Ortaköy Mosque, formally the Büyük Mecidiye Camii (lit. ‘Great Mosque of Sultan Abdulmejid’) in Beşiktaş, Istanbul, Turkey, is a masjid situated at the water side of the Ortaköy pier square. It was commissioned by the Ot toman sultan Abdülmecid I and its construction was completed around 1854 or 1856.

CAS (controlled atmosphere stunning) is the controversial method of gas-stunning, which is widely used in the billion dollar meat industry today, before the animal is slaughtered. For us, the most important question is whether this method will make the animal haram even if it is slaughtered according to Islamic law. The article on CAS is the fatwa issued by the eminent panel of scholars at Darul Uloom Chatham, summing up months of research on the gas-stunning process, study of the jurisprudential texts, and after numerous sittings on the topic.

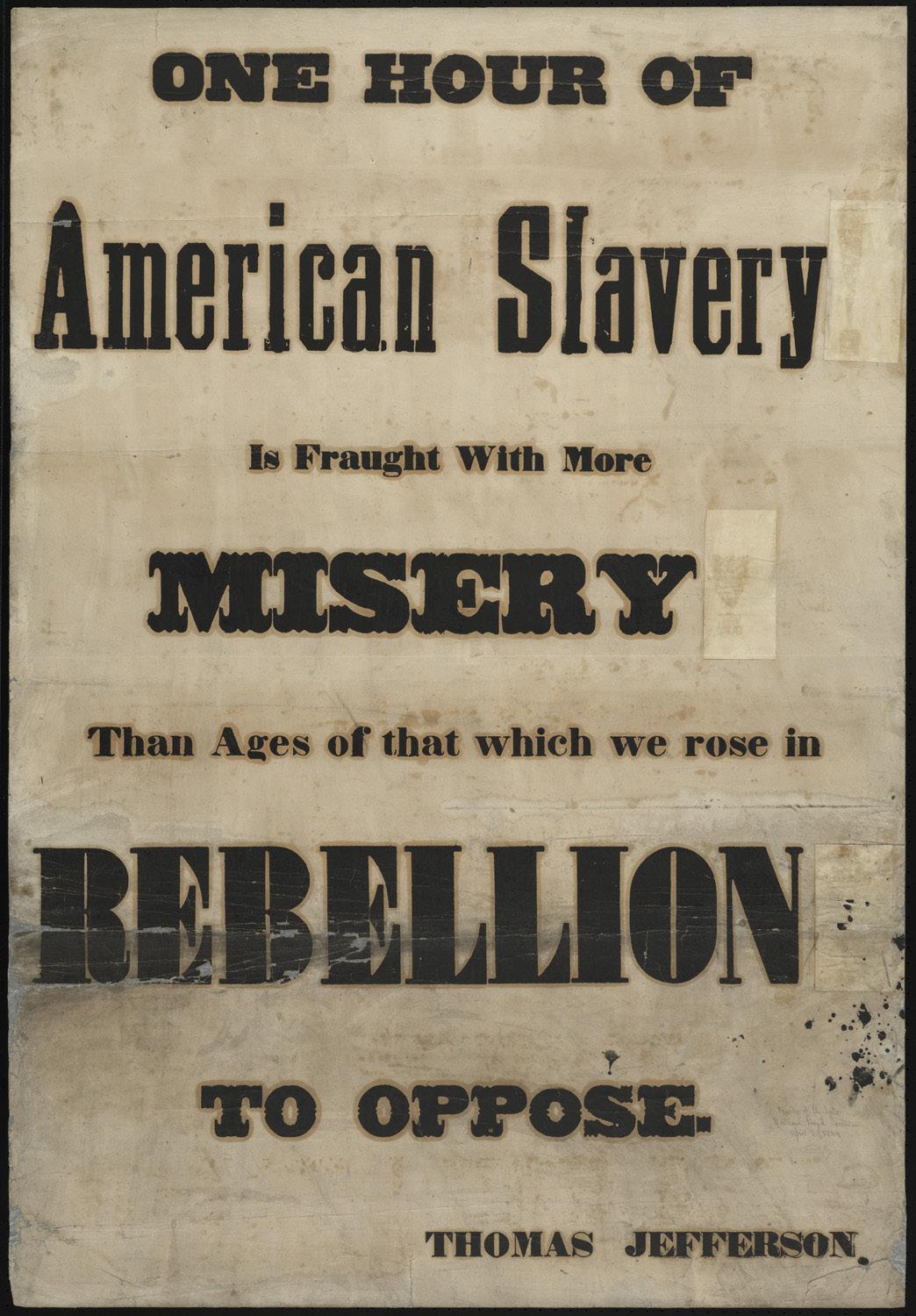

In Forgotten Voices, the author tells the story of the first Muslims who introduced Islam to America during the antebellum era. The most prominent of them was the slave Bilali Muhammad who upheld his faith living, dressing and worshipping like a Muslim in a land that was stranger to everything Islam.

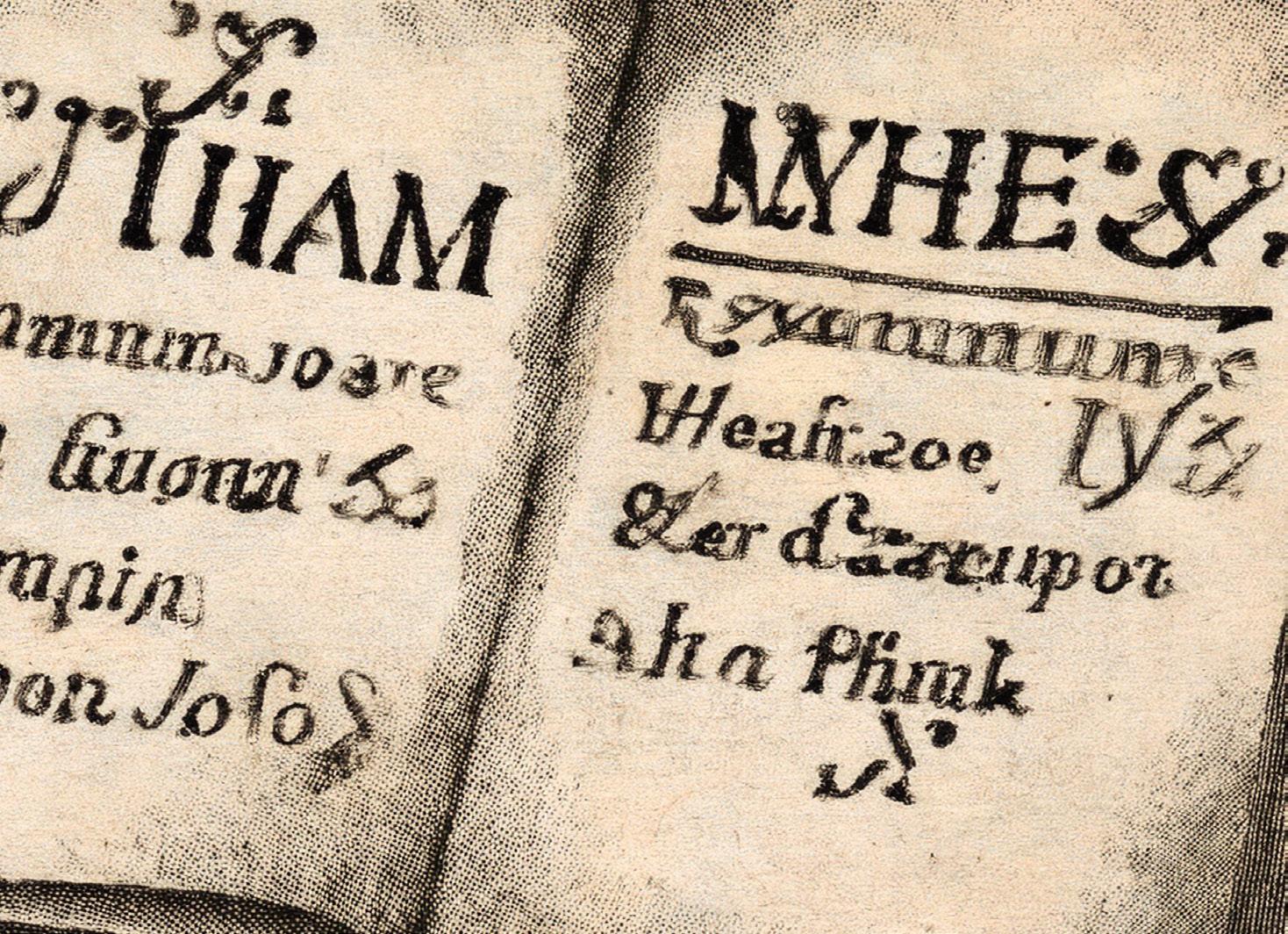

Bilali Muhammad wrote a religious document, which until recently was assumed to be his own work, but was later discovered to be the text ‘The Treatise of Ibn Abi Zayd Al Qayrawani’ which he recalled from memory. This document known as the Bilali Document is now showcased in the museum at Georgia University.

Patron

Hazrat Dr. Ismail Memon

Fatawa

Mufti Husain Ahmad Badri

Contributors

Mufti Omar Baig

Maulana Dr. Mateen Khan

Dr. Kamran Karatela

M. Zubair Ahmad

M. Ahmad Amin

Ishtiyaq Ahmad

Shakib Hassan

Sharakh Hussain

Editor

Asim Ahmad

Attribution

Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0 <https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

“African slave ship diagram” by Jbolden030170 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

“NO VOMITING!” by weirdpercent is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

E-mail office@ducanada.org Website www.ducanada.org

Address

51 Prince St. N, Chatham, ON N7M 4J7, Canada

The views expressed in the columns of Insight magazine do not necessarily represent those of Darul Uloom Canada.

The articles published in this magazine may be reproduced with due acknowledgment.

by Khadija Kamran Karatela

In the rich tapestry of American history, the stories of enslaved individuals often remain obscured. One such remarkable figure is Bilali Muhammad, a Muslim African slave whose life and legacy provide a profound insight on the complexities of identity, religion, culture, and resilience during the early 19th century.

Bilali Muhammad was born around 1770 in modern-day Guinea and Sierra Leone, Africa. As a member of the Fulani ethnic group, Bilali was raised in a society deeply rooted in Islamic education and religious practices. He was well-educated, fluent in the Arabic language, and well-versed in Islamic theology and concepts regarding the teachings of Islamic Law. Bilali has come to be known as the first Muslim-American scholar.

Although it is unclear when Bilali was initially taken from Africa, it is known that he was first enslaved in the Caribbean. In the early 18th century, he was enslaved by oppressors from Europe and sold to various slave masters until he was purchased by Thomas Spalding in Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Despite the brutal conditions of slavery and the torment he faced, Bilali retained his cultural identity and faith, which became his major sources of strength and resilience.

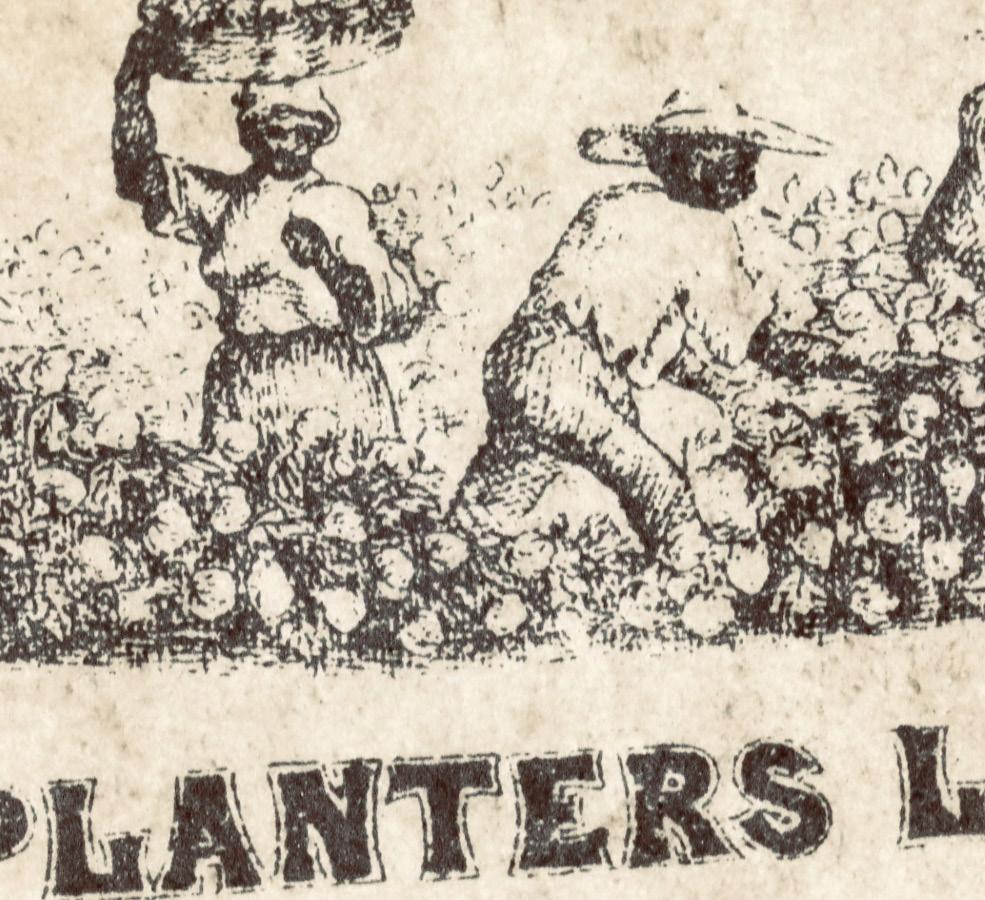

Bilali was enslaved on a rice plantation owned by Thomas Spalding. There they focused on the cultivation of Sea Island cotton, sugar cane, and other secondary crops, as well as lumbering. He quickly distinguished himself not only for his work ethic, but also for his intellectual prowess. Spalding recognized Bilali’s skills and appointed him as an overseer, allowing him to manage the labor of other enslaved individuals. This position, although still

within the confines of slavery, granted Bilali a degree of authority and responsibility.

Much has been made of Muhammad’s role during the War of 1812. Spalding gave Muhammad eighty or so muskets to use with other enslaved persons to defend Sapelo Island against a potential British landing. That Muhammad was so entrusted by Spalding has suggested to some that the two had a close relationship.

Muhammad and Spalding did not, however, have a comparable power dynamic. Spalding was known to be “quick-tempered” and Muhammad must have had to walk a fine line

with him. Without doubt, Muhammad had a strong spine and spirit.

As historian Melissa L. Cooper has put it, “the fact that Muhammad…did not surrender his religion is in and of itself an act of resistance.”

Throughout his time on the planta-

care to implement the teachings of his faith in every aspect of their lives. His efforts to maintain his religious and cultural identity in a foreign land are a testament to his resilience and determination.

A Writer and a Scholar

tion, Bilali’s adherence to Islam remained unwavering. He continued to practice his faith, remaining consistent in his daily prayers and teaching others about Islamic principles, which fostered a sense of community among the enslaved Muslims in the area. Bilali was an imām of the other enslaved African Muslims, leading them in prayer regularly and taking

Bilali’s most significant contribution to history came in the form of his writings. When Bilali passed away in around 1857, it was discovered that he had handwritten a thirteen page Arabic manuscript. This document became known as the “Bilali Document,” composed of prayers, supplications, and religious teachings. For over one hundred years this manuscript was thought to have been his diary, but upon closer examination it was revealed that the manuscript was in fact the famous text The Treatise of Ibn Abi Zayd Al Qayrawani which Bilali Muhammad had written

from memory.

The author, Ibn Abi Zayd r was a well-known Tunisian scholar and a Berber, who passed away around 996 C.E.

The first work of Islamic scholarship in this country, now home to roughly 3.45 million Muslims, was the fruit of an African man’s efforts to uphold his religion. Living during a time of institutionalized racism and facing degradation for his skin color, and then being forcibly shipped to a new land, Bilali Muhammad left his legacy of scholarship for generations upon generations to come. This document stands as a symbol of hope and resilience, illustrating how even in the face of oppression, people can hold onto their religious beliefs and cultural heritage.

His Legacy

Austin summarized Mohammed’s habits and customs: “He regularly wore a fez…he prayed facing the East on his carefully preserved prayer rug, and he always observed Muslim fasts and feast-day celebrations.” Austin added that Muhammad was buried “with his rug and Qur’an.”

Bilali Muhammad’s life story is emblematic of the broader experience of enslaved Africans in America. His contributions to the preservation of Islamic culture and education have left an indelible mark on the history of African American Islam. Today, scholars and historians continue to study his personal writings, recognizing their importance in understanding the diverse narratives within the African American experience.

Remembrances of Muhammad indicate that on Sapelo Island he lived publicly as a Muslim in the face of a predominant Christian culture. Historian Allan D.

Bilali’s legacy serves as a reminder of the strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity. His story resonates not only within the context of American history, but also within the broader conversation about faith, identity, and religious resilience. He stands as a testament to the strength of identity and faith in the

face of unimaginable hardship. His story, though marked by the darkness of slavery, is ultimately one of resilience and determination—an enduring legacy that continues to inspire future generations.

From Bilali Muhammad’s story, we learn of a man who never hid his faith, though he risked death with each public gesture of adherence to Islam. He serves as an inspiration to all those struggling today to practice their faith without fear, and of course, with true gratefulness. While we live in a time that requires us to be cautious and on guard, we must recognize the vastly more difficult struggles those before us endured. Even having to live in such difficult environments, our Muslim forefathers in this country like Bilali Muhammad managed to plant a seed of Islam in American soil. Our re-

ligion’s history began as early as anyone else in this country. The more we learn about its roots, the more we can educate others, be thankful for our circumstances and the sacrifices of those before us and practice our faith in its entirety.

As we reflect on Bilali Muhammad’s life, we are reminded of the importance of recognizing and honoring the diverse voices that have shaped our shared history. His journey from Senegal to Georgia is not just a tale of suffering but also one of endurance and hope, inviting us to appreciate the rich cultural mosaic that defines America today. n

The first work of Islamic scholarship in this country, now home to roughly 3.45 million Muslims, was the fruit of an African man’s efforts to uphold his religion. Living during a time of institutionalized racism and facing degradation for his skin color, and then being forcibly shipped to a new land, Bilali Muhammad left his legacy of scholarship for generations upon generations to come.

Sanad. You may have heard this word in relation to hadith. It derives from al-sanad, which means any tract of land that rises up to a valley or mountain. The verb form is in the meaning of to ascend; to lean, rest on.

to attribute something to its source.

leaned, rested, or stayed against something.

In Arabic grammar, a predicate or attribute of a subject

In Arabic grammar, the subject of a sentence.

The people ascended the mountain. I saw the women ascend (yusnidna) the mountain (hadith).

He set up something [wood, prop] against a wall. He wore a berd (shawl) of the kind called sanad.

Anvil of the blacksmith

Something that is strong or great [like a man or animal].

to help one another, as if leaning on each other for help.

a thing upon which one leans; rests [as in a couch, cushion, back of a chair].

Something that is supported, propped up; hadith with uninterrupted chain to the Prophet s

Someone is murdered. The murderer is charged with a life sentence. The news channels and social media outlets are buzzing about the story, candlelight vigils are being held and the murderer is being damned at every moment.

Why?

What exactly did he do wrong? Is murder wrong? If so, then where is the hard evidence for that? It is easy to claim something is immoral because it “feels” wrong, however it is also necessary to prove it is immoral. All these questions are answered by referring back to Islamic morals.

Morality is of two types, objective and subjective. Objective morality rests on a foundation. A basis that is outside the scope of human emotion and thoughts. This makes objective morality simple and straightforward, since individual opinions don’t affect them whatsoever. The basis of said morality can be any doctrine or belief system, ours being Islam. On the other hand, subjective morality

by Azeem Abdul

belief system, ours being Islam. On the other hand, subjective morality is completely based on human emotions and thoughts. This morality would differ from person to person. For example, the LGBTQ movement. Some would say that it’s a shining example of freedom of speech and expression.

Be comfortable identifying yourself according to your feelings, no matter how outrageous it may be. Others would call it an egregious abomination and perversion of the laws of nature. A radical form of acting upon your desires. Based on each individual paradigm, the ideology can be judged as moral or immoral.

It should come as no shock that as Muslims, we follow the objective morality derived from Islam. These morals stem from the belief in an existing God. This does not mean that an atheist cannot display virtuous behavior, nor does it mean that by believing in a God, one becomes intrinsically virtuous. Rather, that

the objective nature of these morals requires a basis which needs to be divine and beyond human comprehension. Notwithstanding the atheist behaving virtuously, his argument for the source of his morality would go back to human reason, which is undeniably subject to change overtime.

Having the existence of God Himself as a basis is foolproof since God transcends human bounds. If that was not the case, then these morals would turn into mere societal norms or social conventions. I am not attempting to dismiss the value of societal norms, rather that they are subject to change. Not that they mean nothing, but they mean just as much as the fact that we know not to pass gas in an elevator or not to stare at others. Morals are based on the whim of every individual with no set standard, unlike that of the word of an all-knowing, perfect God. We as Muslims believe that God is all good, therefore what He commands can only be good. Allah says in the Qur’an, “Forbids immorality and bad conduct [16:90], that god forbids from indecency and evil. Thus concluding that the morals coming from such a source can be nothing but virtuous.

It’s worth mentioning the Euthyphro (Plato’s) Dilemma at this stage. The Euthyphro Dilemma is the dilemma that ‘is something good because God commands it, or does God command it because it’s good?’ Atheists use this to try to undermine God’s command, but it raises two complications. The first being that morality is defined by God’s commands. In this case, every label of a “bad” deed is arbitrary. Killing an innocent man isn’t objectively evil, rather it is evil because of an arbitrary label. If we, as theists, accept this at face value then the atheist has an argument against our claim of objective morality. The second complication is that there would be some kind of morality outside of the command of God, which He Himself must adhere to. This premise destroys our concept of an Almighty God. The dilemma relates to the objective morality argument because it seemingly forces the theist to choose one of these two detrimental stances. However, this dilemma is based on a false dichotomy. The moral standard is never outside the essence of God, but in fact, derived essentially from the absolute good and perfection of God. These commands and rulings are not arbitrary whatsoever, rather they follow the necessary moral standard that is within the essence of God, not an external standard that God himself adheres to. This rids us of both complications. Ibn Al-Qayyim defends the

The moral standard is never outside the essence of God, but in fact, derived essentially from the absolute perfection of God.

rationality of God’s command and morals in his Ranks Of The Divine Seekers where he says: “If [an act’s] being good or evil or insalubrious or wholesome were only related to command and prohibition and permission and forbiddance, it would be tantamount to saying: He commands what He commands and prohibits what He prohibits; He permits what He permits and forbids what He forbids. And what benefit is there in that? And how does this substantiate the prophethood of the Prophet s? God’s speech is innocent of such a thing and ought not to be thought of in that way. For praise, acclaim, and the sign that prove his prophethood consist in the fact that what he commands, sound intellect testifies to its being good; and what he prohibits, [sound intellect] testifies to its undesirability and evil. What he permits, [reason] testifies to its being wholesome; and what he forbids, [reason] testifies to its being unwholesome. This is the invitation of the messengers, God’s peace and blessings be upon them, in contrast to the invitation of falsifiers, liars, and sorcerers.”

These morals come not only in the form of The Holy Quran, the speech of Allah himself, and the hadith, the speech and actions of The Final Messenger s it also has a considerable amount to do with pure human nature or what Islam refers to as fitra. The Prophet is recorded to have said in a narration, “Every newborn is born on the fitra (nature)” (Muslim). Fitrah, in short, is the pure, unadulterated,

innate disposition. It is what leads us to immediately believe in one God and a complete understanding of right and wrong. This fitrah further strengthens the objectivity of Islamic morals, aligning with them in many ways, highlighting the objective truth behind God’s divine commands. Allah

Qur’an, “And by the soul and He who has fashioned it. And inspired it [with discernment of] its wickedness and its righteousness [91:7-8]. These verses clearly show that Allah Himself placed this natural disposition of right and wrong in us.

In conclusion, Islamic morals are objective, rooted in the existence of God, and thus unchanging and sound. Unlike the subjective, wishy-washy morals of those adhering to no legitimate doctrine, declaring what is right today to be wrong tomorrow. The Islamic objective moral system being derived from the commands of an All-Powerful AllGood God coupled with the natural disposition that discerns good from bad creates a moral system that is universal and inherently good, flowing from the unchanging essence of a perfect God.

Darul Uloom Canada Academy of Sacred Knowledge

In January 2024, a team from the Halal Monitoring Authority (HMA) visited Darul Uloom to present their research on Controlled Atmosphere Stunning (CAS). Following this presentation, HMA invited representatives from Darul Uloom to visit their facility in May 2024 to observe the slaughter process involving stunned chickens. After thoroughly reviewing the relevant data and studying the works of Ḥanafī jurists, the Dārul Iftā was inclined towards the view that the controls implemented by HMA were sufficient to ensure the animals were alive at the time of slaughter, thereby meeting halal standards. While the stunning method was not ideal, the requirements for halal slaughter appeared to be fulfilled.

On August 7, 2024, the Darul Ifta issued an opinion paper outlining its findings and shared it with the Ulama. After a month of consultation with various scholars, we revisited a number of concerns. Although we believe HMA’s controls meet the requirements for halal certification, we are of the view that not everything halal should necessarily be certified. This is particularly important given the diversity of legal opinions across the mazhabs, with many potentially not considering gas-stunned chickens as halal.

Furthermore, although HMA’s testing confirms that the birds are slaughtered while still alive, their proximity to death raises potential confusion within the Muslim community. This is especially true if other certifiers begin approving CAS without the same level of scrutiny or clarity as HMA. Should any adjustments to CAS settings be made in the future, the entire testing process would need to be repeated, further complicating matters.

In conclusion, we reaffirm our stance that HMA-certified CAS chicken is halal according to the Ḥanafī mazhab. However, we strongly recommend that HMA exercise caution in what it chooses to certify and consider the future implications of certifying such chickens even if they meet minimum halal standards.

And Allāh knows best.

Written by: Mawlana Omar Baig

For any stunning method to be compliant with Sharī’ah, it must ensure that the animal remains alive at the time of slaughter. Evaluating whether the Controlled Atmosphere Stunning (CAS) method used by the facility results in the death of the animal involves addressing three critical issues:

1. If an animal is on the verge of death due to the stun (i.e., the stun is irreversible), can it still be slaughtered and deemed halal?

2. What constitutes life/death according to the jurists?

3. Does there need to be absolute certainty (yaqīn) of the bird being alive after CAS, or is ghalaba ann (having reasonable assurance) sufficient?

These questions are fundamental in determining the Sharī’ah compliance of the stunning process.

Does an Irreversible Stun Render an Animal arām?

Controlled Atmosphere Stunning (CAS) is an irreversible form of stunning, meaning that the stunned animal will inevitably die if not slaughtered promptly. This raises the question: Can an animal on the verge of death due to CAS still be slaughtered and considered halal? It should be noted that this discussion is separate from whether such a stunning method is ideal or not. One can say that the method is not ideal or even severely disliked, but the subsequent slaughter would still be considered halal to consume.

According to the preferred position within the anafī school of thought, an animal on the verge of death remains halal as long as it is

slaughtered before actual death occurs. If one has ghalaba ann (reasonable assurance) that the animal was alive before slaughter, there is no need to look for signs of life. However, if it was doubtful, the animal can still be considered halal provided there are signs of life present in the animal (even if they are minute).

The scientific definition of death has evolved significantly over time, influenced by advancements in medical science and shifting perspectives. Originally, death was defined by the absence of a heartbeat. This cardiorespiratory definition persisted for most of history. The neuro-centric definition, which focuses on the irreversible loss of brain function, gained prominence in the mid-20th century with advancements in neuroscience.

By the 1950s, Europe began applying this neurocentric diagnosis, refining the procedure over subsequent decades. Today, the United States and Canada define death as the irreversible loss of function of the entire brain, including the brainstem. In contrast, the United Kingdom and some European countries define it as the irreversible loss of brainstem function alone. Despite these advancements, no universal criteria exist, and confirmation tests for brain death vary globally.

According to the neuro-centric definition of death, CAS-stunned poultry is “dead” after brain activity ceases, even if the heart is still beating. Conversely, according to the cardiorespiratory definition of death, poultry would still be considered alive even if brain activity has

ceased, provided the heart is still beating. This discrepancy in definitions may explain why some scientists and medical professionals consider an animal that has been stunned by CAS to be dead while others do not. The various settings of CAS may also play a role in this discrepancy.

Within the framework of Islamic scholarship and considering the texts of the anafī mazhab, it proves challenging to assert that the understanding of death among jurists aligned with the concept of brain death. This assertion is particularly complicated due to the historical context, where neurology, as a scientific discipline, was either non-existent or at its nascent stages over 1400 years ago. The anafī jurists have not explicitly defined death by the cessation of the heartbeat either; instead, they have only mentioned visible signs of life and death. Visible signs of life mentioned by the anafī jurists include the pulsation of blood at the time of slaughter , breathing, minimal controlled movement, etc. The presence of any of these signs is sufficient to consider the animal alive. Therefore, an animal may scientifically be regarded as dead but still considered alive, according to Sharī’ah.

During a visit to the facility in May 2024 and through subsequent evidence provided by HMA, the Darul Iftaa observed blood pulsation after slaughter. From a Sharī’ah perspective, this indicator alone is sufficient to consider the animal alive. Additionally, the Halal Monitoring Authority (HMA) recorded the consistent presence of a heartbeat within the stunned poultry. Although the jurists did not explicitly mention the heartbeat as a primary sign of life, it may be considered a secondary indicator that further solidifies the animal’s status as alive at the time of slaughter. Other criteria used by HMA, such as temperature and flaccidity, also support the determination of life, although they are less robust indicators.

anafī jurists outline two scenarios for determining the halal status of an animal at the time of slaughter. The first scenario involves there already being a reasonable amount of surety that the animal was alive at the time of slaughter. In this case, the animal is considered halal even if no indicators of life are observed. The second scenario arises when a person is entirely unsure about the animal’s life status. In such situations, observable indicators of life are required for the animal to be deemed halal. These indicators do not provide absolute certainty of life but allow for a ghalaba ann (reasonable assurance) that the animal was alive at the time of slaughter. This level of reasonable assurance is sufficient to consider the animal halal .

Based on the factors outlined above, we believe that HMA’s protocols and controls for CAS provide sufficient ghalaba zann (reasonable assurance) that the animal remains alive after stunning and is properly slaughtered before death. Therefore, the consumption of such poultry would be considered halal according to the Hanafī school of thought. However, despite meeting the minimum halal criteria under this fatwā, the differing opinions in other schools of thought and the potential confusion that may arise—especially if other certifiers approve CAS chicken with less rigorous scrutiny—suggest that certification

“A time will come upon you when men will suffice with men and women with women.” Kanz al-’Ummal 14/241

Q: Does vomiting break the fast?

A : Vomiting does not break the fast unless it is one of the two following scenarios:

1) A full mouth of uninduced vomit is intentionally swallowed

2) Any full mouth of induced vomit occurs, regardless of swallowing.

In principle, it is permissible to use alcohol- based perfumes as long as the alcohol is not derived from grape or date.

Q: Is it permissible to use alcohol-based perfumes?

A: In principle, it is permissible to use alcohol-based perfumes as long as the alcohol is not derived from grape or date.

However, in the unusual case where the alcohol is derived from these sources, it would not be permitted.

Q: Can a missed salah be prayed at any time?

A: A missed salah can be prayed at any time, except during the three prohibited times: (1) sunrise, (2) zawal (midday), and (3) sunset. Outside these times, one should hasten to make up missed prayers.

Q: Is it okay to give zakah to people who aren’t Muslim? And do the same rules apply to sadaqah in terms of its recipients?

A: Zakah is only for eligible Muslims, while voluntary sadaqah can be given to anyone in need, including non-Muslims.

However, obligatory sadaqah has the same restrictions as zakah and can be given exclusively to eligible Muslims.

Q: I was doing sajda with the imam, the imam was taking long so I had thought that he had already gotten up and forgot to say Allahu Akbar out loud. I came into the standing position and saw everyone was still in sajda. Will my salah count if I go back down since it as if I have performed an extra sajda?

A: In principle, when one prays in a congregation, they follow the imam. Therefore, once a person has realized that they have gotten up before the imam, they will go back into sajdah, and it would not be considered an extra sajda.

Q:

If I remove my khuffain while in a state of wudhu, will my wudhu remain valid? If it does, how long can I continue performing masah if I put my khuffain back on? Do I need to perform a new wudhu before putting the khuffain back on? Also, does the 24-hour period for masah reset or continue from where it left off?

Akhuffain while in a state of wud hu. However, to put your khuf fain back on, you must wash your feet first.

The 24-hour period for perform ing masah begins when you first break your wudhu after putting on the khuffain. If a person is to remove their khuffain and wash their feet, the 24-hour period will reset from the time they subsequently break their wudu (after washing their feet and put ting on their khuffain again).

For example: you perform wudhu at Fajr on Tuesday morn ing and put on your khuffain.

Your wudhu breaks at 10 AM on Tuesday, and you renew your wudhu, performing masah over the khuffain. The 24-hour period from masah would start from this time.

DespiteAllah’s vast mercy, there is no one more frail and wretched than Shaytan. He is the dog who remains outside the door like the bloodthirsty guard dogs that stand guard outside the gates of huge villas and mansions. When someone wishes to enter, the dogs bark hysterically. But if the visitor calls upon the owner, the owner quiets the dogs and says, “Shush, he is my man!”

The dogs [calm down and] wag their tails in submission. Likewise, Allah has put Shaytan outside the door of His majestic court. Whoever wishes to enter the divine court, Shaytan barks and puts waswasa in his heart. If you respond to the waswasa, he only barks more. The divine rule is: Call upon us because he is Our dog and will listen to Our order only. Say, “I seek refuge in Allah from the accursed Satan,” i.e. I seek refuge in the Owner of this dog. The following hadith makes this same point: La Haula wa la quwwata Illa billah. The servant wields no power nor does he have the capability to engage Shaytan. He must call upon the Owner and ask Him to bring the accursed one under control.

In summary, the servant has no power to subdue Shaytan. He is commanded, “Turn to your Lord and seek His help against the accursed one.”

And we have enjoined upon man, to his parents, good treatment. His mother carried him with hardship and gave birth to him with hardship, and his gestation and weaning [period] is thirty months [46:15]. While enjoining man to be

good to his parents, this ayah mentions a distinct right of the mother. This right of the mother is stated separately because she carried him in her womb with hardship and then delivered him with hardship and then weaned him for a period of roughly 30 months. It is understood from this ayah that the right of the mother is greater than the right of the father as is mentioned in a hadith of Bukhari that a sahabi asked, “Who should I serve more?”

The Prophet s replied, “The mother.”

“Then whom?”

“The mother.”

The sahabi then asked for the third time, “Then whom?”

The Prophet s replied, “The mother.”

On the fourth time the Prophet s said, “The father.”

Hafiz ibn Hajar says that this hadith is the commentary of the ayah, “And we have enjoined upon man, to his parents, good treatment. His mother carried him with hardship… And Muhasibi has declared a consensus that the mother precedes the father in right and virtue.

Whatif a wife had numerous husbands at different periods [of her life]? Which will she join in Jannah?

Will it be the last of her husbands or the first? So the answer is that she will choose whichever she found the most loving toward her to be her eternal husband in Jannah (Ruh al-Ma’ani).

What about the Muslim wife of a disbelieving husband?

When the Muslim wife of a disbelieving husband enters

Jannah, Allah will marry her to whom He wishes.

Thekamil (consummate) believer is the one from whose hands and tongue other Muslims are safe. Someone asked Maulana Shah Abrar al-Haqq that the hadith, “The believer is one from whom whose hands and tongue other Muslims are safe,” does not make any mention of disbelievers. Does that mean that it’s okay to harm the disbeliever?

He replied, “Since believers deal with each other more frequently, they are told to be cautious in their internal affairs. If they are cautious with those they deal with most frequently, they will be even more cautious in their interactions with the non-believing communities whom they deal with less.

Abu Ya’la narrates that the Prophet s said that Allah will say to the angel scribes [the recorder of good and bad deeds], “Write this-and-that much reward for my servant.” They will say “O Lord, but we never noted him doing any such thing.” He will reply, “He made the intention.”

Mulla Ali Qari writes that once a sahabi from the Bani Israel once passed by a sand dune during a drought. He said to himself in his heart that I wish that this dune was wheat that I could distribute it among the poor.

Allah sent a revelation upon the prophet of the time to tell the sahabi, “Allah has accepted this intention of yours and your good deed, and you have received the reward according to the amount of wheat equal to the sand dune given in charity.

Seerah: Chapter nine

by Maulana Dr. Mateen Khan

The creation of mankind was an act of unadulterated love, an expression of divine generosity that knows no bounds. Since Allah is absolutely independent (al-Ghanī), this act was free from any possibility of remuneration, a gift given purely out of His infinite mercy. He perfected the gift of existence with guidance (hidāya), making it the key to His pleasure and Jannah. Yet, guidance is not imposed but offered, for it becomes meaningful only through acceptance. This ability to choose, to embrace or reject, sets humans apart from the beasts and inanimate elements of the universe. It is this agency, this trust bestowed upon humanity, that elevates them to a position of divine favor or disobedience. Our beloved Prophet s was entrusted with the noble task of presenting this guidance to humanity and laying before them the consequential choice. Thus, every human being came into existence with an invitation to Allah’s pleasure and Jannah, each step of the way unfolding as an act of love—each greater than the last.

Yet, most of the Makkans chose to reject Allah’s Messenger s and His message. Instead of mere indifference, they opted for obstinate oppression. They mocked, ridiculed, and actively worked to silence the Prophet s. Similarly, the people of Ṭā’if, unlike the steadfast hills flanking their city, degraded themselves through their vehement opposition. The people’s arrogance and refusal to listen contrasted sharply with the Prophet’s unyielding compassion. Following the Ascension (al-miʻrāj), the Prophet s renewed and expanded his call. With a heart brimming with hope and love for humanity, he ventured into the tents of visiting tribes during the days of Hajj, presenting the metaphysical truths of existence, a divine moral code, and the path to eternal bliss. Yet, like a pestilent bug feeding upon the seed before its germination, Abū Lahab and others shadowed him, attempting to thwart the message. His efforts were relentless—a whisper of discord at every turn. While one voice called to taqlīd of the prior prophets, the other clung to the ill-fated ways of forefathers. Despite widespread rejection, the seeds of faith found soil in a few hearts, nurtured by the warm light of divine truth.

Sayyidunā Abū Dharr was one such soul of fertile disposition. A man of simplicity and honesty, he stood in stark contrast to his clan, the Ghifārīs, known for polytheism and looting. The moral uprightness of Abū Dharr, despite the prevailing corruption around him, speaks to the purity of his heart and his natural inclination toward truth. Upon hearing

of the Prophet’s s moving message, he journeyed from the outskirts of Yathrib to Makkah. The journey itself was an act of faith, a testament to his yearning for clarity and guidance. Amid a town rife with disbelief, he encountered Sayyidunā ‘Alī, who embraced the truth wholeheartedly. Sayyidunā Abū Dharr met the Prophet s in secret, bore witness to his prophethood, and boldly declared his faith at the Kaʼbah. Such courage and conviction, even in the face of violent opposition, underscored his unwavering belief. Enduring the brutal blows of the disbelievers, he returned to his clan, carrying with him the light of guidance. Among the Ghifārīs, Īmān grew until they collectively migrated to Madīnah. Sayyidunā ‘Alī would later testify to Abū Dharr’s courage, saying, “Today, there is no one left who does not fear the criticism of the criticizer for the sake of Allah except Abū Dharr, not even myself.” Such a statement from Sayyidunā ‘Alī himself speaks volumes of Abū Dharr’s fortitude and loyalty to the prophetic way.

Generations before, a group of Jews had settled in Yathrib, recognizing signs of the awaited prophet’s arrival. They had awaited his coming with a hope born of sacred texts, their hearts heavy with anticipation. Misinterpreting the signs, they believed he would emerge from their own lineage. Their hearts, however, became ensnared by jealousy and arrogance, a toxic combination that would later blind many of them to the truth. Taunting the town’s Arabs, they boasted of the day their promised prophet would lead them to dominance. Ironically, their words planted seeds of prophethood in the hearts of the Arabs, who would ultimately precede them in accepting the Prophet s. During Hajj, a group of Yathrib Arabs encountered the Prophet s at ʻAqabah. These Arabs, from the feuding tribes of Aws and Khazraj, bore years of battle scars—sword against sword, heart against heart. Yet, beneath their conflict lay soft, generous, and loving natures. Allah the Exalted says about them, “[The Anṣār] have love for those who emigrated to them, and do not feel in their hearts any ambition for what is given to the former ones, and give pref-

erence (to them) over themselves, even though they are in poverty. And those who are saved from the greed of their hearts are the successful.” These visitors arrived at Minā with heartfelt duʻās for healing and peace. Unlike other pilgrims, they inclined toward the Prophet s and embraced his guidance. Meeting with them individually and in groups, often under the cover of night to avoid Quraysh’s meddling, the Prophet s witnessed their immediate love for him. Through this love, Allah united their hearts, ending their feuds. So profound was their collective acceptance that Yathrib became Madīnah al-Nabī, the City of the Prophet. In contrast, many Madinan Jews, despite recognizing him as the promised prophet, were blinded by obstinacy and jealousy, depriving themselves of love, guidance, and ultimately, residence in the blessed city.

Madīnah: The City of the Prophet

Sayyiduna ‘Ali would later testify to Abū Dharr’s courage, saying, “Today, there is no one left who does not fear the criticism of the criticizer for the sake of Allah except Abū Dharr, not even myself.”

Madīnah stood as a fortress of gentle soil and fertile hearts, cradled by mountains; an oasis amid barren times and corrupted lands. It’s been said that every person is buried in the soil from which he was formed. Thus, Madinah waited patiently since the dawn of time for the Prophet’s s return to her soil. One even imagines the womb yearning to fulfill its destined role as the cradle of a blessed lineage. Salmā bint ‘Amr, the mother of ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib and a noblewoman of the Banū Najjār of Madinah, carried within her the seeds that would culminate in the Prophet’s s anticipated return to Madinah. Sayyidunā Sa‘d ibn Mu‘ādh was the first to embrace Islam, and through the tireless efforts of Sayyidunā Muṣ‘ab ibn ‘Umayr, the faith took root, grew swiftly, and extended to every home in Madīnah. Muṣ‘ab’s efforts in spreading Islam showcased the transformative power of a message delivered with sincerity and love. How admirable is the Islam of one who loved the Messenger through his messenger!

From this

land, the tree of Islam branched further, bearing fruits that reached every corner of the globe. The fragrance of Madīnah’s faith would inspire countless generations, its roots anchoring the global ummah.

But first, the Makkan Muslims had to undertake their migration (hijrah) to Madīnah. On the Prophet’s s instructions, they left one by one, each carrying the hope of reuniting with him. Perhaps the greatest test of love lies in separation at the request of the beloved. This migration tore apart families, both extended and immediate. For instance, Sayyidunā Abū Salamah prepared to migrate with his wife and son, only for his wife’s clan to seize her and his son’s clan to snatch him away. Abū Salamah reached Madīnah, separated from all three. Yet, his sacrifice did not go unnoticed by Allah, for he was later reunited with them in Madīnah and will be again in the hereafter.

Such trials, though heart-wrenching, underscored the depth of commitment and faith among the believers. Their migration was not merely a physical journey but a profound testament to their love and trust in Allah and His Messenger.

This was merely the beginning for the Anṣār. They understood their assistance would come at a price, for no claim to love remains untested. Unlike other helpers, the Anṣār were exceptional. When Sayyidunā Mūsā’s followers said, “So go, you and your Lord, and fight. As for us, we are sitting right here,” and Sayyidunā ‘Īsā’s helpers demanded, “Would your Lord be willing to send down to us a table spread with food from heaven?”, the Anṣār sought nothing from the Prophet s and offered him everything. Their love was pure, untainted by conditions or demands, a reflection of true devotion.

True love is losing oneself entirely to the beloved. It is a flame that consumes all else, leaving only the Beloved. The Anṣār gave everything for the Prophet s without hesitation or condition. They abandoned their worldly comforts and personal desires to aid him. When the Prophet s asked the Anṣār to welcome the Muhājirūn, they did so not only with open arms but with open hearts, sharing their homes, wealth, and even land without reservation. This was love in its purest form, a burning flame that left no room for selfishness, illuminating only devotion to the Beloved.

Echoing the spirit of the Anṣār, a poet once wrote:

Love is that flame which, when it blazes up, Burns everything except the Beloved.

Likewise, the Prophet s said to them, “I am of you, and you are of me.” No greater honor can be claimed in this world, for this bond between the Prophet s and the Anṣār was forged in love, solidified in sacrifice, and destined to echo throughout eternity.