for use with Ruhof’s Prepzyme® Forever Wet Enzymatic Pre-Cleaner

The cleaning process begins at the point of use. When soils dry, they become harder to remove and increase the risk of corrosion, biofilm formation, and HAI’s. The Forever Wet Auto Sprayer delivers a consistent application of Prepzyme® Forever Wet in less than half the time—keeping instruments moist for up to 72 hours.

OCTOBER 2025

Sourcing & Logistics

8 > How Pharmacy Leaders Are Rewriting the Supply Chain Playbook

KARA NADEAU

34 > Our Similarities Make the Difference: A UK View of the US Healthcare Supply Chain

KAREN CONWAY

Infection Prevention

14 > Artificial Intelligence in Infection Prevention

MATT MACKENZIE

Sterile Processing

18 > 7 Steps Toward HLD Improvements in Healthcare Organizations

KARA NADEAU

26 > External Transport of Medical Devices

SUSAN KLACIK

31 > Sterile Processing Week Is Oct. 12–18: Honor the Team’s Vital Contributions

JULIE WILLIAMSON

32 > Common Mistakes in the SPD: Part 1

ADAM OKADA

Departments

6 > A New Chapter at HPN

7 > What’s on the Web

7 > Advertiser Index

Enzymatic Sponge Soiled Transport IAC Recommended Electrical Leakage Testing

Bedside Cleaning

Procedure

Procedure Transport

BY DANIEL BEAIRD

I’m pleased to introduce myself to you as the new Editor-in-Chief of Healthcare Purchasing News. It is an honor to join a publication that, for nearly 50 years, has been a trusted voice for professionals in supply chain management, surgical services, sterile processing, infection prevention, and product evaluation. I look forward to building on this legacy with the help of our dedicated editorial team and the expertise of our readers and contributors.

That tradition has been sustained in recent months by the leadership of Associate Editor Matt MacKenzie, who has guided our newsletter, website, and print magazine. His steady hand ensured continuity and quality during the search for new editorial leadership, and I am grateful for his efforts.

My career in B2B healthcare media has focused on telling stories that connect with people and highlighting the challenges and innovations shaping our industry. In recent years, I’ve covered issues spanning pandemic response to supply chain resilience, gaining a deeper appreciation for the professionals who keep healthcare functioning, often out of public view.

In this issue, we examine how pharmacy leaders are confronting rising drug costs, shortages, workforce constraints, and regulatory pressures. Many are borrowing proven strategies from medical-surgical supply chain management, such as

integration, automation, and datadriven decision making, to strengthen pharmacy operations and improve patient safety.

We also continue our series on the complexities of centralizing highlevel disinfection under sterile processing department oversight. While centralization is considered the ideal, each hospital or health system handles HLD differently and variations in practices and circumstances create challenges. Instead of offering a onesize-fits-all roadmap, successful HLD centralization depends on addressing unique organizational nuances and stakeholder input.

Finally, we feature a Q&A that highlights AI’s exciting potential in drug discovery, especially for antimicrobial resistance, helping labs collaborate with clinicians to select appropriate therapies. And in infection prevention, AI can do so many things to ultimately reduce healthcare-associated infections and improve patient safety from predicting outbreaks to guiding targeted antimicrobial therapies.

I welcome your ideas and feedback as we move forward. As Matt mentioned in his Editor’s Note last month, we want to ask you, our readers, what topics you’re most interested in being covered. Please send me a line at dbeaird@endeavorb2b.com. Together, we will continue advancing HPN as a vital resource for healthcare professionals everywhere.

October 2025, Vol. 49, No. 9

Editor-in-Chief

Daniel Beaird

dbeaird@endeavorb2b.com

Associate Editor

Matt MacKenzie mmackenzie@endeavorb2b.com

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau knadeau@hpnonline.com

Advertising Sales

East & West Coast

Kristen Hoffman khoffman@endeavorb2b.com | 603-891-9122

Midwest & Central

Brian Rosebrook brosebrook@endeavorb2b.com | 918-728-5321

Advertising & Art Production

Production Manager | Ed Bartlett

Art Director | Kelli Mylchreest

Advertising Services

Karen Runion | krunion@endeavorb2b.com

Audience Development

Laura Moulton | lmoulton@endeavorb2b.com

Endeavor Business Media, LLC

CEO Chris Ferrell

COO Patrick Rains

CRO Paul Andrews

CDO Jacquie Niemiec

CALO Tracy Kane

CMO Amanda Landsaw

EVP Infrastructure & Public Sector Group

Kylie Hirko

VP of Content Strategy, Infrastructure & Public Sector Group

Michelle Kopier

Healthcare Purchasing News USPS Permit 362710, ISSN 1098-3716 print, ISSN 2771-6716 online is published 11 times annually - Jan, Feb, Mar, Apr, Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep, Oct, Nov/Dec, Nov/Dec IBG, by Endeavor Business Media, LLC. 201 N Main St 5th Floor, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538. Periodicals postage paid at Fort Atkinson, WI, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Healthcare Purchasing News, PO Box 3257, Northbrook, IL 600653257. SUBSCRIPTIONS: Publisher reserves the right to reject non-qualified subscriptions. Subscription prices: U.S. $160.00 per year; Canada/Mexico $193.75 per year; All other countries $276.25 per year. All subscriptions are payable in U.S. funds. Send subscription inquiries to Healthcare Purchasing News, PO Box 3257, Northbrook, IL 60065-3257. Customer service can be reached toll-free at 877-382-9187 or at HPN@omeda.com for magazine subscription assistance or questions.

Printed in the USA. Copyright 2025 Endeavor Business Media, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication should be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopies, recordings, or any information storage or retrieval system without permission from the publisher. Endeavor Business Media, LLC does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any person or company for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in the material herein, regardless of whether such errors result from negligence, accident, or any other cause whatsoever. The views and opinions in the articles herein are not to be taken as official expressions of the publishers, unless so stated. The publishers do not warrant either expressly or by implication, the factual accuracy of the articles herein, nor do they so warrant any views or opinions by the authors of said articles.

Jimmy Chung, MD, MBA, FACS, FABQAURP, CMRP, Chief Medical Officer, Advantus Health Partners and Bon Secours Mercy Health, Cincinnati, OH

Joe Colonna, Chief Supply Chain and Project Management Officer, Piedmont Healthcare, Atlanta, GA; Karen Conway, Vice President, Healthcare Value, GHX, Louisville, CO

Dee Donatelli, RN, BSN, MBA, Senior Director Spend symplr and Principal Dee Donatelli Consulting LLC, Austin, TX

J. Hudson Garrett Jr. PhD, FNAP, FSHEA, FIDSA, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Medicine, Infectious Diseases, University of Louisville School of Medicine

Melanie Miller, RN, CVAHP, CNOR, CSPDM, Value Analysis Consultant, Healthcare Value Management Experts Inc. (HVME) Los Angeles, CA

Dennis Orthman, Consulting, Braintree, MA

Janet Pate, Nurse Consultant and Educator, Ruhof Corp.

Richard Perrin, CEO, Active Innovations LLC, Annapolis, MD

Jean Sargent, CMRP, FAHRMM, FCS, Principal, Sargent Healthcare Strategies, Port Charlotte, FL

Richard W. Schule, MBA, BS, FAST, CST, FCS, CRCST, CHMMC, CIS, CHL, AGTS, Senior Director Enterprise Reprocessing, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

Barbara Strain, MA, CVAHP, Principal, Barbara Strain Consulting LLC, Charlottesville, VA

Deborah Petretich Templeton, RPh, MHA,Chief Administrative Officer (Ret.), System Support Services, Geisinger Health, Danville, PA

Ray Taurasi, Principal, Healthcare CS Solutions, Washington, DC

Many previously healthy patients who died of sepsis ultimately died because it was too late to intervene, the study also found..

T he patients in this cohort who died “tended to be older, and had more acute respiratory dysfunction, altered mental status, and shock upon admission to the hospital.” These patients also “received vasopressors and invasive mechanical ventilation more o en than survivors.” Most of their deaths were “deemed to be unpreventable due to how sick they were when they arrived at the hospital.”

Read on: hpnonline.com/55311059

Reportage from CNN said that BARDA is terminating “22 mRNA vaccine development investments…despite evidence they protect against severe disease and death from COVID-19 and show promise against influenza.” The HHS also says that the money could be rerouted to other technologies, like “whole-virus vaccines and novel platforms.”

Read on: hpnonline.com/55308066

to Protect Against VentilatorAssociated Pneumonia

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) affects about one in 10 ventilated patients and is “responsible for the majority of deaths from healthcare associated infections,” adding “about nine days to intensive care unit stays” and costing more than $40,000 per case. The mouthguard “absorbs secretions before harmful bacteria can reach the lungs,” aiming to reduce rates of VAP where many other clinical workarounds have failed.

Read on: hpnonline.com/55304149

Pharmaceuticals Ramp Up U.S. Investment as Tariff Plans Loom

The Associated Press has reported that President Donald Trump is vowing to slap tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals, a category largely shielded from trade duties until now. A new U.S. and Europe trade deal already includes a 15% levy on some European drugs, and Trump is threatening tariffs as high as 200% on those from elsewhere.

Read on: hpnonline.com/ 55313747

Facing rising drug costs, shortages, workforce pressures, and regulations, health systems are adopting new strategies to modernize pharmacy operations and strengthen patient care.

BY KARA NADEAU

Pharmacy leaders in U.S. health systems and hospitals are navigating mounting challenges—a convergence of rising drug costs, persistent shortages, workforce constraints, and complex

regulatory requirements. These pressures are prompting a renewed focus on pharmacy supply chain operations to identify opportunities for greater efficiency, cost reduction, and improved patient safety.

To meet these demands, many leaders are leveraging strategies proven in medical-surgical supply chain optimization—such as system integration, process automation, and data-driven decision-making—to modernize pharmacy operations and drive better outcomes.

HPN explores the current pharmacy landscape today, shares one U.S. pharmacy leader’s vision, strategy, and tactics for his health system’s pharmacy supply chain transformation, and presents insights on pharmacy operations optimization from service and solutions providers in this space.

The pharmacy supply chain is notoriously complex with its wide range of drug products to be managed—many with specific storage requirements (e.g., temperature and humidity control), multifaceted pricing programs (e.g., CMS 340 Pricing Program), and stringent regulations (e.g., DSCSA).

In recent years, health system and hospital pharmacy leaders have been forced to manage this complexity with a shrinking workforce. At the same time, drug prices continue to rise, and shortages show no end in sight. Consider the following:

• 208 drugs on the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) current drug shortages list*, including widespread shortages of sodium chloride irrigation and dextrose intravenous injections1

• Hospitals across the U.S. spent roughly 20 million hours managing a range of drug shortages, which translates to nearly $900 million annually in labor costs, according to Vizient2

• More than 80% of pharmacy directors report perceived shortages of experienced technicians, and about 60% report perceived shortages of clinical specialists and clinical coordinators, according to the ASHP3

* At the time this article was written in August 2025

Published survey findings point to an increased focus on supply chain challenges and opportunities among pharmacy leaders.

• 30% of U.S. health system pharmacy leaders consider lack of visibility into potential shortages to be “a significant threat to their organizations in the next five years” according to a McKinsey & Company survey.4

• 77% of hospital pharmacy teams are actively focused on “cutting costs through improved operations and more innovative procurement,” according to a Bluesight report.5

Pharmacy supply chain transformation at IU Health

When Derek Imars, PharmD, MBA, BCPS, joined Indiana University (IU) Health as Executive Director of Pharmacy Supply Chain last year, he set out to build a comprehensive

roadmap for the future. His vision: A pharmacy supply chain that integrates all decisions under one strategy and provides the infrastructure needed to fully support a clinically integrated supply chain.

“We’re working to centralize purchasing and ensure that if inventory is managed through our consolidated service center (CSC), it’s the slowmoving items most prone to expiration,” Dr. Imars explained.

“We’re also insourcing shortage mitigation by creating critical product lists—defining the items essential to running a hospital—and strategically sourcing six months of supply, whether through a group purchasing organization (GPO) run program or direct allocations.” This approach, he added, is both cost-effective and foundational to long-term resilience.

chain stakeholders have led the way in areas such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) system integration, standardized contracting, centralized purchasing, and data-driven decisionmaking. These practices, he noted, have consistently driven savings for health systems.

“When I look across the aisle at the medical/surgical supply chain, I see opportunities to take pieces of what they’ve perfected and adapt them for pharmacy workflows,” he said. “It can be a culture shock for pharmacy leaders, but it’s where we need to go.”

At the same time, Dr. Imars believes medical/surgical supply chain teams can learn from pharmacy. While most have only recently advanced toward clinical integration, pharmacy has operated as a clinically integrated supply chain for decades.

Dr. Imars compared pharmacy’s progress to that of the medical/surgical supply chain. Over the past 25 years, medical/surgical supply

“Pharmacists are often viewed as clinical facilitators, but our identity is broader than that—we’re also supply chain managers,” he said. “When

we bring that expertise forward, the benefits are significant. Pharmacy has been practicing clinically integrated supply chain management for 25 years or more, long before it became a buzzword.”

Collaboration between the two supply chain teams has been key at IU Health. Dr. Imars meets monthly with medical/surgical supply chain partners to align on overlapping product categories, such as IV fluids and surgical items.

“If we don’t channel products through the right distribution pathway, it can create confusion for caregivers and lead to issues with contracts, vendors, and purchasing,” he said. “By right sizing our portfolios together, we’re eliminating redundancies and creating clarity.”

Beyond collaboration, IU Health has taken a holistic approach to pharmacy supply chain optimization, investing in infrastructure and

technology to support all classes of trade—from acute care to retail, specialty, and infusion.

In acute care, where bundled payments make cost reduction essential, the focus is on savings strategies. In retail and specialty pharmacy,

“If we don’t channel products through the right distribution pathway, it can create confusion for caregivers and lead to issues with contracts, vendors, and purchasing.”

DR. IMARS

growth opportunities are prioritized to strengthen margins. A centralized compounding team plays a pivotal role across both domains, flexing from routine production to shortage mitigation. During the Baxter IV shortage, for example, IU Health was able to repackage products internally, avoid surgery cancellations, and preserve revenue.

Dr. Imars is also preparing his team for broader market and regulatory pressures, particularly in infusion services. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) CY 2026 Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical C nter (ASC) Payment System proposed rule includes updates to Medicare payment policies and rates for hospital outpatient and ASC services. OPPS rule and payer mandates are accelerating the shift from hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) to lower-cost infusion settings, such as ambulatory clinics and home care.

“The pressures are very real,” he said. “We’re building a central access team to work with physicians on referrals and payer requirements, ensuring patients can transition smoothly while keeping care within our system.”

Finally, IU Health continues to optimize its participation in the CMS 340B Pricing Program, partnering with a third-party administrator (TPA) and leveraging software to ensure compliance while aligning product distribution with the right site of care.

For Dr. Imars, the future of pharmacy supply chain lies in this balance: Adopting the medical/surgical supply chain’s data-driven efficiencies, elevating pharmacy’s longstanding clinical integration, and fostering collaboration across teams. The result is a model that not only reduces costs and mitigates shortages

but also strengthens the connection between supply chain performance and patient care.

Industry insights on pharmacy supply chain optimization Service and solutions providers in the pharmacy supply chain space offered their insights on the current environment and what health systems and hospitals need to optimize pharmacy operations.

Valerie Bandy,

Valerie Bandy

PharmD, vice president of Pharmacy Solutions at Tecsys

“Pharmacy supply chain is growing into an advanced practice. If you’re not keeping up, you’re missing cost savings, efficiencies, and compliance gains. Investing here means closing regulatory gaps, automating the

routine, and freeing staff to focus on patients.

“The real win in optimizing your supply chain is letting people do the work that matters. When you automate and optimize the repetitive tasks and link supply chain to clinical goals, you give staff the space to focus on safety, care and operating at the top of their license.

“We’re seeing new titles emerge — pharmacy ops strategy, revenue cycle and finance, pharmacy IT. It’s a really important shift for the industry. What it shows is that pharmacy leadership is expanding, blending deep clinical and operational knowledge with supply chain expertise to manage everything end to end. That combination is what’s driving better control, efficiency, and patient safety.”

Tecsys helps health systems optimize pharmacy supply chains by improving visibility, control, compliance, and patient safety. From centralized procurement to efficient replenishment, Tecsys solutions reduce waste, cut costs, and strengthen regulatory readiness. At the core is Elite for Pharmacy, which applies proven healthcare supply chain practices with advanced tools like predictive analytics, shortage and recall management, expiration monitoring, and support for DSCSA and 340B. The result is a reliable, cost-efficient pharmacy supply chain that minimizes risk and frees resources to advance patient care.

Lani Bertrand, RPh, senior director, Clinical Marketing & Thought Leadership, Omnicell

“Despite advances in medication management technology, many health systems still struggle with visibility into medication inventory and use. As telehealth and virtual care shorten hospital stays, medications move through more locations than ever, making it difficult to maintain a clear, end-to-end view from admission to discharge.

“Hospitals are also managing a mix of new digital solutions, outdated software, and standalone dispensing tools that don’t always work together. This creates data silos, making it hard to assess inventory enterprise-wide or use patient information to anticipate needs. Growing drug shortages add another challenge, complicating demand forecasting and procurement optimization, often leading to costly and wasteful stockpiling.

“Closing visibility gaps starts with addressing fragmented technology. Pharmacy teams need easy access to details such as which medications are about to expire, where stock-outs are occurring, and where medications are stored across the health system. Achieving this requires system connectivity and consolidation so all inventory data is accessible in one place.

“With the launch of OmniSphere, a secure, cloud-native platform that connects Omnicell devices to unify medication management, we’re creating a safe, intelligent, and integrated ecosystem. Built on scalable infrastructure and world-class cyber and data security, OmniSphere provides pharmacies with a single access point and source of truth for inventory data. Centralizing

this information enables real-time optimization, more efficient workflows, and more informed decision-making by integrating data from connected automation across care areas.”

“Pharmacy leaders today are facing unprecedented challenges—from drug shortages and rising costs to regulatory pressures and workforce constraints. What we’re seeing is that success requires more than simply keeping shelves stocked; it demands a smarter, more resilient supply chain.

“A growing number of health systems and hospitals are taking strategic steps to gain visibility into their pharmacy inventory, automate drug management processes, and leverage actionable, data-driven insights to help reduce pharmacy waste, improve compliance, and focus on what matters most—delivering safe, reliable care to patients.”

GHX Inventory Count Services provides accurate, process-driven, point-in-time inventory counting and documentation for clinical and pharmacy locations. A full-service project management team helps ensure an efficient count from start to finish supported by on-site credentialed, trained professional GHX employees. A suite of detailed reports provides actionable insights to stock level visibility and inventory valuations helping to inform supply chain purchasing decisions.

Ammie

McAsey, president,

McKesson Health Systems

“As the role of pharmacy continues to expand across the care continuum, the supply chain must evolve to meet new demands. At McKesson, we’re helping health systems move beyond transactional models to strategic, data-driven partnerships.

“By leveraging advanced analytics, global supplier relationships, and innovative distribution strategies, we’re building resilient, responsive supply chains that reduce waste, increase visibility, and improve patient outcomes. It’s about enabling pharmacy to do more—clinically and operationally—for the advancement of patient health.”

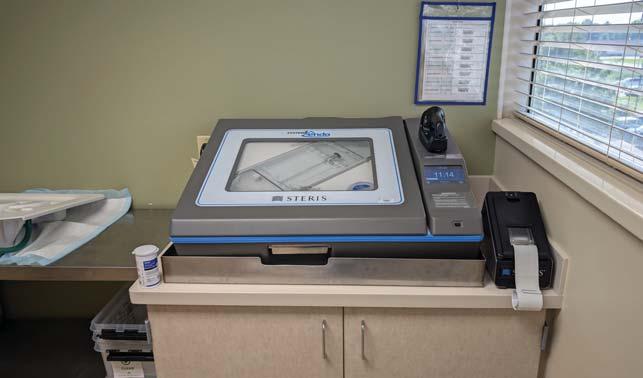

The Pharmacy Integrated Service Center supports a broad range of clinically integrated, pharmacy supply chain–driven services for acute care hospitals, provider clinics, IU Health retail pharmacies, and mail-order — all from this state-of-the-art facility.

Mittal Sutaria, senior vice president, Contract and Program Services, Pharmacy, Vizient

Tom Strohl, president of Oliver Wight Americas

“One of the biggest challenges is the fragility of the generics supply chain. Generics represent approximately 90% of all prescriptions filled. Margins are thin compared to their branded counterparts, creating the need for careful management of their supply chain and working capital. Only about 12% of active pharmaceutical ingredients are produced domestically, which means pharmaceutical companies are heavily reliant on offshore manufacturing.6

“This creates significant risk—minor disruptions like shipping delays can quickly escalate into drug shortages and increased costs for both hospitals and patients. While offshore production was once considered more cost-effective, it often hides broader issues such as long lead times, logistical complexity, inventory risk, and tariffs. The pandemic highlighted how a ‘low-cost’ strategy can undermine resilience and patient access to medicines.”

Oliver Wight helps its pharmaceutical clients adopt an Integrated Business Planning (IBP) approach.

IBP provides a structured view into future requirements and a way to evaluate tactical decisions not just by cost, but by their impact on resilience, service levels, and long-term sustainability. With better visibility across the supply chain and clearer understanding of tradeoffs, companies can make more informed decisions that improve reliability and protect patient access to essential medicines.

“In 2023, hospitals spent nearly 20 million labor hours managing drug shortages, costing almost $900 million— more than double 2019 levels. These shortages are no longer isolated events; they drain budgets, burden operations, and impact patient care. The future of the pharmacy supply chain must be built on resiliency through transparency, proactive sourcing, and strategic solutions— such as those that increase supply with access to pooled or dedicated inventory in times of disruption—to help health systems safeguard essential medications and ensure continuity of care.” HPN

1. Drug Shortages List, ASHP, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages

2. New Vizient survey finds drug shortages cost hospitals nearly $900M annually in labor expenses, Vizient, July 17, 2025, https://www.vizientinc.com/newsroom/news-releases/2025/ new-vizient-survey-finds-drug-shortages-cost-hospitals-nearly-900m-annually-in-laborexpenses

3. Craig A Pedersen, Ryan W Naseman, Philip J Schneider, Michael C Ganio, Douglas J Scheckelhoff, ASHP National Survey of Pharmacy Practice in Hospital Settings: Clinical Services and Workforce—2024, American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 2025;, zxaf150, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxaf150

4. Untapped opportunities for health system pharmacies, McKinsey & Company, November 7, 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/untapped-opportunitiesfor-health-system-pharmacies

5. New Bluesight report details how hospitals are modernizing pharmacy purchasing. News release. Bluesight. August 6, 2025. Accessed August 6, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/ news-releases/new-bluesight-report-details-how-hospitals-are-modernizing-pharmacypurchasing-302522618.html

6. Over half of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) for prescription medicines in the U.S. come from India and the European Union, USP, April 17, 2025, https://qualitymatters. usp.org/over-half-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-api-prescription-medicines-us-comeindia-and-european

BY MATT MACKENZIE

Artificial intelligence offers seemingly limitless potential on its face. Reading headlines coming out of practically every industry on the planet over the past couple years or so, you’d be forgiven for thinking that we’re all

just waiting for an AI development that will solve any intractable problem across any discipline. The truth is obviously more nuanced than that, but in a field like healthcare where mistakes can be life or death, demand for simple solutions for complex problems

is only growing, and the problems themselves remain as nuanced and numerous as ever, you’d be forgiven for pinning a lot of hope on AI tools to help navigate the morass of keeping patients healthy and happy as efficiently as possible.

Luckily, there are a number of studies and testimonies from seasoned veterans in the field that posit we may be right to pin a lot of hope on artificial intelligence to help us make sense of complicated questions. One of them,

published in the NIH’s PubMed database, specifically evaluated the potential for AI to help “prevent, detect, and manage” healthcare-associated infections. The researchers found that “AI models demonstrated high predictive accuracy for the detection, surveillance, and prevention of multiple HAIs, with models for surgical site infections and urinary tract infections frequently achieving area-underthe-curve (AUC) scores exceeding 0.80, indicating strong reliability. … Advanced algorithms, including neural networks, decision trees, and random forests, significantly improved detection rates when integrated with EHRs, enabling real-time surveillance and timely interventions. In resourceconstrained settings, non-real-time

AI models utilizing historical EHR data showed considerable scalability, facilitating broader implementation in infection surveillance and control. AI-supported surveillance systems outperformed traditional methods in accurately identifying infection rates and enhancing compliance with hand hygiene protocols.”

In addition, AI “played a pivotal role in antimicrobial stewardship by predicting the emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms and guiding optimal antibiotic usage, thereby reducing reliance on secondline treatments. However, challenges including the need for comprehensive clinician training, high integration costs, and ensuring compatibility with existing workflows were identified as barriers to widespread adoption.” This piece of the study further emphasizes the notion that these tools have enormous promise yet significant barriers to widespread adoption still exist. Regardless, those barriers don’t negate the promise these tools hold.

Another important piece of AI implementation is garnering and facilitating clinicians’ trust in the tools and models. This study also demonstrated that certain interpretability tools “increased clinician trust and facilitated actionable insights.” Following off of this, the authors of the study further emphasized that “successful implementation necessitates standardized validation protocols, transparent data reporting, and the development of user-friendly interfaces to ensure seamless adoption by healthcare professionals. Variability in data sources and model validations across studies underscores the necessity for multicenter collaborations and external validations to ensure consistent performance across diverse healthcare environments.” These

conclusions and suggestions lend credence to the notion that it will be difficult to implement artificial intelligence across healthcare disciplines at a large scale, but the learning curve will likely lead to great improvements in the end to help with patient care.

Healthcare Purchasing News spoke with Dr. Rodney Rohde, PhD, MS, SM(ASCP)CM, SVCM, MBCM, FACSc, Regents’ Professor at Texas State University System, to get a better sense of how healthcare systems are using artificial intelligence on the ground, and to hear an expert’s accounting of the benefits, shortcomings, and promise these tools and technologies hold.

How is artificial intelligence being used in health systems and hospitals?

Rohde : Artificial intelligence is increasingly transforming healthcare by enhancing the way hospitals and health systems deliver care. For example, AI is used to assist in diagnosing diseases and detecting conditions early via medical imaging, pathology, and radiology. Using predictive analytics for patient outcomes such as diabetes, heart conditions, or which patients may be at risk for readmission. AI is also being used for personalized medicine, clinical decision support, personal health assistants, robotics (e.g., surgery), administrative automation like email management and brainstorming for process improvement, drug discovery, population health, mental health, supply chain logistics, and dosing medications.

Are there any particularly exciting advancements in artificial intelligence you’re aware of?

Rohde: Personally, all of the answers are exciting. However, as someone

who is involved in antimicrobial resistance, I am excited about drug discovery and managing the complicated world of selecting appropriate antimicrobial agents while reducing the risk of increasing resistance patterns. AI can also help the medical laboratory collaborate more effectively with physicians and pharmacists to maintain the interplay between “antimicrobial breakpoints” and the correct therapy.

proper training for healthcare professionals are crucial to addressing these concerns.

Are there any untapped areas where you could see AI helping?

Rohde: AI has untapped potential in areas like improving diagnostic accuracy for rare diseases, enhancing real-time surveillance of infectious disease outbreaks, and streamlining laboratory processes. AI could also play a key role in analyzing vast amounts of epidemiological data to predict future health trends, helping public health officials respond more effectively to emerging threats. Additionally, AI’s ability to process complex genomic data holds promise for personalized medicine and targeted therapies.

Does AI have any shortcomings in infection prevention?

What potential does AI have in infection prevention?

AI has significant potential in infection prevention by enabling early detection, monitoring, and response. It can analyze patient data, medical records, and environmental factors to predict outbreaks and identify high-risk individuals. AI-powered systems can also monitor hand hygiene compliance, track infection spread within hospitals and optimize infection control protocols. Additionally, AI can assist in designing targeted antimicrobial therapies and predicting resistance patterns, ultimately reducing healthcare-associated infections and improving patient safety.

What hesitancies, if any, do you have when it comes to incorporating AI in hospitals’ operations?

Rohde: I think I would be most concerned about data privacy and security, as patient information is highly sensitive. There are also risks of AI bias, which could lead to unequal care or misdiagnoses, especially for underrepresented populations. Additionally, reliance on AI could diminish human oversight in critical decisions, and the technology may face regulatory hurdles or ethical challenges. Ensuring transparency, accountability, and

Rohde: While AI offers significant promise in infection prevention, it has shortcomings, particularly in its reliance on high-quality, comprehensive data. Incomplete or biased data can lead to inaccurate predictions or misidentifications of risks. Additionally, AI systems may struggle to account for complex, real-world variables, such as human behavior and environmental factors, which are crucial in preventing infections. There’s also the challenge of integrating AI seamlessly into existing healthcare systems and ensuring that staff are adequately trained to use these tools effectively.

Are there any technologies for infection prevention, AI or not, you would like to spotlight?

Rohde: Wow, there are so many things coming out almost weekly now that are interesting. It’s difficult to keep track of them all. However, for me, technologies like advanced biosensors, machine learning-based predictive models, and automated disinfecting robots as key innovations in infection prevention. AI-powered predictive analytics can help forecast outbreaks and identify high-risk patients, while biosensors and wearables monitor real-time health data to prevent infections. Automated robots, equipped with UV light or chemical disinfectants, help reduce human error and ensure consistent sanitation in high-risk areas, such as operating rooms and intensive care units.

Anything else you’d like to tell our readers?

Rohde: AI is absolutely going to transform our world. I continue to tell my students, alumni, and colleagues that I hope “we” all embrace the idea of “augmented intelligence.” In other words, we must all ensure that AI is utilized and developed in the most ethical way possible going forward. It’s an exciting time. HPN

With no one-size-fits-all approach, how do stakeholders drive HLD effectiveness and safety?

BY KARA NADEAU

As a sterile processing leader, you’ve been asked to assume oversight of high-level disinfection (HLD) of devices that takes place outside of your department. The ideal scenario presented is centralizing HLD to the sterile processing department (SPD).

In my October 2025 HPN article on this topic (“Taming the Beast: Best Practices for Managing HLD Inside and Outside the SPD”), I presented a high-level view of challenges, opportunities, and best practices for making this happen. My initial thought for this follow-up piece was to offer a clear and concrete roadmap for getting from point A to Z with HLD centralization.

But the more I spoke with stakeholders to this process, including sterile processing and infection prevention professionals, it became clear that the topic was not so cut and dry. Each health system or hospital is different when it comes to where and how HLD is performed. While the priority is to reprocess in alignment with industry standards and manufacturer instructions for use (IFU), there are many nuances that can make or break HLD centralization efforts.

Furthermore, if a clinical department – onsite at a hospital or offsite in a clinic – is successfully performing HLD in alignment with industry standards and their healthcare organization’s protocols, why try to fix what isn’t broken? Most SPDs are resource strained, specifically when it comes to staffing. If a clinical department has the resources to perform HLD of their devices, and they are doing it well, keeping it there takes the burden off the SPD team.

As Amy DeGraw, BSHA, CRCST, CHL, clinical educator for the Healthcare Sterile Processing Association (HSPA), pointed out, managing HLD is not an easy task nor is it a one-and-done project. “It’s difficult to do and ongoing. It never ends. It’s always transforming and evolving.”

While there doesn’t seem to be a one-size-fits-all solution for the HLD model – centralization to the SPD might make sense in one hospital but is not feasible or reasonable for another – the aim of this article is to provide SPD leaders with concrete steps they can take to help improve HLD efficacy and safety regardless of where it takes place.

DeGraw returns for this second article in the series, and she brings along former colleagues with whom she has collaborated on HLD optimization efforts: Mindy Nicklas, MPH, MT(ASCP), CIC, senior education & events specialist for the

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), and Matthew Hadley, CRCST, CIS, CHL, education coordinator for Mercyhealth in Janesville, Wis. They provide real-world examples from their experiences managing HLD across various U.S. health systems and hospitals and pro tips that SPD leaders can implement in their healthcare organizations.

“Infection prevention is sterile processing’s greatest ally,” said Nicklas, who collaborated with DeGraw on ambulatory HLD and sterilization, maintaining oversight and standardization for a 10-hospital network. “It seems obvious that IP and SPD leaders would be in alignment on driving safe and effective HLD practices, but sometimes it’s like IPs don’t realize they should lean into SPD and SPD doesn’t always realize that they should lean into IP.”

“The work of both SPD and IP is tied closely to patient safety,” said DeGraw. “We are the ones who will have to answer for the ramifications of poor HLD reprocessing, whether it is by the SPD team or clinical staff members.”

Pro tip: Bring them into your reality

Hadley, who served under DeGraw over a decade ago, climbing the SPD career ladder from third shift technician to educator, implemented a job shadowing initiative at Mercyhealth to foster a collaborative relationship between the SPD and IP teams.

“While we had a good rapport initially because of our joint quarterly rounding, the IPs have told me the experience of coming into the SPD and seeing our processes firsthand has been eye opening for them,” he stated. “Together, we follow a case cart from the soiled elevator, through decontamination, washing, tray assembly, and sterilization so

IP can understand our work and the complexity of the steps involved.”

Any change to HLD processes, whether it is fostering improvements within clinical departments where they are performed or centralizing them to the SPD, will require buy-in from physicians impacted and resources from the C-suite (e.g., funding for equipment, supplies, FTEs).

“If you find an HLD process failure in a clinical department, you must take into consideration whether you have the authority to stop it,” said Nicklas. “Because there are big implications to telling a physician, ‘Your team can’t process scopes anymore,’ including potential revenue losses. Having someone at the physician leader level to be your champion, acknowledge the SPD team are the experts in performing HLD effectively and safely, and be willing to fix what is wrong will make or break your success in enacting change.”

DeGraw explained that her efforts with Hadley to centralize HLD processing in the SPD at Mercyhealth were easier to achieve from a physician buy-in standpoint because the initiative had strong support from senior leadership. In contrast, at another health system, centralizing HLD was more of a challenge.

“In this instance, trying to align the different services and locations was a challenge because we couldn’t necessarily have a phased roll-out,” said DeGraw. “Physicians often worked at multiple sites, and they had concerns about varying practices between locations. This required addressing an entire service line across the system, not just focusing on a single location, requiring larger buy-in from the start. This also required aligning multiple C-suite executives to ensure we provided a unified message.”

Pro tip: Engage leaders early and often

DeGraw stressed the importance of engaging physician and C-suite leaders before changes are proposed to frontline clinical teams and keeping them engaged throughout the process.

“It’s very important to have leaders with you when performing risk assessments of their departments,” she explained. “When you are walking through their space, have them at your side seeing exactly what you are seeing, where there are issues with HLD, why it is wrong, and how to do it right. That way, when you send them your audit report, they will have context around it.”

answers from DeGraw, Hadley, and Nicklas could have filled an entire article. They cited evaluation of the physical space where HLD is performed, workflows used, IFU adherence, and staff training, among many other factors for consideration.

Space, storage, and equipment for HLD

“A big part of risk analysis is assessing the physical space to determine if they can safely perform HLD in the space they have available,” said Nicklas. “Often the answer to the question is ‘No’ in the ambulatory setting.”

“It’s easier and more effective to identify and address issues with department leaders in person, in the moment so they can have real-time conversations with their staff members as opposed to sending them an email after the fact,” said Nicklas.

Step 3. Develop and apply a standardized risk assessment

When asked what SPD and IP should look for when assessing HLD processes in clinical departments, the

“I’ve walked into spaces where HLD is shared with the lab or there are biohazards stored right next to their sterile supplies,” said DeGraw. “In another, they had only a tiny handwashing sink for HLD.”

Hadley recounted how one department had installed a motion sensorcontrolled sink in their HLD area, stating: “They had just finished the space and were told they needed to install new plumbing fixtures. That was a lesson learned. But it was a valuable lesson.”

“It goes to show there are things that clinical staff members don’t

consider when it comes to HLD,” said DeGraw. “That’s why it is so important to have SPD and IP walk through their space with them to identify overlooked items that could pose risk.”

People and processes

According to Nicklas, process issues are high on the list when performing HLD risk assessments. She stated, “They’re just not following the correct steps. They’re not following the equipment IFUs.”

“In most cases, they are not intentionally doing it wrong,” she added. “The people performing HLD in clinical departments aren’t typically asking to do this work but rather they are stuck with it, especially in ambulatory settings. If you’re lucky enough to have somebody in that department who truly gets it, wants to own that process, and do the right thing, that’s tremendous. But it isn’t always the case.”

Pro tip: Revisit to reassess

examples of where reassessment uncovered previously hidden issues.

“In one department, staff placed towels on counters to dry instruments, with the expectation they be changed daily,” DeGraw said. “During our initial assessment, the team claimed this was done, but I was skeptical. So, I used a pen to put my initials on a towel used for this purpose, flipped it over so my initials were hidden, and returned a week later. It was the same towel being used.”

“Inconsistent use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during HLD reprocessing is another common problem,” said Hadley. “I’ve seen PPE covered in dust and asked clinical staff if they use it regularly. Although they told me ‘Yes,’ I returned three months later and the same dusty PPE was still in the drawer.”

“Many times, policies and procedures for reprocessing are written with just the SPD in mind and don’t always touch on what’s happening outside the department,” said DeGraw. “That’s why it’s important to evaluate what your hospital has in place before doing a deep dive into HLD changes.”

The process of refining HLD policies and procedures can present the opportunity for clinical departments to align with industry guidance and guidelines. In other cases, where the departments just don’t have the space and resources of an SPD, it can make sense for SPD and IP team members to revise HLD policies and procedures to align with what the departments have available – if they are able to perform HLD effectively and safely.

When performing an HLD risk assessment in a clinical space, IP and SPD team members can’t always catch process failures in the moment. DeGraw and Hadley provided two

DeGraw, Hadley, and Nicklas acknowledge how some health systems and hospitals have HLD policies and procedures that are specific to the SPD and do not address the realities of reprocessing in clinical departments.

Pro tip: Consider your options

To determine the best path forward, DeGraw suggests asking the following questions:

• Are your current HLD processes and procedures realistic in the clinical department setting?

• Do they need to be rewritten to align with what clinical departments have available?

• Should you develop a separate document that provides guidance in alignment with industry standards for HLD performed outside of the SPD?

Step 5. Define the target HLD operating model

Once a united SPD and IP team understands where HLD is being performed and whether it is being performed in alignment with policies and procedures, they can leverage this knowledge to guide decisions on their approach moving forward.

Does it make sense to keep HLD in clinical departments? Should HLD be centralized to the SPD? Is there a hybrid approach where only some departments transition HLD to SPD? Or is there a completely different alternative?

“If a department has the right space and the right processes for HLD to be safe and effective, those who are performing it are dedicated to doing it right, everything is just spot on, then it could make sense to leave HLD where it is,” said DeGraw. “Especially if it is a busy practice, you don’t want to unnecessarily disrupt their workflows.”

“But in instances where processes are unsafe and jeopardize patient care and safety, there must be a hard stop,” DeGraw continued. “There are times when we have identified issues and provided training and competencies, only to come back and find the process still isn’t being done correctly. Quality keeps slipping and the staff can’t maintain it.”

Pro tip: Take a hybrid approach

Hadley acknowledged how there are times when a clinical department is compliant with most devices they are processing on-site, but there is one item with which they struggle.

In this case, it could make sense for the SPD to take over reprocessing of this item for the department.

Pro tip: Consider disposables

During their risk assessments, DeGraw, Hadley, and Nicklas consider not only whether a department’s items should remain on-site for HLD or be moved to the SPD, but also whether switching from reusable to disposable products makes sense. Nicklas commented on how she recommended the transition to singleuse bronchoscopes in the hospital and single-use cystoscopes and rhinolaryngoscopes in the ambulatory setting. Hadley noted how Mercyhealth’s urology clinics are currently transitioning to disposables.

Regardless of the chosen model –working to improve the effectiveness and safety of HLD reprocessing in clinical areas, centralizing HLD to the SPD, switching to disposables for some items, or some combination of these approaches – change management is critical to success.

And change isn’t easy in healthcare. DeGraw, Hadley, and Nicklas acknowledge how they have experienced push back from the various stakeholders impacted by the change, primarily the clinical and SPD teams.

As DeGraw noted in the first article in this series, clinicians worry that if they allow the SPD team to take over HLD, their equipment will get lost or damaged. As for proposals to switch to disposable items, questions around quality and cost will likely arise.

“Some clinicians like the quality and feel of reusable devices so it can be an uphill battle to make the change to disposables,” said Hadley.

“I’ve had pushback from clinicians on the cost of disposable items, with comments on how they are too expensive,” said DeGraw. “So, it is important to know going into it the financial impact of the proposed change.”

As for the SPD team, concerns around the idea of taking on the additional work of HLD are common, as DeGraw explained: “I’ve had SPD teams give me a hard ‘No’ when asked

to take on HLD and that was a hard pill to swallow. If the directive is coming from senior leadership and centralization must happen, you have to come up with ideas on how to make it work for the SPD.”

Pro tip: Ask SPD what they need When faced with SPD team pushback, DeGraw suggests advocating for an open dialogue to identify what resources—such as equipment, workspace, or staffing—would be needed to make a change feasible.

By focusing on solutions, clear communication, and concrete metrics, DeGraw believes SPD and other departments can find mutually beneficial approaches that balance workloads and improve outcomes.

(Read the first article in this two-part series, “Taming the Beast: Best Practices for Managing HLD Inside and Outside the SPD,” for advice on key factors for consideration and metrics to measure and track when centralizing HLD).

Hadley added how SPD staff education and training is another

important fact to consider. If an SPD team has only been performing HLD on a limited basis, or perhaps not at all, they can face a steep learning curve when HLD centralization is proposed. Beyond training and competencies, Hadley provides his team with easy access to valuable resources they can reference when a question on HLD arises. He stated:

“I have developed a unified, standardized format for cleaning procedures in decontamination. It is like a little library where, based on a reference number, a technician can find a laminated document with step-by-step instructions for that device. They simply put it up on the wall in front of them and have everything they need.”

Pro tip: Turn to a neutral project manager

DeGraw stressed that large-scale HLD process changes can be overwhelming for all departments involved—not just SPD—and often come with emotional and operational challenges.

She highlighted the value of having a neutral project manager or facilitator who is not tied to any one department. This dedicated resource can coordinate efforts, keep stakeholders focused, build business cases, and guide discussions toward shared goals.

DeGraw believes such leadership helps prevent projects from stalling and ensures forward momentum, particularly in larger facilities where the scope and complexity of changes can easily derail progress.

One way to help manage HLD reprocessing changes is to pilot the proposed model. That way, stakeholders can identify challenges—and work to overcome them—on a small scale.

“Sometimes no amount of preparedness can assure you will get

everything right on day one of a transition,” said Hadley. “Therefore, take the time to simulate proposed workflows, perform test runs, and trace the entire life cycle of the impacted devices in advance. It’s extremely enlightening.”

“Start small,” said Nicklas. “Pilot a change with one department or one device at a time. Measure turnaround time, compliance, and staff feedback before expanding.”

Nicklas and DeGraw recounted an HLD centralization project that moved too fast, with the SPD team overwhelmed by higher instrument and device volumes. The result was a shift back to clinical departments performing HLD and the SPD and IP teams having to continuously monitor and address “bad practices.”

“SPD preparedness can make or break your whole project,” said Nicklas.

“It literally broke our project in one case,” DeGraw added.

Pro tip: Decide on transport in advance

A major challenge with centralizing HLD to the SPD is transporting devices to/from the clinical depart-

decontam. My advice is to establish clear rules for transport that are set in stone before any changes are initiated, and a process for ensuring compliance with the rules.”

“I’ve been in those conversations where clinical and SPD teams are going back and forth on who will bring the instruments into SPD and who will return them to the department,” said DeGraw. “Sometimes you just have to meet in the middle, and it becomes a shared responsibil-

“Start small, pilot a change with one department or one device at a time. Measure turnaround time, compliance, and staff feedback before expanding.”

MINDY NICKLAS

ments using them. As our experts point out, it is not only time and distance that must be taken into consideration, but also the labor involved.

“One of the things I typically encounter, whatever department is the end user, is that they’re always too busy to deliver their devices to the SPD,” said Hadley. “They want SPD to start reprocessing their items as soon as possible but claim they don’t have the resources to get them into

ity. Perhaps the clinical department agrees to deliver soiled items to the SPD, and the SPD team agrees to return the clean and sterilized items back to the department.”

“In some cases, other resources need to be tapped,” she continued. “Maybe it is designating a runner who does the transport back and forth? Consider hospital volunteers who can help with tasks like this to take the burden off the clinical and SPD teams.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer for HLD. The right model—whether centralization, targeted improvements, or selective disposables—depends on each organization’s realities. What’s universal is the need for collaboration, clear communication, and shared ownership. When SPD, infection prevention, and clinical leaders align around patient safety, HLD processes can evolve to be safer, smarter, and more sustainable.

“My words for encouragement to SPD and IP teams leading the charge for change in HLD – this doesn’t happen overnight,” said Nicklas. “It is often a many years long process because healthcare doesn’t change quickly.”

“Take it in small bites,” said DeGraw. “This isn’t a sprint; it’s a marathon.”

Hadley reminded SPD and IP teams that they don’t have to go it alone, stating:

“We have some major stakeholders involved in our cross disciplinary group and that’s really been shown to work for us – not only to get the ball rolling with change but to enforce policies and procedures and sustain improvements.” HPN

and

Exploring these key focus areas:

• Sourcing + Logistics

• Sterile Processing

• Surgical + Critical Care

• Patient Satisfaction

• Infection Prevention

• EVS + Facility Services

• Healthcare IT

• Regulatory

BY SUSAN KLACIK

1.Describe the concerns related to shock and vibration during transport.

2.Examine methods to maintain the integrity of sterile packages.

3.Describe how to safely transport contaminated items.

Sponsored by:

In recent years, there has been a shift in sterile processing. Previously, nearly all processing was performed in the same healthcare facility where the instrumentation was used. Recently, this trend is changing. For a variety of reasons, instrumentation used at a facility may be processed at an off-site location that is across campus, across town, or elsewhere. In the past, sterile processing departments were located near surgery departments. However, this space is valuable and often needed for other important uses, such as patient care procedures near surgery or to expand the surgical department.

Semi-critical devices that were previously high-level disinfected (HLD) are transitioning to low temperature sterilization methods. This

sterilization process can be expensive due to equipment and operational costs. To reduce costs, low-temperature sterilization is centralized in one facility. Many new medical devices are complex and may require specialized training and equipment. Processing these types of devices is also centralized to one facility to keep costs down.

Processing medical devices off-site has solved many of these problems. However, the external transport of medical devices has resulted in new concerns. When medical devices are moved within a healthcare facility, they are transported on smooth floors in a controlled environment, temperature and humidity are monitored, and transport is completed within minutes. In contrast, when

medical devices are transported over roadways, they are exposed to new risks that can harm the integrity of the device and its packaging. The environment is not controlled, and temperature and humidity may not be monitored during transport. Roadways are uneven, which expose devices to shock and vibration. Additionally, if contaminated devices are not transported correctly, they can pose safety and regulatory risks. The transport time is extended from minutes to hours, or even days in some cases. This lesson plan discusses these risks and how they are addressed in the new AAMI TIR 109:202, which focuses on the external transport of reusable medical devices for processing.1

Objective 1: Describe the concerns related to shock and vibration during transport.

reduces its movement during transport. The scope fits snugly in the foam, which is placed in a protective case. Medical device manufacturers design their packages to prevent damage during transport. The manufacturer performs specific testing of the package to demonstrate it can safely transport items over roadways and deliver them to healthcare facilities without damage.

This lesson was developed by Solventum. Lessons are administered by Endeavor Business Media.

New equipment received at a healthcare facility is delivered in a box that is specially packaged to reduce shock and vibration experienced over roadways. For example, scopes are packaged in foam with cutouts specifically designed for each scope, which

Single-use chemical indicator (referred to as critical temperature indicators)

Electronic temperature indicator

Electronic data logging monitor

Electronic data integrator

Typically, when a healthcare facility transports an item over public roadways, it is in a sterilization package or biohazard container that was not intended for transportation over public roadways. This can result in damage to the item. Shock and vibration can occur due to improper handling, speed, maneuvers, road conditions, sudden stops, or similar factors. Some damage may be visual and easily detected during inspection. However, some damage may not be noticed immediately as failure can occur slowly over time, causing parts to become loose, displaced, or misaligned.

Monitors are available to measure shock and vibration, helping to accurately determine if conditions are serious enough to cause damage.

The result is based on a phase change or chemical reaction that occurs as a function of temperature.

A compact, portable monitor that measures temperature over time by means of a built-in sensor.

A small portable monitor that measures and stores temperature at pre-determinded time intervals by means of an electronic sensor

A monitor that combines features of an electronic temperature indicator with the report/data producing capabilities of an electronic data logging monitor that combines the features and functions of a Go/No-Go device with the record retention and data.

Table 1: Electronic monitors for tracking temperature during transport

A er careful study of the lesson, complete the examination online at educationhub.hpnonline.com. You must have a passing score of 80% or higher to receive a certificate of completion.

The Certification Board for Sterile Processing and Distribution has preapproved this in-service unit for one (1) contact hour for a period of five (5) years from the date of original publication. Successful completion of the lesson and post-test must be documented by facility management and those records maintained by the individual until recertification is required. DO NOT SEND LESSON OR TEST TO CBSPD. www.cbspd.net

Sterile Processing Association, myhspa.org, has pre-approved this in-service for 1.0 Continuing Education Credits for a period of three years, until August 25, 2027.

For more information, direct any questions to Healthcare Purchasing News editor@hpnonline.com.

This information could be used to prevent damage during transport. Using the right monitoring devices can provide a traceable record that can improve transport by changing the route, time of day, or by identifying poor driving habits. Real-time shock and vibration monitoring devices can show unacceptable shock and vibration levels and can alert the receiver of a potential problem. This allows the item to be inspected or rejected before use.

When medical devices are transported over roadways, they should be assembled in a manner that prevents shock and vibration. When possible, instrument trays with specific instrument holders that secure instruments to a tray should be used. These trays should be placed into a transport carrier in a way that helps prevent damage. Using packing materials such as bubble cushioning (a plastic material with small air-filled bubbles), packing foam, or packing paper should be considered. For sterile items, protective packaging should also be considered.

methods to maintain the integrity of sterile packages.

To prevent damage to packages or medical devices that are externally transported, they should be prepared to provide additional protection. The risks to sterile packages from exposure to the external environment include contamination from moisture, excessive humidity, condensation caused by exposure to temperature extremes, and microorganisms. When preparing sterile items for external transport, protective packaging can be used to provide better safety. Protective packaging can be both internal and external. Internal protective packaging is used inside the package to protect it from breaches. For example, a corner guard helps protect the package from tears.

External protective packaging is used outside of the sterile barrier system and is not a replacement for it but rather is used in conjunction with it. External protective packaging is referred to as sterility maintenance covers in ANSI/AAMI ST 79:2017 Comprehensive Guide to Steam Sterilization and Sterility Assurance in Health Care Facilities 2 According to this sterilization standard, they are designed to provide protection against environmental contaminants such as dust, and not to provide a microbial barrier. They consist of a plastic material that provides a barrier to moisture and dust. This additional barrier may help maintain the sterile integrity of the package when exposed to uncontrolled environments such as external transport.

Sterility maintenance covers are designed to protect the integrity of the sterile barrier system. Only protective packaging that has been designed and validated by the manufacturer and intended for this purpose should be used. Sterility maintenance covers should be applied as

soon as possible after sterilization when the packages are cooled and dry. Applying a sterility maintenance cover on a package that is not cool and dry could result in condensation, rendering it contaminated and not sterile. They should be sealed following the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU) and the package content label should be visible through the protective packaging. If needed, a duplicate label should be placed on the protective packaging.

To further protect processed items during external transportation, they should be carefully placed in transport carriers that protect package integrity. A transport carrier is a portable, closeable, rigid, and leak-proof enclosure specifically designated to temporarily contain medical devices during transit from one facility to another facility. Safety issues of ergonomics and weight should also be considered. To prevent shock and vibration, packing material may be used to further safeguard the items. Staff transporting tote boxes and carts should be able to transport them safely.

Reusable transport carriers such as tote bins or carts should be clean. Carrier construction should have surfaces that tolerate thorough cleaning and disinfection. Prior to use, transport carriers should be inspected for visible soils or debris. Tamper evident locks on transport carriers may be used to identify if they were opened. The transport carrier should be labeled with a description of the contents, date and time, package origin and destination, if hazardous medication is included and its processed status noting clean, disinfected and/or sterile. The items should be recorded either manually or electronically for both the sending and receiving facility and the records should be maintained.

Contaminated items that are transported internally and externally must follow the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogen Standard [29 CFR 1910.1030] requiring that the container be puncture-resistant, leak-proof on the sides and bottom, closeable, and labeled with the biohazard label, a red bag, or other means of identifying contaminated contents. Additionally, when items are transported on public roadways, they must also meet the requirements of the Department of Transportation (DOT), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The DOT requires hazardous communication labeling for infectious materials. It is important to note that state and local governments may have their own requirements.

Once soils dry on instrumentation, they are difficult to clean. Keeping soiled instruments moist reduces the risk of corrosion and biofilm formation and facilitates

the decontamination process. Recent research has shown the effects of time, temperature, and humidity on soiled devices.3 This research supports concerns about transporting soiled medical devices in uncontrolled environments. Soils that were allowed to dry on medical devices at approximately 71 F became less soluble the longer they were allowed to dry. There was no statistical difference in the change of solubility between one and eight hours of dry time. A statistical difference was observed between 8 and 15 hours, with the most soil retention at 72 hours. The temperature research demonstrated that as temperature rises after 22 C/71.2 F the solubility decreases, and the soils dry onto the device. Humidity research demonstrated that at less than 50% relative humidity (RH) the soil retention was higher than at higher levels of humidity. At 100% humidity the soil did not dry. This research shows the importance of maintaining moisture content for soiled instruments.

Contaminated items should be prepared in a manner that prevents debris from drying. Methods to prevent the drying of soils on medical devices include using a towel moistened with water (not saline), a point-of-use treatment product specifically intended for this use, or by placing items inside a package that maintains moist conditions. The IFU for medical devices and the product used to prevent drying should be reviewed and followed.

Contaminated instruments should be carefully placed into a clean, biohazard-labeled transport carrier, such as a tote bin or cart. Care should be taken to prevent shock and vibration during transport. Safety considerations of ergonomics and weight should be addressed. The transport carrier should also be labeled with a description of contents, date and time, package origin and destination. The items should be recorded either manually or electronically

for both the sending and receiving facility, and the records should be maintained.

Monitoring devices are available to track temperature and humidity during transport (Table 1). They can be used to determine if an item was exposed to environmental conditions outside of the acceptable range, as a post-use analytical tool for identifying weaknesses in the transport system, conducting a trend analysis, or collecting performance data.

The external transportation of medical devices comes with new challenges that need attention. Exposing medical devices to uncontrolled environments increases the risk of damage and contamination. In 2025, AAMI released a new guidance document to address these concerns, the Technical Information Report AAMI TIR109:2025 External transport of reusable medical devices for processing HPN

1.AAMI TIR109:2025 External transport of reusable medical devices for processing

2.ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017, Comprehensive guide to steam sterilization and sterility assurance in health care facilities

3.Kremer TA, Carfaro C, Klacik S. Effects of time, temperature, and humidity on soil drying on medical devices. BI&T. 2023, pp 58-66 https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-57.2.58 Accessed 15 August 2023.

Susan Klacik is a Clinical Educator for The International Association of Healthcare Central Service Materiel Management (IAHCSMM). She is the IAHCSMM voting member for the Association of the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI), a role she has held since 1997. A member of the Association of perioperative Registered Nurses (AORN) Guidance Advisory Board. Klacik has authored numerous articles and served as a contributing author to the IAHCSMM textbooks. She is the author of the IAHCSMM magazine’s column “Inside Washington” and the OR Manager column “Sterilization and Infection Prevention”. She has spoken domestically and internationally on sterile processing related subject matters as well as webinar presentations.

1.Which reason below is not a reason to relocate sterile processing to an off-site facility?

A.The space is needed for other necessities, typically for patient care procedures closer to surgery.

B.Semi-critical devices that were previously highlevel disinfected (HLD) are being transitioned to sterilization using a low temperature sterilization modality. To reduce costs low temperature sterilization is centralized to one facility.

C.The union contract mandates only one processing center.

D.New specialized medical devices are complex to process; this specialized processing is centralized at one center.

2. What has been identified as a concern for external transportation of medical devices?

A.Smooth floors

B.Regulated environment

C.Shock and vibration

D.Quick turn-around

3.Which of the following variables can be controlled when performing external medical device transportation?

A.Transport route

B.Temperature

C.Humidity

D.Shock and vibration

4.Equipment received at a healthcare facility from a manufacturer is packaged in a manner that:

A.Provides promotional material.

B.Shows the route taken to the facility.

C.Shows the temperature it was exposed to.

D.Is packaged in a manner that greatly reduces the shock and vibration experienced over the roadways.

5.Which of the following actions below do not result in shock and vibration damage?

A.Transport over smooth floors

B.Improper handling

C.Sudden stops on the roadway

D.Poor road conditions

6.Which of the following items could be considered as an external transport carrier?

A.A corrugated box

B.A cardboard box

C.A closable plastic tote bin

D.A shopping bag

7.Which of the following material can be used as packing materials to reduce shock and vibration?

A.Newspaper

B.Cotton balls

C.Packing foam

D.Packing gauze

8.What is considered as an internal protective packaging?

A.Packing gauze

B.Corner protectors

C.Packing foam

D.Cotton balls

9.When should a sterility maintenance cover be placed on a sterile instrument set?

A.Before it is placed into a transport carrier

B.Prior to sterilization

C.As soon as possible after sterilization when the packages are cooled and dry

D.When the sterile package has a hole in it

10.What could occur if a package is placed into a sterility maintenance cover immediately after sterilization before it is allowed to cool and dry?

A.Dust and debris build up would be prevented.

B.Condensation could form inside the sterility maintenance cover rendering it contaminated.

C.It could be safely transported outside of the building without another covering.

D.The inner package could deteriorate.

11.The use of tamper-evident locks on transport carriers indicates:

A.It passed inspection.

B.It has been received.

C.It was subjected to shock and vibration.

D.Identifies the carrier was opened.

12.What does not need to be included in the labeling of a transport carrier?

A.Description of contents

B.Date and Time

C.Package destination

D.When it will be used

13.To prevent the risk of corrosion and biofilm formation and facilitate the decontamination process, contaminated (soiled) instruments should be kept

A.Moist

B.In a dark area

C.At a high temperature

D.In a cool room before transport

14.Which of the following is not an acceptable method of keeping contaminated instruments moist?

A.Use of towel moistened with saline

B.Use of a towel moistened with water

C.A point of use treatment product specifically intended for this use

D.Placing contaminated instruments inside a package that will maintain moist conditions

15.Which of the following documents provides information on the proper external transportation of medical devices?

A.FDA Guidance on Medical Device Patient Labeling; Final Guidance

B.U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR), 49 CFR

C.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines Environmental Infection Control in Healthcare Facilities

D.AAMI TIR109:2025 External transport of reusable medical devices for processing

BY JULIE WILLIAMSON

For decades, the Healthcare Sterile Processing Association has formally designated the second Sunday of October through the following Saturday as Sterile Processing Week. During this week of honor, we highlight how SP professionals support patient care, infection prevention, and positive outcomes and seek to celebrate and elevate the profession in meaningful ways— while encouraging every facility, C-suite, and SP leader to do the same. The 2025 SP Week theme is “Service with a Purpose,” a nod to how every technician, supervisor, manager, and educator uses their knowledge and specialized skills to serve and support others.

Every SPD has its stars, and SP Week provides a golden opportunity to help them shine brighter. A practical approach is for managers to post photos of employees across all shifts and an accompanying write-up that highlights some or all of the following:

• Certifications held by the employee

• Time employed at the facility or total years of experience

• The employee’s favorite role within the department

• Why the employee enjoys working in the profession

• Examples of a shining moment (success story, achievement, etc.) over the past year

• The employee’s future professional goals

• Something personal about each team member (hobbies, favorite off-the-clock activities)

These details can be compiled as a “team document” that can be shared with the healthcare organization’s Human Resources department and, ideally, published in an employee newsletter or other community site. Doing so helps put a face and name on the department’s inner workings, which can improve employee morale and contribute to improved understanding and appreciation from the departments the SPD serves.