Author Declarations

This dissertation is protected by copyright. Do not copy any part of it for any purpose other than personal academic study without the permission of the author.

2

3

Abstract

‘Is Architecture Dead?’

Elizabeth Wilson

Course: BSc Architecture

The aim of this study was to explore if Arthur C.Danto’s argument for the end of art (Danto.A

1997) when applied to architecture, draws the conclusion that architecture has reached an end.

Questioning if and with what did Architecture end with, or If it hasn’t ended why didn’t it follow art, or follow art fully?

There are two main assumptions that underpin this study. Firstly, that Architecture and arts historical narratives can be compared, and secondly that Art has reached an end.

This is a qualitative, exploratory, comparative study between Art and Architecture. The main body is divided into two sections. The first section analyses Danto’s end of art argument.

The second section then using the arguments laid out in the first section places works of art and architecture in dialogue with one another that in my opinion form a parallel to one another. This study’s frame of reference relates to writings emerging from Western or westernised contexts. Consequently, it should be read throughout as referring to a limited set of cultural circumstances. Despite the wideranging scope of the study, it’s a fragmentary one whose associated conclusions are far from being claimed as definitive. The conclusion of this study is the answer that architecture is not dead.

4

5

List of images

Ahrends Burton & Koralek Wilkins. (1983) Design for the National Gallery Extension [Model]. At: RIBAPix.

Aldo Rossi. (1991) Biennale of architecture [Poster]. At:

https://www.labiennale.org/en/historybiennale-architettura

Andy Warhol. (1964) Brillo Box [Sculpture].

At: The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, US.

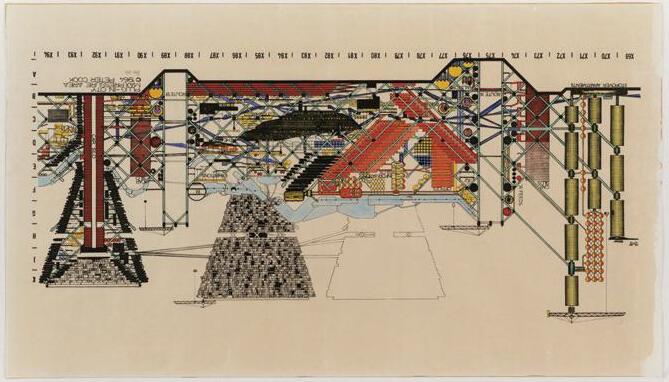

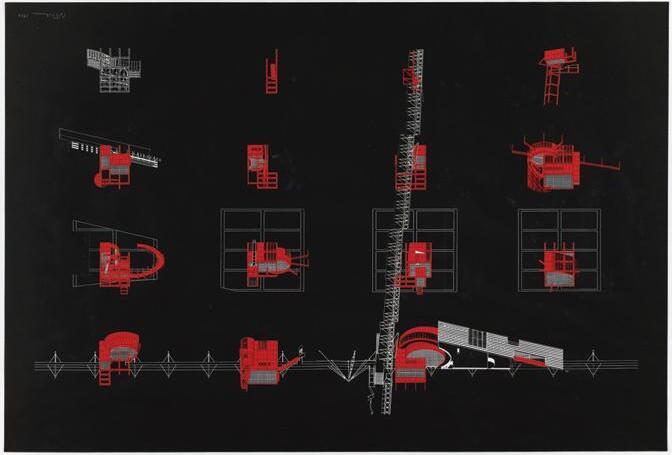

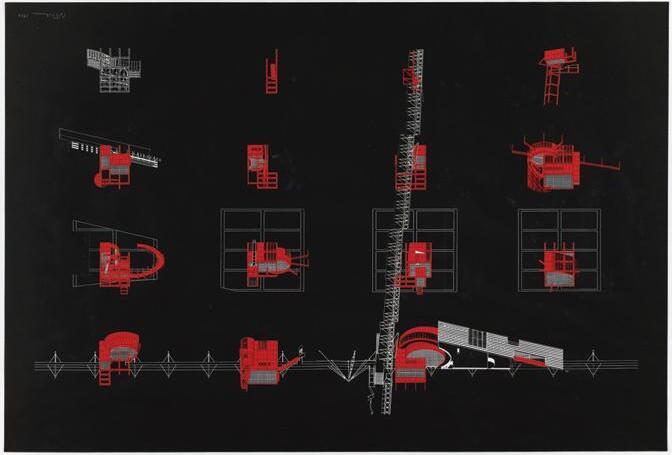

Archigram Group, Peter cook. (1964) Plug-in City: Maximum Pressure Area [Section Drawing]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Barbara Kruger. (1985) Untitled (No), from the Untitled Portfolio [Photography]. At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

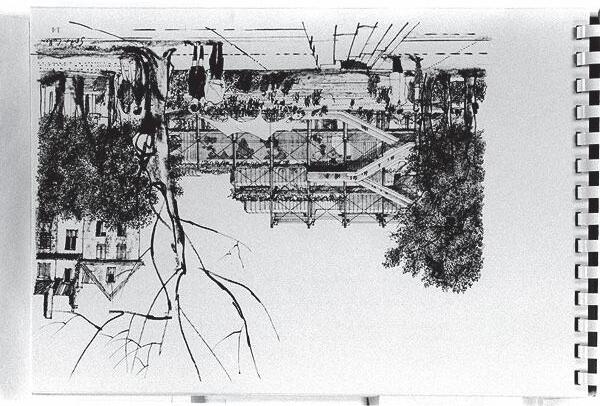

Bernard Tschumi. (1986) Parc de la Villette, Paris, France [Follies and Galleries, isometrics]

At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Carolee Schneemann. (1975) Interior Scroll [performance art]. At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

Clement Greenberg. (1964) Post-Painterly

Abstraction [Exhibition] Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Morris Louis. (1961) Beta Lambda [painting].

At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Damien Hirst. (19 ) ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone

Living’ [Sculpture]. At: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US.

Damien Hirst. (1990) ‘A Thousand Years’ [Sculpture]. First exhibition located at Gambler, Building One, London, United Kingdom.

6

Decorated cave of Pont d’Arc. (Dated to the Aurignacian period) Known as Grotte ChauvetPont d’Arc. [cave painting]. At: Ardeche.

Foster and Partners. (1983) Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters [Drawings, Hand drawn and CAD]. At:

https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/hon gkong-and-shanghai-bank-headquarters/

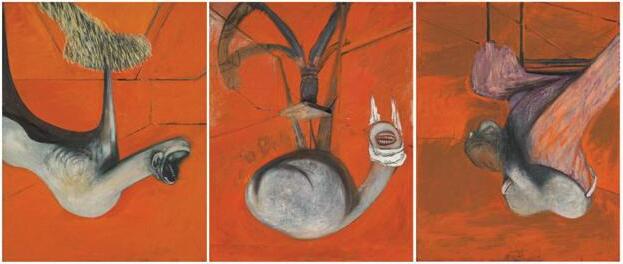

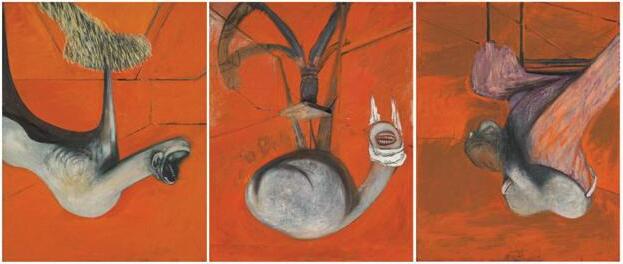

Francis Bacon. (1994) Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion [Painting].

At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

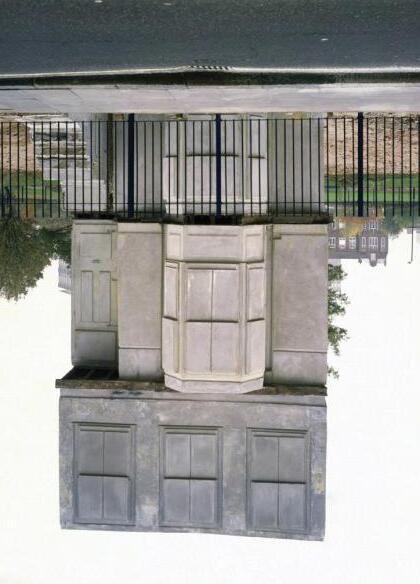

Gordon Matta-Clark. (1974) Splitting [Film].

At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Henry Matisse. H (1912) The Blue Window.

[painting. At: Museum of Modern Art, New York

James Stirling. (1978) Neue Staatsgaleire

[Drawing] At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Jencks. C (2000) Evolutionary tree [Diagram]

At: Architectural Review.

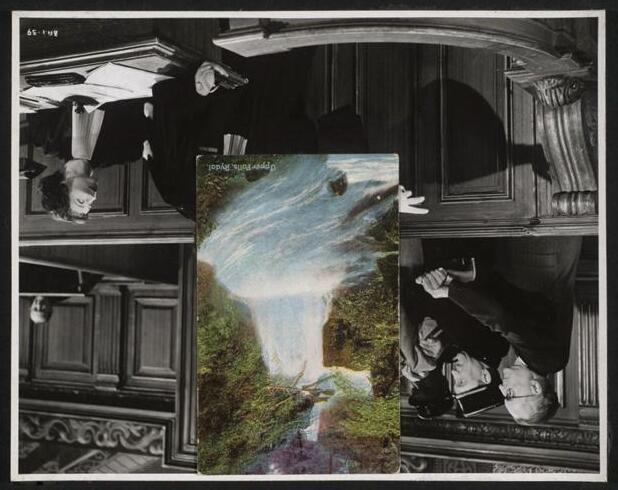

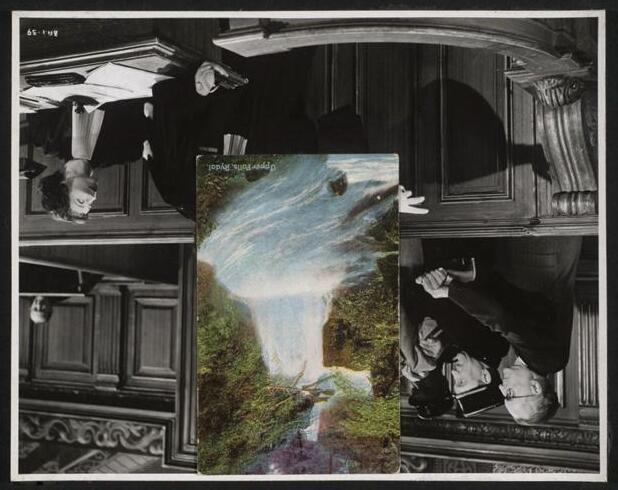

John Stezaker. (1978) The Trial [photography].

At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

Joseph Kosuth (1965) One and Three Chairs [sculpture].

Lev Kuleshov. (developed in 1920’s) The Kuleshov effect [Film]. At: Location unavailable.

Liz Diller and Ricardo Scofidio. (1991) The Slow House [model and drawing]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

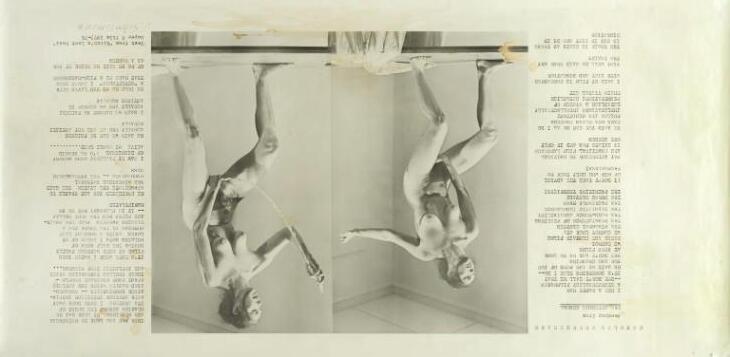

Liz Diller and Ricardo Scofidio. (1992)

Desiring Eye: Reviewing the Slow House [multimedia installation]. First shown at: The Gallery Ma, Tokyo, Japan.

7

Morris Louis. (1961) Beta Lambda [painting].

At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

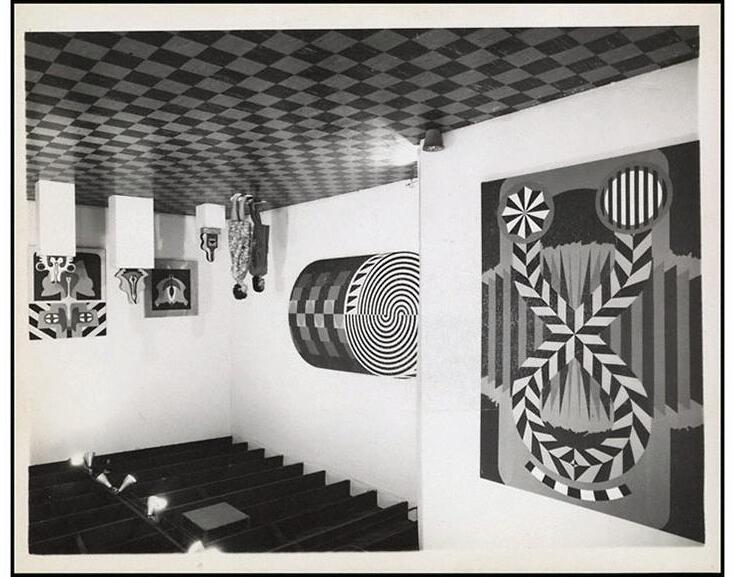

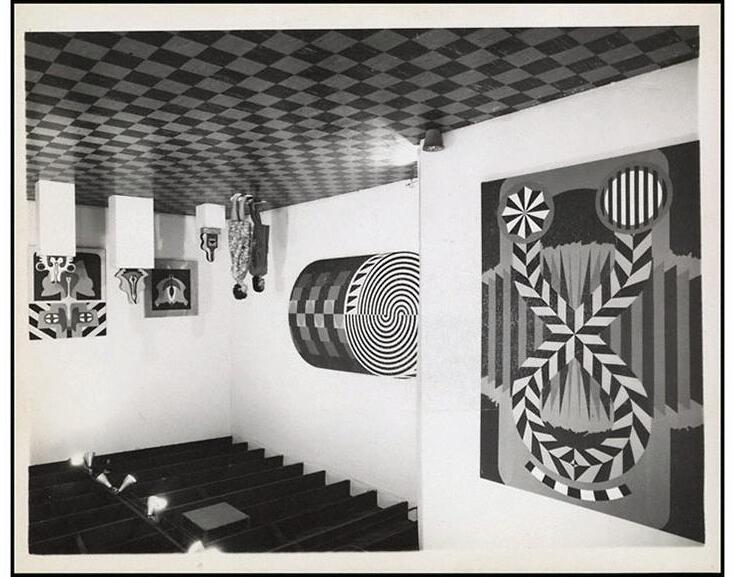

Multiple Artists (1988) Deconstructivist architecture [Exhibition] At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Multiple Artists. (1985) Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern [Exhibition]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Paul Klee. (1920) Angelus Novus [monoprint].

At: The Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

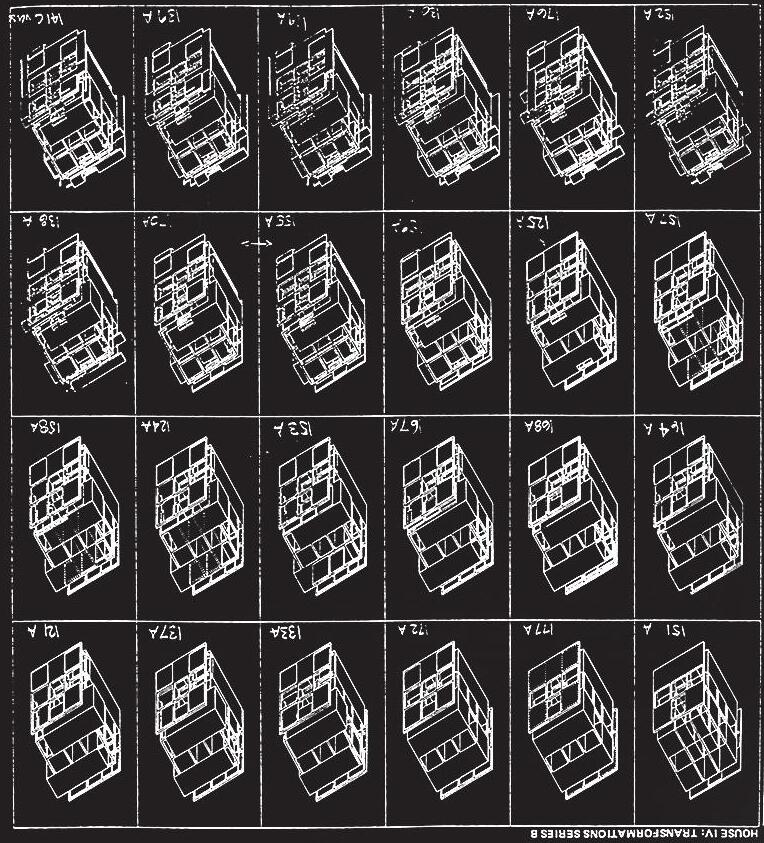

Peter Eisenman and Robert Cole. (1975) House IV Project [Multiple axonometrics]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

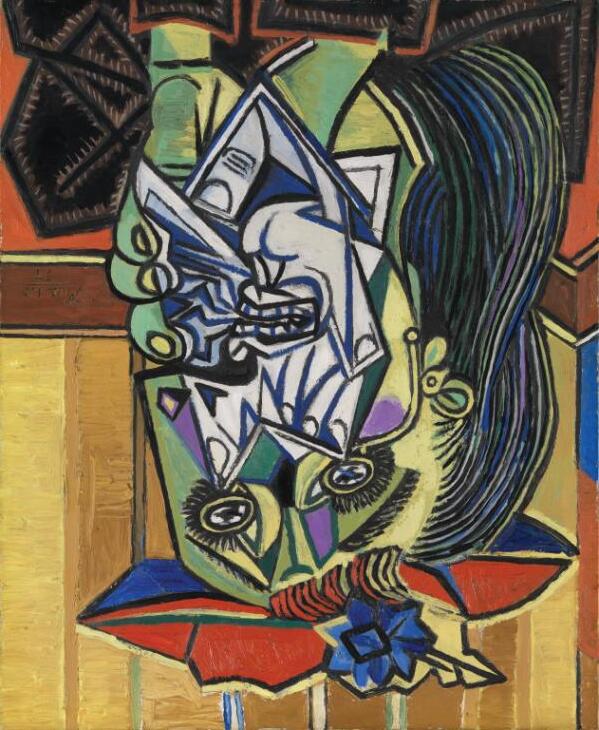

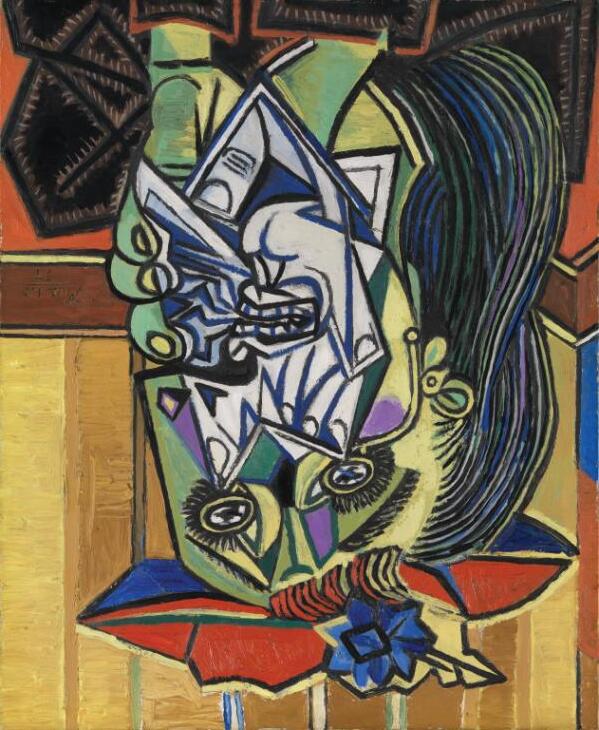

Picasso. P (1937) The Weeping Woman.

[painting] At: Tate Modern, London

Pollock. J (1951) Number 4 [painting].

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. (1971) Drawing presented for the Centre Pompidou contest [Drawing]. At: http://mediation.centrepompidou.fr/education/re ssources/ENS-architecture-CentrePompidou/au_coeur_de_paris/p3.htm#

Richard Serra. (1981) Tilted Arc [Sculpture]. At: Dismantled and in storage in US since 1989.

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Stephen Izenour’s Learning From Las Vegas.

Sara Fanelli. (2006) ‘The artists timeline’ [mural]. At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

Short section of the Berlin Wall remaining at Potsdamer Platz. Location unavailable.

Sindy Sheerman. (1975) Untitled A [photography]. At: The Tate modern, London, UK.

Steven Spielberg. (1985) The Color Purple [film still]. Distributed by: Warner bros.

8

The Documenta Art Show (1972) Documenta 5 [Exhibition] At:Kassel, Germany.

Victor Pasmore. (1967) Apollo Pavilion [Model] At: Paetelee, Durham, England, UK.

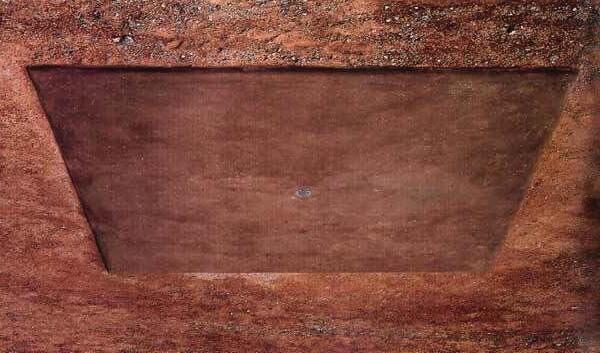

Walter De Maria. (1977) The Vertical Earth Kilometre [earth art]. At: Friedrichspatz Park, Kassel, Germany.

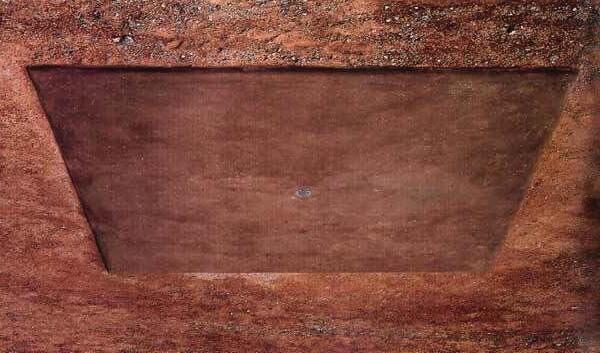

Whiteread.R (1993) House [Sculpture]. At: (Now demolished), London.

Wifredo Lam. (1943) The Jungle [Painting]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

City, NY, US.

9

10

11

Table of contents

Author Declarations

Abstract List of images

Introduction

Literature Review

Methodology

Research Implementation Section One

Section Two

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendices

12

13

Introduction

Since the paintings found in the Grotte Chauvet-Pont d'Arc cave (Dated to the Aurignacian period) works of art have touched us through their capacity to evoke experiences of timeless humanity, without requiring any knowledge of the artist’s intention. Contrastingly, today certain works of art would be unrecognisable as works of art without knowledge of the artwork’s respective theoretical foundations. This shift in how we experience art led to Arthur C. Danto’s view that art has turned into its own philosophy and artworks exist only in coexistence with their own theory (Arthur C. Danto. 1997).

Arguably the line of reasoning by Danto casts light on the currently confusing scene of architecture. Often, an intellectually qualified stance is more essential than the sensory embodiment of the material language of the

building. As the formal art forms such as painting have arguably arrived at a decisive limit and paradigm shift, is it reasonable to expect architecture to have continued unaffected without its foundations being shaken and questioned in an equally fundamental way?

14

15

Literature Review

Theorised and Interdisciplinary Studies is a growing area in architectural research which has emerged as architectural writers have begun to look to other disciplines to find interpretative frameworks in order to explain architectural issues. (Lucas.R. 2016) As demonstrated by the interdisciplinary essays that address gender in relation to architectural discourse in Sexuality and Space. (Colomina. 1996).

The title of this study ‘Is Architecture Dead?’ is a play on words referencing Nietzsche’s argument of ‘God is dead’. (Nietzsche.F. 1974).

Nietzsche’s ideas have been pivotal in criticism. The art critic, Boris Groys explicitly references Nietzsche in his motivation behind reevaluating Socialist Art: “I will only criticize that which seems valuable, worthy and fateful to me, as Nietzsche said.” (Groys.B. 2016).

The portrayal of progress, which is central to our understanding of present-day architecture, has been called into question by the critic Walter Benjamin in perhaps one of the most pivotal statements in 20th-century art in his description of the art piece ‘Angelus Novus’. Benjamin reflected most profoundly on what he saw in Paul Klee’s painting in his 1940 essay

‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in thesis

IX.An English translation by Harry Zohn is included in the collection of essays by Walter Benjamin in Illuminations (Benjamin.W. 1968).

Walter Benjamin’s criticism of modernity’s portrayal of progress has arguably been echoed in the works of critics ever since. Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows alludes to an ending caused by modernity’s progress and in the concluding chapters presents the reader with the hopeful idea that there’s “somewhere in arts that could be saved”. (Tanizaki. J. 1977)

The American political historian Francis

16

Fukuyama brought the notion of an end into a wider context in his controversial essay entitled ‘The End of History.’ (Fukuyama.F. 1992).

Fukuyama’s basis in the works of Hegel and Alexander Kojeve. is important in understanding the symbolism of announcing an end. Hegel foreshadowed that the end of art would be reached when art “attains its own nature” implying an exhaustion of essence on arrival at self-knowledge. (Hegel. G.W.F. 1988).

Hegel, and writers that choose to base their work on his such as Fukuyama, associate an end with freedom. The notion of an end leading to freedom is an integral part of the Marxist ideology. The neo-Marxist understanding of an ‘end’ is evidenced in contemporary works in a variety of research fields. Within Architecture

Peter Eisenman’s 1983 Persecta article, The End of the Classical. (Eisenman.P. 1983).

Within art Hans Belting, the German art

historian,) The end of Art History. (Belting.H. 1997) and within a similar time, frame Arthur C Danto’s After the end of Art. (Danto.A. 1997).

Arthur.C Danto like Fukuyama adopts a neoMarxist interpretation of freedom that’s achieved through an end. Danto makes this explicit in his adoption of creative writing, using the phrase: “As Marx might say” to locate his views in the neo-Marxist context. (Danto.A. 1984).

Whilst Arthur.C Danto is not a historically significant figure, as an experienced writer and academic Danto’s work is built upon the work of significant writers of the 20th century. His writings offer an accessible argument for those without an art history background and has arguably been influential in forming ‘countercriticism.’ Rebecca Solnit in Men Explain Things To Me, defines counter-criticism as “Not against interpretation, but against confinement,

17

against the killing of the spirit. Such criticism is itself great art.” (Solnit.R. 2014).

kind of alternative modernity in the face of the advent of postmodernity.”(Edelson.Z. 2018).

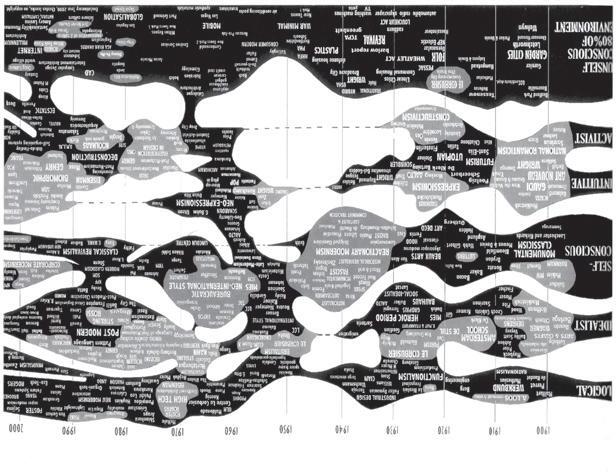

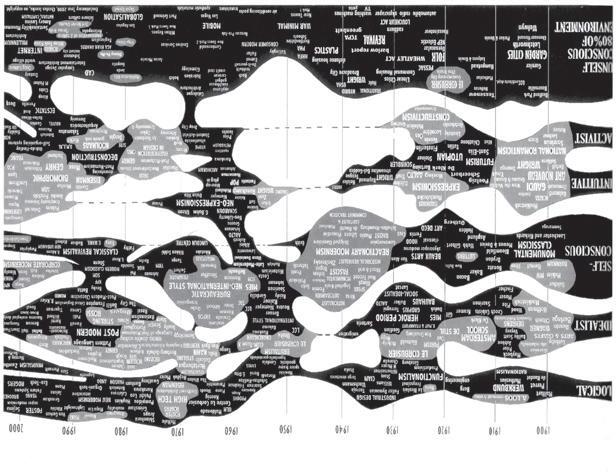

Danto’s framework for interpreting art proposed a revolutionary shift in the way we understand art, removed from the art critic Clement Greenberg’s obsession with progress which is seen as beginning in Greenberg’s 1939 essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” (Greenberg.C. 1939). The emphasis Greenberg places on progress draws a parallel to Architectures Charles Jencks who attempted to chart the dominant architectural forces of the 20th century in what he famously called an evolutionary tree. (Jencks.C. 2000). This reliance on a progressive model is also evidenced (although to a lesser extent than Jencks) in Kenneth Frampton’s (1992) ‘Modern Architecture, a critical history’ which Frampton describes: “is really an attempt to formulate a

Arguably Danto’s end of art argument is relevant to art criticism today. As James Elkins writes: “art criticism is in worldwide crisis, diaphanous … like a veil, floating in the breeze of cultural conversations and never quite settling anywhere… critics have begun to avoid judgments altogether, preferring to describe or evoke the art rather than say what they think of it.” (Elkins.J. 2004)

. Thierry Duve in ‘This Is

Art’ concludes that the question of artists today is ‘what is art?’ (Duve.T. 2014). This draws a parallel to Juhani Pallasmaa’s conclusion on architectures focus shifting to describing what architecture is, over what is good architecture in his essay ‘Brillo Box dilemma’. (Pallasmaa.J. 2012).

Danto’s the end of art, and subsequently, this study has its limitations. One of the limitations

18

built into Danto’s argument is the way he conceives the nature of art. For Danto Art has content which it then articulates. This relies on the idea that artists have meanings. While Danto doesn’t claim artworks always have meaning, he claims its always legitimate to ask what an artwork means, but it may be that some artworks are beneath meaning. A baroque string quartet may simply be about ravishing you in terms of its beauty. As a result, a pluralistic view is argued by the critic Brodsky to have been rejected by Danto because it didn’t fit neatly into Danto’s unifying theory. (Brodsky.J. 1984)

Richard Kuhns offers a critique of Danto’s theory in his essay "the end of All". Kuhns argues, "The very stuff of art is the stuff of culture and culture never ends as long as there are human societies." Kuhns admits that art may have ended according to the three models of art which Danto offers but that those three models

do not represent the full nature of art. (Kuhns.R. 1984).

The conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth also responded to the end of art argument and declares, in "Art after Philosophy” that "The twentieth-century brought in a time that could be called the 'end of philosophy and the beginning of art.'" Kosuth used a similar line of argument to Danto’s yet came to a seemingly opposing conclusion. (Kosuth.J. 1969).

Joseph Kosuth also sheds light on artists shift to conceptual art in an essay simply entitled "Intentions". Kosuth explains that the reason artists shifted to the conceptual was so that they could retain more control over their work. Kosuth argues that abstract expressionists, such as Jackson Pollock, created objects which were shipped off to critics who assigned them meaning. This casts significant doubt on Danto’s interpretation that conceptual art was

19

the result of artists reaching higher levels of self-consciousness. (Kosuth.J. 1996).

The appropriateness of embracing post-critical framework was questioned by Hal Foster who draws upon Debord’s commentary of Dadaism and surrealism (Debord.G 1994) to build an argument that our current cultural situation evokes the past concluding: “If there is anything to this echo, then surely it is a bad time to go post-critical.” (Foster.H. 2012).

The limitations of Danto’s argument of the end of art arguably reflects the nature of study within the visual arts as worded by the art critic Roberta Smith: “Everything around you can be analysed in terms of its visual presence…the great thing about art is that there’s more than you can ever know about, you can’t learn it all. And you’re lucky if you get to spend your lifetime trying to.” (Smith.R. 2009).

20

21

Methodology

This is a qualitative, exploratory, comparative study between Art and Architecture exploring if Arthur C. Danto’s argument for the end of art holds significance for architecture. Qualitative research is appropriate as it is most suited for questions of history, theory, philosophy and the social aspects of architecture (Lucas, 2016). The methodology used in this study is textbased secondary research and visual analysis. The use of text-based research enabled a wide range of resources to be reviewed ranging from historical materials to the present day. Secondary qualitative data has the advantage of providing access to a wide range of valuable research material that has been collected by professionals that are experts in their respective fields. Artworks, architecture representations and exhibitions will be used as evidence in the argument. The visual analysis of architectural

representations such as drawings and models was chosen with the intention to be removed from ‘Real-world’ Architectural issues. The use of visual analysis is notable in key architectural texts published in the 20th century such as Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Stephen Izenour’s Learning From Las Vegas.

The main body will be divided into two sections. In the first section, I will analyse Danto’s argument for the end of art. In the second section, I shall use the arguments I have laid out in the previous section to apply to architectural works that in my judgment form a parallel with artworks. Comparisons made between respective works will be presented in chronological order at fiver year intervals to replicate the linear understanding of history that we are commonly presented with, as evidenced by a timeline of artistic movements by Sara Fanelli commissioned by Tate Modern.

22

23

Research implementation

Section One

In this section, I will systematically analyse Danto’s arguments with reference to the works he sites. Danto in After the end of Art (Danto.A. 1997) proposes a unifying theory to explain the contemporary condition of art. Danto begins his discussion by arguing that the two most common models of art history do not sufficiently explain the course of contemporary art. After this, he goes onto propose his own model of art history.

Danto firstly addresses the progressive model of art history, sometimes referred to as the conquest of perceptual appearances. Danto credits Giorgio Vasari, for this model which views art as a continuous attempt to image reality. (Vasari.G. 2007). For Danto, the problem with the progressive model of art is that during the 20th-century artists left behind

their historical commitment to mimesis, due to the emergence of photography and film.

As art shed its mimetic quality, individual expression in art came to the forefront. The second model of art history is that in which art becomes a communication of feeling. Danto provides the Fauvists as an example. This expression in art suggested to Danto that art does not progress along a linear path, but is rather a manifestation of each artist's independent attempt at self-expression. This view is questionable as no artist exists in a vacuum and is likely to have been aware and influenced by what came before them. This is evidenced by the obvious progression even in expressionistic art with the Fauvists eventually giving way to the cubists.

For Danto, both models of art history fail to explain the advent of conceptual art in the twentieth century. Arguably the modern thought

24

task had become to reflect on the nature of art through artistic means as evidenced by Morris Louis’s exploration of flat paintings to explore the 2D nature of painting. This notion of using painting to reveal the nature of painting and in effect the nature of art relies on looking, that something could be seen in a piece of art that would explain its nature. This notion of looking is what Danto built his theory upon after seeing Andy Warhol's (1964) exhibition of Brillo boxes.

Danto’s theory emphasises the singularity of the artwork. Art, as defined by Danto, is Art if it’s about something and embodies what’s it about in an appropriate form. This was a revolutionary shift in understanding artworks as object rather than fitting artworks in a development or having to relate to other artworks in a trajectory of history.

Danto’s model of art history is a combination of the previously mentioned two models combined

with Hegelian philosophy (Hegel. 1988). Danto cites the numerous and highly varied movements in art of the twentieth century as having one common thread; As Danto describes: “[artworks] approach zero as their theory approaches infinity so that virtually all there is at the end is theory, art having finally become vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought about itself, and remaining, as it were, solely as the object of its own theoretical consciousness.”

(Danto.A. 1997).

Danto does not suggest that the end of art causes an end to art-making. Danto likens his age of pluralism in art to the state which Karl Marx referred to as the Post-Historical Period (Danto.A 1997). In this view, the end of art is not a catastrophic apocalypse in which art ceases to exist, instead, art has reached a Utopian state in which all striving can cease and art can exist for its own sake.

25

Section Two

In this section, I shall use the arguments I have laid out in the previous section to apply to the architecture of buildings that in my judgment form a parallel between art and architecture. These buildings range from the built (Tschumi. 1986) to the unbuilt (Diller and Scofidio. 1991) from the Rejected (Burton and Wilkins.1983) to the celebrated (Piano and Rogers. 1971); and the visionary (Peter cook. 1964) to the pragmatic (Foster. 1983). This argument will develop chronologically with parallels between art and architecture being made at roughly fiveyear intervals, beginning in 1964, the same year Andy Warhol exhibited his Brillo Boxes.

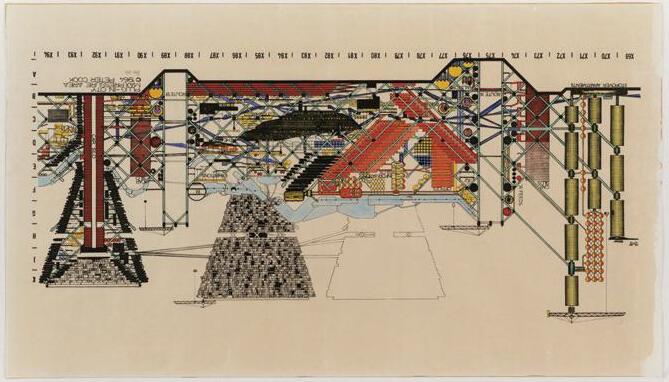

The age of pluralism described by Danto implies the disappearance of Utopian and visionary perspectives. Arguably, architecture had not reached this condition as illustrated by the drawings produced by Archigram in the

same year Danto saw Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes. Archigram’s Plug-in City (1964) embodies the pop art movement stylistically with the use of colour and the intention of presenting radical ideas. While the graphic utopias of the Archigram group in the 1960’s may appear naïve to today’s disillusioned eyes, they nonetheless reveal the existence of a visionary horizon that could be achieved through technological advancements. Within the art world, the Pop movement shook the foundations of the art institutions so deeply that as Hans Belting has stated: “There will have to be either a discipline for before 1960 and a discipline for after, or a history that has stopped forever a few years ago to be followed by ahistorical happenings.” (Belting. H 1997). Although architecture hadn’t reached an age of pluralism, the embodiment of the pop art movement by Archigram arguably set a path

26

towards it by challenging the upholding of the progressive model of history.

In light of these ‘ahistorical happenings’ as described by Hans Belting, architecture like Art entered a battle of styles, challenging the institutionally dominant views and giving rise to the self-expression of artists and architects alike. While architects were not free to pursue any direction, the critical architectural texts of Architecture Without Architects (Rodofsky.B. 1964) and The New Brutalism (Banham.R. 1966) evidence the eruption of manifesto styled texts in which each author seeks clarity in their differing answers of what architecture is and should be. Arguably, architecture like art had begun to pursue the modern thought task of questioning what architecture is.

Banham’s 'New Brutalism' offered guidance towards a new socially oriented architectural style. This draws a parallel to the art world where a group of social art historians such as

T.J. Clark looked towards a Marxist critique of capitalism. Clark’s critique in the Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution, rapidly became the paradigm for a theoretically-informed yet empirically-rooted Marxist account of art practice. (Clark. T.J. 1982). As a result, an institutionally dominant art world and architecture found itself challenged in the upholding formalistic approaches due to the emergence of new socially oriented ones. Arguably as a result of this tension artists and architects were unable to pursue any direction described in Danto’s age of pluralism (Danto.A 1997). This is evidenced by Victor Pasmore’s (1967) Apollo Pavilion which is completed in a brutalist style exemplary of Banham’s New brutalism. The pavilion is a mediation between a work of architecture and art evidencing the parallelistic nature between art and architecture, and the new socially oriented approaches they adopted.

27

The techno-scientific developments that were expected to provide tools for the materialisation of the Utopias presented in the 1960s arguably led to the decline of visionary perspectives. This disillusionment contributed to the beginnings of the age of pluralism due to the following decades subsequent questioning of the traditional hierarchy of art and architectural works.

The Centre Pompidou (1971-77) by Renzo

Piano and Richard Rogers is emblematic of the celebration of technological developments of the time. This celebration of technology was criticized in Norman Mailer’s A Fire on the Moon, where Mailer argues that the materialisation of technological advancements ended poetic exploration. (Mailer.N. 1970).

Mailers argument is built upon by the Finnish architect, Juhani Pallasmaa in Encounters, where Pallasmaa writes “pre-empting the God of poetry, Apollo, for the name of the mission,

28

and transforming the traditional symbol of the romantic imagination, the moon, into a lifeless scientific object.” (Pallasmaa.J. 2012). This suggests that the freedom architects had begun to experience through the advancements in technology resulted in the loss of poetic visionary perspectives. This is evidenced by an interview conducted for the Architects Journal when the interviewer Will Hurst, asked how Rogers and Piano coped with criticism of their design [For the Centre Pompidou], Rogers answering that: ‘[we were] very naive … Youth is blind, thank God for that.’ (Youde.K. 2017) highlighting the contemporary disillusionment. Arguably as a result of the disillusionment of the visionary, architecture turned to becoming socially and politically engaged.

This draws a parallel to the art world where, in the same way, that architecture was consumed by advancements in technology, art was taken ahold by upcoming conceptual art and

happenings with Harald Szeemann the Swiss curator of the 1972 The Documenta Art Show in Kassel, Germany, equalizing the classical genres of painting and sculpture with upcoming conceptional art and happenings, breaking down the traditional hierarchy of artworks. This breaking down of hierarchies led to the emergence of new and multi-genre artworks (at the same time buildings such as Centre Pompidou had emerged in architecture) as demonstrated by the conceptual Film art, by Gordon Matta-Clark in 1974 titled Splitting.

‘Splitting’ is remembered today as “one of the premier moments of a period in which anarchistic, architecturally oriented sculpture coexisted with Conceptual art.”. (The Art Institute of Chicago. 2018). However, the freedom that art and architecture experienced was constrained by the contemporary context of the 1970s, architecture by limited knowledge of the application of the technological advancements, and art by the social context as

29

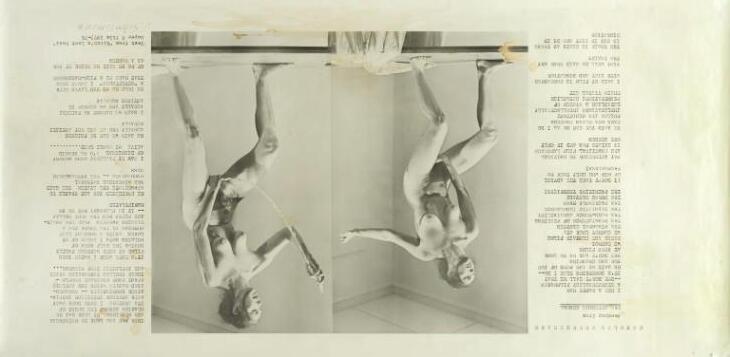

evidenced by Robert C. Morgan’s reflection of the artwork ‘Interior Scroll’ by Carolee Schneemann, which Morgan argues must be understood within the context of feminist performance art. (Morgan.R. 1997).

30

The loss of the visionary perspective led to the Emergence of Postmodernism, which boldly declared an end to modernism. The modern thought task of questioning what architecture is led to greater emphasis placed on the theoretical and the adoption of an intellectual approach in the creation of postmodern art and architectural works.

This shift in the importance given to the theoretical suggests that works had begun to be understood through their own theory. This is evidenced within the art world with the conceptual earth artwork The Vertical Earth by Walter De Maria. the underlying idea of creating an actual yet invisible work of art. Its concealed quality makes it anti-expressive and consistent with the period’s many paradoxical negations of the visual in visual arts. It would be difficult to interpret The Vertical Earth without being aware of the underlying idea. This emphasis

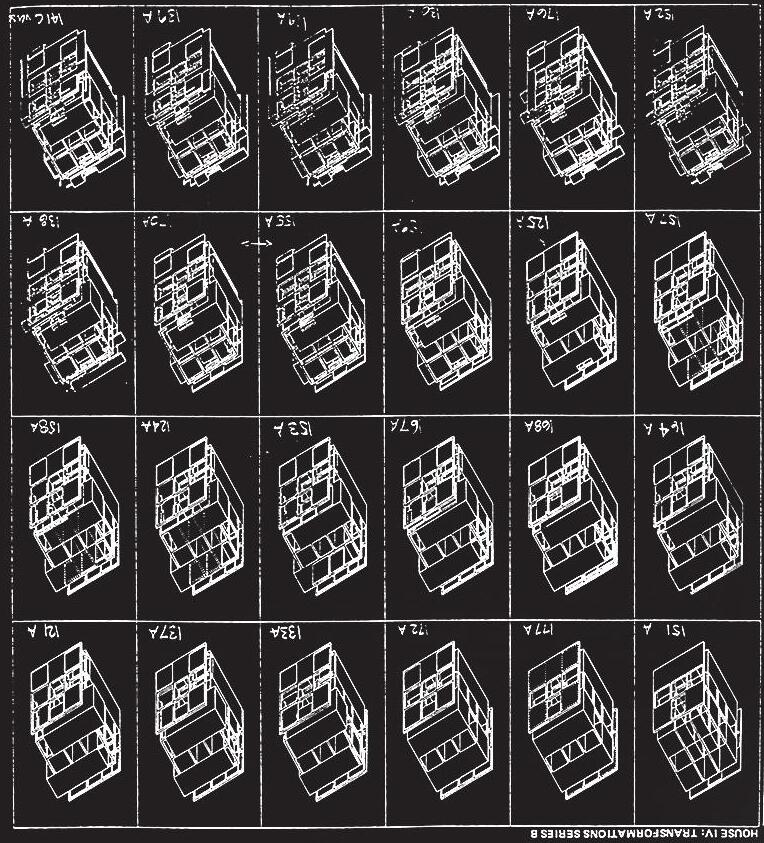

placed on the theoretical draws a parallel to the 1977 Architectural project House IV Project by Peter Eisenman and Robert Cole, that consists of a sequence of axonometric drawings which act as a diagram for the transformation of a basic cube into a highly developed spatial configuration. This shift in understanding architecture through its own theory is evidenced by the MoMA curatorial label for House IV:

“shelter is the result of cerebral processes that speak of architecture’s ability to generate its own logic and authority.” (MoMA. 2013). This exploration of using architecture to explore architecture arguably led to history forming a part of later postmodern works.

The use of pleasure, The History of Sexuality

Volume 2 by Michel Foucault’s is arguably a text for the postmodern condition. Foucault suggested that history should be used as a storehouse of good ideas. (Foucault.M. 1985).

Foucault’s ideas on using history were arguably

31

adopted in later postmodern works, evidenced through the use of juxtaposition. In the art world John Stezaker’s use of juxtaposition of the idyllic sylvan scene of a waterfall, with the human drama depicted in a 1940s film still, in artwork The Trial arouses a sense of the uncanny. This use of juxtaposition draws a parallel to what’s often regarded as the epitome of postmodernist architecture, James Stirling’s in Stuttgart, Germany. The building is simultaneously a monumental civic structure and an informal one, "High tech" in some respects while traditional in others. The design combines a wide range of architectural references both general and particular: Romanesque windows and allusions to specific buildings such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Altes Museum in Berlin. These eclectic juxtapositions of traditional elements, along with the more contemporary presence of components in coloured metals, resulted in an inventive and vibrant postmodern building.

Arguably an intellectually qualified stance is more important than the sensory embodiment of the material language in later Postmodern architectural works, suggesting architectures theory is ‘approaching infinity’. (Danto.A. 1997).

32

Postmodernism as Jean-Francois Lyotard would put it in his groundbreaking The Postmodern Condition was the end of a unifying, underlying ‘grand story’ that would justify knowledge, behaviour and action. (Lyotard.J. 2004).

Lyotard argued that postmodernisms

‘incredulity toward the meta-narrative’ would affect the emergence of distinct communities with a shared ‘language game’ (a way of seeing the world which only that community could access).

Architecture’s loss of its language game arguably evidences a shift away from architecture being understood through a progressive model of history. This shift away from a progressive model is arguably best shown by the rejection of Burton. A & Wilkins.K winning 1983 Design for the National Gallery Extension in Prince Charles 'monstrous carbuncle' Speech. (BBC, 2009). In his speech, Prince Charles presented an

33

absolutist view of formalist Modernism that arguably broke down architectures shared language game by rejecting the postmodern work and its associated placement in a ‘grand narrative’. This loss of architectures language game and thus underlying narrative is evidenced by Foster and Partners (1983) Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters in Hong Kong. Structural Expressionism (which is generally understood as being a revamped modernism), is blurred with postmodernism and the later neo-futurism movement making this architectural work’s placement in a progressive narrative questionable. This questionability of placing works within a progressive model of history draws a parallel to the art world where Thomas McEvilley’s 1984 essay, Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief for Artforum criticised MoMA’s rootedness in modernism and reliance on placing works in a narrative, as seen in the MoMA exhibition

Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern. The fact that the primitive “looks like” the Modern is interpreted as validating the Modern by showing that its values are universal. McEvilley presents a counter view: that primitivism, on the contrary, invalidates Modernism by showing it to be derivative. McEvilley concludes by questioning the absolutist view of modernism and the validity of placing artworks in a narrative: “At one level this show undertakes precisely to coopt that question by answering it before it has really been asked, and by burying it under a mass of information.” (McEvilley.T 1984).

While Danto’s post-historical state had not been met, the breaking down of architectures language game created space for the deconstructivist critiques (that were proactively removed from the modernist trajectory’s) which will now be explored.

34

In 1988 Mark Wigley and Phillip Johnson curated the MoMA Deconstructivist architecture exhibition which crystallized the deconstructivist movement. Deconstructivist architecture sought to produce stimulation rather than closure, arguably this laid the path for architecture to exist for its own sake. Danto likens his age of pluralism to the state which Karl Marx referred to as the Post-Historical Period, a Utopian state in which all striving can cease. (Danto. A 1997).

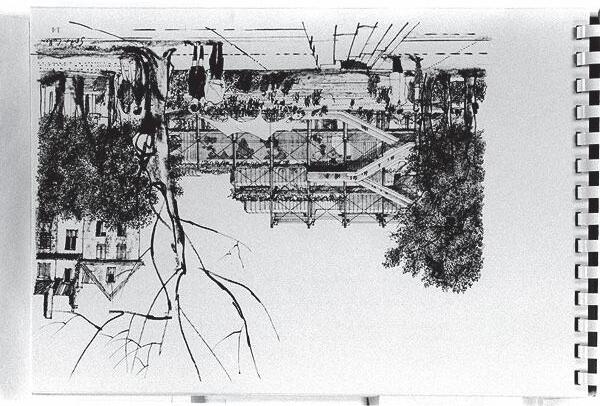

One of the architects presented at the 1988 MoMA exhibition was Bernard Tschumi. Tschumi’s 1986 Parc de la Villette in Paris, France sits separately from the ideologies of the museum and the Grande Hall that juxtaposes its boundaries. As Tschumi said himself: ‘’[L]a Villette, aims to be an architecture that means nothing; an architecture of the signifier rather than the signified’ (Tschumi.B 1994). This is evidenced in Tschumi’s follies that lack any

35

sense of symbolism in their form or function. Instead, they are merely directional vectors of our perception of space in that they pronounce an ‘Explicit rejection of authorship and meaning […] each observer will project his own meaning, looking to produce stimulation rather than closure’ (Cruickshank, 2009).

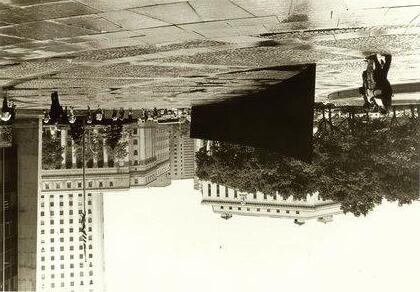

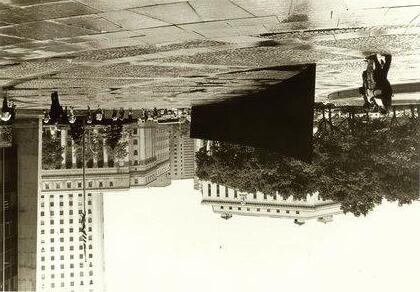

This draws a parallel to the art world with the manipulation of the editing technique ‘The Kuleshov effect’ by Steven Spielberg, known today as ‘the Spielberg face’. While not inventing the technique, Spielberg applied it prolifically in films using a close-up shot of the face to signify cues to the audience. Spielberg, like Tschumi, did with follies, removed the symbolism of the Kuleshov effect and instead looked to produce stimulation.

This deconstruction of form in both Parc La Villette and the Kuleshov effect is important because ‘the only political act of which cinema [and architecture] is capable [of is] keeping the

idea of change going” (Hoffman, 1996, 53). This suggests the revolutionary shift in focus on Art as an object rather than fitting art in a development or having to relate to other artworks in a trajectory of history. As a result, by the end of the 1980s, modernism’s exclusionary framework was no longer considered pragmatic. This is further evidenced by John Yau’s (1988) essay Please wait by the Coatroom. Yau illustrates how formalism, as adapted by museum institutions (Such as MoMA), became a method for reinforcing the exclusionary framework that excluded women and black artists for centuries citing Wilfredo Lam’s artwork the Jungle in his essay. While deconstructivism adopted Danto’s emphasis on the singularity of the architectural work, the movement was preoccupied with the rejection of one thing over another, with architecture maintaining a political agenda. Thus, the utopian state of striving ceasing had not been reached.

36

By 1991 the western world found itself at a pivotal moment, the Berlin wall had only just fallen, and the end of ideologies presented itself. the age of pluralism described by Danto was embraced as something liberating. (Danto.A. 1997).

The age of pluralism described by Danto necessitated freedom with an end. Arguably, this freedom within architecture is evidenced by Liz Diller and Ricardo Scofidio’s interrogative and iconoclastic attitude toward conventional architectural discourse and representation. In their proposal for the 1991 Slow house, the creation of the drawing apparatus (an idiosyncratic drafting tool to create a succession of cross-sections) to evoke the cinematic movement through space is highly expressionistic, indicative of the freedom from a single style or the limitations of a political or

37

social agenda. The freedom of materials and processes evidenced by Diller and Scofidio’s drafting tool draws a parallel to the art worlds Young British Artists (YBA’s), A Term first used by Michael Corris (Corris.M 1992). The YBA’s definingly had no single style or approach with the era being marked by a complete openness towards materials and the processes with which art can be made, and the form that it can take.

Within the age of pluralism described by Danto art would experience a utopian state where art would exist for its own sake. Arguably this is evidenced within the wider context of architecture in Janny Rodermond’s review of the 1991 Architecture Biennale. Rodermond concluded that the organisers “evidently opted for the path of least resistance by addressing no explicit themes”. (Rodermond.J. 1991). The 1991 biennale of architecture was radically mimetic. Arguably this lack of theme suggests

that the biennale of architecture was architecture for architectures sake. This draws a parallel to the art world where critics were equally frustrated. While one of the most celebrated YBA’s Damian Hirst’s earlier artwork ‘A Thousand Years’, (1990), is described as a ‘living Bacon Painting’, with allusions to the figurative painter Francis Bacon. (Sylvester.D. 2007). Hirst later work ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ (1991), resulted in British critic Julian Spalding labelling contemporary conceptual art as a con art, as he argues it ‘cons’ people and is not art because it lacks the necessary element of creation.

Spalding particularly focuses on Hirst’s artwork evidenced by the title of Spalding’s book: Con

Art, Why you should sell your Damien Hirst while you can. (Spalding.J 2012). The frustration by critics such as Spalding in the art world prevents Hirst’s artwork ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone

38

Living’ from being manipulated into a narrative leaving it as art for art's sake.

While the Slow House by Diller and Scofidio 1991 is an enigmatic gesture of architectural thought and invention from its exploration of mediating the ‘view’. It may be that when architecture becomes, as Danto suggests ‘solely’ ‘vaporized in a dazzle of pure thought’ (Danto. A 1997) that it can no longer be architecture. This is evidenced by the later exploration of Diller and Scofidio’s the slow house (1991), through the multimedia installation titled Desiring Eye: Reviewing the Slow House (1992) which explores the work in 47 views. Arguably the slow house does become ‘vaporized’ by its exploration of itself with the installations cinematic quality being dominant over its architectural focus. Although this study has failed in drawing an architectural parallel to the end to art, it has raised the unanswered question of if architecture

transitions into art when it does become ‘solely’ ‘vaporised in a dazzle’. This is suggested by the decades following explorations of the barrier between works of art and architecture, most notably Rachel Whiteread’s 1993 House Sculpture.

39

40

41

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to explore if Arthur C. Danto’s argument for the end of art holds significance for architecture by questing if architecture, like art, had reached an end. Due to significant areas of uncertainty and the new questions raised from the research, the only conclusion to be made is the answer that architecture is not dead. Arguably, art and architecture are both processes of discovery so as long as there are theories that seek to question their validity and vitality, art and architecture will thrive, being propelled forward. One of the aims of this study was to place works of art and architecture in dialogue with one another which has led to the personal learning of understanding architecture from a different perspective.

During the research, many criticisms of Danto’s argument for the end of art came to light by

critics (Brodsky. J 1984) and artists alike (Kosuth.J 1969). These criticisms and subsequent alternative theories to explain the condition of art today exemplify the placement of Danto’s argument as a single thread in a tapestry of possible conjectures about art. This led to the understanding that the limitations experienced in this study would likely be replicated to some degree in any research utilising an art theory to apply to architecture. Arguably art history is made of opinions and opinions are by nature limited. As a result, art history is a topic where areas of uncertainty are inevitable. The unresolved question that emerged from this study is ‘when does architecture become art?’

As concluded in the main body arguably when architecture becomes ‘solely’ ‘vaporized in a dazzle’ as Danto suggests (Danto. A 1997), architecture can no longer be architecture and converges into art.

42

43

Bibliography

Banham. R. (1966) The New Brutalism. The Architectural Press, London.

Belting.H (1997) The end of Art History.

Translated from the [German] by Christopher S.Wood. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Benjamin. W (1968). Illumination.

Translated from the [German] by Harry

Zohn. Germany, Suhkamp verlag, Frankfurt

a.M.

Brodsky.J (1984) Only the end of art. The Death of Art. New York, New Haven Publications. p57-76.

Chave. A (1990) Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power. Arts Magazine.

Clark. T.J (1982) Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution.

1982 Edition. London, Thames and Hudson Ltd. Colomina. (Editor) Various contributors

(1996) Sexuality and Space. New York, Princeton Architectural Press.

Corris. M (1992) Openings: Damien Hirst. Artforum.

Cruickshank. L (2009) The Case For A Reevaluation of Deconstruction and Design; Against Derrida, Eisenman and Their Choral Works. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26

2212554_The_Case_for_a_ReEvaluation_of_Deconstruction_and_Design _Against_Derrida_Eisenman_and_their_Ch oral_Works [Accessed 10 November 2019]

Danto. A (1984) The Disenfranchisement of Art. New York, Columbia University Press.

Danto. A (1997) After the end of Art.

Princeton, Princeton University Press.

44

Debord. G. (1994) The Society of the Spectacle. 1994 edition. Translated from the [French] by Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zone Books

Duve. T (2014) ‘This Is Art’: Anatomy of a Sentence. Artforum

Edelson.Z. (2018) Interview with Kenneth Frampton. Available at:

https://www.metropolismag.com/architectur

e/kenneth-frampton-interview/ [ Accessed 20 December 2019].

Eisenman.P (1983) The End of the Classical: The End of the Beginning, the End of the End.’ Perspecta. Volume 21, 154-173.

Elkins.J (2004) What Happened to Art Criticism? Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Foster.H (2012) Post-Critical. October [online]. Volume No.139, Winter 2012, p38.[Accessed 1 October 2019].

Foucault. M (1985) The use of pleasure, The history of sexuality Volume 2. Translated from the [French] by Robert Hurley. New York, Pantheon Books, Random House.

Frampton, K (1992) Modern design a critical history of architecture. 3rd ed.

London: Thames and Hudson.

Fukuyama. F (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. Reissued in his edition 2012. London, Penguin Group.

Greenberg.C (1939) Avant-Garde and Kitsch. New York, Partisan Review.

Groys, B. (2016) The Shock of socialism is gone. Interview with Hegemann, Carl. Eflux [online]. Available from:

https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/borisgroys-in-conversation-with-carl-hegemann-

45

the-shock-of-socialism-is-gone/4098

[Accessed 18 December 2019].

Hegel. G.W.F. (1988) Aesthetics, Lectures on fine art, Volume 1. Translated from the [German] by T.M. Knox. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Hoffman. M (1997) Act Of Seeing. Faber and Faber Ltd.

Jencks.C (2000) The Century is Over, Evolutionary Tree of Twentieth-Century Architecture. Architectural Review. July 2000, p. 77.

Kosuth.J (1969) Art after Philosophy. 1999 edition. Cambridge, The MIT Press. p158177.

Kosuth.J (1996) Intentions. 1999 edition. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kuhns.R (1984) The End of all. The Death of Art. New York, New Haven Publications. p39-53.

Lucas.R (2016) Research methods for architecture. Oxford, Laurence King Publishing.

Lyotard. J (2004) The Postmodern Condition. Translated from the [French] by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi.

Manchester, Manchester University Press.

Mailer. M (1970) A Fire on the Moon.

Little, Brown and Company.

McEvilley. T (1984) Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief. Artforum.

MoMA Gallery label. (2013) House IV

Project [Multiple axonometrics]. At: 9+1

Ways of Being Political: 50 Years of Political Stances in Architecture and Urban Design, September 2012 – March 2013.

46

Morgan. R (1997) Carolee Schneemann: The Politics of Eroticism. Volume 56, Art Journal on JSTOR.

Nietzsche, F. and Kaufmann, W. (1974) The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. New York: Vintage Books.

Pallasmaa.J (2012) Encounters. Second edition. Finland, Rakennustieto Publishing.

Prince Charles (1984) Prince on 'monstrous carbuncle'. BBC [video]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8046449.stm

[Accessed 10 November 2019].

Rodermond. J (1991) Architectuurbienale

1991. Manifestatie van gevestigde orde. De Architect.

Rodofsky. B (1964) Architecture Without Architects [Book]. At: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

Smith.R. (2009) Roberta S mith, Criticism: A Life Sentence, Part One, November 5th, 2009. Vimeo [video].

Available from: https://vimeo.com/9651694

[Accessed 10 December 2019].

Solnit. R (2014) Men Explain Things To Me. Chicago, Haymarket Books.

Spalding. J (2012) Con Art, Why you should sell your Damien Hirst while you can.

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Sylvester. D (2007) Foreword on the interviews with Francis Bacon. The Guardian. Tanizaki. J (1977) In Praise of Shadows.

Leete’s Island Books.

The Art Institute of Chicago (2018) Splitting

Available from:

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/187171/split

ting [Accessed 12 December 2019].

47

Tschumi. B (1994) Architecture and Disjunction. Massachusetts. The MIT Press

Vasari.G (2007) The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Translated from [Italian] by Gaston du C.de Vere. New York, The Modern Library. Venturi. R, Scott-Brown. D (2007) Learning From Las Vegas. 2007 edition. London, Routledge.

Yau. J (1988) Please wait by the Coatroom [essay]. Arts Magazine.

Youde.K (2017) Rogers: 'I didn't want to design the Pompidou Centre'. Architects Journal [online]. [Accessed 20 December 2019].

48