One of the many impacts of the COVID pandemic has been the change in workplace environments. Many pre-COVID office workers were confronted with the challenge of working from home or adopting a hybrid model of home and office. For some, that pivot was relatively simple and efficient. For others, the challenges of establishing a home office were more complex. Issues of space, technology, and the presence of new “office mates” such as children or other family members (even pets) presented serious hurdles for many.

However, two working authors engaged architectural firms to create a unique alternative to working from inside their residences: a writing cabin. Both these cabins were designed not only to foster creativity (one includes a daybed; another, plentiful shelves), but also to access conveniently. (Both cabins are a short stroll across the backyards of the authors’ homes.)

COVID has also encouraged some people to spend more time outdoors: dining, exercising, or simply enjoying the open air. Two other cabins—designed to allow the individual to decide the purpose (a retreat, a teahouse, or anything in between)—demonstrate how buildings can facilitate communing with nature.

While these structures have a permanent footprint, another, a temporary wood installation in a small town in Italy, provided a venue for local residents to meet and socialize as COVID restrictions eased.

Regardless of whether you prefer your own company in a small cabin or the dynamic energy of a larger community gathering in an outdoor space, all of us are redefining our comfort levels for both indoor and outdoor spaces in a postpandemic world.

Enjoy the issue!

Brooke Smith Editor

Wood Design & Building magazine invites you to submit your project for consideration and possible publication. We welcome contributed projects, bylined articles, and letters to the editor, as well as comments or suggestions for improving our magazine. Please send your submissions to wood.editorial@dvtail.com.

We are thrilled to welcome Martin Richard as incoming publisher of Wood Design & Building magazine, and the new Vice-president, Market Development and Communications, at the Canadian Wood Council.

Richard is a seasoned communications and marketing professional, having worked in senior positions in the area of sports and entertainment for over two decades.

As the executive director, communications and brand for the Canadian Paralympic Committee (CPC), for the past decade, Richard oversaw the broadcast and digital media, public relations, athlete marketing, branding, and corporate communications portfolios of the organization. Under his leadership, the CPC has become an international leader in marketing for the Paralympics.

Richard also served 10 years as the director of communications of Swimming Canada where he led the communications activities for national teams at two Paralympic Games, four Olympic Games, two Commonwealth Games, and several world championships, Pan Am Games, and World Cups. He was named Swimming World magazine’s 2012 Sport Information Director of the Year and is a recipient of the Aquatic Federation President’s Award.

In March 2020, he was appointed to the Board of Directors for World Wheelchair Rugby.

As 2022 comes to a close, and we get ready to welcome 2023, it's exciting to share this great news. Wood Design & Building wishes everyone a safe and happy holiday season. See you next year!

sponsored by

It looks as relaxing as its name: Balmy Palmy House. This second home for a semi-retired couple and their family and friends sits among the trees overlooking the Palm Beach peninsula, about 40 km from Sydney’s central business district.

It’s a simple timber structure that “floats” above a steep slope. Oversized hardwood timber columns and beams (290 x 45 cm) contrast with the thin, lightweight roof and stilt legs.

If you think it’s like living in a treehouse, you’re right. There are no “traditional” hallways, so the kitchen, living room, bathroom, and two bedrooms are placed beside one another, facing outwards. You’re immersed in nature each time you leave a room.

“The design was all about firmly planting the home in the canopies, opening it up to the sunshine, leaves, breeze, and birdlife,” says Clinton Cole, managing director of CplusC Architectural Workshop.

The house was built during two citywide COVID-19 lockdowns. Although construction sites were allowed to continue operations, they had to follow strict guidelines. Still, CplusC’s builders managed to stay on schedule, and the home was completed in less than a year—thanks to the “Meccano set” design. The builders were able to quickly assemble all the prefabricated components, including structural members, doors, windows, and panels, as they arrived on-site.

www.WoodDesignandBuilding.com Fall 2022, Volume 21, Issue 92

PUBLISHER MARTIN RICHARD mrichard@cwc.ca

SENIOR MANAGER, BARBARA MURRAY MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS bmurray@cwc.ca

SENIOR MANAGER, SPECIAL PROJECTS IOANA LAZEA ilazea@cwc.ca

EDITOR BROOKE SMITH wood.editorial@dvtail.com

CONTRIBUTORS MITCHELL BROWN

JOEL KRANC CLAUDE LAMOTHE CAROLINE MARCH-LONG JIM TAGGART

COPY EDITOR MITCHELL BROWN

ART DIRECTOR SHARON MACINTOSH smacintosh@dvtail.com

SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE DINAH QUATTRIN dquattrin@dvtail.com 905.886.6641 ext. 308

PRODUCTIO N MANAGER CRYSTAL HIMES chimes@dvtail.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS PRESIDENT SUSAN A. BROWNE sbrowne@dvtail.com

BOARD

Shelley Craig, Principal, Urban Arts Architecture, Vancouver, BC Gerry Epp, President & Chief Engineer, StructureCraft Builders Inc., Vancouver, BC

Hartman, Principal, Fernau & Hartman Architects, Berkeley, CA

Kober, Master Lecturer, Faculty of Architecture, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON

PUBLICATION PARTNERS wdesign@publicationpartners.com

or visit our website to subscribe. Subscription inquiries and customer service: 1.866.559.WOOD or email wdesign@publicationpartners.com Send address changes to: PUBLICATION PARTNERS Garth Atkinson 1025 Rouge Valley Dr., Pickering, ON Canada L1V 4N8

Published by: DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC 30 East Beaver Creek Rd., Suite 202, Richmond Hill, ON Canada L4B 1J2 905.886.6640 Toll-free 1.888.232.2881 www.dvtail.com

For: CANADIAN WOOD COUNCIL 99 Bank St., Suite 400, Ottawa, ON Canada K1P 6B9 1.800.463.5091 www.cwc.ca www.WoodDesignandBuilding.com www.WoodDesignAwards.com ISSN 1206-677X

Copyright by Canadian Wood Council. All rights reserved. Contents may not be reprinted or reproduced without written permission. Views expressed herein are those of the authors exclusively. Publication Mail Agreement #40063877

Printed on PEFC certified paper

Printed in Canada

Forget the holiday season. For many parents and caregivers, the start of the school year is actually the “most wonderful time of the year.” And while students might be glum about the prospect of sitting inside after a summer spent in the fresh air, a few innovative schools are finding interesting ways to bring the outdoors and indoors together.

In Idaho, A.B. McDonald Elementary has long advocated for outdoor learning and allows students to use the green space surrounding the school for educational activities. The school’s earlier outdoor seating was removed in 2018 for safety reasons. During the pandemic, the K–5 school recognized the need to rebuild an outdoor space that would allow students to socially distance and safely enjoy the benefits of the outdoors while giving the teachers the structure needed to guide a class.

Forests and the great outdoors are a part of life in British Columbia, a reality reflected in the Castlegar & District Community Complex Child Care Centre. The colorful face of the building provides a playful and distinguishing feature to welcome children and their families. The brightly stained cedar shingles, with a color palette inspired by the surrounding buildings and trees, contrast with the clear-coat finish on the CLT canopy and glulam supports.

Further to the west, Vancouver Island’s Kwakiutl Wagalus School serves K–7 students in the rural community of Port Hardy. The use of wood in buildings is an integral part of the heritage and culture of the Kwakiutl First Nation, who reside at the northern tip of Vancouver Island. The Kwakiutl people consider Western red cedar to be the tree of life, so it was only fitting that their new school feature this species from local forests.

Over in Denmark, the House of Nature is a school building designed to accommodate the teaching of nature and outdoor life at the Silkeborg Folk High School. The building itself was conceived as a lesson in sustainable construction. The timber structure, acacia shingle cladding, Douglas fir interiors, and wood fiber insulation are all part of a strategy to design a building that incorporates wood as much as possible—creating a connection to the surrounding forest.

Naturally Perfect ® Factory Finishes with Proven Protection and Performance.

Sansin Precision Coat products offer unparalleled beauty and durability in an environmentally friendly formula. Contact us about our specification program so we can help you achieve the perfect finish and protection, every time. Warrantied for up to 20 years, Precision Coat factory finishes deliver the color, transparency and performance that architects, engineers and builders can count on.

sansinfactoryfinish.com

After more than a year of construction, the first two buildings of Hines’ mass timber office development T3 Sterling Road in Toronto’s west end are close to completion. The East Building, at six stories, is located beside the Toronto Museum of Contemporary Art in the Tower Automotive Building. The West Building reaches eight stories. The two buildings together will provide 275,000 sq.ft. of office space. Expected completion of Phase 1 is set for fall 2023, after which Phase 2 will begin.

Vancouver Island University’s Nanaimo Campus is getting a new housing unit. British Columbia will pay $87 million (of the $87.8 million price tag) for the new residence, which will house more than 260 students and include a dining hall. The hybrid mass timber building will be nine stories.

Two mass timber residential developments will come to the Vancouver market, courtesy of Adera Development Corp. Pura is a 248-unit townhouse and condo project, and Sol is a 201-unit residential development. Both projects begin Phase 1 construction in November.

Domaine Willamette—in the Dundee Hills about 30 miles southwest of Portland, Oregon—will be the latest building in the state to include mass timber as part of its design. The roof of the winery’s outdoor pavilion is made from thick panels of mass plywood. Domaine Willamette opened to the public on September 19. The pavilion is expected to be completed by November 2022.

Construction of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s new San Mateo County Civic Center is underway in Redwood City. The fivestory, 208,000-sq.ft. building is expected to house roughly 600 government employees. The mass timber design will feature all wood columns, beams, walls, and ceilings. Completion is expected in late 2023.

NO ARCHITECTURE released its design for the 8,250-sq.ft. house—aptly named Risingmountain—on Red Mountain. The design will comprise five terraced glass, stone, and timber pavilions that ascend along the mountain ridge. Each of the pavilions will orient differently to the surrounding views, extending over the natural topography. Mass timber construction will be used for the house, which is 72 ft. top to bottom and on a site with a 30% slope.

Ennead Architects revealed its competition design entry for the Chilean-Argentine border complex along the Cardenal Antonio Samoré Pass. The complex is designed to serve as a welcoming station and refuge for travelers, and is separated into a series of buildings for cars, buses, and trucks, connected by a network of pathways. The complex will be built primarily from mass timber constructed from sustainably sourced timber from the region.

A Toronto home gets a new addition.

Behind a Toronto brick house in the west end of the city sits Parkdale Laneway House. It was once the owner’s dilapidated garage, but now it’s a remodelled 1,080-sq.ft., two-bedroom home, with a 330-sq.ft. wood working studio.

The owners, originally wanting to build a new workshop to replace their old shed, opted instead for a laneway home once the city permitted this type of residential construction. They decided to build one with

a garage/workshop integrated into it.

The home takes the form of two shifted boxes stacked on top of one another, creating a covered ground level outdoor space on the laneway side. Wood and engineered wood were used to frame the structure as much as possible, in order to reduce the amount of steel used. Although the wall along the property line had to be built from concrete blocks, the other three walls were framed in 2 x 6-in. studs.

The home’s overall width is narrower than the full width allowed, thus creating a private yard at the side. The remaining original backyard is for the main house, where the visual impact of the laneway home is minimized by the terracing of the second-floor box.

On the main floor, past the staircase, is the galley kitchen, dining area, and bathroom. Sliding glass doors open out to a laneway-fronting terrace that’s enclosed with planters.

The living room and two bedrooms are on the second level. A long horizontal window in the side wall frames views of the neighborhood trees, while the massive windows in front bring in the sunlight.

One of the challenges of building this laneway home was the 100-year-old walnut tree which is under the protection of Toronto Urban Forestry. This required the massive root system to be protected throughout construction. The builder kept the concrete slab of the wooden garage in place as long as possible to protect the soil, and was careful when running sewer, water, and electrical utilities through the backyard to the basement of the main house. In addition, a Legalett slab was used for the foundation, requiring only shallow digging, and therefore keeping the excavation minimal.

Solares Architecture Toronto, ON BUILDER

Laneway Custom Build Toronto, ON PHOTOGRAPHY

Nanne Springer Montréal, QC

The two-acre Elephant Park in London, England, is part of a £2.3-billion regeneration scheme to create 3,000 new homes and new public green spaces in south London.

In June, the park’s pavilion was completed. Named the Tree House, the new building is designed in three sections, all connected by a roof terrace. The pavilion encircles a mature London plane tree and includes a café kiosk and a multifunctional internal space, which can be either closed off to form a contained room or opened up to the wider park setting. The roof terrace acts as a viewing gallery where visitors can look out onto the park below.

Given the climate crisis, the architects sought to create a building with low operational and embodied energy. They considered how the building and its materials could be deconstructed and its constituent elements reused or disposed of at the end of its life.

They used CLT for the main structure, alongside sustainably sourced timber cladding and bamboo decking. The structure celebrates the natural hues, tones, and textures of its materials, which are allowed to weather and develop a patina over time that will further embed the pavilion within its park setting.

By using these lightweight materials, the structure minimizes its physical impact on the adjacent trees and their root systems. The park’s trees are a constant in the evolving context of the urban site, and they’re an important asset, providing character, biodiversity, and shade. The architects wanted to celebrate the trees within and around the pavilion, allowing visitors to experience them in a different way.

Bell Phillips Architects London, England

Webb Yates London, England

Kilian O’Sullivan London, England

A temporary installation provided a place for residents of an Italian town to gather outdoors.

The historic town of Lugo, in the northern Italian province of Ravenna, added a touch of the modern in June.

Architects’ collective Orizzontale—in partnership with Italian door and window manufacturer Edilpiù—designed a circular wood installation, named LuOgo (Italian for place).

Situated at the bottom of the 14th-century Italian bastion fortress Rocca Estense (which now houses municipal services), LuOgo was created to foster communal gatherings in the town throughout the summer.

“The main square of Lugo is a monumental space….At the same time, this large, orderly, and measurable space is crossed daily by discontinuous and unpredictable flows,” said Margherita Manfra, one Orizzontale’s founders. “In this dialectic between the defined urban context and the incessant transformation dictated by the human factor, ephemeral architecture finds a new typicality and new forms of expression.”

LuOgo is an intimate yet public area in which citizens can enjoy “living” outdoors in this open-air room. Simple and functional modules, which made the construction site accessible to everyone, were combined to create a singular yet heterogeneous piece.

Within the circle itself were yellow wooden benches and red sling-style beach chairs running the perimeter. They all faced toward a raised wooden mini stage in the center. On the outside,

shading sheets and metal nets covered in foliage provided protection between the interior and exterior.

Adorned with swings and slides to encourage play and movement, and equipped with LED lighting, LuOgo was accessible day or night for residents of the town to gather and hold events such as concerts, performances, and talks.

As a shared space, LuOgo brought the community back into the collective spaces of a small urban center.

Orizzontale Rome, Italy

Gianluca Gasperoni Ravenna, Italy

The new MTWS joins a growing selection of mass timber tension straps from Simpson Strong-Tie.

Attain higher loads with our new MTWS washer strap. The MTWS is versatile, pre-engineered and load-rated for a variety of diaphragm and wall applications. You can specify it for CLT panel to panel, CLT to concrete, and CLT to steel connections. Installation is fast with our Strong-Drive ® SDCF TIMBER-CF screws and MTW45-8 washers, which allow the MTWS to achieve loads with fewer fasteners. The MTWS is widely available, more economical than custom-fabricated straps, and backed by our expert service and support.

Plan your next mass timber project with connectors and fasteners from Simpson Strong-Tie. To learn more, visit go.strongtie.com/masstimber or call (800) 999-5099.

Parc de la Chute Montmorency

Photo credit: Maxime

Parc de la Chute Montmorency

Photo credit: Maxime

A cabin in the woods provides a place to escape, find peace of mind, or connect with nature—particularly if you reside in a bustling urban center for most of the year.

With many people spending the last two years in lockdown and various forms of isolation, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, a little escape can go a long way.

Space of Mind—designed by Finland’s Studio Puisto—is a reimagined cabin for people to think, recharge, and unwind. It was initially developed in response to the pandemic, as many people were spending much more time at home than they ever had before. The architects wanted to redefine the collective notion of a “home away from home” to reflect the limited range for travel.

The modular 10-sq.m cabin can be sited anywhere—a backyard, a rooftop terrace, or even a nearby forest—and situated almost anywhere in the world. It’s light enough to be transported by crane or helicopter with a resilient foundation that supports almost any site.

The architects—aware that peace of mind looks different for everyone—considered this aspect when designing the structure. Versatility and adaptability are integral to the design. The outer wooden structure has a simple, universal appeal, while the interior can be modified to suit individual needs and preferences. In one application, a gym; in another, a home office. Custom furniture attaches to the rungs in the interior.

The cabin is also an exemplar in showing efficient use of space. The architects wanted to convey in the design how even a minimal space can offer individuals the headspace to enjoy what matters most.

Not insulated, Space of Mind allows a connection to the raw, natural elements and ever-changing weather conditions. Constructed of ecologically sourced Finnish wood, the mass timber cabin can withstand even the harshest of Arctic winters and remain aesthetically cozy and nest-like inside through its warm wooden tones and colors.

Studio Puisto Helsinki, Finland

Archmospheres, Marc Goodwin London, England

Meet a modular cabin that can be placed just about anywhere in the world.

A

The Hermitage, a prototype from architectural firm Llabb, is built using a simple, modular system that responds to environmental and social needs. It exemplifies minimalist living and a relationship to the outdoors.

Made entirely of wood, the 12-sq.m cabin, located in Trebbia Valley, Italy, is designed as a space for contemplation and introspection. It’s left up to the individual to decide its function: a studio, a retreat, a teahouse, or a guesthouse.

Though the rectangular structure stands off the ground, it leaves no permanent footprint on the ground, as no concrete was used. The construction is supported by four metal brackets, fitted with wide 60 x 60 cm bases, which rest on sandstone beds. The four legs are composed of six paired wooden elements.

Horizontal plywood walls enclose the cabin on three sides. The fourth side extends into a terrace separated by four full-height glazed panels, one of which can be opened. The fenestration follows the modularity of the brise-soleil that surmounts the terrace, which, in turn, continues the roof structure. There is a small horizontal window on the southwest side. The entrance door is accessible through a small boardwalk.

The boards of the three exterior walls are mounted in such

a way as to leave a gap that produces a filter effect. Where the walls enclose the interior space, this gap is filled with thin, slightly protruding profiles.

At the floor level and at the top of the structure, cornices run uninterrupted, projecting from the walls and delimiting the composition.

“The simple modularity of the structure makes it easily scalable and adaptable into different compositions. The basicness of construction, the minimal impact on the land, and the use of natural materials that can be easily sourced locally enable a respectful installation in natural contexts,” says Luca Scardulla, co-founder of Llabb.

At the entrance level, a countertop runs along the entire right wall and serves as a seat, a desk, and storage space. The third level, to which one descends after going through the entrance, defines the largest surface area and extends onto the terrace. The wall that encloses the tiny bathroom accommodates a foldout bed that, when open, hovers above the sofa.

“We paid special attention to the design of the interior space. Minimal and flexible, with the expansive glass wall facing the terrace, the space feels light and contemplative. The interplay

between different levels offers the possibility to better manage storage spaces and technical compartments, while contributing to the definition of a graceful atmosphere,” says Federico Robbiano, co-founder of Llabb.

The walls, floor, and ceiling were pre-assembled and composed of 70 panels of weather-resistant Okoumè marine plywood (approximately 2 tons). The façades are mounted on spacer battens to create an air gap between the façade and the walls, improving the insulation. The roof is made of corrugated sheet metal. Above it, there are two photovoltaic panels, connected to a storage battery.

The Hermitage is designed to be completely off-grid. There is a compostable toilet and water canisters. However, the structure can easily be connected to a sewer system and water supply.

Llabb Genoa, Italy

Anna Positano, Gaia Cambiaggi Genoa, Italy

Writing is a solitary pursuit, and most creatives who put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) need quiet to arrange their thoughts. Author Virginia Woolf said it: “A woman must have…a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

No matter the genre, having a place to write is even better when it embraces its natural surroundings.

Two writing cabins, both completed in 2021 during lockdown, provide their authors with solace—and a connection to the outdoors.

The Writer’s Cabin, designed by MuDD Architects, was designed and built in just a few months for an author of children’s books who wanted the space to be a source of inspiration for her writing.

The cabin—in the north of Madrid—is a technological first for the architectural firm; they used digital fabrication combined with highly skilled master builders.

The envelope of the house roof is made of folded oxidated iron. The most challenging part of the structure was the complex curvy bookshelves—made of locally sourced pine— which were adapted to fit the cabin’s high sloped roof.

The shelves comprise 100 different pieces cut with CNC, and they were left untreated on purpose, providing a keen contrast with the maple cladding panels inside.

A dimmer light allows the author to change the ambiance of the space, and smaller lights are placed inside the bookshelves. Two technical lights illuminate the writing table from above.

The oxidated iron frame of the main façade allows the laminated glass to meld into the garden, highlighting its different plant species.

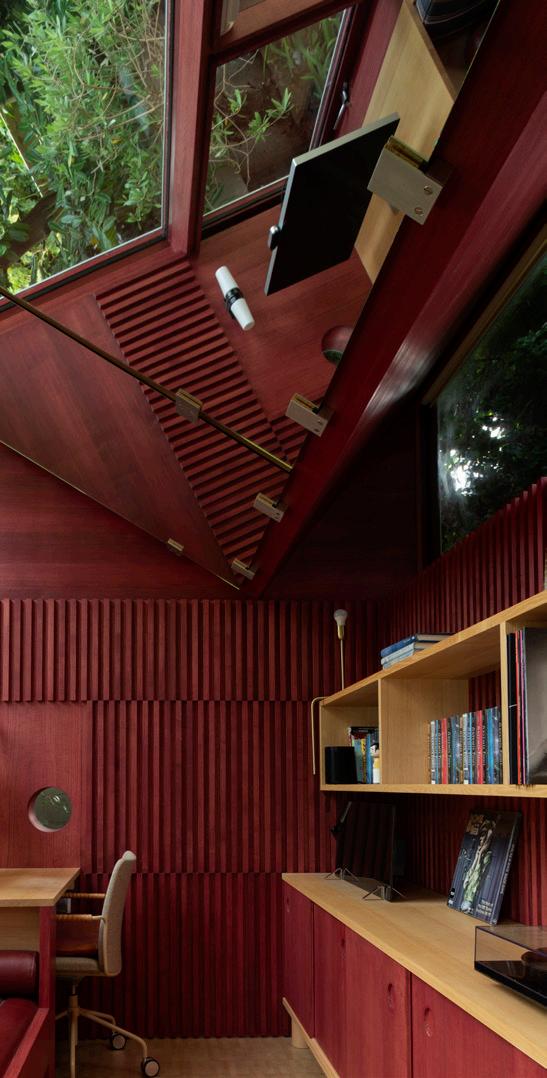

Another enclosed writing space, The Writer’s Room, sits in a corner of the back garden of a house on Alma Road in Dublin. According to Clancy Moore Architects, the author “needed seclusion, to be able to work without being seen, and yet to feel connected with the house.”

As the author’s home is part of an existing terrace of houses, the site was inaccessible for the builders and so the architects designed the cabin so it could be constructed off-site and then craned into place.

Angular in structure, the room is lined in red-stained beech and mirrors, and contains a desk, a daybed, and storage. There’s a sense of coziness and comfort amid the textured red walls.

Recognizing that rest is as important as production in the creative process, the architects designed the cabin to reach beyond the back garden. Through the mirrored ceiling, the cabin provides a distant view to the sea from the daybed.

Clancy Moore Dublin, Ireland

Fionn McCann Dublin, Ireland

Choose the right hue for your timber structure… for perfection and protection.

Caroline March-LongPickled White is a popular color inside and out and contributes to a cozy, rustic charm, as illustrated by this building in England.

When it comes to protecting wood, there are as many colors for architectural finishes as there are professionals bringing their visions to life. The color chosen for wood finishes can make a bold statement, lean toward the trendy or traditional, or be treated to allow for natural weathering with protection. Often, architects choose colors that enhance the natural notes of certain wood species, such as Western red cedar or Douglas fir. But what are the best practices for getting the desired look while still offering the wood maximum protection?

For more than 35 years, Sansin has helped architects and builders protect some of the world’s most beautiful wooden structures. Director of marketing and s ales Caroline MarchLong shares expert advice, along with

examples of projects that have used Sansin finishes to showcase wood in beautiful and creative ways.

What are the most requested hues in wood stain colors?

We work with some of the most renowned architects and builders in the industry, and it’s very inspiring to see how they’re designing with wood and thinking carefully about what type of stain and color they want to highlight the wood. We’ve been seeing a lot of bold Onyx, which is nearly black, and this creates a very modern feel. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Pickled White is a popular choice for rustic chic, coastal, or country designs. Autumn Gold is one of our most popular shades. It’s golden brown with rich honey undertones and is a

classic choice that defines and enhances the natural character of wood. Gray hues continue to trend, too, for both traditional and contemporary designs.

What factors should you consider when selecting a shade for wood protection?

The most important factor is the wood’s exposure to UV light. Generally, the darker the pigment, the more substantial the UV protection, and the longer the expected time between maintenance coats. When recommending a coating system and color, we take into account how UV exposure may lighten the coating over time, along with exposure factors.

As for the exteriors, UV exposure and moisture management are the most

important considerations, so we need to think about the building location’s climate, the orientation of the building, and the design features that impact UV exposure. For example, some exterior surfaces have limited contact with sun because there are well-protected soffits under the roofline or vertical cladding under ample overhangs. Conversely, other areas like decks get lots of sun and moisture exposure.

This can typically be addressed with the selection of color and the use of topcoats. Since our products are waterborne, penetrating formulas, the first coat is most important for getting the product into the wood. Subsequent topcoats can provide added UV protection and increase water repellency.

Another consideration to keep in mind is that the color can vary dramatically from one substrate to another. The same color applied to pine may look quite different if applied to cedar, for example. Additionally, you can control the level of protection with the number of coats you apply. This is why when we work with architects and builders, we ask them to send us samples of the substrate they plan on working with, along with details on the project—including the factors mentioned above—so we can recommend the appropriate type of finish and color formulation to offer maximum protection while achieving the desired look.

How can you achieve a “natural” look while still protecting the wood? Most important, we recommend waterborne finishes that penetrate the wood rather than sit on the surface. This enables the coating to dive deep into the wood fiber and allows the wood to “breathe” more freely so moisture doesn’t get caught inside the wood.

However, you mustn’t confuse the goal of achieving a natural look with the approach of using a non-tinted, clear coating on exterior exposed wood. As mentioned, color equals UV

protection. An absolutely clear coating is simply unlikely to meet maintenance expectations or be durable enough under exposed conditions.

If the intent is to allow the finish to naturally fade to gray, we still need to protect the wood substrate from any intruding moisture, which can lead to biodeterioration. We recommend a low-VOC waterborne protective wood treatment that aggressively repels water while allowing wood to breathe. Over a short time, the wood will weather uniformly to a beautiful silver-gray tone.

Is it possible to get a “weathered look” while also protecting the wood?

For architects who want to have an on-trend weathered look without sacrificing wood protection for aesthetics, a weathering treatment with high water repellency is the best option. There are specially formulated waterborne products that offer premium

protection with the look of naturally weathered wood, and some offer a variety of barnboard colors, from gray and red to brown. With these treatments, the wood will weather uniformly to a beautiful silver-gray tone over time, yet maintain water repellency and protection against weathering and wood rot.

How important are undercoats, and is it possible to use one and still achieve the look you want, especially if you want a “natural” finish?

Application of a waterborne protective undercoat is an important first step for any architectural coating system, especially if the wood needs protection in transit from the factory to the job site. These broad-spectrum protective coatings can be applied in a clear, imperceptible coat or a tinted color— depending on the final coating system and desired aesthetic.

Further benefits of an undercoat

include dimensional stability of the wood components and moisture management. Absorption of the undercoat also increases topcoat performance. It’s imperative that the undercoat allows subsequent topcoats to sink in and penetrate the wood for optimal clarity, color, and protection. When used as part of an architectural coating system, the undercoat can be tinted and used as the first coat.

What are the best practices of wood stain no matter the color choice?

First and foremost, you should always follow the manufacturer’s application instructions. We strongly recommend— especially for large projects—that at least the first one or two coats of the product be applied in a factory setting where factors like pigment load, temperature, humidity, and dust can be precisely controlled. This also ensures

the wood will be protected in transit and on the construction site.

For waterborne finishes specifically, proper sanding is a critical first step to remove any mill glaze, open the pores, and allow the waterborne finish to penetrate deep into the wood tissue. To achieve a longer maintenance interval, we recommend applying product to all six sides of the wood. Also, applying the appropriate mil thickness for each coat is important for pigment loading and proper protection.

One final, yet important, note: we recommend checking the coating every six months (but no less than annually) to identify any worn areas that need to be addressed. If problems are caught early, maintenance can amount to simply washing the surface and then applying a maintenance coat of finish. However, if the wear gets through to the exposed wood, you could be looking at a much more time-intensive and expensive maintenance process.

As the waves of COVID-19 ebb and flow with the seasons, and the general population is trying its best to move on with some sense of normalcy, a few concerns remain in focus. First, mental health issues—resulting from the uncertainty of the pandemic and extended isolation—persist and will likely be felt for years to come. Second, indoor spaces and cramped gatherings are not as welcome as they used to be.

Re-engaging with nature has, in many ways, addressed both of those issues. People are looking to relieve their stress in any

number of ways now more than ever. They’re also looking for outdoor spaces to enjoy. Note the rise in pool construction. According to IMARC Group, the size of the global swimming pool construction market hit US$6.7 billion in 2021, and is expected to reach US$8.4 billion by 2027.

How does a reconnection with nature manifest itself into our environment going forward? Design and architecture professionals are taking note of these new needs/concerns and are incorporating more natural elements into their projects.

Biophilic design is a concept used within the building industry to increase occupant connection with the natural environment through the use of direct nature, indirect nature, and space and place conditions. Used at both the building and city scale, biophilic design, experts argue, has health, environmental, and economic benefits for both building occupants and urban environments.

Practically speaking, wood in the biophilic design environment provides easier-to-construct, high-quality facilities that minimize carbon footprints. The energy required to provide a wood building is less than steel; carbon is taken out of the atmosphere, and wood is renewable and sustainable.

David Fell is a B.C. researcher who has studied the positive impacts of incorporating wood into the design of buildings and co-author of a report on how wood can be a restorative material in healthcare environments.

For example, the report, quoting other studies, indicates the following:

• Adding cedar wood panels and rice straw paper to the walls of a hospital isolation room reduced stress levels (measured by cortisol levels) experienced by people in the space compared to people who spent time in the room when it had its original concrete walls (Ohta, et. al, 2008).

• When plants and natural materials (e.g., wood, cane) for furniture are used in communal spaces in care homes, the subjective well-being of people living in those homes is enhanced compared to situations where these are absent (Weenig & Staats, 2010).

• Assisted living facilities are seen as homier—by patients and their families—when more natural materials, such as wood (as in siding), are used on the outside of their structures (Marsden, 1999).

One area where wood and mass timber are making a noticeable difference in the health of individuals is within the aging population and assisted living facilities. Case in point is the Gateway Lodge Long-term Care facility in Prince George, B.C.

Gateway Lodge Long-term Care provides 94 complex care beds using a decentralized approach that places small groupings of 14 to 20 residents into linear “home areas.” The residential rooms are located along the perimeter of each home area and have views to the site’s many gardens and courtyards. The double exposure of each home area ensures abundant access to natural light, views, and fresh air.

The architects used a shorter than usual construction timeframe to implement a 2 x 6 dimensional lumber and Douglas fir plywood prefabricated wall panel system, which allowed the construction team to frame the entire 13,750-sq.m facility in only 12 weeks. As foundation work progressed, the panels were manufactured off-site and delivered as the foundation of each “home area” was completed.

Another facility featuring wood in its biophilic design is the Minoru Centre for Active Living in Richmond, B.C. The decision to use wood over other available construction materials was due to the City of Richmond’s high water table, and geotechnical concerns such as soil instability and buoyancy, which would put a considerable amount of pressure on the underground pool tanks. Because wood is significantly lighter than steel or concrete, the structural load of the roof was reduced, minimizing the facility’s foundation requirements.

“The City of Richmond’s goal was to develop an iconic facility, so wood became a material of choice for the undulating roof. Wood has a highly aesthetic appeal, while delivering required durability, acoustic, and structural characteristics for the project,” according to Jim Young, director, Facilities and Project Development, with the City of Richmond.

The timing of the growth of biophilic design in Canada is not a coincidence. There are changes emerging that have made the design more attractive and easier to apply. According to Graham Lowe’s report Wood, Well-being and Performance: The Human and Organizational Benefits of Wood Buildings, there are changes emerging that have made biophilic design more attractive and easier to apply. These changes include the following:

• Building code updates that permit larger and taller wood buildings, including the 2020 National Building Code of Canada provisions that now permit encapsulated mass timber construction in buildings up to 12 stories;

• A move towards climate change action and the adoption of more sustainable construction and building renovation practices;

• Employers’ focus on improving employee well-being that allows for opportunities to change the physical workspace; and

• Corporate sustainability strategies that are more closely linking environmental and human resources department goals.

It would seem that the intersection of sustainable design and biophilic design is driving design decisions that will help improve lives.

“We’ve just secured the green roofs on a $1-billion hospital project in Vancouver called St. Paul’s,” notes Ronald Schwenger, principal and founder of Architek. “It wasn’t that long ago that when they looked at a hospital, they didn’t consider green roofs or any natural element on them because

they felt hospitals needed to be sterile. And it’s now exactly the opposite. They know that patients’ well-being is greatly improved when they’re around natural light and biophilic elements,” he adds.

Schwenger says he’s 100% convinced that our direct connection with nature has a profound effect on well-being, mentally and physically. Most of the projects he works on are in the residential space, made of wood frames. “There is a myth floating around that green roofs or biophilic elements like living walls don’t work well on wood-frame buildings. But if they’re engineered and done correctly, they actually protect the building.”

Research done by the Canada Green Building Council in its report Healthier Buildings in Canada 2016: Transforming Building Design and Construction suggests that “the prognosis is good for increased investment for health and well-being as an integral part of green building design and construction in the years to come.” This goes for wood-based biophilic designs.

In addition, happy employees help with the bottom line. Working in a green building can improve an employee’s job performance. Studies show that office workers in greencertified buildings, compared to those in conventional buildings, have better cognitive functioning (decisionmaking), mainly due to better-quality indoor environments.

In his report, Fell adds that “the psycho-physiological reactions of human beings to wood are based on two major systems of reaction to stress; namely, the autonomic nervous

system and the endocrine system. One particular research project on the response of the autonomic nervous system to wood observed lower levels of blood pressure and heart rate in an environment where wood is present, compared with one where it is absent.”

The Wood Products Council, quoting the report Economics of Biophilia , takes a bottom-line approach as well. Retention of employees is an investment worth taking. Termination, the report suggests, costs $1,000; replacements cost $9,000; and lost productivity costs $15,875. The total cost for the employer losing one employee is $25,875. The connection to visible wood and other natural elements allows employees to remain connected, have enhanced concentration, improve their overall mood, and lower stress. Therefore, biophilic design is not simply good design, it also makes good business sense.

Despite the ever present and continued construction of glass and steel towers around the world, biophilic design—and its incorporation of wood and mass timber—is being proven as healthier, more aesthetic, and, over time, a more cost-efficient alternative. Wood form and function are turning new biophilic-designed structures inside out.

Joel Kranc is an experienced and award-winning editor, writer, and communications professional. Currently, he serves as director of KRANC COMMUNICATIONS, a full-scale marketing and content firm founded in 2011 serving a global financial services clientele.

When measured by total constructed area (square footage built), the low-rise market (three stories and under) is the most important new market segment available to the wood industry. An article about this market was published in the Winter 2022 edition of Wood Design & Building describing, in detail, the process used by the Canadian Wood Council (CWC) to develop six new design templates. (These design templates were published in the CWC’s Low-Rise Commercial Construction in Wood: A Guide for Architects and Engineers.)

Here, we’ll focus on a light-framing application for a one-story commercial rental unit, the kind typically found in strip malls.

As with the other design examples published in the CWC’s Low-Rise guide, the wood option for this building typology (Figure 1) focuses on simplicity, economy, and replicability in all regions of the country. It is the result of a collaboration among architects, structural engineers, contractors, and developers with experience in the demands of this market sector. The materials and fabrication methods required for this solution are similar to those used across Canada in residential construction, leveraging well-established industry standards and capabilities.

This commercial rental unit—measuring 144 x 64 ft. (43.90 x 19.5 m) and with a clear height of 16 ft. (4.88 m) from the concrete floor slab to the underside of the roof

structure—replicates a typical single-story Group D (Business and Personal Services Occupancy) or Group E (Mercantile Occupancies) building. Structures falling under Groups D and E are typically built in steel and can be found in numerous strip malls across the country.

For this unit, the structural grid of 24 x 32 ft. (7.32 x 9.75 m) was determined in consultation with developers in this sector. Their concern was to minimize the number of internal columns required and to maximize flexibility in the arrangement of interior space—in terms of either the division between adjacent units or the relationship between the frontof-house and the back-of-house areas.

With a building area of 9,417 sq.ft. (875 sq.m), this unit fits within the maximum 9,688 sq.ft. (900 sq.m) permitted by the National Building Code of Canada (NBC) for an unsprinklered, combustible building that faces one street. Similar buildings with areas of up to 16,146 sq.ft. (1,500 sq.m) and up to two stories are permitted when facing three streets (as per the NBC). However, these figures can be doubled when the buildings are sprinklered.

The building is of light-wood frame construction, using dimensional lumber and trusses, LVL beams, hollow structural steel (HSS) columns, and a concrete slab on grade

(610 mm) centers. Along the center line of the building, these trusses bear on a double-span, six-ply plated truss girder that, in turn, spans 24 ft. (7.32 m) between the HSS columns and the exterior walls (Figure 2).

At the perimeter of the building, the trusses bear directly on the exterior walls, which comprise nominal 2 x 6 studs on the back and side walls and 2 x 8 studs on the front wall. Because of the higher diaphragm stresses, triple plates are specified to reduce the tension in the top plate splices. Exterior plywood or oriented strand board (OSB) structural sheathing is required for those sections of the exterior back and side walls that act as shear walls, forming part of the lateral system for the building. Size and positioning of window and door openings on these elevations will be determined by the length of the shear walls required. As the front elevation requires no shear walls, it can be fully glazed. The open front elevation was a feature highly sought after by the developers. Studs are positioned directly under the bearing point of the roof trusses, which are tied down using fabricated steel anchors to resist wind uplift.

The roof trusses have gently inward-sloping top chords, to which plywood or OSB roof sheathing is fastened directly. Drainage slopes must therefore be achieved using tapered rigid insulation, sloping toward the locations of the interior columns,

roof diaphragms (Figure 3, with gray shading).

As depicted in the street view (Figure 1), the front elevation of the building has been articulated with rectangular frame elements that project out from the main façade and extend above roof level. The design intent behind this strategy is to differentiate between adjacent retail units and, through the use of wood cladding, communicate the nature of the building construction.

As shown in this example, the building is clad externally in a combination of horizontal tongue and groove, charred white cedar siding, and fiber cement panels, complemented by glazed aluminum-framed storefront walls and doors and insulated spandrel panels.

The extensive use of wood not only reduces the environmental footprint of this building type, when compared

economies through the increased use of regional materials and labor.

Jim Taggart is an award-winning Vancouver-based architectural writer whose credits include the books Toward a Culture of Wood Architecture and Tall Wood Buildings: Design, Construction and Performance, as well as dozens of technical case studies for BC Wood WORKS! He is the recipient of the 2012 Premier of British Columbia’s Wood Champion award.

Claude Lamothe has worked for engineered wood products and forest products companies for close to 25 years, and founded his own consulting firm, Intra-Bois Inc. It offers structural engineering services and has performed several market studies for major North American forest products companies.

The Tour de France—known more for the cycling materials of carbon fiber and pneumatic rubber— added wood to its roster this year.

A temporary installation—created from locally sourced spruce in the Swiss countryside—was commissioned by the Vallée de Joux Tourisme in honor of the prestigious men’s 21-stage cycling race. Its focus was to “promote the cultural, natural, and industrial heritage of the region.”

The Ephemeral Ring, as it was called, was created by Swiss designer and architect Fabien Roy. Roy worked as an architect for more than 10 years, but then set up his own studio for furniture and product design and interior architecture.

The circular creation, which sat 4 m tall and 50 m in diameter, looked like a clock face when

seen from above, giving nod to the region’s watchmaking history. The Vallée de Joux, a valley in the Jura Mountains, is home to several luxurious Swiss watch brands, including Breguet and Jaeger-LeCoultre.

The construction was made of 20 m3 of wood, making 5 km of wooden sticks; two lines of wood in the middle of the installation formed the clock’s hands.

On Saturday, July 9, cyclists rode past within 20 m of the installation during Stage 8 of the Tour.

The Ephemeral Ring was disassembled before the end of the summer, but there will be minimal environmental footprint. The pieces will be used in the construction field, showing, once again, that wood has a timeless tradition.