OliviaShao MarkvonSchlegell PaulChan

For all the fathers who took the spaceship.

Laura Hoptman

It defies reason to think that we are alone in this universe or the universes that surround us. Even those with no access to scientific discoveries understood this, so speculation on the issue is universal in visual culture. Artists—often aliens in their own cultures—have frequently depicted extraterrestrial images from myth and fantasy, from flying saucers to green humanoids with antennae. This is not a show nor a publication about these kinds of images. Rather, Voice of Space looks at the phenomenon of UFO sightings as a universal metaphor for contact between the known (the self, in many cases) and the unknown (the Other in any guise).

Instead of esoteric and spooky, the works on paper in Voice of Space are open and inquiring; some have religious overtones; others delve into the fascinating study of alien qualities in natural phenomena. Still others are diagrammatic depictions of not only what was seen but also how to see what has, heretofore, been hidden from us. Taken together, the group of drawings from vastly different time periods and cultures offers a speculative essay in images, exploring a fundamental mystery of human perception that can only be met by the powers of the human imagination.

This flying saucer–less exhibition and publication, then, might not offer answers to impossible questions like, “Are we alone in the universe?” but they do address quotidian and arguably more important life-affirming ones, like, “Can art tackle the mysteries of human existence?” Immersing oneself in each of the speculative, hilarious, sobering, mad works on paper that make up this show proves that the answer is yes.

Voice of Space contains artworks made over the past century, yet it is still a very contemporary exhibition. We are particularly grateful to those supporters who realized the relevance of a discussion about the unknown in our universe and beyond, including Stephen Cheng, Kent Shao, the Teiger Foundation, Sarah Arison, Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, and Laurie and David Wolfert. The Drawing Center also thanks the lenders to this exhibition (mentioned elsewhere) and the experts who helped Olivia Shao, the curator of the show, with her research. All of these individuals and entities care deeply about contemporary visual art and The Drawing Center’s mandate to share contemporary drawing and contemporary ideas with our public. We thank them profoundly for their belief in this exhibition, one that is fundamentally about belief—not in little green men, but in the power of art as a mode of inquiry and, ultimately, as a force for the good of humanity.

Olivia Shao

My deepest appreciation to all the artists and their visionary work. I would also like to thank the amazing team at The Drawing Center for their help, with special appreciation to Laura Hoptman, Izzy Kapur, Doruk Eliacik, Rebecca Bonini, Sarah Fogel, and Aaron Zimmerman.

The works in Voice of Space come from essential lenders, and their important participation makes this exhibition possible. My thanks go to Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller, for their generosity and insight, Peter Currie, and the team at Galerie Buchholz—Katharina Forero, Tonio Kröner, and Friederike Gratz; Matthew Marks Gallery; Stephanie Dorsey, for her patience and massive help; Florence Bonnefous at Air de Paris; The Peggy Guggenheim Foundation; Eden Deering at PPOW Gallery; Andrew Edlin, for his generosity; Anna Tripamer from the Walter Pichler Estate; Paula Tsai and Vesper Lu from Gladstone Gallery; Eleanor Cayre; Susan Harris; Alexander Gorlizki; Gisela Capitain and Marco Zeppenfeld at Galerie Gisela Capitain; Robbie Fitzpatrick and Fitzpatrick Gallery; Donald Ellis, for his invaluable insight; Andrew Kreps Gallery; Oskar Weiss; Garth Greenan Gallery; Goodman Gallery; Lucy Mitchell-Innes; Claudia Ascott from the Roy Ascott Estate; Edward Shanken; Mark Feldman, Marco Nocella, and Burcu Oz at Ronald Feldman Gallery; Victoria Miro Gallery; Gordon VeneKlasen; and Christian Schmidt from Eva Presenhuber. Paul Chan’s and Mark von Schlegell’s thought-provoking texts in this catalogue add an important context and dimension to the exhibition. Thanks also to the wonderful team at Pacific for the design of this book. A special thank you to Rich Aldrich, Stephen Cheng, Trisha Donnelly (for our endless conversations and letting me use your words in the dedication), Alex Lau, Kathy Halbreich, Jutta Koether, Annie Ochmanek, Tony Oursler, Jay Sanders, Michael Sanchez, Phillippa Shao, Kent Shao, Anita Shao, Chiu Yuk Tung, John Zorn, the UFO club: Arias Abbruzzi Davis, Elise Duryee-Browner, Danny Dixon, Ryan Foerster, Brad Kronz, Claire Lehmann, Adam Putnam, John Sandroni, Enzo Shalom, and anyone I might have accidentally forgotten.

Mark von Schlegell

“This, then, is to be remembered—the form of an enchanted thing is a fiction and a caprice.”

—W.

B. Yeats, “The Irish Fairies” (1888)

August 17, 1977: Varied witnesses report two round or cigar-shaped objects seen passing in tandem along a zigzagging line through the Connemara hills, eventually disappearing over the horizon of the western ocean. To call them hills is a mistranslation. These volcanic mountainlings loom into astonishing, dreamlike vistas, breathing fog, rainbows, sunsets, and wicked storms.

In my mind, the two sliding chrome or shining white (reports differ) modernist minimal objects set off perfectly the paranormal romanticism of the Connemara sublime. There are no pictures, only witness accounts. But having spent childhood summers in 1970s Ireland, a good deal in the west, I found myself particularly haunted by this sighting. It was as if I could picture these objects more clearly than my real memories of those unreal landscapes.

In 1977, ufology was at a high point. For three decades, a minority of “enthusiasts” and “crackpots” had built up stubborn networks for information gathering and exchange, even against a barrage of mockery, fraud, and hoax. Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind opened that year and introduced ufology to the mainstream. But after that high mark, despite the growth of abduction lore in the 1980s and 1990s, very little progress was made toward anything like proving or understanding an alien presence on Earth. As the 1970s spiritualism faded into 1980s corporate chic, the subculture was clearly in decline.

Then came December 17, 2017. The front-page story “Glowing Auras and ‘Black Money’: The Pentagon’s Mysterious U.F.O. Program” jump-started ufology from the front page of The New York Times. Freelance

enthusiasts Leslie Kean and Ralph Blumenthal joined Times Pentagon correspondent Helene Cooper to trace a real $22 million government black fund for the investigation of UFOs. But the fund was not the article’s only news. It went on to describe and confirm the legitimacy of three leaked videos from the US Navy. With apparent, if unstated, government sanction, new viral archetypes “Tic Tac,” “Gimbal,” and “Go Fast” have mainstreamed the phenomenon again. Curiously, though recorded on the most expensive, accurate cameras in the world, the videos entirely maintain the fuzzy, ambiguous aesthetics of the flying-saucer subculture, continuing to weave the real with the dream and the hoax.

The US military’s tacit takeover of ufology remains impossible to interpret. Now, a new language was being imprinted, as if from above, on the collaborative, self-published, extra-capitalist subculture that had created and promoted this particular imaginary. A 2023 US Senate hearing of intelligence officer David Grusch’s testimony concerning the Pentagon black projects suddenly promoted the designation UAP over UFO and NHI (nonhuman intelligence) over ET (extraterrestrial). The latter changes brought into the record speculation that UFOs may originate from inside the Earth, or from under the ocean, or that ETs may have been visiting the surface for so much of Earth’s history that they constitute a feature of it.1

None of these ideas were original. Many can already be found lurking in Jacques Vallée’s Passport to Magonia, the ufology classic that has adorned the shelves of a million used bookshops ever since its 1969 publication, proposing and giving evidence for a deep, historical, fully global phenomenology of UFOs, going back to the wheel of Ezekiel and beyond. “Especially interesting to us will be the fact that these reports of celestial objects are linked with claims of contact with strange creatures, a situation parallel to that of modern-day UFO landings.”2

Reading the book with Connemara 1977 in mind, I was astonished to see how much of Vallée’s research draws on the Irish imaginary tradition. And virtually all of this research from a single, albeit multi-sourced volume: 1911’s anthropological oddity, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries by Walter Y. Evans-Wentz.

Vallée cites Evans-Wentz more than sixty times in Passport, often transferring entire anecdotes whole. And Passport has been so influential that, today, we can recognize the fairy faith resonating all over ufology, from journalist John Keel researching the Mothman Prophecies in 1975 in Pennsylvania, to billionaire Robert Bigelow spending pentagon dollars

investigating mischievous entities on Skinwalker Ranch in the 1990s, to the so-called “4Chan leaker” of 2023 who anonymously posted a story about an alien drone factory going about the ocean floor printing UFOs for shape-shifting abductors preying on common people and their farm animals.3

Raised by nineteenth-century Theosophists in New Jersey, Evans-Wentz went to Stanford to study anthropology. Thrilled by visiting lectures from religious theorist William James and Irish poet and visionary W. B. Yeats, he resolved to study the Celtic religions properly. From 1906 until 1909, young Evans-Wentz tramped about the whole of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, collecting lore on the ground for his Oxford PhD. He was by no means the first to do so. A generation earlier, late Victorians like George MacDonald (Scottish fantasist), Lady Jane Wilde (Oscar’s mother), Yeats himself, and Douglas Hyde (Evans-Wentz’s thesis advisor) had been publishing popular collections of gathered folklore. Their work helped inspire an Irish cultural renaissance and the 1916 political rising that would fatally challenge English control of Éire.

The book is passionately dedicated to Yeats and Æ (George W. Russell), fairy painter, poet, Theosophist visionary, labor organizer, and activist. Under the spell of, but perhaps misunderstanding, their mystical take on the Irish experience, Evans-Wentz gathered his material when London and Dublin intellectuals believed spiritualism had been proven true. Consequently, Evans-Wentz adopted a blind rationalist faith in the reality of the psychical experiences he collected, entirely convinced that “there is a spectral reality of spirits scientifically proven.”4

The resulting respect for his interlocutors and their visionary powers means that their stories are often preserved enough to undermine later interpretations of them. After associating flying saucer sightings with “the discovery of circular depressions, on the ground,” Vallée cites The Fairy Faith as if it shows similar patterns:

One Sunday in August, as he wandered over the hills of Howth, Wentz met some local people with whom he discussed these old tales. After he had tea with the man and his daughter, they took him to a field close by to show him a “fairy-ring,” and while he stood in

the ring, they told him: “Yes, the fairies exist, and this is where they have often been seen dancing. The grass never gets high in the lines of the ring, for it is only the shortest and the finest kind that grows there. In the middle, fairy-mushrooms grow in a circle.”5

Neither of our psychic anthropologists quite realizes that the story is being told up against metropolitan Dublin, only a stroll from the last stop of the very “Howth Tram” Stephen Dedalus rode into town back on Bloomsday, 1904. Or that “fairy-mushrooms” might be something of particular interest here themselves.

Character-rich, dramatic, speculative, creative, the storytellings in Evans-Wentz’s volume become their own message, and we must note that every new speaker provides a different, unique theoretical perspective on “The Good People” and their “Otherworld.” Every tale has variations, and every variation its own tale. Evans-Wentz’s belief in the reality of the parallel world somehow better transfers storytelling itself as a living literature, not only for the release of psychic tension but also for creative engagement with a cruel, mystically beautiful environment, and for the deconstruction of oppressive, ideological control thousands of years old.

In his very useful Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky, Carl G. Jung, first and foremost, classifies the flying saucer as an archetype of the “mandala” symbol of “union” that “encompasses, protects, and defends the psychic totality against outside influences and seeks to unite the inner opposites.”6 No wonder, then, that the 1977 object could seem so easily to serve as a passport into Tír na nÓg—the “Otherworld” I had heard reported just over the western ocean horizon, linking me back to some totality I once believed in.

I decided to return again and to investigate. Like Evans-Wentz, and Yeats before him, I would find the “real” Irish, their perspective on the 1977 sighting, and, if possible, further uncover the relation of the UFO to the fairy faith.

After some fruitless weeks visiting the scenes, I was stonewalled. I’d only proven that no records or images could be found. I decided my ’77 saucers (or cigars) were very likely lost to time. But then, in the remote village of C., pressed up against the Wild Atlantic Way, I got lucky.

“You’ll be looking for Pádraig Niall, a regular down at the pub,” my

host told me, not without amusement. “He sees the saucers.”

The Irish-speaking locals at the bar abruptly fell silent when we entered and went so far as to leave when we sat down at a table by the fire. After ordering dinner, I asked the barkeep if there was a Pádraig Niall around. She gruffly shrugged and retreated. It was only then I noticed, to my surprise, a local still remained in the corner. The fifty-something localin a puffy jacket and baseball cap lifted his empty glass. “I’m your man. Are you here to interview me about saucers?”

He told the story as if he’d memorized it. “I was seven years old in 1979, in the back seat of my aunt’s car. She was singing with my cousin, whilst in the back, I was looking out the window at these sliding, silver— jewels—slipping over the lake. When a story went about the next day about flying saucers over Ballynahinch and then over Glassilaun Strand, I said ‘I saw them moving over the lake.’ But ever after, it’s gone about that I see things, which I do. So I’ve studied up on the phenomenon.”

“Do you remember them as saucers? Or cigar-shaped?”

“The cigar and the oval. C. G. Jung says: ‘When one appears, then comes its partner.’7 I thought a cigar could just be a cigar. Now, it’s a Tic Tac? What does the analyst reckon that may sign? The truth is, I don’t know what I saw that day and couldn’t tell you. With UFOs, the child is an unreliable witness.”

And so I met the learned Pádraig Niall Ó Súilleabháin, the village’s leading authority on the UFO and its relation to the old fairy faith of Ireland, as well as on Gaelic football and its significance to the history of Earth-sport.

I mentioned the famous 1992 sighting at the fairy-named Ariel School in Ruwe, Zimbabwe, in which sixty-two children under twelve reported seeing two silver objects land behind their school and emit uncanny occupants with telepathic messages about the endangered environment. Tele-investigated by Harvard ufologist (and Evans-Wentz citer) John C. Mack, the rare mass-sighting remains one of the most pored-over cases in history.

“There has to be a story,” Pádraig said. “I heard the rumor that hippies were camping the night before by the Ariel School, and they had driven their silver Econoline vans off-road to camp for the night. Yes. That story works. These were upper-class suburban kids who hadn’t seen Western-style hippies before. It explains why the aliens delivered their important message only to children.

“I watch sheep by day. With the colors of Sligo Rovers Football Club on their backs, they are perhaps the least visible in the country. I can pick them out in any weather at any distance. Even a sheep, a white and colored thing high up a mountain, can become something it may not have been before. But what it becomes must have its own reason to be there.”

As locals began to return for the game, the enormous digital live display reminded me that Ireland is perhaps the most wired of all European nations, with 5G towers standing like sinister alien sculptures among the ancient stones of the countryside. The Irish-speaking communities may be tight-knit and unwelcoming toward strangers, but they’re in streaming touch with strong, global Gaelic networks.

Pádraig refused to comment again on the ’77 sightings. But when asked if he believed in the existence of the sidhe (“the Gentry,” “Good People,” or “Fair Folk” [hence “fairies”]8), he immediately answered in the affirmative.

“My aunt saw a little princess, who’d caught her pretty wing on a briar. As big as a dragonfly. She helped her get free.”

Was it possible that UFOs could be responsible for some of the lore?

“There have been reports of at least one faction among the sidhe being from another star system. But you must understand, the alien is often less interesting than the things that are already populating our paranormal: the pookahs, banshees, wee shoemakers, witches, the lunantishees that guard the blackthorn trees, your various merrows, your dead Irish queens and heroes—not to mention rogue druids managing dimensional shifts with their brass-works. Of course, this is a land thick with ghosts, as well. No, ‘you can not lift your hand,’ says Yeats, ‘without influencing and being influenced by hoards.’9

“Invisibility can be seen. I once traveled to Glendalough to investigate the upper lake there, near where St. Kevin is said to have resided. There is a curse on that place. I had binoculars and stayed for seven hours. I saw not a single bird or dog dare penetrate the invisible barrier.

“Sidhe simply means ‘hill,’ originally. But our land is so alive and full of poetry that it became the name for those who made them, and still live within them. You’ll mind many of the tales involve particular hills or rises in the ground, or ponds or loughs. Particular haunted shrubs abound,

and many other natural freaks. Our tales are psychic mappings across ever-changing boundaries, property lines, place names, and way-markers. They are quantum-mechanical with respect to possibility and observation, and relativistic with respect to space and time.

By now, the pub was filling up again.

“All of sport comes out of hill worship. The Gaelic football was originally punted up to the Fair Ones for the counting.”

Was Pádraig Niall putting us on after all? One was never quite sure.

Walking home that night, the sky was overcast and oppressive. The lights of houses and cottages still burning in the distant east made it seem like the stars had fallen to the ground.

I’ve always been fascinated that the first generic American sciencefiction story came into the world, in fact, as a hoax.

April 13, 1844. On what friends later called the “happiest day of his life,” thirty-three-year-old Edgar A. Poe went to Herald Square in New York to watch the riotous commotion occasioned by the anonymous front-page report of the New York Sun extra he himself had authored.

ASTOUNDING NEWS! BY EXPRESS VIA NORFOLK: THE ATLANTIC CROSSED IN THREE DAYS! SIGNAL TRIUMPH OF MR. MONCK MASON’S FLYING MACHINE!!!

Riffing on the Sun’s already famous “Moon Hoax of 1835,” which stole from his own story, “Hans Pfaall, A Tale,” of the same year, Poe’s return to the balloon now specifically heralded and satirized the age of technological hype to come and, by so doing, created the blueprint for a new kind of scientific spectacular—the “ASTOUNDING” tale.10 It is reported that what pleased Poe most of all that day were not those who believed the story was true, but those rioting because they were certain it was not.11

After reading Jung on the UFO, I remembered the single image Poe’s story carried with it—an oval, mechanically enhanced balloon. The only image on the broadside of text beneath the EXTRA SUN masthead, that saucer shape looms in the fabric of the violated present like a wormhole into a weird future.

Vallée and his followers overdo the relation of alien abduction lore to fairies. The Secret Life of Puppets, Victoria Nelson’s mytho-critical

argument about the persistence of an archaic human “transcendental impulse” surviving into the technological ages, leads us to more of the sort of abduction that the fairy faith perpetrates.

Within the euphemistic construct of “science” fiction, the machine (as “spaceship,” “time machine,” “transcender” and most recently computer is the enabling conceit that gives us rationalists permission to journey to the transcendental otherworld as a fantasy experience without having to acknowledge a direct contradiction to our world view.12

Poe’s anarchist intervention shows science fiction’s secret awareness of its own ability to take us away from the present, faster, farther, than even the machine it describes. In the storytelling traditions of Poe’s Scotch-Irish grandparents, the living literature of the lore was its own magical source. Gaelic bards (many of whose tales are collected by Evans-Wentz) were very likely the most practiced satirists in the history of language. Their words could enact the real equivalent of many a fairy curse. “A satire could fill a whole country-side with famine,” Yeats tells us.13 Gaelic-language storytellers, in particular, maintained their own para-universe within and by their extraordinarily adaptable, poetic language, as direct contradictions of invading storytellings for millennia.

Nelson relates how pre-Christian art, by its very falseness, could intersect with the real transcendent god. The imperfect work was worshipped as “literal congruence between transcendental spirit and physical matter,” so “we as sentient, self-conscious beings” can “share a mysterious and direct connection with a second reality that lies beyond the material realm.”14 By the purposefully maintained ambiguity and constant masking of its literary identity, the fairy faith can break through to the “total mental field” that rationalism can never observe.15

As we neared our shelter for the night, stars appeared like sudden diamonds in one-third of the suddenly purple sky. I thought of the fairy painting by Æ, Lordly Ones Appear to a Turf-Cutter, recently available in an online auction. In that image, suddenly brilliant stars just like those above us emerge to adorn the shining band of visioned Fair Ones. These shining beings burst up from the earth to grace the night laborer with the dignity of vision and the pomp of magical embassy. Like many educated in the wake of Irish modernism, I never took Æ seriously enough. I’ve come

now to appreciate why, among self-organized fans and in the best esoteric bookshops, his visionary paintings of fairies, his thousands of pages exploring the alien roots of Irish heroes, his cosmic retellings of ancient myths, and his pacifist yet radical political influence in those revolutionary days are themselves the stuff of legend.16 In all his work, Æ affirmed the psychical world’s connection to the land, and to the Earth, in particular—the “Mighty Mother” celebrated in his poems.17

“There is the true, the only light. But do not dream it will lead you further away from the earth, but rather deeper into its heart.”

—Æ, “Yes, and Hope,” in Æ in the Irish Theosophist (1895)

April 25, 1995. The New York Times front page reports “Astronomers Detect a Possible Signature of Life on a Distant Planet.” Life, the talking heads are all saying again, is teeming in the universe. Why are we so eager to dismiss the rarity of Earth? In the wake of Pádraig Niall, I somehow know that the headline is another science fiction.18

An old pensioner at Kiltartan says, “He was standing under a bush one time, and he talked to it, and it answered him back in Irish. Some say it was the bush that spoke, but it must have been an enchanted voice in it, and it gave him the knowledge of all the things of the world. The bush withered up afterwards, and it is to be seen on the roadside now between this and Rahasine.19

Still smarting from its struggles against organized religion, science fails to communicate what these storytellers literally map and prove: how peculiar, how dense with individual lifeforms and multiple consciousnesses this planet remains.

“No spirit exists,” insists critical theorist Theodor W. Adorno, warning of the hypnotic power of the occult as a precursor to totalitarianism.20

But Earth exists. Sailing through outer space, Earth is literally swarming with inner spaces, generating beings with interrelated desires and emotions that most of them cannot begin to perceive and understand. Are these forms-in-time not spirits? If life is but a dream, it is a dream that can move bodies about and imagine, so as to be able to see and outrun the speed of light. Einstein was picturing relativity exactly as the storytellers

described time-dilation to Evans-Wentz. This planet contradicts and illuminates the void like an extra sun. Messengers from the sky exist; the imaginary fields are real, raised around us now. Let us make contact.

01 For the complete transcript of Grusch’s testimony, see David Grusch, “Opening Statement,” Committee on Oversight website, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Dave _G_HOC_Speech_FINAL_For_Trans.pdf.

02 Jacques Vallée, Passport to Magonia: from Folklore to Flying Saucers (H. Regnery Co., 1969), 20.

03 The 4Chan leaker is often hard to find online. Try @Seesyounaked, “Since People Keep Referencing It,” r/UFOs, December 2024, Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/UFOs/ comments/1hfpg0k/since_people_keep_referencing_it_while_talking/.

04 Walter Y. Evans-Wentz, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (University Books, 1966), 19.

05 Passport to Magonia, 37–48.

06 Carl G. Jung, Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, trans. R. F. Hull (Princeton University Press, 1978), 20.

07 Jung, Flying Saucers, 44.

08 Bards named them favorably so as not to invite their displeasure.

09 W. B. Yeats, Writings on Irish Folklore, Legend and Myth (Penguin Books, 2000), 51.

10 The pulp magazine Astounding! Stories of Super-Science became the central organ of what is now known as the Golden Age of US science fiction throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

11 See Mark von Schlegell, Realometer: American Romance (Merve Verlag, 2009).

12 Victoria Nelson, The Secret Life of Puppets (Harvard University Press, 2001), 21.

13 Yeats, “Bardic Ireland,” in Writings, 51.

14 Nelson, The Secret Life of Puppets, 30.

15 Nelson, The Secret Life of Puppets, 20.

16 “Æ, WHOSE UNWAVERING LOYALTY TO THE FAIRY-FAITH HAS INSPIRED MUCH THAT I HAVE HEREIN WRITTEN, WHOSE FRIENDLY GUIDANCE IN MY STUDY OF IRISH MYSTICISM I MOST GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE.” The all-caps dedication to Russell comes from Yeats. In Ulysses, he is present from the first pages—first popping up in Stephen’s mind, and then appearing live. Stephen, who owes him a pound, says: “A.E.I.O.U.”

17 “Mother, thy rudest sod to me / Is thrilled with fire of hidden day / And haunted by all mystery.” Æ, “Dust,” in Æ in the Irish Theosophist (1895).

18 On May 23, 2025, the Times published “New Studies Dismiss Signs of Life on Distant Planet,” https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/23/science/astronomy-extraterrestrial-life-k218b.html#: ~:text=In%20April%2C%20astronomers%20said%20they,independent%20analyses%20 discount%20the%20evidence.

19 W. B. Yeats, The Celtic Twilight (1902), Gutenberg website, https://www.gutenberg.org/ cache/epub/10459/pg10459-images.html.

20 Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott (Verso, 1978), 244.

Paul Chan

For Andrew Natale (1968–2017)

One cold night in 1996, I sat next to a dilapidated, black mailbox on an empty stretch of highway in rural Nevada, staring up at the sky. My friend Andrew (or Drew) sat on the hood of our rental car doing the same. The stars were so bright, the sky glowed like the shimmering surface of a bioluminescent sea. But we weren’t looking for stars.

The black mailbox is legendary in UFO lore. It services a free-range cattle ranch adjacent to Area 51, the ultra-secretive Air Force base that has been rumored, since the 1950s, as the site of a crashed UFO, a meeting place for aliens and US military officials, proving grounds for developing alien flight technology, all of the above, or none of the above. People have gathered around the black mailbox for decades to watch the skies above and around Area 51. It’s a kind of pilgrimage for anyone looking for signs of alien life.

We spent the night before in Rachel, Nevada, which is about an hour’s drive away. Rachel is home to the Lil A’le’Inn, a place where people typically stay and stock up on supplies, like water, food, and glow-in-the-dark alien masks, before heading out to the black mailbox. That night, as Drew and I were trying to settle into our room (a makeshift trailer parked behind the inn’s diner), there came a knock on our door. Drew opened it, and there stood the curly-haired blonde woman who had just served us surprisingly good biscuits and gravy for dinner.

She cast a quick glance at me lying on my bed and then looked Drew over as he stood next to the door. She then said, in a flat, matterof-fact voice, “You guys like to party?” Drew turned to me, stone-faced (which I knew meant he was dying with laughter inside), and asked, “Do we like to party?” I looked at Drew, smiled wistfully, and said, “No.” He then turned to the woman, as if relaying the message, and said in the same wistful tone, “No.”

She looked flummoxed at first. Then said in an even louder voice, “Okay. Then do you have any weed?”

Extraordinary beliefs serve extraordinary needs. They direct our attention to phenomena and experiences that allow us to grapple with what we legitimately lack, without succumbing to shame, anxiety, or fear. The enduring fascination with the possibility of the existence of alien life strikes me as one of those beliefs. It serves, in part, to satisfy one of the most curious and deep-seated needs at the core of life as we know it: to establish ourselves as definitively, unequivocally human. Because by many accounts and across different dimensions of consideration, it is not clear this is the case at all.

Take our biological makeup, for instance. The ratio between human cells and nonhuman cells in the human body is one to one (1:1). This means the human cell count (3.0×1013), which consists of red blood cells, muscle cells, and other cellular entities, is numerically equivalent to the sum of all the nonhuman microbes, eukaryotes, and archaea found on human skin, in saliva, the gastrointestinal tract, and elsewhere. In other words, the human body is as much nonhuman as it is human. If only nucleated cells (or cells that possess human DNA in their nuclei) are taken into account, the ratio between nonhuman cells to human cells jumps to ten to one (10:1).

Before he became the second Trump administration’s secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth worked as a host for Fox News. And in a TV segment that has since gone viral, he explained on air in 2019 that he doesn’t wash his hands—and hasn’t done so for over ten years. “Germs are not a real thing. I can’t see them, therefore they’re not real,” he said. Besides being totally gross, what Hegseth said neatly captures an attitude that typifies one way people police and protect their own sense of sanctity: by denigrating or simply ignoring what doesn’t rise to the level of humankind.

Then there is the flip side, where someone is obsessively washing their hands for fear of being contaminated by bacteria and other microbes. Here, what is invisible is a very real and persistent threat. What does it threaten? A sense of health and well-being underwritten by the idea that this is only achievable if what constitutes one’s body remains distinctly, exclusively, human. There is a terrible symmetry: Hegseth is, in a sense, “blind” to what is outside him, whereas the person afraid of contamination is “blind” to what is inside them.

Not only is the human body made of as many nonhuman cells as human ones, but the deeper truth is that the body needs both kinds in order to function at all. Microbiomes (or communities of microorganisms)

throughout our bodies contribute to our overall health. When they are disturbed or harmed, our fitness suffers. What has emerged since the 1990s in scientific literature is how the boundaries that define a human are much more porous and fluid than the term “being” suggests. The phrase “I contain multitudes” comes to take on a literal meaning.

In 1991, evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis (1938–2011) introduced the idea of a holobiont. She was arguing for a version of Darwinian evolution inspired by organisms that thrived through cooperation and symbiosis rather than competition. Holobiont was originally conceived by Margulis to describe a biological entity where its fitness depends on the symbiotic relationship between a “host” and a single symbiont. And where this relationship is so integrated, the host and symbiont really exist as one “unit” of life. The term has evolved over time to define a host and its associated microbiomes. Today, it may be more apt to say the concept that best describes the human form isn’t “being” but rather “ensemble,” or even “environment.”

The inability or unwillingness to accept this “multitude” from within, along with our deepest, most existential need to believe one is human above all else (or others), has led to an unimaginable degree of meaningless and arbitrary suffering. The ancient Greeks believed that people who did not hail from the same tiny region in the Mediterranean were βάρβαρος, or “barbarians”: primitive, uncultured, barely human, if at all. Even within classical Greek society, free males were the only ones who had the right to claim themselves fully human. Women, for example, were viewed as more creaturely than human and, therefore, were barred from participating in administrative and political affairs or holding any real seat of power in Athens.

The spirit of this anthropocentrism has been passed down from generation to generation like an accursed inheritance. It animates our most regressive tendencies, irrespective of religion, creed, or ethnicity, by offering justifications for the exploitation and abuse of others on the grounds that they are less than wholly human. I think Theodor Adorno had something like this in mind when he wrote, “History is what hurts.”

Whenever broad questions arise about who gets to count as human, collective attention tends to turn toward the idea of alien life. In the modern era, World War II became a catalyst for rising public consciousness about the possibility of extraterrestrials visiting Earth. In our living memory, the age of globalization, starting in the early 1990s, was another moment when

curiosity about the existence of alien life reached a new apex. I want to suggest that this was due, in part, to how questions about who benefits from this new political economy, and who should be exploited for it to function, were at the forefront of people’s minds worldwide. The case is as true today as it was then.

It is interesting that the very need to secure a self-understanding that we are indeed human may be hampering the actual scientific search for the existence of alien life on other planets. In the 1970s, NASA successfully sent the first missions to Mars. When Viking I and Viking II landed on the Martian surface, one of the experiments they conducted was designed to detect the presence of microbial life. A sample of Martian soil was collected and exposed to organic molecules. The idea was that if microbial life-forms existed in the soil, they would metabolize the molecules (essentially feeding off of them) and then release CO2 gas as a result.

According to Gilbert Levin, who designed the experiment, CO2 was detected, which met the then–agreed upon standard for discovering life on Mars. But the results were also confusing, because how the gas was released did not match the pattern of how microbes metabolize molecules on Earth in controlled settings. Other experiments on Mars were conducted, with varying results. CO2 was found, but the way it appeared was inconsistent with established biological interpretations.

Forty years later, NASA still considers these results to be inconclusive. But some astro-biologists today have put forward the argument that the results look confusing because human-centered interests predominate the very definition of life in general. And since there is a tendency to view humankind as the quintessence of life itself, it follows that the blueprint for how life exists at all ought to reflect how we do it and see things. But this is precisely the problem. When the distinction between life and non-life hinges on the assumption that a human being is definitionally life par excellence, how can one ever presume to be able to acknowledge, much less recognize, life when it is genuinely alien?

Sometime later that night, a Nevada state trooper’s car pulled over and stopped in front of the black mailbox. The trooper got out but left his high beams on, shining them directly at me and Drew, essentially blinding us. He asked in a steady, unnerving voice, “What are you doing here?”

I replied that we were making a video about UFOs. He chortled. “Looking for lil’ green men, are you?” he said sarcastically. We didn’t say a word. There were no signs of anyone for miles. The vast Nevada desert was completely silent, except for an eerie, humanlike moaning in the distance, which we found out later was from cattle roaming the surrounding hills.

He glanced at the license plate on our rental car. “You don’t belong here,” the trooper said, “I suggest you leave.” He then got back into his car and drove off, leaving us in the safety of the dark again.

Drew and I both exhaled and looked at each other. Then we turned our attention back up to the vast expanse of the night sky above. We didn’t see anything that night. But we didn’t leave either.

Olivia Shao

From as early as 1460 BCE, archives and libraries across cultures—from China to the Roman Empire, Japan to North America and the Middle East— have held documents containing descriptions of unexplained phenomena and activity in the sky. Mysterious fireballs, spheres, lights, flying wheels, and beings are interpreted through each civilization’s distinct culture and belief systems, offering rich insights into how humanity has historically perceived the unknown. Recently declassified governmental reports and heightened media coverage have given UFOs and the potential for life outside our galaxy even more prominence.

Voice of Space explores this terrain, focusing specifically on UFOs and paranormal phenomena, and turns to both contemporary and historical artworks to examine the cultural, psychological, and metaphysical dimensions of the extraterrestrial. What roles do UFOs and the paranormal play in shaping our understanding of the universe? And how do they challenge and expand our beliefs about humanity’s place within it? Drawing from diverse religious traditions, psychology, technological advancements, and personal visions—from ancient spirit drawings to speculative visions of the future—this exhibition offers an expansive view of how humanity has sought to depict, interpret, and question our boundaries of experience and knowledge. Voice of Space invites viewers to consider the ways in which these themes live in our collective memory and how they have influenced our individual imaginations.

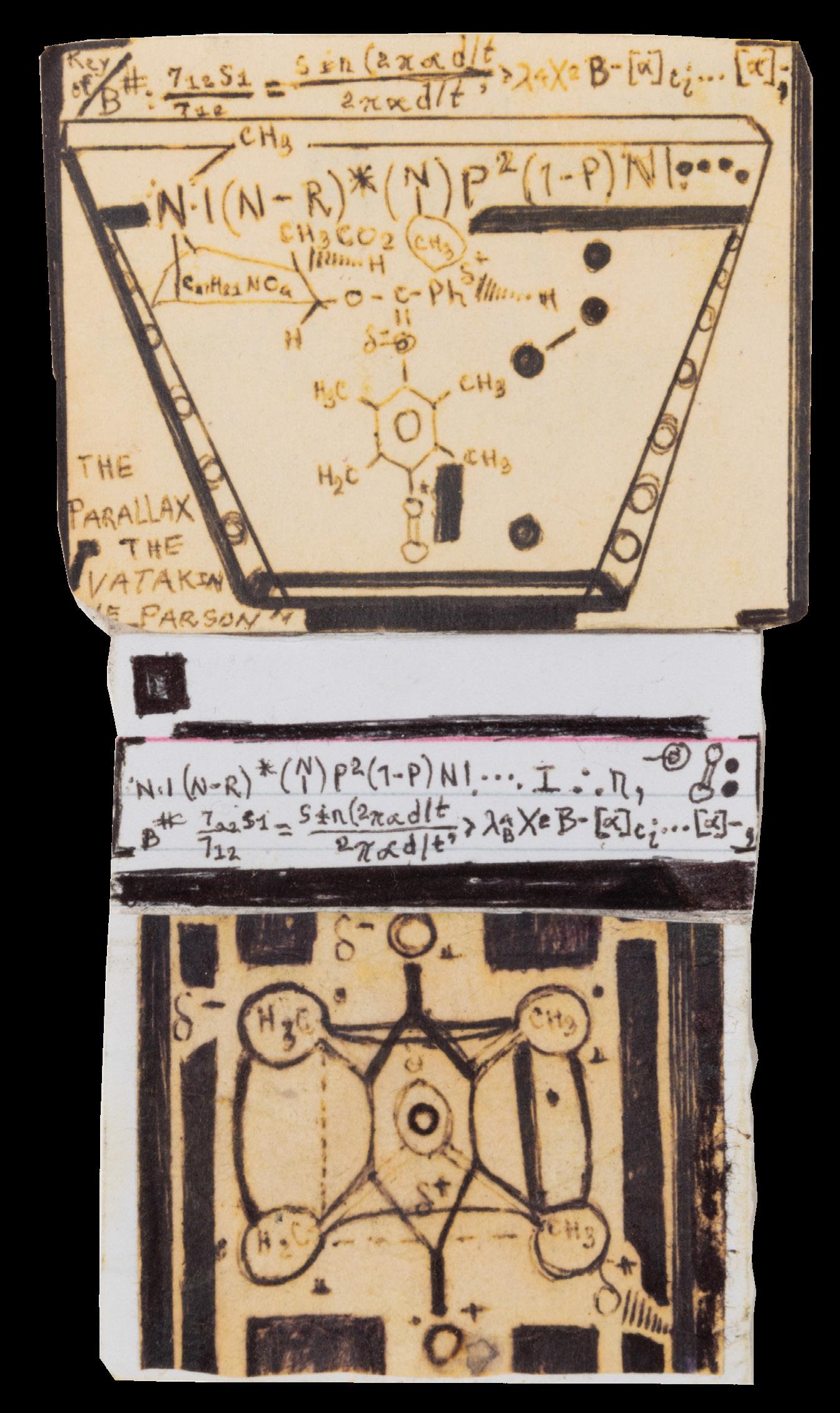

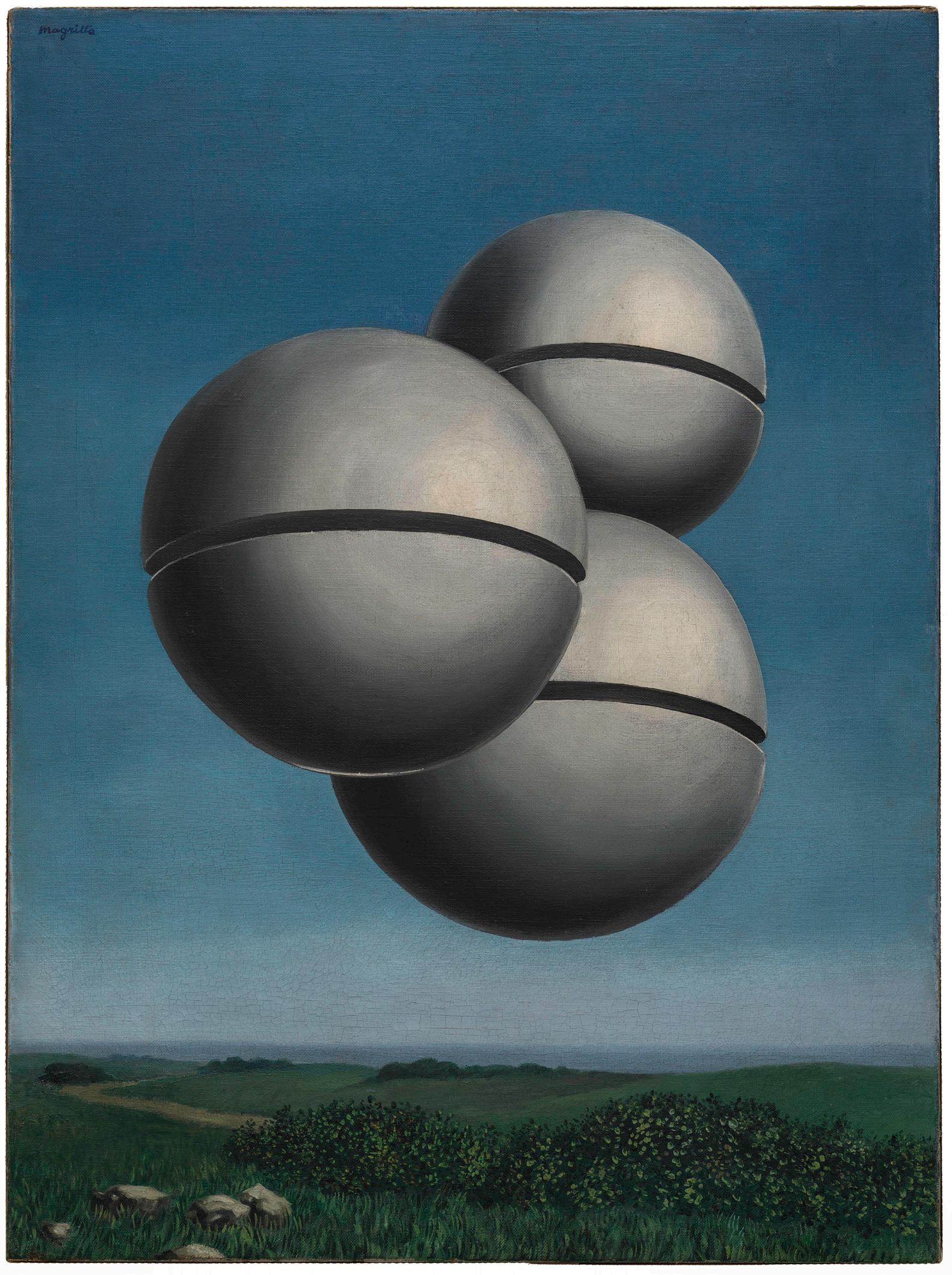

The show takes its title from a 1931 painting by Surrealist René Magritte depicting enigmatic orbs—an otherworldly presence looming over a pastoral scene. As Magritte described it: “I caused the iron bells hanging from the necks of our admirable horses to sprout like dangerous plants at the edge of an abyss.”1 As with many of Magritte’s paintings, the work disrupts typical planes of perception, acting as a signal from beyond—perhaps technological, perhaps a transmitter, perhaps a gateway to other dimensions or altered states of consciousness. Similar alternative realities appear in Adam Putnam’s microcosmic drawings. His small, intricate visualizations seem to capture dream fragments or psychic portals, revealing unseen forces

and evoking both the universal mind theory and the Theosophical concept of the Akashic Records.2

In his 1959 study Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, psychologist Carl Jung offered a psychological interpretation of UFOs as projections of the collective unconscious—archetypal images that express modern anxieties and beliefs. These spherical forms resonate across cultures and epochs: from Christian iconography and Eastern mandalas to medieval alchemical emblems. Expanding on Jung’s ideas, astronomer and computer scientist Jacques Vallée proposed that these phenomena are interdimensional, psychic, and ancient—more like portals than physical crafts. These manifestations question our concepts of reality, offering glimpses into the structure of existence itself.

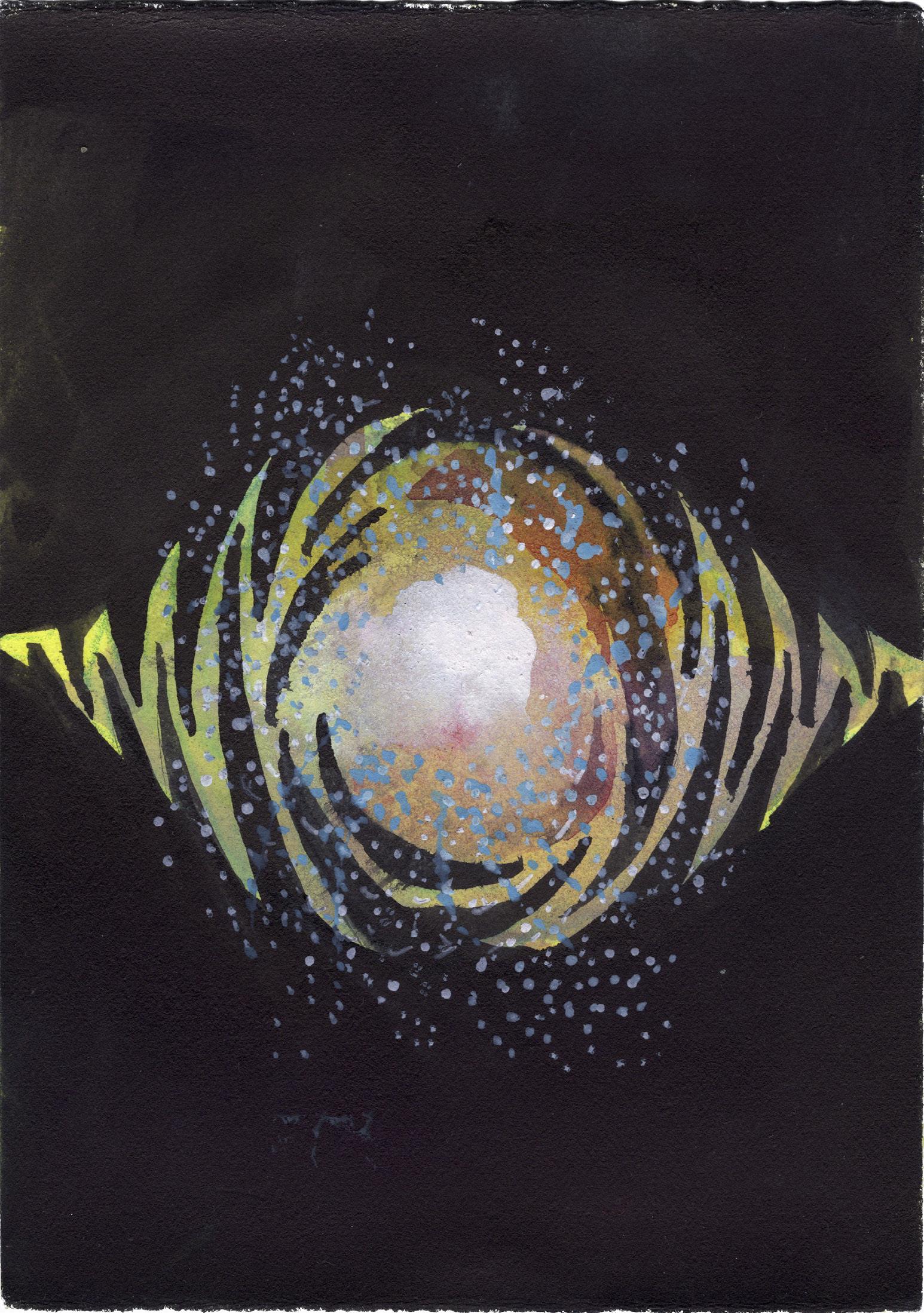

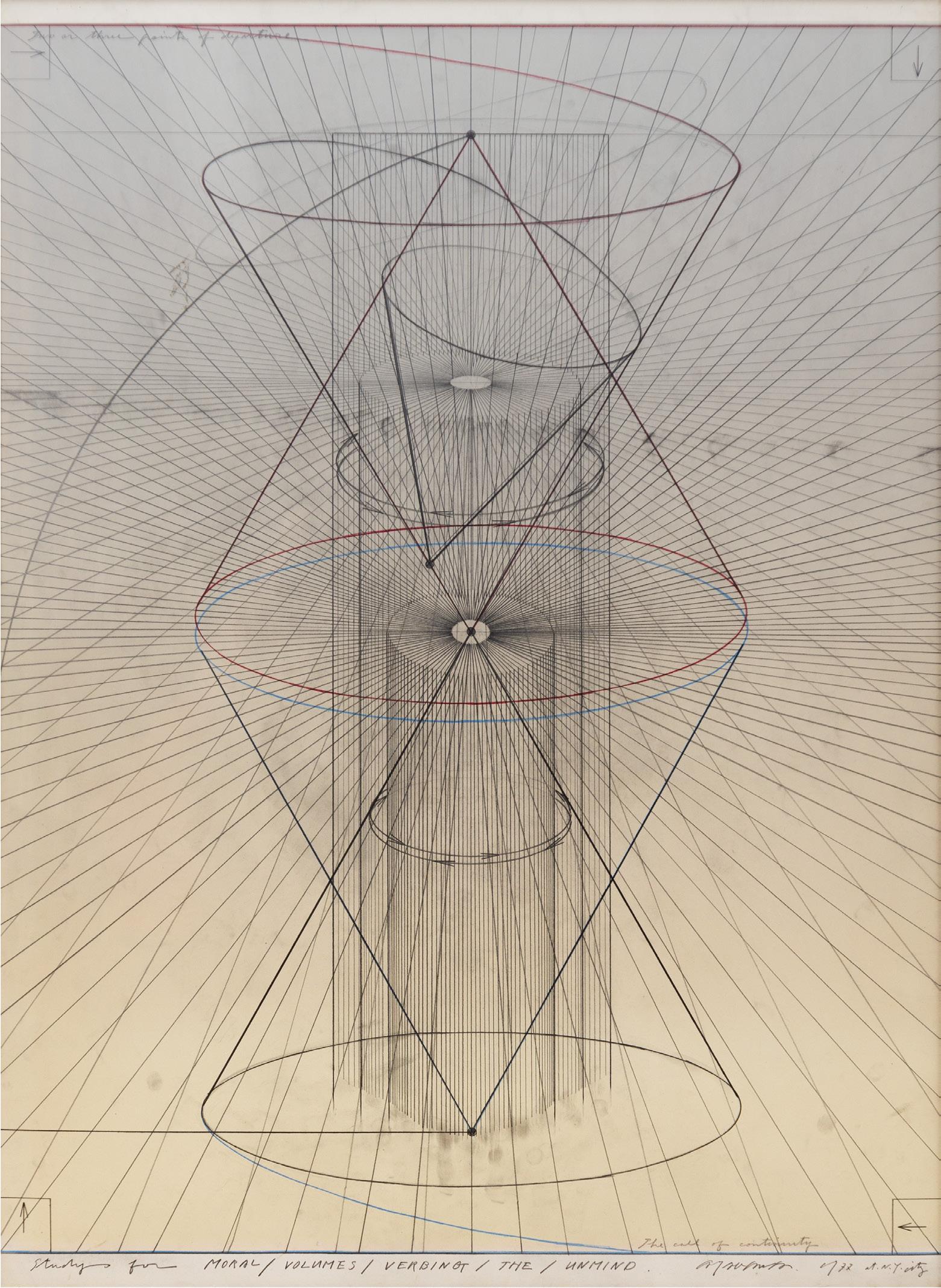

Shusaku Arakawa creates symbols, signs, and forms that are the renderings of realities, creating different symbols and signs of the unknown. In Arakawa’s Study for Moral/Volumes/Verbing/The/Unmind (1977), the artist explores the depths of the psyche, metaphysics, expansion of perception, and dimensionality through visual puzzles composed of radiating forms, grids, and intersecting geometries. His work invites the contemplation of language, embodiment, and spatial reasoning. Depictions of interdimensional space and exploration in non-Euclidian geometry challenge conventional understanding of reality, space, and the human experience. Later, the architecture he developed with his partner, Madeline Gins, defies everyday notions of spatial relationships, creating new ways of thinking and experiencing the world.

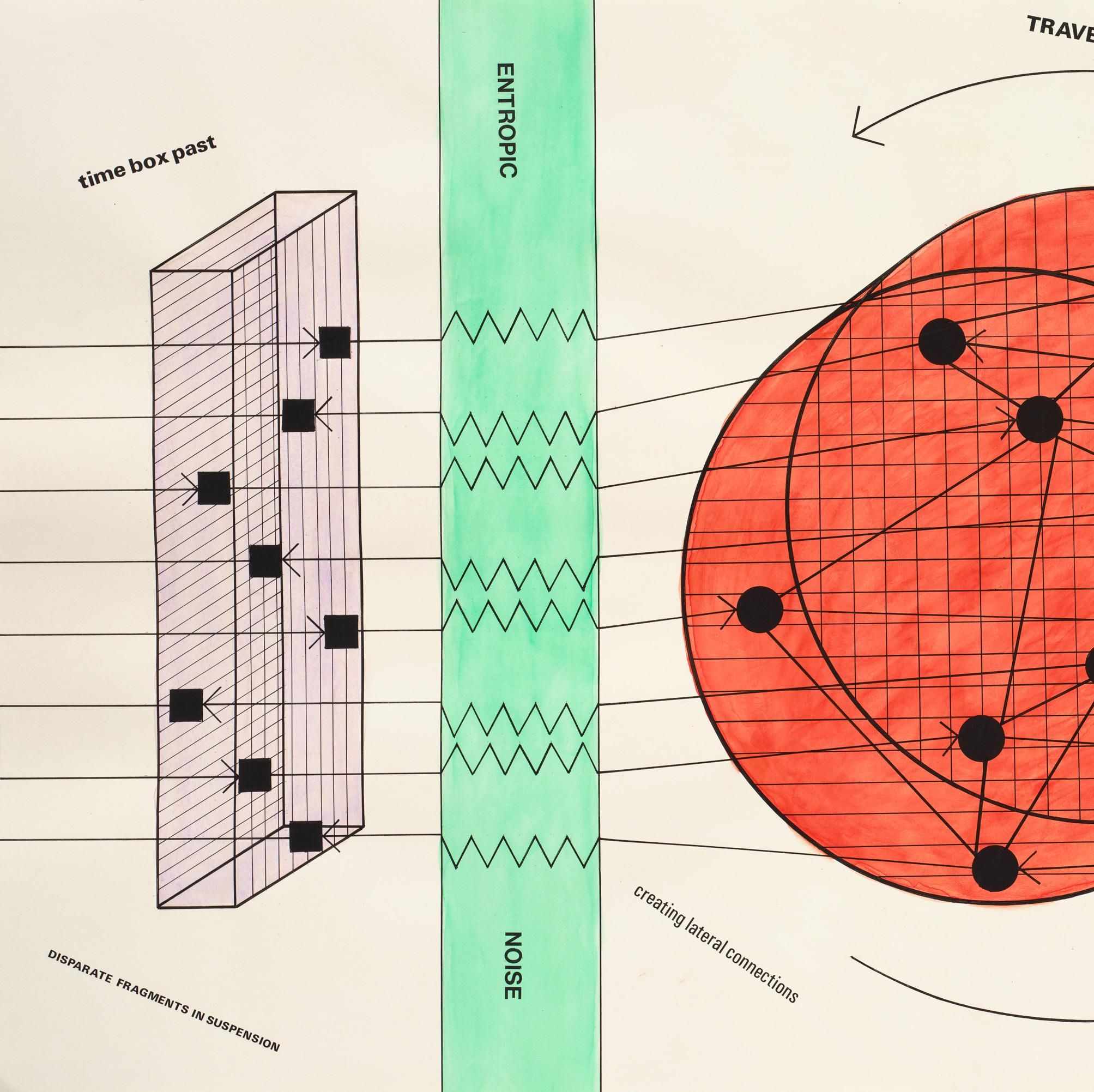

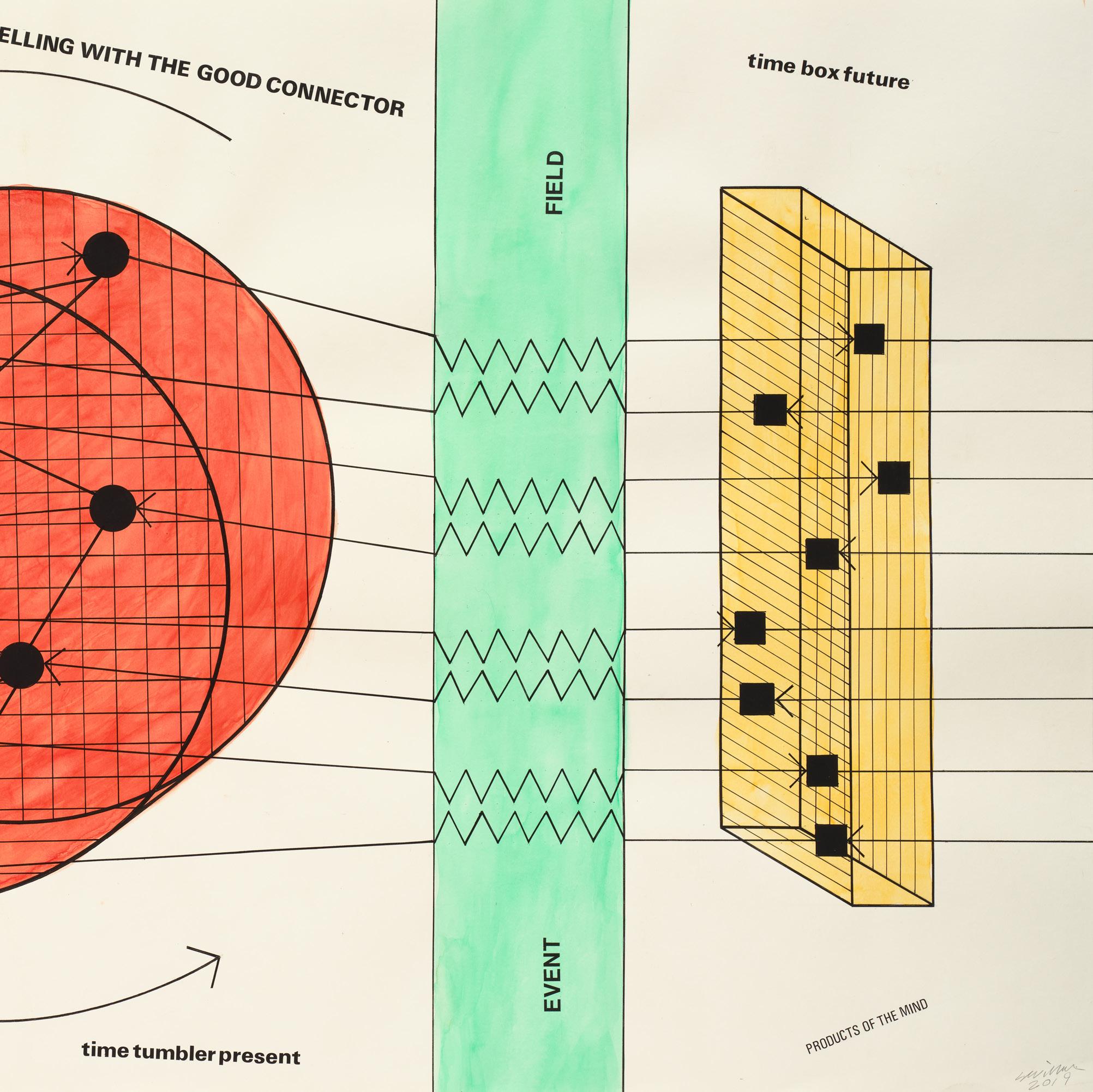

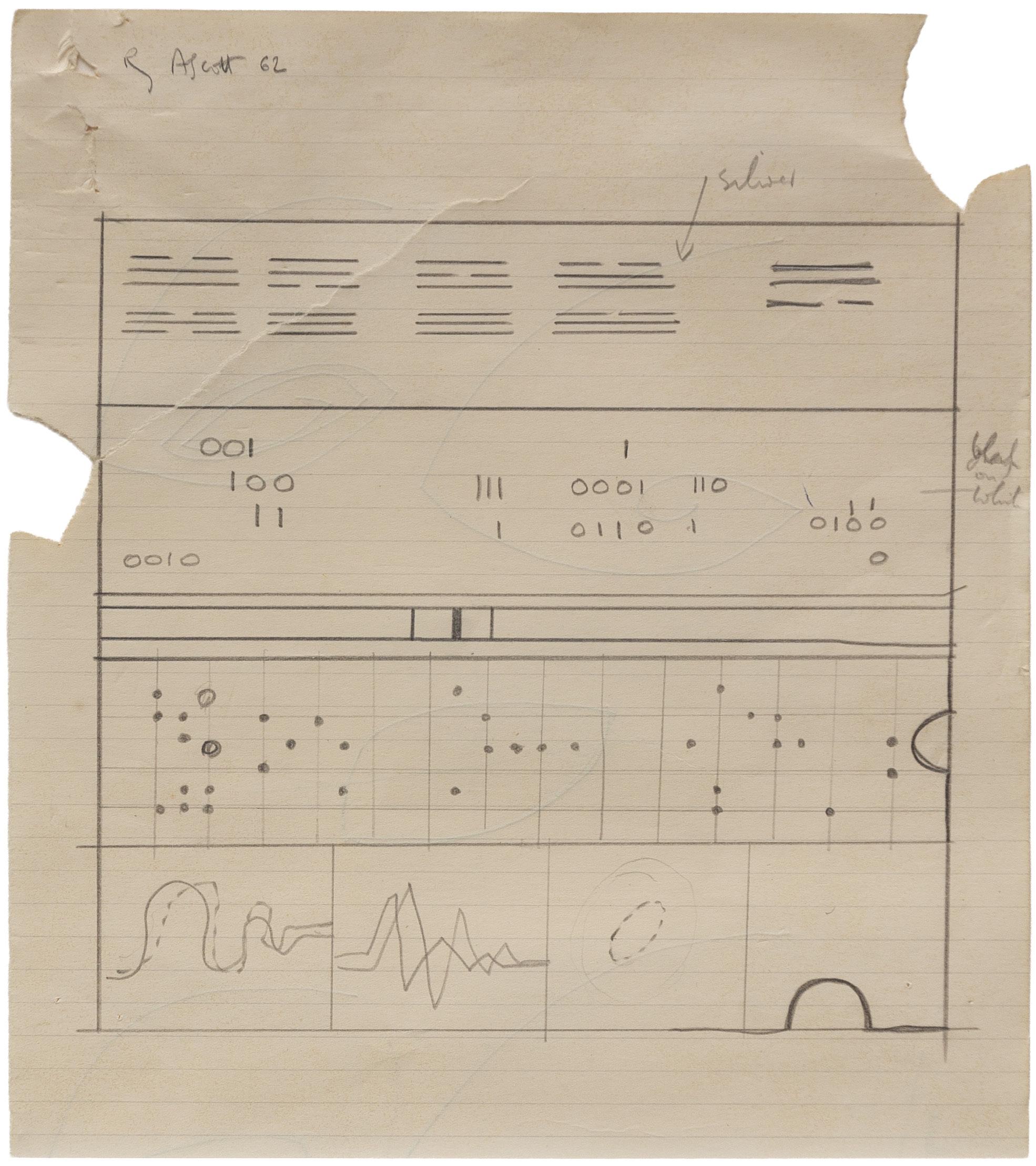

Futurologist artist Roy Ascott blends Eastern metaphysics with cybernetics in a theory he called “The Psibernetic Arch,” linking extrasensory perception (ESP) and information systems. “ESP is instant but sporadic. Cybernetics is universal but entropic,”3 he once wrote, and by connecting these forms of communication, Ascott opens the space for a new form of exchange. His Change Paintings (1959–60) and an untitled work from 1962 connect hexagrams from the I Ching with binary code, waveforms, and parapsychology, prefiguring ideas central to internet connectivity and network theory. Sharing an interest in the relationship where the receiver is also the producer, Stephen Willats’s diagrammatic drawings of squares, circles, and arrows visualize systems of thought, energy, vibration, and time. “The circle is like a ball of thought. Everything goes into it, and everything comes out—only differently,” Willats explained.4 Works like Travelling with the Good Connector and Time Tumbler (both 2018–23) propose speculative

networks for transcending human constructs of time and dimensionality.

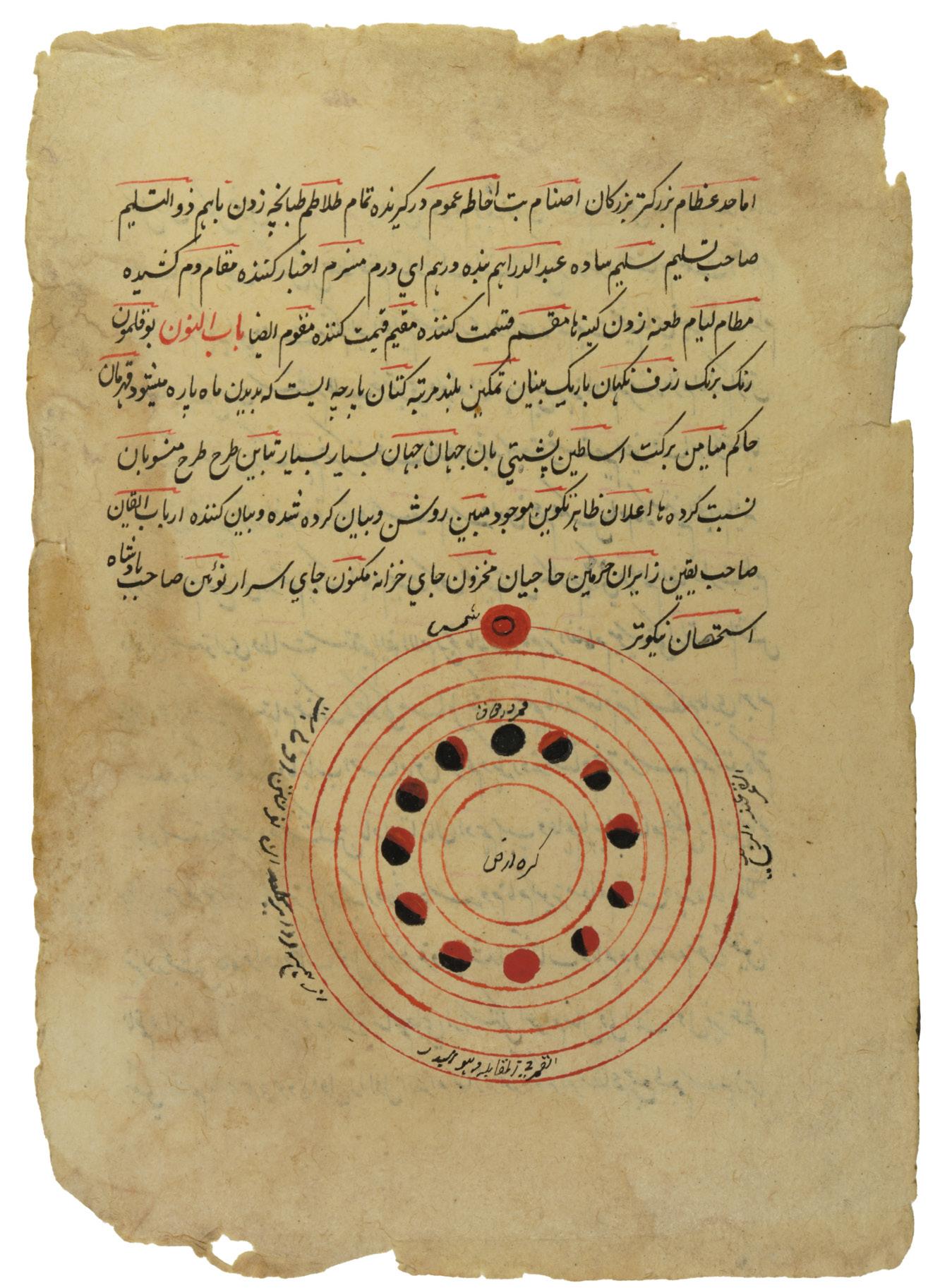

In Islamic mystical traditions, the concept of Tay al-Ard translates as “folding of the earth,” or traveling vast distances in the blink of an eye.5 The exhibition includes a nineteenth-century diagrammatic map used in ritual practice, in which a person sits in the center of a candlelit circle with twelve candles representing the months of the year. Although little has been formally written on the subject, the esoteric principles behind this practice mirror those found in ancient Egyptian, Native American, Indian, Daoist, Theosophical, and Rosicrucian systems, where techniques like astral travel and out-of-body experience transcend physical boundaries through consciousness and will. Native American visionary drawings often depict these journeys as spiritual traversals into alternate realms, accessed through trance, dreams, or meditative states.

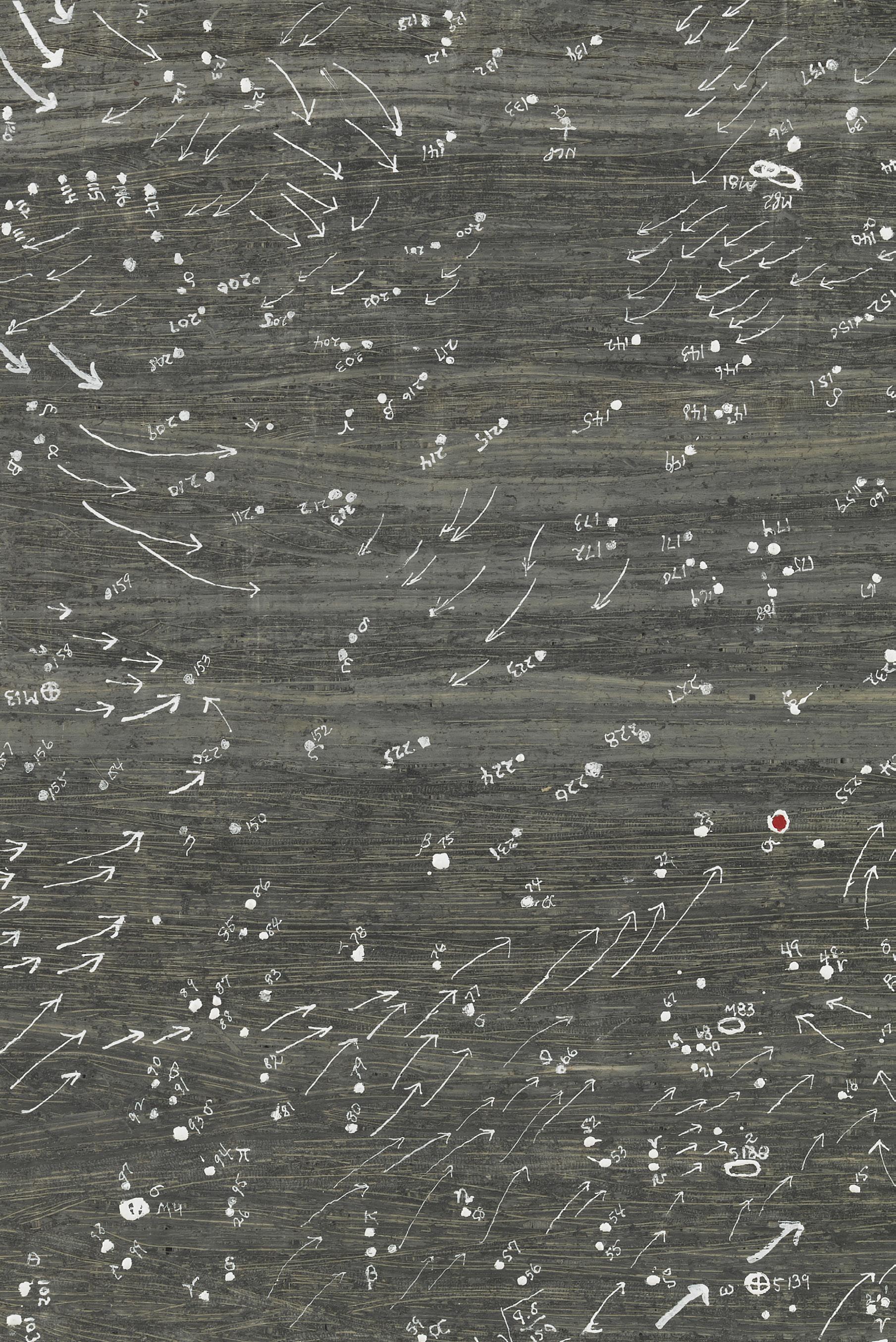

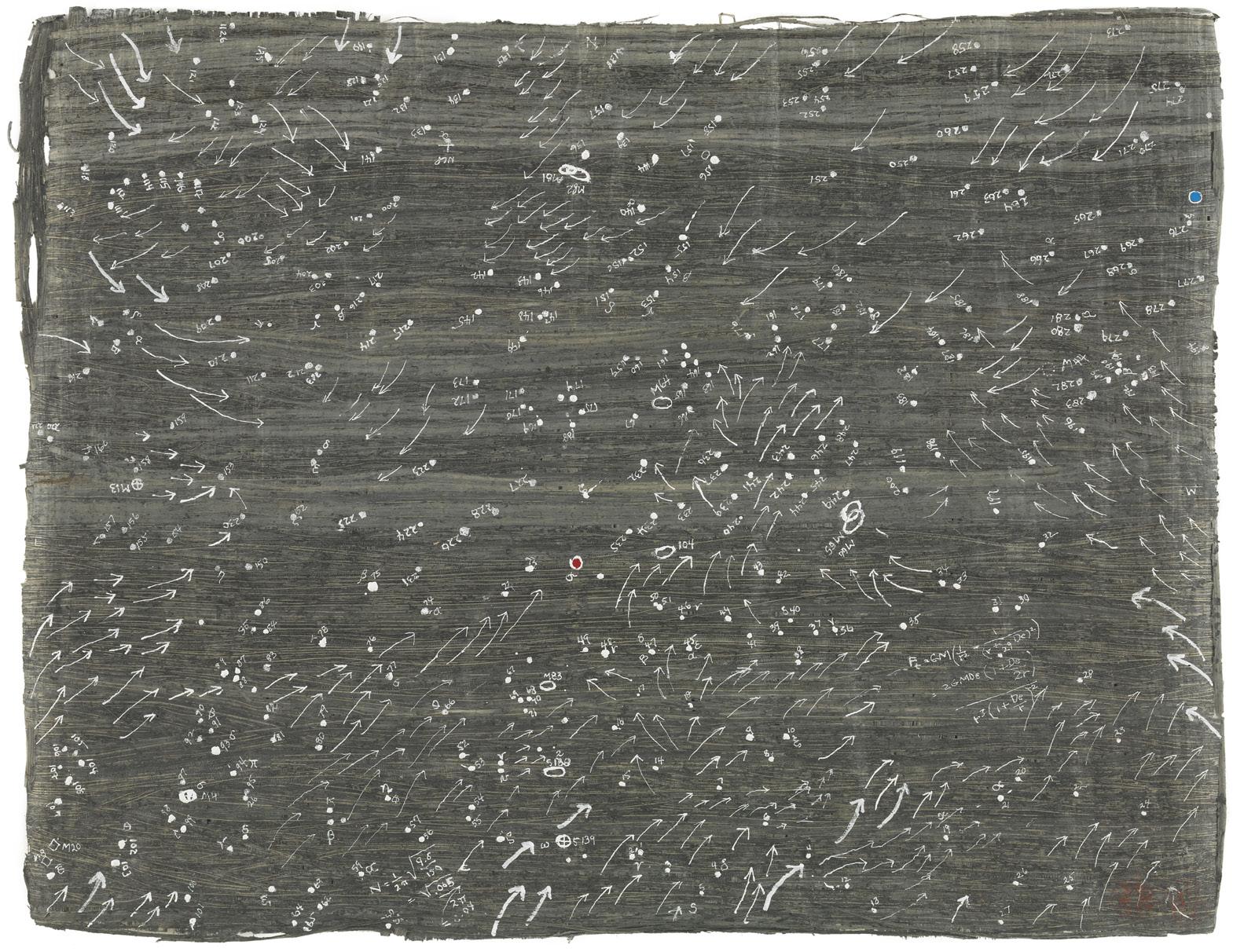

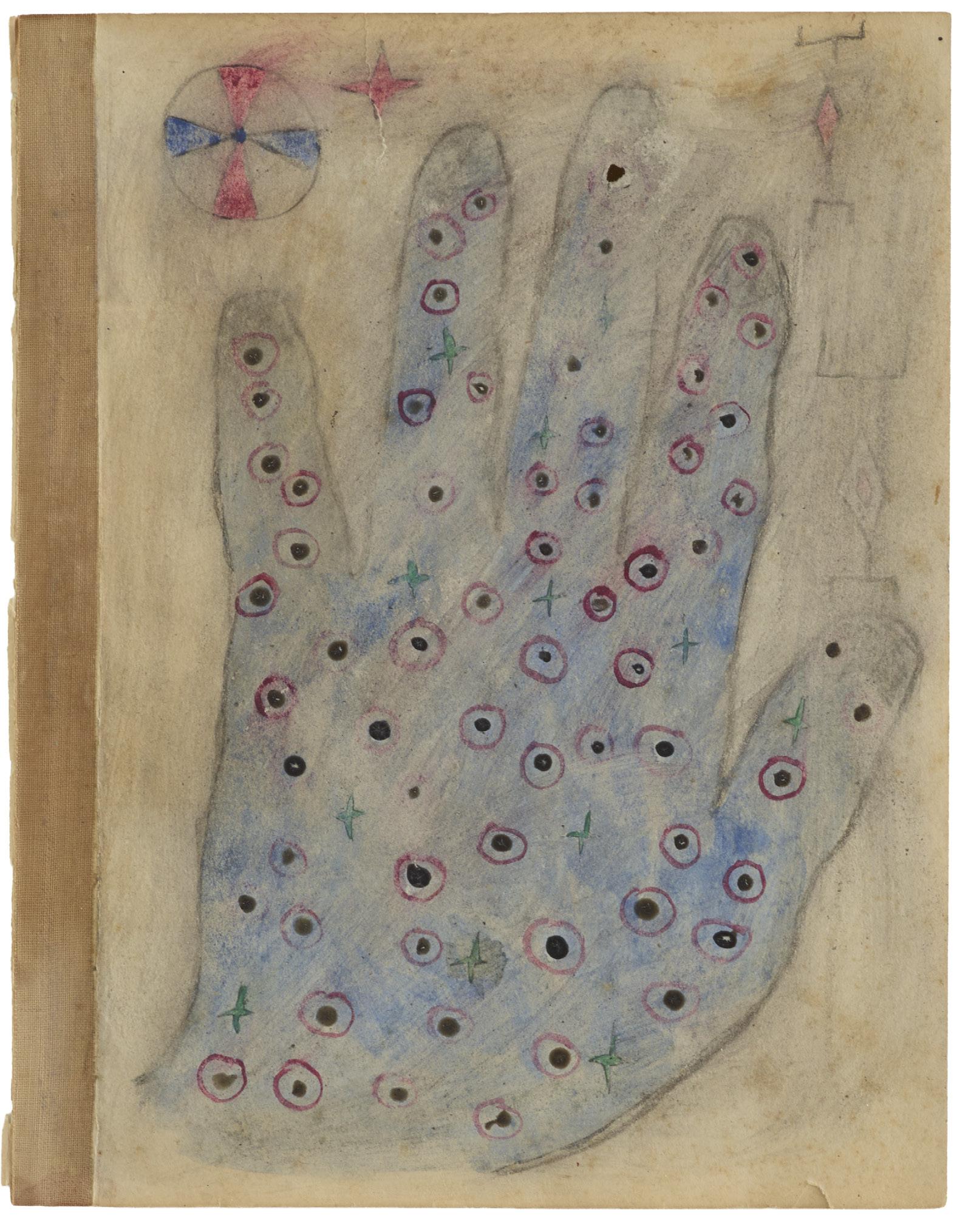

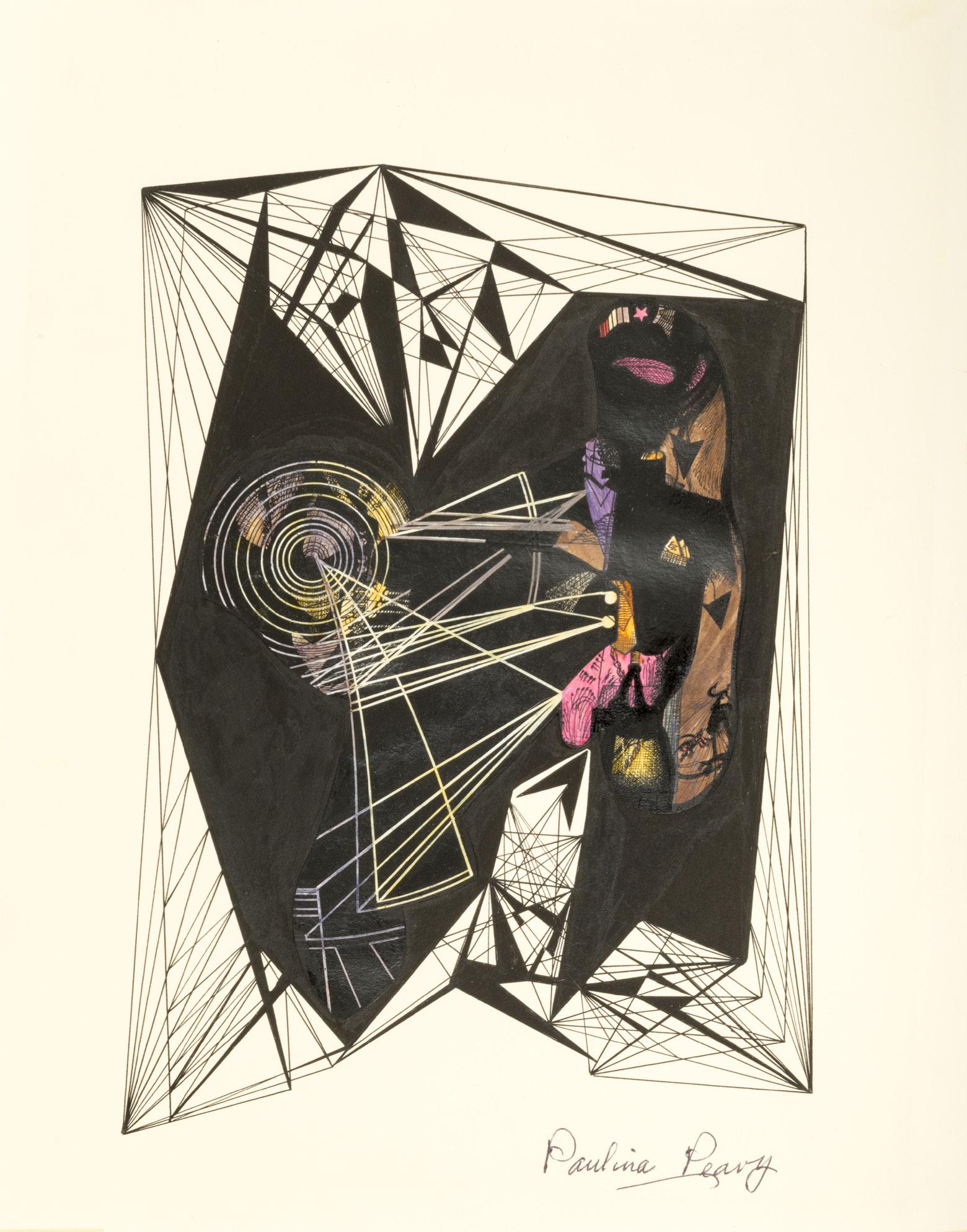

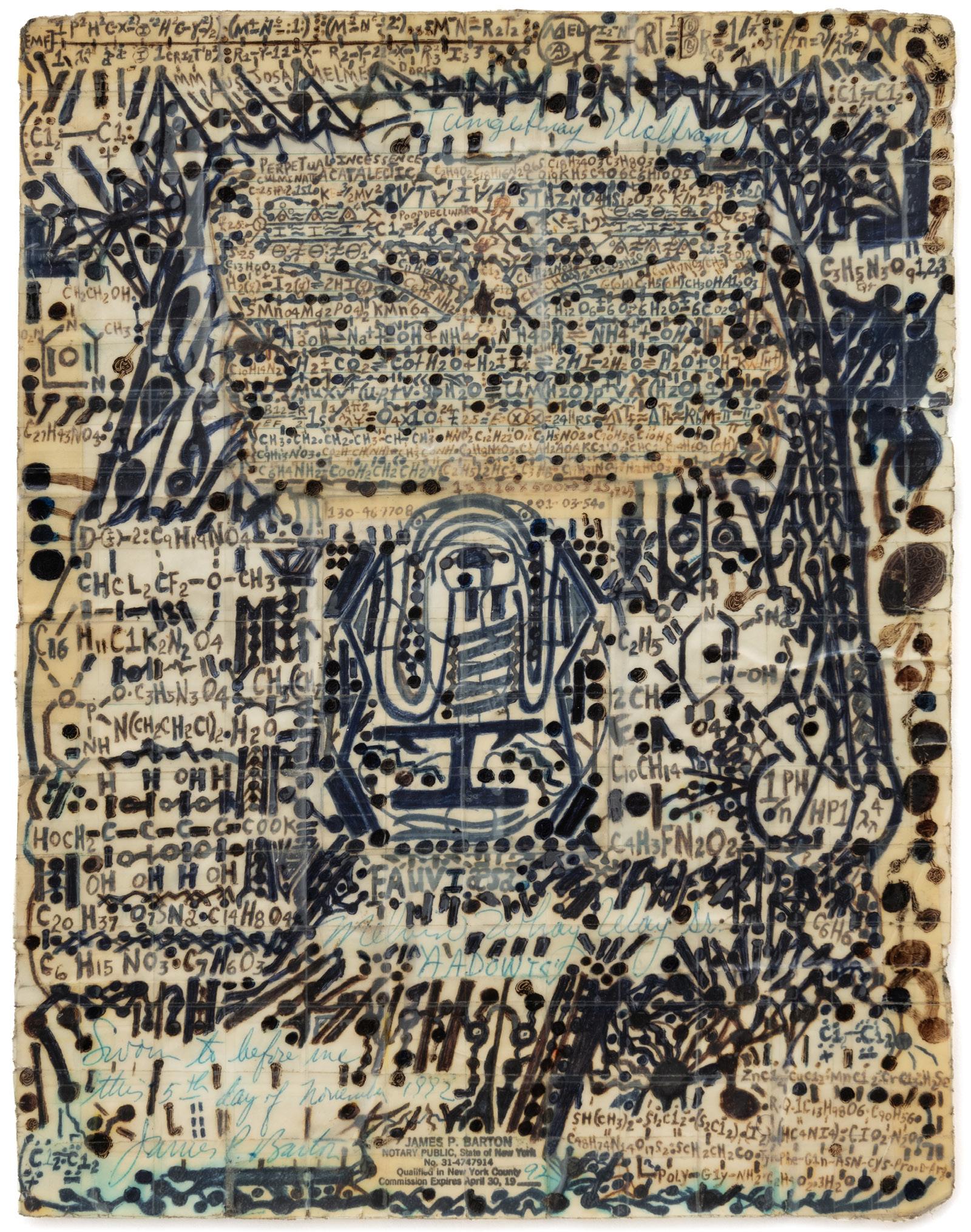

Beginning in the 1930s, visionary artist Paulina Peavy claimed to communicate with her personal UFO named Lacamo. Her multimedia works—paintings, drawings, performances, and writings—depict a cosmology in which humans evolve into spirits or UFOs over a twelve-thousand-year cycle divided into four three-thousand-year periods, corresponding to the four seasons. These abstract, spiraling compositions map multidimensional space and portray divine or extraterrestrial consciousness. Similarly, Melvin Way’s dense, formula-filled drawings transmit messages of esoteric knowledge through symbolic languages that combine math, chemistry, and physics. Way kept these intricate drawings, made on scraps of paper covered in scotch tape, in his pocket like talismans until they were ready to be shown. In these equations, Way explored his own written form of infinity, which comprised chemical compounds that represent life forces, the secret of youth and immortality, sound and musical notations, travel in the space-time continuum, and the inner mechanics and mysteries of the cosmos.

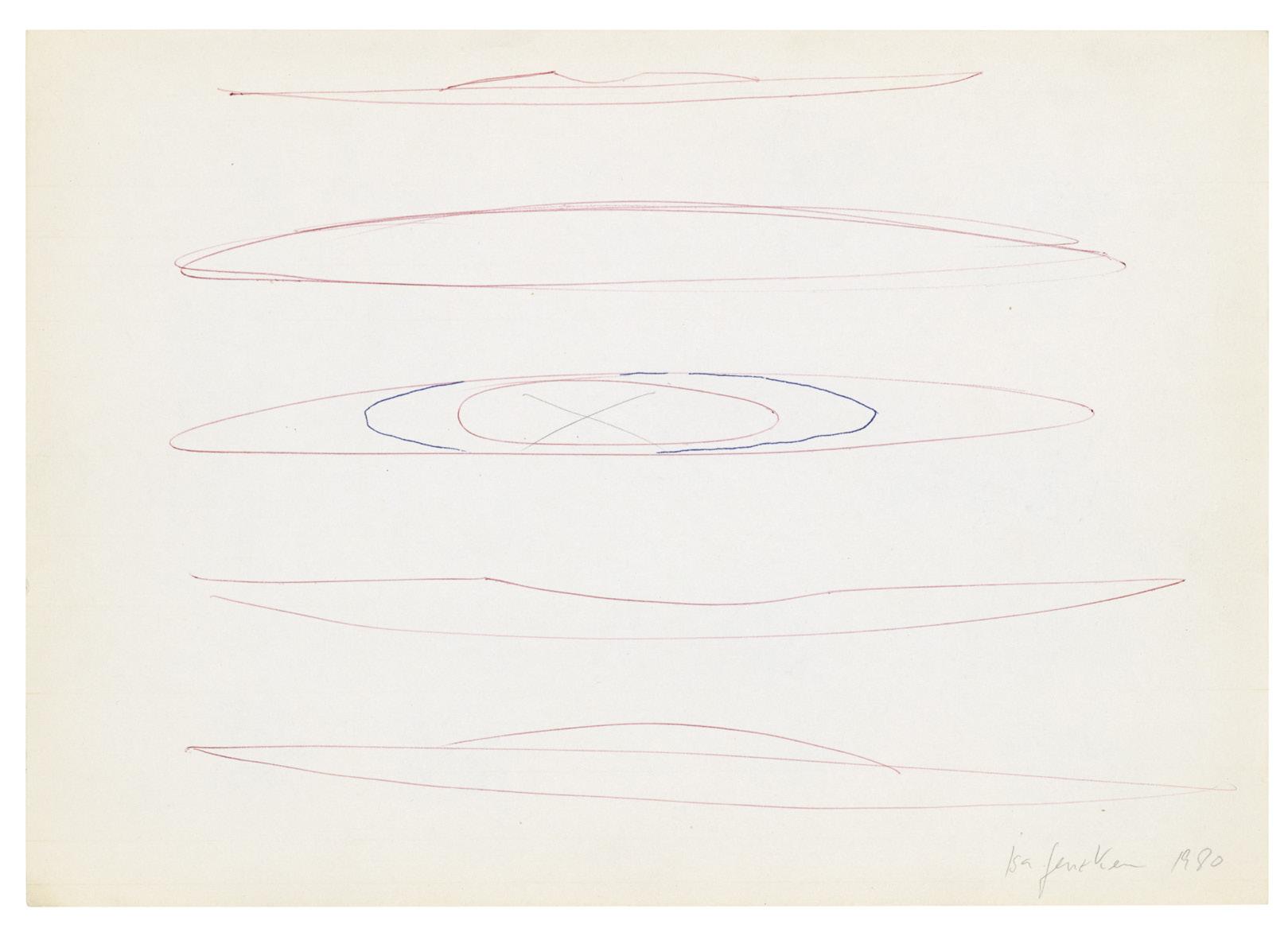

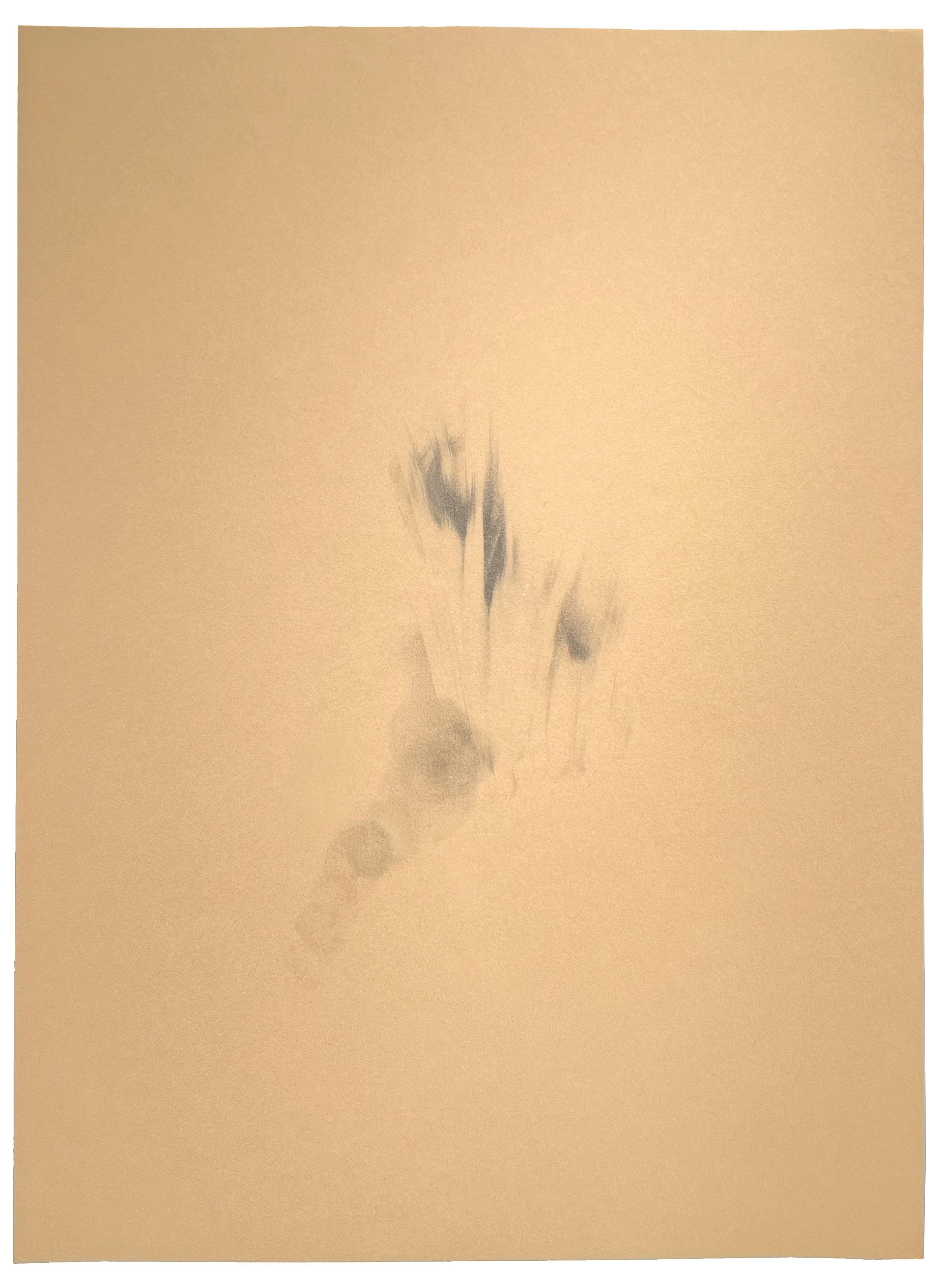

Isa Genzken’s drawings and wooden sculptures titled Ellipsoids (1980) were designed using early computer modeling yet challenge industrial Minimalism with their handcrafted intricacy. Working against the grid structures found in the works of many Conceptual artists and their Minimalist predecessors, Genzken’s sculptures pose complex forms of spatial understanding and reach toward infinite distance. The hovering forms, touching the ground at only one center point, suggest both the technological and the metaphysical, like shapes from beyond. In her Weltempfänger (World Receivers; 1987–2018), concrete blocks with antennae

operate as psychic conduits, capturing signals and energies and opening channels to connect all existence across the cosmos. Her works function as UFOs themselves—technical, sculptural, spiritual transmitters linking to alternate realms of perception and being.

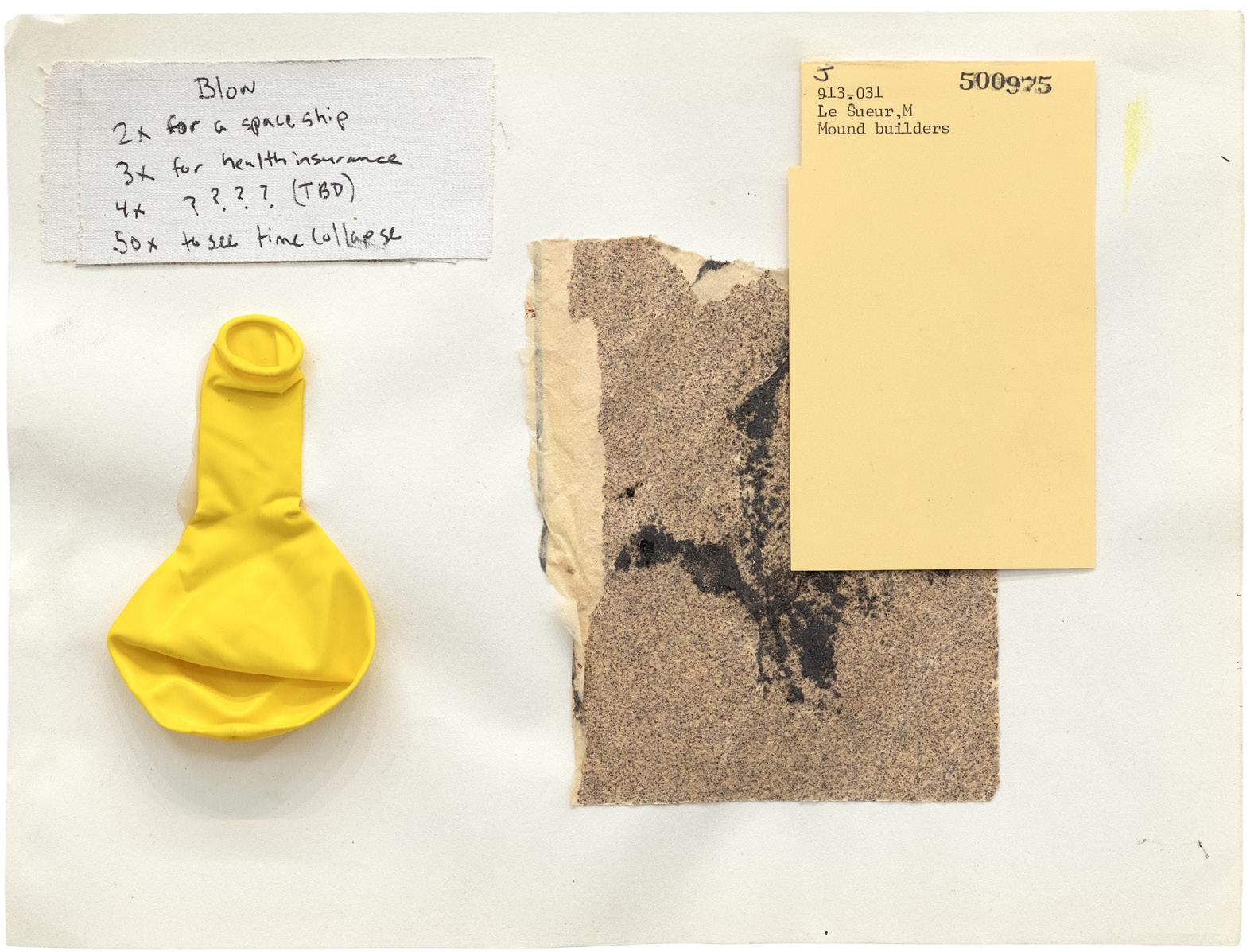

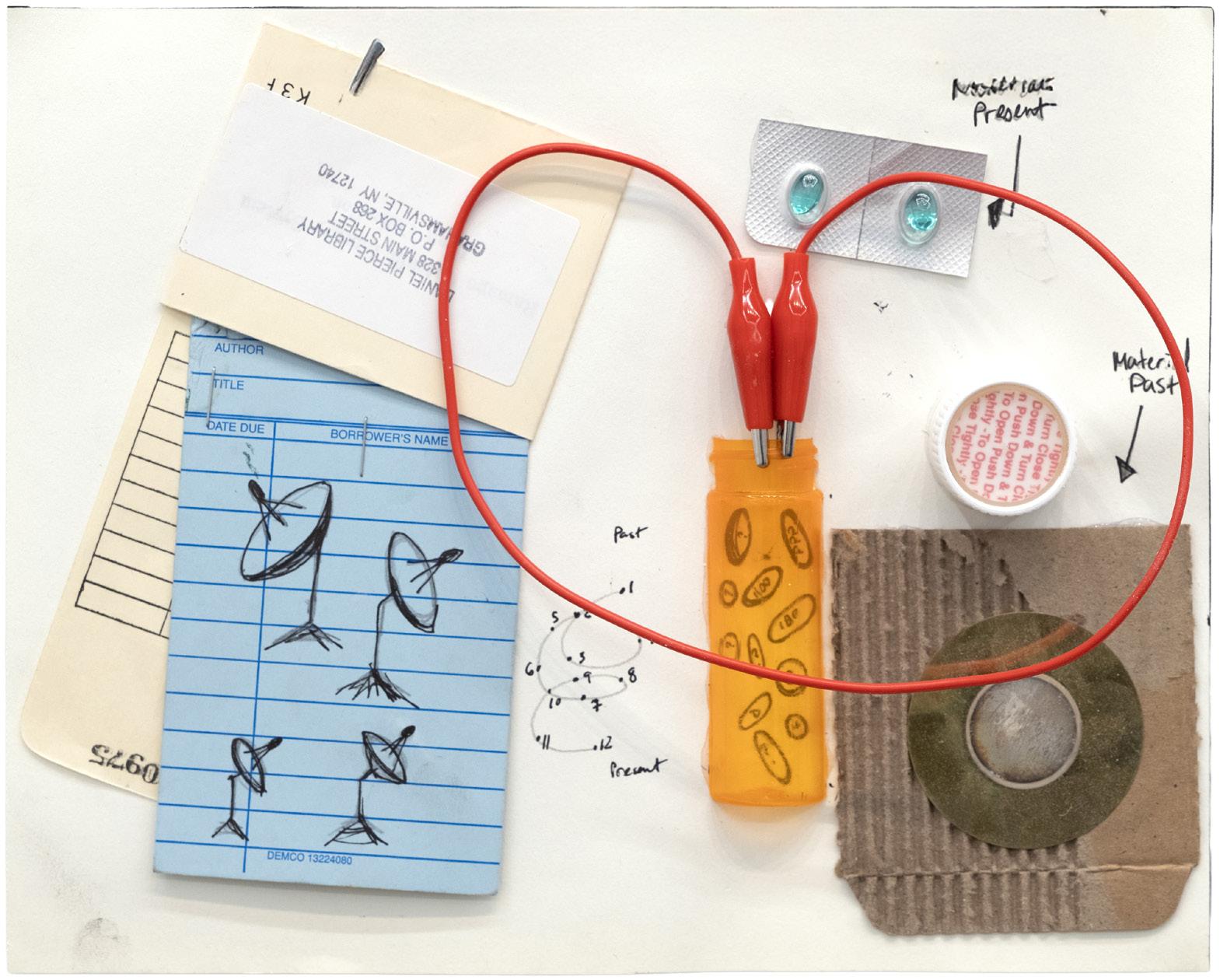

Working in a range of disciplines, spanning sound, installation, sculpture, painting, video, and film, Char Jeré has an artistic vision rooted in a philosophy they have coined Afro-fractalism, a term that builds on the foundations of Afrofuturism. Within this framework, time is conceived as nonlinear and multidimensional, a conduit that connects the past, present, and future through intergenerational communication with ancestors. In their work, Jeré investigates fractures and connections within a Black diasporic history, along with the possibilities for reclaiming and reshaping narratives around race and technology. Their collages, which synthesize a range of materials, incorporate incantations for time collapse and the summoning of spaceships, as well as references to ancient cultural histories while challenging conventional boundaries of space and time. In parallel, Nolan Oswald Dennis’s “para-disciplinary” practice explores new models for Black consciousness and planetary connectedness through the intersections of cosmology, geology, race, and decolonial theory. Their diagrammatic works reference science and speculative fiction, including Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel R. Delany, and Octavia Butler, alongside the anti-imperialism of Frantz Fanon.

Plant intelligence, as advocated by ethnobiologist and mystic Terence McKenna, is a means for humans to engage with and acquire knowledge from life-forms that differ from us. These chemically complex, visionary “guides” open pathways to higher dimensions, as well as expand our states of reality, according to McKenna. His extensive research on mycelium (underground networks that link ecosystems together) hypothesized that mushroom spores came from outer space:

[When taken] at active levels, psilocybin induces visionary ideation of spacecraft, alien creatures, and alien information. The flying saucer represents a form of matter and mind which is, in this universe, transient and very mercurial. It is something that is both mind and matter, and as such it casts enormous shadows back over the temporal landscape.6

These highly complex species with biological compositions unique to Earth play a role in the development of human intelligence and self-awareness,

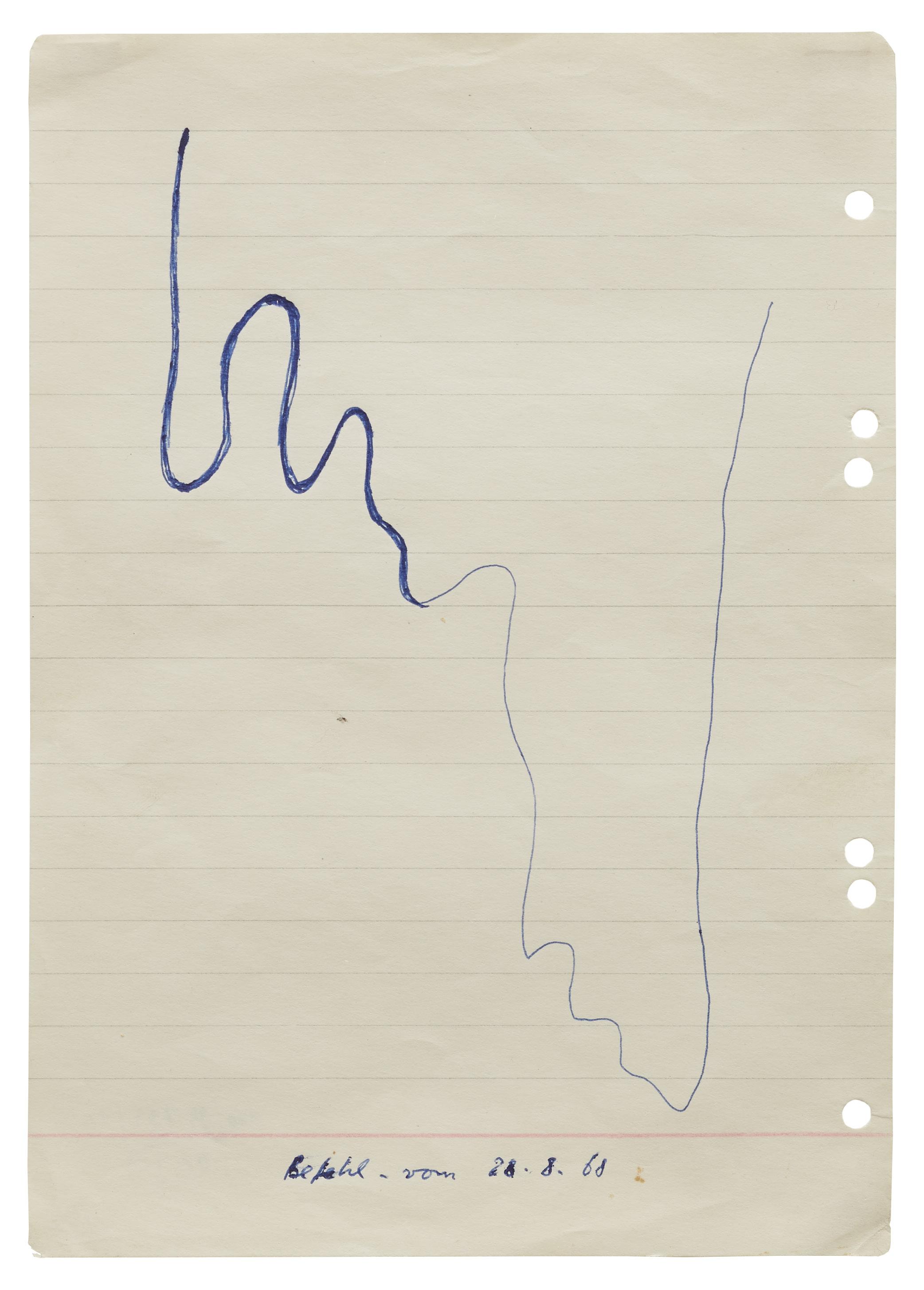

exposing us to a deeper understanding of the universe. Similar themes were explored throughout the work of the artist, alchemist, and polymath Sigmar Polke. Several works, for example, reference receiving the “command of higher beings.” Beckoned in a manner both serious and with a sense of humor, these higher beings may be any form of authority or inspiration— from psychedelic mushrooms and the extraterrestrial to the divine, parapsychological, and other various forces and states of consciousness referenced in Polke’s vast, eclectic cosmology. In Command of 28.8.68 (1968)—a possible communication or representation of a waveform signal—we witness energy forms capturing a life force.

Throughout history, art has served as a medium for interpreting the unknown, the divine, the mystical, or the extraterrestrial. Celestial orbs in Renaissance paintings, beams of light from the heavens, and visions of saints and spirits can be recontextualized within a broader continuum of humans’ attempts to understand what lies beyond perception. In today’s technologically mediated world, UFOs may function as a new kind of religious symbol, a vessel for collective anxiety, spiritual longing, and speculative belief. As quantum interpretations of reality challenge classical ideas of consciousness, the boundaries between science, technology, faith, and imagination blur even further. And through their creative practices, artists and thinkers continue to decode signals, interpret dreams, and summon alternate dimensions.

Perhaps, in the same way that certain parables are retold across different religious traditions, in the various artistic treatments of higher beings, we are perceiving different facets of a greater truth. Each document, artwork, or set of beliefs present in this exhibition offers a partial glimpse of the whole, limited in its perspective but valid in its insight. Across these artifacts, then, the UFO becomes not a singular object but a mirror reflecting our most profound questions about existence, consciousness, and interconnectedness. In this open field of speculation, the unknown remains not something to be solved, but something to be experienced, imagined, and believed in. Voice of Space invites us to look beyond the visible, to consider what might lie outside our perceptual reach, and to rethink our place not only on this planet but also in the vast, mysterious architecture of the universe.

01 Suzi Gablik, Magritte (New York Graphic Society, 1970), 183.

02 This theory, proposed in the nineteenth century by Helena Blavatsky, is considered a universal, non-physical compilation of every thought, idea, and event from a shared cosmic “record” and memory.

03 Roy Ascott and Edward A. Shanken, eds., Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness (University of California Press, 2007), 161.

04 John Kelsey, “We Are All Time Tumblers!,” in Stephen Willats: Time Tumbler, ed. Jelena Kristic (Victoria Miro, 2023), 14.

05 See Wikipedia, “Tay al-Ard,” last modified November 3, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Tay_al-Ard.

06 Terence McKenna, The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History (Harper One, 1991), 58.

September 1997), 2000—01

PL. 15, Attributed to Arapaho Artist B Henderson Ledger Book (pg 60/ 61) Arapaho Central Plains, Visionary Drawing, 2018

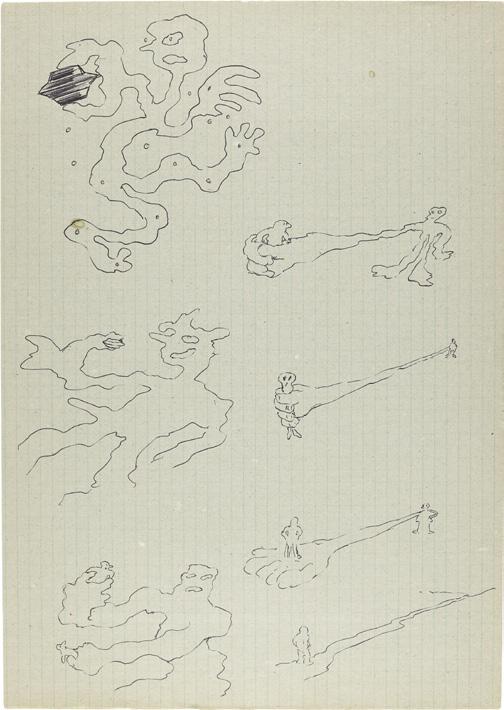

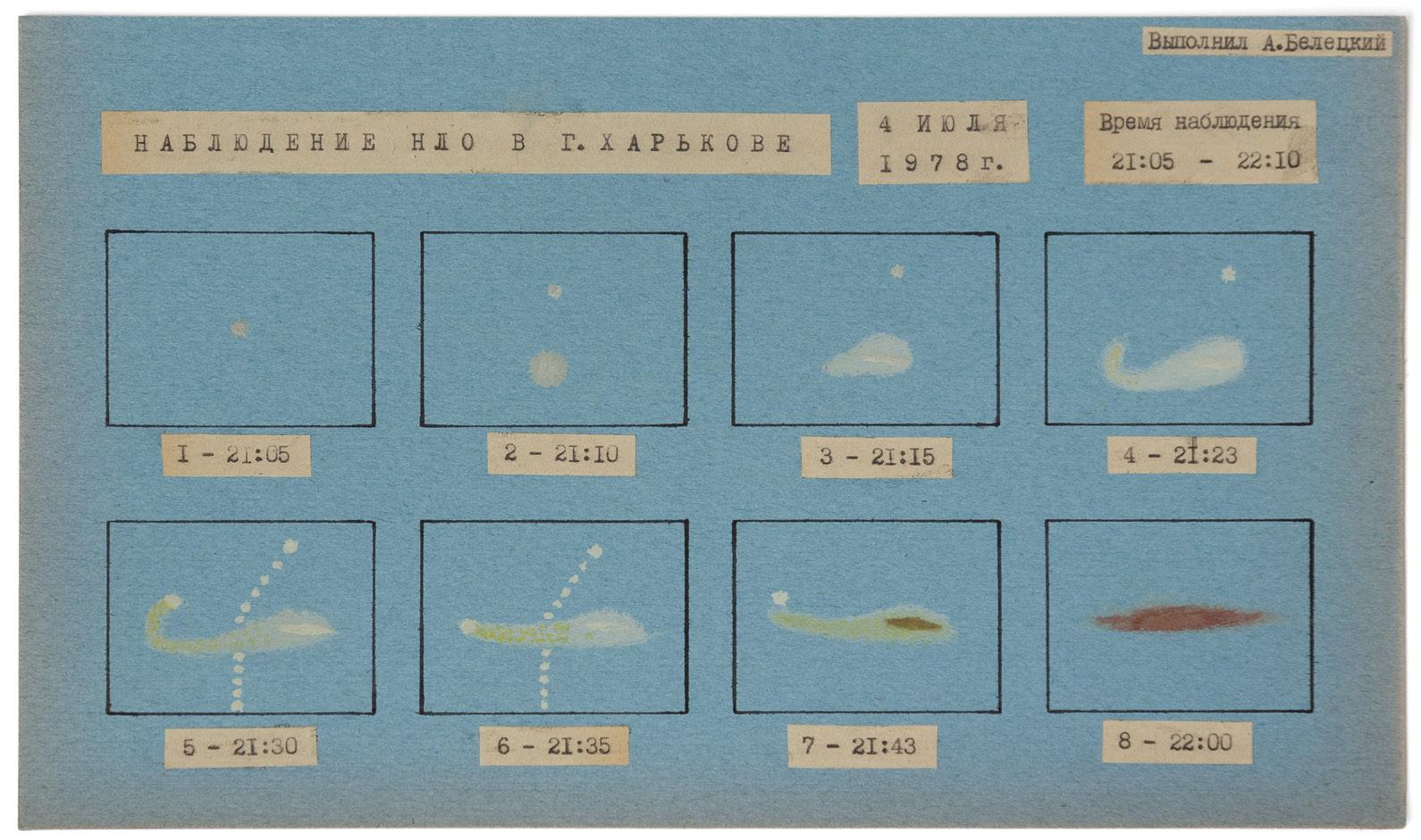

PL. 18, Attributed to M.A. Ulyashev, Sketch of the trajectory of a UFO (

), 1975

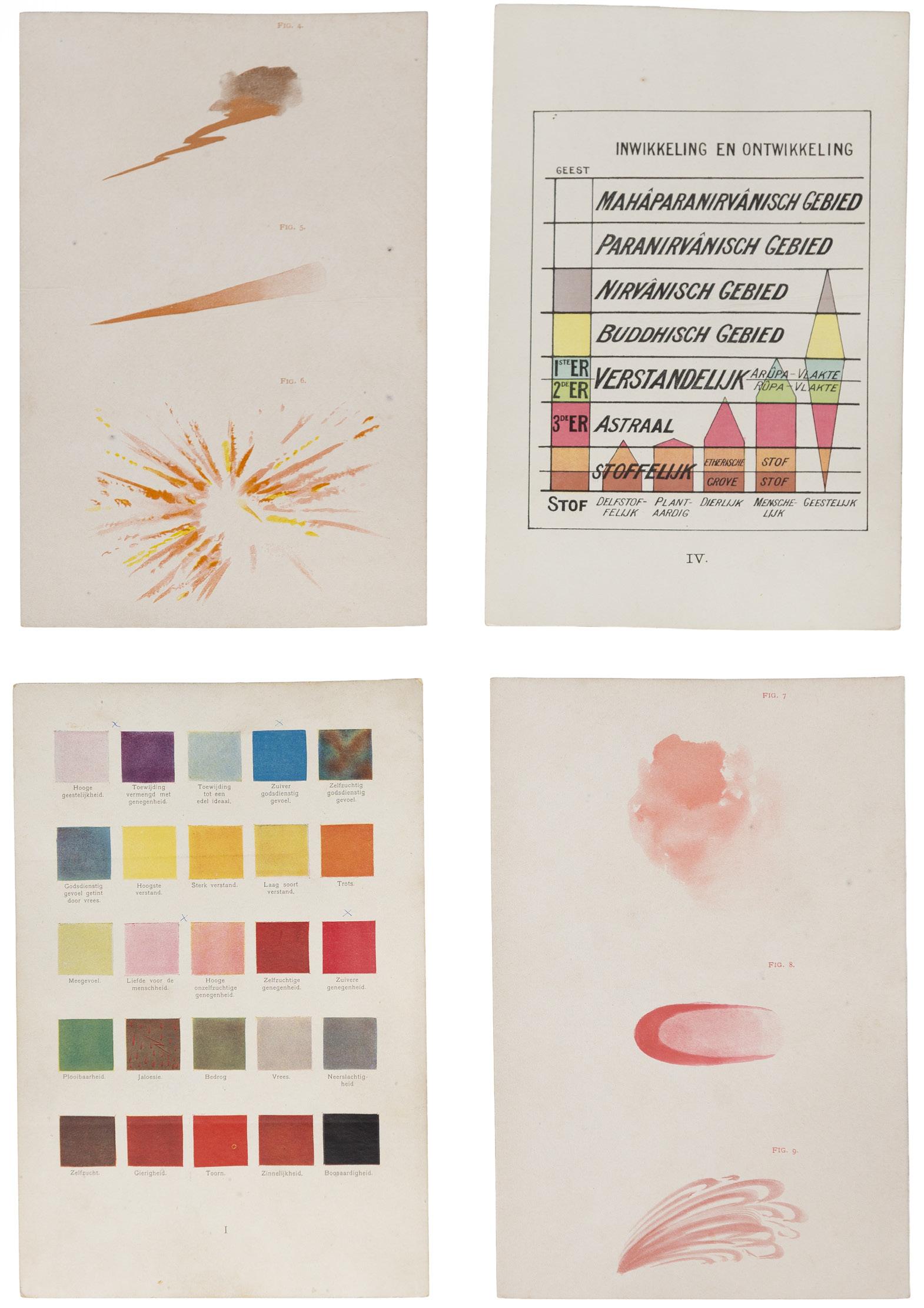

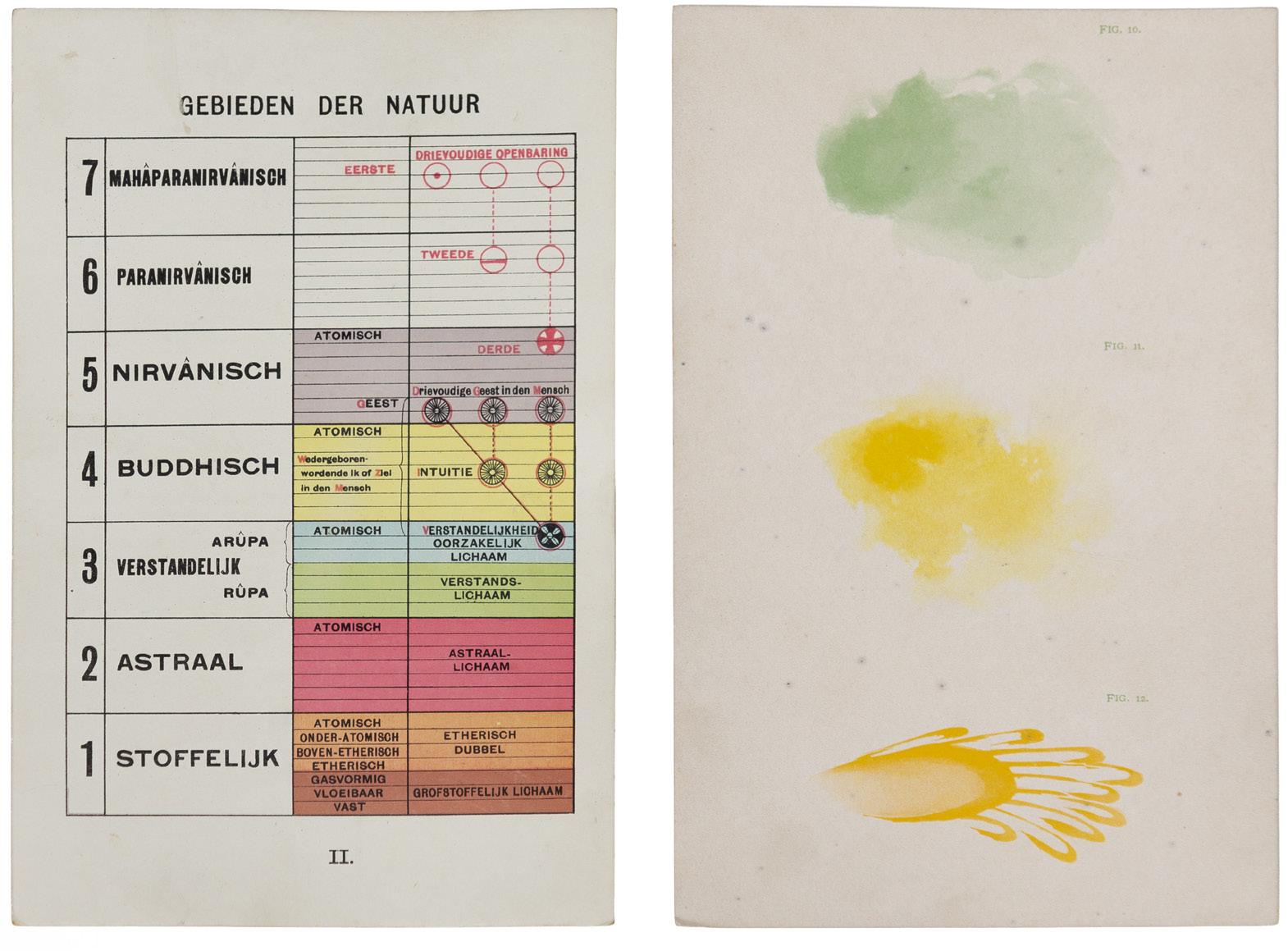

22, C.W. Leadbeater, De Zichtbare en Onzichtbare Mensch (Man, Visible and Invisible), 1903

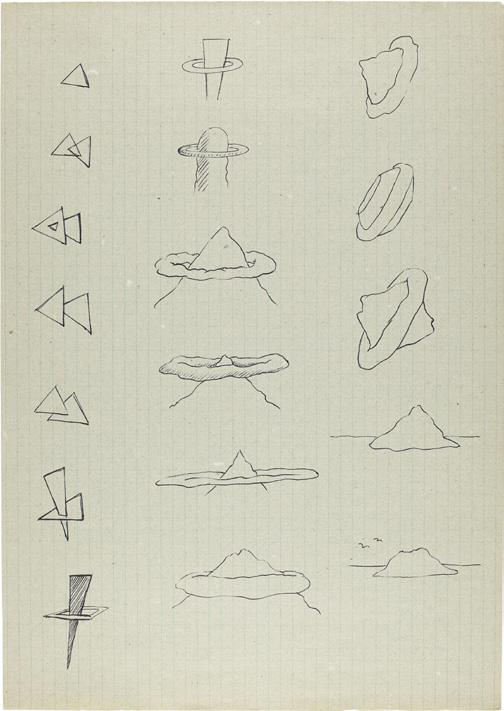

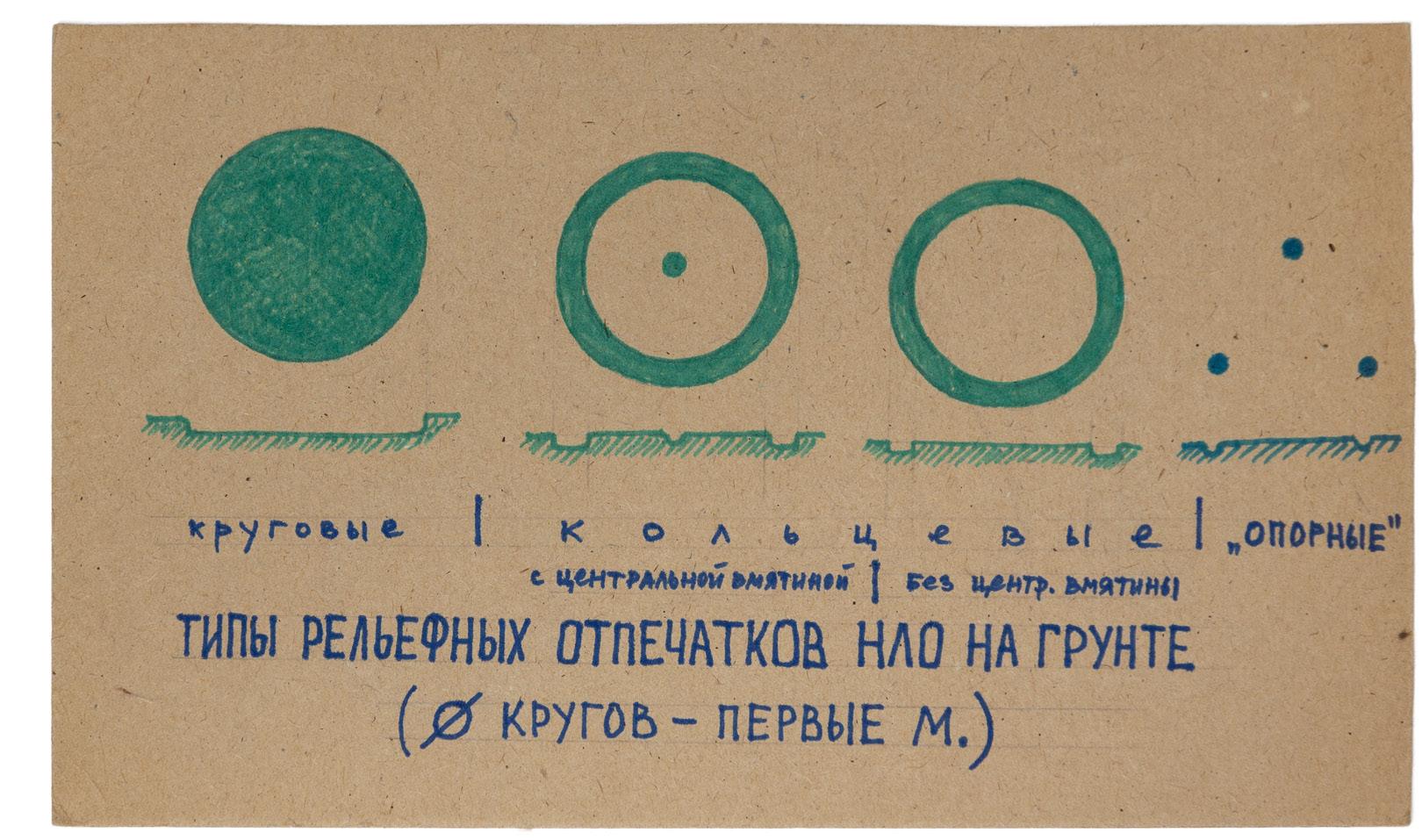

PL. 25, Unknown artist, Types of UFO relief impressions on the ground

PL. 26, Attributed to A. Beletskiy, UFO observation in the city of Kharkiv July 4, 1978, Observation time 21:05–22:10 (

PL. 29, Shusaku Arakawa, Study for Moral/Volumes/ Verbing/ The /Unmind, 1977

Adorno, T. W. “Theses Upon Art and Religion Today.” The Kenyon Review 7, no. 4 (1945): 677–82.

Anderson, Jonathan A. The Invisibility of Religion in Contemporary Art. University of Notre Dame Press, 2025.

Arakawa and Madeline Gins. Making Dying Illegal: Architecture Against Death: Original to the 21st Century. Roof Books, 2006.

Ascott, Roy. “Behaviourist Art and the Cybernetic Vision (1966–67).” In Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, edited by Edward A. Shanken. University of California Press, 2003.

Ascott, Roy. “Technoetic Pathways Toward the Spiritual in Art: A Transdisciplinary Perspective on Connectedness, Coherence and Consciousness.” Leonardo 39, no. 1 (2006): 65–69.

Asprem, Egil. “Dis/Unity of Knowledge: Models for the Study of Modern Esotericism and Science.” Numen 62, no. 5/6 (2015): 538–67.

Bader, Christopher D., Joseph O. Baker, and F. Carson Mencken. Paranormal America: Ghost Encounters, UFO Sightings, Bigfoot Hunts, and Other Curiosities in Religion and Culture. 2nd ed. New York University Press, 2017.

Birnes, William J. The UFO Magazine UFO Encyclopedia. Pocket Books/ Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Blažan, Sladja. Ghosts and Their Hosts: The Colonization of the Invisible World in Early America. University of Virginia Press, 2024.

Briefel, Aviva. “‘Freaks of Furniture’: The Useless Energy of Haunted

Things.” Victorian Studies 59, no. 2 (2017): 209–34.

Bullard, Thomas E. The Myth and Mystery of UFOs. University Press of Kansas, 2016.

Cardeña, Etzel, Steven Jay Lynn, and Stanley Krippner, eds. Varieties of Anomalous Experience: Examining the Scientific Evidence. American Psychological Association, 2014.

Caterine, Darryl. “The Haunted Grid: Nature, Electricity, and Indian Spirits in the American Metaphysical Tradition.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 82, no. 2 (2014): 371–97.

Clark, Jerome. The UFO Encyclopedia: The Phenomenon from the Beginning. 4th ed. Relevant Information, 2024.

Clarke, Ardy Sixkiller. Sky People: Untold Stories of Alien Encounters in Mesoamerica. New Page Books, The Career Press, 2015.

Clarke, Timothy. Navigating UFO/UAP: A Comprehensive Guide to the UFO/UAP Subject and Key Information Sources. Alephraez Publishing, 2023.

Debies-Carl, Jeffrey S. If You Should Go at Midnight: Legends and Legend Tripping in America. University Press of Mississippi, 2023.

Dewan, William J. “‘A Saucerful of Secrets’: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of UFO Experiences.” Journal of American Folklore 119, no. 472 (2006): 184–202.

Dick, Stephen J. “Anthropology and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence: An Historical Review.” Anthropology Today 22, no. 2 (2006): 3–7.

Eaton, Marc A. “‘Give Us a Sign of Your Presence’: Paranormal Investigation as a Spiritual Practice.” Sociology of Religion 76, no. 4 (2015): 389–412.

Eburne, Jonathan. Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox

Ideas. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Finley, Stephen C. In and Out of This World: Material and Extraterrestrial Bodies in the Nation of Islam. Duke University Press, 2022.

Finley, Stephen C. “The Meaning of ‘Mother’ in Louis Farrakhan’s ‘Mother Wheel’: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Cosmology of the Nation of Islam’s UFO.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80, no. 2 (2012): 434–65.

Flaherty, Robert Pearson. “‘These Are They’: ET-Human Hybridization and the New Daemonology.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 14, no. 2 (2010): 84–105.

Frank, Adam. The Little Book of Aliens. Harper, 2023.

Geertz, Armin W. “A Reed Pierced the Sky: Hopi Indian Cosmography on Third Mesa, Arizona.” Numen: International Review for the History of Religions 31, no. 2 (1984): 216–41.

Goldstein, Diane E., Sylvia Ann Grider, and Jeannie Banks Thomas. Haunting Experiences: Ghosts in Contemporary Folklore. University Press of Colorado, 2007.

Graff, Garrett M. UFO: The Inside Story of the US Government’s Search for Alien Life Here and Out There. Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 2023.

Hayes, Kelly E. “Intergalactic Space-Time Travelers: Envisioning Globalization in Brazil’s Valley of the Dawn.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 16, no. 4 (2013): 63–92.

Hopkins, Budd. Missing Time: A Documented Study of UFO Abductions. August Night Press, 2021 (1981).

Jacobsen, Annie. Phenomena: The Secret History of the U.S. Government’s Investigations Into Extrasensory Perception and Psychokinesis. Little, Brown and Company, 2017.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton University Press/Bollingen Series, 1991 (1978).

Kaku, Michio. Parallel Worlds: A Journey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos. Vintage Books, 2006.

Knight, David C. UFOs: A Pictorial History From Antiquity to the Present. McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Kripal, Jeffrey J. How to Think Impossibly: About Souls, UFOs, Time, Belief and Everything Else. University of Chicago Press, 2024.

Mack, John E. Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens. Charles Scribner’s Sons/Macmillan, 2007.

Marsching, Jane D. “Orbs, Blobs, and Glows: Astronauts, UFOs, and Photography.” Art Journal 62, no. 3 (2003): 56–65.

Matthews, Washington. Navaho Legends. University of Utah Press, 1994.

McKenna, Terence. “Questioning Terence McKenna.” Interview by Vicki Cooper. UFO: A Forum on Extraordinary Theories and Phenomena 8, no. 4 (1993): 22–26.

McKenna, Terence. The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History. HarperOne, 1991.

Messeri, Lisa. Placing Outer Space: An Earthly Ethnography of Other Worlds. Duke University Press, 2016.

Mullins, G. W. Star People, Sky Gods, and Other Tales of the Native American Indians. Light of the Moon Publishing, 2017.

Neal, Mark. “Preparing for Extraterrestrial Contact.” Risk Management 16, no. 2 (2014): 63–87.

Owens, Ted. How to Contact Space People. New Saucerian, 1969.

Partridge, Christopher. “Inner Space/Outer Space: Terence McKenna’s Jungian Scientific Mythology.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 23, no. 3 (2020): 31–59.

Pasulka, D. W. American Cosmic: UFOs, Religion, Technology. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Peavy, Paulina. The Story of My Life with a “UFO.” Unpublished manuscript, 1993.

Rice, Tom W. “Believe It or Not: Religious and Other Paranormal Beliefs in the United States.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42, no. 1 (2003): 95–106.

Richards, William A. “The Phenomenology and Potential Religious Import of States of Consciousness Facilitated by Psilocybin.”

Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion 30 (2008): 189–99.

Rimell, Bruce. They Shimmer Within: Cognitive-Evolutionary Perspectives on Visionary Beings. Xibalba Books, 2018.

Saethre, Eirik. “Close Encounters: UFO Beliefs in a Remote Australian Aboriginal Community.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13, no. 4 (2007): 901–15.

Santo, Diana Espírito, and Jack Hunter, eds. Mattering the Invisible: Technologies, Bodies, and the Realm of the Spectral. 1st ed. Berghahn Books, 2021.

Strieber, Whitley. Communion: A True Story. William Morrow Paperbacks, 2008.

Strieber, Whitley. The Fourth Mind. Walker & Collier, Inc., 2025.

Szendy, Peter. Kant in the Land of Extraterrestrials: Cosmopolitical Philosofictions. Translated by Will Bishop. Fordham University Press, 2013.

Talbot, Michael. The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality. HarperCollins, 2011.

Tsing, Anna, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Tumminia, Diana, ed. Alien Worlds: Social and Religious Dimensions of Extraterrestrial Contact. Syracuse University Press, 2007.

Vakoch, Douglas A., and Albert A. Harrison, eds. Civilizations Beyond Earth: Extraterrestrial Life and Society. 1st ed. Berghahn Books, 2011.

Vallée, Jacques. Dimensions: A Casebook of Alien Contact. Anomalist Books, 2008 (1988).

Vallée, Jacques. Passport to Magonia: From Folklore to Flying Saucers. Daily Grail Publishing, 2014.

Vallée, Jacques, and Chris Aubeck. Wonders in the Sky: Unexplained Aerial Objects from Antiquity and Modern Times. Tarcher/Penguin, 2010.

Wendt, Alexander, and Raymond Duvall. “Sovereignty and the UFO.” Political Theory 36, no. 4 (2008): 607–33.

Willats, Stephen. The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour. Occasional Papers, 2010.

Wilson, Peter Lamborn. “Shower of Stars” Dream & Book: The Initiatic Dream in Sufism and Taoism. Autonomedia, 1996.

Young, Jane M. “‘Pity the Indians of Outer Space’: Native American Views of the Space Program.” Western Folklore 46, no. 4 (1987): 269–79.

PL. 01

Melvin Way

Untitled, c. 2013

Ballpoint pen, marker, and Scotch tape on paper

6 × 3 1/2 inches (15.2 × 8.9 cm)

Courtesy of the Estate of Melvin Way and Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York

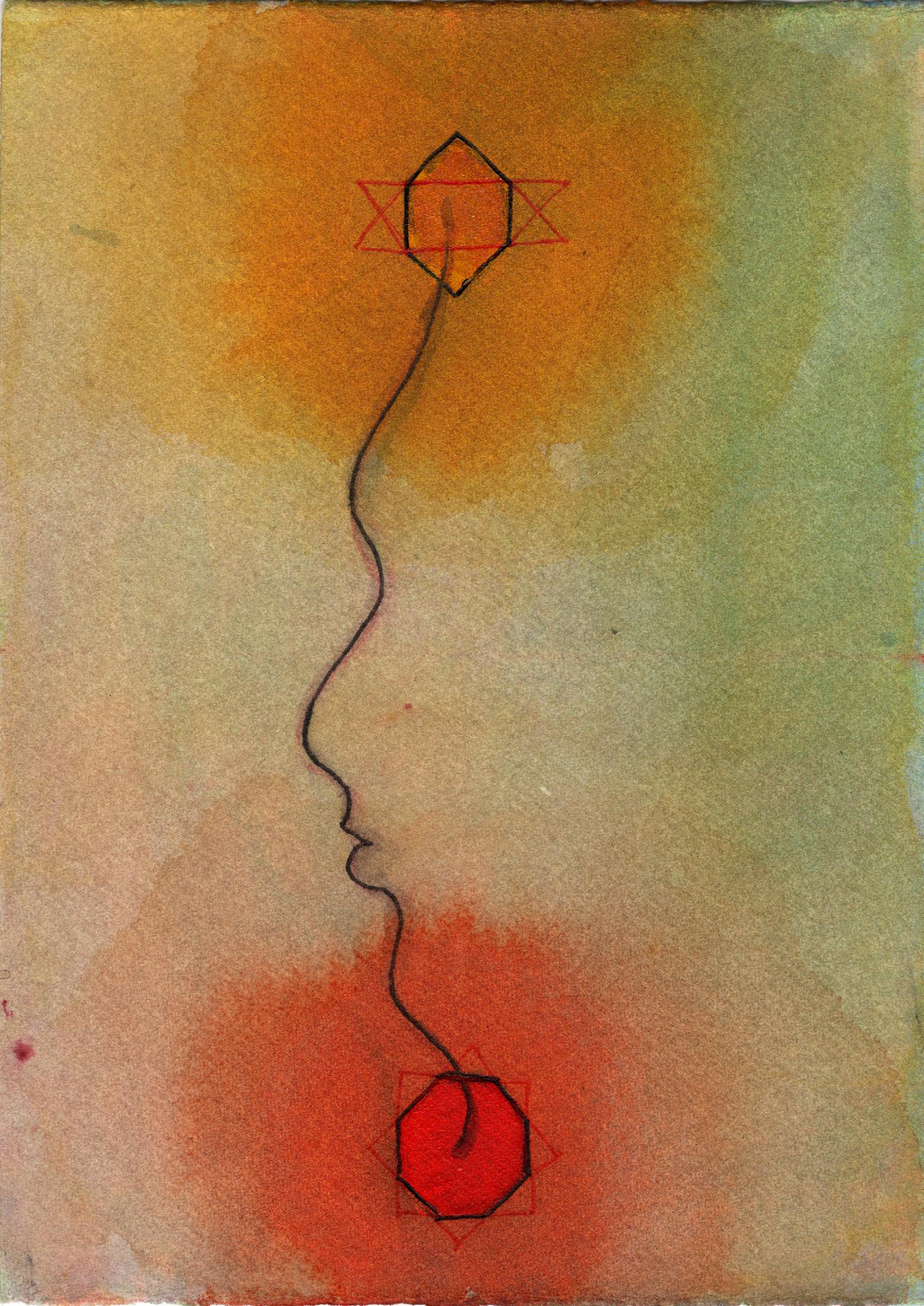

PL. 02

Adam Putnam

Visualization #136, 2021–22

Ink on paper

5 1/2 × 4 inches (14 × 10.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York

© Adam Putnam

PL. 03

Adam Putnam

Visualization #59, 2021–22

Ink on paper

5 1/2 × 4 inches (14 × 10.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York

© Adam Putnam

PL. 04

Isa Genzken

Untitled, 1980

Pencil and ballpoint pen on paper

8 1/4 × 11 3/4 inches (21 × 29.7 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

© 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PL. 05

Isa Genzken

Untitled, n.d. 1973/2003

Ink, watercolor, and mirror foil on paper

11 3/4 × 8 1/4 inches (29.8 × 21 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz© 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PL. 06

René Magritte

Voice of Space, 1931

Oil on canvas

28 5/8 × 21 3/8 inches (72.7 × 54.3 cm)

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

© 2025 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

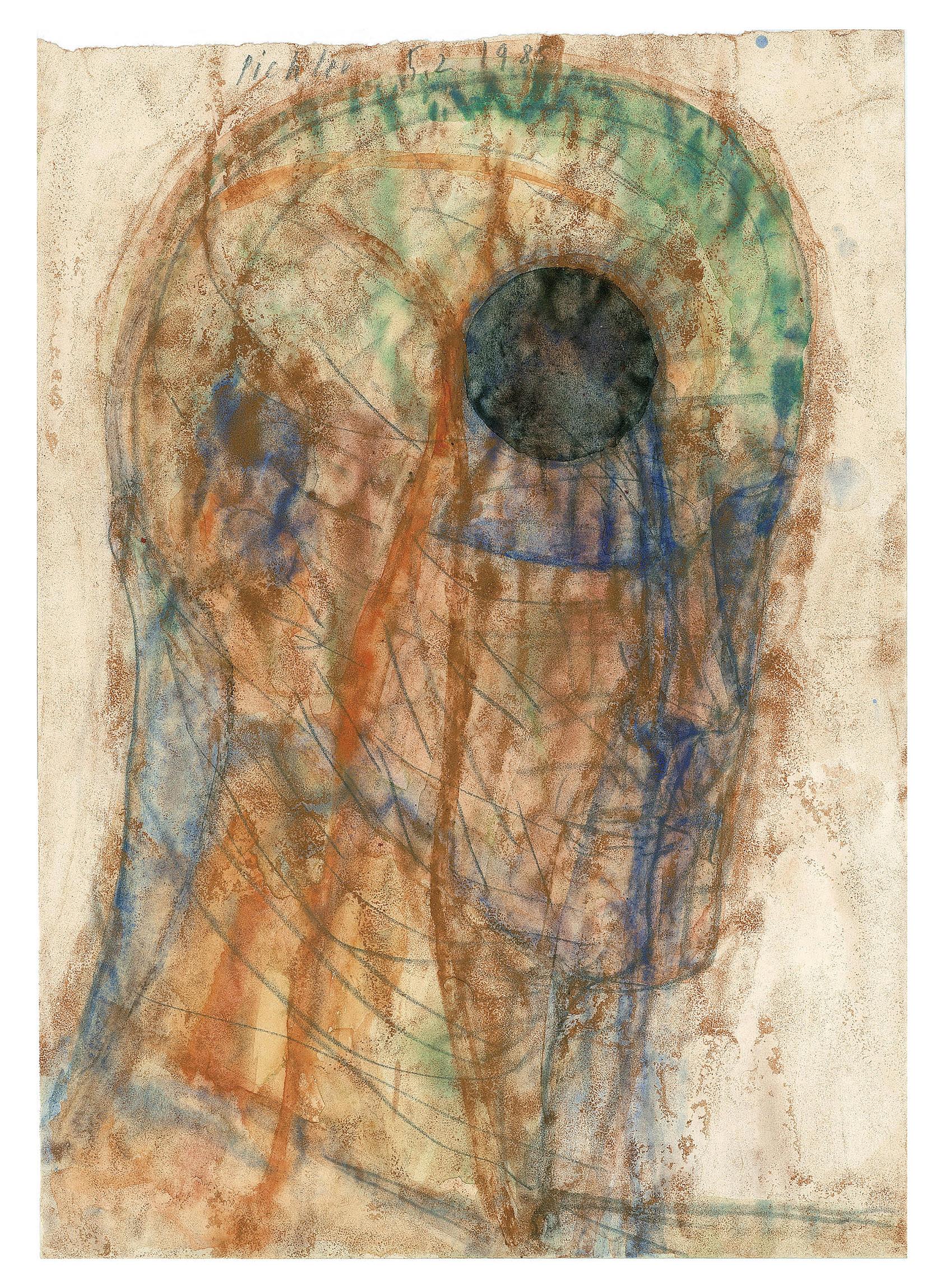

PL. 07

Walter Pichler

Loch im Kopf, 1985

Pencil and tempera on paper

11 1/2 × 8 1/4 inches (29.2 × 21 cm)

Courtesy of the Walter Pichler Estate and Gladstone Gallery

© Walter Pichler

Courtesy of the Estate and Gladstone

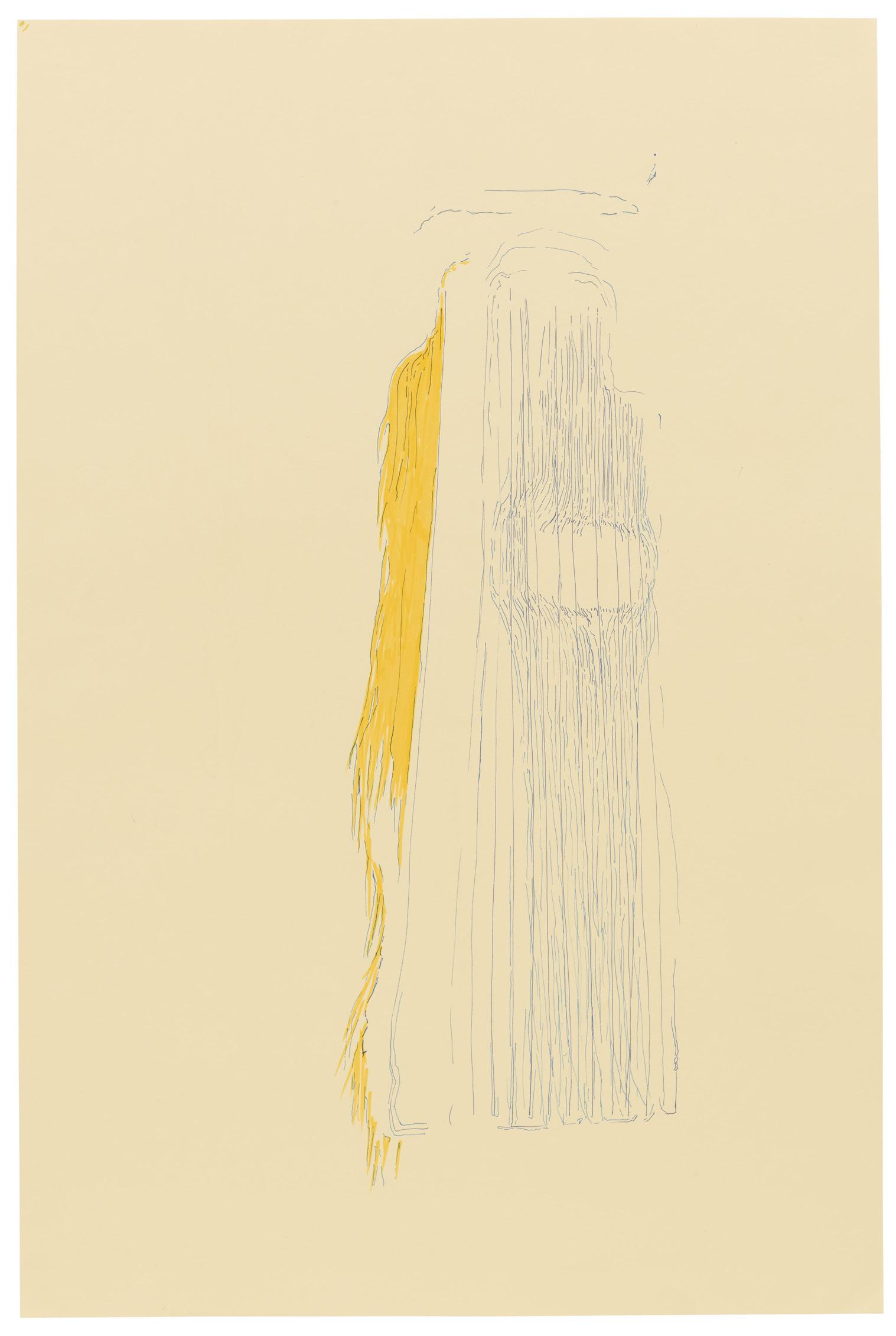

PL. 08

Trisha Donnelly

Untitled, 2025

Ink, graphite, and color pencil on paper

30 3/4 × 20 1/2 inches (78.1 × 52.1 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Matthew

Marks Gallery

©Trisha Donnelly, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

PL. 09

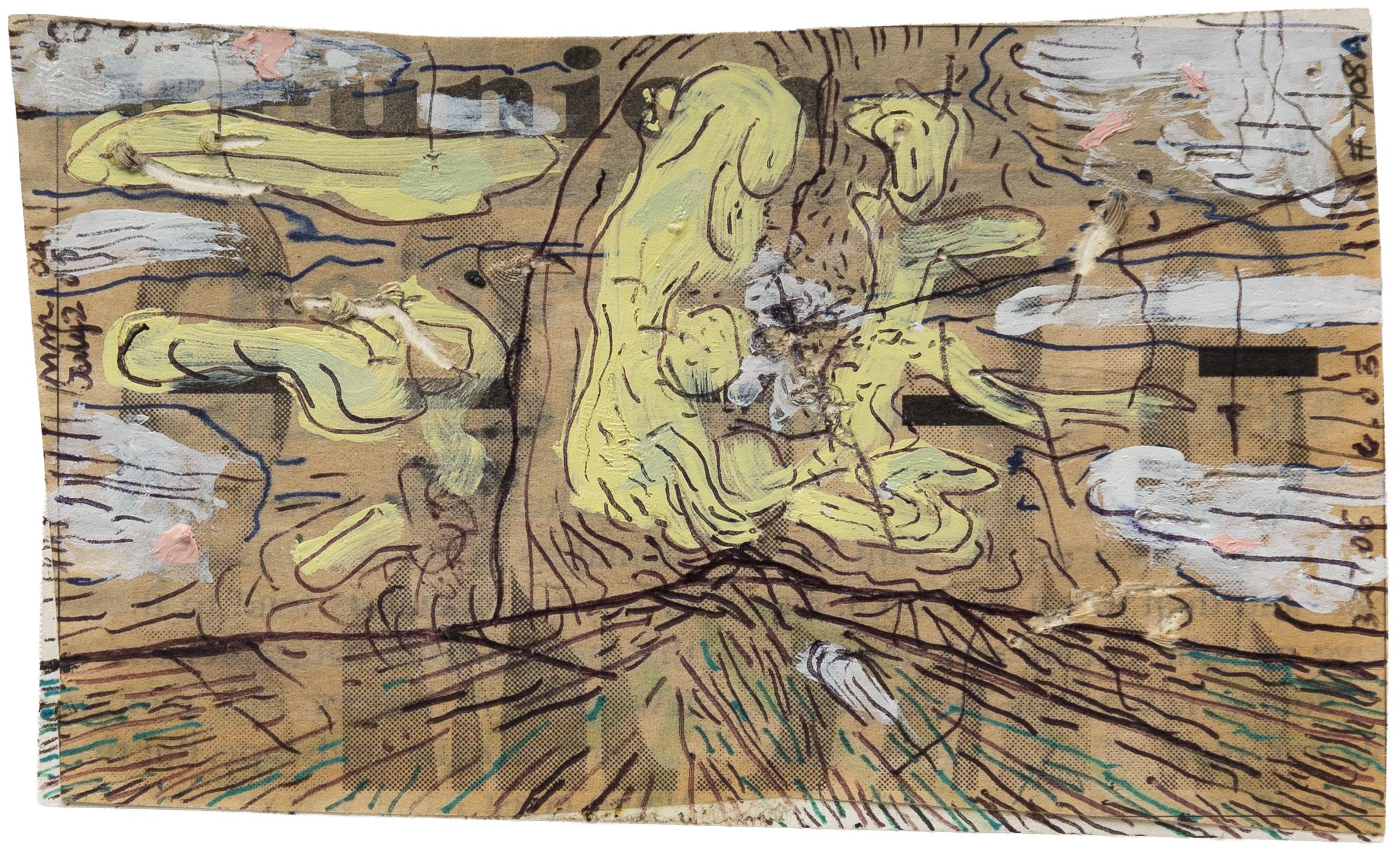

Pope.L

Failure Drawing #708A Even the Mountain is Ash, 2004–06

Ballpoint pen, ink, and acrylic on newsprint on paper

3 1/8 × 5 inches (7.9 × 12.7 cm)

Courtesy of the Estate of Pope.L and MitchellInnes & Nash, New York

Photography by Daniel Terna

PL. 10

Howardena Pindell

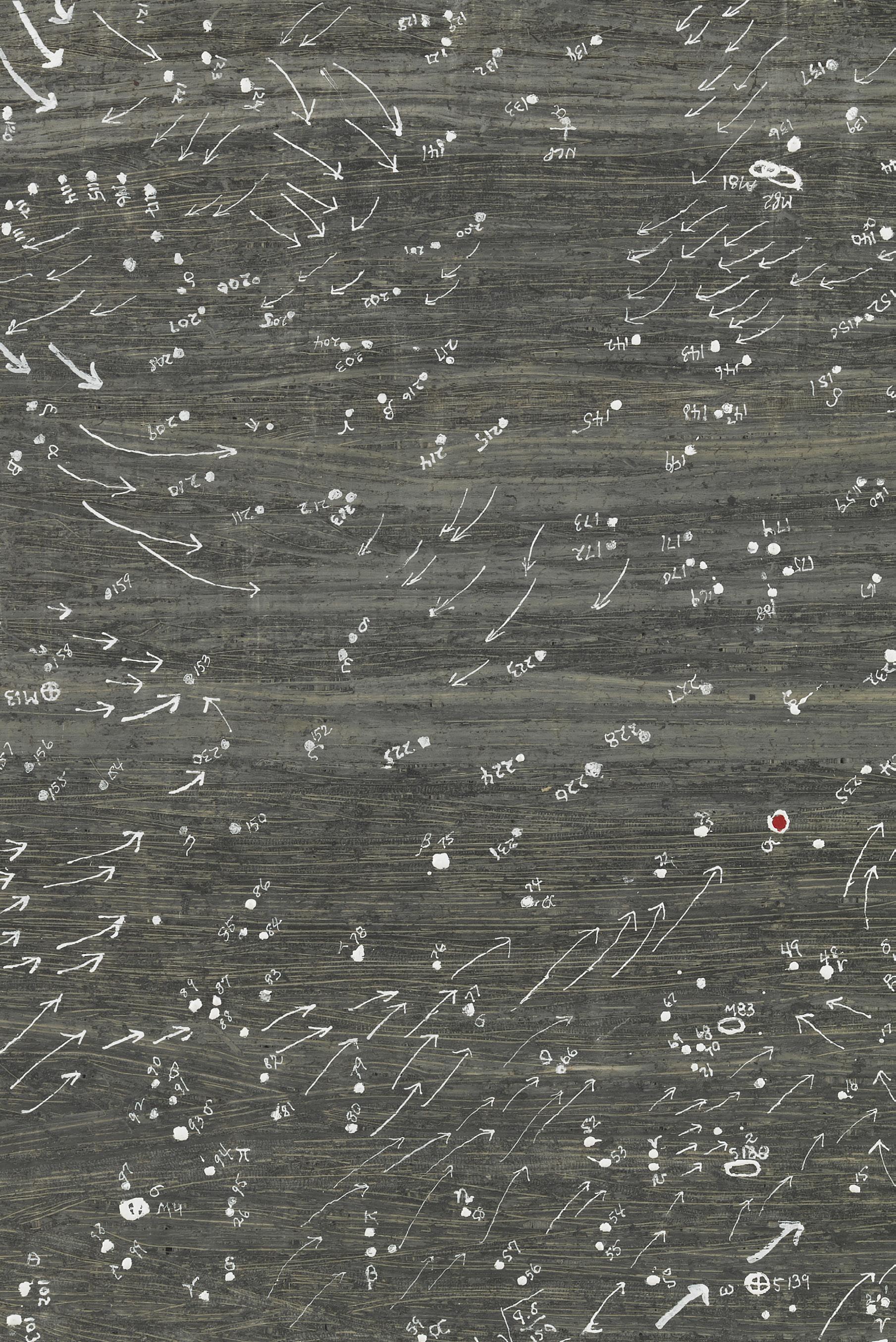

Astronomy: Northern Hemisphere (August–September 1997), 2000–01

Ink, acrylic, and gouache on paper

13 × 17 inches (33 × 43.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY

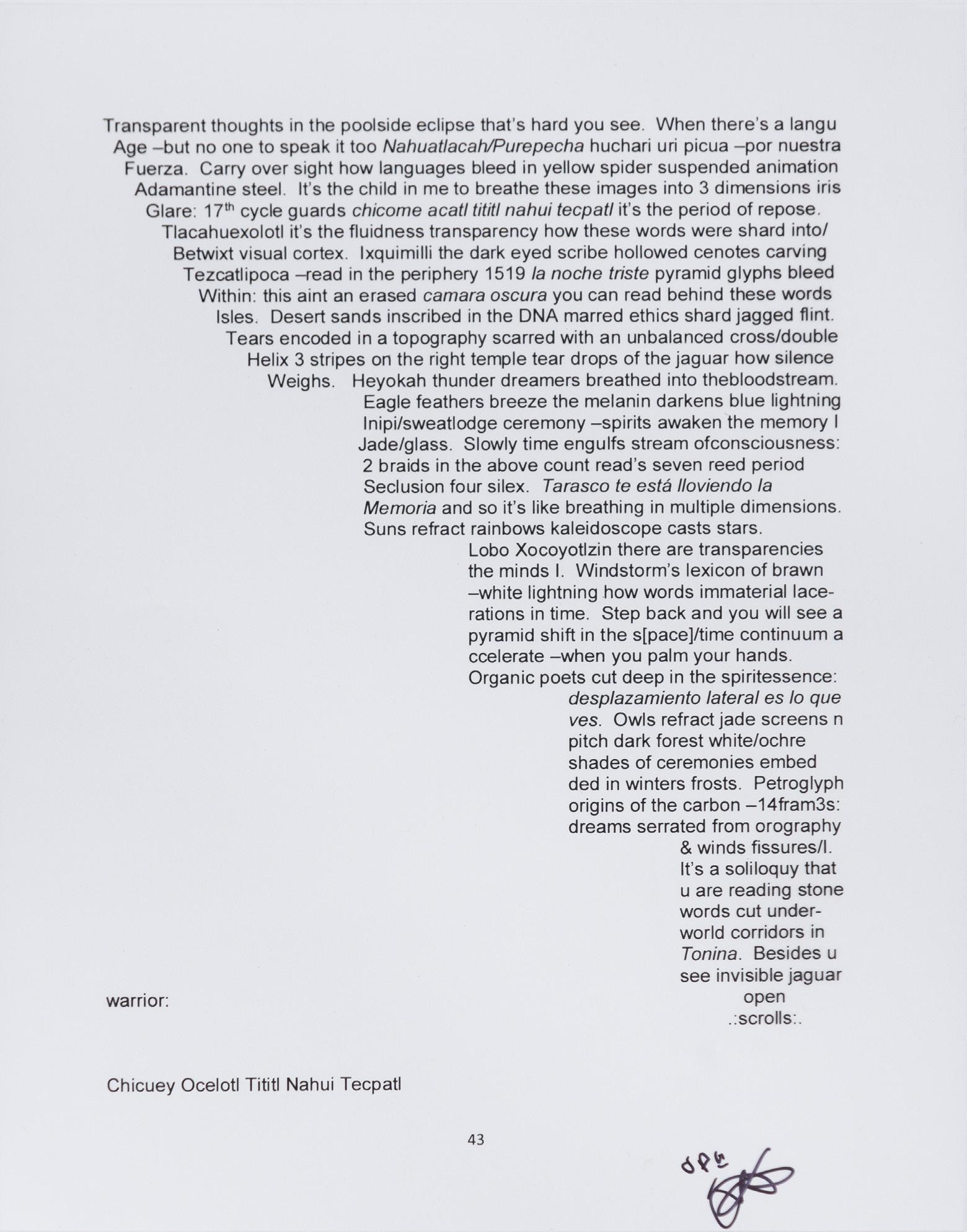

PL. 11

José Trejo-Maya

Transparent Thoughts, 2020

Print on transparency

8 1/2 × 11 inches (21.6 × 27.9 cm)

Private collection

Photography by Daniel Terna

PL. 12

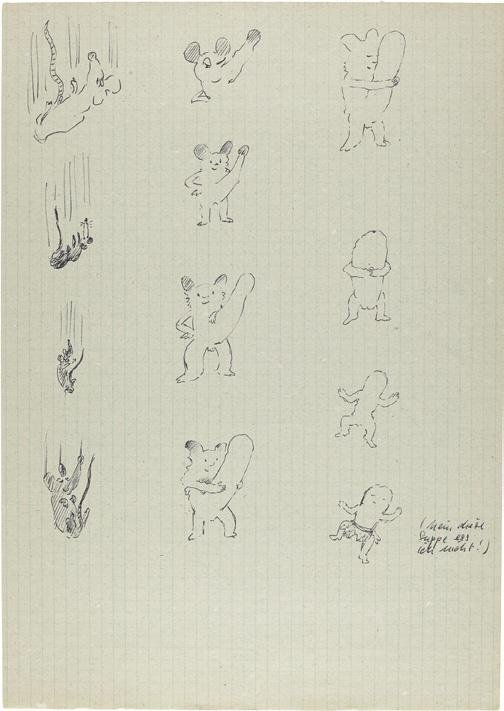

Sigmar Polke

Command of 28.8.68, 1968

Ballpoint pen on lined paper

8 1/4 × 6 inches (21 × 15.2 cm)

From the Collection of Gordon VeneKlasen

© The Estate of Sigmar Polke, Cologne / ARS, New York, 2025

PL. 13

John Zorn

No Title, 2024

Pencil on paper

15 3/16 × 11 3/16 inches (38.6 × 28.4 cm)

Courtesy of the artist

PL. 14

Attributed to He Nupa Wanica

(Joseph No Two Horns)

Visionary Drawing, 1920

Watercolor, graphite, and color pencil on paper

9 3/16 × 7 1/2 inches (23.3 × 19.1 cm)

Donald Ellis Gallery / Galerie Gisela Capitain

Photography by Simon Vogel, Cologne

PL. 15

Attributed to Arapaho Artist B Henderson

Ledger Book (pg 60/61) Arapaho Central Plains

Visionary Drawing, 1880

Diptych recto/verso, graphite and color pencil on lined paper

10 1/2 × 11 3/4 inches (26.7 × 29.8 cm)

Susan Harris, New York

Photography by Daniel Terna

PL. 16

Stephen Willats

Travelling with the Good Connector, 2019 Watercolor, ink and letraset text on paper

27 1/8 × 54 inches (68.9 × 137.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro

PL. 17

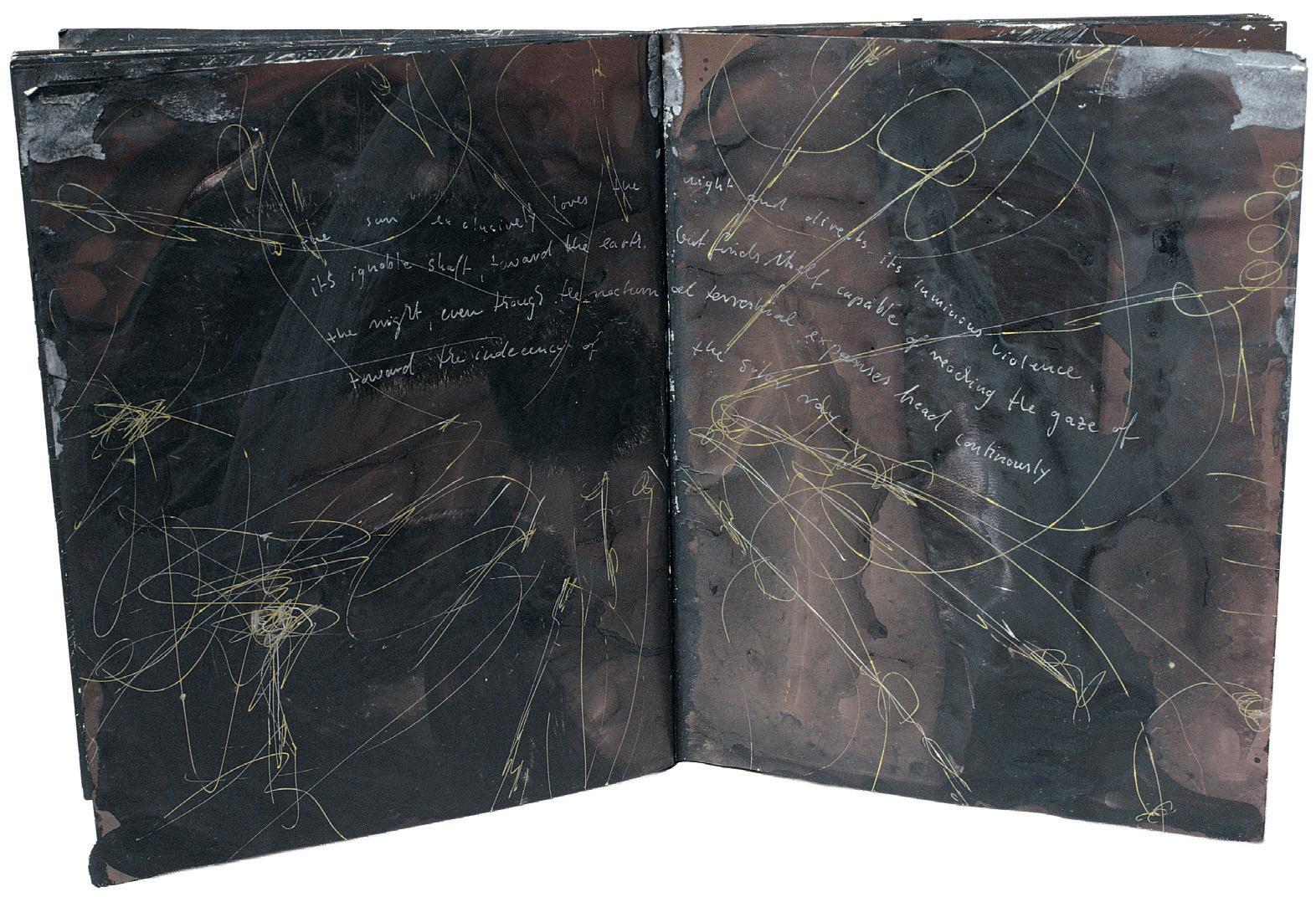

Jutta Koether

You 4, 1999

Artist book, Prada lookbook, magnifying sheet, acrylic, and ink

Approximately 11 3/4 × 18 1/8 inches (30 × 46 cm)

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York

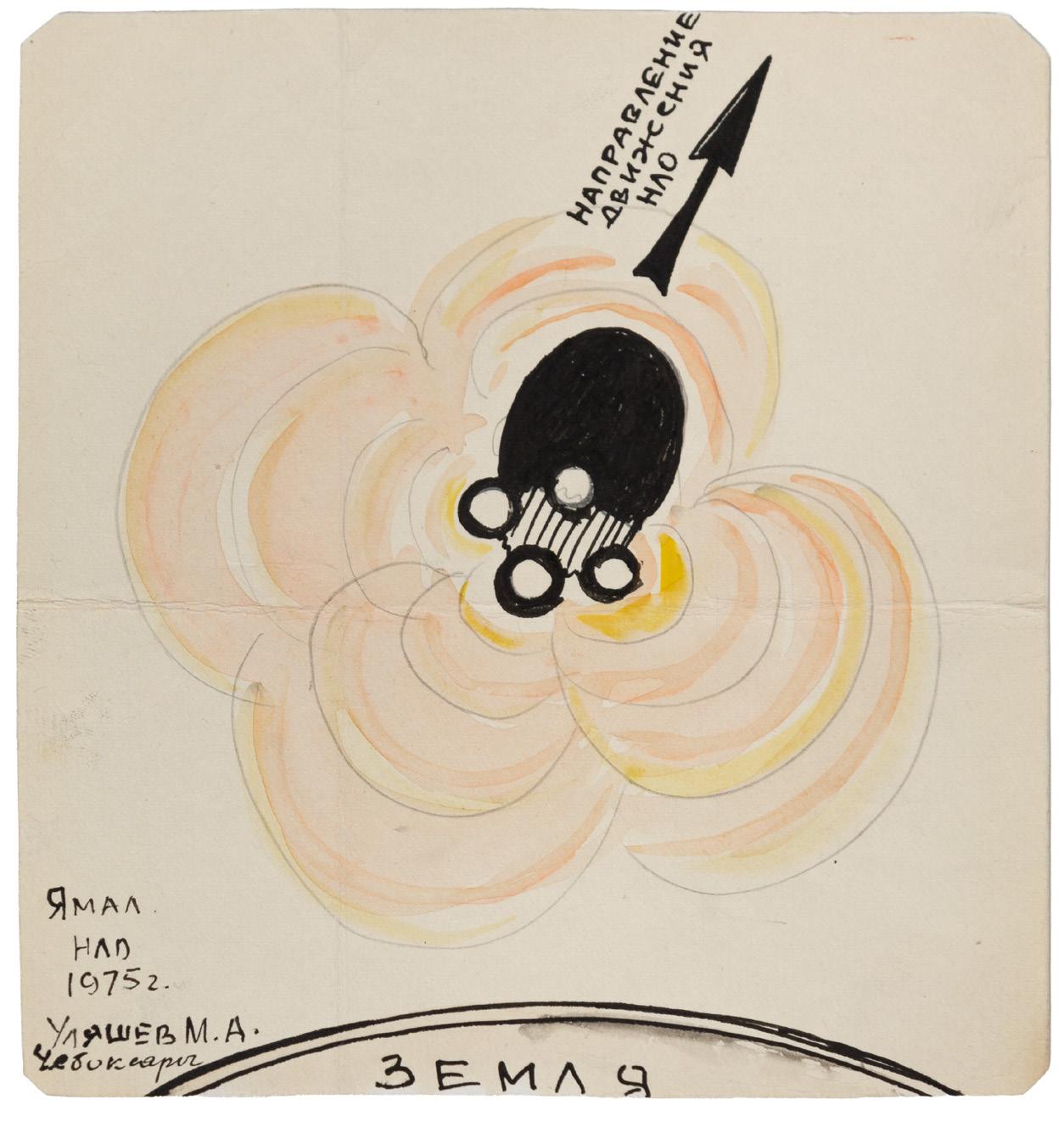

PL. 18

Attributed to M.A. Ulyashev

Sketch of the trajectory of a UFO (Направление движения НЛО), 1975

Ink, pencil, and watercolor on paper

7 3/8 × 7 inches (18.7 × 17.8 cm)

Tony Oursler Studio

Photography by Daniel Terna

PL. 19

Paulina Peavy

Untitled, 1960s–early 1970s

Ink and marker on paper

14 × 11 inches (35.6 × 27.9 cm)

Courtesy of the Estate of Paulina Peavy and Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York

PL. 20

Noland Oswald Dennis studio notes II, 2021

Ink, pencil, vellum on paper

15 3/4 × 12 1/4 inches (40.1 × 31.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery

PL. 21—22

C.W. Leadbeater

De Zichtbare en Onzichtbare Mensch

(Man, Visible and Invisible), 1903

Two books

Closed book 9 3/4 × 7 inches (24.8 × 17.8 cm)

Loose cards 8 3/4 × 5 3/4 inches (22.2 × 14.6 cm)

Private collection

Photography by Daniel Terna

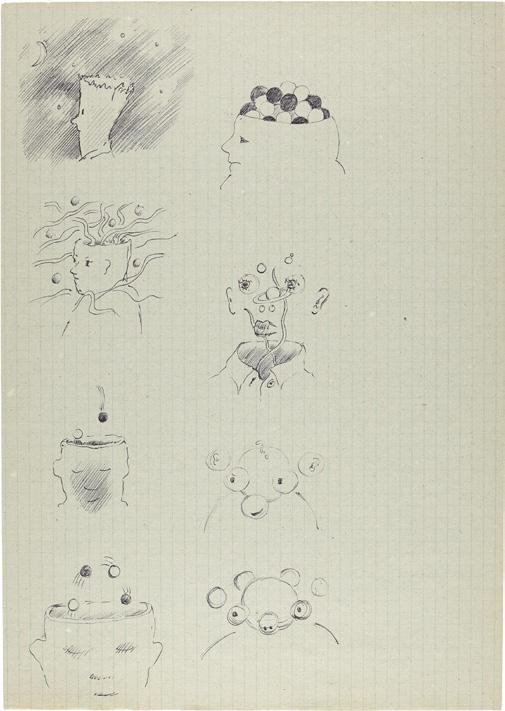

PL. 23

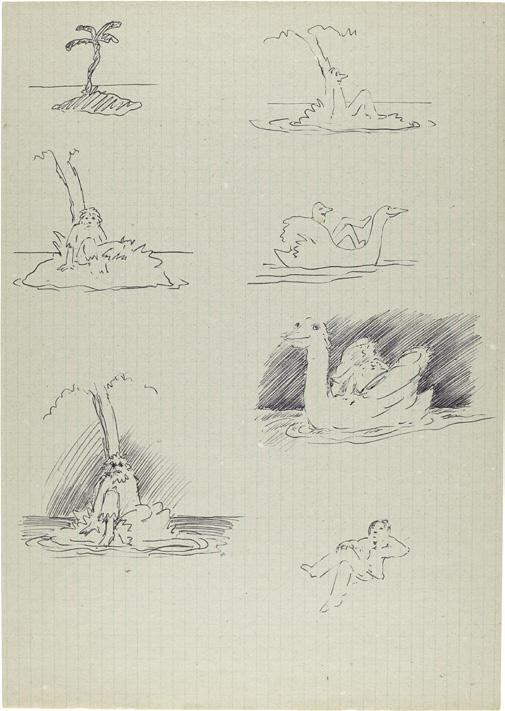

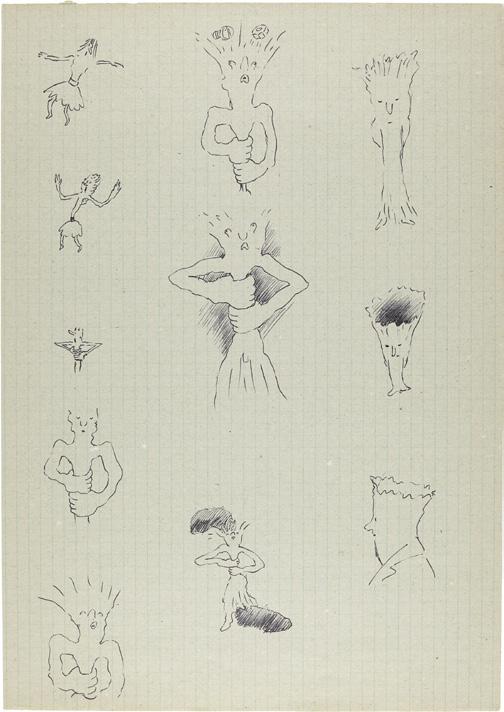

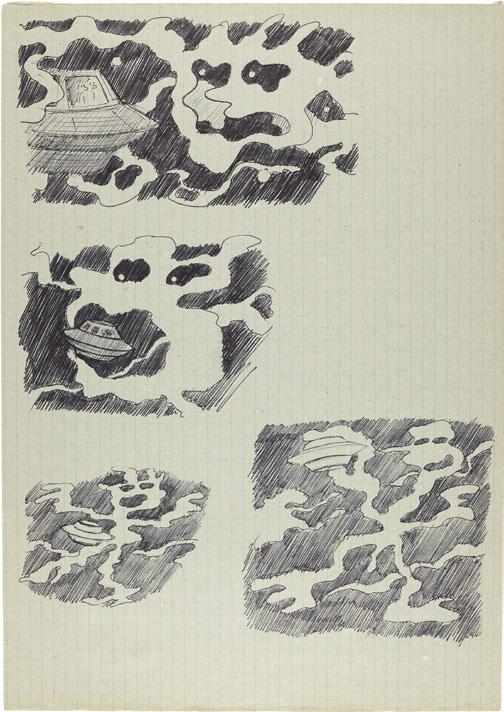

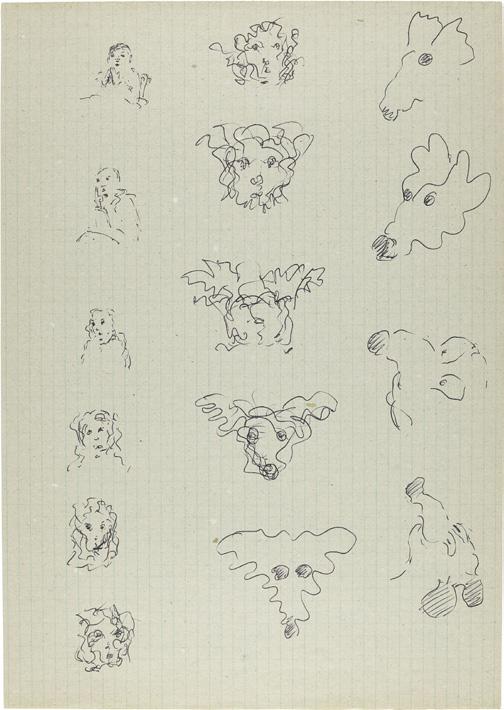

David Weiss

Untitled (Wandlungen), 1975

Ink on paper

11 5/8 × 8 1/4 inches (29.5 × 21 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Oskar Weiss, Zürich and The Estate of David Weiss

PL. 24

Adam Putnam

Visualization #174, 2021–22

Ink on Paper

5 1/2 × 4 inches (14 × 10.2 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York

© Adam Putnam

PL. 25

Unknown artist

Types of UFO relief impressions on the ground (Типы рельефных отпечатков НЛО

на грунте), n.d.

Pencil and marker on paper

7 1/2 × 12 3/8 inches (19.1 × 31.4 cm)

Tony Oursler Studio

Photography by Daniel Terna

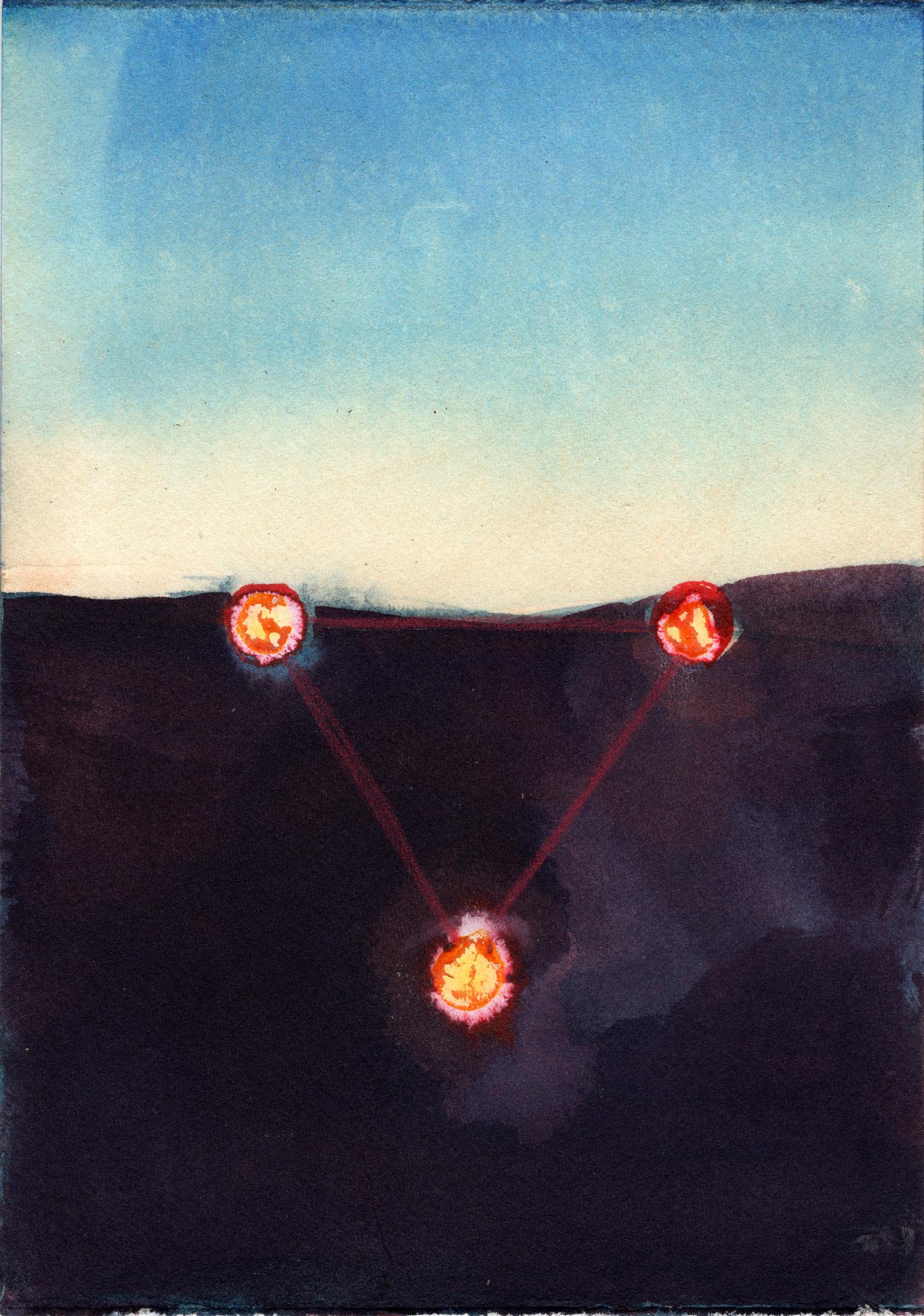

PL. 26

Attributed to A. Beletskiy

UFO observation in the city of Kharkiv

July 4, 1978, Observation time 21:05–22:10

(Наблюдение НЛО в г. Харикове 4 июль 1978

г. Время наблюдения 21:05–22:10), 1978

Ink, paint, and collage

6 3/4 × 11 1/4 inches (17.1 × 28.6 cm)

Tony Oursler Studio

Photography by Daniel Terna

PL. 27

Char Jeré

Boundless, 2024

Mixed media

8 × 10 inches (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery

PL. 28

Char Jeré

Go Bag, 2024

Mixed media

8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery

PL. 29

Shusaku Arakawa

Study for Moral/Volumes/Verbing/

The/Unmind, 1977

Pencil, crayon, acrylic, and lithography

46 5/8 × 34 1/8 inches (118.4 × 86.7 cm)

Courtesy of Mark and Nikki Feldman

PL. 30

Roy Ascott Untitled, 1962

Pencil on paper

8 1/2 × 11 inches (21.6 × 27.9 cm)

Collection of Edward A. Shanken

PL. 31

Isa Genzken

Weltempfänger Daniel (World Receiver), 1990

Concrete and antenna

6 7/8 × 16 1/2 inches (17.5 × 42 cm)

Collection of Eleanor and Bobby Cayre, New York

© 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PL. 32

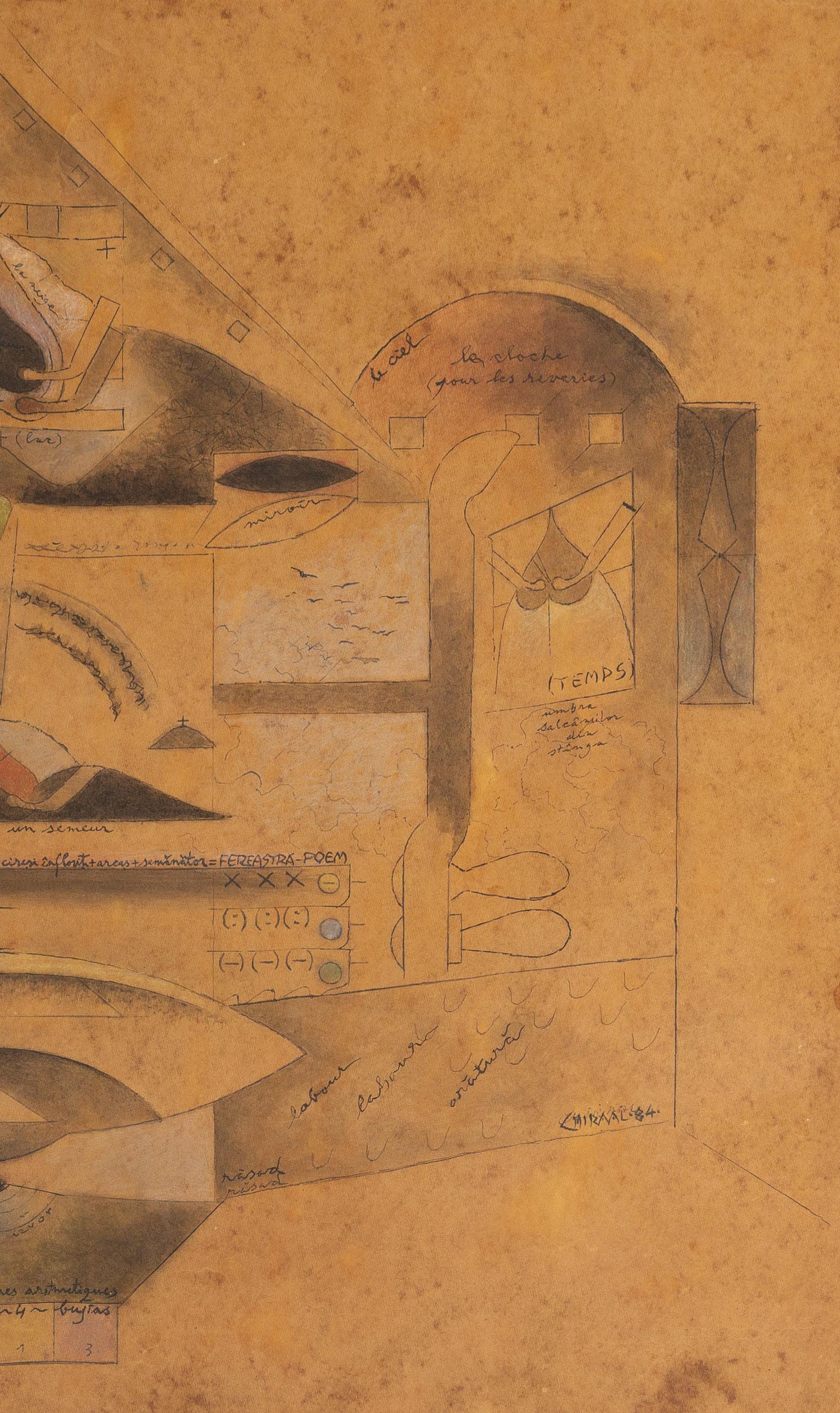

Alexandru Chira

Installation for Invoking Rain and RainbowColorful Project (Instalatje pentru sugestionat ploaia si curcubeu- proiect colorat), 1986

Pencil, color pencil, ink, and color ink on paper collated on cardboard

21 5/8 × 27 1/2 inches (55 × 70 cm)

Courtesy of the estate and Fitzpatrick Gallery

© 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VISARTA, Bucharest

PL. 33

Unknown artist

Farsi Drawing, n.d.

Ink on paper

11 × 7 3/4 inches (27.9 × 19.7 cm)

Courtesy of Alexander Gorlizki

PL. 34

Melvin Way

Fauvi, c. 1989

Ballpoint pen and Scotch tape on paper

10 3/4 × 8 1/2 inches (27.3 × 21.6 cm)

Courtesy of the Estate of Melvin Way and Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York

PL. 35

Jutta Koether

Untitled, 1984

Oil on canvas board

8 × 6 inches (20.3 × 15.2 cm)

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York

Stanley Brouwn

Use this Light Brouwn, 1964

Ink stamp on paper

10 7/8 × 8 1/4 inches (27.5 × 21 cm)

Private collection

Trisha Donnelly

Untitled (Bells), 2007

Audio CD, 1:52 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris Gallery

Jutta Koether

Untitled, 1999

Ten parts, acrylic, ink, collage on paper and on tracing paper

Approximately 11 3/4 × 9 inches (30 × 23 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York

Jutta Koether

Untitled, 1999

Ten parts, collage, ink and acrylic on tracing paper

Approximately 11 3/4 × 9 inches (30 × 23 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York

Jutta Koether

Untitled, 1999

Ten parts, collage, ballpoint pen, ink and acrylic on paper and on tracing paper

Approximately 11 3/4 × 9 inches (30 × 23 cm)

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York

Paul Chan

Paul Chan is an artist based in New York.

Olivia Shao

Olivia Shao is the Burger Collection & TOY Meets Art Curator at The Drawing Center.

Mark von Schlegell

Irish/American writer Mark von Schlegell (b. New York, 1967) has been based in Cologne, Germany since 2006. His novels include Venusia (Semiotext(e), 2005), honor’s listed for the James Tiptree Jr. award in science fiction, Mercury Station (Semiotext(e) 2009) New Dystopia (Sternberg, 2011) and Sundogz (Semiotext(e), 2015).

Co-Chairs

Valentina Castellani

Hilary Hatch

Treasurer

Jane Dresner Sadaka

Secretary Iris Z. Marden

Dita Amory

Frances Beatty Adler

David R. Baum

Brad Cloepfil

Andrea Crane

Stacey Goergen

Amy Gold

Harry Tappan Heher

Priscila Hudgins

KAWS

Rhiannon Kubicka

Adam Pendleton

David M. Pohl

Nancy Poses

Almine Ruiz-Picasso

David Salle

Curtis Talwst Santiago

Joyce Siegel

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Barbara Toll

Jean-Edouard van Praet d’Amerloo

Waqas Wajahat

Linda Yablonsky

Emeritus

Eric Rudin

Laura Hoptman Executive Director

Olga Valle Tetkowski Deputy Director

Rebecca Brickman Director of Development

Rebecca DiGiovanna Administrative Manager

Neal Flynn Education Associate

Sarah Fogel Registrar

Aimee Good Director of Education and Community Programs

Isabella Kapur Assitant Curator of Research

Valerie Newton Director of Retail and Vistor Services

Anna Oliver Bookstore Manager

Nona Poydras Visitor Services Associate

Isa Riquezes Communications and Marketing Associate

Olivia Shao Burger Collection and TOY Meets Art Curator

Tiffany Shi Development Manager

Nathaniel Steen Vistor Services Associate

Allison Underwood Director of Communications

Aaron Zimmerman Operations Manager & Head Preparator

Generous support for Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena is provided by Stephen Cheng, Kent Shao, the Teiger Foundation, Sarah Arison, Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, and Laurie and David Wolfert.

Publication © 2025

Texts © 2025

Graphic Design: Pacific

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photographing, recording, or information storage and retrieval, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-942324-08-2