TopStory

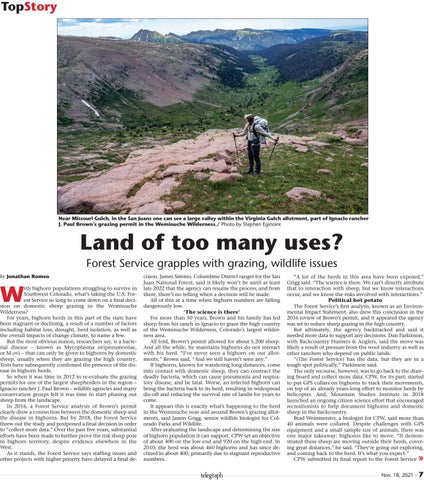

Near Missouri Gulch, in the San Juans one can see a large valley within the Virginia Gulch allotment, part of Ignacio rancher J. Paul Brown’s grazing permit in the Weminuche Wilderness./ Photo by Stephen Eginoire

Land of too many uses? Forest Service grapples with grazing, wildlife issues by Jonathan Romeo

W

ith bighorn populations struggling to survive in Southwest Colorado, what’s taking the U.S. Forest Service so long to come down on a final decision on domestic sheep grazing in the Weminuche Wilderness? For years, bighorn herds in this part of the state have been stagnant or declining, a result of a number of factors including habitat loss, drought, herd isolation, as well as the overall impacts of change climate, to name a few. But the most obvious reason, researchers say, is a bacterial disease – known as Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, or M.ovi – that can only be given to bighorns by domestic sheep, usually when they are grazing the high country. Tests have subsequently confirmed the presence of the disease in bighorn herds. So when it was time in 2012 to re-evaluate the grazing permits for one of the largest sheepherders in the region – Ignacio rancher J. Paul Brown – wildlife agencies and many conservation groups felt it was time to start phasing out sheep from the landscape. In 2016, a Forest Service analysis of Brown’s permit clearly drew a connection between the domestic sheep and the disease in bighorns. But by 2018, the Forest Service threw out the study and postponed a final decision in order to “collect more data.” Over the past five years, substantial efforts have been made to further prove the risk sheep pose in bighorn territory, despite evidence elsewhere in the West. As it stands, the Forest Service says staffing issues and other projects with higher priority have delayed a final de-

cision. James Simino, Columbine District ranger for the San Juan National Forest, said it likely won’t be until at least late 2022 that the agency can resume the process, and from there, there’s no telling when a decision will be made. All of this at a time when bighorn numbers are falling dangerously low. ‘The science is there’ For more than 50 years, Brown and his family has led sheep from his ranch in Ignacio to graze the high country of the Weminuche Wilderness, Colorado’s largest wilderness area. All told, Brown’s permit allowed for about 5,200 sheep. And all the while, he maintains bighorns do not interact with his herd. “I’ve never seen a bighorn on our allotments,” Brown said. “And we still haven’t seen any.” If bighorns, known for wandering long distances, come into contact with domestic sheep, they can contract the deadly bacteria, which can cause pneumonia and respiratory disease, and be fatal. Worse, an infected bighorn can bring the bacteria back to its herd, resulting in widespread die-off and reducing the survival rate of lambs for years to come. It appears this is exactly what’s happening to the herd in the Weminuche near and around Brown’s grazing allotments, said Jamin Grigg, senior wildlife biologist for Colorado Parks and Wildlife. After evaluating the landscape and determining the size of bighorn population it can support, CPW set an objective of about 400 on the low end and 920 on the high end. In 2010, the herd was about 460 bighorns and has since declined to about 400, primarily due to stagnant reproductive numbers.

telegraph

“A lot of the herds in this area have been exposed,” Grigg said. “The science is there. We can’t directly attribute that to interaction with sheep, but we know interactions occur, and we know the risks involved with interactions.” Political hot potato The Forest Service’s first analysis, known as an Environmental Impact Statement, also drew this conclusion in the 2016 review of Brown’s permit, and it appeared the agency was set to reduce sheep grazing in the high country. But ultimately, the agency backtracked and said it needed more data to support any decisions. Dan Parkinson, with Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, said the move was likely a result of pressure from the wool industry as well as other ranchers who depend on public lands. “(The Forest Service) has the data, but they are in a tough spot politically,” Parkinson said. The only recourse, however, was to go back to the drawing board and collect more data. CPW, for its part, started to put GPS collars on bighorns to track their movements, on top of an already years-long effort to monitor herds by helicopter. And, Mountain Studies Institute in 2018 launched an ongoing citizen science effort that encouraged recreationists to help document bighorns and domestic sheep in the backcountry. Brad Weinmeister, a biologist for CPW, said more than 40 animals were collared. Despite challenges with GPS equipment and a small sample size of animals, there was one major takeaway: bighorns like to move. “It demonstrated these sheep are moving outside their herds, covering great distances,” he said. “They’re going out exploring, and coming back to the herd. It’s what you expect.” CPW submitted its final report to the Forest Service

»

Nov. 18, 2021 n 7