6 minute read

How to Acclimate Cattle

By: Dr. Tom Noffsinger and Dr. Kip Lukasiewicz, Production Animal Consultation, & Dr. LeeAnn Hyder, Robinson Hospital for Animals

Excerpt from “Feedlot Processing and Arrival Cattle Management,” Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 31.3 (2015): 323-340.

The primary focus of acclimation is stress reduction. The signs of stress are many, and stressed animals exhibit a mixture of these signs. Stressed cattle are often wary of their surroundings and their new caregiver. They tend to be herd bound and congregate in a chosen corner of their new pen. These animals keep whatever and whomever they view as a threat in their line of vision. Stressed cattle have spacious flight zones and are reluctant to pass by or engage with a handler. These animals are reluctant to travel in straight lines and exhibit aimless circling. Stressed cattle may or may not vocalize or exhibit decreased abdominal fill. One of the main negative effects of stressed animals is that they hide subtle signs of injury and disease. Cattle are a prey species and do not wish to be identified by what they consider a threat. Until cattle trust their caregiver, the caregiver is viewed as a threat and cattle do not present disease symptoms honestly.

Cattle in the process of relocation search for guidance and instruction. Positive first impressions are an efficient way to improve cattle confidence and create proper animal behavior. Greeting cattle as they file off a truck or trailer or into their new pen is an appropriate first step. Cattle crave to easily visualize their source of guidance and their destination simultaneously. By positioning themselves to accommodate this instinct, handlers can start the process of convincing cattle they can pass by without incurring harm. Handler posture can also be used to convince cattle to trust the handler and to accept increasing degrees of pressure. Sensitive cattle refuse to pass by a handler with frontal focus; instead, handlers should turn their shoulder, side, or back toward the cattle. A relaxed posture is more encouraging than a confrontational, rigid, fixed posture with a puffed-up chest and broad shoulders. Handlers should encourage cattle to pass by through the application of the least amount of pressure that is effective in initiating and maintaining movement. Owing to poor depth perception, cattle are suspicious of handlers that stand still. Gentle swaying movements by handlers convince cattle that handlers understand their lack of depth perception and are willing to be clearly visible.

Once unloading is complete, it is time to send cattle to their new home pen. Proper emptying of the holding pen is the first step in this process. As handlers approach the holding pen, they should respond to the first signs of cattle acknowledgment by halting or changing angles. The most sensitive cattle in the holding area acknowledge handler presence by either raising their heads or moving away. The goal is for handlers to create orderly cattle flow out of the holding pen by working near the gate.

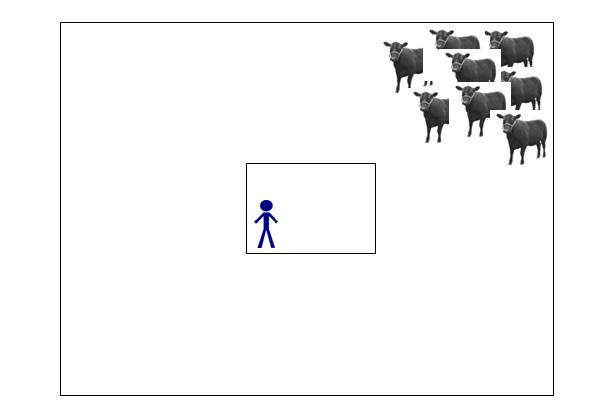

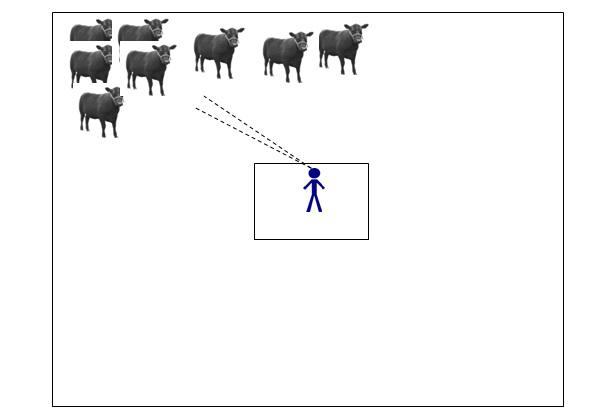

The handler should enter the pen and move along the side of the pen that allows cattle to see the handler and their destination simultaneously (Fig. 1). As soon as cattle initiate motion, the handler should release pressure.

Cattle choose to turn around the handler as they enter the alley; this prevents them from rushing out of the pen, losing their footing, and striking their shoulders or hips as they exit.

Cattle should move into their new home pen voluntarily. If possible, allow cattle to go past their designated gate and volunteer to stop at a check gate or at the end of a drover’s alley. Cattle instinctively return in the direction they came from; this creates voluntary motion and provides another opportunity to show cattle they can safely pass by a handler into their new home. After the cattle have volunteered to stop at the check gate or end of the drover’s alley, the caregiver can then ask the cattle to move into their new home pen.

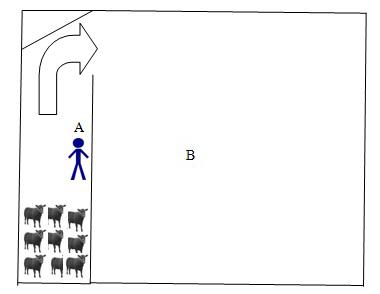

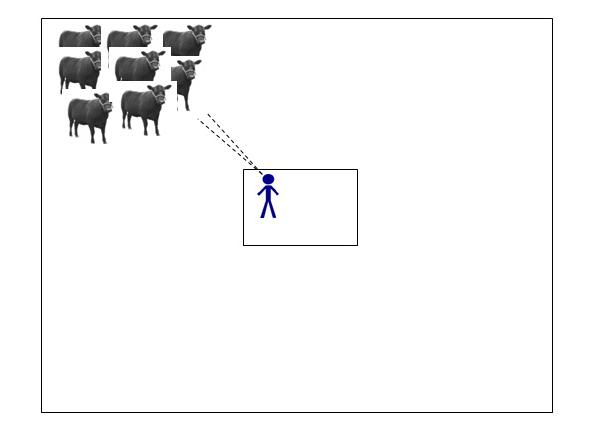

Fig. 2. To establish trust and provide guidance, the handler should be positioned at location A or B depending on the sensitivity of the cattle.

The caregiver should interact with the animals at the front of the group. Gentle pressure within the flight zone should be applied to ask the animals at the front to move past the caregiver. Once the first animal begins moving forward, the caregiver should move with that animal to relieve pressure from the remainder of the group. This action allows the caregiver to guide the front of the group while the remaining cattle follow. Because new cattle tend to have a large flight zone, being in the alley with them can place excessive pressure on these animals.

Cattle that are under too much pressure turn into the check gate, press against their herd mates, and avoid eye contact with the handler. In these cases, the handler should move out of the alley and work with the cattle from a neighboring pen (Fig. 2). Gently moving cattle into their home pen establishes the caregiver as the provider of food and water. The bunk should be filled with grass hay and ration and the water tank filled with clean water before cattle arrival to encourage immediate nourishment and rehydration.

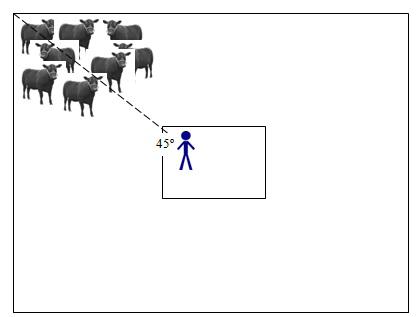

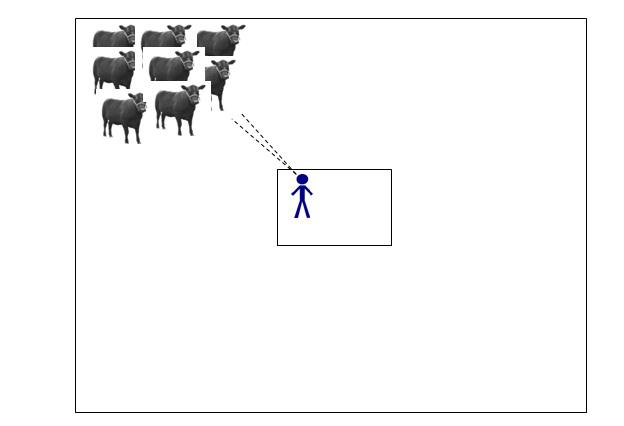

It is worthwhile to follow cattle into their home pen and move across the bottom third of the pen parallel to the bunk, allowing cattle to use their peripheral vision to view the handler. Cattle ideally begin consuming food and water and may be left alone for the time being. In situations in which cattle do not go to or remain at the bunk, a caregiver who has followed the cattle into the pen is in the appro- priate position to work with those animals. Cattle that lack trust in their handlers initially circle around handlers and avoid straight motion. The presence of the caregiver in the pen influences the herd to gather in a preferential corner. It is the handler’s responsibility to use position, stimulus, and release to guide the herd to each corner of the pen. Moving cattle to each corner of the pen introduces them to the entirety of their new space; this is accomplished by working in a small square within the center of the pen. The handler should initially be orientated at a 45-degree angle to the corner where cattle are gathered (Fig. 3).

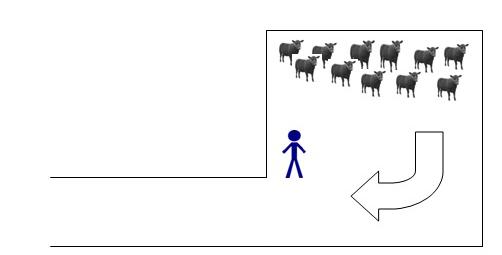

Cattle attention on the handler is necessary before motion within the group can be created. Uniform attention or alignment of the cattle is achieved by lateral movements of the handler parallel to the front of the group (Fig. 4). Once alignment is achieved, the group should be surveyed by the handler to identify the individual animals requesting guidance through their posture (Fig. 5). These animals are the front of the herd. The posture described is an animal standing broadside bending its neck to view the handler (Fig. 6).

Learning how to perpetuate straight motion is the key to guiding the front of the herd. Once the handler moves to a spot that allows the guidance-seeking animal to straighten its neck, the handler simply moves straight past the nearside eye. This handler movement encourages that animal to step forward. Once cattle motion is initiated, the handler should back up in a divergent line at a 45-degree angle with the motion of the cattle. This handler movement maintains motion by guiding the front animals and releasing pressure on the timid herd mates, allowing them to follow the leaders (Fig. 7). Once animals are willing to travel in a straight line from corner to corner around the pen, the handler can choose to leave the cattle at the bunk (Fig. 8). Pressure is applied in the back corner of the pen and released as the cattle arrive at the bunk area, encouraging bunk confidence.

A completely calm and confident herd does not develop with a single training session. Multiple sessions are needed over several days, and multiple training sessions within a single day are encouraged for new arrivals.

Initially, training sessions should not be longer than 7 to 9 minutes because cattle become overwhelmed and the training becomes ineffective. Breaks lasting 30 minutes to several hours should be taken when cattle start to show fatigue. Indications that cattle are becoming tired are cattle lose focus on the handler, leaders are difficult to identify, and cattle stop motion more often.

Training sessions should occur regularly for the first week after arrival. The sessions become longer than 7 to 9 minutes as cattle gain trust in the handler and decrease in length again when the group is consistently willing to work for the handler.