The EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL

A Link to Educational Excellence in East Asia WINTER 2025/26

Featured in this Issue

Governance

Five Board Chairs, One Vision: Building the Future of Governance

Together Leadership

Growing as a Pedagogical Leader

College Admissions

Would Confucius Understand US College Admissions?

Curriculum

Engaging Every Sense: A Three-Phase Framework for Language Teaching

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School), President

James Dalziel (NIST International School), Vice President

Jim Gerhard (Seoul International School), Secretary

Rami Madani (The International School of Kuala Lumpur), Treasurer

Gregory Hedger (The International School Yangon), WASC Representative

Karrie Dietz (* Incoming Head of School (August 2026)

Nexus International School Singapore)

Marta Medved Krajnovic (Western Academy of Beijing)

Maya Nelson (Jakarta Intercultural School)

Matthew Parr (Nagoya International School)

Margaret Alvarez (WASC), Ex-Officio

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou), Past President

Andrew Hoover (Office of Overseas Schools, REO, East Asia Pacific)

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Cameron Janzen, Deputy Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director Emeritus

Kristine De Castro, Office Manager & Assistant to the Executive Director

Maica Cruz, Events Coordinator

Porntip (Joom) Rattanapetch, Administrative Assistant & Membership Coordinator (Bangkok Office)

Kanjanarat (KJ) Visanjaron, Professional Learning Events Coordinator (Bangkok Office)

Edzel Drilo, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator, Webmaster

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Staff

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

Satellite Office

39/7 Soi Nichada Thani, Samakee Road, Bangtalad Sub-District, Pakkret District Nonthaburi 11120, Thailand

In this Issue

Five Board Chairs, One Vision: Building the Future of Governance Together By Dr. Hyungji Park, Anna- Marie Pampellonne, Emily Chan, Dr. Grace Lee, and Maria S. Chung

Would Confucius Understand US College

Growing as a Pedagogical Leader By Eric Sheninger

Working in the Eye of the Storm: Taming the Turbulence in Educational Leadership By Jennifer D. Klein

Igniting Innovation: Cultivating Entrepreneurial Thinking in Educational Leadership By Dr. Christopher Allen

Building a Crisis-Ready Culture in International Schools By Gregory A. Hedger & Sandy Sheppard

Curriculum Engaging Every Sense: A ThreePhase Framework for Language Teaching By Sophia Suo

Cinderella in Three Languages: Theatre as a Tool for Intercultural Learning By Ira Mathur

The Time for an Ecological Humanities is Now By Jared Rock

Unknowable Potentialities: Weaving a Shared Narrative of Pedagogical Identity By Nitasha Crishna, Kay Strenio, & Anne Van Dam

Language Integration In The Art Room: A Case Study of Collaboration between the Visual Arts Teacher and EAL By Nan Zhang & Amy Kerr

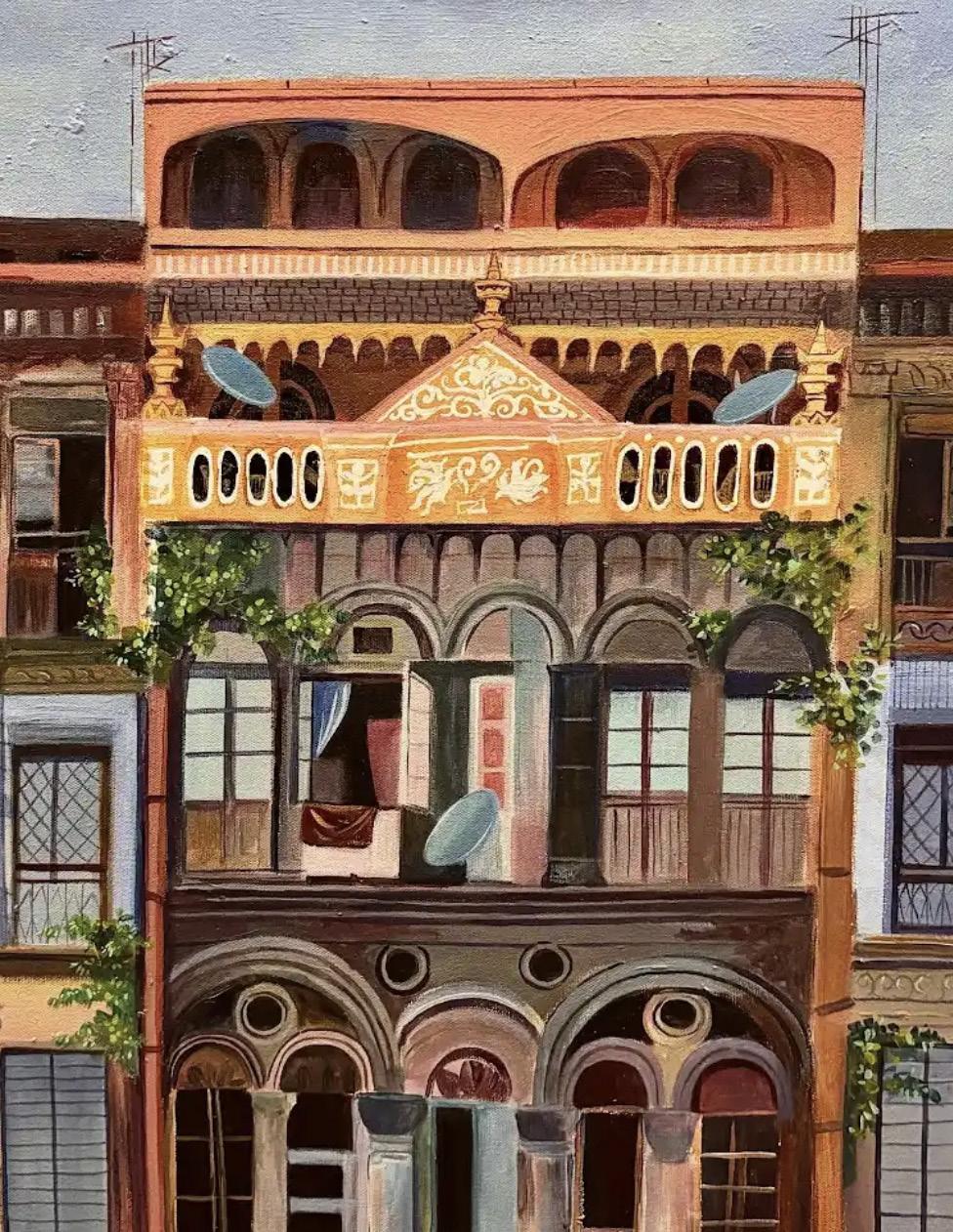

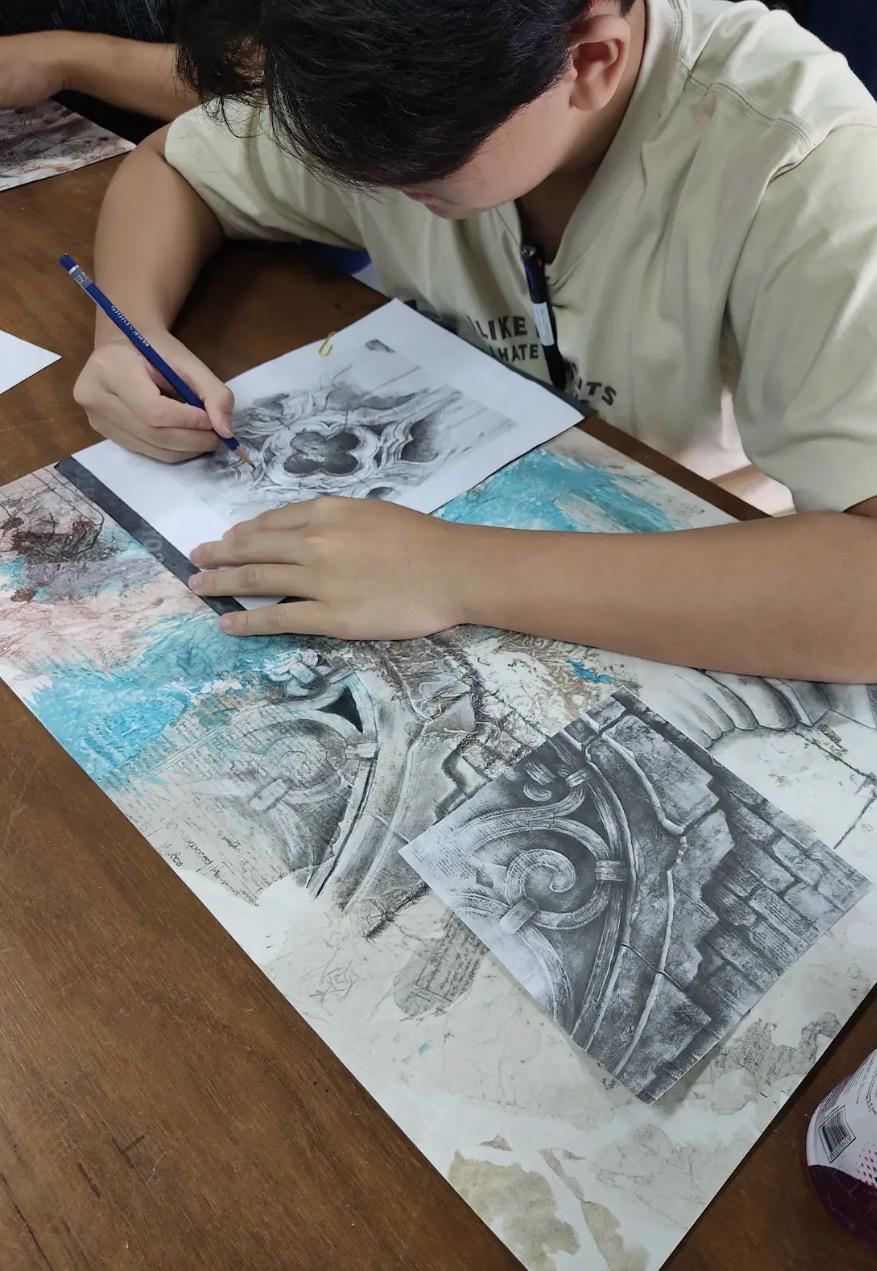

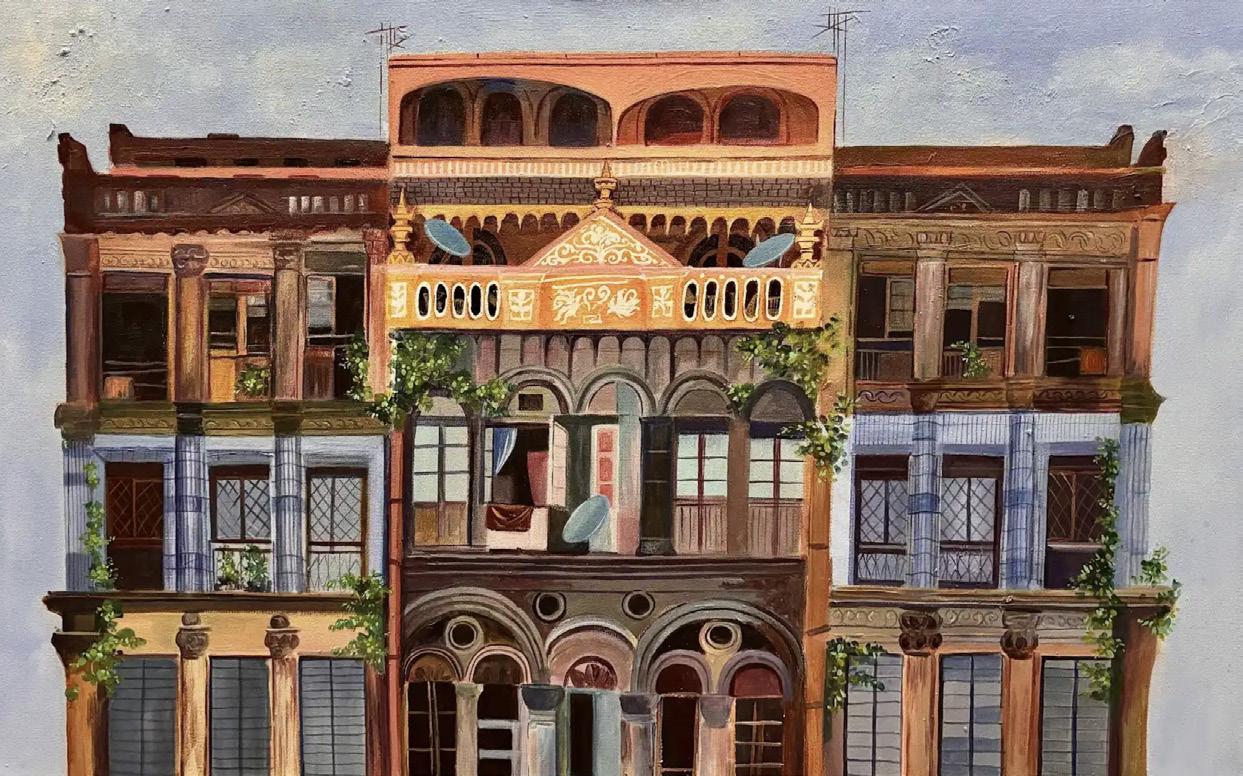

My City: Connecting Students to Yangon’s Living History By Leah Wilks

Action Research

Standards-Based Grading: Perceptions and Impact on Concordia’s Student Mastery By Shane Twaddell & Vanessa Vanek 52 Press Release

Building What Didn’t Exist: The Story of ISCA and the International Model By Cheryl Brown & Brooke Fezler

The Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award: Growing Together with Refugee Communities By Sophia Hamilton

Poem

Booking a Worldwide Literacy Adventure through a Collaborative Poem

Middle School Art Gallery

Welcome from the Executive Director

As always, it is a pleasure to welcome our readers from across this vast region of international schools to the latest issue of the EARCOS Tri-annual Journal. I think, at times, many have come to undervalue the contributions a journal like ET offers. In today’s world of social media and its nearly instantaneous commentaries on all subjects—great and trivial, a journal such as this can seem like an artefact from a by-gone age. May that never be the case.

This issue contains another collection of carefully constructed and edited articles written by fellow-educators and thinkers who share a commitment to the wonders and challenges of international education. This issue of ET reflects the incredible richness, diversity and remarkable opportunities that are available to all who are so fortunate to be international educators today. I do hope you will carve out time to read what our colleagues have shared in this issue—and to take time to reflect on what they are sharing and how it might help your school and students enhance your own journey.

This journal is the created not only by those educators who have taken time to share their ideas with us, but by two individuals who work quietly and diligently behind the scenes bring ET to life three times each year. Together, for nearly two decades, editors Edzel Drilo and Bill Oldread solicit, review, edit, prepare, layout and ‘print’ each issue of this journal. I want to express my deep appreciation to them both for the many, many hours they give to ensure that this journal reaches educators across East Asia and beyond. Our schools, our students and communities are indebted to Edzel and Bill for their dedication to sharing the very best of international education through this journal’s pages. Please join me in thanking them both for the gift they have created for this region.

Please remember that this journal is YOUR journal. We look forward to receiving your ideas, reflections, program reports and insights. Please let us hear from you.

In the meantime, all best wishes from all of us at EARCOS for a wonderful start to 2026!

Thank you,

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

STRANDS

Literacy/Reading

Early Childhood

Special Needs

Modern Languages

Media Technology/Libraries

Counselors

EAL Technology

Children's Authors

Child Protection

General Education

PRE-CONFERENCES MARCH 18, 2026

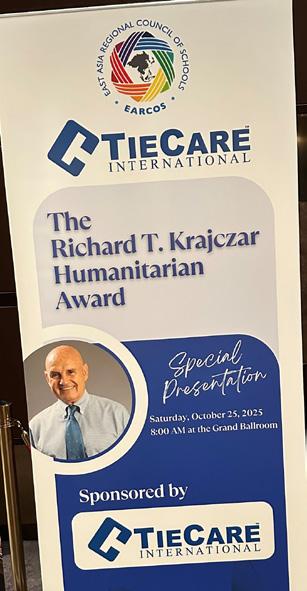

Joy House Project takes home Dr. Krajczar Humanitarian Award for 2024

The Joy House Project collaborated with the PhuLiPhay Service Group, through NIST International School in Bangkok, Thailand, to develop the winning humanitarian initiative.

TieCare International sponsored and presented the award at the 2025 EARCOS ELC in Bangkok.

PhuLiPhay Service Group is a youth-led service group based out of NIST International School. The group has partnered with the Joy House to support refugees, channeling student passion into action.

In collaboration with NIST, the group was the recipient of the 2024 Richard Krajczar Humanitarian Award from the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS).

Joy House is an organization based in Mao Sot, a town in Western Thailand near the border with Myanmar. Its mission involves fostering cross-cultural exchange and understanding between Thai and Myanmar children.

The project provides support and services to the local community, including refugees from Myanmar.

Together, the two groups have worked on specific projects, potentially including the use of a US$10,000 grant awarded through the EARCOS award to support their shared goals.

Together, the two groups have worked on specific projects, potentially including the use of a US$10,000 grant awarded through the EARCOS award to support their shared goals.

Mark Tomaszewski President, TieCare International

The Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award Special Presentation.

Aly S. and Ben D. are part of the acceptance team of the 2024 Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award.

Ms. Melanie Mazza (left) and Mr. Mark Tomaszewski (right) of TieCare International congratulate the winners of the 2024 award.

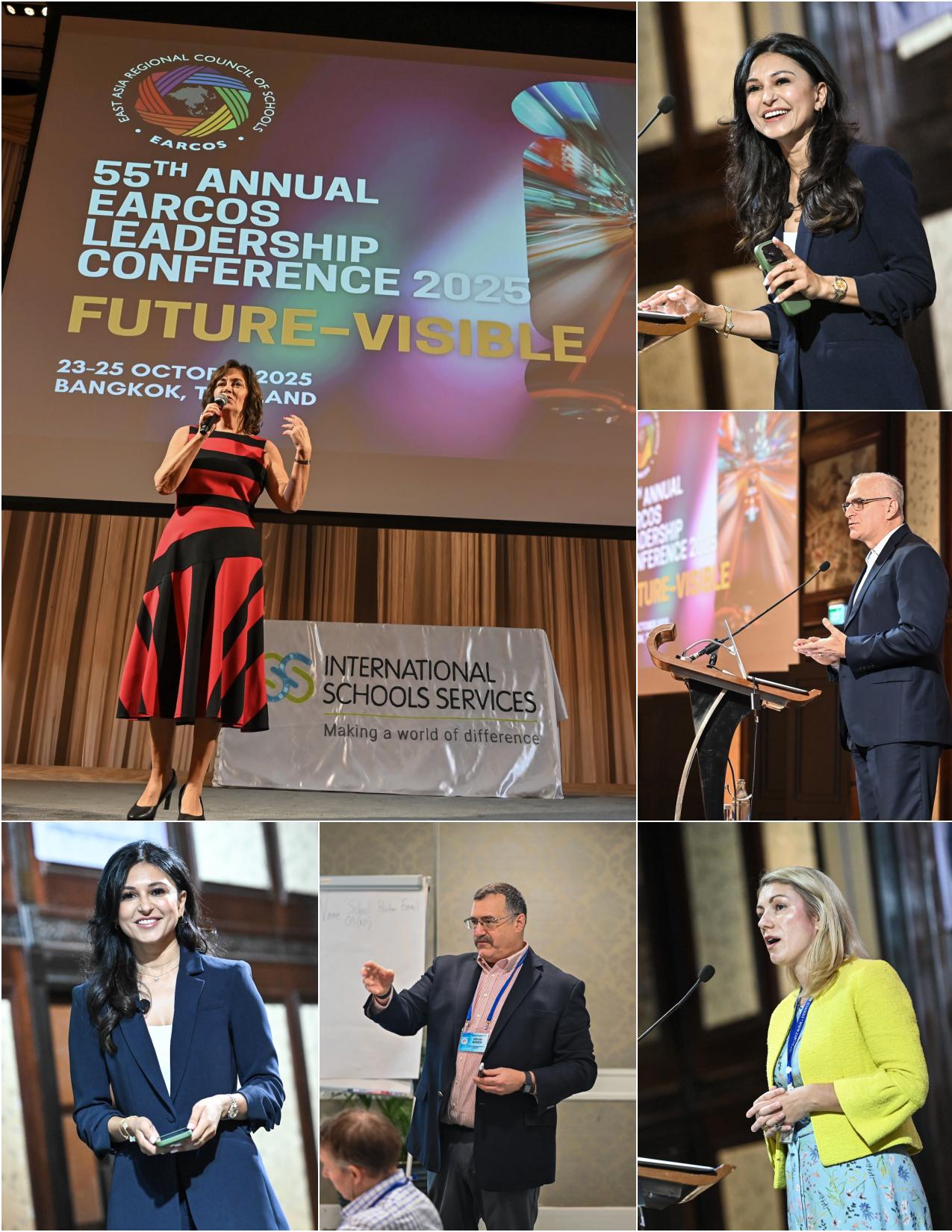

The 55th EARCOS Leadership Conference 2025

“Future—Visible”

The 55th Annual EARCOS Leadership Conference brought together more than 1,000 international school leaders from across the EARCOS region and around the world for three inspiring days of learning, connection, and forward-thinking dialogue. Trustees, heads of school, principals, directors of learning, business managers, admissions officers, and Associate members gathered to explore how leadership can intentionally shape what lies ahead.

The conference opened with a warm welcome from Dr. Edward E. Greene, EARCOS Executive Director, who greeted delegates and reflected on the strength of the EARCOS community and its shared commitment to high-quality international education. He was followed by EARCOS Board President Dr. Catriona Moran, Head of School at Saigon South International School, who officially welcomed participants and set the tone for the conference—inviting leaders to engage deeply, challenge assumptions, and collaborate in making the future of education visible.

Guided by the conference theme, “Future—Visible,” participants examined how today’s leadership decisions can create schools that are innovative, inclusive, and prepared for an increasingly complex world. The conference provided a vibrant platform for collaboration, reflection, and the exchange of ideas that continue to strengthen the international education community.

Visionary Voices, Powerful Conversations

Each day opened with a plenary session featuring thought-provoking keynote presentations from respected leaders in education and organizational change.

The conference began with Debra P. Wilson, who delivered the opening keynote, “Trends and Transformations.” Drawing on her extensive experience in higher education and independent schools, she explored the evolving landscape of international education, highlighting shifts in governance, leadership expectations, and workforce dynamics. Her address challenged leaders to anticipate change and respond with agility, insight, and purpose.

On the second day, Dr. Sabba Quidwai took the stage with her keynote, “The New Leadership Advantage: Turning AI Tools into Trusted Teammates.” She invited leaders to rethink their relationship with artificial intelligence—positioning AI not merely as a technical tool, but as a catalyst for innovation when guided by empathy, ethics, and human-centered leadership.

The conference concluded with the plenary panel, “Between Rocks and Hard Places,” featuring experienced international school leaders in an open and reflective conversation about

ethical leadership. Through real-world scenarios, panelists examined the complex decisions leaders face, offering practical frameworks for navigating moral dilemmas, maintaining trust, and leading with integrity in challenging times.

Also on the second day, the Women in Leadership Luncheon, led by Meike Ziervogel, offered a powerful and inspiring forum dedicated to women leaders in the EARCOS community. Meike shared the remarkable story of the Alsama Project—an initiative that supports education and leadership development for refugee girls in Lebanon, transforming pathways from illiteracy to university. Her session highlighted resilience, empowerment, and the ways in which education and community leadership can drive transformative impact.

Learning That Matters

Complementing the plenary sessions, the conference offered more than 180 workshops spanning a wide range of leadership topics, including strategic planning, governance, AI in schools, DEIJ, child protection and safeguarding, risk management, recruitment, trust-building, and women in leadership. These sessions provided practical strategies and actionable insights that participants could immediately apply within their own school contexts.

Community, Connection, and Celebration

The conference was not only a space for professional learning but also a celebration of the EARCOS community. Networking opportunities throughout the event fostered meaningful connections and renewed partnerships. Evening receptions— marked by excellent food, lively music, and warm conversation—created a strong sense of camaraderie among attendees.

Looking Ahead

The 55th Annual EARCOS Leadership Conference reaffirmed the power of collective leadership. Through visionary keynotes, rich professional learning, and authentic connection, the conference made the future not only visible—but attainable. As participants returned to their schools, they carried with them renewed purpose, fresh perspectives, and a shared commitment to leading schools that serve students, staff, and communities with clarity and courage.

Governance

Five Board Chairs, One Vision: Building the Future of Governance Together

By Dr. Hyungji Park, Anna-Marie Pampellonne, Emily Chan, Dr. Grace Lee, and Maria S. Chung

At an EARCOS Leadership Conference panel in Bangkok in October 2025, Emily Chan, Shanghai American School’s Board Chair, spoke about how lonely her job could be. She noted that Board Chairs are sometimes described as “superheroes conducting orchestras,” and yet with few mentors, few coaches, and even fewer colleagues. This need for a community led to the creation of “Women in Governance.”

“Women in Governance”–or WIG–is an informal group of women Board Chairs of five international schools in the AsiaPacific region who came together to share ideas, support each other, and serve as sounding boards as we all navigate our “jobs”--unpaid and yet bearing significant responsibility and a major time commitment–as Board Chairs of our respective schools. We met in the fall of 2024 at the Governance as Leadership Training Institute (GALTI) hosted at UNIS Hanoi, and bonded as fellow women board chairs, and thought that we could benefit from sharing information and ideas. What began as a simple, fortuitous get-together grew into much more than we could have ever imagined: a robust community that ranges over a WhatsApp chat that pings at all hours of the day and night, site visits to each other’s schools, and a true friendship where we bond over dimsum, health concerns, and Labubus.

Our mandate, as we state on our newly minted website, is the following:

Founded in 2024, Women in Governance is a global community of women board leaders in international schools, championing excellence in governance and educational leadership through peer support, the exchange of diverse best practices, lifelong learning, and purposeful connection.

Behind this abstract statement of purpose, however, is a very real sense that we are doing something very new, even perhaps revolutionary, as we help shape the future of international education in the Asia-Pacific region. For one, we are acutely aware that our Heads of School have their own communities where they share information about everything from AI in K-12 education to compensation trends to common challenges associated with board continuity. Until now, Board Chairs haven’t had a comparable forum for communication and sharing.

For another, we are aware that it is a powerful move to bring together five women leaders who bring diverse individual perspectives and voices based upon their lived experience in and out of Asia as well as their professional backgrounds. Between the five of us, we sport decades of life in Asia, the United States, and Europe; multiple Ivy League professional and doctoral degrees; and long-term careers in business, law, and higher education. One of us even has an ancestral chateau in France to boast of! A recent report from the World Economic Forum states that gender equality is 123 years away. And when we ask AI to produce images of boardrooms, we rarely see our own images–as (mostly Asian) women of a certain age–reflected in the output. This is why WIG is powerful: because it provides a space where Board Chairs of major international schools in the Asia-Pacific region come together in solidarity over ethnicity, gender, and our dedication to the schools that we help direct.

After our initial meeting at GALTI in September 2024 in Hanoi, we met again as a group at EARCOS Leadership Conference (ELC) in Bangkok a month later, and then we went on a site visit to one of our schools, Taipei American School (TAS), in May 2025. TAS was a terrific host, inviting us to their school-wide professional development workshop and providing us with WIG-tailored small-group training with their visiting speakers. It was there in Taipei that we also decided to share our story at the next ELC, and where we ended up proposing and presenting at a session entitled “Common Ground, Unique Paths: Insights and Lessons from International School Boards.” In this debut appearance at the ELC, we shared stories grounded in our individual schools but that reflected universal concerns of EARCOS schools.

Our five testimonials centered around topics on cultivating the Board Chair’s relationship with the HOS; managing the various expectations placed on Board Chairs; how Boards can contribute to curricular innovation; what effective Board training looks like; and how Boards work together with school administrators even as we navigate our separate lanes. We invited Homa Tavangar to serve as our moderator, and the entire session was intended to share insight into how Boards think as we go about our work. For our first panel appearance at ELC, we were secretly thrilled to discover that our session had to be moved to a larger meeting room because so many people signed up in advance to attend our session.

Our fellowship as WIG started as a way to help our work as Board Chairs. Sometimes isolated, sometimes lonely, we also found ourselves with limited access to information needed to succeed

in our roles. At odd hours of the day or night, we will ask each other arcane questions over WhatsApp, questions that no one but a fellow Board Chair in the region would ever care about. Do your TAs get tuition discounts? What number Board Chair are you, for your HOS? Is such-and-such rumor about your school, in fact, true? And while we share information and swap stories, we have chosen to bind ourselves by a signed confidentiality agreement. (Or, truth be told, the lawyer among us made us sign it!)

But over the past year-plus, our community has flowered into a lot more than that. When one of us went through a health crisis, we all bonded and powwowed on how we could show our support (could we secretly contact her HOS for a home address where we can send flowers?) and ended up getting her a rare initialed mini-labubu as a “so glad you’re better” gift (and if you know, you know). And we’ve made time for each other outside of our official meetings–we’ve crashed parties in Seoul, sampled coffee in Kuala Lumpur, and bonded over late-night nachos in Chicago. Oh, and for our debut panel at Bangkok, we all wore matching silk scarves, freshly manufactured in Shanghai and printed with our “official” WIG logo, just in time for the ELC.

What does the future hold for WIG? Our honest answer is that we haven’t the faintest idea. We are aware that our community-building is important, ground-breaking, and also fragile. Our terms as Board Chairs are finite, and we discuss expansion and succession plans (should we welcome new members? Is it more important that they are Board Chairs or that they are women? What happens when many of us, founding members, are no longer Board Chairs of our respective schools?) We are, of course, in touch with other Board Chairs and members beyond our five schools. We don’t have the answers to our questions, but we have come so far in the last year or so, and we expect continuing growth and evolution. Right now, we revel in our community of support, information-sharing, and friendship. We are grateful, and when that WIG WhatsApp pings, day or night, we answer right away.

Women in Governance can be reached at wigovorg@gmail.com.

About the Authors

Dr. Hyungji Park (Board Chair, Seoul Foreign School), Anna-Marie Pampellonne (Board Chair, International School of Kuala Lumpur), Emily Chan (Board Chair, Shanghai American School), Dr. Grace Lee (Board Chair, Taipei American School), and Maria S. Chung (Board Chair, United Nations International School of Hanoi) bring together extensive leadership experience from some of the most respected international schools in the region. Their collective perspectives reflect a deep commitment to educational excellence, governance, and the advancement of global learning communities.

College Admissions

Would Confucius Understand

US College Admissions?

By Grace Cheng Dodge

In the Spring 2024 issue, I wrote an article titled “College Admissions is Not a Competition” focusing on the fact that students get themselves into universities by being their true genuine selves. The best schools can do is to encourage students to be themselves, choose to study subjects and participate in activities they love, and to be able to demonstrate a lifelong love of learning that will carry them way past their college years. This is crucial for their parents and for international school communities to know and to appreciate about school missions and visions, especially throughout East Asia.

I also stated that it is crucially important for school communities to understand that in most cases, especially in American colleges and universities, the admissions process is incredibly human. A GPA or a test score or a certain number of honors/AP/IB courses is not the reason anyone gets into college. Where a student goes to high school is also NOT the reason anyone gets an admissions offer. At this year’s 2025 EARCOS Leadership Conference, I led a mock selective admissions committee with Heads/ Directors/administrators for them to discuss the application files of three high-achieving and compelling students. Unfortunately, we could not admit all three!

What did the participants spend time fighting over? They did not fight over anyone’s grades or scores, because we were already assured they could do university-level work. They also did not discuss where students were from or from what high school. Gender, race, and ethnicity also didn’t play a role at all. Instead, the participants saw firsthand the importance of a student’s voice in his or her own writing, the power of words used in faculty and counselor recommendation letters, and the experienced the “gut” feeling of wanting a student to join the deliberate college community we were trying to put together. In reality, admissions committee members are between the ages of 18-80. They could possibly be a future classmate, a residential advisor, professor, or the director of academic support and health services, and care deeply about every new batch of students admitted to join the community.

No one is ever guaranteed to be admitted on credentials alone, nor should be led to believe they are entitled to be admitted, or that someone else is “taking their spot”. All too often, students do not do enough research on colleges and universities to be able to put together a balanced list of schools to which they want to apply. More often than not, counselors see students have a hard time articulating why they actually want to attend a certain institution (a very important college essay question!) as sometimes the clout of the name, the expectations of others, and the noise around “good colleges” cloud their abilities to truly think for themselves.

We as educators have to keep reminding our students, parents, and community members that not getting into a top choice college is NOT a judgment on a student or the high school! Colleges and universities around the world have many more qualified students apply than there is room to admit them. As the participants in my ELC session experienced for themselves, they could only admit the student who received the majority vote. The admissions committee speaks with one voice and there is no such thing as a student who is admitted (or not admitted) by mistake. But I hope you see the inherent problem when prospective families care so deeply about where your graduates go on to matriculate. This is a worldwide dilemma, but I will speak to it from my Asian perspective, both lived and observed. When a family’s perspective is that a college admissions system is based solely on testing, families want assurance that the high school they

have chosen for their children is teaching effectively enough for students to be able to score high on a national college entrance exam. But when admissions systems (most in the West) are not based solely on academic grades nor testing, and instead focus on intangible skills, SEL knowledge and EQ applicability in order to deliberately put together a freshman class of residential students who will live and learn together, herein lies the dilemma for so many international schools. Asking for proof of “soft skills” has disrupted Confucian beliefs of traditional testing and the ranking of students based on said tests.

Now add a layer of external independent counselors who have never worked in an admissions office in Western countries or even in an international high school as a counselor, and no wonder families are confused, anxious, and willing to pay for any advice as they don’t know what they don’t know to distinguish bad advice from the good. Third, add on a real societal pressure that the name of the university from which you graduate determines where you are allowed to live and where you can work, a concept that is inconceivable and relatively unknown to admissions officers just trying to do their best job at admitting students holistically.

So when families automatically now hear that colleges look at more than grades, they believe there must be a magic formula that can be cloned consisting of extracurriculars (supercurriculars!), summer activities, and every other fad-of-the-year activity that must go on a college application. It is much easier to tell a student what to do and do it well, instead of patiently waiting for

them to explore for themselves and allowing them the time and the grace to make mistakes. Education is treated much more as a transaction in the East, and any loss of face or reputational damage for the family from a simple failure (made by a child) may not be worth the longer term learning lesson for the student. From a Western perspective, the more a student’s life is curated, the more everyone loses sight of who the actual teenager really is.

Here in Asia, we are all trying to best explain and reconcile more familiar Eastern philosophies of education with Western college results that many families desire. I have asked many parents bluntly if they even know who their actual teenager is, what they love to do, and how they think for themselves. I push parents to think about what topics they love to continually learn as adults and how they are modeling this curiosity for their children. As parent education is important in all of our communities, the more they understand the values of our schools and those of prospective universities they want their children to attend, the better equipped they will be to live your school missions with you.

I mentioned last year that the best we can do is to stay true to your school missions, trust the expertise and networks of your counselors with those who will read your students’ applications on the other side of the desk, and cheer on all students alongside their parents. The more we understand the cultural differences at play against a very uniquely American concept of “college fit” and “joy of learning”, the better we can celebrate the strengths of each individual student, no matter their destination after our schools.

Confucius too preached self-reflection, integrity, curiosity, lifelong learning, and role modeling to help others learn. He advised letting go of worrying about external events not under one’s control. He might not be rolling in his grave after all, but is instead cheering on all our seniors as they prepare to head for amazing destinations all over the world.

About the Author

Grace Cheng Dodge retired as Head of School of Taipei American School. She served as the school’s second Director of College Counseling in 2011. Grace is also a former Director of Admission at Wellesley College and former Associate Director of Undergraduate Admissions at Harvard University. She currently consults for Heads and trains school counselors to increase their knowledge of worldwide college admissions and can be reached at grace@dodgeconsultants.com

SPONSORED WEBINARS

Multilingualism in International Schools: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

Presented by: Jon Nordmeyer and Dr. Virginia Rojas

Saturday, January 31, 2026

Time: 9:00-10:20 AM HKT

Free for EARCOS Members / $100 for Non-Members. Visit Website

Archaeology of the Self: Toward Sustaining Racial Literacy in Education

Presented by: Dr. Yolanda Sealey Ruiz

Saturday, February 14, 2026

Time: 9:00-10:30 AM HKT

Fee: Free for EARCOS Members / $100 for Non-Members. Visit Website

“At

Standard Application Online (SAO)

•

•

•

Leadership

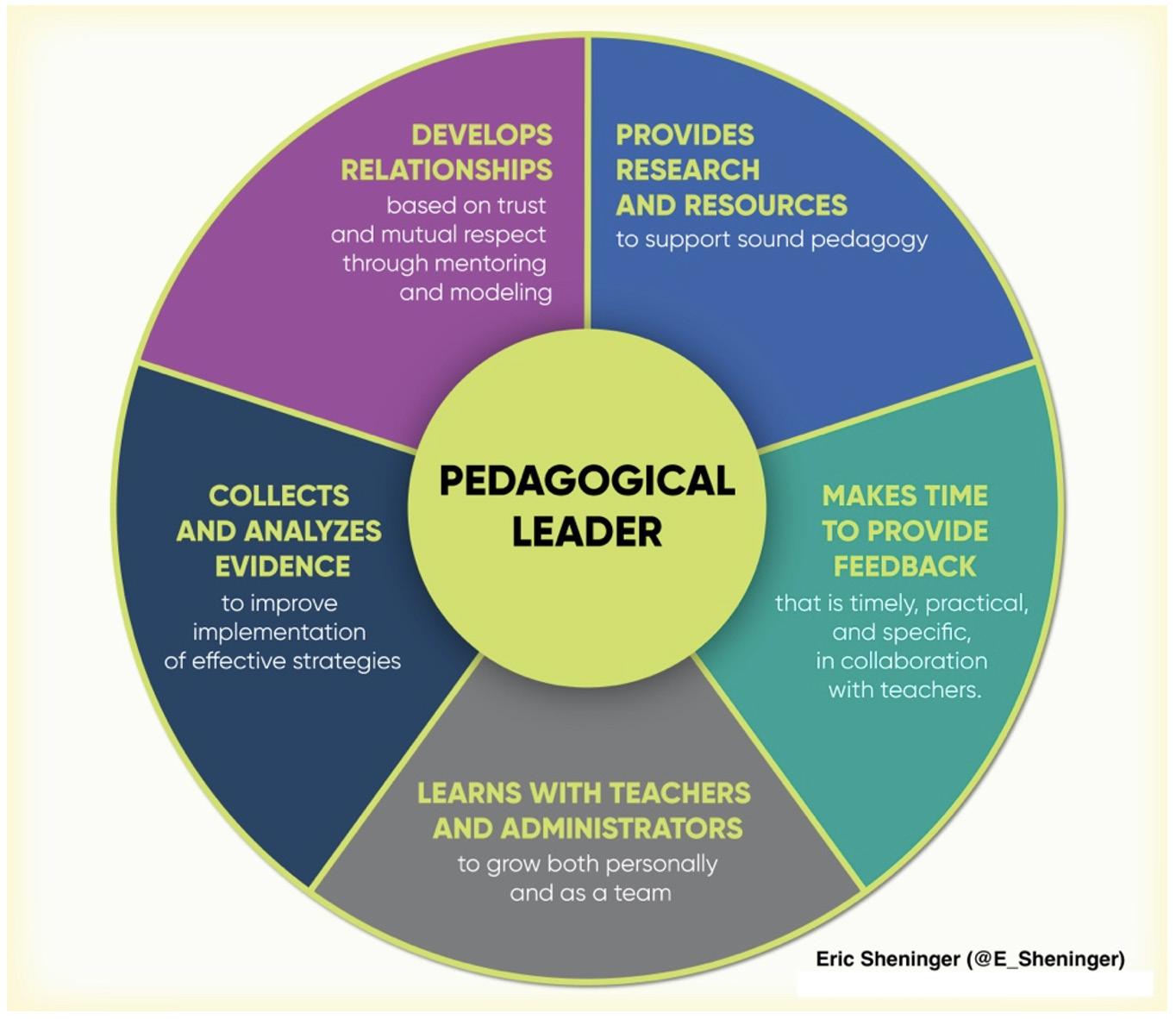

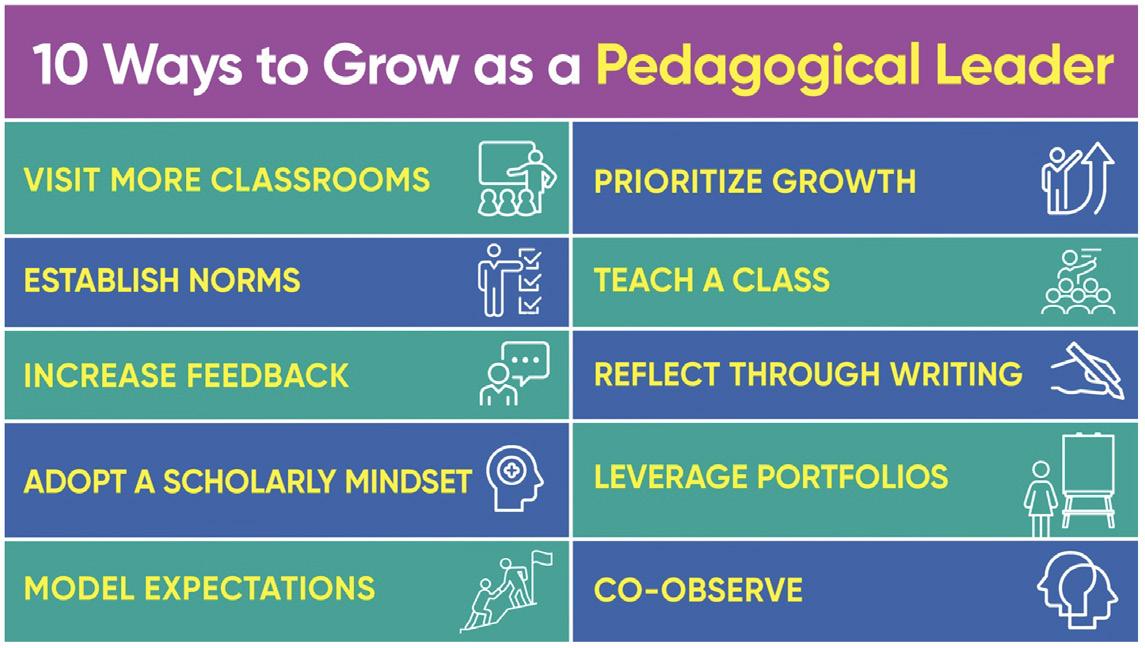

Growing as a Pedagogical Leader

By Eric Sheninger

Pedagogical leadership encompasses all the many ways to support effective teaching and learning. Instructional design is a significant component as teachers need continuous feedback on how to implement the curriculum in innovative ways that result in improved outcomes. While instruction is important, it is only one of many aspects that need attention. Instruction is what the teacher does, whereas learning is what the student does. Here is where a sole emphasis on instructional leadership might not lead to efficacy at scale. Pedagogical leadership focuses on numerous responsibilities and roles that work to ensure a vibrant learning culture that helps to meet the needs of all students (Ailincăi, 2020).

The main differentiator here is a broader view that includes more attention to what the learner is doing and the supports needed for success. The pedagogical leader works to create collaborative benchmarks that lead to continuous improvement across the system. It requires a deeper understanding of how the brain works and research-based strategies that teachers can readily implement in their classrooms (Day & Leithwood, 2007). Observations, both evaluative and non-evaluative, still have immense value. However, the pedagogical leader doesn’t stop here. The use of data is extremely important. Efforts are made to help teachers analyze and use it effectively while the pedagogical leader is doing the same to find ways to close achievement gaps, scale differentiation, and create an equitable culture (Harris, Jones, & Adams, 2018).

The work doesn’t stop with the above. Investments in time and resources are made to establish ongoing and job-embedded professional learning for staff. One-and-done, drive-by, the flavor of the month, or substance-less sessions are seen, not entertained. Pedagogical leaders are constantly trying to ensure learner success by employing effective strategies to improve family engagement. While working directly with teachers is of utmost importance, empowering parents and guardians to assist in the process is vital (Leithwood & Mascall, 2008).

It's simple to offer advice on improving in this area or anything else, but putting it into practice can be a constant challenge. To help you get started, I've compiled ten specific strategies that I used during my tenure as a high school principal and now help other leaders with during coaching cycles.

Visit more classrooms

Firstly, begin by increasing the number of formal observations conducted each year and sticking to a schedule to ensure that all teachers are observed three times annually, regardless of experience. Secondly, develop an informal walk-through schedule with your leadership team, mandating at least five walks per day for each member, and track visits and improvement comments on a color-coded Google Doc.

Establish norms

Establishing a shared vision and expectations for all teachers is crucial. You can do this by utilizing the Rigor Relevance Framework to provide them with consistent, concrete elements to focus on when developing lessons and deciding which high-effect strategies to use. Abolishing the routine of announced observations, having teachers provide artifacts of evidence to show the bigger picture since you can never see all that is done in a single observation, and prioritizing the collection assessments over lesson plans can also be effective.

Increase feedback

When observing lessons, always provide at least one practical suggestion for improvement, no matter how excellent the lesson was. These suggestions should be clear, straightforward, actionable, and timely. For learning, consider curating data weekly and present at an upcoming staff meeting. Feedback is critical to encourage growth and development.

Adopt a scholarly mindset

Improving professional practice as a leader is not the only benefit of being a scholar. It also enables you to have more effective conversations with teachers about their own growth, adding credibility to post-conference feedback. You can align critical feedback to current research by keeping a document of effective pedagogical techniques found in your readings. This approach saved time when writing up observations and improved relationships with staff as the instructional leader. When in doubt, lean on Google Scholar. Another key aspect of a scholarly mindset was brought to my attention by Thomas William Miller and that is to get curious and ask questions. When it comes to leading pedagogical change, questions are often more important than answers.

Model expectations

As I shared in Digital Leadership, leaders should lead by example and not ask teachers to do anything they wouldn't do themselves, especially regarding technology integration and improving practice. When a teacher struggles with assessments, provide or co-create an example assessment. Developing and implementing professional learning is also an effective way to lead by example and build better relationships with staff.

Prioritize growth

Attending at least one conference or workshop a year that aligns with a significant school or district initiative and reading one education book and one from another field, such as general leadership strategies or self-help, can yield powerful lessons and ideas. Creating or further developing a Personal Learning Network (PLN) is also essential to access 24/7 ideas, strategies, feedback, resources, and support.

Teach a class

One can achieve this regularly throughout the year or by coteaching with both struggling and exceptional teachers. I personally taught a high school biology class during my first few years as an administrator, which is an excellent example of leading by example. This approach also provides a better understanding of teachers' changing role in the disruption age. When a pedagogical leader sets an example, it strengthens relationships with staff and puts them in a better position to discuss and enhance learning.

Reflect through writing

As a connected educator, writing has been a valuable tool for me to process my thoughts and critically reflect on my teaching, learning, and leadership work. Our reflections aid in our personal growth and serve as a catalyst for others to reflect on their own practice and develop professionally. Encouraging teachers to write brief reflections before post-conferences can foster a more collaborative conversation on improvement.

Leverage portfolios

Incorporating portfolios into our observation process was a helpful way to provide more detailed insight into pedagogical practices over the course of the school year. Portfolios can showcase personalized learning activities, assessments, unit plans, student work, and other forms of evidence to enhance instructional effectiveness and validate good practice.

Co-observe

During the first quarter of each year, I collaborated with members of my administrative team to co-observe lessons. This allowed us to benefit from each other's perspectives and expertise and provided opportunities for us to improve our pedagogical leadership skills and reflect on our observations. In my role as a coach, I have K-12 leaders visit classrooms beyond the grade levels they serve when working with districts. For example, elementary will conduct walks in secondary to provide feedback and vice versa. We then share collective insight while processing the feedback. Gaining a perspective of strategies used at various grade levels is invaluable.

Ultimately, ensuring quality learning takes place in our classrooms is of utmost importance. These ten strategies can be implemented immediately to improve pedagogical leadership, but there may be additional strategies that others find effective.

References

Ailincăi, E. (2020). The role of pedagogical leadership in promoting quality education. EuropeanJournalofEducationalResearch, 9(2), 659-670.

Day, C., & Leithwood, K. (2007). Leadership for student learning: The contribution of leaders’ qualities and practices. Journal of Educational Administration, 45(6), 661-682.

Harris, A., Jones, M., & Adams, D. (2018). The role of school leadership in promoting student achievement. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(3), 433–453.

Leithwood, K., & Mascall, B. (2008). Collective efficacy and student achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(2), 195–210.

Supporting Books

• Disruptive Thinking in Our Classrooms

• Digital Leadership

• Learning Transformed

• BrandED

• Uncommon Learning

About the Author

Eric Sheninger is a Google Certified Innovator and an Adobe Education Leader, known for his work in advancing innovative practices in education. More information about his work and publications can be found at ericsheninger.com.

SPONSORED WEEKEND WORKSHOP

Concept-Based Inquiry in Action Workshop

February 7-8, 2026

St. Johnsbury Academy Jeju

Consultant: Rachel French

Format: In-Person

Coordinator: Matthew Riniker, matthew.riniker@sjajeju.kr

Explore the new career-connected AP® course that helps students understand business and make confident financial decisions: AP Business with Personal Finance Engages students with real-world financial scenarios Fits into existing CTE programs of study or as a standalone course Helps students earn college credit and an employer-endorsed credential

Leadership

Working in the Eye of the Storm: Taming the Turbulence in Educational Leadership

By Jennifer D. Klein

What gives light must endure burning.

--Viktor Frankl

Ihad no idea what I was getting myself into when I started writing my newest book. As soon as I started interviewing educational leaders around the world and heard their stories of resistance and challenge, I knew I was on a path that would force me and my interviewees to acknowledge and process our passion for the work and the grief we experience every time we lose a fight that would have benefited learners. For me personally, writing this book was a journey; each leader’s story required I face myself as former head of an international PreK-12 school. Sometimes, leaders’ choices reflected my own and I felt validated; in other moments, their interviews brought me face to face with my own mistakes.

Across the world, educators are facing unprecedented levels of resistance to practices we know are good for learners. Whether the push back is political, cultural, religious, or simply a fear of the unknown, school leaders have to manage resistance to their efforts to meet the needs of learners while simultaneously keeping teachers safe and holding onto their jobs. Especially for schools prioritizing equity, innovation and inclusion that are located in polarized or conservative contexts, the stakes couldn’t be higher. But what I’ve learned is that visionary leaders look straight into the eye of the storm and serve their learners first and foremost, no matter how ferocious the backlash becomes.

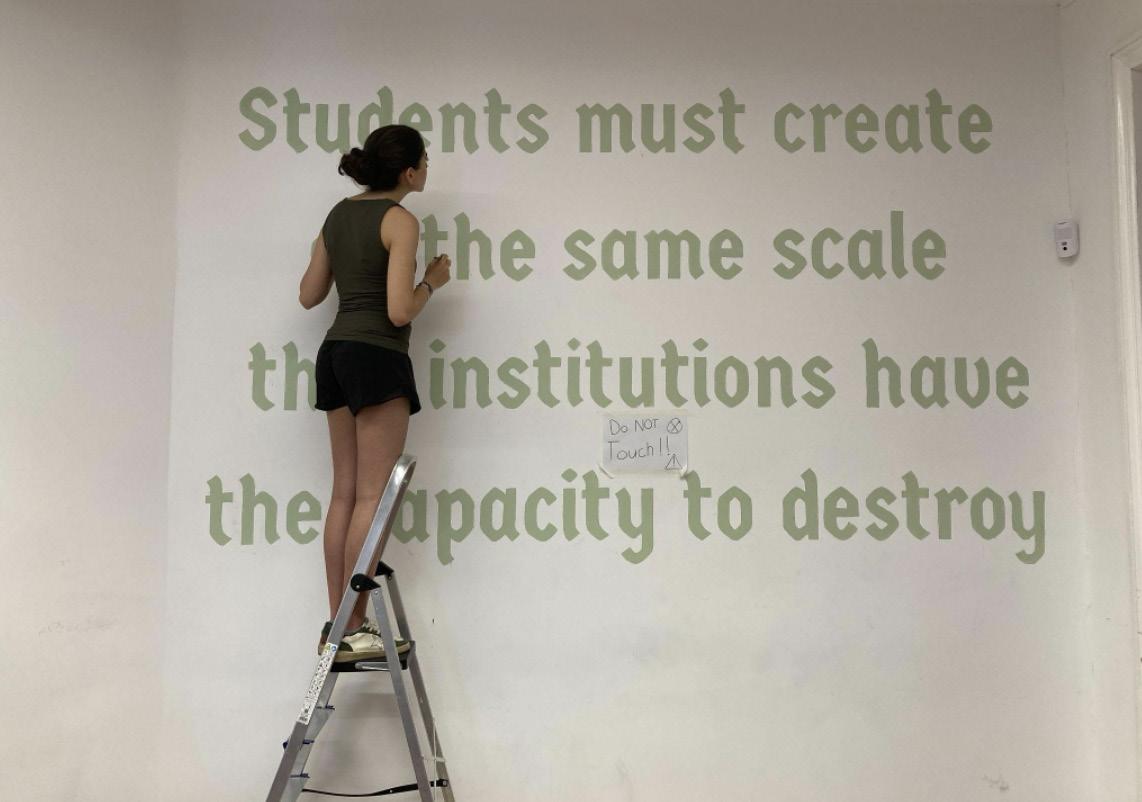

Taming the Turbulence in Educational Leadership: Doing Right By Learners Without Losing Your Job, explores how educational leaders are confronting and “taming” resistance so they can meet students’ needs. Based on my experiences leading student-centered learning in a conservative context outside of Bogotá, Colombia, and on interviews with 67 educational leaders around the world, the book explores how leaders are navigating pushback from more traditionally-minded legislators, extremist groups, school boards, and caregivers. Their stories are sometimes heartbreaking and always inspiring, demonstrating that leaders who keep learners in the center have an internal “North Star” that isn’t swayed or misdirected by the noise when they know that what they’re doing is good for learners.

The good news is that leaders everywhere are putting learners first, making choices that move education toward more equitable and innovative practices that improve the school experience for learners. The 67 leaders I interviewed were proud to share their work on a variety of initiatives that have garnered resistance, all of which fit into two core avenues of educational thinking:

1. Pedagogical and instructional innovations that prioritize student-centered learning, helping ensure all students learn and thrive, regardless of where they live and attend school. This includes schools that are redefining what they mean by success, are ensuring innovation and opportunity for all learners, particularly through career technical education and cognitively- and physically-responsive practices, are innovating outside the system when necessary, are finding ways to innovate in more academically-driven contexts, and are working to sustain that innovation.

2. Identity-responsive programming and equity work that honors place, culture, and learners’ full spectrum of identities, perspectives and needs, ensuring all students see themselves reflected in the curriculum, are supported for who they are, and feel safe and appreciated as learners. This includes schools that are prioritizing culturally-responsive learning and teaching in communities of color and Indigenous schools, social emotional learning and wellness initiatives, gender and sexual identity inclusion, and programs that support critical thinking, pluralism, and intercultural competency development.

I heard incredible stories from these leaders about the work happening in their schools. They told me about learners who shape their own schedules, evaluate themselves without grades, and work to solve authentic problems in their communities. They shared stories about championing all learners, of how they stepped up to protect members of their communities even when others didn’t understand the need or struggled to accept their identities. Every story illuminated these leaders’ journeys and the myriad strategies they used to advance work considered controversial in their contexts, with hope and courage, for the benefit of the young people in their care. Not every story had a happy ending, but these leaders know what they stand for and which hills they’re willing to die on, myself included.

My interviews revealed an array of strategies that have allowed leaders to “do right by learners” with fewer explosions and confrontations:

• Build trusting relationships and deep connection by seeking to understand why constituents are resistant, by managing the pace of controversial work carefully, and by creating intentional structures that support relationship building.

• Use a variety of data metrics and other ways of knowing,

including a wide array of quantitative metrics, qualitative “street data” (Safir & Dugan, 2021), and other cultural ways of knowing in an effort to redefine success and how we measure it.

• Leverage community voice to shape and support change by including students in the development and advancement of work that benefits them, as well as the voices of alumni, teachers, and caregivers.

• Communicate purposefully and proactively, with an emphasis on communicating the connection between new initiatives and the existing identity of the school, finding language that doesn’t trigger our constituents, and proactively addressing the resistance we know will come.

• Prepare and protect the community through transformative professional learning, adapting systems that create obstacles for teachers, and protecting them from harm or attack so they feel safe enough to do challenging work.

• Lead with humility, courage and hope, recognizing that leaders can’t do this work without networks and partnerships, that change work is a journey, and that hope should be considered an invitation to action.

It breaks my heart to think that educators need so much courage to lead good work in schools today. It seems completely logical that the needs of learners should matter more than anything else—ensuring their well-being isn’t political or even debatable, in my opinion. Children deserve schools that support their healthy growth in communities that honor every voice, and they need leaders willing to lean into hard work because they know what matters. When leaders center their work on what learners need, and make choices based on what will benefit them—their growth, their well-being—we demonstrate that education isn’t about mandates and executive orders. Instead, it’s about the love we bring to our work every day as educators.

I hope this book provides community and solidarity for the thousands of educational leaders I didn’t interview who are facing similar storms across the world. I pray that walking together on this difficult path will serve as ballast and lift all of us, making the path a little smoother as we strive for better practices. While schools that prioritize innovative, identity-responsive education may be few, when we work together we become a global network, a powerful argument for what matters most: our learners.

About the Author

Jennifer D. Klein is a product of experiential project-based education herself, and she lives and breathes the student-centered pedagogies used to educate her. She became a teacher during graduate school in 1990, quickly finding the intersection between her love of writing and her fascination with educational transformation and its potential impact on social change. She spent nineteen years in the classroom, including several years in Costa Rica and eleven in all-girls education, before leaving the classroom to support educators’ professional learning in public, private, and international schools. Motivated by her belief that all children deserve a meaningful, relevant education like the one she experienced herself, and that giving them such an education will catalyze positive change in their communities and beyond, Jennifer strives to inspire educators to shift their practices in schools worldwide. Jennifer’s first book, The Global Education Guidebook, was published in 2017, and her second, The Landscape Model of Learning: Designing Student-Centered Experiences for Cognitive and Cultural Inclusion, written with coauthor Kapono Ciotti, was published in 2022.

Igniting Innovation: Cultivating Entrepreneurial Thinking in Educational Leadership

By Dr. Christopher Allen Sekolah Ciputra

There is a common area of tension that can been seen in many schools between the pedagogical side (the educators) and the business side (finance, admissions, etc.). One side thinks there is too much focus on money and the other side thinks there isn’t enough focus on it. The conversation often gets simplified into “for-profit” schools versus “not for profit” ones, and has been a topic of conversation for many years. More than 10 years ago there were panel discussions at the EARCOS Leadership Conference on this topic (including Heads of School, such as Anne Fowles, Chip Barder and James MacDonald), and at this year’s conference there were multiple sessions that included information on bringing the business and pedagogical sides of schools together.

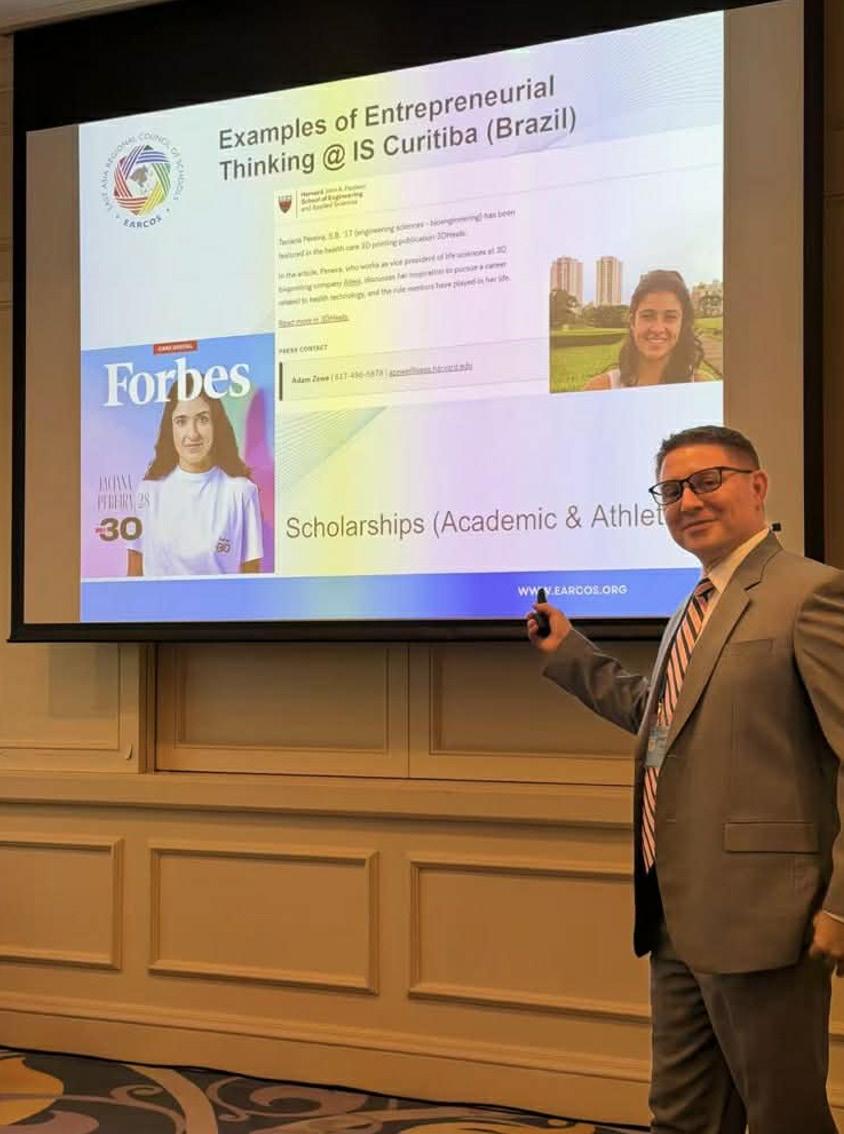

There have been several podcast episodes on shows such as “Where’s Your Head At,” with co-hosts James MacDonald, James Dalziel and Richard Henry that discussed the growing need for educators (and particularly leaders in schools that may not have had this training through the traditional teacher training process) to gain a better understanding of the financial side of schools (Dalziel et al., 2025). As is often the case, once a need has been established, people quickly look for a way to fill the gap, which has led to courses being offered by The Principals’ Training Center (PTC course schedule: The PTC, 2025), The Academy of International School Heads (AISH Leadership Series - Academy for International School Heads, 2025), as well as the more traditional MBA’s being pursued by an increasing number of educators. And this brings us to the topic of conversation on my presentation at the most recent EARCOS Leadership Conference- Igniting Innovation: Cultivating Entrepreneurial Thinking in Educational Leadership.

In education we have actively promoted different types of thinking, such as Creativity (or Creative Thinking), Critical Thinking, Analytical Thinking and Design Thinking. You can find numerous books for sale, TED Talks given and workshops offered to help educators learn more about and hopefully unlock each of these in themselves and those they help educate. An area that has had much less focus over the years is Entrepreneurial Thinking and how it can not only be taught to students in schools, but actually needs to be embraced by educators, and particularly educational leaders. As Dr. Sabba Quidwai said during her Keynote Speech at the recent EARCOS Leadership Conference, “Yesterday having an entrepreneurial mindset gave you an edge. Today is it your entry ticket.”

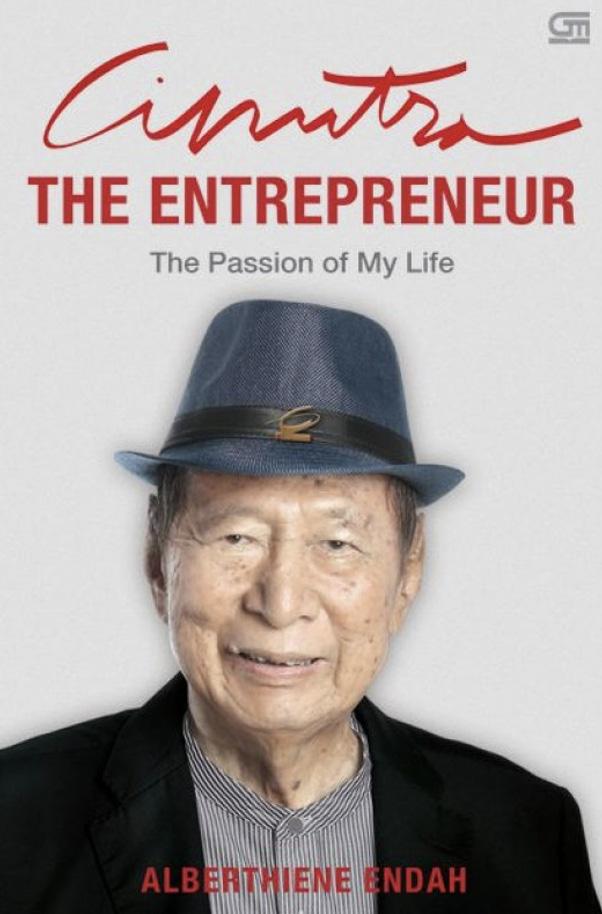

Mr. Ciputra founder of Sekolah Ciputra and mother company,

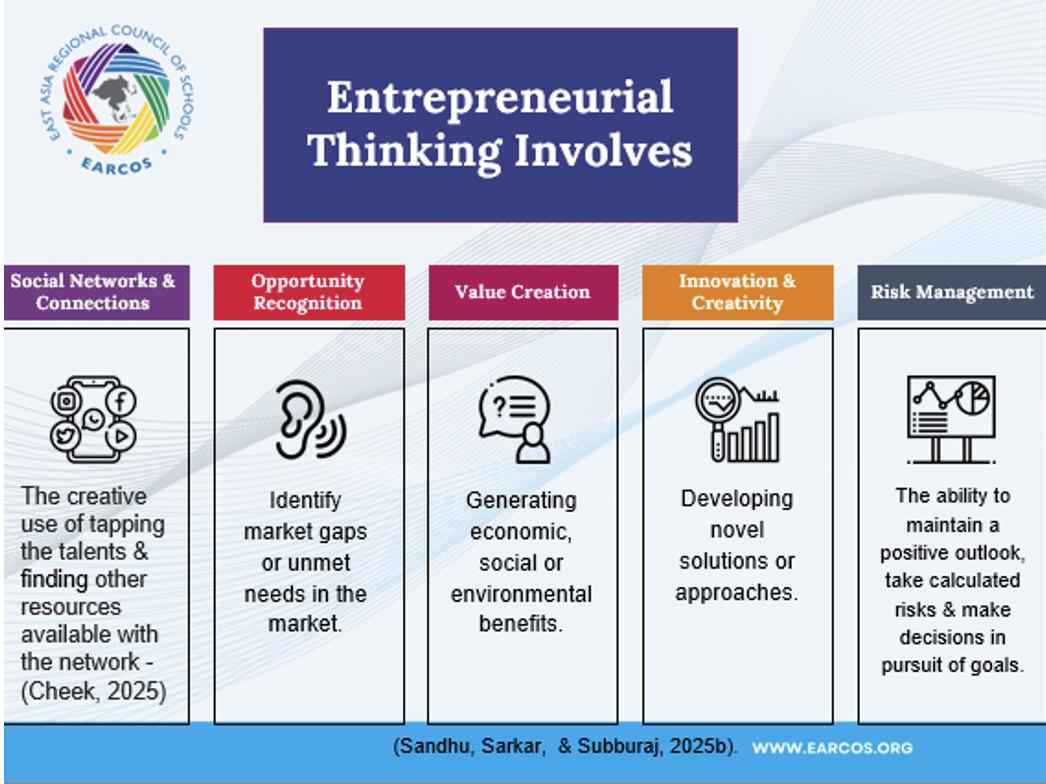

Research shows that there is some overlap between these other types of thinking and Entrepreneurial Thinking (Sandhu, K., Sarkar, P., & Subburaj, K., 2025a). Findings of further research concludes there are several key aspects of entrepreneurial thinking that are most relevant for educational leaders to learn more about and pursue. These include: Opportunity Recognition, Value Creation, Innovation and Creativity and Risk Management. An area that needs further attention is Social Networks and Connections, which Dr. Dennis Cheek, Dean of the School of Entrepreneurship at Universitas Ciputra Surabaya, said is lacking in much of the current entrepreneurial education (Cheek, 2025).

The founder of our school and “mother company,” Mr. Ciputra, believed in the power of entrepreneurial thinking and entrepreneurship education. He created the 3 pillars of the Ciputra Group: Integrity, Professionalism and Entrepreneurship, which are embedded not only in the wider company, but more importantly in our each of our educational ventures. When our school opened 30 years ago, it was the first of its kind and enrolled approximately 250 students. Now we have 12 schools and 3 universities across Indonesia, with close to 18,000 students. Mr. Ciputra’s vision is alive and well, and we hope to spread his message to other educators and educational leaders throughout the EARCOS region, which led to the initial creation of the conference presentation and now this article.

Universities and governments have given increased focus to entrepreneurship education in recent years. In 1970 there were only 16 colleges in the United States that emphasized entrepreneurship education, while there are now over 2,300 that do (Sandhu, Sarkar & Subburaj, 2025b), with over 160 having it as a major. The OECD is now studying the entrepreneurial ecosystem diagnostics in 28 nations for future measurement purposes across the OECD and beyond (Cheek, 2025). In 2013 the European Commission highlighted that acquiring entrepreneurship education and skills was critical to sustained economic growth and competitiveness. “By positioning entrepreneurship as a tool kit comprising essential skills and mindsets, educators can equip students with the ability to navigate uncertainty, think strategically and lead interdisciplinary teams” (Sandhu, Sarkar & Subburaj, 2025b). This belief aligns with what leaders in academia, industry and entertainment said during the “Global Grand Challenges Summit” I attended in Beijing in 2015. During this conference, which mainly focused on engineers and engineering students, the message was repeated by different experts in different ways: you (engineers) will need to work with and gain support from non-engineers. It doesn’t matter how great your idea or solution to the given problem is if you cannot gain funding for it and market the idea to a broader audience to buy it.

This brings us back to the idea of entrepreneurial thinking and entrepreneurial education, and more importantly, why entrepreneurial thinking for educational leaders? There are several benefits to educational leaders who actively use entrepreneurial thinking in their roles. First, they can inspire change and innovation, as well as the attitude that trying new things and methods is welcome in their school. Second, the leader can make more targeted and faster decisions on the basis of their knowledge of the situation. Next, they have the opportunity to generate income through appropriate initiatives and then use this income for the achievement of pedagogical purposes. Finally, they can build, develop and maintain a good image of the school, making them more interesting, which will usually help them get noticed by the broader public (Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz & Pashiardis, 2020). When a school leader operates like an entrepreneur, they:

“…forge strategic alliances outside the school with parents as well as with other organizations, companies or non-governmental organizations, which they think will help them enhance their capacity to do better work for their schools. Moreover, these school leaders are innovative, risk-takers and creative in the acquisition of new resources in order to do more with less…entrepreneurial leadership is associated with external engagement, parental involvement, and networking, all of which assist school organizations to gain a better outcomes. Such partnerships can contribute to creating a secure school environment, enhancing welfare services, improving academic performance, and supporting the achievement of various school objectives” (Kafa, Pashiardis & Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz, 2025).

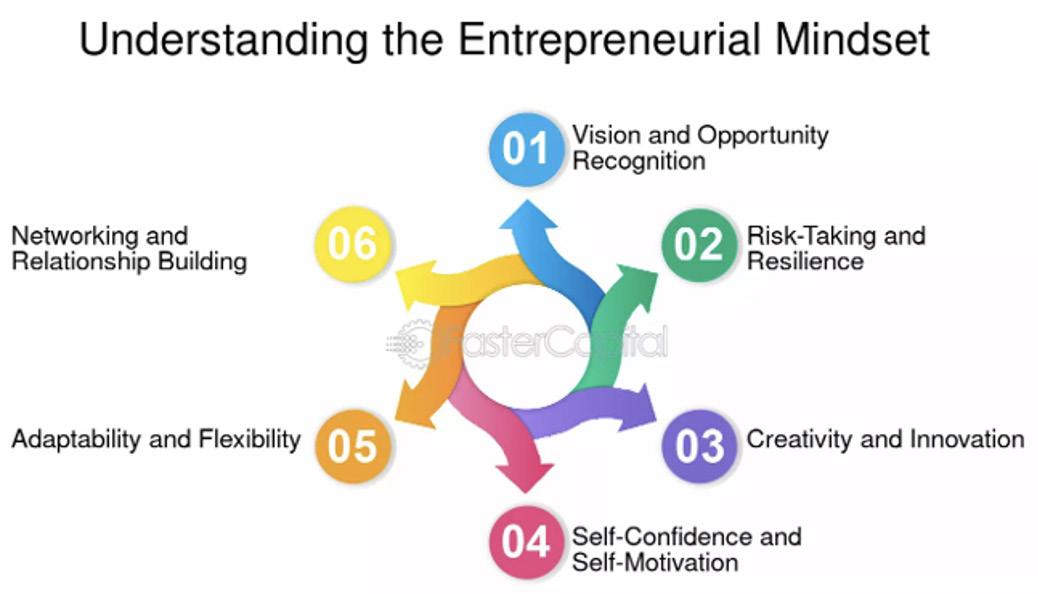

Key characteristics of entrepreneurial leadership in school contexts includes innovation, strategic risk taking, opportunity seeking, resource acquisition, trust and relationship building, parent and community involvement and adaptability to system contexts. These can be seen in the following cycle, which brings to mind the Design Thinking Cycle, where you work your way through the different stages, moving backwards and forwards as needed, in order to solve the challenge being faced.

(Entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial education: How to develop the skills and attitudes of successful entrepreneurs, 2025)

I have experienced several examples of entrepreneurial thinking from educational leaders in different international schools I have worked in over the past 20 years. I have also seen other examples in the schools of friends and former colleagues during this time as well. Here are some of these examples, with a brief explanation as to how they fit the description:

1. During my time in Suzhou Singapore International School, we saw an opportunity during the summer break, where we had quite a few families that either did not leave the city during the break, or if they did, it was not for the entire time the school was closed. While we routinely completed facilities upgrades at this time, we also had many facilities unused that could generate additional income. We also had a number of prospective students that hoped to join our school, but had not passed our entrance test yet. We were able to create a summer school program that was not only available to our own students, but also those prospective students hoping to join the school the following year. This was a highly successful program for the school and the broader community.

2. During my time at the International School of Curitiba we created an athletic scholarship program to help increase student enrollment, but also improving our athletic program and the opportunities it could give, attracting even more students to the school. We were lucky enough to have some of these students accepted to top universities around the world (including Harvard University) which led to even more families looking to join the school in the hopes their own children would have similar success.

3. One of my favorite examples of a school leader using an entrepreneurial mindset to try to solve a challenge was from Tarek Razik, former Head of School at the International School of Beijing. As told by he and members of his leadership team at a number of educational conferences and broader media coverage, the Futures Academy was created to provide alternative educational opportunities for students (with the hopes of differentiating themselves from other students in the region in the eyes of prestigious universities, such as Stanford University) while combating relatively new threats from other schools in the city to being the international school of choice for families there. Unfortunately, the program did not have a long life within the school, but it helped to raise the profile and increase interest in the school not only in Beijing, but throughout the broader international school world.

I will close this article in the same way I closed the presentation I gave back in October. Learning about something is great, but creating action from this knowledge is much more important. What entrepreneurial opportunities might you have in your current context? What needs in your community are currently not being met? What opportunities might be introduced that they don’t know they are missing or need? What opportunities for revenue generation, which could be reinvested into the educational program, might be created? Make a list of possibilities and prioritize them however you like.

Next, we will have you create a network map, to try to find possible connections you have that could help you and your school achieve some of these entrepreneurial opportunities. As shown in The Power of Connections: Tools to Leverage Networks, Mentors & Sponsors (Duffy, L. & Waller, A., 2023), there are three kids of networks:

• Operational- relationships with people at work that allow you to get today’s work done

• Personal- relationships of your choosing, people you like to hang out with informally

• Strategic- relationships that help you envision your future, sell your ideas and get the information and resources that you need. This group is the most important for achieving your entrepreneurial goals!

Now that you have a better understanding of the three types of networks, create a list for each group, adding everyone you can think of and what they might be able to give (help with) and what they might need. Look for connections between people in each group and your proposed entrepreneurial opportunities. Connect the dots, finding possible solutions you had not previously considered from your different networks (and your connections’ networks as well). These network maps can be used to look at any number of opportunities that come up. I wish you all success as you embark on your own entrepreneurial journey!

References

AISH Leadership Series - Academy for International School Heads. (2025). https://www.academyish.org/content. aspx?page_id=22&club_id=921789&module_id=377296

Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz, S., & Pashiardis, P. (2020). Entrepreneurial leadership in schools: linking creativity with accountability. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(5), 787–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1804624

Cheek, D. (2025). Personal Communication.

Dalziel, J., Henry, R., & MacDonald, J. (2025). Podcast. Where’s Your Head At Podcast. https://education2morrow.com/podcast/

Duffy, L., & Waller, A. (2023). The Power of Connections: Tools to Leverage Networks, Mentors & Sponsors. ISS Eduplatform. https://eduplatform.iss.edu/s/external-courses/details?course Id=a0x3t0000081f54AAA

Entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial education: How to develop the skills and attitudes of successful entrepreneurs www.fastercapital.com. (2025, April 3). https://fastercapital. com/content/Entrepreneurial-mindset-and-entrepreneurialeducation--How-to-develop-the-skills-and-attitudes-of-successful-entrepreneurs.html#Understanding-the-Entrepreneurial-Mindset

Kafa, A., Pashiardis, P., & Brauckmann-Sajkiewicz, S. (2025). When successful school leaders go entrepreneurial: empirical insights from Cyprus. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2025.25413 58

PTC course schedule: The PTC. TIE Online. (2025). https:// www.theptc.org/s/77/5/1/principals-training-center-courseschedule

Sandhu, K., Sarkar, P., & Subburaj, K. (2025a). Entrepreneurial Thinking in Engineering Design Education: A comparative study of cognitive paradigms with insights from industry and Academia. Entrepreneurship Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s41959-025-00158-5

Sandhu, K., Sarkar, P., & Subburaj, K. (2025b). Understanding entrepreneurial thinking for designers: Perspectives from entrepreneurs, academicians, product designers, and students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 56, 101728. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024. 101728

SPONSORED WEEKEND WORKSHOPS

Integrating Generative AI into the School Accreditation Process – Ethical Processes and Strategic Advantages

February 21-22, 2026

Brent International School Manila

Consultant: Dr. Rolly Alfonso-Maiquez

Coordinator: Mr. John Whalley, jwhalley@brent.edu.ph

Registration

Thriving Couples in Leadership Retreat

March 6-7, 2026

Consultants: Dee & Kevin Baker, American International School of Guangzhou and Lyn & Chris Jansen, Leadership Lab Global Venue: Nirwana Resort, Bintan Island, Indonesia

Host school: American International School of Guangzhou Format: Face-to-face retreat

Registration

Crises in schools can take many forms, including political unrest, natural disasters, or medical emergencies. Through our various international leadership experiences, we have developed firsthand knowledge of how unpredictable these situations can be. We have discovered that the strength of a school's response is defined by the culture that existed before the crisis began.

When discussing crisis situations, it is important to have a shared understanding of what constitutes a crisis. As school leaders, it can sometimes feel like every day brings a new crisis, and all we do is move from one to another. While we agree with this feeling, our combined experience dealing with crisis situations like a hurricane, child sexual abuse, political strife, economic meltdown, evacuation, and a coup has led us to an understanding of a crisis as being an abnormal and unstable situation that threatens an organization’s strategic objectives, reputation, or viability. This common understanding helps us better develop the crisis-ready culture that is so important to our preparedness for any situation that may come our way.

The first step in fostering this preparedness culture is for schools to define "crisis" according to their own criteria and to build that common understanding within their school community. Coordination and well-informed decision-making are made possible by a common understanding.

Planning, Adaptability, and Trust

A comprehensive plan of action becomes the heart of a school's preparedness. However, being prepared also entails realizing that no plan can cover every possibility. The schools that foster adaptability, a mindset that enables staff to make deliberate decisions even when circumstances deviate from the plan, are often the most resilient. Here at ISY, we have decision-making matrices in place. These help us plan for different emergencies, identify trigger points to consider as a situation develops, and develop possible responses. We do not share these matrices with the community because we want to maintain that adaptive capability. However, we do make it known that we have these matrices in place and we do explain why we don’t share them out. This type of planning helps build trust in the school during a crisis.

A crisis-ready culture is built over time, not during a crisis, through relationships, trust, and a common objective. How people interact, treat one another, and take decisive action in unforeseen circumstances determines their level of preparedness. It is based on the idea that everyone has a responsibility to be prepared and that the trust that is developed through a strong sense of community cannot ever be completely replaced by planning. An example of such an approach is how information is shared out at ISY. We make every effort to ensure we are clear about the information. Clarity of information is different from transparency. This difference matters because full transparency isn't always possible; when we can't achieve it, we clearly explain why. This small difference and clarification contribute to a sense of trust that carries over when communicating during a crisis.

Living Plans and Continuous Learning

A comprehensive crisis management plan remains essential, but it must be a living document, regularly reviewed, practiced, and refined. These plans should be reviewed regularly and shared often as new faculty join the school, etc. Roles, communication procedures, and important decision-making pathways are

part of this sharing, so everyone is informed. Plans must also be adaptable enough to change, as each experience is different. After every drill or real incident, reflection is crucial. Schools should not only discuss logistics but also human reactions, what went well, what confused people, and how to strengthen communication and leadership. Over time, these reflections transform a plan into an institutional memory that strengthens community confidence.

Engaging with globally recognized accreditation frameworks, like those of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, can support crisis readiness. Accreditation requires schools to have strong governance structures, clear policies, and documented procedures. These are all important parts of good crisis management. Beyond ensuring compliance, schools can evaluate their ability to respond, recover, and learn from crises thanks to the self-study and reflection procedures included in accreditation. Accreditation strengthens a school's dedication to safety and ongoing improvement when viewed not only as an accountability measure but also as a resilience tool. We were lucky at ISY, having just completed our re-accreditation self-study and visit the year prior to the coup that occurred here in Myanmar. This process ensured we had reviewed our planning materials and established processes. During emergencies, that accreditation connection becomes more important, as it provides a resource for discussing the situation and ensuring that the best needs of students and the community continue to be met.

Training, Collaboration, and Shared Resilience

For students and staff to respond appropriately in uncertain times, schools must actively train them. This includes tabletop simulations, scenario-based practice, and regular drills. International school leaders can also learn from each other by sharing resources and building local support systems. These relationships improve our ability as a group to deal with challenging circumstances and bounce back more quickly.

It is how successful schools learn from one another and from the resources available to them that makes them unique. Sharing knowledge across borders is a special benefit of international education. Despite the differences in crises, the leadership principles are strikingly similar. Openly sharing and documenting their experiences through peer connections, associations, and regional networks fosters a shared understanding that benefits all. This networked approach transforms crisis management from an isolated reaction to a shared resilience.

Building a Crisis-Ready Community

In the end, being prepared for emergencies involves much more than following protocols. A community that trusts, communicates, and learns together during a crisis is better prepared. Our response, planning, documentation, and review processes are what build our school’s strength. The more we learn from each setback, the more capable we become in the future.

To support international school heads, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) and the Academy for International School Heads (AISH) have partnered to develop resources for crisis leadership. As a part of this project, we plan to feature stories from school heads who have led during a crisis. If you are a head who would be interested in sharing your story, please contact Gregory Hedger at ghedger@acswasc.org for more information.

Curriculum

Engaging Every Sense: A Three-Phase Framework for Language Teaching

By Sophia Suo Western Academy of Beijing

Abstract

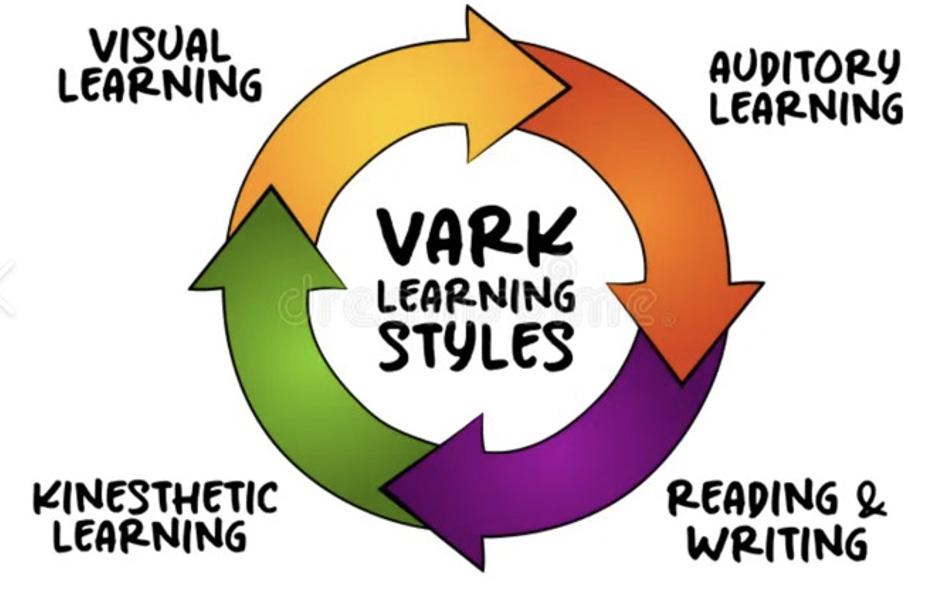

How can language teachers engage students fully in the classroom and provide a practical yet enjoyable learning experience? This article introduces a practical teaching approach— the Three-Phase Framework for Language teaching—based on VARK learning style preferences, enabling students to naturally acquire language through multimodal classrooms that integrate sensory experiences, reading and writing, and kinesthetic activities.

Introduction

Often, when teachers focus on book knowledge and rely on oral explanations or reading and writing exercises to achieve the teaching goal in a lesson, they find that students respond passively, lacking active thinking and responses. It is not because they don't like language learning, but because the lesson doesn't suit their learning styles. Traditional teaching ignores individual preferences.

Neuroeducation research indicates the brain possesses a remarkable capacity to process information via multiple parallel channels. If students receive the outside information from multiple sensory channels, including sight, hearing, touch, smell, etc., the brain can interactively and intensively process such information effectively. According to this, coupled with actual needs and some vital language acquisition theory, I developed a Three-Phase Framework rooted in multimodal and sensory approaches.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1 VARK Model and Multimodal Learning

The VARK model divides learners into four types of preferences: visual preference learners are sensitive to spatial information such as images, charts, and videos; Auditory learners tend to learn by listening and discussing; Reading and writing learners are good at studying classics and papers, expressing their opinions and organizing knowledge through writing; Kinesthetic learners acquire knowledge through hands-on practice, by touching, feeling, and operating. The vast majority of people are blended learners, and multiple stimuli can promote the internalization of knowledge.

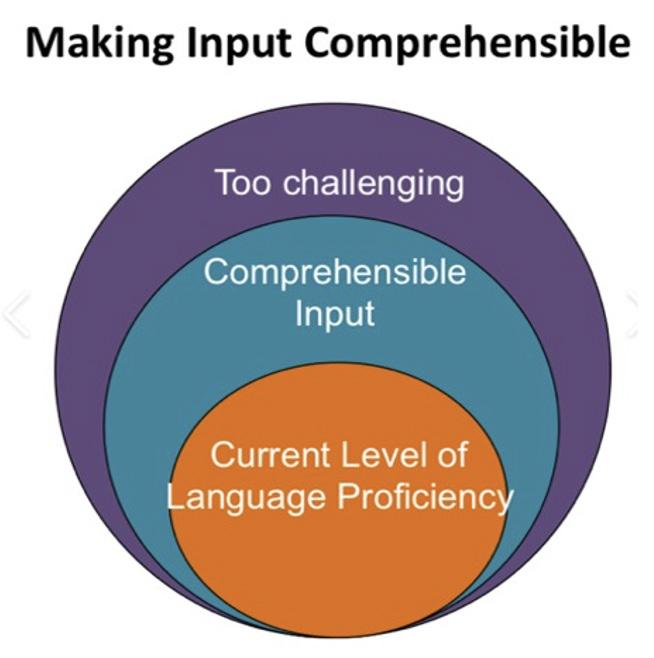

2.2 The "Input -Output" Theory in Second Language Acquisition

As Krashen suggested, when providing learners with language input slightly above their current level (i+1)—i.e., when new knowledge falls within a moderately challenging range—contextual input can stimulate their interest and curiosity, and enhance their understanding of the knowledge. Suppose the class consists of intermediate learners who have mastered basic daily

vocabulary and simple sentence structures. Giving a familiar and comprehensible context with an appropriate language challenge will help them acquire the language without frustration.

Swain proposed the key role of comprehensible output in the language acquisition process. When students output the target language, they can consolidate knowledge, connect fragmented grammar and vocabulary, and identify knowledge gaps promptly. Students can make targeted learning improvements if they know their grammar usage problems.

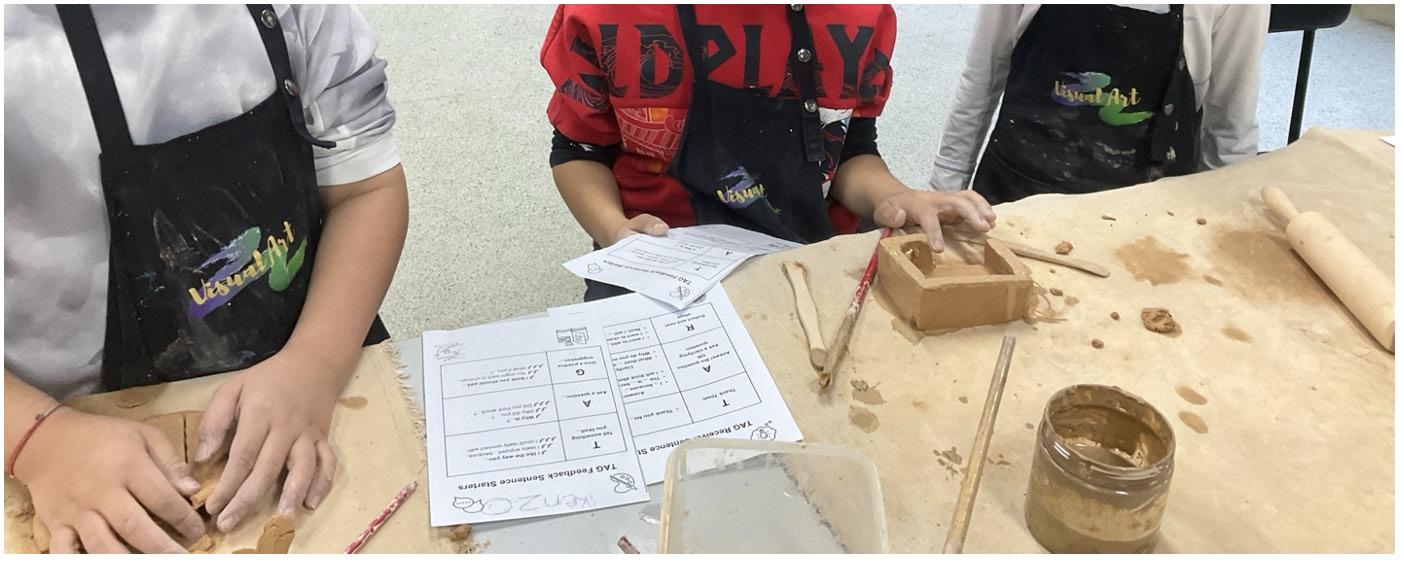

3. The Three-Phase Instructional Framework

3.1

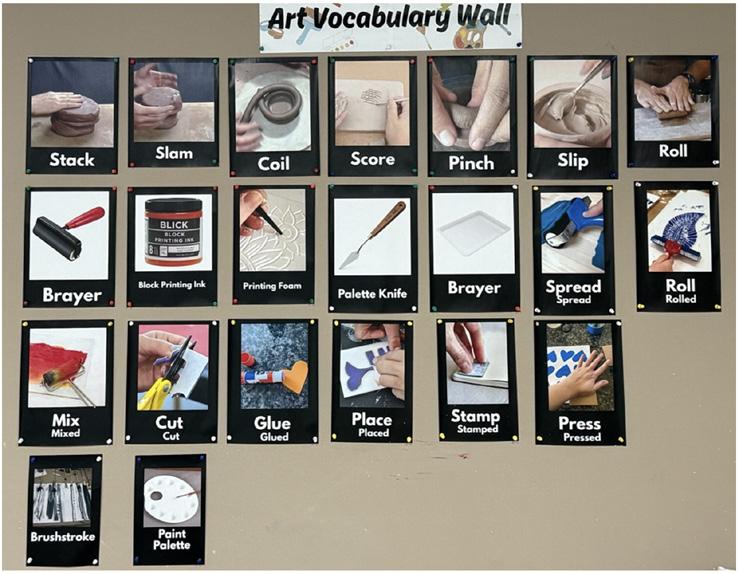

Phase 1: Activating Prior Knowledge

Before language classes begin, teachers can use various sensory stimulants to create an environment for comprehensible input and quickly bring students into specific course situations. The teacher can explain abstract knowledge with concrete perception by showing pictures, videos, colors, and kinesthesis. For example, when teaching verbs and their expressions, teachers should advise students to learn how to use these words through pictures, body postures, and actions, which helps the learners to strengthen their understanding via practical applications, and reduces learning anxiety. The "mystery bag" can arouse students' curiosity when teaching adjectives. By grabbing the objects with different textures, such as the smoothness of silk and the sandpaper, students can feel these things and even produce more desire to know and express. During the lesson on "season" or "natural environment", playing music and natural sound corresponding to the themes can activate and inspire students' listening sense, and smells from nature can also stimulate their learning.

This process tests students’ prior knowledge, provides insights into their learning styles and levels, and offers a solid guarantee for building a new understanding "bridge" in the next step.

3.2 Phase 2: Multimodally Scaffolding i+1 Input

Typically, teachers need to guarantee that 85% of the words, sentence structures, and expressions are familiar to the students in the language classroom teaching, so that it is easier for the learner to build up confidence and maintain the continuity and energy of learning. The "i+1" (which are newly introduced) challenge and promote learners to step into the "zone of proximal development" to realize a gradual growth in language competence.

When introducing new knowledge, the coordinated use of multiple cognitive channels, engaging the learner's sensory (vision, hearing, touch, smell, taste) and kinesthesis, helps them immerse themselves in numerous real situations and stimulates their ability to acquire, organize, and process information. At the same time, it enables learners to quickly establish connections between the newly acquired knowledge and the real world, allowing them to understand the interweaving of language and cultural elements in real-world scenarios, thereby bridging the gap between abstract textbook knowledge and vivid, authentic culture.

Rich pictures, videos, and logically clear timelines can make abstract knowledge comprehensible.

For instance, all kinds of different sound signals can activate the class. When students listen to prose descriptions of natural

scenes, the teacher can play musical works that convey melodies and emotions to stimulate students' initial cognition of the rhythmic beauty, and the background music can build a concentrated climate. And then, enter nature, hear the wind, rain, and the birds' sound, and let students describe and express them, which can deepen students' closeness to nature.

In the "blind box" where there are all kinds of items, students guess the names of the items and describe the feelings with eyes closed, which could also facilitate vocabulary memorization and expression.

Bringing students into a particular situation with imitation activities, such as body movement, is a form of kinesthetic learning. For instance, while learning prepositions, students who can practice themselves the positioning of objects on the table while explaining the placement of objects through action and their movement in the body can learn best. Sense of smell and taste can give an exceptional language experience that includes the scent of flowers (roses), the freshness of lemons, and the richness of coffee. Students will recognize language while smelling and improve their learning experience by explaining the smell.

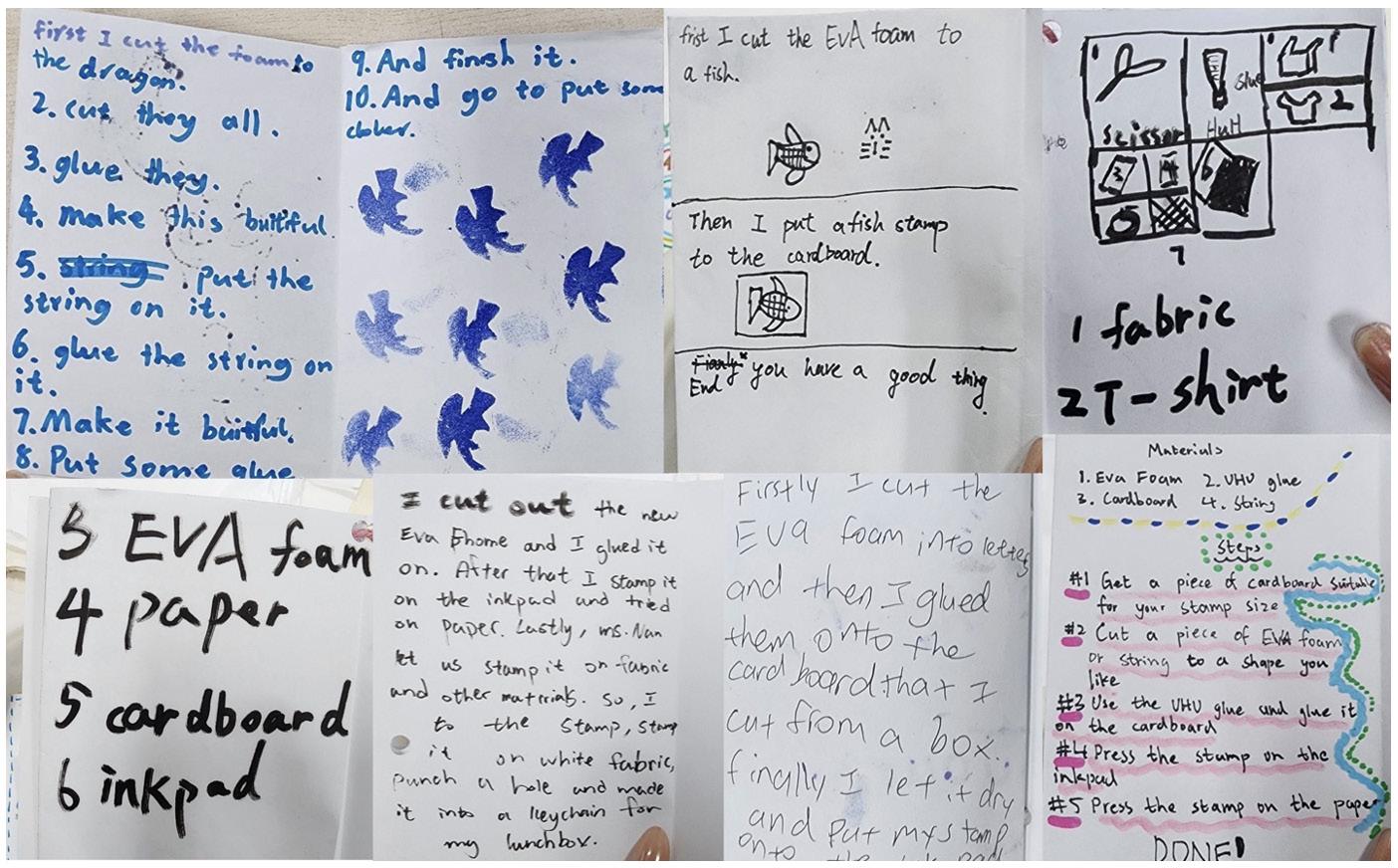

3.3 Phase 3: Creative Output

Creative output is a key link in students' acquisition and elevation of knowledge. Teachers provide demonstration samples to guide students in understanding the forms and key points of knowledge output. Showing excellent articles or videos that build up the logic can help students structurally sort out and reconstruct new knowledge from Phase 2. For example, encourage students to make vlogs, incorporate new words, sentence structures, and culture explorations into video creation, capture daily life, add explanatory text, and demonstrate understanding and application through text, images, and sound; Create interactive e-books that incorporate elements such as audio, video, and animation to encourage learners to present their knowledge diversely.

It is crucial to respect students' autonomy in choosing their output methods and topics based on their interests and strengths. At the same time, guide students to reflect and sort out their work, understand their strengths and weaknesses, all of which can recreate the learning experience in the output process.

4.

Observed Outcomes