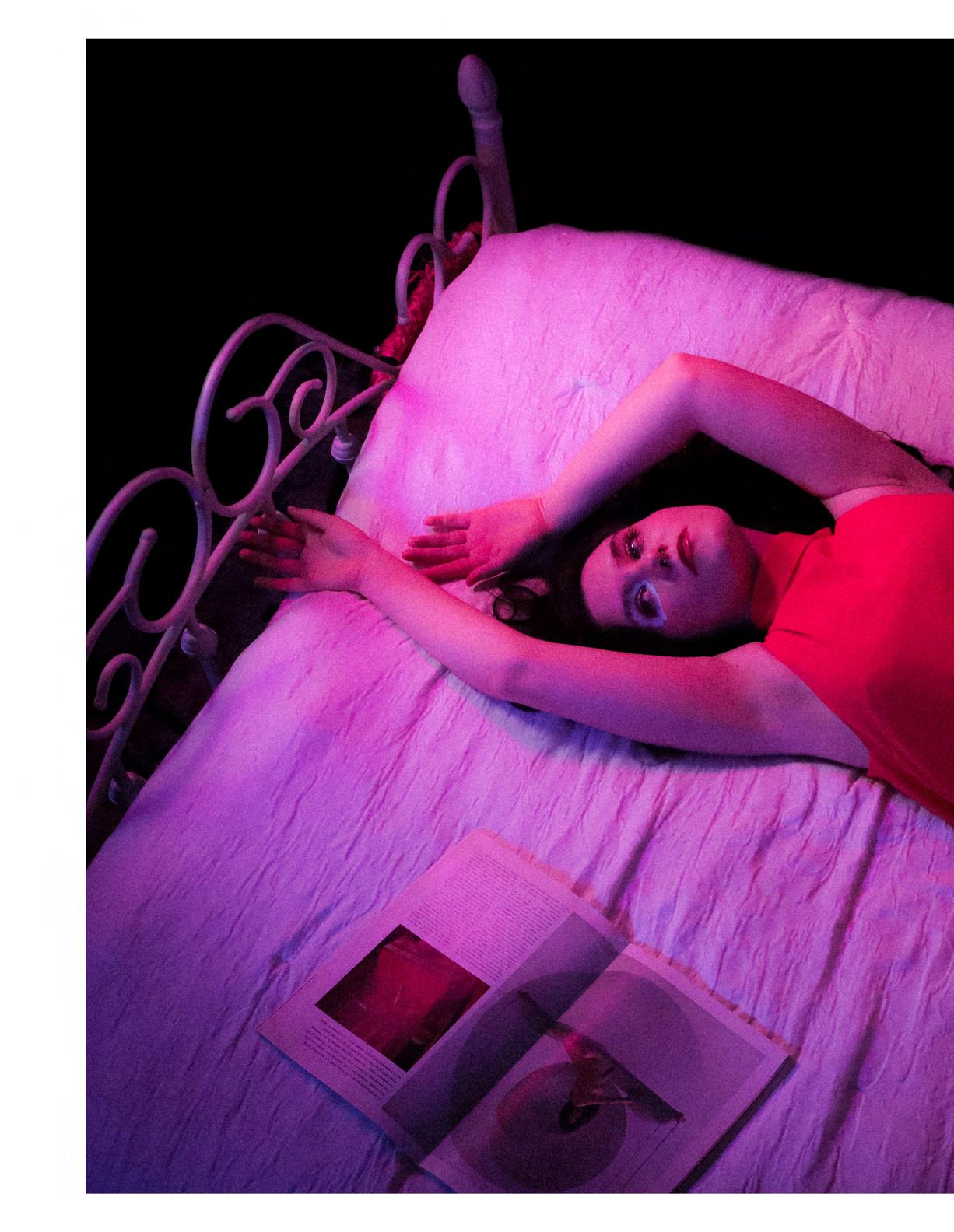

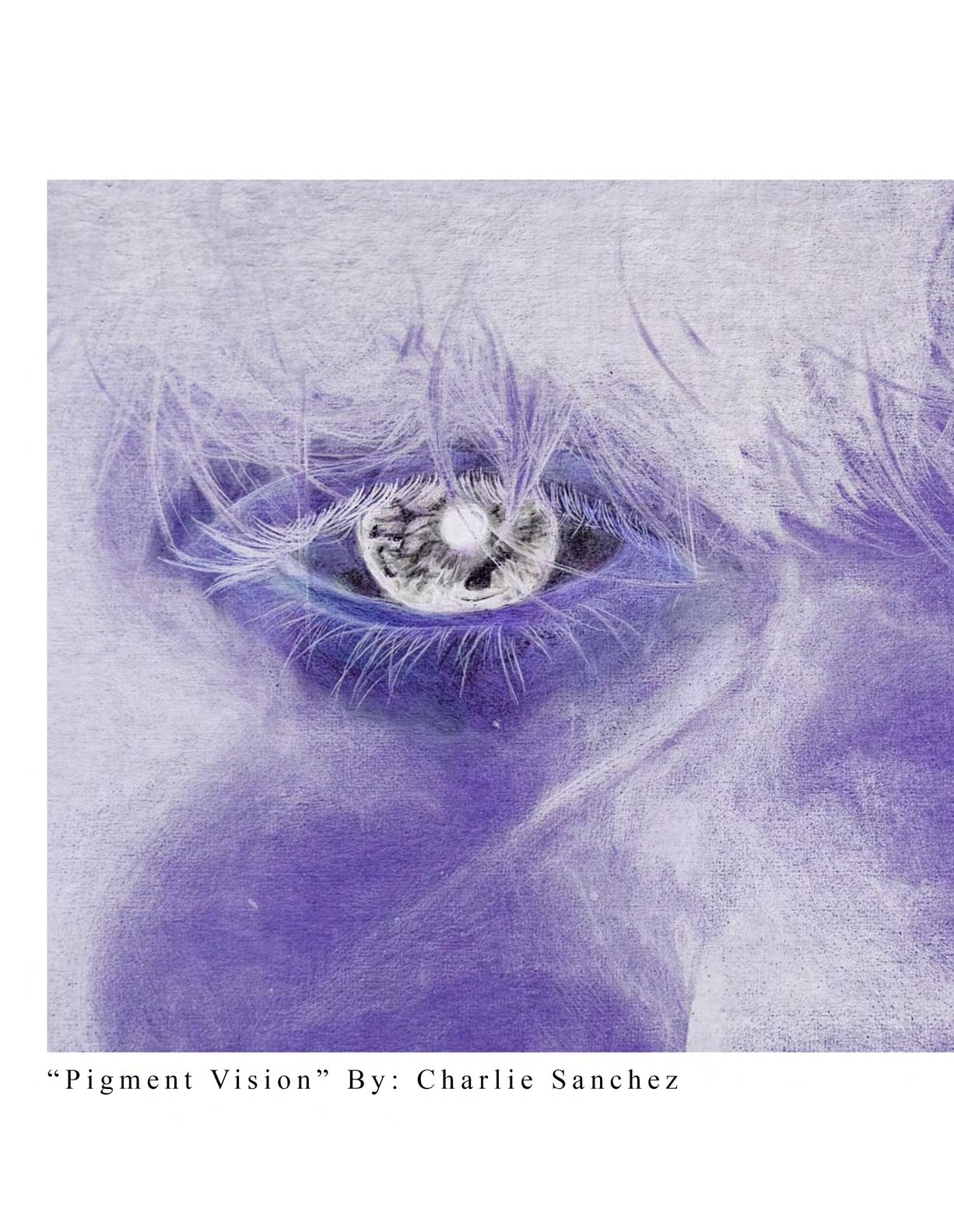

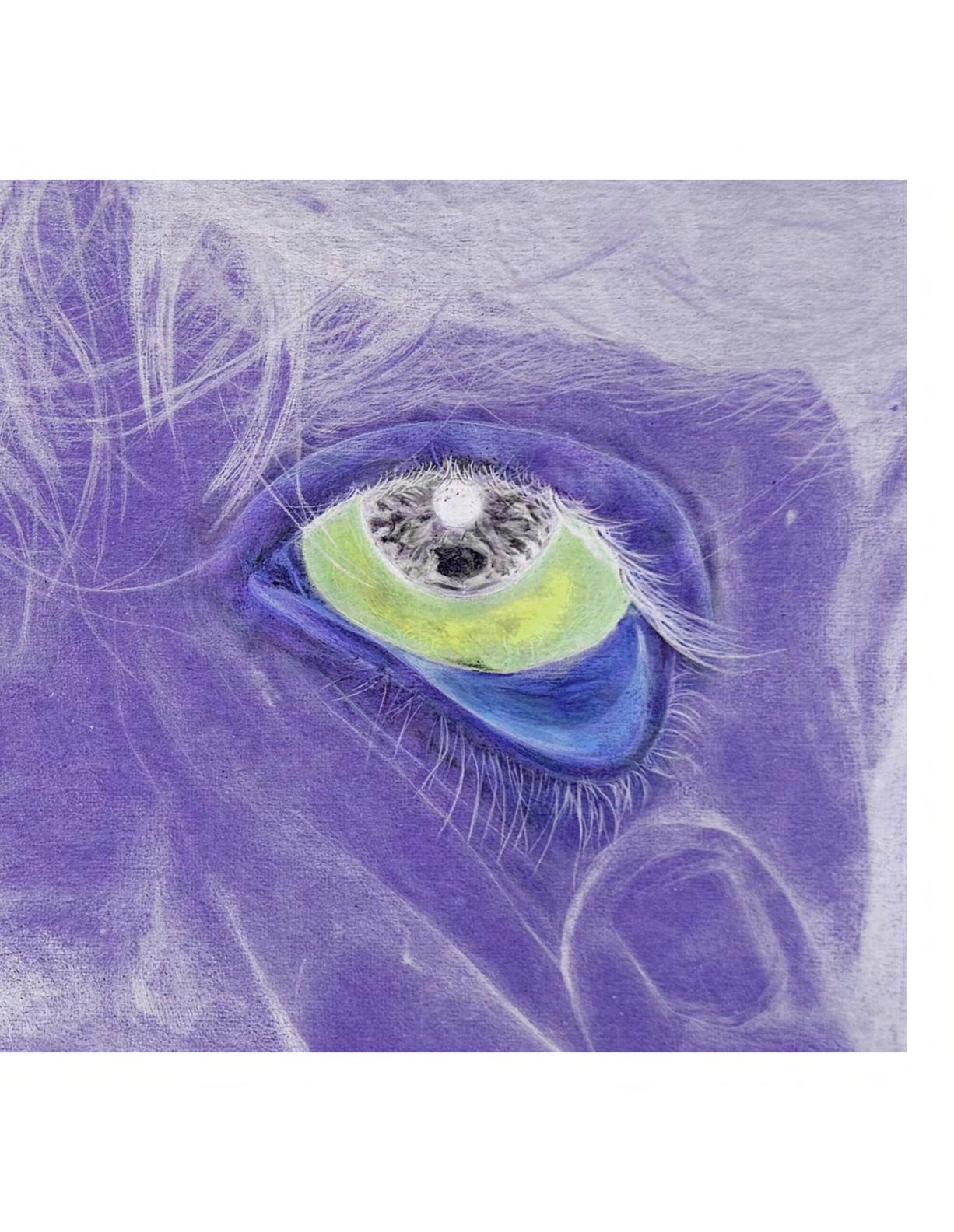

By: Jennifer Gheorghe

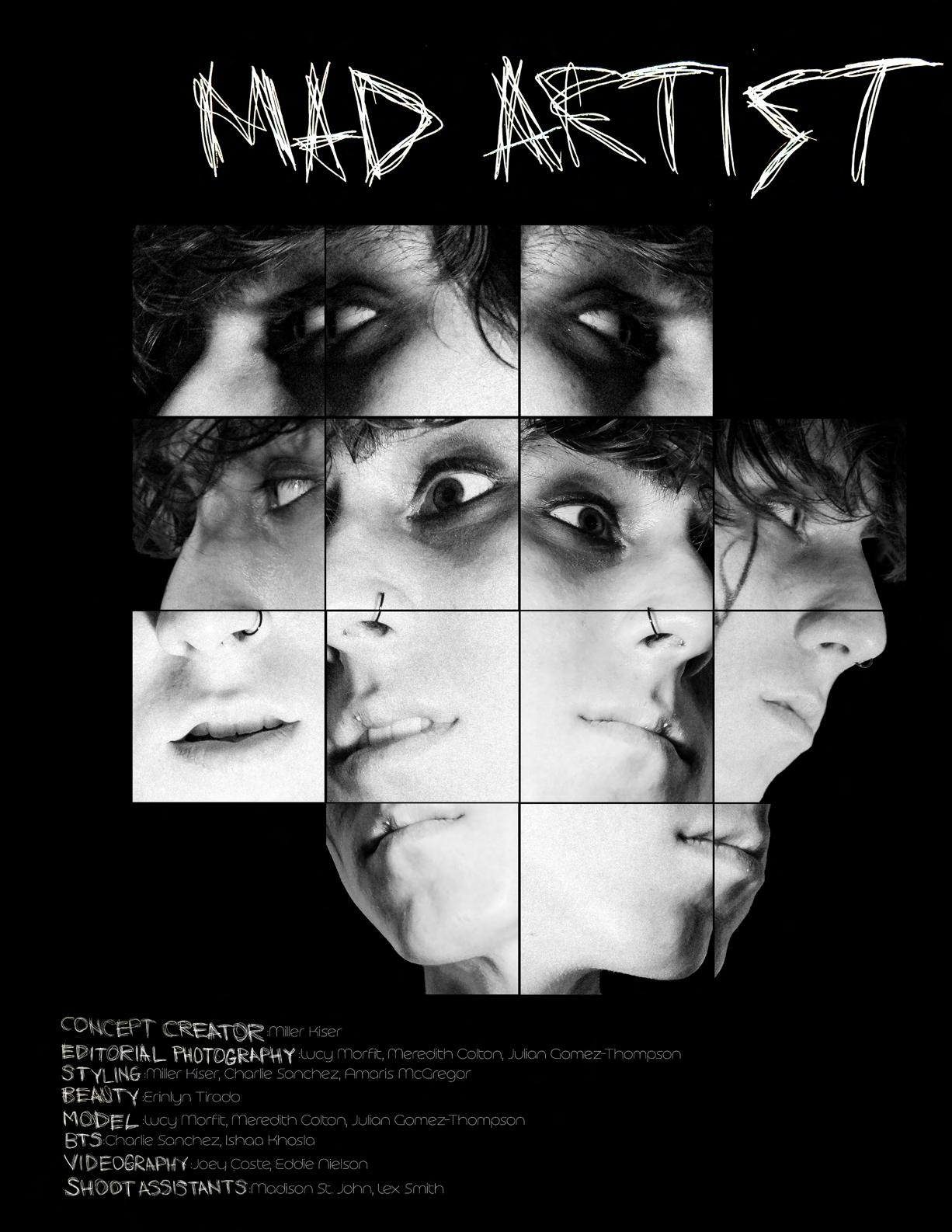

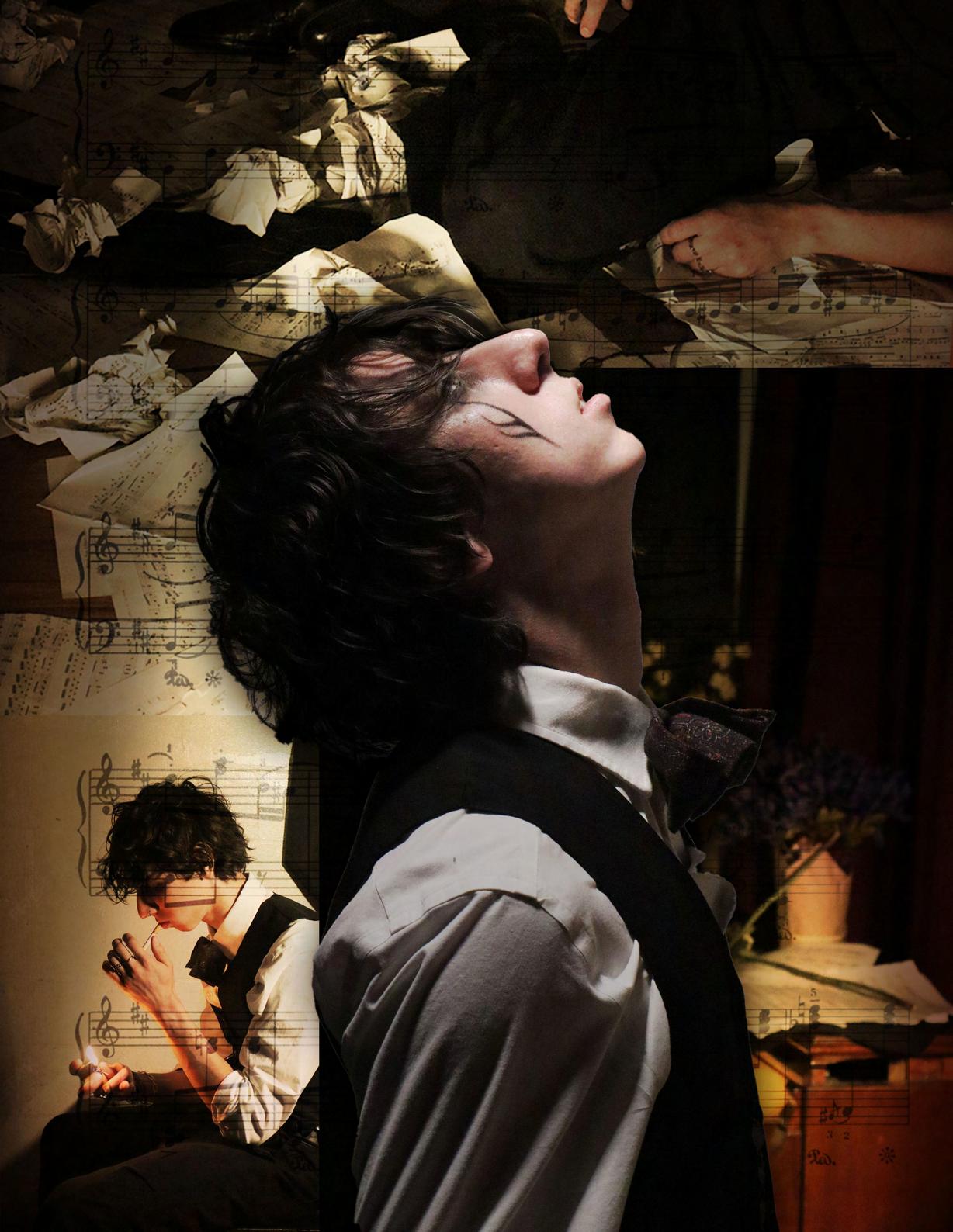

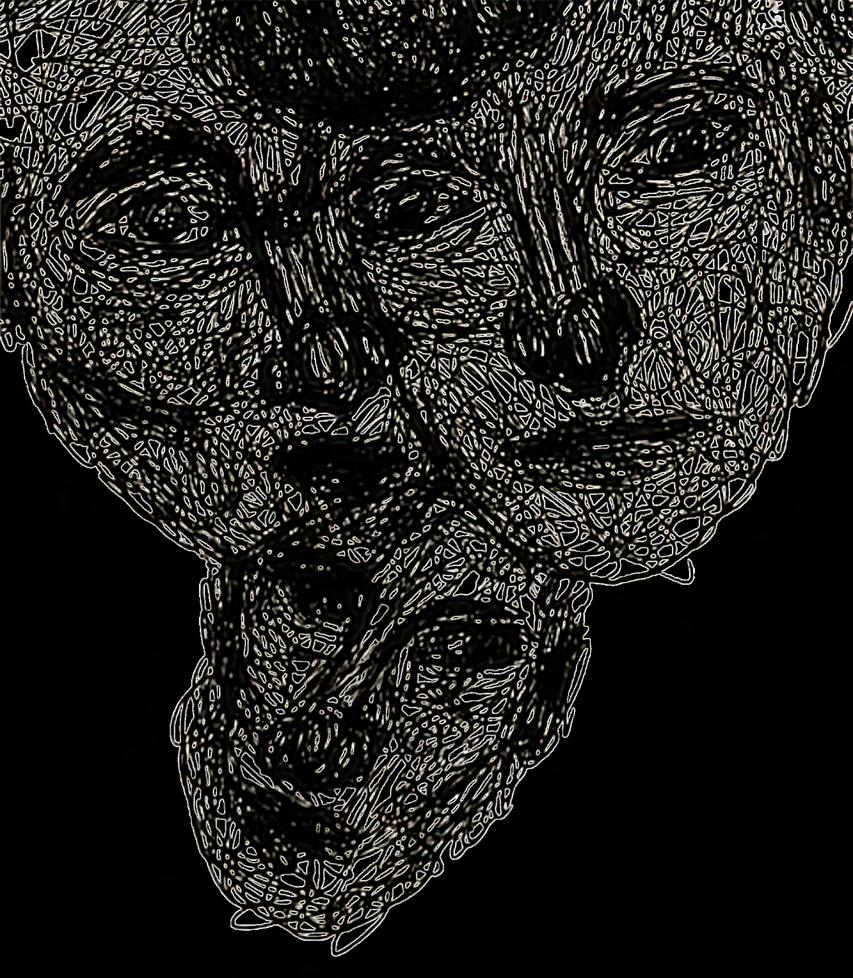

We are taught from a young age that happiness and worth are factors measurable through outside forces- to look externally for fulfilment within all aspects of life. Through this we find ourselves situated in a society that abides by a lifelong search of validation, quantifying and evaluating our merit through our relationships and the identities we hold within them. You are a daughter, a hard worker, a student, a friend. You are academically intelligent, extroverted, creative. We live alongside these conventional framings, framings which fabricate an existence that allow us to diminish into the confines of our descriptions. We’re reduced to labels that become so dominating we can barely hear ourselves think, and sometimes lose sight of how to listen altogether.

It is easy to be distracted by identity—to grasp for it, even. It’s stable and trustworthy, always fulfilling us with immediate rewards of confidence rooted in social acceptance. When we recognize identities’ infringement on our entire reality, it seems natural that a concept as powerful as art can begin to mirror this mentality.

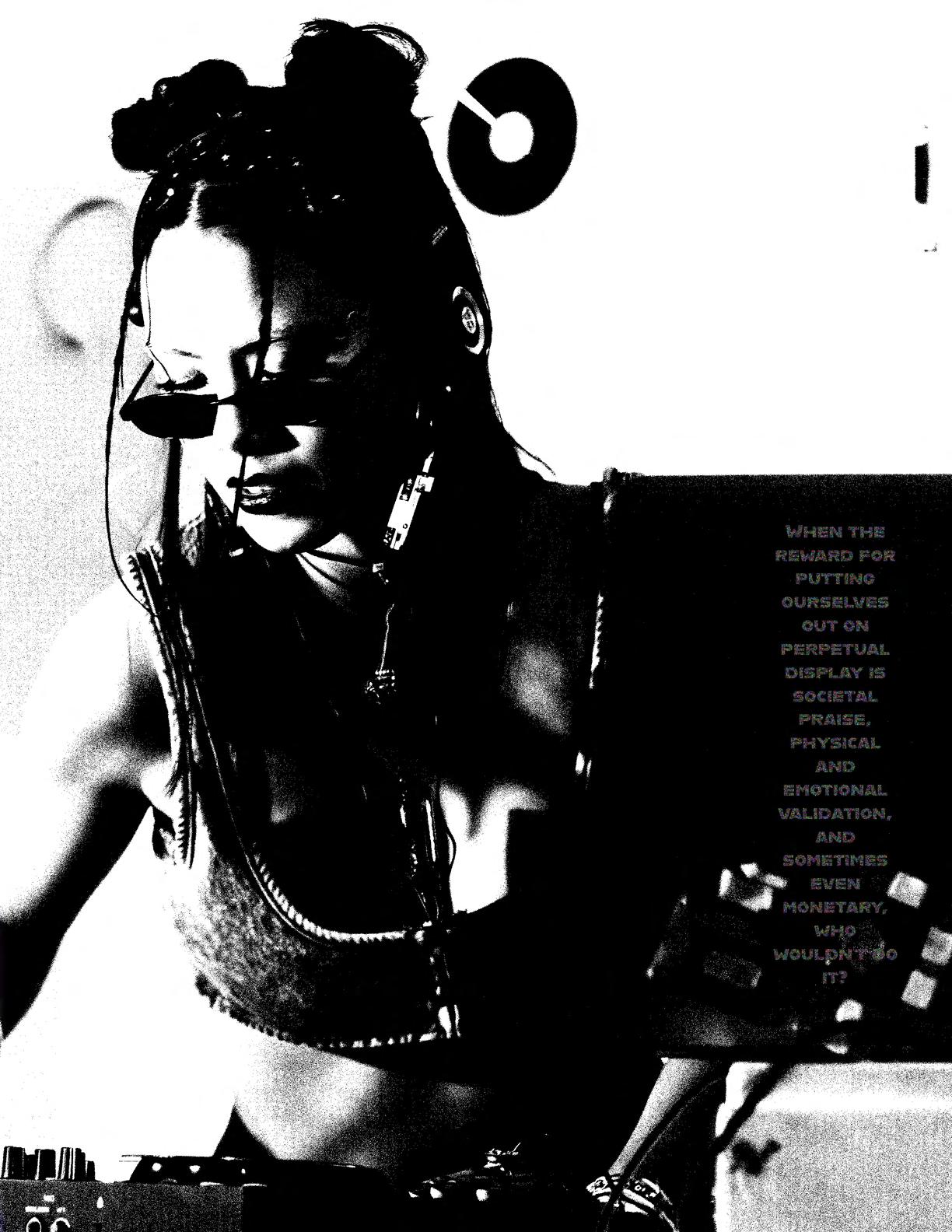

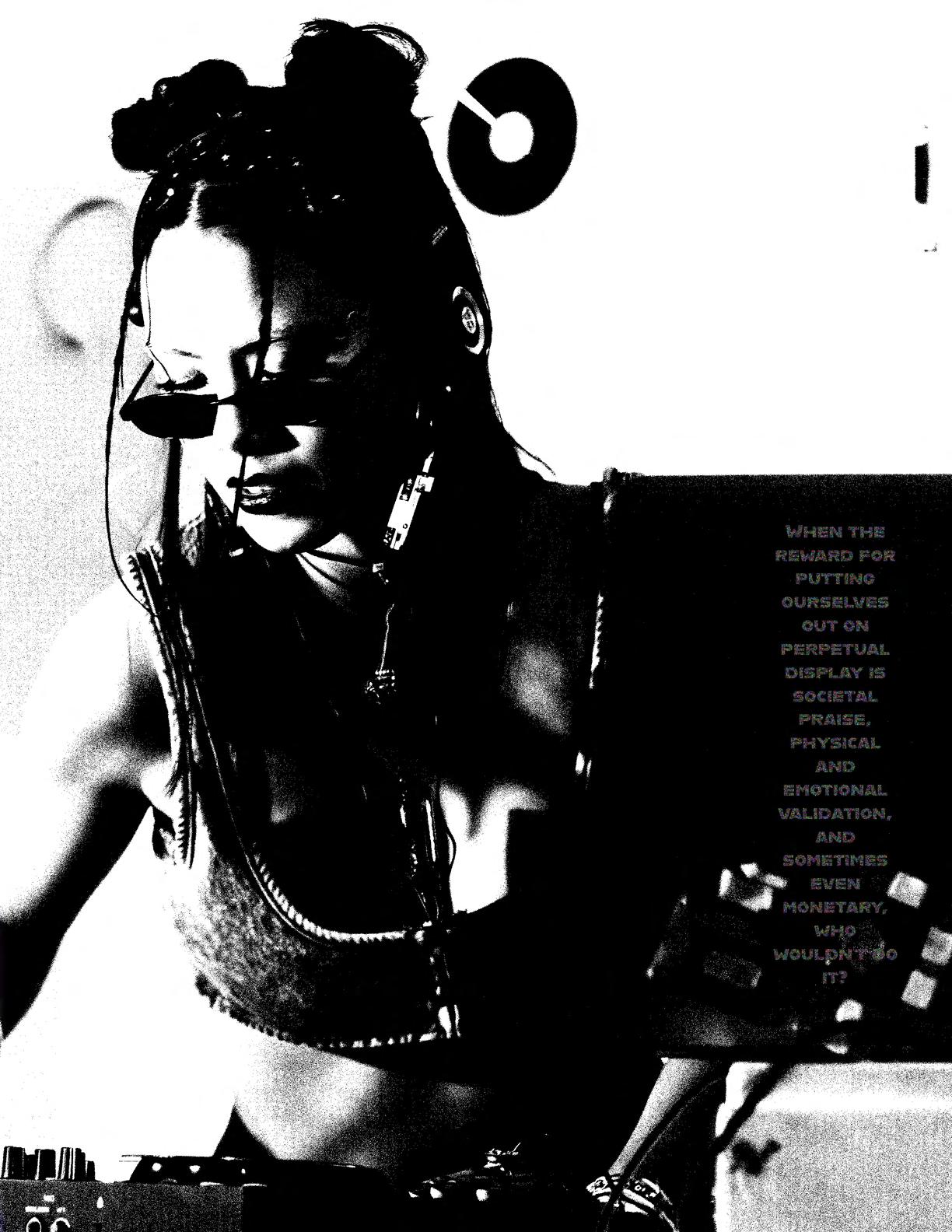

It makes sense to want the identity of a “good artist”—to create things that will be appreciated by others, in hopes to seem inspiring and to make things “worth sharing.” However, when creating from a space that leads with anticipation of external perspectives, the intrinsic authenticity that defines art is risked. Attaching what you create to how it is perceived inhibits artistic expression’s inherent significance through devaluing our unique and vulnerable interpretations into concepts given importance by external opinions. This mentality not only limits creativity but also attacks our self-value by reinforcing an inability to recognize ourselves outside of how we are perceived.

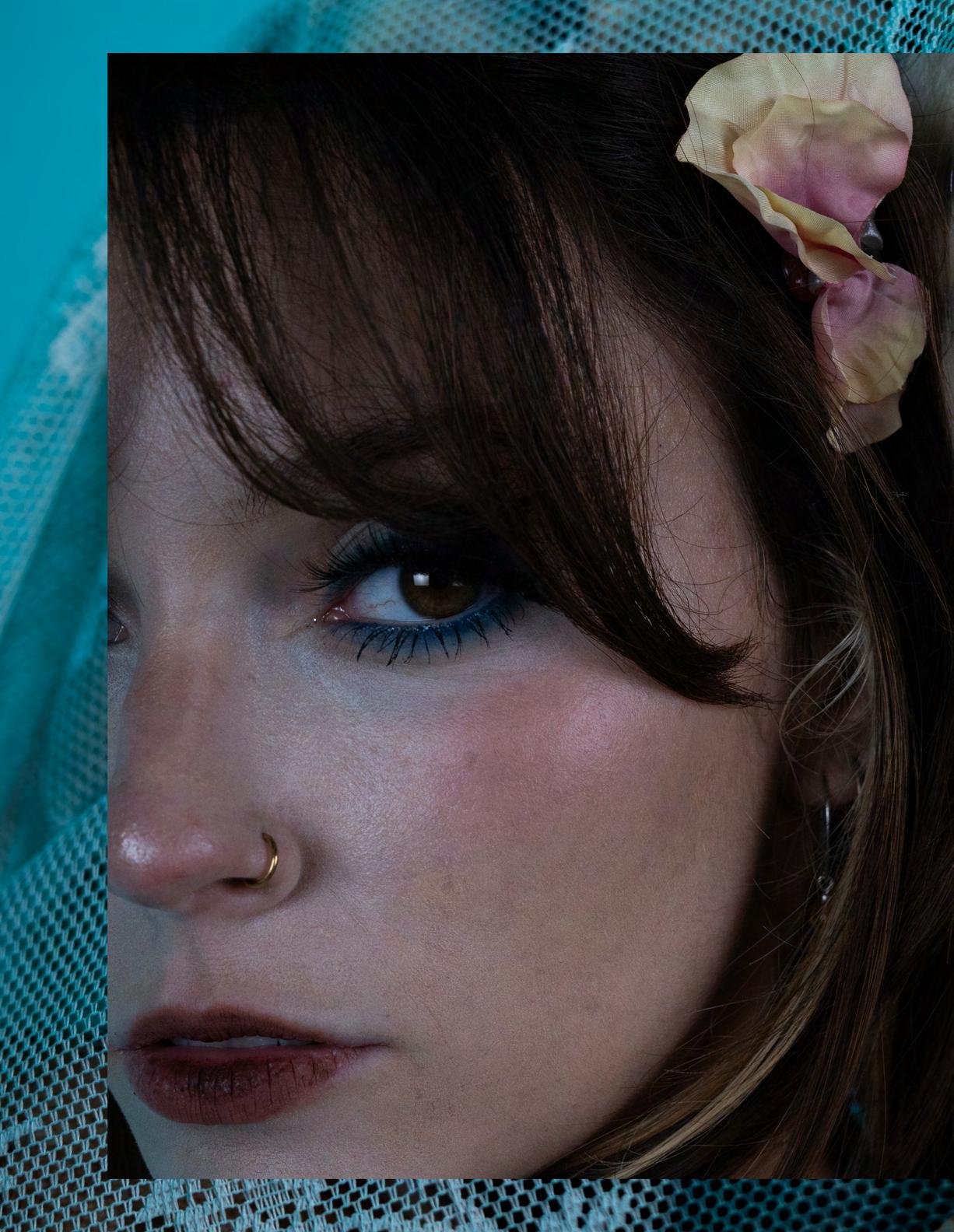

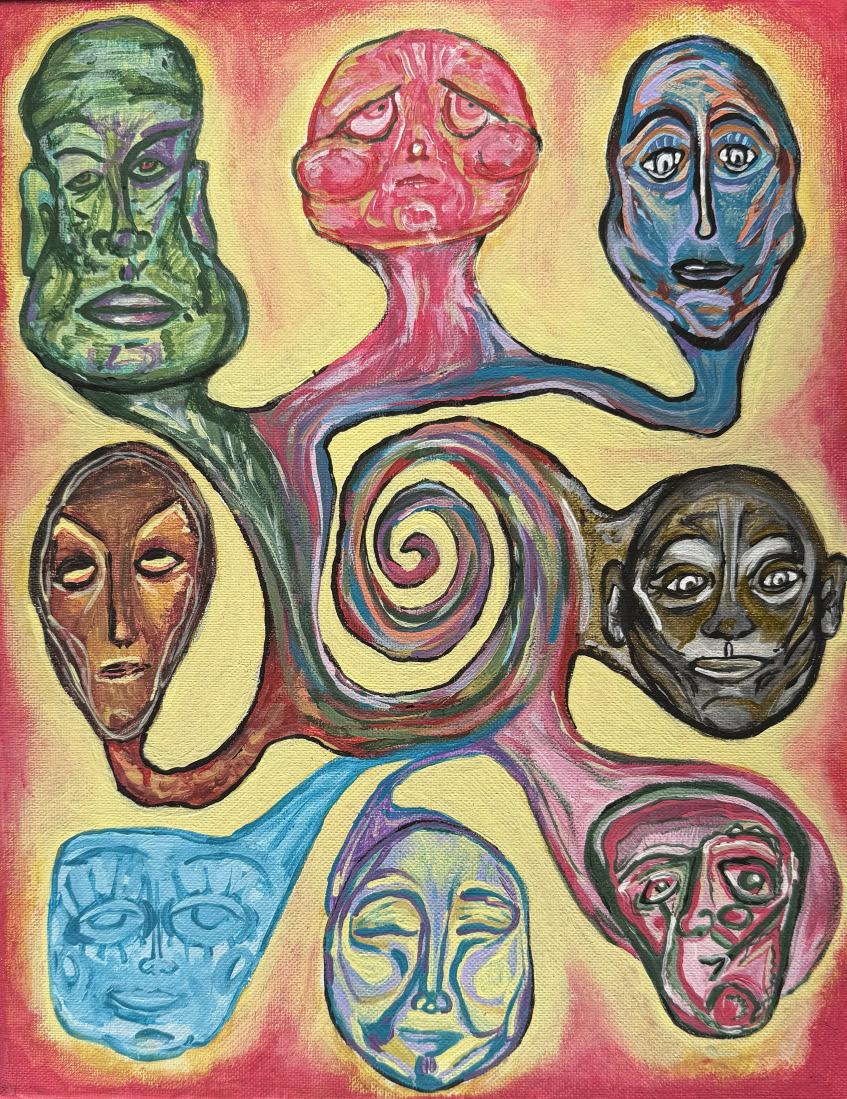

So then, what is art? Painter Wassily Kandinsky writes in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art that art’s purpose is to “refine the human soul”, to strip away all pretense until you are left with an authentic expression of your experience and then create from this space. When recognizing ourselves through our numerous individual labels, we are pulled into different versions of ourselves, each dragging alongside them certain expectations for who this version is supposed to be. The self-policing that comes with self-categorization creates a separation between us and the soul. This disjunction directly opposes creativity, as identity creates limitations and expectations, whereas creativity is boundless. To refine the soul, one must create from the collective space that lies at the center of these various pieces of self—the space that observes these identities rather than attaches to them. But, in order to be successful in creating from a perspective of unbounded truth and vulnerability, one must first be able to meet themselves in those places.

Despite the fact that everything we say, do, or create is in response to some dimension of ourselves, it can be hard to recognize how deeply these layers truly permeate. Are we drawing from surface qualities, or from a space that requires self-honesty and internal vulnerability? The disconnect between these can easily go unnoticed, as to create art that speaks from the soul, one must first confront the soul. There is a necessary push to want and understand the parts of you that are often left ignored, as they hold pain and imperfection. In a world where we can constantly be stimulated outside of ourselves, truly exploring our minds—how we feel about things and why we feel that way—takes dedicated time and emotional stamina. We cannot be authentic without allowing ourselves the space to sit with our thoughts, be in our own energy, and feel and accept without judgment or agitation whatever arises.

However, even when we do turn inward and confront the truth of our experience, creating something is only half the battle— sharing it is an entirely new feat. Displaying that which is authentic can be terrifying. It opens you up to the possibility of criticism, and when someone critiques pieces of you that express the deepest parts of your experience, it can feel profoundly isolating. But art is risky, and it requires putting yourself in a position that might leave you hurt and misunderstood. Art shouldn’t be “good.” It doesn’t need to be something “worth sharing”. Rather art is the experience of the soul solidifying itself in ways that can be interpreted in our tactile world. Each one of us perceives life uniquely and creatively, and to make art is to express this perception passionately in ways that invite connection and understanding. To be human is to want to be understood—and although art doesn’t guarantee this, it creates a space where being seen becomes a possibility. However, to feel seen, you must first see yourself. If not, the connections being facilitated are rooted in illusory pillars held up by versions of you that don’t truly resonate.

When we create art from a perspective that defines worth through socially contextualized aspects of life, we are constraining both our creativity and our value. These limited perspectives often become a tool used to look away from our truest selves. Identity places limits on how we feel recognized and the extent of what we believe our capabilities to be, both of which compile into disorienting noise masking authenticity. As Kandinsky said, to create art we must strip away the unnecessary and tap into something genuinely, unapologetically ours. Through honest self-exploration we are not only able to achieve creation in its truest form but are also given the opportunity to use our creations to process and understand our own experiences more deeply. Thus, to achieve expression in its most vulnerable and creative manifestation, you can’tlookaway from yourself—for neglection of the soul inhibits expression of its truth.

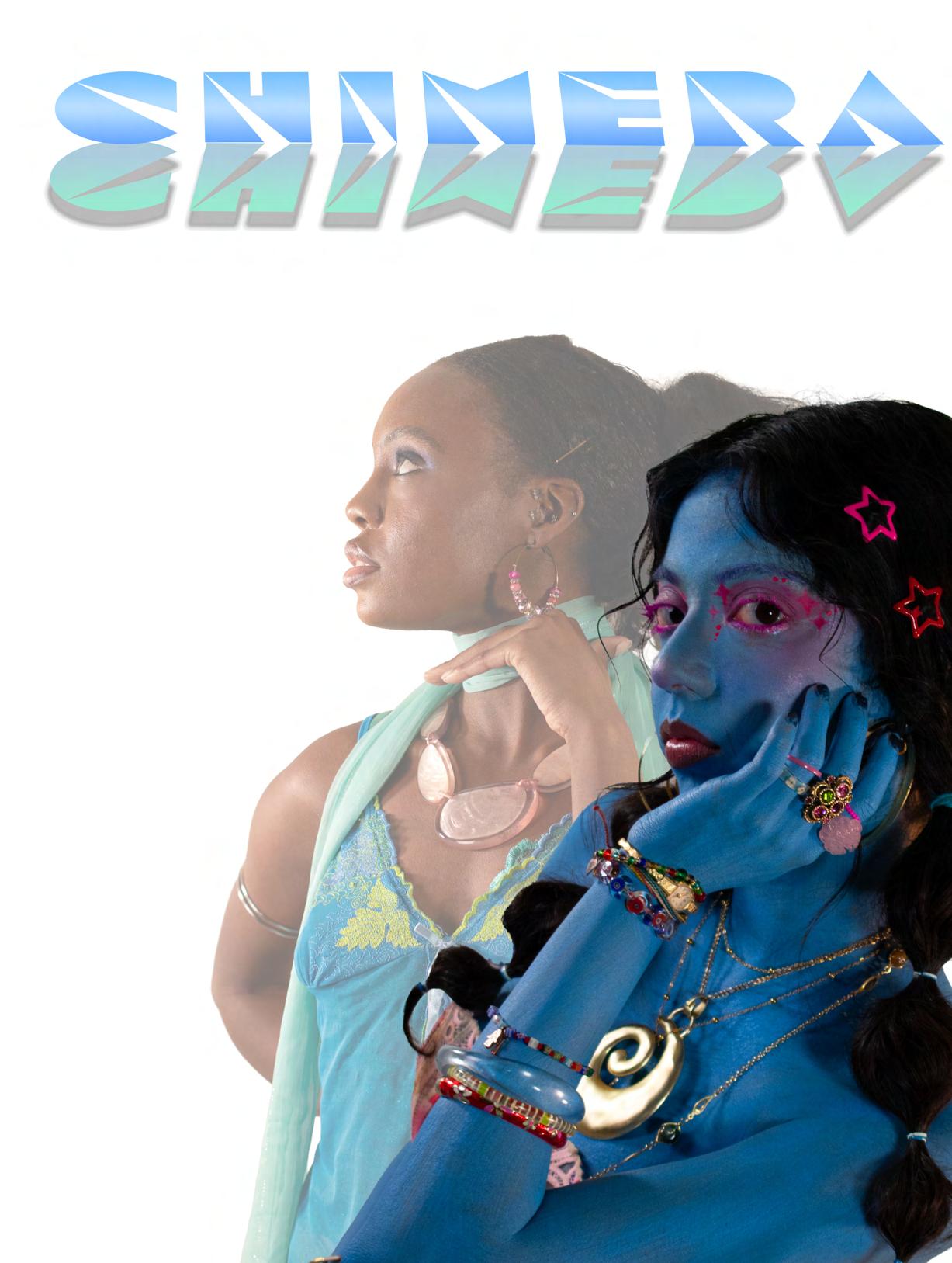

By: Mikayla Green

In nature, neon is a warning: the brighter the creature, the more dangerous it might be. Fashion has always borrowed from this same instinct, turning bright and bold colors into means of self-expression and statements of danger, rebellion, and power. From the poisonous shimmer of Victorian ballgowns to the acid renched leathers of 1980s punk style, fashion, in its infinite appetite for the dramatic, has never shied away from a little danger. Color in fashion has dared to demand attention, even when it proved fatal.

Your parIt’s almost ironic that green– a color most abundant in nature– was once the hardest dye for people to create. In the Victorian era, few colors were more coveted than green. Grass, leaves, emeralds: green was the color of vitality and renewal, yet was everywhere in the natural world. But in fashion, green was elusive, unstable and unnatural, nearly impossible to achieve. Which, of course, only made people want it more.

In the 19th century, color was status. In the smog-choked streets of Victorian England, life was painted in industrial browns and grays-- cheap, practical shades for a world thick with coal smoke and factory grime. A dress made of green fabric, something notoriously difficult to create, advertised wealth, taste, and status. It was the height of sophistication. And so, things progressed, as many fashion don’ts do, with trying something new.

Your parIn 1775, a Swedish chemist named Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered a new pigment: an almost supernatural green that had the rich and fashionable of Europe smitten. By the mid 1800’s, “Scheele’ s Green” and its yellowish-green hue had swept across Europe. Victorian England was in a chokehold: saturating everything from wallpaper, paint, candles, toys, and, of course, fabrics with this hypnotizing color. In 1814, 'Paris Green' emerged as an even more brilliant emerald shade designed to improve Scheele’ s Green.

What no one realized was that as the upper class paraded in their finery, they were oblivious to the poison seeping through their gloves, gowns, and into their skin. Scheele’ s Green had a secret: the pigment was a concoction of copper, acetic acid, and arsenic– yes, the same compound used to kill rats and, occasionally, inconvenient spouses. It destroyed organs, corroded through cells, and when heated or degraded, released arsine gas lethal enough to suffocate an entire room. Victorian fashionistas were quite literally dying to look good.

Your paragraph

Eventually, people began to believe that their gowns shouldn’t double as chemical weapons, and manufacturers found safer alternatives for green dye around 1938. Phthalocyanine Green’ s name was a mouthful, but unlike arsenic green, it was the only thing about it that might choke you.

damage to green's reputation, er, had been done. Fashion ed cautiously around it for When green finally returned, color had lost its dangerous No longer exclusive to the o the wearer, green faded background of fashion history.

danger never vanished, it Victorians chose beauty worth dying for; punks in the 1970s chose rebellion worth being ostracized for. Where arsenic green once signaled deadly elegance, the punk scene of the 80’s screamed rebellion in neon.

The elite weren’t the only victims of this slow poisoning. While the rich wore it, the poor made it. Nineteen-year-old Matilda Scheurer was one of thousands of industrial workers who handled the pigments with bare hands, spending their days crafting the wallpapers, fabrics, and household goods that filled Victorian homes. Day after day, green dust settled into her cuticles and lungs until, one afternoon, she collapsed at her bench. When they examined her body after she died, even her fingernails were green. Socialites fainted at balls and people developed mysterious illnesses, but still there was no better compliment than being told you looked radiant, even if that glow came from mild arsenic poisoning. paragraph text

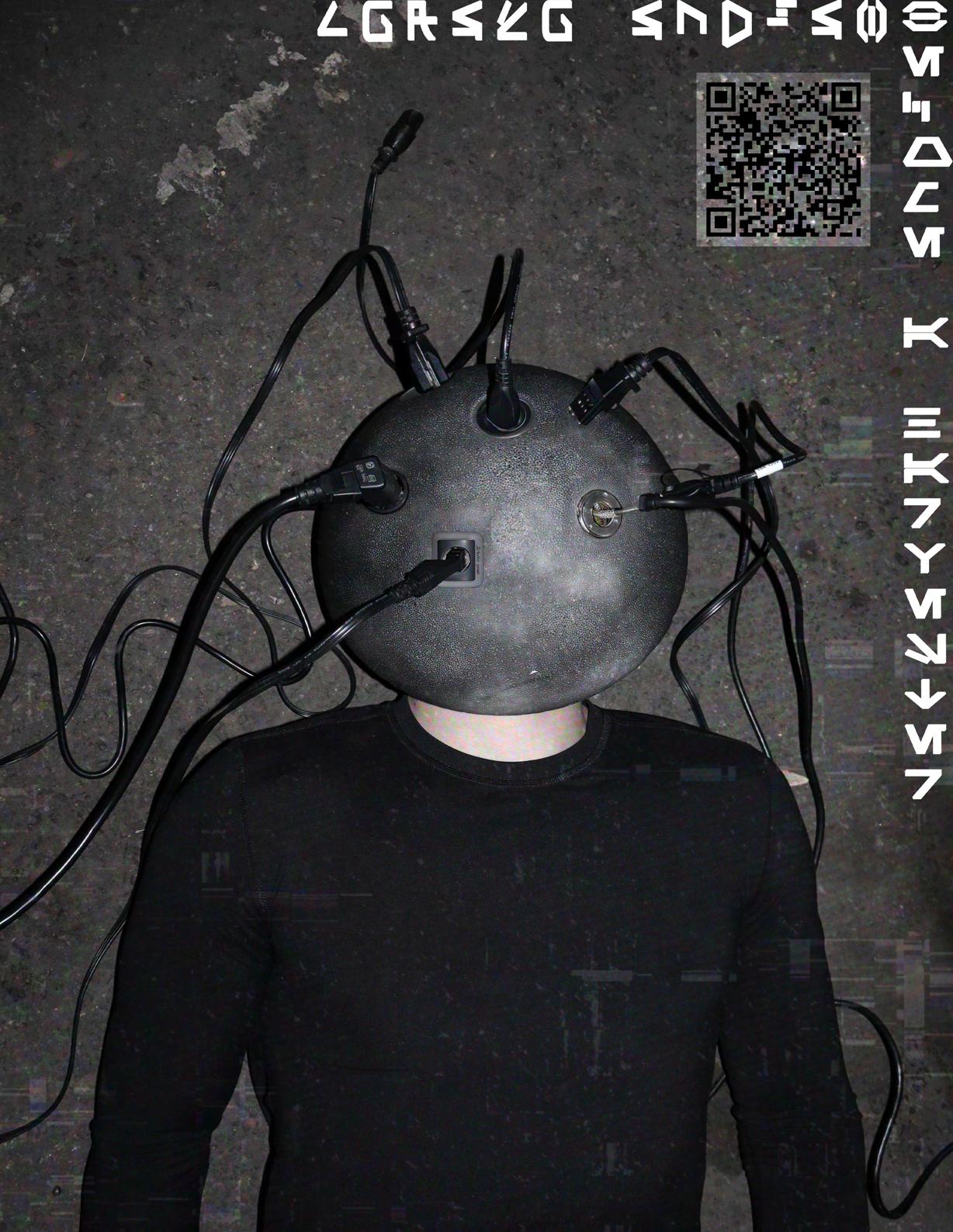

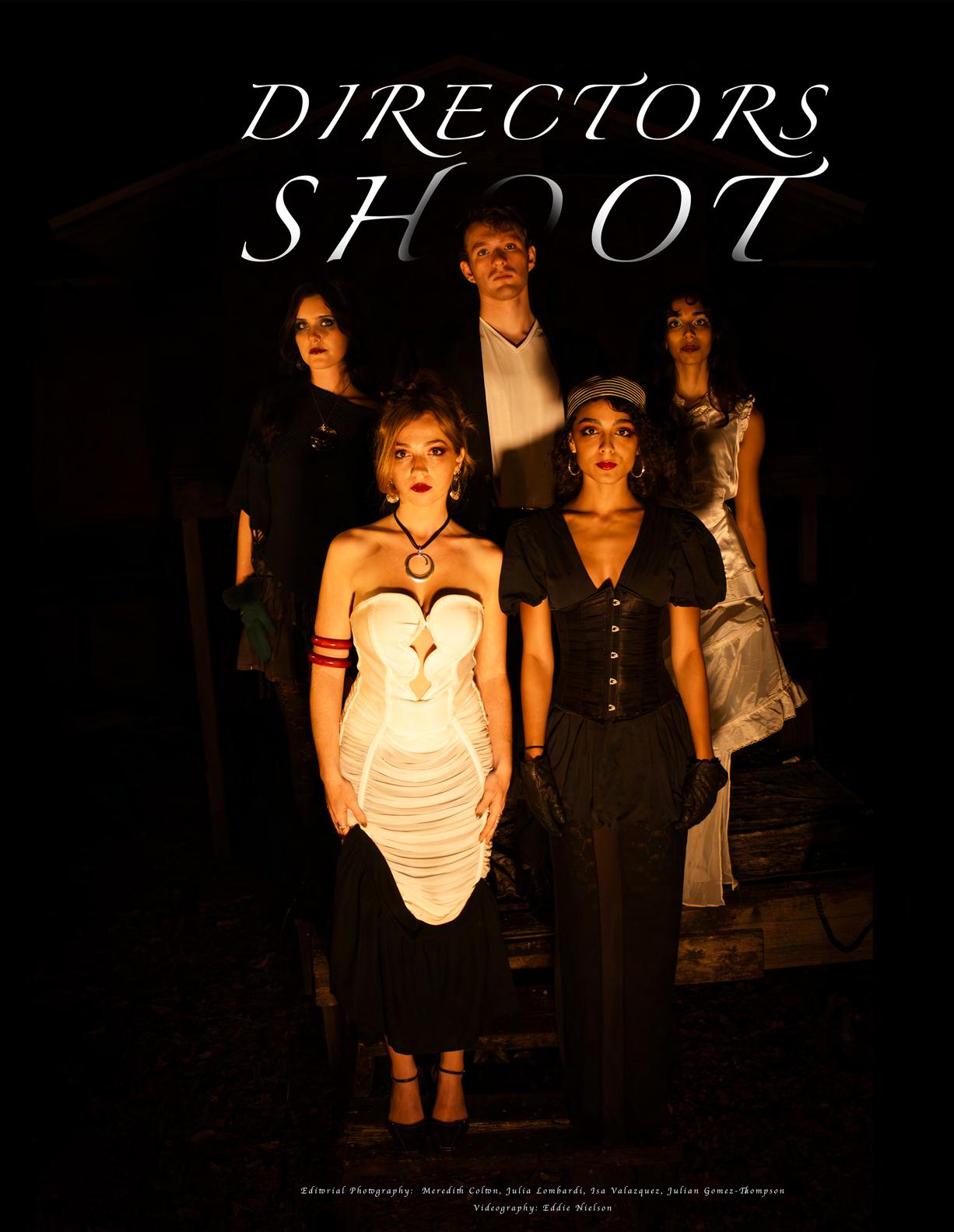

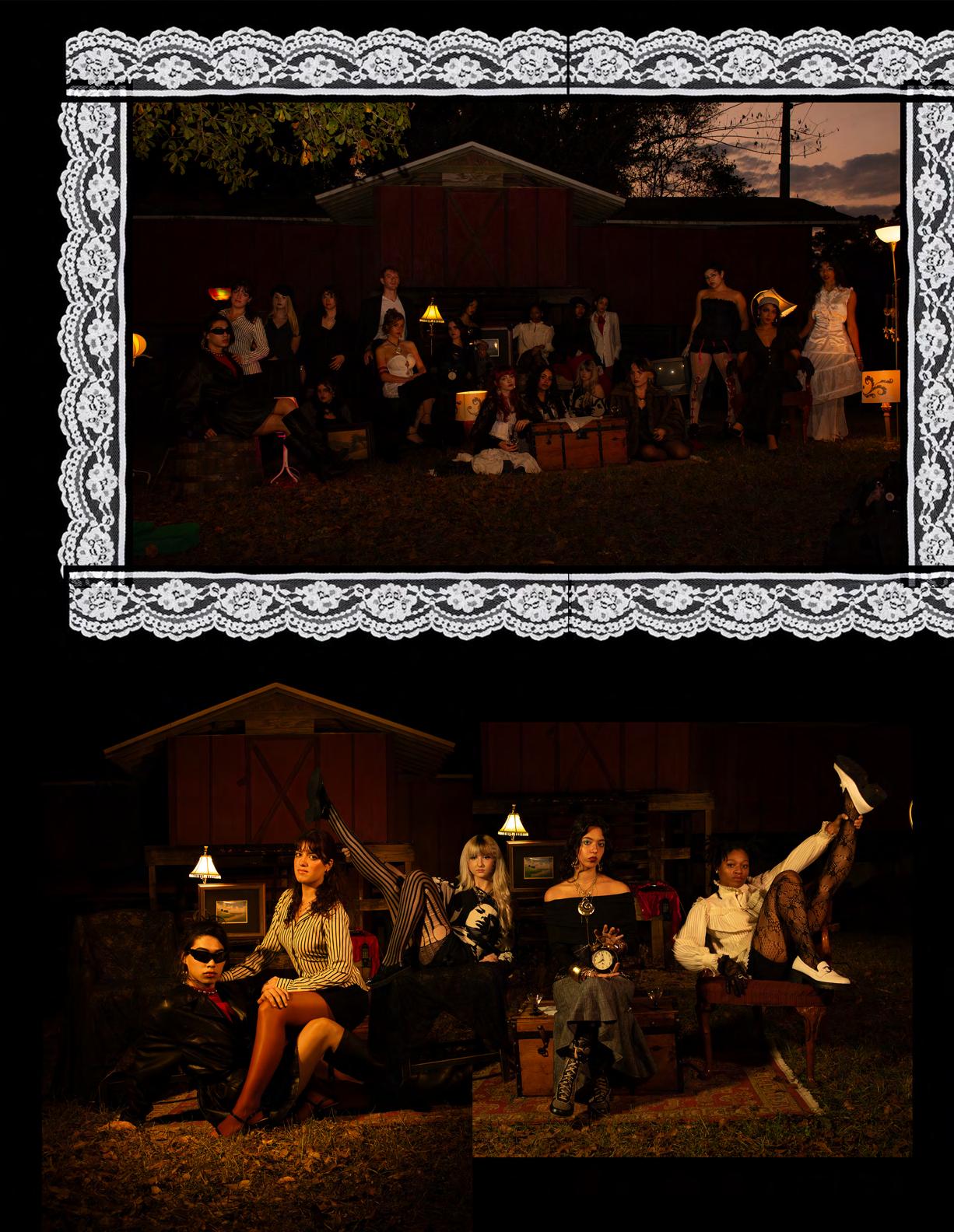

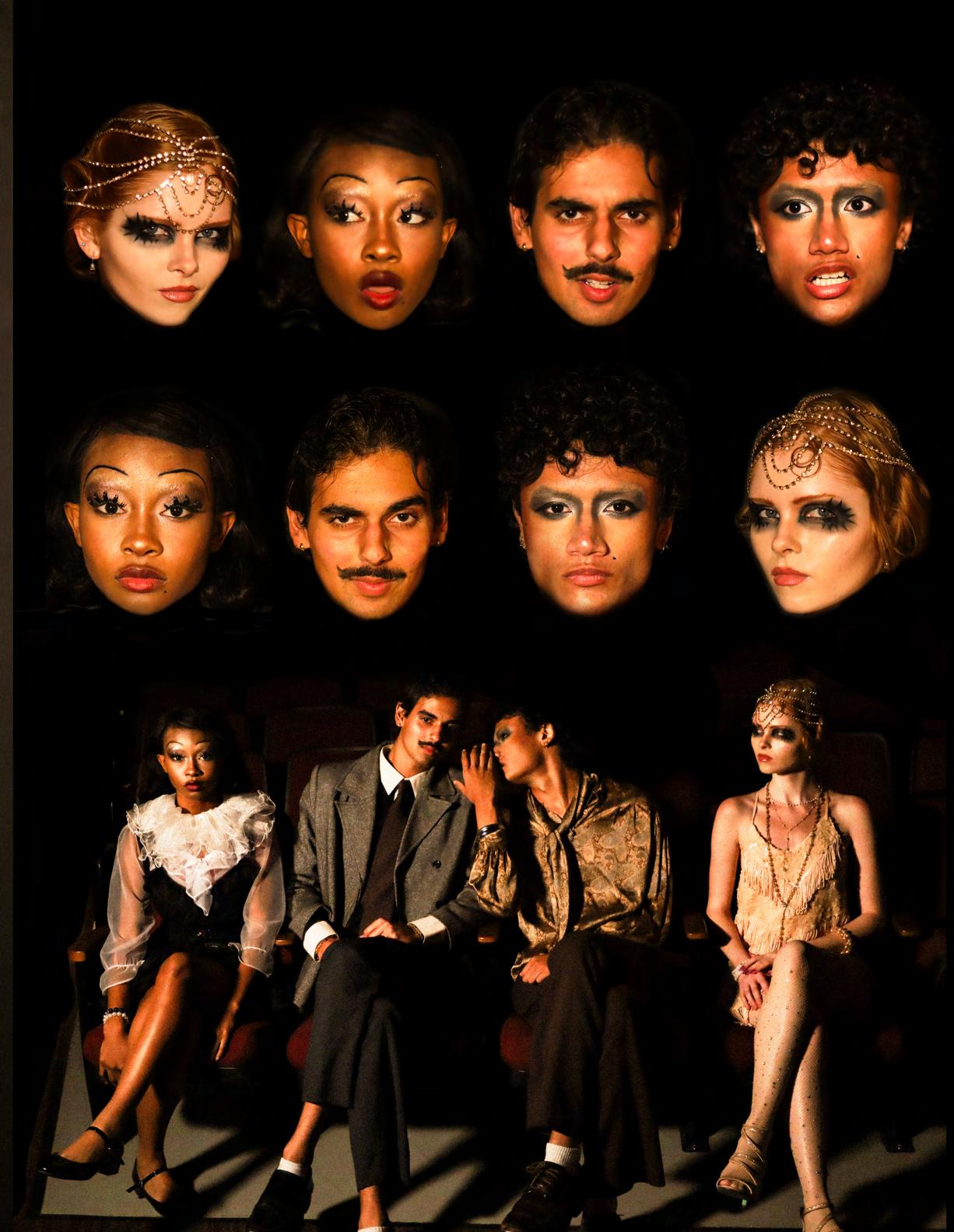

BTS