UBT College

Faculty of Integrated Design

“Designing for Emotional Continuity: An Exploration of Adaptive Reuse in Interior Spaces”

Bachelor Degree

Drilon Gashi

June 2023

Prishtinë

UBT College

Faculty of Integrated Design

Diploma Thesis

Academic year 2019/2020

“Designing for Emotional Continuity: An Exploration of Adaptive Reuse in Interior Spaces”

Mentor: Prof. Aferdita Statovci

Drilon Gashi

June 2023

This paper has been compiled and submitted to partially fulfill the requirements for the completion of the Bachelor's Degree.

ABSTRACT

Built environment that surrounds us is not merely a physical space, but also a reflection of our culture, history and emotions. Adaptive reuse of existing buildings is becoming increasingly popular as a way to preserve our architectural heritage while also meeting the changing needs ofsociety. However,this process ofadaptation can oftenstrip abuilding ofits primaryfunction and change its form of use and identity, leading to a loss of the emotional connections that people have with the building.

This paper explores the concept of adaptive reuse in interior design, with a focus on understandinghow the emotionalconnections that peoplehave with buildings can bepreserved during the adaptation process. Through research and case studies, it examines the ways in which a building's past and history can inform and inspire the design of its adaptive reuse, while also considering the practical needs of the new use.

The objective is to delve into an in-depth exploration of the potential for adaptive reuse to preserve not only the physical structure of a building but also its emotional significance and cultural identity. Additionally, it analyzes how adaptive reuse can create new emotional connections with a building, through the design of interior spaces that are mindful to the building’s history, past and context.

This research exemplifies how Rilindja interior spaces could have been adapted applying reuse principles but preserving and respecting the building's past and history, and enabling for the establishment of new emotional connections; while also contributes to the ongoing discussion regarding the significance of maintaining our built heritage and also creating spaces that are meaningful and emotionally resonant for those who use them.

Keywords: adaptive reuse, interior design, Rilindja, emotional attachment.

III

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation and gratitude to all those who have played a significant role in successfully completing my thesis research. I humbly acknowledge the profound impact and influence.

Foremost, I am deeply indebted and profoundly grateful to my esteemed professors for their guidance, expertise, and dedication to my academic development. Their mentorship has expanded my intellectual horizons and instilled a passion for pushing the boundaries of design creativity. In particular, I am indebted to Prof. Statovci for her mentorship and unhesitating belief in my capabilities. Her profound wisdom and encouragement have been a guiding light throughout this arduous journey.

To my family, especially my dear parents and sisters, I am forever indebted to their unconditional love, support, and belief in my potential. Their unyielding commitment to my education, both emotionally and financially, has been a constant source of motivation and inspiration. Their sacrifices and faith in myabilities have fueled mydetermination to persevere and excel. In gratitude, I sincerely appreciate my dear friends, who have been my pillars of support, understanding, and encouragement throughout this journey.

Lastly, Imust acknowledge myself forthe courage,alongthepath, self-doubt andintrospection have intertwined with self-belief and resilience. Through these moments of vulnerability and triumph, I have grown not only as a designer but also as an individual. It is the recognition of my own strength, the perseverance through challenges, and the unwavering belief in my vision that have propelled me forward.

To each individual who has played a part, be it large or small, in my thesis research, I express my deepest gratitude. Your collective contributions, whether in the form of knowledge, support, or kind gestures, have left an indelible mark on my journey. It is through the interplay of intellect, emotion, and human connection that I have been able to weave together the fabric of my research. Thank you, from the depths of my soul, for being a part of this transformative chapter in my life

IV

V CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................VI 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................2 2.1. Who/what are we? 2 2.2 Why do we build?........................................................................................3 2.3 Attachment, in a psychological perspective................................................4 2.3.1 Emotional Attachment and Buildings.......................................................4 2.4. An ever-changing world, need for change. 6 2.5. Adaptive Reuse...........................................................................................7 2.6. Keeping the Building, Losing the Soul. .....................................................9 3. METHODOLOGY..........................................................................................10 3.1. Case study method....................................................................................10 4. CASE STUDIES.............................................................................................11 4.1. Rilindja Tower..........................................................................................11 5. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ..................................................................14 6. CONCLUSION 16 7. PROJECT........................................................................................................17 7.1. Rebirth of Rilindje....................................................................................20 7.2. Materials ...................................................................................................22 7.3. Floor plan..................................................................................................23 7.4. Spaces 24 8. REFERENCES................................................................................................32

LIST OF FIGURES

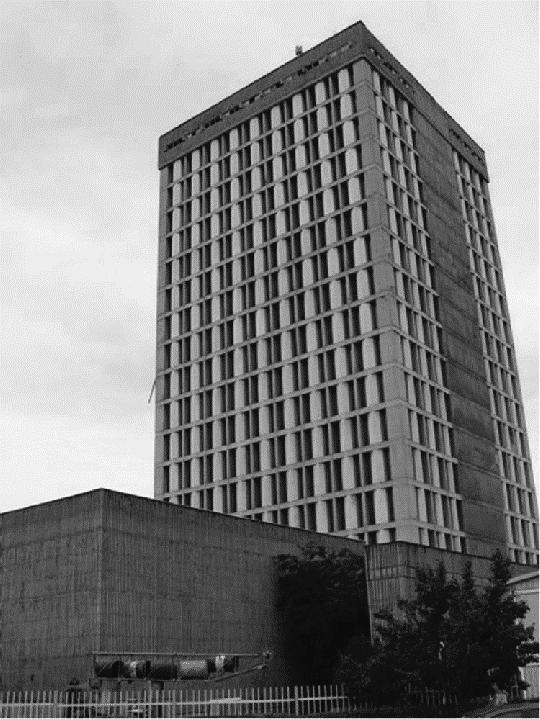

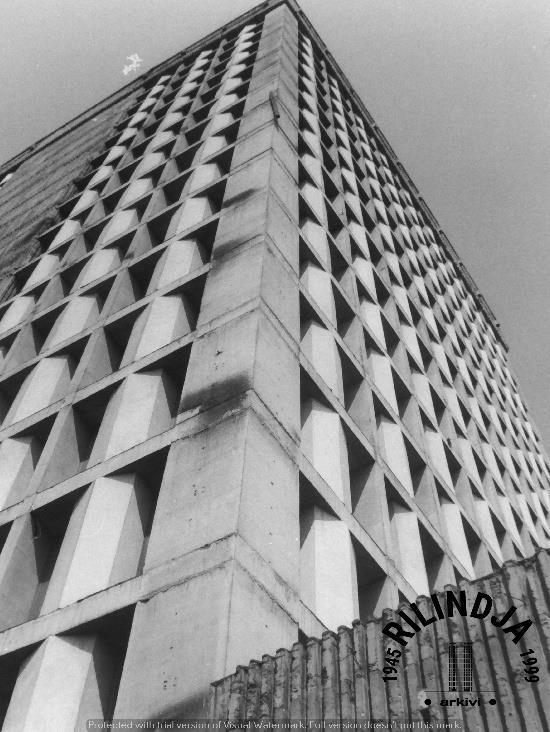

Image.1: Rilindja Printing House Tower. Original design (Photo: Petrit Rrahmani)...........11

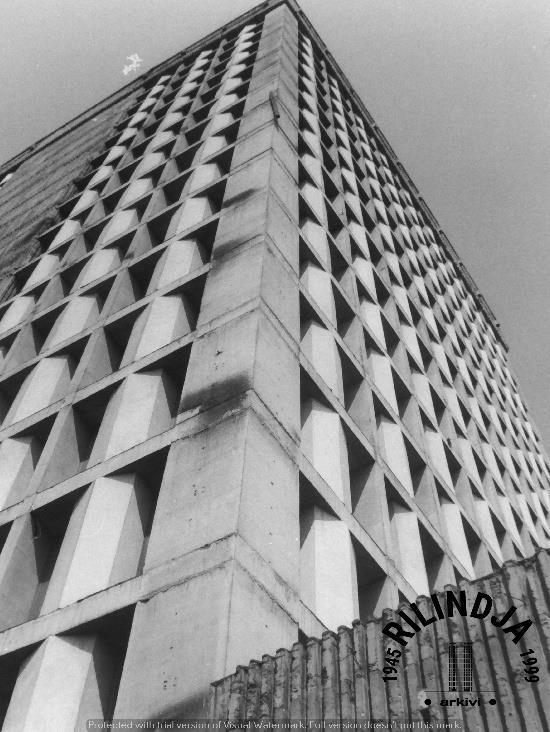

Image.2: Rilindja Printing House upclose. 1981 (Photo: Arkivi Rilindja)

VI

12

13 Image.4: Rilindja

............................................................................................................17

19 Image.7:

20 Image.8: Terrazzo Texture

22 Image.9: Dark Oak Texture (Source: Architextures) ..............................................................22 Image.10: Stone textured plaster (Source: Architextures) 22 Image.11: Floor Plan (Source: Author) 23 Image.12: Main Hall (Render: Author) 24 Image.13:

Image.14:

Author)...................................................................................26 Image.15: Auditorium

Author) 27 Image.16:

Image.17: Exhibit Space (Depicted:

Author) 29 Image.18: Co-working space,

Author) 30

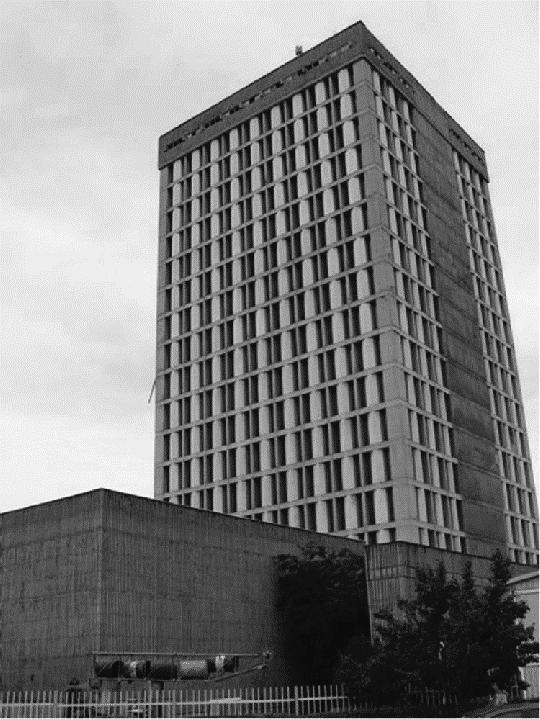

Image.3: Rilindja Tower, after renovation (Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0)

Logo

Image.5: Collage (Source: Ilir Kasneci Archive, Collage: Author)........................................18 Image.6: Prishtina Map in 2022 (Source: Google Earth)

Rilindja Tower Aerial Image (Source: Google Earth, Collage: Author)

(Source: Architextures)

Main Hall (Render: Author)...................................................................................25

Main Hall (Render:

(Render:

Exhibit Space (Depicted: Contaniporary, the Republic of Kosovo Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, Render: Author)..................................................................................28

Permanent archival exhibit, Render:

(Render:

1. INTRODUCTION

When we walk around our cities, it is evident that there exists a clear dichotomy between the old and the new. There are structures whom we have witnessed their birth, and on the other hand there are ones who have witnessed ours. Their standing tells us about the past, while our creations teaches the future about our present.

As inhabitants of our communities we contribute by making, but we also do a great deal of contribution preserving. Adapting and re-using has been a part of human history since its inception, yet in recent times, there has been a heightened awareness and appreciation of the benefits of incorporating adaptive reuse into our designs, architecture, and daily lives. Today the modern world's transformation and the need to adapt can be seen in many examples of our everyday life.

Post-war Kosovo itself was a subject of this rapid change and alteration and I think can be seen as a clear representation of adaptive re-use, even if not done in the best form. Last war caused widespread destruction of homes, cultural heritage sites, and other civilian infrastructure. In some cases, entire neighborhoods were razed to the ground. According to the United Nations, the Kosovo War resulted in an estimated over 1 million displaced individuals; upon returning home after the war, the need to rebuild the country rose. Ground floor apartments turned into shops, old industrial structures turned into offices and different buildings into administrative spaces.

War is not the only thing that brings the need to adopt, revitalizing communities by bringing new life to abandoned or underutilized spaces creates new opportunities for social and economic growth, need for affordable housing and the need for new public spaces, cultural amenities bring to attention the need to adjust and fit the old buildings to the new needs. In the end, our cities and communities are a reflection of our past, present, and future. Old and new they are a reminder of our history and the memories we carry with us. Adaptive reuse gives us the opportunity to keep these memories alive, to breathe new life into old spaces, and to create a better future for ourselves and generations to come. By embracing this approach, we don’t only create sustainable communities but also preserve the sense of belonging and connection to the place we call home.

1

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

To understand the matter at hand, one must understand themselves first. In an interdisciplinary approach, we try to understand our beliefs, values and bias, that make us and our life, we seek to understand our thoughts and emotions, and the profound thing that makes us human, thus to find a way to incorporate the way we are, into the way we build and preserve.

2.1. Who/what are we?

This is a question that has plagued humanity for millennia. The Oxford dictionary defines a human being as a man, woman, or child of the species Homo sapiens, distinguished from other animals by superior mental development, the power of articulate speech, and an upright stance 1

While our planet is estimated to be 4.54 billion years old2, humans as species appeared just over 2 million years ago3, not in the exact form that we see today, but in a form similar to ours. According to the theory of evolution, one of the earliest human forms, Homo habilis or “handyman,” lived about 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago in Eastern and Southern Africa,4 while Homo rudolfensis is thought to have lived in Eastern Africa about 1.9 million to 1.8 million years ago5. Homo erectus, the “upright man,” ranged from Southern Africa to modern day China and Indonesia from about 1.89 million to 110,000 years ago6. It was among this group that the ancestors of modern humans emerged.

Modern human originated in Africa within the past 200,000 years and evolved from their most likely recent common ancestor, Homo erectus7. However, evolutionary theorists are not the only ones who claim to have an answer to where we come from.

We created man from sounding clay, from mud molded into shape…8the holy Quran of the Muslims describes how Allah, their god, created Adam, the first man. The Lord God formed the man from the soil of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being9; the holy Bible of the Christians claims. Some of us; are followers of science and some of theology and ideologies.

2

But ofall things, despite thedifferingperspectives onhumanorigins, oneattributesets humans apart and both parties agree on one thing in common; “distinguished … by superior mental development”. Humans have capabilities that other primates simply don’t. In many forms, we differ; we think, we reason, and we feel; better and stronger than anything else that lives and breathes the earth.

We create complex scenarios and exchange thoughts with others. Other primates live inconspicuously in dwindling habitats, but humans have expanded and changed our surroundings to an astounding degree. It is not our body that differentiates us, it’s our intellect.

2.2 Why do we build?

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs10 puts physiological and safety needs at the base of the pyramid, on which human needs are built. Food, water, warmth and rest are the basic necessities; so practical purposes such as providing shelter and protection from the elements are the reasons the first known buildings were constructed.

After we are reassured that we are safe and sound, we have the need to feel belong and loved, so we create relationships, and make friends; we build communities. We start to divide into groups that share the same ideas, beliefs and values, and we start to attribute buildings to those things; places that serve as communal spaces, where people can gather and socialize, satisfying the need for social interaction and a sense of belonging.

This hierarchy suggests that people are motivated to fulfill basic needs before moving on to other, more advanced ones. It is the fourth level in Maslow's hierarchy - esteem; that refers to the desire for recognition, respect, and self-esteem where we see the construction of significant and impressive buildings that provide recognition and prestige, boost one's self-esteem and sense of accomplishment. Grandiose buildings, lavish palaces and iconic structures demonstrate wealth, power, and prestige, satisfying the need for status and recognition.

At the point of self-actualization, which is the highest level, we comprehend our complete capabilities and the aspiration to persistently progress as an individual.

3

This stage enables us to unlock our creativity and produce original solutions, leading us to establish structures that hold substantial and valuable meaning, providing us with a sense of direction and satisfaction, and empowering us to make a significant and enduring influence on the world.

It has always fascinated me what an important role plays the invisible world of thinking and feelings into the visible, touchable physical world. We turn bricks and mortar into homes, stack rumbles of rocks and worship there. We build because we are humans, and building is a natural human tendency as it is a way for us to shape and create our physical surroundings to meet our needs, desires and beliefs.

2.3 Attachment, in a psychological perspective

Attachment is the affective link that people make with others. Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, posits that attachment is a universal human experience required for survival and well-being.12 13

A deep emotional relationship or connection that a person feels with someone or something is referred to as attachment. This relationship can be developed through shared experiences and memories with that person or object, leading to sentiments of love, affection, security, and familiarity.

Attachment is relevant not only to personal relationships, but also to other parts of life like spirituality, and even objects.

2.3.1 Emotional Attachment and Buildings

It is natural for humans to develop a strong connection to things and places due to the psychological and emotional advantages it confers. Attachment can instill a sense of comfort, security, and familiarity, which are indispensable for our overall well-being and contentment. Attachment theory asserts that attachment is a universal human experience that is necessary for survival and wellness.

4

Various emotions can arise as a result of experiences and memories shared with the object of attachment, thus forming an emotional attachment. Buildings are not exempt from this phenomenon. Theyhave a unique abilityto elicit emotional responses in humans, rangingfrom awe and wonder to comfort and familiarity. These emotional responses are often a result of the emotional attachment that individuals form with buildings.

In fact, buildings often play a significant role in the formation of emotional attachments. For example, childhood homes are often associated with feelings of comfort, safety, and security, leading individuals to form strong emotional attachments to these buildings.

Emotional attachment to buildings can have significant impacts on individuals and communities. Buildings that evoke positive emotional responses can contribute to a sense of identity and pride in a community, while buildings that elicit negative emotional responses can contribute to a sense of discomfort and unrest.

Tim de Lisle, in the Emotional Life on Buildings; an article for The Guardian says that: Buildings can change the way we feel, and the way we see the world. They can make us feel small or large, comforted or intimidated, welcome or excluded.14 they communicate meaning and convey emotions through their design and architecture, and people form emotional attachments to buildings based on their experiences and memories associated with them. If buildings are ever going to be loved, they need to tell stories - about people, about place, and about us. - he says.15

He explores the idea that buildings have the power to shape our emotions and our sense of identity so buildings should be designed to evoke emotional responses, rather than simply functioning as functional or aesthetic objects.

We often say, home is where your heart is, suggesting that home is not necessarily a physical place, but rather a place where you feel emotionally and spiritually connected. It implies that a sense of belonging and comfort can be found in experiences and memories, rather than just a physical location

It reminds us that our sense of belonging and comfort is not always tied to a concrete structure, but can also be found in emotional connections. However, emotions and feelings are experienced internally, we carry them within us.

5

Despite this fact, it is the moment we have to leave that we come to realize that we cannot take memories, experiences, nostalgia with us, they are attached to the buildings we made them in.

This realization underscores the importance of a physical location in the experience of them, alongside the emotional one. In this context, we see that home is a place too, rather than just a state of feeling, and see how these two intimately intertwined, and how the physical world can contribute to the emotional one.

From the beginning of time, it is estimated that over 108 billion people lived on the earth16, as of today, we surpassed the 8th billion and at no point in history have this many people lived at the same time. The current global population of over 8 billion people is a historical peak, and it’s expected to continue to increase in the coming decades. According to United Nations projections, the global population is expected to reach around 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.9 billion by 2100.17 Everyday, we grow; we change.

2.4. An ever-changing world, need for change.

Today, change is the only constant. Rapid advances in technology, shifting demographics, population growth and the changing norms of society are just a few of the forces that are constantlyshapingand reshaping our world. As a result of all this the need for change is greater than ever; whether it is adaptingour lifestyle, the waywe consume, work, reside or even gather and we make interactions with one another; we must be prepared to embrace change if we are to thrive in this ever-changing world.

Essential in this demand for change it’s that we understand that the world is interconnected and mutually dependent; that the world is ours, and not one’s individual needs and desires.

It is to beunderstoodthat subjective necessities can nolongerdefinethewaywelive,eat, build, oroverallexist.Oneofthebiggestchallenges wefacetodayisclimatechange,extremeweather conditions such as floods, droughts, and hurricanes come as a direct result of human ways of living. Burning fossil fuels releases gases into the atmosphere that gradually contribute to an increase in global temperatures and changes in climate patterns. Besides all this, deforestation, land usage, and industrial processes can all contribute to this change in different ways.

6

The impact of these changes on the environment presents a challenge as every day the world is becomingmoreand moreurbanized,with morepeoplemovingto thecities,exertingpressure on urban infrastructure and posing new challenges, such as how to build more sustainable, resilient and livable cities that can accommodate the growing population but also reduce the environmental impact it has.

It is important to bear in mind that our earth’s resources are finite. Some materials can be depleted or become scarce over time due to human consumption and usage. So it's important to note the need to make changes in our consuming behavior. We must utilize the resources we currently possess, we need to adapt our building and living practices to be more sustainable and resource-efficient.

2.5. Adaptive Reuse.

Repurposing existing buildings and structures for a new or different use, rather than demolishing and building new ones from scratch is a practice that offers numerous benefits. The adaptive reuse approach serves new purposes or accommodates new functions on an existing building by renovating, refurbishing, or retrofitting. Adaptive reuse is an environmentally sustainable and cost-effective approach to design, as it can save energy and materials, reduce waste, and preserve historical and cultural heritage. For centuries, people have repurposed buildings and structures for new uses. The utilization of existing structures for new or different purposes is a historical practice that can be traced back to ancient civilizations. While repurposing buildings and structures for new uses has been a common practice for centuries, it wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s that adaptive reuse as a formal approach to architecture and design gained attention, coinciding with a renewed interest in historic preservation, environmentalism, and sustainability. During the 1950s and 1960s, a significant number of historical buildings were being destroyed to create room for new constructions. Architects and designers came to realize the benefits of reusing existing buildings and structures, rather than demolishing them and starting anew.

One of the earliest and most influential pioneers was the architect and preservationist James Marston Fitch. He founded the historic preservation program at Columbia University in 1964, he strongly advocated for the adaptive reuse of historic buildings as a means of preserving cultural heritage, promoting sustainable development, and conserving resources.

7

He believed that the adaptive reuse of historic buildings is an act of sustainability. It allows us to make the most of our resources, reduce waste, and create buildings that are both functional and beautiful.18 Fitch believed that adaptive reuse was an essential approach to architecture and design.

Adaptive use is not about freezing the past, - he says; it's about breathing new life into historic buildings and making them relevant to the present.19

The process of adaptive reuse is intricate and demands meticulous planning, design, and implementation. It necessitates striking a balance between the requirement of contemporary facilities and systems with the imperative of maintaining the historical or cultural importance of the structure. We begin with evaluation of the building to determine its potential for reuse, which may involve a thorough historical or cultural assessment, as well as an analysis of the building’s structural integrity.

Planning involves developing a detailed plan for the adaptive reuse project. Potential uses for the building must be identified, and the scope of the project, budget, and timeline must be determined. Following planning, the design phase begins, in which a comprehensive plan is developed for how the building will be adapted for its new use. This phase may involve modifying the building's layout, adding new amenities or features, and incorporating modern systems and technologies.

Throughout the process, preservation plays a crucial role; if not the most important one, it is important to preserve the historic or cultural significance of the building, because it allows for the building's values to be maintained while adapting it for modern use. Preserving helps we maintain a connection to our cultural heritage and collective memory. Buildings often serve as physical symbols of a community's history and identity, and they can be deeply connected to people’s emotional attachment and sense of place.

When we preserve a historic building, we are not just saving a structure, we are preserving the collective memory of a community. - says James Marston Fitch. The places we value as part of our history are those that have meaning to us, and that meaning is what we seek to preserve through adaptive reuse.20

8

Out of all the steps of adapting, we sometimes give the least importance to the last and most important one. In some cases, developers or designers prioritize the functional aspects of a building over its historic or cultural significance, leading to a loss of identity or character.

When it comes to adaptive reuse, we must be careful not to sacrifice the soul of a building for the sake of function. – he says. The process of preservation is not simply a matter of keeping the structure standing; it's about preserving the meaning and cultural identity of the building as well.21

2.6. Keeping the Building, Losing the Soul.

To destroy a building of significance it’s a crime, but to keep them standing, stripped of their identity and history, covered in beautiful makeup; it is a sin. In many cases this has been done in the name of adapting. They have been changed to an extent that one cannot even recognize them, we have kept the buildings, but lost their souls.

I was born and raised in my city, I have walked, laughed, played, fought, and cried, in the streets filled with structures I can barely recognize now. We are shaped by what surrounds us, so change to this degree estranges us from what nurtured us once, and it leaves us feeling alienated or isolated, feeling emotionally disconnected from places that were once familiar.

The need and desire to fulfill never-ending wants and desires always leads to an architectural massacre.

9

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Case study method

For this research, the case study method will be utilized to explore the concept of emotional continuity in adaptive reuse of interior spaces. The selected case study is the Rilindja Tower in Prishtina, which has undergone significant changes and alterations over the years, resulting in the loss of its original character and identity.

The selection of this case study was based on several criteria, including its relevance to the research topic, its availability of data, and its representativeness of the adaptive reuse phenomenon in Kosovo.

10

4. CASE STUDIES

4.1. Rilindja Tower

The Rilindja Tower is a notable skyscraper located at the heart of Prishtina, the capital of Kosovo, and is considered one of the tallest buildings in the city, standing at a height of 74 meters with 18 floors. The tower was designed by Georgi Konstantinovski, a Macedonian architect who was known for his work on several notable buildings throughout Yugoslavia during the 1970s and 1980s.

The building was constructed during the 1970s as part of a citywide modernization effort under the Yugoslavian government, and it quicklybecame an iconic landmark in Prishtina. The tower served as the headquarters for the influential Rilindja newspaper, which was one of the most important publications in Kosovo at that time. It was also used as a broadcasting center for Radio Television of Prishtina, which was the primary broadcaster in Kosovo.

Image.1: Rilindja Printing House Tower. Original design (Photo: Petrit Rrahmani)

As a symbol of modernity and progress, the Rilindja Tower played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and political discourse in Kosovo. Its distinctive triangular shape and modernist design reflected the Yugoslavian government's commitment to modernizing and developing the city, and it quickly became a recognizable symbol of Prishtina urban landscape.

During the 1990s, Kosovo experienced significant political turmoil andunrest, culminatingin theKosovoWarbetween1998 and1999.Thetower was heavily damaged during this time and remained abandoned and unused for several years after the war ended. After years of neglect following the Kosovo War, the Rilindja Tower underwent extensive renovations in the early 2000s to restore the building to its former glory. However, some critics have argued that the renovations erased much of the building's historical

11

and cultural significance and that the tower now lacks the character and authenticity of the original building.

The renovations prioritized modern aesthetics over historical preservation. The tower's unique triangular shapeandmodernistdesign,whichweresoemblematic of the building's historical significance, were lost in the renovation process. Furthermore, the building's former function as the headquarters of Rilindja newspaper and a broadcasting center for Radio Television of Prishtina has been largely erased, as the tower is now primarily used for commercial office space.

Rilindja has become an important cultural and historical symbol for the people of Kosovo, representing the country's struggle for independence and its aspirations for a brighter future. Today, the tower is not only a hub of commercial and governmental activity and a landmark of Prishtina’s modernization, but it also serves as a reminder of the country's complex history and the resilience of its people in the face of adversity. It’s striking design, complex history and past continues to play an important role in shaping the identity and character of Prishtina.

But, the iconic landmark today can only be related to Rilindja Newspaper, rather than the building itself, asking people around Prishtine not many can direct you to the tower, and only a handful of people of art, history, architecture, enthusiasts or people that worked and lived around, can remember the face Rilindja Tower once had, the brutalist concrete facade. Today, it is covered in large panels of glass; ‘shining clothes’, as Konstantinovski called them himself. After the war and the alterations were made, even he could barely recognize the building he designed.

When asked how would he describe the situation of Kosovar architecture over the years 70-80 hesaid the essence of this question is that with intervention in the Rilindja building, a historical period of architecture has been erased from that time and this is only a small example of the treatment of the architecture of that time.22 Leaving us no wonder to understand the situation.

12

Image.2: Rilindja Printing House upclose. 1981 (Photo: Arkivi Rilindja)

The new intervention they made works22 - he continues, but what has been done is a historical mistake; and not an architectural one. The tower indeed was in need of significant upgrades to meet modern standards. Today, a part of the Government of Kosovo is located there, and this says that I have made an object that can also accept other functions. - says Konstantinovski. Was the best done? Well, time will judge that22. It is not even a decade since the building was renovated, and we’ve come to see that what was done cannot be justified, Rilindja was not upgraded, or ‘renovated’ it was downgraded and stolen its identity.

Rilindja is not the only case, there are many of them, throughout our country; throughout the world, where historic buildings or landmarks have undergone drastic renovations or alterations that have eroded their original identity and architectural significance.

There are countless examples that illustrate the complex and often contentious issues that arise when historic structures undergo renovations or alterations that impact their original design and identity. While such interventions may be necessary to ensure the functionality and safety of a building, they can also erase important cultural and historical markers and raise questions about the appropriate balance between preservation and modernization.

13

Image.3: Rilindja Tower, after renovation (Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0)

5. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Initially, I held a preconceived notion that buildings should be treated with the utmost respect but always retain their original and primarypurpose when I began this thesis. Inow realize that this perspective may come across as selfish. Despite not being an anthropologist, I attempted to comprehend the essence of human existence and our raison d'être, we humans, are quite complex beings. What I think is that we construct buildings not just because we need them, but also because we want to be remembered. We understand that we are mortal and transient on this earth, so we leave our mark, as to say we were here, way before you were.

Buildings are the physical embodiment of our history, culture, and identity. They are a reflection of our past, present, and future aspirations. As time passes, these structures age and many of them become outdated, redundant, or unsuitable for their original purpose, so here the concept of adaptive reuse comes into play.

At first, I was skeptical of the idea of changing the function of a building, as it seemed to go against the principles of preservation. As I delved deeper, I realized that this approach is not onlypractical but also necessaryfor thesurvival of ourbuilt environment. It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. - says Charles Darwin. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change. The world we live in is constantly changing, and we must adapt in order to survive. The same goes for buildings - they too must adapt in order to remain relevant and useful. It is selfish to leave a building to decay and fall apart simply because we are attached to its original purpose. As society evolves and changes, so do our needs and expectations of the built environment.

Adaptive reuse is a way to ensure that buildings can continue to serve a purpose, even if that purpose is different from its original function. It is a way to breathe new life into a structure that mayotherwise have been forgotten and left to decay. Nevertheless, we must also be careful not to erase the history and character of these buildings in the process of adaptation. We must find a balance between preserving their cultural significance and adapting them to meet the needs of the present and future.

14

There are many good cases of adapting, The High Line in New York City is a great example of landscape adaptation. The park preserves the historic character of the railway line while providing a unique green space in the city. The Tate Modern in London, was created by converting a former power station. There we see how the building's industrial character was preserved and enhanced with modern additions. These are just two examples of many where we see how we have succeeded adapting for the new needs but also preserving for the sake of our feelings.

The good and bad can be seen everywhere, Rilindja is a case where the true nature of the building has been changed and converted, rather than adapted and preserved. There are times where there has been no attempt at adapting at all; the Penn Station in New York City, a Beaux Arts masterpiece, was demolished in 1963 to make way for a new station. This demolition of the building would then spark a preservation movement in the city.

It's true that adaptive reuse often involves changing the original function of a building, and sometimes altering its physical appearance as well. This can make it difficult to maintain the emotional continuity that comes with a building's history and cultural significance. However, by carefully preserving and incorporating elements of the building's past, we can create a new sense of emotional continuity that honors its heritage while also adapting to modern needs.

15

6. CONCLUSION

As humans, we have an innate desire to create connections and attachments with our surroundings, and buildings play a significant role in this. We attach meaning and emotions to buildings, as they are often the backdrops to our memories and experiences.

It's important to recognize that both humans and buildings are constantly evolving and changing. In a world where resources are becomingscarce, it is essential that we make the most of what we have and adapt existing buildings to meet our changing needs. Adaptive reuse not only reduces waste but also promotes sustainable development by conserving embodied energy, reducing carbon emissions, and preserving cultural heritage.

In the end, it is a balancing act between preserving the past and creating a future. We can honor the past by preserving the identity and cultural significance of the building while adapting it to meet the needs of the present and future. When a building is adapted to a new function, it doesn't necessarily mean that its collective memory is lost forever. In fact, by preserving the building's unique qualities and incorporating them into its new use, it can create new emotions and memories that are just as significant as the old ones.

Adapting a building can create opportunities for new emotional connections with the community.Byrepurposingabuildingintoaspacethatis usefulandmeaningful,it can become a focal point for social interaction and a source of pride for the community. It can create a sense of ownership and responsibilityfor the building's future, which can strengthen the community's emotional attachment to the building and its collective memory. So in conclusion; when done right, adapting a building may change its function and physical appearance, but it doesn't necessarily erase its emotional continuity. By preserving the building’s unique qualities and creating new emotional connections, adaptive reuse can actually strengthen the collective memory and emotional attachment to a building.

16

7. PROJECT

17

Image.4: Rilindja Logo

Image.5: Collage (Source: Ilir Kasneci Archive, Collage: Author)

18

Re-purposing is often not merely a matter of choice but a necessity born out of the evolution of cities and communities. As we progress and expand, societal norms and functions undergo transformations, leaving an indelible impact on our environment.

Prishtine, a vibrant city in its own right, has been no exception to this remarkable growth. From a population of approximately 70,000 in 1971, it has burgeoned to an astonishing quarter of a million residents in the year 2023. Such rapid urban development demands a thoughtful response to repurpose existing structures, breathing new life into them to meet the changing needs and aspirations of the community.

19

Image.6: Prishtina Map in 2022 (Source: Google Earth)

7.1. Rebirth of Rilindje

Rilindja Tower occupies a prime and strategic location at the heart of the city, positioning it as a significant focal point for urban connectivity. Situated at the intersection of key thoroughfares like Garibaldi Street, Tirana Street, and Kosta Novakivic Street, the tower enjoys unparalleled accessibility and visibility. Its strategic placement facilitates seamless movement and ensures a steady flow of people from various directions, making it an ideal hub for social interaction and cultural exchange. Furthermore, the tower's advantageous proximity to notable architectural landmarks, such as the Grand Hotel, Palace of Youth, and the Newborn Monument, enhances its significance within the urban fabric. These iconic structures, just a short walk away, collectively contribute to a vibrant and dynamic urban environment.

20

Image.7: Rilindja Tower Aerial Image (Source: Google Earth, Collage: Author)

In the realm of architectural conservation and adaptive reuse, the Rilindje Tower stands as a poignant symbol of missed opportunities and the loss of emotional continuity with our built heritage. Though a recent renovation attempted to breathe new life into the structure, it regrettably fell short of respecting its storied past. Stripped of its historical essence, the tower lost its ability to connect with the collective memory of the community it once served. However, within the realm of imagination and visionary design, an alternative narrative emerges - a narrative that speaks of a more meaningful and inclusive approach to revitalization. In envisioning the 16th floor as a vibrant communityart and literature space, mydesign project resounds with the notion of what the tower could have become; a testament to the inherent power of adaptive reuse when executed with utmost care and reverence.

Through my vision, the tower tells a tale of a lost opportunity to create a transformative space that would have fostered a deep and profound connection with its surroundings.

Within the context of repurposing the Rilindja Tower, it is crucial to acknowledge that the transformation into office spaces was driven by a genuine need to accommodate the evolving demands of the city. However, reflection upon the project prompts contemplation on what could have been done differently to honor the tower's original essence.

One key aspect lies in staying true to the authenticity of the building's design and materials. Concrete, as the fundamental component of its construction, holds both historical and aesthetic significance. Embracing and preserving the original elements would have ensured a seamless continuity with the towers past, fostering a stronger emotional connection to its heritage.

Furthermore, when replacement materials were necessary, a more thoughtful approach could have been taken to select materials that evoked the same sense of timelessness and emotional resonance. For instance, replacing the carpet with terrazzo flooring could have upheld the tower's character while offering a practical advantage in terms of ease of maintenance. Terrazzo, with its unique blend of durability and artistic flair, has long been associated with iconic architectural landmarks, and its implementation would have added a touch of elegance and longevity to the redesigned spaces.

By recognizing the value of the original plan, materials, and their inherent emotional significance, a better approach to the tower's redesign could have been achieved. Such an approach would have not only respected the building's architectural heritage but also allowed for a deeper connection between its past, present, and future, fostering a sense of emotional continuity that would resonate with the community.

21

While the building may have originally featured carpeting, opting for terrazzo flooring during the adaptation process wouldbehighlyadvisablefor several reasons. Firstly, terrazzo offers exceptional durability and longevity. Considering the high foot traffic that a community center is likely to experience, choosing a flooring material that can withstand heavy use and frequent cleaning is crucial. Choosing terrazzo flooring for theproject would not only be considering the practical benefits but would also acknowledge and respect the building's heritage.

Dark oak flooring symbolizes a harmonious blend of history and modernity. Inspired by the building's past constructed in the1970s, darkoak embodies timeless elegance and pays tribute to the time it was build. With its warm hues and durable nature, this material sets the stage for a vibrant and inviting community art and literature center, bridging the gap between tradition and contemporary creativity.

22

7.2. Materials

Image.8: Terrazzo Texture (Source: Architextures)

Image.9: Dark Oak Texture (Source: Architextures)

Image.10: Stone textured plaster (Source: Architextures)

23

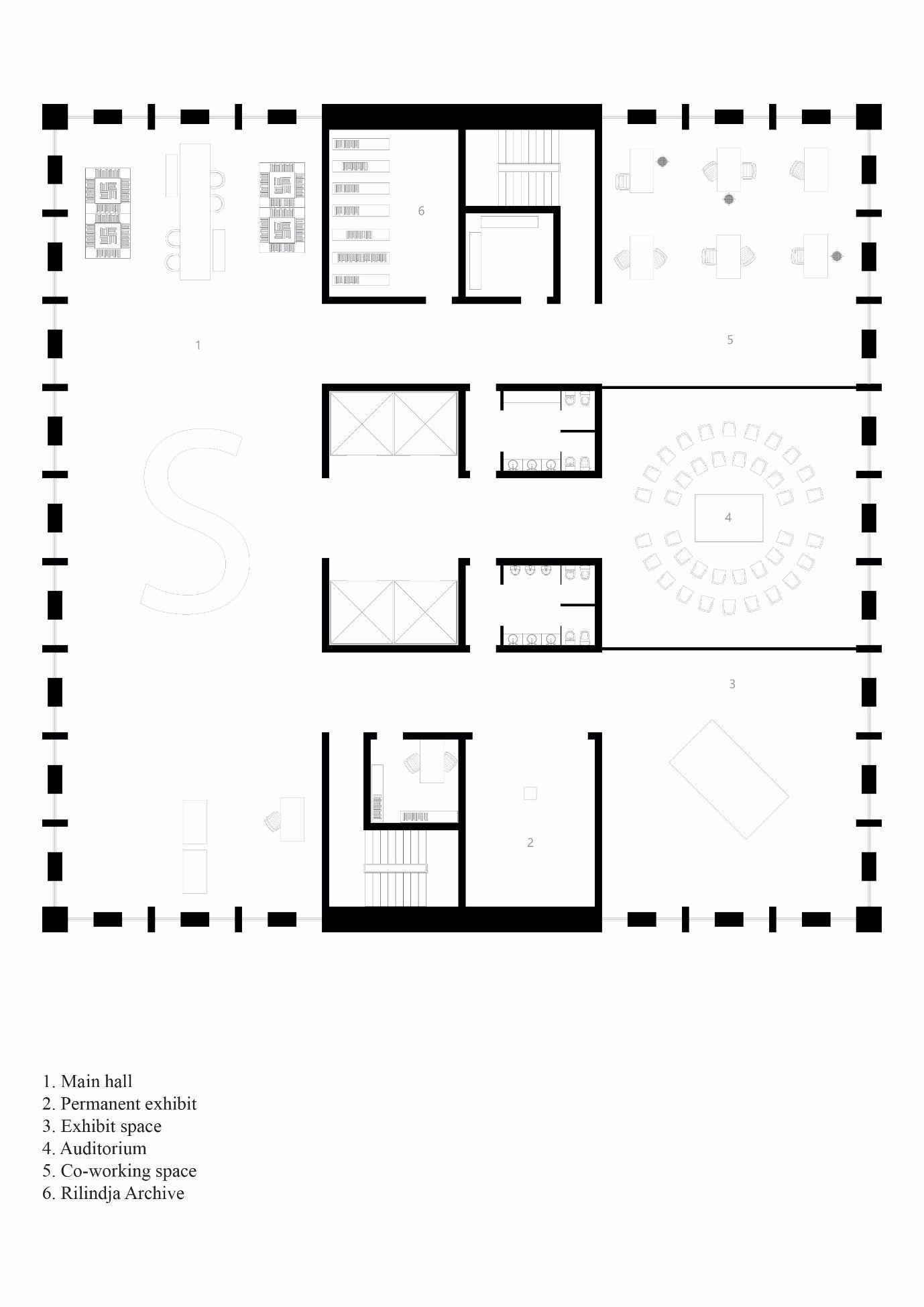

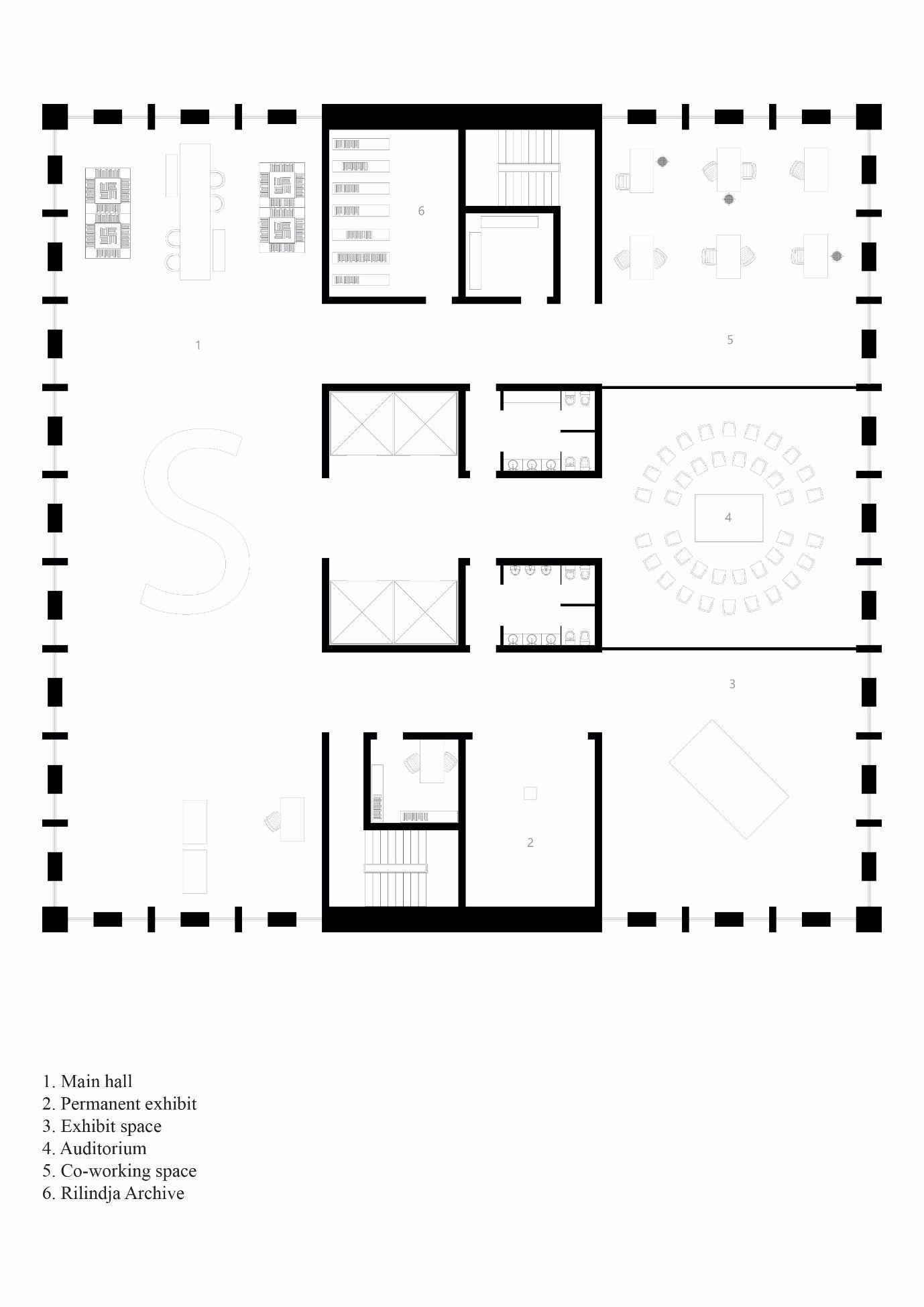

7.3. Floor plan

Image.11: Floor Plan (Source: Author)

7.4. Spaces

In the heart of the redesigned Rilindja Tower, a captivating main space unfolds, blending the nostalgic echoes of its printing heritage with the spirit of creativity. As one enters this multifaceted area, a sense of reverence permeatestheair, atributeto theTower's rich past as the place of Rilindja Newspaper. The siting area welcomes visitors with comfortable seating arrangements, inviting them to unwind, engage in conversation, and immerse themselves in the ambience of literary appreciation.

24

Image.12: Main Hall (Render: Author)

Adjacent to the sitting area, a dedicated reading area beckons with shelves lined with carefully curated books, celebrating the written word in its myriad forms. Here, amidst the soft glow of light, book lovers can lose themselves in the immersive world of literature, connecting with diverse narratives and exploring the depth of human imagination.

25

Image.13: Main Hall (Render: Author)

In the workshop area - a homage to the art of printing and bookmaking is payed. Stations equipped with specialized tools and materials cater to the needs of creative enthusiasts seeking to delve into the realms of printing techniques, zine production, and bookbinding. Workshops conducted by skilled artisans and artists inspire participants to master the craft, cultivating a community of book lovers and creators who revel in the tactile beauty of paper and ink.

A subtle aroma of ink and freshly printed pages lingers, evoking a tangible connection to the past while invigorating the present. In this captivating main space, the essence of paper and printing intertwines with the spirit of artistic exploration, fostering a haven for bibliophiles, creative souls, and seekers of knowledge.

26

Image.14: Main Hall (Render: Author)

In a nod to the dynamic nature of intellectual exchange and engaging discussions, the auditorium space within Rilindja Tower takes on a unique and inclusive design; a circular forum arrangement centered around a traditional rug, evokinga sense of unityand collaboration. This innovative layout encourages participants to gather in a circular configuration, symbolizingequalityandopen dialogue. As attendees find their places, the seating arrangement envelops themin asense of togetherness, eliminating hierarchical boundaries and emphasizing the importance of every individual's voice. The circular design fosters an atmosphere of inclusivity, where ideas flow freely and participants feel connected on an equal footing. This distinctive auditorium space is a testament to the Tower's profound legacy of intellectual discourse and further inspires meaningful conversations within the space.

27

Image.15: Auditorium (Render: Author)

The exhibit space within Rilindja Tower stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of political activism and artistic expression. In an act of protest and cultural empowerment, the space annually showcases the prestigious Kosovo Venice Biennial artwork, bringing the acclaimed pieces to the local community who are unable to travel to Venice due to visa restrictions. Bydisplaying these artworks, Rilindja Tower boldly asserts theright of Kosovarpeopleto experienceand appreciate their own cultural heritage, makingapowerfulpolitical statementagainst external barriers. Alongside the Biennial showcase, the exhibit space also hosts a variety of other exhibitions throughout the year, fostering dialogue and celebrating the diverse expressions of human creativity.

28

Image.16: Exhibit Space (Depicted: Contaniporary, the Republic of Kosovo Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, Render: Author)

Adjacent, a projector brings scanned archival works of Rilindja to life. Through the projector's display, vivid images and captivating headlines adorn the walls, offering a glimpse into the newspaper's significant influence on Kosovo's political, social, and cultural landscape. In this room, thetowerhonors thelegacyofthepublication and provides an opportunity for visitors to engage with the timeless narratives and visuals that have shaped the collective memory of Kosovo. Within Rilindja Tower, a dedicated space now houses Rilindja Archive. This area safeguards historical treasures such as original newspapers, photographs, and manuscripts, signifying a poignant tribute to the lasting impact of the publication. By preserving these invaluable materials, the archive becomes a vital resource for researchers and historians, immortalizing Kosovo's socio-political narrative.

29

Image.17: Exhibit Space (Depicted: Permanent archival exhibit, Render: Author)

Acknowledging the ever-changing needs of the community, an energetic co-working space has been integrated within the confines of Rilindja Tower. This inclusion demonstrates a progressive mindset, attuned to adaptabilityand collaborativeefforts in the contemporary era. The space acts as a central nexus for entrepreneurs, freelancers, and creative individuals to convene, motivate one another, and cultivate groundbreaking ideas. An environment that encourages interdisciplinary collaboration, nurtures a sense of togetherness and offers unwavering support for individuals to engage in their work, expand their networks, and prosper. With its focus on versatility, ingenuity, and collective advancement, the co-working space truly embodies the ethos of Rilindja Tower as a vibrant catalyst for progress and empowerment.

30

Image.18: Co-working space, (Render: Author)

In conclusion, my design project for Rilindja Tower represents a respectful homage to the building's rich history and the vision of its original architect, Georgi Konstantinovski. Rather than extensively altering the structure, I aimed to enhance its inherent character by carefully preserving and reimagining its spaces. Bypayingtribute to the building's past, mydesign seeks to honor the legacyit carries, allowing it to gracefullyevolve and adapt to contemporaryneeds.

In the process of renovation, I believe they should have chosen not to mask the building with superficial enhancements, but rather to reveal its authentic essence. Like when borrowing a book from a library, I believe we should enter old buildings with a sense of reverence, quietly and respectfully revitalizing them, and leaving them ready for the next generation to cherish. When we borrow a book, we read it, we use it, but we do not annotate it, it’s not ours to do it.

In the course of my research and design exploration, I have come to deeply contemplate the ever-changing world we inhabit. It has become evident to me that our planet is not simply a collection of individual needs and desires, but a shared heritage that belongs to all of us. We are interconnected, bound by the responsibility to preserve and nurture the spaces we occupy, not only for our own benefit but for the generations yet to come.

As architects and designers, we should better understand that we are temporary custodians of the built environment. Like guests on this Earth, we have the privilege and dutyto tread lightly, leaving a positive imprint during our brief presence. It is our role to carefully consider the impact of our actions, both in the renovation of existing structures and in the creation of new ones.

While some may perceive my approach as blending into the background or being overly attentive to the building's past, I believe that in the face of rapid urbanization, evolving societal needs, and environmental challenges, it is essential to sometimes embrace a selfless perspective.

Ultimately, our purpose as architects and designers goes beyond individual achievements. You know - David Chipperfield says; isn't it valid for an architect to suppress their ego for a while and polish somebody else’s? It is about recognizing our place in the grander scheme of things and acknowledging the interconnectedness of all life on Earth. By designing with empathy, respect forhistory,and acommitmenttosustainability,wecancontributetoamoreharmonious coexistence between humanity and the built environment. Through our designs, we can strive to create spaces that honor our collective past, cater to our present needs, and inspire a sustainable and inclusive future.

31

8. REFERENCES

[1] Oxford Dictionary of Terms

[2] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/resource-library-age-earth

[3] https://www.history.com/news/humans-evolution-neanderthals-denisovans

[4] Leakey, L.S.B., Tobias, P.V., Napier, J.R., 1964. A new species of the genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge. Nature 202, 7-9.

[5] Alexeev, V.P., 1986. The Origin of the Human Race. Moscow, Progress Publishers.

[6] Dubois, E.,. 1894. Pithecanthropus erectus: eine menschenaehnlich Uebergangsform aus Java. Batavia: Landsdrukerei.

[7] https://www.yourgenome.org/stories/evolution-of-modern-humans/

[8] Quran (15:26)

[9] Bible Gen. 2:7

[10] Maslow’s hierarchy

[11] Rodger Kamenetz

[12] Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

[13] Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

[14] De Lisle, Tim. "The Emotional Life of Buildings." Intelligent Life, Summer 2013, pp. 8489.

[15] De Lisle, Tim. "The Emotional Life of Buildings." Intelligent Life, Summer 2013, pp. 8489.

[16] “How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth?" Population Reference Bureau, 2011. Accessed 21 March 2023.

[17] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423).

[18]Fitch,JamesMarston."TheGreeningofHistoricPreservation."APT Bulletin:TheJournal of Preservation Technology, vol. 37, no. 3, 2006, pp. 19-23.

[19] Fitch, James Marston. Historic Preservation: Curatorial Management of the Built World. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990. Print.

[20] Fitch, James Marston. "Preservation: A Timeless Concept in Changing Times." APT

Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology, vol. 23, no. 4, 1992, pp. 5-10.

32

[21] Fitch, James Marston. "The Power of Adaptive Reuse." Traditional Building Magazine, vol. 11, no. 3, May-June 1998, pp. 54-57.

[22] Modernizmi Kosovar – NjëAbetare e Arkitekturës / Intervistame Georgi Konstantinovski

/page.135

33