PIPPA CARTER

Becoming Female - The Cycle of Abjection

May 2025

DOI 10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission.

Fine Art BA Hons Dissertation

Becoming Female - The Cycle ofAbjection

Exhibition Project

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to those who have supported me throughout the writing of this dissertation. Firstly, to Jan Patience for her kindness and time. To my tutor, Anna Notaro for their support and encouragement. Finally, to Waterstones for providing me with comfort and coffee without which this dissertation would not have been possible.

Personal Statement

I am a Dundee based artist originally from Dunbar, Scotland.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Winant, C (2018) My Birth. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/222741

Figure 2. Lucas, S(1997)Chicken Knickers.Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lucas-chickenknickers-p78210

Figure 3. Hughes, B (2016-2017) Cycles. Available at: https://www.beehughes.co.uk/selectedworks/60n2r5k9enfl163dwyp0ot5yuym54y

Figure4. Tompkins B, (1976)Cow Cunt.Available at: https://www.artbasel.com/catalog/artwork/83503/BettyTompkins-Cow-Cunt-1?lang=en

Figure5. NengudiS, (1977/2003)R.S.V.P.Available at:https://www.moma.org/collection/works/151035

Figure6. HenrotC, (2020)Wetjob. Available at: https://www.hauserwirth.com/artists/35528-camille-henrot/#

Figure 7. Crabbe L, (2014)PurgingAbjection. Available at: https://posturemag.com/online/artist-loren-crabbediscusses-abjection-trauma-and-the-human-body/

Figure 8. Smith K, (1997) Pee Body. Available at: https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/220259?position=1

Figure 9. Bašić I, (2017) I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms.Available at: https://www.ivanabasic.com/solo-show-marlborough-contemporary

Figure 10. MinterM, (2009) Green Pink Cavier.Available at: https://landmarks.utexas.edu/video-art/greenpink-caviar

Figure 11. Exhibition Layout. FloorPlan Courtesy ofDundee ContemporaryArts. Available at: https://www.dca.org.uk/plan-your-visit/getting-around-the-building/

Figure 12. Carter, P. (2024) Model of the entrance to Dundee ContemporaryArt’s (DCA) gallery space for proposed exhibition [Photograph]

Figure 13. Carter, P. (2024)Model ofDCA’s [Photograph]

Figure 14. Carter, P. (2024) Model of DCAgallery 1 space showing Winant’s and Lucas’art works [Photograph]

Figure 15. Carter, P. (2024) Model of DCAgallery 1 space showing Hughes, Henrots and Crabbes art works [Photograph]

Figure 16. Carter, P. (2024) Model of DCAgallery 1 space showing Bašić and Smiths art works [Photograph]

Figure 17. Carter, P. (2024) Model of DCA gallery 2 space showing Minter’s film [Photograph]

Abstract

This proposal presents Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection, an exhibition exploring the abject as articulated in Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, with a focus on the female body’s marginalization. The exhibition examines the grotesque, unsettling aspects of womanhood through from menstruation, childbirth, menopause, and death; the exhibition highlights how these experiences are culturally and commercially abjected. The show will feature works by contemporary female artists that confront societal taboos, evoking both disgust and fascination.

Held at Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA), the exhibition will take over the traditional white cube gallery to immerse viewers in a linear display that reflects on the female life cycle. By exploring themes of the grotesque, autonomy, and resistance, the exhibition draws inspiration from the writing of Virginia Woolf, aiming to spark dialogue around female representation and the need for cultural spaces celebrating the female experiences.

Introduction

‘The time of abjection is double: a time of oblivion and thunder, of veiled infinity and the moment when revelation bursts forth.’ (Kristeva, 1980, p. 9)

The following proposal acts as a critical analysis of Kristeva's abject as seen in contemporary feminist art works. The exhibition aims to explore the abject as proposed in Kristeva's powers of horror; capturing the feeling of morbid curiosity, through art works that provoke feelings of being unsettled and disgusted. The proposed exhibition suggests that women are characteristically abjected through every aspect of their lives – from female sexuality, to childbirth, menopause – and ultimately death. The abject explores the grotesque and the unsettling. This, having an innately female context, seen through the body; period blood and discharge. This can be seen both culturally and commercially. In advertisements for period products, blood-like liquid has been avoided. It was only in 2017, that the company which manufactures Bodyform period products started using red liquid instead of blue to demonstrate the absorbency of its period products; making it the first period product company in the UK to show a red blood-like liquid in a bid to diminish the taboo. (BBC, 2017)

The abject captures unsettling topics which are usually dismissed or avoided in everyday life. It explores the idea of morbid curiosity – the inability to avert your eyes from what lies before despite an uncomfortable nature; this sensation capturing the paradox of horror as understood by Berys Gaut (1993, p. 33). The philosopher Immanuel Kant (1788) explores this idea further when he reflects on whether we can experience both desire and disgust simultaneously. This proposal looks at how these two contrasting emotions impact the viewer's perception of certain art works. The exhibition will display works that mimic ideas of the abject creating an environment for the grotesque and the unsettling to exist. The grotesque being understood as the repulsive, ugly and distorted, this being inseparable from the body, exploring the boundaries of societal norms especially in the context of the female body. The idea of the grotesque historically has had this tie to the female body; prostitutes, sorcerers, femme fatales. (Marshik, 1995)

The proposed exhibition will take place at Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA). The aim of the exhibition is to take over the traditional 'White Cube gallery’, a rebuttal to the predisposed trajectories of galleries being primarily male spaces (Chalabi, 2019). The space will be set up to encourage the viewer to walk around and view the work in a linear display, mimicking that of some archival and historical exhibitions; the first works depict childbirth and ultimately going through the ageing process. The works displayed will be by contemporary female presenting artists.

If artists are generally boundary-crossers, a younger generation of (mostly women) artists is going for full penetration making artworks that speak to something deep in the body, producing responses that range from carnal attraction to disgust. (Thackara, 2019)

Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection intends to celebrate this idea of boundary-crossers. It is crucial that there is a space that celebrate all aspects of being female to insure culturally we continue to go forwards. This being especially prevalent considering the current recession of female autonomy in America – a supposedly progressive and influential western country - with the overturning of Roe V wade (Totenberg, McCammon, 2022). The exhibition draws on a desire for full comprehensible female autonomy.

The need for such female focused exhibitions stems from a wider feminist context, a desire for continual progression. The writing of Virginia Woolf acts as an anchor in the development of this exhibition. Further the creative works of the guerrilla girls and Carolee Schneemann act as an inspiration in their disruptive and interpersonal art works.

Chapter One: Curatorial Thesis

The Abject

The art world is a place free of inhibitions, creative flow, and self-expression, but it is also one dominated by men. The Guerrilla Girls famously highlighted the discrepancies between female and male artists in their artwork DO WOMEN HAVE TO BE NAKED TO GET IN THE MET? (1989). They found that only 4% of modern artists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art are female, a number that is inexplicably low, especially when considering that 72% of the nude portraits there are of women. This is especially concerning when we consider that 51% of contemporary visual artists are women, making them severely under-represented in gallery spaces (TATE, 2024).

In Linda Nochlin's essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) she challenges the reasons why women and men are viewed and represented so differently. This shift in feminist art theory began the 1970s first-wave feminist movement. Atthe time, nothing was off-limits. The works delved into the female body through form and fluidity, challenging the patriarchal order in art. Historically, women have been subjected to two reinforced stereotypes: the ‘sex sells’narrative and the ‘perfect fertile body,’both portraying women as entities to be viewed and desired for their physical form and sexuality (Collier-Doyle, 2020).

The male gaze theoryas developed by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’examines how women are depicted in media as objects to be consumed; catering to male desires. When depicted by men, the male gaze creates an unrealistic sexualized or ‘fertile’ being. Art critic John Berger reflects on this idea in his book Ways of Seeing:

Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. (1972, p. 47)

Western art replicates and reinforces the unequal relationship between men and women already embedded in society. This is particularly evident in the ‘sex sells’ narrative – often seen in advertisements - which reinforces idealistic standards driven by the male gaze. In advertisements, sex is used a symbol for selling items. It doesn't matter how far removed the item is, anything can be made erotic with the right imagery selling the narrative that ‘if you buy this you will get that’ (Seward, 2017), be that sex or an idealised view of a female body. Furthermore, this issue goes into self-sexualization, the CSE Institue (2022) investigated how athletes make the most of their profits from content creation and for women the content is encouraged to emphasize sexuality over strength. It has been found that posts catering to the male gaze portraying women in a sexualized nature attract a higher amount of engagement subsequently encouraging athletes to display their conventionally attractive looks for income rather than showcasing their talents.

It has been found that this sexually objectifying content on social networking sites lowers self-esteem and body satisfaction, particularly with women. This suggests the only ones benefiting from this ‘sex sells’narrative are men gaining gratification. (Plieger, 2021) The issues raised by the ‘sex sells’ narrative reinforces female shame. The burden of this shame can be traced to patriarchal standards, which impose shame on women's sexuality, pride, and bodies (Reenkola, 2013). One study found that female body shame increases in the premenstrual phase of the cycle, stating,

The construction of the premenstrual body as abject, manifested by the positioning of the body and self as fat, leaking, and dirty. (Ryan, Ussher & Hawkey, 2022)

This illustrates how female shame is experienced. For many women, the burden of shame sparks a lifelong internal conflict.

Contemporary feminist artists, such as Judy Chicago, Pipilotti Rist, and Carolee Schneemann, work to break down these barriers, disrupting the idealized and toxic narratives of women in art. These artists create works that encapsulate and mirror Julia Kristeva's theory of abjection.

Abjection, as a theory, was first developed in Kristeva's Powers of Horror (1980). It can be understood as subjective horror an overwhelming feeling of disgust and the urge to look away, particularly in relation to human bodily functions. Kristeva understood the abject with the analogy of milk: imagine the milk has been sitting out, forming a skin on top (p.3). You desire the milk, as it will nourish and refresh you, but the skin on the milk causes discomfort, making you want to look away. This skin represents the abject, the layer between you and the milk that causes both desire and disgust. This being understood as the loss of distinction between subject and object, or between self and other.

The theory of abjection forces us to reflect on all bodily functions, even those traditionally not for public display things considered impure and grotesque, such as blood, discharge, piss, shit, and sperm. The unsettling feelings associated with abjection are connected to what we reject or exclude from our personalities Kristeva states

It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order (p. 4).

Kristeva's abject theory plays on the line between disgustand desire. This is why the theory has such a strong feminist context. Under patriarchal social orders, female bodily functions have traditionally been abjected. For example, when a woman gives birth, the experience is often marked by bewilderment, blood and other body fluids, and flesh. This encapsulates the paradox of horror: the inability to avert your eyes despite the feelings of revolt and disgust.

In Critique of Practical Reason (1788, p.9), philosopher Immanuel Kant explored how our emotions can conflict with our inclinations. He acknowledged that disgust and desire are opposing emotions that exist outside of rational thought, but that they can coexist. Kant believed this emotional complexity could promote self-reflection and lead to more ethical decisions. By experiencing both disgust and desire, we are made moral agents.

The abject also connects to the idea of scopophilia – a psychological term meaning the love of looking. It refers to the pleasure derived from looking at a person or object, drawing a connection between abjection and voyeuristic desire. Psychologists Sigmund Freud’s ‘The Uncanny’ reinforces this fascination with all that disturbs and unsettles. He describes the uncanny as something that is both familiar and frightening, which is familiar and congenial, and on the other, that which is concealed and kept out of sight. (Freud,1919)

This concept links to repressed fears and desires that surface in response to unsettling stimuli. Both Kristeva and Freud are concerned with the fascination of the ugly and the grotesque. The uncanny can be understood as the aesthetics of anxiety the unsettling and disturbing.

The exhibition title explores the paradox of women being perceived as both sexual and repulsive; a model for blood, fear, and sex. The theory of abjection explains the gut-curdling sensation people feel towards women’s bodily functions. The exhibition aims to confront this paradox, presenting a body of works that appreciate the intersection of the beautiful and the grotesque.

The grotesque is seen within art and literature and can be understood as a questioning of societal norms, within beauty and morality. The style of the grotesque explores discomfort and distortion through the absurd and monstrous, the grotesque aims to elicit fascination and discomfort. The grotesque primarily refers to the unnatural and bizarre eg: exaggerated distorted human forms challenging notions of beauty and normality. The grotesque as seen in the era of carnivals mirrors the philosophy of Kristeva's abject and reflects on the contemporary art works in this proposal. In renaissance and early modern European festivals, the idea of carnival was linked to subverting expected norms, defying authority and celebrating transgression. In carnivals the use of costume and performance emphasized the body acting as a vessel for rebellion often depicting fat bodies, disfigured faces and exaggerated sexual imagery. In doing so, the carnival created a platform for the impure and undesirable. (Goody, 2007)

Traditionally, the depiction of women in art has been portrayed by male artists. It is no surprise, then, that many aspects of the female experience, including female bodily functions, have only recently been explored in contemporary art. Art historian Frances S. Connelly (2012) discusses this phenomenon in The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture She examines the grotesque not just in art

but within everyday culture, challenging traditional aesthetic notions. She explores how repulsion is inseparable from the body, especially the female body. In an interview, she stated:

What is most regulated in any culture is the body, particularly women’s bodies. (Thackara, 2019)

The female body is often bound to the idea of being grotesque, with one aspect seemingly tied to the other. Kristeva’s abject acts as a confrontation of patriarchal rule it is a raw and honest opposition to the male gaze and the ‘sex sells’narrative. The abject encourages the creation of a female space, accepting female bodily functions as part of the natural human experience. Ultimately, this exhibition explores disgust as unity with desire. While disgust is typically seen as complete opposition to desire, the works presented in this exhibition allow us to explore this paradox.

Chapter 2: Curatorial choices

Artists and Their Art Works

There will be ten artworks displayed within Dundee Contemporary Art’s (DCA) two gallery spaces. The series of chosen works encompass a range of media, including mixed media, sculpture, and film. The artworks aim to capture the female experience of abjection, invoking that paradoxical feeling of wanting to look away while simultaneously being drawn to stare. As one walks through the gallery, the artworks will take you on a journey through the stages of the female lifecycle: adolescence, reproductive years, midlife, and postmenopausal.

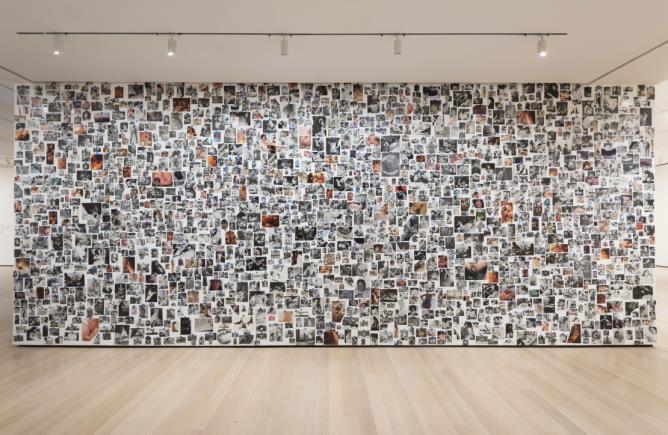

For this exhibition we will commission Carmen Winant to replicate this photo collage to the dimensions of the entrance wall in the DCA. Winant’s photo collage depicts the birth experiences of hundreds of women; the work impactfully spans the length and height of the wall. My Birth consists of over 2000 photographs with images sourced from old books and magazines. Winant comments on how women are both visible and invisible, the act of giving birth is essential and common, but documentation is majorly underrepresented in a culture soconcerned with photographing everything. The piece acts as a voice for those who have given birth she comments on how no one asked about her labour - perhaps no one knows how to ask, but when you have created life and a body has come out of your body, there should be a platform and a place to speak about it comfortably. This piece confronts this idea by showing the scope of childbirth; capturing women falling into their partner's arms or submitting their bodies to medical devices, depicting pain, discomfort and joy. (Regensdorf, 2018)

Birth: Carmen Winant (2018) My Birth, Variable Size

Figure 1

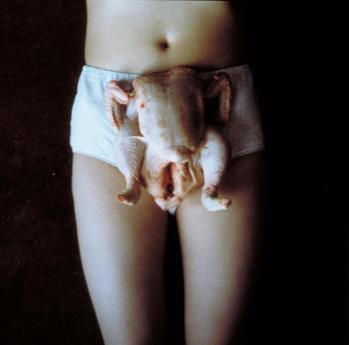

Adolescence: Sarah Lucas (1997) Chicken knickers, 42.5 x 42.5cm

2

Sarah Lucas explores the boundaries of sex and gender throughout her works by using humour to touch up on darker topics. Chicken Knickers acts as a reference to the embedded experience of sexual innuendos in Western culture. The photograph is concerned with the sexual violation that comes with such jokes. The photograph captures the corporeality of a young adolescent female. There is a sense of vulnerability and unease; seeing human flesh met with raw meat. The unplucked, unstuffed chicken is a sinister depiction of the unwarranted sexualization and objection that comes packaged within socalled ‘lighthearted’ comments. (TATE, 2024)

ReproductiveYears: Bee Hughes (2016-2017) Cycles, 0.2 x 3m

3

Dr Bee Hughes from Liverpool John Moors University is an artist and researcher. Her works explore the female experience through themes of menstruation, rituals and routines. The artwork Cycles is a series of scrolls divided into 28 sections attributed to the traditional menstruation cycle and depicts body prints of the vagina – created by applying body paint with fingers or sometimes a brush to the vagina and then imprinting them onto the fabric - one per evening over six months; it was later red stitching was attached. The work began as a way for Hughs to confront her painful and inconsistent menstrual cycle. It confronts the expected cycle as seen in medical texts. It allows Hughes as the

Figure

Figure

menstruator to express the challenge and individuality that comes with having a period. Culturally the period has always been averted away from the topic, this artwork created from raw flesh confronts this predisposed taboo. (Hughes, 2020)

ReproductiveYears: Betty Tompkins (1976) Cow Cunt, 213.4 x 152.4cm

Over her five-decade career, Betty Tompkins has both been celebrated and criticized for her provocative feminist imagery. By reinterpreting pornographic visuals designed for male pleasure, she challenges longstanding taboos surrounding the content, questioning what the female narrative is in a place of sexualized female imagery. This piece depicted in our exhibition is a tribute to female sexuality Cow Cunt #1 is a compelling painting (acrylic on canvas) of a dairy cow resting on a vagina. This piece exemplifies Tompkins' distinctive style and shows her confrontation of patriarchal norms. Her works celebrate graphic sexuality; previously her works were disregarded by the feminist movement for the pornographic content to which she responded “They look like they're having fun. Let's all have fun," (Jansen, 2017) her works are now appreciated as a distinctly feminist response to current issues.

Figure 4

Midlife: Senga Nengudi (1975 - 2019) RSVP

Nengudi is famous for her series that paired sculptural exploration of pantyhose with artistic performative dance. The series represents a progressive and situational body of work spanning several decades of creativity. The works consist of previously worn pantyhose, distorted and combined with sand and metal pieces to explore the ever-changing nature of the female body. The nylon tights are inherently symbolic of the female genitalia. Nengudirefers to them as ‘Abstracted reflections of used bodies' (Fruit Market, 2024) The flexible nature of the nylon captures the elasticity and change of the human body, an appreciation of the body's ability to withstand so much push and pull but also an acceptance that it will never return to the original shape.An appreciation that with ageing and childbearing, the body evolves.

Midlife: Camille Henrot (2019) Wet Job 1, 45.7. x 61 x 5.1cm

Figure 6

Wet Job (2019) Depicts the abject reality of creating milk for a child. It confronts the internal loss –the loss of individuality that comes with being a carer to be relied on by another; no longer oneself as an artist, but exclusively someone's mother. Henrot’s painting (Oil, Acrylic and watercolour on canvas) reflects on the breakdown of becoming a mother - a producer of milk “an endless source of

Figure 5

soft labour”. It addresses the conflict of these hours of unpaid work, the expectation to be gracious whilst hours of life go into the exhaustive caring and producing for a child which has already spent nine months draining of energy.At the same time, in this patriarchal world, very little value is placed on the job of mother and baby maker. Henrot has been internationally acclaimed for her works on maternity as she addresses the exhaustion and conflict ofbeing a mother. “I wanted to try to dismantle the expectation of the ‘good mother’ and think about motherhood as a state in which contradictions, ambivalence, and inner conflict could arise and be acceptable,” (Welgos, 2021) comments on women being stripped of their potential outside of the home and addresses the becoming of undervalued domestic laborers.

Purging Abjection was a 2014 room-sized exhibition depicting household objects which have been modified and rendered useless. For this exhibition, we will be displaying the sculpture of the taps with feminine breast-like modifications, Crabbe speaks of the sculptures as items of uselessness, old worn, modified with impractical materials – perhaps a reflection of a women being past her prime. Crabbe speaks on the impact of the abject within her work. “This ambiguous concept of the abject is used in my work to define the horrors and emotions that we have all experienced and how they remain locked up inside of us.” (Rose, 2014) The use of twisting taps and modifications within this piece are a comment on vulnerability, sexual abuse and violence; capturing a lack of control and loss of autonomy.

Post Menopausal: Loren Crabbe (2014) Purging Abjection

Figure 7

Post Menopausal: Kiki Smith (1992) Pee Body, 68.6 x 71.1 x 71.1cm

Kiki Smith takes from her experience working as an emergency medical technician to understand the human body. Her works are concerned with human experience regarding social, political and physical issues - often depicting bodily excrement. When speaking on the significance of her works she has stated, “I always think the whole history of the world is in your body” (BOMB Magazine, 1994)

The sculpture, Pee Body, depicts a life-size woman’s body constructed of wax crouched on the gallery floor with yellow beads – representative of urine – coming out of her. The piece strips the nude female form of the predisposed eroticisms, the posture of the figure suggests a vulnerability and creates this unsettling voyeuristic feeling as the onlooker.

Her works often concern what a women do and control of her own body, this piece has been chosen as a note to urinary incontinence an inability and struggle to control ones bladder - which can be one of the many struggles that come with menopause, stripping the women of an act that should be private (Naji, n.d.) The work perfectly captures this fragile state.

Figure 8

Death: Ivana Bašic (2017) I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms

Ivana Bašic is a Serbianartist practicing in NewYork. She is known for her mixed media sculptures which lend themselves to surrealism. Becoming Female – The cycle of abjection will take the sculpture I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms which previously was exhibited surrounded by other similarly composed sculptures at Bašic's solo exhibition, Through the hum of black velvet sheep (2017). The piece is constructed usingWax, glass, stainless steel, oil paint, silicone, silk cushioning and marble dust. This piece is the penultimate artwork in our exhibition it portrays the loss of distinction between life and death, it encapsulates the body through the cyclical stages of lifebecoming, being, declining and ceasing to be. I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms addresses the innately vulnerable essence of the human body. Bašic's piece confronts us with our own mortality showing the passing of time, unsettling the onlooker to address one’s internal existentialism.

This piece finishes the narrative of female experience with a symbol for our demise we show an equality between men and women, a shared natural experience, a gesture that only in death can we experience the same reality.

Figure 9

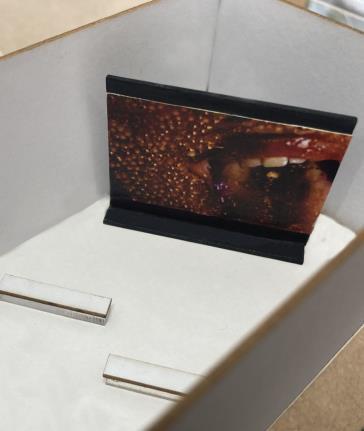

ReproductiveYears: Marilyn Minter(2009) Green Pink Caviar

The final piece of our exhibition is Marilyn Minter's 2009 short film, Green Pink Caviar. The film comes out of the linear storytelling of the life cycle within this exhibition and goes back to representing the reproductive years. The film stands alone in the gallery two space, allowing for an immersive watching experience. Green Pink Caviar encapsulates the experience of discomfort and desire. Minter uses vibrant colours, unsettling textures and long feminine movements to create an abstractapproach to eroticism. Minter's works have beena long-standing tribute to female sexuality. She aims to create imagery for women's enjoyment and amusement. Creating a space where beauty intertwines with the grotesque.

Floor Plan

Figure 10

Exhibition Model

This Exhibition model has been laser cut and is constructed to the scale of 1:100

Dundee ContemporaryArts

Entrance into Gallery 1 (a)

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Gallery 1 (b) into Gallery 2

Figure 16

Figure 17

Chapter Three: Curatorial Aims and Influences

3.1 Intended audience and Exhibition Space

Dundee'sWoman’s Festival takes place annually in March around International Women's Day on the 8th of March, the festival aims to capture Dundee’s rich history of women past and present. Having Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection take place in unison or as part of the programme for Dundee’s Woman’s Festival would attracta wider audience (Creative Dundee, 2024). Not just those who tend to visit gallery spaces, but people with a fascination for feminism. Dundee also acts as a relevant place for the exhibition due to its historic ties to female workers. Dundee was once known as She Town because it had three times as many female workers in the jute mills than male workers.

(Dundee Heritage Trust, 2023)

The exhibition aims to draw in people with a fascination with the topic and also equally those who are unsettled by the works. The proposed works aim to cultivate an experience drawn from relation with the innately female and unsettling – with the primary audience - female art aesthete’s and enthusiastscreating a connection or bond through an understanding of experience. For the secondary audience –male and the public the works will aim to be an influence in the conversation challenging feminine taboo, creating an open space to discuss issues of biology that in other circumstances can feel alienating. For those who do not relate through biological experience it opens a conversation to consider these issues, empathy and understanding for peers.

Dundee Contemporary Arts is a vibrant creative space in the centre of Dundee. The gallery spaces in the building are easily accessible for everyone being on the floor as you enter with large open spaces. The gallery has flexibility on the installation of walls for exhibitions, requiring that they connect to the tracks that run parallel down the roof. This allowing the installation of two walls for the exhibition; one running freely with the track on the right-hand side to create an ‘alley’ to enter through, the second breaking up the gallery one space down the middle, encouraging a certain path for the viewer to walk up on.

3.2 Curatorial influences / decisions

An exhibition space which encourages you to walk around following through a period is a narrative which can primarily be seen from archival and historical exhibitions: the display of archival footage and artifacts is a traditional way of moving round a space clockwise or anticlockwise and pulls you on a journey. Rip it up: the story of Scottish pop (2018) was particularly influential. This exhibition had you move clockwise through the space showing works from the 1960s all the way up to the present

day. Taking this approach to an art exhibition – i.e. showing time pass in a linear way – acts as a means of immersing the viewers in the life cycle of the female, creating a space for the viewer to reflect on their own relationship to life, ageing and decay.Instead of being archival and presenting the works in chronological order, the exhibition charts the chronological process which the human female develops, from birth to death. The positioning of the installed walls is essential to this feeling of time passing.

At the end of the gallery one space where we have life size sculptures, it is crucial that these sculptures appear in an open area of the gallery to allow the viewer to walk around and engage with the sculptures from different angles. The two sculptures are equally spaced apart and are the primary focus of the third section of the gallery. It is important that there is enough space between the two sculptures for them to be fully appreciated and valued in their own right as art works. This applies to all artworks allowing space for each individual space.

In the exhibition space, it is important that all works are well lit, and the colour of the lighting does not affect how the artwork is perceived. The exhibition will be lit with ambient lighting color will be graded between 3000k – 4000k, so that the lighting is the most natural and undistracting. We will use assent lighting to highlight the sculptural pieces, acting as a spotlight pulling ultimate focus on to these pieces when needed, it is important this lightning is not overpowering though must allow all details to still be viewed as intended and not to create any harsh shadows.

In the gallery two space, we will be projecting the film Green Pink Caviar. We will install a white wall to project on, the projector will sit in front of the benches so that people passing through will not disrupt the image. We will have benches for people to sit up on and view the piece which will be in a continuous loop. With speakers facing out from the screen to engage the audience with the sound and visuals. The room will have no additional lighting, this allows the film to be the focus of the space.

3.3 Reclamation of male spaces / ‘White Cube’galleries

The art works proposed are fully by female presenting artists as a response to the trajectory of the under-representation of female artists, especially in traditional ‘White Cube’galleries (Chalabi, 2019). These spaces have historically been dominated by men, with women facing stronger barriers to get and advance by exhibiting their work. Even when women were able to exhibit work it has been viewed as an anomaly and stands out with the usual artistic conversation. The exclusion from institutions meant female artists have often been undervalued. Art critics, who are historically predominantly male have played a role in perpetuating gender unbalance, being considerably less

likely to acknowledge or praise the work of female artists. (Cooper, 2015) picture. Often women's art works were viewed and critiqued within a stereotype of perceived femininity – commenting on domesticity and sentimentally, contrasting from that of their male counterparts, who would be praised for innovation. This gender bias between female and male artists perpetuated the dismissal of female artists. Furthermore, female artists had an expectation of what their works should depict, with certain contents being viewed as appropriate for women, less ambitious, aggressive, grotesque influencing an expectation to create decorative ‘appropriate’ works. (Taylor Brown, 2019)

In recent years there has been efforts to improve women's representation in artistic spaces, with feminist and art history movements bringing awareness to the imbalance highlighting how women's contributions have been presented. (Ashby, 2022) The process of creating a more equal art world is ongoing. Art institutions are actively working to collect and exhibit more art works from women, this progress is still ongoing and there is a long way to go for equitability. Despite efforts at the current rate of growth art works in the auction market won't see gender parity until 2053 (Burns and Halperin 2022). Feminist modernist poet Mina Loy reflects on this idea of inequality

No scratching on the surface of the rubbish heap of tradition, Will bring about reform, The only method is absolute demolition (Feminist Manifesto, 1914)

The concept that women were not expected to push boundaries reinforces and encourages the need for exhibitions and spaces which celebrate works which veer away from expected narratives and depict raw and honest works, confronting and challenging expectations. One of the most revolutionary and inspiring works in the feminist movement is Judy Chicago’s Women House (1972) a collaborative installation which brought public attention to widely experienced female issues. The installation was radical for the time and at the forefront of abject art being deeply inspirational for this proposed exhibition.

Chapter Four: Other Cultural Influences

This exhibition has been cultivated by a selection of inspirational feminist creatives. These artists capture the nuances of being a woman while protesting about patriarchal rule. At the core of this exhibition surrounding abject art, is the feminist issue of being restrained and silenced in a perceived narrative. Woolf, Schneeman and The Guerrilla Girls have all acted as an intrinsic part in the process of collation for this exhibition, inspiring the motive and the thesis. By reflecting up on previous works and texts it creates a premise and a core understanding to Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection.

4.1 VirginiaWoolf

The works of influential literature on the creation of art are undeniable. Throughout history, the two practices ebb and flow, each benefiting from the creation of the other (Patel, L. 2023). The author, Virginia Woolf, was a powerhouse in the fight for women's suffrage. Woolf’s writing has undeniable influence culturally, which further transgresses into art. The extended essay, A Room of One's Own (1929), details how men and women are equals in abilities, and posits the theory that women have not been given the same spaces and opportunity as their counterpart–male writer, who historically produced more impressive works, but only because they have been given consistent advantageous opportunities.

It would be a thousand pities if women wrote like men, or lived like men, or looked like men, for if the two sexes are quite inadequate, considering the vastness and variety of the world, how should we manage with one only (Woolf, 1929, p.74)

This quote from A Room of One's Own encapsulates the idea that a women would need her own space, intellectual and financial freedom to be able to write freely. This measures out with literature and into all aspects of the creative field, that there is an underinvestment into women's works and a major gap in women telling their own stories. This idea that a women must be able to tell her own story and experience is crucial to the curation of this exhibition.

In Dr. Birbal Saha’s essay on ‘Feminism in Society, Art and Literature: An Introspection’, it is proposed that in feminist analysis, it is much more important to focus on what is being discussed and how we analyse, rather than formally repeat restrictive structures.

Let go of the formalists' ideological dogma because the content and method of examining social situations, rather than the form, are what give feminism its greater validity (Saha, 2023, p.2)

This ideology criticizes overly theoretical approaches to feminist theory – expressing that we must priorities real social issues relevant at the times of discussion. This expands on the message within

Woolf’s book and the way in which it consistently shifts with the times lining up with the suffragette movement through to present day contemporary feminist movement.

A Room of One's Own has aged timelessly and stands as a staple piece of feminist literature, arguably even more prevalent now. It has taken almost a century for the art world to begin to catch up with Her ideologies. Woolf encouraging women to correct discrepancies by creating their own artistic traditions and shaping history. This exhibition aims to act as a way for to depict the female experience from a female perspective. It is worth noting how the depiction of how women are presented in art changes with the culture and the opportunity that surrounds the artist. The shift from when Woolf’s essay was first published, depicting women in the home and a domestic environment in line with women's suffrage, to a period almost a century later, when this stereotype has begun to be broken down, presents the home now as a place to express identity and have personal freedom. The improved access to art education and networks makes the presence for an increase presence of women in the art world encouraging a shift in narrative. Artists are now representing women as individuals rather than as background figures.

4.2 Guerrilla girls

The Guerrilla Girls group, mentioned previously for its role in producing thought-provoking graphics, which bring attention to discrepancies in the art world – is a collective of anonymous radical feminist artists. Established in 1985 in New York, the group originally protested outside the Museum of ModernArt in NewYork (MoMA) against sexism and racism. The collective uses satirical graphics to have an accessible reach to people, displaying their works in place of advertisements and using statistical figures to power the influence of the graphics. Artists within the group use synonyms and wear gorilla masks to remain completely anonymous. This allows the group to bring absolute focus to their graphics in their battle against institutionalism and elitism.

The collective has been influential to the curation of Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection. A representative of The Guerrilla Girls said in an interview,

How can you really tell the story of a culture when you don’t include all the voices within the culture? (Kahlo, NY Times.)

This narrative is echoed in this exhibition, reinforced with ideas of autonomy and self-representation. The exhibition aims to steer away from the ways in which art has historically prioritized privileged white men as highlighted by this group.

The Guerrilla Girls poster, The Birth of Feminism (2001) depicts three prevalent actresses in reveling clothing holding up banners depicting texts promoting the feminist movement. The poster acts as an argument for any preconceived ideas of what a feminist must look like. It challenges the idea in which feminism is an exclusionary movement and must have a certain box ticked. The poster challenges the idea that female sexuality is destructive of the movement and counters this suggesting it is in fact acting more as a symbol of inclusion.

We should strive to be inclusive for the purpose of supporting a common cause. (Hanson, 2013)

A woman should be able to embrace conventional ideologies of the preconceived women or alternatively be able to step away from any expectations. It is a necessity that the feminist movement is not exclusionary and thatall archetypes of women are included and accepted, to have a world with full personal autonomy.

4.3 Carolee Schneeman

One particularly influential artist for this exhibition is Carolee Schneeman. She led an incredibly empowering life and created countless standout art pieces. The work which resonated the most and acted as the starting point for the exhibition was Kitch's last meal (1973), in which she documents the death of her cat but through the film uses this as a platform to discuss the discrepancies between men and women, the act of male authority in the art world and the presumption of how she should be as an artist, engaging with feminist and conceptual practices.

“he said we can be friends equally though we are not artists equally I said we cannot be friends equally and we cannot be artists equally” (0:7:11 – 0:7:19)

This quote from the film perfectly encapsulates the power which the film holds. The narrative presents an imagery drawing a parallel between the dead cat and the objectified female body; a symbol of all that is consumed, manipulated and discarded with in society; reflecting on the woman sexually and culturally. The film came out in the early 1970s as the feminist movement was beginning to gain popularity and acted as a channel to speak about the female body and male desire. The work finds itself bordering on surrealism and allows itself the use of monologue to comment on dynamics of control and domination between men and women.

A further piece that has lent itself to the creation of this proposal is the controversial Interior Scroll (1975) Schneeman's provocative performance piece in which she pulls a scroll from her vagina and reads from it. The act of pulling a scroll from her body is disturbing and intense; encapsulating the abject. The contrast between the physical act and the dialogue read from the scroll creates a powerful indulgent experience for the audience. By forcing the audience to look at a body on display it forces them to confront predisposed assumptions about sexuality and objectification. Schneemann, as the artist, takes full control of her body and uses this piece as an opportunity to confront societal expectations of femininity. She reclaims sexuality within this performative piece as a narrative that she the women should have control over.

The dialogue read from Schneemann's scroll addresses her frustration with the art world and frustration with male dominated societal structures which control and limit the voices of women and marginalize and exclude women from the male domineering narrative within. Schneeman expresses frustration with how women are often viewed as less serious and valuable than their male counterparts. This narrative is carried through her life works, pioneering a rebuttal against the patriarchal art world and creating a voice for women.

Conclusion

This exhibition proposal responds to the imbalance between the male and female in art - the art world has historically been dominated by patriarchal values that perpetuate the objectification and marginalization of women. The artworks introduced explore the abject through ambiguity. The theory of abjection, as developed by Julia Kristeva, provides a powerful framework for understanding the ways in which the female body has been both fetishized and repulsed in art. This reveals the deep tensions between desire and disgust that often define the female experience. This exhibition, by confronting and reimagining these tensions, seeks to disrupt the traditional narratives that have long defined a women’s place in art. It invites a more nuanced understanding of the female body – one that acknowledges its complexity, its agency, and its power, ultimately pushing back against the restrictive boundaries of the patriarchy.

Becoming Female – The Cycle of Abjection is designed to not only address the underrepresentation of female artists in traditional gallery spaces but also to challenge the longstanding patriarchal narratives embedded in art history. Set in the context of Dundee's Women's Festival, the exhibition aims to attract a diverse audience, including both those familiar with feminist discourse and those who may feel unsettled by the exploration of female bodily functions and experiences. The flexible space at Dundee Contemporary Art allows for thoughtful curation and planned lighting, enhancing an immersive experience that encourages reflection on the passage of time, the female life cycle, and the complexities of body and identity. By reclaiming a male-dominated space and spotlighting works by female-presenting artists, this exhibition seeks to disrupt traditional expectations, confronting societal taboos and opening vitalconversations about gender, biology, and representation. Drawing inspiration from pioneering feminist thinkers, art movements and artists who without the influences of the exhibition would not hold possible. The exhibition endeavors to continue the work of reclaiming space for women in the art world, ultimately contributing to the ongoing effort for gender equality in the arts.

The art works presented are powerful pieces honouring the full spectrum of the female experience, it creates a space that refuses to shy away from the visceral, messy reality of the body, in doing so, offers a powerful critique of the traditional male gaze. They do this by confronting the paradox of beauty and grotesque, the works inviting us to reflect on the ways in which disgust and desire are interlinked and how they shape our understanding of femininity. From the representation of the female body through the male gaze to the reinforcement of stereotypes that position women as either sexual objects or idealized maternal figures, these dynamics have shaped both the creation and reception of art. The artworks proposed aim to act as a tool for progression and disruption. Ultimately the

exhibition opens new possibilities for how women are seen and represented, not as passive subjects, but as active creators and protagonists of their own stories.

Reference List

Ashby, C. (2022) Women Artists Have Been Ignored For Far Too Long. Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/women-artists-have-been-ignored-for-far-toolong/#:~:text=Women%20artists%20have%20been%20ignored%20for%20far,puts%20women%20art ists%20firmly%20in%20the%20 (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. 1st edn. Great Britain: The British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

BOMB Magazine (1994) Kiki Smith by Chuck Close. Available at: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/1994/10/01/kiki-smith-1/(Accessed:02/12/24).

Bodyform advert replaces blue liquid with red 'blood' (2017) Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk41666280#:~:text=Bodyform's%20video%20campaign%20%2C%20%23bloodnormal%2C,bike%20r iding%2C%20boxing%20and%20running. (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Burns, C and Halperin, J. (2022) Letter from the Editors: Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report Available at: https://studioburns.media/letter-from-the-editors/ (Accessed: 20/12/24).

Chalabi, M. (2019) Museum art collections are very male and very white. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2019/may/21/museum-art-collections-study-very-malevery-white (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Collier-Doyle, P. (2020) The Representation of Women in Art Throughout History. Available at: https://www.poppycd.art/the-representation-of-women-in-art-throughouthistory/#:~:text=The%20historical%20representation%20of%20women,work%20of%20the%20Guerr illa%20Girls (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Cooper, A. (2015) The Problem of the Overlooked Female Artist: An Argument for Enlivening a Stale Model For Discussion. Available at: https://hyperallergic.com/173963/the-problem-of-theoverlooked-female-artist-an-argument-for-enlivening-a-stale-model-ofdiscussion/#:~:text=My%20intention%20here%20is%20not,women's%20art%20making%20looks%2 0like (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Connelly, F. (2012) The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture, [1st edn] Great Britain. Cambridge University Press.

CreativeDundee (2024)Available at: https://creativedundee.com/2024/02/dundee-womens-festival2024/ (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Dundee Heritage Trust (2023). A Brief History of Verdant Works. Available at: https://www.dundeeheritagetrust.co.uk/story/history-of-verdant-works/(Accessed:02/12/24).

Freud, S. (1919) The Uncanny [No Edition Found]. Translated by David McLintock. Great Britain: Penguin Books.

Fruit Market (2024) Senga Nengudi. Available at:https://www.fruitmarket.co.uk/archive/senganengudi2019/ (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Gaut, B. (1993) 'The Paradox of Horror', British Journal ofAesthetics, Volume 33, Page 333.

Goody,A. (2007). Carnival Bodies, the Grotesque, and BecomingAnimal. ModernistArticulations. Palgrave Macmillan, London. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230288300_6

Hanson, M. (2013) 'The Guerrilla Girls: Art, Gender, and Communication', Drake University, page 12.

Hughes, B. (2020) 'Performing Periods: Challenging Menstrual Normativity through Art Practice', Volume 1, Page 24.

Jansen, C. (2017) Betty Tompkins Is the Feminist Artist You Need to Know. Available at: https://www.elle.com/uk/life-and-culture/culture/longform/a40061/betty-tompkins-feminist-art/ (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Kant, I. (1788) In Critique of Practical Reason. Published online by Cambridge University Press.

Kristeva, J. (1980) Powers of Horror. 1st edn. Translated by L. S. Roudiez. NewYork: Columbia University Press.

Loy, M. (1982) Feminist Manifesto, in The Last Lunar Baedeker.

Marshik, C. (1995) "The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess and Modernity." Modernism/modernity, vol. 2 no. 3, p. 183-185. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/mod.1995.0048.

Mulvey, L. (1975) 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema', Screen, 16 (3), pp. 6-8

Naji, O. (no date) Menopause and Urinary Incontinence. Available at: https://guysandstthomasspecialistcare.co.uk/news/menopause-and-urinaryincontinence/#:~:text=As%20explained%20above%2C%20menopause%20can,hold%20in%20urine% 20and%20faeces (Accessed: 02/12/24).

New York Times (2015) The Guerrilla Girls, After Three Decades, Still Rattling the Art World. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/09/arts/design/the-guerrilla-girls-after-3-decades-stillrattling-art-worldcages.html#:~:text=KAHLO%20How%20can%20you%20really,and%20the%20story%2C%20of%20 power. (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Nochlin, L. (1971) Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists. 50thAnniversary edn. Great Britain: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Patel, L. (2023) The Connection Between Art and Literature. Available at: https://www.1st-artgallery.com/article/the-connection-between-art-andliterature/#:~:text=Literature%20has%20stirred%20the%20imagination,paintings%20inspired%20by %20literary%20works (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Plieger, T. (2021) The Association Between Sexism, Self-Sexualization, and the Evaluation of Sexy Photos on Instagram. Available at:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8423916/ (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Reenkola, E. (2013) Female Shame as an Unconscious Inner Conflict. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01062301.2005.10592765(Accessed:02/12/24).

Regensdorf, L. (2018) Artist Carmen Winant on Why 2,000 Images of Childbirth Belong at MoMA. Availableat:https://www.vogue.com/article/carmen-winant-my-birth-being-photography-exhibitionmuseum-of-modern-art-moma-womens-health-feminism (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Rose,A. (2014) Artist Loren Crabbe Discusses Abjection, Trauma, and the Human Body. Available at: https://posturemag.com/online/artist-loren-crabbe-discusses-abjection-trauma-and-the-human-

body/#:~:text=The%20abject%20is%20not%20a,locked%20up%20inside%20of%20us (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Ryan, S., Ussher, J. M, &Hawkey,A. (2022). Mapping the Abject: Women's Embodied Experiences of Premenstrual Body Dissatisfaction Through Body-Mapping. Feminism & Psychology, 32(2), 199–223.Availableat: https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535211069290 (Accessed:02/12/24).

Saha, B. (2023) 'Feminism In Society, Art and Literature: An Introspection’, Galore International Journal of Applied Sciences and Humanities, Volume 7 Issue 1, Page 2.

Seward, L. (2017) Sex Sells Available at: https://medium.com/writing-in-the-media/sex-sellsbec257f030ea (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Sex Sells: The Self-Sexualization Pressures on Female College Athletes and the “Othering” of Women in Sports (2022) Available at: https://cseinstitute.org/sex-sells-the-self-sexualization-pressures-onfemale-college-athletes-and-the-othering-of-women-in-sports/ (Accessed:: 02/12/24).

Tate(2024) Chicken Knickers. Availableat:https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lucas-chickenknickers-p78210 (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Tate(2024) Women in Art. Availableat:https://www.tate.org.uk/art/women-in-art(Accessed: 02/12/24).

Taylor Brown, T. (2019) Why is Work by Female Artists Still Valued Less Than Work by Male Artists. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-work-female-artists-valued-work-male-artists (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Thackara,T.(2019) Why Contemporary Women Artists are Obsessed with the Grotesque. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-contemporary-women-artists-obsessed-grotesque (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Totenberg, N &McCammon, S. (2022) Supreme Court Overturns Roe v. Wade, Ending Right to Abortion Upheld for Decades. Availableat:https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1102305878/supremecourt-abortion-roe-v-wade-decision-overturn (Accessed: 02/12/24).

Woolf, V. (1929) A Room of One's Own. 1st edn. Great Britain. Penguin Random House UK.

Welgos, L. (2021) Camille Henrot: On Climate Grief, Soft Labor, and “Mother Tongue”. Available at: https://topicalcream.org/features/camille-henrot-on-climate-grief-soft-labor-and-mother-tongue/ (Accessed: 02/12/24).