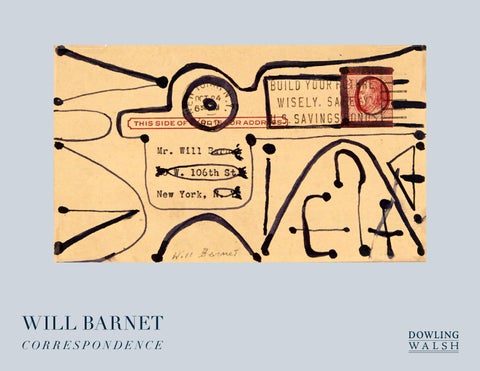

WILL BARNET correspondence

July 5–July 31, 2025

Essay by Christopher B. Crosman

WILL BARNET

correspondence

Christopher B. Crosman

“Which of us can control our scribblings. They are the script of one’s personality like your voice or your walk.”

—James Joyce, quoted by Will Barnet in a conversation with Emily Goldstein, 1997

I first met Will Barnet (1911 – 2012) in 1988, during my first few days as director of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. He was, even then, a legendary presence on the New York contemporary art scene, where he knew, taught, and nurtured many of the most important artists of his own generation, as well as rising artists of the next. In Maine, his work would, at first glance, be an odd fit among scrimshaw carvings, ship models, Lucy Farnsworth’s European chromolithographs, and Victorian decor. Or maybe not? As I would learn over the years, Barnet’s eye was visually voracious, all-consuming, and encompassing. His work not only fit comfortably in a collection that celebrated Maine’s role in the history of American art but also centered it in the wider, seminal realms of the twentieth-century American avant-garde.

His work comfortably conversed with, corresponded with, sturdy, direct portraits of stiff 19th-century New Englanders, or with the luminous stillness of “down east” schooners by Fitz Henry Lane, and formally with much newer abstract art in the stacked wooden boxes and early, painterly paintings by his longtime New York friend and peer, Louise Nevelson who had been raised in Rockland. Eventually, his paintings would be accompanied by Kenneth Noland’s glowing color abstractions—made,

according to the artist, by Maine light, something they shared with Barnet’s own crepuscular Women by the Sea series of paintings. The art of all museums, in dialogue with and correspondence between old and new, is and was always central to Barnet’s work, as well. Barnet adored art history, oftentimes as sources of competition, analogy, or aesthetic argument, correspondences, both celebrated and damned by the artist himself!

A relatively unexplored aspect of Barnet’s work, especially as related to his small drawings and watercolors, is to what extent childhood memories of growing up in working-class Beverly, MA, imprinted themselves on Barnet’s imaginative consciousness. Wooden ships and fishing boats still sailed out of Beverly’s harbor, built by local residents from gracefully handworked, curving timbers and canvas sails of all shapes and sizes, often with patchwork repairs. More immediately, Barnet’s father was a skilled machinist in a shoemaking factory. The artist and father shared an epic work ethic, to be sure. But shoemaking, even with machines, is a kind of collage process; small, organic abstract shapes precisely pieced together into something new, strong, and necessary—along with continuous reinvention in accordance with changing styles and fashions. Attention to craft, detail, and workmanship, and how to balance parts to create a unified whole are integral to why Barnet’s work—abstract or representational—holds together. Barnet’s distinctive palette often relates to New England’s quiet, muted reticence: shoe-leather tans, blacks, ochres. And scuffed, earthen browns, greys, and sea-dark skies and watery-wintry undertones—perhaps, remnants of a subconscious childhood memory, as well.

For an artist who lived and worked for the better part of the 20th century and into the 21st, “correspondence” is an evocative title for an exhibition of small drawings and watercolors on postcards and scraps of paper, here accompanied by his last major oil paintings. These small early abstractions anticipate and expand upon Barnet’s last outpouring of abstract energy and release. His late abstract oil paintings harken back to these earlier works through (mostly) muted colors—cochineal greens, dusky yellows, somber ochres, shadowy, dense greys, and blacks. It’s among those clichés that survive because they are true that great artists always

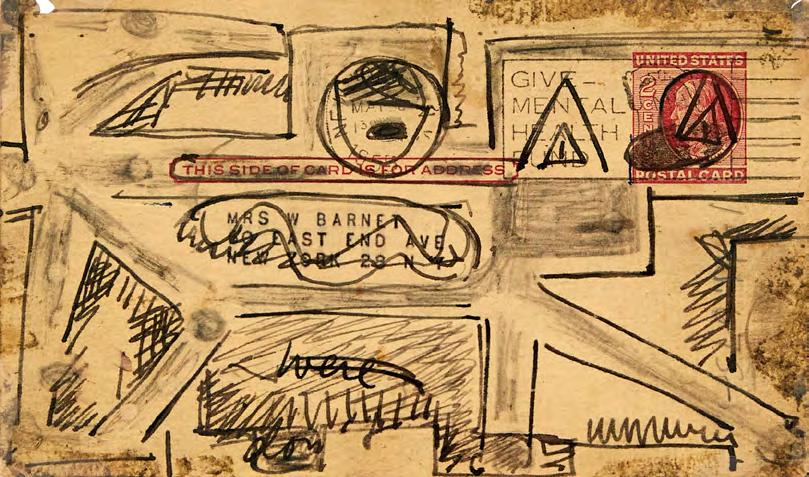

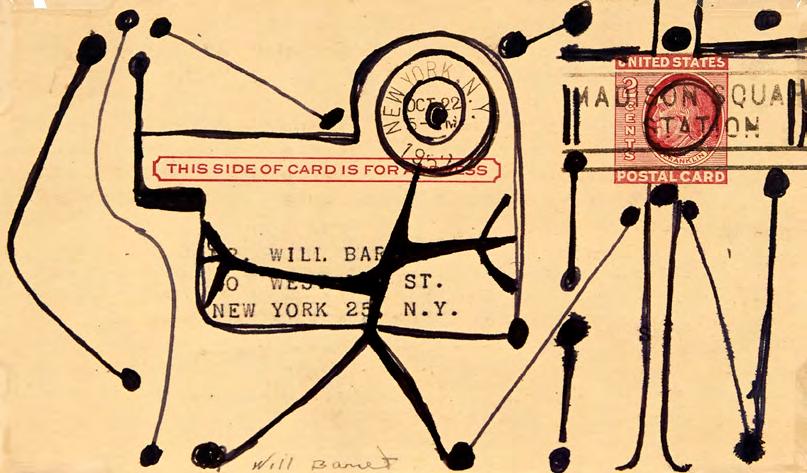

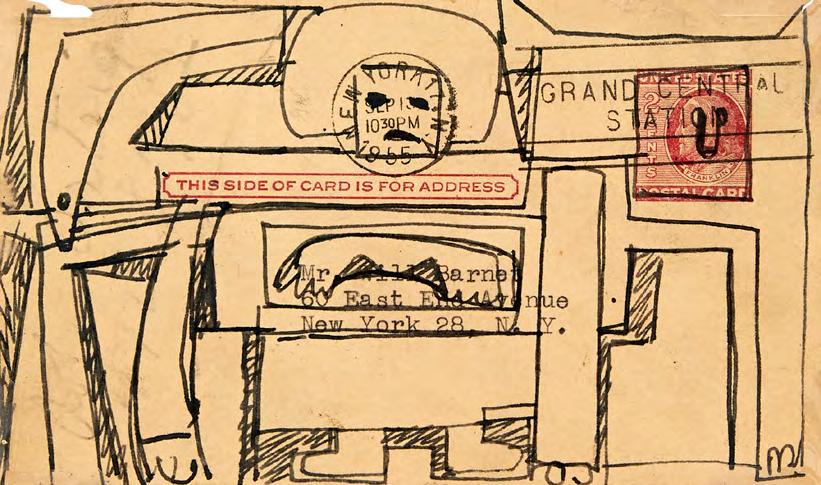

Correspondence 11, 1956, ink on 2 cent postcard, 5 ½ x 3 ¼ in.

break their own rules. Bright colors on vellum allowed Barnet to celebrate a summer on Cape Cod or the excitement of starting a new family. Abstract compositions attempt to contain ambiguous figure-ground relationships, segmented and organic shapes, and a sense of the human hand working these surfaces with fierce, practiced urgency. His very last paintings mine these earlier, spontaneous “scribblings,” simultaneously loosening and fixing the play of shape and color.

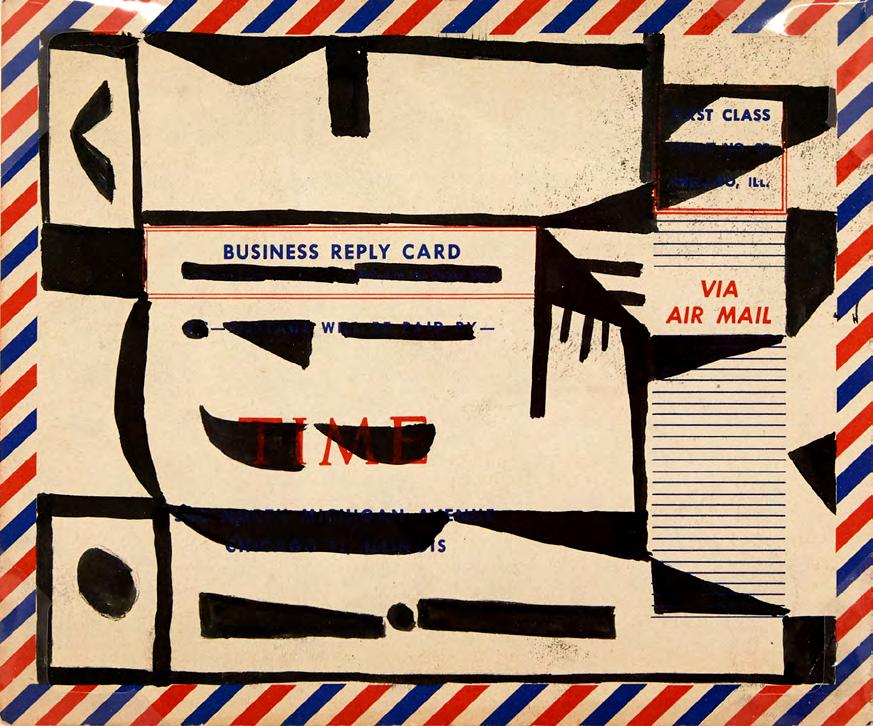

The postcards carry traces of their origins—post office place names, dates and times, typed addresses, canceled stamps, and the occasional, mostly illegible hand-written word. One example is an airmail envelope edged with red, white, and blue stripes, which carries black, floating shapes across the empty whiteness of the envelope. Those small, black forms seem to articulate some kind of proto-literate inscription, linking faraway cultures or perhaps just a fleeting visual thought. Other small scraps of paper are torn, bent, or stained from use when retrieved from wastepaper bins or the depths of desktop drawers’ nooks and crannies.

Several small-scale works suggest pen and ink doodles from telephone conversations or bored scribbles—musings from an art class lecture hall? With such a diminutive size, every decision by the artist takes on a larger measure. In the current exhibition, correspondences between the early and late works are those of memory and imagination, conveyed through a language of stacked planes and clear, flat colors, which offer close kinship with his earlier, better-known figurative paintings, featuring portraits of family members, friends, and colleagues.

Although proudly an outsider, Barnet had, by the time we met, become an informal ambassador to the broader cultural milieu in New York and beyond (one of his paintings is in the permanent collection of the Vatican in Rome that is reportedly regularly on view). If you needed an introduction to practically any artist living or exhibiting in New York, Will could arrange an audience, often over cigars and brandy, in the ornate, Edwardian-era National Arts Club bar. He taught for much of his career at the Art Students League, where works by his students bear little resemblance to Barnet’s. They flourished under his open-minded and, most

importantly, open-hearted instruction—Eva Hesse, Cy Twombly, and James Rosenquist, among many others.

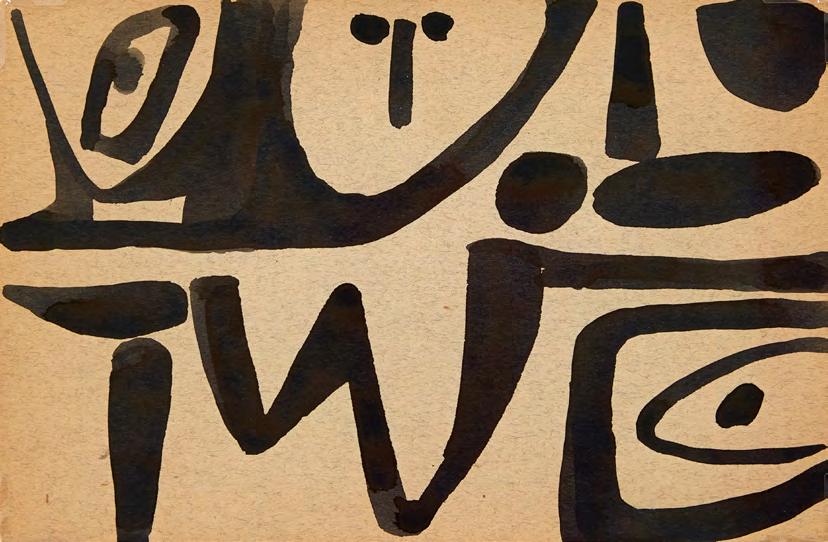

Barnet, among a handful of others, looked for indigenous American sources of abstraction while rejecting much of the dominant theoretical basis for Abstract Expressionism. Even so, he was drawn to American archetypes and sources of an authentic, primeval atavism, as seen in southwestern pottery, basketry, rock paintings, and especially in motifs from Pacific Northwest carvings and textiles. Barnet liked clarity, concision, and balance—correspondences, if you will, that could carry both representation and abstraction.

The late forties and fifties saw Barnet’s teaching career blossom. In addition to the Art Students League, Cooper Union, and the New School for Social Research in Manhattan, Barnet was invited to teach at universities in Iowa, Duluth, Minnesota, and Spokane, Washington, as well as at Yale and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Invitations to lecture and present workshops and studio “crits” took him across the U.S.

Ever the teacher, Barnet argued that American modernism should look closer to home for inspiration, especially ancient, nature-based abstraction inspired by indigenous cultures where nature still firmly abides. For instance, muted, deeply saturated earth colors and organic, flowing abstract shapes suggest natural forms, ranging from clouds to rivers, birds, and totemic beings, both animal and human. For Barnet, totemic structure— stacked abstract and representational forms supporting and commenting upon one another—became a way of thinking about and making an art rooted in nature.

Following teaching stints in the upper Midwest and Pacific Northwest, Barnet appears to have discovered what he believed were connecting threads among these lost Native American cultures that could be tied back to principles of European modernism. Barnet saw correspondences in the art of Cézanne and in the 14th-century origins of Western abstraction, as exemplified by Giotto and the proto-Renaissance. The child of Eastern European immigrants and a witness to two world wars, Barnet’s synthesizing eye saw possibilities for a new, American abstract art rising

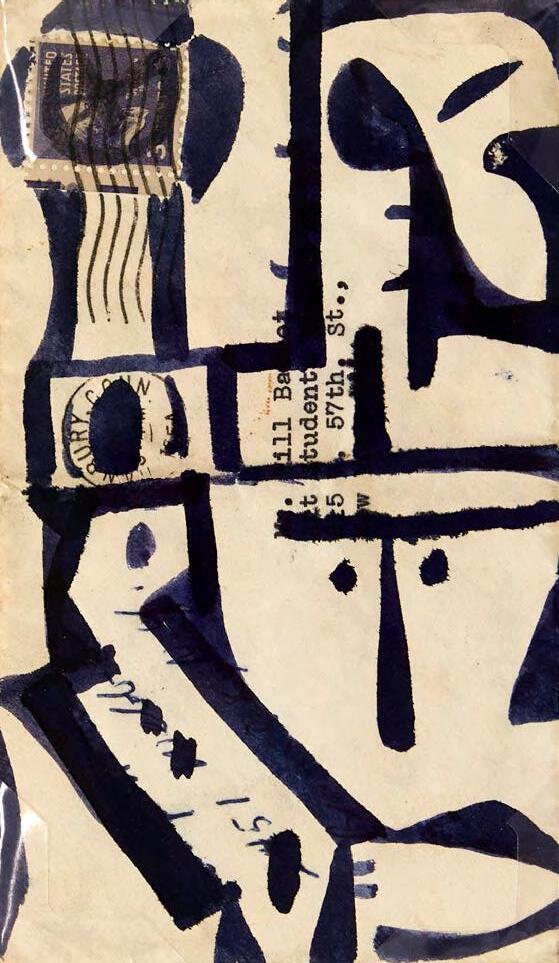

Correspondence 19, c. 1952-55, ink on National Arts Club envelope, 6 ¼ x 4 ¼ in.

Correspondence 18, 1952, ink on envelope, 7 ½ x 4 in.

out of indigenous culture and European precedent—as radical an idea as any by contemporary critics, including Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, or Leo Steinberg.

And Barnet may have anticipated, by more than half a century, critic John Yau’s observations about recent art by younger, Indigenous American artists: “[they] did not reject mysticism, otherworldliness, and nonwestern sources, or what could be called alternative systems. For them, nature was part of the cosmos, teeming with unseen energy…[Their] resistance to aesthetic agendas and group think was important then and urgently so now.”

Having endured the ‘waste-not’ Great Depression wartime shortages, these small, often used postcards were gifts to himself, replete with the business of everyday life—intimations of travel and distant relationships throughout the country. While the mainstream art world of the Post-War era mainly spoke to itself, the postcards became moments and memories to be permanently marked—literally as “real” correspondence with himself.

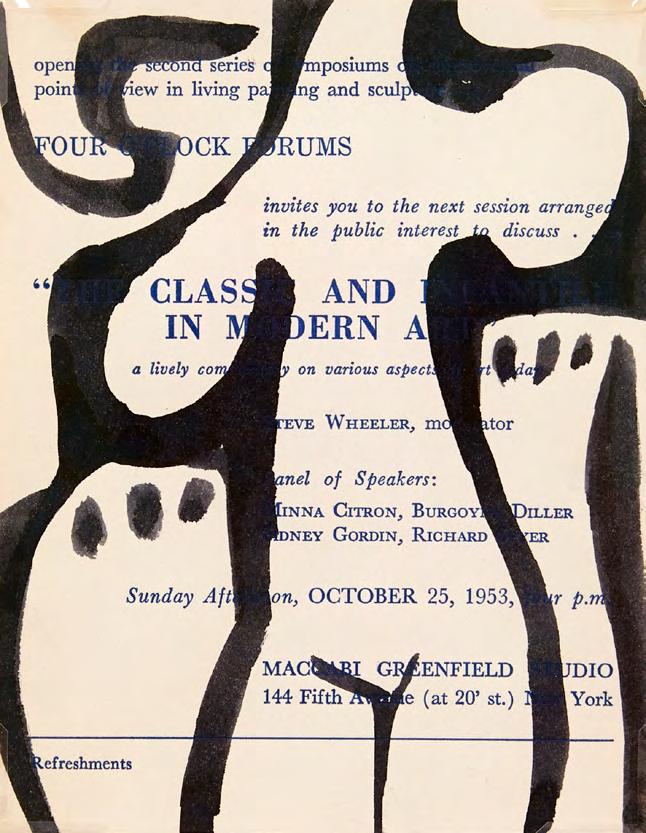

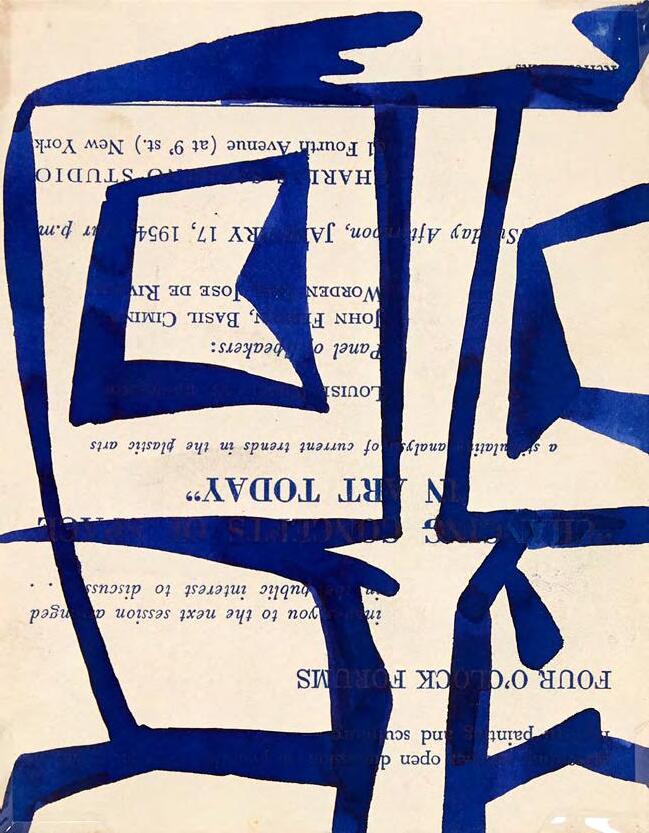

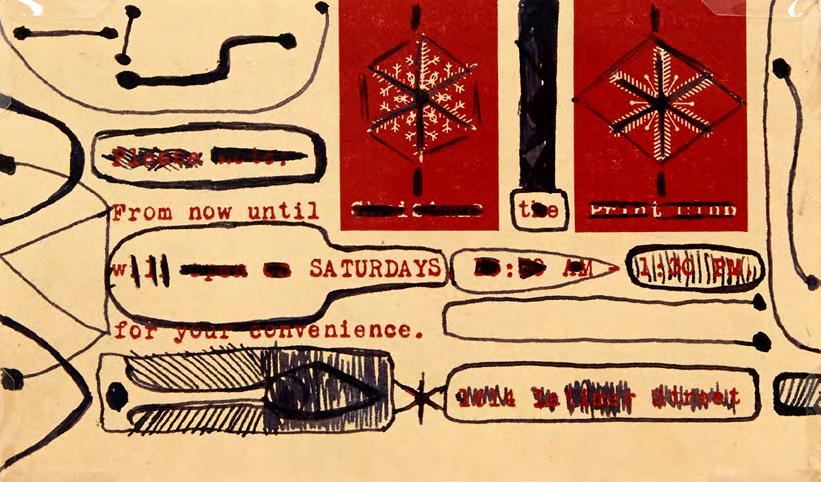

Barnet explains, “The stamp was a visual object that, “I could tie into, almost like a figure. It gave me focus—a form that I could take off from.” Most importantly, his marriage to Elena Ciurlys in 1953 and the birth of their daughter, Ona, appears to have reinvigorated his early interest in transformative experience and family relationships. It is tempting to relate the quasi-abstract figures on the Four O’clock Forum program announcements to Matisse’s late “cutouts” of dancers—possibly the artist’s visual love letters to himself and his new bride (who was herself trained in professional dance). Barnet had the long, elegant fingers of a concert pianist, and they were never still. No scrap of paper was safe from his near compulsion to make art out of whatever materials were at hand or what might catch his eye at the moment.

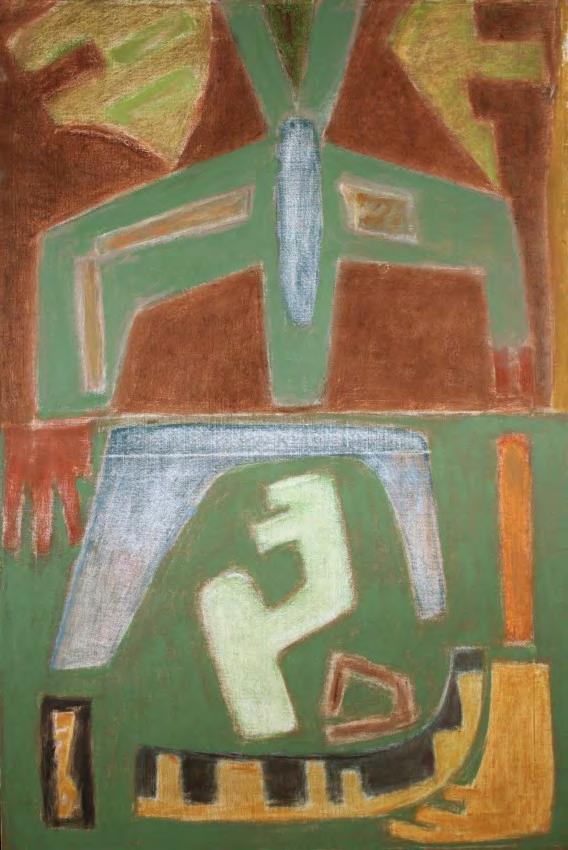

Late in the last decade of his life, Barnet would return to early sources of abstraction, especially the “Indian space” paintings. A soaring, monumental image, like The Spokane Yellow Cloud, 2003, is composed of green, forest-like prongs surrounded by a trailing, stream-like band of blue. Both representational and abstract paintings play with figure-ground

relationships and positive-negative space; a yellow green “cloud” hovers above the flattened landscape. (with “Ws” for Washington in the Spokane painting?). Barnet is recalling the towering forests and plunging waterfalls of Spokane and the American Pacific Northwest without describing anything more specific than a sharply, vividly remembered place and time.

The sense of time (or timelessness) embedded in the seeming quickness and ease of the small paintings and drawings was important to Barnet, an artist who worked every day for nearly a century without repeating himself. The small works on paper kept his mind and hand loose and supple, the lightness of touch keyed to washes or pen and pencil drawings—his mind’s eye looking at nothing in particular—where muscle memory guides the hand. He could freeze time in the larger oil paintings of his adored family who become actors in classic plays where every gesture and every stage prop are purposeful, significant, and eternal—the Women by the Sea series, for example. Or in abstractions that remain fundamentally concerned with universal relationships intrinsic to painting—the tuning of scale to shape to composition, and organic forms that attach to the psyche like music and dreams—unfixed and unreal but somehow familiar and affecting. All of this and more—spontaneity permeates the small postcards and scraps of paper. Barnet’s warm though restless persona is deeply embodied in these small, hermetic works. They record private moments, daydreams where he might linger indefinitely and perhaps live forever. Like the U.S. Post Office, he could “cancel” the place and time of their making with a few opaque lozenges of red or black paint.

With both the early abstract works on paper and his late paintings, Barnet was in advance of the mainstream, critical avant-garde more than most imagined during his lifetime. I suspect Will would deeply respect and understand the work of younger Indigenous American artists, like Dakota Mace, Diné (Navajo), whose ancestral forms he might recognize as belonging to traditions he deeply loved but never fully apprehended: “… in Diné philosophy, time is not a line; it’s a series of layers, movements unfolding simultaneously. The past isn’t something distant or detached— it’s woven into the present, and the present is braided with the future.” •

PAINTINGS & WORKS ON PAPER

The Spokane Yellow Cloud, 2003, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 in.

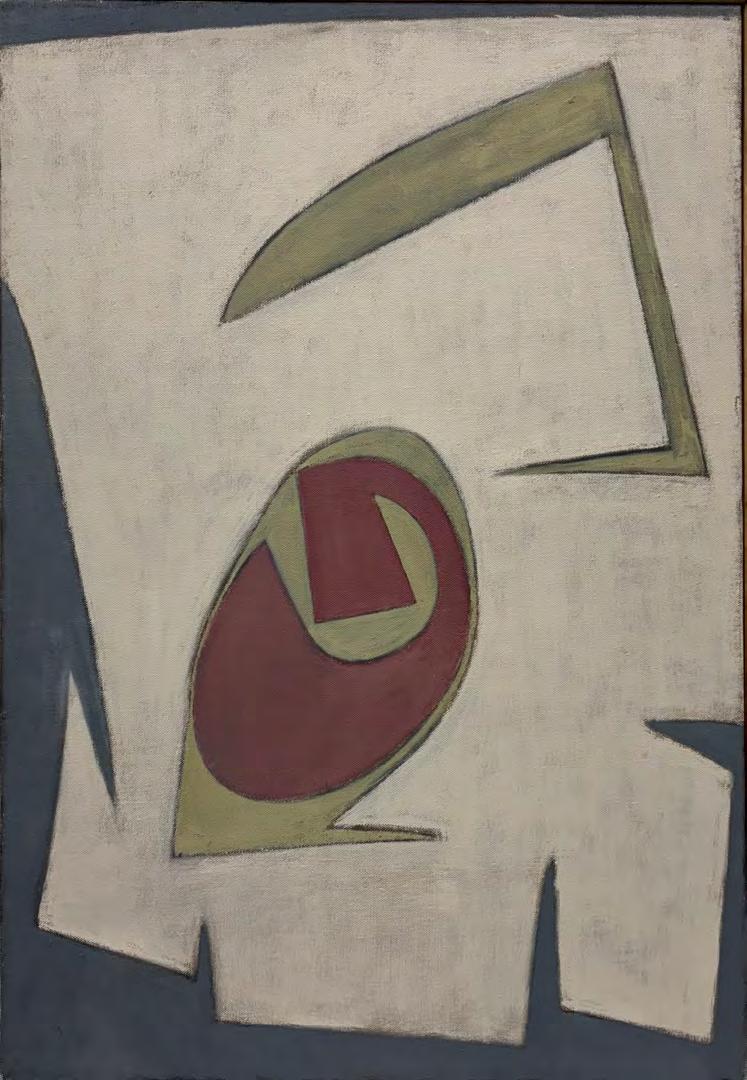

Lightning, 2008, oil on canvas, 40 x 28 in.

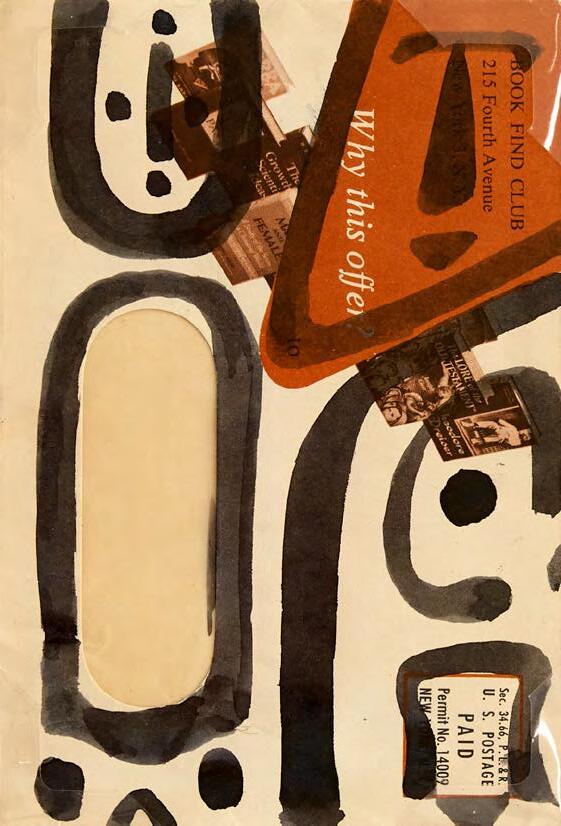

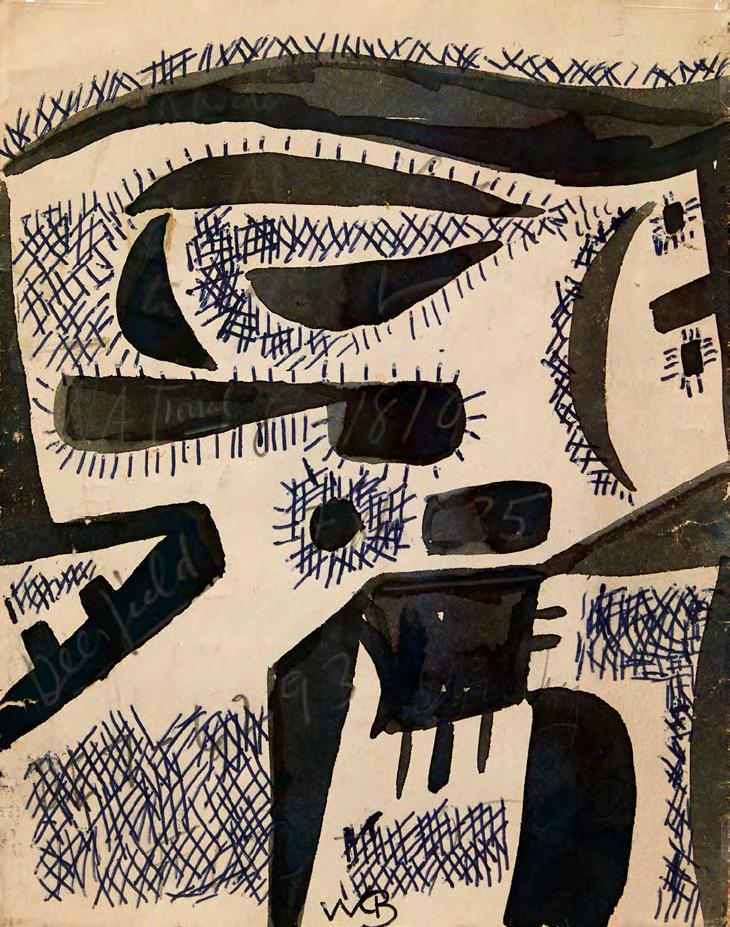

Correspondence 5, c, 1952-55, ink on envelope, 8 ¾ x 6 ½ in.

Joyous, 2006, oil on canvas, 32 ½ x 24 ½ in.

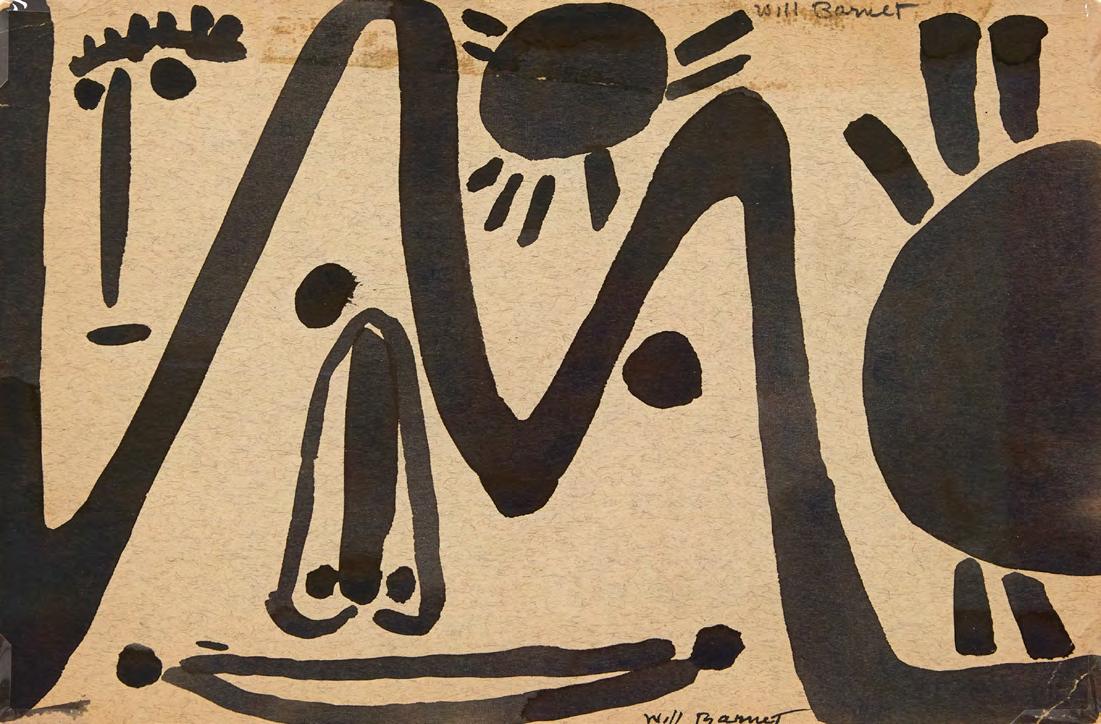

Correspondence 1, c. 1952-55, ink on paper, 6 ¼ x 9 ½ in.

Correspondence 3, c. 1952-55, ink on paper, 6 ¼ x 9 ½ in.

Strolling, 2008 oil on canvas

30 x 35 in.

Correspondence 21, c. 1954-55, ink on paper, 20 x 25 ½ in.

Correspondence 12, c. 1952-55, ink on envelope, 6 ½ x 5 in.

Overview, 2005, oil on canvas, 40 x 28 in.

Correspondence 13, c. 1952-55

ink on 4 O’clock Forums card

5 ¾ x 4 ½ in.

Correspondence 15, c. 1952-55

watercolor on 4 O’clock Forums card

5 ¾ x 4 ½ in.

Moving Forms, 2007

38 ½ x 34 ½ in.

oil on canvas

4,

Correspondence 2, c. 1952-55, ink on paper, 6 ¼

x 9 ½ in.

Correspondence

c. 1952-55, ink on paper, 7 ½ x 5 in.

Hands, 2009, oil on canvas, 43 x 29 in.

Correspondence 7, c. 1952-55, ink on blue envelope, 6 ¾ x 4 ½ in.

Correspondence 6, c. 1952-55, ink on envelope, 6 ½ x 5 in.

Tom, 2003, oil on canvas, 32 ¼ x 21 in.

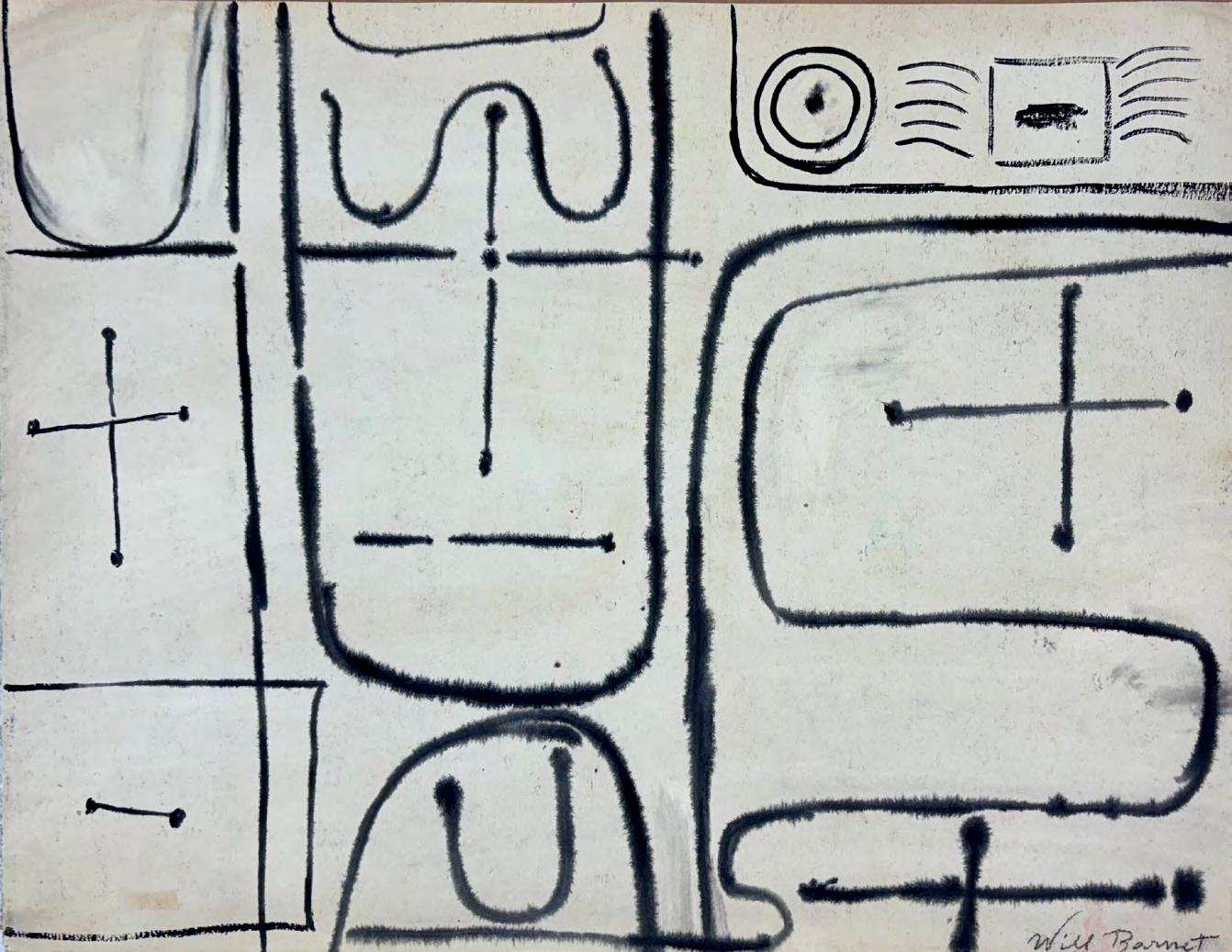

Correspondence 10, 1955 ink on 2 cent postcard

3 ¼ x 5 ½ in

Correspondence 8, 1955

ink on 2 cent postcard

3 ¼ x 5 ½ in.

Enclosed, 2004, oil on canvas, 32 x 22 in.

Correspondence 22, 1954, ink on envelope, 6 ¼ x 3 ½ in.

Correspondence 17, c. 1952-55, ink on Airmail envelope, 5 ½ x 6 ½ in.

Landscape with Hibiscus, 2008, oil on canvas, 27 x 34 in.

Correspondence 9, 1955

ink on 2 cent postcard

3 ¼ x 5 ½ in.

Correspondence 16, c. 1952-55

3 1/4 x 5 1/2 in.

The Voice, 2008, oil on canvas, 35 ½ x 30 in.

Correspondence 14, c. 1952-55, watercolor on envelope, 7 x 5 in.

Correspondence 20, c. 1952-55, ink on envelope, 6 1/2 x 3 1/2 in.

Correspondence 23, 1952, ink on 2 cent postcard, 3 1/4 x 5 1/2 in.

WILL BARNET

(1911 – 2012) was born in Beverly, Massachusetts, and knew by age ten that he wanted to be an artist. He trained at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston before moving to New York City in 1930 to study at the Art Students League. By 1936, he had established himself as a professional printer and the youngest instructor of graphic arts ever to hold a faculty position at the League, where he influenced generations of students. He also taught at Cooper Union, Yale University, Cornell University, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, among other leading schools. Throughout his long career, spanning eight decades, he moved between different stylistic periods, from early social realist work to modernist abstractions, to his well-known refined figurative style, and finally, his return to abstraction in his last decade.

Barnet was a longtime resident of the National Arts Club. He died on November 13, 2012, at the age of 101, in New York City. His artworks are in museum collections throughout the U.S. and abroad, including the British Museum, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, The Vatican Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Jewish Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and many others. He has been the subject of over eighty solo exhibitions, including at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, the National Museum of American Art, the Montclair Art Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and the Worcester Art Museum. In 2011, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama, and in 2012, received the insignia of Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters from France.

The Gull, 1994 oil on canvas

x 31 in.