3 minute read

Reflecting on the Impact of Extended Days on Feed Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic on Feedlot Mortality

By Jacob Hagenmaier DVM, PhD, Production Animal Consultation

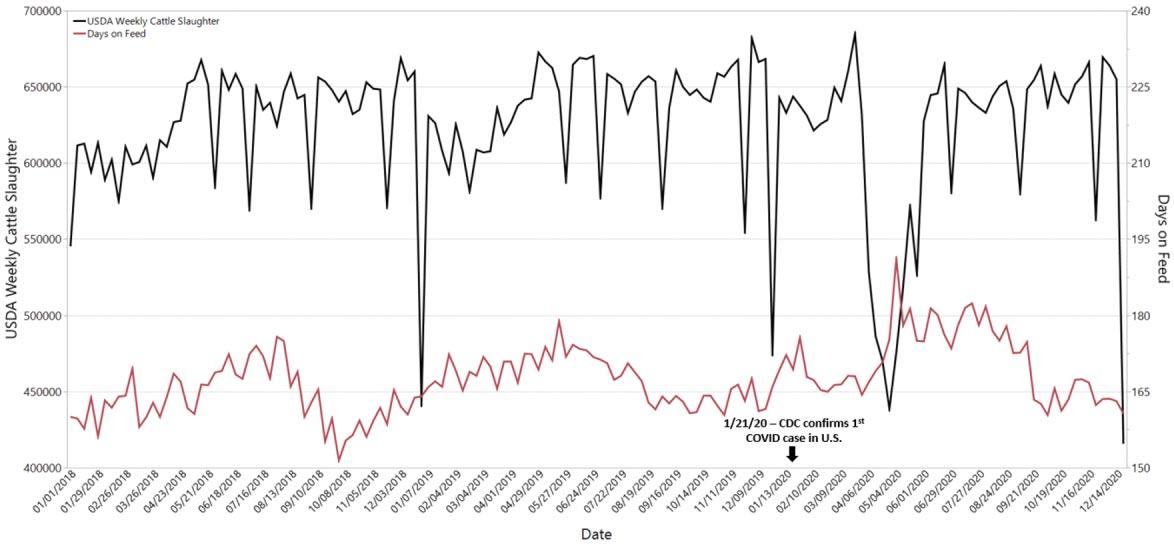

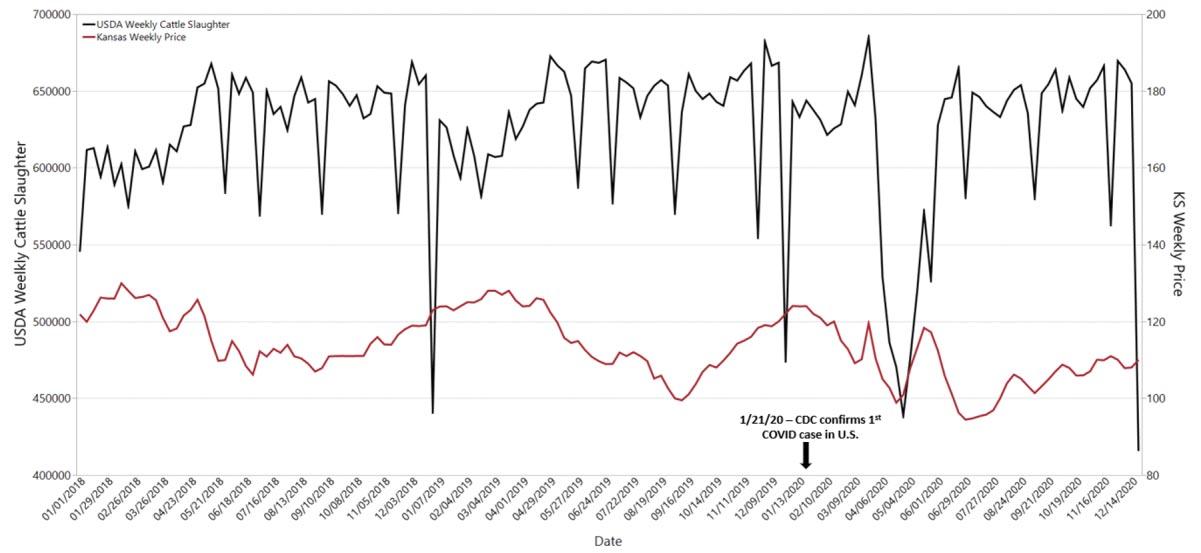

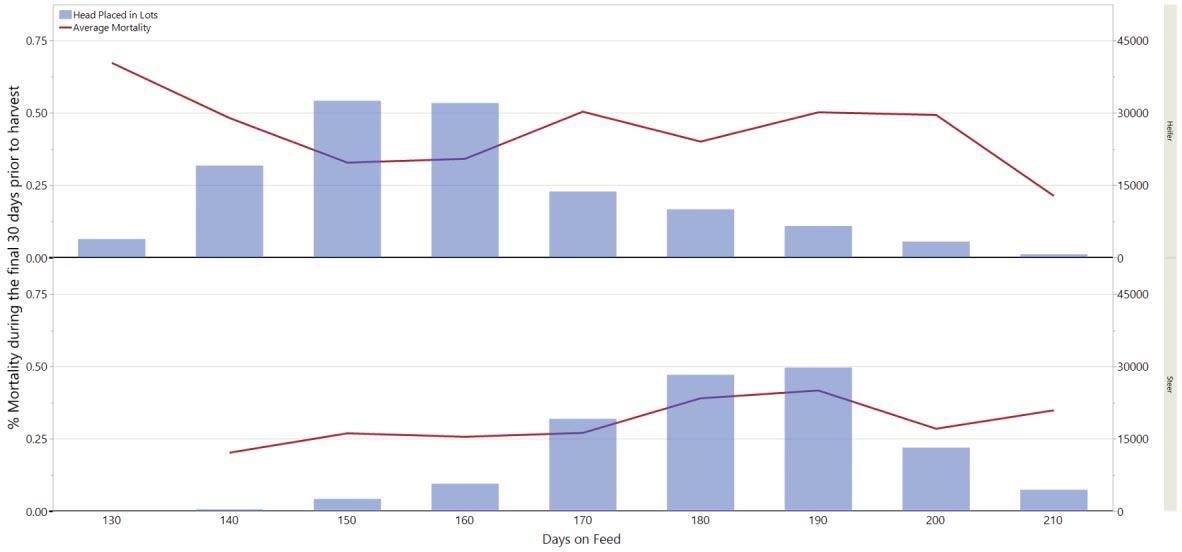

It would be an understatement to say the fed cattle market has been dynamic over the last 18 months. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on harvest capacities and consequently the ability for feedyard inventory to stay current put downward pressure on cash cattle prices and extended days on feed in the second and third quarters of 2020 (Figures 1a and 1b). While harvest capacities have since rebounded and cattle inventories have become much more current, PAC veter i narians continue to field ques tions regarding the effect of extended days on feed on health outcomes. In order to help an swer some of these questions, an exploratory data analysis was performed using PAC’s closeout database.

Endpoint management is a common discussion as it pertains to growth, especially when trying to project marginal profit and the optimal endpoint for a pen of cattle. Generally speaking, live weight gain becomes less efficient as cattle approach physiological maturity and lean tissue accretion gives way to adipose tissue deposition. The good news for dressed and grid sellers is this decrease in efficiency is at least partially offset as carcass transfer (the proportion of gain realized in the carcass) increases late in the feeding period. From a health perspective, the cost of extending days on feed is a bit more ambiguous. It seems logical to surmise extending days on feed increases mortality simply because of the fact there are more days of risk, which is indeed the case (Figure 2). As a wise man once said, the number one predisposing risk to death is to be alive! Therefore, the question is not whether more cattle die if fed longer, but rather does the rate at which mortality occurs increase during this added period of risk?

Figure 1b shows the 3-week period beginning in late April 2020 when the average days on feed extended 20 to 30 days. This reflects the COVID-19 landscape whereby reduced harvest capacities at beef abattoirs pushed finished cattle out further days on feed. I recall conversations within PAC at this time focusing on strategies to mitigate late-day death loss and challenging ourselves to help our clients not surrender a higher incidence rate of mortality during these additional 30 days. This was going to be easier said than done, as not only are there additional musculoskeletal and physiological stressors that accompany later endpoints, but the extension of days on feed occurred concurrent with the transition into spring when digestive and AIP death loss historically begins increasing.

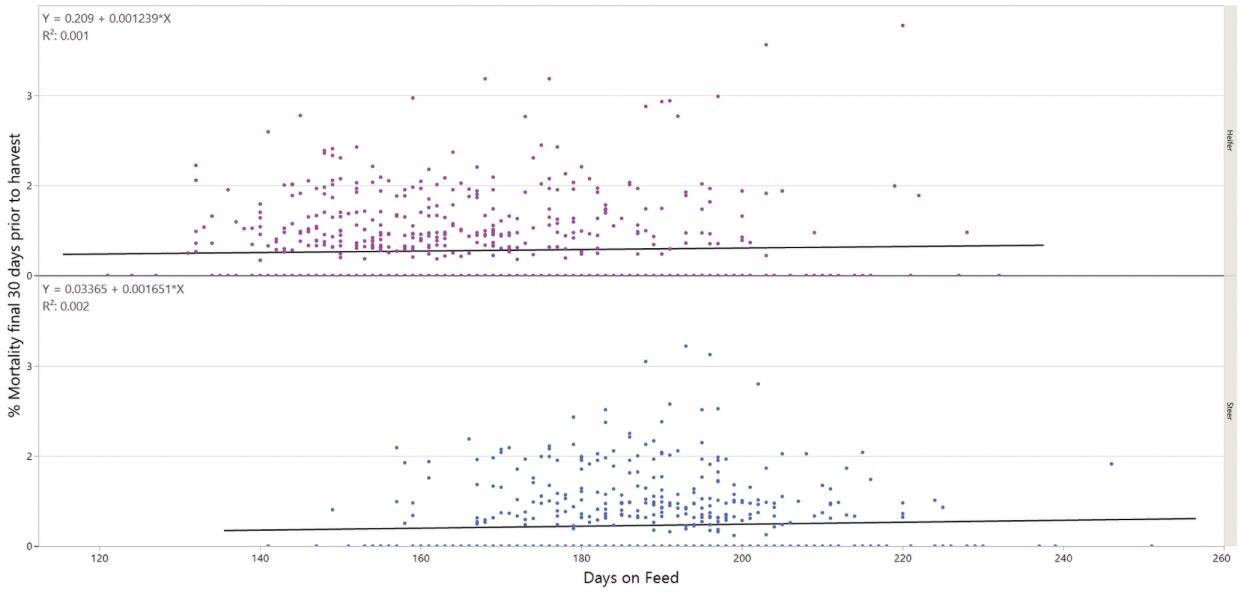

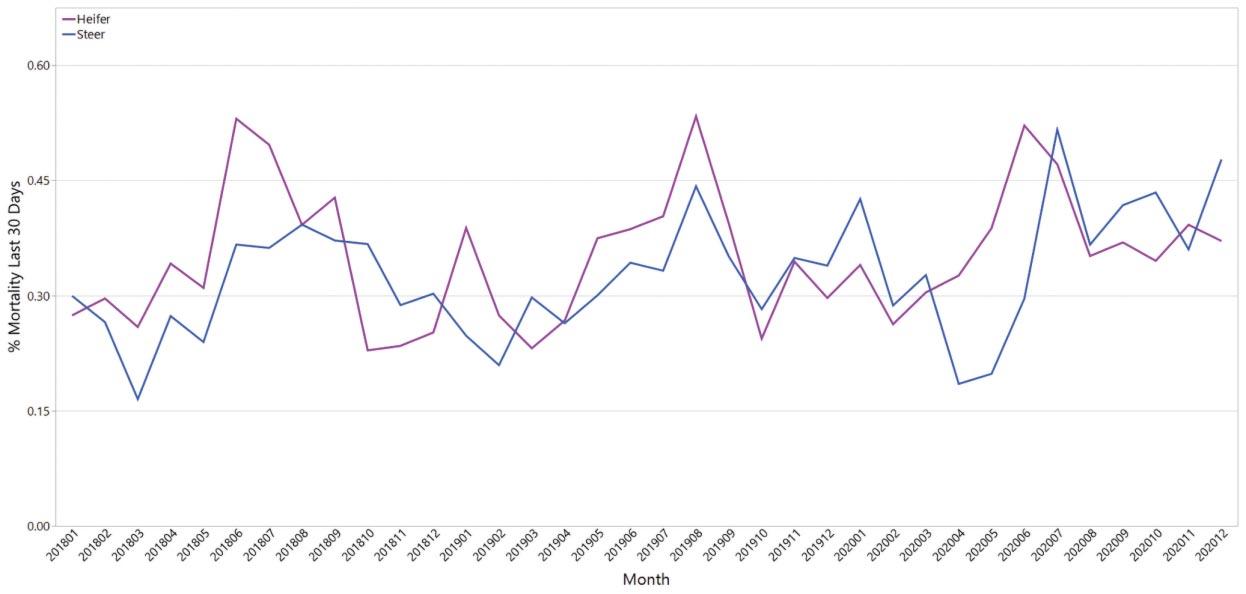

Days on feed is confounded by placement weight, which is our best gauge of age and immunocompetence and typically the best indicator of risk for health challenges in the feedlot. To fairly evaluate the effect of adding days at the end of the feeding period, it is important to not only look at mortality specifically near the end of the feeding period, but also to account for potential confounding factors such as gender, placement weight, and closeout date. PAC was encouraged upon reviewing the data for 700pound steers and heifers to find that mortality rate during the final 30 days on feed remained flat as days on feed increased during the second and third quarter of 2020 (Figure 3). More broadly, mortality during the final 30 days stayed relatively static when monthly closeouts were considered retrospectively over a 3-year period (Figure 4). This is consistent with simple linear regression models incorporating data over the same timeframe that suggest days on feed only explains 0.1% and 0.2% of the mortality occurring in heifers and steers during the final 30 days, respectively (Figure 5). So, increasing days on feed may have had impact on performance but it did not have a considerable impact on the rate of death loss during the final 30 days. It should be noted that the inability to project shipping dates during the second and third quarter of 2020 was an impetus for many yards to periodically stop feeding the beta-agonist ractopamine during the final 28 to 42 days, another potential confounder that was not accounted for in this analysis.

One limitation of evaluating population data to answer these types of questions is that no two pens of cattle are the same, and there can be significant variation across feedyards. With a randomized research trial, variation attributable to factors such as genetics, vaccination history, prior health challenges, environment, and nutrition (betaagonists) can be controlled to isolate the true effect on health outcomes of adding days to the feeding period. Yet, the increase in late-day mortality by adding days is likely so small that designing a study to test this question would require extremely large numbers of cattle. With that said, PAC veterinarians continue to frequently utilize data to not only help guide research questions but also turn data into knowledge to identify opportunities to help our clients’ operations. Macroscopic trends such as those explored in this analysis often lead to more granular analyses within individual feedlot operations and produce actionable items. Reach out to your PAC veterinarian if you have questions specific to your operation that custom analytics can help in answering.

Increasing days on feed may have had impact on performance but it did not have a considerable impact on the rate of death loss during the final 30 days.

While patience can be learned, it is best obtained when gifted and installed by the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) – GOD.