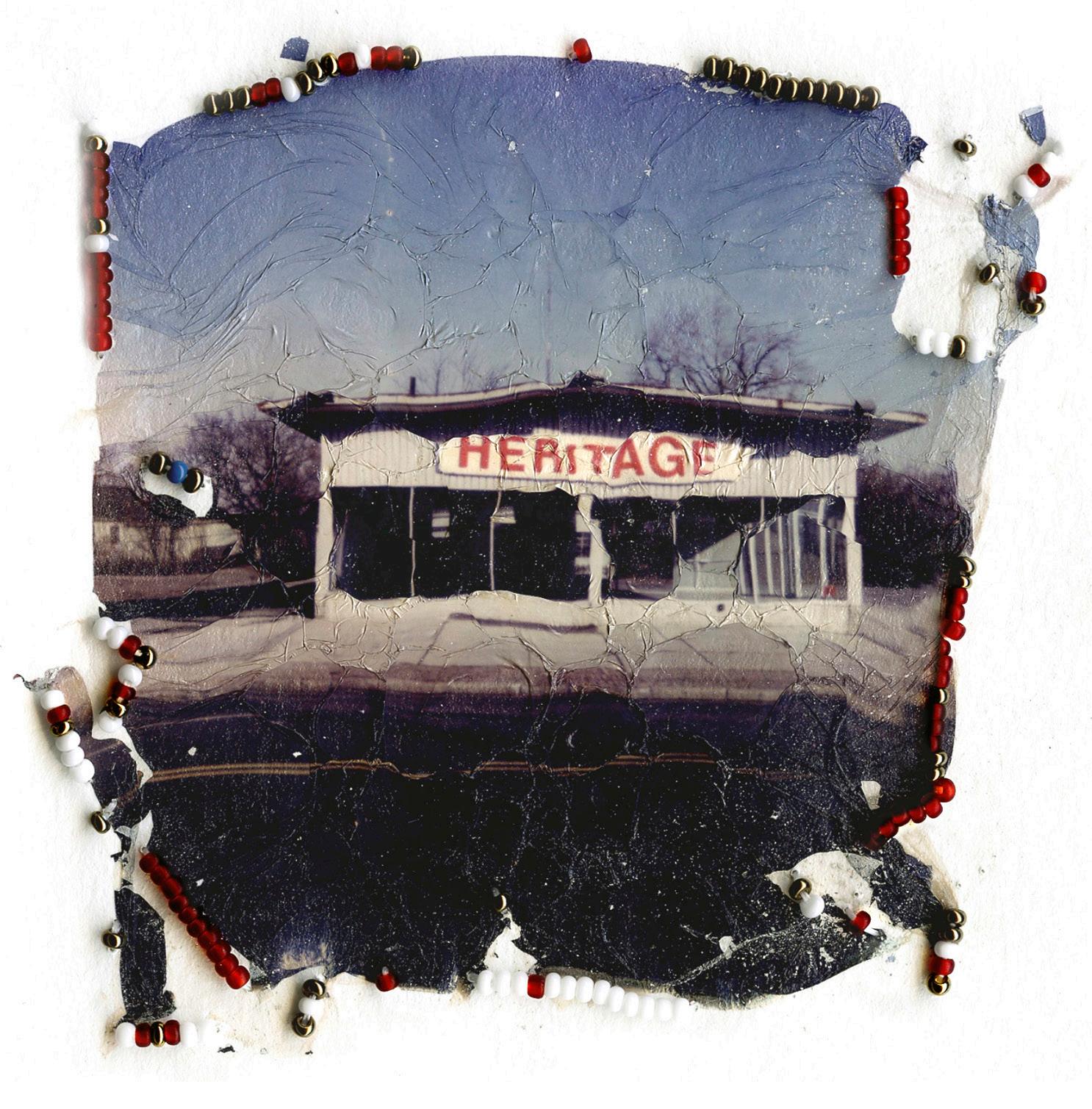

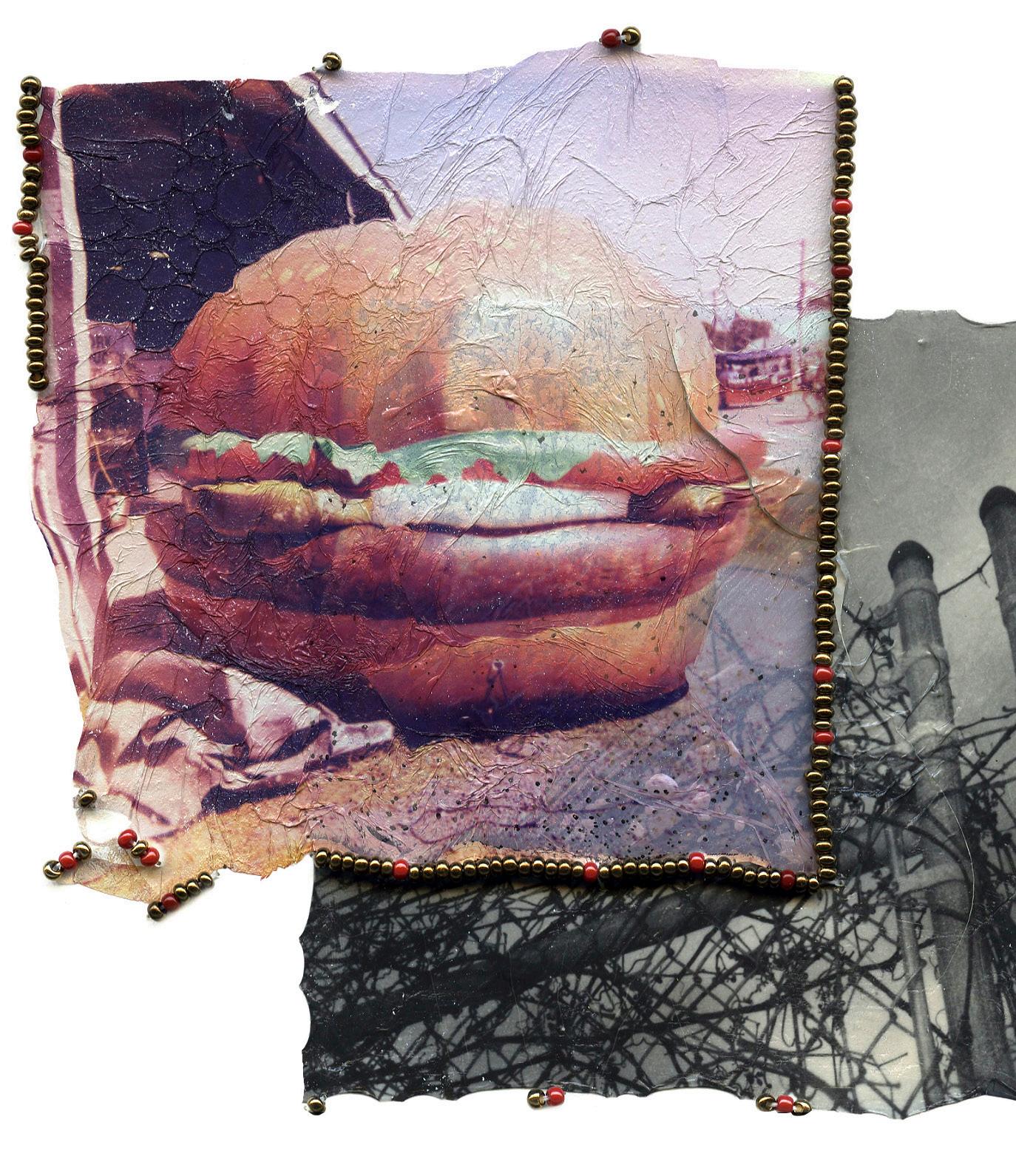

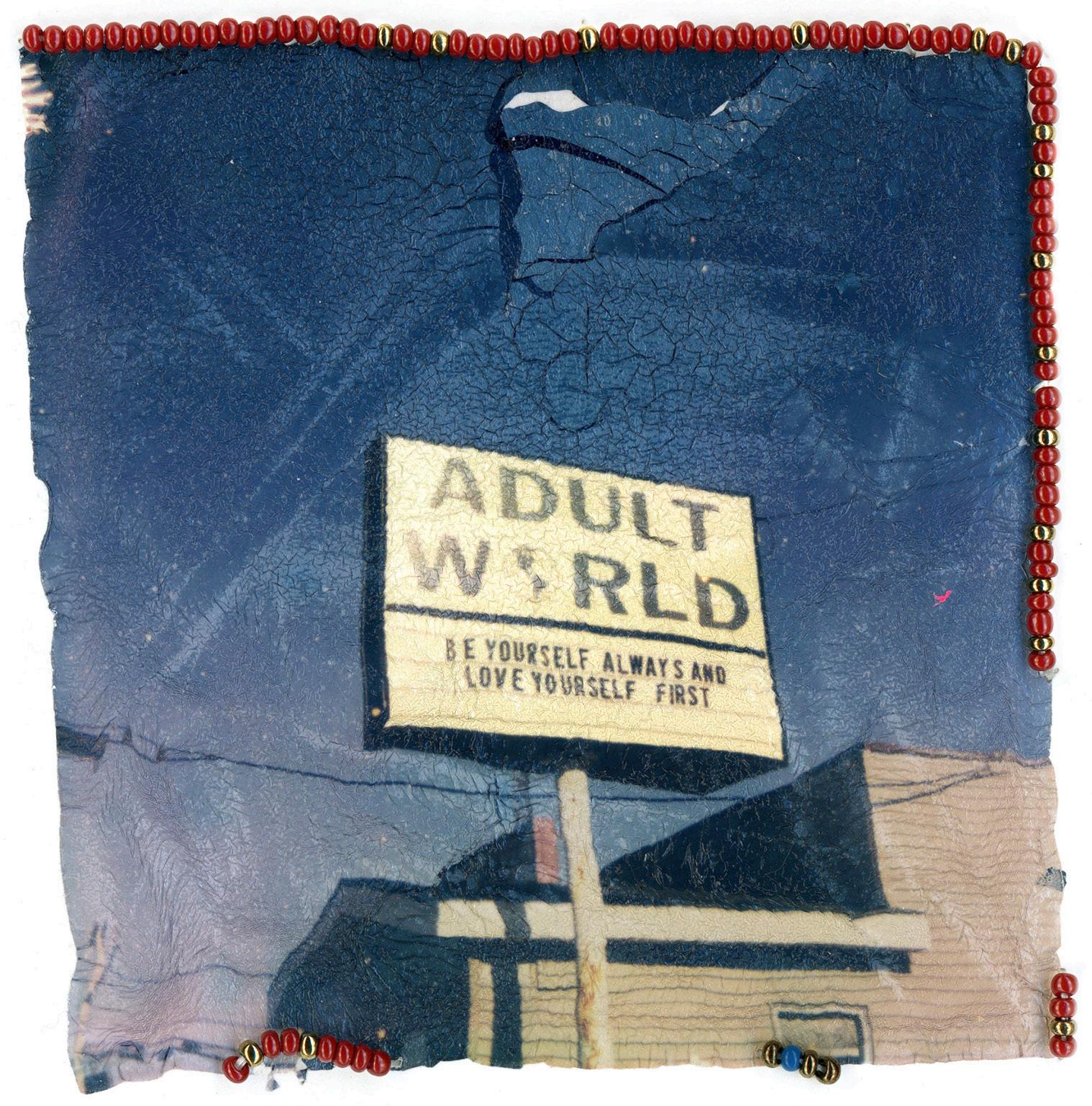

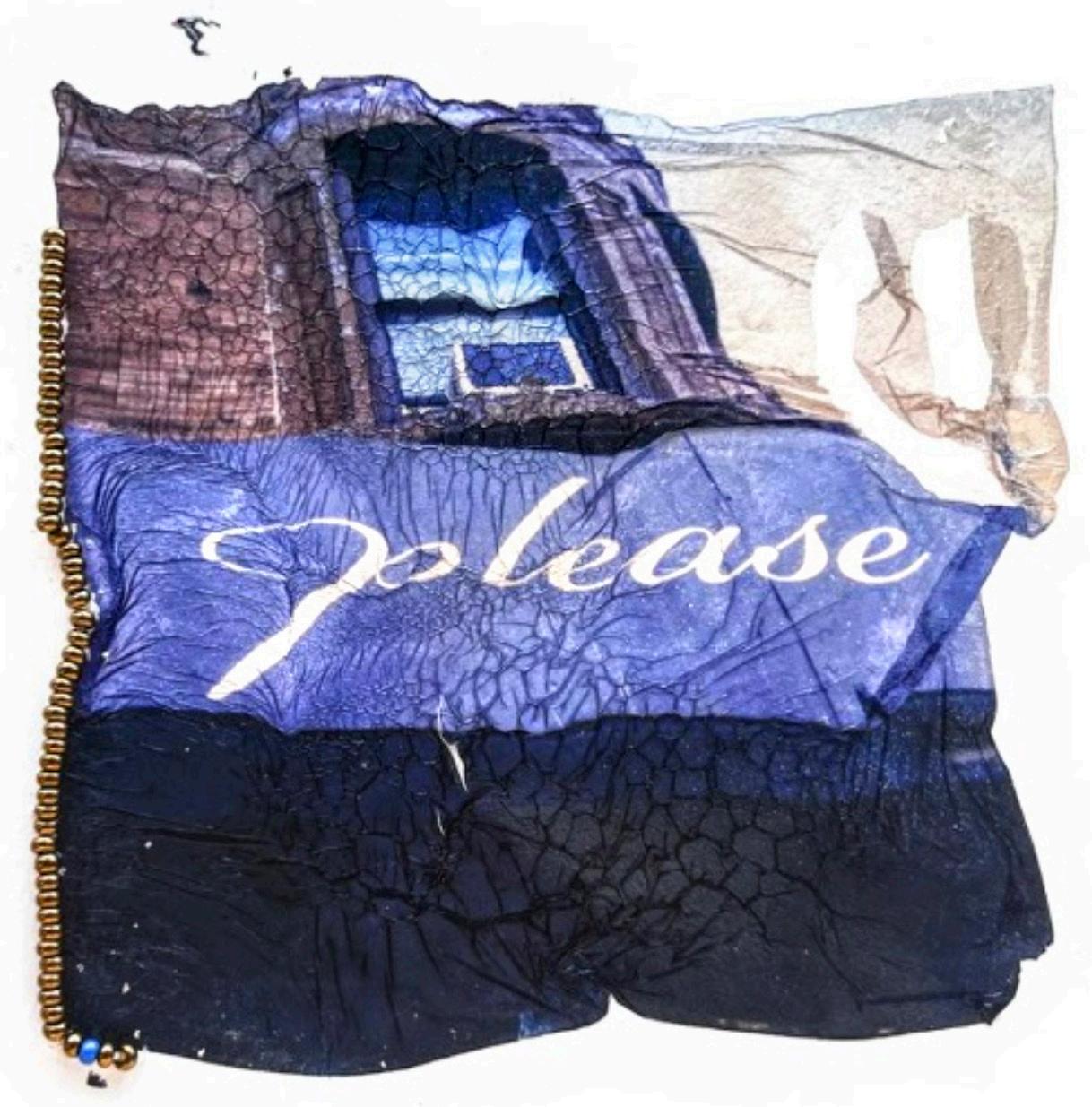

CALI M. BANKS (Munsee Lenape/ Scottish) is a lens-based artist currently based in Syracuse, NY. She holds an MFA in Interdisciplinary Media Arts Practices from the University of Colorado Boulder and a BA in Art and Technology and Global Health Studies from Allegheny College.

Cali is the Communications Coordinator for Light Work and is also an Adjunct Professor of Photography, Video Art and Filmmaking for Syracuse University and Indiana University campuses. Cali is also a 2024 En Foco Photography Fellow.

Her work explores personal and collective histories, relational intimacies, and the expansion of narrow, flattened definitions of Indigenous art while challenging essentialism. Banks’s practice also explores the layers of existence through materialistic remnants and non-tangibility. She is interested in the idea of image-making as a timeor record-keeper to recreate memories, history, and methods of healing. She is reclaiming what she still has left of her culture, and honoring those rituals in her work.

In recent times, she has exhibited work at Art Basel Miami, Every Woman Biennial London, RedLine Contemporary Art Center, Tiger Strikes Asteroid Philadelphia, Atlanta Film Festival, and Anthology Film Archives. She is also a featured artist in Issue # 24, #26, and #38 of The Hand Magazine and has been published on Lomography and Lenscratch.

Close Enough To Touch is a series of Polaroid emulsion transfers that are handbeaded with traditional Indigenous technique. Each image was captured in Brooklyn and combines self-portraiture, still lifes, architecture that is specific to this borough, and symbolism depicting bodies, ritual, and sensuality. Red, black, and white are consistent colors throughout the work as a representation of the Lenape tribe. Black is indicative of power, strength, aggression, and victory. Red represents happiness and beauty but also violence and bloodshed. White is indicative of sharing and light. Gold is used to represent value and validation. Each beaded image contains one blue bead, historically known as a “spirit bead” in Indigenous beadwork. This is not only a signature in every piece but also an act of recognition to her maternal grandfather and mother.

AMY GLEN BOBEDA I’m a poet, artist, teacher, dream worker, adventurer, and menstrual advocate with an MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics from Naropa University, where I serve as the director of the Naropa Writing Center and sometimes teach art, writing, and pedagogy. I share stories, hold space for women, and work in the realm of bridging sacred and mundane in personal and group gathering. My research comprises human origins, menstrual symbolism, and the somatic relationship between voice, body, and the origins of language. In 2020, five women from the Kerouac School and I founded Wisdom Body Collective. We are a process-oriented collective rooted in the sacred feminine. We publish chapbooks and full-length works. I spend most of my time with the birds of Eastern Colorado and occasionally Central Park.

SOME PEOPLE GO TO THERAPY

Some people draw birds, my mother builds wings, fashions ceramic pinions like an hourglass

grounded by weight, pinching perfect glassy beaks and eyes suspending fragility

porcelain exceeds strength of bone hollow, pressed together two concave bodies

become the breast of a single bird inhaling as her lips blow air into the bird, slip the cavern closed

—what do they call it, wings against their sides, ballistic with a small amount of lift–—bullets off a veranda, an artery thrumming beyond skin in the kiln a catacomb of words bounding.

UNTITLED

a pink chalk uterus lines the sidewalk outside the high school allison calls it medicinal pink, my favorite color and on twitter a dozen people can’t identify the wings of a clitoris a goat head catching the foam of my sneaker on her porch we strategize mutual aid and resistance how to show up with energy our bodies/their bodies/this body tired oh so tired deserves support the great resistance in bodies that count within state lines bodies within bodies chalking medicinal pink lines invisible pink lines talking

DREW AUSTIN ( b.1996) is an interdisciplinary artist and curator living and working in Denver, Colorado. He grew up in Great Falls, Montana, and attended the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design in Denver, where he graduated as Valedictorian with his BFA in 2017.

Austin is the Program Manager for The Wayfaring Band, an organization that creates inclusive experiences that amplify the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, cultivate connections, and transform perspectives to alter the way people view disability. He previously worked as the Curator of Visual Arts at The Dairy Arts Center, Exhibitions Curator for ReCreative Denver, as well as put together independent curatorial projects in spaces such as Redline Denver, The Temple Artist Studios, The Digital Armory, and Alto Gallery. Portrayed primarily through drawing, sculpture, and light-based installation, Austin’s work functions as a conduit for understanding and comprehension of everyday things—mundane situations, domestic space, slow growth, and light—both large and small in a human-dominated world.

CASS EDDINGTON is a poet, teacher, and translator from Utah. Recent work can be found in Deluge, DREGINALD, and La Vague, and in the chapbook VERNAL HURT (Magnificent Field, Spring 2020). They currently love from Denver, where they are a PhD candidate at the University of Denver. They also teach at Lighthouse Writers Workshop and serve as Poetry Editor for Denver Quarterly

FROM THE MANIFOLD

I wanted to emerge for one night from the outfall pipe clear my name— a genuflection, a song spread beyond— from the sewage that falls into the stream

If you are going to join me, elbow deep in this accretion, try to maintain contradictory sensations.

Two hands stay with me; no one replaces anyone else. Pull on the collective garb, its sagging crotch and twisted seams, its bustle and darts. Festoons swathe and gather around the figure of a body. You stumble into the parade.

Here we could say it begins: mid-summer mythic, anywhere arid and western will do.

Dragging one sodden foot from the mud of the poached riverbank, breathless I stood sucking my hair. Taste has something to teach. This wasn’t Sisyphean, but I’ll invoke what I must so you understand I was taught to blend my voice in a choir, I slipped under barbed wire.

Various landscapes and objects emerge: ruby-bellied newts swimming in the kiddie pools of fourplexes. Locate the body. Uniform of want I was born wearing, its reinforced stitches and heraldic epaulettes, without troop.

I said I am not the mother, we are playing orphans.

The tendency for the sacramental kitten—I still have it. And still, we know what becomes of the outdoor cat who finds more than one porch from which to feed,

kept trim stalking fieldmice. Semis whistling their chrome tones in the near-flung semi-arid distance.

I began collecting the outdoor kind. He wanted an anchor to call home, as did I, both of us prone to wander so that each act became a bond to be dissolved. In the night, with the humpyard crash filling the small house, we stilled each other.

Whoever endured a feeling with a dirty face, delinquent tendencies remaining, would be either bright geyser or slut, boiling under the surface. What properties of force! Slow-cooker pot-roast Sundays made a garment drape from the shoulders, salvific! Yet the end of the day pooled indiscernibly about the ankles, the white undies of any other day.

The tedium we endure becomes the ground we require to vault from fall to cartwheel. Inimitable and inevitable, it takes time for the book to be disassembled. The body takes a long time to resemble itself.

Of our debt we were born knowing. If we could sell enough calendars, we thought, we could stand upright.

Others only flirted, they only would be kissed in the split-level architecture of elsewhere. I was slick as a newly dropped calf. My lips were wounded, but my gait was not evil. As if we could simply shorten our stride to prevent this hitch. Notice the body’s articulation, where it snags and catches, the discovery of your own stench, necessary knowledge. Out institutional windows we wondered: when would the pheromones bear their truth? When did the skort become skirt? When will the feral find each other?

How many I name baby: my baby eating trash and dry leaves, my baby rocking the cage. I say this as if to pocket it.

To pet and be the pet ‘til the death of another day parts us, the sun parting horizon and sky. My attention, another kind of vow I am sounding out into the depths of night. We listen for the echo to ricochet our own voices decayed and sustained.

Easily we make room for another body while we survey the space to house our voice.

Asked not quite audibly: is every day a loop to a hare, every bird a bell to a god?

Pressed to my ear, the conch lets me hear a small portion of my sorrow.

Here, another cairn whose shadow I am building. See it become substance in the sun’s movement, see it darken and sharpen.

This pitcher may be cracked but grasp the handle, see what pours out.

The poem joins up with contingent truth. Hands greasing a pan, shaping a loaf. The wood piled high for the winter where the mice live. Of all the great dangers, work was the most imperceptible, its idling engine keeps you warm.

Surface is needed to expel what is stupid: also to get purchase on what is true. Seasonally outfitted with a bag of salt or kitty litter, we get ourselves unstuck on backroads with others’ names on them.

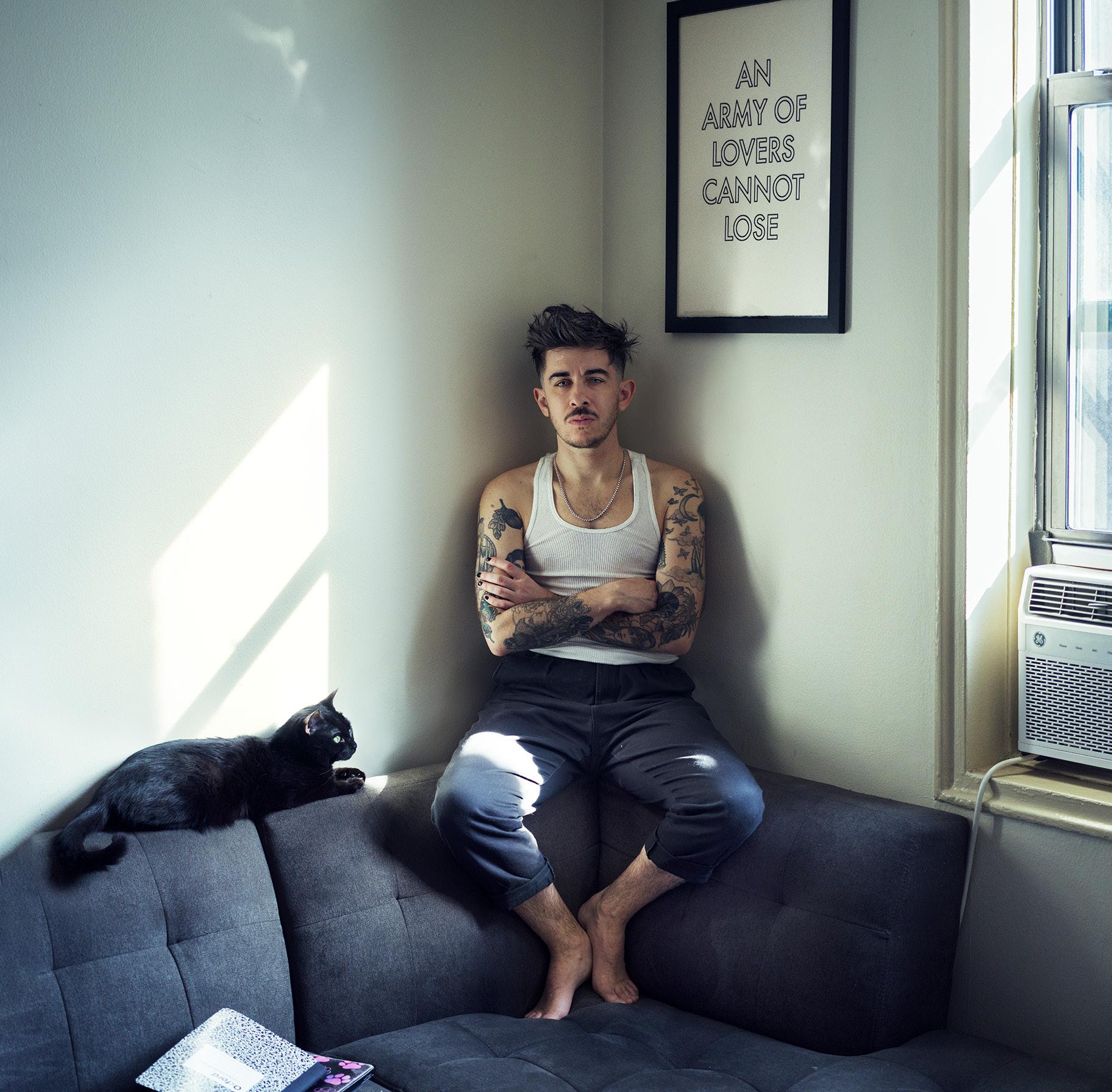

STAS GINZBURG is a Brooklyn-based artist and queer refugee from Russia. A 2006 Parsons graduate, he focuses on portrait photography, emphasising LGBTQIA+ communities and activism. His work has been featured at the Queens Museum, Photoville, and the National Portrait Gallery in London. His images are included in Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation, a book published by Aperture in fall 2022. Ginzburg’s project Sanctuary, an intimate collection of portraits of queer, trans, and non-binary individuals in their homes, was shortlisted for the Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture in 2024 and the Sony World Photography Awards in 2025.

Alexey

a gender-fluid photographer from Kazakhstan, in their bedroom, Harlem, NYC, December 2024.

Sanctuary is a series of intimate portraits of queer, trans, and non-binary individuals in their living spaces, celebrating the diversity of experiences within the LGBTQIA+ community. To create these portraits, I spend time with each individual, engaging in conversation to capture authentic moments that reflect their true selves and the environments they have crafted. The interiors become as important as the people, creating an archive of objects and memorabilia that further tell the narrative of the queer and trans experience.

In these portraits, everyone is free to exist in their truth, away from the threats of police violence, external homophobia, and politicized transphobia that remain deeply rooted in American society. As the current administration escalates efforts to erase trans existence through executive orders and policy rollbacks, restricting access to healthcare, gender recognition, and basic civil rights, it is more urgent than ever for this community representation to exist and be amplified

Chase and Raven the first openly transgender attorney to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, challenging Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming healthcare for minors, in his living room, Jackson Heights, Queens, February 2025.

Qween Jean a transgender activist, stage and film costume designer, and the founder of Black Trans Liberation, in her workroom, Crown Heights, Brooklyn, January 2023.

West and Grimm a transgender man, with his cat, Grimm, in his living room, Kensington, Brooklyn, January 2024.

Pride Flag LA Pride, Los Angeles, CA, June 2024.

Euro a transgender fitness coach, in his temporary housing, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, April 2024.

Neptunite a gender-fluid activist and caretaker, in their living room, Washington Heights, NYC, July 2024.

KAZIM ALI was born in the United Kingdom and has lived transnationally in the United States, Canada, India, France, and the Middle East. His books encompass multiple genres, including the volumes of poetry Inquisition, Sky Ward, winner of the Ohioana Book Award in Poetry; The Far Mosque, winner of Alice James Books’ New England/New York Award; The Fortieth Day; All One’s Blue; and the cross-genre texts Bright Felon and Wind Instrument. His novels include the recently published The Secret Room: A String Quartet, and among his books of essays are the hybrid memoir Silver Road: Essays, Maps & Calligraphies and Fasting for Ramadan: Notes from a Spiritual Practice. He is also an accomplished translator (of Marguerite Duras, Sohrab Sepehri, Ananda Devi, Mahmoud Chokrollahi and others) and an editor of several anthologies and books of criticism. In 2003 Ali co-founded Nightboat Books and served as the press’s publisher until 2007. After a career in public policy and organizing, Ali taught at various colleges and universities, including Oberlin College, Davidson College, St. Mary’s College of California, and Naropa University. He is currently a Professor of Literature at the University of California, San Diego. His newest books are a volume of three long poems entitled The Voice of Sheila Chandra and a memoir of his Canadian childhood, Northern Light

HOME

My father had a steel comb with which he would comb our hair.

After a bath the cold metal soothing against my scalp, his hand cupping my chin.

My mother had a red pullover with a little yellow duck embroidered on it and a pendant made from a gold Victoria coronation coin.

Which later, when we first moved to Buffalo, would be stolen from the house.

The Sunn’i Muslims have a story in which the angels cast a dark mark out of Prophet Mohammad’s heart, thus making him pure, though the Shi’a reject this story, believing in his absolute innocence from birth.

Telling the famous Story of the Blanket in which the Prophet covers himself with a Yemeni blanket for his afternoon rest. Joined under the blanket first by his son-in-law Ali, then each of his grandchildren Hassan and Hussain and finally by his daughter Bibi Fatima.

In Heaven Gabriel asks God about the five under the blanket and God says, those are the five people whom I loved the most out of all creation, and I made everything in the heavens and the earth for their sake.

Gabriel, speaker on God’s behalf, whisperer to Prophets, asks God, can I go down and be the sixth among them.

And God says, go down there and ask them. If they consent you may go under the blanket and be the sixth among them.

Creation for the sake of Gabriel is retroactively granted when the group under the blanket admits him to their company.

Is that me at the edge of the blanket asking to be allowed inside.

Asking the 800 hadith be canceled, all history re-ordered.

In Hyderabad I prayed every part of the day, climbed a thousand steps to the site of Maula Ali’s pilgrimage.

I wanted to be those stairs, the hunger I felt, the river inside.

I learned to pronounce my daily prayers from transliterated English in a book called “Know Your Islam,” dark blue with gold calligraphed writing that made the English appear as if it were Arabic complete with marks above and below the letters.

I didn’t learn the Arabic script until years later and never learned the language itself.

God’s true language: Hebrew. Latin. Arabic. Sanskrit.

As if utterance fit into the requirements of the human mouth.

I learned how to find the new moon by looking for the circular absence of stars.

When Abraham took Isaac up into the thicket his son did not know where he was being led.

When his father bound him and took up the knife he was shocked.

And said, “Father, where is the ram?”

Though from Abraham’s perspective he was asked by God to sacrifice his son and proved his love by taking up the knife.

Thinking to himself perhaps, Oh Ismail, Ismail, do I cut or do I burn.

I learned God’s true language is only silence and breath.

Fourth son of a fourth son, my father was afflicted as a child and as was the custom in those days a new name was selected for him to protect his health.

Still the feeling of his rough hand, gently cupping my cheek, dipping the steel comb in water to comb my hair flat.

My hair was kept so short, combed flat when wet. I never knew my hair was wavy until I was nearly twenty-two and never went outside with wet and uncombed hair until I was twenty-eight.

At which point I realized my hair was curly.

My father’s hands have fortune-lines in them cut deeply and dramatic.

The day I left his house for the last time I asked him if I could hold his hand before I left.

There are two different ways of going about this.

If you have known this for years why didn’t you ask for help, he asked me.

Each time I left home, including the last time, my mother would hold a Qur’an up for me to walk under. Once under, one would turn and kiss the book.

There is no place in the Qur’an which requires acts of homosexuality to be punishable by lashings and death.

Hadith or scripture. Scripture or rupture.

Should I travel out from under the blanket.

Comfort from a verse which also recurs: “Surely there are signs in this for those of you who would reflect.”

Or the one hundred and four books of God. Of which only four are known— Qur’an, Injeel, Tavrat, Zubuur.

There are a hundred others—Bhagavad-Gita, Lotus Sutra, Song of Myself, the Gospel of Magdalene, Popul Vuh, the book of Black Buffalo Woman somewhere unrevealed as such.

Dear mother in the sky you could unbuckle the book and erase all the annotations.

What I always remember about my childhood is my mother whispering to me, telling me secrets, ideas, suggestions.

She named me when I moved in her while she was reading a calligraphy of the Imam’s names. My name: translated my whole life for me as Patience.

In India we climbed the steps of the Maula Ali mountain to the top, thirsting for what.

My mother had stayed behind in the house, unable to go on pilgrimage. She had told me the reason why.

Being in a state considered unacceptable for prayers or pilgrimages.

I asked if she would want more children and she told me the name she would give a new son.

I always attribute the fact that they did not, though my eldest sister’s first son was given the same name she whispered to me that afternoon, to my telling of her secret to my sisters when we were climbing the stairs.

It is the one betrayal of her—perhaps meaningless—that I have never forgiven myself.

There are secrets it is still hard to tell, betrayals hard to make. You hope like anything that though others consider you unclean God will still welcome you.

My name is Kazim. Which means patience. I know how to wait.

FERN MANDEL WOOD

Who is FERN? the truth. a tree.

A WARM AND WONDERFUL dead person

a soft sweet creature of an indeterminate sex

FOUR PUZZLES OF INCREASING DIFFICULTY...

I am where the weather is getting cold. a 3–7-year-old a denizen of the outer solar system I am at sea. In extreme cases, the calculator a dream— I dreamed you

A cool anthropomorphic albino bat carrying a chainsaw about 4000 million years in the wrong room Nothing. Draw a circle around the right answer :)

MECA’AYO (Tameca L. Coleman) is a queer singer, multi-genre writer, itinerant nerd, massage therapist, and point-and-shoot art dabbler in Denver, Colorado. Their writing and photography are featured in literary magazines, art exhibits, newspapers, and other venues and publications. Their first book, an identity polyptych, debuted from The Elephants in 2021 and considers familial estrangement, being in-between things as a mixedrace Black person, and moving towards reconciliation. Meca’Ayo is a published author of poetry, creative nonfiction, journalism, fiction, and hybrid works and was a two-time poet laureate finalist in Adams County and for Colorado State in 2023. They create many communitycentered projects, gatherings and collaborations.

AM I BLACK?

I put my hand to the drum, straddled the woodburned neck, pounded into the skin whose spine ran down the center. I wrote my own message under the rim, cut and wetted the drumhead, tightened and tuned the drum.

I wore cowries around my neck stared into their mouths and palmed them, ran my fingers down their teeth.

I tied them on with bells and danced the Damballa in my living room. I danced to CD drummers and rain forest people’s singing. I danced stories about moving forward even when the wind pushes you back. Was it parable from my ancestors?

I do not know. I do not know them.

I watched the dances at an opening ceremony for Adefua. I danced at dancehall night in Oakland. I tried to do the Electric Slide at a summer cookout. I listened to the elders speak. I sang songs to Kori, I tried to beckon Chango.

I made my voice ring like the Ba-Benzélé.

I layered my voice like the Ba-Benzélé. I looped rhythms to emulate them. I know what Uhuru means.

Uhuru Uhuru Laiye Freedom! I have sung that freedom song from a stage in Idaho.

And I have been in the church even if I am not of it. I sang “He ‘rose. He ‘rose. He ‘rose from the dead.” I watched women talk in tongues there. I ate their home cooking after the service. They pinched my cheeks and called me Beautiful.

They asked me whose daughter I was. I do not know whose daughter I am.

A friend of mine says that to call myself brown in any context is a choice, and a privilege that undercuts this question of Blackness. [I am Black.]

On the bus, a woman looks straight at me, and says: You know you Black, right? I tentatively nod. She says: I’m just making sure, because sometimes y’all don’t know you Black. [I am Black.]

In Oakland, a sweet Black man asks: Who that big pretty brown girl is? We play slap-’em-on-the-table dominoes. I wish I was staying. [I am Black.]

. . . And so often brown or POC seems so much more right or safer, because how many times have I been told I’m not really Black, or I’m not Black enough? [I am Black.]

. . . And so often brown or POC seems so much more right or safer, because how many times have I seen privilege denied when you are

anything more than quiet and ambiguous? [I am Black.]

A Black girlfriend reminds: “If I’m doing it, Black people do it.” [I am Black. I am Black. I am Black.]

MY BLACK

1. is an actual infinity.

I am the transformative dark.

In the night, there are stars: cubed and repeating, fashioning after a multitude.

These eyes are portals squared.

2. is the safe bet. and the one drop rule still applies.

I tell them I am not convenient. They tell me they need more Black friends.

3. is a judgement against me.

The kids on the bus called me one name after another. This time, “Zebra.”

I spent the whole next night attempting to create a good comeback. I lay in my bed long past bedtime, smiling when at last I had it. In the morning on the way to school, I asked: Where are the stripes? They said: Melted in.

The class bully decided he could get away with it. He said: You’re nothing but a nigger. I told him that nigger was a river in Africa.

He said: No. It’s Niger, Stupid.

That night I consulted the dust caked encyclopedias on our bookshelves. Niger has one g. Nigger has two.

4. is half magic between things limbo tweenie dusk and twilight a steam between the windows

frost on the glass froth on the glasshouse half-caste magistrate.

I am between a steamroller and the windpipes, a half-day frown on the glaze.

I am a half-life magnet steel between windshields. Fruitcake on the glen

between half-notes a steelworker a halfpenny between thirsts a steeple between wings, half-sister magic deathflowers in her hair crooning crooning still strange fruit hanging on the tree.

I am between thistles a steeplechase halftone magpie inside two thoraxes a heifer between winks fuddy-duddy on the glimpse. half-wit between thorns,

a pedestrian that glistens and burns.

I am between thoughts a line inside the shoulder a fugitive between thrashes a stenographer without tools fulminating against the globe.

5. makes one man on the phone tell me my name is a Black girl’s name. This midwestern schoolgirl speak— He wants to know why I have a Black girl’s name. “Yes,” I say. “I am part that.” And, “what is the reason for your call?” He still wants to know why I have a Black girl’s name.

6. is [?]: ?

They think I am approachable because I render myself nondescript. My clothes are utilitarian, mostly black, no labels facing. I have cut my hair. No one touches it anymore and they’ve stopped asking me what I am.

7. is blood.

Should I cut out my [fair] mother burning red in the sun?

A CAT NAMED NIGGER

At fifteen, I was good with being paid under the table. That’s why I was watching this worn, wrinkled woman tug on a third long cigarette as she interviewed me.

The woman needed someone to housesit a couple of nights. She seemed to like me. I didn’t have classes till Monday, and I could get away from Mom’s house as much as I wanted to. The woman said she had a cat. I liked cats.

I don’t remember what we talked about. I only remember that she had stacks and stacks of yellowed Harlequin Romances on a table. I remember she wore short shorts and a tank top that day, pastel. She was thin, her skin was thin, her fingernails were painted and her hair was cropped short. She lit another cigarette.

A cat trill interrupted us. I turned to see it. It was black but for its eyes and whiskers. It looked like a stray.

“Come here, Nigger,” the woman said, crouching down as she clicked her tongue and wiggled her fingers. Then she paused, sat up abruptly, and then looked at me with a strain on her face. I held my breath. The cat ignored the woman as it passed, arching its back away from my hand.

“Oh, that’s the cat’s name,” the woman said, smashing the end of her cigarette into an already full ashtray. “I hope that wasn’t offensive.” She waited for me to answer.

I shrugged to put the woman at ease, and I housesat for her anyway.

HOLY GHOST POWER

I fell asleep with the light still on and woke, head covered to deflect a bright dissonance. A voice from that in-between place of sleeping and waking demanded through gritted teeth, “Give your life.”

No. I could not shake it, the whole night could not shake it.

In dreams, he told me to make my decision over and over. Give me your life. I tossed and turned, brow sweat

souring, the scrape and the burn of a memory (No!):

My father said what matters is blood and God. His wife said “The daughters always return.”

The next day I could not shake it. I could not shake it. How free I’d been. How free.

I woke the next morning with my left hand on my chest, face in the pillows.

I woke up and smiled, turned over onto my back hand still on my chest, thankful for my life.

I began the next day face down in prostration. I pushed my face into the pillows, stretched my arms and legs as far as they would go.

Then a text from my father: “my wife is dying”, followed by three sad face emojis.

At the bus stop, on the way to work, someone chalked HOLY GHOST! POWER onto the sidewalk.

I stared for twenty minutes at what felt like a command.

He said, my wife is dying. He said, make your decision. He said, curse your problems.

I checked my account and I had just enough. I bought the ticket. I flew east. I looked into his eyes, and I didn’t know him. He said he thought he got Parkinson’s because there were so many things he was never able to say.

[ . . . coal and kindling . . . . ]

[This little light is memory, a composite of many days made one. ]

In a sweltering church where music so big and bright it could ignite this room, blow everything open from the bench splinters out

[This little light is a hymnal page turning. ] voices rise up; the house band keeps time; the pastor stirs up the congregation.

Benches begin to rock and tremble like the quaking of God might— women fly out their seats shouting Hallelujah Amen Praise Him Oh Jesus Sweet Jesus Praise Him and god! Their tongues twisting

joy and sorrow, babble as their bodies writhe out of time in the music.

They speak into the air, their eyes wild as they sift into god.

They are raptured, holy, swept into their most private ecstasies. The benches tremble. The floor thumps. The congregation knows the song.

[This little light is a shout Hallelujah! Amen. ]

I want to hold that power.

[This little light is tongue speaking women. ]

[This little light is sinners come to be reborn. ]

I hold the book, stare at the words and the dots and lines, listen to the song but I cannot sing. I listen to the song, yearn to fly up or burst open.

[This little light warms as the hymnal pages turn, dots and lines along the page: coal and kindling. ]

Big brown curvy angels—their hands, their husbands’ hands, their lovers, their children, clap more rhythm into the driving beat. They clap more rhythm and I cannot move from this seat. They clap more rhythm, amplifying tension, sound, vibration, the heat in these packed pews. Their throats, upturned, fill the room.

[This little light is a prickling in my skin. ]

The whole building is shaking now—this god’s house— this beautiful turbulence, veritable hells being sweated out of their temples and out of every crevice God gave them.

[This little light is sudden devotion. ]

I turn to see my father beside me. It is the first memory I have of him. And I am confused seeing him like this:

A strain marks his face, his hat is in his lap, crushed by his fidgeting fingers; his body rocks and sweat pools, drips a waterline from his temples to his collarbones, separating himself from who he was and who is becoming.

[This little light is a cleansing fire. Amen. ]

He is no longer an angry ghost of flying hands. “God wants me back,” he says. “God wants me back.”

[This little light is my father beside me. ]

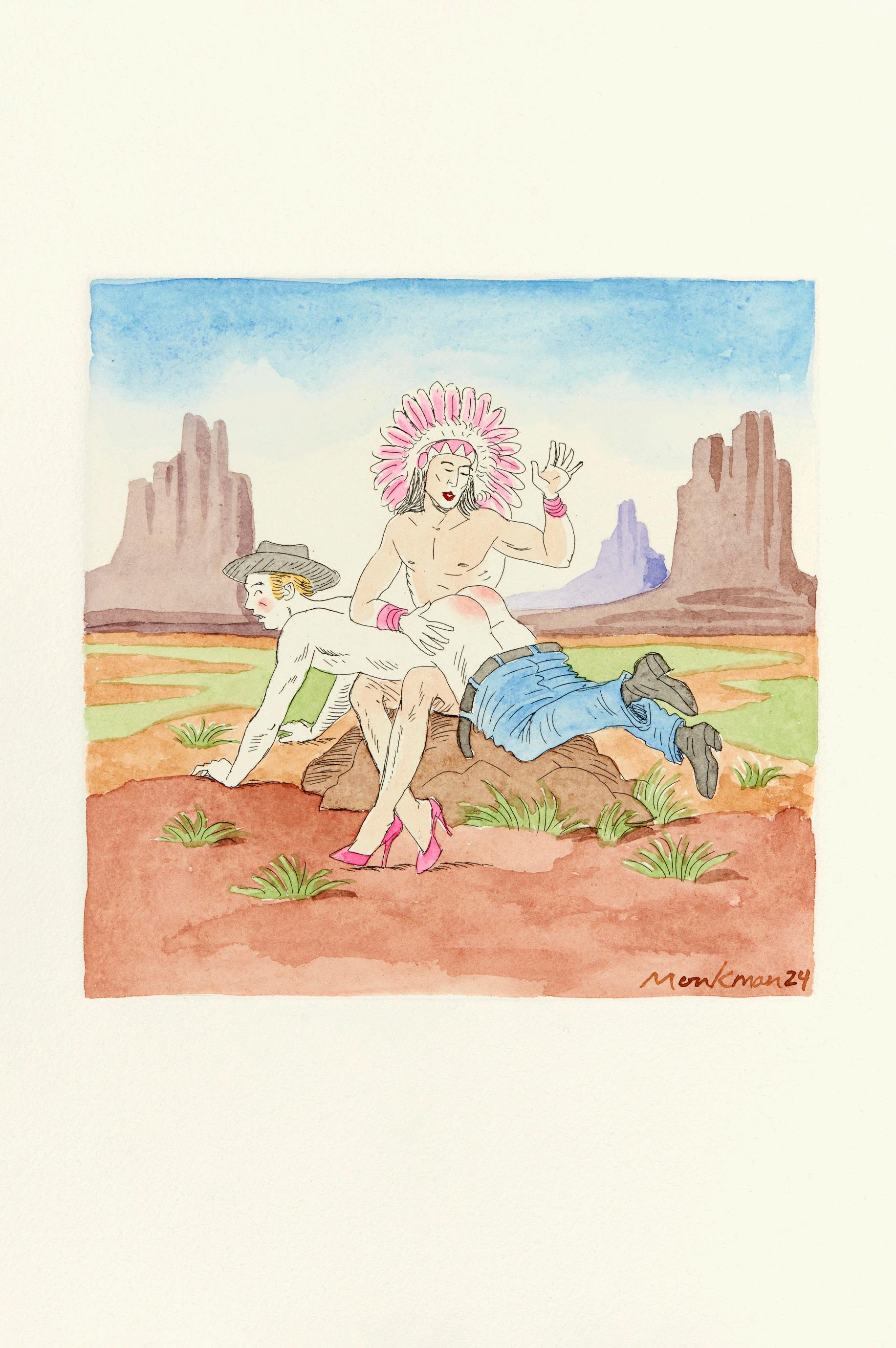

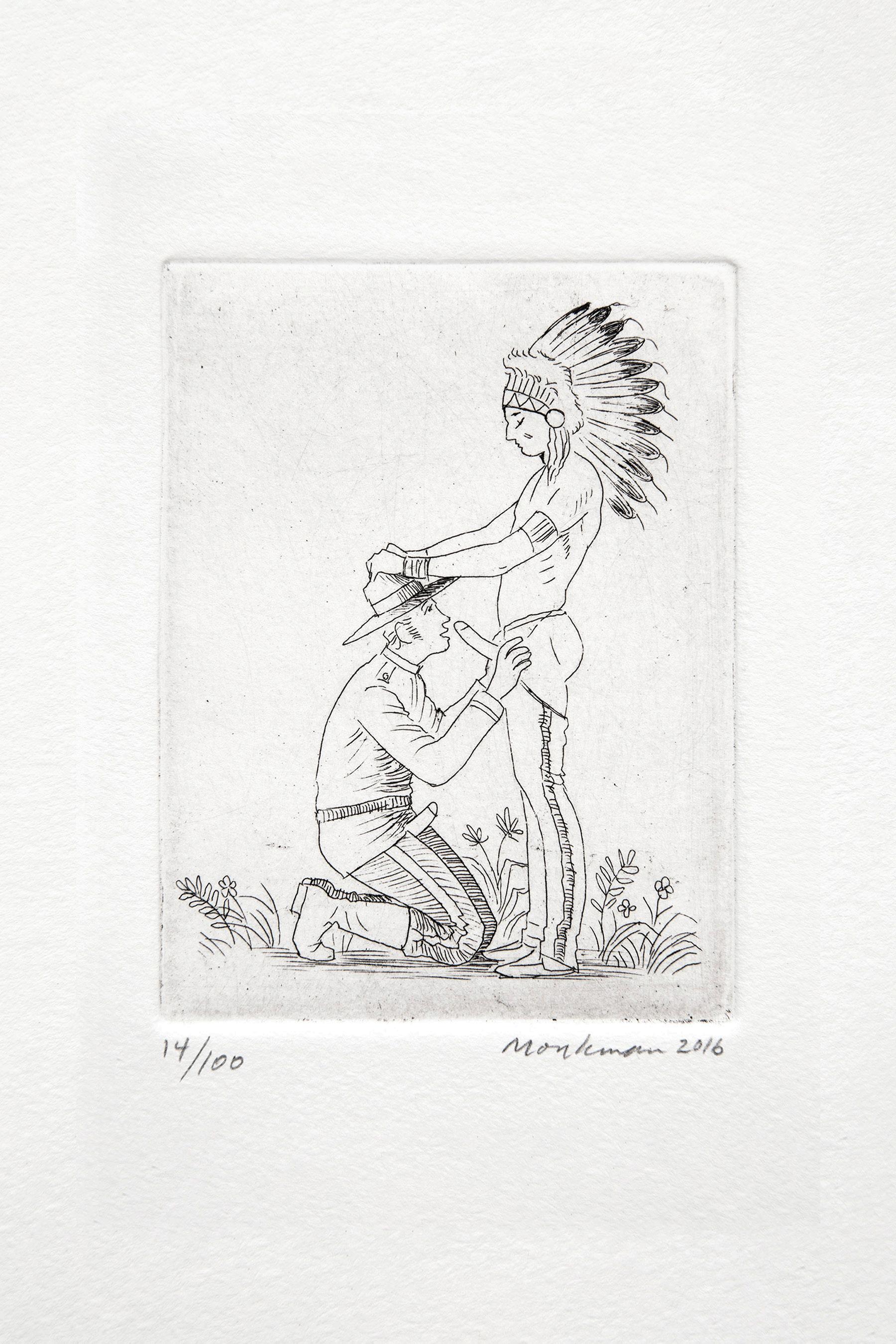

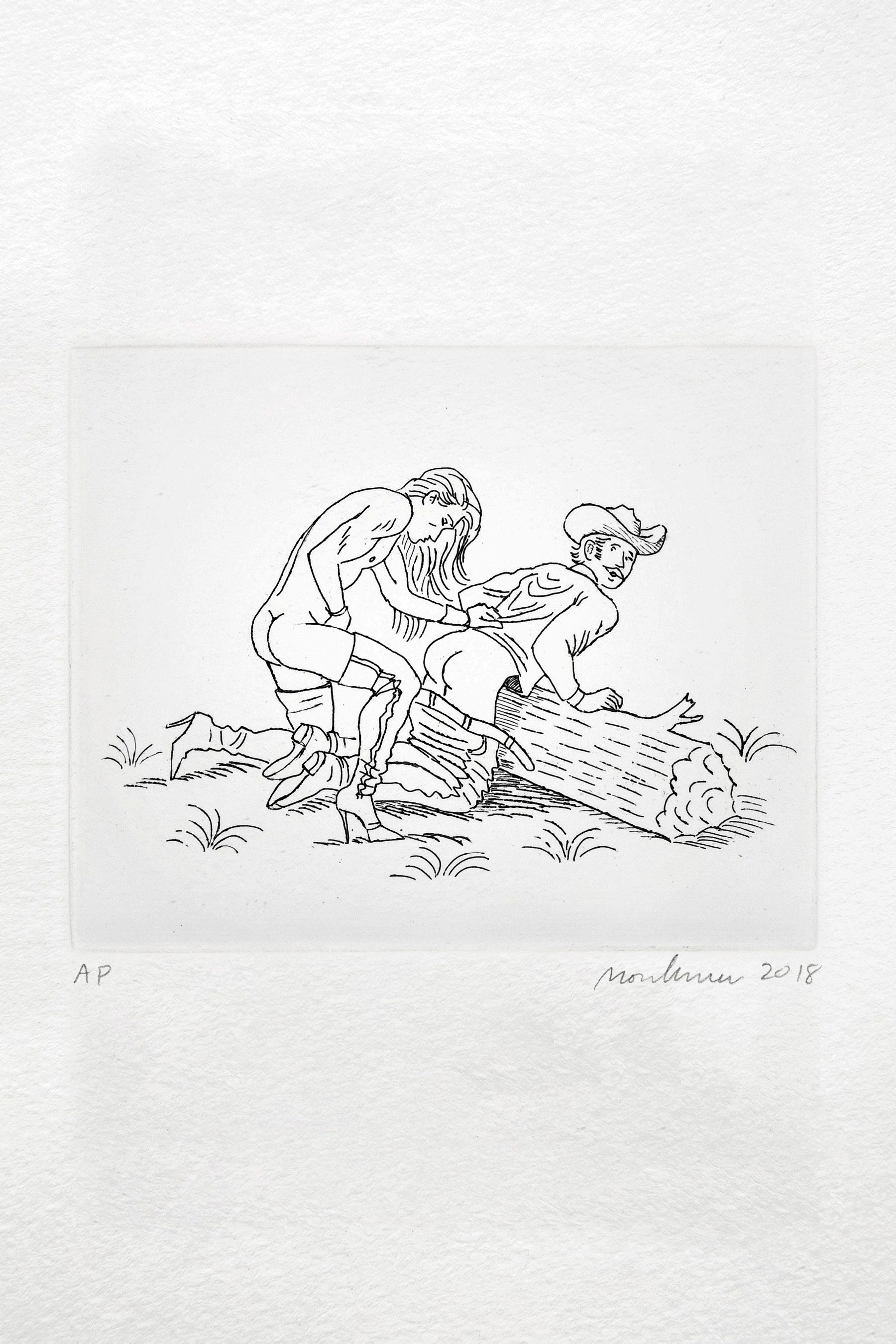

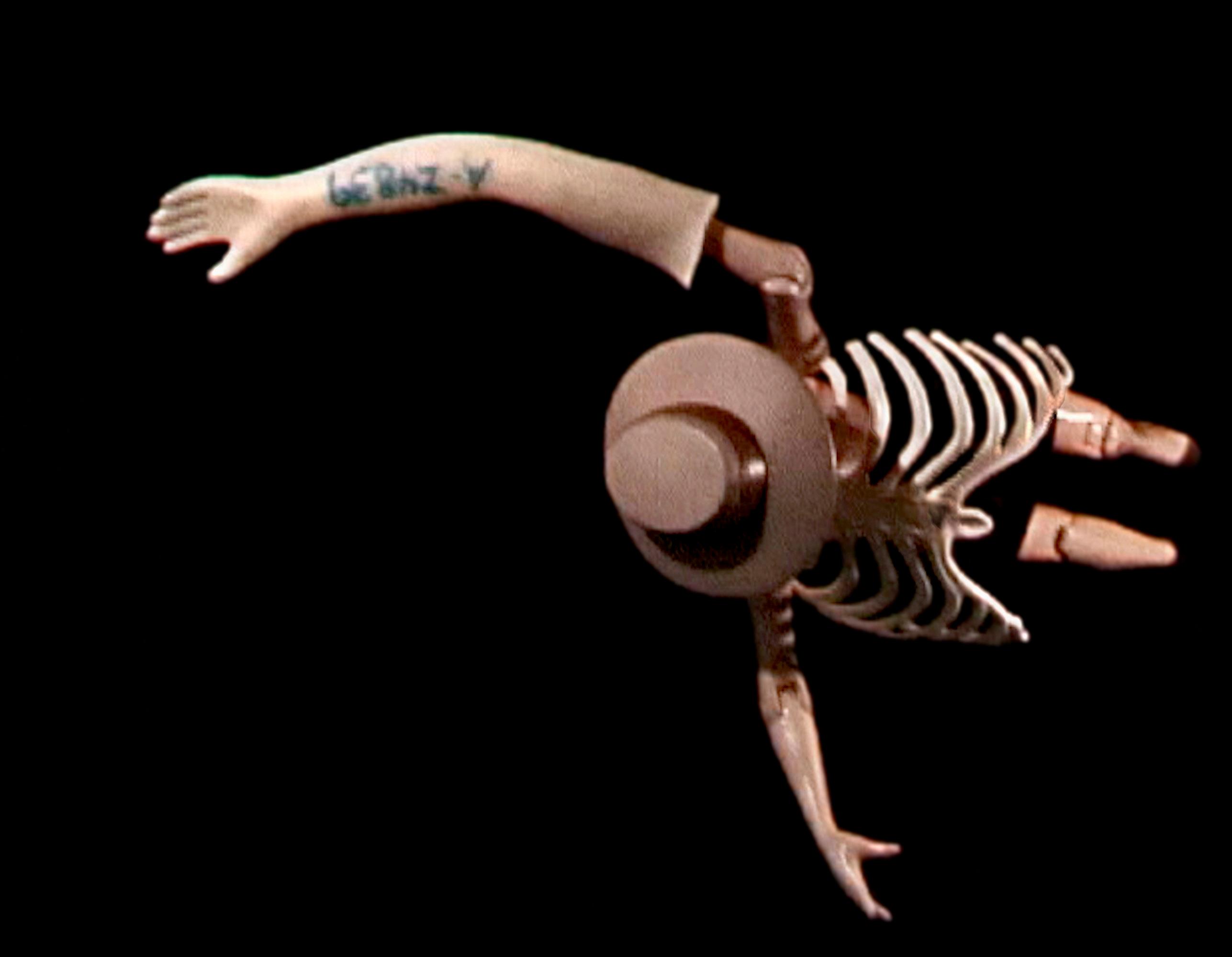

KENT MONKMAN (b. 1965) is an interdisciplinary Cree visual artist. A member of Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 Territory (Manitoba, Canada), he lives and works between New York City and Toronto. Known for his thought-provoking interventions into Western European and American art history, Monkman explores themes of colonization, sexuality, loss, and resilience—the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous experiences—across painting, film/ video, performance, and installation. Monkman’s gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle often appears in his work as a time-traveling, shape-shifting, supernatural being who reverses the colonial gaze to challenge received notions of history and Indigenous peoples. Monkman’s artworks are held in the permanent collections of numerous institutions around the world.

LAUREN SAMBLANET (they/she) is a hybrid writer who cross-pollinates with other forms of making & other makers of forms. while she studied poetry, they most often write essays and fiction that intermingle with poetics, performance, sound, video and visual art. they are disabled, chronically ill, neurodivergent, gender fluid, and queer. she received her mfa from temple university, and currently resides in colorado. punctum books published her first book, like a dog some of their publications include: a shadow map: an anthology by survivors of sexual assault, FENCE, just femme and dandy, dreginald, entropy, bedfellows, and the tiny. lauren is a teacher and guide, offering workshops, creative process support for individuals and collaborators through their passion project, reinventing creative process. her dream is to guide other creators toward more embodied, pleasurable, and emotionally safe creative processes that help their creative ideas thrive.

dear h,

did i ever tell you about the good girl thing? does that ring a bell already, from your own sex life?

i first noticed it with c.

i know, i shouldn’t bring him up after all the time it took for me to get over him, but it’s important. it didn’t happen at first though, because before c found out that i told a lie about how long i’d been with g, he acted differently toward me. at first, we had this insane, lustful, romantic sex that in retrospect seems like something he used to lure in all the women that he fucked. then, g confronted him, and suddenly things changed. he became much less emotionally available to me, though as you know, he didn’t even seem available to himself that often.

the sex also changed. it seemed that my lying about g made less romantic sex more appropriate.

still, the sex was hot and he is one of only a few men that have made getting my pussy eaten feel amazing, and the orgasms were wild. every time i came, c would say: good girl. when i asked him about it, he said that it was exciting for him that i was cumming, and he just meant like: good things are happening for this girl. i wonder if he was already fucking the other women when this good girling began.

o also said it. but in more of his dominating way: be a good girl and , where the blank became things like watch yourself get fucked, or suck my dick like a whore. when o said it, it felt more degrading than when c did, even though c was lying to me and o was never cruel to me outside of our fucking.

x said good girl also. he said it both times we fucked, in the cow field and after my art show. didn’t he also use the word slut or maybe it was whore? which is interesting because he was cheating on his girlfriend to sleep with me, so by definition, he was the slut.

anyway, i think he said good girl when he fit his entire dick, which was delightfully long and thick, into my pussy. he mentioned that his current girlfriend and many other girls couldn’t take his whole cock.

why was hearing that satisfying for me?

am i a good girl?

this seems to imply that, in sexual settings, i fulfill men’s sexual desires without putting up a fight.

or that i seem to truly enjoy sex without holding back?

i like that second option better, l dear v,

i know you never used the actual word, but i’ve felt like you believe that during periods of my life i’ve been a slut.

in trying to think of the way slut is used in porn, in films, in life, my brain gets tangled in a knot. maybe there are three types of sluts:

sometimes, in porn, slut is used in a positive way. you can be a type of slut that is approved of, which means that you please all the many people you sleep with. it means that sleeping around results in you knowing how to please your partners.

the second type of slut has a negative definition. the nasty or dirty slut who deserves to get fucked because she’s already been used and is therefore tainted and damaged. this usage of the word slut is all too familiar since it seems to be the reasoning gg used to excuse his sexual aggressions toward me.

there is a third type of slut and this type is what i imagine you would have called me. it’s the slut who has a lot of sex and really enjoys it, regardless of what external forces say of her sluttiness. while this kind of sluttiness seems positive to me because it requires that pleasure be accepted and prioritized internally,

i have been assuming that you disapprove of this type of sluttiness because of the way you talk about sex. it appears as though some part of you believes that sex has to be meaningful and should only be shared between two people who love each other, and therefore, you find this slut’s sexual encounters to be disgusting.

i’ve been wondering about the word nymphomaniac lately, too. h and i have used that word to describe ourselves before. here are two definitions via the internet:

a) a woman who has abnormally excessive and uncontrollable sexual desire

b) (of a woman) afflicted with abnormally excessive sexual desire

the words that unsettle me here are abnormally, afflicted, and excessive. while being a nymphomaniac is different than simply having a sexual appetite, it concerns me that women can have abnormally excessive sexual desire. at what point does a woman’s sexual desire become not normal? at what point is it too much?

it concerns me even more that having an excessive sexual desire, for a woman, is an affliction. it concerns me that my excessive sexual desire makes others uncomfortable, and it concerns me that others get to decide when my sexual desire becomes abnormally excessive.

recently, i found this definition of a similar word, whore, in an essay by chanelle gallant in the book pleasure activism: “we use the term ‘whore’ to refer to the feminine sin of demanding too much.”

and here we find all these words aforementioned and all the many other words i have not yet used in this project that describe women who have sex, who give into desire, who allow themselves to enjoy the pleasures of bodies. women who are abnormally excessive in their sexuality, who are afflicted with abnormally excessive sexual desire are women demanding more than society tells them they can.

what are we told to want from society? to be chaste but not too chaste. to give ourselves to one who loves us but not to explore our sexuality deeply or with multiple partners.

i wonder what you would have been like in another reality—the one in which you didn’t see sex as an act of love, but rather the one in which you saw sex as an act of pure pleasure.

what would sexuality be like if it could exist outside of ideology?

l dear t,

when you died, this question repeated in my mind: how was i the one that survived all of it?

you, d, and i became friends in middle school. you and d first, then you and i, then the three of us, dressed in black, not talking about what caused our depression, but acting out from that depression with actions like self-harm.

now i know that what we had in common can best be described by a scene from the l word. the l word is terribly flawed, problematic, and even harmful, particularly toward bisexual and transgender people. however, some scenes from it have stuck with me, and while most people hate jenny’s character, i was always drawn to her. i had never seen a character on television who survived childhood sexual assault. and in moments, her character reminded me of myself— not just her pain and how it manifested, but also her initial fear of her sexuality.

jenny, one of the main characters of the show, discovered her queerness in the first season through an affair. in the second season, jenny is involved in a love triangle with her friend and her roommate’s lover. jenny and this roommate, shane, can’t afford their rent so they find a third roommate, a man named mark. mark is a filmmaker who is hoping to get out of the porn industry and into documentary film making. he decides that his perfect documentary topic is now right before him—the secret life of lesbians. his friend convinces him to install hidden cameras all over the house so he can better capture his subjects.

one day, jenny finds mark’s recordings, and through them, she also discovers her girlfriend is still in love with her roommate. it’s not the discovery that her girlfriend isn’t in love with her that causes her to spiral into a full blown mental

health crisis. it’s the violation of being watched and recorded without consent.

when mark tries to make amends with jenny, she refuses and challenges him. in a scene that i remember often, especially when i am met with a new violation or memories of past violations, jenny confronts mark:

jenny: i want you to ask your sisters about the very first time they were intruded upon by some man or boy.

mark: what makes you think my sisters have been intruded upon?

jenny: because there isn’t a single girl or woman in this world who hasn’t been intruded upon, and sometimes it’s relatively benign, and sometimes it’s so fucking painful, but you have no idea what this feels like.

and there. that was our link, t, and our link to d. the initial intrusion.

it’s not as if we were the only girls who had experienced male intrusion at an early age, but we were the only ones at our school that we knew of. even if it wasn’t for years that we knew exactly what had happened to ourselves and to one another. we were the only girls in all black who had to slink to the bathroom sometimes to cry or to cut or to pick. and when we found each other, it felt like we might, by sticking together, be able to survive it.

but then i went to a different high school, and you began to use drugs to cope, and d began to drink, and we drifted apart.

you cut a hole in me with language, claiming that you could not be my friend. perhaps the hole was cut with silence too because no reason was ever listed for the dissolution of our friendship—i simply became unworthy of your time.

i know now, two and half years after your death, that class played a major role in why i lived and you died. we were both raped again, though how many times you were raped, i do not know. but i was able to move out of state, to go to college, to afford therapy. you couldn’t afford college. your mom spent her excess money buying drugs from g rather than contributing to your life. you never went to therapy. you moved out of town and then you died of a heroin overdose.

g told me once that you couldn’t take a cock as well as i could. when he told me, i was so pleased—my pussy, flooding and pulsing outward. g and i were older then—i had just moved in with him. i never asked him whether you liked being eaten out or fingered, whether you could handle his intense eating out style, whether it made you uncomfortable like it made me.

g told me about the time you two were high on prescription pills and you passed out and he fucked you in your ass even though he knew you didn’t want to have anal sex.

he told me this after we’d been together for at least a year. it dismantled me. i could no longer fuck him. if i tried, i had flashbacks to my own traumas. you hadn’t died yet. he said he would reach out to you to apologize. but an apology does so little in the face of sexual violence.

the problem with trying to understand sexuality is trying to decipher what is us and what is ideology. this ideology becomes doubled for the childhood sexual assault survivor, for those of us who have early memories of being sexually touched against our will before we can understand if it’s against our will or not.

what is me, what is my will, what is consent?

which sexual desires are trauma responses and which are healthy desires to explore?

i don’t think you ever had a chance to figure these things out. d seems to be figuring it out. but i can’t bring myself to talk to her. something about your death makes it too hard for me. but i hope she’s okay.

i sometimes have fantasies about being reborn so that my body is now free from the memory held in its cells of sexual violence. if we had new bodies, we could have sex free from trauma. but then i realized, it isn’t our bodies.

it isn’t our bodies at all that are the problem, l

dear h,

i was recently preoccupied with the idea of women’s aggression. it seemed that women’s aggression, as suggested by jackie wang in her response to nymphomaniac in her 2014 interview on entropy.com, could be used to combat, heal, or displace feminized guilt. i imagined aggression as a sort of inner versus outer dynamic.

guilt is an inward aggression—an aggression toward oneself for things one has done wrong. sometimes this guilt is warranted, but sometimes this guilt is caused by societal forces. for women, this guilt arises both when in concordance with and when in resistance to patriarchy.

thus aggression when turned outward, for women, can become a reclamation. an understanding that feminized guilt is both unwarranted and undeserved. this realization leads to anger. this anger is no longer placed on the self but is displaced outwardly.

wang discusses this aggression in relation to joe in nymphomaniac. joe comes across as heartless at most points in the film. she is not concerned with the consequences of her sexual choices, nor is she terribly concerned with those she has hurt. she simply fucks for herself with no regard for what society thinks of her. while she is aware that her actions come across as cruel, she refuses to change them.

this is not to say she is without guilt. as she tells her stories to seligman, she acknowledges: i’m just a bad human being. this becomes somewhat of a refrain. i can’t help but imagine lars himself believing that joe is bad. creating another bad character who is a woman, just so he can abuse her—after all, isn’t this what lars is always doing?

on the contrary, lars seems just as confused as i am about joe. he seems to at once be condoning her actions and blaming society for her guilt, while also punishing joe for these actions, thus implying that there is something inherently and grotesquely wrong with them. and as he punishes joe, we witness her aggression turn inward.

i think as women we float in and out of guilt and aggression.

when i recall high school, i remember outward aggression. i could not take inward this aggression—perhaps it was the hormones of youth that allowed me to push outward. in fact, now looking back, when i think of the times that i felt most sexually free, i remember aggression. an unwillingness to feel guilty for fucking. but this intense rejection of guilt led to cruel behavior on my part. not being clear with men whom i just wanted to fuck. not calling men back who genuinely liked me. how much i resembled joe then.

when i think of guilt, i think of my sexual dysfunction within monogamous relationships. how after several months or a year, it becomes hard for me to keep fucking my partner. usually this is because a fear of abandonment sweeps over me.

and if i can’t fuck, i feel like a failure. if i feel like a failure, i become guilty, angry at myself. everything is funneled inward until i become overwhelmed with guilt.

with p, this guilt eventually dispersed again into aggression. i’m not sure what set it off. well, i suppose it was a desire to stop feeling like the one at fault. it was a desire to let go of the guilt, but in letting go, i became an angry force, and that anger was unleashed toward p and ultimately toward myself.

i don’t fully know how to explain this, h. there were a lot of factors. i felt like i was failing him, both sexually and emotionally. i was afraid he might leave me. i began to sabotage the relationship. this is not uncommon for those with ptsd, but linking it to my mental health disorder does not excuse my behavior. i began to hide things, to stop talking to him. i began to say things to sabotage the relationship—awful things that i didn’t mean. i became angry. that anger should have been dispersed further outward, away from me, away from p.

when p and i saw nymphomaniac and i said that i felt, at times, very much like joe, he was put off. not because she was sexual, but because she was so cruel, so self-focused, so harmful to others. when i think of the dissolution of our relationship, i felt like joe.

h, i don’t want to be like joe. at my core, i’m not. at my core, i am kind. but i don’t know how to turn this feminized guilt outward in a way that doesn’t harm others. and i don’t know how to be sexual without falling into this aggression-guilt loop.

h, you’re married now, and we haven’t spoken in months. do you still believe you’re a nymphomaniac? what have you done with your aggression? is it guilt you feel now, or are you free from it? if you feel aggression, have you learned how to direct it?

may we both be kind but also guilt-free, l dear s,

i was thinking about collaboration and friendships with women. or i suppose i should say friendship as collaboration.

when we were collaborating, the final work was, of course, important to me. but of more importance than the project itself were our sweet meetings. drinking tea, dancing and writing about each other’s movements, sharing the photographs and paintings and poems that were informing our creative interests.

there is something so lovely about our friendship. when i’m with you, my movements become more careful, my voice grows softer but still speaks, i feel cozy. and while we do not share the intimate details of our sex lives, we share so many other intimate details, and our bodies are a focal point in our conversations. through these sweet meetings, we create something much richer than our collaborative artistic projects.

your friend, y, was here this weekend. we had such a wonderful time, and now i’m wondering about creating networks of friendships. how much richness would be added to our lives if we collaborated not just in art, but also in building up our connections with the powerful, lovely, intelligent, kind women that we know.

might this help us to reclaim our lives, our bodies, our sexualities? l

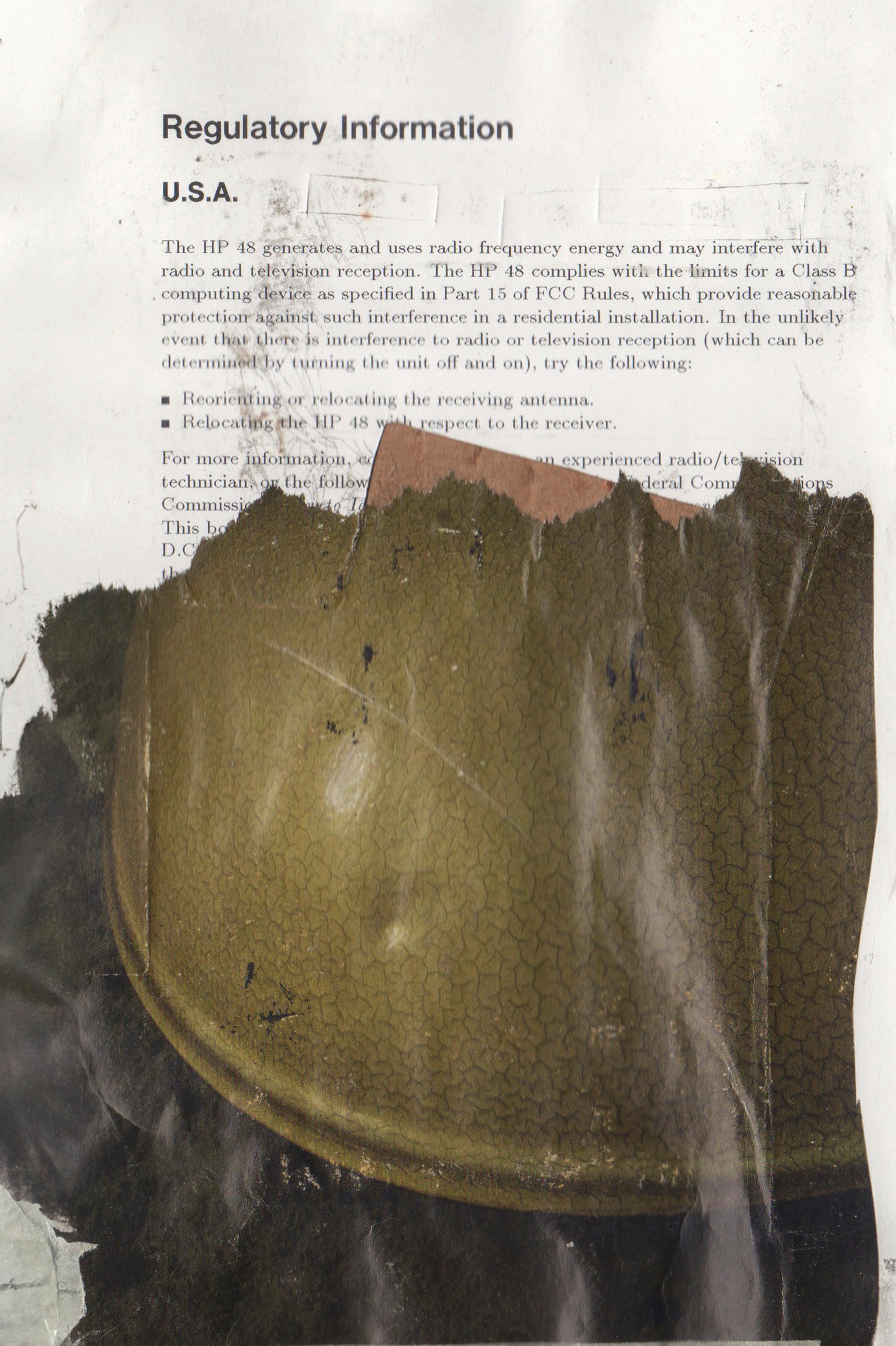

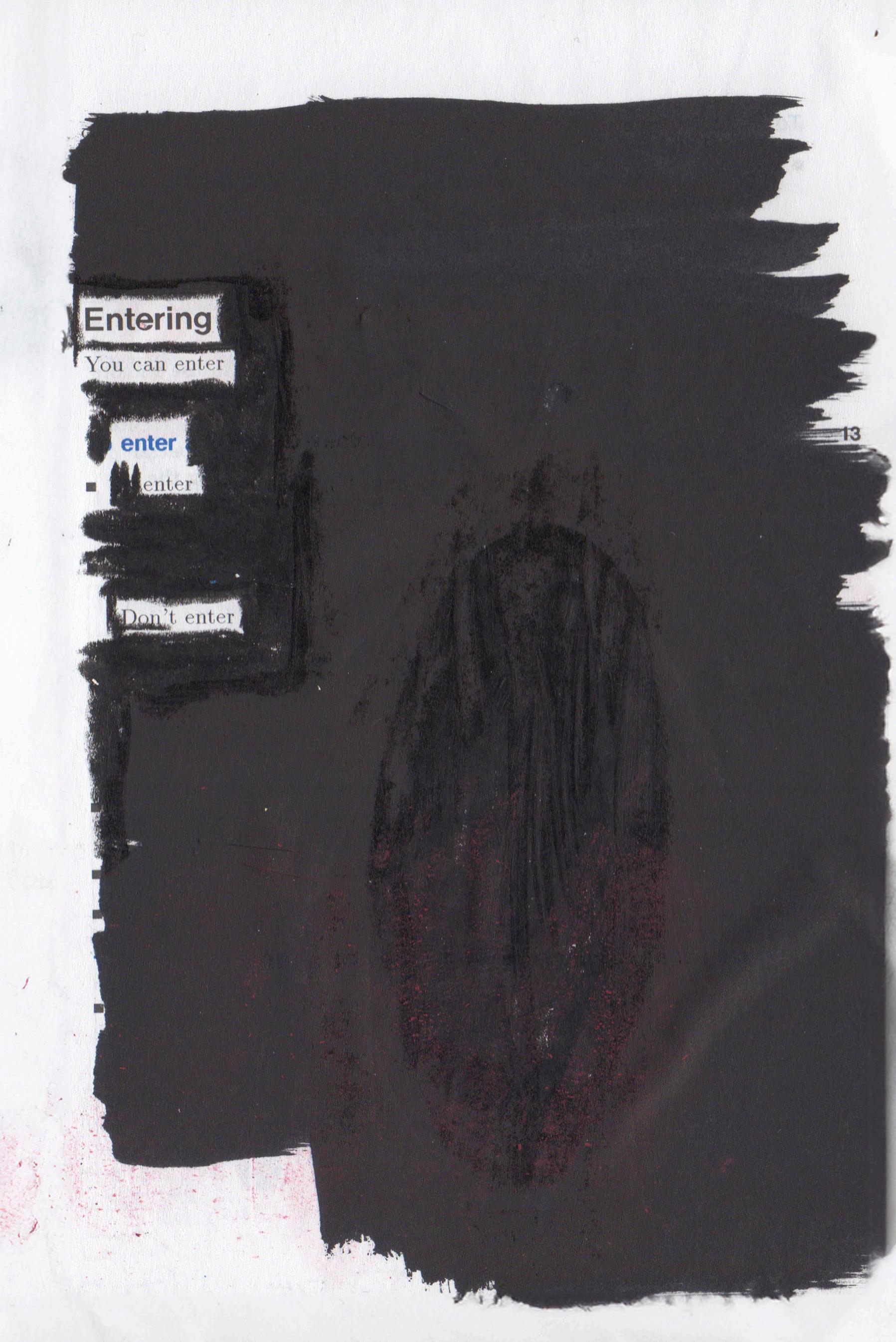

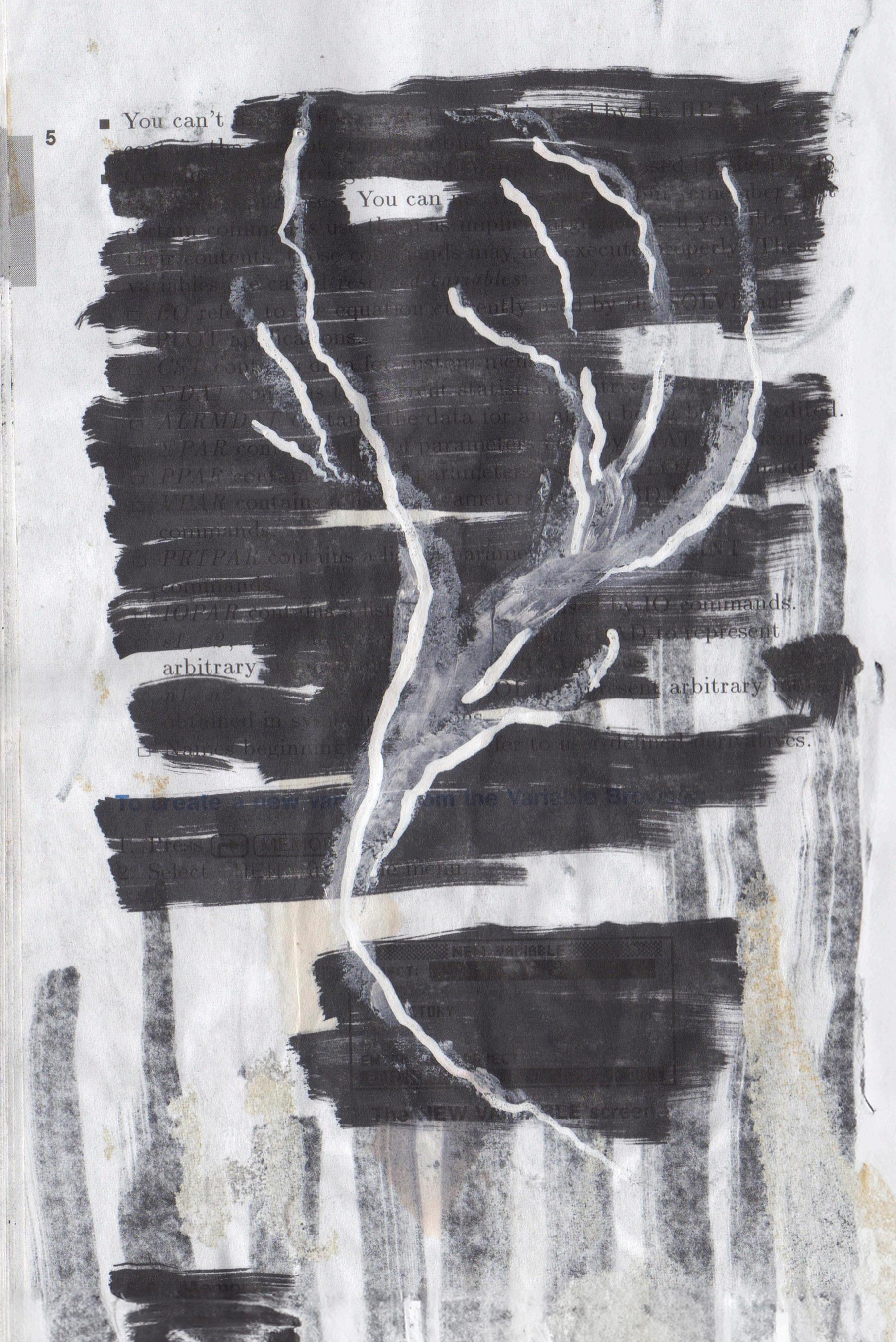

NATHAN STOREY is an interdisciplinary artist, curator, writer, educator, and facilitator based in Boulder, Colorado. His work traces the relationship between printed matter and queer desire, memory, and loss. Storey’s work has been supported by ICA San Diego, 80WSE New York, and galleries internationally. He has attended workshops and residencies at the Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown; Anderson Ranch Art Center, Snowmass; and the Prattsville Art Center, Catskills. Storey’s work has been featured in MATTE Editions, Queer Aesthetics Journal, HereIn Journal, and the San Diego Union-Tribune In 2019, he founded SUBLIMATION, an artist-run space supporting multidisciplinary exhibitions by underrepresented artists in New York’s Lower East Side. In 2024, Storey established UNDERTOW, an artist-run press supporting queer artists’ printed matter and ephemera. He is a 2025 Queer|Art|Mentorship fellow working with Ken Gonzales-Day. Storey is the curator of the iterative exhibition RUINS: PERFORMING QUEER

HISTORY. He holds a BFA from NYU and an MFA from UC San Diego. He is currently a professor at the Rocky Mountain College of Art & Design.

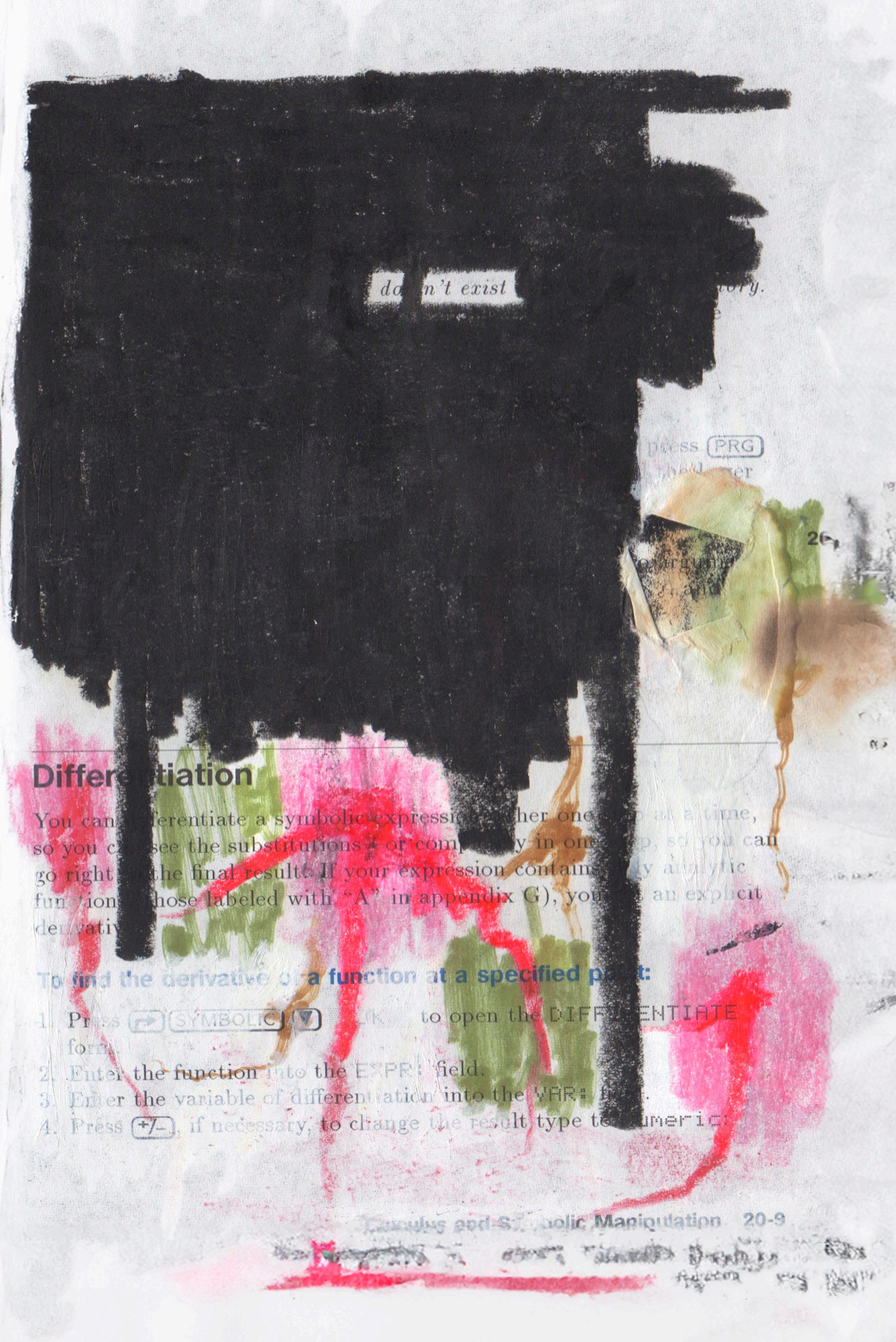

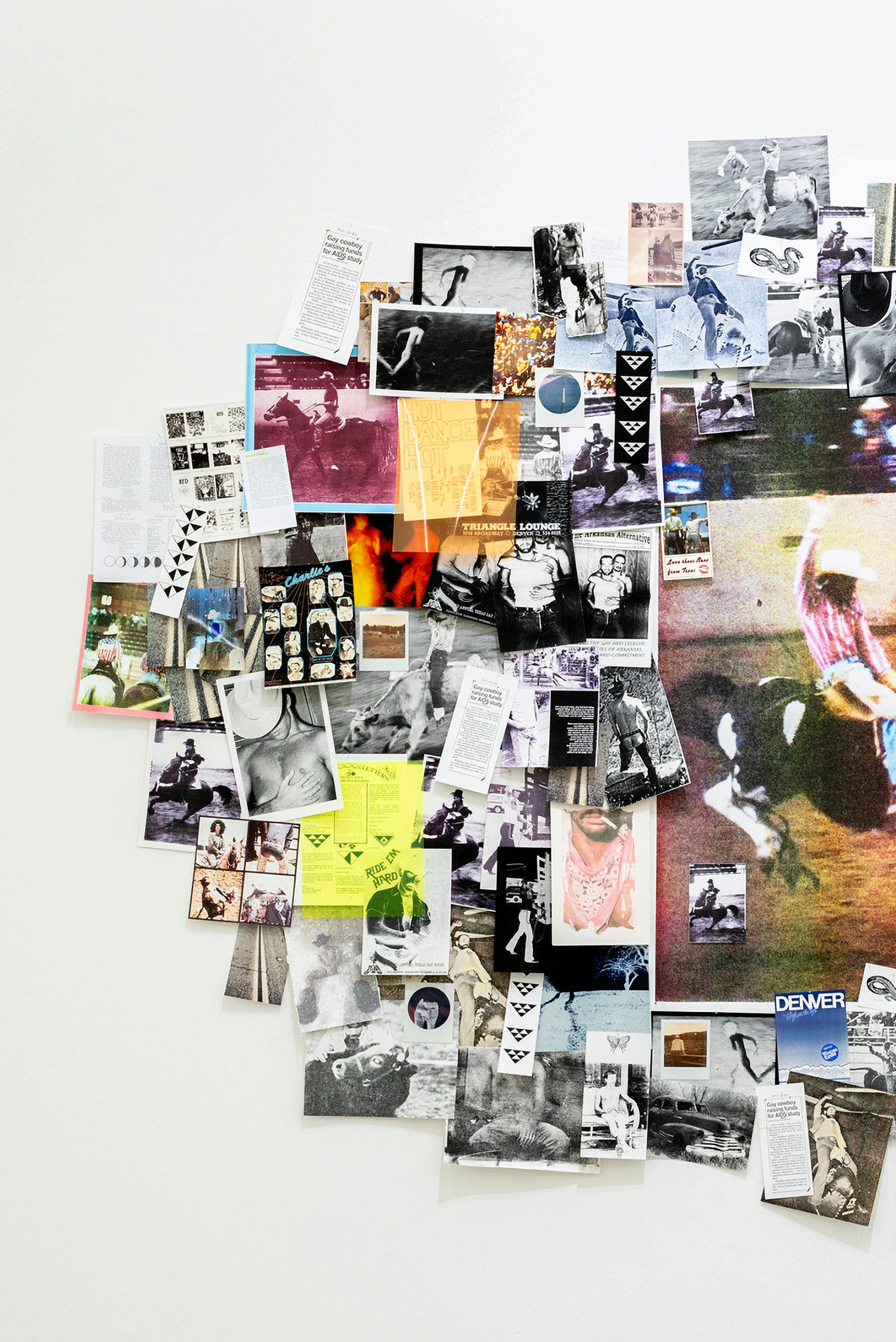

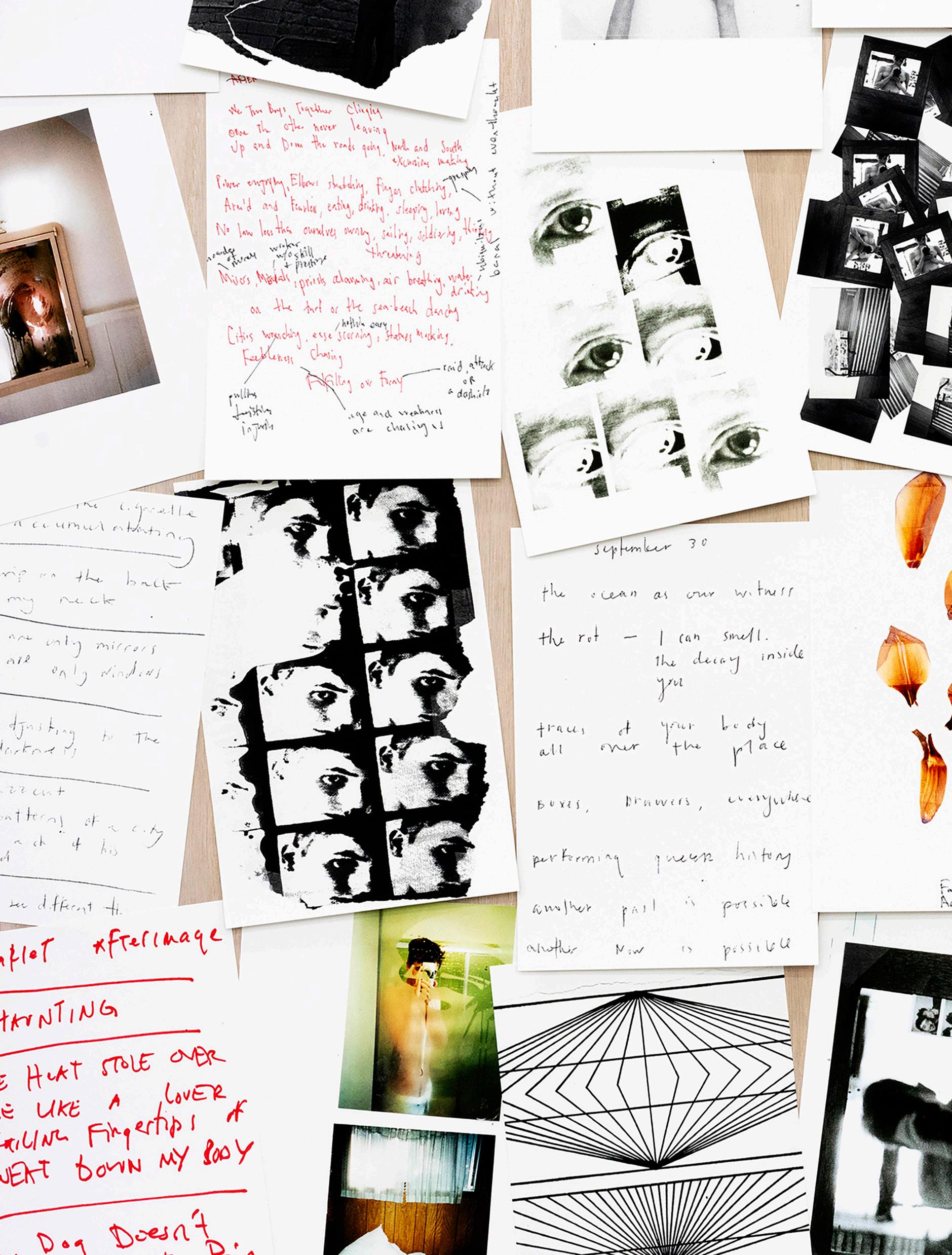

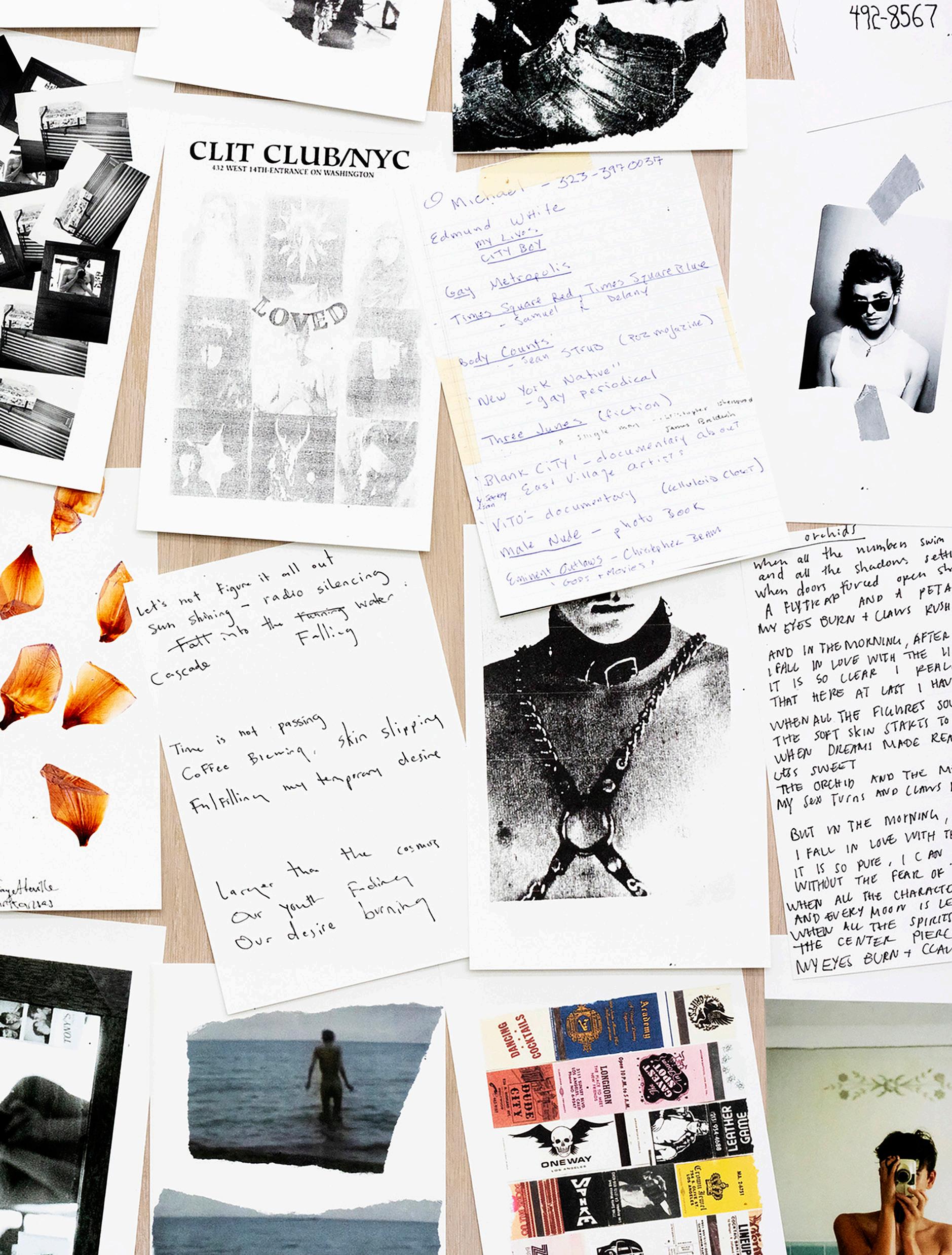

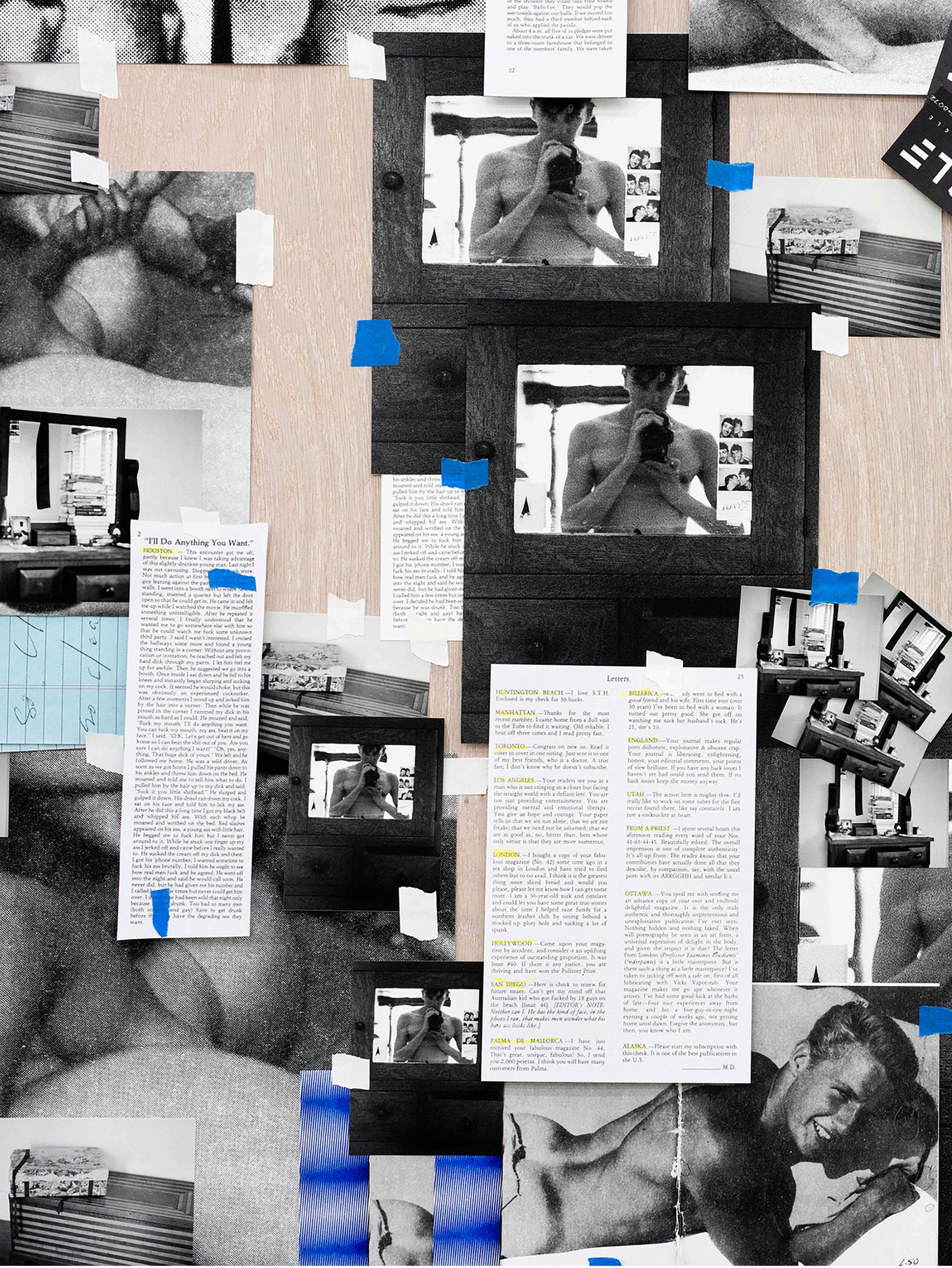

My interdisciplinary studio practice traces the relationship between printed matter and queer memory, history, collectivity, liberation, and loss. My current bodies of work, TRACES and STAINS, suggest printed matter as a facilitator, witness, and residue of gay desire. In Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz contends, “the key to queering evidence…is by suturing it to the concept of ephemera”. Ephemera—traces, residues, stain—are the windows into queerness.

My praxis reckons with the archive in order to trace gay and queer desire through time while questioning what is remembered and what is left behind, what is preserved and what has disappeared. In looking, accumulating, and sorting through gay material and ephemera, I seek something unknown (and possibly unknowable) that has been lost. Lost futures? Lost desires? Lost dreams? I am not stitching the fragmentary pieces of the archive perfectly back together but aggregating, merging, and rearranging its immense belongings. Through this weaving, disparate images, ideas, traces, and stains, are both concealed and revealed. Among all the layers, moments are both illuminated and in the dark. Is another past possible?

The work engages with materials from queer archives such as nightclub flyers, ephemera from the Gay Rodeo, and queer zines. I simultaneously construct and accumulate my own diaristic archive of gay intimacy, longing, and pain. I hold onto personal and raw materials: taping photographs, snapshots, and pictures to notebooks; throwing notes and letters into shoeboxes kept under my mattress or on the back shelf of my closet. Through various methods of collage, fragmentation, repetition, and assemblage, the work ultimately blurs the juncture at which the personal and collective memory meet—but does not erase the seams.

My practice ruminates on a longing for an interconnectedness to queer histories and pasts, often lingering in the shadows. Printed matter contains vestiges of loss, intimacy, and melancholy. To touch the queer archive is to encounter stains of memory and desire.

TERÉ FOWLER-CHAPMAN

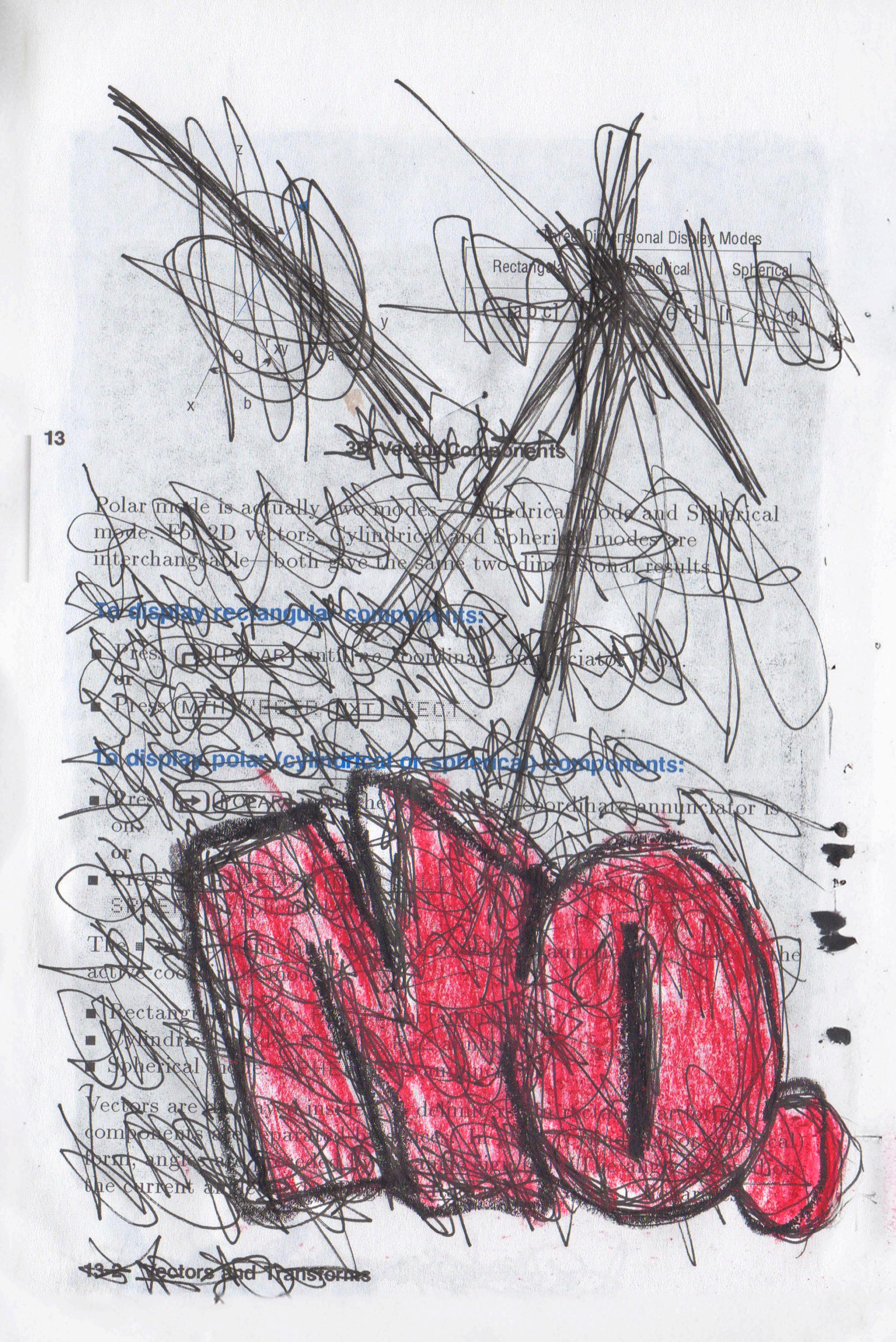

(he/they) BFA, CLC, PRC poet, educator, life and recovery coach, is a dynamic cultural worker, educator, and youth advocate whose multifaceted work spans poetry, visual arts, and community engagement. Whether pulling poems off the page, creating blackout poetry, cutting up images from old worlds, or crafting new ones through intuitive card-making, their art centers on blackness, trans identity, queerness, spirituality, and sobriety. Teré’s work embodies a heartbeat and a tongue, engaging folx in meaningful discourse. For Teré, home is wherever their heart resides, and they are passionate about planting creative expression through workshops, exhibits, and performances. Their deepest commitment lies in planting poems behind bars with incarcerated youth. Teré’s workshops often weave inner child work, meditation, play, and creative expression. Always found crafting poems in classrooms, Teré believes they learn more from the future generation and are honored to cultivate a body of work that teaches the power of vulnerability by fostering others’ creativity. Although they reluctantly work with adults, Teré aims to create inclusive and equitable spaces for youth by exploring biases and privileges. They also facilitate workshops around self-care and inner child work within the community. Fowler-Chapman is the author of M O O N S H i N E (R&r Press 2023).

GLORY HOMETOWN

for Isaac Benjamin Kirkman - rest in power

The first time I saw a museum of tattooed graffiti and portraits every image etched into the fire of your body— a flame that never asked permission to burn

My eyes tried not to follow the hallway of the cathedral—thin-layered concrete and gold— but they did.

I like it in the city when two worlds collide

You get the people and the government

Somewhere between the knuckle and nail-bend said:

h o l y p o e t

From his fists, the delivery of the haunting and the most high all balled up at once

Everybody taking different sides

I am a city of renaissance, of hope, in constant rebirth and repetition brilliantly battling and becoming even before the poem left the town.

Shows that we ain’t gonna stand. Shows that we are united. Shows that we ain’t gonna take it

I am a city that has lost more wars than I’ve won.

In a country, where everything ruined, is a ruin called beautiful.

Somehow we found the first town that felt like home— and became buildings.

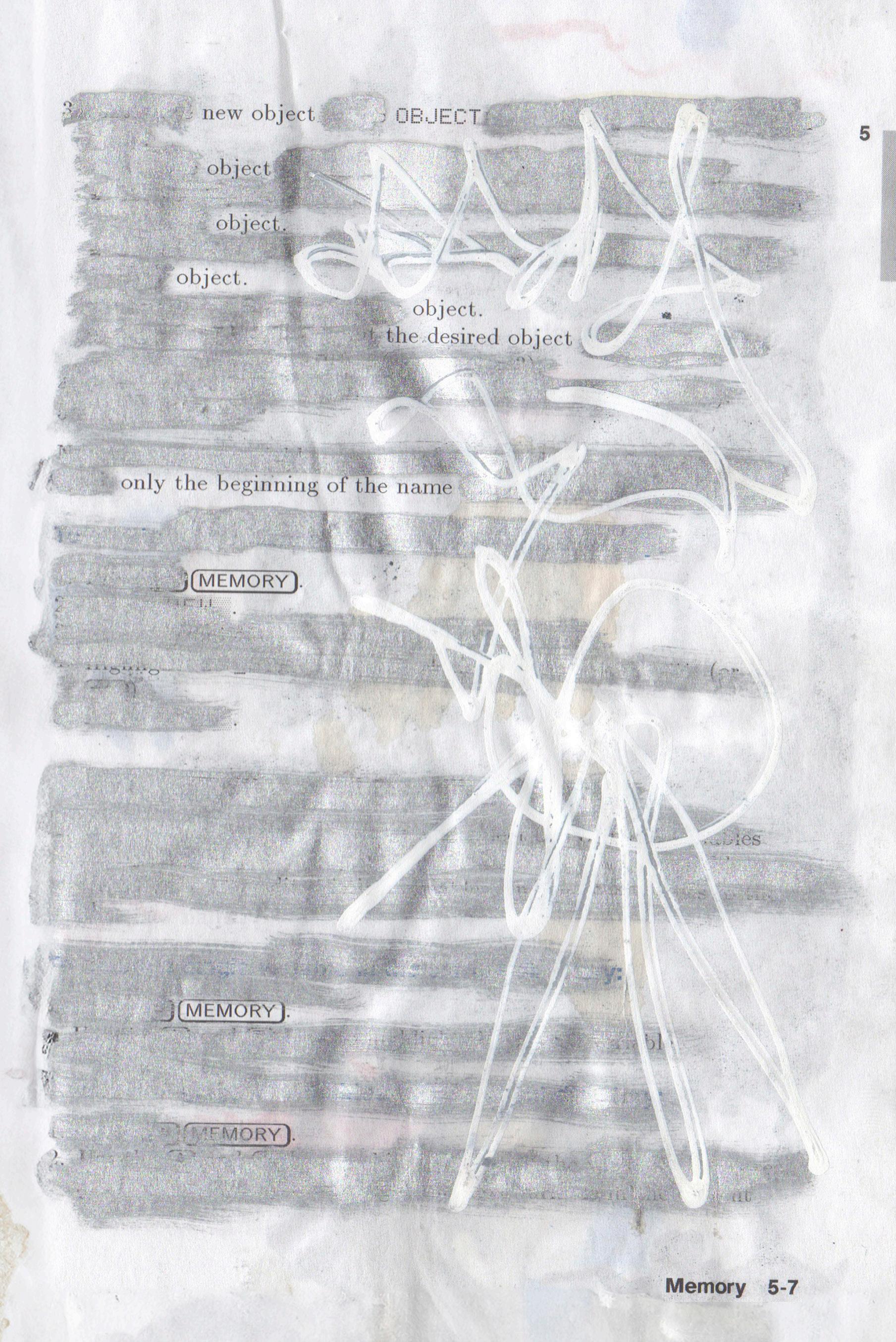

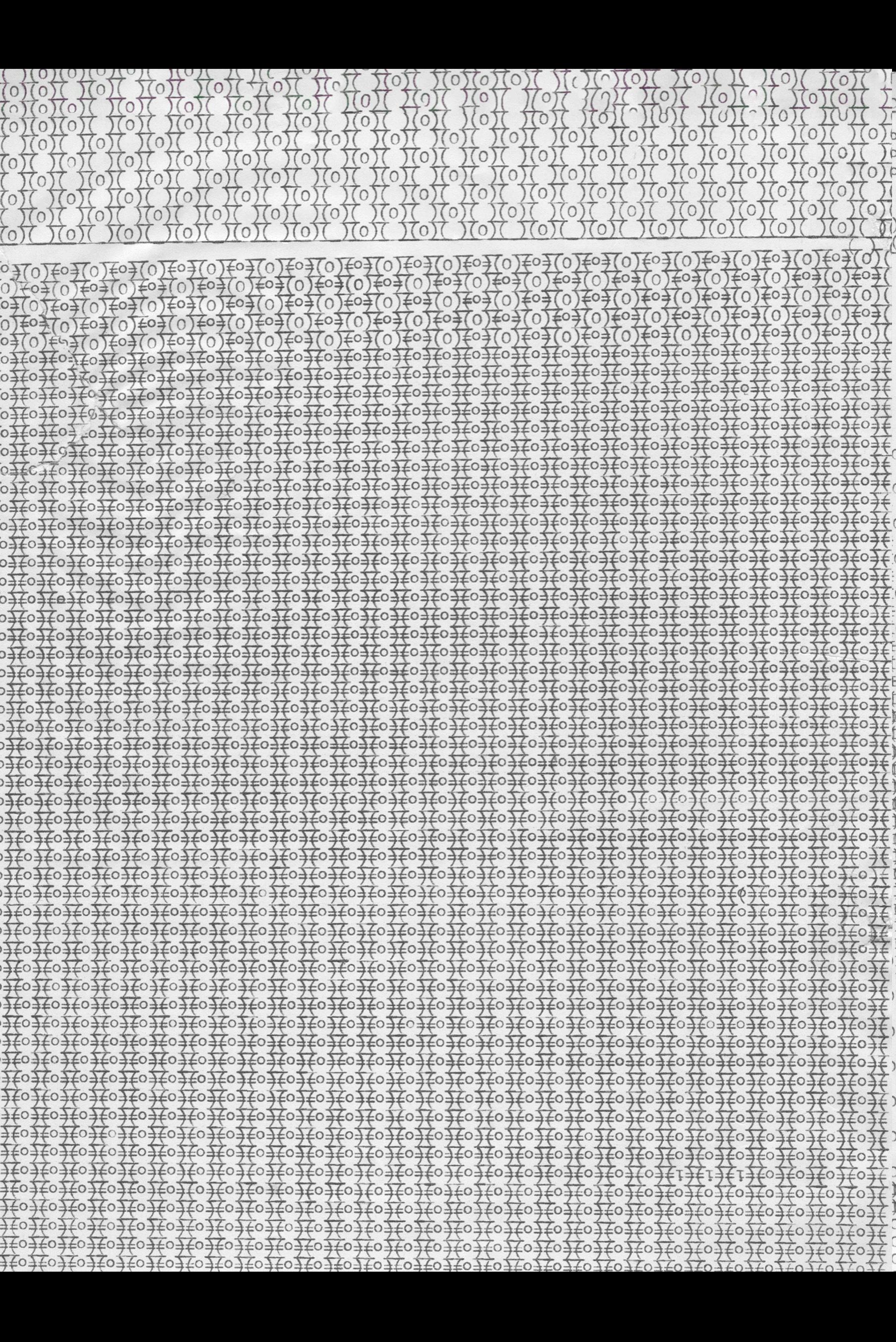

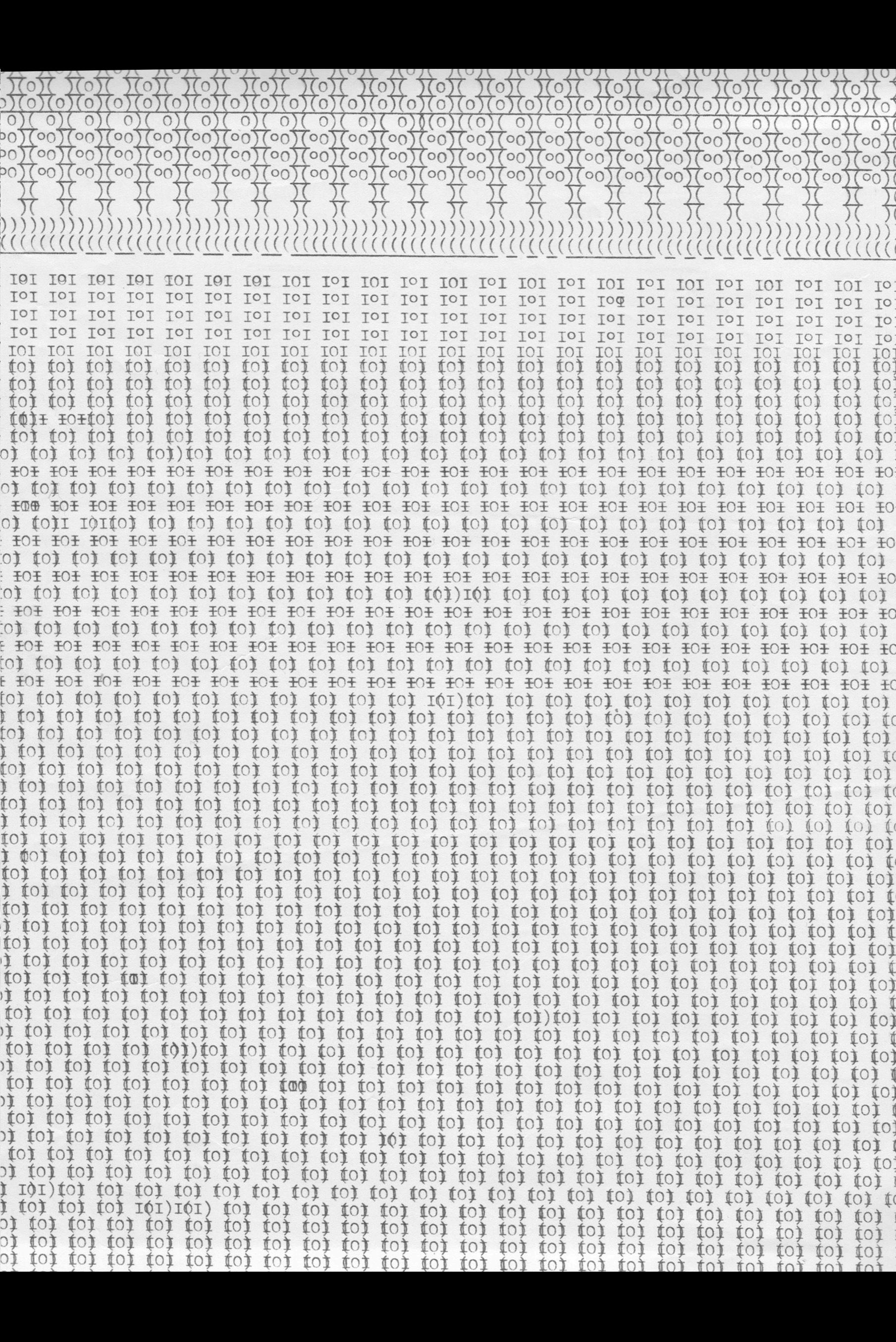

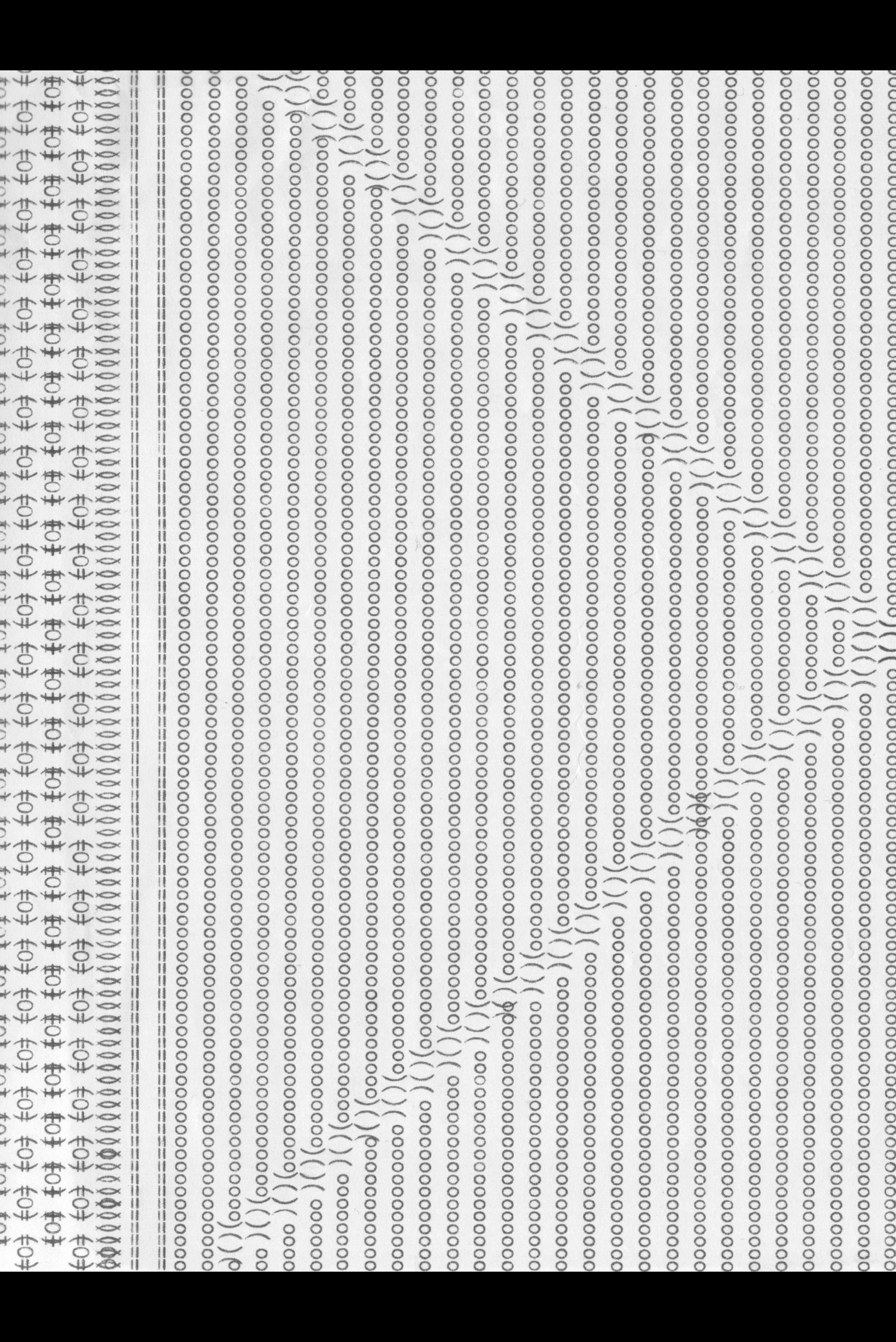

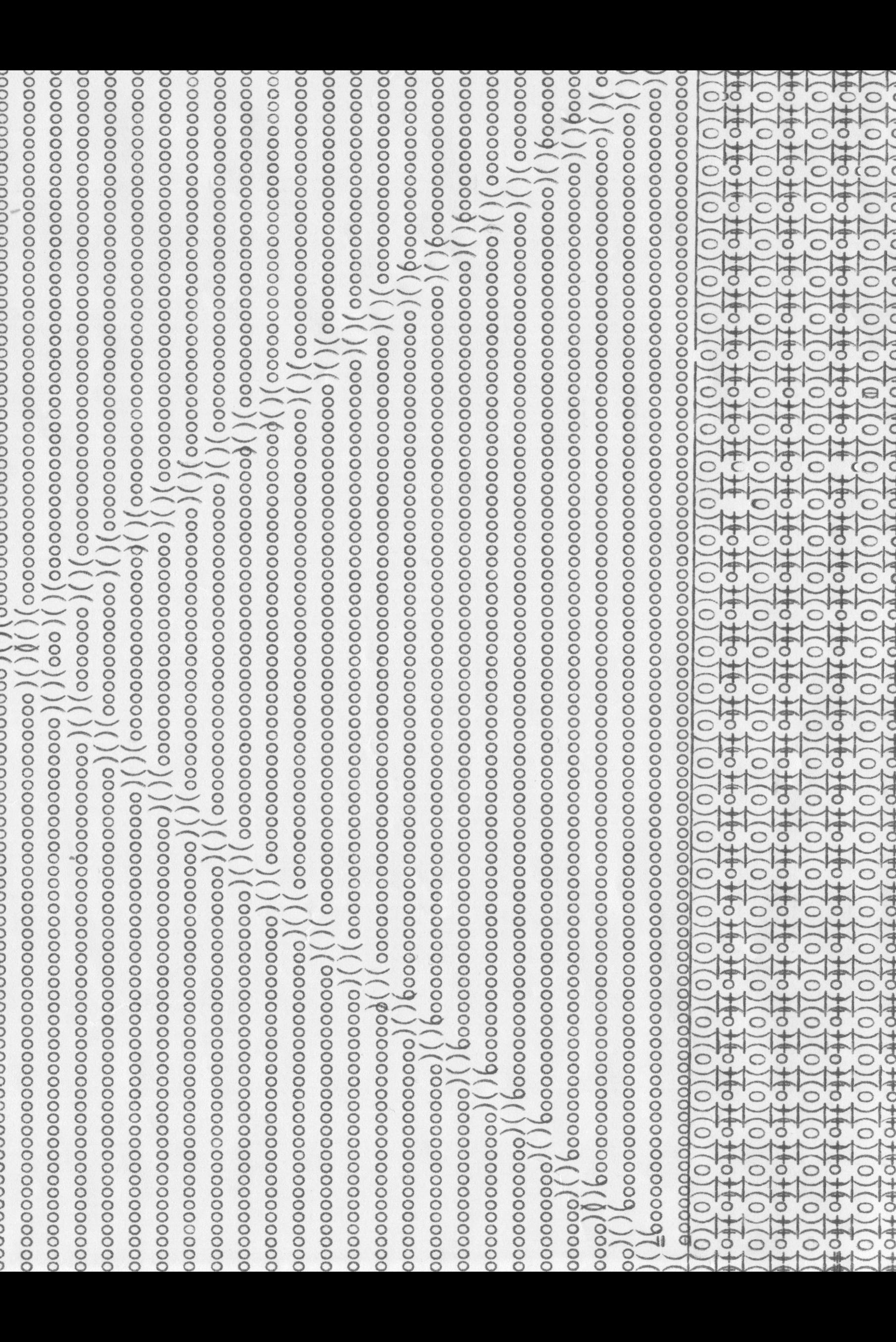

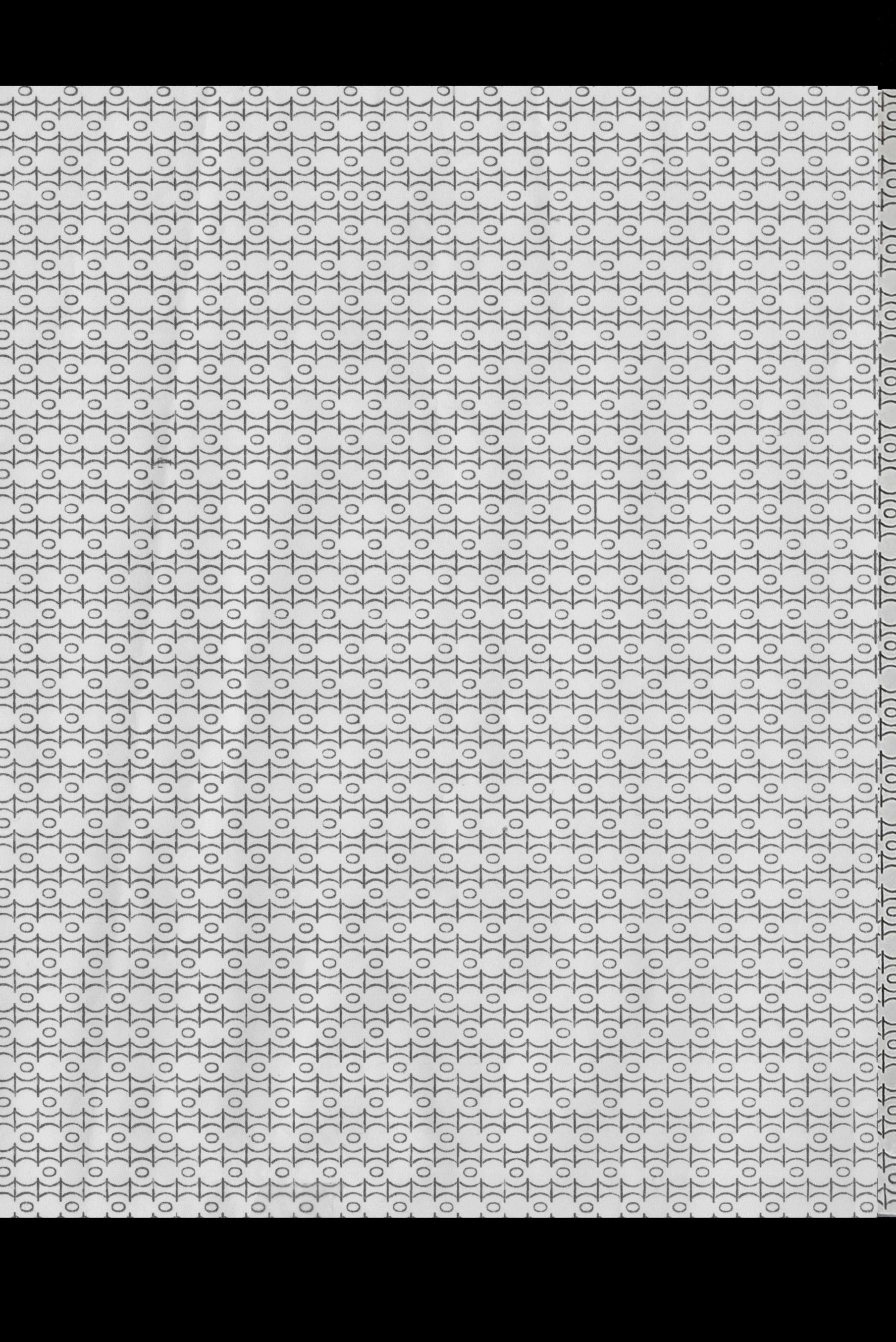

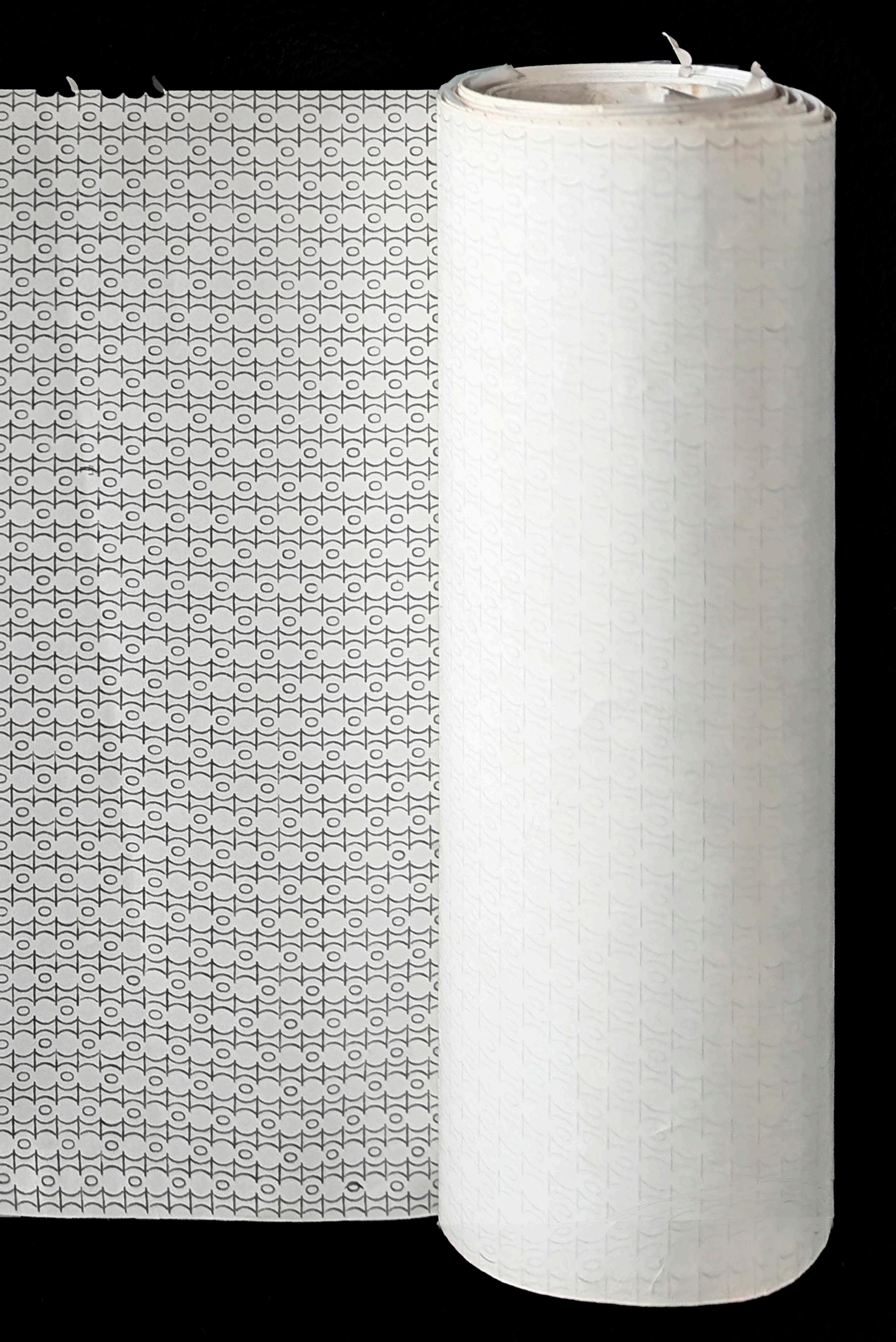

AMIR ALSDI I am half Iranian, half Iraqi, and transgender. I was born and raised in Iran and am currently pursuing my MFA in Sculpture Post-Studio Practice while teaching at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

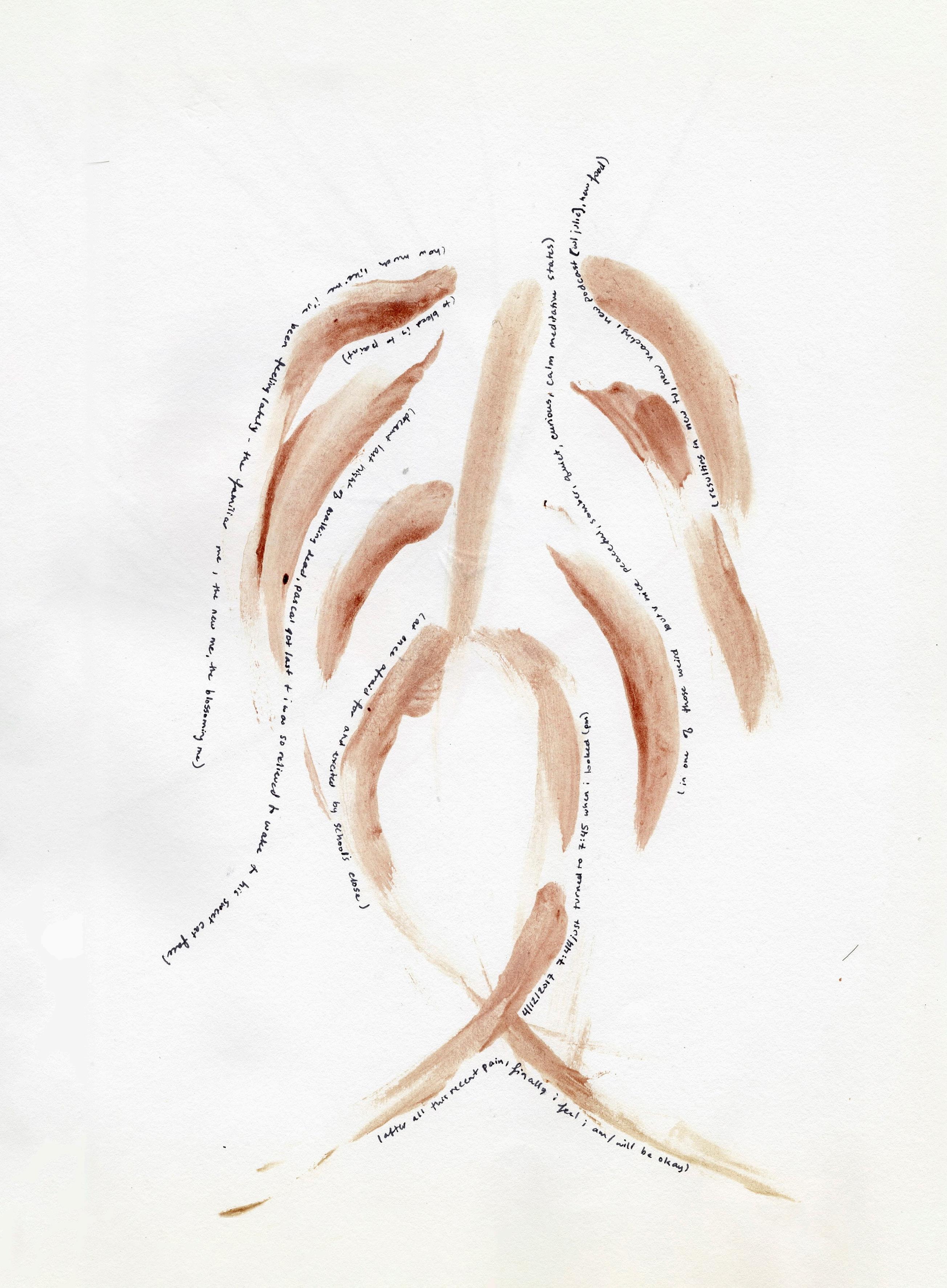

I live with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), a result of surviving long-term trauma. Growing up in a culture where divergence from the norm is punished, I had to conceal my true self to survive. Art became a space where I could fully exist, even when I didn’t yet understand what that meant. My work is influenced by themes of invisibility, memory, fragmentation, and the act of creation itself. Through therapy, I have come to recognize 13 different selves within me. Five of us are artists: Amir, Dati, Neel, Kiddo, and Warrior. Each of us has a unique perspective on seeing, remembering, and creating.

Though our materials and methods vary, I, Amir, found my primary tool for creation in the typewriter—a medium that reflects the repetition, rhythm, and physical intensity of living with both visible and invisible challenges.

Our work does not adhere to a single narrative or style; instead, it represents a dialogue across time, identities, and ways of being. The shared act of making becomes a connective tissue among our different selves—one that honors our differences without demanding coherence.

WHEN WE WERE ONE THROUGH THE HANDS

For two weeks, I typed obsessively. I barely ate or slept, and I didn’t leave the house. I was completely immersed—entranced. It felt like my body became a vessel, with each part of me taking turns sitting in a circle to tell our story through my hands. You can see it in the piece: every shift in the pattern marks a change in who’s typing. It wasn’t just about making art; it was an all-consuming occupation for my body and mind. We were all present. We were alive in this experience. For the first time, I felt whole.