for use with Ruhof’s Prepzyme® Forever Wet Enzymatic Pre-Cleaner

The cleaning process begins at the point of use. When soils dry, they become harder to remove and increase the risk of corrosion, biofilm formation, and HAI’s. The Forever Wet Auto Sprayer delivers a consistent application of Prepzyme® Forever Wet in less than half the time—keeping instruments moist for up to 72 hours.

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

Sourcing & Logistics

8 Unlocking the Potential of ValueBased Procurement for Payors

BRIAN MANGAN, RANDY V. BRADLEY

12 Bringing Order to the ‘Wild West’ of Purchased Services

JOHN WRIGHT

34 Resiliency Begins with Us

KAREN CONWAY

Infection Prevention

14 Tracking a New Way to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

MATT MACKENZIE

Sterile Processing

18 Hospital Leaders: It’s Time to Give SPD a Seat at the Table

KARA NADEAU

24 Troubleshooting WasherDisinfector Performance

SHELLEY OLDHAM, CODY MCELROY

28 Finish the Year Strong by Assessing SPD’s Needs

DEBRA SAMS

30 Top 10 Common Mistakes in the SPD, Part 2

ADAM OKADA

As 2025 draws to a close, one idea stands above all others. Real progress in healthcare comes not from any single technology, department, or contract. It comes from collaboration.

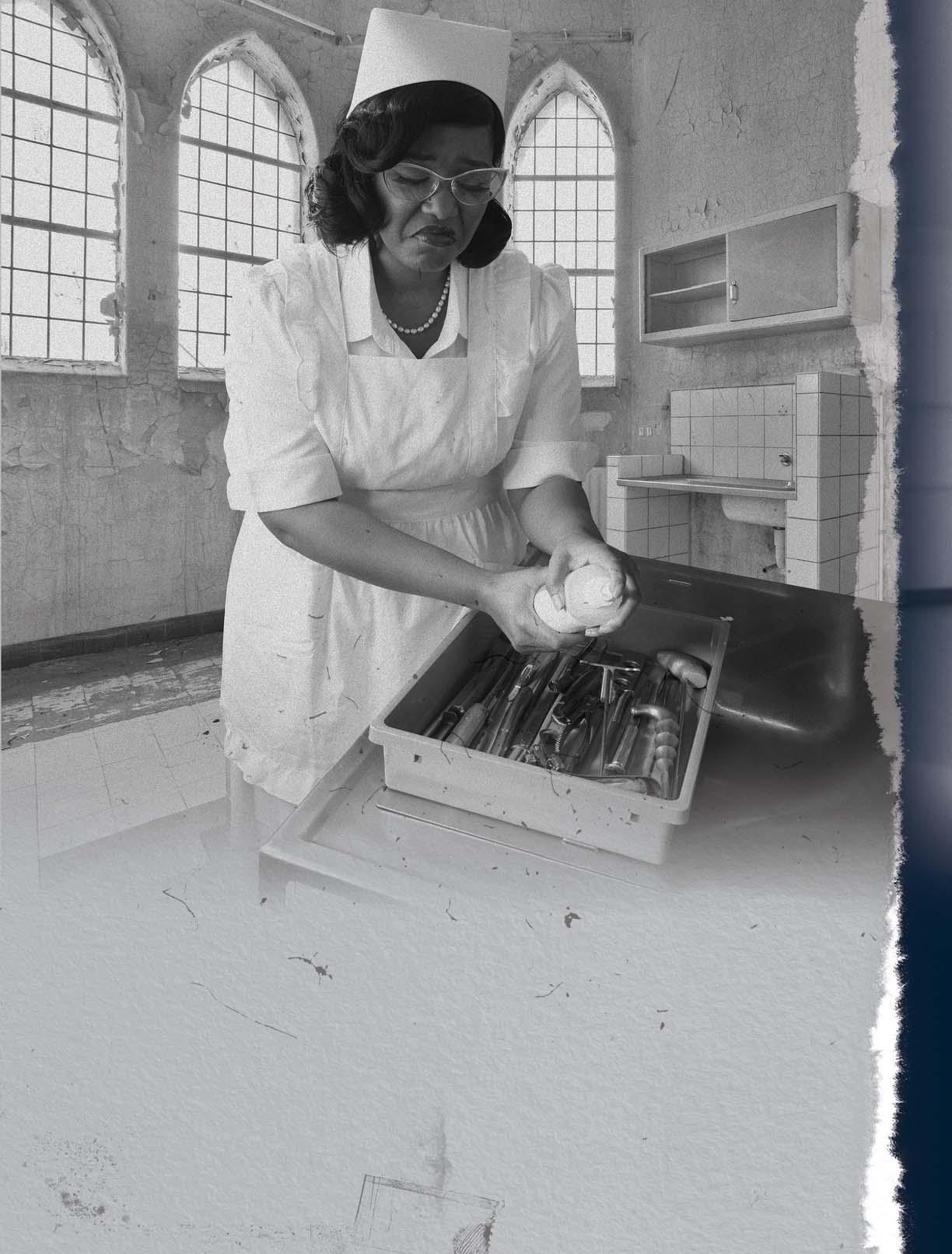

Nowhere is that more evident than in the world of sterile processing. In her cover feature, Kara Nadeau captures an important truth. Sterile processing professionals are among healthcare’s most vital yet often overlooked experts.

These are the people who ensure that every instrument touching a patient is safe, compliant, and ready. Yet, they are still fighting for visibility in conversations that shape their work, from purchasing and facility design to manufacturer instructions for use (IFUs) and surgical scheduling. The stakes are high. As one expert shared, a single oversight in reprocessing led to a $20.6 million lawsuit after a patient suffered a deep infection from improperly sterilized implants.

When SPD is absent from decision-making, hospitals risk far more than inefficiency. They risk patient safety, regulatory compliance, and financial stability.

Across the country, forward-thinking systems are beginning to change that. UCSF Health includes SPD leaders in new product evaluations through the GHX Lumere platform to confirm devices can be safely reprocessed. Nemours Children’s Hospital routes all instrument purchases through SPD to prevent reprocessing of single-use items. And at UC Davis

Health, SPD professionals contribute to facility design to ensure sterilization workflows are built in and not bolted on.

That same spirit of collaboration fueled innovations like Michigan Medicine’s antimicrobial mouthguard, designed to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. It’s an illustration of how multidisciplinary teams with clinicians, engineers, procurement, and infection prevention can turn simple ideas into breakthrough solutions, as Matt MacKenzie discovered in his feature story.

But 2025 has also seen a broader redefinition of value in healthcare procurement, one that extends beyond the walls of any single hospital. In their series on value-based procurement, Brian Mangan and Randy Bradley challenge both payors and providers to move from simply cutting costs to creating value. Their most recent installment argues that the next frontier in procurement is about aligning incentives across the entire healthcare ecosystem, including payors, providers, and suppliers alike.

Their R.E.W.A.R.D. framework offers a roadmap for payors to lead. By incentivizing efficiency and improved patient outcomes rather than chasing transactional savings, payors can accelerate systemwide change. As Mangan and Bradley note, “Whether we like it or not, money talks.” The challenge is ensuring it speaks the language of value, not volume.

Group Content Director Healthcare

Jennifer Breedlove jbreedlove@endeavorb2b.com

Editor-in-Chief

Daniel Beaird dbeaird@endeavorb2b.com

Associate Editor Matt MacKenzie mmackenzie@endeavorb2b.com

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau knadeau@hpnonline.com

Advertising Sales

East & West Coast

Kristen Hoffman khoffman@endeavorb2b.com | 603-891-9122

Midwest & Central

Brian Rosebrook brosebrook@endeavorb2b.com | 918-728-5321

Advertising & Art Production

Production Manager | Ed Bartlett

Art Director | Kelli Mylchreest

Advertising Services

Karen Runion | krunion@endeavorb2b.com

Audience Development Laura Moulton | lmoulton@endeavorb2b.com

Endeavor Business Media, LLC

CEO Chris Ferrell

COO Patrick Rains

CDO Jacquie Niemiec

CALO Tracy Kane

CMO Amanda Landsaw

EVP Infrastructure & Public Sector Group

Kylie Hirko

VP of Content Strategy, Infrastructure & Public Sector Group Michelle Kopier

Healthcare Purchasing News USPS Permit 362710, ISSN 1098-3716 print, ISSN 2771-6716 online is published 11 times annually - Jan, Feb, Mar, Apr, Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep, Oct, Nov/Dec, Nov/Dec IBG, by Endeavor Business Media, LLC. 201 N Main St 5th Floor, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538. Periodicals postage paid at Fort Atkinson, WI, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Healthcare Purchasing News, PO Box 3257, Northbrook, IL 600653257. SUBSCRIPTIONS: Publisher reserves the right to reject non-qualified subscriptions. Subscription prices: U.S. $160.00 per year; Canada/Mexico $193.75 per year; All other countries $276.25 per year. All subscriptions are payable in U.S. funds. Send subscription inquiries to Healthcare Purchasing News, PO Box 3257, Northbrook, IL 60065-3257. Customer service can be reached toll-free at 877-382-9187 or at HPN@omeda.com for magazine subscription assistance or questions.

Printed in the USA. Copyright 2025 Endeavor Business Media, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication should be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopies, recordings, or any information storage or retrieval system without permission from the publisher. Endeavor Business Media, LLC does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any person or company for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in the material herein, regardless of whether such errors result from negligence, accident, or any other cause whatsoever. The views and opinions in the articles herein are not to be taken as official expressions of the publishers, unless so stated. The publishers do not warrant either expressly or by implication, the factual accuracy of the articles herein, nor do they so warrant any views or opinions by the authors of said articles.

Jimmy Chung, MD, MBA, FACS, FABQAURP, CMRP, Chief Medical Officer, Advantus Health Partners and Bon Secours Mercy Health, Cincinnati, OH

Joe Colonna, Chief Supply Chain and Project Management Officer, Piedmont Healthcare, Atlanta, GA; Karen Conway, Vice President, Healthcare Value, GHX, Louisville, CO

Dee Donatelli, RN, BSN, MBA, Senior Director Spend symplr and Principal Dee Donatelli Consulting LLC, Austin, TX

J. Hudson Garrett Jr., PhD, FNAP, FSHEA, FIDSA, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Medicine, Infectious Diseases, University of Louisville School of Medicine

Melanie Miller, RN, CVAHP, CNOR, CSPDM, Value Analysis Consultant, Healthcare Value Management Experts Inc. (HVME) Los Angeles, CA

Dennis Orthman, Consulting, Braintree, MA

Janet Pate, Nurse Consultant and Educator, Ruhof Corp.

Richard Perrin, CEO, Active Innovations LLC, Annapolis, MD

Jean Sargent, CMRP, FAHRMM, FCS, Principal, Sargent Healthcare Strategies, Port Charlotte, FL

Richard W. Schule, MBA, BS, FAST, CST, FCS, CRCST, CHMMC, CIS, CHL, AGTS, Senior Director Enterprise Reprocessing, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

Barbara Strain, MA, CVAHP, Principal, Barbara Strain Consulting LLC, Charlottesville, VA

Deborah Petretich Templeton, RPh, MHA,Chief Administrative Officer (Ret.), System Support Services, Geisinger Health, Danville, PA

Ray Taurasi, Principal, Healthcare CS Solutions, Washington, DC

CDC Rolls Back Recommendation for MMRV Vaccine in Children Under 4

The move comes amid heightening scrutiny for the vaccine advisory group as it makes its mark on federal vaccine policy.

A hearing probing the recent firing of CDC director Susan Monarez also revealed that she “was fired a er refusing to pre-approve ACIP recommendations, regardless of scientific evidence.” She also stated her fear that “diseases like measles, polio, diphtheria, and whooping cough will return” as a result of HHS secretary Kennedy-led vaccine policy changes.

Read on: hpnonline.com/55317926

Supply Chain Technology Companies Curvo and BroadJump

Curvo, which has over 1,500 customers, will merge with BroadJump to provide hospitals with a be er view of non-labor costs.

Curvo “delivers a modern SaaS [so ware as a service] platform built exclusively for healthcare to transform clinical spend management.” The platform is in use in over 1,500 hospitals, surgery centers, medical device companies, and consulting firms. BroadJump “standardizes and aggregates information to provide neutral, unbiased analyses of non-labor costs.”

Read on: hpnonline.com/55320158

From 2019 through 2023, NDM-CRE infections, which are deadly and difficult to treat and detect, surged by over 460% in the U.S.

The rise in NDM-CRE threatens to increase CRE infections and deaths. In 2020, there were approximately 12,700 infections and 1,100 deaths in the U.S. due to CRE.

Read on: hpnonline.com/55318897

U.S. Launches National Security Probes into Medical and Industrial Imports

Commerce Department reviews PPE, medical devices, and machinery under Section 232, raising the prospect of new tariffs or trade restrictions.

The U.S. Commerce Department began Section 232 national security investigations on Sept. 2 into PPE, medical devices, and industrial machinery, though the move was not disclosed until late September. The reviews could pave the way for tariffs or other trade restrictions across a broad range of healthcare and industrial products.

Read on: hpnonline.com/55319933

From cu ing costs to creating value: the payor’s role in procurement’s future.

BY BRIAN MANGAN, RANDY V. BRADLEY

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment in a four-part series exploring the challenges and opportunities of adopting value-based procurement (VBP) in healthcare.

In our first article, “Value-Based Procurement: What’s in it for Provider Supply Chains?,” we considered the need for a more holistic approach to the strategic contribution the procurement function can play in reducing costs and improving efficiency and patient care. In our second article, “Are Suppliers, Vendors Fit for a Value-Based Procurement Future?,” we focused on the changing healthcare environment and its potential impact and opportunities for suppliers. We recommended

suppliers be more vested in pursuing a long-term partnership approach that would deliver financial return, rather than pursuing unsustainable short-term, profit-driven strategies. We further explained how the adoption of a true value-based procurement approach can deliver financial, efficiency, patient, and environmental benefits across patient pathways.

So, if the concept of value is such a persuasive argument for change in healthcare, why isn’t value-based procurement and value-based healthcare the go-to approach for single-payor or multi-payor health systems? In our view, value must be translated into tangible and measurable benefits that health systems are prepared to invest both time and money into changing the way they work. Given that some of the drivers and aims of single-payor and multi-payor health systems are different, it is important to ensure the specific value-based procurement arrangements are structured in such a way as to yield benefits that resonate with the respective payor system. Whether we like it or not, money talks. This is why we believe payors in both nationalized and privatized health systems have a key role to play.

There are several key shared characteristics between single- and multipayor systems, also referred to as nationalized and privatized health care systems, respectively, that create a need for a value-based procurement approach—resource scarcity, thirst for innovation, and payor-provider relationship dynamics.

Both systems have a need to allocate financial resources to improve care delivery and the patient experience in the face of limited human and financial resources because of dwindling labor pools and rising operating costs, driven by supply shortages, a growing number of critical supplies

on backorder, inflation, and geopolitical upheaval.

There is an increasing thirst for innovation -- which will only speed up with advances in AI -- to ensure payors and providers are maximizing opportunities to eliminate unneces-

Like providers, payors are motivated to find solutions that lead to cost reductions and more affordable and easily accessible healthcare.

sary cost and deliver improved patient care, efficiency, and cost benefits across the total patient pathway.

Despite some areas of commonality between single-payor and multi-payor systems, there is one major difference that requires a more nuanced approach to value-based purchasing; who is the central target of value? In a single-payor system the most likely central figure is the government payor, whereas the care delivery organization is the more likely central figure in a multi-payor system.

Given that both types of payor systems are reliant on global medical device and pharmaceutical manufacturers, a value-based procurement model that is unique to each type of payor environment is likely to have negative implications for healthcare globally. For example, assume a multinational medical device company is working with the NHS in the U.K., various health systems in the U.S., and at a provincial or country level in Canada. If each of those entities pursued a VBP program that is unique to them, it would be overwhelming for the device manufacturer to manage the multitude of VBP arrangement, let alone benefit from them. Having said that, each payor system has its own reasons and motivations to consider new approaches to delivering

value, regardless of the central figure, so there is nothing wrong with allowing some autonomy in devising VBP arrangements.

How can payors take the lead?

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nationalized and privatized health systems were straining under the weight of increased demand for services, spiraling costs, and dwindling budgets and profit margins. This situation was exacerbated by the pandemic. Like providers, payors are motivated to find solutions that lead to cost reductions and more affordable and easily accessible healthcare. This must be done while also ensuring patient outcomes improve. As such, payors ultimately need to incentivize value realization along the healthcare value chain,

The benefits of value-based procurement (VBP) in healthcare can be looked at from the perspective of each stakeholder, but they all tie back to one central goal: be er outcomes at sustainable cost. For payors, which can include insurers, governments, and employers, this can mean a be er return on investment with healthcare spending tied to measurable improvements. VBP shi s the focus from the cheapest option today to what delivers the best value over time for the healthcare ecosystem. The goal is to create a winning model for patients receiving be er care, providers and suppliers sharing responsibility, payors spending more effectively, and more benefits from a more sustainable system.

not just at the point of care. Payors can, in turn, reduce insurance premiums for patients and employers, offer improved contract terms to providers, provide incentive gain share payments for healthcare partners and suppliers to support the delivery of long-term system goals like the skins game referenced in our second article, and/or, in the case of a purely commercially enterprise, maximize shareholder value.

What could that look like? Instead of continuing to perpetuate a common procurement approach of standardization and aggregation with the hopes of product price savings, discounts, or rebates—which are often modest at best—payors should incentivize healthcare providers to think more broadly by focusing on targeted reduction in total procedure costs. The resulting financial benefits would be considerably more than the realized savings on specific supplies and materials needed for a procedure. Further, reducing total procedure costs is likely to have tangential benefits including increased efficiency and improved patient care, which are likely to cascade into longterm savings for payors.

Our assertion is that there needs to be a co-creation of value that involves a three-way collaboration between payors, providers, and suppliers wherein they work together to identify areas of opportunity and deliver efficiencies across the entire patient pathway from diagnosis to treatment and promote engagement across the entire healthcare supply chain. Given each party’s common need to address financial challenges, payors in both types of health systems are uniquely positioned to influence the adoption of value-based practices. The path forward is payors setting the strategic

direction for healthcare by establishing a R.E.W.A.R.D. plan.

Reimburse – Follow the money and look at financial flows throughout the patient pathway. Ask whether payment/reimbursement strate-

benefits of a focus on value for your stakeholders. Pilot studies can create momentum to accelerate broader adoption, and they are highly effective in payor environments that are more risk adverse.

Results and Reward – Determine at the outset of the value-based proj-

Value-based procurement and value-based healthcare are not magic wands that will cure all the ailments in privatized and nationalized healthcare systems.

gies incentivize improved efficiency and patient care or if there are unintended real or perceived negative consequences of creating system-wide efficiencies. Determine how reimbursement strategies and tactics can be better aligned to achieve enduring value-based goals.

Enlighten – Payors need to enlighten both internal and external partners to the benefits of a VBP approach and secure their commitment to the value journey. Value-based terminology has permeated healthcare language, books, and seminars since the early 2000s, much in the same way quality was a buzzword of the 1990s. As such, payors will need to approach VBP pragmatically with a focus on pathways/care continuums and partnerships to deliver the improved outcomes espoused by the value-based healthcare movement.

Who, What, When, Where, and Why? – This is a technique used by journalists in their craft. Use this as the basis for creating your own story towards VBP. Who needs to be involved? What pathway should you focus on with providers? When will you do it and over what time frame? Where will it be done? Why are you on this VBP journey? After soundly answering these questions, a payor will be in a much better position to communicate the benefits of VBP.

Act Now – Start with smallscale projects that demonstrate the

ect the results you need to demonstrate that your objectives have been achieved. Also determine how the players in the system will share in the rewards resulting from the value creation. Establish a robust contracting framework and management plan that is supported by simple, effective, and tangible metrics that are visible to all stakeholders.

Danger – Single- or multi-payor systems need to “wake up and smell the coffee” and recognize there is real danger in doing nothing. Health systems are crumbling under the weight of delivering population health while recovering from the financial strain of the COVID-19 pandemic and facing healthcare worker shortages and continued supply chain disruptions.

Value-based procurement and valuebased healthcare are not magic wands that will cure all the ailments in privatized and nationalized healthcare systems. However, they do offer an approach that can facilitate waste reduction in processes, services, and labor utilization in the healthcare system. Further, valuebased arrangements have inherited accountability components to foster triadic partnerships between suppliers, providers, and payors that ensure each is working in the best interest of patients and the healthcare ecosystem. HPN

BY JOHN WRIGHT

Complicated,” “untamed,” and “chaos”—all words used to describe the state of purchased services by supply chain leaders from 10 leading U.S. health systems in a recent focus group held at the 2025 IDN Summit and Reverse Expo. In contrast, executives used the words “opportunity,” “growth,” and “optimization.”

The variance is understandable given that purchased services are fraught with challenges, many specific to the

size and structure of a health system. It’s a quandary for many supply chain leaders who recognize the potential for improving performance—given that purchased services make up an estimated 40-50% of a health system’s supply chain budget—but don’t have the resources or knowhow to fast-track a better strategy.

Purchased services refer to the non-labor expenditures that healthcare organizations outsource to specialized vendors instead of managing in-house. These contracted

services cover a wide range of critical operations, from technology management to facility maintenance.

Optimization of purchased services requires an approach that improves operational efficiency while optimizing purchasing power. It necessitates greater collaboration and communication across the procurement management process, which is best described as disjointed in many of today’s health systems.

Focus group participants spoke to their current challenges managing purchased services and tactics needed to overcome them. Three critical strategies bubbled up from the discussion that leaders believe must be deployed to bring order to chaos.

Most supply chain leaders acknowledged that they are operating in a hybrid environment for purchased services, with procurement happening through both centralized supply chain teams as well as other departments. This is problematic for effective management of expenses given the sheer volume—often reaching into the hundreds—of purchased services contracts across a health system. Lack of visibility and oversight also leads to unnecessary variations and duplications of services.

To optimize management of purchased services contracts, health systems must achieve a standard of clinical and economic value that drives decision-making. Individual preferences must be put aside to realize the cost benefits of collective purchasing power with a single vendor. In tandem with cost advantages, narrowing the vendor playing field also streamlines management of purchased services and ensures a consistent patient experience.

The first step to minimizing variation and creating a centralized standard starts with a value chain analysis to determine the best choices in services. By evaluating the activities in an organization’s value chain, health systems can garner an understanding of where waste is occurring as well as which vendors are performing best in terms of financial performance, initiative success rates, patient outcomes/ satisfaction, utilization management, and waste reduction.

Focus group participants said they struggle communicating both upstream and downstream in their organization about purchased services, covering everyone from the C-suite to department directors and site managers. In addition, a general lack of education for system and purchased services staff continues to create inconsistencies and ineffective management of costs and contracts.

This current state of limited communication and working in silos will limit a health system’s ability to create

centralized efficiencies that improve costs and quality. Supply chain leaders must prioritize internal alignment and bridge communication gaps between front-line staff, clinical teams, and executive leadership. Such consistency can be achieved by facilitating closer collaboration between

The first step to minimizing variation and creating a centralized standard starts with a value chain analysis to determine the best choices in services.

supply chain, clinical staff, and finance teams, developing shared communication protocols and creating cross-functional education around organizational goals.

In addition to improved internal relationships, building strong, transparent relationships with suppliers that are willing to share goals and collaborate for the best outcomes is fast becoming best practice. This model runs in contrast to traditional GPO approaches that focus on a large supplier playing field by intensifying partnerships with organizations that provide the highest value to hospitals and their patients.

Most focus group participants graded their health systems at a “C” or below while assessing the integration, depth, and connectivity of their technology systems. Yet the imperative role of technology in delivering deeper insights from supply chain operations cannot be denied.

Health systems need robust solutions that can pull external data points from multiple sources, link them all together, and provide supply chain leaders insights in an actionable format. GPOs should play a key role in providing support and helping supply chain leaders maximize the value of data insights.

When it comes to creating supply chain efficiencies, purchased services offer true untapped potential for many health systems. Unfortunately, the complexities involved in getting a better handle on this cost center are a nonstarter for many resource-strapped health systems. The good news is that this is an operational area where the ROI potential makes the business case for outsourcing an easy one to make. In addition, bringing a third-party to the table can often help health systems avoid internal conflicts that often occur with the introduction of standardized and centralized systems. Bottom line: As health system leaders look for ways to improve margin, purchased services optimization is a significant opportunity. HPN

BY MATT MACKENZIE

Healthcare-associated infections come in so many forms, affecting so many different populations of patients, that it can be difficult to come up with comprehensive plans to address each and every one. Some common types include urinary tract infections and surgicalsite infections, both of which can introduce dangerous (not to mention expensive) complications when a patient is trying to get back on their feet following a procedure or a hospital stay.

Another healthcare-acquired infection that wreaks havoc on patients is ventilator-associated pneumonia. As the name suggests, ventilator-associated pneumonia, or VAP, is “associated with prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay.” A study published in the NIH’s PubMed Central database sought to provide a high-level overview of VAP, examining its rates, prevention methods, diagnosis and treatment, and more. The authors wrote that “prevention of VAP is based on minimizing the exposure to mechanical ventilation and encouraging early liberation.”

Incidence rates “vary greatly based on the studied population,” seeming to affect patients with cancer and major traumatic injury more than other populations, as well as those with COPD. Steps taken to diagnose the disease begin with clinical suspicion, and a number of scores have been suggested in an attempt to make diagnosis more precise. The most common diagnostic tool for VAP is the “Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score,” or CPIS, but studies have found that using this tool “may be associated with undue antibiotic use due to its low specificity.” Another issue in diagnosing the disease is that many of the criteria used to identify VAP are not specific, and “can often be observed in the many conditions that mimic VAP.”1

VAP can also lead to more severe outcomes in patients. A study in Nature Communications said that “reported mortality rates for VAP span a wide range (24–76%); however, attributing mortality solely to VAP is complex due to the severity of underlying illnesses and diagnostic heterogeneity within ICU populations. VAP can lead to the development of septic shock or acute respiratory distress syndrome if the treatment is delayed or inappropriate. VAP results in substantial antibiotic prescription pressure, accounting for half of all antibiotics used in the ICU.” However, “the prolific use of antibiotic therapy contributes to a vicious cycle of increasing multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and mortality. Treatment failure increases the risk of mortality and may occur in a third to two-thirds of VAP cases, with inappropriate antibiotic use the most common cause.”2

As mentioned earlier, the surest way to prevent VAP is to attempt to move the patient out of intubation as quickly as possible, or to use lessintensive methods. However, since that’s sometimes simply not an option, it is imperative to search for other ways to reduce incidence rates of the disease. Enter a team from Michigan Medicine, who developed a “soft, antimicrobial mouthguard that absorbs secretions before harmful bacteria can reach the lungs.”3

Healthcare Purchasing News reached out to Michigan Medicine and was able to speak with Dr. J. Scott VanEpps, MD, PhD, associate professor of emergency medicine, University of Michigan Health, who was part of the interdisciplinary team that developed the mouthguard.

How significant of a threat does ventilator-associated pneumonia pose to patients?

VanEpps: 1 in 10 patients on a ventilator will get ventilator-associated pneumonia. That comes out to over 75,000 patients each year.

Who is most at risk of acquiring a severe case of VAP?

VanEpps: The risk of VAP increases each day the patient remains intubated and on mechanical ventilation. Other risks include patients with immune suppression or prolonged hospitalization.

How does the mouthguard work to prevent VAP?

VanEpps: Bacteria-laden saliva pools in the back of the throat, forms biofilms on the breathing tube, and ultimately leaks into the lower respiratory tract causing pneumonia. Most of the bacteria come from the gingiva, or gums. The mouthguard reduces the risk of VAP by absorbing that saliva from around the gingiva and teeth and rapidly killing the

bacteria. In essence the device captures and kills VAP causing bacteria in the oral cavity before they reach the lungs.

How was the mouthguard workshopped and how did the idea come about?

VanEpps: The mouthguard was developed by combining the ideas of absorbing the saliva that carries the bacteria to the lungs and the rapid killing of the bacteria in place.

Are human trials forthcoming / have they happened already?

VanEpps: We are designing the first human trials now.

Does the mouthguard hold potential for working to prevent other HAIs?

VanEpps: While VAP is the most expensive HAI to treat, the mouthguard could immediately be leveraged to reduce healthcare-associated pneumonia even in patients without breathing tubes or respirators. More broadly, the material science used in the technology could be adapted for other medical devices such as catheters or prosthetics.

Are the mouthguards easily sterilized? How can patients be protected from infections spread by the mouthguard itself?

VanEpps: The mouthguards come sterilized like any other medical device. However, they are disposable. Specifically, they are placed in the mouth for only 12 hours and then replaced with a fresh one.

How does the timeline look for integration in hospitals / with patients?

VanEpps: We anticipate completion of first clinical trials and obtaining FDA approval in 2-4 years.

At the Weil Institute at the University of Michigan, researchers are developing other tools to help prevent infections across the healthcare spectrum beyond healthcare-associated infections. Another such tool, the so-called “MicroGas Chromatography” or Micro-GC, utilizes a breathalyzer-type device to enable rapid COVID diagnosis at the bedside.

This device is backed by studies that affirm its efficacy. The team was granted a “$2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to test their device’s ability to detect and monitor COVID-19 breath markers. They defined four sets of VOCs [volatile organic compounds] that were able to distinguish between COVID-19 and non-COVID illness. However, when the team applied the same VOCs in a setting of presumed [Covid variant] Omicron, sensitivity decreased drastically. They undertook additional biomarker searchers and defined new VOCs to discern between Omicron and Delta, Omicron and non-COVID illness, and between patients with COVID-19 and non-COVID illness regardless of variants.”

The tool was able to “detect COVID-19 infected patients (regardless of variant) from non-COVID patients with a sensitivity of 89.4%, a specificity of 91.0%, and an accuracy of 90.2%. This performance was shown to be close to that of RT-PCR tests (the gold standard) and better than many rapid antigen tests.”4

This same technology was later expanded to include a diagnostic tool to “quickly and accurately diagnose acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequently track its progress.” By using the breathalyzer-type device, the researchers hope to “gain fundamental insights into the presence and dynamics of VOCs/VICs in exhaled breath which present as inflammatory and metabolic markers of ARDS pathophysiology. Most importantly, the portable GC technology will bring molecular diagnostics to the bedside, enabling earlier initiation of ARDS treatments that improve outcomes, as well as novel trajectory monitoring to inform prognosis and downstream critical-care decision-making.”5

Again, there are so many massively prevalent conditions and infections to prevent against that it feels overwhelming in the aggregate. Faced with so many different ailments, however, innovation continues to ensure specific and simple care and treatment, making the lives of clinicians and their patients easier. HPN

References are available online at mlo-online.com/55322534.

Enzymatic Sponge

Bedside Cleaning

Procedure

Soiled Transport IAC Recommended Electrical Leakage Testing

Procedure Transport

BY KARA NADEAU

January 2026 marks 13 years since I joined the HPN editorial team and much of that time has been spent covering sterile processing departments (SPD). I have interviewed countless sterile processing professionals and experts in the field. Their passion for patient care and safety never ceases to amaze me.

While I hear more stories of SPD teams who have built strong, collaborative relationships with their hospitals’ executive leadership and other key partners (e.g., perioperative, infection prevention), there are

other professionals who report they are still fighting to be heard.

So, as we close out 2025, I reached out to the sterile processing community to ask, “Where should SPD professionals have a seat at the table, but don’t?”

The response was tremendous— both to my post on LinkedIn and the direct emails and one-on-one conversations I had with SPD professionals.

What follows is a summary of these responses, including realworld stories that highlight the importance of hospital leaders and

other stakeholders tapping into the knowledge and expertise of their SPD teams—and the risks of overlooking this critical resource.

Sterile processing professionals must play a role in the development of standards, policies, and other guidance and recommendations that impact their work.

“We should be involved in strategic discussions within our organizations and industries as subject matter experts in operations management and patient safety,” said Courtney Mace Davis, MBA, CHL, CRCST, AVP, Sterile Processing for Endeavor Health. “The sterile processing solutions of today may not have the same impact in five years. We can learn from other departments, healthcare organizations, and industries as long as we lean in and are willing to learn from others. These same groups can also learn from some of the great things SPD is doing.”

Manufacturer IFUs

Shawn Flynn, business unit director, SPD, for Skytron, who brings comprehensive experience as a surgical technician in the U.S. Army, medical device manufacturing, regulatory/compliance, SPD operations, and as a medical device entrepreneur, commented on regulatory gaps and their impacts on sterile processing teams, stating:

“There are all these gaps in regulatory pathways leading up to a device being cleared by the FDA where sterile processing professionals don’t have a seat at the table—and we definitely don’t have a seat when it comes to IFU validation. When a manufacturer is drafting an IFU, they are typically doing it from their perspective, and not through the lens of sterile processing.”

Garland-Rhea Grisby, BA, CER, CRCST, manager, Sterile Processing, Sutter Health, and host of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation’s (AAMI) Below the Hospital podcast, spoke to the real-world challenges sterile processing leaders face with IFUs today.

“We’re not the instrument manufacturer, but we’re the ones who have to handle, care for, store, and process these products,” said Grisby. “If there’s something out of whack with an IFU that we cannot do, then we need to go back to the manufacturer and ask, ‘Have you heard these complaints, and what did you do about it?’”

He pointed to numerous examples of IFU conflicts. Two nearly identical instruments from the same manufacturer—differing only in size—called for vastly different reprocessing requirements: Sterile gloves for one, nitrile for the other; sterile water for one, potable water for the other. “Then we’re left to figure it out, and risk being cited by surveyors.”

Garland-Rhea Grisby, BA, CER, CRCST, offers these recommendations for closing the gap between IFUs and real-world practice.

What

• Involve SPD teams in IFU development: Test instructions in real-world sterile processing environments to ensure they are practical.

• Notify SPDs of updates: Establish a reliable system to quickly alert facilities when IFUs change.

• Collaborate across companies: Work together to standardize requirements— especially for sterilization—rather than competing with conflicting instructions.

• Read and track IFUs: Never assume requirements are unchanged; even small updates can affect compliance.

• Raise concerns: Engage manufacturers when IFUs are unclear or unworkable, and request clarification or customer le ers when needed.

• Use professional standards: Reference guidance documents (e.g., AAMI) to support best practices when IFUs leave room for interpretation.

There can be broad variabilities across manufacturer IFUs, even for something as seemingly straightforward as steam sterilization. “It should be standard across the board, but it’s not,” said Grisby. “One manufacturer says four minutes, another says six. What do you do when those instruments are in the same tray?”

Compounding the issue, hospitals often face mixed fleets of old and new instruments and sole-source contracts for high-level disinfectants and other chemicals that limit their options. “We get stuck between a rock and a hard place,” Grisby explained. “If an instrument’s IFU calls for a disinfectant outside our contract, we can’t process it—even if it’s best for the patient.”

Sterile processing professionals should also be involved in the development of quality management systems (QMS), said Mace Davis, stating:

“I think about ANSI/AAMI ST90:2017(R2024) – Processing of health care products – Quality management systems for processing in health care facilities. There are so many vital relationships that go into creating a robust QMS. SPD should not only be included but should think about how we can be leaders in collaboration. For example, our managers host and lead monthly ‘Connections’ meetings that bring together leaders and educators from the OR, EVS, CE, facilities, and infection prevention to celebrate wins and identify (and address) opportunities for improvement.”

Supply chain & purchasing

The issue of IFUs crosses over to decisions related to new equipment and

“Sterile processing definitely needs to be involved when manufacturers develop IFUs,” Grisby added. “At the end of the day, we’re the ones who have to make it work.”

instrument purchases. “Any time new medical equipment is being considered for purchase/trial, someone from SPD needs to look over the manufacturer’s IFU to determine if the facility can reprocess it,” said James Carlock, regional director of Sterile Processing for Mercy in Oklahoma City.

Several sterile processing professionals voiced the need for SPD teams to play a central role in procurement decisions, especially those around new surgical instruments and devices.

Assessment Team Project Lead for Advantage Support Services (ASSI) Janene McGlynn, CRCST, CIS, CER, CHL, emphasized the importance of giving SPD teams a seat at the table whenever a facility brings on new surgeons or expands into new or specialized clinics.

“Typically, that’s going to mean looking at inventory, new equipment/instruments, and soft goods,” said McGlynn.

At UCSF Health, SPD is a stakeholder in the new product request process, as Gene Ricupito, CRCST, CIS, CHL, CFER, PMP, MBA(c), system director, Sterile Processing, explained:

“UCSF employs the GHX Lumere platform as part of the structured approach to ensure all aspects of a new product are evaluated prior to approval for introduction. This requires review of the IFU and acknowledgement to the decision-makers that the device can be effectively supported so that there are no 11th hour surprises when it comes time to implement.”

Edna Gilliam, DNP, MBA, RN, CNOR, NEA-BC, assistant vice president, Perioperative Services & SPD, DV, Nemours Children’s Hospital, pointed out how SPD teams are often responsible for instrumentation both inside and outside of the operating room (OR). She shared a story of where the SPD team was lacking visibility to clinic instrument purchases,

This article is not meant to be a complete list of decision-making areas, functions, and processes where sterile processing input is vital but rather a summary of what experts have shared with HPN

Here are additional areas that surfaced in response to the LinkedIn post and in direct correspondence/conversations with sterile processing professionals.

• Accreditation

• Apprenticeship program development

• Capital purchases

• Career growth structure

• Emergency preparedness teams

• Environmental Services (EVS)

• Facilities

• Finance (opportunities for revenue preservation)

the ramifications, and how her hospital resolved the issue.

At one point, clinic staff were independently ordering instruments— without involving the SPD and in some cases, unknowingly purchased single-use items. “That becomes a serious issue if those singleuse instruments make their way back to SPD,” Gilliam noted. “Reprocessing them could pose significant risks to patient safety and regulatory compliance.”

• Hazardous duty pay

• Industry organizations

• Learning and development (not only front-line staff but also leaders)

• OR point of use (POU) compliance

• Pay and compensation structures

• Tracking system planning meetings

• Vendor selection and feedback

committee for review, where SPD confirms the instrument can be cleaned and identifies any necessary education. Gilliam said the centralized process has been “largely successful,” enhancing oversight, validating SPD expertise, and giving the department a stronger voice in decision-making.

To address it, Nemours changed its process so that all instrumentation purchases now go through SPD. The SPD team verifies the order, ensures the product is appropriate, receives it, trains and educates staff, and then distributes it to the clinic.

Nemours also established a HighLevel Disinfection and Sterilization Committee, co-led by the SPD manager, infection control director, and regulatory director. Any new device approved through value analysis must go to this

Early involvement of the SPD team in facility design can avoid costly gaps later, as Rebecca Alvino, system director, Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Prevention for UC Davis Health, explained:

“Sterile processing professionals must be at the table during the input phase of designs for renovations or new constructions. It’s time to put a stop to the idea of building a space for teams to figure out how to operationalize instead of getting their input from the start.”

Sterile processing’s expertise is critical not only in the design of inhospital SPDs, but also anywhere reprocessing is performed. Gilliam offered this example:

“When Nemours Children’s Hospital was planning a new ambulatory surgery center in Malvern, PA in 2024, the C-suite brought our sterile processing leaders to the table right away to talk through the design and equipment required for high-level disinfection and sterilization.”

“SPD’s expertise is critical to ensuring patient safety and efficiency, especially in construction projects involving equipment installation and high-level disinfection areas,” she added. “During this new build, the SPD team offered advice as to new innovations that could make reprocessing workflows more seamless in the ASC setting.”

Our experts say SPD teams must also be involved in planning for new specialties, block time scheduling, and determining whether there is realistic instrument availability.

Alvino spoke about including sterile processing professionals in discussions around block times for surgeons or service lines, stating:

“You have an ortho doc who wants two rooms of arthroplasties 1-2 days a week? Have a conversation first with SPD to ensure they have the instrumentation —and if not, bring the vendors into the conversation.”

“But don’t just set up whimsical scenarios of surgeons running 10-15 total knees and hips over two rooms in a day with only two sets of instrumentation each for knees and hips and demand SPD to urgently turn them over,” she added. “Not only is it creating an environment to encourage corner-cutting, but it also jeopardizes the other service lines operating that day and the next day.”

Shawn Flynn, then an independent consultant and now business unit director, SPD, for Skytron, shared an intriguing legal case where he was asked to serve as an expert. It underscores what can happen when sterile processing professionals are excluded from critical decisions in the operating room (OR).

A professional Major League Soccer player underwent surgery at an ambulatory surgery center (ASC) to repair shin splints. During the procedure, the surgeon realized a six-hole plate needed for the repair was not available. Instead of using alternative plates that had already gone through terminal sterilization, the surgeon ordered a borrowed tray from a nearby hospital and instructed the SPD team to run it through immediate use steam sterilization (IUSS).

“That decision was in direct opposition to the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU), ASC policy, and industry standards,” Flynn explained. “The surgeon told the jury, ‘…and with direct respect to the policies and procedures, these are primarily manuals for employees of the surgery center. These are – not directed at the surgeons that are utilizing those.’”

Flynn was tasked with educating the jury on why the shortcut was taken. “The right approach, terminal sterilization, would have taken more time while the patient was still on the table. To save time, the instruments went through an abbreviated process that wasn’t compliant,” he said.

Within 30 days, the patient developed a deep bone infection at the implant site. Multiple follow-up surgeries were required, and the hardware had to be removed, ending the athlete’s career. The jury awarded him $20.6 million.

“The jury was very clear — ‘I wouldn’t want this done to me,’” Flynn said. “When I was asked if I would ever approve flashing implants, my answer was simple: ‘no.’ The IFU specifically says do not IUSS implants.”

Flynn stressed the accountability that comes with sterile processing documentation. “Every record you generate can be subpoenaed. If SPD records show that an implant was flashed, then responsibility essentially falls on them. That’s why, if I were in that situation, I would insist on a release policy signed by infection control, perioperative services, and administration. Once faced with that accountability, most leaders would refuse and instead agree to a compliant alternative.”

He also posed a provocative question: “Should patients be asked to consent to IUSS in emergencies—to educate them on what constitutes an emergency, the risks, and to get their approval? That’s the level of transparency this case raises.”

Flynn’s takeaway: “This case is the perfect example of why hospital leaders must support sterile processing professionals. Nobody wants to be in that situation.”

McGlynn recommends SPD teams ask the following questions:

• What are the block times going to look like?

• Does SPD need to be in-serviced on instruments?

• When is the go live date for these cases?

• Are the instruments in the building? Are they on consignment or a loaner?

• Do we need a capital purchase for equipment to properly follow the IFU?

• Is the OR team on the same page on all these questions?

According to Leslie Kronstedt, LPN, BHCA, CRCST, CIS, CHL, CER, CSF, sterile processing’s voice is critical not only in surgical services decisions but anywhere in a hospital where reprocessed devices/instruments are used.

“Decisions in departments such as labor & delivery, the ICU, and even satellite clinics are directly influenced by the quality and consistency of SPD practices,” said Kronstedt. “Yet too often, those with the deepest expertise in these processes are excluded from the discussions where protocols and procedures are set.”

Sterile processing, when performed in compliance with manufacturers’ IFUs, industry guidance, and hospital protocols, plays a primary role in infection prevention anywhere reprocessed instruments and devices are used in patient care. Therefore, the importance of collaboration among sterile processing and infection prevention teams cannot be overstated.

At UCSF Health, SPD is a critical participant in the organization’s Infection Prevention Sterilization & Disinfection subcommittee. “As SPD system director, I am a co-chair,” Ricupito explained. “This is a multidisciplinary forum that reviews challenges the organization may face with ensuring compliance with IFUs both within the realm of SPD and endoscopy but also at the point-of-use.”

“SPD is viewed as a valued partner in evaluating the entire reprocessing cycle,” he added. “Our clinical partners also provide tremendously valuable feedback to SPD on performance, particularly in the area of service levels and logistics. I am fortunate to work for an organization that not only recognizes the importance of SPD in the support of patient safety, but has also taken steps to establish a constructive, collaborative culture where SPD is an integral partner.”

While the infection prevention team can serve as the SPD team’s greatest ally in some cases, Gilliam warns that in other cases, a contentious relationship can arise between the teams.

“The partnership between sterile processing and infection prevention opens the door to bringing another party into your space who will critique your processes,” she explained. “But when the relationship has mutual respect and you have a shared vision, the dynamic can be very

positive and impactful. We have worked very hard to create that partnership here at Nemours.”

As with infection prevention, sterile processing has a direct connection with safety in patient care, as Ricupito described:

“Sterile processing plays a critical role in patient safety by ensuring that all instruments and medical devices are properly cleaned, disinfected, sterilized, and maintained. These efforts support the prevention of surgical site infections, as well as reduce the risks of cross-contamination.”

To strengthen the SPD team’s voice in pressing for safe reprocessing practices, Gilliam said sterile processing leaders need partnerships with their perioperative leaders, chief nursing officers, and whoever manages patient safety in their hospital, which might look very different from one organization to the next.

“Titles may vary depending on an organization’s structure,” she explained. “In some cases, responsibilities for regulatory compliance and patient safety may overlap. However, because regulatory bodies—such as The Joint Commission and state Departments of Health—place such a strong emphasis on patient safety, sterile processing is often the first area they inspect.”

“To capture the attention of your C-suite, emphasize that a single issue in the SPD has the potential to halt surgical operations across the hospital,” said Gilliam. “If you come across a story in HPN or another publication where a regulatory agency suspends procedures due to contaminated instruments, share it with your executive leadership. That scenario represents one of the most serious threats a hospital can face.”

While the role of sterile processing professionals in patient care and safety should be enough to secure them seats at the decision-making table, often a department’s level of influence in a hospital comes down to the bottom line.

“Including SPD at both clinical and administrative tables strengthens outcomes for patients, improves staff collaboration, and supports organizational sustainability,” said Kronstedt. “On the administrative side, SPD performance has a direct impact on hospital revenue and reimbursement. Sterile processing efficiency and equipment choices influence surgical workflows, case delays, or cancellations, and the risk of hospital-acquired infections.

“These factors ripple into reimbursement structures— from fee-for-service and global billing for surgical procedures to penalties tied to HAIs,” she continued. “In short, SPD professionals sit at the intersection of patient safety and financial health, and their voice is essential.” HPN

BY CODY MCELROY, SHELLEY OLDHAM

Washer-disinfectors play a pivotal role in ensuring the safe and effective reprocessing of medical devices, but even well-maintained washer-disinfectors can occasionally produce unsatisfactory results. When residual soil or debris is found after a cycle, it can compromise patient safety, delay procedures, and prompt compliance concerns. Understanding the underlying causes—ranging from equipment malfunctions to improper loading techniques—is essential for identifying and resolving these issues efficiently.

Beyond troubleshooting, it’s equally important to distinguish between true washer-disinfector performance problems and external factors that may mimic them, such as poor point of use

1.List reasons for residual soil and debris after a washer-disinfector cycle

2.Distinguish between washer-disinfector performance issues and other causes

3.Prevent washerdisinfector performance issues through planning

Contributed by:

practices, inadequate manual cleaning, or water quality inconsistencies. Proactive planning, including routine maintenance, staff training, and workflow optimization, can significantly reduce the likelihood of performance failures. This article will guide readers through identifying common causes of residual contamination, differentiating between machine-related and non-machine-related issues, and implementing preventive strategies to maintain consistent washer-disinfector performance.

Successful cleaning inside a washerdisinfector depends on key mechanical parts functioning properly so that water and detergent touch every

surface of the instruments. Spray arms play a critical role in the washerdisinfector by distributing water and detergent throughout the racks.

Rotating spray arms distribute fluids in multiple directions ensuring full coverage. When spray arms become blocked with organic debris, such as blood or tissue, or inorganic debris, such as pieces of locking clips, broken components, or container tags that were not removed, it can significantly reduce fluid flow and prevent rotation compromising cleaning effectiveness.

Clogged drain screens may slow drainage, causing fluid to remain in the chamber. The residual fluid can potentially recirculate recontaminating instruments with residual cleaning solution or soils. Common

inorganic debris left in the drain screen includes instrument fragments (e.g., broken tips, wires, screws) and dislodged accessories (e.g., broken lock tags). For best performance and safety, the drain screen should be checked and cleaned at least daily, or more often if visibly soiled.

The effectiveness of the washerdisinfector process depends not only on mechanical function but also on proper cleaning chemistry and cycle choice. Instrument cleaning chemistries that are utilized in these cycles are specifically formulated to break down and remove organic and inorganic soil from medical devices. If the incorrect detergent is used, or if it is not compatible with the washerdisinfector settings, water temperature, or the type of soil present, residual debris may remain on instruments following the cycle.

Along with choosing the right detergent, selecting the proper cycle is just as important for effective cleaning. If the wrong cycle is used for instance, running a gentle cycle for orthopedic instruments with joints or reamers, it may not provide enough cleaning power, this can leave behind residual soil, especially in areas that are difficult to reach.

Delicate instruments (e.g., ophthalmic, or microsurgical instruments) require gentler spray distribution and low impingement cleaning. Running these instruments in high impingement with forceful sprays and water pressures can bend or misalign fine tips, break off small components, and distort hinges or locking mechanisms. This type of damage may bend hinges preventing

instruments from fully opening, which is necessary for thorough exposure to cleaning action.

Common sources of use errors affecting washerdisinfector performance

Overloading in a washer-disinfector is a major cause for residual soil and debris. When instruments are stacked too close or overlapping it can block the spray arms from reaching all surfaces and limits the mechanical action needed to remove contaminants. This creates areas of shadowing where water and detergent cannot effectively clean, leading to trapped debris, especially in hinges, joints, and between instruments.

Improper placement, such as closed hinged instruments or cannulated instruments without proper fluid flow, prevent contact with cleaning solutions and rinse waters. The medical

Manual cleaning is a critical first step in the decontamination process when reprocessing medical devices.

device should be fully opened or taken apart so that all areas are properly exposed to the automated washerdisinfector for thorough cleaning.

Manual cleaning is a critical first step in the decontamination process when reprocessing medical devices. If this step is missed or not done properly, debris and dried blood can remain on instruments even after going through the washer-disinfector cycle.

Lumened instruments are especially vulnerable to retained soil, particularly if allowed to dry before cleaning. Using brushes that are the wrong size, have inappropriate bristle type, or are worn or damaged can result in residual debris

November-December 2025

This lesson was developed by STERIS. Lessons are administered by Endeavor Business Media.

A er careful study of the lesson, complete the examination online at educationhub.hpnonline.com. You must have a passing score of 80% or higher to receive a certificate of completion.

The Certification Board for Sterile Processing and Distribution has pre-approved this in-service unit for one (1) contact hour for a period of five (5) years from the date of original publication. Successful completion of the lesson and post-test must be documented by facility management and those records maintained by the individual until recertification is required. DO NOT SEND LESSON OR TEST TO CBSPD. www.cbspd.net.

Healthcare Sterile Processing Association, myhspa.org, has pre-approved this in-service for 1.0 Continuing Education Credits for a period of three years, until October 10,2027.

For more information, direct any questions to Healthcare Purchasing News editor@hpnonline.com.

Quiz Answers: 1. B, 2. C, 3. B, 4. D, 5. C, 6. B, 7. B, 8. A, 9. D, 10. A

being left behind. Once dried, blood, protein, and tissue harden, making them much harder to remove in the washer-disinfector.

Deciphering the root cause for washerdisinfector performance

Identifying the root cause of washerdisinfector performance issues requires a systematic approach.

Cleaning effectiveness can be compromised long before instruments reach the washer-disinfector—due to poor point-of-use treatment, inadequate manual cleaning, or insufficient supplies.

It can be easy to blame the equipment. While some issues stem directly from the washer-disinfector— such as faulty detergent injection, temperature deviations, or weak spray impingement—others may be misattributed, including improper instrument loading, incorrect detergent selection, or unsuitable cycle choice.

Items to investigate to rule out washer-disinfector issues:

•Spray arm rotation

•Spray clogs

•Drain screen debris

•Cleaning chemistry dosing

•Cleaning chemistry suitability

Items to consider that affect washer-disinfector performance:

•Cleaning cycle selected

•Instrument placement

•Rack loading

•Manual cleaning effectiveness

•Point-of-use treatment procedures

•Appropriate cleaning brushes

Prevent washer-disinfector performance issues

Preventing washer-disinfector performance issues begins with proactive planning that integrates routine monitoring, proper equipment setup, and staff training. One of the most effective strategies is the use of validated cleaning indicators that mimic clinical soil to routinely challenge the cleaning

performance of the washer-disinfector and its racks. Monitoring every rack, rack level, and washer-disinfector cycle used ensures that no part of the washer-disinfector is overlooked, and that cleaning outcomes are uniform across all instrument sets.

To be effective, cleaning Indicators must be sensitive enough to detect

competence in using these tools and maintaining equipment. Competencybased training helps prevent errors and ensures consistent cleaning outcomes.

When combined with remote diagnostics and rack-level monitoring, these strategies enable real-time issue detection and support a robust pre-

Competency-based training helps prevent errors and ensures consistent cleaning outcomes.

failures such as detergent omission or incorrect temperature settings, while remaining fully cleanable under optimal conditions. Cleaning indicators which are designed to be visual and easy to read are ideal for daily use in Sterile Processing Departments (SPDs).

Remote service monitoring adds another layer of protection by tracking key parameters such as water temperature and detergent levels and alerting teams to maintenance needs. Daily maintenance tasks—like cleaning the drain screen, checking spray arms, and verifying detergent levels—should follow OEM instructions for use and be documented for regulatory compliance.

Equally important is ensuring staff are trained and can demonstrate

ventive maintenance program that enhances compliance, minimizes downtime, and strengthens infection control.

Ensuring the consistent performance of washer-disinfectors is critical to safe and effective instrument reprocessing. Visible residue or debris on instruments is a clear sign that the cleaning process has failed—whether due to equipment issues, improper loading, or missed manual cleaning steps. By identifying the root causes and distinguishing between equipment-related and process-related errors, healthcare teams can implement targeted corrective actions.

Proactive strategies such as validated cleaning indicators, remote service monitoring, and strict adherence to daily maintenance protocols empower facilities to maintain high standards in sterile processing. By adhering to established procedures and ensuring equipment operates as designed, facilities can consistently achieve high standards of cleanliness, instilling confidence in the reprocessing workflow and ensuring instruments are safe for patient care. HPN

1.American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI). (2020). ASNI/AAMI ST79: 2017 comprehensive guide to steam sterilization and sterility assurance in health care facilities. Arlington, VA: Author.

2.Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. (2025). AORN standards (pp. 428-430). AORN.

3.National Standard of Canada. (2023) Decontamination of reusable medical devices

Cody McElroy is the manager of sterile processing and high-level disinfection at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, a Level One trauma center with over 500 beds. Cody has a BBA from Kent State University and an MBA from Cleveland State University. He also holds CSPDT and CSPM

certifications from CBSPD. Cody also teaches the sterile processing program at Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, Ohio.

Shelley Oldham brings over 20 years of expertise in medical device reprocessing, with a strong focus on supporting healthcare professionals through education, mentorship, and adherence to CSA standards. An active member of the HSPA and CSA communities, she maintains certifications and stays current with best practices. Shelley has led multiple Lean Kaizen events in reprocessing and operating rooms and has delivered hands-on training and in-services to frontline staff and leadership across Western Canada.

1.Why might debris still be present on instruments after a washer-disinfector cycle?

A.The sterilizer did not reach the correct temperature.

B.The instruments were not manually cleaned before the washer-disinfector cycle.

C.The washer-disinfector is designed to sterilize not clean.

D.Staff should air-dry the Instruments before proper loading into the washer-disinfector.

2.Why is proper instrument placement in the washer-disinfector important?

A.To allow for faster sterilization

B.To prevent items from getting lost

C.To ensure effective spray arm coverage

D.To keep the washer-disinfector looking organized

3.What could happen if the spray arms in the washerdisinfector are blocked or not rotating properly?

A.Instruments will dry faster.

B.It will significantly reduce water and detergent flow.

C.The washer-disinfector will use less water.

D.Cleaning will be more efficient.

4.What is a washer-disinfector performance issue rather than an external cause?

A.Improper instrument loading

B.Incorrect cycle selection

C.Inadequate detergent choice

D.Malfunctioning detergent injection

5.What is a common mistake when evaluating washer-disinfector performance?

A.Using cleaning indicators

B.Focusing on cleaning outcomes

C.Assuming one cycle fits all instruments

D.Monitoring each rack and cycle

All CEU quizzes must be taken online at: educationhub.hpnonline.com. The cost to take the quiz is $10.

6.What is one benefit of using validated cleaning indicators?

A.They eliminate the need for manual cleaning

B.They simulate real-world soiling conditions

C.They replace OEM maintenance tasks

D.They reduce the need for staff training

7.Which daily maintenance task is recommended by OEMs for washer-disinfectors?

A.Replacing cleaning indicators

B.Cleaning the drain screen

C.Running extra cycles

D.Reprocessing unused instruments

8.Why is monitoring each washer-disinfector rack important in washer-disinfector performance?

A.To ensure uniform cleaning outcomes across all instrument sets

B.To check water pressure

C.To speed up the thermal disinfection process

D.To avoid using cleaning indicators

9.What is one key benefit of integrating remote diagnostics with washer-disinfector monitoring?

A.It eliminates the need for OEM maintenance

B.It reduces the need for documentation

C.It replaces the need for cleaning indicators

D.It allows facilities to identify performance issues in real time

10.What should be considered when selecting a cleaning indicator for washer-disinfector performance testing?

A.Its sensitivity to detect failures like detergent omission

B.Its ability to clean all instruments regardless of cycles

C.Its compatibility with visual inspection only

D.Its cost-effectiveness over performance

BY DEBRA SAMS

As the year draws to a close, sterile processing (SP) educators and leaders should aim to complete competency assessments, close out calendar audits, address staffing gaps, and manage employee burnout.

Completing annual competencies allows departments to plan and budget for new employees, processes, and equipment for the upcoming year. Further, it allows for assessing employee knowledge and addressing any gaps that may exist. Annual competencies also help ensure technicians’ skills stay current, while providing a safety net during staff shortages that can occur during the holiday season. Assessing competencies provides metrics that allows educators to know who they can utilize as mentors or preceptors to prepare for anticipated staff shortages. SP leaders and educators must assess the work that needs to be done and the volume of that work and implement strategies for this potentially taxing time.

If the operating room (OR) is not experiencing staffing shortages, for example, consider assigning surgical technologists to assemble trays. Although they will need to be trained on the automated system and preparation and packaging assembly, the training should go smoothly if surgical technologists are familiar with the instruments in use. If it is in the budget, SP leaders should consider offering overtime to technicians but

setting a cap on available overtime to prevent excessive hours that can contribute to burnout and diminished quality. Also, they may wish to consider bringing in travelers to help cover breaks and lunch hours during peak times. Instead of working a typical day or evening shift, consider assigning temporary employees off-shift hours, such as 11 a.m. to 7:30 p.m.

It is prudent for the SP leader or educator to conduct a yearend readiness check to address gaps and determine the emphasis of internal audits. It can be helpful to create a year-end calendar that maps out who is responsible for certain tasks and deadlines. Ideally, audits should be automated for ease of accessibility, but if that is not possible, ensure the audits are streamlined and available, especially to those needing to know the results.

is crucial to normalize complicated feelings and practice listening without judgment.

Before the end of the year, schedule inservices on employee burnout, worklife balance and other topics that teach and empower staff to make appropriate trade-offs under pressure. If the facility has an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) or provides mental health support, those details should be shared with employees as well. Leaders should know how to recognize employee burnout and aim to spend more time in the department to lend support, listen to, address concerns, and help during high-volume shifts.

Now is also the perfect time to review completed tasks to ensure that the SP team has practiced quality and

To further address and mitigate employee stress, which can be compounded during the holidays, educators and leaders should ensure employees can safely communicate their needs. Employees need to be heard, and their feelings matter. It

safety throughout the year (or reveal opportunities for improvement). And do not forget to celebrate progress and notable accomplishments.

As we look forward to a fresh start in the new year, SP leaders must ensure their teams have the support, tools and resources needed to succeed in their vital roles. Doing so will help ensure that all SP professionals remain committed to maintaining service quality and keeping their teammates and patients safe. HPN

BY ADAM OKADA

Q: I have a fun question for you: What are the 10 most common mistakes that you see in sterile processing departments today?

A: Last month in Part 11, we had a cliffhanger ending at common mistake #6!

So, where was I? Ah, yes, the IFU issue!

Since I started consulting on facility practices (in nearly every facility I have ever been to), the conversations that occur (with their obvious nuances) have always been essentially the same.

For this play, I will assume the role of Adam while filling in the gaps in the conversation with what I imagine as the internal monologue (or otherwise a terrible case of mistaken identity).

Adam: “How do you access your IFU?”

Tech: “We have them online.”

Adam: “Fantastic! Can you show me the IFU for this shaver?”

Adam points at a shaver on the workstation. The tech looks at Adam in panic. They suddenly realize that they haven’t accessed the online database in years, and they don’t remember how to use it.

Tech (hesitantly): “Um. Suuurrre.”

There is an awkward silence of about 5 minutes (some stalling and changing the subject) while the tech hopes that Adam will forget about asking them for the actual IFU.

After delaying, asking for login information, and trying to navigate a complicated sequence of steps in the database, the tech will eventually show Adam the correct IFU.

The moral of this story is: You may have an online database for your IFU, but can you access it?

This is my second Malinda Elammari reference in this two-part article. Malinda (an international success on the topic of packaging) is known as the “Packaging Princess.” She is one of the industry’s foremost experts on sterile barriers, focusing on issues related to peel pouches.

There are numerous modern-day SPD locations we could go to, but let’s start with the heat sealer. If you have a “bar” heat sealer, did you know that the bar needs to be rotated?

Many departments are not aware of this, but, eventually, they will notice gaps or breaks in their seals due to burns from being sealed in the same spot repeatedly over years. Which brings me to self-seal pouches. Most of the better-quality pouches on the market have a dotted line denoting the section that should be folded over to create a seal directly over the opening at the top of the pouch, thereby creating an airtight seal after sterilization. This is what makes it an effective sterile barrier; however, I’ve seen much variation here.

I see low-quality (read: cheap) pouches that don’t have a line, which makes us guess as to where the fold should go, or techs go too quickly during the folding process and seal off-center or leave big gaps in the seal. Regardless of the issue, if there is a gap in the seal, you will not have a sterile barrier. I guess a better name would be that your device is not in an unsterile, loose, open bag. But that name doesn’t have a great ring to it, especially to a surveyor

On the main stage at the 2025 HSPA conference in Louisville, Ky., Cori Ofstead spoke about the dangers of shavers, their complexity, and how difficult (nigh impossible) they can be to clean properly.2 Even following the cleaning IFU to the letter often doesn’t produce a clean device.

Last year, at the 2024 HSPA conference in Las Vegas, Ofstead spoke about—um—the dangers of shavers, their complexity, and how difficult (nigh impossible) they can be to clean properly.3

Noticing a theme yet?

Healthmark’s “Ask the Educator Podcast”4 has done almost a half-dozen podcasts on the dangers of shavers going back to the very first episodes in 2020.

These devices are complex, difficult to clean, and most departments are woefully unaware of how dangerous they can be. So spread the word to everyone in the industry that you see!

Look at your shavers. Inspect them with a borescope. Take pictures and videos of the nasty stuff that’s stuck inside and send them to me. I have a rapidly growing collection.

And the silver medal goes to—it’s a tie!

Yes, I am cheating here and including two subjects for the price of one, but these two often go together at departments that find themselves in hot water with surveyors.

Policies

Let’s start with policies. Surveyors survey according to regulations, standards, best practices, and other documents, but they are primarily surveying the facility’s own policies. This is like taking an open-book test. We write our own policies, and we can write them so that we are in compliance with them. But it rarely works out that way.

I’ve seen a lot of old, dusty, out-of-date policies with strange references from bygone eras in them. This is usually the first place I point to for a new manager, director, supervisor, educator, or whoever is in charge of reviewing policies to start. Check the policies to see if the references are current and applicable to your actual practices.

The story with competencies is similar, which is why I included them together.

At the end of a survey, surveyors want to see the competency documentation for the staff they spoke with. Sometimes, those competencies either can’t be found, haven’t received an annual update (with a job title change), or never existed in the first place.

Moral of the story: If you’re looking for a life hack on dealing with surveyors, start with your policies and competencies.