CAMERON TUCKER

Art As A Tool For Survival Through Adaptive Memory

DOI 10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4 0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission

Abstract

This dissertation examines art as a tool for survival through adaptive memory, which evolved to retain survival information for early humans but now allows us to adapt to living in the modern world.Art engages with thereconstructivenatureofmemory.Fromtheearliest caveimages, which encoded survival knowledge, to contemporary works, addressing humans’ disconnection from nature, art has aided us to process, reshape, and reinterpret experiences to help us in the present. Nostalgia or episodic adaptive memory serves to navigate both personal and collective histories. Artists like Salvador Dalí, Makiko Kudo, and Yayoi Kusama use the malleability of memory to evoke emotional responses, reflecting the adaptive processes of memory. The use of nostalgic elements in art, through the oeuvres of Do Ho Suh,Ai Wei Wei, provide insight into how memory functions to reconnect with the past, offering solace and emotional continuity amid modern life's uncertainties. This dissertation argues that art, through adaptive memory, has evolved to support psychological and emotional processing, allowing individuals to cope with the complexities of modern existence. Both art and memory serve as both a mirror to our past and a tool for reimagining our present. We live in our own illusion of reality to survive in an artificial world we have little affinity with and seek to return to nature, such as Andrew Millner’s Fantastic Garden. Through dreamscape, escapism, reflective nostalgia and retromania, replacing belonging with belongings, we search for our own paradise lost by creating an imaginary utopia or haven to seek seclusion in the modern world.

List of Figures

Figure 1: (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 248) Lascaux Cave Painting: A rhinoceros, figure of a man, wounded bison and bird on top of a staff.

Figure 2: (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 127) South Africa San Polychrome painting of a cloaked antelope-headed figure.

Figure 3: (Guettler, 2017) Lascaux Painting of animals indicating a spiritual expression of existence.

Figure 4: (Guettler, 2017) Lascaux Cave Images represented the animals needed for survival, but also depicted predators.

Figure 5: (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 241) Conquers Cave Horse Painting over finger fluted patterns in soft mud on the walls; illustrating that touching was part of a ritual.

Figure 6: (Brumm et al., 2021), Figurative paintings of pigs at Leang Tedongnge Cave.

Figure 7: (Oktaviana et al., 2024) 51,200-year-old Rock DatedArt at Leang Karampuang.

Figure 8: (Millner,A. 2019), Painting Heliotrope, 2019.

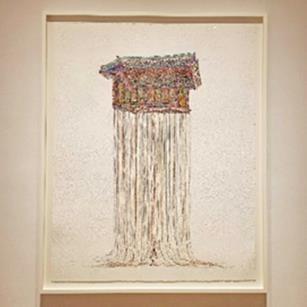

Figure 9: (Millner,A. 2019), Waterfall, 2019.

Figure 10: (Weichbrodt, 2024) Do Ho Suh, Rubbing/ Loving Project: Seoul Home, 2012.

Photograph Tim Tiebout Philadelphia Museum ofArt.

Figure 11: (Cumming, 2024) Do Ho Suh Self-portrait, 2017. Tracing Time Exhibition National Gallery Scotland Modern 1.

Figure 12: (Victoria, 2018) Song to Qing Dynasties, 2015.AiWei Wei’s Spouts exhibit at Marciano Foundation in LosAngelos.

Figure 13: (Kudo, 2016) Picture Nanohana Ramem, Exhibition at the Tomio Kayama Gallery.

Figure 14: (Kudo, 2018) Makiko Kudo Installations at the Tomio Koyama Gallery, 2018.

Figure 15: (Ulster Museum 2024). Makiko Kudo I Overslept Until the Evening, 2014. Ulster Museum, oil on canvas.

Figure 16: (Wilkinson, 2012) Makiko Kudo, Floating Island, 2012. Anthony Wilkinson Gallery London Oil on Canvas.

Figure 17: (Tate, 2024) Salvador Dalí Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937. Tate Gallery Oil on Canvas.

Figure 18: (MoMa, 2024) Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931. MoMa.

Figure 19: (Totally History, 2013) Salvador Dalí, The Disintegration of Memory, oil on canvas, 1952-1954. Salvador Dalí Museum, Sr Petersburg Florida.

Figure 20: (Popova, 2016) Salvador Dalí, The Mad Tea Party Illustration, 1969. “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, Rediscovered and Resurrected.

Figure 21: (Conflict Textiles, 2024) Chilean Arperilla, 1979. anonymous. Installation Ulster MuseumAugust 2024 Exhibition.

Figure 22: (Conflict Textiles, 2024),Ana Zlatkes, Let us Play in the Woods While the Air is Still Here 2, 2015.

Figure 23: (Zwirner, 2024) Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrored Room – Phalli’s Field, 1965.

Figure 24: (Van Beuningen, 2024) Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field (Floor Show), 1965.

Introduction

Art is frequently described as “therapeutic, emotionally evocative, and generative of aesthetic experience” (Durkin et al., 2020). However, the intricate relationship between art and cognitive processes remains a relatively under-explored area. This dissertation investigates the role of art as a tool for survival, focusing on the role of adaptive memory in both early human evolution and contemporary life. I explore how art serves as a means of navigating and processing the challenges of survival, from encoding essential survival knowledge in prehistoric times to addressing psychological and emotional complexities in the modern world.

In Chapter One, I explore the origins of art as both a cultural and survival tool, examining how early symbolic and representational art facilitated spiritual expression and communication. I also discuss humanity’s evolving relationship with nature, highlighting our struggle to thrive in an increasingly artificial world, as noted by Roszak (2001, p. 331), drawing on Andrew Millner's Floating World (Millner, 2019).

ChapterTwoexplores the "epidemic" ofnostalgia,examining whyweseeknostalgicre-encounters and how nostalgia functions as a coping mechanism, using adaptive memory to pursue the unattainable (Boym, 2001, p.11). I also address Bauman’s (2017) concept of Retrotopia, exploring how yearning for the past helps individuals navigate modern life. I analyse nostalgia’s link to adaptive memory and survival strategy; with art playing a key role. Focusing on the artists Do Ho Suh and Ai Wei Wei (Horvath, 2018, p.152), I explore how their work reflects nostalgia’s emotional pull while acknowledging the impossibility of fully reclaiming the past (Horvath, 2018, p.152; Stone, 2024).

Building on the themes of nostalgia, I explore the imaginative reconstruction of memory through the works of artists Mikiko Kudo and Salvador Dalí, in Chapter 3. I examine Kudo’s innocent dreamlike childhood imagery with Dalis’s paranoiac Surrealism and exploration of the subconscious.Theseexamples illustratehowartserves as apowerful tool forreprocessingthepast, shaping new identities, and navigating the complexities of modern life through dreamscape and escapism.

Chapter Four compares Conflict Textiles art drawing on the Threads of Empowerment exhibition at the Ulster MuseumAugust 2024, with the oeuvres of Yayoi Kusama (Conflict Textiles, 2024). I explore how these artists employ psychological distance and audience participation, creating spaces for reflection and emotional engagement with trauma through workshops and installations. I explore how art can function as a mechanism for reshaping and reprocessing memories through the concept of adaptive memory, offering a means to cope with the past while fostering resilience and healing.

This dissertation concludes by exploring the interplay between memory and art, highlighting how both coevolved to help us navigate a complex world. I will examine the disconnect between humanity and nature, and how art, through natural symbolism, offers reconnection and escape. Ultimately, I argue that art serves as a mirror to our emotional landscapes and a vital survival tool using adaptive memory to process and reshape our experiences, fostering resilience and a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world.

Chapter One

Emergence ofArt andAdaptive Memory

Following a recent discovery in Sulawesi, Indonesia, cave art is thought to date back to 51,200 years ago (Oktaviana et al., 2024; Ghosh, 2024). These paintings and engravings, made with natural pigments like red and black minerals, include pictographs, petroglyphs, engravings, petroforms, and geoglyphs (Clottes, 2024). While these artworks were primarily symbolic in nature, serving as expressions of cultural and spiritual significance, or communication, their exact meanings are unknown. However, recent discoveries of representational cave art, with recognisable elements, point to increased utility for the propagation of knowledge (Aubert et al., 2019). The global spread of cave art highlights its importance in early human life (Clottes, 2024). In Europe, Cro-Magnon ancestors created diverse cave paintings, including a rhinoceros, a human figure, a wounded bison, and a bird on a staff, Figure 1. These artworks also feature unique shamanistic imagery, reflecting personal and spiritual significance (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p.195). The cave, with its unique features, symbolises a subterranean, otherworldly realm for shamans on their spiritual quests (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p.210-212).

Figure 1: (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p.248) Lascaux Cave Painting.

Depictions of therianthropic figures, part human and part animal, are linked to early shamanic practices and the development of cultural and spiritual beliefs (Aubert et al., 2019; LewisWilliams, 2002, p. 202; Mithen, 2005, p.198; Oktaviana et al., 2024). Images of shamans, such as one with blood falling from his nose, suggest altered states of consciousness and journeys to the spirit world, where animal traits are assumed, Figure 2. This imagery highlights the connection between ritual, transformation, and spiritual exploration in early societies, though the true nature of these practices remains speculative (Ghosh, 2024; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024).

Figure 2: (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 127) SouthAfrican San polychrome painting of a cloaked antelope-headed figure.

Pictorial art likely served as a universal communication tool during a time when verbal language was still in its early development stages (Guettler, 2017). As Aubert et al., (2019) notes, humans “have an adaptive predisposition for inventing, telling and consuming stories”.Throughout human evolution, cave art facilitated communication and cultural expression. Early humans used visual art to express beliefs and engage in cultural and religious practices, illustrating how language and culture intertwined to shape their worldview (Everett, 2017, p.33).

In addition to cultural significance, cave art was crucial for survival. The paintings at Lascaux, France, Figures 3 and 4, created over 16,500 years ago, depicting herds of buffalo and bulls, likely represented prey and predators as teaching tools (Guettler, 2017). These images blend practical survival with spiritual and ritualistic elements. Similarly, finger-fluted patterns in soft mud, Figure 5, demonstrate the ritualistic and cultural importance of tactile engagement, linking touch to knowledge transmission (Mithen, 2005, p. 195). The 40,000-year-old Sulawesi warty pig paintings, Figure 6, further highlight art’s role in survival, the spiritual need to touch the subterranean world through hand-images and cultural storytelling (Brumm et al., 2021). These examples suggest that art, as a cognitive tool, extended the adaptive nature of memory, helping to encode and reinforce survival information in a meaningful way (Nairne et al., 2008).

Figure 3: (Guettler, 2017) Lascaux Cave Painting of animals.

Figure 6: (Brumm et al., 2021), Photostitched figurative paintings of pigs at Leang Tedongnge Cave.

Figure 4: (Guettler, 2017) Lascaux Cave

Figure 5: (Lewis-Williams, 2022, p.241) Painting, Images. Cosquer Cave Horse.

Awakening of the Human Mind

TherecentdiscoveryofearlynarrativeartinSulawesi,Indonesia,provides evidenceofpalaeolithic human storytelling (Oktaviana et al., 2024; Ghosh, 2024). The artwork, Figure 7, depicts three humanoid figures with sticks interacting with a wild pig displaying cognitive complexity and an ability to represent detailed narratives (Mithen, 2005). The discovery emphasises the importance of storytelling in human culture, reflecting our capacity for creative and abstract thought, which laid the foundation for both art and science (Ghosh, 2024). These scenes served as tools for survival, preserving knowledge and traditions. Framing this with adaptive memory theory, cave art highlights how memory evolved to retain essential information for survival (Nairne et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2014, p.5).

Figure 7: (Oktaviana et al., 2024), 51,200-year-old Rock DatedArt at Leang Karampuang: a) Photostitched panorama of rock art panel; b) Tracing of rock panel; c) Tracing of painted scene showing human – like figures H1, H2, H3.

The Sulawesi paintings raise key questions about the origins of human cognitive abilities, marking a significant moment in evolution where humans began to appreciate beauty, represent myth, and enhance their survival (Ghosh, 2024; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024).

Art, Nature and the Human Psyche

Our ancestors were deeply connected to nature, a bond essential for survival. Today, however, our well-being is affected by a world increasingly detached from the natural environment (Roszak, 2001, p.331). Ecopsychology, the study of the mental health benefits of immersion in nature, emphasises this connection, with Roszak (2001, p.331) noting that "the needs of the person and the needs of the planet are a continuum”; reflecting that the minds of early humans were intertwined with the living world.

Although the environment we evolved in no longer exists, we still yearn to reconnect with it.Artist Andrew Millner explores this struggle in his work, depicting the "duality of man and nature" and the challenges we face adapting to a world increasingly divorced from our ancestral roots (Melandri, 2021). His artworks capture the metaphor of displacement, highlighting our escalating disconnection with the natural environment that shaped us.

Millner’s Floating World viewing room, a series of large-scale prints on paper mounted onto linen, collaging digitalised flower prints created over 15 years, Figures 8 and 9 (Millner, 2019). Drawing on Japanese influences, particularly the concept of negative space, Millner invites viewers to reconnect with nature (Melandri, 2021). These prints are "infused with memory and trace, absence as well as presence”, embodying the passage of time and the enduring connection between humans and the natural world (Melandri, 2021).

Figure 8: (Millner,A. 2019),

Figure 9: (Millner,A. 2019), Picture, Heliotrope, 2019.

Picture, Waterfall, 2019.

Floating World is a translation of the Japanese ukiyo, a term historically associated with life during the Edo period, and now ingrained in modern Tokyo culture. During this time, ukiyo-e, emerged as an art form depicting a world of pleasure, contrasting the sorrow of life's fleeting nature, tied to the Buddhist concept of the “Sorrowful World” (Marks, 2021, p.9-11). Millner’s work invites the viewer to bask in “the wealth of beauty”, yet with an underlying sense of melancholy, at the unobtainable (Melandri, 2021).

The abundance in Millner’s Garden symbolises the transient cycles of life (Melandri, 2021).

Floating World presents an “alternative universe", where familiar objects are “transformed into dreamscapes”, offering a space to escape modern constraints and reconnect with an “ethereal universe” (Melandri, 2021).

Summary One

Through the passage of time ancestral knowledge is lost, yet cave art offers a rare glimpse into their worldview, highlighting similarities to our own beliefs and ways of life. Just as our ancestors adapted to their environment for survival, we too must now learn to navigate and adapt to a fabricated modern world (Melandri, 2024 Nairne et al., 2007).

Roszak (2001, p.331) believes that while our minds are “shaped by the modern world”, they “originate in nature” and that “we have suffered from this disconnect” (Bailey, 2020a). Biologist Edward Osborne Wilson suggests that beneath the "veneer of 21st-century cool", humans still instinctually crave an emotional connection with nature (Bailey, 2020a; Bailey, 2020b). Our accelerated, manufactured lives leave us alienated from our natural environment (Melandri, 2021).

In a world increasingly detached from natural rhythms, we strive for meaning and connection, mourning “the impossibility of a mythical return to an enchanted world” (Boym, 2001, p.8).

Through art we attempt to re-establish this lost connection, unifying the present and a harmonious primitive past. Ornstein (1991, p. xiv) refers to this idea as "conscious evolution", where art becomes intertwined with community and tradition. Today, conscious evolution remains essential as we use art to express our emotions, connect with others, and navigate the complexities of the modern world.

Chapter Two

Seeking Nostalgic Re-encounters

The twentieth century, which began with a vision of a “futuristic utopia”, ended in nostalgia; a defence against the "epidemic of modernity" (Bauman, 2017, p.5; Boym, 2001, p. xiv). This shift reflects our collective longing for stability amid the momentum and uncertainty of modern life. In an era marked by disconnection, we yearn for an idealised past that offers refuge from contemporary chaos (Bauman, 2017 p. 152; Boym, 2007).

SvetlanaBoym(2001)describesthislongingasan"epidemicofnostalgia",tomediatethedemands of modernity, serving as a defence mechanism in turbulent times (Boym, 2001, p. xiv) as we crave the slower pace of life of our ancestors (Boym, 2001 p. xv). To cope with modern life’s complexities, we often create a “virtual reality” in the form of an imaginary utopia or nostalgic past (Boym, 2001 p. 17; Ornstein, 1991). A constructed past, whether real or imagined, provides solace regardless of personal experience (Boym, 2007 p. 7). Memories become a “selective pick” of the past (Boym, 2007, p.8), often producing longing for a home that no longer exists or never did (Boym, 2001, p. xviii).

As Robert Ornstein (1991, p. 248) suggests, we live within this "illusion of reality" to avoid being overwhelmed by the harshness of the world if we “experienced it raw”. Modern survival is often aided by nostalgic remembrances, leading us to surround ourselves with objects, or practices, which offer comfort and continuity (Boym, 2001, p. 11). Nostalgia can manifest in a lifestyle influenced by vintage design or, as Boym notes, by “replacing belonging with belongings” (Krotoski, 2015). This longing for the past also takes the form of retromania, where retro pop culture,vintageitems,andcollectiblesprovidean adaptivemeansofcoping withourdisconnection from the natural world (Reynolds, 2011).

The Lost World of Nostalgia

Endel Tulving's (1983, p.171-172) research on episodic memory suggests that sensory cues, such as touch, sound, or smell trigger memories. Both Tulving (1983, p.171-172) and Boym (2001, p.15) emphasise that we need a “strong retrieval cue for accessing memories easily and accurately”. Nostalgia is easily triggered by sensory experiences, as "nothing reforms nostalgia in the present like the senses" (Boym, 2001, p.15). For example, the tactile rituals of vinyl records; the sense of touch in cleaning, the crackling atmospheric sound. Similarly, the scent of paper from reading old books, all appeal to the senses to evoke memories, providing comfort and relief from modern life’s pressures through nostalgic re-encounters (Boym, 2001, p.15; Elan, 2022; Krotoski, 2015).

Artist Do Ho Suh creates retrieval cues by focusing on minute details and textures, recording them in his work to be stored as experiences. Suh’s sculptural installation Seoul Home/ L.A. Home/ New York, Figure 10, explores his connection to his childhood home in South Korea, contrasting it with the feelings of displacement he experienced as a student in 1990s United States (Tate, 2024).

Through his art, Suh creates an emotional bridge between physical spaces and memories, using sensory cues to convey the personal process of adapting to new environments while longing for the past. He achieves this by embedding minuscule details and textures, creating tangible experiences that serve as retrieval cues. In his “rubbings/memories" of his apartment at 348 West 22nd Street, Suh immortalises his living space, carrying it with him "likeasnail" (Cumming, 2024; Suh, 2016). Suh’s work reflects that memories offer protection but also a burden, which is difficult to leave behind. His sense of home, he notes, “began only when he no longer had it”, a sentiment shaped by his experience as a Korean migrant (Cumming, 2024, p.6).

Figure 10: (Weichbrodt, 2024) Do Ho Suh, Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home, 2012. Photography Tim Tiebout Philadelphia Museum ofArt.

The Korean house is a recurring motif in Suh’s work, particularly in his Tracing Time exhibition (Cumming, 2024). Suh explores how the past, present, and future collectively shape our sense of identity, examining the "enigma of home" (Cumming, 2024). He questions whether home is a physical place, an emotional state, or a vision in the mind, Figure 11. For Suh, home is not a static location but a dynamic, evolving concept shaped by time and movement (Cumming, 2024). While his identity is deeply rooted in his family home, his work reflects how the idea of home transforms as we travel and change. Suh’s art explores themes of migration, loss, and longing for his past self, expressing his yearning for the home and family left behind (Stone, 2024). In this way, Suh’s work acts as a mediator between the familial life he misses and the modern world in which he resides.

Figure 11: (Cumming, 2024) Do Ho Suh. Thread Embedded in Handmade Cotton Paper, Selfportrait, 2017. Tracing Time Exhibition National Gallery Scotland Modern 1.

True nostalgia cannot be recreated, as it is the “materialisation of the immaterial” (Boym, 2001, p.17). Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei illustrates this concept through his reconstruction of a traditional timber house. Originally carved by a local craftsman near his birthplace, the house was deconstructed and then reconstructed in two halves, exhibited separately. Through this act, Wei Wei symbolises “the desire to put back together something united in the past”, while acknowledging that, “the rupture could not be mended” (Horvath, 2018, p.152).

Similarly, in his installation Song to Qing Dynasties, Figure 12, Wei Wei presents 10,000 broken spouts from antique teapots, creating a visual imprint prompting imagination. This work reflects the impermanence of culture, illustrating that lost Chinese culture can only be restored through imagination (Horvath, 2018, p.152). For Wei Wei who escaped Chinese detention, this act of nostalgia becomes particularly poignant. It is impossible for him to fully recreate the Chinese culture of his past, as it no longer exists (Boym, 2001. p.17).

“Nostalgia is a method to logically confront the past, but a partly cognitive, partly affective way to processing it” (Boym, 2001). Through their work, both Wei Wei and Suh engage with the tension between past and present, exploring the impossibility of fully recreating a lost world. Each artist reflects on themes of loss and cultural rupture, examining the complex relationship between memory and reality. Their art explores how we process the irretrievable past, confronting the emotional and intellectual challenges in an imaginative way.

Figure 12: (Victoria, 2018) Song to Qing Dynasties, 2015. Ai Wei Wei’s Spouts exhibit at Marciano Foundation in LosAngeles.

Summary Two

The shift from a "futuristic Utopia" to a contemporary era increasingly defined by nostalgia, is a consequence of rapid technological and cultural evolution within a short timescale. This accelerated change has sparked a collective longing for the past, as we struggle to keep pace with the overwhelming speed of progress and the disorienting effects of modernity. In this context, nostalgia becomes an adaptive coping mechanism, offering comfort and refuge in the present, while helping us process and reconcile the past. This emotional reconnection is tied to sensory processing, explaining the appeal of imperfect media and the rise of retromania.

BothAi Wei Wei and Do Ho Suh use art to express their sense of loss, offering nostalgic glimpses of their early lives and former homelands. Through their works, they explore the complexities of displacement and the longing for a time and place that no longer exist, using nostalgia not just as a memory of the past, but as a means of navigating their present. In doing so, both artists highlight how nostalgia serves as a bridge between past and present, allowing them to process their feelings of displacement while confronting present challenges. Their art becomes a space where the past and present coexist, providing a form of emotional resilience and a way to reclaim agency in a world that feels increasingly fragmented.

Chapter Three

Reimagining Childhood - imaginative reconstruction of memory

Nostalgia is not only a retrospective emotion but can also be prospective, shaped by present needs and influencing our future (Boym, 2007, p.17). Through art, nostalgia becomes a mechanism for processing the past and projecting it into the future (Boym, 2001, p.10). Similarly, Macpherson and Dorsch (2018, p.18-23) suggest memory is reimagining shaped by the past.

Makiko Kudo imaginatively reconstructs her childhood memories through,fantasy-filled paintings reflecting a lost sense of carefree innocence. Her works, featuring meadows, small animals, and dreamlike landscapes, offer a playful contrast to the rigid social conformity she faced (Wilkinson, 2012). These vibrant scenes provide an escape for processing her past, with works like Nanohana Ramen, Figure 13, blending nostalgia with fantasy, producing a liberating reality (Kudo, 2016).

13: (Kudo, 2016) Picture Nanohana Ramem, Exhibition at the Tomio Kayama Gallery.

Kudo’s art critiques societal norms and resists the constraints of adult autocracy and social conformity, allowing her to craft a new identity freed from the limits of her upbringing. Her paintings serve as a form of “mental time travel” (Schacter, 2012), revisiting and reshaping the lost wonder of her youth (Boym, 2001; Horvath, 2018). Kudo describes her art as a reflection of “waking life, yet with added surrealism”, blending imagination and emotion, much like a dream (Kudo, 2018). Her vibrant, chaotic energy captures the emotional intensity of fleeting moments, echoing the fluidity of memory, Figure 14 (Kudo, 2016).

Figure

Painting, Umi’s, installation at the Tomio Koyama Gallery, 2018.

Kudo’s nostalgic creations not only reflect on the past but also help forge a new path forward. As Horvath (2018) suggests, nostalgia can shape the future. Her work is a form of “virtual reality”, where she exists beyond her past (Boym, 2001). Curator David Pagel (2011) notes the paradox in Kudo’s art: “Escaping a place that never really felt like home is Kudo’s great subject”.

For Kudo’s generation, particularly those growing up in rural Japan, escapism often took the form ofMangaandanimation,offeringrefugefromdailylife(Wilkinson,2012).Kudo’swork,similarly, filledwithnarrativeandfantasy,reflectsthisbroaderculturalmovement,blurringthelinesbetween imagination and reality resulting in personal liberation, Figure 15.

Figure 14: (Kudo, 2018) Makiko Kudo

Painting, I Overslept Until the Evening, 2014. Ulster Museum, oil on canvas.

Kudo’s paintings embody paradoxes, blending the familiar and the unknown, the haunting and the beautiful, like the dual nature of ukiyo in Japanese culture. Her dreamlike landscapes, populated by small creatures, evoke a childhood sense of wonder and connect her work to the visual language of animation and Manga, Figure 16. These contrasts echo her riposte to adulthood social conformity while creating innocence and imagination of childhood.

Figure 15: (Ulster Museum 2024). Makiko Kudo

Figure 16: (Wilkinson, 2012) Makiko Kudo,

Painting, Floating Island, 2012.Anthony Wilkinson Gallery London.

Surreal Subconscious

In contrast to Kudo's playful exploration of childhood dreams, Salvador Dalí explores the darker realms of the subconscious, using paradoxes to examine the fluidity of time. Through his "paranoiac-critical method", an adaptive technique requiring self-inflicted psychosis, Dalí accessed delirious states of mind resulting in his most famous surrealist works (Artsper Magazine, 2022). This method, designed to encourage a hallucinatory state where fantasy could flow unimpeded, is depicted in pieces like Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Figure 17, where forms shift and dissolve in a fevered exploration of the unconscious. Similar to the shamans of ancient cultures, Dalí intentionally entered an altered state of consciousness, resulting in works like The Persistence of Memory, which exemplify his ability to manipulate the boundaries between reality and subconscious, Figure 18, (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p.273).

The Persistence of Memory,

Figure 17: (Tate, 2024) Salvador Dalí, Figure 18: (MoMa, 2024) Salvador Dalí, Painting, oil on Canvas, Painting, oil on Canvas, Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937. Tate Gallery.

1931. MoMa.

Sigmund Freud upon viewing Metamorphosis of Narcissus, famously remarked, “in classical paintings I look for the unconscious, but in your paintings, I look for the conscious” (Marianski, 2019). This statement highlights Dalí’s unique approach to surrealism, melding conscious thought and unconscious desire, inviting the viewer into a hallucinatory landscape where reality and imagination are indistinguishable.

The iconic melting clocks, distorted landscapes, and surreal atmosphere of The Persistence of Memory conjure a world where time becomes fluid, defying logical understanding. Through this method, Dalí dismantled the barriers between the rational and irrational, transforming his inner visions into a visual reality that challenges our worldview.

The melting clocks in Dalí’s paintings may symbolise the fragility of memory, reflecting increased unreliability over time (Schacter, 2012). Dalí alludes to the fading of memories, including those of his Catalonian homeland, which, are subject to time's erosion. This background anchors the piece in nostalgia, suggesting that, like a snail’s shell, we carry the memory of home as a form of protection (Cumming, 2024, p.6). The mirror represents "temporal planes of reality and imagination", serving as a portal to a dreamlike state where the boundaries between the conscious and unconscious blur (Artsper Magazine, 2022; Ornstein, 1991; Boym, 2001, p.17). The dark, barren foreground, reminiscent of an overwhelming world, reflects the emotional weight of turbulent times (Artsper Magazine, 2022). The sleeping figure, possibly represents his inner self, reinforces themes of death, subconscious, and the interplay between dreams, memory, and identity (Artsper Magazine, 2022).

The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, Figure 19, painted two decades later, portrays a world where, past, present, and future converge, embodying what Boym (2001, p.16) terms "retrospective and prospective nostalgia". In this fragmented reality, objects seem to "flicker in and out of evidence at the same time”, reflecting concepts in quantum physics (Totally History, 2013). The painting suggests that memory itself is in a constant state of flux, dissolving into atoms; a symbolicreflection ofthe overwhelming tideoftechnological progress andscientificadvancement (Bauman, 2017, p.1).

Figure 19: (Totally History, 2013) Salvador Dalí, Painting, oil on Canvas, The Disintegration of Memory, 1952-1954. Museum, St Petersburg Florida.

Dalí’s illustrations for the 150th anniversary of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Figure 20, inject nostalgic surrealism into the whimsical world of Wonderland (Popova, 2016). His art transforms the narrative into a visual journey, inviting readers into a dreamlike realm where imagination has no limits. Dalí’s recurring motif of melting clocks in Mad Tea Party, Figure 20, reinforces the idea of time distortion, signalling a world where time and reality are suspended. This surreal imagery creates a space defined by imaginative reconstruction, where memory is fluid, and escape from the mundane is possible.

Figure 20: (Popova, 2016) Salvador Dali, Print, The Mad Tea Party Illustration, 1969.

Book Alice in Wonderland, Rediscovered and Resurrected

Summary Three

Kudos art is profoundly autobiographical, reflecting both vulnerability and resilience (Kudo, 2016).AyaTakanodescribesKudo’sworkas“enteringanotheruniverse”,capturingtheimmersive, ethereal quality of her worlds where memory, imagination, and reality intertwine (Kudo, 2016). In this way, Kudo’s art becomes a vehicle for personal exploration and a riposte to social conformity.

In contrast to Kudo's playful exploration of childhood dreams, Salvador Dali explores the darker realms of the subconscious, using paradoxes to examine the fluidity of time. Through his "paranoiac-critical method", a technique developed to induce a self-inflicted psychosis, Dali accessed delirious states of mind that gave rise to some of his most famous surrealist works (Artsper Magazine, 2022). This method, designed to encourage a hallucinatory state where fantasy could flow unimpeded, is portrayed in pieces like Metamorphosis of Narcissus, (Figure 17), where forms shift and dissolve in a fevered exploration of the unconscious.

Through escapism and dreamscapes, Dalí and Kudo create powerful, ambiguous mechanisms for processing memory through adaptive traits. They examine our capacity to forget aspects of reality, retreating into self-absorption and narcissism, as seen in Dalí’s Metamorphosis of Narcissus (Ornstein, 1991). They also explore our conscious evolution, selectively remembering only what serves us while detaching from the past, providing a means for escape (Boym, 2001, p. 18; Kudo, 2016; Ornstein, 1991).

Dalí's illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland echo the dreamlike nature of Kudo’s imaginary landscapes, as both artists venture down the rabbit hole employing their unique visual languages. While Kudo employs vibrant colours and intricate, playful imagery to evoke a sense of wonder, Dalí uses darker tones and elongated figures to convey a surreal and unsettling interpretation. Kudo's work seeks to rewrite and reclaim lost childhood memories, transforming them into liberating fantasies, whereas Dalí focuses on the dissolution and distortion of those memoriesover time,highlighting theirfragilityand impermanence.Despitethesedifferences, both artists use nostalgic imagery as a powerful tool for introspection, offering contrasting yet complementary perspectives on memory, identity, and the fluidity of time.

Chapter Four

Art of Healing

Conflict Textiles provide a powerful outlet for personal catharsis and healing through art (Conflict Textiles, 2024). These textiles offer a means for individuals to express and process internalised emotions, particularly those linked to trauma and conflict of the past in an adaptive creative way. The genre itself reflects the struggles and challenges both retrospective and prospective periods in time, often giving voice to ordinary people. For instance, the Threads of Empowerment exhibition enables people worldwide to communicate their experiences through Arperillas, wall hangings or quilts, as poignant testimonies of personal and collective suffering, focusing on themes of conflict and human rights abuses or predicted future disasters such as climate change, Figure 22 (Conflict Textiles, 2024). Chilean Arperilliste, Mireya Rivera Veliz (Sepúlveda, 1996), is one such artist whose work has become a symbol of resistance and remembrance. The Arperillas serve as a powerful way to make visiblethesearchforthedisappeared,politicalactivistswhoopposedthePinochetregime(Conflict Textiles, 2024). As described by Rivera Veliz, these textile pieces "interpret my pain and at the same time communicate it to others" (Conflict Textiles, 2024). One particularly moving example, Figure 21: depicts a grieving mother, kneeling in sorrow over the disappearance of her children. This wall hanging that captures the anguish and resilience of families torn apart by political violence. Through such works, Conflict Textiles not only offer a space for personal expression and examining the past in the present but also a collective means of bearing witness to social issues.

Figure 21: (Conflict Textiles, 2024) Chilean Arperillas, 1979 anonymous. Installations

Ulster MuseumAugust 2024 Exhibitions

Figure 22: (Conflict Textiles, 2024),Ana Zlatkes, Embroidered Wall Hanging, Let us Play in the Woods While the Air is Still Here 2, 2015.

Art toAid Modern Survival

Yayoi Kusama does not see herself as an artist; rather, she views her art “as a tool” for coping with her mental health struggles, particularly schizophrenia (Mert, 2022). For Kusama, art serves as a means of navigating a complex reality and a way to confront and manage the daily battles with pain, anxiety, and mental turmoil (Lamberg, 2017, p.1). She has testified that art quite literally saved her life, providing an escape from the burdens of society and the confines it imposes on individuals (Lamberg, 2017, p.1).

Kusama has described her hallucinations as "patterns that move, multiply, devour everything around her, and eventually consume her" (Unit London, 2018). These vivid visions, which began as a reflection of her mental health struggles, evolved into the foundation of her artistic practice. Her art, characterised by repeating patterns, became a therapeutic tool to help her manage "severe psychological turmoil" (Unit London, 2018).

Kusama’s art also addresses the pressures of "standardisation and uniformity" within society, portraying the gap between individuals and the "strange jungle of civilised society," where psychosomatic problems arise (Morris et al., 2011). She refers to her art as "psychosomatic", born out of deep "spiritual wars", a creative escape when faced with overwhelming psychological challenges (Mert, 2022, p.3).

Repetition is a central theme in Kusama’s work, most prominently seen in her signature "infinity web",whichreflectsherpersonalstrugglesandattemptstoprocessherinternalworldin thepresent (Mert, 2022, p. 3). Influenced by childhood hallucinations and the visual impact of red polka dots, Kusama’s Accumulation Series (1964), along with works like Mirror Infinity – Phalli’s Field (1965), Figure 22, explores these themes through overwhelming repetition (Morris et al., 2011).

Phalli’s Field, for example, immerses viewers in a dizzying array of forms, evoking the disorienting sensation of her hallucinations. Despite this, the piece is described as a space of "support and safety" offering a complex interplay between the personal and universal (Morris et al., 2011; Van Beuningen, 2024). Kusama’s art not only serves as an outlet for her mental health struggles but also offers a powerful commentary on the human condition and the transformative potential of creativity.

Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, Figure 23, extend this exploration by inviting viewers into endless expanses of repetitive imagery, where they experience a loss of self, a sensation drawn directly from her own hallucinations (Mert, 2022, p. 3). In her later works, Kusama continues to build immersive worlds, often using pumpkins, spotlights, winding tendrils, and polka dots, all motifs that, while beautiful, are also the source of her anxiety (Morris et al., 2011). By embedding this unsettling experience within her art, Kusama creates a “therapeutic space” for both her and her audience, confronting the boundaries of identity and perception (Mert, 2022, p.8).

23: (Zwirner,

Installation: Infinity Mirrored Room – Phalli’s Field, 1965.

Figure

2024) Yayoi Kusama,

Figure 24: (Van Beuningen, 2024) Yayoi Kusama,

Installation: Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field (Floor Show), 1965.

These works allow for a transformative encounter with trauma and beauty, where psychological struggles are transmitted into a powerful form of artistic expression and personal resilience (Mert, 2022, p.8).

Kusama’s Happenings and Body Festivals from 1968 further shift this focus from private psychological expression to public, participatory engagement. In these works, the rules of participation are loosely defined, creating a scenario where both the artist and the audience navigate a shared, open-ended narrative (Morris et al., 2011).

Summary Four

Both the Arperilliste producing the Conflict Textiles, including Mireya Rivera Veliz, and Yayoi Kusamaexplorehowartserves asanadaptivetoolforpersonalexpressionandhealing,particularly in the face of trauma and mental health struggles. However, the works discussed differ in their focus, medium, and approach to healing.

Mireya Rivera Veliz uses textiles, such as Arperillas, Chilean quilts and wall hangings, to confront political trauma and human rights abuses. These works serve as both a personal outlet for pain and acollectiveplatform for bearingwitnessto historical injustices. Fortheartists,theact ofphysically creating these pieces provides catharsis, allowing them to transcend their individual experiences and process their past trauma in the present. The use of textiles is particularly significant, as the craft requires focused concentration and engages the brain in ways that offers the artist a sense of control and agency over their narrative, providing a powerful adaptive tool for emotional and psychological healing.

In contrast, Yayoi Kusama’s art focuses on her deeply personal inner world, using repetition as a rhythmic structure. By visualising her trauma, Kusama confronts dissociated memories in a meaningful way. The repetitive patterns and immersive environments serve as a tool for her mind to release and process emotions, transforming her psychological struggles into a tangible, cathartic experience.

Kusama’s Happenings and Body Festivals, introduce a participatory element, inviting audiences to engage with the artistic process. Kusama’s installations encourage viewers to step into a shared experience mirroring her own psychological struggles, blurring the line between artist and audience and fostering collective vulnerability and healing (Mert, 2022; Van Beuningen, 2024). Similarly, the Conflict Textiles exhibitions offer firsthand workshops that provide participants with

a tangible insight into the healing process, allowing them to engage in textile creation as a form of personal expression and collective remembrance. Involving viewers in the creation process, these workshops promote empowerment and connection, encouraging reflection while engaging with a shared history of trauma and resilience (Conflict Textiles, 2024). Both Kusama’s and the Conflict Textiles exhibitions emphasise the transformative power of art, moving beyond passive observation to active involvement in the healing journey.

Kusama and the Arperillistes involved with Conflict Textiles demonstrate how art can serve as a transformative and healing force and help mediate survival in a complex world. While their approachesdifferinmediumandfocus,bothusearttogivevoicetopersonalandcollectivetrauma, offering opportunities for catharsis, reflection, and connection. Through their immersive and participatory practices, they create spaces where healing is communal. Whether through textiles or immersive installations, their work exemplifies the profound capacity of creative expression to foster resilience, understanding, and collective healing to cope in the modern world.

Reflections and FurtherAnalysis

The concept of adaptive memory suggests that memory is not a static repository of past events, but a dynamic process shaped by both internal and external influences. Memory influenced by process of “recovering the visible” according to Magill, “lies more in its emotional and narrative potentialities rather than its scientific, masterly content of the image”, (Magill, 2004, p.50) so is unique to everyone.

Therefore, each recollection involves an imaginative component, as we constantly reconstruct our memories in the present, predict future events and speculate on what might have been (Magill, 2008).Art engages deeply with this fluidity of memory, allowing exploration of hypothetical realities and emotions.Artists like Salvador Dalí harness this cognitive flexibility, using surreal imagery such as his iconic melting clocks to emphasises the fragility of memory, dissolution, and distortion over time. Similarly, Makiko Kudo creates imaginary childhood memories, whileAi Wei Wei addresses that some ruptures can only be recreated in the imagination of the viewer, as true nostalgia and memory cannot be recreated.

These artistic processes are constructions of the mind that serve as mental simulations, “reconstructed in the present” helping us navigate the complexities of life and experience (Boym, 2001, p.10; Schacter, 2012). Furthermore, the differences in both subject and style highlight the subjective nature of memories, which are shaped by individual cognition (Magill, 2004, p.50).

In contemporary art, memory often intertwines with ritual repletion of important themes as seen in the works of Yayoi Kusama and Andrew Millner. Kusama’s obsessive use of repetition and her disorienting patterns, representing hallucinations, mirror the overwhelming feeling of being lost and helplessness, yet it is also her well known sanctuary.

Similarly, Millner’s exploration of memory and repetition in nature underscores the essential role of rhythmic patterns in both the environment and human mind just like our ancestors’ repetitive ritualistic drawings. Our ability to recognise and respond to such patterns is an adaptive memory mechanism, rooted in the need to retain survival-related information. This connection between memory, repetition, and nature reflects how cognitive processes that once helped our ancestors survive, continue to shape how we perceive and interact with the world.

Early cave art provides a clear example of how art functions as a tool for survival by encoding information. Representations of animals, especially predators, were more than decoration; they were a means of conveying survival knowledge, essential for safety and continuity.As art evolved, early humans began transitioning from shamanistic symbols to more detailed depictions of their environment, illustrating a shift in cognitive complexity. This transition is often viewed as a sign of the "awakening" of human thought, where art was no longer only symbolic or ritualistic, but a means of storytelling and preserving critical knowledge through representational art and narrative (Ghosh, 2024).

According to Schwartz et al. (2014), the ability to create and interpret complex visual narratives was closely tied to adaptive memory, a cognitive trait that allowed humans adapt to organise and retain survival-related information.

As art evolved, so did the ways we engage with it. Representational art taps into our capacity to recall specific images and events, while more conceptual art challenges us to move beyond traditional cognitive patterns of object recognition (Durkin et al., 2020). Imaginative or surreal works, such as those by Kusama, Millner, and Dalí, force the viewer to engage with the artwork in unconventionalways.Thesepiecesoftendistilemotionsandformsymbolicorambiguouspatterns, creating psychological distance that encourages critical thought and emotional exploration.

The creation of distance can be therapeutic, helping viewers process memory by providing a safe space for indirect engagement with difficult emotions. For example, Kusama’s Infinity Rooms,

such as Figure. 23 Phalli’s Field, where the viewer becomes enveloped in a disorienting sea of mirrors and dots, reduces psychological distance by immersing the viewer in the artist's own experience of disorientation, thus bridging the gap between the viewer's and the artist’s emotional states.

Artists like Ai Wei Wei and Do Ho Suh also engage with memory and displacement, using their work to explore the emotional complexities of home, safety, and nostalgia. Suh’s representations of homes, carried like a snail’s shell, evoke a deep longing for stability, mirroring Dalí’s incorporationofhishomelandinhiswork.BothAiWeiWei andSuhreflectonthelossofafamiliar environment and the challenges of displacement.

Similar themes emerge in the Conflict Textiles exhibits, where the tactile nature of textiles creates a direct connection to memory, while also serving as a form of therapy and a way of processing our past; not an objective complete image of the past, but reprocessed by, “our values and aims in the present” (Boym, 2007, p.8; Boym, 2001, p. xviii).

Nostalgic elements in art provide valuable insight into the adaptive function of memory, as these works help us navigate the changes and uncertainties of modern life by tapping into the emotional resonance of the past. This shift toward nostalgia in art mirrors the phenomenon of retromania where belongings replace belonging and sensory retrieval cues provide a gateway to catharsis (Krotoski, 2015). In contrast, the evolution from representational cave art, which encoded survival knowledge, to art forms that reflect a growing human need for emotional and psychological support, prioritises introspection and emotional expression over concrete, survival-focused information. While memory once evolved to store information crucial for immediate survival, in the modern world it has adapted to support psychological processing in an increasingly unnatural and human fabricated world.

Conclusion

Inconclusion,artserves asapowerfultoolforengagingwiththecomplexitiesofmemory,emotion, and survival. Through adaptive memory, we observe that art is not simply a reflection of reality, but a dynamic means of processing and reconstructing our experiences. From the surreal distortions of Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks to the hypothetical explorations of Makiko Kudo, artists harness the malleability of memory to create works that invite viewers into new realms of thought and emotion. Contemporary artists like Yayoi Kusama and Andrew Millner continue this exploration, using ritualistic repetition to reflect the psychological and emotional processes that shape our understanding of the world. In this way, both art and memory evolve from a repository of survival knowledge, such as with early cave art, to a means of emotional and psychological processing, helping individuals navigate the shifting uncertainties of modern life. The incorporation of nostalgic elements, such as those seen in the works ofAiWeiWei and Do Ho Suh, portray an adaptive need to reconnect with the past to find stability and meaning in an increasingly complex world. Art, as a tool for survival, and the adaptive nature of memory extend beyond physical safety, offering a space for self-analysis, reflection, emotional healing by the exploration ofbothpersonaland collectivememories.Artcontinuestobridgethegapbetweenpastandpresent, Self and other, reality and imagination. Through the adaptive power of memory, art offers a means of escape, allowing us to transcend the chaos of the modern world and retreat into a realm of our own illusion of reality where we can reimagine, process, and survive the complexities of our existence.

Word count: 7303

Bibliography

Artsper Magazine (2022). The Persistence of Memory: Understanding Dalí’s Masterpiece. [online] artsper.com.Available at: https://blog.artsper.com/en/a-closer-look/the-persistenceofmemory-understanding-dalis-masterpiece/ [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Aubert, M., Lebe, R., Oktaviana,A.A., Tang, M., Burhan, B., Hamrullah, Jusdi,A.,Abdullah, Hakim, B., Zhao, J., Geria, I.M., Sulistyarto, P.H., Sardi, R. and Brumm,A. (2019). Earliest Hunting Scene in PrehistoricArt. Nature, 576(7787), pp. 442–445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y.

Bailey, B. (2020a). Bill Bailey on the Joys of Being in Nature. [online] CPRE. Available at: https://www.cpre.org.uk/opinions/bill-bailey-on-the-joys-of-being-in-nature/ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024].

Bailey, B. (2020b). Bill Bailey’s Remarkable Guide to Happiness. Quercus.

Bauman, Z. (2017). Retrotopia. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 1.

Boym, S. (2001). The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books. pp. xvii, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 18.

Boym, S. (2007). Nostalgia and Its Discontents. [online] hedgehogreview.com.Available at: https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/the-uses-of-the-past/articles/nostalgia-and-its-discontents [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Brumm,A., Oktaviana, A.A., Burhan, B., Hakim, B., Lebe, R., Zhao, J., Sulistyarto, P.H., Ririmasse, M.,Adhityatama, S., Sumantri, I. and Aubert, M. (2021). Oldest cave art found in Sulawesi. ScienceAdvances, [online] 7(3), p.eabd4648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4648.

Clottes, J. (2024). Cave Art. [online] www.britannica.com. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/cave-art [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Conflict Textiles (2024). Threads of Empowerment Conflict Textiles’International Journey. Ulster Museum, [online] pp. 1, 2.Available at: https://www.ulstermuseum.org/temporaryexhibition/threads-empowerment-conflict-textilesinternational-journey [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Cumming, L. (2024). Do Ho Suh: Tracing Time Review – an Extraordinarily Beautiful Search for Home. The Observer, [online] 10 Mar., pp. 1–9.Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/mar/10/do-ho-suh-tracing-time-reviewscottishnational-gallery-of-modern-art-modern-one-edinburgh [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024].

Durkin, C., Hartnett, E., Shohamy, D. and Kandel, E.R. (2020).An Objective Evaluation of the beholder’s Response toAbstract and FigurativeArt Based on Construal Level Theory. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 117(33). doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001772.

Elan, P. (2022). The latest social media trend? Being Imperfect and Other Trends to Know. [online] thetimes.com.Available at: https://www.thetimes.com/life-style/article/the-latestsocialmedia-trend-being-imperfect-and-other-trends-to-know-8kjxj8rx9 [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024]. Everett, 2017

Everett, D.L. (2017). How Language Began: The Story of humanity’s Greatest Invention. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a Division of W.W. Norton & Company, p. 33.

Ghosh, P. (2024). World’s oldest cave art found in Indonesia showing humans and pig. [online] BBC News.Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c0vewjq4dxwo [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024].

Guettler, T. (2017). Cave Paintings of Lascaux. [online] Deep Thinking. Available at: https://thomasguettler.com/2017/01/04/cave-paintings-of-lascaux/ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024].

Horvath, G. (2018). Faces of nostalgia. Restorative and Reflective Nostalgia in the FineArts.

Jednak Książki. Gdańskie Czasopismo Humanistyczne, [online] (9), pp. 145–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.26881/jk.2018.9.13.

Krotoski, A. (2015). BBC Radio 4 - the Digital Human, Series 6, Episode 2, Nostalgia. [online] BBC.Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04n31cr [Accessed 21 Feb. 2023].

Kudo, M. (2016). Makiko Kudo at the Tomio Koyama Gallery. [online] http://tomiokoyamagallery.com/.Available at: http://tomiokoyamagallery.com/en/exhibitions/makiko-kudo-3/ [Accessed 12 Mar. 2024].

Kudo, M. (2018). Blending Memory and Imagination to Create Serene, Contemplative Dreamscapes. [online] avantarte.com. Available at: https://avantarte.com/artists/makiko-kudo [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Lamberg, L. (2017).Artist Describes HowArt Saved Her Life. Psychiatrics News, 52(18), pp. 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.pn.2017.9a21.

Lewis-Williams, D. (2002). The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins ofArt. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 189–227, 241, 248, 273

Macpherson, F. and Dorsch, F. (2018). Perceptual Imagination and Perceptual Memory. NewYork: Oxford University Press, pp. 18-23.

Magill, E. (2004). Fish and Fleur de Lys (1989). Ikon Gallery, p.50.

Magill, E. (2008). Northern Carmine (2007) from Chronicle of Orange Exhibition. Wilkinson Gallery, p. 39.

Marianski, S. (2019). When Dalí Met Freud, Freud Museum London. [online] Freud Museum London.Available at: https://www.freud.org.uk/2019/02/04/when-dali-met-freud/ [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Marks, A. (2021). Japanese Woodblock Prints. 40th ed. Hohenzollernring, Cologne: Taschen GmbH, pp. 9–11, 16, 19, 40, 41, 72, 85, 91, 92, 101, 208–210.

Melandri, L. (2021). Fantastic Garden: Andrew Millner’s Floating World. [online] www.andymillner.com.Available at: https://www.andymillner.com/floating-world-viewingroom [Accessed 12 Mar. 2024].

Mert, T. (2022).ALife Between Going Crazy and Healing: Yayoi Kusama. [online] Mercado. Available at: https://en.studiomercado.com/post/a-life-between-going-crazy-and-healingyayoikusama [Accessed 23 Mar. 2024]. pp. 1-9.

Millner, A. (2019). Floating World - Viewing Room. [online] Andy Millner. Available at: https://www.andymillner.com/floating-world-viewing-room [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Mithen, S. (2005). The Prehistory of the Mind: the Cognitive Origins ofArt, Religion and Science. 3rd ed. London: Thames and Hudson, pp.175–190, 195, 198

MoMa (2024). The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali, 1931. [online] The Museum of Modern Art.Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79018 [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Morris, F.,Applin, J., Mitchell, J. and Tate Modern (Gallery (2011). Yayoi Kusama. London: Tate Publishing.

Nairne, J.S., Pandeirada, J.N.S. and Thompson, S.R. (2008).Adaptive Memory: the Comparative Value of Survival Processing. Psychological Science, [online] 19(2), pp.176–180.Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40064689 [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Oktaviana, A.A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakin, B., Burhan, B., Sardi, R.,Adhityatama, S., Hamrullah, Sumantri, I., Tang, M., Lebe, R., Ilyas, I., Abbas, A., Jusdi, A., Mahardian, D.E., Noerwidi, S., Ririmasse, M.N.R., Mahmud, I., Duli,A.,Aksa, L.M. and McGahan, D. (2024).

Narrative Cave in Indonesia by 51,200 YearsAgo Art. Nature, [online] 631, pp.814–818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07541-7.

Ornstein, R. (1991). The Evolution of Consciousness. New York: Prentice Hall Press. p. xiv.

Pagel, D. (2011). Makiko Kudo at Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo. [online] tomiokoyamagallery.com.Available at: https://artmap.com/tomiokoyama/exhibition/makikokudo-2011 [Accessed 28 Jan. 2024].

Popova, M. (2016). Salvador Dalí’s Rare 1969 Illustrations for ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,’Rediscovered and Resurrected. [online] The Marginalian.Available at: https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/09/02/salvador-dali-alices-adventures-in-wonderland/ [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Reynolds, S. (2011). Retromania: Pop culture’sAddiction to Its Own past. London: Faber. Roszak, T. (2001). The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology; with a New Afterword. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Mi: Phanes Press, Cop. p. 331.

Royal Society of Chemistry (2024). CaveArt History. [online] RSC Education.Available at: https://edu.rsc.org/resources/cave-art-history/1528.article [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024]. Schacter, 2012, p. 1.

Schacter, D.L. (2012). Adaptive Constructive Processes and the Future of memory. American Psychologist, [online] 67(8), pp. 603–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029869.

Schwartz, B.L., Howe, M.L.,Toglia, M.P. and Otgaar, H. (2014).What IsAdaptive aboutAdaptive Memory? New York: Oxford University Press. p. 5.

Stone, S. (2024). Do Ho Suh: Tracing Time - EdinburghArt Festival. [online] EdinburghArt Festival.Available at: https://www.hippystitch.co.uk/2024/09/do-ho-suh-tracing-time-atmodern1.html [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024].

Suh, D.H. (2016). ‘Rubbing / Loving’|Art21 ‘Extended Play’.Art21.Available at: https://art21.org/artist/do-ho-suh/ [Accessed 24 Jan. 2024].

Tate (2024a). Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Salvador Dalí, 1937, Tate. [online] Tate.Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dali-metamorphosis-of-narcissus-t02343 [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Tate (2024b). The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House – Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home, 2013-2022. [online] Tate.Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/press/pressreleases/do-ho-suh-tate-modern [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Totally History (2013). The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí. [online] Totally History.Available at: https://totallyhistory.com/the-disintegration-ofthepersistence-of-memory/ [Accessed 7 Dec. 2024].

Tulving, E. (1983). Oxford Psychology Series: Elements of Episodic Memory. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, USA, pp.171, 172. 174.

Unit London (2018). Yayoi Kusama and Psychedelic Schizophrenia. [online] Unit London. Available at: https://unitlondon.com/2018-05-14/yayoi-kusama-and-psychedelic-schizophrenia/.

Van Beuningen, B. (2024). Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field (Floor Show) (1965) - Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. [online] Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.Available at: https://www.boijmans.nl/en/collection/artworks/141180/infinity-mirror-room-phalli-s-fieldfloorshow# [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

Victoria (2018). Ai Wei Wei Song Dynasty Teapot Spout Shards at Marciano in LA. [online] TeaForum.org.Available at: https://www.teaforum.org/viewtopic.php?t=708 [Accessed 14 Dec. 2024].

Weichbrodt, E.Y. (2024). The Perfect Home: Do Ho Suh on Longing and Displacement. [online] AsianAmerican Christian Collaborative (AACC).Available at: https://www.asianamericanchristiancollaborative.com/article/the-perfect-home [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

Wilkinson,A. (2012). MAKIKO KUDO | 1 March - 15April 2012 - Overview. [online]Anthony Wilkinson Gallery. Available at: https://anthonywilkinsongallery.org/exhibitions/26/overview/ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2024]. p. 1.

Zwirner, D. (2024). Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrored Room – Phalli’s Field, 1965. [online] David Zwirner.Available at: https://www.davidzwirner.com/artworks/yayoi-kusamayayoikusama-with-infinity-mirrored-room-phalli-s-field-install-169d4 [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].