2

Dukes - Founded 2015

Foreword

As Dukes Education goes from strength to strength, it is hard to believe how far, and how fast, our family has grown. We wanted to mark this point in our story with some other stories – the founding stories of a selection of our schools. Because each of our amazing schools has its own origin story, whether it’s Broomfield House, founded by the redoubtable Victorian, Miss Mead, in 1876 or Hampstead Fine Arts, which has grown from a good idea that Candida Cave had in 1978. Our schools are different and unique in their own way, but they have one mission - to give each child an extraordinary education - which is what unites us all as a family at Dukes.

I hope you enjoy this book and the many stories that make up our story, here at Dukes Education.

Aatif Hassan, Founder & Chairman

3

“I hope you enjoy this book and the many stories that make up our story at Dukes Education.”

4

5 Contents Aatif Hassan Foreword ............................................................................................................ 03 Daisy Harrison Miss Daisy’s 06 Alex Rentoul Bassett House, Orchard House & Prospect House Schools ............................. 14 Martin Pace Reflections Nursery and Forest School ............................................................ 22 Norton York Broomfield House School .................................................................................. 30 Magoo Giles Knightsbridge School........................................................................................ 40 Candida Cave Fine Arts College ............................................................................................... 48 Tim & Julie Fish Earlscliffe........................................................................................................... 56 Luchie Cawood Eaton House Schools ......................................................................................... 64 Dr Harriet Sturdy Sancton Wood ................................................................................................... 70

6

Daisy Harrison with some of her young charges

Daisy Harrison with some of her young charges

Daisy Harrison, Miss Daisy’s

I had always wanted to work with children; I started babysitting and nannying from the age of 15. My mother used to say that I should be a teacher because I was good with children, but I had to grow up a bit before I realised that she was right.

After completing Montessori training and then a teaching degree, I taught reception at Thomas’s in Battersea, before going to Garden House boys’. It was at Garden House where I had my idea for creating a nursery school. I didn’t enjoy school, and my happiest memories were from the nursery I went to in Fulham, Miss Dinah’s. I remember learning to write my name there, and

I am still friends with friends I made at nursery school. I just assumed that all nursery schools were like that. At Garden House I visited the nurseries that were feeding the school, and was shocked by what I saw. A lot of these, in the poshest parts of London, where parents were paying very high fees, were in dark, damp church halls with teachers that didn’t understand early years. I was watching children come into Garden House ill-prepared – they couldn’t look me in the eye, or follow instructions. The important skills that they should have learnt at nursery just weren’t there.

I started doing some research and realised that 30 years ago there had been some very good nursery schools in London, and I was lucky to go to one. Since then, they had got a bit lost. I knew in my heart that I had to start my

own nursery school – somewhere that you would want to send your child to, and somewhere that you would love to work as a teacher. I wanted to create a nursery where every teacher would know every child and their needs.

For what became Miss Daisy’s Belgravia, which opened in September 2006, I bought an existing nursery school that had once been one of the best in London. It was in a room underneath a block of council flats, and painted bright yellow. I changed everything. It was just me, and four others. I was headmistress, bursar, registrar, teacher, and right from the beginning I said that there would be no hierarchy – everyone would be washing up paint pots.

When we opened, it was all through word of mouth. I wasn’t just creating a nursery school, but a community, so I tried to find families who lived locally.

By 2010, our waiting list was growing and because siblings got priority I couldn’t offer places to new families. Everyone said don’t do it, but I approached St Luke’s & Christ Church on Sydney Street, and asked them about the space under the church. I knew I could make it nice. When Miss Daisy’s Chelsea opened that year, I split my time as headmistress between Belgravia and Chelsea, getting a secretary to help me with the admin. When Chelsea opened, it was full from day one, with a waiting list. That’s when people started approaching me saying I had created a brand, and that one day I could sell it.

I hadn’t thought of that at all.

9

Miss Daisy celebrating with everyone at the Summer Staff Party 2018

Miss Daisy celebrating with everyone at the Summer Staff Party 2018

When I started Miss Daisy’s Belgravia I would read the dummy’s guide to running a business on the bus to school.

I definitely made mistakes along the way, but I’m pleased that I learnt how to do it myself. I was way too trusting at the start – I couldn’t believe that a parent just wouldn’t pay fees. When you’ve got your rent and payroll every month you have to grow up and be responsible.

Because I had such a big waiting list in Chelsea I opened Miss Daisy’s Knightsbridge in 2014. I had to fight to get the space on Milner Street, and it took me a year to renovate it. That was also full with 60 children, with a waiting list, from day one. At around this time, Aatif approached me. I had just bought an existing nursery school in Brook Green, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t have carried on much longer on my own. When Aatif came to see me it was a different conversation from the other school groups that I had spoken to. He had secretly visited my schools, and said ‘Daisy, I will not change anything’. This was music to my ears. If you visit Miss Daisy’s nowadays, the schools have got better, I can see that. There are better resources, and the staff training is amazing.

We now have five Miss Daisy’s. Aatif owned a nursery in Connaught Village on the north side of Hyde Park, and he asked if it would work as a Miss Daisy’s. I went to see it, with its huge gardens, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness!’ Miss Daisy’s was always meant to be a country school in London, and I had struggled with the lack of outdoor space.

11

“When I started Miss Daisy’s Belgravia I would read the dummy’s guide to running a business on the bus to school.

I definitely made mistakes along the way, but I’m pleased that I learnt how to do it myself.”

“I rang Aatif and said, ‘100 per cent, this has to be a Miss Daisy’s.’

That opened three years ago, and it’s completely full.”

Daisy Harrison wielding the hammer at Miss Daisy’s Knightsbridge during renovations ahead of its opening in 2014

Daisy Harrison wielding the hammer at Miss Daisy’s Knightsbridge during renovations ahead of its opening in 2014

I rang Aatif and said, ‘100 per cent, this has to be a Miss Daisy’s.’ That opened three years ago, and it’s completely full.

We will open one more nursery at some point, but we’re not in a rush. All of the sites are currently being renovated, and the original nursery in Belgravia is moving to a building on Eccleston Street, which I am quite emotional but excited about. It will be exactly the same, but just better.

At Miss Daisy’s, we care about manners, kindness, and building children’s confidence. I’ve had some pushy parents, but never an unhappy child. The children have always come first for me. If a parent says, ‘why is my child not reading Harry Potter’, I say, ‘when he can play, share, and help tidy up, that’s when he’ll start’. You’ve got to lay the foundations.

Daisy Harrison in front of the new Miss Daisy’s Belgravia which opened in 2006

Daisy Harrison in front of the new Miss Daisy’s Belgravia which opened in 2006

14

“If you want your child taught properly but in a home environment and also given a nourishing lunch, it’s ten shillings a week.”

In the playground at Orchard House

In the playground at Orchard House

Alex Rentoul, Bassett House, Orchard House & Prospect House Schools

Bassett House School in Notting Hill was founded in 1947 by my mother Sylvia Rentoul. Having sent my five-year-old eldest brother to the local state primary school, she was appalled when she asked him where his book was at the end of the first week, and he said, ‘Don’t be silly, mum, we don’t do books, we just do letters this year.’ She complained to his headmaster, who said, ‘It’s just post-war, there are 40 children in the class, and we’re not going to do reading until next year at the earliest.’ She was so cross that she took my brother out of the school to teach him at home. The local education officer said that children must be taught in a school, so she must either send him back to the primary school, or to a private school. Not having the funds for a private school, my mother got out her typewriter, and typed out loads of slips which she delivered to local nurseries saying, ‘If you want your child taught properly but in a home environment and also given a nourishing lunch, it’s ten shillings a week.’ She worked out if she had more than six children she could officially call herself a school, and the next week she had eight children, which is how Bassett House began.

The school kept growing and, out of the blue in the mid-1980s my mother summoned my two older brothers and me and said that she was retiring. She announced that either she could sell the business, or we could run it, but she wanted a salary. We decided that we would go ahead and run the school, but that she wouldn’t get a salary – instead, she would get all of the profit. We also said she couldn’t cross the school’s doorstep without a written invitation. She was furious about that, but reluctantly accepted. Sometimes after working on a City deal I would drive past in the small hours and see that the lights were on, and think, ‘that’s not the cleaners’, and I’d go in to find her there.

I had known the school quite well before we took it over, as I had done its accounts for many years. I went to Bassett House as a pupil to begin with, before going to prep school in the country, and then on to Westminster, which was full of very clever children. I wasn’t nearly clever enough. It was a strange school – if you weren’t going to get into Oxford or Cambridge, you were considered thick. The only other school that we thought was on an intellectual par was Winchester College. My parents would have been insulted had someone suggested that I should go to Eton. I did get into Oxford, but not from Westminster – I took a year out and did different subjects, and then got into Worcester College, where I read Politics, Philosophy and Economics.

17

“My mother made Bassett House a very special school. She was a workaholic – she’d be up at the crack of dawn, and would still be working at midnight. My mother didn’t care about what kind of families she was attracting to Bassett House. She would take the duke’s son along with the dustbin man’s son.”

18

Sylvia Rentoul with her granddaughters at the unveiling of the new west wing at Orchard House in 1999

My mother made Bassett House a very special school. She was a workaholic –she’d be up at the crack of dawn, and would still be working at midnight. My mother didn’t care about what kind of families she was attracting to Bassett House. She would take the duke’s son along with the dustbin man’s son. During Harold Wilson’s regime as prime minister, his PA had her son at the school, and some afternoons he was picked up by the prime ministerial car. My mother met my father, who was Hungarian and therefore an alien in London during the war, in 1940 or 1941, and he went on to run the BBC’s Hungarian service. My parents both drove ambulances in London during the Blitz, and my father was a fire-watcher at night. But it was my mother who was the force behind Bassett House. She was a very doughty, formidable lady. She was firm, yet I never saw her raise her voice to a child, and they all adored her.

I always thought I’d have a career in business, which I have had – I didn’t think I’d run a school. In 1993, we bought the building in Chiswick that became Orchard House School. When we opened, I wanted the school to have 20 to 30 children. One day I went in and the registrar said how awfully well the list for the new school was doing. I asked how many children we had, and she said, ‘well as of this morning it’s 67’. We had only planned to have two classrooms ready for September, so after a big gulp I upped the building works, and we had four ready. After refurbishing the whole building and adding a new wing, we opened another building about a quarter of a mile away.

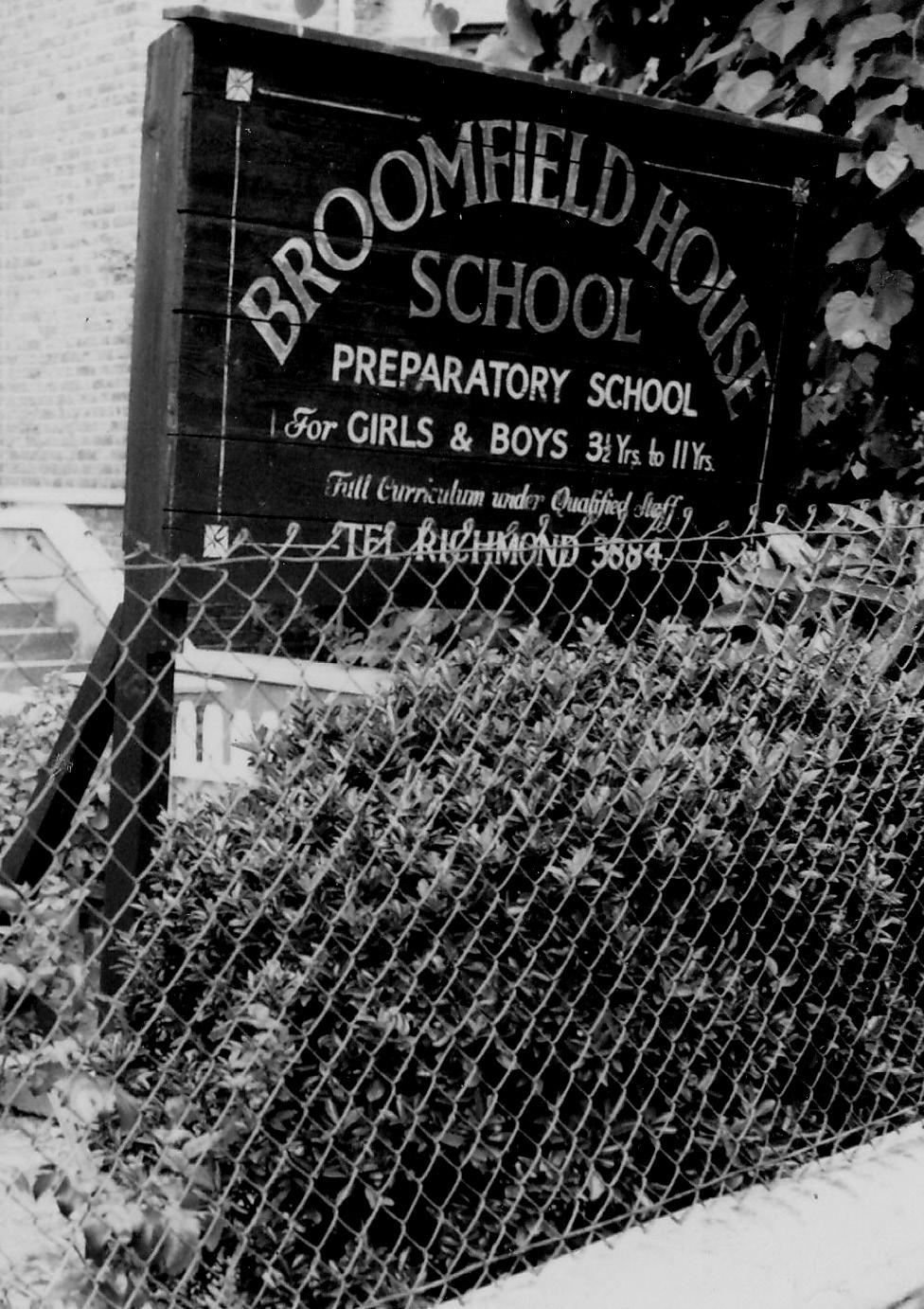

Sally Hobbs, the first Headmistress of Orchard House, presents a young swimmer with a winner’s cup

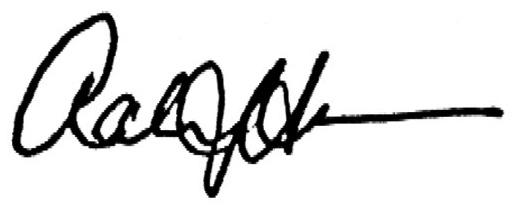

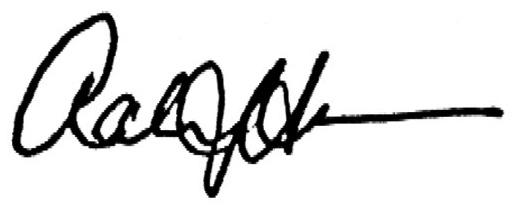

Letter from Boris Johnson to Sally Hobbs, Oct 2006

Sally Hobbs, the first Headmistress of Orchard House, presents a young swimmer with a winner’s cup

Letter from Boris Johnson to Sally Hobbs, Oct 2006

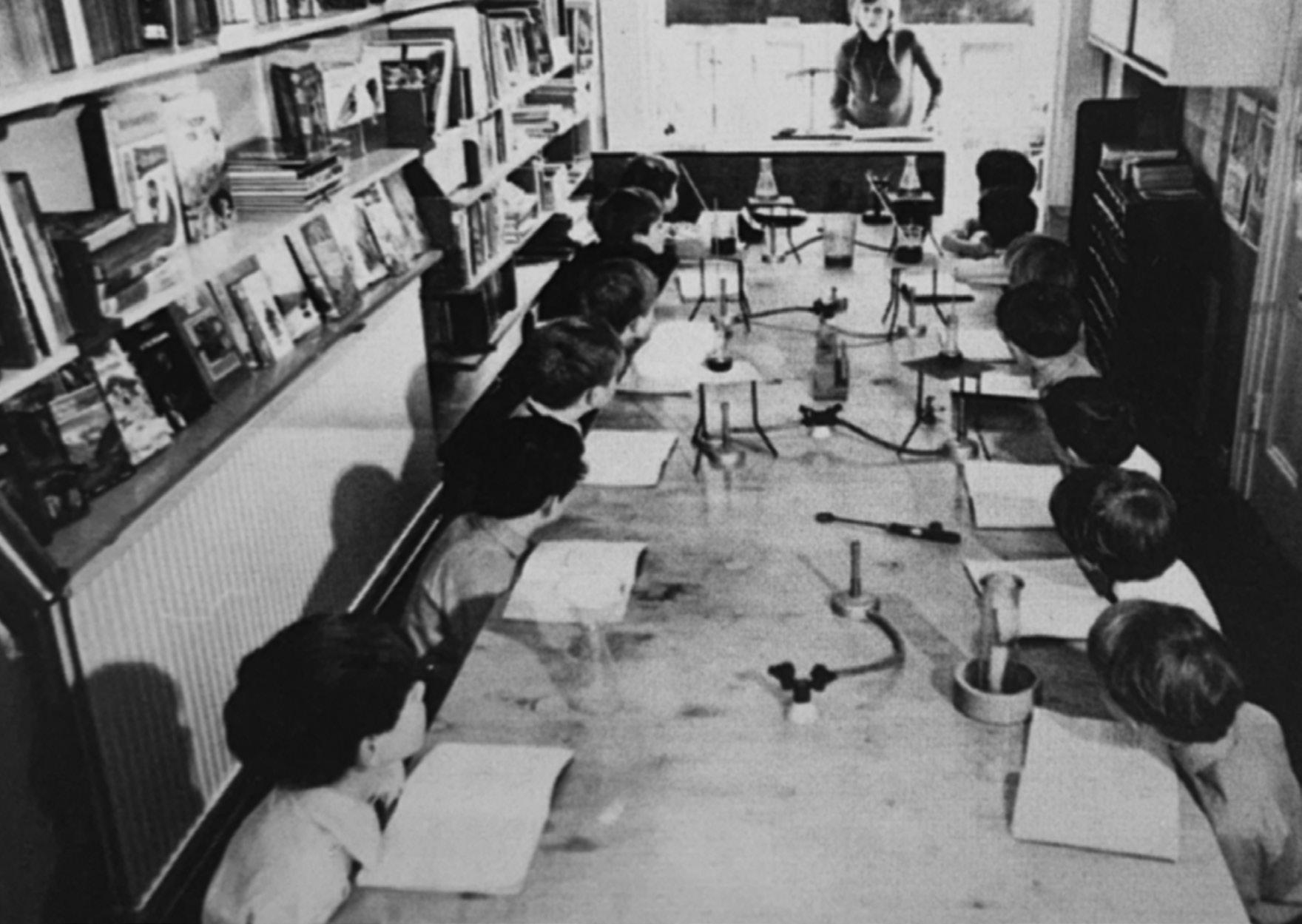

Young Orchard House pupils

Orchard House Sports Day 1999

The first cohort at Orchard House1993 Teatime with Sally Hobbs

Young Orchard House pupils

Orchard House Sports Day 1999

The first cohort at Orchard House1993 Teatime with Sally Hobbs

My mother died in 2000, but shortly before her death she had put me in touch with Prospect House School’s owners. It had started as a nursery in Barnes in the 1960s, and moved to its current building in Putney Hill in 1991. By 2001, one of its partners wanted to sell, and they loved our other two schools, so agreed to sell to us. It was only then that I thought why don’t I concentrate on doing this full-time, and spend the next few years building the group, which is what I did. In 2010, we bought another building for Prospect House nearby, and it has carried on expanding.

Every month or so, people would approach me saying that they wanted to buy the three schools, and if we’d open our books to them, they could give us a price. When Aatif came to us, his approach was more subtle. It was the right time for me to move on, and we sold to Dukes in February 2020. A school is like a fish – it rots from the head down, and it was time to quit. My mother would have been ecstatic about the sale. At the end of the day, schools are a business. The way you keep bums on seats is by being the best in your area.

I think every child has a unique quality that can be grown and celebrated. You compete to offer a service where you have two constituents – the children, and their parents. I think we got that right.

“I think every child has a unique quality that can be grown and celebrated.”

Story time with Sally Hobbs

Some young pupils

22

23

“My daughter had some problems early on, so in a way she was a bit of a precious child - and I was already a bit of a precious parent. I looked around a couple of nurseries but I thought that children deserved better.”

Martin Pace, Reflections Nursery and Forest School

When I first became a parent nearly 30 years ago, I was living in west London, working for the World Wildlife Fund. Like most couples, we were looking for childcare. My daughter had some problems early on, so in a way she was a bit of a precious child – and I was already a bit of a precious parent. I looked around a couple of nurseries but I thought that children deserved better. A job for a marketing director arose at a nursery group developing purposebuilt workplace nurseries parks, and I did that for two years, before taking up a similar role at another nursery group. After a further two years, I thought I should give it a go on my own. I got involved with a City finance house to raise funds, but the timing conceded with the Dotcom boom, and there was little interest in the modest returns from a nursery business. I wrote a book entitled How to start a nursery, despite not having been able to do so, which got me noticed by an entrepreneur with a potential nursery site. In 2000, he and I set up Dolphin Nurseries, along with venture capital funding, which we grew into an eight-nursery group in four years. When we sold Dolphin in 2004, I exited with enough capital to buy my own nursery.

By then, I had a clear vision for my nursery. In 2002 I had studied in the city of Reggio Emilia in northern Italy, famous for their approach to early education. I was inspired by the Reggio approach and with two colleagues, Linda Thornton and Pat Brunton, we set out to offer children a project-based learning experience supported by creative educators. Looking for a location,

I immediately thought of Brighton, and for over a year I made offers on potential sites. Eventually, a traditional English nursery in Worthing came on the market, and in 2006 I bought it and changed the name to Reflections. We changed the use of the rooms, threw out three skips of plastic toys, and began working towards our approach.

The pre-schools in Reggio Emilia employ artists to support children’s learning, which they call ‘Atelieristas’, and by 2009 we had trained our first Atelierista, and won Nursery World’s UK Nursery of the Year award.

25

The Reggio Emilia approach is not a method or an educational model. It begins with the image of the child as strong, powerful and competent. Children work on a project basis: an idea develops from adults really listening to the children, and together we decide on a starting point for work which might last up to a year. The children work together with educators who are able to support an emergent curriculum, constantly observing the children, and feeding their ideas back into the project – it takes considerable skill to work in this way.

By 2009 we had also become an early adopter of Forest School for young children, and Reflections now runs Beach School as well. We find the environment generates big thinking in children. One nursery project developed when a three-year-old wanted to build a water feature in the garden, and the inspiration for the design came from children pouring water down a fungus in the woodland.

I was always excited by the work I saw in Reggio Emilia where they can continue working with children up to the age of six before they start school.

In 2017 we set our Small School, an independent infant school for children aged five to eight, following a similar approach to the nursery. We take up to 24 children and they work on a project basis three days a week, and then spend a full day at the beach, and another in the forest. Our approach is deliberately alternative and may be less formal than in traditional state schools, but there is deep learning and the children’s motivation is palpable.

“Children are the best of us –their imaginations are so alive, and I really enjoy being around their creativity and energy.”

Reflections

Nursery - the Tudor Court building

I suspect that one of the reasons I’m interested in working with children is because I didn’t have the best childhood myself. My parents divorced when I was young, and I rebelled at school. The idea of being ‘seen and not heard’, or apologising to an adult when they had been in the wrong were deeply unfair concepts to me as a child. For me, the rights of the child should be respected, and respect for the child and giving the child a voice are two principles which underpin everything we do at Reflections.

When setting up Reflections, I wasn’t looking to build a group of nurseries, or to grow a business. I wanted to prove that you can create a UK-based nursery which draws inspiration from the preschools of Reggio Emilia, notwithstanding the differences of culture. Reggio is more of a philosophy about working with children – they talk of it as an approach of ‘constant research and action’, working with intelligent, caring people, at the centre of which is the capable child.

In 2018 I had some back problems which made me worry about how much I could give to Reflections if I didn’t always have the energy. We were introduced to Dukes by Courtney Donaldson from Christie & Co, and I instantly saw in Aatif someone I could trust. Dukes’ values resonated with my own and I could see that Reflections would be safe in their hands. We sold the nursery to them in 2019.

I’m not around as much at Reflections anymore, and I miss the ring of children’s voices. Children are the best of us – their imaginations are so alive, and I really enjoy being around their creativity and energy. I deeply miss colleagues, and I am very thankful to have worked with some of the most amazing, creative, motivated people. The 15 years I spent with Reflections have been the most exciting of my career so far, and I feel that together we created something of value. I have just planted a vineyard in East Sussex, so I’m kept pretty busy, but I hope that I will soon find another outlet for the ideas and experience of working with children.

Reflections Nursery - the Westerfields House building

Reflections Nursery - the Westerfields House building

30

“Every Tuesday we’d go to the cash and carry and buy the week’s school food. Mum would send me and my brother off to get the best deal on baked beans.”

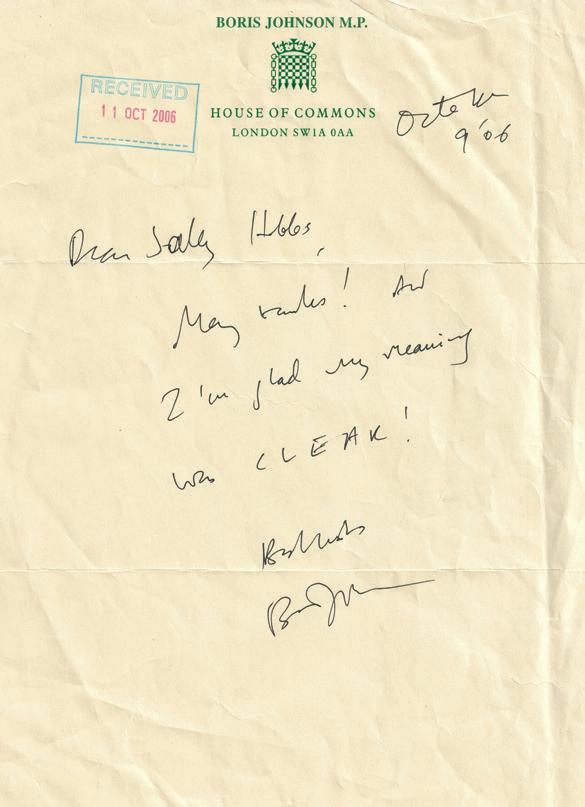

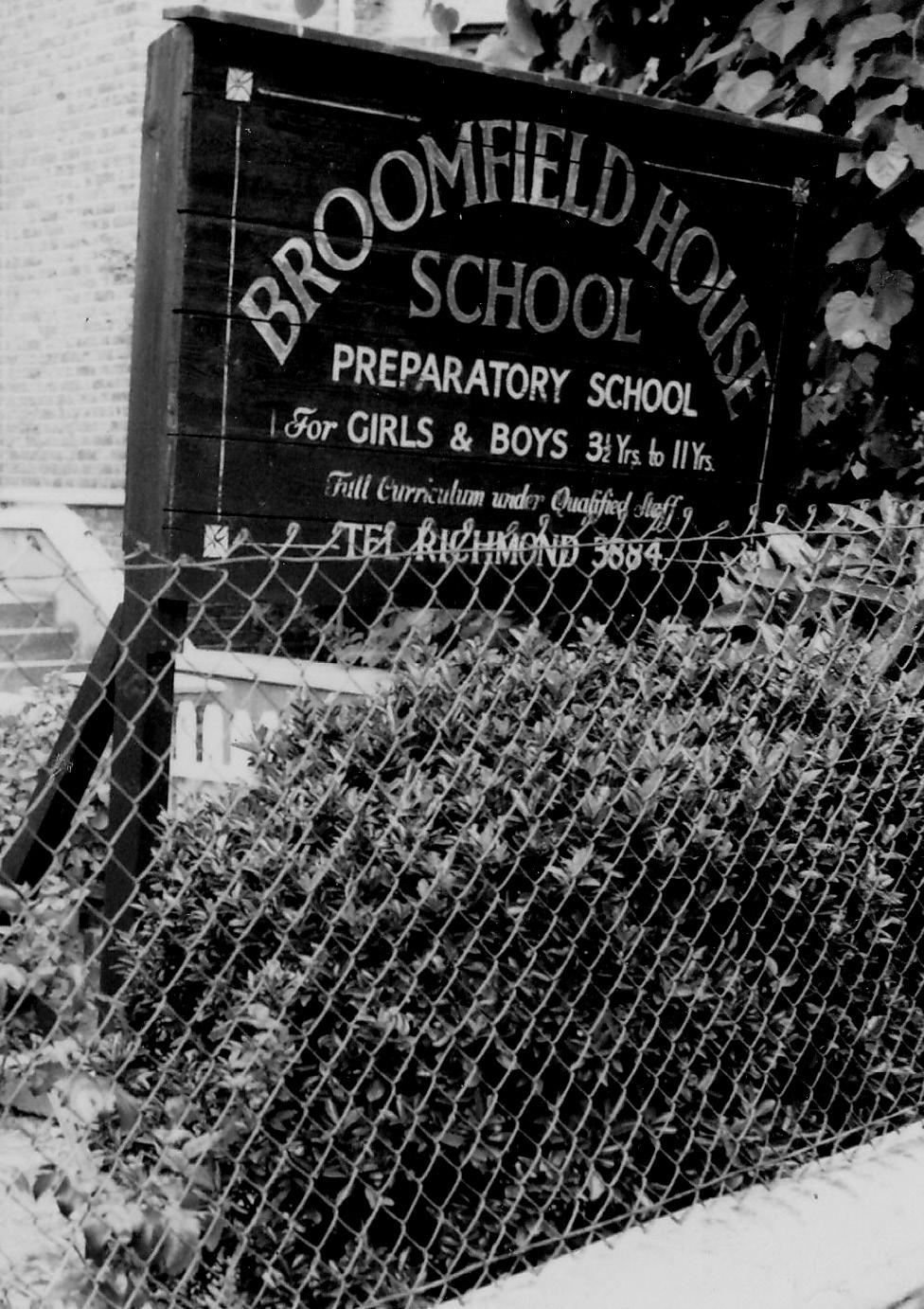

The first cohort of pupils at Broomfield House in 1876 The founder, Miss Mead is seated in the centre of the second row

The first cohort of pupils at Broomfield House in 1876 The founder, Miss Mead is seated in the centre of the second row

Norton York, Broomfield House School

My mum, Irma York, bought Broomfield House School in 1969. She had been a music teacher at Sutton Court House School in Chiswick, but after it was sold, she got a job at Broomfield. Within a year or two, the headteacher Mrs Rose was looking to retire, and my mother agreed that she would buy the school. Mum bet everything she had to raise a mortgage, and she bought the school at considerable risk. It was old-fashioned capitalism: people bought schools as if they were buying a house. You would go to the bank and get a loan, and pay for it over 25 years.

Mum had always wanted to be a headteacher, and we lived in the flat above the school. I started answering the phone saying, ‘Broomfield House School, how can I help you?’ When I was old enough to hold a telephone. Life in a school was lovely. The playground was my back garden once the children went home, and I learnt to budget when every Tuesday we’d go to the cash and carry and buy the week’s school food. Mum would send me and my brother off to get the best deal on baked beans. When I was Head, I used to serve lunch just as my mum did, five days a week. Some days that went well and some days it didn’t. I only had to physically cook lunch once; my wife talked me through how to make fish pie remotely. But it was more fun than not – I wouldn’t have ended up running the school otherwise.

My brother and I went to Broomfield until we were in year three, when we went to Colet Court, and then on to St Paul’s. This was the path of most Broomfield boys; though the school was co-ed to 11, most boys left aged eight. When I took over that was the first thing I changed. I made a commitment to any existing families who had come to the school with that aim, but almost all of the boys in the school decided to stay. It meant that the school was filled up to Year Six with boys and girls quite evenly. What parents want has changed since I was at school. Back then, parents wanted their children to go to singlesex public schools, and now people want a more local experience, and for their boys and girls to be educated together for as long as possible.

Having grown up at Broomfield, I could imagine that running a school was something I might do in the future, but I didn’t expect to do it. I was a professional trombone player in pop bands for quite a long time, and I had a career teaching in universities. In 1991, I founded my own business, RSL Awards, a music exam board. By 2002, my mum had run Broomfield for 32 years single-handedly, and it was my turn. She was very good at giving up control of it. From the day I took over, she didn’t really appear in school apart from visiting on special occasions, but she was there in the background so I could phone her any time. When I took over, parents immediately assumed that I knew intimately which senior school each of their children was going to get into. I quickly built a database, but in the interim I would phone my mum for help. She was really great at supporting me privately.

33

Original school name plate

Norton York standing in front of the new brass name plate in 1970

Original school name plate

Norton York standing in front of the new brass name plate in 1970

Broomfield fairies

Broomfield footballers

Broomfield boxing

Broomfield fancy dress

Broomfield girls in 1927

Mr Peter Smith, Headmaster of Gunnersbury

Broomfield fairies

Broomfield footballers

Broomfield boxing

Broomfield fancy dress

Broomfield girls in 1927

Mr Peter Smith, Headmaster of Gunnersbury

36

“Broomfield always had a strong local community base, and a happy kindness about the way everyone was treated.”

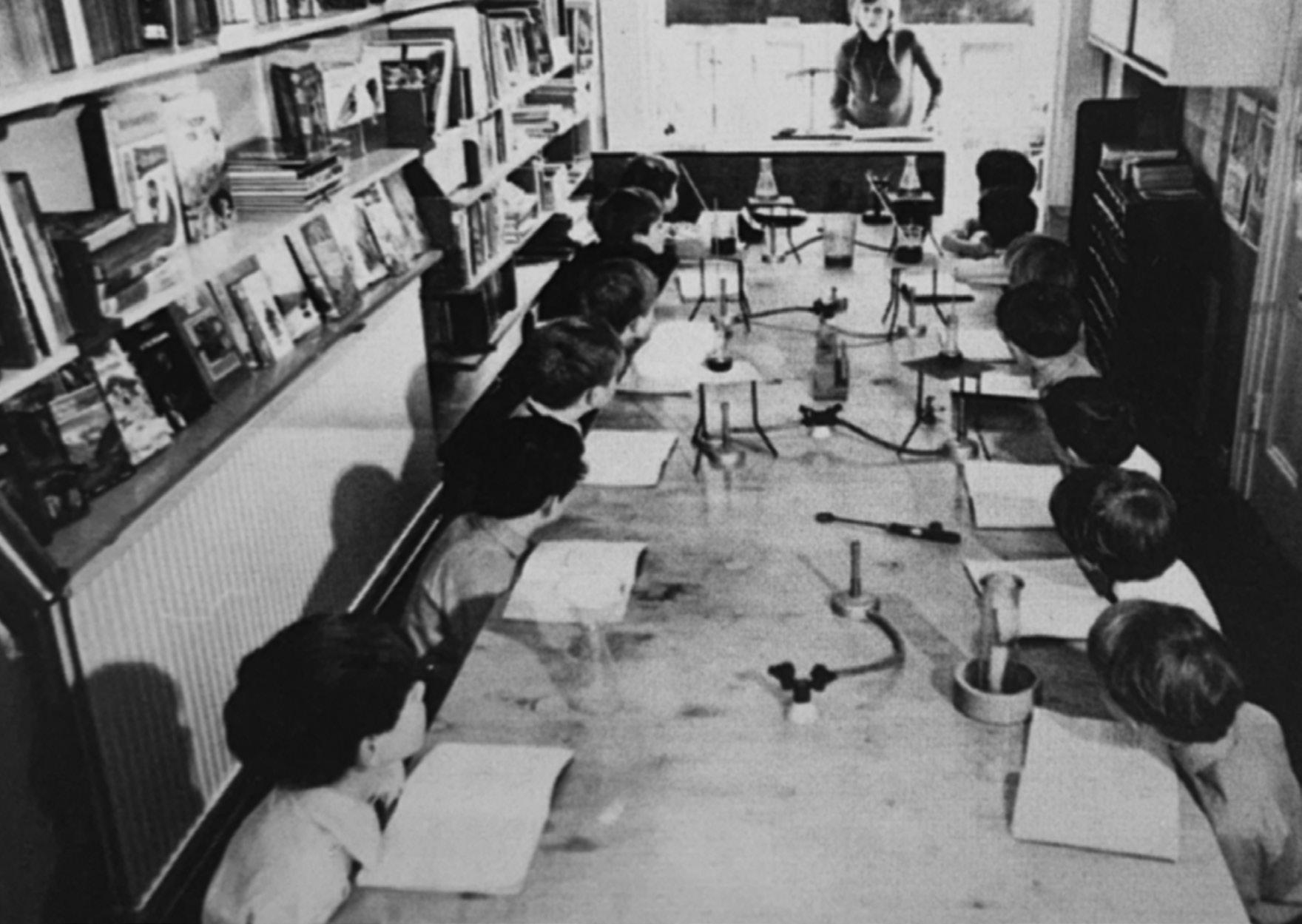

A girls’ class in the 1950s Nativity 1958

I inherited a strong team from her – a few of them had been teaching together for 30 years. Some things did need modernising, as it was run in an oldfashioned way, but Broomfield always had a strong local community base, and a happy kindness about the way everyone was treated. We tried to run it as an egalitarian family where everyone was looked after, and people were not left behind. We wouldn’t ask any of our staff to do something that we weren’t prepared to do ourselves, whether it was cleaning the toilets, or teaching Year Six maths. Because I grew up at Broomfield, I wasn’t surprised by much when I took over – except the finances. The sheer amount of money going in and out is quite shocking. It’s huge sums all the time, so it was unnerving to learn to live with a degree of uncertainty about where you stood financially.

A class in the summer of 1975 - Irma York is in the centre back row in black Mr Viney’s form in the summer of 1975

A class in the summer of 1975 - Irma York is in the centre back row in black Mr Viney’s form in the summer of 1975

Broomfield House School Centenary

Mum is in a care home now, aged 87. When we sold to Dukes, she was sad inasmuch as we had owned the school for 50 years between us, but she understood that we had taken it as far as we could as a family. My children are now 18 and 21, and I’m in my late 50s, so I would have had to have carried on for at least another 10 years for one of them to be anywhere near old enough to take over from me. That wasn’t a choice I wanted to make, and mum understood that. Plus, we couldn’t expand without borrowing huge amounts of money, and I thought I was too old to do that. We had identified that being a single-operator school business had real long-term dangers if anything difficult ever happened – like a pandemic.

1876 -1976

38

Our life in Kew changed when we stopped being involved at Broomfield. I still bump into parents and former pupils, and I’m no longer wary of saying hello because I know I’m not having to address their current issues. I’m no longer asked my opinion on how everyone’s child will do in their 11+ – it was like being a high priest for 11+ ambition.

Being a headteacher and a proprietor is a wonderful thing to do if you love it, and you are happy to live the life. If you don’t love it, it must be a nightmare. I was always very happy to do it, but it wasn’t the thing that defines me as a person.

The 1980s - Irma York is seated front and centre in the navy and white dress. Norton is standing at the back.

Fun at the natvity play in 1958

The 1980s - Irma York is seated front and centre in the navy and white dress. Norton is standing at the back.

Fun at the natvity play in 1958

40

41

“I don’t know many people who have built a school and put their children into it – I put my children where my mouth is.”

Magoo Giles, Knightsbridge School

I went to prep school at Summer Fields in Oxford, where my hero was a teacher called Piggy Prior. He was extraordinary, the inspiration for Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s nettle soup, who used to make up wonderful things like ‘Captain Raindrop and his crew’ to help us learn stuff. I hope people might say the same about me in some ways. Because I was an October baby, I was put in the year above, having moved to Summer Fields from a primary school in Scotland, where my father, who was in the Parachute Regiment, was based for a while. We were all dropped off on Sunday nights for chapel, where we’d sing the hymn ‘The day thou gavest, Lord, is ended’. Everybody was always blubbing.

When I started at Eton many of the boys were very academic, but there were people like me who were what my father would call decent, rounded and grounded chaps, late developers, or ‘bloody good at sport’. He used to say, ‘just remember, you’re bottom of the top’. I don’t want children to think that today – I don’t want them to think ‘I’m thick’. I used to be told that. It was a very easy way of kicking somebody while they were down. I was on a mission to make everyone I came into contact with feel good about themselves.

After Eton, I knew I wanted to join the British Army like my father. For my gap year I went to Australia and worked on Captain Crook cruises in Sydney, in camper vans on the Sunshine Coast, and as a jackaroo in South Australia. Having employed many gap-year students at Knightsbridge I would have

loved to have done that. When I came back from Australia I did an eight-week course called Brigade Squad, to see if I was up for the Army. That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. After that, I went to the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, where the motto is ‘serve to lead’, and that’s what I tell parents now – you have to serve your children to lead. I had some wonderful jobs in the Army, including working as equerry to HM the Queen, before I went to Bosnia with the Coldstream Guards, where, as adjutant, I put on parties for the Serbs, the Bosnians, and the Croatians. People would say I was good with children, and that I had the gift of enthusiasm. After 11 years in the Army, that was my penny-dropping moment. When my commanding officer asked me whether I was going to stay in, or leave and do something else, I said I was going to go and work with kids.

When I left the Army, I went to do work experience at St Gabriel’s Primary School in Pimlico. I was very sporty, and I played a lot of cricket at the Royal Hospital. Playing there one day, a teacher from Garden House School said I should come in and see what it was like there. I started off doing work experience before working my way up doing many coaching qualifications until I became head of sport, having convinced the Royal Hospital to let Garden House use their grounds. Later, I was asked if I would stand in as head of school, which I did for six years.

43

“I phoned my best friend from school, Sir William Russell [Lord Mayor of London, 20192021], and said that we needed to raise about £4.5m.”

Founder and Principal, Magoo Giles, with Head Shona Colaco

Founder and Principal, Magoo Giles, with Head Shona Colaco

When we had our son, Otis, in 2006, I thought, now I need to plan this little person’s life – how am I going to do that? I had heard about a school that was closing, the Hellenic College, so I spoke to the chairman about taking it on. I phoned my best friend from school, Sir William Russell [Lord Mayor of London, 2019-2021], and said that we needed to raise about £4.5m. Three months later we walked into the empty shell, and off we went – Knightsbridge School was born.

One of the reasons I was able to buy the school was because I was the only human bid – I said that I would keep any children that wanted to stay from the Hellenic. We kept 39 children, and one day one I had 89 pupils, having picked up 50 over the summer. The draw for parents, to send their children to this brand new school, was that I had been at Garden House for ten years, and had been head there – I wasn’t just a chap off the street.

The Poetry Together performers with Magoo Giles and some Chelsea Pensioners

The Poetry Together performers with Magoo Giles and some Chelsea Pensioners

Before that, a friend had asked if I would be interested in setting up Notting Hill Prep, but they didn’t have enough facilities, and the extra-curricular, sporting angle was important to me. I wanted to have a school where languages were central too. The Knightsbridge area has changed a lot in this sense. When I started at Garden House 25 years ago, it was home to mainly English and American families, and by 2006 this had evolved into the many European and South American families. I saw a massive change in clientele, and when I set up Knightsbridge School we put in three languages for every child, which attracted a lot of people. I only studied French at school myself, and I have regretted it all my life.

My two children, Otis, 16, and Lola, 15, both went to Knightsbridge School, and are now at boarding school. I don’t know many people who have built a school and put their children into it – I put my children where my mouth is. The school is my third baby and I’m so proud of it. The point of it goes back to my military roots – ‘keep it simple’, thus ‘KS’. This also stands for ‘keep studying’, ‘keeping soldiering on’, ‘keep safe and sound’.

I’ve worked really hard all my life to build a reputation. I’m not the brightest tool, but I’m a hard-working chap who has had a lot of luck, and a lot of fun. The parents know that I have created my school’s values, and I ask everybody in the community to follow them. I least by example, I hope – but I’m only human. At the end of the day, it’s about being a role model, and serving to lead.

48

“She had fallen in love with an Italian racing driver and had decided to move to Italy and live with him the following week. The problem was, she had to find a tutor for her two private students who she was teaching art and history of art A Level.”

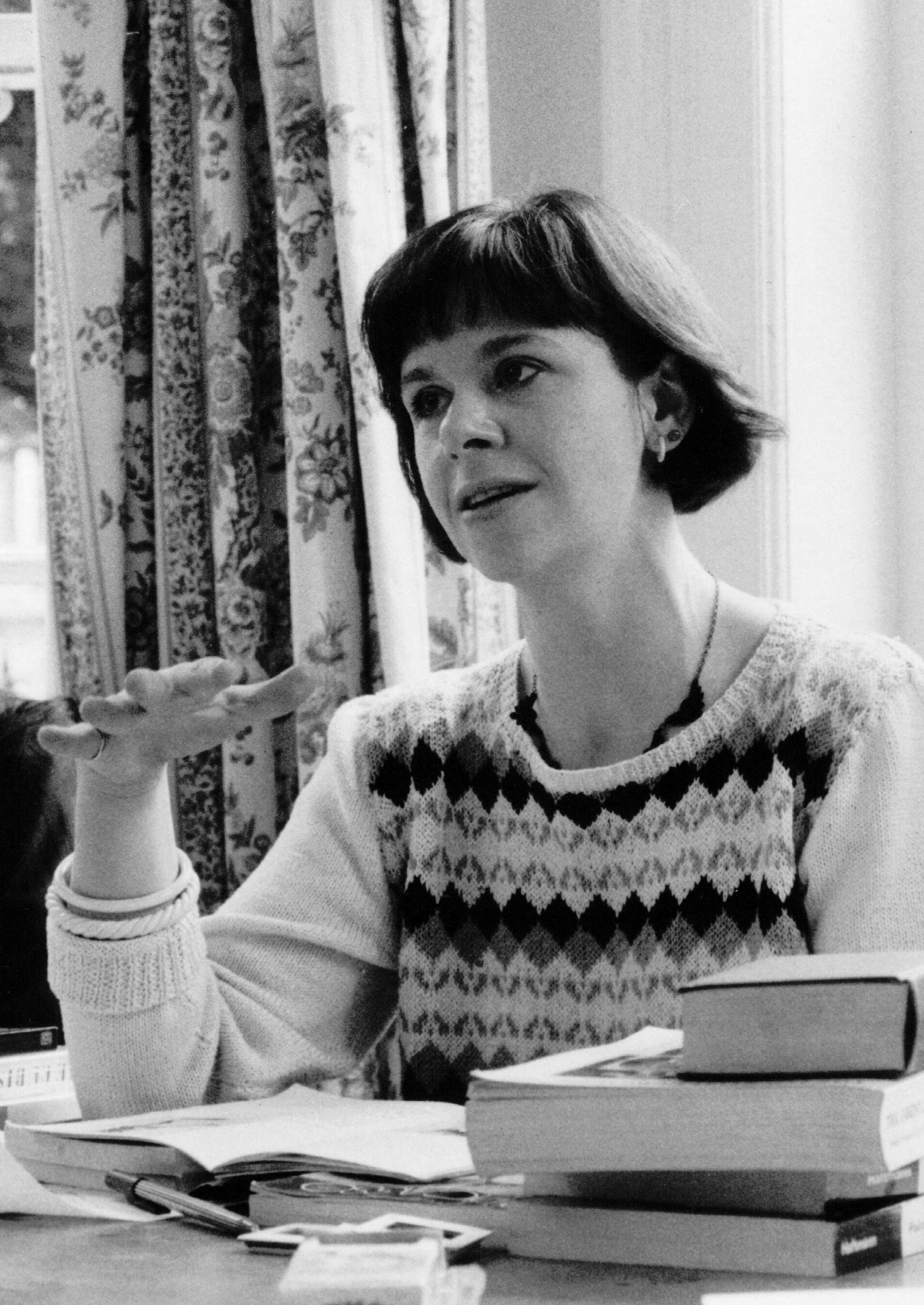

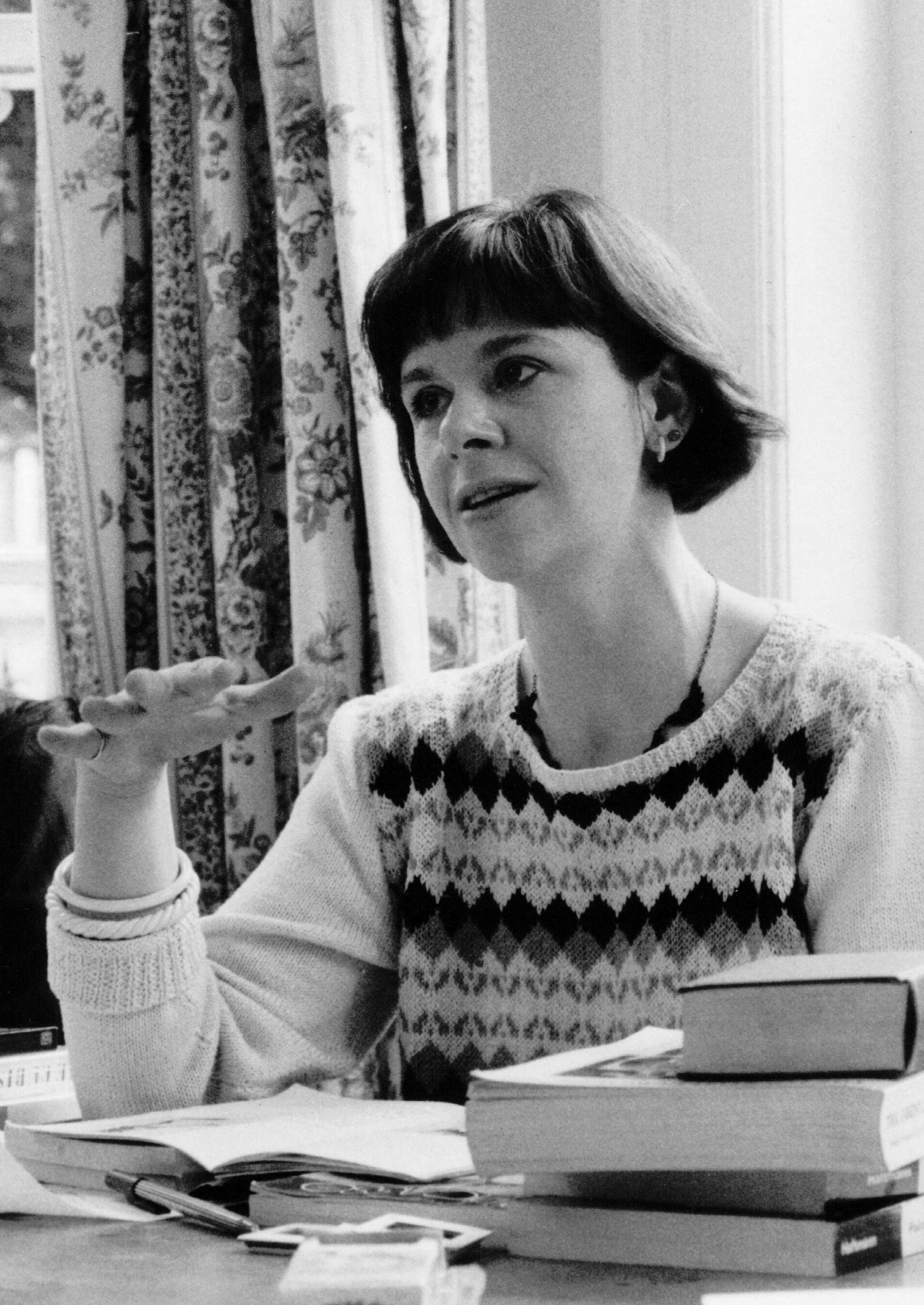

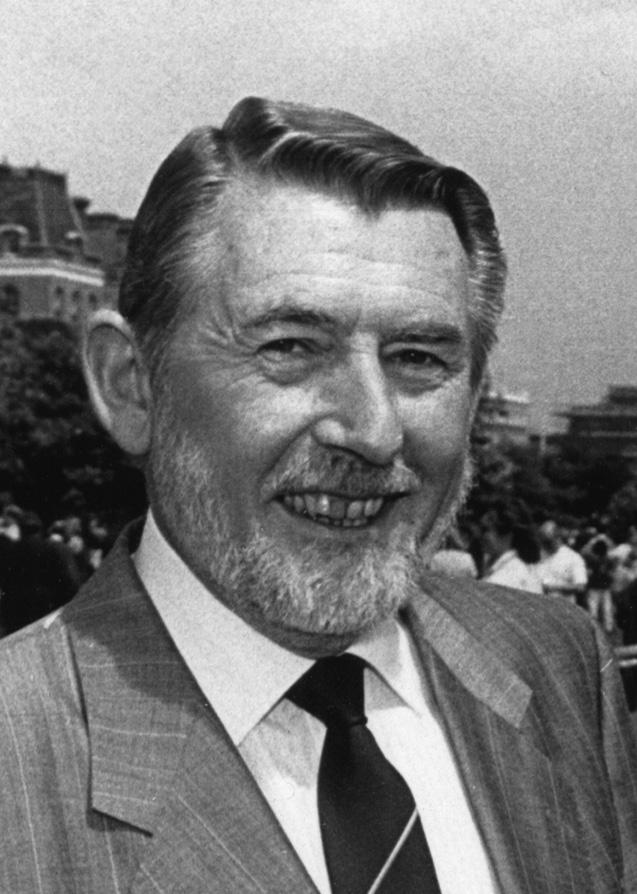

Candida Cave. Founder of Fine Arts College

Candida Cave. Founder of Fine Arts College

Candida Cave, Fine Arts College

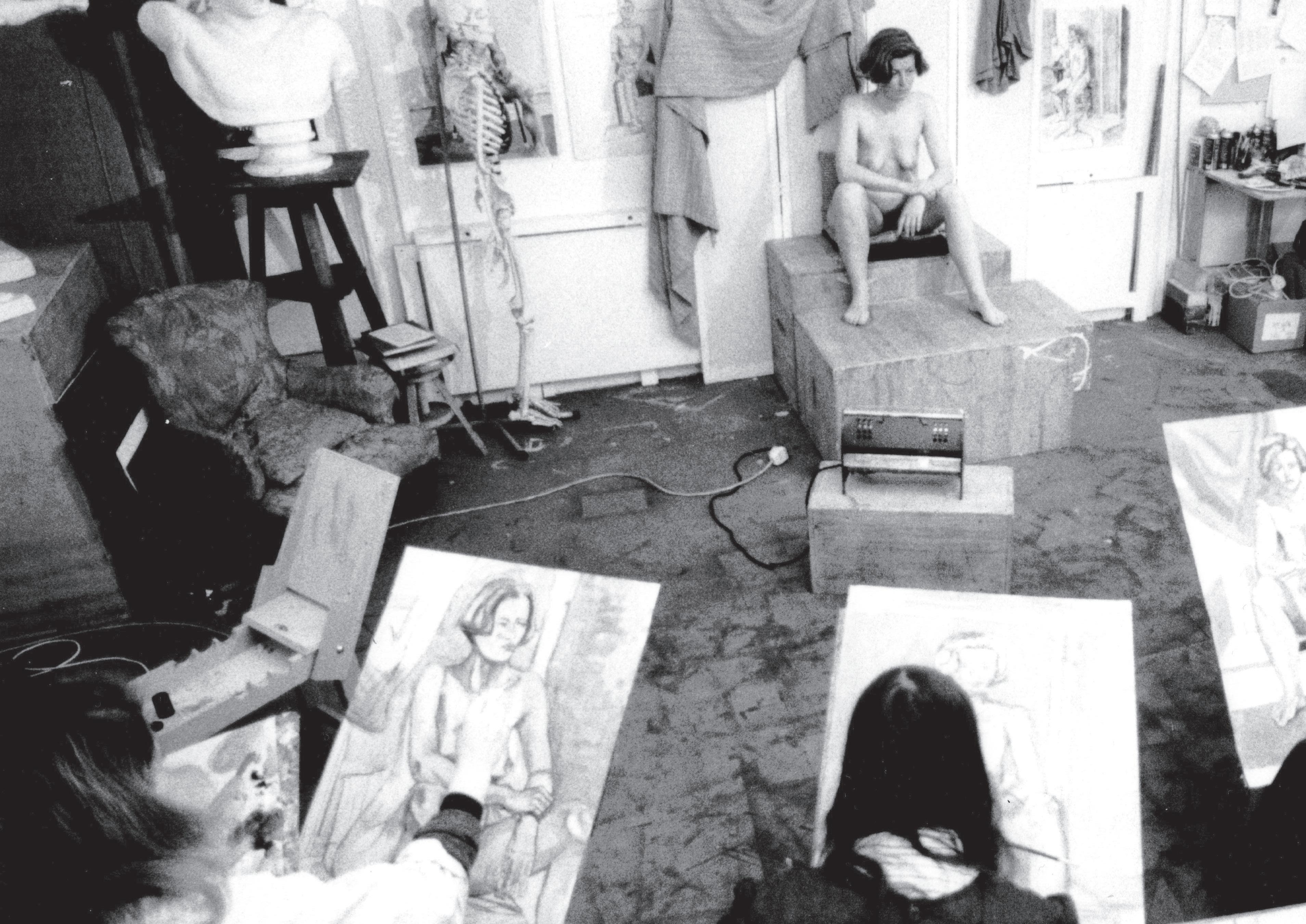

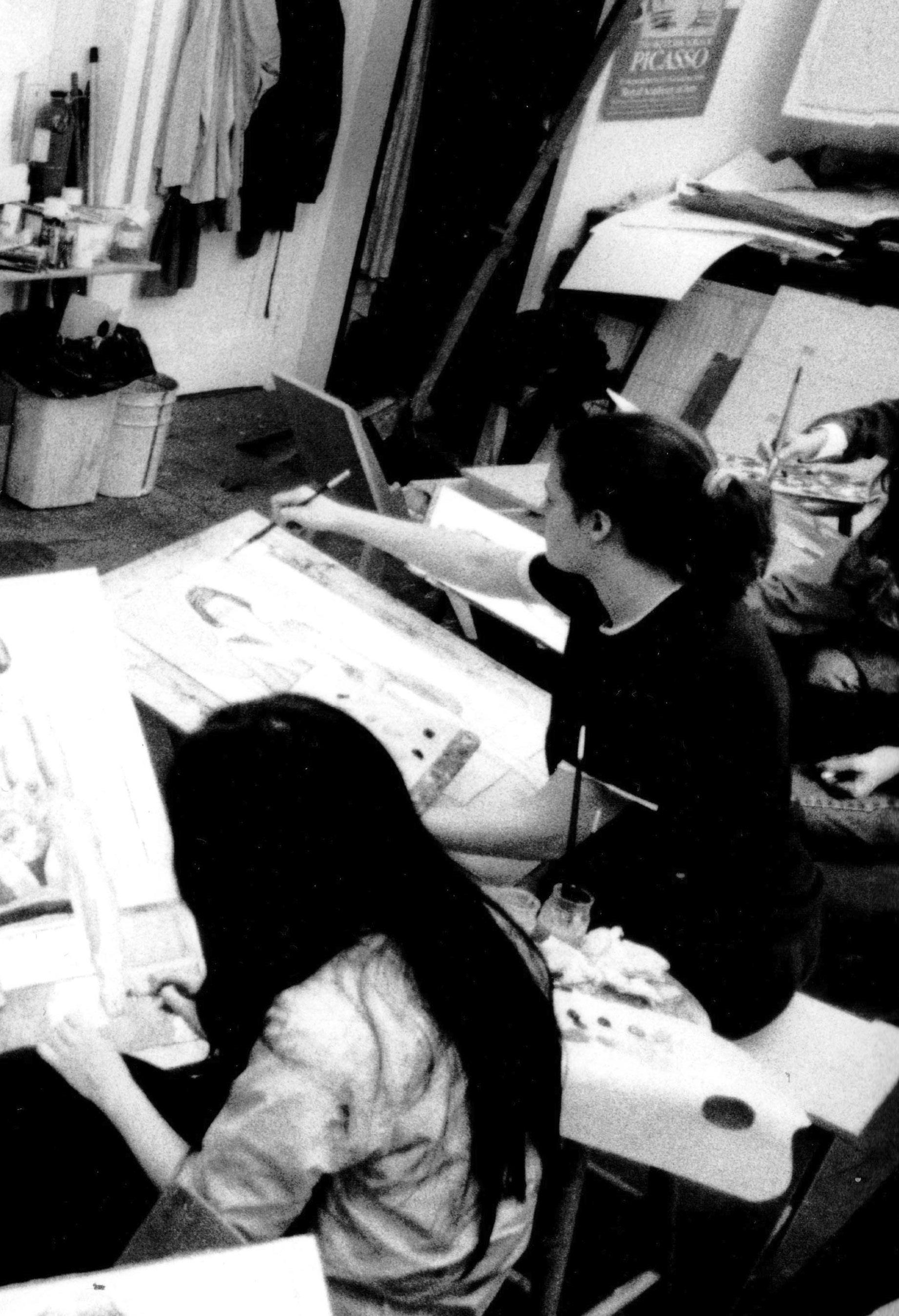

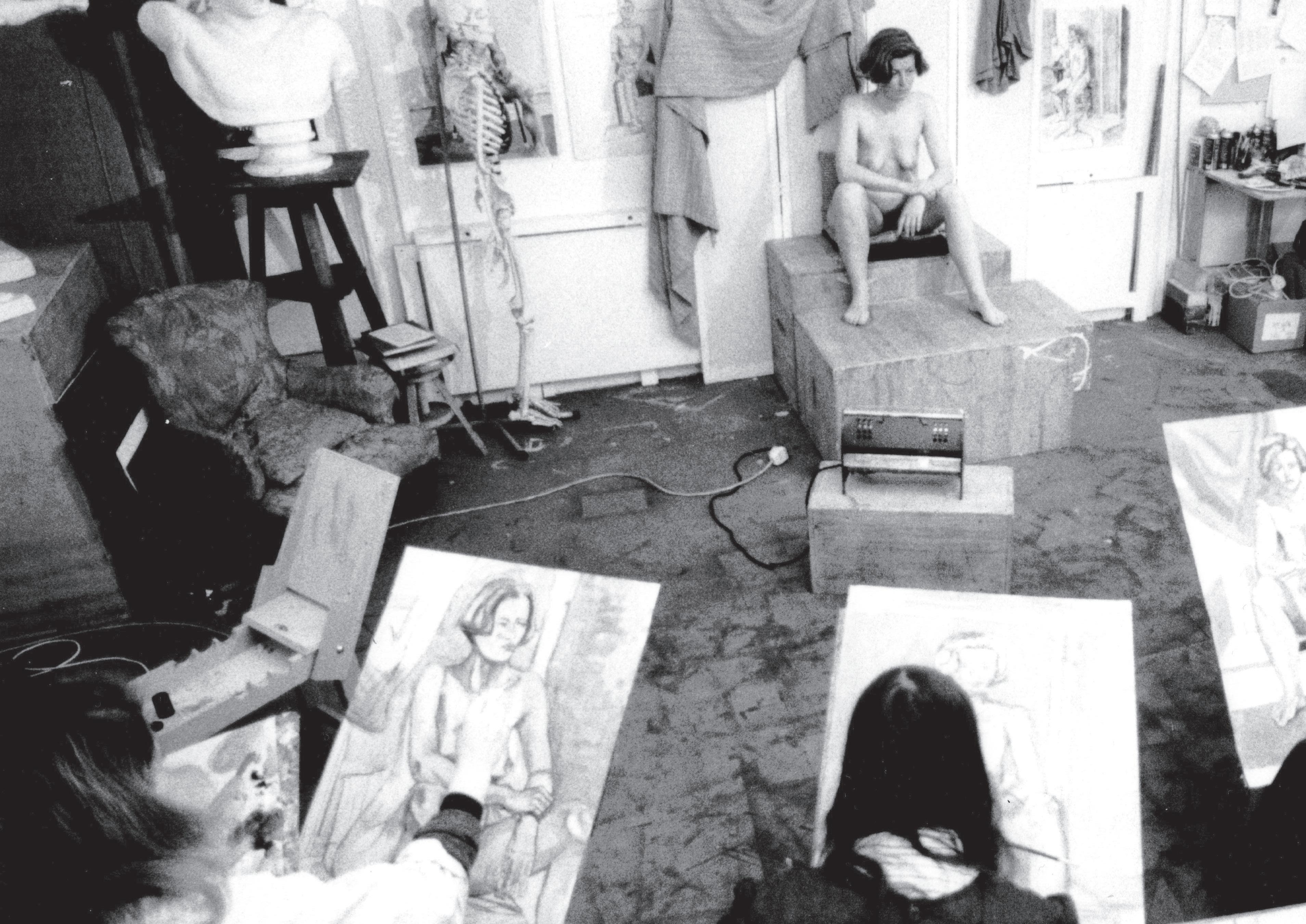

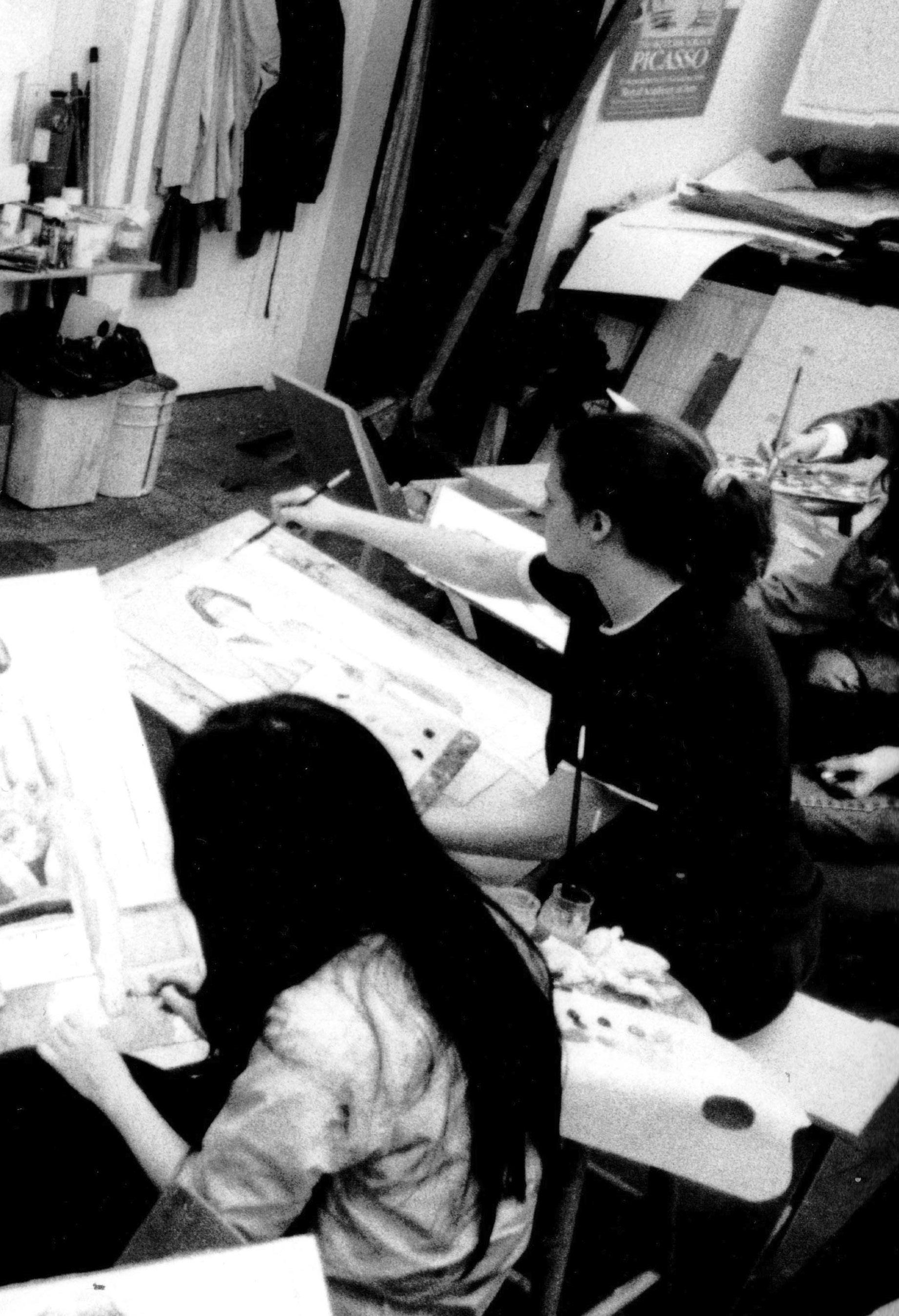

We never had the intention of starting a college – it happened by chance and developed organically. In November 1978, I was contacted out of the blue by a friend I had shared a flat with at university in Oxford. She had fallen in love with an Italian racing driver and had decided to move to Italy and live with him the following week. The problem was, she had to find a tutor for her two private students who she was teaching art and history of art A-level. The following week I began teaching them. They took the A-levels the following June, did very well and both got places at their chosen universities. Consequently, the next academic year we had 20 students wanting to study A-levels with us. The artist Nicholas Cochrane started teaching with me and we divided the lessons, both teaching Art and History of Art – Fine Art Tutors was born!

Nick and I gave lessons from our one-bedroom flat in Hampstead. Each morning we would move all the furniture from the sitting room and pile it up in the kitchen. We then turned the sitting room into teaching space –an art studio with a large table for seated lessons – and taught groups of seven at a time. As numbers increased, we hired rooms at the Central YMCA and the seminar rooms at the National Gallery. The YMCA provided us with photographic and sculpture studios, so we added those subjects to the curriculum. In August 1982, encouraged by contemporaries and former students, we bought a house in Belsize Park. Funded by a mortgage and back loans – the security was generously provided with the deeds of my father’s

house – we opened for 60 students a few weeks later. We lived on the top floor, by then with our two children, and the college was situated on the other two floors. We were determined that Fine Art Tutors, as it was originally called, should be a college that we ourselves would have wanted to attend. That has remained our guiding principle.

When we moved to the house we offered A-levels in the Arts and Humanities in about 15 different subjects, and in 1993 we introduced GCSEs, both as one and two-year full-time courses. Three years ago, following market demand, we added a Year 9 group. We decided these pre-A-level groups should remain small so we could give the students the best quality education in the most nurturing environment. We became part of Dukes in November 2015, which has given us an extra impetus and focus. It is wonderful to be part of a family of colleges which, although so different in the choice of size and subjects, is essentially the same in the desire for excellence. Over the last 40 years little has changed. Our ethos has remained the same: we concentrate on the individual to help students develop confidence and resilience as well as passing exams and getting into first rate universities. I frequently marvel at the fact that despite the passing years and changing fashions, our students have remained essentially the same.

51

Candida Cave teaching in the early days

Candida Cave teaching in the early days

Until my friend Kerry de-camped to Italy, I hadn’t considered teaching as a full-time career, let alone running a college. I had worked in galleries for a few years and taught an evening life-drawing class for adults and a proficiency English course for au pairs, which both proved an excellent way to learn teaching skills. At Fine Arts, I quickly settled in to specialising in teaching history of art, which I continue to do. Now, rather than teaching the A-level, I teach on our adult evening-course programme.

In the 1980s, the education consultancy Gabbitas Thring recommended us to students, as did various London embassies. Our numbers quickly grew through word of mouth, partly because there were no specialist arts colleges, and also because we were young and enthusiastic about education. In those days, creative subjects were considered rather second-rate and were often badly taught. I think by giving these the same status as STEM subjects, as a college we have made our most important contribution to education. We were one of the first colleges to offer Theatre Studies, History of Art, Photography, and Philosophy, subjects that are now taught in many Sixth Forms.

Students come to us from all over London, from both the independent and state sector, and a few students travel daily from Oxford, Cambridge, Brighton and even further afield. Some stay in London Monday to Thursday, travelling from Liverpool, Isle of Wight and Wales. We have always enjoyed having international students, who contribute very positively to the ethos of the college, and they now make up about 10 per cent of our number.

“We have former students teaching here, with others’ children and relatives on our current roll.”

“I’m not giving you written homework this week. Instead, go to the Tate and look at Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, and you’ll see what the play’s about.”

We have former students teaching here, with others’ children and relatives on our current roll. Over the last few years, we have welcomed a trickle of girls joining from my old school, St Augustine’s Priory in Ealing. I love to see them spread their wings and flourish in a more adult environment. After St Augustine’s, I studied fine art at the Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, and have subsequently studied English, History of Art and Philosophy at various levels in different universities. I have always enjoyed learning and try to foster a similar passion in students.

I will never forget how my A-level English teacher inspired me: we were studying T.S. Eliot’s, The Family Reunion and she said, ‘I’m not giving you written homework this week. Instead, go to the Tate and look at Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, and you’ll see what the play’s about.’ That taught me a lot about opening a person’s eyes to self-discovery rather than just learning facts. Every time I go to the Tate, Miss Thickett’s face flashes before my eyes.

56

“The house was built in 1870 as a summer home for the Boddam-Whetham family of Kirklington Hall in Nottinghamshire. The house was called Earlscliffe then and so it remains today.”

58

Earlscliffe in the early days

Tim and Julie Fish, Earlscliffe

We had been running a summer school business for 11 years before we set up Earlscliffe. Tim had been a headteacher in an international school in Sussex, and we wanted to do something in the post-16 international boarding sector that would provide a much more personalised approach, and which would also be a more intensive and fulfilling experience for students and staff alike. Looking back, people would probably call it ‘boutique’, though that’s not the word we used at the time!

Sourcing a suitable site for our new Sixth Form college, we were limited by availability and budget. Eventually we decided upon the current main college building on Shorncliffe Road in Folkestone: the location was good – within walking distance of the high-speed rail link, close to sports centres, the town centre, and the coast, all of which we thought would be attractive to older teenagers, who were the decision-makers more often than not. The house was built in 1870 as a summer home for the Boddam-Whetham family of Kirklington Hall in Nottinghamshire. The house was called Earlscliffe then and so it remains today. Dr Leonore Goldschmidt had founded her eponymous ‘Schule’ for German-Jewish children in Berlin after Jewish children were barred from enrolling in regular education in Germany, and in September 1939 she came to Britain along with 80 students and some of her teachers. It was at Earlscliffe that they found their first home and teaching centre, before moving to Wales later in the war. We love the fact that a spirit of internationalism and crosscultural understanding underpins everything that happens at Earlscliffe.

When we bought the building from the Folkestone Estate it needed total restoration, which took about nine months, given its state of disrepair: the abiding memory is of a downed flock of dead pigeons scattered around disused toilets and storage rooms in the darkest and dankest of basements. In designing the school, we liked the idea of no one bedroom being the same as any other, which fitted with the ethos of a personalised education. We had a nice mix of twin and single rooms, and we were able to retain that feeling of spaciousness and light. Prospective students on a tour enjoyed the fact that the rooms were not dormitory style, but en-suite, and the décor managed to be modern yet warm and welcoming.

We had a high-quality prospectus produced – by Clare Playne, who is also responsible for Dukes’ ‘Insight’ journal – which made a really strong impact on people. Visiting a snow-clad St Petersburg one January and sitting in an education adviser’s office, Tim was taken aback when the potential partner took the brochure, opened the middle pages, pressed them to his face, inhaled deeply and then announced ‘Mmm, good – no chemicals!’ It was a great example of how a product could be accepted as being of high-quality through its representation.

59

The first Sixth Form cohort, summer 2013

The first Sixth Form cohort, summer 2013

We opened with 17 students in September 2012, and by the end of the year we had hit a milestone number of 30. We quickly grew to over 100 students from over 30 nations, and have maintained that, with close to 120 boarders at present. The success was hard-fought in the very early days, but things came together relatively quickly when the college gained a reputation for maintaining a consistent culture of high expectation, open communication, and 1:1 guidance across all areas, notably after-hours academic help and university counselling.

Opening a school is not a small endeavour, but at no point did either of us worry about it too much. We were confident that people would follow us. Tim’s previous school had grown sixfold over a decade and his job as a headteacher evolved, too; he wanted to go back to the parts of the job he really enjoyed, which was the face-to-face interaction with students and having opportunities to make a positive impact on young careers. In a lot of boarding schools international students are seen as cash cows. Our aim was to integrate everyone by creating a wider mix of international students than that are ordinarily found in much larger institutions, and by offering genuine scholarships in non-traditional markets. As a ‘start-up’ school without the centuries of history and tradition offered by so-called ‘heritage schools’, we felt it pretentious to have a Latin motto, and instead opted for a fresh ‘whole school aim’ each year, inevitably rooted in the tenets of ambition, reflection and compassion.

61

“The success was hardfought in the very early days, but things came together relatively quickly when the college gained a reputation for maintaining a consistent culture of high expectation, open communication, and 1:1 guidance across all areas, notably after-hours academic help and university counselling.”

Earlcliffe Valedictory dinner 2014

Earlcliffe Valedictory dinner 2014

Over the last decade, we have learned that you can never rest on your laurels. We joined Dukes in 2017; the Brexit vote had taken place the year before and it seemed like a good moment to gain a bigger partner. Aatif’s family values and work ethic chimed with ours and it has proven to be a great fit. Over the next 10 years, we’re looking to grow again by an additional 50 students. The challenge is in keeping the ‘big family’ atmosphere and environment wherein we still offer personalised pathways for every student alongside organic growth. We believe that by maintaining a strong culture this will be achieved. We have rekindled the link with the Dr Leonore Goldschmidt Schule, which has recently been reestablished in northern Germany, and September 2022 will see the opening of Earlscliffe’s new student residence - Goldschmidt House.

Mohammed, Earlscliffe summer school student, 2011

A trip to the London Dungeons 2014

Mohammed, Earlscliffe summer school student, 2011

A trip to the London Dungeons 2014

64

The early days at Eaton House

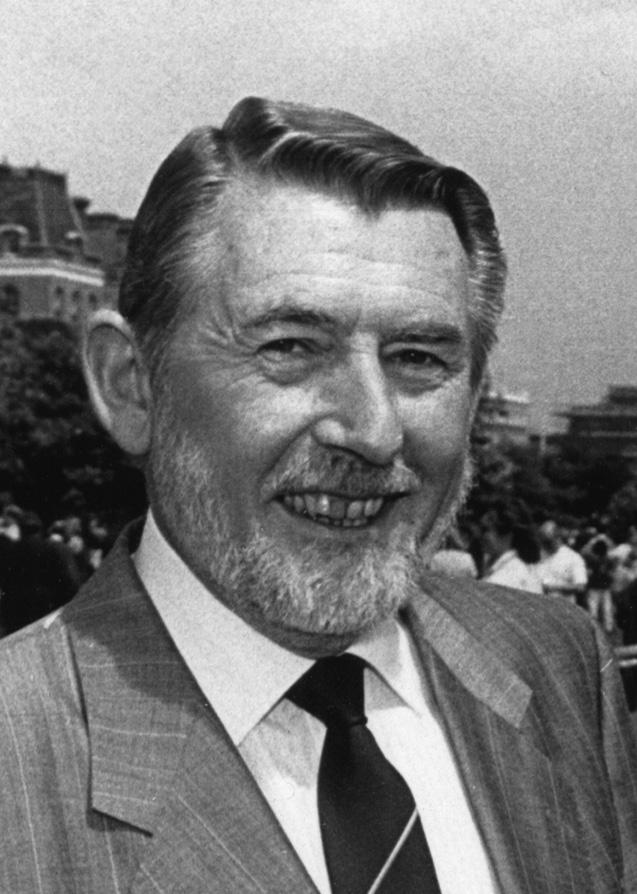

Don Harper, Luchie’s father, who bought Eaton House Belgravia in 1978

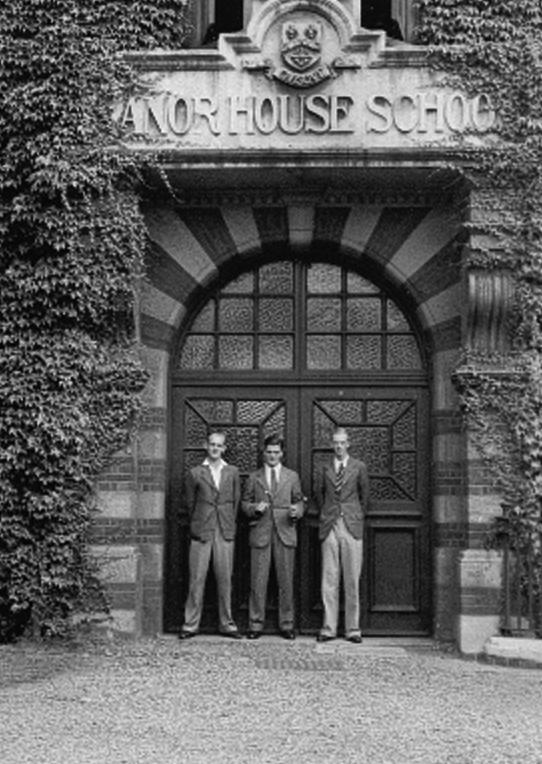

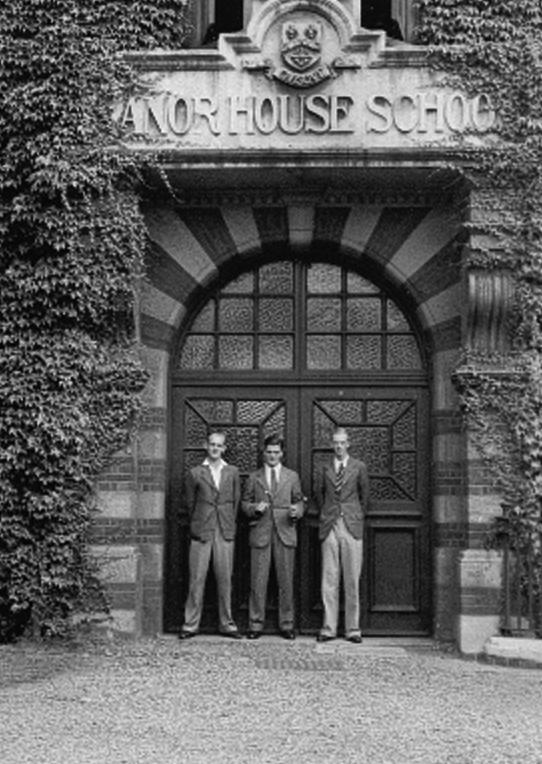

A great shot of Manor House School in the 1950s

Luchie Cawood Head of Eaton House School

The early days at Eaton House

Don Harper, Luchie’s father, who bought Eaton House Belgravia in 1978

A great shot of Manor House School in the 1950s

Luchie Cawood Head of Eaton House School

Luchie Cawood, Eaton House Schools

My parents bought Eaton House Belgravia in 1978. My mum had been a teacher there, but had left to have children, and they had stayed in contact with the owners, the Inghams. When the Inghams decided that they wanted to retire, they said to my parents that if they wanted to buy the school to let them know.

My father was then financial director for Calor Gas, and he thought it was a good idea; my mum having been a teacher there, she loved the school. My sister and I went to Falkner House School for prep school; one of the Belgravia parents had a daughter at Falkner House, and after dropping off their son would take my sister and I to Falkner House. I lived at Eaton House Belgravia from 1978, on and off until 1993 when we bought the site in Clapham, and I went to live there. In 1981 I went to Woldingham School to board, but came home every weekend, so Eaton House was home. When my sister and I were little, we would potter down to the kitchen to see the cook, and be allowed to lick the cake bowl.

As my sister and I got older we became more involved in the life of the school. We helped with accounts, and as I got older I moved on to running the payroll, and was sent around the corner to Barclays on Lowndes Square with the banking, which felt very grown up. When I left Woldingham in 1988, my parents took an extended trip from September to December, and with the headteacher I ran the business myself.

After I left Woldingham, I joined the Royal Air Force as a pilot, but moved to British Airways where I trained as a commercial pilot, flying 737s. My heart just wasn’t in university – I wanted to fly, so I did. In 1993, my parents saw a for-sale sign go up outside Byrom House at 58 Clapham Common Northside. They pulled the car up onto the pavement, and rang the number on the sign. They got the price, and phoned my fiancé and I to say this opportunity had come up – if we wanted to join the family business then we had 48 hours to make a decision. We looked at our life plan, and decided to give it a go. We were both pilots and had worked hard to get to where we were, but joining the family business was a quality of life that couldn’t be matched anywhere else. About three weeks later we owned the business; I was 23.

The market in Clapham was then, and remains, a different market to that of Belgravia. Thomas’s came south of the river at the same time as we did, and by that time the phrase ‘Nappy Valley’ had been coined, so we were moving into something that had already been recognised. People knew the name Eaton House, too, and we had a good reputation. We expected to open with just a reception class, but managed to open Eaton House The Manor with children in nursery, and all pre-prep classes. Sarah Segrave, our prep school Headteacher, was interviewed in June 1993 for a job at the Clapham site as a newly-qualified teacher; she’s been with me for 29 years.

67

“After I left Woldingham, I joined the Royal Air Force as a pilot, but moved to British Airways where I trained as a commercial pilot, flying 737s. My heart just wasn’t in university – I wanted to fly, so I did.”

68

Luchie in her pilot’s uniform with her parents, Hilary and Don Harper

Luchie with her brothers and parents

I did well enough at school, got the grades I needed, and am still close with people I was at school with. But I’m not a natural conformist, or somebody who likes to hear the word ‘no’, and I always want to know ‘why’ – I need a reason behind something, and education doesn’t always work that way. At Eaton House we have a diverse staff who bring with them different skill sets, but to get that in order for a child to learn, you have to light the flame. The child has to want to come into school, and not really want to go home. It has to be exciting – you’re not going to get that every moment of the day, or with every child, but that’s what we should be aiming for.

The schools are run differently from the way my parents ran the school. I wanted the headteacher to be fully available to the parents, and also qualified; I’m not a qualified teacher, and I thought that you needed someone to be able to understand and work with teaching staff, but also hold the parents’ absolute trust, and for that I think you need that qualification. We made the differentiation of having Headteachers in place, and managing from above. At the moment, all of my sons work for Eaton House: one is in HR, two are in marketing, and one is a teacher.

In 2016 we transacted with private equity house Sovereign Capital. I remained in the business, while my mother and my sister sold their shareholding, and Sovereign came in as majority shareholder. They were brilliant to work for, and I had an amazing five years. We knew going in that they were always going to exit, and in the summer of 2021 they reached that point. I decided to exit at the same time, so I am now Principal, but I don’t have a stake in the business. We had known Aatif for a long time before Dukes bought Eaton House, so he was a familiar face. During the process we met with a number of lovely education providers, but it was a case of finding the best fit. Dukes stand by their word not to interfere, and on a day-to-day basis there’s been very little change, so when Dukes bought Eaton House it was business as usual.

Neither of my parents sat me down and showed me how to run a school, but they taught me that it’s about personal integrity, and about making sure that you always maintain that – that’s what parents buy.

69

70

“We had lots of animals at Sancton Wood, including a python called Hephzibah who would sometimes sit around my mother’s neck.”

Children at play at Sancton Wood

Dr Harriet Sturdy, Sancton Wood

My mother, Jill Sturdy, opened Sancton Wood School in Cambridge in 1976. We were a large family: my parents had 12 children, nine of whom were adopted. One of my siblings was adopted before I was born, and she was of British Guyanan descent. She had a really hard time at her local school and experienced significant racial bullying. My mother was motivated to open a school to protect her children, and ensure that they would never again be teased at school for the colour of their skin.

My father John Sturdy was a priest, and Dean of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge. He was a gentle, hardworking theologian, driven by wanting to help people. I remember us going into college for the Sunday services that he’d take, and the undergraduates would see the Rev. Sturdy with his large family of children from many different backgrounds. My father supported my mother in many aspects of running the school, and took on much of the financial management; my mother’s skills were far better used in the day-today education of the children. The fees at Sancton Wood were comparatively modest, with a generous amount of bursaries available for those my mother thought would benefit from attending the school but did not have the financial means to do so. As a result, we had many families who were moving into independent education for the first time and some of those children have, in recent years, sent their own children to the school.

Sancton Wood opened at 9 Station Road, in a building that we rented from Jesus College. Every quarter mum would say, ‘we’ve got to pay Jesus now’. I remember us sitting down trying to think of a name for the school. We spent some interesting hours considering all sorts of names, and in the end my parents chose Sancton Wood after the architect of the railway station. My older sister, Rebecca, drew the unicorn for the logo, and I have clear memories of us going to Jarrolds in Norwich to buy the exercise books for the school, and buying pencils and paper from the local post office on Hills Road.

My mother was quite unconventional. We had lots of animals at Sancton Wood, including a python called Hephzibah who would sometimes sit around my mother’s neck, countless pet rats, guinea pigs, gerbils, the more unusual black Vietnamese pot-bellied pig called Blossom, and Lucifer the donkey. Mum liked exotic animals, and we had two or three Anglo-Nubian goats, several dogs and five cats.

It was not until she was married and had five young children that she went to university, reading English at New Hall in Cambridge (now Murray Edwards). After that, she did her PGCE. Sancton Wood thrived from the day it opened, providing a nurturing loving environment for all the students and staff.

73

My father died in 1996 and I came back to Cambridge to help with Sancton Wood. Our family suffered further great loss the next summer with the death of our youngest sister, Tabitha, from bone cancer a week after her 17th birthday. After Tabitha died, my mother wasn’t sure whether to sell the school and retire, or keep it going. She never got to make the choice, dying a year later, in 1998, of cancer. After she died, the question for the family was whether we should keep the school, and we agreed that as long as it covered its costs we would do our very best to keep it open and to honour our parents’ achievement. I remember one day, shortly after my mother had died, seeing all the children walking along the road to the church for assembly and being struck by the realisation that this was a real community, successful and happy, and a legacy that we should do our best to protect.

We appointed a new headteacher and took on the management of Sancton Wood. It went from strength to strength. We undertook a programme of building work and created two new classrooms, a lovely spacious art room, and in 2001 we opened Baby Unicorns Nursery. The first child to join the nursery was my son, who, prior to its opening, spent time with me or my husband in various classrooms and offices, playing with his trains and absorbing Latin from a very young age. As time passed, and as we felt the school was secure, we looked for ways to ensure it would always have a stable future. As a family,

we loved the school, and had very fond memories of living alongside a school, sharing the building, and for most of my siblings attending as pupils. However, we were not physically based there anymore and having extended our area of focus into other forms of schooling, we looked into the next steps to safeguard the school. We knew it had to go to someone who would love and care for the school and whose priorities lay in providing excellence and happy experiences for the children.

Eventually we met Aatif who we really liked. We felt sure that our parents would have liked and admired him and his attitude towards education. We thought he was a good man, and that was the most important thing – we wanted a decent person who would honour the way our mother had run Sancton Wood. Aatif was clearly committed to loving the school. He promised he would look after it and that he would continue to be generous with children when they needed it.

For Sancton Wood, it’s been the best thing. For us it’s a loss. I miss it hugely, but I know that it’s safe. I can see excellence and happy children – three of my parents’ grandchildren still attend. In losing it for us, we have enabled it to have an exciting future, always acknowledging its past and its origins and knowing that, in line with the school motto, we acted to ‘give grace to do always those things which are right’.

74

Some one-on-one teaching at Sancton Wood

Some one-on-one teaching at Sancton Wood

Daisy Harrison with some of her young charges

Daisy Harrison with some of her young charges

Miss Daisy celebrating with everyone at the Summer Staff Party 2018

Miss Daisy celebrating with everyone at the Summer Staff Party 2018

Daisy Harrison wielding the hammer at Miss Daisy’s Knightsbridge during renovations ahead of its opening in 2014

Daisy Harrison wielding the hammer at Miss Daisy’s Knightsbridge during renovations ahead of its opening in 2014

Daisy Harrison in front of the new Miss Daisy’s Belgravia which opened in 2006

Daisy Harrison in front of the new Miss Daisy’s Belgravia which opened in 2006

In the playground at Orchard House

In the playground at Orchard House

Sally Hobbs, the first Headmistress of Orchard House, presents a young swimmer with a winner’s cup

Letter from Boris Johnson to Sally Hobbs, Oct 2006

Sally Hobbs, the first Headmistress of Orchard House, presents a young swimmer with a winner’s cup

Letter from Boris Johnson to Sally Hobbs, Oct 2006

Young Orchard House pupils

Orchard House Sports Day 1999

The first cohort at Orchard House1993 Teatime with Sally Hobbs

Young Orchard House pupils

Orchard House Sports Day 1999

The first cohort at Orchard House1993 Teatime with Sally Hobbs

Reflections Nursery - the Westerfields House building

Reflections Nursery - the Westerfields House building

The first cohort of pupils at Broomfield House in 1876 The founder, Miss Mead is seated in the centre of the second row

The first cohort of pupils at Broomfield House in 1876 The founder, Miss Mead is seated in the centre of the second row

Original school name plate

Norton York standing in front of the new brass name plate in 1970

Original school name plate

Norton York standing in front of the new brass name plate in 1970

Broomfield fairies

Broomfield footballers

Broomfield boxing

Broomfield fancy dress

Broomfield girls in 1927

Mr Peter Smith, Headmaster of Gunnersbury

Broomfield fairies

Broomfield footballers

Broomfield boxing

Broomfield fancy dress

Broomfield girls in 1927

Mr Peter Smith, Headmaster of Gunnersbury

A class in the summer of 1975 - Irma York is in the centre back row in black Mr Viney’s form in the summer of 1975

A class in the summer of 1975 - Irma York is in the centre back row in black Mr Viney’s form in the summer of 1975

The 1980s - Irma York is seated front and centre in the navy and white dress. Norton is standing at the back.

Fun at the natvity play in 1958

The 1980s - Irma York is seated front and centre in the navy and white dress. Norton is standing at the back.

Fun at the natvity play in 1958

Founder and Principal, Magoo Giles, with Head Shona Colaco

Founder and Principal, Magoo Giles, with Head Shona Colaco

The Poetry Together performers with Magoo Giles and some Chelsea Pensioners

The Poetry Together performers with Magoo Giles and some Chelsea Pensioners

Candida Cave. Founder of Fine Arts College

Candida Cave. Founder of Fine Arts College

Candida Cave teaching in the early days

Candida Cave teaching in the early days

The first Sixth Form cohort, summer 2013

The first Sixth Form cohort, summer 2013

Earlcliffe Valedictory dinner 2014

Earlcliffe Valedictory dinner 2014

Mohammed, Earlscliffe summer school student, 2011

A trip to the London Dungeons 2014

Mohammed, Earlscliffe summer school student, 2011

A trip to the London Dungeons 2014

The early days at Eaton House

Don Harper, Luchie’s father, who bought Eaton House Belgravia in 1978

A great shot of Manor House School in the 1950s

Luchie Cawood Head of Eaton House School

The early days at Eaton House

Don Harper, Luchie’s father, who bought Eaton House Belgravia in 1978

A great shot of Manor House School in the 1950s

Luchie Cawood Head of Eaton House School

Some one-on-one teaching at Sancton Wood

Some one-on-one teaching at Sancton Wood