Sustainable Trade Index

The race for resilience 2024

Chief Executive Officer

Hinrich F o undation

In recent times, the need to achieve and maintain resilience in our economies has had a powerful influence on trade policy. At the Hinrich Foundation, we believe that global trade has the power to strengthen relationships between nations and improve people’s lives. We also recognize that this potential can only be fully realized when trade is mutually beneficial and sustainable.

The Sustainable Trade Index (STI) allows us to track how effectively trading economies are meeting the three pillars of sustainability: economic growth, societal advancement, and environmental stewardship. Achieving balanced outcomes between the three pillars is essential for resilience.

As they navigate the challenges of balancing open trade with prudent societal and environmental policies, the 30 economies tracked by the STI are each at different stages of their trade sustainability journey. Policymakers must juggle domestic perceptions of the benefits and disadvantages of open trade whilst at the same time pushing back on the industrial policies and manufacturing overcapacity of their trading partners.

Despite these challenges, some trading nations are making notable progress in promoting sustainable trade and building their resilience. The STI spotlights their efforts and, at the same time, identifies areas where others are falling behind. It serves as a vital reminder that we must remain steadfast in our commitment to achieving balanced economic, societal, and environmental outcomes through global trade.

We are delighted to unveil the 2024 Hinrich-IMD Sustainable Trade Index (STI). Global trade growth is as predicted rebounding in 2024, after a slowdown in 2023. The path ahead, however, will not be linear, as geopolitical strains and climate change factors create risk and complexity. In addition, trade growth is proving uneven across regions: Europe is performing below par, while other regions are exceeding expectations.

The STI is intended to add some order to the chaos, with data presented in three pillars: economic, societal, and environmental.

At the IMD World Competitiveness Center, we believe that trade is a driver of national economic competitiveness, but that it should also be a means for achieving global economic, social, and environmental goals. We also know that cooperation delivers better outcomes for global prosperity.

Our findings this year highlight how protectionist policies are reshaping the global flow of goods and services. The STI’s tracking of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade has underscored the growing complexity and fragmentation of the global trade landscape. The question is, how can we encourage cooperation going forward?

We are delighted to see the rise of mid-ranking countries such as Vietnam, Chile, and Thailand in this year’s STI. For Vietnam to achieve sustainable growth, a major challenge is to diversify the risks of a trade structure that relies on certain export items and to stabilize the power supply. Chile, meanwhile, signed a seminal agreement with the EU in December 2023 to strengthen political cooperation and foster trade and investment. OECD recommendations for Thailand are to introduce carbon pricing consisting of a mandatory cap-and-trade system for key sectors and a complementary carbon tax for the remaining sectors, consistent with the country’s planned emission trajectory to net zero.

We hope this report will serve as a valuable resource and reference for all those who operate in the public and private sectors to build cooperative trade policies that support sustainable development.

The Hinrich-IMD Sustainable Trade Index (STI) offers a detailed analysis of how countries manage the complex interplay between economic growth, societal well-being, and environmental stewardship within the global trade system. As the world emerges from the pandemic, resilience has become a central theme, shaped by concerns over future health crises, climate change, and geopolitical tensions. In response, industrial policies and economic alliances are increasingly focused on building resilience, contributing to a noticeable shift in global trade systems. This year’s STI identifies three major trends driving sustainable trade:

1. Global trade is undergoing a protectionist reconfiguration, with nations adopting policies to strengthen domestic industries and secure supply chains. There is a growing emphasis on industrial policy and trade barriers, reflected in a rise in both tariff and non-tariff barriers in this year’s STI and a shift towards prioritizing national resilience over global trade interdependence.

2. Workforce resilience plays a critical role in sustainable trade. A strong, healthy, educated workforce allows economies to better withstand shocks and seize emerging opportunities. In recognition of this, the STI has this year introduced a new indicator – Universal Health Coverage from the WHO’s Global Health Observatory – bolstering the healthcare aspect of societal resilience.

3. Environmental sustainability remains paramount. Trade policy and climate goals are increasingly aligned. The STI tracks global commitments to environmental conventions, revealing a steady rise in efforts to integrate sustainability into trade. This reflects a broader global push towards greener economies, where trade policies and environmental stewardship work handin-hand.

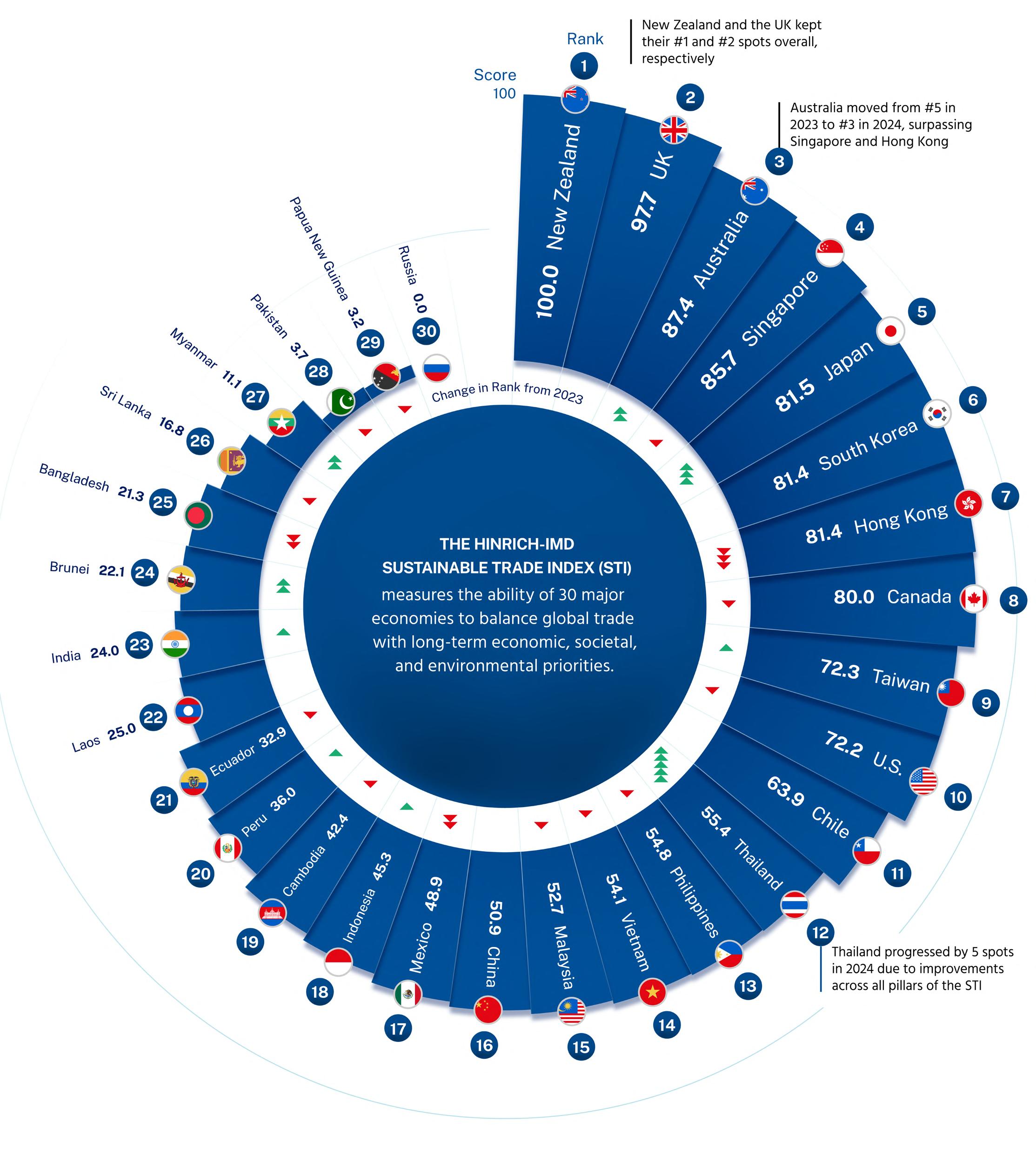

The 2024 results see New Zealand followed by the United Kingdom as the top two performers for the third consecutive year. Australia climbs two spots to take third place, while Singapore and Hong Kong SAR are ranked fourth and fifth, respectively. The top performers demonstrate they are achieving a strategic balance across economic, societal, and environmental pillars.

The economic pillar reveals that top-performing countries excel through strong technological infrastructure, innovation, and efficient trade policies, including low tariff and non-tariff barriers to enhance trade competitiveness and attract foreign investment. They also exhibit robust GDP growth, controlled inflation, labor force expansion, and diversification in exports and trading partners, key indicators of economic resilience. Countries like Hong Kong SAR, the United States, South Korea, China, and the United Kingdom lead in this pillar.

In the societal pillar, countries that prioritize labor rights, political stability, and social mobility tend to perform best. These economies promote inclusive growth, safeguard labor standards, and provide quality healthcare and education, creating resilient workforces. Such societal investments foster both economic and social stability. New Zealand, Canada, Australia, Taiwan, and Singapore rank highest in this pillar, excelling in fostering societal resilience.

The environmental pillar underscores the importance of sustainability within the trade framework. Countries that rank highly in this area, such as New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Mexico, and Australia, are distinguished by their strong environmental regulations and commitments to international environmental agreements. These nations effectively manage carbon emissions, maintain low pollution levels, and prioritize renewable energy sources. Their efficient use of energy, combined with policies aimed at reducing their ecological footprints, positions them as global leaders in sustainable trade.

This edition also highlights “rising stars” – countries in the middle of the index that are making significant strides.

Ultimately, the STI serves as a vital benchmark for economies seeking to navigate the interconnected challenges of global trade. By promoting technological innovation, fostering societal well-being, and enforcing stringent environmental standards, leading nations offer a blueprint for harmonizing economic growth with long-term sustainability. And, as the geopolitical and economic landscapes continue to shift, the STI remains an essential tool for building a more resilient and sustainable global economy.

We are excited to unveil the third edition of the Hinrich-IMD Sustainable Trade Index (STI), a comprehensive ranking that explores the delicate intersection between economic growth, societal well-being, and environmental stewardship for economies engaged in global trade. The STI evaluates how 30 diverse economies are prepared to thrive in the global trade system while balancing these three interdependent dimensions.

Post-pandemic, policy narratives focus on promoting an ‘era of resilience’. In anticipation of potential future pandemics, climate issues, and geopolitical shifts, we are seeing a surge in industrial policy designed to build economic resilience whilst at the same time fragmenting the global trading system. This is the first key trend in this year’s STI.

People are at the heart of resilience. A resilient workforce, as we explore in our second key trend, facilitates recovery from external shocks by enabling businesses to recalibrate supply chains, diversify product offerings, explore new markets, and enhance productivity. An economy’s resilience therefore requires a healthy, educated, and unexploited workforce.

There is also the pressing issue of climate resilience, as seen in the third key trend . The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by all UN member states set an ambitious and sometimes conflicting agenda to be achieved by 2030; in just six years’ time. Sustainability is demanding our attention, but there is a catch: tackling climate change and the related externalities often requires regulatory interventions, whereas global trade flourishes with fewer barriers and regulations.

In the race to achieve resilience, how do we reconcile these seemingly opposing demands? The answer lies in innovative thinking, a willingness to adapt, and an integrated approach that considers many factors simultaneously.

The STI aims to guide us through the complexities of global trade, offering essential insights for the practice of sustainable trade. By sustainable trade, we mean trade that delivers mutually acceptable benefits between trading partners and achieves balanced economic, social, and environmental outcomes.

Countries are increasingly turning to industrial policy as part of their resilience-building efforts, regardless of whether it is sustainable in the long term. Rising geopolitical tensions have led many economies to adopt policies with two primary objectives: first, to protect and strengthen domestic industries while reducing reliance on imports, and second, to secure the availability of intermediate products (i.e., component inputs to end products) and build more resilient supply chains.

Examples of such policies are plentiful and impactful. From China’s Dual Circulation Strategy to the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme, the United Kingdom’s Post-Brexit Trade Policies, and the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), such initiatives are reshaping the global flow of goods and services.

This trend does not seem to be a temporary shift but a longer-term reconfiguration of global supply chains and trade interactions. The STI monitors this significant trend by tracking both tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. Between 2023 and 2024, we observed a substantial increase in these barriers across the 30 economies we analyzed. Tariff barriers jumped from approximately 19,000 in 2023 to 21,500 in 2024, while non-tariff barriers have risen from 392,000 in 2023 to 483,000 in 2024. These figures underscore the growing complexity and fragmentation of the global trade landscape.

Navigating the intersection of economic growth, societal well-being, and environmental responsibility requires a resilient workforce; one that can adapt to rapid changes and cope with setbacks. The STI measures the resilience of the workforce and, by extension, of society, using the following key components:

The health of the workforce is a critical factor in societal resilience. This year, we introduced the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) indicator, recognizing that access to healthcare is essential for maintaining a productive and resilient workforce. The UHC is closely linked to the overall income level of an economy and serves as a foundation for the well-being of society.

Education is another key component of resilience. In the STI, we measure educational attainment, which equips the workforce with the skills and flexibility needed to navigate economic challenges and seize new opportunities. A well-educated workforce is better prepared to adapt to changes and contribute to sustainable economic growth.

Additionally, there is a need to recognize and mitigate the adverse effects that economic expansion and production can have on human labor. By eliminating labor exploitation in the production of goods, we significantly enhance societal well-being. The STI evaluates these adverse effects by measuring indicators such as forced and child labor, human trafficking, and modern slavery. Raising awareness of these issues is crucial, as evidenced by the European Parliament’s April 2024 regulation prohibiting the import and export of goods made by forced labor. Expanding such actions will help minimize these exploitative practices and promote social justice.

Trend 3: Improving environmental sustainability while enhancing trade

The urgency of addressing climate change has become a central focus of many industrial policies today. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are key examples, alongside Canada’s Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act and Japan’s Green Growth Strategy. These initiatives aim to achieve carbon neutrality, often by incorporating actions aligned with the SDGs into domestic policies.

In July 2024, trade ministers from Costa Rica, Iceland, New Zealand, and Switzerland concluded negotiations for the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade, and Sustainability (ACCTS). This landmark agreement, which aims to eliminate tariffs on environmental goods, and facilitate trade in environmental and environmentally related services, represents a step towards reconciling the paradox of promoting open trade while addressing climate change.

Within the STI, we account for a range of international conventions that address climate externalities, from hazardous wastes and chemicals to marine pollution, timber, ozone depletion, endangered species, and climate change itself. We track the number of countries in our sample that ratify and implement these conventions, and the trend is clear: more countries are stepping up, albeit modestly, to meet these global environmental commitments. In the following section, we will delve into the findings of this year’s STI, highlighting the top performers and examining the strengths and weaknesses of the countries reviewed. Although the way forward is complex, economies can collectively build a more sustainable and resilient global trade system with the right insights and strategies.

The STI analyzes 30 economies including members and applicants of major trade alliances such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

To provide a comprehensive evaluation, the index employs 72 indicators, which are categorized into three pillars: economic, societal, and environmental.

The economic pillar assesses an economy’s ability to stimulate and sustain economic growth through international trade. It evaluates the quality of trade-related infrastructure, the investment climate, business accessibility, and the presence of trade barriers. Additionally, it considers the diversification of trade partners and the concentration of exports in specific goods. The indicators provide insights into how effectively an economy can navigate and capitalize on global trade opportunities.

The societal pillar focuses on the social dimensions that underline the development of human capital essential for international trade. It examines educational attainment and labor standards which are critical for building a skilled labor force. Moreover, it assesses the societal readiness for trade expansion by considering factors such as income inequality, political stability, and the prevalence of exploitative practices like child labor, forced labor, and human trafficking in an economy’s trade activities. It evaluates how well an economy manages to balance the benefits of economic growth through trade with the social costs associated with increased trade and, therefore, with the needs and welfare of its population.

The environmental pillar evaluates how an economy manages its natural resources and mitigates the environmental impact of its economic activities, particularly in the context of global trade. It looks at responsible stewardship over natural resources and efforts to reduce negative externalities. Key indicators include levels of air and water pollution, adherence to national environmental standards, carbon emissions, and a reliance on natural resources within export portfolios. This pillar is critical in understanding the ecological implications of trade practices and how an economy integrates environmental sustainability into its growth strategy.

Together these pillars provide a detailed and balanced perspective on each economy’s performance in the global trading system, making sure that economic progress is weighted alongside societal well-being and environmental responsibility. The STI is designed to provide public and private sector decision-makers, as well as practitioners, with actionable insights into the strengths and challenges faced by economies involved in these critical trade partnerships.

2.1 The top 10 and their evolution between 2023 and 2024

Figure 2 presents the top 10 economies in the STI 2024

2.2 Key takeaways from the top 10

New Zealand retains its top spot for the third consecutive edition, given an outstanding performance across all pillars. The economy climbed one place in both the economic pillar, where it now ranks seventh, and the societal pillar, where it holds first position. New Zealand continues to lead in the environmental pillar.

The United Kingdom (UK) also remains second for the third edition in a row. Compared to 2023, the UK has slipped one place to sixth in the economic pillar but held steady at fourth in the societal pillar and second in the environmental pillar.

Australia rose to third place overall, improving by two positions. This success is due to gains across all pillars. In the economic pillar, Australia gained two positions to reach 10th and maintained third place in the societal pillar. The most significant progress was in the environmental pillar where Australia jumped four spots, up to sixth from 10th last year.

Singapore dropped one position to fourth this year. It slipped to second in the economic pillar, losing one place, but improved in the societal pillar climbing two spots to sixth from eighth last year. However, Singapore fell five places in the environmental pillar, now ranking 10th.

Japan improved its overall ranking by three positions, reaching fifth from eighth last year. Despite a slight decline in the economic pillar, dropping one spot to 11th, and a three-position fall in the societal pillar to eighth from fifth, Japan made a significant improvement in the environmental pillar, climbing eight positions to fourth from 12th last year.

South Korea remains in sixth in the overall ranking. Although it lost one position in the economic pillar, now ranking third, it held steady at seventh in the societal pillar. South Korea saw an improvement in the environmental pillar, moving up two positions to 15th from 17th last year.

Hong Kong, SAR fell three positions to seventh. At the pillar level, Hong Kong gained two positions to top the economic pillar. However, it remained 10th in the societal pillar and seventh in the environmental pillar.

Canada lost one position to take eighth. In the economic pillar, the country gained one position to take eighth. However, it fell one place in the societal pillar, ranking second. In the environmental pillar, Canada gained one position, ranking 18th – up one from 19th last year.

Figure 3

Bottom 10 economies in the STI 2024

Taiwan gained one position to take ninth. While it dropped three positions (to ninth) in the economic pillar, it gained one spot in the societal pillar, ranking fifth from sixth last year. Taiwan made a notable leap in the environmental pillar rising ten positions to 17th from 27th in 2023.

The United States dropped one position to take 10th in the overall STI ranking. The country maintained its fourth place in the economic pillar and was ninth in the societal pillar, but it fell one position in the environmental pillar, now ranking 16th compared to 15th last year.

2.3 The bottom 10 and the evolution between 2023 and 2024

Figure 3 presents the bottom 10 economies in the STI 2024

2.4 Key takeaways from the bottom 10

Ecuador dropped one position to 21st in the overall ranking. Despite this, the country saw an improvement in the economic pillar, moving up one position to 23rd from 24th last year. Ecuador made a significant improvement in the societal pillar, climbing three places to 13th. However, it experienced a setback in the environmental pillar, dropping three positions to 21st from 18th last year.

Laos maintained its 22nd place in the overall ranking. It gained one place in the economic pillar, rising to 28th from 29th. However, it faced challenges in the societal pillar, falling by four places to 23rd from 19th, and in the environmental pillar where it dropped two positions to eighth from sixth last year.

India moved up by one position to 23rd in the overall ranking. The country made notable gains in the economic pillar, climbing three places to 16th from 19th while it retained 28th place in both the societal and environmental pillars.

Brunei improved by two positions to reach 24th in the overall STI ranking. At the pillar level, Brunei retained 21st place in the economic pillar and 29th in the environmental pillar. However, it gained a position in the societal pillar, now ranking 17th.

Bangladesh dropped two spots to 25th in the overall ranking. Bangladesh lost one position in the economic pillar, ranking 24th, while it retained its positions in both the societal pillar at 26th and the environmental pillar at 22nd.

Sri Lanka dropped one place to 26th. In the economic pillar, it gained one spot moving up to 29th. However, the country lost three positions in the societal pillar, ranking 16th. A notable decline is visible in the environmental pillar, where the economy dropped by seven places to 23rd.

Myanmar advanced by two places to 27th in the overall ranking. Despite its overall improvement, Myanmar fell one spot in the economic pillar, coming in at 27th, and five spots in the environmental pillar moving to 26th from 21st last year. On the positive side, the country gained one position in the societal pillar, ranking 29th.

Pakistan dropped by one position to 28th place. While Pakistan declines by two places in the economic pillar – now at 30th – the country retains its 27th spot in the societal pillar. In the environmental pillar, Pakistan moved up by two positions to 24th.

Papua New Guinea also dropped by one position to 29th in the overall ranking. The country made a slight improvement in the economic pillar, rising to 26th from 27th last year. However, in the societal pillar, Papua New Guinea slipped one position to rank 30th, and in the environmental pillar, the country dropped by two positions to 27th.

Russia remains at the bottom of the overall STI ranking. The country retained 25th place in the economic pillar and 30th place in the environmental pillar. However, in the societal pillar, Russia gained two positions to rank 22nd.

Economies positioned in the middle of the index demonstrate notable positive trajectories and from year to year, we see some competitive movements amongst them. Some of these economies have shown consistent progress or stability over the last three years. Three of them stand out:

Thailand ranked 15th in 2022, before slipping to 17th in 2023. In 2024, it has rebounded impressively by five positions to reach the 12th spot. This resurgence is driven by its consistent improvement across all pillars: in the economic pillar, it returned to 12th from 14th in 2023; in the societal pillar, it maintained its three-position increased between 2022 and 2023 to hold onto 12th; and in the environmental pillar, the country improved by five places to reach 19th position.

Vietnam’s upward trajectory is also striking; it went from 20th place in 2022 to 14th in 2024, a substantial six-place rise fueled by improvements across all pillars. In the economic pillar, Vietnam has progressed two places each year since 2022 (when it was 17th), to secure 13th in 2024. Similarly, the environmental pillar has enjoyed a four-place improvement over the same period, to reach 13th in 2024. Finally, the societal pillar mirrors this steady improvement with Vietnam rising one position each year, moving from 16th in 2022 to 14th in 2024.

Chile stands out for its consistency, maintaining 11th position in the last three editions. Its stable performance reflects balanced rankings across all pillars. In the economic pillar, Chile reached 15th place in 2024, the same position it held in 2022. Its societal pillar performance remained stable at 11th place across all editions. However, in the environmental pillar, Chile’s path was more varied. After dropping from ninth place in 2022 to 14th in 2023, it rebounded to 11th in 2024.

These mid-ranking countries exhibit adaptability and strategic foresight. Their progression, resilience, and balanced development in the STI offer valuable lessons for nations striving to enhance their rankings and overall performance.

Figure 4 Economic pillar indicator list

Hong Kong SAR reclaimed the top spot after dropping to third place in 2023, and this return to form was driven by several factors. The postpandemic economic recovery played a significant role in boosting real GDP growth. An improvement in the economy, combined with the relaxation of immigration policies, led to a notable increase in labor force growth compared to the previous year. Additionally, Hong Kong saw significant improvements in tariff and non-tariff barriers indicators, securing the top position in both categories, which further enhanced its position in this pillar.

Hong Kong continues to excel in technological infrastructure, where it holds first position, as well as in foreign trade and payments risk, ranking second, and technological innovation, where it is placed seventh. However, there were some declines relative to 2023, particularly in high technology exports as a percentage of manufactured goods and in consumer price inflation, ranking fourth in both from first the year before. Moreover, Hong Kong exhibits significant concentration in both export destinations and exported products.

Despite losing its top position since last year, Singapore continues to perform exceptionally well, securing second place in the economic pillar. The nation’s strong emphasis on technological infrastructure and trade liberalization is evident as it ranks second in these areas. Additionally, Singapore’s ranking of third in technological innovation underscores its role as a key driver of its success. The country excels in trade-related factors, with top rankings in trade costs, including logistics, rule of law, and perceptions of corruption.

Singapore also made significant strides in labor force growth, advancing from 27th to ninth place. This improvement is partly due to new measures aimed at supporting wages by upgrading skills across an increasing number of sectors.

However, challenges remain, such as its 23rd place in real GDP per capita growth and inflation management, where it ranked 16th. Two additional challenges include a decline in Singapore’s ranking related to tariff and nontariff barriers dropping from 12th to 22nd, primarily due to issues with the non-tariff barriers in force. The country also faces difficulties in monetary policy intervention where it is currently ranked last.

Nevertheless, Singapore’s innovative culture, diversified trade portfolio,and strong domestic credit to the private sector make it a highly appealing destination for international investors. This is reflected in its second position for net inflows of foreign direct investments.

South Korea dropped one place to third in the economic pillar. The country remains a leader in technological innovation, leading in R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP and in patent applications. South Korea ranks third in technological infrastructure, boasting the highest number of fixed broadband subscriptions among those countries analyzed.

Committed to trade liberalization, South Korea ranks seventh in this indicator, with strong performances in capital account liberalization and regional trade agreements. The economy benefits from robust domestic credit to the private sector and favorable foreign trade and payments risk, ranking sixth in both categories.

However, challenges remain in enhancing economic resilience. The country ranks 22nd in labor force growth, a critical area for improvement given its demographic challenges. Additionally, South Korea saw a decline in real GDP growth per capita, dropping from 12th in 2023 to 22nd in 2024, and a drop in inflation from 10th in 2023 to 12th in 2024. These declines, combined with a high export concentration, where it ranked 24th – down from 10th last year – and a high concentration of trading partners, where it fell to 27th from 14th, could weaken the economy’s resilience.

Another challenge is the worsening of the standing in the tariff and nontariff barriers, with non-tariff barriers ranking 18th down from 15th. Despite these challenges, South Korea remains a top performer, though it must focus on maintaining its competitive position.

The United States (US) retained fourth position, thanks to strong performances in technological infrastructure, where it ranks fifth, and innovation, where it took sixth place. The country’s strength in innovation is a result of its excellent ranking in R&D expenditures (second), patent applications (fourth), and researchers per capita (eighth).

The post-pandemic economic recovery contributed to a decrease in inflation (improving to 15th from 23rd) and an increase in real GDP growth per capita (rising to 15th from 18th).

China advanced two positions to secure fifth place. The post-pandemic economic recovery boosted China’s real GDP per capita growth, elevating it to fourth place, an increase of six positions from the previous year. China also maintained its leading position in consumer price inflation and gross fixed capital formation. Additionally, it achieved second place in the exports of goods and services. Figure 5

In terms of trade, the US remains a dominant force, ranking first in exports of goods and services, fourth in export concentration, and eighth in trade costs. However, ongoing trade tensions and policy changes have introduced uncertainties. The US continues to rank last in tariff and non-tariff barriers. An additional challenge is the decline in the labor force growth rate, where it fell from 12th to 17th.

China’s strong exporting economy benefits from solid technological infrastructure (ranked 12th) and technological innovation (11th place). The country ranks fifth in R&D expenditures, sixth in patent applications, and ninth in high-technology exports as a percentage of total exports. Moreover, China exhibits a strong presence in managing trade costs (14th place) and foreign trade and payments risk (12th place). Finally, China holds sixth place in exchange rate stability.

However, China faces significant challenges, including its 25th ranking in trade liberalization and 28th in tariff and non-tariff barriers. The country is also ranked 23rd in monetary policy interventions. One of the most pressing challenges is the demographic issue and weak growth in the labor force, where China ranks 28th.

6

7

Papua New Guinea advanced to 26th place, reflecting the persistent structural challenges it faces. The country ranks last in technological infrastructure, which significantly contributes to its struggles with high trade costs (25th), low exports of goods and services (29th), and limited foreign direct investments, despite an improvement to 23rd from 30th last year. In terms of trade, there was a slight improvement in exchange rate stability (20th), but the country remained relatively unchanged in areas like foreign trade and payments risk (24th), trade liberalization (28th), and export concentration (29th). However, Papua New Guinea shows strength in tariff and non-tariff barriers, where it ranks seventh. This, combined with low inflation (seventh) and high labor force growth (12th), has contributed to an improved ranking in real GDP growth per capita (13th).

Myanmar dropped one place to 27th. The country faces significant challenges, particularly in technological infrastructure (28th) and technological innovation (30th) which in turn affects its performance in exports of goods and services (27th), trade liberalization (29th), and trade costs (30th).

The macroeconomic situation reveals high inflation (29th) and relatively high export concentration (20th). However, Myanmar saw notable improvements in real GDP per capita growth (14th, up from 25th last year) and labor force growth (14th, up from 30th in 2023). The country ranks well in monetary policy intervention (fifth) and foreign trade and payments risk (ninth), as well as tariff and non-tariff barriers (16th). To achieve sustainable economic growth, Myanmar needs to focus on improving infrastructure and trade openness.

Laos improved to 28th place in the economic pillar, showing gains in macroeconomic areas. The country saw a substantial rise in real GDP per capita growth, moving to eighth place from 22nd, and labor force growth improved to 10th. Despite a decline, Laos still holds a strong position in foreign direct investment (eighth). However, Laos continues to struggle with high inflation (28th), poor exchange rate stability (30th), and high foreign trade and payments risk (29th). The country also faces challenges in its technological infrastructure (28th), technological innovation (23rd), and trade costs (27th). Laos ranks 26th in trade liberalization and has substantial export concentration (23rd) but it does show a commitment to open trade, ranking ninth in tariff and non-tariff barriers.

Sri Lanka gained one place in 2024 reaching the 29th position. The macroeconomic framework exhibits substantial structural issues. The country ranks last in inflation, real GDP per capita growth, and foreign trade and payments risk. It ranks 29th in labor force growth, and 25th in exchange rate stability. Investor confidence is low, as reflected by its 21st place in foreign direct investments. Structural weaknesses are also evident in trade, with low rankings in technological innovation (28th), technological infrastructure (23rd), and exports of goods and services (26th). Despite

these challenges, Sri Lanka ranks 14th in tariff and non-tariff barriers, although it sits at the bottom in trade liberalization.

Pakistan ranks last in the economic pillar, reflecting the numerous challenges it faces. The country suffers from low economic growth (28th), high inflation (27th), poor exchange rate stability (29th), and low domestic credit to the private sector (27th). Technological infrastructure challenges are evident in its 29th position in this measure, and it struggles with technology innovation, ranking 27th. Pakistan also has relatively high tariff and non-tariff barriers (21st), low trade liberalization (22nd), and high trade costs (21st). While export concentration is relatively low (11th), there is a mixed picture: the country has a high number of trading partners (sixth), but its export products are highly concentrated (20th).

In summary, the economic pillar analysis reveals that top-performing countries excel in technological infrastructure, which is vital for innovation, trade efficiency, and economic resilience. Additionally, effective trade policies – including low tariff and non-tariff barriers – are essential for enhancing trade competitiveness and attracting foreign investment. Strong performances in real GDP growth, inflation control, and labor force growth are also critical. Lastly, maintaining a well-diversified export base with multiple trading partners contributes to economic resilience.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Societal pillar indicator list

2.01

2.05

2.06

2.07

2.08

2.09

2.10

2.11

New Zealand excels in the societal pillar, ranking first overall. This top position is sustained by a slight improvement in labor standards, moving second place from third last year, demonstrating the country’s strong commitment to gender equality and worker protection. New Zealand also maintains second place in political stability and absence of violence, which, alongside its efforts to promote even economic development, ensures a safe and inclusive environment with equal opportunities for all. The country also does well for its strong stand against goods produced by forced labor or child labor, ranking fourth, and in goods at risk of modern slavery where it ranks seventh. Additionally, New Zealand continues to perform well in government response to human trafficking (12th). Importantly, New Zealand is holding steady at seventh place in educational attainment which contributes to its overall societal resilience, meaning the existence of a more educated workforce that can cope better with uncertainty in market conditions.

Canada ranks second in the societal pillar slipping from its previous first-place position. The decline is primarily due to a drop in labor standards falling from first to fifth and a decrease in political stability and absence of violence where it now ranks seventh down from fifth. The country also saw a two-place drop in its ranking for trade in goods at risk of modern slavery, now at 17th.

Despite these declines, Canada continues to excel in key areas ranking first in social mobility, even economic development, and universal health coverage, which ensures widespread economic and health benefits across society. Canada also maintains a strong educational attainment ranking at fifth and continues to address the adverse effects of trade by holding a strong position against goods produced by forced labor (sixth) and responding to human trafficking (fifth).

Australia retains its third place in the societal pillar by building on its existing strengths. The country significantly improved its labor standards, moving up to third place from eighth last year, and improved its ranking in political stability and absence of violence, now at fifth. However, there was a noticeable decline in its performance in trading goods at risk of modern slavery dropping to 22nd from 13th. In addition, life expectancy fell to fifth from third.

Despite these setbacks, the country has a strong standing towards other adverse effects of trade such as goods produced by forced or child labor and the response of the government to human trafficking, both ranked third. Australia also ranks fifth in universal health coverage and maintains strong positions in even economic development (second), social mobility (third), and educational attainment (third), ensuring an equal and inclusive distribution of benefits within the society.

The United Kingdom (UK) maintains its fourth place primarily by strengthening its existing performance in key areas. The economy performs admirably in educational attainment, improving its ranking by one position to second and increasing its labor standards ranking to seventh from ninth.

However, the UK experienced a significant decline in its ranking for trading goods at risk of modern slavery by dropping to 24th from 16th. It also lost a position in political stability and absence of violence, now ranking 11th, and in even economic development which is now at ninth.

Despite these declines, the UK holds strong positions in other areas, ranking first in the government’s response to human trafficking, and fifth in goods produced by forced or child labor. The UK also ranks fifth in social mobility and fourth in universal health coverage.

Taiwan advanced to fifth place in the societal pillar, driven by improvements in key indicators. The country moved up one position in educational attainment – to eighth – and made significant progress in reducing the trade of goods at risk of modern slavery, jumping four positions to 18th. Taiwan remains committed to addressing the negative impacts of trade, where it ranks seventh in its response to human trafficking; and eighth in addressing goods produced by forced or child labor. Despite a slight decline in political stability and absence of violence, where it now ranks eighth, Taiwan continues to perform admirably in balancing societal well-being with the benefits of trade.

1-year rank +/-

Bangladesh remains in 26th place, holding onto some of its previous strengths while showing improvement in a few indicators. The country saw a significant decline in the ranking for traded goods produced by forced or child labor, dropping to 28th from 22nd, and a slight decline in its response to human trafficking, falling to 15th.

Major challenges persist in educational attainment (25th), labor standards (26th), and political stability and absence of violence (28th). In the newly included indicator for 2024, universal health coverage, the country ranks 26th.

However, Bangladesh made notable progress in the ranking for traded goods at risk of modern slavery, improving to ninth from 12th and it enjoys a relatively high ranking in income inequality, positioning seventh. Prioritizing making progress in areas like even economic development (23rd), and social mobility (23rd) could improve the societal well-being of its citizens.

Pakistan retains 27th place with mixed performance across various indicators. The country saw further declines in educational attainment (28th), life expectancy at birth (28th), government response to human trafficking (22nd), and goods produced by forced and child labor, where it dropped three places to 29th. Political stability and absence of violence also rank poorly at 29th.

Pakistan’s performance in social mobility (24th) and universal health coverage (27th) remain weak. However, the country saw a significant improvement in the ranking for trade in goods at risk of modern slavery, jumping 10 positions to 10th, and it tops the ranking for income inequality. Despite a drop to 16th in labor standards, these improvements may provide a foundation for future progress in social capital.

India remains in 28th place in this pillar, with several indicators showing no change. Improvements are needed in areas such as life expectancy at birth (26th), educational attainment (24th), social mobility (22nd), and universal health coverage (29th). The country experienced a significant decline in the ranking for traded goods produced by forced or child labor where it now places last.

Myanmar moved up one position to 29th in the societal pillar, exhibiting modest improvements in some indicators. The country made substantial gains in trade in goods at risk of modern slavery, moving up to 11th from 21st, and in goods produced by forced or child labor, improving to 17th from 30th. Life expectancy at birth also increased by one position to 27th, the same position as even economic development.

However, Myanmar still faces considerable challenges, ranking 26th in educational attainment and 24th in universal health coverage. The country’s labor standards remain very low, and it ranks last in terms of political

stability and absence of violence. Its highest-ranked indicator is the Gini coefficient where it takes second place. Nevertheless, these rankings highlight some deep-rooted social and economic challenges, and the country needs to build a strategy to address these effectively.

Papua New Guinea dropped one position to rank last (30th), illustrating its significant challenges in both economic and social dimensions. The country ranks 30th in educational attainment and the government’s response to human trafficking. It ranks 29th in life expectancy at birth, and 28th in both economic development and universal health coverage. The economy is characterized by low labor standards, poor political stability and absence of violence (the latter two forming one indicator), ranking 23rd across the board.

However, Papua New Guinea performs well in the areas of goods produced by forced or child labor and trade in goods at risk of modern slavery, ranking second in both. To improve societal well-being, Papua New Guinea would benefit from developing a clear strategy towards focusing on enhancing these critical areas.

In summary, countries that excel in the societal pillar exhibit a strong commitment to key indicators such as labor standards, political stability, social mobility, and even economic development. These nations effectively safeguard labor rights, maintain stable political environments, and promote inclusive economic growth alongside high levels of educational attainment.

Figure 16

Environmental pillar indicator list

Indicator

3.01 Air pollution, PM2.5 micrograms per cubic metre

3.02 Deforestation, index

3.03 % of wastewater treated

3.04 Energy intensity, energy consumed for each US$1,000 of GDP in TOE

3.05 Ecological footprint

3.06 Renewable energy, %

3.07 Environmental standards in trade, count

3.08 Transfer emissions, million tonnes carbon

3.09 Share of natural resources in trade, %

3.10 Carbon

New Zealand retains first place in the environmental pillar and continues to excel across multiple indicators. The country remains first in air quality (having the lowest air pollution) and adoption of environmental standards in trade, showcasing its commitment to environmental quality. Although it dropped to third place in share of natural resources in trade, it improved to take fourth place in renewable energy usage and sixth in energy intensity. Additionally, New Zealand ranks fifth in carbon and 10th in the percentage of wastewater treated, reflecting its effective natural resources management and low carbon intensity.

However, despite these strengths, New Zealand faces some challenges. The country ranks 14th in deforestation, 18th in transfer emissions, and 20th in ecological footprint. These figures highlight that even the top economy in the environmental pillar needs to address significant environmental challenges to continue its economic growth in a sustainable manner.

The United Kingdom (UK) maintains second place, driven by a strong performance across several key indicators. The UK remains an active participant in international environmental agreements, ranking first in environmental standards in trade and improving to take second place in transfer emissions. The country also performs robustly in energy intensity (second), wastewater treatment, and carbon (both fourth). Additionally, the UK ranks sixth in air pollution and eighth in deforestation.

However, challenges persist, particularly in the areas of ecological footprint (16th), renewable energy usage (17th), and share of natural resources in trade (20th).

The Philippines climbs to third place in the environmental pillar, reflecting a mix of strengths and challenges. The country ranks first in environmental standards in trade and shows solid performance in ecological footprint (fifth), renewable energy (sixth), share of national resources in trade (seventh), and transfer emissions (eighth). Notably, the Philippines witnessed a significant improvement in carbon indicators, rising from 18th to ninth place, and holds 10th place in energy intensity.

Challenges for the Philippines include wastewater treatment (12th), air pollution (18th), and deforestation (19th). However, its overall strong performance underscores the country’s commitment to environmentally sound trade practices.

Figure 17

Japan made a significant leap rising eight places to fourth in the environmental pillar. This improvement is primarily due to a remarkable jump from 25th to first in environmental standards in trade as Japan now ratifies and implements all seven international conventions that the ranking measures under this indicator (“measure” meaning whether they have been ratified and implemented by the economy in question). The country also performs well in transfer emissions (third), energy intensity (fifth), wastewater treatment (sixth), and air pollution (eighth).

Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly in ecological footprint (18th), renewable energy (22nd), and deforestation (26th). Additionally, Japan ranks 13th in the crucial indicator of share of natural resources in trade.

Mexico stays within the top five highest-ranked economies in the environmental pillar, ranking fifth despite dropping two places. The country’s strengths lie in high environmental standards in trade (first), and in low carbon emissions (second), with solid performances in energy intensity (eighth) and transfer emissions (ninth). Mexico also ranks 10th in air pollution and 11th in share of natural resources in trade.

However, Mexico faces challenges in ecological footprint and wastewater treatment, (both 14th) as well as deforestation (16th) and renewable energy usage (19th).

Figure 19

Myanmar drops five places to 26th in the 2024 environmental pillar. This decline is due to a relatively poor performance in environmental standards in trade (22nd from 20th last year), carbon management (20th from 13th), and wastewater treatment (26th from 25th). The country also ranks 27th in energy intensity and 26th in air pollution.

However, Myanmar shows strengths in renewable energy (second), ecological footprint (fourth), and deforestation (10th). Share of natural resources in trade ranks 17th. Significant efforts are needed to strengthen environmental governance and integrate sustainability effectively.

Papua New Guinea drops two places to 27th due to its performance in areas such as wastewater treatment (29th), share of natural resources in trade (26th), and deforestation (24th). The country also slipped in carbon management (18th from 14th), while air pollution remains at 13th. The country’s strengths include a sixth place in ecological footprint, and 10th in environmental standards in trade.

India remains in 28th place, illustrating a performance hindered by several challenges. It ranks last with the highest air pollution (30th) and attains low rankings in transfer emissions (26th), energy intensity (25th), wastewater treatment (24th), and deforestation (20th). However, India shows strengths in its ecological footprint (third) – its highest ranking – and environmental standards in trade (10th). Renewable energy and carbon management both rank 11th.

Brunei holds steady at 29th place, reflecting its poor performance across most indicators. Its highest-ranked indicator is air pollution (third), with energy intensity at 14th. However, Brunei struggles significantly in areas such as share of natural resources (30th), renewable energy (29th), deforestation and carbon (both 27th), and environmental standards in trade (27th).

Russia remains at the bottom – in 30th place – in the environmental pillar, highlighting the substantial challenges it faces. As a major energy producer, Russia relies heavily on fossil fuels exports, leading to poor rankings in carbon management, energy intensity, and share of natural resources in trade (all 29th). The country also ranks 30th in environmental standards in trade, and 27th in both transfer emissions and wastewater treatment. Russia’s best rankings are in air pollution (seventh), and deforestation (11th). To improve its performance, Russia must address these significant environmental challenges effectively.

In summary, countries that rank highest in the environmental pillar demonstrate strong environmental standards in trade, actively participate in international agreements, and enforce robust regulations. These nations typically have low air pollution levels and a high share of renewable energy in their energy mix, significantly reducing their carbon footprint. Additionally, they showcase efficient energy intensity, producing more economic output with less energy, and they also manage carbon emissions effectively. High-ranking countries in this pillar also excel in wastewater treatment and maintain a low ecological footprint, balancing resource consumption with environmental regeneration.

The global trade landscape is undergoing a significant transformation driven by geopolitical tensions and evolving industrial policies. Economies are increasingly focused on protecting domestic industries, reducing reliance on imports, and ensuring resilient supply chains. This shift, as is evident from the rise in both tariff and non-tariff barriers, marks a longer-term reconfiguration of global trade, with implications for the flow of goods and services.

At the same time, the urgent need to address climate change has driven the integration of sustainability into trade and industrial policies. Initiatives like the EU CBAM and US IRA demonstrate a commitment to achieving carbon neutrality. Importantly, agreements like the recent ACCTS represent a critical step towards reconciling the complexities of global trade with the demands of environmental sustainability.

Additionally, workforce resilience emerges as a cornerstone of sustainable trade. By addressing issues like labor exploitation, enhancing educational opportunities, and ensuring access to healthcare, economies can develop workforces capable of adapting to rapid changes and contributing to sustainable growth.

The STI captures these critical dimensions providing a comprehensive view of how economies can balance economic growth, societal well-being, and environmental responsibility within an increasingly complex global trade environment.

The economic pillar highlights how top-performing economies are distinguished by robust technological infrastructure which drives innovation and enhances trade efficiency and economic resilience. Policies that promote trade, characterized by low tariffs and non-tariff barriers, are crucial for boosting trade competitiveness and attracting foreign investment. Additionally, maintaining a diversified export base with a broad range of trading partners significantly contributes to their economic stability.

On the societal front, leading countries show a firm commitment to upholding labor standards, ensuring political stability, and fostering social mobility. These nations safeguard labor rights, maintain stable political climates, and promote inclusive economic development, while also investing in human capital through quality education and healthcare services.

Environmentally, the top-ranking countries excel by adhering to stringent sustainability standards. They actively engage in international environmental agreements, enforce strong regulations, and maintain low air pollution levels. Their energy mix includes a high percentage of renewables, and they demonstrate efficient energy use by producing more with less. These nations also effectively manage carbon emissions, prioritize wastewater treatment, and maintain a low ecological footprint, ensuring a balance between resource use and environmental preservation.

In summary, the STI not only highlights the best practices of top-performing economies but also serves as a roadmap for others striving to achieve a sustainable balance in the intricate web of global trade By implementing stringent environmental standards, fostering societal well-being through robust labor and social policies, and leveraging advanced technological infrastructure, these leading nations exemplify how to harmonize economic growth and sustainability. Their emphasis on economic and societal resilience and the way they take proactive measures to address climate change are examples of the dynamics we need more of in today’s trade policies. As global trade continues to evolve amidst geopolitical tensions and shifting industrial strategies, the STI remains a vital tool, guiding economies toward a more balanced, resilient, and sustainable future.

The Hinrich-IMD Sustainable Trade Index

The Hinrich-IMD Sustainable Trade Index measures 30 economies’ readiness and capacity to participate in the global trading system in a manner that supports the long-term goals of economic growth, environmental protection, and societal development.

The economic pillar

The economic pillar measures an economy’s ability to ensure and promote economic growth through international trade. In this category, economies receive scores for indicators that demonstrate a link between the trading system and economic growth.

Some indicators capture the quality of trade infrastructure, while others measure the ease of conducting international trade, such as current account, exchange rate stability, and trade costs.

We measure export diversification by evaluating an economy’s trade destinations and how heavily its exports are concentrated by sector –because economies with diversified export markets and products are better equipped to absorb external economic shocks.

Furthermore, we consider the technological infrastructure and innovation capabilities of an economy by assessing its emphasis on research and development investments and digital technologies, which are key drivers for the production of sophisticated and sustainable goods and services.

The societal pillar

Social factors matter in an economy’s capacity to trade internationally over the long term. Economies are evaluated on the encouragement and support of the development of human capital, such as the extent of education, healthcare, and labor standards.

This pillar also captures factors that influence public support for trade expansion. These include income inequality, political stability, goods produced by forced and child labor, and the government response to human trafficking.

The environmental pillar

The environmental pillar measures the extent to which an economy’s trade supports sustainable resources. The factors include measurements of non-renewable natural resources in trade and the management of externalities that arise from economic growth and participation in the global trading system.

While an economy’s capacity to participate in the global trading system is dependent on economic development, achieving sustainable trade requires prudent stewardship of natural resources and acknowledgment of the externalities to promote its overall environmental capital. The indicators chosen in this section measure an economy’s environmental capital and include measures for air and water pollution. In terms of future impact, we measure national environmental standards, carbon emissions, and share of natural resources in exports.

We establish a reference year for each indicator or sub-indicator. Generally, it is the previous full year, but it may be earlier for some data. For the reference year:

1.0 We first check if data is available for the reference year, if this is the case the data will be considered for calculation.

2.0 If data for the reference year is unavailable, we generally check the previous four years before the reference year. We choose the closest year to the reference year or we categorize that particular indicator as not available, and the data field is left empty.

1.0 An economy showing an empty data field for a certain indicator will therefore not be listed and ranked for that specific indicator.

In this document, ‘values’ denote the raw data of indicators in their original measurement units. ‘Scores’ represent these values rescaled between 0-100, as derived in the third step of our data processing procedure. For all indicators, pillars, and the overall STI, a higher score indicates superior performance in that specific category, while a lower score suggests subpar performance. Lastly, ‘rankings’ are determined by arranging the scores of each indicator in descending order, from highest to lowest.

1.0 We check each indicator for outliers:

1.1 Outliers are identified using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method. This is calculated by taking the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles for each indicator, with the IQR being the difference between these two values (IQR = Q3-Q1). Data points falling below [Q1 – (4×IQR)] or above [Q3 + (4×IQR)] are classified as outliers.

1.2 The identified outliers are then winsorized. This process involves capping the extreme values to reduce the effect of possibly spurious outliers.

1.3 To address the variance among outliers, a logarithmic transformation is then applied to the winsorized data. This transformation helps to stabilize the variance and make the data more normally distributed.

2.0 For those indicators that contain sub-indicators (or sub-sub indicators):

2.1 At the sub-indicator level, values are rescaled between 0 and 100. The optimal value receives a score of 100, while the least favorable gets 0. If a higher value for an indicator signifies a better outcome, the economy with the highest value scores 100, and the one with the lowest scores 0. Conversely, if a lower value indicates a better outcome, the economy with the lowest value scores 100, and the highest scores 0. For specifics on what determines the best or worst outcome for each indicator, refer to the Notes and Sources section.

2.2 Sub-indicator values are then averaged to form the primary indicator.

2.3 For indicators comprising sub-sub-indicators, we first construct the sub-indicator as per step 2.2. Once the sub-indicators are established, the same process is applied to derive the subsub-indicator.

3.0 All indicators are rescaled between 0 and 100, with the best value scoring 100 and the worst 0. This rescaling facilitates indicator comparisons.

4.0 Within each pillar all indicators are averaged to construct the pillar.

5.0 All pillars undergo rescaling between 0 and 100. This step minimizes the influence of uneven indicator distribution within pillars, ensuring comparability.

6.0 The three pillars are averaged to determine the overall score, presented as a value between 0 and 100. This consistent scoring range, from sub-sub-indicators to the overall score, ensures uniformity across all analysis levels.

We have added some new indicators and updated other components to further refine the index from prior iterations.

1.0 Under the Societal pillar, a new indicator, 2.11, Universal Health Coverage Index has been introduced.

2.0 Under the Economic Pillar, for the indicators 1.06.01 b New tariff barriers and 1.06.02 b New non-tariff barriers, the year has been updated from 2022 (in STI 2023), to 2023 for STI 2024.

3.0 Under the Economic Pillar, the indicators 1.06.01 c and 1.06.02 c have been updated to Net percentage of imports affected by new tariff barriers (2023) and Net percentage of imports affected by new nontariff barriers (2023) respectively.

4.0 Under the Economic Pillar, for the indicator 1.08 Exchange rate stability, parity change from national currency to SDR, the year is updated from 2022/2020 to 2023/2021.

[H]

High value promotes global trade [L] Low value promotes global trade [Sum] Indicator has sub-indicators

Background data

Population

GDP per capita

1.01

1.02 Real GDP Growth per capita, % GDP

1.03

Growth in labor force, %

Source

IMF WEO

IMF WEO

Definition

Population in millions (estimates for 2023)

The total value at current prices of final goods and services produced within a country (in USD) during a specified time period divided by the average population for the same year.

WEO, Taiwan: DGBAS

WEO, Taiwan: DGBAS

1.04

Foreign direct investment, net inflows, % GDP

1.05 Gross fixed capital formation, % GDP

World Bank, Taiwan: Central Bank, Balance of Payments Quarterly

World Bank, Taiwan: DGBAS

inflation rates, year average. [L]

GDP is expressed in current US dollars per person. Data is derived by first converting GDP in national currency to US dollars and then dividing it by total population. [H]

People aged 15+, who are currently employed and people who are unemployed but seeking work as well as first-time jobseekers. Unpaid workers, family workers, and students are often omitted, and some countries do not count members of the armed forces. [H]

Net inflows of foreign investment to acquire a lasting management interest (10%+ of voting stock) in an enterprise. Sum of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, other long-term capital, and short-term capital as shown in the balance of payments. [H]

Includes land improvements; plant, machinery, and equipment purchases; construction of roads, railways, schools, offices, hospitals, private residences, and commercial & industrial buildings. Net acquisitions of valuables are considered capital formation. [H]

Indicator Source Definition

1.06.02.b New non-tariff barriers 2023

1.06.02.c Net percentage of imports affected by new non-tariff barriers (2023)

1.07

1.07.01

1.07.02

Trade liberalization

Regional Trade Agreements, number in force

Capital account liberalization, Index

Global Trade Alert

Global Trade Alert

WTO, KAOPEN, Freedom House

WTO

KAOPEN

1.07.03

Investment Freedom, Index Heritage Foundation

1.08 Exchange rate stability, parity change from national currency to SDR, 2023/2021

1.09 Domestic credit to private sector, % of GDP

IFS

Count of new (2023) ‘harmful’ non-tariff measures currently in force. [L]

Estimates of the import shares potentially affected by ‘harmful’ non-tariff measures currently in force. [L]

Three indicators measuring trade liberalization. [sum]

Any reciprocal trade agreement between two or more partners, not necessarily belonging to the same region. [H]

The Chinn-Ito index (KAOPEN) is an index measuring a country’s degree of capital account openness. The index was initially introduced by Chinn and Ito (Journal of Development Economics, 2006). KAOPEN is based on the binary dummy variables that codify the tabulation of restrictions on cross-border financial transactions reported in the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER). [H]

Investment freedom evaluates a variety of regulatory restrictions that typically are imposed on investment. Points are deducted from the ideal score of 100 for each of the restrictions found in a country’s investment regime. [H]

Parity changes are in absolute values. Period average for all countries. [L]

IMF (via World Bank) Domestic credit to private sector refers to financial resources provided to the private sector by financial corporations, such as through loans, purchases of nonequity securities, and trade credits and other accounts receivable, that establish a claim for repayment. For some countries, these claims include credit to public enterprises. The financial corporations include monetary authorities and deposit money banks, as well as other financial corporations where data is available (including corporations that do not accept transferable deposits but do incur such liabilities as time and savings deposits). Examples of other financial corporations are finance and leasing companies, money lenders, insurance corporations, pension funds, and foreign exchange companies. [H]

1.10 Foreign trade and payments risk IMF, SP, Moody’s, Fitch Two indicators measuring foreign trade and payment risk. [sum]

1.10.01

1.10.02

Country credit rating SP, Moody’s, Fitch IMD WCC created an Index of three country credit ratings (Fitch, Moody’s, S&P). Each, including the outlook, is converted to a numerical score, and averaged for each country, with a possible range of 0-60. [H]

Gross debt, % GDP WEO

Private nonguaranteed external debt comprises long-term external obligations of private debtors that are not guaranteed for repayment by a public entity. Data is in current US dollars. [L]

Indicator Source

1.11 Trade costs Transparency International, World Bank

1.11.01 Logistics performance, index World Bank

1.11.02 Corruption perceptions, index Transparency International

Three indicators measuring country-specific external, indirect costs on trade (rule of law, corruption, logistics) [sum]

LPI ranks countries on six dimensions of trade, including customs performance, infrastructure quality, and timeliness of shipments. The data used in the ranking comes from a survey of logistics professionals. [H]

The CPI is calculated using 13 different data sources from 12 different institutions that capture perceptions of corruption within the past two years. The data sources are standardized to a scale of 0-100 where 0 equals the highest level of perceived corruption and 100 equals the lowest level of perceived corruption. [H]

1.11.03 Rule of law, index World Bank

1.12 Monetary policy intervention

1.12.01 Current account balance, % GDP

1.12.02

Change (1-year) in total reserves (includes gold), % GDP

1.13 Export concentration

1.13.01

1.13.02

Export market concentration, Top 5 as % total UNCTAD

Export product concentration, Top 5 as % total UNCTAD

1.14 Exports of goods and services

1.14.01 Merchandise exports, US$ millions

1.14.02 Commercial services exports, US$ millions

1.15 Technological innovation

Perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. [H]

Two indicators measuring an economy’s potential capacity to intervene in and influence exchange rates. [sum]

Current account balance is the sum of net exports of goods and services, net primary income, and net secondary income. [L]

Total reserves comprise holdings of monetary gold, special drawing rights, reserves of IMF members held by the IMF, and holdings of foreign exchange under the control of monetary authorities. The gold component of these reserves is valued at year-end (December 31) London prices. Data is in current US dollars. [L]

Two indicators measuring the export concentration in markets and products. [sum]

The top five named export countries as a percentage of total exports. [L]

The top five named export products, as a percentage of total exports, using the UNCTAD product data based on the SITC commodity classification, Revision 3, at the two-digit level: giving 65 product categories. [L]

Two indicators measuring merchandise and commercial services exports. [sum]

Compiled from national data sources, WTO, IMF International Financial Statistics, and the Trade Data Monitor online database. If data from national sources are not available at the time of release, estimates are produced based on partner trade statistics. [H]

Commercial services include transport, travel, and other private services (communication; construction; insurance; financial; computer and information (including news), royalties and license fees; other business services (legal, accounting, consulting, public relations, advertising, market research, architectural, engineering, and other technical services) [H]

Five indicators measuring research and development. [sum]

1.15.01

1.15.02

Indicator Source Definition

R&D expenditure, % GDP

UNESCO, Taiwan: OECD MSTI

1.15.03

1.15.04

Researchers in R&D, per capita

1.15.05

UNESCO, Taiwan: OECD MSTI & WEO, Peru: National Council for Science, Technology and Technological Innovation

Patent applications, per million inhabitants WIPO, WEO, Taiwan: TIPO

High-technology exports, % of manufactured exports

Scientific articles, per million people

1.16 Technological infrastructure

COMTRADE

NSF National Science & Engineering Indicators Hong Kong, SAR: University Grants Committee

ITU (via World Bank), Ookla, M-Labs, The Bandwidth Place

1.16.01 Fixed internet speed, Mbps Ookla, M-Labs, The Bandwidth Place

1.16.02

Internet users, % population ITU via World Bank, Taiwan: National Communications Commission

1.16.03 Fixed broadband subscriptions (per 100 people)

ITU via World Bank, Taiwan: National Communications Commission

The sum of financial resources (national and foreign) used for the execution of research and experimental development (R&D) works on the national territory by the public sector and by the business enterprise sector. It includes current expenditure (annual wages and salaries of R&D personnel and operating expenses) and capital expenditure (purchases of equipment required for R&D). [H]

Researchers in R&D are professionals engaged in the conception or creation of new knowledge. Products, processes, methods, or systems and in the management of the projects concerned. [H]

Total patent applications (Direct and PCT national phase entries per million inhabitants. [H]

High-technology exports are products with high R&D intensity, such as in aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments, and electrical machinery. [H]

Article counts are from a selection of journals, books, and conference proceedings in S&E from Scopus. [H]

Four indicators measuring the technological infrastructure, internet quality and penetration, and mobile penetration. [sum]

Average connection speed in Mbps: data transfer rates for Internet access by end users. The values presented are a weighted average of three internet speed tests Ookla, M-Lab, SpeedTestNet.io. [H]

Internet users are individuals who have used the Internet (from any location) in the last 3 months. The Internet can be used via a computer, mobile phone, personal digital assistant, games machine, digital TV, etc. [H]

Fixed broadband subscriptions refer to fixed subscriptions to high-speed access to the public Internet (a TCP/IP connection), at downstream speeds equal to, or greater than, 256 kbit/s. This includes cable modem, DSL, fiber-to-the-home/building, other fixed (wired)-broadband subscriptions, satellite broadband, and terrestrial fixed wireless broadband. This total is measured irrespective of the method of payment. It excludes subscriptions that have access to data communications (including the Internet) via mobile-cellular networks. It should include fixed WiMAX and any other fixed wireless technologies. It includes both residential subscriptions and subscriptions for organizations. [H]

1.16.04

Indicator Source

Mobile subscriptions (per 100 people)

2.01 Inequality (Gini coefficient)

ITU via World Bank, Taiwan: National Communications Commission

World Bank, Taiwan: Report on the Survey of Family Income and Expenditure, R.O.C., 2020, Hong Kong, SAR: Census and Statistics Department, New Zealand: OECD

Mobile cellular telephone subscriptions are subscriptions to a public mobile telephone service that provides access to the PSTN using cellular technology. The indicator includes (and is split into) the number of post-paid subscriptions, and the number of active prepaid accounts (i.e., that have been used during the last three months). The indicator applies to all mobile cellular subscriptions that offer voice communications. It excludes subscriptions via data cards or USB modems, subscriptions to public mobile data services, private trunked mobile radio, telepoint, radio paging, and telemetry services. [H]

The Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income (or, in some cases, consumption expenditure) among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Lorenz curve plots the cumulative percentages of total income received against the cumulative number of recipients, starting with the poorest individual or household. The Gini index measures the area between the Lorenz curve and a hypothetical line of absolute equality, expressed as a percentage of the maximum area under the line. Thus, a Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality, while an index of 100 implies perfect inequality. [L]

2.02 Educational attainment HDR, THES, World Bank Three indicators measuring the attainment and quality of education. [sum]

2.02.01 Mean years of schooling

UN HDR, Taiwan: DirectorateGeneral of Budget, Accounting, and Statistics, Taiwan (ROC)

2.02.02 University education Index THES

2.02.03 Tertiary enrollment World Bank, Taiwan: Ministry of Education

The average number of years of education received by people ages 25 and older, converted from education attainment levels using official durations of each level. [H]

2.03 Labor standards World Bank, Global State of Democracy Indices

2.03.01 Gender nondiscrimination in hiring World Bank Women, Business and the Law

2.03.02 Freedom of association and assembly

Global State of Democracy Indices

IMD constructed index to capture the quality of universities. Measures the (1) number, (2) score, (3) score per capita, of the universities in THES 1’000. [H]

Gross enrollment ratio is the ratio of total enrollment, regardless of age, to the population of the age group that officially corresponds to the level of education shown. Tertiary education, whether to an advanced research qualification, normally requires, as a minimum condition of admission, the successful completion of education at the secondary level. [H]

Two indicators measuring employee rights, including gender equality and collective bargaining. [sum]

Two indicators measuring employee rights, including gender equality and collective bargaining. [sum]