CLAUDIA MINDANG

Her Many Resurrections: Fine Art's Evolving Relationship with Feminine Horror

10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4 0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission

Her Many Resurrections: Fine Art’s Evolving Relationship with Feminine Horror

Abstract

In this Dissertation, I tracked the changes in how tropes of the ‘monstrous feminine’ have evolved in the fine art world. I investigated, through a feminist lens, how various artists have used visual media to bring subconscious fears of women, femininity, and gender non-conformity to life and what they can tell us about attitudes towards those themes. I have outlined plans for an exhibition highlighting the evolution of these themes, deciphering the motifs within the featured artworks and how these represent themes ranging from fear to celebration of the feminine.

I have supported my analysis with Barbara Creed’s 1993 book, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, and Erin Harrington’s 2018 book Women, Monstrosity and Horror Film: Gynaehorror, which further expands on Creed’s ideas. Using these Film analyses as a foundation, I have adapted these concepts to apply to artworks; paintings, sculptures and one song.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my Dissertation tutor, Ellie Harrison, for her excellent guidance and Helen Gorrill and Nikki Reed for their encouragement and support.

I relied on 2024 graduate and bestie Jae Lawson to compile various academic guides and provide constant emotional support, cheering me on the whole time.

I am incredibly grateful for Misha Kaznacheyva’s contribution to the proposed exhibition. Finally, I thank my friend Iona Kuhn for accompanying me to Arbroath Abbey and being one of my creative muses.

List of Figures

Figure 1 - ‘Medusa’ or ‘The Head of Medusa’ - (Rubens, 1618) Sourced Via: www.artmajeur.com

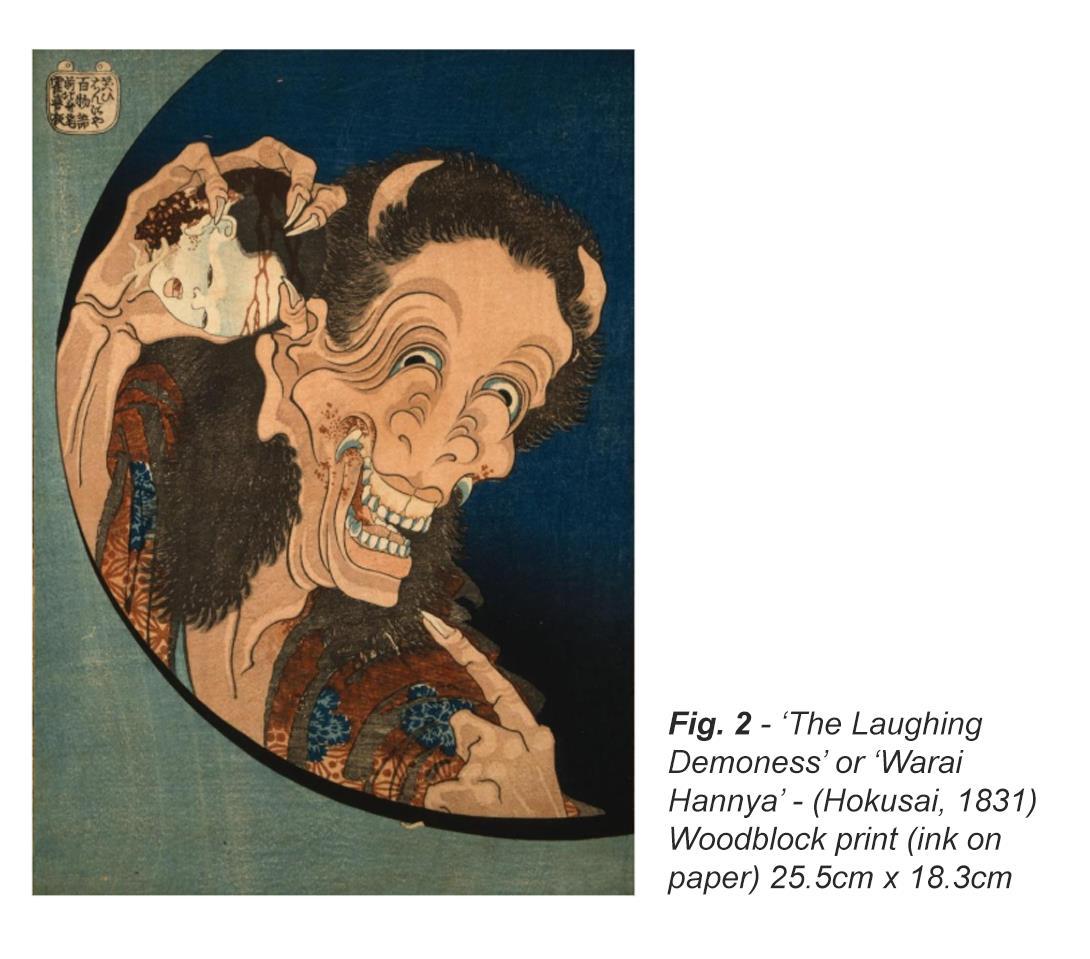

Figure 2 - ‘The Laughing Demoness’ or ‘Warai Hannya’ - (Hokusai, 1831) Sourced Via: www.meisterdrucke.us

Figure 3 - ‘L'oiseau Amoureux’ - (Saint Phalle, 1990/92) Sourced Via: www.artnet.com

Figure 4 - ‘Maman’ - (Bourgeois, 1999) Sourced Via: www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus

Figure 5 - ‘The Hungry Purse’ - (Mitchell, 2014-24) Sourced Via: allysonmitchell.com

Figure 6 - ‘She-Devil’ - (Cox, 2017) Legs 11 11 performing indoors/ in front of an audience. Sourced Via: www.cybelecox.com. Video of performance accessible via: YouTube

Figure 7 - ‘Akai Onryō’ - (Mindang, 2024) Mask mounted on a wall.

Figure 8 - ‘Lady Hagatha’ - (Mindang, 2024) Mask mounted on a wall.

Figure 9 - ‘Virelia Sees’ - (Mindang, 2024) Mask mounted on a wall.

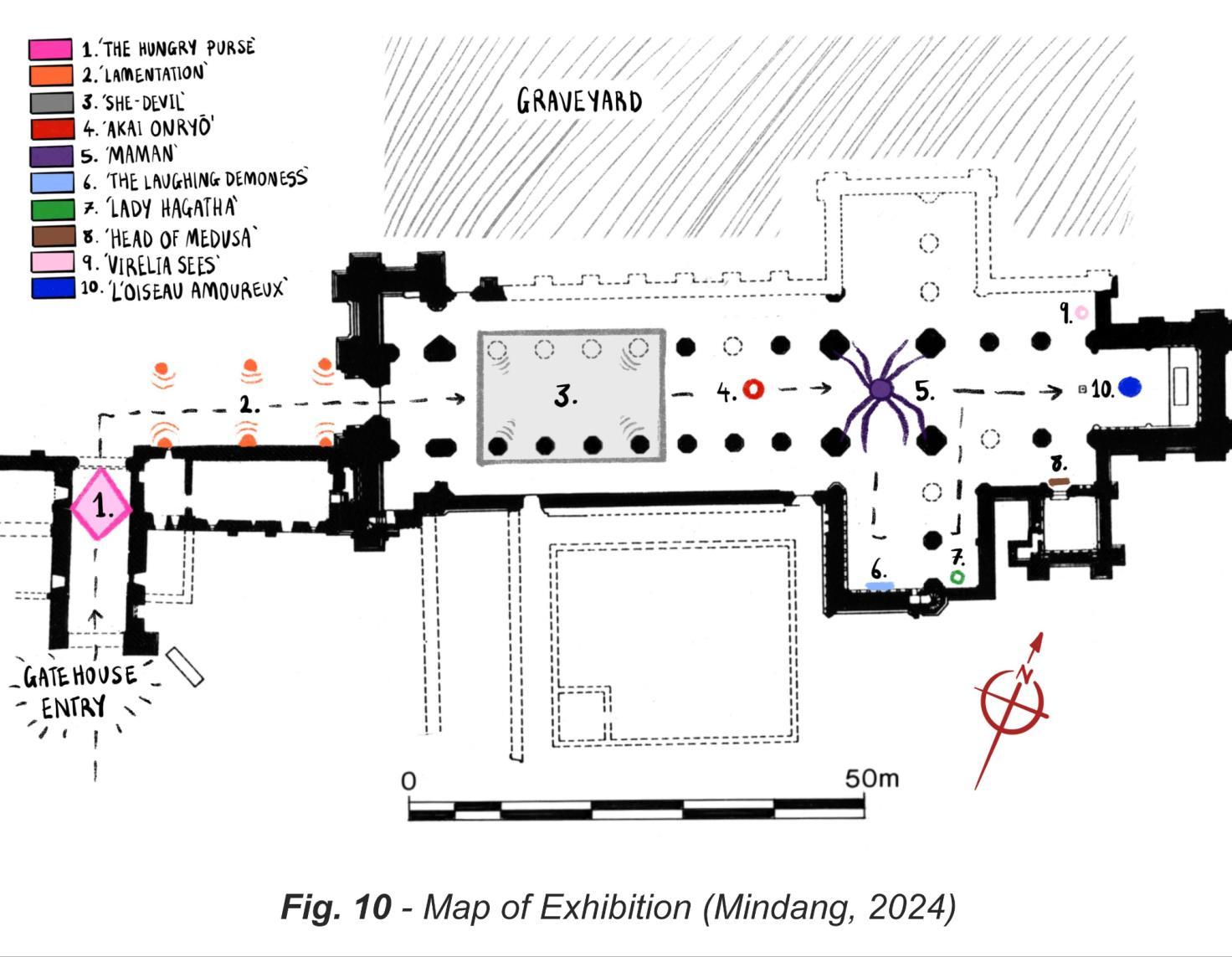

Figure 10 - Map of Exhibition (Mindang, 2024) Arbroath Abbey Floor Plan Purchased from: Historic Environment Scotland and illustrated over using Procreate.

Figure 11 - Gatehouse Entry and Western Gable (Mindang, 2024) Illustration of art and building to scale, made on Procreate.

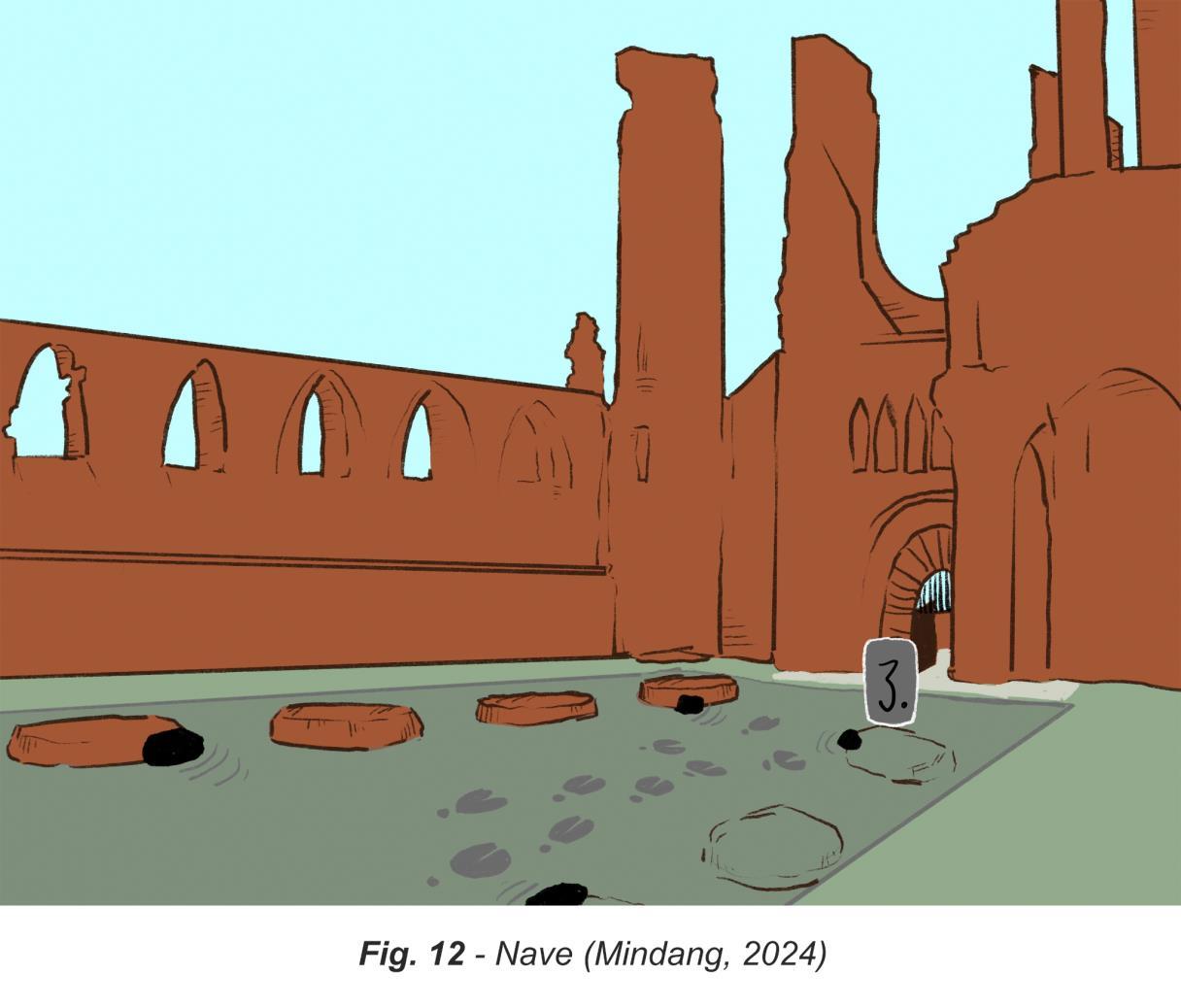

Figure 12 - Nave (Mindang, 2024) Illustration of art and building to scale, made on Procreate.

Figure 13 - Tomb of William I and The Main Body of Arbroath Abbey (Mindang,2024) Illustration of art and building to scale, made on Procreate.

Figure 14 - South transept and Sacristy (Mindang, 2024) Illustration of art and building to scale, made on Procreate.

Figure 15 - Choir and Presbytery (Mindang, 2024) Illustration of art and building to scale, made on Procreate.

Introduction

The monstrous feminine has long served as an impactful archetype within cultural imagination, serving as a conduit for societal anxieties surrounding women and femininity through abstract constructs. (Creed,1993)

This dissertation investigates the evolution of this archetype through the framework of a proposed exhibition, Her Many Resurrections, to be held within the ruins of Arbroath Abbey. Rooted in mythological, historical, and literary traditions, it often opposes patriarchal structures through figures such as Medusa, witches, and demons and their contemporary reimaginations in art and film. The increased representation of female monsters in media correlates with the European and American women’s movements. (Hogan, 1997)

The exhibition highlights and examines the works of Allyson Mitchell, Peter Paul Rubens, Katsushika Hokusai, Cybele Cox, Louise Bourgeois, Nikki de Saint Phalle, and some works of my own Through an engagement with Professor Barbara Creed’s theoretical framework set out in her 1993 book, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, this project explores how the monstrous feminine has been constructed, deconstructed and reconceptualised in the context of fine art. At the heart of this inquiry lies an analysis of these works' symbolism and visual motifs, which articulate and interrogate shifting narratives around acceptable and desirable femininity. (Benton, 2021)

This selection aims to build a conversation between historical and contemporary artworks, establishing a symbiosis between past understandings of femininity and contemporary ones. In this way, the exhibition recontextualises mythological figures amid contemporary (re)interpretations of myth-adjacent tropes, challenging preconceived biases. This project aims to investigate the frontier that separates tradition and subversion critically. Expanding on the monstrous feminine as a figure of potentiality rather than pathology (Harrington, 2018), the

exhibition makes a compelling case for its abiding cultural and artistic relevance. Her Many Resurrections seeks to show the transfigurative potential of the monstrous feminine, or transgressive womanhood at large, retooling it as a space for critique and creativity and creating an environment where ingrained misogynistic ideals are subverted.

I have endeavoured to contribute to ongoing academic discussions on gender, power, and representation, offering a platform for examining the complexities of feminine identity across temporal and cultural landscapes in the art world.

Chapter 1: Curatorial Thesis

"All human societies have a conception of the monstrous-feminine, of what it is about Woman that is shocking, horrific and abject" - (Creed, 1993, p.1)

In this proposition, I will outline an exhibition featuring artists from the Baroque and Edo periods alongside contemporary and modern works. The exhibition will focus on how these artists have represented themes of horror and the abject, particularly about women and femininity. It offers a unique opportunity to trace the evolution of visual motifs associated with the 'monstrous feminine' across time, presented in a manner reminiscent of a museum display displaying artefacts from various historical periods, with a foundational understanding of Carl Jung’s concept of ‘The collective unconscious’, which states that all societies on a global scale share a fundamental set of related unconscious beliefs that stands aside from personal experience or recorded history, something innate that lies dormant in all cultures which shines through in mythologies, symbolism and universal patterns (Jung, 1936). These beliefs can be reduced to archetypes, which resonate across cultures and represent the distilled essence of humanity's repeated experiences, shaping perceptions and actions. For the sake of this dissertation, this concept can be observed particularly relating to ‘the mother’ or, more broadly, ‘the feminine’ (Woodman, 1998).

Across cultures, storytelling has shaped collective consciousness, especially fears about women and femininity. Themes of the monstrous feminine, as outlined by Barbara Creed in The Monstrous-Feminine, can be seen in almost any depiction of the abject, the horrifying and the 'other'. This is not only caused by generations of profoundly ingrained misogyny by patriarchal societies that have controlled women's narratives over centuries but also because human nature and the fundamentality of life, death, and our existence between is inescapably bound to the feminine, for better or worse. (Creed,1993) (Kristeva, 1980)

In this exhibition, I aim to unify some of these shared ideas of the monstrous feminine and how they’ve evolved into the contemporary collective unconscious.

Horror themes linked to femininity and the notion of feminine traits as both irresistible and cosmically destructive have long resonated in the human psyche, tracing back to ancient Greek mythology and beyond. Figures like the Sirens, Gorgons, Harpies, and Gaea, the "mother of monsters" (Gresseth, 1970), embody these ideas within the Western canon. These archetypes, often portrayed through feminine forms, were later shaped and amplified by institutions of religion. (Raitt, 1980)

During the Baroque period, such art became a tool to inspire religious fear and devotion following the Reformation of the late 16th century, which challenged the Church’s authority in Europe. To reclaim power, the Church commissioned profoundly emotive works that conveyed morality, Christian values, and theocratic mythology (Carl and Charles, 2009). A striking example is Peter Paul Rubens’ The Head of Medusa, featured in this exhibition. The piece vividly blends classical mythology and horror with Christian themes, to spark fear and wonder while reflecting the period's spiritual intensity (Bantinaki, 2024).

In pre-colonial Filipino culture, women and gender-nonconforming individuals often served as shamans, healers, and spiritual leaders, holding significant roles within their communities. However, colonisation by the Portuguese and Spanish starting in 1521 introduced Christian beliefs about witches or Brujas, which influenced local narratives. From this emerged the figure of the aswang: women who, by day, were beautiful but transformed at night into disembodied heads or monstrous beings that consumed crops, attacked pregnant women and infants, and drank blood, akin to the Western vampire. Similar myths, such as the Penanggalan in Malaysia and Indonesia, usually a woman who dies during childbirth and terrorises villagers as a flying, disembodied head, reflect shared Southeast Asian folklore (Nadeau, 2011). These stories

served to discredit women involved in vital but gory practices like midwifery or those who held significant power, threatening the patriarchal structures emerging under colonisation.

The exhibition will be hosted at Arbroath Abbey, a location of enormous historical significance. Its ties to the fraught history of the Christian church, most recently to be found during the Scottish witch trials (Goodare, 2005), render it also poignant to the themes explored. Finally, the Abbey is also significant as the site where the Declaration of Arbroath was promulgated, a document that played a key role in Scotland’s struggle against England’s oppressive rule (Brown, 2006). It thus serves as an overarching background for considering gender and power and invokes a broader cultural and political context for analysis.

Even within feminist spaces, the structural imbalance rooted in a patriarchal society persists. Inequalities between white women and women of colour, especially in Western and historically colonised societies, have led to the development of concepts like 'white feminism' and 'choice feminism.' These terms often highlight the tensions where the needs and perspectives of women of colour are sidelined (Liska, 2015). Similarly, transgender, and non-binary individuals usually feel excluded from spaces that claim to champion equal rights. (Doyle, 2022)

Concepts such as ‘respectability politics’ have gained notoriety, especially with the rise of social media, allowing individuals to broadcast themselves to the world and be open to criticism from online audiences. Contemporary media must actively combat these regulatory and exclusionary confines around who deserves to be treated with respect and dignity, often based on bigoted ideals that reaffirm patriarchal and white colonial standards (Jones, 2021). Now is the time for alternative and misrepresented communities to experience the freedom of expression and the platform to empower others who can identify; this includes people who are authentic to their own identities and, in doing so, transgress pre-ordained rules around physical appearance, ability and unconventional lifestyles (Howell and Baker, 2022). (Read more about this in Appendix 1)

As the global psyche evolves, horror-themed narratives have resurged, becoming accessible through movies, books, and other mass media (Church, 2021). The internet and social media have democratised these themes, allowing broader engagement with ideas once confined to academia or elites.

This democratisation has profound implications for art and culture, especially regarding women and queerness. With each wave of activism and shifts in gender and racial equality, art serves as a lens to reflect and analyse the ideas of its time through symbolism, techniques, and composition (McEvilley, 1992). This exhibition offers an intellectual exploration of these themes, providing visibility, scrutiny, and deeper insight into societal constructs and their portrayal in art.(Benton, 2021)

This exhibition provides a space for reflection and honours historical and mythical figures like Medusa, a symbol of suffering, transformation, and vengeance. Once a victim of sexual violence, Medusa’s transformation into a monstrous antagonist has become a key figure for examining feminine narratives. Her story is a blueprint for many monstrous women in art and storytelling throughout history (Bowers, 1990).

This narrative of suffering and transformation is reflected in the artworks displayed in the exhibition, highlighting the recurring tropes of the monstrous feminine. The ‘villain arc’ is commonly used for female or feminine characters due to traditional expectations of women as ‘the softer sex,’ which implies they are less likely to show aggression or confrontational behaviour. This leads to the portrayal of women as passive victims, naive, meek and dependent upon the men around them. For female characters with agency, however, these traits begin to fall short, given this stereotype, combined with the historical vilification of women who are assertive or dominant. Beginning in Greek mythology, one can observe that within these characters, the transformation into monstrous figures becomes a way of reconciling these contradictions (Moss, 1988).

As well as being another form of policing womanhood (Meisler, 2023), fears surrounding transgender and subversive gender identities may stem from societal anxieties about transformation and change, as well as misplaced fears of feminine erasure. Some cisgender women may perceive these identities as further “othering” of womanhood, buying into conservative ideologies presenting transness as a threat to traditional notions of femininity (Alexandre, 2024). However, embracing identities that blur binary understandings can enrich and expand the concept of gender. Rather than limiting ourselves to rigid ideas of “correct womanhood,” this perspective has the potential to empower not only women but all gender identities and marginalised groups as a whole (Veldhuis, C.B, Drabble, L, Riggle, E.D.B, Wootton, A.R. and Hughes, T.L,2018).

Ancient myths may have catalysed this unease by portraying influential female figures as either stripped of their femininity or characterised as “man-like” to make them more acceptable (Moss, 1988). For instance, in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Clytemnestra’s power is framed through her rejection of traditional femininity. At the same time, the Goddess Athena embodies an idealised, unnatural version of womanhood detached from maternal origins (Zolotnikova, 2016), having emerged fully formed from Zeus’s head. This “father-bound virginal feminine principle” (Lee, Marchiano and Stewart, 2023) underscores Athena’s alignment with patriarchal ideals rather than natural femininity.

Athena’s treatment of Medusa further illustrates subjugation of unruly femininity. After Medusa’s assault in Athena’s temple, the goddess punishes her, reinforcing a morality rooted in patriarchal control. This act exemplifies how myths construct femininity as both idealised and punitive, often distorting female power into something threatening or monstrous (Bowers, 1990).

'The creation and normalisation of asymmetrical relationships between the one (the norm, the centre, the reasoned, the mind, Man) and the Other (the abnormal, the periphery, the uncontained, the body, Woman).' - (Harrington, 2018, pg. 5)

If we are supposed to believe that men, heterosexuality, and patriarchal society are 'correct' and 'natural', it is only inevitable that we begin to connote women, queerness, and social structures that decentre masculinity with 'the other'- all that is unnatural, or even supernatural. In addition to tracking the art world's progressing relationship with women and what has been condemned and sidelined by history books, this exhibition aims to challenge these ingrained stereotypes and offer an alternative way of viewing monstrous femininity as sublime and worthy of respect. It is a celebration of diversity, a platform that values and includes all forms of femininity, regardless of societal norms.

Chapter 2: Curatorial Choices

Venue

The atmosphere of the proposed exhibition will pay tribute to the qualities of the monstrous: dark and unsettling but also colourful and inviting, as if to imitate the allure of a witch's house, welcoming visitors into the belly of the beast.

Arbroath’s history is deeply tied to the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries, when women who defied societal norms were scapegoated for misfortunes and faced brutal interrogations, torture, and executions. These trials reflect societal fears of the feminine as ‘monstrous,’ with independence or knowledge perceived as threats to the patriarchal order. Arbroath Abbey, a central site in the town’s history, is a poignant reminder of these often-gendered injustices. The Church’s active role, alongside the monarchy, in witch hunts highlights how non-Christian authority or feminine power was viewed as dangerous. The archetype of the "witch" symbolised a moral panic surrounding community leaders that threatened these institutions, including men and women who were autonomous, knowledgeable, or critical of the church (Goodare, 2005).

Women were not the only victims, although notably, it is women who were most vulnerable throughout the Renaissance, medieval era and beyond. According to The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft (Lawson, 2019), 455 men, 2,664 women, and 26 individuals of unidentified sex were accused in Scotland during the witch trials. In Arbroath alone, thirteen women were investigated and charged with witchcraft, underscoring the local impact of these historical injustices. (See Appendix 2 for the names of these individuals.)

Beyond the witch trials, there remained systems that sought to contain people that threatened the status quo; following its time as a place of worship, the Abbey was repurposed to confine individuals declared ‘lunatics’ in the old sacristy, earning the nickname ‘Jenny Batter’s Hole’

after its last known resident in the 18th century. Records of this individual are scarce, as inquisition documents often list only names and verdicts, much of which has been lost over time (Houston, 2000).

Now in ruins, the Abbey attracts visitors as a site of historical significance, embodying themes of marginalisation and reclamation. Hosting the exhibition within the Abbey’s symbolic ‘body’ reimagines the monstrous feminine not as a source of fear but of power and transformation.

Reclaiming this space for the feminine spirit, its history of exclusion and suppression becomes a narrative of resilience and renewal.

The Church embodies the monstrous itself through its ties to a history of regulation of women’s bodies, demonisation of those defying traditional gender roles, and historical control of female power (Solomon, 2000). By repressing female sexuality, punishing independence, and excluding women from religious authority, it constructs femininity as either saintly (e.g., the Virgin Mary) or monstrous (e.g., witches or Medusa) to uphold patriarchal values.

Arbroath Abbey, also known as the Monastery of St Mary and St Thomas, bore a seal depicting the Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus on one side and St Thomas Becket, a Catholic martyr canonised for his faith, on the other (Robertson, 1908). This imagery ties the location to themes of death and motherhood, deepening its resonance as a potent symbol for exploring the complexities of the monstrous feminine.

Artworks

The exhibition will feature nine artworks listed below in chronological order of their creation. They will be followed by a piece of music.

Peter Paul Rubens - ‘Medusa’ or ‘The Head of Medusa’

Peter Paul Rubens’ painting depicts Medusa’s decapitated head; her bulging eyes cast downward as if fixated on her severed neck wound. Her face is frozen in rage, horror, and pain, immortalising the moment Perseus killed her. Once a winged, autonomous monster, Medusa is now reduced to a weapon in her slayer’s hands. Surrounding her head are creatures like a lizard, scorpion, spiders, and a two-headed snake (amphisbaena), symbolising fear and conflict.

Marcus Annaeus Lucan described the amphisbaena as being born from Medusa’s blood (Mazza, 2008). Medusa’s deadly gaze, which could turn men to stone, is instead directed at her wound, emphasising her defeat. Often symbolising the ‘female gaze’ itself, this can be interpreted as celebrating its antithesis, the ‘male gaze’, and its triumph over the unyielding feminine (Bowers, 1990).

Formerly renowned for her beauty, particularly her hair, she incurred Athena’s wrath after being pursued by Poseidon in Athena’s temple. Often depicted naked and otherwise conventionally attractive, embodying the femme fatale trope (Cain, 2018), this painting focuses solely on her severed head. This dismemberment symbolises a profound loss: the detachment of feminine power and autonomy (Beard, 2017), with the absence of limbs and sexual organs suggesting the defeat of her capacity to seduce or maintain agency over her body.

Medusa parallels snake-related deities like Corra from Celtic mythology and the Minoan snake goddess, symbols of nature in ‘pre-civilised’ societies (Zolotnikova, 2016). These societies, often matriarchal, are thought to have embraced female nudity and sexuality, contrasting with today’s patriarchal purity culture, which ties modesty and meekness to morality, particularly for women and femmes (Lee, Marchiano and Stewart, 2023). This artwork represents the feminine

in Western mythology as something terrifying, and therefore, in death as the monstrous feminine contained and subdued.

Katsushika Hokusai - ‘The Laughing Demoness’ or ‘Warai Hannya’

This image portrays Kishimojin, also known as Hāritī or "The Mother of Demons." Initially an ogre-like figure, she terrorised villagers by stealing children to feed her own. Her reign of fear ended when Shakyamuni Buddha took her youngest son, hiding him from her. Buddha returned the child only after Kishimojin vowed never to harm another human child (Murray, 1981).

This act of redemption transformed her into a goddess of fertility and protector of children (Cotterell, 1997). The print powerfully conveys the monstrous feminine by showing Kishimojin at the precipice of this transformation.

This artwork depicts the aftermath of her evil deeds, illustrated by the decapitated head of a child; Kishimojin herself represents the monstrous maternal figure, reminiscent of the ‘castrating mother,’ a concept explored in horror and psychoanalysis as mothers who are violent towards their children (Creed, 1993).

Hokusai’s woodblock print depicts Kishimojin with a grotesque, distorted expression. Her face contorts into a gleeful grin, with cleft gums, serpentine nostrils, and wild hair evoking a feral, monstrous quality. The use of Prussian blue and blood red adds a supernatural and regal feel to the image, reflecting the dual nature of her character; both feared for her demonic past and revered as a Buddhist deity. Prussian blue, in particular, due to its production involving animal blood (Gottesman, 2016), is particularly tied to a mysterious, somewhat demonised history in the art world (Pendle, 2024). Kishimojin was worshipped across Southeast Asia and Japan from the 7th to 17th centuries (Smith, 2016).

Warai hannya (1831) encapsulates the duality of maternal figures as instinctively nurturing yet capable of horror, embodying Kristeva’s concept of the ‘abject mother,’ a tyrannical and suffocating figure. Kishimojin’s transition from a demonic entity to a loving protector highlights the complexity of motherhood, offering a narrative of salvation through patriarchal intervention, where her monstrous devotion becomes both her strength and vulnerability.

Niki de Saint Phalle - ‘L'oiseau Amoureux’

This sculpture, translating to ‘the lovebird’ in English (Saint Phalle, 1990/1992), is one of the most celebratory in the exhibition, with vibrant colours, dynamic patterns, and floral motifs

merging with rounded, inflated forms to create a totem of joy and optimism. The interplay of form and colour exudes playful energy, exemplifying Niki de Saint Phalle’s mastery of blending whimsy with profound themes. This vibrant art style has become widely associated with a newer archetype of the free, uninhibited feminine (Riley, 2016).

At its core is one of Saint Phalle’s iconic Nana figures, embraced by an anthropomorphic “lovebird.” The Nana, a recurring symbol of love, fertility, and feminine beauty, is tenderly cradled, forming a metaphor for harmony, connection, and empowerment. This imagery celebrates vitality and serves as a tribute to the strength and joy of womanhood.

Unlike traditional depictions of the monstrous feminine that evoke fear or repulsion, L’Oiseau Amoureux transforms boldness and surreal elements into sources of strength and vitality, echoing the fecund mother trope outlined by Creed (1993). Saint Phalle’s use of the bird motif, as she noted in an interview with Joan Simon, reflects themes of freedom and spirituality: “I hope if I get reincarnated, I’ll get turned into a bird. I love their magic, their freedom” (Niki de Saint Phalle - Sun God, 2024).

The sculpture also invites queer interpretations with its stylised roundness and gender ambiguity. The intimate pose of the Nana embracing the lovebird disrupts traditional gender roles (Riley, 2016) as she is the one wrapped around or ‘surrounding’ the bird figure, celebrating an active, autonomous, engaging depiction of femininity. It encourages viewers to find power, wonder, and depth in women’s relationships with themselves and each other.

Louise Bourgeois - ‘Maman’

This monumental sculpture, Maman, (Bourgeois,1999) is both awe-inspiring and horrifying. The colossal arachnid evokes a blend of arachnophobia and megalophobia, instilling fear and fascination. Drawing from Louise Bourgeois' relationship with her mother and the profound tragedy of her death, the twelve marble egg sacs in the sculpture’s abdomen confront the complex and ambivalent theme of motherhood.

Spiders, often associated with fear, darkness, and death, also symbolise creativity and transformation, mainly through their ability to weave silk an act historically tied to women (Thomas, 2023). Bourgeois likened the spider to her creative process, comparing it to producing ideas and emotions akin to bodily secretion. Kristeva (1980) has connected bodily functions such as defecation and menstruation to maternal authority, highlighting our dependence on

mothers and our eventual transformation from helpless infants to autonomous beings. This dual symbolism in the spider reflects the feminine's nurturing and destructive aspects.

In horror, mothers and spiders are frequently depicted as menacing figures. Maman embodies the immense power of the feminine, linking creativity and death (Gibson, 2013). The sculpture underscores the connection between the feminine as both life-giving and life-taking. The book

The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (Creed,1993) includes this text describing the archaic mother "A mother-thing situated beyond good and evil... a shadowy and deep unity... an absolute being." (Dadoun, 1979). In Bourgeois’ work, the spider represents this all-encompassing, sometimes overwhelming maternal force, both protective and threatening.

Allyson Mitchel - ‘The Hungry Purse’

Allyson Mitchell’s The Hungry Purse installation draws on the ancient archetype of 'Vagina Dentata' to critique late-stage capitalism, intertwining themes of consumption and appetite (Mitchell, 2014). The space, enveloped in plush, colourful textiles, transforms into a womb-like sanctuary, contrasting the hyper-consumerist world outside. The entrance, a crocheted vulva, marks the beginning of a journey through an immersive experience mimicking the feminine reproductive system.

The environment is alluring and primal, offering comfort while feeling cramped and confrontational. Soft furnishings create spaces for reflection, challenging viewers with taboo imagery of female genitalia, the cycles of life and death, and the tension between human nature and mass production. The Hungry Purse thus becomes a space for reconnecting with the feminine as a divine force, a refuge from patriarchal society. Symbolically, ‘the vagina dentata’ is the opposite or inverse of ‘Immaculatus Uterus Divinus Fontis’ or the immaculate womb, as represented by Mary, Mother of Jesus, or even the archaic mother idea of the earth itself (Raitt, 1980) being a womb; us it’s children- making us contemplate the damage of consumerism to the earth.

Mitchell’s installation engages with Kristeva’s concept of the abject:

“Devotees of the abject... do not cease looking... for the desirable and terrifying, nourishing and murderous, fascinating and abject inside of the maternal body” (Kristeva, 1980)

The plush, tactile nature of the space celebrates femininity’s softness while overwhelming and soothing the senses. Engaging with this structure symbolises embracing or being embraced by the feminine, feeding the 'hungry' interpretation of the vagina dentata.

Cybele Cox - ‘She-Devil’

Cybele Cox’s She-Devil (Cox, 2017) performance explores the monstrous feminine, blending allure and intimidation through animalistic movements that evoke attraction and aggression. These erratic gestures, reminiscent of bird mating rituals, reflect an animalistic, unsettling form of femininity, inviting reflection on sexuality, power, and connection.

Cox’s use of masks and ceremonial attire draws from ancient rituals, allowing her to embody a primal persona (Pollock, 1995). Phallic imagery in the nose and tail elements challenges traditional gender roles, while the stark contrast between white, often symbolising purity and virginity (Hart, 2020), and the deep reds and browns, reminiscent of blood and dirt, adds to the piece’s haunting effect. This colour symbolism represents the tension between innocence and corruption, power and aggression.

She-Devil combines medieval symbolism, mask traditions, and the duality of the monstrous feminine, provoking thought on femininity, power, and transformation. Featured in the From the Other Side exhibition, the performance sparked discussions on contemporary identity and gender, including a talk by Barbara Creed.

Claudia Mindang – ‘The Masks; Akai Onryō, Lady Hagatha and Virelia Sees’

These masks are part of a series reimagining the archetypes, or "Faces," of the "monstrousfeminine" (Creed, 1993), challenging patriarchal constructs that label femininity as "monstrous." By exaggerating these traits, the masks compel viewers to confront and question ingrained biases. Like many ritual masks, these reclaim fearsome archetypes, reframing them as symbols of rebellion, beauty, and humour rather than fear or revulsion (Pollock, 1995). Gold highlights key features of these "faces," symbolising status and the resplendence hidden beneath the surface of the abject.

The Akai Onryō mask embodies the vengeful spirit archetype, drawing on the wrathful imagery of traditional Japanese oni masks with its blood-red, horned visage and golden tusks. Unlike conventional depictions that vilify such entities, this mask reframes rage as a form of justice, reclaiming the power often denied to women in patriarchal narratives, where vengeance is relegated to supernatural forces. This theme is prevalent in Japanese folklore through yokai like

Akai Onryō

Oiwa, Hannya, and Kuchisake-onna, (Tsuchiya, 2010). Also, it appears in European lore with figures such as the Furies and Spain's La Llorona. The mask’s mirthful, demonic grin and associations with blood confront abject fears of the feminine, insisting unapologetically on the recognition of fury and retribution.(Roberts, 2018)

Lady Hagatha

Lady Hagatha is an aged, grotesque figure with sagging skin, elongated ears, green stringy hair, and a macabre grin of golden teeth. Inspired by the hag archetype, traditionally tied to decay and death (Harrington, 2018), this mask reclaims the figure as a symbol of resilience, wisdom, and defiance of societal norms on ageing and beauty.

Blind with age, the mask also blinds its wearer, confronting the inevitable bodily changes of ageing, such as blindness or reduced mobility. Lady Hagatha’s exaggerated features reject pity, asserting her as a force of nature. Her golden eyelids, teeth, and green hair radiate vitality, contrasting her pallor and reshaping the fear of ageing into a celebration of strength and wisdom.

Virelia Sees

This mask presents a human face with four piercing gold eyes framed by dark, dripping lashes, merging beauty with unsettling multiplicity. Soft pink tones and red lips contrast sharply with the vivid gaze, blurring the line between allure and terror.

Reimagining the witch or seer archetype, the mask challenges the vilification of women possessing "forbidden" knowledge or sexual appetite (Goodare, 2005). The additional eyes symbolise hyperawareness and insight, traits often punished in women. They are also a habit developed by people who have been oppressed as a defence mechanism, hence why women are both feared for their insight and yet forced to remain hyper-vigilant. Virelia Sees reclaims omniscience as a source of power, not fear. Its unwavering ‘female’ gaze compels viewers to confront their discomfort with unapologetically empowered femininity (Bowers, 1990).

Misha Kaznacheyeva - ‘Lamentation’

I am honoured to feature Lamentation, a song by my close friend Misha Kaznacheyeva. It was written in tribute to her late grandmother, Nadezhda Kaznacheyeva, who endured hardship in post-Soviet Belarus. The song tells the story of a woman who worked herself to death for her family, embodying the struggles of women who bear immense burdens while their own needs go unmet.

The song explores themes of sacrifice, loss, and women's often-unheard stories. Just as Nadezhda prayed and provided for her family, listening to this song becomes a shared act of remembrance and reverence, a prayer from Kaznacheyeva to their grandmother that transcends time and space. This connection between past and present resonates with the exhibition’s central themes.

The solemn tones of Lamentation (Kaznacheyeva, 2023) mirror the reflective nature of church hymns, expressing grief, hope, and resilience. In this context, the song becomes a secular hymn, reframing devotion and suffering through a feminist lens. It aligns with the exhibition’s exploration of women's monstrous experience, transforming stories of sacrifice into powerful statements of resilience and the enduring strength of women’s voices.

Chapter 3: Significant ideas about curation

Curatorial context

In line with the analysis of 'the archaic mother' (Creed,1993) encompassing contradictory ideas of 'the abyss' and dark, empty spaces, as well as the womb and cavernous, textured interiors, I selected Arbroath Abbey as the focal site. This derelict religious structure, with its corridors and open hall spaces, facilitates transitions between these contrasting environments. Christianity itself epitomises the mythology that teaches us themes of worship, divinity, humanity's desire for a higher power, and notions of loss, death, and the distant past. (Jung et al., 1989)

The Abbey’s beautiful red sandstone bricks, sourced from nearby quarries, evoke flesh-like imagery, aligning with its metaphorical representation of churches as a ‘body’ (Hammond, 1962). These bricks also draw modern associations between the colour pink and femininity. Following the Reformation, the Abbey’s decline saw its materials repurposed for other buildings in Arbroath, such as a church constructed in the 1580s (Burnet and Scot, 2024). This history of transformation reassures me that using the Abbey in this contemporary and symbolic way honours its past, paying tribute to women and other groups once excluded from its walls.

The Church has historically solidified the concept of the monstrous feminine through its demonisation of women who wielded power, knowledge, or independence. Women who defied patriarchal expectations of meekness and submission, especially unmarried, argumentative or older women. Joseph Campbell (1973) describes in The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology that women’s capacity to create life was regarded as magical and mysterious, linking femininity to the supernatural and perpetuating fears of women as witches

This demonisation aligns with broader efforts to regulate and suppress women’s bodies. The Virgin Mary, a symbol of unattainable purity, embodies an ideal imposed on women, while those who deviate from this are less valued. (Raitt, 1980)

The exhibition begins at the Abbey’s Gatehouse, its striking entrance symbolically akin to entering a human body. It moves through the main structure, culminating at the presbytery and choir, once the most sacred focal point of the Abbey where the priest led mass (Hammond, 1962). This exhibition invites visitors to congregate in a new kind of ‘mass,’ celebrating the impure, imperfect, and unholy.

Audience

This exhibition invites a diverse audience, from those deeply engaged with feminist art and representation to individuals without formal art education. Addressing marginalised histories and identities encourages introspection and challenges visitors to explore themes of erasure and transformation within a striking historical setting.

For some, the exhibition may hold the allure of a feminist art pilgrimage. Like visiting sacred sites, these individuals are drawn to the opportunity to experience works by internationally celebrated artists such as Niki de Saint Phalle and Louise Bourgeois. Their pieces, steeped in themes of creation, destruction, and the complexities of womanhood, echo the transformative power often associated with religious or spiritual spaces. Hosting this exhibition within Arbroath Abbey, a historic symbol of Scottish identity and faith, adds a layer of meaning, connecting the contemporary exploration of feminist art to the Abbey’s enduring role as a site of reflection and cultural significance.

At the same time, the exhibition also appeals to the local Arbroath community, who may be curious about the latest transformation of their town’s landmark. As an important historical and cultural site, the Abbey’s repurposing as a venue for provocative and globally relevant art offers a new way for residents to engage with its legacy. This dialogue between the past and the present fosters a sense of pride while introducing challenging and contemporary themes to a familiar space. (Mike Christenson, 2011)

The exhibition’s inclusivity extends to a broad spectrum of visitors, including those who might feel discomfort with its focus on the monstrous feminine or question the role of radical progressive spaces. Inviting them to partake offers an opportunity to experience the unsettling feelings that marginalised groups often face in spaces not designed with them in mind. This deliberate invitation to confront discomfort fosters empathy and deeper reflection.

Whether drawn by a personal connection to feminist discourse, the allure of internationally renowned works, or the Abbey’s historical significance, visitors will encounter an experience that transcends traditional boundaries, uniting themes of history, identity, and transformation in a space as monumental as the art it houses.

Exhibition Layout

This exhibition is organised thematically to evoke distinct emotional atmospheres in each section, guiding visitors through a rich and immersive experience. While a chronological layout was initially considered to trace the evolution of the monstrous feminine, from early male depictions to contemporary female self-representation, the stark contrasts between these periods felt visually and emotionally jarring. Instead, a thematic structure was adopted, prioritising visual cohesion and interpretive depth.

In the main body of the Abbey, mask sculptures (Mindang, 2024) will be mounted on 1.5-metertall bronze spikes, evoking imagery of medieval punishment and the stakes associated with witch trials. These impactful installations will act as pivotal markers, defining transitions between sections. Each mask’s placement will be intentional, aligned with the archetype it represents, guiding viewers on a symbolic journey through shifting depictions of feminine power from the monstrous to the romantic.

At the entrance, the open-ceilinged gatehouse features Allyson Mitchell’s The Hungry Purse (2014-2024), with its crocheted vulva opening positioned within the gatehouse entry as you approach the abbey from the southwest. This transforms the gatehouse into a metaphorical entry into the feminised body of the Abbey. Visitors are encouraged to gather here, adjusting to

the exhibition’s provocative themes in an environment designed for comfort and introspection. This reflective space fosters patience and openness, inviting visitors to approach the works thoughtfully. The Abbey’s solemnity and historical weight amplify this contemplative atmosphere, deepening connections to the artworks and their themes.

To ensure smooth flow, an additional exit at the rear of the installation will be commissioned. This exit leads out through the left gatehouse archway, allowing visitors to continue their journey while maintaining the immersive experience seamlessly.

Along the pathway beside the long guesthouse wall, six speakers, three on either side, will play Lamentation (Kaznacheyeva, 2023) on a continuous loop as visitors pass through the western gable into the more extensive section of the exhibition. The song reverberates through the space, enveloping visitors in a poignant soundscape. Much like church music fosters contemplation and reverence, Lamentation transforms the Abbey’s sacred architecture into a site for reflection.

Continuing through this section, visitors encounter remnants of what was once an imposing stained-glass window (Burnet and Scot, 2024). As they approach the western entrance, they are confronted with the crumbling lower arch of a circular frame. These ruins serve as a powerful metaphor: just as the Abbey’s walls hold centuries of stories, Kaznacheyeva’s song gives voice to the silenced narratives of women.

After passing through the musical space at the west entrance, visitors enter the open ruins of the Abbey (Fig. 12). Without ceilings, the structure consists of a few surviving walls. To the east, a wall with seven tall, arched windows runs along the length of the Nave, up to the Tomb of William I. Leading up to the tomb, there were originally nine pillars along each side of the Abbey, but now only remnants remain (Burnet and Scot, 2024)

These heptagonal, plinth-like structures resemble miniature stages. The west side of the Abbey has entirely disappeared, exposing the left side to an expansive graveyard.

These remnants will serve as the performance space for She-Devil by Cybele Cox, a work previously staged by Legs 11 11 in 2017 and 2023 (Cox, 2014). As the performance unfolds, Legs 11 11 will navigate through the audience, using the plinths as dynamic movement and dance platforms. The space will transform into an arena, either sparking a sense of spectacle and celebration or an unsettling tension of conflict and competition. While Lamentation may still be audible in the background, the music from the 2023 performance, Anarchy in the UK by The Sex Pistols, will be played through four speakers strategically positioned around the ‘arena’: one at the base of a plinth on its outskirts. This inclusion preserves the lively, rebellious energy of

the original rock-infused atmosphere. The potential overlap of these two songs creates a dissonant, multifaceted soundscape, deepening the complexity of the experience.

Looming beyond this performance setting, placed next to it. Akai Onryō (Mindang, 2024) separates it from other exhibition segments, acting as a boundary marker. Akai Onryō (Mindang, 2024) is linked to traditional Japanese folklore, representing malevolent spirits and demons. Placing this mask in proximity to She-Devil (Cox, 2017) intensifies the idea of feminine monstrosity as something that exists at the boundary between the sacred and the profane, emphasising the hybridisation of cultures and the fearsome power of the ‘demonic’ feminine.

Straddling the largest four pillar remains and encircling the tomb of William I, Maman (Bourgeois,1999), with its towering spider form, embodies a complex interplay of maternal strength, protection, and danger. Positioned above the tomb, the sculpture evokes themes of life, death, and the sublime of the feminine, as this maternal force oversees and dominates the patriarchal resting place - and, due to its immense size, the entire surrounding structure.

Facing Maman stands Lady Hagatha (Mindang, 2024), positioned beside Hokusai’s Laughing Demoness (1831) print. This deliberate arrangement accentuates the contrast between motherhood's nurturing, protective qualities and the darker, destructive forces often associated with older female figures in folklore. The hag, embodying age, wisdom, and malice, challenges

the maternal figure's authority (Harrington, 2018) within the traditionally patriarchal space of the royal tomb. This creates a provocative dialogue on maternal authority, spanning life’s beginnings and exploring the enduring associations between femininity and death.

The sacristy, one of the abbey's best-preserved structures, historically known as "Jenny Batter's Hole," reflects the cruelty and suppression of vulnerable individuals. Its name recalls a woman once confined here as a "lunatic" (Jooste, 2024), embodying themes of societal control. This history echoes the myth of Medusa, a monstrous feminine figure punished after enduring sexual violence.(Bowers, 1990)

The Head of Medusa (Rubens, 1618), suspended by two chords over the sacristy’s locked door, explores themes of containment, punishment, and the suppression of women's autonomy. It symbolises the plight of misunderstood, mistreated, and ostracised women. Reclaimed, the sacristy transforms into a space honouring these suppressed feelings, reflecting society’s rejection of women who defied norms and were met with cruelty instead of compassion.

With its four eyes, the Virelia Sees (Mindang, 2024) marks the exhibition’s conclusion, symbolising the ‘female gaze’ and the journey's final destination. This mask evokes a supernatural or transcendent vision, connecting to female monstrosity, knowledge, learning, and love themes. Positioned in the presbytery, (Fig. 15) traditionally a sacred space, L’Oiseau

Amoureux is a counterpoint to the more threatening masks and sculptures. Representing romance and liberated femininity, it parallels the brightness of the first installation, The Hungry Purse, at the start of the exhibition, contrasting with the monstrous, dangerous archetypes explored in between.

This creates an ‘alter’ at a pivotal point in the Abbey, encapsulating the feminine. It represents the exhibition’s ultimate goal: to celebrate and explore how these themes positively resonate in

the collective unconscious and manifest in art. After this, Visitors are welcome to explore the grounds as they please.

Chapter 4: Other influences and sources

The Author’s Studio Practice

The concept of the "monstrous feminine" and broader horror themes are central to my practice. I aim to create artwork that embraces grotesque and otherworldly forms by visually disrupting traditional notions of beauty and femininity.

Like many queer individuals or those who have experienced anxiety and depression, I find that confronting otherness can be incredibly liberating. Exposing these identity conflicts through visual media, which others can process, even if they don’t fully understand or enjoy, helps me bridge the gap between my inner world and the people and places around me. Horror and surrealism often seek to destabilise rigid boundaries and normative categories (Bantinaki, 2024), and the artworks I create, and those I deeply enjoy from other artists, embody this sense of destabilisation.

Discomfort, negativity, rage, sadness, and hopelessness are among some aspects of the human psyche. I often include abstracted body imagery, merging of human and non-human characteristics, distorted skin, and detailed facial adornments, which can be read as embracing nonconformity in gender, identity, and self-expression. I rely on heavy, textured layers and black, red and pink to suggest internalised and externalised horrors, bringing conflicting ideas and narratives to collide.

Exhibitions of influence

‘From the Other Side’

Hosted at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne, Australia. This exhibit was held from the 9th of December, 2023, until the 3rd of March, 2024. Included in this exhibition was Cybele Cox’s The Hag (2023) sculpture, amongst eighteen other artists, which depicted femininity in liminal, unsettling ways. Guest Speaker at this exhibition was Professor Barbara Creed herself, who talked about women directors and the feminist horror film resurgence.

‘Tremble Tremble’ - Jesse Jones

Hosted at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Bilbao, Spain. This exhibit featured musical and visual artworks and significant items from October 31, 2019, to March 1, 2020. Jesse Jones was a guest speaker for the University’s Contemporary Art Practice (CAP) Speaker’s programme on the 20th of November 2024, where she told the story of how she collaborated with friends, prioritising community in her creative process. Tremble Tremble (Jones, 2019-2020) was explained to us as a reimagining of history, wherein the magical and supernatural exist in tandem with liberated women one wherein capitalism and patriarchy never took hold.

‘The Yorkshire Sculpture Park’

This permanent exhibition is held in an 18th-century park in Wakefield, Yorkshire, and is open to the public year-round. Visitors explore the expansive grounds, which feature ninety sculptures from various internationally acclaimed artists. The grounds are home to Nikki de Saint Phalle’s Buddha

sculpture (2000) and Leika Ikemura’s Usagi Kannon II sculpture (2013-2018), which particularly inspired my investigation into sculptures that serve as shelters or furniture to a certain extent. Buddha (Saint Phalle, 2000) has an alcove in the back of this meditative figure, which visitors can sit in, and Usagi Kannon II (Ikemura, 2013-2018) depicts a rabbit ‘Madonna’ figure with a skirt that forms a dome shelter. On my visit to this sculpture park in 2018, I was able to experience the yearlong installation of Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads (2010), with 10-foot-tall bronze animal heads mounted on spikes, which greatly inspired my own work.

Conclusion

At the atmospheric ruins of Arbroath Abbey, the art exhibition Her Many Resurrections investigates the changing faces of the grotesque or monstrous feminine. Based on my research about the overlapping worlds of femininity and horror, the curated works of Allyson Mitchell, Peter Paul Rubens, Katsushika Hokusai, Cybele Cox, Louise Bourgeois, Nikki de Saint Phalle, and my mask sculptures speak to how archetypes of feminine monstrosity have slowly evolved alongside internationally changing views on women’s rights and roles in society. The Head of Medusa (Rubens, 1618) grounds the historical exhibition, demonstrating classical myth's indicative demonisation of strong women. Medusa's metamorphosis into a monster symbolises the patriarchal dread of female autonomy and desirability. Such a narrative is echoed in The Laughing Demoness (Hokusai, 1831), which presents a venerated Buddhist deity embedded in fear and monstrous motherhood. These works show that worries about women's rage and autonomy are not limited by cultural borders.

Contemporary points of view arise in The Hungry Purse (Mitchell, 2014-24) and She-Devil (Cox, 2017) performance. Mitchell calls out consumerism's commodifying effect on women's bodies, and Cox's outsized, grotesque performance undermines normative femininity. These works reclaim the monstrous feminine and comical interpretations of the female form in more conscious ways to build community and promote uplifting conversations in the systems of power that reproduce its imagery.

Maman (Bourgeois,1999) and L'oiseau Amoureux (Saint Phalle, 1990/1992) take this further, investigating the monstrous feminine through motherhood, creation, and love. Bourgeois's

monumental spider, sublime and threatening yet a symbol of reverence, challenges the sacrosanct conception of maternal care, putting viewers' complicated feelings around the maternal figure on blast. By contrast, Saint Phalle's joyful sculpture enacts renewal, suggesting reconciliation is possible even inside the monstrous.

My mask sculptures aim to punctuate these conversations, reanimating archetypes from Creed's work: the ‘femme castratrice’, the ‘archaic mother’, and the woman as Vampire and Witch (1993). These masks connect historical and contemporary interpretations of monstrosity through abstract and idiosyncratic expressions. Set in the atmospheric ruins of Arbroath Abbey, they heighten the dialogue between history, space and our expectations of femininity. The location of Arbroath Abbey deepens the exhibition's message. As a location of both religious celebration and ruin, it speaks to themes of transformation and resurrection that are fundamental to the monstrous feminine. The remnants of the Abbey's architecture, shown alongside the artworks, deepen the conversation between the respected and the reviled, the past and the present. Her Many Resurrections invites consideration of the monstrous feminine's durable power and adaptability.

Creed's theories, backed by other feminist and progressive interpretations, show how these archetypes have been used to enforce women's behaviour and keep patriarchal norms in check. At the same time, they pinpoint their potential as tools for feminist critique and power. The varied works, eclectic in their origins, periods, and modes, echo the ubiquity of these archetypes throughout generations and cultures. Embracing the other, the unconventional and weird, hopefully, underscores the importance of visibility and acceptance, especially when addressing groups that have been systematically oppressed.

Appendix 1

Full Exhibition Programme

This was made using Procreate. It laid out the pieces that would be exhibited, a map of the exhibition, and an events programme.

‘Lamentation’

by

Misha

Kaznacheyeva:

Lyrics and More Information

Here is some elaboration on the song featured in the exhibition and a brief explanation of its impact on me as a way to applaud the talent of my friend and appreciate their work. I have permission to include this song.

QR Code to Access ‘Lamentation’ (Kaznacheyeva,2023) on SoundCloud ‘A couple of years have passed, though time doesn't mean a thing to her, ceasing.

I bet you'd hardly even understand.

The God of yours destroyed the tower for a reason.

Pack your lunch, keep on breathing and sing until you're saved.

Bring something to feed the swans, their bones will soak in peroxide.

Who will write a story about a tired girl?

About the woman who gave up her life to God and evening prayer.’

Misha Kaznacheyva’s grandmother, Nadezhda, profoundly religious and devoted to prayer, never learned English or had the opportunity to travel due to poverty. The song’s reference to the Tower of Babel highlights the poignancy of her isolation: even if she could hear this tribute, she would not understand it. Despite her many struggles, including caring for an alcoholic husband, Nadezhda maintained unwavering faith. Like many, she found solace in the church and prayed for her family to manifest goodwill as an extension of her love and dedication to them.

The title Lamentation draws inspiration from the biblical Book of Lamentations, a text steeped in mourning and reflection. By framing the song as a secular psalm, Misha connects the cathartic traditions of church laments to the deeply personal themes of this exhibition. Misha fondly recalls that despite severely chapping and sore hands from working, Nadezhda often made paper swans with them, fostering Misha’s formative love for crafts and bringing them to the park to feed swans. This association is punctuated by the title ‘Lamentation’, also the name for a flock of swans.

As well as this, it was vital for me to include this piece in my proposed exhibition because I was inspired by the lecture from Jesse Jones with the University’s CAP Speakers Programme, where she underscored the importance of collaboration with friends and peers when putting together an impactful exhibition. Not only does this song bring me to tears when I listen to it, knowing my friend’s feelings of loss and mourning their late Grandmother, but it also mirrors the stories of countless women that I recognise from my own family. I feel many can identify these feelings concerning their own lives.

Community, sharing experiences, and art are forms of spiritual practice. I felt that, especially given the exhibition's feminist and mystical undertones, sharing this song with potential audiences would be healing and empowering.

Available at: Soundcloud (Accessed: 19 December 2024)

‘Terfs’ and Respectability Politics

The rise of "Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists" (TERFs), a term applied to those who exclude trans women from their advocacy or actively position transness as a barrier to women’s liberation (Doyle, 2022), further reveals the divisions within movements that profess equality. These divisions reflect broader societal power structures, showing that not all marginalised groups are treated equally within feminist or progressive spaces.(Veldhuis et al., 2018)

Respectability politics, a term introduced by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham in Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920, is critical in perpetuating inequality. It refers to the judgment of marginalised groups based on their adherence to mainstream norms rather than addressing systemic issues like racism, sexism, and ableism. This focus on individual behaviour implies that inequality results from personal shortcomings rather than structural injustice (Jones, 2021). Those deemed "unrespectable" include the poor, visibly queer, or those whose identities exist at multiple intersections of marginalisation.

These individuals are often viewed as "too much" and expected to minimise their differences to align with a patriarchal ideal: non-disabled, cisgender, and white. This results in the false belief that overcoming personal deficiencies will allow marginalised groups to succeed within capitalist frameworks rather than challenging the systems perpetuating inequality. As Harris (2014) notes, "Respectability politics can have the effect of steering 'unrespectables' away from making demands on the state to intervene on their

behalf and toward self-correction and the false belief that the market economy alone will lift them out of their plight."

Subcultures have long resisted societal standards, fostering movements that challenge traditional notions of respectability and prioritise freedom of expression and inclusivity. These spaces often attract marginalised groups, including queer individuals, who are drawn to horror and dark themes through subcultures like Goth, Punk, Emo, and Scene (Searle, 2023). These movements embrace disorder and darkness, defying societal expectations and reflecting human and natural complexities.

Appendix 2

Names and other information about those accused of Witchcraft in Arbroath

All of this information was found through the interactive map available at

https://witches.is.ed.ac.uk/, visualising the data from ‘The Survey Of Scottish Witchcraft’, an online database recording the period from 1563 until 1736, when ‘The Scottish Witchcraft Act’ was repealed. This data was made available online in 2003 through the University of Edinburgh and the work of Professor Julian Goodare.

Jonet Gardyn

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Jonet Barroman

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Bessye Brodye

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Bessie Lamb

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Maldye Sturrok

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Agnes Peramorris

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Elizabeth Hunter

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Social Class: middling

Residence: Arbroath

Agnes Fergusson

Investigation Date: 01/01/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Dame Logye

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Geilis Feirour

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Agnes Gordoun

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Gelis Durye

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Bessie Ramsay

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Issobell Robertsoun

Investigation Date: 01/04/1568

Sex: Female

Residence: Arbroath

Exhibition models and layout plans

Initially, I made a model with cardboard, air-dry clay and acrylic to visually map out Arbroath Abbey and which areas suited the artworks displayed. This model is not to scale, and I later re-arranged the artwork to fit the space better. This model was useful for conceptualising colours and aesthetic harmonies and familiarising myself with this unconventional exhibition space.

I was unsatisfied that this model effectively represented the dimensions and proportions of the space. Given that I selected Arbroath Abbey as the venue for this exhibition, which is a

historic landmark, it plays a crucial role in shaping the atmospheric and environmental context for the display.

I aimed to offer readers an authentic representation of the building and its diverse artworks. However, the Abbey's ruins lack recorded wall heights and scales, likely due to the structure's susceptibility to damage and ongoing deterioration in certain areas. To estimate the size of each piece within the space as accurately as possible, I utilized photographs from my visit and documented the dimensions of the artworks along with the floor plan of the Abbey ruins.

I used cardboard boxes, cutting them to represent smaller areas where I could more easily deduce the height based on the information I had. I created proportionately sized models of the artworks and, using Procreate, recontextualised the photos of these models by adding more extensive architectural features of the Abbey to create a more accurate illustration of each section of the exhibition.

Reference List

(Website hyperlinks appear as blue underlined words)

Alexandre, L. (2024) The Feminist to Far-Right Pipeline, www.youtube.com. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Bantinaki, K. (2024) ‘The Paradox of Horror: Fear as a Positive Emotion on JSTOR’, Jstor.org [Preprint]. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Beard, M. (2017) Women in Power, London Review of Books. Link available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Bowers, S. (1990) ‘Medusa and the Female Gaze’, NWSA Journal, 2(2), pp. 217–235. Link available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Brown, M. (2006) ‘The Declaration of Arbroath: History, Significance, Setting (review)’, The Scottish Historical Review, 85(1), pp. 145–146. Link available here.

Burnet, A. and Scot, N. (2024) Arbroath Abbey. Historic Scotland Alba Aosmhor.

Cain, A. (2018) What Depictions of Medusa Say about the Way Society Views Powerful Women, Artsy. Link available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Campbell, J. (1973) The masks of God. 1. London: Souvenir Press.

Carl, K.H. and Charles, V. (2009) Baroque Art, Google Books. Parkstone International. Link available here. (Accessed: 5 January 2025).

Church, D. (2021) Post-Horror, Google Books. Edinburgh University Press. Link available here. (Accessed: 5 December 2024).

Cotterell, A. (1997) A Dictionary of World Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cox, Cybele (2014) Performances, Cybele Cox. Link available here. (Accessed: 21 December 2024).

Creed, B. (1993) The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

Dadoun, R. (1979) ‘Fetishism and the Horror Film’, Fantasy and the Cinema, 1(2), pp. 39–63.

Doyle, J.E.S. (2022) StackPath, xtramagazine.com. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Erin Jean Harrington (2018) Women, monstrosity and horror film : Gynaehorror. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, Ny: Routledge, An Imprint Of The Taylor & Francis Group.

Gibson, S. (2013) The Spider: Encounters with the Dark Feminine, Sandplay Therapists of America. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Goodare, J. (2005) ‘The Scottish Witchcraft Act’, Church History, 74(1), pp. 39–67. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Gottesman, S. (2016) A Brief History of Blue, Artsy. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Gresseth, G.K. (1970) ‘The Homeric Sirens’, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 101, p. 203/218. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Hammond, P. (1962) Towards a Church Architecture. Architectural Press.

Harris, F.C. (2014) ‘The Rise of Respectability Politics’, Dissent, 61(1), pp. 33–37. Link available here.

Hart, I. (2020) Hidden Symbols, Cent Magazine. Link available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Hogan, D.J. (1997) Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. McFarland & Co.

Housten, R.A. (2000) Madness and Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland, Google Books. Clarendon Press. Link available here. (Accessed: 21 December 2024).

Howell, A. and Baker, L. (2022) ‘Introduction: The Monstrous-Feminine Protagonist in Twenty-First-Century Screen Cultures’, Monstrous Possibilities, pp. 1–23. Link available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Janetta Rebold Benton (2021) How to Understand Art. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Jones, P.E. (2021) ‘Respectability Politics and Straight Support for LGB Rights’, Political Research Quarterly, Volume 75, issue 4, Link available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Jooste, P. (2024) Arbroath Abbey & Mary, Queen of Scots, Marie-stuart.co.uk. Link available here. (Accessed: 14 December 2024).

Jung, C. (1936) The Concept of the Collective Unconscious. Link to PDF document here.

(Accessed: 23 December 2024).

Jung, C.G., Jaffé, A., Winston, C. and Winston, R. (1989) Memories, dreams, reflections. New York: Vintage Books, A Division Of Random House, Inc.

Kaznacheyeva, M. (2023) Lamentation (jazzschool Exam ver.), SoundCloud. Link available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Kristeva, J. (1980) Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lawson, R. (2019) witches, witches.is.ed.ac.uk. The University of Edinburgh. Link available here.(Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Lee, J., Marchiano, L. and Stewart, D. (2023) MEDUSA’S MANY FACES: the Evolution of a Myth – This Jungian Life, thisjungianlife.com. Link available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Liska, S. (2015) ‘Talking Back to White Feminism: An Intersectional Review’, Liberated Arts: a Journal for Undergraduate Research, 1(1). Link available here.(Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Mazza, G. (2008) Amphisbaena fuliginosa - Monaco Nature Encyclopedia, Monaco Nature Encyclopedia. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Mcevilley, T. (1992) Art & otherness : crisis in cultural identity. Kingston, NY: McPherson & Co.

McNaught, R. (2023) From the Other Side, ACCA. Link available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Meisler, H. (2023) Happy Pride. Don’t Be a TERF., National Women’s Law Center. Link available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Mike Christenson (2011) ‘Viewpoint: “From the Unknown to the Known”: Transitions in the Architectural Vernacular’, Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, 18(1), p. 1. Link available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Mitchell, A. (2014) Allyson Mitchell, allysonmitchell.com. Link available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Moss, L. (1988) ‘The Critique of the Female Stereotype in Greek Tragedy’, Soundings: an Interdisciplinary Journal, 71, pp. 515–532. Link available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Murray, J.K. (1981) ‘Representations of Hariti, the Mother of Demons, and the Theme of “Raising the Alms-Bowl” in Chinese Painting’, Artibus Asiae, 43(4), p. 253. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Nadeau, K. (2011) ‘Aswang and Other Kinds of Witches: a Comparative Analysis.’, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 39, pp. 250–266. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Niki de Saint Phalle - Sun God (2024) Ucsd.edu. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Pendle, G. (2024) Colors / Prussian Blue | George Pendle, Cabinetmagazine.org. Available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Pollock, D. (1995) ‘Masks and the Semiotics of Identity’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 1(3), p. 581. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Raitt, J. (1980) ‘The “Vagina Dentata” and the “Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis”’, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 48(3), pp. 415–431. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Riley, L. (2016) Niki De Saint Phalle: The Female Figure and Her Ambiguous Place in Art History. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Roberts, R. (2018) Subversive Spirits: The Female Spirits in British and American Popular Culture, Google Books. The University Press of Mississippi . Available here. (Accessed: 6 January 2025).

Robertson, T.S. (1908) ‘ARBROATH ABBEY’, Transactions of the Glasgow Archaeological Society, 5(3), pp. 234–240. Available here.(Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Smith, R. (2016) A Chameleonic Icon: Questioning the Underground Christian Identity of an Edo-period Amida Sculpture in the Nyoirin Kannon-dō, Kawaguchi City, Uoregon.edu. University of Oregon. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Solomon, G. (2000) ‘Two Stories About Evil: Christianity and the Creation of Witches’, The Western Ontario series in philosophy of science, 65, pp. 3–9. Available here.(Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Thomas, D. (2023) The Intricate Web: Exploring the Symbolic Connection Between Spiders and Older Women, Medium. Available here. (Accessed: 22 December 2024).

Tsuchiya, D.H. (2010) ‘“Shōjo” Spirits in Horror Manga’, U.S.Japan Women’s Journal, (38), pp. 59–80. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Veldhuis, C.B., Drabble, L., Riggle, E.D.B., Wootton, A.R. and Hughes, T.L. (2018) ‘“I Fear for My Safety, but Want to Show Bravery for Others”: Violence and Discrimination Concerns Among Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Individuals After the 2016 Presidential Election’, Violence and Gender, 5(1), pp. 26–36. Available here. (Accessed: 15 December 2024).

Woodman, M. (1998) Betwixt & Between, Google Books. Available here. (Accessed: 23 December 2024).

Zolotnikova, O. (2016) ‘A Hideous Monster or a Beautiful maiden?’, Philosopher Kings and Tragic Heroes: Essays on Images and Ideas from Western Greece. Edited by H. Reid and D. Tanasi, 1, pp. 353–370. Available here. (Accessed: 15 December 2024).

Supporting Research

A discussion of Head of Medusa by Rubens (2020) TripImprover - Get More out of Your Museum Visits! Available here. (Accessed: 15 December 2024).

Arbroath Abbey, Arbroath – Churches, Cathedrals & Abbeys (no date) www.visitscotland.com. Available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Books 'n' Cats (2024) Shirley Jackson and Daemonic Patriarchy, YouTube. Available here. (Accessed: 15 December 2024).

Briefel, A. (2005) ‘Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation, and Identification in the Horror Film’, Film Quarterly, 58(3), pp. 16–27. Available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Cox, C. (2014) She-devil Performance, Cybele Cox. Available here. (Accessed: 21 December 2024).

Croizat-Glazer, Y. (2020) Rethinking Halloween: Female Monsters and Why They Rule | a Women’s Thing, A WOMEN’S THING. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Definition of Respectability Politics | Dictionary.com (no date) www.dictionary.com.

Available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Final Girls Berlin Film Festival (2022) The Monstrous Feminine & Political Abjection, YouTube. Available here.

Gerakiti, E. (2022) Masterpiece Story: Maman by Louise Bourgeois, DailyArt Magazine. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Girl On Film (2023) Women in Horror: Exploring the Monstrous Feminine Theory, YouTube.

Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

History (no date) www.historicenvironment.scot. Available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Hodson, G., Earle, M. and Craig, M.A. (2022) ‘Privilege Lost: How Dominant Groups React to Shifts in Cultural Primacy and Power’, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(3), pp. 625–641. Available here.(Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Hultgren, N. (2013) ‘Queer Others in Victorian Gothic’, The Wilkie Collins Journal, 12.

Available here. (Accessed: 23 December 2024).

In Praise of Shadows (2019) ‘The Burning Times | The History of Witches Part 1’, YouTube. Available here. (Accessed: 23 December 2024).

L´oiseau Amoureux Fontaine (2021) Ekebergparken. Available here. (Accessed: 22 October 2024).

LeMoine, G. (2003) ‘Woman of the House: Gender, Architecture, and Ideology in Dorset Prehistory’, Arctic Anthropology, 40(1), pp. 121–138. Available here.

Mantha-Blythe, V. (2021) The Witch’s House, Uwaterloo.ca. University of Waterloo.

Available here. (Accessed: 5 January 2025).

Muñoz‐Puig, M. (2023) ‘Intersectional power struggles in feminist movements: An analysis of resistance and counter‐resistance to intersectionality’, Gender, Work & Organization, 31(3). Available here.

Natashamoura (2017) Maman by Louise Bourgeois, Women’n Art. Available here.

(Accessed: 21 October 2024).

NCAF (2021) ‘Meet You at The Sun God’, Niki Charitable Art Foundation. Available here. (Accessed: 19 December 2024).

Paper, J. (1990) ‘The Persistence of Female Dieties in Patriarchal China’, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 6, pp. 25–40. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Searle, A. (2023) Women in Revolt! review – orgasms, punk protests and one long scream, Theguardian.com. The Guardian. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Stanford (2015) ‘Stanford Student Studies the Monstrous Feminine in Medieval Literature’, YouTube. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Sutcliffe, J. (2021) Magic. London: Whitechapel Gallery ; Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2019) ‘Reformation’, Encyclopædia Britannica Available here. (Accessed: 15 December 2024).

The Laughing Demoness (Warai Hannya), from the series ‘One Hundred Ghost Tales (Hyaku monogatari)’ (1831) Art Institute of Chicago. Available here. (Accessed: 22 October 2024).

The Selfless Watcher (2021) The Monstrous Feminine, YouTube. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Topical Bible: Call to Lamentation (2025) Biblehub.com. Available here. (Accessed: 5 January 2025).

Willis, E. (1994) ‘Villains and Victims: “Sexual Correctness” and the Repression of Feminism’, Salmagundi, no.101/102, pp. 68–78. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Witches (no date) National Library of Scotland. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

Yhara zayd (2020) A Monstress Comes of Age: Horror & Girlhood, YouTube. Available here. (Accessed: 20 October 2024).