Expansive services. Compassionate care. All right here.

We’re raising the standard of great care right here in eastern North Carolina. We’re expanding our services and our team to ensure that you and your family have access to the care you deserve—whenever you need it. From advanced specialties to everyday wellness, we are committed to serving our region with compassion and expertise. Because our purpose always remains the same—we help people live their healthiest lives.

Businesses thrive here, too. These magnificent loblolly pines are a fitting symbol of a regional environment that encourages growth—in nature and in human enterprise. It’s why Brooks Pierce, with over 125 years supporting businesses in the state, maintains an office here. We love the habitat—both natural and economic.

From paddling quiet coastal waters to biking sunset trails, Eastern North Carolina offers more than just stunning views, it offers space to breathe, room to grow, and a way of life that inspires. Here, business success and quality of life go hand in hand. Whether you’re expanding, relocating, or launching something new, Eastern NC is ready to welcome you with open skies and open opportunity.

14

88

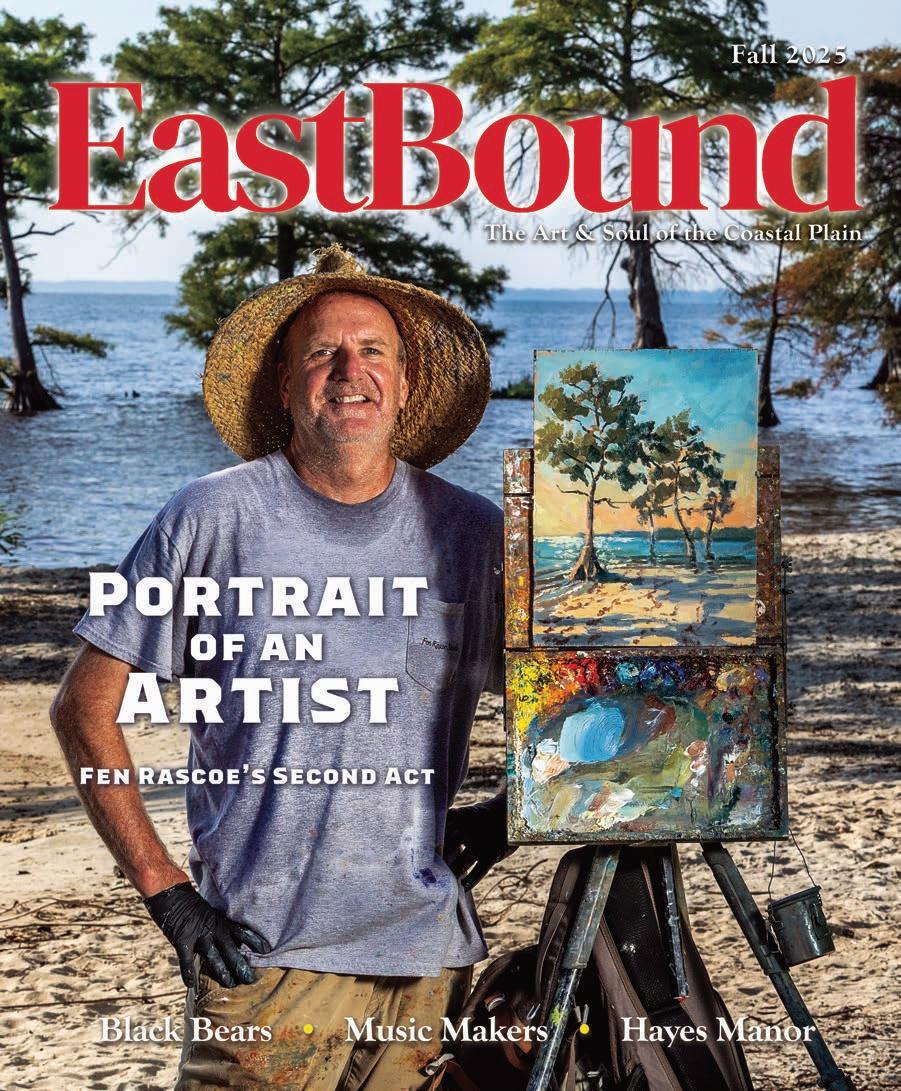

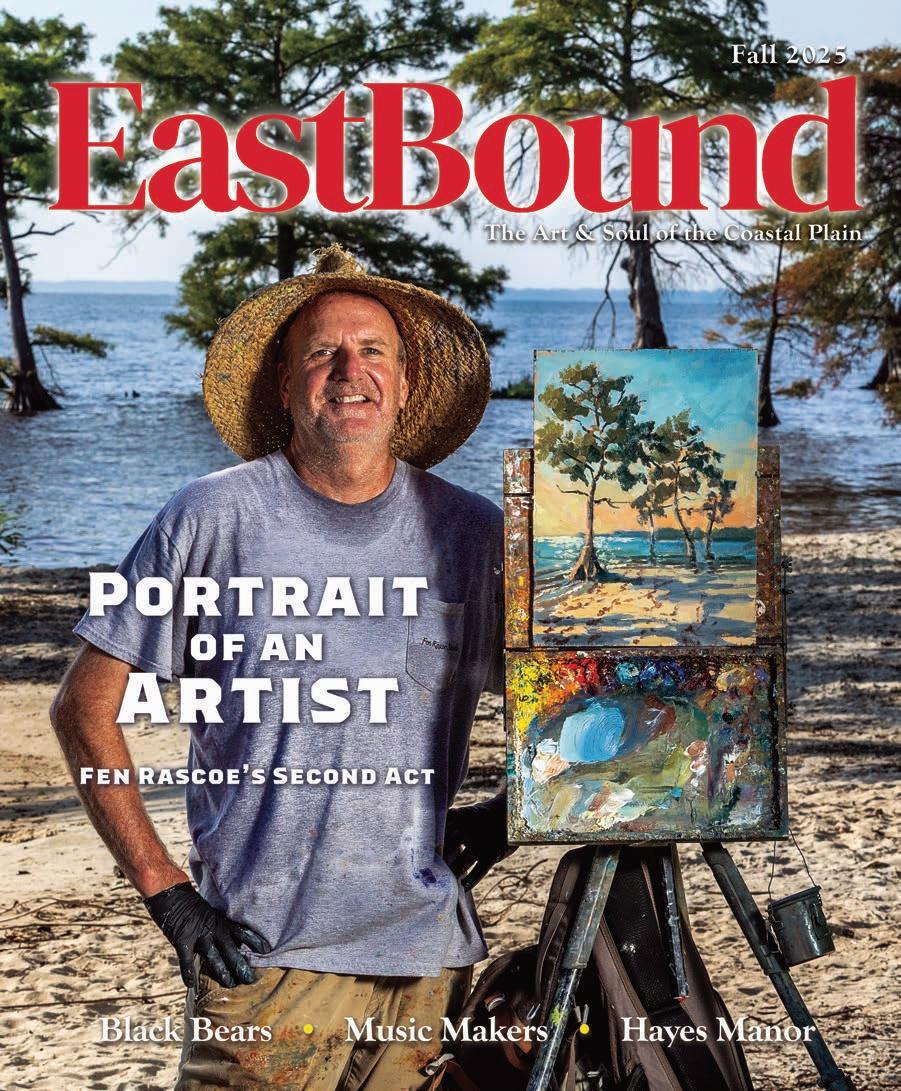

by Jim Moriarty

Rascoe’s

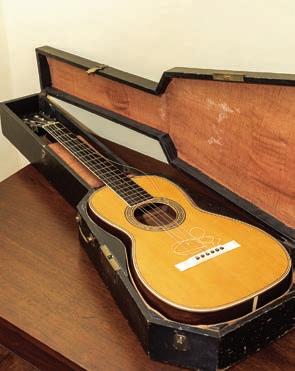

52 FOUNDATION OF CULTURE by Tom Maxwell

Documenting our hidden musical treasures

58 RESTORE, PROTECT, PRESERVE by Teri Saylor

One man’s quest to save the storied Frying Pan Tower

66 THE BEAR NECESSITIES by Todd Pusser

North Carolina’s Coastal Plain is a mecca for black bears

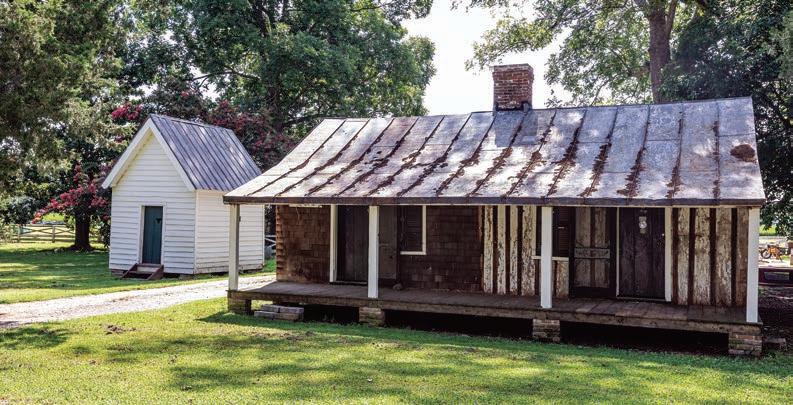

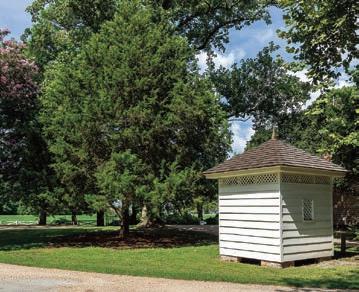

72 HISTORIC HAYES by Samuel Bobbitt Dixon

The stately elegance of an Edenton treasure

Cover Photogra Ph by John gessner

We help the owners of closely held businesses tackle their most important legal issues, each and every day.

Our law firm “grew up” in small towns across eastern North Carolina, serving family-owned and locally managed businesses. Today, we’ve grown to five offices, with over 100 attorneys practicing from the mountains to the coast, to cover the entire state. Our attorneys regularly advise owners, managers, stakeholders, and family members of closely held and family businesses to resolve the questions that keep them awake at night.

Celebrating 25 years of building a better future — one innovative, sustainable project at a time. From classrooms to communities, we've shaped how people learn, live, and grow. Proudly rooted in Eastern North Carolina, we've laid the foundation for what’s next!

David Woronoff, President david@thepilot.com

Ben Kinney, Publisher bkinney@businessnc.com

Jim Moriarty, Editor jjmpinestraw@gmail.com

Andie Stuart Rose, Art Director

Keith Borshak, Senior Designer

Alyssa Kennedy, Digital Art Director

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Joseph Bathanti, Anne Blythe, Susan Campbell, Samuel Bobbitt Dixon, Jim Dodson, Jason Frye, Tom Maxwell, T. Edward Nickens, Mary Novitsky, Todd Pusser, Celia Rivenbark, Liza Roberts, Teri Saylor, Scott Sheffield, Kimberly Daniels Taws, Harris Vaughan, John Wolfe

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

John Gessner, Todd Pusser

ADVERTISING SALES

Melanie Weaver Lynch, Sales Manager 919.696.6838 mweaver@businessnc.com

Erika Leap, 910.693.2514 erika@thepilot.com

Julie Nickens, 919.622.5720 julie@waltermagazine.com

ADVERTISING GRAPHIC DESIGN

Lauren Ellis

Scott Yancey EB

Henry Hogan, Finance Director 910.693.2497

OWNERS

Jack Andrews, Frank Daniels III, David Woronoff In memoriam Frank Daniels Jr. eastboundmag.com 1230 West Morehead St., Suite 308 Charlotte, NC 28208

We believe banking is personal. That’s why we keep our decision-making local and our service rooted in relationships. We're not just in your neighborhood, we’re part of it.

Put the power of local to work for you.

Before a student builds a business, leads a team, or launches a career — a teacher lit the spark.

At STEM East, we believe that educators are the first-line economic developers, shaping the minds that will drive our region’s future. By investing in teacher training and classroom innovation, we’re equipping students with the skills they need to thrive in high-demand careers — right here in Eastern North Carolina.

When teachers are empowered, students succeed. And when students succeed, communities grow.

The future of our workforce starts with the educators leading it today. Somewhere please include, for more information visit www.stemeast.org

grew up in Greenville during the 1970s. Way back then, Little League baseball reigned supreme over all organized sports.

My college roommate, Richard Pace, suited up for the North State League’s perennial powerhouse, CocaCola, and he still teases me mercilessly about my recordsetting futility playing for the Tar Heel League’s Pepsi Cola. We went 0-15 my 11-year-old season.

All these years later, I don’t remember any of my toomany-to-count errors and losses but I can still recall the Little League Pledge, recited without fail before every game. We scrambled around the diamonds at Elm Street Park and Guy Smith Stadium in jerseys sponsored by civic clubs like the Lions, Moose, Jaycees, Optimists and Kiwanis. I have no recollection of the Rotarians playing the Little League sponsorship game though their motto of “Service Above Self,” as well as their Four Way Test, would be a saving grace for organized sports — in any era.

In your hands, you’re holding my Rotarian-inspired attempt to give something back to this special part of the world, which helped shape the course of my life.

From Wilson to Wanchese and all points in between, this magazine will tell the stories of the people and places that make the Coastal Plain such a distinctive place to call home. Our pages will celebrate the culture — whether that’s baseball, barbecue or boating — that has defined Eastern North Carolina for the better part of four centuries.

EastBound ’s slogan is “The Art and Soul of The Coastal Plain.” That’s because we intend to create a magazine that touches the heart and stirs the soul — just as we have done with our award-winning publications in Charlotte, Greensboro, Raleigh and Southern Pines/Pinehurst.

Once a quarter, we will endeavor to become the thread that binds the patchwork quilt comprised of Eastern North Carolina’s 41 counties. We’ll illustrate your magazine with dynamic photography and design that we hope makes your chest swell with pride.

EastBound will introduce you to the remarkable people who have shaped our shared past and to your contemporaries who are busy building us a brighter future.

We take a broad view of the arts. So, we will fill every

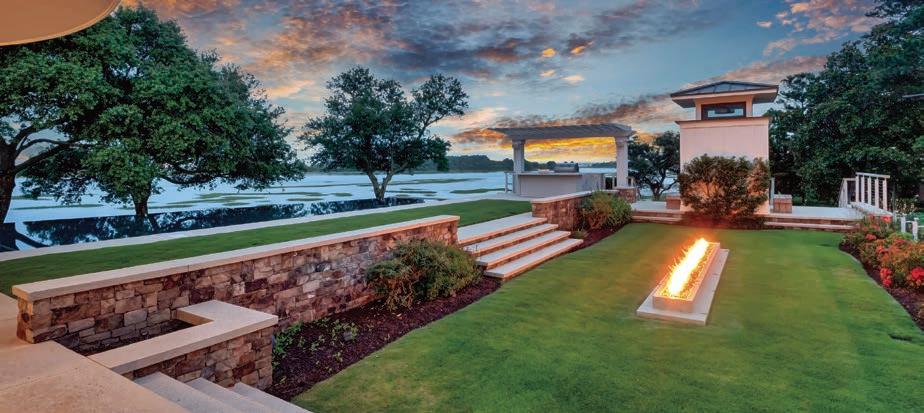

one of our editions with traditional artistic fare — short fiction, photography and poetry. Beyond the canvas and the page, though, we believe a well-crafted cocktail and a well-appointed home are, indeed, works of art, too.

In every issue, we’ll delve into our passions for food and drink, celebrate the beauty of homes and gardens, and revel in the call of the outdoors — from the quiet thrill of fishing and hunting to the exhilarating freedom of sailing and surfing.

We want to create a magazine that shimmers with energy, enthusiasm and entrepreneurial spirit — just like Eastern North Carolina itself.

Those qualities along with a heaping helping of Down East authenticity will propel both EastBound and our special community for years to come.

We intend to follow musician Jerry Reed’s keen insight. In his 1977 hit song, “East Bound and Down,” our patron saint said it best: “We’ve got a long way to go and a short time to get there. We’re gonna do what they say

We couldn’t agree more wholeheartedly. So, let’s get

David Woronoff President Old North State Magazines

By

T. Edward NickENs

by bEN wEsTEr, Zach wiggiN & camEroN Luck

for centuries, anglers have set their sails, or pointed the bow of their boats, or poled their shallowwater skiffs towards the marsh-rimmed waters of southeastern North Carolina. You can feel that legacy in every tide change, and in every breeze that ripples the salt marsh.

This is a place where passion, dedication and integrity can make dreams come true. It’s a place where a couple of locals can turn a few hundred square feet of concrete block and waterway views into something much bigger than a local fishing hub: a place that honors the angling legacy of the past by building a business that casts towards the future.

As a writer and journalist, I’ve wandered through a world of wild places across North America. But I can’t seem to shake the sand of Eastern North Carolina out of my shoes. We’ve got miles of cypress-shaded creek and rivers. Marsh coves and big woods. Worlds to explore, all without leaving the land of wholehog barbecue.

Eastern North Carolina’s story is as old as a time-blackened shark’s tooth. But it’s a new story, too, and it’s being shaped today by those who have looked around and seen the deer and bear feeding in those big sprawling farm fields, heard the redwinged blackbirds calling from the marsh and decided: This is where I’ll make my stand. This is home.

Two anglers, John Mauser and Perry McDougald, put down their roots in the picture-perfect town of Swansboro. They’ve

built businesses here. Built a solid path to a sustainable future in Eastern North Carolina. They’re making their mark out there where a lot of people seem to want to be these days: on the water.

The story of Sound Side Outfitters, Tailing Tide Guide Service and Mauser Fly Rods isn’t just about making the perfect rod, or the perfect catch. It’s about a deep-rooted connection to this land and to the waters that define it. It turns out that Mauser and McDougald couldn’t shake the sand of Eastern North Carolina out of their shoes, either.

Whether it’s a solo paddle, a family hike, or a backcountry adventure, Eastern North Carolina has it all—and we’re here to get you ready for the journey.

John Mauser and Perry McDougald found themselves a little spot, called a few friends to help move them in and built themselves a couple of businesses. More than that, they built a bridge between eastern North Carolina’s past and their future. And now, when the sun sets over the marshes outside Swansboro, North Carolina, one of the last places to hold onto the light is a little shop by water. It’s a place built on dreams, whether that dream is the dream of a fish of a lifetime . . . or simply a life well made. EB

Scan to hear the story of Sound Side Outfitters in Episode 1 of an Eastern NC video series produced by NC East Alliance

Campbell University invests in each student. We prepare each one to make a life, to make a living and to make a difference. Our students are welcomed into an inclusive community of family, and mentored to become leaders who will impact the world. Inspired by our faith and belief in the power of education, we encourage each student to grow academically, spiritually and socially through the world of opportunities that surround them. Beyond education, transformation. campbell.edu

By Jim DoDson

September may be the ultimate month of change.

As summer’s lease runs out, the garden fades, and days become noticeably shorter and sometimes even cooler, hinting at autumn on the doorstep. After Labor Day, summer’s farewell gig, in 39 percent of American households — those with school-age kids — the days bring new schedules and an accelerated pace of life.

she flew away, sitting together by a lake in a park, I played her a traditional French lullaby on my guitar, an ancient song her father sang to her when she was little. During the drive back to her host’s residence, we even discussed the crazy idea that, when I graduated in the spring, I might forego college in America for the time being in favor of finding a newspaper job in France so we could stay together.

As we said goodbye under the porch light, she leaned forward and gave me our first — and last — kiss.

Just down the street, a dear neighbor’s firstborn is settling into her dorm at Penn State University. Her mom admits to having tender emotions over this rite of passage.

I know the feeling well. I remember driving both my children to their respective universities in Vermont and North Carolina, sharing stories with their mother on the way about their growing up and marveling how time could possibly have passed so quickly. Without question, dropping my kids off at college was a ritual of parting that stirred both pride and emotion.

On a funnier note, September’s arrival reminds me of my own unexpected journey to East Carolina University half a century ago. On a blazing afternoon, my folks dropped me off at Aycock dorm, now Legacy Hall, with my bicycle, a new window fan and 50 bucks for the university food plan.

Not surprisingly, my mom hugged and kissed me, and wiped away a tiny tear; my dad merely smiled and wished me good luck. He also looked visibly relieved.

“You made the right decision, son,” he said. “I think you’ll really enjoy it here.”

The previous winter, you see, I fell hard for a beautiful French exchange student at my high school named Francoise Roux. During the last few weeks before she headed home to France, we had a two-week courtship that included long walks and deep conversations about life, love and the future.

I was too nervous to kiss her. Instead, on the last night before

It was a sweet but improbable dream. Yet, having won Greensboro’s annual O. Henry Writing Award the previous spring (and consumed far too much Ernest Hemingway for my own good), I decided to skip applying to college and seek a job in Paris. Touting my “major” writing award and one full summer internship at my hometown newspaper, I brazenly applied for a job as a stringer for the International Herald Tribune’s Paris bureau.

Amazingly, I never heard back from the famous newspaper.

Come middle May, still waiting for a reply, I was having lunch with my dad at his favorite deli when he casually wondered why “we” hadn’t yet heard from the four colleges I’d applied to for admission.

“Actually, Dad,” I said, “I didn’t apply to them. I have a better plan in mind.”

I sketched out my grand scheme to spend a year working in Paris, where I would cover important news stories and gain valuable life experience in the same “City of Lights” that he fell in love with during the last days of World War II. I mentioned that I was waiting for a job offer from the International Herald Tribune. He listened politely and smiled. At least he didn’t laugh out loud. He was an adman with a poet’s heart.

“This wouldn’t have anything to do with a certain pretty French girl named Francoise, would it?”

“Not really,” I said. “Well, a little bit.”

He nodded, evidently understanding. “Unfortunately, Bo, you will have to get a draft number this September. And if you get a low

At Barton College, we do more than prepare you for a career — we help you discover your voice, build your confidence, and pursue your calling. Through personalized learning, forward-thinking programs, and a close-knit community that champions your growth, Barton empowers you to uncover your strengths and shape your future with purpose.

From day one, you’re surrounded by faculty and mentors who believe in your potential — and by opportunities that both challenge and elevate you. That includes access to immersive VR labs, outdoor classrooms that inspire creativity, and off-campus learning experiences that connect you with the real world.

Whether you’re exploring your passions or chasing a dream career, Barton empowers you to think boldly, act confidently, and lead with purpose.

number and aren’t in a college somewhere, you might well be drafted. That will break your mother’s heart. How about this idea?”

He suggested that I simply get admitted to a college somewhere — anywhere — until we could see how things panned out with the draft. There were rumors that Nixon might soon end it. Until then, a college deferment would keep me from going to Vietnam.

Reluctantly, I took his advice and applied to several top universities. None had room for me, though UNC-Chapel Hill said I could apply for the spring term. Too late to be of use.

On a lark at the end of May, my buddy Virgil Hudson said he was going down to East Carolina University for an orientation weekend and invited me to tag along. I’d never been east of Raleigh.

Your voice, your vision, your future. SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT TODAY! 1-800-345-4973 | enroll@barton.edu

25 East Bound Ad BNC.indd 1 7/23/25 9:38 AM

pickles, pickle-themed merchandise, daily pickle tastings, Mt. Olive Pickle history displays and artifacts, facility tour video

Open 8-5 weekdays 109 N. Center Street Downtown Mount Olive

On our way into Greenville that beautiful spring afternoon, we passed the Kappa Alpha fraternity house, where a lively keg party was happening on the lawn. I’d never seen more beautiful girls in my life. Young love, as sages warn, is both fickle and fleeting.

“Hey, Virge,” I said, “could you drop me off at the admissions office?”

The office was about to close, but the kind admissions director allowed me to phone my guidance counselor back home and have my transcripts faxed. I filled out the form and paid the $30 admission fee on the spot, leaving me 10 bucks for the weekend.

By some miracle I still can’t fathom, ECU took me in.

The first thing I did on the September morning before classes got underway was get on my bike and ride due east toward New Bern. As a son of the western hills, I simply wanted to see what this new, green countryside looked like.

The land was flat as a pancake and the old highway wound through beautiful farm fields and dense pine forests. A couple hours later, I stopped at a roadside produce stand to buy a peach and had a nice conversation with an older farming couple who’d been married since the Great Depression.

I had no idea how far I’d pedaled.

It’s the CCX Carolina Connector Intermodal, located near the state’s top shovel-ready megasite at the Kingsboro Business Park. Reaching 5 million people living within a 120-mile radius, the CCX is located just 5 miles from I-95. And it’s only a few hours by rail or truck from the NC, VA, SC & GA ports. Close by are development sites for your business, within 10 hours of nearly half the American buying-public.

For more information, go to econdev.org or call 252-442-0114.

“Why, sonny, you only have 10 more miles to New Bern,” the old gent told me with a soft cackle. I got back to my dorm room after dusk — having fallen in a different sort of love.

There was something about this vast, green land with its rich, black soil and friendly people that quietly took hold of my heart.

My freshman year turned out to be a joy. My professors were terrific, and my new friend and future roommate was a lanky country kid from Watts Crossroads, wherever the hell that was. His name was Hugh Kluttz.

We are best friends to this day.

Having “gone east and fallen in love,” as my mother liked to tell her chums at church, I became features editor of the school newspaper — artfully named The Fountainhead — where I wrote a silly column that undoubtedly shaped my writing life.

In 2002, upon being named Outstanding Alumni for my books and journalism career, I confessed to an audience of old friends and university bigwigs that “going east and becoming an accidental Pirate turned out to be the smartest move of my young life — one I indirectly owe to a beautiful French exchange student I never saw again.”

Funny how life surprises us. A few years ago, out of the blue, I received a charming email from Francoise Roux, wondering if I was the same “romantic boy who once played me a lullaby on his guitar?”

We’ve exchanged many emails since then, sharing how our lives have gone along since that first and last kiss under the porch light. Francoise is a devoted grandmother and I’m about to become a first-time grandfather around Christmas. Soon enough, I'll be playing that old French lullaby to a new baby girl, marveling alongside my daughter and her husband as they embark on their own, uncharted journey. EB

Jim Dodson’s 17th book, The Road That Made America: A Modern Pilgrim Travels the Great Wagon Road, is available wherever books are sold.

More North Carolinians look to East Carolina University® for their business education and expertise than any other school in the state. You can too when you choose to pursue an MBA through ECU. You’ll be part of a nationally ranked program that allows flexibility without sacrificing quality.

our program is designed for students from all academic backgrounds.

When you cross the bridge from Morehead City to Atlantic Beach, a left on Fort Macon Road takes you to the state park and the fort that was built following the War of 1812 to guard the entrance to Beaufort Inlet. Hang a right — toward Pine Knoll Shores, Indian Beach and Emerald Isle — and in a few blocks you’ll see the Caribbean-colored yellow fence and palm trees of the Shark Shack, where they serve up the tastiest beach treats on the island. Danish chef Tom Christensen opened the Shark Shack in 2011 after being the head chef at the Mid Pines hotel in Southern Pines for 19 years. He came to Mid Pines after working as a chef at Cable Beach in Nassau in the Bahamas for five years, hence the tip of the cap to the décor. In 2017, Christensen turned the business over to his daughter, Taylor, and son-in-law, Jeremy Thomas. “He’s trying his best to settle into retirement,” says Jeremy, who has his own chef credentials from the Pinehurst Resort and Mid Pines. The seafood tacos remain a Shark Shack staple, along with its nine homemade sauces, but if they happen to have the softshell crab or tuna steak sandwiches on offer (availability varies), don’t pass them up. EB

By A nne Blythe

If you’re one of those people who like to walk on the beach and dream up scenarios for what might be happening in some of those homes looking out over the ocean, Kristie Woodson Harvey has a whale of a tale for you.

In Beach House Rules, the Beaufort-based author takes readers inside a massive two-story oceanfront home enveloped by “the salt air and rhythmic shush of the waves” in fictional Juniper Shores, North Carolina. Harvey’s 11th book, which she describes as “an ode to female friendship,” also has mystery, a touching exploration into what makes a family and, of course, a love story or two — many of the elements for a breezy, easy beach read.

Inside Alice Bailey’s massive beach house is the “mommune,” an intriguing co-living situation that — because of a variety of individual crises — brings a cast of women and their children together. Charlotte Sitterly and her teenage daughter, Iris, are the newest “mommune” residents, having found themselves in need of shelter, hugs and support after being locked out of their fivebedroom, four-and-a-half bath shorefront home by the FBI.

Bill, husband of Charlotte and dad of Iris, is in the local jail, accused of a white collar crime that thrusts their family into the glaring spotlight of an anonymous gossipy Instagram account that revels in “sharing bad behavior and delicious drama in North Carolina’s most exclusive coastal ZIP code.”

Charlotte, Bill and Iris came to Juniper Shores during the height of the pandemic, refugees from a locked-down New York City. While snuggling on the wide-open beach during what was supposed to be a temporary visit, soaking up the orange glow of a Mayflower moon and watching their daughter make friends with a neighbor girl, Bill suggested they build a house there, miles and worlds away from their hectic and confined city life. Charlotte leaned into her husband and quickly said yes. Fast forward to Charlotte’s meltdown in the lobby of Suncoast Bank, three days after coming home to a swarm of police cars and FBI agents combing through her dream house. With the family’s financial assets seized, Charlotte needed a job. Her work history was in finance, so she thought she would try the local bank, but convincing a bank or investment firm to take on the spouse of a man accused of stealing large sums of money from his clients was a tough sell.

Alice, known around town as the woman with three dead husbands in 12 years, offered Charlotte a supportive ear and refuge at her former bed-and-breakfast where women and their children facing hardships comprise the “mommune.” With only enough cash to afford two more weeks at a modest hotel, Charlotte agreed. Her mind raced as she walked into the Bailey house. What if Alice was a creepy killer who’d offed her husbands? Was she a lunatic or a saint? And always in the back of her mind, what if Bill had, indeed, committed the financial crimes he was accused of? Charlotte tamped down those questions as Alice took her through the unlocked door into a haven with a chef’s kitchen, an open-plan dining room, a living room that stretched across the entire house and an array of comfortable bedrooms.

Through the alternate narratives of Charlotte, Iris and Alice, Harvey weaves in the many side stories. We learn about Julie Dartmouth, Alice’s niece and a dogged reporter who was the first woman to take up residence, along with her children, in the Bailey house. Before Charlotte and Iris arrived she “seemed to absolutely revel in writing about Bill’s arrest.” But “beach house rules” changed that.

Grace, Julie’s best friend and an Instagram influencer who has gained a large following sharing her recipes on “Growing with Grace,” was the second mom to join the so-called “lost ladies club.” She moved in after her husband split to Tokyo, leaving her with a mortgage to pay and children to raise, one of whom is a star high school quarterback and heartthrob, an added bonus for Iris, a 14-year-old navigating the highs and lows of teenage years.

Elliott Palmer, Alice’s former boyfriend who wants to reignite their love story, has the potential to upend this makeshift family. He’s not deterred by Alice’s wake of dead husbands or other claims that she’s cursed. “You’re not going to kill me,” he tells her over a bottle of Champagne and a remote table for two overlooking the water.

Harvey weaves all these storylines together, thread by thread, mystery by mystery, to an end that reveals whether or not Alice — who, not coincidentally, had taken a financial hit from the white-collar crime Bill is accused of — had ulterior motives when she invited Charlotte and her daughter to stay with her.

While there are dark clouds that hang over the many mysteries within this mystery, the romance and light fun make it more about community and the friendships that can unexpectedly occur when it seems like everything is falling apart.

According to the Beach House Rules, setbacks can be blessings in disguise. EB

Anne Blythe has been a reporter in North Carolina for more than three decades covering city halls, higher education, the courts, crime, hurricanes, ice storms, droughts, floods, college sports, health care and the many wonderful characters who make this state such an interesting place.

Crisp

The Last Assignment, by Erika Robuck

It’s the fall of 1956 and award-winning but often-maligned combat photojournalist Georgette “Dickey” Chapelle works for the International Rescue Committee — started by Albert Einstein during the Second World War — to bring the plight of the world’s war refugees to the attention of the American people. Still grieving the death of her mother, just two years after the death of her father, and in the midst of a prolonged and painful separation from her philandering husband, Dickey identifies deeply with displaced people — particularly women, children and orphans. After a refugee rescue goes wrong, Dickey finds herself imprisoned in a Soviet camp, and it’s there that a flame is lit deep inside her to show the world what war really means. Her journey places Dickey in the most perilous of dangers where she realizes that, in trying to galvanize support to save oppressed peoples, she is saving herself.

Saltcrop, by Yume Kitasei

In Earth’s not too distant future, seas consume coastal cities, highways disintegrate underwater, and mutant fish lurk in pirate-controlled depths. Skipper, a skilled sailor and the youngest of three sisters, earns money skimming and reselling plastic from the ocean to care for her ailing grandmother. But then her eldest sister, Nora, who left home a decade ago in pursuit of a cure for the world’s failing crops, goes missing. When Skipper and her other sister, Carmen, receive a cryptic plea for help, they must put aside their differences and set out across the sea to find, and save, Nora. As they voyage through a dying world both beautiful and strange, encountering other travelers along the way, they learn more about their sister’s work and the corporations that want what she has discovered. The farther they

go, the more uncertain their mission becomes: What dangerous attention did Nora attract, and how well do they really know their sister — or each other?

Hot Desk, by Laura Dickerman

In the post-pandemic publishing industry, two rival editors are forced to share a “hot desk” on different days of the week, much to their chagrin. Having never set eyes on each other, Rebecca Blume and Ben Heath begin leaving passive-aggressive Post-it notes on the pot of their shared cactus. But when revered literary legend Edward David Adams (known as “the Lion”) dies, leaving his estate up for grabs, their banter escalates as both work feverishly to land this career-making opportunity. As their battle grows more heated, Rebecca learns of a connection between Jane (her mother) and the Lion. The story travels back four decades to when Jane arrived in Manhattan and meets Rose, soon her best friend. Jane and Rose are two strong, talented young women trying to make their mark in the publishing world at a time when art, the written word, and creative expression were at their height. One fateful day during the April blizzard of 1982 will change the course of Jane’s life, and of their friendship, forever.

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys, by Mariana Enriquez

Fascinated by the haunting beauty of cemeteries since she was a teenager, Enriquez visits them frequently on her travels around the world. When the body of a friend’s mother who was “disappeared” during Argentina’s military dictatorship is found in a common grave, Enriquez begins to examine the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. She journeys across North and South America, Europe

and Australia, visiting Paris’ catacombs, Prague’s Old Jewish Cemetery, New Orleans’ above-ground mausoleums and the opulent Recoleta in her hometown of Buenos Aires. Enriquez investigates each cemetery’s history and architecture, its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors, and, of course, its dead. Fascinating and spooky, weaving personal stories with reportage, interviews, myths, hauntology, personal photographs, and more, Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave reveals as much about Enriquez’s own life and unique sensibility as the graveyards she tours.

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed and Happiness, by Morgan Housel

Doing well with money isn’t necessarily about what you know. It’s about how you behave. And behavior is hard to teach, even to really smart people. Investing, personal finance and business decisions are typically taught as a math-based field, where data and formulas tell us exactly what to do. But in the real world people don’t make financial decisions on a spreadsheet. They make them at the dinner table, or in a meeting room, where personal history, your own unique view of the world, ego, pride, marketing and odd incentives are scrambled together. In The Psychology of Money, Housel shares 19 short stories exploring the strange ways people think about money and teaches you how to make better sense of one of life’s most important topics.

The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces, by

Seth Harp

In December 2020, a deer hunter discovered two dead bodies that had been riddled with bullets and dumped in a forested corner of Fort Bragg, North Carolina. One of the dead men, Master Sgt. William “Billy” Lavigne, was a member of Delta Force, the most secretive black ops unit in the military. A deeply traumatized veteran of America’s classified assassination program, Lavigne had done more than a dozen deployments in his lengthy career, was addicted to crack cocaine, dealt drugs on base, and had committed a series of violent crimes before he was mysteriously killed. The other victim, Chief Warrant Officer Timothy Dumas, was a quartermaster attached to the Special Forces who used his proximity to clandestine missions to steal guns and traffic drugs into the United States, and had written a letter threatening to expose criminality in the Special Operations task force in Afghanistan. When Harp, an Iraq war veteran and investigative reporter, begins looking into the double murder, he learns that there have been other unexplained deaths at Fort Bragg, some connected to drug trafficking in elite units, and dozens of fatal overdoses. Harp tells a scathing story of narco-trafficking in the Special Forces, drug conspiracies abetted by corrupt police, military coverups, American complicity in the Afghan heroin trade, and the pernicious consequences of continuous war. EB

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws.

At Chowan, you don’t have to choose between community and opportunity. With a welcoming campus and quick access to the coast and cities, you can stay connected while reaching farther.

Aunt Ruby’s Peanuts providing the best quality Virginia-style nuts to peanut lovers for more than 40 years. We are family-owned and operated company located in historic Halifax County. We offer nut varieties, sweet treats and create-your-own combinations. North Carolina’s finest peanuts make great gifts.

By h A rris VAugh A n

The smell hits you first.

Cedar and sawdust hang heavy in the humid Outer Banks air. Casey McPherson moves through the darkened twists and turns of his workshop like a curator of a rare book collection, past a vast library of weathered boards and forgotten timber, knowing each one and its story in detail. His calloused hands pause on a piece of wood, fingers reading the grain like braille.

“This one’s been talking to me for three years,” he says, his voice carrying the soft coastal drawl common to these parts. “Just figured out what it wants to be.”

In the basement of his 20,000-square-foot workshop in Wanchese, 10,000 pieces of wood, give or take a walnut or a maple, wait in patient rows — each one a story, each one a possibility that others have overlooked, even discarded. Here, in this collection of cast-offs, McPherson practices an art form as old as creation itself: seeing potential where others see problems.

The wood comes from everywhere and nowhere — shipping containers that once carried seafood from Brazil to Alaska, their exotic floorboards destined for demolition until McPherson knocked on the door with a day to spare; storm-felled trees from neighborhood yards, their owners grateful for free cleanup; a 1948 house torn down in the spring, its heart pine and chestnut beams rescued from the landfill.

“Most people’s trash is some of the prettiest stuff in the world,” McPherson says, a touch of redeeming hope in his voice.

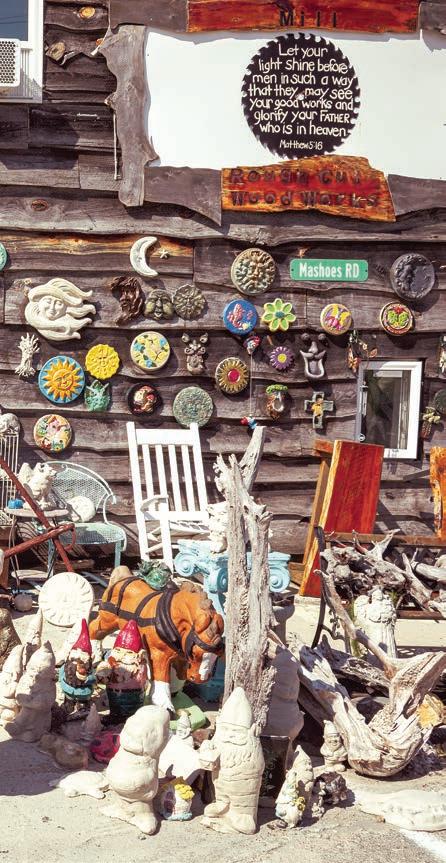

This gift for seeing the overlooked began in childhood, in a place called Mashoes — a dot on the map near Manns Harbor,

Transworld Business Advisors of Eastern NC

Tony Khoury, MBA, CBI, M&AMI M&A Advisor | Managing Director tkhoury@tworld.com 252-347-9606 www.transworldeast.com

• Want to understand what your business is worth?

• Interested in learning more about the process of selling your business?

• Need a regional firm with global reach to help maximize your exit?

Call or email for a confidential conversation to learn more. Our Business is Selling Your Business

just down the road from Wanchese — where dirt roads wind through a maritime forest, and 8-year-old boys can disappear into a wave of imagination until sunset. Growing up with only his younger brother for company, McPherson learned to find stories in everything: the curve of a twisted oak, the pattern of light through the marsh, the long calls of the gulls overhead.

“I couldn’t go anywhere,” McPherson says. “It was just me and my imagination, mostly.”

That imagination, honed in solitude and sharpened by necessity, now serves as the primary tool of his craft. Where others see rot, McPherson sees character. Where they see flaws, he sees focal points. His philosophy is elegantly simple: Highlight the damage instead of hiding it. And make it art.

In his hands, a piece of World War II-era wood, waterlogged

and shot through with decay, becomes something transcendent. He cleans out the rot, then fills the voids with colored epoxy, creating veins of light that follow the wood’s original wounds. The result transforms uselessness into art, weakness into beauty.

“A lot of times the prettiest part is the rot,” he says, describing a piece where blue resin flows like captured lightning through what was once damaged heartwood. “Sometimes people’s flaws are just things that need to be worked on, and then they become positive things.”

The approach extends beyond his workshop. McPherson collects not just wood, but stories; the origin of each piece matters as much as its grain. He knows which tree came from which storm, which beam came from which century-old house. When customers buy his work, they’re purchasing memory along with

Understanding what people are passionate about is how we help them plan for what’s most important. Backed by sophisticated resources, a Raymond James financial advisor gets to know you and everything that makes your life uniquely complex. That’s Life Well Planned.

BYNUM SATTERWHITE

Vice President, Wealth Management Branch Manager

2635 Charles Blvd., Greenville, NC 27858

T 252.439.1100 // F 855.594.6683 bynum.satterwhite@raymondjames.com satterwhiteandblackwood.com

craftsmanship: a table made from a tree that once shaded a grandfather’s farm, a mantel crafted from timbers that held up a neighbor’s barn for 90 years.

The organization of his inventory reflects his deeper relationship with material. Oak lives with oak, pine with pine, but within each species, pieces are arranged by age and made more meaningful by story. The historical section holds treasures from an 1856 house, every carefully salvaged window frame and stair tread purposefully sorted. The exotic woods tell tales of international commerce: Brazilian teak from shipping containers, Honduras mahogany from forgotten freight.

“I can tell you where every piece of wood came from,” McPherson says, navigating the maze of lumber with the confidence of a shrimp boat captain returning to harbor. “Who it came from, the story behind the wood. For some reason my brain keeps all that up there.”

Most telling are the pieces set aside in what he calls his “art section” — boards that have caught his eye for reasons he can’t immediately explain. These are the ones that speak to him visually, pieces that demand patience, pieces that reveal their purpose only after months or years of contemplation.

“Every once in a while, a piece of wood just jumps out at me,” he says. “My brain tells me to do something with it, and so I’ll pull it to the side and look at it. Takes weeks sometimes, months sometimes, years sometimes. But that piece of wood always becomes one of my favorites.”

This patience, this willingness to wait for understanding, sets McPherson apart in a world increasingly driven by immediate gratification. He works with wood the way a good mentor works with people: listening more than speaking, observing more than acting, trusting that time will reveal what force cannot extract.

The methodology extends to his relationship with customers. Rather than advertising or pushing his vision, McPherson lets people discover his work organically. “I like people to just stumble in and see it,” he says. “If I advertised, I’d get every person in the world coming

down here, and probably 60 percent would hate it.”

Instead, he reads his visitors the way he reads wood grain — sensing their stories, understanding their needs, matching them with pieces that resonate. A nature lover gets directed to the driftwood sculptures. Someone wearing a vintage brand T-shirt might find themselves drawn to the reclaimed barn wood table with its decades of accumulated character.

As the morning woodshop routine ends, and the store is readied for afternoon shoppers, McPherson admires his collection like a grandfather dotes over his grandchildren. Each piece of wood represents not just raw material, but possibility itself, the chance to transform the discarded into the treasured pieces, the broken into the beautiful works of art.

“I don’t see anything in this world that can’t be fixed,” he says, surveying his domain of rescued timber. “There’s nothing unfixable, because there’s always hope.”

In McPherson’s hands, that hope becomes tangible, one piece

of overlooked wood at a time, one story at a time, one vision at a time. His workshop stands as a testament to a simple truth: The eyes of a craftsman will find beauty and purpose in anything, if they’re willing to look patiently beyond the surface and see what others cannot.

The sawdust settles. The wood waits. And somewhere in the stacks, another piece is ready to reveal its secret. EB

Harris Vaughan is a strategic communications executive, certified whole hog barbecue judge, and Edenton native who has raised three children with his wife, Ashley. When not judging barbecue competitions, you’ll find him exploring the Outer Banks and Cape Fear region.

To visit Casey McPherson’s shop, take a right off Highway 64 East toward Wanchese. McPherson’s Mill and Rough Cut Woodwork is on the left just before you get to the marina docks.

BY JOHN JESSO

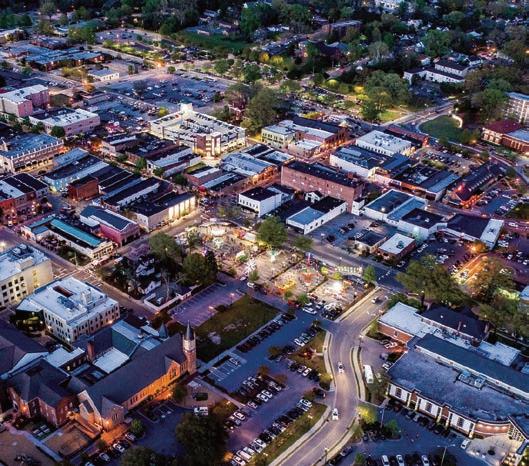

In searching for a new place to live starting our next chapter we chose to be a part of a growing city offering a great combination of affordability with opportunity: Beaufort County and the Greater Washington Region offer a wonderful place to live, work, and play. The recent influx of individuals/ families to the region from across the country shows: the grass might not always be greener outside of the Old North State.

We chose to move to Washington, dubbed an All-America city, as it becomes a vibrant place bustling with life, where historic landmarks and bustling energy meet creating a unique urban experience. The city is recognized as a diverse, artistic community, has casual eateries, bars, upscale fine-dining establishments, including a James Beard Award Chef, and everything in between offering a wide range of flavors and cuisines. You can find anything from classic Southern food to modern interpretations of international cuisine. Not to mention, its cultural institutions, great music scene, live events, festivals, beautiful parks, and diverse outdoorsy activities all along the holy grail of river life

“The Pamlico” making it a perfect place to move to or start a new life and call home. Whether you’re looking to spend time outdoors, or stroll the streets of the historic downtown, want to enjoy the flavors of one of the unique restaurants or take in a show at the Turnage, explore the world’s first Estuarium, or relish in the comforts of a local B&B, Washington is a place with an extraordinary waterfront, and the sunsets wondrous.

Where the beautiful tide of the Pamlico River meets swaying spartina of the salt marsh, cattail adorned swamp pours into pine forests filled with cedar, sassafras, and cypress trees leading into rich, fertile farmlands. It is a nature and history lover’s paradise worthy of anglers, sailors, and explorers. Hidden away from the hustle and bustle of urban life, filled with gorgeous sunsets from the North end to the South end of the county. The real magic of this place though is the warmth and welcoming hospitality of its people.

124 S Market Street, Washington, NC 27889

Come sit on the pier. Enjoy the river breeze. Beaufort County is a treasure to behold.

By susA n CA mpBell

The swallow-tailed kite is, without a doubt, the most unmistakable of birds in our state — and perhaps anywhere in the world. This large raptor with a long, forked tail is capable of endless, highly acrobatic flight. The size, as well as long, narrow wings, may cause one to think ”osprey” at first glance, but one glimpse of that unique tail gives its true identity away, even at a great distance. This majestic bird is black on top with a white head and belly as well as white wing linings. As with all kite species, the bill is stout and heavily curved, but the legs and feet, instead of being yellow, are a grayish hue.

It has only been in the last decade that this magnificent species has become regular in the summer months in certain locations of eastern North Carolina. Swallow-tailed individuals were seen mixed in with Mississippi kites along the Cape Fear River in the summer of 2003. Ten years later, swallow-tailed kites were found nesting along the river, and since then, more pairs have been seen well up into Dare County on the Outer Banks. Far more likely to be spotted in coastal South Carolina and farther south, these birds have plenty of feeding habitat here as well as tall trees to use for nesting.

Swallow-taileds are found in wet coastal habitat where their preferred prey, large flying insects, are abundant. Adults feed entirely on the wing. When foraging for nestlings, this bird is so agile that it not only preys on bugs such as dragonflies and beetles, but readily snatches snakes, lizards and even nestlings of other species from the canopy. Swallow-taileds are not at all choosy. Males forage for a good deal of the food for the growing family, carrying food items back to the nest in their talons, transferring

them to their bills and carefully passing them to their mates, who will tear them into pieces and feed them to their young.

This species is a loosely communal breeder like its cousin the Mississippi kite. Swallow-tailed pairs can be found in adjacent treetops when they find a particularly good piece of habitat. Nonbreeding males may also associate with established pairs. These individuals may bring gifts of sticks and even food to breeding females, but interestingly, these offerings usually go ignored.

Swallow-taileds have been found to consume a large number of highly venomous insects. Wasps and hornets are not uncommon food items, as are fire ants. This is possible due to the fact that they have developed a much fleshier stomach than other birds. Interestingly, an adult kite may bring an entire wasps’ nest to its own nest and, after consuming the larvae, incorporate it into its nest. The motivation for doing so is unclear.

Post-breeding dispersal of swallow-taileds begins in mid-July. They may be found anywhere in the state and are frequently seen mixed in with loafing Mississippi kites at this time of the year. Congregations of kites can number in the dozens over agricultural fields where beetles, grasshoppers, dragonflies and other large invertebrates are plentiful. As days shorten, the birds begin to head southward to wintering grounds in Central and South America. But rest assured they will be back by mid-May.

So, make a note to be on the lookout for these majestic birds as the weather warms across the coastal plain. EB

Susan Campbell would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photos. She can be contacted by email at susan@ncaves.com.

Laughing gulls hover: a story below, their shadows slide and crux across the deck of the Silver Lake — painted white by convicts from the Hyde County camp — bound over the slick-cam Pamlico, past a dredge-spoil island where cormorants in black frock coats congregate, exiled, penitent, eyeing the ferry with Calvinist reproach.

— Joseph Bathanti

Joseph Bathanti is a member of the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. His novella, Too Glorious to Even Long for on Certain Days, will be released this summer by Regal House Press. His next volume of poetry, Steady Daylight, will be published in 2026 by the Louisiana State University Press.

Fen

By Liza RoBeRts • PhotogR a Phs By John gessneR

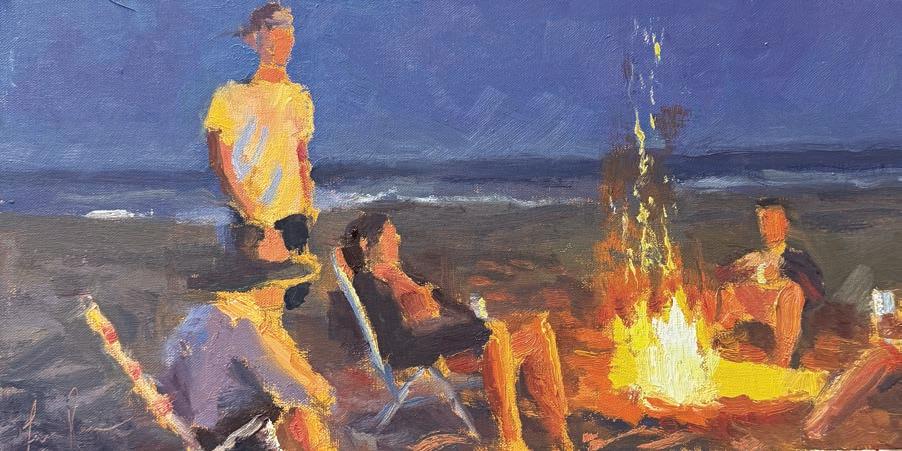

Fen Rascoe’s studio at his house in Windsor, North Carolina, is filled with paintings, but he doesn’t paint them there. He sets up his easel outdoors instead, under Eastern North Carolina’s boundless skies, in its flat fields and deep woods, its dank wetlands and hidden coves. It’s land he has long worked as a farmer and known as a sportsman, where he played and helped in the fields as a child, where his family roots run nearly 250 years deep.

It’s also where Rascoe began painting seriously in 2010, where he learned to paint outside, or en plein air, with oil on linen, and where he developed an ability to capture the enduring beauty of Bertie County and other sublime places in an Impressionist style that has earned him countless awards

in juried competitions around the country.

On a hot summer day, Rascoe is eager to show a visitor one of his favorite spots to paint. “Your feet are going to get wet,” he says. “That OK?”

He grabs a worn straw hat and makes his way down the back steps of his resolute 1913 Sears kit house, the air thick, the vegetation luminously green after several days of heavy rain. “And we might have some yellow flies.” He swats the air.

It’s midday, but Rascoe’s back lawn is damp; so is his towering magnolia and a tilting wood plank pier he built 20 or so years ago to get through the cypress wetland beyond. His 16-year-old sidekick, a gentle Boykin spaniel named Susie Q, leads the way down several dozen yards of slippery pier to a dock in deep shade on a bend of the slow moving, blackwater Cashie River.

Rascoe’s house, his bright lawn and his downtown street all fall away, and the deep, cypress-flanked Cashie (pronounced cash-eye in Windsor) is all there is to see. There’s a musty mineral smell coming off the water, the trill of a wood warbler, and Rascoe’s deep bass tones as he describes this place.

“I paint out here all the time,” he says. “When I don’t feel like going anywhere else, I know it’s going to be pretty.” He and his dog stand still, surveying the water. “You see the reflections. Even in reflection, close to the cloud, it’s that light blue, greenish blue. And then you look straight down here, you’re seeing almost a purple.”

While the artist in Rascoe looks at the river and sees color, the farmer, hunter and fisherman in him sees wildlife. “In late February, early March,” he says, pointing upriver, “the herring and the hickory shad run up here and spawn. Every year, you can

see them. You smell them, there’re so many of them back there. Swirling on top. You can smell the fish.”

There’s another angle, too: The sixth-generation North Carolinian in Rascoe looks at this river and sees history. “Not two blocks from here was the last place on the river wide enough for a schooner to get up and still turn back around,” he says. “That’s how this became a port city. That’s why my ancestors were here.”

Chartered as a town in 1768, Windsor’s location on the Cashie — an inner banks waterway reached via Albermarle Sound — meant its local farmers had a ready market for the produce of their richly soiled land. Sometime in the early 1780s, Rascoe’s ancestor, a Virginia schooner captain named Peter Rascoe (1763-1843, whose family was originally from Lincolnshire, England), arrived in Windsor on “Nancy,” his 41ton schooner, from Hog Island, Virginia. He was there to trade rum and molasses for cotton and tobacco. But after meeting and marrying Ann Clarry Smithwick, the daughter of a Bertie County cotton farmer, Peter Rascoe ended up trading his life as

I paint out here all the time. When I don’t feel like going anywhere else, I know it’s going to be pretty.

a Virginia schooner captain for that of a North Carolina cotton farmer, beginning with his wife’s family farm.

Today, those lands and more make up the expansive Rascoe farm, jointly owned and farmed by Rascoe and his brothers. A 10-minute drive from his house, it’s home to hundreds and hundreds of acres of soybeans and peanuts in precision rows, long low chicken houses and wildlife.

Suzie Q rides shotgun on a Gator trip through a swath of the property. Beyond and between the fields lies a varied landscape, creeks and woods and long views, ideal for hunting, perfect for painting. There’s a deer stand and a low-lying area that’s flooded in the winter for duck hunting. There are rows of sawtooth oak saplings, some of the 50-odd oaks Rascoe plants every year in an effort to replace hardwoods that were cut back in the 1800s.

Suddenly, Rascoe and his dog are alert to movement up ahead: A wild turkey runs between a stand of trees, then disappears into the shadows. Rascoe takes a turn into those woods. “I paint here a lot,” he says, pointing to a clearing near some tupelos. Exiting near a field with rows that stretch toward the west, he points out another spot. “I’ve painted a lot of sunrise paintings over there.”

Years ago, when Rascoe was working full time as the accountant in charge of the finances of the farm, painting it wasn’t on his to-do list. Even though he had enjoyed drawing and painting all his life — and had even resuscitated a foundering college career with the straight A’s he earned in summer school art classes — his parents had insisted he get a real job after graduation. So Rascoe earned a master’s degree in accounting and got to work on the farm.

That changed in 2010 when Rascoe discovered his old brushes in the basement of his house and began to paint again. He jokes that he wanted to get out of helping his kids with their homework more than anything else, but soon he was entering his canvases in competitions, winning awards, selling paintings, taking commissions and putting the money toward his kids’ tuition bills.

Still, it took an old family friend, a retired doctor and inveterate plein air painter named Fred Saunders, to urge him outdoors. Saunders insisted Rascoe needed to be in the landscape to paint it honestly.

Rascoe was reluctant. “I was just having a good time in the basement, listening to rock ’n’ roll, drinking beer, and painting,” he recalls.

To be polite, he finally agreed to join Saunders one late afternoon at an old farm nearby. A series of three barns was their subject. Rascoe still remembers every detail: “They were all red. One of them was a tobacco barn, one of them was an old smokehouse. They were lined up in a good composition. There’s an old field going toward them, and pine trees on the left, and a shadow going in their direction. The rows of the field had been harvested. And then the light source, the sun,

was shining on their front side.”

The experience was a revelation. “When I got through, I was completely transformed,” Rascoe says. “To be outside and paint from life, the sounds, the smells, the life of it. It translates in there, in the painting, whether it’s conscious or unconscious, it translates.”

He also had to learn to paint quickly to capture the changing light, wet oil paint on wet oil paint (known as alla prima), grabbing the heart of the subject and committing to it. Rascoe painted outdoors with Saunders until his friend died two years ago, and she’s never looked back. He even carries his paints and brushes in the back of his truck in what he calls his “Doc bag” like Saunders did — a country doctor always ready to paint.

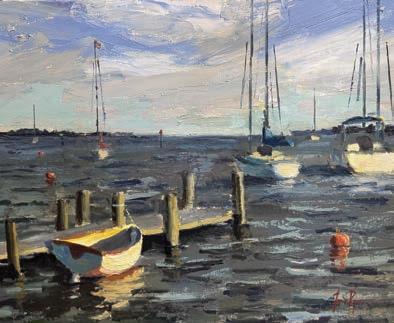

Back in his studio, Rascoe points to a recent painting of sailboats. “I can hear the rigging on the sailboat, clinking against the post,” he says. “You can probably smell the fuel coming from the fuel truck. It is just a lot more to it. I couldn’t replicate that from a photograph.”

Painting en plein air has become Rascoe’s signature. In the last few years alone, he has exhibited his work and brought home honors from plein air painting shows in Maryland, Missouri, Virginia and North Carolina, among others, and been featured in the popular Outdoor Channel show The Obsession of Carter Andrews.

Back on the farm, the sun’s a little lower in the sky. Rascoe turns the Gator out of the woods on a path near a soybean field that stretches into the seeable distance. He’s quiet for a minute.

“I can get lost back here real quick,” he says. “This is my kind of day, right here.” EB

Liza Roberts is the author of Art of the State: Celebrating the Visual Art of North Carolina , published by UNC Press in 2022. She was the founding editor and general manager of Walter magazine and is grateful for the opportunity to write about the remarkable visual artists of our state.

By tom maxweLL PhotogRaPhs

By John gessneR

If you happen to drive into Fountain on a bleak Tuesday morning, the tiny Pitt County town might look a bit forlorn. In fact, it's just the opposite. The row of brick buildings that line Wilson Street — Fountain is a one-block town — are positively vibrating with history and culture.

“Fountain is a very small town, but the community is so supportive of what we’re doing here,” says Denise Duffy who, along with her husband, Tim, is a founding member of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, a nonprofit based in Hillsborough. “The Fountain General Store is a small music venue, and a lot of times the artists we’re working with will perform there. It’s a great little community. We’re hoping to create a musical hub here in Pitt County.”

The organization’s goal is to lovingly tend to the roots of American music, including the day-to-day needs of the artists who create “our nation’s hidden musical treasures.” The day I visited with the Duffys, Music Maker Recordings was working on a new album by North Mississippi Hill Country bluesman Trenton Ayers in its new, state-of-the-art recording studio, composed of three buildings right next to the R.A. Fountain General Store.

“They were commercial buildings,” says Denise, “originally dry goods and general stores, built about 100 years ago. One was the old pharmacy. One was used as a food bank for a while, but it was in pretty poor shape. We basically gutted it and rebuilt the whole interior.”

That studio, known as Music Maker East, opened in May of 2024. Ayers’ new album will be the eighth one recorded there in just a year’s time. “We’ve had a variety of ways of producing records over the last 30 years,” Denise says, “but this is the first time Music Maker had a fully owned facility.”

The Duffys met as teenagers growing up in Connecticut but didn’t start dating

until they were finishing up their undergraduate studies. Tim spent the first two years of college in Swannanoa and loved the music. The couple relocated to North Carolina in 1987 because of it. He earned his master’s degree in UNC’s Folklore Program while Denise pursued a career in the apparel industry.

Although Tim’s studies focused on Appalachian string band music, he was assigned field work involving some Greensborobased blues musicians in 1989 and never looked back.

“Tim found senior roots musicians struggling in both these communities, and the same with Indigenous, gospel and other folk musicians throughout the state,” Denise says. “Few had access to decent stages, and everyone wanted gigs more than anything. Almost none of them had been recorded or documented for posterity, so whenever one of them died, their songs were gone from our culture forever.”

Nearly all were working class and broke. Their meager Social Security payments couldn’t cover basic rent and living expenses. Sometimes artists didn’t have access to their own guitar because they pawned it to pay the electric bill. Even if they had a decent gig, they might not be able to afford to fix their van to get there.

“Tim was interested in helping musicians overcome these barriers to artistic excellence and keep traditions alive,” Denise says. “I was interested in small business, so we started Music Maker to see if we could find a new model that would work for these artists and their communities. We’re still here after 31 years because these musical traditions remain strong, but also because the need for artist support and documentation remains. The music industry has changed in many ways over the past three decades, but the economic landscape for musicians is no better now than when we began. The industry exists to turn a profit, not safeguard American culture, so that responsibility remains on us.”

Over the years, Music Maker has relied on donations from individuals as well as grants from groups like the Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Foundation to bring its music to the world.

In the early days, the Duffys either produced recordings out of a tiny makeshift studio in their Hillsborough office or worked with producers like Bruce Watson of Fat Possum Records. Watson, who has been associated with Music Maker almost since its inception, was also instrumental in getting the Fountain

studio up and running. “Tim asked me if he should open up a studio — it’s Tim and Denise’s brainchild — but I gave them my opinion and helped when I could,” says Watson. “It’s been amazing to see it go from dirt floors to where it is now. The whole mission is working with these artists who probably never would have had any chance to record. The music is obscure and totally out of the mainstream. What Music Maker Foundation does is very special. It actually gives these artists the chance to be heard. Outside of all of the other help they give artists with their health and finances, it gives them the chance to be heard. And that’s what any artist wants.”

In 2006, Tim saw the Carolina Chocolate Drops perform at the Shakori Hills GrassRoots Festival in Chatham County and offered them a management contract. Music Maker Recordings issued the group’s first record, Dona Got a Ramblin’ Mind, later that year. Under Tim’s management, the Chocolate Drops won a Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album.

The number of artists Music Maker Recordings has worked with is upwards of a hundred, including people like Alvin “Little Pink” Anderson (son of the great Piedmont blues musician Pink Anderson), Ernie K-Doe, who topped the Billboard charts in 1961 with the drop-dead R&B groove of “Mother in Law,” and Pura Fé, a musician and storyteller from North Carolina’s Tuscarora Nation — artists who would have had little chance of having their work documented had it not been for Music Maker.

“The music industry is selling units and streams, so there is no one there whose mission it is to document our culture,” Denise says. “We want a variety of voices to be heard, and we’re here to support musicians who are often marginalized. Not everybody is going to be out there on the road 28 nights a month or suit a record company’s model of what’s worthwhile. We think all sorts of community-based artists are worthy of being heard.”

It is no accident that Music Maker chooses to be in North Carolina, the birthplace of a lot of American musical traditions. Eastern North Carolina, in particular, has been incredibly fertile soil. “The coastal plains of the Carolinas, between Jamestown and Charleston, first had Indigenous people making music here for 8,000 years,” Denise says. “Then you had Europeans bring their ballad-singing traditions and their stringed instruments, and then you had Africans come here — not necessarily by choice, but they were brought here nonetheless — and they contributed their harmony and percussion traditions. The one place those people could freely associate was in church on Sunday, and they came up with the gospel tradition. That tradition is still deeply ingrained in this culture.”

The Duffys were introduced to Fountain by Freeman Vines,

a luthier and blues musician whose family — including gospel quartet legends The Glorifying Vines Sisters — still live in the area. When Tim met Vines, the luthier showed him some black walnut planks he planned to use for making a guitar. The man who sold Vines the wood told him at the time, “You’re black, and I’m white. That wood there came off a hanging tree.” When Vines expressed disbelief, the man retorted, “I don’t give a damn what you believe. They used to hang people on that tree.” The tree, Tim discovered after some investigating, once stood outside of the home of Oliver Moore, who in 1930 was pulled from an Edgecomb County jail and lynched there. Freeman Vines turned its wood into musical instruments he called the Hanging Tree guitars.

In a 1917 issue of the Farmville Enterprise, Fountain was praised for its prime location in the center of “one of the most progressive farming sections” in the state, calling it “the biggest little town” in North Carolina. It was named after R.A. Fountain, who along with his cousin opened a small store there on March 19, 1901, a few months before the completion of the East Carolina Railway. It became one of several temporary terminus points for the railway as it continued its expansion connecting Tarboro to eastward logging opportunities. An excursion train called the Yellowhammer brought people into town for sightseeing and shopping. Fountain’s store provided cradle-to-grave services: Downstairs was a mercantile; upstairs a coffin manufacturer.

In its heyday the hamlet was visited by North Carolina luminaries like Andy Griffith, Ava Gardner, and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. Eventually the railroad moved on to Hookertown, and the town’s dealership in the nascent automobile business went bankrupt and returned to being a mule stable. Fountain withered on the vine.

The old general store — next door to Music Maker East — reopened as the R.A. Fountain General Store in 2004. Since its return, it has served as a gathering place and music venue, as well as a boutique publishing house and the sole distributor of books originally published by North Carolina Wesleyan College Press.

Fountain is a few miles from Interstate 87 and less than an hour from Raleigh. Nearby, Wilson’s visual art scene is thriving, and Greenville’s bohemian vibe is a short drive east. High speed internet is being installed as the population boom in North Carolina pushes toward the Inner Banks.

In a place no longer forgotten, the glass and brick veneer of Music Maker East reverberates with the sounds of history and hope — a place to come home to. EB

Tom Maxwell is an author and musician. A member of Squirrel Nut Zippers in the late 1990s, he wrote their Top 20 hit “Hell.” His most recent book, A Really Strange and Wonderful Time: The Chapel Hill Music Scene 1989-1999, was published in 2024.

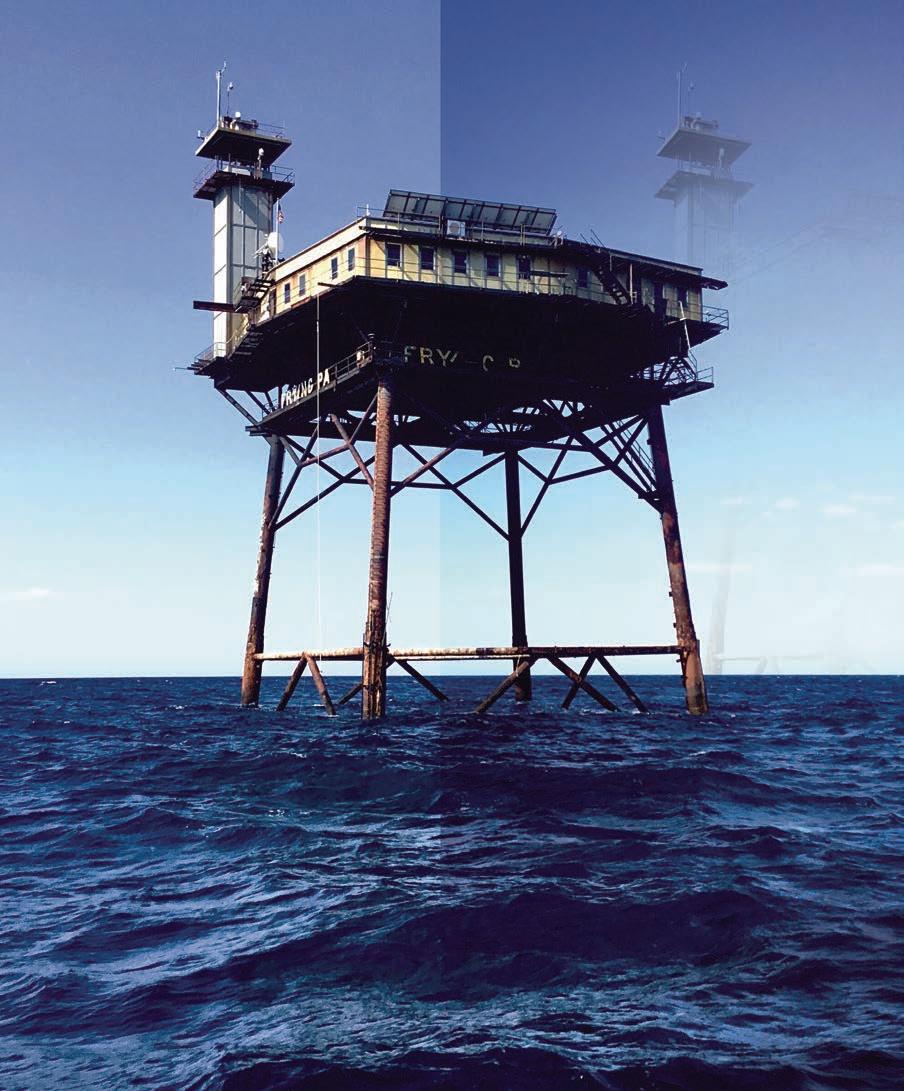

he sunrise is beautiful after a long, stormy night at the Frying Pan Tower.

On these perfect mornings, the panoramic view from the helipad atop the tower shows off a welcome sight to the east as the sun peers over a calm horizon and watches the angry clouds retreat westward.

Across its 60-year lifespan 32 miles off the Brunswick County coastline, the tower has weathered many stormy nights — and the years have not been kind. Decades sitting in seawater under the blistering sun, buffeted by wind, rain and hurricanes, have rendered the tower a rusting hulk, testament to the notion that, despite man’s best efforts, nature is always in control. For the last 14 years, Richard Neal has been that man.

Neal purchased the decommissioned Coast Guard light tower in 2010, and through the sheer force of labor, sweat — and some might say, pure hard-headedness — he has fought to bring the Frying Pan Tower within range of its glory days. Through it all, he’s never hesitated to welcome people eager for an adventure and a unique perspective on nature and life.

“I believe the tower is safe or I would never bring anyone onto it,” he tells a group of weekend visitors. “That said, it is an older structure, and as you can see from just looking around, there is a lot of rust and parts occasionally fall off.” He breaks off a small flake of rusty metal to make his point.

From the beginning, Neal has marshalled bands of volunteers willing to pay for spending days and weeks welding and replacing broken parts, tightening bolts, shoring up beams, painting, polishing, and doing the heavy lifting right alongside him. Recently, his crew made a giant leap when they replaced a series

of crumbling walkways and a ladder to provide critical access to the tower.

Considering its age, Frying Pan Tower is surprisingly high tech. Neal and his volunteers installed 52 donated solar panels along the tower’s periphery. With the addition of 15 more panels, the tower will generate nearly all its electricity from the sun and rely less on the diesel generators that have supplied power for years.

“We’ve also secured additional charge controllers and inverters boosting the available power up to 20,000 watts,” Neal says. “We’ll even be able to run the air conditioning on solar power, which will be nice during the summer months.”

In an industrial building constructed of metal and steel, Neal has added amenities that make it feel like home. The tower’s box-like structure is a furnished living space of about 5,000 square feet with a fully equipped stainless steel kitchen, large common area for dining, living and recreation, seven bedrooms and a crew room with five twin beds. There’s also a workroom, a utility room with a washer and dryer, and a bathroom featuring hot showers. The roof doubles as a helicopter landing pad. A filtration system provides potable water, and the facility is equipped with high-speed internet, using a microwave dish located on a communication tower 56 miles away, in Leland.

Neal, who lives in Wilmington, is the heart and soul of Frying Pan Tower and steadfast in his mission to keep watch over mariners, provide a facility for environmental research and education, and serve as a haven for the lively marine ecosystem underneath a structure that rises 135 feet above the Atlantic with legs 42 inches in diameter, anchored nearly 300 feet into the seabed.

Some may view Frying Pan Tower as a lonely destination, but for Neal, people are what it’s all about. “Over the years, we’ve participated in several rescues, including divers who were drowning, boats that caught fire or went missing, and medical emergencies,” he says. “I’ve hosted marriage proposals and weddings, someone celebrating being cancer free, Scouts working on their merit badges, and a team of science teachers.”

Last summer, a group of teachers made a life-changing pilgrimage to Frying Pan Tower to study the ocean, the environment and marine life. Erika Young, the coastal and marine education specialist at NOAA’s North Carolina Sea Grant program headquartered at N.C. State University, received a $15,000 grant

to design “Teachers on the Tower” as an extraordinary learning experience for educators and an opportunity to pass their knowledge along to their students back home.

For Young, the journey was more than an opportunity to take some teachers on a cool trip: It was a way to give back. Growing up in Robeson County with not much more than dreams, Young earned a Ph.D. in marine sciences at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her role at Sea Grant is one of those dreams come true.

“I mean, it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me because I never thought somebody from a trailer park could grow up to become a marine biologist,” she says. “I really want to open doors for others.”

Young received 130 applications from teachers all over the world and selected five from underserved rural school districts in North Carolina. Planning for maximum flexibility on Frying Pan Tower, she packed up GoPro cameras, microscopes, computers and any other equipment she could think of.

“The environment is fickle on the tower, and you never know what you might face on any given day, so I was ready for every activity I could think of regardless of weather conditions,” she says. “We were prepared for a week of birding, water sampling, pH testing for ocean acidification, and observing creatures from both the tower and in the water.”

The group made salt from sea water and viewed hundreds of microscopic organisms drawn from the ocean. They spent hours lying prone on top of the sea, clad in wetsuits, masks, flippers and snorkels gazing at the ecosystem under the tower.

“When it was clear, we could see all the way down to the ocean floor, where fish and sand sharks swim around, and many species of marine life grow on and around the tower’s legs,” Young says.

It’s a 90-minute boat ride from Morningstar Marina in Southport to Frying Pan Tower. When you are speeding out to sea, the tower first appears as a tiny speck on the horizon and grows larger as it gradually comes into focus.

Adam Smith, an eighth-grade biology teacher at South Stanly Middle School near Albemarle, was astounded when he saw the tower rising out of the sea on its spindly legs.

“It was one of those ‘holy cow’ moments,” he says. “Just being in a place completely different from anywhere I’ve ever been before felt like a dream.” On the tower, Smith conducted ocean acidification experiments, and after returning home demonstrated them for his students, with Young participating as a guest speaker.

Kimberly Miller, the dean of arts and sciences at Brunswick Community College, grew up in Wilmington and had seen the tower from her family’s fishing boat, never dreaming she’d someday climb aboard it. After her “Teachers on the Tower” experience, she created a new field biology course at BCC, which launched last October.

Frying Pan Tower sits on the southern edge of the Graveyard of the Atlantic, which runs northward along the Outer Banks past Nags Head and is notorious for its strong currents, shifting sands and storms. The shoals were formed by silt carried down the Cape Fear River and deposited into the ocean, creating shallow sandbars, shaped like a skillet, extending 28 miles into the ocean from the southeastern point of Bald Head Island.

Frying Pan Tower is one of two decommissioned Coast Guard light towers off the North Carolina coast. The other is the Diamond Shoals Tower, and like Frying Pan, it is privately owned. Dave Schneider, a Minnesota business executive, purchased it in 2013, sight unseen, for $20,000. Over the last decade, it has sat mostly unoccupied. The Coast Guard erected the Frying Pan and Diamond Shoals towers to replace historic light ships, which were stationed near the shoals to warn mariners of the shallow water and strong currents. Both towers were active for about 40 years.

For visitors arriving at the Frying Pan Tower by boat, boarding the looming structure is both tantalizing and terrifying. At first it seems impossible, but Neal has it figured out. The journey up to the tower involves climbing from the bow of the bouncing boat onto a wooden swing or a bosun chair and riding a high-speed hoist up 80 feet to the main level, a trip that takes about 30 thrilling seconds.

Neal’s journey onto the tower is a bit different. At 65, he is spry, athletic and adventurous. He boards the tower first by grabbing a rope and swinging, Tarzan-style, from the boat over to one of the tower’s rusty legs, where he grabs a ladder and climbs like a nautical Spider-man onto the main deck to ready the hoist for hauling up guests, supplies and gear.

Neal was strangely drawn to Frying Pan Tower after spotting it for sale on a government auction site. “I saw a picture of an odd structure that looked like an oil rig, and the more I thought about it, the more I wanted it,” he says. Neal bid on the tower and lost out on his first try, but when the original bidders failed to follow through on the purchase, he bid again and settled on paying $85,000 for it.

In 2018, he divested his ownership and sold shares to nine individuals. He created FPTower Inc. and registered it as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit foundation. He’s now the nonprofit’s executive director and earns a small salary.

Time on the tower never gets old. Neal has witnessed hurricanes and brilliant sunsets, whales leaping out of the water, and millions of stars in the night sky.

“You can go onto the tower’s helipad at night and watch the satellites slide by or catch a glimpse of a meteorite shooting across the sky, or gaze at the Milky Way and watch the constellations shift from day to day,” he says. “You get a good sense of where you fit in the universe.”

Managing and restoring the Frying Pan Tower has taught Neal patience, flexibility, peace in the simple things and the thrill

of taking a leap of faith, even if that meant buying an old rusty light tower in the middle of the ocean for no other reason than because he wanted to. And that in itself is a life lesson.

“I’m not saying be foolish, but I am saying you only get one life, so live it,” he says. “And be nice to people.” EB

Teri Saylor, a North Carolina native, has spent her career in journalism and public affairs. She lives in Raleigh and writes for a variety of local newspapers, magazines and niche publications.

The late June morning was clear and bright. A long dirt road, bordered by thick pocosin and murky canals, stretched for miles and miles through the rural heart of Tyrell County. With windows rolled down and the radio turned off, I drove my old truck slowly down the dusty strip, taking in the sights and sounds of the forest. The sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet! song of a lemon-yellow prothonotary warbler rang out from a nearby patch of bay trees. Off to the right, in the canal, a dozen yellowbelly sliders and painted turtles basked in an orderly line on a partially submerged log.

Large black and yellow spicebush swallowtail butterflies fluttered around a blooming thistle growing on the shoulder of the road. A bullfrog bellowed.

It was one of those rare, glorious days when it seemed as if every critter in the woods was out and about. The first few miles of the morning drive had already produced enough wildlife sightings to make David Attenborough envious.

Just after sunrise, as I turned onto the dirt road, a pair of river otters scampered across and took a nosedive into the canal. I followed their trail of bubbles as they navigated the waters, stained the color of coffee, in search of fish. Not long after, a hen turkey stepped out onto the road, followed closely by a dozen fuzzy chicks. A mile or two later, I spied a raccoon foraging in the shallow water, its dexterous paws busily