Chapter One - 19th Century Hysteria Through the Lens of Girlhood

The Historical Narrative of Hysteria

Johanna Braun introduces her novel Performing Hysteria (2020) by stating “We seem to be living in hysterical times” (Braun, 2020, pp. 11). Braun is stating here that hysteria is still a common word used in association with people in today’s culture. Hysteria is a buzzword phenomenon that has resurfaced to aid the description of a person reacting to a situation. However, the word has much different ancient roots, stemming from the Greek word hystera meaning ‘uterus’. In the times of the ancient Greek, it was suspected that a woman’s womb could move around her body to cause symptoms that made her uncontrollable, known as ‘the wandering womb’ (Faraone, 2011, pp.1). The Greek believed that menstruation and pregnancy made women physically and mentally weaker than men through the symptoms that the wandering womb caused.

When exploring the connection between girlhood and hysteria, it is important to discuss the historical narratives that reveal how societal expectations have shaped the experiences of adolescent girls. In the late 1800s, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot founded the neurology clinic at La Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, where he began to study the psychological symptoms that were predominant in hysterical women. It was Charcot’s medical practice that reconstructed hysteria, where girls were romanticised by male representatives and placed on a pedestal that based their worth on a combination of beauty and madness. Iona Gilburt compares the parallels of beauty and madness in her text The Phototextual Emergence of Hysteria (2020) stating the girl’s symptoms:

…frequently included excessive laughing or crying, wild bodily movements, paralysis, numbness, or temporary deafness and blindness’, hyper-sensitivity to touch, fainting spells, as well as ‘a predilection for drama and deception’. (Gilburt, 2020 and Wickens, 2014 as cited in Gilburt, 2020, pp. 130).

Here Gilburt is suggesting that although the women displayed typically unattractive symptoms of illness, these were overlooked due to their appearance. The stereotypes of hysteria were tied to adolescence as expectations in society placed pressure on young girls to conform to idealized versions of femininity. During this time, the transition from childhood to womanhood was marked as a pivotal point in their lives. The typical lifestyle of a woman would be to care for their home and children whilst living in the shadow of their husband, which created feelings of isolation and depression. Fiona Handyside validates this argument stating that:

Women’s high rate of mental disorder is a product of their social situation, both their confining roles as daughters, wives, and mothers and their mistreatment by maledominated and possibly misogynistic psychiatric profession (Handyside, 1985, pp. 3).

As a result of this, many girls found themselves trapped in a system that stripped them of their identity, their emotional responses being deemed as unnatural and signs of mental instability. The phenomenon of hysterical girlhood invites us to reconsider how we view female adolescence, not as a transitional phase, but as a complex stage of selfdiscovery.

Despite isolation being a cause of hysteria, those suffering were often prescribed ‘the rest cure’ as a treatment for the disorder. This typically meant confinement from all social and domestic environments, in hope that they would return to their normal state. Charlotte

Perkins Gilman’s semi-autobiographical short story The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) is an insightful example of the mental affects the rest cure had on a patient. Gilman wrote The Yellow Wallpaper after her own diagnosis with hysteria, using the protagonist not only as a representation of herself, but of the girls also suffering. Vivian Delchamps breaks down the narrative of The Yellow Wallpaper in her essay ‘A Slight Hysterical Tendency’:

Performing Diagnosis in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ (Delchamps, 2019, as cited in Braun, 2020), by considering Gilman’s own experiences as a hysteric.

After self-diagnosing with hysteria, the protagonist becomes unsatisfied with the treatment plan made by her husband, much like how Gilman felt in denial when she received her diagnosis from Dr Silas Weir Mitchell. The protagonist states that “John [her husband] does not know how much I really suffer. He knows there is no reason to suffer, and that satisfies him”(Gilman, 1892, pp. 4). Here Gilman is highlighting that her husband did not understand that isolation may be a cause of the depression prominent in hysterical patients. Delchamps writes that the narrators “…first person account articulates the complexity of disorder…” (Delchamps, 2019, as cited in Braun, 2020, pp. 107). When comparing the protagonist’s experience to Gilman’s, Delchamps makes it clear that Gilman’s personal treatment plan “…illuminates the damaging quality of the ideologies of cure” (Delchamps, 2019, as cited in Braun, 2020, pp. 111), showing that the rest cure simply allowed men authorship over a woman’s life as they did not view hysteria as a mental illness.

Tony Robert Fleury’s ‘Phillippe Pinel freeing the insane from their chains’ (1886)

Feminist literary critic Elaine Showalter examines the portrayal of the hysterical girl in her novel The Female Malady (1985). Showalter states that there is a double representation of the insane woman. Madness is shown “…as one of the wrongs of a woman…” but also “…the essential feminine nature…” (Showalter, 1985, pg.3). Here Showalter is examining hysteria as both a flaw in the feminine figure and a necessary part of their being through the male lens.

Showalter’s theory can be backed up by looking at the ways in which mental illness was romanticised in paintings such as Philippe Pinel Freeing the Insane from their Chains (Fleury, 1886). There was an underlying sexual interpretation to the feminisation of madness, with artists “playing down unpleasant details” to “accentuate aesthetic qualities” (Smart, 1992, pp. 121). Mary Ann Smart’s analysis of Phillippe Pinel Freeing the Insane from their chains places the central woman as a sexual object (see figure 1.1). The painting shows a woman dressed in a white gown, a common factor in paintings representing hysteria as a suggestion that her figure and body position is to obtain male desire. The central figure outreaches her arm as she stares at the viewer with a transcendent gaze. Showalter discusses the objectification of this woman, and how she is portrayed like a doll. It looks as though she is wound-up like a toy by the man trying to unchain her, like he is bringing her back to life and sanity. This shows the “complex tension with male control” (Showalter, 1985, pp. 3). The composition portrays the split between sanity and insanity, with women sprawled in various positions across the right, looking manic and dishevelled in comparison to the well-dressed men on the left. Smart describes the painting’s composition as allowing the male viewer to see woman as a

pornographic possession, which is done by using what is known as ‘the gaze’ in feminist film theory (Smart, 1992). However, Smart argues that the ways in which hysteria is represented in the painting makes it “…essential for viewers of either sex to avoid identification, to remain outside the madness, as observers and consumers.” (Smart,1992, pp. 121). Smart is saying that the viewer must stay as an out looker rather than involve themselves in the chaos.

Fig 1.1, Phillipe Pinel Freeing the Insane from their Chains (Fleury, 1886), image courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

Augustine as a Representation of Girlhood Hysteria

One of Charcot’s methods of understanding hysteria involved photography, as he believed it could be used as physical evidence to prove that hysteria was of the mind. Ullrich Baer describes this as Charcot’s attempt “… to demonstrate the split between seeing and knowing” (Baer, 2002, pp.14). The mainstream emergence of photographic hysteria came from the publication of Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière

(Bourneville, 1876), which contained images taken by medical intern Paul Regnard of Charcot’s patients. Louise Augustine Gleizes is crucial to discuss in context of the collaboration of girlhood and hysteria, who was admitted to the Salpêtrière aged fourteen. Augustine was known for manic outbursts but also her appearance. Known as “the dark-haired beauty” (Gilburt, 2020, pg. 138), she became a central character in Charcot’s lectures, where she was turned into a trope where viewers were invited to watch her episodes first hand from an audience.

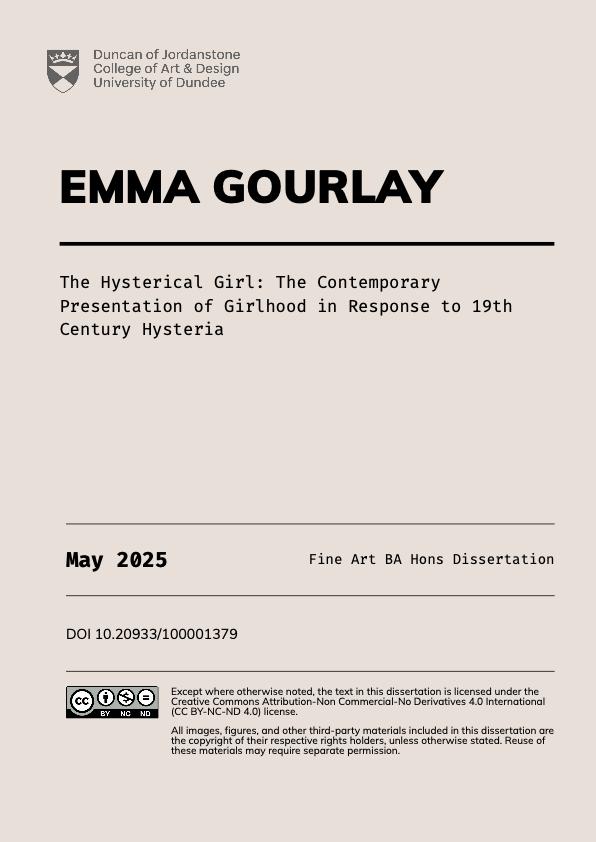

The image of Augustine in her normal state, as presented in volume two of Iconographie

Photographique de la Salpêtrière (Bourneville, 1878, pp. 128), shows a well-presented young woman (see figure 1.2). Her posture is casual and confident, with her arm propped up on the chair resting against her face as she looks directly at the camera with a normal gaze. Her physical appearance is cared for, her collar and jewellery adjusted so that she is neat, with “the ribbon around her neck [extending] the covering of her body” (Gilburt, 2020, pp. 136) showing self-respect and modesty. Regnard’s photographic technique has made it that all highlights and shadows have been eliminated from the image which gives her a graceful, soft appearance (Gilburt, 2020).

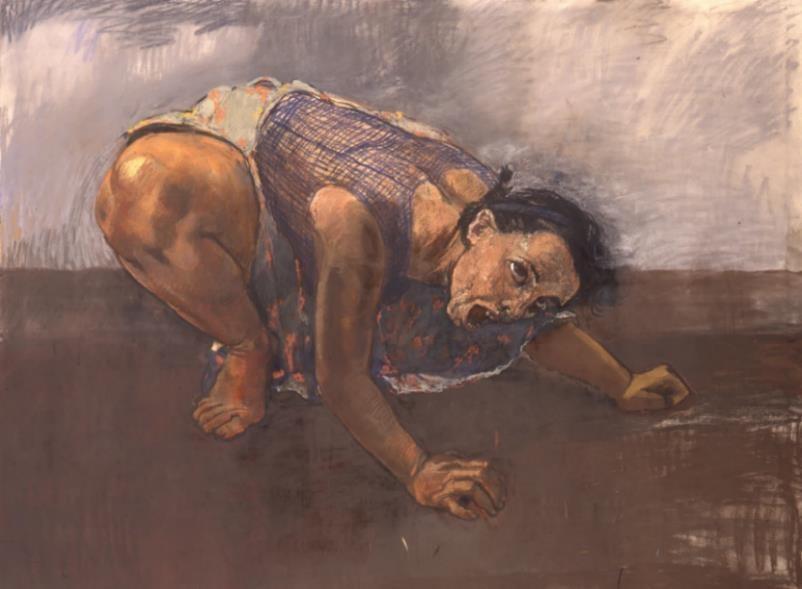

On the other hand, Augustine in her hysterical state appears to be restless and manic (see figure 1.3). She is sat up in bed, draped in white sheets which appear luminous in the flash of the image. Her skin is the same glowing white as her bedding, making her look pale and ghastly. Her arm is twisted round, her fingers clenched into a fist reaching downwards. Her gaze, although still looking directly at the camera, is different. She tilts her head downwards, the image making it look as though her eyebrows are darker and closer together. Her hair is now down, a frizz seen in the lighter aura surrounding her body.

These tangled shorter strands of hair show her now careless attitude to her appearance.

As mentioned by Baer, Charcot states:

Everything about her, finally, announces the hysteric. The care applied to her make-up…; the arranging of her hair, the ribbons which she loves to put on. This need to adorn herself is so strong that during a [hysterical] attack, if there is a momentary respite, she utilizes this moment to attach a ribbon to her gown; this amuses her …and gives her pleasure… it follows that she enjoys looking at men, and that she loves to show herself and desires that one spend time with her. (Charcot, 1876, as cited in Baer, 2002).

Here Charcot characterises female hysteria by highlighting Augustine’s desire for male attention during a hysterical episode, proving the theatrical fabrication of symptoms as a way of self-expression.

Fig 1.2 (Above left), Hystéro-Épilepsie État Normal (Regnard,1878), photograph courtesy of Getty Museum

Fig 1.3 (Above Right), Hystero-Epilepsy Contraction (Regnard,1878), photograph courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Augustine is a figure that is relevant in today’s portrayal of girlhood hysteria, having parallel traits with Cecelia Lisbon in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), which is discussed further in chapter two. Both Augustine and Cecelia represent the exploration of youthful dreams and disillusionment. Cecelia, the youngest Lisbon sister, is the embodiment of the fragility of youth with her feelings of isolation causing her tragic suicide. In comparison to Augustine, Cecelia creates the fate of her sisters, and acts as the catalyst of a set of tragic events exploring how confinement from social settings can be critical in development for teenagers. Augustine shows signs of externalised hysteria, while Cecelia has more subtle ways of showing her mental distress such as her manic love for nature that considers her as the most sensitive sister. Modern hysteria tends to be more subtle and private than the likes of Augustine who is a figure that is very expressive in terms of her emotional outlet. Both show the complexities of mental distress, presenting different angles of hysteria.

Paula Rego’s ‘Dog Woman’ (1994)

It became clear that Regnard’s photographs would later be used not only as art themselves but as reference images for artists to support their practice. An artist that must be mentioned is Paula Rego (1935 – 2022), who’s work explores themes of female hysteria through provocative imagery. Rego was a Portuguese British visual artist who had

been addressing female injustices in her work since her late-teen years. She worked in a multi-disciplinary manner, using oil paint, pastel and chalk to depict political issues and personal subjects. Described by Elaina Crippa as having an “unbounded imagination, empathy and generosity”(Crippa, 2021, pp. 6), her works sets out to represent vulnerable women and give them their freedom. By using photographs from La Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière, she reflects on how women grasp their identities and the struggles of how women’s mental health has been romanticised through the objectification of the female body. By introducing themes of madness, her work highlights women’s resilience against confinement.

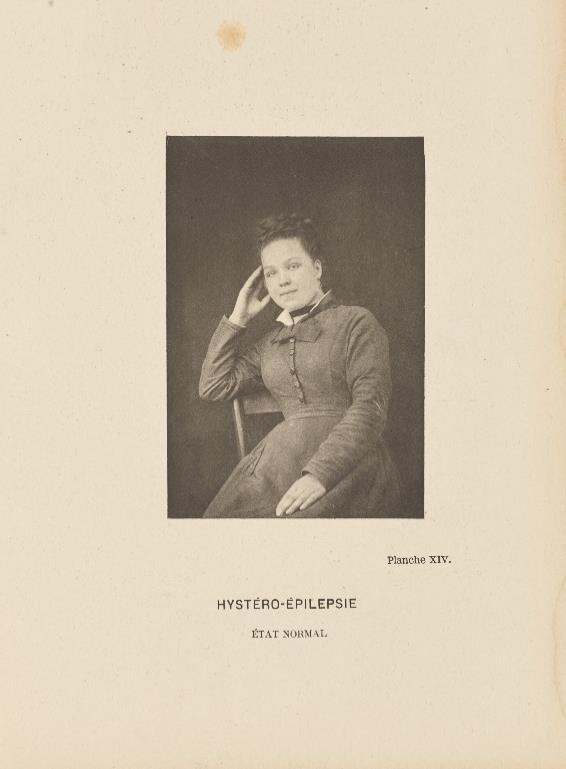

In her series Dog Woman (1994), she turns the manic woman into an animal, showing a female with her limbs outstretched in an unruly position (see figure 1.4). The series originated from a set of sketches taken of Lila Nunes, Rego’s husband’s nurse who became a model, collaborator, and friend. Nunes became the first dog woman, Rego stating “She’s trapped, but can bite” (Rego, interviewed by Eastham and Graham, 2011).

The poses of Dog Woman can be identified from images of hysterics, and although many of Augustine’s images were taken in a seated position, characteristics such as facial expressions can link both Rego’s painting and Regnard’s photography (Crippa, 2021).

Crippa describes the pose of Dog Woman as Rego’s “desire to focus on the body as a vessel of emotions” (Crippa, 2021, pp.16), highlighting her identification with portraying her as a lively and self-expressional figure.

Rego’s use of pastel rather than her typical use of oil paint or charcoal here is described as offering her the experimental pleasures for “deep scratching, scoring and smearing, and for building up form and colour through repeated and effortful overlaying of material

without the paintbrush as intermediary” (Rees-Jones, 2019, pp.156). The used material allows Rego to portray the anger of the dog woman through its application. The woman’s role in society is highlighted in this series. Although they are shown as powerful in terms of their strength. Reese-Jones compares Rego’s collection of works Girl and Dog (1986) to Dog Woman (1994), stating that she:

…fuses girl and dog, self and other, in a moment of genesis. This is a radical transformation, as the ability to identify with the other becomes a capacity not simply to find the dog-self within, but to blur the distinction between human and animal together.

(Reese-Jones, 2019, pp. 160)

Rego has successfully used Augustine’s characterisation by Charcot to create a picturesque representation of the 19th century manic women. Taking another image of Augustine into account, her bodily position can be compared to Rego’s hysteric in Dog Woman. In the image Augustine has her mouth agape, and eyes rolled back, as she gazes up. Rego’s woman looks more frustrated than her opposing character, as though she is roaring out of rage. Augustine looks like she is curious and appears to be signing with her hands whilst her limbs are tucked under her, in comparison to Rego’s woman who is up on all fours ready to pounce with her legs bent and palms on the ground. Rego has tried to dehumanise the hysterical women of the 19th century by giving her animalistic characteristics that have been over exemplified to highlight the ways in which men viewed women. She clenches the floor, the look of tension building up in her elbows, giving an “…overwhelming sense of desolation” (Reese-Jones, 2019, pp. 160). Rego’s hysteric wears a floral frock that swarms her lower half, her muscly thigh lifting out from within the skirt. Her knee is chunky, seen in the dents and shadows created. Augustine is in a seated position that makes her look fragile, as though she is perched in the position

due to self-awareness, something Rego’s character lacks. Overall, Rego’s depiction of hysteria highlights the ways men viewed hysteria in the 19th century compared to how hysterics truly acted.

1.4, Dog Woman (Rego, 1994), photograph courtesy of Victoria Miro.

Getty Museum.

Fig

Fig 1.5, Attitudes Passionnelles Moquerie (Regnard, 1878) Photograph courtesy of

Chapter Two – The Visual Presentation of Contemporary Hysteria

Feminist Critique on the Representation of Hysteria

Proceeding from the 19th century to the 21st century, women have more rights, personal space, and freedom to act upon their own desires. In today’s girlhood culture, hysteria is often dismissed as an emotional outburst reflecting societal pressure and lack of selfexpression. However, by creating feminine spaces, individualism can be expressed as more girls feel as though they can form a personal identity. The work of sociologist Angela McRobbie proposes the argument that mainstream culture is influential on adolescent girls. As mentioned by Catherine Grant and Lori Waxman in Girls! Girls! Girls! In Contemporary Art (2011), they discuss McRobbie’s work saying girls are:

Focused on both the creation of a sexualized identity that conforms with mainstream notions of femininity and as a potential space of resistance to the requirements of heterosexuality and motherhood through the creation of an all-girl subculture (Grant and Waxman, 2012, pp. 2).

When girls use their bedrooms to create comfort spaces, they are noticing that although mainstream ideas of womanhood are influential, they can resist these notions by forming groups with their peers as an act of objection. The formation of peer groups shows how society has changed since the 19th century, as girls today have a better support network to channel feelings of discontent.

Feminine theorist Catherine Driscoll’s work explores girlhood as the primary focus in a woman’s life, rather than as a biological age (Grant and Waxman, 2012). The ways in which girlhood is presented in society questions whether girls are truly a collection of

these characteristics or if the stereotypes of girls have built the idea of true femininity. Driscoll argues that:

Girlhood is made up and girls are brought into existence in statements and knowledge about girls, and some of the most widely shared or commonsensical knowledge about girls and feminine adolescence provides some of the clearest examples of how girls are constructed by changing ways of speaking about girls. (Driscoll, 2002, pp. 5).

This statement suggests that the fabrication of girlhood as an identifiable time in a woman’s life is ever changing due to social structures. This explains why girlhood in the 19th century was not studied as a link to hysteria, as placing these two together seemed unnatural at the time due to the ways girlhood was presented to society.

Sofia Coppola’s ‘The Virgin Suicides’ as a Depiction of Hysteria

In contemporary art and film, the concept of hysteria has been re-examined to challenge feminine stereotypes and address issues surrounding mental health. An example of this is Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), an adaption of the 1993 novel by Jeffrey Eugenides. The film explores the suffocation of suburban life as an adolescent and the effects this can have on a girl’s existence. Set in the 1970s, the film follows the mysterious lives of the five Lisbon sisters, Cecelia, Lux, Bonnie, Therese, and Mary, who become a fixation for the neighbourhood boys. Coppola uses ethereal cinematography to capture the complexities of youth, isolation and the unseen struggles girls encounter in a repressive environment. Although The Virgin Suicides is a fictional representation of adolescent hysteria, it acts as a handbook on how hysteria is treated in modern culture, showing how feelings manifest through loss of identity and isolation. The film’s aesthetic

appearance and sexualized narrative portrays the Lisbon sister’s world as luminous yet merely depressing, as if they are a theatrical act to keep the neighbourhood boys – the narrators of the film – amused.

Laura Mulvey’s essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (2013) is a revolutionary text that highlights the role of female protagonists in Hollywood cinema. She argues that a woman’s visual presence in a film halts the production of a storyline as her sexualisation becomes the key theme at that moment. This is an element of The Virgin Suicides that Coppola plays into, allowing the boys to create their ideal vision of the girls that romanticises them but also makes the boys in control of the narrative. Mulvey backs this up stating:

The man controls the film phantasy and also emerges as the representative of power in a further sense; as the bearer of the look of the spectator, transferring it behind the screen to neutralise the extra-diegetic tendencies represented by the woman as spectacle (Mulvey, 2013, pp. 12).

Here Mulvey is addressing the issues of a power dynamic where the male takes on the role of the protagonist even though he is not truly the leading role, making the woman appear as an object in the film’s narrative. This is an element of The Virgin Suicides, as the narrators are male. The girls’ pain is turned into a fantasy, as if they were never real, but made-up figures of the boys’ imaginations. Debora Shostak highlights that the boys identify the girls as one collective feminine body and not as individuals, where they “construct the girls uniformly as priestesses of burgeoning sexuality whose knowledge of death seems inextricable from their sensuality” (Shostak, 2013, pp. 187). This underlines the importance of identity within the narrative of the film, and how the girls are still viewed

as the protagonists despite being the narrators. When reading Cecelia’s journal, the boys refer to the feminine energy that changed their beliefs of girlhood, rather than the individual identities of each girl, concluding that they learn little about the girls, yet a lot about what it means to be a woman.

We felt the imprisonment of being a girl, the way it made your mind active and dreamy, and how you ended up knowing which colours went together. We knew that the girls were our twins, that we all existed in space like animals with identical skins, and that they knew everything about us though we couldn’t fathom them at all. We knew, finally, that the girls were really woman in disguise, that they understood love and even death, and that our job was merely to create the noise that seemed to fascinate them (Eugenides, 1993, pp. 40).

It is recognised that Sofia Coppola has a “unique vision of girlhood” (Handyside, 2012, pp. 42). She keeps the realness of adolescence in The Virgin Suicides (1999) yet overemphasises the aesthetic of typical girlhood. This is presented through the Lisbon sister’s bedrooms as these spaces are a representation of their identities, and a stereotype of girly spaces. Coppola uses pink to assert a girlish nature, using accents of magnolia, floral bedding, and baby pink walls to give the whole shot a rose-tinted effect. The warm lighting of lamps and candles reflects the softness of the girls and their delicate nature. Fiona Handyside argues that Coppola plays with opposite factors such as interior and exterior, inside, and outside in her films (Handyside, 2012). Entertainment critic Bree Hoskin expands on this stating:

Adolescence might be seen as a time when there is a fantasised inversion of boundaries. To put it very simply: we exist on a terrain where what is inside finds itself outside (acne, menstrual blood, rage) and what should be visibly outside (heroic dreams, attractiveness,

sexual organs) remains resolutely inside and hidden (Bree Hoskin, 2007, as stated in Handyside, 2017, pp. 10).

Hoskin’s argument can be linked to hysteria, showing that the suburban environment is in fact a constraint on the girl’s freedom. They are stuck inside a home that strips them of their personality, but their outdoor environment fetishises their adolescence. Bettis and Adams discuss girlhood spaces in Geographies of Girlhood: Identities in-between (2005), stating, “it is the in-between spaces and places found within and outside the formal domain of schools that we believe to be central to how girls make sense of themselves” (Bettis and Adams, 2005, pp. 5). Here the authors are underlining the importance of connecting with peers, something in which many girls in the 19th century were deprived of, that would have allowed them to thrive.

The Lisbon sisters share many characteristics with Charcot’s hysterics. Not only are the girls also placed in a dramatic light for male entertainment, but they experience a repressive environment in which confinement becomes the breeding ground for their hysteria. After disobeying their mother’s curfew for a school dance, the girls are withdrawn from school and locked up at home. Their mother believes that their desire to break rules is a result of socialisation, so thinks that by locking the girls up they will relearn values, much like the woman prescribed with ‘the rest cure’ in the 19th century. Bettis and Adams argue that the years twelve to eighteen are crucial for development saying:

During this time period, adolescents exhibit particular characteristics such as: increased physical growth with a focus on secondary sexual attributes; a desire to rebel against the mores of the adult world and to exert more independence; a desire to associate more closely with peers; a need for self-expression as seen through consumer choices of

clothing and music; and a time to explore one’s sexuality (Bettis and Adams, 2004, pp. 7).

They state that self-expression is born through owning items that help form an identity.

This is something stripped from the Lisbon girls by their mother. An example of this is a shot of Lux Lisbon sobbing as she is told to burn her vinyl records in the fireplace. Their mother thinks that by stripping her daughter of music it will prevent her from acting out, however; this instead causes Lux to reach for any attainable way of exploring her sexuality.

The various narrative tones and language used in The Virgin Suicides are what make it clear adolescence is not considered to be a cause of the girl’s depression, as it goes undiscussed by their parents, peers, and medical experts. In Narrative Matters: Understanding The Virgin Suicides (2020), authors Clare Hayes-Brady and Elizabeth Barrett consider the narration of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel, which is later integrated into the script of the film adaption. A notable example of medical language is used during the films’ opening credits, when a doctor comments to Cecelia, “What are you even doing here, honey? You’re too young to even know how bad life gets”, and she responds,

“Obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl” (Hannah R. Hall as Cecelia Lisbon in The Virgin Suicides, Coppola, 1999). The doctor proceeds to disregard Cecelia’s comment as a witty gesture than a confession that her adolescence caused her to try to take her own life.

The second narrative voice, the unreliable male, is an issue that confronts men discussing woman’s issues. The idea of having a male narrator telling the story of five adolescent girls shows that regardless of a girl’s situation or upbringing, her desirability will always override the suffering she is enduring.

The third narrative voice is introduced by Fiona Handyside which explains the ways in which objects are used to serve girl culture and represent the Lisbon sisters. A key scene that displays Cecelia’s hysteria through feminine objects is after her first suicide attempt. After getting the consent to throw a party, Lux, Bonnie, and Mary are getting ready whilst Therese tapes childish bracelets and bangles to Cecelia’s wrists on top of her self-harm bandages (See figure 2.1). Handyside analyses this scene comparing the “seriousness of Cecelia’s depression and the banality of the bracelets” (Handyside, pp. 65). The idea that Cecelia is not confronting her depression and hiding it beneath girlish jewellery is visually striking, as she is directly showing that she is feeling nostalgic of a simpler time by soothing her adolescence with childhood. Here Cecelia is portrayed as these objects, she is still a child having to navigate the world like a woman, thus creating her hysteria.

Fig 2.1, film still from The Virgin Suicides (Coppola, 1999), image courtesy of Paramount Vantage.

The Ophelia Narrative – Cecelia Lisbon and Millais ‘Ophelia’ (1852)

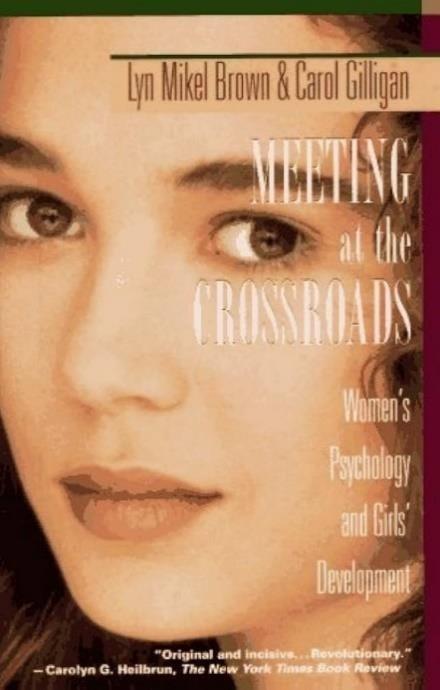

There are striking factors that relate Cecelia Lisbon to Millais’ Ophelia (1852), as well as the general characterisation of the Ophelia figure in history. Ophelia, originally from Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1601) is a representation of the vulnerable adolescent girl in the history of girlhood. Ophelia acts as the link between western culture’s preconceptions of women and the hysterical girls of the 19th century. Her emotional instability narrates the social expectations of young girls. In Schooling Ophelia: hysteria memory and adolescent femininity (Marshall, 2007), the author compares the front cover designs of two adolescent self-help books published in the 1990s, Meeting at Crossroads (Brown and Gilligan, 1992) and Reviving Ophelia (Pipher, 1994). Both book covers show a portrait of a young girl represented as an Ophelia figure, gazing away from the viewer (see figures 2.2 and 2.3). Marshall describes these girls as “…vulnerable and in some way resistant” (Marshall, 2007, pp. 714) in the ways she has been presented to the reader. Adolescent self-help books such as those stated above are important in girlhood history. Marshall states

These critiques underscore how the Ophelia narratives bring attention to adolescent girls, an often underrepresented group in social science research; and’ at the same time, point out the ways in which these texts normalize adolescent girlhood as White, privileged and heterosexual (Marshall, 2007, pp. 709). Here he is underpinning that although these books emphasize the important of adolescence in a girl’s life, and allow those around her to understand her more, they also bring attention to the commodity of research done towards non-coloured and entitled

young women, the stereotypical Ophelia figure, rather than girl groups as a collective. Such representations of girlhood, including Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), only bring attention to one ethnicity which weakens their reliability when it comes to standing for girls.

Fig 2.2 (upper left), Book cover of Meeting at Crossroads (Brown and Gilligan, 1993), image courtesy of Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Fig 2.3 (upper right), Book cover of Reviving Ophelia (Pipher, 1994), image courtesy of Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

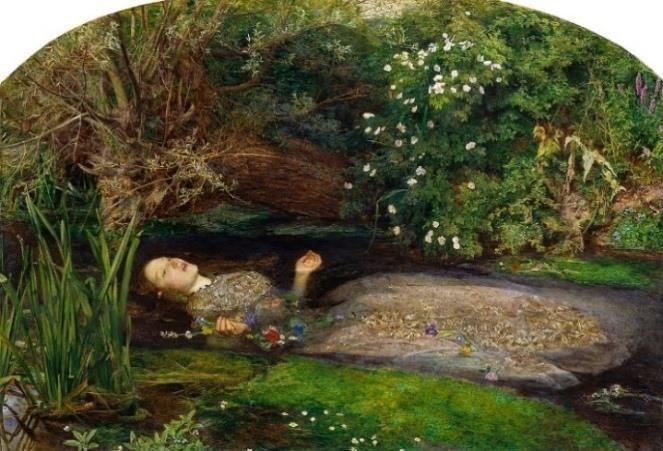

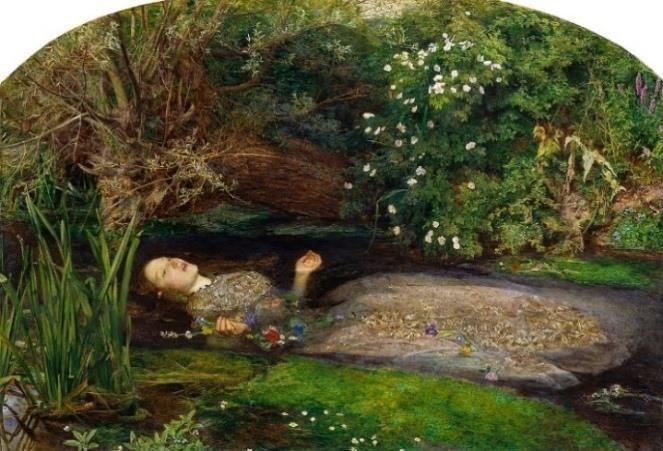

Coppola creates a sense of peace intertwined with the tragedy of Cecelia’s death during the opening credits of the film (see figure 2.3) which highlight adolescent mental health. The camera moves to a shot of Cecelia Lisbon’s pale body floating lifeless in the bath water which is coloured a murky red. A blue light reflects into the water and across Cecelia’s forehead, the red and blue complimenting each other unlike the pinks and greens that are the constant colour pallet throughout the film, making this shot standout as the greatest tragedy. Anna Backman Rodger’s discusses the paradox between the shot

of Cecelia’s death and Sir John Everett Millais Ophelia (1852) (see figure 2.4). She analyses Cecelia’s suicide suggesting that “Even in near death she is brought into the lines of symmetry that help to ensure she remains an eternally poised, mysterious and even saintly figure” (Rodgers, 2019, pp.27). This is a factor that Coppola manages to contribute to all the Lisbon sisters, by using the narration of the neighbourhood boys, and the appearance of the girls to create the sense of immortality and spirituality in their nature. There are striking factors that relate Cecelia to Millais’ Ophelia (1852), as well as the general characterisation of an Ophelia figure in history. Comparing the figurative Ophelia in the painting to Cecelia laying in the bath, both figures have their eyes open. In Ophelia (Millais, 1852) (see figure 2.5), her stare is distant, as though she is gazing right past everything above her and surrendering herself to death, much like Cecelia. Her hair appears to cushion her head as it floats in the water, the dark brown encapsulating her face to focus the viewer on her pale complexion. Rodgers states that Millais paints Ophelia as a “tragic, sacrificial and iconic female figure” which relates to how the shot of Cecelia is “highly aestheticized” (Backman Rodgers, pp. 27). Cecelia is seen to be sacrificing her body to stop herself from reaching adulthood and conforming to the ideologies of a woman, much like Ophelia.

Anna Gaskell’s ‘Override’ (1997)

An artist that critiques the male narrator through her photography is Anna Gaskell, an Iowa born artist who gained her MFA from Yale University in 1995. Her earlier works were predominantly self-portraits, then she began taking photographs of girls embodying characters and reimagining stories (Guggenheim Museum, 2007). Gaskell’s series’

Fig 2.4, Ophelia (Millais, 1852), image courtesy of Tate Britain.

Figure 2.5, film still from The Virgin Suicides (Coppola, 1999), image courtesy of Paramount Vantage.

Override (1997) and Wonder (1998) reimagines the story of Alice in Wonderland (Carroll, 1865) from the perspective of how Alice would have deciphered her own story rather than through the narration of a man. The series depicts five blonde Alice’s ages twelve to seventeen wearing identical pinafores. Gaskell’s girls are not individualised, but represent the commodity of girlhood through their identical clothing and the ritual acts they are taking part in. We see Alice change in size, as if she has drunk the potions from Carroll’s tale that allow her to grow and shrink. Howard Hale discusses Gaskell’s work in New Wave: Four Emerging Photographers (1998), saying, “One way to look at the original text is a metaphor for anxiety growing up, perhaps for the anxiety of the onset of menstruation; Gaskell’s version suggests as much, as well as a metaphor for the contemporary obsession with body image”(Halle, 1998, pp. 35). Alice’s mental instability and anxiety is a factor present in Gaskell’s work that both relates a text from the time of Charcot’s hysterical women, Alice in Wonderland, and the present day.

Untitled #25 (Override) (Gaskell, 1997) reveals a spider-like composition of legs that are sprawled out at different angles (see figure 2.6). These legs are those of Gaskell’s Alice’s, which are all wearing white tights and Mary-Jane shoes to portray the conventional appearance of Carroll’s Alice. The composition depicts the messiness of girlhood and the interwoven aspects of the collective struggles of teenage adolescence. The white legs work in contrast with the dark background and despite putting the Alice’s in a conventional fairytale setting adds the depth of isolation to the image.

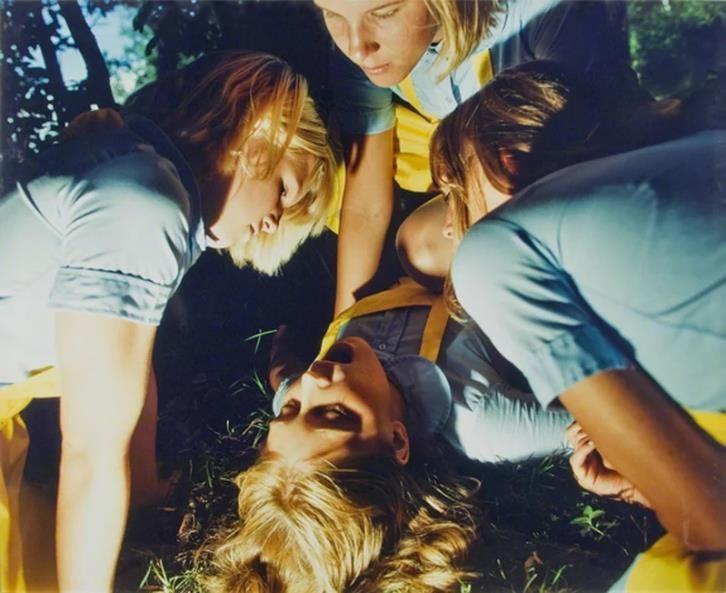

We see the girl’s faces in Untitled #27 (Override) (Gaskell, 1997). The photograph shows a group of three Alice’s pinning another to the ground as she lays with her eyes closed and mouth agape (see figure 2.7). It appears as if a torch light is held from out with the frame

as there is a white glow radiating from the left-hand side of the photo, highlighting the yellow tones of the girls’ hair. Gaskell is hinting at the anger and frustration that comes with adolescence, as if Alice is attacking herself in a different form. Guggenheim Museum, the credited owners of Gaskell’s series, analyse the photographs by comparing the reversing roles of the Alice’s as “victim or aggressor” (Guggenheim, 2024). They take turns holding each other down and controlling each other’s bodies to create the metaphor of anxiety. Gaskell’s Override is an uncanny comparison of Coppola’s girls, whom all five are blonde, and are represented as one entity of girlhood by their narrators rather than five individuals.

As discovered in Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel of The Virgin Suicides (1993) it is clear that the stereotypical acts of femininity represented in literature can disguise the lens of the male narrator. Howard Halle discusses Gaskell’s use of narration in New Wave: Four Emerging Photographers (1998), saying, “Gaskell maintains Carroll’s literary conceits while peeling then back to reveal the author’s sexual desire” (Hale, 1998, pp. 35). Here Hale suggests that Gaskell has created a physical representation of how Carroll viewed Alice, by using a stereotypical, slightly fetishised outfit she manages to portray Alice as a sexualised teen rather than a young girl. Halle further states:

The author of the Alice books was essentially erecting a monument to his unrequited love for the real-life child who was the model for his protagonist. Both the real and fictive Alices were the object of an especially complicated male longing – one that sought control yet could yield a surprisingly tender and empathetic portrayal of one little girl’s sexual awakening (Halle, 1998, pp. 35).

However, art critic Bruce Hainley disagrees with the way Gaskell has portrayed teenage adolescence by stating that “If she has chosen really to explore the trauma of girlhood,

things would have been a lot more disturbing” (Hainley, 1998). His 1998 review of Override (1997) lists the ways in which Gaskell could have shown emotional turmoil yet chose to turn it into a vision of aestheticized girlhood. However, the argument of a man discussing feminine work made to portray a woman is confusing. Taking a story about a young girl written by a man, to then allow the girl to rewrite her tale as Gaskell has done, is a remarkable attempt to reclaim girlhood. When a man chooses to not see that vision, it is his way of only seeing the presentation of girlhood, rather than the double-narrative created by Gaskell which shows Alice thrive in the world Carroll, a man, has created.

Fig 2.6 (Above left), Untitled #25 (Override) (Gaskell, 1997), photograph courtesy of Guggenheim Museum.

Fig 2.7 (Above Right), Untitled #27 (Override) (Gaskell, 1997), photograph courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Conclusion

This dissertation aimed to outline the ways in which the contemporary presentation of girlhood responds to 19th century hysteria. This was succeeded by investigating the interwoven aspects of hysteria from the late 19th century to 21st century girlhood. An objective of this dissertation was to argue that hysteria is rooted in all adolescent girls regardless of their social background but through their core being. This was presented through the presentation of Jean-Martin Charcot’s hysterics and Sofia Coppola’s Lisbon sisters in The Virgin Suicides (1999). I raised the question ‘how is 19th century hysteria linked to present day girlhood’ and explored the links that responded to this question through visual and critical analysis.

Through the exploration of historical narratives, looking at texts such as Elaine Showalter’s The Female Malady (1985) allowed for a well-rounded argument suggesting that feminine stereotypes allowed for the misrepresentation of woman, thus broadening

hysteria to a characteristic of all women. By looking at historical backgrounds of hysteria such as the young age of girl’s entering the Salpêtrière hospital, there is a clear pattern that suggests adolescence was a cause for manic tendencies. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper was used as a historical aid to show the treatment of hysterical woman and the ways in which men thrived from controlling the care of women. Through dissecting Paul Regnard’s photography of Augustine in La Iconographie Photographique de la Salpetriere (Bourneville, 1876) and comparing characteristics to contemporary artworks, it is obvious that the presentation of women was narrowed down to physical representations that fetishised mental illness. Paula Rego’s Dog Woman (1994) is a great example of the ways in which Regnard’s images were carried into contemporary art. Rego challenged Regnard’s stereotypes by highlighting the woman’s pose and facial expressions, showing the difference between repressing and expressing female rage in a feminist manner.

The second chapter broke down the narrative of Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), a film that explores the world of the five Lisbon sisters who reach their tragic end through suicide in their suburban town. Direct links between Coppola’s Lisbon sisters and Charcot’s key hysterics are discussed through the ways in which their characteristics display the repression of feminine rage. The comparison of Cecelia Lisbon, the youngest sister to commit suicide, and the character of Ophelia in Millais’ Ophelia (1852) further strengthens evidence that 19th century hysteria is relevant in today’s culture. By visually comparing the body language of Ophelia in the water and Cecelia in the bath, it is clear that the tragic female is a character passed down through history. Their ways of acting out against society conform to historical aspects of hysteria, with their dreamlike natures

allowing for unique ways of self-expression despite their circumstances. This comparison expands when the work of Anna Gaskell is considered as another representation of adolescent hysteria, this time through the lens of photography.

Gaskell’s series Override highlights girlhood as a collective experience, allowing the character Alice from Alice in Wonderland to rewrite her own story through the female lens, creating a sense of rage and discomfort.

In an overall conclusion, it is evident that 19th century hysteria shares many characteristics with the representation of hysteria in 21st century girlhood. Hysteria and girlhood have been intertwined throughout art history, and the hysteric’s legacy will continue forwards.

Reference List

Anna Gaskell (1997) Untitled #25 (Override) [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/4426 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Anna Gaskell (1997) Untitled #27 (Override) [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/anna-gaskell-untitled-number-27-override (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Backman Rogers, A. (2019) Sofia Coppola: the politics of visual pleasure. New York; Berghahn Books. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781785339660

Baer, U. (2002) Spectral Evidence: the photography of trauma. Cambridge, Mass; London: MIT Press.

Bettis, P. and Adams, N.G. (2005) Geographies of Girlhood: identities in-between. 1st ed. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Braun, J (2020) Performing Hysteria: Images and Imaginations of Hysteria. Leuven University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18dvt2d (Accessed: 18th November 2024).

Hoskin, Bree (2007) ‘Playground Love: Landscape and Longing in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides’, Literature/Film Quarterly, 35(3), pp. 214-225.

Brown, L.M and Gilligan, C. (1993) Meeting at the crossroads: women’s psychology and girls’ development. New York: Ballantine Books.

Carroll, L. (1967) Alice in Wonderland. Dobson

Crippa, E. et al. (2021) Paula Rego. Edited by E. Crippa. London: Tate Publishing.

Delchamps, V. (2020) ‘“A Slight Hysterical Tencancy” Performing Diagnosis in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”’, in Braun, J (ed.) Performing Hysteria: Images and Imaginations of Hysteria. Leuven University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18dvt2d (Accessed: 18th November 2024).

Desire Magloire Bourneville (1878) Iconographie Photgraphique de la Salpetriere [Book]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/104GBN (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Driscoll, C. (2002) Girls: feminine adolescence in popular culture and cultural theory New York: Columbia University Press.

Eugenides, J. (1993) The Virgin Suicides. New York: Harper Collins.

Faraone, C.A. (2011) ‘Magical and Medical Approaches to the Wandering Womb in the Ancient Greek World’, Classical Antiquity, 30(1), pp. 1–32. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/ca.2011.30.1.1.

Gilburt, I. (2020) ‘The Phototextual Emergence of Hysteria: From the Iconographie

Photographique de la Salpêtrière to J. M. Coetzee’s Slow Man’, Kronos, 1(46), pp. 129–146. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27011697 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Gilman, C.P. (1892) The Yellow Wallpaper. The New England Magazine.

Guggenheim Museum (2024) Anna Gaskell. Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/4430 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Hainly, B. (1998) Anna Gaskell. Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/annagaskell (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Halle, H. (1998) ‘Next Wave: Four Emerging Photographers’, On paper, 2(4), pp. 32–37

Handyside, F. (2017) Sofia Coppola: a cinema of girlhood. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Hayes‐Brady, C. and Barrett, E. (2020). ‘Narrative Matters: Understanding the Virgin Suicides – myth, memory and the medical gaze’. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 25(3), pp.189–191. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12413

Hoskin, Bree (2007) ‘Playground Love: Landscape and Longing in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides’, Literature/Film Quarterly, 35(3), pp. 214-225.

Hustvedt, A (2012) Medical muses: hysteria in nineteenth-century Paris. London: Bloomsbury.

Marshall, E. (2007) ‘Schooling Ophelia: hysteria, memory and adolescent femininity’, Gender and Education, 19(6), pp. 707–728. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701650656.

McRobbie, A. (1990) ‘Settling Accounts with Subcultures: A Feminist Critique’. Feminism and Youth Culture. London: Red Globe Press, 16-34.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and Other Pleasures. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.14–26.

Paul Regnard (1878) Attitudes Passionelles Moquerie [Photograph]. Available at:

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P14 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paul Regnard (1878) Hystero-Epilepsie Etat Normal [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P0R (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paul Regnard (1878) Hystero-Epilepsy Contraction [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P0R (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paula Rego (1986) Girl and Dog [Acrylic on paper]. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/untitled-girl-and-dog-series-176992 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paula Rego (1994) Dog Woman [Pastel on canvas]. Available at: https://www.victoriamiro.com/artworks/29910/ (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Pipher, M. (1994) Reviving Ophelia. New York: Ballantine.

Rees-Jones, D. and Rego, P. (2019) Paula Rego: the art of story. London: Thames & Hudson.

Rego, P. (2011) ‘Interview with Paula Rego’. Interview with Paula Rego. Interviewed by Ben Eastham and Helen Graham for The White Review, 11th January. Available at: https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-paula-rego/ (Accessed: 13th November 2024).

Shakespeare, W. (2016) Hamlet. Revised edition. Edited by A. Thompson and N. Taylor. London; Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare.

Shostak, D. (2013). ‘“Impossible Narrative Voices”: Sofia Coppola’s Adaption of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides’. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 15(2), pp. 180-202.

Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/intelitestud.15.2.0180 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Showalter, E. (1987) The Female Malady: women, madness and English culture 18301980. Virago.

Sir John Everett Millais (1851-2) Ophelia [Oil on canvas}. Available: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millaisophelian01506#:~:text=Christ%20in%20the%20House%20of%20His%20Parents%20( %E2%80 %98The (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Smart, M.A. (1992) ‘The silencing of Lucia’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 4(2), pp. 119– 141. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954586700003694. (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M.G. and Fadda, B. (2012) ‘Women and Hysteria in The History of Mental Health’, Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8(1).

Available at: https://doi.org/10.2174%2F1745017901208010110. The Virgin Suicides (1999) Directed by Sofia Coppola [Feature film]. S.L: Paramount Vantage.

Tony Robert Fleury (1876) Philippe Pinel Freeing the Insane from their Chains [Oil on canvas]. Available: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/qqynunrp (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Waluskinski, O (2014) ‘The girls of the Salpetriere’, Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience (33), pp.65-77. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000359993 (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Waxman, L.G., Grant, C. and Waxman, L. (2011) Girls! Girls! Girls! in contemporary art Bristol: Intellect.

Bibliography

Aapola, S, Gonick, M, Harris, A (2005) Young femininity: girlhood, power, and social change. Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anna Gaskell (1997) Untitled #25 (Override) [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/4426 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Anna Gaskell (1997) Untitled #27 (Override) [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/anna-gaskell-untitled-number-27-override (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Anna Gaskell (1996) Wonder [Chromogenic print]. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/165770 (Accessed: 14th March 2024).

Backman Rogers, A. (2019) Sofia Coppola: the politics of visual pleasure. New York; Berghahn Books. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781785339660

Bae, M.S. (2011) ‘Interrogating Girl Power: Girlhood, Popular Media, and Postfeminism’, Visual Arts Research, 37(2), pp. 28–40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5406/visuartsrese.37.2.0028.

Baer, U. (2002) Spectral Evidence: the photography of trauma. Cambridge, Mass; London: MIT Press.

Bell, K, (2020) Sofia Coppola on the 20th Anniversary of The Virgin Suicides: “It Means a Lot to Me That It Has a Life Now”. Available at:

https://www.vogue.com/article/sofiacoppola-interview-the-virgin-suicides-20thanniversary (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

Bettis, P. and Adams, N.G. (2005) Geographies of girlhood identities in-between. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bourneville, D.M, Regnard, P. (1876) Iconographie photographique de La Salpetriere.

Bradley, F. (2002) Paula Rego. London: Tate Publishing.

Bradshaw, P (2023) The Virgin Suicides review – Sofia Coppola’s debut rereleased with solemn trigger-warning. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/jul/26/the-virgin-suicides-reviewsofiacoppolas-debut-rereleased-with-solemn-trigger-warning (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

Braun, J (2020) Performing Hysteria: Images and Imaginations of Hysteria. Leuven University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18dvt2d (Accessed: 18th November 2024).

Brown, L.M and Gilligan, C. (1993) Meeting at the crossroads: women’s psychology and girls’ development. New York: Ballantine Books.

Carroll, L. (1967) Alice in Wonderland. Dobson

Crippa, E. et al. (2021) Paula Rego. Edited by E. Crippa. London: Tate Publishing.

Cutter, K. and Moshfegh, O. (2018) ‘Sleeping Beauty’, The Women’s Review of Books, 35(4), pp. 6–7. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26501085.

Dashkin, M. (2012) ‘Mark, Mary Ellen. Prom,’ Library Journal. Library Journals, LLC, pp. 77-

Delchamps, V. (2020) ‘“A Slight Hysterical Tencancy” Performing Diagnosis in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”’, in Braun, J (ed.) Performing Hysteria: Images

and Imaginations of Hysteria. Leuven University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18dvt2d (Accessed: 18th November 2024).

Delmar, R. and Hustvedt, A. (2011) ‘The Hysteria Capital of the World’, The Women’s Review of Books, 28(6), pp. 10–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/41553063.

Desire Magloire Bourneville (1878) Iconographie Photgraphique de la Salpetriere [Book].

Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/104GBN (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Dick, T. (2004) Girl Trouble: Teenage Girls in Contemporary Art, 23(1), pp. 76-81. Available at:

Douglas, S.J. (Susan J. (1995) Where the girls are: growing up female with the mass media. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Driscoll, C. (2002) Girls: feminine adolescence in popular culture and cultural theory New York: Columbia University Press.

Edward-Burne Jones (1880) The Golden Staircase [oil on panel]. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/burne-jones-the-golden-stairs-n04005 (Accessed: 14th March 2024).

Eisenhauer, J. (2008) ‘A Visual Culture of Stigma: Critically Examining Representations of Mental Illness’, Art Education, 61(5), pp. 13–18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/20694752.

Eugenides, J. (1993) The Virgin Suicides. New York: Harper Collins.

Faraone, C.A. (2011) ‘Magical and Medical Approaches to the Wandering Womb in the Ancient Greek World’, Classical Antiquity, 30(1), pp. 1–32. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/ca.2011.30.1.1.

Gilburt, I. (2020) ‘The Phototextual Emergence of Hysteria: From the Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière to J. M. Coetzee’s Slow Man’, Kronos, 1(46), pp. 129–146. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27011697 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Gilburt, I. (2020) ‘The Phototextual Emergence of Hysteria: From the Iconographie

Photographique de la Salpêtrière to J. M. Coetzee’s Slow Man’, Kronos, 1(46), pp. 129–146. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27011697 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Gilman, C.P. (1892) The Yellow Wallpaper. The New England Magazine.

Gilman, C.P. (1892) The Yellow Wallpaper. The New England Magazine.

Girlhood (2021) [Exhibition]. National Museum of Woman in The Arts: Washington. March 3 – August 8. Available at: https://nmwa.org/whatson/exhibitions/online/maryellen-mark-girlhood/ (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

Gonick, M. (2006) ‘Between “Girl Power” and “Reviving Ophelia”: Constituting the Neoliberal Girl Subject’, NWSA Journal, 18(2), pp. 1–23. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4317205.

Grant, C. and Waxman, L. (2011) Girls! Girls! Girls! In Contemporary Art. Bristol: Intellect.

Grauer, K. (2002) ‘Teenagers and Their Bedrooms’, Visual Arts Research, 28(2), pp. 86–93. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20716067.

Guggenheim Museum (2024) Anna Gaskell. Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/4430 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Hainly, B. (1998) Anna Gaskell. Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/annagaskell (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Halle, H. (1998) ‘Next Wave: Four Emerging Photographers’, On paper, 2(4), pp. 32–37

Handyside, F. (2017) Sofia Coppola: a cinema of girlhood. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Harris, M (1997) Mary Ellen Mark. Available at: https://archive.aperture.org/article/1997/01/01/mary-ellen-mark (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

Hayes-Brady, C. and Barret, E. (2020). ‘Narrative Matters: Understanding the Virgin Suicides – myth, memory and the medical gaze,’ Child and adolescent mental health, 25(3), pp.189-191. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12413

Healy Claire. (2023) Girlhood. 1st Edn. London: Tate Publishing

Hoskin, Bree (2007) ‘Playground Love: Landscape and Longing in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides’, Literature/Film Quarterly, 35(3), pp. 214-225.

Hustvedt, A (2012) Medical muses: hysteria in nineteenth-century Paris. London: Bloomsbury.

Jansen, C. (2017) Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of Female Gaze. London: Laurence King Publishing.

John Everett Millais (1851-1852) Ophelia [oil on canvas]. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506 (Accessed: 14th March 2024).

Juno Calypso (2015) The Honeymoon Sweet [Photograph] Available at: https://www.junocalypso.com/honeymoon/kd0v7lml0hi6gea393xmahjhcpuy9g (Accessed: 14th March 2024).

Krasny, E. (2020). ‘HYSTERIA ACTIVISM: Feminist Collectives for the Twenty-First Century,’ Performing Hysteria: Images and Imaginations of Hysteria, edited by Johanna Braun, Leuven University Press, pp. 125-146. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18dvt2d.10.

Lyn Mikel Brown and Gilligan, C. (1993) Meeting at the crossroads: women’s psychology and girls’ development. New York: Ballantine Books.

Macedo, A.G. (2008) ‘Paula Rego’s Sabotage of Tradition: “Visions” of Femininity’, Luso-Brazilian Review, 45(1), pp. 164–181. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30219063.

Mark, M. Ellen. and Bell, Martín. (2012) Prom. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Mark, Mary. E. (1997) ‘Mary Ellen Mark’. Interviewed by Mellissa Harris for Aperture, Winter edn. Available at: https://archive.aperture.org/article/1997/01/01/maryellenmark (Accessed: 20th March 2024).

Marshall, E. (2007) ‘Schooling Ophelia: hysteria, memory and adolescent femininity’, Gender and Education, 19(6), pp. 707–728. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701650656.

McRobbie, A. (1990) ‘Settling Accounts with Subcultures: A Feminist Critique’.

Feminism and Youth Culture. London: Red Globe Press, 16-34.

Micale, M.S. (1985) ‘The Salpêtrière in the Age of Charcot: An Institutional Perspective on Medical History in the Late Nineteenth Century’, Journal of Contemporary History, 20(4), pp. 703–731. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/260404.

Micale, M.S. (1993) ‘On the “Disappearance” of Hysteria: A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction of a Diagnosis’, Isis, 84(3), pp. 496–526. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/235644.

Mistry, P. et al. (2023) Paula Rego: Crivelli’s garden. London: National Gallery Global. Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and Other Pleasures. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.14–26.

Museum of Modern Art (2024) Anna Gaskell. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/165770 (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

National Museum of Woman in Art (2021) Mary Ellen Mark: Girlhood. Available at: https://nmwa.org/exhibitions/mary-ellen-mark-girlhood/ (Accessed: 20th March 2024).

Nightingale, F. (2010)‘Florence Nightingale. Cassandra: an essay. 1979’, American journal of public health (1971), 100(9), pp. 1586–1587.

Paul Regnard (1878) Attitudes Passionelles Moquerie [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P14 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paul Regnard (1878) Hystero-Epilepsie Etat Normal [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P0R (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paul Regnard (1878) Hystero-Epilepsy Contraction [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108P0R (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paula Rego (1986) Girl and Dog [Acrylic on paper]. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/untitled-girl-and-dog-series-176992 (Accessed: 10th December 2024).

Paula Rego (1994) Dog Woman [Pastel on canvas]. Available at: https://www.victoriamiro.com/artworks/29910/ (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Pipher, M. (1994), Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls. New York: Putnam

Rees-Jones, D. and Rego, P. (2019) Paula Rego: the art of story. London: Thames & Hudson.

Rego, P. (2011) ‘Interview with Paula Rego’. Interview with Paula Rego. Interviewed by Ben Eastham and Helen Graham for The White Review, 11th January. Available at: https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-paula-rego/ (Accessed: 13th November 2024).

Rego, P. (2011) ‘Interview with Paula Rego’. Interview with Paula Rego. Interviewed by Ben Eastham and Helen Graham for The White Review, 11th January. Available at: (Accessed: 13th November 2024).

Rego, Paula. (2021) Paula Rego. Edited by E. Crippa. London: Tate Publishing.

Schiff, J.L. (2021) Hysteria and Victorian Women in Art, researchgate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352198074.

Shakespeare, W. (2016) Hamlet. Revised edition. Edited by A. Thompson and N. Taylor. London; Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare.

Shambroom, H. (2021) A Closer Look – Mary Ellen Mark: Girlhood. Available at:

https://nmwa.org/blog/nmwa-exhibitions/a-closer-look-mem/ (Accessed: 18th March 2024).

Shostak, D. (2013). ‘“Impossible Narrative Voices”: Sofia Coppola’s Adaption of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides’. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 15(2), pp. 180-202.

Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/intelitestud.15.2.0180 (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Showalter, E. (1987) The Female Malady: women, madness and English culture 18301980. Virago.

Showalter, E. (1993) ‘On Hysterical Narrative’, Narrative, 1(1), pp. 24–35. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20106990.

Sir John Everett Millais (1851-2) Ophelia [Oil on canvas}. Available: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millaisophelian01506#:~:text=Christ%20in%20the%20House%20of%20His%20Parents%20( %E2%80 %98The (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Smart, M.A. (1992) ‘The silencing of Lucia’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 4(2), pp. 119– 141.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954586700003694. (Accessed: 5th November 2024).

Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M.G. and Fadda, B. (2012) ‘Women and Hysteria in The History of Mental Health’, Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.2174%2F1745017901208010110.

The Virgin Suicides (1999) Directed by Sofia Coppola [Feature film]. S.L: Paramount Vantage.

Tony Robert Fleury (1876) Philippe Pinel Freeing the Insane from their Chains [Oil on canvas]. Available: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/qqynunrp (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Waluskinski, O (2014) ‘The girls of the Salpetriere’, Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience (33), pp.65-77. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000359993 (Accessed: 4th October 2024).

Waxman, L.G., Grant, C. and Waxman, L. (2011) Girls! Girls! Girls! in contemporary art Bristol: Intellect.