SIDEWALK CULTURE

& ITS INFLUENCE ON PUBLIC SPACES IN HO CHI MINH CITY

JENNY DO

Ho Chi Minh City is a populated city where the sidewalks reflect most of its character. And by character, I am not mentioning the electic architecture, the spatial arrangment, I am talking of the senses of its existence. The sidewalks witness so much of the history where people fight for their country, and on the sidewalks, the lives of millions of Vietnamese start daily through informal vendors (food sellers, Babers, gasoline, newsstands,...). Born and raised in Ho Chi Minh City, I feel the responsibility of finding how this unique character of the lives takes place on the sidewalks, and the streets themselves. For me, the sidewalks have been taken for granted. I did not recognize the importance of them until I recall all the evenings I spent playing and chilling with my friends, mostly every day. Before coming to this research, I was struggling with finding the right topic to discuss on. Then looking at my background and ethnicity, I realize there is no other way to look at it than study the sidewalk. First, I would like to thank my supervisor-Ms.Susana Constantino for her great dedication in guiding me during my thesis and her critics in my methodology to achieve the complete research at the end. Second, I would like to thank my family for giving me a chance to study in the Netherlands, where I have met so many inspriring human beings. And last but not least, I would like to thank my best friend, my soulmate, Anthony Hsu for his support in photographing references to use in this thesis. My position in this research and my findings can be one of the various proposal for further case studies.

Jenny DoPROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCH QUESTION

LITERATURE REVIEW

METHODOLOGY

CHAPTER 01 – SIDEWALK ACTIVITIES MANIFESTATION & VIETNAMESE HISTORICAL INFLUENCES

1. Explanation of how the history of Saigon has affected the sidewalk culture

2. The infiltration of the sidewalk culture to the life of Vietnamese working class

CHAPTER 02 – THE ASSOCIATION OF URBANIZATION WITH STREET VENDORS

1. The paradox of sidewalk priorities

2. Attempts on reorganizing the sidewalk of Ho Chi Minh City authorities

CHAPTER 03 – A CASE STUDY OF TWO OLDEST STREETS IN HO CHI MINH CITY

1. Ho Thi Ky Street

2. Ton That Dam Street CONCLUSION

If there is one adjective to define, and accurately describe the public space of Ho Chi Minh City, then it must be vibrant.

vehicles exist and occupy almost every corners of the city, mainly, motorcycles, which take up approximately 74 percent comparing to other automobiles. Pedestrians are just one of the very few urban commuters in Vietnam as many activities of the day take place on the streets, dinning, playing, entertaining, and exercising. Therefore, it can be said that Vietnamese people are very fond of the outside appearance of their house.1 Activities taking place on the sidewalks, alleys, and streets in Ho Chi Minh City form a complex informal economic network that can be introduced by a more comprehensible term called “Sidewalk economy”, or in terms of society, “Sidewalk culture”, which will be explained further in this research by means of literatures and visual references. In this research, I will address the issue of the sidewalk economy, a narrative and controversial topic in my country, from explaining the different form of spatial configuration, studying their presence on the sidewalk to analyzing the spatial arrangement of the vendors, and arguing that this form of business should be considered and maintained as part of urban spatial design in Ho Chi Minh City. Due to living in long distance while doing this paper, by terms of using sources and tools on the internet, for instance, Google Earth, I will address the differences in characteristics of each form of vendors and how they manage to work on the sidewalk. And more importantly, from the lens of an ordinary citizen thus of a spatial designer, arguing of the inclusivity of the vendors in Ho Chi Minh City public space, and discussing their appearance as an unremovable figure with the social context in modern Vietnam. Additionally, it is essential to emphasize that this paper aim is far from solving the puzzles on the sidewalks, rather my research focus on studying how the vendors organize themselves, the method of making sidewalks as a working space and engaging the urban spatial planning.

in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), the biggest metropolitan in Vietnam, with the population up to 9 million,2 and having lived in the city center, more than often, I have been too familiar with the bustling images of the central streets centers and burdens on sidewalk corners. These sidewalk activities had been a strong attachment between the city itself and me throughout 25 years and they continue to grow, especially in big metropolitans, for instance Hanoi and HCMC. Additionally, these street-oriented occupations are unofficially controlled under any organizations or official authorities, mostly they are spontaneously occurred on the pavements of most cities and take turns to open and close during one day. Vietnam “Sidewalk economy” or “informal economy” sector has a thick history from the feudal times, undergoing many periods of the country’s history, but until now the official definition of informality did not occur in any Vietnamese regulation text, there are also no current policies targeting the informal sector.3

2 Ho Chi Minh City covers a sizeable surface area with a total of 2,061.2 square kilometers (795.3 square miles). The city is quite densely populated, but somehow it all seems to work as Ho Chi Minh City continues to grow. The population density states that 4,097 individuals are residing per square kilometer (approximately 10,610 residents per square mile) within the city. <https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/ho-chi-minh-city-population>

3 The Hien Dang, Street Life as the negotiation process: case study of Sidewalk Informal Economy in Ho Chi Minh City, IOP Publishi, 2018, 1.

takes off from the close relationship between the sellers, more particularly, street vendors, and their influences on the sidewalk pattern of Vietnam in terms of design, architecture, culture, and urban life. The sector of sidewalk informality has become an unfinished discussion for the authorities for a decade, I believe that a complex issue creates many opportunities for solutions or promising proposals for future implementation. The solutions that the local authorities have introduced in recent years, in particular, “Sidewalk cleanup campaign in Vietnam 2017” when Vietnamese authorities made plans to organize and redesign the sidewalks and main roads in the central areas in HCMC. Implemented since January of 2017,4 the plans focused to reorganize sidewalks and walking streets in the center as there is a high volume of traffic and pedestrians participate daily, the latest plan of the central areas also partly re-create the urban landscape for the area, however, these impacts still leave many questions and complications because of its policy to solving solely the sidewalks encroachment of residential or small-scale peddlers, which is in the center, regardless of the city images of highly occupied sidewalks. I began this research by documenting national, international articles and research publications from Vietnam and related institutions. Although there are aspects stated that Sidewalk Economy has brought many controversy among the authorities whether or not it should be considered a legal form of business, I personally contemplate this based on a design point of view. Although there are very few evidence and limited literature investigation on this form of marginal activities throughout history, recent Vietnamese generations, especially those of the millennials and baby-boomers, are intimately attached to this unique culture of Saigon.

I find it very fascinating of how the history of Saigon attached to the young, heterogeneous and hybrid residents, and how HCMC sidewalk culture has for itself a very unique sense of characteristic, which cannot be duplicated. Regardless of the scale, residents and vendors negotiate to come up with ways of arrangement on the sidewalk. In fact, it is not easy to accept that this form of sidewalk business has become a problem that hinders the development of modern society. However, there must be a facture making this sidewalk business sustain and thrive in a developing city. Therefore, this research will partly seek to find an answer on how this unique social activity influence on the street pattern and and how to include sidewalk culture in the design of public space in Vietnam?

4 “Sidewalk clean-up campaign” established in Vietnam 2017 was the fight against sidewalk encroachment, regaining sidewalks for pedestrians starting on January 16 in District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, then Hanoi and other provinces, cities and localities in Vietnam.Public space is defined as space to which people normally have unrestricted access and right of way, therefore, in other words, public places, and spaces are public because anyone is entitled to be physically present in them. As public stands for "people" and space is known as "place", so in other words, “public space” is “a place of the people”.5 The difference between public space and private space in Vietnam, however, has been known to be more complicated due to its cultural orientation.6 The term “The Sidewalk Economy” has been created due to a form of business developed by vendors at sidewalks, pavements. This term also targets seller with little income, especially, working class, trying to make ends meet. Therefore, the sidewalk has been the place to create fortune. Although “Sidewalk Economy” appears mostly around the world but there is no place like Vietnam, where sidewalk has become a crucial part of local culture and most importantly, this has been considered, by The Hien Dang, an unique pin point of public informality.7

5 R Sendi & B. G. Marušić, 2012, International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, 21-28.

6 Lisa B. W. Drummon, Street Scenes: Practices of Public and Private Space in Urban Vietnam, 2000, 2380.

7 The Hien Dang, Street Life as the negotiation process: case study of Sidewalk Informal Economy in Ho Chi Minh City, IOP Publishi, 2018, 1.

as portrayed in a 2020 article from the Vietnamese e-magazine – Vnexpress, is facing many obstacles and challenges despite its convenience and distinctive facts, mainly because its affect on the city urban planning, which occurs to be true, for example many city-dwellers realize they do not have the time to browse in supermarkets and find it more convenient to purchase what they need from the vendors that roam the streets and sidewalks 8. On the other hand, thanks to the rapid development in ecocomy by 2000s, which has been addressed strongly by Dapice, Gomez-Ibanez, & Nguyen that HCMC has transformed into a potential land for investors and developers. However, this also created a gap in social ladder, which pushed the people, mostly working class, who were unable to afford living in the center, to move to others sub-urban but at the same time are obliged to make their living in the streets.9 Besides, it seems clear to me that whatever they do, Vietnamese clearly likes the idea of having leisure time outside of their house. It is common to see Vietnamese enjoy their evening time by sidewalk, pavement.10 To thoroughly understand the reasons, and to clarify this matter, it is necessary to dive deeply into the characteristics of Vietnamese culture, people's mindset, climate, and mixed-zoning environment. To Vietnamese, this way of commercial business term has been so common, it is argued that it is so embedded in the city culture, so familiar that it has turned into a new form of occupation, I will argue that it is so embedded in the city’s culture that it has been called “Sidewalk Culture”, even though we have little evidence on how the name was come up. Street culture is just what we call it because what is good on the sidewalk is called sidewalk culture, so there will be nothing else. A Vietnamese researcher, Dr.Nguyen Khac Thuan, claims that Vietnamese Sidewalk culture will never disappear. And if a new element come up, it will also be brought up on the street, and it will have a new cultural structure without having to give up the old one.11

8 What the future holds for Vietnam’s street vendors by VnExpress E-magazine <https://e.vnexpress.net/projects/sidewalk-economicswhat-the-future-holds-for-vietnam-s-ubiquitous-street-vendors-3565620/index.html>

9 David Dapice, Jose A. Gomez-Ibanez & Nguyen Xuan Thanh , Ho Chi Minh City: The Challenges of Growth. Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: United Nations Development Programme, Havard Kennedy School, 2010, 6.

10 Lisa B. W. Drummon, Street Scenes: Practices of Public and Private Space in Urban Vietnam, 2000, 2383.

11 “Sidewalk culture’ in Vietnam will never be lost?”. Vietnammoi. Khai An. 13th June 2017. <https://vietnammoi.vn/van-hoa-via-he-oviet-nam-se-khong-bao-gio-mat-di-35344.htm>

“Sidewalk Economy”,

Sidewalk Culture, according to Vietnam Architecture Magazine, was originated from the consequences of urbanization of agriculture-based country. On the other hand, "Sidewalk culture" has been investigated by domestic and foreign sociologists, and narratives have been surrounded around the discussions of Vietnamese city culture from history, activities happening on the sidewalks. Gradually the sidewalk has become an adjective meaning "informal" or "inauthentic", which are used to describe the properties of attached nouns in many cases.12 Therefore, it can be said that sidewalk culture is not an easy thing to detach from, while maintaining activities on the street in a reasonable way are considered to be a problem. Dang has studied how the urban divide has pushed the working classes out of the city centers and this reform is partly responsible for taking the sidewalk as an informal location for the working class to produce more economically. However, from the perspective of history, culture, and sociology, the form of street commerce took place in Vietnam in the previous centuries, in the 19th and 20th centuries (Figure 1) and it is also one of the typical cultural features of Vietnam for large and small urban areas, where people connect and interact with each other, especially in the day time. And after a period of formation and development, the sidewalk informality, sidewalk culture has become essential for people's lives in Vietnam up to the present time despite its limitation in studies and supportive data.13 Informality sector can be an interesting discussion if it was put into context of the world in 20th century, particularly in 1970s. According to Alsayyad’s paper on Urban Informality as A New Way of Life, the discussion was ultimately rooted in descriptions of the movement of labor to cities in the 1950s and '60s. Among the earliest to identify this trend, the discourse proposed a two sector model for understanding the new migration of people and the manner of their employment, which later Lloyd George Reynolds identified these groups as a state sector and a “trade-service” sector. He described the latter as a multitude of people whom one sees thronging the city streets, sidewalks and back alleys in the developing countries: the petty trader, street vendors, coolies, and porters, small artisans, messengers, barbers, shoe-shine boys, and personal servants.14

12 Sidewalk Commercial Econom: negotiation and Purpose. Kien Truc Vietnam Magazine<https://kientrucvietnam.org.vn/van-hoathuong-mai-via-he-thoai-thuan-va-muc-dich/>

13The Hien Dang, Street Life as the negotiation process: case study of Sidewalk Informal Economy in Ho Chi Minh City, IOP Publishi, 2018, 2.

14Nezar Alsayyad, Urban Informality as A New Way of Life, University of California, 2004, 10.

Withinthree chapters of this research, in chapter 01, for the objectives of this study, I will introduce shortly into the history of Saigon, which is already layered by colonization periods, besides, take preferences from certain periods of time from there as a premise to understand the sidewalk culture from the historical standpoint and describe the infiltration of marginal activities in the daily life of the working class by literature evidence and historical events. In relation to this chapter, I would seek to understand how the colonized and diverse ethnological history of Saigon has affected on the development of the sidewalk, and the difference from its counterpart, Cho Lon, which, until these days, remains to be the source of many controversial narratives by visually supporting with historical, contemporary images of different patterns of occupation of the street. Also in this chapter, I will introduce how the Doi Moi Policy in 1986 has affected the living conditions on the streets and how the trend of migration into the city has transformed the face of Ho Chi Minh City sidewalks. As well as taking references of the 20th century movies that included the evidence of how the dwellers occupied the arrangement of the city urban planning. Besides, introducing the type of street occupations which was mentioned in modern literatures and research papers. From there using that form of occupation to demonstrate and analyze the method of working in the lens of design and architecture.

In the second chapter of this research proposal, there will be a discussion where I will contribute my perspective on the close association of urban planning on the Vietnamese street culture. More clearly, I will put to use the existence of this culture appeared in cinema and theater in the 20th century before the Independence Day in 1975. Followed the introduction of the urbanization in the late 90s and its impact on the life of the pavement economy; and a recall of the unsuccessful efforts to reorganize the street order occurred since 2017 in HCMC. On the other hand, giving the example taken from Singapore signature hawker stalls and explain the differences in organization of the hawker, in short, discuss how this form or arrangement is incompatible to Ho Chi Minh City. In explanation, answer the question: How are these failed organizations of rebuilding and returning the sidewalk spaces still carry on? Why is it that implementing stringent and anti-sidewalk-activity policies is counterproductive to most sections of the street lives? How can the new arrangement of sidewalk vendors be obtained in Singapore? To answer all of these questions, I will use references of the commuter behavior from research papers, latest news and existing proposals from other countries to support my thesis.

In the last chapter of this paper, I choose to look at the tight bonding between local culture and sidewalk activities in HCMC and the possibilities from the point of view of social patterns of the vendors on the sidewalk by looking at the distinguished map of Ho Chi Minh City. Chapter 03 will use 2 case studies on two roads in different areas, the first is Ho Thi Ki Street where is mostly well known as Ho Thi Ki Flower Market, the second is Ton That Dam street, district 1, where Cu Market is formed (Old Market). Thus, I focus on stating my position as a designer to explain, and navigating the sidewalk advantages as well as the disadvantages. In particular, taking the starting point from 3 types of economy activities presented in economic studies from Annemarie M.F. Hiemstra, Koen

G. Van Der Kooy & Michael Frese, I will analyze from the design point of view how different types of economic activities (stationary, ambulatory and residential vendors) positioned in these streets. With the support of architectural diagram, Google Earth, the current master plan and visual sketches to

portrait the patterns and their spatial appropriation and applying visual methods (drawings, sections, plans/layouts as analytic and comparative tools) to survey, map and illustrate these patterns of occupation and try to understand the differences and scales of occupation of the public space in a spatial context. How do vendors occupy the street? Is there a different spatial occupation/organization according to the location? Which activities occur on the sidewalk? What are their spatial practices? What kind of spaces they use? Which vendors are permanent and can be changed over each period of time?

Spaces of the sidewalk is made up of basic concepts, just as the space seemingly random and simple that are often overlooked by us every day,15 somehow forming a very unique culture of the sidewalk in Vietnam. Being a Saigonese (people of Saigon, HCMC), I utterly agree with putting forward a more reasonable planning and policies, in which provides solutions for the lower-class workers and preserves the history, culture, and their influence on the urban design. At the same time, being an interior architect, sidewalk encroachment and its influence on architectural design is something that should be considered and developed based on. Before any conception of interior architecture design, the vendors are originally the architects and designers of the own business and corners they establish. Therefore, the methodology of this research seek to find alternatives that can be acknowledged in similar cases, and make use of the aesthetic aspects of street vendors to create a more effective alternative. At the end of this paper, questions and possibilities are expected to be concluded as this matter of society is underrated and being sided in compared with other traditions. Accordingly, my position of the research and my final assessment can be one of the various viable practice which may trigger a propose for further case studies.

the busy streets or into the small alleys of HCMC, it is not difficult to run into a small coffee stand, a food stall, a newsstand, a small bikes repair in the corner of a hustling main road. If it were to cover all the activities taking place in the streets, it would take quite a while to compile and publish a more detailed article. On a usual day, if you were born in the hustle and bustle of HCMC, the image of sellers sitting on the sidewalk has become an indispensable cultural impression. The sound of carts creaking, or the sound of the salesmen untying the rolls of tarpaulins, the shrill opening sound of the old iron doors, the chatter of vendors, laughter, the sound of the rushing delivery trucks will wake you up every morning. Having lived for seven years in the center, on Nguyen Thiep Street, which is few minutes away from downtown; then, about two years in Cho Lon (Chinese district in HCMC), needless to say, I had a splendid time to experience all the excitement of the city regardless of its noise, pollution, disorganization. Despite the disorientation in setting up the lives of the street, I always ask the question, if history changed and urban Vietnam was organized more scientifically, what would the current situation be? Of course, in reality, historical accounts cannot be easily changed, cannot be rewritten, and cannot be erased. So, from a historical, social, and cultural perspective, although it is not fully explained, we can partly illustrate how modern Vietnamese society was built upon. Although being a significant character of the city to many, it is true that the history of Saigon and the literature that create the picture of sidewalk culture still remain unclear. There is almost no official survey on what people in the informal business really do, how they feel or care about their work (in some cases, their only means of survival), their living condition, their future, or what the citizens of HCMC think about these economies on the pavements. Arguments are just arguments when everyone keeps their standpoints and this situation would not lead the issue to anywhere.16 Therefore, does sidewalk culture belong and make a part of public spaces?

Figure 1.1 Ceramics and pottery shop, from Ky Hoa Ve Dông Duong: Nam Ky, 2015, p.57. British Library, OIJ.915.97

Figure 1.1 Ceramics and pottery shop, from Ky Hoa Ve Dông Duong: Nam Ky, 2015, p.57. British Library, OIJ.915.97

According to Kim, present day HCMC actually started as two separate but symbiotic towns: the French colonist built Saigon as a tropical mini-Paris with monumental buildings connected by boulevards and traffic circles, and the Chinese immigrants built the neighborhood of Cho Lon, an area which belongs to mostly Chinese citizen, with narrow streets that curved towards the river.17 As urban planning design from the French colony implemented on the city of Saigon and Cho Lon, separation in the population has started to arise between people who worked for the municipality and people who were small sellers. Therefore, Saigon and its center only allowed people who had the residency to accommodate (politicians, French, Vietnamese bourgeoisie) and pushed the people of working class and without residency to make a living on the river or in other regions nearby Saigon and Cho Lon. This can be considered the begin of sidewalk culture.

Long before the sidewalk culture was formed and popularized to the present, the street trade was born in the first Northern period 179 BC, there has not been any specific research on the trading route. Although it can be seen that Vietnam’s agricultural economy has had a strong impact on mobile commerce or the presence of a centralized form of commerce (market hall) and decentralized (peddling market). When the French colonized Vietnam in the late 19th century, to ensure the rule and management of the colony, they gave a definitive physical impact to destroy many centralized buildings, and communities at that time, including temples (chua) and communal houses (dinh).18 Instead, the French constructed their new Administrative centers, Post office, and City Hall. And in the following years until the 20th century, the constant change in the government system and the fighting between the different regimes in the north (Hanoi) and the south (Saigon), except for the household businesses. At home, the majority of small individuals or individual sellers cannot concentrate on one place to trade, therefore, they have formed small retail clusters on the street, both convenient for commuting, also flexible, and can be reachable to more consumers (Figure 1.1 & 1.2). The reason for this can be traced back to the tightening of community activities in the Post-colonial state. Although up to the current time, there has been limited research on Vietnam’s street culture from a historical standpoint, nor has there been an in-depth assessment of the sociological background of street culture. One thing is clear, throughout history, the impression of street vendors and small-scale merchants has played a significant role in building the distinctive sidewalk culture of Vietnam.

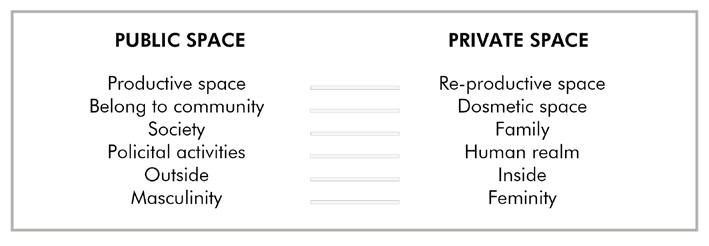

To answer the question whether sidewalk belong to public space, it is essential to look into the different arguments and how researchers define the interrelationship between public and private space. Taking Lisa Drummond’s discussion on public space and private space in Vietnam as an example (Table 1), although giving examples of the differences, mentioned them as inside and outside spaces, either comparing them as community versus domesticity, masculinity versus femininity, although there is little evidence of the public “sphere” in Vietnamese society during the pre-colonial, colonial, post-colonial period, it is not impossible to realize that all of these period has strongly influence the way Vietnamese arranged the public space as their private space. Public spaces in Ho Chi Minh City, according to the research of Hiemstra, van der Kooy and Frese, fabricated a female-dominated environment where women join the informal sector of the economy19 which goes against the

18

SAGE, 2000, 2381.

relation of public and private space argued by Lisa Drummond. In reality, the historical evidence of this can be found in paintings which illustrates the life on the street (Figure 1.1 & 1.2). As a result, the presence of women in the urban pictures appeared to be recognizable. Historical documents in the past and modern show that the public space appears a lot of street vendors, stalls selling goods on the sidewalk, or images of women wearing conical hats contrasting with the urban (Figure 1.7). A survey by UNFPA shows that the Vietnamese population dropped since the war, the man who fought the battle lost their lives during the war. Therefore, it can be considered an explanation on how women dominates the informal sector of the economy in this period of time. Shortages of man in the household created a need for income among woman to raise their children and make ends meet for the entire family.

Since the reformation in policy -Vietnam’s Doi Moi (“Renovation”) in 1986, the national communist political economy now established a domestic free market, private ownership, and participation in international free trade.20 Therefore, the boundaries between public and private spaces, sidewalks and the residences are blurred due to the need of making living. Thanks to this new establishment, the national economy has been transformed incredibly and encourage all class of the population to join in the mission of developing the city. On the street, the vendors and the residents negotiated to create a beneficial relationship since retal prices in central areas were out of reach for them. Luckily, for those who can afford the rent, they shared the space with the owner and manage to separate their working zones with the other part of the house. In fact, the sidewalk is the transition of the spaces in the city, of private spaces and public spaces. What have been established on the street was mantained as daily activities due to the habits of using the public spaces, fast and effective. The consumers creates a habit for the vendors and vice versa, as habit, unlike instinct, is learned, cultivated.21

Figure 1.2 Ba Chieu vegetable market, Saigon, from Ký Hoa Ve Dong Duong: Nam Ky, 2015, p.22. British Library, OIJ.915.97

Figure 1.2 Ba Chieu vegetable market, Saigon, from Ký Hoa Ve Dong Duong: Nam Ky, 2015, p.22. British Library, OIJ.915.97

The

Hanoi and HCMC, two metropolitans of Vietnam both experience the similarities and differences in culture and history. Although when it comes to street culture, the majority of studies focus on the large northern urban area, Hanoi. Thus, it is impossible not to mention the area of 36 Streets Old Quarter in the center of Hoan Kiem District. Report from the field: “Street Vendors and the Informal Sector in Hanoi”, Martha Lincoln described the livelihood in the central area as:

“…heavily staffed, energetic, and ubiquitous. In the Old Quarter, women with shoulder poles carry meat, fish, eggs, bread, vegetables, bananas, mangoes, fresh coconuts, flowers, and plastic bags of sliced pineapple all over town; tourists sometimes borrow the vendor’s baskets and conical hat to pose for a photograph. From early morning to midnight, vendors maneuver bicycles, carts, and wagons stacked with merchandise through traffic. Vending is highly specialized and the goods are diverse: baskets, feather dusters, lottery tickets, incense, haircuts, chewing gum, and motorbike taxis; for tourists, postcards, purses, and photocopy editions of Bao Ninh’s The Sorrow of War and Graham Greene’s The Quiet American are on offer.” 22

In Pedestrian and Street Culture research by Mateo-Babiano and Ieda, informal economy agglomerations are mostly found near activity central such as school entrances, in front of shops and stores, churches, shopping malls, access towards train stations and at intersections. This provides them assurance of steady flow of customers. The type of economic activity is dependent on the activity generator, usually complementing such enterprise. Most common goods sold by these sidewalk peddlers and hawkers are consumables such as food products. Within the central business districts, the most common stalls are shops providing lunch, snacks and drinks. Sometimes, tables and chairs would complete the ensemble creating a distinct street architecture, however inferior the materials used or shabby it may seem to onlookers. The inventive minds of these store owners allow them to create and put apart such stalls within few minutes.23

The Sidewalk economy has strongly influenced and deeply ingrained in the social life of every Vietnamese. In the biggest metropolitan of southern Vietnam - Saigon, the images of street vendors, roadside stalls, and sidewalks are best depicted through contemporary photographs and film footage. The most famous footage can be found in the French movie L’amant (Annaud, 1992) (Figure 1.3, 1.4 & 1.5), which is based on the novel of the same name by French writer Marguerite Duras. Saigon is known for its vibrant and bustling, modern mixed with ancient features, wealth contrasts between the poor working class, and those working classes are the people who make up the culture. typical sidewalk. The film depicts the cries of street vendors, the sound of bells, the sound of motorbike engines running through the crowded alleys Cho Lon,24 the smoky image of the restaurants in the process of being prepared, tailors sitting fixed in a corner of the sidewalk, work hard to finish a day, buyers, regardless of class and status are welcomed. Besides, other movies about Saigon that illustrates the picture of Saigon sidewalk lives can be mentioned as The Quiet American(2002), Stars and Roses(1989). The illustration of the streets and scenes the director has shown that sidewalk culture has been a part of the image of HCMC.

22 Martha Lincoln, Street Vendors and the Informal Sector in Hanoi. Dialectical Anthropology, 2008,1.

23 Hitoshi Ieda & Iderlina Mateo-Babiano, Street Space Sustainability In Asia: The Role Of The Asian Pedestrian And Street Culture, Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol. 7, 2007, 1925

24 “Cho Lon mostly evokes one of the neighborhoods of the city, roughly corresponding to the fifth district (quan 5) adjacent to the central districts. This apparent banality, however, masks the extraordinary destiny of what was for a long time a city in its own right.” <http://www.gis-reseau-asie.org/en/cholon-little-china-heart-saigon>

Figure 1.3 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Figure 1.3 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Figure 1.4 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Figure 1.4 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Figure 1.5 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Figure 1.5 Scenes taken from the movie L’amant, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1992.

Unlikeentering a high-end restaurant, where people have to dress up in fancy and formal clothes, on the sidewalk, everyone is equal. Regardless of your age, education, gender, background, occupation, class, or social status, in the oldest and crowdest markets, you can always come across people who informally dressed up sitting between the ordinary working people. They are all exposed facing the street and transparent to the eye of every one passing by. The most well-known example of this is an article writing on the 48th US President Obama, during his visit to Vietnam,25 a series of newspapers published a picture of him with Anthony Bourdain in a small tiny street shop. A similar event occured with the Australian Prime Minister, during his diplomatic trip to Vietnam, the image of a man wearing a suit and white collar coming to buy food at a roadside restaurant went viral on newspapers and the internet at that time.26 As a result, it will not be surprising to see visitors from other countries trying to squeeze themselves into the narrow space of the vendors, in which the space includes a small knee-high foled-table, some tiny plastic chairs that are only meant for small-figure individual. However, despite the uncomfort, extreme heat, humidity, and inconvenience, no one complains or acknowledges about considering the non-standard proportions of these small-scale vendors, nor the fact that restaurant owners should renovate their corner. As Kim also stated that another common mistake of an outsider is to impute one’s own values, tastes, or interpretations onto subjects or a situation. What is crowded to some people maybe cozy to others, what is enjoyably sunny to some might be unpleasantly bright to others.27 Needless to say, these incredible real-life images had made up the undeniable democracy of the Vietnamese sidewalk culture and filled the gap in cultural differences.

As a form of small-scale populist capitalism, street vending is cited approvingly by pro-market sources like the DFID and the Asian Development Bank, who point out that street vendors embody capitalist “self-help” and also serve as a lifeline for poor and working people. In this vein, Vietnamese street vending is figured as a form of “microbusiness” and, as such, a subject of study for economists, business and management researchers, and contributors to journals like Vietnam Investment Review.28 According to a research paper investigated by Hiemstra, van der Kooy, & Frese on the Assessment of Psychological Success and Failure Factors in2006, street vendors are defined by three identical characters. The first is a configuration of small-scale business which operate from fixed spots at a specific location, in which there are usually accessible site, for instance, marketplaces, busy street corners. These businesses can be classified as stationary (Figure 1.6). Some sellers prepare their products at home and sell it while moving across the city. Most of the time, their location frequently changes from one place to another, commonly by bicycle or on foot, to advertise their goods. That form of businesses can be defined as ambulatory (Figure 1.7). There are also vendors who choose to prepare and sell their foods at home, this type of street vendors can be named as residential (Figure 1.8).29 These three type of vendor have constructed a solid foundation for the sidewalk culture in HCMC in the current time. They can be seen as individuals or in groups, and mostly owned by women. In other cases, the vendor can be run by a group of relatives where their shift changes during the day.

25 Barack Obama Drop-In for Pork Soup Stuns Vietnam Street Shop Owner. <https://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/barack-obama-drop-in-forpork-soup-stuns-vietnam-street-shop-owner-1409378>

26 Foreign Prime Minister Tastes Vietnamese Street Food . <https://iut.vn/news/foreign-prime-minister-tastes-vietnamese-street-food>

27 Annette Miae Kim, Sidewalk City: Remapping Public Space in Ho Chi Minh City, The University of Chicago Press, 2015, 14.

28 Martha Lincoln, Street Vendors and the Informal Sector in Hanoi. Dialectical Anthropology, 2008,2.

29 Annemarie M.F. Hiemstra, Koen G. Van Der Kooy & Michael Frese , Entrepreneurship in The Street Food Sector of Vietnam– Assessment of Psychological Success and Failure Factors, Journal of Small Business Management, 2006,4-5.

A vendor’s workday can be divided into different periods within 24 hours. In contrast to officers, who are privileged to get an 8-hour job, the vendor takes over and change their shift depending on the amount of targeted customers and the products. As according Dang, he conlcuded 5 periods of times in a day: 6AM-10AM, 10AM-1PM, 1PM-7PM, 7PM-10PM, and 10PM-1AM to match with the main actives of a day: Breakfast time, Lunch time, After lunch time, Out for Dinner time, and Late night. There are three objects of observation: Food stall, Coffee stand (which not only sells coffee but also other drinks), and other informal street economic activities.30 Other activities that was not listed by Dang can be mentioned as: bike repairs, tobasco, barber, lottery tickets, kid toys, insects, pets and birds, worshiping items, flowers, scrap collectors, knives/scissors repair, newstands and gasoline.

30 The Hien Dang, Street Life as the negotiation process: case study of Sidewalk Informal Economy in Ho Chi Minh City, IOP Publishing, 2018, 2.

30 The Hien Dang, Street Life as the negotiation process: case study of Sidewalk Informal Economy in Ho Chi Minh City, IOP Publishing, 2018, 2.

It is inevitable to discuss that sidewalk economy sector plays an essential role in forming a network of activities between sellers and consumers in HCMC (Table 2). The reason for the emergence of these forms is the slow development of the urban public transport infrastructure. In HCMC, the majority of workers travel by personal transportation (motorbikes, cars and bicycle), rather than using public transport, such as buses, which fail to meet the demand of commuters travelling in a day. In addition, the operating time of the bus is also limited from 6:00 am to 7:00 pm, causing a shortage in the needs of the people. Due to the mobile convenience and the large occupation of motorbikes, the sidewalk has become a perfect place to display commercial activities during the day, where sellers creates favorable conditions for traffic users to interact, exchange, as well as faster and more convenient transactions. On the other hand, that will be very unlikely in the case of a car, bus, metro or tram. Therefore, the infiltration and influence of sidewalk culture into the lives of every citizen in HCMC is a long historical process, from the way people communicate, the distribution of public space, the small house area to Typical form of urban transport of Saigon.

In addition to the operation of the dense and overloaded traffic system (in reality), the characteristics of tube houses (Figure 1.9) and small personal spaces have partly formed the outdoor living habits of the people. citizen. Different from garden houses in suburban areas, tube houses are a feature not only in HCMC but also in Vietnam in general. The narrow and long tube houses with a narrow width have created a unique architectural culture of Vietnam. That can be seen most easily in large urban areas like HCMC. Due to the shortage of land and the increase in urban population, the tube house has become a signature architectural type of buildings. With the lack of open space and yards, residential sellers also take advantage of this type of architecture to divide working and living spaces, and make use of the sidewalk area as a place to socialize, sell and display (Figure 1.10)