ringgold saar

MEETING ON THE MATRIX

THE DAVID C. DRISKELL CENTER AT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK

THE DAVID C. DRISKELL CENTER AT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK

THE DAVID C. DRISKELL CENTER AT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK

THE DAVID C. DRISKELL CENTER AT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK

Acknowledgements

This exhibition was collaboratively curated by graduate students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology, including: Maura Callahan, Ashley Cope, Montia Daniels, JooHee Kim, Caroline Kipp, Cléa Massiani, Maggie Mastrandrea, Dominic Pearson, and Gabrielle Tillenburg, with support from Dr. Jordana Moore Saggese, Professor of American Art, and the staff of the David C. Driskell Center. This exhibition was sponsored by The David C. Driskell Center, the Maryland State Arts Council, the Elizabeth Carter Foundation, The Art Gallery at the University of Maryland, and the Arts for All Initiative. Special thanks to the Department of Art History and Archeology at the University of Maryland for their generous support.

Special thank you to Amadi Boone, ACA Galleries, Cleophus Thomas, Lewis Tanner Moore, Julie Farr, Kevin Cole, Curlee R Holton, John Williams, and the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African-American Art. Many thanks also to The David C. Driskell Center Staff, the Department of Art and Archeology at the University of Maryland, Taras Matla, Quint Gregory, Marco Polo Juarez, Alicia Perkovich, Clare Daly, Nan Zhong and Aaron Rice.

This catalogue was made possible thanks to the generous support of Cleophus Thomas Jr, Cheryl Edwards, Robert Steel and Curlee Raven Holton.

@The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at University of Maryland, College Park. 2023

979-8-9870316-1-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023904959

CURLEE RAVEN HOLTONRINGGOLD SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix is an exhibition that brings two major Black women artists together in a powerful, visual, and politically-charged dialogue. Focused on the way in which each artist uniquely utilizes the matrix—highlighting the exploration and engagement between the physical surfaces used in the printmaking process of transference—RINGGOLD SAAR showcases the possibilities of experimentation, storytelling, and activism. Faith Ringgold and Betye Saar hold long and distinguished careers that delve into the reframing of the political, domestic, cultural and artistic experiences of African Americans. Their work implores viewers to reconsider what it has meant to be an American, while also reckoning with the contradictions and negative stereotypes embedded in America’s history of racism, segregation, and discrimination.

I have had the distinct privilege of working and collaborating with Faith Ringgold directly for over twentyfive years. I first met Faith in 1993. She was a visiting lecturer at Lafayette College, where I was an assistant professor of art at the time. During her visit to my classroom, had prepared an etching plate for her in the hope that she would respond favorably. I placed the plate in front of her, while she spoke with my students. She

proceeded to draw her iconic image of Cassie flying up over the George Washington Bridge. The etching, titled Anyone Can Fly (1997), was the first of more than forty prints and portfolios that we would create together. In 1996, began the Experimental Printmaking Institute (EPI), a visiting artist program at Lafayette College in Easton, PA, with the explicit mission to explore and to expand a shared, creative spirit between artist and printmaker. The EPI aims to provide an environment in which professional artists and students can create work as well as investigate new (and often experimental) approaches to the print medium. Faith personified this mission by collaboratively engaging the various printmaking mediums along with students.

Faith and I have continued to work together as part of my private workshop, Raven Fine Art Editions, with another three editions this year alone. Although we have produced many notable editions of prints together, perhaps one project that best personifies her artistic, cultural, and political commitment to reveal the truth of the contradictions of the American Dream is the portfolio Declaration of Freedom and Independence (2009).

Inspired by The Declaration of Independence –a document that is one of the most significant in American history

that is a clarion call for freedom from oppression and a pledge to fight for freedom –the portfolio captures not only images of critical moments in the evolution of the American Dream, but it presents the contradictions as well.

Faith and are both honored that this body of work is central to this exhibition and is receiving attention from artists, scholars, students, and the wider community. can think of no other artist who possesses the personal integrity, artistic genius and cultural knowledge required to articulate a truer meaning of this document at such a critically important time in American History.

Curlee Raven Holton Artist, Printmaker, CollaboratorWhen in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

. . I long to hear that you have declared an independence and by the way in the New Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make. I desire you to Remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all the Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebellion and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or Representation. That your sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend why then not put it out of the power of the vicious and Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity and impunity. Men of sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the Vessels of your sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection as in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our Happiness.

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and separations, all having in direct object the establishment of absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offenses:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighboring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.

In every stage of these oppressions, We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

— John HancockAs a historian of modern and contemporary American art, with a special interest in critical expressions of Blackness, am keenly aware of the lack of scholarly attention given to artists of African descent. However, most art historians (including myself at one point) have only a passing knowledge of the medium of printmaking –excluding perhaps early modern engagements with etching or the impacts of letterpress and lithography on the dissemination of important texts and popular images in the decades surrounding the first industrial revolution. It was only when I moved to the University of Maryland, and most importantly, into the realm of The David C. Driskell Center when my true understanding of the challenges and the promises of the printmaking medium–and its intrinsic connections to Black innovation–began.

Inspired by the collections of the David C. Driskell Center and the legacies of Washington DC area printmakers–most of whom existed in the orbit of Professor Driskell–I organized my fall 2022 seminar for the graduate students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology around the history of Black printmaking. Entitled “Blackness in Relief,” our inquiry centered on a primary question: What would it mean to tell a history of printmaking from a Black perspective? While we have many histories of printmaking in the modern American context (e.g., the densely-

collaged silkscreen prints of Robert Rauschenberg), we know much less about the workshops–many established by Black artists–who made this work possible. In seminar meetings with my students, I frequently witnessed their surprise in hearing for the first time about the Experimental Print Workshop, founded in New York City by Robert Blackburn in 1947 or about the innovations of James L. Wells, a faculty member in the Department of Art at Howard University who taught the first universitylevel course in the linocut medium in the United States. Together we studied the ecosystems of the Works Progress Administration workshops in Philadelphia and of Howard University, which functioned as centers of gravity for so many Black printmakers. And we realized early on that any study of printmaking must necessarily include a deep consideration of the materials and techniques at play.

For the final project in the course, I asked students to propose an exhibition that would demonstrate their knowledge of the medium and its history, as well as draw primarily from the permanent collection of the David C. Driskell Center. Much to their discomfort, I presented no other specific agenda; my aim was instead to provide the space for these students to develop their own lines of inquiry. The resulting exhibition RINGGOLD | SAAR:

Meeting on the Matrix which debuted only weeks after the end of our semester together, perfectly demonstrates their engagement of the complexity of the printmaking medium. Using the “matrix” as a conceptual device, rather than just as a formal component of printmaking, was their solution to addressing the many points of intersection that all printmakers must navigate–between the image and its surface, between the artist and the printmaker, between public-facing work and a privatized art world. In the case of the artists Faith Ringgold and Betye Saar, the matrix framework allows us to think about these artists intersectionally–as Black women, as mothers, as artists working across media, and as political activists. As you explore the exhibition, I hope that you are inspired to look more closely at these prints and to consider how the subjects and themes on display may intersect with your own experiences.

In fall of 1963, when my sister Barbara and I were 11 and 12, we were moved from the Bronx (663 Westchester Avenue) into a three-bedroom apartment at 345 West 145th Street in Harlem. We were so excited and enchanted by the larger space that we convinced our mother to allow us to remain in the apartment overnight (it was late) and she bedded us down in the bathtub. That’s just how small we were, that we could sleep head to foot in the bathtub together. By the time we woke up, the move was in full progress.

The building was built in the 1950s and it still stands. That apartment was previously occupied by only one other person, Dinah Washington, the brilliant singer who died soon after.

Not only was she a famous and proficient jazz and gospel singer (originating in Chicago) with a long history among aficionados of African American music, in the building she was a local legend who had occupied the largest corner apartment, the penthouse. Her parties, which were languorous and well attended by the music greats of the time and often stretched into the night, were the stuff of local legend. Another jazz legend lived in the building in the C section, which is where Mom’s sister Aunt Barbara lived. His name was Johnny Hartmann, and I will never get enough of the album he did with John Coltrane but at that

time he was just another famous person in the black world (which was not the white world) who lived in the building. It was one of the benefits of segregation that we all lived together, rich and poor, famous and not, Duke Ellington, W.E.B. Dubois and Count Basie, just around the corner. Louis Armstrong never left his home in Corona Queens because by the time the white hotels wanted him to stay, he didn’t want to stay.

A large collection of jazz and classical lps accompanied us to 345, the move executed by Burdette Ringgold, who had married Faith in 1962.

Aidan Levy, a music historian who teaches at Columbia University has recently published a biography of Sonny Rollins called Saxophone Colossus, which focuses heavily on his early life in Harlem on Edgecombe Avenue. He has included a photograph of Sonny Rollins when he was a teenager (the property of Faith and Burdette Ringgold Estate) and would use a eyebrow pencil to draw a mustache on his upper lip in order to slip into Birdland and other jazz clubs to hear the greats—Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Thelonious Monk. Levy included stories as well about his friendship as a teenager with Faith, attending her 14th birthday party at her home at 363 Edgecombe Avenue, 4th floor front,

where they had a chance to play a clandestine game of post office in a closet. In this game, one child signals to another that he or she has a postal delivery. The postal delivery is a kiss. Sonny Rollins who had a crush on Faith called for Faith who gave him his kiss. But when her turn came, she called Earl Wallace, “a hip, silver-tongued pianist who would become her first husband.”

He never recovered from his childhood crush on Faith, Levy writes.

But what none of the so-called Sugar Hill gang ever recovered from was their passionate love for jazz and the musical education provided from growing up in Harlem surrounded by so much Avant Garde African American music and culture, and the informal contest which pitted them against the dominant educational values in the arts: classical was king in the classroom and jazz was the black sheep.

Faith’s Jazz Stories are represented here by prints executed with the assistance of master printmaker Curlee Holton. Mom has been surrounded by Jazz aficionados much of her life. As a child there was her mother who took her to see great performers at the Apollo Theater when she was quite small. She had asthma. Therefore her doctors deemed kindergarten and first grade not entirely safe spaces. Instead Momma Jones, who had aspired to

be a dancer and participated in dance competitions in her teens (partnered by her boyfriend Thomas Morrison who would later become her second husband) took her to the Apollo and other Harlem theaters to see Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald and Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, all the greats. As she would later tell me in an interview with her in 1978, “you would never ever want to go downtown to be entertained.”

So Faith’s relationship to the jazz tradition is long and yet the series Jazz Stories didn’t emerge until after 2007 when she was already 77 years old.

From the time Faith was a child in the 1930 through my own adolescence and youth in the 1960s Harlem was a Mecca of live music from block to block—jazz from multiple eras, blues in the bars and gospel in the storefront churches on every block—as well as the record shops which broadcast the latest R&B hits to the sidewalks.

All Faith’s circle of friends were either ardent jazz fans or aspiring soon to be successful musicians themselves. Meanwhile the classics of jazz in the form of stereo lps provided the background to everything in our lives particularly once we had moved back to Sugar Hill and 145th Street.

Printmaking was Betye Saar’s entrance into the world of fine art, and one of many mediums she would become known for in her six-decades long career. As a graduate student at California State University, Long Beach, she began creating prints in the early 1960s relating to her family and the natural world. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, her subject matter grew to encompass identity, mysticism, gender, and race. RINGGOLD | SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix includes works that speak to each of these themes in Saar’s oeuvre.

This exhibition features two etchings of her young daughters: Alison (1963) and Jump on One Foot (1964). Betye, my grandmother, told me that as a mother of three, she had to find the time to create her art somehow. Family time could double as studio time if she could, for example, draw her kids while they were watching television or jumping rope. A reporter once asked her what it was like to be a mother and an artist and she replied, “They’re both about creation. Overall, I approach motherhood as do art.”1

It was with this philosophy that her home in Laurel Canyon also became her printmaking studio, allowing Saar to transition from mother to artist when needed. My mother has memories of seeing printmaking acid in the kitchen at

times. Her early prints depicting her family are composed not only from the perspective of a mother’s gaze, but also the embodied lived experience of motherhood. Jump on One Foot (1964) evokes movement, capturing the fleeting nature of watching your child grow up. Alison (1963) is drawn from the point of view of a mother looking at her child gazing up from her lap. Tender but visionary, her early prints lay the groundwork for Saar’s unique voice as a black feminist icon who created art simultaneously about the personal and the political.

During the late 1960s, she became interested in astrology, palmistry, and the occult. Although she was drawn to the aesthetic of mysticism, she was never a traditional practitioner. Known for recycling found materials, she sometimes reincorporated pieces of older prints or sketches into her window assemblages and used recurring mystical symbols in her work throughout her career. The Mystic Galaxy (1966), one of her signature prints that includes imagery of the sun, moon, and stars, would be partially reincorporated into Black Girl’s Window (1968), one of her most well-known works. LA Sky (1989) and Mystic Sky with Self Portrait (1992) represent a playful and colorful interpretation of these symbols. In the latter, she included a rendering of her face into the corner of the

1 https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/arts-and-culture/a34346786/betye-saar-artist-motherhood/

piece, situating the symbols abstractly as if ideas were floating in Saar’s head.

Saar utilizes found imagery of black figures of the past, such as Aunt Jemima, as a lens through which to see the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow. In National Racism: We was mostly ‘bout Survival (1998), a faded image of an enslaved woman ironing is centered on a washboard, an object that typically signifies servitude, transformed into a portrait of someone whose reality is rarely subjectified. Juxtaposing the ubiquitous household washboard used by enslaved people and domestic servants with an adage and her “Liberate Aunt Jemima” slogan, Saar gives dignity to the black ancestral struggle for survival.

Printmaking is a democratic artistic medium which lends itself to conveying political messages by virtue of allowing its imagery to be reproduced and viewed by wider audiences. Faith Ringgold, who designed posters for the Black Panther Party, also used this medium to connect artistry and activism. The matrix of printmaking almost never gets exhibited, but serves as a blueprint, a prototype to be replicated but always hidden. Ironically, in creating a matrix—a mold—both artists also managed to break it.

For Faith Ringgold, the gendered hierarchies built into the Black Power movement were a continuous point of critique. Although the Black Panther Party relied on the labor of female members, men held most leadership positions. Despite the significant contributions of artists such as Barbara Jones-Hogu and poets like Nikki Giovanni, the public face of the Black Arts Movement was likewise predominantly male. Writing about the political and countercultural shifts of the late sixties in her 2005 memoir, Ringgold expressed her ambivalence toward the Black Power movement: “For me the concept of Black Power carried with it a big question mark. Was it intended only for the black men or would black women have power too?”1

Despite her reservations, Ringgold’s devotion to the cause of Black liberation never waned. In 1970—the same year she claimed she “became a feminist”—Ringgold produced two collaged posters to raise funds for the legal defenses of detained Black Panther Party members.2 But the predominantly white fundraising committee to whom Ringgold offered her work rejected them. While Ringgold’s posters were not reproduced as originally intended, their recent revival as serigraphs printed by master printmaker Curlee Raven Holton warrants a critical return to their

significance in the context of the Black Power movement. Although the posters initially appear to operate squarely within the visual language of Black Power, Ringgold’s deployment of this language was more fragmented than coherent, and more productively tested than strictly observed.

Ringgold’s complex relationship to Black Power radicalism, as well as her unapologetically Black feminist position, is on full display in the poster depicting an armed Black family. On one hand, by literally weaponizing the family against the state, her design subverts the state’s exploitation of the nuclear family as a contained hierarchical unit in the service of capitalism. The child’s presence in the poster also serves as a reminder of the Panthers’ support of Black families, which included free breakfast programs, after-school education, and health services—initiatives intentionally obscured by the white mainstream media, which focused exclusively on the Party’s militancy. Ringgold does not downplay the important role of armed confrontation in the Panthers’ platform, but instead uses the image of a gun-carrying family to encapsulate both the Party’s controversial tactics and its undervalued community service.

In other ways, Ringgold’s representation of the Panthers

departs from the Party’s official branding. Women and children carrying guns frequently appeared in visual media created by the party’s Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas. In these images, however, the mother is shown in an explicitly maternal position (i.e. holding or attending to the child), in the absence of a father. Knowing that the Black Panthers repudiated the nuclear family model, which Party co-founder Huey Newton condemned as “imprisoning, enslaving, and suffocating,” Ringgold’s revolutionary family is unusual in its inclusion of a man, woman, and child together. They appear individually armed, in contrast to both the Panthers’ rejection of traditional family structures and their discontinuously paradoxical reinforcement of women’s subordination.3 The poster redresses the hierarchical and exclusionary tendencies of Black nationalism, visualizing Frances Beale’s call to action in her formative text “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female,” written the year before Ringgold designed her posters:

To relegate women to purely supportive roles or to simply cultural considerations is a dangerous doctrine to project. Unless black men who are preparing themselves for armed struggle understand that the society which we are trying to create is one in which the oppression of all

members of that society is eliminated, then the revolution will have failed in its avowed purpose.4

Ringgold’s support for the Panthers transcends uncritical endorsement. By breaking away from the patriarchal doctrine which threatened to undermine the revolution’s efficacy, her poster affirms the Party’s fight for comprehensive liberation.

The transformation of Ringgold’s original collage posters to print in 2022 positions them within the narrative of printmaking as resistance. This is a history that extends back to the antiwar etchings of Francisco Goya (1746–1828), with whom Holton has compared Ringgold for their mutually “deep sense of public responsibility.”5

This is evident not only in Ringgold’s art, but also in the various protests she organized against racism and misogyny in the art world and beyond. Her insistence on recognizing both the promise and limitations of radical movements—artistic and otherwise—has solidified her unique, self-determined position within Black Power. In her posters, this vantage point materializes, and thanks to the reproductive power of print, has been realized once again.

Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) and Betye Saar (b. 1926) are artists who tell important histories with mundane, repurposed objects. Ringgold’s painted Story Quilts combine the ancestral and the familial traditions of quilting with political messages derived from her own beliefs and lived experiences as a Black woman. Saar, who is known primarily for her assemblage works, brings together family history, mystical inspiration, and derogatory images of African Americans in order to rewrite harmful narratives and imagine brighter futures instead.

Beginning in the 1960s, both Ringgold and Saar began to address the complex layers of their own lives as Black women in their artworks. At the same time, social and artistic movements which addressed issues of racism and gender inequality intensified, though the priorities of these two interest groups seldom overlapped. Whereas the Black Power and Black Arts movements were dominated by Black men, the women’s liberation and Feminist Art movements were primarily directed by white women. In response to the Civil Rights movement and to the women’s liberation movement—as well as their exclusion from these efforts—both Ringgold and Saar drew on their personal experiences as Black women to bring critical attention to the pervasive issues of racist and gendered exclusion. As part of that mission, both artists rewrote the story of Aunt Jemima, giving an alternative life to the stereotypical ‘mammy’ figure that appeared on

syrup bottles and pancake boxes until the products were rebranded in 2021. Both artists addressed Aunt Jemima as a distinctly Black feminist issue in a period when movements dedicated to Black Civil Rights efforts and women’s issues were divided and gender and race lines. In the hands of Ringgold and Saar, Aunt Jemima— a derogatory caricature of a Black woman—emerged as a subject that addressed their unique experiences and their double exclusion from prominent social movements of the 1960 and 1970s.

The window is an important conceptual and formal device for the artists Betye Saar and Faith Ringgold. From her studio window, Ringgold sees her “determination to be free in America,” 1 while for Saar, “the window is a way of traveling from one level of consciousness to another, like the physical looking into the spiritual.” 2 The window is thus an interface between the private, individual space and the public, exterior world.

In the artists’ print series—Declaration of Freedom and Independence (2009) by Ringgold and Bookmarks in the Pages of Life (2000) by Saar—we see a similar oscillation, this time between image and surface. In these works, Saar and Ringgold weave, overlap, and engage with stories of racism and misogyny through serigraph printmaking. In their printmaking method, ink is squeegeed through a mesh screen that is partially blocked to achieve the desired stenciled shapes, and multiple screens are used to build each image layer by layer, color by color. With each squeegee movement, the ink traces left behind become crucial ingredients for the final form. In other words, this process superimposes past and present histories and transforms the external world into a contemplative surface for the viewer.

Saar’s Bookmarks consists of six multicolored serigraphs of the African American author Zora Neale Hurston’s short stories on slavery from the 1930s and 1940s in Harlem

and small-town Florida. Weaving Hurston’s stories with real history and places, Saar reconstructs the scenes of racial struggles that Hurston observed in the American South, using fragmented fabric, faded photos, text, and patterned paper. By illustrating individual African American stories, Saar stacks each personal story onto the larger image of public history. On the other hand, Ringgold focuses exclusively on U.S. history in her Declaration series. Ringgold directs us toward the harsh realities of Black people and women in a racist and misogynistic society through her subjects, while within the window of the print we find a self-reflective silhouette. Although the dominant view “American” history frequently fails to consider the individual, here the two views—social and personal—converge.

Ringgold and Saar are active participants in history, rather than passive onlookers. Recognizing that the contributions and experiences of Black women were undervalued in both the Feminist and the Civil Rights movements, they create a new, liminal space for themselves. Their creativity allows for a space belonging, outside of the binaries of sex and race.3 Through their works, Ringgold and Saar encourage us to both reflect on this shared history and to make a conscious decision about the lens through which we view it.

Textiles and prints exist in a place of multiplicity and ambivalence: they are simultaneously a form of traditional or technical material culture, and a resource for nonconventional artistic, social, and political enactments.1 These opposed readings subvert attempts at definitive interpretations, turning them into sites of contradiction that contain multiple histories and meanings. While Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) and Betye Saar (b. 1926) are well-known for their innovative and experimental uses of diverse media, their works straddling between contemporary printmaking and craft have received little critical attention given to. These hybrid objects integrate the technical, the material, and the conceptual from both fields, bridging two mediums that rarely engage in sustained dialogue. Exploring Ringgold’s Tar Beach #2 (1990) and Saar’s Takin’ a Chance on Luv’ (1984), created during their individual artist-in-residence experiences at The Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM) in Philadelphia, presents an opportunity to consider these intersections across two artistic practices, providing a rare insight into their individual creative processes. Through a repertoire of symbols and piecework construction, Takin’ A Chance on Luv’ functions as a conceptual and material meeting

point between Saar’s prints and three-dimensional works. For Ringgold, Tar Beach #2 exists between her published texts and painted story quilts, illustrating the way images shift across media to accommodate creative agency and to facilitate communication.

The multiple layers of material and meaning present in Ringgold and Saar’s printed textiles also speak to the theory of “functional abstractions,” as argued by the visual historian Sampada Aranke. In Aranke’s view, these are works that are not only abstract for the sake of formal exercise. Instead, these “functional abstractions” figure the Black body “ as a series of substitutive, sensorial objects that give rise to a sense of how Black life is aesthetically imagined,” subverting the boundaries that white supremacy culture would seek to confine Black experience within. 2 In other words, these works simultaneously illustrate and subvert the constructs of Blackness. While Aranke’s ideas are developed in relation to formal appearance, we could perhaps extend their resonance to consider materiality as well. After all, materials carry embedded histories, and these associations can lend greater significance to the artist’s concepts. For example, given cotton’s historical ties to

enslavement in the United States, Saar and Ringgold’s material choices reflect their deep and nuanced understanding of the multiplicity of meanings called upon when textiles are used in artmaking. Thus, harnessing this multivalent signaling turns their printed images on textiles into acts of reappropriation, subverting media hierarchies and the limitations placed on Black freedom and creativity. Through this lens, the domestic textiles and hand drawn images composing Saar and Ringgold’s artworks can be read as a shared repository where “the sensorial and the visual, the embodied and the illustrated, the deeply abstracted and representational qualities of Black life” can all be found conversing at once.3

For decades, Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) and Betye Saar (b. 1926) have incorporated printmaking as a vital component of their multidisciplinary practices, yet their mutual connection to printmaking remains underrecognized. RINGGOLD | SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix highlights the print work of these two landmark artists, providing a window into the material and conceptual explorations at play in their distinct practices. Both artists have uniquely utilized the matrix—the printmaking surface which transfers ink onto paper or fabric—as a site of possibilities for experimentation, storytelling, and activism.

RINGGOLD | SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix will be the first time the works of Ringgold and Saar are featured together in an exhibition devoted solely to prints. Drawn from the robust print collection of the David C. Driskell Center and supporters of the Center, Meeting on the Matrix juxtaposes over fifty prints, archival materials, and videos illuminating the printmaking practices of both Ringgold and Saar over six decades.

The matrix is any printmaking surface which transfers ink onto another material, such as paper or fabric. It can be a template which allows imagery to be produced multiple times, or it can be a vehicle for a one-off design. All matrices require controlled physical contact to imprint their images onto another material, creating prints. In RINGGOLD | SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix, the gallery space functions as a matrix—a site of contact between visitors and the artists, their prints, imagery, and ideas.

Faith Ringgold is a painter, sculptor, teacher, activist and author of numerous award winning children’s books. Ringgold received her B.S. and M.A. degrees in visual art from the City College of New York in 1955 and 1959. Professor Emeritus of Art at the University of California in San Diego, Faith Ringgold has received 23 Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees. Faith Ringgold is the recipient of more than 80 awards and honors including the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship; two National Endowment for the Arts Awards; The American Academy of Arts and Letters Award and the Medal of Honor for Fine Arts from the National Arts Club. In 2017 Faith Ringgold was elected as a member into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston, MA. Known for her oil paintings from the 1960s and Faith Ringgold’s narrative painted story quilts, she created a body of work in the 1970s that reflected Ringgold’s political activism and her personal story within the context of the women’s movement. Faith Ringgold was one of a very small group of Black women who helped galvanize the Black and Feminist Art Movements in New York in the 1970s. This body of work, including tankas and soft sculptures, led to Faith Ringgold’s painted story quilts. Faith Ringgold is as important to the overall culture of America as she is to the specifics of contemporary American art. From her earliest breakthroughs during the turbulent decade of the 1960s and continuing into the new millennium, Faith Ringgold maintains her stature as a creative and cultural force. She is a role model for artists and scholars and continues to influence and inspire others. Faith Ringgold has been represented worldwide exclusively by ACA Galleries since 1995.

As one of the artists who ushered in the development of Assemblage art, Betye Saar’s practice reflects on African American identity, spirituality and the connectedness between different cultures. Her symbolically rich body of work has evolved over time to demonstrate the environmental, cultural, political, racial, technological, economic, and historical context in which it exists. For over six decades, Saar has created assemblage works that explore the social, political, and economic underpinnings of America’s collective memory. She began her career at the age of 35 producing work that dealt with mysticism, nature and family. Saar’s art became political in the 1970’s namely with the assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima in 1972. As did many of the women who came to consciousness in the 1960’s, Saar takes on the feminist mantra “the personal is political” as a fundamental principle in her assemblage works. Her appropriation of Black collectibles, heirlooms, and utilitarian objects are transformed through subversion, and yet given her status as a pioneer of the Assemblage movement, the impact of Saar’s oeuvre on contemporary art has yet to be fully acknowledged or critically assessed. Among the older generation of Black American artists, Saar is without reproach and continues to both actively produce work and inspire countless others.

View of RINGGOLD SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix at the David C. Driskell Center. March 2023.

Image credit: photo by Greg Staley

View of RINGGOLD SAAR: Meeting on the Matrix at the David C. Driskell Center. March 2023.

Image credit: photo by Greg Staley

“Trying to get the black man a place in the white art establishment left me no time to consider women’s rights... In the 1970s, being black and a feminist was equivalent to being a traitor to the cause of black people”

—FAITH RINGGOLD

Committee to Defend the Panthers 2022 (original from 1970)

Serigraph

All Power to the People 2022 (original 1970)

Serigraph

Portfolio of Declaration of Freedom and Independence

2009

Serigraph, digital print, letterpress

For Whites Only (Funtown is closed to colored children)

Print from Martin Luther King, Jr. Letter from Birmingham City Jail.

2007

Artist book containing eight serigraphs

“I have spent a lifetime listening to the great music of Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, and others. Many of these musicians also lived in Harlem, so, even though they were stars, they were also neighbors. These silkscreens were part of my first jazz series, which I dedicated to Romare Bearden, the greatest of the jazz painters. I could easily spend the rest of my life singing my song in pictures.”

—FAITH RINGGOLD

“The window is a way of traveling from one level of consciousness to another, like the physical looking into the spiritual… It is a way of sharing an inner me, a looking into.”

—BETYE SAAR

Everyday Tumbling

1979

1992

Mystic Sky with Self Portrait

1992

Offset lithograph, collage, construction

LA Sky with Spinning Hearts

1989

Offset printing, silkscreen, stitching

Bookmarks in the Pages of Life 2000

Artist book cover

The Conscience of the Court from Bookmarks in the Pages of Life 2000

Serigraph

“I think the chanciest thing is to put spirituality in art. Because people don’t understand it. Writers don’t know what to do with it. They’re scared of it, so they ignore it. But if there’s going to be any universal consciousnessraising, you have to deal with it, even though people will ridicule you.”

—BETYE SAAR

Committee to Defend the Panthers 2022 (original 1970)

Serigraph

25.75 x 20 in.

Loan from the Collection of Curlee R. Holton

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

All Power to the People 2022 (original 1970)

Serigraph

28 x 19 in.

Loan from the Collection of Curlee R. Holton

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

Portfolio of Declaration of Freedom and Independence 2009

Serigraph, digital print, letterpress

11 x 16 in.

Loan from the Collection of Curlee Raven Holton

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by David C. Driskell Center, 2023.

For Whites Only (Funtown is closed to colored children)

Print from Martin Luther King, Jr. Letter from Birmingham City Jail. 2007

Artist book containing eight serigraphs

11.63 x 8.68 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Collection of Sandra and Lloyd Baccus, 2015.14.001.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2015.

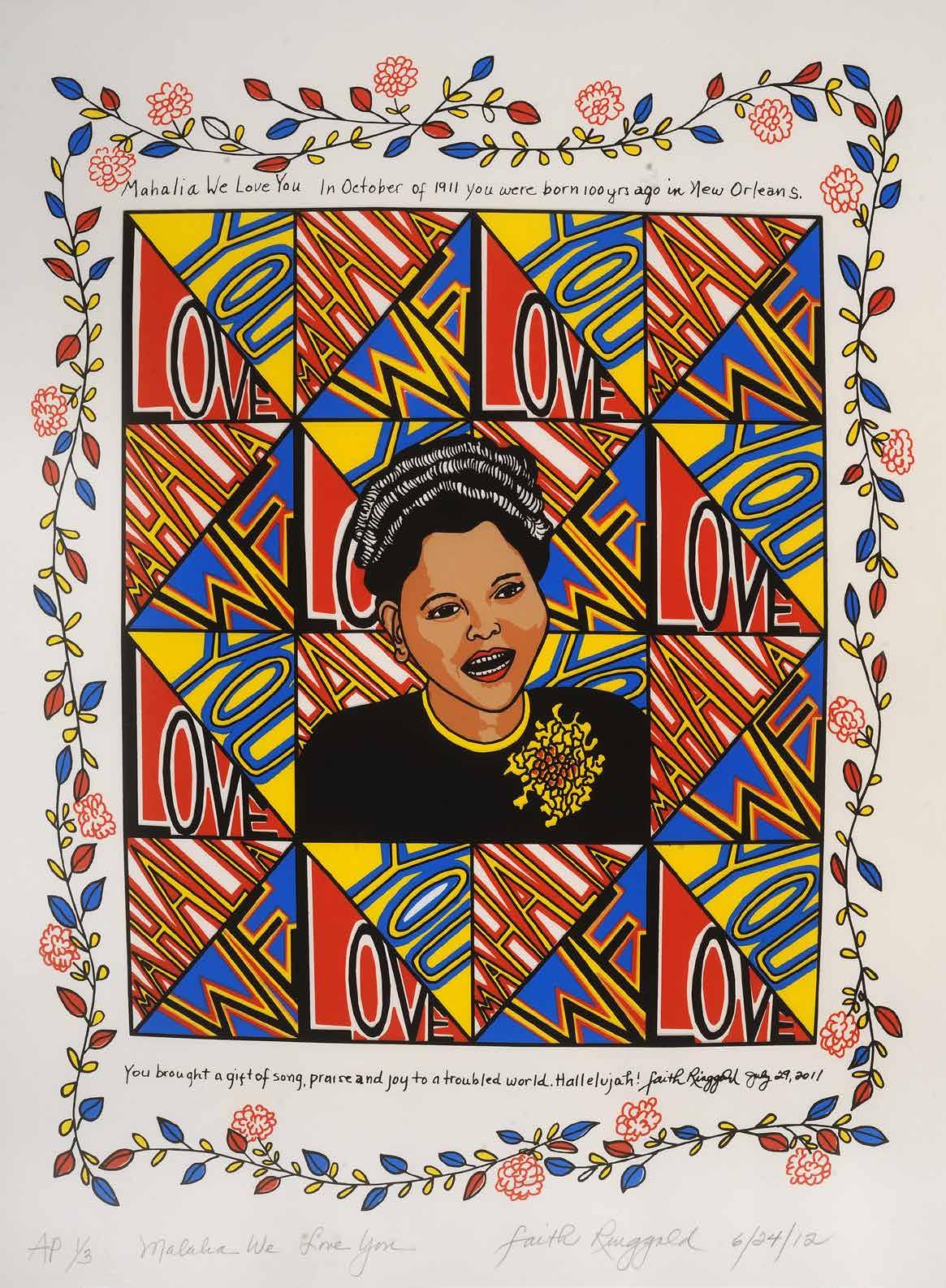

Mahalia We Love You, 6/24/2012

Serigraph

25.25 x 19.25 in.

Permanent collection of the David C. Driskell Center.

Gift from Dorit Yaron, 2017.06.001.

Image credit:Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

Romie We Love You 7/20/2012

Serigraph

19 x 24 in.

Permanent collection of the David C. Driskell Center.

Gift from Che Alexander Holton, 2012.11.001.

Image credit:Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2018

Henry Ossawa Tanner: His Boyhood Dream Comes True 2010

Serigraph

22.25 x 30 in.

Loan from Raven Edition Collection Press.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2023.

Jo Baker’s Birthday, 1995

Serigraph

16.25 x 17.50 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2017.08.017.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2018.

Mama Can Sing 2004

Serigraph

21.50 x 16.50 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Commissioned by the David C. Driskell Center, printed with Prof. Curlee R. Holton at the EPI, Lafayette College, Easton, PA, 2004.01.001.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

Papa Can Blow 2005

Serigraph 21.50 x 16.50 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2017.08.018.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2018.

Wynton’s Tune 2004

Serigraph 28 x 19 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2017.08.020.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2018.

Nobody Will Ever Love You Like Do 2006

Serigraph 24.50 x 18.50 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2017.08.019

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

You Put the Devil In Me 2004

Serigraph 28 x 19 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2011.14.008.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #2: Come on Dance with Me, 2004

Acrylic on canvas with pieced fabric border

80-1/2 x 67 in

Loan form the Collection of ACA Galleries

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY. Photo by Greg Staley, 2023.

Angels Whispering In the Night, 2005 (in collaboration with Grace Matthews)

Lithograph

15 x 25 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2022.04.007.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist, Member of Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and ACA Galleries, NY.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

HooDoo #19, 1992

Mixed media assemblage

9.5 x 7.5 in.

Loan from the Collection of the Petrucci Family Foundation

Image Credits: Courtesy of The Petrucci Family Foundation, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Phil Stein.

Everyday Tumbling 1979

Mixed media assemblage

5 x 7 x 1 in.

Loan from the Collection of Amadi and Monique

Boone

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

National Racism: We Was Mostly ‘Bout Survival 1998

Color offset lithograph

20.50 x 14 in.

Loan from the Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by David C. Driskell Center, 2023.

Alison 1963

Etching

8.4 x 6.5 in.

Loan from the Collection of Julie Farr

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

Jump on One Foot, One Foot, 1984 Oil monotype

25 x 19 in.

Loan from the Collection of Cleophus Thomas

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

Acrobats 1960

Etching

14.50 x 6 in.

Loan from the Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

Untitled (Drawing Study), 1965 Drawing, etching

16 x 9.5 in.

Loan from the Collection of Cleophus Thomas

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022..

Untitled, 1963

Mixed media collage

18 x 15 in.

Loan from the Collection of Kevin Cole

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

Mystic Sky with Self Portrait, 1992

Offset lithograph, collage, construction

21.50 x 25.25 in.

Loan from the Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

LA Sky with Spinning Hearts, 1989

Offset printing, silkscreen, stitching

25 x 29 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from Jean and Robert E. Steele Collection, 2017.08.023.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

Mystic Galaxy 1966

Etching with relief-printed found objects

17 x 8 in.

Loan from the Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore.

Image credit:Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

The Long Memory 1998

Serigraph

14.50 x 11.75 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Courtesy of Steven Scott Gallery, 2012.16.001.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2017.

Bookmarks in the Pages of Life 2000 Artist book cover

16.75 x 12.75 in.

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection.

Gift from the Sandra and Lloyd Baccus Collection, 2012.13.169.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2022.

The Conscience of the Court from Bookmarks in the Pages of Life 2000

Serigraph

11.50 x 7.75 in. edition 15/75

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection. Gift from the Sandra and Lloyd Baccus Collection, 2012.13.170d.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2019.

Now You Cookin’ with Gas from Bookmarks in the Pages of Life Series 2000

Serigraph

11.50 x 7.75 in. edition 15/75

David C. Driskell Center Permanent Collection. Gift from the Sandra and Lloyd Baccus Collection, 2012.13.170f.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

Photo by Greg Staley, 2019.

“I’m always thinking about what can be better. And if you don’t get it out there, the situation will never change.”

—FAITH RINGGOLD“If you are a mom with three kids, you can’t go to a march…but you can make work that deals with your anger.”

—BETYE SAAR